автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу In the Land of Mosques & Minarets

Francis Miltoun

In the Land of Mosques & Minarets

CHAPTER I

GOING AND COMING

“Say, dear friend, wouldst thou go to the land where pass the caravans beneath the shadow of the palm trees of the Oasis; where even in mid-winter all is in flower as in spring-time elsewhere.” – Villiers de l’Isle Adam.

THE taste for travel is an acquired accomplishment. Not every one likes to rough it. Some demand home comforts; others luxurious appointments; but you don’t get either of these in North Africa, save in the palace hotels of Algiers, Biskra and Tunis, and even there these things are less complete than many would wish.

We knew all this when we started out. We had become habituated as it were, for we had been there before. The railways of North Africa are poor, uncomfortable things, and excruciatingly slow; the steamships between Marseilles or Genoa and the African littoral are either uncomfortably crowded, or wobbly, slow-going tubs; and there are many discomforts of travel – not forgetting fleas – which considerably mitigate the joys of the conventional traveller who affects floating hotels and Pullman car luxuries.

The wonderful African-Mediterranean setting is a patent attraction and is very lovely. Every one thinks that; but it is best always to take ways and means into consideration when journeying, and if the game is not worth the candle, let it alone.

This book is not written in commendation only of the good things of life which one meets with in North Africa, but is a personal record of things seen and heard by the artist and the author. As such it may be accepted as a faithful transcript of sights and scenes – and many correlative things that matter – which will prove to be the portion of others who follow after. These things have been seen by many who have gone before who, however, have not had the courage to paint or describe them as they found them.

Victor Hugo discovered the Rhine, Théophile Gautier Italy, De Nerval the Orient, and Merimée Spain; but they did not blush over the dark side and include only the more charming. For this reason the French descriptive writer has often given a more faithful picture of strange lands than that limned by Anglo-Saxon writers who have mostly praised them in an ignorant, sentimental fashion, or reviled them because they had left their own damp sheets and stogy food behind, and really did not enjoy travel – or even life – without them. There is a happy mean for the travellers’ mood which must be cultivated, if one is not born with it, else all hope of pleasurable travel is lost for ever.

The comparison holds good with regard to North Africa and its Arab population. Sir Richard Burton certainly wrote a masterful work in his “Pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina,” and set forth the Arab character as no one else has done; but he said some things, and did some things, too, that his fellow countrymen did not like, and so they were loth to accept his great work at its face value.

The African Mediterranean littoral, the mountains and the desert beyond, and all that lies between, have found their only true exponents in Mme. Myriam Harry, MM. Louis Bertrand, Arnaud and Maryval, André Gide and Isabelle Eberhardt, and Victor Barrucaud. These and some others mentioned further on are the latter-day authorities on the Arab life of Africa, though the makers of English books on Algeria and Tunisia seem never to have heard of them, much less profited by their next-to-the-soil knowledge. Instead they have preferred to weave their romances and novels on “home-country” lines, using a Mediterranean or Saharan setting for characters which are not of Africa and which have no place therein.

This book is a record of various journeyings in that domain of North Africa where French influence is paramount; and is confidently offered as the result of much absorption of first-hand experiences and observations, coupled with authenticated facts of history and romance. All the elements have been found sur place and have been woven into the pages which follow in order that nothing desirable of local colour should be lost by allowing too great an expanse of sea and land to intervene.

The story of Algeria and Tunisia has so often been told by the French, and its moods have so often been painted by les “gens d’esprit et de talent,” that a foreigner has a considerable task laid out for him in his effort to do the subject justice. Think of trying to catch the fire and spirit of Fromentin, of Loti, of the Maupassants or Masqueray, or the local colour of the canvases of Dinet, Armand Point, Potter, Besnard, Constant, Cabannes, Guillaumet, or Ziem! Then go and try to paint the picture as it looks to you. Yet why not? We live to learn; and, as all the phases of this subtropical land have not been exploited, why should we – the author and artist – not have a hand in it?

So we started out. The mistral had begun to blow at Martigues (la Venise Provençal known by artist folk of all nationalities, but unknown – as yet – to the world of tourists), where we had made our Mediterranean headquarters for some years, but the sirocco was still blowing contrariwise from the south on the African coast, and it was for that reason that the author, the artist and another – the agreeable travelling companion, a rara avis by the way – made a hurried start.

We were tired of the grime and grind of cities of convention; and were minded, after another round of travel, to repose a bit in some half-dormant, half-progressive little town of the Barbary coast, or some desert oasis where one might, if he would, still dream the dreams of the Arabian nights and days, regardless of a certain reflected glamour of vulgar modernity which filters through to the utmost Saharan outposts from the great ports of the coast.

By a fortunate chance weather and circumstances favoured this last journey, and thus the making of this book became a most enjoyable labour.

We left Marseilles for the land of the sun at six of an early autumn evening, the “heure verte” of the Marseillais, when the whole Cannebière smells of absinthe, alcohol, and anise, and all the world is at ease after a bustling, rustling day of busy affairs. These men of the Midi, though they seemingly take things easy are a very industrious race. There is no such virile movement in Paris, even on the boulevards, as one may witness on Marseilles’ famous Cannebière at the seducing hour of the Frenchman’s apéritif. Marseilles is a ceaseless turmoil of busy workaday affairs as well. From the ever-present gaiety of the Cannebière cafés it is but a step to the great quais and their creaking capstans and shouting longshoremen.

From the quais of La Joliette all the world and his wife come and go in an interminable and constant tide of travel, to Africa, to Corsica and Sardinia; to Jaffa and Constantinople; to Port Said and the East, India, Australia, China and Japan; and westward, through Gibraltar’s Strait to the Mexican Gulf and the Argentine. The like of Marseilles exists nowhere on earth; it is the most brilliant and lively of all the ports of the world. It is the principal seaport of the Mediterranean and the third city of France.

Our small, tubby steamer slipped slowly and silently out between the Joliette quais and past the towering Notre Dame de la Garde and the great Byzantine Cathedral of Sainte Marie Majeur, leaving the twinkling lights of the Vieux Port and the Pharo soon far behind. Past Château d’If, the Point des Catalans, Ratonneau and Pomègue we steamed, all reminiscent of Dumas and that masterpiece of his gallant portrait gallery, – “The Count of Monte Cristo.”

The great Planier light flashed its rays in our way for thirty odd miles seaward, keeping us company long after we had eaten a good dinner, a very good dinner indeed, with café-cognac– or chartreuse, real chartreuse, not the base imitation, mark you, tout compris, to top off with. The boat was a poor, wallowing thing of eight hundred tons or so, but the dinner was much better than many an Atlantic liner gives. It had character, and was served in a tiny saloon on deck, with doors and ports all open, and a gentle, sighing Mediterranean brise wafting about our heads.

We were six passengers all told, and we were very, very comfortably installed on the Isly of the Compagnie Touache, in spite of the fact that the craft owned to twenty-seven years and made only ten knots. The Compagnie Générale Transatlantique has boats of the comparatively youthful age of twelve and seventeen, but they are so crowded that one is infinitely less comfortable, though they make the voyage at a gait of fifteen or sixteen knots. Then again the food is by no means so good or well served as that we had on the Isly. We have tried them both, and, as we asked no favours of price or accommodation in either case, the opinion may be set down as frank, truthful and personal. What others may think all depends on themselves and circumstance.

In Algeria, at any rate, one doesn’t find trippers, and there are surprisingly few of what the French call “Anglaises sans-gêne” and “Allemands grotesques.”

The traveller in Algeria should by all means eliminate his countrymen and study the native races and the French colons, if he wishes to know something of the country. Otherwise he will know nothing, and might as well have gone to a magic-lantern show at home.

It is a delightfully soft, exotic land which the geographers know as Mediterranean Africa, and which is fast becoming known to the world of modern travellers as the newest winter playground. The tide of pleasure-seeking travel has turned towards Algeria and Tunisia, but the plea is herein made to those who follow after for the better knowing of the places off the beaten track, Bou-Saada, Kairouan, the Oasis of Gabès, Oued-Souf or Tlemcen, for instance, something besides Mustapha, Biskra and Tunis.

