автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Demonology and Devil-lore

Demonology and Devil-lore

By

Moncure Daniel Conway, M.A.

B. D. of Divinity College, Harvard University

Member of the Anthropological Institute, London

With numerous illustrations

New York

Henry Holt and Company

1879

Copyright, 1879, by

Moncure Daniel Conway.

Preface.

Three Friars, says a legend, hid themselves near the Witch Sabbath orgies that they might count the devils; but the Chief of these, discovering the friars, said—‘Reverend Brothers, our army is such that if all the Alps, their rocks and glaciers, were equally divided among us, none would have a pound’s weight.’ This was in one Alpine valley. Any one who has caught but a glimpse of the world’s Walpurgis Night, as revealed in Mythology and Folklore, must agree that this courteous devil did not overstate the case. Any attempt to catalogue the evil spectres which have haunted mankind were like trying to count the shadows cast upon the earth by the rising sun. This conviction has grown upon the author of this work at every step in his studies of the subject.

In 1859 I contributed, as one of the American ‘Tracts for the Times,’ a pamphlet entitled ‘The Natural History of the Devil.’ Probably the chief value of that essay was to myself, and this in that its preparation had revealed to me how pregnant with interest and importance was the subject selected. Subsequent researches in the same direction, after I had come to reside in Europe, revealed how slight had been my conception of the vastness of the domain upon which that early venture was made. In 1872, while preparing a series of lectures for the Royal Institution on Demonology, it appeared to me that the best I could do was to print those lectures with some notes and additions; but after they were delivered there still remained with me unused the greater part of materials collected in many countries, and the phantasmal creatures which I had evoked would not permit me to rest from my labours until I had dealt with them more thoroughly.

The fable of Thor’s attempt to drink up a small spring, and his failure because it was fed by the ocean, seems aimed at such efforts as mine. But there is another aspect of the case which has yielded me more encouragement. These phantom hosts, however unmanageable as to number, when closely examined, present comparatively few types; they coalesce by hundreds; from being at first overwhelmed by their multiplicity, the classifier finds himself at length beating bushes to start a new variety. Around some single form—the physiognomy, it may be, of Hunger or Disease, of Lust or Cruelty—ignorant imagination has broken up nature into innumerable bits which, like mirrors of various surface, reflect the same in endless sizes and distortions; but they vanish if that central fact be withdrawn.

In trying to conquer, as it were, these imaginary monsters, they have sometimes swarmed and gibbered around me in a mad comedy which travestied their tragic sway over those who believed in their reality. Gargoyles extended their grin over the finest architecture, cornices coiled to serpents, the very words of speakers started out of their conventional sense into images that tripped my attention. Only as what I believed right solutions were given to their problems were my sphinxes laid; but through this psychological experience it appeared that when one was so laid his or her legion disappeared also. Long ago such phantasms ceased to haunt my nerves, because I discovered their unreality; I am now venturing to believe that their mythologic forms cease to haunt my studies, because I have found out their reality.

Why slay the slain? Such may be the question that will arise in the minds of many who see this book. A Scotch song says, ‘The Devil is dead, and buried at Kirkcaldy;’ if so, he did not die until he had created a world in his image. The natural world is overlaid by an unnatural religion, breeding bitterness around simplest thoughts, obstructions to science, estrangements not more reasonable than if they resulted from varying notions of lunar figures,—all derived from the Devil-bequeathed dogma that certain beliefs and disbeliefs are of infernal instigation. Dogmas moulded in a fossil demonology make the foundation of institutions which divert wealth, learning, enterprise, to fictitious ends. It has not, therefore, been mere intellectual curiosity which has kept me working at this subject these many years, but an increasing conviction that the sequelæ of such superstitions are exercising a still formidable influence. When Father Delaporte lately published his book on the Devil, his Bishop wrote—‘Reverend Father, if every one busied himself with the Devil as you do, the kingdom of God would gain by it.’ Identifying the kingdom here spoken of as that of Truth, it has been with a certain concurrence in the Bishop’s sentiment that I have busied myself with the work now given to the public.

Contents

Volume I.

Part I.

Chapter I.

Dualism.

Page

Origin of Deism—Evolution from the far to the near—Illustrations from Witchcraft—The primitive Pantheism—The dawn of Dualism 1

Chapter II.

The Genesis of Demons.

Their good names euphemistic—Their mixed character—Illustrations: Beelzebub, Loki—Demon-germs—The knowledge of good and evil—Distinction between Demon and Devil 7

Chapter III.

Degradation.

The degradation of Deities—Indicated in names—Legends of their fall—Incidental signs of the divine origin of Demons and Devils 15

Chapter IV.

The Abgott.

The ex-god—Deities demonised by conquest—Theological animosity—Illustration from the Avesta—Devil-worship an arrested Deism—Sheik Adi—Why Demons were painted ugly—Survivals of their beauty 22

Chapter V.

Classification.

The obstructions of man—The twelve chief classes—Modifications of particular forms for various functions—Theological Demons 34

Part II.

Chapter I.

Hunger.

Hunger-demons—Kephn—Miru—Kagura—Ráhu the Hindu sun-devourer—The earth monster at Pelsall—A Franconian custom—Sheitan as moon-devourer—Hindu offerings to the dead—Ghoul—Goblin—Vampyres—Leanness of demons—Old Scotch custom—The origin of sacrifices 41

Chapter II.

Heat.

Demons of fire—Agni—Asmodeus—Prometheus—Feast of fire—Moloch—Tophet—Genii of the lamp—Bel-fires—Hallowe’en—Negro superstitions—Chinese fire-god—Volcanic and incendiary demons—Mangaian fire-demon—Demons’ fear of water 57

Chapter III.

Cold.

Descent of Ishtar into Hades—Bardism—Baldur—Herakles—Christ—Survivals of the Frost Giant in Slavonic and other countries—The Clavie—The Frozen Hell—The Northern abode of Demons—North side of churches 77

Chapter IV.

Elements.

A Scottish Munasa—Rudra—Siva’s lightning eye—The flaming sword—Limping Demons—Demons of the storm—Helios, Elias, Perun—Thor arrows—The Bob-tailed Dragon—Whirlwind—Japanese Thunder God—Christian survivals—Jinni—Inundations—Noah—Nik, Nicholas, Old Nick—Nixies—Hydras—Demons of the Danube—Tides—Survivals in Russia and England 92

Chapter V.

Animals.

Animal demons distinguished—Trivial sources of Mythology—Hedgehog—Fox—Transmigrations in Japan—Horses bewitched—Rats—Lions—Cats—The Dog—Goethe’s horror of dogs—Superstitions of the Parsees, people of Travancore, and American Negroes, Red Indians, &c.—Cynocephaloi—The Wolf—Traditions of the Nez Perces—Fenris—Fables—The Boar—The Bear—Serpent—Every animal power to harm demonised—Horns 121

Chapter VI.

Enemies.

Aryas, Dasyus, Nagas—Yakkhos—Lycians—Ethiopians—Hirpini—Polites—Sosipolis—Were-wolves—Goths and Scythians—Giants and Dwarfs—Berserkers—Britons—Iceland—Mimacs—Gog and Magog 150

Chapter VII.

Barrenness.

Indian Famine and Sun-spots—Sun-worship—Demon of the Desert—The Sphinx—Egyptian Plagues described by Lepsius: Locusts, Hurricane, Flood, Mice, Flies—The Sheikh’s ride—Abaddon—Set—Typhon—The Cain wind—Seth—Mirage—The Desert Eden—Azazel—Tawiscara and the Wild-rose 170

Chapter VIII.

Obstacles.

Mephistopheles on crags—Emerson on Monadnoc—Ruskin on Alpine peasants—Holy and unholy mountains—The Devil’s Pulpit—Montagnards—Tarns—Tenjo—T’ai-shan—Apocatequil—Tyrolese legends—Rock ordeal—Scylla and Charybdis—Scottish giants—Pontifex—Devil’s bridges—Le géant Yéous 190

Chapter IX.

Illusion.

Maya—Natural Treacheries—Misleaders—Glamour—Lorelei—Chinese Mermaid—Transformations—Swan Maidens—Pigeon Maidens—The Seal-skin—Nudity—Teufelsee—Gohlitsee—Japanese Siren—Dropping Cave—Venusberg—Godiva—Will-o’-Wisp—Holy Fräulein—The Forsaken Merman—The Water-Man—Sea Phantom—Sunken Treasures—Suicide 210

Chapter X.

Darkness.

Shadows—Night Deities—Kobolds—Walpurgisnacht—Night as Abettor of Evil-doers—Nightmare—Dreams—Invisible Foes—Jacob and his Phantom—Nott—The Prince of Darkness—The Brood of Midnight—Second-Sight—Spectres of Souter Fell—The Moonshine Vampyre—Glamour—Glam and Grettir—A-Story of Dartmoor 231

Chapter XI.

Disease.

The Plague Phantom—Devil-dances—Destroying Angels—Ahriman in Astrology—Saturn—Satan and Job—Set—The Fatal Seven—Yakseyo—The Singhalese Pretraya—Reeri—Maha Sohon—Morotoo—Luther on Disease-demons—Gopolu—Madan—Cattle-demon in Russia—Bihlweisen—The Plough 249

Chapter XII.

Death.

The Vendetta of Death—Teoyaomiqui—Demon of Serpents—Death on the Pale Horse—Kali—War-gods—Satan as Death—Death-beds—Thanatos—Yama—Yimi—Towers of Silence—Alcestis—Herakles, Christ, and Death—Hell—Salt—Azraël—Death and the Cobbler—Dance of Death—Death as Foe and as Friend 269

Part III.

