автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Complete Works of Dio Chrysostom. Illustrated

The Complete Works of Dio Chrysostom. Illustrated

Dio Chrysostom

Dio Chrysostom (surname literally means "golden-mouthed") was part of the Second Sophistic school of Greek philosophers which reached its peak in the early 2nd century. He was considered one of the most eminent of the Greek rhetoricians and sophists by the ancients who wrote about him, such as Philostratus, Synesius, and Photius.

Eighty of his Discourses are extant, as well as a few Letters and a funny mock essay "In Praise of Hair", as well as a few other fragments. These orations appear to be written versions of his oral teaching, and are like essays on political, moral, and philosophical subjects.

Discourses

Encomium on hair

Fragments

The Complete Works of Dio Chrysostom

Illustrated

Discourses. Encomium on hair and others

The Translations

DISCOURSES

Translated by J. W. Cohoon

Dio Chrysostom was born at Prusa, now Bursa, in the Roman province of Bithynia in AD 40. His father, Pasicrates, is believed to have taken great care of his son’s education and the early training of his mind. At first Dio occupied himself in his native town, where he held important offices, while composing speeches and other rhetorical and sophistical essays, but he later devoted himself with zeal to the study of philosophy, travelling to Rome to extend his learning, where he was eventually converted to Stoicism.

Dio formed part of the Second Sophistic school of Greek philosophers that reached its peak in the early second century. He was considered as one of the most eminent of the Greek rhetoricians by the ancients that wrote about him, including Philostratus, Synesius and Photius. His eighty extant Orations appear to be written versions of his oral teaching, similar in style to essays on political, moral and philosophical subjects. They include four orations on kingship addressed to Trajan on the virtues of a sovereign; four on the character of Diogenes of Sinope. Other topics include the troubles that men expose themselves to by deserting the path of Nature and the difficulties that a sovereign has to encounter.

There are also discourses on slavery and freedom, on the means of attaining eminence as an orator, as well as political essays addressed to various towns that Dio both praises and censures, though always with moderation and wisdom. The discourses also cover subjects of ethics and practical philosophy, which he treats in a popular and attractive manner; and lastly, there are orations on mythical subjects and show-speeches.

Dio wrote many other philosophical and historical works, none of which survive, except for fragments. The works that survive confirm his prominent influence in reviving Greek literature in the Roman Empire, marking the beginning of the Second Sophistic movement. Dio was committed to defending the ethical values of the Greek cultural tradition, as reflected by his sober and elegant style.

THE FIRST DISCOURSE ON KINGSHIP

The first Discourse as well as the following three has for its subject Kingship, and from internal evidence is thought to have been first delivered before Trajan in Rome immediately after he became emperor. At any rate Dio does not address the Emperor in those terms of intimacy that he uses in the third Discourse.

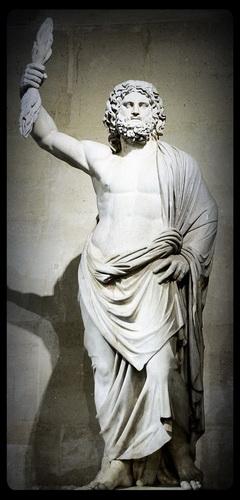

Dio’s conception of the true king is influenced greatly by Homer and Plato. The true king fears the gods and watches over his subjects even as Zeus, the supreme god, watches over all mankind. At the end is a description of the choice made by Heracles, who is the great model of the Cynics.

The First Discourse on Kingship

The story goes that when the flute-player Timotheus gave his first exhibition before King Alexander, he showed great musical skill in adapting his playing to the king’s character by selecting a piece that was not languishing or slow nor of the kind that would cause relaxation or listlessness, but rather, I fancy, the ringing strain which bears Athena’s name and none other. [2] They say, too, that Alexander at once bounded to his feet and ran for his arms like one possessed, such was the exaltation produced in him by the tones of the music and the rhythmic beat of the rendering. The reason why he was so affected was not so much the power of the music as the temperament of the king, which was high-strung and passionate. [3] Sardanapallus, for example, would never have been aroused to leave his chamber and the company of his women even by Marsyas himself or by Olympus, much less by Timotheus or any other of the later artists; nay, I believe that had even Athena herself – were such a thing possible – performed for him her own measure, that king would never have laid hand to arms, but would have been much more likely to leap up and dance a fling or else take to his heels; to so depraved a condition had unlimited power and indulgence brought him.

[4] In like manner it may fairly be demanded of me that I should show myself as skilful in my province as a master flautist may be in his, and that I should find words which shall be no whit less potent than his notes to inspire courage and high-mindedness – [5] words, moreover, not set to a single mood but at once vigorous and gentle, challenging to war yet also speaking of peace, obedience to law, and true kingliness, inasmuch as they are addressed to one who is disposed, methinks, to be not only a brave but also a law-abiding ruler, one who needs not only high courage but high sense of right also. [6] If, for instance, the skill which Timotheus possessed in performing a warlike strain had been matched by the knowledge of such a composition as could make the soul just and prudent and temperate and humane, and could arouse a man not merely to take up arms but also to follow peace and concord, to honour the gods and to have consideration for men, it would have been a priceless boon to Alexander to have that man live with him as a companion, and to play for him, not only when he sacrificed but at other times also: [7] when, for example, he would give way to unreasoning grief regardless of propriety and decorum, or would punish more severely than custom or fairness allowed, or would rage fiercely at his own friends and comrades or disdain his mortal and real parents. [8] But unfortunately, skill and proficiency in music cannot provide perfect healing and complete relief for defect of character. No indeed! To quote the poet:

“E’en to Asclepius’ sons granted not god this boon.”

Nay, it is only the spoken word of the wise and prudent, such as were most men of earlier times, that can prove a competent and perfect guide and helper of a man endowed with a tractable and virtuous nature, and can lead it toward all excellence by fitting encouragement and direction.

[9] What subject, then, will clearly be appropriate and worthy of a man of your earnestness, and where shall I find words so nearly perfect, mere wanderer that I am and self-taught philosopher, who find what happiness I can in toil and labour for the most part and employ eloquence only for the encouragement of myself and such others as I meet from time to time? My case is like that of men who in moving or shifting a heavy load beguile their labour by softly chanting or singing a tune – mere toilers that they are and not bards or poets of song. [10] Many, however, are the themes of philosophy, and all are worth hearing and marvellously profitable for any who listen with more than casual attention; but since we have found as our hearer one who is near at hand and ready eagerly to grasp our words, we must summon to our aid Persuasion, the Muses, and Apollo, and pursue our task with the greatest possible devotion.

[11] Let me state, then, what are the characteristics and disposition of the ideal king, summarizing them as briefly as possible – the king

“to whom the son

Of Saturn gives the sceptre, making him

The lawgiver, that he may rule the rest.”

[12] Now it seems to me that Homer was quite right in this as in many other sayings, for it implies that not every king derives his sceptre or this royal office from Zeus, but only the good king, and that he receives it on no other title than that he shall plan and study the welfare of his subjects; he is not to become licentious or profligate, [13] stuffing and gorging with folly, insolence, arrogance, and all manner of lawlessness, by any and every means within his power, a soul perturbed by anger, pain, fear, pleasure, and lusts of every kind, but to the best of his ability he is to devote his attention to himself and his subjects, becoming indeed a guide and shepherd of his people, not, as someone has said, a caterer and banqueter at their expense. Nay, he ought to be just such a man as to think that he should sleep at all the whole night though as having no leisure for idleness. [14] Homer, too, in agreement with all other wise and truthful men, says that no wicked or licentious or avaricious person can ever become a competent ruler or master either of himself or of anybody else, nor will such a man ever be a king even though all the world, both Greeks and barbarians, men and women, affirm the contrary, yea, though not only men admire and obey him, but the birds of the air and the wild beasts on the mountains no less than men submit to him and do his bidding.

