автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Life of Sir Isaac Newton

E-text prepared by Sonya Schermann, Charlie Howard,

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

from page images generously made available by

Internet Archive

(https://archive.org)

Note:

Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See

https://archive.org/details/56010330R.nlm.nih.govHARPER’S FAMILY LIBRARY.

DESIGNED FOR ADULT PERSONS.

“Books that you may carry to the fire, and hold readily in your hand, are the most useful after all. A man will often look at them, and be tempted to go on, when he would have been frightened at books of a larger size, and of a more erudite appearance.”—Dr. Johnson.

The proprietors of the Family Library feel themselves stimulated to increased exertions by the distinguished favour with which it has already been received.

The volumes now before the public may be confidently appealed to as proofs of zeal on the part of the publishers to present to their readers a series of productions, which, as they are connected, not with ephemeral, but with permanent subjects, may, years hence as well as now, be consulted for lively amusement as well as solid instruction.

To render this Library still more worthy of patronage, the proprietors propose incorporating in it such works of interest and value as may appear in the various Libraries and Miscellanies now preparing in Europe, particularly “Constable’s Miscellany,” the “Edinburgh Cabinet” Library, &c. All these productions, as they emanate from the press, will be submitted to literary gentlemen for inspection; and none will be reprinted but such as shall be found calculated to sustain the exalted character which this Library has already acquired.

Several well-known authors have been engaged to prepare for it original works of an American character, on History, Biography, Travels, &c. &c.

Every distinct subject will in general be comprehended in one volume, or at most in three volumes, which may form either a portion of the series or a complete work by itself; and each volume will be embellished with appropriate engravings.

The entire series will be the production of authors of eminence, who have acquired celebrity by their literary labours, and whose names, as they appear in succession, will afford the surest guarantee to the public for the satisfactory manner in which the subjects will be treated.

Such is the plan by which it is intended to form an American Family Library, comprising all that is valuable in those branches of knowledge which most happily unite entertainment with instruction. The utmost care will be taken, not only to exclude whatever can have an injurious influence on the mind, but to embrace every thing calculated to strengthen the best and most salutary impressions.

With these arrangements and facilities, the publishers flatter themselves that they shall be able to present to their fellow-citizens a work of unparalleled merit and cheapness, embracing subjects adapted to all classes of readers, and forming a body of literature deserving the praise of having instructed many, and amused all; and above every other species of eulogy, of being fit to be introduced, without reserve or exception, by the father of a family to the domestic circle. Meanwhile, the very low price at which it is charged renders more extensive patronage necessary for its support and prosecution. The immediate encouragement, therefore, of those who approve its plan and execution is respectfully solicited. The work may be obtained in complete sets, or in separate numbers, from the principal booksellers throughout the United States.

OPINIONS OF THE FAMILY LIBRARY.

“The publishers have hitherto fully deserved their daily increasing reputation by the good taste and judgment which have influenced the selections of works for the Family Library.”—Albany Daily Advertiser.

“The Family Library—A title which, from the valuable and entertaining matter the collection contains, as well as from the careful style of its execution, it well deserves. No family, indeed, in which there are children to be brought up, ought to be without this Library, as it furnishes the readiest resources for that education which ought to accompany or succeed that of the boarding-school or the academy, and is infinitely more conducive than either to the cultivation of the intellect.”—Monthly Review.

“It is the duty of every person having a family to put this excellent Library into the hands of his children.”—N. Y. Mercantile Advertiser.

“It is one of the recommendations of the Family Library, that it embraces a large circle of interesting matter, of important information and agreeable entertainment, in a concise manner and a cheap form. It is eminently calculated for a popular series—published at a price so low, that persons of the most moderate income may purchase it—combining a matter and a style that the most ordinary mind may comprehend it, at the same time that it is calculated to raise the moral and intellectual character of the people.”—Constellation.

“We have repeatedly borne testimony to the utility of this work. It is one of the best that has ever been issued from the American press, and should be in the library of every family desirous of treasuring up useful knowledge.”—Boston Statesman.

“We venture the assertion that there is no publication in the country more suitably adapted to the taste and requirements of the great mass of community, or better calculated to raise the intellectual character of the middling classes of society, than the Family Library.”—Boston Masonic Mirror.

“We have so often recommended this enterprising and useful publication (the Family Library), that we can here only add, that each successive number appears to confirm its merited popularity.”—N. Y. American.

“The little volumes of this series truly comport with their title, and are in themselves a Family Library.”—N. Y. Commercial Advertiser.

“We recommend the whole set of the Family Library as one of the cheapest means of affording pleasing instruction, and imparting a proper pride in books, with which we are acquainted.”—U. S. Gazette.

“It will prove instructing and amusing to all classes. We are pleased to learn that the works comprising this Library have become, as they ought to be, quite popular among the heads of families.”—N. Y. Gazette.

“The Family Library is, what its name implies, a collection of various original works of the best kind, containing reading useful and interesting to the family circle. It is neatly printed, and should be in every family that can afford it—the price being moderate.”—New-England Palladium.

“We are pleased to see that the publishers have obtained sufficient encouragement to continue their valuable Family Library.”—Baltimore Republican.

“The Family Library presents, in a compendious and convenient form, well-written histories of popular men, kingdoms, sciences, &c. arranged and edited by able writers, and drawn entirely from the most correct and accredited authorities. It is, as it professes to be, a Family Library, from which, at little expense, a household may prepare themselves for a consideration of those elementary subjects of education and society, without a due acquaintance with which neither man nor woman has claim to be well bred, or to take their proper place among those with whom they abide.”—Charleston Gazette.

BOY’S AND GIRL’S LIBRARY.

PROSPECTUS.

The Publishers of the “Boy’s and Girl’s Library” propose, under this title, to issue a series of cheap but attractive volumes, designed especially for the young. The undertaking originates not in the impression that there does not already exist in the treasures of the reading world a large provision for this class of the community. They are fully aware of the deep interest excited at the present day on the subject of the mental and moral training of the young, and of the amount of talent and labour bestowed upon the production of works aiming both at the solid culture and the innocent entertainment of the inquisitive minds of children. They would not therefore have their projected enterprise construed into an implication of the slightest disparagement of the merits of their predecessors in the same department. Indeed it is to the fact of the growing abundance rather than to the scarcity of useful productions of this description that the design of the present work is to be traced; as they are desirous of creating a channel through which the products of the many able pens enlisted in the service of the young may be advantageously conveyed to the public.

The contemplated course of publications will more especially embrace such works as are adapted, not to the extremes of early childhood or of advanced youth, but to that intermediate space which lies between childhood and the opening of maturity, when the trifles of the nursery and the simple lessons of the school-room have ceased to exercise their beneficial influence, but before the taste for a higher order of mental pleasure has established a fixed ascendency in their stead. In the selection of works intended for the rising generation in this plastic period of their existence, when the elements of future character are receiving their moulding impress, the Publishers pledge themselves that the utmost care and scrupulosity shall be exercised. They are fixed in their determination that nothing of a questionable tendency on the score of sentiment shall find admission into pages consecrated to the holy purpose of instructing the thoughts, regulating the passions, and settling the principles of the young.

In fine, the Publishers of the “Boy’s and Girl’s Library” would assure the Public that an adequate patronage alone is wanting to induce and enable them to secure the services of the most gifted pens in our country in the proposed publication, and thus to render it altogether worthy of the age and the object which calls it forth, and of the countenance which they solicit for it.

SIR. G. KNELLER PINX.

ENG.d BY GIMBER.

SIR ISAAC NEWTON.

HARPER’S FAMILY LIBRARY

Printed by R. Miller

Harper’s Stereotype Edition.

THE

LIFE

OF

SIR ISAAC NEWTON.

BY

DAVID BREWSTER, LL.D. F.R.S.

Ergo vivida vis animi pervicit, et extra Processit longe flammantia mœnia mundi; Atque omne immensum peragravit mente amimoque.

Lucret. lib. i. 1. 73.

The Birthplace of Newton.

NEW-YORK:

PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY J. & J. HARPER;

NO. 82 CLIFF-STREET,

AND SOLD BY THE BOOKSELLERS GENERALLY THROUGHOUT

THE UNITED STATES.

1833.

TO

THE RIGHT HONOURABLE

LORD BRAYBROOKE.

The kindness with which your lordship intrusted to me some very valuable materials for the composition of this volume has induced me to embrace the present opportunity of publicly acknowledging it. But even if this personal obligation had been less powerful, those literary attainments and that enlightened benevolence which reflect upon rank its highest lustre would have justified me in seeking for it the patronage of a name which they have so justly honoured.

DAVID BREWSTER.

Allerly, June 1st, 1831.

PREFACE.

