автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The British Expedition to the Crimea

Every attempt has been made to replicate the original as printed.

No attempt has been made to correct or normalize the spelling of non-English words.

Some typographical errors have been corrected; a list follows the text.

Some illustrations have been moved from mid-paragraph for ease of reading.

In certain versions of this etext, in certain browsers, clicking on this symbol

Contents.

Appendix.

Index.

(etext transcriber's note)

THE

B R I T I S H E X P E D I T I O N

TO THE

C R I M E A

BY

WILLIAM HOWARD RUSSELL, LL.D.

NEW AND REVISED EDITION

WITH MAPS AND PLANS

LONDON

G E O R G E R O U T L E D G E A N D S O N S

THE BROADWAY, LUDGATE

NEW YORK: 416, BROOME STREET

1877

THE INDIAN MUTINY.

In crown 8vo, cloth, price 7s. 6d.

MY DIARY IN INDIA,

In the Year 1858-9.

BY

WILLIAM HOWARD RUSSELL, LL.D.

SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT OF "THE TIMES."

NOTICE TO THE READER.

EDITION OF 1858.

THE interest excited by the events of the Campaign in the Crimea has not died away. Many years, indeed, must elapse ere the recital of the details of that great struggle, its glories, and its disasters, cease to revive the emotions of joy or grief with which a contemporary generation regarded the sublime efforts of their countrymen. As records on which the future history of the war must be founded, none can be more valuable than letters written from the scene, read by the light documents, such as those which will shortly be made public, can throw upon them.[1] There may be misconception respecting the nature of the motives by which statesmen and leaders of armies are governed, but there can be no mistake as to what they do; and, although one cannot always ascertain the reasons which determine their outward conduct, their acts are recorded in historical memoranda not to be disputed or denied. For the first time in modern days the commanders of armies have been compelled to give to the world an exposition of the considerations by which they were actuated during a war, in which much of the sufferings of our troops was imputed to their ignorance, mismanagement, and apathy. They were not obliged to adopt that course by the orders of their superiors, but by the pressure of public opinion; and that pressure became so great that each, as he felt himself subjected to its influence, endeavoured to escape from it by throwing the blame on the shoulders of his colleagues, or on a military scapegoat, known as "the system." As each in self-defence flourished his pen or his tongue against his brother, he made sad rents in the mantle of official responsibility and secrecy. Even in Russia the press, to its own astonishment, was called on to expound the merits of captains and explain grand strategical operations; and the public there, read in the official organs of their Government very much the same kind of matter as our British public in the evidence given before the Chelsea Commissioners. Much of what was hidden has been revealed. We know more than we did; but we never shall know all.

I avail myself of a brief leisure to revise, for the first time, letters written under very difficult circumstances, and to re-write those portions of them which relate to the most critical actions of the war. From the day the Guards landed in Malta down to the fall of Sebastopol, and the virtual conclusion of the war, I had but one short interval of repose. I was with the first detachment of the British army which set foot on Turkish soil, and it was my good fortune to land with the first at Scutari, at Varna, and at Old Fort, to be present at Alma, Balaklava, Inkerman, to accompany the Kertch and the Kinburn expeditions, and to witness every great event of the siege—the assaults on Sebastopol, and the battle of the Tchernaya. It was my still greater good fortune to be able to leave the Crimea with the last detachment of our army. My sincere desire is, to tell the truth, as far as I knew it, respecting all I have witnessed. I had no alternative but to write fully, freely, fearlessly, for that was my duty, and to the best of my knowledge and ability it was fulfilled. There have been many emendations, and many versions of incidents in the war, sent to me from various hands—many now cold forever—of which I have made use, but the work is chiefly based on the letters which, by permission of the proprietors of the Times, I was allowed to place in a new form before the public.

W. H. RUSSELL.

July, 1858.

PREFACE TO THE EDITION OF 1876.

For several years the "History of the British Expedition to the Crimea," founded on the "Letters from the Crimea of the Times Correspondent," has been out of print, and the publishers have been unable to execute orders continually arriving for copies of the work. At the present moment the interest of the public in what is called the Eastern Question has been revived very forcibly, and the policy of this country in entering upon the war of 1854, has been much discussed in the Press and in Parliament. "Bulgaria,"[2] in which the allied armies failed to discover the misery or discontent which might, at the time, have been found in Ireland or Italy, is now the scene of "atrocities," the accounts of which are exercising a powerful influence on the passions and the judgment of the country, and the balance of public opinion is fast inclining against the Turk, for whom we made so many sacrifices, and who proved that he was a valiant soldier and a faithful and patient ally. The Treaty of Paris has been torn up, the pieces have been thrown in our faces, and a powerful party in England is taking, in 1876, energetic action to promote the objects which we so strenuously resisted in 1854. "Qui facit per alium facit per se." Prince Gortschakoff must be very grateful for effective help where Count Nesselrode encountered the most intense hostility. He finds "sympathy" as strong as gunpowder, and sees a chance of securing the spoils of war without the cost of fighting for them. Since 1854-6 the map of Europe has undergone changes almost as great as those temporary alterations which endured with the success of the First French Empire, and these apparently are but the signs and tokens of changes to come, of which no man can forecast the extent and importance.

The British fleet is once more in Besika Bay, but there is now no allied squadron by its side. No British minister ventures to say that our fleet is stationed there to protect the integrity of Turkey. If the record of what Great Britain did in her haste twenty-two years ago be of any use in causing her to reflect on the consequences of a violent reaction now, the publication of this revised edition of the "History of the Expedition to the Crimea," may not be quite inopportune.

W. H. RUSSELL.

Temple, August, 1876.

Note.—In addition to the despatches relating to the landing in the Crimea, the battles of the Alma, Balaklava, Inkerman, and the Tchernaya, the assaults on the place, &c., there will be found in the present edition the text of the most important clauses of the Treaty of Paris in 1856, the correspondence between Prince Gortschakoff and Lord Granville on the denunciation of the Treaty in 1870, &c.

CONTENTS.

BOOK I.THE CONCENTRATION OF THE BRITISH TROOPS IN TURKEY—THEIR CAMPS AND CAMP-LIFE AT GALLIPOLI, SCUTARI, AND IN BULGARIA

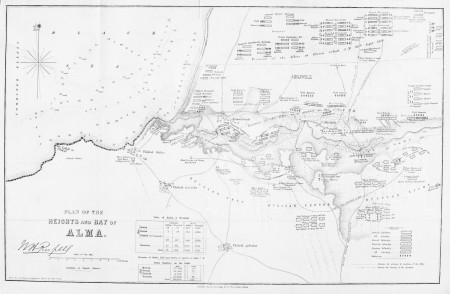

BOOK II.DEPARTURE OF THE EXPEDITION FOR THE CRIMEA—THE LANDING—THE MARCH—THE AFFAIR OF BARLJANAK—THE BATTLE OF THE ALMA—THE FLANK MARCH

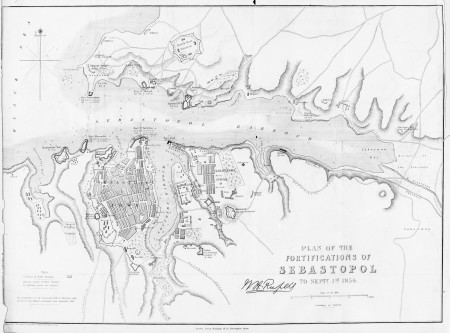

BOOK III.THE COMMENCEMENT OF THE SIEGE—THE FIRST BOMBARDMENT—ITS FAILURE—THE BATTLE OF BALAKLAVA—CAVALRY CHARGE—THE BATTLE OF INKERMAN—ITS CONSEQUENCES

BOOK IV.PREPARATIONS FOR A WINTER CAMPAIGN—THE HURRICANE—THE CONDITION OF THE ARMY—THE TRENCHES IN WINTER—BALAKLAVA—THE COMMISSARIAT AND MEDICAL STAFF

BOOK V.THE COMMENCEMENT OF ACTIVE OPERATIONS—THE SPRING—REINFORCEMENTS—THE SECOND BOMBARDMENT—ITS FAILURE—THIRD BOMBARDMENT, AND FAILURE—PERIOD OF PREPARATION

BOOK VI.COMBINED ATTACKS ON THE ENEMY'S COUNTER APPROACHES—CAPTURE OF THE QUARRIES AND MAMELON—THE ASSAULT OF THE 18TH OF JUNE—LORD RAGLAN'S DEATH

BOOK VII.EFFORTS TO RAISE THE SIEGE—BATTLE OF THE TCHERNAYA—THE SECOND ASSAULT—CAPTURE OF THE MALAKOFF—RETREAT OF THE RUSSIANS TO THE NORTH SIDE

BOOK VIII.THE ATTITUDE OF THE TWO ARMIES—THE DEMONSTRATIONS FROM BAIDAR—THE RECONNAISSANCE—THE MARCH FROM EUPATORIA—ITS FAILURE—THE EXPEDITION TO KINBURN AND ODESSA

BOOK IX.THE WINTER—POSITION OF THE FRENCH—THE TURKISH CONTINGENT—PREPARATIONS FOR THE NEXT CAMPAIGN—THE ARMISTICE—THE PEACE AND THE EVACUATION

Appendix

Index:

A,

B,

C,

D,

E,

F,

G,

H,

I,

J,

K,

L,

M,

N,

O,

P,

Q,

R,

S,

T,

U,

V,

W,

Y,

ZTHE BRITISH EXPEDITION TO THE

CRIMEA.