[15] Let me speak, then, of the king as Homer conceives him, of him who is in very truth a king; for this discourse of mine, delivered in all simplicity without any flattery or abuse, of itself discerns the king that is like the good one, and commends him in so far as he is like him, while the one who is unlike him it exposes and rebukes. Such a king is, in the first place, regardful of the gods and holds the divine in honour. [16] For it is impossible that the just and good man should repose greater confidence in any other being than in the supremely just and good – the gods. He, however, who, being wicked, imagines that he at any time pleases the gods, in that very assumption lacks piety, for he has assumed that the deity is either foolish or evil. [17] Next after the gods the good king has regard for his fellow-men; he honours and loves the good, yet extends his care to all. Now who takes better care of a herd of cattle than does the herdsman? Who is more helpful and better to flocks of sheep than a shepherd? Who is a truer lover of horses than he who controls the greatest number of horses and derives the greatest benefit from horses? [18] And so who is presumably as great a lover of his fellow-man as he who exercises authority over the greatest number of men and enjoys the highest admiration of men? For it would be strange if men governing beasts, wild and of another blood than theirs, prove more kindly to these their dependants than a monarch to civilized men who are of the same flesh and blood as himself. [19] And further, cattle love their keepers best and are most submissive to them; the same is true of horses and their drivers; hunters are protected and loved by their dogs, and in the same way other subject creatures love their masters. [20] How then would it be conceivable that, while beings devoid of intelligence and reason recognize and love those who care for them, that creature which is by far the most intelligent and best understands how to repay kindness with gratitude should fail to recognize, nay, should even plot against, its friends? No indeed! For of necessity the kindly and humane king is not only beloved but even adored by his fellow-men. And because he knows this and is by nature so inclined, he displays a soul benignant and gentle towards all, inasmuch as he regards all as loyal and as his friends.

[21] The good king also believes it to be due to his position to have the larger portion, not of wealth or of pleasures, but of painstaking care and anxieties; hence he is actually more fond of toil than many others are of pleasure or of wealth. For he knows that pleasure, in addition to the general harm it does to those who constantly indulge therein, also quickly renders them incapable of pleasure, whereas toil, besides conferring other benefits, continually increases a man’s capacity for toil. [22] He alone, therefore, may call his soldiers “fellow-soldiers” and his associates “friends” without making mockery of the word friendship; and not only may he be called by the title “Father” of his people and his subjects, but he may justify the title by his deeds. In the title “master,” however, he can take no delight, nay, not even in relation to his slaves, much less to his free subjects; [23] for he looks upon himself as being king, not for the sake of his individual self, but for the sake of all men.

Therefore he finds greater pleasure in conferring benefits than those benefited do in receiving them, and in this one pleasure he is insatiable. For the other functions of royalty he regards as obligatory; that of benefaction alone he considers both voluntary and blessed. [24] Blessings he dispenses with the most lavish hand, as though the supply were inexhaustible; but of anything hurtful, on the contrary, he can no more be the cause than the sun can be the cause of darkness. Men who have seen and associated with him are loath to leave him, while those who know him only by hearsay are more eager to see him than children are to find their unknown fathers. [25] His enemies fear him, and no one acknowledges himself his foe; but his friends are full of courage, and those exceeding near unto him deem themselves of all men most secure. They who come into his presence and behold him feel neither terror nor fear; but into their hearts creeps a feeling of profound respect, something much stronger and more powerful than fear. For those who fear must inevitably hate and want to escape; those who feel respect must linger and admire.

[26] He holds that sincerity and truthfulness are qualities befitting a king and a prudent man, while unscrupulousness and deceit are for the fool and the slave, for he observes that among the wild beasts also it is the most cowardly and ignoble which surpass all the rest in lying and deceiving.

[27] Though naturally covetous of honour, and knowing that it is the good that men are prone to honour, he has less hope of winning honour from the unwilling than he has of gaining the friendship of those who hate him.

He is warlike to the extent that the making of war rests with him, and peaceful to the extent that there is nothing left worth his fighting for. For assuredly he is well aware that they who are best prepared for war have it most in their power to live in peace.

[28] He is also by nature fond of his companions, fellow-citizens, and soldiers in like measure; for a ruler who is suspicious of the military and has never or rarely seen those who face peril and hardship in support of his kingdom, but continually flatters the unprofitable and unarmed masses, is like a shepherd who does not know those who help him to keep guard, never proffers them food, and never shares the watch with them; for such a man tempts not only the wild beasts, but even his own dogs, to prey upon the fold. [29] He, on the contrary, who pampers his soldiers by not drilling them or encouraging them to work hard and, at the same time, evinces no concern for the people at large, is like a ship-captain who demoralizes his crew with surfeit of food and noonday sleep and takes no thought for his passengers or for his ship as it goes to ruin. [30] And yet if one is above reproach in these two matters, but fails to honour those who are close to him and are called his friends, and does not see to it that they are looked upon by all men as blessed and objects of envy, he becomes a traitor to himself and his kingdom ere he is aware by disheartening those who are his friends and suffering nobody else to covet his friendship and by robbing himself of that noblest and most profitable possession: friendship. [31] For who is more indefatigable in toil, when there is occasion for toil, than a friend? Who is readier to rejoice in one’s good fortune? Whose praise is sweeter than that of friends? From whose lips does one learn the truth with less pain? What fortress, what bulwarks, what arms are more steadfast or better than the protection of loyal hearts? [32] For whatever is the number of comrades one has acquired, so many are the eyes with which he can see what he wishes, so many the ears with which he can hear what he needs to hear, so many the minds with which he can take thought concerning his welfare. Indeed, it is exactly as if a god had given him, along with his one body, a multitude of souls all full of concern in his behalf.

[33] But I will pass over most of the details and give the clearest mark of a true king: he is one whom all good men can praise without compunction not only during his life but even afterwards. And yet, even so, he does not himself covet the praise of the vulgar and the loungers about the market-place, but only that of the free-born and noble, men who would prefer to die rather than be guilty of falsehood. [34] Who, therefore, would not account such a man and such a life blessed? From what remote lands would men not come to see him and to profit from his honourable and upright character? What spectacle is more impressive than that of a noble and diligent king? What can give greater pleasure than a gentle and kindly ruler who desires to serve all and has it in his power so to do? [35] What is more profitable than an equitable and just king? Whose life is safer than his whom all alike protect, whose is happier than his who esteems no man an enemy, and whose is freer from vexation than his who has no cause to blame himself? Who is more fortunate, too, than that man whose goodness is known of all?

[36] In plain and simple language I have described the good king. If any of his attributes seem to belong to you, happy are you in your gracious and excellent nature, and happy are we who share its blessings with you.

[37] It was my purpose, after finishing the description of the good king, to discuss next that supreme king and ruler whom mortals and those who administer the affairs of mortals must always imitate in discharging their responsibilities, directing and conforming their ways as far as possible to his pattern. [38] Indeed, this is Homer’s reason for calling true kings “Zeus-nurtured” and “like Zeus in counsel”; and Minos, who had the greatest name for righteousness, he declared was a companion of Zeus. In fact, it stands to reason that practically all the kings among Greeks or barbarians who have proved themselves not unworthy of this title have been disciples and emulators of this god. [39] For Zeus alone of the gods has the epithets of “Father” and “King,” “Protector of Cities,” “Lord of Friends and Comrades,” “Guardian of the Race,” and also “Protector of Suppliants,” “God of Refuge,” and “God of Hospitality,” these and his countless other titles signifying goodness and the fount of goodness. [40] He is addressed as “King” because of his dominion and power; as “Father,” I ween, on account of his solicitude and gentleness; as “Protector of Cities” in that he upholds the law and the commonweal; as “Guardian of the Race” on account of the tie of kinship which unites gods and men; as “Lord of Friends and Comrades” because he brings all men together and wills that they be friendly to one another and never enemy or foe; [41] as “Protector of Suppliants” since he inclines his ear and is gracious to men when they pray; as “God of Refuge” because he gives refuge from evil; as “God of Hospitality” because it is the very beginning of friendship not to be unmindful of strangers or to regard any human being as an alien; and as “God of Wealth and Increase” since he causes all fruitage and is the giver of wealth and substance, not of poverty and want. For all these functions must at the outset be inherent in the royal function and title.

