автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Poetical Works of William Wordsworth — Volume 8 (of 8)

THE POETICAL WORKS

OF

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH

VOL. VIII

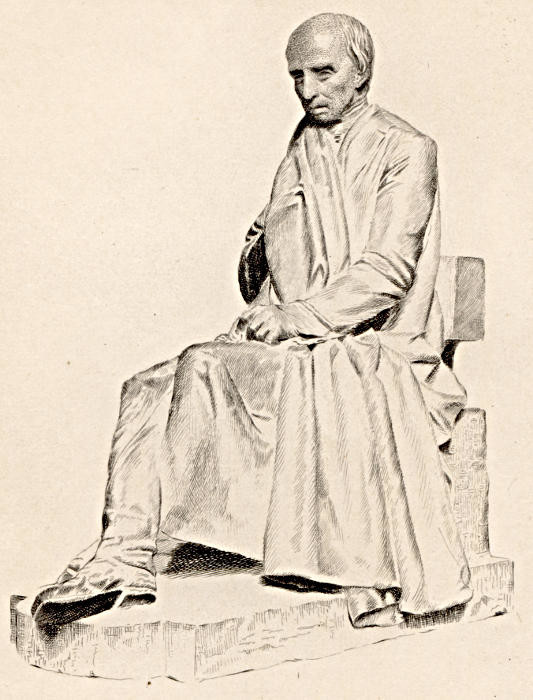

William Wordsworth

after Thomas Woolner

Printed by Ch Wittmann Paris

THE POETICAL WORKS

OF

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH

EDITED BY

WILLIAM KNIGHT

VOL. VIII

Gallow Hill

Yorkshire

London

MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd.

New York: Macmillan & Co.

1896

All rights reserved.

CONTENTS

PAGE

1834Lines suggested by a Portrait from the Pencil of F. Stone

1The foregoing Subject resumed

6To a Child

7Lines written in the Album of the Countess of Lonsdale, Nov. 5, 1834

8 1835“Why art thou silent? Is thy love a plant”

12To the Moon

13To the Moon

15Written after the Death of Charles Lamb

17Extempore Effusion upon the Death of James Hogg

24Upon seeing a Coloured Drawing of the Bird of Paradise in an Album

29“Desponding Father! mark this altered bough”

31“Four fiery steeds impatient of the rein”

31To ——

32Roman Antiquities discovered at Bishopstone, Herefordshire

33St. Catherine of Ledbury

34“By a blest Husband guided, Mary came”

35“Oh what a Wreck! how changed in mien and speech!”

36 1836November 1836

37To a Redbreast—(In Sickness)

38 1837“Six months to six years added he remained”

39Memorials of a Tour in Italy, 1837—To Henry Crabb Robinson

41 I.Musings near Aquapendente, April, 1837

42 II.The Pine of Monte Mario at Rome

58 III.At Rome

59 IV.At Rome—Regrets—in Allusion to Niebuhr and other Modern Historians

60 V.Continued

61 VI.Plea for the Historian

61 VII.At Rome

62 VIII.Near Rome, in Sight of St. Peter’s

63 IX.At Albano

64 X.“Near Anio’s stream, I spied a gentle Dove”

65 XI.From the Alban Hills, looking towards Rome

65 XII.Near the Lake of Thrasymene

66 XIII.Near the same Lake

67 XIV.The Cuckoo at Laverna

67 XV.At the Convent of Camaldoli

72

XVI.Continued

73 XVII.At the Eremite or Upper Convent of Camaldoli

74 XVIII.At Vallombrosa

75 XIX.At Florence

78 XX.Before the Picture of the Baptist, by Raphael, in the Gallery at Florence

79 XXI.At Florence—From Michael Angelo

80 XXII.At Florence—From Michael Angelo

81 XXIII.Among the Ruins of a Convent in the Apennines

82 XXIV.In Lombardy

83 XXV.After leaving Italy

84 XXVI.Continued

85At Bologna, in Remembrance of the late Insurrections, 1837.—

I. 86 II.Continued

86 III.Concluded

87“What if our numbers barely could defy”

87A Night Thought

88The Widow on Windermere Side

89 1838To the Planet Venus

92“Hark! ’tis the Thrush, undaunted, undeprest”

93“’Tis He whose yester-evening’s high disdain”

94Composed at Rydal on May Morning, 1838

94Composed on a May Morning, 1838

97A Plea for Authors, May 1838

99“Blest Statesman He, whose Mind’s unselfish will”

101Valedictory Sonnet

102 1839Sonnets upon the Punishment of Death—

I.Suggested by the View of Lancaster Castle (on the Road from the South)

103 II.“Tenderly do we feel by Nature’s law”

104 III.“The Roman Consul doomed his sons to die”

105 IV.“Is

Death, when evil against good has fought”

106 V.“Not to the object specially designed”

106 VI.“Ye brood of conscience—Spectres! that frequent”

107 VII.“Before the world had past her time of youth”

107 VIII.“Fit retribution, by the moral code”

108 IX.“Though to give timely warning and deter”

109 X.“Our bodily life, some plead, that life the shrine”

109 XI.“Ah, think how one compelled for life to abide”

110 XII.“See the Condemned alone within his cell”

110 XIII.Conclusion

111 XIV.Apology

112“Men of the Western World! in Fate’s dark book”

112 1840To a Painter

114On the same Subject

115Poor Robin

116On a Portrait of the Duke of Wellington upon the Field of Waterloo, by Haydon

118 1841Epitaph in the Chapel-Yard of Langdale, Westmoreland

120 1842“Intent on gathering wool from hedge and brake”

122Prelude, prefixed to the Volume entitled “Poems chiefly of Early and Late Years”

123Floating Island

125“The Crescent-moon, the Star of Love”

127“

A Poet!—He hath put his heart to school”

127“The most alluring clouds that mount the sky”

128“Feel for the wrongs to universal ken”

129In Allusion to various Recent Histories and Notices of the French Revolution

130Continued

131Concluded

131“Lo! where she stands fixed in a saint-like trance”

132The Norman Boy

132The Poet’s Dream

135Suggested by a Picture of the Bird of Paradise

140To the Clouds

142Airey-Force Valley

146“Lyre! though such power do in thy magic live”

147Love lies Bleeding

148“They call it Love lies bleeding! rather say”

150Companion to the Foregoing

150The Cuckoo-Clock

151“Wansfell! this Household has a favoured lot”

153“Though the bold wings of Poesy affect”

154“Glad sight wherever new with old”

154 1843“While beams of orient light shoot wide and high”

156Inscription for a Monument in Crosthwaite Church, in the Vale of Keswick

157To the Rev. Christopher Wordsworth, D.D., Master of Harrow School

162 1844“So fair, so sweet, withal so sensitive”

164On the projected Kendal and Windermere Railway

166“Proud were ye, Mountains, when, in times of old”

167At Furness Abbey

168 1845“Forth from a jutting ridge, around whose base”

170The Westmoreland Girl

172At Furness Abbey

176“Yes! thou art fair, yet be not moved”

176“What heavenly smiles! O Lady mine”

177To a Lady

177To the Pennsylvanians

179“Young England—what is then become of Old”

180 1846Sonnet

181“Where lies the truth? has Man, in wisdom’s creed”

182To Lucca Giordano

183“Who but is pleased to watch the moon on high”

184Illustrated Books and Newspapers

184Sonnet. To an Octogenarian

185“I know an aged Man constrained to dwell”

186“The unremitting voice of nightly streams”

187“How beautiful the Queen of Night, on high”

188On the Banks of a Rocky Stream

188Ode. Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood

189POEMS BY WILLIAM WORDSWORTH AND BY DOROTHY WORDSWORTH

NOT INCLUDED IN THE EDITION OF 1849-50

1787Sonnet, on seeing Miss Helen Maria Williams weep at a Tale of Distress

209Lines written by William Wordsworth as a School Exercise at Hawkshead, Anno Ætatis 14

211 1792 (or earlier)“Sweet was the walk along the narrow lane”

214“When Love was born of heavenly line”

215The Convict

217 1798“The snow-tracks of my friends I see”

219The Old Cumberland Beggar (MS. Variants, not inserted in Vol. I.)

