автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Master; a Novel

Some typographical errors have been corrected; a list follows the text.

Contents.

List of Illustrations

(In certain versions of this etext [in certain browsers] clicking on this symbol

(etext transcriber's note)

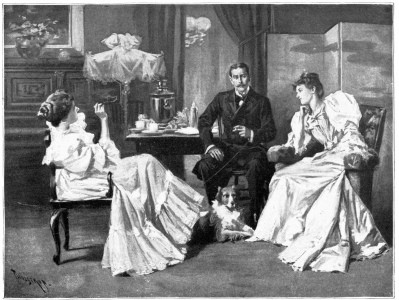

â âTHERE!â SAID OLIVE, PUFFING OUT A THIN CLOUDâ Page 379

THE MASTER

A Novel

BY

I. ZANGWILL

AUTHOR OF âTHE KING OF SCHNORRERSâ âCHILDREN OF THE GHETTOâ ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK AND LONDON

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1895, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

CONTENTS

PAGE PROEM 1 Book I CHAP.

I.SOLITUDE

5 II.THE DEAD MAN MAKES HIS FIRST AND LAST APPEARANCE

23 III.THE THOUGHTS OF YOUTH

33 IV.âMAN PROPOSESâ

45 V.PEGGY THE WATER-DRINKER

58 VI.DISILLUSIONS

69 VII.THE APPRENTICE

83 VIII.A WANDER-YEAR

99 IX.ARTIST AND PURITAN

113 X.EXODUS

123 Book II I.IN LONDON

132 II.GRAINGERâS

145 III.THE ELDER BRANCH

161 IV.THE PICTURE-MAKERS

181 V.A SYMPOSIUM

202 VI.THE OUTCAST

218 VII.TOWARDS THE DEEPS

229 VIII.âGOLD MEDAL NIGHTâ

245 IX.DEFEAT

259 X.MATT RECEIVES SUNDRY HOSPITALITIES

273 XI.A HOSTAGE TO FORTUNE

290 Book III I.CONQUEROR OR CONQUERED?

308 II.âSUCCESSâ

325 III.âVAIN-LONGINGâ

342 IV.FERMENT

364 V.A CELEBRITY AT HOME

384 VI.A DEVONSHIRE IDYL

408 VII.THE IDYL CONCLUDES

438 VIII.ELEANOR WYNDWOOD

460 IX.RUTH HAILEY

487 X.THE MASTER

499ILLUSTRATIONS

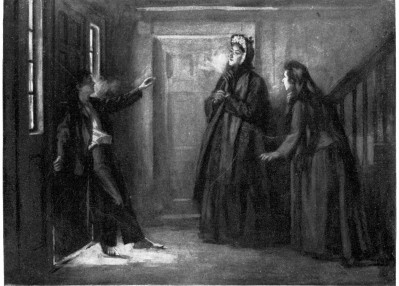

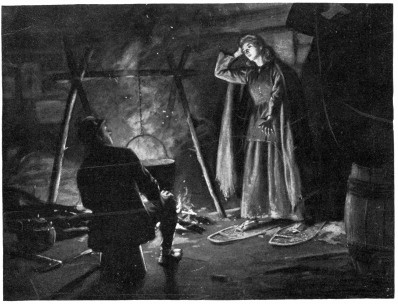

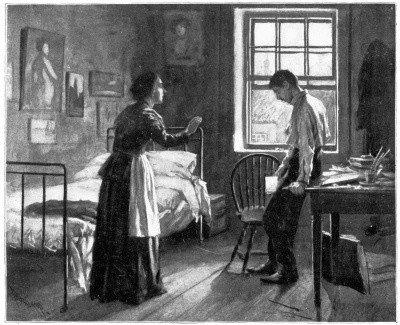

â âTHERE!â SAID OLIVE, PUFFING OUT A THIN CLOUDâ Frontispiece âHE PLACED HIMSELF WITH HIS BACK TO THE DOORâ Facing p. 12 â âI AM AFIRE WITH THIRST,â SHE CRIEDâ â 64 â âLORâ BLESS YOU, SIR,â SAID SHE, âIâM NOT WORRYINâ ABOUT THE RENTâ â â 226 â âGOOD-NIGHT,â SHE SAID, SOFTLYâ â 290 âMATT DINED WITH HERBERT AT A LITTLE TABLEâ â 338 âALL WAS VERY STILL, SAVE FOR THE ETERNAL MONOTONE OF THE SEAâ â 424 âSOMETHING IN THE SCENE THRILLED HIM WITH A SENSE OF RESTFUL KINSHIPâ â 516THE MASTER

