автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу In Darkest Africa, Vol. 1; or, The Quest, Rescue, and Retreat of Emin, Governor of Equatoria

Every attempt has been made to replicate the original as printed.

The

footnotesfollow the text.

Some illustrations have been moved from mid-paragraph for ease of reading.

(etext transcriber's note)

COPYRIGHT 1890 BY CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

IN DARKEST AFRICA

OR THE

QUEST, RESCUE, AND RETREAT OF EMIN

GOVERNOR OF EQUATORIA

BY

HENRY M. STANLEY

WITH TWO STEEL ENGRAVINGS, AND ONE HUNDRED AND

FIFTY ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS

IN TWO VOLUMES

Vol. I

"I will not cease to go forward until I come to the place where the two seas meet,

though I travel ninety years."—Koran, chap. xviii., v. 62.

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

1890

[All rights reserved]

Copyright, 1890, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

Press of J. J. Little & Co.,

Astor Place, New York.

CONTENTS OF VOLUME I.

PAGEPrefatory Letter to Sir William Mackinnon, Chairman of the Emin Pasha relief expedition

1 CHAPTER I.INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER.

The Khedive and the Soudan—Arabi Pasha—Hicks Pasha's defeat—The Mahdi—Sir Evelyn Baring and Lord Granville on the Soudan—Valentine Baker Pasha—General Gordon: his work in the Upper Soudan—Edward Schnitzler (or Emin Effendi Hakim) and his Province—General Gordon at Khartoum: and account of the Relief Expedition in 1884 under Lord Wolseley—Mr. A. M. Mackay, the missionary in Uganda—Letters from Emin Bey to Mr. Mackay, Mr. C. H. Allen, and Dr. R. W. Felkin, relating to his Province—Mr. F. Holmwood's and Mr. A. M. Mackay's views on the proposed relief of Emin—Suggested routes for the Emin Relief Expedition—Sir Wm. Mackinnon and Mr. J. F. Hutton—The Relief Fund and preparatory details of the Expedition—Colonel Sir Francis De Winton—Selection of officers for the Expedition—King Leopold and the Congo Route—Departure for Egypt

11 CHAPTER II.EGYPT AND ZANZIBAR.

Surgeon T. H. Parke—Views of Sir Evelyn Baring, Nubar Pasha, Professor Schweinfurth and Dr. Junker on the Emin Relief Expedition—Details relating to Emin Pasha and his Province—General Grenfell and the ammunition—Breakfast with Khedive Tewfik: message to Emin Pasha—Departure for Zanzibar—Description of Mombasa town—Visit to the Sultan of Zanzibar—Letter to Emin Pasha sent by messenger through Uganda—Arrangements with Tippu-Tib—Emin Pasha's Ivory—Mr. MacKenzie, Sir John Pender, and Sir James Anderson's assistance to the Relief Expedition

49 CHAPTER III.BY SEA TO THE CONGO RIVER.

The Sultan of Zanzibar—Tippu-Tib and Stanley Falls—On board s.s. Madura—"Shindy" between the Zanzibaris and Soudanese—Sketches of my various Officers—Tippu-Tib and Cape Town—Arrival at the mouth of the Congo River—Start up the Congo—Visit from two of the Executive Committee of the Congo State—Unpleasant thoughts

67 CHAPTER IV.TO STANLEY POOL.

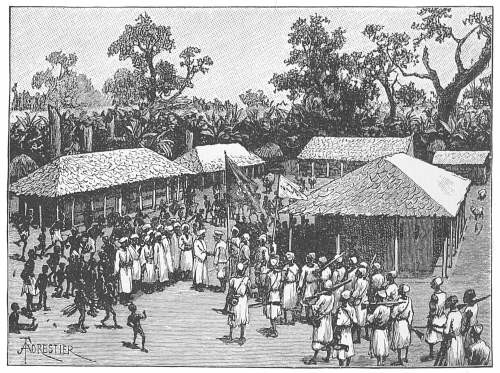

Details of the journey to Stanley Pool—The Soudanese and the Somalis—Meeting with Mr. Herbert Ward—Camp at Congo la Lemba—Kindly entertained by Mr. and Mrs. Richards—Letters from up river—Letters to the Rev. Mr. Bentley and others for assistance—Arrival at Mwembi—Necessity of enforcing discipline—March to Vombo—Incident at Lukungu Station—The Zanzibaris—Incident between Jephson and Salim at the Inkissi River—A series of complaints—The Rev. Mr. Bentley and the steamer Peace—We reach Makoko's village—Leopoldville—Difficulties regarding the use of the Mission steamers—Monsieur Liebrichts sees Mr. Billington—Visit to Mr. Swinburne at Kinshassa—Orders to, and duties of, the officers

79 CHAPTER V.FROM STANLEY POOL TO YAMBUYA.

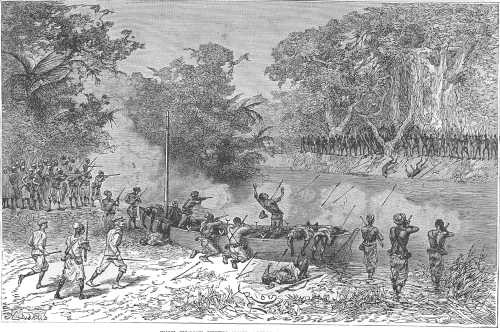

Upper Congo scenery—Accident to the Peace—Steamers reach Kimpoko—Collecting fuel—The good-for-nothing Peace—The Stanley in trouble—Arrival at Bolobo—The Relief Expedition arranged in two columns—Major Barttelot and Mr. Jameson chosen for command of Rear Column—Arrival at Equator and Bangala Stations—The Basoko villages: Baruti deserts us—Arrival at Yambuya

99 CHAPTER VI.AT YAMBUYA.

We land at Yambuya villages—The Stanley leaves for Equator Station—Fears regarding Major Barttelot and the Henry Reed—Safe arrival—Instructions to Major Barttelot and Mr. Jameson respecting the Rear Column—Major Barttelot's doubts as to Tippu-Tib's good faith—A long conversation with Major Barttelot—Memorandum for the officers of the Advance Column—Illness of Lieutenant Stairs—Last night at Yambuya: statements as to our forces and accoutrements

111 CHAPTER VII.TO PANGA FALLS.

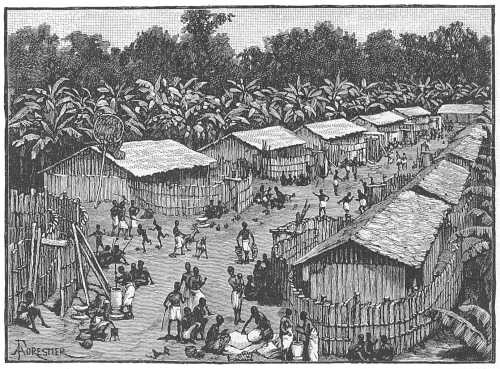

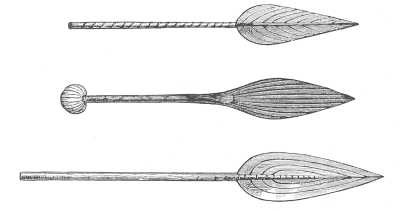

An African road—Our mode of travelling through the forests—Farewell to Jameson and the Major—160 days in the forest—The Rapids of Yambuya—Attacked by natives of Yankonde—Rest at the village of Bahunga—Description of our march—The poisoned skewers—Capture of six Babali—Dr. Parke and the bees—A tempest in the forest—Mr. Jephson puts the steel boat together—The village of Bukanda—Refuse heaps of the villages—The Aruwimi river scenery—Villages of the Bakuti and the Bakoka—The Rapids of Gwengweré—The boy Bakula-Our "chop and coffee"—The islands near Bandangi—The Baburu dwarfs—The unknown course of the river—The Somalis—Bartering at Mariri and Mupé—The Aruwimi at Mupé—The Babé manners, customs, and dress—Jephson's two adventures—Wasp Rapids—The chief of the Bwamburi—Our camp at My-yui—Canoe accident—An abandoned village—Arrival at Panga Falls—Description of the Falls

134 CHAPTER VIII.FROM TANGA FALLS TO UGARROWWA'S.

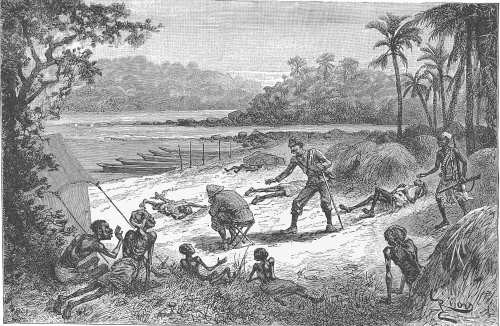

Another accident at the Rapids—The village of Utiri—Avisibba settlement—Enquiry into a murder case at Avisibba—Surprised by the natives—Lieutenant Stairs wounded—We hunt up the enemy—The poisoned arrows—Indifference of the Zanzibaris—Jephson's caravan missing—Our wounded—Perpetual rain—Deaths of Khalfan, Saadi, and others—Arrival of caravan—The Mabengu Rapids—Mustering the people—The Nepoko river—Remarks by Binza—Our food supply—Reckless use of ammunition—Half-way to the Albert Lake—We fall in with some of Ugarrowwa's men—Absconders—We camp at Hippo Broads and Avakubi Rapids—The destroyed settlement of Navabi—Elephants at Memberri—More desertions—The Arab leader, Ugarrowwa—He gives us information—Visit to the Arab settlement—First specimen of the tribe of dwarfs—Arrangements with Ugarrowwa

171 CHAPTER IX.UGARROWWA'S TO KILONGA-LONGA'S.

Ugarrowwa sends us three Zanzibari deserters—We make an example—The 'Express' rifles—Conversation with Rashid—The Lenda river—Troublesome rapids—Scarcity of food—Some of Kilonga-Longa's followers—Meeting of the rivers Ihuru and Ituri—State and numbers of the Expedition—Illness of Captain Nelson—We send couriers ahead to Kilonga-Longa's—The sick encampment—Randy and the guinea fowl—Scarcity of food—Illness caused by the forest pears—Fanciful menus—More desertions—Asmani drowned—Our condition in brief—Uledi's suggestion—Umari's climb—My donkey is shot for food—We strike the track of the Manyuema and arrive at their village

211 CHAPTER X.WITH THE MANYUEMA AT IPOTO.

The ivory hunters at Ipoto—Their mode of proceeding—The Manyuema headmen and their raids—Remedy for preventing wholesale devastations—Crusade preached by Cardinal Lavigerie—Our Zanzibar chiefs—Anxiety respecting Captain Nelson and his followers—Our men sell their weapons for food—Theft of rifles—Their return demanded—Uledi turns up with news of the missing chiefs—Contract drawn up with the Manyuema headmen for the relief of Captain Nelson—Jephson's report on his journey—Reports of Captain Nelson and Surgeon Parke—The process of blood brotherhood between myself and Ismaili—We leave Ipoto