220 1800Andrew Jones

221“There is a shapeless crowd of unhewn stones”

223 1802“Among all lovely things my Love had been”

231“Along the mazes of this song I go”

233“The rains at length have ceas’d, the winds are still’d”

233“Witness thou”

234Wild-Fowl

234Written in a Grotto

234Home at Grasmere

235“Shall he who gives his days to low pursuits”

257 1803“I find it written of Simonides”

258 1804“No whimsey of the purse is here”

258 1805“Peaceful our valley, fair and green”

259“Ah! if I were a lady gay”

262 1806To the Evening Star over Grasmere Water, July 1806

263Michael Angelo in Reply to the Passage upon his Statue of Night sleeping

263“Come, gentle Sleep, Death’s image tho’ thou art”

264“Brook, that hast been my solace days and week”

265Translation from Michael Angelo

265 1808George and Sarah Green

266 1818“The Scottish Broom on Bird-nest brae”

270Placard for a Poll bearing an old Shirt

271“Critics, right honourable Bard, decree”

271 1819“Through Cumbrian wilds, in many a mountain cove”

272“My Son! behold the tide already spent”

273 1820Author’s Voyage down the Rhine

273 1822“These vales were saddened with no common gloom”

275Translation of Part of the First Book of the

Æneid 276 1823“Arms and the Man I sing, the first who bore”

281 1826Lines addressed to Joanna H. from Gwerndwffnant in June 1826

282Holiday at Gwerndwffnant, May 1826

284Composed when a Probability existed of our being obliged to quit Rydal Mount as a Residence

289“I, whose pretty Voice you hear”

295 1827To my Niece Dora

297 1829“My Lord and Lady Darlington”

298 1833To the Utilitarians

299 1835“Throned in the Sun’s descending car”

300“And oh! dear soother of the pensive breast”

301 1836“Said red-ribboned Evans”

301 1837On an Event in Col. Evans’s Redoubted Performances in Spain

303 1838“Wouldst thou be gathered to Christ’s chosen flock”

303Protest against the Ballot, 1838

304“Said Secrecy to Cowardice and Fraud”

304A Poet to his Grandchild

305 1840On a Portrait of I.F., painted by Margaret Gillies

306To I.F.

307“Oh Bounty without measure, while the Grace”

308 1842The Eagle and the Dove

309Grace Darling

310“When Severn’s sweeping flood had overthrown”

314The Pillar of Trajan

314 1846“Deign, Sovereign Mistress! to accept a lay”

319 1847Ode, performed in the Senate-House, Cambridge, on the 6th of July 1847, at the First Commencement after the Installation of His Royal Highness the Prince Albert, Chancellor of the University

320To Miss Sellon

325“The worship of this Sabbath morn”

325 Bibliographies— I. Great Britain 329 II. America 380 III. France 421 Errata and Addenda List 431 Index to the Poems 433 Index to the First Lines 451PREFATORY NOTE

The American Bibliography is almost entirely the work of Mrs. St. John of Ithaca, and is the result of laborious and careful critical research on her part. The French Bibliography is not so full. I have been assisted in it mainly by M. Legouis at Lyons, and by workers at the British Museum. I have also collected a German Bibliography, but it is in too incomplete a state for publication in its present form.

The English Bibliography is fuller than any of its predecessors; but there is no such thing as finality in such work, especially when an addition to the literature of the subject is made nearly every week. Many kind friends, and coadjutors, have assisted me in it, amongst whom I may mention Dr. Garnett of the British Museum, and very specially Mr. Tutin, of Hull, and also Mr. John J. Smith, St. Andrews, and Mr. Maclauchlan, Dundee. If I omit, either here or elsewhere, to record the assistance which I have received from any one, in my efforts to make this edition of Wordsworth as perfect as is possible at this stage of literary criticism and editorship, I sincerely regret it; but many of my correspondents have specially requested that no mention should be made of their names or their services.

In the Preface to the first volume of this edition there was an unfortunate omission. In returning the final proofs to press, I accidentally transmitted an uncorrected one, in which two names did not appear. They were those of Mr. Thomas Hutchinson, Dublin, and Mr. S. C. Hill, of Hughli College, Bengal. The former kindly revised most of the sheets of Volumes I. and II., and corrected errors, besides making other valuable suggestions and additions. When his own Clarendon Press edition of Wordsworth was being prepared for press, Mr. Hutchinson asked permission to incorporate in it materials which were not afterwards inserted. This I granted cordially, as a similar permission had been given to Professor Dowden for his Aldine edition. The unfortunate omission of Mr. Hutchinson’s name was not discovered by me till after the issue of volumes I. and II. (which appeared simultaneously), and it was first brought under my notice by Mr. Hutchinson’s own letters to the newspapers. My debt to Mr. Hutchinson is great; and, although I have already thanked him for the services which he has rendered to the world in connection with Wordsworthian literature, I may perhaps be allowed to repeat the acknowledgment now. The revised sheets of Vols. I. and II. of this edition were, however, submitted to others at the same time that they were sent to Mr. Hutchinson; more especially to the late Mr. Dykes Campbell, and on his death to Mr. Belinfante, and then to the late Mr. Kinghorn, all of whom were engaged by my publishers to assist in the work entrusted to me. They “turned on the microscope” on my own work, and Mr. Hutchinson’s; and to them I have been indebted in many ways.

Mr. Hill’s services, in tracing the sources of numerous quotations from other poets which occur in Wordsworth’s text, have been great. He sent me his discoveries, unsolicited, and I wish to express very cordially my indebtedness to him. To discover some of these quotations—there are several hundreds of them—cost me much labour, before I had the pleasure of hearing from, or knowing, Mr. Hill; and his assistance in this matter has been greater than that of any other person. It will be seen that I have failed—after much study and extensive correspondence—to discover them all.

In addition to actual quotations—indicated by Wordsworth by inverted commas in his poems—to trace parallel passages from other poets, or phrases which may have suggested to him what he recast and glorified, has seemed to me work not unworthy of accomplishment. At the same time, and in the same connection, to discover the somewhat similar debts of later poets to Wordsworth, and to indicate this here and there in footnotes, may not be wholly useless to posterity.

My obligations to my friend, Mr. Dykes Campbell, are greater than I can adequately express. He supplied me with much material, drawn from many quarters; and, although he did not always mention his sources, I had implicit confidence in him, both as a literary man and a friend. After his death, through the kindness of Mrs. Campbell, I examined some MS. volumes of Wordsworthiana written by him, which were of much use to me.

Some of these were from unknown sources, which I should perhaps have traced out before making use of them, but, in all my Wordsworth work, I have acted from first to last on the legal opinion of a distinguished Judge, that the heir of the writer of literary work could alone authorise its subsequent publication; and, since the heirs of the Poet had kindly given me permission to collect and publish his works, I did so, with a view to the benefit of posterity.

Some of Mr. Campbell’s material was derived from MSS. now in the possession of Mr. T. Norton Longman, and I have to express my sincere regret that in the earlier volumes I copied from Mr. Campbell’s transcripts of these MSS.—which were lent to him on the condition that no public use should be made of them without Mr. Longman’s permission—some variations of the text, without mentioning the source whence they were derived.

I was unaware that these MSS. were lent to Mr. Campbell with the condition attached, and regret very much that I am unable to trust my memory to indicate now what variations of text I have quoted from them. But I may add that Mr. Longman is about to publish a work which will enable Wordsworth students to become practically acquainted with the contents of his MSS.

In reference to the poems not published by Wordsworth or his sister during their lifetime, I have included in this volume not only fugitive pieces printed in Magazines and elsewhere, but also those which have been since recovered from numerous manuscript sources. They are of varying merit. It would be interesting to know, and to record in every instance, where these manuscripts now are; but this is impossible. In many cases the manuscripts have recently changed ownership. I have obtained a sight of many of them, and have been granted permission to transcribe them, from the fortunate possessors of large autograph collections, and also from dealers in autographs; but, after the sale of manuscripts at public auction-rooms, it is, as a rule, impossible to trace them.

In many cases the MS. variants which have been published in previous volumes occur in copies of the poems, transcribed by the Wordsworth household in private letters to friends. I have occasionally indicated this in footnotes; but, to have done so always would have disfigured the pages, and frequently the notes would have been longer than the text. To trace the present possessors of the MSS. would be well-nigh impossible. It is perhaps worth mentioning that in several cases Wordsworth entered as “misprints” in future editions, what some of his editors have considered “new readings.” E.g. in The Excursion, book ix. l. 679, “wild” demeanour, instead of “mild” demeanour.

On Nov. 4, 1893, Mr. Aubrey de Vere wrote to me—

1834

So spake the mild Jeronymite, his griefs

Melting away within him like a dream

Ere he had ceased to gaze, perhaps to speak: 120

And I, grown old, but in a happier land,

Domestic Portrait! have to verse consigned

In thy calm presence those heart-moving words:

Words that can soothe, more than they agitate;

Whose spirit, like the angel that went down 125

Into Bethesda’s pool, with healing virtue

Informs the fountain in the human breast

Which[5] by the visitation was disturbed.

