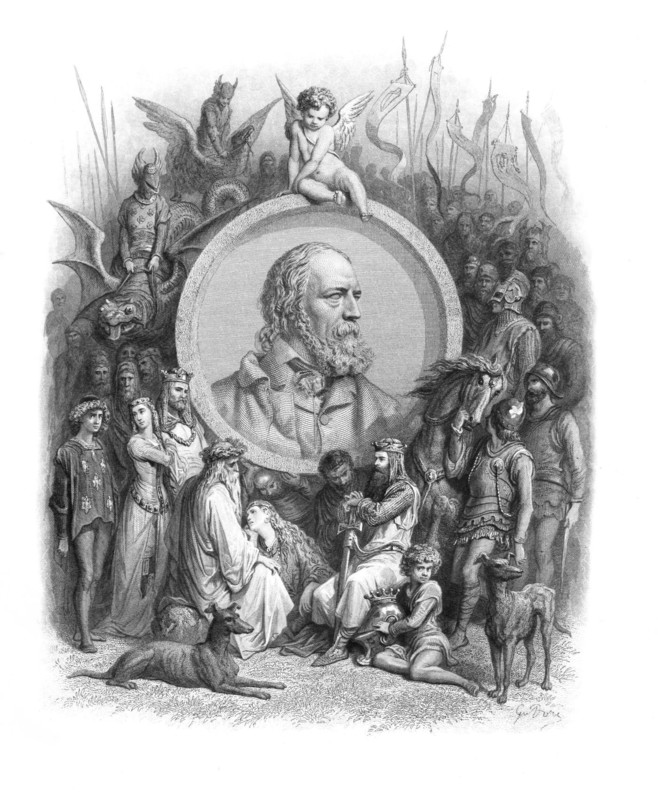

автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Idylls of the King

Dedication

These to His Memory—since he held them dear,

Perchance as finding there unconsciously

Some image of himself—I dedicate,

I dedicate, I consecrate with tears—

These Idylls.

And indeed He seems to me

Scarce other than my king’s ideal knight,

“Who reverenced his conscience as his king;

Whose glory was, redressing human wrong;

Who spake no slander, no, nor listened to it;

Who loved one only and who clave to her—”

Her—over all whose realms to their last isle,

Commingled with the gloom of imminent war,

The shadow of His loss drew like eclipse,

Darkening the world. We have lost him: he is gone:

We know him now: all narrow jealousies

Are silent; and we see him as he moved,

How modest, kindly, all-accomplished, wise,

With what sublime repression of himself,

And in what limits, and how tenderly;

Not swaying to this faction or to that;

Not making his high place the lawless perch

Of winged ambitions, nor a vantage-ground

For pleasure; but through all this tract of years

Wearing the white flower of a blameless life,

Before a thousand peering littlenesses,

In that fierce light which beats upon a throne,

And blackens every blot: for where is he,

Who dares foreshadow for an only son

A lovelier life, a more unstained, than his?

Or how should England dreaming of his sons

Hope more for these than some inheritance

Of such a life, a heart, a mind as thine,

Thou noble Father of her Kings to be,

Laborious for her people and her poor—

Voice in the rich dawn of an ampler day—

Far-sighted summoner of War and Waste

To fruitful strifes and rivalries of peace—

Sweet nature gilded by the gracious gleam

Of letters, dear to Science, dear to Art,

Dear to thy land and ours, a Prince indeed,

Beyond all titles, and a household name,

Hereafter, through all times, Albert the Good.

Break not, O woman’s-heart, but still endure;

Break not, for thou art Royal, but endure,

Remembering all the beauty of that star

Which shone so close beside Thee that ye made

One light together, but has past and leaves

The Crown a lonely splendour.

May all love,

His love, unseen but felt, o’ershadow Thee,

The love of all Thy sons encompass Thee,

The love of all Thy daughters cherish Thee,

The love of all Thy people comfort Thee,

Till God’s love set Thee at his side again!

Idylls of the King

The Coming of Arthur

Leodogran, the King of Cameliard,

Had one fair daughter, and none other child;

And she was the fairest of all flesh on earth,

Guinevere, and in her his one delight.

For many a petty king ere Arthur came

Ruled in this isle, and ever waging war

Each upon other, wasted all the land;

And still from time to time the heathen host

Swarmed overseas, and harried what was left.

And so there grew great tracts of wilderness,

Wherein the beast was ever more and more,

But man was less and less, till Arthur came.

For first Aurelius lived and fought and died,

And after him King Uther fought and died,

But either failed to make the kingdom one.

And after these King Arthur for a space,

And through the puissance of his Table Round,

Drew all their petty princedoms under him.

Their king and head, and made a realm, and reigned.

And thus the land of Cameliard was waste,

Thick with wet woods, and many a beast therein,

And none or few to scare or chase the beast;

So that wild dog, and wolf and boar and bear

Came night and day, and rooted in the fields,

And wallowed in the gardens of the King.

And ever and anon the wolf would steal

The children and devour, but now and then,

Her own brood lost or dead, lent her fierce teat

To human sucklings; and the children, housed

In her foul den, there at their meat would growl,

And mock their foster mother on four feet,

Till, straightened, they grew up to wolf-like men,

Worse than the wolves. And King Leodogran

Groaned for the Roman legions here again,

And Caesar’s eagle: then his brother king,

Urien, assailed him: last a heathen horde,

Reddening the sun with smoke and earth with blood,

And on the spike that split the mother’s heart

Spitting the child, brake on him, till, amazed,

He knew not whither he should turn for aid.

But—for he heard of Arthur newly crowned,

Though not without an uproar made by those

Who cried, “He is not Uther’s son”—the King

Sent to him, saying, “Arise, and help us thou!

For here between the man and beast we die.”

And Arthur yet had done no deed of arms,

But heard the call, and came: and Guinevere

Stood by the castle walls to watch him pass;

But since he neither wore on helm or shield

The golden symbol of his kinglihood,

But rode a simple knight among his knights,

And many of these in richer arms than he,

She saw him not, or marked not, if she saw,

One among many, though his face was bare.

But Arthur, looking downward as he past,

Felt the light of her eyes into his life

Smite on the sudden, yet rode on, and pitched

His tents beside the forest. Then he drave

The heathen; after, slew the beast, and felled

The forest, letting in the sun, and made

Broad pathways for the hunter and the knight

And so returned.

For while he lingered there,

A doubt that ever smouldered in the hearts

Of those great Lords and Barons of his realm

Flashed forth and into war: for most of these,

Colleaguing with a score of petty kings,

Made head against him, crying, “Who is he

That he should rule us? who hath proven him

King Uther’s son? for lo! we look at him,

And find nor face nor bearing, limbs nor voice,

Are like to those of Uther whom we knew.

This is the son of Gorlois, not the King;

This is the son of Anton, not the King.”

And Arthur, passing thence to battle, felt

Travail, and throes and agonies of the life,

Desiring to be joined with Guinevere;

And thinking as he rode, “Her father said

That there between the man and beast they die.

Shall I not lift her from this land of beasts

Up to my throne, and side by side with me?

What happiness to reign a lonely king,

Vext—O ye stars that shudder over me,

O earth that soundest hollow under me,

Vext with waste dreams? for saving I be joined

To her that is the fairest under heaven,

I seem as nothing in the mighty world,

And cannot will my will, nor work my work

Wholly, nor make myself in mine own realm

Victor and lord. But were I joined with her,

Then might we live together as one life,

And reigning with one will in everything

Have power on this dark land to lighten it,

And power on this dead world to make it live.”

Thereafter—as he speaks who tells the tale—

When Arthur reached a field-of-battle bright

With pitched pavilions of his foe, the world

Was all so clear about him, that he saw

The smallest rock far on the faintest hill,

And even in high day the morning star.

So when the King had set his banner broad,

At once from either side, with trumpet-blast,

And shouts, and clarions shrilling unto blood,

The long-lanced battle let their horses run.

And now the Barons and the kings prevailed,

And now the King, as here and there that war

Went swaying; but the Powers who walk the world

Made lightnings and great thunders over him,

And dazed all eyes, till Arthur by main might,

And mightier of his hands with every blow,

And leading all his knighthood threw the kings

Carados, Urien, Cradlemont of Wales,

Claudias, and Clariance of Northumberland,

The King Brandagoras of Latangor,

With Anguisant of Erin, Morganore,

And Lot of Orkney. Then, before a voice

As dreadful as the shout of one who sees

To one who sins, and deems himself alone

And all the world asleep, they swerved and brake

Flying, and Arthur called to stay the brands

That hacked among the flyers, “Ho! they yield!”

So like a painted battle the war stood

Silenced, the living quiet as the dead,

And in the heart of Arthur joy was lord.

He laughed upon his warrior whom he loved

And honoured most. “Thou dost not doubt me King,

So well thine arm hath wrought for me today.”

“Sir and my liege,” he cried, “the fire of God

Descends upon thee in the battle-field:

I know thee for my King!” Whereat the two,

For each had warded either in the fight,

Sware on the field of death a deathless love.

And Arthur said, “Man’s word is God in man:

Let chance what will, I trust thee to the death.”

Then quickly from the foughten field he sent

Ulfius, and Brastias, and Bedivere,

His new-made knights, to King Leodogran,

Saying, “If I in aught have served thee well,

Give me thy daughter Guinevere to wife.”

Whom when he heard, Leodogran in heart

Debating—“How should I that am a king,

However much he holp me at my need,

Give my one daughter saving to a king,

And a king’s son?”—lifted his voice, and called

A hoary man, his chamberlain, to whom

He trusted all things, and of him required

His counsel: “Knowest thou aught of Arthur’s birth?”

