автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу One Irish Summer

Transcriber’s Note

Please consult the detailed notes at the end of this text for the resolution of any transcription issues that were encountered.

ONE IRISH SUMMER

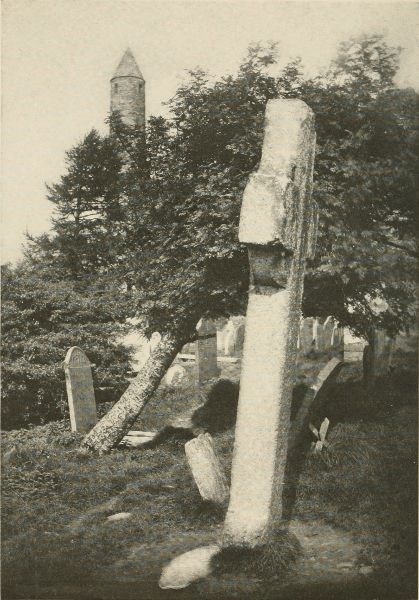

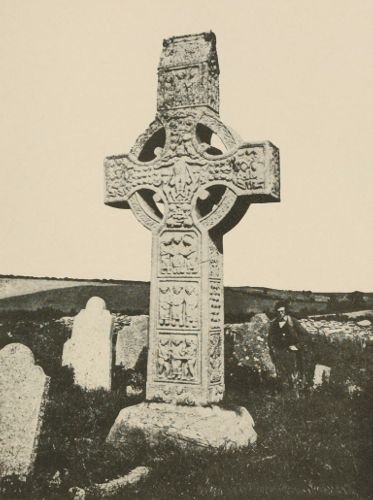

An Ancient Celtic Cross at Glendalough

ONE IRISH SUMMER

BY

WILLIAM ELEROY CURTIS

AUTHOR OF

“The Yankees of the East,” “Between the Andes and the Ocean” “Modern India,” “The Turk and his Lost Provinces” “To-day in Syria and Palestine,” etc.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

DUFFIELD & COMPANY

1909

Copyright, 1908, By William E. Curtis

Copyright, 1909, By Duffield & Company

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U.S.A.

CONTENTS

PageI.

A Summer in Ireland

1II.

The Cathedrals and Dean Swift

15III.

How Ireland is Governed

34IV.

Dublin Castle

53V.

The Redemption of Ireland

60VI.

Sacred Spots in Dublin

77VII.

The Old and New Universities

97VIII.

Round about Dublin

115IX.

The Landlords and the Landless

130X.

Maynooth College and Carton House

143XI.

Drogheda, and the Valley of the Boyne

159XII.

Tara, the Ancient Capital of Ireland

174XIII.

Saint Patrick and his Successor

188XIV.

The Sinn Fein Movement

202XV.

The North of Ireland

209XVI.

The Thriving City of Belfast

222XVII.

The Quaint Old Town of Derry

237XVIII.

Irish Emigration and Commerce

247XIX.

Irish Characteristics and Customs

260XX.

Wicklow and Wexford

268XXI.

The Land of Ruined Castles

283XXII.

The Irish Horse and his Owner

300XXIII.

Cork and Blarney Castle

312XXIV.

Reminiscences of Sir Walter Raleigh

330XXV.

Glengariff, the Loveliest Spot in Ireland

343XXVI.

The Lakes of Killarney

366XXVII.

Intemperance, Insanity, and Crime

391XXVIII.

The Education of Irish Farmers

404XXIX.

Limerick, Askeaton, and Adare

417XXX.

County Galway and Recent Land Troubles

432XXXI.

Connemara and the Northwest Coast

443XXXII.

Work of the Congested Districts Board

459INDEX

475LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

An Ancient Celtic Cross at Glendalough

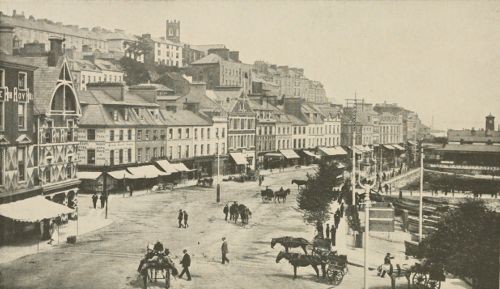

Frontispiece Facing PageQueenstown

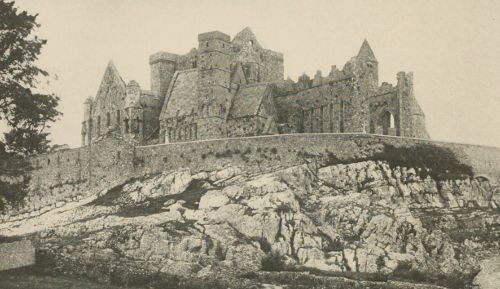

4The Rock of Cashel, County Tipperary

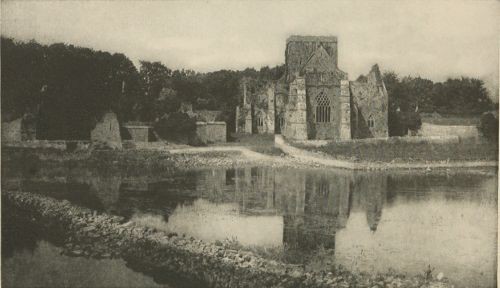

8Holycross Abbey, County Tipperary

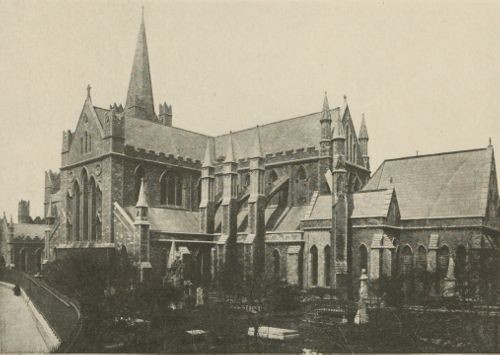

10St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin

16The Tomb of Strongbow, Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin

32The Earl of Aberdeen, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1906–9

34The Countess of Aberdeen

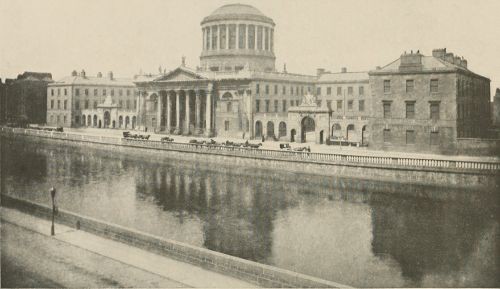

36The Four Courts, Dublin

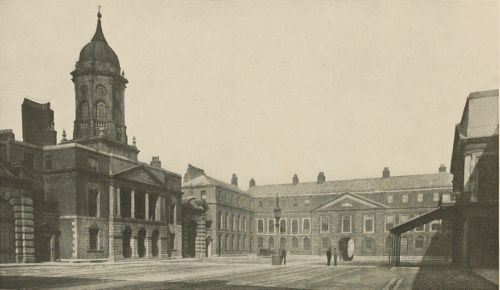

48The Castle, Dublin; Official Residence of the Lord Lieutenant and Headquarters of the Government

