автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Jane Austen and Her Times

JANE AUSTEN AND HER TIMES

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

- A Bachelor Girl in London

- The Gifts of Enemies

- The Children’s Book of London

MORNING EMPLOYMENTS

JANE AUSTEN

AND HER TIMES

BY

G. E. MITTON

WITH TWENTY-ONE ILLUSTRATIONS

METHUEN & CO.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

First Published in 1905

CONTENTS

CHAP.

PAGE

I.PRELIMINARY AND DISCURSIVE

1

II.CHILDHOOD

22

III.THE POSITION OF THE CLERGY

34

IV.HOME LIFE AT STEVENTON

49

V.THE NOVELS

80

VI.LETTERS AND POST

105

VII.SOCIETY AND LOVE-MAKING

117

VIII.VISITS AND TRAVELING

148

IX.CONTEMPORARY WRITERS

161

X.A TRIO OF NOVELS

176

XI.THE NAVY

196

XII.BATH

212

XIII.DRESS AND FASHIONS

229

XIV.AT SOUTHAMPTON

249

XV.CHAWTON

266

XVI.IN LONDON

278

XVII.FANNY AND ANNA

296

XVIII.THE PRINCE REGENT AND

EMMA303

XIX.LAST DAYS

313

INDEX327

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

MORNING EMPLOYMENTS

From a Painting by Bunbury. Frontispiece

THE REV. GEORGE AUSTEN

From a Family Miniature. Facing page 16

THE REV. JAMES AUSTEN

From a Family Miniature. 16

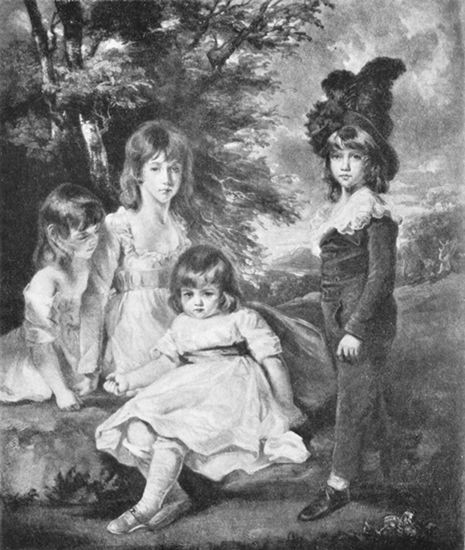

JUVENILE RETIREMENT

From a Painting by John Hoppner. 26

THE VICAR RECEIVING HIS TITHES

From a Drawing by H. Singleton. 42

JANE AUSTEN

From a Portrait by her Sister Cassandra. 58

THE HAPPY COTTAGERS

From a Painting by George Morland. 74

MISS BURNEY (MADAME D’ARBLAY)

From a Portrait by Edward Burney. 96

FROM A SUMMER’S EVENING

From a Drawing by de Loutherbourg. 156

TRAVELLERS ARRIVING AT EAGLE TAVERN, STRAND

From an Old Engraving. 159

DOMESTIC HAPPINESS

From a Painting by George Morland. 170

COWPER

From a Painting by George Romney, in the possession of B. Vaughan Johnson, Esq. 192

VICTORY OF LORD DUNCAN (CAMPERDOWN), 1797

From a Painting by J. S. Copley. 208

FAÇADE OF THE PUMP ROOM, BATH, IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

From a Contemporary Engraving. 220

DRESSING TO GO OUT

From a Drawing by P. W. Tomkins. 230

INIGO JONES, HON. H. FANE, AND C. BLAIR

From a Painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds. 246

A PLATE FROM THE GALLERY OF FASHION 260

CHARING CROSS, 1795

From an Engraving in the Crace Collection. 285

THE LITTLE THEATRE, HAYMARKET

From an Engraving by Wilkinson in Londina Illustrata. 291

THE REV. GEORGE CRABBE

From a Drawing by Sir F. Chantrey, in the National Portrait Gallery. 293

THE GARDEN OF CARLTON HOUSE

From a Painting by Bunbury. 304

THE REV. GEORGE AUSTEN

THE REV. JAMES AUSTEN

JUVENILE RETIREMENT

THE VICAR RECEIVING HIS TITHES

JANE AUSTEN

THE HAPPY COTTAGERS

MISS BURNEY (MADAME D’ARBLAY)

FROM “A SUMMER’S EVENING”

TRAVELLERS ARRIVING AT ‘EAGLE TAVERN,’ STRAND

DOMESTIC HAPPINESS

COWPER

VICTORY OF LORD DUNCAN (CAMPERDOWN) 1797

FAÇADE OF THE PUMP ROOM, BATH, IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

DRESSING TO GO OUT

INIGO JONES, HON. H. FANE, AND C. BLAIR

FASHIONS FOR LADIES IN 1795

CHARING CROSS, 1795

THE LITTLE THEATRE, HAYMARKET

THE REV. GEORGE CRABBE

THE GARDEN OF CARLTON HOUSE

JANE AUSTEN AND HER TIMES

CHAPTER I PRELIMINARY AND DISCURSIVE

Of Jane Austen’s life there is little to tell, and that little has been told more than once by writers whose relationship to her made them competent to do so. It is impossible to make even microscopic additions to the sum-total of the facts already known of that simple biography, and if by chance a few more original letters were discovered they could hardly alter the case, for in truth of her it may be said, “Story there is none to tell, sir.” To the very pertinent question which naturally follows, reply may thus be given. Jane Austen stands absolutely alone, unapproached, in a quality in which women are usually supposed to be deficient, a humorous and brilliant insight into the foibles of human nature, and a strong sense of the ludicrous. As a writer in The Times (November 25, 1904) neatly puts it, “Of its kind the comedy of Jane Austen is incomparable. It is utterly merciless. Prancing victims of their illusions, her men and women are utterly bare to our understanding, and their gyrations are irresistibly comic.” Therefore as a personality, as a central figure, too much cannot be written about her, and however much is said or written the mystery of her genius will still always baffle conjecture, always lure men on to fresh attempts to analyse and understand her.

The data of Jane Austen’s life have been repeated several times, as has been said, but beyond a few trifling allusions to her times no writer has thought it necessary to show up the background against which her figure may be seen, or to sketch from contemporary records the environment amid which she developed. Yet surely she is even more wonderful as a product of her times than considered as an isolated figure; therefore the object of this book is to show her among the scenes wherein she moved, to sketch the men and women to whom she was accustomed, the habits and manners of her class, and the England with which she was familiar. Her life was not long, lasting only from 1775 to 1817, but it covered notable times, and with such an epoch for presentation, with such a central figure to link together the sequence of events, we have a theme as inspiring as could well be found.

In many ways the times of Jane Austen are more removed from our own than the mere lapse of years seems to warrant. The extraordinary outburst of invention and improvement which took place in the reign of Queen Victoria, lifted manners and customs in advance of what two centuries of ordinary routine would have done. Sir Walter Besant in his London in the Eighteenth Century says, “The passing of the Reform Bill in 1832, the introduction of steamers on the sea, the beginning of railways on land, make so vast a break between the first third and last two-thirds of the nineteenth century, that I feel justified in considering the eighteenth century as lasting down to the year 1837; in other words, there were so few changes, and these so slight, in manners, customs, or prevalent ideas, between 1700 and 1837, that we may consider the eighteenth century as continuing down to the beginning of the Victorian era, when change after change—change in the constitution, change in communications, change in the growth and extension of trade, change in religious thought, change in social standards—introduced that new time which we call the nineteenth century.”

According to this reckoning, Jane Austen may be counted as wholly an eighteenth-century product, and such a view is fully justified, for the differences between her time and ours were enormous. It is impossible to summarise in a few sentences changes which are essentially a matter of detail, but in the gradual unfolding of her life I shall attempt to show how radically different were her surroundings from anything to which we are accustomed.

