автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The War with Mexico, Volume 1 (of 2)

Transcriber’s Note

Please consult the notes at the end of this text for a detailed discussion of the various footnotes, endnotes, and navigation through this text, as well as any other textual issues.

Topic descriptions

Right-side page headers contained descriptions of the current topic covered by the two open pages. These were retained and are placed as marginal notes. The choice of that position is not always obvious and should be regarded as approximate.

Illustrations are placed at approximately the point where they were printed. The captions are usually printed on the maps themselves. Where there is no obvious title to the map, the caption has been provided from the table of illustrations, in mixed case.

Larger images of full-page maps are available by using the hyperlink added to the caption. These may be opened in separate windows.

This is the first of two volumes of The War with Mexico. The index, which is contained in Volume II, refers to both volumes. References to Volume II have been included as hyperlinks.

Volume II of can be found at Project Gutenberg with the following address:

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/44438

The cover image was created by the transcriber, and is placed in the public domain.

THE WAR WITH MEXICO

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The

Annexation of Texas

Octavo ix + 496 pages

By mail, postpaid, $3.00

This is the only work attempting to deal thoroughly with an affair that was intrinsically far more important than had previously been supposed, and was also of no little significance on account of its relation to the war with Mexico.

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

THE

WAR WITH MEXICO

BY

JUSTIN H. SMITH

FORMERLY PROFESSOR OF MODERN HISTORY

AT DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

AUTHOR OF “THE ANNEXATION OF TEXAS,” “OUR

STRUGGLE FOR THE FOURTEENTH COLONY,”

“ARNOLD’S MARCH FROM

CAMBRIDGE TO QUEBEC,”

ETC.

VOLUME I

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1919

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1919,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up and printed. Published December, 1919.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing Co.–Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

TO

HENRY CABOT LODGE, LL.D.

SENATOR OF THE UNITED STATES

HISTORIAN

PRESIDENT OF THE MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL SOCIETY

WHO GAVE THE AUTHOR INVALUABLE ASSISTANCE

IN THE COLLECTION OF MATERIAL RELATING

TO THE WAR WITH MEXICO

THIS WORK

IS VERY RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED

PREFACE

As every one understands, our conflict with Mexico has been almost entirely eclipsed by the greater wars following it. But in the field of thought mere size does not count for much; and while the number of troops and the lists of casualties give the present subject little comparative importance, it has ample grounds for claiming attention. As a territorial stake New Mexico, Arizona and California were of immense value. National honor was involved, and not a few of the Mexicans thought their national existence imperilled. Some of the diplomatic questions were of the utmost difficulty and interest. The clash of North and South, American and Mexican, produced extraordinary lights and shades, and in both countries the politics that lay behind the military operations made a dramatic and continual by-play. The military conduct of the governments—especially our own—and the behavior of our troops on foreign soil afforded instruction worthy to be pondered. While vast concentrations of forces and complicated tactical operations on a great scale were out of the question, the handling of even small armies at a long distance from home and in a region that was not only foreign but strange, created problems of a peculiar interest and afforded lessons of a peculiar value, such as no earlier or later war of ours has provided; and the examples of courage, honor and heroism exhibited in a conflict not only against man but against nature merited correct appreciation and lasting remembrance.[1][A]

The warrant for offering another work on the subject rests primarily on the extent and results of the author’s investigations. His intention was to obtain substantially all the valuable information regarding it that is in existence, and no effort was spared to reach his end. The appendix of volume II gives a detailed account of the sources. By special authorization from the Presidents of the United States and Mexico it was possible to examine every pertinent document belonging to the two governments. The search extended to the archives of Great Britain, France, Spain, Cuba, Colombia and Peru, those of the American and Mexican states, and those of Mexican cities. The principal libraries here, in Mexico and in Europe, the collections of our historical societies, and papers belonging to many individuals in this country and elsewhere were sifted. It may safely be estimated that the author examined personally more than 100,000 manuscripts bearing upon the subject, more than 1200 books and pamphlets, and also more than 200 periodicals, the most important of which were studied, issue by issue, for the entire period.[B] Almost exclusively the book is based upon first-hand sources, printed matter having been found of little use except for the original material it contains or for data regarding biography, geography, customs, industries and other ancillary subjects.[2]

The author also talked or corresponded with as many of the veterans as he could reach, and he spent more than a year, all told, in Mexico, where he not only studied the chief battlefields but endeavored, through conversations with Mexicans of all grades and by the aid of foreigners long resident in the country, to become well acquainted with the character and psychology of the people. As the war was fought almost exclusively among them, and its inception, course and results depended in large part upon these factors, the author attaches not a little importance to his opportunities for such personal investigations and to his Mexican data in general.[2]

Probably more than nine tenths of the material used in the preparation of this work is in fact new. No previous writer on the subject had been through the diplomatic and military archives of either belligerent nation, for example. Virtually a still larger percentage is new, for the published documents needed to be compared with the originals. In the printed American reports relating to the battles of September 8 and 13, 1847, for instance, over fifty departures from the manuscripts, that seemed worth noting, were found. Nor did the additional documents prove by any means to supply mere details. A great number of unprinted statements from subordinate officers, who were nearer to the facts than their superiors could be, were discovered. The major official reports needed both to be supplemented and to be corrected. Such reports were in most instances colored more or less, and in some radically distorted, for personal reasons or from a justifiable desire to produce an effect on the subordinates concerned, the army in general, the writer’s government, the enemy, and the public at home and abroad; while, as General Scott stated in orders, unintentional omissions and mistakes were “common.” Taylor’s account of the battle of May 9, 1846, for example, failed completely to explain his victory. It has been only by obtaining and comparing a large number of statements that approximate verity has been reached. The same has been true of the diplomatic and political aspects of the subject. The reports of the British, French and Spanish ministers residing at Mexico, to cite one illustration, proved indispensable. In reality, therefore, aside from its broader outlines the field presented ample opportunities for study; and while no doubt so extended an investigation included many facts of slight value, La Rochefoucauld was right when he said, “To know things perfectly, one should know them in detail.”[3]

As a particular consequence of this full inquiry, an episode that has been regarded both in the United States and abroad as discreditable to us, appears now to wear quite a different complexion. Such a result, it may be presumed, will gratify patriotic Americans, but the author must candidly admit that he began with no purpose or even thought of reaching it. His view of the war at the outset of his special inquiries coincided substantially with that prevailing in New England, and the subject was taken up simply because he felt convinced that it had not been studied thoroughly. This conviction, indeed, has seemed to be gaining ground rapidly for some time, and hence it is believed that new opinions, resting upon facts, will be acceptable now in place of opinions resting largely upon traditional prejudices and misinformation.

Some might suggest that only a military man could properly write this work. But, in the first place, the author did not wish to prepare a technical military account of the war. His aim was to offer a correct and complete view of it suitable for all interested in American history, and it will be found that politics, diplomacy and other phases of the subject required as full investigation as did its military aspects.

Secondly, the author took pains to qualify himself for his task. The real difficulty of the commanding general consists in applying the principles of war under complicated, obscure and changeful conditions, and in overcoming “friction” of many sorts. The intellectual side of the art is readily enough understood. “In war everything is very simple,” wrote Clausewitz, the fountainhead of the modern system. “The theory of the great speculative combinations of war is simple enough in itself,” said Jomini; “it only requires intelligence and attentive reflection.” “Strategy is the application of common sense to the conduct of war,” declared Von Moltke. Arnold in his Lectures on Modern History said: “An unprofessional person may, without blame, speak or write on military subjects, and may judge of them sufficiently;” and the eminent military authority, G. F. R. Henderson, endorsed this view. “The theory of war is simple,” wrote another expert, “and there is no reason why any man who chooses to take the trouble to read and reflect carefully on one or two of the acknowledged best books thereon, should not attain to a fair knowledge thereof.” As may be seen from the list of printed sources, the present author—beginning with the volumes recommended by a board of officers to the graduates of the United States Military Academy—did much more than is here proposed.