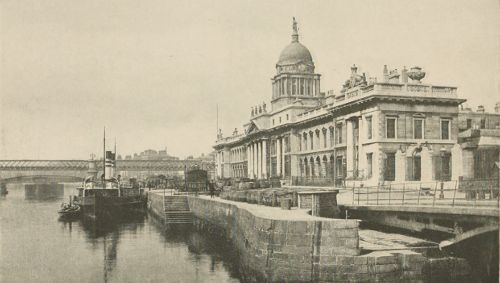

54The Customs House, Dublin

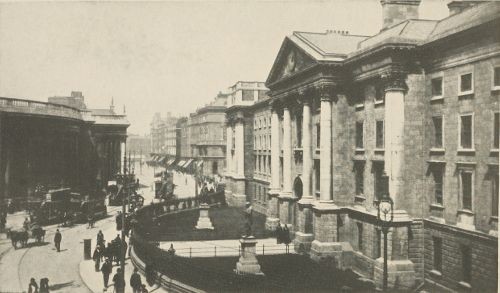

78The Bank of Ireland, Old Parliament House, Dublin

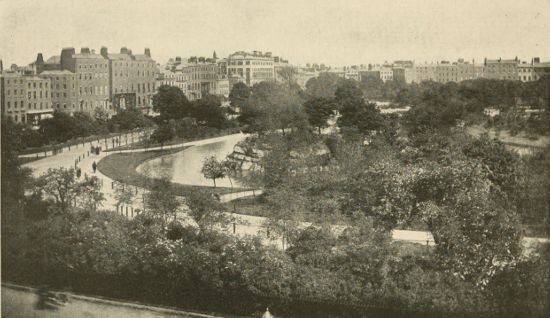

80St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin

90Quadrangle, Trinity College, Dublin

98Main Entrance, Trinity College, Dublin

102Sackville Street, Dublin, showing Nelson’s Pillar

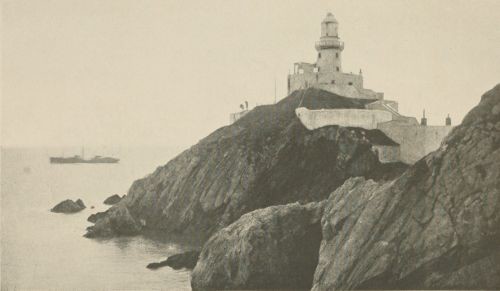

116Lighthouse at Howth, Mouth of Dublin Bay

122Portumna Castle, County Galway; the Seat of the Earl of Clanricarde

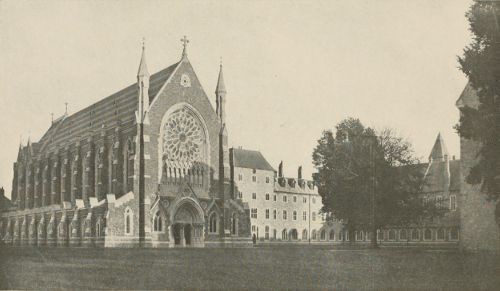

138Maynooth College, County Kildare

144Carton House, Maynooth, County Kildare; the Residence of the Duke of Leinster

152A Celtic Cross at Monasterboice, County Louth

166Ruins of Mellifont Abbey, near Drogheda, County Louth

168Carrickfergus Castle

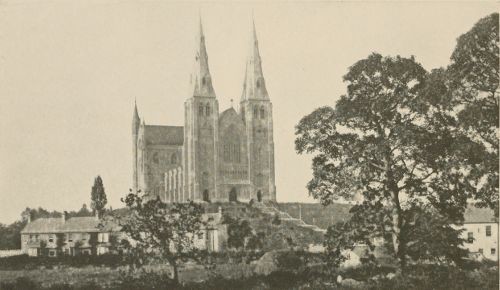

180St. Patrick’s Cathedral at Armagh, the Seat of Cardinal Logue, the Roman Catholic Primate of Ireland

194Cathedral, Downpatrick, where St. Patrick lived, and in the Churchyard of which he was buried

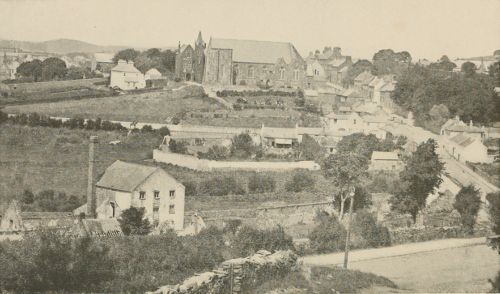

196The Village of Downpatrick

200Rosstrevor House, near Belfast, the Residence of Sir John Ross, of Bladensburg

210Shane’s Castle, near Belfast, the Ancient Stronghold of the O’Neills, Kings of Ulster

216Queen’s College, Belfast

226Albert Memorial, Belfast

228The Giant’s Causeway, Portrush, near Belfast

244Bishop’s Gate, Derry

297Irish Market Women

260An Ancient Bridge in County Wicklow

268The Vale of Avoca, County Wicklow

272The River Front at Waterford

290Lismore Castle, Waterford County; Irish Seat of the Duke of Devonshire

292An Irish Jaunting Car

308Going to Market

310Queen’s College, Cork

314Blarney Castle, County Cork

322Kilkenny Castle; Residence of the Duke of Ormonde

326The Ancient City of Youghal, County Cork; the Home of Sir Walter Raleigh

330Myrtle Lodge; the Home of Sir Walter Raleigh

338Lake Gougane-Barra, County Cork

348Chapel erected by Mr. John R. Walsh of Chicago on the Island of Gougane-Barra

350The Pass of Keimaneigh through the Mountains between Cork and Glengariff

352Glengariff Bridge

356Kenmare House, Killarney

372Upper Lake, Killarney

376Ross Castle, Killarney

380Muckross Abbey, Killarney

384A Window of Muckross Abbey, Killarney

388Treaty Stone, Limerick

422Adare Abbey, in the Private Grounds of the Earl of Dunraven, near Limerick

428Fish Market, Galway

438Salmon Weir, Galway

442A Scene in Connemara

444Clifden Castle, County Galway

448A Scene in the West of Ireland; Lenane Harbor

450Barnes Gap, County Donegal

460An Irish Cabin in County Donegal

464The Old: A Laborer’s Sod Cabin; The New: Example of the Cottages built in Connemara by the Congested Districts Board

470Interior and Exterior of One-Story Cottages erected by the Congested Districts Board

472ONE IRISH SUMMER

I

A SUMMER IN IRELAND

For those who have never spent a summer in Ireland there remains a delightful experience, for no country is more attractive, unless it be Japan, and no people are more genial or charming or courteous in their reception of a stranger, or more cordial in their hospitality. The American tourist usually lands at Queenstown, runs up to Cork, rides out to Blarney Castle in a jaunting car, and across to Killarney with a crowd of other tourists on the top of a big coach, then rushes up to Dublin, spends a lot of money at the poplin and lace stores, takes a train for Belfast, glances at the Giant’s Causeway, and then hurries across St. George’s Channel for London and the Continent. Hundreds of Americans do this each year, and write home rhapsodies about the beauty of Ireland. But they have not seen Ireland. No one can see Ireland in less than three months, for some of the counties are as different as Massachusetts and Alabama. Six weeks is scarcely long enough to visit the most interesting places.

The railway accommodations, the coaches, the steamers, and other facilities for travel are as perfect as those of Switzerland. The hotels are not so good, and there will be a few discomforts here and there to those who are accustomed to the luxuries of London and Paris, but they can be endured without ruffling the temper, simply by thinking of the manifold enjoyments that no other country can produce.

And Ireland is particularly interesting just now because of the mighty forces that are engaged in the redemption of the people from the poverty and the wretchedness in which a large proportion of them have been submerged for generations. No government ever did so much for the material welfare of its subjects as Great Britain is now doing for Ireland, and the improvement in the condition of affairs during the last few years has been extraordinary.

In order to observe and describe this economic evolution, the author spent the summer of 1908 visiting various parts of the island and has endeavored to narrate truthfully what he saw and heard. This volume contains the greater part of a series of letters written for The Chicago Record-Herald and also published in The Evening Star of Washington, The Times of St. Louis, and other American papers. By permission of Mr. Frank B. Noyes, editor and publisher of The Chicago Record-Herald, and to gratify many readers who have asked for them, they are herewith presented in permanent form.

About three hundred passengers landed with us at Queenstown. Most of them were young men and young women of Irish birth, returning after a few years’ experience in the United States. Several had come home to be married, but most of them were on a visit to their parents and other relatives. Among those who disembarked were several older men and women who were born in Ireland, but had been taken to America in infancy or in childhood and were now looking upon the fair face of Erin for the first time.

There is an astonishing difference in the appearance and behavior of the steerage passengers who are sailing east from those who are sailing west. A few years, or even a few months, in America causes an extraordinary change in the dress and the manners of a European peasant. You can see it in the passengers that land at Genoa and Naples, and those that land at Hamburg and Trieste. But it is even more noticeable in the Americanized Irish who land at Queenstown by the thousand every summer from New York. The Italian, the Hungarian, or the Pole who goes aboard a steamer to America with his humble belongings and his quaint looking garments is a very different person from the man who sails from New York back to the fatherland a few years later. And the Irish boys and girls who went ashore with us just as the sun was waking up Ireland were as hearty, well dressed, and prosperous looking as you would wish to see. And every young woman had a big “Saratoga” in place of the “cotton trunk with the pin lock” that she carried away with her when she left the old country for America the first time. I don’t know what was in those big trunks, although one can get a glimpse of their contents if he stands by while the customs officers are inspecting them, but you can see the names “Delia O’Connell, New York,” “Katherine Burke, Chicago,” and “Mary Murphy, Baltimore,” marked in big black letters at either end. And what is most noticeable, the trunks are all new. They have never crossed the ocean before, but will be going back again to America in a few months. Their owners will not be contented with the discomforts they will find at their old homes. Ireland is more prosperous today than for generations, but conditions among the poorer classes are very different from those that exist in the new world.

The purser told me that he changed nearly $4,000 of American into English money the day before we landed, for third-class passengers alone. One man had $400; that was the maximum, but the rest of those who disembarked at Queenstown had from $50 up to $250 and thereabouts in cash, with their return tickets.

Queenstown makes a brave appearance from the deck of a ship in the bay, even before sunrise. It lies along a steep slope, with green fields and forests on either side, and the most conspicuous building is a beautiful gothic cathedral, with an unfinished tower, that was commenced in 1868 and has cost nearly a million dollars already. The hill is so steep that a heavy retaining wall has been built as a buttress to make the cathedral foundations secure, and the worshipers must climb a winding road or a sharp stairway to reach it. A little farther along the hillside is an imposing marine hospital and group of barracks, from which we could hear the bugles sounding “reveille” as we landed. There are compensations to those who are marooned at Queenstown before daylight, and one of them is the picturesque surroundings of the ancient homes of the O’Mahony’s, who ruled this part of Ireland for many generations long ago.