BOOK I.

CHAPTER I.

Causes of the quarrel—Influence of the press—Preparations—Departure from England—Malta—Warnings.

THE causes of the last war with Russia, overwhelmed by verbiage, and wrapped up in coatings of protocols and dispatches, at the time are now patent to the world. The independence of Turkey was menaced by the Czar, but France and England would have cared little if Turkey had been a power whose fate could affect in no degree the commerce or the reputation of the allies. France, ever jealous of her prestige, was anxious to uphold the power of a nation and a name which, to the oriental, represents the force, intelligence, and civilization of Europe. England, with a growing commerce in the Levant, and with a prodigious empire nearer to the rising sun, could not permit the one to be absorbed and the other to be threatened by a most aggressive and ambitious state. With Russia, and France by her side, she had not hesitated to inflict a wound on the independence of Turkey which had been growing deeper every day. But when insatiable Russia, impatient of the slowness of the process, sought to rend the wounds of the dying man, England felt bound to stay her hands, and to prop the falling throne of the Sultan.

Although England had nothing to do with the quarrels of the Greek and Latin Churches, she could not be indifferent to the results of the struggle. If Russia had been permitted to exercise a protectorate over the Greek subjects of the Porte, and to hold as material guarantee the provinces of the Danube, she would be the mistress of the Bosphorus, the Dardanelles, and even the Mediterranean. France would have seen her moral weight in the East destroyed. England would have been severed from her Indian Empire, and menaced in the outposts of her naval power. All Christian States have now a right to protect the Christian subjects of the Porte; and in proportion as the latter increase in intelligence, wealth, and numbers, the hold of the Osmanli on Europe will relax. The sick man is not yet dead, but his heirs and administrators are counting their share of his worldly goods, and are preparing for the suit which must follow his demise. Whatever might have been the considerations and pretences which actuated our statesmen, the people of England entered, with honesty of purpose and singleness of heart, upon the conflict with the sole object of averting a blow aimed at an old friend. To that end they devoted their treasure, and in that cause they freely shed their blood.

Conscious of their integrity, the nation began the war with as much spirit and energy as they continued it with calm resolution and manly self-reliance. Their rulers were lifted up by the popular wave, and carried further than they listed. The vessel of the State was nearly dashed to pieces by the great surge, and our dislocated battalions, swept together and called an army, were suddenly plunged into the realities of war. But the British soldier is ready to meet mortal foes. What he cannot resist are the cruel strokes of neglect and mal-administration. In the excitement caused by the news of victory the heart's pulse of the nation was almost frozen by a bitter cry of distress from the heights of Sebastopol. Then followed accounts of horrors which revived the memories of the most disgraceful episodes in our military history. Men who remembered Walcheren sought in vain for a parallel to the wretchedness and mortality in our army. The press, faithful to its mission, threw a full light on scenes three thousand miles from our shores, and sustained the nation by its counsels. "Had it not been for the English press," said an Austrian officer of high rank, "I know not what would have become of the English army. Ministers in Parliament denied that it suffered, and therefore Parliament would not have helped it. The French papers represented it as suffering, but neither hoping nor enduring. Europe heard that Marshal St. Arnaud won the Alma, and that the English, aided by French guns, late in the day, swarmed up the heights when their allies had won the battle. We should have known only of Inkerman as a victory gained by the French coming to the aid of surprised and discomfited Englishmen, and of the assaults on Sebastopol as disgraceful and abortive, but your press, in a thousand translations, told us the truth all over Europe, and enabled us to appreciate your valour, your discipline, your élan, your courage and patience, and taught us to feel that even in misfortune the English army was noble and magnificent."

DEPARTURE OF THE GUARDS.

The press upheld the Ministry in its efforts to remedy the effects of an unwise and unreasoning parsimony, prepared the public mind for the subversion of an effete system, encouraged the nation in the moment of depression by recitals of the deeds of our countrymen, elevated the condition and self-respect of the soldiery, and whilst celebrating with myriad tongues the feats of the combatants in the ranks, with all the fire of Tyrtæus, but with greater power and happier results, denounced the men responsible for huge disasters—"told the truth and feared not"—carried the people to the battlefield—placed them beside their bleeding comrades—spoke of fame to the dying and of hope to those who lived—and by its magic power spanned great seas and continents, and bade England and her army in the Crimea endure, fight, and conquer together.

The army saved, resuscitated, and raised to a place which it never occupied till recently in the estimation of the country, has much for which to thank the press. Had its deeds and sufferings never been known except through the medium of frigid dispatches, it would have stood in a very different position this day, not only abroad but at home. But gratitude is not a virtue of corporations. It is rare enough to find it in individuals; and, although the press has permission to exhaust laudation and flattery, its censure is resented as impertinence. From the departure of our first battalions till the close of the war, there were occasions on which the shortcomings of great departments and the inefficiency of extemporary arrangements were exposed beyond denial or explanation; and if the optimist is satisfied they were the inevitable consequences of all human organization, the mass of mankind will seek to provide against their recurrence and to obviate their results. With all their hopes, the people at the outset were little prepared for the costs and disasters of war. They fondly believed they were a military power, because they possessed invincible battalions of brave men, officered by gallant, high-spirited gentlemen, who, for the most part, regarded with dislike the calling, and disdained the knowledge, of the mere "professional" soldier. There were no reserves to take the place of those dauntless legions which melted in the crucible of battle, and left a void which time alone could fill. When the Guards[3] left London, on 22nd February, 1854, those who saw them march off to the railway station, unaccustomed to the sight of large bodies of men, and impressed by the bearing of those stalwart soldiers, might be pardoned if they supposed the household troops could encounter a world in arms. As they were the first British regiments which left England for the East, as they bore a grand part worthy of their name in the earlier, most trying, and most glorious period of our struggles, their voyage possesses a certain interest which entitles it to be retained in this revised history; and with some few alterations, it is presented to the reader.

Their cheers—re-echoed from Alma and Inkerman—bear now a glorious significance, the "morituri te salutant" of devoted soldiers addressed to their sorrowing country.

"They will never go farther than Malta!"—Such was the general feeling and expression at the time. It was supposed that the very news of their arrival in Malta would check the hordes of Russia, and shake the iron will which broke ere it would bend. To that march, in less than one year, there was a terrible antithesis. A handful of weary men—wasted and worn and ragged—crept slowly down from the plateau of Inkerman where their comrades lay thick in frequent graves, and sought the cheerless shelter of the hills of Balaklava. They had fought and had sickened and died till that proud brigade had nearly ceased to exist.

The swarm of red-coats which after a day of marching, of excitement, of leave-taking, and cheering, buzzed over the Orinoco, Ripon, Manilla, in Southampton Docks, was hived at last in hammock or blanket, while the vessels rode quietly in the waters of the Solent. Fourteen inches is man-of-war allowance, but eighteen inches were allowed for the Guards. On the following morning, February 23rd, the steamers weighed and sailed. The Ripon was off by 7 o'clock A.M., followed by the Manilla and the Orinoco. They were soon bowling along with a fresh N.W. breeze in the channel.