——But why this stealing tear? Companion mute,

On thee I look, not sorrowing; fare thee well, 130

My Song’s Inspirer, once again farewell![6]

Among a grave fraternity of Monks,

For One, but surely not for One alone,

Triumphs, in that great work, the Painter’s skill,

Humbling the body, to exalt the soul;

Yet representing, amid wreck and wrong 5

And dissolution and decay, the warm

And breathing life of flesh, as if already

Clothed with impassive majesty, and graced

With no mean earnest of a heritage

Assigned to it in future worlds. Thou, too, 10

With thy memorial flower, meek Portraiture!

From whose serene companionship I passed

Pursued by thoughts that haunt me still; thou also—

Though but a simple object, into light

Called forth by those affections that endear 15

The private hearth; though keeping thy sole seat

In singleness, and little tried by time,

Creation, as it were, of yesterday—

With a congenial function art endued

For each and all of us, together joined 20

In course of nature under a low roof

By charities and duties that proceed

Out of the bosom of a wiser vow.

To a like salutary sense of awe

Or sacred wonder, growing with the power 25

Of meditation that attempts to weigh,

In faithful scales, things and their opposites,

Can thy enduring quiet gently raise

A household small and sensitive,—whose love,

Dependent as in part its blessings are 30

Upon frail ties dissolving or dissolved

On earth, will be revived, we trust, in heaven.[7]

1835

Why art thou silent? Is thy love a plant

Of such weak fibre that the treacherous air

Of absence withers what was once so fair?

Is there no debt to pay, no boon to grant?

Yet have my thoughts for thee been vigilant— 5

Bound to thy service with unceasing care,[17]

The mind’s least generous wish a mendicant

For nought but what thy happiness could spare.

Speak—though this soft warm heart, once free to hold

A thousand tender pleasures, thine and mine, 10

Be left more desolate, more dreary cold

Than a forsaken bird’s-nest filled with snow

’Mid its own bush of leafless eglantine—

Speak, that my torturing doubts their end may know!

Yes, lovely Moon! if thou so mildly bright 40

Dost rouse, yet surely in thy own despite,

To fiercer mood the phrenzy-stricken brain,

Let me a compensating faith maintain;

That there’s a sensitive, a tender, part

Which thou canst touch in every human heart, 45

For healing and composure.—But, as least

And mightiest billows ever have confessed

Thy domination; as the whole vast Sea

Feels through her lowest depths thy sovereignty;

So shines that countenance with especial grace 50

On them who urge the keel her plains to trace

Furrowing its way right onward. The most rude,

Cut off from home and country, may have stood—

Even till long gazing hath bedimmed his eye,

Or the mute rapture ended in a sigh— 55

Touched by accordance of thy placid cheer,

With some internal lights to memory dear,

Or fancies stealing forth to soothe the breast

Tired with its daily share of earth’s unrest,—

Gentle awakenings, visitations meek; 60

A kindly influence whereof few will speak,

Though it can wet with tears the hardiest cheek.

O still belov’d (for thine, meek Power, are charms

That fascinate the very Babe in arms,

While he, uplifted towards thee, laughs outright,

Spreading his little palms in his glad Mother’s sight) 20

O still belov’d, once worshipped! Time, that frowns

In his destructive flight on earthly crowns,

Spares thy mild splendour; still those far-shot beams

Tremble on dancing waves and rippling streams

With stainless touch, as chaste as when thy praise 25

Was sung by Virgin-choirs in festal lays;

And through dark trials still dost thou explore

Thy way for increase punctual as of yore,

When teeming Matrons—yielding to rude faith

In mysteries of birth and life and death 30

And painful struggle and deliverance—prayed

Of thee to visit them with lenient aid.

What though the rites be swept away, the fanes

Extinct that echoed to the votive strains;

Yet thy mild aspect does not, cannot, cease 35

Love to promote and purity and peace;

And Fancy, unreproved, even yet may trace

Faint types of suffering in thy beamless face.

O gift divine of quiet sequestration!

The hermit, exercised in prayer and praise,

And feeding daily on the hope of heaven,

Is happy in his vow, and fondly cleaves

To life-long singleness; but happier far 125

Was to your souls, and, to the thoughts of others,

A thousand times more beautiful appeared,

Your dual loneliness. The sacred tie

Is broken; yet why grieve? for Time but holds

His moiety in trust, till Joy shall lead 130

To the blest world where parting is unknown.[35]

“Wait, prithee, wait!” this answer Lesbia[51] threw

Forth to her Dove, and took no further heed.

Her eye was busy, while her fingers flew

Across the harp, with soul-engrossing speed;

But from that bondage when her thoughts were freed 5

She rose, and toward the close-shut casement drew,

Whence the poor unregarded Favourite, true

To old affections, had been heard to plead

With flapping wing for entrance. What a shriek

Forced from that voice so lately tuned to a strain 10

Of harmony!——a shriek of terror, pain,

And self-reproach! for, from aloft, a Kite

Pounced,——and the Dove, which from its ruthless beak

She could not rescue, perished in her sight!

While poring Antiquarians search the ground

Upturned with curious pains, the Bard, a Seer,

Takes fire:——The men that have been reappear;

Romans for travel girt, for business gowned;

And some recline on couches, myrtle-crowned, 5

In festal glee: why not? For fresh and clear,

As if its hues were of the passing year,

Dawns this time-buried pavement. From that mound

Hoards may come forth of Trajans, Maximins,

Shrunk into coins with all their warlike toil: 10

Or a fierce impress issues with its foil

Of tenderness—the Wolf, whose suckling Twins

The unlettered ploughboy pities when he wins

The casual treasure from the furrowed soil.

1836

1837

I saw far off the dark top of a Pine

Look like a cloud—a slender stem the tie

That bound it to its native earth—poised high

’Mid evening hues, along the horizon line,

Striving in peace each other to outshine. 5

But when I learned the Tree was living there,

Saved from the sordid axe by Beaumont’s care,[104]

Oh, what a gush of tenderness was mine!

The rescued Pine-tree, with its sky so bright

And cloud-like beauty, rich in thoughts of home, 10

Death-parted friends, and days too swift in flight,

Supplanted the whole majesty of Rome

(Then first apparent from the Pincian Height)[105]

Crowned with St. Peter’s everlasting dome.[106]

Is this, ye Gods, the Capitolian Hill?

Yon petty Steep in truth the fearful Rock,

Tarpeian named of yore,[107] and keeping still

That name, a local Phantom proud to mock

The Traveller’s expectation?—Could our Will

Destroy the ideal Power within, ’twere done

Thro’ what men see and touch,—slaves wandering on,

Impelled by thirst of all but Heaven-taught skill.

Full oft, our wish obtained, deeply we sigh;

Yet not unrecompensed are they who learn, 10

From that depression raised, to mount on high

With stronger wing, more clearly to discern

Eternal things; and, if need be, defy

Change, with a brow not insolent, though stern.

Forbear to deem the Chronicler unwise,

Ungentle, or untouched by seemly ruth,

Who, gathering up all that Time’s envious tooth

Has spared of sound and grave realities,

Firmly rejects those dazzling flatteries, 5

Dear as they are to unsuspecting Youth,

That might have drawn down Clio from the skies

To vindicate the majesty of truth.

Such was her office while she walked with men,[109]

A Muse, who,[110] not unmindful of her Sire 10

All-ruling Jove, whate’er the[111] theme might be

Revered her Mother, sage Mnemosyne,

And taught her faithful servants how the lyre

Should[112] animate, but not mislead, the pen.[113]

They—who have seen the noble Roman’s scorn

Break forth at thought of laying down his head,

When the blank day is over, garreted

In his ancestral palace, where, from morn

To night, the desecrated floors are worn 5

By feet of purse-proud strangers; they—who have read

In one meek smile, beneath a peasant’s shed,

How patiently the weight of wrong is borne;

They—who have heard some learned Patriot treat[114]

Of freedom, with mind grasping the whole theme 10

From ancient Rome, downwards through that bright dream

Of Commonwealths, each city a starlike seat

Of rival glory; they—fallen Italy—

Nor must, nor will, nor can, despair of Thee!

Forgive, illustrious Country! these deep sighs,

Heaved less for thy bright plains and hills bestrown

With monuments decayed or overthrown,

For all that tottering stands or prostrate lies,

Than for like scenes in moral vision shown, 5

Ruin perceived for keener sympathies;

Faith crushed, yet proud of weeds, her gaudy crown

Virtues laid low, and mouldering energies.

