автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу In Darkest Africa, Vol. 2; or, The Quest, Rescue, and Retreat of Emin, Governor of Equatoria

Every attempt has been made to replicate the original as printed.

Some illustrations have been moved from mid-paragraph for ease of reading.

The

footnotesfollow the text.

In certain versions of this etext, in certain browsers, clicking on this symbol(etext transcriber's note)

COPYRIGHT 1890 BY CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

IN DARKEST AFRICA

OR THE

QUEST, RESCUE, AND RETREAT OF EMIN

GOVERNOR OF EQUATORIA

BY

HENRY M. STANLEY

WITH TWO STEEL ENGRAVINGS, AND ONE HUNDRED AND

FIFTY ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS

IN TWO VOLUMES

Vol. II

“I will not cease to go forward until I come to the place where the two seas meet,

though I travel ninety years.”—Koran, chap. xviii., v. 62.

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1890

[All rights reserved]

Copyright, 1890, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Press of J. J. Little & Co.,

Astor Place, New York.

CONTENTS OF VOLUME II.

CHAPTER XXI.WE START OUR THIRD JOURNEY TO THE NYANZA.

PAGEMr. Bonny and the Zanzibaris—The Zanzibaris’ complaints—Poison of the Manioc—Conversations with Ferajji and Salim—We tell the rear column of the rich plenty of the Nyanza—We wait for Tippu-Tib at Bungangeta Island—Muster of our second journey to the Albert—Mr. Jameson’s letter from Stanley Falls dated August 12th—The flotilla of canoes starts—The Mariri Rapids—Ugarrowwa and Salim bin Mohammed visit me—Tippu-Tib, Major Barttelot and the carriers—Salim bin Mohammed—My answer to Tippu-Tib—Salim and the Manyuema—The settlement of the Batundu—Small-pox among the Madi carriers and the Manyuema—Two insane women—Two more Zanzibari raiders slain—Breach of promises in the Expedition—The Ababua tribe—Wasp Rapids—Ten of our men killed and eaten by natives—Canoe accident at Manginni—Lakki’s raiding party at Mambanga—Feruzi and the bush antelope—Our cook, Jabu, shot dead by a poisoned arrow—Panga Falls—Further casualties by the natives—Nejambi Rapids—The poisoned arrows—Mabengu Rapids—Child-birth on the road—Our sick list—Native affection—A tornado at Little Rapids—Mr. Bonny discovers the village of Bavikai—Remarks about Malaria—Emin Pasha and mosquito curtain—Encounter with the Bavikai natives—A cloud of moths at Hippo Broads—Death of the boy Soudi—Incident at Avaiyabu—Result of vaccinating the Zanzibaris—Zanzibari stung by wasps—Misfortunes at Amiri Rapids—Our casualities—Collecting food prior to march to Avatiko

1 CHAPTER XXII.ARRIVAL AT FORT BODO.

Ugarrowwa’s old station once more—March to Bunda—We cross the Ituri River—Note written by me opposite the mouth of the Lenda River—We reach the Avatiko plantations—Mr. Bonny measures a pigmy—History and dress of the pigmies—A conversation by gesture—The pigmy’s wife—Monkeys and other animals in the forest—The clearing of Andaki—Our tattered clothes—The Ihuru River—Scarcity of food; Amani’s meals—Uledi searches for food—Missing provisions—We reach Kilonga-Longa’s village again—More deaths—The forest improves for travelling—Skirmish near Andikumu—Story of the pigmies and the box of ammunition—We pass Kakwa Hill—Defeat of a caravan—The last of the Somalis—A heavy shower of rain—Welcome food discovery at Indemau—We bridge the Dui River—A rough muster of the people—A stray goat at our Ngwetza camp—Further capture of dwarfs—We send back to Ngwetza for plantains—Loss of my boy Saburi in the forest—We wonder what has become of the Ngwetza party—My boy Saburi turns up—Starvation Camp—We go in search of the absentees, and meet them in the forest—The Ihuru River—And subsequent arrival at Fort Bodo

37 CHAPTER XXIII.THE GREAT CENTRAL AFRICAN FOREST.

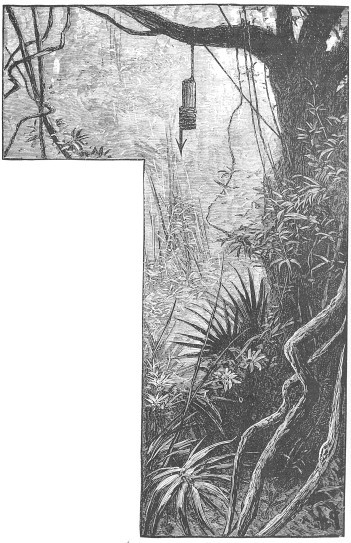

Professor Drummond’s statements respecting Africa—Dimensions of the great forest—Vegetation—Insect life—Description of the trees, &c.—Tribes and their food—The primæval forest—The bush proper—The clearings: wonders of vegetable life—The queer feeling of loneliness—A forest tempest—Tropical vegetation along the banks of the Aruwimi—Wasps’ nests—The forest typical of human life—A few secrets of the woods—Game in the forest—Reasons why we did not hunt the animals—Birds—The Simian tribe—Reptiles and insects—The small bees and the beetles—The “jigger”—Night disturbances by falling trees, &c.—The Chimpanzee—The rainiest zone of the earth—The Ituri or Upper Aruwimi—The different tribes and their languages—Their features and customs—Their complexion—Conversation with some captives at Engweddé—The Wambutti dwarfs: their dwellings and mode of living—The Batwa dwarfs—Life in the forest villages—Two Egyptians captured by the dwarfs at Fort Bodo—The poisons used for the arrows—Our treatment for wounds by the arrows—The wild fruits of the forest—Domestic animals—Ailments of the Madis and Zanzibaris—The Congo Railway and the forest products

73 CHAPTER XXIV.IMPRISONMENT OF EMIN PASHA AND MR. JEPHSON.

Our reception at Fort Bodo—Lieut. Stairs’ report of what took place at the Fort during our relief of the rear column—No news of Jephson—Muster of our men—We burn the Fort and advance to find Emin and Jephson—Camp at Kandekoré—Parting words to Lieut. Stairs and Surgeon Parke, who are left in charge of the sick—Mazamboni gives us news of Emin and Jephson—Old Gavira escorts us—Two Wahuma messengers bring letters from Emin and Jephson—Their contents—My replies to the same handed to Chief Mogo for delivery—The Balegga attack us, but, with the help of the Bavira, are repulsed—Mr. Jephson turns up—We talk of Emin—Jephson’s report bearing upon the revolt of the troops of Equatoria, also his views respecting the invasion of the province by the Mahdists, and its results—Emin Pasha sends through Mr. Jephson an answer to my last letter

112 CHAPTER XXV.EMIN PASHA AND HIS OFFICERS REACH OUR CAMP AT KAVALLI.

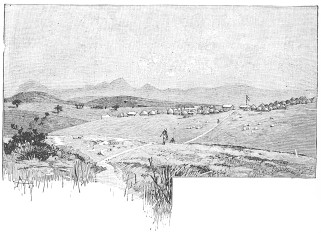

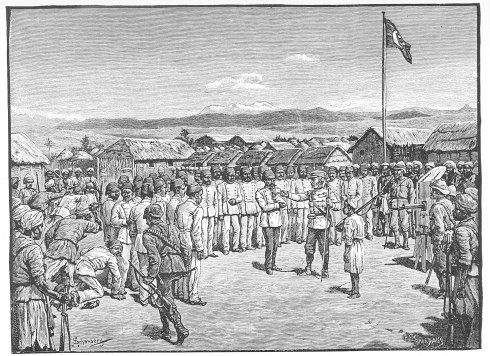

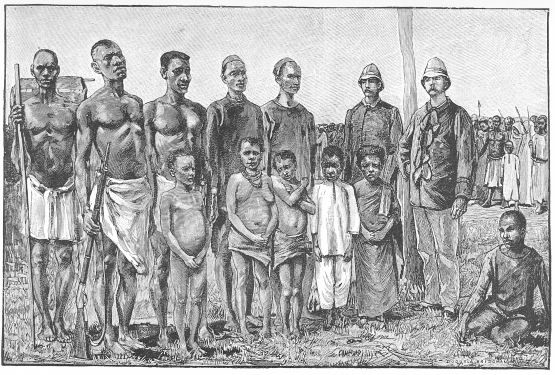

Lieut. Stairs and his caravan are sent for—Plans regarding the release of Emin from Tunguru—Conversations with Jephson by which I acquire a pretty correct idea of the state of affairs—The rebel officers at Wadelai—They release Emin, and proceed in the s.s. Khedive and Nyanza to our camp at Kavalli—Emin Pasha’s arrival—Stairs and his caravan arrive at Mazamboni’s—Characteristic letter from Jephson, who is sent to bring Emin and his officers from the Lake to Kavalli—Short note from the Pasha—Arrival of Emin Pasha’s caravan—We make a grand display outside our camp—At the grand divan: Selim Bey—Stairs’ column rolls into camp with piles of wealth—Mr. Bonny despatched to the Nyanza to bring up baggage—Text of my message to the rest of the revolted officers at Wadelai—Note from Mr. Bonny—The Greek merchant, Signor Marco, arrives—Suicide of Zanzibari named Mrima—Neighbouring chiefs supply us with carriers—Captain Nelson brings in Emin’s baggage—Arrangements with the chiefs from the Ituri River to the Nyanza—The chief Kabba-Rega—Emin Pasha’s daughter—Selim Bey receives a letter from Fadl-el-Mulla—The Pasha appointed naturalist and meteorologist to the Expedition—The Pasha a Materialist—Dr. Hassan’s arrival—My inspection over the camp—Capt. Casati arrives—Mr. Bonny appears with Awash Effendi and his baggage—The rarest doctor in the world—Discovery of some chimpanzees—The Pasha in his vocation of “collecting”—Measurements of the dwarfs—Why I differ with Emin in the judgment of his men—Various journeys from the camp to the Lake for men and baggage—The Zanzibaris’ complaints of the ringleaders—Hassan Bakari—The Egyptian officers—Interview with Shukri Agha—The flora on the Baregga Hills—The chief of Usiri joins our confederacy—Conversation with Emin regarding Selim Bey and Shukri Agha—Address by me to Stairs, Nelson, Jephson and Parke before Emin Pasha—Their replies—Notices to Selim Bey and Shukri Agha