Good domestic beef, sea-pudding, and excellent bread, with pea-soup every second day, formed substantial pieces of resistance to the best appetites. Half a gill of rum to two of water was served out once a day to each man. On the first day Tom Firelock was rather too liberal to his brother Jack Tar. On the next occasion, the ponderous Sergeant-Major of the Grenadiers presided over the grog-tub, and delivered the order, "Men served—two steps to the front, and swallow!" The men were not insubordinate.

The second day the long swell of Biscay began to tell on the Guards. The figure-heads of the ships plunged deep, and the heads of the soldiers hung despondingly over gunwale, portsill, stay, and mess-tin, as their bodies bobbed to and fro. At night they brightened up, and when the bugle sounded at nine o'clock, nearly all were able to crawl into their hammocks for sleep. On Saturday the speed of the vessels was increased from nine-and-a-half to ten knots per hour; and the little Manilla was left by the large paddle-wheel steamers far away. On Sunday all the men had recovered; and when, at half-past ten, the ship's company and troops were mustered for prayers, they looked as fresh as could be expected under the circumstances;—in fact, as the day advanced, they became lively, and the sense of joyfulness for release from the clutches of their enemy was so strong that in reply to a stentorian demand for "three cheers for the jolly old whale!" they cheered a grampus which blew alongside.

ARRIVAL AT MALTA.

On Tuesday the Ripon passed Tarifa, at fifty minutes past five A.M., and anchored in the quarantine ground of Gibraltar to coal half-an-hour afterwards. In consequence of the quarantine regulations there was no communication with the shore, but the soldiers lined the walls, H.M.S. Cruiser manned yards, and as the Ripon steamed off at half-past three P.M., after taking on board coals, tents and tent-poles, they gave three hearty cheers, which were replied to with goodwill. On Thursday a target painted like a Russian soldier was run up for practice. The Orinoco reached Malta on Sunday morning at ten A.M., and the Ripon on Saturday night soon after twelve o'clock. The Coldstreams were disembarked in the course of the day, and the Grenadiers were all ashore ere Monday evening, to the delight of the Maltese, who made a harvest from the excursions of the "plenty big men" to and from the town.

The Manilla arrived at Malta on the morning of March 7th, after a run of eighteen days from Southampton. The men left their floating prisons only to relinquish comfort and to "rough it." One regiment was left without coals, another had no lights or candles, another suffered from cold under canvas, in some cases short commons tried the patience of the men, and forage was not to be had for the officers' horses. Acting on the old formula when transports took eight weeks to Malta, the Admiralty supplied steamers which make the passage in as many days with eight weeks' "medical comforts." By a rigid order, the officers were debarred from bringing more than 90lb. weight of baggage. Many of them omitted beds, canteen and mess traps, and were horror-stricken when they were politely invited to pitch their tents and "make themselves comfortable" on the ravelins, outside Valetta.

The arrival of the Himalaya before midnight on the same day, after a run of seven days and three hours from Plymouth, with upwards of 1,500 men on board, afforded good proof of our transport resources. Ordinary troop-ships would have taken at least six weeks, and of course it would have cost the Government a proportionate sum for their maintenance, while they were wasting precious moments, fighting against head winds. The only inconvenience attendant on this great celerity is, that many human creatures, with the usual appetites of the species, are rapidly collected upon one spot, and supplies can scarcely be procured to meet the demand. The increase of meat-consuming animals at Malta nearly produced the effects of a famine; there were only four hundred head of cattle left in the island and its dependencies, and with a population of 120,000—with the Brigade of Guards and 11 Regiments in garrison, and three frigates to feed, it may easily be imagined that the Commissariat were severely taxed to provide for this influx.

The Simoom, with the Scots Fusileer Guards, sixteen days from Portsmouth, reached Malta on the 18th of March. The troops were disembarked the following day, in excellent order. A pile of low buildings running along the edge of the Quarantine Harbour, with abundance of casements, sheltered terraces, piazzas, and large arched rooms, was soon completely filled. The men in spite of the local derangements caused on their arrival by "liberty" carousing in acid wine and fiery brandy, enjoyed good health, though the average of disease was rather augmented by the results of an imprudent use of the time allowed to them in London, to bid good-bye to their friends.

For the three last weeks in March, Valetta was like a fair. Money circulated briskly. Every tradesman was busy, and the pressure of demand raised the cost of supply. Saddlers, tinmen, outfitters, tailors, shoemakers, cutlers, increased their charges till they attained the West-End scale. Boatmen and the amphibious harpies who prey upon the traveller reaped a copper and silver harvest of great weight. It must, however, be said of Malta boatmen, that they are a hardworking, patient, and honest race; the latter adjective is applied comparatively, and not absolutely. They would set our Portsmouth or Southampton boatmen an example rather to be wondered at than followed. The vendors of oranges, dates, olives, apples, and street luxuries of all kinds, enjoyed a full share of public favour; and (a proof of the fine digestive apparatus of our soldiery) their lavish enjoyment of these delicacies was unattended by physical suffering. A thirsty private, after munching the ends of Minié cartridges for an hour on the hot rocks at the seaside, would send to the rear and buy four or five oranges for a penny. He ate them all, trifled with an apple or two afterwards, and, duty over, rushed across the harbour or strutted off to Valetta. A cool café, shining out on the street with its tarnished gilding and mirrors more radiant than all the taps of all our country inns put together, invited him to enter, and a quantity of alcoholic stimulus was supplied, at the small charge of one penny, quite sufficient to encourage him to spend two-pence more on the same stuff, till he was rendered insensible to all sublunary cares, and brought to a state which was certain to induce him to the attention of the guard and to a raging headache. "I can live like a duke here—I can smoke my cigar, and drink my glass of wine, and what could a duke do more?" But the cigar made by very dirty manufacturers, who might be seen sitting out in the streets compounding them of the leaves of plants and saliva was villanous; and the wine endured much after it had left Sicily. As to the brandy and spirits, they were simply abominable, but the men were soon "choked off" when they found that indulgence in them was followed by punishment worse than that of the black hole or barrack confinement. The biscuit mills were baking 30,000lb. of biscuit per day. Bills posted in every street for "parties desirous of joining the commissariat department, under the orders of Commissary-General Filder, about to proceed with the force to the East, as temporary clerks, assistant store-keepers, interpreters," to "freely apply to Assistant Commissary-General Strickland;" had this significant addition,—"those conversant with English, Italian, modern Greek, and Turkish languages, or the Lingua-Franca of the East will be preferred." Warlike mechanics, armourers, farriers, wheelwrights, waggon-equipment and harness-makers, were in request.

WARNINGS.

As might naturally be expected where so great a demand, horses were scarcely to be obtained. To Tunis the contagion of high prices spread from Malta, and the Moors asked £25 and £30 for the veriest bundles of skin and bone that were ever fastened together by muscle and pluck. Our allies began to show themselves. The Christophe Colomb, steam-sloop, towing the Mistral, a small sailing transport, laden with 27 soldiers' and 40 officers' horses arrived in Malta Harbour on the night of the 7th, and ran into the Grand Harbour at six A.M. the following morning. On board were Lieutenant-General Canrobert, and his Chef d'État; Major Lieutenant-General Martimprey, 45 officers, 800 soldiers, 150 horses. Their reception was most enthusiastic. The French Generals were lodged at the Palace, and their soldiers were fêted in every tavern. Reviews were held in their honour, and the air rang with the friendly shouts and answering cheers of "natural enemies".

In a few days after the arrival of the Guards, it became plain that the Allies were to proceed to Turkey, and that hostilities were inevitable. On the 28th March war was declared, but the preparations for it showed that the Government had looked upon war as certain some time previously.

Every exertion was made by the authorities to enable the expedition to take the field. General Ferguson and Admiral Houston Stewart received the expression of the Duke of Newcastle's satisfaction at the manner in which they co-operated in making "the extensive preparations for the reception of the expeditionary force, which could only have been successfully carried on by the absence of needless departmental etiquette,"—a virtue which has been expected to become more common after this official laudation. This expression of satisfaction was well deserved by both these gallant officers, and Sir W. Reid emulated them in his exertions to secure the comfort of the troops. The Admiral early and late worked with his usual energy. He had a modus operandi of making the conditional mood mean the imperative. Soldiers were stowed away in sailors' barracks and penned up in hammocks under its potent influence; and ships were cleared of their freight, or laden with a fresh one, with extraordinary facility.