Chapter I.

Decline of Demons.

The Holy Tree of Travancore—The growth of Demons in India, and their decline—The Nepaul Iconoclast—Moral Man and unmoral Nature—Man’s physical and mental migrations—Heine’s ‘Gods in Exile’—The Goban Saor—Master Smith—A Greek caricature of the Gods—The Carpenter v. Deity and Devil—Extermination of the Were-wolf—Refuges of Demons—The Giants reduced to Little People—Deities and Demons returning to nature 299

Chapter II.

Generalisation of Demons.

The Demons’ bequest to their conquerors—Nondescripts—Exaggerations of Tradition—Saurian Theory of Dragons—The Dragon not primitive in Mythology—Monsters of Egyptian, Iranian, Vedic, and Jewish Mythologies—Turner’s Dragon—Della Bella—The Conventional Dragon 318

Chapter III.

The Serpent.

The beauty of the Serpent—Emerson on ideal forms—Michelet’s thoughts on the viper’s head—Unique characters of the Serpent—The Monkey’s horror of Snakes—The Serpent protected by superstition—Human defencelessness against its subtle powers—Dubufe’s picture of the Fall of Man 325

Chapter IV.

The Worm.

An African Serpent-drama in America—The Veiled Serpent—The Ark of the Covenant—Aaron’s Rod—The Worm—An Episode on the Dii Involuti—The Serapes—The Bambino at Rome—Serpent-transformations 332

Chapter V.

Apophis.

The Naturalistic Theory of Apophis—The Serpent of Time—Epic of the Worm—The Asp of Melite—Vanquishers of Time—Nachash-Beriach—The Serpent-Spy—Treading on Serpents 340

Chapter VI.

The Serpent in India.

The Kankato na—The Vedic Serpents not worshipful—Ananta and Sesha—The Healing Serpent—The guardian of treasures—Miss Buckland’s theory—Primitive rationalism—Underworld plutocracy—Rain and lightning—Vritra—History of the word ‘Ahi’—The Adder—Zohak—A Teutonic Laokoon 348

Chapter VII.

The Basilisk.

The Serpent’s gem—The Basilisk’s eye—Basiliscus mitratus—House-snakes in Russia and Germany—King-snakes—Heraldic Dragon—Henry III.—Melusina—The Laidley Worm—Victorious Dragons—Pendragon—Merlin and Vortigern—Medicinal dragons 361

Chapter VIII.

The Dragon’s Eye.

The Eye of Evil—Turner’s Dragons—Cloud-phantoms—Paradise and the Snake—Prometheus and Jove—Art and Nature—Dragon forms: Anglo-Saxon, Italian, Egyptian, Greek, German—The modern conventional Dragon 372

Chapter IX.

The Combat.

The pre-Munchausenite world—The Colonial Dragon—Io’s journey—Medusa—British Dragons—The Communal Dragon—Savage Saviours—A Mimac helper—The Brutal Dragon—Woman protected—The Saint of the Mikados 384

Chapter X.

The Dragon-slayer.

Demi-gods—Alcestis—Herakles—The Ghilghit Fiend—Incarnate deliverer of Ghilghit—A Dardistan Madonna—The religion of Atheism—Resuscitation of Dragons—St. George and his Dragon—Emerson and Ruskin on George—Saintly allies of the Dragon 394

Chapter XI.

The Dragon’s Breath.

Medusa—Phenomena of recurrence—The Brood of Echidna and their survival—Behemoth and Leviathan—The Mouth of Hell—The Lambton Worm—Ragnar—The Lambton Doom—The Worm’s Orthodoxy—The Serpent, Superstition, and Science 406

Chapter XII.

Fate.

Doré’s ‘Love and Fate’—Moira and Moiræ—The ‘Fates’ of Æschylus—Divine absolutism surrendered—Jove and Typhon—Commutation of the Demon’s share—Popular fatalism—Theological fatalism—Fate and Necessity—Deification of Will—Metaphysics, past and present 420

Volume II.

Part IV.

Chapter I.

Diabolism. Page

Dragon and Devil distinguished—Dragons’ wings—War in Heaven—Expulsion of Serpents—Dissolution of the Dragon—Theological origin of the Devil—Ideal and Actual—Devil Dogma—Debasement of ideal persons—Transmigration of phantoms 1

Chapter II.

The Second Best.

Respect for the Devil—Primitive Atheism—Idealisation—Birth of new gods—New gods diabolised—Compromise between new gods and old—Foreign deities degraded—Their utilisation 13

Chapter III.

Ahriman, the Divine Devil.

Mr. Irving’s impersonation of Superstition—Revolution against pious privilege—Doctrine of ‘Merits’—Saintly immorality in India—A Pantheon turned Inferno—Zendavesta on Good and Evil—Parsî Mythology—The Combat of Ahriman with Ormuzd—Optimism—Parsî Eschatology—Final Restoration of Ahriman 20

Chapter IV.

Viswámitra, the Theocratic Devil.

Priestcraft and Pessimism—An Aryan Tetzel and his Luther—Brahman Frogs—Evolution of the Sacerdotal Saint—Viswámitra the Accuser of Virtue—The Tamil Passion-Play ‘Harischandra’—Ordeal of Goblins—The Martyr of Truth—Virtue triumphant over ceremonial ‘Merits’—Harischandra and Job 31

Chapter V.

Elohim and Jehovah.

Deified power—Giants and Jehovah—Jehovah’s manifesto—The various Elohim—Two Jehovahs and two Tables—Contradictions—Detachment of the Elohim from Jehovah 46

Chapter VI.

The Consuming Fire.

The Shekinah—Jewish idols—Attributes of the fiery and cruel Elohim compared with those of the Devil—The powers of evil combined under a head—Continuity—The consuming fire spiritualised 54

Chapter VII.

Paradise and the Serpent.

Herakles and Athena in a holy picture—Human significance of Eden—The legend in Genesis puzzling—Silence of later books concerning it—Its Vedic elements—Its explanation—Episode of the Mahábhárata—Scandinavian variant—The name of Adam—The story re-read—Rabbinical interpretations 63

Chapter VIII.

Eve.

The Fall of Man—Fall of gods—Giants—Prajápati and Ráhu—Woman and Star-Serpent in Persia—Meschia and Meschiane—Bráhman legends of the creation of Man—The strength of Woman—Elohist and Jehovist creations of Man—The Forbidden Fruit—Eve reappears as Sara—Abraham surrenders his wife to Jehovah—The idea not sensual—Abraham’s circumcision—The evil name of Woman—Noah’s wife—The temptation of Abraham—Rabbinical legends concerning Eve—Pandora—Sentiment of the Myth of Eve 73

Chapter IX.

Lilith.

Madonnas—Adam’s first wife—Her flight and doom—Creation of Devils—Lilith marries Samaël—Tree of Life—Lilith’s part in the Temptation—Her locks—Lamia—Bodeima—Meschia and Meschiane—Amazons—Maternity—Rib-theory of Woman—Káli and Durga—Captivity of Woman 91

Chapter X.

War in Heaven.

The ‘Other’—Tiamat, Bohu, ‘the Deep’—Ra and Apophis—Hathors—Bel’s combat—Revolt in Heaven—Lilith—Myth of the Devil at the creation of Light 105

Chapter XI.

War on Earth.

The Abode of Devils—Ketef—Disorder—Talmudic legends—The restless Spirit—The Fall of Lucifer—Asteria, Hecate, Lilith—The Dragon’s triumph—A Gipsy legend—Cædmon’s Poem of the Rebellious Angels—Milton’s version—The Puritans and Prince Rupert—Bel as ally of the Dragon—A ‘Mystery’ in Marionettes—European Hells 115

Chapter XII.

Strife.

Hebrew God of War—Samaël—The father’s blessing and curse—Esau—Edom—Jacob and the Phantom—The planet Mars—Tradesman and Huntsman—‘The Devil’s Dream’ 130

Chapter XIII.

Barbaric Aristocracy.

Jacob, the ‘Impostor’—The Barterer—Esau, the ‘Warrior’—Barbarian Dukes—Trade and War—Reconciliation of Jacob and Esau—Their Ghosts—Legend of Iblis—Pagan Warriors of Europe—Russian Hierarchy of Hell 138

Chapter XIV.

Job and the Divider.

Hebrew Polytheism—Problem of Evil—Job’s disbelief in a future life—The Divider’s realm—Salted sacrifices—Theory of Orthodoxy—Job’s reasoning—His humour—Impartiality of Fortune between the evil and good—Agnosticism of Job—Elihu’s Eclecticism—Jehovah of the Whirlwind—Heresies of Job—Rabbinical legend of Job—Universality of the legend 147

Chapter XV.

Satan.

Public Prosecutors—Satan as Accuser—English Devil-Worshipper—Conversion by Terror—Satan in the Old Testament—The trial of Joshua—Sender of Plagues—Satan and Serpent—Portrait of Satan—Scapegoat of Christendom—Catholic ‘Sight of Hell’—The ally of Priesthoods 159

Chapter XVI.

Religious Despotism.

Pharaoh and Herod—Zoroaster’s mother—Ahriman’s emissaries—Kansa and Krishna—Emissaries of Kansa—Astyages and Cyrus—Zohák—Bel and the Christian 172

Chapter XVII.

The Prince of this World.

Temptations—Birth of Buddha—Mara—Temptation of Power—Asceticism and Luxury—Mara’s menaces—Appearance of the Buddha’s Vindicator—Ahriman tempts Zoroaster—Satan and Christ—Criticism of Strauss—Jewish traditions—Hunger—Variants 178

Chapter XVIII.

Trial of the Great.