PROEM

Despite its long stretch of winter, in which May might wed December in no incompatible union, âtwas a happy soil, this Acadia, a country of good air and great spaces; two-thirds of the size of Scotland, with a population that could be packed away in a corner of Glasgow; a land of green forests and rosy cheeks; a land of milk and molasses; a land of little hills and great harbors, of rich valleys and lovely lakes, of overflowing rivers and oversurging tides that, with all their menace, did but fertilize the meadows with red silt and alluvial mud; a land over which France and England might well bicker when first they met oversea; a land which, if it never reached the restless energy of the States, never retained the Old World atmosphere that long lingered over New England villages; save here and there in some rare Acadian settlement that dreamed out its life in peace and prayer among its willow-trees and in the shadows of its orchards.

At Minudie, at Clare in Annapolis County, where the goodly apples grew, lay such fragments of old France, simple communities shutting out the world and time, marrying their own, tilling their good dyke land, and picking up the shad that the retreating tide left on the exposed flats; listening to the Angelus, and baring their heads as some Church procession passed through the drowsy streets. They had escaped the Great Expulsion, nor had joined in the exodus of âEvangeline,â and, sprinkled about the country, were compatriots of theirs who had drifted back when the times grew more sedate; but for the most part it was the Saxon that profited by the labors of the pioneer Gaul, repairing the tumble-down farms and the dilapidated dykes, possessing himself of embanked marsh lands, and replanting the plum-trees and the quinces his predecessor had naturalized. For the revolt of the States against Britain sent thousands of American loyalists flocking into this âNew Scotland,â which thus became a colony of âNew England.â Scots themselves flowed in from auld Scotland, and the German came to sink himself in the Briton, and a band of Irish adventurers, under the swashbuckling Colonel McNutt, arrived with a grant of a million acres that they were not destined to occupy. The Acadian repose had fled forever. The sparse Indian hastened to make himself scarcer, conscious there was no place for him in the new order, and disappearing deliciously in hogsheads of rum. The virgin greenwood rang with axes, startling the bear and the moose. Crash! Down went pine and beech, hemlock and maple, their stumps alone left to rot and enrich the fields. Crash!—thud! The weasel grew warier, the astonished musquash vanished in eddying circles. Bridges began to span the rivers where the beaver built its dams in happy unconsciousness of the tall cylinder that was about to crown civilization. The caribou and the silver fox pressed inland to save their skins. The snare was set in the wild-wood, and the crack of the musket followed the ring of the axe. The mackerel and the herring sought destruction in shoals, and the seines brimmed over with salmon and alewives and gaspereux. The wild land that had bloomed with golden-rod and violets was tamed with crops, and plump sheep and fat oxen pastured where the wild strawberry vine had trailed or the bull-frog had croaked under the alders. A sturdy, ingenious race the fathers of the new settlement, loving work almost as much as they feared God; turning their hand to anything, and opening it wide to the stranger. They raised their own houses, and fashioned their own tools, and shod their own horses, and later built their own vessels, and even sailed them to the great markets laden with the produce of their own fields and the timber from their own saw-mills. There were women in this workaday paradise—shapely, gentle creatures, whose hands alone were rough with field and house-work; women who span and sang when the winter night-winds whistled round the settlement. The dramas of love and grief began to play themselves out where the raccoon and the chickadee had fleeted the golden hours in careless living. Children came to make the rafters habitable, and Death to sanctify them with memories. The air grew human with the smoke of hearths, the forest with legends and histories. And as houses grew into homes and villages into townships, Church and State arose where only Faith and Freedom had been.

