автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Italian Highways and Byways from a Motor Car

Francis Miltoun

Italian Highways and Byways from a Motor Car

CHAPTER I

THE WAY ABOUT ITALY

ONE travels in Italy chiefly in search of the picturesque, but in Florence, Rome, Naples, Venice or Milan, and in the larger towns lying between, there is, in spite of the romantic association of great names, little that appeals to one in a personal sense. One admires what Ruskin, Hare or Symonds tells one to admire, gets a smattering of the romantic history of the great families of the palaces and villas of Rome and Florence, but absorbs little or nothing of the genuine feudal traditions of the background regions away from the well-worn roads.

Along the highways and byways runs the itinerary of the author and illustrator of this book, and they have thus been able to view many of the beauties and charms of the countryside which have been unknown to most travellers in Italy in these days of the modern railway.

Alla Campagna was our watchword as we set out to pass as many of our Italian days and nights as possible in places little celebrated in popular annals, a better way of knowing Italy than one will ever know it when viewed simply from the Vatican steps or Frascati’s gardens.

The palaces and villas of Rome, Florence and Venice are known to most European travellers – as they know Capri, Vesuvius or Amalfi; but of the grim castles of Ancona, of Rimini and Ravenna, and of the classic charms of Taormina or of Sarazza they know considerably less; and still less of Monte Cristo’s Island, of Elba, of Otranto, and of the little hidden-away mountain towns of the Alps of Piedmont and the Val d’Aoste.

The automobile, as a means of getting about, has opened up many old and half-used byways, and the automobile traveller of to-day may confidently assert that he has come to know the countryside of a beloved land as it was not even possible for his grandfathers to know it.

The Italian tour may be made as a conducted tour, as an educative tour, as a mere butterfly tour (as it often has been), or as a honeymoon trip, but the reason for its making is always the same; the fact that Italy is a soft, fair, romantic land where many things have existed, and still exist, that may be found nowhere else on earth.

The romance of travel and the process of gathering legends and tales of local manners and customs is in no way spoiled because of modern means of travel. Many a hitherto unexploited locality, with as worthy a monumental shrine as many more celebrated, will now become accessible, perhaps even well known.

The pilgrim goes to Italy because of his devotion to religion, or to art or architecture, and, since this is the reason for his going, it is this reason, too, which has caused the making of more travel books on Italy than on all other continental countries combined. There are some who affect only “old masters” or literary shrines, others who crave palaces or villas, and yet others who haunt the roulette tables of Monte Carlo, Biarritz, or some exclusive Club in the “Eternal City.” European travel is all things to all men.

The pilgrims that come to Italy in increasing numbers each year are not all born and bred of artistic tastes, but the expedition soon brings a glimmer of it to the most sordid soul that ever took his amusements apart from his edification, and therein lies the secret of pleasurable travel for all classes. The automobilist should bear this in mind and not eat up the roadway through Æmilia at sixty miles an hour simply because it is possible. There are things to see en route, though none of your speeding friends have ever mentioned them. Get acquainted with them yourself and pass the information on to the next. That is what the automobile is doing for modern travel – more than the stage or the railway ever did, and more than the aeroplane ever will!

One does not forget the American who went home to the “Far West” and recalled Rome as the city where he bought an alleged panama hat (made probably at Leghorn). He is no myth. One sees his like every day. He who hurried his daughter away from the dim outlined aisles of Milan’s Gothic wonder to see the new electric light works and the model tramway station was one of these, but he was the better for having done a round of the cathedrals of Italy, even if he did get a hazy idea of them mixed up with his practical observations on street-lighting and transportation.

Superficial Italian itineraries have been made often, and their chronicles set down. They are still being made, and chronicled, but the makers of guide books have, as yet, catered but little to the class of leisurely travellers, a class who would like to know where some of these unexploited monuments exist; where these unfamiliar histories and legends may be heard, and how they may all be arrived at, absorbed and digested. The people of the countryside, too, are usually more interesting than those of the towns. One has only to compare the Italian peasant and his picturesque life with the top-hatted and frock-coated Roman of to-day to arrive quickly to a conclusion as to which is typical of his surroundings. The Medicis, the Borgias, and the Colonnas have gone, and to find the real romantic Italian and his manner of life one has to hunt him in the small towns.

The modern traveller in Italy by road will do well to recall the conditions which met the traveller of past days. The mere recollection of a few names and dates will enable the automobilist to classify his impressions on the road in a more definite and satisfying manner than if he took no cognizance of the pilgrims who have gone before.

Chaucer set out ostensibly for Genoa in 1373 and incidentally met Petrarch at Padua and talked shop. A monk named Felix, from Ulm on the banks of the Danube, en route for Jerusalem, stopped off at Venice and wrote things down about it in his diary, which he called a “faithful description.” Albrecht Durer visited Venice in 1505 and made friends with many there, and from Venice went to Bologna and Ferrara. An English crusading knight in the same century “took in” Italy en route to the Holy Land, entering the country via Chambéry and Aiguebelle – the most delightful gateway even to-day. Automobilists should work this itinerary out on some diagrammatic road map. Martin Luther, “with some business to transact with the Pope’s Vicar,” passed through Milan, Pavia, Bologna and Florence on his way to Rome, and Rabelais in 1532 followed in the train of Cardinal du Bellay, and his account of how he “saw the Pope” is interesting reading in these days when even personally-conducted tourists look forward to the same thing. Joachim du Bellay’s “visions of Rome” are good poetry, but as he was partisan to his own beloved Loire gaulois, to the disparagement of the Tiber latin, their topographical worth is somewhat discounted.

Sir Philip Sidney was in Padua and Venice in 1573, and he brought back a portrait of himself painted in the latter city by Paul Veronese, as tourists to-day carry away wine glasses with their initials embossed on them. The sentiment is the same, but taste was better in the old days.

Rubens was at Venice in 1600, and there are those who say that Shakespeare got his local colour “on the spot.” Mr. Sidney Lee says no!

Back to the land, as Dante, Petrarch, even Horace and Virgil, have said. Dante the wayfarer was a mighty traveller, and so was Petrach. Horace and Virgil took their viewpoints from the Roman capital, but they penned faithful pictures which in setting and colouring have, in but few instances, changed unto this day.

Dante is believed to have been in Rome when the first sentence was passed upon him, and from the Eternal City one can follow his journeyings northward by easy stages to Siena and Arezzo, to the Alps, to Padua, on the Aemilian Way, his wandering on Roman roads, his flight by sea to Marseilles, again at Verona and finally at Ravenna, the last refuge.

This was an Italian itinerary worth the doing. Why should we modern travellers not take some historical personage and follow his (or her) footsteps from the cradle to the grave? To follow in the footsteps of Jeanne d’Arc, of Dante Alighieri, or of Petrarch and his Laura – though their ways were widely divergent – or of Henri IV, François I, or Charles V, would add a zest and reason for being to an automobile tour of Europe which no twenty-four hour record from London to Monte Carlo, or eighteen hours from Naples to Geneva could possibly have.

There is another class of travellers who will prefer to wax solemn over the notorious journey to Italy of Alfred de Musset and Georges Sand. It was a most romantic trip, as the world knows. De Musset even had to ask his mother’s consent to make it. The past mistress of eloquence appeared at once on the maternal threshold and promised to look after the young man – like a mother.

De Musset’s brother saw the pair off “on a misty melancholy evening,” and noted amongst other dark omens, that “the coach in which the travellers took their seats was the thirteenth to leave the yard,” but for the life of us we cannot share his solemnity. The travellers met Stendhal at Lyons. After supper “he was very merry, got rather drunk and danced round the table in his big topboots.” In Florence they could not make up their minds whether to go to Rome or to Venice, and settled the matter by the toss of a coin. Is it possible to care much for the fortunes of two such heedless cynics?

