автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Modern Painters, Volume 5 (of 5)

Library Edition

THE COMPLETE WORKS

OF

JOHN RUSKIN

MODERN PAINTERS

VolumeIV—

OF MOUNTAIN BEAUTY

VolumeV

OF LEAF BEAUTY

OF CLOUD BEAUTY

OF IDEAS OF RELATION

NATIONAL LIBRARY ASSOCIATION

NEW YORK CHICAGO

MODERN PAINTERS.

VOLUME V.,

COMPLETING THE WORK AND CONTAINING

PARTS

VI. OF LEAF BEAUTY.—VII. OF CLOUD BEAUTY.

VIII. OF IDEAS OF RELATION.

1. OF INVENTION FORMAL.

IX. OF IDEAS OF RELATION.

2. OF INVENTION SPIRITUAL.

PREFACE.

The disproportion, between the length of time occupied in the preparation of this volume, and the slightness of apparent result, is so vexatious to me, and must seem so strange to the reader, that he will perhaps bear with my stating some of the matters which have employed or interrupted me between 1855 and 1860. I needed rest after finishing the fourth volume, and did little in the following summer. The winter of 1856 was spent in writing the “Elements of Drawing,” for which I thought there was immediate need; and in examining with more attention than they deserved some of the modern theories of political economy, to which there was necessarily reference in my addresses at Manchester. The Manchester Exhibition then gave me some work, chiefly in its magnificent Reynolds’ constellation; and thence I went on into Scotland, to look at Dumblane and Jedburgh, and some other favorite sites of Turner’s; which I had not all seen, when I received notice from Mr. Wornum that he had obtained for me permission, from the Trustees of the National Gallery, to arrange, as I thought best, the Turner drawings belonging to the nation; on which I returned to London immediately.

In seven tin boxes in the lower room of the National Gallery I found upwards of nineteen thousand pieces of paper, drawn upon by Turner in one way or another. Many on both sides; some with four, five, or six subjects on each side (the pencil point digging spiritedly through from the foregrounds of the front into the tender pieces of sky on the back); some in chalk, which the touch of the finger would sweep away;1 others in ink, rotted into holes; others (some splendid colored drawings among them) long eaten away by damp and mildew, and falling into dust at the edges, in capes and bays of fragile decay; others worm-eaten, some mouse-eaten, many torn half-way through; numbers doubled (quadrupled, I should say) up into four, being Turner’s favorite mode of packing for travelling; nearly all rudely flattened out from the bundles in which Turner had finally rolled them up and squeezed them into his drawers in Queen Anne Street. Dust of thirty years’ accumulation, black, dense, and sooty, lay in the rents of the crushed and crumpled edges of these flattened bundles, looking like a jagged black frame, and producing altogether unexpected effects in brilliant portions of skies, whence an accidental or experimental finger mark of the first bundle-unfolder had swept it away.

About half, or rather more, of the entire number consisted of pencil sketches, in flat oblong pocket-books, dropping to pieces at the back, tearing laterally whenever opened, and every drawing rubbing itself into the one opposite. These first I paged with my own hand; then unbound; and laid every leaf separately in a clean sheet of perfectly smooth writing paper, so that it might receive no farther injury. Then, enclosing the contents and boards of each book (usually ninety-two leaves, more or less drawn on both sides, with two sketches on the boards at the beginning and end) in a separate sealed packet, I returned it to its tin box. The loose sketches needed more trouble. The dust had first to be got off them (from the chalk ones it could only be blown off); then they had to be variously flattened; the torn ones to be laid down, the loveliest guarded, so as to prevent all future friction; and four hundred of the most characteristic framed and glazed, and cabinets constructed for them which would admit of their free use by the public. With two assistants, I was at work all the autumn and winter of 1857, every day, all day long, and often far into the night.

The manual labor would not have hurt me; but the excitement involved in seeing unfolded the whole career of Turner’s mind during his life, joined with much sorrow at the state in which nearly all his most precious work had been left, and with great anxiety, and heavy sense of responsibility besides, were very trying; and I have never in my life felt so much exhausted as when I locked the last box, and gave the keys to Mr. Wornum, in May, 1858. Among the later colored sketches, there was one magnificent series, which appeared to be of some towns along the course of the Rhine on the north of Switzerland. Knowing that these towns were peculiarly liable to be injured by modern railroad works, I thought I might rest myself by hunting down these Turner subjects, and sketching what I could of them, in order to illustrate his compositions.

As I expected, the subjects in question were all on, or near, that east and west reach of the Rhine between Constance and Basle. Most of them are of Rheinfelden, Seckingen, Lauffenbourg, Schaffhausen, and the Swiss Baden.

Having made what notes were possible to me of these subjects in the summer (one or two are used in this volume), I was crossing Lombardy in order to examine some points of the shepherd character in the Vaudois valleys, thinking to get my book finished next spring; when I unexpectedly found some good Paul Veroneses at Turin. There were several questions respecting the real motives of Venetian work that still troubled me not a little, and which I had intended to work out in the Louvre; but seeing that Turin was a good place wherein to keep out of people’s way, I settled there instead, and began with Veronese’s Queen of Sheba;—when, with much consternation, but more delight, I found that I had never got to the roots of the moral power of the Venetians, and that they needed still another and a very stern course of study. There was nothing for it but to give up the book for that year. The winter was spent mainly in trying to get at the mind of Titian; not a light winter’s task; of which the issue, being in many ways very unexpected to me (the reader will find it partly told towards the close of this volume), necessitated my going in the spring to Berlin, to see Titian’s portrait of Lavinia there, and to Dresden to see the Tribute Money, the elder Lavinia, and girl in white, with the flag fan. Another portrait, at Dresden, of a lady in a dress of rose and gold, by me unheard of before, and one of an admiral, at Munich, had like to have kept me in Germany all summer.

Getting home at last, and having put myself to arrange materials of which it was not easy, after so much interruption, to recover the command;—which also were now not reducible to a single volume—two questions occurred in the outset, one in the section on vegetation, respecting the origin of wood; the other in the section on sea, respecting curves of waves; to neither of which, from botanist or mathematicians, any sufficient answer seemed obtainable.

In other respects also the section on the sea was wholly unsatisfactory to me: I knew little of ships, nothing of blue open water. Turner’s pathetic interest in the sea, and his inexhaustible knowledge of shipping, deserved more complete and accurate illustration than was at all possible to me; and the mathematical difficulty lay at the beginning of all demonstration of facts. I determined to do this piece of work well, or not at all, and threw the proposed section out of this volume. If I ever am able to do what I want with it (and this is barely probable), it will be a separate book; which, on other accounts, I do not regret, since many persons might be interested in studies of the shipping of the old Nelson times, and of the sea-waves and sailor character of all times, who would not care to encumber themselves with five volumes of a work on Art.

The vegetation question had, however, at all cost, to be made out as best might be; and again lost me much time. Many of the results of this inquiry, also, can only be given, if ever, in a detached form.

During these various discouragements, the preparation of the Plates could not go on prosperously. Drawing is difficult enough, undertaken in quietness: it is impossible to bring it to any point of fine rightness with half-applied energy.

Many experiments were made in hope of expressing Turner’s peculiar execution and touch by facsimile. They cost time, and strength, and, for the present, have failed; many elaborate drawings, made during the winter of 1858, having been at last thrown aside. Some good may afterwards come of these; but certainly not by reduction to the size of the page of this book, for which, even of smaller subjects, I have not prepared the most interesting, for I do not wish the possession of any effective and valuable engravings from Turner to be contingent on the purchasing a book of mine.2

Feebly and faultfully, therefore, yet as well as I can do it under these discouragements, the book is at last done; respecting the general course of which, it will be kind and well if the reader will note these few points that follow.

The first volume was the expansion of a reply to a magazine article; and was not begun because I then thought myself qualified to write a systematic treatise on Art; but because I at least knew, and knew it to be demonstrable, that Turner was right and true, and that his critics were wrong, false, and base. At that time I had seen much of nature, and had been several times in Italy, wintering once in Rome; but had chiefly delighted in northern art, beginning, when a mere boy, with Rubens and Rembrandt. It was long before I got quit of a boy’s veneration for Rubens’ physical art-power; and the reader will, perhaps, on this ground forgive the strong expressions of admiration for Rubens, which, to my great regret, occur in the first volume.

Finding myself, however, engaged seriously in the essay, I went, before writing the second volume, to study in Italy; where the strong reaction from the influence of Rubens threw me at first too far under that of Angelico and Raphael, and, which was the worst harm that came of that Rubens influence, blinded me long to the deepest qualities of Venetian art; which, the reader may see by expressions occurring not only in the second, but even in the third and fourth volumes, I thought, however powerful, yet partly luxurious and sensual, until I was led into the final inquiries above related.

These oscillations of temper, and progressions of discovery, extending over a period of seventeen years, ought not to diminish the reader’s confidence in the book. Let him be assured of this, that unless important changes are occurring in his opinions continually, all his life long, not one of those opinions can be on any questionable subject true. All true opinions are living, and show their life by being capable of nourishment; therefore of change. But their change is that of a tree—not of a cloud.

In the main aim and principle of the book, there is no variation, from its first syllable to its last. It declares the perfectness and eternal beauty of the work of God; and tests all work of man by concurrence with, or subjection to that. And it differs from most books, and has a chance of being in some respects better for the difference, in that it has not been written either for fame, or for money, or for conscience-sake, but of necessity.

It has not been written for praise. Had I wished to gain present reputation, by a little flattery adroitly used in some places, a sharp word or two withheld in others, and the substitution of verbiage generally for investigation, I could have made the circulation of these volumes tenfold what it has been in modern society. Had I wished for future fame, I should have written one volume, not five. Also, it has not been written for money. In this wealth-producing country, seventeen years’ labor could hardly have been invested with less chance of equivalent return.

Also, it has not been written for conscience-sake. I had no definite hope in writing it; still less any sense of its being required of me as a duty. It seems to me, and seemed always, probable, that I might have done much more good in some other way. But it has been written of necessity. I saw an injustice done, and tried to remedy it. I heard falsehood taught, and was compelled to deny it. Nothing else was possible to me. I knew not how little or how much might come of the business, or whether I was fit for it; but here was the lie full set in front of me, and there was no way round it, but only over it. So that, as the work changed like a tree, it was also rooted like a tree—not where it would, but where need was; on which, if any fruit grow such as you can like, you are welcome to gather it without thanks; and so far as it is poor or bitter, it will be your justice to refuse it without reviling.

1 The best book of studies for his great shipwrecks contained about a quarter of a pound of chalk débris, black and white, broken off the crayons with which Turner had drawn furiously on both sides of the leaves; every leaf, with peculiar foresight and consideration of difficulties to be met by future mounters, containing half of one subject on the front of it, and half of another on the back.

2 To Mr. Armytage, Mr. Cuff, and Mr. Cousen, I have to express my sincere thanks for the patience, and my sincere admiration of the skill, with which they have helped me. Their patience, especially, has been put to severe trial by the rewardless toil required to produce facsimiles of drawings in which the slightness of subject could never attract any due notice to the excellence of workmanship.

Aid, just as disinterested, and deserving of as earnest acknowledgment, has been given me by Miss Byfield, in her faultless facsimiles of my careless sketches; by Miss O. Hill, who prepared the copies which I required from portions of the pictures of the old masters; and by Mr. Robin Allen, in accurate line studies from nature, of which, though only one is engraved in this volume, many others have been most serviceable, both to it and to me.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

—————

PART VI.

ON LEAF BEAUTY.

—————

PAGE

Prefacev

ChapterI.

—The Earth-Veil

1”

II.

—The Leaf Orders

6”

III.

—The Bud

10”

IV.

—The Leaf

21”

V.

—Leaf Aspects

34”

VI.

—The Branch

39”

VII.

—The Stem

49”

VIII.

—The Leaf Monuments

63”

IX.

—The Leaf Shadows

77”

X.

—Leaves Motionless

88—————

PART VII.

OF CLOUD BEAUTY.

—————

ChapterI.

—The Cloud Balancings

101”

II.

—The Cloud-Flocks

108”

III.

—The Cloud-Chariots

122”

IV.

—The Angel of the Sea

133—————

PART VIII.

OF IDEAS OF RELATION:—I. OF INVENTION FORMAL.

—————

ChapterI.

—The Law of Help

153”

II.

—The Task of the Least

164”

III.

—The Rule of the Greatest

175”

IV.

—The Law of Perfectness

180—————

PART IX.

OF IDEAS OF RELATION:—II. OF INVENTION SPIRITUAL.

—————

ChapterI.

—The Dark Mirror

193”

II.

—The Lance of Pallas

202”

III.

—The Wings of the Lion

214”

IV.

—Durer and Salvator

230”

V.

—Claude and Poussin

241”

VI.

—Rubens and Cuyp

249”

VII.

—Of Vulgarity

261”

VIII.

—Wouvermans and Angelico

277”

IX.

—The Two Boyhoods

286”

X.

—The Nereid’s Guard

298”

XI.

—The Hesperid Æglé

314”

XII.

—Peace

339—————

Local Index.

Index to Painters and Pictures.

Topical Index.

LIST OF PLATES TO VOL. V.

