автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Letters on Natural Magic Addressed to Sir Walter Scott, Bart

LETTERS

ON

NATURAL MAGIC,

ADDRESSED TO

SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART.

BY

SIR DAVID BREWSTER, LL.D., F.R.S.

SEVENTH EDITION.

LONDON:

WILLIAM TEGG AND Co., 85, QUEEN STREET.

CHEAPSIDE.

1856.

CONTENTS.

LETTER I.

Extent and interest of the subject—Science employed by ancient governments to deceive and enslave their subjects—Influence of the supernatural upon ignorant minds—Means employed by the ancient magicians to establish their authority—Derived from a knowledge of the phenomena of Nature—From the influence of narcotic drugs upon the victims of their delusion—From every branch of science—Acoustics—Hydrostatics—Mechanics—Optics—M. Salverte’s work on the occult sciences—Object of the following letters

Page 1

LETTER II.

The eye the most important of our organs—Popular description of it—The eye is the most fertile source of mental illusions—Disappearance of objects when their images fall upon the base of the optic nerve—Disappearance of objects when seen obliquely—Deceptions arising from viewing objects in a faint light—Luminous figures created by pressure on the eye, either from external causes or from the fulness of the blood-vessels—Ocular spectra or accidental colours—Remarkable effects produced by intense light—Influence of the imagination in viewing these spectra—Remarkable illusion produced by this affection of the eye—Duration of impressions of light on the eye—Thaumatrope—Improvements upon it suggested—Disappearance of halves of objects or of one of two persons—Insensibility of the eye to particular colours—Remarkable optical illusion described

8

LETTER III.

Subject of spectral illusions—Recent and interesting case of Mrs. A.—Her first illusion affecting the ear—Spectral apparition of her husband—Spectral apparition of a cat—Apparition of a near and living relation in grave-clothes, seen in a looking-glass—Other illusions, affecting the ear—Spectre of a deceased friend sitting in an easy-chair—Spectre of a coach-and-four filled with skeletons—Accuracy and value of the preceding cases—State of health under which they arose—Spectral apparitions are pictures on the retina—The ideas of memory and imagination are also pictures on the retina—General views of the subject—Approximate explanation of spectral apparitions

37

LETTER IV.

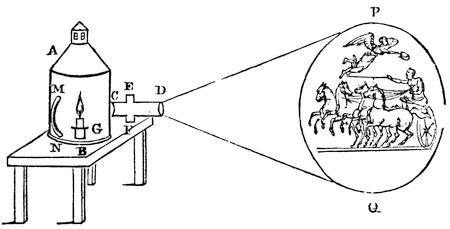

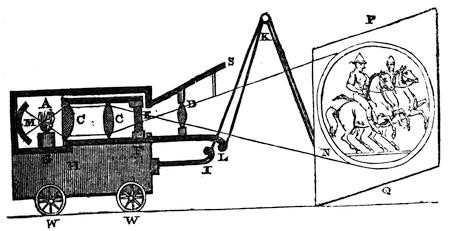

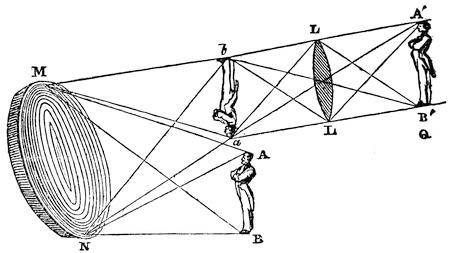

Science used as an instrument of imposture—Deceptions with plane and concave mirrors practised by the ancients—The magician’s mirror—Effects of concave mirrors—Aërial images—Images on smoke—Combination of mirrors for producing pictures from living objects—The mysterious dagger—Ancient miracles with concave mirrors—Modern necromancy with them, as seen by Cellini—Description and effects of the magic lantern—Improvements upon it—Phantasmagoric exhibitions of Philipstall and others—Dr. Young’s arrangement of lenses, &c., for the Phantasmagoria—Improvements suggested—Catadioptrical phantasmagoria for producing the pictures from living objects—Method of cutting off parts of the figures—Kircher’s mysterious hand-writing on the wall—His hollow cylindrical mirror for aërial images—Cylindrical mirror for re-forming distorted pictures—Mirrors of variable curvature for producing caricatures

56

LETTER V.

Miscellaneous optical illusions—Conversions of cameos into intaglios, or elevations into depressions, and the reverse—Explanation of this class of deceptions—Singular effects of illumination with light of one simple colour—Lamps for producing homogeneous yellow light—Methods of increasing the effects of this exhibition—Method of reading the inscription of coins in the dark—Art of deciphering the effaced inscription of coins—Explanation of these singular effects—Apparent motion of the eyes in portraits—Remarkable examples of this—Apparent motion of the features of a portrait, when the eyes are made to move—Remarkable experiment of breathing light and darkness

98

LETTER VI.

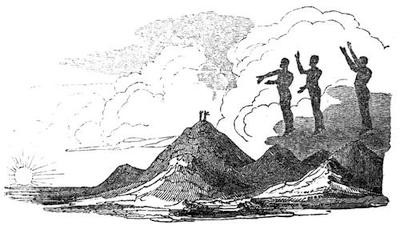

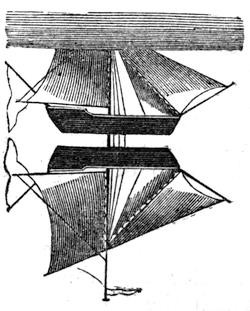

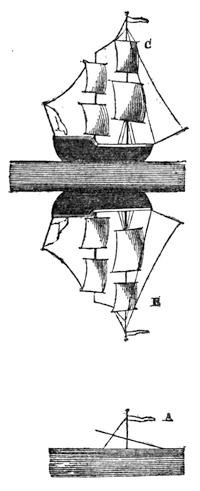

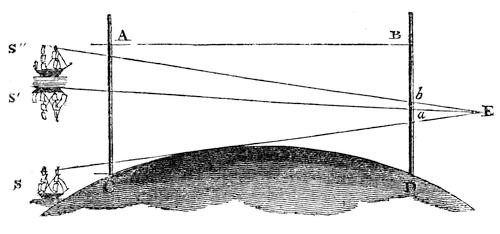

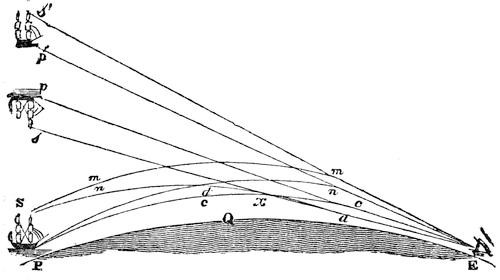

Natural phenomena marked with the marvellous—Spectre of the Brocken described—Analogous phenomena—Aërial spectres seen in Cumberland—Fata Morgana in the Straits of Messina—Objects below the horizon raised and magnified by refraction—Singular example seen at Hastings—Dover Castle seen through the hill on which it stands—Erect and inverted images of distant ships seen in the air—Similar phenomena seen in the Arctic regions—Enchanted coast—Mr. Scoresby recognizes his father’s ship by its aërial image—Images of cows seen in the air—Inverted images of horses seen in South America—Lateral images produced by refraction—Aërial spectres by reflexion—Explanation of the preceding phenomena

127

LETTER VII.

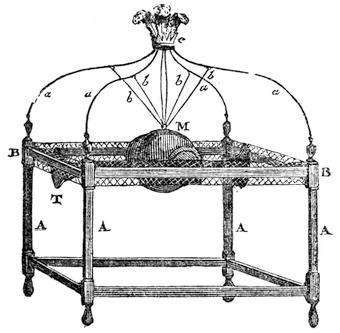

Illusions depending on the ear—Practised by the ancients—Speaking and singing heads of the ancients—Exhibition of the Invisible Girl described and explained—Illusions arising from the difficulty of determining the direction of sounds—Singular example of this illusion—Nature of ventriloquism—Exhibitions of some of the most celebrated ventriloquists—M. St. Gille—Louis Brabant—M. Alexandre—Capt. Lyon’s account of Esquimaux ventriloquists

157

LETTER VIII.

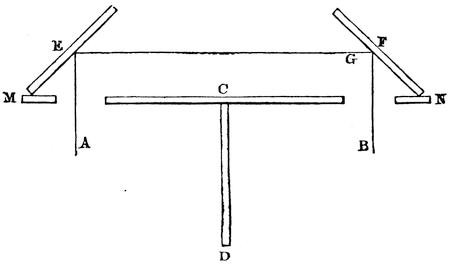

Musical and harmonic sounds explained—Power of breaking glasses with the voice—Musical sounds from the vibration of a column of air—and of solid bodies—Kaleidophone—Singular acoustic figures produced on sand laid on vibrating plates of glass—and on stretched membranes—Vibration of flat rulers and cylinders of glass—Production of silence from two sounds—Production of darkness from two lights—Explanation of these singular effects—Acoustic automaton—Droz’s bleating sheep—Maillardet’s singing-bird—Vaucanson’s flute-player—His pipe and tabor-player—Baron Kempelen’s talking-engine—Kratzenstein’s speaking-machine—Mr. Willis’s researches

179

LETTER IX.