It is such itineraries as have here been outlined, the picking up of more or less indistinct trails and following them a while, that gives that peculiar charm to Italian travel. Not the dreamy, idling mood that the sentimentalists would have us adopt, but a burning feverishness that hardly allows one to linger before any individual shrine. Rather one is pushed from behind and drawn from in front to an ever unreachable goal. One never finishes his Italian travels. Once the habit is formed, it becomes a disease. We care not that Cimabue is no longer considered to be throned the painter of the celebrated Madonna in Santa Maria Novella, or that Andrea del Sarto and his wife are no longer Andrea del Sarto and his wife, so long as we can weave together a fabric which pleases us, regardless of the new criticism, – or the old, for that matter.

We used to go to the places marked on our railway tickets, and “stopped off” only as the regulations allowed. Now we go where fancy wills and stop off where the vagaries of our automobile force us to. And we get more notions of Italy into our heads in six weeks than could otherwise be acquired in six months.

One need not go so very far afield to get away from the conventional in Italy. Even that strip of coastline running from Menton in France to Reggio in Calabria is replete with unknown, or at least unexploited, little corners, which have a wealth of picturesque and romantic charm, and as noble and impressive architectural monuments as one may find in the peninsula.

Com è bella, say the French honeymoon couples as they enter Italy via the Milan Express over the Simplon; com è bella, say one and all who have trod or ridden the highways and byways up and down and across Italy; com è bella is the pæan of every one who has made the Italian round, whether they have been frequenters of the great cities and towns, or have struck out across country for themselves and found some creeper-clad ruin, or a villa in some ideally romantic situation which the makers of guide-books never heard of, or have failed to mention. All this is possible to the traveller by road in Italy, and one’s only unpleasant memories are of the buona mano of the brigands of hotel servants which infest the large cities and towns – about the only brigands one meets in Italy to-day.

The real Italy, the old Italy, still exists, though half hidden by the wall of progress built up by young liberty-loving Italy since the days of Garibaldi; but one has to step aside and look for the old régime. It cannot always be discovered from the window of a railway carriage or a hotel omnibus, though it is often brought into much plainer view from the cushions of an automobile. “Motor Cars and the Genus Loci” was a very good title indeed for an article which recently appeared in a quarterly review. The writer ingeniously discovered – as some of the rest of us have also – the real mission of the automobile. It takes us into the heart of the life of a country instead of forcing us to travel in a prison van on iron rails.

Let the tourist in Italy “do” – and “do” as thoroughly as he likes – the galleries of Rome, Florence, Siena, and Venice, but let him not neglect the more appealing and far more natural uncontaminated beauties of the countryside and the smaller towns, such as Caserta, Arezzo, Lucca, Montepulciana, Barberino in Mugello and Ancona, and as many others as fit well into his itinerary from the Alps to Ætna or from Reggio to Ragusa. They lack much of the popular renown that the great centres possess, but they still have an aspect of the reality of the life of mediævalism which is difficult to trace when surrounded by all the up-to-date and supposedly necessitous things which are burying Rome’s ruins deeper than they have ever yet been buried. It is difficult indeed to imagine what old Rome was like, with Frascati given over to “hunt parties” and the hotel drawing rooms replete with Hungarian orchestras. It is difficult, indeed!

Italy is a vast kinetoscope of heterogeneous sights and scenes and memories and traditions such as exist on no other part of the earth’s surface. Of this there is no doubt, and yet each for himself may find something new, whether it is a supposed “secret of the Vatican” or an unheard of or forgotten romance of an Italian villa. This is the genus loci of Italy, the charm of Italy, the unresistible lodestone which draws tens of thousands and perhaps hundreds of thousands thither each year, from England and America. Italy is the most romantic touring ground in all the world, and, though its highways and byways are not the equal in surface of the “good roads” of France, they are, in good weather, considerably better than the automobilist from overseas is used to at home. At one place we found fifty kilometres of the worst road we had ever seen in Italy immediately followed by a like stretch of the best. The writer does not profess to be able to explain the anomaly. In general the roads in the mountains are better than those at low level, so one should plan his itineraries accordingly.

The towns and cities of Italy are very well known to all well-read persons, but of the countryside and its manners and customs this is not so true. Modern painters have limned the outlines of San Marco at Venice and the Castle of St. Angelo at Rome, on countless canvases, and pictures of the “Grand Canal” and of “Vesuvius in Eruption” are familiar enough; but paintings of the little hill towns, the wayside shrines, the olive and orange groves, and vineyards, or a sketch of some quaint roadside albergo made whilst the automobile was temporarily held up by a tire blow out, is quite as interesting and not so common. There is many a pine-clad slope, convent-crowned hill-top and castled crag in Italy as interesting as the more famous, historic sites.

To appreciate Italy one must know it from all sides and in all its moods. The hurried itinerary which comprises getting off the ship at Naples, doing the satellite resorts and “sights” which fringe Naples Bay, and so on to Rome, Florence and Venice, and thence across Switzerland, France and home is too frequently a reality. The automobilist may have a better time of it if he will but be rational; but, for the hurried flight above outlined, he should leave his automobile at home and make the trip by “train de luxe.” It would be less costly and he would see quite as much of Italy – perhaps more. The leisurely automobile traveller who rolls gently in and out of hitherto unheard of little towns and villages is in another class and learns something of a beloved land and the life of the people that the hurried tourist will never suspect.

The genuine vagabond traveller, even though he may be a lover of art and architecture, and knows just how bad Canova’s lions really are, is quite as much concerned with the question as to why Italians drink wine red instead of white, or why the sunny Sicilian will do more quarrelling and less shovelling of dirt on a railroad or a canal job than his northern brother. It is interesting, too, to learn something – by stumbling upon it as we did – about Carrara marble, Leghorn hats and macaroni, which used to form the bulk of the cargoes of ships sailing from Italian ports to those of the United States. The Canovas, like the Botticellis, are always there – it is forbidden to export art treasures from Italy, so one can always return to confirm his suspicions – but the marble has found its competitor elsewhere, Leghorn hats are now made in far larger quantities in Philadelphia, and the macaroni sent out from Brooklyn in a month would keep all Italy from starvation for a year.

The Italian picture and its framing is like no other, whether one commences with the snow-crested Alps of Piedmont and finishes with Bella Napoli and its dazzling blue, or whether he finishes with the Queen of the Adriatic and begins with Capri. It is always Italy. The same is not true of France. Provence might, at times, and in parts, be taken for Spain, Algeria or Corsica; Brittany for Ireland and Lorraine for Germany. On the contrary Piedmont, in Italy, is nothing at all like neighbouring Dauphiné or Savoie, nor is Liguria like Nice.

As for the disadvantages of Italian travel, they do undoubtedly exist, as well for the automobilist as for him who travels by rail. In the first place, in spite of the picturesque charm of the Italian countryside, the roads are, as a whole, not by any means the equal of those of the rest of Europe – always, of course, excepting Spain. They are far better indeed in Algeria and Tunisia. Hotel expenses are double what they are in France for the same sort of accommodation – for the automobilist at any rate. Garage accommodation is seldom, if ever, to be found in the hotel, at least not of a satisfactory kind, and when found costs anywhere from two to three, or even five, francs a night. Gasoline and oil are held at inflated figures, though no one seems to know who gets all the profit that comes from the fourteen to eighteen francs which the Italian garage keeper or grocer or druggist takes for the usual five gallons.

With this information as a forewarning the stranger automobilist in Italy will meet with no undue surprises except that bad weather, if he happens to strike a spell, will considerably affect a journey that would otherwise have proved enjoyable.

The climate of Italy is far from being uniform. It is not all orange groves and palm trees. Throughout Piedmont and Lombardy snow and frost are the frequent accompaniments of winter. On the other hand the summers are hot and prolific in thunder storms. In Venetia, thanks to the influence of the Adriatic, the climate is more equable. In the centre, Tuscany has a more nearly regular climate. From Naples south, one encounters almost a North African temperature, and the south wind of the desert, the sirocco, here blows as it does in Algeria and Tunisia, though tempered somewhat by having crossed the Mediterranean.