—————

Drawn by

Engraved by

Frontispiece, Ancilla Domini

Fra Angelico

Wm. HallPlate

Facing page

51. The Dryad’s Toil

J. Ruskin

J. C. Armytage 1252. Spirals of Thorn

R. Allen

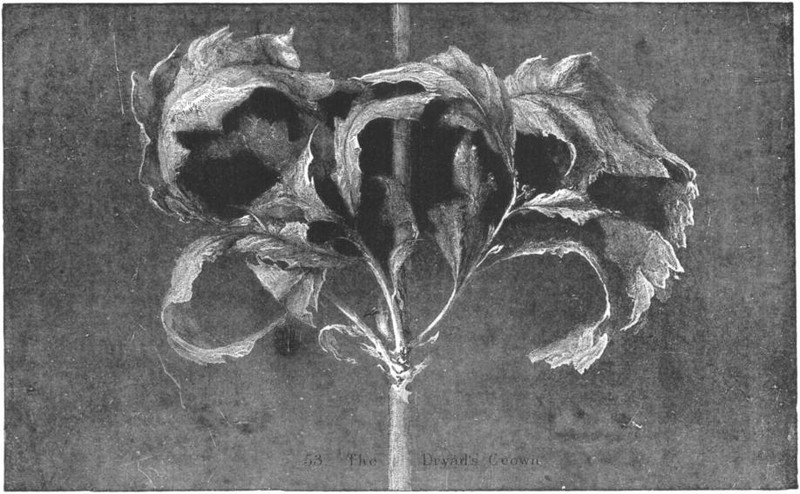

R. P. Cuff 2653. The Dryad’s Crown

J. Ruskin

J. C. Armytage 3654. Dutch Leafage

Cuyp and Hobbima

J. Cousen 3755. By the Way-side

J. M. W. Turner

J. C. Armytage 3856. Sketch by a Clerk of the Works

J. Ruskin

J. Emslie 6157. Leafage by Durer and Veronese

Durer and Veronese

R. P. Cuff 6558. Branch Curvature

R. Allen

R. P. Cuff 6959. The Dryad’s Waywardness

J. Ruskin

R. P. Cuff 7160. The Rending of Leaves

J. Ruskin

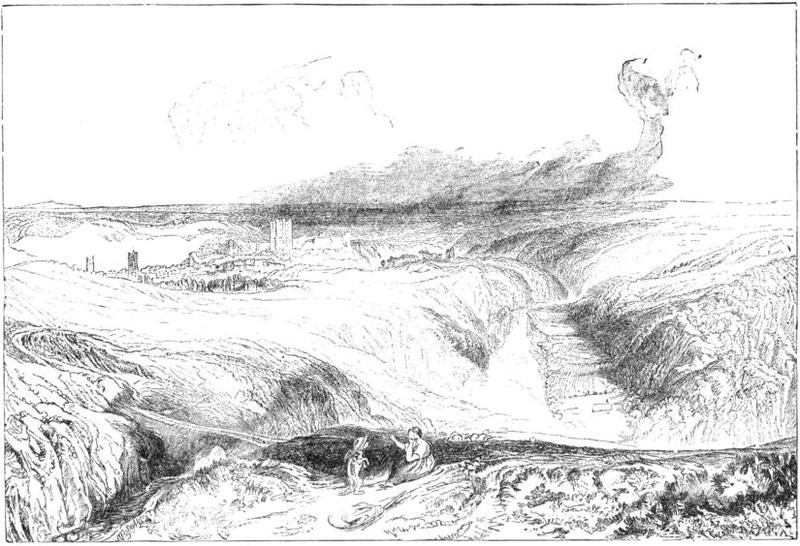

J. Cousen 9461. Richmond, from the Moors

J. M. W. Turner

J. C. Armytage 9862. By the Brookside

J. M. W. Turner

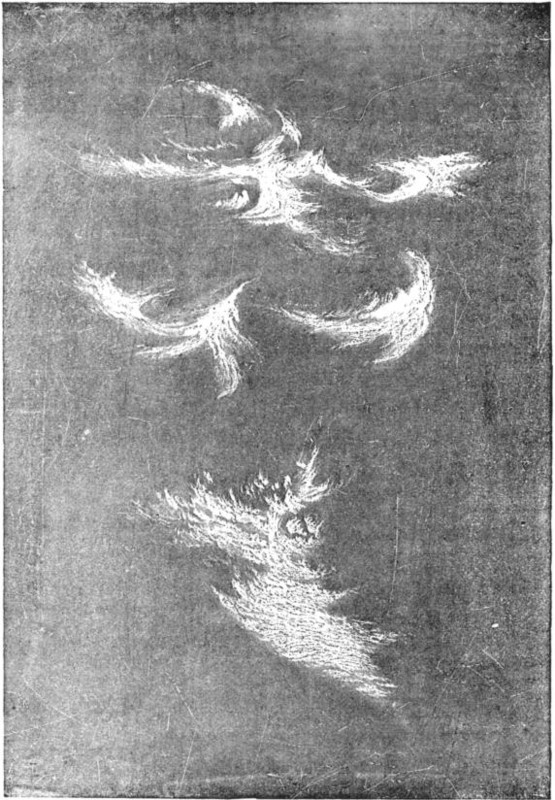

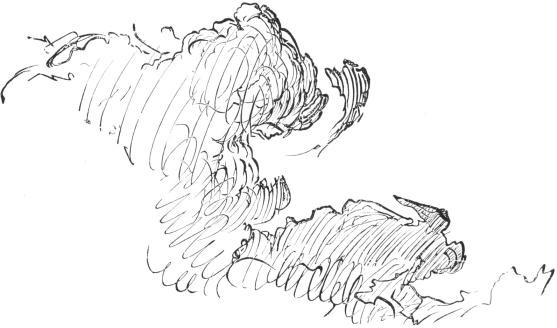

J. C. Armytage 9863. The Cloud Flocks

J. Ruskin

J. C. Armytage 10964. Cloud Perspective (Rectilinear)

J. Ruskin

J. Emslie 11565. Cloud Perspective (Curvilinear)

J. Ruskin

J. Emslie 11666. Light in the West, Beauvais

J. Ruskin

J. C. Armytage 12167. Clouds

J. M. W. Turner

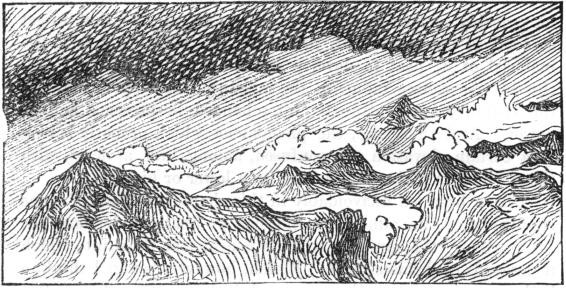

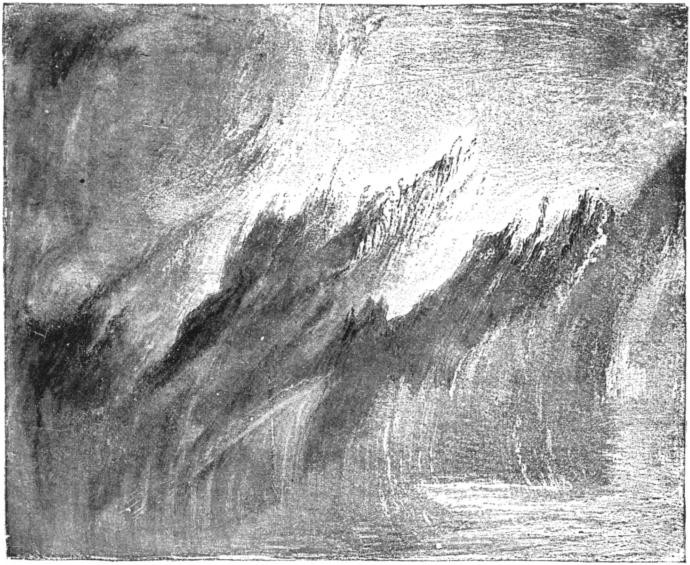

J. C. Armytage 11868. Monte Rosa

J. Ruskin

J. C. Armytage 33969. Aiguilles and their Friends

J. Ruskin

J. C. Armytage 12570. The Graiæ

J. Ruskin

J. C. Armytage 12771. “Venga Medusa”

J. Ruskin

J. C. Armytage 12772. The Locks of Typhon

J. M. W. Turner

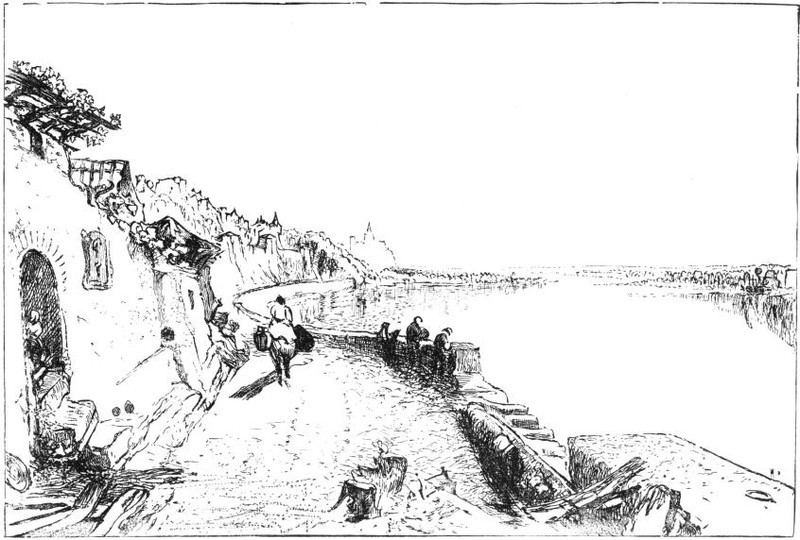

J. C. Armytage 14273. Loire Side

J. M. W. Turner

J. Ruskin 16574. The Mill Stream

J. M. W. Turner

J. Ruskin 16875. The Castle of Lauffen

J. M. W. Turner

R. P. Cuff 16976. The Moat of Nuremberg

J. Ruskin

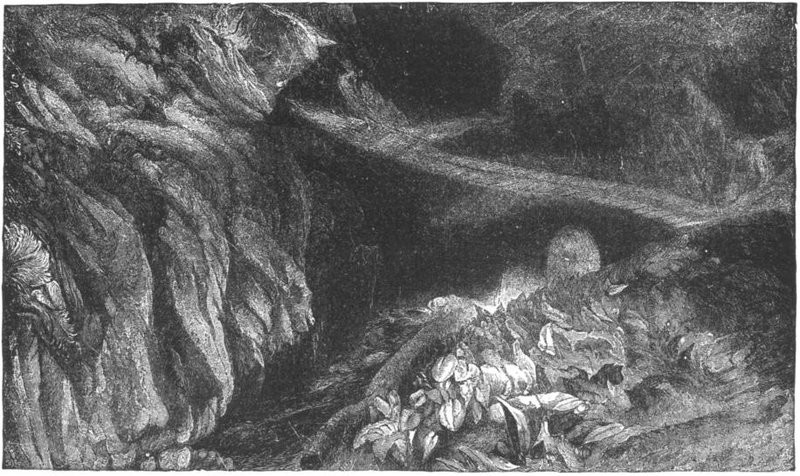

J. H. Le Keux 23378. Quivi Trovammo

J. M. W. Turner

J. Ruskin 29879. Hesperid Æglé

Giorgione

Wm. Hall 31480. Rocks at Rest

J. Ruskin, from J. M. W. Turner

J. C. Armytage 31981. Rocks in Unrest

J. Ruskin, from J. M. W. Turner

J. C. Armytage 32082. The Nets in the Rapids

J. M. W. Turner

J. H. Le Keux 33683. The Bridge of Rheinfelden

J. Ruskin

J. H. Le Keux 33784. Peace

J. Ruskin

J. H. Le Keux 338SEPARATE ENGRAVINGS ON WOOD.

Figure

56,

to face page

65”

61,

”

69”

75 to 78,

”

97”

85,

”

118”

87,

”

127”

88 to 90,

”

128”

98,

”

184”

100,

”

284

Ancilla Domini.

MODERN PAINTERS.

—————

PART VI.

OF LEAF BEAUTY.

—————

CHAPTER I.

THE EARTH-VEIL.

§ 1. “To dress it and to keep it.”

That, then, was to be our work. Alas! what work have we set ourselves upon instead! How have we ravaged the garden instead of kept it—feeding our war-horses with its flowers, and splintering its trees into spear-shafts!

“And at the East a flaming sword.”

Is its flame quenchless? and are those gates that keep the way indeed passable no more? or is it not rather that we no more desire to enter? For what can we conceive of that first Eden which we might not yet win back, if we chose? It was a place full of flowers, we say. Well: the flowers are always striving to grow wherever we suffer them; and the fairer, the closer. There may indeed have been a Fall of Flowers, as a Fall of Man; but assuredly creatures such as we are can now fancy nothing lovelier than roses and lilies, which would grow for us side by side, leaf overlapping leaf, till the Earth was white and red with them, if we cared to have it so. And Paradise was full of pleasant shades and fruitful avenues. Well: what hinders us from covering as much of the world as we like with pleasant shade and pure blossom, and goodly fruit? Who forbids its valleys to be covered over with corn, till they laugh and sing? Who prevents its dark forests, ghostly and uninhabitable, from being changed into infinite orchards, wreathing the hills with frail-floretted snow, far away to the half-lighted horizon of April, and flushing the face of all the autumnal earth with glow of clustered food? But Paradise was a place of peace, we say, and all the animals were gentle servants to us. Well: the world would yet be a place of peace if we were all peacemakers, and gentle service should we have of its creatures if we gave them gentle mastery. But so long as we make sport of slaying bird and beast, so long as we choose to contend rather with our fellows than with our faults, and make battlefield of our meadows instead of pasture—so long, truly, the Flaming Sword will still turn every way, and the gates of Eden remain barred close enough, till we have sheathed the sharper flame of our own passions, and broken down the closer gates of our own hearts.

§ 2. I have been led to see and feel this more and more, as I considered the service which the flowers and trees, which man was at first appointed to keep, were intended to render to him in return for his care; and the services they still render to him, as far as he allows their influence, or fulfils his own task towards them. For what infinite wonderfulness there is in this vegetation, considered, as indeed it is, as the means by which the earth becomes the companion of man—his friend and his teacher! In the conditions which we have traced in its rocks, there could only be seen preparation for his existence;—the characters which enable him to live on it safely, and to work with it easily—in all these it has been inanimate and passive; but vegetation is to it as an imperfect soul, given to meet the soul of man. The earth in its depths must remain dead and cold, incapable except of slow crystalline change; but at its surface, which human beings look upon and deal with, it ministers to them through a veil of strange intermediate being; which breathes, but has no voice; moves, but cannot leave its appointed place; passes through life without consciousness, to death without bitterness; wears the beauty of youth, without its passion; and declines to the weakness of age, without its regret.

§ 3. And in this mystery of intermediate being, entirely subordinate to us, with which we can deal as we choose, having just the greater power as we have the less responsibility for our treatment of the unsuffering creature, most of the pleasures which we need from the external world are gathered, and most of the lessons we need are written, all kinds of precious grace and teaching being united in this link between the Earth and Man: wonderful in universal adaptation to his need, desire, and discipline; God’s daily preparation of the earth for him, with beautiful means of life. First a carpet to make it soft for him; then, a colored fantasy of embroidery thereon; then, tall spreading of foliage to shade him from sunheat, and shade also the fallen rain, that it may not dry quickly back into the clouds, but stay to nourish the springs among the moss. Stout wood to bear this leafage: easily to be cut, yet tough and light, to make houses for him, or instruments (lance-shaft, or plough-handle, according to his temper); useless it had been, if harder; useless, if less fibrous; useless, if less elastic. Winter comes, and the shade of leafage falls away, to let the sun warm the earth; the strong boughs remain, breaking the strength of winter winds. The seeds which are to prolong the race, innumerable according to the need, are made beautiful and palatable, varied into infinitude of appeal to the fancy of man, or provision for his service: cold juice, or glowing spice, or balm, or incense, softening oil, preserving resin, medicine of styptic, febrifuge, or lulling charm: and all these presented in forms of endless change. Fragility or force, softness and strength, in all degrees and aspects; unerring uprightness, as of temple pillars, or undivided wandering of feeble tendrils on the ground; mighty resistances of rigid arm and limb to the storms of ages, or wavings to and fro with faintest pulse of summer streamlet. Roots cleaving the strength of rock, or binding the transience of the sand; crests basking in sunshine of the desert, or hiding by dripping spring and lightless cave; foliage far tossing in entangled fields beneath every wave of ocean—clothing with variegated, everlasting films, the peaks of the trackless mountains, or ministering at cottage doors to every gentlest passion and simplest joy of humanity.