Singular effects in nature depending on sound—Permanent character of speech—Influence of great elevations on the character of sounds, and on the powers of speech—Power of sound in throwing down buildings—Dog killed by sound—Sounds greatly changed under particular circumstances—Great audibility of sounds during the night explained—Sounds deadened in media of different densities—Illustrated in the case of a glass of champagne—and in that of new-fallen snow—Remarkable echoes—Reverberations of thunder—Subterranean noises—Remarkable one at the Solfaterra—Echo at the Menai suspension bridge—Temporary deafness produced in diving-bells—Inaudibility of particular sounds to particular ears—Vocal powers of the statue of Memnon—Sounds in granite rocks—Musical mountain of El-Nakous

212

LETTER X.

Mechanical inventions of the ancients few in number—Ancient and modern feats of strength—Feats of Eckeberg particularly described—General explanation of them—Real feats of strength performed by Thomas Topham—Remarkable power of lifting heavy persons when the lungs are inflated—Belzoni’s feat of sustaining pyramids of men—Deception of walking along the ceiling in an inverted position—Pneumatic apparatus in the foot of the house-fly for enabling it to walk in opposition to gravity—Description of the analogous apparatus employed by the gecko lizard for the same purpose—Apparatus used by the Echineis remora, or sucking-fish

244

LETTER XI.

Mechanical automata of the ancients—Moving tripods—Automata of Dædalus—Wooden pigeon of Archytas—Automatic clock of Charlemagne—Automata made by Turrianus for Charles V.—Camus’s automatic carriage made for Louis XIV.—Degenne’s mechanical peacock—Vaucanson’s duck which ate and digested its food—Du Moulin’s automata—Baron Kempelen’s automaton chess-player—Drawing and writing automata—Maillardet’s conjurer—Benefits derived from the passion for automata—Examples of wonderful machinery for useful purposes—Duncan’s tambouring machinery—Watt’s statue-turning machinery—Babbage’s calculating machinery

264

LETTER XII.

Wonders of chemistry—Origin, progress, and objects of alchemy—Art of breathing fire—Employed by Barchochebas, Eunus, &c.—Modern method—Art of walking upon burning coals and red-hot iron, and of plunging the hands in melted lead and boiling water—Singular property of boiling tar—Workmen plunge their hands in melted copper—Trial of ordeal by fire—Aldini’s incombustible dresses—Examples of their wonderful power in resisting flame—Power of breathing and enduring air of high temperatures—Experiments made by Sir Joseph Banks, Sir Charles Blagden, and Mr. Chantrey

227

LETTER XIII.

Spontaneous combustion—In the absorption of air by powdered charcoal—and of hydrogen by spongy platinum—Dobereiner’s lamp—Spontaneous combustion in the bowels of the earth—Burning cliffs—Burning soil—Combustion without flame—Spontaneous combustion of human beings—Countess Zangari—Grace Pett—Natural fire-temples of the Guebres—Spontaneous fires in the Caspian Sea—Springs of inflammable gas near Glasgow—Natural light-house of Maracaybo—New elastic fluids in the cavities—of gems—Chemical operations going on in their cavities—Explosions produced in them by heat—Remarkable changes of colour from chemical causes—Effects of the nitrous oxide or Paradise gas when breathed—Remarkable cases described—Conclusion

313

LETTERS

ON

NATURAL MAGIC;

ADDRESSED TO

SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART.

LETTER I.

Extent and interest of the subject—Science employed by ancient governments to deceive and enslave their subjects—Influence of the supernatural upon ignorant minds—Means employed by the ancient magicians to establish their authority—Derived from a knowledge of the phenomena of Nature—From the influence of narcotic drugs upon the victims of their delusion—From every branch of science—Acoustics—Hydrostatics—Mechanics—Optics—M. Salverte’s work on the occult sciences—Object of the following letters.

MY DEAR SIR WALTER,

As it was at your suggestion that I undertook to draw up a popular account of those prodigies of the material world which have received the appellation of Natural Magic, I have availed myself of the privilege of introducing it under the shelter of your name. Although I cannot hope to produce a volume at all approaching in interest to that which you have contributed to the Family Library, yet the popular character of some of the topics which belong to this branch of Demonology may atone for the defects of the following Letters; and I shall deem it no slight honour if they shall be considered as forming an appropriate supplement to your valuable work.

The subject of Natural Magic is one of great extent as well as of deep interest. In its widest range, it embraces the history of the governments and the superstitions of ancient times,—of the means by which they maintained their influence over the human mind,—of the assistance which they derived from the arts and the sciences, and from a knowledge of the powers and phenomena of nature. When the tyrants of antiquity were unable or unwilling to found their sovereignty on the affections and interests of their people, they sought to entrench themselves in the strongholds of supernatural influence, and to rule with the delegated authority of Heaven. The prince, the priest, and the sage, were leagued in a dark conspiracy to deceive and enslave their species; and man, who refused his submission to a being like himself, became the obedient slave of a spiritual despotism, and willingly bound himself in chains when they seemed to have been forged by the gods.

This system of imposture was greatly favoured by the ignorance of these early ages. The human mind is at all times fond of the marvellous, and the credulity of the individual may be often measured by his own attachment to the truth. When knowledge was the property of only one caste, it was by no means difficult to employ it in the subjugation of the great mass of society. An acquaintance with the motions of the heavenly bodies, and the variations in the state of the atmosphere, enabled its possessor to predict astronomical and meteorological phenomena with a frequency and an accuracy which could not fail to invest him with a divine character. The power of bringing down fire from the heavens, even at times when the electric influence was itself in a state of repose, could be regarded only as a gift from heaven. The power of rendering the human body insensible to fire was an irresistible instrument of imposture; and in the combinations of chemistry, and the influence of drugs and soporific embrocations on the human frame, the ancient magicians found their most available resources.

The secret use which was thus made of scientific discoveries and of remarkable inventions, has no doubt prevented many of them from reaching the present times; but though we are very ill informed respecting the progress of the ancients in various departments of the physical sciences, yet we have sufficient evidence that almost every branch of knowledge had contributed its wonders to the magician’s budget, and we may even obtain some insight into the scientific acquirements of former ages, by a diligent study of their fables and their miracles.

The science of Acoustics furnished the ancient sorcerers with some of their best deceptions. The imitation of thunder in their subterranean temples could not fail to indicate the presence of a supernatural agent. The golden virgins whose ravishing voices resounded through the temple of Delphos;—the stone from the river Pactolus, whose trumpet notes scared the robber from the treasure which it guarded;—the speaking head which uttered its oracular responses at Lesbos; and the vocal statue of Memnon, which began at the break of day to accost the rising sun,—were all deceptions derived from science, and from a diligent observation of the phenomena of nature.

The principles of Hydrostatics were equally available in the work of deception. The marvellous fountain which Pliny describes in the island of Andros as discharging wine for seven days, and water during the rest of the year;—the spring of oil which broke out in Rome to welcome the return of Augustus from the Sicilian war,—the three empty urns which filled themselves with wine at the annual feast of Bacchus in the city of Elis,—the glass tomb of Belus which was full of oil, and which when once emptied by Xerxes could not again be filled,—the weeping-statues, and the perpetual lamps of the ancients,—were all the obvious effects of the equilibrium and pressure of fluids.

Although we have no direct evidence that the philosophers of antiquity were skilled in Mechanics, yet there are indications of their knowledge by no means equivocal in the erection of the Egyptian obelisks, and in the transportation of huge masses of stone, and their subsequent elevation to great heights in their temples. The powers which they employed, and the mechanism by which they operated, have been studiously concealed, but their existence may be inferred from results otherwise inexplicable; and the inference derives additional confirmation from the mechanical arrangements which seemed to have formed a part of their religious impostures. When, in some of the infamous mysteries of ancient Rome, the unfortunate victims were carried off by the gods, there is reason to believe that they were hurried away by the power of machinery; and when Apollonius, conducted by the Indian sages to the temple of their god, felt the earth rising and falling beneath his feet, like the agitated sea, he was no doubt placed upon a moving floor capable of imitating the heavings of the waves. The rapid descent of those who consulted the oracle in the cave of Trophonius,—the moving tripods which Apollonius saw in the Indian temples,—the walking statues at Antium, and in the temple of Hierapolis,—and the wooden pigeon of Archytas, are specimens of the mechanical resources of the ancient magic.