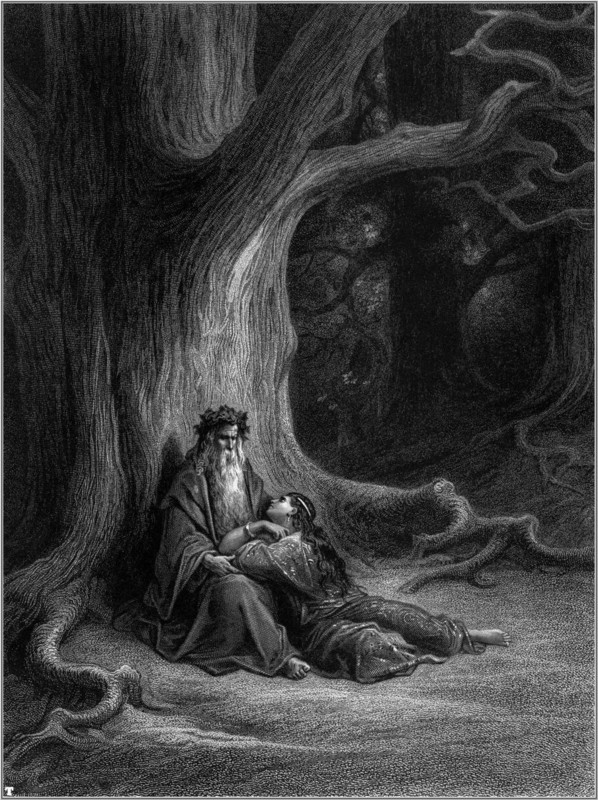

Then spake the hoary chamberlain and said,

“Sir King, there be but two old men that know:

And each is twice as old as I; and one

Is Merlin, the wise man that ever served

King Uther through his magic art; and one

Is Merlin’s master (so they call him) Bleys,

Who taught him magic, but the scholar ran

Before the master, and so far, that Bleys,

Laid magic by, and sat him down, and wrote

All things and whatsoever Merlin did

In one great annal-book, where after-years

Will learn the secret of our Arthur’s birth.”

To whom the King Leodogran replied,

“O friend, had I been holpen half as well

By this King Arthur as by thee today,

Then beast and man had had their share of me:

But summon here before us yet once more

Ulfius, and Brastias, and Bedivere.”

Then, when they came before him, the King said,

“I have seen the cuckoo chased by lesser fowl,

And reason in the chase: but wherefore now

Do these your lords stir up the heat of war,

Some calling Arthur born of Gorlois,

Others of Anton? Tell me, ye yourselves,

Hold ye this Arthur for King Uther’s son?”

And Ulfius and Brastias answered, “Ay.”

Then Bedivere, the first of all his knights

Knighted by Arthur at his crowning, spake—

For bold in heart and act and word was he,

Whenever slander breathed against the King—

“Sir, there be many rumours on this head:

For there be those who hate him in their hearts,

Call him baseborn, and since his ways are sweet,

And theirs are bestial, hold him less than man:

And there be those who deem him more than man,

And dream he dropt from heaven: but my belief

In all this matter—so ye care to learn—

Sir, for ye know that in King Uther’s time

The prince and warrior Gorlois, he that held

Tintagil castle by the Cornish sea,

Was wedded with a winsome wife, Ygerne:

And daughters had she borne him—one whereof,

Lot’s wife, the Queen of Orkney, Bellicent,

Hath ever like a loyal sister cleaved

To Arthur—but a son she had not borne.

And Uther cast upon her eyes of love:

But she, a stainless wife to Gorlois,

So loathed the bright dishonour of his love,

That Gorlois and King Uther went to war:

And overthrown was Gorlois and slain.

Then Uther in his wrath and heat besieged

Ygerne within Tintagil, where her men,

Seeing the mighty swarm about their walls,

Left her and fled, and Uther entered in,

And there was none to call to but himself.

So, compassed by the power of the King,

Enforced was she to wed him in her tears,

And with a shameful swiftness: afterward,

Not many moons, King Uther died himself,

Moaning and wailing for an heir to rule

After him, lest the realm should go to wrack.

And that same night, the night of the new year,

By reason of the bitterness and grief

That vext his mother, all before his time

Was Arthur born, and all as soon as born

Delivered at a secret postern-gate

To Merlin, to be holden far apart

Until his hour should come; because the lords

Of that fierce day were as the lords of this,

Wild beasts, and surely would have torn the child

Piecemeal among them, had they known; for each

But sought to rule for his own self and hand,

And many hated Uther for the sake

Of Gorlois. Wherefore Merlin took the child,

And gave him to Sir Anton, an old knight

And ancient friend of Uther; and his wife

Nursed the young prince, and reared him with her own;

And no man knew. And ever since the lords

Have foughten like wild beasts among themselves,

So that the realm has gone to wrack: but now,

This year, when Merlin (for his hour had come)

Brought Arthur forth, and set him in the hall,

Proclaiming, ‘Here is Uther’s heir, your king,’

A hundred voices cried, ‘Away with him!

No king of ours! a son of Gorlois he,

Or else the child of Anton, and no king,

Or else baseborn.’ Yet Merlin through his craft,

And while the people clamoured for a king,

Had Arthur crowned; but after, the great lords

Banded, and so brake out in open war.”

Then while the King debated with himself

If Arthur were the child of shamefulness,

Or born the son of Gorlois, after death,

Or Uther’s son, and born before his time,

Or whether there were truth in anything

Said by these three, there came to Cameliard,

With Gawain and young Modred, her two sons,

Lot’s wife, the Queen of Orkney, Bellicent;

Whom as he could, not as he would, the King

Made feast for, saying, as they sat at meat,

“A doubtful throne is ice on summer seas.

Ye come from Arthur’s court. Victor his men

Report him! Yea, but ye—think ye this king—

So many those that hate him, and so strong,

So few his knights, however brave they be—

Hath body enow to hold his foemen down?”

“O King,” she cried, “and I will tell thee: few,

Few, but all brave, all of one mind with him;

For I was near him when the savage yells

Of Uther’s peerage died, and Arthur sat

Crowned on the dais, and his warriors cried,

‘Be thou the king, and we will work thy will

Who love thee.’ Then the King in low deep tones,

And simple words of great authority,

Bound them by so strait vows to his own self,

That when they rose, knighted from kneeling, some

Were pale as at the passing of a ghost,

Some flushed, and others dazed, as one who wakes

Half-blinded at the coming of a light.

“But when he spake and cheered his Table Round

With large, divine, and comfortable words,

Beyond my tongue to tell thee—I beheld

From eye to eye through all their Order flash

A momentary likeness of the King:

And ere it left their faces, through the cross

And those around it and the Crucified,

Down from the casement over Arthur, smote

Flame-colour, vert and azure, in three rays,

One falling upon each of three fair queens,

Who stood in silence near his throne, the friends

Of Arthur, gazing on him, tall, with bright

Sweet faces, who will help him at his need.

“And there I saw mage Merlin, whose vast wit

And hundred winters are but as the hands

Of loyal vassals toiling for their liege.

“And near him stood the Lady of the Lake,

Who knows a subtler magic than his own—

Clothed in white samite, mystic, wonderful.

She gave the King his huge cross-hilted sword,

Whereby to drive the heathen out: a mist

Of incense curled about her, and her face

Wellnigh was hidden in the minster gloom;

But there was heard among the holy hymns

A voice as of the waters, for she dwells

Down in a deep; calm, whatsoever storms

May shake the world, and when the surface rolls,

Hath power to walk the waters like our Lord.

“There likewise I beheld Excalibur

Before him at his crowning borne, the sword

That rose from out the bosom of the lake,

And Arthur rowed across and took it—rich

With jewels, elfin Urim, on the hilt,

Bewildering heart and eye—the blade so bright

That men are blinded by it—on one side,

Graven in the oldest tongue of all this world,

‘Take me,’ but turn the blade and ye shall see,

And written in the speech ye speak yourself,

‘Cast me away!’ And sad was Arthur’s face

Taking it, but old Merlin counselled him,

‘Take thou and strike! the time to cast away

Is yet far-off.’ So this great brand the king

Took, and by this will beat his foemen down.”

Thereat Leodogran rejoiced, but thought

To sift his doubtings to the last, and asked,

Fixing full eyes of question on her face,

“The swallow and the swift are near akin,

But thou art closer to this noble prince,

Being his own dear sister;” and she said,

“Daughter of Gorlois and Ygerne am I;”

“And therefore Arthur’s sister?” asked the King.

She answered, “These be secret things,” and signed

To those two sons to pass, and let them be.

And Gawain went, and breaking into song

Sprang out, and followed by his flying hair

Ran like a colt, and leapt at all he saw:

But Modred laid his ear beside the doors,

And there half-heard; the same that afterward

Struck for the throne, and striking found his doom.

And then the Queen made answer, “What know I?

For dark my mother was in eyes and hair,

And dark in hair and eyes am I; and dark

Was Gorlois, yea and dark was Uther too,

Wellnigh to blackness; but this King is fair

Beyond the race of Britons and of men.

Moreover, always in my mind I hear

A cry from out the dawning of my life,

A mother weeping, and I hear her say,

‘O that ye had some brother, pretty one,

To guard thee on the rough ways of the world.’ ”

“Ay,” said the King, “and hear ye such a cry?

But when did Arthur chance upon thee first?”

“O King!” she cried, “and I will tell thee true:

He found me first when yet a little maid:

Beaten I had been for a little fault

Whereof I was not guilty; and out I ran

And flung myself down on a bank of heath,

And hated this fair world and all therein,

And wept, and wished that I were dead; and he—

I know not whether of himself he came,

Or brought by Merlin, who, they say, can walk

Unseen at pleasure—he was at my side,

And spake sweet words, and comforted my heart,

And dried my tears, being a child with me.

And many a time he came, and evermore

As I grew greater grew with me; and sad

At times he seemed, and sad with him was I,

Stern too at times, and then I loved him not,

But sweet again, and then I loved him well.

And now of late I see him less and less,

But those first days had golden hours for me,

For then I surely thought he would be king.

“But let me tell thee now another tale:

For Bleys, our Merlin’s master, as they say,

Died but of late, and sent his cry to me,

To hear him speak before he left his life.