139 CHAPTER XXVI.WE START HOMEWARD FOR ZANZIBAR.

False reports of strangers at Mazamboni’s—Some of the Pasha’s ivory—Osman Latif Effendi gives me his opinions on the Wadelai officers—My boy Sali as spy in the camp—Capt. Casati’s views of Emin’s departure from his province—Lieut. Stairs makes the first move homeward—Weights of my officers at various places—Ruwenzori visible—The little girl reared by Casati—I act as mediator between Mohammed Effendi, his wife, and Emin—Bilal and Serour—Attempts to steal rifles from the Zanzibari’s huts—We hear of disorder and distress at Wadelai and Mswa—Two propositions made to Emin Pasha—Signal for general muster under arms sounded—Emin’s Arabs are driven to muster by the Zanzibaris—Address to the Egyptians and Soudanese—Lieut. Stairs brings the Pasha’s servants into the square—Serour and three others, being the principal conspirators, placed under guard—Muster of Emin Pasha’s followers—Osman Latif Effendi and his mother—Casati and Emin not on speaking terms—Preparing for the march—Fight with clubs between the Nubian, Omar, and the Zanzibaris—My judgments on the combatants—We leave Kavalli for Zanzibar—The number of our column—Halt in Mazamboni’s territory—I am taken ill with inflammation of the stomach—Dr. Parke’s skilful nursing—I plan in my mind the homeward march—Frequent reports to me of plots in the camp—Lieut. Stairs and forty men capture Rehan and twenty-two deserters who left with our rifles—At a holding of the court it is agreed to hang Rehan—Illness of Surgeon Parke and Mr. Jephson—A packet of letters intended for Wadelai falls into my hands, and from which we learn of an important plot concocted by Emin’s officers—Conversation with Emin Pasha about the same—Shukri Agha arrives in our camp with two followers—Lieut. Stairs buries some ammunition—We continue our march and camp at Bunyambiri—Mazamboni’s services and hospitality—Three soldiers appear with letters from Selim Bey—Their contents—Conversation with the soldiers—They take a letter to Selim Bey from Emin—Ali Effendi and his servants accompany the soldiers back to Selim Bey

182 CHAPTER XXVII.EMIN PASHA—A STUDY.

The Relief of David Livingstone compared with the Relief of Emin Pasha—Outline of the journey of the Expedition to the first meeting with Emin—Some few points relating to Emin on which we had been misinformed—Our high conception of Emin Pasha—Loyalty of the troops, and Emin’s extreme indecision—Surprise at finding Emin a prisoner on our third return to the Nyanza—What might have been averted by the exercise of a little frankness and less reticence on Emin’s part—Emin’s virtues and noble desires—The Pasha from our point of view—Emin’s rank and position in Khartoum, and gradual rise to Governor of Equatoria—Gordon’s trouble in the Soudan—Emin’s consideration and patience—After 1883 Emin left to his own resources—Emin’s small explorations—Correctness of what the Emperor Hadrian wrote of the Egyptians—The story of Emin’s struggles with the Mahdi’s forces from 1883 to 1885—Dr. Junker takes Emin’s despatches to Zanzibar in 1886—Kabba Rega a declared enemy of Emin—The true position of Emin Pasha prior to his relief by us, showing that good government was impossible—Two documents (one from Osman Digna, and the other from Omar Saleh) received from Sir Francis Grenfell, the Sirdar

228 CHAPTER XXVIII.TO THE ALBERT EDWARD NYANZA.

Description of the road from Bundegunda—We get a good view of the twin peaks in the Ruwenzori range—March to Utinda—The Pasha’s officers abuse the officer in command: which compels a severe order—Kaibuga urges hostilities against Uhobo—Brush with the enemy: Casati’s servant, Akili, killed—Description of the Ruwenzori range as seen from Mboga—Mr. Jephson still an invalid—The little stowaway named Tukabi—Captain Nelson examines the Semliki for a suitable ferry—We reach the Semliki river: description of the same—Uledi and Saat Tato swim across the river for a canoe—A band of Wara Sura attack us—All safely ferried across the river—In the Awamba forest—Our progress to Baki-kundi—We come across a few Baundwé, forest aborigines—the Egyptians and their followers—Conversation with Emin Pasha—Unexplored parts of Africa—Abundance of food—Ruwenzori from the spur of Ugarama—Two native women give us local information—We find an old man at Batuma—At Bukoko we encounter some Manyuema raiders: their explanation—From Bakokoro we arrive at Mtarega, the foot of the Ruwenzori range—Lieutenant Stairs with some men explore the Mountains of the Moon—Report of Lieutenant Stairs’ experiences—The Semliki valley—The Rami-lulu valley—The perfection of a tropical forest—Villages in the clearing of Ulegga—Submission of a Ukonju chief—Local knowledge from our friends the Wakonju—Description of the Wakonju tribe—The Semliki river—View of Ruwenzori from Mtsora—We enter Muhamba, and next day camp at Karimi—Capture of some fat cattle of Rukara’s—the Zeriba of Rusessé—Our first view of Lake Albert Edward Nyanza

250 CHAPTER XXIX.THE SOURCES OF THE NILE—THE MOUNTAINS OF THE MOON, AND THE FOUNTAINS OF THE NILE.

Père Jerome Lobo and the Nile—The chartographers of Homer’s time—Hekatæus’s ideas of Africa—Africa after Hipparchus—The great Ptolemy’s map—Edrisi’s map—Map of the Margarita Philosophica—Map of John Ruysch—Sylvannus’ map—Sebastian Cabot’s map—The arbitrariness of the modern map maker—Map of Constable, Edinburgh—What Hugh Murray says in his book published in 1818—A fine dissertation on the Nile by Father Lobo—Extracts from part of a MS. in the possession of H. E. Ali Pasha Moubarek—Plan of Mount Gumr—A good description of Africa by Scheabeddin—The Nile according to Abdul Hassen Ali—Abu Abd Allah Mohammed on the Nile river

291 CHAPTER XXX.RUWENZORI: THE CLOUD KING.

Recent travellers who have failed to see this range—Its classical history—The range of mountains viewed from Pisgah by us in 1887—The twin cones and snowy mountain viewed by us in 1888 and January 1889—Description of the range—The Semliki valley—A fair figurative description of Ruwenzori—The principal drainage of the snowy range—The luxurious productive region known as Awamba forest or the Semliki valley—Shelter from the winds—Curious novelties in plants in Awamba forest—The plains between Mtsora and Muhamba—Changes of climate and vegetation on nearing the hills constituting the southern flank of Ruwenzori—The north-west and west side of Ruwenzori—Emotions raised in us at the sight of Ruwenzori—The reason why so much snow is retained on Ruwenzori—The ascending fields of snow and great tracts of débris—Brief views of the superb Rain Creator or Cloud King—Impression made on all of us by the skyey crests and snowy breasts of Ruwenzori

313 CHAPTER XXXI.RUWENZORI AND LAKE ALBERT EDWARD.

Importance of maps in books of travels—The time spent over my maps—The dry bed of a lake discovered near Karimi; its computed size—Lessons acquired in this wonderful region—What we learn by observation from the Semliki valley to the basin of the twin lakes—Extensive plain between Rusessé and Katwé—The Zeribas of euphorbia of Wasongora—The raid of the Waganda made eighteen years ago—The grass and water on the wide expanses of flats—The last view and southern face of Ruwenzori—The town of Katwé—The Albert Edward Nyanza—Analysis of the brine obtained from the Salt Lake at Katwé—Surroundings of the Salt Lake—The blood tints of its waters—The larger Salt Lake of Katwé, sometimes called Lake of Mkiyo—The great repute of the Katwé salt—The Lakists of the Albert Edward—Bevwa, on our behalf, makes friends with the natives—Kakuri appears with some Wasongora chiefs—Exploration of the large Katwé lake—Kaiyura’s settlement—Katwé Bay—A black leopard—The native huts at Mukungu—We round an arm of the lake called Beatrice Gulf, and halt at Muhokya—Ambuscade by some of the Wara-Sura, near the Rukoki: we put them to flight—And capture a Mhuma woman—Captain Nelson and men follow up the rear guard of Rukara—Halt at Buruli: our Wakonju and Wasongora friends leave us—Sickness amongst us through bad water—The Nsongi River crossed—Capture of a Wara-Sura—Illness and death among the Egyptians and blacks—Our last engagement with the Wara-Sura at Kavandaré pass—Bulemo-Ruigi places his country at our disposal—The Pasha’s muster roll—Myself and others are smitten down with fever at Katari Settlement—The south side of Lake Albert Edward and rivers feeding the Lake—Our first and last view, also colour of the Lake—What we might have seen if the day had been clearer

334 CHAPTER XXXII.THROUGH ANKORI TO THE ALEXANDRA NILE.

The routes to the sea, viâ Uganda, through Ankori, to Ruanda and thence to Tanganika—We decide on the Ankori route—We halt at Kitété, and are welcomed in the name of King Antari—Entertained by Masakuma and his women—A glad message from King Antari’s mother—Two Waganda Christians, named Samuel and Zachariah, appear in camp: Zachariah relates a narrative of astounding events which had occurred in Uganda—Mwanga, King of Uganda; his behaviour—Our people recovering from the fever epidemic—March up the valley between Iwanda and Denny Range—We camp at Wamaganga—Its inhabitants—The Rwizi River crossed—Present from the king’s mother—The feelings of the natives provoked by scandalous practices of some of my men—An incident illustrating the different views men take of things—Halt at the valley of Rusussu—Extract from my diary—We continue our journey down Namianja Valley—The peaceful natives turn on us, but are punished by Prince Uchunku’s men—I go through the rite of blood-brotherhood with Prince Uchunku—The Prince’s wonder at the Maxim gun—A second deputation from the Waganda Christians: my long cross-examination of them: extract from my journal—My answer to the Christians—We enter the valley of Mavona—And come in sight of the Alexandra Valley—The Alexandra Nile