There are a hundred and twenty-five varieties of mosquitoes in Italy, but with most of them their singing is worse than their stinging. The Pontine Marches have long been the worst breeding places for mosquitoes known to a suffering world. The mosquitoes of this region were supposed to have been transmitters of malaria, so one day some Italian physicians caught a good round batch of them and sent them up into a little village in the Apennines whose inhabitants had never known malaria. Straightway the whole population began to shake with the ague. That settled it, the mosquito was a breeder of disease.

The topography of Italy is of an extraordinary variety. The plains and wastes of Calabria are the very antitheses of that semi-circular mountain rampart of the Alps which defines the northern frontier or of the great solid mass of the Apennines in Central Italy. Italy by no means covers the vast extent of territory that the stranger at first presupposes. From the northern frontier of Lombardy to the toe of the Calabrian boot is considerable of a stretch to be sure, but for all that the actual area is quite restricted, when compared with that of other great continental powers. This is all the more reason for the automobilist to go comfortably along and not speed up at every town and village he comes to.

The automobilist in Italy should make three vows before crossing the frontier. The first not to attempt to see everything; the second to review some of the things he has already seen or heard of; and the third to leave the beaten track at least once and launch out for himself and try to discover something that none of his friends have ever seen.

The beaten track in Italy is not by any means an uninteresting itinerary, and there is no really unbeaten track any more. What one can do, and does, if he is imbued with the proper spirit of travel, is to cover as much little-travelled ground as his instincts prompt him. Between Florence and Rome and between Rome and Naples there is quite as much to interest even the conventional traveller as in those cities themselves, if he only knows where to look for it and knows the purport of all the remarkable and frequent historical monuments continually springing into view. Obscure villages, with good country inns where the arrival of foreigners is an event, are quite as likely to offer pleasurable sensations as those to be had at the six, eight or ten franc a day pension of the cities.

The landscape motives for the artist, to be found in Italy, are the most varied of any country on earth. It is a wide range indeed from the vineyard covered hillsides of Vicenza to the more grandiose country around Bologna, to the dead-water lagoons before Venice is reached, to the rocky coasts of Calabria, or to the chestnut groves of Ætna and the Roman Campagna.

The travelling American or Englishman is himself responsible for many of the inconveniences to which he is subjected in Italy. The Italian may know how to read his own class distinctions, but all Americans are alike to him. Englishmen, as a rule, know the language better and they get on better – very little. The Frenchman and the German have very little trouble. They have less false pride than we.

The American who comes to Italy in an automobile represents untold wealth to the simple Italian; those who drive in two horse carriages and stop at big hotels are classed in the same category. One may scarcely buy anything in a decent shop, or enter an ambitious looking café, but that the hangers-on outside mark him for a millionaire, while, if he is so foolish as to fling handfuls of soldi to an indiscriminate crowd of ragamuffins from the balcony of his hotel, he will be pestered half to death as long as he stays in the neighbourhood. And he deserves what he gets! There is a way to counteract all this but each must learn it for himself. There is no set formula.

Beggars are importunate in certain places in Italy be-ridden of tourists, but after all no more so than elsewhere, and the travelling public, as much as anything else, conduces to the continued existence of the plague. If Italy had to choose between suppressing beggars or foregoing the privilege of having strangers from overseas coming to view her monuments she would very soon choose the former. If the beggars could not make a living at their little game they too would stop of their own accord. The question resolves itself into a strictly personal one. If it pleases you to throw pennies from your balcony, your carriage or your automobile to a gathered assembly of curious, do so! It is the chief means of proving, to many, that they are superior to “foreigners!” The little-travelled person does this everywhere, – on the terrace of Shepheard’s at Cairo, on the boulevard café terraces at Algiers, from the deck of his ship at Port Said, from the tables even of the Café de la Paix; – so why should he not do it at Naples, at Venice, at Rome? For no reason in the world, except that it’s a nuisance to other travellers, decidedly an objectionable practice to hotel, restaurant and shop keepers, and a cause of great annoyance and trouble to police and civic authorities. The following pages have been written and illustrated as a truthful record of what two indefatigable automobile travellers have seen and felt.

We were dutifully ravished by the splendours of the Venetian palaces, and duly impressed by the massiveness of Sant’Angelo; but we were more pleased by far in coming unexpectedly upon the Castle of Fénis in the Valle d’Aoste, one of the finest of all feudal fortresses; or the Castle of Rimini sitting grim and sad in the Adriatic plain; or the Villa Cesarini outside of Perugia, which no one has ever reckoned as a wonder-work of architecture, but which all the same shows all of the best of Italian villa elements.

Our taste has been catholic, and the impressions set forth herein are our own. Others might have preferred to admire some splendid church whilst we were speculating as to some great barbican gateway or watch tower. A saintly shrine might have for some more appeal than a hillside fortified Rocca; and again some convent nunnery might have a fascination that a rare old Renaissance house, now turned into a macaroni factory, or a wine press, might not.

CHAPTER II

OF ITALIAN MEN AND MANNERS

ITALIAN politics have ever been a game of intrigue, and of the exploiting of personal ambition. It was so in the days of the Popes; it is so in these days of premiers. The pilots of the ships of state have never had a more perilous passage to navigate than when manœuvring in the waters of Italian politics.

There is great and jealous rivalry between the cities of Italy. The Roman hates the Piedmontese and the Neapolitan and the Bolognese, and they all hate the Roman, – capital though Rome is of Church and State.

The Evolution of Nationality has ever been an interesting subject to the stranger in a strange land. When the national spirit at last arose Italy had reached modern times and become modern instead of mediæval. National character is born of environment, but nationalism is born only of unassailable unity, a thorough absorbing of a love of country. The inhabitant of Rouen, the ancient Norman capital, is first, last and all the time a Norman, but he is also French; and the dweller in Rome or Milan is as much an Italian as the Neapolitan, though one and all jealously put the Campagna, Piedmont, or the Kingdom of Naples before the Italian boot as a geographical division. Sometimes the same idea is carried into politics, but not often. Political warfare in Italy is mostly confined to the unquenchable prejudices existing between the Quirinal and the Vatican, a sort of inter urban warfare, which has very little of the aspect of an international question, except as some new-come diplomat disturbs the existing order of things. The Italian has a fondness for the Frenchman, and the French nation. At least the Italian politician has, or professes to have, when he says to his constituency: “I wish always for happy peaceful relations with France … but I don’t forget Magenta and Solferino.”

The Italians of the north are the emigrating Italians, and make one of the best classes of labourers, when transplanted to a foreign soil. The steamship recruiting agents placard every little background village of Tuscany and Lombardy with the attractions of New York, Chicago, New Orleans and Buenos Ayres, and a hundred or so lire paid into the agent’s coffers does the rest.

Calabria and Sicily are less productive. The sunny Sicilian always wants to take his gaudily-painted farm cart with him, and as there is no economic place for such a useless thing in America, he contents himself with a twenty-hour sea voyage to Tunisia where he can easily get back home again with his cart, if he doesn’t like it.

Every Italian peasant, man, woman and child, knows America. You may not pass the night at Barberino di Mugello, may not stop for a glass of wine at the Osteria on the Futa Pass, or for a repast at some classically named borgo on the Voie Æmilia but that you will set up longings in the heart of the natives who stand around in shoals and gaze at your automobile.

They all have relatives in America, in New York, New Orleans or Cripple Creek, or perhaps Brazil or the Argentine, and, since money comes regularly once or twice a year, and since thousands of touring Americans climb about the rocks at Capri or drive fire-spouting automobiles up through the Casentino, they know the new world as a land of dollars, and dream of the day when they will be able to pick them up in the streets paved with gold. That is a fairy-tale of America that still lives in Italy.

Besides emigrating to foreign lands, the Italian peasant moves about his own country to an astonishing extent, often working in the country in summer, and in the towns the rest of the time as a labourer, or artisan. The typical Italian of the poorer class is of course the peasant of the countryside, for it is a notable fact that the labourer of the cities is as likely to be of one nationality as another. Different sections of Italy have each their distinct classes of country folk. There are landowners, tenants, others who work their land on shares, mere labourers and again simple farming folk who hire others to aid them in their work.