[42] I might well speak next of the administration of the universe and tell how the world – the very embodiment of bliss and wisdom – ever sweeps along through infinite time in infinite cycles without cessation, guided by good fortune and a like power divine, and by foreknowledge and a governing purpose most righteous and perfect, and renders us like itself since, in consequence of the mutual kinship of ourselves and it, we are marshalled in order under one ordinance and law and partake of the same polity. [43] He who honours and upholds this polity and does not oppose it in any way is law-abiding, devout and orderly; he, however, who disturbs it, as far as that is possible to him, and violates it or does not know it, is lawless and disorderly, whether he be called a private citizen or a ruler, although the offence on the part of the ruler is far greater and more evident to all. [44] Therefore, just as among generals and commanders of legions, cities or provinces, he who most closely imitates your ways and shows the greatest possible conformity with your habits would be by far your dearest comrade and friend, while he who showed antagonism or lacked conformity would justly incur censure and disgrace and, being speedily removed from his office as well, would give way to better men better qualified to govern; [45] so too among kings, since they, I ween, derive their powers and their stewardship from Zeus; the one who, keeping his eyes upon Zeus, orders and governs his people with justice and equity in accordance with the laws and ordinances of Zeus, enjoys a happy lot and a fortunate end, [46] while he who goes astray and dishonours him who entrusted him with his stewardship or gave him this gift, receives no other reward from his great authority and power than merely this: that he has shown himself to all men of his own time and to posterity to be a wicked and undisciplined man, illustrating the storied end of Phaethon, who mounted a mighty chariot of heaven in defiance of his lot but proved himself a feeble charioteer. [47] In somewhat this wise Homer too speaks when he says:

“Whoso bears

A cruel heart, devising cruel things,

On him men call down evil from gods

While living, and pursue him, when he dies,

With scoffs. But whoso is of generous heart

And harbours generous aims, his guests proclaim

His praises far and wide to all mankind,

And numberless are they who call him good.”

[48] For my part, I should be most happy and eager, as I have said, to speak on this subject – on Zeus and the nature of the universe. But since it is altogether too vast a theme for the time now at my command and requires a somewhat careful demonstration, perhaps in the future there may be leisure for its presentation. [49] But if you would like to hear a myth, or rather a sacred and withal edifying parable told under the guise of a myth, perhaps a story which I once heard an old woman of Elis or Arcadia relate about Heracles will not appear to you out of place, either now or hereafter when you come to ponder it alone.

[50] Once when I chanced to be wandering in exile – and great is my gratitude to the gods that they thus prevented my becoming an eye-witness of many an act of injustice – I visited as many lands as possible, at one time going among the Greeks, at another among barbarians, assuming the guise and dress of a vagabond beggar,

“Demanding crusts, not caldrons fine or swords.”

[51] At last I arrived in the Peloponnesus, and keeping quite aloof from the cities, spent my time in the country, as being quite well worth study, mingling with herdsmen and hunters, an honest folk of simple habits. [52] As I walked along the Alpheus on my way from Heraea to Pisa, I succeeded in finding the road for some distance, but all at once I got into some wood land and rough country, where a number of trails led to sundry herds and flocks, without meeting anybody or being able to inquire my way. So I lost my direction, and at high noon was quite astray. But noticing on a high knoll a clump of oaks that looked like a sacred grove, I made my way thither in the hope of discovering from it some roadway or house. [53] There I found blocks of stone set roughly together, hanging pelts of animals that had been sacrificed, and a number of clubs and staves – all evidently being dedications of herdsmen. At a little distance I saw a woman sitting, strong and tall though rather advanced in years, dressed like a rustic and with some braids of grey hair falling about her shoulders. [54] Of her I made full inquiry about the place, and she most graciously and kindly, speaking in the Dorian dialect, informed me that it was sacred to Heracles and, regarding herself, that she had a son, a shepherd, whose sheep she often tendered herself. She also said that the Mother of the Gods had given her the gift of divination and that all the herdsmen and farmers round about consulted her on the raising and preservation of their crops and cattle. [55] “And you too,” she continued, “have come into this place by no mere human chance, for I shall not let you depart unblest.” Thereupon she at once began to prophesy, saying that the period of my wandering and tribulation would not be long, nay, nor that of mankind at large. [56] The manner of her prophesying was not that of most men and women who are said to be inspired; she did not gasp for breath, whirl her head about, or try to terrify with her glances, but spoke with entire self-control and moderation.

“Some day,” she said, “you will meet a mighty man, the ruler of very many lands and peoples. Do not hesitate to tell him this tale of mine even if there be those who will ridicule you for a prating vagabond. [57] For the words of men and all their subtleties are as naught in comparison with the inspiration and speech due to the promptings of the gods. Indeed, of all the words of wisdom and truth current among men about the gods and the universe, none have ever found lodgment in the souls of men except by the will and ordering of heaven and through the lips of the prophets and holy men of old. [58] For instance, they say there once lived in Thrace a certain Orpheus, a Muse’s son; and on a certain mountain of Boeotia another, a shepherd who heard the voices of the Muses themselves. Those teachers, on the other hand, who without divine possession and inspiration have circulated as true stories born of their own imaginings are presumptuous and wicked.

“Hear, therefore, the following tale and listen with vigilance and attention that you may remember it clearly and pass it on to that man whom I say you will meet. It has to do with this god in whose presence we now are. [59] Heracles was, as all men agree, the son of Zeus and Alcmene, and he was king not only of Argos but of all Greece. (Most people, however, do not know that Heracles was continually absent from Argos because he was engaged in making expeditions and defending his kingdom, but they assert that Eurystheus was king at this time. These, however, are but their idle tales.) [60] And he was not only king of Greece, but also held empire over every land from the rising of the sun to the setting thereof, aye, over all peoples where are found shrines of Heracles. [61] He had a simple education too, with none of the elaboration and superfluity devised by the unscrupulous cleverness of contemptible men.

“This, also, is told of Heracles: that he went unclothed and unarmed except for a lion’s skin and a club, [62] and they add that he did not set great store by gold or silver or fine raiment, but considered all such things worth nothing save to be given away and bestowed upon others. At any rate he made presents to many men, not only of money without limit and lands and herds of horses and cattle, but also of whole kingdoms and cities. For he fully believed that everything belonged to him exclusively and that gifts bestowed would call out the good-will of the recipients. [63] Another story which men tell is untrue: that he actually went about alone without an army. For it is not possible to overturn cities, cast down tyrants, and to dictate to the whole world without armed forces. It is only because, being self-reliant, zealous of soul, and competent in body, he surpassed all men in labour, that the story arose that he travelled alone and accomplished single-handed whatsoever he desired.

[64] “Moreover, his father took great pains with him, implanting in him noble impulses and bringing him into the fellowship of good men. He would also give him guidance for each and every enterprise through birds and burnt offerings and every other kind of divination. [65] And when he saw that the lad wished to be a ruler, not through desire for pleasure and personal gain, which leads most men to love power, but that he might be able to do the greatest good to the greatest number, he recognized that his son was naturally of noble parts, and yet suspected how much in him was mortal and thought of the many baneful examples of luxurious and licentious living among mankind, and of the many men there were to entice a youth of fine natural qualities away from his true nature and his principles even against his will. [66] So with these considerations in mind he despatched Hermes after instructing him as to what he should do. Hermes therefore came to Thebes, where the lad Heracles was being reared, and told him who he was and who had sent him. Then, taking him in charge, he led him over a secret path untrodden of man till he came to a conspicuous and very lofty mountain-peak whose sides were dreadfully steep with sheer precipices and with the deep gorge of a river that encompassed it, whence issued a mighty rumbling and roaring. Now to anyone looking up from below the crest above seemed single; but it was in fact double, rising from a single base; and the two peaks were far indeed from each other. [67] The one of them bore the name Peak Royal and was sacred to Zeus the King; the other, Peak Tyrannous, was named after the giant Typhon. There were two approaches to them from without, each having one. The path that led to Peak Royal was safe and broad, so that a person mounted on a car might enter thereby without peril or mishap, if he had the permission of the greatest of the gods. The other was narrow, crooked, and difficult, so that most of those who attempted it were lost over the cliffs and in the flood below, the reason being, methinks, that they transgressed justice in taking that path. [68] Now, as I have said, to most persons the two peaks appear to be practically one and undivided, inasmuch as they see them from a distance; but in fact Peak Royal towers so high above the other that it stands above the clouds in the pure and serene ether itself, whereas the other is much lower, lying in the very thick of the clouds, wrapped in darkness and fog.