Yet why prolong this mournful strain?—Fallen Power,

Thy fortunes, twice exalted,[122] might provoke 10

Verse to glad notes prophetic of the hour

When thou, uprisen, shalt break thy double yoke,

And enter, with prompt aid from the Most High,

On the third stage of thy great destiny.[123]

When here with Carthage Rome to conflict came,[124]

An earthquake, mingling with the battle’s shock,

Checked not its rage;[125] unfelt the ground did rock,

Sword dropped not, javelin kept its deadly aim.—

Now all is sun-bright peace. Of that day’s shame, 5

Or glory, not a vestige seems to endure,

Save in this Rill that took from blood the name[126]

Which yet it bears, sweet Stream! as crystal pure.

So may all trace and sign of deeds aloof

From the true guidance of humanity, 10

Thro’ Time and Nature’s influence, purify

Their spirit; or, unless they for reproof

Or warning serve, thus let them all, on ground

That gave them being, vanish to a sound.

Grieve for the Man who hither came bereft,

And seeking consolation from above;

Nor grieve the less that skill to him was left

To paint this picture of his lady-love:

Can she, a blessed saint, the work approve? 5

And O, good Brethren of the cowl, a thing

So fair, to which with peril he must cling,

Destroy in pity, or with care remove.

That bloom—those eyes—can they assist to bind

Thoughts that would stray from Heaven? The dream must cease 10

To be; by Faith, not sight, his soul must live;

Else will the enamoured Monk too surely find

How wide a space can part from inward peace

The most profound repose his cell can give.

The world forsaken, all its busy cares

And stirring interests shunned with desperate flight,

All trust abandoned in the healing might

Of virtuous action; all that courage dares,

Labour accomplishes, or patience bears— 5

Those helps rejected, they, whose minds perceive

How subtly works man’s weakness, sighs may heave

For such a One beset with cloistral snares.

Father of Mercy! rectify his view,

If with his vows this object ill agree; 10

Shed over it thy grace, and thus subdue[142]

Imperious passion in a heart set free:—

That earthly love may to herself be true,

Give him a soul that cleaveth unto thee.

What aim had they, the Pair of Monks, in size[143]

Enormous, dragged, while side by side they sate,

By panting steers up to this convent gate?

How, with empurpled cheeks and pampered eyes,

Dare they confront the lean austerities 5

Of Brethren, who, here fixed, on Jesu wait

In sackcloth, and God’s anger deprecate

Through all that humbles flesh and mortifies?

Strange contrast!—verily the world of dreams,

Where mingle, as for mockery combined, 10

Things in their very essences at strife,

Shows not a sight incongruous as the extremes

That everywhere, before the thoughtful mind,

Meet on the solid ground of waking life.[144]

Vallombrosa! of thee I first heard in the page 25

Of that holiest of Bards, and the name for my mind

Had a musical charm, which the winter of age

And the changes it brings had no power to unbind.

And now, ye Miltonian shades! under you

I repose, nor am forced from sweet fancy to part, 30

While your leaves I behold and the brooks they will strew,

And the realised vision is clasped to my heart.

Under the shadow of a stately Pile,

The dome of Florence, pensive and alone,

Nor giving heed to aught that passed the while,

I stood, and gazed upon a marble stone,

The laurelled Dante’s favourite seat.[154] A throne, 5

In just esteem, it rivals; though no style

Be there of decoration to beguile

The mind, depressed by thought of greatness flown.

As a true man, who long had served the lyre,

I gazed with earnestness, and dared no more. 10

But in his breast the mighty Poet bore

A Patriot’s heart, warm with undying fire.

Bold with the thought, in reverence I sate down,

And, for a moment, filled that empty Throne.

[It was very hot weather during the week we stayed at Florence; and, never having been there before, I went through much hard service, and am not therefore ashamed to confess I fell asleep before this picture and sitting with my back towards the Venus de Medicis. Buonaparte—in answer to one who had spoken of his being in a sound sleep up to the moment when one of his great battles was to be fought, as a proof of the calmness of his mind and command over anxious thoughts—said frankly, that he slept because from bodily exhaustion he could not help it. In like manner it is noticed that criminals on the night previous to their execution seldom awake before they are called, a proof that the body is the master of us far more than we need be willing to allow. Should this note by any possible chance be seen by any of my countrymen who might have been in the gallery at the time (and several persons were there) and witnessed such an indecorum, I hope he will give up the opinion which he might naturally have formed to my prejudice.—I.F.]

[However at first these two sonnets from Michael Angelo may seem in their spirit somewhat inconsistent with each other, I have not scrupled to place them side by side as characteristic of their great author, and others with whom he lived. I feel, nevertheless, a wish to know at what periods of his life they were respectively composed.[156] The latter, as it expresses, was written in his advanced years, when it was natural that the Platonism that pervades the one should give way to the Christian feeling that inspired the other: between both there is more than poetic affinity.—I.F.]

Eternal Lord! eased of a cumbrous load,

And loosened from the world, I turn to Thee;

Shun, like a shattered bark, the storm, and flee

To thy protection for a safe abode.

The crown of thorns, hands pierced upon the tree, 5

The meek, benign, and lacerated face,

To a sincere repentance promise grace,

To the sad soul give hope of pardon free.

With justice mark not Thou, O Light divine,

My fault, nor hear it with thy sacred ear; 10

Neither put forth that way thy arm severe;

Wash with thy blood my sins; thereto incline

More readily the more my years require

Help, and forgiveness speedy and entire.

Ye Trees! whose slender roots entwine

Altars that piety neglects;

Whose infant arms enclasp the shrine

Which no devotion now respects;

If not a straggler from the herd 5

Here ruminate, nor shrouded bird,

Chanting her low-voiced hymn, take pride

In aught that ye would grace or hide—

How sadly is your love misplaced,

Fair Trees, your bounty run to waste! 10

What if our numbers barely could defy

The arithmetic of babes, must foreign hordes,

Slaves, vile as ever were befooled by words,

Striking through English breasts the anarchy

Of Terror, bear us to the ground, and tie 5

Our hands behind our backs with felon cords?

Yields every thing to discipline of swords?

Is man as good as man, none low, none high?—

Nor discipline nor valour can withstand

The shock, nor quell[163] the inevitable rout, 10

When in some great extremity breaks out

A people, on their own beloved Land

Risen, like one man, to combat in the sight

Of a just God for liberty and right.

Lo! where the Moon along the sky

Sails with her happy destiny;[164]

Oft is she hid from mortal eye

Or dimly seen,

But when the clouds asunder fly 5

How bright her mien![165]

1838

What strong allurement draws, what spirit guides,

Thee, Vesper! brightening still, as if the nearer

Thou com’st to man’s abode the spot grew dearer

Night after night? True is it Nature hides

Her treasures less and less.—Man now presides 5

In power, where once he trembled in his weakness;

Science[171] advances with gigantic strides;

But are we aught enriched in love and meekness?[172]

Aught dost thou see, bright Star! of pure and wise

More than in humbler times graced human story; 10

That makes our hearts more apt to sympathise

With heaven, our souls more fit for future glory,

When earth shall vanish from our closing eyes,

Ere we lie down in our last dormitory?[173]

1839

This Spot—at once unfolding sight so fair

Of sea and land, with yon grey towers that still

Rise up as if to lord it over air—

Might soothe in human breasts the sense of ill,

Or charm it out of memory; yea, might fill 5

The heart with joy and gratitude to God

For all his bounties upon man bestowed:

Why bears it then the name of “Weeping Hill”?[197]

Thousands, as toward yon old Lancastrian Towers,

A prison’s crown, along this way they past 10

For lingering durance or quick death with shame,

From this bare eminence thereon have cast

Their first look—blinded as tears fell in showers

Shed on their chains; and hence that doleful name.

Tenderly do we feel by Nature’s law

For worst offenders: though the heart will heave

With indignation, deeply moved we grieve,

In after thought, for Him who stood in awe

Neither of God nor man, and only saw, 5

Lost wretch, a horrible device enthroned

On proud temptations, till the victim groaned

Under the steel his hand had dared to draw.

But O, restrain compassion, if its course,

As oft befalls, prevent or turn aside 10

Judgments and aims and acts whose higher source

Is sympathy with the unforewarned, who died[199]

Blameless—with them that shuddered o’er his grave,

And all who from the law firm safety crave.

Not to the object specially designed,

Howe’er momentous in itself it be,

Good to promote or curb depravity,

Is the wise Legislator’s view confined.

His Spirit, when most severe, is oft most kind; 5

As all Authority in earth depends

On Love and Fear, their several powers he blends,

Copying with awe the one Paternal mind.