It is an endless puzzle why, when her books so faithfully represent the society and manners of a time so unlike our own, they seem so natural to us. If you tell any half-dozen people, who have not made a special study of the subject, at what date these novels were written, you will find that they are all surprised to hear how many generations ago Jane Austen lived, and that they have always vaguely imagined her to be very little earlier than, if not contemporary with, Charlotte Brontë or George Eliot. So far as I am aware, no writer on Jane Austen has ever touched on this problem before. Her stories are as fresh and real as the day they were written, her characters might be introduced to us in the flesh any time, and, with the exception of a certain quaintness of eighteenth-century flavouring, there is nothing to bring before us the striking difference between their environment and our own. It is true that the long coach journeys stand out as an exception to this, but they are the only marked exception. If we had never had an illustrated edition of Jane Austen, nine people out of ten at least would have formed mental pictures of the characters dressed in early Victorian, or perhaps even in present-day, costume. It is only since Hugh Thompson and C. E. Brock have put before us the costumes of the age, that our ideas have accommodated themselves, and we realise how Catherine Morland and Isabella Thorpe looked in their high-waisted plain gowns, when they had arrived at that stage of intimacy which enabled them to pin “up each other’s trains for the dance.” Or how attractive Fanny Price was in her odd high-crowned hat, with its nodding plume, and the open-necked short-sleeved dress, as she surveyed herself in the glass while Miss Crawford snapped the chain round her neck. The knee-breeches of the men, their slippers and cravats, the neat, close-fitting clerical garb, these things we owe to the artists,—they are taken for granted in the text. It would have seemed as ridiculous to Jane Austen to describe them, as for a present-day novelist to mention that a London man made a call in a frock-coat and top-hat.

Yet her word-pictures are living and detailed, filled in with innumerable little touches. How can we reconcile the seeming inconsistency? The explanation probably is, that without acting consciously, she, with the unerring touch of real genius, chose that which was lasting, and of interest for all time, from that which was ephemeral. In her sketches of human nature, in the strokes with which she describes character, no line is too fine or too delicate for her attention; but in the case of manners and customs she gives just the broad outlines that serve as a setting. Her novels are novels of character.

But the problem is not confined to the books; in her letters to her sister, though there is abundant comment on dress, food, and minor details which should mark the epoch, yet the letters might have been written yesterday. Austin Dobson in one of his admirable prefaces to the novels says: “Going over her pages, pencil in hand, the antiquarian annotator is struck by their excessive modernity, and after a prolonged examination discovers, in this century-old record, nothing more fitted for the exercise of his ingenuity that such an obsolete game at cards as ‘Casino’ or ‘quadrille.’”

And this is true also of her letters. More remarkable still is the entire absence of comment on the great events which thrilled the world; with the exception of an allusion to the death of Sir John Moore, we hear no whisper of the wars and upheavals which happened during her life. It is true that the Revolution in France, which shook monarchs on their thrones, occurred before the first date of the published letters, yet her correspondence covers a time when battles at sea were chronicled almost continuously, when an invasion by France was an ever-present terror; Trafalgar and Waterloo were not history, but contemporary events; but though Jane must have heard and discussed these matters, no echo finds its way into her lively and amusing budgets of chit-chat to her sister. Of course women were not supposed to read the papers in those days, but with two sailor brothers the news must have often been personal and intimate, and she was, according to the notions of her time, well educated; yet we search in vain for any allusion to such contemporary matters. It may be objected that the letters of a modern girl to a sister would hardly touch on questions which agitate the public, but there are several replies to this: in the first place, few such exciting events have occurred in recent times as happened during Jane Austen’s life; our war in Africa was a mere trifle in comparison with the bloody field of Waterloo, where Blucher and Wellington lost 30,000 men, or the thrilling naval victory of Trafalgar; and stupendous as have been the recent battles between Russia and Japan, they affect us only indirectly—England is not herself involved in them, nor are her sons being slain daily. In the second place, surely even the South African War would probably produce some comment in letters, especially if the writer had brothers in the army as Jane had brothers in the navy. Thirdly, letters in Jane Austen’s time were one great means of news, for newspapers were not so easy to get, and were much more costly than now, so that we expect to find more of contemporary events in letters than at a time like the present, when telegrams and columns of print save us the trouble of recording such matters in private.

In the forty-two years between 1775 and 1817, vast discoveries of world-wide importance were made. When Jane Austen was born, Captain Cook was still in the midst of his exploration, and the map of the world was being unrolled day by day. Though New Zealand and Australia had been discovered by the Dutch in the previous century, they were all but unknown to England. Six years only before her birth had the great navigator charted and mapped New Zealand for the first time, also the east coast of Australia, and had christened New South Wales. When she was four years old, Cook was murdered by the natives at Hawaii.

The atlas from which she learnt her earliest geography lessons was therefore very different from those now in use. The well-known cartographer, S. Dunn, published an atlas in 1774, where Australia is marked certainly, but as though one saw it through distorted glasses; the east coast, Cook’s discovery, is clearly defined, the rest is very vague; and the fact that Tasmania was an island had not then been discovered, for it appears as a projecting headland. In the same general way is New Zealand treated, and neither has a separate sheet to itself; beyond their appearance on the map of the world, they are ignored. Japan also looks queer to modern eyes, it almost touches China at both ends, enclosing a land-locked sea.

The epoch was one of change and enlargement in other than geographical directions. In the thirty years before Jane Austen’s birth an immense improvement had taken place in the position of women. Mrs. Montagu, in 1750, had made bold strokes for the freedom and recognition of her sex. The epithet “blue-stocking,” which has survived with such extraordinary tenacity, was at first given, not to the clever women who attended Mrs. Montagu’s informal receptions, but to her men friends, who were allowed to come in the grey or blue worsted stockings of daily life, instead of the black silk considered de rigueur for parties. Up to this time, personal appearance and cards had been the sole resources for a leisured dame of the upper classes, and the language of gallantry was the only one considered fitting for her to hear. By Mrs. Montagu’s efforts it was gradually recognised that a woman might not only have sense herself, but might prefer it should be spoken to her; and that because the minds of women had long been left uncultivated they were not on that account unworthy of cultivation. Hannah More describes Mrs. Montagu as “not only the finest genius, but the finest lady I ever saw ... her form (for she has no body) is delicate even to fragility; her countenance the most animated in the world; the sprightly vivacity of fifteen, with the judgment and experience of a Nestor.”

In art there had never before been seen in England such a trio of masters as Reynolds, Gainsborough, and Romney. Isolated portrait painters of brilliant genius, though not always native born, there had been in England,—Holbein, Vandyke, Lely, Kneller, and Hogarth are all in the first rank,—but that three such men as the trio above should flourish contemporaneously was little short of miraculous.

In 1775, Sir Joshua had passed the zenith of his fame, though he lived until 1792. Gainsborough, who was established in a studio in Schomberg House, Pall Mall, was in 1775 at the beginning of his most successful years; his rooms were crowded with sitters of both sexes, and no one considered they had proved their position in society until they had received the hall-mark of being painted by him. He was only sixty-one at his death in 1788. Romney, who lived to 1802, never took quite the same rank as the other two, yet he was popular enough at the same time as Gainsborough; Lady Newdigate (The Cheverels of Cheverel Manor) mentions going to have her portrait painted by him, and says that “he insists upon my having a rich white satin with a long train made by Tuesday, and to have it left with him all the summer. It is the oddest thing I ever knew.” Sir Thomas Lawrence and Hoppner carried on the traditions of the portrait painters, the former living to 1830; with names such as these it is easy to judge art was in a flourishing condition.

Among contemporary landscape painters, Richard Wilson, who has been called “the founder of English Landscape,” lived until 1782. But his views, though vastly more natural than the stilted conventional style that preceded them, seem to our modern eyes, trained to what is “natural,” still to be too much conventionalised. Among others the names of Gillray, Morland, Rowlandson stand out, all well on the way to fame while Jane was still a child.

These preliminary remarks have been made with a view to giving some general idea of that England into which she was born, and they refer to those subjects which only affected her indirectly. All those things which entered directly into her life, such as her country surroundings, contemporary books, prices of food, fashions, and a host of minor details, are dealt with more particularly in the course of the narrative.

As we have said, matters of history are not mentioned or noticed in Jane Austen’s correspondence, which is taken up with her own environment, her neighbours, their habits and manners, and illumined throughout by a bright insight at times rather too biting to be altogether pleasant. Of her immediate surroundings we have a very clear idea.