§ 4. Being thus prepared for us in all ways, and made beautiful, and good for food, and for building, and for instruments of our hands, this race of plants, deserving boundless affection and admiration from us, become, in proportion to their obtaining it, a nearly perfect test of our being in right temper of mind and way of life; so that no one can be far wrong in either who loves the trees enough, and every one is assuredly wrong in both, who does not love them, if his life has brought them in his way. It is clearly possible to do without them, for the great companionship of the sea and sky are all that sailors need; and many a noble heart has been taught the best it had to learn between dark stone walls. Still if human life be cast among trees at all, the love borne to them is a sure test of its purity. And it is a sorrowful proof of the mistaken ways of the world that the “country,” in the simple sense of a place of fields and trees, has hitherto been the source of reproach to its inhabitants, and that the words “countryman,” “rustic,” “clown,” “paysan,” “villager,” still signify a rude and untaught person, as opposed to the words “townsman,” and “citizen.” We accept this usage of words, or the evil which it signifies, somewhat too quietly; as if it were quite necessary and natural that country-people should be rude, and towns-people gentle. Whereas I believe that the result of each mode of life may, in some stages of the world’s progress, be the exact reverse; and that another use of words may be forced upon us by a new aspect of facts, so that we may find ourselves saying: “Such and such a person is very gentle and kind—he is quite rustic; and such and such another person is very rude and ill-taught—he is quite urbane.”

§ 5. At all events, cities have hitherto gained the better part of their good report through our evil ways of going on in the world generally;—chiefly and eminently through our bad habit of fighting with each other. No field, in the middle ages, being safe from devastation, and every country lane yielding easier passage to the marauders, peacefully-minded men necessarily congregated in cities, and walled themselves in, making as few cross-country roads as possible: while the men who sowed and reaped the harvests of Europe were only the servants or slaves of the barons. The disdain of all agricultural pursuits by the nobility, and of all plain facts by the monks, kept educated Europe in a state of mind over which natural phenomena could have no power; body and intellect being lost in the practice of war without purpose, and the meditation of words without meaning. Men learned the dexterity with sword and syllogism, which they mistook for education, within cloister and tilt-yard; and looked on all the broad space of the world of God mainly as a place for exercise of horses, or for growth of food.

§ 6. There is a beautiful type of this neglect of the perfectness of the Earth’s beauty, by reason of the passions of men, in that picture of Paul Uccello’s of the battle of Sant’ Egidio,1 in which the armies meet on a country road beside a hedge of wild roses; the tender red flowers tossing above the helmets, and glowing between the lowered lances. For in like manner the whole of Nature only shone hitherto for man between the tossing of helmet-crests; and sometimes I cannot but think of the trees of the earth as capable of a kind of sorrow, in that imperfect life of theirs, as they opened their innocent leaves in the warm spring-time, in vain for men; and all along the dells of England her beeches cast their dappled shade only where the outlaw drew his bow, and the king rode his careless chase; and by the sweet French rivers their long ranks of poplar waved in the twilight, only to show the flames of burning cities, on the horizon, through the tracery of their stems: amidst the fair defiles of the Apennines, the twisted olive-trunks hid the ambushes of treachery; and on their valley meadows, day by day, the lilies which were white at the dawn were washed with crimson at sunset.

§ 7. And indeed I had once purposed, in this work, to show what kind of evidence existed respecting the possible influence of country life on men; it seeming to me, then, likely that here and there a reader would perceive this to be a grave question, more than most which we contend about, political or social, and might care to follow it out with me earnestly.

The day will assuredly come when men will see that it is a grave question; at which period, also, I doubt not, there will arise persons able to investigate it. For the present, the movements of the world seem little likely to be influenced by botanical law; or by any other considerations respecting trees, than the probable price of timber. I shall limit myself, therefore, to my own simple woodman’s work, and try to hew this book into its final shape, with the limited and humble aim that I had in beginning it, namely, to prove how far the idle and peaceable persons, who have hitherto cared about leaves and clouds, have rightly seen, or faithfully reported of them.

1 The best book of studies for his great shipwrecks contained about a quarter of a pound of chalk débris, black and white, broken off the crayons with which Turner had drawn furiously on both sides of the leaves; every leaf, with peculiar foresight and consideration of difficulties to be met by future mounters, containing half of one subject on the front of it, and half of another on the back.

2 To Mr. Armytage, Mr. Cuff, and Mr. Cousen, I have to express my sincere thanks for the patience, and my sincere admiration of the skill, with which they have helped me. Their patience, especially, has been put to severe trial by the rewardless toil required to produce facsimiles of drawings in which the slightness of subject could never attract any due notice to the excellence of workmanship.

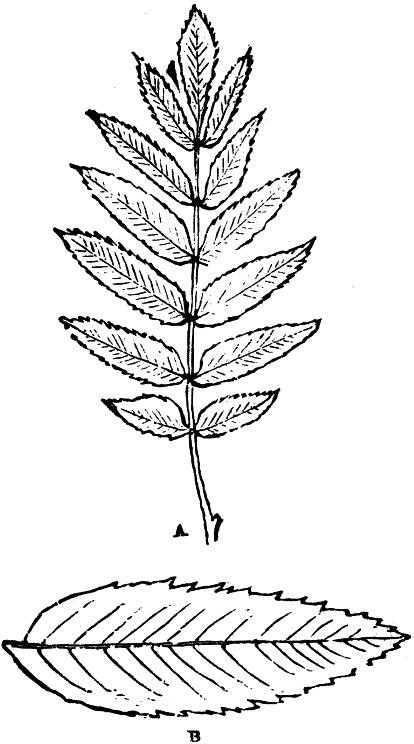

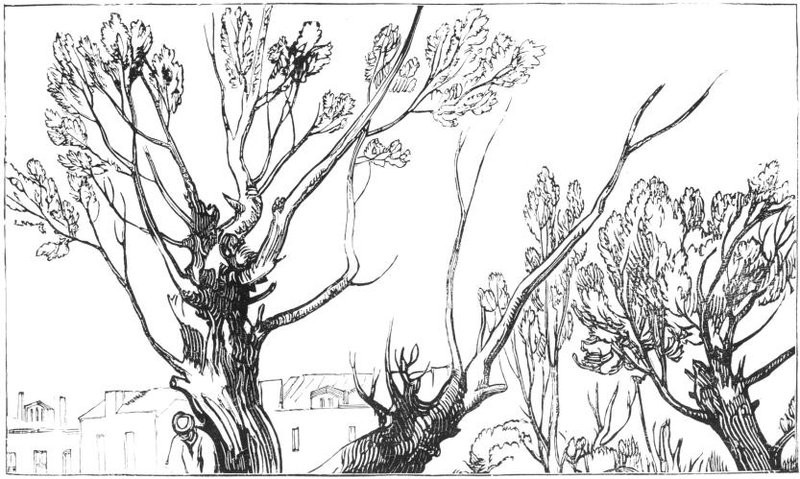

In strong-leaved shrubs or trees it is shown with great distinctness and beauty: the phillyrea shoot, for instance, Fig. 24, is almost in as true symmetry as a Greek honeysuckle ornament. In the hawthorn shoot, central in Plate 52, opposite, the law is seen very slightly, yet it rules all the play and fantasy of the varied leaves, gradually depressing their lines as they are set lower. In crowded foliage of large trees the disposition of each separate leaf is not so manifest. For there is a strange coincidence in this between trees and communities of men. When the community is small, people fall more easily into their places, and take, each in his place, a firmer standing than can be obtained by the individuals of a great nation. The members of a vast community are separately weaker, as an aspen or elm leaf is thin, tremulous, and directionless, compared with the spear-like setting and firm substance of a rhododendron or laurel leaf. The laurel and rhododendron are like the Athenian or Florentine republics; the aspen like England—strong-trunked enough when put to proof, and very good for making cartwheels of, but shaking pale with epidemic panic at every breeze. Nevertheless, the aspen has the better of the great nation, in that if you take it bough by bough, you shall find the gentle law of respect and room for each other truly observed by the leaves in such broken way as they can manage it; but in the nation you find every one scrambling for his neighbor’s place.

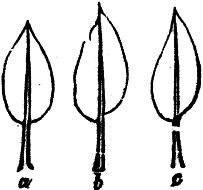

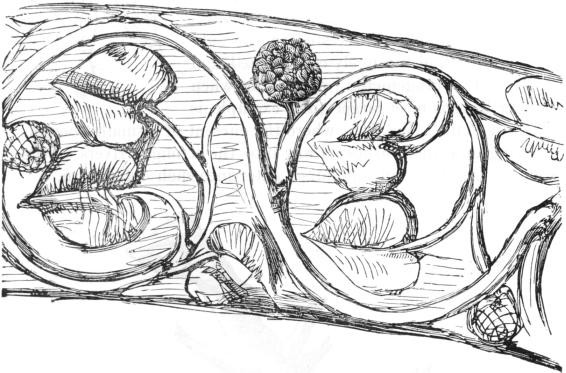

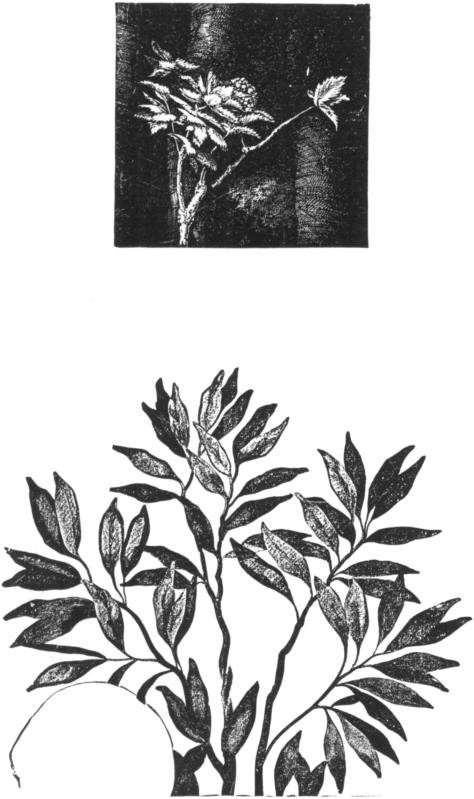

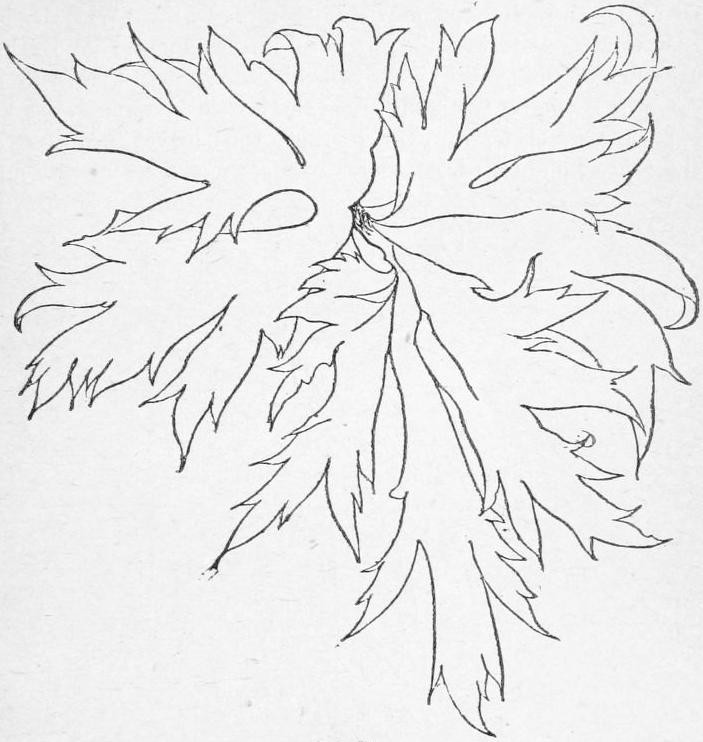

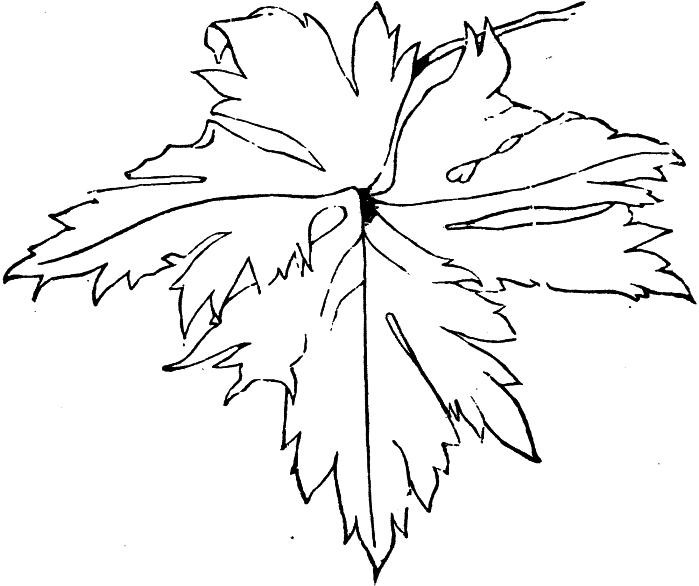

§ 5. The greatest draughtsmen draw leaves, like everything else, of their full-life size in the nearest part of the picture. They cannot be rightly drawn on any other terms. It is impossible to reduce a group so treated without losing much of its character; and more painfully impossible to represent by engraving any good workman’s handling. I intended to have inserted in this place an engraving of the cluster of oak-leaves above Correggio’s Antiope in the Louvre, but it is too lovely; and if I am able to engrave it at all, it must be separately, and of its own size. So I draw, roughly, instead, a group of oak-leaves on a young shoot, a little curled with autumn frost: Plate 53. I could not draw them accurately enough if I drew them in spring. They would droop and lose their relations. Thus roughly drawn, and losing some of their grace, by withering, they, nevertheless, have enough left to show how noble leaf-form is; and to prove, it seems to me, that Dutch draughtsmen do not wholly express it. For instance, Fig. 3, Plate 54, is a facsimile of a bit of the nearest oak foliage out of Hobbima’s Scene with the Water-mill, No. 131, in the Dulwich Gallery. Compared with the real forms of oak-leaf, in Plate 53, it may, I hope, at least enable my readers to understand, if they choose, why, never having ceased to rate the Dutch painters for their meanness or minuteness, I yet accepted the leaf-painting of the pre-Raphaelites with reverence and hope.

§ 8. Hence what I said in our first inquiry about foliage, “A single dusty roll of Turner’s brush is more truly expressive of the infinitude of foliage than the niggling of Hobbima could have rendered his canvas, if he had worked on it till doomsday.” And this brings me to the main difficulty I have had in preparing this section. That infinitude of Turner’s execution attaches not only to his distant work, but in due degree to the nearest pieces of his trees. As I have shown in the chapter on mystery, he perfected the system of art, as applicable to landscape, by the introduction of this infiniteness. In other qualities he is often only equal, in some inferior, to great preceding painters; but in this mystery he stands alone. He could not paint a cluster of leaves better than Titian; but he could a bough, much more a distant mass of foliage. No man ever before painted a distant tree rightly, or a full-leaved branch rightly. All Titian’s distant branches are ponderous flakes, as if covered with seaweed, while Veronese’s and Raphael’s are conventional, being exquisitely ornamental arrangements of small perfect leaves. See the background of the Parnassus in Volpato’s plate. It is very lovely, however.