As this is the only Life of Sir Isaac Newton on any considerable scale that has yet appeared, I have experienced great difficulty in preparing it for the public. The materials collected by preceding biographers were extremely scanty; the particulars of his early life, and even the historical details of his discoveries, have been less perfectly preserved than those of his illustrious predecessors; and it is not creditable to his disciples that they have allowed a whole century to elapse without any suitable record of the life and labours of a master who united every claim to their affection and gratitude.

In drawing up this volume, I have obtained much assistance from the account of Sir Isaac Newton in the Biographia Britannica; from the letters to Oldenburg, and other papers in Bishop Horsley’s edition of his works; from Turnor’s Collections for the History of the Town and Soke of Grantham; from M. Biot’s excellent Life of Newton in the Biographie Universelle; and from Lord King’s Life and Correspondence of Locke.

Although these works contain much important information respecting the Life of Newton, yet I have been so fortunate as to obtain many new materials of considerable value.

To the kindness of Lord Braybrooke I have been indebted for the interesting correspondence of Newton, Mr. Pepys, and Mr. Millington, which is now published for the first time, and which throws much light upon an event in the life of our author that has recently acquired an unexpected and a painful importance. These letters, when combined with those which passed between Newton and Locke, and with a curious extract from the manuscript diary of Mr. Abraham Pryme, kindly furnished to me by his collateral descendant Professor Pryme of Cambridge, fill up a blank in his history, and have enabled me to delineate in its true character that temporary indisposition which, from the view that has been taken of it by foreign philosophers, has been the occasion of such deep distress to the friends of science and religion.

To Professor Whewell, of Cambridge, I owe very great obligations for much valuable information. Professor Rigaud, of Oxford, to whose kindness I have on many other occasions been indebted, supplied me with several important facts, and with extracts from the diary of Hearne in the Bodleian Library, and from the original correspondence between Newton and Flamstead, which the president of Corpus Christi College had for this purpose committed to his care; and Dr. J. C. Gregory, of Edinburgh, the descendant of the illustrious inventor of the reflecting telescope, allowed me to use his unpublished account of an autograph manuscript of Sir Isaac Newton, which was found among the papers of David Gregory, Savilian Professor of Astronomy at Oxford, and which throws some light on the history of the Principia.

I have been indebted to many other friends for the communication of books and facts, but especially to Sir William Hamilton, Bart., whose liberality in promoting literary inquiry is not limited to the circle of his friends.

D. B.

Allerly, June 1st, 1831.

CONTENTS.

Page

CHAPTER I.The Pre-eminence of Sir Isaac Newton’s Reputation—The Interest attached to the Study of his Life and Writings—His Birth and Parentage—His early Education—Is sent to Grantham School—His early Attachment to Mechanical Pursuits—His Windmill—His Water-clock—His Self-moving Cart—His Sun-dials—His Preparation for the University

17

CHAPTER II.Newton enters Trinity College, Cambridge—Origin of his Propensity for Mathematics—He studies the Geometry of Descartes unassisted—Purchases a Prism—Revises Dr. Barrow’s Optical Lectures—Dr. Barrow’s Opinion respecting Colours—Takes his Degrees—Is appointed a Fellow of Trinity College—Succeeds Dr. Barrow in the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics

26

CHAPTER III.Newton occupied in grinding Hyperbolical Lenses—His first Experiments with the Prism made in 1666—He discovers the Composition of White Light, and the different Refrangibility of the Rays which compose it—Abandons his Attempts to improve Refracting Telescopes, and resolves to attempt the Construction of Reflecting ones—He quits Cambridge on account of the Plague—Constructs two Reflecting Telescopes in 1668, the first ever executed—One of them examined by the Royal Society, and shown to the King—He constructs a Telescope with Glass Specula—Recent History of the Reflecting Telescope—Mr. Airy’s Glass Specula—Hadley’s Reflecting Telescopes—Short’s—Herschel’s—Ramage’s—Lord Oxmantown’s

30

CHAPTER IV.He delivers a Course of Optical Lectures at Cambridge—Is elected Fellow of the Royal Society—He communicates to them his Discoveries on the different Refrangibility and Nature of Light—Popular Account of them—They involve him in various Controversies—His Dispute with Pardies—Linus—Lucas—Dr. Hooke and Mr. Huygens—The Influence of these Disputes on the mind of Newton

47

CHAPTER V.Mistake of Newton in supposing that the Improvement of Refracting

Telescopes was hopeless—Mr. Hall invents the Achromatic Telescope—Principles of the Achromatic Telescope explained—It is reinvented by Dollond, and improved by future Artists—Dr. Blair’s Aplanatic Telescope—Mistakes in Newton’s Analysis of the Spectrum—Modern Discoveries respecting the Structure of the Spectrum

63

CHAPTER VI.Colours of thin Plates first studied by Boyle and Hooke—Newton determines the Law of their Production—His Theory of Fits of easy Reflection and Transmission—Colours of thick Plates

75

CHAPTER VII.Newton’s Theory of the Colours of Natural Bodies explained—Objections to it stated—New Classification of Colours—Outline of a new Theory proposed

82

CHAPTER VIII.Newton’s Discoveries respecting the Inflection or Diffraction of Light—Previous Discoveries of Grimaldi and Dr. Hooke—Labours of succeeding Philosophers—Law of Interference of Dr. Young—Fresnel’s Discoveries—New Theory of Inflection on the Hypothesis of the Materiality of Light

98

CHAPTER IX.Miscellaneous Optical Researches of Newton—His Experiments on Refraction—His Conjecture respecting the Inflammability of the Diamond—His Law of Double Refraction—His Observations on the Polarization of Light—Newton’s Theory of Light—His “Optics”

106

CHAPTER X.Astronomical Discoveries of Newton—Necessity of combined Exertion to the completion of great Discoveries—Sketch of the History or Astronomy previous to the time of Newton—Copernicus, 1473–1543—Tycho Brahe, 1546–1601—Kepler, 1571–1631—Galileo, 1564–1642

110

CHAPTER XI.The first Idea of Gravity occurs to Newton in 1666—His first Speculations upon it—Interrupted by his Optical Experiments—He resumes the Subject in consequence of a Discussion with Doctor Hooke—He discovers the true Law of Gravity and the Cause of the Planetary Motions—Dr. Halley urges him to publish his Principia—His Principles of Natural Philosophy—Proceedings of the Royal Society on this Subject—The Principia appears in 1687—General Account of it, and of the Discoveries it contains—They meet with great Opposition, owing to the Prevalence of the Cartesian System—Account of the Reception and Progress of the Newtonian Philosophy in Foreign Countries—Account of its Progress and Establishment in England

140

CHAPTER XII.Doctrine of Infinite Quantities—Labours of Pappus—Kepler—Cavaleri—Roberval—Fermat—Wallis—Newton discovers the Binomial Theorem and the Doctrine of Fluxions in 1606—His Manuscript Work containing this Doctrine communicated to his Friends—His Treatise on Fluxions—His Mathematical Tracts—His Universal Arithmetic—His Methodus Differentialis—His Geometria Analytica—His Solution of the Problems proposed by Bernouilli and Leibnitz—Account of the celebrated Dispute respecting the Invention of Fluxions—Commercium Epistolicum—Report of the Royal Society—General View of the Controversy

168

CHAPTER XIII.James II. attacks the Privileges of the University of Cambridge—Newton chosen one of the Delegates to resist this Encroachment—He is elected a Member of the Convention Parliament—Burning of his Manuscript—His supposed Derangement of Mind—View taken of this by foreign Philosophers—His Correspondence with Mr. Pepys and Mr. Locke at the time of his Illness—Mr. Millington’s Letter to Mr. Pepys on the subject of Newton’s Illness—Refutation of the Statement that he laboured under Mental Derangement

200

CHAPTER XIV.No Mark of National Gratitude conferred upon Newton—Friendship between him and Charles Montague, afterward Earl of Halifax—Mr. Montague appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1694—He resolves upon a Recoinage—Nominates Mr. Newton Warden of the Mint in 1695—Mr. Newton appointed Master of the Mint in 1699—Notice of the Earl of Halifax—Mr. Newton elected Associate of the Academy of Sciences in 1699—Member for Cambridge in 1701—and President of the Royal Society in 1703—Queen Anne confers upon him the Honour of Knighthood in 1705—Second Edition of the Principia, edited by Cotes—His Conduct respecting Mr. Ditton’s Method of finding the Longitude