A ‘Morality’ at Tours—The ‘St. Anthony’ of Spagnoletto—Bunyan’s Pilgrim—Milton on Christ’s Temptation—An Edinburgh saint and Unitarian fiend—A haunted Jewess—Conversion by fever—Limit of courage—Woman and sorcery—Luther and the Devil—The ink-spot at Wartburg—Carlyle’s interpretation—The cowled Devil—Carlyle’s trial—In Rue St. Thomas d’Enfer—The Everlasting No—Devil of Vauvert—The latter-day conflict—New conditions—The Victory of Man—The Scholar and the World 190

Chapter XIX.

The Man of Sin.

Hindu myth—Gnostic theories—Ophite scheme of redemption—Rabbinical traditions of Primitive Man—Pauline Pessimism—Law of death—Satan’s ownership of Man—Redemption of the Elect—Contemporary statements—Baptism—Exorcism—The ‘new man’s’ food—Eucharist—Herbert Spencer’s explanation—Primitive ideas—Legends of Adam and Seth—Adamites—A Mormon ‘Mystery’ of initiation 206

Chapter XX.

The Holy Ghost.

A Hanover relic—Mr. Atkinson on the Dove—The Dove in the Old Testament—Ecclesiastical symbol—Judicial symbol—A vision of St. Dunstan’s—The witness of chastity—Dove and Serpent—The unpardonable sin—Inexpiable sin among the Jews—Destructive power of Jehovah—Potency of the breath—Third persons of Trinities—Pentecost—Christian superstitions—Mr. Moody on the sin against the Holy Ghost—Mysterious fear—Idols of the cave 226

Chapter XXI.

Antichrist.

The Kali Age—Satan sifting Simon—Satan as Angel of Light—Epithets of Antichrist—The Cæsars—Nero—Sacraments imitated by Pagans—Satanic signs and wonders—Jerome on Antichrist—Armillus—Al Dajjail—Luther on Mohammed—‘Mawmet’—Satan ‘God’s ape’—Mediæval notions—Witches’ Sabbath—An Infernal Trinity—Serpent of Sins—Antichrist Popes—Luther as Antichrist—Modern notions of Antichrist 240

Chapter XXII.

The Pride of Life.

The curse of Iblis—Samaël as Democrat—His vindication by Christ and Paul—Asmodäus—History of the name—Aschmedai of the Jews—Book of Tobit—Doré’s ‘Triumph of Christianity’—Aucassin and Nicolette—Asmodeus in the convent—The Asmodeus of Le Sage—Mephistopheles—Blake’s ‘Marriage of Heaven and Hell’—The Devil and the artists—Sádi’s Vision of Satan—Arts of the Devil—Suspicion of beauty—Earthly and heavenly mansions—Deacon versus Devil 260

Chapter XXIII.

The Curse on Knowledge.

A Bishop on intellect—The Bible on learning—The Serpent and Seth—A Hebrew Renaissance—Spells—Shelley at Oxford—Book-burning—Japanese ink-devil—Book of Cyprianus—Devil’s Bible—Red Letters—Dread of Science—Roger Bacon—Luther’s Devil—Lutherans and Science 277

Chapter XXIV.

Witchcraft.

Minor gods—Saint and Satyr—Tutelaries—Spells—Early Christianity and the poor—Its doctrine as to pagan deities—Mediæval Devils—Devils on the stage—An Abbot’s revelations—The fairer deities—Oriental dreams and spirits—Calls for Nemesis—Lilith and her children—Neoplatonicism—Astrology and Alchemy—Devil’s College—Shem-hammphorásch—Apollonius of Tyana—Faustus—Black Art Schools—Compacts with the Devil—Blood covenant—Spirit-seances in old times—The Fairfax delusion—Origin of its devil—Witch, goat, and cat—Confessions of Witches—Witchcraft in New England—Witch trials—Salem demonology—Testing witches—Witch trials in Sweden—Witch Sabbath—Mythological elements—Carriers—Scotch Witches—The cauldron—Vervain—Rue—Invocation of Hecaté—Factors of Witch persecution—Three centuries of massacre—Würzburg horrors—Last victims—Modern Spiritualism 288

Chapter XXV.

Faust and Mephistopheles.

Mephisto and Mephitis—The Raven Book—Papal sorcery—Magic seals—Mephistopheles as dog—George Sabellicus alias Faustus—The Faust myth—Marlowe’s ‘Faust’—Good and evil angels—‘El Magico Prodigioso’—Cyprian and Justina—Klinger’s ‘Faust’—Satan’s sermon—Goethe’s Mephistopheles—His German characters—Moral scepticism—Devil’s gifts—Helena—Redemption through Art—Defeat of Mephistopheles 332

Chapter XXVI.

The Wild Huntsman.

The Wild Hunt—Euphemisms—Schimmelreiter—Odinwald—Pied Piper—Lyeshy—Waldemar’s Hunt—Palne Hunter—King Abel’s Hunt—Lords of Glorup—Le Grand Veneur—Robert le Diable—Arthur—Hugo—Herne—Tregeagle—Der Freischütz—Elijah’s chariot—Mahan Bali—Déhak—Nimrod—Nimrod’s defiance of Jehovah—His Tower—Robber Knights—The Devil in Leipzig—Olaf hunting pagans—Hunting-horns—Raven—Boar—Hounds—Horse—Dapplegrimm—Sleipnir—Horse-flesh—The mare Chetiya—Stags—St. Hubert—The White Lady—Myths of Mother Rose—Wodan hunting St. Walpurga—Friar Eckhardt 353

Chapter XXVII.

Le Bon Diable.

The Devil repainted—Satan a divine agent—St. Orain’s heresy—Primitive universalism—Father Sinistrari—Salvation of demons—Mediæval sects—Aquinas—His prayer for Satan—Popular antipathies—The Devil’s gratitude—Devil defending innocence—Devil against idle lords—The wicked ale-wife—Pious offenders punished—Anachronistic Devils—Devils turn to poems—Devil’s good advice—Devil sticks to his word—His love of justice—Charlemagne and the Serpent—Merlin—His prison of Air—Mephistopheles in Heaven 381

Chapter XXVIII.

Animalism.

Celsus on Satan—Ferocities of inward nature—The Devil of Lust—Celibacy—Blue Beards—Shudendozi—A lady in distress—Bahirawa—The Black Prince—Madana Yaksenyo—Fair fascinators—Devil of Jealousy—Eve’s jealousy—Noah’s wife—How Satan entered the Ark—Shipwright’s Dirge—The Second Fall—The Drunken curse—Solomon’s Fall—Cellar Devils—Gluttony—The Vatican haunted—Avarice—Animalised Devils—Man-shaped Animals 401

Chapter XXIX.

Thoughts and Interpretations 421

List of Illustrations

Volume I.

Fig.

Page

1.

Beelzebub (Calmet)9

2.

Handle of Hindu Chalice31

3.

A Swallower44

4.

St. Anthony’s Lean Persecutor54

5.

Ancient Persian Medal103

6.

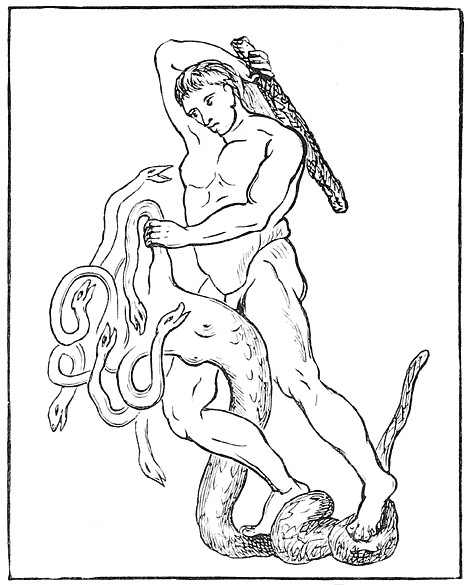

Hercules and the Hydra (Louvre)114

7.

Japanese Demon123

8.

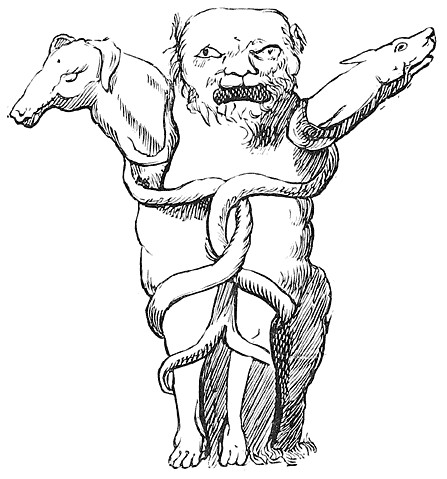

Cerberus (Calmet)133

9.

Canine Lar (Herculaneum)135

10.

The Wolf as Confessor (probably Dutch)143

11.

Singhalese Demon of Serpents148

12.

American Indian Demon149

13.

Italian and Roman Genii157

14.

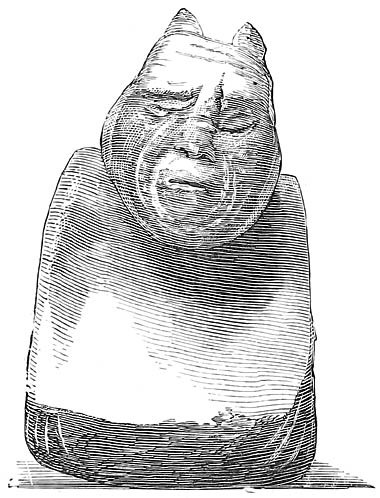

Typhon (Wilkinson)185

15.

Snouted Demon197

16.

Demon found at Ostia265

17.

