автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Diary of a Drug Fiend

To ALOSTRAEL

Virgin Guardian of the Sangraal in the Abbey of Thelema in “Telepylus,” and to

ASTARTE LULU PANTHEA

its youngest member, I dedicate this story of its Herculean labours toward releasing Mankind from every form of bondage.

PREFACE

This is a true story.

It has been rewritten only so far as was necessary to conceal personalities.

It is a terrible story; but it is also a story of hope and of beauty.

It reveals with startling clearness the abyss on which our civilisation trembles.

But the self-same Light illuminates the path of humanity: it is our own fault if we go over the brink.

This story is also true not only of one kind of human weakness, but (by analogy) of all kinds; and for all alike there is but one way of salvation.

As Glanvil says: Man is not subjected to the angels, nor even unto death utterly, save through the Weak-ness of his own feeble will.

Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.

ALEISTER CROWLEY.

CONTENTS

BOOK I — PARADISO

CHAP.

I. A KNIGHT OUT

II. OVER THE TOP!

III. PHAETON

IV. AU PAYS DE COCAINE

V. A HEROIN HEROINE

VI. THE GLITTER ON THE SNOW

VII. THE WINGS OF THE OOF-BIRD

VIII. VEDERE NAPOLI E POI—PRO PATRIA—MORI

IX. THE GATTO FRITTO

X. THE BUBBLE BURSTS

BOOK II — INFERNO

I. SHORT COMMONS

II. INDIAN SUMMER

III. THE GRINDING OF THE BRAKES

IV. BELOW THE BRUTES

V. TOWARDS MADNESS

VI. COLD TURKEY

VII. THE FINAL PLUNGE

BOOK III — PURGATORIO

I. KING LAMUS INTERVENES

II. FIRST AID

III. THE VOICE OF VIRTUE

IV. OUT OF HARM'S WAY

V. AT TELEPYLUS

VI. THE TRUE WILL

VII. LOVE UNDER WILL

BOOK I

PARADISO

CHAPTER I

A KNIGHT OUT

YES, I certainly was feeling depressed.

I don't think that this was altogether the reaction of the day. Of course, there always is a reaction after the excitement of a flight; but the effect is more physical than moral. One doesn't talk. One lies about and smokes and drinks champagne.

No, I was feeling quite a different kind of rotten. I looked at my mind, as the better class of flying man soon learns to do, and I really felt ashamed of myself. Take me for all in all, I was one of the luckiest men alive.

War is like a wave; some it rolls over, some it drowns, some it beats to pieces on the shingle; but some it shoots far up the shore on to glistening golden sand out of the reach of any further freaks of fortune.

Let me explain.

My name is Peter Pendragon. My father was a second son; and he had quarrelled with my Uncle Mortimer when they were boys. He was a struggling general practitioner in Norfolk, and had not made things any better for himself by marrying.

However, he scraped together enough to get me some sort of education, and at the outbreak of the war I was twenty-two years old and had just passed my Intermediate for M.D. in the University of London.

Then, as I said, the wave came. My mother went out for the Red Cross, and died in the first year of the war. Such was the confusion that I did not even know about it till over six months later.

My father died of influenza just before the Armistice.

I had gone into the air service; did pretty well, though somehow I was never sure either of myself or of my machine. My squadron commander used to tell me that I should never make a great airman.

“Old thing,” he said, “you lack the instinct,” qualifying the noun with an entirely meaningless adjective which somehow succeeded in making his sentence highly illuminating.

“Where you get away with it,” he said, “is that you have an analytic brain.”

Well, I suppose I have. That's how I come to be writing this up. Anyhow, at the end of the war I found myself with a knighthood which I still firmly believe to have been due to a clerical error on the part of some official.

As for Uncle Mortimer, he lived on in his crustacean way; a sulky, rich, morose, old bachelor. We never heard a word of him.

And then, about a year ago, he died; and I found to my amazement that I was sole heir to his five or six thousand a year, and the owner of Barley Grange; which is really an awfully nice place in Kent, quite near enough to be convenient for the prosperous young man about town which I had become; and for the best of it, a piece of artificial water quite large enough for me to use for a waterdrome for my seaplane.

I may not have the instinct for flying, as Cartwright said; but it's the only sport I care about.

Golf? When one has flown over a golf course, those people do look such appalling rotters! Such pigmy solemnities!

Now about my feeling depressed. When the end of the war came, when I found myself penniless, out of a job, utterly spoilt by the war (even if I had had the money) for going on with my hospital, I had developed an entirely new psychology. You know how it feels when you are fighting duels in the air, you seem to be detached from everything. There is nothing in the Universe but you and the Boche you are trying to pot. There is something detached and god-like about it.

And when I found myself put out on the streets by a grateful country, I became an entirely different animal. In fact, I've often thought that there isn't any “I” at all; that we are simply the means of expression of something else; that when we think we are ourselves, we are simply the victims of a delusion.

Well, bother that! The plain fact is that I had become a desperate wild animal. I was too hungry, so to speak, even to waste any time on thinking bitterly about things.

And then came the letter from the lawyers.

That was another new experience. I had no idea before of the depths to which servility could descend.

“By the way, Sir Peter,” said Mr. Wolfe, “it will, of course, take a little while to settle up these matters. It's a very large estate, very large. But I thought that with times as they are, you wouldn't be offended, Sir Peter, if we handed you an open cheque for a thousand pounds just to go on with.”

It wasn't till I had got outside his door that I realised how badly he wanted my business. He need not have worried. He had managed poor old Uncle Mortimer's affairs well enough all those years; not likely I should bother to put them in the hands of a new man.

The thing that really pleased me about the whole business was the clause in the will. That old crab had sat in his club all through the war, snapping at everybody he saw; and yet he had been keeping track of what I was doing. He said in the will that he had made me his heir “for the splendid services I had rendered to our beloved country in her hour of need.”

That's the true Celtic psychology. When we've all finished talking, there's something that never utters a word, but goes right down through the earth, plumb to the centre.

And now comes the funny part of the business. I discovered to my amazement that the desperate wild animal hunting his job had been after all a rather happy animal in his way, just as the desperate god battling in the air, playing pitch and toss with life and death, had been happy.

Neither of those men could be depressed by misfortune; but the prosperous young man about town was a much inferior creature. Everything more or less bored him, and he was quite definitely irritated by an overdone cutlet. The night I met Lou, I turned into the Café Wisteria in a sort of dull, angry stupor. Yet the only irritating incident of the day had been a letter from the lawyers which I had found at my club after flying from Norfolk to Barley Grange and motoring up to town.

Mr. Wolfe had very sensibly advised me to make a settlement of a part of the estate, as against the event of my getting married; and there was some stupid hitch about getting trustees.

I loathe law. It seems to me as if it were merely an elaborate series of obstacles to doing things sensibly. And yet, of course, after all, one must have formalities, just as in flying you have to make arrangements for starting and stopping. But it is a beastly nuisance to have to attend to them.

I thought I would stand myself a little dinner. I hadn't quite enough sense to know that what I really wanted was human companions. There aren't such things. Every man is eternally alone. But when you get mixed up with a fairly decent crowd, you forget that appalling fact for long enough to give your brain time to recover from the acute symptoms of its disease—that of thinking.

My old commander was right. I think a lot too much; so did Shakespeare. That's what worked him up to write those wonderful things about sleep. I've forgotten what they were; but they impressed me at the time. I said to myself, “This old bird knew how dreadful it is to be conscious.”

So, when I turned into the café, I think the real reason was that I hoped to find somebody there, and talk the night out. People think that talking is a sign of thinking. It isn't, for the most part; on the contrary, it's a mechanical dodge of the body to relieve oneself of the strain of thinking, just as exercising the muscles helps the body to become temporarily unconscious of its weight, its pain, its weariness, and the foreknowledge of its doom.

You see what gloomy thoughts a fellow can have, even when he's Fortune's pet. It's a disease of civilisation. We're in an intermediate stage between the stupor of the peasant and—something that is not yet properly developed.