236 CHAPTER XI.THROUGH THE FOREST TO MAZAMBONI'S PEAK.

In the country of the Balessé—Their houses and clearings—Natives of Bukiri—The first village of dwarfs—Our rate of progress increased—The road from Mambungu's—Halts at East and West Indékaru—A little storm between "Three o'clock" and Khamis—We reach Ibwiri—Khamis and the "vile Zanzibaris"—The Ibwiri clearing—Plentiful provisions—The state of my men; and what they had recently gone through—Khamis and party explore the neighbourhood—And return with a flock of goats—Khamis captures Boryo, but is released—Jephson returns from the relief of Captain Nelson—Departure of Khamis and the Manyuema—Memorandum of charges against Messrs. Kilonga-Longa & Co. of Ipoto—Suicide of Simba—Sali's reflections on the same—Lieutenant Stairs reconnoitres—Muster and reorganisation at Ibwiri—Improved condition of the men—Boryo's village—Balessé customs—East Indenduru—We reach the outskirts of the forest—Mount Pisgah—The village of Iyugu—Heaven's light at last; the beautiful grass-land—We drop across an ancient crone—Indésura and its products—Juma's capture—The Ituri river again—We emerge upon a rolling plain—And forage in some villages—The mode of hut construction—The district of the Babusessé—Our Mbiri captives—Natives attack the camp—The course of the Ituri—The natives of Abunguma—Our fare since leaving Ibwiri—Mazamboni's Peak—The east Ituri—A mass of plantations—Demonstration by the natives—Our camp on the crest of Nzera-Kum—"Be strong and of a good courage"—Friendly intercourse with the natives—We are compelled to disperse them—Peace arranged—Arms of the Bandussuma

255 CHAPTER XII.ARRIVAL AT LAKE ALBERT AND OUR RETURN TO IBWIRI.

We are further annoyed by the natives—Their villages fired—Gavira's village—We keep the natives at bay—Plateau of Unyoro in view—Night attack by the natives—The village of Katonza's—Parley with the natives—No news of the Pasha—Our supply of cartridges—We consider our position—Lieutenant Stairs converses with the people of Kasenya Island—The only sensible course left us—Again attacked by natives—Scenery on the lake's shore—We climb a mountain—A rich discovery of grain—The rich valley of Undussuma—Our return journey to Ibwiri—The construction of Fort Bodo

319 CHAPTER XIII.LIFE AT FORT BODO.

Our impending duties—The stockade of Fort Bodo—Instructions to Lieutenant Stairs—His departure for Kilonga-Longa's—Pested by rats, mosquitoes, &c.—Nights disturbed by the lemur—Armies of red ants—Snakes in tropical Africa—Hoisting the Egyptian flag—Arrival of Surgeon Parke and Captain Nelson from Ipoto—Report of their stay with the Manyuema—Lieutenant Stairs arrives with the steel boat—We determine to push on to the Lake at once—Volunteers to convey letters to Major Barttelot—Illness of myself and Captain Nelson—Uledi captures a Queen of the Pigmies—Our fields of corn—Life at Fort Bodo—We again set out for the Nyanza

350 CHAPTER XIV.TO THE ALBERT NYANZA A SECOND TIME.

Difficulties with the steel boat—African forest craft—Splendid capture of pigmies, and description of the same—We cross the Ituri River—Dr. Parke's delight on leaving the forest—Camp at Bessé—Zanzibari wit—At Nzera-Kum Hill once more—Intercourse with the natives—"Malleju," or the "Bearded One," being first news of Emin—Visit from chief Mazamboni and his followers—Jephson goes through the form of friendship with Mazamboni—The medicine men, Nestor and Murabo—The tribes of the Congo—Visit from chief Gavira—A Mhuma chief—The Bavira and Wahuma races—The varying African features—Friendship with Mpinga—Gavira and the looking-glass—Exposed Uzanza—We reach Kavalli—The chief produces "Malleju's" letter—Emin's letter—Jephson and Parke convey the steel boat to the lake—Copy of letter sent by me to Emin through Jephson—Friendly visits from natives

373 CHAPTER XV.THE MEETING WITH EMIN PASHA.

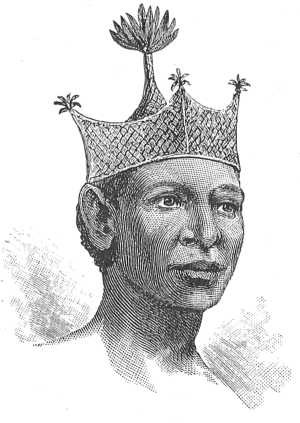

Our camp at Bundi—Mbiassi, the chief of Kavalli—The Balegga granaries—Chiefs Katonza and Komubi express contrition—The kites at Badzwa—A note from Jephson—Emin, Casati and Jephson walk into our camp at old Kavalli—Descriptions of Emin Pasha and Captain Casati—The Pasha's Soudanese—Our Zanzibaris—The steamer Khedive—Baker and the Blue Mountains—Drs. Junker and Felkin's descriptions of Emin—Proximity of Kabba Rega—Emin and the Equatorial Provinces—Dr. Junker's report of Emin—I discuss with Emin our future proceedings—Captain Casati's plans—Our camp and provisions at Nsabé—Kabba Rega's treatment of Captain Casati and Mohammed Biri—Mabruki gored by a buffalo—Emin Pasha and his soldiers—My propositions to Emin and his answer—Emin's position—Mahomet Achmet—The Congo State—The Foreign Office despatches

393 CHAPTER XVI.WITH THE PASHA—

continued.

Fortified stations in the Province—Storms at Nsabé—A nest of young crocodiles—Lake Ibrahim—Zanzibari raid on Balegga villages—Dr. Parke goes in search of the two missing men—The Zanzibaris again—A real tornado—The Pasha's gifts to us—Introduced to Emin's officers—Emin's cattle forays—The Khedive departs for Mswa station—Mabruki and his wages—The Pasha and the use of the sextant—Departure of local chiefs—Arrival of the Khedive and Nyanza steamers with soldiers—Made arrangements to return in search of the rear-column—My message to the troops—Our Badzwa road—A farewell dance by the Zanzibaris—The Madi carriers' disappearance—First sight of Ruwenzori—Former circumnavigators of the Albert Lake—Lofty twin-peak mountain near the East Ituri River—Aid for Emin against Kabba Rega—Two letters from Emin Pasha—We are informed of an intended attack on us by chiefs Kadongo and Musiri—Fresh Madi carriers—We attack Kadongo's camp—With assistance from Mazamboni and Gavira we march on Musiri's camp which turns out to be deserted—A phalanx dance by Mazamboni's warriors—Music on the African Continent—Camp at Nzera-kum Hill—Presents from various chiefs—Chief Musiri wishes for peace

418 CHAPTER XVII.PERSONAL TO THE PASHA.

Age and early days of Emin Pasha—Gordon and the pay of Emin Pasha—Last interview with Gordon Pasha in 1877—Emin's last supply of ammunition and provisions—Five years' isolation—Mackay's library in Uganda—Emin's abilities and fitness for his position—His linguistic and other attainments—Emin's industry—His neat journals—Story related to me by Shukri Agha referring to Emin's escape from Kirri to Mswa—Emin confirms the story—Some natural history facts related to me by Emin—The Pasha and the Dinka tribe—A lion story—Emin and "bird studies"

422 CHAPTER XVIII.START FOR THE RELIEF OF THE REAR COLUMN.

Escorted by various tribes to Mukangi—Camp at Ukuba village—Arrival at Fort Bodo—Our invalids in Ugarrowwa's care—Lieut. Stairs' report on his visit to bring up the invalids to Fort Bodo—Night visits by the malicious dwarfs—A general muster of the garrison—I decide to conduct the Relief force in person—Captain Nelson's ill-health—My little fox-terrier "Randy"—Description of the fort—The Zanzibaris—Estimated time to perform the journey to Yambuya and back—Lieut. Stairs' suggestion about the steamer Stanley—Conversation with Lieut. Stairs in reference to Major Barttelot and the Rear Column—Letter of instructions to Lieut. Stairs

452 CHAPTER XIX.ARRIVAL AT BANALYA: BARTTELOT DEAD!

The Relief Force—The difficulties of marching—We reach Ipoto—Kilonga Longa apologises for the behaviour of his Manyuema—The chief returns us some of our rifles—Dr. Parke and fourteen men return to Fort Bodo—Ferrying across the Ituri River—Indications of some of our old camps—We unearth our buried stores—The Manyuema escort—Bridging the Lenda River—The famished Madi—Accidents and deaths among the Zanzibaris and Madi—My little fox-terrier "Randy"—The vast clearing of Ujangwa—Native women guides—We reach Ugarrowwa's abandoned station—Welcome food at Amiri Falls—Navabi Falls—Halt at Avamburi landing-place—Death of a Madi chief—Our buried stores near Basopo unearthed and stolen—Juma and Nassib wander away from the Column—The evils of forest marching—Conversation between my tent-boy, Sali, and a Zanzibari—Numerous bats at Mabengu village—We reach Avisibba, and find a young Zanzibari girl—Nejambi Rapids and Panga Falls—The natives of Panga—At Mugwye's we disturb an intended feast—We overtake Ugarrowwa at Wasp Rapids and find our couriers and some deserters in his camp—The head courier relates his tragic story—Amusing letter from Dr. Parke to Major Barttelot—Progress of our canoe flotilla down the river—The Batundu natives—Our progress since leaving the Nyanza—Thoughts about the Rear Column—Desolation along the banks of the river—We reach Banalya—Meeting with Bonny—The Major is dead—Banalya Camp

468 CHAPTER XX.THE SAD STORY OF THE REAR COLUMN.

Tippu-Tib—Major E. M. Barttelot—Mr. J. S. Jameson—Mr. Herbert Ward—Messrs. Troup and Bonny—Major Barttelot's Report on the doings of the Rear Column—Conversation with Mr. Bonny—Major Barttelot's letter to Mr. Bonny—Facts gleaned from the written narrative of Mr. Wm. Bonny—Mr. Ward detained at Bangala—Repeated visits of the Major to Stanley Falls—Murder of Major Barttelot—Bonny's account of the murder—The assassin Sanga is punished—Jameson dies of fever at Bangala Station—Meeting of the advance and rear columns—Dreadful state of the camp—Tippu-Tib and Major Barttelot—Mr. Jameson—Mr. Herbert Ward's report

498 APPENDIX.Copy of Log of Rear Column

527LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

VOLUME I.

STEEL ENGRAVING.

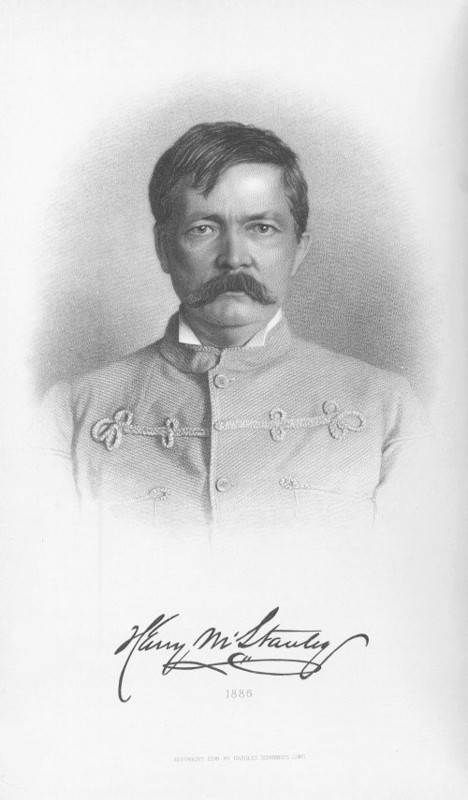

Portrait of Henry M. Stanley Frontispiece(From a Photograph by Elliott & Fry, 1886)

FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS.