It was at this time that in a letter to the Times I wrote as follows:—"With our men well clothed, well fed, well housed (whether in camp or town does not much matter), and well attended to, there is little to fear. They were all in the best possible spirits, and fit to go anywhere, and perhaps to do anything. But inaction might bring listlessness and despondency, and in their train follows disease. What is most to be feared in an encampment is an enemy that musket and bayonet cannot meet or repel. Of this the records of the Russo-Turkish campaign of 1828-9, in which 80,000 men perished by 'plague, pestilence, and famine,' afford a fearful lesson, and let those who have the interests of the army at heart just turn to Moltke's history of that miserable invasion, and they will grudge no expense, and spare no precaution, to avoid, as far as human skill can do it, a repetition of such horrors. Let us have plenty of doctors. Let us have an overwhelming army of medical men to combat disease. Let us have a staff—full and strong—of young and active and experienced men. Do not suffer our soldiers to be killed by antiquated imbecility. Do not hand them over to the mercies of ignorant etiquette and effete seniority, but give the sick every chance which skill, energy, and abundance of the best specifics can afford them. The heads of departments may rest assured that the country will grudge no expense on this point, nor on any other connected with the interest and efficiency of the corps d'élite which England has sent from her shores.[4] There were three first-class staff-surgeons at Constantinople—Messrs. Dumbreck Linton, and Mitchell. At Malta there were—Dr. Burrell, at the head of the department; Dr. Alexander, Dr. Tice, Mr. Smith, and a great accession was expected every day."

The commissariat department appeared to be daily more efficient, and every possible effort was made to secure proper supplies for the troops. This, however, was a matter that could be best tested in the field.

On Tuesday, the 28th of March, the Montezuma, and the Albatross with Chasseurs, Zouaves, and horses, arrived in the Great Harbour. The Zouave was then an object of curiosity. The quarters of the men were not by any means so good as our own. A considerable number had to sleep on deck, and in rain or sea-way they must have been wet. Their kit seemed very light. The officers did not carry many necessaries, and the average weight of their luggage was not more than 50lb. They were all in the highest spirits, and looked forward eagerly to their first brush in company with the English.

Sir George Brown and staff arrived on the 29th in the Valetta. The 2nd Battalion Rifle Brigade, the advance of the Light Division, which Sir George Brown was to command, embarked on board the Golden Fleece. On the 30th, Sir John Burgoyne arrived from Constantinople in the Caradoc.

The Pluton and another vessel arrived with Zouaves and the usual freight of horses the same day, and the streets were full of scarlet and blue uniforms walking arm and arm together in uncommunicative friendliness, their conversation being carried on by signs, such as pointing to their throats and stomachs, to express the primitive sensations of hunger and thirst. The French sailed the following day for Gallipoli.

When the declaration of war reached Malta, the excitement was indescribable. Crowds assembled on the shores of the harbours and lined the quays and landing-places, the crash of music drowned in the enthusiastic cheers of the soldiers cheering their comrades as the vessels glided along, the cheers from one fort being taken up by the troops in the others, and as joyously responded to from those on board.

CHAPTER II.

Departure of the first portion of the British Expedition from Malta—Sea passage—Classical Antiquities—Caught in a Levanter—The Dardanelles—Gallipoli—Gallipoli described—Turkish Architecture—Superiority of the French arrangements—Close shaving, tight stocking, and light marching.

DEPARTURE FROM MALTA.

Whilst the French were rapidly moving to Gallipoli, the English were losing the prestige which might have been earned by a first appearance on the stage, as well as the substantial advantages of an occupation of the town. But on 30th March Sir George Brown and Staff, the 2nd Battalion of the Rifle Brigade, under Lt. Colonel Lawrence, Colonel Victor, R.E., Captain Gibb, R.E., and two companies of Sappers, embarked in the Golden Fleece, and a cabin having been placed at my disposal, I embarked and sailed with them for Gallipoli, at five A.M. on 31st.

An early fisherman, a boatman in the Great Harbour, solitary sentinels perched here and there on the long lines of white bastions, were the only persons who saw the departure of the advanced guard of the only British expedition that has ever sailed to the land of the Moslem since the days of the great Plantagenet. The morning was dark and overcast. The Mediterranean assumed an indigo colour, stippled with patches of white foam, as heavy squalls of wind and drenching rain flew over its surface. The showers were tropical in their vehemence and suddenness. Nothing was visible except some wretched-looking gulls flapping in our wake hour after hour in the hope of unintentional contributions from the ship, and two or three dilapidated coasters running as hard as they could for the dangerous shelter of the land. Jason himself and his crew could scarcely have looked more uncomfortable than the men, though there was small resemblance indeed between the cruiser in which he took his passage and the Golden Fleece. "It all comes of sailing on a Friday," said a grumbling forecastle Jack.

The anticipations of the tarry prophet were not fully justified. Towards evening the sky cleared, the fine sharp edge of the great circle of waters of which we were the black murky centre, revealed itself, and the sun rushed out of his coat of cumuli, all bright and fervent, and sank to rest in a sea of fire. Even the gulls brightened up and began to look comfortable, and the sails of the flying craft, far away on the verge of the landscape, shone white. The soldiers dried their coats, and tried to forget sloppy decks and limited exercise ground, and night closed round the ship with peace and hilarity on her wings. As the moon rose a wonder appeared in the heavens—"a blazing comet with a fiery tail," which covered five or six degrees of the horizon, and shone through the deep blue above. Here was the old world-known omen of war and troubles! Many as they gazed felt the influence of ancient tales and associated the lurid apparition with the convulsion impending over Europe, though Mr. Hind and Professor Airy and Sir J. South might have proved to demonstration that the comet aforesaid was born or baptized in space hundreds of centuries before Prince Menschikoff was thought of.

At last the comet was lost in the moon's light, and the gazers put out their cigars, forgot their philosophy and their fears, and went to bed. The next day, Saturday (1st April), passed as most days do at sea in smooth weather. The men ate and drank, and walked on deck till they were able to eat and drink again, and so on till bed time. Curious little brown owls, as if determined to keep up the traditions of the neighbourhood, flew on board, and were caught in the rigging. They seemed to come right from the land of Minerva. In the course of the day small birds fluttered on the yards, masts, and bulwarks, plumed their jaded wings, and after a short rest launched themselves once more across the bosom of the deep. Some were common titlarks, others greyish buntings, others yellow and black fellows. Three of the owls and a titlark were at once introduced to each other in a cage, and the ship's cat was thrown in by way of making an impromptu "happy family." The result rather increased one's admiration for the itinerant zoologist of Trafalgar-square and Waterloo Bridge, inasmuch as pussy obstinately refused to hold any communication with the owls—they seemed in turn to hate each other—and all evinced determined animosity towards the unfortunate titlark, which speedily languished and died.

This and the following day there was a head wind. No land appeared, and the only object to be seen was a French paddle-wheel steamer with troops on board and a transport in tow, which was conjectured to be one of those that had left Malta some days previously. After dinner, when the band had ceased playing, the Sappers assembled on the quarter-deck, and sang glees excellently well, while the Rifles had a select band of vocal performers of their own of comic and sentimental songs. Some of these, à propos of the expedition, were rather hard on the Guards and their bearskins. At daylight the coast was visible N. by E.—a heavy cloudlike line resting on the grey water. It was the Morea—the old land of the Messenians. If not greatly changed, it is wonderful what attractions it could have had for the Spartans. A more barren-looking coast one need not wish to see. It is like a section of the west coast of Sutherland in winter. The mountains—cold, rocky, barren ridges of land—culminate in snow-covered peaks, and the numerous villages of white cabins or houses dotting the declivity towards the sea did not relieve the place of an air of savage primitiveness, which little consorted with its ancient fame. About 9.40 A.M. we passed Cape Matapan, which concentrated in itself all the rude characteristics of the surrounding coast. We passed between the Morea and Cerigo. One could not help wondering what on earth could have possessed Venus to select such a wretched rock for her island home. Verily the poets have much to answer for. Not the boldest would have dared to fly into ecstasies about the terrestrial landing-place of Venus had he once beheld the same. The fact is, the place is like Ireland's Eye, pulled out and expanded. Although the whole reputation of the Cape was not sustained by our annihilation, the sea showed every inclination to be troublesome, and the wind began to rise.