I went into the café and sat down at one of the marble tables. I had a momentary thrill of joy—it reminded me of France so much—of all those days of ferocious gambling with Death.

I couldn't see a soul I knew. But at least I knew by sight the two men at the next table. Every one knew that gray ferocious wolf—a man built in every line for battle, and yet with a forehead which lifted him clean out of the turmoil. The conflicting elements in his nature had played the devil with him. Jack Fordham was his name. At sixty years of age he was still the most savage and implacable of publicists. “Red in tooth and claw,” as Tennyson said. Yet the man had found time to write great literature; and his rough and tumble with the world had not degraded his thought or spoilt his style.

Sitting next him was a weak, good-natured, working journalist named Vernon Gibbs. He wrote practically the whole of a weekly paper—had done, year after year with the versatility of a practised pen and the mechanical perseverance of an instrument which has been worn by practice into perfect easiness.

Yet the man had a mind for all that. Some instinct told him that he had been meant for better things. The result had been that he had steadily become a heavier and heavier drinker.

I learnt at the hospital that seventy-five per cent, of the human body is composed of water; but in this case, as in the old song, it must have been that he was a relation of the McPherson who had a son,

“That married Noah's daughter And nearly spoilt the flood By drinking all the water. And this he would have done, I really do believe it, But had that mixture been Three parts or more Glen Livet.”

The slight figure of a young-old man with a bulbous nose to detract from his otherwise remarkable beauty, spoilt though it was by years of insane passions, came into the café. His cold blue eyes were shifty and malicious. One got the impression of some filthy creature of the darkness—a raider from another world looking about him for something to despoil. At his heels lumbered his jackal, a huge, bloated, verminous creature like a cockroach, in shabby black clothes, ill-fitting, unbrushed and stained, his linen dirty, his face bloated and pimpled, a horrible evil leer on his dripping mouth, with its furniture like a bombed graveyard.

The café sizzled as the men entered. They were notorious, if nothing else, and the leader was the Earl of Bumble. Every one seemed to scent some mischief in the air. The earl came up to the table next to mine, and stopped deliberately short. A sneer passed across his lips. He pointed to the two men.

“Drunken Bardolph and Ancient Pistol,” he said, with his nose twitching with anger.

Jack Fordham was not behindhand with the repartee.

“Well roared, Bottom,” he replied calmly, as pat as if the whole scene had been rehearsed beforehand.

A dangerous look came into the eyes of the insane earl. He took a pace backwards and raised his stick. But Fordham, old campaigner that he was, had anticipated the gesture. He had been to the Western States in his youth; and what he did not know about scrapping was not worth being known. In particular, he was very much alive to the fact that an unarmed man sitting behind a fixed table has no chance against a man with a stick in the open.

He slipped out like a cat. Before Bumble could bring down his cane, the old man had dived under his guard and taken the lunatic by the throat.

There was no sort of a fight. The veteran shook his opponent like a bull-dog; and, shifting his grip, flung him to the ground with one tremendous throw. In less than two seconds the affair was over. Fordham was kneeling on the chest of the defeated bully, who whined and gasped and cried for mercy, and told the man twenty years his senior, whom he had deliberately provoked into the fight, that he mustn't hurt him because they were such old friends!

The behaviour of a crowd in affairs of this kind always seems to me very singular. Every one, or nearly every one, seems to start to interfere; and nobody actually does so.

But this matter threatened to prove more serious. The old man had really lost his temper. It was odds that he would choke the life out of the cur under his knee.

I had just enough presence of mind to make way for the head waiter, a jolly, burly Frenchman, who came pushing into the circle. I even lent him a hand to pull Fordham off the prostrate form of his antagonist.

A touch was enough. The old man recovered his temper in a second, and calmly went back to his table with no more sign of excitement than shouting “sixty to forty, sixty to forty.”

“I'm on,” cried the voice of a man who had just come in at the end of the café and missed the scene by a minute. “But what's the horse?”

I heard the words as a man in a dream; for my attention had suddenly been distracted.

Bumble had made no attempt to get up. He lay there whimpering. I raised my eyes from so disgusting a sight, and found them fixed by two enormous orbs. I did not know at the first moment even that they were eyes. It's a funny thing to say; but the first impression was that they were one of those thoughts that come to one from nowhere when one is flying at ten thousand feet or so. Awfully queer thing, I tell you—reminds one of the atmospherics that one gets in wireless; and they give one a horrible feeling. It is a sort of sinister warning that there is some person or some thing in the Universe outside oneself: and the realisation of that is as frankly frightening as the other realisation, that one is eternally alone, is horrible.

I slipped out of time altogether into eternity. I felt myself in the presence of some tremendous influence for good or evil. I felt as though I had been born—I don't know whether you know what I mean. I can't help it, but I can't put it any different.

It's like this: nothing had ever happened to me in my life before. You know how it is when you come out of ether or nitrous-oxide at the dentist's—you come back to somewhere, a familiar somewhere; but the place from which you have come is nowhere, and yet you have been there.

That is what happened to me.

I woke up from eternity, from infinity, from a state of mind enormously more vital and conscious than anything we know of otherwise, although one can't give it a name, to discover that this nameless thought of nothingness was in reality two black vast spheres in which I saw myself. I had a thought of some vision in a story of the middle ages about a wizard, and slowly, slowly, I slid up out of the deep to recognise that these two spheres were just two eyes. And then it occurred to me—the thought was in the nature of a particularly absurd and ridiculous joke—that these two eyes belonged to a girl's face.

Across the moaning body of the blackmailer, I was looking at the face of a girl that I had never seen before. And I said to myself, “Well, that's all right, I've known you all my life.” And when I said to myself “my life,” I didn't in the least mean my life as Peter Pendragon, I didn't even mean a life extending through the centuries, I meant a different kind of life—something with which centuries have nothing whatever to do.

And then Peter Pendragon came wholly back to himself with a start, and wondered whether he had not perhaps looked a little rudely at what his common sense assured him was quite an ordinary and not a particularly attractive girl.

My mind was immediately troubled. I went hastily back to my table. And then it seemed to me as if it were hours while the waiters were persuading the earl to his feet.

I sipped my drink automatically. When I looked up the girl had disappeared.

It is a trivial observation enough which I am going to make. I hope at least it will help to clear any one's mind of any idea that I may be an abnormal man.

As a matter of fact, every man is ultimately abnormal, because he is unique. But we can class man in a few series without bothering ourselves much about what each one of them is in himself.

I hope, then, that it will be clearly understood that I am very much like a hundred thousand other young men of my age. I also make the remark, because the essential bearing of it is practically the whole story of this book. And the remark is this, after that great flourish of trumpets: although I was personally entirely uninterested in what I had witnessed, the depression had vanished from my mind. As the French say, “Un clou chasse I'autre.”

I have learnt since then that certain races, particularly the Japanese, have made a definite science starting from this fact. For example, they clap their hands four times “in order to drive away evil spirits.” That is, of course, only a figure of speech. What they really do is this: the physical gesture startles the mind out of its lethargy, so that the idea which has been troubling it is replaced by a new one. They have various dodges for securing a new one and making sure that the new one shall be pleasant. More of this later.

What happened is that at this moment my mind was seized with sharp, black anger, entirely objectless. I had at the time not the faintest inkling as to its nature, but there it was. The café was intolerable—like a pest-house. I threw a coin on the table, and was astonished to notice that it rolled off. I went out as if the devil were at my heels.

I remember practically nothing of the next halfhour. I felt a kind of forlorn sense of being lost in a world of incredibly stupid and malicious dwarfs.

I found myself in Piccadilly quite suddenly. A voice purred in my ear, “Good old Peter, good old sport, awfully glad I met you—we'll make a night of it.”

The speaker was a handsome Welshman still in his prime. Some people thought him one of the best sculptors living. He had, in fact, a following of disciples which I can only qualify as “almost unpleasantly so.”

He had no use for humanity at the bottom of his heart, except as convenient shapes which he might model. He was bored and disgusted to find them pretending to be alive. The annoyance had grown until he had got into the habit of drinking a good deal more and a good deal more often than a lesser man might have needed. He was a much bigger man than I was physically, and he took me by the arm almost as if he had been taking me into custody. He poured into my ear an interminable series of rambling reminiscences, each of which appeared to him incredibly mirthful.