Teoyaomiqui273

18.

Kali277

19.

Dives and Lazarus (Russian, seventeenth century)281

20.

The Knight and Death293

21.

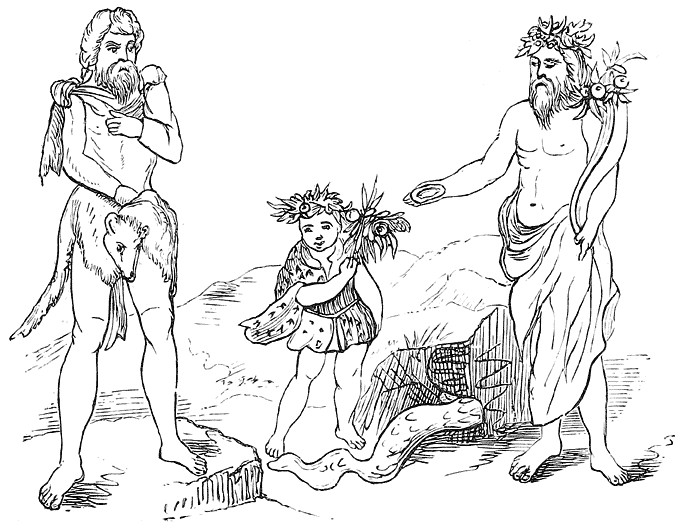

Greek Caricature of the Gods311

22.

A Witch Mounted (Della Bella)323

23.

Serpent and Egg (Tyre)325

24.

Serpent and Ark (from a Greek coin)334

25.

Anguish358

26.

Swan-Dragon (French)379

27.

Anglo-Saxon Dragons (Cædmon MS., tenth century)379

28.

From the Fresco at Arezzo380

29.

From Albert Durer’s ‘Passion’381

30.

Chimæra382

31.

Bellerophon and Chimæra (Corinthian)386

32.

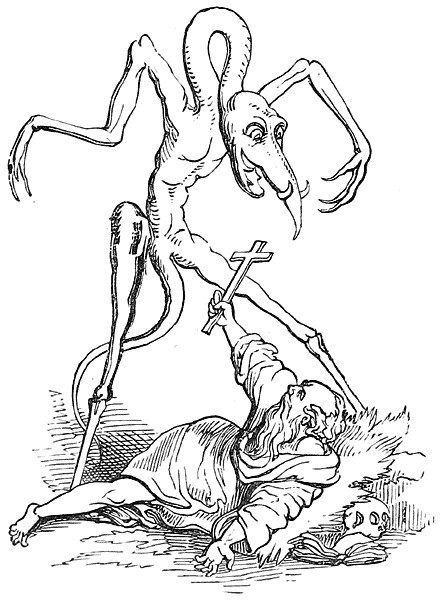

From the Temptation of St. Anthony417

Volume II.

Fig.

Page

1.

Lilith and Eve96

2.

Temptation and Expulsion of Adam and Eve97

3.

Satan Punished125

4.

Hierarchy of Hell144

5.

Gnostic Figure of Satan168

6.

Temptation of Christ185

7.

Adam Signing Contract for his Posterity to Satan214

8.

Seth Offering a Branch to Adam222

9.

Procession of the Serpent of Sins253

10.

Ancient Russian Wall-Painting254

11.

Alexander VI. as Antichrist255

12.

The Pope nursed by Megæra256

13.

Antichrist’s Descent257

14.

Luther’s Devil as seen by Catholics258

15.

The Pride of Life260

16.

The Artist’s Rescue271

17.

Luther’s Devil286

18.

Devils from Old Missal294

19.

Carving at Corbeil295

20.

Lilith as Cat301

21.

A Witch from Lyons Cathedral312

22.

Seal from Raven Book335

23.

The Wicked Ale-Wife390

24.

A Mediæval Death-Bed394

25.

From Hogarth’s ‘Raree Show’399

26.

A Soul’s Doom403

27.

Cruelty and Lust407

28.

Jealousy410

29.

Satan and Noraita413

30.

Monkish Gluttony417

31.

Devil of Danegeld Treasure418

32.

St. James and Devils419

33.

Devil from Notre Dame, Paris456

Part I.

Demonolatry.

Chapter I.

Dualism.

Origin of Deism—Evolution from the far to the near—Illustrations from witchcraft—The primitive Pantheism—The dawn of Dualism.

A college in the State of Ohio has adopted for its motto the words ‘Orient thyself.’ This significant admonition to Western youth represents one condition of attaining truth in the science of mythology. Through neglect of it the glowing personifications and metaphors of the East have too generally migrated to the West only to find it a Medusa turning them to stone. Our prosaic literalism changes their ideals to idols. The time has come when we must learn rather to see ourselves in them: out of an age and civilisation where we live in habitual recognition of natural forces we may transport ourselves to a period and region where no sophisticated eye looks upon nature. The sun is a chariot drawn by shining steeds and driven by a refulgent deity; the stars ascend and move by arbitrary power or command; the tree is the bower of a spirit; the fountain leaps from the urn of a naiad. In such gay costumes did the laws of nature hold their carnival until Science struck the hour for unmasking. The costumes and masks have with us become materials for studying the history of the human mind, but to know them we must translate our senses back into that phase of our own early existence, so far as is consistent with carrying our culture with us.

Without conceding too much to Solar mythology, it may be pronounced tolerably clear that the earliest emotion of worship was born out of the wonder with which man looked up to the heavens above him. The splendours of the morning and evening; the azure vault, painted with frescoes of cloud or blackened by the storm; the night, crowned with constellations: these awakened imagination, inspired awe, kindled admiration, and at length adoration, in the being who had reached intervals in which his eye was lifted above the earth. Amid the rapture of Vedic hymns to these sublimities we meet sharp questionings whether there be any such gods as the priests say, and suspicion is sometimes cast on sacrifices. The forms that peopled the celestial spaces may have been those of ancestors, kings, and great men, but anterior to all forms was the poetic enthusiasm which built heavenly mansions for them; and the crude cosmogonies of primitive science were probably caught up by this spirit, and consecrated as slowly as scientific generalisations now are.

Our modern ideas of evolution might suggest the reverse of this—that human worship began with things low and gradually ascended to high objects; that from rude ages, in which adoration was directed to stock and stone, tree and reptile, the human mind climbed by degrees to the contemplation and reverence of celestial grandeurs. But the accord of this view with our ideas of evolution is apparent only. The real progress seems here to have been from the far to the near, from the great to the small. It is, indeed, probably inexact to speak of the worship of stock and stone, weed and wort, insect and reptile, as primitive. There are many indications that such things were by no race considered intrinsically sacred, nor were they really worshipped until the origin of their sanctity was lost; and even now, ages after their oracular or symbolical character has been forgotten, the superstitions that have survived in connection with such insignificant objects point to an original association with the phenomena of the heavens. No religions could, at first glance, seem wider apart than the worship of the serpent and that of the glorious sun; yet many ancient temples are covered with symbols combining sun and snake, and no form is more familiar in Egypt than the solar serpent standing erect upon its tail, with rays around its head.

Nor is this high relationship of the adored reptile found only in regions where it might have been raised up by ethnical combinations as the mere survival of a savage symbol. William Craft, an African who resided for some time in the kingdom of Dahomey, informed me of the following incident which he had witnessed there. The sacred serpents are kept in a grand house, which they sometimes leave to crawl in their neighbouring grounds. One day a negro from some distant region encountered one of these animals and killed it. The people learning that one of their gods had been slain, seized the stranger, and having surrounded him with a circle of brushwood, set it on fire. The poor wretch broke through the circle of fire and ran, pursued by the crowd, who struck him with heavy sticks. Smarting from the flames and blows, he rushed into a river; but no sooner had he entered there than the pursuit ceased, and he was told that, having gone through fire and water, he was purified, and might emerge with safety. Thus, even in that distant and savage region, serpent-worship was associated with fire-worship and river-worship, which have a wide representation in both Aryan and Semitic symbolism. To this day the orthodox Israelites set beside their dead, before burial, the lighted candle and a basin of pure water. These have been associated in rabbinical mythology with the angels Michael (genius of Water) and Gabriel (genius of Fire); but they refer both to the phenomenal glories and the purifying effects of the two elements as reverenced by the Africans in one direction and the Parsees in another.

Not less significant are the facts which were attested at the witch-trials. It was shown that for their pretended divinations they used plants—as rue and vervain—well known in the ancient Northern religions, and often recognised as examples of tree-worship; but it also appeared that around the cauldron a mock zodiacal circle was drawn, and that every herb employed was alleged to have derived its potency from having been gathered at a certain hour of the night or day, a particular quarter of the moon, or from some spot where sun or moon did or did not shine upon it. Ancient planet-worship is, indeed, still reflected in the habit of village herbalists, who gather their simples at certain phases of the moon, or at certain of those holy periods of the year which conform more or less to the pre-christian festivals.

These are a few out of many indications that the small and senseless things which have become almost or quite fetishes were by no means such at first, but were mystically connected with the heavenly elements and splendours, like the animal forms in the zodiac. In one of the earliest hymns of the Rig-Veda it is said—‘This earth belongs to Varuna (Οὐρανός) the king, and the wide sky: he is contained also in this drop of water.’ As the sky was seen reflected in the shining curve of a dew-drop, even so in the shape or colour of a leaf or flower, the transformation of a chrysalis, or the burial and resurrection of a scarabæus’ egg, some sign could be detected making it answer in place of the typical image which could not yet be painted or carved.