358 CHAPTER XXXIII.THE TRIBES OF THE GRASS-LAND.

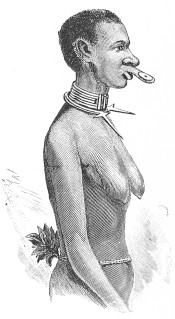

The Wahuma: the exact opposite of the Dwarfs: their descendants—Tribes nearly allied to the true negro type—Tribes of the Nilotic basin—The Herdsmen—The traditions of Unyoro—My experiences of the Wahuma gained while at Kavalli—View of the surrounding country from Kavalli camp—Chiefs Kavalli, Katto, and Gavira, unbosom their wrongs to me—Old Ruguji’s reminiscences—The pasture-land lying between Lake Albert and the forest—The cattle in the district round Kavalli: their milk-yield—Three cases referring to cattle which I am called upon to adjudicate—Household duties of the women—Dress among the Wahuma—Old Egyptian and Ethiopian characteristics preserved among the tribes of the grass-land—Customs, habits, and religion of the tribes—Poor Gaddo suspected of conspiracy against his chief, Kavalli: his death—Diet of the Wahuma—The climate of the region of the grass-land

384 CHAPTER XXXIV.TO THE ENGLISH MISSION STATION, SOUTH END OF VICTORIA NYANZA.

Ankori and Karagwé under two aspects—Karagwé; and the Alexandra Nile—Mtagata Hot Springs—A baby rhinoceros, captured by the Nubians, shows fight in camp—Disappearance of Wadi Asmani—The Pasha’s opinion of Capt. Casati—Surgeon Parke and the pigmy damsel—Conduct of a boy pigmy—Kibbo-bora loses his wife at the Hot Springs—Arrival at Kufurro—Recent kings of Karagwé—Kiengo and Captain Nelson’s resemblance to “Speke”—The King of Uganda greatly dreaded in Karagwé—Ndagara refuses to let our sick stay in his country—Camp at Uthenga: loss of men through the cold—We throw superfluous articles in Lake Urigi in order to carry the sick—We enter the district of Ihangiro: henceforward our food has to be purchased—the Lake of Urigi—At the village of Mutara, Fath-el-Mullah runs amuck with the natives, and is delivered over to them—The Unyamatundu plateau—Halt at Ngoti: Mwengi their chief—Kajumba’s territory—We obtain a good view of Lake Victoria—The country round Kisaho—Lions and human skulls in the vicinity of our camp—The events of 1888 cleared our track for a peaceful march to the sea—We reach Amranda and Bwanga—The French missionaries and their stations at Usambiro—Arrival at Mr. Mackay’s, the English Mission station—Mr. Mackay and his books—We rest, and replenish our stores, etc.—Messrs. Mackay and Deakes give us a sumptuous dinner previous to our departure—The last letter from Mr. A. M. Mackay, dated January 5, 1890

404 CHAPTER XXXV.FROM THE VICTORIA NYANZA TO ZANZIBAR.

Missionary work along the shores of the Victoria Nyanza and along the Congo river—The road from Mackay’s Mission—The country at Gengé—Considerable difficulty at preserving the peace at Kungu—Rupture of peace at Ikoma—Capture and release of Monangwa—The Wasukuma warriors attack us, but finally retire—Treachery—The natives follow us from Nera to Seké—We enter the district of Sinyanga; friendship between the natives and our men—Continued aggression of the natives—Heavy tributes—Massacre of caravan—The district of Usongo, and its chief Mittinginya—His surroundings and neighbours—Two French missionaries overtake us—Human skulls at Ikungu—We meet one of Tippu-Tib’s caravans from Zanzibar—Troubled Ugogo—Lieutenant Schmidt welcomes us at the German station of Mpwapwa—Emin Pasha visits the Pères of the French Mission of San Esprit—The Fathers unacquainted with Emin’s repute—Our mails in Africa continually going astray—Contents of some newspaper clippings—Baron von Gravenreuth and others meet us at Msua—Arrival of an Expedition with European provisions, clothing and boots for us—Major Wissman—He and Schmidt take Emin and myself on to Bagamoyo—Dinner and guests at the German officer’s mess house—Major Wissman proposes the healths of the guests; Emin’s and my reply to the same—Emin’s accident—I visit Emin in the hospital—Surgeon Parke’s report—The feeling at Bagamoyo—Embark for Zanzibar—Parting words with Emin Pasha—Illness of Doctor Parke—Emin Pasha enters the service of the German Government—Emin Pasha’s letter to Sir John Kirk—Sudden termination of Emin’s acquaintance with me—Three occasions when I apparently offended Emin—Emin’s fears that he would be unemployed—The British East African Company and Emin—Courtesy and hospitality at Zanzibar—Monies due to the survivors of the Relief Expedition—Tippu-Tib’s agent at Zanzibar, Jaffar Tarya—The Consular Judge grants me an injunction against Jaffar Tarya—At Cairo—Conclusion

432 APPENDICES.

A.—

Congratulations by Cable received at Zanzibar 481 B.—

Comparative Tables of Forest and Grass-land Languages 490 C.—

Itinerary of the Journeys made in 1887, 1888, 1889 496 D.—

Balance Sheet, &c., of the Relief Expedition 513 General Index 515LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

VOLUME II.

STEEL ENGRAVING.

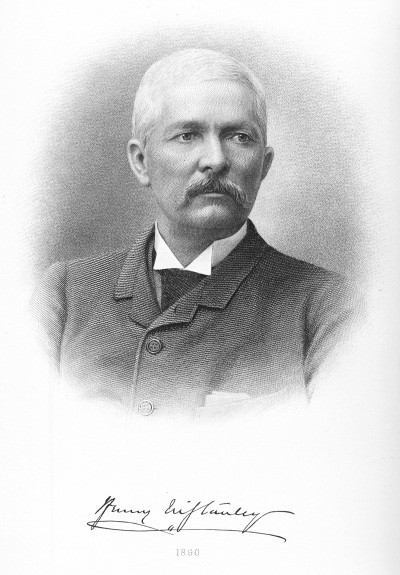

Portrait of Henry M. Stanley Frontispiece.

(From a Photograph taken at Cairo, March, 1890.)

FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS.