For about half a minute I resented him; then I let myself go and found myself soothed almost to slumber by the flow of his talk. A wonderful man, like an imbecile child nine-tenths of the time, and yet, at the back of it all, one somehow saw the deep night of his mind suffused with faint sparks of his genius.

I had not the slightest idea where he was taking me; I did not care. I had gone to sleep inside. I woke to find myself sitting in the Café Wisteria once more.

The head waiter was excitedly explaining to my companion what a wonderful scene he had missed.

“Mr. Fordham, he nearly kill' ze Lord,” he bubbled, wringing his fat hands. “He nearly kill' ze Lord.”

Something in the speech tickled my sense of irreverence. I broke into a high-pitched shout of laughter.

“Rotten,” said my companion. “Rotten! That fellow Fordham never seems to make a clean job of it anyhow. Say, look here, this is my night out. You go 'way like a good boy, tell all those boys and girls come and have dinner.”

The waiter knew well enough who was meant; and presently I found myself shaking hands with several perfect strangers in terms which implied the warmest and most unquenchable affection. It was really rather a distinguished crowd. One of the men was a fat German Jew, who looked at first sight like a piece of canned pork that has got mislaid too long in the summer. But the less he said the more he did; and what he did is one of the greatest treasures of mankind.

Then there was a voluble, genial man with a shock of gray hair and a queer twisted smile on his face. He looked like a character of Dickens. But he had done more to revitalise the theatre than any other man of his time.

I took a dislike to the women. They seemed so unworthy of the men. Great men seem to enjoy going about with freaks. I suppose it is on the same principle as the old kings used to keep fools and dwarfs to amuse them. “Some men are born great, some achieve greatness, some have greatness thrust upon them.” But whichever way it is, the burden is usually too heavy for their shoulders.

You remember Frank Harris's story of the Ugly Duckling? If you don't, you'd better get busy and do it.

That's really what's so frightful in flying—the fear of oneself, the feeling that one has got out of one's class, that all the old kindly familiar things below have turned into hard monstrous enemies ready to smash you if you touch them.

The first of these women was a fat, bold, red-headed slut. She reminded me of a white maggot. She exuded corruption. She was pompous, pretentious, and stupid. She gave herself out as a great authority on literature; but all her knowledge was parrot, and her own attempts in that direction the most deplorably dreary drivel that ever had been printed even by the chattering clique which she financed. On her bare shoulder was the hand of a short, thin woman with a common, pretty face and a would-be babyish manner. She was a German woman of the lowest class. Her husband was an influential Member of Parliament. People said that he lived on her earnings. There were even darker whispers. Two or three pretty wise birds had told me they thought it was she, and not poor little Mati Hara, who tipped off the Tanks to the Boche.

Did I mention that my sculptor's name was Owen? Well, it was, is, and will be while the name of Art endures. He was supporting himself unsteadily with one hand on the table, while with the other he put his guests in their seats. I thought of a child playing with dolls.

As the first four sat down, I saw two other girls behind them. One I had met before, Violet Beach. She was a queer little thing—Jewish, I fancy. She wore a sheaf of yellow hair fuzzed out like a Struwwelpeter, and a violent vermilion dress—in case any one should fail to observe her. It was her affectation to be an Apache, so she wore an old cricket cap down on one eye, and a stale cigarette hung from her lip. But she had a certain talent for writing, and I was very glad indeed to meet her again. I admit I am always a little shy with strangers. As we shook hands, I heard her saying in her curious voice, high-pitched and yet muted, as if she had something wrong with her throat:—

“Want you to meet Miss-------------”

I didn't get the name; I can never hear strange words. As it turned out, before forty-eight hours had passed, I discovered that it was Laleham—and then again that it wasn't. But I anticipate—don't try to throw me out of my stride. All in good time.

In the meanwhile I found I was expected to address her as Lou. “Unlimited Lou” was her nickname among the initiate.

Now what I am anxious for everybody to understand is simply this. There's hardly anybody who understands the way his mind works; no two minds are alike, as Horace or some old ass said; and, anyhow, the process of thinking is hardly ever what we imagine.

So, instead of recognising the girl as the owner of the eyes which had gripped me so strangely an hour earlier, the fact of the recognition simply put me off the recognition—I don't know if I'm making myself clear. I mean that the plain fact refused to come to the surface. My mind seethed with questions. Where had I seen her before?

And here's another funny thing. I don't believe that I should have ever recognised her by sight. What put me on the track was the grip of her hand, though I had never touched it in my life before.

Now don't think that I'm going off the deep end about this. Don't dismiss me as a mystic-monger. Look back each one into your own lives, and if you can't find half a dozen incidents equally inexplicable, equally unreasonable, equally repugnant to the better regulated type of mid-Victorian mind, the best thing you can do is to sleep with your forefathers. So that's that. Good-night.

I told you that Lou was “quite an ordinary and not a particularly attractive girl.” Remember that this was the first thought of my “carnal mind” which, as St. Paul says, is “enmity against God.”

My real first impression had been the tremendous psychological experience for which all words are inadequate.

Seated by her side, at leisure to look while she babbled, I found my carnal mind reversed on appeal. She was certainly not a pretty girl from the standpoint of a music-hall audience. There was something indefinably Mongolian about her face. The planes were flat; the cheek-bones high; the eyes oblique; the nose wide, short, and vital; the mouth a long, thin, rippling curve like a mad sunset. The eyes were tiny and green, with a piquant elfin expression. Her hair was curiously colourless; it was very abundant; she had wound great ropes about her head. It reminded me of the armature of a dynamo. It produced a weird effect—this mingling of the savage Mongol with the savage Norseman type. Her strange hair fascinated me. It was that delicate flaxen hue, so fine—no, I don't know how to tell you about it, I can't think of it without getting all muddled up.

One wondered how she was there. One saw at a glance that she didn't belong to that set. Refinement, aristocracy almost, were like a radiance about her tiniest gesture. She had no affectation about being an artist. She happened to like these people in exactly the same way as a Methodist old maid in Balham might take an interest in natives of Tonga, and so she went about with them. Her mother didn't mind. Probably, too, the way things are nowadays, her mother didn't matter.

You mustn't think that we were any of us drunk, except old Owen. As a matter of fact, all I had had was a glass of white wine. Lou had touched nothing at all. She prattled on like the innocent child she was, out of the sheer mirth of her heart. In an ordinary way, I suppose, I should have drunk a lot more than I did. And I didn't eat much either. Of course, I know now what it was—that much-derided phenomenon, love at first sight.

Suddenly we were interrupted. A tall man was shaking hands across the table with Owen. Instead of using any of the ordinary greetings, he said in a very low, clear voice, very clear and vibrant, as though tense with some inscrutable passion:—

“Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.”

There was an uneasy movement in the group. In particular, the German woman seemed distressed by the man's mere presence.

I looked up. Yes, I could understand well enough the change in the weather. Owen was saying—

“That's all right, that's all right, that's exactly what I do. You come and see my new group. I'll do another sketch of you—same day, same time. That's all right.”

Somebody introduced the new-comer—Mr. King Lamus—and murmured our names.

“Sit down right here,” said Owen, “what you need is a drink. I know you perfectly well; I've known you for years and years and years, and I know you've done a good day's work, and you've earned a drink. Sit right down and I'll get the waiter.”

I looked at Lamus, who had not uttered a word since his original greeting. There was something appalling in his eyes; they didn't focus on the foreground. I was only an incident of utter insignificance in an illimitable landscape. His eyes were parallel; they were looking at infinity. Nothing mattered to him. I hated the beast!

By this time the waiter had approached.

“Sorry, sir,” he said to Owen, who had ordered a '65 brandy.

It appeared that it was now eight hours forty-three minutes thirteen and three-fifth seconds past noon. I don't know what the law is; nobody in England knows what the law is—not even the fools that make the laws. We are not under the laws and do not enjoy the liberties which our fathers bequeathed us; we are under a complex and fantastic system of police administration nearly as pernicious as anything even in America.