Facing

page

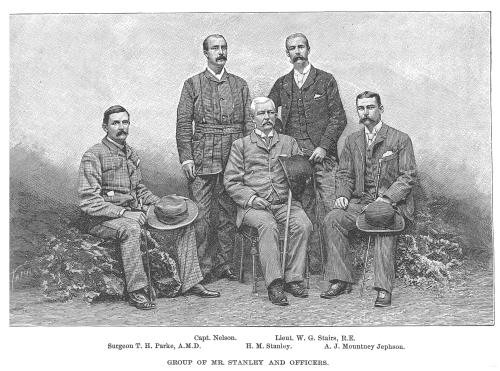

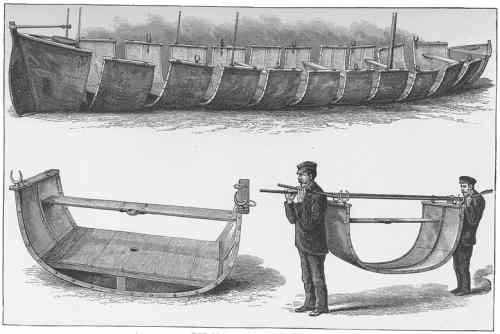

Group—Mr. Stanley and his Officers. 1 The Steel Boat "Advance" 80 In the Night and Rain in the Forest 146 The Fight with the Avisibba Cannibals 174 The River Column Ascending the Aruwimi River with the "Advance" and Sixteen Canoes. 184 Wooden Arrows of the Avisibba 180 "The Pasha is Coming" 196 The Relief of Nelson and Survivors at Starvation Camp 250 Gymnastics in a Forest Clearing 258 Iyugu; a Call to Arms 286 Emerging from the Forest 292 First Experiences with Mazamboni's People. View from Nzera Kum Hill 306 View of the South End of Albert Nyanza 324 Sketch-Map: "Return to Ugarrowa's." By Lieutenant Stairs 365 Emin and Casati Arrive at Lake Shore Camp 396 A Phalanx Dance by Mazamboni's Warriors 438 Meeting with the Rear Column at Banalya 494OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS.

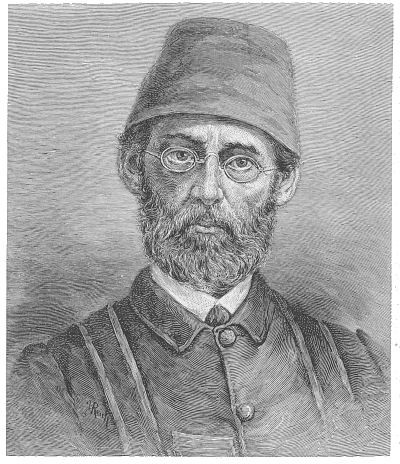

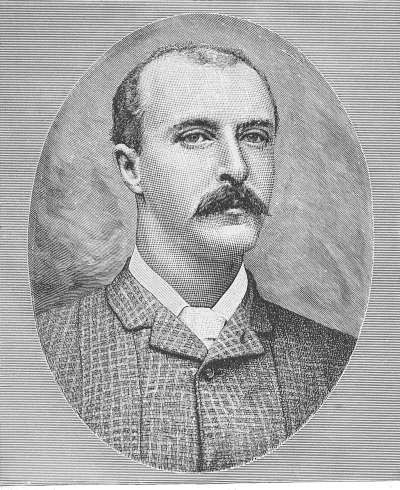

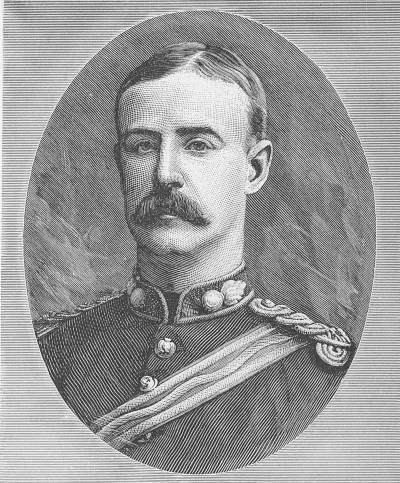

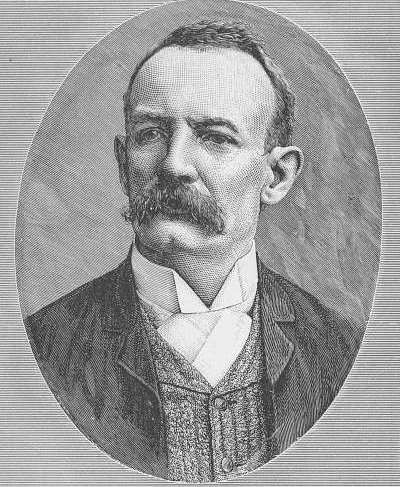

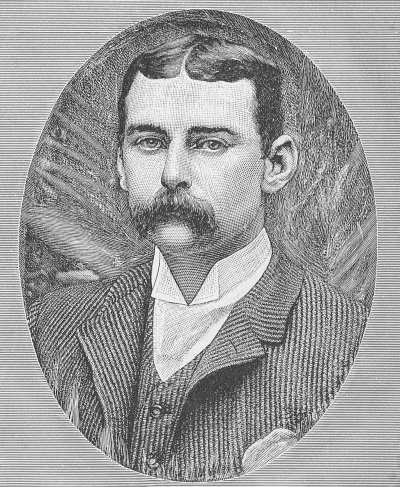

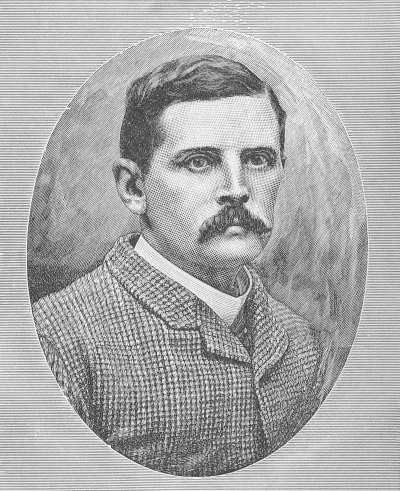

Portrait of Emin Pasha 18 Portrait of Captain Nelson 39 Portrait of Lieutenant Stairs 40 Portrait of William Bonny 41 Portrait of A. J. Mounteney Jephson 42 Portrait of Surgeon Parke, A. M. D. 50 Portrait of Nubar Pasha 51 Portrait of The Khedive Tewfik 55 Portrait of Tippu-Tib 68 Maxim Automatic Gun 83 Launching the Steamer "Florida" 96 Stanley Pool 100 Baruti Finds his Brother 109 A Typical Village on the Lower Aruwimi 112 Landing at Yambuya 113 Diagram Of Forest Camps 130 Marching Through the Forest 135 The Kirangozi, or Foremost Man 137 Head-Dress—Crown of Bristles 160 Paddle of the Upper Aruwimi or Ituri 160 Wasps' Nests 164 Fort Island, Near Panga Falls 168 Panga Falls 169 View of Utiri Village 172 Leaf-Bladed Paddle of Avisibba 174 A Head-Dress of Avisibba Warriors 178 Coroneted Avisibba Warrior—Head-Dress 179 Cascades of the Nepoko 193 View of Bafaido Cataract 202 Attacking an Elephant in the Ituri River 203 Randy Seizes the Guinea Fowl 224 Kilonga Longa's Station 234 Shields of the Balessé 256 View of Mount Pisgah from the Eastward 281 Villages of the Bakwuru on a Spur of Pisgah 283 A Village at the Base of Pisgah 284 Chief of the Iyugu 285 Pipes of Forest Tribes 290 Shields of Babusessé 299 Suspension Bridge Across the East Ituri 304 Shield of the Edge of the Plains 317 The South End of the Albert Nyanza, Dec. 13, 1887 318 Corn Granary of the Babusessé 342 A Village of the Baviri: Europeans Tailoring 345 Great Rock Near Indétonga 348 Exterior View of Fort Bodo 349 Interior View of Fort Bodo 351 Plan of Fort Bodo and Vicinity, by Lieutenant Stairs 354 The Queen of the Dwarfs 368 Within Fort Bodo 371 One of Mazamboni's Warriors 384 Kavalli, Chief of the Babiassi 389 Milk Vessel of the Wahuma 392 The Steamers "Khedive" and "Nyanza" on Lake Albert 426 View of Banalya Curve 493 Portrait of Major Barttelot 499 Portrait of Mr. Jameson 501MAP.

A Map of the Great Forest Region, Showing the Route of the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition from the River Congo to Victoria Nyanza. By Henry M. Stanley.In Pocket.

GROUP OF MR. STANLEY AND OFFICERS.

IN DARKEST AFRICA.

PREFATORY LETTER

My Dear Sir William,

I have great pleasure in dedicating this book to you. It professes to be the Official Report to yourself and the Emin Relief Committee of what we have experienced and endured during our mission of Relief, which circumstances altered into that of Rescue. You may accept it as a truthful record of the journeyings of the Expedition which you and the Emin Relief Committee entrusted to my guidance.

I regret that I was not able to accomplish all that I burned to do when I set out from England in January, 1887, but the total collapse of the Government of Equatoria thrust upon us the duty of conveying in hammocks so many aged and sick people, and protecting so many helpless and feeble folk, that we became transformed from a small fighting column of tried men into a mere Hospital Corps to whom active adventure was denied. The Governor was half blind and possessed much luggage, Casati was weakly and had to be carried, and 90 per cent. of their followers were, soon after starting, scarcely able to travel from age, disease, weakness or infancy. Without sacrificing our sacred charge, to assist which was the object of the Expedition, we could neither deviate to the right or to the left, from the most direct road to the sea.

You who throughout your long and varied life have steadfastly believed in the Christian's God, and before men have professed your devout thankfulness for many mercies vouchsafed to you, will better understand than many others the feelings which animate me when I find myself back again in civilization, uninjured in life or health, after passing through so many stormy and distressful periods. Constrained at the darkest hour to humbly confess that without God's help I was helpless, I vowed a vow in the forest solitudes that I would confess His aid before men. A silence as of death was round about me; it was midnight; I was weakened by illness, prostrated with fatigue and worn with anxiety for my white and black companions, whose fate was a mystery. In this physical and mental distress I besought God to give me back my people. Nine hours later we were exulting with a rapturous joy. In full view of all was the crimson flag with the crescent, and beneath its waving folds was the long-lost rear column.

Again, we had emerged into the open country out of the forest, after such experiences as in the collective annals of African travels there is no parallel. We were approaching the region wherein our ideal Governor was reported to be beleaguered. All that we heard from such natives as our scouts caught prepared us for desperate encounters with multitudes, of whose numbers or qualities none could inform us intelligently, and when the population of Undusuma swarmed in myriads on the hills, and the valleys seemed alive with warriors, it really seemed to us in our dense ignorance of their character and power, that these were of those who hemmed in the Pasha to the west. If he with his 4000 soldiers appealed for help, what could we effect with 173? The night before I had been reading the exhortation of Moses to Joshua, and whether it was the effect of those brave words, or whether it was a voice, I know not, but it appeared to me as though I heard: "Be strong, and of a good courage, fear not, nor be afraid of them, for the Lord thy God He it is that doth go with thee, He will not fail thee nor forsake thee." When on the next day Mazamboni commanded his people to attack and exterminate us, there was not a coward in our camp, whereas the evening before we exclaimed in bitterness on seeing four of our men fly before one native, "And these are the wretches with whom we must reach the Pasha!"