Darkest Africa is no more darkest Africa. That idea was exploded when Stanley uttered his famous words: “Doctor Livingstone, I presume.” And since that day the late Cecil Rhodes launched his Cape to Cairo scheme, and Africa has been given over to diamond-mine exploiters, rubber collectors and semi-invalids, who, hearing wonderful tales of the climatic conditions of Assouan and Biskra, have foregathered in these places, to the joy of the native and the profit of the hotel director – usually a Swiss.

Occasionally one has heard of an adventurous tourist who has hunted the wild gazelle in the Atlas or the mountains of Kabylie, the gentlest man-fearing creature God ever made, or who has “camped-out” in a tent furnished by Cook, and has come home and told of his exploits which in truth were more Tartarinesque than daring.

The trail of the traveller is over all to-day; but he follows as a rule only the well-worn pistes. In addition to those strangers who live in Algiers or Tunis and have made of those cities weak imitations of European capitals and their suburbs as characterless as those of Paris, London or Chicago, they have also imported such conventions as “bars” and “tea-rooms” to Biskra and Hammam-R’hira.

Tlemcen and its mosques, however; Figuig and its fortress-looking Grand Hôtel du Sahara at Beni-Ounif; Touggourt and its market and its military posts; and Bou-Saada and Tozeur with their oases are as yet comparatively unknown ground to all except artists who have the passion of going everywhere and anywhere in search of the unspoiled.

When it comes to Oued-Souf with its one “Maison française,” which, by the way, is inhabited by the Frenchified Sheik of the Msaâba to whom a chapter is devoted in this book later on; or Ghardaïa, the Holy City of the Sud-Constantinois, the case were still more different. This is still virgin ground for the stranger, and can only be reached by diligence or caravan.

The railway with a fairly good equipment runs all the length of Algeria and Tunisia, from the Moroccan frontier at Tlemcen to Gabès and beyond, almost to the boundary of Tripoli in Barbary. An automobile would be much quicker, and in some parts even a donkey, but the railway serves as well as it ever does in a new-old country where it has recently been installed.

If one enters by Algiers or Oran and leaves by Tunis or even Sfax or Gabès he has done the round; but if opportunity offers, he should go south from Tlemcen into the real desert at Figuig; from Biskra to Touggourt; or from Gabès to Tozeur. Otherwise he will have so kept “in touch” with things that he can, for the asking, have oatmeal for breakfast and marmalade for tea, which is not what one comes, or should come, to Africa for. One takes his departure from French Mediterranean Africa from Tunis or Bizerte.

Leaving Tunis and its domes and minarets behind, his ship makes its way gingerly out through the straight-cut canal, a matter of six or eight miles to La Goulette, a veritable Italian fishing village in Africa which the Italian population themselves call La Goletta. Here the pilot is sent ashore, – he was a useless personage anyway, but he touches a hundred and fifty francs for standing on the bridge and doing nothing, – the ship turns a sharp right angle and sets its course northward for Marseilles, leaving Korbus and the great double-horned mountain far in the distance to starboard.

Carthage and its cathedral, and Sidi-bou-Saïd and its minarets are to port, the red soil forming a rich frame for the scintillating white walls scattered here and there over the landscape. La Marsa and the Bey’s summer palace loom next in view, Cap Carthage and Cap Bon, and then the open sea.

Midway between Tunis and Marseilles, one sees the red porphyry rocks of Sardinia. Offshore are the little isles which terminate the greater island, the “Taureau,” the “Vache” and the “Veau.” They are only interesting as landmarks, and look like the outcroppings of other Mediterranean islands. In bad weather the mariners give them a wide berth.

The sight of Sardinia makes no impression on the French passengers. They stare at it, and remark it not. The profound contempt of the Frenchman of the Midi for all things Italian is to be remarked. Corsica is left to starboard, still farther away, in fact not visible, but the Frenchman apparently does not regret this either, even though it has become a French Département. “Peuh: la Corse,” he says, “un vilain pays,” where men pass their existence killing each other off. Such is the outcome of traditional, racial rancour, and yet the most patriotic Frenchman the writer has ever known was a Corsican.

“Voilà! le Cap Sicié!” said the commandant the second morning at ten o’clock, as he stood on the bridge straining his eyes for a sight of land. We didn’t see it, but we took his word for it. A quarter of an hour later it came into view, the great landmark promontory, which juts out into the Mediterranean just west of Toulon.

Just then with a swish and a swirl, and with as icy a breath as ever blew south from the snow-clad Alps, down came the mistral upon us, and we all went below and passed the most uncomfortable five hours imaginable, anchored off the Estaque, in full view of Marseilles, and yet not able to enter harbour. The Gulf of Lyons and the mistral form an irresistible combination of forces once they get together.

At last in port; the douanier keeps a sharp lookout for cigars and cigarettes (which in Algeria and Tunisia sell for about a quarter of what they do in France), and in a quarter of an hour we are installed in that remarkably equipped “Touring Hotel” of Marseilles’ Cours Belzunce. Art nouveau furniture, no heavy rugs or draperies, metallic bedsteads, and hot and cold running water in every room. This is a good deal to find on this side of the Atlantic. The house should be made note of by all coming this way. Not in the palace hotels of Algiers, Biskra or Tunis can you find such a combination.

CHAPTER II

THE REAL NORTH AFRICA

“Africque apporte tousjours quelque chose de nouveau.”

– Rabelais

Algeria and Tunisia are already the vogue, and Biskra, Hammam-R’hira and Mustapha are already names as familiar as Cairo, Amalfi or Teneriffe, even though the throng of “colis vivants expédiés par Cook,” as the French call them, have not as yet overrun the land. For the most part the travellers in these delightful lands, be they Americans, English or Germans (and the Germans are almost as numerous as the others), are strictly unlabelled, and each goes about his own affairs, one to Tlemcen to paint the Moorish architecture of its mosques, another to Biskra for his health, and another to Tunis merely to while away his time amid exotic surroundings.

This describes well enough the majority of travellers here, but the other categories are increasing every day, and occasionally a “tourist-steamship” drops down three or four hundred at one fell swoop on the quais of Algiers or Tunis, and then those cities become as the Place de l’Opéra, or Piccadilly Circus. These tourists only skirt the fringe of this interesting land, and after thirty-six hours or so go their ways.

One does not become acquainted with the real North Africa in any such fashion.

The picturesque is everywhere in Algeria and Tunisia, and the incoming manners and customs of outre-mer only make the contrast more remarkable. It is not the extraordinary thing that astonishes us to-day, for there is no more virgin land to exploit as a touring-ground. It is the rubbing of shoulders with the dwellers in foreign lands who, after all, are human, and have relatively the same desires as ourselves, which they often satisfy in a different manner, that makes travel enjoyable.

What Nubian and Arab Africa will become later, when European races have still further blended the centuries-old tropical and subtropical blood in a gentle assimilated adaptation of men and things, no one can predict. The Arab has become a very good engineer, the Berber can be trained to become a respectable herder of cattle, as the Egyptian fellah has been made into a good farmer, or a motorman on the electric railway from Cairo to the Pyramids.

What the French call the “Empire Européen” is bound to envelop Africa some day, and France will be in for the chief part in the division without question. The French seem to understand the situation thoroughly; and, with the storehouse of food products (Algeria and Tunisia, and perhaps by the time these lines are printed, Morocco) at her very door, she is more than fortunately placed with regard to the development of this part of Africa. The individual German may come and do a little trading on his own account, but it is France as a nation that is going to prosper out of Africa. This is the one paramount aspect of the real North Africa of to-day as it has been for some generations past, a fact which the Foreign Offices of many powers have overlooked.

It is a pity that the whole gamut of the current affairs of North Africa is summed up in many minds by the memory of the palpably false sentiment of the school of fictionists which began with Ouida. Let us hope it has ended, for the picturing of the local colour of Mediterranean and Saharan Africa is really beyond the romancer who writes love-stories for the young ladies of the boarding-schools, and the new women of the art nouveau boudoirs. The lithe, dreamy young Arab of fiction, who falls in love with lonesome young women en voyage alone to some tourist centre, is purely a myth. There is not a real thing about him, not even his clothes, much less his sentiments; and he and his picturesque natural surroundings jar horribly against each other at best.

The Cigarette of “Under Two Flags” was not even a classically conventional figure, but simply a passionate, tumultuous creature, lovable only for her inconsistencies, which in reality were nothing African in act or sentiment, though that was her environment.

