автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Capitals of Spanish America

Contents.

Index:A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, W, Y.

Some typographical errors have been corrected; a list follows the text.

List of Illustrations

(In certain versions of this etext [in certain browsers] clicking on this symbol

(etext transcriber's note)

THE CAPITALS

OF

SPANISH AMERICA

BY

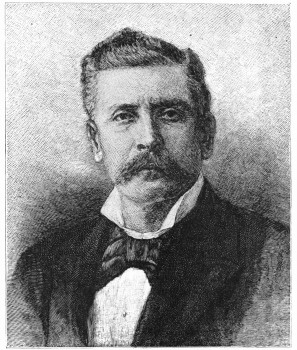

WILLIAM ELEROY CURTIS

LATE COMMISSIONER FROM THE UNITED STATES TO THE GOVERNMENTS OF

CENTRAL AND SOUTH AMERICA

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

HARPER & BROTHERS, FRANKLIN SQUARE

Copyright, 1888, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

TO

THE MEMORY OF

CHESTER ALAN ARTHUR

TWENTY-FIRST PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES

THIS BOOK IS

Dedicated

HIS KINDNESS MADE ITS PUBLICATION POSSIBLE; AND HIS

AFFECTIONATE INTEREST ADDED PLEASURE TO ITS PREPARATION

Mr. Arthur’s Acceptance of the Dedication.

New York, April 7, 1887.

William E. Curtis, Esquire, Washington:

Dear Sir,—In compliance with your request, I enclose an unsigned draft of a letter dictated by Mr. Arthur last November. It was submitted to him a few days before he died, and as he desired to make no further changes in the text, I was to have a clean copy made for his signature; but he was fatally stricken before that was done.

Very respectfully yours,

James C. Reed.

November 13, 1886.

My dear Curtis,—The graceful terms in which you propose to dedicate your book to me add still another obligation that I may not be able to repay.

I appointed you Secretary of the South American Commission without your solicitation, because I knew your ability, energy, and industry would be felt as they have been in the effort to bring our Spanish-American neighbors into closer commercial and political relations with us.

I had given much consideration to the subject, and realized what is made so clear in the Reports of the South American Commission, that the future commercial prosperity of the United States required something to be done to extend our trade with the continent southward. The Commission, of which you were Secretary and subsequently became a member, was intended as an initiatory step in that direction.

In my judgment, it is not only the duty of the United States to encourage and assist our merchants and manufacturers in the expansion of their foreign trade, by seeking new markets and furnishing facilities for reaching them, but there is a higher achievement in promoting the welfare of our sister republics through the consistent exercise of every friendly office tending to secure their peaceable development and national prosperity.

I am sure your “The Capitals of Spanish America” will furnish our own people with trustworthy and late news about our neighbors to the southward, and that your graphic pen will make the book as interesting as it is instructive. I shall await its publication with very deep interest.

If my strength permits, it will give me great pleasure to act upon your suggestion,[A] but just now I am hardly equal to the demands of my private correspondence. With cordial regard,

I am faithfully yours,

—————

To William E. Curtis,

Washington, D. C.

[A] To write an Introduction to this volume.

CONTENTS.

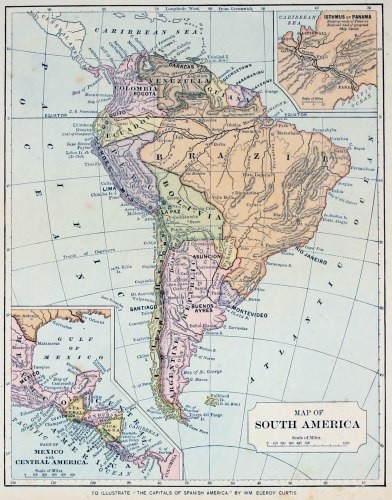

PAGE MEXICO. The Capital of Mexico 1 GUATEMALA CITY. The Capital of Guatemala 60 COMAYAGUA. The Capital of Honduras 114 MANAGUA. The Capital of Nicaragua 138 SAN SALVADOR. The Capital of San Salvador 171 SAN JOSÉ. The Capital of Costa Rica 196 BOGOTA. The Capital of Colombia 225 CARACAS. The Capital of Venezuela 257 QUITO. The Capital of Ecuador 298 LIMA. The Capital of Peru 355 LA PAZ DE AYACUCHO. The Capital of Bolivia 416 SANTIAGO. The Capital of Chili 454 PATAGONIA 516 BUENOS AYRES. The Capital of the Argentine Republic 542 MONTEVIDEO. The Capital of Uruguay 591 ASUNCION. The Capital of Paraguay 623 RIO DE JANEIRO. The Capital of Brazil 660 INDEX:

A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, W, Y. 707ILLUSTRATIONS.

[A] To write an Introduction to this volume.

If my strength permits, it will give me great pleasure to act upon your suggestion,[A] but just now I am hardly equal to the demands of my private correspondence. With cordial regard,

Señor Sinibaldi, the Vice-president of the republic, called the Congress together, and a new election was ordered, at which Señor Barrillas, a man of excellent ability and wise discretion, was chosen President of the republic.

in conversation. Before Morazan was of age he was prominent in Honduras, and became the governor of the city in 1824, when he was but twenty-five. For fourteen years thereafter his career was one of singular activity and success, and the people of the entire continent followed him with feelings akin to idolatry. He was so far ahead of them in ideas and enterprise that his counsels were not followed, and he was overthrown by a combination of priests, who took up a cruel Indian of Guatemala named Rafael Carera, and succeeded in overthrowing the power of Morazan, not only in Honduras, but throughout the entire confederacy. The patriot and liberator was afterwards assassinated at Cartago, Costa Rica, by men whom he trusted as his friends.

Since the charter of the Interoceanic Canal Company by the Congress of the United States, and the actual commencement of work upon the long-projected enterprise, under the direction of Chief-engineer Menocal, the republic of Nicaragua assumes a position of more prominence among nations, and of greater interest to the public at large, than it has ever had before. The failure of the Panama Canal Company, and the apparent impossibility of piercing the Isthmus at its narrowest part, has also given the Nicaragua Company increased importance, but Mr. Menocal and the company of capitalists who stand behind him feel no doubt of ultimate success.

There is one railroad in San Salvador, extending from Acajutla to the city of Sonsonate, the centre of the sugar district, and it is being extended to Santa Ana, the chief town of the Northern Province. It is owned by a native capitalist, and operated under the management of an American engineer. The plan is to extend the track parallel with the sea through the entire republic, in the valley back of the mountain range, with branches through the passes to the principal cities. It now passes two-thirds of the distance around the base of the volcano Yzalco, and from the cars is furnished a most remarkable view of that sublime spectacle. The entire system when completed will not consist of more than two hundred and fifty miles of track, and the work of construction is neither difficult nor expensive.

The extreme ultramontanism of Dr. Nuñez awakened a series of revolutions, and resulted in his abdication of the Presidency; his successor being Dr. Holguin, one of the most prominent and learned leaders of the Clerical party, who has spent his life in Congress, in the executive departments of the Government, and in the diplomatic service.

South of Curaçoa is Maracaibo, with its curious lake, in which are towns built upon stilts, that give the name of Venezuela, or Little Venice, to this land. The explorers, like tourists of modern times, were given to tracing resemblances in America to what they were familiar with in Europe, and they imagined these huts rising on piles above the water looked like the city of canals and gondolas. But there is no more resemblance to Venice than to Chicago, and the name of Venezuela, like that of the continent, is a falsehood which the world has allowed to stand uncontradicted.

arrived upon the dock there was a group to illustrate the cosmopolitan character of the citizens. A Chinaman, an Arab, a negro, and a Frenchman were sitting upon a box, while around them were clustered Spaniards, Englishmen, Irishmen, Germans, and Italians. The city is irregular and shabby-looking, but has been a place of great wealth. Millions after millions of dollars’ worth of silver have been shipped from here by the Spaniards—silver stolen from the temples of the Incas, or dug from the mines which they operated before the Spaniards came. It was here that the old buccaneers used to rendezvous and waylay the galleons on their way to Spain. Of recent years the importance of Callao has very much decreased. A constant succession of wars and revolutions in Peru has destroyed its commerce; and although there is usually a great deal of shipping in the harbor, the present amount of trade is below that of the past. There are two lines of railroad to Lima, the capital of the republic, which lies six miles up in the foot-hills of the Andes.

The most curious things in Peru are the mummies’ eyes—petrified eyeballs—which are usually to be found in the graves, if one is careful in digging. The Incas had a way of preserving the eyes of the dead from decay, some process which modern science cannot comprehend, and the eyeballs make very pretty settings for pins. They are yellow, and hold light like an opal. It is an accepted theory among scientists, however, that before the burial of their mummies the Incas replaced the natural eye with that of the squid, or cuttle-fish, and that these beautiful things are shams.

No one ever goes to Juan Fernandez without bringing away rocks and sticks as relics of the place. There is a very fine sort of wood peculiar to the island which makes beautiful canes, as it has a rare grain and polishes well.

The journey on mule-back usually takes five days of travel, at the rate of twenty or thirty miles a day, but good riders, with relays of mules, often make it in three days. The whole route is historical, as it has been in use for centuries. There is scarcely a mile without some romantic association, not a rock without its incident; and tradition, incident, and romance line the path from end to end. The Incas used the path before the Spaniards conquered the country, and Don Diego de Almagro crossed it in 1535 as he passed southward to Chili after the conquest of Peru.

birds have the advantage of being “artful dodgers,” and as they carry so much less weight, can turn and reverse quite suddenly. The usual mode of hunting them is for a dozen or so Indians to surround a herd and charge upon it suddenly. In this way several are usually brought down before they can scatter, and those that get away are pursued. As they dodge from one hunter they usually run afoul of another, and before they are aware they are tripped by the entangling bolas. People who are passing through the strait often stop over and await another steamer at Punta Arenas to enjoy an ostrich chase. They can secure trained horses and guides at moderate rates. One who has never thrown the bolas will be amazed, the first time he tries it, to find how difficult it is to do a trick that looks so easy.

There is a curious story about an island in the River Plata which was a horse ranch in early Spanish times. The animals became so numerous that there was not grass enough to feed them, and no demand for their export. The owners decided to reduce their stock in a barbarous way, and when the grass was dry they set fire to it. Every horse on the island was burned to death except those that ran into the river and were drowned. The stench was so great that navigation was almost entirely suspended on the river. The result of this method of reducing stock was a little more complete than the owners anticipated, so when the grass grew up again they had to buy stallions and mares and start anew. Singularly enough, every animal placed on the island since that fire has died of a mysterious disease, and no colt has been foaled there for one hundred and fifty years. Various breeds of stock have been tried, but never a hoof has left the island alive. Three months there finishes them. The island was unoccupied for fifty or sixty years, but is now used as a cattle ranch, and horned stock do not appear to be subject to the mysterious malady.

It is not generally known that “Liebig’s Extract of Beef,” which, like quinine, is a standard tonic throughout the world, and is used by every physician, in every hospital, on every ship, and in every army, is a product of Uruguay. The cans in which it comes are labelled as if their contents were manufactured at Antwerp, where the original extract was invented by Professor Liebig, the famous German chemist, and the preparation was formerly made there; but in 1866, the patent having passed into the control of an English company, the works were removed to Uruguay, where cattle are cheaper than elsewhere, and the entire supply is now produced at a place called Fray Bentos, about one hundred and seventy miles above Montevideo, on the Uruguay River, whence it is shipped in bulk to London and Antwerp, where it is packed in small tins for the market. An attempt was made to do the packing in Uruguay, but the Government of that republic imposed so high a tariff upon the tins that the scheme was abandoned. The chemical process by which the juice of the beef is extracted and mixed with the blood of the animal is supposed to be a secret, but as the patent has long since expired, it could be easily discovered, and thus the manufacture of an almost necessary article would become general.