Of all the writers of fiction, Jane Austen is most thoroughly English. She never went abroad, and though her native good sense and shrewd gift of observation saved her from becoming insular, yet she cannot be conceived as writing of any but the sweet villages and the provincial towns of her native country. Even the Brontës, deeply secluded as their lives were, crossed the German Ocean, and saw something of Continental life from their school at Brussels. Nothing of this kind fell to Jane Austen’s share. Yet people did travel in those days, travelled amazingly considering the difficulties they had to encounter, among which were the horrors of a sailing-boat with its uncertain hours. Fielding, in going to Lisbon, was kept waiting a month for favourable winds! There was also the terrible embarking and landing from a small boat before such conveniences as landing-stages were built.

In one of Lord Langdale’s letters, dated 1803, we have a vivid description of these horrors: “We left that place [Dover] about six o’clock last Saturday morning, and arrived at Calais at four in the afternoon. Our passage was rather disagreeable, the wind being chiefly against us, and rain sometimes falling in torrents. I never witnessed a more curious scene than our landing. When the packet-boat had come to within two miles of the coast of France, we were met by some French rowing boats in which we were to be conveyed on shore. The French sailors surrounded us in the most clamorous and noisy manner, leaping into the packet and bawling and shouting so loud as to alarm the ladies on board very much. To these men, however, we were to consign ourselves, and we entered their boats, eight passengers going in each. When we got near the shore, we were told it was impossible for the boat to get close to land, on account of the tide being so low, and that we must be carried on the men’s shoulders. We had no time to reflect on this plan before we saw twelve or fourteen men running into the water,—they surrounded our boat and laid hold of it with such violence, that one might have thought they meant to sink it, and fairly pulled us into their arms.... For my part I laughed heartily all the time, but a lady who was with us was so much frighted, that I was obliged to support her in my arms a considerable time before she was able to stand.”

It was not only in the arms of men that passengers were thus carried ashore, in Napoleon’s British Visitors and Captives, by J. G. Alger, there is a still more extraordinary account quoted from a contemporary letter. “In an instant the boathead was surrounded by a throng of women up to their middles and over, who were there to carry us on shore. Not being aware of this manœuvre, we did not throw ourselves into the arms of these sea-nymphs so instantly as we ought, whereby those who sat at the stern of the boat were deluged with sea spray. For myself, I was in front, and very quickly understood the clamour of the mermaids. I flung myself upon the backs of two of them without reserve, and was safely and dryly borne on shore, but one poor gentleman slipped through their fingers, and fell over head and ears into the sea.”

From the same entertaining book we learn that, “For £4, 13s. you could get a through ticket by Dover and Calais, starting either from the City at 4.30 a.m. by the old and now revived line of coaches connected with the rue Notre Dame des Victoires establishment in Paris, or morning and night by a new line from Charing Cross. Probably a still cheaper route, though there were no through tickets, was by Brighton and Dieppe, the crossing taking ten or fifteen hours. By Calais it seldom took more than eight hours, but passengers were advised to carry light refreshments with them. The diligence from Calais to Paris, going only four miles an hour, took fifty-four hours for the journey, but a handsome carriage drawn by three horses, in a style somewhat similar to the English post-chaise, could be hired by four or five fellow-travellers, and this made six miles an hour.”

During a great part of Jane Austen’s life, much of the Continent was closed to English people because of the perpetual state of war between us and either Spain or France, but in any case such an expedition would seem to have lain quite outside her limited daily round, and was never even mooted.

Steventon Rectory, where she was born on December 16, 1775, has long ago vanished, and a new rectory, more in accordance with modern luxurious notions, has been built. Of the old house, Lord Brabourne, great-nephew to Jane Austen, writes: “The house standing in the valley was somewhat better than the ordinary parsonage houses of the day; the old-fashioned hedgerows were beautiful, and the country around sufficiently picturesque for those who have the good taste to admire country scenery.”

Steventon is a very small place, lying in a network of lanes about seven miles from Basingstoke. The nearest points on the high-roads are Deane, on the Andover Road, and Popham Lane on the Winchester Road. There is an inn at the corner of Popham Lane to this day, and that there was an inn there in Jane Austen’s time we know, for Mrs. Lybbe Powys, writing in 1792, says: “We stopped at Winchester and lay that night at a most excellent inn at Popham Lane.” At this time, curiously enough, her fellow-travellers were Dr. Cooper, Jane Austen’s uncle, and his son and daughter, though whether the party made a détour to visit the rectory we do not know. Of course at that time Jane was of no greater importance than any seventeen-year-old daughter of a country clergyman, and there would be no reason to mention her.

It is difficult to find Steventon, so little is there of it, and that so much scattered; a few cottages, a farm, and beyond, half a mile away, the church, with a pump in a field near to mark the site of the old rectory house where Jane Austen was born. This is all that remains of her time. The new rectory stands on the other side of the narrow road, raised above it, and sheltered by a warm backing of trees in which evergreens are conspicuous. A very substantial-looking building it is, much superior to what was considered good enough for a clergyman in the eighteenth century. The country is well wooded, and the roads undulating, so that there are no distant views. Probably a good deal of the planting has been done since Jane Austen’s time, but that there were trees then we know from her own account, and some of the fine oaks that still stand can have altered but little since then. Mr. Austen-Leigh’s account of the house in which she was born is worth quoting—

“North of the house, the road from Deane to Popham Lane ran at a sufficient distance from the front to allow a carriage drive through turf and trees. On the south side, the ground rose gently, and was occupied by one of those old-fashioned gardens in which vegetables and flowers are combined, flanked and protected on the east by one of the thatched mud walls common in that country, and overshadowed by fine elms. Along the upper or southern side of this garden ran a terrace of the finest turf, which must have been in the writer’s thoughts when she described Catherine Morland’s childish delight in ‘rolling down the green slope at the back of the house.’”

Though there is so little left to see, and the church has been “restored,” yet it is worth while to pass through this country to realise the environment in which the authoress spent her childhood. There are still left in the neighbourhood, notably at North Waltham, some of the old diamond-paned, heavily-timbered brick houses with thatched roofs, to which she must have been accustomed. The gentle curves of the roads, the oak and beech and fir overshadowing the sweet lanes, the wild clematis, which grows so abundantly that in autumn it looks like hoar-frost covering all the hedgerows, these things were prominent objects in the scenery amid which she lived. It is not likely she looked on her surroundings in the same way as any ordinarily educated person would now look on them. Love of scenery had not then been developed. The artificial and formal landscape gardening, with “made” waterfalls, was the correct thing to admire. Genuine nature, much less homely nature, was only then beginning to be observed. This is strange to us, for, as Professor Geikie says, “At no time in our history as a nation has the scenery of the land we live in been so intelligently appreciated as it is to-day.”

But Jane was not in advance of her times, and though she loved her trees and flowers, we find in her writings no reflections of the scenes amid which she daily walked; in her books scenery is simply ignored. We know if it rained, because that material fact had an influence on the actions of her heroines, but beyond that there is little or nothing; yet she greatly admired Cowper, one of the earliest of the “natural” poets.

Mr. Austen-Leigh, her own nephew, speaks of the scenery around her first home as “tame,” and says that it has no “grand or extensive views,” though he admits it has its beauties, and says that Steventon “from the fall of the ground, and the abundance of its timber, is certainly one of the prettiest spots.” But this quiet prettiness, without the excessive richness to be found in other south-country villages, is perhaps more thoroughly characteristic of England than any other.

The impressions of childhood are invariably deep, and are cut with a clearness and minuteness to which none others of later times attain. Just as a child examines a picture in a story-book with anxious and searching care, while an adult gains only a general impression of the whole, so a child knows the place where it has played in such detail that every bough of the trees, every root of the lilacs, every tiny depression or ditch is familiar. And thus Jane must have known the home at Steventon.