The harbor is like an amphitheatre, entirely inclosed by hills, three hundred or four hundred feet high, that are covered with frowning battlements. Every hilltop is strongly fortified. The bay, which is four miles long and about two miles wide, contains several islands, upon which the government has built warehouses, repair shops, shipyards, and the other appurtenances of a naval station, guarded by Fort Carlisle, Fort Camden, and other modern fortresses. Upon Haulbowline Island is a depot for ammunition and other ordnance stores, and the pilot told me that on Rocky Island near by were two magazines—great chambers chiseled out of the living rock by Irish convicts who were formerly confined there—and that each of them contained twenty-five thousand barrels of powder belonging to the British navy.

Queenstown has many handsome estates overlooking the sea and the bay from the hills that inclose the harbor. There is an old ruined castle at Monkstown that was built in 1636 by Anastasia Gould, wife of John Archdecken, while her husband was at sea. She determined that she would surprise him when he returned home. So she hired a lot of men to build a castle with only the material they found on the estate, and made an agreement with them that they should buy the food and clothing necessary for their families from herself alone. It is the first record of a “company store” that I know of. When the castle was finished and the accounts were balanced it was found that the cost of the labor had been entirely paid for by the profits of this thrifty woman’s mercantile transactions, with the sum of four pence as a balance to her credit. Her husband returned in due time and was so delighted with his new home that he never went to sea again. His estimable wife died in 1689, and was buried in the churchyard of Team-*pulloen-Bryn, where this story is inscribed with her epitaph.

On Wood’s Hill, overlooking the bay, is a handsome estate that once belonged to Curran, the famous lawyer and orator, whose daughter was the sweetheart of Robert Emmet, the Irish martyr. Her melancholy romance is related in Washington Irving’s story called “The Broken Heart” and in one of Tom Moore’s ballads.

Queenstown

It is 165 miles from Queenstown to Dublin, and the railroad passes through several of the counties whose names are most familiar to Americans, for they have furnished the greater portion of our Irish immigrants—Cork, Limerick, Tipperary, Queens, and Kildare. Most of the passengers who landed with us took the same train, and they were so many that they crowded the little railway station to overflowing and created a scene of lively confusion. Some of them had been met by brothers, fathers, sweethearts, and friends, who were waiting two hours before daylight, and the hearty greetings and enthusiasm they showed were contagious. The sweethearts were easy to identify. The demonstrations of affection left no doubt, but all the world loves a lover, and we rejoiced with them. In the long line that stood before the ticket seller’s window at the railway station they chattered unconsciously like so many sparrows, their arms around each other, with an occasional embrace, a sly kiss and a slap to pay for it, tender caresses upon the shoulder or the head, and other expressions of a happiness that could not have been concealed. The home-bred young men gazed with wonder and admiration at the finery worn by their sweethearts from America, who, by the way, although they came third class, and were undoubtedly chambermaids or shop girls in our cities, were the best-looking and the best-dressed women we saw in Ireland. The pride of the parents at the appearance and the manners of their sons or daughters showed that they appreciated the accomplishments that American experience acquires.

One of the younger passengers, a boy of twenty years, perhaps, told me that he had come from Ohio to persuade his father to send his two younger brothers back with him. They live in Tipperary, where “there is no show for a young man now.” Another young man had a tiny American flag pinned to the lapel of his coat, and when I said, “You show your colors,” the lassie who clung to his arm turned at me with a determined expression on her face and remarked:

“I’ll be takin’ that off and pinnin’ a piece of green in its place vera soon.”

“No, you don’t, darlin’; none o’ that,” he replied. “I’m an American citizen, and I don’t care who knows it. If you don’t want to be one yourself, I know another girl who does.”

The country through which the railway to Dublin runs affords a beautiful example of Irish scenery. As far as Cork the track follows the bank of the River Lee, which is inclosed on either side by a high ridge crowned with stately mansions, glorious trees, and handsome gardens. Several of the places are historic, and the scenery has been frequently described in verse by the Irish poets.

Father Prout, a celebrated rhymemaker of Cork, has described one of the villages as follows:

“The town of Passage is both large and spacious,

And situated upon the say;

’Tis nate and dacent and quite adjacent

To Cork on a summer’s day.

There you may slip in and take a dippin’

Foreninst the shippin’ that at anchor ride,

Or in a wherry you can cross the ferry

To Carrigaloe on the other side.”

We could not see much from the car window, but we saw enough on the journey to understand why it is called “The Emerald Isle” and why the Irish people are so enthusiastic over its landscapes. The river is walled in nearly all the distance to Cork, and there are many factories, storehouses, and docks on both sides. Quite a fleet of steamers ply between Queenstown and Cork, and trains on the railroad are running every hour. Small seagoing vessels can go up as far as Cork, but the larger ones discharge and receive their cargoes at Queenstown. We couldn’t see much of the towns because the railway tracks are either elevated so that only the roofs and chimney pots are visible, or else they are buried between impenetrable walls or pass through tunnels on either side of the station. But when the train passed out into the open a succession of most attractive landscapes was spread before us as far as the horizon on either side, and the fields were alive with bushes of brilliant orange-colored gorse, or furze, as it is sometimes called. They lit up the atmosphere as the burning bush of Moses might have done. Very little of the ground is cultivated. Only here and there is a field of potatoes and cabbages, but the pastures are filled with fine looking cattle and sheep, for this is the grazing district of Ireland, from whence her famous dairy products and the best beef and mutton come.

Beyond Portarlington we got our first glimpses of the bogs, with which we are told one-sixth of the surface of Ireland is covered, an area of not less than 2,800,000 acres. Bogs were formerly supposed to be due to the depravity of the natives, who are too lazy to drain them and have allowed good land to run to waste and become covered with water and rotten vegetation, but this theory has been effectively disposed of by science. Everybody should know that the bogs of Ireland are not only due to the natural growth of a spongy moss called sphagnum, but furnish an inexhaustible fuel supply to the people and have a value much greater than that of the drier and higher land. The report of a “bogs commission” describes them as “the true gold mines of Ireland,” and estimates them as “infinitely more valuable than an inexhaustible supply of the precious metal.” The average Irish bog will produce 18,231 tons of peat per acre, which is equivalent to 1,823 tons of coal, thus making the total supply of peat equivalent to 5,104,000 tons of coal, capable of producing 300,000 horse power of energy daily for manufacturing purposes for a period of about four hundred and fifty years. With coal selling at $2 a ton in Ireland to-day, this makes the bogs of Ireland worth $10,000,000,000. The “bog trotter” is an individual to be cultivated, for when our coal deposits in the United States are exhausted we may have to send over and buy some of his peat for fuel. It is proposed to utilize these deposits and save transportation charges by erecting power-houses at the peat beds and furnish electricity over wires to the neighboring towns and cities for lighting, power, and other purposes, “for anybody having work to do from curling a lady’s hair to running tramways and driving machinery.” The writer refers to recent installations of electric works in Mysore, India, for working gold fields ninety miles distant, and quotes the late Lord Kelvin’s opinion that the city of New York will soon be getting its power from Niagara, four hundred miles away. We saw them digging peat in the fields and piling it up like damp bricks to dry in the sun. Freshly dug peat contains about seventy per cent of moisture, but when cured the ratio is reduced to fifteen or twenty per cent.

A peat bog is not always in a hollow, but often on a hillside, and sometimes at considerable height, which contradicts the theory that bogs are due to defective drainage. Science long ago determined that Irish peat was the accumulation of a peculiar kind of moss which grows like a coral bank in the damp soil, and continues to pile up in layers year after year, century after century, until it forms a solid mass, several feet thick, seventy per cent moisture and thirty per cent fibre, which burns slowly and furnishes a high degree of heat. We see bogs on all sides of us where the peat is three and four feet thick, and with a long straight spade that is as sharp as a knife, it is cut into blocks about eight or ten inches long and about four inches square. A sharp spade will slice it just as a knife would cut cheese or butter, and after the blocks have lain on the ground a while they are stacked up on end in little piles to dry. Then, when they have been exposed to the weather for three or four weeks, they are stacked in larger piles, from which they are carted away and sold or used as they are needed.

The Rock of Cashel, County Tipperary

Four tons of peat are equal in caloric energy to one ton of coal. I noticed in the papers that a bill is pending before the House of Commons to grant a charter to a company to erect a station in a bog near Robertson, Kings County, twenty-five miles from Dublin, for generating electricity from peat, the power to be transmitted to Dublin and the suburban towns for lighting, transportation, and manufacturing purposes. Several other projects of a similar sort have been suggested for utilizing the peat at the bog instead of carting it into town.

Beyond the peat beds rises a chain of low mountains with a curious profile that runs west of the town of Templemore. Like every other freak of nature in Ireland, they are the scenes of many interesting legends. The highest peak is called “The Devil’s Bit,” and the queer shape is accounted for by the fact that the Prince of Darkness in a fit of hunger and fatigue once took a bite out of the mountain, and, not finding it to his taste, spat it out again some miles to the eastward, where it is now famous as the Rock of Cashel.