Shrunk like a fairy changeling lay the mage;

And when I entered told me that himself

And Merlin ever served about the King,

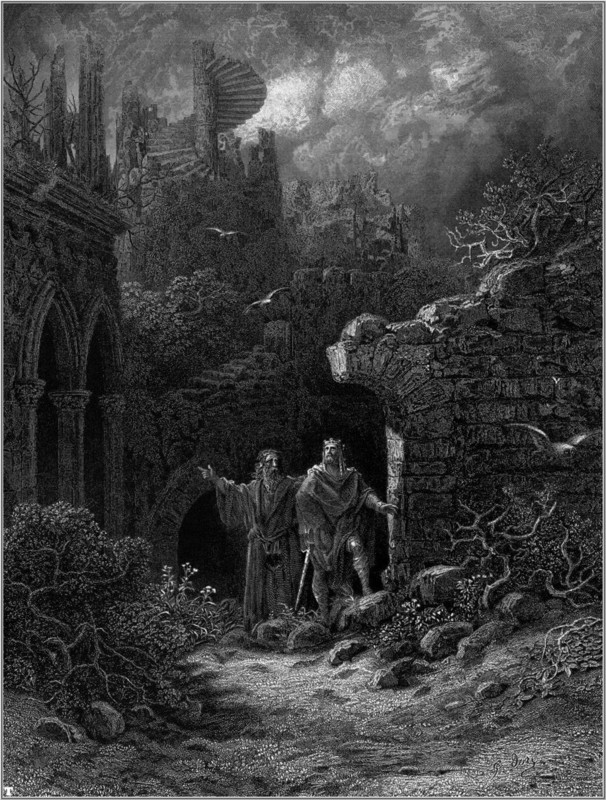

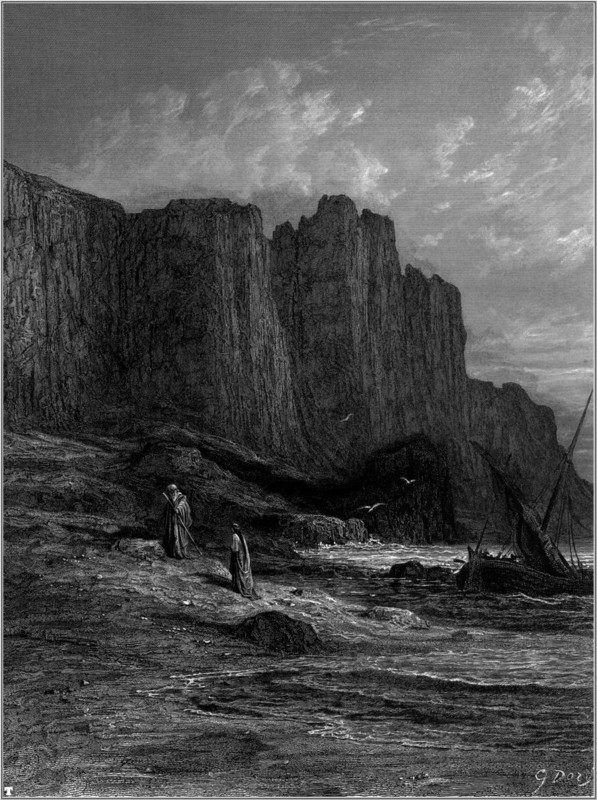

Uther, before he died; and on the night

When Uther in Tintagil past away

Moaning and wailing for an heir, the two

Left the still King, and passing forth to breathe,

Then from the castle gateway by the chasm

Descending through the dismal night—a night

In which the bounds of heaven and earth were lost—

Beheld, so high upon the dreary deeps

It seemed in heaven, a ship, the shape thereof

A dragon winged, and all from stern to stern

Bright with a shining people on the decks,

And gone as soon as seen. And then the two

Dropt to the cove, and watched the great sea fall,

Wave after wave, each mightier than the last,

Till last, a ninth one, gathering half the deep

And full of voices, slowly rose and plunged

Roaring, and all the wave was in a flame:

And down the wave and in the flame was borne

A naked babe, and rode to Merlin’s feet,

Who stoopt and caught the babe, and cried ‘The King!

Here is an heir for Uther!’ And the fringe

Of that great breaker, sweeping up the strand,

Lashed at the wizard as he spake the word,

And all at once all round him rose in fire,

So that the child and he were clothed in fire.

And presently thereafter followed calm,

Free sky and stars: ‘And this the same child,’ he said,

‘Is he who reigns; nor could I part in peace

Till this were told.’ And saying this the seer

Went through the strait and dreadful pass of death,

Not ever to be questioned any more

Save on the further side; but when I met

Merlin, and asked him if these things were truth—

The shining dragon and the naked child

Descending in the glory of the seas—

He laughed as is his wont, and answered me

In riddling triplets of old time, and said:

“ ‘Rain, rain, and sun! a rainbow in the sky!

A young man will be wiser by and by;

An old man’s wit may wander ere he die.

Rain, rain, and sun! a rainbow on the lea!

And truth is this to me, and that to thee;

And truth or clothed or naked let it be.

Rain, sun, and rain! and the free blossom blows:

Sun, rain, and sun! and where is he who knows?

From the great deep to the great deep he goes.’

“So Merlin riddling angered me; but thou

Fear not to give this King thy only child,

Guinevere: so great bards of him will sing

Hereafter; and dark sayings from of old

Ranging and ringing through the minds of men,

And echoed by old folk beside their fires

For comfort after their wage-work is done,

Speak of the King; and Merlin in our time

Hath spoken also, not in jest, and sworn

Though men may wound him that he will not die,

But pass, again to come; and then or now

Utterly smite the heathen underfoot,

Till these and all men hail him for their king.”

She spake and King Leodogran rejoiced,

But musing, “Shall I answer yea or nay?”

Doubted, and drowsed, nodded and slept, and saw,

Dreaming, a slope of land that ever grew,

Field after field, up to a height, the peak

Haze-hidden, and thereon a phantom king,

Now looming, and now lost; and on the slope

The sword rose, the hind fell, the herd was driven,

Fire glimpsed; and all the land from roof and rick,

In drifts of smoke before a rolling wind,

Streamed to the peak, and mingled with the haze

And made it thicker; while the phantom king

Sent out at times a voice; and here or there

Stood one who pointed toward the voice, the rest

Slew on and burnt, crying, “No king of ours,

No son of Uther, and no king of ours;”

Till with a wink his dream was changed, the haze

Descended, and the solid earth became

As nothing, but the King stood out in heaven,

Crowned. And Leodogran awoke, and sent

Ulfius, and Brastias and Bedivere,

Back to the court of Arthur answering yea.

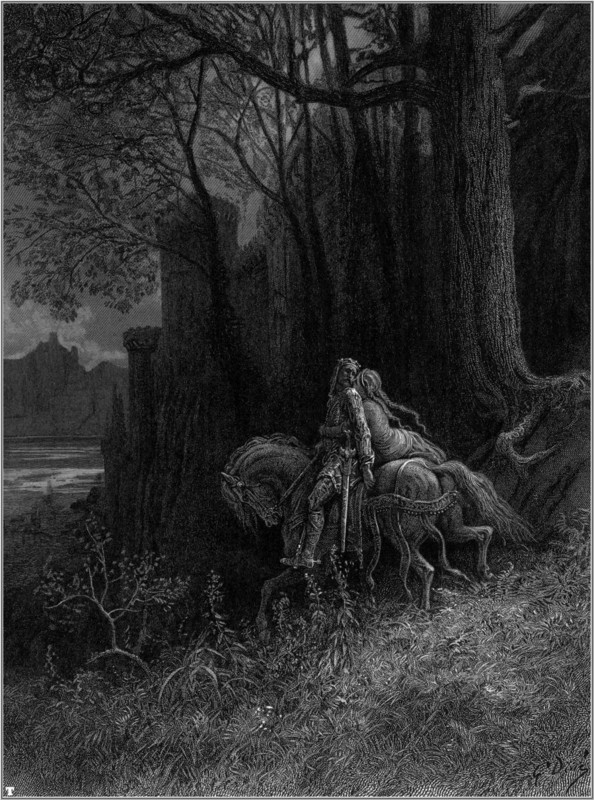

Then Arthur charged his warrior whom he loved

And honoured most, Sir Lancelot, to ride forth

And bring the Queen;—and watched him from the gates:

And Lancelot past away among the flowers,

(For then was latter April) and returned

Among the flowers, in May, with Guinevere.

To whom arrived, by Dubric the high saint,

Chief of the church in Britain, and before

The stateliest of her altar-shrines, the King

That morn was married, while in stainless white,

The fair beginners of a nobler time,

And glorying in their vows and him, his knights

Stood around him, and rejoicing in his joy.

Far shone the fields of May through open door,

The sacred altar blossomed white with May,

The Sun of May descended on their King,

They gazed on all earth’s beauty in their Queen,

Rolled incense, and there past along the hymns

A voice as of the waters, while the two

Sware at the shrine of Christ a deathless love:

And Arthur said, “Behold, thy doom is mine.

Let chance what will, I love thee to the death!”

To whom the Queen replied with drooping eyes,

“King and my lord, I love thee to the death!”

And holy Dubric spread his hands and spake,

“Reign ye, and live and love, and make the world

Other, and may thy Queen be one with thee,

And all this Order of thy Table Round

Fulfil the boundless purpose of their King!”

So Dubric said; but when they left the shrine

Great Lords from Rome before the portal stood,

In scornful stillness gazing as they past;

Then while they paced a city all on fire

With sun and cloth of gold, the trumpets blew,

And Arthur’s knighthood sang before the King:—

“Blow, trumpet, for the world is white with May;

Blow trumpet, the long night hath rolled away!

Blow through the living world—‘Let the King reign.’

“Shall Rome or Heathen rule in Arthur’s realm?

Flash brand and lance, fall battleaxe upon helm,

Fall battleaxe, and flash brand! Let the King reign.

“Strike for the King and live! his knights have heard

That God hath told the King a secret word.

Fall battleaxe, and flash brand! Let the King reign.

“Blow trumpet! he will lift us from the dust.

Blow trumpet! live the strength and die the lust!

Clang battleaxe, and clash brand! Let the King reign.

“Strike for the King and die! and if thou diest,

The King is King, and ever wills the highest.

Clang battleaxe, and clash brand! Let the King reign.

“Blow, for our Sun is mighty in his May!

Blow, for our Sun is mightier day by day!

Clang battleaxe, and clash brand! Let the King reign.

“The King will follow Christ, and we the King

In whom high God hath breathed a secret thing.

Fall battleaxe, and flash brand! Let the King reign.”

So sang the knighthood, moving to their hall.

There at the banquet those great Lords from Rome,

The slowly-fading mistress of the world,

Strode in, and claimed their tribute as of yore.

