автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Pongo papers : and the Duke of Berwick

The Pongo Papers and the Duke of Berwick

BY LORD ALFRED DOUGLAS

PREFACE

Some sort of explanation seems advisable as to the reasons for the appearance of this book of rhymes. N ow-a-days it is apparently required of an author that he should give reasons for doing anything at all different from what he or others have done before. About a year ago, I ventured to publish a volume of rhymes entitled The Placid Pug, and I ventured, with the advice of the publishers, to issue it as an illustrated book, and to allow it to appear at or about Christmas. But it appears that I ought not to have done this. Illustrated books which appear in the Christmas season are, I gather, considered the property of children, and my book was not a book for children, (the publishers of the book actually went to the length of enclosing a printed notice to that effect with every copy that was sent for review,) and my book was therefore a source of annoyance in some cases, of anger in others. Most of the critics who reviewed my book treated it in the very kindest manner, and some of them praised it in an altogether extravagant manner; others were less enthusiastic, and one gentleman in the Saticrday Review, said that “no child would trouble to read it,” which seemed to me rather unkind. Not unkind because I wished it to be read by children, but unkind because it seemed to imply that the gentleman in question had ignored the message which my publisher has endeavoured to convey to intending critics.

There is, as all readers of the advertisements on the hoardings of railway stations and building-plots, and the front-sheets of daily newspapers are aware, a soap which will not wash clothes, and when I read that cruel comment on my book I felt much as the proprietors of that soap would have felt had they submitted it to a soap-expert, and had that soap-expert, after prolonged and careful examination of the soap, summed up his opinion in the words, “No clothes could ever be washed by this soap.”

Now all this only shows how very careful one ought to be to explain carefully and accurately what a book is intended to be, if it is at all different from the average book, and it behoves me to endeavour to make it as clear as possible that this book, The Pongo Papers, is a book of nonsense rhymes. Now I make no pretence to be an authority on nonsense rhymes, and my knowledge of them is confined to a very limited area. I am not aware of the existence of any nonsense rhymes in the English language before those of Edward Lear. Edward Lear wrote perhaps the most perfect specimens of the nonsense verse, from the point of view of nonsense. Where he failed was in form. In that respect he is easily out-classed by Lewis Carroll and by Sir W. S. Gilbert. As the most perfect nonsense rhyme ever written I should be inclined to name the rhyme in Alice through the Looking-Glass.

“I sent a message to the fish,

I told them this is what I wish.

“The little fishes of the sea

They sent an answer back to me.

“The little fishes’ answer was:

‘We cannot do it, sir, because.’”

and so on. It is quite perfect, it is absolute nonsense, untainted by the least trace of satire or parody or caricature. This is one of the most difficult things in the world to attain to, and I may say at once that I have not attempted to do it, either in the “Pongo Papers” or in the “Duke of Berwick.” The latter approaches much nearer to pure nonsense than the former, but it is distinctly tainted with satire. While the “Pongo Papers” are almost pure satire, and only escape being classed as satire altogether by the fact that their subject matter is nonsensical.

I once wrote a book of real pure nonsense; it was called Tails with a Twist, and achieved great successes, among them the flattering but (to me) not altogether satisfactory one of being very closely imitated by Mr. Hilaire Belloc, in a book which he called the Bad Child's Book of Beasts. This book actually appeared before Tails with a Twist, but most of the rhymes contained in my book had been written at least two years before Mr. Belloc’s, and were widely known and quoted at Oxford where Mr. Belloc was my contemporary, and in other places. I have no grievance against Mr. Belloc—as I have already said, his imitation of my rhymes was flattering, and it was quite legitimate. But as I have been constantly accused of plagiarising Mr. Belloc’s rhymes, I take this opportunity of stating exactly how things happened. But to return to my point, these rhymes were pure nonsense rhymes. Those I have written since have become less and less purely nonsensical. Partly I regret it, partly I recognise that it is the inevitable result of the development which is inherent in every art. The desire to be more sophisticated and to show off technical accomplishment has gradually superseded the original devotion to what I still recognise as the higher form of nonsense. I claim for The Pongo Papers (and also for The Placid Pug) that they are by far the most elaborate nonsense rhymes that have ever been attempted. I have devoted as much time and trouble, and fundamental brain-work to their production, as I have ever done to writing sonnets, and though I will not say they were as difficult to write as sonnets, I will say that they were very nearly as difficult. This is the excuse for their existence. If they were pure nonsense rhymes they would need no excuse. Being a hybrid article they need the excuse of elaborate technical perfection to justify them. I am quite aware that these rhymes simply irritate some people, and I am not going to make the foolish mistake of charging people with a lack of sense of humour because they don’t care for them; nothing is so impossible to define as the sense of humour.