Writing about a storm in 1800, she says: “I was just in time to see the last of our two highly valued elms descend into the Sweep!!! The other, which had fallen, I suppose, in the first crash, and which was the nearest to the pond, taking a more easterly direction, sunk amid our screen of chestnuts and firs, knocking down one spruce fir, beating off the head of another, and stripping the two corner chestnuts of several branches in its fall. This is not all. One large elm out of the two on the left-hand side as you enter, what I call, the elm walk, was likewise blown down; the maple bearing the weathercock was broke in two, and what I regret more than all the rest is that all the three elms which grew in Hall’s meadow, and gave such ornament to it, are gone.”

This bespeaks her intimate acquaintance with the trees, of which each one was a friend.

The country and the writer suited each other so wonderfully, that one pauses for a moment wondering whether, after all, environment may not have that magic influence claimed for it by some who hold it to be more powerful than inherited qualities. Influence of course it has, and one wonders what could possibly have been the result if two such natures as those of Jane Austen and Charlotte Brontë had changed places; if Jane had been brought up amid the wild, bleak Yorkshire moors, and Charlotte amid the pleasant fields of Hampshire. As it is, the surroundings of each intensified and developed their own peculiar genius.

Jane was born of the middle class, her father, George Austen, being a clergyman in a day when clergymen were none too well thought of, yet taking a better position than most by reason of his own family and good connections. George Austen had early been left an orphan, and had been adopted by an uncle. He showed the possession of brains by obtaining first a scholarship at St. John’s College, Oxford, and subsequently a fellowship.

He took Orders which, in the days when rectories were looked upon simply as “livings,” was a recognised mode of providing for a young man, whether he had any vocation for the ministry or not. But he seems to have fulfilled his duties, or what were then considered sufficient duties, creditably enough. Of George Austen one of his sons wrote—

“He resided in the conscientious and unassisted discharge of his ministerial duties until he was turned of seventy years.” He was a “profound scholar” and had “exquisite taste in every species of literature.”

The subject of the clergy at that date, and the examples of them which Jane has herself given us in her books, is an interesting one, and we shall return to it. The rectory of Steventon was presented to George Austen by Mr. Knight, the same cousin who afterwards adopted his son Edward; and the rectory of Deane, a small place about a mile distant, was bought by an uncle who had educated him, and given to him. The villages were very small, only containing about three hundred persons altogether. In those days parish visiting or parochial clubs and entertainments were unthought of, Sunday schools in their earliest infancy, and we hear nothing whatever throughout the whole of Jane Austen’s correspondence which leads us to think that she, in any way, carried out the duties which in these days fall to the lot of every clergyman’s daughter. This is not to cast blame upon her, it only means that she was the child of her times; these things had not then been organised.

THE REV. JAMES AUSTEN

THE REV. GEORGE AUSTEN

George Austen married Cassandra, youngest daughter of the Rev. Thomas Leigh, who was of good family, her uncle was Dr. Theophilus Leigh, Master of Balliol College, a witty and well-known man. These things are not of importance in themselves, but they serve to show that the family from which Jane sprang was on both sides of some consideration. The Austens lived first at Deane, but moved to Steventon in 1771. They had undertaken the charge of a son of Warren Hastings, who died young, and they had a large family of their own, as was consistent in days when families of ten, eleven, and even fifteen were no uncommon thing.

There were five sons and two daughters in all, and Jane was the youngest but one. (See Table, p. 326.) James, the eldest, was probably too far removed in age from his younger sister ever to have been very intimate with her. It is said that he had some share in her reading and in forming her taste, but though she was very fond of him she never seems, as was very natural, to have had quite the same degree of intimate affection for him as she felt for those of her brothers nearer to her own age. James was twice married, and his only daughter by his first wife was Anna, of whom Jane makes frequent mention in her letters, and to whom some of the published correspondence was addressed. His second wife was Mary Lloyd, whose sister Martha was the very devoted friend, and frequent guest, of the girl Austens, and who late in life married Francis, one of Jane’s younger brothers. The son of James and Mary was James Edward, who took the additional name of Leigh, and was the writer of the Memoir which supplies one of the only two sources of authoritative information about Jane Austen. He died in 1874.

The next brother, Edward, as already stated, was adopted by his cousin Mr. Knight, whose name he took. He came into the fine properties of Chawton House in Hampshire and Godmersham in Kent, even during the lifetime of Mr. Knight’s widow, who looked on him as a son and retired in his favour. Edward married Elizabeth Bridges, and had a family of eleven children, of whom the eldest, Fanny Catherine, married Sir Edward Knatchbull, and their eldest son was created Lord Brabourne; to him we owe the Letters which are the second of the authoritative books on Jane Austen.

Jane Austen was attached to her niece Fanny Knight in a degree only second to that of her attachment to her own sister Cassandra. Fanny’s mother, Mrs. Edward Austen or Knight (for the change of name seems not to have taken place until her death), died comparatively young, and the great responsibility thrown upon Fanny doubtless made her seem older, and more companionable, than her years; of her, her famous aunt writes—

“I found her in the summer just what you describe, almost another sister, and could not have supposed that a niece would ever have been so much to me. She is quite after one’s own heart. Give her my best love and tell her that I always think of her with pleasure.”

The third Austen brother, Henry, interested himself much in his sister’s writing, and saw about the business arrangements for her, when, after many years, she decided to publish one of her own books at her own risk. He was something of a rolling stone, filling various positions in turn, and at length taking Orders and succeeding his brother James in the Steventon living. During part of his life he lived in London, where Jane often stayed with him. He married first his cousin Eliza, the daughter of George Austen’s sister; she was the widow of a Frenchman, the Count de Feuillade, who had suffered death by the guillotine. Eliza was very popular with her girl cousins, as we can see from Jane’s remarks; she died in 1813, and in 1820 Henry married Eleanor, daughter of Henry Jackson. The two youngest brothers, Francis and Charles, came above and below Jane, with about three years’ interval on either side. They both entered the navy, and both became admirals.

Frank rose to be Senior Admiral of the Fleet, and was created G.C.B.; he lived to be ninety-two. He, like another of his brothers, was twice married,—a habit that ran abnormally in the family,—and his second wife was Martha, the sister of his brother James’s wife, mentioned above. Charles married first Fanny Palmer, and was left a widower in 1815 with three small daughters. He married secondly her sister Harriet. The two Fannies, Mrs. Charles Austen and the eldest daughter of Edward Knight, sometimes cause a little confusion. Jane Austen mentions calling with the younger Fanny on the motherless children of her brother, one of whom was also Fanny, soon after their loss. “We got to Keppel Street, however, which was all I cared for, and though we could only stay a quarter of an hour, Fanny’s calling gave great pleasure, and her sensibility still greater; for she was very much affected at the sight of the children. Little Fanny looked heavy. We saw the whole party.”

It has been necessary to give a few details respecting the brothers who played so large a part in Jane’s life, because her visits away from home were nearly all to their houses, her letters are full of allusions to them, and the great family affection which subsisted between them all made the griefs and joys of the others the greatest events in a very uneventful life. The dearest, however, of the whole family was the one sister Cassandra, who, like Jane herself, never married, which seems the stranger when we consider how many of the brothers married twice. There was a sad little love-story in Cassandra’s life. She was engaged to a young clergyman who had promise of promotion from a nobleman related to him. He accompanied this patron to the West Indies as chaplain to the regiment, and there died of yellow fever. There is perhaps something more pathetic in such a tale than in any other, the glowing ideal has not been smirched by any touch of the actual sordid daily life, it is snatched away and remains an ideal always, and the happiness that might have been is enhanced by romance so as to be a greater deprivation than any loss of the actual.

The two sisters were sisters in reality, sharing the same views, the same friendships, the same interests. When away, Jane’s letters to Cassandra are full and lively, telling of all the numberless little events that only a sister can enjoy. And if Jane’s own estimate is to be believed, Cassandra’s are to the full as vivacious.

“The letter which I have this moment received from you has diverted me beyond moderation. I could die of laughter at it, as they used to say at school. You are indeed the finest comic writer of the present age.”

Cassandra lived to 1845, long enough to see that her beloved sister’s letters would in all probability be published; she was of a reticent nature, with a strong dislike to revealing anything personal or intimate to the public, she therefore went through all these neatly written letters from Jane, which she had so carefully preserved, and destroyed anything of a personal nature. One cannot altogether condemn the action, greatly as we have been the losers; the letters that remain, many in number, deal almost entirely with outside matters, trivialities of everyday life, and they are written so brightly that we can judge how interesting the bits of self-revelation by so expressive a pen would have been.