Uncaught by processes in show humane,

He feels how far the act would derogate 10

From even the humblest functions of the State;

If she, self-shorn of Majesty, ordain

That never more shall hang upon her breath

The last alternative of Life or Death.

Before the world had past her time of youth

While polity and discipline were weak,

The precept eye for eye, and tooth for tooth,

Came forth—a light, though but as of day-break,

Strong as could then be borne. A Master meek 5

Proscribed the spirit fostered by that rule,

Patience his law, long-suffering his school,

And love the end, which all through peace must seek.

But lamentably do they err who strain

His mandates, given rash impulse to controul 10

And keep vindictive thirstings from the soul,

So far that, if consistent in their scheme,

They must forbid the State to inflict a pain,

Making of social order a mere dream.

Our bodily life, some plead, that life the shrine

Of an immortal spirit, is a gift

So sacred, so informed with light divine,

That no tribunal, though most wise to sift

Deed and intent, should turn the Being adrift 5

Into that world where penitential tear

May not avail, nor prayer have for God’s ear

A voice—that world whose veil no hand can lift

For earthly sight. “Eternity and Time”

They urge, “have interwoven claims and rights 10

Not to be jeopardised through foulest crime:

The sentence rule by mercy’s heaven-born lights.”

Even so; but measuring not by finite sense

Infinite Power, perfect Intelligence.

See the Condemned alone within his cell

And prostrate at some moment when remorse

Stings to the quick, and, with resistless force,

Assaults the pride she strove in vain to quell.

Then mark him, him who could so long rebel, 5

The crime confessed, a kneeling Penitent

Before the Altar, where the Sacrament

Softens his heart, till from his eyes outwell

Tears of salvation. Welcome death! while Heaven

Does in this change exceedingly rejoice; 10

While yet the solemn heed the State hath given

Helps him to meet the last Tribunal’s voice

In faith, which fresh offences, were he cast

On old temptations, might for ever blast.

1840

All praise the Likeness by thy skill portrayed;[211]

But ’tis a fruitless task to paint for me,

Who, yielding not to changes Time has made,

By the habitual light of memory see

Eyes unbedimmed, see bloom that cannot fade, 5

And smiles that from their birth-place ne’er shall flee

Into the land where ghosts and phantoms be;

And, seeing this, own nothing in its stead.

Couldst thou go back into far-distant years,

Or share with me, fond thought! that inward eye,[212] 10

Then, and then only, Painter! could thy Art

The visual powers of Nature satisfy,

Which hold, whate’er to common sight appears,

Their sovereign empire in a faithful heart.

1841

1842

Southey, in an unpublished letter to Sir George Beaumont (10th July 1824), thus describes the Island at Derwentwater: “You will have seen by the papers that the Floating Island has made its appearance. It sank again last week, when some heavy rains had raised the lake four feet. By good fortune Professor Sedgewick happened to be in Keswick, and examined it in time. Where he probed it a thin layer of mud lies upon a bed of peat, which is six feet thick, and this rests upon a stratum of fine white clay,—the same I believe which Miss Barker found in Borrowdale when building her unlucky house. Where the gas is generated remains yet to be discovered, but when the peat is filled with this gas, it separates from the clay and becomes buoyant. There must have been a considerable convulsion when this took place, for a rent was made in the bottom of the lake, several feet in depth, and not less than fifty yards long, on each side of which the bottom rose and floated. It was a pretty sight to see the small fry exploring this new made strait and darting at the bubbles which rose as the Professor was probing the bank. The discharge of air was considerable here, when a pole was thrust down. But at some distance where the rent did not extend, the bottom had been heaved up in a slight convexity, sloping equally in an inclined plane all round: and there, when the pole was introduced, a rush like a jet followed, as it was withdrawn. The thing is the more curious, because as yet no example of it is known to have been observed in any other place.”

[I was impelled to write this Sonnet by the disgusting frequency with which the word artistical, imported with other impertinences from the Germans, is employed by writers of the present day: for artistical let them substitute artificial, and the poetry written on this system, both at home and abroad, will be for the most part much better characterised.—I.F.]

The most alluring clouds that mount the sky

Owe to a troubled element their forms,

Their hues to sunset. If with raptured eye

We watch their splendour, shall we covet storms,

And wish the Lord of day his slow decline 5

Would hasten, that such pomp may float on high?

Behold, already they forget to shine,

Dissolve—and leave to him who gazed a sigh.

Not loth to thank each moment for its boon

Of pure delight, come whensoe’er[223] it may, 10

Peace let us seek,—to stedfast things attune

Calm expectations, leaving to the gay

And volatile their love of transient bowers,

The house that cannot pass away be ours.[224]

Feel for the wrongs to universal ken

Daily exposed, woe that unshrouded lies;

And seek the Sufferer in his darkest den,

Whether conducted to the spot by sighs

And moanings, or he dwells (as if the wren 5

Taught him concealment) hidden from all eyes

In silence and the awful modesties

Of sorrow;—feel for all, as brother Men!

Rest not in hope want’s icy chain to thaw

By casual boons and formal charities;[225] 10

Learn to be just, just through impartial law;

Far as ye may, erect and equalise;

And, what ye cannot reach by statute, draw

Each from his fountain of self-sacrifice!

Long-favoured England! be not thou misled

By monstrous theories of alien growth,

Lest alien frenzy seize thee, waxing wroth,

Self-smitten till thy garments reek dyed red

With thy own blood, which tears in torrents shed 5

Fail to wash out, tears flowing ere thy troth

Be plighted, not to ease but sullen sloth,

Or wan despair—the ghost of false hope fled

Into a shameful grave. Among thy youth,

My Country! if such warning be held dear, 10

Then shall a Veteran’s heart be thrilled with joy,

One who would gather from eternal truth,

For time and season, rules that work to cheer—

Not scourge, to save the People—not destroy.

The Boy no answer made by words, but, so earnest was his look,

Sleep fled, and with it fled the dream—recorded in this book, 70

Lest all that passed should melt away in silence from my mind,

As visions still more bright have done, and left no trace behind.

A sense of seemingly presumptuous wrong

Gave the first impulse to the Poet’s song;

But, of his scorn repenting soon, he drew

A juster judgment from a calmer view; 30

And, with a spirit freed from discontent,

Thankfully took an effort that was meant

Not with God’s bounty, Nature’s love, to vie,

Or made with hope to please that inward eye

Which ever strives in vain itself to satisfy, 35

But to recal the truth by some faint trace

Of power ethereal and celestial grace,

That in the living Creature find on earth a place.

Nor less the joy with many a glance 25

Cast up the Stream or down at her beseeching,

To mark its eddying foam-balls prettily distrest

By ever-changing shape and want of rest;

Or watch, with mutual teaching,

The current as it plays 30

In flashing leaps and stealthy creeps

Adown a rocky maze;

Or note (translucent summer’s happiest chance!)

In the slope-channel floored with pebbles bright,

Stones of all hues, gem emulous of gem, 35

So vivid that they take from keenest sight

The liquid veil that seeks not to hide them.[254]

Never enlivened with the liveliest ray

That fosters growth or checks or cheers decay,

Nor by the heaviest rain-drops more deprest,

This Flower, that first appeared as summer’s guest,

Preserves her beauty ’mid autumnal leaves 5

And to her mournful habits fondly cleaves.

And know—that, even for him who shuns the day

And nightly tosses on a bed of pain;

Whose joys, from all but memory swept away, 25

Must come unhoped for, if they come again;

Know—that, for him whose waking thoughts, severe

As his distress is sharp, would scorn my theme,

The mimic notes, striking upon his ear

In sleep, and intermingling with his dream, 30

Could from sad regions send him to a dear

Delightful land of verdure, shower and gleam,

To mock the wandering Voice[257] beside some haunted stream.[258]

1843

While beams of orient light shoot wide and high,

Deep in the vale a little rural Town[266]

Breathes forth a cloud-like creature of its own,

That mounts not toward the radiant morning sky,

But, with a less ambitious sympathy, 5

Hangs o’er its Parent waking to the cares

Troubles and toils that every day prepares.

So Fancy, to the musing Poet’s eye,

Endears that Lingerer. And how blest her sway[267]

(Like influence never may my soul reject)[268] 10

If the calm Heaven, now to its zenith decked[269]

With glorious forms in numberless array,

To the lone shepherd on the hills disclose

Gleams from[270] a world in which the saints repose.