Finally, during the entire time occupied in writing this work he fortunately enjoyed the advantage of corresponding and occasionally conferring with Brigadier General Oliver L. Spaulding, Jr., of the United States Field Artillery, formerly instructor at the Army Service Schools, Fort Leavenworth, and more recently Assistant Commandant of the School of Fire, Fort Sill, who had distinguished himself not only in the service but as a writer on professional subjects. General Spaulding has kindly discussed with the author such military questions as have arisen, and has read critically all the battle chapters. No responsibility should, however, be attached to him, if a mistake is detected.[4]

A word must be added with reference to the notes. These have been placed at the ends of the volumes because the author believes the best plan will be to read the text of each chapter before looking at the notes that bear upon it, and also in part because he did not wish any one to feel that he was parading his discussions and citations. The notes contain supplementary material designed to make the work a critical as well as a narrative history, and contain also specific references to the sources on which the text is based. These references involved a most annoying problem. When one’s citations are limited in number and proceed in single file, as it were, they can be handled easily. But in the present instance as many as 1800 documents were used for a chapter, not a few of which were cited more than once; and each sentence of the text—to speak broadly—resulted from comparing a number of sources. Under these conditions the usual method would have produced a repellent mass of references, perhaps greater in extent than the text itself, which would have been very expensive to print and from their multiplicity would have been extremely inconvenient. Where that method appeared feasible it was adopted, but as a rule the references have been grouped by paragraphs or topics. In many cases, however, pains have been taken to indicate in the text itself the basis of important statements, and further hints will be found in the notes. The reader can thus always ascertain in general the basis of the text, and will find specific references wherever the author has thought it likely they would be desired. The special student will wish to look up all the citations bearing on any topic that interests him. No doubt the plan is somewhat unsatisfactory, but after studying the subject for a dozen years the author feels sure that any other would have been more so.[5]

To thank all who kindly assisted the author to obtain material is practically impossible; but a number of names appear in the list of MS. sources, and others must be mentioned here. Without the cordial support of Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Porfirio Diaz, Secretary of State Elihu Root, Minister of Relations Ignacio Mariscal, and Senator Henry Cabot Lodge this history could not have been written; and the author acknowledges with no less pleasure his special obligations to Whitelaw Reid, American Ambassador to Great Britain, Joseph E. Willard, Ambassador to Spain; Henri Vignaux, First Secretary of our embassy at Paris; J. J. Limantour, Minister of Hacienda, Mexico; Major General J. Franklin Bell, Chief of Staff; Major General F. C. Ainsworth, Adj. Gen.; Admiral Alfred T. Mahan; Admiral French E. Chadwick; Brigadier General J. E. Kuhn, Head of the War College, Washington; Dr. J. Franklin Jameson, Director of the Department of Historical Research, Carnegie Institution; Dr. Gaillard Hunt, Chief of the Division of MSS., Library of Congress; Dr. St. George L. Sioussat, Brown University; Dr. Eugene C. Barker, University of Texas; Dr. Herbert E. Bolton, Professor Frederick J. Teggart and Dr. H. I. Priestley of the University of California; Dr. R. W. Kelsey of Haverford College; Dr. J. W. Jordan, Pennsylvania Historical Society; Dr. Worthington C. Ford, Editor for the Massachusetts Historical Society; Dr. Solon J. Buck of the Minnesota Historical Society; R. D. W. Connor, Secretary of the Historical Commission of North Carolina; Dr. R. P. Brooks of the University of Georgia; Dr. Dunbar Rowland, Director of the Archives and Historical Department of Mississippi; T. M. Owen, Director of the Historical Department of Alabama; Dr. George M. Philips, State Normal School, West Chester, Pa.; Waldo G. Leland, Secretary of the American Historical Association; W. B. Douglas and Miss Stella M. Drumm, Librarian, of the Missouri Historical Society; Dr. Clarence E. Alvord of the University of Illinois and Mrs. Alvord (formerly Miss Idress Head, Librarian of the Missouri Historical Society); Ignacio Molina, Head of the Cartography Section, Department of Fomento, Mexico; Charles W. Stewart, Librarian of the Navy Department; James W. Cheney, long the Librarian of the War Department; Major Gustave R. Lukesh, Director, and Henry E. Haferkorn, Librarian of the United States Engineer School, Washington Barracks; D. C. Brown, Librarian of the Indiana State Library; Victor H. Paltsits, Department of MSS., New York Public Library; W. L. Ostrander of the library at West Point; Lieutenant James R. Jacobs, 28th United States Infantry; Dr. Katherine J. Gallagher; Dr. Martha L. Edwards. To the widow of Admiral Charles S. Sperry and their son, Professor Charles S. Sperry, the author is particularly indebted for an opportunity to examine important papers left by William L. Marcy. Valuable suggestions were most kindly given by Dr. William A. Dunning of Columbia University and Dr. Davis R. Dewey of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who read portions of the text, by Francis W. Halsey, Esq., of New York, who read nearly all of it, and by Dr. Edward Channing of Harvard University, who was so good as to look over more or less closely all of the proofs. To the helpers not mentioned by name the author begs leave to offer thanks no less sincere.

Finally, the author desires to mention the enterprise and public spirit shown by the publishers in bringing out so expensive a work at this time of uncertainty.

The Century Club, New York

September, 1919.

CONTENTS OF VOLUME I

PAGE Maps and Plans in Volume I xvii Conspectus of Events xix Pronunciation of Spanish xxi CHAPTERI.

Mexico and the Mexicans 1II.

The Political Education of Mexico 29III.

The Relations between the United States and Mexico, 1825–1843 58IV.

The Relations between the United States and Mexico, 1843–1846 82V.

The Mexican Attitude on the Eve of War 102VI.

The American Attitude on the Eve of War 117VII.

The Preliminaries of the Conflict 138VIII.

Palo Alto and Resaca de Guerrero 156IX.

The United States Meets the Crisis 181X.

The Chosen Leaders Advance 204XI.

Taylor Sets out for Saltillo 225XII.

Monterey 239XIII.

Saltillo, Parras, and Tampico 262XIV.

Santa Fe 284XV.

Chihuahua 298XVI.

The California Question 315XVII.

The Conquest of California 331XVIII.

The Genesis of Two Campaigns 347XIX.

Santa Anna Prepares to Strike 370XX.

Buena Vista 384 Notes on Volume I 402 Appendix (Manuscript Sources) 565MAPS AND PLANS IN VOLUME ONE

As equally good sources disagree sometimes, a few inconsistencies are unavoidable. Numerous errors have been corrected. An asterisk indicates an unpublished original. Statements, cited in the notes, have also been used.

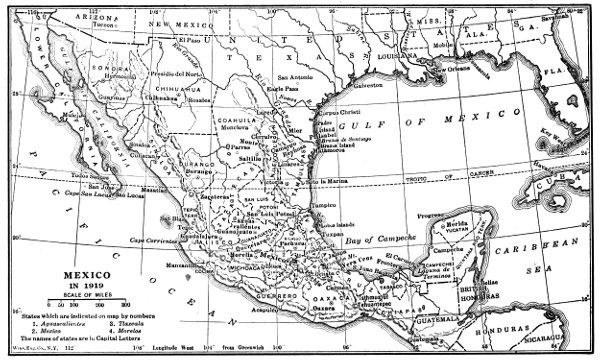

1.

Mexico in 1919. Based upon standard maps

xxii2.

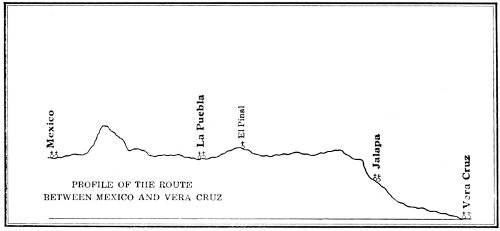

Profile of the Route between Vera Cruz and Mexico

2Drawn by Lieut. Hardcastle (Sen. Ex. Doc. 1; 30 Cong., 1 sess.).

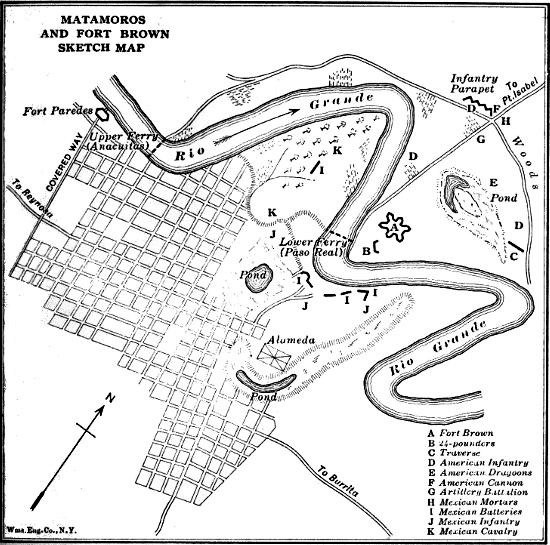

3.

Matamoros and Fort Brown

159Sketch map based on a *map drawn by Luis Berlandier, Arista’s chief engineer (War Dept., Mexico); Meade, Letters, i, 73; McCall, Letters, 444; New Orleans

Picayune, June 28, 1846; *sketch by Mansfield, Taylor’s chief engineer (War Dept., Washington); and an anonymous plan (Mass. Hist. Society).

