автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Indoor and Outdoor Recreations for Girls

RECREATIONS FOR GIRLS

Indoor

and

Outdoor

RECREATIONS FOR GIRLS

BY

Lina Beard

and

Adelia B. Beard

New York

Charles Scribner's

Sons

1914

Copyright, 1904, 1906, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

SPECIAL NOTICE

The publishers hereby give warning that the unauthorized printing of any portion of the text of this book, and the reproduction of any of the illustrations or diagrams, are expressly forbidden.

EXPLANATORY NOTE TO NEW EDITION

Since the publication of this volume two years ago as "Handicraft and Recreation for Girls," it has occurred to us that "Recreations" alone much more accurately defines the contents, for the handicrafts represented are only those that in effect are recreations. Therefore we have thought it best to drop the word Handicraft and issue the new edition under the more appropriate title, "Recreations for Girls."

Lina Beard

Adelia B. Beard.

September, 1906.

PREFACE

This book, like a girl's life, is divided into two parts: occupation and amusement, or handicraft and recreation.

It is not equally divided, for handicraft is so much more like play than work, and is so entertaining in itself, we find difficulty in drawing a distinct line between that and recreation. The one insists upon blending with the other and the book, after all, is a book of entertainment.

With the old handicrafts coming back into favor and new ones constantly being brought forward, a girl's life may be full of delightful employment. To work with joyous enthusiasm and self-reliant energy, as well as to play with light-hearted enjoyment, cannot fail to make her sensible, wholesome, and happy, and it is with this end in view that we have written and illustrated the book. Our wish is to help our girl friends to make the most of their girlhood and to enjoy it to its fullest extent.

We have had practical experience in the actual working out of all the various handicrafts and recreations, and therefore give only that which we know can be well and easily done by the average girl.

Thanks are due to the Delineator, Harper's Bazar, Woman's Home Companion, and Good Housekeeping, for their courtesy in promptly returning for this work the original drawings and material used in their respective magazines.

The Author.

Flushing, August 2, 1904.

CONTENTS

PART I

HANDICRAFT

CHAPTER I.

PAGE Spinning 3The Spinning-Wheel, 4; The Spindle, 5; The Distaff, 7; Thoroughly Cleaned, 8; The Band, 8; To Adjust the Band, 9; The Flax, 10; Practice, 11; How to Spin, 12; When the Thread Breaks, 12.

CHAPTER II.

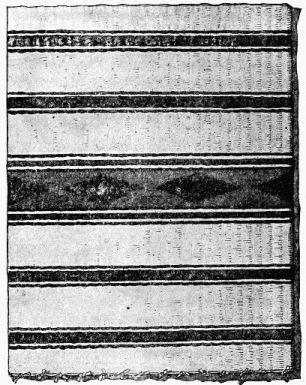

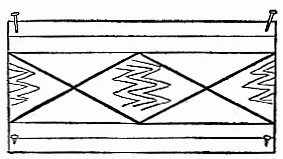

Weaving on a Home-made Loom 15The Pin Loom, 16; The Heddles, 17; The Shuttle, 19; To Adjust the Warp, 19; The Woof, 20; How to Weave a Miniature Navajo Blanket, 20; Blankets for Dolls' Beds, 26.

CHAPTER III.

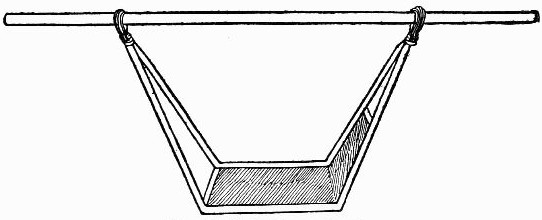

A Ball of Twine and What May Be Made of It 27Making a Little Hammock, 27; How to Tie the Twine, 29; A School-Bag, 31; Twine Curtains, 34.

CHAPTER IV.

An Armful of Shavings, and What to Do with Them 36Selecting the Shavings, 36; A Soft Little Basket, 36; How to Prepare the Shavings, 37; How to Weave the Shavings, 39; Bind the Edges, 40; The Handle, 40; A Handkerchief Case, 41.

CHAPTER V.

Primitive Reed Curtains 43The Reeds, 43; Raw Material, 43; The Twine-Stick Weave, 44; The Finished Curtain, 46; Curtain-Bee Frolic, 48; Door-way Screens, 49.

CHAPTER VI.

Things to Make of Common Grasses 53A Grasshopper House, 53; A Doll's Hammock, 56; A Bouquet-Holder, 58; Weaving a Napkin-Ring, 59.

CHAPTER VII.

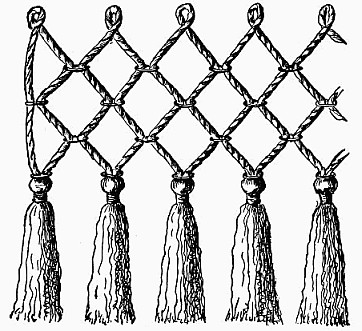

Possibilities of a Clothes Line 62Adapted to Decoration, 62; Rope Wood-Basket, 62; Rope Net Fringe, 65; The Tassels, 65.

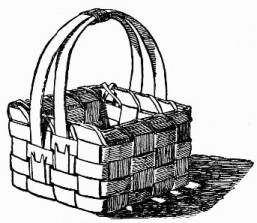

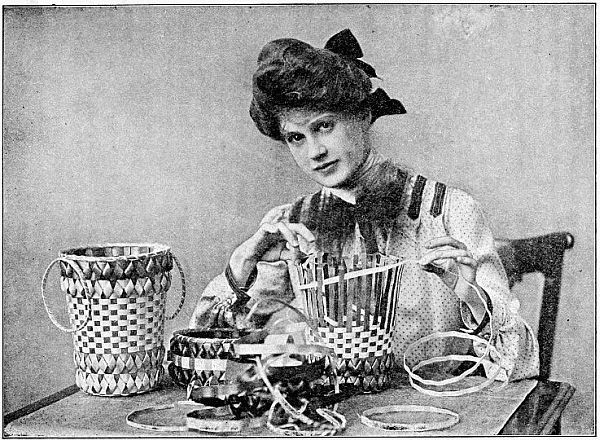

CHAPTER VIII.

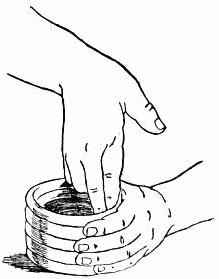

How to Weave a Splint Basket 68The Material, 68; The Spokes, 68; The Weavers, 70; Weaving the Basket, 71; Binding Off, 71; Trimming, 73.

CHAPTER IX.

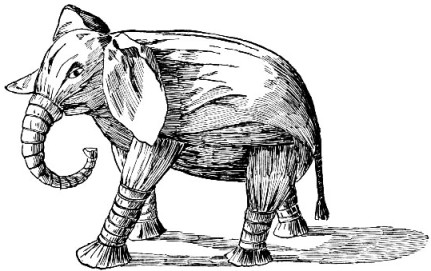

Modelling in Tissue-Paper 75Modelling a Chicken, 75; A Turkey, 81; The Sturdy Little Elephant, 83.

CHAPTER X.

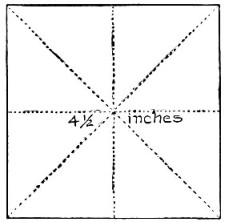

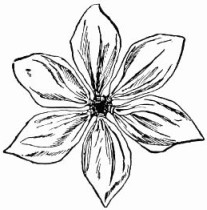

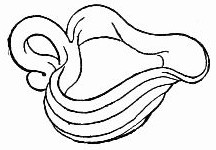

Nature Study with Tissue-Paper 86All Flowers from Squares and Circles, 86; The Best Models, 86; Material, 87; The Carnation, 87; How to Cut a Circle, 88; The Morning-Glory, 94; The Daffodil, 99.

CHAPTER XI.

A New Race of Dolls 103Dolls of Substance and Form, 103; The Paper, 104; Making the Head, 104; The Arms, 105; The Body, 105; The Legs, 106; The Feet and Shoes, 107; Doll's Hair, 106; The Dress, 108; The Cap, 110.

CHAPTER XII.

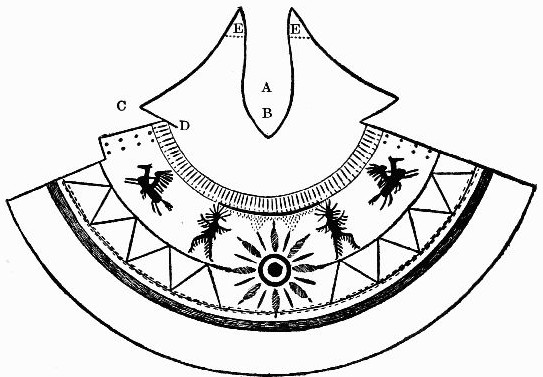

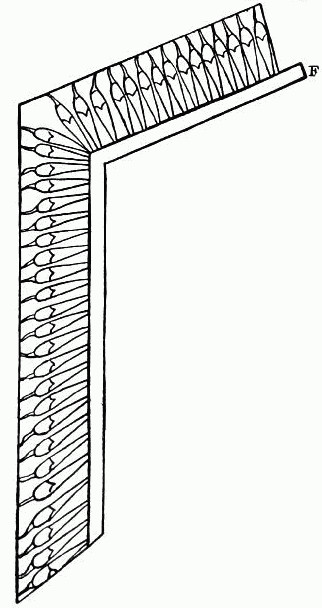

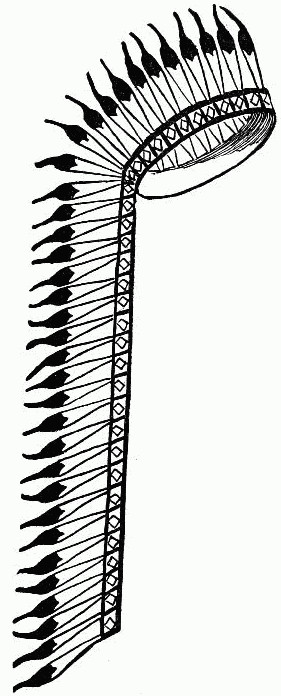

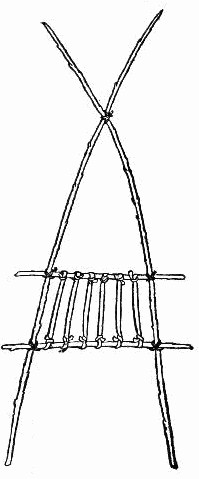

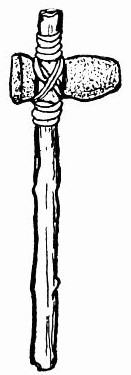

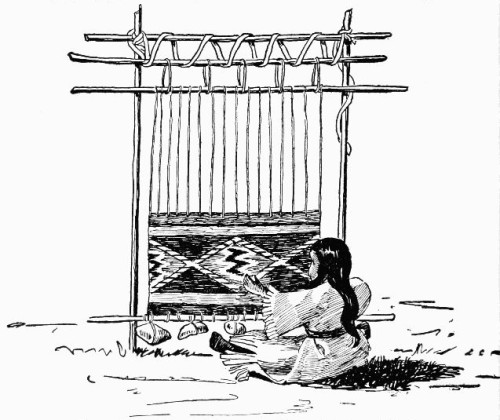

An Indian Encampment on a Pastry-Board 111The Ground, 111; The Wigwam, 112; Decorating the Wigwam, 114; The Fire, 114; The Doll Indian, 115; The War Head-Dress, 116; A Travois, 118; Pipe of Peace, 119; A Perfect Little Tomahawk, 120; The Chieftain's Shield, 120; Arrow-Heads and Arrows, 122; A Bow That Will Shoot, 124; The Doll Squaw, 125; Squaw's Chamois Gown, 125; Primitive Loom and Navajo Blanket, 125; Papoose, 130; Cradle for Papoose, 130; Indian Money, 131; Wampum Necklace, 131.

CHAPTER XIII.

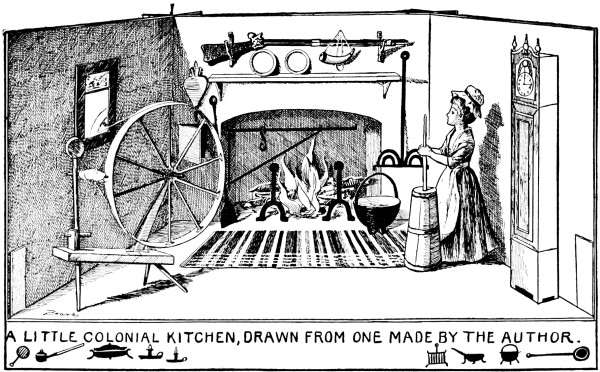

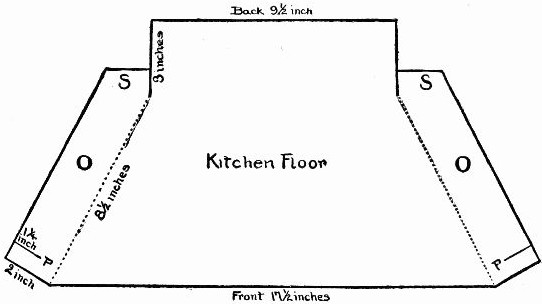

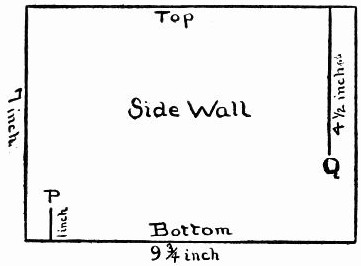

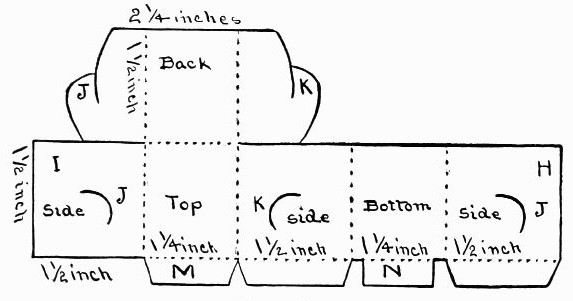

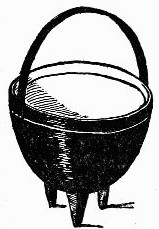

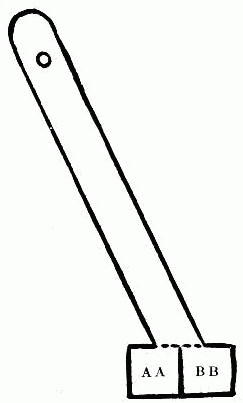

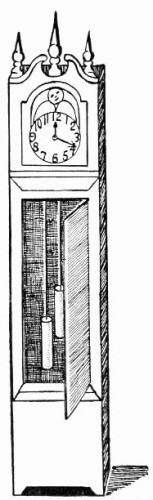

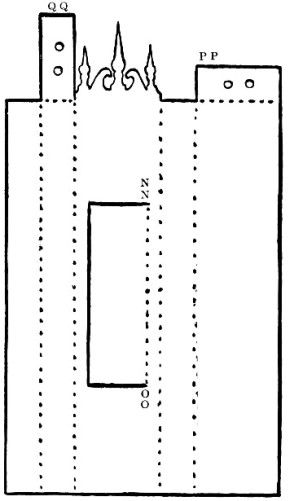

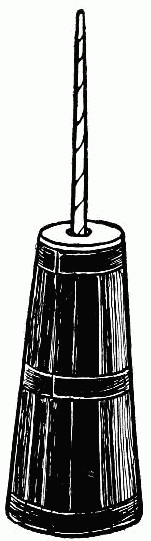

A Toy Colonial Kitchen with Fac-simile Colonial Furnishings 133The Floor, 135; The Fireplace, 138; A Hair-pin Crane, 138; Little Dutch Oven, 139; Two Andirons, 141; The Fire, 142; Iron Pot, 143; The Peel, 144; The Toaster, 144; Pot-Hooks, 145; The Spinning-Wheel, 147; The Little Spinner, 150; The Costume, 150; Flint-Lock Rifle, 151; The Bellows, 153; Colonial Pewter Dish, 154; Grandfather's Clock, 155; Colonial Churn, 160.