The number of horned cattle in Paraguay is now estimated at six hundred thousand, and there is said to be pasturage for several million within the limits of the republic, and an unlimited area in El Gran Chaco beyond the timber regions on a plain similar to New Mexico, rising in great terraces or steppes to the foot-hills of the Andes. The elevation of this area above the sea is from four to eight thousand feet, and although it borders upon the tropics, it is said to be an excellent range, and the ranchmen of the Argentine Republic are contemplating it with covetous eyes. No industry pays so well in Paraguay as cattle-raising. The severe frosts and droughts which at times annoy the ranchmen of the Argentine Republic are unknown there; the streams are numerous and perennial, the cattle fatten quicker, attain greater weight, and afford a better quality of beef, owing to the nutritious grass and abundance of water. Young cattle, as before stated, may be bought in the Argentine Republic and transported by river steamer to Paraguay for twelve or thirteen dollars per head, and land can be purchased at about twenty cents an acre from the Government.

There are a great many Germans going into the country, forming colonies in the interior, opening up sugar plantations, planting coffee, gathering rubber, and engaging in all sorts of agricultural employment; but the climate is so enervating that after an experience of two years the German colonist will be found by his Portuguese predecessor sitting in the shade of the fig-tree and hiring a negro to do his work. Everywhere in hot climates the people become enervated, and Brazil will scarcely form an exception to other countries in the same latitude. In the more southern provinces and on the higher levels white colonists may succeed if there is nothing but climatic differences to oppose them. There has been a small number of immigrants from the United States to the southern provinces of Brazil; and after the war a great many Confederates flooded in there for the purpose of establishing plantations and raising sugar and coffee, but their success has not been great. Most of the colonies have broken up, and the members have been scattered over different parts of the country. Some engage in one undertaking, some in another, but many have succumbed to the influences of the climate and died of fever.