Some people, for whose judgment I have the greatest respect, and whose praise is the breath of life to me, have said to me, “How can you, who have written real and beautiful poetry in The City of the Soul\ waste your talents on writing nonsense rhymes?” Now, with all due deference to these critics. I take leave to say that this seems to me very much like saying to a playwright, “How can you, who have written such fine tragedies, waste your talents on writing comedies?” It is not, perhaps, quite strictly a fair analogy, but it is near enough to serve as an illustration of my point of view. I am not one of those who think that because a man has written good poetry, it becomes a sacred duty for him to go on writing it all the rest of his life. There is hardly a poet who has ever lived who has not written far too much. Poor Keats would turn in his grave if he could see Mr. Buxton Forman’s complete edition of his works, and if he were suddenly restored to life his first step, I am sure, would be to demand its suppression, and to destroy all traces of at least two-thirds of it; leaving only the supreme and perfect pieces which are the absolute crown and summit, not only of his own work, but of all English poetry. One should only write poetry when one has something definite to say, and something, moreover, that cannot possibly be said in prose. Writing nonsense rhymes has no effect one way or the other on one’s ability or desire to write poetry. It simply has nothing to do with it at all. But people who think it is very easy, or that any one with a tolerable knowledge of versification and an ordinary educated vocabulary could do it if he took the trouble, had better try.

Alfred Douglas.

P.S.—All the rhymes in the “Pongo Papers” appeared in Vanity Fair, to whose editor I am indebted for permission to reprint them. “The Duke of Berwick” appeared in 1900, with some very clever illustrations by “Tony Ludovici,” but, owing to the failure of its publisher within a week of the issue of the book, it never had a real life as a book at all. My reason for reproducing it is that I have found that there is a very large demand for the text.

Alfred Douglas.

The Pongo Papers consist principally of a reprint of a controversy which was carried on in the columns of the East Sheen Gazette and Balham Independent (with which is incorporated the Clapham Cuckoo and Mice) between those celebrated publicists Professor Percival Pondersfoot Pongo, regius Professor of Swiss in the University of Liptonville, U.S.A., and the well-known critic who hides his modest identity under the world-renowned pseudonym “The Belgian Hare.” The letters which passed between these two giants of ornithological knowledge are reproduced exactly as they appeared in the aforementioned journal, in consequence of repeated prayers, entreaties and threats from various influential readers, and in consideration of certain cash payments. Any one desiring any further information as to the meaning of these letters, and evidences of the bona fides of the parties to the controversy, can obtain the same by applying at the offices of the East Sheen Gazette and Balham Independent on deposit of a guarantee fee of five guineas 5), it being understood that the said fee is to be forfeited in case the inquiries are considered frivolous or otherwise objectionable. The Editor’s decision on this point is in all cases to be considered final. No applications will be entertained from minors.

THE OSTRICH

[Being a reply from “The Belgian Hare” to some remarks recently made by Professor Pongo in the course of his biennial lecture at the University of Liptonville, U.S.A., in which he compared one of his opponents on the governing body of that seat of learning to the “fond and foolish ostrich who imagines that by hiding his head in the sand, or behind a bush, he can elude his hunters, whereas in reality he is only blinding himself to his own obvious danger.”]

I

The Ostrich, fortified by common sense

And strong in every tactical resource,

When he perceives the enemy in force

Conceals his head behind a bush (or fence),

And leaves affairs to take their natural course.

II

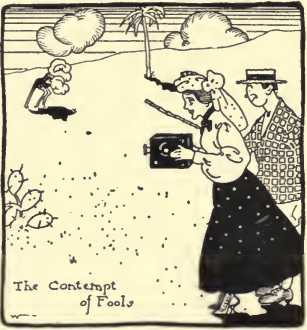

This brilliant, because obvious, device

Has drawn upon him the contempt of fools

Whose ignorance of all strategic rules

Would leave them helpless with a cockatrice

And paralysed before a pack of mules.