After breakfast the men were mustered, and the captain read prayers. When prayers were over, we had a proof that the Greeks were tolerably right about the weather. Even bolder boatmen than the ancients might fear the heavy squalls off these snowy headlands, which gave a bad idea of sunny Greece in early spring. Their writers represented the performance of a voyage round Capes Matapan and Malea as attended with danger; and, if the best of triremes was caught in the breeze encountered by the Golden Fleece hereabouts, the crew would never have been troubled to hang up a votive tablet to their preserving deity.

[1] The letter which appeared in the Times giving an account of the Battle of the Alma was written at a plank which Captain Montagu's sappers put on two barrels to form a table.

[2] The districts which were the scenes of such brutal excesses in the suppression of a conspiracy are not in Bulgaria.

Monday, September the 4th, was spent by the authorities in final preparations, in embarking stragglers of all kinds, in closing the departments no longer needed at Varna, such as the principal commissariat offices, the post-office, the ordnance and field train, &c. The narrow lanes were blocked up with mules and carts on their way to the beach with luggage, and the happy proprietors, emerging from the squalid courtyards of their whilome quarters, thronged the piers in search of boats, the supply of which was not by any means equal to the demand. Some of those most industrious fellows, the Maltese, who had come out and taken their harbour boats with them, made a golden harvest, for each ceased his usual avocation of floating stationer, baker, butcher, spirit merchant, tobacconist, and poultryman for the time, and plied for hire all along the shores of the bay.

Dr. Thomson, of the 44th, and Mr. Reade, Assistant-Surgeon Staff, died of cholera on the 5th of October, in Balaklava. The town was in a revolting state. Lord Raglan ordered it to be cleansed, but there was no one to obey the order, and consequently no one attended to it.

The Brigade of the Guards lost fourteen officers killed; the wonder is that any escaped the murderous fire. The Alma did not present anything like the scene round the Sandbag Battery. Upwards of 1,200 dead and dying Russians laid behind and around and in front of it, and many a tall English Grenadier was there amid the frequent corpses of Chasseur and Zouave. At one time, while the Duke was rallying his men, a body of Russians came at him. Mr. Wilson, surgeon, 7th Hussars, attached to the brigade, perceived the danger of his Royal Highness, and with great gallantry assembled a few Guardsmen, led them to the charge, and dispersed the Russians. The Duke's horse was killed. At the close of the day he called Mr. Wilson in front and thanked him for having saved his life.

In addition to the old lines thrown up by Liprandi close to the Woronzoff road, the Russians erected, to the rear and north of it, a very large hexagonal work, capable of containing a large number of men, and of being converted into a kind of intrenched camp. The lines of these works were very plain as they were marked out by the snow, which lay in the trench after that which fell on the ground outside and inside had melted. There were, however, no infantry in sight, nor did any movement of troops take place over the valley of the Tchernaya. Emboldened by the success of the 24th, the Russians were apparently preparing to throw up another work on the right of the new trenches, as if they had made up their minds to besiege the French at Inkerman, and assail their right attack. They sent up two steamers to the head of the harbour, which greatly annoyed the right attack, and it occurred to Captain Peel, of the Diamond, that it would be quite possible to get boats down to the water's edge and cut these steamers out, or sink them. Lord Raglan and Sir Edmund Lyons reconnoitred their position, but on reflection the latter refused to sanction an operation which would have gone far to raise the prestige of our navy, and to maintain their old character for dash and daring.

Subsequently an attack was made on Taganrog, but the depth of water off the port did not permit the larger vessels to approach near enough to cover the landing of armed parties, to destroy the immense stores of corn effectually; nevertheless a good deal of harm was done to the Russians, and public and private property largely injured. It was on the occasion of the demonstration against this important town, apparently, that the germ of the great idea of the Monitor, which has revolutionized the navies of the world, was developed by Lt. Cowper Coles, R.N. He mounted a gun on a raft and defended it with gabions, and he was enabled to bring this floating battery, which he called the Lady Nancy, into action with great effect against Taganrog. In the development of that idea called the Captain he lost his life in 1870. These operations along the coasts of the Sea of Azoff certainly caused losses to the enemy, and may have done something to create temporary inconvenience; they were effected in a legitimate if rather barbarous exercise of the rights of war, but when a few months subsequently the British Army before Sebastopol was in such need of corn that contractors were sent out to buy it in the United States, it must have occurred to the authorities that they had countenanced senseless waste, and authorized wanton destruction, to their great eventual detriment. As the naval forces were obliged to retire after each bombardment, and the landing of armed parties was only temporary, the enemy generally claimed the credit of having repulsed them, and Russia was inundated with accounts of the disasters caused by the bravery of priests and peasants, and divine interposition, to the audacious invaders who had ventured to pollute her holy soil. Cheap prints of the defence of Taganrog, &c., were published and sold by the thousand, and the people were excited by accounts of the death of innocent people, of the sacking of undefended cities, and of arson and pillage and wreck. Kertch and Yenikale were placed in a state of defence and garrisoned, and eventually the Turkish Contingent was stationed on the coast and in the town, and a small force of infantry and cavalry was detached from the British to aid them. The Contingent, composed of Turks under British officers, became a highly disciplined body, fit for any duty, but its value and conduct were not exhibited in the field, and it was employed as a corps of defence and observation on the Bay of Kertch till the war was over, when it and the other corps raised abroad under British officers, such as the Swiss Legion, the German Legion, &c., were disbanded. The Russians soon sent a corps to observe the movements of the force stationed at Kertch and Yenikale, and hemmed them in with Cossacks, and some slight affairs of outposts and reconnoitring parties occurred during the autumn and winter, in one of which a party of the 10th Hussars had difficulty in extricating itself, and suffered some loss from a larger body of the enemy. The work of the expedition to Kertch having been accomplished by the occupation of the town and straits, and by obtaining complete command of the entrance of the Sea of Azoff, the Allied fleets returned to Kamiesh and to the anchorage off Sebastopol, to participate as far as they could in the task of the siege.

On the 21st, Captain Lushington, who had been promoted to the rank of Admiral, was relieved in the command of the Naval Brigade by Captain the Hon. H. Keppel. Commissary-General Filder, at the same date, returned home on the recommendation of a Medical Board.

Many of the officers were hutted, some constructed semi-subterranean residences, and the camp was studded all over with the dingy roofs, which at a distance looked much like an aggregate of molehills. In order to prevent ennui or listlessness after the great excitement of so many months in the trenches, the Generals of Division began to drill our veterans, and to renew the long-forgotten pleasures of parades, field-days, and inspections. In all parts of the open ground about the camps, the visitor might have seen men with Crimean medals and Balaklava and Inkerman clasps, practising goose-step or going through extension movements, learning, in fact, the A B C of their military education, though they had already seen a good deal of fighting and soldiering. Still there were periods when the most inveterate of martinets rested from their labour, and the soldier, having nothing else to do, availed himself of the time and money at his disposal to indulge in the delights of the canteen. Road-making occupied some leisure hours, but the officers had very little to do, and found it difficult to kill time, riding about Sebastopol, visiting Balaklava, foraging at Kamiesch, or hunting for quail, which were occasionally found in swarms all over the steppe, and formed most grateful additions to the mess-table. There was no excitement in front; the Russians remained immovable in their position at Mackenzie's Farm. The principal streets of Sebastopol lost the charm of novelty and possession. Even Cathcart's Hill was deserted, except by the "look-out officer" for the day, or by a few wandering strangers and visitors.

The extraordinary fineness of the weather all this time afforded a daily reproach to the inactivity of our armies. Within one day of the first anniversary of that terrible 14th of November, which will never be forgotten by those who spent it on the plateau of Sebastopol, the air was quite calm. From the time the expedition returned from Kinburn not one drop of rain fell, and each day was cloudless, sunny, and almost too warm. The mornings and nights, however, began to warn us that winter was impending. It is certainly to be regretted that the Admirals could not have undertaken their expedition against Kaffa, for the only ostensible obstacle to the enterprise was the weather, and our experience and traditions of the year before certainly suggested extreme caution ere we ventured upon sending a flotilla, filled with soldiers, on such an awful coast, even for the very short passage to Theodosia.