In 1869, when Mr. Austen-Leigh published his Memoir, only one or two of Jane Austen’s letters were available; but in 1882, on the death of Lady Knatchbull (née Fanny Knight), the letters above referred to, which Cassandra Austen had retained, were found among her belongings, having come to her on her aunt’s death. Her son, created Lord Brabourne, therefore published these in two volumes in 1884, and when quotations and extracts are given in this book without further explanation, it must be inferred that these are taken from letters of Jane to Cassandra, as given by Lord Brabourne.

CHAPTER II CHILDHOOD

Of Jane Austen’s childhood in the quiet country rectory we know little, probably because there is not a great deal to know. It was the custom in those days to put babies out to nurse in the village, sometimes until they were as much as two years old, a point often overlooked when the mothers of what is now extolled as a domestic period are held up as patterns to a more intellectual and roving generation. Certainly it was an easy and cheap method of getting rid of the care and trouble involved by a baby in the house, and it probably answered well, as the child would learn to do without too much attention, and at an early age, faddists notwithstanding, could hardly suffer from any influence of its surroundings, other than physically, and it may be taken for granted that the material necessities were well provided and kept under supervision. Nevertheless, a mother who adopted this course at the present day could hardly escape the epithet of “heartless,” which would assuredly be levelled at her.

In the time of Jane’s childhood the old days of rigid severity toward children were past, no longer were mere babies taken to see executions and whipped on their return to enforce the example they had beheld. In fact a period of undue indulgence had set in as a reaction, but this does not seem to have affected the Austen family, who were brought up very wisely, and perhaps even a little more repressively than would be the case in a similar household to-day. Jane herself was evidently a diffident child.

She says of a little visitor many years afterwards: “Our little visitor has just left us, and left us highly pleased with her; she is a nice natural open-hearted, affectionate girl, with all the ready civility one sees in the best children in the present day; so unlike anything that I was myself at her age, that I am often all astonishment and shame.

“What is become of all the shyness in the world? Moral as well as natural diseases disappear in the progress of time and new ones take their place. Shyness and the sweating sickness have given way to confidence and paralytic complaints.”

Her own attitude toward children is peculiar. Though on indisputable testimony she was the most popular and best loved of aunts, the fact remains that she had no great insight into child nature, nor does she seem to have had any general love of children beyond those who were specially connected with her by close ties. She loved her nieces, but much more as they grew older than as children.

Mr. Austen-Leigh says: “Aunt Jane was the delight of all her nephews and nieces. We did not think of her as being clever, still less as being famous; but we valued her as one always kind, sympathising, and amusing,” and he quotes “the testimony of another niece—’Aunt Jane was the general favourite with children, her ways with them being so playful, and her long circumstantial stories so delightful.’” And again, “Her first charm to children was great sweetness of manner ... she could make everything amusing to a child.”

The truth probably is that her innate kindness of heart and unselfishness compelled her to be as amusing as possible when thrown with little people, but perhaps because she took so much trouble to entertain them she found children more tiresome than other people who accept their company more placidly. However this may be, it is undeniable that the attitude she takes toward children in her books is almost always that of their being tiresome, there never appears any genuine love for them or realisation of pleasure in their society; and she continually satirises the foolish weakness of their doting parents. It is recorded as a great feature in the character of Mrs. John Knightley “that in spite of her maternal solicitude for the immediate enjoyment of her little ones, and for their having instantly all the liberty and attendance, all the eating and drinking, and sleeping and playing, which they could possibly wish for, without the smallest delay, the children were never allowed to be long a disturbance to him [their grandfather] either in themselves or in any restless attendance on them.”

Poor Anne in Persuasion is tormented by “the younger boy, a remarkably stout forward child of two years old, ... as his aunt would not let him tease his sick brother, [he] began to fasten himself upon her, in such a way, that busy as she was about Charles, she could not shake him off. She spoke to him, ordered, entreated, insisted in vain. Once she did contrive to push him away, but the boy had the greater pleasure in getting upon her back again directly.”

Perhaps to Anne this annoyance was a blessing in disguise, as it brought forward the whilom lover to her assistance, but that is beside the point!

The children of Lady Middleton in Sense and Sensibility are particularly badly behaved and odious.

“Fortunately for those who pay their court through such foibles, a fond mother, though in pursuit of praise for her children the most rapacious of human beings, is likewise the most credulous; her demands are exorbitant, but she will swallow anything, and the excessive affection and endurance of the Miss Steeles towards her offspring were reviewed therefore by Lady Middleton without the smallest surprise or distrust. She saw with maternal complacency all the impertinent encroachments and mischievous tricks to which her cousins submitted. She saw their sashes untied, their hair pulled about their ears, their workbags searched and their knives and scissors stolen away, and felt no doubt of its being a reciprocal enjoyment.

“‘John is in such spirits to-day!’ said she, on his taking Miss Steele’s pocket-handkerchief and throwing it out of the window, ‘he is full of monkey-tricks.’

“And soon afterwards on the second boy’s violently pinching one of the same lady’s fingers, she fondly observed, ‘How playful William is!’

“‘And here is my sweet little Anna-Maria,’ she added, tenderly caressing a little girl of three years old, who had not made a noise for the last two minutes; ‘and she is always so gentle and quiet, never was there such a quiet little thing!’

“But unfortunately in bestowing these embraces a pin in her ladyship’s head-dress slightly scratching the child’s neck produced from this pattern of gentleness such violent screams as could hardly be outdone by any creature professedly noisy ... her mouth stuffed with sugar-plums ... she still screamed and sobbed lustily, and kicked her two brothers for offering to touch her.

················

“‘I have a notion,’ said Lucy [to Elinor] ‘you think the little Middletons are too much indulged. Perhaps they may be the outside of enough, but it is so natural in Lady Middleton, and for my part I love to see children full of life and spirits; I cannot bear them if they are tame and quiet.’

“‘I confess,’ replied Elinor, ‘that while I am at Barton Park I never think of tame and quiet children with any abhorrence!’”

Those children in the novels who are not detestable are usually lay-figures, such as Henry and John Knightley, rosy-faced little boys not distinguished by any individuality. Others are merely pegs on which to hang their parents’ follies, such as little Harry Dashwood, who serves his parents as an excuse for their unutterable meanness. The fact remains there are only two passable children in the whole gallery, and one is the slightest of slight sketches in that little-known and half-finished story The Watsons. Here the little boy, Charles, spoken of as “Mrs. Blake’s little boy,” is a real flesh-and-blood child, who at his first ball when thrown over remorselessly by his grown-up partner, though “the picture of disappointment, with crimsoned cheeks, quivering lips, and eyes bent on the floor,” yet contrives to utter bravely, “‘Oh, I do not mind it!’” and whose naïve enjoyment at dancing with Emma Watson, who offers herself as a substitute, is well done. His conversation with her is also very natural, and his cry, “‘Oh, uncle, do look at my partner; she is so pretty!’” is a human touch.

JUVENILE RETIREMENT

The other instance is a sample of a very nervous, shy child, perhaps drawn from the recollections of Jane Austen’s own feelings in childhood, this is Fanny Price, whose loneliness on her first coming to Mansfield Park is carefully depicted, but Fanny herself is unchildlike and exceptional. Her younger brothers rank among the gallery of bad children, for by “the superior noise of Sam, Tom, and Charles chasing each other up and down stairs, and tumbling about and hallooing, Fanny was almost stunned. Sam, loud and overbearing as he was, ... was clever and intelligent.... Tom and Charles being at least as many years as they were his juniors distant from that age of feeling and reason which might suggest the expediency of making friends, and of endeavouring to be less disagreeable. Their sister soon despaired of making any impression on them; they were quite untamable by any means of address which she had spirits or time to attempt.... Betsy, too, a spoilt child, trained up to think the alphabet her greatest enemy, left to be with servants at her pleasure, and then encouraged to report any evil of them.”