“Don't apologise,” said Lamus to the waiter in a tone of icy detachment. “This is the freedom we fought for.”

I was entirely on the side of the speaker. I hadn't wanted a drink all evening, but now I was told I couldn't have one, I wanted to raid their damn cellars and fight the Metropolitan Police and go up in my 'plane and drop a few bombs on the silly old House of Commons. And yet I was in no sort of sympathy with the man. The contempt of his tone irritated me. He was in-human, somehow; that was what antagonised me.

He turned to Owen.

“Better come round to my studio,” he drawled; “I have a machine gun trained on Scotland Yard.” Owen rose with alacrity.

“I shall be delighted to see any of you others,” continued Lamus. “I should deplore it to the day of my death if I were the innocent means of breaking up so perfect a party.”

The invitation sounded like an insult. I went red behind the ears; I could only just command myself enough to make a formal apology of some sort.

As a matter of fact, there was a very curious reaction in the whole party. The German Jew got up at once—nobody else stirred. Rage boiled in my heart. I understood instantly what had taken place. The intervention of Lamus had automatically divided the party into giants and dwarfs; and I was one of the dwarfs.

During the dinner, Mrs. Webster, the German woman, had spoken hardly at all. But as soon as the three men had turned their backs, she remarked acidly:—

“I don't think we're dependent for our drinks on Mr. King Lamus. Let's go round to the Smoking Dog.”

Everybody agreed with alacrity. The suggestion seemed to have relieved the unspoken tension.

We found ourselves in taxis, which for some inscrutable reason are still allowed to ply practically unchecked in the streets of London. While eating and breathing and going about are permitted, we shall never be a really righteous race!

CHAPTER II

OVER THE TOP!

IT was only about a quarter of an hour before we reached “The Dog”; but the time passed heavily. I had been annexed by the white maggot. Her presence made me feel as if I were already a corpse. It was the limit.

But I think the ordeal served to bring up in my mind some inkling of the true nature of my feeling for Lou.

The Smoking Dog, now ingloriously extinct, was a night club decorated by a horrible little cad who spent his life pushing himself into art and literature. The dancing room was a ridiculous, meaningless, gaudy, bad imitation of Klimmt.

Damn it all, I may not be a great flyer, but I am a fresh-air man. I detest these near-artists with their poses and their humbug and their swank. I hate shams.

I found myself in a state of furious impatience before five minutes had passed. Mrs. Webster and Lou had not arrived. Ten minutes—twenty—I fell into a blind rage, drank heavily of the vile liquor with which the place was stinking, and flung myself with I don't know what woman into the dance.

A shrill-voiced Danish siren, the proprietress, was screaming abuse at one of her professional entertainers—some long, sordid, silly story of sexual jealousy, I suppose. The band was deafening. The fine edge of my sense was dulled. It was in a sort of hot nightmare that I saw, through the smoke and the stink of the club, the evil smile of Mrs. Webster.

Small as the woman was, she seemed to fill the doorway. She preoccupied the attention in the same way as a snake would have done. She saw me at once, and ran almost into my arms excitedly. She whispered something in my ear. I didn't hear it.

The club had suddenly been, so to speak, struck dumb. Lou was coming through the door. Over her shoulders was an opera cloak of deep rich purple edged with gold, the garment of an empress, or (shall I say?) of a priestess.

The whole place stopped still to look at her. And I had thought she was not beautiful!

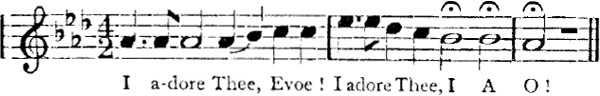

She did not walk upon the ground. “Vera incessu patuit dea,” as we used to say at school. And as she paced she chanted from that magnificent litany of Captain J. F. C. Fuller, “Oh Thou golden sheaf of desires, that art bound by a fair wisp of poppies! I adore thee, Evoe! I adore thee, I A O!”

She sang full-throated, with a male quality in her voice. Her beauty was so radiant that my mind ran to the breaking of dawn after a long night flight.

“In front the sun climbs slow, how slowly, but westward, look! the land is bright!”

As if in answer to my thought, her voice rolled forth again:—

“O Thou golden wine of the sun, that art poured over the dark breasts of night! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

The first part of the adoration was in a sort of Gregorian chant varying with the cadence of the words. But the chorus always came back to the same thing.

EE-AH-OH gives the enunciation of the last word. Every vowel is drawn out as long as possible. It seemed as if she were trying to get the last cubic millimetre of air out of her lungs every time she sang it.

“O Thou crimson vintage of life, that art poured into the jar of the grave! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

Lou reached the table, with its dirty, crazy cloth, at which we were sitting. She looked straight into my eyes, though I am sure she did not see me.

“O Thou red cobra of desire, that art unhooded by the hands of girls! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

She went back from us like a purple storm-cloud, sun-crested, torn from the breasts of the morning by some invisible lightning.

“O Thou burning sword of passion, that art torn on the anvil of flesh! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

A wave of almost insane excitement swept through the club. It was like the breaking out of anti-aircraft guns. The band struck up a madder jazz.

The dancers raved with more tumultuous and breathless fury.

Lou had advanced again to our table. We three were detached from the world. Around us rang the shrieking laughter of the crazy crowd. Lou seemed to listen. She broke out once more.

“O Thou mad whirlwind of laughter, that art meshed in the wild locks of folly! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

I realised with nauseating clarity that Mrs. Webster was pouring into my ears an account of the character and career of King Lamus.

“I don't know how he dares to come to England at all,” she said. “He lives in a place called Telepylus, wherever that is. He's over a hundred years old, in spite of his looks. He's been everywhere, and done everything, and every step he treads is smeared with blood. He's the most evil and dangerous man in London. He's a vampire, he lives on ruined lives.”

I admit I had the heartiest abhorrence for the man. But this fiercely bitter denunciation of one who was evidently a close friend of two of the world's greatest artists, did not make his case look blacker. I was not impressed, frankly, with Mrs. Webster as an authority on other people's conduct.

“O Thou Dragon-prince of the air, that art drunk on the blood of the sunsets! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

A wild pang of jealousy stabbed me. It was a livid, demoniac spasm. For some reason or other I had connected this verse of Lou's mysterious chant with the personality of King Lamus.

Gretel Webster understood. She insinuated another dose of venom.

“Oh yes, Mr. Basil King Lamus is quite the ladies' man. He fascinates them with a thousand different tricks. Lou is dreadfully in love with him.”

Once again the woman had made a mistake. I resented her reference to Lou. I don't remember what I answered. Part of it was to the effect that Lou didn't seem to have been very much injured.

Mrs. Webster smiled her subtlest smile.

“I quite agree,” she said silkily, “Lou is the most beautiful woman in London to-night.”

“O Thou fragrance of sweet flowers, that art wafted over blue fields of air! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

The state of the girl was extraordinary. It was as if she possessed two personalities in their fullest possibilities—the divine and the human. She was intensely conscious of all that was going on around her, absolute mistress of herself and of her environment; yet at the same time she was lost in some unearthly form of rapture of a kind which, while essentially unintelligible to me, reminded me of certain strange and fragmentary experiences that I had had while flying.

I suppose every one has read The Psychology of Flying by L. de Giberne Sieveking. All I need do is to remind you of what he says:—

“All types of men who fly are conscious of this very obscure, subtle difference that it has wrought in them. Very few know exactly what it is. Hardly any of them can express what they feel. And none of them would admit it if they could…. One realises without any formation into words how that one is oneself, and that each one is entirely separate and can never enter into the recesses of another, which are his foundation of individual life.”

One feels oneself out of all relation with things, even the most essential. And yet one is aware at the same time that everything of which one has ever been aware is a picture invented by one's own mind. The Universe is the looking-glass of the soul.

In that state one understands all sorts of nonsense.

“O Thou foursquare Crown of Nothing, that circlest the destruction of Worlds! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

I flushed with rage, understanding enough to know what Lou must be feeling as she rolled forth those passionate, senseless words from her volcanic mouth. Gretel's suggestion trickled into my brain.