CHAPTER XIV.

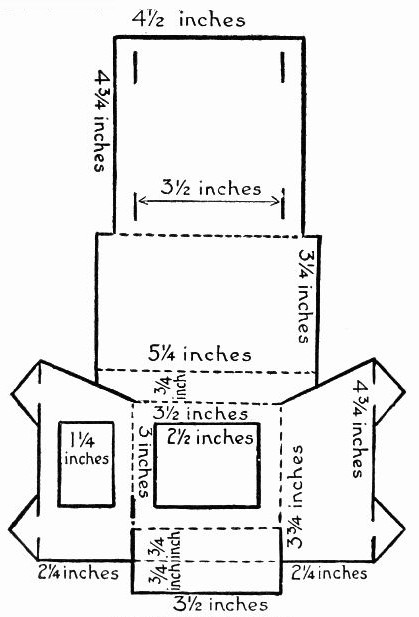

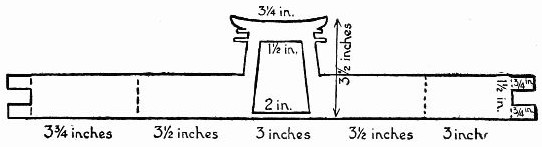

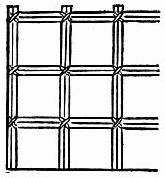

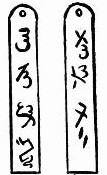

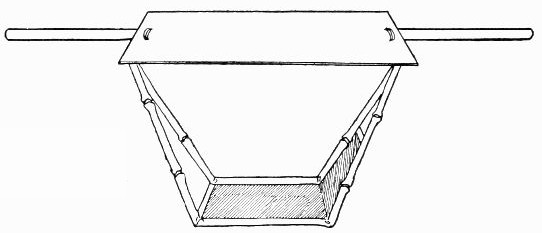

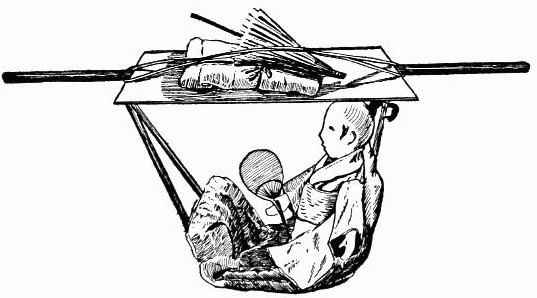

Little Paper Houses of Japan 162How the People Live, 162; The House, 162; The Floors, 167; The Fence, 168; The Gateway, 169; Birthday Festivals, 169; The Koi, 171; A Kago, 172.

CHAPTER XV.

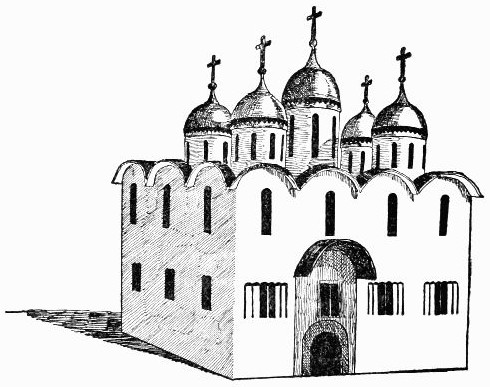

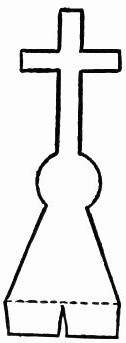

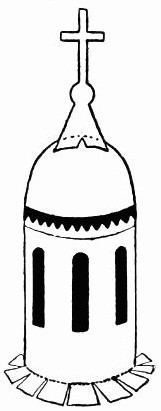

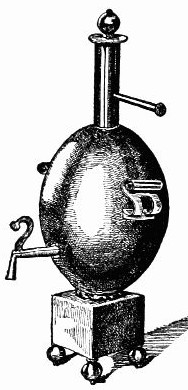

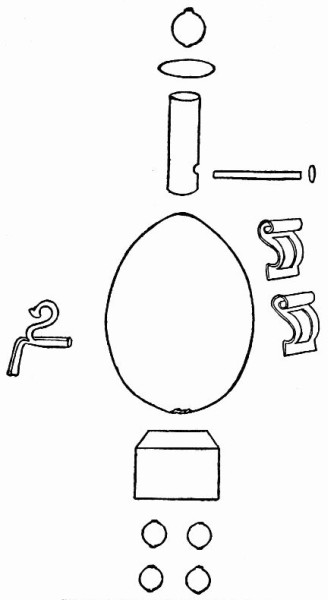

Some Odd Things in Russia 175The Coronation Cathedral, 175; Door-way, 177; Cupolas, 178; A Russian Peasant Doll, 180; A Little Samovar, 182.

CHAPTER XVI.

Pottery Without a Potter's Wheel 185Primitive Pottery, 185; The Clay, 187; Moulded on Baskets, 187; The Table, 188; The Roll, 189; To Coil the Clay, 189.

CHAPTER XVII.

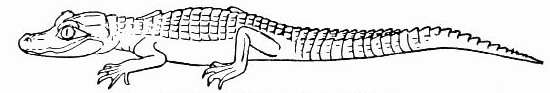

Baby Alligators and Other Things of Clay 193The Head, 195; The Body, 196; The Tail, 196; Coat of Armor, 197; The Legs and Feet, 198; A Banana, 201; A Little Bust of Washington, 202.

CHAPTER XVIII.

Funny Little Apple Toys 206The Porcupine, 206; Sally Walker's Head, 208; Sally's Curls, 208; The Indian, 209; A Comical Little Jap, 211; An Apple Tower, 214.

CHAPTER XIX.

Marvel Pictures 215Mary, 215; Her Dress, 217; Sun-Bonnet, 218; How to Draw the Lamb, 219; How to Make the Wool Grow, 219; How to Draw the Goose, 221; How to Feather the Goose, 223.

PART II RECREATIONCHAPTER XX.

Egg Games for the Easter Holidays Lifting for Pasch Eggs 227How to Prepare the Egg-Shells, 227; Hanging the Eggs, 228; The Players, 228; The Lifting, 229; The Egg Dance, 230; Placing the Eggs, 230; Dividing the Players, 230; The Dance, 230; The Reward, 231; Easter Angling, 231; Materials for the Game, 231; Fish-poles, 231; Eggs, 232; Rules of the Game, 234; Table Egg-Rolling, 235.

CHAPTER XXI.

May Day Amusements 237How the May King and Queen Are Chosen, 237; Archery, 237; The Bows, 238; Arrows, 238; Floral Target, 240; Keeping Score, 243; May Baskets and Spring Flowers, 246; How to Erect the Pole, 249; Dressing the May-Pole, 250; The Balls, 252; The Game, 252.

CHAPTER XXII.

Hallowe'en Revels 254Gold Nuggets, 254; The Mine, 255; The Miners, 255; The Apple Witch, 256; Witch's Hair, 257; Hat, 257; Broom, 258; Ghost Writing, 259; Four-Leaved Clover, 260; Apple-seed Fortune Telling; 261; Fortune Bags, 262.

CHAPTER XXIII.

The Magic Cloth and What It Will Do 264Magic in India, 264; A Jumping Frog, 264; The Hungry Birds, 267; To make the Children Talk, 268; Moving Faces, 269; The High Note, 270.

CHAPTER XXIV.

Finger Plays for Little Folk 273The Teeter, 273; Church, 275; Steeple, 275; Open Door, 276; The People, 276; The Preacher, 277; Man Chopping Wood, 277; My Mother's Knives and Forks, 279; My Father's Table, 280; My Sister's Looking-Glass, 280; The Little Black Birds, 280; The Baby's Cradle, 281; Chin Chopper Chin, 282; Build the Tower, 282; The Five Little Pigs, 285; Little Heads for Little Fingers, 285.

CHAPTER XXV.

How to Arrange Fresh Flowers 289Selecting the Flowers, 289; A Number of Nasturtiums, 290; Do not Crowd the Flowers, 290; Green Leaves with Flowers, 291; Color Schemes, 291; The Vases, 292; Colorless Transparent Vases, 292; Arrangement, 293; Flower Lifter, 294; Symmetry, 295; Wild Flowers, 295.

CHAPTER XXVI.

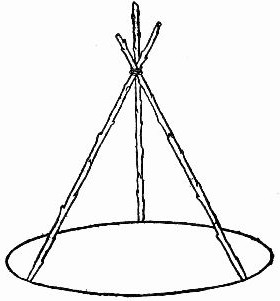

Open Air Playhouses 298A Florida Playhouse, 298; Palm Decorations, 298; Other Decorations, 298; An Umbrella Playhouse, 299; A Real Teepee, 302; An African Hut, 306; The Floral Tent, 307.

CHAPTER XXVII.

Keeping Store 308The Counter, 308; The Scales, 309; Groceries, 312; Vegetables, 312; Candy, 313; Wrapping Paper, 313; Money, 314; Paper Pocket-Books, 314; Keeping Accounts, 316; Bars of Soap, 319; Butter Clay, 319.

CHAPTER XXVIII.

A Frolic with the Roses 320Beauty of the Rose, 320; Rose Petal Fleet, 321; Green Leaf-Boats, 322; The Lake, 323; A Little Rose Girl, 325; A Garden, 325; A Peachblow Vase, 327; Candied Rose Petals, 327; Rose Petal Cap, 328; Conventional Designs, 330; A Wreath of Roses, 332; A Rose Book, 332.

CHAPTER XXIX.

A Straw Ride Picnic 333The Season, 333; Games for the Wagon, 333; Simon Says, 335; Bird Wish, 337; Lines to Be Recited Rapidly, 337; At the Grounds, 338; Chasing the Deer, 338; The Swing, 338; Teeter-Tarter, 338; The Dinner, 339; Dishes, 339; Camp-Fire, 342; After Luncheon, 342; Telling Stories, 343; Game of Menagerie, 343.

CHAPTER XXX.

A Paper Chase 345The Hares and Hounds, 345; The Start, 347; False Scents, 347; The Finish, 348; How to Dress, 348.

PART I

HANDICRAFT

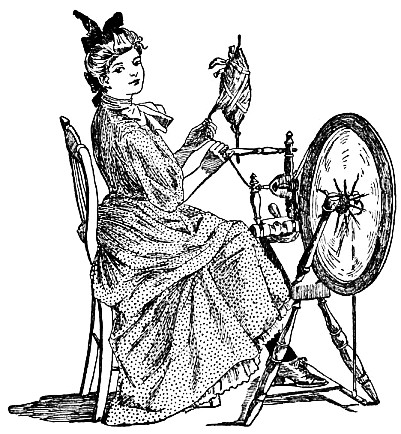

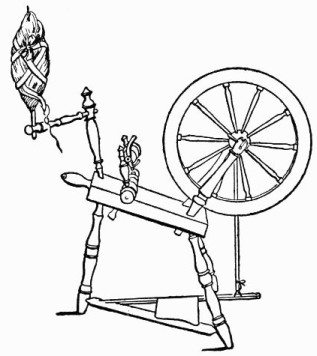

All the old handicrafts are coming back again, and ere long we shall be as proud as the maids in Revolutionary times of our hand-spun and hand-woven fabrics. To be able to spin and weave is to be accomplished in the newest as well as the oldest of household arts.

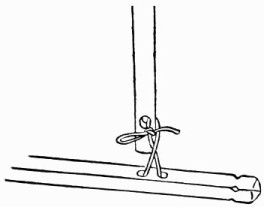

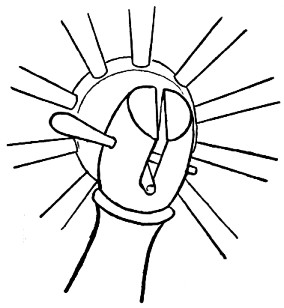

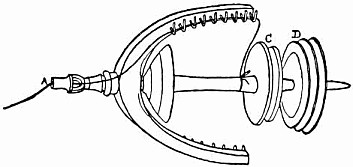

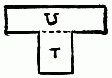

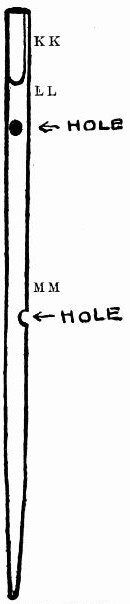

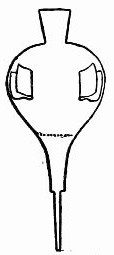

In the two uprights of the spindle-frame there must be leather rings like Fig. 4, one ring in each upright. The narrow strip extending outward from the ring is pushed through the hole in the upright, and the edge of the ring fitted into the little grooves just above and below one of the holes (Fig. 5). These two leather rings hold the ends of the spindle, which can be easily taken out and put in by bending one of the rings backward or slightly turning one of the uprights. Fig. 6 shows the spindle with the spool, or bobbin, and the small, double-grooved wheel. The spindle proper is simply the metal rod and horseshoe-shaped piece of wood with its two rows of little hooks or teeth. Besides the wheel and spindle there must be

These are all the parts of the spinning-wheel, but before you can "see the wheels go round" every piece of metal must be

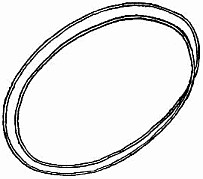

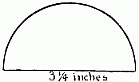

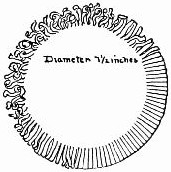

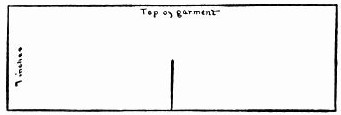

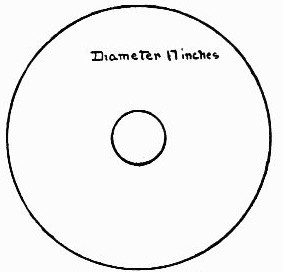

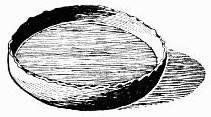

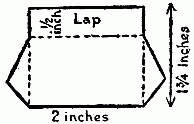

is hand spun, but at present it is possible to obtain them only of old-fashioned spinners who make their own bands. You can, however, make a band of cotton cord, such as is used for cording dresses. Fig. 9 gives the exact size. The length of cord for a wheel measuring eighteen and a half inches in diameter is about ten feet five inches. This allows for a lap of one inch at the joint. Sew together with silk, wrapping and sewing until the joint is almost invisible.

