автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Story of Sir Launcelot and His Companions

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Story of Sir Launcelot and His

Companions, by Howard Pyle

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The Story of Sir Launcelot and His Companions

Author: Howard Pyle

Release Date: September 10, 2010 [EBook #33702]

Language: English

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE STORY OF SIR LAUNCELOT ***

Produced by Sharon Verougstraete, Suzanne Shell and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The Story of Sir LAUNCELOT and his Companions by HOWARD PYLE.

NEW YORK: Dover Publications, Inc.

Published in Canada by General Publishing Company, Ltd., 30 Lesmill Road, Don Mills, Toronto, Ontario.

Published in the United Kingdom by Constable and Company, Ltd., 3 The Lanchesters, 162-164 Fulham Palace Road, London W6 9ER.

This Dover edition, first published in 1991, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, in 1907.

Manufactured in the United States of America. Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N. Y. 11501

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pyle, Howard, 1853-1911.

The story of Sir Launcelot and his companions / by Howard Pyle.

p. cm.

Reprint. Originally published: New York: Scribner, 1907.

Summary: Follows Sir Launcelot of the Round Table as he rescues Queen Guinevere, fights in the tournament at Astolat, and pursues other adventures.

ISBN 0-486-26701-6

1. Lancelot (Legendary character)—Romances. 2. Arthurian romances. [1. Lancelot (Legendary character) 2. Knights and knighthood—Folklore. 3. Arthur, King. 4. Folklore—England.] 1. Title.

PZ8.1.P994Sr 1991

843'.1—dc20

[398.2] 90-22326

CIP

AC

With this begins the third of those books which I have set myself to write concerning the history of King Arthur of Britain and of those puissant knights who were of his Court and of his Round Table.

In the Book which was written before this book you may there read the Story of that very noble and worthy knight, Sir Launcelot of the Lake; of how he dwelt within a magic lake which was the enchanted habitation of the Lady Nymue of the Lake; of how he was there trained in all the most excellent arts of chivalry by Sir Pellias, the Gentle Knight—whilom a companion of the Round Table, but afterward the Lord of the Lake; of how he came forth out of the Lake and became after that the chiefest knight of the Round Table of King Arthur. All of this was told in that book and many other things concerning Sir Launcelot and several other worthies who were Companions of the Round Table and who were very noble and excellent knights both in battle and in court.

So here followeth a further history of Sir Launcelot of the Lake and the narrative of several of the notable adventures that he performed at this time of his life.

Wherefore if it will please you to read that which is hereinafter set forth, you will be told of how Sir Launcelot slew the great Worm of Corbin; of the madness that afterward fell upon him, and of how a most noble, gentle, and beautiful lady, hight the Lady Elaine the Fair, lent him aid and succor at a time of utmost affliction to him, and so brought him back to health again. And you may herein further find it told how Sir Launcelot was afterward wedded to that fair and gentle dame, and of how was born of that couple a child of whom it was prophesied by Merlin (in a certain miraculous manner fully set forth in this book) that he should become the most perfect knight that ever lived and he who should bring back the Holy Grail to the Earth.

For that child was Galahad whom the world knoweth to be the flower of all chivalry; a knight altogether without fear or reproach of any kind, yet, withal, the most glorious and puissant knight-champion who ever lived.

So if the perusal of these things may give you pleasure, I pray you to read that which followeth, for in this book all these and several other histories are set forth in full.

PART I

THE CHEVALIER OF THE CART

Chapter First

How Denneys Found Sir Launcelot, and How Sir Launcelot Rode Forth for to Rescue Queen Guinevere From the Castle of Sir Mellegrans, and of What Befell Him Upon the Assaying of that Adventure 11

Chapter Second

How Sir Launcelot Rode in a Cart to Rescue Queen Guinevere and How He Came in that Way to the Castle of Sir Mellegrans 19

Chapter Third

How Sir Launcelot was Rescued From the Pit and How He Overcame Sir Mellegrans and Set Free the Queen and Her Court From the Duress They Were in 29

PART II

THE STORY OF SIR GARETH OF ORKNEY

Chapter First

How Gareth of Orkney Came to the Castle of Kynkennedon Where King Arthur was Holding Court, and How it Fared With Him at that Place 39

Chapter Second

How Gareth set Forth Upon an Adventure with a Young Damsel Hight Lynette; how he Fought with Sir Kay, and How Sir Launcelot Made him a Knight. Also in this it is Told of Several Other Happenings that Befell Gareth, Called Beaumains, at this Time 49

Chapter Third

How Sir Gareth and Lynette Travelled Farther Upon Their way; how Sir Gareth Won the Pass of the River against Two Strong Knights, and How he Overcame the Black Knight of the Black Lands. Also How He Saved a Good Worthy Knight From Six Thieves who Held Him in Duress 63

Chapter Fourth

How Sir Gareth Met Sir Percevant of Hind, and How He Came to Castle Dangerous and Had Speech with the Lady Layonnesse. Also How the Lady Layonnesse Accepted Him for Her Champion 77

Chapter Fifth

How Sir Gareth Fought with the Red Knight of the Red Lands and How it Fared with Him in that Battle. Also How His Dwarf was Stolen, and How His Name and Estate Became Known and Were Made Manifest 91

PART III

THE STORY OF SIR LAUNCELOT AND ELAINE THE FAIR

Chapter First

How Sir Launcelot Rode Errant and How He Assumed to Undertake the Adventure of the Worm of Corbin 107

Chapter Second

How Sir Launcelot Slew the Worm of Corbin, and How He was Carried Thereafter to the Castle of Corbin and to King Pelles and to the Lady Elaine the Fair 117

Chapter Third

How King Arthur Proclaimed a Tournament at Astolat, and How King Pelles of Corbin Went With His Court Thither to that Place. Also How Sir Launcelot and Sir Lavaine had Encounter with two Knights in the Highway Thitherward 125

Chapter Fourth

How Sir Launcelot and Sir Lavaine Fought in the Tournament at Astolat. How Sir Launcelot was Wounded in that Affair, and How Sir Lavaine Brought Him Unto a Place of Safety 137

Chapter Fifth

How Sir Launcelot Escaped Wounded into the Forest, and How Sir Gawaine Discovered to the Court of King Pelles who was le Chevalier Malfait 147

Chapter Sixth

How the Lady Elaine Went to Seek Sir Launcelot and How Sir Launcelot Afterwards Returned to the Court of King Arthur 159

PART IV

THE MADNESS OF SIR LAUNCELOT

Chapter First

How Sir Launcelot Became a Madman of the Forest and How He Was Brought to the Castle of Sir Blyant 171

Chapter Second

How Sir Launcelot Saved the Life of Sir Blyant. How He Escaped From the Castle of Sir Blyant, and How He Slew the Great Wild Boar of Lystenesse and Saved the Life of King Arthur, His Liege Lord 181

Chapter Third

How Sir Launcelot Returned to Corbin Again and How the Lady Elaine the Fair Cherished Him and Brought Him Back to Health. Also How Sir Launcelot with the Lady Elaine Withdrew to Joyous Isle 191

PART V

THE STORY OF SIR EWAINE AND THE LADY OF THE FOUNTAIN

Chapter First

How Sir Ewaine and Sir Percival Departed Together in Quest of Sir Launcelot, and How They Met Sir Sagramore, Who Had Failed in a Certain Adventure. Also How Sir Sagramore Told His Story Concerning That Adventure 201

Chapter Second

How Sir Ewaine Undertook That Adventure in Which Sir Sagramore Had Failed, and How it Sped with Him Thereafter 213

Chapter Third

How a Damsel, Hight Elose, Who Was in Service With the Lady Lesolie of the Fountain, Brought Succor to Sir Ewaine in His Captivity 223

Chapter Fourth

How Sir Ewaine Returned to the Court of King Arthur, and How he Forgot the Lady Lesolie and His Duty to the Fountain 237

Chapter Fifth

How Sir Ewaine was Succored and Brought Back to Life by a Certain Noble Lady, How He Brought Aid to that Lady in a Time of Great Trouble, and How He Returned Once Again to the Lady Lesolie of the Fountain 249

PART VI

THE RETURN OF SIR LAUNCELOT

Chapter First

How Sir Percival Met His Brother, and How They Two Journeyed to the Priory where their Mother Dwelt and What Befell Them Thereafter 263

Chapter Second

How Sir Percival and Sir Ector de Maris Came to a Very Wonderful Place Where was a Castle in the Midst of a Lake 279

Chapter Third

How Sir Launcelot and Sir Percival and Sir Ector and the Lady Elaine Progressed to the Court of King Arthur, and How a Very Good Adventure Befell Them Upon Their Way 293

PART VII

THE NATIVITY OF GALAHAD

Chapter First

How Sir Bors de Ganis and Sir Gawaine Went Forth in Search of Sir Launcelot. How They Parted Company, and What Befell Sir Gawaine Thereafter 311

Chapter Second

How Sir Bors and Sir Gawaine Came to a Priory in the Forest, and How Galahad Was Born at That Place 325