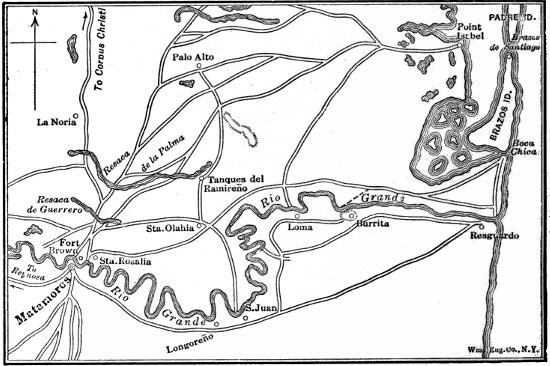

4.

Fort Brown to Brazos Island

162Sketch map based principally upon the map in Apuntes para la Historia de la Guerra entre México y los Estados-Unidos and a map by Eaton of Third Infantry (Ho. Ex. Doc. 209; 29 Cong., 1 sess.).

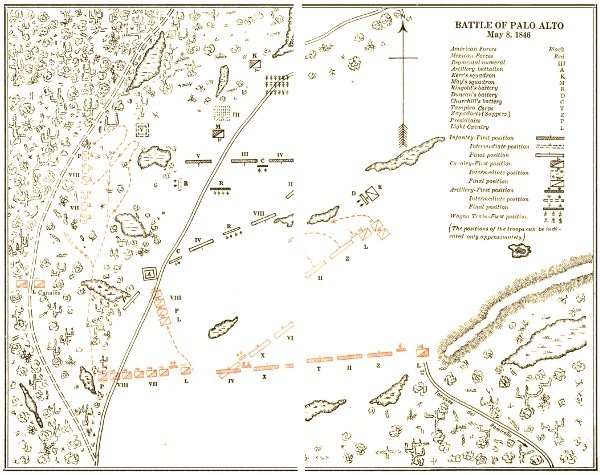

5.

Battle of Palo Alto

164Sketch map drawn by a U. S. army officer. Based on Eaton’s plan (Ho. Ex. Doc., 209; 29 Cong., 1 sess.); a *sketch by Berlandier (War Dept., Mexico); Apuntes; México á través de los Siglos, iv, 562;

El Republicano(Berlandier); a map in Campaña contra los Norte-Americanos; a map by Lieut. Dobbins in Life of General Taylor; and

Journal of Milit. Service Institution, xli, 96.

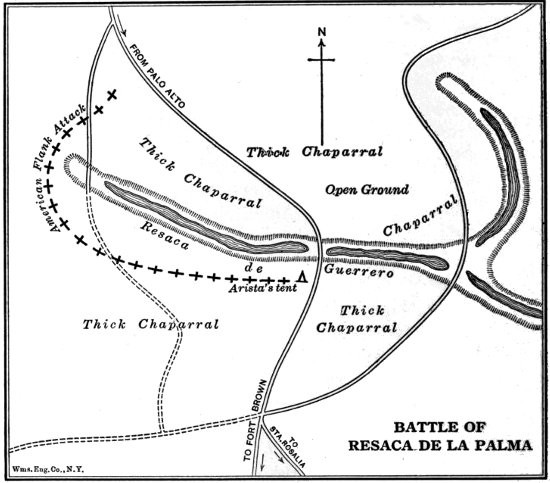

6.

Battle of Resaca de la Palma (

i.e.Resaca de Guerrero)

170Sketch map based on Apuntes; New Orleans

Picayune, June 25, 1846, from official drawings; a plan by Dobbins in Life of General Taylor; a map in Campaña contra,

etc.; a plan by Berlandier in

El Republicano; a plan by Eaton (Ho. Ex. Doc. 209; 29 Cong., 1 sess.); French, Two Wars, 52; and

Journal of Milit. Service Instit., xli, 100.

7.

From Matamoros to Monterey

210Based on an official Mexican map prepared by the Fomento Dept. and on Gen. Arista’s map.

8.

Battles of Monterey: General Map

232Based on *three plans drawn by Lieut. Gardner from surveys of Lieut. Scarritt (War Dept., Washington);

PicayuneExtra, Nov. 19, 1846 (Lieut. Benjamin); a *drawing by Adjutant Heiman (Tennessee Hist. Society); a map in Apuntes; and a plan by Balbontín (Invasión Americana).

9.

Battles of Monterey. Central Operations

240Based on the same sources as No. 8

supra.

10.

General Wool’s March

271Based on reconnaissances of Capt. Hughes, Lieut. Sitgreaves, and Lieut. Franklin (Sen. Ex. Doc. 32; 31 Cong., 1 sess.).

11.

Tampico and Its Environs

276Based on a sketch by Lee and Gilmer (War Dept., Washington); and a Fomento Dept. Map (

seeNo. 7

supra).

12.

General Kearny’s March to Santa Fe

287From a sketch drawn by A. Wislizenus (Sen. Misc. Doc. 26; 30 Cong., 1 sess.).

13.

El Paso to Rosales, Mexico

305From a U. S. War College map, Washington.

14.

Battle of Sacramento

307Based on a map in Sen. Ex. Doc. 1; 30 Cong., 1 sess.; and a plan in México á través de los Siglos, iv, 644.

15.

California in 1846

316Based on a map in Sen. Ex. Doc. 1; 30 Cong., 1 sess.

16.

Northern California

317From a sketch by Lieut. Derby (Sen. Ex. Doc. 18; 31 Cong., 1 sess.) and recent maps.

17.

Fight at San Pascual

341From a plan in Sen. Ex. Doc. 1; 30 Cong., 1 sess.

18.

Fight near Los Angeles

344From a plan in Sen. Ex. Doc. 1; 30 Cong., 1 sess.

19.

General Patterson’s March

360From a map in Ho. Ex. Doc. 13; 31 Cong., 2 sess.

20.

From Mexico City to Agua Nueva

381From a Fomento Dept. map.

21.

From Monterey to La Encarnación

382Based on a map in Rápida Ojeada sobre la Campaña,

etc.; and a *sketch by Lee and Gilmer (War Dept., Washington).

22.

Battle of Buena Vista

387Based on a map drawn by Capt. Linnard from the surveys of Capt. Linnard and Lieuts. Pope and Franklin (Sen. Ex. Doc. 1; 30 Cong., 1 sess.); *two plans by the same officers (War Dept., Washington); a *map based on a sketch by Dr. Vanderlinden, chief Mexican surgeon (War Dept., Mexico); a map by Balbontín (Invasión Americana); a *map drawn by Stanislaus Lasselle (Indiana State Library); a plan by Lieut. Green (Scribner, Campaign in Mexico); *Croquis para la intelligencia de la Batalla de la Angostura (War Dept., Washington).

CONSPECTUS OF EVENTS

1845

March.

The United States determines to annex Texas; W. S. Parrott sent to conciliate Mexico.

July.

Texas consents; Taylor proceeds to Corpus Christi.

Oct.

17.

Larkin appointed a confidential agent in California.

Nov.

10.

Slidell ordered to Mexico.

Dec.

20.

Slidell rejected by Herrera.

1846

Jan.

13.

Taylor ordered to the Rio Grande.

Mar.

8.

Taylor marches from Corpus Christi.

21.

Slidell finally rejected by Paredes.

28.

Taylor reaches the Rio Grande.

Apr.

25.

Thornton attacked.

May

8.

Battle of Palo Alto.

9.

Battle of Resaca de la Palma.

13.

The war bill becomes a law.

June

5.

Kearny’s march to Santa Fe begins.

July

7.

Monterey, California, occupied.

14.

Camargo occupied.

Aug.

4.

Paredes overthrown.

7.

First attack on Alvarado.

13.

Los Angeles, California, occupied.

16.

Santa Anna lands at Vera Cruz.

18.

Kearny takes Santa Fe.

19.

Taylor advances from Camargo.

Sept.

14.

Santa Anna enters Mexico City.

20–24.

Operations at Monterey, Mex.

22–23.

Insurrection in California precipitated.

23.

Wool’s advance from San Antonio begins.

25.

Kearny leaves Santa Fe for California.

Oct.

8.

Santa Anna arrives at San Luis Potosí.

Oct.

15.

Second attack on Alvarado.

24.

San Juan Bautista captured by Perry.

28.

Tampico evacuated by Parrodi.

29.

Wool occupies Monclova.

Nov.

15.

Tampico captured by Conner.

16.

Saltillo occupied by Taylor.

18.