But Jane Austen’s abundant pictures of over-indulged, badly-behaved children are not the only ones to be found in contemporary fiction; in Hannah More’s Cœlebs in Search of a Wife the children come in for dessert, “a dozen children, lovely, fresh, gay, and noisy ... the grand dispute, who should have oranges, and who should have almonds and raisins, soon raised such a clamour that it was impossible to hear my Egyptian friend ... the son and heir reaching out his arm to dart an apple across the table at his sister, roguishly intending to overset her glass, unluckily overthrew his own brimful of port wine.” And of another and better behaved family it is observed as a splendid innovation that the children are not allowed to come into dessert, to clamour and make themselves nuisances, but are limited to appearing in the drawing-room later.

One of the characters in Cœlebs is made to observe, “This is the age of excess in everything; nothing is a gratification of which the want has not been previously felt. The wishes of children are all so anticipated, that they never experience the pleasure excited by wanting and waiting.” He speaks also of the “too great profusion and plethora of children’s books,” which is certainly not a thing we are used to attribute to that age.

Several of the children’s books of that date are kept alive to the present day by a salt of insight into child nature, and are published and re-published perennially. Many a child still knows and loves The Story of the Robins, by Mrs. Trimmer, first brought out in 1786; and as for Sandford and Merton, by Thomas Day, which was at first in three volumes, published respectively in 1783, 1787, and 1789, many a boy has revelled in it, not perhaps entirely from the point of view in which it was written, but with a keen sense of the ridiculous in the behaviour of the little prig Harry. Mrs Barbauld’s (and her brother’s) Evenings at Home still delights many children; and Miss Edgeworth’s Parent’s Assistant, of which the first volume appeared in 1796, is a perennial source of amusement in nurseries and schoolrooms. The Fairchild Family suffers from an excess of religiosity, and a terrible belief in the innate wickedness of a little child’s heart, which is not now tolerated. When Emily and Lucy indulge in a childish quarrel, they are taken to see what remains of a murderer who has hung on a gibbet until his clothes are rotting from him, and the warning is enforced by a long sermon; but in spite of much that would not be suitable according to present ideas for a child to hear, The Fairchild Family, the first part of which came out a year subsequently to the death of Jane Austen, contains much that is very human in behaviour and action. Though later in date than the others mentioned as surviving, it really is quite as early in treatment, as it is a record of what Mrs. Sherwood, born in the same year as Jane Austen, remembered of her own childhood.

The book contains many examples of the spoilt-child phase, in contrast with which the strict upbringing of the young Fairchilds is shown as the better way. What Mrs. Sherwood puts into the mouth of Mrs. Fairchild about her childhood is probably autobiographical, and may be quoted as an instance of the sterner modes which were then rapidly passing out of vogue.

“I was but a very little girl when I came to live with my aunts, and they kept me under their care until I was married. As far as they knew what was right, they took great pains with me. Mrs. Grace taught me to sew, and Mrs. Penelope taught me to read; I had a writing and music master, who came from Reading to teach me twice a week; and I was taught all kinds of household work by my aunts’ maid. We spent one day exactly like another. I was made to rise early, and to dress myself very neatly, to breakfast with my aunts. After breakfast I worked two hours with my aunt Grace, and read an hour with my aunt Penelope; we then, if it was fine weather, took a walk; or, if not, an airing in the coach, I and my aunts, and little Shock, the lap-dog, together. At dinner I was not allowed to speak; and after dinner I attended my masters or learned my tasks. The only time I had to play was while my aunts were dressing to go out, for they went out every evening to play at cards. When they went out my supper was given to me, and I was put to bed in a closet in my aunts’ room.”

A modern child under such treatment would probably develop an acute form of melancholia.

The home education of the time, for girls at least, was very superficial. We gather something of what was supposed to be taught from the remarks of the Bertram girls in Mansfield Park when they plume themselves on their superiority to Fanny—

“‘Dear mamma, only think, my cousin cannot put the map of Europe together—or my cousin cannot tell the principal rivers in Russia, or she never heard of Asia Minor, or she does not know the differences between water colours and crayons! How strange! Did you ever hear anything so stupid?’

“‘My dear,’ their considerate aunt would reply, ‘it is very bad, but you must not expect everybody to be as forward and quick at learning as yourself.’

“‘But, aunt, she is really so very ignorant. Do you know we asked her last night which way she would go to get to Ireland, and she said she should cross to the Isle of Wight. I cannot remember the time when I did not know a great deal that she has not the least notion of yet. How long ago is it, aunt, since we used to repeat the chronological order of the kings of England, with the dates of their accession, and most of the principal events of their reigns?’

“‘Yes,’ added the other, ‘and of the Roman Emperors as low as Severus, besides a great deal of the heathen mythology, and all the metals, semi-metals, planets, and distinguished philosophers.’”

The rattle-pate, Miss Amelia, in Cœlebs thus gives an account of her education: “I have gone on with my French and Italian of course, and I am beginning German. Then comes my drawing-master; he teaches me to paint flowers and shells, and to draw ruins and buildings, and to take views.... I learn varnishing, gilding, and Japanning. And next winter, I shall learn modelling and etching and engraving in mezzotint and aquatinta. Then I have a dancing-master who teaches me the Scotch and Irish steps, and another who teaches me attitudes, and I shall soon learn to waltz. Then I have a singing-master, and another who teaches me the harp, and another for the pianoforte. And what little time I can spare from these principal things, I give by odd minutes to ancient and modern history, and geography and astronomy, and grammar and botany, and I attend lectures on chemistry, and experimental chemistry.”

Jane’s early childhood was probably a very happy one; what with the companionship of Cassandra, with the liveliness and constant comings and goings of the brothers who were educated at home by Mr. Austen himself, with all the romps of a large family having unlimited country as a playground, it can hardly have failed to be so. While she was still too young to profit much by school teaching on her own account, she was sent to a school at Reading kept by a Mrs. Latournelle, because Cassandra was going, and the two sisters could not bear to be parted. How long she was at this school I do not know, but the subjects taught were probably those scheduled in the comprehensive summary of smatterings given by the two Miss Bertrams. This school was a notable one, and among the later pupils was Mrs. Sherwood, who followed Jane after an interval of nine years. She probably went to school as late as Jane went early, which would account for the gap in time between two who should have been contemporary.

Miss Mitford was also a pupil; she went in 1798 when the school had been removed to Hans Place, London. She gives a lively account of it. It was kept by M. St. Quintin, “a well-born, well-educated, and well-looking French emigrant,” who “was assisted, or rather chaperoned, in his undertaking by his wife, a good-natured, red-faced Frenchwoman, much muffled up in shawls and laces; and by Miss Rowden, an accomplished young lady, the daughter and sister of clergymen, who had been for some years governess in the family of Lord Bessborough. M. St. Quintin himself taught the pupils French, history, geography, and as much science as he was master of, or as he thought it requisite for a young lady to know; Miss Rowden, with the assistance of finishing masters for Italian, music, dancing, and drawing, superintended the general course of study; while Madame St. Quintin sat dozing, either in the drawing-room, with a piece of work, or in the library with a book in her hand, to receive the friends of the young ladies or any other visitors who might chance to call.”

Miss Mitford says further that the school was “excellent,” that the pupils were “healthy, happy, well-fed, and kindly treated,” and that “the intelligent manner in which instruction was given had the effect of producing in the majority of the pupils a love of reading and a taste for literature.”

Of course Jane, being such a child when she went, can hardly have taken full use of the opportunities which were afforded her, but perhaps she laid at school the foundations of that cleverness in neat sewing and embroidery which is manifested in the specimens still in the possession of her relatives.

There is a portrait of Jane painted when she was about fifteen. It shows a bright child with shining eyes and one loose lock of hair falling over her forehead; not particularly pretty, but intelligent and with character. She is standing, and is dressed in the simple white gown, high waist, short sleeves, and low neck which little girls wore as well as their elders, and round her neck is a large locket slung on a slender chain. Her portrait was painted by Zoffany when she was about fifteen, on her first visit to Bath, but whether this reproduction, which appears in the beginning of Lord Brabourne’s Letters of Jane Austen, is from that picture I have not been able to ascertain.