Map of South America Frontispiece. PAGE

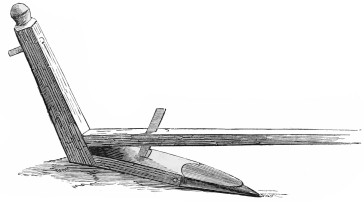

It was used in the Days of Moses

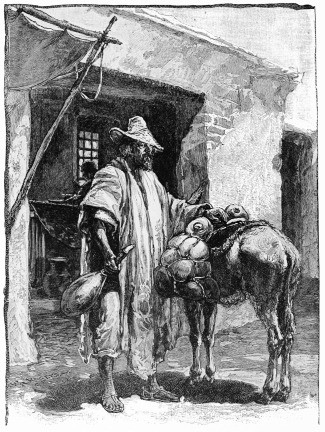

2A Water-carrier

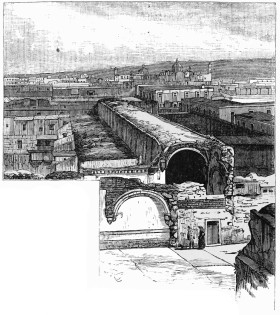

3Ruins of the Covered Way to the Inquisition

4Mexican Muleteer

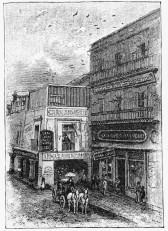

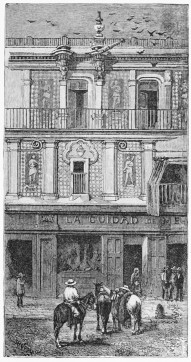

5Shops

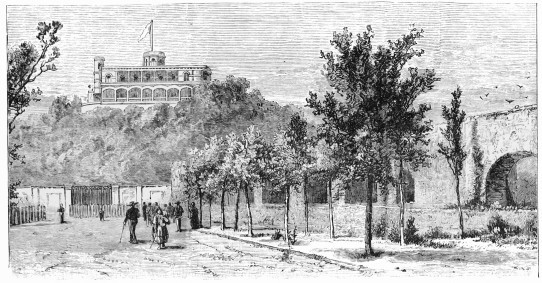

6Castle of Chapultepec

7Tile Front

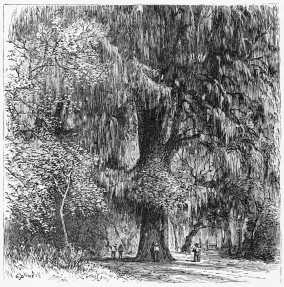

9The Tree of Montezuma

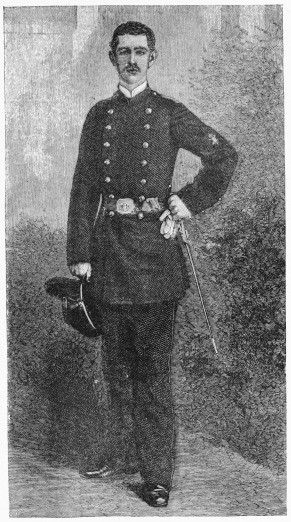

10Prince Yturbide

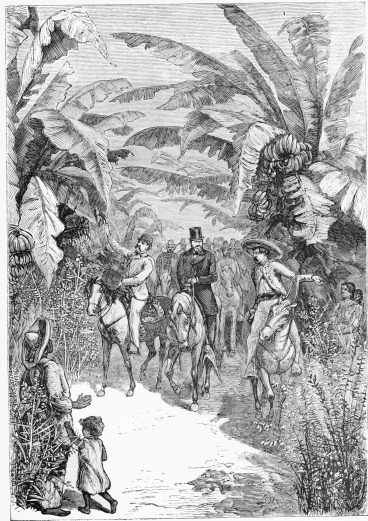

11General Grant on a Banana Plantation

15Church of Guadalupe

19Iztaccihuatl

20Ex-President Gonzales

22President Porfirio Diaz

23The Dome

25San Cosme Aqueduct, City of Mexico

27The Palace of Mexico

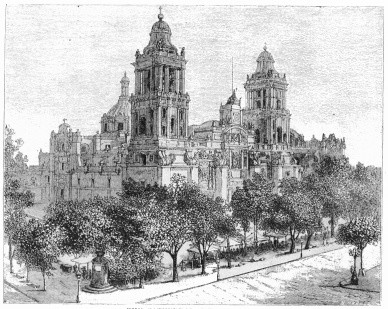

29The Cathedral, City of Mexico

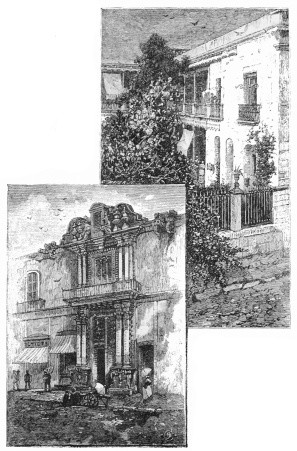

33Styles of Architecture

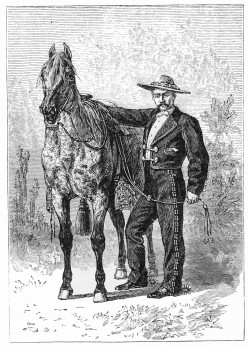

35A Mexican Caballero

38Noche Triste Tree

41The Picadors

45Teasing the Bull

45The Encore

46Mexican Beggar

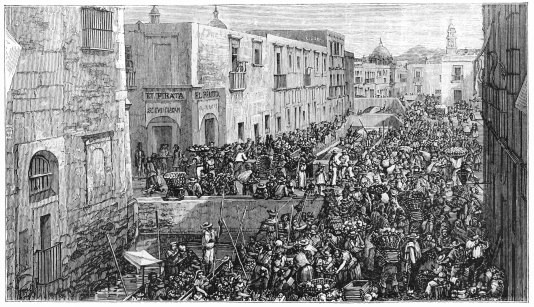

48On Market-day

51Sunday at Santa Anita

53A Mexican Belle

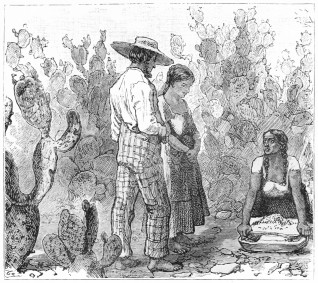

54Cactus, and Woman kneading Tortillas

55First Protestant Church in Mexico

57The first Christian Pulpit in America—Tlaxcala

58Font in old Church of San Francisco

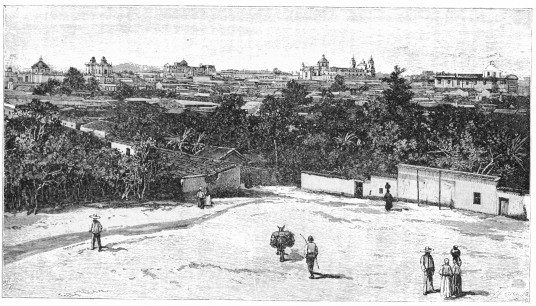

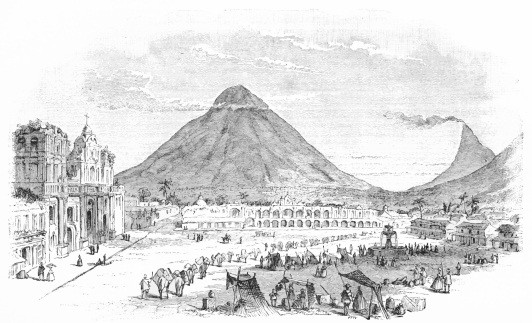

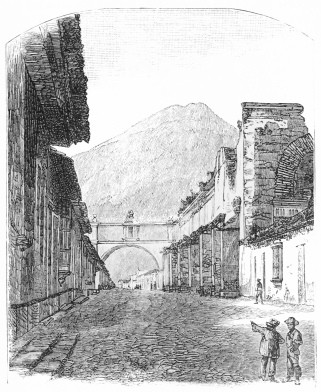

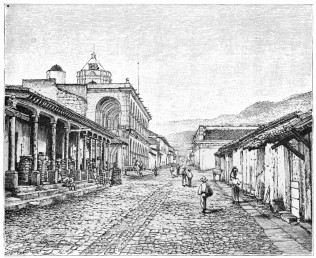

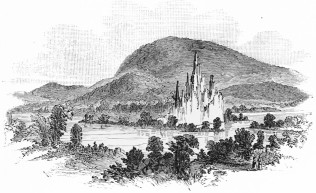

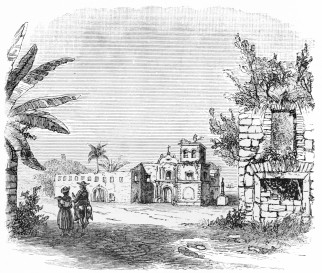

59View of Guatemala City

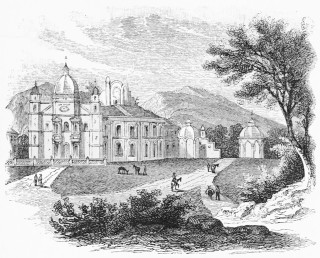

61Ruins of the old Palace at Antigua Guatemala

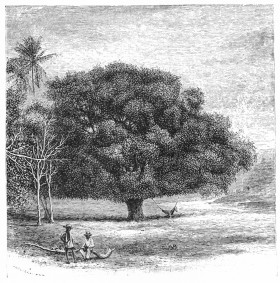

65Alvarado’s Tree

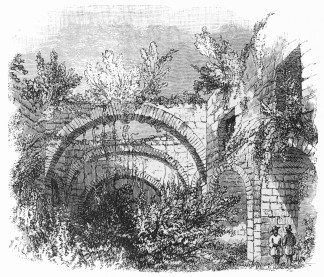

69Ancient Arches

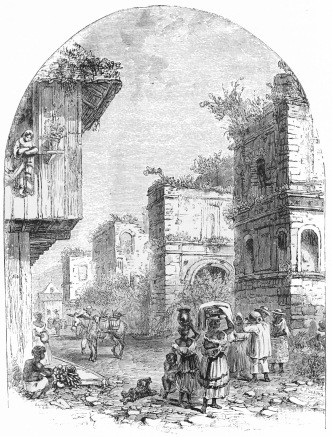

70The Old and the New

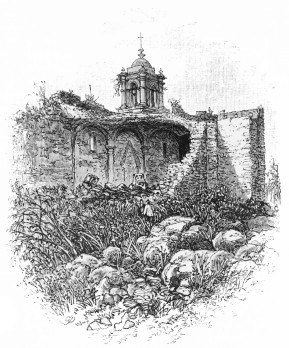

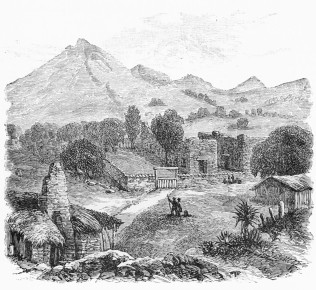

71How the Old Town looks now

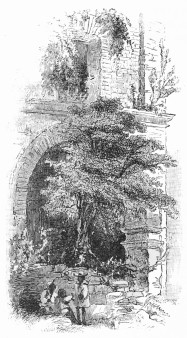

73Fragment of a Ruined Monastery

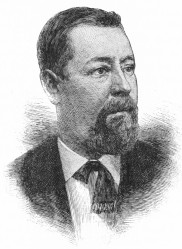

74José Rufino Barrios

75Francisco Morazan

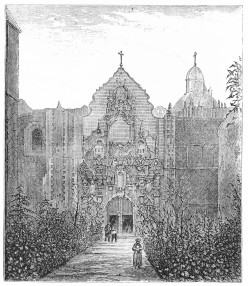

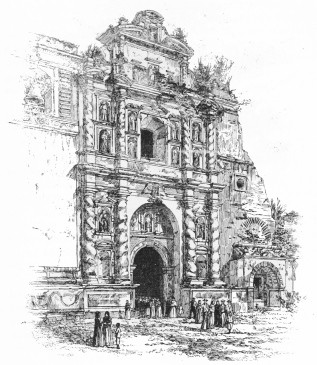

77Church of San Francesca, Guatemala la Antigua

79One of fifty-seven Ruined Monasteries

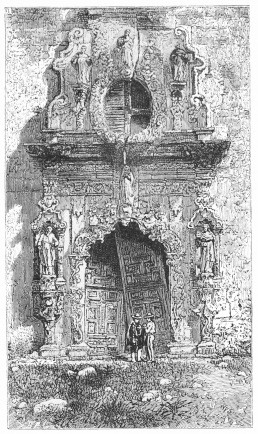

81Façade of an old Church

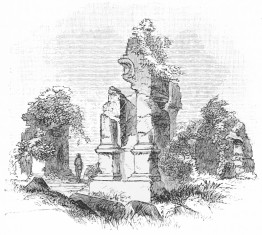

83A Remnant

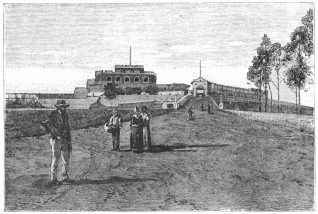

85Fort of San José, Guatemala

87Yniensi Gate, Guatemala

89A Volcanic Lake

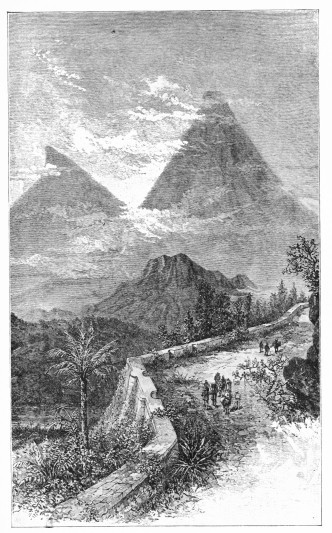

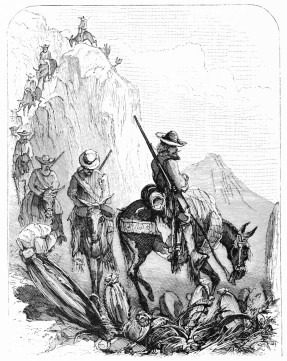

91On the Road to the Capital

93Tiled House-tops

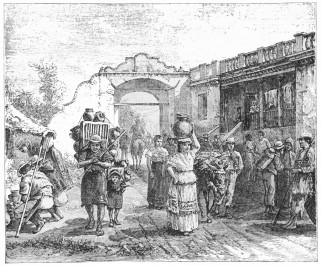

99Market-place, Guatemala

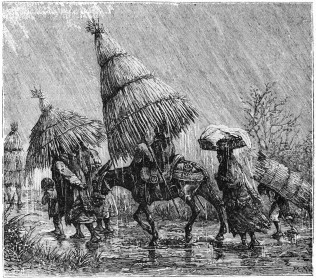

101In the Rainy Season

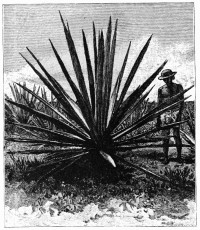

102Maguey Plant

103A Native Sandal

107Ornamental, but noisy

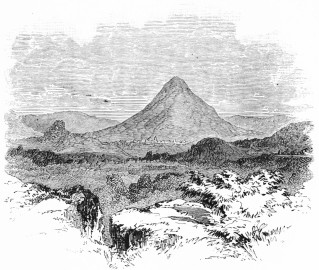

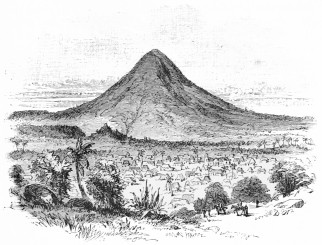

109A Conspicuous Landmark

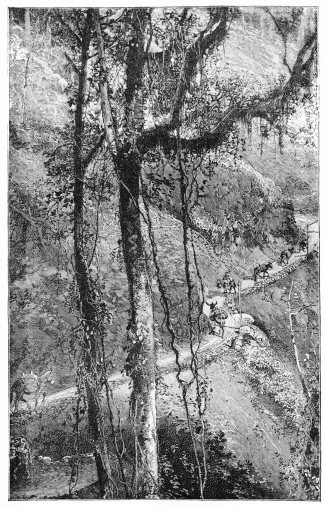

115The Trail to the Capital

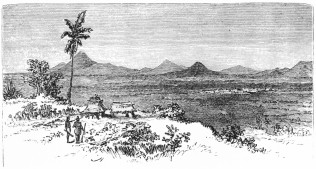

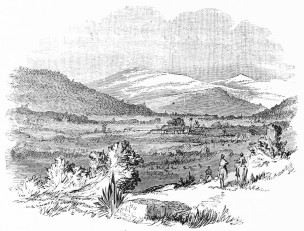

116A Glimpse of the Interior

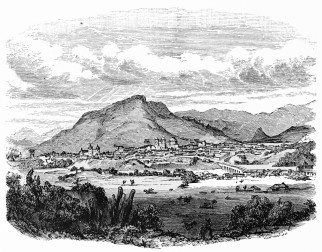