Cashel, at present a miserable, deserted village, was once the rich and proud capital of Munster. Adjoining the ruins of the cathedral is the ancient and weather-worn “Cross of Cashel,” which was raised upon a rude pedestal, where the kings of Munster were formerly crowned. The ruins are more extensive than anywhere else in Ireland, for Cashel at one time was the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland and its greatest educational centre. Here the Pope’s legates resided and here Henry II., in 1172, received the homage of the Irish kings. But what gives the place its greatest sanctity is the fact that St. Patrick spent much time there and held there the first synod that ever assembled in Ireland, about the middle of the fifth century. That is supposed to have been the reason for the erection of so many sacred edifices and monasteries in early days. St. Declan lived there, too, and commemorated his conversion to Christianity by the erection of one of the churches. Donald O’Brien, King of Limerick, erected another, and his son Donough founded an abbey in 1182. Holy Cross, beautifully situated in a thick grove on the banks of the River Suir, was built in 1182 for the Cistercian order of monks. It derived its name because a piece of the true cross, set with precious stones and presented to a grandson of Brian Boru by Pope Pascal II., was kept there for centuries, and made the abbey the object of pilgrimages of the faithful from all parts of Ireland. This precious relic is now in the Ursuline convent at Cork.

Cashel was destroyed during the civil wars. The famous Gerald Fitzgerald, the great Earl of Kildare, had a grudge against Archbishop Cragh and burned the cathedral and the bishop’s palace. He excused the act before the king on the ground that he “believed the archbishop was in it.”

A little beyond Templemore, at Ballybrophy Junction, a branch of the main line of the railway leads to the town of Birr, which is famous as the seat of the late Earl of Rosse, whose father erected an observatory there many years ago, with one of the largest and finest telescopes in the world. It is twenty-seven feet long, with a lens three feet in diameter. Some of the most important discoveries of modern astronomy have been made there, and Birr has been the object of pilgrimages for scientific men for more than half a century. The old Birr castle has been much enlarged and modernized by the late earl, who died in September, 1908, and is surrounded by an estate of thirty-six thousand acres, upon which is one of the best built and well kept towns in Ireland. He was a scholar and scientist of reputation, president of the Royal Irish Academy and the Royal Dublin Society, and interested in important manufactories and enterprises. He was especially active in developing the steam turbine.

All of that section of Ireland covered by the journey between Dublin and Cork is associated with heroic struggles. It has been fought over time and again by the clans and the factions that have struggled to rule the state. Every town and every castle has its tragic and romantic history. Almost every valley is associated with a legend or an important event. The woods and the hills are still peopled with fairies, and local traditions among the humble folks are the themes of fascinating tales and songs. But the natives one sees at the railway stations do not look at all romantic. A sentimental person is compelled to endure many severe shocks when he comes in contact with the present generation of Irish peasants.

ONE IRISH SUMMER

II

THE CATHEDRALS AND DEAN SWIFT

III

HOW IRELAND IS GOVERNED

IV

DUBLIN CASTLE

V.

THE REDEMPTION OF IRELAND

VI

SACRED SPOTS IN DUBLIN

VII

THE OLD AND NEW UNIVERSITIES

VIII

ROUND ABOUT DUBLIN

IX

THE LANDLORDS AND THE LANDLESS

X

MAYNOOTH COLLEGE AND CARTON HOUSE

XI

DROGHEDA, AND THE VALLEY OF THE BOYNE

XII

TARA—THE ANCIENT CAPITAL OF IRELAND

XIII

SAINT PATRICK AND HIS SUCCESSOR

XIV

THE SINN FEIN MOVEMENT

XV

THE NORTH OF IRELAND

XVI

THE THRIVING CITY OF BELFAST

XVII

THE QUAINT OLD TOWN OF DERRY

XVIII

IRISH EMIGRATION AND COMMERCE

XIX

IRISH CHARACTERISTICS AND CUSTOMS

XX

WICKLOW AND WEXFORD

XXI

THE LAND OF RUINED CASTLES

XXII

THE IRISH HORSE AND HIS OWNER

XXIII

CORK AND BLARNEY CASTLE

XXIV

REMINISCENCES OF SIR WALTER RALEIGH

XXV

GLENGARIFF, THE LOVELIEST SPOT IN IRELAND

XXVI

THE LAKES OF KILLARNEY

XXVII

INTEMPERANCE, INSANITY, AND CRIME

XXVIII

THE EDUCATION OF IRISH FARMERS

XXIX

LIMERICK, ASKEATON, AND ADARE

XXX

COUNTY GALWAY AND RECENT LAND TROUBLES

XXXI

CONNEMARA AND THE NORTHWEST COAST

XXXII

WORK OF THE CONGESTED DISTRICTS BOARD

Interior and Exterior of One Story Cottages Erected by the Congested Districts Board

THE END

INDEX

Queenstown

The Rock of Cashel, County Tipperary

Holycross Abbey, County Tipperary

St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin

The Tomb of Strongbow, Christ Church, Dublin

The Earl of Aberdeen, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1906–8

The Countess of Aberdeen

The Four Courts, Dublin

The Castle, Dublin; Official Residence of the Lord Lieutenant and Headquarters of the Government

The Customs House, Dublin

The Bank of Ireland, Dublin

St. Stephen’s Green. Dublin

Quadrangle, Trinity College, Dublin

Main Entrance, Trinity College, Dublin

Sackville Street, Dublin, Showing Nelson’s Pillar.

Bailey Light at Howth, Mouth of Dublin Bay

Portumna Castle, County Galway; the Seat of the Earl of Clanricarde

Maynooth College County Kildare

Carton House, Maynooth, County Kildare; the Residence of the Duke of Leinster

A Celtic Cross at Monasterboice, County Louth

Ruins of Mellifont Abbey, near Drogheda, County Louth

Carrickfergus Castle

St. Patrick’s Cathedral at Armagh, the Seat of Cardinal Logue, the Roman Catholic Primate of Ireland

Down Cathedral, Downpatrick, where St. Patrick Lived, and in the Churchyard of which He Was Buried

The Village of Downpatrick

Rosstrevor House, near Belfast, the Residence of Sir John Ross of Bladensburg

Shane’s Castle, near Belfast, the Ancient Stronghold of the O’Neills, Kings of Ulster

Queen’s College, Belfast

Albert Memorial, Belfast

The Giant’s Causeway, Portrush, near Belfast

Bishop’s Gate, Derry

Irish Market Women

An Ancient Bridge in County Wicklow

The Vale of Avoca, County Wicklow

The River Front at Waterford

Lismore Castle, Waterford County; Irish Seat of the Duke of Devonshire

An Irish Jaunting Car

Going to Market

Queen’s College, Cork

Blarney Castle, County Cork

Kilkenny Castle; Residence of the Duke of Ormonde

The Ancient City of Youghal, County Cork; the Home of Sir Walter Raleigh

Myrtle Lodge; the Home of Sir Walter Raleigh

Lake Gougane-Barra, County Cork

Chapel Erected by Mr. John R. Walsh of Chicago on the Island of Gougane-Barra

The Pass of Keimaneigh Through the Mountains Between Cork and Glengariff

Glengariff Bridge

Kenmare House, Killarney

Upper Lake, Killarney.

Ross Castle, Killarney

Muckross Abbey, Killarney

A Window of Muckross Abbey, Killarney

Treaty Stone, Limerick

Adare Abbey, in the Private Grounds of the Earl of Dunraven, near Limerick

Fish Market, Galway

Salmon Weir, Galway

A Scene in Connemara

Clifden Castle, County Galway

A Scene in the West of Ireland; Lenane Harbor

Barne’s Gap, County Donegal.

An Irish Cabin in County Donegal.

The Old: a Laborer’s Sod Cabin

Interior and Exterior of One Story Cottages Erected by the Congested Districts Board

Holycross Abbey, County Tipperary

The people of Ireland are more prosperous to-day (July, 1908) than they have been for generations. Their financial condition is better than it ever has been, and is improving every year. The bank deposits, the deposits in postal savings banks, the government returns of the taxable property, have advanced steadily every year for the last ten years, and in Ireland, during the last ten years, there has been a gradual and healthful improvement in every branch of trade and industry. The people are more prosperous than in England or Scotland, except in certain sections where poverty is chronic because of climatic reasons and the barrenness of the soil. Nevertheless, they are not so prosperous as they ought to be under the circumstances, and it would require a book, and a large book, to repeat the many theories that are offered to explain the situation. It is a question upon which very few people agree, and they probably never will agree. There are almost as many theories as there are people. Therefore a discussion is not only disagreeable but it would lead immediately into politics. It is safe to say, however, that every Irishman who is willing to take a farm and cultivate it with intelligence and industry will prosper if he will let politics and whisky alone. Idleness, neglect, intemperance, and other vices produce the same results in Ireland as elsewhere, and under present conditions industry and thrift will make any honest farmer prosperous.

The moral and intellectual regeneration of the country is keeping step with the material regeneration. All religious qualifications and disqualifications have been removed; the church has been divorced from the state, and each religious denomination stands upon an equality in every respect.

The penal laws have been repealed and the tithe system has been abolished.

Local representative government prevails everywhere.

Nearly every official in Ireland is a native except the lord-lieutenant, the treasury remembrancer, and several agricultural experts who are employed as instructors for the farmers and fishermen by the Agricultural Department, and the Congested Districts Board.

The primary schools of Ireland are now free; free technical schools have been established at convenient locations for the training of mechanics, machinists, electricians, engineers, and members of the other trades.

Two new universities have been authorized,—one in the north and the other in the south of Ireland,—for the higher education of young men and women.