The braccianti, or farm labourers, are worthy fellows and seemingly as intelligent workers as their class elsewhere. In Calabria they are probably less accomplished than in the region of the great areas of worked land in central Italy and the valley of the Po.

The mezzadria system of working land on shares is found all over Italy. On a certain prearranged basis of working, the landlord and tenant divide the produce of the farm. There are, accordingly, no starving Italians, a living seemingly being assured the worker in the soil. In Ireland where it is rental pure and simple, and foreclosure and eviction if the rent is not promptly paid, the reverse is the case. Landlordism of even the paternal kind – if there is such a thing – is bad, but co-operation between landlord and tenant seems to work well in Italy. It probably would elsewhere.

The average Italian small farm, or podere, worked only by the family, is a very unambitious affair, but it produces a livelihood. The house is nothing of the vine-clad Kent or Surrey order, and the principal apartment is the kitchen. One or two bedrooms complete its appointments, with a stone terrace in front of the door as it sits cosily backed up against some pleasant hillside.

There are few gimcracks and dust-harbouring rubbish within, and what simple furniture there is is clean – above all the bed-linen. The stable is a building apart, and there is usually some sort of an out-house devoted to wine-pressing and the like.

A kitchen garden and an orchard are near by, and farther afield the larger area of workable land. A thousand or twelve hundred lire a year of ready money passing through the hands of the head of the family will keep father, mother and two children going, besides which there is the “living,” the major part of the eatables and drinkables coming off the property itself.

The Italians are as cleanly in their mode of life as the people of any other nation in similar walks. Let us not be prejudiced against the Italian, but make some allowance for surrounding conditions. In the twelfth century in Italy the grossness and uncleanliness were incredible, and the manners laid down for behaviour at table make us thankful that we have forks, pocket-handkerchiefs, soap and other blessings! But then, where were we in the twelfth century!

No branch of Italian farming is carried on on a very magnificent scale. In America the harvests are worked with mechanical reapers; in England it is done with sickle and flail or out of date patterns of American machines, but in Italy the peasant still works with the agricultural implements of Bible times, and works as hard to raise and harvest one bushel of wheat as a Kansas farmer does to grow, harvest and market six. The American farmer has become a financier; the Italian is still in the bread-winning stage. Five hundred labourers in Dakota, of all nationalities under the sun, be it remarked, on the Dalrymple farm, cut more wheat than any five thousand peasants in Europe. The peasant of Europe is chiefly in the stage of begging the Lord for his daily bread, but as soon as he gets out west in America, he buys store things, automatic pianos and automobile buggies. No wonder he emigrates!

The Italian peasant doesn’t live so badly as many think, though true it is that meat is rare enough on his table. He eats something more than a greasy rag and an olive, as the well-fed Briton would have us believe; and something more than macaroni, as the American fondly thinks. For one thing, he has his eternal minestra, a good, thick soup of many things which Anglo-Saxons would hardly know how to turn into as wholesome and nourishing a broth; meat of any kind, always what the French call pate d’Italie, and herbs of the field. The macaroni, the olives, the cheese and the wine – always the wine – come after. Not bad that; considerably better than corned beef and pie, and far, far better than boiled mutton and cauliflower as a steady diet! Britons and Americans should wake up and learn something about gastronomy.

The general expenses of middle-class domestic town life in Italy are lower than in most other countries, and the necessities for outlay are smaller. The Italian, even comfortably off in the working class, is less inclined to spend money on luxurious trivialities than most of us. He prefers to save or invest his surplus. One takes central Italy as typical because, if it is not the most prosperous, considered from an industrial point of view, it is still the region endowed with the greatest natural wealth. By this is meant that the conditions of life are there the easiest and most comfortable.

A middle class town family with an income of six or seven thousand lire spends very little on rent to begin with; pretence based upon the size of the front door knob cuts no figure in the Italian code of pride. This family will live in a flat, not in a villini as separate town houses are called. One sixth of the family income will go for rent, and though the apartment may be bare and grim and lack actual luxury it will possess amplitude, ten or twelve rooms, and be near the centre of the town. This applies in the smaller cities of from twenty to fifty thousand inhabitants. With very little modification the same will apply in Rome or Naples, and, with perhaps none at all, at Florence.

The all important servant question would seem to be more easily solved in Italy than elsewhere, but it is commonly the custom to treat Italian servants as one of the family – so far as certain intimacies and affections go – though, perhaps this of itself has some unanticipated objections. The Italian servants have the reputation of becoming like feudal retainers; that is, they “stay on the job,” and from eight to twenty-five lire a month pays their wages. In reality they become almost personal or body servants, for in few Italian cities, and certainly not in Italian towns, are they obliged to occupy themselves with the slogging work of the London slavey, or the New York chore-woman. An Italian servant, be she young or old, however, has a seeming disregard for a uniform or badge of servitude, and is often rather sloppy in appearance. She is, for that, all the more picturesque since, if untidy, she is not apt to be loathsomely dirty in her apparel or her manner of working.

The Italian of all ranks is content with two meals a day, as indeed we all ought to be. The continental morning coffee and roll, or more likely a sweet cake, is universal here, though sometimes the roll is omitted. Lunch is comparatively a light meal, and dinner at six or seven is simply an amplified lunch. The chianti of Tuscany is the usual wine drunk at all meals, or a substitute for it less good, though all red wine in Italy seems to be good, cheap and pure. Adulteration is apparently too costly a process. Wine and biscuits take the place of afternoon tea – and with advantage. The wine commonly used en famille is seldom bought at more than 1.50 lira the flagon of two and a half litres, and can be had for half that price. Sugar and salt are heavily taxed, and though that may be a small matter with regard to salt it is something of an item with sugar.

Wood is almost entirely the fuel for cooking and heating, and the latter is very inefficient coming often from simple braziers or scaldini filled with embers and set about where they are supposed to do the most good. If one does not expire from the cold before the last spark has departed from the already dying embers when they are brought in, he orders another and keeps it warm by enveloping it as much as possible with his person. Italian heating arrangements are certainly more economical than those in Britain, but are even less efficient, as most of the caloric value of wood and coal goes up the chimney with the smoke. The American system of steam heat – on the “chauffage centrale” plan – will some day strike Europe, and then the householder will buy his heat on the water, gas and electric light plan. Till then southern Europe will freeze in winter.

In Rome and Florence it is a very difficult proceeding to be able to control enough heat – by any means whatever – to properly warm an apartment in winter. If the apartment has no chimney, and many haven’t in the living rooms, one perforce falls back again on the classic scaldini placed in the middle of the room and fired up with charcoal. Then you huddle around it like Indians in a wigwam and, if you don’t take a short route into eternity by asphyxiation, your extremities ultimately begin to warm up; when they begin to get chilly again you recommence the firing up. This is more than difficult; it is inconvenient and annoying.

The manners and customs of the Italians of the great cities differ greatly from those of the towns and villages, and those of the Romans differ greatly from those of the inhabitants of Milan, Turin or Genoa. The Roman, for instance, hates rain – and he has his share of it too – and accordingly is more often seen with an umbrella than without one. Brigands are supposedly the only Italians who don’t own an umbrella, though why the distinction is so apparent a mere dweller beyond the frontier cannot answer.

In Rome, in Naples, and in all the cities and large towns of Italy, the population rises early, but they don’t get down to business as speedily as they might. The Italian has not, however, a prejudice against new ideas, and the Italian cities and large towns are certainly very much up-to-date. Italians are at heart democrats, and rank and title have little effect upon them.

The Italian government still gives scant consideration to savings banks, but legalizes, authorizes and sometimes backs up lotteries. At all times it controls them. This is one of the inconsistencies of the tunes played by the political machine in modern Italy. Anglo-Saxons may bribe and graft; but they do not countenance lotteries, which are the greatest thieving institutions ever invented by the ingenuity of man, in that they do rob the poor. It is the poor almost entirely who support them. The rich have bridge, baccarat, Monte Carlo and the Stock Exchange.

It may be bad for the public, this legalized gambling, but all gambling is bad, and certainly state-controlled lotteries are no worse than licensed or unlicensed pool-rooms and bucket shops, winked-at dice-throwing in bar rooms, or crap games on every corner.