Sir George Cathcart's resting-place was marked by a very fine monument, for which his widow expressed her thanks to those who raised it to the memory of their beloved commander. There was an inscription upon it commemorating the General's services, and the fact that he served with the Russian armies in one of their most memorable campaigns—the date of his untimely and glorious death, and an inscription in the Russian language stating who and what he was who reposed beneath. In the second row to the east there were two graves, without any inscription on the stones; the third was marked by a very handsome circular pillar of hewn stone, surmounted by a cross, and placed upon two horizontal slabs. On the pillar below the cross in front was this inscription: "To Lieutenant-Colonel C. F. Seymour, Scots Fusileer Guards, killed in action, November 5, 1854." Beneath these words were a cross sculptured in the stone, and the letters "I.H.S.;" and a Russian inscription on the back, requesting that the tomb might be saved from desecration. At the foot of the tomb there was an elaborately carved stone lozenge surmounting a slab, and on the lozenge was engraved the crest of the deceased, with some heraldic bird springing from the base of a coronet, with the legend "Foy pour devoir, C.F.S. Æt. 36." How many an absent friend would have mourned around this tomb! Close at hand was a handsome monument to Sir John Campbell, than whom no soldier was ever more regretted or more beloved by those serving under him; and not far apart in another row was a magnificent sarcophagus in black Devonshire marble, to the memory of Sir R. Newman, of the Grenadier Guards, who also fell at Inkerman. With all these memorials of death behind us, the front wall at Cathcart's Hill was ever a favourite spot for gossips and spectators, and sayers of jokes, and raconteurs of bons mots or such jeux d'esprit as find favour in military circles.

[3] The 3rd Battalion Grenadier Guards, and 1st Battalion Coldstream Guards. The 1st Battalion Scots Fusilier Guards embarked on February 28th.

[4] This was a timely warning—almost a prophetic warning—sounded long ere a British soldier set foot in the East.

CAUGHT IN A LEVANTER.

From 10 o'clock till 3.30 P.M. the ship ran along the diameter of the semicircle between the two Capes which mark the southern extremities of Greece. Cape Malea, or St. Angelo, is just such another bluff, mountainous, and desolate headland as Cape Matapan, and is not so civilized-looking, for there are no villages visible near it. However, in a hole on its south-east face resides a Greek hermit, who must have enormous opportunities for improving his mind, if Zimmerman be at all trustworthy. He is not quite lost to the calls of nature, and has a great tenderness for ships' biscuit. He generally hoists a little flag when a vessel passes near, and is often gratified by a supply of hard-bake. Had we wished to administer to his luxuries we could not have done so, for the wind off this angle rushed at us with fury, and the instant we rounded it we saw the sea broken into crests of foam making right at our bows. The old mariners were not without warranty when they advised "him who doubled Cape Malea to forget his home." We had got right into the Etesian wind—one of those violent Levanters which the learned among us said ought to be the Euroclydon which drove St. Paul to Malta. Sheltered as we were to eastward by clusters of little islands, the sea got up and rolled in confused wedges towards the ship. She behaved nobly, but with her small auxiliary steam power she could scarcely hold her own. We were driven away to leeward, and did not make much headway. The gusts came down furiously between all kinds of classical islands, which we could not make out, for our Maltese pilot got frightened, and revealed the important secret that he did not know one of them from the other. The men bore up well against their Euroclydon, and emulated the conduct of the ship. Night came upon us, labouring in black jolting seas, dashing them into white spray, and running away into dangerous unknown parts. It passed songless, dark, and uncomfortable: much was the suffering in the hermetically sealed cells in which our officers "reposed" and grumbled at fortune.

At daylight next morning, Falconero was north, and Milo south. The clouds were black and low, the sea white and high, and the junction between them on the far horizon of a broken and promiscuous character. The good steamer had run thirty miles to leeward of her course, making not the smallest progress. Grey islets with foam flying over them lay around indistinctly seen through the driving vapour from the Ægean. To mistrust of the pilot fear of accident was added, so the helm was put up, and we wore ship at 6.30 A.M. in a heavy sea-way. A screw-steamer was seen on our port quarter plunging through the heavy sea, and we made her out to be the Cape of Good Hope. She followed our example. The gale increased till 8 A.M.; the sailors considered it deserved to be called "stormy, with heavy squalls." The heavy sea on our starboard quarter, as we approached Malea, caused the ship to roll heavily; the men could only hold on by tight grip, and they and their officers were well drenched by great lumbering water louts, who tossed themselves in over the bulwarks. At 3.30 P.M., the ship cast anchor in Vatika Bay, in twenty fathoms. A French steamer and brig lay close in the shore. We cheered them vigorously, but the men could not hear us. Some time afterwards the Cape of Good Hope and a French screw-steamer also ran in and anchored near us. This little flotilla alarmed the inhabitants, for the few who were fishing in boats fled to shore, and we saw a great effervescence at a distant village. No doubt the apparition in the bay of a force flying the tricolor and the union-jack frightened the people. They could be seen running to and fro along the shore like ants when their nest is stirred.

At dusk our bands played, and the mountains of the Morea, for the first time since they rose from the sea, echoed the strains of "God save the Queen." Our vocalists assembled, and sang glees or vigorous choruses, and the night passed pleasantly in smooth water on an even keel. The people lighted bonfires upon the hills, but the lights soon died out. At six o'clock on Tuesday morning the Golden Fleece left Vatika Bay, and passed Poulo Bello at 10.45 A.M. The Greek coast trending away to the left, showed in rugged masses of mountains capped by snowy peaks, and occasionally the towns—clusters of white specks on the dark purple of the hills—were visible; and before evening, the ship having run safely through all the terrors of the Ægean and its islands, bore away for the entrance to the Dardanelles. At 2 A.M. on Wednesday morning, however, it began to blow furiously again, the wind springing up as if "Æolus had just opened and put on fresh hands at the bellows," to use the nautical simile. The breeze, however, went down in a few hours, with the same rapidity with which it rose. Smooth seas greeted the ship as she steamed by Mitylene. On the left lay the entrance to the Gulf of Athens—Eubœa was on our left hand—Tenedos was before us—on our right rose the snowy heights of Mount Ida—and the Troad (atrociously and unforgivably like the "Bog of Allen!") lay stretching its brown folds, dotted with rare tumuli, from the sea to the mountain side for leagues away. Athos (said to be ninety miles distant) stood between us and the setting sun—a pyramid of purple cloud bathed in golden light; and the Leander frigate showed her number and went right away in the very waters that lay between Sestos and Abydos, past the shadow of the giant mountain, stretching away on our port beam. As the vessel entered the portals of the Dardanelles, and rushed swiftly up between its dark banks, the sentinels on the forts and along the ridges challenged loudly—shouting to each other to be on the alert—the band of the Rifles all the while playing the latest fashionable polkas, or making the rocks acquainted with "Rule Britannia," and "God save the Queen."

At 9.30 P.M., our ship passed the Castles of the Dardanelles. She was not stopped nor fired at, but the sentinels screeched horribly and showed lights, and seemed to execute a convulsive pas of fright or valour on the rocks. The only reply was the calm sounding of second post on the bugles—the first time that the blast of English light infantry trumpets broke the silence of those antique shores.[5]

GALLIPOLI.

After midnight we arrived at Gallipoli, and anchored. No one took the slightest notice of us, nor was any communication made with shore. When the Golden Fleece arrived there was no pilot to show her where to anchor, and it was nearly an hour ere she ran out her cable in nineteen fathoms water. No one came off, for it was after midnight, and there was something depressing in this silent reception of the first British army that ever landed on the shores of these straits.

When morning came we only felt sorry that nature had made Gallipoli, a desirable place for us to land at. The tricolor was floating right and left, and the blue coats of the French were well marked on shore, the long lines of bullock-carts stealing along the strand towards their camp making it evident that they were taking care of themselves.