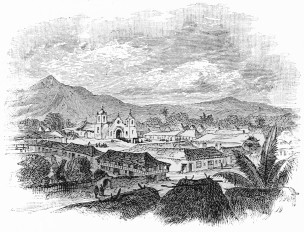

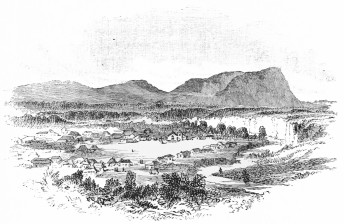

117View of the Capital

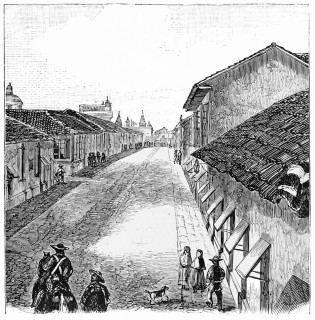

118A Popular Thoroughfare

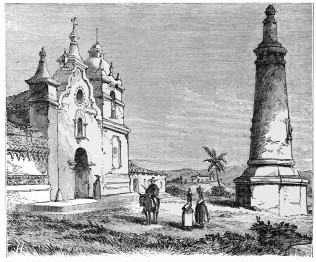

119Church of Merced and Independence Monument, Comayagua

120Rubber Hunters

121The Pita Plant

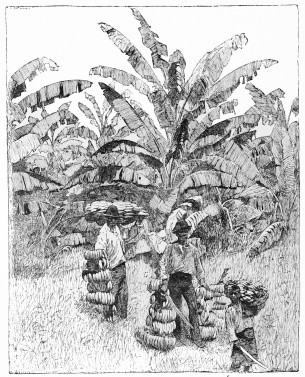

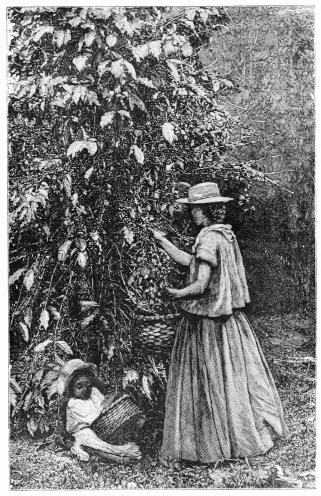

122Harvesting one of the Staples

123The Floating Population

124Branch of the Rubber-tree

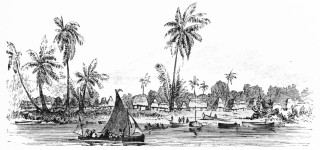

125A Modern Town

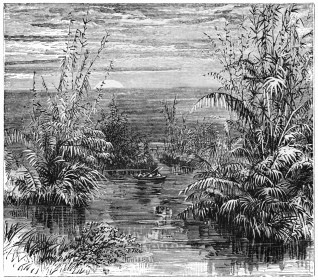

126Up the River

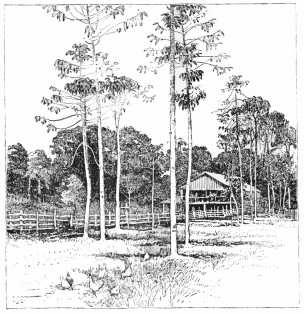

127A Mining Settlement

128View in Nicaragua

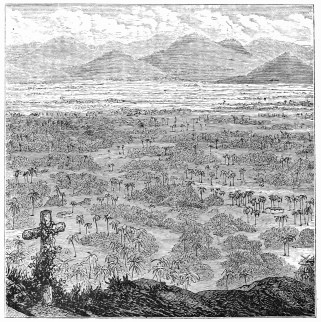

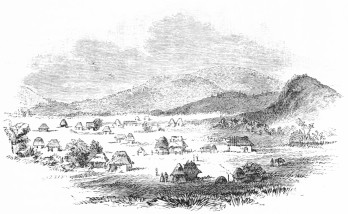

129An Interior Plain

130One of the Back Streets

132Plaza of Tegucigalpa

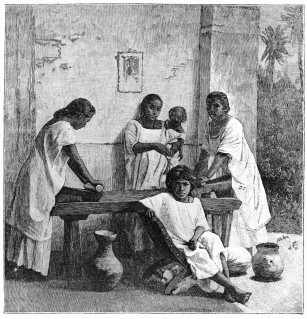

133Making Tortillas

134Indigo Works

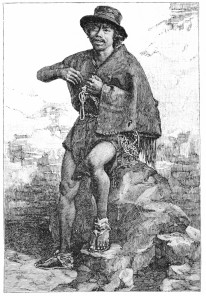

135The Tlachiguero

136View of Lake from Beach at Managua

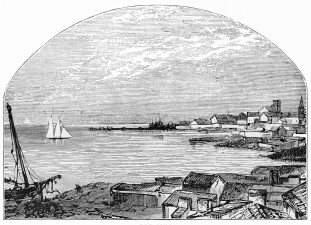

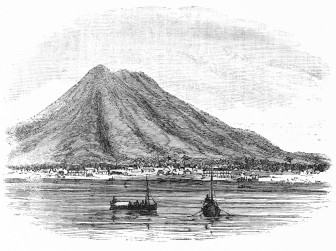

139Corinto

140Hide-covered Cart

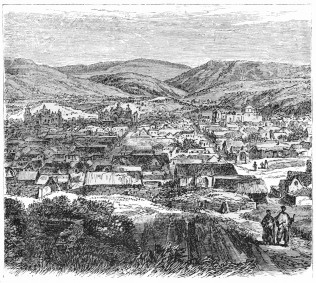

141An Interior Town

143The Indigo Plant

144The King of the Mosquitoes

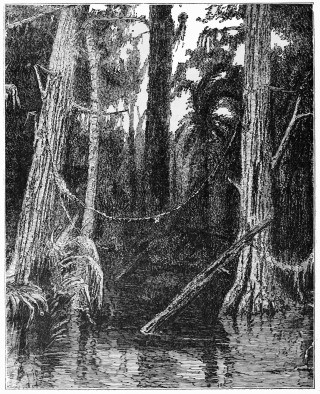

145A Mahogany Swamp

148Internal Commerce

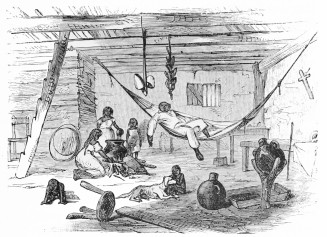

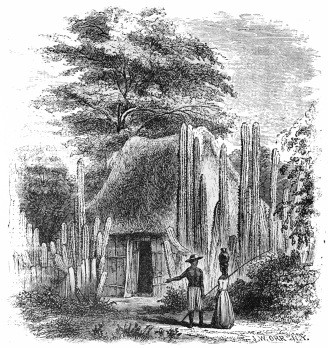

149How the Peons live

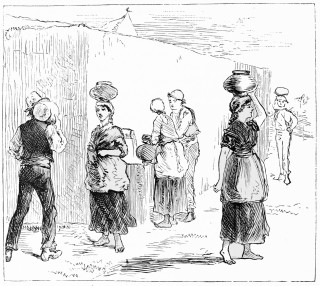

150A Familiar Scene

152A Country Chapel

153The United States Consulate

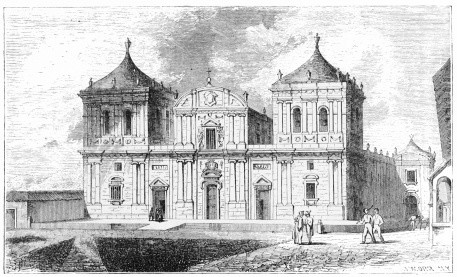

154Cathedral of St. Peter, Leon

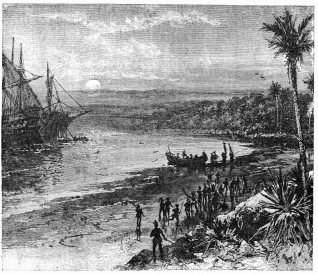

155The Pacific Coast of Nicaragua

158Antics on the Bridge

159In the Upper Zone

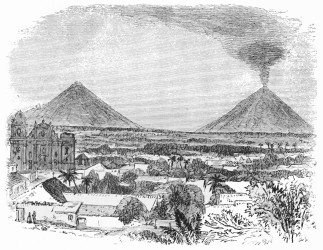

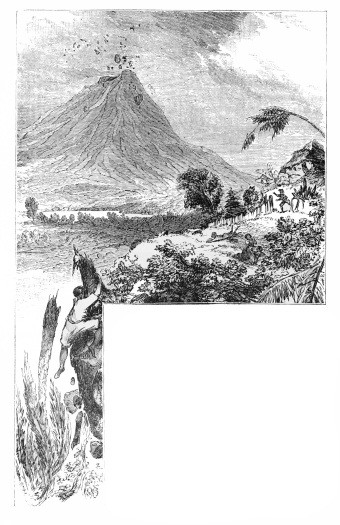

161Volcanoes of Axusco and Momotombo, from the Cathedral

162Volcano of Cosequina, from the Sea

163La Union and Volcano of Conchagna

164The Fate of Filibusters

165A Farming Settlement

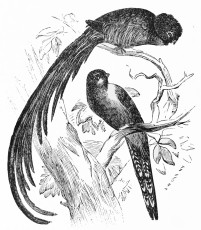

167The Quesal

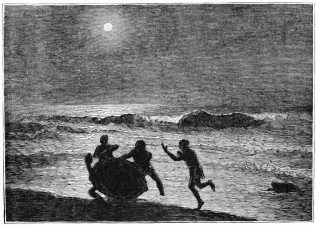

168Landing at La Libertad

173En Route to the Interior

175The Peak of San Salvador

177The Plaza

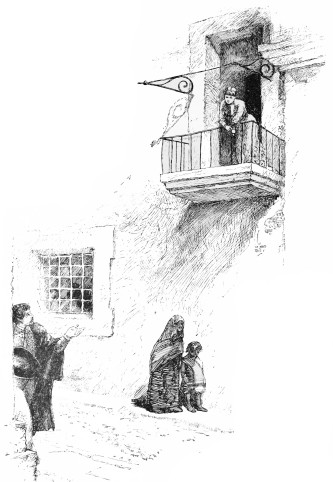

179Spanish-American Courtship

180A Hacienda

182Interior of a San Salvador House

183A Typical Town

185What alarms the Citizens

186Yzalco from a Distance

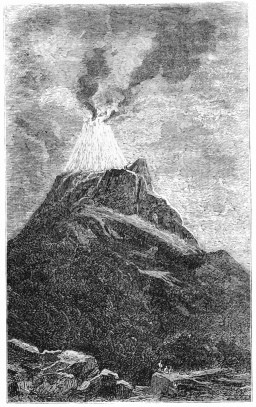

189Yzalco

191In the Interior

193Hauling Sugar-cane

194Crater of a Volcano

197Rubber-trees

199The Road from Port Limon to San José

201A Peon

203A Banana Plantation

206Picking Coffee

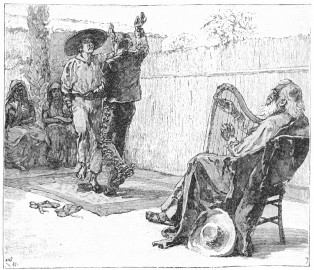

209The Marimba

215Coffee-drying

217Don Bernardo de Soto, President of Costa Rica

222Barranquilla

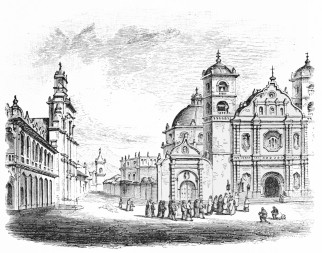

226Carthagena

227Entrance to the Old Fortress, Carthagena

230Colombian Military Men

233On the Magdalena

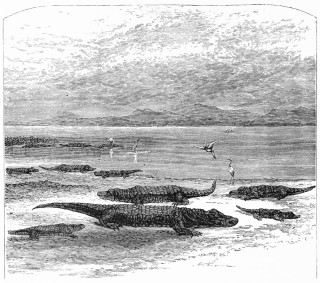

235Colombian ’Gators

237Vegetable Ivory Plant

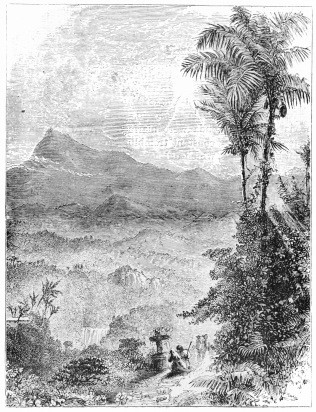

239En Route to Bogota

241Sabana of Bogota

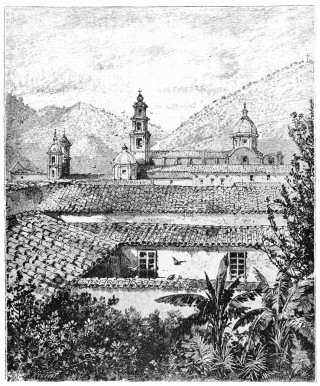

243Santa Fé de Bogota

245Monument in the Plaza of Los Martirs

246Plaza, and Statue of Bolivar

247Going to the Market

249A Caballero

250An Orchid

251Over the Mountains in a “Silla”