223

CHAPTER XV.Respect in which Newton was held at the Court of George I.—The Princess of Wales delighted with his Conversation—Leibnitz endeavours to prejudice the Princess against Sir Isaac and Locke—Controversy occasioned by his Conduct—The Princess obtains a Manuscript Abstract of his System of Chronology—The Abbé Conti is, at her request, allowed to take a Copy of it on the promise of Secrecy—He prints it surreptitiously in French, accompanied with a Refutation by M. Freret—Sir Isaac’s Defence of his System—Father Souciet attacks it, and is answered by Dr. Halley—Sir Isaac’s larger Work on Chronology published after his Death—Opinions respecting it—Sir Isaac’s Paper on the Form of the most ancient Year

234

CHAPTER XVI.Theological Studies of Sir Isaac—Their Importance to Christianity—Motives to which they have been ascribed—Opinions of Biot

and La Place considered—His Theological Researches begun before his supposed Mental Illness—The Date of these Works fixed—Letters to Locke—Account of his Observations on Prophecy—His Lexicon Propheticum—His Four Letters to Dr. Bentley—Origin of Newton’s Theological Studies—Analogy between the Book of Nature and that of Revelation

242

CHAPTER XVII.The Minor Discoveries and Inventions of Newton—His Researches on Heat—On Fire and Flame—On Elective Attraction—On the Structure of Bodies—His supposed Attachment to Alchymy—His Hypothesis respecting Ether as the Cause of Light and Gravity—On the Excitation of Electricity in Glass—His Reflecting Sextant invented before 1700—His Reflecting Microscope—His Prismatic Reflector as a Substitute for the small Speculum of Reflecting Telescopes—His Method of varying the Magnifying Power of Newtonian Telescopes—His Experiments on Impressions on the Retina

265

CHAPTER XVIII.His Acquaintance with Dr. Pemberton—Who edits the Third Edition of the Principia—His first Attack of ill Health—His Recovery—He is taken ill in consequence of attending the Royal Society—His Death on the 20th March, 1727—His Body lies in state—His Funeral—He is buried in Westminster Abbey—His Monument described—His Epitaph—A Medal struck in honour of him—Roubiliac’s full-length Statue of him erected in Cambridge—Division of his Property—His Successors

284

CHAPTER XIX.Permanence of Newton’s Reputation—Character of his Genius—His Method of Investigation similar to that used by Galileo—Error in ascribing his Discoveries to the Use of the Methods recommended by Lord Bacon—The Pretensions of the Baconian Philosophy examined—Sir Isaac Newton’s Social Character—His great Modesty—The Simplicity of his Character—His Religious and Moral Character—His Hospitality and Mode of Life—His Generosity and Charity—His Absence—His Personal Appearance—Statues and Pictures of him—Memorials and Recollections of him

292

Appendix, No. I.—Observations on the Family of Sir Isaac Newton

307

Appendix, No. II.—Letter from Sir Isaac Newton to Francis Aston, Esq., a young Friend who was on the eve of setting out on his Travels

316

Appendix, No. III.—“A Remarkable and Curious Conversation between Sir Isaac Newton and Mr. Conduit.”

320

LIFE OF SIR ISAAC NEWTON.

CHAPTER I.

The Pre-eminence of Sir Isaac Newton’s Reputation—The Interest attached to the Study of his Life and Writings—His Birth and Parentage—His early Education—Is sent to Grantham School—His early Attachment to Mechanical Pursuits—His Windmill—His Waterclock—His Self-moving Cart—His Sundials—His Preparation for the University.

The name of Sir Isaac Newton has by general consent been placed at the head of those great men who have been the ornaments of their species. However imposing be the attributes with which time has invested the sages and the heroes of antiquity, the brightness of their fame has been eclipsed by the splendour of his reputation; and neither the partiality of rival nations, nor the vanity of a presumptuous age, has ventured to dispute the ascendency of his genius. The philosopher,1 indeed, to whom posterity will probably assign the place next to Newton, has characterized the Principia as pre-eminent above all the productions of human intellect, and has thus divested of extravagance the contemporary encomium upon its author,

Nec fas est propius mortali attingere Divos.

Halley.

So near the gods—man cannot nearer go.

The biography of an individual so highly renowned cannot fail to excite a general interest. Though his course may have lain in the vale of private life, and may have been unmarked with those dramatic events which throw a lustre even round perishable names, yet the inquiring spirit will explore the history of a mind so richly endowed,—will study its intellectual and moral phases, and will seek the shelter of its authority on those great questions which reason has abandoned to faith and hope.

If the conduct and opinions of men of ordinary talent are recorded for our instruction, how interesting must it be to follow the most exalted genius through the incidents of common life;—to mark the steps by which he attained his lofty pre-eminence; to see how he performs the functions of the social and the domestic compact; how he exercises his lofty powers of invention and discovery; how he comports himself in the arena of intellectual strife; and in what sentiments, and with what aspirations he quits the world which he has adorned.

In almost all these bearings, the life and writings of Sir Isaac Newton abound with the richest counsel. Here the philosopher will learn the art by which alone he can acquire an immortal name. The moralist will trace the lineaments of a character adjusted to all the symmetry of which our imperfect nature is susceptible; and the Christian will contemplate with delight the high-priest of science quitting the study of the material universe,—the scene of his intellectual triumphs,—to investigate with humility and patience the mysteries of his faith.

* * * * *

Sir Isaac Newton was born at Woolsthorpe, a hamlet in the parish of Colsterworth, in Lincolnshire, about six miles south of Grantham, on the 25th December, O. S., 1642, exactly one year after Galileo died, and was baptized at Colsterworth on the 1st January, 1642–3. His father, Mr. Isaac Newton, died at the early age of thirty-six, a little more than a year after the death of his father Robert Newton, and only a few months after his marriage to Harriet Ayscough, daughter of James Ayscough of Market Overton in Rutlandshire. This lady was accordingly left in a state of pregnancy, and appears to have given a premature birth to her only and posthumous child. The helpless infant thus ushered into the world was of such an extremely diminutive size,2 and seemed of so perishable a frame, that two women who were sent to Lady Pakenham’s at North Witham, to bring some medicine to strengthen him, did not expect to find him alive on their return. Providence, however, had otherwise decreed; and that frail tenement which seemed scarcely able to imprison its immortal mind was destined to enjoy a vigorous maturity, and to survive even the average term of human existence. The estate of Woolsthorpe, in the manor-house of which this remarkable birth took place, had been more than a hundred years in the possession of the family, who came originally from Newton in Lancashire, but who had, previous to the purchase of Woolsthorpe, settled at Westby, in the county of Lincoln. The manor-house, of which we have given an engraving, is situated in a beautiful little valley, remarkable for its copious wells of pure spring water, on the west side of the river Witham, which has its origin in the neighbourhood, and commands an agreeable prospect to the east towards Colsterworth. The manor of Woolsthorpe was worth only 30l. per annum; but Mrs. Newton possessed another small estate at Sewstern,3 which raised the annual value of their property to about 80l.; and it is probable that the cultivation of the little farm on which she resided somewhat enlarged the limited income upon which she had to support herself, and educate her child.

For three years Mrs. Newton continued to watch over her tender charge with parental anxiety; but in consequence of her marriage to the Reverend Barnabas Smith, rector of North Witham, about a mile south of Woolsthorpe, she left him under the care of her own mother. At the usual age he was sent to two day-schools at Skillington and Stoke, where he acquired the education which such seminaries afforded; but when he reached his twelfth year he went to the public school at Grantham, taught by Mr. Stokes, and was boarded at the house of Mr. Clark, an apothecary in that town. According to information which Sir Isaac himself gave to Mr. Conduit, he seems to have been very inattentive to his studies, and very low in the school. The boy, however, who was above him, having one day given him a severe kick upon his stomach, from which he suffered great pain, Isaac laboured incessantly till he got above him in the school, and from that time he continued to rise till he was the head boy. From the habits of application which this incident had led him to form, the peculiar character of his mind was speedily displayed. During the hours of play, when the other boys were occupied with their amusements, his mind was engrossed with mechanical contrivances, either in imitation of something which he had seen, or in execution of some original conception of his own. For this purpose he provided himself with little saws, hatchets, hammers, and all sorts of tools, which he acquired the art of using with singular dexterity. The principal pieces of mechanism which he thus constructed were a windmill, a waterclock, and a carriage put in motion by the person who sat in it. When a windmill was erecting near Grantham on the road to Gunnerby, Isaac frequently attended the operations of the workmen, and acquired such a thorough knowledge of the machinery that he completed a working model of it, which excited universal admiration. This model was frequently placed on the top of the house in which he lodged at Grantham, and was put in motion by the action of the wind upon its sails. Not content with this exact imitation of the original machine, he conceived the idea of driving it by animal power, and for this purpose he enclosed in it a mouse which he called the miller, and which, by acting upon a sort of treadwheel, gave motion to the machine. According to some accounts, the mouse was made to advance by pulling a string attached to its tail, while others allege that the power of the little agent was called forth by its unavailing attempts to reach a portion of corn placed above the wheel.