III

The Ostrich and his friends can well afford

To hear with silent scorn the quaint recital

Of the mob’s views. There’s really nothing vital

In the reproach of fools, and (praise the Lord!) .

It is, as Blake observes, a Kingly title.

IV

But when a savant like Professor Pongo—

A scholar of advanced (if narrow) culture,

The author of “The Life-force of the Vulture,”

A man whose recent trouvaille in the Congo

Has revolutionised Leporiculture.

V

Who, at an age when most young men at college

Have views on life less grave than Lady Teazle’s,

Had finished the first part of “Walks with Weasels,”

And told us the last word in Ferret-knowledge—

Becomes infected with these mental measles,

VI

His best admirer can but shake his head

And own that Providence ordains, things darkly.

If the Professor is not raving starkly

He must be ill and ought to be in bed.

Or has he never heard of Bishop Berkeley?

VII

Meanwhile the Ostrich, unaffected by

The echoes of this Professorial chatter,

Continues by his attitude to shatter

The “reasoning” of those who would deny

The perfect subjectivity of matter.

The Belgian Hare.

THE OSTRICH

(A Reply from Professor Pongo)

I

Sir, your contributor, the Belgian Hare,

A youth, I take it, fresh from school or college,

(And, by the way, what did they teach him there?),

Is pleased to credit me with Ferret knowledge

Far beyond that which falls to my poor share.

II

My "trouvailleas" he calls it (why not find?),

Has scarcely caused a “revolution” yet,

Nor is its application so designed,

Though it may modify the Leveret—

The Belgian Hare is really much too kind.

Ill

Nor do I claim to be a “savant” no,

If (in the intervals of “mental measles”)

I have, perhaps, been privileged to throw

Some humble light upon the ways of weasels,

I still must say “I think,” and not “I know.”

IV

But when it comes to Ostriches, I stand

Upon quite different ground; and so with fences,

With trees and bushes, or a stretch of sand;

That these exist I know, because my senses

Have, to impart that knowledge, so been planned.

V

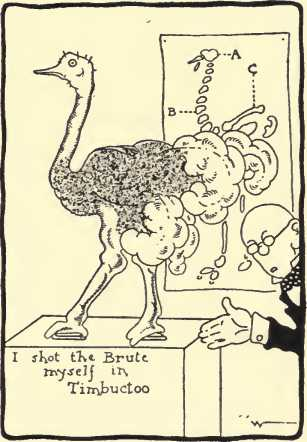

Before me stands an Ostrich, dead and stuffed

(I shot the brute myself in Timbuctoo);

It hid its head behind the usual tuft,

Thinking, no doubt, my spectacles of blue

Betrayed a disposition to be “bluffed.”

VI

(Whence comes, I wonder, the absurd conviction,

Dear to the minds of the untutored classes,

That men and women with a predilection

For safe-guarding their eyesight with blue glasses

Can be deceived by any obvious fiction?

Blue glasses may disguise a great detective.)

But pardon me this “Professorial chatter,”

And to resume: My bullet proved effective;

It killed the bird, and thereby proved that matter

Is, shall we say, not wholly un-objective?

VIII

The Belgian Hare inquires, with coruscation,

If I have heard of Berkeley. Let me see,

I seem to know the name and reputation.

But has the Bishop ever heard of me?

A much more interesting speculation.

Percival Pondersfoot Pongo.

THE OSTRICH

I

Professor Pongo’s laboured modesty,

And his inveterate determination

To underrate the services which he

Has done to science by the publication

Of his famed works, do not impose on me.

II

The greatest living specialist in ferrets

Adopts the stale stump-orator device

Of deprecating his own obvious merits,

And thereby hoping to “send up the price”.

Of unsound reasoning. It damps ones spirits

III

To find a person of Herr Pongo’s worth

Indulging in that form of idiocy

Which makes the date of his opponents birth

The basis of a childish repartee.

Teutonic “wit” does not conduce to mirth!