253Natural Bridge of Pandi, Colombia

255Don Rafael Nuñez, President

256Waiting for the New York Steamer

259In the Suburbs of La Guayra

261Still more Suburban

263On a Coffee Plantation

267On a Back Street

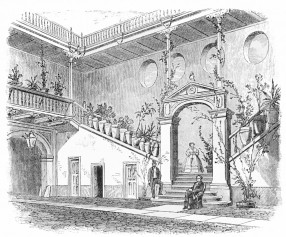

269Interior Court of a Caracas House

273Spanish Missionary Work

276Woman’s chief Occupation

277A Bodega

279A Glass of Aguardiente

281A Venezuela Belle

283The Lower Floor of the House

285An Old Patio

289Chocolate in the Rough

293Separating the Cocoa-beans

294Puerto Cabello

296Along the Coast

299The River at Guayaquil

301The River above Guayaquil

303An average Dwelling

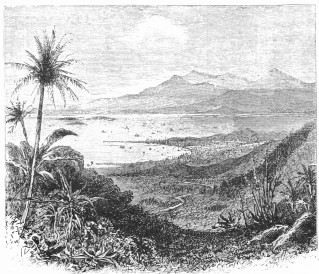

304Guayaquil

305A Person of Influence

306A Family Circle

307Cathedral at Guayaquil, built of Bamboo

308A Commercial Thoroughfare

309The President’s Palace

310The Outskirts of Guayaquil

311A Business of Importance

312A Pineapple Farm

313A Water Merchant

314A Freight Train on the Way

315A Passenger Train

316The Common Carrier

317Hotel on the Route to Quito

318Waiting for the Mules to Feed

319En Route to the Sea

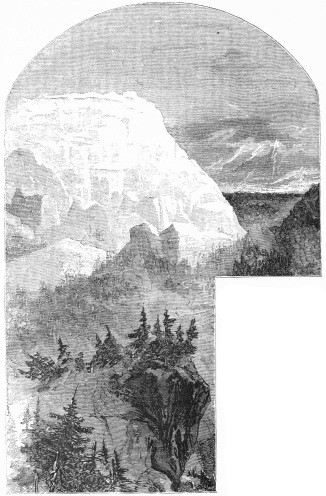

320Somewhere near the Summit

321The Altar

323A Street in Quito

324Where Pizarro first Landed

325Equipped for the Andes

327The Old Inca Trail

329A Typical Country Mansion

331A Wayside Shrine

332Charcoal Peddler

333Government Building at Quito

335Court of a Quito Dwelling

336What the Earthquakes left

338A Professional Beggar

339An Ecuador Belle

340A Hotel on the Coast

343Customs Officers

346A Home on the Coast

347Peruvian Soldier and Rabona

349Looking Seaward

352A Boatman on the Coast

354Lima and its Environs

356A Peruvian Interior

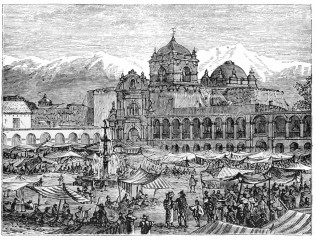

358Grand Plaza, Lima

363A Peruvian Chamber

366Interior of a Lima Dwelling

368A Peruvian Palace

369A Peruvian Belle

370Watching the Procession

371The Daughter of the Incas

373Ruins of the War

375Interior of the ordinary Sort of House

378A very Common Spectacle

379A Peruvian Milk-peddler

381Mindless of Care

383View of Cuzco and the Nevado

of Asungata from the Brow of the Sacsahuaman

389Between Battles, Balls

393A Warrior at Rest

397Gate-way to the Andes

399Henry Meiggs

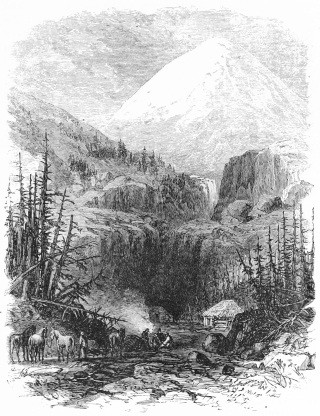

402The Heart of the Andes

404An Inca Reminiscence

405Cowhide Bridge over the Rimac

407Inca Ruins of Unknown Age

408A Settlement of this Century

409A City of Four Centuries Ago

410A Bit of Inca Architecture

411Relic of a Past Civilization

412Ruins of the Temple of the Sun

413An Old Settler

414Fresh from the Tomb

414Where Peru’s Wealth came from

417A Peruvian Port

419The Old Trail

420Arequipa

421The Vicuña

424Lake Titicaca

425A Street in Cuzco

428Ruins of an Inca Temple

429Convent of Santa Domingo, Cuzco

430What the Spaniards left

431Where the Guano Lies

432A Nitrate Mining Town

433Guano Islands

435Across the Continent

437A Station on the Road

438Chasquis at Rest

440Chasquis Asleep in the Mountains

441A Bit of La Paz

442The Cathedral at La Paz

443An Ancient Bridge in La Paz

445A Bolivian Elevator

446A Bolivian Cavalryman

447A Home in the Andes

448Juan Fernandez

450Cumberland Bay

451Tablet to Alexander Selkirk

453The Harbor of Valparaiso

455Victoria Street, Valparaiso

459Santa Lucia

467The Zama-cuaca

469Exposition Building, Santiago

471Statue of Bernard O’Higgins, Santiago

474Patrick Lynch

475Peons of Chili

477The “Esmeralda”

481Inca Queen and Princess

485Señora Cousino

491A Belle of Chili dressed for Morning Mass

497A Solid Silver Spur

505Over the Andes

506Mount Aconcagua

507Uspallata Pass

509Caught in the Snow

511Road Cut in the Rocks

512A Station in the Mountains

513The Condor

515Cape Froward (Patagonia), Strait of Magellan

517Fuegians Visiting a Man-of-war

519A Fuegian Feast

521The Signs of Civilization

523Port Famine

526Starvation Beach

529Use of Lasso and Bolas

531In their Ostrich Robes

532A Patagonian Belle

533The Guanaco

539Patagonian Indians

541The Harbor, Buenos Ayres

542The City of Buenos Ayres

545Loading Cargo at Buenos Ayres

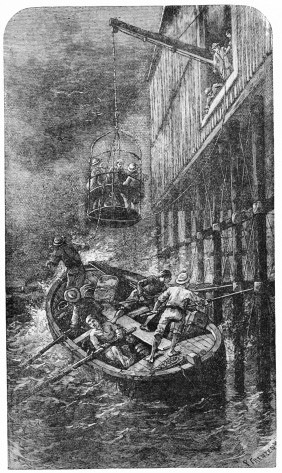

548Going Ashore at Buenos Ayres

549A Private Residence in Buenos Ayres

552The Colon Theatre, Buenos Ayres

554An Argentine Ranchman

564The Cathedral of Buenos Ayres

567The Gaucho

570General Rosas

573Palace of Don Manuel Rosas

575Map of the Argentine Republic

580Country Scene in the Argentine Republic

584Juarez Celman, President of the Argentine Republic

587The City of Montevideo, looking towards the Harbor

591Harbor of Montevideo

593Maximo Santos, of Uruguay

595One of the Old Streets

597Montevideo—the Ocean Side

603Scene in Montevideo

608Gaspar Francia, First President of Paraguay

624Street in Asuncion

625Lopez, the Tyrant

626After the War

627Asuncion, from the West

628Asuncion—the Palace and Cathedral

629Wreck of the Old Cathedral

631Station on the Asuncion Railway

633A Visit to the Spring

634The Paraguayans at Home

635Paraguay Flower-girl

636Remains of the Palace of Lopez

637Interior of the Lopez Palace

639The Cathedral, Asuncion

640Market-place at Asuncion

641A Paraguay Horseman

642Paraguay Belles

643Costumes of the Interior

644An Interior Town

645Home, Sweet Home

646The Mandioca

647Ox-cart on the Pampas

649Curing Yerba Mate

650A Siesta

651A Paraguay Hotel

653Native Pappoose and Cradle

654A Hacienda

655People of “El Gran Chaco”

656An Armadillo

657A Ranch on El Gran Chaco

658Bay of Rio de Janeiro

661A Street in Rio

662The City of Rio from the Bay

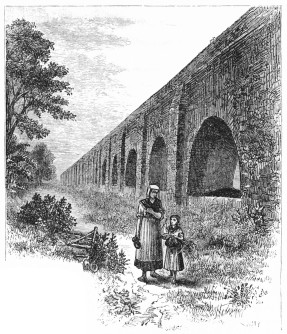

663Aqueduct at Rio

665The Avenue of Royal Palms—Rio

666The Prettiest Things in Brazil

667A Brazilian Hacienda

669The Old City Palace

671In the Suburbs

672Cottages in the Interior

673The Iguana

675A Brazilian Laundry

676A Country School

677Brazilian Country-house

679Up the River

681Dom Pedro II.

682On the Way to Petropolis

683The Empress of Brazil

685Dom Pedro’s Palace at Petropolis

687The Colored Saint

691Statue of Dom Pedro I.

693Carrying Coffee to the Steamer

696Market-place in Country Town

697“Sereno-o-o-o-o-o! Sereno-o-o-o-o-o!”

699Slave Quarters in the Country

702The Political Issue in Brazil

703Military Men

705The people are highly civilized in spots. Besides the most novel and recent product of modern science, one finds in use the crudest, rudest implement of antiquity. Types of four centuries can be seen in a single group in any of the plazas. Under the finest palaces, whose ceilings are frescoed by Italian artists, whose walls are covered with the rarest paintings, and shelter libraries selected with the choicest taste, one finds a common bodega, where the native drink is dealt out in gourds, and the peon stops to eat his tortilla. Women and men are seen carrying upon their heads enormous burdens through streets lighted by electricity, and stop to ask through a telephone where their load shall be delivered.

The correspondence of the Government is dictated to stenographers and transcribed upon type-writers; and every form of modern improvement for the purpose of economizing time and saving labor is given the opportunity of a test, even if it is not permanently adopted. There is no Government that gives greater encouragement to inventive genius than the administration of President Diaz, and it has been one of the highest aims of his official career to modernize Mexico. The twelve years from 1876, when he came into power, until 1889, when his third term commenced, may be reckoned the progressive age of our neighborly republic; but the common people are still prejudiced against innovations, and resist them. In all the public places, and at the entrance of the post-office, are men squatting upon the pavement, with an inkhorn and a pad of paper, whose business is to conduct the correspondence of those whose literary attainments are unequal to the task. Such odd things are still to be seen at the capital of a nation that subsidizes steamship lines and railways, and supports schools where all the modern languages and sciences are taught, and has a compulsory education law upon its statute-books. In the old Inquisition Building, where the bodies of Jews and heretics have been racked and roasted, is a medical college, sustained by the Government for the free education of all students whose attainments reach the standard of matriculation; and bones are now sawn asunder in the name of science instead of religion.

The political struggle in Mexico, since the independence of the Republic, has been, and will continue to be, between antiquated, bigoted, and despotic Romanism, allied with the ancient aristocracy, under whose encouragement Maximilian came, on the one hand, and the spirit of intellectual, industrial, commercial, and social progress on the other. The pendulum has swung backward and forward with irregularity for sixty years; every vibration has been registered in blood. All of the weight of Romish influence, intellectual, financial, and spiritual, has been employed to destroy the Republic and restore the Monarchy, while the Liberal party has strangled the Church and stripped it of every possession. Both factions have fought under a black flag, and the war has been as cruel and vindictive on one side as upon the other; but the result is apparent and permanent.

No priest dare wear a cassock in the streets of Mexico; the confessional is public, parish schools are prohibited, and although the clergy still exercise a powerful influence among the common people, whose superstitious ignorance has not yet been reached by the free schools and compulsory education law, in politics they are powerless. The old clerical party, the Spanish aristocracy, whose forefathers came over after the Conquest, and reluctantly surrendered to Indian domination when the Viceroys were driven out and the Republic established, have given up the struggle, and will probably never attempt to renew it. They were responsible for the tragic episode of Maximilian, and still regret the failure to restore the Monarchy. The Aztecs sit again upon the throne of Mexico, after an interval of three hundred and fifty years, and the men whose minds direct the affairs of the Republic have tawny skins and straight black hair.

The beautiful castle of Chapultepec, which was dismantled during the last revolution, but has been restored and fitted up as a beautiful suburban retreat for the Presidents of Mexico, was occupied by Maximilian and Carlotta in imitation of the Montezumas, whose palace stood upon the rocky eminence. Around the place is a grove of monstrous cypress-trees, whose age is numbered by the centuries, and whose girth measures from thirty to fifty feet. It is the finest assemblage of arborial monarchs on the continent, and sheltered imperial power hundreds of years before Columbus set his westward sails. Before the Hemisphere was known or thought of, here stood a gorgeous palace, and its foundations still endure. Here the rigid ceremonial etiquette of Aztec imperialism was enforced, and human sacrifice was made to invoke the favor of the Sun.

The acknowledged heir to the throne of Mexico is young

Augustin Yturbide, according to the feelings of the few and feeble remnants of the Monarchical party; but it may be said to the young man’s credit that he entirely repudiates their homage, although he is the heir to two brief and ill-starred dynasties. He is the grandson of the Emperor Augustin Yturbide, and the adopted heir of Maximilian and Carlotta. The Yturbide they call “Emperor” was an officer in the Spanish army when Mexico was a colony, and during the revolution headed by the priest Hidalgo, in 1810, he fought on the side of the King. But, being dismissed from the army in 1816, he retired to seclusion, to remain until the movement of 1820, when he placed himself at the head of an irregular force, and captured a large sum of money that was being conveyed to the sea-coast. With these resources he promulgated what is known in history as “the plan of Iguala,” which proposed the organization of Mexico into an independent empire, and the election of a ruler by the people. The revolution was bloodless, and in May, 1822, Yturbide proclaimed himself Emperor, declared the crown hereditary, and established a court. He was formally crowned in the July following, but in December Santa Anna proclaimed the Republic, and after a brief and ignominious reign Yturbide left Mexico on May 11, 1822, just a year, lacking a week, from the date he assumed power. The Congress gave him a pension of $25,000 yearly, and required that he should live in Italy; but impelled by an insane desire to regain his crown, in May, 1824, he returned to Mexico, and was shot in the following July.