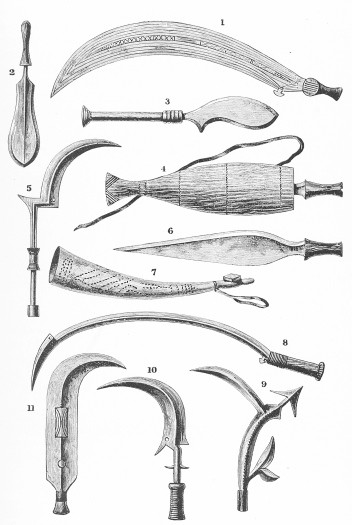

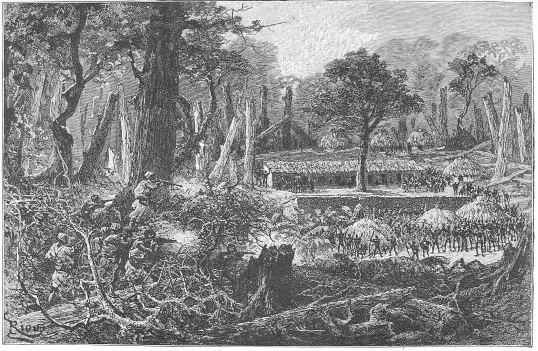

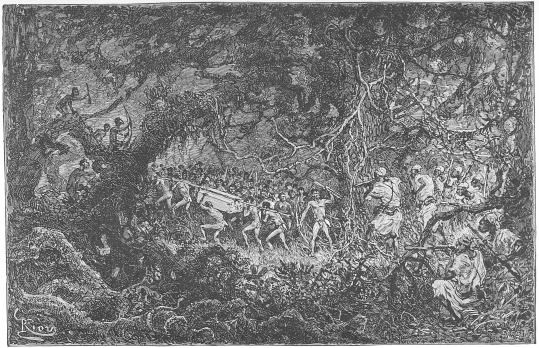

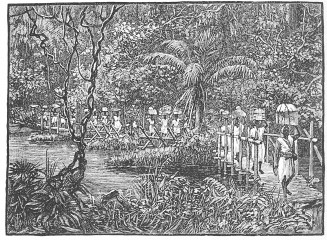

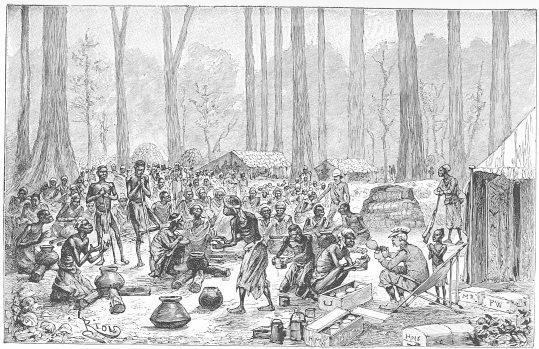

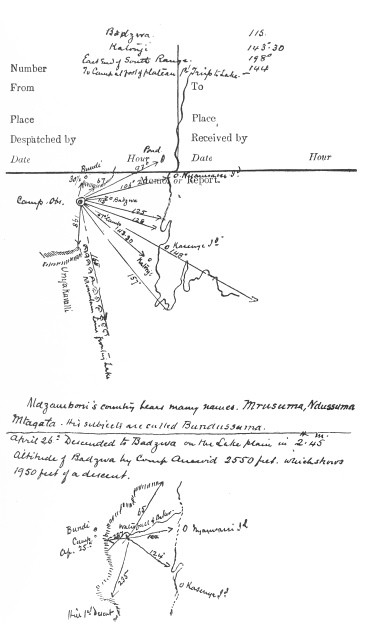

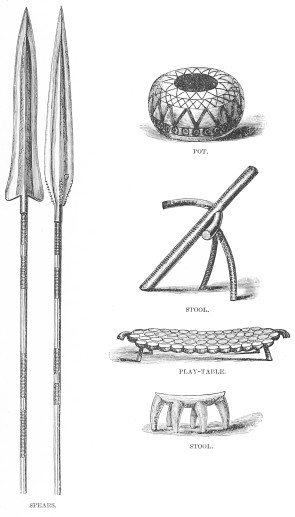

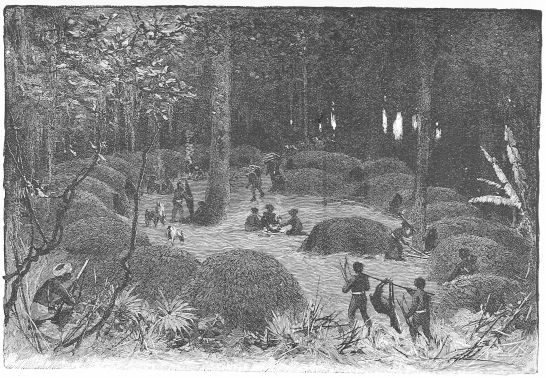

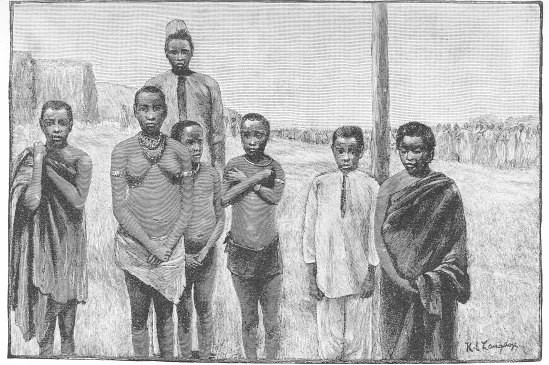

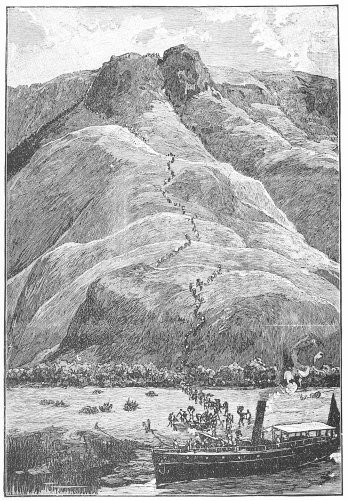

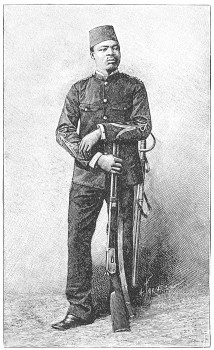

Facingpage Swords and Knives of the Ababua 22 Entering Andikumu 50 The Scouts Discover the Pigmies Carrying away the Case of Ammunition 54 Starvation Camp: Serving out Milk and Butter for Broth 66 A Page from Mr. Stanley’s Note-Book—Sketch-Maps 94 The Pigmies at Home—A Zanzibar Scout Taking Notes 104 Address to Rebel Officers at Kavalli 148 The Pigmies as Compared with the English Officers, Soudanese, and Zanzibaris 152 The Pigmies under the Lens, as Compared to Captain Casati’s Servant Okili 164 Climbing the Plateau Slopes 170 Rescued Egyptians and Their Families 220 Ruwenzori, from Kavalli’s 252 Ruwenzori, from Mtsora 286 Bird’s-Eye View of Ruwenzori, Lake Albert Edward, and Lake Albert 318 Ruwenzori, from Karimi 328 Expedition Winding up the Gorge of Karya-Muhoro 362 A Page from Mr. Stanley’s Note-Book—Musical Instruments 396 Weapons of the Balegga and Wahuma Tribes 400 Baby Rhinoceros Showing Fight in Camp 406 South-West Extremity of Lake Victoria Nyanza 419 Stanley, Emin, and Officers at Usambiro 425 Experiences in Usukuma 438 Banquet at Msua 450 Under the Palms at Bagamoyo 454 The Relief Expedition Returning to Zanzibar 462 The Faithfuls at Zanzibar 474

OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS.

A Swimming Race after a Bush Antelope 25 Dwarf Captive at Avitako 41 Bridging the Dui River 60 Two-Edged Spears 99 Play-Table 99 Back-Rest and Stool 99 Decorated Earthen Pot 99 Arrows of the Dwarfs 101 Elephant Trap 102 A Belle of Bavira 130 View of Camp at Kavalli 140 Shukri Agha, Commandant of Mswa Station 173 Sali, Head-Boy 185 An Ancient Egyptian Lady 207 Attack by the Wanyoro at Semliki Ferry 260 Houses on the Edge of the Forest 264 Egyptian Women and Children 266 The Tallest Peak of Ruwenzori, from Awamba Forest 274 South-West Twin Cones of Ruwenzori—Sketch. By Lieut. Stairs 278 [1]Africa in Homer’s World 293 “ Map of Hekatæus 294 “ Hipparchus, 100 b.c. 295 Ptolemy’s Map of Africa, a.d. 150 295 Central Africa according to Edrisi, a.d. 1154 296 Map of the Margarita Philosophica, a.d. 1503 296 “ John Ruysch, a.d. 1508 297 Map, Sylvanus', a.d. 1511 297 Hieronimus de Verrazano’s Map, a.d. 1529 298 Sebastian Cabot’s Map of the World, 16th Century 298 The Nile’s Sources According to Geographers of the 16th and 17th Centuries 299 Map of the Nile Basin, a.d. 1819 301 Mountains of the Moon—Massoudi, 11th Century 308 Map of Nile Basin to-day from the Mediterranean to S. Lat. 4° 311 View of Ruwenzori from Bakokoro Western Cones 326 The Little Salt Lake at Katwé 342 Section of a House near Lake Albert Nyanza 348 A Village in Ankori 361 Expedition Climbing the Rock in the Valley of Ankori 362 Musical Instruments of the Balegga 399 A Hot Spring, Mtagata 406 Lake Urigi 415 View from Mackay’s Mission, Lake Victoria 428 Rock Hills, Usambiro 437 House and Balcony from which Emin Fell 454 Sketch of Casket containing the Freedom of the City of London 488 Sketch of Casket, the Gift of King Leopold 489MAPS.

A Map of the Route of the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition through Africa. In Pocket. A Map of Emin Pasha’s Province. In Pocket. Profile Sketch of Ruwenzori and the Valley of the Semliki. Facing page 335FOOTNOTES:

On the afternoon of the 21st I was gratified to see that the people had been very successful. How many had followed my advice it was impossible to state. The messes had sent half their numbers to gather the food, and every man had to contribute two handfuls for the officers and sick. It only remained now for the chiefs of the messes to be economical of the food, and the dreaded wilderness might be safely crossed.

On the 20th we cut a track through the deserted plantations, and after an hour’s hard work reached our well-known road, which had been so often patrolled by us. We soon discovered traces of recent travel, and late foraging in piles of plantain skins near the track; but we could not discover by whom these were made. Probably the natives had retired to their settlements; perhaps the dwarfs were now banqueting on the fat of the land. We approached the end of our broad western military road, and at the turning met some Zanzibari patrols who were as much astonished as we were ourselves at the sudden encounter. Volley after volley soon rang through the silence of the clearing. The fort soon responded, and a stream of frantic men, wild with joy, advanced by leaps and bounds to meet us; and among the first was my dear friend the Doctor, who announced, with eyes dancing with pleasure, “All is well at Fort Bodo.”

Respecting the productions of the forest I have written at such length in “The Congo and the Founding of its Free State” that it is unnecessary to add any more here. I will only say that when the Congo Railway has been constructed, the products of the great forest will not be the least valuable of the exports of the Congo Independent State. The natives, beginning at Yambuya, will easily be induced to collect the rubber, and when one sensible European has succeeded in teaching them what the countless vines, creepers, and tendrils of their forest can produce, it will not be long before other competitors will invade the silent river, and invoke the aid of other tribes to follow the example of the Baburu.

I am, Sir,

Your obedient servant,

(Signed) Dr. Emin Pasha.

The guides promised to this dilatory and obtuse Soudanese colonel were despatched, according to promise, with a letter from the Pasha; and though we loitered, and halted, and made short journeys of between one and three hours’ march for a month longer, this was the last communication we had with Selim Bey. What became of him we never discovered, and it is useless to try to conjecture. He was one of those men with whom it was impossible to reason, and upon whose understanding sense has no effect. He was not wicked nor designing, but so stupid that he could only comprehend an order when followed by a menace and weighted with force; but to a man of his rank and native courage, no such order could be given. He was therefore abandoned as a man whom it was impossible to persuade, and still less compel.

On the 16th June, after a long march of four and three-quarter hours, we arrived at the zeriba of Rusessé. We descended from Karimi about 700 feet to the plain of Eastern Usongora, and an hour later we came to Ruverahi River, 40 feet wide, and a foot deep; an ice-cold stream, clear as crystal and fresh from the snows. Ruwenzori was all the morning in sight, a bright vision of mountain beauty and glory. As we approached Rusessé a Msongora herdsman, in the employ of Rukara, the General of the Wara-Sura, came across the plain, and informed us that he could direct us to one of Rukara’s herds. We availed ourselves of his kind offices, which he was performing as a patriot son of the soil tyrannised over and devastated by Rukara; and fifty rifles were sent with him, and in fifteen minutes we were in possession of a fine herd of twenty-five fat cattle, which we drove without incident with our one hundred head to the zeriba of Rusessé. From a bank of cattle-dung, so high as to be like a great earthwork round about the village, we gained our first view of the Albert Edward Nyanza, at a distance of three miles.