It seems a simple thing to work the treadle, but you will find that without previous practice you will forget to make your foot go in the absorbing interest of getting the flax ready to run on the spindle. Curb your impatience a little while therefore, and resolutely turn the distaff, with its pretty load, away from you. Place one foot on the treadle, give the large wheel a turn to the right, or away from the spindle, and try to keep a steady, even motion with your foot. The jerks caused by uneven pedalling will always break the thread, so you must learn to make the wheel turn smoothly and easily, without hurry and without stopping. Some spinners place only the toe of the foot on the treadle, others rest on it the heel also; it matters little which method you adopt so long as the wheel turns evenly. When you are quite satisfied that you can keep the wheel going without giving it a thought you may begin

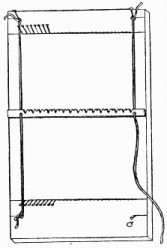

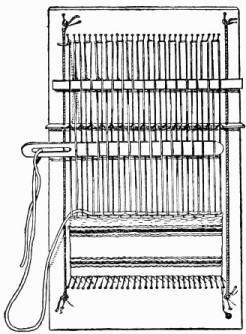

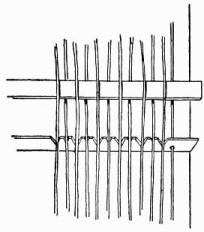

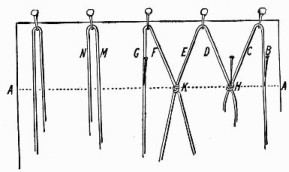

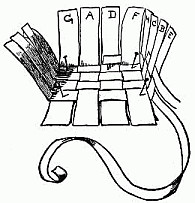

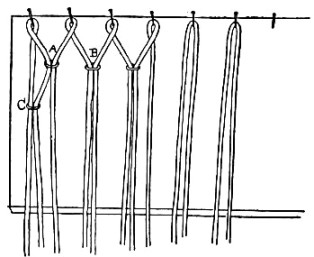

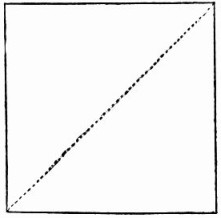

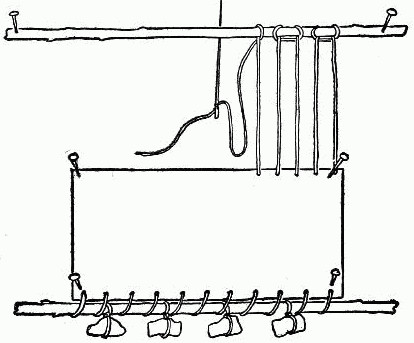

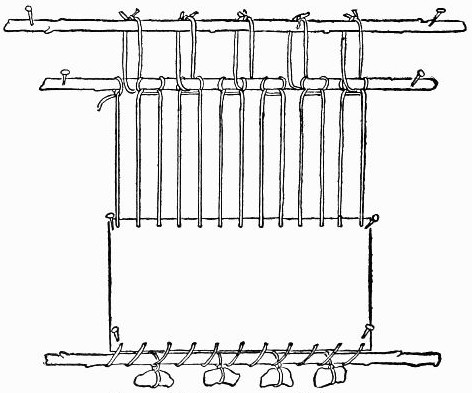

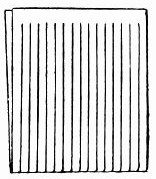

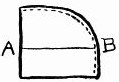

With a pencil and ruler draw two straight lines across the board, the first one inch and a half from the top edge, the other two inches and a half from the bottom edge. This will make the lines just eleven inches apart. On these lines, beginning one inch from the side edge of the board, make a row of dots exactly one-quarter of an inch apart, twenty-nine dots on each line, as in Fig. 12. At each corner of the board, one inch above the upper line and one inch below the lower line, draw a short line, and on each short line, three-quarters of an inch from the side edge, make one dot.

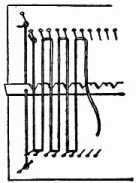

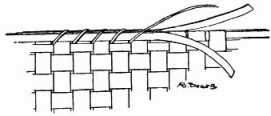

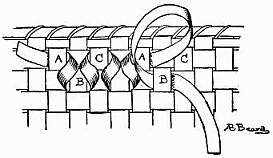

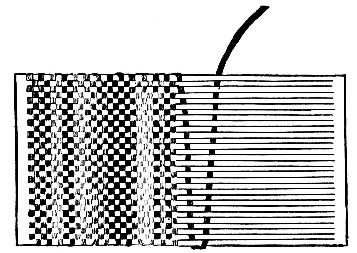

Tie the end of the warp securely to the first pin on the long line at the upper left-hand corner of the loom (Fig. 18). Bring the string down and around the first two pins on the lower line, up again and around the second and third pins on the upper line, and then down and around the third and fourth pins on the lower line. Up again, down again, crossing two pins each time, back and forth until the last pin on the lower line has been reached. Wrap the warp around this pin several times, and then around the tack, tying it here so that it cannot slip. The warp must lie flat on the board where it passes around the pins, and in stringing up it must be drawn rather tight, though not with sufficient force to pull the pins out of place.

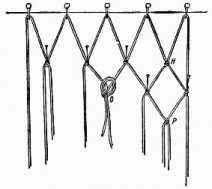

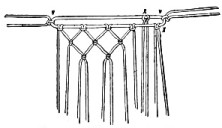

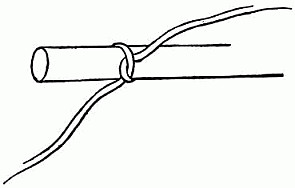

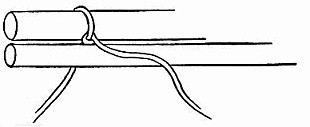

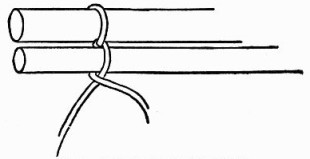

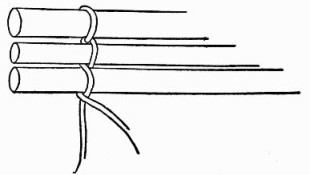

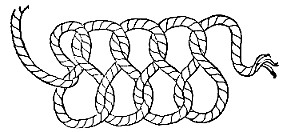

of string on each side of the hammock. In Fig. 30, T shows how to place a strand for the fringe under one side of the mesh on the edge of the net: and S gives the manner of bringing the ends of the strand down over the string forming the mesh and under the loop made by the centre of the fringe-strand. Pull the two ends of the strand down evenly, and bring the knot up close and tight to the hammock-mesh as shown in the finished fringe in Fig. 30.

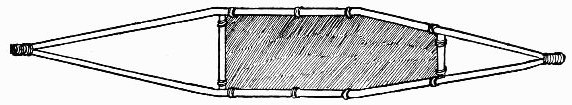

which is easier to make than the hammock. Take a piece of heavy cord twenty inches long, lap one end to the distance of an inch over the other and sew the two lapped ends firmly together; then bind them neatly around and around with string. Bring the two edges or sides of the circle together, forming two ends (V V, Fig. 34). Tie a strong string on each end (Fig. 34) and fasten each of the strings to the back of a chair; you will then have a circle of heavy cord securely suspended in mid-air. Cut twenty-four lengths of twine, each twenty-five inches long; double each piece and fasten all the strands on the circle of heavy cord in the same way you made the fringe on the hammock (X X, Fig. 34), except that this time the strands must be quite a distance apart. Let all the spaces between the strands be equal. Having fastened the lengths of twine on the circle, net them together exactly as you netted the hammock, but you must depend upon your eye to keep the meshes even and of the same size, as there will be no board with lines to guide you (Fig. 34). Tie the knots in circular rows, going around on both sides of the circle for each row. Continue the meshes until within three and a half inches of the bottom, then tie the two sides together, closing the bottom of the bag and forming the fringe shown in Fig. 33.

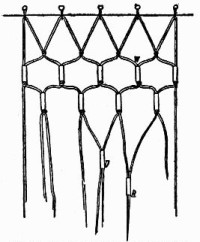

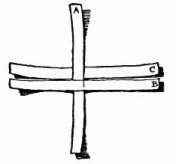

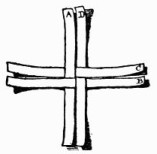

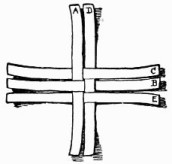

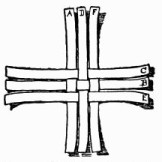

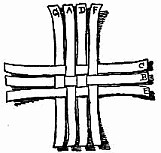

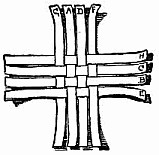

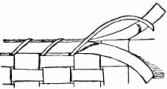

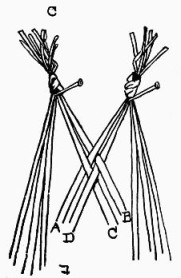

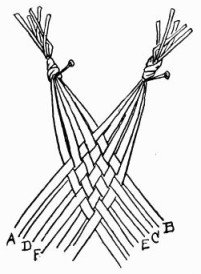

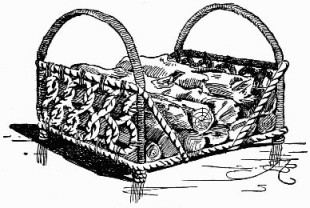

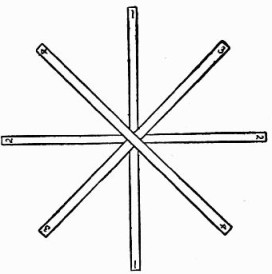

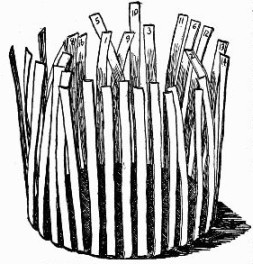

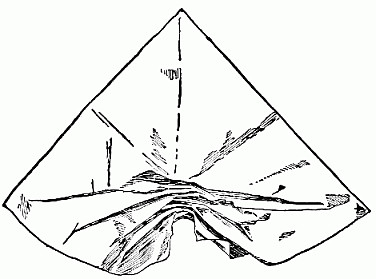

Pine-shavings are the best to use, as they are less brittle than those of harder woods. Select a number and put them to soak in cold water to make them soft and pliable. Then, lifting out those of an even width, place them before you on a lap-board or table, and after passing them between your fingers several times to take the curl out, cut eight pieces eleven inches long. Directly across the centre of two of the strips draw a straight line, as in Fig. 36. Place one of these strips, A, flat on the table and lay the other, B, across it so that the upper edge of B will touch the dividing line of A and the mark on B will be on a line with right-hand edge of A, Fig. 37. Under A slide another strip, C, Fig. 38. Over B and under C slide the strip D, Fig. 39. Over D and under A pass the strip E, Fig. 40. Under E, over B and under C weave the strip F, Fig. 41. Under E, over B, and under C weave the strip G, Fig. 42. Over F, under D, over A, and under G weave the strip H, Fig. 43. This forms a square for the bottom of the basket.

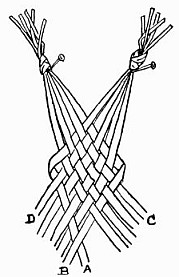

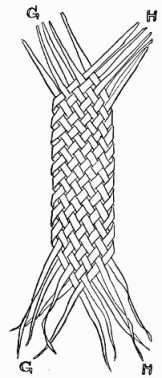

Weave all the way around, turning the corners sharply, until the weaver meets the first end; lap it over this, cut it off and tuck the last end under H. Start the next weaver at C, weave it around and tuck under E. Weave five weavers around the sides of the basket, beginning each time in a new place that the joints may not all come together, then bend the upright shavings over the edge of the top weaver, tucking the ends of each under the third weaver, one inside, the next outside, as they may come inside or outside the basket (Fig. 45).

Loop the handle diagonally over the basket and fasten the other end on the second weaver on the side. Secure the ends of the long strip on the third weaver, allowing it to cross the other side of the handle at the top, then bind the two pieces together at the middle by wrapping with a shaving of the same width over and over. Split this wrapper at the last end and tuck the two ends in at the sides. Fig. 48 shows the under part of the handle with one end of the wrapper tucked in.

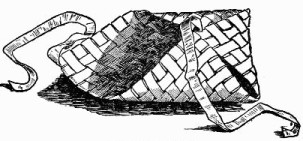

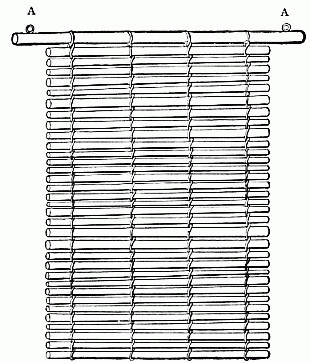

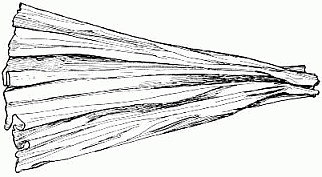

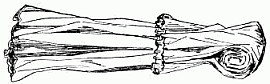

out in the open. So away to the spot where the finest cat-tails grow, gather a lot of them, cutting the stalks off clean and smooth at the base, that the cat-tails may not be bent or split, for as reeds in your curtain they must be as near perfect as possible. Cut the velvety brown head off from each one, making all of the stalks the same in length; then, with several long leaves twisted together for string, tie the stalks into a bundle and march home with the treasure.