[69] “Hermes then explained the nature of the place to Heracles as he led him thither. But when Heracles, ambitious youth that he was, longed to see what was within, he said, ‘Follow, then, that you may see with your own eyes the difference in all other respects also, things hidden from the foolish.’ [70] He therefore took him first to the loftier peak and showed him a woman seated upon a resplendent throne. She was beautiful and stately, clothed in white raiment, and held in her hand a sceptre, not of gold or silver, but of a different substance, pure and much brighter – a figure for all the world like the pictures of Hera. [71] Her countenance was at once radiant and full of dignity, so that all the good could behold it without fear, but no evil person could gaze upon it any more than a man with weak eyes can look up at the orb of the sun; composed and steadfast was her mien, and her glance did not waver. [72] A profound stillness and unbroken quiet pervaded the place; everywhere were fruits in abundance and thriving animals of every species. And immense heaps of gold and silver were there, and of bronze and iron; yet she heeded not at all the gold, nor did she take delight in it, but rather in the fruits and living creatures.

[73] “Now when Heracles beheld the woman, he was abashed and blushes mantled his cheeks, for he felt that respect and reverence for her which a good son feels for a noble mother. Then he asked Hermes which of the deities she was, and he replied, ‘Lo, that is the blessed Lady Royalty, child of King Zeus.’ And Heracles rejoiced and took courage in her presence. And again he asked about the women who were with her. ‘Who are they?’ said he; ‘how decorous and stately, like men in countenance!’ [74] ‘Behold,’ he replied, ‘she who sits there at her right hand, whose glance is both fierce and gentle, is Justice, aglow with a surpassing and resplendent beauty. Beside her sits Civic Order, who is very much like her and differs but slightly in appearance. [75] On the other side is a woman exceeding beautiful, daintily attired, and smiling benignly; they call her Peace. But he who stands near Royalty, just beside the sceptre and somewhat in front of it, a strong man, grey-haired and proud, has the name of Law; but he has also been called Right Reason, Counsellor, Coadjutor, without whom these women are not permitted to take any action or even to purpose one.’

[76] “With all that he heard and saw Heracles was delighted, and he paid close attention, determined never to forget it. But when they had come down from the higher peak and were at the entrance to Tyranny, Hermes said, ‘Look this way and behold the other woman. It is with her that the majority of men are infatuated and to win her they give themselves much trouble of every kind, committing murder, wretches that they are, son often conspiring against father, father against son, and brother against brother, since they covet and count as felicity that which is the greatest evil – power conjoined with folly.’ [77] He then began by showing Heracles the nature of the entrance, explaining that whereas only one pathway appeared to view, that being about as described above – perilous and skirting the very edge of the precipice – yet there were many unseen and hidden corridors, and that the entire region was undermined on every side and tunnelled, no doubt up to the very throne, and that all the passages and bypaths were smeared with blood and strewn with corpses. Through none, however, of these passages did Hermes lead him, but along the outside one that was less befouled, because, I think, Heracles was to be a mere observer.

[78] “When they entered, they discovered Tyranny seated aloft, of set purpose counterfeiting and making herself like to Royalty, but, as she imagined, on a far loftier and more splendid throne, since it was not only adorned with innumerable carvings, but embellished besides with inlaid patterns of gold, ivory, amber, ebony, and substances of every colour. Her throne, however, was not secure upon its foundation nor firmly settled, but shook and slouched upon its legs. [79] And in general things were in disorder, everything suggesting vainglory, ostentation, and luxury – many sceptres, many tiaras and diadems for the head. Furthermore, in her zeal to imitate the character of the other woman, instead of the friendly smile Tyranny wore a leer of false humility, and instead of a glance of dignity she had an ugly and forbidding scowl. [80] But in order to assume the appearance of pride, she would not glance at those whom came into her presence but looked over their heads disdainfully. And so everybody hated her, and she herself ignored everybody. She was unable to sit with composure, but would cast her eyes incessantly in every direction, frequently springing up from her throne. She hugged her gold to her bosom in a disgusting manner and then in terror would fling it from her in a heap, then she would forthwith snatch at whatever any passer-by might have, were it never so little. [81] Her raiment was of many colours, purple, scarlet and saffron, with patches of white, too, showing here and there from her skirts, since her cloak was torn in many places. From her countenance glowed all manners of colours according to whether she felt terror or anguish or suspicion or anger; while at one moment she seemed prostrate with grief, at another she appeared to be in an exaltation of joy. At one time a quite wanton smile would come over her face, but at the next moment she would be in tears. [82] There was also a throng of women about her, but they resembled in no respect those whom I have described as in attendance upon Royalty. These were Cruelty, Insolence, Lawlessness, and Faction, all of whom were bent upon corrupting her and bringing her to ignoble ruin. And instead of Friendship, Flattery was there, servile and avaricious and no less ready for treachery than any of the others, nay rather, zealous above all things to destroy.

[83] “Now when Heracles had viewed all this also to his heart’s content, Hermes asked him which of the two scenes pleased him and which of the two women. ‘Why, it is the other one,’ said he, ‘whom I admire and love, and she seems to me a veritable goddess, enviable and worthy to be accounted blest; this second woman, on the other hand, I consider so utterly odious and abominable that I would gladly thrust her down from this peak and thus put an end to her.’ Whereupon Hermes commended Heracles for this utterance and repeated it to Zeus, who entrusted him with the kingship over all mankind as he considered him equal to the trust. [84] And so wherever Heracles discovered a tyranny and a tyrant, he chastised and destroyed them, among Greeks and barbarians alike; but wherever he found a kingdom and a king, he would give honour and protection.”

This, she maintained, was what made him Deliverer of the earth and of the human race, not the fact that he defended them from the savage beasts – for how little damage could a lion or a wild bear inflict? – nay, it was the fact that he chastised savage and wicked men, and crushed and destroyed the power of overweening tyrants. And even to this day Heracles continues this work and you have in him a helper and protector of your government as long as it is vouchsafed you to reign.

THE SECOND DISCOURSE ON KINGSHIP

The second Discourse on Kingship is put dramatically in the form of a dialogue between Philip of Macedon and his son Alexander, and in it the son is Dio’s mouthpiece, in marked contrast to the situation in the fourth Discourse, where Diogenes – and therefore Dio – is opposed to Alexander. We are shown here the way in which the true king acts in the practical affairs of life, and the Stoic ideal, drawn largely from Homer, is set forth. Toward the end the true king is contrasted with the tyrant.

Although this Discourse is addressed to no one, von Arnim is led to conjecture from its martial tone that it was delivered before Trajan in A.D. 104 on the eve of the Second Dacian War.

The Second Discourse on Kingship

It is said that Alexander, while still a lad, was once conversing with Philip his father about Homer in a very manly and lofty strain, their conversation being in effect a discussion of kingship as well. For Alexander was already to be found with his father on his campaigns, although Philip tried to discourage him in this. Alexander, however, could not hold himself in, for it was with the lad as with young dogs of fine breed that cannot brook being left behind when their masters go hunting, but follow along, often breaking their tethers to do so. [2] It is true that sometimes, because of their youth and enthusiasm, they spoil the sport by barking and starting the game too soon, but sometimes too they bring down the game themselves by bounding ahead. This, in fact, happened to Alexander at the very beginning, so that they say he brought about the battle and victory of Chaeronea when his father shrank from taking the risk.