And yet again. Between the confluence of the Ihuru and the Dui rivers in December 1888, 150 of the best and strongest of our men had been despatched to forage for food. They had been absent for many days more than they ought to have been, and in the meantime 130 men besides boys and women were starving. They were supported each day with a cup of warm thin broth, made of butter, milk and water, to keep death away as long as possible. When the provisions were so reduced that there were only sufficient for thirteen men for ten days, even of the thin broth with four tiny biscuits each per day, it became necessary for me to hunt up the missing men. They might, being without a leader, have been reckless, and been besieged by an overwhelming force of vicious dwarfs. My following consisted of sixty-six men, a few women and children, who, more active than the others, had assisted the thin fluid with the berries of the phrynium and the amomum, and such fungi as could be discovered in damp places, and therefore were possessed of some little strength, though the poor fellows were terribly emaciated. Fifty-one men, besides boys and women, were so prostrate with debility and disease that they would be hopelessly gone if within a few hours food did not arrive. My white comrade and thirteen men were assured of sufficient for ten days to protract the struggle against a painful death. We who were bound for the search possessed nothing. We could feed on berries until we could arrive at a plantation. As we travelled that afternoon we passed several dead bodies in various stages of decay, and the sight of doomed, dying and dead produced on my nerves such a feeling of weakness that I was well-nigh overcome. Every soul in that camp was paralysed with sadness and suffering. Despair had made them all dumb. Not a sound was heard to disturb the deathly brooding. It was a mercy to me that I heard no murmur of reproach, no sign of rebuke. I felt the horror of silence of the forest and the night intensely. Sleep was impossible. My thoughts dwelt on these recurring disobediences which caused so much misery and anxiety. "Stiff-necked, rebellious, incorrigible human nature, ever showing its animalism and brutishness, let the wretches be for ever accursed! Their utter thoughtless and oblivious natures and continual breach of promises kill more men, and cause more anxiety, than the poison of the darts or barbs and points of the arrows. If I meet them I will—" But before the resolve was uttered flashed to my memory the dead men on the road, the doomed in the camp, and the starving with me, and the thought that those 150 men were lost in the remorseless woods beyond recovery, or surrounded by savages without hope of escape, then do you wonder that the natural hardness of the heart was softened, and that I again consigned my case to Him who could alone assist us. The next morning within half-an-hour of the start we met the foragers, safe, sound, robust, loaded, bearing four tons of plantains. You can imagine what cries of joy these wild children of nature uttered, you can imagine how they flung themselves upon the fruit, and kindled the fires to roast and boil and bake, and how, after they were all filled, we rode back to the camp to rejoice those unfortunates with Mr. Bonny.

As I mentally review the many grim episodes and reflect on the marvellously narrow escapes from utter destruction to which we have been subjected during our various journeys to and fro through that immense and gloomy extent of primeval woods, I feel utterly unable to attribute our salvation to any other cause than to a gracious Providence who for some purpose of His own preserved us. All the armies and armaments of Europe could not have lent us any aid in the dire extremity in which we found ourselves in that camp between the Dui and Ihuru; an army of explorers could not have traced our course to the scene of the last struggle had we fallen, for deep, deep as utter oblivion had we been surely buried under the humus of the trackless wilds.

It is in this humble and grateful spirit that I commence this record of the progress of the Expedition from its inception by you to the date when at our feet the Indian Ocean burst into view, pure and blue as Heaven when we might justly exclaim "It is ended!"

What the public ought to know, that have I written; but there are many things that the snarling, cynical, unbelieving, vulgar ought not to know. I write to you and to your friends, and for those who desire more light on Darkest Africa, and for those who can feel an interest in what concerns humanity.

My creed has been, is, and will remain so, I hope, to act for the best, think the right thought, and speak the right word, as well as a good motive will permit. When a mission is entrusted to me and my conscience approves it as noble and right, and I give my promise to exert my best powers to fulfil this according to the letter and spirit, I carry with me a Law, that I am compelled to obey. If any associated with me prove to me by their manner and action that this Law is equally incumbent on them, then I recognize my brothers. Therefore it is with unqualified delight that I acknowledge the priceless services of my friends Stairs, Jephson, Nelson and Parke, four men whose devotion to their several duties were as perfect as human nature is capable of. As a man's epitaph can only be justly written when he lies in his sepulchre, so I rarely attempted to tell them during the journey, how much I valued the ready and prompt obedience of Stairs, that earnestness for work that distinguished Jephson, the brave soldierly qualities of Nelson, and the gentle, tender devotion paid by our Doctor to his ailing patients; but now that the long wanderings are over, and they have bided and laboured ungrudgingly throughout the long period, I feel that my words are poor indeed when I need them to express in full my lasting obligations to each of them.

Concerning those who have fallen, or who were turned back by illness or accident, I will admit, with pleasure, that while in my company every one seemed most capable of fulfilling the highest expectations formed of them. I never had a doubt of any one of them until Mr. Bonny poured into my ears the dismal story of the rear column. While I possess positive proofs that both the Major and Mr. Jameson were inspired by loyalty, and burning with desire throughout those long months at Yambuya, I have endeavoured to ascertain why they did not proceed as instructed by letter, or why Messrs. Ward, Troup and Bonny did not suggest that to move little by little was preferable to rotting at Yambuya, which they were clearly in danger of doing, like the 100 dead followers. To this simple question there is no answer. The eight visits to Stanley Falls and Kasongo amount in the aggregate to 1,200 miles; their journals, log books, letters teem with proofs that every element of success was in and with them. I cannot understand why the five officers, having means for moving, confessedly burning with the desire to move, and animated with the highest feelings, did not move on along our tract as directed; or, why, believing I was alive, the officers sent my personal baggage down river and reduced their chief to a state of destitution; or, why they should send European tinned provisions and two dozen bottles of Madeira down river, when there were thirty-three men sick and hungry in camp; or, why Mr. Bonny should allow his own rations to be sent down while he was present; or, why Mr. Ward should be sent down river with a despatch, and an order be sent after him to prevent his return to the Expedition. These are a few of the problems which puzzle me, and to which I have been unable to obtain satisfactory solutions. Had any other person informed me that such things had taken place I should have doubted them, but I take my information solely from Major Barttelot's official despatch (See Appendix). The telegram which Mr. Ward conveyed to the sea requests instructions from the London Committee, but the gentlemen in London reply, "We refer you to Mr. Stanley's letter of instructions." It becomes clear to every one that there mystery here for which I cannot conceive a rational solution, and therefore each reader of this narrative must think his own thoughts but construe the whole charitably.

After the discovery of Mr. Bonny at Banalya, I had frequent occasions to remark to him that his goodwill and devotion were equal to that shown by the others, and as for bravery, I think he has as much as the bravest. With his performance of any appointed work I never had cause for dissatisfaction, and as he so admirably conducted himself with such perfect and respectful obedience while with us from Banalya to the Indian Sea, the more the mystery of Yambuya life is deepened, for with 2,000 such soldiers as Bonny under a competent leader, the entire Soudan could be subjugated, pacified and governed.

It must thoroughly be understood, however, while reflecting upon the misfortunes of the rear-column, that it is my firm belief that had it been the lot of Barttelot and Jameson to have been in the place of, say Stairs and Jephson, and to have accompanied us in the advance, they would equally have distinguished themselves; for such a group of young gentlemen as Barttelot, Jameson, Stairs, Nelson, Jephson, and Parke, at all times, night or day, so eager for and rather loving work, is rare. If I were to try and form another African State, such tireless, brave natures would be simply invaluable. The misfortunes of the rear-column were due to the resolutions of August 17th to stay and wait for me, and to the meeting with the Arabs the next day.

What is herein related about Emin Pasha need not, I hope, be taken as derogating in the slightest from the high conception of our ideal. If the reality differs somewhat from it no fault can be attributed to him. While his people were faithful he was equal to the ideal; when his soldiers revolted his usefulness as a Governor ceased, just as the cabinet-maker with tools may turn out finished wood-work, but without them can do nothing. If the Pasha was not of such gigantic stature as we supposed him to be, he certainly cannot be held responsible for that, any more than he can be held accountable for his unmilitary appearance. If the Pasha was able to maintain his province for five years, he cannot in justice be held answerable for the wave of insanity and the epidemic of turbulence which converted his hitherto loyal soldiers into rebels. You will find two special periods in this narrative wherein the Pasha is described with strictest impartiality to each, but his misfortunes never cause us to lose our respect for him, though we may not agree with that excess of sentiment which distinguished him, for objects so unworthy as sworn rebels. As an administrator he displayed the finest qualities; he was just, tender, loyal and merciful, and affectionate to the natives who placed themselves under his protection, and no higher and better proof of the esteem with which he was regarded by his soldiery can be desired than that he owed his life to the reputation for justice and mildness which he had won. In short, every hour saved from sleep was devoted before his final deposition to some useful purpose conducive to increase of knowledge, improvement of humanity, and gain to civilization. You must remember all these things, and by no means lose sight of them, even while you read our impressions of him.

I am compelled to believe that Mr. Mounteney Jephson wrote the kindliest report of the events that transpired during the arrest and imprisonment of the Pasha and himself, out of pure affection, sympathy, and fellow-feeling for his friend. Indeed the kindness and sympathy he entertains for the Pasha are so evident that I playfully accuse him of being either a Mahdist, Arabist, or Eminist, as one would naturally feel indignant at the prospect of leading a slave's life at Khartoum. The letters of Mr. Jephson, after being shown, were endorsed, as will be seen by Emin Pasha. Later observations proved the truth of those made by Mr. Jephson when he said, "Sentiment is the Pasha's worst enemy; nothing keeps Emin here but Emin himself." What I most admire in him is the evident struggle between his duty to me, as my agent, and the friendship he entertains for the Pasha.

While we may naturally regret that Emin Pasha did not possess that influence over his troops which would have commanded their perfect obedience, confidence and trust, and made them pliable to the laws and customs of civilization, and compelled them to respect natives as fellow-subjects, to be guardians of peace and protectors of property, without which there can be no civilization, many will think that as the Governor was unable to do this, that it is as well that events took the turn they did. The natives of Africa cannot be taught that there are blessings in civilization if they are permitted to be oppressed and to be treated as unworthy of the treatment due to human beings, to be despoiled and enslaved at will by a licentious soldiery. The habit of regarding the aborigines as nothing better than pagan abid or slaves, dates from Ibrahim Pasha, and must be utterly suppressed before any semblance of civilization can be seen outside the military settlements. When every grain of corn, and every fowl, goat, sheep and cow which is necessary for the troops is paid for in sterling money or its equivalent in necessary goods, then civilization will become irresistible in its influence, and the Gospel even may be introduced; but without impartial justice both are impossible, certainly never when preceded and accompanied by spoliation, which I fear was too general a custom in the Soudan.

Those who have some regard for righteous justice may find some comfort in the reflection that until civilization in its true and real form be introduced into Equatoria, the aborigines shall now have some peace and rest, and that whatever aspects its semblance bare, excepting a few orange and lime trees, can be replaced within a month, under higher, better, and more enduring auspices.

If during this Expedition I have not sufficiently manifested the reality of my friendship and devotion to you, and to my friends of the Emin Belief Committee, pray attribute it to want of opportunities and force of circumstances and not to lukewarmness and insincerity; but if, on the other hand, you and my friends have been satisfied that so far as lay in my power I have faithfully and loyally accomplished the missions you entrusted to me in the same spirit and to the same purpose that you yourself would have performed them had it been physically and morally possible for you to have been with us, then indeed am I satisfied, and the highest praise would not be equal in my opinion to the simple acknowledgment of it, such as "Well done."

My dear Sir William, to love a noble, generous and loyal heart like your own, is natural. Accept the profession of mine, which has been pledged long ago to you wholly and entirely.

Henry M. Stanley.

To Sir William Mackinnon, Bart.,

of Balinakill and Loup,

in the County of Argyleshire,

The Chairman of the Emin Pasha Relief Committee.

&c. &c. &c.

FOOTNOTES.

PREFATORY LETTER

INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER.

EGYPT AND ZANZIBAR.

BY SEA TO THE CONGO RIVER.

TO STANLEY POOL.

FROM STANLEY POOL TO YAMBUYA.

AT YAMBUYA.

TO PANGA FALLS.

FROM PANGA FALLS TO UGARROWWA'S.

UGARROWWA'S TO KILONGA-LONGA'S.

WITH THE MANYUEMA AT IPOTO.

THROUGH THE FOREST TO MAZAMBONI'S PEAK.

ARRIVAL AT LAKE ALBERT, AND OUR RETURN TO IBWIRI.

LIFE AT FORT BODO.

TO THE ALBERT NYANZA A SECOND TIME.

THE MEETING WITH EMIN PASHA.

WITH THE PASHA (continued).

PERSONAL TO THE PASHA.

START FOR THE RELIEF OF THE REAR COLUMN.