The Italian administration received the enormous total of 74,400,000 lire for lottery tickets in 1906, and of this sum 35,000,000 lire were returned in prizes, and 6,500,000 went for expenses. A fine net profit of 33,000,000 lire, all of which, save what stuck to the fingers of the bureaucracy in passing through, went to reduce taxation which would otherwise be levied.

The Italian plays the lottery with the enthusiastic excitement of a too shallow and too confident brain.

Various combinations of figures seem possible of success to the Italian who at the weekend puts some bauble in pawn with the hope that something will come his way. After the drawing, before the Sunday dawns, he is quite another person, considerably less confident of anything to happen in the future, and as downcast as a sunny Italian can be.

This passion for drawing lots is something born in him; even if lotteries were not legalized, he would still play lotto in secret, for in enthusiasm for games of chance, he rivals the Spaniard.

But Italy is not the country of illiterates that the stranger presupposes. Campania is the province where one finds the largest number of lettered, and Basilicate the least.

Military service begins and is compulsory for all male Italians at the age of twenty. It lasts for nineteen years, of which three only are in active service. The next five or six in the reserve, the next three or four in the Militia and the next seven in the “territorial” Militia, or landguard.

Conscription also applies to the naval service for the term of twelve years.

The military element, which one meets all over Italy, is astonishingly resplendent in colours and plentiful in numbers. At most, among hundreds, perhaps thousands, of officers of all ranks, there can hardly be more than a few score of privates. It is either this or the officers keep continually on the move in order to create an illusion of numbers!

Class distinctions, in all military grades, and in all lands, are very marked, but in Italy the obeisance of a private before the slightest loose end of gold braid is very marked. The Italian private doesn’t seem to mark distinctions among the official world beyond the sight of gold braid. A steamboat captain, or a hall porter in some palatial hotel would quite stun him.

The Italian gendarmes are a picturesque and resplendent detail of every gathering of folk in city, town or village. On a festa they shine more grandly than at other times, and the privilege of being arrested by such a gorgeous policeman must be accounted as something of a social distinction. The holding up of an automobilist by one of these gentry is an affair which is regulated with as much pomp and circumstance as the crowning of a king. The writer knows!!

Just how far the Italian’s criminal instincts are more developed than those of other races and climes has no place here, but is it not fair to suppose that the half a million of Italians – mostly of the lower classes – who form a part of the population of cosmopolitan New York are of a baser instinct than any half million living together on the peninsula? Probably they are; the Italian on his native shore does not strike us as a very villainous individual.

But he is usually a lively person; there is nothing calm and sedentary about him; though he has neither the grace of the Gascon, the joy of the Kelt, or the pretence of the Provençal, he does not seem wicked or criminal, and those who habitually carry dirks and daggers and play in Black Hand dramas live for the most part across the seas.

The Italian secret societies are supposed hot beds of crime, and many of them certainly exist, though they do not practise their rites in the full limelight of publicity as they do in America.

The Neapolitan Camarra is the best organized of all the Italian secret societies. It is divided, military-like, into companies, and is recruited, also in military fashion, to make up for those who have died or been “replaced.”

The origin of secret societies will probably never be known. Italy was badly prepared to gather the fruits to be derived from the French Revolution, and it is possible that then the activity of the Carbonari, Italy’s most popular secret society, began. The Mafia is more ancient and has a direct ancestry for nearly a thousand years.

A hundred and twenty-five years ago the seed of secret dissatisfaction had already been spread for years through Italy. The names of the societies were many. Some of them were called the Protectori Republicani, the Adelfi, the Spilla Nera, the Fortezza, the Speranza, the Fratelli, and a dozen other names. On the surface the code of the Carbonari reads fairly enough, but there is nothing to show that any attempt was made to stamp out perhaps the most generally honoured of the traditions of Naples – that of homicide.

The long political blight of the centuries, the curse of feudalism, the rottenness of ignorance and superstition, had eaten out nearly every vestige of political and self-respecting spirit. After the restoration of the Bourbons the influences of the secret societies in Southern Italy were manifested by the large increase of murders.

CHAPTER III

CHIANTI AND MACARONIA

Chapter for Travellers by Road or Rail

THE hotels of Italy are dear or not, according to whether one patronizes a certain class of establishment. At Trouville, at Aix-les-Bains in France, at Cernobbio in the Italian Lake region, or on the Quai Parthenope at Naples, there is little difference in price or quality, and the cuisine is always French.

The automobilist who demands garage accommodation as well will not always find it in the big city hotel in Italy. He may patronize the F. I. A. T. Garages in Rome, Naples, Genoa, Milan, Florence, Venice, Turin and Padua and find the best of accommodation and fair prices. For a demonstration of this he may compare what he gets and what he pays for it at Pisa – where a F. I. A. T. garage is wanting – and note the difference.

The real Italian hotel, outside the great centres, has less of a clientèle of snobs and malades imaginaires than one finds in France – in the Pyrenees or on the Riviera, or in Switzerland among the Alps, and accordingly there is always accommodation to be found that is in a class between the resplendent gold-lace and silver-gilt establishments of the resorts and working-men’s lodging houses. True there is the same class of establishment existing in the smaller cities in France, but the small towns of France are not yet as much “travelled” by strangers as are those of Italy, and hence the difference to be remarked.

The real Italian hotels, not the tourist establishments, will cater for one at about one half the price demanded by even the second order of tourist hotels, and the Italian landlord shows no disrespect towards a client who would know his price beforehand – and he will usually make it favourable at the first demand, for fear you will “shop around” and finally go elsewhere.

The automobile here, as everywhere, tends to elevate prices, but much depends on the individual attitude of the traveller. A convincing air of independence and knowledge on the part of the automobilist, as he arrives, will speedily put him en rapport with the Italian landlord. Look as wise as possible and always ask the price beforehand – even while your motor is still chugging away. That never fails to bring things to a just and proper relation.

It is at Florence, and in the environs of Naples, of all the great tourist centres, that one finds the best fare at the most favourable prices, but certainly at Rome and Venice, in the great hotels, it is far less attractive and a great deal dearer, delightful though it may be to sojourn in a palace of other days.

The Italian wayside inns, or trattoria, are not all bad; neither are they all good. The average is better than it has usually been given the credit of being, and the automobile is doing much here, as in France, towards a general improvement. A dozen automobiles, with a score or more of people aboard, may come and go in a day to a little inn in some picturesque framing on a main road, say that between Siena and Rome via Orvieto, or to Finale Marina or Varazze in Liguria, to one carriage and pair with two persons and a driver. Accordingly, this means increased prosperity for the inn-holder, and he would be a dull wit indeed if he didn’t see it. He does see it in France, with a very clear vision; in Italy, with a point of view very little dimmed; in Switzerland, when the governmental authorities will let him; and in England, when the country boniface comes anywhere near to being the intelligent person that his continental compeer finds himself. This is truth, plain, unvarnished truth, just as the writer has found it. Others may have their own ideas about the subject, but this is the record of one man’s experiences, and presumably of some others.

The chief disadvantages of the hotel of the small Italian town are its often crowded and incomplete accessories, and its proximity to a stable of braying donkeys, bellowing cows, or an industrious blacksmith who begins before sun-up to pound out the same metallic ring that his confrères do all over the world. There is nothing especially Italian about a blacksmith’s shop in Italy. All blacksmith interiors are the same whether painted by “Old Crome,” Eastman Johnson or Jean François Millet.

The idiosyncrasies of the inns of the small Italian towns do not necessarily preclude their offering good wholesome fare to the traveller, and this in spite of the fact that not every one likes his salad with garlic in liberal doses or his macaroni smothered in oil. Each, however, is better than steak smothered in onions or potatoes fried in lard; any “hygienist” will tell you that.