He left a son, Angel de Yturbide, who came to the United States with his mother, and was educated at the Jesuit College at Georgetown, District of Columbia, the Government having given them a liberal pension. There he fell in love

It created a sensation in Mexico when the pretty peon girl, Dolores Testa, was suddenly raised from abject poverty to affluence. The Dictator ordered all to address his bride as “Your Highness,” ladies-in-waiting were appointed in order to teach the bewildered little Dolores how to play her rôle in the great world, and then the President organized for her a body-guard of twenty-five military men, who were uniformed in white and gold, and were styled “los Guardias de la Alteza” (her Highness’s Body-guard). When the President’s wife attended the theatre these guards rode in advance of and at the sides of the coach, each bearing a lighted torch. During the performance they remained in the patio or foyer of the theatre, and then escorted her Highness back to the palace in the same order. Such was the power of General Santa Anna in those days that even the clergy bent before him; and when

This Guadalupe shrine is the most sacred spot in Mexico, and to it come, on the 12th of each December, the anniversary of the appearance of the Virgin, thousands upon thousands of pilgrims, bringing their sick and lame and blind to drink of the miraculous waters of a spring which the Virgin opened on the mountain-side to convince the sceptical shepherd of her divine power. The waters have a very strong taste of sulphur, and are said to be a potent remedy for diseases of the blood. In testimony of this the walls of the chapel, which is built over the spring, are covered with quaint, rudely written certificates of people who claim to have been miraculously cured by its use. In the cathedral are multitudes of other testimonials from people who have been preserved from death in danger by having appealed for protection to the Virgin of Guadalupe; but nowadays, instead of sending jewels and other articles of value as they did when the Church was able to protect its property, they hang up gaudily painted inscriptions reciting specifically the blessings they have received. On the crest of the hill is a massive shaft of stone, representing the main-mast of a ship with the yards out and sails spread. This was erected many years ago by a sea-captain who was caught in a storm at sea, and who made a vow to the Virgin that if she would bring him safe to land he would carry his main-mast and sails to Guadalupe, and raise them there as an evidence of his gratitude for her mercy. He fulfilled his vow, and within the double tiers of stone are the masts and canvas.

In the cathedral is the original blanket, or serape, which

I witnessed the inauguration of President Diaz on the 1st of December, 1884. The ceremonies, which were simple enough to satisfy the most critical of Democrats, took place in the handsome theatre erected in 1854, and named in honor of the Emperor Yturbide. It is now called the Chamber of Deputies, and is occupied by the lower branch of the National Legislature, a body of some two hundred and twenty-seven men. The Senate, composed of fifty-six members, meets in a long, narrow room in the old National Palace which was formerly used as a chapel by the Viceroys. The viceregal throne, a massive chair of carved and gilded rosewood, still stands upon a platform opposite the entrance, under a canopy of crimson velvet, but upon its crest is carved the American eagle, with a snake in its mouth, the emblem of Republican Mexico. Maximilian hung a golden crown over the eagle; Juarez tore it down and placed the broken sword of the Emperor in the talons of the bird. The Aztecs say that the founders of their empire, whose origin is lost in the mists of fable, were told to march on until they found an eagle sitting upon a cactus with a snake in its mouth, and there they should rest and build a great city. The bird and the bush were discovered in the valley that is shadowed by the twin volcanoes, and there the imperishable walls were laid which are now bidding farewell to their seventh century.

The old Theatre Yturbide has not been remodelled since it became the shelter of legislative power, and all the natural light it gets is filtered through the opaque panels of the dome, so that during the day sessions the Deputies are always in a state of partial eclipse. It is about as badly off for light as our own Congress. The members occupy comfortable arm-chairs in the parquet, arranged in semicircular rows. The presiding officer and the secretaries sit upon the stage, and at either side is a sort of pulpit from which formal addresses are made, although conversational debates are conducted from the floor. The orchestra circle and galleries are divided into boxes, and are reserved for spectators, but are seldom occupied, as the proceedings of the Congress are not regarded with much public interest.

In appearance the members will compare favorably with those of our Congress, and they are far in advance of the average State Legislature in ability and learning. The first features that strike a visitor familiar with legislative bodies in the United States is the decorum with which proceedings are conducted, and the scrupulous care with which every one is clothed. On certain formal occasions it is usual for all of the members to appear in evening dress, which gives the body the appearance of a social gathering rather than a legislative assembly. Nine-tenths of the members are white, and the other tenth show little trace of Aztec blood. There is never anything like confusion, and the laws of propriety are never transgressed. One hears no bad syntax or incorrect pronunciation in the speeches; no coarse language is used, and no wrangles ever occur like those which so often disgrace our own Congress. The statesmen never tilt their chairs back, nor lounge about the chamber; their feet are never raised upon the railings or desks; there is no letter-writing going on; the floor is never littered with scraps of paper; no spittoons are to be seen, and no conversation is permitted. Extreme dignity and decorum mark the proceedings, which are always short and silent, and the solemnity which prevails gives a funereal aspect to the scene.

The last days of the term of Gonzales were stormy. His attempt to secure certain unpopular financial legislation created great excitement, and the students of the universities, who numbered six or seven thousand, made a protest which would have ended in violence and assassination but for the overpowering military guard that surrounded the palace. The students would have resisted any attempt of Gonzales to prevent the inauguration of his successor, and kept up a demonstration against the existing Government until that event occurred.

But the excitement was not abated. The oath had been taken, but the outgoing administration by its absence from the ceremonies had intensified the anxiety lest the admission of Diaz to the Palace might be denied. Accompanied by a committee of Senators and an escort of cavalry. President Diaz drove half a mile to the Government building, and to his gratification the column of soldiers which was drawn up before the entrance opened to let him pass. The plaza which the building fronts was crowded with thousands of people, who announced the arrival of the new President by a deafening cheer, and the chimes of the old cathedral rang a melodious welcome.

Among the upper classes of Mexico will be found as high a degree of social and intellectual refinement as exists in Paris, as quick a reception and as cordial a response to all the sentiments that elevate society, and a knowledge of the arts and literature that few people of the busy cities of the United States have acquired.

The oddities of Mexican life and customs strike the tourist in a most forcible manner. The first thing he observes among the common people is that the men wear extremely large hats, and the women no hats at all. The ordinary sombrero costs fifteen dollars, while those bearing the handsome ornaments so universally popular run in price all the way from twenty-five to two hundred and fifty dollars. The Mexican invests all his surplus in his hat. Men whose wages are not more than twelve dollars a month often wear sombreros which represent a whole quarter’s income. A servant at the house of a friend was paid off one day for the three months his employer had been absent. He got forty-two dollars, of which he paid thirty-five dollars for a hat and gave seven dollars to his family.

Horseback riding is the national amusement, and the streets are full of horsemen, particularly in the cooler hours of the morning and evening. The proper thing to wear is a wide sombrero, very tight trousers of leather or cassimere, with rows of silver buttons up and down the outer seam, a handsomely embroidered velvet jacket, a scarlet sash, a sword, and two revolvers, not to mention spurs of marvellous size and design, and a saddle of surpassing magnificence. A Mexican caballero often spends one thousand dollars for an equestrian outfit. His saddle costs from fifty dollars to five hundred dollars, his sword fifty dollars, his silver-mounted bridle twenty-five dollars, his silver spurs as much more, the solid silver buttons on his trousers one hundred dollars, his hat fifty dollars, and the rest of his rig in proportion. The Mexican small boy, if he has wealthy parents, is mounted after a similar fashion, even to the revolver and sword. An equestrian costume for a boy of ten years can be purchased for about fifty dollars, not including saddle and bridle.

Pulque (pronounced poolkee) is the national drink, and is

A band of music played lively airs, and played them well, to entertain the people until the Governor came, whose presence being recognized, the people gave a cordial cheer by way of welcome. Then the herald in the Governor’s box blew a signal which sounded like the “water call” of the United

States Cavalry, the doors of the pit were opened, and in marched a dozen or so of matadors, in the same sort of jackets and breeches which they wear in the pictures of Spanish life so familiar to all. Each wore a plumed hat, a scarlet sash, a poniard, and the gold lace upon the black velvet showed their lithe and supple forms to advantage. They looked as Don Juan looks in the opera, while the leader, Bernardo Cavino, “del decano de los toreros,” I was a veritable Figaro, in appearance at least. Each carried a scarlet cloak upon his arm, and in the other hand a pikestaff. Behind them came a troop of eight horsemen upon gayly caparisoned steeds, with the usual amount of silver and leather trappings in which the Mexicans delight. The procession tailed up with a team of four mules hitched abreast, dragging a whiffletree and a long rope. These, we are told, were for the purpose of dragging out the dead. The cavalcade made a circuit of the amphitheatre, like the grand entrée at a circus, and upon reaching the Governor’s box stopped, saluted him, and received a short address in Spanish, which probably was simply one of approval and congratulation at their fine appearance. There was a rack in front of the Governor’s box upon which hung several rows of darts, gayly decorated with paper rosettes and paper fringes of gold and other brilliant tints. Upon these racks the matadors hung their plumed hats, and stood a while to give the ladies and gentlemen of the audience an opportunity to see and admire.

The bull having given up all idea of escape, plunges at everything he sees, and the second horse is ridden up before him. No attempt is made to get the animal out of the way. He was brought there to be slaughtered, and took his turn. Both horses having been disposed of, and the bull being completely exhausted, the bugle gives the signal, the matadors enter the arena, and tease him with their scarlet cloaks. At frequent intervals around the ring are placed heavy planks, behind which the matadors run for protection when they were pursued. The bull had no chance at all; he was there simply to be teased and killed by slow degrees. One matador more agile than the rest baits the animal with his lance, and when the bull turns upon him, vaults over the down-turned horns by resting his lance upon the ground. Then they bring out the ornamented darts, and thrust them into the bull’s hide. The animal jumps and plunges with pain, and tries to shake them off, but the barbs cling to the hide, and the more he struggles the farther they penetrate the flesh. His shoulders are covered with them, and the crimson blood trickles down his sides. He stands panting with distress, his tongue hanging out, and is thoroughly exhausted.

On Easter-Sunday the strangest of all Mexican ceremonies takes place in the burning of the traitor. During all Holy-week men are continually perambulating the streets, holding high above the heads of the multitude long poles encircled by hoops, upon which are suspended the most grotesque figures, in every conceivable color, shape, and degree of deformity, and all with horns and crooked backs and twisted limbs. These are filled with fire-crackers, the mustache forming the fuse, and millions of them are annually exploded. Many are life-size, some having faces to represent politicians who are unpopular at the time. Some are hung by the neck to wires stretched across the streets, or to the balconies of houses. Every horse-car and railroad engine and donkey-cart is decked with one, and even every mule-driver has one or more tied on his breast. At ten o’clock on Easter-Sunday, when the cathedral bells peal forth in commemoration of Christ’s resurrection, they are all touched off at once, and the air is filled with flying traitors everywhere over the length and breadth of Mexico.