These brief—too brief—views of the superb Rain-Creator or Cloud-King, as the Wakonju fondly termed their mist-shrouded mountains, fill the gazer with a feeling as though a glimpse of celestial splendour was obtained. While it lasted, I have observed the rapt faces of whites and blacks set fixed and uplifted in speechless wonder towards that upper region of cold brightness and perfect peace, so high above mortal reach, so holily tranquil and restful, of such immaculate and stainless purity, that thought and desire of expression were altogether too deep for utterance. What stranger contrast could there be than our own nether world of torrid temperature, eternally green sappy plants, and never-fading luxuriance and verdure, with its savagery and war-alarms, and deep stains of blood-red sin, to that lofty mountain king, clad in its pure white raiment of snow, surrounded by myriads of dark mountains, low as bending worshippers before the throne of a monarch, on whose cold white face were inscribed “Infinity and Everlasting!” These moments of supreme feeling are memorable for the utter abstraction of the mind from all that is sordid and ignoble, and its utter absorption in the presence of unreachable loftiness, indescribable majesty, and constraining it not only to reverentially admire, but to adore in silence, the image of the Eternal. Never can a man be so fit for Heaven as during such moments, for however scornful and insolent he may have been at other times, he now has become as a little child, filled with wonder and reverence before what he has conceived to be sublime and Divine. We had been strangers for many months to the indulgence of any thought of this character. Our senses, between the hours of sleeping and waking, had been occupied by the imperious and imminent necessities of each hour, which required unrelaxing vigilance and forethought. It is true we had been touched with the view from the mount called Pisgah of that universal extent of forest, spreading out on all sides but one, to many hundreds of miles; we had been elated into hysteria when, after five months’ immurement in the depths of forest wilds, we once again trod upon green grass, and enjoyed open and unlimited views of our surroundings—luxuriant vales, varying hill-forms on all sides, rolling plains over which the long spring grass seemed to race and leap in gladness before the cooling gale; we had admired the broad sweep and the silvered face of Lake Albert, and enjoyed a period of intense rejoicing when we knew we had reached, after infinite trials, the bourne and limit of our journeyings; but the desire and involuntary act of worship were never provoked, nor the emotions stirred so deeply, as when we suddenly looked up and beheld the skyey crests and snowy breasts of Ruwenzori uplifted into an inaccessible altitude, so like what our conceptions might be of a celestial castle, with dominating battlement, and leagues upon leagues of unscaleable walls.

But alas! alas! In vain we turned our yearning eyes and longing looks in their direction. The Mountains of the Moon lay ever slumbering in their cloudy tents, and the lake which gave birth to the Albertine Nile remained ever brooding under the impenetrable and loveless mist.

The Alexandra Nile at this place was about 125 yards wide, and an average depth of nine feet, flowing three knots per hour in the centre.

The climate of the region is agreeable. Five hours’ work per day can be performed, even out-door, without discomfort from excessive heat, and three days out of seven during the whole of daylight, because of the frequent clouded state of the sky. When, however, the sky is exposed, the sun shines with a burning fervour that makes men seek the shelter of their cool huts. The higher portions of the grass-land—as at Kavalli’s, in the Balegga Hills, and on the summit of the Ankori pastoral ranges—range from 4,500 to 6,500 feet above the sea, and large extents of Toro and Southern Unyoro as high as 10,000, and promise to be agreeable lands for European settlers when means are provided to convey them there. When that time arrives they will find amiable, quiet, and friendly neighbours in that fine-featured race, of which the best type are the Wahuma, with whom we have never exchanged angry words, and who bring up vividly to the mind the traits of those blameless people with whom the gods deigned to banquet once a year upon the heights of Ethiopia.

To my great grief, I learn that Mr. Mackay, the best missionary since Livingstone, died about the beginning of February. Like Livingstone, he declined to return, though I strongly urged him to accompany us to the coast.

The Thanks be to God for ever and ever. Amen.

The design of the casket is Arabesque, and it stands upon a base of Algerine onyx, surmounted by a plinth of ebony, the corners of which project and are rounded. On each of these, at the angle of the casket, stands an ostrich carved in ivory; behind each bird and curving over it projects an elephant’s tusk, which is looped to three spears placed in the panelled angle of the casket, the pillars of which are of crocidolite, resting in basal sockets of gold, and surmounted by capitals of the same metal. The panels of the casket and also the roof are of ivory richly overlaid with ornamental work in fine gold of various colours. The back panel bears the City arms emblazoned in the proper heraldic colours. Of the end panels, one bears the tricoloured monogram “H.M.S.” surrounded by a wreath-emblem of victory, and the other that of the Lord Mayor of London. The front panel, which is also the door of the casket, bears a miniature map of Africa surmounting the tablet bearing the inscription: “Presented to Henry Morton Stanley with the freedom of the City.” Above both the front and back panels on the roof are the standards of America and Great Britain, and, surmounting the whole, on an oval platform is an allegorical figure of the Congo Free State, seated by the source of the river from which it derives its name, and holding the horn of plenty, which is overflowing with native products. The design was selected from among a large number submitted by the leading London goldsmiths, and reflects great credit upon the taste and workmanship of the designers and makers, Messrs. George Edward & Son, Glasgow, and Poultry, London.

But any person who has travelled with the writer thus far will have observed that almost every fatal accident hitherto in this Expedition has been the consequence of a breach of promise. How to adhere to a promise seems to me to be the most difficult of all tasks for every 999,999 men out of every million whom I meet. I confess that these black people who broke their promises so wantonly were the bane of my life, and the cause of continued mental disquietude, and that I condemned them to their own hearing as supremest idiots. Indeed, I have been able to drive from one to three hundred cattle a five hundred mile journey with less trouble and anxiety than as many black men. If we had strung them neck and neck along a lengthy slave-chain they would certainly have suffered a little inconvenience, but then they themselves would be the first to accuse us of cruelty. Not possessing chains, or even rope enough, we had to rely on their promises that they would not break out of camp into the bush on these mad individual enterprises, which invariably resulted in death, but never a promise was kept longer than two days.

On the 12th, we followed a track, along which quite a tribe of pigmies must have passed. It was lined with amoma fruit-skins, and shells of nuts, and the crimson rinds of phrynia berries. No wood-beans, or fenessi, or mabungu, are to be found in this region, as on the south bank of Ituri River. On reaching camp, I found that at the ferry, near the native camp at which we starved four days, six people had succumbed—a Madi, from a poisonous fungus, the Lado soldier, who was speared above Wasp Rapids, two Soudanese of the rear-column, a Manyuema boy in the service of Mr. Bonny, and Ibrahim, a fine young Zanzibari, from a poisoned skewer in the foot.

Arriving near the spot, they saw quite a tribe of pigmies, men, women and children, gathered around two pigmy warriors, who were trying to test the weight of the box by the grummet at each end. Our headmen, curious to see what they would do with the box, lay hidden closely, for the eyes of the little people are exceedingly sharp. Every member of the tribe seemed to have some device to suggest, and the little boys hopped about on one leg, spanking their hips in irrepressible delight at the find, and the tiny women carrying their tinier babies at their backs vociferated the traditional wise woman’s counsel. Then a doughty man put a light pole, and laid it through the grummets, and all the small people cheered shrilly with joy at the genius displayed by them in inventing a method for heaving along the weighty case of Remington ammunition. The Hercules and the Milo of the tribe put forth their utmost strength, and raised the box up level with their shoulders, and staggered away into the bush. But just then a harmless shot was fired, and the big men rushed forward with loud shouts, and then began a chase; and one over-fat young fellow of about seventeen was captured and brought to our camp as a prize. We saw the little Jack Horner, too fat by many pounds; but the story belongs to the headmen, who delivered it with infinite humour.

On the sixth day we made the broth as usual, a pot of butter and a pot of milk for 130 people, and the headmen and Mr. Bonny were called to council. On proposing a reverse to the foragers of such a nature as to cause an utter loss of all, they appeared unable to comprehend such a possibility, though folly after folly, madness after madness, had marked every day of my acquaintance with them. The departure of men secretly on raids, and never returning, the leaping of fifty men into the river after a bush antelope, the throwing away of their rations after fifteen months’ experiences of the forest, the reckless rush into guarded plantations, skewering their feet, the inattention they paid to abrasions leaving them to develope into rabid ulcers; the sale of their rifles to men who would have enslaved them all, follies practised by blockheads day after day, week after week; and then to say they could not comprehend the possibility of a fearful disaster. Were not 300 men with three officers lost in the wood for six days? Were not three persons lost close to this camp yesterday and they have not returned? Did I not tell these men that we should all die if they were not back on the fourth day? Was not this the sixth day of their absence? Were there not fifty people close to death now? and much else of the same kind?

In 1887 rain fell during eight days in July, ten days in August, fourteen days in September, fifteen days in October, seventeen days in November, and seven days in December, = seventy-one days. From the 1st of June, 1887, to the 31st of May, 1888, there were 138 days, or 569 hours of rain. We could not measure the rain in the forest in any other way than by time. We shall not be far wrong if we estimate this forest to be the rainiest zone on the earth.

The pigmies arrange their dwellings—low structures of the shape of an oval figure cut lengthways; the doors are from two feet to three feet high, placed at the ends—in a rough circle, the centre of which is left cleared for the residence of the chief and his family, and as a common. About 100 yards in advance of the camp, along every track leading out of it, is placed the sentry-house, just large enough for two little men, with the doorway looking up the track. If we assumed that native caravans ever travelled between Ipoto and Ibwiri, for instance, we should imagine, from our knowledge of these forest people, that the caravan would be mulcted of much of its property by these nomads, whom they would meet in front and rear of each settlement, and as there are ten settlements between the two points, they would have to pay toll twenty times, in tobacco, salt, iron, and rattan, cane ornaments, axes, knives, spears, arrows, adzes, rings, &c. We therefore see how utterly impossible it would be for the Ipoto people to have even heard of Ibwiri, owing to the heavy turnpike tolls and octroi duties that would be demanded of them if they ventured to undertake a long journey of eighty miles. It will also be seen why there is such a diversity of dialects, why captives were utterly ignorant of settlements only twenty miles away from them.