But of all the sciences Optics is the most fertile in marvellous expedients. The power of bringing the remotest objects within the very grasp of the observer, and of swelling into gigantic magnitude the almost invisible bodies of the material world, never fails to inspire with astonishment even those who understand the means by which these prodigies are accomplished. The ancients, indeed, were not acquainted with those combinations of lenses and mirrors which constitute the telescope and the microscope, but they must have been familiar with the property of lenses and mirrors to form erect and inverted images of objects. There is reason to think that they employed them to effect the apparition of their gods; and in some of the descriptions of the optical displays which hallowed their ancient temples, we recognize all the transformations of the modern phantasmagoria.

It would be an interesting pursuit to embody the information which history supplies respecting the fables and incantations of the ancient superstitions, and to show how far they can be explained by the scientific knowledge which then prevailed. This task has, to a certain extent, been performed by M. Eusebe Salverte, in a work on the occult sciences which has recently appeared; but notwithstanding the ingenuity and learning which it displays, the individual facts are too scanty to support the speculations of the author, and the descriptions are too meagre to satisfy the curiosity of the reader.1

In the following letters I propose to take a wider range, and to enter into more minute and popular details. The principal phenomena of nature, and the leading combinations of arts, which bear the impress of a supernatural character, will pass under our review, and our attention will be particularly called to those singular illusions of sense, by which the most perfect organs either cease to perform their functions, or perform them faithlessly; and where the efforts and the creations of the mind predominate over the direct perceptions of external nature.

In executing this plan, the task of selection is rendered extremely difficult by the superabundance of materials, as well as from the variety of judgments for which these materials must be prepared. Modern science may be regarded as one vast miracle, whether we view it in relation to the Almighty Being by whom its objects and its laws were formed, or to the feeble intellect of man, by which its depths have been sounded, and its mysteries explored; and if the philosopher who is familiarized with its wonders, and who has studied them as necessary results of general laws, never ceases to admire and adore their Author, how great should be their effect upon less gifted minds, who must ever view them in the light of inexplicable prodigies!—Man has in all ages sought for a sign from heaven, and yet he has been habitually blind to the millions of wonders with which he is surrounded. If the following pages should contribute to abate this deplorable indifference to all that is grand and sublime in the universe, and if they should inspire the reader with a portion of that enthusiasm of love and gratitude which can alone prepare the mind for its final triumph, the labours of the author will not have been wholly fruitless.

1 We must caution the young reader against some of the views given in M. Salverte’s work. In his anxiety to account for everything miraculous by natural causes, he has ascribed to the same origin some of these events in sacred history which Christians cannot but regard as the result of divine agency.

LETTER II.

The eye the most important of our organs—Popular description of it—The eye is the most fertile source of mental illusions—Disappearance of objects when their images fall upon the base of the optic nerve—Disappearance of objects when seen obliquely—Deceptions arising from viewing objects in a faint light—Luminous figures created by pressure on the eye, either from external causes or from the fulness of the blood-vessels—Ocular spectra or accidental colours—Remarkable effects produced by intense light—Influence of the imagination in viewing these spectra—Remarkable illusion produced by this affection of the eye—Duration of impressions of light on the eye—Thaumatrope—Improvements upon it suggested—Disappearance of halves of objects or of one of two persons—Insensibility of the eye to particular colours—Remarkable optical illusion described.

Of all the organs by which we acquire a knowledge of external nature, the eye is the most remarkable and the most important. By our other senses the information we obtain is comparatively limited. The touch and the taste extend no farther than the surface of our own bodies. The sense of smell is exercised within a very narrow sphere, and that of recognizing sounds is limited to the distance at which we hear the bursting of a meteor and the crash of a thunderbolt. But the eye enjoys a boundless range of observation. It takes cognizance not only of other worlds belonging to the solar system, but of other systems of worlds infinitely removed into the immensity of space; and when aided by the telescope, the invention of human wisdom, it is able to discover the forms, the phenomena, and the movements of bodies whose distance is as inexpressible in language as it is inconceivable in thought.

While the human eye has been admired by ordinary observers for the beauty of its form, the power of its movements, and the variety of its expression, it has excited the wonder of philosophers by the exquisite mechanism of its interior, and its singular adaptation to the variety of purposes which it has to serve. The eyeball is nearly globular, and is about an inch in diameter. It is formed externally by a tough opaque membrane called the sclerotic coat, which forms the white of the eye, with the exception of a small circular portion in front called the cornea. This portion is perfectly transparent, and so tough in its nature as to afford a powerful resistance to external injury. Immediately within the cornea, and in contact with it, is the aqueous humour, a clear fluid, which occupies only a small part of the front of the eye. Within this humour is the iris, a circular membrane, with a hole in its centre called the pupil. The colour of the eye resides in this membrane, which has the curious property of contracting and expanding so as to diminish or enlarge the pupil,—an effect which human ingenuity has not been able even to imitate. Behind the iris is suspended the crystalline lens, in a fine transparent capsule or bag of the same form with itself. It is then succeeded by the vitreous humour, which resembles the transparent white of an egg, and fills up the rest of the eye. Behind the vitreous humour, there is spread out on the inside of the eyeball a fine delicate membrane, called the retina, which is an expansion of the optic nerve, entering the back of the eye and communicating with the brain.

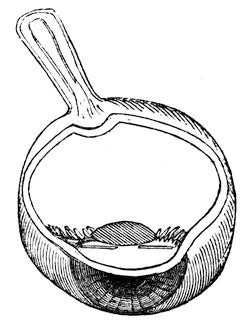

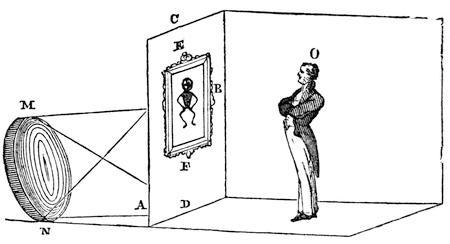

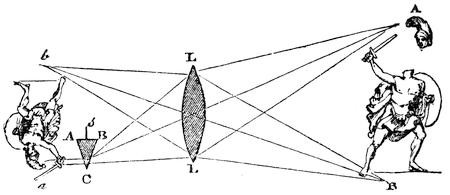

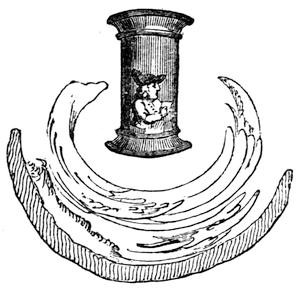

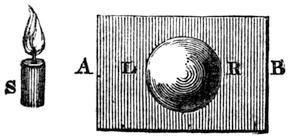

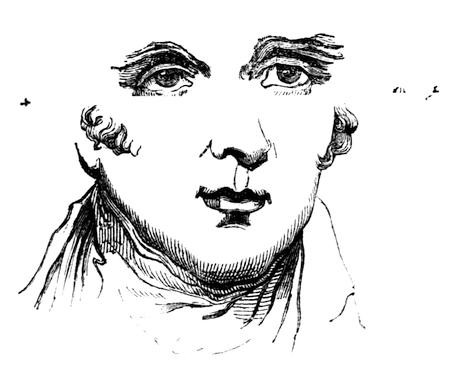

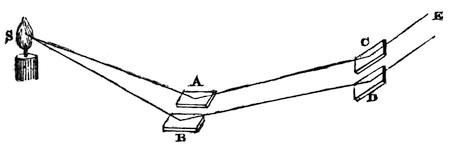

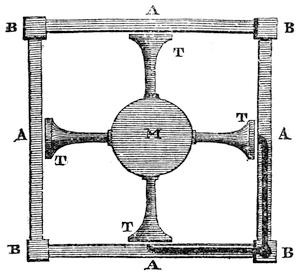

A perspective view and horizontal section of the left eye, shown in the annexed figure, will convey a popular idea of its structure. It is, as it were, a small camera obscura, by means of which the pictures of external objects are painted on the retina, and, in a way of which we are ignorant, it conveys the impression of them to the brain.

Fig. 1.

This wonderful organ may be considered as the sentinel which guards the pass between the worlds of matter and of spirit, and through which all their communications are interchanged. The optic nerve is the channel by which the mind peruses the hand-writing of Nature on the retina, and through which it transfers to that material tablet its decisions and its creations. The eye is consequently the principal seat of the supernatural. When the indications of the marvellous are addressed to us through the ear, the mind may be startled without being deceived, and reason may succeed in suggesting some probable source of the illusion by which we have been alarmed: but when the eye in solitude sees before it the forms of life, fresh in their colours and vivid in their outline; when distant or departed friends are suddenly presented to its view; when visible bodies disappear and reappear without any intelligible cause; and when it beholds objects, whether real or imaginary, for whose presence no cause can be assigned, the conviction of supernatural agency becomes, under ordinary circumstances, unavoidable.