But Arthur spake, “Behold, for these have sworn

To wage my wars, and worship me their King;

The old order changeth, yielding place to new;

And we that fight for our fair father Christ,

Seeing that ye be grown too weak and old

To drive the heathen from your Roman wall,

No tribute will we pay:” so those great lords

Drew back in wrath, and Arthur strove with Rome.

And Arthur and his knighthood for a space

Were all one will, and through that strength the King

Drew in the petty princedoms under him,

Fought, and in twelve great battles overcame

The heathen hordes, and made a realm and reigned.

Gareth and Lynette

The last tall son of Lot and Bellicent,

And tallest, Gareth, in a showerful spring

Stared at the spate. A slender-shafted Pine

Lost footing, fell, and so was whirled away.

“How he went down,” said Gareth, “as a false knight

Or evil king before my lance if lance

Were mine to use—O senseless cataract,

Bearing all down in thy precipitancy—

And yet thou art but swollen with cold snows

And mine is living blood: thou dost His will,

The Maker’s, and not knowest, and I that know,

Have strength and wit, in my good mother’s hall

Linger with vacillating obedience,

Prisoned, and kept and coaxed and whistled to—

Since the good mother holds me still a child!

Good mother is bad mother unto me!

A worse were better; yet no worse would I.

Heaven yield her for it, but in me put force

To weary her ears with one continuous prayer,

Until she let me fly discaged to sweep

In ever-highering eagle-circles up

To the great Sun of Glory, and thence swoop

Down upon all things base, and dash them dead,

A knight of Arthur, working out his will,

To cleanse the world. Why, Gawain, when he came

With Modred hither in the summertime,

Asked me to tilt with him, the proven knight.

Modred for want of worthier was the judge.

Then I so shook him in the saddle, he said,

‘Thou hast half prevailed against me,’ said so—he—

Though Modred biting his thin lips was mute,

For he is alway sullen: what care I?”

And Gareth went, and hovering round her chair

Asked, “Mother, though ye count me still the child,

Sweet mother, do ye love the child?” She laughed,

“Thou art but a wild-goose to question it.”

“Then, mother, an ye love the child,” he said,

“Being a goose and rather tame than wild,

Hear the child’s story.” “Yea, my well-beloved,

An ’twere but of the goose and golden eggs.”

And Gareth answered her with kindling eyes,

“Nay, nay, good mother, but this egg of mine

Was finer gold than any goose can lay;

For this an Eagle, a royal Eagle, laid

Almost beyond eye-reach, on such a palm

As glitters gilded in thy Book of Hours.

And there was ever haunting round the palm

A lusty youth, but poor, who often saw

The splendour sparkling from aloft, and thought

‘An I could climb and lay my hand upon it,

Then were I wealthier than a leash of kings.’

But ever when he reached a hand to climb,

One, that had loved him from his childhood, caught

And stayed him, ‘Climb not lest thou break thy neck,

I charge thee by my love,’ and so the boy,

Sweet mother, neither clomb, nor brake his neck,

But brake his very heart in pining for it,

And past away.”

To whom the mother said,

“True love, sweet son, had risked himself and climbed,

And handed down the golden treasure to him.”

And Gareth answered her with kindling eyes,

“Gold? said I gold?—ay then, why he, or she,

Or whosoe’er it was, or half the world

Had ventured—had the thing I spake of been

Mere gold—but this was all of that true steel,

Whereof they forged the brand Excalibur,

And lightnings played about it in the storm,

And all the little fowl were flurried at it,

And there were cries and clashings in the nest,

That sent him from his senses: let me go.”

Then Bellicent bemoaned herself and said,

“Hast thou no pity upon my loneliness?

Lo, where thy father Lot beside the hearth

Lies like a log, and all but smouldered out!

Forever since when traitor to the King

He fought against him in the Barons’ war,

And Arthur gave him back his territory,

His age hath slowly droopt, and now lies there

A yet-warm corpse, and yet unburiable,

No more; nor sees, nor hears, nor speaks, nor knows.

And both thy brethren are in Arthur’s hall,

Albeit neither loved with that full love

I feel for thee, nor worthy such a love:

Stay therefore thou; red berries charm the bird,

And thee, mine innocent, the jousts, the wars,

Who never knewest finger-ache, nor pang

Of wrenched or broken limb—an often chance

In those brain-stunning shocks, and tourney-falls,

Frights to my heart; but stay: follow the deer

By these tall firs and our fast-falling burns;

So make thy manhood mightier day by day;

Sweet is the chase: and I will seek thee out

Some comfortable bride and fair, to grace

Thy climbing life, and cherish my prone year,

Till falling into Lot’s forgetfulness

I know not thee, myself, nor anything.

Stay, my best son! ye are yet more boy than man.”

Then Gareth, “An ye hold me yet for child,

Hear yet once more the story of the child.

For, mother, there was once a King, like ours.

The prince his heir, when tall and marriageable,

Asked for a bride; and thereupon the King

Set two before him. One was fair, strong, armed—

But to be won by force—and many men

Desired her; one good lack, no man desired.

And these were the conditions of the King:

That save he won the first by force, he needs

Must wed that other, whom no man desired,

A red-faced bride who knew herself so vile,

That evermore she longed to hide herself,

Nor fronted man or woman, eye to eye—

Yea—some she cleaved to, but they died of her.

And one—they called her Fame; and one—O Mother,

How can ye keep me tethered to you—Shame.

Man am I grown, a man’s work must I do.

Follow the deer? follow the Christ, the King,

Live pure, speak true, right wrong, follow the King—

Else, wherefore born?”

To whom the mother said

“Sweet son, for there be many who deem him not,

Or will not deem him, wholly proven King—

Albeit in mine own heart I knew him King,

When I was frequent with him in my youth,

And heard him Kingly speak, and doubted him

No more than he, himself; but felt him mine,

Of closest kin to me: yet—wilt thou leave

Thine easeful biding here, and risk thine all,

Life, limbs, for one that is not proven King?

Stay, till the cloud that settles round his birth

Hath lifted but a little. Stay, sweet son.”

And Gareth answered quickly, “Not an hour,

So that ye yield me—I will walk through fire,

Mother, to gain it—your full leave to go.

Not proven, who swept the dust of ruined Rome

From off the threshold of the realm, and crushed

The Idolaters, and made the people free?

Who should be King save him who makes us free?”

So when the Queen, who long had sought in vain

To break him from the intent to which he grew,

Found her son’s will unwaveringly one,

She answered craftily, “Will ye walk through fire?

Who walks through fire will hardly heed the smoke.

Ay, go then, an ye must: only one proof,

Before thou ask the King to make thee knight,

Of thine obedience and thy love to me,

Thy mother—I demand.”

And Gareth cried,

“A hard one, or a hundred, so I go.

Nay—quick! the proof to prove me to the quick!”

But slowly spake the mother looking at him,

“Prince, thou shalt go disguised to Arthur’s hall,

And hire thyself to serve for meats and drinks

Among the scullions and the kitchen-knaves,

And those that hand the dish across the bar.

Nor shalt thou tell thy name to anyone.

And thou shalt serve a twelvemonth and a day.”

For so the Queen believed that when her son

Beheld his only way to glory lead

Low down through villain kitchen-vassalage,

Her own true Gareth was too princely-proud

To pass thereby; so should he rest with her,

Closed in her castle from the sound of arms.

Silent awhile was Gareth, then replied,

“The thrall in person may be free in soul,

And I shall see the jousts. Thy son am I,

And since thou art my mother, must obey.

I therefore yield me freely to thy will;

For hence will I, disguised, and hire myself

To serve with scullions and with kitchen-knaves;

Nor tell my name to any—no, not the King.”

Gareth awhile lingered. The mother’s eye

Full of the wistful fear that he would go,

And turning toward him wheresoe’er he turned,

Perplext his outward purpose, till an hour,

When wakened by the wind which with full voice

Swept bellowing through the darkness on to dawn,

He rose, and out of slumber calling two

That still had tended on him from his birth,

Before the wakeful mother heard him, went.

The three were clad like tillers of the soil.

Southward they set their faces. The birds made

Melody on branch, and melody in mid air.

The damp hill-slopes were quickened into green,

And the live green had kindled into flowers,

For it was past the time of Easterday.

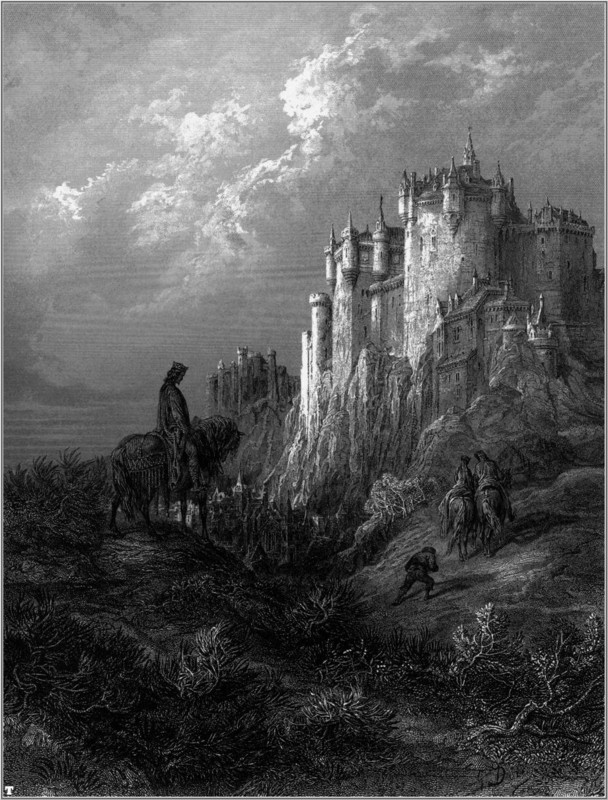

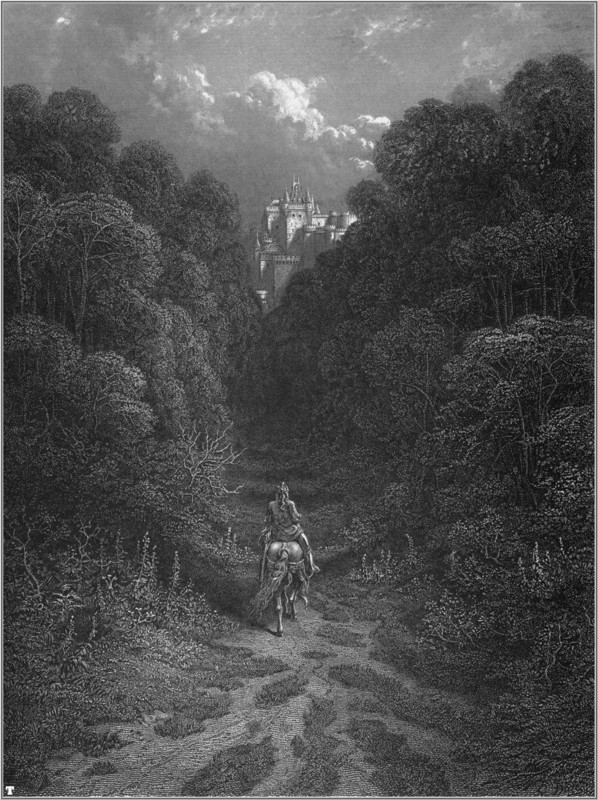

So, when their feet were planted on the plain

That broadened toward the base of Camelot,

Far off they saw the silver-misty morn

Rolling her smoke about the Royal mount,

That rose between the forest and the field.