Scott appointed to command the Vera Cruz expedition.

Dec.

5.

Wool occupies Parras.

6.

Kearny’s fight at San Pascual.

25.

Doniphan’s skirmish at El Brazito.

27.

Scott reaches Brazos Id.

29.

Victoria occupied.

1847

Jan.

3.

Scott orders troops from Taylor.

8.

Fight at the San Gabriel, Calif.

9.

Fight near Los Angeles, Calif.

11.

Mexican law regarding Church property.

28.

Santa Anna’s march against Taylor begins.

Feb.

5.

Taylor places himself at Agua Nueva.

19.

Scott reaches Tampico.

22–23.

Battle of Buena Vista.

27.

Insurrection at Mexico begins.

28.

Battle of Sacramento.

Mar.

9.

Scott lands near Vera Cruz.

29.

Vera Cruz occupied.

30.

Operations in Lower California opened.

Apr.

8.

Scott’s advance from Vera Cruz begins.

18.

Battle of Cerro Gordo; Tuxpán captured by Perry.

19.

Jalapa occupied.

May

15.

Worth enters Puebla.

June

6.

Trist opens negotiations through the British legation.

16.

San Juan Bautista again taken.

Aug.

7.

The advance from Puebla begins.

20.

Battles of Contreras and Churubusco.

Aug. 24–Sept. 7. Armistice.

Sept.

8.

Battle of Molino del Rey.

13.

Battle of Chapultepec; the “siege” of Puebla begins.

14.

Mexico City occupied.

22.

Peña y Peña assumes the Presidency.

Oct.

9.

Fight at Huamantla.

20.

Trist reopens negotiations.

Nov.

11.

Mazatlán occupied by Shubrick.

1848

Feb.

2.

Treaty of peace signed.

Mar.

4–5.

Armistice ratified.

10.

Treaty accepted by U. S. Senate.

May

19, 24.

Treaty accepted by Mexican Congress.

30.

Ratifications of the treaty exchanged.

June

12.

Mexico City evacuated.

July

4.

Treaty proclaimed by President Polk.

THE PRONUNCIATION OF SPANISH

The niceties of the matter would be out of place here, but a few general rules may prove helpful.

A as in English “ah”; e, at the end of a syllable, like a in “fame,” otherwise like e in “let”; i like i in “machine”; o, at the end of a syllable, like o in “go,” otherwise somewhat like o in “lot”; u like u in “rude” (but, unless marked with two dots, silent between g or q and e or i); y like ee in “feet.”

C like k (but, before e and i, like [C]th in “thin”); ch as in “child”; g as in “go” (but, before e and i, like a harsh h); h silent; j like a harsh h; ll like [D]lli in “million”; ñ like ni in “onion”; qu like k; r is sounded with a vibration (trill) of the tip of the tongue (rr a longer and more forcible sound of the same kind); s as in “sun”; x like x in “box” (but, in “México” and a few other names, like Spanish j); z like [C]th in “thin.”

Words bearing no mark of accentuation are stressed on the last syllable if they end in any consonant except n or s, but on the syllable next to the last if they end in n, s or a vowel.

Transcriber’s Note

1. Another reason for the neglect of the Mexican War has been its unpopularity. But for that, it would no doubt have been thoroughly studied sooner.

[A] The notes to which this and the other “superior figures” invite attention will be found immediately after the text of the volume. In the notes only brief titles of books are given, but these may be supplemented by reference to the list of printed sources given in the appendix of the second volume. Citations (in the notes) preceded by a number in black type refer to the list of MS. sources standing at the end of the notes.

[B] These figures cover also the author’s “Annexation of Texas,” which is virtually an introduction to the present work.

2. A second reason for preparing this history was that a number of important topics—such as the conditions existing in the two countries just before the war, the war in American politics, our conduct and methods in occupied territory, the finances of the war, its foreign relations, etc.—had been treated most superficially or not at all. In the third place it was hoped to handle more carefully the material previously used. The bound volumes entitled “Archivo de Guerra” in the Archivo General y Público at Mexico occupy some 200 feet of shelf room, and the papers examined in the Archivo de Guerra y Marina, which had to be examined one by one, would probably, if placed one on another, make a pile sixty feet high.

3. The printed versions of diplomatic and military documents, when substantially correct, are usually cited in the notes, because they are easily accessible; but so far as possible they have been collated with the originals. On the value of official military reports the author presented some remarks in the American Historical Review, vol. xxi, p. 96. Gen. Worth said privately that Scott’s report on the battle of Cerro Gordo was “a lie from beginning to end,” and in a sense different from what this language would at first sight appear to mean, it was fairly correct (chap. xxiii, note 33). Subordinate officers not infrequently brought all possible influence, both personal and political, to bear upon the general whose report they knew would be printed. A general naturally favored in his report the regiment and the officers with whom he had been formerly associated. An undue regard for rank was often felt. Taylor asked a promotion for Brig Gen. Twiggs after the capture of Monterey though Twiggs had been ostensibly ill at the time and had taken no material part in the fight. Captain (later General) Bragg wrote: “The feelings succeeding a great victory caused many things to be forgotten and forgiven which would sound badly in history, and which will never be known except in private correspondence” (210to Gov. Hammond, May 4, 1848). An important document issued by our government was privately described by the adj. gen. as “full of inaccuracies” (117R.Jones to B. Mayer, Oct. 10, 1848).

4. Particular reasons why a civilian could venture to prepare the history of this war were that (1) owing largely to the smallness of the numbers engaged, the operations were simple; (2) the reports were written for non-military readers; and (3) a large amount of good criticism was written at the time or soon afterwards—mostly in a private way—by competent officers who were personally familiar with the circumstances. As a matter of fact military men’s technical knowledge does not necessarily enable them to reach correct historical conclusions. This is proved by their radical differences of opinion (e.g. compare the articles on Wilcox’s History of the Mexican War, Journal of U.S. Artillery, July and Oct., 1892) and their manifest errors of judgment. Gen. U. S. Grant pronounced Scott’s strategy on Aug. 20, 1847, faultless as a result of the perfect work of his engineer officers (Pers. Mems., i, 145); but the engineer from whose report Scott’s essential orders regarding the battle of Churubusco resulted admitted privately that he blundered (xxvi, notes, remarks on Churubusco). The dicta of military authorities are not often quoted by the author, because war cannot be made by rule and it would be necessary to consider in each case whether the dictum was applicable.

5. As the author was compelled to depart in many cases from the familiar method of referring to the sources, he feels bound to explain how these were handled. All the material, condensed as much as it safely could be, was marked in the margin with Roman figures, indicating to what chapter each sentence or larger section would belong. Then the sections were copied into packets, each of which contained all the material of a chapter. Next the material of each packet was analyzed into topical items, and the items were numbered with Arabic figures. In writing a chapter the author placed after each sentence (or, if the case demanded, after each clause, phrase or word) the Arabic figures numbering the items upon which it rested. These figures were retained through the successive revisions until the MS. was ready to print, and were used in the re-examination of the work. By this routine every document was considered at least five times. Of course care was taken at all stages to ensure correct copying; yet in the final revision the author went back, unless there was a good reason for not doing so, to originals or to trustworthy copies from the originals—doing this not merely to verify the references but also to see, in the light of the completed investigation of the subject, whether he had omitted or misunderstood anything of importance in making notes and condensations. The text and remarks as written looked thus:

XIV

SANTA FE

June-September, 1846

PROFILE OF THE ROUTE BETWEEN MEXICO AND VERA CRUZ

MATAMOROS AND FORT BROWN SKETCH MAP

Fort Brown to Brazos Island

BATTLE OF PALO ALTO

May 8, 1846

BATTLE OF RESACA DE LA PALMA

From Matamoros to Monterey

BATTLE OF MONTEREY

GENERAL PLAN

BATTLE OF MONTEREY DETAILED PLAN

WOOL’S MARCH

Tampico and Its Environs

GENERAL KEARNY’S MARCH

EL PASO TO ROSALES

BATTLE OF SACRAMENTO

Feb. 28, 1847

CALIFORNIA COAST

1846

NORTHERN CALIFORNIA

Fight at San Pascual

Fight near Los Angeles

General Patterson’s March

MEXICO TO AGUA NUEVA

MONTEREY TO LA ENCARNACIÓN

BATTLE OF BUENA VISTA

Larger image

[C] In Mexico, however, usually like s in “sun.”

[D] In Mexico usually like y.