Hence it is not only an amusing but a useful occupation to acquire a knowledge of those causes which are capable of producing so strange a belief, whether it arises from the delusions which the mind practises upon itself, or from the dexterity and science of others. I shall therefore proceed to explain those illusions which have their origin in the eye, whether they are general, or only occasionally exhibited in particular persons, and under particular circumstances.

There are few persons aware that when they look with one eye, there is some particular object before them to which they are absolutely blind. If we look with the right eye, this point is always about 15° to the right of the object which we are viewing, or to the right of the axis of the eye or the point of most distinct vision. If we look with the left eye, the point is as far to the left. In order to be convinced of this curious fact, which was discovered by M. Mariotte, place two coloured wafers upon a sheet of white paper at the distance of three inches, and look at the left-hand wafer with the right eye at the distance of about 11 or 12 inches, taking care to keep the eye straight above the wafer, and the line which joins the eyes parallel to the line which joins the wafers. When this is done, and the left eye closed, the right-hand wafer will no longer be visible. The same effect will be produced if we close the right eye and look with the left eye at the right-hand wafer. When we examine the retina to discover to what part of it this insensibility to light belongs, we find that the image of the invisible wafer has fallen on the base of the optic nerve, or the place where this nerve enters the eye and expands itself to form the retina. This point is shown in the preceding figure by a convexity at the place where the nerve enters the eye.

But though light of ordinary intensity makes no impression upon this part of the eye, a very strong light does, and even when we use candles or highly luminous bodies in place of wafers, the body does not wholly disappear, but leaves behind a faint cloudy light, without, however, giving anything like an image of the object from which the light proceeds.

When the objects are white wafers upon a black ground, the white wafer absolutely disappears, and the space which it covers appears to be completely black; and as the light which illuminates a landscape is not much different from that of a white wafer, we should expect, whether we use one or both eyes,2 to see a black or a dark spot upon every landscape, within 15° of the point which most particularly attracts our notice. The Divine Artificer, however, has not left his work thus imperfect. Though the base of the optic nerve is insensible to light that falls directly upon it, yet it has been made susceptible of receiving luminous impressions from the parts which surround it; and the consequence of this is, that when the wafer disappears, the spot which is occupied, in place of being black, has always the same colour as the ground upon which the wafer is laid, being white when the wafer is placed upon a white ground, and red when it is placed upon a red ground. This curious effect may be rudely illustrated by comparing the retina to a sheet of blotting-paper, and the base of the optic nerve to a circular portion of it covered with a piece of sponge. If a shower falls upon the paper, the protected part will not be wetted by the rain which falls upon the sponge that covers it, but in a few seconds it will be as effectually wetted by the moisture which it absorbs from the wet paper with which it is surrounded. In like manner the insensible spot on the retina is stimulated by a borrowed light, and the apparent defect is so completely removed, that its existence can be determined only by the experiment already described.

Of the same character, but far more general in its effects, and important in its consequences, is another illusion of the eye which presented itself to me several years ago. When the eye is steadily occupied in viewing any particular object, or when it takes a fixed direction while the mind is occupied with any engrossing topic of speculation or of grief, it suddenly loses sight of, or becomes blind to, objects seen indirectly, or upon which it is not fully directed. This takes place whether we use one or both eyes, and the object which disappears will reappear without any change in the position of the eye, while other objects will vanish and revive in succession without any apparent cause. If a sportsman, for example, is watching with intense interest the motions of one of his dogs, his companion, though seen with perfect clearness by indirect vision, will vanish, and the light of the heath or of the sky will close in upon the spot which he occupied.

In order to witness this illusion, put a little bit of white paper on a green cloth, and, within three or four inches of it, place a narrow strip of white paper. At the distance of twelve or eighteen inches, fix one eye steadily upon the little bit of white paper, and in a short time a part or even the whole of the strip of paper will vanish as if it had been removed from the green cloth. It will again reappear, and again vanish, the effect depending greatly on the steadiness with which the eye is kept fixed. This illusion takes place when both the eyes are open, though it is easier to observe it when one of them is closed. The same thing happens when the object is luminous. When a candle is thus seen by indirect vision, it never wholly disappears, but it spreads itself out into a cloudy mass, the centre of which is blue, encircled with a bright ring of yellow light.

This inability of the eye to preserve a sustained vision of objects seen obliquely, is curiously compensated by the greater sensibility of those parts of the eye that have this defect. The eye has the power of seeing objects with perfect distinctness only when it is directed straight upon them; that is, all objects seen indirectly are seen indistinctly: but it is a curious circumstance, that when we wish to obtain a sight of a very faint star, such as one of the satellites of Saturn, we can see it most distinctly by looking away from it, and when the eye is turned full upon it it immediately disappears.

Effects still more remarkable are produced in the eye when it views objects that are difficult to be seen from the small degree of light with which they happen to be illuminated. The imperfect view which we obtain of such objects forces us to fix the eye more steadily upon them; but the more exertion we make to ascertain what they are, the greater difficulties do we encounter to accomplish our object. The eye is actually thrown into a state of the most painful agitation, the object will swell and contract, and partly disappear, and it will again become visible when the eye has recovered from the delirium into which it has been thrown. This phenomenon may be most distinctly seen when the objects in a room are illuminated with the feeble gleam of a fire almost extinguished; but it may be observed in daylight by the sportsman when he endeavours to mark upon the monotonous heath the particular spot where moor-game has alighted. Availing himself of the slightest difference of tint in the adjacent heath, he keeps his eye steadily fixed on it as he advances, but whenever the contrast of illumination is feeble, he will invariably lose sight of his mark, and if the retina is capable of taking it up, it is only to lose it a second time.

This illusion is likely to be most efficacious in the dark, when there is just sufficient light to render white objects faintly visible, and to persons who are either timid or credulous must prove a frequent source of alarm. Its influence, too, is greatly aided by another condition of the eye, into which it is thrown during partial darkness. The pupil expands nearly to the whole width of the iris, in order to collect the feeble light which prevails; but it is demonstrable that in this state the eye cannot accommodate itself to see near objects distinctly, so that the forms of persons and things actually become more shadowy and confused when they come within the very distance at which we count upon obtaining the best view of them. These affections of the eye are, we are persuaded, very frequent causes of a particular class of apparitions which are seen at night by the young and the ignorant. The spectres which are conjured up are always white, because no other colour can be seen, and they are either formed out of inanimate objects which reflect more light than others around them, or of animals or human beings whose colour or change of place renders them more visible in the dark. When the eye dimly descries an inanimate object whose different parts reflect different degrees of light, its brighter parts may enable the spectator to keep up a continued view of it; but the disappearance and reappearance of its fainter parts, and the change of shape which ensues, will necessarily give it the semblance of a living form, and if it occupies a position which is unapproachable, and where animate objects cannot find their way, the mind will soon transfer to it a supernatural existence. In like manner a human figure shadowed forth in a feeble twilight may undergo similar changes, and after being distinctly seen while it is in a situation favourable for receiving and reflecting light, it may suddenly disappear in a position fully before, and within the reach of, the observer’s eye; and if this evanescence takes place in a path or road where there was no side-way by which the figure could escape, it is not easy for an ordinary mind to efface the impression which it cannot fail to receive. Under such circumstances we never think of distrusting an organ which we have never found to deceive us; and the truth of the maxim that “seeing is believing” is too universally admitted, and too deeply rooted in our nature, to admit on any occasion of a single exception.

In these observations we have supposed that the spectator bears along with him no fears or prejudices, and is a faithful interpreter of the phenomena presented to his senses; but if he is himself a believer in apparitions, and unwilling to receive an ocular demonstration of their reality, it is not difficult to conceive the picture which will be drawn when external objects are distorted and caricatured by the imperfect indications of his senses, and coloured with all the vivid hues of the imagination.

Another class of ocular deceptions have their origin in a property of the eye which has been very imperfectly examined. The fine nervous fabric which constitutes the retina, and which extends to the brain, has the singular property of being phosphorescent by pressure. When we press the eyeball outwards by applying the point of the finger between it and the nose, a circle of light will be seen, which Sir Isaac Newton describes as “a circle of colours like those in the feather of a peacock’s tail.” He adds, that “if the eye and the figure remain quiet, these colours vanish in a second of time; but if the finger be moved with a quavering motion, they appear again.” In the numerous observations which I have made on these luminous circles, I have never been able to observe any colour but white, with the exception of a general red tinge which is seen when the eyelids are closed, and which is produced by the light which passes through them. The luminous circles, too, always continue while the pressure is applied, and they may be produced as readily after the eye has been long in darkness as when it has been recently exposed to light. When the pressure is very gently applied, so as to compress the fine pulpy substance of the retina, light is immediately created when the eye is in total darkness; and when in this state light is allowed to fall upon it, the part compressed is more sensible to light than any other part, and consequently appears more luminous. If we increase the pressure, the eyeball, being filled with incompressible fluids, will protrude all round the point of pressure, and consequently the retina at the protruded part will be compressed by the outward pressure of the contained fluid, while the retina on each side, namely, under the point of pressure and beyond the protruded part, will be drawn towards the protruded part or dilated. Hence the part under the finger which was originally compressed is now dilated, the adjacent parts compressed, and the more remote parts immediately without this dilated also. Now we have observed, that when the eye is, under these circumstances, exposed to light, there is a bright luminous circle shading off externally and internally into total darkness. We are led, therefore, to the important conclusions, that when the retina is compressed in total darkness it gives out light; that when it is compressed when exposed to light, its sensibility to light is increased; and that when it is dilated under exposure to light, it becomes absolutely blind, or insensible to all luminous impressions.