Temperance reforms are being gradually accomplished by the church and secular temperance societies, which are working in harmony; the license law has been amended so as to reduce the number of saloons, and three-fourths of the saloons are closed on Sunday throughout the island. The Father Mathew societies are gaining in numbers; the use of liquor at wakes and on St. Patrick’s Day has been prohibited by the Roman Catholic bishops, and the number of persons arrested for drunkenness and disorderly conduct is decreasing annually.

Every tenant that has been evicted in Ireland during the last thirty years has been restored to his old home, and the arrears of rent charged against him have been canceled.

The land courts have adjusted the rentals of 360,135 farms, and have reduced them more than $7,500,000 a year.

More than one hundred and twenty-six thousand families have been enabled to purchase farms with money advanced by the government to be repaid in sixty-eight years at nominal interest.

Several thousand families have been removed at government expense from unproductive farms to more fertile lands purchased for them with government money to be repaid in sixty-eight years.

Thousands of cottages, stables, barns, and other farm buildings have been built and repaired by the government for the farmers, and many millions of dollars have been advanced them for the purchase of cattle, implements, and other equipment through agents of the Agricultural Department.

More than twenty-three thousand comfortable cottages have been erected for the laborers of Ireland with money advanced by the government to be repaid in small instalments at nominal interest.

The landlord system of Ireland is being rapidly abolished; the great estates are being divided into small farms and sold to the men who till them. The agricultural lands of Ireland will soon be occupied by a population of independent farm owners instead of rent-paying tenants.

The Agricultural Department is furnishing practical instructors to teach the farmers how to make the most profitable use of their land and labor, how to improve their stock, and how to produce better butter, pork, and poultry.

The Agricultural Department furnishes seeds and fertilizers to farmers and instructs them how they should be used to the best advantage.

The Irish Agricultural Organization Society has instructed thousands of farmers in the science of agriculture and has established thousands of co-operative dairies and supply stores to assist the farmers in getting higher prices for their products and lower prices for their supplies.

The Congested Districts Board has expended seventy million dollars to improve the condition of the peasants in the west of Ireland; to provide them better homes and to place them where they can get better returns for their labor.

Thousands of fishermen have been furnished with boats, nets, and other tackle; they have been supplied with salt for curing their fish; casks and barrels for packing them; have been provided with wharves for landing places and warehouses for the storage of their implements and supplies; and government agents have secured a market for their fish and have supervised the shipments and sales.

Thousands of weavers have been furnished with looms in their cottages at government expense, so that they can increase their incomes by manufacturing home-made stuffs.

Schools have been established at many convenient points in the west of Ireland, where peasant women and girls may learn lace-making. The government furnishes the instruction free, supplies the materials used, and provides for the sale of the articles made.

Work has been furnished with good wages for thousands of unemployed men in the construction of roads and other public improvements.

District nurses have been stationed at convenient points along the west coast, where there are no physicians, to attend the sick and aged and relieve the distress among the peasant families, and hospitals have been established for the treatment of the ill and injured at government expense.

II

THE CATHEDRALS AND DEAN SWIFT

St. Patrick’s Cathedral is, perhaps, the most notable building in Ireland, and one of the oldest. During the religious wars and the clashes of the clans in the early history of Ireland it was the scene and the cause of much contention and violence. Its sacred walls were originally arranged as fortifications to defend it against the savage tribes and to protect the dignitaries of the church, who resided behind embattled gates for centuries. At one time St. Patrick’s was used as a barrack for soldiers, and the verger will show you an enormous baptismal font, from which he says the dragoons used to water their horses, and the interior was fitted up for courts of law. Henry VIII. confiscated the property and revenues because the members of its chapter refused to accept the new doctrines, and nearly all of them were banished from Ireland. He abolished a small university that was attached to the cathedral by the pope in 1320 for the education of priests. For five hundred years there was a continuous quarrel between St. Patrick’s and Christ Church Cathedral, which stands only two blocks away, because of rivalries over ecclesiastical privileges, powers, and revenues. Finally a compromise was reached, under which there has since been peace between the two great churches and relations similar to those of Westminster Abbey and St. Paul’s in London. Christ Church is the headquarters of the episcopal see of Dublin, and St. Patrick’s is regarded as a national church. The chief reason why St. Patrick’s has such a hold upon the affections and reverence of the people is because it stands upon the site of a small wooden church erected by St. Patrick himself in the year 450 and within a few feet of a sacred spring or well at which he baptized thousands of pagans during his ministry. The exact site of the well was identified in 1901 by the discovery of an ancient Celtic cross buried in the earth a few feet from the tower of the cathedral. The cross is now exhibited in the north aisle. The floor of the church is only seven feet above the waters of a subterranean brook called the Poddle, and during the spring floods is often inundated, but in the minds of the founders the sanctity of the spot compensated for the insecure foundations.

St. Patrick’s little wooden building, which is supposed to be the first Christian sanctuary erected in Ireland, was replaced in 1191 by the present lofty cruciform edifice, three hundred feet long and one hundred and fifty-seven feet across the transepts. It was designed and erected by Comyn, the Anglo-Norman archbishop of Dublin, is supposed to have been completed in 1198, and was raised to the rank of a cathedral in 1219. There were frequent alterations and repairs during the first seven centuries of its existence, until 1864-68, when it was perfectly restored by Sir Benjamin Guinness, the great brewer, who also purchased several blocks of dilapidated slums that surrounded it, tore down the buildings, and turned the land into a park which not only affords an opportunity to see the beauties of the cathedral, but gives the poor people who dwell in that locality a playground and fresh air. Sir Benjamin purchased several of the adjoining blocks and erected upon them a series of model tenement-houses, the best in Dublin, and rents them at nominal rates to his employees and others. On the other side of the cathedral are several blocks of the most miserable tenements in the city, and sometime they also will be cleared away. A bronze statue has been erected in the churchyard as a reminder of his generosity.

St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin

Benjamin Guinness was the great brewer of Dublin. In 1756 one of his ancestors started a little brewing establishment down on the bank of the Liffey River in the center of the city, which has been extended from time to time until the buildings now cover an area of more than forty acres. The property and good will were transferred by the Guinness family to a stock company for $30,000,000 in 1886, and since then the plant has been enlarged until it now exceeds in extent all other breweries in the world, represents an investment of $50,000,000, and turns out an average of two thousand one hundred barrels of beer a day.

Sir Benjamin’s son, Edward Cecil Guinness, was elevated to the peerage as Lord Iveagh and is the richest man in Ireland to-day. He is highly respected, has married into the nobility, is a great favorite with the king, is generous and philanthropic, encourages and patronizes both science and athletic sports, and is said to be “altogether a very good fellow.” Another son is Lord Ardilaun, who is equally rich and popular, and owns several of the finest estates in the kingdom.

Sir Benjamin expended $1,200,000 in restoring St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and Lord Iveagh, his son, added $350,000 more. The driver of the jaunting car that carried us there told me how many billion of glasses of beer those gifts represented, and made some funny remarks about all the profit being in the froth. But if all men were to make such good use of their money there would be no reason to complain.

St. Patrick’s Cathedral is the official seat of the Knights of St. Patrick, and their banners, helmets, and swords hang over the choir stalls, while in one of the chapels is an ancient table and a set of ancient chairs formerly used at their gatherings. Since 1869 they have met at Dublin castle. Many tattered and bullet-riddled battle flags carried by Irish regiments hang in other parts of the cathedral, and if they could tell the stories of the many brave Irishmen who have fought and perished under their silken folds, it would be more thrilling than fiction. Ireland has furnished the best fighting men in the British Army, both generals and privates, since the invasion of the Normans. The king’s bodyguard of Highlanders is now almost exclusively composed of Irish lads. In the north transept is a flag that was carried by an Irish regiment at the skirmish at Lexington at the beginning of our Revolution and at the attack on Bunker Hill. They brought it away with them to hang it here with the trophies of Irish valor of a thousand years.

St. Patrick’s is the Westminster Abbey of Ireland, and many of her most famous men are either buried within its walls or have tablets erected to their memory. John Philpott Curran, the great advocate and orator, and Samuel Lover, the song writer and novelist, whose “Handy Andy” and “Widow Machree,” are perhaps the best examples of Irish humor in literature, are honored with tablets; and Carolan, the last of the bards for whom Ireland was once so celebrated. He died in 1788. M.W. Balfe, author of that pretty little opera, “The Bohemian Girl,” and many beautiful ballads, including “I Dreamt I Dwelt in Marble Halls,” has a tablet inscribed with these words:

“The most celebrated, genial and beloved of Irish musicians, commendatore of Carlos III. of Spain, Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. Born in Dublin, 15 May, 1808, died 20th of Oct., 1870.”

Balfe was born in a small house on Pitt Street, Dublin, which bears a tablet announcing the fact.

The man who wrote that stirring poem, “The Burial of Sir John Moore,” which begins,

“Not a drum was heard, not a funeral note,

As his corse to the rampart we hurried,”—

lies in St. Patrick’s. His name was Charles Wolfe, and he was once the dean of the cathedral.

In the right-hand corner of the east transept is a monument to the memory of a certain dame of the time of Elizabeth, named Mrs. St. Leger. She was thirty-seven years old at the time of her death, and, her epitaph tells us, had “a strange, eventful history,” with four husbands and eight children, all of whom she made comfortable and happy.