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

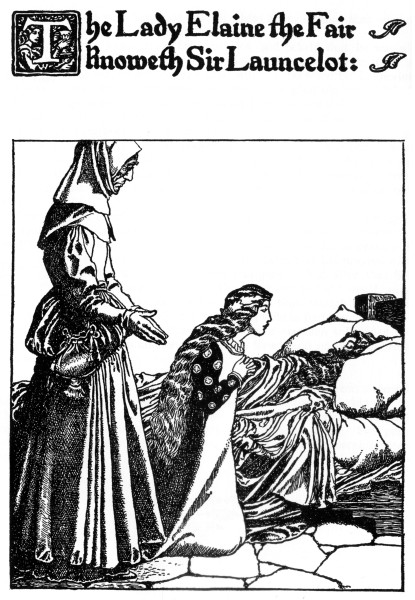

The Lady Elaine the FairFrontispiece

PAGE

Head Piece—Table of Contentsv

Tail Piece—Table of Contentsx

Head Piece—List of Illustrationsxi

Tail Piece—List of Illustrationsxii

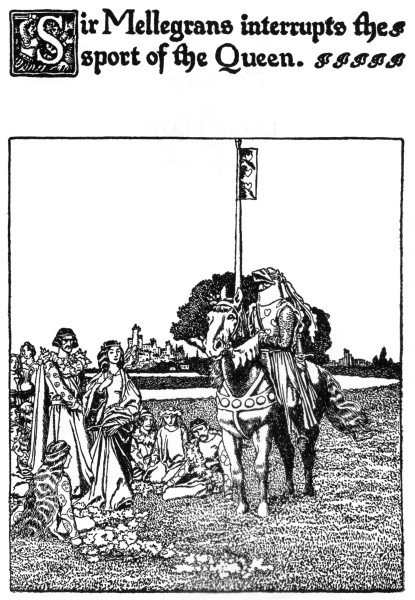

Sir Mellegrans interrupts the sport of the Queen2

Head Piece—Prologue3

Tail Piece—Prologue8

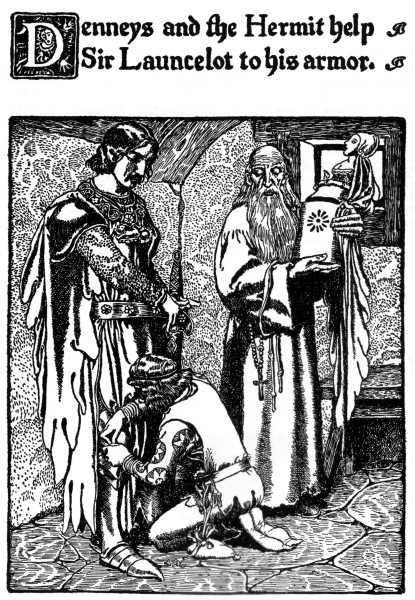

Denneys and the Hermit help Sir Launcelot to his Armor10

Head Piece11

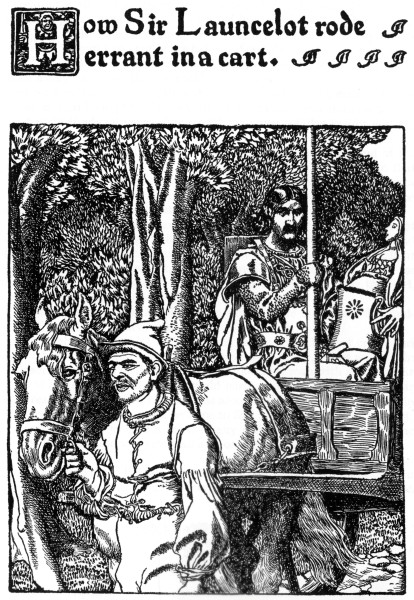

How Sir Launcelot rode errant in a cart18

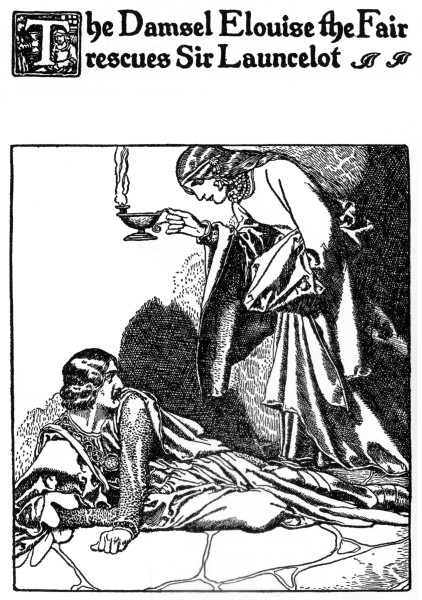

The Damsel Elouise the Fair rescues Sir Launcelot28

Sir Gareth of Orkney38

Head Piece39

The Damsel Lynette48

Sir Gareth doeth Battle with the Knight of the River Ford62

The Lady Layonnesse76

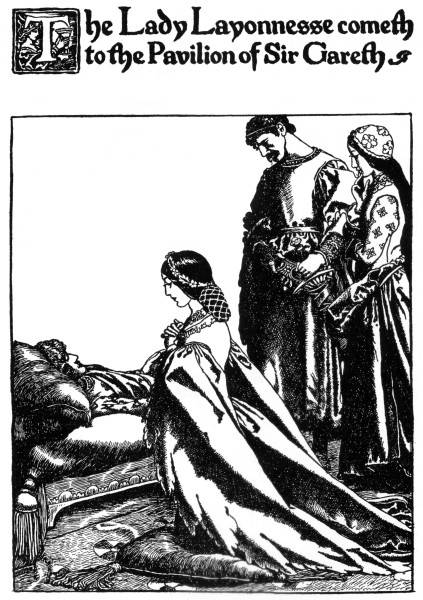

The Lady Layonnesse cometh to the Pavilion of Sir Gareth90

Tail Piece104

How Sir Launcelot held discourse with ye Merry Minstrels106

Head Piece107

Sir Launcelot slayeth the Worm of Corbin116

Sir Launcelot confideth his Shield to Elaine the Fair124

Sir Launcelot and Sir Lavaine overlook the Field of Astolat136

Sir Gawaine knoweth the shield of Sir Launcelot146

Sir Launcelot leapeth from the window158

Tail Piece168

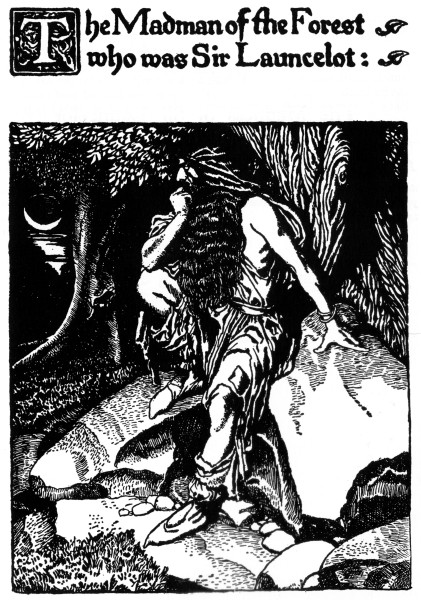

The Madman of the Forest who was Sir Launcelot170

Head Piece171

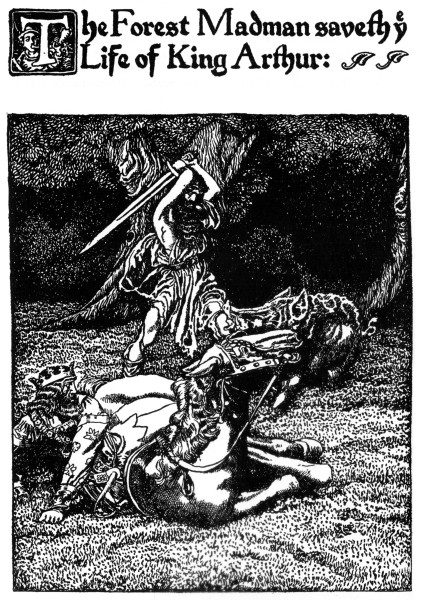

The Forest Madman saveth ye Life of King Arthur180

Tail Piece188

The Lady Elaine the Fair knoweth Sir Launcelot190

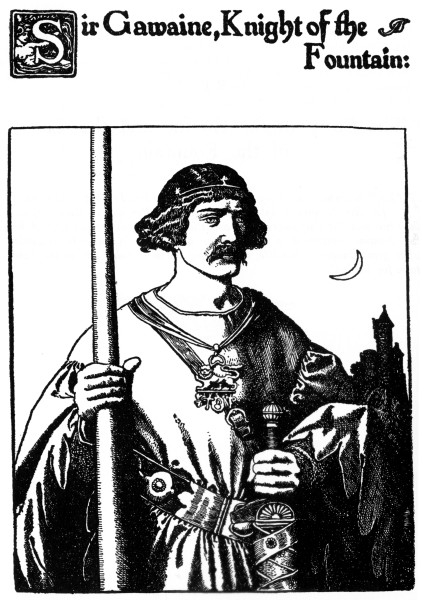

Sir Gawaine, Knight of the Fountain200

Head Piece201

Sir Ewaine poureth water on the slab212

The Damsel Elose giveth a ring to Sir Ewaine222

The Lady of the Fountain236

A Damsel bringeth aid unto Sir Ewaine248

Sir Lamorack and Sir Percival receive their Mother's Blessing262

Head Piece263

Sir Percival and Sir Ector look upon the Isle of Joy278

Sir Lavaine the Son of Pelles292

Merlin Prophesieth from a Cloud of Mist310

Head Piece311

Tail Piece322

Sir Bors de Ganis, the good324

The Barge of the Dead334

It befel upon a very joyous season in the month of May that Queen Guinevere was of a mind to take gentle sport as folk do at that time of the year; wherefore on a day she ordained it in a court of pleasure that on the next morning certain knights and ladies of the court at Camelot should ride with her a-maying into the woods and fields, there to disport themselves amid the flowers and blossoms that grew in great multitudes beside the river.