When the body is in a state of perfect health, this phosphorescence of the eye shows itself on many occasions. When the eye or the head receives a sudden blow, a bright flash of light shoots from the eyeball. In the act of sneezing, gleams of light are emitted from each eye both during the inhalation of the air, and during its subsequent protrusion, and in blowing air violently through the nostrils, two patches of light appear above the axis of the eye and in front of it, while other two luminous spots unite into one, and appear as it were about the point of the nose when the eyes are directed to it. When we turn the eyeball by the action of its own muscles, the retina is affected at the place where the muscles are inserted, and there may be seen opposite each eye, and towards the nose, two semicircles of light, and other two extremely faint towards the temples. At particular times, when the retina is more phosphorescent than at others, these semicircles are expanded into complete circles of light.

In a state of indisposition, the phosphorescence of the retina appears in new and more alarming forms. When the stomach is under a temporary derangement accompanied with headache, the pressure of the blood-vessels upon the retina shows itself, in total darkness, by a faint blue light floating before the eye, varying in its shape, and passing away at one side. This blue light increases in intensity, becomes green and then yellow, and sometimes rises to red, all these colours being frequently seen at once, or the mass of light shades off into darkness. When we consider the variety of distinct forms which in a state of perfect health the imagination can conjure up when looking into a burning fire, or upon an irregularly shaded surface,3 it is easy to conceive how the masses of coloured light which float before the eye may be moulded by the same power into those fantastic and natural shapes, which so often haunt the couch of the invalid, even when the mind retains its energy, and is conscious of the illusion under which it labours. In other cases, temporary blindness is produced by pressure upon the optic nerve, or upon the retina; and under the excitation of fever or delirium, when the physical cause which produces spectral forms is at its height, there is superadded a powerful influence of the mind, which imparts a new character to the phantasms of the senses.

In order to complete the history of the illusions which originate in the eye, it will be necessary to give some account of the phenomena called ocular spectra, or accidental colours. If we cut a figure out of red paper, and, placing it on a sheet of white paper, view it steadily for some seconds with one or both eyes fixed on a particular part of it, we shall observe the red colour to become less brilliant. If we then turn the eye from the red figure upon the white paper, we shall see a distinct green figure, which is the spectrum, or accidental colour of the red figure. With differently coloured figures we shall observe differently coloured spectra, as in the following table:—

COLOUR OF THEORIGINAL FIGURES

.

COLOUR OF THESPECTRAL FIGURES

.

Red,

Bluish-green.

Orange,

Blue.

Yellow,

Indigo.

Green,

Reddish-violet.

Blue,

Orange-red.

Indigo,

Orange-yellow.

Violet,

Yellow.

White,

Black.

Black,

White.

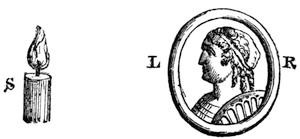

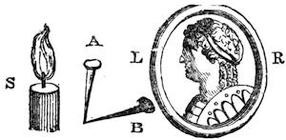

The two last of these experiments, viz., white and black figures, may be satisfactorily made by using a white medallion on a dark ground, and a black profile figure. The spectrum of the former will be found to be black, and that of the latter white.

These ocular spectra often show themselves without any effort on our part, and even without our knowledge. In a highly painted room, illuminated by the sun, those parts of the furniture on which the sun does not directly fall have always the opposite or accidental colour. If the sun shines through a chink in a red window-curtain, its light will appear green, varying as in the above table, with the colour of the curtain; and if we look at the image of a candle, reflected from the water in a blue finger-glass, it will appear yellow. Whenever, in short, the eye is affected with one prevailing colour, it sees at the same time the spectral or accidental colour, just as when a musical string is vibrating, the ear hears at the same time its fundamental and its harmonic sounds.

If the prevailing light is white and very strong, the spectra which it produces are no longer black, but of various colours in succession. If we look at the sun, for example, when near the horizon, or when reflected from glass or water so as to moderate its brilliancy, and keep the eye upon it steadily for a few seconds, we shall see, even for hours afterwards, and whether the eyes are open or shut, a spectrum of the sun varying in its colours. At first, with the eye open, it is brownish-red with a sky-blue border, and when the eye is shut, it is green with a red border. The red becomes more brilliant, and the blue more vivid, till the impression is gradually worn off; but even when they become very faint, they may be revived by a gentle pressure on the eyeball.

Some eyes are more susceptible than others of these spectral impressions, and Mr. Boyle mentions an individual who continued for years to see the spectre of the sun when he looked upon bright objects. This fact appeared to Locke so interesting and inexplicable, that he consulted Sir Isaac Newton respecting its cause, and drew from him the following interesting account of a similar effect upon himself:—“The observation you mention in Mr. Boyle’s book of colours, I once made upon myself with the hazard of my eyes. The manner was this: I looked a very little while upon the sun in the looking-glass with my right eye, and then turned my eyes into a dark corner of my chamber, and winked, to observe the impression made, and the circles of colours which encompassed it, and how they decayed by degrees, and at last vanished. This I repeated a second and a third time. At the third time, when the phantasm of light and colours about it were almost vanished, intending my fancy upon them to see their last appearance, I found, to my amazement, that they began to return, and by little and little to become as lively and vivid as when I had newly looked upon the sun. But when I ceased to intend my face upon them, they vanished again. After this I found that as often as I went into the dark, and intended my mind upon them, as when a man looks earnestly to see anything which is difficult to be seen, I could make the phantasm return without looking any more upon the sun; and the oftener I made it return, the more easily I could make it return again. And at length, by repeating this without looking any more upon the sun, I made such an impression on my eye, that, if I looked upon the clouds, or a book, or any bright object, I saw upon it a round bright spot of light like the sun, and, which is still stranger, though I looked upon the sun with my right eye only, and not with my left, yet my fancy began to make an impression upon my left eye as well as upon my right. For if I shut my right eye, and looked upon a book or the clouds with my left eye, I could see the spectrum of the sun almost as plain as with my right eye, if I did but intend my fancy a little while upon it: for at first, if I shut my right eye, and looked with my left, the spectrum of the sun did not appear till I intended my fancy upon it; but by repeating, this appeared every time more easily. And now in a few hours’ time I had brought my eyes to such a pass, that I could look upon no bright object with either eye but I saw the sun before me, so that I durst neither write nor read; but to recover the use of my eyes, shut myself up in my chamber, made dark, for three days together, and used all means in my power to direct my imagination from the sun. For if I thought upon him, I presently saw his picture, though I was in the dark. But by keeping in the dark; and employing my mind about other things, I began, in three or four days, to have more use of my eyes again; and by forbearing to look upon bright objects, recovered them pretty well; though not so well but that, for some months after, the spectrums of the sun began to return as often as I began to meditate upon the phenomena, even though I lay in bed at midnight with my curtains drawn. But now I have been well for many years, though I am apt to think, if I durst venture my eyes, I could still make the phantasm return by the power of my fancy. This story I tell you, to let you understand, that in the observation related by Mr. Boyle, the man’s fancy probably concurred with the impression made by the sun’s light to produce that phantasm of the sun which he constantly saw in bright objects.”4

I am not aware of any effects that had the character of supernatural having been actually produced by the causes above described; but it is obvious, that if a living figure had been projected against the strong light which imprinted these durable spectra of the sun, which might really happen when the solar rays are reflected from water, and diffused by its ruffled surface, this figure would have necessarily accompanied all the luminous spectres which the fancy created. Even in ordinary lights, strange appearances may be produced by even transient impressions; and if I am not greatly mistaken, the case which I am about to mention is not only one which may occur, but which actually happened. A figure dressed in black, and mounted upon a white horse, was riding along, exposed to the bright rays of the sun, which, through a small opening in the clouds, was throwing its light only upon that part of the landscape. The black figure was projected against a white cloud, and the white horse shone with particular brilliancy by its contrast with the dark soil against which it was seen. A person interested in the arrival of such a stranger had been for some time following his movements with intense anxiety, but, upon his disappearance behind a wood, was surprised to observe the spectre of the mounted stranger in the form of a white rider upon a black steed, and this spectre was seen for some time in the sky, or upon any pale ground to which the eye was directed. Such an occurrence, especially if accompanied with a suitable combination of events, might, even in modern times, have formed a chapter in the history of the marvellous.