Ye torrents, foaming down the rocky steeps,

Ye lakes, wherein the spirit of water sleeps,

Ye vales and hills, whose beauty hither drew

The Poet’s steps and fixed him here, on you

His eyes have closed! and ye, loved books, no more

Shall Southey feed upon your precious lore,

To works that ne’er shall forfeit their renown

Adding immortal labours of his own—

Whether he traced historic truth, with zeal

For the State’s guidance or the Church’s weal,

Or Fancy, disciplined by studious art,

Informed his pen, or wisdom of the heart,

Or judgments sanctioned in the Patriot’s mind

By reverence for the rights of all mankind.

Wide were his aims, yet in no human breast

Could private feelings find a holier nest.

His joys, his griefs, have vanished like a cloud

From Skiddaw’s top; but he to Heaven was vowed

Through a long life, and calmed by Christian faith,

In his pure soul, the fear of change and death.

1844

Is then no nook of English ground secure

From rash assault?[278] Schemes of retirement sown

In youth, and ’mid the busy world kept pure

As when their earliest flowers of hope were blown,

Must perish;—how can they this blight endure? 5

And must he too the ruthless change bemoan

Who scorns a false utilitarian lure

’Mid his paternal fields at random thrown?

Baffle the threat, bright Scene, from Orrest-head[279]

Given to the pausing traveller’s rapturous glance: 10

Plead for thy peace, thou beautiful romance

Of nature; and, if human hearts be dead,

Speak, passing winds; ye torrents, with your strong

And constant voice, protest against the wrong.

1845

Yes! thou art fair, yet be not moved

To scorn the declaration,

That sometimes I in thee have loved

My fancy’s own creation.

Still as we look with nicer care,

Some new resemblance we may trace:

A Heart’s-ease will perhaps be there,

A Speedwell may not want its place. 20

And so may we, with charmèd mind

Beholding what your skill has wrought,

Another Star-of-Bethlehem find,

A new[298] Forget-me-not.

Days undefiled by luxury or sloth,

Firm self-denial, manners grave and staid,

Rights equal, laws with cheerfulness obeyed,

Words that require no sanction from an oath,

And simple honesty a common growth— 5

This high repute, with bounteous Nature’s aid,

Won confidence, now ruthlessly betrayed

At will, your power the measure of your troth!—

All who revere the memory of Penn

Grieve for the land on whose wild woods his name[299] 10

Was fondly grafted with a virtuous aim,

Renounced, abandoned by degenerate Men

For state-dishonour black as ever came

To upper air from Mammon’s loathsome den.[300]

1846

Why should we weep or mourn, Angelic boy,

For such thou wert ere from our sight removed,

Holy, and ever dutiful—beloved

From day to day with never-ceasing joy,

And hopes as dear as could the heart employ 5

In aught to earth pertaining? Death has proved

His might, nor less his mercy, as behoved—

Death conscious that he only could destroy

The bodily frame. That beauty is laid low

To moulder in a far-off field of Rome; 10

But Heaven is now, blest Child, thy Spirit’s home:

When such divine communion, which we know,

Is felt, thy Roman-burial place will be

Surely a sweet remembrancer of Thee.

Discourse was deemed Man’s noblest attribute,

And written words the glory of his hand;

Then followed Printing with enlarged command

For thought—dominion vast and absolute

For spreading truth, and making love expand. 5

Now prose and verse sunk into disrepute

Must lacquey a dumb Art that best can suit

The taste of this once-intellectual Land.

A backward movement surely have we here,[306]

From manhood—back to childhood; for the age— 10

Back towards caverned life’s first rude career.

Avaunt this vile abuse of pictured page!

Must eyes be all in all, the tongue and ear

Nothing? Heaven keep us from a lower stage!

Thus in the chosen spot a tie so strong

Was formed between the solitary pair,

That when his fate had housed him ’mid a throng

The Captive shunned all converse proffered there.

1787

When Superstition left the golden light

And fled indignant to the shades of night; 30

When pure Religion rear’d the peaceful breast

And lull’d the warring passions into rest,

Drove far away the savage thoughts that roll

In the dark mansions of the bigot’s soul,

Enlivening Hope display’d her cheerful ray, 35

And beam’d on Britain’s sons a brighter day,

So when on Ocean’s face the storm subsides,

Hush’d are the winds and silent are the tides;

The God of day, in all the pomp of light,

Moves through the vault of heaven, and dissipates the night; 40

Wide o’er the main a trembling lustre plays,

The glittering waves reflect the dazzling blaze;

Science with joy saw Superstition fly

Before the lustre of Religion’s eye;

With rapture she beheld Britannia smile, 45

Clapp’d her strong wings, and sought the cheerful isle.

The shades of night no more the soul involve,

She sheds her beam, and, lo! the shades dissolve;

No jarring monks, to gloomy cell confined,

With mazy rules perplex the weary mind; 50

No shadowy forms entice the soul aside,

Secure she walks, Philosophy her guide.

Britain, who long her warriors had adored,

And deemed all merit centred in the sword;

Britain, who thought to stain the field was fame, 55

Now honour’d Edward’s less than Bacon’s name.

Her sons no more in listed fields advance

To ride the ring, or toss the beamy lance;

No longer steel their indurated hearts

To the mild influence of the finer arts; 60

Quick to the secret grotto they retire

To court majestic truth, or wake the golden lyre;

By generous Emulation taught to rise,

The seats of learning brave the distant skies.

Then noble Sandys, inspir’d with great design, 65

Rear’d Hawkshead’s happy roof, and call’d it mine;

There have I loved to show the tender age

The golden precepts of the classic page;

To lead the mind to those Elysian plains

Where, throned in gold, immortal Science reigns; 70

Fair to the view is sacred Truth display’d,

In all the majesty of light array’d,

To teach, on rapid wings, the curious soul

To roam from heaven to heaven, from pole to pole,

From thence to search the mystic cause of things 75

And follow Nature to her secret springs;

Nor less to guide the fluctuating youth

Firm in the sacred paths of moral truth,

To regulate the mind’s disorder’d frame,

And quench the passions kindling into flame; 80

The glimmering fires of Virtue to enlarge,

And purge from Vice’s dross my tender charge.

Oft have I said, the paths of Fame pursue,

And all that virtue dictates, dare to do;

Go to the world, peruse the book of man, 85

And learn from thence thy own defects to scan;

Severely honest, break no plighted trust,

But coldly rest not here—be more than just;

Join to the rigours of the sires of Rome

The gentler manners of the private dome; 90

When Virtue weeps in agony of woe,

Teach from the heart the tender tear to flow;

If Pleasure’s soothing song thy soul entice,

Or all the gaudy pomp of splendid Vice,

Arise superior to the Siren’s power, 95

The wretch, the short-lived vision of an hour;

Soon fades her cheek, her blushing beauties fly,

As fades the chequer’d bow that paints the sky,

So shall thy sire, whilst hope his breast inspires,

And wakes anew life’s glimmering trembling fires, 100

Hear Britain’s sons rehearse thy praise with joy,

Look up to heaven, and bless his darling boy.

If e’er these precepts quell’d the passions’ strife,

If e’er they smooth’d the rugged walks of life,

If e’er they pointed forth the blissful way 105

That guides the spirit to eternal day,

Do thou, if gratitude inspire thy breast,

Spurn the soft fetters of lethargic rest.

Awake, awake! and snatch the slumbering lyre,

Let this bright morn and Sandys the song inspire. 110

’Tis said Enjoyment (who averr’d

The charge belong’d to her alone)

Jealous that Hope had been preferr’d 30

Laid snares to make the babe her own.

1798

But now he half-raises his deep-sunken eye,

And the motion unsettles a tear;

The silence of sorrow it seems to supply,

And asks of me why I am here.

Why do I watch those running deer?

And wherefore, wherefore come they here? 10

And wherefore do I seem to love

The things that live, the things that move?

Why do I look upon the sky?

I do not live for what I see.

Why open thus mine eyes? To die 15

Is all that now is left for me,

If I could smother up my heart

My life would then at once depart.

My friends, you live, and yet you seem

To me the people of a dream; 20

A dream in which there is no love,

And yet, my friends, you live and move.

1800

(l. 24) He travels on, a solitary man.

His age has no companion. He is weak,

So helpless in appearance that, for him

The sauntering horseman-traveller does not throw

With careless hand his pence upon the ground

But stops that he may lodge the coin

Safe in the old man’s hat: nor quits him so,

But as he goes towards him turns a look

Sidelong and half-reverted.…

1802

No doubt if you in terms direct had asked

Whether he loved the mountains, true it is

That with blunt repetition of your words

He might have stared at you, and said that they

Were frightful to behold, but had you then

Discoursed with him …

Of his own business, and the goings on

Of earth and sky, then truly had you seen

That in his thoughts there were obscurities,

Wonder, and admiration, things that wrought

Not less than a religion in his heart.