Take some hundreds of dilapidated farms, outhouses, a lot of rickety tenements of Holywell-street, Wych-street, and the Borough—catch up, wherever you can, any of the seedy, cracked, shutterless structures of planks and tiles to be seen in our cathedral towns—carry off odd sheds and stalls from Billingsgate, add to them a selection of the huts along the Thames between London-bridge and Greenwich—bring them, then, all together to the European side of the Straits of the Dardanelles, and having pitched on a bare round hill sloping away to the water's edge, on the most exposed portion of the coast, with scarcely tree or shrub, tumble them "higgledy piggledy" on its declivity, in such wise that the lines of the streets may follow on a large scale the lines of a bookworm through some old tome—let the roadways be very narrow, of irregular breadth, varying according to the bulgings and projections of the houses, and paved with large round slippery stones, painful and hazardous to walk upon—here and there borrow a dirty gutter from a back street in Boulogne—let the houses lean across to each other so that the tiles meet, or a plank thrown across forms a sort of "passage" or arcade—steal some of the popular monuments of London, the shafts of national testimonials, a half dozen of Irish Round Towers—surround these with a light gallery about twelve feet from the top, put on a large extinguisher-shaped roof, paint them white, and having thus made them into minarets, clap them down into the maze of buildings—then let fall big stones all over the place—plant little windmills with odd-looking sails on the crests of the hill over the town—transport the ruins of a feudal fortress from Northern Italy, and put it into the centre of the town, with a flanking tower at the water's edge—erect a few wooden cribs by the waterside to serve as café, custom-house, and government stores—and, when you have done this, you have to all appearance imitated the process by which Gallipoli was created. The receipt, if tried, will be found to answer beyond belief.

To fill up the scene, however, you must catch a number of the biggest breeched, longest bearded, dirtiest, and stateliest old Turks to be had at any price in the Ottoman empire; provide them with pipes, keep them smoking all day on wooden stages or platforms about two feet from the ground, everywhere by the water's edge or up the main streets, in the shops of the bazaar which is one of the "passages" or arcades already described; see that they have no slippers on, nothing but stout woollen hose, their foot gear being left on the ground, shawl turbans (one or two being green, for the real descendant of the Prophet), flowing fur-lined coats, and bright-hued sashes, in which are to be stuck silver-sheathed yataghans and ornamented Damascus pistols; don't let them move more than their eyes, or express any emotion at the sight of anything except an English lady; then gather a noisy crowd of fez-capped Greeks in baggy blue breeches, smart jackets, sashes, and rich vests—of soberly-dressed Armenians—of keen-looking Jews, with flashing eyes—of Chasseurs de Vincennes, Zouaves, British riflemen, vivandières, Sappers and Miners, Nubian slaves, Camel-drivers, Commissaries and Sailors, and direct them in streams round the little islets on which the smoking Turks are harboured, and you will populate the place.

It will be observed that women are not mentioned in this description, but children were not by any means wanting—on the contrary, there was a glut of them, in the Greek quarter particularly, and now and then a bundle of clothes, in yellow leather boots, covered at the top with a piece of white linen, might be seen moving about, which you will do well to believe contained a woman neither young nor pretty. Dogs, so large, savage, tailless, hairy, and curiously-shaped, that Wombwell could make a fortune out of them if aided by any clever zoological nomenclator, prowled along the shore and walked through the shallow water, in which stood bullocks and buffaloes, French steamers and transports, with the tricolor flying, and the paddlebox boats full of troops on their way to land—a solitary English steamer, with the red ensign, at anchor in the bay—and Greek polaccas, with their beautiful white sails and trim rig, flying down the straits, which are here about three and a half miles broad, so that the villages on the rich swelling hills of the Asia Minor side are plainly visible,—must be added, and then the picture will be tolerably complete.

In truth, Gallipoli is a wretched place—picturesque to a degree, but, like all picturesque things or places, horribly uncomfortable. The breadth of the Dardanelles is about five miles opposite the town, but the Asiatic and the European coasts run towards each other just ere the Straits expand into the Sea of Marmora. The country behind the town is hilly, and at the time of our arrival had not recovered from the effects of the late very severe weather, being covered with patches of snow. Gallipoli is situated on the narrowest portion of the tongue of land or peninsula which, running between the Gulf of Saros on the west and the Dardanelles on the east, forms the western side of the strait. An army encamped here commands the Ægean and the Sea of Marmora, and can be marched northwards to the Balkan, or sent across to Asia or up to Constantinople with equal facility.

SUPERIORITY OF FRENCH ARRANGEMENTS.

As the crow flies, it is about 120 miles from Constantinople across the Sea of Marmora. If the capital were in danger, troops could be sent there in a few days, and our army and fleet effectually commanded the Dardanelles and the entrance to the Sea of Marmora, and made it a mare clausum. Enos, a small town, on a spit of land opposite the mouth of the Maritza, on the coast of Turkey to the north-east of Samothrace, was surveyed and examined for an encampment by French and English engineers. It is obvious that if some daring Muscovite general forcing the passage across the Danube were to beat the Turks and cross the western ridges of the Balkans, he might advance southwards with very little hindrance to the Ægean; and a dashing march to the south-east would bring his troops to the western shore of the Dardanelles. An army at Gallipoli could check such a movement, if it ever entered into the head of any one to attempt to put it in practice.

Early on the morning after the arrival of the Golden Fleece a boat came off with two commissariat officers, Turner and Bartlett, and an interpreter. The consul had gone up the Dardanelles to look for us. The General desired to send for the Consul, but the only vessel available was a small Turkish Imperial steamer. The Consul's dragoman, a grand-looking Israelite, was ready to go, but the engineer had just managed to break his leg. He requested the loan of our engineer, as no one could be found to undertake the care of the steamer's engines.

After breakfast, Lieutenant-General Brown, Colonel Sullivan, Captain Hallewell, and Captain Whitmore, started to visit the Pasha of Adrianople (Rustum Pasha), who was sent here to facilitate the arrangements and debarkation of the troops. On their return, about half-past two o'clock, Lieutenant-General Canrobert came on board the vessel, and was received by the Lieutenant-General. The visit lasted an hour, and was marked at its close with greater cordiality, if possible, than at the commencement.

In the evening the Consul, Mr. Calvert, came on board, when it turned out that no instructions whatever had been sent to prepare for the reception of the force, except that two commissariat officers, without interpreters or staff, had been dispatched to the town a few days before the troops landed. These officers could not speak the language. However, the English Consul was a man of energy. Mr. Calvert went to the Turkish Governor, and succeeded in having half of the quarters in the town reserved. Next day he visited and marked off the houses; but the French authorities said they had made a mistake as to the portion of the town they had handed over to him. They had the Turkish part of the town close to the water, with an honest and favourable population; the English had the Greek quarter, further up the hill, and perhaps the healthier, and a population which hated them bitterly.

Sir George Brown arrived on Wednesday, the 5th of April, but it was midday on Saturday the 8th, ere the troops were landed and sent to their quarters. The force consisted of only some thousand and odd men, and it had to lie idle for two days and a half watching the seagulls, or with half averted eye regarding the ceaseless activity of the French, the daily arrival of their steamers, the rapid transmission of their men to shore. On our side not a British pendant was afloat in the harbour! Well might a Turkish boatman ask, "Oh, why is this? Oh, why is this, Chelebee? By the beard of the Prophet, for the sake of your father's father, tell me, O English Lord, how is it? The French infidels have got one, two, three, four, five, six, seven ships, with fierce little soldiers; the English infidels, who say they can defile the graves of these French (may Heaven avert it!), and who are big as the giants of Asli, have only one big ship. Do they tell lies?" (Such was the translation given to me of my interesting waterman's address.)

The troops were disembarked in the course of the day, and marched out to encamp, eight miles and a half north of Gallipoli, at a place called Bulair. The camp was occupied by the Rifles and Sappers and Miners, within three miles of the village. It was seated on a gentle slope of the ridge which runs along the isthmus, and commanded a view of the Gulf of Saros, but the Sea of Marmora was not visible. Sanitary and certain other considerations may have rendered it advisable not to select this village itself, or some point closer to it, as the position for the camp; but the isthmus was narrower at Bulair, could be more easily defended, would not have required so much time or labour to put it into a good state of defence, and appeared to be better adapted for an army as regards shelter and water than the position chosen. Bulair is ten and a half miles from Gallipoli, so the camp was about seven and a half from the port at which its supplies were landed, and where its reinforcements arrived.

SCARCITY OF PROVISIONS.