Mr. Jephson with your people have arrived yesterday, and we propose to start to-morrow morning; I shall therefore have the pleasure to see you the day after to-morrow. My men are very anxious to hear from your own lips that their foolish behaviour in the past will not prevent you from guiding them.

Well, I said, open your ears that the words of truth may enter. The English people, hearing from your late guest, Dr. Junker, that you were in sore distress here, and sadly in need of ammunition to defend yourselves against the infidels and the followers of the false prophet, have collected money, which they entrusted to me to purchase ammunition, and to convey it to you for your needs. But as I was going through Egypt, the Khedive asked me to say to you, if you so desired you might accompany us, but that if you elected to stay here, you were free to act as you thought best; if you chose the latter, he disclaimed all intention of forcing you in any manner. Therefore you will please consult your own wishes entirely, and speak whatever lies hidden in your hearts.

Each morning his clerk Rajab roams around to murder every winged fowl of the air, and every victim of his aim he brings to his master, and then after lovingly patting the dead object he coolly gives the order to skin it. By night we see it suspended, with a stuffing of cotton within, to be in a day or two packed up as a treasure for the British Museum!

Near sunset, Hassan Bakari having absented himself without permission, was lightly punished with a cane by the captain of his company. On being released, he rushed in a furious temper to his hut, vowing he would shoot himself. He was caught in the act of preparing his rifle for the deed. Five men were required to restrain him. Hearing the news, I proceeded to the scene, and gently asked the reason of this outburst. He declaimed against the shame which had been put on him, as he was a freeman of good family and was not accustomed to be struck like a slave. Remarks appropriate to his wounded feelings were addressed to him, to which he gratefully responded. His rifle was restored to him with a smile. He did not use it.

“But after the 5th of April this method was altered. I should have been wrong were I to separate from you, because I had a proof sufficient for myself and officers that you had no people, neither soldiers nor servants; that you were alone. I proposed then as I propose now; should Selim Bey reach us, not to allow Selim Bey, or one single soldier of his force, to approach my camp with arms. Long before they approach us we shall be in position along the track, and if they do not ground arms at command—why, then the consequences will be on their heads. Thus you see that since the 5th of April I have been rather wishing that they would come. I should like nothing better than to bring this unruly mob to the same state of order and discipline they were in before they became infatuated with Arabi, Mahdism, and chronic rebellion. But if they come here they must first be disarmed; their rifles will be packed up into loads, and carried by us. Their camp shall be at least 500 yards from us. Each march that removes them further from Wadelai will assist us in bringing them into a proper frame of mind, and by-and-by their arms will be restored to them, and they will be useful to themselves as well as to us.”

On the morning of this day, Ruwenzori came out from its mantle of clouds and vapours, and showed its groups of peaks and spiny ridges resplendent with shining white snow; the blue beyond was as that of ocean—a purified and spotless translucence. Far to the west, like huge double epaulettes, rose the twin peaks which I had seen in December, 1887, and from the sunk ridge below the easternmost rose sharply the dominating and unsurpassed heights of Ruwenzori proper, a congregation of hoary heads, brilliant in white raiment; and away to the east extended a roughened ridge, like a great vertebra—peak and saddle, isolated mount and hollow, until it passed out of sight behind the distant extremities of the range we were then skirting. And while in constant view of it, as I sat up in the hide hammock suspended between two men, my plan of our future route was sketched. For to the west of the twin peaks, Ruwenzori range either dropped suddenly into a plain or sheered away S.S.W. What I saw was either an angle of a mass or the western extremity. We would aim for the base of the twin peaks, and pursue our course southerly to lands unknown, along the base-line. The guides—for we had many now—pointed with their spears vaguely, and cried out “Ukonju” and (giving a little dab into the air with their spear-points) “Usongora,” meaning that Ukonju was what we saw, and beyond it lay Usongora, invisible.

From an anthill near Mtsora, I observed that from W.N.W., a mile away, commenced a plain, which was a duplicate of that which had so deceived the Egyptians, and caused them to hail it as their lake, and that it extended southerly, and appeared as though it were the bed of a lake from which the waters had recently receded. The Semliki, which had drained it dry, was now from 50 to 60 feet below the crest of its banks. The slopes, consisting of lacustrine deposits, grey loam, and sand, could offer no resistance to a three-mile current, and if it were not for certain reefs, formed by the bed-rock under the surface of the lacustrine deposit, it is not to be doubted that such a river would soon drain the upper lake. The forest ran across from side to side of the valley, a dark barrier, in very opposite contrast to the bleached grass which the nitrous old bed of the lake nourished.

The average European reader will perfectly understand the character of the Semliki Valley and the flanking ranges, if I were to say that its average breadth is about the distance from Dover to Calais, and that in length it would cover the distance between Dover and Plymouth, or from Dunkirk to St. Malo in France. For the English side we have the Balegga hills and rolling plateau from 3,000 to 3,500 feet above the valley. On the opposite side we have heights ranging from 3,000 to 15,500 feet above it. Now, Ruwenzori occupies about ninety miles of the eastern line of mountains, and projects like an enormous bastion of an unconquerable fortress, commanding on the north-east the approaches by the Albert Nyanza and Semliki Valley, and on its southern side the whole basin of the Albert Edward Lake. To a passenger on board one of the Lake Albert steamers proceeding south, this great bastion, on a clear day, would seem to be a range running east and west; to a traveller from the south it would appear as barring all passage north. To one looking at it from the Balegga, or western plateau, it would appear as if the slowly rising table-land of Unyoro was but the glacis of the mountain range. Its western face appears to be so precipitous as to be unscaleable, and its southern side to be a series of traverses and ridges descending one below the other to the Albert Edward Lake. While its eastern face presents a rugged and more broken aspect, lesser bastions project out of the range, and is further defended by isolated outlying forts like Gordon Bennett Mountain, 14,000 to 15,000 feet high, and the Mackinnon Mountain of similar height. That would be a fair figurative description of Ruwenzori.

Sometimes these ascending fields of snow, by the velocity of their movements, grinding and dragging power, weight and compactness of their bodies, cause extensive landslips, when tracts of wood and bush are borne sheer down, with all the soil which nourished them, to the bed rock, from which it will be evident that enormous masses of material, consisting of boulders, rock fragments, pebbles, gravel, sand trees, plants, and soil, are precipitated from the countless mountain slopes and ravine sides into the valley of the Semliki.

From Kitété a considerable portion of the south-east extremity of Lake Albert Edward appeared in view. We were a thousand feet above it. The sun shone strongly, and for once we obtained about a ten-mile view through the mist. From 312½° to 324° magnetic, the flats below were penetrated with long-reaching inlets of the lake, surrounding numbers of little low islets. To 17½° magnetic rose Nsinda Mountain, 2500 feet above the lake; and behind, at the distance of three miles, rose the range of Kinya-magara; and on the eastern side of a deep valley separating it from the uplands of Ankori rose the western face, precipitous and gray, the frowning walls of the Denny range.

The next case that I had to judge was somewhat difficult. Chief Mpigwa having appeared at the Barza (Durbar), a man stepped up to complain of him, because he withheld two cows that belonged to his tribe. Mpigwa explained that the man had married a girl belonging to his tribe and had paid two cows for her, that she had gone to his house, and in course of time had become a mother, and had borne three children to her husband. The man died, whereupon his tribe accused the woman of having contrived his death by witchcraft, and drove her home to her parents. Mpigwa received her into the tribe with her children, and now the object of complaint was the restoration of the two cows to the husband’s tribe. “Was it fair,” asked Mpigwa, “after a woman had become the mother of three children in the tribe to demand the cattle back again after the husband’s death, when they had sent the woman and her infants away of their own accord?” The decision upheld Mpigwa in his views, as such conduct was not only heartless and mean, but tended to bring the honoured custom of marriage contracts into contempt.

In looking over Wilkinson’s ‘Ancient Egyptians’ the other day I was much struck with the conservative character of the African, for among the engravings I recognize in plate 459 the form of dress most common among the Wahuma, Watusi, Wanyambu, Wahha, Warundi, and Wanyavingi, and which were in vogue thirty-five centuries ago among the black peoples who paid tribute to the Pharaohs. The musical instruments also, such as are figured in plates 135, 136—a specimen of which is in the British Museum—we discovered among the Balegga and Wahuma, and in 1876 among the Basoga. The hafts of knives, the grooves in the blades and their form, the triangular decorations in plaster in their houses, or on their shields, bark clothes, boxes, cooking utensils, and in their weapons, spears, bows, and clubs; in their mundus, which are similar in form to the old pole-axe of the Egyptians, in the curved head-rests, their ivory and wooden spoons; in their eared sandals, which no Mhuma would travel without; in their partiality to certain colours, such as red, black, and yellow; in their baskets for carrying their infants; in their reed flutes; in the long walking-staffs; in the mode of expressing their grief, by wailing, beating their breasts, and their gestures expressive of being inconsolable; in their sad, melancholy songs; and in a hundred other customs and habits, I see that old Egyptian and Ethiopian characteristics are faithfully preserved among the tribes of the grass-land.

We are now in Karagwé. The Alexandra Nile—drawing its waters from Ruanda, Mpororo, to the west; and from north, Uhha; and north-east, Urundi and Kishakka—runs north along the western frontier of Karagwé, and reaching Ankori, turns sharply round to eastward to empty into the Victorian Sea; and as we leave its narrow valley, and ascend gradually upward, along one of those sloping narrow troughs so characteristic of this part of Central Africa, we camp at Unyakatera, below a mountain ridge of that name, and like the view obtained from that summit two score of times repeated, is all Karagwé. It is a system of deep narrow valleys running between long narrow ranges as far as the eye can reach. In the north of Karagwé they are drained by small streams which flow into the Alexandra.

We cut across a broad cape-like formation of land and passed from the bay of Kisaho to a bay near Itari on the 20th, and from the summit of a high ridge near the latter place I perceived by compass bearings and solar observation, that we were much south of the south-west coast line, as marked on my map in “Through the Dark Continent.” From this elevated ridge could be seen the long series of islands overlapping one another, which, in our flight from the ferocious natives of Bumbiré in 1875, without oars, had been left unexplored, and which, therefore, I had sketched as mainland.