And if it was his fortune to converse

With any who could talk of common things

In an unusual way, and give to them

Unusual aspects, or by questions apt

Wake sudden recognitions, that were like

Creations in the mind (and were indeed

Creations often), then when he discoursed

Of mountain sights, this untaught shepherd stood

Before the man with whom he so conversed

And looked at him as with a poet’s eye.

But speaking of the vale in which he dwelt,

And those bare rocks, if you had asked if he

For other pastures would exchange the same

And dwell elsewhere, …

… you then had seen

At once what spirit of love was in his heart.

…

I have related that this Shepherd loved

The fields and mountains, not alone for this

That from his very childhood he had lived

Among them, with a body hale and stout,

And with a vigorous mind …

… But exclude

Such reasons, and he had less cause to love

His native vale and patrimonial fields

Than others have, for Michael had liv’d on

Childless, until the time when he began

To look towards the shutting in of life.

I cannot affirm, with any certainty, that these lines were written by Wordsworth; but I agree with Mr. Ernest Coleridge in thinking that they were. He showed them to his relative—the late Chief Justice—who said that he did not know who else could have written them, at that time. Lord Coleridge said the same to myself.—Ed.

1803

1804

1805

Writing to Sir George Beaumont, on Christmas Day, 1804, Wordsworth said: “We have lately built in our little rocky orchard a circular hut, lined with moss, like a wren’s nest, and coated on the outside with heath, that stands most charmingly, with several views from the different sides of it, of the Lake, the Valley, and the Church.… I will copy a dwarf inscription which I wrote for it” (i.e. the circular hut, in his Orchard-Garden) “the other day before the building was entirely finished, which indeed it is not yet.”[376]—Ed.

Beneath that rock my course I stay’d

And, looking to its summit high, 70

“Thou wear’st,” said I, “a splendid garb,

Here winter keeps his revelry.

1806

In the first volume of a copy of the edition of 1836,—long kept by Wordsworth at Rydal Mount, and afterwards the property of the late Lord Coleridge—which has been referred to in the Preface to Vol. 1., and very often in the footnotes to all the volumes, signed C.—Wordsworth wrote in MS. two translations of a fragment of Michael Angelo’s on Sleep, and a translation of some Latin verses by Thomas Warton on the same subject. These fragments were never included in any edition of his published works, and it is impossible to say to what year they belong. From their close relation to other translations from Michael Angelo, made by Wordsworth in 1806, I assign them, conjecturally, to the same year. The title is from Wordsworth’s own MS.—Ed.

1808

Rid of a vexing and a heavy load,

Eternal Lord! and from the world set free,

Like a frail Bark, weary I turn to Thee,—

From frightful storms into a quiet road.

On much repentance Grace will be bestow’d. 5

The nails, the thorns, and thy two hands, thy face

Benign, meek, …, offers grace

To sinners whom their sins oppress and goad.

Let not thy justice view, O Light Divine,

My fault, and keep it from thy sacred ear. 10

…

Cleanse with thy blood my sins, to this incline

More readily, the more my years require

Prompt aid, forgiveness speedy and entire.

1818

But from the Castle turret blew

A chill forbidding blast,

Which the poor Broom no sooner felt

Than she shrank up so fast; 20

Her wished-for yellow she forswore,

And since that time has cast

Fond looks on colours three or four

And put forth Blue at last.

And now, my lads, the Election comes 25

In June’s sunshining hours,

When every field and bank and brae

Is clad with yellow flowers.

While faction Blue from shops and booths

Tricks out her blustering powers, 30

Lo! smiling Nature’s lavish hand

Has furnished wreaths for ours.

1819

1820

1822

There are also numerous allusions in Mrs. Wordsworth’s Journal to this early tour; e.g. under date August 13. “We left Meyringen; soon reached a sort of Hotel, which Wm. pointed out to us with great interest, as being the only spot where he and his friend Jones were ill used, during the course of their adventurous journey—a wild looking building, a little removed from the road, where the vale of Hasli ends.” Again, in describing the sunset from the woody hill Colline de Gibet, overlooking the two lakes of Brienz and Thun, at Interlaken, “with the loveliest of green vallies between us and Jungfrau,” “Surely William must have had this Paradise in his thoughts when he began his Descriptive Sketches—

These vales were saddened with no common gloom

When good Jemima perished in her bloom;

When, such the awful will of heaven, she died

By flames breathed on her from her own fireside.

On earth we dimly see, and but in part 5

We know, yet faith sustains the sorrowing heart;

And she, the pure, the patient and the meek,

Might have fit epitaph could feelings speak;

If words could tell and monuments record,

How Treasures lost are inwardly deplored, 10

No name by grief’s fond eloquence adorned

More than Jemima’s would be praised and mourned.

The tender virtues of her blameless life,

Bright in the daughter, brighter in the wife,

And in the cheerful mother brightest shone,— 15

That light hath past away—the will of God[394] be done.

1823

Graced with redundant hair, Iopas sings

The lore of Atlas, to resounding strings,

The labours of the Sun, the lunar wanderings;

Whence human kind, and brute; what natural powers

Engender lightning, whence are falling showers. 125

He haunts Arcturus,—that fraternal twain

The glittering Bears,—the Pleiads fraught with rain;

—Why suns in winter, shunning heaven’s steep heights

Post seaward,—what impedes the tardy nights.

The learned song from Tyrian hearers draws 130

Loud shouts,—the Trojans echo the applause.

—But, lengthening out the night with converse new,

Large draughts of love unhappy Dido drew;

Of Priam ask’d, of Hector—o’er and o’er—

What arms the son of bright Aurora wore;— 135

What steeds the car of Diomed could boast;

Among the leaders of the Grecian host

How look’d Achilles, their dread paramount—

“But nay—the fatal wiles, O guest, recount,

Retrace the Grecian cunning from its source, 140

Your own grief and your friends’—your wandering course;

For now, till this seventh summer have ye rang’d

The sea, or trod the earth, to peace estrang’d.”

1826

Now thou art gone—belike ’tis best—

And I remain a passing guest, 50

Yet for thy sake, beloved Friend,

When from this spot my way shall tend,

And every day of festival

Gratefully shall ye then recal,

Less for their own sakes than for this,

That each shall be a resting-place

For memory, and divide the race 160

Of childhood’s smooth and happy years,

Thus lengthening out that term of life

Which governed by your parents’ care

Is free from sorrow and from strife.

The doubt to which a wavering hope had clung

Is fled; we must depart, willing or not;

Sky-piercing Hills! must bid farewell to you

And all that ye look down upon with pride,

With tenderness, embosom; to your paths, 5

And pleasant dwellings, to familiar trees

And wild-flowers known as well as if our hands

Had tended them: and O pellucid Spring!

Unheard of, save in one small hamlet, here

Not undistinguished, for of wells that ooze 10

Or founts that gurgle from yon craggy steep,

Their common sire, thou only bear’st his name.

Insensibly the foretaste of this parting

Hath ruled my steps, and seals me to thy side,

Mindful that thou (ah! wherefore by my Muse 15

So long unthanked) hast cheered a simple board

With beverage pure as ever fixed the choice

Of hermit, dubious where to scoop his cell;

Which Persian kings might envy; and thy meek

And gentle aspect oft has ministered 20

To finer uses. They for me must cease;

Days will pass on, the year, if years be given,

Fade,—and the moralising mind derive

No lessons from the presence of a Power

By the inconstant nature we inherit 25

Unmatched in delicate beneficence;

For neither unremitting rains avail

To swell thee into voice; nor longest drought

Thy bounty stints, nor can thy beauty mar,

Beauty not therefore wanting change to stir 30

The fancy pleased by spectacles unlooked for.

Nor yet, perchance, translucent Spring, had tolled

The Norman curfew bell when human hands

First offered help that the deficient rock

Might overarch thee, from pernicious heat 35

Defended, and appropriate to man’s need.

Such ties will not be severed: but, when we

Are gone, what summer loiterer will regard,

Inquisitive, thy countenance, will peruse,

Pleased to detect the dimpling stir of life, 40

The breathing faculty with which thou yield’st

(Tho’ a mere goblet to the careless eye)

Boons inexhaustible? Who, hurrying on

With a step quickened by November’s cold,

Shall pause, the skill admiring that can work 45

Upon thy chance-defilements—withered twigs

That, lodged within thy crystal depths, seem bright,

As if they from a silver tree had fallen—

And oaken leaves that, driven by whirling blasts,

Sunk down, and lay immersed in dead repose 50

For Time’s invisible tooth to prey upon

Unsightly objects and uncoveted,

Till thou with crystal bead-drops didst encrust

Their skeletons, turned to brilliant ornaments.