MEXICO IN 1919

Larger image

THE WAR WITH MEXICO

I

MEXICO AND THE MEXICANS

1800–1845

Mexico, an immense cornucopia, hangs upon the Tropic of Cancer and opens toward the north pole. The distance across its mouth is about the same as that between Boston and Omaha, and the line of its western coast would probably reach from New York to Salt Lake City. Nearly twenty states like Ohio could be laid down within its limits, and in 1845 it included also New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, California and portions of Colorado and Wyoming.[1]

On its eastern side the ground rises almost imperceptibly from the Gulf of Mexico for a distance varying from ten to one hundred miles, and ascends then into hills that soon become lofty ranges, while on the western coast series of cordilleras tower close to the ocean. Between the two mountain systems lies a plateau varying in height from 4000 to 8000 feet, so level—we are told—that one could drive, except where deep gullies make trouble, from the capital of Montezuma to Santa Fe, New Mexico. The country is thus divided into three climatic zones, in one or another of which, it has been said, every plant may be found that grows between the pole and the equator.[1][E]

Except near the United States the coast lands are tropical or semi-tropical; and the products of the soil, which in many quarters is extraordinarily deep and rich, are those which naturally result from extreme humidity and heat. Next comes an intermediate zone varying in general height from about 2000 to about 4000 feet, where the rainfall, though less abundant than on the coast, is ample, and the climate far more salubrious than below. Here, in view of superb mountains and even of perpetual snows, one finds a sort of eternal spring and a certain blending of the tropical and the temperate zones. Wheat and sugar sometimes grow on the same plantation, and both of them luxuriantly; while strawberries and coffee are not far apart.[1]

PROFILE OF THE ROUTE BETWEEN MEXICO AND VERA CRUZ

The central plateau lacks moisture and at present lacks trees. The greater part of it is indeed a semi-desert, though a garden wherever water can be supplied. During the wet season—June to October—it is covered with wild growths, but the rains merely dig huge gullies or barrancas, and almost as soon as they are over, most of the vegetation begins to wither away. The climate of the plateau is quite equable, never hot and never cold. Wheat, Indian corn and maguey—the plant from which pulque, the drink of the common people, is made—are the most important products; and at the north great herds of cattle roam. In the mountains, finally, numberless mines yield large quantities of silver, some gold, and a considerable amount of copper and lead.[1]

The principal cities on the eastern coast are Vera Cruz, the chief seaport, and Tampico, not far south of the Rio Grande River. In the temperate zone between Vera Cruz and Mexico lie Jalapa and Orizaba, and behind Tampico lies Monterey. On the central plateau one finds the capital reposing at an elevation of about eight thousand feet and, about seventy miles toward the southeast, Puebla; while on the other side of the capital are the smaller towns of Querétaro and San Luis Potosí toward the north, and Zacatecas and Chihuahua toward the northwest. In the middle zone of the Pacific slope rises the large city of Guadalajara, capital of Jalisco state; and along the coast below may be found a number of seaports, the most important of which are Guaymas, far to the north, Mazatlán opposite the point of Lower California, San Blas a little farther down, and Acapulco in the south.[1]

THE PEOPLE

Exactly how large the population of Mexico was in 1845 one cannot be sure, and it included quite a number of racial mixtures; but for the present inquiry we may suppose it consisted of 1,000,000 whites, 4,000,000 Indians, and 2,000,000 of mixed white and Indian blood.[2] The Spaniards from Europe, called Gachupines in Mexico, were of two principal classes during her colonial days. Many had been favorites of the Spanish court, or the protégés of such favorites, and had exiled themselves to occupy for a longer or shorter time high and lucrative posts; but by far the greater number were men who had left home in their youth—poor, but robust, energetic and shrewd—to work their way up. With little difficulty such immigrants found places in mercantile establishments or on the large estates. Merciless in pursuit of gain yet kind to their families, faithful to every agreement, and honest when they could afford to be, they were intrinsically the strongest element of the population, and almost always they became wealthy.[3]

Their sons, poorly educated, lacking the spur of poverty, and finding themselves in a situation where idleness and self-indulgence were their logical habits, commonly took “Siempre alegre” (Ever light-hearted) for their motto, and spent their energy in debauchery and gambling. To this result their own fathers, while disgusted with it, usually contributed. Spanish pride revolted at the ladder of subordination by which these very men had climbed. They felt ambitious to make gentlemen of their sons, and some easy position in the army, church or civil service—or, in default of it, idleness—was the career towards which they pointed; and naturally the heirs to their wealth, whose ignoble propensities had prevented them from acquiring efficiency or sense of responsibility, made haste, on getting hold of the paternal wealth, to squander it. If the pure whites, with some exceptions of course, fell into this condition, nothing better could fairly be expected of those who were partly Indian; and before the revolution it was almost universally felt in Spain and among the influential class of colonials themselves, that nothing of much value could be expected of Creoles, as the whites born in Mexico and the half-breeds were generally called. The achievement of independence naturally tended to increase their self-respect, broaden their views and stimulate their ambition; but the less than twenty-five years that elapsed between 1821 and 1846, when the war between Mexico and the United States began, were not enough to transform principles, reverse traditions and uproot habits.[3]

The pure-blooded Indians—of whom there were many tribes, little affiliated if at all—had changed for the worse considerably since the arrival of the whites. In their struggles against conquest and oppression the most intelligent, spirited and energetic had succumbed, and the rest, deprived of strength, happiness, consolation and even hope, and aware that they existed merely to fill the purses or sate the passions of their masters, had rapidly degenerated. Their natural apathy, reticence and intensity were at the same time deepened. While apparently stupid and indifferent, they were capable of volcanic outbursts. Though fanatically Christian in appearance, they seem to have practiced often a vague nature worship under the names and forms of Catholicism. Indeed they were themselves almost a part of the soil, bound in soul to the spot where they were born; and, although their women could put on silk slippers to honor a church festival and every hut could boast a crucifix or a holy image, they lived and often slept beside their domestic animals with a brutish disregard for dirt.[3]

Legally they had the rights of freemen and were even the wards of the government, and a very few acquired education and property; but as a rule they had to live by themselves in little villages under the headship of lazy, ignorant caciques and the more effective domination of the priests. As the state levied a small tax upon them and the Church several heavy ones, their scanty earnings melted fast, and if any surplus accumulated they made a fiesta in honor of their patron saint, and spent it in masses, fireworks, drink, gluttony and gambling. When sickness or accident came they had to borrow of the landowner to whose estate they were attached; and then, as they could not leave his employ until the debt had been discharged, they not only became serfs, but in many cases bequeathed their miserable condition to their children. Silent and sad, apparently frail but capable of great exertion, trotting barefooted to and from their huts with their coarse black hair flowing loosely or gathered in two straight braids, watching everything with eyes that seemed fixed on the ground, loving flowers much but a dagger more, fond of melody but preferring songs that were melancholy and wild, always tricky, obstinate, indolent, peevish and careless yet affectionate and hospitable, often extracting a dry humor from life as their donkeys got nourishment from the thistles, they went their wretched ways as patient and inscrutable as the sepoy or the cat—infants with devils inside.[3]

THE CLASSES

At the head of the social world stood a titled aristocracy maintained by the custom of primogeniture. But as the nobles were few in number, and for a long time had possessed no feudal authority, their influence at the period we are studying depended mainly upon their wealth. Next these came aristocrats of other kinds. Some claimed the honor of tracing their pedigree to the conquerors, and with it enjoyed great possessions; and others had the riches without the descent. The two most approved sources of wealth were the ownership of immense estates and the ownership of productive mines. On a lower level stood certain of the rich merchants, and lower still, if they were lucky enough to gain social recognition, a few of those who acquired property by dealing in the malodorous government contracts. To these must be added in general the high dignitaries of the church, the foreign ministers, the principal generals and statesmen and the most notable doctors and lawyers. Such was the upper class.[4]

A sort of middle class included the lesser professional men, prelates, military officers and civil officials, journalists, a few teachers, business men of importance and some fairly well-to-do citizens without occupations. Of small farms and small mines there were practically none, and the inferior clergy signified little. The smaller importing and wholesale merchants came to be almost entirely British, French and German soon after independence was achieved, and the retailers were mostly too low in the scale to rank anywhere. The case of those engaged in the industries was even more peculiar. Working at a trade seemed menial to the Spaniard, especially since the idea of labor was associated with the despised Indians, and most of the half-breeds and Indians lacked the necessary intelligence. Skilled workers at the trades were therefore few, and these few mostly high-priced foreigners. Articles of luxury could be had but not comforts; pastries and ices but not good bread; saddles covered with gold and embroidery, but not serviceable wagons; and the highly important factor of intelligent, self-respecting handicraftsmen was thus well-nigh missing.[4]