IV

The slipshod fault of using such a word

As “Brute” when speaking of an animal

So purely and essentially a

Bird As the wild ostrich is, is typical

Of the Professor’s logic. As absurd

V

Is his ridiculous and crude suggestion

That the fact that his “bullet proved effective”

In the remotest way bears on the question

Of whether matter is, or not, subjective.

Such bosh would give an ostrich indigestion.

VI

I really don’t propose to criticise

His cryptic utterance on Bishop Berkeley;

Is this more humour in Teutonic guise?

Or is Herr Pongo merely hinting darkly

What I for one would hear without surprise,

VII

That he has definitely joined the rank

Of those who disbelieve in future life?

Is this the latest Professorial prank?

At any rate, if such a view is rife

Herr Pongo only has himself to thank.

The Belgian Hare.

THE NATIONALITY OF PROFESSOR PONGO

I

Sir, I have neither time nor energy

To fill the nescience of the Belgian Hare

With elements of sane philosophy;

Nor, if I had them, would I greatly care

To grapple with an “unknown quantity.”

II

The Belgian Hare resents my reference

To what I took to be his tender years;

I judged him youthful by his lack of sense.

If I was wrong in this, as it appears,

So much the worse for his intelligence.

Ill

Shakespeare has told us that “an old hoar hare”

Is recommendable as Lenten food.

(Presumably as penitential fare.)

But I prefer a young one. Is this rude?

Perhaps it is, but really I don’t care.

IV

There’s always hope for youth; but if ripe age

Has not brought sense to your contributor,

I greatly fear that he has reached the stage

When he must be adjudged “past praying for,”

A painful period in Life’s pilgrimage.

V

I am not anxious to discuss with him

The subject of his puerile delusions,

To do so I should be obliged to swim

Through seas of fallacies and false conclusions

Which it would take me days merely to skim.

VI

On one point only I would “pick a bone:”

He has the very gross impertinence

To write my name-style as “Herr Pongo,” shown.

Why so? On what conceivable pretence?

Since when has Pongo to be German grown?

VII

Its sound proclaims its English origin,

And, by authentic legends, it appears

That Pongos have been settled in East Lynne

For rather more than seven hundred years.

The name was formerly pronounced Pig-kin.

VIII

With this and Piuk-eyne there’s an obvious link,

And Percival de Pink-eye we can trace

(So called, of course, because his eyes were pink)

Was wounded in the fray of Chevy Chase

(The ear-lobe punctured by a dart, I think).

[Exigencies of space have here reluctantly compelled us to omit seventeen stanzas in which Professor Pongo traces the gradual corruption of the name de Pink-eye into Pongo, and also his explanation of the fact that though the family of Pink-eye or Pongo emigrated to Germany in the seventeenth century, and his (the Professor’s) father was actually bom in Berlin, the family always retained its essentially British, not to say Saxon, characteristics, which were emphasised by the marriage in 1825 of Professor Pongo’s father to the beautiful and accomplished Miss Hartman, only child of that distinguished merchant and financier Mr. Isaac Abraham Hartman, a partner in the well-known British firm of Mosenthal, Hartman and Gibbs. We proceed to the 26th and last stanza.]

XXVI

Quite early in the nineteenth century

We find the name, spelt in the modern way

As Pongo, in the East Lynne registry,

Where my respected parents, one fine day,

Were married by the Reverend Lovejoy Lee.

Percival Pondersfoot Pongo.

PROFESSOR PONGO AGAIN

I

Professor Pongo foiled in argument,

And conscious of the weakness of his case,

In his anxiety to “save his face,”

Has most incontinently given vent

To violent language which would not disgrace

A Peri at the gates of Parliament.

II

But while he so intemperately girds

At my “delusions,” while his angry mood

Breaks out in ravings about “lenten food”

And “unknown quantities” of furious words,

He is extremely careful to elude

Any remarks on ostriches qua birds.

Ill

This being so, I make bold to assume

That he has nothing further to advance;

Then why this vast display of petulance?

Why this propensity to foam and fume?

No one requires the elephant to dance,

Or looks for comic singing to the Pume.

IV

(I mean the Puma, but the rhyme compels

Some small poetic licence here and there)

Professor Pongo has received his share

Of Nature’s choicest gifts. But Nature sells

Her gifts at a high price (which don’t seem fair;

But Nature is unfair, experience tells).