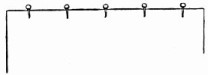

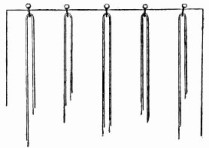

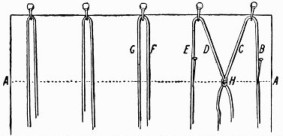

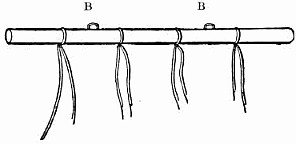

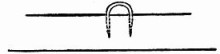

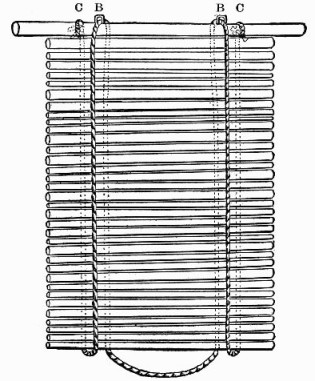

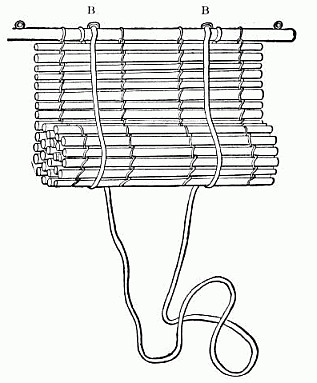

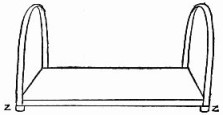

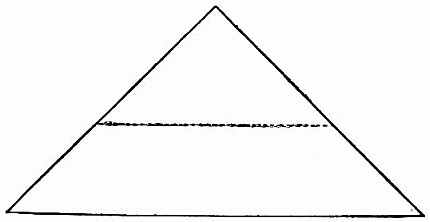

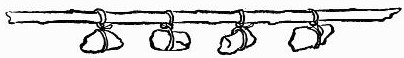

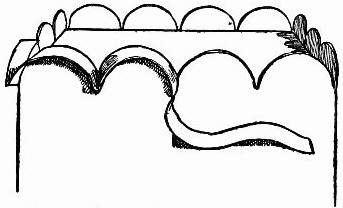

and adding cat-tails until the curtain is of the desired length. Tie the ends of the string on each line securely together and tuck them under the weave, hiding the ends on the wrong side of the curtain (Fig. 55). At equal short distances from the tips of the head-pole fasten in a screw-eye large enough to pass readily over the two hooks immediately above the window where the curtain is to hang (Fig. 55, A, A). On the centre of the space along the upper side of the top pole, between the first and second cord and the third and fourth cord, drive in a staple-nail (Fig. 49, B, B), shown more plainly in Fig. 56. These staple-nails are for holding in place the long cord used in rolling up the curtain (Fig. 57, B, B, and Fig. 58, B, B). Thread one end of a long piece of cord from the back of the curtain through one staple-nail and the other end through the other staple-nail. Bring both ends of the cord down over the front of the curtain around the bottom and up over the back; then tie the ends on the pole (Fig. 57, C, C). Dotted lines show how the cord runs along the back of the curtain. Have the cord sufficiently long to allow of the stretch between the two staple-nails B and B (Figs. 57 and 58), to hang down over the back and extend in a loop below the bottom edge of the curtain (Fig. 57, D). When you wish to raise the curtain, pull the bottom loop and up will go the curtain (Fig. 58). These primitive hangings are just the thing for outing cottages on the sea-shore or log-houses in the mountains. You can have fun weaving them while at your summer home and in place of the old-fashioned quilting-bee you might give a

and adding cat-tails until the curtain is of the desired length. Tie the ends of the string on each line securely together and tuck them under the weave, hiding the ends on the wrong side of the curtain (Fig. 55). At equal short distances from the tips of the head-pole fasten in a screw-eye large enough to pass readily over the two hooks immediately above the window where the curtain is to hang (Fig. 55, A, A). On the centre of the space along the upper side of the top pole, between the first and second cord and the third and fourth cord, drive in a staple-nail (Fig. 49, B, B), shown more plainly in Fig. 56. These staple-nails are for holding in place the long cord used in rolling up the curtain (Fig. 57, B, B, and Fig. 58, B, B). Thread one end of a long piece of cord from the back of the curtain through one staple-nail and the other end through the other staple-nail. Bring both ends of the cord down over the front of the curtain around the bottom and up over the back; then tie the ends on the pole (Fig. 57, C, C). Dotted lines show how the cord runs along the back of the curtain. Have the cord sufficiently long to allow of the stretch between the two staple-nails B and B (Figs. 57 and 58), to hang down over the back and extend in a loop below the bottom edge of the curtain (Fig. 57, D). When you wish to raise the curtain, pull the bottom loop and up will go the curtain (Fig. 58). These primitive hangings are just the thing for outing cottages on the sea-shore or log-houses in the mountains. You can have fun weaving them while at your summer home and in place of the old-fashioned quilting-bee you might give a

The girls and boys could readily make a number of hangings in one afternoon, and while weaving the reeds together they would weave into the work all sorts of bright speeches and gay laughter, so that ever after the curtains would be filled with delightful associations of the charming summer afternoon. Reed curtains can be fashioned in any width. If very narrow hangings are in demand, cut your reeds to measure the length needed for the curtain-width and weave them together with the same twine cross-weave used in Fig. 55.

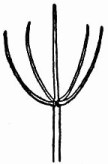

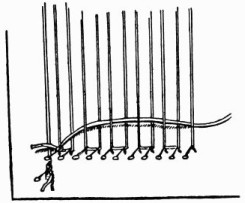

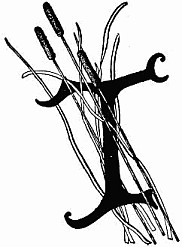

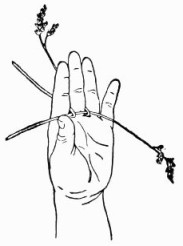

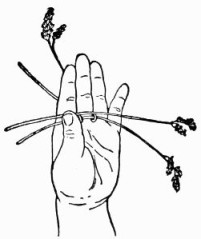

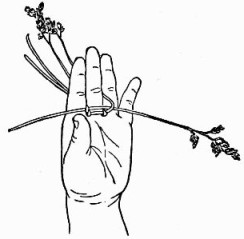

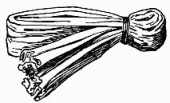

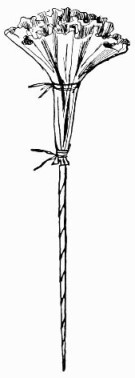

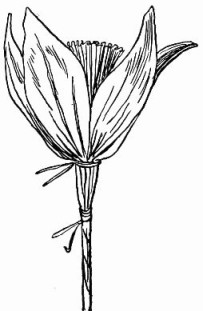

Bunch together seven fine, strong seed-grass stalks and tie just below the blossoms, with the root-end of your long-blade grass (Fig. 71). The stems of the seed-grasses are the spokes, the long grass the weaver. Turn the blossom-ends down, the stem-ends up, and close to where it is tied, begin to weave the long grass in and out, under one spoke, over the next, under the third, over the fourth, going around and around spirally until the end of the weaver is reached, then tie it to one of the spokes. Keep forcing the spokes farther and farther apart as you weave until the holder is shaped like a cone. As you see in the illustration, the weaver never passes over one of the spokes twice in succession. In one row it goes over a spoke, in the next row under it, in the third over again, and so on. In order that it may always come this way you must have an uneven number of spokes. Four will not do, nor six, nor eight, but five, seven, or nine spokes will bring the weave out all right.

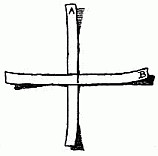

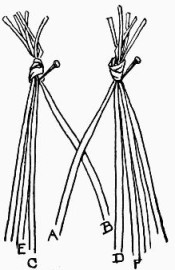

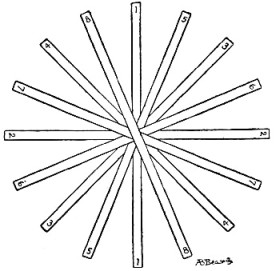

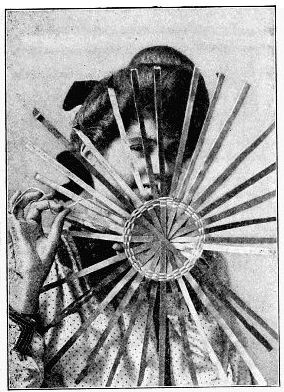

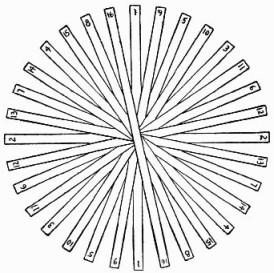

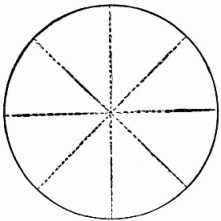

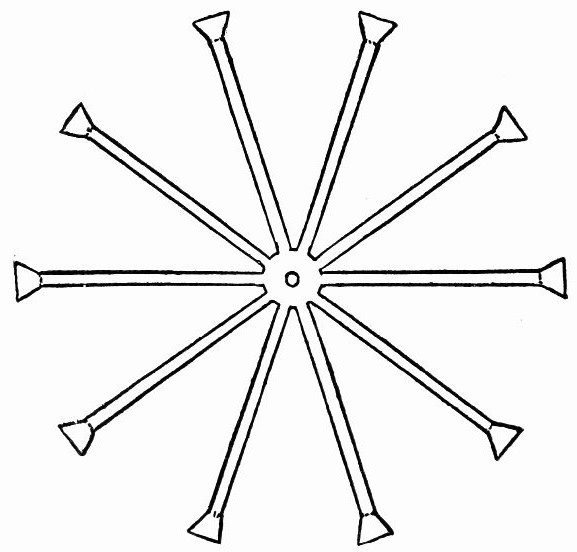

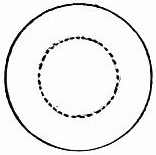

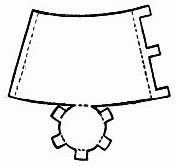

For instance, the ninth spoke should come between No. 1 and No. 5, the tenth spoke between No. 5 and No. 3, the eleventh spoke between No. 3 and No. 6, and so on around the circle (Fig. 87). Be sure the lower end of a spoke fits between the same numbers as the upper end. When all the spokes are placed hammer a strong pin directly through the centre where they are crossed, to hold them together while you begin.

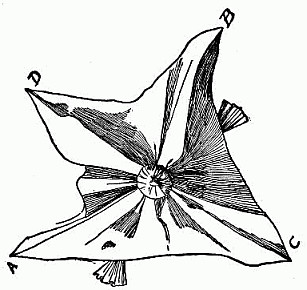

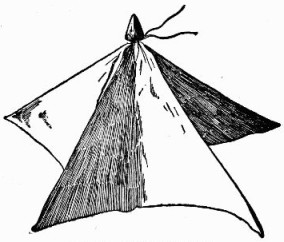

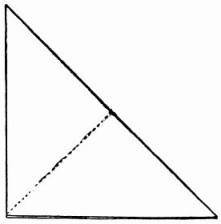

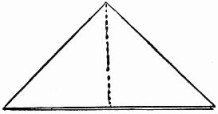

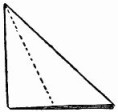

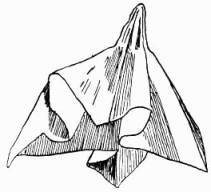

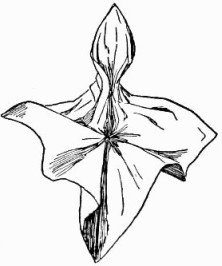

Cut a square of the same kind of tissue paper, measuring nine and one-half inches on all four sides; fold diagonally twice across the square as when making a paper pin-wheel. The centre of the square is exactly where the diagonal lines meet and cross; pinch the centre portion up into a beak and tie it with a string (Fig. 101); then fit the beak over the centre of the chicken's head, bringing the paper entirely over the head on all sides; tie the square around the chicken's neck close up to the head (Fig. 102). The two points A and B of the square must form the wings, while C is carried backward over the under portion of the body and D back over the upper part, the two ends C and D being brought together and tied tight up to the body to form the tail. In Fig. 103 you will see exactly how to pinch up the wing if you notice particularly the upper part of the wing B, next to the body. The wing A on Fig. 103 shows how the two wings must be tied close to, but not on, the body. When each wing is tied, make the tail of C and D by tying the extensions together as explained above; that done, bend down the legs, spread out the wings and tail, open out and flatten the feet, then stand the little chicken on a level surface (Fig. 104). Remember always to crease the tissue-paper with the grain of the paper; if you attempt to cross the grain the paper will be very apt to tear.

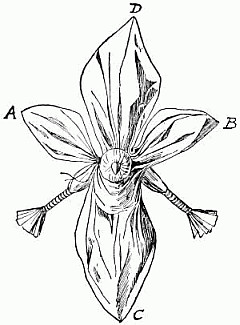

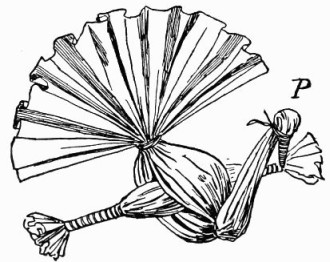

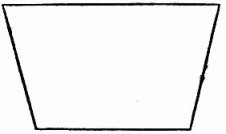

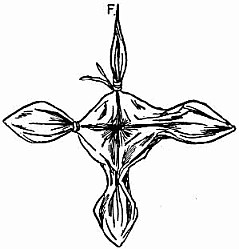

(Fig. 105) is also modelled from half a sheet of tissue-paper as near the general color of a turkey as can be found. Make Fig. 92 and Fig. 93 of the paper; then fold Fig. 93 five and three-quarter inches from one end (Fig. 106, F). Three inches from this end tie the two layers together (Fig. 106, G). Fold the strips back and tie a string through the lower loop up over the loose top layer (Fig. 106, H). Wind the extreme end of the paper (Fig. 106, O), with string to form the beak (Fig. 107), bend the beak down and tie it to the neck to form the top of the head (Fig. 108, P). Make the legs and feet as you did those for the chicken (Fig. 98) and slide them through the body so that one fold of the body will be above and two beneath the legs (Fig. 107). Cut the wings from a separate piece of tissue-paper (Fig. 109). Let the paper measure seven inches on the widest side, five on the opposite side, and four and one-half on each of the other sides. Pinch the paper together through the centre and tie (Fig. 110). Gather up one wing, so that it will not tear, and slip it through the body, immediately over the legs, with the widest side toward the front (Fig. 105), leaving the other wing out free on the other side of the turkey. Bend down the legs, spread the tail out fan shape and bend it up; open out the wings and drop them downward and forward (Fig. 105). Flatten out the feet and stand up the turkey (Fig. 105).

Ordinary garden flowers and those most easily procured make the best models. The carnation-pink, the morning-glory, and the rarer blossoms of the hibiscus, are well adapted to the work, also the daffodil and some of the wonderful orchids.

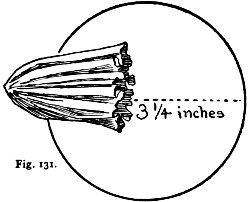

is made of a circle of dark-green paper the diameter of which is three and one-quarter inches (Fig. 130). Gather this circle between your fingers as you did the others and crimp the edge with the scissors. It will then form a little bag or cup like Fig. 131. Slip the bag over the head of a lighter and tie at the bottom as in Fig. 132. If the bud does not take the proper shape at first, model it with your fingers until it is correct. Start the wrapping of the stem just above where the bud is tied and finish as you did the stem of the pink. Use small leaves on the bud stem, having the strip of paper just as wide, but considerably shorter than for the leaves on the stem of the open flower.