The English lord who became a “Chasseur d’Afrique” was even more unreal – he wasn’t a “Chasseur d’Afrique,” anyway, he was simply a member of the “Légion Étrangère;” but doubtless Ouida cared less for minutely precise detail than she did to exploit her unconventional convictions. The best novels of to-day are something our parents never dreamed of! Exclamations and exhortations of the characters of “Under Two Flags,” “Mon Amour,” “Ma Patrie,” “Les Enfants,” are not African. They belong to the parasite faubourgs of Paris’ fortifications. Let no one make the mistake, then, of taking this crop of North African novels for their guide and mentor. Much better go with Cook and be done with it, if one lacks the initiative to launch out for himself, and make the itinerary by railway, diligence and caravan. If he will, one can travel by diligence all over Mediterranean Africa, and by such a means of locomotion he will best see and know the country.

The diligence of the plain and mountain roads of Algeria and Tunisia is as remarkable a structure as still rolls on wheels. Its counterpart does not exist to-day in France, Switzerland or Italy. It is generally driven by a portly Arab, with three wheelers and four leaders, seven horses in all. It is made up of many compartments and stories. There is a rez-de-chaussée, a mezzanine floor and a roof garden, with prices varying accordingly as comfort increases or decreases. A fifty or a hundred kilometre journey therein, or thereon, is an experience one does not readily forget. To begin with, one usually starts at an hour varying from four to seven in the morning, an hour which, even in Algeria, in winter, is dark and chill.

The stage-driver of the “Far West” is a fearsome, capable individual, but the Arab conductor of a “voiture publique,” with a rope-wound turban on his head, a flowing, entangling burnous, and a five-yard whip, can take more chances in getting around corners or down a sharp incline than any other coach-driver that ever handled the ribbons. Sometimes he has an assistant who handles a shorter whip, and belabours it over the backs of the wheelers, when additional risks accrue. Sometimes, even, this is not enough and the man-at-the-wheel jumps down and runs alongside, slashing viciously at the flying heels of the seven horse power, after which he crawls up aloft and dozes awhile.

Under the hood of the impériale is stowed away as miscellaneous a lot of baggage as one can imagine, including perhaps a dozen fowls, a sheep or two, or even a calf. Amidst all this, three or four cross-legged natives wobble and lurch as the equipage makes its perilsome way.

Down below everything is full, too; so that, with its human freight of fifteen or sixteen persons, and the unweighed kilos of merchandise on the roof, the journey may well be described as being fraught with possibilities of disaster. There is treasure aboard, too, – a strong-box bolted to the floor beneath the drivers’ feet; and at the rear a weather-proof cast-iron letter-box, padlocked tight and only opened at wayside post-offices. The sequestered colonist, living far from the rail or post, has his only communication with the outside world through the medium of this mobile bureau de poste.

The roads of Algeria and Tunisia are marvellously good – where they exist. The Arab roads and routes of old were simple trails, trod down in the herb-grown, sandy soil by the bare feet of men, or camels, or the hoofs of horses and mules. So narrow were these trails that two caravans could not pass each other, so there were two trails, like the steamship “lanes” of the Atlantic.

Tradition still prompts the Kabyles to march in single file on the sixteen meter wide high-roads, which now cross and recross their country, the results of a beneficent French administration. Morocco some day will come in line.

In Tunisia, the roads are as good as they are in Algeria, and they are many and being added to yearly.

There are still to be seen, in the interior, little pyramids of stones, perhaps made up of tens of thousands, or a hundred thousand even, of desert pebbles, each unit placed by some devoted traveller who has recalled that on that spot occurred the death, or perhaps murder, of some pioneer. The Arabs call these monuments Nza, and would not think for a moment of passing one by without making their offering. It is a delicate, natural expression of sentiment, and one that might well be imitated.

There is no more danger to the tourist travelling through Algeria and Tunisia by road than there would be in France or Italy – and considerably less than might be met with in Spain. There are some brigands and robbers left hiding in the mountains, perhaps, but their raids are on flocks and herds, and not for the mere dross of the gold of tourists, or the gasolene of automobilists. The desert lion is a myth of Tartarinesque poets and artists, and one is not likely to meet anything more savage than a rabbit or a hedgehog all the fifteen hundred or two thousand kilometres from Tlemcen to Gabès.

The African lion is a dweller only in the forest-grown mountains; and the popular belief that it can track for weeks across the desert, drinking only air, and eating only sand, is pure folly of the romantic brand perpetuated by the painter Gérome.

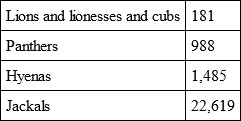

During the last ten years, in all Algeria there were killed only: —

It may be taken for granted, then, that there are no great dangers to be experienced on the well-worn roads and pistes of Tunisia and Algeria. The hyenas and lions are hidden away in the great mountain fastnesses, and the jackals themselves are harmless enough so far as human beings are concerned. The sanglier, or wild boar, is savage enough if attacked when met with, otherwise it is he who flees, whilst the jack-rabbits and the gazelles make up the majority of the “savage life” seen contiguous to the main travelled roads away from the railways.

Scorpions and horned vipers are everywhere – if one looks for them, otherwise one scarcely ever sees one or the other. The greatest enemy of mankind hereabouts is the flea; and, as the remedy is an obvious and personal one, no more need be said. Another plague is the cricket, grasshopper or sauterelle. The sauterelle, says the Arab, is the wonder among nature’s living things. It has the face of a horse, the eyes of an elephant, the neck of a bull, the horns of a deer, the breast of a lion, the stomach of a scorpion, the legs of an ostrich, the tail of a snake, and is more to be feared than any of the before enumerated menagerie. It all but devastated the chief wheat-growing lands of the plateaux of the provinces of Alger and Constantine a generation or more ago, and brought great misery in its wake.

The scorpion and the gazelle are the two chief novelties among living things (after the camel) with which the stranger makes acquaintance here. The former is unlovely but not dangerous. “Il pique, mais ne mord pas,” say the French; but no one likes to find them in his shoes in the morning all the same. The gazelle is more likable, a gentle, endearing creature, with great liquid eyes, such as poets attribute to their most lovely feminine creations.

The gazelle is an attribute of all fountain courtyards. It lives and thrives in captivity, can be tamed to follow you like a dog, and is as affectionate as a caressing kitten. It will eat condensed milk, dates, cabbage and cigarettes; but it balks at Pear’s soap.

In the open country the nomad Arab or even the house-dweller that one meets by the roadside is an agreeable, willing person, and when he understands French (as he frequently does), he is quite as “useful” as would be his European prototype under similar conditions. The country Arab is courteous, for courtesy’s sake, moreover, and not for profit. This is not apt to be the case in the cities and towns.

The Arab speech of the ports and railway cities and towns is of the solicitous kind. One can’t learn anything here of phraseology that will be useful to him in the least and it’s bad French. “Sidi mousi! Moi porter! Moi forsa besef!” is nothing at all, though it is eloquent, and probably means that the gamin, old or young, wants to carry your baggage or call a cab. And for this you pay in Algiers and Tunis as you pay in London or Paris, but you are not blackmailed as you are in Alexandria or Cairo.

One may not rest two minutes on the terrace of any café in a large Algerian town without having an Arab, a Kabyle, or a Jewish ragamuffin come up and bawl at one incessantly, “Ciri, ciri, ciri!” If you have just left your hotel, your boots brilliant as jet from the best Algerian substitute for “Day & Martin’s Best,” it doesn’t matter in the least; they still cry, “Ciri, ciri, ciri, m’siou!” Sometimes it is, “Ciri bien, m’siou!” and sometimes “Ciri, kif, kif la glace de Paris!” But the object of their plaint is always the same. Finally, if you won’t let them dull the polish of your shine, they will cire their faces and demand “quat’ sous” from you because you witnessed the operation. Very businesslike are the shoeblacks of Algiers; they don’t mind what they cire as long as they cire something.

The Café d’Apollon in Algiers is the rendezvous of the “high-life Arab.” Here Sheiks from the deserts’ great tents, Caïds from the settlements, and others of the vast army of great and small Arab officialdom assemble to take an afternoon bock or apéritif; for in spite of his religion the Mussulman will sometimes drink beer and white wine. Some, too, are “decorated,” and some wear even the ruban or bouton of the Legion of Honour on their chests where that otherwise useless buttonhole of the coat of civilization would be. Grim, taciturn figures are these, whose only exclamation is a mechanical clacking of the lips or a cynical, gurgling chuckle coming from deep down, expressive of much or little, according as much or little is meant.