It is a curious circumstance, that when the image of an object is impressed upon the retina only for a few moments, the picture which is left is exactly of the same colour with the object. If we look, for example, at a window at some distance from the eye, and then transfer the eye quickly to the wall, we shall see it distinctly, but momentarily, with light panes and dark bars; but in a space of time incalculably short, this picture is succeeded by the spectral impression of the window, which will consist of black panes and white bars. The similar spectrum, or that of the same colour as the object, is finely seen in the experiment of forming luminous circles by whirling round a burning stick, in which case the circles are always red.

In virtue of this property of the eye, an object may be seen in many places at once; and we may even exhibit at the same instant the two opposite sides of the same object, or two pictures painted on the opposite sides of a piece of card. It was found by a French philosopher, M. D’Arcet, that the impression of light continued on the retina about the eighth part of a second after the luminous body was withdrawn, and upon this principle Dr. Paris has constructed the pretty little instrument called the Thaumatrope, or the Wonder-turner. It consists of a number of circular pieces of card, about two or three inches broad, which may be twirled round with great velocity by the application of the fore-finger and thumb of each hand to pieces of silk string attached to opposite points of their circumference. On each side of the circular piece of card is painted part of a picture, or a part of a figure, in such a manner that the two parts would form a group or a whole figure, if we could see both sides at once. Harlequin, for example, is painted on one side, and Columbine on the other, so that by twirling round the card the two are seen at the same time in their usual mode of combination. The body of a Turk is drawn on one side, and his head on the reverse, and by the rotation of the card the head is replaced upon his shoulders. The principle of this illusion may be extended to many other contrivances. Part of a sentence may be written on one side of a card, and the rest on the reverse. Particular letters may be given on one side, and others upon the other, or even halves or parts of each letter may be put upon each side, or all these contrivances may be combined, so that the sentiment which they express can be understood only when all the scattered parts are united by the revolution of the card.

As the revolving card is virtually transparent, so that bodies beyond it can be seen through it, the power of the illusion might be greatly extended by introducing into the picture other figures, either animate or inanimate. The setting sun, for example, might be introduced into a landscape; part of the flame of a fire might be seen to issue from the crater of a volcano, and cattle grazing in a field might make part of the revolutionary landscape. For such purposes, however, the form of the instrument would require to be completely changed, and the rotation should be effected round a standing axis by wheels and pinions, and a screen placed in front of the revolving plane with open compartments or apertures, through which the principal figures would appear. Had the principle of this instrument been known to the ancients, it would doubtless have formed a powerful engine of delusion in their temples, and might have been more effective than the optical means which they seem to have employed for producing the apparitions of their gods.

In certain diseased conditions of the eye, effects of a very remarkable kind are produced. The faculty of seeing objects double is too common to be noticed as remarkable; and though it may take place with only one eye, yet, as it generally arises from a transient inability to direct the axis of both eyes to the same point, it excites little notice. That state of the eye, however, in which we lose sight of half of every object at which we look, is more alarming and more likely to be ascribed to the disappearance of part of the object than to a defect of sight. Dr. Wollaston, who experienced this defect twice, informs us that, after taking violent exercise, he “suddenly found that he could see but half of a man whom he met, and that on attempting to read the name of JOHNSON over a door, he saw only SON, the commencement of the name being wholly obliterated from his view.” In this instance, the part of the object which disappeared was towards his left; but on a second occurrence of the same affection, the part which disappeared was towards his right. There are many occasions on which this defect of the eye might alarm the person who witnessed it for the first time. At certain distances from the eye one of two persons would necessarily disappear; and by a slight change of position either in the observer or the person observed, the person that vanished would reappear, while the other would disappear in his turn. The circumstances under which these evanescences would take place could not be supposed to occur to an ordinary observer, even if he should be aware that the cause had its origin in himself. When a phenomenon so strange is seen by a person in perfect health, as it generally is, and who has never had occasion to distrust the testimony of his senses, he can scarcely refer it to any other cause than a supernatural one.

Among the affections of the eye which not only deceive the person who is subject to them, but those also who witness their operation, may be enumerated the insensibility of the eye to particular colours. This defect is not accompanied with any imperfection of vision, or connected with any disease either of a local or a general nature, and it has hitherto been observed in persons who possess a strong and a sharp sight. Mr. Huddart has described the case of one Harris, a shoemaker at Maryport in Cumberland, who was subject to this defect in a very remarkable degree. He seems to have been insensible to every colour, and to have been capable of recognizing only the two opposite tints of black and white. “His first suspicion of this defect arose when he was about four years old. Having by accident found in the street a child’s stocking, he carried it to a neighbouring house to inquire for the owner. He observed the people call it a red stocking, though he did not understand why they gave it that denomination, as he himself thought it completely described by being called a stocking. The circumstance, however, remained in his memory, and, with other subsequent observations, led him to the knowledge of his defect. He observed also, that when young, other children could discern cherries on a tree by some pretended difference of colour, though he could only distinguish them from the leaves by their difference of size and shape. He observed also, that by means of this difference of colour, they could see the cherries at a greater distance than he could, though he could see other objects at as great a distance as they, that is, where the sight was not assisted by the colour.” Harris had two brothers, whose perception of colours was nearly as defective as his own. One of these, whom Mr. Huddart examined, constantly mistook light green for yellow, and orange for grass green.

Mr. Scott has described, in the Philosophical Transactions, his own defect in perceiving colours. He states that he does not know any green in the world; that a pink colour and a pale blue are perfectly alike; that he has often thought a full red and a full green a good match; that he is sometimes baffled in distinguishing a full purple from a deep blue, but that he knows light, dark, and middle yellows, and all degrees of blue except sky-blue. “I married my daughter to a genteel, worthy man, a few years ago; the day before the marriage, he came to my house dressed in a new suit of fine cloth clothes. I was much displeased that he should come, as I supposed, in black, and said that he should go back to change his colour. But my daughter said, No, no; the colour is very genteel; that it was my eyes that deceived me. He was a gentleman of the law, in a fine, rich, claret-coloured dress, which is as much black to my eyes as any black that ever was dyed.” Mr. Scott’s father, his maternal uncle, one of his sisters, and her two sons, had all the same imperfection. Dr. Nichol has recorded a case where a naval officer purchased a blue uniform coat and waistcoat with red breeches to match the blue, and Mr. Harvey describes the case of a tailor at Plymouth, who on one occasion repaired an article of dress with crimson in place of black silk, and on another patched the elbow of a blue coat with a piece of crimson cloth. It deserves to be remarked that our celebrated countrymen, the late Mr. Dugald Stewart, Mr. Dalton, and Mr. Troughton, have a similar difficulty in distinguishing colours. Mr. Stewart discovered this defect when one of his family was admiring the beauty of a Siberian crab-apple, which he could not distinguish from the leaves but by its form and size. Mr. Dalton cannot distinguish blue from pink, and the solar spectrum consists only of two colours, yellow and blue. Mr. Troughton regards red ruddy pinks, and brilliant oranges, as yellows, and greens as blues, so that he is capable only of appreciating blue and yellow colours.

In all those cases which have been carefully studied, at least in three of them, in which I have had the advantage of making personal observations, namely, those of Mr. Troughton, Mr. Dalton, and Mr. Liston, the eye is capable of seeing the whole of the prismatic spectrum, the red space appearing to be yellow. If the red space consisted of homogeneous or simple red rays, we should be led to infer that the eyes in question were not insensible to red light, but were merely incapable of discriminating between the impressions of red and yellow light. I have lately shown, however, that the prismatic spectrum consists of three equal and coincident spectra of red, yellow, and blue light, and consequently, that much yellow and a small portion of blue light exist in the red space; and hence it follows, that those eyes which see only two colours, viz. yellow and blue, in the spectrum, are really insensible to the red light of the spectrum, and see only the yellow with the small portion of blue with which the red is mixed. The faintness of the yellow light which is thus seen in the red space, confirms the opinion that the retina has not appreciated the influence of the simple red rays.

If one of the two travellers who, in the fable of the chameleon, are made to quarrel about the colour of that singular animal, had happened to possess this defect of sight, they would have encountered at every step of their journey, new grounds of dissension, without the chance of finding an umpire who could pronounce a satisfactory decision. Under certain circumstances, indeed, the arbiter might set aside the opinions of both the disputants, and render it necessary to appeal to some higher authority,

---- to beg he’d tell them if he knew

Whether the thing was red or blue.