The sons and heirs of the fathers did not always cling to the tradition of piety and perseverance. The âBluenoseâ grew apathetic, content with the fatness of the day; or, if he exerted himself, it was too often to best a neighbor. The great magnets of New York and Boston drew off or drew back all that was iron in the race.

And amid these homely emotions of yeomen, amid the crude pieties or impieties of homespun souls, amid this sane hearty intercourse with realities or this torpor of sluggish spirits, was born ever and anon a gleam of fantasy, of imagination: bizarre, transfiguring, touching things with the glamour of dream. Blind instincts—blinder still in their loneliness—yearned towards light; beautiful emotions stirred in dumb souls, emotions that mayhap turned to morbid passion in the silence and solitude of the woods, where character may grow crabbed and gnarled, as well as sound and straight. For whereas to most of these human creatures, begirt by the glory of sea and forest, the miracles of sunrise and sunset were only the familiar indications of a celestial timepiece, and the starry heaven was but a leaky ceiling in their earthly habitation, there was here and there an eye keen to note the play of light and shade and color, the glint of wave and the sparkle of hoar-frost and the spume of tossing seas; the gracious fairness of cloud and bird and blossom, the magic of sunlit sails in the offing, the witchery of white winters, and all the changing wonder of the woods; a soul with scanty self-consciousness at best, yet haply absorbing Nature, to give it back one day as Art.

Ah, but to see the world with other eyes than oneâs fellows, yet express the vision of oneâs race, its subconscious sense of beauty, is not all a covetable dower.

The islands of Acadia are riddled with pits, where men have burrowed for Captain Kiddâs Treasure and found nothing but holes. The deeper they delved the deeper holes they found. Whoso with blood and tears would dig Art out of his soul may lavish his golden prime in pursuit of emptiness, or, striking treasure, find only fairy gold, so that when his eye is purged of the spell of morning, he sees his hand is full of withered leaves.

Book I—CHAPTER I

SOLITUDE

âMatt, Matt, whatâs thet thar noise?â

Matt opened his eyes vaguely, shaking off his younger brotherâs frantic clutch.

âItâs onây the frost,â he murmured, closing his eyes again. âGo to sleep, Billy.â

Since the sled accident that had crippled him for life, Billy was full of nervous terrors, and the night had been charged with mysterious noises. Within the lonely wooden house weather-boards and beams cracked; without, twigs snapped and branches crashed; at times Billy heard reports as loud as pistol-shots. One of these shots meant the bursting of the wash-basin on the bedroom bench, Matt having forgotten to empty its contents, which had expanded into ice.

Matt curled himself up more comfortably and almost covered his face with the blanket, for the cold in the stoveless attic was acute. In the gray half-light the rough beams and the quilts glistened with frozen breaths. The little square window-panes were thickly frosted, and below the crumbling rime was a thin layer of ice left from the day before, solid up to the sashes, and leaving no infinitesimal dot of clear glass, for there was nothing to thaw it except such heat as might radiate through the bricks of the square chimney that came all the way from the cellar through the centre of the flooring to pop its head through the shingled roof.

âMatt!â Billy was nudging his brother in the ribs again.

âHullo!â grumbled the boy.

âThet thar ainât the frost. Hark!â

â âTis, I tell ye. Donât you hear the pop, pop, pop?â

âNot thet; tâother down-stairs.â

âOh, thetâs the wind, I reckon.â

âNo; itâs some âun screaminâ!â

Matt raised himself on his elbow, and listened.

âWhy, you gooney, itâs onây mother rowinâ Harriet,â he said, reassuringly, and snuggled up again between the blankets.

The winter, though yet young, had already achieved a reputation. Blustrous north winds had driven inland, felling the trees like lumbermen. In the Annapolis Basin myriads of herrings, surprised by Jack Frost before their migratory instinct awoke, had been found frozen in the weirs, and the great salt tides overflowing the high dykes had been congealed into a chocolate sea that, when the liquid water beneath ran back through the sluices, lay solid on the marshes. By the shores of the Basin of Minas sea-birds flapped ghostlike over amber ice-cakes, whose mud-streaks under the kiss of the sun blushed like dragonâs blood.