Mr. Austen-Leigh says of her—

“In childhood every available opportunity of instruction was made use of. According to the ideas of the time she was well-educated, though not highly accomplished, and she certainly enjoyed that important element of mental training, associating at home with persons of cultivated intellect.” He says in another place, “Jane herself was fond of music, and had a sweet voice, both in singing and conversation; in her youth she had received some instruction on the pianoforte ... she read French with facility, and knew something of Italian.”

In French she had at one time a great advantage in the continual association with Madame de Feuillade, her cousin, and afterwards her sister-in-law, who, as already mentioned, had been married to a Frenchman.

The illustration on p. 26 is a portrait group of the children of the Hon. John Douglas of the Morton family. It was painted by Hoppner, who lived 1758-1810; and, in the costumes of the little boy and elder girl especially, gives a good notion of the dress of the better-class children of the period.

CHAPTER III THE POSITION OF THE CLERGY

Jane Austen was a clergyman’s daughter. At the present time there are undoubtedly wide differences in the social standing of the clergy according to their own birth and breeding, but yet it may be taken for granted that a clergyman is considered a fit guest for any man’s table. It was not always so. There was a time when a clergyman was a kind of servant, ranking with the butler, whose hospitality he enjoyed; we have plenty of pictures of this state of affairs in The Vicar of Wakefield, to go no further. But before Jane was born, matters had changed. The pendulum had not yet swung to the opposite extreme of our own day, when the fact of a man’s being ordained is supposed to give him new birth in a social sense, and a tailor’s son passes through the meagrest of the Universities in order that he may thus be transformed into a gentleman without ever considering whether he has the smallest vocation for the ministry. In the Austens’ time the status of a clergyman depended a very great deal on himself, and as the patronage of the Church was chiefly in the hands of the well-to-do lay-patrons, who bestowed the livings on their younger sons or brothers, there was very frequently a tie of relationship between the vicarage and the great house, which was sufficient to ensure the vicar’s position. In the case of relationship the system was probably at its best, obviating any inducement to servility; but there was a very evil side to what may be called local patronage, which was much more in evidence than it is in our time. Archbishop Secker, in his charges to the clergy of the diocese of Oxford, when he was their Bishop in 1737, throws a very clear light on this side of the question. He expressly enjoins incumbents to make no promise to their patrons to quit the benefice when desired before entering into office. “The true meaning therefore is to commonly enslave the incumbent to the will and pleasure of the patron.” The motive for demanding such a promise was generally that the living might be held until such time as some raw young lad, a nephew or younger son of the lord of the manor, was ready to take it. The evils of such a system are but too apparent. We can imagine a nervous clergyman who would never dare to express an opinion contrary to the will of the benefactor who had the power to turn him out into the world penniless; we can imagine the time-server courting his patron with honied words. This debased type is inimitably sketched in the character of Mr. Collins in Pride and Prejudice. “‘It shall be my earnest endeavour to demean myself with grateful respect towards her ladyship, and be very ready to perform those rites and ceremonies which are instituted by the Church of England.’ Lady Catherine [he said] had been graciously pleased to approve of both the discourses which he had already had the honour of preaching. She had also asked him twice to dine at Rosings, and had sent for him only the Saturday before, to make up her pool of quadrille in the evening. Lady Catherine was reckoned proud, he knew, by many people, but he had never seen anything but affability in her. She had always spoken to him as she would to any other gentleman; she made not the smallest objection to his joining in the society of the neighbourhood.”

In his delightful exordium to Elizabeth as to his reasons for proposing to her, he says—

“‘My reasons for marrying are, first, that I think it a right thing for every clergyman in easy circumstances (like myself) to set the example of matrimony in his parish; secondly, that I am convinced it will add very greatly to my happiness; and, thirdly, which perhaps I ought to have mentioned earlier, that it is the particular advice and recommendation of the very noble lady whom I have the honour of calling patroness. Twice has she condescended to give me her opinion (unasked too!) on this subject; and it was but the very Saturday night before I left Hunsford—between our pools at quadrille while Mrs. Jenkinson was arranging Miss de Bourgh’s footstool—that she said, ‘Mr. Collins, you must marry. A clergyman like you must marry. Choose properly, choose a gentlewoman for my sake, and for your own; let her be an active useful sort of person, not brought up high, but able to make a small income go a good way.’”

And when, after his marriage with her friend, Elizabeth goes to stay with them, and is invited to dine with them at the Rosings, Lady Catherine’s place, he thus encourages her—

“‘Do not make yourself uneasy, my dear cousin, about your apparel. Lady Catherine is far from requiring that elegance of dress in us which becomes herself and daughter. I would advise you merely to put on whatever of your clothes is superior to the rest, there is no occasion for anything more. Lady Catherine will not think the worse of you for being simply dressed. She likes to have the distinction of rank preserved.’”

In the case of Mr. Collins, the patron happened to be a lady, but the instances were numberless in which clergymen spent all their time toadying and drinking with a fox-hunting squire.

Arthur Young says of the French clergy—

“One did not find among them poachers or fox-hunters, who, having spent the morning scampering after hounds, dedicate the evening to the bottle, and reel from inebriety to the pulpit,” from which we may infer that many English clergymen did.

Cowper’s satire on the way in which preferment is secured is worth quoting in full—

“Church-ladders are not always mounted best

By learned clerks and Latinists professed.

The exalted prize demands an upward look,

Not to be found by poring on a book.

Small skill in Latin, and still less in Greek,

Is more than adequate to all I seek.

Let erudition grace him or not grace,

I give the bauble but the second place;

His wealth, fame, honours, all that I intend

Subsist and centre in one point—a friend.

A friend whate’er he studies or neglects,

Shall give him consequence, heal all defects.

His intercourse with peers and sons of peers—

There dawns the splendour of his future years;

In that bright quarter his propitious skies

Shall blush betimes, and there his glory rise.

‘Your lordship’ and ‘Your Grace,’ what school can teach

A rhetoric equal to those parts of speech?

What need of Homer’s verse or Tully’s prose,

Sweet interjections! if he learn but those?

Let reverend churls his ignorance rebuke,

Who starve upon a dog-eared pentateuch,

The parson knows enough who knows a duke.”

At the end of the eighteenth century the Church was at its deadest, enthusiasm there was none. Torpid is the only word that fitly describes the spiritual condition of the majority of the clergy. Secker says, “An open and professed disregard of religion is become, through a variety of unhappy causes, the distinguishing character of the present age”; and the clergy, as the salt of the earth, had certainly lost their savour, and did little or nothing to resist an apathy which, too commonly, extended to themselves.

The duties of clergymen were therefore almost as light as they chose to make them. One service on Sunday, and the Holy Communion three times yearly, at Christmas, Easter, and Whitsuntide, was considered enough.

“A sacrament might easily be interposed in the long interval between Christmas and Whitsuntide, and the usual season for it, the Feast of St. Michael, is a very proper time, and if afterwards you can advance from a quarterly communion to a monthly one, I make no doubt you will.” (Secker.)

Baptisms, marriages, and funerals were looked on as nuisances; the clergyman ran them together as much as possible, and often arrived at the last minute, flinging himself off his smoking horse to gabble through the service with the greatest possible speed; children were frequently buried without any service at all.

The churches were for the most part damp and mouldy; there were, of course, none of the present conveniences for heating and lighting. Heavy galleries cut off the little light that struggled through the cobwebby windows. There were mouse-eaten hassocks, curtains on rods thick with dust, a general smell of mouldiness and disuse, and a cold, but ill-ventilated, atmosphere.

In some old country churches there still survive the family pews, which were like small rooms, and in which the occupants could read or sleep without being seen by anyone; in one or two cases there are fire-grates in these; and in one strange example at Langley, in Bucks, the pew is not only roofed in, but it has a lattice in front, with painted panels which can be opened and shut at the occupants’ pleasure, and there is a room in connection with it in which is a library of books, so that it would be quite possible for anyone to retire for a little interlude without the rest of the congregation’s being aware of it!