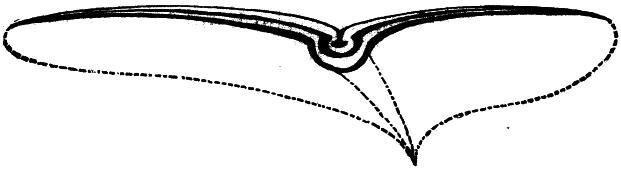

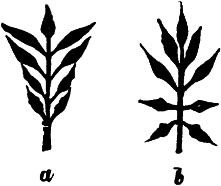

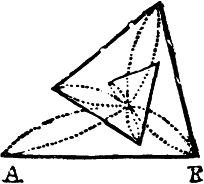

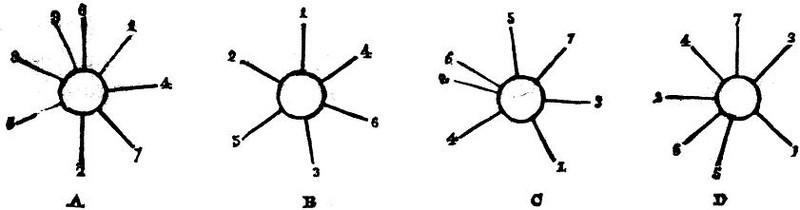

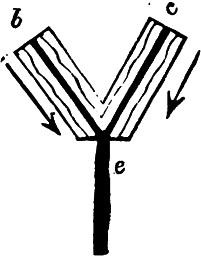

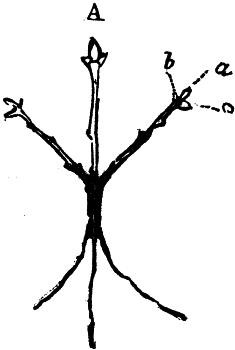

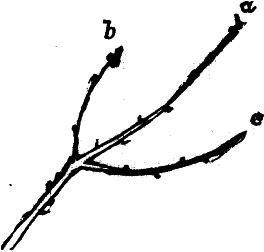

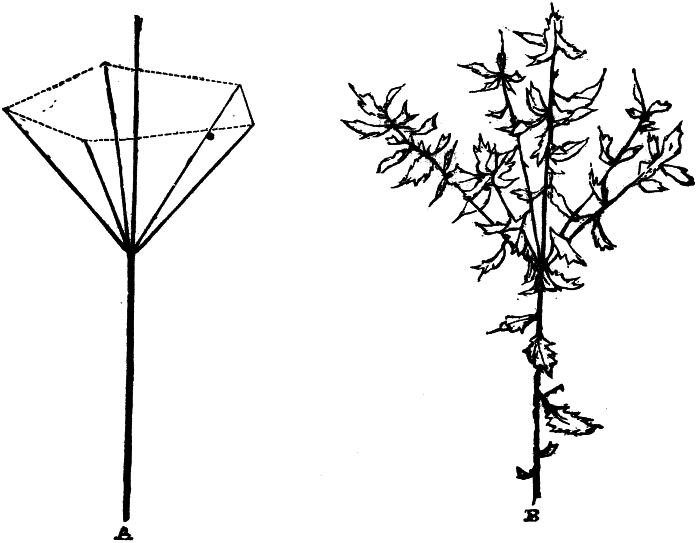

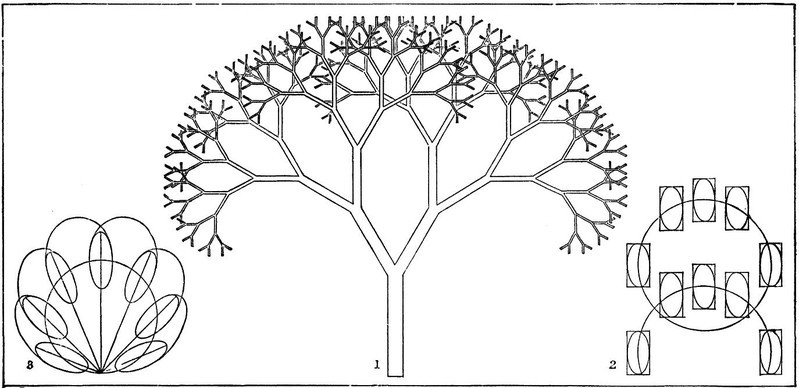

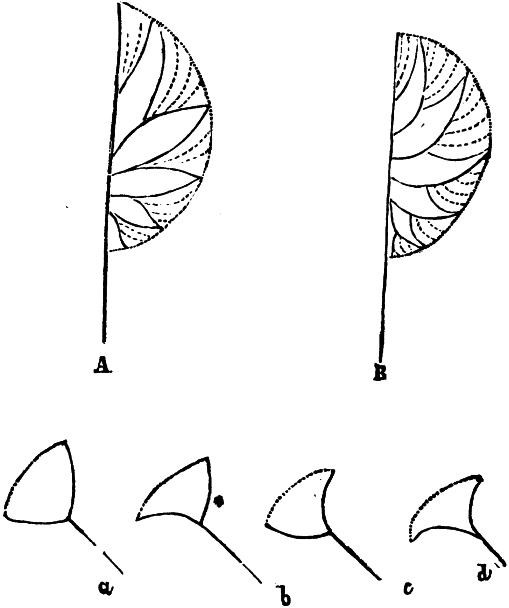

§ 17. Let X, Fig. 54, represent a shoot of any opposite-leaved tree. The mode in which it will grow into a tree depends, mainly, on its disposition to lose the leader or a lateral shoot. If it keeps the leader, but drops the lateral, it takes the form A, and next year by a repetition of the process, B. But if it keeps the laterals, and drops the leader, it becomes first, C and next year, D. The form A is almost universal in spiral or alternate trees; and it is especially to be noted as bringing about this result, that in any given forking, one bough always goes on in its own direct course, and the other leaves it softly; they do not separate as if one was repelled from the other. Thus in Fig. 55, a perfect and nearly symmetrical piece of ramification, by Turner (lowest bough but one in the tree on the left in the “Château of La belle Gabrielle”), the leading bough, going on in its own curve, throws off, first, a bough to the right, then one to the left, then two small ones to the right, and proceeds itself, hidden by leaves, to form the farthest upper point of the branch.

§ 5. I am not sure how far, by any illustration, I can exemplify these subtle conditions of form. All my plans have been shortened, and I have learned to content myself with yet more contracted issues of them after the shortening, because I know that nearly all in such matters must be said or shown, unavailably. No saying will teach the truth. Nothing but doing. If the reader will draw boughs of trees long and faithfully, giving previous pains to gain the power (how rare!) of drawing anything faithfully, he will come to see what Turner’s work is, or any other right work, but not by reading, nor thinking, nor idly looking. However, in some degree, even our ordinary instinctive perception of grace and balance may serve us, if we choose to pay any accurate attention to the matter.

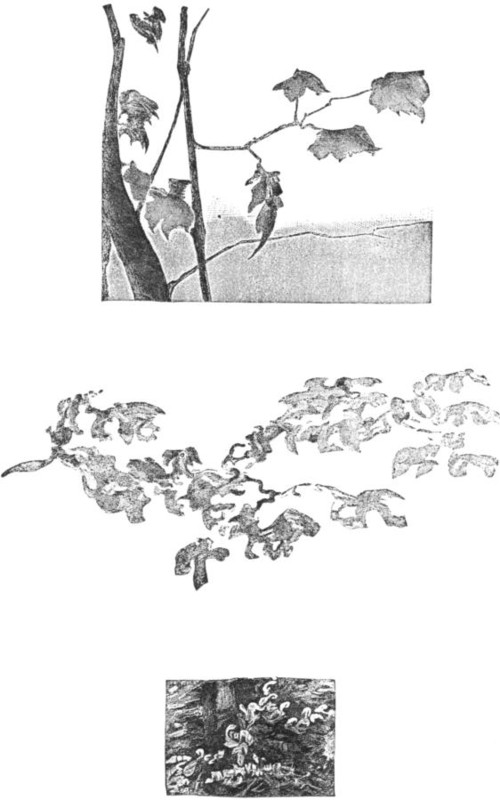

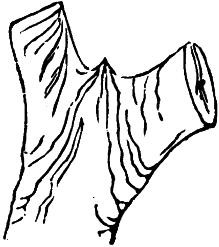

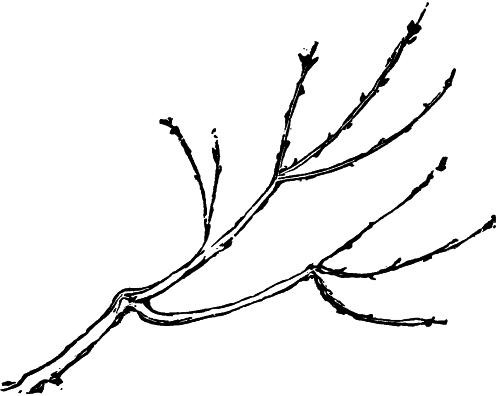

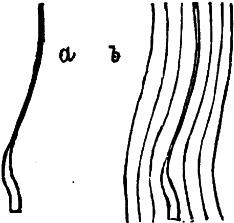

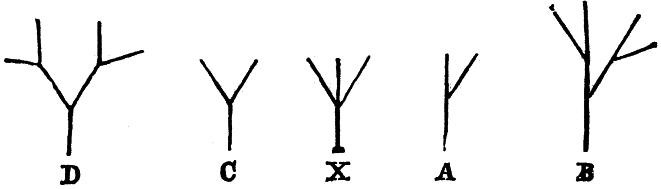

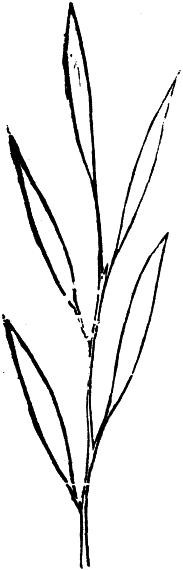

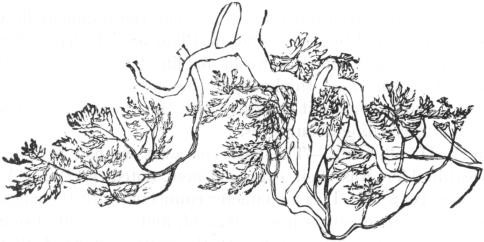

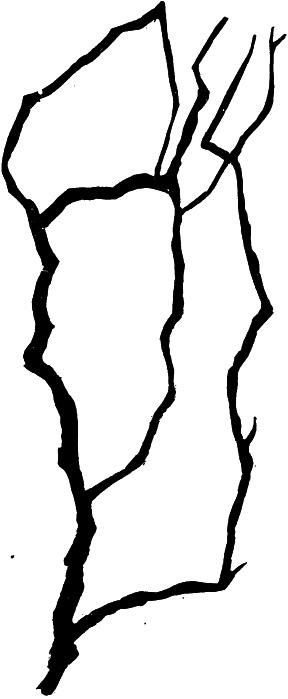

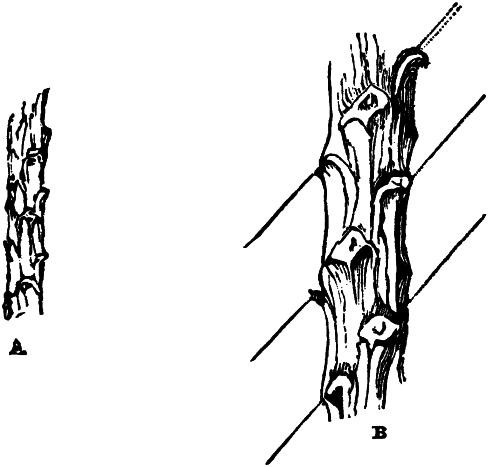

§ 10. To show how the principle of balance is carried out by Nature herself, here is a little terminal upright spray of willow, the most graceful of English trees (Fig. 59). I have drawn it carefully; and if the reader will study its curves, or, better, trace and pencil them with a perfectly fine point, he will feel, I think, without difficulty, their finished relation to the leaves they sustain. Then if we turn suddenly to a piece of Dutch branch-drawing (Fig. 60), facsimiled from No. 160, Dulwich Gallery (Berghem), he will understand, I believe, also the qualities of that, without comment of mine. It is of course not so dark in the original, being drawn with the chance dashes of a brush loaded with brown, but the contours are absolutely as in the woodcut. This Dutch design is a very characteristic example of two faults in tree-drawing; namely, the loss not only of grace and spring, but of woodiness. A branch is not elastic as steel is, neither as a carter’s whip is. It is a combination, wholly peculiar, of elasticity with half-dead and sapless stubbornness, and of continuous curve with pauses of knottiness, every bough having its blunted, affronted, fatigued, or repentant moments of existence, and mingling crabbed rugosities and fretful changes of mind with the main tendencies of its growth. The piece of pollard willow opposite (Fig. 61), facsimiled from Turner’s etching of “Young Anglers,” in the Liber Studiorum, has all these characters in perfectness, and may serve for sufficient study of them. It is impossible to explain in what the expression of the woody strength consists, unless it be felt. One very obvious condition is the excessive fineness of curvature, approximating continually to a straight line. In order to get a piece of branch curvature given as accurately as I could by an unprejudiced person, I set one of my pupils at the Working Men’s College (a joiner by trade) to draw, last spring, a lilac branch of its real size, as it grew, before it budded. It was about six feet long, and before he could get it quite right, the buds came out and interrupted him; but the fragment he got drawn is engraved in flat profile, in Plate 58. It has suffered much by reduction, one or two of its finest curves having become lost in the mere thickness of the lines. Nevertheless, if the reader will compare it carefully with the Dutch work, it will teach him something about trees.