At times the summit of the high city flashed;

At times the spires and turrets half-way down

Pricked through the mist; at times the great gate shone

Only, that opened on the field below:

Anon, the whole fair city had disappeared.

Then those who went with Gareth were amazed,

One crying, “Let us go no further, lord.

Here is a city of Enchanters, built

By fairy Kings.” The second echoed him,

“Lord, we have heard from our wise man at home

To Northward, that this King is not the King,

But only changeling out of Fairyland,

Who drave the heathen hence by sorcery

And Merlin’s glamour.” Then the first again,

“Lord, there is no such city anywhere,

But all a vision.”

Gareth answered them

With laughter, swearing he had glamour enow

In his own blood, his princedom, youth and hopes,

To plunge old Merlin in the Arabian sea;

So pushed them all unwilling toward the gate.

And there was no gate like it under heaven.

For barefoot on the keystone, which was lined

And rippled like an ever-fleeting wave,

The Lady of the Lake stood: all her dress

Wept from her sides as water flowing away;

But like the cross her great and goodly arms

Stretched under the cornice and upheld:

And drops of water fell from either hand;

And down from one a sword was hung, from one

A censer, either worn with wind and storm;

And o’er her breast floated the sacred fish;

And in the space to left of her, and right,

Were Arthur’s wars in weird devices done,

New things and old co-twisted, as if Time

Were nothing, so inveterately, that men

Were giddy gazing there; and over all

High on the top were those three Queens, the friends

Of Arthur, who should help him at his need.

Then those with Gareth for so long a space

Stared at the figures, that at last it seemed

The dragon-boughts and elvish emblemings

Began to move, seethe, twine and curl: they called

To Gareth, “Lord, the gateway is alive.”

And Gareth likewise on them fixt his eyes

So long, that even to him they seemed to move.

Out of the city a blast of music pealed.

Back from the gate started the three, to whom

From out thereunder came an ancient man,

Long-bearded, saying, “Who be ye, my sons?”

Then Gareth, “We be tillers of the soil,

Who leaving share in furrow come to see

The glories of our King: but these, my men,

(Your city moved so weirdly in the mist)

Doubt if the King be King at all, or come

From Fairyland; and whether this be built

By magic, and by fairy Kings and Queens;

Or whether there be any city at all,

Or all a vision: and this music now

Hath scared them both, but tell thou these the truth.”

Then that old Seer made answer playing on him

And saying, “Son, I have seen the good ship sail

Keel upward, and mast downward, in the heavens,

And solid turrets topsy-turvy in air:

And here is truth; but an it please thee not,

Take thou the truth as thou hast told it me.

For truly as thou sayest, a Fairy King

And Fairy Queens have built the city, son;

They came from out a sacred mountain-cleft

Toward the sunrise, each with harp in hand,

And built it to the music of their harps.

And, as thou sayest, it is enchanted, son,

For there is nothing in it as it seems

Saving the King; though some there be that hold

The King a shadow, and the city real:

Yet take thou heed of him, for, so thou pass

Beneath this archway, then wilt thou become

A thrall to his enchantments, for the King

Will bind thee by such vows, as is a shame

A man should not be bound by, yet the which

No man can keep; but, so thou dread to swear,

Pass not beneath this gateway, but abide

Without, among the cattle of the field.

For an ye heard a music, like enow

They are building still, seeing the city is built

To music, therefore never built at all,

And therefore built forever.”

Gareth spake

Angered, “Old master, reverence thine own beard

That looks as white as utter truth, and seems

Wellnigh as long as thou art statured tall!

Why mockest thou the stranger that hath been

To thee fair-spoken?”

But the Seer replied,

“Know ye not then the Riddling of the Bards?

‘Confusion, and illusion, and relation,

Elusion, and occasion, and evasion’?

I mock thee not but as thou mockest me,

And all that see thee, for thou art not who

Thou seemest, but I know thee who thou art.

And now thou goest up to mock the King,

Who cannot brook the shadow of any lie.”

Unmockingly the mocker ending here

Turned to the right, and past along the plain;

Whom Gareth looking after said, “My men,

Our one white lie sits like a little ghost

Here on the threshold of our enterprise.

Let love be blamed for it, not she, nor I:

Well, we will make amends.”

With all good cheer

He spake and laughed, then entered with his twain

Camelot, a city of shadowy palaces

And stately, rich in emblem and the work

Of ancient kings who did their days in stone;

Which Merlin’s hand, the Mage at Arthur’s court,

Knowing all arts, had touched, and everywhere

At Arthur’s ordinance, tipt with lessening peak

And pinnacle, and had made it spire to heaven.

And ever and anon a knight would pass

Outward, or inward to the hall: his arms

Clashed; and the sound was good to Gareth’s ear.

And out of bower and casement shyly glanced

Eyes of pure women, wholesome stars of love;

And all about a healthful people stept

As in the presence of a gracious king.

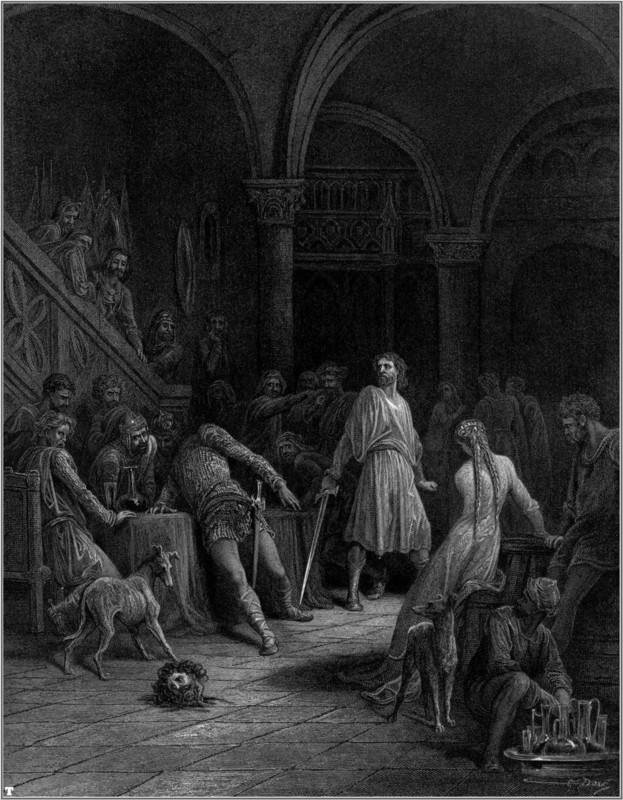

Then into hall Gareth ascending heard

A voice, the voice of Arthur, and beheld

Far over heads in that long-vaulted hall

The splendour of the presence of the King

Throned, and delivering doom—and looked no more—

But felt his young heart hammering in his ears,

And thought, “For this half-shadow of a lie

The truthful King will doom me when I speak.”

Yet pressing on, though all in fear to find

Sir Gawain or Sir Modred, saw nor one

Nor other, but in all the listening eyes

Of those tall knights, that ranged about the throne,

Clear honour shining like the dewy star

Of dawn, and faith in their great King, with pure

Affection, and the light of victory,

And glory gained, and evermore to gain.

Then came a widow crying to the King,

“A boon, Sir King! Thy father, Uther, reft

From my dead lord a field with violence:

For howsoe’er at first he proffered gold,

Yet, for the field was pleasant in our eyes,

We yielded not; and then he reft us of it

Perforce, and left us neither gold nor field.”

Said Arthur, “Whether would ye? gold or field?”

To whom the woman weeping, “Nay, my lord,

The field was pleasant in my husband’s eye.”

And Arthur, “Have thy pleasant field again,

And thrice the gold for Uther’s use thereof,

According to the years. No boon is here,

But justice, so thy say be proven true.

Accursed, who from the wrongs his father did

Would shape himself a right!”

And while she past,

Came yet another widow crying to him,

“A boon, Sir King! Thine enemy, King, am I.

With thine own hand thou slewest my dear lord,

A knight of Uther in the Barons’ war,

When Lot and many another rose and fought

Against thee, saying thou wert basely born.

I held with these, and loathe to ask thee aught.

Yet lo! my husband’s brother had my son

Thralled in his castle, and hath starved him dead;

And standeth seized of that inheritance

Which thou that slewest the sire hast left the son.

So though I scarce can ask it thee for hate,

Grant me some knight to do the battle for me,

Kill the foul thief, and wreak me for my son.”

Then strode a good knight forward, crying to him,

“A boon, Sir King! I am her kinsman, I.

Give me to right her wrong, and slay the man.”

Then came Sir Kay, the seneschal, and cried,

“A boon, Sir King! even that thou grant her none,

This railer, that hath mocked thee in full hall—

None; or the wholesome boon of gyve and gag.”

But Arthur, “We sit King, to help the wronged

Through all our realm. The woman loves her lord.

Peace to thee, woman, with thy loves and hates!

The kings of old had doomed thee to the flames,

Aurelius Emrys would have scourged thee dead,

And Uther slit thy tongue: but get thee hence—

Lest that rough humour of the kings of old

Return upon me! Thou that art her kin,

Go likewise; lay him low and slay him not,

But bring him here, that I may judge the right,

According to the justice of the King:

Then, be he guilty, by that deathless King

Who lived and died for men, the man shall die.”