ARRIVAL AT BANALYA: BARTTELOT DEAD.

THE SAD STORY OF THE REAR COLUMN.

THE STEEL BOAT ADVANCE.

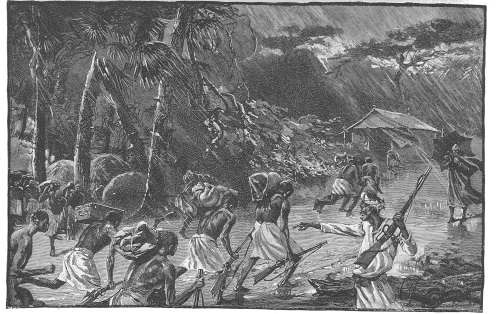

IN THE NIGHT AND RAIN IN THE FOREST.

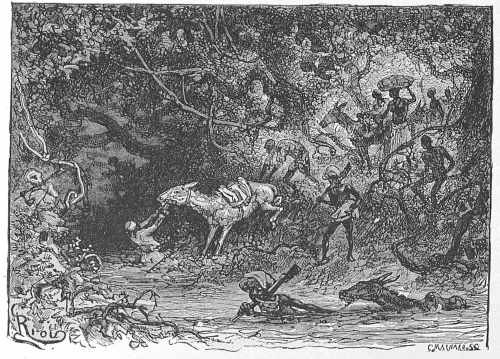

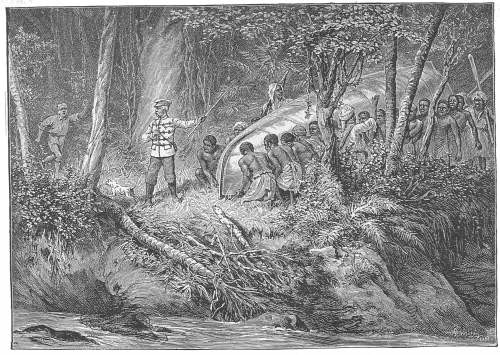

THE FIGHT WITH THE AVISIBBA CANNIBALS.

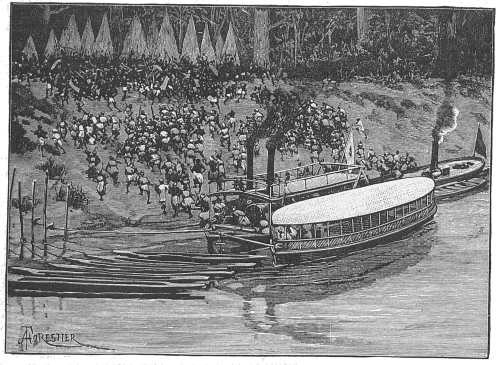

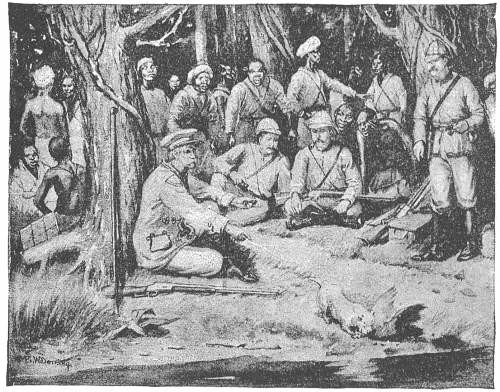

THE RIVER COLUMN ASCENDING THE ARUWIMI RIVER WITH "ADVANCE" AND SIXTEEN CANOES.

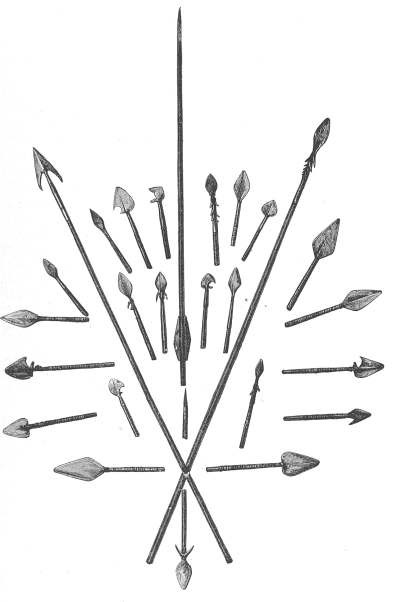

WOODEN ARROWS OF THE AVISIBBA.

(From a photograph.)

"THE PASHA IS COMING."

THE RELIEF OF NELSON AND SURVIVORS AT STARVATION CAMP.

GYMNASTICS IN A FOREST CLEARING.

IYUGU; A CALL TO ARMS.

EMERGING FROM THE FOREST.

OUR FIRST EXPERIENCES WITH MAZAMBONI'S PEOPLE. VIEW FROM NZERA KUM HILL.

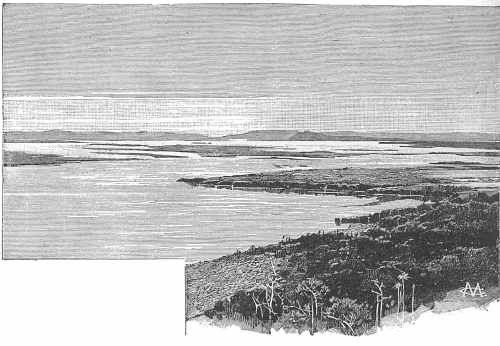

VIEW OF THE SOUTH END OF ALBERT NYANZA. (See page 306.)

Stanford's Geographical Estab.

EMIN AND CASATI ARRIVE AT OUR LAKE SHORE CAMP.

A PHALANX DANCE BY MAZAMBONI'S WARRIORS.

MEETING WITH THE REAR COLUMN AT BANALYA.

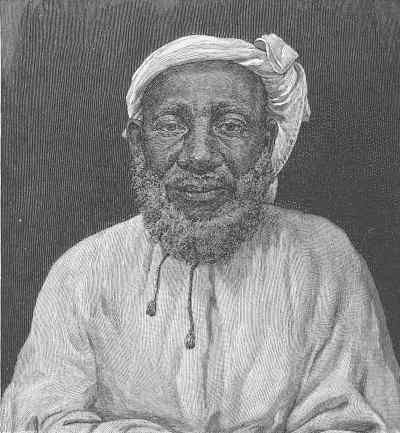

EMIN PASHA.

CAPTAIN NELSON.

LIEUTENANT STAIRS.

MR. WILLIAM BONNY.

MR. A. J. MOUNTENEY JEPHSON.

SURGEON PARKE, A. M. D.

NUBAR PASHA.

THE KHEDIVE TEWFIK.

PORTRAIT OF TIPPU-TIB.

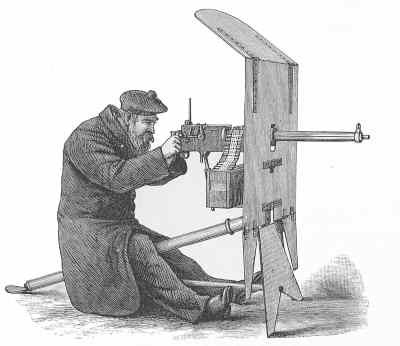

MAXIM AUTOMATIC GUN.

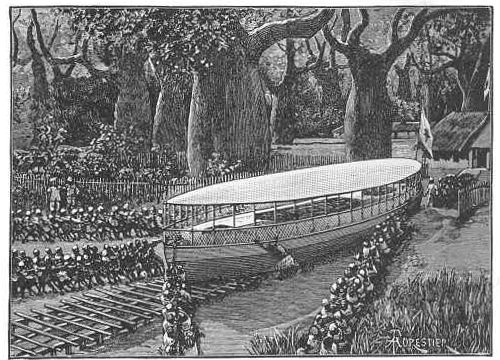

LAUNCHING THE STEAMER "FLORIDA."

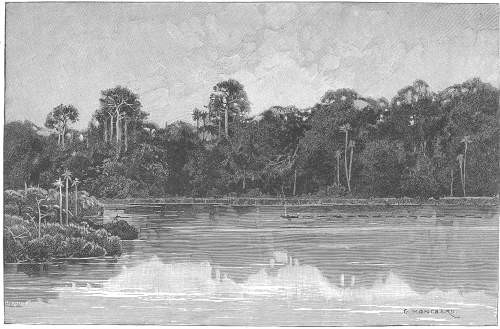

STANLEY POOL.

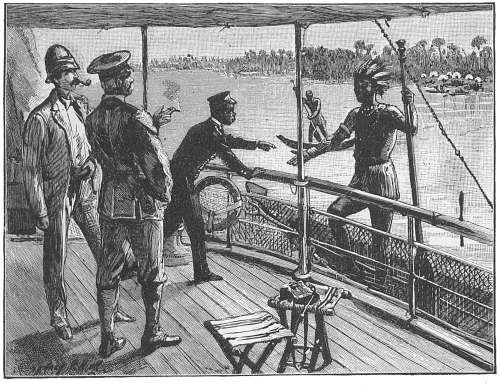

BARUTI FINDS HIS BROTHER.

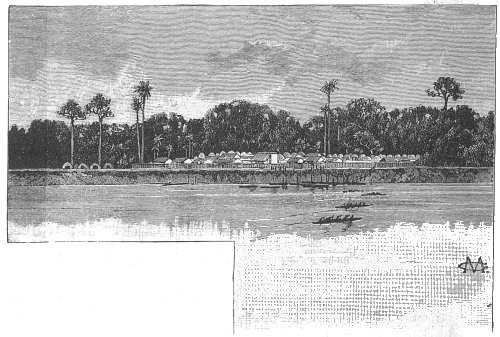

A TYPICAL VILLAGE ON THE LOWER ARUWIMI.

OUR LANDING AT YAMBUYA.

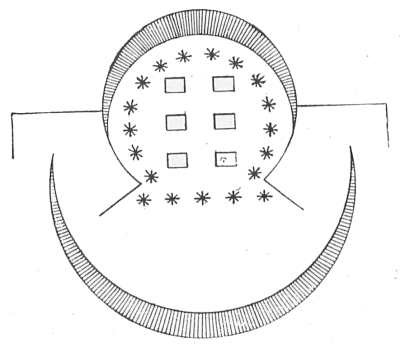

DIAGRAM OF OUR FOREST CAMPS.

MARCHING THROUGH THE FOREST.

THE KIRANGOZI, OR FOREMOST MAN.

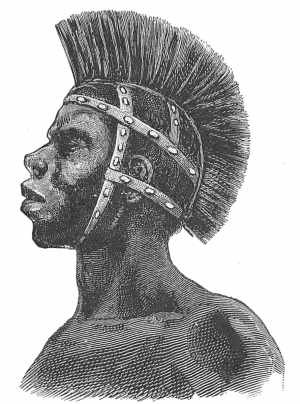

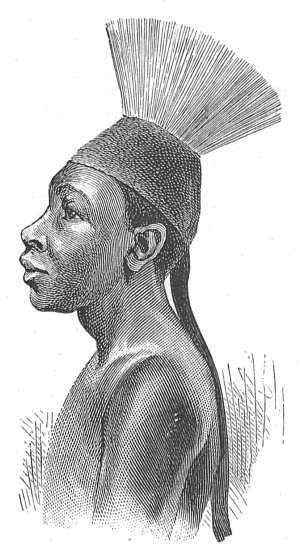

HEAD-DRESS—CROWN OF BRISTLES.

PADDLE OF THE UPPER ARUWIMI OR ITURI.

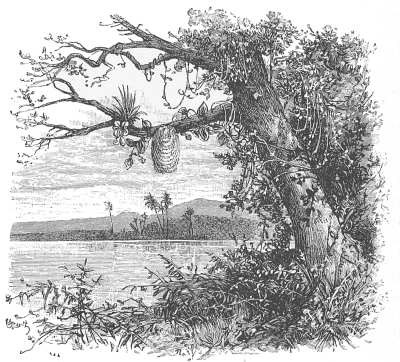

WASPS' NESTS, ETC.