“This beastly alcohol brutalises men. Why is Lou so superb? She has breathed the pure snow of Heaven into her nostrils.”

“O Thou snow-white chalice of Love, that art filled up with the red lusts of man! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

I tingled and shivered as she sang; and then something, I hardly know what, made me turn and look into the face of Gretel Webster. She was sitting at my right; her left hand was beneath the table, and she was looking at it. I followed her glance.

In the little quadrilateral of the veins whose lower apex is between the first and middle fingers, was a tiny heap of sparkling dust. Nothing I had ever seen before had so attracted me. The sheer bright infinite beauty of the stuff! I had seen it before of course, often enough, at the hospital; but this was quite a different thing. It was set off by its environment as a diamond is by its setting. It seemed alive. It sparkled intensely. It was like nothing else in Nature, unless it be those feathery crystals, wind-blown, that glisten on the lips of crevasses.

What followed sticks in my memory as if it were a conjurer's trick. I don't know by what gesture she constrained me. But her hand slowly rose not quite to the level of the table; and my face, hot, flushed, angry and eager, had bent down towards it. It seemed pure instinct, though I have little doubt now that it was the result of an unspoken suggestion. I drew the little heap of powder through my nostrils with one long breath. I felt even then like a choking man in a coal mine released at the last moment, filling his lungs for the first time with oxygen.

I don't know whether this is a common experience. I suspect that my medical training and reading, and hearing people talk, and the effect of all those ghoulish articles in the newspapers had something to do with it.

On the other hand, we must make a good deal of allowance, I think, for such an expert as Gretel Webster. No doubt she was worth her wage to the Boche. No doubt she had picked me out for part of “Die Rache.” I had downed some pretty famous flyers.

But none of these thoughts occurred to me at the time. I do not think I have explained with sufficient emphasis the mental state to which I had been reduced by the appearance of Lou. She had become so far beyond my dreams—the unattainable.

Leaving out of account the effect of the alcohol, this had left me with an intolerable depression. There was something brutish, something of the baffled rat, in my consciousness.

“O Thou vampire Queen of the Flesh, wound as a snake around the throats of men! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

Was she thinking of Gretel or of herself? Her beauty had choked me, strangled me, torn my throat out. I had become insane with dull, harsh lust. I hated her. But as I raised my head; as the sudden, the instantaneous madness of cocaine swept from my nostrils to my brain—that's a line of poetry, but I can't help it—get on!—the depression lifted from my mind like the sun coming out of the clouds.

I heard as in a dream the rich, ripe voice of Lou:—

“O Thou fierce whirlpool of passion, that art sucked up by the mouth of the sun! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

The whole thing was different—I understood what she was saying, I was part of it. I recognised, for one swift second, the meaning of my previous depression. It was my sense of inferiority to her! Now I was her man, her mate, her master!

I rose to catch her by the waist; but she whirled away down the floor of the club like an autumn leaf before the storm. I caught the glance of Gretel Webster's eyes. I saw them glitter with triumphant malice; and for a moment she and Lou and cocaine and myself were ah inextricably interlocked in a tangled confusion of ruinous thought.

But my physical body was lifting me. It was the same old, wild exhilaration that one gets from rising from the ground on one's good days. I found myself in the middle of the floor without knowing how I had got there. I, too, was walking on air. Lou turned, her mouth a scarlet orb, as I have seen the sunset over Belgium, over the crinkled line of shore, over the dim blue mystic curve of sea and sky; with the thought in my mind beating in tune with my excited heart. We didn't miss the arsenal this time. I was the arsenal too. I had exploded. I was the slayer and the slain! And there sailed Lou across the sky to meet me.

“O Thou outrider of the Sun, that spurrest the bloody flanks of the wind! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

We came into each other's arms with the inevitableness of gravitation. We were the only two people in the Universe—she and I. The only force that existed in the Universe was the attraction between us. The force with which we came together set us spinning.

We went up and down the floor of the club; but, of course, it wasn't the floor of the club, there wasn't the club, there wasn't anything at all except a dcliiious feeling that one was everything, and had to get on with everything. One was the Universe eternally whirling. There was no possibility of fatigue; one's energy was equal to one's task.

“O Thou dancer with gilded nails, that unbraidest the star hair of the night! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

Lou's slim, lithe body lay in my arm. It sounds absurd, but she reminded me of a light overcoat. Her head hung back, the heavy coils of hair came loose.

All of a sudden the band stopped. For a second the agony was indescribable. It seemed like annihilation. I was seized with an absolute revulsion against the whole of my surroundings. I whispered like a man in furious haste who must get something vital done before he dies, some words to the effect that I couldn't “stick this beastly place any longer—”

“Let's get some air.”

She answered neither yes nor no. I had been wasting words to speak to her at all.

“O Thou bird-sweet river of Love, that warblest through the pebbly gorge of Life! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

Her voice had sunk to a clear murmur. We found ourselves in the street. The chucker-out hailed us a taxi. I stopped her song at last. My mouth was on her mouth. We were driving in the chariot of the Sun through the circus of the Universe. We didn't know where we were going, and we didn't care. We had no sense of time at all. There was a sequence of sensations; but there was no means of regulating them. It was as if one's mental clock had suddenly gone mad.

I have no gauge of time, subjectively speaking, but it must have been a long while before our mouths separated, for as this happened I recognised the fact that we were very far from the club.

She spoke to me for the first time. Her voice thrilled dark unfathomable deeps of being. I tingled in every fibre. And what she said was this:—

“Your kiss is bitter with cocaine.”

It is quite impossible to give those who have no experience of these matters any significance of what she said.

It was a boiling caldron of wickedness that had suddenly bubbled over. Her voice rang rich with hellish glee. It stimulated me to male intensity. I caught her in my arms more fiercely. The world went black before my eyes. I perceived nothing any more. I can hardly even say that I felt. I was Feeling itself! I was all the possibilities of Feeling fulfilled to the uttermost. Yet, coincident with this, my body went on automatically with its own private affairs.

She was escaping me. Her face eluded mine.

“O Thou storm-drunk breath of the winds, that pant in the bosom of the mountains! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

Her breast sobbed out its song with weird intensity.

I understood in a flash that this was her way of resistance. She was trying to insist to herself that she was a cosmic force; that she was not a woman at all; that a man meant nothing to her. She fought desperately against me, sliding so serpent-like about the bounds of space. Of course, it was really the taxi—but I didn't know it then, and I'm not quite sure of it now.

“I wish to God,” I said to myself in a fury, “I had one more sniff of that Snow. I'd show her!”

At that moment she threw me off as if I had been a feather. I felt myself all of a sudden no more good. Quite unaccountably I had collapsed, and I found myself, to my amazement, knocking out a little pile of cocaine from a ten-gramme bottle which had been in my trousers' pocket, on to my hand, and snifhng it up into my nostrils with greedy relish.

Don't ask me how it got there. I suppose Gretel Webster must have done it somehow. My memory is an absolute blank. That's one of the funny things about cocaine. You never know quite what trick it is going to play you.

I was reminded of the American professor who boasted that he had a first-class memory whose only defect was that it wasn't reliable.

I am equally unable to tell you whether the fresh supply of the drug increased my powers, or whether Lou had simply tired of teasing me, but of her own accord she writhed into my arms; her hands and mouth were heavy on my heart. There's some more poetry—that's the way it takes one—rhythm seems to come natural—everything is one grand harmony. It is impossible that anything should be out of tune. The voice of Lou seemed to come from an enormous distance, a deep, low, sombre chant:—

“O Thou low moan of fainting maids, that art caught up in the strong sobs of Love! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

That was it—her engine and my engine for the first time working together! All the accidents had disappeared. There was nothing but the unison of two rich racing rhythms.

You know how it is when you are flying—you see a speck in the air. You can't tell by your eyes if it is your Brother Boche coming to pot you, or one of our own or one of the allied 'planes. But you can tell them apart, foe from friend, by the different beat of their engines. So one comes to apprehend a particular rhythm as sympathetic—another as hostile.