Then came in hall the messenger of Mark,

A name of evil savour in the land,

The Cornish king. In either hand he bore

What dazzled all, and shone far-off as shines

A field of charlock in the sudden sun

Between two showers, a cloth of palest gold,

Which down he laid before the throne, and knelt,

Delivering, that his lord, the vassal king,

Was even upon his way to Camelot;

For having heard that Arthur of his grace

Had made his goodly cousin, Tristram, knight,

And, for himself was of the greater state,

Being a king, he trusted his liege-lord

Would yield him this large honour all the more;

So prayed him well to accept this cloth of gold,

In token of true heart and fealty.

Then Arthur cried to rend the cloth, to rend

In pieces, and so cast it on the hearth.

An oak-tree smouldered there. “The goodly knight!

What! shall the shield of Mark stand among these?”

For, midway down the side of that long hall

A stately pile—whereof along the front,

Some blazoned, some but carven, and some blank,

There ran a treble range of stony shields—

Rose, and high-arching overbrowed the hearth.

And under every shield a knight was named:

For this was Arthur’s custom in his hall;

When some good knight had done one noble deed,

His arms were carven only; but if twain

His arms were blazoned also; but if none,

The shield was blank and bare without a sign

Saving the name beneath; and Gareth saw

The shield of Gawain blazoned rich and bright,

And Modred’s blank as death; and Arthur cried

To rend the cloth and cast it on the hearth.

“More like are we to reave him of his crown

Than make him knight because men call him king.

The kings we found, ye know we stayed their hands

From war among themselves, but left them kings;

Of whom were any bounteous, merciful,

Truth-speaking, brave, good livers, them we enrolled

Among us, and they sit within our hall.

But as Mark hath tarnished the great name of king,

As Mark would sully the low state of churl:

And, seeing he hath sent us cloth of gold,

Return, and meet, and hold him from our eyes,

Lest we should lap him up in cloth of lead,

Silenced forever—craven—a man of plots,

Craft, poisonous counsels, wayside ambushings—

No fault of thine: let Kay the seneschal

Look to thy wants, and send thee satisfied—

Accursed, who strikes nor lets the hand be seen!”

And many another suppliant crying came

With noise of ravage wrought by beast and man,

And evermore a knight would ride away.

Last, Gareth leaning both hands heavily

Down on the shoulders of the twain, his men,

Approached between them toward the King, and asked,

“A boon, Sir King (his voice was all ashamed),

For see ye not how weak and hungerworn

I seem—leaning on these? grant me to serve

For meat and drink among thy kitchen-knaves

A twelvemonth and a day, nor seek my name.

Hereafter I will fight.”

To him the King,

“A goodly youth and worth a goodlier boon!

But so thou wilt no goodlier, then must Kay,

The master of the meats and drinks, be thine.”

He rose and past; then Kay, a man of mien

Wan-sallow as the plant that feels itself

Root-bitten by white lichen,

“Lo ye now!

This fellow hath broken from some Abbey, where,

God wot, he had not beef and brewis enow,

However that might chance! but an he work,

Like any pigeon will I cram his crop,

And sleeker shall he shine than any hog.”

Then Lancelot standing near, “Sir Seneschal,

Sleuth-hound thou knowest, and gray, and all the hounds;

A horse thou knowest, a man thou dost not know:

Broad brows and fair, a fluent hair and fine,

High nose, a nostril large and fine, and hands

Large, fair and fine!—Some young lad’s mystery—

But, or from sheepcot or king’s hall, the boy

Is noble-natured. Treat him with all grace,

Lest he should come to shame thy judging of him.”

Then Kay, “What murmurest thou of mystery?

Think ye this fellow will poison the King’s dish?

Nay, for he spake too fool-like: mystery!

Tut, an the lad were noble, he had asked

For horse and armour: fair and fine, forsooth!

Sir Fine-face, Sir Fair-hands? but see thou to it

That thine own fineness, Lancelot, some fine day

Undo thee not—and leave my man to me.”

So Gareth all for glory underwent

The sooty yoke of kitchen-vassalage;

Ate with young lads his portion by the door,

And couched at night with grimy kitchen-knaves.

And Lancelot ever spake him pleasantly,

But Kay the seneschal, who loved him not,

Would hustle and harry him, and labour him

Beyond his comrade of the hearth, and set

To turn the broach, draw water, or hew wood,

Or grosser tasks; and Gareth bowed himself

With all obedience to the King, and wrought

All kind of service with a noble ease

That graced the lowliest act in doing it.

And when the thralls had talk among themselves,

And one would praise the love that linkt the King

And Lancelot—how the King had saved his life

In battle twice, and Lancelot once the King’s—

For Lancelot was the first in Tournament,

But Arthur mightiest on the battle-field—

Gareth was glad. Or if some other told,

How once the wandering forester at dawn,

Far over the blue tarns and hazy seas,

On Caer-Eryri’s highest found the King,

A naked babe, of whom the Prophet spake,

“He passes to the Isle Avilion,

He passes and is healed and cannot die”—

Gareth was glad. But if their talk were foul,

Then would he whistle rapid as any lark,

Or carol some old roundelay, and so loud

That first they mocked, but, after, reverenced him.

Or Gareth telling some prodigious tale

Of knights, who sliced a red life-bubbling way

Through twenty folds of twisted dragon, held

All in a gap-mouthed circle his good mates

Lying or sitting round him, idle hands,

Charmed; till Sir Kay, the seneschal, would come

Blustering upon them, like a sudden wind

Among dead leaves, and drive them all apart.

Or when the thralls had sport among themselves,

So there were any trial of mastery,

He, by two yards in casting bar or stone

Was counted best; and if there chanced a joust,

So that Sir Kay nodded him leave to go,

Would hurry thither, and when he saw the knights

Clash like the coming and retiring wave,

And the spear spring, and good horse reel, the boy

Was half beyond himself for ecstasy.

So for a month he wrought among the thralls;

But in the weeks that followed, the good Queen,

Repentant of the word she made him swear,

And saddening in her childless castle, sent,

Between the in-crescent and de-crescent moon,

Arms for her son, and loosed him from his vow.

This, Gareth hearing from a squire of Lot

With whom he used to play at tourney once,

When both were children, and in lonely haunts

Would scratch a ragged oval on the sand,

And each at either dash from either end—

Shame never made girl redder than Gareth joy.

He laughed; he sprang. “Out of the smoke, at once

I leap from Satan’s foot to Peter’s knee—

These news be mine, none other’s—nay, the King’s—

Descend into the city:” whereon he sought

The King alone, and found, and told him all.

“I have staggered thy strong Gawain in a tilt

For pastime; yea, he said it: joust can I.

Make me thy knight—in secret! let my name

Be hidden, and give me the first quest, I spring

Like flame from ashes.”

Here the King’s calm eye

Fell on, and checked, and made him flush, and bow

Lowly, to kiss his hand, who answered him,

“Son, the good mother let me know thee here,

And sent her wish that I would yield thee thine.

Make thee my knight? my knights are sworn to vows

Of utter hardihood, utter gentleness,

And, loving, utter faithfulness in love,

And uttermost obedience to the King.”

Then Gareth, lightly springing from his knees,

“My King, for hardihood I can promise thee.

For uttermost obedience make demand

Of whom ye gave me to, the Seneschal,

No mellow master of the meats and drinks!

And as for love, God wot, I love not yet,

But love I shall, God willing.”

And the King

“Make thee my knight in secret? yea, but he,

Our noblest brother, and our truest man,

And one with me in all, he needs must know.”

“Let Lancelot know, my King, let Lancelot know,

Thy noblest and thy truest!”

And the King—

“But wherefore would ye men should wonder at you?

Nay, rather for the sake of me, their King,

And the deed’s sake my knighthood do the deed,

Than to be noised of.”

Merrily Gareth asked,

“Have I not earned my cake in baking of it?

Let be my name until I make my name!

My deeds will speak: it is but for a day.”

So with a kindly hand on Gareth’s arm

Smiled the great King, and half-unwillingly

Loving his lusty youthhood yielded to him.

Then, after summoning Lancelot privily,

“I have given him the first quest: he is not proven.

Look therefore when he calls for this in hall,

Thou get to horse and follow him far away.

Cover the lions on thy shield, and see

Far as thou mayest, he be nor ta’en nor slain.”

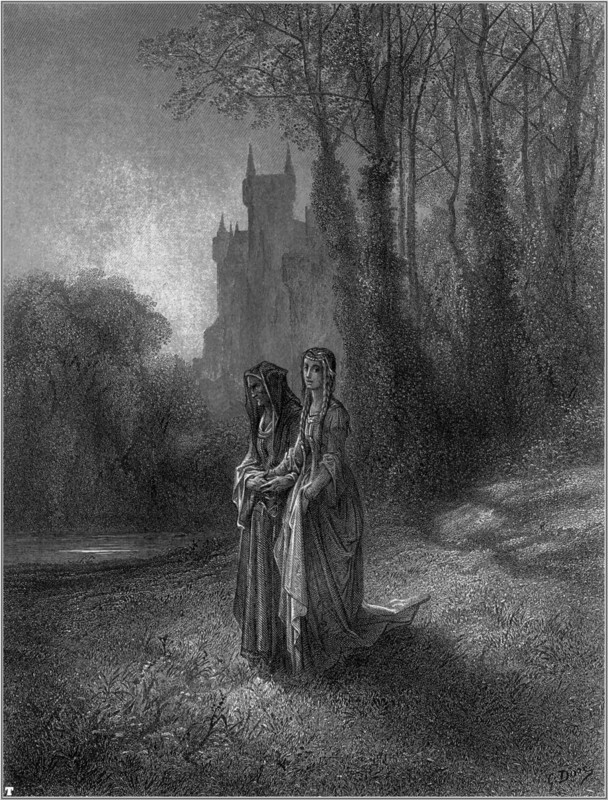

Then that same day there past into the hall

A damsel of high lineage, and a brow

May-blossom, and a cheek of apple-blossom,

Hawk-eyes; and lightly was her slender nose

Tip-tilted like the petal of a flower;

She into hall past with her page and cried,

“O King, for thou hast driven the foe without,

See to the foe within! bridge, ford, beset

By bandits, everyone that owns a tower

The Lord for half a league. Why sit ye there?