Now it was on this occasion, when they were at Dium in Pieria on their way home from the campaign and were sacrificing to the Muses and celebrating the Olympic festival, which is said to be an ancient institution in that country, [3] that Philip in the course of their conversation put this question to Alexander: “Why, my son, have you become so infatuated with Homer that you devote yourself to him alone of all the poets? You really ought not to neglect the others, for the men are wise.” And Alexander replied: “My reason, father, is that not all poetry, any more than every style of dress, is appropriate to a king, as it seems to me. [4] Now consider the poems of other men; some I consider to be suitable indeed for the banquet, or for love, or for the eulogy of victorious athletes or horses, or as dirges for the dead, and some as designed to excite laughter or ridicule, like the works of the comic writers and those of the Parian poet. [5] And perhaps some of them might be called popular also, in that they give advice and admonition to the masses and to private citizens, as, for instance, the works of Phocylides and Theognis do. What is there in them by which a man could profit, who, like you or me,

‘aspires to be

The master, over all to domineer.’

[6] The poetry of Homer, however, I look upon as alone truly noble and lofty and suited to a king, worthy of the attention of a real man, particularly if he expects to rule over all the peoples of the earth – or at any rate over most of them, and those the most prominent – if he is to be, in the strict sense of the term, what Homer calls a ‘shepherd of the people.’ Or would it not be absurd for a king to refuse to use any horse but the best and yet, when it is a question of poets, to read the poorer ones as though he had nothing else to do? [7] On my word, father, I not only cannot endure to hear any other poet recited but Homer, but even object to any other metre than Homer’s heroic hexameter.”

Then Philip admired his son greatly for his noble spirit, since it was plain that he harboured no unworthy or ignoble ideas but made the heroes and demigods his examples. [8] Nevertheless, in his desire to arouse him, he said, “But take Hesiod, Alexander; do you judge him of little account as a poet?” “Nay, not I,” he replied, “but of every account, though not for kings and generals, I suppose.” “Well, then, for whom?” And Alexander answered with a smile: “For shepherds, carpenters, and farmers; since he says that shepherds are beloved by the Muses, and to carpenters he gives very shrewd advice as to how large they should cut an axle, and to farmers, when to broach a cask.” [9] “Well,” said Philip, “and is not such advice useful to men?” “Not to you and me, father,” he replied, “nor to the Macedonians of the present day, though to those of former times it was useful, when they lived a slave’s life, herding and farming for Illyrians and Triballians.” “But do you not like these magnificent lines of Hesiod about seed-time and harvest?” said Philip:

“Mark well the time when the Pleiads, daughters of Atlas, are rising;

Then begin with the harvest, but do not plough till their setting.”

[10] “I much prefer what Homer says on farm-life,” said Alexander. “And where,” Philip asked, “has Homer anything to say about farming? Or do you refer to the representations on the shield of men ploughing and gathering the grain and the grapes?” “Not at all,” said Alexander, “but rather to these well-known lines:

‘As when two lines of reapers, face to face,

In some rich landlord’s field of barley or wheat

Move on, and fast the severed handfuls fall,

So, springing on each other, they of Troy

And they of Argos smote each other down,

And neither thought of ignominious flight.’

[11] “And yet, in spite of such lines as these,” said Philip, “Homer was defeated by Hesiod in the contest. Or have you not heard of the inscription which is inscribed upon the tripod that stands on Mount Helicon?

‘Hesiod offered this gift to the Muses on Helicon’s mountain

When at Chalcis in song he had vanquished Homer, the godlike.’”

[12] “And he richly deserved to be defeated,” rejoined Alexander, “for he was not exhibiting his skill before kings, but before farmers and plain folk, or, rather, before men who were lovers of pleasure and effeminate. And that is why Homer used his poetry to avenge himself upon the Euboeans.” “How so?” asked Philip in wonder. “He singled them out among all the Greeks for a most unseemly haircut, for he makes them wear their hair in long locks flowing down their backs, as the poets of to-day do in describing effeminate boys.”

[13] Philip laughed and said, “You observe, Alexander, that one must not offend good poets or clever writers, since they have the power to say anything they wish about us.” “Not absolute power,” said he; “it was a sorry day for Stesichorus, at any rate, when he told the lies about Helen. As for Hesiod, it seems to me that he himself, father, was not unaware of how much inferior his powers were to Homer’s.” [14] “How is that?” “Because, while Homer wrote of heroes, he composed a Catalogue of Fair Women, and in reality made the women’s quarters the subject of his song, yielding to Homer the eulogy of men.”

Philip next asked him: “But as for you, Alexander, would you like to have been Agamemnon or Achilles or any one of the heroes of those days, or Homer?” [15] “No, indeed, said Alexander, “but I should like to go far beyond Achilles and the others. For you are not inferior to Peleus, in my opinion; nor is Macedonia less powerful than Phthia; nor would I admit that Olympus is a less famous mountain than Pelion; and, besides, the education I have gained under Aristotle is not inferior to that which Achilles derived from Amyntor’s son, Phoenix, an exiled man and estranged from his father. Then, too, Achilles had to take orders from others and was sent with a small force of which he was not in sole command, since he was to share the expedition with another. I, however, could never submit to any mortal whatsoever being king over me.” [16] Whereupon Philip almost became angry with him and said: “But I am king and you are subject to me, Alexander.” “Not I,” said he, “for I hearken to you, not as king, but as father.” “I suppose you will not go on and say, will you, that your mother was a goddess, as Achilles did,” said Philip, “or do you presume to compare Olympias with Thetis?” At this Alexander smiled slightly and said, “To me, father, she seems more courageous than any Nereid.” [17] Whereupon Philip laughed and said, “Not merely more courageous, my son, but also more warlike; at least she never ceases making war on me.” So far did they both go in mingling jest with earnest.

Philip then went on with his questioning: “If, then, you are so enthusiastic an admirer of Homer, how is it that you do not aspire to his poetic skill?” “Because,” he replied, “while it would give me the greatest delight to hear the herald at Olympia proclaim the victors with strong and clear voice, yet I should not myself care to herald the victories of others; I should much rather hear my own proclaimed.” [18] With these words he tried to make it clear that while he considered Homer to be a marvellous and truly divine herald of valour, yet he regarded himself and the Homeric heroes as the athletes who strove in the contest of noble achievement. “Still, it would not be at all strange, father,” he continued, “if I were to be a good poet as well, did nature but favour me; for you know that a king might find that even rhetoric was valuable to him. You, for example, are often compelled to write and speak in opposition to Demosthenes, a very clever orator who can sway his audience – to say nothing of the other political leaders of Athens.” [19] “Yes,” said Philip playfully, “and I should have been glad to cede Amphipolis to the Athenians in exchange for that clever Demosthenes. But what do you think was Homer’s attitude regarding rhetoric?” “I believe that he admired the study, father,” said he, “else he would never have introduced Phoenix as a teacher of Achilles in the art of discourse. Phoenix, at any rate, says that he was sent by Achilles’ father,

‘To teach thee both, that so thou mightst become

In words an orator, in warlike deeds

A doer.’

[20] And as for the other chieftains, he depicted the best and the best qualified for kingly office as having cultivated this art with no less zeal: I mean Diomede, Odysseus, and particularly Nestor, who surpassed all the others in both discernment and persuasiveness. Witness what he says in the early part of his poem:

‘whose tongue

Dropped words more sweet than honey.’

[21] It was for this reason that Agamemnon prayed that he might have ten such elders as counsellors rather than youths like Ajax and Achilles, implying that the capture of Troy would thus be hastened. And, indeed, in another instance he showed the importance of rhetorical skill. [22] For when the Greeks had at last become faint-hearted in pursuing the campaign because the war had lasted so long and the siege was so difficult, and also, no doubt, because of the plague that laid hold of them and of the dissensions between the kings, Agamemnon and Achilles; and when, in addition, a certain agitator rose to oppose them and threw the assembly into confusion – at this crisis the host rushed to the ships, embarked in hot haste, and were minded to flee. Nobody was able to restrain them, and even Agamemnon knew not how to handle the situation. [23] Now in this emergency the only one who was able to call them back and change their purpose was Odysseus, who finally, by the speech he made, and with the help of Nestor, persuaded them to remain. Consequently, this achievement was clearly due to the orators; and one could point to many other instances as well. [24] It is evident, then, that not only Homer but Hesiod, too, held this view, implying that rhetoric in the true meaning of the term, as well as philosophy, is a proper study for the king; for the latter says of Calliope,

‘She attendeth on kings august that the daughters of great Zeus

Honour and watch at their birth, those kings that of Zeus are nurtured.’