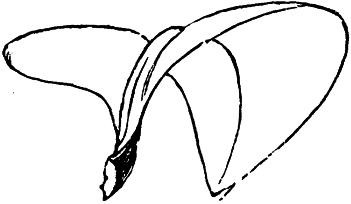

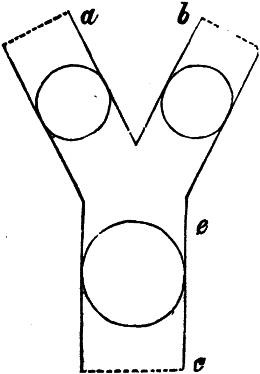

§ 12. Again: As it seldom struck the old painters that boughs must cross each other, so it never seems to have occurred to them that they must be sometimes foreshortened. I chose this bit from “Aske Hall,” that you might see at once, both how Turner foreshortens the main stem, and how, in doing so, he shows the turning aside, and outwards, of the one next to it, to the left, to get more air.6 Indeed, this foreshortening lies at the core of the business; for unless it be well understood, no branch-form can ever be rightly drawn. I placed the oak spray in Plate 51 so as to be seen as nearly straight on its flank as possible. It is the most uninteresting position in which a bough can be drawn; but it shows the first simple action of the law of resilience. I will now turn the bough with its extremity towards us, and foreshorten it (Plate 59), which being done, you perceive another tendency in the whole branch, not seen at all in the first Plate, to throw its sprays to its own right (or to your left), which it does to avoid the branch next it, while the forward action is in a sweeping curve round to your right, or to the branch’s left: a curve which it takes to recover position after its first concession. The lines of the nearer and smaller shoots are very nearly—thus foreshortened—those of a boat’s bow. Here is a piece of Dutch foreshortening for you to compare with it, Fig. 64.7

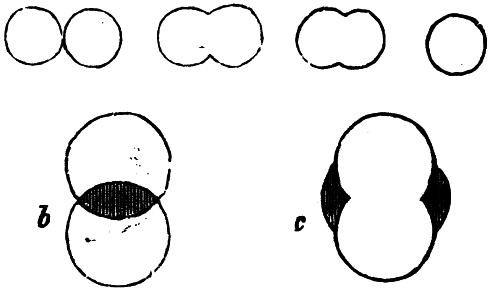

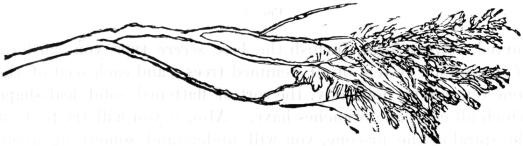

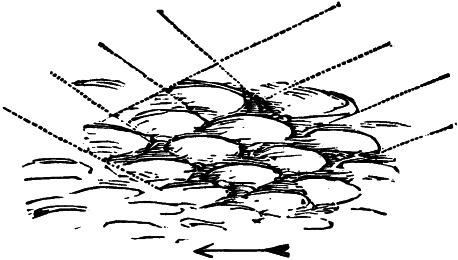

§ 12. One class, however, of these torn leaves, peculiar to the tented plants, has, it seems to me, a strange expressional function. I mean the group of leaves rent into alternate gaps, typically represented by the thistle. The alternation of the rent, if not absolutely, is effectively, peculiar to the earth-plants. Leaves of the builders are rent symmetrically, so as to form radiating groups, as in the horse-chestnut, or they are irregularly sinuous, as in the oak; but the earth-plants continually present forms such as those in the opposite Plate: a kind of web-footed leaf, so to speak; a continuous tissue, enlarged alternately on each side of the stalk. Leaves of this form have necessarily a kind of limping gait, as if they grew not all at once, but first a little bit on one side, and then a little bit on the other, and wherever they occur in quantity, give the expression to foreground vegetation which we feel and call “ragged.”

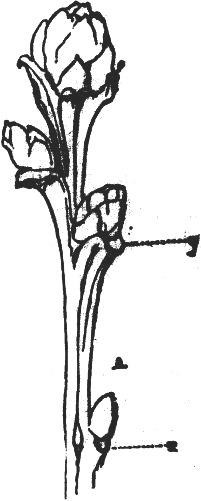

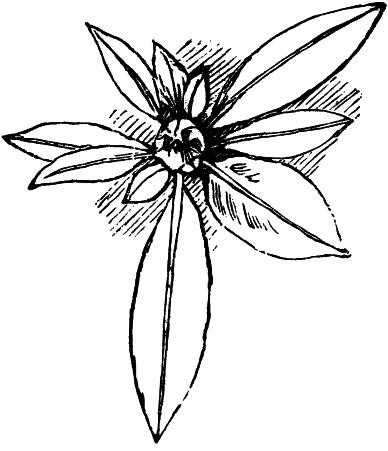

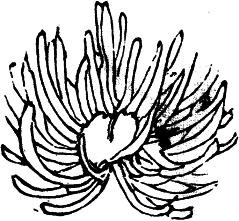

§ 19. I feel sorely tempted to draw one of these same spires of the fine grasses, with its sweet changing proportions of pendent grain, but it would be a useless piece of finesse, as such form of course never enters into general foreground effect.3 I have, however, engraved, at the top of the group of woodcuts opposite (Fig. 74), a single leaf cluster of Durer’s foreground in the St. Hubert, which is interesting in several ways; as an example of modern work, no less than old; for it is a facsimile twice removed; being first drawn from the plate with the pen, by Mr. Allen, and then facsimiled on wood by Miss Byfield; and if the reader can compare it with the original, he will find it still come tolerably close in most parts (though the nearest large leaf has got spoiled), and of course some of the finest and most precious qualities of Durer’s work are lost. Still, it gives a fair idea of his perfectness of conception, every leaf being thoroughly set in perspective, and drawn with unerring decision. On each side of it (Figs. 75, 76) are two pieces from a fairly good modern etching, which I oppose to the Durer in order to show the difference between true work and that which pretends to give detail, but is without feeling or knowledge. There are a great many leaves in the piece on the left, but they are all set the same way; the draughtsman has not conceived their real positions, but draws one after another as he would deliver a tale of bricks. The grasses on the right look delicate, but are a mere series of inorganic lines. Look how Durer’s grass-blades cross each other. If you take a pen and copy a little piece of each example, you will soon feel the difference. Underneath, in the centre (Fig. 77), is a piece of grass out of Landseer’s etching of the “Ladies’ Pets,” more massive and effective than the two lateral fragments, but still loose and uncomposed. Then underneath is a piece of firm and good work again, which will stand with Durer’s; it is the outline only of a group of leaves out of Turner’s foreground in the Richmond from the Moors, of which I give a reduced etching, Plate 61, for the sake of the foreground principally, and in Plate 62, the group of leaves in question, in their light and shade, with the bridge beyond. What I have chiefly to say of them belongs to our section on composition; but this mere fragment of a Turner foreground may perhaps lead the reader to take note in his great pictures of the almost inconceivable labor with which he has sought to express the redundance and delicacy of ground leafage.

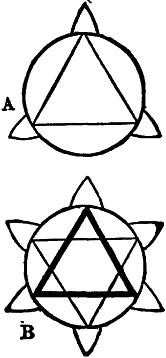

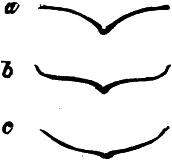

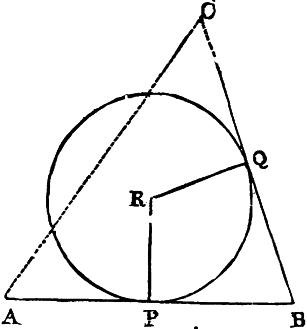

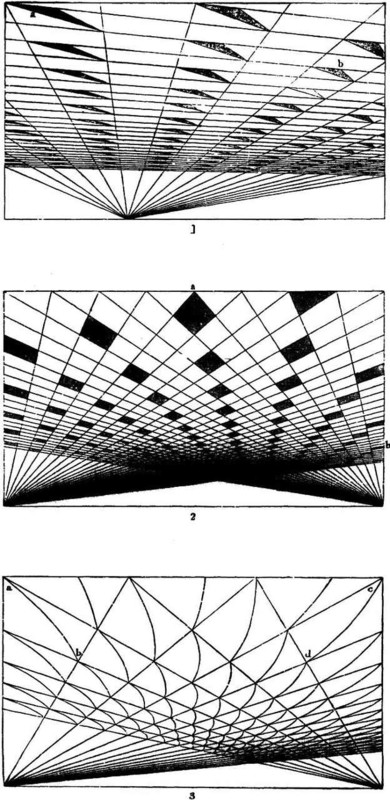

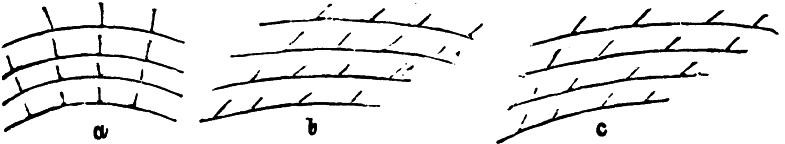

§ 11. Referring the reader to my Elements of Perspective for statements of law which would be in this place tiresome, I can only ask him to take my word for it that the three figures in Plate 64 represent limiting lines of sky perspective, as they would appear over a large space of the sky. Supposing that the breadth included was one-fourth of the horizon, the shaded portions in the central figure represent square fields of cloud,2 and those in the uppermost figure narrow triangles, with their shortest side next us, but sloping a little away from us.

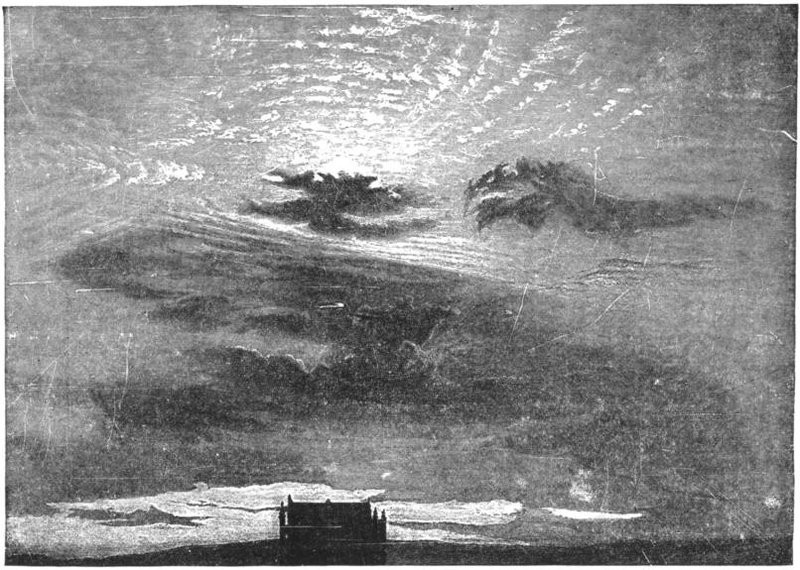

§ 12. Still greater confusion in aspect is induced by the apparent change caused by perspective in the direction of the wind. If Fig. 3 be supposed to include a quarter of the horizon, the spaces, into which its straight lines divide it, represent squares of sky. The curved lines, which cross these spaces from corner to corner, are precisely parallel throughout; and, therefore, two clouds moving, one on the curved line from a to b, and the other on the other side, from c to d, would, in reality, be moving with the same wind, in parallel lines. In Plate 66, which is a sketch of an actual sunset behind Beauvais cathedral (the point of the roof of the apse, a little to the left of the centre, shows it to be a summer sunset), the white cirri in the high light are all moving eastward, away from the sun, in perfectly parallel lines, curving a little round to the south. Underneath, are two straight ranks of rainy cirri, crossing each other; one directed south-east; the other, north-west. The meeting perspective of these, in extreme distance, determines the shape of the angular light which opens above the cathedral. Underneath all, fragments of true rain-cloud are floating between us and the sun, governed by curves of their own. They are, nevertheless, connected with the straight cirri, by the dark semi-cumulus in the middle of the shade above the cathedral.

§ 19. Without, however, troubling ourselves at all about laws, or causes of color, the visible consequences of their operation are notably these—that when near us, clouds present only subdued and uncertain colors; but when far from us, and struck by the sun on their under surfaces—so that the greater part of the light they receive is reflected—they may become golden, purple, scarlet, and intense fiery white, mingled in all kinds of gradations, such as I tried to describe in the chapter on the upper clouds in the first volume, in hope of being able to return to them “when we knew what was beautiful.”

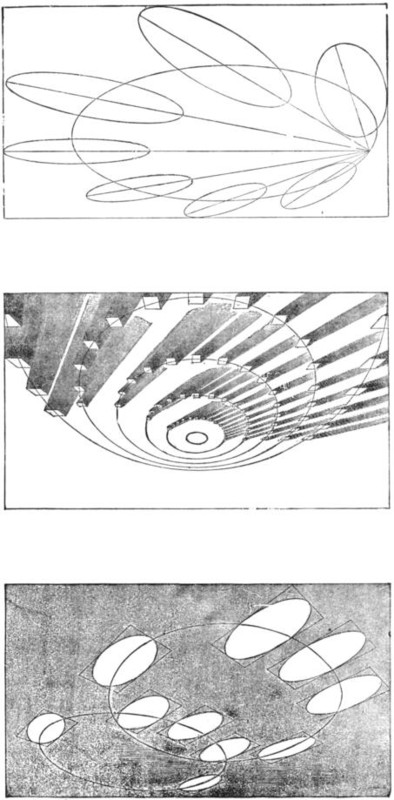

§ 14. And in these figures, which, if we look up the subject rightly, would be but the first and simplest of the series necessary to illustrate the action of the upper cirri, the reader may see, at once, how necessarily painters, untrained in observance of proportion, and ignorant of perspective, must lose in every touch the expression of buoyancy and space in sky. The absolute forms of each cloud are, indeed, not alike, as the ellipses in the engraving; but assuredly, when moving in groups of this kind, there are among them the same proportioned inequalities of relative distance, the same gradated changes from ponderous to elongated form, the same exquisite suggestions of including curve; and a common painter, dotting his clouds down at random, or in more or less equal masses, can no more paint a sky, than he could, by random dashes for its ruined arches, paint the Coliseum.