Fold the square twice diagonally across from corner to corner to find its centre; then begin at one corner and gather along one of the creases until you reach the centre (Fig. 139). Start again at the opposite corner, gather along the crease to the centre, then wrap and tie (Fig. 140). Pinch each leaf from underneath along the crease in the middle, to give the depression at the midrib. Straighten the leaf out a little at its widest part and you will find you have made a pair of leaves which are surprisingly natural. Wrap and tie these to the stem and make as many more as you think are needed.

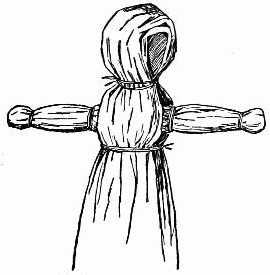

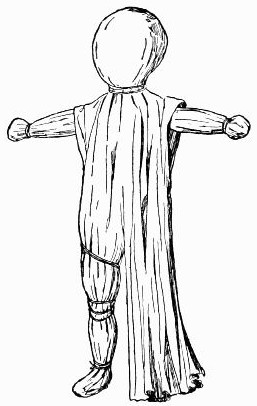

you will need eight sheets of white tissue-paper, two sheets of flesh pink, not too deep in color, a quarter of a sheet of light-brown or yellow, and a small piece of black. Her underclothes will require one sheet of white and her dress and bonnet one sheet of any color you consider most becoming.

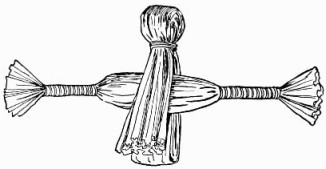

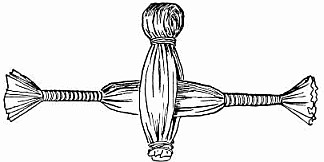

Take one sheet of the white paper at a time and draw it lengthwise through your hands, creasing or crimping it as in Fig. 149. Do this to all the eight sheets. Then, pulling six of them partly open, place them evenly one on top of another and fold through the middle (Fig. 150). Take another sheet of the crimped paper and roll it into a ball like Fig. 151. Open the folded paper, place the ball in the middle, bring the paper down over the ball and wrap and tie just below with coarse linen thread or white darning-cotton (Fig. 152). This is the head, which you must model into shape with your fingers, squeezing it out to make it fuller and rounder at the back and pinching it to give a chin to the face. Fold another crimped sheet like Fig. 153 for the arms. You will notice the ends do not quite reach the folds. The space left should measure a little over one inch. Crimp half a sheet of the pink paper and with it cover the arms; allow the pink to extend equally at each end beyond the white and fold over the ends, tying them as in Fig. 154. Then tie the loose ends down as in Fig. 155. Open the paper just below the head, slip the arms in place and tie below (Fig. 156).

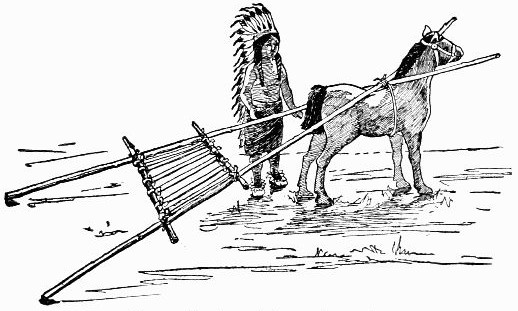

a common pastry-board or any kind of board of the desired size—about nineteen by twenty-six inches—and for grass cover one side and the four edges of the board with a piece of light-green cotton flannel stretched tight, fleece side up, and tacked to the under side of the board. Sprinkle sand and small stones on the grass at one side of the wigwam, to show where the grass has been worn off by the tramping of the Indians, the bronco pony, and the dog, for all Indians possess dogs of some description. If you have a toy dog of suitable size, stand him by the fire where he will be comfortable. Before the red men owned horses, a dog was always used to drag the travois, and to this day the braves care as much for a dog as does any pale-faced boy—which is saying much, for a white boy and any kind of a dog make devoted friends and comrades.

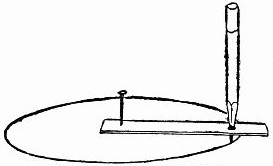

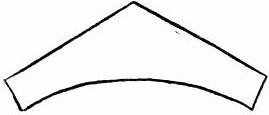

Make the cover of unbleached or brown-tinted cotton cloth cut like Fig. 170. Mark the curved lower edge with the home-made compass used for the grass circle. Fasten the pin and pencil in the paper strip nine and one-half inches apart; draw almost a half circle, then an inch and a half from the spot A (Fig. 170), where the pin is stationed, begin to cut the opening for the top of the wigwam poles, B (Fig. 170). Slash the point C in as far as D, sew pieces of cloth over the points E and E, leaving the opening at dotted lines to form pockets for the smoke-poles. Cut two rows of little holes on each side of the upper part of the wigwam to run the pinsticks through when fastening the wigwam together (Fig. 171).

If you can find a Zulu doll of the required size, with long, straight black hair, and give him a wash of dull red paint, you can turn him into a fine Indian. Failing these dolls, make an Indian doll of dull red raffia or cloth. This you can do if you try, and remember to have your red man a little more slender than store dolls; most of these are rather too stout to make good Indians.

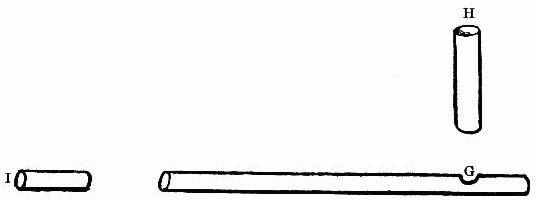

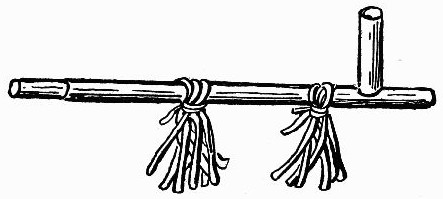

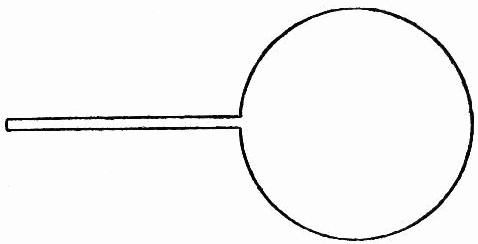

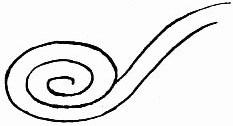

or "pipe of peace," to smoke and pass around the council circle, when all the leaders of the different tribes meet to talk over important matters concerning the welfare of their people. Real calumets are generally large and of goodly length, some of them being four feet long. They are made of dull-red stone, which, when first cut from the large mass, is soft enough to be carved out with a knife; later the pipe becomes hard and capable of receiving a polish. But as the red stone is not within our reach, we must use dull red-colored straw for the calumet. Soak the straw in hot water to render it less brittle. Then cut a three-inch length piece; make a hole in it a short distance from one end (Fig. 176, G) and insert a three-quarter inch length of straw for the pipe bowl (Fig. 176, H). For the mouthpiece take a half-inch length of white straw (Fig. 176, I), and slide it in the other end of the pipe. Glue both bowl and mouthpiece in place and decorate the calumet with red, green, and white silk floss tied on the pipe stem (Fig. 177).

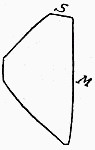

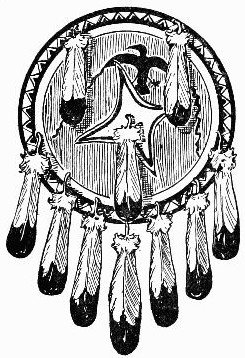

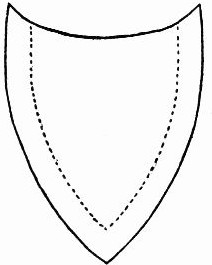

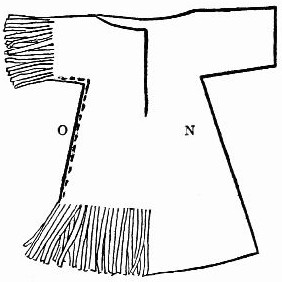

Bison hide is something you cannot obtain, so take writing paper for the shield. Cut it into a circle an inch and a half in diameter, with an extension for the handle (Fig. 180). Glue the free end of the handle on the opposite side of the back of the shield. Make ten paper eagle feathers (Fig. 181), hang seven on the bottom of the shield with red thread, after first decorating the centre of the shield with given designs and the edge with colored bands, using any or all of the following colors, but no others: positive red, blue for the sky, green for the grass, yellow for the sun, white for the clouds and snow, and black. To the Indian color is a part of religion. Purple, pinks, and some other colors, the red man, loyal to his beliefs, can never bring himself to use. Attach two of the remaining feathers at the top and another on the centre of the shield, as shown in Fig. 182.

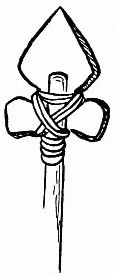

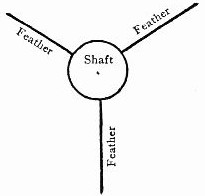

Cut three paper feather strips (Fig. 186), each an inch in length, paint black bands on them, bend at dotted line and glue the feathers on the shaft one-quarter of an inch from the notch, allowing them to stand out at angles equally distant from each other (Fig. 187). Bind the extensions L and M (Fig. 186) to the shaft, and tie tufts of white and red worsted on immediately above the feathers to help in finding the arrow (Fig. 188). Paint the shaft in brilliant colors.

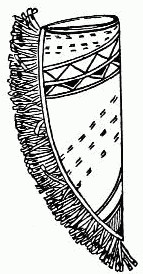

Make the bow case (Fig. 192) of ordinary wrapping paper cut like Fig. 191, three and a half inches long and two and a half inches wide. Fold the paper lengthwise through the centre and glue the sides together along the dotted lines; then fringe the edge up to the dotted line and decorate with gay paint.

(Fig. 199). Sharpen the bottom and drive it into a hole in the ground. For the foliage cut a fringe of soft green and olive-brown tissue-paper folded lengthwise in strips. Crimp the strips with a blade of the scissors, then open out the fringe; gather each one through the centre, give the paper a twist, and the two ends will form bunches of foliage. Work the twisted centre of one piece down into a crack at the top of the tree. Over across this at right angles in another opening, fit in the second twist of paper foliage and crown all with a bunch standing upright as shown at Fig. 199.

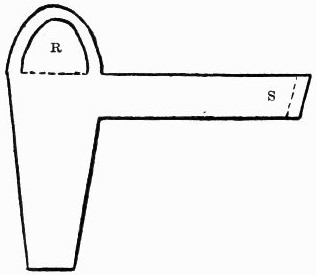

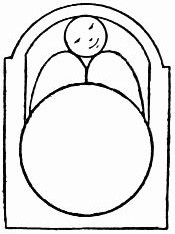

bound in its stiff cradle is one of the drollest things imaginable. Paint a small doll copper color, make its hair black, and bind the baby in a cradle cut from brown pasteboard (Fig. 200). Cut along heavy line and bend forward the tongue R along the dotted line, bring the strap S across and glue the end on the under side of the cradle; then line the cradle with white tissue-paper and place the Indian child on it; spread a piece of vivid red tissue-paper over the infant, bringing the sides of the cover on the under side of the cradle, where you must glue them. Fold over the lower end of the paper and glue that also on the back of the cradle. Paint the cradle and portions of the cover white, green, black, and yellow (Fig. 200); then hang the cradle and baby on the limb of the tree (Fig. 199), where the little papoose will be safe while his squaw-mother works at her weaving.

[134]

[135]

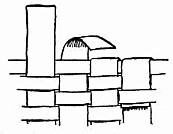

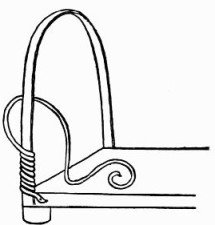

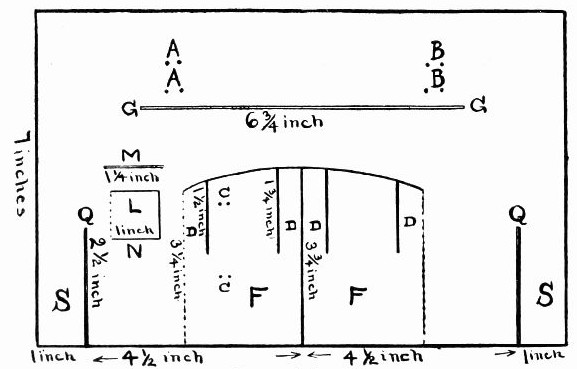

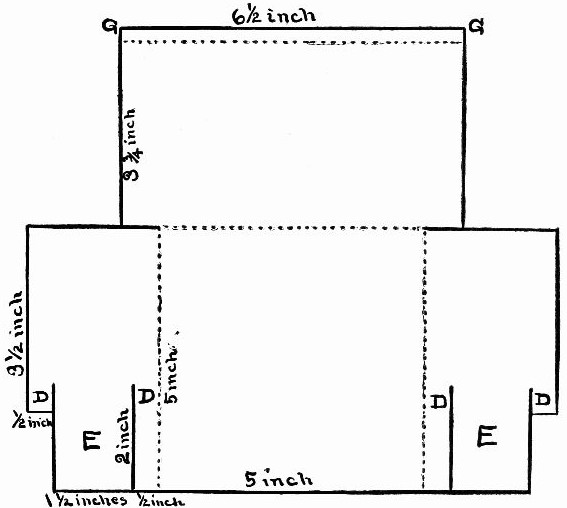

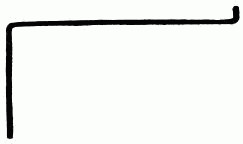

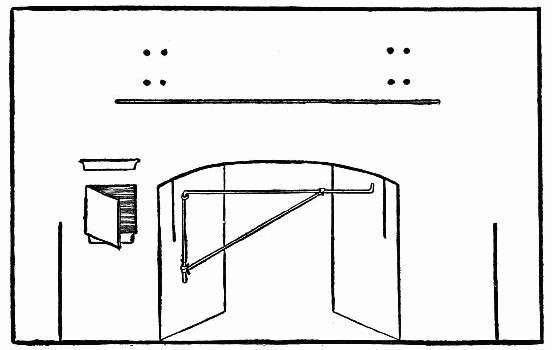

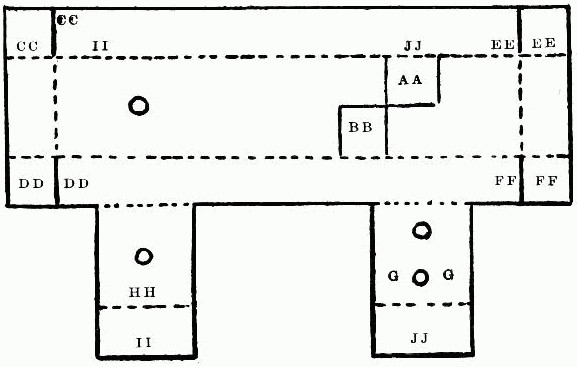

upon which to hang the pots and kettles over the fire. One end of the crane was bent down and attached to the side chimney wall by iron rings. These rings allowed the crane to turn so that the extending iron rod could be swung forward to receive the hanging cooking utensils and then pushed back, carrying the pot and kettles over the fire for the contents to cook. The crane was black and of iron. A hair-pin (Fig. 211) makes a fine crane. Bend yours, as shown in Fig. 212, then with two socket-rings made with stitches of black darning-cotton fasten the crane to the side of the chimney at the dots C and C (Fig. 207), and tie a piece of the darning-cotton on the little crane immediately below the lower socket-ring; bring the thread diagonally across to the top arm of the crane an inch and a quarter from the free end and again tie it securely (Fig. 213).