His waterclock was formed out of a box which he had solicited from Mrs. Clark’s brother. It was about four feet high, and of a proportional breadth, somewhat like a common houseclock. The index of the dialplate was turned by a piece of wood, which either fell or rose by the action of dropping water. As it stood in his own bedroom he supplied it every morning with the requisite quantity of water, and it was used as a clock by Mr. Clark’s family, and remained in the house long after its inventor had quitted Grantham.4 His mechanical carriage was a vehicle with four wheels, which was put in motion with a handle wrought by the person who sat in it, but, like Merlin’s chair, it seems to have been used only on the smooth surface of a floor, and not fitted to overcome the inequalities of a road. Although Newton was at this time “a sober, silent, thinking lad,” who scarcely ever joined in the ordinary games of his schoolfellows, yet he took great pleasure in providing them with amusements of a scientific character. He introduced into the school the flying of paper kites; and he is said to have been at great pains in determining their best forms and proportions, and in ascertaining the position and number of the points by which the string should be attached. He made also paper lanterns, by the light of which he went to school in the winter mornings, and he frequently attached these lanterns to the tails of his kites in a dark night, so as to inspire the country people with the belief that they were comets.

In the house where he lodged there were some female inmates in whose company he appears to have taken much pleasure. One of these, a Miss Storey, sister to Dr. Storey, a physician at Buckminster, near Colsterworth, was two or three years younger than Newton, and to great personal attractions she seems to have added more than the usual allotment of female talent. The society of this young lady and her companions was always preferred to that of his own schoolfellows, and it was one of his most agreeable occupations to construct for them little tables and cupboards, and other utensils for holding their dolls and their trinkets. He had lived nearly six years in the same house with Miss Storey, and there is reason to believe that their youthful friendship gradually rose to a higher passion; but the smallness of her portion and the inadequacy of his own fortune appear to have prevented the consummation of their happiness. Miss Storey was afterward twice married, and under the name of Mrs. Vincent, Dr. Stukely visited her at Grantham in 1727, at the age of eighty-two, and obtained from her many particulars respecting the early history of our author. Newton’s esteem for her continued unabated during his life. He regularly visited her when he went to Lincolnshire, and never failed to relieve her from little pecuniary difficulties which seem to have beset her family.

Among the early passions of Newton we must recount his love of drawing; and even of writing verses. His own room was furnished with pictures drawn, coloured, and framed by himself, sometimes from copies, but often from life.5 Among these were portraits of Dr. Donne, Mr. Stokes, the master of Grantham school, and King Charles I. under whose picture were the following verses.

A secret art my soul requires to try, If prayers can give me what the wars deny. Three crowns distinguished here, in order do Present their objects to my knowing view. Earth’s crown, thus at my feet I can disdain, Which heavy is, and at the best but vain. But now a crown of thorns I gladly greet, Sharp is this crown, but not so sharp as sweet; The crown of glory that I yonder see Is full of bliss and of eternity.

These verses were repeated to Dr. Stukely by Mrs. Vincent, who believed them to be written by Sir Isaac, a circumstance which is the more probable, as he himself assured Mr. Conduit, with some expression of pleasure, that he “excelled in making verses,” although he had been heard to express a contempt for poetical composition.

But while the mind of our young philosopher was principally occupied with the pursuits which we have now detailed, it was not inattentive to the movements of the celestial bodies, on which he was destined to throw such a brilliant light. The imperfections of his waterclock had probably directed his thoughts to the more accurate measure of time which the motion of the sun afforded. In the yard of the house where he lived, he traced the varying movements of that luminary upon the walls and roofs of the buildings, and by means of fixed pins he had marked out the hourly and half-hourly subdivisions. One of these dials, which went by the name of Isaac’s dial, and was often referred to by the country people for the hour of the day, appears to have been drawn solely from the observations of several years; but we are not informed whether all the dials which he drew on the wall of his house at Woolsthorpe, and which existed after his death, were of the same description, or were projected from his knowledge of the doctrine of the sphere.

Upon the death of the Reverend Mr. Smith in the year 1656, his widow left the rectory of North Witham, and took up her residence at Woolsthorpe along with her three children, Mary, Benjamin, and Hannah Smith. Newton had now attained the fifteenth year of his age, and had made great progress in his studies; and as he was thought capable of being useful in the management of the farm and country business at Woolsthorpe, his mother, chiefly from a motive of economy, recalled him from the school at Grantham. In order to accustom him to the art of selling and buying, two of the most important branches of rural labour, he was frequently sent on Saturday to Grantham market to dispose of grain and other articles of farm produce, and to purchase such necessaries as the family required. As he had yet acquired no experience, an old trustworthy servant generally accompanied him on these errands. The inn which they patronised was the Saracen’s Head at West Gate; but no sooner had they put up their horses than our young philosopher deserted his commercial concerns, and betook himself to his former lodging in the apothecary’s garret, where a number of Mr. Clark’s old books afforded him abundance of entertainment till his aged guardian had executed the family commissions, and announced to him the necessity of returning. At other times he deserted his duties at an earlier stage, and intrenched himself under a hedge by the way-side, where he continued his studies till the servant returned from Grantham. The more immediate affairs of the farm were not more prosperous under his management than would have been his marketings at Grantham. The perusal of a book, the execution of a model, or the superintendence of a waterwheel of his own construction, whirling the glittering spray from some neighbouring stream, absorbed all his thoughts when the sheep were going astray, and the cattle were devouring or treading down the corn.

Mrs. Smith was soon convinced from experience that her son was not destined to cultivate the soil, and as his passion for study, and his dislike for every other occupation increased with his years, she wisely resolved to give him all the advantages which education could confer. He was accordingly sent back to Grantham school, where he continued for some months in busy preparation for his academical studies. His uncle, the Reverend W. Ayscough, who was rector of Burton Coggles, about three miles east of Woolsthorpe, and who had himself studied at Trinity College, recommended to his nephew to enter that society, and it was accordingly determined that he should proceed to Cambridge at the approaching term.6

CHAPTER II.

Newton enters Trinity College, Cambridge—Origin of his Propensity for Mathematics—He studies the Geometry of Descartes unassisted—Purchases a Prism—Revises Dr. Harrow’s Optical Lectures—Dr. Barrow’s Opinion respecting Colours—Takes his Degrees—Is appointed a Fellow of Trinity College—Succeeds Dr. Barrow in the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics.

To a young mind thirsting for knowledge, and ambitious of the distinction which it brings, the transition from a village school to a university like that of Cambridge,—from the absolute solitude of thought to the society of men imbued with all the literature and science of the age,—must be one of eventful interest. To Newton it was a source of peculiar excitement. The history of science affords many examples where the young aspirant had been early initiated into her mysteries, and had even exercised his powers of invention and discovery before he was admitted within the walls of a college; but he who was to give philosophy her laws did not exhibit such early talent; no friendly counsel regulated his youthful studies, and no work of scientific eminence seems to have guided him in his course. In yielding to the impulse of his mechanical genius, his mind obeyed the laws of its own natural expansion, and, following the line of least resistance, it was thus drawn aside from the strongholds with which it was destined to grapple.

When Newton, therefore, arrived at Trinity College, he brought with him a more slender portion of science than falls to the lot of ordinary scholars; but this state of his acquirements was perhaps not unfavourable to the development of his powers. Unexhausted by premature growth, and invigorated by healthful repose, his mind was the better fitted to make those vigorous and rapid shoots which soon covered with foliage and with fruit the genial soil to which it had been transferred.

Cambridge was consequently the real birthplace of Newton’s genius. Her teachers fostered his earliest studies;—her institutions sustained his mightiest efforts;—and within her precincts were all his discoveries made and perfected. When he was called to higher official functions, his disciples kept up the pre-eminence of their master’s philosophy, and their successors have maintained this seat of learning in the fulness of its glory, and rendered it the most distinguished among the universities of Europe.

It was on the 5th of June, 1660, in the 18th year of his age, that Newton was admitted into Trinity College, Cambridge, during the same year that Dr. Barrow was elected professor of Greek in the university. His attention was first turned to the study of mathematics by a desire to inquire into the truth of judicial astrology; and he is said to have discovered the folly of that study by erecting a figure with the aid of one or two of the problems of Euclid. The propositions contained in this ancient system of geometry he regarded as self-evident truths; and without any preliminary study he made himself master of Descartes’s Geometry by his genius and patient application. This neglect of the elementary truths of geometry he afterward regarded as a mistake in his mathematical studies, and he expressed to Dr. Pemberton his regret that “he had applied himself to the works of Descartes, and other algebraic writers, before he had considered the elements of Euclid with that attention which so excellent a writer deserved.7 Dr. Wallis’s Arithmetic of Infinites, Saunderson’s Logic, and the Optics of Kepler were among the books which he had studied with care. On these works he wrote comments during their perusal; and so great was his progress, that he is reported to have found himself more deeply versed in some branches of knowledge than the tutor who directed his studies.