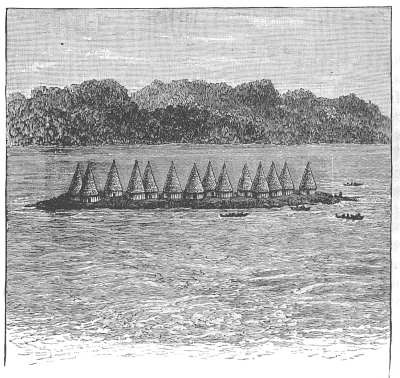

FORT ISLAND, NEAR PANGA FALLS.

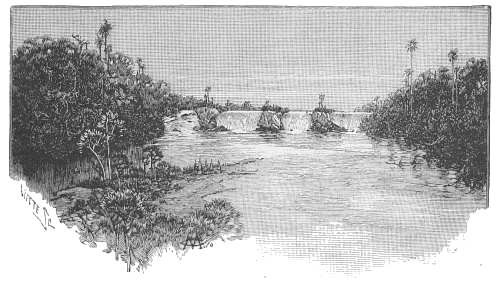

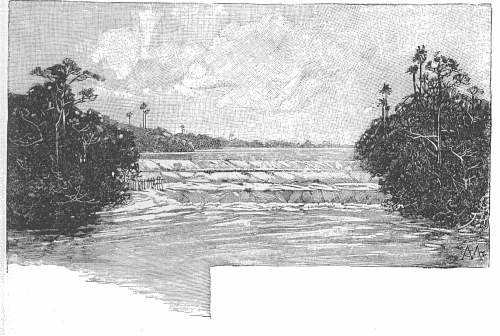

PANGA FALLS.

VIEW OF UTIRI VILLAGE.

LEAF-BLADED PADDLE OF AVISIBBA.

A HEAD-DRESS OF AVISIBBA WARRIORS.

CORONETED AVISIBBA WARRIOR—HEAD-DRESS.

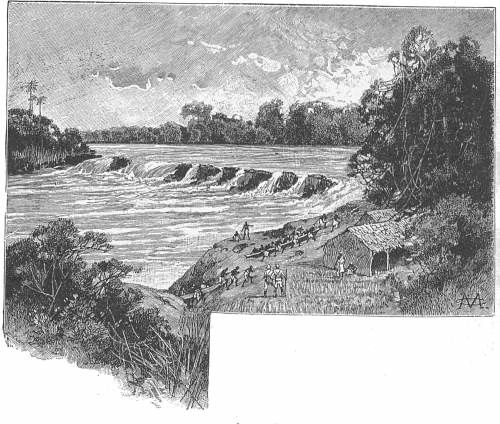

CASCADES OF THE NEPOKO.

VIEW OF BAFAIDO CATARACT.

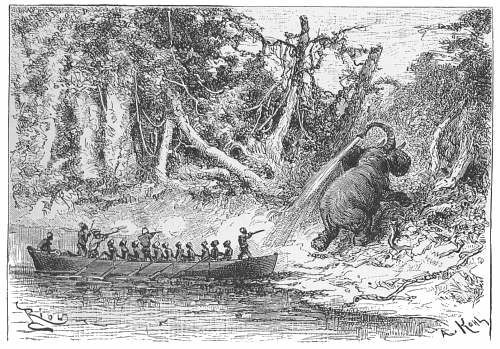

ATTACKING AN ELEPHANT IN THE ITURI RIVER.

RANDY SEIZES THE GUINEA FOWL.

KILONGA LONGA'S STATION.

SHIELDS OF THE BALESSÉ.

VIEW OF MOUNT PISGAH FROM THE EASTWARD.

VILLAGES OF THE BAKWURU ON A SPUR OF PISGAH.

A VILLAGE AT THE BASE OF PISGAH.

CHIEF OF THE IYUGU.

PIPES.

SHIELDS OF BABUSESSÉ.

SUSPENSION BRIDGE ACROSS THE E. ITURI.

SHIELD OF THE EDGE OF THE PLAINS.

THE SOUTH END OF THE ALBERT NYANZA, DEC. 13, 1887.

CORN GRANARY OF THE BABUSESSÉ.

A VILLAGE OF THE BAVIRI: EUROPEANS TAILORING, ETC.

GREAT ROCK NEAR INDE-TONGA.

VIEW OF FORT BODO.

VIEW OF FORT BODO.

PLAN OF FORT BODO AND VICINITY. By Lieut. Stairs, R.E.

THE QUEEN OF THE DWARFS.

WITHIN FORT BODO.

ONE OF MAZAMBONI'S WARRIORS.

KAVALLI, CHIEF OF THE BA-BIASSI.

MILK VESSEL OF THE WAHUMA.

THE STEAMERS "KHEDIVE" AND "NYANZA" ON LAKE ALBERT.

VIEW OF BANALYA CURVE.

MAJOR BARTTELOT.

MR. JAMESON.

CHAPTER I.

INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER.

The Khedive and the Soudan—Arabi Pasha—Hicks Pasha's defeat—The Mahdi—Sir Evelyn Baring and Lord Granville on the Soudan—Valentine Baker Pasha—General Gordon: his work in the Upper Soudan—Edward Schnitzler (or Emin Effendi Hakim) and his province—General Gordon at Khartoum: and account of the Belief Expedition in 1884, under Lord Wolseley—Mr. A. M. Mackay, the missionary in Uganda—Letters from Emin Bey to Mr. Mackay, Mr. C. H. Allen, and Dr. R. W. Felkin, relating to his Province—Mr. F. Holmwood's and Mr. A. M. Mackay's views on the proposed relief of Emin—Suggested routes for the Emin Relief Expedition—Sir Wm. Mackinnon and Mr. J. F. Hutton—The Relief Fund and Preparatory details of the Expedition—Colonel Sir Francis De Winton—Selection of officers for the Expedition—King Leopold and the Congo Route—Departure for Egypt.

Only a Carlyle in his maturest period, as when he drew in lurid colours the agonies of the terrible French Revolution, can do justice to the long catalogue of disasters which has followed the connection of England with Egypt. It is a theme so dreadful throughout, that Englishmen shrink from touching it. Those who have written upon any matters relating to these horrors confine themselves to bare historical record. No one can read through these without shuddering at the dangers England and Englishmen have incurred during this pitiful period of mismanagement. After the Egyptian campaign there is only one bright gleam of sunshine throughout months of oppressive darkness, and that shone over the immortals of Abu-Klea and Gubat, when that small body of heroic Englishmen struggled shoulder to shoulder on the sands of the fatal desert, and won a glory equal to that which the Light Brigade were urged to gain at Balaclava. Those were fights indeed, and atone in a great measure for a series of blunders, that a century of history would fail to parallel. If only a portion of that earnestness of purpose exhibited at Abu-Klea had been manifested by those responsible for ordering events, the Mahdi would soon have become only a picturesque figure to adorn a page or to point a metaphor, and not the terrible portent of these latter days, whose presence blasted every vestige of civilization in the Soudan to ashes.

In order that I may make a fitting but brief introduction to the subject matter of this book, I must necessarily glance at the events which led to the cry of the last surviving Lieutenant of Gordon for help in his close beleaguerment near the Equator.

To the daring project of Ismail the Khedive do we owe the original cause of all that has befallen Egypt and the Soudan. With 5,000,000 of subjects, and a rapidly depleting treasury, he undertook the expansion of the Egyptian Khediviate into an enormous Egyptian Empire, the entire area embracing a superficial extent of nearly 1,000,000 square miles—that is, from the Pharos of Alexandria to the south end of Lake Albert, from Massowah to the western boundary of Darfur. Adventurers from Europe and from America resorted to his capital to suggest the maddest schemes, and volunteered themselves leaders of the wildest enterprises. The staid period when Egyptian sovereignty ceased at Gondokoro, and the Nile was the natural drain of such traffic as found its way by the gentle pressure of slow development, was ended when Captains Speke and Grant, and Sir Samuel Baker brought their rapturous reports of magnificent lakes, and regions unmatched for fertility and productiveness. The termination of the American Civil War threw numbers of military officers out of employment, and many thronged to Egypt to lend their genius to the modern Pharaoh, and to realize his splendid dreams of empire. Englishmen, Germans, and Italians, appeared also to share in the honours that were showered upon the bold and the brave.

While reading carefully and dispassionately the annals of this period, admiring the breadth of the Khedive's views, the enthusiasm which possesses him, the princely liberality of his rewards, the military exploits, the sudden extensions of his power, and the steady expansions of his sovereignty to the south, west, and east, I am struck by the fact that his success as a conqueror in Africa may well be compared to the successes of Alexander in Asia, the only difference being that Alexander led his armies in person, while Ismail the Khedive preferred the luxuries of his palaces in Cairo, and to commit his wars to the charge of his Pashas and Beys.

To the Khedive the career of conquest on which he has launched appears noble; the European Press applaud him; so many things of grand importance to civilization transpire that they chant pæans of praise in his honour; the two seas are brought together, and the mercantile navies ride in stately columns along the maritime canal; railways are pushed towards the south, and it is prophesied that a line will reach as far as Berber. But throughout all this brilliant period the people of this new empire do not seem to have been worthy of a thought, except as subjects of taxation and as instruments of supplying the Treasury; taxes are heavier than ever; the Pashas are more mercenary; the laws are more exacting, the ivory trade is monopolised, and finally, to add to the discontent already growing, the slave trade is prohibited throughout all the territory where Egyptian authority is constituted. Within five years Sir Samuel Baker has conquered the Equatorial Province, Munzinger has mastered Senaar, Darfur has been annexed, and Bahr-el-Ghazal has been subjugated after a most frightful waste of life. The audacity manifested in all these projects of empire is perfectly marvellous—almost as wonderful as the total absence of common sense. Along a line of territory 800 miles in length there are only three military stations in a country that can only rely upon camels as means of communication except when the Nile is high.

In 1879, Ismail the Khedive having drawn too freely upon the banks of Europe, and increased the debt of Egypt to £128,000,000, and unable to agree to the restraints imposed by the Powers, the money of whose subjects he had so liberally squandered, was deposed, and the present Khedive, Tewfik, his son, was elevated to his place, under the tutelage of the Powers. But shortly after, a military revolt occurred, and at Kassassin, Tel-el-Kebir, Cairo, and Kafr Dowar, it was crushed by an English Army, 13,000 strong, under Lord Wolseley.

During the brief sovereignty of Arabi Pasha, who headed the military revolt, much mischief was caused by the withdrawal of the available troops from the Soudan. While the English General was defeating the rebel soldiers at Tel-el-Kebir, the Mahdi Mohamet-Achmet was proceeding to the investment of El Obeid. On the 23rd of August he was attacked at Duem with a loss of 4500. On the 14th he was repulsed by the garrison of Obeid, with a loss, it is said, of 10,000 men. These immense losses of life, which have been continuous from the 11th of August, 1881, when the Mahdi first essayed the task of teaching the populations of the Soudan the weakness of Egyptian power, were from the tribes who were indifferent to the religion professed by the Mahdi, but who had been robbed by the Egyptian officials, taxed beyond endurance by the Government, and who had been prevented from obtaining means by the sale of slaves to pay the taxes, and also from the hundreds of slave-trading caravans, whose occupation was taken from them by their energetic suppression by Gordon, and his Lieutenant, Gessi Pasha. From the 11th of August, 1881, to the 4th of March, 1883, when Hicks Pasha, a retired Indian officer, landed at Khartoum as Chief of the Staff of the Soudan army, the disasters to the Government troops had been almost one unbroken series; and, in the meanwhile, the factious and mutinous army of Egypt had revolted, been suppressed and disbanded, and another army had been reconstituted under Sir Evelyn Wood, which was not to exceed 6000 men. Yet aware of the tremendous power of the Mahdi, and the combined fanaticism and hate, amounting to frenzy, which possessed his legions, and of the instability, the indiscipline, and cowardice of his troops—while pleading to the Egyptian Government for a reinforcement of 5000 men, or for four battalions of General Wood's new army—Hicks Pasha resolves upon the conquest of Kordofan, and marches to meet the victorious Prophet, while he and his hordes are flushed with the victory lately gained over Obeid and Bara. His staff, and the very civilians accompanying him, predict disaster; yet Hicks starts forth on his last journey with a body of 12,000 men, 10 mountain guns, 6 Nordenfelts, 5500 camels, and 500 horses. They know that the elements of weakness are in the force; that many of the soldiers are peasants taken from the fields in Egypt, chained in gangs; that others are Mahdists; that there is dissension between the officers, and that everything is out of joint. But they march towards Obeid, meet the Mahdi's legions, and are annihilated.