The church, only opened as a rule once a week, was left for the rest of the time to the bats and birds. Compare this with one of the neat, warm, clean churches to be found almost everywhere at present; churches with polished wood pews, shining brass fittings, tessellated floor in place of uneven bricks, a communion table covered by a cloth worked by the vicar’s wife, and bearing white flowers placed by loving hands. A pulpit of carved oak, alabaster, or marble, instead of a dilapidated old three-decker in which the parish clerk sat below and gave out the tunes in a droning voice.

Organs were of course very uncommon at the end of the eighteenth century in country parishes, and though there might be at times a little local music, as an accompaniment, the hymns were generally drawled out without music at all. This is Horace Walpole’s idea of church in 1791: “I have always gone now and then, though of late years rarely, as it was most unpleasant to crawl through a churchyard full of staring footmen and apprentices, clamber a ladder to a hard pew, to hear the dullest of all things, a sermon, and croaking and squalling of psalms to a hand organ by journey-men brewers and charity children.”

The sermons were peculiarly dry and dull, and it would have taken a clever man to suck any spiritual nourishment therefrom. They were generally on points of doctrine, read without modulation; and if, as was frequently the case, the clergyman had not the energy to prepare his own, a sermon from any dreary collection sufficed. The black gown was used in the pulpit.

Cowper gives a picture of how the service was often taken—

“I venerate the man whose heart is warm;

Whose hands are pure, whose doctrine and whose life

Coincident, exhibit lucid proof

That he is honest in the sacred cause.

A messenger of grace to guilty men.

Behold the picture! Is it like? Like whom?

The things that mount the rostrum with a skip,

And then skip down again; pronounce a text,

Cry, ahem! and reading what they never wrote,

Just fifteen minutes, huddle up their work,

And with a well-bred whisper, close the scene.”

In this dismal account the average only is taken, and there were many exceptions; we have no reason to suppose, for instance, that the Rev. George Austen marred his services by slovenliness or indifference, though no doubt the most earnest man would find it hard to struggle against the disadvantages of his time, and the damp mouldy church must have been a sore drawback to church-going.

Twining’s Country Clergyman gives us a picture of an amiable sort of man of a much pleasanter type than those of Cowper or Crabbe.

We gain an idea of a man of a genial, pleasant disposition, cultured enough, and fond of the classics; who kept his house and garden well ordered, who enjoyed a tour throughout England in company with his wife, who thoroughly appreciated the lines in which his lot was cast, but who looked upon the living as made for him, and not he for the parishioners. A writer in the Cornhill some years ago gives a series of pleasant little pen-pictures of typical clergymen of this date. “Who cannot see it all—the curate-in-charge himself sauntering up and down the grass on a fine summer morning, his hands in the pockets of his black or drab ‘small clothes,’ his feet encased in broad-toed shoes, his white neckcloth voluminous and starchless, his low-crowned hat a little on one side of his powdered head, his eye wandering about from tree to flower, and from bird to bush, as he chews the cud of some puzzling construction in Pindar, or casts and recasts some favourite passage in his translation of Aristotle.”

There was the fox-hunter who in the time not devoted to sport was always “welcome to the cottager’s wife at that hour in the afternoon when she had made herself tidy, swept up the hearth, and was sitting down before the fire with the stockings of the family before her. He would chat with her about the news of the village, give her a friendly hint about her husband’s absence from church, and perhaps, before going, would be taken out to look at the pig.”

Or “the pleasant genial old gentleman in knee-breeches and sometimes top-boots, who fed his poultry, and went into the stable to scratch the ears of his favourite cob, and round by the pig-stye to the kitchen garden, where he took a turn for an hour or two with his spade or his pruning knife, or sauntered with his hands in his pockets in the direction of the cucumbers ... coming in to an early dinner.”

Mr. Austen seems to have been a mixture of the first and third of these types, for he was certainly a good scholar, and yet some of his chief interests in life were connected with his pigs and his sheep.

But though these are charming sketches, and their counterparts were doubtless to be found, we fear they are too much idealised to be a true representation of the generality of the clergy of that time; and, charming as they are, there is an easy freedom from the responsibility of office which is strange to modern ideas.

Livings, many of which are bad enough now, were then even worse paid; £25 a year was the ordinary stipend for a curate who did most of the work. Massey (History of England in the Reign of George II.) estimates that there were then five thousand livings under £80 a year in England; consequently pluralism was oftentimes almost a necessity. Gilbert White, the naturalist, was a shining light among clergymen; he was vicar of Selborne, in Hampshire, until his death in 1793; but while he was curate of Durley, near Bishop’s Waltham, the actual expenses of the duty exceeded the receipts by nearly twenty pounds in the one year he was there. To reside at all was a great thing for a clergyman to do, and we may be sure, from what we gather, that the Rev. George Austen had this virtue, for he resided all the time at Steventon.

But though the clergy frequently left all the work to their curates, they always took care to receive the tithes themselves. In the picture engraved by T. Burke after Singleton, in the period under discussion, we see the fat and somewhat cross-looking vicar receiving these tithes in kind from the little boy, who brings his basket containing a couple of ducks and a sucking pig into the vicarage study.

THE VICAR RECEIVING HIS TITHES

Hannah More gives us an account of the usual state of things in regard to non-residence—

“The vicarage of Cheddar is in the gift of the Dean of Wells; the value nearly fifty pounds per annum. The incumbent is a Mr. R., who has something to do, but I cannot find out what, in the University of Oxford, where he resides. The curate lives at Wells, twelve miles distant. They have only service once a week, and there is scarcely an instance of a poor person being visited or prayed with. The living of Axbridge ... annual value is about fifty pounds. The incumbent about sixty years of age. Mr. G. is intoxicated about six times a week, and very frequently is prevented from preaching by two black eyes, honestly earned by fighting.”

“We have in this neighbourhood thirteen adjoining parishes without so much as even a resident curate.”

“No clergyman had resided in the parish for forty years. One rode over three miles from Wells to preach once on a Sunday, but no weekly duty was done or sick persons visited; and children were often buried without any funeral service. Eight people in the morning, and twenty in the afternoon, was a good congregation.”

She evidently means that the service was sometimes held in the morning, and sometimes in the afternoon, as she says there were not two services.

She also speaks of it as an exceptionally disinterested action of Dr. Kennicott that he had resigned a valuable living because his learned work would not allow him to reside in the parish.

By far the best account of what was expected from a contemporary clergyman is to be gathered from Jane Austen’s own books. It is one of her strong points that she wrote only of what she knew, and as her own father and two of her brothers were clergymen, we cannot suppose that she was otherwise than favourably inclined to the class. Her sketch of Mr. Collins is no doubt something of a caricature, but it serves to illustrate very forcibly one great error in the system then in vogue—that of local patronage.

The other clergymen in her books are numerous: we have Mr. Elton in Emma, Edmund Bertram and Dr. Grant in Mansfield Park, Henry Tilney in Northanger Abbey, and Edward Ferrars in Sense and Sensibility.

It is impossible to deny that Edmund Bertram is a prig, or perhaps, to put it more mildly, is inclined to be sententious, so sometimes one almost sympathises with the gay Miss Crawford, whose ideas so shocked him and Fanny; yet though those ideas only reflected the current opinion of the times, they were reprehensible enough. When Miss Crawford discovers, to her chagrin, that Edmund, whom she is inclined to like more than a little, is going to be a clergyman, she asks—

“‘But why are you to be a clergyman? I thought that was always the lot of the youngest, where there were many to choose before him!’

“‘Do you think the Church itself never chosen, then?’

“‘Never is a black word. But yes, in the never of conversation which means not very often, I do think it. For what is to be done in the Church? Men love to distinguish themselves, and in either of the other lines distinction may be gained, but not in the Church. A clergyman is nothing.’”

And in reply to Edmund’s defence, she continues—

“‘You assign greater consequence to a clergyman than one has been used to hear given, or than I can quite comprehend. One does not see much of this influence and importance in society, and how can it be acquired where they are so seldom seen themselves? How can two sermons a week, even supposing them worth hearing, supposing the preacher to have the sense to prefer Blair’s to his own, do all that you speak of, govern the conduct and fashion and manners of a large congregation for the rest of the week? One scarcely sees a clergyman out of his pulpit!’

“‘You are speaking of London, I am speaking of the nation at large.’”