So here were Lou and I flying together beyond the bounds of eternity, side by side; her low, persistent throb in perfect second to my great galloping boom.

Things of this sort take place outside time and space. It is quite wrong to say that what happened in the taxi ever began or ended. What happened was that our attention was distracted from the eternal truth of this essential marriage of our souls by the chauffeur, who had stopped the taxi and opened the door.

“Here we are, sir,” he said, with a grin.

Sir Peter Pendragon and Lou Laleham automatically reappeared. Before all things, decorum!

The shock bit the incident deeply into my mind. I remember with the utmost distinctness paying the man off, and then being lost in absolute blank wonder as to how it happened that we were where we were. Who had given the address to the man, and where were we?

I can only suppose that, consciously or subconsciously, Lou had done it, for she showed no embarrassment in pressing the electric bell. The door opened immediately. I was snowed under by an avalanche of crimson light that poured from a vast studio.

Lou's voice soared high and clear:—

“O Thou scarlet dragon of flame, enmeshed in the web of a spider! i adore Thee, Evoe! i adore Thee, I A O!”

A revulsion of feeling rushed over me like a storm; for in the doorway, with Lou's arms round his neck, was the tall, black, sinister figure of King Lamus.

“I knew you wouldn't mind our dropping in, although it is so late,” she was saying.

It would have been perfectly simple for him to acquiesce with a few conventional words. Instead, he was pontifical.

“There are four gates to one palace; the floor of that palace is of silver and gold; lapis-lazuli and jasper are there; and all rare scents; jasmine and rose, and the emblems of death. Let him enter in turn or at once the four gates; let him stand on the floor of the palace.”

I was unfathomably angry. Why must the man always act like a cad or a clown? But there was nothing to do but to accept the situation and walk in politely.

He shook hands with me formally, yet with greater intensity than is customary between well-bred strangers in England. And as he did so, he looked me straight in the face. His deadly inscrutable eyes burned their way clean through to the back of my brain and beyond. Yet his words were entirely out of keeping with his actions.

“What does the poet say?” he said loftily— “Rather a joke to fill up on coke—or words to that effect, Sir Peter.”

How in the devil's name did he know what I had been taking?

“Men who know things have no right to go about the world,” something said irritably inside myself. But something else obscurely answered it.

“That accounts for what the world has always done—made martyrs of its pioneers.”

I felt a little ashamed, to tell the truth; but Lamus put me at my ease. He waved his hand towards a huge arm-chair covered with Persian tapestries. He gave me a cigarette and lighted it for me. He poured out a drink of Benedictine into a huge curved glass, and put it on a little table by my side. I disliked his easy hospitality as much as anything else. I had an uncomfortable feeling that I was a puppet in his hands.

There was only one other person in the room. On a settee covered with leopard skins lay one of the strangest women I had ever seen. She wore a white evening dress with pale yellow roses, and the same flowers were in her hair. She was a half-blood negress from North Africa.

“Miss Fatma Hallaj,” said Lamus.

I rose and bowed. But the girl took no notice. She seemed in utter oblivion of sublunary matters. Her skin was of that deep, rich night-sky blue which only very vulgar eyes imagine to be black. The face was gross and sensual, but the brows wide and commanding.

There is no type of intellect so essentially aristocratic as the Egyptian when it happens to be of the rare right strain.

“Don't be offended,” said Lamus, in a soft voice, “she includes us all in her sublime disdain.”

Lou was sitting on the arm of the couch; her ivory-white, long crooked fingers groping the dark girl's hair. Somehow or other I felt nauseated; I was uneasy, embarrassed. For the first time in my life I didn't know how to behave.

A thought popped into my mind: it was simply fatigue—I needn't bother about that.

As if in answer to my thought, Lou took a small cut-glass bottle with a gold-chased top from her pocket, unscrewed it and shook out some cocaine on the back of her hand. She flashed a provocative glance in my direction.

The studio suddenly filled with the reverberation of her chant:—

“O Thou naked virgin of love, that art caught in a net of wild roses! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

“Quite so,” agreed King Lamus cheerfully. “You'll excuse me, I know, if I ask whether you have any great experience of the effects of cocaine.”

Lou glowered at him. I preferred to meet bim frankly. I deliberately put a large dose on the back of my hand and sniffed it up. Before I had finished, the effect had occurred. I felt myself any man's master.

“Well, as a matter of fact,” I said superciliously, “to-night's the first time I ever took it, and it strikes me as pretty good stuff.”

Lamus smiled enigmatically.

“Ah, yes, what does the old poet say? Milton, is it?

“‘Stab your demoniac smile to my brain, Soak me in cognac, love, and cocaine.’”

“How silly you are,” cried Lou. “Cocaine wasn't invented in the time of Milton.”

“Was that Milton's fault? “retorted King Lamus. The inaptitude, the disconnectedness, of his thought was somehow disconcerting.

He turned his back on her and looked me straight in the face.

“It strikes you as pretty good stuff, Sir Peter,” he said, “and so it is. I'll have a dose myself to show there's no ill-feeling.”

He suited the action to the words.

I had to admit that the man began to intrigue me. What was his game?

“I hear you're one of our best flying men, Sir Peter,” he went on.

“I have flown a bit now and then,” I admitted.

“Well, an aeroplane's a pretty good means of travel, but unless you're an expert, you're likely to make a pretty sticky finish.”

“Thank you very much,” I said, nettled at his tone. “As it happens, I'm a medical student.”

“Oh, that's all right, then, of course.”

He agreed with a courtesy which somehow cut deeper into my self-esteem than if he had openly challenged my competence.

“In that case,” he continued, “I hope to arouse your professional interest in a case of what I think you will agree is something approaching indiscretion. My little friend here arrived to-night, or rather last night, full up to the neck with morphia. Dissatisfied with results, she swallowed a large dose of Anhalonium Lewinii, reckless of the pharmaceutical incompatability. Presumably to pass away the time, she has drunk an entire bottle of Grand Marnier Cordon Rouge; and now, feeling herself slightly indisposed, for some reason at which it would be presumptuous to guess, she is setting things right by an occasional indulgence in this pretty good stuff of yours.”

He had turned away from me and was watching the girl intently. My glance followed his. I saw her deep blue skin fade to a dreadful pallor. She had lost her healthy colour; she suggested a piece of raw meat which is just beginning to go bad.

I jumped to my feet. I knew instinctively that the girl was about to collapse. The owner of the studio was bending over her. He looked at me over his shoulder out of the corners of his eyes.

“A case of indiscretion,” he observed, with bitter irony.

For the next quarter of an hour he fought for the girl's life. King Lamus. was a very skilled physician, though he had never studied medicine officially.

But I was not aware of what was going on. Cocaine was singing in my veins. I cared for nothing. Lou came over impulsively and flung herself across my knees. She held the goblet of Benedictine to my mouth, chanting ecstatically:—

“O Thou sparkling wine-cup of light, whose foaming is the heart's blood of the stars! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

We swooned into a deep, deep trance. Lamus interrupted us.

“You mustn't think me inhospitable,” he said. “She's come round all right; but I ought to drive her home. Make yourselves at home while I'm away, or let me take you where you want to go.”

Another interruption occurred. The bell rang. Lamus sprang to the door. A tall old man was standing on the steps.

“Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law,” said Lamus.

“Love is the law, love under will,” replied the other.

It was like a challenge and countersign.

“I've got to talk to you for an hour.”

“Of course, I'm at your service,” replied our host.

“The only thing is-----------” He broke off.

My brain was extraordinarily clear. My self-confidence was boundless. I felt inspired. I saw the way out.

A little devil laughed in my heart: “What an excellent scheme to be alone with Lou!”

“Look here, Mr. Lamus,” I said, speaking very quickly, “I can drive any kind of car. Let me take Miss Hallaj home.”

The Arab girl was on her feet behind me.

“Yes, yes,” she said, in a faint, yet excited voice. “That will be much the best thing. Thanks awfully.”

They were the first words she had spoken.