Neither history nor tradition has handed down to us any particular account of his progress during the first three years that he spent at Cambridge. It appears from a statement of his expenses, that in 1664 he purchased a prism, for the purpose, as has been said, of examining Descartes’s theory of colours; and it is stated by Mr. Conduit, that he soon established his own views on the subject, and detected the errors in those of the French philosopher. This, however, does not seem to have been the case. Had he discovered the composition of light in 1664 or 1665, it is not likely that he would have withheld it, not only from the Royal Society, but from his own friends at Cambridge till the year 1671. His friend and tutor, Dr. Barrow, was made Lucasian Professor of Mathematics in 1663, and the optical lectures which he afterward delivered were published in 1669. In the preface of this work he acknowledges his obligations to his colleague, Mr. Isaac Newton,8 for having revised the MSS., and corrected several oversights, and made some important suggestions. In the twelfth lecture there are some observations on the nature and origin of colours, which Newton could not have permitted his friend to publish had he been then in possession of their true theory. According to Dr. Barrow, White is that which discharges a copious light equally clear in every direction; Black is that which does not emit light at all, or which does it very sparingly. Red is that which emits a light more clear than usual, but interrupted by shady interstices. Blue is that which discharges a rarified light, as in bodies which consist of white and black particles arranged alternately. Green is nearly allied to blue. Yellow is a mixture of much white and a little red; and Purple consists of a great deal of blue mixed with a small portion of red. The blue colour of the sea arises from the whiteness of the salt which it contains, mixed with the blackness of the pure water in which the salt is dissolved; and the blueness of the shadows of bodies, seen at the same time by candle and daylight, arises from the whiteness of the paper mixed with the faint light or blackness of the twilight. These opinions savour so little of genuine philosophy that they must have attracted the observation of Newton, and had he discovered at that time that white was a mixture of all the colours, and black a privation of them all, he could not have permitted the absurd speculations of his master to pass uncorrected.

That Newton had not distinguished himself by any positive discovery so early as 1664 or 1665, may be inferred also from the circumstances which attended the competition for the law fellowship of Trinity College. The candidates for this appointment were himself and Mr. Robert Uvedale; and Dr. Barrow, then Master of Trinity, having found them perfectly equal in their attainments, conferred the fellowship on Mr. Uvedale as the senior candidate.

In the books of the university, Newton is recorded as having been admitted sub-sizer in 1661. He became a scholar in 1664. In 1665 he took his degree of Bachelor of Arts, and in 1666, in consequence of the breaking out of the plague, he retired to Woolsthorpe. In 1667 he was made Junior Fellow. In 1668 he took his degree of Master of Arts, and in the same year he was appointed to a Senior Fellowship. In 1669, when Dr. Barrow had resolved to devote his attention to theology, he resigned the Lucasian Professorship of Mathematics in favour of Newton, who may now be considered as having entered upon that brilliant career of discovery the history of which will form the subject of some of the following chapters.

CHAPTER III.

Newton, occupied in grinding Hyperbolical Lenses—His first Experiments with the Prism made in 1666—He discovers the Composition of White Light, and the different Refrangibility of the Rays which compose it—Abandons his Attempts to improve Refracting Telescopes and resolves to attempt the Construction of Reflecting ones—He quits Cambridge on account of the Plague—Constructs two Reflecting Telescopes in 1668, the first ever executed—One of them examined by the Royal Society, and shown to the King—He constructs a Telescope with Glass Specula—Recent History of the Reflecting Telescope—Mr. Airy’s Glass Specula—Hadley’s Reflecting Telescopes—Short’s—Herschel’s—Ramage’s—Lord Oxmantown’s.

The appointment of Newton to the Lucasian chair at Cambridge seems to have been coeval with his grandest discoveries. The first of these of which the date is well authenticated is that of the different refrangibility of the rays of light, which he established in 1666. The germ of the doctrine of universal gravitation seems to have presented itself to him in the same year, or at least in 1667; and “in the year 1666 or before”9 he was in possession of his method of fluxions, and he had brought it to such a state in the beginning of 1669, that he permitted Dr. Barrow to communicate it to Mr. Collins on the 20th of June in that year.

Although we have already mentioned, on the authority of a written memorandum of Newton himself, that he purchased a prism at Cambridge in 1664, yet he does not appear to have made any use of it, as he informs us that it was in 1666 that he “procured a triangular glass prism to try therewith the celebrated phenomena of colours.”10 During that year he had applied himself to the grinding of “optic glasses, of other figures than spherical,” and having, no doubt, experienced the impracticability of executing such lenses, the idea of examining the phenomena of colour was one of those sagacious and fortunate impulses which more than once led him to discovery. Descartes in his Dioptrice, published in 1629, and more recently James Gregory in his Optica Promota published in 1663, had shown that parallel and diverging rays could be reflected or refracted, with mathematical accuracy, to a point or focus, by giving the surface a parabolic, an elliptical, or a hyperbolic form, or some other form not spherical. Descartes had even invented and described machines by which lenses of these shapes could be ground and polished, and the perfection of the refracting telescope was supposed to depend on the degree of accuracy with which they could be executed.

In attempting to grind glasses that were not spherical, Newton seems to have conjectured that the defects of lenses, and consequently of refracting telescopes, might arise from some other cause than the imperfect convergency of rays to a single point, and this conjecture was happily realized in those fine discoveries of which we shall now endeavour to give some account.

When Newton began this inquiry, philosophers of the highest genius were directing all the energies of their mind to the subject of light, and to the improvement of the refracting telescope. James Gregory of Aberdeen had invented his reflecting telescope. Descartes had explained the theory and exerted himself in perfecting the construction of the common refracting telescope, and Huygens had not only executed the magnificent instruments by which he discovered the ring and the satellites of Saturn, but had begun those splendid researches respecting the nature of light, and the phenomena of double refraction, which have led his successors to such brilliant discoveries. Newton, therefore, arose when the science of light was ready for some great accession, and at the precise time when he was required to propagate the impulse which it had received from his illustrious predecessors.

The ignorance which then prevailed respecting the nature and origin of colours is sufficiently apparent from the account we have already given of Dr. Barrow’s speculations on this subject. It was always supposed that light of every colour was equally refracted or bent out of its direction when it passed through any lens or prism, or other refracting medium; and though the exhibition of colours by the prism had been often made previous to the time of Newton, yet no philosopher seems to have attempted to analyze the phenomena.

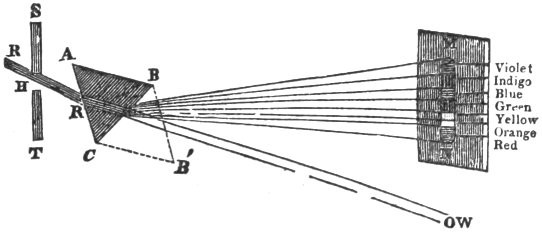

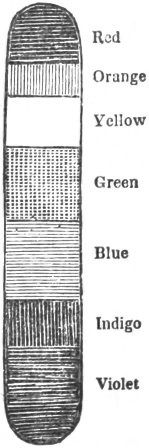

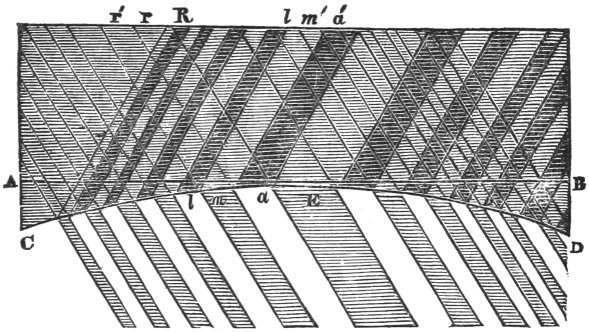

Fig. 1.