How the Lady Guinevere rode a-maying.

Of this May-party it stands recorded several times in the various histories of chivalry that the knights she chose were ten in all and that they were all Knights of the Round Table, to wit, as followeth: there was Sir Kay the Seneschal, and Sir Agravaine, and Sir Brandiles, and Sir Sagramour the Desirous, and Sir Dodinas, and Sir Osanna, and Sir Ladynas of the Forest Sauvage, and Sir Persavant of India, and Sir Ironside and Sir Percydes, who was cousin to Sir Percival of Gales. These were the ten (so sayeth those histories aforesaid) whom the Lady Guinevere called upon for to ride a-maying with her all bright and early upon the morning of the day as aforesaid.

And the Queen further ordained that each of these knights should choose him a lady for the day. And she ordained that each lady should ride behind the knight upon the horse which he rode. And she ordained that all those knights and ladies and all such attendants as might be of that party should be clad entirely in green, as was fitting for that pleasant festival.

Such were the commands that the Queen ordained, and when those who were chosen were acquainted with their good fortune they took great joy therein; for all they wist there would be great sport at that maying-party.

So when the next morning was come they all rode forth in the freshness of dewy springtide; what time the birds were singing so joyously, so joyously, from every hedge and coppice; what time the soft wind was blowing great white clouds, slow sailing across the canopy of heaven, each cloud casting a soft and darkling shadow that moved across the hills and uplands as it swam the light blue heaven above; what time all the trees and hedgerows were abloom with fragrant and dewy blossoms, and fields and meadow-lands, all shining bright with dew, were spread over with a wonderful carpet of pretty flowers, gladdening the eye with their charm and making fragrant the breeze that blew across the smooth and grassy plain.

For in those days the world was young and gay (as it is nowadays with little children who are abroad when the sun shines bright and things are a-growing) and the people who dwelt therein had not yet grown aweary of its freshness of delight. Wherefore that fair Queen and her court took great pleasure in all the merry world that lay spread about them, as they rode two by two, each knight with his lady, gathering the blossoms of the May, chattering the while like merry birds and now and then bursting into song because of the pure pleasure of living.

They feast very joyously.

So they disported themselves among the blossoms for all that morning, and when noontide had come they took their rest at a fair spot in a flowery meadow that lay spread out beside the smooth-flowing river about three miles from the town. For from where they sat they might look down across the glassy stream and behold the distant roofs and spires of Camelot, trembling in the thin warm air, very bright and clear, against the blue and radiant sky beyond. And after they were all thus seated in the grass, sundry attendants came and spread out a fair white table-cloth and laid upon the cloth a goodly feast for their refreshment—cold pasties of venison, roasted fowls, manchets of white bread, and flagons of golden wine and ruby wine. And all they took great pleasure when they gazed upon that feast, for they were anhungered with their sporting. So they ate and drank and made them merry; and whilst they ate certain minstrels sang songs, and certain others recited goodly contes and tales for their entertainment. And meanwhile each fair lady wove wreaths of herbs and flowers and therewith bedecked her knight, until all those noble gentlemen were entirely bedight with blossoms—whereat was much merriment and pleasant jesting.

Thus it was that Queen Guinevere went a-maying, and so have I told you all about it so that you might know how it was.

A knight cometh forth from the forest.

Now whilst the Queen and her party were thus sporting together like to children in the grass, there suddenly came the sound of a bugle-horn winded in the woodlands that there were not a very great distance away from where they sat, and whilst they looked with some surprise to see who blew that horn in the forest, there suddenly appeared at the edge of the woodland an armed knight clad cap-a-pie. And the bright sunlight smote down upon that armed knight so that he shone with wonderful brightness at the edge of the shadows of the trees. And after that knight there presently followed an array of men-at-arms—fourscore and more in all—and these also were clad at all points in armor as though prepared for battle.

This knight and those who were with him stopped for a little while at the edge of the wood and stood regarding that May-party from a distance; then after a little they rode forward across the meadow to where the Queen and her court sat looking at them.

Now at first Queen Guinevere and those that were with her wist not who that knight could be, but when he and his armed men had come nigh enough, they were aware that he was a knight hight Sir Mellegrans, who was the son of King Bagdemagus, and they wist that his visit was not likely to bode any very great good to them.

For Sir Mellegrans was not like his father, who (as hath been already told of both in the Book of King Arthur and in The Story of the Champions of the Round Table) was a good and worthy king, and a friend of King Arthur's. For, contrariwise, Sir Mellegrans was malcontented and held bitter enmity toward King Arthur, and that for this reason:

A part of the estate of Sir Mellegrans marched upon the borders of Wales, and there had at one time arisen great contention between Sir Mellegrans and the King of North Wales concerning a certain strip of forest land, as to the ownership thereof. This contention had been submitted to King Arthur and he had decided against Sir Mellegrans and in favor of the King of North Wales; wherefore from that time Sir Mellegrans had great hatred toward King Arthur and sware that some time he would be revenged upon him if the opportunity should offer. Wherefore it was that when the Lady Guinevere beheld that it was Sir Mellegrans who appeared before her thus armed in full, she was ill at ease, and wist that that visit maybe boded no good to herself and to her gentle May-court.

Sir Mellegrans affronts the May-party.

So Sir Mellegrans and his armed party rode up pretty close to where the Queen and her party sat in the grass. And when he had come very near he drew rein to his horse and sat regarding that gay company both bitterly and scornfully (albeit at the moment he knew not the Queen who she was). Then after a little he said: "What party of jesters are ye, and what is this foolish sport ye are at?"

Then Sir Kay the Seneschal spake up very sternly and said: "Sir Knight, it behooves you to be more civil in your address. Do you not perceive that this is the Queen and her court before whom you stand and unto whom you are speaking?"

Then Sir Mellegrans knew the Queen and was filled with great triumph to find her thus, surrounded only with a court of knights altogether unarmed. Wherefore he cried out in a great voice: "Hah! lady, now I do know thee! Is it thus that I find thee and thy court? Now it appears to me that Heaven hath surely delivered you into my hands!"

To this Sir Percydes replied, speaking very fiercely: "What mean you, Sir Knight, by those words? Do you dare to make threats to your Queen?"

Quoth Sir Mellegrans: "I make no threats, but I tell you this, I do not mean to throw aside the good fortune that hath thus been placed in my hands. For here I find you all undefended and in my power, wherefore I forthwith seize upon you for to take you to my castle and hold you there as hostages until such time as King Arthur shall make right the great wrong which he hath done me aforetime and shall return to me those forest lands which he hath taken from me to give unto another. So if you go with me in peace, it shall be well for you, but if you go not in peace it shall be ill for you."

Then all the ladies that were of the Queen's court were seized with great terror, for Sir Mellegrans's tones and the aspect of his face were very fierce and baleful; but Queen Guinevere, albeit her face was like to wax for whiteness, spake with a great deal of courage and much anger, saying: "Wilt thou be a traitor to thy King, Sir Knight? Wilt thou dare to do violence to me and my court within the very sight of the roofs of King Arthur's town?"

"Lady," said Sir Mellegrans, "thou hast said what I will to do."

At this Sir Percydes drew his sword and said: "Sir Knight, this shall not be! Thou shalt not have thy will in this while I have any life in my body!"

Then all those other gentlemen drew their swords also, and one and all spake to the same purpose, saying: "Sir Percydes hath spoken; sooner would we die than suffer that affront to the Queen."

"Well," said Sir Mellegrans, speaking very bitterly, "if ye will it that ye who are naked shall do battle with us who are armed, then let it be even as ye elect. So keep this lady from me if ye are able, for I will herewith seize upon you all, maugre anything that you may do to stay me."

Then those ten unarmed knights of the Queen and their attendants made them ready for battle. And when Sir Mellegrans beheld what was their will, he gave command that his men should make them ready for battle upon their part, and they did so.

Then in a moment all that pleasant May-party was changed to dreadful and bloody uproar; for men lashed fiercely at men with sword and glaive, and the Queen and her ladies shrieked and clung in terror together in the midst of that party of knights who were fighting for them.

Of the battle with the party of Sir Mellegrans.

And for a long time those ten unarmed worthies fought against the armed men as one to ten, and for a long time no one could tell how that battle would end. For the ten men smote the others down from their horses upon all sides, wherefore, for a while, it looked as though the victory should be with them. But they could not shield themselves from the blows of their enemies, being unarmed, wherefore they were soon wounded in many places, and what with loss of blood and what with stress of fighting a few against many without any rest, they presently began to wax weak and faint. Then at last Sir Kay fell down to the earth and then Sir Sagramour and then Sir Agravaine and Sir Dodinas and then Sir Ladynas and Sir Osanna and Sir Persavant, so that all who were left standing upon their feet were Sir Brandiles and Sir Ironside and Sir Percydes.