The laboring class consisted almost entirely of half-breeds and Indians. In public affairs they were not considered, and their own degraded state made them despise their tasks. Finally, the dregs of the population, especially in the large cities, formed a vicious, brutal and semi-savage populace. At the capital there were said to be nearly 20,000 of the léperos, as they were called, working a little now and then, but mainly occupied in watching the religious processions, begging, thieving, drinking and gambling. In all, Humboldt estimated at 200,000 or 300,000 the number of these creatures, whose law was lawlessness and whose heaven would have been a hell.[4]

THE CHURCH

The only church legally tolerated was that of Rome; and this, as the unchallenged authority in the school and the pulpit, the keeper of confessional secrets and family skeletons, and the sole dispenser of organized charity, long wielded a tremendous power. The clerical fuero, which exempted all ecclesiastics from the jurisdiction of the civil courts, reinforced it, and the wealth and financial connections of the Church did the same. In certain respects, however, the strength of the organization began to diminish early in the nineteenth century; and in particular the Inquisition was abolished in Mexico, as it was in Spain. Soon after the colony became independent, a disposition to bar ecclesiastics from legislative bodies, to philosophize on religious matters and to view Protestants with some toleration manifested itself. Ten years more, and the urgent need of public schools led to certain steps, as we shall see, toward secular education. Political commotions, the exactions of powerful civil authorities under the name of loans, and various other circumstances cut into the wealth of the Church; and the practical impossibility of selling the numberless estates upon which it had mortgages or finding good reinvestments in the case of sales, compelled it, as the country became less and less prosperous, to put up with delays and losses of interest.[5]

Moreover the Church was to no slight extent a house divided against itself. Under Spanish rule and substantially down to 1848, all the high dignities fell to Gachupines, who naturally faced toward Spain, whereas the parish priests were mainly Creoles with Mexican sympathies; and while the bishops and other managers had the incomes of princes, nearly all of the monks and ordinary priests lived in poverty. There was, therefore, but little in common between the two ranks except the bare fact of being churchmen, which was largely cancelled on the one side by contempt and on the other side by envy; and the common priests, having generally sided against Spain during the revolution and always been closely in touch with the people, exercised, in spite of their pecuniary exactions, an influence that largely balanced the authority of their heads. Finally, the ignorance of most ecclesiastics and the immorality of nearly all greatly diminished their moral force. A large number, even among the higher clergy, were unable to read the mass; and the monks, who in the early days of the colony had rendered good service as missionaries, were now recruited—wrote an American minister—from “the very dregs of the people,” and constituted a public scandal.[5]

Still, the Church wielded immense power as late as 1845, and this was reinforced by the type of religion that it offered. High and low alike, the Mexicans, with some exceptions, lived in the senses, differing mainly in the refinement of the gratifications they sought; and the priests offered them a sensuous worship. Sometimes, almost crazed by superstitious fears, men would put out the lights in some church, strip themselves naked, and ply the scourge till every blow fell with a splash. It was pleasanter, however, and usually edifying enough, to kneel at the mass, gaze upon the extraordinary display of gold and silver, gorgeous vestments, costly images and elaborately carved and gilded woodwork, follow the smoke of the incense rolling upward from golden censers, listen to sonorous incantations called prayers, and confess to some fat priest well qualified to sympathize with every earthy desire. A man who played this game according to the rule was good and safe. A brigand counting the chances of a fray could touch his scapularies with pious confidence, and the intending murderer solicit a benediction on his knife. Enlightened Catholics as well as enlightened non-Catholics deplored the state of religion in Mexico.[5]

Next after the Church came the “army,” which meant a social order, a body of professional military men—that is to say, officers–exempted by their fuero from the jurisdiction of the civil law and almost exclusively devoted to the traditions, principles and interests of their particular group. As the Church held the invisible power, the army held the visible; and whenever the bells ceased to ring, the roll of the drum could be heard. Every President and almost every other high official down to the close of our Mexican war was a soldier, and sympathized with his class; and as almost every family of any importance included members of the organization, its peculiar interests had a strong social backing. By force of numbers, too, this body was influential, for at one time, when the army contained scarcely 20,000 soldiers, it had 24,000 officers; and so powerful became the group that in 1845, when the real net revenue of the government did not exceed $12,000,000, its appropriation was more than $21,000,000.[5]

Under Spanish rule, although the army enjoyed great privileges, it had been kept in strict subordination, and usefully employed on the frontiers; but independence changed the situation. Apparently the revolution was effected by the military men, and they not merely claimed but commonly received the full credit. Not only did a large number of unfit persons, who pretended to have commanded men during the struggle, win commissions, but wholesale promotions were made in order to gain the favor of the officers; and in these ways the organization was both demoralized and strengthened. Over and over again military men learned to forswear their allegiance, and at one time the government actually set before the army, as a standard of merit, success in inducing soldiers of the opposite party to change sides.[5]

THE ARMY

In the course of political commotions, to be reviewed in the next chapter, the armed forces were more and more stationed at the cities, where they lost discipline and became the agents of political schemers; and naturally, when the government admitted their right to take part as organized bodies in political affairs, the barracks came to supersede the legislative halls, bullets took the place of arguments, and the military men, becoming the arbiters on disputed points, regarded themselves as supreme. Moreover, every administration felt it must have the support of this organization, and, not being able to dominate it, had to be dominated by it. Political trickery could therefore bring the officer far greater rewards than professional merit, and success in a revolt not only wiped away all stains of insubordination, cowardice and embezzlement, but ensured promotion. A second lieutenant who figured in six affairs of that sort became almost necessarily a general, and frequently civilians who rendered base but valuable services on such occasions were given high army rank. No doubt some risk was involved, but it was really the nation as a whole that paid the penalties; and anyhow one could be bold for a day far more easily than be courageous, patient, studious, honest and loyal for a lifetime. All true military standards were thus turned bottom-side up, and some of the worst crimes a soldier can perpetrate became in Mexico the brightest of distinctions.[5]

Of course the discovery that rank and pay did not depend upon deserving them set every corrupt officer at work to get advanced, while it drove from the service, or at least discouraged, the few men of talents and honor; and as all subordination ceased, a general not only preferred officers willing to further his dishonorable interests, but actually dreaded to have strong and able men serve in his command. In 1823 the Mexican minister of war reported to Congress, “Almost the whole army must be replaced, for it has contracted vices that will not be removed radically in any other way,” and four years later a militia system was theoretically established with a view to that end; but the old organization continued to flourish, and in April, 1846, the British minister said, “The Officers ... are, as a Corps, the worst perhaps to be found in any part of the world. They are totally ignorant of their duty, ... and their personal courage, I fear, is of a very negative character.”[5]

In 1838, a German visitor stated there were a hundred and sixty generals for an army of thirty thousand, and this was perhaps a fair estimate of the usual proportion; but out of all these, every one of whom could issue a glowing proclamation, probably not a single “Excellency” could properly handle a small division, while few out of thousands of colonels could lead a regiment on the field, and some were not qualified to command a patrol. A battle was almost always a mob fight ending in a cavalry charge; and Waddy Thompson, an American minister to Mexico, said he did not believe a manoeuvre in the face of the enemy was ever attempted. Naturally the general administration of military affairs became a chaos; and, worst of all, a self-respecting general thought it almost a disgrace to obey an order—even an order from the President.[5]

The privates and non-commissioned officers, on the other hand, mainly Indians with a sprinkling of half-breeds, were not bad material. The Indians in particular could be described as naturally among the best soldiers in the world, for they were almost incredibly frugal, docile and enduring, able to make astonishing marches, and quite ready—from animal courage, racial apathy or indifference about their miserable lives—to die on the field. But usually they were seized by force, herded up in barracks as prisoners, liberally cudgelled but scantily fed, and after a time driven off to the capital, chained, in a double file, with distracted women beside them wailing to every saint. When drilled enough to march fairly well through the street in column, clothed in a serge uniform or a coarse linen suit, and equipped with an old English musket and some bad powder, they were called soldiers, and were exhorted to earn immortal glory; but naturally they got away if they could, and frequently on a long expedition half a corps deserted.[5]

Such men were by no means “thinking bayonets,” and as a rule they shot very badly, often firing with their guns at the hip in order to avoid the heavy recoil. Not only did they lack the inspiration of good officers, but in pressing times it was customary to empty the prisons, and place their inmates in the ranks to inculcate vice. The government furnished their wages, upon which as a rule they had to live from day to day, even more irregularly than it paid the officers, and the latter frequently embezzled the money; so that it became a common practice to sell one’s arms and accoutrements, if possible, for what they would bring. Finally, the duty always enjoined upon the troops was “blind obedience,” not the use of what little intelligence they possessed; and their bravery, like that of such officers as had any, was mainly of the impulsive, passionate and therefore transient sort, whereas Anglo-Saxon courage is cool, calculating, resolute and comparatively inexhaustible.[5]