The foreign population in Algeria and Tunisia is very mixed; and though all nationalities mingle in trade the foreigners will not become naturalized to any great extent. Out of forty-one naturalized foreigners in Tunis in 1891, 27 were Italians, 2 Alsatians, 2 Luxembourgeois, 2 Maltese, 1 German, 1 Belgian, 1 Moroccan, and 5 individuals of undetermined nationality.

Civilization and progress has marked North Africa for exploitation, but it will never overturn Mohammedanism. The trail of Islam is a long one and plainly marked. From the Moghreb to the Levant and beyond extends the memory and tradition of Moorish civilization of days long gone by. The field is unlimited, and ranges from the Giralda of Andalusia to the Ottoman mosques of the Dardanelles, though we may regret, with all the Arab poets and historians, the decadence of Granada more than all else. The Arab-Moorish overrunning of North Africa defined an epoch full of the incident of romance, whatever may have been the cruelties of the barbarians. This period endured until finally the sombre cities of the corsairs became the commercial capitals of to-day, just as glorious Carthage became a residential suburb of Tunis. The hand of time has left its mark plainly imprinted on all Mediterranean Africa, and not even the desire for up-to-dateness on the part of its exploiters will ever efface these memories, nor further desecrate the monuments which still remain.

The French African possessions include more than a third of the continent, an area considerably more extensive than the United States, Alaska, Porto Rico, and the Philippines combined. One hears a lot about the development of the British sphere of influence in Africa; but not much concerning that of the French which, since the unhappy affair of Fashoda, has been more active than ever. The French are not the garrulous nation one sometimes thinks them. They have a way of doing things, and saying nothing, which is often fraught with surprises for the outside world. Perhaps Morocco and Tripoli de Barbarie may come into the fold some day; and, then, with the French holding the railways of Egypt and the Suez Canal, as at present, they will certainly be the dominant Mediterranean and African power, if they may not be reckoned so already.

The Saharan desert is French down to its last grain of sand and the last oasis palm-tree, and it alone has an area half the size of the United States.

Of Mediterranean French Africa, Tunisia is a protectorate, but almost as absolutely governed by the French as if it were a part of the Ile de France. Algérie is a part of France, a Department across the seas like Corse. It holds its own elections and has three senators and six deputies at Paris. Its governor-general is a Frenchman (usually promoted from the Préfecture of some mainland Département) and most of the officialdom and bureaucracy are French.

Trade between Algeria and France, mostly in wines and food stuffs on one side, and manufactured products on the other, approximates three hundred millions of francs in each direction. Algeria, “la belle Algérie” as the French fondly call it, is not a mere strip of mountain land and desert. It is one of the richest agricultural lands on earth, running eastward from the Moroccan frontier well over into Tunisia; and, for ages, it has been known as the granary of Europe. The Carthaginians and the Phœnicians built colonies and empires here, and Rome was nourished from its wheat-fields and olive-groves.

The wheat of Africa was revered by the Romans of the capital above all others. One of the pro-consuls sent Augustus a little packet of four hundred grains, all grown from one sole seed, whereupon great national granaries were built and the commerce in the wheat of Africa took on forthwith almost the complexion of a monopoly. The sowing and the harvest were most primitive. “I have seen,” wrote Pliny (H. N. XVIII, 21), “the sowing and the reaping accomplished here by the aid of a primitive plough, an old woman and a tiny donkey.” The visitor may see the same to-day!

At the moment of the first autumn rains the Arab or Berber cultivator works over his soil, or sets his wives on the job, and sows his winter wheat. The planting finished, the small Arab farmer seeks the sunny side of a wall and basks there, watching things grow, smoking much tobacco and drinking much coffee, each of these narcotics very black and strong. Four months later his ample, or meagre, crop comes by chance. Then he flays it, not by means of a flail swung by hand, but by borrowing a little donkey from some neighbour, – if he hasn’t one of his own, – and letting the donkey’s hoofs trample it out. Now he takes it – or most likely sends it – to market, and his year’s work is done. He rolls over to the shady side of his gourbi (the sunny side is getting too warm) and loafs along until another autumn. He might grow maize in the interval, but he doesn’t.

The Barbary fig, or prickly-pear cactus, is everywhere in Algeria and Tunisia. It grows wild by the roadside, in great fields, and as a barrier transplanted to the top of the universal mud walls. Frost is its only enemy. Everything and everybody else flees before it except the native who eats its spiny, juicy bulbs and finds them good. The rest of us only find the spines, and throw the fruit away in disgust when we attempt to taste it. The Barbary fig is the Arab’s sole food supply when crops fail, the only thing which stands between him and starvation – unless he steals dates or figs from some richer man’s plantation. The Arab’s wants are not great, and with fifty francs and some ingenuity he can live a year.

The palm-trees of Africa number scores of varieties, but those of the Mediterranean states and provinces, the date-bearing palm, come within three well-defined classes: the Phœnix-dactylifera, the chamaerops-humilis and the cucifera-thebaica.

Even the smallest Arab proprietor of land or sheep or goats pays taxes. The French leave its collection to the local Caïds or Sheiks, but it gets into the official coffers ultimately, – or most of it does.

In Algeria there are four principal taxes, or impôts:

The Achour on cereals; the Zekai, on sheep and cattle to-day, but originally a tax collected for the general good, as prescribed by the Koran; the Hokar (in Constantine), a tax on land; the Lezma, the generic term for various contributions, such as the right to carry firearms (the only tax levied in Kabylie), and the tax on date-palms in the Sud-Algérie and Sud-Oranais. The Arab carries a gun only after he gets a permit, which he must show every time he buys powder or shot.

In Tunisia the taxes are much the same; but there is a specific tax on olive-trees as well as date-palms, and on the markets and the products sold there.

The wines of Algeria and Tunisia are the product of foreign vines whose roots were transplanted here but little more than half a century ago. These vines came from all parts, from France, Switzerland, Spain, Italy, Malta and America; and now the “vin d’Algérie” goes out to the ends of the earth, – usually under the name of a cru more famous. It is very good wine nevertheless, this rich, hybrid juice of the grape; and, though the Provençal of Chateauneuf, the sons of the Aude, the Garde and the Hérault, or the men of Roussillon do not recognize Algerian wine as a worthy competitor of their own vintages, it is such all the same. And the Peroximen, supposed to be a product only of Andalusia, and the Muscatel of Alexandria, are very nearly as good grown on Algerian soil as when gathered in the place of their birth.

The “vin rosé” of Kolea, the really superb wines of Médea, and the “vin blanc de Carthage,” should carry the fame of these North African vintages to all who are, or think they are, judges of good wine.

With such a rich larder at their very doors, the mediæval Mediterranean nations were in a constant quarrel over its possession. Vandals and Greeks fought for the right to populate it after the Romans, but the Moorish wave was too strong; the Arab crowded the Berber to the wall and made him a Mussulman instead of a Christian, a religious faith which the French have held inviolate so far as proselytizing goes. It is this one fundamental principle which has done much to make the French rule in Algeria the success that it is. Britain should leave religion out of her colonizing schemes if she would avoid the unrest which is continually cropping up in various parts of the empire; and the United States should leave the friars of the Philippines alone, and let them grow fat if they will, and develop the country on business lines. We are apt to think that the French are slow in business matters, but they get results sometimes in an astonishingly successful manner, and by methods which they copy from no one.

The ports of Algeria and Tunisia are of great antiquity. The Romans, not content with the natural advantages offered as harbours, frequently cut them out of the soft rock itself, or built out jetties or quais, as have all dock engineers since when occasion demanded. There are vestiges of these old Roman quais at Bougie, at Collo, at Cherchell, at Stora and at Bona. These Roman works, destroyed or abandoned at the Vandal invasion, were never rebuilt; and the great oversea traders of the Italian Republics, of France and of Spain, merely hung around offshore and transacted their business, as do the tourist steamers at Jaffa to-day, while their personally conducted hordes descend upon Jerusalem and the Jordan.