But still these three set themselves back to back and thus fought on in that woful battle. And still they lashed about them so fiercely with their swords that the terror of this battle filled their enemies with fear, insomuch that those who were near them fell back after a while to escape the dreadful strokes they gave.

So came a pause in the battle and all stood at rest. Meantime all around on the ground were men groaning dolorously, for in that battle those ten unarmed knights of the Round Table had smitten down thirty of their enemies.

So for a while those three stood back to back resting from their battle and panting for breath. As for their gay attire of green, lo! it was all ensanguined with the red that streamed from many sore and grimly wounds. And as for those gay blossoms that had bedecked them, lo! they were all gone, and instead there hung about them the dread and terror of a deadly battle.

Then when Queen Guinevere beheld her knights how they stood bleeding from many wounds and panting for breath, her heart was filled with pity, and she cried out in a great shrill voice: "Sir Mellegrans, have pity! Slay not my noble knights! but spare them and I will go with thee as thou wouldst have me do. Only this covenant I make with thee: suffer these lords and ladies of my court and all of those attendant upon us, to go with me into captivity."

Then Sir Mellegrans said: "Well, lady, it shall be as you wish, for these men of yours fight not like men but like devils, wherefore I am glad to end this battle for the sake of all. So bid your knights put away their swords, and I will do likewise with my men, and so there shall be peace between us."

The Queen putteth an end to the battle.

Then, in obedience to the request of Sir Mellegrans, the Lady Guinevere gave command that those three knights should put away their swords, and though they all three besought her that she should suffer them to fight still a little longer for her, she would not; so they were obliged to sheath their swords as she ordered. After that these three knights went to their fallen companions, and found that they were all alive, though sorely hurt. And they searched their wounds as they lay upon the ground, and they dressed them in such ways as might be. After that they helped lift the wounded knights up to their horses, supporting them there in such wise that they should not fall because of faintness from their wounds. So they all departed, a doleful company, from that place, which was now no longer a meadow of pleasure, but a field of bloody battle and of death.

Thus beginneth this history.

And now you shall hear that part of this story which is called in many books of chivalry, "The Story of the Knight of the Cart."

For the further history hath now to do with Sir Launcelot of the Lake, and of how he came to achieve the rescue of Queen Guinevere, brought thither in a cart.

PART I

The Chevalier of the Cart

Here followeth the story of Sir Launcelot of the Lake, how he went forth to rescue Queen Guinevere from that peril in which she lay at the castle of Sir Mellegrans. Likewise it is told how he met with a very untoward adventure, so that he was obliged to ride to his undertaking in a cart as aforesaid.

Chapter First

How Denneys Found Sir Launcelot, and How Sir Launcelot Rode Forth for to Rescue Queen Guinevere from the Castle of Sir Mellegrans, and of What Befell him upon the Assaying of that Adventure.

Now after that sad and sorrowful company of the Queen had thus been led away captive by Sir Mellegrans as aforetold of, they rode forward upon their way for all that day. And they continued to ride after the night had fallen, and at that time they were passing through a deep dark forest. From this forest, about midnight, they came out into an open stony place whence before them they beheld where was built high up upon a steep hill a grim and forbidding castle, standing very dark against the star-lit sky. And behind the castle there was a town with a number of lights and a bell was tolling for midnight in the town. And this town and castle were the town and the castle of Sir Mellegrans.

How Denneys escaped.

Now the Queen had riding near to her throughout that doleful journey a young page named Denneys, and as they had ridden upon their way, she had taken occasion at one place to whisper to him: "Denneys, if thou canst find a chance of escape, do so, and take news of our plight to some one who may rescue us." So it befel that just as they came out thus into that stony place, and in the confusion that arose when they reached the steep road that led up to the castle, Denneys drew rein a little to one side. Then, seeing that he was unobserved, he suddenly set spurs to his horse and rode away with might and main down the stony path and into the forest whence they had all come, and so was gone before anybody had gathered thought to stay him.

Then Sir Mellegrans was very angry, and he rode up to the Queen and he said: "Lady, thou hast sought to betray me! But it matters not, for thy page shall not escape from these parts with his life, for I shall send a party after him with command to slay him with arrows."

So Sir Mellegrans did as he said; he sent several parties of armed men to hunt the forest for the page Denneys; but Denneys escaped them all and got safe away into the cover of the night.

And after that he wandered through the dark and gloomy woodland, not knowing whither he went, for there was no ray of light. Moreover, the gloom was full of strange terrors, for on every side of him he heard the movement of night creatures stirring in the darkness, and he wist not whether they were great or little or whether they were of a sort to harm him or not to harm him.

How Denneys rideth through the forest.

Yet ever he went onward until, at last, the dawn of the day came shining very faint and dim through the tops of the trees. And then, by and by, and after a little, he began to see the things about him, very faint, as though they were ghosts growing out of the darkness. Then the small fowl awoke, and first one began to chirp and then another, until a multitude of the little feathered creatures fell to singing upon all sides so that the silence of the forest was filled full of their multitudinous chanting. And all the while the light grew stronger and stronger and more clear and sharp until, by and by, the great and splendid sun leaped up into the sky and shot his shafts of gold aslant through the trembling leaves of the trees; and so all the joyous world was awake once more to the fresh and dewy miracle of a new-born day.

So cometh the breaking of the day in the woodlands as I have told you, and all this Denneys saw, albeit he thought but little of what he beheld. For all he cared for at that time was to escape out of the thick mazes of the forest in which he knew himself to be entangled. Moreover, he was faint with weariness and hunger, and wist not where he might break his fast or where he could find a place to tarry and to repose himself for a little.

But God had care of little Denneys and found him food, for by and by he came to an open space in the forest, where there was a neatherd's hut, and that was a very pleasant place. For here a brook as clear as crystal came brawling out of the forest and ran smoothly across an open lawn of bright green grass; and there was a hedgerow and several apple-trees, and both the hedge and the apple-trees were abloom with fragrant blossoms. And the thatched hut of the neatherd stood back under two great oak-trees at the edge of the forest, where the sunlight played in spots of gold all over the face of the dwelling.

How Denneys findeth food.

So the Queen's page beheld the hut and he rode forward with intent to beg for bread, and at his coming there appeared a comely woman of the forest at the door and asked him what he would have. To her Denneys told how he was lost in the forest and how he was anhungered. And whilst he talked there came a slim brown girl, also of the woodland, and very wild, and she stood behind the woman and listened to what he said. This woman and this girl pitied Denneys, and the woman gave command that the girl should give him a draught of fresh milk, and the maiden did so, bringing it to him in a great wooden bowl. Meanwhile, the woman herself fetched sweet brown bread spread with butter as yellow as gold, and Denneys took it and gave them both thanks beyond measure. So he ate and drank with great appetite, the whiles those two outland folk stood gazing at him, wondering at his fair young face and his yellow hair.

After that, Denneys journeyed on for the entire day, until the light began to wane once more. The sun set; the day faded into the silence of the gloaming and then the gloaming darkened, deeper and more deep, until Denneys was engulfed once more in the blackness of the night-time.

Then lo! God succored him again, for as the darkness fell, he heard the sound of a little bell ringing through the gathering night. Thitherward he turned his horse whence he heard the sound to come, and so in a little he perceived a light shining from afar, and when he had come nigh enough to that light he was aware that he had come to the chapel of a hermit of the forest and that the light that he beheld came from within the hermit's dwelling-place.

As Denneys drew nigh to the chapel and the hut a great horse neighed from a cabin close by, and therewith he was aware that some other wayfarer was there, and that he should have comradeship—and at that his heart was elated with gladness.

Denneys cometh to the chapel of the hermit.

So he rode up to the door of the hut and knocked, and in answer to his knocking there came one and opened to him, and that one was a most reverend hermit with a long beard as white as snow and a face very calm and gentle and covered all over with a great multitude of wrinkles.

(And this was the hermit of the forest several times spoken of aforetime in these histories.)

When the hermit beheld before him that young lad, all haggard and worn and faint and sick with weariness and travel and hunger, he took great pity and ran to him and catched him in his arms and lifted him down from his horse and bare him into the hermitage, and sat him down upon a bench that was there.

Denneys said: "Give me to eat and to drink, for I am faint to death." And the hermit said, "You shall have food upon the moment," and he went to fetch it.

Then Denneys gazed about him with heavy eyes, and was aware that there was another in the hut besides himself. And then he heard a voice speak his name with great wonderment, saying: "Denneys, is it then thou who hast come here at this time? What ails thee? Lo! I knew thee not when I first beheld thee enter."

Then Denneys lifted up his eyes, and he beheld that it was Sir Launcelot of the Lake who spoke to him thus in the hut of the hermit.

Denneys findeth Sir Launcelot.

At that, and seeing who it was who spake to him, Denneys leaped up and ran to Sir Launcelot and fell down upon his knees before him. And he embraced Sir Launcelot about the knees, weeping beyond measure because of the many troubles through which he had passed.