F and F (Fig. 207) as in Fig. 213. Bend forward the interior of the fireplace (Fig. 208) at dotted lines, and fit Fig. 208 on the back of Fig. 207 to form the inside of the fireplace and the mantel-piece. Slide the slashed top strips of the sides of the fireplace D,D,D,D (Fig. 207), back of the slashed strips D,D,D,D (Fig. 208), which will bring the two centres E and E of the sides in Fig. 208 behind F and F in Fig. 207, and will thus form two layers on the sides of the chimney. Push the edge G and G of Fig. 208 through the slit G and G in Fig. 207 to form the mantel-piece, then bend down the edge of mantel-piece along dotted line.

Chicken and other eatables were placed between the front and back rings on the toaster and broiled before the fire, which was so hot that it was necessary to have long handles on all cooking utensils.

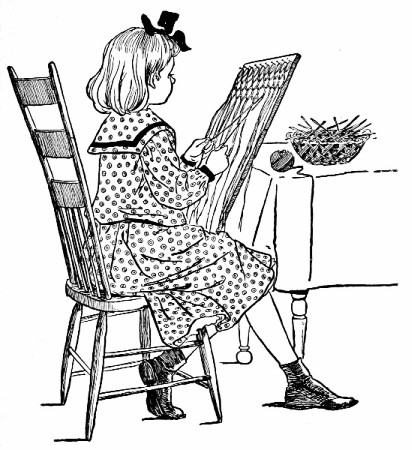

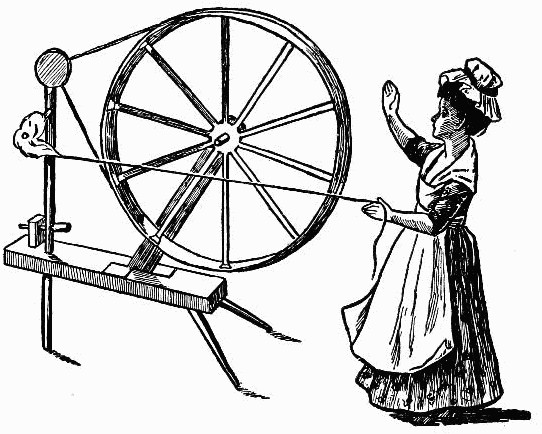

Just look at your little colonial friend, Thankful Parker! (Fig. 228). The tiny maid seems almost to be stepping lightly forward and backward as she spins out long threads of the soft, warm yarn, singing softly all the while a little old-fashioned song. How busily she works, and listen! you can all but hear the wheel's cheery hum, hum, hum! That's the way the real colonial dames used to spin. Such a

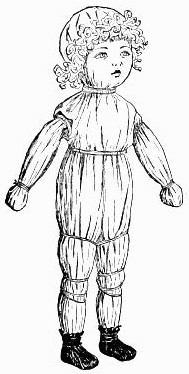

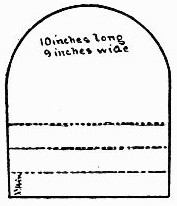

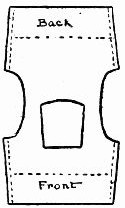

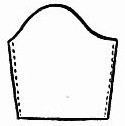

Make the cap (Fig. 243) of thin white material cut like Fig. 242, and the band (Fig. 244) of the same color as the dress. Cut the thin white kerchief like Fig. 245, and fold it as in Fig. 246. Fig. 247 gives the design for the dress waist, and Fig. 248 the sleeve. The skirt is a straight piece gathered into a waistband. The apron (Fig. 249) is white. When the doll is dressed it should resemble little Thankful Parker (Fig. 228). An

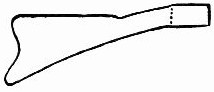

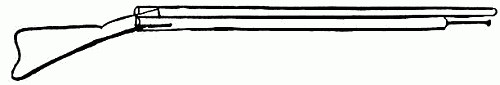

Lay the gun-barrel above the wooden part (Fig. 254) and fasten the two together with the four bands of tinfoil (Fig. 255), allowing the top part of Fig. 250 to stand up free to represent the flintlock. We must be content without a trigger unless you can manage to make one by bending down and cutting a part of Fig. 250. Paint the butt and wooden portion of the gun brown before binding on the barrel, and you will find that you have made a very real-looking little rifle to hang upon the rustic brackets over the mantel-piece.

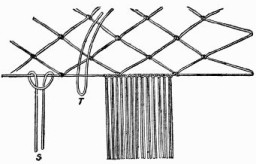

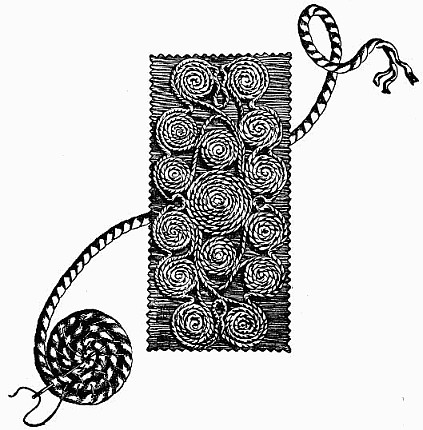

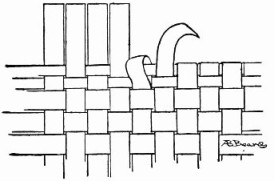

to place over the bare board floor, and it will be fun for you to weave it. Take a piece of smooth brown wrapping-paper the size you want your mat, fold it crosswise through the centre and cut across the fold (Fig. 259), making a fringe of double pieces which we will call the warp. Unfold the paper and weave various colored tissue-strips in and out through the brown foundations (Fig. 260), until the paper warp is all filled in with pretty, bright colors. You can weave the rug "hit or miss" or in stripes wide or narrow as you choose, only make the rugs as pretty as possible.

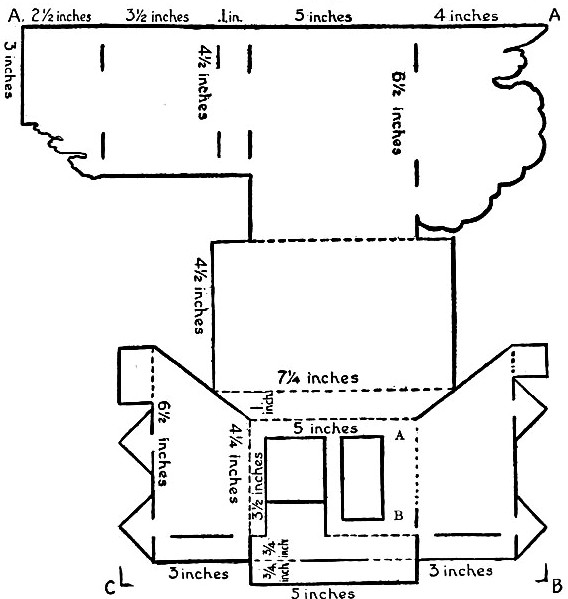

The sides of the house are supposed to be formed of paper-covered screens which slide in grooves and may be removed entirely when desired. The interior of a real Japanese house is divided into rooms merely by the use of sliding paper screens, and the entire floor may readily be thrown into one large apartment, there being no solid partitions as in our houses. Cut out flat round paper lanterns, paint them with the gayest of colors and make the small top and bottom bands black; then with needle and thread fasten the lanterns along the top front of the large opening of the small room (Fig. 282).

the floor is set instead of a table, and each person receives his own little lacquer tray placed on the floor, or on a low wooden stool, with the individual portion of rice in a delicate china bowl, pale tea in dainty teacups and shredded or diced raw fish in china a queen might envy. On the tray are also a pair of ivory chopsticks, which even a little child can manage skilfully, in place of the spoon, knife, or fork that our girls or boys would use. The Japanese do not have bread, butter, milk, or coffee, and never any meat, but they cultivate a mammoth radish which is cut up, pickled and eaten with relish. For dinner they take pale tea, rice, and fish, and for supper fish, pale tea, and rice. Often the fish is cooked, sweetmeats are served and pickled radish also, but frequently the breakfast consists of merely a bowl of cold rice. These unique people do not seem to think or care much about their food; many times they deny themselves a meal that they may spend the money on a feast of flowers in some garden where they can enjoy gazing upon masses of exquisite cherry blossoms, chrysanthemums, or other flowers. No nation in the world loves flowers more than the Japanese, and none can rival them in the beautiful arrangement of their blossoms.

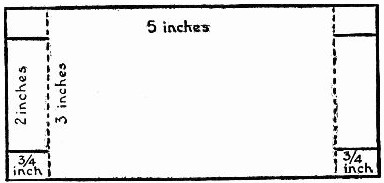

Make your fence of paper cut according to Fig. 287, and mark the pattern (Fig. 288) on it with two tones of yellow paint. Paint the convex top of the gate-way a bright red with narrow black border, and mark the white gate-posts with black Japanese lettering like Fig. 289. Paint the remaining portions of the gate-way yellow, the edges black. Fig. 282 will help you to grasp the idea of the fence and gate-way. The names of the streets are not on the corners as in our cities, so a panel of white wood is nailed to the gate-posts with both the name of the street and householder on it, and often a charm sign is added.

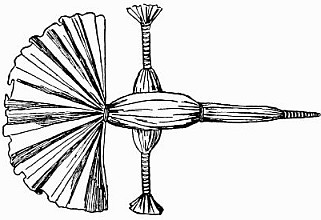

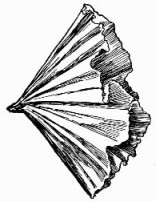

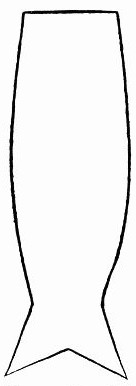

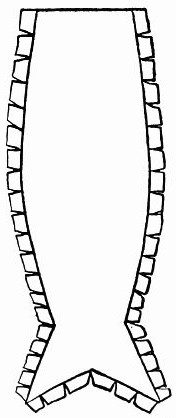

for the pole to be placed in front of the little paper house; they look very comical, bobbing and swinging high in air with their wide-open mouths. Cut Fig. 290 of white tissue-paper, also Fig. 291, which is a trifle larger than the first and is slashed along three edges. Lay Fig. 290 on top of Fig. 291; bend the flaps over and paste them on Fig. 290. Form a little hoop of a strip of stiff paper with the ends pasted together; blow the fish open, then paste the hoop on the inside of the open edge of the head to form its immense mouth. When dry mark the fish with red paint like Fig. 292. Tie a thread on the two opposite sides of the mouth and with another thread attach the loop to a slender stick on the end of which you have fastened a gold disk made of two pieces of gilt paper. This is intended to represent the rice ball with which the real fish are fed. The fish banners are hollow so that the wind may fill them, causing the fish to rise and fall as the breeze comes and goes. Push the end of your fish-pole through the centre of a small box-lid or button mould (Fig. 293) and stand the decoration outside the gate-way of the little house. The fish used on this eventful day are the famous carp, which the natives call koi, the unconquerable. The Japanese carp stands for good cheer, indomitable will, perseverance and fortitude, and it is used to impress these virtues upon the boys, but all the good qualities named are fully as necessary for girls even though the Japanese do not mention the fact, but girls are not forgotten. The nation gives them the third day of the third month for their festival. It is called the

for the pole to be placed in front of the little paper house; they look very comical, bobbing and swinging high in air with their wide-open mouths. Cut Fig. 290 of white tissue-paper, also Fig. 291, which is a trifle larger than the first and is slashed along three edges. Lay Fig. 290 on top of Fig. 291; bend the flaps over and paste them on Fig. 290. Form a little hoop of a strip of stiff paper with the ends pasted together; blow the fish open, then paste the hoop on the inside of the open edge of the head to form its immense mouth. When dry mark the fish with red paint like Fig. 292. Tie a thread on the two opposite sides of the mouth and with another thread attach the loop to a slender stick on the end of which you have fastened a gold disk made of two pieces of gilt paper. This is intended to represent the rice ball with which the real fish are fed. The fish banners are hollow so that the wind may fill them, causing the fish to rise and fall as the breeze comes and goes. Push the end of your fish-pole through the centre of a small box-lid or button mould (Fig. 293) and stand the decoration outside the gate-way of the little house. The fish used on this eventful day are the famous carp, which the natives call koi, the unconquerable. The Japanese carp stands for good cheer, indomitable will, perseverance and fortitude, and it is used to impress these virtues upon the boys, but all the good qualities named are fully as necessary for girls even though the Japanese do not mention the fact, but girls are not forgotten. The nation gives them the third day of the third month for their festival. It is called the

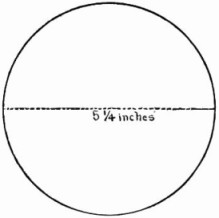

To give a true conception of the wonderful interior of the sacred cathedral to one who has never seen it, is impossible, but we can gain an idea of the general appearance of the exterior by making a miniature Cathedral of the Assumption (Fig. 299). Find, or make, a firm white pasteboard box seven inches long, five and one-quarter inches wide, and four and one-half inches high; this is for the body of the building. Fold a strip of paper seven inches in length, crosswise, through the centre, and bring the ends together, making another fold crosswise through the centre of the doubled strip, which will give four layers of paper of equal length. Cut this into a scallop three-quarters of an inch deep, open out the strip and you will have four scallops, each one and three-quarters inch wide, at its base. Lay the strip in turn along each of the top edges of the sides of the box, and mark the box around the edges of the scallops, drawing four scallops on the two long sides of the box, and three on each of the short sides. Cut out the scallops on top of the box; then take the cover of the box, which must form the roof of the structure, and remove the bent-down sides; trim off with scissors the extreme edge of one long side and one short side, until the cover forms a tight fit in the top of the box, but may, with gentle pressure, be made to slide down one inch. Fasten the roof in place at each corner by running a strong pin from the outside wall through into the roof, until the pin is embedded its full length in the roof.