But, from thy bosom, should some venturous[396] hand 55

Abstract those gleaming relics, and uplift them,

However gently, toward the vulgar air,

At once their tender brightness disappears,

Leaving the intermeddler to upbraid

His folly. Thus (I feel it while I speak), 60

Thus, with the fibres of these thoughts it fares;

And oh! how much, of all that love creates

Or beautifies, like changes undergo,

Suffers like loss when drawn out of the soul,

Its silent laboratory! Words should say 65

(Could they depict the marvels of thy cell)

How often I have marked a plumy fern

From the live rock with grace inimitable

Bending its apex toward a paler self

Reflected all in perfect lineaments— 70

Shadow and substance kissing point to point

In mutual stillness; or, if some faint breeze

Entering the cell gave restlessness to one,

The other, glassed in thy unruffled breast,

Partook of every motion, met, retired, 75

And met again. Such playful sympathy,

Such delicate caress as in the shape

Of this green plant had aptly recompensed

For baffled lips and disappointed arms

And hopeless pangs, the spirit of that youth, 80

The fair Narcissus by some pitying God

Changed to a crimson flower; when he, whose pride

Provoked a retribution too severe,

Had pined; upon his watery duplicate

Wasting that love the nymphs implored in vain. 85

Thus while my Fancy wanders, thou, clear Spring,

Moved (shall I say?) like a dear friend who meets

A parting moment with her loveliest look,

And seemingly her happiest, look so fair

It frustrates its own purpose, and recalls 90

The grieved one whom it meant to send away—

Dost tempt me by disclosures exquisite

To linger, bending over thee: for now,

What witchcraft, mild enchantress, may with thee

Compare! thy earthly bed a moment past 95

Palpable to sight as the dry ground,

Eludes perception, not by rippling air

Concealed, nor through effect of some impure

Upstirring; but, abstracted by a charm

Of my own cunning, earth mysteriously 100

From under thee hath vanished, and slant beams

The silent inquest of a western sun,

Assisting, lucid well-spring! Thou revealest

Communion without check of herbs and flowers,

And the vault’s hoary sides to which they cling, 105

Imaged in downward show; the flower, the Herbs,[397]

These not of earthly texture, and the vault

Not there diminutive, but through a scale

Of vision less and less distinct, descending

To gloom imperishable. So (if truths 110

The highest condescend to be set forth

By processes minute), even so—when thought

Wins help from something greater than herself—

Is the firm basis of habitual sense

Supplanted, not for treacherous vacancy 115

And blank dissociation from a world

We love, but that the residues of flesh,

Mirrored, yet not too strictly, may refine

To Spirit; for the idealising Soul

Time wears the features of Eternity; 120

And Nature deepens into Nature’s God.

Millions of kneeling Hindoos at this day

Bow to the watery element, adored

In their vast stream, and if an age hath been

(As books and haply votive altars vouch) 125

When British floods were worshipped, some faint trace

Of that idolatry, through monkish rites

Transmitted far as living memory,

Might wait on thee, a silent monitor,

On thee, bright Spring, a bashful little one, 130

Yet to the measure of thy promises

True, as the mightiest; upon thee, sequestered

For meditation, nor inopportune

For social interest such as I have shared.

Peace to the sober matron who shall dip 135

Her pitcher here at early dawn, by me

No longer greeted—to the tottering sire,

For whom like service, now and then his choice,

Relieves the tedious holiday of age—

Thoughts raised above the Earth while here he sits 140

Feeding on sunshine—to the blushing girl

Who here forgets her errand, nothing loth

To be waylaid by her betrothed, peace

And pleasure sobered down to happiness!

But should these hills be ranged by one whose soul 145

Scorning love-whispers shrinks from love itself

As Fancy’s snare for female vanity,

Here may the aspirant find a trysting-place

For loftier intercourse. The Muses crowned

With wreaths that have not faded to this hour 150

Sprung from high Jove, of sage Mnemosyne

Enamoured, so the fable runs; but they

Certes were self-taught damsels, scattered births

Of many a Grecian vale, who sought not praise,

And, heedless even of listeners, warbled out 155

Their own emotions given to mountain air

In notes which mountain echoes would take up

Boldly and bear away to softer life;

Hence deified as sisters they were bound

Together in a never-dying choir; 160

Who with their Hippocrene and grottoed fount

Of Castaly, attest that Woman’s heart

Was in the limpid age of this stained world

The most assured seat of [ ]

And new-born waters, deemed the happiest source 165

Of inspiration for the conscious lyre.

Lured by the crystal element in times

Stormy and fierce, the Maid of Arc withdrew

From human converse to frequent alone

The Fountain of the Fairies. What to her, 170

Smooth summer dreams, old favours of the place.

Pageant and revels of blithe elves—to her

Whose country groan’d under a foreign scourge?

She pondered murmurs that attuned her ear

For the reception of far other sounds 175

Than their too happy minstrelsy,—a Voice

Reached her with supernatural mandate charged

More awful than the chambers of dark earth

Have virtue to send forth. Upon the marge

Of the benignant fountain, while she stood 180

Gazing intensely, the translucent lymph

Darkened beneath the shadow of her thoughts

As if swift clouds swept o’er it, or caught

War’s tincture, ’mid the forest green and still,

Turned into blood before her heart-sick eye. 185

Erelong, forsaking all her natural haunts,

All her accustomed offices and cares

Relinquishing, but treasuring every law

And grace of feminine humanity,

The chosen Rustic urged a warlike steed 190

Toward the beleaguered city, in the might

Of prophecy, accoutred to fulfil,

At the sword’s point, visions conceived in love.

The cloud of rooks descending thro’ mid air

Softens its evening uproar towards a close[398] 195

Near and more near; for this protracted strain

A warning not unwelcome. Fare thee well!

Emblem of equanimity and truth,

Farewell!—if thy composure be not ours,

Yet as thou still, when we are gone, wilt keep 200

Thy living chaplet of fresh flowers and fern,

Cherished in shade tho’ peeped at[399] by the sun;

So shall our bosoms feel a covert growth

Of grateful recollections, tribute due

To thy obscure and modest attributes 205

To thee, dear Spring,[400] and all-sustaining Heaven!

1827

1829

1833

My Lord and Lady Darlington,

I would not speak in snarling-tone;

Nor, to you, good Lady Vane,

Would I give one moment’s pain;

Nor Miss Taylor, Captain Stamp, 5

Would I your flights of memory cramp.

Yet, having spent a summer’s day

On the green margin of Loch Tay,

And doubled (prospect ever bettering)

The mazy reaches of Loch Katerine, 10

And more than once been free at Luss,

Loch Lomond’s beauties to discuss,

And wished, at least, to hear the blarney

Of the sly boatmen of Killarney,

And dipped my hand in dancing wave 15

Of Eau de Zurich, Lac Genève,

And bowed to many a major domo

On stately terraces of Como,

And seen the Simplon’s forehead hoary,

Reclined on Lago Maggiore 20

At breathless eventide at rest

On the broad water’s placid breast,

I, not insensible, Heaven knows,

To all the charms this Station shows,

Must tell you, Captain, Lord, and Ladies— 25

For honest worth one poet’s trade is—

That your praise appears to me

Folly’s own hyperbole.

1835

Thy shades, thy silence, now be mine

Thy charms my only theme; 10

1836

1837

1838

Said Secrecy to Cowardice and Fraud,

Falsehood and Treachery, in close council met,

Deep under ground, in Pluto’s cabinet,

“The frost of England’s pride will soon be thawed;

Hooded the open brow that overawed 5

Our schemes; the faith and honour, never yet

By us with hope encountered, be upset;—

For once I burst my bands, and cry, applaud!”

Then whispered she, “The Bill is carrying out!”

They heard, and, starting up, the Brood of Night 10

Clapped hands, and shook with glee their matted locks;

All Powers and Places that abhor the light

Joined in the transport, echoed back their shout,

Hurrah for ——, hugging his Ballot-box![406]

1840

We gaze—nor grieve to think that we must die,

But that the precious love this friend hath sown

Within our hearts, the love whose flower hath blown

Bright as if heaven were ever in its eye,

Will pass so soon from human memory; 5

And not by strangers to our blood alone,

But by our best descendants be unknown,

Unthought of—this may surely claim a sigh.

Yet, blessèd Art, we yield not to dejection:

Thou against Time so feelingly dost strive; 10

Where’er, preserved in this most true reflection,

An image of her soul is kept alive,

Some lingering fragrance of the pure affection,