The necessities of expression would, of course, operate to invest the primitive conceptions and interpretations of celestial phenomena with those pictorial images drawn from earthly objects of which the early languages are chiefly composed. In many cases that are met in the most ancient hymns, the designations of exalted objects are so little descriptive of them, that we may refer them to a period anterior to the formation of that refined and complex symbolism by which primitive religions have acquired a representation in definite characters. The Vedic comparisons of the various colours of the dawn to horses, or the rain-clouds to cows, denotes a much less mature development of thought than the fine observation implied in the connection of the forked lightning with the forked serpent-tongue and forked mistletoe, or symbolisation of the universe in the concentric folds of an onion. It is the presence of these more mystical and complex ideas in religions which indicate a progress of the human mind from the large and obvious to the more delicate and occult, and the growth of the higher vision which can see small things in their large relationships. Although the exaltation in the Vedas of Varuna as king of heaven, and as contained also in a drop of water, is in one verse, we may well recognise an immense distance in time between the two ideas there embodied. The first represents that primitive pantheism which is the counterpart of ignorance. An unclassified outward universe is the reflection of a mind without form and void: it is while all within is as yet undiscriminating wonder that the religious vesture of nature will be this undefined pantheism. The fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil has not yet been tasted. In some of the earlier hymns of the Rig-Veda, the Maruts, the storm-deities, are praised along with Indra, the sun; Yama, king of Death, is equally adored with the goddess of Dawn. ‘No real foe of yours is known in heaven, nor in earth.’ ‘The storms are thy allies.’ Such is the high optimism of sentences found even in sacred books which elsewhere mask the dawn of the Dualism which ultimately superseded the harmony of the elemental Powers. ‘I create light and I create darkness, I create good and I create evil.’ ‘Look unto Yezdan, who causeth the shadow to fall.’ But it is easy to see what must be the result when this happy family of sun-god and storm-god and fire-god, and their innumerable co-ordinate divinities, shall be divided by discord. When each shall have become associated with some earthly object or fact, he or she will appear as friend or foe, and their connection with the sources of human pleasure and pain will be reflected in collisions and wars in the heavens. The rebel clouds will be transformed to Titans and Dragons. The adored Maruts will be no longer storm-heroes with unsheathed swords of lightning, marching as the retinue of Indra, but fire-breathing monsters—Vritras and Ahis,—and the morning and evening shadows from faithful watch-dogs become the treacherous hell-hounds, like Orthros and Cerberus. The vehement antagonisms between animals and men and of tribe against tribe, will be expressed in the conception of struggles among gods, who will thus be classified as good or evil deities.

This was precisely what did occur. The primitive pantheism was broken up: in its place the later ages beheld the universe as the arena of a tremendous conflict between good and evil Powers, who severally, in the process of time, marshalled each and everything, from a world to a worm, under their flaming banners.

Chapter II.

The Genesis of Demons.

Their good names euphemistic—Their mixed character—Illustrations: Beelzebub, Loki—Demon-germs—The knowledge of good and evil—Distinction between Demon and Devil.

The first pantheon of each race was built of intellectual speculations. In a moral sense, each form in it might be described as more or less demonic; and, indeed, it may almost be affirmed that religion, considered as a service rendered to superhuman beings, began with the propitiation of demons, albeit they might be called gods. Man found that in the earth good things came with difficulty, while thorns and weeds sprang up everywhere. The evil powers seemed to be the strongest. The best deity had a touch of the demon in him. The sun is the most beneficent, yet he bears the sunstroke along with the sunbeam, and withers the blooms he calls forth. The splendour, the might, the majesty, the menace, the grandeur and wrath of the heavens and the elements were blended in these personifications, and reflected in the trembling adoration paid to them. The flattering names given to these powers by their worshippers must be interpreted by the costly sacrifices with which men sought to propitiate them. No sacrifice would have been offered originally to a purely benevolent power. The Furies were called the Eumenides, ‘the well-meaning,’ and there arises a temptation to regard the name as preserving the primitive meaning of the Sanskrit original of Erinyes, namely, Saranyu, which signifies the morning light stealing over the sky. But the descriptions of the Erinyes by the Greek poets—especially of Æschylus, who pictures them as black, serpent-locked, with eyes dropping blood, and calls them hounds—show that Saranyu as morning light, and thus the revealer of deeds of darkness, had gradually been degraded into a personification of the Curse. And yet, while recognising the name Eumenides as euphemistic, we may admire none the less the growth of that rationalism which ultimately found in the epithet a suggestion of the soul of good in things evil, and almost restored the beneficent sense of Saranyu. ‘I have settled in this place,’ says Athene in the ‘Eumenides’ of Æschylus, ‘these mighty deities, hard to be appeased; they have obtained by lot to administer all things concerning men. But he who has not found them gentle knows not whence come the ills of life.’ But before the dread Erinyes of Homer’s age had become the ‘venerable goddesses’ (σεμναὶ θεαὶ) of popular phrase in Athens, or the Eumenides of the later poet’s high insight, piercing their Gorgon form as portrayed by himself, they had passed through all the phases of human terror. Cowering generations had tried to soothe the remorseless avengers by complimentary phrases. The worship of the serpent, originating in the same fear, similarly raised that animal into the region where poets could invest it with many profound and beautiful significances. But these more distinctly terrible deities are found in the shadowy border-land of mythology, from which we may look back into ages when the fear in which worship is born had not yet been separated into its elements of awe and admiration, nor the heaven of supreme forces divided into ranks of benevolent and malevolent beings; and, on the other hand, we may look forward to the ages in which the moral consciousness of man begins to form the distinctions between good and evil, right and wrong, which changes cosmogony into religion, and impresses every deity of the mind’s creation to do his or her part in reflecting the physical and moral struggles of mankind.

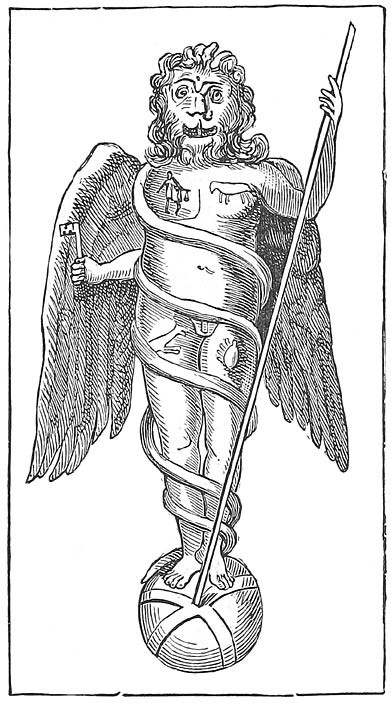

Fig. 1.—Beelzebub (Calmet).

The intermediate processes by which the good and evil were detached, and advanced to separate personification, cannot always be traced, but the indications of their work are in most cases sufficiently clear. The relationship, for instance, between Baal and Baal-zebub cannot be doubted. The one represents the Sun in his glory as quickener of Nature and painter of its beauty, the other the insect-breeding power of the Sun. Baal-zebub is the Fly-god. Only at a comparatively recent period did the deity of the Philistines, whose oracle was consulted by Ahaziah (2 Kings i.), suffer under the reputation of being ‘the Prince of Devils,’ his name being changed by a mere pun to Beelzebul (dung-god). It is not impossible that the modern Egyptian mother’s hesitation to disturb flies settling on her sleeping child, and the sanctity attributed to various insects, originated in the awe felt for him. The title Fly-god is parallelled by the reverent epithet ἀπόμυιος, applied to Zeus as worshipped at Elis,1 the Myiagrus deus of the Romans,2 and the Myiodes mentioned by Pliny.3 Our picture is probably from a protecting charm, and evidently by the god’s believers. There is a story of a peasant woman in a French church who was found kneeling before a marble group, and was warned by a priest that she was worshipping the wrong figure—namely, Beelzebub. ‘Never mind,’ she replied, ‘it is well enough to have friends on both sides.’ The story, though now only ben trovato, would represent the actual state of mind in many a Babylonian invoking the protection of the Fly-god against formidable swarms of his venomous subjects.

Not less clear is the illustration supplied by Scandinavian mythology. In Sæmund’s Edda the evil-minded Loki says:—

Odin! dost thou remember

When we in early days

Blended our blood together?

The two became detached very slowly; for their separation implied the crumbling away of a great religion, and its distribution into new forms; and a religion requires, relatively, as long to decay as it does to grow, as we who live under a crumbling religion have good reason to know. Protap Chunder Mozoomdar, of the Brahmo-Somaj, in an address in London, said, ‘The Indian Pantheon has many millions of deities, and no space is left for the Devil.’ He might have added that these deities have distributed between them all the work that the Devil could perform if he were admitted. His remark recalled to me the Eddaic story of Loki’s entrance into the assembly of gods in the halls of Oegir. Loki—destined in a later age to be identified with Satan—is angrily received by the deities, but he goes round and mentions incidents in the life of each one which show them to be little if any better than himself. The gods and goddesses, unable to reply, confirm the cynic’s criticisms in theologic fashion by tying him up with a serpent for cord.

The late Theodore Parker is said to have replied to a Calvinist who sought to convert him—‘The difference between us is simple: your god is my devil.’ There can be little question that the Hebrews, from whom the Calvinist inherited his deity, had no devil in their mythology, because the jealous and vindictive Jehovah was quite equal to any work of that kind,—as the hardening of Pharaoh’s heart, bringing plagues upon the land, or deceiving a prophet and then destroying him for his false prophecies.4 The same accommodating relation of the primitive deities to all natural phenomena will account for the absence of distinct representatives of evil of the most primitive religions.