(Fig. 300) of light reddish-brown paper; make it three inches high and one and one-half inch wide. Let the door proper (Fig. 301) be of inked paper an inch and a half high by an inch and a quarter wide, the door-window (Fig. 302) one inch and a quarter high by three-quarters of an inch wide. Cut the upper row of windows like Fig. 303 and the lower front windows according to Fig. 304. Make the lower side windows double (Fig. 305). The door-arch (Fig. 306) must be a trifle over two and one-quarter inches long. Curve the arch by drawing it across a blade of the scissors, paint it green on both sides, bend down the slashed portion, and paste the arch over the door-way, as in Fig. 299.

ready for use you will find at any pottery. If it is dry break into small pieces, put it in a large stone jar, and cover with cold water; let it stand until thoroughly soaked through and then stir with a stick until well mixed, and work with your hands—squeezing and kneading until free from lumps and perfectly smooth. When it is dry enough not to be muddy, and is of the consistency of dough, it is in good working condition.

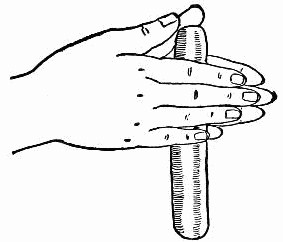

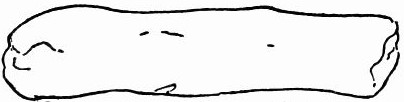

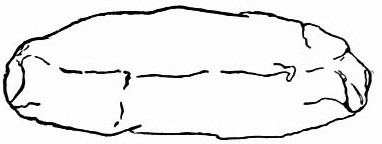

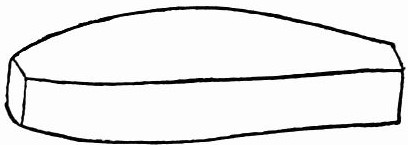

All you need for the work is a lump of soft clay, a hat-pin, your fingers, and determination to succeed. Take a piece of clay (Fig. 330) and roll it between your hands until it resembles Fig. 331. Push the two ends together, causing the roll to hump up slightly near the centre, lay it down on a board or any hard, flat surface, and with the fingers carefully pat, squeeze, and push it into the form of Fig. 332. Gently smooth out all roughness; then nip off little pieces of clay from the big lump for the nose and two eyes; stick them on as in Fig. 333. Again smooth the rough edges until the clay looks like Fig. 334. With a little careful modelling you can make the head exactly like Fig. 335. Mark the eyes, mouth, and nose with the flat point of the pin. If portions of the head become too thick, take off some of the clay, and if at any time the head is worked down too thin fill in the hollow spots with clay. In modelling one can always pinch off pieces here and there when necessary; or add little bits, smooth it all down, and the places altered will never show the marks of the change.

All you need for the work is a lump of soft clay, a hat-pin, your fingers, and determination to succeed. Take a piece of clay (Fig. 330) and roll it between your hands until it resembles Fig. 331. Push the two ends together, causing the roll to hump up slightly near the centre, lay it down on a board or any hard, flat surface, and with the fingers carefully pat, squeeze, and push it into the form of Fig. 332. Gently smooth out all roughness; then nip off little pieces of clay from the big lump for the nose and two eyes; stick them on as in Fig. 333. Again smooth the rough edges until the clay looks like Fig. 334. With a little careful modelling you can make the head exactly like Fig. 335. Mark the eyes, mouth, and nose with the flat point of the pin. If portions of the head become too thick, take off some of the clay, and if at any time the head is worked down too thin fill in the hollow spots with clay. In modelling one can always pinch off pieces here and there when necessary; or add little bits, smooth it all down, and the places altered will never show the marks of the change.

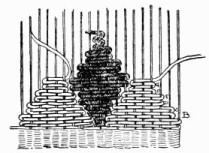

Mould another piece of clay like Fig. 336. Run the ball of your thumb along the sides, making the body the form of Fig. 337, broader and thicker through the centre than at the two ends. For the tail pull from the large lump a smaller amount of clay, roll it and model it like Fig. 338, larger at one end than at the other. The last portion (Fig. 339), like the others, is flat on the bottom, and with the exception of a small triangle at the heavy end of the tail the two sides meet at the top, forming a sharp ridge which decreases in height as it tapers down to a point at the extreme end. As each part is finished keep it moist with a wet cloth, and when the four sections are made place them in a row (Fig. 340), then join them together, rounding all the edges slightly. Fig. 341 shows how to mark the back of the alligator.

formed of small plates or shields, and in the clay one must imitate the real. Use the hat-pin for marking the lines on the head, and trace stripes sidewise across the entire length of the body in the manner shown by Fig. 341 from C to D, continuing the stripes down each side of the first section of the tail (Fig. 329). Next run a line lengthwise through the entire centre. D to E (Fig. 341) shows how to begin, only you must commence the central lengthwise line at C. Mark the plates on one side starting at C, as indicated from E to F (Fig. 341); then make them on the other side, which will cause a pointed scallop to stand out and up on both sides of the space from G to H (Fig. 341). On the last section the top ridge will be scalloped H to K (Fig. 341). The nostrils are distinctly marked by two round holes; make these with the point of the pin. Cover the alligator over with a wet cloth while you model his

Model two front and two hind legs and feet; see that the hind feet and legs are larger and differently formed from the front ones. The hind feet have only four toes (Fig. 351). The line A (Fig. 340) designates the place where the front legs should be joined to the body, and the line B (Fig. 340) shows where to fasten on the hind legs. That you may have a thorough understanding of the manner and direction in which the joints of the legs bend, we will suppose that you rest on the floor on your knees and elbows. You will then find that your knees bend forward and your elbows backward, with your arms corresponding to the front legs and your legs to the hind legs. Now, when you draw or model hereafter, you will not make any mistake in regard to it. Look again at Fig. 349. The foot, V, corresponds to or rudely resembles your hand; T, your wrist; P, your elbow; O, your shoulder. Examine Fig. 329. On the hind leg are the foot, ankle, knee and hip joint. While the alligator is in a plastic state make him open his mouth, by cutting a slit in the head from the front along the waved line up back beyond the eye; carefully pull apart the jaws (Fig. 352). Have your alligator measure at least fourteen inches from tip to tip, for it will be more difficult to model a smaller one. Once having made the little creature, you will find it easy to model similar animals; select something else in the same line and try to make it.

is very simple to copy. Roll a piece of clay, making the ends bluntly pointed; bend it slightly as in Fig. 353 and, paying strict attention to proportion, carefully form the work like the original, adding, taking from, smoothing and flattening as may be required (Fig. 354).

If you can find an apple with a bump on one side, you may make a porcupine in less than five minutes, for all that is necessary is to stick the apple full of wooden toothpicks, and that work will be as easy as putting pins into a cushion. Let the bump on the apple form the head of the animal. Bend four toothpicks like Fig. 361 and push them up into the apple to serve as legs and feet. Make the bent toothpicks balance the apple perfectly, so that the porcupine will stand firmly on its feet without other support. Use black pins for eyes and broom straws for the whiskers. Stick them into the head of the animal as shown in Fig. 362. Begin at the extreme back of the porcupine to insert the wooden toothpicks that are to serve as quills; although they are not hollow it makes very little difference, as this wee creature cannot shake them, causing the quills to knock against each other, as does the real animal when he wants to produce a rustling sound to warn off an enemy. Continue pushing in the toothpicks until the apple resembles Fig. 362. Keep the quills inclined backward and be careful not to have them stand out too far; slant the quills as much as possible, as the length of the porcupine must appear greater than the breadth. Now, if you could endow the animal with life, you would find that he was a vegetarian; that is, he could not eat meat, and you would be obliged to feed him on fruit, roots, and certain kinds of bark. You may be glad, though, that this porcupine is only a "make-believe one," for, if he lived, he would sleep all day and want to run about and take his exercise during the night; and, more than that, you would feel very sorry for the poor little fellow, because he would be extremely lonesome so far away from his native land of India, Africa, or some part of Southern Europe. So of the two, all things considered, the apple porcupine makes a better pet for the small members of the household.

(Fig. 363). With the small blade of a pocket-knife cut the eyes near the centre of the apple, placing them far apart to give an innocent expression to the face (Fig. 363). Cut the lower line of the eyes straight and the upper curved, as in Fig. 364; then push the small, pointed end of an apple-seed in the centre of each eye; run the seed in so far that only a small portion of the blunt end stands out (Fig. 365). Cut away a small, half-moon-shaped piece of the skin (Fig. 366) to indicate the nose. The mouth must be open and made the shape of Fig. 367. Cut it into the apple a trifle more than an eighth of an inch in depth. Make the curls of two narrow strips of paper rolled up tight like Fig. 368; then pulled out as in Fig. 369. Pin one curl on each side of the head (Fig. 363). Cut a round piece of white paper for Sally's collar. Make a small hole in its centre and slip the collar on the end of a stick; then push the stick well up into the lower part of the head (Fig. 363). Keep the collar in place by two pins stuck through it into the apple.

is very different in coloring and expression from Sally (Fig. 370). Notice how near together his eyes are; and see how long and narrow his nose is. If you examine the face of the next red man you see, or the picture of one, you will probably find that he has two deep, decided lines from his nose to his mouth, and that the mouth itself is firm and straight. Remember these hints when making the Indian's head. Select a dark-red apple, one that is rather long and narrow, if possible, for the red man seldom has a round face. Cut two eyes of white paper and pin them on the apple with black-headed pins pierced through the centre of each eye. Make the long nose of paper (Fig. 371). Cut two slits close together on the face and slide the sides of the nose (AA, Fig. 371) into the slits (Fig. 370). Cut two more slits, one on each side of the nose, down to the corners of the mouth, and insert in each a piece of narrow white paper to form the lines; then cut one more slit for the mouth and push in a strip of white paper, which may be bent down to show a wider portion (Fig. 370). Last, but not least, come the ornamental feathers. If you can obtain natural ones so much the better; if not, make paper feathers of bright, differently colored paper. Fig. 372 shows how to cut them. Roll the bottom portion to make a stiff stem and after punching holes in the top of the apple, forming them in a row around the crown of the head, push each feather in place, having the tallest in the centre, as in Fig. 370. Run a slender stick up into the bottom of the head and you will have something better than taffy-on-a-stick.

[213]

[214]

[216]

[217]

Fig. 382 is the pattern, which you must make by tracing it on tissue-paper and then cutting it out. Choose any material you like—wool, cotton, or silk, for her dress and any color, only let it be quite smooth. Lay the tissue-paper pattern down on the goods, pin it in place and cut around close to the edges. Try the dress on Mary to see that it fits perfectly; then cover the wrong side thinly with paste, adjust it to the little figure and press down firmly, smoothing out any wrinkles that may appear. Cut a white lawn apron like the pattern (Fig. 383), and paste it over the dress bringing the upper edge up to the waist line.

and transferred it to a sheet of cardboard, you must collect a number of small feathers as much as possible like the shapes given in the page of diagrams. Perhaps you can get those plucked from the chicken for to-day's dinner, or you may be allowed to take a few from mother's feather pillows or cushions. If you do not find feathers of just the right shapes take a pair of sharp scissors and trim them down to suit.

Cut from gilt or colored paper three scalloped disks four inches in diameter (Fig. 400). Through the centre of each disk pass a needle threaded with doubled black linen thread, cover the under side of the disk with paste, separate the two ends of the thread and hold them down on each side of the large end of a shell, as shown in Fig. 401; then draw the disk down and paste it upon the shell over the threads. If the ends of the thread extend below the disk, clip them off with sharp scissors. Wait until the paste is quite dry and the paper firmly attached to the shells, then hang the eggs by their threads in a door-way so that they will be just one foot higher than you can reach.

It is not necessary to expend any strength in the "lifting," for the players should jump, and not depend upon the helpers to be lifted up within reach of the eggs. When the eggs have been pulled down, the fun consists in eating the candy, with always the certainty of finding some bitter drops among the sweet, and the uncertainty of how soon and how often the bitter will be found.

The eggs being arranged the company is divided into couples, each in turn to try the dance. The first couple takes position within the outer circle—that is, between the red eggs and the gilded ones—and, to waltz music, they dance around the circle three times, keeping within the space between the two circles. Entering the inner circle they waltz three times around the central egg, and all this must be done without breaking or greatly disturbing any of the eggs. When an egg is broken or knocked more than twelve inches from its position, the dancers retire and give place to the next couple. The broken eggs are not replaced, but those out of position are set in order before the succeeding couple commence the dance. When each couple has had a turn and none have accomplished the feat, all change partners and the trial begins again.

A piece of narrow white satin ribbon, three inches long, is folded and pushed through the hole in the centre of the star, forming a loop; the ends are then pasted to the point on either side of the star.

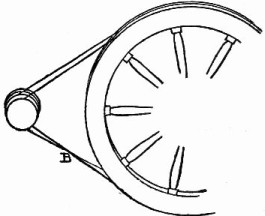

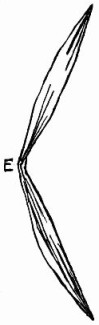

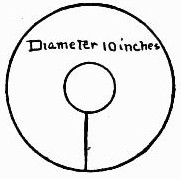

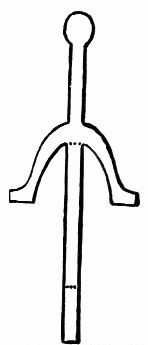

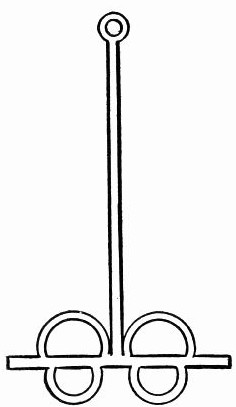

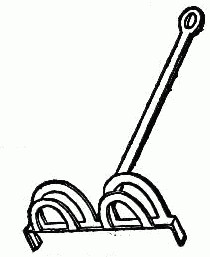

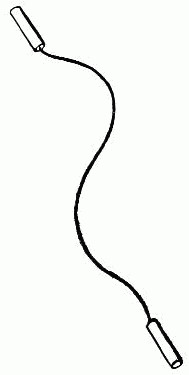

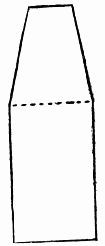

and arrows will be needed for the sport, and these we will make at home. They will be quite small and easy to manufacture, but the bows, though tiny, will work to a charm and send the home-made arrows flying with swiftness and precision to their goal. Look up a piece of flat rattan, from which to form the bow, such as is often used to stiffen stays and dress waists; cut it eleven and one-half inches in length and burn a hole in each end by boring through the rattan with a hair-pin heated red hot at one end (Fig. 407). Holes made in this way will not split or break the rattan. Pass a strong linen thread through the hole in one end of the bow and tie it firmly (Fig. 408); then bring the thread across to the other end, pass it through the hole, leaving a stretch of eight and one-quarter inches from end to end of the bow, and tie the end securely (Fig. 410).