Sir Launcelot said: "Denneys, what is it ails thee? Where is the Queen, and how came you here at this place and at this hour? Why look you so distraught, and why are you so stained with blood?"

Then Denneys, still weeping, told Sir Launcelot all that had befallen, and how that the Lady Guinevere was prisoner in the castle of Sir Mellegrans somewhere in the midst of that forest.

Sir Launcelot rides forth to save the Queen.

But when Sir Launcelot heard what Denneys said, he arose very hastily and he cried out, "How is this! How is this!" and he cried out again very vehemently: "Help me to mine armor and let me go hence!" (for Sir Launcelot had laid aside his armor whilst he rested in the hut of the hermit).

At that moment the hermit came in, bringing food for Denneys to eat, and hearing what Sir Launcelot said, he would have persuaded him to abide there until the morrow and until he could see his way. But Sir Launcelot would listen to nothing that might stay him. So Denneys and the hermit helped him don his armor, and after that Sir Launcelot mounted his war-horse and rode away into the blackness of the night.

So Sir Launcelot rode as best he might through the darkness of the forest, and he rode all night, and shortly after the dawning of the day he heard the sound of rushing water.

So he followed a path that led to this water and by and by he came to an open space very stony and rough. And he saw that here was a great torrent of water that came roaring down from the hills very violent and turbid and covered all over with foam like to cream. And he beheld that there was a bridge of stone that spanned the torrent and that upon the farther side of the bridge was a considerable body of men-at-arms all in full armor. And he beheld that there were at least five-and-twenty of these men, and that chief among them was a man clad in green armor.

Then Sir Launcelot rode out upon the bridge and he called to those armed men: "Can you tell me whether this way leads to the castle of Sir Mellegrans?"

They say to him: "Who are you, Sir Knight?"

"I am one," quoth Sir Launcelot, "who seeks the castle of Sir Mellegrans. For that knight hath violently seized upon the person of the Lady Guinevere and of certain of her court, and he now holds her and them captive and in duress. I am one who hath come to rescue that lady and her court from their distress and anxiety."

Upon this the Green Knight, who was the chief of that party, came a little nearer to Sir Launcelot, and said: "Messire, are you Sir Launcelot of the Lake?" Sir Launcelot said: "Yea, I am he." "Then," said the Green Knight, "you can go no farther upon this pass, for you are to know that we are the people of Sir Mellegrans, and that we are here to stay you or any of your fellows from going forward upon this way."

Then Sir Launcelot laughed, and he said: "Messire, how will you stay me against my will?" The Green Knight said: "We will stay you by force of our numbers." "Well," quoth Sir Launcelot, "for the matter of that, I have made my way against greater odds than those I now see before me. So your peril will be of your own devising, if you seek to stay me."

How Sir Launcelot assailed his enemies.

Therewith he cast aside his spear and drew his sword, and set spurs to his horse and rode forward against them. And he rode straight in amongst them with great violence, lashing right and left with his sword, so that at every stroke a man fell down from out of his saddle. So fierce and direful were the blows that Sir Launcelot delivered that the terror of his rage fell upon them, wherefore, after a while, they fell away from before him, and left him standing alone in the centre of the way.

Sir Launcelot, his horse is slain.

Now there were a number of the archers of Sir Mellegrans lying hidden in the rocks at the sides of that pass. These, seeing how that battle was going and that Sir Launcelot had driven back their companions, straightway fitted arrows to their bows and began shooting at the horse of Sir Launcelot. Against these archers Sir Launcelot could in no wise defend his horse, wherefore the steed was presently sorely wounded and began plunging and snorting in pain so that Sir Launcelot could hardly hold him in check. And still the archers shot arrow after arrow until by and by the life began to go out of the horse. Then after a while the good steed fell down upon his knees and rolled over into the dust; for he was so sorely wounded that he could no longer stand.

But Sir Launcelot did not fall, but voided his saddle with great skill and address, so that he kept his feet, wherefore his enemies were not able to take him at such disadvantage as they would have over a fallen knight who lay upon the ground.

So Sir Launcelot stood there in the midst of the way at the end of the bridge, and he waved his sword this way and that way before him so that not one of those, his enemies, dared to come nigh to him. For the terror of him still lay upon them all and they dreaded those buffets he had given them in the battle they had just fought with him.

Wherefore they stood at a considerable distance regarding Sir Launcelot and not daring to come nigh to him; and they stood so for a long time. And although the Green Knight commanded them to fight, they would not fight any more against Sir Launcelot, so the Green Knight had to give orders for them to cease that battle and to depart from that place. This they did, leaving Sir Launcelot standing where he was.

Thus Sir Launcelot with his single arm won a battle against all that multitude of enemies as I have told.

But though Sir Launcelot had thus won that pass with great credit and honor to himself, fighting as a single man against so many, yet he was still in a very sorry plight. For there he stood, a full-armed man with such a great weight of armor upon him that he could hardly hope to walk a league, far less to reach the castle of Sir Mellegrans afoot. Nor knew he what to do in this extremity, for where could he hope to find a horse in that thick forest, where was hardly a man or a beast of any sort? Wherefore, although he had won his battle, he was yet in no ease or satisfaction of spirit.

Thus it was that Sir Launcelot went upon that adventure; and now you shall hear how it sped with him further, if so be you are pleased to read that which followeth.

Chapter Second

How Sir Launcelot rode in a cart to rescue Queen Guinevere and how he came in that way to the castle of Sir Mellegrans.

Now after Sir Launcelot was thus left by his enemies standing alone in the road as aforetold of, he knew not for a while what to do, nor how he should be able to get him away from that place.

As he stood there adoubt as to what to do in this sorry case, he by and by heard upon one side from out of the forest the sound of an axe at a distance away, and thereat he was very glad, for he wist that help was nigh. So he took up his shield on his shoulder and his spear in his hand and thereupon directed his steps toward where he heard that sound of the axe, in hopes that there he might find some one who could aid in his extremity. So after a while, he came forth into a little open glade of the forest where he beheld a fagotmaker chopping fagots. And he beheld the fagotmaker had there a cart and a horse for to fetch his fagots from the forest.

But when the fagotmaker saw an armed knight come thus like a shining vision out of the forest, walking afoot, bearing his shield upon his shoulder, and his spear in his hand, he knew not what to think of such a sight, but stood staring with his mouth agape for wonders.

Sir Launcelot said to him, "Good fellow, is that thy cart?" The fagotmaker said, "Yea, Messire." "I would," quoth Sir Launcelot, "have thee do me a service with that cart," and the fagotmaker asked, "What is the service that thou wouldst have of me, Messire?" Sir Launcelot said: "This is the service I would have: it is that you take me into yonder cart and hale me to somewhere I may get a horse for to ride; for mine own horse hath just now been slain in battle, and I know not how I may go forward upon the adventure I have undertaken unless I get me another horse."

Now you must know that in those days it was not thought worthy of any one of degree to ride in a cart in that wise as Sir Launcelot said, for they would take law-breakers to the gallows in just such carts as that one in which Sir Launcelot made demand to ride. Wherefore it was that that poor fagotmaker knew not what to think when he heard Sir Launcelot give command that he should be taken to ride in that cart. "Messire," quoth he, "this cart is no fit thing for one of your quality to ride in. Now I beseech you let me serve you in some other way than that."

But Sir Launcelot made reply as follows: "Sirrah, I would have thee know that there is no shame in riding in a cart for a worthy purpose, but there is great shame if one rides therein unworthily. And contrariwise, a man doth not gain credit merely for riding on horseback, for his credit appertains to his conduct, and not to what manner he rideth. So as my purpose is worthy, I shall, certes, be unworthy if I go not to fulfil that purpose, even if in so going I travel in thy poor cart. So do as I bid thee and make thy cart ready, and if thou wilt bring me in it to where I may get a fresh horse, I will give thee five pieces of gold money for thy service."

Now when the fagotmaker heard what Sir Launcelot said about the five pieces of gold money, he was very joyful, wherefore he ran to make ready his cart with all speed. And when the cart was made ready, Sir Launcelot entered into it with his shield and his spear.

Sir Launcelot rideth in a cart.

So it was that Sir Launcelot of the Lake came to ride errant in a cart, wherefore, for a long time after, he was called the Chevalier of the Cart. And many ballads and songs were made concerning that matter, which same were sung in several courts of chivalry by minstrels and jongleurs, and these same stories and ballads have come down from afar to us of this very day.

Meantime Sir Launcelot rode forward at a slow pass and in that way for a great distance. So, at last, still riding in the cart, they came of a sudden out of the forest and into a little fertile valley in the midst of which lay a small town and a fair castle with seven towers that overlooked the town. And this was a very fair pretty valley, for on all sides of the town and of the castle were fields of growing corn, all green and lush, and there were many hedgerows and orchards of fruit-trees all abloom with fragrant blossoms. And the sound of cocks crowing came to Sir Launcelot upon a soft breeze that blew up the valley, and on the same breeze came the fragrance of apple blossoms, wherefore it seemed to Sir Launcelot that this valley was like a fair jewel of heaven set in the rough perlieus of the forest that lay round about.