England at this time directs the affairs of Egypt with the consent of the young Khedive, whom she has been instrumental in placing upon the almost royal throne of Egypt, and whom she is interested in protecting. Her soldiers are in Egypt; the new Egyptian army is under an English General; her military police is under the command of an English ex-Colonel of cavalry; her Diplomatic Agent directs the foreign policy; almost all the principal offices of the State are in the hands of Englishmen.

The Soudan has been the scene of the most fearful sanguinary encounters between the ill-directed troops of the Egyptian Government and the victorious tribes gathered under the sacred banner of the Mahdi; and unless firm resistance is offered soon to the advance of the Prophet, it becomes clear to many in England that this vast region and fertile basin of the Upper Nile will be lost to Egypt, unless troops and money be furnished to meet the emergency. To the view of good sense it is clear that, as England has undertaken to direct the government and manage the affairs of Egypt, she cannot avoid declaring her policy as regards the Soudan. To a question addressed to the English Prime Minister in Parliament, as to whether the Soudan was regarded as forming a part of Egypt, and if so, whether the British Government would take steps to restore order there, Mr. Gladstone replied, that the Soudan had not been included in the sphere of English operations, and that the Government was not disposed to include it within the sphere of English responsibility. As a declaration of policy no fault can be found with it; it is Mr. Gladstone's policy, and there is nothing to be said against it as such; it is his principle, the principle of his associates in the Government, and of his party, and as a principle it deserves respect.

The Political Agent in Egypt, Sir Evelyn Baring, while the fate of Hicks Pasha and his army was still unknown, but suspected, sends repeated signals of warning to the English Government, and suggests remedies and means of averting a final catastrophe. "If Hicks Pasha is defeated, Khartoum is in danger; by the fall of Khartoum, Egypt will be menaced."

Lord Granville replies at various times in the months of November and December, 1883, that the Government advises the abandonment of the Soudan within certain limits; that the Egyptian Government must take the sole responsibility of operations beyond Egypt Proper; that the Government has no intention of employing British or Indian troops in the Soudan; that ineffectual efforts on the part of the Egyptian Government to secure the Soudan would only increase the danger.

Sir Evelyn Baring notified Lord Granville that no persuasion or argument availed to induce the Egyptian Minister to accept the policy of abandonment. Cherif Pasha, the Prime Minister, also informed Lord Granville that, according to Valentine Baker Pasha, the means at the disposal were utterly inadequate for coping with the insurrection in the Soudan.

Then Lord Granville replied, through Sir Evelyn Baring, that it was indispensable that, so long as English soldiers provisionally occupied Egypt, the advice of Her Majesty's Ministers should be followed, and that he insisted on its adoption. The Egyptian Ministers were changed, and Nubar Pasha became Prime Minister on the 10th January, 1884.

On the 17th December, Valentine Baker departed from Egypt for Suakim, to commence military operations for the maintenance of communication between Suakim and Berber, and the pacification of the tribes in that region. While it was absolutely certain in England that Baker's force would suffer a crushing defeat, and suspected in Egypt, the General does not seem to be aware of any danger, or if there be, he courts it. The Khedive, fearful that to his troops an engagement will be most disastrous, writes privately to Baker Pasha: "I rely on your prudence and ability not to engage the enemy except under the most favourable conditions." Baker possessed ability and courage in abundance; but the event proved that prudence and judgment were as absent in his case as in that of the unfortunate Hicks. His force consisted of 3746 men. On the 6th of February he left Trinkitat on the sea shore, towards Tokar. After a march of six miles the van of the rebels was encountered, and shortly after the armies were engaged. It is said "that the rebels displayed the utmost contempt for the Egyptians; that they seized them by the neck and cut their throats; and that the Government troops, paralysed by fear, turned their backs, submitting to be killed rather than attempt to defend their lives; that hundreds threw away their rifles, knelt down, raised their clasped hands, and prayed for mercy."

The total number killed was 2373 out of 3746. Mr. Royle, the excellent historian of the Egyptian campaigns, says: "Baker knew, or ought to have known, the composition of the troops he commanded, and to take such men into action was simply to court disaster." What ought we to say of Hicks?

We now come to General Gordon, who from 1874 to 1876 had been working in the Upper Soudan on the lines commenced by Sir Samuel Baker, conciliating natives, crushing slave caravans, destroying slave stations, and extending Egyptian authority by lines of fortified forts up to the Albert Nyanza. After four months' retirement he was appointed Governor-General of the Soudan, of Darfur, and the Equatorial Provinces. Among others whom Gordon employed as Governors of these various provinces under his Vice-regal Government was one Edward Schnitzler, a German born in Oppeln, Prussia, 28th March, 1840, of Jewish parents, who had seen service in Turkey, Armenia, Syria, and Arabia, in the suite of Ismail Hakki Pasha, once Governor-General of Scutari, and a Mushir of the Empire. On the death of his patron he had departed to Niesse, where his mother, sister, and cousins lived, and where he stayed for several months, and thence left for Egypt. He, in 1875, thence travelled to Khartoum, and being a medical doctor, was employed by Gordon Pasha in that capacity. He assumed the name and title of Emin Effendi Hakim—the faithful physician. He was sent to Lado as storekeeper and doctor, was afterwards despatched to King Mtesa on a political mission, recalled to Khartoum, again despatched on a similar mission to King Kabba-Rega of Unyoro, and finally, in 1878, was promoted to Bey, and appointed Governor of the Equatorial Province of Ha-tal-astiva, which, rendered into English, means Equatoria, at a salary of £50 per month. A mate of one of the Peninsular and Oriental steamers, called Lupton, was promoted to the rank of Governor of the Province of Bahr-el-Ghazal, which adjoined Equatoria.

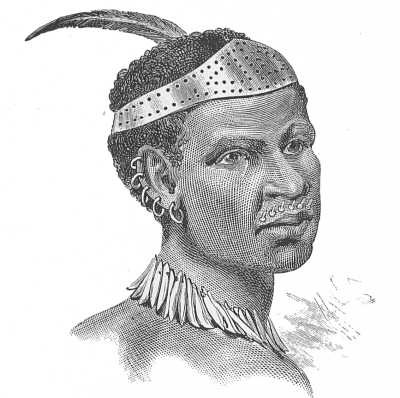

EMIN PASHA.

On hearing of the deposition of Ismail in 1879, Gordon surrendered his high office in the hands of Tewfik, the new Khedive, informing him that he did not intend to resume it.

In 1880 he accepted the post of Secretary under the Marquis of Ripon, but resigned it within a month.

In 1881 he is in Mauritius as Commandant of the Royal Engineers. In about two months he abandons that post to proceed to the assistance of the Cape authorities in their difficulty with the Basutos, but, after a little experience, finds himself unable to agree with the views of the Cape Government, and resigns.

Meantime, I have been labouring on the Congo River. Our successes in that immense territory of Western Africa have expanded into responsibilities so serious that they threaten to become unmanageable. When I visit the Lower Congo affairs become deranged on the Upper Congo; if I confine myself to the Upper Congo there is friction in the Lower Congo. Wherefore, feeling an intense interest in the growth of the territory which was rapidly developing into a State, I suggested to His Majesty King Leopold, as early as September, 1882, and again in the spring of 1883, that I required as an associate a person of merit, rank, and devotion to work, such as General Gordon, who would undertake either the management of the Lower or Upper Congo, while I would work in the other section, as a vast amount of valuable time was consumed in travelling up and down from one to the other, and young officers of stations were so apt to take advantage of my absence. His Majesty promised to request the aid of General Gordon, but for a long time the replies were unfavourable. Finally, in the spring of 1884, I received a letter in General Gordon's well-known handwriting, which informed me I was to expect him by the next mail.

It appears, however, that he had no sooner mailed his letter to me and parted from His Majesty than he was besieged by applications from his countrymen to assist the Egyptian Government in extricating the beleaguered garrison of Khartoum from their impending fate. Personally I know nothing of what actually happened when he was ushered by Lord Wolseley into the presence of Lord Granville, but I have been informed that General Gordon was confident he could perform the mission entrusted to him. There is a serious discrepancy in the definition of this mission. The Egyptian authorities were anxious for the evacuation of Khartoum only, and it is possible that Lord Granville only needed Gordon's services for this humane mission, all the other garrisons to be left to their fate because of the supposed impossibility of rescuing them. The Blue Books which contain the official despatches seem to confirm the probability of this. But it is certain that Lord Granville instructed General Gordon to proceed to Egypt to report on the situation of the Soudan, and on the best measures that should be taken for the security of the Egyptian garrisons (in the plural), and for the safety of the European population in Khartoum. He was to perform such other duties as the Egyptian Government might wish to entrust to him. He was to be accompanied by Colonel Stewart.

Sir Evelyn Baring, after a prolonged conversation with Gordon, gives him his final instructions on behalf of the British Government.

A precis of these is as follows:—

1. "Ensure retreat of the European population from 10,000 to 15,000 people, and of the garrison of Kartoum."[1]

2. "You know best the when and how to effect this."

3. "You will bear in mind that the main end (of your Mission) is the evacuation of the Soudan."

4. "As you are of opinion it could be done, endeavour to make a confederation of the native tribes to take the place of Egyptian authority."

5. "A credit of £100,000 is opened for you at the Finance Department."

Gordon has succeeded in infusing confidence in the minds of the Egyptian Ministry, who were previously panic-stricken and cried out for the evacuation of Khartoum only. They breathe freer after seeing and hearing him, and according to his own request they invest him with the Governor-Generalship. The firman, given him, empowers him to evacuate the respective territories (of the Soudan) and to withdraw the troops, civil officials, and such of the inhabitants as wish to leave for Egypt, and if possible, after completing the evacuation (and this was an absolute impossibility) he was to establish an organized Government. With these instructions Lord Granville concurs.

I am told that it was understood, however, that he was to do what he could—do everything necessary, in fact, if possible; if not all the Soudan, then he was to proceed to evacuating Khartoum only, without loss of time. But this is not on official record until March 23rd, 1884, and it is not known whether he ever received this particular telegram.[2]

General Gordon proceeded to Khartoum on January 26th, 1884, and arrived in that city on the 18th of the following month. During his journey he sent frequent despatches by telegraph abounding in confidence. Mr. Power, the acting consul and Times correspondent, wired the following despatch—"The people (of Khartoum) are devoted to General Gordon, whose design is to save the garrison, and for ever leave the Soudan—as perforce it must be left—to the Soudanese."

The English press, which had been so wise respecting the chances of Valentine Baker Pasha, were very much in the condition of the people of Khartoum, that is, devoted to General Gordon and sanguine of his success. He had performed such wonders in China—he had laboured so effectually in crushing the slave-trade in the Soudan, he had won the affection of the sullen Soudanese, that the press did not deem it at all improbable that Gordon with his white wand and six servants could rescue the doomed garrisons of Senaar, Bahr-el-Ghazal and Equatoria—a total of 29,000 men, besides the civil employees and their wives and families; and after performing that more than herculean—nay utterly impossible task—establish an organized Government.