The Barbary pirates had little inlets and outlets which they alone knew, and flitted in and out of on their nefarious projects; but only at Algiers, until in comparatively recent times, were there any ports or harbours, legitimately so called, in either Algeria or Tunisia, though the Spaniards, when in occupation of Oran in the eighteenth century, made some inefficient attempts towards waterside improvements of a permanent character.

In thinking of North Africa it is well to recall that it is not a tropical belt, nor even a subtropical one. It is very like the climate of the latitude of Washington, though perhaps with less rain in winter. It is not for a moment to be compared with California or Bermuda.

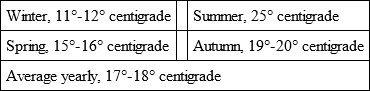

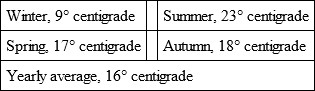

The temperature on the Algerian coast is normally as follows: —

As compared with the temperature of the French Riviera, taking Nice as an example, the balance swings in favour of Algeria in winter, and a trifle against it for summer, as the following figures show: —

One pertinent observation on North Africa is that regarding the influx of outside civilizing influences. The American invasion of manufactured products is here something considerable; but as yet it has achieved nothing like its possibilities, save perhaps in electrical tramway installation, sewing machines and five-gallon tins of kerosene. The French have got North Africa, mostly; the Germans the trade in cutlery; the English (or the Scotch) that in whiskey and marmalade; but the American shipments of “Singers” and “Standards” must in total figures swamp any of the other single “foreign imports” in value. One does not speak of course of imports from France. As the argument of the dealers, who push the sewing-machine into the desert gourbis of the nomads and the mountain dwellings of the Kabyles, has it, the civilizing influences of Algeria have been railways, public schools and “Singers.” What progressive Arab could be expected to resist such an argument for progress, with easy-payment terms of a franc a week as the chief inducement? The only objection seems to be that his delicately fashioned, creamy, woollen burnous of old is fast becoming a ready-made “lock-stitch” affair, which lacks the loving marks of the real hand-made article. Other things from America are agricultural machinery, ice-cream freezers, oil-stoves, corn meal, corned beef, salmon from Seattle, and pickles from Bunker Hill. As yet the trade in these “staples” is infinitesimal when compared with what it might be if “pushed,” which it is not because all these things come mostly through London warehouse men, who “push” something else when they can.

A few things America will not be able to sell in North Africa are boots and shoes, the Arab wears his neatly folded down at the heel, and ours are not that kind; nor socks, nor stockings, the Arab buys a gaudy “near-silk,” made in the Vosges, when he buys any, and the women don’t wear them; nor hats, though a Stetson, No. 7, would please them mightily, all but the price. There is no demand for folding-beds or elastic bookcases. The Arab sleeps on the floor, and the only book he possesses, if he can read, is a copy of the Koran, which he tucks away inside his burnous and carries about with him everywhere. Chairs he has no need for; when the Arab doesn’t lie or huddle on the ground, he sits dangle-legged or cross-legged on a bench, which is a home-made affair. The women mostly squat on their heels, which looks uncomfortable, but which they seem to enjoy.

Besides the American invasion, there is the German occupation to reckon with – in a trade sense.

“Those terrible Germans,” is a newspaper phrase of recent coinage which is applicable to almost any reference to the German trade invasion of every country under the sun, save perhaps the United States and Canada. In South America, in Russia, and in the African Mediterranean States and Provinces, the Teuton has pushed his trading instincts to the utmost. He may be no sort of a colonizer himself, but he knows how to sell goods. In North Africa, in the coast towns, over a thousand German firms have established themselves within the last ten years, all the way from Tangier to Port Saïd. This may mean little or nothing to the offhand thinker; but when one recalls that the blackamoor and the Arab have learned to use matches and folding pocket-knives, and have even been known to invest in talking machines, it is also well to recall that the German can produce these things, “machine-made,” and market them cheaper than any other nation. For this reason he floods the market, where the taste is not too critical, and the cry is here for cheapness above all things. This is the Arab’s point of view, hence the increasing hordes of German traders.

To show the German is indefatigable, and that he knows North Africa to its depths, the case of the late German consul at Cairo, Paul Gerhard, who wrote a monumental work on the butterflies of North Africa, is worth recalling.

CHAPTER III

ALGERIA OF TO-DAY

“Le coq Gaulois est le coq de la gloire.

Il chante bien fort quand il gagne une victoire

Et encore plus fort quand il est battu.”

Algeria is by no means savage Africa, even though its population is mostly indigène. It forms a “circonscription académique” of France. It has a national observatory, a branch of that at Paris, founded in 1858; a school of medicine and pharmacy; a school of law; a faculty of letters and sciences, and three endowed chairs of Arabic, at Algiers (founded in 1836); Oran (1850) and Constantine (1858).

Algeria has a great future in store, although it has cost France 8,593,000,000 francs since its occupation seventy years ago, and has only produced a revenue of 2,330,000,000 francs, which represents the loss of a sum greater than the war indemnity of 1870. The Algerian budget balanced for the first time in 1901 without subsidies from home.

The entire population of Algeria is 4,124,732, of which 3,524,000 are Arabs, Kabyles or

Berbers, and the subdivided races hereafter mentioned, leaving in the neighbourhood of 600,000 Europeans, whose numbers are largely increasing each year.

The rate of increase of the European population, from 1836, when the French first occupied the country, has been notable. In 1836 there were 14,561 Europeans in the colony; in 1881, 423,881, of which 233,937 were French, 112,047 Spanish, and 31,865 Italians, and to-day the figure is over 600,000.

The Arab and Berber population, too, are notably increasing; they are not disappearing like the red man. From 2,320,000, in 1851, they have increased, in 1891, to 3,524,000.

In addition to the Arab and Berber population of Algeria, and the “foreigners” and Europeans, there are the following:

Moors – (90,500), the mixed issue of the Berbers and all the races inhabiting Algeria.

Koulouglis – (20,000), born of Turks and Moorish women.

Jews – (47,667), who by the decree of 1870 were made French. (This does not include unnaturalized Jews.)

Negroes – (5,000), the former slaves who were freed in 1848.

The French colonist in Algeria, the man on the spot, understands the Arab question better than the minister and officials of the Colonial Office of the Pavilion Sully, though the French have succeeded in making of Algeria what they have never accomplished with their other colonies – a paying proposition at last. Still France governs Algeria under a sort of “up-the-state,” “Raines-law” rule, and treats the indigène of Laghouat or Touggourt as they would a boatman of Pontoise or a farm labourer of Étampes. The French colonial howls against all the mistakes and indiscretions of a “Boulevard Government” for the Sahara, and even revile the Governor General, whom he calls a civilian dressed up in military garb and no governor at all. Que diable! This savours of partisanship and politics, but it is an echo of what one hears as “café talk” any time he opens his ears in Algiers.

All is peace and concord within, however, in spite of the small talk of the cafés; and the Arab and European live side by side, each enjoying practically the same rights and protection that they would if they lived in suburban Paris.

The Caïd or Sheik or head man of a tribe is the go-between in all that concerns the affairs of the native with the French government.

The name Caïd was formerly given to the governors of the provinces of the Barbary States, but to-day that individual has absolutely disappeared, though he still remains as an administrator of French law, under the surveillance of the military government. In reality the Caïd still remains the official head of his tribe, and in this position is sustained by the French authorities.

The Arab has adopted the new order of things very graciously, but he can’t get over his ancient desire to hoard gold; and, for that reason, no Algerian gold coin exists, and there is no gold in circulation to speak of. The Arab, when he gets it, buries it, forgets where, or dies and forgets to tell any one where, which is the same thing, and thus a certain very considerable amount is lost to circulation.

Paper money, in values of twenty and fifty francs, takes the place of gold; the Arab thinks that it is something that is perishable, and accordingly spends it and keeps the country prosperous. The French understand the Arab and his foibles; there is no doubt about that. They solved the question of a circulating currency in Algeria. New York and Washington representatives of haute finance might take a few lessons here.

With regard to the money question, the stranger in Algeria must beware of false and non-current coin. Anything that’s a coin looks good to an Arab, and for that reason a large amount of spurious stuff is in circulation. It was originally made by counterfeiters to gull the native, but to-day the stranger gets his share, or more than his share.

To replace the gold “louis” of France, the Banque d’Algérie issues “shin-plasters” of twenty francs. They are convenient, but one must get rid of them before leaving the country or else sell them to a money changer at a discount. These Algerian bank-notes now pass current in Tunisia, a branch of the parent bank having recently been opened there.