[25] But to write epic poetry, or to compose pieces in prose like those letters of yours, father, which are said to have won you high repute, is not altogether essential for a king, except indeed when he is young and has leisure, as was the case with you when, as they say, you diligently cultivated rhetorical studies in Thebes. [26] Nor, again, is it necessary that he study philosophy to the point of perfecting himself in it; he need only live simply and without affectation, to give proof by his very conduct of a character that is humane, gentle, just, lofty, and brave as well, and, above all, one that takes delight in bestowing benefits – a trait which approaches most nearly to the nature divine. He should, indeed, lend a willing ear to the teachings of philosophy whenever opportunity offers, inasmuch as these are manifestly not opposed to his own character but in accord with it; [27] yet I should especially counsel the noble ruler of princely soul to make poetry his delight and to read it attentively – not all poetry, however, but only the most beautiful and majestic, such as we know Homer’s alone to be, and of Hesiod’s the portions akin to Homer’s, and perhaps sundry edifying passages in other poets.”

[28] “And so, too, with music,” continued Alexander; “for I should not be willing to learn all there is in music, but only enough for playing the cithara or the lyre when I sing hymns in honour of the gods and worship them, and also, I suppose, in chanting the praises of brave men. It would surely not be becoming for kings to sing the odes of Sappho or Anacreon, whose theme is love; but if they do sing odes, let it be some of those of Stesichorus or Pindar, if sing they must. [29] But perhaps Homer is all one needs even to that end.” “What!” exclaimed Philip, “do you think that any of Homer’s lines would sound well with the cithara or the lyre?” And Alexander, glaring at him fiercely like a lion, said: “For my part, father, I believe that many of Homer’s lines would properly be sung to the trumpet – not, by heavens, when it sounds the retreat, but when it peals forth the signal for the charge, and sung by no chorus of women or maids, but by a phalanx under arms. They are much to be preferred to the songs of Tyrtaeus, which the Spartans use.” [30] At this Philip commended his son for having spoken worthily of the poet and well. “And indeed,” Alexander continued, “Homer illustrates the very point we have just mentioned. He has represented Achilles, for instance, when he was loitering in the camp of the Achaeans, as singing no ribald or even amorous ditties – though he says, to be sure, that he was in love with Briseis; nay, he speaks of him as playing the cithara, and not one that he had bought, I assure you, or brought from his father’s house, but one that he had plucked from the spoils when he took Thebe and slew Eëtion, the father of Hector’s wife. Homer’s words are:

[31] ‘To sooth his mood he sang

The deeds of heroes.’

Which means that a noble and princely man should never forget valour and glorious deeds whether he be drinking or singing, but should without ceasing be engaged in some great and some admirable action himself, or in recalling deeds of that kind.”

[32] In this fashion Alexander would talk with his father, thereby revealing his innermost thoughts. The fact is that while he loved Homer, for Achilles he felt not only admiration but even jealousy because of Homer’s poesy, just as handsome boys are sometimes jealous of others who are handsome, because these have more powerful lovers. To the other poets he gave hardly a thought; but he did mention [33] Stesichorus and Pindar, the former because he was looked upon as an imitator of Homer and composed a “Capture of Troy,” a creditable work, and Pindar because of the brilliancy of his genius and the fact that he had extolled the ancestor whose name he bore: Alexander, nicknamed the Philhellene, to whom the poet alluded in the verse

“Namesake of the blest sons of Dardanus.”

This is the reason why, when later he sacked Thebes, he left only that poet’s house standing, directing that this notice be posted upon it:

“Set not on fire the roof of Pindar, maker of song.”

Undoubtedly he was most grateful to those who eulogized him worthily, when he was so particular as this in seeking renown.

[34] “Well, then, my son,” said Philip, “since I am glad indeed to hear you speak in this fashion, tell me, is it your opinion that the king should not even make himself a dwelling beautified with precious ornaments of gold and amber and ivory to suit his pleasure?” “By no means should he, father,” he replied; “such ornaments should consist rather of spoils and armour taken from the enemy. He should also embellish the temples with such ornaments and thus propitiate the gods. This was Hector’s opinion when he challenged the best of the Achaeans, declaring that if victorious he would deliver the body to the allied host, ‘but the arms,’ said he, ‘I shall strip off and

‘hang them high

Within the temple of the archer-god Apollo.’

[35] For such adornment of sacred places is altogether superior to jasper, carnelian, and onyx, with which Sardanapallus bedecked Nineveh. Indeed, such ostentation is by no means seemly for a king though it may furnish amusement to some silly girl or extravagant woman. [36] And so I do not envy the Athenians, either, so much for the extravagant way they embellished their city and their temples as for the deeds their forefathers wrought; for in the sword of Mardonius and the shields of the Spartans who were captured at Pylos they have a far grander and more excellent dedication to the gods than they have in the Propylaea of the Acropolis and in Olympieum, which cost more than ten thousand talents.” [37] “In this particular, then,” said Philip, “you could not endorse Homer; for he has embellished the palace of Alcinoüs, a Greek and an islander, not only with gardens and orchards and fountains, but with statues of gold also. Nay, more, does he not describe the dwelling of Menelaus, for all that he had just got back from a campaign, as though it were some Persian or Median establishment, almost equalling the palaces of Semiramis, or of Darius and Xerxes? [38] He says, for instance:

‘A radiance bright, as of the sun or moon.

Throughout the high-roofed halls of Atreus’ son

Did shine.’

‘The sheen of bronze,

Of gold, of silver, and of ivory.’

[39] And yet, according to your conception, it should have shone, not with such materials, but rather with Trojan spoils!” Here Alexander checked him and said, “I have no notion at all of letting Homer go undefended. For it is possible that he described the palace of Menelaus to accord with his character, since he is the only one of the Achaeans whom he makes out to be a faint-hearted warrior. [40] Indeed it is fairly clear that this poet never elsewhere speaks without a purpose, but repeatedly depicts the dress, dwelling, and manner of life of people so as to accord with their character. This is why he beautified the palace of the Phaeacians with groves, perennial fruits, and ever-flowing springs; [41] and again, with even greater skill, the grotto of Calypso, since she was a beautiful and kindly goddess living off by herself on an island. For he says that the island was wonderfully fragrant with the odours of sweetest incense burning there; and again, that it was overshadowed with luxuriant trees; that round about the grotto rambled a beautiful vine laden with clusters, while before it lay soft meadows with a confusion of parsley and other plants; and, finally, that in its centre were four springs of crystal-clear water which flowed out in all directions, seeing that the ground was not on a slope or uneven. Now all these touches are marvellously suggestive of love and pleasure, and to my thinking reveal the character of the goddess. [42] The court of Menelaus, however, he depicts as rich in possessions and rich in gold, as though he were some Asiatic king, it seems to me. And, in fact, Menelaus was not far removed in line of descent from Tantalus and Pelops; which I think is the reason why Euripides has his chorus make a veiled allusion to his effeminacy when the king comes in:

‘And Menelaus,

By his daintiness so clear to behold,

Sprung from the Tantalid stock.’

[43] The dwelling of Odysseus, however, is of a different kind altogether; he being a cautious man, Homer has given him a home furnished to suit his character. For he says:

‘Rooms upon rooms are there: around its court

Are walls and battlements, and folding doors

Shut fast the entrance; no man may contemn

Its strength.’