On the other side is a tablet to commemorate the fact that Sir Edward Fitten, who died in 1579, was married at the age of twelve years and became the father of fifteen children,—nine sons and six daughters.

The famous Archbishop Whately, the gentleman who wrote the rhetoric we studied in college, and who once presided over this diocese, is buried in a stately tomb, and his effigy, beautifully carved in marble, lies upon it.

The most imposing monument of all, and one which is associated with much history and tragedy, was erected in honor of his own family by Richard Boyle, the first Earl of Cork, who was a great man in his day. So pretentious was the monument that Archbishop Laud ordered it removed from the cathedral. This was done by Thomas Wentworth, afterward Earl of Strafford, who was sent over by King Charles with an armed force to govern Ireland. Boyle, who had himself designed and expended a great deal of money upon “the famous, sumptuous, and glorious tomb,” which was to immortalize him and sixteen members of his family, was so indignant that he never forgave Strafford, and afterward caused the latter to be betrayed to a shameful death at the hands of his enemies.

The most interesting historic relic in the cathedral is an ancient oaken door with a large hole cut in the center of it. It bears an explanatory inscription as follows:

“In the year 1492 an angry conference was held at St. Patrick, his church, between the rival nobles, James Butler, Earl of Ormonde, and Gerald Fitzgerald, Earl of Kildare, the said deputies, and their armed retainers. Ormonde, in fear of his life, fled for refuge to the Chapiter House, and Kildare, pressing Ormonde to the Chapiter House door, undertooke on his honor that he should receive no villanie. Whereupon the recluse, craving his lordship’s hand to assure him his life, there was a clift in the Chapiter House door pearced at trice to the end that both Earls should shake hands and be reconciled. But Ormonde surmising that the clift was intended for further treacherie refused to stretch out his hand—” and the inscription goes on to relate that Kildare, having no such nervousness, thrust his hand through the hole and without the slightest hesitation. Ormonde shook it heartily and peace was made.

For centuries it was said that whoever might be Viceroy of Ireland it was the Earl of Kildare who governed the country. A long line of Kildares succeeded each other, and their living successor, better known as the Duke of Leinster, is now the premier of the Irish nobility, although he is still a boy, just twenty-one. Both the Kildares and the Earls of Desmond were descended from Gerald Fitzgerald, who in the thirteenth century founded that powerful clan known as the Geraldines. In the fifteenth, and at the beginning of the sixteenth, century they exercised absolute control in Ireland, and Garrett, or Gerald Fitzgerald, the eighth Earl of Kildare, known as “The Great Earl,” had greater authority than any other Irishman has ever displayed in his native island since the days of Brian Boru. At one time his daughter, wife of the Earl of Clanricarde, appealed to her father from a quarrel with her husband. The old gentleman took her part, ordered out his army, and met his son-in-law in the battle of Knockdoe, where it is said eight thousand men were slain.

Near the entrance to St. Patrick’s Cathedral is a long, narrow, brass tablet upon which are inscribed the names of the fifty-seven deans who have had ecclesiastical jurisdiction there from 1219 to 1902. The most famous in the list is that of the Rev. Jonathan Swift, D.D., author of “Gulliver’s Travels,” “The Tale of a Tub,” and other equally well-known works. He presided here for more than thirty years, and was undoubtedly the most brilliant as well as the most remarkable clergyman in the history of the diocese of Dublin. He was the greatest of all satirists, one of the most brilliant of all wits, and an all-around genius, but was entirely without moral consciousness, altogether selfish, inordinately vain, and one of the most eccentric characters in the history of literature. He was born in Dublin Nov. 30, 1667; educated at Trinity College, where he distinguished himself only by his eccentricities; was curate of two churches, and dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral for more than thirty years, although neither his manners nor his morals conformed to the standards that are fixed for clergymen in these days. He was more famous for his wit than his wisdom; for his piquancy than for piety. He spent most of his life in Dublin, died there, was buried in St. Patrick’s Cathedral by the side of a woman whose life he wrecked, and left his money to found an insane asylum which is still in existence.

The house in which Jonathan Swift was born can still be seen in Hoey’s Court, which once was a popular place of residence for well-to-do people, and has several mansions of architectural pretensions, but has degenerated into a slum, one of the many that may be found in the very center of the business section of the city. He came of a good Yorkshire family; his mother had aristocratic connections and was one of those women who seem to have been born to suffer from the failings of men. His father was a shiftless adventurer, following several professions and occupations in turn without even ordinary success in any. Jonathan went to the parish schools in Kilkenny for a time when his father happened to be living in that locality, and when he was seventeen years old passed the entrance examinations to Trinity College, Dublin. He was a willful, independent, eccentric person, of a lonely and sour disposition, and refused to be bound by the rules of the university. He would not study mathematics or physics, but delighted in classical literature, and furnished many witty contributions to college literature which gave promise of genius. He wrote a play that was performed by the college students with great success. His degree was reluctantly conferred by the faculty through the influence of Sir William Temple, a famous statesman of those days, whose wife was a distant relative of Swift’s mother.

Shortly after graduation he became private secretary to Sir William Temple and attended him in London during several sessions of parliament. While there, under some influence that has never been explained in a satisfactory manner, Swift decided to enter the ministry, and took a course of theology at Oxford. After his ordination in 1695 Sir William Temple got him a living in a quiet, secluded village called Laracor, in central Ireland, near Tara, the ancient capital, in a church that long ago crumbled to ruins and has been replaced by a modern building. It was a small parish consisting of not more than ten or twelve aristocratic families, among them the ancestors of the great Duke of Wellington. The young curate’s congregation was not very regular in its attendance, and you will remember, perhaps, an amusing story, how the Rev. Mr. Swift, when he came from the vestry one Sabbath morning, found no one but the sexton, Roger Morris, in the pews. He read the service, as usual, however, and with that quaint sense of humor which cropped out in everything he did, began solemnly:

“Dearly beloved Roger, the Scripture moveth us in sundry places,” etc.

Coming to the conclusion that he was not fitted for parish work, Swift obtained the position of private secretary to Earl Berkeley, one of the lord justices of Ireland, but, after a while, got another church, and tried preaching again. But he spent more of his time in writing political satires than in prayer or sermonizing. He edited Sir William Temple’s speeches and wrote his biography, and went to London, where he became a member of an interesting group of politicians and pamphleteers, who supported Lord Bolingbroke. He contributed to The Tattler, The Spectator, and other publications of the time, and soon became recognized as one of the most brilliant and savage satirists and influential political writers of the day. Through political influence, and not because of his piety, he was appointed dean of St. Patrick’s, the most prominent and famous church in Dublin. He had not been in his new position long before he created a tremendous sensation and set all Ireland aflame by writing a political pamphlet signed “M.B. Drapier.”

In 1723 Walpole’s government gave to the Duchess of Kendall, the mistress of George I., a concession to supply an unlimited amount of copper coinage to Ireland, and she took William Wood, an iron manufacturer of Birmingham, into partnership. There was no mint in Dublin and no limitation in the contract, so the firm of Kendall & Wood flooded the island with new copper pence and half-pence upon which they made a profit of 40 per cent. The coins became so abundant that they lost their value. Naturally the contract created not only scandal, but an intense indignation. Many pamphlets were published and speeches were made denouncing the transaction. The most telling attack came from what purported to be an unpretentious Dublin dry goods merchant, who told in simple language the story of the coinage contract and related anecdotes of Dublin women going from shop to shop followed by carloads of copper coins from the factory of the Duchess of Kendall. He mentioned a workingman who gave a pound of depreciated pennies for a mug of ale, and declared that they were so worthless that even the beggars would not accept them.

The money was not really so much depreciated as Swift represented, but the merchants of Dublin followed the advice of the simple draper and refused to accept it any longer in trade. The government authorities made a great fuss and arrested many of the repudiators, but the grand juries refused to indict them, and on the contrary threatened to indict merchants who accepted the shameful money. The printer of the pamphlet was arrested, but never punished. The authorship became an open secret, but the authorities dared not arrest the dean, whose popularity was so great and who exercised such an extraordinary influence over the common people that they accepted whatever he said as inspired and paid him the greatest respect possible. His influence is illustrated by a story that is related about a crowd which blocked the street around St. Patrick’s Cathedral one night to watch for an eclipse of the moon, and obstructed traffic, but promptly dispersed when he sent one of his servants to tell them that the eclipse had been postponed by his orders. He wrote “Gulliver’s Travels” about this period of his life in the deanery of St. Patrick’s, which was a part of what is now the barracks of the Dublin police force. The present deanery, a modern building near by, contains portraits of Swift and other of the fifty-seven clergymen who have served as deans of St. Patrick’s.

About the same time he wrote another masterpiece of satire upon the useless and impractical measures of charity for the poor adopted by the government. It was entitled:

A MODEST PROPOSAL

FOR PREVENTING THE CHILDREN OF

POOR PEOPLE IN IRELAND

FROM BEING A BURDEN TO

THEIR PARENTS BY

FATTENING AND EATING THEM.