When he had procured his triangular glass prism, a section of which is shown at ABC, (fig. 1,) he made a hole H in one of his window-shutters, SHT, and having darkened his chamber, he let in a convenient quantity of the sun’s light RR, which, passing through the prism ABC, was so refracted as to exhibit all the different colours on the wall at MN, forming an image about five times as long as it was broad. “It was at first,” says our author, “a very pleasing divertisement to view the vivid and intense colours produced thereby,” but this pleasure was immediately succeeded by surprise at various circumstances which he had not expected. According to the received laws of refraction, he expected the image MN to be circular, like the white image at W, which the sunbeam RR had formed on the wall previous to the interposition of the prism; but when he found it to be no less than five times larger than its breadth, it “excited in him a more than ordinary curiosity to examine from whence it might proceed. He could scarcely think that the various thickness of the glass, or the termination with shadow or darkness, could have any influence on light to produce such an effect: yet he thought it not amiss first to examine those circumstances, and so find what would happen by transmitting light through parts of the glass of divers thicknesses, or through holes in the window of divers bignesses, or by setting the prism without (on the other side of ST), so that the light might pass through it and be refracted before it was terminated by the hole; but he found none of these circumstances material. The fashion of the colours was in all those cases the same.”

Newton next suspected that some unevenness in the glass, or other accidental irregularity, might cause the dilatation of the colours. In order to try this, he took another prism BCB′, and placed it in such a manner that the light RRW passing through them both might be refracted contrary ways, and thus returned by BCB′ into that course RRW, from which the prism ABC had diverted it, for by this means he thought the regular effects of the prism ABC would be destroyed by the prism BCB′, and the irregular ones more augmented by the multiplicity of refractions. The result was, that the light which was diffused by the first prism ABC into an oblong form, was reduced by the second prism BCB′ into a circular one W, with as much regularity as when it did not pass through them at all; so that whatever was the cause of the length of the image MN, it did not arise from any irregularity in the prism.

Our author next proceeded to examine more critically what might be effected by the difference of the incidence of the rays proceeding from different parts of the sun’s disk: but by taking accurate measures of the lines and angles, he found that the angle of the emergent rays should be 31 minutes equal to the sun’s diameter, whereas the real angle subtended by MN at the hole H was 2° 49′. But as this computation was founded on the hypothesis, that the sine of the angle of incidence was proportional to the sine of the angle of refraction, which from his own experience he could not imagine to be so erroneous as to make that angle but 31′, which was in reality 2° 49′, yet “his curiosity caused him again to take up his prism” ABC, and having turned it round in both directions, so as to make the rays RR fall both with greater and with less obliquity upon the face AC, he found that the colours on the wall did not sensibly change their place; and hence he obtained a decided proof that they could not be occasioned by a difference in the incidence of the light radiating from different parts of the sun’s disk.

Newton then began to suspect that the rays, after passing through the prism, might move in curve lines, and, in proportion to the different degrees of curvature, might tend to different parts of the wall; and this suspicion was strengthened by the recollection that he had often seen a tennis-ball struck with an oblique racket describe such a curve line. In this case a circular and a progressive motion is communicated to the ball by the stroke, and in consequence of this, the direction of its motion was curvilineal, so that if the rays of light were globular bodies, they might acquire a circulating motion by their oblique passage out of one medium into another, and thus move like the tennis-ball in a curve line. Notwithstanding, however, “this plausible ground of suspicion,” he could discover no such curvature in their direction, and, what was enough for his purpose, he observed that the difference between the length MN of the image, and the diameter of the hole H, was proportional to their distance HM, which could not have happened had the rays moved in curvilineal paths.

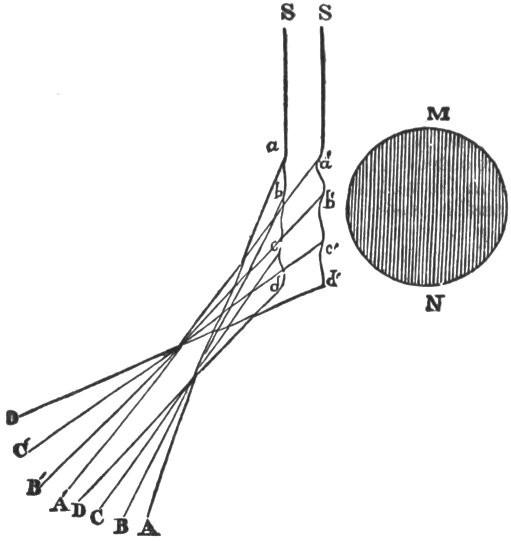

These different hypotheses, or suspicions, as Newton calls them, being thus gradually removed, he was at length led to an experiment which determined beyond a doubt the true cause of the elongation of the coloured image. Having taken a board with a small hole in it, he placed it behind the face BC of the prism, and close to it, so that he could transmit through the hole any one of the colours in MN, and keep back all the rest. When the hole, for example, was near C, no other light but the red fell upon the wall at N. He then placed behind N another board with a hole in it, and behind this board he placed another prism, so as to receive the red light at N, which passed through this hole in the second board. He then turned round the first prism ABC so as to make all the colours pass in succession through these two holes, and he marked their places on the wall. From the variation of these places, he saw that the red rays at N were less refracted by the second prism than the orange rays, the orange less than the yellow, and so on, the violet being more refracted than all the rest.

Hence he drew the grand conclusion, that light was not homogeneous, but consisted of rays, some of which were more refrangible than others.

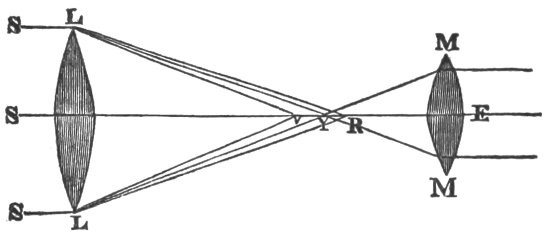

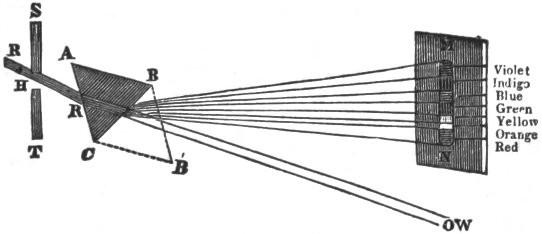

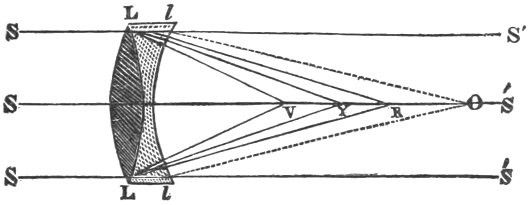

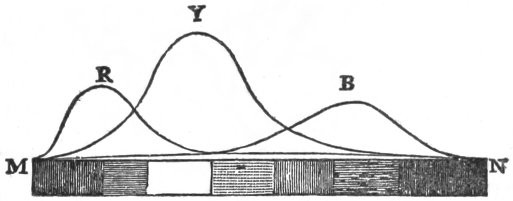

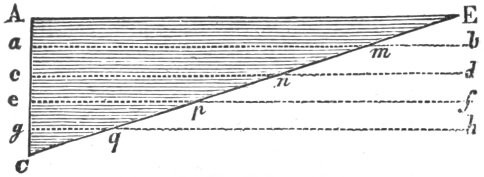

As soon as this important truth was established, Sir Isaac saw that a lens which refracts light exactly like a prism must also refract the differently coloured rays with different degrees of force, bringing the violet rays to a focus nearer the glass than the red rays. This is shown in fig. 2, where LL is a convex lens, and S, L, SL rays of the sun falling upon it in parallel directions. The violet rays existing in the white light SL being more refrangible than the rest, will be more refracted or bent, and will meet at V, forming there a violet image of the sun. In like manner the yellow rays will form an image of the sun at Y, and so on, the red rays, which are the least refrangible, being brought to a focus at R, and there forming a red image of the sun.

Fig. 2.

Hence, if we suppose LL to be the object-glass of a telescope directed to the sun, and MM an eye-glass through which the eye at E sees magnified the image or picture of the sun formed by LL, it cannot see distinctly all the different images between R and V. If it is adjusted so as to see distinctly the yellow image at Y, as it is in the figure, it will not see distinctly either the red or violet images, nor indeed any of them but the yellow one. There will consequently be a distinct yellow image, with indistinct images of all the other colours, producing great confusion and indistinctness of vision. As soon as Sir Isaac perceived this result of his discovery, he abandoned his attempts to improve the refracting telescope, and took into consideration the principle of reflection; and as he found that rays of all colours were reflected regularly, so that the angle of reflection was equal to the angle of incidence, he concluded that, upon this principle, optical instruments might be brought to any degree of perfection imaginable, provided a reflecting substance could be found which could polish as finely as glass, and reflect as much light as glass transmits, and provided a method of communicating to it a parabolic figure could be obtained. These difficulties, however, appeared to him very great, and he even thought them insuperable when he considered that, as any irregularity in a reflecting surface makes the rays deviate five or six times more from their true path than similar irregularities in a refracting surface, a much greater degree of nicety would be required in figuring reflecting specula than refracting lenses.