The commercial possibilities of Algeria have hardly, as yet, begun to be exploited, though the wine and wheat-growing lands are highly developed; and, since their opening, have suffered no lack of prosperity, save for a plague of phylloxera which set back the vines on one occasion, and a plague of locusts which one day devastated almost the entire region of the wheat-growing plateaux. It was then the Arabs became locust-eaters, though indeed they are not become a cult as in Japan. With the Arab it was a case of eating locusts or nothing, for there was no grain.

This plague of locusts fell upon the province of Constantine in 1885, and from Laghouat to Bou-Saada, and from Kenchela to Aumale they were brought in myriads by the sirocco of the desert from no one knows where.

For two years these great cereal-growing areas were cleared of their crops as though a wild-fire had passed over them, until finally the government by strenuous efforts, and the employment of many thousands of labourers, was able to control and arrest the march of the plague.

During this period many of the new colonists saw their utmost resources disappear; but gallantly they took up their task anew, and for the past dozen years only occasional slight recurrences of the pest have been noted, and they, fortunately, have been suppressed as they appeared.

Besides wheat and wine, tobacco is an almost equal source of profit to Algeria. In France no one may grow a tobacco plant, even as an embellishment to his garden-plot, without first informing the excise authorities, who, afterwards, will come around periodically and count the leaves. In Africa the tobacco crop is something that brings peace and plenty to any who will cultivate it judiciously, for the consumption of the weed is great.

Manufactured tobacco is cheap in Algeria. Neither cigars, cigarettes nor pipe mixtures, nor snuff either, pay any excise duties; and even foreign tobaccos, which mostly come from Hungary and the Turkish provinces, pay very little.

Two-thirds of the Algerian manufactured product is made from home-grown tobacco, and a very large quantity of the same is sent to France to be sold as “Maryland;” though, indeed, if the original plants ever came from the other side of the water, it was by a very roundabout route. Certainly the broom-corn tobacco of France does not resemble that of Maryland in the least. The hope of France and her colonies is to grow all the tobacco consumed within her frontiers, whether it is labelled “Maryland,” “Turkish” or “Scaferlati.” The French government puts out some awful stuff it calls tobacco and sells under fancy names.

The tobacco tax in Algeria is nil, and that on wine is nearly so. Four sous a hectolitre (100 litres) is not a heavy tax to pay, though when it was first applied (in 1907) it was the excuse for the retail wine dealer (who in Algeria is but human, when he seeks to make what profit he can) to add two sous to the price of his wine per litre. There is a law in France against unfair trading, and the same applies to Algeria. It has been a dead law in many places for many years, but when a tax of four sous a hectolitre, originally paid to the state, by the dealer, finally came out of the consumer’s pocket as ten francs, an increase of 5,000 per cent., popular clamour and threats of the law caused the dealer to drop back to his original price. This is the way Algeria protects its growing wine industry. Publicists and economists elsewhere should study the system.

The African landscape is very simple and very expressive, severe but not sad, lively but not gay. The great level horizon bars the way south towards the wastes of the Sahara, and the mountains of the Atlas are ever present nearer at hand. The desert of romance, le vrai désert, is still a long way off; and, though there is now a macadamized road to Bou-Saada and Biskra, and a railway to Figuig and beyond, civilization is still only at the vestibule of the Sahara. The real development and exploitation of North Africa and its peoples and riches is yet to come.

As for the climate, that of California is undoubtedly superior to that of Algeria, but the topographical and agricultural characteristics are much the same. The greatest difference which will be remarked by an American crossing Algeria from Oran to Souk-Ahras will be the distinct “foreign note” of the installation of its farming communities. Haystacks are plastered over with mud; carts are drawn by mules or horses hitched tandemwise, three, four or five on end, and the carts are mostly two-wheeled at that. There are no fences and no great barns for stocking fodder or sheltering cattle; the farmhouses are all of stone, bare or stucco-covered, and range in colour from sky-blue to pale pink and vivid yellow. There is some American farming machinery in use, but the Arab son of the soil still largely works with the implements of Biblical times.

The winter of Algeria is the winter of Syria, of Japan, and reminiscent to some extent of California; perhaps not so mild on the whole, but still something of an approach thereto. Another contrast favourable to California is that in Algeria there is a lack of certain refinements of modern travel which are to be had in the “land of sunshine.” Winter, properly speaking, does not come to Algeria except on the high plateaux of the provinces of Oran, Alger and Constantine, and on the mountain peaks of the Atlas, and in Kabylie.

South of Algiers stretches the great plain of the Mitidja, which is like no other part of the earth’s surface so much as it is like Normandy with respect to its prairies, “la Beauce” for its wheat-fields and its grazing-grounds, and the Bordelais for its vineyards.

At the western extremity of the Mitidja commence the orange-groves of Blida, the forests of olive-trees, and the eucalyptus of La Trappe. The scene is immensely varied and suggestive of untold wealth and prosperity at every kilometre.

Suburban Algiers is thickly built with villas, more or less after the Moorish style, but owned by Europeans. Recently the wealthy Arab has taken to building his “country house” on similar gracious lines; and, when he does, he keeps pretty near to accepted Moorish elements and details, whereas the European, the colon, or the commerçant grown rich, carries out his idea on the Meudon or St. Cloud plan. The Moorish part is all there, but the thing often doesn’t hang together.

To the eastward back of the mountains of Kabylie lies the great plateau region of the Tell.

The Tell is a region vastly different in manners and customs from either the desert or the Algerian littoral. The manners of the nomad of the Sahara here blend into those of the farming peasant; but, by the time Batna is reached, they become tainted with the commercialism of the outside world. At Constantine there is much European influence at work, and at the seacoast towns of Bona or Philippeville the Oriental perfume of the date-palm is lost in that of the smells and cosmopolitanism usually associated with great seaports. These four distinct characteristics mark four distinct regions of the Numidia of the ancients, to-day the wheat-growing region of the Tell.

The principal mountain peaks in Algeria rise to no great heights. Touabet, near Tlemcen, is 1,620 metres in height; the highest peak of the Grand Kabylie Range, in the province of Alger, is 2,308 metres; and Chelia, in Constantine, 2,328 metres. They are not bold, rugged mountains, but rolling, rounded crests, often destitute of verdure to the point of desolation.

The development of the regions forming the hinterland– practically one may so call the Sahara – is of constant and assiduous care to the authorities. They have done much and are doing much more as statistics indicate.

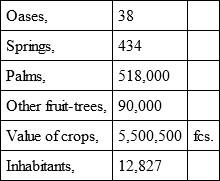

In the valley of the Oued-Righ and the Ziban, one of the most favoured of these borderlands, the government statistics of springs and oases are as follows (1880-90): —

And as the population increases and fruit-growing areas are further developed, the military engineers come along and dig more wells.

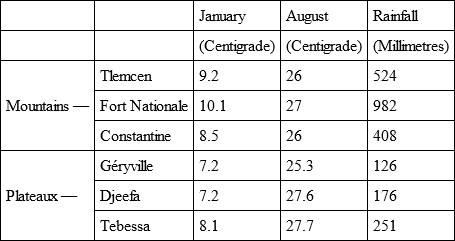

The following average temperatures and rainfall show the contrast between various regions: —

It will be noted that, normally, there is very little difference in temperature, and a very considerable difference in rainfall.

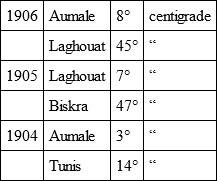

The extreme recorded winter temperatures are as follows: —

Algeria has something like 3,100 kilometres of standard gauge railway, and various light railways, or narrow gauge roads, of from ten to fifty kilometres in length, aggregating perhaps five hundred kilometres more. Railway building and development is going on constantly, but they don’t yet know what an express train is, and the sleeping and dining car services are almost as bad as they are in England. The real up-to-date sleeping-car has electric lights and hot and cold water as well as steam heat. They have dreamed of none of these things yet in England or Africa.

The railway is the chief civilizing developer of a country. The railway receipts in Algeria in 1870 were 2,500,000 francs. In 1900 they were 26,000,000 francs. That’s an increase of a thousand per cent., and it all came out of the country.