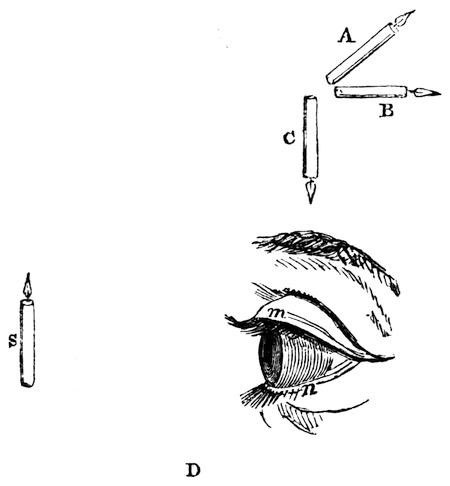

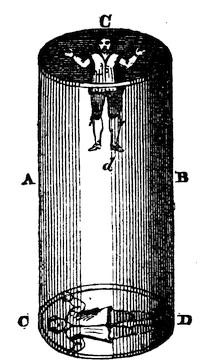

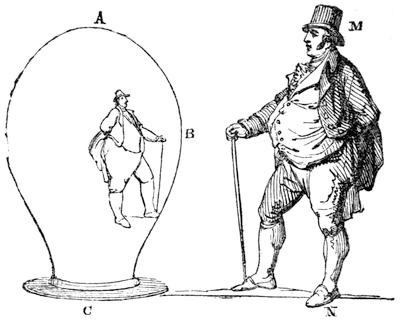

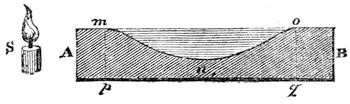

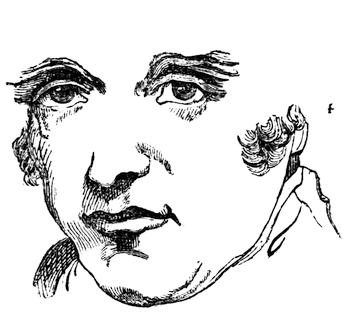

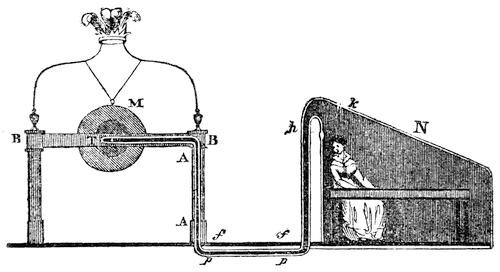

Fig. 2.

In the course of writing the preceding observations an ocular illusion occurred to myself of so extraordinary a nature, that I am convinced it never was seen before, and I think it far from probable that it will ever be seen again. Upon directing my eyes to the candles that were standing before me, I was surprised to observe, apparently among my hair, and nearly straight above my head, and far without the range of vision, a distinct image of one of the candles inclined about 45° to the horizon, as shown at A in Fig. 2. The image was as distinct and perfect as if it had been formed by reflection from a piece of mirror glass, though of course much less brilliant, and the position of the image proved that it must be formed by reflection from a perfectly flat and highly polished surface. But where such a surface could be placed, and how, even if it were fixed, it could reflect the image of the candle up through my head, were difficulties not a little perplexing. Thinking that it might be something lodged in the eyebrow, I covered it up from the light, but the image still retained its place. I then examined the eyelashes with as little success, and was driven to the extreme supposition that a crystallization was taking place in some part of the aqueous humour of the eye, and that the image was formed by the reflection of the light of the candle from one of the crystalline faces. In this state of uncertainty, and, I may add, of anxiety, for this last supposition was by no means an agreeable one, I set myself down to examine the phenomenon experimentally. I found that the image varied its place by the motion of the head and of the eyeball, which proved that it was either attached to the eyeball or occupied a place where it was affected by that motion. Upon inclining the candle at different angles, the image suffered corresponding variations of position. In order to determine the exact place of the reflecting substance, I now took an opaque circular body and held it between the eye and the candle till it eclipsed the mysterious image. By bringing the body nearer and nearer the eyeball till its shadow became sufficiently distinct to be seen, it was easy to determine the locality of the reflector, because the shadow of the opaque body must fall upon it whenever the image of the candle was eclipsed. In this way I ascertained that the reflecting body was in the upper eyelash; and I found, that, in consequence of being disturbed, it had twice changed its inclination, so as to represent a vertical candle in the horizontal position B, and afterwards in the inverted position C. Still, however, I sought for it in vain, and even with the aid of a magnifier I could not discover it. At last, however, Mrs. B., who possesses the perfect vision of short-sighted persons, discovered, after repeated examinations, between two eyelashes, a minute speck, which, upon being removed with great difficulty, turned out to be a chip of red wax not above the hundredth part of an inch in diameter, and having its surface so perfectly flat and so highly polished that I could see in it the same image of the candle, by placing it extremely near the eye. This chip of wax had no doubt received its flatness and its polish from the surface of a seal, and had started into my eye when breaking the seal of a letter.

That this reflecting substance was the cause of the image of the candle, cannot admit of a doubt; but the wonder still remains how the images which it formed occupied so mysterious a place as to be seen without the range of vision, and apparently through the head. In order to explain this, let m n, Fig. 2, be a lateral view of the eye. The chip of wax was placed at m at the root of the eyelashes, and being nearly in contact with the outer surface of the cornea, the light of the candle, which it reflected, passed very obliquely through the pupil and fell upon the retina somewhere to the left of n, very near where the retina terminates; but a ray thus falling obliquely on the retina is seen, in virtue of the law of visible direction already explained, in a line n C perpendicular to the retina at the point near n, where the ray fell. Hence the candle was necessarily seen through the head as it were of the observer, and without the range of ordinary vision. The comparative brightness of the reflected image still surprises me; but even this, if the image really was brighter, may be explained by the fact, that it was formed on a part of the retina upon which light had never before fallen, and which may therefore be supposed to be more sensible, than the parts of the membrane in constant use, to luminous impressions.

Independent of its interest as an example of the marvellous in vision, the preceding fact may be considered as a proof that the retina retains its power to its very termination near the ciliary processes, and that the law of visible direction holds true even without the range of ordinary vision. It is therefore possible that a reflecting surface favourably placed on the outside of the eye, or that a reflecting surface in the inside of the eye, may cause a luminous image to fall nearly on the extreme margin of the retina, the consequence of which would be, that it would be seen in the back of the head, half way between a vertical and a horizontal line.

2 When both eyes are open, the object whose image falls upon the insensible spot of the one eye is seen by the other, so that, though it is not invisible, yet it will only be half as luminous and, therefore two dark spots ought to be seen.

3 A very curious example of the influence of the imagination in creating distinct forms out of an irregularly shaded surface, is mentioned in the life of Peter Heaman, a Swede, who was executed for piracy and murder at Leith in 1822. We give it in his own words:—

4 See the Edinburgh Encyclopædia, Art. Accidental Colours.

LETTER III.

Subject of spectral illusions—Recent and interesting case of Mrs. A.—Her first illusion affecting the ear—Spectral apparition of her husband—Spectral apparition of a cat—Apparition of a near and living relation in grave-clothes, seen in a looking-glass—Other illusions, affecting the ear—Spectre of a deceased friend sitting in an easy-chair—Spectre of a coach-and-four filled with skeletons—Accuracy and value of the preceding cases—State of health under which they arose—Spectral apparitions are pictures on the retina—The ideas of memory and imagination are also pictures on the retina—General views of the subject—Approximate explanation of spectral apparitions.

The preceding account of the different sources of illusion to which the eye is subject is not only useful as indicating the probable cause of any individual deception, but it has a special importance in preparing the mind for understanding those more vivid and permanent spectral illusions to which some individuals have been either occasionally or habitually subject.

In these lesser phenomena, we find the retina so powerfully influenced by external impressions, as to retain the view of visible objects long after they are withdrawn: we observe it to be so excited by local pressures of which we sometimes know neither the nature nor the origin, as to see in total darkness moving and shapeless masses of coloured light; and we find, as in the case of Sir Isaac Newton, and others, that the imagination has the power of reviving the impressions of highly luminous objects, months and even years after they were first made. From such phenomena, the mind feels it to be no violent transition to pass to those spectral illusions which, in particular states of health, have haunted the most intelligent individuals, not only in the broad light of day, but in the very heart of the social circle.

This curious subject has been so ably and fully treated in your Letters on Demonology, that it would be presumptuous in me to resume any part of it on which you have even touched; but as it forms a necessary branch of a Treatise on Natural Magic, and as one of the most remarkable cases on record has come within my own knowledge, I shall make no apology for giving a full account of the different spectral appearances which it embraces, and of adding the results of a series of observations and experiments on which I have been long occupied, with the view of throwing some light on this remarkable class of phenomena.