Snow had fallen heavily, whitening the âevergreenâ hemlocks, and through the shapeless landscape half-buried oxen had toiled to clear the blurred roads bordered by snow-drifts, till the three familiar tracks of hoofs and sleigh-runners came in sight again. The stage to Truro ploughed its way along, with only dead freight on its roof and a furred animal or two, vaguely human, shivering inside. Sometimes the mail had to travel by horse, and sometimes it altogether disappointed Billy and his brothers and sisters of the excitement of its passage; for the stage road ran by the small clearing, in the centre of which their house and barn had been built—a primitive gabled house, like a Noahâs ark, ugliness unadorned, and a cheap log barn of the âlean-toâ type, with its cracks corked with moss, and a roof of slabs.

Jack Frost might stop the mail, but he could not stop the gayeties of the season. âWooden frolicsâ and quilting-parties and candy-pullings and infares and Baptist revival-meetings had been as frequent as ever; and part of Mattâs enjoyment of his couch was a delicious sense of oversleeping himself legitimately, for even his mother could hardly expect him to build the fire at five when he had only returned from Deacon Haileyâs âmuddinâ frolicâ at two. He saw himself coasting down the white slopes in his hand-sled, watching the wavering radiance of the northern lights that paled the moon and the stars, and wishing his mother would not spoil the after-glow of the nightâs pleasure and the poetic silence of the woods by grumbling about his grown-up sister Harriet, who had deserted them for an earlier escort home. He felt himself well rewarded for his afternoonâs labor in loading marsh mud for the top-dressing of Deacon Haileyâs fields; and a sudden remembrance of how his mother had been rewarded for helping Mrs. Hailey to prepare the feast made him nudge Billy in his turn.

âCheer up, Billy. Weâve brought back a basket oâ goodies: thereâs plum-cake, doughnuts—â

âItâs gettinâ worst,â said Billy. âHark!â

Matt mumbled impatiently and redirected his thoughts to the âmuddinâ frolic.â The images of the night swept before him with almost the vividness of actuality; he lost himself in memories as though they were realities, and every now and then a dash of sleep streaked these waking visions with the fantasy of dream.

âMy, how the fiddle shrieks!â runs the boyâs reminiscence. âWhy donât ole Jupe do his tuninâ to home, the pesky nigger? Weâre all waitinâ for the reel—the âfoursâ are all made up; Ruth Hailey and me hev took the floor. Ruth looks jest great with thet white frock anâ the pink sash, thetâs a fact. Hooray!—âThe Devil among the Tailors!â—La, lalla, lalla, lalla, lalla, flip-flop!â He hears the big winter top-boots thwack the threshing-floor. Keep it up! Whoop! Faster! Ever faster! Oh, the joy of life!