So the fagotmaker drove Sir Launcelot in the cart down into that valley toward the castle, and as they drew near thereunto Sir Launcelot was aware of a party of lords and ladies who were disporting themselves in a smooth meadow of green grass that lay spread out beneath the castle walls. And some of these lords and ladies tossed a ball from one to another, and others lay in the grass in the shade of a lime-tree and watched those that played at ball. Then Sir Launcelot was glad to see those gentle folk, for he thought that here he might get him a fresh horse to take him upon his way. So he gave command to the fagotmaker to drive to where those people were.

But as Sir Launcelot, riding in the fagotmaker's cart, drew near to those castle-folk, they ceased their play and stood and looked at him with great astonishment, for they had never beheld an armed knight riding in a cart in that wise. Then, in a little, they all fell to laughing beyond measure, and at that Sir Launcelot was greatly abashed with shame.

Then the lord of that castle came forward to meet Sir Launcelot. He was a man of great dignity of demeanor—gray-haired, and clad in velvet trimmed with fur. When he came nigh to where Sir Launcelot was, he said, speaking as with great indignation: "Sir knight, why do you ride in this wise in a cart, like to a law-breaker going to the gallows?"

"Sir," quoth Sir Launcelot, "I ride thus because my horse was slain by treachery. For I have an adventure which I have undertaken to perform, and I have no other way to go forward upon that quest than this."

The lord of a castle chideth Sir Launcelot.

Then all those who heard what Sir Launcelot said laughed again with great mirth. Only the old lord of the castle did not laugh, but said, still speaking as with indignation: "Sir Knight, it is altogether unworthy of one of your degree to ride thus in a cart to be made a mock of. Wherefore come down, and if you prove yourself worthy I myself will purvey you a horse."

But by this time Sir Launcelot had become greatly affronted at the laughter of those who jeered at him, and he was furthermore affronted that the lord of the castle should deem him to be unworthy because he came thither in a cart; wherefore he said: "Sir, without boasting, methinks I may say that I am altogether as worthy as any one hereabouts. Nor do I think that any one of you all has done more worthily in his degree than I have done in my degree. As for any lack of worship that may befall me for riding thus, I may say that the adventure which I have undertaken just now to perform is in itself so worthy that it will make worthy any man who may undertake it, no matter how he may ride to that adventure. Now I had thought to ask of you a fresh horse, but since your people mock at me and since you rebuke me so discourteously, I will ask you for nothing. Wherefore, to show you that knightly worthiness does not depend upon the way a knight may ride, I herewith make my vow that I will not mount upon horseback until my quest is achieved; nor will I ride to that adventure in any other way than in this poor cart wherein I now stand."

So Sir Launcelot rode away in his cart from those castle-folk. And he rode thus down into the valley and through the town that was in the valley in the fagotmaker's cart, and all who beheld him laughed at him and mocked him. For, as he passed along the way, many came and looked down upon him from out of the windows of the houses; and others ran along beside the cart and all laughed and jeered at him to see him thus riding in a cart as though to a hanging. But all this Sir Launcelot bore with great calmness of demeanor, both because of his pride and because of the vow that he had made. Wherefore he continued to ride in that cart although he might easily have got him a fresh horse from the lord of the castle.

Now turn we to the castle of Sir Mellegrans, where Queen Guinevere and her court were held prisoners.

First of all you are to know that that part of the castle wherein she and her court were held overlooked the road which led up to the gate of the castle. Wherefore it came about that one of the damsels of the Queen, looking out of the window of the chamber wherein the Queen was held prisoner, beheld a knight armed at all points, coming riding thitherward in a cart. Beholding this sight, she fell to laughing, whereat the Queen said, "What is it you laugh at?" That damsel cried out: "Lady, Lady, look, see! What a strange sight! Yonder is a knight riding in a cart as though he were upon his way to a hanging!"

The Queen beholds Sir Launcelot riding in a cart.

Then Queen Guinevere came to the window and looked out, and several came and looked out also. At first none of them wist who it was that rode in that cart. But when the cart had come a little nearer to where they were, the Queen knew who he was, for she beheld the device upon the shield, even from afar, and she knew that the knight was Sir Launcelot. Then the Queen turned to the damsel and said to her: "You laugh without knowing what it is you laugh at. Yonder gentleman is no subject for a jest, for he is without any doubt the worthiest knight of any who ever wore golden spurs."

Sir Percydes is offended with Sir Launcelot.

Now amongst those who stood there looking out of the window were Sir Percydes and Sir Brandiles and Sir Ironside, and in a little Sir Percydes also saw the device of Sir Launcelot and therewith knew who it was who rode in the cart. But when Sir Percydes knew that that knight was Sir Launcelot, he was greatly offended that he, who was the chiefest knight of the Round Table, should ride in a cart in that wise. So Sir Percydes said to the Queen: "Lady, I believe yonder knight is none other than Sir Launcelot of the Lake." And Queen Guinevere said, "It is assuredly he." Sir Percydes said: "Then I take it to be a great shame that the chiefest knight of the Round Table should ride so in a cart as though he were a felon law-breaker. For the world will assuredly hear of this and it will be made a jest in every court of chivalry. And all we who are his companions in arms and who are his brethren of the Round Table will be made a jest and a laughing-stock along with him."

Thus spake Sir Percydes, and the other knights who were there and all the ladies who were there agreed with him that it was great shame for Sir Launcelot to come thus to save the Queen, riding in a cart.

But the Queen said: "Messires and ladies, I take no care for the manner in which Sir Launcelot cometh, for I believe he cometh for to rescue us from this captivity, and if so be he is successful in that undertaking, then it will not matter how he cometh to perform so worthy a deed of knighthood as that."

Thus all they were put to silence by the Queen's words; but nevertheless and afterward those knights who were there still held amongst themselves that it was great shame for Sir Launcelot to come thus in a cart to rescue the Queen, instead of first getting for himself a horse whereon to ride as became a knight-errant of worthiness and respect.

Now you are to know that the Green Knight, who was the head of that party that tried to stand against Sir Launcelot at the bridge as aforesaid, when he beheld that the horse of Sir Launcelot was shot, rode away from the place of battle with his men, and that he never stopped nor stayed until he had reached the castle of Sir Mellegrans. There coming, he went straightway to where Sir Mellegrans was and told Sir Mellegrans all that had befallen, and how that Sir Launcelot had overcome them all with his single hand at the bridge of the torrent. And he told Sir Mellegrans that haply Sir Launcelot would be coming to that place before a very great while had passed, although he had been delayed because his horse had been slain.

Sir Mellegrans feareth Sir Launcelot.

At that Sir Mellegrans was put to great anxiety, for he also knew that Sir Launcelot would be likely to be at that place before a very great while, and he wist that there would be great trouble for him when that should come to pass. So he began to cast about very busily in his mind for some scheme whereby he might destroy Sir Launcelot. And at last he hit upon a scheme; and that scheme was unworthy of him both as a knight and as a gentleman.

So when news was brought to Sir Mellegrans that Sir Launcelot was there in front of the castle in a cart, Sir Mellegrans went down to the barbican of the castle and looked out of a window of the barbican and beheld Sir Launcelot where he stood in the cart before the gate of the castle. And Sir Mellegrans said, "Sir Launcelot, is it thou who art there in the cart?"

Sir Launcelot replied: "Yea, thou traitor knight, it is I, and I come to tell thee thou shalt not escape my vengeance either now or at some other time unless thou set free the Queen and all her court and make due reparation to her and to them and to me for all the harm you have wrought upon us."

Sir Mellegrans speaketh to Sir Launcelot.

To this Sir Mellegrans spake in a very soft and humble tone of voice, saying: "Messire, I have taken much thought, and I now much repent me of all that I have done. For though my provocation hath been great, yet I have done extremely ill in all this that hath happened, so I am of a mind to make reparation for what I have done. Yet I know not how to make such reparation without bringing ruin upon myself. If thou wilt intercede with me before the Queen in this matter, I will let thee into this castle and I myself will take thee to her where she is. And after I have been forgiven what I have done, then ye shall all go free, and I will undertake to deliver myself unto the mercy of King Arthur and will render all duty unto him."

At this repentance of Sir Mellegrans Sir Launcelot was very greatly astonished. But yet he was much adoubt as to the true faith of that knight; wherefore he said: "Sir Knight, how may I know that that which thou art telling me is the truth?"

"Well," said Sir Mellegrans, "it is small wonder, I dare say, that thou hast doubt of my word. But I will prove my faith to thee in this: I will come to thee unarmed as I am at this present, and I will admit thee into my castle, and I will lead thee to the Queen. And as thou art armed and I am unarmed, thou mayest easily slay me if so be thou seest that I make any sign of betraying thee."

But still Sir Launcelot was greatly adoubt, and wist not what to think of that which Sir Mellegrans said. But after a while, and after he had considered the matter for a space, he said: "If all this that thou tellest me is true, Sir Knight, then come down and let me into this castle as thou hast promised to do, for I will venture that much upon thy faith. But if I see that thou hast a mind to deal falsely by me, then I will indeed slay thee as thou hast given me leave to do." And Sir Mellegrans said, "I am content."

Sir Mellegrans kneels to Sir Launcelot.

So Sir Mellegrans went down from where he was and he gave command that the gates of the castle should be opened. And when the gates were opened he went forth to where Sir Launcelot was. And Sir Launcelot descended from the fagotmaker's cart, and Sir Mellegrans kneeled down before him, and he set his palms together and he said, "Sir Launcelot, I crave thy pardon for what I have done."