The “Routes Nationales” of Algeria (not counting by-roads, etc.), the real arteries of the life-blood of the country, at the same periods numbered almost an equal extent, and they are still being built. Give a new country good roads and good railways and it is bound to prosper.

Four millions of the total population of Algeria (including something over two hundred thousand Europeans) are dependent upon agriculture for their livelihood. Wheat, wine and tobacco rank in importance in the order named.

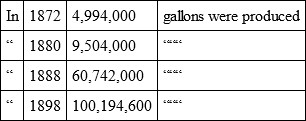

The growth of the wine industry has been most remarkable.

None of it is sold as Bordeaux or Burgundy, at least not by the Algerian grower or dealer. It is quite good enough to sell on its own merits. Let Australia, then, fabricate so-called “Burgundy” and Germany “Champagne” – Algeria has no need for any of these wiles.

Grapes, figs and plums are seemingly better in Algeria than elsewhere. Not better, perhaps, but they are so abundant that one eats only of the best. The rest are exported to England and Germany. The little mandarin oranges from Blida and about there, are one of the stand-bys of Algerian trade. So are olives and dates.

CHAPTER IV

THE RÉGENCE OF TUNISIA AND THE TUNISIANS

FOR twenty years France has been putting forth her best efforts and energies into the development of Tunisia, to make it a worthy and helpful sister to Algeria. From a French population of seven hundred at the time of the occupation in 1882, the number has risen to fifty thousand.

Tunisia of to-day was the Lybia of the ancients; but whether it was peopled originally from Spain, from Egypt or from peoples from the south, history is silent, or at least is not convincingly loud-voiced.

Lybian, Punic, Roman, Vandal and Byzantine, the country became in turn, then Mussulman; for the native Tunisian has not yet become French. The Bey still reigns, though with a shorn fragment of his former powers. The Bey is still the titular head of his Régence, but the French Résident Général is really the premier fonctionnaire, as also he is the Bey’s Ministère des Affaires Étrangères.

The ancient governmental organization of the Bey has been retained with respect to interior affairs. The Caïds are the local governors or administrators of the territorial divisions and are appointed by the Bey himself. They are charged with the policing of their districts, the collecting of taxes, and are vested with a certain military authority with which to impress their tribes. Associated with the Caïds, as seconds in command, are a class called Khalifas, and as tax collectors, mere civil authorities, there are finally the Sheiks.

It was a bitter pill for Italy when France took the ascendancy in Tunis. The population of the city of Tunis to-day still figures 30,000 Italians and Maltese as against 10,000 French, – and ever have the French anti-expansionists called it a “chinoiserie.” Call it what you will, Tunis, in spite of its preponderant Italian influence, is fast becoming French. It is also becoming prosperous, which is the chief end of man’s existence. This proves France’s intervention to have been a good thing, in spite of the fact that it accounts for seventy-five per cent. of the Italian’s animosity towards his Gallic sister.

The death of S. A. Saddok-Bey in 1882, by which the Tunisian sovereign became subservient to the French Resident, was an event which caused some apprehension in France.

The new ruler, Si-Ali-Bey, embraced gladly the French suzerainty in his land that his sons might see the institutions of the Régence prosper under the benign guidance of a world power. Ali-Bey resisted nothing French, – even as a Prince, – and when he came to the Beylicale throne in 1882 he gave no thought whatever to the ultimate political independence of his country. He was ever, until his death, the faithful, liberal coöperator with the succession of Résidents Généreaux who superseded him in the control of the real destinies of Tunisia.

As a sovereign he formerly stood as the absolute ruler of a million souls, not only their political ruler, but their religious head as well. The latter title still belongs to the Bey. (The present ruler, Mohammed-en-Nacer-Bey, came into power upon the death of his predecessor, Mohammed-el-Hadi-Bey in 1906.)

French political administration has robbed the power of the Bey of many of its picturesque and romantic accessories; but the usages of Islam are tolerated not only in the entourage of the Bey, but in all his subjects as well. This toleration even grants them the sanctity of their mosques, and does not allow the hordes of Christian tourists, who now make a playground of Mediterranean Africa from Cairo to Fez, to desecrate them by writing their names in Mohammedan sacred places. In other words, Europeans are forbidden to enter any of the Tunisian mosques save those at Kairouan.

It was Ali-Bey who achieved the task of making the masses understand that their duty was to obey the new régime; that it was a law common to them all that would assure the prosperity of the nation; and that it was he, the Bey, who was still the titular head of their religion, which, after all, is the Mussulman’s chief concern in life.

Might makes right, often enough in a maladroit fashion, but sometimes it comes as a real blessing. This was the case with the coming of the French to Tunisia. A highly organized army was a necessity for Tunisia, and within the last quarter of a century she has got it. The French were far-seeing enough to anticipate the probable eventuality which might grow out of England’s side-long glances towards Bizerte, and the Italian sphere of influence in Tripoli. Now those fears, not by any means imaginary ones at the time, are dead. England must be content with Gibraltar, and Italy with Sardinia. There are no more Mediterranean worlds to conquer, or there will not be after France absorbs Tripoli in Barbary, and Morocco, and the mortgages are maturing fast.

To-day the Tunisians are taxed less than they ever were before, and are better policed, protected and cared for in every way. Their millennium seems to have arrived. France, with the coöperation of the Bey, dispenses the law and the prophets after the patriarchal manner which Saint Louis inaugurated at Carthage in the thirteenth century.

The justice of Ali-Bey and Mohammed-el-Hadi-Bey was an improvement over that of their predecessors, which was tyrannical to an extreme. The Spartan or Druidical under-the-oak justice, and worse, gave way to a formal recognized code of laws which the French authorities evolved from the heritage of the Koran, and very well indeed it has worked.

The Bey had become a veritable father of his people, and was accessible to all who had business with him, meriting and receiving the true veneration of all the Tunisian population of Turks, Jews and Arabs. He interpreted the laws of Mahomet with liberality to all, and from his palace of La Marsa dispensed an incalculable charity.

The present Bey is not an old and tried law-maker or soldier like his predecessors, and beyond a few simple phrases is not even conversant with the French language. He is a Mussulman in toto, but his régime seems to run smoothly, and day by day the country of his forefathers prospers and its people grow fat. Some day an even greater prosperity is due to come to Tunisia, and then the Beylicale incumbent will be covered with further glories, if not further powers. This will come when the great trade-route from the Mediterranean to the heart of Africa, to Lake Tchad, is opened through the Sud-Tunisien and Tripoli, which will be long before the African interior railway dreamed of by the late Cecil Rhodes comes into being.

French influence in Africa will then receive a commercial expansion that is its due, and another Islamic land will come unconsciously under the sway of Christian civilization.

The obsequies of the late Bey of Tunis were an impressive and unusual ceremony. The eve before, the prince who was to reign henceforth received the proclamation of his powers at the Bardo, when he was invested with the Beylicale honours by the authorities of France and Tunisia.

The funeral of the dead Bey was more pompous than any other of his predecessors. He died at his palace at La Marsa and lay in state for a time in his own particular “Holy City,” Kassar-Saïd, on the route to Bizerte, where were present all his immediate family. Prince Mohammed-en-Nacer, the Bey to be, was so overcome with a crisis of nerves that he fell swooning at the ceremony, with difficulty pulling himself together sufficiently to proceed.

The progress of the cortége towards Tunis, the capital, was through the lined-up ranks of fifty thousand Mussulmans lying prostrate on the ground. Entrance to the city was by the Sidi-Abdallah Gate, and thence to the Kasba. The Mussulman population crowded the roof-tops and towers of the entire city. The military guard of the Zouaves, the Chasseurs d’Afrique, and the Beylicale cavalry formed a contrasting lively note to the solemnity of the religious proceedings, though nothing could drown the fervent wails and shouts of “La illah allah, Mohammed Rassone Allah! Sidi Ali-Bey!” the Arabic substitute for “The King is dead! Long live the King!”

Before the Grande Mosquée the Unans-Muftis and the Bach-Muftis recited their special prayers, and all the dignitaries of the new court came to kiss the hand of the reigning prince, who, at the Gate of Dar-el-Bey, was saluted by the Résident Général of France.

The Tomb of the Beys, the Tourbet et Bey, is the sepulchre of all the princes of the house, each being buried in a separate marble sarcophagus, but practically in a common grave.