V

The price paid in Professor Pongo’s case

Amounts to this: a serious limitation

In the intrinsic powers of observation,

Amounting to sheer impotence to trace

Inter-phenomenal co-allocation,

As of the nasal organ and the face.

VI

Mention of noses somehow seems to bear on

Professor Pongos precious pedigree.

Whether the famous Pink-eye family tree

Is rooted in the land that fostered Aaron

Or Germany or England or all three,

Take my advice, Herr Pongo, “keep your hair on.”

The Belgian Hare.

THE LOBSTER

[Being a specimen chapter selected from Professor Pongo’s epoch-making work, “The Principles of Retrocessional Progression; or, Why not advance backwards?” which has produced such a soul-stirring effect in the United States of America. It was of this book that President Roosevelt is reported to have said, “It knocks spots off Socrates.”]

I

The Lobster in his search for primal truth,

Scorning convention and the beaten track,

And yearning to imbed his mental tooth

Deep in the tree of knowledge, turns his back

On the accepted codes that guide raw youth,

Into the usual channels of attack.

II

Determined to command enforced success

And capture triumph in the last long lap,

Not by the facile arts of speciousness,

Nor by the vulgar methods of clap-trap,

He has devised to make his gait no less

Than a designed, deliberate handicap.

III

While all the world walks forward (save the crab,

Whose side-long walk stands in a class apart,

As must be obvious to the meanest Dab),

The Lobster cultivates the curious art

Of moving backward like a hansom cab

When the reluctant horse declines to start.

IV

And if we ask the “why” of this retreat,

The “wherefore” of this retrograde progression,

The locus standi of this rearward beat,

The cause of this deliberate recession,

The answer is that Duty guides his feet,

And Duty is the Lobsters chief obsession.

V

Though Love and Life and Pleasure urge him on,

And strive to lure him down the forward road,

And every word in Youth’s bright lexicon

Sings in his ear and spurs him like a goad,

Suggesting many a fond comparison

With forward-moving beasts from Teal to Toad,

VI

He perseveres and treads the narrow track,

Though Shrimp and Sprat and Haddock scoff and jeer;

To find perfected Truth he still falls back

On that strategic movement to the rear,

Which Duty points him out, and bears his pack

In Virtue’s path a cheerful pioneer.

THE CORMORANT

I

The marked supremacy which in all mundane spheres

Attends the efforts of the Cormorant,

The fine and healthy progeny he rears,

His general immunity from want,

And that contended aspect which appears

Fixed on his face as though in adamant;

II

His sleek ensemble of beak and wing and feather,

The small amount of water he displaces,

Whereby he swims in what seem altogether

Unnavigable shallows and sea-spaces,

His calm acceptance, in unpleasant weather,

Of all the damp discomfort that he faces;

III

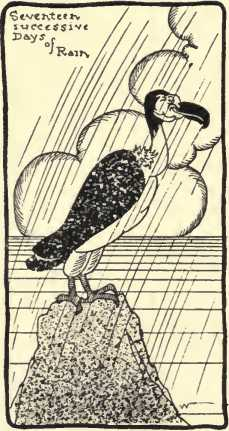

His breezy optimism when his nest

Is swamped by billows from the angry main,

Or when quite swept away, the cheerful zest

With which he quickly builds it up again,

His genial humour even undepressed

By seventeen successive days of rain:

IV

All these and many other happy traits

Which place him in the ranks of the dlite,

Are in Professor Pongo’s “Sea-Bird’s Ways”

Attributed to pre-organic heat,

To nitric acid and the Roentgen rays,

Combined with the possession of web-feet!

V

This coarse materialistic explanation

Of the morale of an unrivalled bird

May satisfy the muddled congregation,

Who recently applauded when they heard

The learned author’s lecture on “gyration”—

Surely the dernier mot of the absurd.

VI

But no man of intelligence will fail

(For all its cleverness) to realise

That the proverbial salt upon the tail

Of the professor’s cormorant supplies

Some needful grains to those who would regale

Their minds on his fantastic theories.

VII

Professor Pongo has his obvious merits,

And we should be the last to cast a stone

At one who so abundantly inherits

The mantle of the gifted “Gramophone.”

He is the first authority on ferrets,

But he should leave the Cormorant alone.

The Belgian Hare.