“Yes, yes,” chimed in Lou. “I want to drive in the moonlight.”

The little group was huddled in the open doorway. On one side the dark crimson tides of electricity; on the other, the stainless splendour of our satellite.

“O Thou frail bluebell of moonlight, that art lost in the gardens of the stars! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

The scene progressed with the vivid rapidity of a dream. We were in the garage—out of it—into the streets—at the Egyptian girl's hotel—and then—

CHAPTER III

PHAETON

LOU clung to me as I gripped the wheel. There was no need for us to speak. The trembling torrent of our passion swept us away. I had forgotten all about Lamus and his car. We were driving like the devil to Nowhere. A mad thought crossed my mind. It was thrown up by my “Unconscious,” by the essential self of my being. Then some familiar object in the streets reminded me that I was not driving back to the studio. Some force in myself, of which I was not aware, had turned my face towards Kent. I was interpreting myself to myself. I knew what I was going to do. We were bound for Barley Grange; and then, oh, the wild moonlight ride to Paris!

The idea had been determined in me without any intervention of my own. It had been, in a way, the solution of an equation of which the terms were: firstly, a sort of mad identification of Lou with all one's romantic ideas of moonlight; then my physical habit as a hying man; and thirdly, the traditional connection of Paris with extravagant gaiety and luxuriant love.

I was quite aware at the time that my moral sense and my mental sense had been thrown overboard for the moment; but my attitude was simply: “Goodbye, Jonah!”

For the first time in my life I was being absolutely myself, freed from all the inhibitions of body, intellect, and training which keep us, normally, in what we call sane courses of action.

I seem to remember asking myself if I was insane, and answering, “Of course I am—sanity is a compromise. Sanity is the thing that keeps one back.”

It would be quite useless to attempt to describe the drive to Barley Grange. It lasted barely half a second. It lasted age-less aeons.

Any doubts that I might have had about myself were stamped under foot by the undeniable facts. I had never driven better in my life. I got out the seaplane as another man might get out a cigarette from his case. She started like an eagle. With the whirr of the engine came Lou's soft smooth voice in exquisite antiphony:—

“O Thou trembling breast of the night, that gleamest with a rosary of moons! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

We soared towards the dawn. I went straight to over three thousand. I could hear the beat of my heart. It was one with the beat of the engine.

I took the pure unsullied air into my lungs. It was an octave to cocaine; the same invigorating spiritual force expressed in other terms.

The magnificently melodious words of Sieveking sprang into my mind. I repeated them rapturously. It is the beat of the British engine.

“Deep lungfuls! Deep mouthfuls! Deep, deep mental mouthfuls!”

The wind of our speed abolished all my familiar bodily sensations. The cocaine combined with it to anaesthetise them. I was disembodied; an eternal spirit; a Thing supreme, apart.

“Lou, sweetheart! Lou, sweetheart! Lou, Lou, perfect sweetheart!”

I must have shouted the refrain. Even amid the roar, I heard her singing back.

“O Thou summer softness of lips, that glow hot with the scarlet of passion! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

I could not bear the weight of the air. Let us soar higher, ever higher! I increased the speed.

“Fierce frenzy! Fierce folly! Fierce, fierce, frenzied folly!”

“O Thou tortured shriek of the storm, that art whirled up through the leaves of the woods! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

And I felt that we were borne on some tremendous tempest. The earth dropped from beneath us like a stone into blind nothingness. We were free, free for ever, from the fetters of our birth!

“Soar swifter! Soar swifter! Soar, soar swifter, swifter!”

Before us, high in the pale gray, stood Jupiter, a four-square sapphire spark.

“O Thou bright star of the morning, that art set betwixt the breasts of the Night! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

I shouted back.

“Star seekers! Star finders! Twin stars, silver shining!”

Up, still up, I drove. There hung a mass of thundercloud between me and the dawn. Damn it, how dared it! It had no business to be there. I must rise over it, trample it under my feet.

“O Thou purple breast of the storm, that art scarred by the teeth of the lightning! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

Frail waifs of mist beset us. I had understood Lou's joy in the cloud. It was I that was wrong. I had not had enough cocaine to be able to accept everything as infinite ecstasy. Her love carried me out of myself up to her triumphal passion. I understood the mist.

” O Thou unvintageable dew, that art moist on the lips of the Morn! I adore Thee, Evoe! I adore Thee, I A O!”

At that moment, the practical part of me asserted itself with startling suddenness. I saw the dim line of the coast. I knew the line as I know the palm of my hand. I was a little out of the shortest line for Paris. I swerved slightly to the south.

Below, gray seas were tumbling. It seemed to me (insanely enough) that their moving wrinkles were the laughter of a very old man. I had a sudden intuition that something was wrong; and an instant later came an unmistakable indication of the trouble. I was out of gas.

My mind shot back with a vivid flash of hatred toward King Lamus. “A case of indiscretion!” He'd as good as called me a fool to my face. I thought of him as the sea, shaking with derisive laughter.

All the time I had been chuckling over my dear old squad commander. Not a great flyer, am I? This will show him! And that was true enough. I was incomparably better than I had ever been before. And yet I had omitted just one obvious precaution.

I suddenly realised that things might be exceedingly nasty. The only thing to be done was to shut off, and volplane down to the straits. And there were points in the problem which appalled me.

Oh, for another sniff! As we swooped down towards the sea in huge wide spirals, I managed to extract my bottle. Of course, I realised instantly the impossibility of taking it by the nose in such a wind. I pulled out the cork, and thrust my tongue into the neck of the bottle.

We were still three thousand feet or more above the sea. I had plenty of time, infinite time, I thought, as the drug took hold, to make my decision. I acted with superb aplomb. I touched the sea within a hundred yards of a fishing smack that had just put out from Deal.

We were picked up as a matter of course within a couple of minutes. They put back and towed the plane ashore.

My first thought was to get more gas and go on, despite the absurdity of our position. But the sympathy of the men on the beach was mixed with a good deal of hearty chaff. Dripping, in evening dress, at four o'clock in the morning! Like Hedda Gabler, “one doesn't do these things.”

But the cocaine helped me again. Why the devil should I care what anybody thought?

“Where can I get gas?” I said to the captain of the smack.

He smiled grimly.

“She'll want a bit more than gas.”

I glanced at the 'plane. The man was perfectly right. A week's repairs, at the least.

“You'd better go to the hotel, sir, and get some warm clothes. Look how the lady's shivering.”

It was perfectly true. There was nothing else to be done. We went together slowly up the beach.

There was no question of sleeping, of course. Both of us were as fresh as paint. What we needed was hot food and lots of it.

We got it.

It seemed as if we had entered upon an entirely new phase. The disaster had purged us of that orchestral oratorio business; but, on the other hand, we were still full of intense practical activity.

We ate three breakfasts each. And as we ate we talked; talked racy, violent nonsense, most of it. Yet we were both well aware that the whole thing was camouflage. What we had to do was to get married as quickly as we could, and lay in a stock of cocaine, and go away and have a perfectly glorious time for ever and ever.

We sent for emergency clothes in the town, and went stalking a parson. He was an old man who had lived for years out of the world. He saw nothing particularly wrong with us except youth and enthusiasm, and he was very sorry that it would take three weeks to turn us off.

The good old boy explained the law.

“Oh, that's easy,” we said in a breath. “Let's get the first train to London.”

There are no incidents to record. We were both completely anaesthetised. Nothing bothered us. We didn't mind the waiting on the platform, or the way the old train lumbered up to London.

Everything was part of the plan. Everything was perfect pleasure. We were living above ourselves, living at a tremendous pace. The speed of the 'plane became merely a symbol, a physical projection of our spiritual sublimity.

The next two days passed like pantomime. We were married in a dirty little office by a dirty little man. We took back his car to Lamus. I was amused to discover that I had left it standing in the open half over the edge of the lake.

I made a million arrangements in a kind of whirling wisdom. Before forty-eight hours had passed we were packed and off for Paris.

I did not remember anything in detail. All events were so many base metals fused into an alloy whose name was Excitement. During the whole time we only slept once, and then we slept well and woke fresh, without one trace of fatigue.