[44] “But there are passages where we must understand the poet to be giving advice and admonition, others where he merely narrates, and many where his purpose is censure and ridicule. Certainly, when he describes going to bed or the routine of daily life, Homer seems a competent instructor for an education that may truthfully be described as heroic and kingly. Lycurgus, for instance, may have got from him his idea of the common mess of the Spartans when he founded their institutions. [45] In fact, the story is that he came to be an admirer of Homer and was the first who brought his poems from Crete, or from Ionia, to Greece. To illustrate my point: the poet represents Diomede as reclining on a hard bed, the ‘hide of an ox that dwelleth afield’; round about him he had planted his spears upright, butts downward, not for the sake of order but to have them ready for use. Furthermore, he regales his heroes on meat, and beef at that, evidently to give them strength, not pleasure. [46] For instance, he is always talking about an ox being slain by Agamemnon, who was king over all and the richest, and of his inviting the chieftains to enjoy it. And to Ajax, after his victory, Agamemnon gives the chine of an ox as a mark of favour. [47] But Homer never represents his heroes as partaking of fish although they are encamped by the sea; and yet he regularly calls the Hellespont fish-abounding, as in truth it is; Plato has very properly called attention to this striking fact. Nay, he does not even serve fish to the suitors at their banquet though they are exceedingly licentious and luxury-loving men, are in Ithaca and, what is more, engaged in feasting. [48] Now because Homer does not give such details without a purpose, he is evidently declaring his own opinion as to what kind of nourishment is best, and what it is good for. If he wishes to commend a feature, he uses the expression ‘might-giving,’ that is to say, ‘able to supply might’ or strength. In the passages in question he is giving instruction and advice as to how good men should take thought even for their table, since, as it happened, he was not unacquainted with food of all kinds and with high living. So true is this that the peoples of to-day who have fairly gone mad in this direction – the Persians, Syrians and, among the Greeks, the Italiots, and Ionians – come nowhere near attaining the prodigality and luxury we find in Homer.”

[49] “But how is it that he does not give the finest possible apparel to his heroes?” Philip enquired. “Why, by Zeus, he does,” replied all, “though it is no womanish or embroidered apparel; Agamemnon is the only one that wears a purple robe, and even Odysseus has but one purple cloak that he brought from home. For Homer believes that a commander should not be mean of appearance or look like the crowd of private soldiers, but should stand out from the rest in both garb and armour so as to show his greater importance and dignity, yet without being a fop or fastidious about such things. [50] He roundly rebuked the Carian, for instance, who decked himself out for war in trappings of gold. These are his words:

‘who, madly vain,

Went to the battle pranked like a young girl

In golden ornaments. They spared him not

The bitter doom of death; he fell beneath

The hand of swift Aeacides within

The river’s channel. There the great in war,

Achilles, spoiled Nomion of his gold.’

[51] Thus he ridicules him for his folly as well as his vanity in that he practically carried to the foemen a prize for slaying him. Homer, therefore, clearly does not approve the wearing of gold, particularly on going into a battle, whether bracelets and necklaces or even such golden head-gear and bridles for one’s horses as the Persians are said to affect; for they have no Homer to be their censor in affairs of war.

[52] “By inculcating such conduct as the following, he has made his officers good and his soldiers well disciplined. For instance, he has them advance

‘silently, fearing their leaders’

whereas the barbarians advance with great noise and confusion, like cranes, thus showing that it is important for safety and victory in battle that the soldiers stand in awe of their commanders. For those who are without fear of their own officers would be the first to be afraid of the enemy. [53] Furthermore, he says that even when they had won a victory the Achaeans kept quiet in their camp, but that among the Trojans, as soon as they thought they had gained any advantage, at once there were throughout the night

‘the sound

Of flutes and fifes, and tumult of the crowd.’

implying that here also we have an excellent indication of virtue according as men bear their successes with self-restraint, or, on the contrary, with reckless abandon. [54] And so to me, father, Homer seems a most excellent disciplinarian, and he who tries to give heed to him will be a highly successful and exemplary king. For he clearly takes for granted himself that pre-eminently kingly virtues are two – courage and justice. Mark what he says,

‘An excellent king and warrior mighty withal.’

as though all the other virtues followed in their train.

[55] “However, I do not believe that the king should simply be distinguished in his own person for courage and dignity, but that he should pay no heed to other people either when they play the flute or the harp, or sing wanton and voluptuous songs; nor should he tolerate the mischievous craze for filthy language that has come into vogue for the delight of fools; [56] nay, he should cast out all such things and banish them to the uttermost distance from his own soul, first and foremost, and then from the capital of his kingdom – I mean such things as ribald jests and those who compose them, whether in verse or prose, along with scurrilous gibes – then, in addition, he should do away with indecent dancing and the lascivious posturing of women in licentious dances as well as the shrill and riotous measures played on the flute, syncopated music full of discordant turns, and motley combinations of noisy clanging instruments. [57] One song only will he sing or permit to be sung – the song that comports with the God of War, full of vigour, ringing clear, and stirring in the hearer no feeling of delight or languidness, but rather an overpowering fear and tumult; in short, such a song as Ares himself awoke, as he

‘shrilly yelled, encouraging

The men of Troy, as on the city heights

He stood.’

or as Achilles when, at the mere sound of his voice and before he could be seen, he turned the Trojans to flight and thus caused the destruction of twelve heroes midst their own chariots and arms. [58] Or it might be like the triumphal song composed by the Muses for the celebration of victory, like the paean which Achilles bade the Achaeans chant as he brought Hector’s body to the ships, he himself leading:

‘Now then, ye Achaean youth, move on and chant

A paean, while, returning to the fleet,

We bring great glory with us; we have slain

The noble Hector, whom, throughout their town,

The Trojans ever worshipped like a god.’

[59] Or, finally, it might be the exhortations to battle such as we find in the Spartan marching songs, its sentiments comporting well with the polity of Lycurgus and the Spartan institutions:

‘Up, ye sons of Sparta,

Rich in citizen fathers;

Thrust with the left your shields forth,

Brandish bravely your spears;

Spare not your lives.

That’s not custom in Sparta.’

[60] “In conformity with these songs, our king should institute dance movements and measures that are not marked by reeling or violent motions, but are as virile and sober as may be, composed in a sedate rhythm; the dance should be the ‘enoplic,’ the execution of which is not only a tribute to the gods but a drill in warfare as well – the dance in which the poet says Meriones was skilful, for he has put these words into the mouth of a certain Trojan:

‘Had I but struck thee, dancer though thou art,

Meriones, my spear had once for all

Ended thy dancing.’

[61] Or do you think that he can have meant that some other dance was known to the son of Molus, who was accounted one of the best of the Achaeans, and not the military dance of the Kouretes, a native Cretan dance, the quick and light movement designed to train the soldiers to swerve to one side and easily avoid the missile? [62] From these considerations, moreover, it follows that the king should not offer such prayers as other men do nor, on the other hand, call upon the gods with such a petition as Anacreon, the Ionian poet, makes:

‘O King with whom resistless love

Disports, and nymphs with eyes so dark,

And Aphrodite, fair of hue,

O thou who rangest mountain crests,

Thee do I beseech, do thou

To me propitious come and hear

With kindly heart the prayer I make:

Cleobulus’ confessor be

And this love of mine approve,

O Dionysus.’

[63] Nor, by heavens, should he ever utter such prayers as those we find in the ballads and drinking-songs of the Attic symposia, for these are suitable, not for kings, but for country folk and for the merry and boisterous clan-meetings. For instance,

‘Would that I became a lovely ivory harp,

And some lovely children carried me to Dionysus’ choir!

Would that I became a lovely massive golden trinket,

And that me a lovely lady wore!’

[64] He would much better pray as Homer has represented the king of all the Greeks as praying:

‘O Zeus, most great and glorious, who dost rule

The tempest – dweller of the ethereal space!

Let not the sun go down and night come on

Ere I shall lay the halls of Priam waste

With fire, and give their portals to the flames,

And hew away the coat of mail that shields

The breast of Hector, splitting it with steel.

And may his fellow-warriors, many a one,

Fall round him to the earth and bite the dust.’