The earliest exceptions to this primeval harmony of the gods, implying moral chaos in man, were trifling enough: the occasional monster seems worthy of mention only to display the valour of the god who slew him. But such were demon-germs, born out of the structural action of the human mind so soon as it began to form some philosophy concerning a universe upon which it had at first looked with simple wonder, and destined to an evolution of vast import when the work of moralising upon them should follow.

Let us take our stand beside our barbarian, but no longer savage, ancestor in the far past. We have watched the rosy morning as it waxed to a blazing noon: then swiftly the sun is blotted out, the tempest rages, it is a sudden night lit only by the forked lightning that strikes tree, house, man, with angry thunder-peal. From an instructed age man can look upon the storm blackening the sky not as an enemy of the sun, but one of its own superlative effects; but some thousands of years ago, when we were all living in Eastern barbarism, we could not conceive that a luminary whose very business it was to give light, could be a party to his own obscuration. We then looked with pity upon the ignorance of our ancestors, who had sung hymns to the storm-dragons, hoping to flatter them into quietness; and we came by irresistible logic to that Dualism which long divided the visible, and still divides the moral, universe into two hostile camps.

This is the mother-principle out of which demons (in the ordinary sense of the term) proceeded. At first few, as distinguished from the host of deities by exceptional harmfulness, they were multiplied with man’s growth in the classification of his world. Their principle of existence is capable of indefinite expansion, until it shall include all the realms of darkness, fear, and pain. In the names of demons, and in the fables concerning them, the struggles of man in his ages of weakness with peril, want, and death, are recorded more fully than in any inscriptions on stone. Dualism is a creed which all superficial appearances attest. Side by side the desert and the fruitful land, the sunshine and the frost, sorrow and joy, life and death, sit weaving around every life its vesture of bright and sombre threads, and Science alone can detect how each of these casts the shuttle to the other. Enemies to each other they will appear in every realm which knowledge has not mastered. There is a refrain, gathered from many ages, in William Blake’s apostrophe to the tiger:—

Tiger! tiger! burning bright

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye

Framed thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies

Burned that fire within thine eyes?

On what wings dared he aspire?

What the hand dared seize the fire?

When the stars threw down their spears

And water heaven with their tears,

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the lamb make thee?

That which one of the devoutest men of genius whom England has produced thus asked was silently answered in India by the serpent-worshipper kneeling with his tongue held in his hand; in Egypt, by Osiris seated on a throne of chequer.5

It is necessary to distinguish clearly between the Demon and the Devil, though, for some purposes, they must be mentioned together. The world was haunted with demons for many ages before there was any embodiment of their spirit in any central form, much less any conception of a Principle of Evil in the universe. The early demons had no moral character, not any more than the man-eating tiger. There is no outburst of moral indignation mingling with the shout of victory when Indra slays Vritra, and Apollo’s face is serene when his dart pierces the Python. It required a much higher development of the moral sentiment to give rise to the conception of a devil. Only that intensest light could cast so black a shadow athwart the world as the belief in a purely malignant spirit. To such a conception—love of evil for its own sake—the word Devil is limited in this work; Demon is applied to beings whose harmfulness is not gratuitous, but incidental to their own satisfactions.

Deity and Demon are from words once interchangeable, and the latter has simply suffered degradation by the conventional use of it to designate the less beneficent powers and qualities, which originally inhered in every deity, after they were detached from these and separately personified. Every bright god had his shadow, so to say; and under the influence of Dualism this shadow attained a distinct existence and personality in the popular imagination. The principle having once been established, that what seemed beneficent and what seemed the reverse must be ascribed to different powers, it is obvious that the evolution of demons must be continuous, and their distribution co-extensive with the ills that flesh is heir to.

1 Pausan. v. 14, 2.

2 Solin. Polyhistor, i.

3 Pliny, xxix. 6, 34, init.

4 Ezekiel xiv. 9.

5 As in the Bembine Tablet in the Bodleian Library.

Chapter III.

Degradation.

The degradation of deities—Indicated in names—Legends of their fall—Incidental signs of the divine origin of demons and devils.

The atmospheric conditions having been prepared in the human mind for the production of demons, the particular shapes or names they would assume would be determined by a variety of circumstances, ethnical, climatic, political, or even accidental. They would, indeed, be rarely accidental; but Professor Max Müller, in his notes to the Rig-Veda, has called attention to a remarkable instance in which the formation of an imposing mythological figure of this kind had its name determined by what, in all probability, was an accident. There appears in the earliest Vedic hymns the name of Aditi, as the holy Mother of many gods, and thrice there is mentioned the female name Diti. But there is reason to believe that Diti is a mere reflex of Aditi, the a being dropped originally by a reciter’s license. The later reciters, however, regarding every letter in so sacred a book, or even the omission of a letter, as of eternal significance, Diti—this decapitated Aditi—was evolved into a separate and powerful being, and, every niche of beneficence being occupied by its god or goddess, the new form was at once relegated to the newly-defined realm of evil, where she remained as the mother of the enemies of the gods, the Daityas. Unhappily this accident followed the ancient tendency by which the Furies and Vices have, with scandalous constancy, been described in the feminine gender.

The close resemblance between these two names of Hindu mythology, severally representing the best and the worst, may be thus accidental, and only serve to show how the demon-forming tendency, after it began, was able to press even the most trivial incidents into its service. But generally the names of demons, and for whole races of demons, report far more than this; and in no inquiry more than that before us is it necessary to remember that names are things. The philological facts supply a remarkable confirmation of the statements already made as to the original identity of demon and deity. The word ‘demon’ itself, as we have said, originally bore a good instead of an evil meaning. The Sanskrit deva, ‘the shining one,’ Zend daêva, correspond with the Greek θεος, Latin deus, Anglo-Saxon Tiw; and remain in ‘deity,’ ‘deuce’ (probably; it exists in Armorican, teuz, a phantom), ‘devel’ (the gipsy name for God), and Persian dīv, demon. The Demon of Socrates represents the personification of a being still good, but no doubt on the path of decline from pure divinity. Plato declares that good men when they die become ‘demons,’ and he says ‘demons are reporters and carriers between gods and men.’ Our familiar word bogey, a sort of nickname for an evil spirit, comes from the Slavonic word for God—bog. Appearing here in the West as bogey (Welsh bwg, a goblin), this word bog began, probably, as the ‘Baga’ of cuneiform inscriptions, a name of the Supreme Being, or possibly the Hindu ‘Bhaga,’ Lord of Life. In the ‘Bishop’s Bible’ the passage occurs, ‘Thou shalt not be afraid of any bugs by night:’ the word has been altered to ‘terror.’ When we come to the particular names of demons, we find many of them bearing traces of the splendours from which they have declined. ‘Siva,’ the Hindu god of destruction, has a meaning (‘auspicious’) derived from Svī, ‘thrive’—thus related ideally to Pluto, ‘wealth’—and, indeed, in later ages, appears to have gained the greatest elevation. In a story of the Persian poem Masnavi, Ahriman is mentioned with Bahman as a fire-fiend, of which class are the Magian demons and the Jinns generally; which, the sanctity of fire being considered, is an evidence of their high origin. Avicenna says that the genii are ethereal animals. Lucifer—light-bearing—is the fallen angel of the morning star. Loki—the nearest to an evil power of the Scandinavian personifications—is the German leucht, or light. Azazel—a word inaccurately rendered ‘scape-goat’ in the Bible—appears to have been originally a deity, as the Israelites were originally required to offer up one goat to Jehovah and another to Azazel, a name which appears to signify the ‘strength of God.’ Gesenius and Ewald regard Azazel as a demon belonging to the pre-Mosaic religion, but it can hardly be doubted that the four arch-demons mentioned by the Rabbins—Samaël, Azazel, Asaël, and Maccathiel—are personifications of the elements as energies of the deity. Samaël would appear to mean the ‘left hand of God;’ Azazel, his strength; Asaël, his reproductive force; and Maccathiel, his retributive power, but the origin of these names is doubtful..

Although Azazel is now one of the Mussulman names for a devil, it would appear to be nearly related to Al Uzza of the Koran, one of the goddesses of whom the significant tradition exists, that once when Mohammed had read, from the Sura called ‘The Star,’ the question, ‘What think ye of Allat, Al Uzza, and Manah, that other third goddess?’ he himself added, ‘These are the most high and beauteous damsels, whose intercession is to be hoped for,’ the response being afterwards attributed to a suggestion of Satan.1 Belial is merely a word for godlessness; it has become personified through the misunderstanding of the phrase in the Old Testament by the translators of the Septuagint, and thus passed into christian use, as in 2 Cor. vi. 15, ‘What concord hath Christ with Belial?’ The word is not used as a proper name in the Old Testament, and the late creation of a demon out of it may be set down to accident.

Even where the names of demons and devils bear no such traces of their degradation from the state of deities, there are apt to be characteristics attributed to them, or myths connected with them, which point in the direction indicated. Such is the case with Satan, of whom much must be said hereafter, whose Hebrew name signifies the adversary, but who, in the Book of Job, appears among the sons of God. The name given to the devil in the Koran—Eblis—is almost certainly diabolos Arabicised; and while this Greek word is found in Pindar2 (5th century B.C.), meaning a slanderer, the fables in the Koran concerning Eblis describe him as a fallen angel of the highest rank.

One of the most striking indications of the fall of demons from heaven is the wide-spread belief that they are lame. Mr. Tylor has pointed out the curious persistence of this idea in various ethnical lines of development.3 Hephaistos was lamed by his fall when hurled by Zeus from Olympos; and it is not a little singular that in the English travesty of limping Vulcan, represented in Wayland the Smith,4 there should appear the suggestion, remarked by Mr. Cox, of the name ‘Vala’ (coverer), one of the designations of the dragon destroyed by Indra. ‘In Sir Walter Scott’s romance,’ says Mr. Cox, ‘Wayland is a mere impostor, who avails himself of a popular superstition to keep up an air of mystery about himself and his work, but the character to which he makes pretence belongs to the genuine Teutonic legend.’5 The Persian demon Aeshma—the Asmodeus of the Book of Tobit—appears with the same characteristic of lameness in the ‘Diable Boiteux’ of Le Sage. The christian devil’s clubbed or cloven foot is notorious.