An American who is married in Mexico finds that he must be three times married: twice in Spanish and once more in Spanish or English, as he prefers, besides having a public notice of his intention of marriage placed on a bulletin-board for twenty days before the ceremony. This is the law. The public notice can be avoided by the payment of a sum of money, but a residence of one month is necessary. The three ceremonies are the contract of marriage, the civil marriage—the only marriage recognized by law since 1858—and the usual, but not obligatory, Church service. The first two must take place before a judge, and in the presence of at least four witnesses and the American consul. The contract of marriage is a statement of names, ages, lineage, business, and residence of contracting parties. The civil marriage is the legal form of marriage. These ceremonies are necessarily in Spanish. Most weddings are confirmed by a church-service.

One of the most singular, and, to the foreigner, most interesting of the institutions of Mexico is the Monte de Piedad. The phrase means “The Mountain of Mercy.” It is the name given to what is in reality a great national pawnshop, which has branches in all the cities of the country, is exclusively under Government control, and is not managed, as in the United States, by guileless Hebrew children. The central office of the Monte de Piedad occupies the building known as the Palace of Cortez, which stands on the site of the ancient Palace of Montezuma, on the Plaza Mayor. It was founded in 1775 by Conde de Regla, the owner of very rich

The Church of England has been established in Mexico for twelve or fifteen years, having been induced to hold services there by the large number of English residents in the city; but no missionary work has been done by that denomination. The Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions several years ago commenced to labor in the Republic under the patronage of Diaz, who was then President, and who gave them substantial

encouragement. Among other things, he presented the American Board with an old Catholic church, where the school is now held daily, and a printing-office, for the purpose of the publication of a weekly newspaper and religious literature, is carried on. There are now at work in Mexico six Protestant clergymen and two lady missionaries from the United States, twenty-four regularly ordained Mexican ministers, six native licentiates, and three native helpers. Seventy-five congregations have been organized, and meet for worship every Sunday, and the number of native members is about three thousand. There is also a Theological Seminary, with two professors from the United States and one native instructor, having a total attendance of twenty-seven young men preparing for the ministry. Fourteen of these are studying theology, and thirteen are in the preparatory department. There is also a school for girls, with two American and one native lady teacher, which has a large attendance. A missionary paper called El Faro (The Light-house) is conducted at the Theological Seminary. The work is rapidly increasing, seven churches having been organized in 1885 and as many more in 1886.

In July, 1885, the Romanists of a small town in the interior entered a Protestant church, carried off all of the valuables, smashed the organ into fragments, emptied kerosene oil upon the benches, and set the place on fire. The furniture of the interior was destroyed, but the walls of the building, being of adobe, and the roof of tiles, the house was not destroyed. For some weeks afterwards several shots were fired at people who were on their way to evening service, and a missionary was attacked in the dark by armed assassins who would have been murdered but for the courageous use of his revolver. Subsequently all the other churches in the neighborhood were similarly treated, and when appeals were made to the local authorities for protection, and for the punishment of those who had committed the outrages, it was decided that it was the work of highwaymen, and a reward was offered for the arrest of the perpetrators. This opinion was thought to be a subterfuge, and it is believed that the authorities were in sympathy with the acts.

Guatemala City is not favorably situated for commerce, as it is a considerable distance from both seas, and is shut out from the most productive portions of the country by walls of mountains. The city is laid out in quadrilateral form, and formerly was surrounded by a great wall through which it was entered by gates opening in various directions. It covers a vast area of territory for a place of its population, as the houses, like those of other Central American cities, are very

The first capital was founded by Alvarado, the Conqueror. The exploits of Cortez in Mexico had become known among

The tree under which tradition says Alvarado and his soldiers first camped, and where Padre Godinez sanctified the city by religious services, is still standing. When I visited it, the most noticeable things about the place were a wagon made by the Studebaker Brothers, of South Bend, Indiana, and several empty beer bottles, bearing the brand of a Chicago brewer.

The fountain of Almolonga, which first induced Alvarado to select this spot as the site of his capital, is a large natural basin of clear and beautiful water shaded by trees. It has been walled up and divided off into apartments for bathing purposes and laundry work; and here all the women of the town come to wash their clothing. The old church was dug out of the sand, and is still standing. In one corner is a chamber filled with the skulls and bones that were excavated from the ruins. The old priest who was responsible for the spiritual welfare of the people showed us over the ruins, and told us stories of Alvarado and his piety. He said that the pictures, hangings, and altar ornaments in the church were the same that were placed there in Alvarado’s time, and unlocking a great iron chest he showed us communion vessels, incense urns, crosses, and banners of solid gold and silver. Among other things was a magnificent crown of gold, which was presented to the church by one of the Philips of Spain. It was originally studded with diamonds, emeralds, and other jewels, but they have been removed, and the settings are now empty. Yankee-like, we tried to buy some of these treasures, for they were the richest I had seen at any place, but the old priest refused all pecuniary temptations, and crossed himself reverently as he put the sacred vessels away. The only people who patronize this church are the Indians, who, to the number of two or three thousand, live in the neighborhood, and the ancient vessels are never used in these days, but are kept as curiosities.

The second city of Guatemala was built about three miles

In the centre of the town is a great plaza, which, as usual in all of the Central American capitals, is surrounded by public buildings and the cathedral. In the centre stands a noble fountain, which is surrounded every morning by market-women selling the fruit and vegetables of the country. The old palace has been partially restored, and displays upon its front the armorial bearing granted by the Emperor Charles the Fifth to the loyal and noble capital in which the Viceroy of Central America lived. Upon the crest of the building is a statue of the Apostle St. James on horseback, clad in armor, and brandishing a sword. The majestic cathedral, 300 feet long, 120 feet broad, 110 feet high, and lighted by fifty windows, has been restored, and within it services are held every morning, the faithful being called to mass by a peon pounding upon a large and resonant gong.

Without warning, on a Sunday night in 1773, the disaster came, and the proudest city in the New World was forever humbled. The roof of the cathedral fell; all the other churches were shaken to pieces; the great monasteries, which had been standing for centuries, and were thought to be useful for many centuries more, crumbled in an instant. The dead were never counted, and the wounded died from lack of relief. Those who escaped fled to the mountains, and the earthquake continued so violent that few returned to the ruins for many days. The volcano, whose single shudder shook down the accumulated grandeur of two hundred and fifty years, has since been almost idle, but is smoking constantly, and emitting sulphurous vapors which tell of the furnace beneath. As if satisfied with its moment’s work, it stands at rest, tempting man to try again to build another magnificent city, as firm as he can make it, for another test of strength. The people, like the dwellers over the buried Herculaneum, seem to have no fear of ruin or disaster, because, as very respectable citizens will tell you, the volcano which did the damage has since been blessed by a priest.

In one of the old monasteries, established by the Franciscan Friars, is a tree from which four different kinds of fruit may be plucked at one time—the orange, lemon, lime, and a sweet fruit called by the Spanish the limone. It was a horticultural experiment of the Friars many hundred years ago, and still stands as a monument of their experimental industry. It was they who first introduced the cultivation of coffee from Arabia into these countries, and who discovered the use of that curious insect the cochineal. The latter used to be an extensive article of commerce, but the cheapness of the aniline dyes has driven it out of the market. Now it is cultivated only for local consumption, and is extensively used by the natives, whose cotton and woollen fabrics are gayly dyed in colors that will endure any amount of water or sunshine. Thirty years ago two million tons were exported annually, but now very little goes out of the country.

The prevailing opinion of President Barrios is that he was a brutal ruffian. He drove out of the country many political opponents who occupied themselves by telling stories of his cruelty, some of which were doubtless true. The methods which he habitually used to keep the people in order would not be tolerated in the more civilized lands. But in estimating his true character, the good he accomplished should be considered as well as the evil. Until the history of Central America shall be written years hence, when the mind can reflect calmly and impartially upon the scenes of this decade, when public benefits can be accurately measured with individual errors, and the strides of progress in material development can be justly estimated, the true character of General Barrios will not be understood or appreciated even by his own countrymen. Like all vigorous and progressive men, like all men of strong character and forcible measures, he had bitter, vindictive enemies, who would have assassinated him had they been able to do so, and repeatedly tried it. There was nothing too harsh for them to say of him, living or dead, no cruelties too barbarous for them to accuse him of, no revenge too severe for them to visit upon him or his memory. But, on the other hand, people who did not cherish a spirit of revenge, who had no political ambition, and no schemes to be disconcerted, who are interested in the development of Central America, and are enjoying the benefits of the progress Guatemala has made, regard Barrios as the best friend and ablest leader, the wisest ruler his country ever had, and would have been glad if his life could have been prolonged and his power extended over the entire continent. They are willing to concede to him not only honorable motives, but the worthy ambition of trying to lift his country to the level with the most advanced nations of the earth. Ten more years of the same progress that Guatemala made under Barrios would place her upon a par with any of the States of Europe, or those of the United States. While he did not furnish a government of the people, by the people, it was a government for the people, provided and administered by a man of remarkable ability, independence, ambition, and extraordinary pride. While his iron hand crushed all opposition, and held a power that yielded to nothing, he was, nevertheless, generous to the poor, lenient to those who would submit to him, and ready to do anything to improve the condition of the people or promote their welfare.

His ambition to reunite the five Central American republics in a confederacy was not successful; but it was inspired by a desire to do for the neighboring States what he had done for Guatemala. His ambition was for the advancement and development of Central America; and while the means he used cannot be entirely approved, his purpose should be applauded. His crusade was quite as important in the civilization of this continent as the bloody work England attempted to accomplish in Egypt and the Soudan. He was better than his race, was far in advance of his generation, and while he did not succeed in lifting his people entirely out of the ignorance and degradation in which they were kept by the priests, what he did do cannot but result in the permanent good, not only of Guatemala, but of the nations which surround that republic.

When Carera died there was no man to take his place, and the Church party began to decay. The Liberals gathered force and began a revolution. In their ranks was an obscure young man from the borders of Mexico, from a valley which produced Juarez, the liberator of Mexico, Diaz, the president of that republic, and other famous men. He began to show military skill and force of character, and when the Church party was overthrown and the Liberal leader was proclaimed President, Rufino Barrios became the general of the army. He soon resigned, however, and returned to his coffee plantation on the borders of Mexico. But the revival of the Church party shortly after caused him to return to military life, and when the Liberal president died, he was, in 1873, chosen his successor.

Under a compulsory education law free public-schools have

Having overthrown the religion in which the people had been reared, Barrios recognized the necessity of providing some better substitute. He therefore, through the British minister, invited the Established Church of England to send missionaries to Guatemala; but owing to the disturbed condition of the country it was not considered advisable to commence work at that time, and the opportunity was neglected. In 1883 President Barrios visited New York, where he had conferences with the officers of the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions, which resulted in diverting the Rev. John C. Hill, of Chicago, who was en route to China, into this field of labor. Mr. Hill returned with the President to Guatemala, receiving a cordial welcome, and the President not only paid the travelling expenses of himself and family from his own pocket, but the freight charges upon his furniture, and purchased the equipment necessary for the establishment of a mission and school.

Mrs. Barrios was the loveliest woman in Guatemala; beautiful in character as well as person, socially brilliant and graceful, charitable beyond all precedent in a country where the poor are usually permitted to take care of themselves, generous and hospitable, a good mother to a fine family of children, and a devoted wife, loyal to all the President’s ambitions, and an enthusiastic supporter of all his schemes. Like a wise man who knows the perils which constantly surround him, and the uncertainty of the head which wears a crown in these countries, he had made ample provision for his family by purchasing for Mrs. Barrios a handsome residence in Fifth Avenue near Sixty-fifth Street, New York, and investing about a million dollars in her name in other New York real estate. His life was also insured for two hundred and fifty thousand dollars in New York companies, which, it must be said, carried a hazardous risk, as there were hundreds of men who lived only to see Barrios buried. Very few of them were in Guatemala, however, during his lifetime. They did not find the atmosphere agreeable there. They were exiles in Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Mexico, California, or elsewhere, waiting for a chance to give him a dose of dynamite or prick him with a dagger.