The trouble with most foreigners in Italy, when they begin to talk about the rancid oil and other strange tasting native products, is that they have not previously known the real thing. Olive oil, real olive oil, tastes like – well, like olive oil. The other kinds, those we are mostly used to elsewhere, taste like cotton seed or peanut oil, which is probably what they are. One need not blame the Italian for this, though when he himself eats of it, or gives it you to eat, it is the genuine article. You may eat it or not, according as you may like it or not, but the Italian isn’t trying to poison you or work off anything on your stomach half so bad as the rancid bacon one sometimes gets in Germany or the kippers of two seasons ago that appear all over England in the small towns.

As before intimated, the chief trouble with the small hotels in Italy is their deficiencies, but the Touring Club Italiano in Italy, like the Touring Club de France in France, is doing heroic work in educating the country inn-keeper. Why should not some similar institution do the same thing in England and America? How many American country hotels, in towns of three or five thousand people, in say Georgia or Missouri, would get up, for the chance traveller who dropped in on them unexpectedly, a satisfactory meal? Not many, the writer fancies.

There is, all over Europe, a desire on the part of the small or large hotel keeper to furnish meals out of hours, and often at no increase in price. The automobilist appreciates this, and has come to learn in Italy that the old Italian proverb “chi tardi arriva mal alloggia” is entirely a myth of the guide books of a couple of generations ago. A cold bird, a dish of macaroni, a salad and a flask of wine will try no inn-keeper’s capabilities, even with no notice beforehand. The Italian would seemingly prefer to serve meals in this fashion than at the tavola rotonda, which is the Italian’s way of referring to a table d’hôte. If you have doubts as to your Italian Boniface treating you right as to price (after you have eaten of his fare) arrange things beforehand a prezzo fisso and you will be safe.

As for wine, the cheapest is often as good as the best in the small towns, and is commonly included in the prezzo fisso, or should be. It’s for you to see that you get it on that basis of reckoning.

The padrona of an Italian country inn is very democratic; he believes in equality and fraternity, and whether you come in a sixty-horse Mercédès or on donkey-back he sits you down in a room with a mixed crew of his countrymen and pays no more attention to you than if you were one of them. That is, he doesn’t exploit you as does the Swiss, he doesn’t overcharge you, and he doesn’t try to tempt your palate with poor imitation of the bacon and eggs of old England, or the tenderloins of America. He gives you simply the fare of the country and lets it go at that.

Of Italian inns, it may be truly said the day has passed when the traveller wished he was a horse in order that he might eat their food; oats being good everywhere.

The fare of the great Italian cities, at least that of the hotels frequented by tourists, has very little that is national about it. To find these one has to go elsewhere, to the small Italian hotels in the large towns, along with the priests and the soldiers, or keep to the byways.

The polenta, or corn-meal bread, and the companatico, sardines, anchovies or herrings which are worked over into a paste and spread on it butter-wise, is everywhere found, and it is good. No osteria or trattoria by the roadside, but will give you this on short order if you do not seek anything more substantial. The minestra, or cabbage soup – it may not be cabbage at all, but it looks it – a sort of “omnium gatherum” soup – is warming and filling. Polenta, companatico, minestra and a salad, with fromaggio to wind up with, and red wine to drink, ought not to cost more than a lira, or a lira and a half at the most wherever found. You won’t want to continue the same fare for dinner the same day, perhaps, but it works well for luncheon.

Pay no charges for attendance. No one does anyway, but tourists of convention. Let the buono mano to the waiter who serves you be the sole largess that you distribute, save to the man-of-all-work who brings you water for the thirsty maw of your automobile, or to the amiable, sunshiny individual who lugs your baggage up and down to and from your room. This is quite enough, heaven knows, according to our democratic ideas. At any rate, pay only those who serve you, in Italy, as elsewhere, and don’t merely tip to impress the waiter with your importance. He won’t see it that way.

The Italian albergo, or hotel of the small town, is apt to be poorly and meanly furnished, even in what may be called “public rooms,” though, indeed, there are frequently no public rooms in many more or less pretentious Italian inns. If there ever is a salon or reception room it is furnished scantily with a rough, uncomfortable sofa covered with a gunny sack, a small square of fibre carpeting (if indeed it has any covering whatever to its chilly tile or stone floor), and a few rush covered chairs. Usually there is no chimney, but there is always a stuffy lambrequined curtain at each window, almost obliterating any rays of light which may filter feebly through. In general the average reception room of any Italian albergo (except those great joint-stock affairs of the large cities which adopt the word hotel) is an uncomfortable and unwholesome apartment. One regrets to say this but it is so.

Beds in Italian hotels are often “queer,” but they are surprisingly and comfortably clean, considering their antiquity. Every one who has observed the Italian in his home, in Italy or in some stranger land, even in a crowded New York tenement, knows that the Italian sets great store by his sleeping arrangements and their proper care. It is an ever-to-be-praised and emulated fact that the common people of continental Europe are more frequently “luxurious” with regard to their beds and bed linen than is commonly supposed. They may eat off of an oilcloth (which by some vague conjecture they call “American cloth”) covered table, may dip their fingers deep in the polenta and throw bones on the tile or brick floor to the dogs and cats edging about their feet, but the draps of their beds are real, rough old linen, not the ninety-nine-cent-store kind of the complete house-furnishing establishments.

The tiled floor of the average Italian house, and of the kitchens and dining room of many an Italian inn, is the ever at hand receptacle of much refuse food that elsewhere is relegated to the garbage barrel. Between meals, and bright and early in the morning, everything is flushed out with as generous a supply of water as is used by the Dutch housvrou in washing down the front steps. Result: the microbes don’t rest behind, as they do on our own carpeted dining rooms, a despicable custom which is “growing” with the hotel keepers of England and America. Another idol shattered!

What you don’t find in the small Italian hotels are baths, nor in many large ones either. When you do find a baignoir in Europe (except those of the very latest fashion) it is a poor, shallow affair with a plug that pulls up to let the water out, but with no means of getting it in except to pour it in from buckets. This is a fault, sure enough, and it’s not the American’s idea of a bath tub at all, though it seems to suit well enough the Englishman en tour.

France is, undoubtedly, the land of good cooks par excellence, but the Italian of all ranks is more of a gourmet than he is usually accounted. There may be some of his tribe that live on bread and cheese, but if he isn’t outrageously poor he usually eats well, devotes much time to the preparing and cooking of his meals, and considerably more to the eating of them. The Italian’s cooking utensils are many and varied and above all picturesque, and his table ware invariably well conditioned and cleanly. Let this opinion (one man’s only, again let it be remembered) be recorded as a protest against the universally condemned dirty Italian, who supposedly eats cats and dogs, as the Chinaman supposedly eats rats and mice. We are not above reproach ourselves; we eat mushrooms, frog legs and some other things besides which are certainly not cleanly or healthful.

More than one Italian inn owes its present day prosperity to the travel by road which frequently stops before its doors. Twenty-five years ago, indeed much less, the vetturino deposited his load of sentimental travellers, accompanied perhaps by a courier, at many a miserable wayside osteria, which fell far short of what it should be. To-day this has all changed for the better.

Tourists of all nationalities and all ranks make Italy their playground to-day, as indeed they have for generations. There is no diminution in their numbers. English minor dignitaries of the church jostle Pa and Ma and the girls from the Far West, and Germans, fiercely and wondrously clad, peer around corners and across lagoons with field glasses of a size and power suited to a Polar Expedition. Everybody is “doing” everything, as though their very lives depended upon their absorbing as much as possible of local colour, and that as speedily as possible. It will all be down in the bill, and they mean to have what they are paying for. This is one phase of Italian travel that is unlovely, but it is the phase that one sees in the great tourist hotels and in the chief tourist cities, not elsewhere.

To best know Italian fare as also Italian manners and customs, one must avoid the restaurants and trattoria asterisked by Baedeker and search others out for himself; they will most likely be as good, much cheaper, more characteristic of the country and one will not be eternally pestered to eat beefsteak, ham and saurkraut, or to drink paleale or whiskey. Instead, he will get macaroni in all shapes and sizes, and tomato sauce and cheese over everything, to say nothing of rice, artichokes and onions now and again, and oil, of the olive brand, in nearly every plat. If you don’t like these things, of course, there is no need going where they are. Stick to the beefsteak and paleale then! Romantic, sentimental Italy is disappearing, the Italians are becoming practical and matter of fact; it is only those with memories of Browning, Byron, Shelley, Leopold Robert and Boeklin that would have Italy sentimental anyway.