Now he is swinging Ruth in his arms. Oh, the merry-go-round! The long rows of candles pinned by forks to the barn walls are guttering in the wind of the movement; the horses tied to their mangers neigh in excitement; from between their stanchions the mild-eyed cows gaze at the dancers, perking their naïve noses and tranquilly chewing the cud. A bat, thawed out of his winter nap by the heat of the temporary stove, flutters drowsily about the candles; and the odors of the stable and of the packed hay mingle with the scents of the ball-room. Mattâs exhaustive eye, though never long off pretty Ruthâs face, takes in even the grains of wheat that gild many a tousled head of swain or lass as the shaking of the beams dislodges the unthreshed kernels in the mow under the eaves, and, keener even than the eye of his collie, Sprat, notes the mice that dart from their holes to seize the fallen drops of tallow. But perhaps Sprat is only lazy, for he will not vacate his uncomfortable snuggery under the stove, though he has to shift his carcass incessantly to escape the jets of tobacco-juice constantly squirted in his direction. It serves him right, thinks his young master, for persisting in coming, though, for the matter of that, the creature, having superintended the mud-hauling, has more right to be present than Bully Preep. âWonder why sister Harriet lets him dance with her so ofân!â the panorama of his thought proceeds. âWhat kin she see in the skunk, fur lanâ sakes? I told her âbout the way he bully-ragged me when he was boss oâ the school and I was a teeny shaver. But she donât seem to care a snap. Girls are queer critters, thetâs a fact. He used to put a chip on my shoulder, anâ egg the fellers on to flick it off. But, gosh! didnât I hit him a lick when he pulled little Ruthâs hair? Heâd a black eye, thetâs a fact, though he givâ me two, anâ mother anâ teacher âud a givâ me one more apiece, but there warnât no more left. I took it out in picters though, I guess. My! didnât ole McTavitâs face jest look reedicâlous when he discovered Bully Preep in the fly-leaf of every readinâ-book. Thetâs jest how mother is glarinâ at Harriet this moment. Pop! pop! pop! What a lot oâ ginger-beer anâ spruce-beer Deacon Hailey is openinâ! Pop! pop! pop! He donât seem to notice them thar black bottles oâ rum. Heâs âtarnal cute, is ole Hey. Seems like heâs talkinâ to mother. Wonder how she kin understand him. He allus talks as if his mouth was full oâ words—but itâs onây tobacco, I reckon. Pop! pop! pop! Thetâs what I allus hear him say, windinâ up with a âHeyâ—anâ it does rile me some to refuse pumpkin-pie, not knowinâ heâs invitinâ me to anythinâ but hay. I âspect motherâs heerd him talk considerable, just es Iâve heerd the jays anâ the woodpeckers; though she kinât tell one from tâother, I vow, through beinâ raised at Halifax. Thunderation! thetâs never her dancinâ with ole Hey! My stars, whatâll her elders say? Well, I wow! She is backslidinâ. Ah, she recollecks! She pulls up, her face is like a beet. Ole Hey is argufyinâ, but she hangs back in her traces. I reckon she kinder thinks sheâs kicked over the dashboard this time. Ah, heâs gone and taken Harriet for a pardner instead; heâll like sister better, I guess. By gum! Heâs kickinâ up his heels like a colt when it fust feels the crupper. I do declare Marm Hailey is lookinâ pesky ugly âbout it. Sheâs a mighty handsome critter, anyways. Pity she kinât wear her hat with the black feather indoors—she does look jest spliffinâ when she drives her horses through the snow. Whoop! Keep it up! Sling it out, ole Jupe! More rosin. Yankee doodle, keep it up, Yankee doodle dandy! Go it, you cripples; Iâll hold your crutches! Why, thereâs Billy dancinâ with the crutch I made him!â he tells himself as his vision merges in dream. âPop! pop! pop! How his crutch thumps the floor! Poor Billy! Fancy hevinâ to hop through life on thet thar crutch, like a robin on one leg! Or shall I hev to make him a longer one when heâs growed up? Mebbe he wonât grow up—mebbe heâll allus be the identical same size; and when heâs an ole man heâll be the right size again, anâ the crutchâll onây be a sorter stick. I wish I hed a stick to make this durned cow keep quiet—I kinât milk her! So! so! Daisy! Ole Jupeâs music ainât for four-legged critters to dance to! My! whatâs thet nonsense âbout a cow? Why, Iâm dreaminâ. Whoa, there! Give her a tickler in the ribs, Billy. Hullo! look out! hereâs father come back from sea! Quick, Billy, chuck your crutch in the hay-mow. Kinât you stand straighter nor that? Unkink your leg, or fatherâll never take you out to be a pirate. Fancy a pirate on a crutch! It was my fault, father, for fixinâ up thet thar fandango, but motherâs lambasted me aâready, anâ she wanted to shoot herself. But it donât matter to you, father—youâre allus away aâmost, anâ Billyâs crutch kinât get into your eye like it does into motherâs. She was afeared to write to you âbout it. Thetâs onây Billy in a fit—you see, Daisy kicked him, and they couldnât fix his leg back proper; it donât fit, so he hes fits now anâ then. Heâll never be a pirate now. Drive the crutch deeper into the ice, Charley; steady there with the long pole. The iron pin goes into the crutch, Billy; donât get off the ashes, youâll slide under the sled. Now, then, is the rope right? Jump on the sled, you girls and fellers! Round with the pole! Whoop! Hooray! Ainât she scootinâ jest! Let her rip! Pop! Snap! Geewiglets! The ropeâs give! Donât jump off, Billy, I tell you; youâll kill yourself! Stick in your toes anâ donât yowl; weâll slacken at the dykes. Look at Ruth—she donât scream. Thunderation! Weâre goinâ over into the river! Hold tight, you uns! Bang! Smash! Weâre on the ice-cakes! Is thet you thetâs screaminâ, Billy? You ainât hurt, I tell you—donât yowl—you gooney—donât—â