On Thursday there was a general hunt for quarters through the town. The General got a very fine place in a beau quartier, with a view of an old Turk on a counter looking at his toes in perpetual perspective. The consul, attended by the dragoman and a train of lodging seekers, went from house to house; but it was not till the eye had got accustomed to the general style of the buildings and fittings that any of them seemed willing to accept the places offered them. The hall door, which is an antiquated concern—not affording any particular resistance to the air to speak of—opens on an apartment with clay walls about ten feet high, and of the length and breadth of the whole house. It is garnished with the odds and ends of the domestic deity—empty barrels, casks of home-made wine, buckets, baskets, &c. At one side a rough staircase, creaking at every step, conducts one to a saloon on the first floor. This is of the plainest possible appearance. On the sides are stuck prints of the "Nicolaus ho basileus," of the Virgin and Child, and engravings from Jerusalem. The Greeks are iconoclasts, and hate images, but they adore pictures. A yellow Jonah in a crimson whale with fiery entrails is a favourite subject, and doubtless bears some allegorical meaning to their own position in Turkey. From this saloon open the two or three rooms of the house—the kitchen, the divan, and the principal bedroom. There is no furniture. The floors are covered with matting, but with the exception of the cushions on the raised platform round the wall of the room (about eighteen inches from the floor), there is nothing else in the rooms offered for general competition to the public. Above are dark attics. In such a lodging as this, in the house of the widow Papadoulos, was I at last established to do the best I could without servant or equipment.

Water was some way off, and I might have been seen stalking up the street with as much dignity as was compatible with carrying a sheep's liver on a stick in one hand, some lard in the other, and a loaf of black bread under my arm back from market. There was not a pound of butter in the whole country, meat was very scarce, fowls impossible; but the country wine was fair enough, and eggs were not so rare as might be imagined from the want of poultry.

While our sick men had not a mattress to lie down upon, and were without blankets, the French were well provided for. No medical comforts were forwarded from Malta,—and so when a poor fellow was sinking the doctor had to go to the General's and get a bottle of wine for him. The hospital sergeant was sent out with a sovereign to buy coffee, sugar, and other things of the kind for the sick, but he could not get them, as no change was to be had in the place. In the French hospital everything requisite was nicely made up in small packages and marked with labels, so that what was wanted might be procured in a minute.

The French Commandant de Place posted a tariff of all articles which the men were likely to want on the walls of the town, and regulated the exchanges like a local Rothschild. A Zouave wanted a fowl; he saw one in the hand of an itinerant poultry merchant, and he at once seized the bird, and giving the proprietor a franc—the tariff price—walked off with the prize. The Englishman, on the contrary, more considerate and less protected, was left to make hard bargains, and generally paid twenty or twenty-five per cent. more than his ally. These Zouaves were first-rate foragers. They might be seen in all directions, laden with eggs, meat, fish, vegetables (onions), and other good things, while our fellows could get nothing. Sometimes a servant was sent out to cater for breakfast or dinner: he returned with the usual "Me and the Colonel's servant has been all over the town, and can get nothing but eggs and onions, Sir;" and lo! round the corner appeared a red-breeched Zouave or Chasseur, a bottle of wine under his left arm, half a lamb under the other, and poultry, fish, and other luxuries dangling round him. "I'm sure I don't know how these French manages it, Sir," said the crestfallen Mercury, retiring to cook the eggs.

The French established a restaurant for their officers, and at the "Auberge de l'Armée Expeditionnaire," close to General Bosquet's quarters, one could get a dinner which, after the black bread and eggs of the domestic hearth, appeared worthy of Philippe.

There seemed to be a general impression among the French soldiers that it would be some time ere they left Gallipoli or the Chersonese. They were in military occupation of the place. The tricolor floated from the old tower of Gallipoli. The café had been turned into an office—Direction du Port et Commissariat de la Marine. French soldiers patrolled the town at night, and kept the soldiery of both armies in order; of course, we sent out a patrol also, but the regulations of the place were directly organized at the French head-quarters, and even the miserable house which served as our Trois Frères, or London Tavern, and where one could get a morsel of meat and a draught of country wine for dinner, was under their control. A notice on the walls of this Restaurant de l'Armée Auxiliaire informed the public that, par ordre de la police Française, no person would be admitted after seven o'clock in the evening. In spite of their strict regulations there was a good deal of drunkenness among the French soldiery, though perhaps it was not in excess of our proportion, considering the numbers of both armies. They had fourgons for the commissariat, and all through their quarter of the town one might see the best houses occupied by their officers. On one door was inscribed Magasin des Liquides, on another Magasin des Distributions. M. l'Aumonier de l'Armée Française resides on one side of the street; l'Intendant Général, &c., on the other. Opposite the commissariat stores a score or two of sturdy Turks worked away at neat little hand-mills marked Moulin de Café—Subsistence Militaire. No. A., Compagnie B., &c., and roasting the beans in large rotatory ovens; the place selected for the operation being a burial-ground, the turbaned tombstones of which seemed to frown severely on the degenerate posterity of the Osmanli. In fact, the French appear to have acted uniformly on the sentiment conveyed in the phrase of one of their officers, in reply to a remark about the veneration in which the Turks hold the remains of the dead—"Mais il faut rectifier tous ces préjuges et barbarismes!"

The greatest cordiality existed between the chiefs of the armies. Sir George Brown and some of his staff dined one day with General Canrobert; another day with General Martimprey; another day the drowsy shores of the Dardanelles were awakened by the thunders of the French cannon saluting him as he went on board Admiral Bruat's flagship to accept the hospitalities of the naval commander; and then on alternate days the dull old alleys of Gallipoli were brightened up by an apparition of these officers and their staffs in full uniform, clanking their spurs and jingling their sabres over the excruciating rocks which form the pavement as they proceeded on their way to the humble quarters of "Sir Brown," to sit at return banquets.

The natives preferred the French uniform to ours. In their sight there can be no more effeminate object than a warrior in a shell jacket, with closely-shaven chin and lip and cropped whiskers. He looks, in fact, like one of their dancing troops, and cuts a sorry figure beside a great Gaul in his blazing red pantaloons and padded frock, epaulettes, beard d'Afrique, and well-twisted moustache. The pashas think much of our men, but they are not struck with our officers. The French made an impression quite the reverse. The Turks could see nothing in the men, except that they thought the Zouaves and Chasseurs Indigènes dashing-looking fellows; but they considered their officers superior to ours in all but exact discipline. One day, as a man of the 4th was standing quietly before the door of the English Consulate, with a horse belonging to an officer of his regiment, some drunken French soldiers came reeling up the street; one of them kicked the horse, and caused it to rear violently; and, not content with doing so, struck it on the head as he passed. Several French officers witnessed this scene, and one of them exclaimed, "Why did not you cut the brigand over the head with your whip when he struck the horse?" The Englishman was not a master of languages, and did not understand the question. When it was explained to him, he said with the most sovereign contempt, "Lord forbid I'd touch sich a poor drunken little baste of a crayture as that!"

TROUBLES OF THE TURKISH COMMISSION.

The Turkish Commission had a troublesome time of it. All kinds of impossible requisitions were made to them every moment. Osman Bey, Eman Bey, and Kabouli Effendi, formed the martyred triumvirate, who were kept in a state of unnatural activity and excitement by the constant demands of the officers of the allied armies for all conceivable stores, luxuries, and necessaries for the troops, as well as for other things over which they had no control. One man had a complaint against an unknown Frenchman for beating his servant—another wanted them to get lodgings for him—a third wished them to send a cavass with self and friends on a shooting excursion—in fact, very unreasonable and absurd requests were made to these poor gentlemen, who could scarcely get through their legitimate work, in spite of the aid of numberless pipes and cups of coffee. One of the medical officers went to make a requisition for hospital accommodation, and got through the business very well. When it was over, the President descended from the divan. In the height of his delusions respecting Oriental magnificence and splendour, led away by reminiscences of "Tales of the Genii" and the "Arabian Nights," the reader must not imagine that this divan was covered with cloth of gold, or glittering with precious stones. It was clad in a garb of honest Manchester print, with those remarkable birds of prey or pleasure, in green and yellow plumage, depicted thereupon, familiar to us from our earliest days. The council chamber was a room of lath and plaster, with whitewashed walls; its sole furniture a carpet in the centre, the raised platform or divan round its sides, and a few chairs for the Franks. The President advanced gravely to the great Hakim, and through the interpreter made him acquainted with particulars of a toothache, for which he desired a remedy. The doctor insinuated that His Highness must have had a cold in the head, from which the symptoms had arisen, and the diagnosis was thought so wonderful it was communicated to the other members of the Council, and produced a marked sensation. When he had ordered a simple prescription he was consulted by the other members in turn: one had a sore chin, the other had weak eyes; and the knowledge evinced by the doctor of these complaints excited great admiration and confidence, so that he departed, after giving some simple prescriptions, amid marks of much esteem and respect.