A fanatical expression which was not countenanced, but which frequently came to pass nevertheless, was the crawling beneath the litter on which reposed the remains of the defunct Bey by numerous Mussulman devotees. The necromancy of it all is to the effect that he who should pass beneath the body of a dead Mussulman ruler would attain pardon for any faults ever afterwards committed. Seemingly it occurred to the authorities that it was putting a premium on crime, and so it was suppressed, and rightly enough.

The political status of the native of Tunisia to-day is similar to that of his brother of Algeria. It is incontestable that the Tunisian’s status under Beylicale rule was not wholly comfortable, for the indigènes were ruled in a manner little short of tyrannical; but the Arab lived always in expectation of bettering his position, in spite of being either a serf or a ground-down menial. To-day he has only the state of the ordinary French citizen to look forward to, and has no hope of becoming a tyrant himself. This is his chief grievance as seen by an outsider, though indeed when you discuss the matter with him he has a long line of complaints to enumerate.

Things have greatly improved in Tunisia since the French came into control. Formerly the native, or the outlander, had no appeal from the Beylicale rule short of being hanged if he didn’t like his original sentence. To-day, with a mixed tribunal of Tunisian and French officials, he has a far easier time of it even though he be a delinquent. He gets his deserts, but no vituperative punishments.

One thing the Tunisian Arab may not do under French rule. He may not leave the Régence, even though he objects to living there. The French forbid this. They keep the indigènes at home for their country’s good, instead of sending them away. It keeps a good balance of things anyway, and the law of the Koran as interpreted by the powers of Tunis is as good for the control of a subject people as that of the Code Napoleon.

The Tunisians, the common people of Tunis, are protégés of France, and France is doing her best to protect them and lead them to prosperity, assisted of course by the good-will and influence of the ruling Bey, whom she keeps in luxury and quasi-power.

Formerly when the native ruler did not care to be bothered with any particular class of subjects, whether they were Turks or Jews, he banished them, but the French officials consider this a superfluous prodigality, and keep all ranks at home and as contented as possible in their work of developing their country.

The one thing that the French will not have is a wholesale immigration of the Arab population of either Algeria or Tunisia. To benefit by a change of air, the indigène of whatever rank must have a special permission from the government before he will be allowed to embark on board ship, or he will have to become a stowaway. Very many get this special permission, for one reason or another, but to many it is refused, and for good and sufficient reasons. To the merchant who would develop a commerce in the wheat of the plateau-lands, the barley of the Sahel, or the dates of the oasis, permission is granted readily enough; and to the young student who would study law or medicine at Aix, Montpellier or Paris; but not to the able-bodied cultivator of the fields. He is wanted at home to grow up with the country.

Tunis la ville and Tunisia le pays are more mediæval and more Oriental than Algiers or Algeria. In Tunis, as in every Arab town, as in Constantinople or Cairo, you may yet walk the streets feeling all the oppression of that silence which “follows you still,” and of a patient, lack-lustre stare, still regarding you as “an unaccountable, uncomfortable work of God, that may have been sent for some good purpose – to be revealed hereafter.”

The morality and the methods of the traders of the bazars and souks remain as Kinglake and Burton described them in their day, something not yet understood by the ordinary Occidental.

This sort of thing is at its best at Tunis. Wine, olives, dates and phosphates are each contributing to the prosperity of Tunis to a remarkable degree, and the development of each industry is increasing as nowhere else, not even in Algeria. In 1900 the vineyards of Tunisia increased over two thousand hectares, and in all numbered nearly twelve thousand hectares, of which one-quarter at least were native owned.

The wine crop in 1900 was 225,000 hectolitres, an increase of nearly thirty per cent, over the season before, and it is still increasing. The olive brings an enormous profit to its exploiters, and the Tunisian olive and Tunisian olive oil rank high in the markets of the world. Originally ancient Lybia was one of the first countries known to produce olive oil on a commercial scale. All varieties of olive are grown on Tunisian soil. The illustration herewith marks the species.

The art of making olive oil goes back to the god Mercury. In the time of Moses and of Job the culture of the olive was greatly in repute. The exotics of the East and of Greece took the olive-leaf for a symbol, but the fighting, quarrelsome Romans would have none of it; the bay leaf and the palm of victory were all-sufficient for them.

They soon came to know its value, however, when they overran North Africa, and they exploited the olive-groves as they did the plateau wheat belt. Cæsar even nourished his armies on such other local products as figs and dates and found them strength-giving and sinew-making. North Africa has ever been a garde-manger of nations.

What Tunisia needs is capital, and everybody knows it. The date-palm and the olive give the greatest return of all the agricultural exploitations of the country, and after them the vine, and finally the orange-tree, the lemon-tree, the fig and the almond. Each and every one of these fruits requires a different condition of soil and climate. Fortunately all are here, and that is why Tunisia is going some day to be a gold mine for all who invest their capital in the exploitation of its soil.

The date requires a warmth and dryness of atmosphere which is found nowhere so suitable as in the Djerid and the Nefzaoua in the south. Here the soil is of just the right sandy composition, and rain is comparatively unknown. For this reason the date here flourishes better than the olive, which accommodates itself readily to the Sahel and the mountains of the north. Of the vast production of dates in this region, by far the greater part is consumed at home, the exportation of a million francs’ worth per annum being but a small proportion of the whole.

Almost every newly exploited tourist ground has an individual brand of pottery which collectors rave over, though it may be the ordinary variety of cooking utensils which are common to the region. This is true of Tunis and the potteries of Nabeul.

Besides mere utilitarian articles for domestic use, the shapes and forms which these Arab pottery-workers give to their vases and jugs make them really characteristic and beautiful objets d’art; and they are not expensive. The loving marks of the potter’s thumb are over all, and his crude ideas of form and colour are something which more highly trained craftsmen often miss when they come to manufacturing “art-pottery,” as the name is known to collectors.

A cruchon decorated with a band of angular camels and queer zigzag rows of green or red has more of that quality called “character” than the finest lustre of the Golfe de Jouan or the faïence of Rouen. For five francs one may buy three very imposing examples of jugs, vases or water-bottles, and make his friends at home as happy as if he brought them a string of coral (made of celluloid, which is mostly what one gets in Italy to-day), or a carved ivory elephant of the Indies (made in Belgium of zylonite). The real art sense often expresses itself in the common, ordinary products of a country, though not every tourist seems to know this. Let the collector who wants a new fad collect “peasant pottery,” and never pay over half a dollar for any one piece.

Closely allied with the pottery of Nabeul is a more commercially grand enterprise which has recently been undertaken in the Sahel south of Tunis. Not all the wealth of the vastly productive though undeveloped countryside lies in cereals, phosphates or olive-trees. There is a species of clay which is suitable, apparently, to all forms of ceramic fabrication.

In one of the most picturesque corners of the littoral, just south of Monastir, is a factory which turns out the most beautiful glazed brick and tiles that one ever cast his eye upon. The red-tiled roof of convention may now be expected to give way to one of iridescent, dazzling green, if the industry goes on prospering; and no more will the brick-yards of Marseilles sell their dull, conventional product throughout Tunisia; and no more will the steamship companies grow wealthy off this dead-weight freight. The Italian or Maltese balancelle will deliver these magnificent coloured bricks and tiles of Monastir all over the Mediterranean shores; and a variety of colour will come into the landscape of the fishermen’s huts and the farmhouses which the artists of a former generation knew not of.

Tunis is undergoing a great commercial development, and if the gold of Ophir is not some day found beneath its soil, many who have predicted its undeveloped riches will be surprised and disappointed.

The railways of Tunisia are not at all adequate to the needs of the country, but they are growing rapidly. When the line is finally built linking Sousse and Sfax (the service is now performed by automobile by travellers, or on camel-back; or by Italian or Arab barques by water, for merchandise), there will be approximately 1,700 kilometres of single-track road. Algeria with an area four times as great has but 3,100 kilometres of railway.

The railway exploitation of Tunisia has not as yet brought any great profit to its founders. The net profit after the cost of exploitation, in 1904, was but half a million francs; but it has a bright future.

Great efforts are being made by the government authorities, and the railway officials as well, towards colonizing the Régence with French citizens. A million and a half of francs have already been spent by the government, in addition to free grants of land, towards this colonization, and in 1904 alone land to the value of a million and a half was sold to French immigrants.