We had called on Gretel and obtained a supply of cocaine. She wouldn't accept any money from her dear Sir Peter, and she was so happy to see Lou Lady Pendragon, and wouldn't we come and see her after the honeymoon?

That call is the one thing that sticks in my mind. I suppose I realised obscurely somehow that the woman was in reality the mainspring of the whole manoeuvre.

She introduced us to her husband, a heavy, pursy old man with a paunch and a beard, a reputation for righteousness, and an unctuous way of saying the right kind of nothing. But I divined a certain shrewdness in his eyes; it belied his mask of ostentatious innocence.

There was another man there too, a kind of halfbaked Nonconformist parson, one Jabez Piatt, who had realised early in life that his mission was to go about doing good. Some people said that he had done a great deal of good—to himself. His principle in politics was a very simple one: If you see anything, stop it; everything that is, is wrong; the world is a very wicked place.

He was very enthusiastic about putting through a law for suppressing the evil of drugs.

We smiled our sympathetic assent, with sly glances at our hostess. If the old fool had only known that we were full of cocaine, as we sat and applauded his pompous platitudes!

We laughed our hearts out over the silly incident as we sat in the train. It doesn't appear particularly comic in perspective; but it's very hard to tell, at any time, what is going to tickle one's sense of humour. Probably anything else would have done just as well. We were on the rising curve. The exaltation of love was combined with that of cocaine; and the romance and adventure of our lives formed an exhilarating setting for those superb jewels.

“Every day, in every way, I get better and better.”

M. Coué's now famous formula is the precise intellectual expression of the curve of the cocaine honeymoon. Normal life is like an aeroplane before she rises. There is a series of little bumps; all one can say is that one is getting along more or less. Then she begins to rise clear of earth. There are no more obstacles to the flight.

But there are still mental obstacles; a fence, a row of houses, a grove of elms or what not. One is a little anxious to realise that they have to be cleared. But as she soars into the boundless blue, there comes that sense of mental exhilaration that goes with boundless freedom.

Our grandfathers must have known something about this feeling by living in England before the liberty of the country was destroyed by legislation, or rather the delegation of legislation to petty officialdom.

About six months ago I imported some tobacco, rolls of black perique, the best and purest in the world. By-and-by I got tired of cutting it up, and sent it to a tobacconist for the purpose.

Oh, dear no, quite impossible without a permit from the Custom House!

I suppose I really ought to give myself up to the police.

Yes, as one gets into the full swing of cocaine, one loses all consciousness of the bumpy character of this funny old oblate spheroid. One is really very much more competent to deal with the affairs of life, that is, in a certain sense of the word.

M. Coué is perfectly right, just as the Christian Scientists and all those people are perfectly right, in saying that half our troubles come from our consciousness of their existence, so that if we forget their existence, they actually cease to exist!

Haven't we got an old proverb to the effect that “what the eye doesn't see, the heart doesn't grieve over?”

When one is on one's cocaine honeymoon, one is really, to a certain extent, superior to one's fellows. One attacks every problem with perfect confidence. It is a combination of what the French call élan and what they call insouciance.

The British Empire is due to this spirit. Our young men went out to India and all sorts of places, and walked all over everybody because they were too ignorant to realise the difficulties in their way. They were taught that if one had good blood in one's veins, and a public school and university training to habituate one to being a lord of creation, and to the feeling that it was impossible to fail, and to not knowing enough to know when one was beaten, nothing could ever go wrong.

We are losing the Empire because we have become “sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought.” The intellectuals have made us like “the poor cat i' the adage.” The spirit of Hamlet has replaced that of Macbeth. Macbeth only went wrong because the heart was taken out of him by Macduff's interpretation of what the witches had said.

Coriolanus only failed when he stopped to think. As the poet says, “The love of knowledge is the hate of life.”

Cocaine removes all hesitation. But our forefathers owed their freedom of spirit to the real liberty which they had won; and cocaine is merely Dutch courage. However, while it lasts, it's all right.

CHAPTER IV

AU PAYS DE COCAINE

I CAN'T remember any details of our first week in Paris. Details had ceased to exist. We whirled from pleasure to pleasure in one inexhaustible rush. We took everything in our stride. I cannot begin to describe the blind, boundless beatitude of love. Every incident was equally exquisite.

Of course, Paris lays herself out especially to deal with people in just that state of mind. We were living at ten times the normal voltage. This was true in more senses than one. I had taken a thousand pounds in cash from London, thinking as I did so how jolly it was to be reckless. We were going to have a good time, and damn the expense!

I thought of a thousand pounds as enough to paint Paris every colour of the spectrum for a quite indefinitely long period; but at the end of the week the thousand pounds was gone, and so was another thousand pounds for which I had cabled to London; and we had absolutely nothing to show for it except a couple of dresses for Lou, and a few not very expensive pieces of jewellery.

We felt that we were very economical. We were too happy to need to spend money. For one thing, love never needs more than a pittance, and I had never before known what love could mean.

What I may call the honeymoon part of the honeymoon seemed to occupy the whole of our waking hours. It left us no time to haunt Montmartre. We hardly troubled to eat, we hardly knew we were eating. We didn't seem to need sleep. We never got tired.

The first hint of fatigue sent one's hand to one's pocket. One sniff which gave us a sensation of the most exquisitely delicious wickedness, and we were on fourth speed again!

The only incident worth recording is the receipt of a letter and a box from Gretel Webster. The box contained a padded kimono for Lou, one of those gorgeous Japanese geisha silks, blue like a summer sky with dragons worked all over it in gold, with scarlet eyes and tongues.

Lou looked more distractingly, deliriously glorious than ever.

I had never been particularly keen on women. The few love affairs which had come my way had been rather silly and sordid. They had not revealed the possibilities of love; in fact, I had thought it a somewhat overrated pleasure, a brief and brutal blindness with boredom and disgust hard on its heels.

But with cocaine, things are absolutely different.

I want to emphasise the fact that cocaine is in reality a local anaesthetic. That is the actual explanation of its action. One cannot feel one's body. (As every one knows, this is the purpose for which it is used in surgery and dentistry.)

Now don't imagine that this means that the physical pleasures of marriage are diminished, but they are utterly etherealised. The animal part of one is intensely stimulated so far as its own action is concerned; but the feeling that this passion is animal is completely transmuted.

I come of a very refined race, keenly observant and easily nauseated. The little intimate incidents inseparable from love affairs, which in normal circumstances tend to jar the delicacy of one's sensibilities, do so no longer when one's furnace is full of coke. Everything soever is transmuted as by “heavenly alchemy” into a spiritual beatitude. One is intensely conscious of the body. But as the Buddhists tell us, the body is in reality an instrument of pain or discomfort. We have all of us a subconscious intuition that this is the case; and this is annihilated by cocaine.

Let me emphasise once more the absence of any reaction. There is where the infernal subtlety of the drug comes in. If one goes on the bust in the ordinary way on alcohol, one gets what the Americans call “the morning after the night before.” Nature warns us that we have been breaking the rules; and Nature has given us common sense enough to know that although we can borrow a bit, we have to pay back.

We have drunk alcohol since the beginning of time; and it is in our racial consciousness that although “a hair of the dog” will put one right after a spree, it won't do to choke oneself with hair.

But with cocaine, all this caution is utterly abrogated. Nobody would be really much the worse for a night with the drug, provided that he had the sense to spend the next day in a Turkish bath, and build up with food and a double allowance of sleep. But cocaine insists upon one's living upon one's capital, and assures one that the fund is inexhaustible.

As I said, it is a local anaesthetic. It deadens any feeling which might arouse what physiologists call inhibition. One becomes absolutely reckless. One is bounding with health and bubbling with high spirits. It is a blind excitement of so sublime a character that it is impossible to worry about anything. And yet, this excitement is singularly calm and profound. There is nothing of the suggestion of coarseness which we associate with ordinary drunkenness. The very idea of coarseness or commonness is abolished. It is like the vision of Peter in the Acts of the Apostles in which he was told, “There is nothing common or unclean.”