The special pride of all military men was the cavalry; but the horses were small, and the riders badly trained and led. “The regular Mexican cavalry is worth nothing,” wrote the British minister early in 1846; and as the mounts were quite commonly hired merely for the parades, just as the rolls of the whole army were stuffed with fictitious names on which the officers drew pay, it was never certain how much of the nominal force could be set in motion. As for the artillery, Waddy Thompson remarked that in a battle of 1841 between the foremost generals of the country, not one ball in a thousand reached the enemy. On the other hand there were excellent military bands, and one of them dispensed lively selections every afternoon in front of the palace at Mexico.[5]

THE CIVIL OFFICIALS

Third in the official order of precedence and in the actual control of affairs came the government officials, and these, like the army and the clergy, formed a special group with a similar fuero, a similar self-interest and a similar disregard for the general good. Once appointed to an office one had a vested right therein, and could not legally be removed without a prosecution. To eliminate a person in that manner was extremely difficult; and when the government, in a few notorious instances, tried ejectment, the newspapers of the opposition hastened to raise an outcry against it for attacking property rights, and the culprits were soon reinstated.[5]

Offering such permanence of tenure, a “genteel” status, idleness even beyond the verge of ennui, a perfect exemption from the burden of initiative, and occasional opportunities for illegitimate profits, government offices appealed strongly to the Mexicans, and a greed for them—dignified with the name of aspirantism when it aimed at the higher positions—was a recognized malady of the nation. To get places, all the tricks and schemes employed in the army and, if possible, still more degrading intrigues were put in play; and offices had to be created by the wholesale to satisfy an appetite that grew by what it fed upon. The clerks became so numerous that work room—or rather desk room—could not be provided for all of them. Only a favored portion had actual employment and received full pay—if they received any—while the rest were laid off on barely enough to support life. Some were competent and willing to be faithful; but when they saw ignorance, laziness, disloyalty and fraud given the precedence, they naturally asked, Why do right? Idleness is the mother of vice; and so there was a very large body of depraved and discontented fellows, wriggling incessantly for preferment, fawning, backbiting, grabbing at any scheme that would advance their interests, intensely jealous of one another, but ready to make common cause against any purification of the civil service.[5]

How justice was administered in Mexico one is now able to surmise. The laws, not codified for centuries, were a chaos. Owing to numberless intricacies and inconsistencies, the simplest case could be made almost eternal, especially as all proceedings were slow and tedious. A litigant prepared to spend money seldom needed to lose a suit. Some cases lasted three generations. The methods of administering justice, reported the British representative in 1835, “afford every facility” for “artifices and manoeuvres.”[6]

Another difficulty was that the courts lacked prestige. During the revolution the magistrates, practically all of them Gachupines, committed so many acts of injustice in behalf of the government, that people forgot the proper connection between crime and retribution. Punishment seemed like a disease that any one might get. In 1833 the minister of this department complained that for five years Congress had almost ignored the administration of justice; and in 1845, the head of the same department said that for a long time the government had systematically reduced the dignity and influence of the judges and magistrates. Their pay was not only diminished but often withheld; and the official journal once remarked, that the authorities had more important business in hand than paying legal functionaries.[6]

This was obviously wrong, but in a sense the judges merited such treatment, for they seem to have lacked even the most necessary qualifications. To make the situation still worse, the executive authorities had a way of stepping in and perverting justice arbitrarily. Even the Mexicans were accustomed to say, “A bad compromise is better than a good case at law”; but it was naturally aliens who suffered most. “The great and positive evil which His Majesty’s subjects, in common with other Foreigners, have to complain of in this country is the corrupt and perverse administration of justice,” reported the minister of England in 1834.[6]

Criminal law was executed no better than civil. The police of the city are a complete nullity, stated the American representative in 1845. A fault, a vice and a crime were treated alike; and the prisons, always crowded with wrongdoers of every class, became schools in depravity, from which nearly all, however bad, escaped in the end to prey upon society. Well-known robbers not only went about in safety, but were treated with kindly attentions even by their late victims, for all understood that if denounced and punished, they would sooner or later go free, and have their revenge.[6]

EDUCATION

Adverting formally before Congress in 1841 to the “notoriously defective” administration of justice, the Mexican President said, “the root of the evil lies in the deplorable corruption which pervades all classes of society and in the absence of any corrective arising from public opinion.” In large measure this condition of things was chargeable to the low state of religion, but in part it could be attributed to the want of education. Spain had required people to think as little as possible, keep still and obey orders; and for such a rôle enlightenment seemed unnecessary and even dangerous. To read and write a little and keep accounts fairly well was about enough secular knowledge for anybody, and the catechism of Father Ripalda, which enjoined the duty of blind obedience to the King and the Pope, completed the circle of useful erudition. In the small towns, as there were few elementary schools, even these attainments could not easily be gained; and as for the Indians they were merely taught—with a whip at the church door, if necessary—to fear God, the priest and the magistrate. Religion gave no help; and the ceremonies of worship benumbed the intellect as much as they fascinated the senses.[6]

When independence arrived, however, there sprang up not a little enthusiasm for the education of the people, and the states moved quite generally in that direction. But there were scarcely any good teachers, few schoolhouses and only the most inadequate books and appliances; money could not be found; and the prelates, now chiefly absorbed in their political avocations, not only failed to promote the cause, but stood in the way of every step toward secular schools. A few of the leaders—notably Santa Anna—professed great zeal, but this was all for effect, and they took for very different uses whatever funds could be extorted from the nation. In 1843 a general scheme of public instruction was decreed, but no means were provided to carry it into effect. The budget for 1846 assigned $29,613 to this field, of which $8000 was intended for elementary schools, while for the army and navy it required nearly twenty-two millions. In short, though of course a limited number of boys and a few girls acquired the rudiments—and occasionally more—in one way or another, no system of popular education existed.[6]

Higher instruction was in some respects more flourishing. Before the revolution the School of Mines, occupying a noble and costly edifice, gave distinction to the country; the university was respectable; an Academy of Fine Arts did good work; and botany received much attention. But at the university mediaeval Latin, scholastic and polemic theology, Aristotle and arid comments on his writings were the staples, and even these innocent subjects had to be investigated under the awful eye of the Inquisition. Speculation on matters of no practical significance formed the substance of the work, and the young men learned that worst of lessons—to discourse volubly and plausibly on matters of which they knew nothing. This course of discipline, emphasizing the natural bent of the Creoles, turned out a set of conceited rhetoricians, ignorant of history and the real world, but eager to distinguish themselves by some brilliant experiment. When the yoke of Spain had been cast off, all these institutions declined greatly, and the university became so unimportant that in 1843 it was virtually destroyed; but the view that speculation was better than inquiry, theory better than knowledge, and talk better than anything—a view that suited Mexican lightness, indolence and vanity so well, and had so long been taught by precept and example—still throve despite a few objectors. Of foreign countries, in particular, very little was commonly known. While elementary education, then, was nothing, higher education was perhaps worse than nothing.[6]

Nor could the printed page do much to supply the lack. Only a few had the taste for reading books or opportunities to gratify the taste, if they possessed it. Great numbers of catchy pamphlets on the topics of the day flew about the streets; newspapers had a great vogue; and there were poor echoes of European speeches, articles and books; but most of the printed material was shockingly partisan, irresponsible and misleading. “Unfortunately for us,” observed the minister of the interior in 1838, “the abuse of the liberty of the press among us is so great, general and constant, that it has only served our citizens as the light of the meteor to one travelling in a dark night, misguiding him and precipitating him into an abyss of evils.”[6]

THE INDUSTRIES

Only some 300,000 out of 3,000,000 white and mixed people were actual producers—three times as many being clericals, military men, civil officials, lawyers, doctors and idlers, and the rest old men, women and children. The most brilliant of their industries was mining, the annual output of which was about $18,000,000 in 1790, fell during the revolution to $5,000,000, and by 1845 rose again—despite the unwise policy of the government—to about the earlier level. During the period of depression most of the old proprietors and many of their properties were ruined; but English companies took up the work, and although for some time their liberal expenditures went largely to waste, they gradually learned the business, and their example encouraged some Germans to enter the field. How greatly the nation profited from the mines was not entirely clear. About as much silver went abroad each year as they produced, paying interest on loans that should not have been made, and buying goods for which substitutes could usually have been manufactured at home. But the government laid valuable taxes on the extraction and export of the precious metals, and there was also a profit in the compulsory minting of them—though, as all the inventiveness of the nation expended itself in politics, the processes at the mints were about as tedious and costly in 1845 as while Cortez ruled the country.[7]