But it was not Billyâs voice that he heard screaming when the films of sleep really cleared away. The little cripple was nestling close up to him with the same panic-stricken air as when they rode that flying sled together. This time it was impossible to mistake their motherâs voice for the wind—it rose clearly in hysterical vituperation.

âAnâ you orter be âshamed oâ yourself, I do declare, goinâ home all alone in a sleigh with a young man—in the dead oâ night, too!â

âThere were more nor ourn on the road; and since Abner Preep was perlite enough—â

âYes, anâ you didnât think oâ me on the road oncet, I bet! If young Preep wanted to do the perlite, heâdâ aâ took me in his fatherâs sleigh, not a wholesome young gal.â

âBut I was tarâd out with dancinâ eâen aâmost, and you onây—â

âDonât you talk about my dancinâ, you blabbinâ young slummix! Jest keep your eye on your Preeps with their bow-legs anâ their pigeon-toes.â

âHis legs is es straight es yourn, anyhow.â

âPâraps youâll say thet Iâve got Injun blood next. Look at his round shoulders and his lanky hair—heâs a Micmac, thetâs what he is. He onây wants a few baskets and butter-tubs to make him look nateral. Ugh! I kin smell spruce every time I think on him.â

âItâs you that hev hed too much spruce-beer, hey?â

âYou sassy minx! Folks hev no right to bring eyesores into the world. Iâd rather stab you than see you livinâ with Abner Preep. Itâs a squaw he wants, thetâs a fact, not a wife!â

âIâd rather stab myself than go on livinâ with you.â

For a moment or two Matt listened in silent torture. The frequency of these episodes had made him resigned, but not callous. Now Harrietâs sobs were added to the horror of the altercation, and Matt fancied he heard a sound of scuffling. He jumped out of bed in an agony of alarm. He pulled on his trousers, caught up his coat, and slipped it on as he flew barefoot down the rough wooden stairs, with his woollen braces dangling behind him.

In the narrow icy passage at the foot of the stairs, in the bleak light from the row of little crusted panes on either side of the door, he found his mother and sister, their rubber-cased shoes half-buried in snow that had drifted in under the door. Mrs. Strang was fully dressed in her âfrolickinâ â costume, which at that period included a crinoline; she wore an astrakhan sacque, reaching to the knees, and a small poke-bonnet, plentifully beribboned, blooming with artificial flowers within and without, and tied under the chin by broad, black, watered bands. Round her neck was a fringed afghan, or home-knit muffler. She was a tall, dark, voluptuously-built woman, with blazing black eyes and handsome features of a somewhat Gallic cast, for she came of old Huguenot stock. She stood now drawing on her mittens in terrible silence, her bosom heaving, her nostrils quivering. Harriet was nearer the door, flushed and panting and sobbing, a well-developed auburn blonde of sixteen, her hair dishevelled, her bodice unhooked, a strange contrast to the otherâs primness.

âWhere you goinâ?â she said, tremulously, as she barred her motherâs way with her body.

âIâm goinâ to drownd myself,â answered her mother, carefully smoothing out her right mitten.

âNonsense, mother,â broke in Matt. âYou kinât go out—itâs snowinâ.â

He brushed past the pair and placed himself with his back to the door, his heart beating painfully. His motherâs mad threats were familiar enough, yet they never ceased to terrify. Some day she might really do something desperate. Who knew?