Even the horns popularly attributed to the devil may possibly have originated with the aureole which indicates the glory of his ‘first estate.’ Satan is depicted in various relics of early art wearing the aureole, as in a miniature of the tenth century (from Bible No. 6, Bib. Roy.), given by M. Didron.6 The same author has shown that Pan and the Satyrs, who had so much to do with the shaping of our horned and hoofed devil, originally got their horns from the same high source as Moses in the old Bibles,7 and in the great statue of him at Rome by Michel Angelo.

It is through this mythologic history that the most powerful demons have been associated in the popular imagination with stars, planets,—Ketu in India, Saturn and Mercury the ‘Infortunes,’—comets, and other celestial phenomena. The examples of this are so numerous that it is impossible to deal with them here, where I can only hope to offer a few illustrations of the principles affirmed; and in this case it is of less importance for the English reader, because of the interesting volume in which the subject has been specially dealt with.8 Incidentally, too, the astrological demons and devils must recur from time to time in the process of our inquiry. But it will probably be within the knowledge of some of my readers that the dread of comets and of meteoric showers yet lingers in many parts of Christendom, and that fear of unlucky stars has not passed away with astrologers. There is a Scottish legend told by Hugh Miller of an avenging meteoric demon. A shipmaster who had moored his vessel near Morial’s Den, amused himself by watching the lights of the scattered farmhouses. After all the rest had gone out one light lingered for some time. When that light too had disappeared, the shipmaster beheld a large meteor, which, with a hissing noise, moved towards the cottage. A dog howled, an owl whooped; but when the fire-ball had almost reached the roof, a cock crew from within the cottage, and the meteor rose again. Thrice this was repeated, the meteor at the third cock-crow ascending among the stars. On the following day the shipmaster went on shore, purchased the cock, and took it away with him. Returned from his voyage, he looked for the cottage, and found nothing but a few blackened stones. Nearly sixty years ago a human skeleton was found near the spot, doubled up as if the body had been huddled into a hole: this revived the legend, and probably added some of those traits which make it a true bit of mosaic in the mythology of Astræa.9

The fabled ‘fall of Lucifer’ really signifies a process similar to that which has been noticed in the case of Saranyu. The morning star, like the morning light, as revealer of the deeds of darkness, becomes an avenger, and by evolution an instigator of the evil it originally disclosed and punished. It may be remarked also that though we have inherited the phrase ‘Demons of Darkness,’ it was an ancient rabbinical belief that the demons went abroad in darkness not only because it facilitated their attacks on man, but because being of luminous forms, they could recognise each other better with a background of darkness.

1 See Sale’s Koran, p. 281.

2 Pindar, Fragm., 270.

3 Tylor’s ‘Early Hist. of Mankind,’ p. 358; ‘Prim. Cult.,’ vol. ii. p. 230.

4 The Gascons of Labourd call the devil ‘Seigneur Voland,’ and some revere him as a patron.

5 ‘Myth. of the Aryan Nations,’ vol. ii. p. 327.

6 ‘Christian Iconography,’ Bohn, p. 158.

7 ‘Videbant faciem egredientis Moysis esse cornutam.’—Vulg. Exod. xxxiv. 35.

8 ‘Myths and Marvels of Astronomy.’ By R. A. Proctor. Chatto & Windus, 1878.

9 ‘Scenes and Legends,’ &c., p. 73.

Chapter IV.

The Abgott.

The ex-god—Deities demonised by conquest—Theological animosity—Illustration from the Avesta—Devil-worship an arrested Deism—Sheik Adi—Why demons were painted ugly—Survivals of their beauty.

The phenomena of the transformation of deities into demons meet the student of Demonology at every step. We shall have to consider many examples of a kind similar to those which have been mentioned in the preceding chapter; but it is necessary to present at this stage of our inquiry a sufficient number of examples to establish the fact that in every country forces have been at work to degrade the primitive gods into types of evil, as preliminary to a consideration of the nature of those forces.

We find the history of the phenomena suggested in the German word for idol, Abgott—ex-god. Then we have ‘pagan,’ villager, and ‘heathen,’ of the heath, denoting those who stood by their old gods after others had transferred their faith to the new. These words bring us to consider the influence upon religious conceptions of the struggles which have occurred between races and nations, and consequently between their religions. It must be borne in mind that by the time any tribes had gathered to the consistency of a nation, one of the strongest forces of its coherence would be its priesthood. So soon as it became a general belief that there were in the universe good and evil Powers, there must arise a popular demand for the means of obtaining their favour; and this demand has never failed to obtain a supply of priesthoods claiming to bind or influence the præternatural beings. These priesthoods represent the strongest motives and fears of a people, and they were gradually intrenched in great institutions involving powerful interests. Every invasion or collision or mingling of races thus brought their respective religions into contact and rivalry; and as no priesthood has been known to consent peaceably to its own downfall and the degradation of its own deities, we need not wonder that there have been perpetual wars for religious ascendency. It is not unusual to hear sects among ourselves accusing each other of idolatry. In earlier times the rule was for each religion to denounce its opponent’s gods as devils. Gregory the Great wrote to his missionary in Britain, the Abbot Mellitus, second Bishop of Canterbury, that ‘whereas the people were accustomed to sacrifice many oxen in honour of demons, let them celebrate a religious and solemn festival, and not slay the animals to the devil (diabolo), but to be eaten by themselves to the glory of God.’ Thus the devotion of meats to those deities of our ancestors which the Pope pronounces demons, which took place chiefly at Yule-tide, has survived in our more comfortable Christmas banquets. This was the fate of all the deities which Christianity undertook to suppress. But it had been the habit of religions for many ages before. They never denied the actual existence of the deities they were engaged in suppressing. That would have been too great an outrage upon popular beliefs, and might have caused a reaction; and, besides, each new religion had an interest of its own in preserving the basis of belief in these invisible beings. Disbelief in the very existence of the old gods might be followed by a sceptical spirit that might endanger the new. So the propagandists maintained the existence of native gods, but called them devils. Sometimes wars or intercourse between tribes led to their fusion; the battle between opposing religions was drawn, in which case there would be a compromise by which several deities of different origin might continue together in the same race and receive equal homage. The differing degrees of importance ascribed to the separate persons of the Hindu triad in various localities of India, suggest it as quite probable that Brahma, Vishnu, and Siva signalled in their union the political unity of certain districts in that country.1 The blending of the names of Confucius and Buddha, in many Chinese and Japanese temples, may show us an analogous process now going on, and, indeed, the various ethnical ideas combined in the christian Trinity render the fact stated one of easy interpretation. But the religious difficulty was sometimes not susceptible of compromise. The most powerful priesthood carried the day, and they used every ingenuity to degrade the gods of their opponents. Agathodemons were turned into kakodemons. The serpent, worshipped in many lands, might be adopted as the support of sleeping Vishnu in India, might be associated with the rainbow (‘the heavenly serpent’) in Persia, but elsewhere was cursed as the very genius of evil.

The operation of this force in the degradation of deities, is particularly revealed in the Sacred Books of Persia. In that country the great religions of the East would appear to have contended against each other with especial fury, and their struggles were probably instrumental in causing one or more of the early migrations into Western Europe. The great celestial war between Ormuzd and Ahriman—Light and Darkness—corresponded with a violent theological conflict, one result of which is that the word deva, meaning ‘deity’ to Brahmans, means ‘devil’ to Parsees. The following extract from the Zend-Avesta will serve as an example of the spirit in which the war was waged:—

‘All your devas are only manifold children of the Evil Mind—and the great one who worships the Saoma of lies and deceits; besides the treacherous acts for which you are notorious throughout the seven regions of the earth.

‘You have invented all the evil which men speak and do, which is indeed pleasant to the Devas, but is devoid of all goodness, and therefore perishes before the insight of the truth of the wise.

‘Thus you defraud men of their good minds and of their immortality by your evil minds—as well through those of the Devas as that of the Evil Spirit—through evil deeds and evil words, whereby the power of liars grows.’2

That is to say—Ours is the true god: your god is a devil.

The Zoroastrian conversion of deva (deus) into devil does not alone represent the work of this odium theologicum. In the early hymns of India the appellation asuras is given to the gods. Asura means a spirit. But in the process of time asura, like dæmon, came to have a sinister meaning: the gods were called suras, the demons asuras, and these were said to contend together. But in Persia the asuras—demonised in India—retained their divinity, and gave the name ahura to the supreme deity, Ormuzd (Ahura-mazda). On the other hand, as Mr. Muir supposes, Varenya, applied to evil spirits of darkness in the Zendavesta, is cognate with Varuna (Heaven); and the Vedic Indra, king of the gods—the Sun—is named in the Zoroastrian religion as one of the chief councillors of that Prince of Darkness.