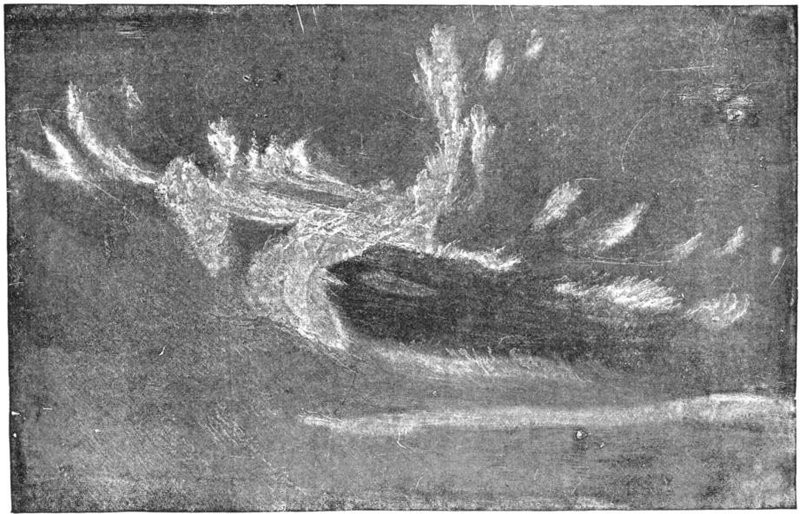

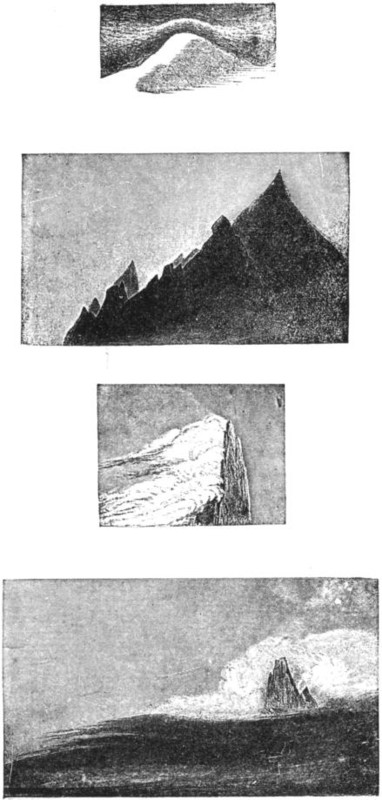

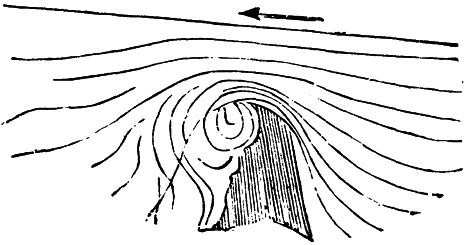

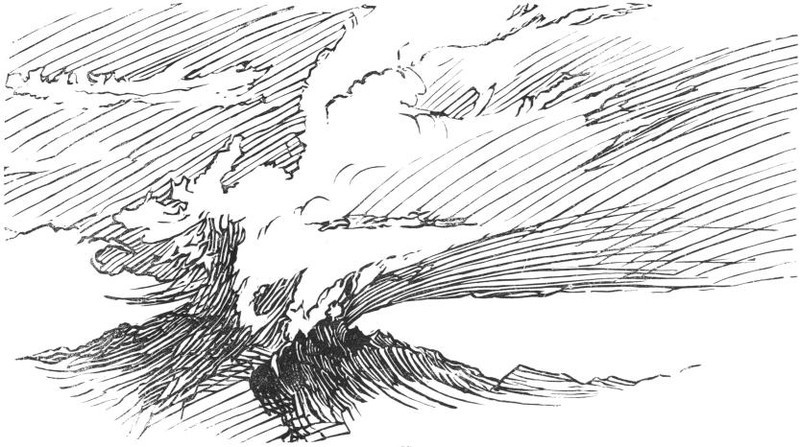

§ 5. The fact is, that the explanation given in that fourth paragraph can, in reality, account only for what may properly be termed “lee-side cloud,” slightly noticed in the continuation of the same chapter, but deserving most attentive illustration, as one of the most beautiful phenomena of the Alps. When a moist wind blows in clear weather over a cold summit, it has not time to get chilled as it approaches the rock, and therefore the air remains clear, and the sky bright on the windward side; but under the lee of the peak, there is partly a back eddy, and partly still air; and in that lull and eddy the wind gets time to be chilled by the rock, and the cloud appears as a boiling mass of white vapor, rising continually with the return current to the upper edge of the mountain, where it is caught by the straight wind, and partly torn, partly melted away in broken fragments. In Fig. 86 the dark mass represents the mountain peak, the arrow the main direction of the wind, the curved lines show the directions of such current and its concentration, and the dotted lines enclose the space in which cloud forms densely, floating away beyond and above in irregular tongues and flakes. The second figure from the top in Plate 69 represents the actual aspect of it when in full development, with a strong south wind, in a clear day, on the Aiguille Dru, the sky being perfectly blue and lovely around.

§ 10. The ordinary mountain cloud, therefore, if well defined, divides itself into two kinds: a broken condition of cumulus, grand in proportion as it is solid and quiet,—and a strange modification of drift-cloud, midway, as I said, between the helmet and the lee-side forms. The broken, quiet cumulus impressed Turner exceedingly when he first saw it on hills. He uses it, slightly exaggerating its definiteness, in all his early studies among the mountains of the Chartreuse, and very beautifully in the vignette of St. Maurice in Rogers’s Italy. There is nothing, however, to be specially observed of it, as it only differs from the cumulus of the plains, by being smaller and more broken.

Yet they never saw it fly, as we may in our own England. So far, at least, as I know the clouds of the south, they are often more terrible than ours, but the English Pegasus is swifter. On the Yorkshire and Derbyshire hills, when the rain-cloud is low and much broken, and the steady west-wind fills all space with its strength,6 the sun-gleams fly like golden vultures: they are flashes rather than shinings; the dark spaces and the dazzling race and skim along the acclivities, and dart and dip from crag to dell, swallow-like;—no Graiæ these,—gray and withered: Grey Hounds rather, following the Cerinthian stag with the golden antlers.

These banks are excavated by the peasantry, partly for houses, partly for cellars, so economizing vineyard space above; and thus a kind of continuous village runs along the river-side, composed half of caves, half of rude buildings, backed by the cliff, propped against it, therefore always leaning away from the river; mingled with overlappings of vineyard trellis from above, and little towers or summer-houses for outlook, when the grapes are ripe, or for gossip over the garden wall.

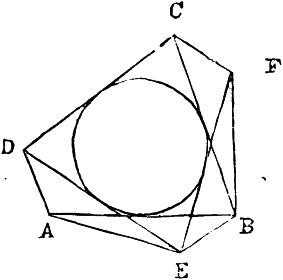

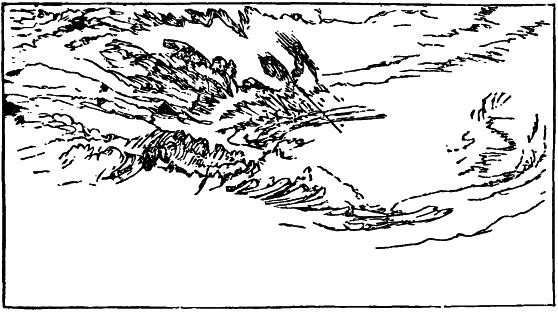

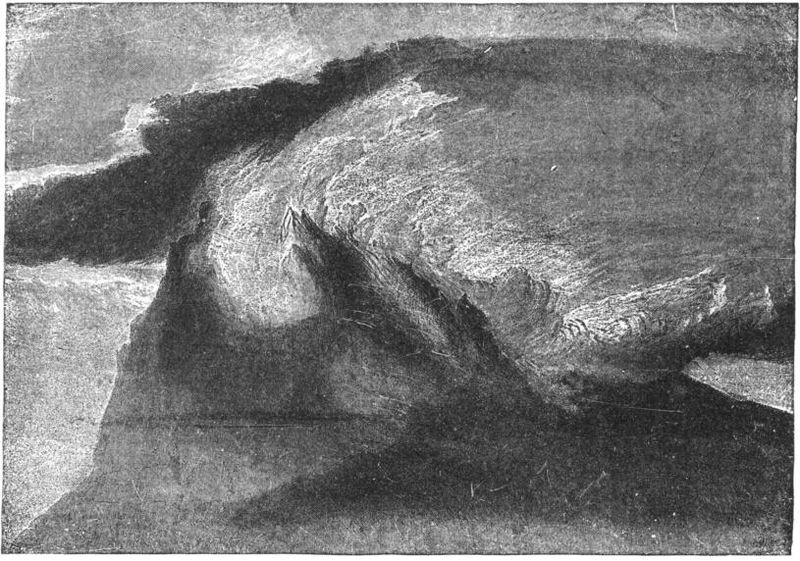

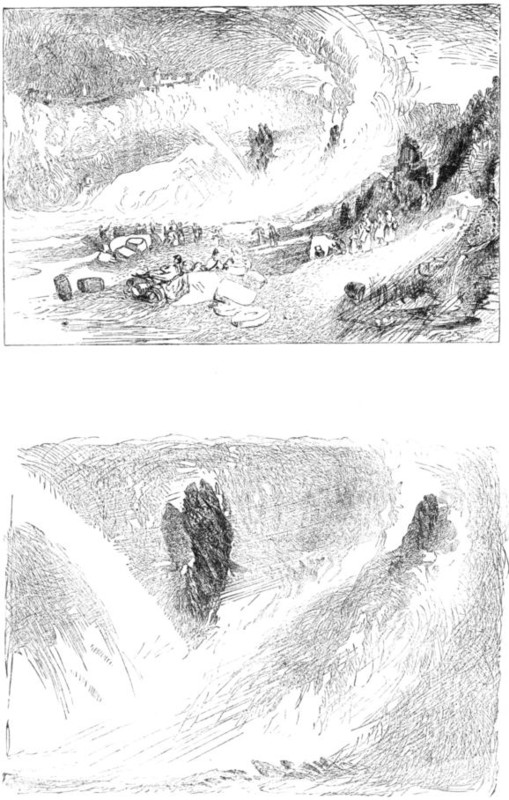

§ 8. Next to this piece of quietness, let us glance at a composition in which the motive is one of tumult: that of the Fall of Schaffhausen. It is engraved in the Keepsake. I have etched in Plate 74, at the top, the chief lines of its composition,2 in which the first great purpose is to give swing enough to the water. The line of fall is straight and monotonous in reality. Turner wants to get the great concave sweep and rush of the river well felt, in spite of the unbroken form. The column of spray, rocks, mills, and bank, all radiate like a plume, sweeping round together in grand curves to the left, where the group of figures, hurried about the ferry boat, rises like a dash of spray; they also radiating: so as to form one perfectly connected cluster, with the two gens-d’armes and the millstones; the millstones at the bottom being the root of it; the two soldiers laid right and left to sustain the branch of figures beyond, balanced just as a tree bough would be.

§ 10. This spring exists on the spot, and so does everything else in the picture; but the combinations are wholly arbitrary; it being Turner’s fixed principle to collect out of any scene whatever was characteristic, and put it together just as he liked. The changes made in this instance are highly curious. The mills have no resemblance whatever to the real group as seen from this spot; for there is a vulgar and formal dwelling-house in front of them. But if you climb the rock behind them, you find they form on that side a towering cluster, which Turner has put with little modification into the drawing. What he has done to the mills, he has done with still greater audacity to the central rock. Seen from this spot, it shows, in reality, its greatest breadth, and is heavy and uninteresting; but on the Lauffen side, exposes its consumed base, worn away by the rush of water, which Turner resolving to show, serenely draws the rock as it appears from the other side of the Rhine, and brings that view of it over to this side. I have etched the bit with the rock a little larger below; and if the reader knows the spot, he will see that this piece of the drawing, reversed in the etching, is almost a bonâ fide unreversed study of the fall from the Lauffen side.3

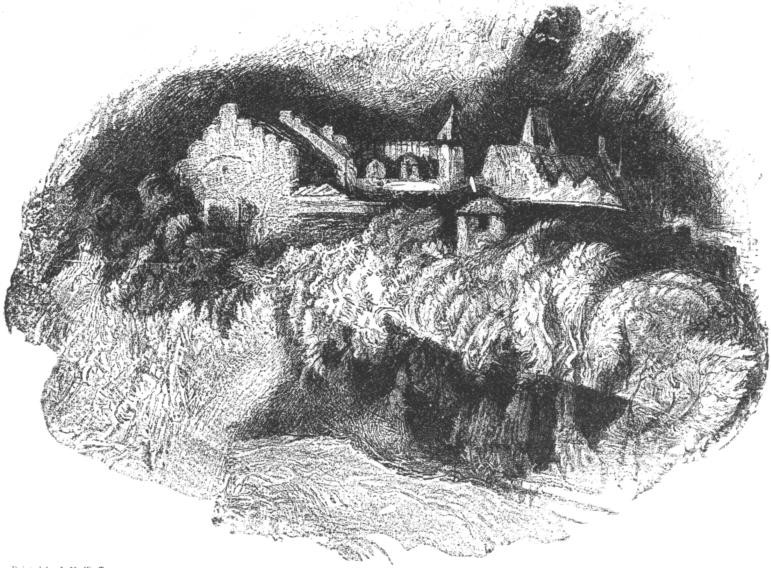

§ 6. Nuremberg is gathered at the base of a sandstone rock, rising in the midst of a dry but fertile plain. The rock forms a prolonged and curved ridge, of which the concave side, at the highest point, is precipitous; the other slopes gradually to the plain. Fortified with wall and tower along its whole crest, and crowned with a stately castle, it defends the city—not with its precipitous side—but with its slope. The precipice is turned to the town. It wears no aspect of hostility towards the surrounding fields; the roads lead down into them by gentle descents from the gates. To the south and east the walls are on the level of the plain; within them, the city itself stands on two swells of hill, divided by a winding river. Its architecture has, however, been much overrated. The effect of the streets, so delightful to the eye of the passing traveller, depends chiefly on one appendage of the roof, namely, its warehouse windows. Every house, almost without exception, has at least one boldly opening dormer window, the roof of which sustains a pulley for raising goods; and the underpart of this strong overhanging roof is always carved with a rich pattern, not of refined design, but effective.1 Among these comparatively modern structures are mingled, however, not unfrequently, others, turreted at the angles, which are true Gothic of the fifteenth, some of the fourteenth, century; and the principal churches remain nearly as in Durer’s time. Their Gothic is none of it good, nor even rich (though the façades have their ornament so distributed as to give them a sufficiently elaborate effect at a distance); their size is diminutive; their interiors mean, rude, and ill-proportioned, wholly dependent for their interest on ingenious stone cutting in corners, and finely-twisted ironwork; of these the mason’s exercises are in the worst possible taste, possessing not even the merit of delicate execution; but the designs in metal are usually meritorious, and Fischer’s shrine of St. Sebald is good, and may rank with Italian work.2

§ 8. Unforeseen requirements have compelled me to disperse through various works, undertaken between the first and last portions of this essay, the examination of many points respecting color, which I had intended to reserve for this place. I can now only refer the reader to these several passages,3 and sum their import: which is briefly, that color generally, but chiefly the scarlet, used with the hyssop, in the Levitical law, is the great sanctifying element of visible beauty inseparably connected with purity and life.

§ 31. I need not trace the dark clue farther, the reader may follow it unbroken through all his work and life, this thread of Atropos.13 I will only point, in conclusion, to the intensity with which his imagination dwelt always on the three great cities of Carthage, Rome, and Venice—Carthage in connection especially with the thoughts and study which led to the painting of the Hesperides’ Garden, showing the death which attends the vain pursuit of wealth; Rome, showing the death which attends the vain pursuit of power; Venice, the death which attends the vain pursuit of beauty.

§ 31. I need not trace the dark clue farther, the reader may follow it unbroken through all his work and life, this thread of Atropos.13 I will only point, in conclusion, to the intensity with which his imagination dwelt always on the three great cities of Carthage, Rome, and Venice—Carthage in connection especially with the thoughts and study which led to the painting of the Hesperides’ Garden, showing the death which attends the vain pursuit of wealth; Rome, showing the death which attends the vain pursuit of power; Venice, the death which attends the vain pursuit of beauty.

§ 32. Vain beauty; yet not all in vain. Unlike in birth, how like in their labor, and their power over the future, these masters of England and Venice—Turner and Giorgione. But ten years ago, I saw the last traces of the greatest works of Giorgione yet glowing, like a scarlet cloud, on the Fondaco de Tedeschi.14 And though that scarlet cloud (sanguigna e fiammeggiante, per cui le pitture cominciarono con dolce violenza a rapire il cuore delle genti) may, indeed, melt away into paleness of night, and Venice herself waste from her islands as a wreath of wind-driven foam fades from their weedy beach;—that which she won of faithful light and truth shall never pass away. Deiphobe of the sea,—the Sun God measures her immortality to her by its sand. Flushed, above the Avernus of the Adrian lake, her spirit is still seen holding the golden bough; from the lips of the Sea Sibyl men shall learn for ages yet to come what is most noble and most fair; and, far away, as the whisper in the coils of the shell, withdrawn through the deep hearts of nations, shall sound for ever the enchanted voice of Venice.