âIâm goinâ to drownd myself,â repeated Mrs. Strang, carefully winding the muffler round her head.

She made a step towards the door, sweeping the limp Harriet roughly behind her.

âYou kinât get out,â Matt said, firmly. âWhy, you hevnât hed breakfast yet.â

âWhat do I want oâ breakfus? Your sister is breakfus ânough for me. Clear out oâ the way.â

âDonât you let her go, Matt!â cried Harriet. âIâll quit instead.â

âYou!â exclaimed her mother, turning fiercely upon her, while her eyes spat fire. âYou are young and wholesome—the world is afore you. You were not brought from a great town to be buried in a wilderness. Marry your Preeps anâ your Micmacs, and nurse your pappooses. God has cursed me with froward children anâ a cripple, anâ a husband that goes gallivantinâ onchristianly about the world with never a thought for his âmortal soul, anâ the Lord has doomed me to worship Him in the wrong church. Mother yourselves; I throw up the position.â

âIs it my fault if father hesnât wrote you lately?â cried Harriet. âIs it my fault if thereâs no Baptist church to Cobequid village?â

âShut your mouth, you brazen hussy! Youâve drove your mother to her death! Stand out oâ my way, Matthew; donât you disobey my dyinâ requesâ.â

âI shaânât,â said the boy, squaring his shoulders firmly against the door. âWhere kin you drownd yourself? The pondâs froze anâ the tideâs out.â

He could think of no other argument for the moment, and he had an incongruous vision of her sliding down to the river on her stomach, as the boys often did, down the steep, reddish-brown slopes of greasy mud, or sinking into a squash-hole like an errant horse.

The islands of Acadia are riddled with pits, where men have burrowed for Captain Kiddâs Treasure and found nothing but holes. The deeper they delved the deeper holes they found. Whoso with blood and tears would dig Art out of his soul may lavish his golden prime in pursuit of emptiness, or, striking treasure, find only fairy gold, so that when his eye is purged of the spell of morning, he sees his hand is full of withered leaves.

âHe never saw you!â she cried, hysterically, closing the wee yawning mouth with kisses. Her eyes fell on Billy limping towards the red-hot stove where the others were already clustered.

In the which far-straggling village (to take time a little by the forelock) his fatherâs death did not remain a wonder for the proverbial nine days. For a week the young men chewing their evening quid round the glowing maple-wood of the store stove, or on milder nights tapping their toes under the verandas of the one village road as they gazed up vacantly at the female shadows flitting across the gabled dormer-windows of the snow-roofed wooden houses, spoke in their slightly nasal accent (with an emphasis on the ârâ) of the âpearâls of the watter,â and calling for their nightâs letters held converse with the postmistress on âthe watter and its pearâls,â and expectorated copiously, presumably in lieu of weeping. And the outlying farmers who dashed up with a lively jingle of sleigh-bells to tether their horses to the hitching-posts outside the stores, or to the picket-fence surrounding the little wooden meeting-house (for the most combined business with religion), were regaled with the news ere they had finished swathing their beasts in their buffalo robes and âbootsâ; and it lent an added solemnity to the appeal of the little snow-crusted spire standing out ghostly against the indigo sky, and of the frosty windows glowing mystically with blood in the gleam of the chandelier lamps, and, mayhap, wrought more than the drawling exposition of the fusty, frock-coated minister. And the old grannies, smoking their clay pipes as they crouched nid-nodding over the winter hearth, their wizened faces ruddy with firelight, mumbled and grunted contentedly over the tidbit, and sighed through snuff-clogged nostrils as they spread their gnarled, skinny hands to the dancing, balsamic blaze. But after everybody had mourned and moralized and expectorated for seven days a new death came to oust David Strangâs from popular favor; a death which had not only novelty, but equal sensationalism, combined with a more genuinely local tang, for it involved a funeral at home. Handsome Susan Hailey, driving her horses recklessly, her black feather waving gallantly in the wind, had dashed her sleigh upon a trunk, uprooted by the storm and hidden by the snow. She was flung forward, her head striking the tree, so that the brave feather dribbled blood, while the horses bolted off to Cobequid Village to bear the tragic news in the empty sleigh. And so the young men, with the carbuncles of tobacco in their cheek, expectorated more and spoke of the âpearâls of the land,â and walking home from the singing-class the sopranos discussed it with the basses, and in the sewing-circles, where the matrons met to make undergarments for the heathen, there was much shaking of the head, with retrospective prophesyings and whispers of drink, and commiseration for âOle Hey,â and all the adjacent villages went to the sermon at the house, the deceased lady being, as the minister (to whose salary she annually contributed two kegs of rum) remarked in his nasal address, âuniversally respected.â And everybody, including the Strangs and their collie, went on to the lonesome graveyard—some on horse and some on foot and some in sleighs, the coffin leading the way in a pung, or long box-sleigh—a far-stretching, black, nondescript procession, crawling dismally over the white, moaning landscape, between the zigzag ridges of snow marking the buried fences, past the trailing disconsolate firs, and under the white funereal plumes of the pines.