He wrote several bitter satires on ecclesiastical matters, which would have caused his separation from the deanery under ordinary circumstances, but the archbishop as well as the civil authorities was afraid of his caustic pen. In discussing the bishops of the Church of Ireland at one time he declared that they were all impostors. He asserted that the government always sent English clergymen of character and piety to Ireland, but they were always murdered on their way by the highwaymen of Hounslow Heath and other brigands, who put on their robes, traveled to Dublin, presented their credentials, and were installed in their places over the several dioceses of Ireland.

In 1729 the parliament of Ireland was installed in the imposing structure that stands in the center of the city of Dublin opposite the main buildings of Trinity College. Although the people had been demanding home rule and a legislature of their own for years, the new parliament soon lost its popularity. Its action provoked the hostility of the fickle people and it was attacked on all sides for everything it did. Swift took his customary part in the criticisms and christened the parliament “The Goose Pie” because, as he said, the chamber had a crust in the form of a dome-shaped roof and it was not remarkable for the intellect or knowledge of its members.

One of his lampoons, directed at parliament under the name of “The Legion Club,” begins as follows:

“As I stroll the city, oft I

See a building large and lofty,

Not a bow-shot from the college,

Half the globe from sense and knowledge.

Tell us what the pile contains?

Many a head that holds no brains.

Such assemblies you might swear

Meet when butchers bait a bear.

Such a noise and such haranguing

When a brother thief is hanging.”

This does not sound very dignified for the dean of a cathedral, but it was characteristic of Swift.

He became a physical and mental wreck in 1742 and died an imbecile from softening of the brain Oct. 9, 1745. His will, written before his mind gave way, was itself a satire, and appropriately left his slender fortune to found an insane asylum. The original copy may be seen in the public records office in a beautiful great building known as the Four Courts, the seat of the judiciary of Ireland, where the archives of the government are kept. The insane asylum is still used for that purpose and is known as St. Patrick’s Hospital for Lunatics. It stands near the enormous brewery of the Guinness company. It was the first of the kind in Ireland, and was built when the insane were restrained by shackles, handcuffs, and iron bars, but more humane modern methods of treatment were introduced long ago and it is considered a model institution. The corridors are three hundred and forty-five feet long by fourteen feet wide, with little cells or bedrooms opening upon them. Swift’s writing desk is preserved in the institution.

His whimsicalities are illustrated in the cathedral more than anywhere else and among them is the “Schomberg epitaph,” found in the north aisle to the left of the choir, chiseled in large letters upon a slab of marble. Duke Schomberg, who commanded the Protestant army of King William of Orange at the Battle of the Boyne, and was killed toward the end of that engagement, July, 1690, was buried in St. Patrick’s at the time of his death, but his grave remained unmarked. His bones were discovered, however, in 1736, during some repairs, while Swift was dean of the cathedral. In order that their ancestor’s character and achievements might be properly recognized and called to the attention of posterity, Swift applied to the head of the Schomberg family for fifty pounds to pay the expense of a memorial, which they declined to contribute. Then Swift, whose indignation was excited, paid for the slab himself and punished them by recording upon it in Latin that the cathedral authorities, having entreated to no purpose the heirs of the great marshal to set up an appropriate memorial, this tablet had been erected that posterity might know where the great Schomberg lies.

“The fame of his valor,” he adds, “is much more appreciated by strangers than by his kinsmen.”

Upon the other farther side of the church, between the tombs of the Right Honorable Lady Elizabeth, Viscountess Donneraile, and Archbishop Whately, the gentleman who wrote the rhetoric we studied at college, is buried the body of an humble Irishman, who was Dean Swift’s body servant for a generation. He was eccentric but loyal, and as witty as his master. One morning the dean, getting ready for a horseback ride, discovered that his boots had not been cleaned, and called to Sandy:

“Why didn’t you clean these boots?”

“It hardly pays to do so, sir,” responded Sandy, “they get muddy so soon again.”

“Put on your hat and coat and come with me to ride,” said the dean.

“I haven’t had my breakfast,” said Sandy.

“There’s no use in eating; you’ll be hungry so soon again,” retorted the dean, and Sandy had to follow him in a mad gallop into the suburbs of Dublin without a mouthful.

When they were three or four miles away they met an old friend who asked them where they were going so early. Before the dean could answer, Sandy replied:

“We’re going to heaven, sir; the dean’s praying and meself is fasting; both of us for our sins.”

The epitaph of Sandy in St. Patrick’s Cathedral reads as follows:

HERE LIES THE BODY OF

ALEXANDER MAGEE,

SERVANT TO DR. SWIFT, DEAN

OF ST. PATRICK’S CATHEDRAL,

DUBLIN.

His Grateful Master Caused This Monument to Be Erected in Memory of His Discretion, Fidelity and Diligence in That Humble Station.

That long-suffering woman known as Stella, whose relations with Dean Swift have been discussed for a century and a half, and are still more or less of a mystery, was Mrs. Hester (sometimes spelled Esther) Johnson, a relative of Sir William Temple, whose private secretary Jonathan Swift, her inconstant and selfish lover, was for several years. Swift called her “Stella” because her name, “Hester,” is the Persian for “star,” and first met her while he was curate of a little village church at Laracor, where she lived with a Mrs. Dingley, a companion or chaperon, who seemed to be always by her side, whether she was in Dublin or London. From the beginning of their acquaintance she shared the inner life of Swift and exercised an extraordinary influence over him. When he left Laracor for London to become the private secretary of Sir William Temple their remarkable correspondence commenced, and he wrote her a daily record of his life, his thoughts, his whims, and his fancies. Those letters have been published under the title of “Swift’s Journal to Stella,” and the book has been described as “a giant’s playfulness, written for one person’s private pleasure, which has had indestructible attractiveness for every one since.”

She followed him to London and, when he became dean of St. Patrick’s, returned with him to Dublin and lived near the deanery with Mrs. Dingley as her chaperon until her death. But Swift was not true to her. This eminent author and satirist, this merciless critic of the shortcomings of others, this doctor of divinity, this dean of the most prominent cathedral in Ireland, had numerous flirtations with other women, and Stella must have known of them, although there is no evidence that her loyal heart ever wavered in its devotion.

In 1694 he fell desperately in love with a Miss Varing, but seems to have escaped without any damage to himself or his reputation, although we do not know what happened to her. A few years later he became involved in an entanglement with a Miss Van Homrigh, which ruined her life and effectually destroyed his peace of mind. The character of their acquaintance is shown by a series of poems which passed between them as her passion developed, and he allowed it to drift on uninterrupted from day to day, evidently giving her encouragement by tongue as well as pen. His poetical communications to her were signed “Cadenus,” the Latin word for dean, and hers were signed “Vanessa,” a combination of her Christian and surname.

It was not a very dignified situation for the dean of St. Patrick’s, and the flirtation caused a decided scandal in Dublin. It appears that Vanessa expected Swift to marry her and he undoubtedly gave her good reasons, while Mrs. Johnson was regarded as his mistress to the day of her death and bore the odium with uncomplaining resignation. Long after both of them were buried under the tiles of St. Patrick’s Cathedral it was discovered that they had been secretly married in 1716, but why she consented to keep that fact a secret has never been explained except upon the theory that she was afraid of what Vanessa Van Homrigh might do. The latter, however, having lost her patience and becoming hysterical with jealousy, wrote to Stella, inquiring as to the real nature of her relations with Swift and demanding that she should relinquish her claims upon him. Stella replied promptly by sending Vanessa indisputable evidence that they had been married seven years before. Vanessa, who lived at Marley Abbey, Celbridge (now Hazelhatch Station), ten miles from Dublin, on the railway to Cork, sent Stella’s letter to Swift and retired to the house of a friend in the country, where she died a few months later of a broken heart. Swift never replied; he never saw her or communicated with her after that day, and seems to have dismissed the affair with the same indifference that he always showed concerning the interests of other people.

Five years later Stella died and was buried in the cathedral at midnight by Swift’s orders, but he did not attend the funeral. She lived in the neighborhood of the deanery, and from one of its windows he witnessed the passage of the casket to the tomb. “This is the night of the funeral,” he writes in his diary, “and I moved into another apartment that I may not see the light in the church, which is just over against the window of my bed chamber.” He then sat down at his desk and described her devotion and her love for himself and her virtues in language of incomparable beauty. His tribute, written at that moment, is one of the most beautiful passages in English literature. He preserved a lock of her hair upon which he inscribed the words:

“Only a woman’s hair!”

“Only a woman’s hair!” comments Thackeray. “Only love, fidelity, purity, innocence, beauty; only the tenderest heart in the world, stricken and wounded, and pushed away out of the reach of joy with the pangs of hope deferred. Love insulted and pitiless desertion. Only that lock of hair left, and memory, and remorse for the guilty, lonely, selfish wretch, shuddering over the grave of his victim.”

Swift’s extraordinary vanity is illustrated in the inscription he placed over Hester Johnson’s grave and his selfishness by his neglect to vindicate her reputation by announcing their marriage. The mistress of a dean is not usually buried in a cathedral over which he presides, but no one has ever questioned the right of Stella’s dust to be there. Her epitaph, which was written by his own pen, runs:

“Underneath is interred the mortal remains of Mrs. Hester Johnson, better known to the world by the name of Stella, under which she was celebrated in the writings of Dr. Jonathan Swift, dean of this cathedral.