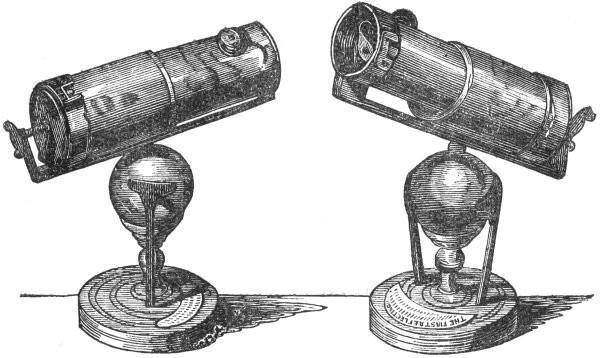

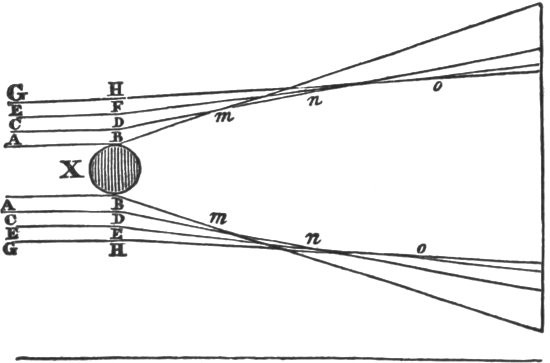

Such was the progress of Newton’s optical discoveries, when he was forced to quit Cambridge in 1666 by the plague which then desolated England, and more than two years elapsed before he proceeded any farther. In 1668 he resumed the inquiry, and having thought of a delicate method of polishing, proper for metals, by which, as he conceived, “the figure would be corrected to the last,” he began to put this method to the test of experiment. At this time he was acquainted with the proposal of Mr. James Gregory, contained in his Optica Promota, to construct a reflecting telescope with two concave specula, the largest of which had a hole in the middle of the larger speculum, to transmit the light to an eye-glass;11 but he conceived that it would be an improvement on this instrument to place the eye-glass at the side of the tube, and to reflect the rays to it by an oval plane speculum. One of these instruments he actually executed with his own hands; and he gave an account of it in a letter to a friend, dated February 23d, 1668–9, a letter which is also remarkable for containing the first allusion to his discoveries respecting colours. Previous to this he was in correspondence on the subject with Mr. Ent, afterward Sir George Ent, one of the original council of the Royal Society, an eminent medical writer of his day, and President of the College of Physicians. In a letter to Mr. Ent he had promised an account of his telescope to their mutual friend, and the letter to which we now allude contained the fulfilment of that promise. The telescope was six inches long. It bore an aperture in the large speculum something more than an inch, and as the eye-glass was a plano-convex lens, whose focal length was one-sixth or one-seventh of an inch, it magnified about forty times, which, as Newton remarks, was more than any six-foot tube (meaning refracting telescopes) could do with distinctness. On account of the badness of the materials, however, and the want of a good polish, it represented objects less distinct than a six-feet tube, though he still thought it would be equal to a three or four feet tube directed to common objects. He had seen through it Jupiter distinctly with his four satellites, and also the horns or moon-like phases of Venus, though this last phenomenon required some niceness in adjusting the instrument.

Although Newton considered this little instrument as in itself contemptible, yet he regarded it as an “epitome of what might be done;” and he expressed his conviction that a six-feet telescope might be made after this method, which would perform as well as a sixty or a hundred feet telescope made in the common way; and that if a common refracting telescope could be made of the “purest glass exquisitely polished, with the best figure that any geometrician (Descartes, &c.) hath or can design,” it would scarcely perform better than a common telescope. This, he adds, may seem a paradoxical assertion, yet he continues, “it is the necessary consequence of some experiments which I have made concerning the nature of light.”

The telescope now described possesses a very peculiar interest, as being the first reflecting one which was ever executed and directed to the heavens. James Gregory, indeed, had attempted, in 1664 or 1665, to construct his instrument. He employed Messrs. Rives and Cox, who were celebrated glass-grinders of that time, to execute a concave speculum of six feet radius, and likewise a small one; but as they had failed in polishing the large one, and as Mr. Gregory was on the eve of going abroad, he troubled himself no farther about the experiment, and the tube of the telescope was never made. Some time afterward, indeed, he “made some trials both with a little concave and convex speculum,” but, “possessed with the fancy of the defective figure, he would not be at the pains to fix every thing in its due distance.”

Such were the earliest attempts to construct the reflecting telescope, that noble instrument which has since effected such splendid discoveries in astronomy. Looking back from the present advanced state of practical science, how great is the contrast between the loose specula of Gregory and the fine Gregorian telescopes of Hadley, Short, and Veitch,—between the humble six-inch tube of Newton and the gigantic instruments of Herschel and Ramage.

The success of this first experiment inspired Newton with fresh zeal, and though his mind was now occupied with his optical discoveries, with the elements of his method of fluxions, and with the expanding germ of his theory of universal gravitation, yet with all the ardour of youth he applied himself to the laborious operation of executing another reflecting telescope with his own hands. This instrument, which was better than the first, though it lay by him several years, excited some interest at Cambridge; and Sir Isaac himself informs us, that one of the fellows of Trinity College had completed a telescope of the same kind, which he considered as somewhat superior to his own. The existence of these telescopes having become known to the Royal Society, Newton was requested to send his instrument for examination to that learned body. He accordingly transmitted it to Mr. Oldenburg in December, 1671, and from this epoch his name began to acquire that celebrity by which it has been so peculiarly distinguished.

On the 11th of January, 1672, it was announced to the Royal Society that his reflecting telescope had been shown to the king, and had been examined by the president, Sir Robert Moray, Sir Paul Neale, Sir Christopher Wren, and Mr. Hook. These gentlemen entertained so high an opinion of it, that, in order to secure the honour of the contrivance to its author, they advised the inventor to send a drawing and description of it to Mr. Huygens at Paris. Mr. Oldenburg accordingly drew up a description of it in Latin, which, after being corrected by Mr. Newton, was transmitted to that eminent philosopher. This telescope, of which the annexed is an accurate drawing, is carefully preserved in the library of the Royal Society of London, with the following inscription:—

“Invented by Sir Isaac Newton and made with his own hands, 1671.”

1 The Marquis La Place.—See Systême du Monde, p. 336.

2 Sir Isaac Newton told Mr. Conduit, that he had often heard his mother say that when he was born he was so little that they might have put him into a quart mug.

3 In Leicestershire, and about three miles south-east of Woolsthorpe.

4 “I remember once,” says Dr. Stukely, “when I was deputy to Dr. Hailey, secretary at the Royal Society, Sir Isaac talked of these kind of instruments. That he observed the chief inconvenience in them was, that the hole through which the water is transmitted being necessarily very small, was subject to be furred up by impurities in the water, as those made with sand will wear bigger, which at length causes an inequality in time.”—Stukely’s Letter to Dr. Mead.—Turnor’s Collections, p. 177.

5 Mr. Clark informed Dr. Stukely that the walls of the room in which Sir Isaac lodged were covered with charcoal drawings of birds, beasts, men, ships, and mathematical figures, all of which were very well designed.

6 “One of his uncles,” says M. Biot, “having one day found him under a hedge with a book in his hand and entirely absorbed in meditation, took it from him, and found that he was occupied in the solution of a mathematical problem. Struck with finding so serious and so active a disposition at so early an age, he urged his mother no longer to thwart him, and to send him back to Grantham to continue his studies.” I have omitted this anecdote in the text, as I cannot find it in Turner’s Collections, from which M. Biot derived his details of Newton’s infancy, nor in any other work.

7 Pemberton’s View of Sir Isaac Newton’s Philosophy. Pref.

8 Peregregiæ vir indolis ac insignis peritiæ.—Epist ad. Lect.

9 See Newton’s Letter to the Abbé Conti, dated February 26, 1715–16, in the Additamenta Comm. Epistolici.

10 Newtoni Opera, tom. iv. p. 205, Letter to Oldenburg.

11 M. Biot, in his Life of Newton, has stated that Newton was preceded in the invention of the reflecting telescope by Gregory, but probably without knowing it. It is quite certain, however, that Newton was acquainted with Gregory’s invention, as appears from the following avowal of it. “When I first applied myself to try the effects of reflection, Mr. Gregory’s Optica Promota (printed in the year 1663) having fallen into my hands, where there is an instrument described with a hole in the midst of the object-glass, to transmit the light to an eye-glass placed behind it, I had thence an occasion of considering that sort of construction, and found their disadvantages so great, that I saw it necessary before I attempted any thing in the practice to alter the design of them, and place the eye-glass at the side of the tube rather than at the middle.”—Letter to Oldenburg, May 4th, 1672.