§ 18. This being so, we find another element of very complex effect added to the others which exist in tented plants, namely, that of minute, granular, feathery, or downy seed-vessels, mingling quaint brown punctuation, and dusty tremors of dancing grain, with the bloom of the nearer fields; and casting a gossamered grayness and softness of plumy mist along their surfaces far away; mysterious evermore, not only with dew in the morning or mirage at noon, but with the shaking threads of fine arborescence, each a little belfry of grain-bells, all a-chime.

§ 12. The absolute scale of such clouds may be seen, or at least demonstrated, more clearly in Fig. 88, which is a rough note of an effect of sky behind the tower of Berne Cathedral. It was made from the mound beside the railroad bridge. The Cathedral tower is half-a-mile distant. The great Eiger of Grindelwald is seen just on the right of it. This mountain is distant from the tower thirty-four miles as the crow flies, and ten thousand feet above it in height. The drift-cloud behind it, therefore, being in full light, and showing no overhanging surfaces, must rise at least twenty thousand feet into the air.

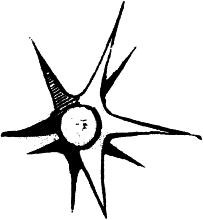

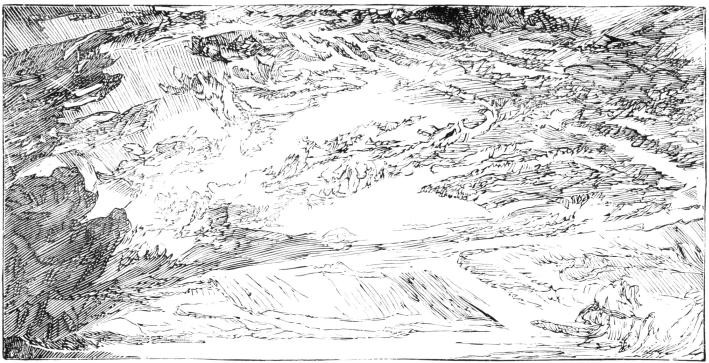

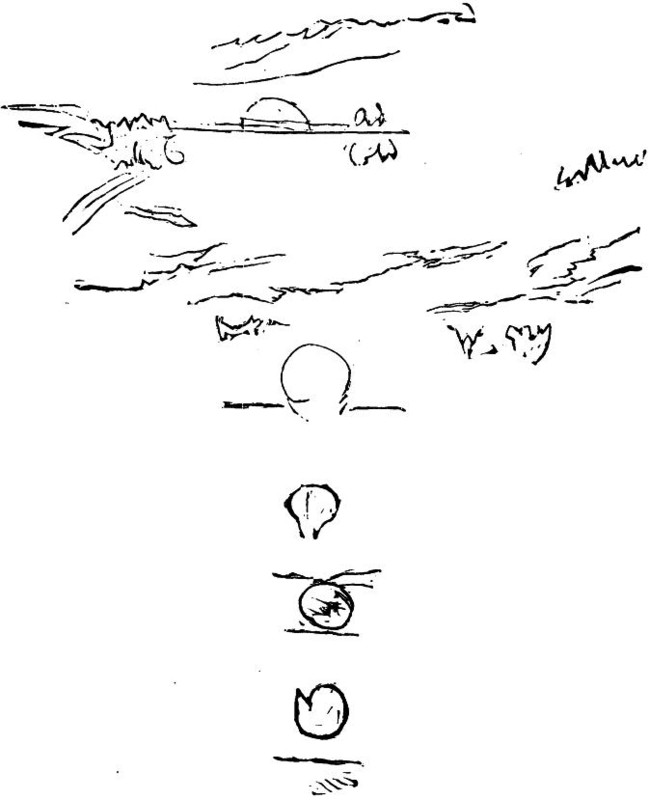

§ 7. When the sketch is made merely as a memorandum, it is impossible to say how little, or what kind of drawing, may be sufficient for the purpose. It is of course likely to be hasty from its very nature, and unless the exact purpose be understood, it may be as unintelligible as a piece of shorthand writing. For instance, in the corner of a sheet of sketches made at sea, among those of Turner, at the National Gallery, occurs this one, Fig. 97. I suppose most persons would not see much use in it. It nevertheless was probably one of the most important sketches made in Turner’s life, fixing for ever in his mind certain facts respecting the sunrise from a clear sea-horizon. Having myself watched such sunrise, occasionally, I perceive this sketch to mean as follows:—

§ 14. In order to mark the temper of Angelico, by a contrast of another kind, I give, in Fig. 99, a facsimile of one of the heads in Salvator’s etching of the Academy of Plato. It is accurately characteristic of Salvator, showing, by quite a central type, his indignant, desolate, and degraded power. I could have taken unspeakably baser examples from others of his etchings, but they would have polluted my book, and been in some sort unjust, representing only the worst part of his work. This head, which is as elevated a type as he ever reaches, is assuredly debased enough; and a sufficient image of the mind of the painter of Catiline and the Witch of Endor.

1: In our own National Gallery. It is quaint and imperfect, but of great interest.

1: In our own National Gallery. It is quaint and imperfect, but of great interest.

CHAPTER II.

THE LEAF ORDERS.

§ 1. As in our sketch of the structure of mountains it seemed advisable to adopt a classification of their forms, which, though inconsistent with absolute scientific precision, was convenient for order of successive inquiry, and gave useful largeness of view; so, and with yet stronger reason, in glancing at the first laws of vegetable life, it will be best to follow an arrangement easily remembered and broadly true, however incapable of being carried out into entirely consistent detail. I say, “with yet stronger reason,” because more questions are at issue among botanists than among geologists; a greater number of classifications have been suggested for plants than for rocks; nor is it unlikely that those now accepted may be hereafter modified. I take an arrangement, therefore, involving no theory; serviceable enough for all working purposes, and sure to remain thus serviceable, in its rough generality, whatever views may hereafter be developed among botanists.

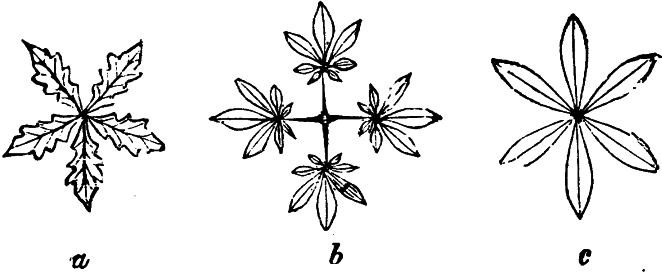

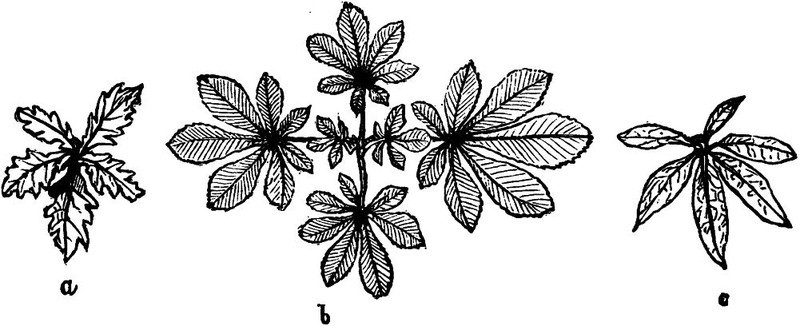

§ 2. A child’s division of plants is into “trees and flowers.” If, however, we were to take him in spring, after he had gathered his lapful of daisies, from the lawn into the orchard, and ask him how he would call those wreaths of richer floret, whose frail petals tossed their foam of promise between him and the sky, he would at once see the need of some intermediate name, and call them, perhaps, “tree-flowers.” If, then, we took him to a birch-wood, and showed him that catkins were flowers, as well as cherry-blossoms, he might, with a little help, reach so far as to divide all flowers into two classes; one, those that grew on ground; and another, those that grew on trees. The botanist might smile at such a division; but an artist would not. To him, as the child, there is something specific and distinctive in those rough trunks that carry the higher flowers. To him, it makes the main difference between one plant and another, whether it is to tell as a light upon the ground, or as a shade upon the sky. And if, after this, we asked for a little help from the botanist, and he were to lead us, leaving the blossoms, to look more carefully at leaves and buds, we should find ourselves able in some sort to justify, even to him, our childish classification. For our present purposes, justifiable or not, it is the most suggestive and convenient. Plants are, indeed, broadly referable to two great classes. The first we may, perhaps, not inexpediently call TENTED PLANTS. They live in encampments, on the ground, as lilies; or on surfaces of rock, or stems of other plants, as lichens and mosses. They live—some for a year, some for many years, some for myriads of years; but, perishing, they pass as the tented Arab passes; they leave no memorials of themselves, except the seed, or bulb, or root which is to perpetuate the race.

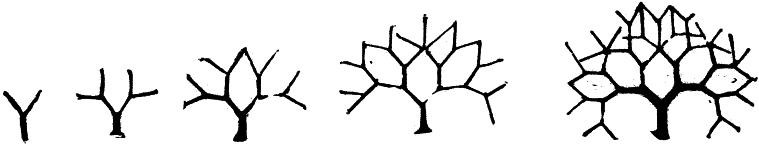

§ 3. The other great class of plants we may perhaps best call BUILDING PLANTS. These will not live on the ground, but eagerly raise edifices above it. Each works hard with solemn forethought all its life. Perishing, it leaves its work in the form which will be most useful to its successors—its own monument, and their inheritance. These architectural edifices we call “Trees.”

It may be thought that this nomenclature already involves a theory. But I care about neither the nomenclature, nor about anything questionable in my description of the classes. The reader is welcome to give them what names he likes, and to render what account of them he thinks fittest. But to us, as artists, or lovers of art, this is the first and most vital question concerning a plant: “Has it a fixed form or a changing one? Shall I find it always as I do to-day—this Parnassia palustris—with one leaf and one flower? or may it some day have incalculable pomp of leaves and unmeasured treasure of flowers? Will it rise only to the height of a man—as an ear of corn—and perish like a man; or will it spread its boughs to the sea and branches to the river, and enlarge its circle of shade in heaven for a thousand years?”

§ 4. This, I repeat, is the first question I ask the plant. And as it answers, I range it on one side or the other, among those that rest or those that toil: tent-dwellers, who toil not, neither do they spin; or tree-builders, whose days are as the days of the people. I find again, on farther questioning these plants who rest, that one group of them does indeed rest always, contentedly, on the ground, but that those of another group, more ambitious, emulate the builders; and though they cannot build rightly, raise for themselves pillars out of the remains of past generations, on which they themselves, living the life of St. Simeon Stylites, are called, by courtesy, Trees; being, in fact, many of them (palms, for instance) quite as stately as real trees.1

These two classes we might call earth-plants, and pillar-plants.

§ 5. Again, in questioning the true builders as to their modes of work, I find that they also are divisible into two great classes. Without in the least wishing the reader to accept the fanciful nomenclature, I think he may yet most conveniently remember these as “Builders with the shield,” and “Builders with the sword.”

Builders with the shield have expanded leaves, more or less resembling shields, partly in shape, but still more in office; for under their lifted shadow the young bud of the next year is kept from harm. These are the gentlest of the builders, and live in pleasant places, providing food and shelter for man. Builders with the sword, on the contrary, have sharp leaves in the shape of swords, and the young buds, instead of being as numerous as the leaves, crouching each under a leaf-shadow, are few in number, and grow fearlessly, each in the midst of a sheaf of swords. These builders live in savage places, are sternly dark in color, and though they give much help to man by their merely physical strength, they (with few exceptions) give him no food, and imperfect shelter. Their mode of building is ruder than that of the shield-builders, and they in many ways resemble the pillar-plants of the opposite order. We call them generally “Pines.”

§ 6. Our work, in this section, will lie only among the shield-builders, sword-builders, and plants of rest. The Pillar-plants belong, for the most part, to other climates. I could not analyze them rightly; and the labor given to them would be comparatively useless for our present purposes. The chief mystery of vegetation, so far as respects external form, is among the fair shield-builders. These, at least, we must examine fondly and earnestly.

1 I am not sure that this is a fair account of palms. I have never had opportunity of studying stems of Endogens, and I cannot understand the description given of them in books, nor do I know how far some of their branched conditions approximate to real tree-structure. If this work, whatever errors it may involve, provokes the curiosity of the reader so as to lead him to seek for more and better knowledge, it will do all the service I hope from it.

CHAPTER III.

THE BUD.

§ 1. If you gather in summer time an outer spray of any shield-leaved tree, you will find it consists of a slender rod, throwing out leaves, perhaps on every side, perhaps on two sides only, with usually a cluster of closer leaves at the end. In order to understand its structure, we must reduce it to a simple general type. Nay, even to a very inaccurate type. For a tree-branch is essentially a complex thing, and no “simple” type can, therefore, be a right one.

This type I am going to give you is full of fallacies and inaccuracies; but out of these fallacies we will bring the truth, by casting them aside one by one.

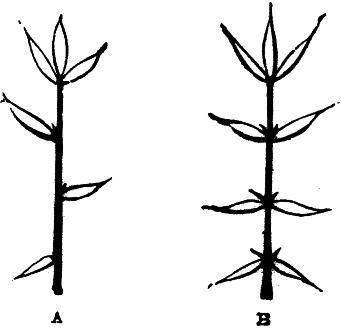

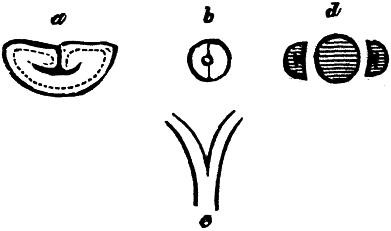

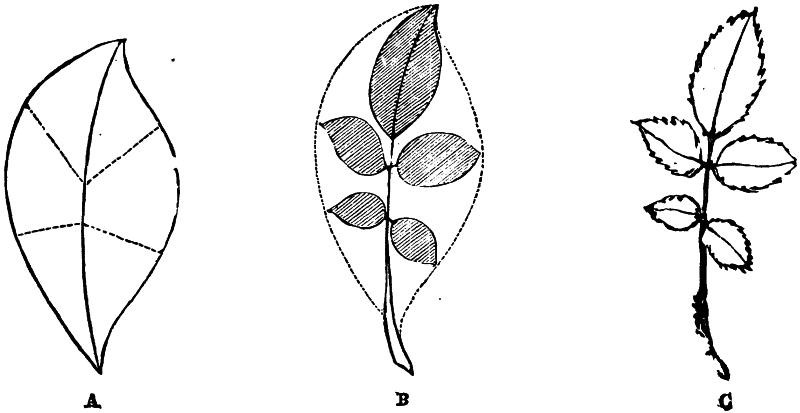

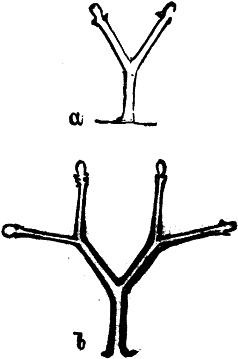

§ 2. Let the tree spray be represented under one of these two types, A or B, Fig. 1, the cluster at the end being in each case supposed to consist of three leaves only (a most impertinent supposition, for it must at least have four, only the fourth would be in a puzzling perspective in A, and hidden behind the central leaf in B). So, receive this false type patiently. When leaves are set on the stalk one after another, as in A, they are called “alternate;” when placed as in B, “opposite.” It is necessary you should remember this not very difficult piece of nomenclature.