A few years ago, I had occasion to spend some days under the same roof with the lady to whose case I have above referred. At that time she had seen no spectral illusions, and was acquainted with the subject only from the interesting volume of Dr. Hibbert. In conversing with her about the cause of these apparitions, I mentioned, that if she should ever see such a thing, she might distinguish a genuine ghost, existing externally, and seen as an external object, from one created by the mind, by merely pressing one eye or straining them both, so as to see objects double; for in this case the external object or supposed apparition would invariably be doubled, while the impression on the retina created by the mind would remain single. This observation recurred to her mind when she unfortunately became subject to the same illusions; but she was too well acquainted with their nature to require any such evidence of their mental origin; and the state of agitation which generally accompanies them seems to have prevented her from making the experiment as a matter of curiosity.

1. The first illusion to which Mrs. A. was subject was one which affected only the ear. On the 26th of December, 1830, about half-past four in the afternoon, she was standing near the fire in the hall, and on the point of going up stairs to dress, when she heard, as she supposed, her husband’s voice calling her by name, “—— Come here! come to me!” She imagined that he was calling at the door to have it opened, but upon going there and opening the door she was surprised to find no person there. Upon returning to the fire, she again heard the same voice calling out very distinctly and loudly, “—— Come, come here!” She then opened two doors of the same room, and upon seeing no person she returned to the fire-place. After a few moments she heard the same voice still calling, “—— ---- Come to me, come! come away!” in a loud, plaintive, and somewhat impatient tone. She answered as loudly, “Where are you? I don’t know where you are;” still imagining that he was somewhere in search of her: but receiving no answer, she shortly went up stairs. On Mr. A.’s return to the house, about half an hour afterwards, she inquired why he called to her so often, and where he was; and she was, of course, greatly surprised to learn that he had not been near the house at the time. A similar illusion, which excited no particular notice at the time, occurred to Mrs. A. when residing at Florence about ten years before, and when she was in perfect health. When she was undressing after a ball, she heard a voice call her repeatedly by name, and she was at that time unable to account for it.

2. The next illusion which occurred to Mrs. A. was of a more alarming character. On the 30th of December, about four o’clock in the afternoon, Mrs. A. came down stairs into the drawing-room, which she had quitted only a few minutes before, and on entering the room she saw her husband, as she supposed, standing with his back to the fire. As he had gone out to take a walk about half an hour before, she was surprised to see him there, and asked him why he had returned so soon. The figure looked fixedly at her with a serious and thoughtful expression of countenance, but did not speak. Supposing that his mind was absorbed in thought, she sat down in an arm-chair near the fire, and within two feet at most of the figure, which she still saw standing before her. As its eyes, however, still continued to be fixed upon her, she said, after the lapse of a few minutes, “Why don’t you speak,——?” The figure immediately moved off towards the window at the further end of the room, with its eyes still gazing on her, and it passed so very close to her in doing so, that she was struck by the circumstance of hearing no step nor sound, nor feeling her clothes brushed against, nor even any agitation in the air. Although she was now convinced that the figure was not her husband, yet she never for a moment supposed that it was anything supernatural, and was soon convinced that it was a spectral illusion. As soon as this conviction had established itself in her mind, she recollected the experiment which I had suggested, of trying to double the object: but before she was able distinctly to do this, the figure had retreated to the window, where it disappeared. Mrs. A. immediately followed it, shook the curtains and examined the window, the impression having been so distinct and forcible that she was unwilling to believe that it was not a reality. Finding, however, that the figure had no natural means of escape, she was convinced that she had seen a spectral apparition like those recorded in Dr. Hibbert’s work, and she consequently felt no alarm or agitation. The appearance was seen in bright daylight, and lasted four or five minutes. When the figure stood close to her it concealed the real objects behind it, and the apparition was fully as vivid as the reality.

3. On these two occasions Mrs. A. was alone, but when the next phantasm appeared her husband was present. This took place on the 4th of January, 1830. About ten o’clock at night, when Mr. and Mrs. A. were sitting in the drawing-room, Mr. A. took up the poker to stir the fire, and when he was in the act of doing this, Mrs. A. exclaimed, “Why there’s the cat in the room!” “Where?” asked Mr. A. “There, close to you,” she replied. “Where?” he repeated. “Why on the rug, to be sure, between yourself and the coal-scuttle.” Mr. A., who had still the poker in his hand, pushed it in the direction mentioned: “Take care,” cried Mrs. A., “take care, you are hitting her with the poker.” Mr. A. again asked her to point out exactly where she saw the cat. She replied, ”Why sitting up there close to your feet on the rug. She is looking at me. It is Kitty—come here, Kitty!”—There were two cats in the house, one of which went by this name, and they were rarely if ever in the drawing-room. At this time Mrs. A. had no idea that the sight of the cat was an illusion. When she was asked to touch it, she got up for the purpose, and seemed as if she were pursuing something which moved away. She followed a few steps, and then said, “It has gone under the chair.” Mr. A. assured her it was an illusion, but she would not believe it. He then lifted up the chair, and Mrs. A. saw nothing more of it. The room was then searched all over, and nothing found in it. There was a dog lying on the hearth, who would have betrayed great uneasiness if a cat had been in the room, but he lay perfectly quiet. In order to be quite certain, Mr. A. rang the bell, and sent for the two cats, both of which were found in the housekeeper’s room.

4. About a month after this occurrence, Mrs. A., who had taken a somewhat fatiguing drive during the day, was preparing to go to bed about eleven o’clock at night, and, sitting before the dressing-glass, was occupied in arranging her hair. She was in a listless and drowsy state of mind, but fully awake. When her fingers were in active motion among the papillotes, she was suddenly startled by seeing in the mirror the figure of a near relation, who was then in Scotland and in perfect health. The apparition appeared over her left shoulder, and its eyes met hers in the glass. It was enveloped in grave-clothes, closely pinned, as is usual with corpses, round the head, and under the chin, and though the eyes were open, the features were solemn and rigid. The dress was evidently a shroud, as Mrs. A. remarked even the punctured pattern usually worked in a peculiar manner round the edges of that garment. Mrs. A. described herself as at the time sensible of a feeling like what we conceive of fascination, compelling her for a time to gaze on this melancholy apparition, which was as distinct and vivid as any reflected reality could be, the light of the candles upon the dressing-table appearing to shine fully upon its face. After a few minutes, she turned round to look for the reality of the form over her shoulder; but it was not visible, and it had also disappeared from the glass when she looked again in that direction.

5. In the beginning of March, when Mr. A. had been about a fortnight from home, Mrs. A. frequently heard him moving near her. Nearly every night, as she lay awake, she distinctly heard sounds like his breathing hard on the pillow by her side, and other sounds such as he might make while turning in bed.

6. On another occasion, during Mr. A.’s absence, while riding with a neighbour, Mr.——, she heard his voice frequently as if he were riding by his side. She heard also the tramp of his horse’s feet, and was almost puzzled by hearing him address her at the same time with the person really in company. His voice made remarks on the scenery, improvements, &c., such as he probably should have done had he been present. On this occasion, however, there was no visible apparition.

7. On the 17th March, Mrs. A. was preparing for bed. She had dismissed her maid, and was sitting with her feet in hot water. Having an excellent memory, she had been thinking upon and repeating to herself a striking passage in the Edinburgh Review, when on raising her eyes, she saw seated in a large easy-chair before her the figure of a deceased friend, the sister of Mr. A. The figure was dressed as had been usual with her, with great neatness, but in a gown of a peculiar kind, such as Mrs. A. had never seen her wear, but exactly such as had been described to her by a common friend as having been worn by Mr. A.’s sister during her last visit to England. Mrs. A. paid particular attention to the dress, air, and appearance of the figure, which sat in an easy attitude in the chair, holding a handkerchief in one hand. Mrs. A. tried to speak to it, but experienced a difficulty in doing so; and in about three minutes the figure disappeared. About a minute afterwards, Mr. A. came into the room, and found Mrs. A. slightly nervous, but fully aware of the delusive nature of the apparition. She described it as having all the vivid colouring and apparent reality of life; and for some hours preceding this and other visions, she experienced a peculiar sensation in her eyes, which seemed to be relieved when the vision had ceased.

8. On the 5th October, between one and two o’clock in the morning, Mr. A. was awoke by Mrs. A., who told him that she had just seen the figure of his deceased mother draw aside the bedcurtains and appear between them. The dress and the look of the apparition were precisely those in which Mr. A.’s mother had been last seen by Mrs. A. at Paris, in 1824.

9. On the 11th October, when sitting in the drawing-room, on one side of the fire-place, she saw the figure of another deceased friend moving towards her from the window at the further end of the room. It approached the fire-place, and sat down in the chair opposite. As there were several persons in the room at the time, she describes the idea uppermost in her mind to have been a fear lest they should be alarmed at her staring, in the way she was conscious of doing, at vacancy, and should fancy her intellect disordered. Under the influence of this fear, and recollecting a story of a similar effect in your work on Demonology, which she had lately read, she summoned up the requisite resolution to enable her to cross the space before the fire-place, and seat herself in the same chair with the figure. The apparition remained perfectly distinct till she sat down, as it were, in its lap, when it vanished.