Rest would I not, Sir King, an I were king,

Till even the lonest hold were all as free

From cursed bloodshed, as thine altar-cloth

From that best blood it is a sin to spill.”

“Comfort thyself,” said Arthur. “I nor mine

Rest: so my knighthood keep the vows they swore,

The wastest moorland of our realm shall be

Safe, damsel, as the centre of this hall.

What is thy name? thy need?”

“My name?” she said—

“Lynette my name; noble; my need, a knight

To combat for my sister, Lyonors,

A lady of high lineage, of great lands,

And comely, yea, and comelier than myself.

She lives in Castle Perilous: a river

Runs in three loops about her living-place;

And o’er it are three passings, and three knights

Defend the passings, brethren, and a fourth

And of that four the mightiest, holds her stayed

In her own castle, and so besieges her

To break her will, and make her wed with him:

And but delays his purport till thou send

To do the battle with him, thy chief man

Sir Lancelot whom he trusts to overthrow,

Then wed, with glory: but she will not wed

Save whom she loveth, or a holy life.

Now therefore have I come for Lancelot.”

Then Arthur mindful of Sir Gareth asked,

“Damsel, ye know this Order lives to crush

All wrongers of the Realm. But say, these four,

Who be they? What the fashion of the men?”

“They be of foolish fashion, O Sir King,

The fashion of that old knight-errantry

Who ride abroad, and do but what they will;

Courteous or bestial from the moment, such

As have nor law nor king; and three of these

Proud in their fantasy call themselves the Day,

Morning-Star, and Noon-Sun, and Evening-Star,

Being strong fools; and never a whit more wise

The fourth, who alway rideth armed in black,

A huge man-beast of boundless savagery.

He names himself the Night and oftener Death,

And wears a helmet mounted with a skull,

And bears a skeleton figured on his arms,

To show that who may slay or scape the three,

Slain by himself, shall enter endless night.

And all these four be fools, but mighty men,

And therefore am I come for Lancelot.”

Hereat Sir Gareth called from where he rose,

A head with kindling eyes above the throng,

“A boon, Sir King—this quest!” then—for he marked

Kay near him groaning like a wounded bull—

“Yea, King, thou knowest thy kitchen-knave am I,

And mighty through thy meats and drinks am I,

And I can topple over a hundred such.

Thy promise, King,” and Arthur glancing at him,

Brought down a momentary brow. “Rough, sudden,

And pardonable, worthy to be knight—

Go therefore,” and all hearers were amazed.

But on the damsel’s forehead shame, pride, wrath

Slew the May-white: she lifted either arm,

“Fie on thee, King! I asked for thy chief knight,

And thou hast given me but a kitchen-knave.”

Then ere a man in hall could stay her, turned,

Fled down the lane of access to the King,

Took horse, descended the slope street, and past

The weird white gate, and paused without, beside

The field of tourney, murmuring “kitchen-knave.”

Now two great entries opened from the hall,

At one end one, that gave upon a range

Of level pavement where the King would pace

At sunrise, gazing over plain and wood;

And down from this a lordly stairway sloped

Till lost in blowing trees and tops of towers;

And out by this main doorway past the King.

But one was counter to the hearth, and rose

High that the highest-crested helm could ride

Therethrough nor graze: and by this entry fled

The damsel in her wrath, and on to this

Sir Gareth strode, and saw without the door

King Arthur’s gift, the worth of half a town,

A warhorse of the best, and near it stood

The two that out of north had followed him:

This bare a maiden shield, a casque; that held

The horse, the spear; whereat Sir Gareth loosed

A cloak that dropt from collar-bone to heel,

A cloth of roughest web, and cast it down,

And from it like a fuel-smothered fire,

That lookt half-dead, brake bright, and flashed as those

Dull-coated things, that making slide apart

Their dusk wing-cases, all beneath there burns

A jewelled harness, ere they pass and fly.

So Gareth ere he parted flashed in arms.

Then as he donned the helm, and took the shield

And mounted horse and graspt a spear, of grain

Storm-strengthened on a windy site, and tipt

With trenchant steel, around him slowly prest

The people, while from out of kitchen came

The thralls in throng, and seeing who had worked

Lustier than any, and whom they could but love,

Mounted in arms, threw up their caps and cried,

“God bless the King, and all his fellowship!”

And on through lanes of shouting Gareth rode

Down the slope street, and past without the gate.

So Gareth past with joy; but as the cur

Pluckt from the cur he fights with, ere his cause

Be cooled by fighting, follows, being named,

His owner, but remembers all, and growls

Remembering, so Sir Kay beside the door

Muttered in scorn of Gareth whom he used

To harry and hustle.

“Bound upon a quest

With horse and arms—the King hath past his time—

My scullion knave! Thralls to your work again,

For an your fire be low ye kindle mine!

Will there be dawn in West and eve in East?

Begone!—my knave!—belike and like enow

Some old head-blow not heeded in his youth

So shook his wits they wander in his prime—

Crazed! How the villain lifted up his voice,

Nor shamed to bawl himself a kitchen-knave.

Tut: he was tame and meek enow with me,

Till peacocked up with Lancelot’s noticing.

Well—I will after my loud knave, and learn

Whether he know me for his master yet.

Out of the smoke he came, and so my lance

Hold, by God’s grace, he shall into the mire—

Thence, if the King awaken from his craze,

Into the smoke again.”

But Lancelot said,

“Kay, wherefore wilt thou go against the King,

For that did never he whereon ye rail,

But ever meekly served the King in thee?

Abide: take counsel; for this lad is great

And lusty, and knowing both of lance and sword.”

“Tut, tell not me,” said Kay, “ye are overfine

To mar stout knaves with foolish courtesies:”

Then mounted, on through silent faces rode

Down the slope city, and out beyond the gate.

But by the field of tourney lingering yet

Muttered the damsel, “Wherefore did the King

Scorn me? for, were Sir Lancelot lackt, at least

He might have yielded to me one of those

Who tilt for lady’s love and glory here,

Rather than—O sweet heaven! O fie upon him—

His kitchen-knave.”

To whom Sir Gareth drew

(And there were none but few goodlier than he)

Shining in arms, “Damsel, the quest is mine.

Lead, and I follow.” She thereat, as one

That smells a foul-fleshed agaric in the holt,

And deems it carrion of some woodland thing,

Or shrew, or weasel, nipt her slender nose

With petulant thumb and finger, shrilling, “Hence!

Avoid, thou smellest all of kitchen-grease.

And look who comes behind,” for there was Kay.

“Knowest thou not me? thy master? I am Kay.

We lack thee by the hearth.”

And Gareth to him,

“Master no more! too well I know thee, ay—

The most ungentle knight in Arthur’s hall.”

“Have at thee then,” said Kay: they shocked, and Kay

Fell shoulder-slipt, and Gareth cried again,

“Lead, and I follow,” and fast away she fled.

But after sod and shingle ceased to fly

Behind her, and the heart of her good horse

Was nigh to burst with violence of the beat,

Perforce she stayed, and overtaken spoke.

“What doest thou, scullion, in my fellowship?

Deem’st thou that I accept thee aught the more

Or love thee better, that by some device

Full cowardly, or by mere unhappiness,

Thou hast overthrown and slain thy master—thou!—

Dish-washer and broach-turner, loon!—to me

Thou smellest all of kitchen as before.”

“Damsel,” Sir Gareth answered gently, “say

Whate’er ye will, but whatsoe’er ye say,

I leave not till I finish this fair quest,

Or die therefore.”

“Ay, wilt thou finish it?

Sweet lord, how like a noble knight he talks!

The listening rogue hath caught the manner of it.

But, knave, anon thou shalt be met with, knave,

And then by such a one that thou for all

The kitchen brewis that was ever supt

Shalt not once dare to look him in the face.”

“I shall assay,” said Gareth with a smile

That maddened her, and away she flashed again

Down the long avenues of a boundless wood,

And Gareth following was again beknaved.

“Sir Kitchen-knave, I have missed the only way

Where Arthur’s men are set along the wood;

The wood is nigh as full of thieves as leaves:

If both be slain, I am rid of thee; but yet,

Sir Scullion, canst thou use that spit of thine?

Fight, an thou canst: I have missed the only way.”

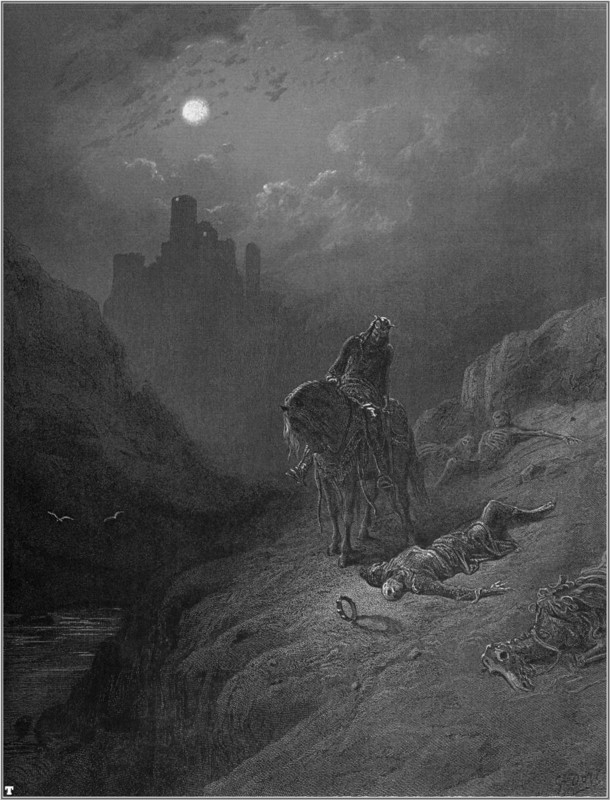

So till the dusk that followed evensong

Rode on the two, reviler and reviled;

Then after one long slope was mounted, saw,

Bowl-shaped, through tops of many thousand pines

A gloomy-gladed hollow slowly sink

To westward—in the deeps whereof a mere,

Round as the red eye of an Eagle-owl,

Under the half-dead sunset glared; and shouts

Ascended, and there brake a servingman

Flying from out of the black wood, and crying,

“They have bound my lord to cast him in the mere.”