Sir Launcelot said: "Sir Knight, if indeed thou meanest no further treachery, thou hast my pardon and I will also intercede with the Queen to pardon thee as well. So take me straightway to her, for until I behold her with mine own eyes I cannot believe altogether in thy repentance." Then Sir Mellegrans arose and said, "Come, and I will take thee to her."

So Sir Mellegrans led the way into the castle and Sir Launcelot followed after him with his naked sword in his hand. And Sir Mellegrans led the way deep into the castle and along several passageways and still Sir Launcelot followed after him with his drawn sword, ready for to slay him if he should show sign of treason.

Sir Launcelot falleth into the pit.

Now there was in a certain part of that castle and in the midst of a long passageway a trap-door that opened through the floor of the passageway and so into a deep and gloomy pit beneath. And this trap-door was controlled by a cunning latch of which Sir Mellegrans alone knew the secret; for when Sir Mellegrans would touch the latch with his finger, the trap-door would immediately fall open into the pit beneath. So thitherward to that place Sir Mellegrans led the way and Sir Launcelot followed. And Sir Mellegrans passed over that trap-door in safety, but when Sir Launcelot had stepped upon the trap-door, Sir Mellegrans touched the spring that controlled the latch with his finger, and the trap-door immediately opened beneath Sir Launcelot and Sir Launcelot fell down into the pit beneath. And the pit was very deep indeed and the floor thereof was of stone, so that when Sir Launcelot fell he smote the stone floor so violently that he was altogether bereft of his senses and lay there in the pit like to one who was dead.

Then Sir Mellegrans came back to the open space of the trap-door and he looked down into the pit beneath and beheld Sir Launcelot where he lay. Thereupon Sir Mellegrans laughed and he cried out, "Sir Launcelot, what cheer have you now?" But Sir Launcelot answered not.

Then Sir Mellegrans laughed again, and he closed the trap-door and went away, and he said to himself: "Now indeed have I such hostages in my keeping that King Arthur must needs set right this wrong he hath aforetime done me. For I now have in my keeping not only his Queen, but also the foremost knight of his Round Table; wherefore King Arthur must needs come to me to make such terms with me as I shall determine."

As for Queen Guinevere, she waited with her court for a long time for news of Sir Launcelot, for she wist that now Sir Launcelot was there at that place she must needs have news of him sooner or later. But no news came to her; wherefore, as time passed by, she took great trouble because she had no news, and she said: "Alas, if ill should have befallen that good worthy knight at the hands of the treacherous lord of this castle!"

But she knew not how great at that very time was the ill into which Sir Launcelot had fallen, nor of how he was even then lying like as one dead in the pit beneath the floor of the passageway.

Chapter Third

How Sir Launcelot was rescued from the pit and how he overcame Sir Mellegrans and set free the Queen and her court from the duress they were in.

Now when Sir Launcelot awoke from that swoon into which he was cast by falling so violently into the pit, he found himself to be in a very sad, miserable case. For he lay there upon the hard stones of the floor and all about him there was a darkness so great that there was not a single ray of light that penetrated into it.

Sir Launcelot lyeth in the pit.

So for a while Sir Launcelot knew not where he was; but by and by he remembered that he was in the castle of Sir Mellegrans, and he remembered all that had befallen him, and therewith, when he knew himself to be a prisoner in so miserable a condition, he groaned with dolor and distress, for he was at that time in great pain both of mind and body. Then he cried out in a very mournful voice: "Woe is me that I should have placed any faith in a traitor such as this knight hath from the very beginning shown himself to be! For here am I now cast into this dismal prison, and know not how I shall escape from it to bring succor to those who so greatly need my aid at this moment."

So Sir Launcelot bemoaned and lamented himself, but no one heard him, for he was there all alone in that miserable dungeon and in a darkness into which no ray of light could penetrate.

Then Sir Launcelot bent his mind to think of how he might escape from that place, but though he thought much, yet he could not devise any way in which he might mend the evil case in which he found himself; wherefore he was altogether overwhelmed with despair. And by that time it had grown to be about the dead of the night.

Now as Sir Launcelot lay there in such despair of spirit as aforetold of, he was suddenly aware that there came a gleam of light shining in a certain place, and he was aware the light grew ever brighter and brighter and he beheld that it came through the cracks of a door. And by and by he heard the sound of keys from without and immediately afterward the door opened and there entered into that place a damsel bearing a lighted lamp in her hand.

The Lady Elouise findeth Sir Launcelot.

At first Sir Launcelot knew not who she was, and then he knew her and lo! that damsel was the Lady Elouise the Fair, the daughter of King Bagdemagus and sister unto Sir Mellegrans; and she was the same who had aforetime rescued him when he had been prisoner to Queen Morgana le Fay, as hath been told you in a former book of this history.

So Elouise the Fair came into that dismal place, bringing with her the lighted lamp, and Sir Launcelot beheld that her eyes were red with weeping. Then Sir Launcelot, beholding that she had been thus weeping, said: "Lady, what is it that ails you? Is there aught that I can do for to comfort you?" To this she said naught, but came to where Sir Launcelot was and looked at him for a long while. By and by she said: "Woe is me to find thee thus, Sir Launcelot! And woe is me that it should have been mine own brother that should have brought thee to this pass!"

Sir Launcelot was much moved to see her so mournful and he said: "Lady, take comfort to thyself, for whatever evil thing Sir Mellegrans may have done to me, naught of reproach or blame can fall thereby upon thee, for I shall never cease to remember how thou didst one time save me from a very grievous captivity."

The Lady Elouise said: "Launcelot, I cannot bear to see so noble a knight as thou art lying thus in duress. So it is that I come hither to aid thee. Now if I set thee free wilt thou upon thy part show mercy unto my brother for my sake?"

"Lady," said Sir Launcelot, "this is a hard case thou puttest to me, for I would do much for thy sake. But I would have thee wist that it is my endeavor to help in my small way to punish evil-doers so that the world may be made better by that punishment. Wherefore because this knight hath dealt so treacherously with my lady the Queen, so it must needs be that I must seek to punish him if ever I can escape from this place. But if it so befalls that I do escape, this much mercy will I show to Sir Mellegrans for thy sake: I will meet him in fair field, as one knight may meet another knight in that wise. And I will show him such courtesy as one knight may show another in time of battle. Such mercy will I show thy brother and meseems that is all that may rightly be asked of me."

Then Elouise the Fair began weeping afresh, and she said: "Alas, Launcelot! I fear me that my brother will perish at thy hands if so be that it cometh to a battle betwixt you twain. And how could I bear it to have my brother perish in that way and at thy hands?"

"Lady," said Sir Launcelot, "the fate of battle lyeth ever in God His hands and not in the hands of men. It may befall any man to die who doeth battle, and such a fate may be mine as well as thy brother's. So do thou take courage, for whilst I may not pledge myself to avoid an ordeal of battle with Sir Mellegrans, yet it may be his good hap that he may live and that I may die."

"Alas, Launcelot," quoth the Fair Elouise, "and dost thou think that it would be any comfort to me to have thee die at the hands of mine own brother? That is but poor comfort to me who am the sister of this miserable man. Yet let it be as it may hap, I cannot find it in my heart to let thee lie here in this place, for thou wilt assuredly die in this dark and miserable dungeon if I do not aid thee. So once more will I set thee free as I did aforetime when thou wast captive to Queen Morgana le Fay, and I will do my duty by thee as the daughter of a king and the daughter of a true knight may do. As to that which shall afterward befall, that will I trust to the mercy of God to see that it shall all happen as He shall deem best."

The Lady Elouise bringeth Sir Launcelot out of a pit.

So saying, the damsel Elouise the Fair bade Sir Launcelot to arise and to follow her, and he did so. And she led him out from that place and up a long flight of steps and so to a fair large chamber that was high up in a tower of the castle and under the eaves of the roof. And Sir Launcelot beheld that everything was here prepared for his coming; for there was a table at that place set with bread and meat and with several flagons of wine for his refreshment. And there was in that place a silver ewer full of cold, clear water, and that there was a basin of silver, and that there were several napkins of fine linen such as are prepared for knights to dry their hands upon. All these had been prepared for him against his coming, and at that sight he was greatly uplifted with satisfaction.

So Sir Launcelot bathed his face and his hands in the water and he dried them upon the napkins. And he sat him down at the table and he ate and drank with great appetite and the Lady Elouise the Fair served him. And so Sir Launcelot was greatly comforted in body and in spirit by that refreshment which she had prepared for him.

Then after Sir Launcelot had thus satisfied the needs of his hunger, the Lady Elouise led him to another room and there showed him where was a soft couch spread with flame-colored linen and she said, "Here shalt thou rest at ease to-night, and in the morning I shall bring thy sword and thy shield to thee." Therewith she left Sir Launcelot to his repose and he laid him down upon the couch and slept with great content.

So he slept very soundly all that night and until the next morning, what time, the Lady Elouise came to him as she promised and fetched unto him his sword and his shield. These she gave unto him, saying: "Sir Knight, I know not whether I be doing evil or good in the sight of Heaven in thus purveying thee with thy weapons; ne'theless, I cannot find it in my heart to leave thee unprotected in this place without the wherewithal for to defend thyself against thine enemies; for that would be indeed to compass thy death for certain."