Maximilien Mission, a Protestant refugee from France in 1688, had something to say of the inns at Venice, which is interesting reading to-day. He says: – “There are some good inns at Venice; the ‘Louvre,’ the ‘White Lyon,’ the ‘Arms of France;’ the first entertains you for eight livres (lire) per day, the other two somewhat cheaper, but you must always remember to bargain for everything that you have. A gondola costs something less than a livre (lire) an hour, or for a superior looking craft seven or eight livres a day.”

This is about the price of the Venetian water craft when hired to-day, two centuries and more after. The hotel prices too are about what one pays to-day in the smaller inns of the cities and in those of the towns. All over Italy, even on the shores of the Bay of Naples, crowded as they are with tourists of all nationalities and all ranks, one finds isolated little Italian inns, backed up against a hillside or crowning some rocky promontory, where one may live in peace and plenitude for six or seven francs a day. And one is not condemned to eating only the national macaroni either. Frankly, the Neapolitan restaurateur often scruples as much to put macaroni before his stranger guests as does the Bavarian inn-keeper to offer sausage at each repast. Some of us regret that this is so, but since macaroni in some form or other can always be had in Italy, and sausages in Germany, for the asking, no great inconvenience is caused.

Macaroni is the national dish of Italy, and very good it is too, though by no means does one have to live off it as many suppose. Notwithstanding, macaroni goes with Italy, as do crackers with cheese. There are more shapes and sizes of macaroni than there are beggars in Naples.

The long, hollow pipe stem, known as Neapolitan, and the vermicelli, which isn’t hollow, but is as long as a shoe string, are the leading varieties. Tiny grains, stars, letters of the alphabet and extraordinary animals that never came out of any ark are also fashioned out of the same pasta, or again you get it in sheets as big as a good sized handkerchief, or in piping of a diameter of an inch, or more.

The Romans kneaded their flour by means of a stone cylinder called a maccaro. The name macaroni is supposed to have been derived from this origin.

Naples is the centre of the macaroni industry, but it is made all over the world. That made in Brooklyn would be as good as that made in Naples if it was made of Russian wheat instead of that from Dakota. As it is now made it is decidedly inferior to the Italian variety. By contrast, that made in Tunis is as good as the Naples variety. Russian wheat again!

A macaroni factory looks, from the outside, like a place devoted to making rope. Inside it feels like an inferno. It doesn’t pay to get too well acquainted with the process of making macaroni.

The flour paste is run out of little tubes, or rolled out by big rollers, or cut out by little dies, thus taking its desired forms. The long, stringy macaroni is taken outside and hung up to dry like clothes on a line, except that it is hung on poles. The workmen are lightly and innocently clad, and the workshops themselves are kept at as high a temperature as the stoke-room of a liner. Whether this is really necessary or not, the writer does not know, but he feels sure that some genius will, some day, evolve a process which will do away with hand labour in the making of macaroni. It will be mixed by machinery, baked by electricity and loaded up on cars and steamships by the same power.

The street macaroni merchants of Naples sell the long ropy kind to all comers, and at a very small price one can get a “filling” meal. You get it served on a dish, but without knives, forks or chop sticks. You eat it with your fingers and your mouth.

The meat is tough in Italy, often enough. There is no doubt about that. But it is usually a great deal better than it is given credit for being. The day is past, if it ever existed, when the Anglo-Saxon traveller was forced to quit Italy “because he could not live without good meat.” This was the classic complaint of the innocents abroad of other days, whether they hailed from Kensington or Kalamazoo. They should never have left those superlatively excellent places. The food and Mazzini were the sole topics of travel talk once, but to-day it is more a question of whether one can get his railway connection at some hitherto unheard of little junction, or whether the road via this river valley or that mountain pass is as good as the main road. These are the things that really matter to the traveller, not whether he has got to sleep in a four poster in a bedroom with a tile or marble floor, or eat macaroni and ravioli when he might have – if he were at home – his beloved “ham” and blood-red beefsteaks.

The Italian waiter is usually a sunny, confiding person, something after the style of the negro, and, like his dark-skinned brother, often incompetent beyond a certain point. You like him for what he is though, almost as good a thing in his line as the French garçon, in that he is obliging and a great deal better than the mutton-chopped, bewhiskered nonentity who shuffles about behind your chair in England with his expectant palm forever outstretched.

The Italian camerière, or waiter, takes a pride in his profession – as far as he knows it, and quite loses sight of its commercial possibilities in the technicalities of his craft, and his seeming desire only to please. Subito momento is his ever ready phrase, though often it seems as though he might have replied never.

Seated in some roadside or seashore trattoria one pounds on the bare table for the camerière, orders another “Torino,” pays his reckoning and is off again. Nothing extraordinarily amusing has happened the while, but the mere lolling about on a terrace of a café overlooking the lapping Mediterranean waves at one’s feet is one of the things that one comes to Italy for, and one is content for the nonce never to recur to palazzos, villas, cathedrals, or picture galleries. There have been too many travellers in past times – and they exist to-day – who do not seek to fill the gaps between a round of churches and art galleries, save to rush back to some palace hotel and eat the same kind of a dinner that they would in London, Paris or New York – a little worse cooked and served to be sure. It’s the country and its people that impress one most in a land not his own. Why do so many omit these “attractions?”

The buona mano is everywhere in evidence in Italy, but the Italian himself seems to understand how to handle the question better than strangers. The Italian guest at a hotel is fairly lavish with the quantity of his tips, but each is minute, and for a small service he pays a small fee. We who like to impress the waiter – for we all do, though we fancy we don’t – will often pay as much to a waiter for bringing us a drink as the price of the drink. Not so the Italian; and that’s the difference.

Ten per cent, on the bill at a hotel is always a lavish fee, and five would be ample, though now and again the head waiter may look askance at his share. Follow the Italian’s own system then, give everybody who serves you something, however little, and give to those only, and then their little jealousies between each other will take the odium off you – if you really care what a waiter thinks about you anyway, which of course you shouldn’t.

These little disbursements are everywhere present in Italy. One pays a franc to enter a museum, a picture gallery or a great library, and one tips his cabman as he does elsewhere, and a dozen francs spent in riding about on Venetian gondolas for a day incurs the implied liability for another two francs as well.

CHAPTER IV

ITALIAN ROADS AND ROUTES

THE cordiality of the Italian for the stranger within his gates is undeniable, but the automobilist would appreciate this more if the Latin would keep his great highways (a tradition left by the Romans of old, the finest road-builders the world has ever known) in better condition.

Italy, next to France, is an ideal touring ground for the automobilist. The Italian population everywhere seems to understand the tourist and his general wants and, above all, his motive for coming thither, and whether one journeys by the railway, by automobile or by the more humble bicycle, he finds a genial reception everywhere, though coupled with it is always an abounding curiosity which is at times annoying. The native is lenient with you and painstaking to the extreme if you do not speak his language, and will struggle with lean scraps of English, French and German in his effort to understand your wants.

Admirably surveyed and usually very well graded, some of the most important of the north and south thoroughfares in Italy have been lately so sadly neglected that the briefest spell of bad weather makes them all but impassable.

There is one stretch between Bologna and Imola of thirty-two kilometres, straightaway and perfectly flat. It is a good road or a bad road, according as one sees it after six weeks of good weather or after a ten days’ rainy spell. It is at once the best and worst of its kind, but it is badly kept up and for that reason may be taken as a representative Italian road. The mountain roads up back of the lake region and over the Alpine passes, in time of snow and ice and rain – if they are not actually buried under – are thoroughly good roads. They are built on different lines. Road-building is a national affair in Italy as it is in France, but the central power does not ramify its forces in all directions as it does across the border. There is only one kind of road-building worth taking into consideration, and that is national road-building. It is not enough that Massachusetts should build good roads and have them degenerate into mere wagon tracks when they get to the State border, or that the good roads of Middlesex should become mere sloughs as soon as they come within the domain of the London County Council. Italy is slack and incompetent with regard to her road-building, but England and America are considerably worse at the present writing.