But in every country conquered by a new religion, there will always be found some, as we have seen, who will hold on to the old deity under all his changed fortunes. These will be called ‘bigots,’ but still they will adhere to the ancient belief and practise the old rites. Sometimes even after they have had to yield to the popular terminology, and call the old god a devil, they will find some reason for continuing the transmitted forms. It is probable that to this cause was originally due the religions which have been developed into what is now termed Devil-worship. The distinct and avowed worship of the evil Power in preference to the good is a rather startling phenomenon when presented baldly; as, for example, in a prayer of the Madagascans to Nyang, author of evil, quoted by Dr. Réville:—‘O Zamhor! to thee we offer no prayers. The good god needs no asking. But we must pray to Nyang. Nyang must be appeased. O Nyang, bad and strong spirit, let not the thunder roar over our heads! Tell the sea to keep within its bounds! Spare, O Nyang, the ripening fruit, and dry not up the blossoming rice! Let not our women bring forth children on the accursed days. Thou reignest, and this thou knowest, over the wicked; and great is their number, O Nyang. Torment not, then, any longer the good folk!’3

This is natural, and suggestive of the criminal under sentence of death, who, when asked if he was not afraid to meet his God, replied, ‘Not in the least; it’s that other party I’m afraid of.’ Yet it is hardly doubtful that the worship of Nyang began in an era when he was by no means considered morally baser than Zamhor. How the theory of Dualism, when attained, might produce the phenomenon called Devil-worship, is illustrated in the case of the Yezedis, now so notorious for that species of religion. Their theory is usually supposed to be entirely represented by the expression uttered by one of them, ‘Will not Satan, then, reward the poor Izedis, who alone have never spoken ill of him, and have suffered so much for him?’4 But these words are significant, no doubt, of the underlying fact: they ‘have never spoken ill of’ the Satan they worship. The Mussulman calls the Yezedi a Satan-worshipper only as the early Zoroastrian held the worshipper of a deva to be the same. The chief object of worship among the Yezedis is the figure of the bird Taous, a half-mythical peacock. Professor King of Cambridge traces the Taous of this Assyrian sect to the “sacred bird called a phœnix,” whose picture, as seen by Herodotus (ii. 73) in Egypt, is described by him as ‘very like an eagle in outline and in size, but with plumage partly gold-coloured, partly crimson,’ and which was said to return to Heliopolis every five hundred years, there to burn itself on the altar of the Sun, that another might rise from its ashes.5 Now the name Yezedis is simply Izeds, genii; and we are thus pointed to Arabia, where we find the belief in genii is strongest, and also associated with the mythical bird Rokh of its folklore. There we find Mohammed rebuking the popular belief in a certain bird called Hamâh, which was said to take form from the blood near the brain of a dead person and fly away, to return, however, at the end of every hundred years to visit that person’s sepulchre. But this is by no means Devil-worship, nor can we find any trace of that in the most sacred scripture of the Yezedis, the ‘Eulogy of Sheikh Adi.’ This Sheikh inherited from his father, Moosafir, the sanctity of an incarnation of the divine essence, of which he (Adi) speaks as ‘the All-merciful.’

By his light he hath lighted the lamp of the morning.

I am he that placed Adam in my Paradise.

I am he that made Nimrod a hot burning fire.

I am he that guided Ahmet mine elect,

I gifted him with my way and guidance.

Mine are all existences together,

They are my gift and under my direction.

I am he that possesseth all majesty,

And beneficence and charity are from my grace,

I am he that entereth the heart in my zeal;

And I shine through the power of my awfulness and majesty.

I am he to whom the lion of the desert came:

I rebuked him and he became like stone.

I am he to whom the serpent came,

And by my will I made him like dust.

I am he that shook the rock and made it tremble,

And sweet water flowed therefrom from every side.6

The reverence shown in these sacred sentences for Hebrew names and traditions—as of Adam in Paradise, Marah, and the smitten rock—and for Ahmet (Mohammed), appears to have had its only requital in the odious designation of the worshippers of Taous as Devil-worshippers, a label which the Yezedis perhaps accepted as the Wesleyans and Friends accepted such names as ‘Methodist’ and ‘Quaker.’

Mohammed has expiated the many deities he degraded to devils by being himself turned to an idol (mawmet), a term of contempt all the more popular for its resemblance to ‘mummery.’ Despite his denunciations of idolatry, it is certain that this earlier religion represented by the Yezedis has never been entirely suppressed even among his own followers. In Dr. Leitner’s interesting collection there is a lamp, which he obtained from a mosque, made in the shape of a peacock, and this is but one of many similar relics of primitive or alien symbolism found among the Mussulman tribes.

Fig. 2.—Handle of Hindu Chalice.

The evolution of demons and devils out of deities was made real to the popular imagination in every country where the new religion found art existing, and by alliance with it was enabled to shape the ideas of the people. The theoretical degradation of deities of previously fair association could only be completed where they were presented to the eye in repulsive forms. It will readily occur to every one that a rationally conceived demon or devil would not be repulsive. If it were a demon that man wished to represent, mere euphemism would prevent its being rendered odious. The main characteristic of a demon—that which distinguishes it from a devil—is, as we have seen, that it has a real and human-like motive for whatever evil it causes. If it afflict or consume man, it is not from mere malignancy, but because impelled by the pangs of hunger, lust, or other suffering, like the famished wolf or shark. And if sacrifices of food were offered to satisfy its need, equally we might expect that no unnecessary insult would be offered in the attempt to portray it. But if it were a devil—a being actuated by simple malevolence—one of its essential functions, temptation, would be destroyed by hideousness. For the work of seduction we might expect a devil to wear the form of an angel of light, but by no means to approach his intended victim in any horrible shape, such as would repel every mortal. The great representations of evil, whether imagined by the speculative or the religious sense, have never been, originally, ugly. The gods might be described as falling swiftly like lightning out of heaven, but in the popular imagination they retained for a long time much of their splendour. The very ingenuity with which they were afterwards invested with ugliness in religious art, attests that there were certain popular sentiments about them which had to be distinctly reversed. It was because they were thought beautiful that they must be painted ugly; it was because they were—even among converts to the new religion—still secretly believed to be kind and helpful, that there was employed such elaboration of hideous designs to deform them. The pictorial representations of demons and devils will come under a more detailed examination hereafter: it is for the present sufficient to point out that the traditional blackness or ugliness of demons and devils, as now thought of, by no means militates against the fact that they were once the popular deities. The contrast, for instance, between the horrible physiognomy given to Satan in ordinary christian art, and the theological representation of him as the Tempter, is obvious. Had the design of Art been to represent the theological theory, Satan would have been portrayed in a fascinating form. But the design was not that; it was to arouse horror and antipathy for the native deities to which the ignorant clung tenaciously. It was to train children to think of the still secretly-worshipped idols as frightful and bestial beings. It is important, therefore, that we should guard against confusing the speculative or moral attempts of mankind to personify pain and evil with the ugly and brutal demons and devils of artificial superstition, oftenest pictured on church walls. Sometimes they are set to support water-spouts, often the brackets that hold their foes, the saints. It is a very ancient device. Our figure 2 is from the handle of a chalice in possession of Sir James Hooker, meant probably to hold the holy water of Ganges. These are not genuine demons or devils, but carefully caricatured deities. Who that looks upon the grinning bestial forms carved about the roof of any old church—as those on Melrose Abbey and York Cathedral7—which, there is reason to believe, represent the primitive deities driven from the interior by potency of holy water, and chained to the uncongenial service of supporting the roof-gutter—can see in these gargoyles (Fr. gargouille, dragon), anything but carved imprecations? Was it to such ugly beings, guardians of their streams, hills, and forests, that our ancestors consecrated the holly and mistletoe, or with such that they associated their flowers, fruits, and homes? They were caricatures inspired by missionaries, made to repel and disgust, as the images of saints beside them were carved in beauty to attract. If the pagans had been the artists, the good looks would have been on the other side. And indeed there was an art of which those pagans were the unconscious possessors, through which the true characters of the imaginary beings they adored have been transmitted to us. In the fables of their folklore we find the Fairies that represent the spirit of the gods and goddesses to which they are easily traceable. That goddess who in christian times was pictured as a hag riding on a broom-stick was Frigga, the Earth-mother, associated with the first sacred affections clustering around the hearth; or Freya, whose very name was consecrated in frau, woman and wife. The mantle of Bertha did not cover more tenderness when it fell to the shoulders of Mary. The German child’s name for the pre-christian Madonna was Mother Rose: distaff in hand, she watched over the industrious at their household work: she hovered near the cottage, perhaps to find there some weeping Cinderella and give her beauty for ashes.

1 ‘Any Orientalist will appreciate the wonderful hotchpot of Hindu and Arabic language and religion in the following details, noted down among rude tribes of the Malay Peninsula. We hear of Jin Bumi, the earth-god (Arabic jin = demon, Sanskrit bhümi = earth); incense is burnt to Jewajewa (Sanskrit dewa = god), who intercedes with Pirman, the supreme invisible deity above the sky (Brahma?); the Moslem Allah Táala, with his wife Nabi Mahamad (Prophet Mohammed), appear in the Hinduised characters of creator and destroyer of all things; and while the spirits worshipped in stones are called by the Hindu term of ‘dewa’ or deity, Moslem conversion has so far influenced the mind of the stone-worshipper that he will give to his sacred boulder the name of Prophet Mohammed.’—Tylor’s ‘Primitive Culture,’ vol. ii. p. 230.

2 Yaçna, 32.

3 ‘The Devil,’ &c., from the French of the Rev. A. Réville, p. 5.

4 Tylor’s ‘Primitive Culture,’ vol. ii. p. 299.

5 ‘The Gnostics,’ &c., by C. W. King, M.A., p. 153.

6 Those who wish to examine this matter further will do well to refer to Badger, ‘Nestorians and their Rituals,’ in which the whole of the ‘Eulogy’ is translated; and to Layard, ‘Ninevah and Babylon,’ in which there is a translation of the same by Hormuzd Rassam, the King of Abyssinia’s late prisoner.