Fig. 3.

Sir Isaac Newton’s Reflecting Telescope.

It does not appear that Newton executed any other reflecting telescopes than the two we have mentioned. He informs us that he repolished and greatly improved a fourteen-feet object-glass, executed by a London artist, and having proposed in 1678 to substitute glass reflectors in place of metallic specula, he tried to make a reflecting telescope on this principle four feet long, and with a magnifying power of 150. The glass was wrought by a London artist, and though it seemed well finished, yet, when it was quicksilvered on its convex side, it exhibited all over the glass innumerable inequalities, which gave an indistinctness to every object. He expresses, however, his conviction that nothing but good workmanship is wanting to perfect these telescopes, and he recommends their consideration “to the curious in figuring glasses.”

For a period of fifty years this recommendation excited no notice. At last Mr. James Short of Edinburgh, an artist of consummate skill, executed about the year 1730 no fewer than six reflecting telescopes with glass specula, three of fifteen inches, and three of nine inches in focal length. He found it extremely troublesome to give them a true figure with parallel surfaces; and several of them when finished turned out useless, in consequence of the veins which then appeared in the glass. Although these instruments performed remarkably well, yet the light was fainter than he expected, and from this cause, combined with the difficulty of finishing them, he afterward devoted his labours solely to those with metallic specula.

At a later period, in 1822, Mr. G. B. Airy of Trinity College, and one of the distinguished successors of Newton in the Lucasian chair, resumed the consideration of glass specula, and demonstrated that the aberration both of figure and of colour might be corrected in these instruments. Upon this ingenious principle Mr. Airy executed more than one telescope, but though the result of the experiment was such as to excite hopes of ultimate success, yet the construction of such instruments is still a desideratum in practical science.

Such were the attempts which Sir Isaac Newton made to construct reflecting telescopes; but notwithstanding the success of his labours, neither the philosopher nor the practical optician seems to have had courage to pursue them. A London artist, indeed, undertook to imitate these instruments; but Sir Isaac informs us, that “he fell much short of what he had attained, as he afterward understood by discoursing with the under workmen he had employed.” After a long period of fifty years, John Hadley, Esq. of Essex, a Fellow of the Royal Society, began in 1719 or 1720 to execute a reflecting telescope. His scientific knowledge and his manual dexterity fitted him admirably for such a task, and, probably after many failures, he constructed two large telescopes about five feet three inches long, one of which, with a speculum six inches in diameter, was presented to the Royal Society in 1723. The celebrated Dr. Bradley and the Rev. Mr. Pound compared it with the great Huygenian refractor 123 feet long. It bore as high a magnifying power as the Huygenian telescope: it showed objects equally distinct, though not altogether so clear and bright, and it exhibited every celestial object that had been discovered by Huygens,—the five satellites of Saturn, the shadow of Jupiter’s satellites on his disk, the black list in Saturn’s ring, and the edge of his shadow cast on the ring. Encouraged and instructed by Mr. Hadley, Dr. Bradley began the construction of reflecting telescopes, and succeeded so well that he would have completed one of them, had he not been obliged to change his residence. Some time afterward he and the Honourable Samuel Molyneux undertook the task together at Kew, and attempted to execute specula about twenty-six inches in focal length; but notwithstanding Dr. Bradley’s former experience, and Mr. Hadley’s frequent instructions, it was a long time before they succeeded. The first good instrument which they finished was in May, 1724. It was twenty-six inches in focal length; but they afterward completed a very large one of eight feet, the largest that had ever been made. The first of these instruments was afterward elegantly fitted up by Mr. Molyneux, and presented to his majesty John V. King of Portugal.

The great object of these two able astronomers was to reduce the method of making specula to such a degree of certainty that they could be manufactured for public sale. Mr. Hauksbee had indeed made a good one about three and a half feet long, and had proceeded to the execution of two others, one of six feet, and another of twelve feet in focal length; but Mr. Scarlet and Mr. Hearne, having received all the information which Mr. Molyneux had acquired, constructed them for public sale; and the reflecting telescope has ever since been an article of trade with every regular optician.

As Sir Isaac Newton was at this time President of the Royal Society, he had the high satisfaction of seeing his own invention become an instrument of public use, and of great advantage to science, and he no doubt felt the full influence of this triumph of his skill. Still, however, the reflecting telescope had not achieved any new discovery in the heavens. The latest accession to astronomy had been made by the ordinary refractors of Huygens, labouring under all the imperfections of coloured light; and this long pause in astronomical discovery seemed to indicate that man had carried to its farthest limits his power of penetrating into the depths of the universe. This, however, was only one of those stationary positions from which human genius takes a new and a loftier elevation. While the English opticians were thus practising the recent art of grinding specula, Mr. James Short of Edinburgh was devoting to the subject all the energies of his youthful mind. In 1732, and in the 22d year of his age, he began his labours, and he carried to such high perfection the art of grinding and polishing specula, and of giving them the true parabolic figure, that, with a telescope fifteen inches in focal length, he read in the Philosophical Transactions at the distance of 500 feet, and frequently saw the five satellites of Saturn together,—a power which was beyond the reach even of Hadley’s six-feet instrument. The celebrated Maclaurin compared the telescopes of Short with those made by the best London artists, and so great was their superiority, that his small telescopes were invariably superior to larger ones from London. In 1742, after he had settled as an optician in the metropolis, he executed for Lord Thomas Spencer a reflecting telescope, twelve feet in focal length, for 630l.; in 1752 he completed one for the King of Spain, at the expense of 1200l.; and a short time before his death, which took place in 1768, he finished the specula of the large telescope which was mounted equatorially for the observatory of Edinburgh by his brother Thomas Short, who was offered twelve hundred guineas for it by the King of Denmark.

Although the superiority of these instruments, which were all of the Gregorian form, demonstrated the value of the reflecting telescope, yet no skilful hand had yet directed it to the heavens; and it was reserved for Dr. Herschel to employ it as an instrument of discovery, to exhibit to the eye of man new worlds and new systems, and to bring within the grasp of his reason those remote regions of space to which his imagination even had scarcely ventured to extend its power. So early as 1774 he completed a five-feet Newtonian reflector, and he afterward executed no fewer than two hundred 7 feet, one hundred and fifty 10 feet, and eighty 20 feet specula. In 1781 he began a reflector thirty feet long, and having a speculum thirty-six inches in diameter; and under the munificent patronage of George III. he completed, in 1789, his gigantic instrument forty feet long, with a speculum forty-nine and a half inches in diameter. The genius and perseverance which created instruments of such transcendent magnitude were not likely to terminate with their construction. In the examination of the starry heavens, the ultimate object of his labours, Dr. Herschel exhibited the same exalted qualifications, and in a few years he rose from the level of humble life to the enjoyment of a name more glorious than that of the sages and warriors of ancient times, and as immortal as the objects with which it will be for ever associated. Nor was it in the ardour of the spring of life that these triumphs of reason were achieved. Dr. Herschel had reached the middle of his course before his career of discovery began, and it was in the autumn and winter of his days that he reaped the full harvest of his glory. The discovery of a new planet at the verge of the solar system was the first trophy of his skill, and new double and multiple stars, and new nebulæ, and groups of celestial bodies were added in thousands to the system of the universe. The spring-tide of knowledge which was thus let in upon the human mind continued for a while to spread its waves over Europe; but when it sank to its ebb in England, there was no other bark left upon the strand but that of the Deucalion of Science, whose home had been so long upon its waters.

During the life of Dr. Herschel, and during the reign, and within the dominions of his royal patron, four new planets were added to the solar system, but they were detected by telescopes of ordinary power; and we venture to state, that since the reign of George III. no attempt has been made to keep up the continuity of Dr. Herschel’s discoveries.

Mr. Herschel, his distinguished son, has indeed completed more than one telescope of considerable size; Mr. Ramage, of Aberdeen, has executed reflectors rivalling almost those of Slough;—and Lord Oxmantown, an Irish nobleman of high promise, is now engaged on an instrument of great size. But what avail the enthusiasm and the efforts of individual minds in the intellectual rivalry of nations? When the proud science of England pines in obscurity, blighted by the absence of the royal favour, and of the nation’s sympathy;—when its chivalry fall unwept and unhonoured;—how can it sustain the conflict against the honoured and marshalled genius of foreign lands?

CHAPTER IV.

He delivers a Course of Optical Lectures at Cambridge—Is elected Fellow of the Royal Society—He communicates to them his Discoveries on the different Refrangibility and Nature of Light—Popular Account of them—They involve him in various Controversies—His Dispute with Pardies—Linus—Lucas—Dr. Hooke and Mr. Huygens—The Influence of these Disputes on the Mind of Newton.