I was ushered into the room of a substantial clay structure, the walls about two feet thick, evenly plastered, and garnished with missionary pictures and placards. There were four separate ranges of shelves filled with choice, useful books. “Allah ho Akbar,” replied Hassan, his Zanzibari head-man, to me; “books! Mackay has thousands of books, in the dining-room, bedroom, the church, everywhere. Books! ah, loads upon loads of them!” And while I was sipping real coffee, and eating home-made bread and butter for the first time for thirty months, I thoroughly sympathised with Mackay’s love of books. But it becomes quite clear why, amongst so many books, and children, and outdoor work, Mackay cannot find leisure to brood and become morbid, and think of “drearinesses, wildernesses, despair and loneliness.” A clever writer lately wrote a book about a man who spent much time in Africa, which from beginning to end is a long-drawn wail. It would have cured both writer and hero of all moping to have seen the manner of Mackay’s life. He has no time to fret and groan and weep, and God knows if ever man had reason to think of “graves and worms and oblivion,” and to be doleful and lonely and sad, Mackay had, when, after murdering his Bishop, and burning his pupils, and strangling his converts, and clubbing to death his dark friends, Mwanga turned his eye of death on him. And yet the little man met it with calm blue eyes that never winked. To see one man of this kind, working day after day for twelve years bravely, and without a syllable of complaint or a moan amid the “wildernesses,” and to hear him lead his little flock to show forth God’s loving kindness in the morning, and His faithfulness every night, is worth going a long journey, for the moral courage and contentment that one derives from it.

The Wasukuma swayed closer up, but cautiously, and, it appeared to me, reluctantly. In front of the mob coming from the south were several skirmishers, who pranced forward to within 300 yards. One of the skirmishers was dropped, and the machine showered about a hundred and fifty rounds in their direction. Not one of the natives was hit, but the great range and bullet shower was enough. They fled; a company was sent out to meet the eastern mob, another was sent to threaten the crowd to the north, and the Wasukuma yielded and finally retired. Only one native was killed out of this demonstration made by probably 2000 warriors.

The précis of the intelligence received having been doctored by a writer at Zanzibar, rendered the message still more unintelligible. The intelligence was received at Zanzibar by an agent of the ivory raider, Ugarrowwa, and was intended to read thus:

On arriving at the ferry of the Kingani River, Major Wissman came across to meet us, and for the first time I had the honour of being introduced to a colleague who had first distinguished himself, at the headquarters of the Kasai River, in the service of the International Association, while I was building stations along the main river. On reaching the right bank of the Kingani we found some horses saddled, and turning over the command of the column to Lieut. Stairs, Emin Pasha and myself were conducted by Major Wissman and Lieut. Schmidt to Bagamoyo. Within the coast-town we found the streets decorated handsomely with palm branches, and received the congratulations of Banian and Hindu citizens, and of many a brave German officer who had shared the fatigues and dangers of the arduous campaign, which Wissman was prosecuting with such well deserved success, against the Arab malcontents of German East Africa. Presently rounding a corner of the street we came in view of the battery square in front of Wissman’s headquarters, and on our left, close at hand, was the softly undulating Indian Sea, one great expanse of purified blue. “There, Pasha,” I said. “We are at home!”

There was not one European at Bagamoyo but felt extremely grieved at the sad event that had wrecked the general joy. The feeling was much deeper than soldiers will permit themselves to manifest. Outwardly there was no manifestation; inwardly men were shocked that his first day’s greeting among his countrymen and friends should have proved so disastrous to him after fourteen years’ absence from them. What the Emir Karamallah and his fanatics, a hundred barbarous negro tribes, conspirators, and rebel soldiery, and fourteen years of Equatorial heat had failed to effect, an innocent hospitality had nearly succeeded in doing. At the very moment he might well have said, Soul, enjoy thyself! behold, the shadow of the grave is thrust across their vision. This extremely dismal prospect and immediate blighting of joy made men chary of speech, and solemnly wonder at the mishap.

The Agent of the East African Company, in company with Lieut. Stairs, having completed their labours, of calculating the sums due to the survivors of the Relief Expedition, and having paid them accordingly, a purse of 10,000 rupees was subscribed thus: 3000 rupees from the Khedive of Egypt; 3000 rupees from the Emin Relief Fund; 3000 rupees from myself personally; 1000 rupees from the Seyyid Khalifa of Zanzibar, which enabled the payees to deliver from 40 to 60 rupees extra to each survivor according to desert. General Lloyd Mathews gave them also a grand banquet, and in the name of the kind-hearted Sultan in various ways showed how merit should be rewarded. An extra sum of 10,000 rupees set apart from the Relief Fund is to be distributed also among the widows and orphans of those who perished in the Yambuya Camp, and with the Advance Column.

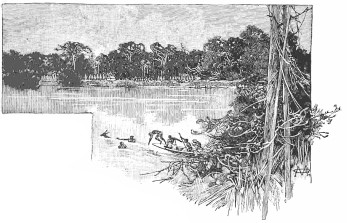

While preparing our forest camps we were frequently startled at the sudden rush of some small animal resembling a wild goat, which often waited in his covert until almost trodden upon, and then bounded swiftly away, running the gauntlet among hundreds of excited and hungry people, who with gesture, voice, and action attempted to catch it. This time, however, the animal took a flying leap over several canoes lying abreast into the river, and dived under. In an instant there was a desperate pursuit. Man after man leaped head foremost into the river, until its face was darkly dotted with the heads of the frantic swimmers. This mania for meat had approached madness. The poisoned arrow, the razor-sharp spear, and the pot of the cannibal failed to deter them from such raids; they dared all things, and in this instance an entire company had leaped into the river to fight and struggle, and perhaps be drowned, because there was a chance that a small animal that two men would consider as insufficient for a full meal, might be obtained by one man out of fifty. Five canoes were therefore ordered out to assist the madmen. About half a mile below, despite the manœuvres of the animal which dived and swam with all the cunning of savage man, a young fellow named Feruzi clutched it by the neck, and at the same time he was clutched by half-a-dozen fellows, and all must assuredly have been drowned had not the canoes arrived in time, and rescued the tired swimmers. But, alas! for Feruzi, the bush antelope, for such it was, no sooner was slaughtered than a savage rush was made on the meat, and he received only a tiny morsel, which he thrust into his mouth for security.

Not one London editor could guess the feelings with which I regarded this mannikin from the solitudes of the vast central African forest. To me he was far more venerable than the Memnonium of Thebes. That little body of his represented the oldest types of primeval man, descended from the outcasts of the earliest ages, the Ishmaels of the primitive race, for ever shunning the haunts of the workers, deprived of the joy and delight of the home hearth, eternally exiled by their vice, to live the life of human beasts in morass and fen and jungle wild. Think of it! Twenty-six centuries ago his ancestors captured the five young Nassamonian explorers, and made merry with them at their villages on the banks of the Niger. Even as long as forty centuries ago they were known as pigmies, and the famous battle between them and the storks was rendered into song. On every map since Hekataeus’ time, 500 years B.C., they have been located in the region of the Mountains of the Moon. When Mesu led the children of Jacob out of Goshen, they reigned over Darkest Africa undisputed lords; they are there yet, while countless dynasties of Egypt and Assyria, Persia, Greece and Rome, have flourished for comparatively brief periods, and expired. And these little people have roamed far and wide during the elapsed centuries. From the Niger banks, with successive waves of larger migrants, they have come hither to pitch their leafy huts in the unknown recesses of the forest. Their kinsmen are known as Bushmen in Cape Colony, as Watwa in the basin of the Lulungu, as Akka in Monbuttu, as Balia by the Mabodé, as Wambutti in the Ihuru basin, and as Batwa under the shadows of the Lunae Montes.

After a halt of five days the Expedition marched from Indemau on the 1st of December for the Dui. Mr. Bonny and old Rashid, with their assistants, were putting the finishing touches to the bridge, a work which reflected great credit on all concerned in its construction, but especially on Mr. Bonny. Without halting an instant the column marched across the five branches of the Dui, over a length of rough but substantial woodwork, which measured in the aggregate eighty yards, without a single accident.

This region, which embraces twelve degrees of longitude, is mainly forest, though to the west it has several reaches of grass-land, and this fact modifies the complexion considerably. The inhabitants of the true forest are much lighter in colour than those of the grass-land. They are inclined normally to be coppery, while some are as light as Arabs, and others are dark brown, but they are all purely negroid in character. Probably this lightness of colour may be due to a long residence through generations in the forest shades, though it is likely to have been the result of an amalgamation of an originally black and light coloured race. When we cross the limits of the forest and enter the grass-land we at once remark, however, that the tribes are much darker in colour.

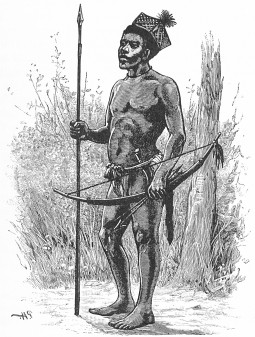

Scattered among the Balessé, between Ipoto and Mount Pisgah, and inhabiting the land situated between the Ngaiyu and Ituri Rivers, a region equal in area to about two-thirds of Scotland, are the Wambutti, variously called Batwa, Akka, and Bazungu. These people are undersized nomads, dwarfs, or pigmies, who live in the uncleared virgin forest, and support themselves on game, which they are very expert in catching. They vary in height from three feet to four feet six inches. A full-grown adult male may weigh ninety pounds. They plant their village camps at a distance of from two to three miles around a tribe of agricultural aborigines, the majority of whom are fine stalwart people. A large clearing may have as many as eight, ten, or twelve separate communities of these little people settled around them, numbering in the aggregate from 2,000 to 2,500 souls. With their weapons, little bows and arrows, the points of which are covered thickly with poison, and spears, they kill elephants, buffalo, and antelope. They sink pits, and cunningly cover them with light sticks and leaves, over which they sprinkle earth to disguise from the unsuspecting animals the danger below them. They build a shed-like structure, the roof being suspended with a vine, and spread nuts or ripe plantains underneath, to tempt the chimpanzees, baboons, and other simians within, and by a slight movement, the shed falls, and the animals are captured. Along the tracks of civets, mephitis, ichneumons, and rodents are bow traps fixed, which, in the scurry of the little animals, are snapped and strangle them. Besides the meat and hides to make shields, and furs, and ivory of the slaughtered game, they catch birds to obtain their feathers; they collect honey from the woods, and make poison, all of which they sell to the larger aborigines for plantains, potatoes, tobacco, spears, knives, and arrows. The forest would soon be denuded of game if the pigmies confined themselves to the few square miles around a clearing; they are therefore compelled to move, as soon as it becomes scarce, to other settlements.