Sir Launcelot hath his weapons again.

Then Sir Launcelot was altogether filled with joy to have his weapons again, and he gave thanks to the Lady Elouise without measure. And after that he hung his sword at his side and set his shield upon his shoulder and thereupon felt fear of no man in all of that world, whomsoever that one might be.

After that, and after he had broken his fast, Sir Launcelot went forth from out of the chamber where he had abided that night, and he went down into the castle and into the courtyard of the castle, and every one was greatly astonished at his coming, for they deemed him to be still a prisoner in that dungeon into which he had fallen.

Sir Launcelot challenges the castle.

So all these, when they beheld him coming, full armed and with his sword in his hand, fled away from before the face of Sir Launcelot, and no one undertook to stay him in his going. So Sir Launcelot reached the courtyard of the castle, and when he was come there he set his horn to his lips, and blew a blast that sounded terribly loud and shrill throughout the entire place.

Meantime, there was great hurrying hither and thither in the castle and a loud outcry of many voices, and many came to the windows and looked down into the courtyard and there beheld Sir Launcelot standing clad in full armor, glistening very bright in the morning light of the sun.

Meantime several messengers had run to where Sir Mellegrans was and told him that Sir Launcelot had escaped out of that pit wherein he had fallen and that he was there in the courtyard of the castle in full armor.

At that Sir Mellegrans was overwhelmed with amazement, and a great fear seized upon him and gripped at his vitals. And after a while he too went by, to a certain place whence he could look down into the courtyard, and there he also beheld Sir Launcelot where he stood shining in the sunlight.

Now at that moment Sir Launcelot lifted up his eyes and espied Sir Mellegrans where he was at the window of that place, and immediately he knew Sir Mellegrans. Thereupon he cried out in a loud voice: "Sir Mellegrans, thou traitor knight! Come down and do battle, for here I await thee to come and meet me."

But when Sir Mellegrans heard those words he withdrew very hastily from the window where he was, and he went away in great terror to a certain room where he might be alone. For beholding Sir Launcelot thus free of that dungeon from which he had escaped he knew not what to do to flee from his wrath. Wherefore he said to himself: "Fool that I was, to bring this knight into my castle, when I might have kept him outside as long as I chose to do so! What now shall I do to escape from his vengeance?"

Sir Mellegrans taketh counsel.

So after a while Sir Mellegrans sent for several of his knights and he took counsel of them as to what he should do in this pass. These say to him: "Messire, you yourself to fulfil your schemes have brought yonder knight into this place, when God knows he could not have come in of his own free will. So now that he is here, it behooves you to go and arm yourself at all points and to go down to the courtyard, there to meet him and to do battle with him. For only by overcoming him can you hope to escape his vengeance."

But Sir Mellegrans feared Sir Launcelot with all his heart, wherefore he said: "Nay, I will not go down to yonder knight. For wit ye he is the greatest knight alive, and if I go to do battle with him, it will be of a surety that I go to my death. Wherefore, I will not go."

Then Sir Mellegrans called a messenger to him and he said: "Go down to yonder knight in the courtyard and tell him that I will not do battle with him."

So the messenger went to Sir Launcelot and delivered that message to him. But when Sir Launcelot heard what it was that the messenger said to him from Sir Mellegrans, he laughed with great scorn. Then he said to the messenger, "Doth the knight of this castle fear to meet me?" The messenger said, "Yea, Messire." Sir Launcelot said: "Then take thou this message to him: that I will lay aside my shield and my helm and that I will unarm all the left side of my body, and thus, half naked, will I fight him if only he will come down and do battle with me."

So saying, the messenger departed as Sir Launcelot bade, and came to Sir Mellegrans and delivered that message to him as Sir Launcelot had said.

Sir Launcelot offers to fight Sir Mellegrans in half-armor.

Then Sir Mellegrans said to those who were with him: "Now I will go down and do battle with this knight, for never will I have a better chance of overcoming him than this." Therewith he turned to that messenger, and he said: "Go! Hasten back to yonder knight, and tell him that I will do battle with him upon those conditions he offers, to wit: that he shall unarm his left side, and that he shall lay aside his shield and his helm. And tell him that by the time he hath made him ready in that wise, I will be down to give him what satisfaction I am able."

So the messenger departed upon that command, and Sir Mellegrans departed to arm himself for battle.

Then, after the messenger had delivered the message that Sir Mellegrans had given him, Sir Launcelot laid aside his shield and his helm as he had agreed to do, and he removed his armor from his left side so that he was altogether unarmed upon that side.

After a while Sir Mellegrans appeared, clad all in armor from top to toe, and baring himself with great confidence, for he felt well assured of victory in that encounter. Thus he came very proudly nigh to where Sir Launcelot was, and he said: "Here am I, Sir Knight, come to do you service since you will have it so."

Sir Launcelot said: "I am ready to meet thee thus or in any other way, so that I may come at thee at all."

After that each knight dressed himself for combat, and all those who were in the castle gathered at the windows and the galleries above, and looked down upon the two knights.

Then they two came slowly together, and when they were pretty nigh to one another Sir Launcelot offered his left side so as to allow Sir Mellegrans to strike at him. And when Sir Mellegrans perceived this chance, he straightway lashed a great blow at Sir Launcelot's unarmed side with all his might and main, and with full intent to put an end to the battle with that one blow.

But Sir Launcelot was well prepared for that stroke, wherefore he very dexterously and quickly turned himself to one side so that he received the blow upon the side which was armed, and at the same time he put aside a part of the blow with his sword. So that blow came to naught.

Sir Launcelot slayeth Sir Mellegrans.

But so violent was the stroke that Sir Mellegrans had lashed that he overreached himself, and ere he could recover himself, Sir Launcelot lashed at him a great buffet that struck him fairly upon the helm. And then again he lashed at him ere he fell and both this stroke of the sword and the other cut deep through the helm and into the brain pan of Sir Mellegrans, so that he fell down upon the ground and lay there without motion of any sort. Then Sir Launcelot stood over him, and called to those who were near to come and look to their lord, and thereat there came several running. These lifted Sir Mellegrans up and removed his helmet so as to give him air to breathe. And they looked upon his face, and lo! even then the spirit was passing from him, for he never opened his eyes to look upon the splendor of the sun again.

Then when those of the castle saw how it was with Sir Mellegrans and that even then he was dead, they lifted up their voices with great lamentation so that the entire castle rang presently with their outcries and wailings.

But Sir Launcelot cried out: "This knight hath brought this upon himself because of the treason he hath done; wherefore the blame is his own." And then he said: "Where is the porter of this castle? Go, fetch him hither!"

So in a little while the porter came, and Sir Launcelot made demand of him: "Where is it that the Queen and her court are held prisoners? Bring me to them, Sirrah?"

Then the porter of the castle bowed down before Sir Launcelot and he said, "Messire, I will do whatever you command me to do," for he was overwhelmed with the terror of Sir Launcelot's wrath as he had displayed it that day. And the porter said, "Messire, have mercy on us all and I will take you to the Queen."

Sir Launcelot rescueth the Queen.

So the porter brought Sir Launcelot to where the Queen was, and where were those others with her. Then all these gave great joy and loud acclaim that Sir Launcelot had rescued them out of their captivity. And Queen Guinevere said: "What said I to you awhile since? Did I not say that it mattered not how Sir Launcelot came hither even if it were in a cart? For lo! though he came thus humbly and in lowly wise, yet he hath done marvellous deeds of knightly prowess, and hath liberated us all from our captivity."

After that Sir Launcelot commanded them that they should make ready such horses as might be needed. And he commanded that they should fetch litters for those knights of the Queen's court who had been wounded, and all that was done as he commanded. After that they all departed from that place and turned their way toward Camelot and the court of the King.

But Sir Launcelot did not again see that damsel Elouise the Fair, for she kept herself close shut in her own bower and would see naught of any one because of the grief and the shame of all that had passed. At that Sir Launcelot took much sorrow, for he was greatly grieved that he should have brought any trouble upon one who had been so friendly with him as she had been. Yet he wist not how he could otherwise have done than as he did do, and he could think of naught to comfort her.

So ends this adventure of the Knight of the Cart with only this to say: that after that time there was much offence taken that Sir Launcelot had gone upon that adventure riding in a cart. For many jests were made of it as I have said, and many of the King's court were greatly grieved that so unworthy a thing should have happened.

His kinsmen chide Sir Launcelot.

More especially were the kinsmen of Sir Launcelot offended at what he had done. Wherefore Sir Lionel and Sir Ector came to Sir Launcelot and Sir Ector said to him: "That was a very ill thing you did to ride to that adventure in a cart. Now prythee tell us why you did such a thing as that when you might easily have got a fresh horse for to ride upon if you had chosen to do so."

To this Sir Launcelot made reply with much heat: "I know not why you should take it upon you to meddle in this affair. For that which I did, I did of mine own free will, and it matters not to any other man. Moreover, I deem that it matters not how I went upon that quest so that I achieved my purpose in a knightly fashion. For I have yet to hear any one say that I behaved in any way such as a true knight should not behave."