Entering Italy by the Riviera gateway one leaves the good roads of France behind him at Menton and, between Grimaldi, where he passes the Italian dogana and its formalities, and Ventimiglia, or at least San Remo, twenty-five kilometres away, punctures his tires one, three or five times over a kilometre stretch of unrolled stone bristling with flints, whereas in France a side path would have been left on which the automobilist might pass comfortably.

It isn’t the Italian’s inability to handle the good roads question as successfully as the French; it is his woefully incompetent, careless, unthinking way of doing things. This is not saying that good roads do not exist in Italy. Far from it. But the good road in Italy suddenly descends into a bad road for a dozen kilometres and as abruptly becomes a good road again, and this without apparent reason. Lack of unity of purpose on the part of individual road-building bodies is what does it.

Road-building throughout Italy never rose to the height that it did in France. The Romans were great exploiters beyond the frontiers and often left things at home to shuffle along as best they might whilst their greatest energies were spent abroad.

One well defined Roman road of antiquity (aside from the tracings of the great trunk lines like the Appian or Æmilian Ways) is well known to all automobilists entering Naples via Posilippo. It runs through a tunnel, alongside a hooting, puffing tram and loose-wheeled iron-tired carts all in a deafening uproar.

This marvellous tunnelled road by the sea, with glimpses of daylight now and then, but mostly as dark as the cavern through which flowed the Styx, is the legitimate successor of an engineering work of the time of Augustus. In Nero’s reign, Seneca, the historian, wrote of it as a narrow, gloomy pass, and mediæval superstition claimed it as the work of necromancy, since the hand of man never could have achieved it. The foundation of the roadway is well authenticated by history however. In 1442 Alphonso I, the Spaniard, widened and heightened the gallery, and Don Pedro of Toledo a century later paved it with good solid blocks of granite which were renewed again by Charles III in 1754. Here is a good road that has endured for centuries. We should do as well to-day.

There are, of course, countless other short lengths of highway, coming down from historic times, left in Italy, but the Roman viae with which we have become familiar in the classical geographies and histories of our schooldays are now replaced by modern thoroughfares which, however, in many cases, follow, or frequently cut in on, the old itineraries. Of these old Roman Ways that most readily traced, and of the greatest possible interest to the automobilist who would do something a little different from what his fellows have done, is the Via Æmilia.

With Bologna as its central station, the ancient Via Æmilia, begun by the Consul Marcus Æmilius Lepidus, continues towards Cisalpine Gaul the Via Flamina leading out from Rome. It is a delightfully varied itinerary that one covers in following up this old Roman road from Placentia (Piacenza) to Ariminum (Rimini), and should indeed be followed leisurely from end to end if one would experience something of the spirit of olden times, which one can hardly do if travelling by schedule and stopping only at the places lettered large on the maps.

The following are the ancient and modern place-names on this itinerary:

Placentia (Piacenza)

Florentia (Firenzuola)

Fidentia (Borgo S. Donnino)

Parma (Parma)

Tannetum (Taneto)

Regium Lepidi (Reggio)

Mutina (Modena)

Forum Gallorum (near Castel Franco)

Bononia (Bologna)

Claterna (Quaderna)

Forum Cornelii (Imola)

Faventia (Faenza)

Forum Livii (Forli)

Forum Populii (Forlimpopoli)

Caesena (Cesena)

Ad Confluentes (near Savignamo)

Ariminum (Rimini)

Connecting with the Via Æmilia another important Roman road ran from the valley of the Casentino across the Apennines to Piacenza. It was the route traced by a part of the itinerary of Dante in the “Divina Commedia,” and as such it is a historic highway with which the least sentimentally inclined might be glad to make acquaintance.

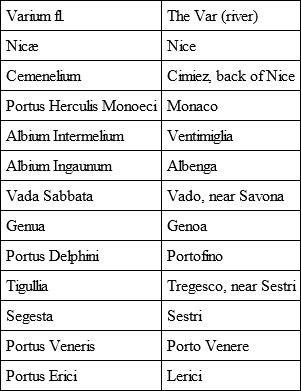

Another itinerary, perhaps better known to the automobilist, is that which follows the Ligurian coast from Nice to Spezia, continuing thence to Rome by the Via Aurelia. This coast road of Liguria passed through Nice to Luna on the Gulf of Spezia, the towns en route being as follows: —

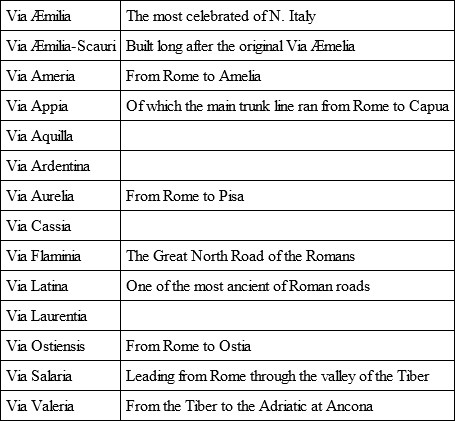

The chief of these great Roman roadways of old whose itineraries can be traced to-day are:

These ancient Roman roads were at their best in Campania and Etruria. Campania was traversed by the Appian Way, the greatest highway of the Romans, though indeed its original construction by Appius Claudius only extended to Capua. The great highroads proceeding from Rome crossed Etruria almost to the full extent; the Via Aurelia, from Rome to Pisa and Luna; the Via Cassia and the Via Clodia.

The great Roman roads were marked with division stones or bornes every thousand paces, practically a kilometre and a half, a little more than our own mile. These mile-stones of Roman times, many of which are still above ground (milliarii lapides), were sometimes round and sometimes square, and were entirely bare of capitals, being mere stone posts usually standing on a squared base of a somewhat larger area.

A graven inscription bore in Latin the name of the Consul or Emperor under whom each stone was set up and a numerical indication as well.

Caius Gracchus, away back in the second century before Christ, was the inventor of these aids to travel. The automobilist appreciates the development of this accessory next to good roads themselves, and if he stops to think a minute he will see that the old Romans were the inventors of many things which he fondly thinks are modern.

The automobilist in Italy has, it will be inferred, cause to regret the absence of the fine roads of France once and again, and he will regret it whenever he wallows into a six inch deep rut and finds himself not able to pull up or out, whilst the drivers of ten yoke ox-teams, drawing a block of Carrara marble as big as a house, call down the imprecations of all the saints in the calendar on his head. It’s not the automobilist’s fault, such an occurrence, nor the ox-driver’s either; but for fifty kilometres after leaving Spezia, and until Lucca and Livorno are reached, this is what may happen every half hour, and you have no recourse except to accept the situation with fortitude and revile the administration for allowing a roadway to wear down to such a state, or for not providing a parallel thoroughfare so as to divide the different classes of traffic. There is no such disgracefully used and kept highway in Europe as this stretch between Spezia and Lucca, and one must of necessity pass over it going from Genoa to Pisa unless he strikes inland through the mountainous country just beyond Spezia, by the Strada di Reggio for a détour of a hundred kilometres or more, coming back to the sea level road at Lucca.

Throughout the peninsula the inland roads are better as to surface than those by the coast, though by no means are they more attractive to the tourist by road. This is best exemplified by a comparison of the inland and shore roads, each of them more or less direct, between Florence and Rome.

The great Strada di grande Communicazione from Florence to Rome (something less than three hundred kilometres all told, a mere mouthful for a modern automobile) runs straight through the heart of old Siena, entering the city by the Porta Camollia and leaving by the Porta Romana, two kilometres of treacherous, narrow thoroughfare, though readily enough traced because it is in a bee-line. The details are here given as being typical of what the automobilist may expect to find in the smaller Italian cities. There are, in Italy, none of those unexpected right-angle turns that one comes upon so often in French towns, at least not so many of them, and there are no cork-screw thoroughfares though many have the “rainbow curve,” to borrow Mark Twain’s expression.