[243]

[244]

While the King and his men are at work digging up the plants the Queen and her ladies can gather the buds and blossoms, picking them with as long stems as possible and remembering to have a few green leaves of each plant with its blossoms. To keep the flowers from wilting, as they would if held in the hand, let each girl be provided with a clean, perfectly dry baking-powder can which has a lid that fits tightly; the blossoms must be without moisture and very carefully placed within the can as soon as they are plucked. When the tin box is filled the cover can be fitted on securely to exclude all the air. The green leaves may be carried in the hand, and when they droop they can be revived by being placed in fresh water. The bit of wildwood brought home in the form of dainty cut flowers could be put in water until dark, when the little

Just at dusk the flowers may be arranged in the baskets with as little handling as possible. Then, when twilight comes, the May day party can steal cautiously to the door of the house fortunate enough to be favored by a May-token, hang one of the little baskets of flowers on the door-knob, ring the bell and scamper away before they are seen, for no one of the party must be present when the door opens.

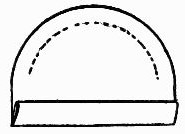

Before placing the pole in the tub nail securely to its base a piece of board eighteen inches square, as shown in Fig. 428. Erect the pole in the middle of the tub, put in cross-pieces (Fig. 428), nailing them at the ends and fill in all around with stones or bricks, as in Fig. 429.

[251]

[252]

nearer home; possibly you may have to work a little for the precious metal, but the exertion will be only fun. Ten little fairies—your ten fingers—will cheerfully supply the gold as well as the mine from which the nuggets must come on the eventful night. The fairies should make a number of small gold parcels which when finished form the nuggets (Fig. 432). Inside of each package is a piece of candy and a strip of paper with a fortune written upon it, so whatever may be the fate sent by the gnomes in the mine, it is sure to be sweet. Have enough lumps of gold to furnish each player with equal portions of one or more nuggets. Let the little fairies secure a tub, half-fill it with sand or saw-dust and hide the gold nuggets well in this home-made gold mine, scattering the little parcels through the sand like plums through a pudding. The fairies must stand a small shovel by the side of the mine, then all will be ready and the miners can dig for their fortunes (Fig. 433).

Each player in turn must take the shovel and dig in the mine until one gold nugget is found. He must then open the package carefully and read aloud the fortune Fate has given him, while the other players look on and listen. The fairies can readily whittle or saw out a wooden mining shovel from a shingle or thin box-lid. Tell them to make it about four inches long and three wide, with a handle eleven inches in length. Try to think of original ideas to write on the slips of fortune paper, or, failing these, look up apt quotations for the prophecies. If you can have the lines bright and witty, writing something that will cause a laugh when read aloud, without hurting anyone's feelings, your Hallowe'en mining will be a great success.

understands well the art of fortune-telling. She is a funny little creature made of a stick (Fig. 434), some yellow tissue-paper and an apple. A strip of the tissue-paper is gathered (Fig. 435), drawn tight together at the top and placed over the stick with a thread wound around a short distance from the top to form the head (Fig. 436). The arms are pieces of tissue-paper (Fig. 437) folded lengthwise (Fig. 438) and run through a hole punched in the body (Fig. 439). The face is marked with ink on the head (Fig. 439). Small strips of tissue-paper gathered like Fig. 440 are sewed on each arm to form the sleeves. Hair of black thread or darning cotton tied in the centre (Fig. 441) is sewed on the yellow paper head.

is a triangular piece of paper (Fig. 442) with edges pasted together and a circular piece of paper slightly slashed around the small hole in the centre (Fig. 443). The circular piece is slid down over the peak to form the brim (Fig. 444), glued on, and the entire hat is inked all over, dried and fitted on the little woman's head. A broom made of a strip of folded tissue-paper (Fig. 445) with a fringed piece of the same paper bound on for the broom part (Fig. 446) is sewed in the folded-over end of the witch's arm. When finished the point of the stick is pushed into an apple, and the apple placed upon a piece of paper divided into squares in which different fortunes are written (Fig. 447). When you want the witch to tell your fortune, spin the apple on the blank centre of the paper and wait until the witch is again quiet, and she will point with her broom to some spot where the fortune is written especially for you. Each girl and boy must be allowed three trials with this apple witch (Fig. 448).

is very mysterious and exciting. Dip a new clean pen in pure lemon juice and with this queer ink write mottoes or charms on a number of pieces of writing-paper. Allow the ink to become perfectly dry, when it will fade out completely; then place the charms in a box and let each girl and boy in turn draw what appears to be a blank slip of paper. After examining it, the paper should be handed to some grown person present who is in the secret and who has provided a lighted candle by means of which he may read the ghost writing. All the young people will cluster around and with bated breath watch the magical developing of the words on the blank paper as the reader moves the message back and forth over the lighted candle. The heat brings out the writing in distinct letters that all may see. A second charm must not be taken from the pile until the first has been read aloud.

which have previously been dampened and each dipped into a separate flavoring. The moisture will cause the spices, etc., to cling to the seed, giving various flavors. Those dipped in liquids must, of course, be afterward dried. If to your lot falls a seed which has been powdered with pulverized cloves, your life companion will never be dull and uninteresting; pepper denotes quick temper; sugar, affection and kindness; cinnamon is lively, buoyant and bright; vinegar, sour and cross; gall, bitter and morose; molasses, loving but stupid; lemon, refreshing and interesting. Add as many more flavors as you wish. When the seeds have been prepared and dried wrap each one in a small piece of white tissue-paper and pass them around to the young people, allowing each girl and boy to take two of the prophecies; then all the children must be quiet while each in turn tastes first one, then the other seed, telling aloud as he does so the particular flavor he has received. Should a player find the first seed sweet and the other sour, it would mean that the disposition of the future wife or husband will vary, partaking more of the stronger flavoring. If the taste of the first apple seed is pleasant, the married life of the player will be reasonably happy. If the flavor is very agreeable, the married life will be very happy; if the flavor proves unpleasant, it is best to remain single.

Look at the frog to be sure he is correctly drawn; then remove the pins and, allowing the cloth to remain on the table over the piece of smooth white paper, spread both of your hands out on the cloth, one at each side of the frog, and, keeping your eyes on the drawing, move your hands gradually outward, at the same time moving the mull with them. The stretching of the bias material will cause the frog to flatten out until he crouches for a spring (Fig. 450). Cautiously raise your hands up and off the cloth and place them down again in a different way; put one above and the other below his Frogship, and, still keeping your eyes on the figure, suddenly move your hands, stretching the square up and down, when the frog will give a quick leap and spring straight upward in the most unexpected manner (Fig. 451).

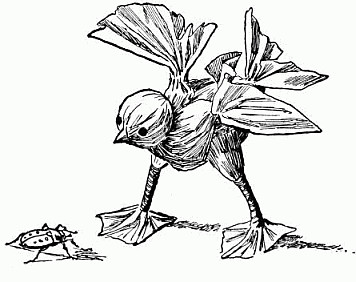

Have you ever seen little young birds in their nest? How they huddle together with their large yellow mouths open wide watching for their mother to return with their dinner! Trace the drawing (Fig. 452) on bias cloth and you can make these little birds move and really stretch up their heads for their dinner as you slowly pull the cloth upward and downward (Fig. 453). Watch them. Then stretch the cloth out sidewise and see the birdlings quietly settle down in their nests with a "Thank you" and "Good-by." (Fig. 454).

Trace the girl and boy (Fig. 455) on bias cloth as you did the frog. Fig. 455 shows how the children appear when they meet. Pull the cloth sidewise and their faces change expression (Fig. 456); they do not seem to enjoy their chat. Now pull the cloth in the opposite direction, and in an instant their faces show surprise and dismay (Fig. 457).

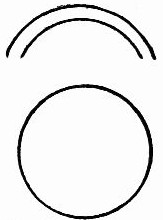

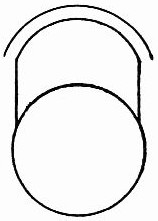

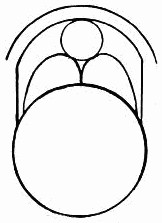

Take the dollies off the teeter and let them rest for a while and watch you build a church. Place your two hands back to back, with the ends of the fingers of the right loosely crossing those of the left hand; then, bring the palms of the hands together, fingers inside and thumbs outside and lo!

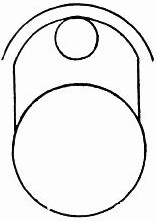

(Fig. 465). But it is without a steeple. Build one by raising the two first fingers, without disturbing the remainder of the hands; bring the raised finger-tips together and, "Here is the steeple" (Fig. 466). A church, like any other building, to be of use, must have people in it, and if we could only look inside this building we might find them; move your thumbs apart, or "Open the doors and see all the people" (Fig. 467). There they are sitting in rows; don't you see them? Now let the people go up-stairs. Cross your two smallest fingers on the inside, which will bring the backs of the hands toward each other; keeping the little fingers together, cross the third fingers, next the second, then the first fingers. The fingers on the left hand form the stairs for the people or fingers of the right hand to climb. Try it again, allowing the people to ascend slowly one by one: "Here are the people climbing up-stairs" (Fig. 468). Keep your hands loosely in the last position and raise your right elbow; while holding that up, twist your left hand around forward until the left thumb rests on the inside of the right hand. Both hands will now be turned downward with the wrists uppermost.

Leaving the hands in this position, turn your two elbows outward and down, which will bring your hands up; slide your right thumb outside and around your left thumb, the left thumb will then be the minister and, though you cannot see them, the fingers clasped inside the hands are the people, but you can see the thumb, preacher, standing up ready to talk to the people, and you may say, "Here is the preacher who for them cares" (Fig. 469).

(Fig. 472). Of course, the fingers are the knives and forks. Turn your hands over while the fingers remain in place, bring the wrists down and say, "Here is my father's table" (Fig. 473). Raise the two first fingers, bringing their tips together, and say, "Here is my sister's looking-glass" (Fig. 474). Then raise your two little fingers and, rocking the hands from side to side, say, "And here is the baby's cradle" (Fig. 475).

Dampen two bits of paper and press one down tight on the nail of the first finger of your right hand and the other on the nail of the first finger of your left hand. The two pieces of paper are the two blackbirds. Now hold your first fingers, on which the birds are resting, out stiff and double up the remaining fingers; then let your father see how well you have taught these little pet birds to mind, for they will do exactly as you say, going and coming at your command. Place the tips of your two first fingers on a chair, which you must pretend is a hill, and raising first one finger to make the bird fly, then the other, keep the pets flying up and down while you repeat these lines:

As you say the last line raise the right finger up and back over your right shoulder; while there, quickly bend down the right finger with Jack on it and stiffen out the second finger in its place. Bring your right hand down with Jack hidden and put the empty second finger on the chair instead of the first. The bird will be gone and lonesome little Jill will perch on the hill with no playmate, so you must let her go too. Repeat these words, "Fly away, Jill," and make her disappear as you did Jack, bringing down the empty second finger of your left hand and your father will find that both birds have gone; but you may make them return by saying, "Come back, Jack," as you raise your right hand and close down the second finger while you straighten out the first and bring it again to the chair with Jack upon it. Call Jill also that Jack may have some one to sing to, and as you say, "Come back, Jill," bend down the second finger and straighten out the first one with Jill on it, and let her fly down to Jack. You may repeat the lines again and again, making the pets come and go.

In a house where good taste always prevailed there stood, one day, on the uncovered top of a grand piano a tall, colorless, transparent vase which held just one long-stemmed American Beauty rose. The queenly flower with its stem showing through the glass and the few green leaves attached were all reflected in the highly polished piano, and the effect of the colors reproduced in deepened, darkened tones by the rich rosewood was indescribably lovely. There were no other flowers and, though the room was a large one, none were needed. One's eyes fell immediately upon the rose when entering, and lingered there with no wish to be drawn away by lesser attractions.

Few flowers look well packed tightly together and all are better for loosening up a trifle. Purple violets are almost the only flowers that will bear crowding, though many think wild daisies adapted to this arrangement, and spoil their beauty by making them into hard, tight bunches. A good rule is to follow Nature as far as possible in this direction. Flowers that grow singly and far apart, should not be crowded, but those which grow thickly clustered may be more closely massed.

that are different in kind or color, it can seldom be done successfully. To be sure, a mass of sweet-peas in all their variety of color is very lovely, but even they are more effective when separated into bunches each of one color. White flowers sometimes are the better for a touch of color, and white and yellow roses make a pretty combination, or white and delicate pink, but the strong contrast of white and dark red is not pleasing. Lilies should always have a vase to themselves, and the Ascension lily must under all circumstances stand alone. Neither the quality of the flower nor the associations connected with it permit of its being grouped with any other.

need not be expensive, for they are now in the market at extremely low prices. Knowing what to choose you can find for a very moderate sum tall, slender vases with almost no markings, that will show the long stem and so display the entire loveliness of the rose. Fig. 493 is one of the least expensive of these vases. Even the colorless glass olive-bottle, shaped like Fig. 494, makes a pretty and suitable vase, and an ordinary fish-globe displays the rose-stems to far greater advantage than a cut-glass rose-bowl. A clear glass water-pitcher without tracing of any kind is another appropriate receptacle for these lovely blossoms. When the stems of any flowers have beauty of their own, they should never be hidden in opaque vases. So it is not for roses alone these transparent vases are suitable.

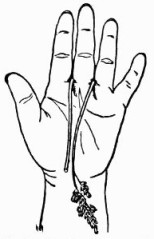

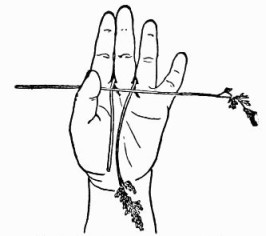

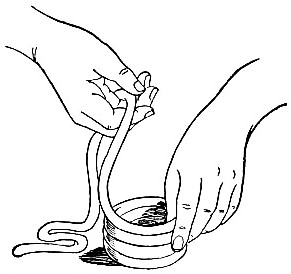

With an old pair of shears, or a wire-cutter, snip off a dozen or more pieces of copper wire of varying lengths between ten inches for the longest and five for the shortest piece. At each end of every wire make a loop like Fig. 498; bend the loops over (Fig. 499), then fasten all the pieces to a brass curtain-ring by twisting each piece once around the ring at the centre of the wire (Fig. 500). Bunch the wires together and stand the lifter in a bowl of water; put your flower-stems through the wire loops, as in Fig. 501, and the wires under water will look like the flower-stems, the loops being hidden by the blossoms.

Similar playhouses may be built by children in any spot where trees grow within a short distance of each other. In place of tropical decorations the young builders can use the most ornamental bouquets within reach, selecting foliage and flowers which will keep fresh at least for a few hours.