On February 29th Gordon telegraphs, "There is not much chance of improving, and every chance is getting worse," and on the 2nd of the month "I have no option about staying at Khartoum, it has passed out of my hands." On the 16th March he predicts that before long "we shall be blocked." At the latter end of March he telegraphs, "We have provisions for five months, and are hemmed in."

It is clear that a serious misunderstanding had occurred in the drawing up of the instructions by Sir Evelyn Baring and their comprehension of them by General Gordon, for the latter expresses himself to the former thus:—

"You ask me to state cause and reason of my intention for my staying at Khartoum. I stay at Khartoum because Arabs have shut us up, and will not let us out."

Meantime public opinion urged on the British Government the necessity of despatching an Expedition to withdraw General Gordon from Khartoum. But as it was understood between General Gordon and Lord Granville that the former's mission was for the purpose of dispensing with the services of British troops in the Soudan, and as it was its declared policy not to employ English or Indian troops in that region, the Government were naturally reluctant to yield to the demand of the public. At last, however, as the clamour increased and Parliament and public joined in affirming that it was a duty on the country to save the brave man who had so willingly volunteered to perform such an important service for his country, Mr. Gladstone rose in the House of Commons on the 5th August to move a vote of credit to undertake operations for the relief of Gordon.

Two routes were suggested by which the Relief Expedition could approach Khartoum—the short cut across the desert from Suakim to Berber, and the other by the Nile. Gordon expressed his preference for that up the Nile, and it was this latter route that the Commanding General of the Relief Expedition adopted.

On the 18th September, the steamer "Abbas," with Colonel Stewart (Gordon's companion), Mr. Power, the Times correspondent, Mr. Herbin, the French Consul, and a number of Greeks and Egyptians on board—forty-four men all told—on trying to pass by the cataract of Abu Hamid was wrecked in the cataract. The Arabs on the shore invited them to land in peace, but unarmed. Stewart complied, and he and the two Consuls (Power and Herbin) and Hassan Effendi went ashore and entered a house, in which they were immediately murdered.

On the 17th November, Gordon reports to Lord Wolseley, who was then at Wady Halfa, that he can hold out for forty days yet, that the Mahdists are to the south, south-west, and east, but not to the north of Khartoum.

By Christmas Day, 1884, a great part of the Expeditionary Force was assembled at Korti. So far, the advance of the Expedition had been as rapid as the energy and skill of the General commanding could command. Probably there never was a force so numerous animated with such noble ardour and passion as this under Lord Wolseley for the rescue of that noble and solitary Englishman at Khartoum.

On December 30th, a part of General Herbert Stewart's force moves from Korti towards Gakdul Wells, with 2099 camels. In 46 hours and 50 minutes it has reached Gakdul Wells; 11 hours later Sir Herbert Stewart with all the camels starts on his return journey to Korti, which place was reached January 5th. On the 12th Sir Herbert Stewart was back at Gakdul Wells, and at 2 P.M. of the 13th the march towards Abu Klea was resumed. On the 17th, the famous battle of Abu Klea was fought, resulting in a hard-won victory to the English troops, with a loss of 9 officers and 65 men killed and 85 wounded, out of a total of 1800, while 1100 of the enemy lay dead before the square. It appears probable that if the 3000 English sent up the Nile Valley had been with this gallant little force, it would have been a mere walk over for the English army. After another battle on the 19th near Metammeh, where 20 men were killed and 60 wounded of the English, and 250 of the enemy, a village on a gravel terrace near the Nile was occupied. On the 21st, four steamers belonging to General Gordon appeared. The officer in command stated that they had been lying for some weeks near an island awaiting the arrival of the British column. The 22nd and 23rd were expended by Sir Chas. Wilson in making a reconnaissance, building two forts, changing the crews of the steamers, and preparing fuel. On the 24th, two of the steamers started for Khartoum, carrying only 20 English soldiers. On the 26th two men came aboard and reported that there had been fighting at Khartoum; on the 27th a man cried out from the bank that the town had fallen, and that Gordon had been killed. The next day the last news was confirmed by another man. Sir Charles Wilson steamed on until his steamers became the target of cannon from Omdurman and from Khartoum, besides rifles from a distance of from 75 to 200 yards, and turned back only when convinced that the sad news was only too true. Steaming down river then at full speed he reached Tamanieb when he halted for the night. From here he sent out two messengers to collect news. One returned saying that he had met an Arab who informed him that Khartoum had been entered on the night of the 26th January through the treachery of Farag Pasha, and that Gordon was killed; that the Mahdi had on the next day entered the city and had gone into a mosque to return thanks and had then retired, and had given the city up to three days' pillage.

In Major Kitchener's report we find a summary of the results of the taking of Khartoum. "The massacre in the town lasted some six hours, and about 4000 persons at least were killed. The Bashi Bazouks and white regulars numbering 3327, and the Shaigia irregulars numbering 2330, were mostly all killed in cold blood after they had surrendered and been disarmed." The surviving inhabitants of the town were ordered out, and as they passed through the gate were searched, and then taken to Omdurman where the women were distributed among the Mahdist chiefs, and the men were stripped and turned adrift to pick a living as they could. A Greek merchant, who escaped from Khartoum, reported that the town was betrayed by the merchants there, who desired to make terms with the enemy, and not by Farag Pasha.

Darfur, Kordofan, Senaar, Bahr-el-Ghazal, Khartoum, had been possessed by the enemy; Kassala soon followed, and throughout the length and breadth of the Soudan there now remained only the Equatorial Province, whose Governor was Emin Bey Hakim—the Faithful Physician.

Naturally, if English people felt that they were in duty bound to rescue their brave countryman, and a gallant General of such genius and reputation as Gordon, they would feel a lively interest in the fate of the last of Gordon's Governors, who, by a prudent Fabian policy, it was supposed, had evaded the fate which had befallen the armies and garrisons of the Soudan. It follows also that, if the English were solicitous for the salvation of the garrison of Khartoum, they would feel a proportionate solicitude for the fate of a brave officer and his little army in the far South, and that, if assistance could be rendered at a reasonable cost, there would be no difficulty in raising a fund to effect that desirable object.

On November 16, 1884, Emin Bey informs Mr. A. M. Mackay, the missionary in Uganda, by letter written at Lado, that "the Soudan has become the theatre of an insurrection; that for nineteen months he is without news from Khartoum, and that thence he is led to believe that the town has been taken by the insurgents, or that the Nile is blocked "; but he says:—

"Whatever it proves to be, please inform your correspondents and through them the Egyptian Government that to this day we are well, and that we propose to hold out until help may reach us or until we perish."

A second note from Emin Bey to the same missionary, on the same date as the preceding, contains the following:—

"The Bahr-Ghazal Province being lost and Lupton Bey, the governor, carried away to Kordofan, we are unable to inform our Government of what happens here. For nineteen months we have had no communication from Khartoum, so I suppose the river is blocked up."

"Please therefore inform the Egyptian Government by some means that we are well to this day, but greatly in need of help. We shall hold out until we obtain such help or until we perish."

To Mr. Charles H. Allen, Secretary of the Anti-Slavery Society, Emin Bey writes from Wadelai, December 31, 1885, as follows:—

"Ever since the month of May, 1883, we have been cut off from all communication with the world. Forgotten, and abandoned by the Government, we have been compelled to make a virtue of necessity. Since the occupation of the Bahr-Ghazal we have been vigorously attacked, and I do not know how to describe to you the admirable devotion of my black troops throughout a long war, which for them at least, has no advantage. Deprived of the most necessary things for a long time without any pay, my men fought valiantly, and when at last hunger weakened them, when, after nineteen days of incredible privation and sufferings, their strength was exhausted, and when the last torn leather of the last boot had been eaten, then they cut away through the midst of their enemies and succeeded in saving themselves. All this hardship was undergone without the least arrière-pensée, without even the hope of any appreciable reward, prompted only by their duty and the desire of showing a proper valour before their enemies."

This is a noble record of valour and military virtue. I remember the appearance of this letter in the Times, and the impression it made on myself and friends. It was only a few days after the appearance of this letter that we began to discuss ways and means of relief for the writer.

The following letter also impressed me very strongly. It is written to Dr. R. W. Felkin on the same date, December 31, 1885.

"You will probably know through the daily papers that poor Lupton, after having bravely held the Bahr-Ghazal Province was compelled, through the treachery of his own people, to surrender to the emissaries of the late Madhi, and was carried by them to Kordofan."

"My province and also myself I only saved from a like fate by a stratagem, but at last I was attacked, and many losses in both men and ammunition were the result, until I delivered such a heavy blow to the rebels at Rimo, in Makraka, that compelled them to leave me alone. Before this took place they informed us that Khartoum fell, in January, 1885, and that Gordon was killed."

"Naturally on account of these occurrences I have been compelled to evacuate our more distant stations, and withdraw our soldiers and their families, still hoping that our Government will send us help. It seems, however, that I have deceived myself, for since April, 1883, I have received no news of any kind from the north."

"The Government in Khartoum did not behave well to us. Before they evacuated Fashoda, they ought to have remembered that Government officials were living here (Equatorial Provinces) who had performed their duty, and had not deserved to be left to their fate without more ado. Even if it were the intention of the Government to deliver us over to our fate, the least they could have done was to have released us from our duties; we should then have known that we were considered to have become valueless."

"Anyway it was necessary for us to seek some way of escape, and in the first place it was urgent to send news of our existence in Egypt. With this object in view I went south, after having made the necessary arrangements at Lado, and came to Wadelai."

"As to my future plans, I intend to hold this country as long as possible. I hope that when our letters arrive in Egypt, in seven or eight months, a reply will be sent to me viâ Khartoum or Zanzibar. If the Egyptian Government still exists in the Soudan we naturally expect them to send us help. If, however, the Soudan has been evacuated, I shall take the whole of the people towards the south. I shall then send the whole of the Egyptian and Khartoum officials viâ Uganda or Karagwé to Zanzibar, but shall remain myself with my black troops at Kabba-Rege's until the Government inform me as to their wishes."

This is very clear that Emin Pasha at this time proposed to relieve himself of the Egyptian officials, and that he himself only intended to remain until the Egyptian Government could communicate to him its wishes. Those "wishes" were that he should abandon his province, as they were unable to maintain it, and take advantage of the escort to leave Africa.

In a letter written to Mr. Mackay dated July 6th, 1886, Emin says:—

"In the first place believe me that I am in no hurry to break away from here, or to leave those countries in which I have now laboured for ten years."

"All my people, but especially the negro troops, entertain a strong objection against a march to the south and thence to Egypt, and mean to remain here until they can be taken north. Meantime, if no danger overtakes us, and our ammunition holds out for sometime longer, I mean to follow your advice and remain here until help comes to us from some quarter. At all events, you may rest assured that we will occasion no disturbance to you in Uganda."

"I shall determine on a march to the coast only in a case of dire necessity. There are, moreover, two other routes before me. One from Kabba-Rega's direct to Karagwé; the other viâ Usongora to the stations at Tanganika. I hope, however, that I shall have no need to make use of either."

"My people have become impatient through long delay, and are anxiously looking for help at last. It would also be most desirable that some Commissioner came here from Europe, either direct by the Masai route, or from Karagwé viâ Kabba-Rega's country, in order that my people may actually see that there is some interest taken in them. I would defray with ivory all expenses of such a Commission."

"As I once more repeat, I am ready to stay and to hold these countries as long as I can until help comes, and I beseech you to do what you can to hasten the arrival of such assistance. Assure Mwanga that he has nothing to fear from me or my people, and that as an old friend of Mtesa's I have no intention to trouble him."