If you examine the branch you have gathered, you will see that for some little way below the full-leaf cluster at the end, the stalk is smooth, and the leaves are set regularly on it. But at six, eight, or ten inches down, there comes an awkward knot; something seems to have gone wrong, perhaps another spray branches off there; at all events, the stem gets suddenly thicker, and you may break it there (probably) easier than anywhere else.

That is the junction of two stories of the building. The smooth piece has all been done this summer. At the knot the foundation was left during the winter.

The year’s work is called a “shoot.” I shall be glad if you will break it off to look at; as my A and B types are supposed to go no farther down than the knot.

The alternate form A is more frequent than B, and some botanists think includes B. We will, therefore, begin with it.

§ 3. If you look close at the figure, you will see small projecting points at the roots of the leaves. These represent buds, which you may find, most probably, in the shoot you have in your hand. Whether you find them or not, they are there—visible, or latent, does not matter. Every leaf has assuredly an infant bud to take care of, laid tenderly, as in a cradle, just where the leaf-stalk forms a safe niche between it and the main stem. The child-bud is thus fondly guarded all summer; but its protecting leaf dies in the autumn; and then the boy-bud is put out to rough winter-schooling, by which he is prepared for personal entrance into public life in the spring.

Let us suppose autumn to have come, and the leaves to have fallen. Then our A of Fig. I, the buds only being left, one for each leaf, will appear as A B, in Fig. 2. We will call the buds grouped at B, terminal buds, and those at a, b, and c, lateral buds.

This budded rod is the true year’s work of the building plant, at that part of its edifice. You may consider the little spray, if you like, as one pinnacle of the tree-cathedral, which has taken a year to fashion; innumerable other pinnacles having been built at the same time on other branches.

§ 4. Now, every one of these buds, a, b, and c, as well as every terminal bud, has the power and disposition to raise himself in the spring, into just such another pinnacle as A B is.

This development is the process we have mainly to study in this chapter; but, in the outset, let us see clearly what it is to end in.

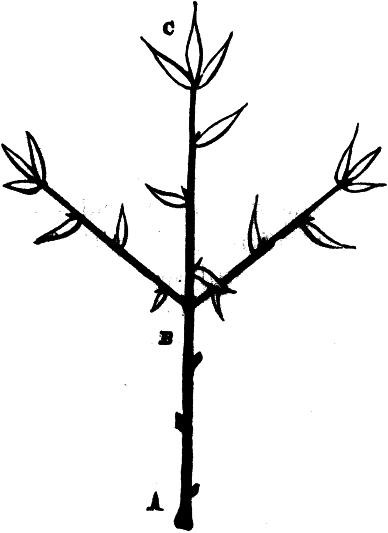

Each bud, I said, has the power and disposition to make a pinnacle of himself, but he has not always the opportunity. What may hinder him we shall see presently. Meantime, the reader will, perhaps, kindly allow me to assume that the buds a, b, and c, come to nothing, and only the three terminal ones build forward. Each of these producing the image of the first pinnacle, we have the type for our next summer bough of Fig. 3; in which observe the original shoot A B, has become thicker; its lateral buds having proved abortive, are now only seen as little knobs on its sides. Its terminal buds have each risen into a new pinnacle. The central or strongest one B C, has become the very image of what his parent shoot A B, was last year. The two lateral ones are weaker and shorter, one probably longer than the other. The joint at B is the knot or foundation for each shoot above spoken of.

Knowing now what we are about, we will go into closer detail.

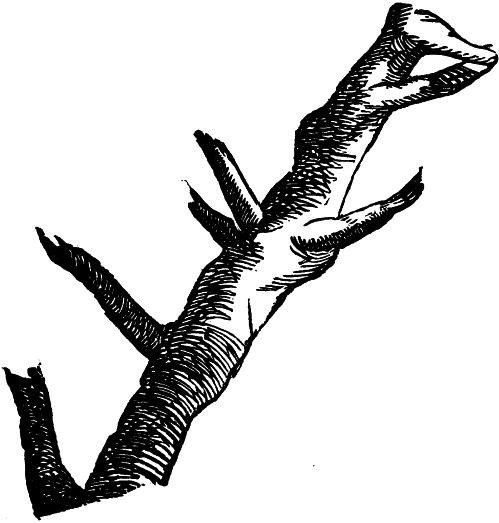

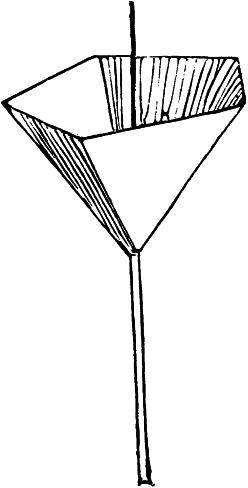

51. The Dryad’s Toil.

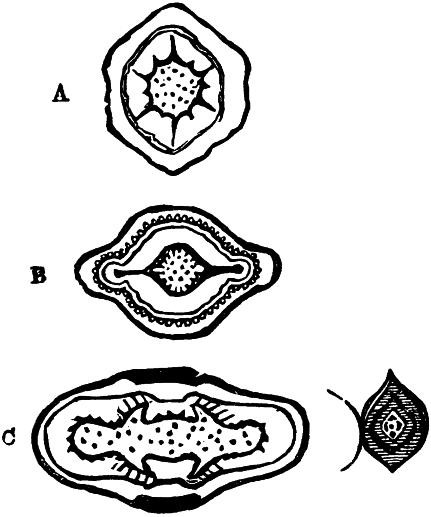

§ 5. Let us return to the type in Fig. 2, of the fully accomplished summer’s work: the rod with its bare buds. Plate 51, opposite, represents, of about half its real size, an outer spray of oak in winter. It is not growing strongly, and is as simple as possible in ramification. You may easily see, in each branch, the continuous piece of shoot produced last year. The wrinkles which make these shoots look like old branches are caused by drying, as the stalk of a bunch of raisins is furrowed (the oak-shoot fresh gathered is round as a grape-stalk). I draw them thus, because the furrows are important clues to structure. Fig. 4 is the top of one of these oak sprays magnified for reference. The little brackets, x, y, &c., which project beneath each bud and sustain it, are the remains of the leaf-stalks. Those stalks were jointed at that place, and the leaves fell without leaving a scar, only a crescent-shaped, somewhat blank-looking flat space, which you may study at your ease on a horse-chestnut stem, where these spaces are very large.

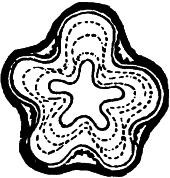

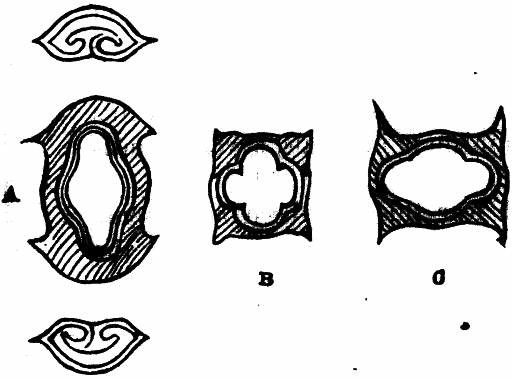

§ 6. Now if you cut your oak spray neatly through, just above a bud, as at A, Fig. 4, and look at it with a not very powerful magnifier, you will find it present the pretty section, Fig. 5.

That is the proper or normal section of an oak spray. Never quite regular. Sure to have one of the projections a little larger than the rest, and to have its bark (the black line) not quite regularly put round it, but exquisitely finished, down to a little white star in the very centre, which I have not drawn, because it would look in the woodcut black, not white; and be too conspicuous.

The oak spray, however, will not keep this form unchanged for an instant. Cut it through a little way above your first section, and you will find the largest projection is increasing till, just where it opens1 at last into the leaf-stalk, its section is Fig. 6. If, therefore, you choose to consider every interval between bud and bud as one story of your tower or pinnacle, you find that there is literally not a hair’s-breadth of the work in which the plan of the tower does not change. You may see in Plate 51 that every shoot is suffused by a subtle (in nature an infinitely subtle) change of contour between bud and bud.

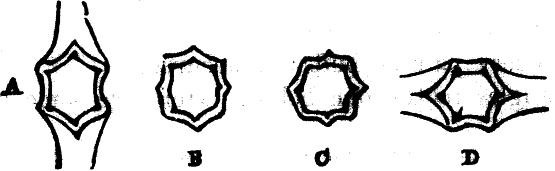

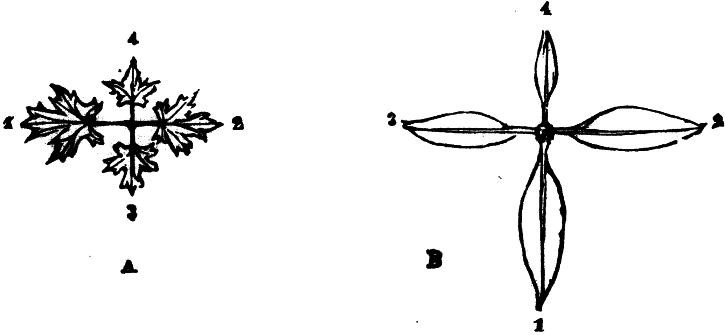

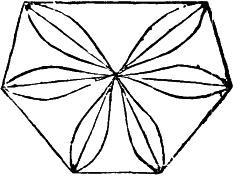

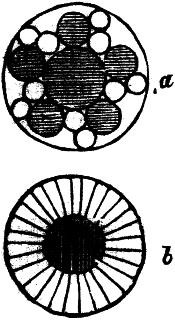

§ 7. But farther, observe in what succession those buds are put round the bearing stem. Let the section of the stem be represented by the small central circle in Fig. 8; and suppose it surrounded by a nearly regular pentagon (in the figure it is quite regular for clearness’ sake). Let the first of any ascending series of buds be represented by the curved projection filling the nearest angle of the pentagon at 1. Then the next bud, above, will fill the angle at 2; the next above, at 3, the next at 4, the next at 5. The sixth will come nearly over the first. That is to say, each projecting portion of the section, Fig. 5, expands into its bud, not successively, but by leaps, always to the next but one; the buds being thus placed in a nearly regular spiral order.

§ 8. I say nearly regular—for there are subtleties of variation in plan which it would be merely tiresome to enter into. All that we need care about is the general law, of which the oak spray furnishes a striking example,—that the buds of the first great group of alternate builders rise in a spiral order round the stem (I believe, for the most part, the spiral proceeds from right to left). And this spiral succession very frequently approximates to the pentagonal order, which it takes with great accuracy in an oak; for, merely assuming that each ascending bud places itself as far as it can easily out of the way of the one beneath, and yet not quite on the opposite side of the stem, we find the interval between the two must generally approximate to that left between 1 and 2, or 2 and 3, in Fig. 8.2

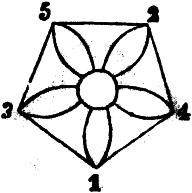

§ 9. Should the interval be consistently a little less than that which brings out the pentagonal structure, the plant seems to get at first into much difficulty. For, in such case, there is a probability of the buds falling into a triangle, as at A, Fig. 9; and then the fourth must come over the first, which would be inadmissible (we shall soon see why). Nevertheless, the plant seems to like the triangular result for its outline, and sets itself to get out of the difficulty with much ingenuity, by methods of succession, which I will examine farther in the next chapter: it being enough for us to know at present that the puzzled, but persevering, vegetable does get out of its difficulty and issues triumphantly, and with a peculiar expression of leafy exultation, in a hexagonal star, composed of two distinct triangles, normally as at B, Fig. 9. Why the buds do not like to be one above the other, we shall see in next chapter. Meantime I must shortly warn the reader of what we shall then discover, that, though we have spoken of the projections of our pentagonal tower as if they were first built to sustain each its leaf, they are themselves chiefly built by the leaf they seem to sustain. Without troubling ourselves about this yet, let us fix in our minds broadly the effective aspect of the matter, which is all we want, by a simple practical illustration.

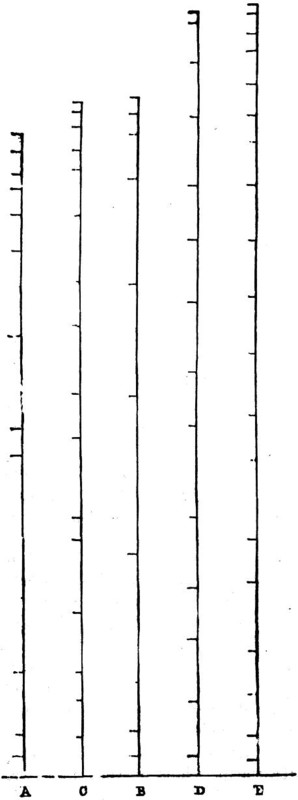

§ 10. Take a piece of stick half-an-inch thick, and a yard or two long, and tie large knots, at any equal distances you choose, on a piece of pack-thread. Then wind the pack-thread round the stick, with any number of equidistant turns you choose, from one end to the other, and the knots will take the position of buds in the general type of alternate vegetation. By varying the number of knots and the turns of the thread, you may get the system of any tree, with the exception of one character only—viz., that since the shoot grows faster at one time than another, the buds run closer together when the growth is slow. You cannot imitate this structure by closing the coils of your string, for that would alter the positions of your knots irregularly. The intervals between the buds are, by this gradual acceleration or retardation of growth, usually varied in lovely proportions. Fig. 10 shows the elevations of the buds on five different sprays of oak; A and B being of the real size (short shoots); C, D, and E, on a reduced scale. I have not traced the cause of the apparent tendency of the buds to follow in pairs, in these longer shoots.

§ 11. Lastly: If the spiral be constructed so as to bring the buds nearly on opposite sides of the stem, though alternate in succession, the stem, most probably, will shoot a little away from each bud after throwing it off, and thus establish the oscillatory form b, Fig. 11, which, when the buds are placed, as in this case, at diminishing intervals, is very beautiful.3

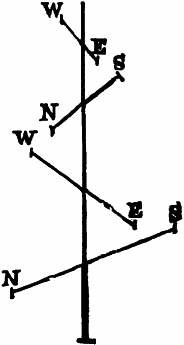

§ 12. I fear this has been a tiresome chapter; but it is necessary to master the elementary structure, if we are to understand anything of trees; and the reader will therefore, perhaps, take patience enough to look at one or two examples of the spray structure of the second great class of builders, in which the leaves are opposite. Nearly all opposite-leaved trees grow, normally, like vegetable weathercocks run to seed, with north and south, and east and west pointers thrown off alternately one over another, as in Fig. 12.