Little more can be said for the cultivation of the soil. When Mexico separated from Spain, the vine and the olive, flax and certain other plants formerly prohibited were acquired, and coffee soon became important; but on the other hand agriculture had met with disaster after disaster in the course of the revolution. “Up to the present,” said a ministerial report in December, 1843, “agriculture among us has not departed from the routine established at the time of the conquest.” A cart-wheel consisted still of boards nailed together crosswise, cut into a circular shape and bored at the centre; a pointed stick, shod sometimes with iron, was still the plough; a short pole with a spike driven through one end served as the hoe; the corn, instead of going to a mill, was ground on a smooth stone with a hand roller; and no adequate means existed of transporting such products as were raised to such markets as could be found. Most of the “roads” made so much trouble even for donkeys and pack-mules that it was seriously proposed to introduce camels; and the most important road of all, the National Highway from the capital to Jalapa and Vera Cruz, was allowed to become almost impassable in spots. Besides poor methods, bad roads, brigands, revolutions and a great number of holidays, there were customhouses everywhere and a system of almost numberless formalities, the accidental neglect of which might involve, if nothing worse, the confiscation of one’s goods. In short, how could agriculture prosper, said a memorial on the subject, when he that sowed was not permitted to gather, and he that gathered could reach no market?[7]

COMMERCE

However, more could be produced than used. The prime requisite was population. So much appeared to be clear; and for that reason, as well as to obtain the profits of the industries and prevent money from going abroad, great efforts were made by independent Mexico to develop manufacturing, which had been prohibited—though not with entire success—by Spain. The year 1830 was a time of golden hopes in this regard. At the instance of Lucas Alamán a grand industrial scheme went into effect, and a bank was founded to promote it by lending public money to intending manufacturers. Cotton fields were to whiten the plains; merino sheep and Kashmir goats to cover the hillsides; mulberry trees to support colonies of silk-worms; imported bees to produce the tons of wax needed for candles; and ubiquitous factories to work up the raw materials. A few men honestly tried to establish plants, but the industry chiefly promoted by the law and the bank was that of prying funds from the national treasury; and when this income failed, as it did in a few years, many half-built mills came to a stop, and much half-installed machinery began to rust. Alamán himself, partner in a cotton factory, became bankrupt in 1841, and the bubble soon burst.[7]

The manufacturers formed, however, a strong political clique, and in their interest a system not only of protection, but of absolutely prohibiting the importation of numerous articles, was adopted by law. This had the effect of making the people pay dearly for many of their purchases. The farmers, who wished raw materials kept out, had influence too, and were always blocking the scheme of the manufacturers to let raw materials in; and, as the cost of producing and transporting made native goods dear, smuggled merchandise undersold Mexican articles even after paying for the necessary bribery and other expenses. In a word, although certain coarse and bulky things continued to be made in the country, the endeavor to build up an industrial population, support agriculture, and thus doubly strengthen the nation was very superficially planned and very unsuccessfully carried out. Nearly all the better manufactures, a large part of the food, most of the clothing, and substantially all the luxuries came from abroad.[7]

The business of importing continued to be mainly in Spanish hands for some years after Mexico became independent, but for reasons that will appear in the next chapter the Spaniard had to retire about 1830. The British then obtained the lion’s share; and as they were Protestants they could not, even when they so desired, identify themselves with the nation, and take a responsible share in public affairs. Commerce was not, in fact, a source of strength. A few raw products were exported, but essentially commerce consisted, as was natural, in merely receiving goods from foreigners and letting the foreigners have money in return. Moreover the volume of commerce dwindled notably, like that of all other business. As for retail trade, when the Spaniards had to retire, it fell mainly into Mexican hands; but it was conducted in a small way, the profits were narrow, and the failures were many.[7]

LIFE IN THE COUNTRY

Even more significant for us, however, than such details were the life and character of the people, and it may be helpful to call back the year 1845 and visit Mexico for a couple of days. First we will stroll along a country road in a fairly typical region. The general aspect is one of semi-wildness, but soon the tops of well-bleached ruins amid the soft green indicate decrepitude instead, suggesting as the national character decay preceding maturity. A long mule team approaches in a waving line, and on a finely equipped horse at the head of it we observe a swarthy man in green broadcloth trousers open on the outside from the knee down, with bright silver buttons in a double row from hip to ankle, and loose linen drawers visible where the trousers open. A closely fitting jacket, adorned with many such buttons and much braid, is turned back at the chin enough to reveal an embroidered shirt; and the costume reaches a climax in a huge sombrero with a wide, rounding brim and high sugar-loaf crown, adorned with tassels and a wide band of silver braid. This gentleman, the arriero, is the railroad king of Mexico, for he and others of his class transport the freight and express. Trust him with anything you please, and it will surely be delivered; but should he be unlucky at cards and out of work, he might rob you the next day.[8]

A group of Indians meet us, little more human in appearance than the donkeys they drive; and we observe how easily they carry loads on their backs, and how quickly and lightly they march. Yonder we see their huts—pigpens, Americans would suppose; and a little apart from these we notice a stone or adobe house. Certainly there is nothing grand about this dwelling, for it contains only a single room, and that half full of implements, horse furniture, charcoal, provisions and what not; but it affords a home for six or eight persons of the two sexes. Presently the master, though not the owner, of the establishment rides up, prodding his active but light and stubby horse with blunt steel spurs almost as large as the palm of one’s hand, to make a dash for our benefit. Swinging his wife from the saddle-bow the ranchero alights, and we find him to be a short, wiry, muscular person, with a bronzed and rather saturnine countenance but friendly and respectful manners. He wears tough leggings, leather trousers, a small rectangular shawl (serape) that falls over his back and breast, allowing his head to protrude through a hole in the middle, and a wide sombrero, while at the saddle-bow hang the inevitable lasso and a bag of corn and jerked beef, one meal a day from which is all he requires. Apparently he does not feel quite at home on the ground, and that is natural, for he spends about half of his waking hours in the saddle. Herdsman, farmer or brigand, according to circumstances, he is also cavalryman at need; and a corps of such fellows, if properly trained and led, would make the best light horse in the world, perhaps. His chief interests in life, however, are gambling and cock-fighting, and he is quite capable of losing all his worldly goods, his wife and even his pony at the national game of monte, and then of lighting a cigarette and sauntering off without a sign of regret.[8]

Now we approach what may be called a village, but one extremely different from a village in the United States. The great things are a handsome grove and in the midst of it one old church of gray stone, full of saints and relics and ancient plate, with a ragged, stupid Indian crouching on the floor. Near by are two or three ranchero cottages with a group of Indian huts in the distance, and yonder stands a large, rambling edifice of stone with a mighty door and heavily barred windows. From the ends of the building run high walls inclosing several acres, and within the protected space may be seen a number of substantial dwellings and what appear to be storehouses and stables, while far away over hill and plain spreads the hacienda, an estate as large as a county. Finally, on a gentle slope not far distant we observe a monastery with a rich garden behind it, and a fat, contented prior riding sleepily up to its arched gateway through a dozen or two of kneeling aborigines.[8]

Toward evening we reach the state capital, and as we cross a bridge on the outskirts, we see a crowd of people bathing. Both sexes are splashing and swimming, all as happy as ducks and all entirely nude. Even the presence of strangers does not embarrass the young women, some of whom are decidedly good-looking; and they even try to draw our attention by extra displays of skill. Looking for an inn we discover two lines of low, rickety buildings alternating with heaps of rubbish, fodder and harness. After some efforts a waiter is found and we obtain a room, with a mule already slumbering in one corner of it and all sorts of household litter thrown about. A wretched cot with a rope bottom, a dirty table and an abundance of saints portrayed in Mexican dress help to make the place homelike. The waiter is amiable, and ejects the mule with a great show of indignation; but when we ask for water and a towel his good nature fails. “Oh, what a man,” he cries, flinging up his hands; “What a lunatic, Ave María Purísima; Ha! Ha! Ha! He wants water, he wants a towel; what the devil—! Good-by.” The dining-room is a hot, steamy cell, fitted up with charcoal furnaces; and for viands we are offered plenty of hard beef, chile (pepper) and tortillas (flapjacks of a sort), besides a number of dishes that only a native could either describe or eat. Chile and tortillas appear, however, to be the essentials; and the latter, partly rolled up, serve also as spoons.[8]