“She was a person of extraordinary endowments and accomplishments in body, mind, and behavior; justly admired and respected by all who knew her on account of her many eminent virtues, as well as for her great natural and acquired perfections.

“She died Jan. 27, 1727, in the forty-sixth year of her age, and by her will bequeathed £1,000 toward the support of the hospital founded in this city by Dr. Steevens.”

Although Swift did his best work after Stella’s death, he was never himself again. He became sour, morose, and misanthropic. His soul burned itself out with remorse. The last four years of his life were inexpressibly sad, and the retribution he deserved came from inward rather than outward causes. He was harassed by periodical attacks of acute dementia, to which his wonderful brain gradually yielded, and before his death he became an utter imbecile. He seemed to anticipate and prepare himself for such a fate, because among his papers was found his will, in which he bequeathed his entire estate to found an asylum for just such creatures as he himself became. He prepared his own epitaph, which reads as follows:

“Hic Depositum est Corpus.

Jonathan Swift, S.T.P.

Hujus, ecclesiae cathedrae decani ubi saeva

Indignatio ulterius cor lacerare nequit.

Abi viator, et imitare, si poteris,

Strenuum pro virili libertatis vindiceim.”

A liberal translation reads: “Here is deposited the body of Jonathan Swift, dean of this cathedral, where cruel indignation can no longer lacerate the heart. Go, stranger, and imitate, if you can, his strenuous endeavors in defense of liberty.”

The vault in which the two bodies rest has been twice disturbed during repairs of the cathedral, in 1835, when casts of their skulls were taken, and in 1882, when a new floor was laid. It is now marked by a modest tablet of tiles near the south entrance to the cathedral. Upon a bracket near by is a bust of Swift contributed by Mr. Faulkner, the nephew and successor of his original publisher.

Many anecdotes are told of Swift’s peculiarities. He must have filled a large place in the life of Dublin during the thirty years that he was the dean of the cathedral. He was prominent in political, social, and ecclesiastical affairs during all that period and always welcome as a guest at the houses of the aristocracy in this neighborhood. In the suburb of Glasnevin was an estate called Hildeville, belonging to a generous but pretentious patron of the arts and sciences, named Dr. Delany, where the brilliant minds of that day used to gather for a good time. Swift is closely associated with the place and was one of Dr. Delany’s most frequent and regular visitors. He called it “Hell-Devil,” and chose for its motto “Fastigia Despicet Urbis,” in which the verb is used in a double sense.

Many of his most stinging satires were written there, including his ferocious libel on the Irish parliament. A reward was offered for the discovery of the author, and although a hundred members of the commons knew that it was from Swift’s pen, no attempt was ever made to punish him and he was never even denounced publicly. And he wasn’t above ridiculing his host, for here is an extract from an ode addressed to Dr. Delany of “Hell-Devil,” when he was the latter’s guest:

“A razor, though to say ’t I’m loath,

Might shave you and your meadow both,

A little rivulet seems to steal

Along a thing you call a vale,

Like tears adown a wrinkled cheek,

Like rain along a blade of leek—

And this you call your sweet meander,

Which might be sucked up by a gander,

Could he but force his rustling bill

To scoop the channel of the rill.

In short, in all your boasted seat,

There’s nothing but yourself is—great.”

“Is it singin’ yees want?” said the verger of Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin, when we entered that ancient sanctuary shortly before the hour for worship on a gloomy, drizzly Sabbath morning. “Then yees have come to the roight place. The choir of Christ Church is the finest in all Ireland, and mebbe in the whole wurrld, I dunno. Thay’s twinty-four b’ys and min, and every mother’s son iv thim is from the first families of Dooblin. The lads has been singin’ frum their cradles, and they make the swatest music that ears ever heard; blessed be the Lord! Not as if they had no mischief in thim, for b’ys will be b’ys, singin’ or no singin’; and thim that has the medals hangin’ on their chists is the best behaved and the least mischaveous.”

We remained after the service to look about, and when the verger asked what I thought of the sermon I told him.

“It’s not of much consequence!” observed the cynic. And when I told him that the singing wasn’t much better than the preaching, and that the boys sang out of tune, he replied apologetically:

“I hope your honor won’t think the liss of thim for that; they’re all honest, well-meaning lads, an’ what harm is it at all, at all, if they do sing out of chune betimes?”

Christ Church is one of the oldest structures in Ireland, was originally erected in 1038 by the Danish king Sigtryg, “Of the Silken Beard,” and in 1152 was made the seat of the archbishop of Dublin. In 1172 Strongbow, the Welch Earl of Pembroke, leader of the Norman invasion, swept away the original building to make room for the present edifice, which was fifty years in building. The present nave, transepts, and crypt are those that Strongbow erected, having been thoroughly repaired and restored by Henry Roe, a wealthy distiller, at a cost of £220,000, between 1870 and 1878. In 1178 Strongbow died of a malignant ulcer of the foot, which his enemies attributed to the vengeance of the early Irish saints whose shrines he had violated, and he is buried within the church he built. His black marble tomb is on the south side, with a recumbent effigy in chain armor lying upon the sarcophagus. A smaller effigy in black marble, representing the upper half of a human form, lies beside him and is said to mark the tomb of Strongbow’s son, whom his father literally cut in half with his mighty sword for showing cowardice in battle. Sir Henry Sidney, who discussed the question at length in 1571, declares that there is no doubt that the remains of Strongbow were deposited here, but there is another tomb, with a similar effigy of one-half of his son lying beside it, in an ancient church at Waterford, where Strongbow dwelt in a castle and made his headquarters. The claims of the Waterford tomb are considered much stronger than those of Christ Church in Dublin, because that was where he died and where his wife and family lived after him.

The interior of the church has many points of beauty, especially the splendid stone work of the nave and aisles and the graceful arches which, although very massive, are chiseled with such delicacy that their heaviness does not appear. The floor is covered with modern tiles which are exact copies of the originals, and in the restoration of the building the architect has shown similar conscientiousness in all his work. The great age of the stone gives it a rich and mellow tone, and although here and there one may come across evidences of decay or damage, it is in better condition than most of the modern churches of Ireland.

Across the street and connected by a bridge with the cathedral is the Synod Hall, the headquarters of the general synod, which has control of the affairs of the Episcopal Church of Ireland since it was separated from the Church of England and made independent of the state by an act of parliament July 26, 1869. This was called “The Disestablishment”—a long and awkward word—but such words are common in English and Irish official literature. It is often difficult for an American to understand the meaning of the terms used in acts of parliament and reports of the officials of the government.

The Tomb of Strongbow, Christ Church, Dublin

III

HOW IRELAND IS GOVERNED

Ireland is nominally governed by a lord lieutenant or viceroy of the king, who, since December, 1905, and at present, is John Campbell Gordon, Earl of Aberdeen. He occupied the same position in the ’90’s, and has since been governor-general of Canada. Both Lord and Lady Aberdeen are well known in the United States, where Lady Aberdeen has taken an active interest in the work of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and many benevolent enterprises and social reforms. She will be particularly remembered as the promoter of the Irish village at the Chicago Exposition in 1893, and for her successful endeavors to introduce Irish homespun, lace, linen, and other products, and to make them fashionable among the American people. She is a woman of great energy, executive ability, and determination, and has been applying those qualities very effectively in Ireland in local reforms. She has organized societies of women throughout the island to encourage the virtues and restrain the vices of the people, to relieve their distress and advance their welfare, physically, mentally, and morally, by a dozen different movements of which she is the leader and director. She started a crusade against the great white plague, brought Dr. Arthur Green from New York as an organizer, while Nathan Straus of New York has been co-operating with her in setting up establishments for the sterilization of the milk sold in Irish cities. She is president of almost everything, has a dozen secretaries and agents carrying out her orders, and is altogether the busiest woman in the United Kingdom.

The Earl of Aberdeen, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1906–8

The Lord Lieutenant of Ireland has very little to do except to open fairs, lay corner stones, preside at public meetings, give dinners, and look pleasant. He is nominally the head of everything as the representative of his sovereign, the king, and is supposed to rule Ireland in his majesty’s name, but, like the Governor-General of Canada, the office is a sinecure. Its incumbent is allowed a salary of $100,000, a castle in the city, and a country lodge in Phœnix Park, a liberal allowance to maintain them and to expend in hospitality, a staff of secretaries and aids-de-camp, a full outfit of servants, and various other perquisites which would be appreciated by our President and all others in authority. And all this without any responsibilities, except to be tactful, amiable, and diplomatic, and to make friends with the people.

The actual ruler of Ireland is the Chief Secretary to the lord lieutenant, who is a member of the cabinet of the king, and spends most of his time in London, where he devises and directs the political policy of the government toward that distracted but improving portion of his majesty’s empire, looks after legislation in parliament, and attends to whatever is necessary for the good of the island. He is the Right Hon. Augustine Birrell, who is carrying out the lines of policy inaugurated by Mr. Bryce at the incoming of the present liberal government. The chief secretary is expected to spend a portion of each year in Ireland, so that he can keep in touch with affairs and get his cues from public opinion. He has a salary of $35,000 and a residence, fully equipped and appointed, near that of the lord lieutenant in Phœnix Park.