They perform other services to the agricultural and larger class of aborigines. They are perfect scouts, and contrive, by their better knowledge of the intricacies of the forest, to obtain early intelligence of the coming of strangers, and to send information to their settled friends. They are thus like voluntary picquets guarding the clearings and settlements. Every road from any direction runs through their camps. Their villages command every cross-way. Against any strange natives, disposed to be aggressive, they would combine with their taller neighbours, and they are by no means despicable allies. When arrows are arrayed against arrows, poison against poison, and craft against craft, probably the party assisted by the pigmies would prevail. Their diminutive size, superior wood-craft, their greater malice, would make formidable opponents. This the agricultural natives thoroughly understand. They would no doubt wish on many occasions that the little people would betake themselves elsewhere, for the settlements are frequently outnumbered by the nomad communities. For small and often inadequate returns of fur and meat, they must allow the pigmies free access to their plantains, groves, and gardens. In a word, no nation on the earth is free from human parasites, and the tribes of the Central African forest have much to bear from these little fierce people who glue themselves to their clearings, flatter them when well fed, but oppress them with their extortions and robberies.

On the evening of the 21st, notice was brought to me that the Balegga were collecting to attack us, and early the following morning sixty rifles, with 1,500 Bavira and Wahuma were sent to meet them. The forces met on the crest of the mountains overlooking the Lake, and the Balegga, after a sharp resistance, were driven to their countrymen among the subjects of Melindwa, who was the ally of Kabba Rega.

On February 7th I decided to send for Lieutenant Stairs and his caravan, and despatched Rashid with thirty-five men to obtain a hundred carriers from Mazamboni to assist the convalescents. My object was to collect the expedition at Kavalli, and send letters in the meantime to Emin Pasha proposing that he should: 1st. Seize a steamer and embark such people as chose to leave Tunguru, and sail for our Lake shore camp. After which we could man her with Zanzibaris, and perform with despatch any further transport service necessary. If this was not practicable, then—

I see the Egyptian officers congregating in special and select groups each day, seated on their mats, smoking cigarettes, and discussing our absolute slavishness. They have an idea that any one of them is better than ten Zanzibaris, but I have not seen any ten of them that could be so useful in Africa as one Zanzibari.

I saw Osman Latif proceed soon after to the Pasha’s quarters, and kiss his hands, and bend reverently before him, and immediately I followed, curious to observe. The Pasha sat gravely on his chair, and delivered his orders to Osman Latif with the air of power, and Osman Latif bowed obsequiously after hearing each order, and an innocent stranger might have imagined that one embodied kingly authority and the other slavish obedience. Soon after I departed absorbed in my own thoughts.

During the sudden muster of the day before yesterday, and the fierce declaration of my intentions, he became energetic himself, and I found that energy, as well as disease, becomes contagious. He had prepared for an immediate start after us. His mother, an old lady, seventy-five years old, with a million of wrinkles in her ghastly white face, was not very fortunate in her introduction to me, for, while almost at white heat, she threw herself before me in the middle of the square, jabbering in Arabic to me, upon which, with an impatient wave of the hand, I cried, “Get out of this; this is not the place for old women.” She lifted her hands and eyes up skyward, gave a little shriek, and cried, “O Allah!” in such tragic tones that almost destroyed my character. Every one in the square witnessed the limp and shrunk figure, and laughed loudly at the poor old thing as she beat a hasty retreat.

At 5 P.M. Mr. Bonny performed signal service. He accepted the mission of leading five Soudanese across the Semliki as the vanguard of the Expedition. By sunset there were fifty rifles across the river.

The 24th of May was a halt, and we availed ourselves of it to despatch two companies to trace the paths, that I might obtain a general idea which would best suit our purposes. One company took a road leading slightly east of south, and suddenly came across a few Baundwe, whom we knew for real forest aborigines. This was in itself a discovery, for we had supposed we were still in Utuku, as the east side of the Semliki is called, and which is under Kabba Rega’s rule. The language of the Baundwe was new, but they understood a little Kinyoro, and by this means we learned that Ruwenzori was known to them as Bugombowa, and that the Watwa pigmies and the Wara Sura were their worst enemies, and that the former were scattered through the woods to the W.S.W.

The Egyptians and their followers had such a number of infants and young children that when the camp space was at all limited, as on a narrow spur, sleep was scarcely possible. These wee creatures must have possessed irascible natures, for such obstinate and persistent caterwauling never tormented me before. The tiny blacks and sallow yellows rivalled one another with force of lung until long past midnight, then about 3 or 4 A.M. started afresh, woke everyone from slumber, while grunts of discontent at the meeawing chorus would be heard from every quarter.

We were told that they had met gangs of the Wara Sura, but had met “bad luck,” and only one small tusk of ivory rewarded their efforts. Ipoto, according to them, was twenty days’ march through the forest from Bukoko.

Shortly after 4 P.M. we halted among some high heaths for camp. Breaking down the largest bushes we made rough shelters for ourselves, collected what firewood we could find, and in other ways made ready for the night. Firewood, however, was scarce, owing to the wood being so wet that it would not burn. In consequence of this, the lightly-clad Zanzibaris felt the cold very much, though the altitude was only about 8,500 feet. On turning in the thermometer registered 60° F. From camp I got a view of the peaks ahead, and it was now that I began to fear that we should not be able to reach the snow. Ahead of us, lying directly in our path, were three enormous ravines; at the bottom of at least two of these there was dense bush. Over these we should have to travel and cut our way through the bush. It would then resolve itself into a question of time as to whether we could reach the summit or not. I determined to go on in the morning, and see exactly what difficulties lay before us, and if these could be surmounted in a reasonable time, to go on as far as we possibly could.

[1] The Sketch Maps on pages 293 to 308 inclusive are from tracings from ancient books in the Khedive’s library at Cairo.

What the chartographers of Homer’s time illustrated of geographical knowledge succeeding chartographers effaced, and what they in their turn sketched was expunged by those who came after them. In vain explorers sweated under the burning sun, and endured the fatigues and privations of arduous travel: in vain did they endeavour to give form to their discoveries, for in a few years the ruthless map-maker obliterated all away. Cast your eyes over these series of small maps, and witness for yourselves what this tribe has done to destroy every discovery, and to render labour and knowledge vain. There is a chartographer living, the chiefest sinner alive. In 1875, I found a bay at the north-east end of Lake Victoria. A large and mountainous island, capacious enough to supply 20,000 people with its products of food, blocked the entrance from the lake into it, but there is a winding strait at either end of sufficient depth and width to enable an Atlantic liner to steam in boldly. The bay has been wiped out, the great island has been shifted elsewhere, and the picturesque channels are not in existence on his latest maps, and they will not be restored until some other traveller, years hence, replaces them as they stood in 1875. And young travellers are known to chuckle with malicious pleasure at all this, forgetful of what old Solomon said in the olden time: “There is no remembrance of former things; neither shall there be any remembrance of things that are to come with those that shall come after.”

So, though it is some satisfaction to be able to vindicate the more ancient geographers to some extent, I publish at the end of the series of old maps the small chart which illustrates what we have verified during our late travels. I do it with the painful consciousness that some stupid English or German map-maker within the next ten years may, from spleen and ignorance, shift the basin 300 or 400 miles farther east or west, north or south, and entirely expunge our labours. However, I am comforted that on some shelf of the British Museum will be found a copy of ‘In Darkest Africa,’ which shall contain these maps, and that I have a chance of being brought forth as an honest witness of the truth, in the same manner as I cite the learned geographers of the olden time to the confusion of the map-makers of the nineteenth century.

Here follows the great Ptolemy, the Ravenstein or Justas Perthes of his period. Some new light has been thrown by his predecessors, and he has revised and embellished what was known. He has removed the sources of the Nile, with scientific confidence, far south of the equator, and given to the easternmost lake the name of Coloe Palus.

Four centuries later we see, by the following map, that the lakes have changed their position. Ambitious chartographers have been eliciting information from the latest traveller. They do not seem to be so well acquainted with the distant region around the Nile sources as those ancients preceding Edrisi. Nevertheless, the latest travellers must know best.

Within three years Africa seems to have been battered out of shape somewhat. The three lakes have been attracted to one another; between two of the lakes the Mountains of the Moon begin to take form and rank. The Mons Lunæ are evidently increasing in height and length. As Topsy might have said, “specs they have grown some.”

In the following map we see a reproduction of Sebastian Cabot’s map in the sixteenth century. I have omitted the pictures of elephants and crocodiles, great emperors and dwarfs, which are freely scattered over the map with somewhat odd taste. The three lakes have arranged themselves in line again, and the Mountains of the Moon are picturesquely banked at the top head of all the streams, but the continent evidently suggests unsteadiness generally, judging from the form of it.

“Eratosthenes compared Africa to a trapezium, of which the Mediterranean coast formed one side, the Nile another, the southern coast the longest side, and the western coast the shortest side. So little were the ancients aware of its extent that Pliny pronounced it to be the least of the continents, and inferior to Europe. Upon the Nile, therefore, they measured the habitable world of Africa, and fixed its limit at the highest known point to which that river had been ascended. This is assigned about three thousand stadia (three or four hundred miles) beyond Meroe. They seem to have been fully aware of two great rivers rising from lakes and called the Astaboras and Astapus, of which the latter (White Nile) flows from the lake to the south, is swelled to a great height by summer rains and forms then almost the main body of the Nile.