[65] “There are many other lessons and teachings in Homer, which might be cited, that make for courage and the other qualities of a king, but perhaps their recital would require more time than we now have. I will say, however, that he not only expresses his own judgment clearly in every instance – that in his belief the king should be the superior of all men – but particularly in the case of Agamemnon, in the passage where for the first time he sets the army in array, calls the roll of the leaders, and gives the tale of the ships. [66] In that scene the poet has left no room for any other hero even to vie with Agamemnon; but as far as the bull surpasses the herd in strength and size, so far does the king excel the rest, as Homer says in these words:

‘And as a bull amid the horned herd

Stands eminent and nobler than the rest,

So Zeus to Agamemnon on that day

Gave to surpass in manly port and mien

The heroes all.’

[67] This comparison was not carelessly chosen, so it seems to me, merely in order to praise the hero’s strength and in the desire to demonstrate it. In that case it seems that he would surely have chosen the lion for his simile and thus have made an excellent characterization. No, his idea was to indicate the gentleness of his nature and his concern for his subjects. For the bull is not merely one of the nobler animals; nor does it use its strength for its own sake, like the lion, the boar, and the eagle, which pursue other creatures and master them for their own bellies’ sake. (For this reason one might in truth say that these animals have come to be symbols of tyranny rather than of kingship.) [68] But clearly, in my opinion, the bull has been used by the poet to betoken the kingly office and to portray a king. For the bull’s food is ready to hand, and his sustenance he gets by grazing, so that he never needs to employ violence or rapacity on that score; but he, like affluent kings, has all the necessaries of life, unstinted and abundant. [69] He exercises the authority of a king over his fellows of the herd with good-will, one might say, and solicitude, now leading the way to pasture, now, when a wild beast appears, not fleeing but fighting in front of the whole herd and bringing aid to the weak in his desire to save the dependent multitude from dangerous wild beasts; just as is the duty of the ruler who is a real king and not unworthy of the highest honour known among men. [70] Sometimes, it is true, when another herd appears upon the scene, he engages its leader and strives for victory so that all may acknowledge his superiority and the superiority of his herd. Consider, again, the fact that the bull never makes war against man, but, notwithstanding that nature has made him of all unreasoning animals the best and best fitted to have dominion, he nevertheless accepts the dominion of his superior; and although he acknowledges his inferiority to none as regards strength, spirit, and might, yet he willingly subordinates himself to reason and intelligence. Why should we not count this a training and lesson in kingship for prudent kings, [71] to teach them that while a king must rule over men, his own kind, because he is manifestly their superior, who justly and by nature’s design exercises dominion over them; and while he must save the multitude of his subjects, planning for them and, if need be, fighting for them and protecting them from savage and lawless tyrants, and as regards other kings, if any such there should be, must strive with them in rivalry of goodness, seeking if possible to prevail over them for the benefit of mankind at large; [72] yet the gods, who are his superiors, he must follow, as being, I verily believe, good herdsmen, and must give full honour to their superior and more blessed natures, recognizing in them his own masters and rulers and showing that the most precious possession which God, the greatest and highest king, can have is, first himself and then those who have beenº appointed to be his subjects?

[73] “Now we know how wise herdsmen deal with a bull. When he becomes savage and hard to handle, and rules outrageously in violation of the law of nature, when he treats his own herd with contempt and harms it, but gives ground before outsiders who plot against it and shields himself behind the helpless multitude, yet, when there is no peril at hand, waxes overbearing and insolent, now bellowing loudly in a menacing way, now goring with levelled horns any who cannot resist, thus making show of his strength upon the weaker who will not fight, while at the same time he will not permit the multitude of the cattle to graze in peace because of the consternation and panic he inspires – when the owners and the herdsmen, I say, have such a bull, they depose and kill him as not being fit to lead the herd nor salutary to it. [74] That bull, on the other hand, which is gentle towards the kine of his following, but valiant and fearless towards wild beasts, that is stately, proud, and competent to protect his herd and be its leader, while yet submissive and obedient to the herdsmen – him they leave in charge til extreme old age, even after he becomes too heavy of body. [75] In like manner do the gods act, and especially the great King of Kings, Zeus, who is the common protector and father of men and gods. If any man proves himself a violent, unjust and lawless ruler, visiting his strength, not upon the enemy, but upon his subjects and friends; if he is insatiate of pleasures, insatiate of wealth, quick to suspect, implacable in anger, keen for slander, deaf to reason, knavish, treacherous, degraded, wilful, exalting the wicked, envious of his superiors, too stupid for education, regarding no man as friend nor having one, as though such a possession were beneath him, – [76] such a one Zeus thrusts aside and deposes as unworthy to be king or to participate in his own honour and titles, putting upon him shame and derision, as methinks he did with Phalaris and Apollodorus and many others like them. [77] But the brave and humane king, who is kindly towards his subjects and, while honouring virtue and striving that he shall not be esteemed as inferior to any good man therein, yet forces the unrighteous to mend their ways and lends a helping hand to the weak – such a king Zeus admires for his virtue and, as a rule, brings to old age, as, for instance, according to tradition, Cyrus and Deïoces the Mede, Idanthyrsus the Scythian, Leucon, many of the Spartan kings, and some of the earlier kings of Egypt. [78] But if the inevitable decree of fate snatches him away before reaching old age, yet Zeus vouchsafes unto him a goodly renown and praise among all men for ever and ever, as indeed,” concluded Alexander, “he honoured our own ancestor, who, because of his virtue, was considered the son of Zeus – I mean Heracles.”

[79] Now when Philip heard all this, he was delighted and said, “Alexander, it wasn’t for naught that we esteemed Aristotle so highly, and permitted him to rebuild his home-town Stagira, which is in the domain of Olynthus. He is a man who merits many large gifts, if such are the lessons which he gives you in government and the duties of a king, be it as interpreter of Homer or in any other way.”

THE THIRD DISCOURSE ON KINGSHIP

Dio’s protest in this Discourse that he is not flattering would seem to indicate clearly that he is addressing Trajan – otherwise his words would be meaningless – and many of the things said point to the existence of very cordial relations between the orator and that emperor. Hence it is inferred that the third Discourse is later than the first. Von Arnim suggests that it was delivered before Trajan on his birthday, September 18th, in A.D. 104.

Stoic and Cynic doctrine as to the nature of the true king is set forth. The reference to the sun is of Stoic origin. Then Trajan, the type of the true king, is contrasted with the Persian king to the latter’s disadvantage.

The Third Discourse on Kingship

When Socrates, who, as you also know by tradition, lived many years ago, was passing his old age in poverty at Athens, he was asked by someone whether he considered the Persian king a happy man, and replied, “Perhaps so”; but he added that he did not really know, since he had never met him and had no knowledge of his character, implying, no doubt, that a man’s happiness is not determined by any external possessions, such as gold plate, cities or lands, for example, or other human beings, but in each case by his own self and his own character.

[2] Now Socrates thought that because he did not know the Persian king’s inner life, he did not know his state of happiness either. I, however, most noble Prince, have been in your company and am perhaps as well acquainted with your character as anyone, and know that you delight in truth and frankness rather than in flattery and guile. [3] To begin with, you suspect irrational pleasures just as you do flattering men, and you endure hardship because you believe that it puts virtue to the test. And when I see you, O Prince, perusing the works of the ancients and comprehending their wise and close reasoning, I maintain that you are clearly a blessed man in that you wield a power second only to that of the gods and nevertheless use that power most nobly. [4] For the man who may taste of everything that is sweet and avoid everything that is bitter, who may pass his life in the utmost ease, who, in a word, may follow his own sweet will, not only without let or hindrance but with the approval of all – [5] when that man, I say, is at once a judge more observant of the law than an empanelled jury, a king of greater equity than the responsible magistrates in our cities, a general more courageous than the soldiers in the ranks, a man more assiduous in all his tasks than those who are forced to work, less covetous of luxury than those who have no means to indulge in luxury, kindlier to his subjects than a loving father to his children, more dreaded by his enemies than are the invincible and irresistible gods – how can one deny that such a man’s fortune is a blessing, not to himself alone, but to all others as well?