Then Gareth, “Bound am I to right the wronged,

But straitlier bound am I to bide with thee.”

And when the damsel spake contemptuously,

“Lead, and I follow,” Gareth cried again,

“Follow, I lead!” so down among the pines

He plunged; and there, blackshadowed nigh the mere,

And mid-thigh-deep in bulrushes and reed,

Saw six tall men haling a seventh along,

A stone about his neck to drown him in it.

Three with good blows he quieted, but three

Fled through the pines; and Gareth loosed the stone

From off his neck, then in the mere beside

Tumbled it; oilily bubbled up the mere.

Last, Gareth loosed his bonds and on free feet

Set him, a stalwart Baron, Arthur’s friend.

“Well that ye came, or else these caitiff rogues

Had wreaked themselves on me; good cause is theirs

To hate me, for my wont hath ever been

To catch my thief, and then like vermin here

Drown him, and with a stone about his neck;

And under this wan water many of them

Lie rotting, but at night let go the stone,

And rise, and flickering in a grimly light

Dance on the mere. Good now, ye have saved a life

Worth somewhat as the cleanser of this wood.

And fain would I reward thee worshipfully.

What guerdon will ye?”

Gareth sharply spake,

“None! for the deed’s sake have I done the deed,

In uttermost obedience to the King.

But wilt thou yield this damsel harbourage?”

Whereat the Baron saying, “I well believe

You be of Arthur’s Table,” a light laugh

Broke from Lynette, “Ay, truly of a truth,

And in a sort, being Arthur’s kitchen-knave!—

But deem not I accept thee aught the more,

Scullion, for running sharply with thy spit

Down on a rout of craven foresters.

A thresher with his flail had scattered them.

Nay—for thou smellest of the kitchen still.

But an this lord will yield us harbourage,

Well.”

So she spake. A league beyond the wood,

All in a full-fair manor and a rich,

His towers where that day a feast had been

Held in high hall, and many a viand left,

And many a costly cate, received the three.

And there they placed a peacock in his pride

Before the damsel, and the Baron set

Gareth beside her, but at once she rose.

“Meseems, that here is much discourtesy,

Setting this knave, Lord Baron, at my side.

Hear me—this morn I stood in Arthur’s hall,

And prayed the King would grant me Lancelot

To fight the brotherhood of Day and Night—

The last a monster unsubduable

Of any save of him for whom I called—

Suddenly bawls this frontless kitchen-knave,

‘The quest is mine; thy kitchen-knave am I,

And mighty through thy meats and drinks am I.’

Then Arthur all at once gone mad replies,

‘Go therefore,’ and so gives the quest to him—

Him—here—a villain fitter to stick swine

Than ride abroad redressing women’s wrong,

Or sit beside a noble gentlewoman.”

Then half-ashamed and part-amazed, the lord

Now looked at one and now at other, left

The damsel by the peacock in his pride,

And, seating Gareth at another board,

Sat down beside him, ate and then began.

“Friend, whether thou be kitchen-knave, or not,

Or whether it be the maiden’s fantasy,

And whether she be mad, or else the King,

Or both or neither, or thyself be mad,

I ask not: but thou strikest a strong stroke,

For strong thou art and goodly therewithal,

And saver of my life; and therefore now,

For here be mighty men to joust with, weigh

Whether thou wilt not with thy damsel back

To crave again Sir Lancelot of the King.

Thy pardon; I but speak for thine avail,

The saver of my life.”

And Gareth said,

“Full pardon, but I follow up the quest,

Despite of Day and Night and Death and Hell.”

So when, next morn, the lord whose life he saved

Had, some brief space, conveyed them on their way

And left them with God-speed, Sir Gareth spake,

“Lead, and I follow.” Haughtily she replied.

“I fly no more: I allow thee for an hour.

Lion and stout have isled together, knave,

In time of flood. Nay, furthermore, methinks

Some ruth is mine for thee. Back wilt thou, fool?

For hard by here is one will overthrow

And slay thee: then will I to court again,

And shame the King for only yielding me

My champion from the ashes of his hearth.”

To whom Sir Gareth answered courteously,

“Say thou thy say, and I will do my deed.

Allow me for mine hour, and thou wilt find

My fortunes all as fair as hers who lay

Among the ashes and wedded the King’s son.”

Then to the shore of one of those long loops

Wherethrough the serpent river coiled, they came.

Rough-thicketed were the banks and steep; the stream

Full, narrow; this a bridge of single arc

Took at a leap; and on the further side

Arose a silk pavilion, gay with gold

In streaks and rays, and all Lent-lily in hue,

Save that the dome was purple, and above,

Crimson, a slender banneret fluttering.

And therebefore the lawless warrior paced

Unarmed, and calling, “Damsel, is this he,

The champion thou hast brought from Arthur’s hall?

For whom we let thee pass.” “Nay, nay,” she said,

“Sir Morning-Star. The King in utter scorn

Of thee and thy much folly hath sent thee here

His kitchen-knave: and look thou to thyself:

See that he fall not on thee suddenly,

And slay thee unarmed: he is not knight but knave.”

Then at his call, “O daughters of the Dawn,

And servants of the Morning-Star, approach,

Arm me,” from out the silken curtain-folds

Bare-footed and bare-headed three fair girls

In gilt and rosy raiment came: their feet

In dewy grasses glistened; and the hair

All over glanced with dewdrop or with gem

Like sparkles in the stone Avanturine.

These armed him in blue arms, and gave a shield

Blue also, and thereon the morning star.

And Gareth silent gazed upon the knight,

Who stood a moment, ere his horse was brought,

Glorying; and in the stream beneath him, shone

Immingled with Heaven’s azure waveringly,

The gay pavilion and the naked feet,

His arms, the rosy raiment, and the star.

Then she that watched him, “Wherefore stare ye so?

Thou shakest in thy fear: there yet is time:

Flee down the valley before he get to horse.

Who will cry shame? Thou art not knight but knave.”

Said Gareth, “Damsel, whether knave or knight,

Far liefer had I fight a score of times

Than hear thee so missay me and revile.

Fair words were best for him who fights for thee;

But truly foul are better, for they send

That strength of anger through mine arms, I know

That I shall overthrow him.”

And he that bore

The star, when mounted, cried from o’er the bridge,

“A kitchen-knave, and sent in scorn of me!

Such fight not I, but answer scorn with scorn.

For this were shame to do him further wrong

Than set him on his feet, and take his horse

And arms, and so return him to the King.

Come, therefore, leave thy lady lightly, knave.

Avoid: for it beseemeth not a knave

To ride with such a lady.”

“Dog, thou liest.

I spring from loftier lineage than thine own.”

He spake; and all at fiery speed the two

Shocked on the central bridge, and either spear

Bent but not brake, and either knight at once,

Hurled as a stone from out of a catapult

Beyond his horse’s crupper and the bridge,

Fell, as if dead; but quickly rose and drew,

And Gareth lashed so fiercely with his brand

He drave his enemy backward down the bridge,

The damsel crying, “Well-stricken, kitchen-knave!”

Till Gareth’s shield was cloven; but one stroke

Laid him that clove it grovelling on the ground.

Then cried the fallen, “Take not my life: I yield.”

And Gareth, “So this damsel ask it of me

Good—I accord it easily as a grace.”

She reddening, “Insolent scullion: I of thee?

I bound to thee for any favour asked!”

“Then he shall die.” And Gareth there unlaced

His helmet as to slay him, but she shrieked,

“Be not so hardy, scullion, as to slay

One nobler than thyself.” “Damsel, thy charge

Is an abounding pleasure to me. Knight,

Thy life is thine at her command. Arise

And quickly pass to Arthur’s hall, and say

His kitchen-knave hath sent thee. See thou crave

His pardon for thy breaking of his laws.

Myself, when I return, will plead for thee.

Thy shield is mine—farewell; and, damsel, thou,

Lead, and I follow.”

And fast away she fled.

Then when he came upon her, spake, “Methought,

Knave, when I watched thee striking on the bridge

The savour of thy kitchen came upon me

A little faintlier: but the wind hath changed:

I scent it twenty-fold.” And then she sang,

“ ‘O morning star’ (not that tall felon there

Whom thou by sorcery or unhappiness

Or some device, hast foully overthrown),

‘O morning star that smilest in the blue,

O star, my morning dream hath proven true,

Smile sweetly, thou! my love hath smiled on me.’

“But thou begone, take counsel, and away,

For hard by here is one that guards a ford—

The second brother in their fool’s parable—

Will pay thee all thy wages, and to boot.

Care not for shame: thou art not knight but knave.”

To whom Sir Gareth answered, laughingly,

“Parables? Hear a parable of the knave.

When I was kitchen-knave among the rest

Fierce was the hearth, and one of my co-mates

Owned a rough dog, to whom he cast his coat,

‘Guard it,’ and there was none to meddle with it.

And such a coat art thou, and thee the King

Gave me to guard, and such a dog am I,

To worry, and not to flee—and—knight or knave—

The knave that doth thee service as full knight

Is all as good, meseems, as any knight

Toward thy sister’s freeing.”

“Ay, Sir Knave!

Ay, knave, because thou strikest as a knight,

Being but knave, I hate thee all the more.”

“Fair damsel, you should worship me the more,

That, being but knave, I throw thine enemies.”

“Ay, ay,” she said, “but thou shalt meet thy match.”

So when they touched the second river-loop,

Huge on a huge red horse, and all in mail

Burnished to blinding, shone the Noonday Sun

Beyond a raging shallow. As if the flower,

That blows a globe of after arrowlets,

Ten thousand-fold had grown, flashed the fierce shield,

All sun; and Gareth’s eyes had flying blots

Before them when he turned from watching him.

He from beyond the roaring shallow roared,

“What doest thou, brother, in my marches here?”

And she athwart the shallow shrilled again,

“Here is a kitchen-knave from Arthur’s hall

Hath overthrown thy brother, and hath his arms.”

“Ugh!” cried the Sun, and vizoring up a red

And cipher face of rounded foolishness,

Pushed horse across the foamings of the ford,

Whom Gareth met midstream: no room was there

For lance or tourney-skill: four strokes they struck

With sword, and these were mighty; the new knight

Had fear he might be shamed; but as the Sun