The prettiest and most picturesque of the native costumes to be found in Spanish America is worn by the women of Guatemala, who are of a dark complexion, nearly that of the mulatto type, but are famous for their beauty of form. A Guatemala girl in her native costume makes as pretty a picture as one can find anywhere. Her face is bright and pretty, her figure as perfect as nature unaided by art can be, and her movements show a supple grace and elasticity that cannot be imitated by those of her sex who are encumbered by modern articles of feminine apparel. Her head is usually bare, in-doors and out, and her thick black tresses hang in braids often reaching to her heels.

The natives are fond of bright colors, and have a remarkable deftness in their fingers, which hold the embroidery-needle as well as the hoe and machete. The guipils are embroidered in gay tints and artistic patterns, and a group of peons

When Barrios issued his decree that the peasants should wear clothing the country narrowly escaped a revolution; but policemen were stationed on all the roads leading into the city, and confiscated all the cargoes borne by those who did

In Guatemala, on the other hand, as in Peru, the pictures of the belles of the city, whether married or maidens, can be purchased by any one who wants them at the photographers’, and often at the shops, and the rank and popularity of the subject is usually estimated by the number of her portraits so disposed of. Codfish is a luxury. It is served at fashionable dinners in the form of a stew or patties, or a salad, and is considered a rare and dainty dish. They call it bacalao (pronounced “backalowoh”), and the shop-windows contain handsomely illuminated signs announcing that it is for sale within. It costs about forty cents a pound, and is therefore used exclusively by the aristocracy.

General Barrios was always dramatic. He was dramatic in the simplicity and frugality of his private life, as he was in the displays he was constantly making for the diversion of the people. In striking contrast with the customs of the country where the garments and the manners of men are the objects of the most fastidious attention, he was careless in his clothing, brusque in his manner, and frank in his declarations.

It is said that the Spanish language was framed to conceal thoughts, but Barrios used none of its honeyed phrases, and had the candor of an American frontiersman. He was incapable of duplicity, but naturally secretive. He had no confidants, made his own plans without consulting any one, and when he was ready to announce them he used language that could not be misunderstood. In disposition he was sympathetic and affectionate, and when he liked a man he showered favors upon him; when he distrusted, he was cold and repelling; and when he hated, his vengeance was swift and sure. To be detected in an intrigue against his life, or the stability of the Government, which was the same thing, was death or exile, and his natural powers of perception seemed almost miraculous. The last time his assassination was attempted he pardoned the men whose hands threw the bomb at him,

but those who hired them saved their lives by flight from the country. If caught, they would have been shot without trial. He was the most industrious man in Central America; slept little, ate little, and never indulged in the siesta that is as much a part of the daily life of the people as breakfast and dinner. He did everything with a nervous impetuosity, thought rapidly, and acted instantly. The ambition of his life was to reunite the republics of Central America in a confederacy such as existed a few years after independence. The benefits of such a union are apparent to all who understand the political, geographical, and commercial conditions of the continent, and are acknowledged by the thinking men of the five States, but the consummation of the plan is prevented by the selfish ambition of local leaders. Each is willing to join the union if he can be Dictator, but none will permit a union with any other man as chief.

The policy of Nicaragua was governed by the influence of a firm of British merchants in Leon with which President Cardenas has a pecuniary interest, and by whom his official acts are controlled. The policy of Costa Rica was governed by a conservative sentiment that has always prevailed in that country, while the influence of Mexico was felt throughout the entire group of nations. As soon as the proclamation of Barrios was announced at the capital of the latter republic, President Diaz ordered an army into the field, and telegraphed offers of assistance to Nicaragua, San Salvador, and Costa Rica, with threats of violence to Honduras if she yielded submission to Barrios. Mexico was always jealous of Guatemala. The boundary-line between the two nations is unsettled, and a rich tract of country is in dispute. Feeling a natural distrust of the power below her, strengthened by consolidation with the other States, Mexico was prepared to resist the plans of Barrios to the last degree, and sent him a declaration of war.

The effect in Guatemala was similar, although not so pronounced. There was a reversion of feeling against the Government. The moneyed men, who in their original enthusiasm tendered their funds to the President, withdrew their promises; the common people were nervous, and lost their confidence in their hero; while the Diplomatic Corps, representing every nation of importance on the globe, were in a state of panic because they received no instructions from home. The German and French ministers, like the minister from the United States, were favorable to the plans of Barrios; the Spanish minister was outspoken in opposition; the English and Italian ministers non-committal; but none of them knew what to say or how to act in the absence of instructions. They telegraphed to their home governments repeatedly, but could obtain no replies, and suspected that the troubles might be in San Salvador. Mr. Hall, the American minister, transmitted a full description of the situation every evening, and begged for instructions, but did not receive a word.

IN 1540 Cortez, the Conqueror of Mexico, directed Alonzo Caceres, one of his lieutenants, to proceed with an army of one thousand men to the Province of Honduras, which had been subdued by Alvarado a few years before, and select a suitable site for a city midway between the two oceans. Caceres was a pioneer of most excellent discretion, and so good a judge of distance was he that if a straight line were drawn from the Atlantic to the Pacific, the centre would be just three miles north of the plaza of Comayagua. A modern engineer, with all the scientific appliances at his disposal, could not have obeyed instructions more accurately; and as for location, there are few finer sites in the world than the elevated plain upon which the little capital of Honduras stands. A semicircle of mountains enclose it, with a wall of peaks six and seven thousand feet high upon one side, while upon the other a great plain stretches away nearly forty miles, gradually sloping to the eastward. The altitude of the city is about twenty-three hundred feet above the sea, and the climate is a perpetual June, the thermometer seldom varying more than twenty degrees during the entire year, and averaging about 75° Fahrenheit. The soil is deep, rich, and fertile, and the productions of the plain are tropical; but beyond the city, in the foothills of the mountains and upon their slopes, corn, wheat, and other staples of the temperate zones can be raised in enormous quantities with a minimum of labor. The pineapple and the palm tree are growing within two hours’ ride of waving wheat-fields, while orange and apple orchards stand within sight of each other.

Comayagua is said to have at one time contained nearly thirty thousand inhabitants, but at present it has no more than one-fifth of that number; for, like all of the Central American cities, its population has been reduced since the independence of the country, and, like the most of them, it is in a state of decay. Everything is dilapidated, and nothing is ever repaired. No sign of prosperity appears anywhere. Commercial stagnation has been its normal condition for sixty years, and the indolence and indifference of the people has not been disturbed for that period, except by political insurrections. No one seems to have anything to do. The aristocrats swing lazily in their hammocks, or discuss politics over the counters of the tiendas, or at the club, while the poor beg in the streets, and manage to sustain life upon the fruits which Nature has so profligately showered upon them. Nowhere upon the earth’s surface exist greater inducements to labor, nowhere can so much be produced with so little effort; and the vast resources of the country present the most tempting opportunity for capital and enterprise, for nearly every acre of the land is susceptible to some sort of profitable development.

The President is General Bogran, a man who came into power by a peaceful revolution in 1885, to succeed Marco A. Soto, who fled that year to San Francisco, and from there sent his resignation to Congress. Bogran is a man of brains and progressive ideas, possessing more of the modern spirit

and broader views than most of his contemporaries, and if he is permitted to carry out his plans Honduras will make rapid speed in the development of her great natural resources. He is offering tempting inducements to foreign capital and immigration, has given liberal concessions to Americans who desire to enter the country, and is wisely endeavoring to induce some one to construct the Interoceanic Railway, which was surveyed fifty years ago, and twenty-seven miles of which has already been built and at intervals operated. But the discontented element in the country, in league with his predecessor, who now lives in New York, are surrounding him with obstacles and harassing him with all sorts of embarrassments, so that his success is made doubtful. Bogran spends very little of his time at Comayagua, and the seat of government has been removed to Tegucigalpa, the largest town in the country, as well as its commercial metropolis. Here the Congress sits also, and the place is to all intents and purposes the capital.

The cathedral of Comayagua is by far the finest building in the country, being an excellent specimen of the semimoresque style, which was so popular among the Spanish provinces. Its walls and roof are of the most solid masonry, but are considerably marred by the revolutions through which the country has passed, for in nearly all of them the cathedral has been used as a fortress and subjected to a shower of lead. Near the cathedral stands a monument originally intended to honor one of the Spanish kings, but after the independence of the country was established the royal symbols were erased by the order of one of the Presidents, the inscription was chiselled off, and the obelisk now stands to commemorate independence. This monument is the place of public execution, and criminals sentenced to death are made to sit blindfolded at its base, where they are shot by the soldiers.

In November, 1886, General Delgrado, the leader of a revolution, with four of his comrades, was executed here. It was the desire of President Bogran to spare Delgrado’s life, and any pretext would have been adopted to save him if the honor of the country could have been vindicated, but he was convicted of treason, and sentenced by the courts to die. The President offered to pardon him if he would take the oath of allegiance and swear never to engage in revolutionary proceedings again; but the old soldier would not even accept life on these terms, and much to the regret of the President,

against whom he had conspired, and the better portion of the people, the sentence had to be executed. On the morning of the day fixed by the courts, the five men were led from the prison to the Church of La Merced, where the last rites were administered to them, and were then conducted to the Peace Monument, where a file of soldiers was drawn up with loaded rifles. The last word of Delgrado was a request that he might give the command to fire, and he did so as coolly as if he had been on dress parade.

Both cotton and silk grow upon trees, the vegetable silk being of very fine and soft fibre, and frequently used by the natives in the manufacture of robosas, serapas, and other articles of wear, while the product of the cotton-tree is utilized in a similar manner.

The interior of the country is beyond the reach of markets, because of the absence of transportation facilities. In this respect the people are no further advanced than they were two hundred years ago. The only wagon-roads in the country are one built by a party of Americans near San Pedro, in the west, and a few miles of a national highway that a century ago was begun for the purpose of connecting Amapala, the Pacific port, with Tegucigalpa.

Honduras has the finest fluvial system in Central America. There are few countries with such available water facilities, both for transportation and manufacturing powers, and it has the finest harbors on both coasts—all wasted because of the indolence of the people. The Government has given several liberal concessions in timber and agricultural lands to secure the opening of its rivers to navigation, and for the construction of railways from the coast to the interior. Some of these grants are in the hands of responsible and capable companies, and if the peace of the country is assured, and immigrants can be induced to settle there, a rapid development of its resources is promised.

Within the last eight years every town of importance has been connected with the capital by lines of telegraph. Before its construction information of the utmost importance could not reach the capital from the remote points in less than ten or twelve days. The Government saw the necessity of some better and quicker method for transmitting information, and constructed these lines. They are owned and operated entirely by the Government, and from them a considerable revenue is realized. For the purpose of sending a message, you must first purchase of the proper Government officer a stamped telegraphic blank, which varies in price from one real (twelve and a half cents) to one or two dollars, in proportion to the number of words which it is to contain. The distance the message is to travel makes no difference in the price, provided its destination is within any of the republics of Central America. When the message is written on the blank it is taken to the telegraph-office, and if the charge for the number of words contained in the message corresponds with the stamped blank it is forwarded.

Every department of Honduras possesses more or less mineral wealth, and within the limits of the country almost every metal known to man is found. The discoveries of gold and silver were made by the aborigines, who possessed much treasure when the Spaniards conquered them, and ever since the Conquest the mines have been worked with great profit; but their development was greater under the viceroys than since the independence of the republic, as this branch of industry has suffered more from civil wars than any other. As a consequence, mine after mine has been abandoned, and the districts where the best mineral deposits exist are marked with depopulated towns and villages.