And the new birch rod made its trial slash at the raised hand.

âOh, heâll be all right if you kinder break the news to him anâ explain the thing proper. I reckon he wonât take to the deacon at first.â

â âTainât your turn yet, Tommy,â he said, waving away the smoke with his hand, and Tommy fell back asleep, as if mesmerized. Matt was as relieved at not having to explain as at Tommyâs momentary wakefulness, which had braced him against the superstitious awe that had been invading him while the mad beauty cursed him with that sweet voice of hers that no anger could make harsh. He thought of the apparition with pity, mingled with a thrill of solemn adoration; she had for him the beauty and wildness of the elemental, like the sky or the sea. And yet she had left in him other feelings—not only the doubt of her reality, but an uneasy stirring of apprehensions. Was there nothing but insane babble in this talk of Ruth Hailey and Abner Preep? A fear he could not define weighed at his heart. Even if he had been dreaming, if he had drowsed over the fire—as he must in any case have done not to have heard the scrape and clatter of snow-shoes entering—the dream portended something evil. But, no! it was not a dream. Assuredly the sap in the barrel had sunk to a lower level. With a new thought he lit a resinous bough and slipped out quickly and examined the dry stiff snow. The double trail of departing snow-shoes was manifest, meandering among the bark dishes and irregularly intersecting the trail of arrival. The radiant moonlight falling through the thin bare maple-boughs made his torch superfluous, except in the fuscous glade of leafy evergreens, along which he followed the giant footmarks for some little distance. He paused, leaning against a tall hemlock. Doubt was impossible. He had really entertained a visitor. Not seldom in former years had he entertained visitors who came to camp out for the night, which they made uproarious. But never had his hut sheltered so strange a guest. He was moved at the thought of her drifting across the wastes of snow like some fallen spirit. He looked up and abstractedly watched a crow sleeping with its head under its wing on the top of the hemlock, then his vision wandered to the flashing streamers of northern light, and, higher still, to those keen depths of frosty sky where the stars stood beautiful, and they drew up his thoughts yearningly to the infinite spaces. Something cried within him for he knew not what—save that it was very great and very majestic and very beautiful, mystically blending the luminousness of light and color with the scent of flowers and the troubled sweetness of music; and at the back of his dim, delicious craving for it was a haunting certainty that he would never reach up to it, never, never. The prophecy of mad Peggy recurred to the boy like a cutting blast of wind. Was it true, then, that he would thirst and thirst, and nothing ever quench his thirst? He held up his torch yearningly to the stars, while the night moaned around him, and the flaring pinewood cast a grotesque shadow of him on the pure white snow, an uncouth image that danced and leered as in mockery.

In moving the âlittle dishâ he laid bare Tommyâs fatherâs calumet, forgotten. He took it up. How the universe had changed since last he held a pipe in his hand—only last night! Again he heard the howl of a wild-cat, and he looked round involuntarily, as if expecting to find Mad Peggy at his elbow. But he had no sense of awe just now—though he had barred his door inhospitably against further bears—only the voluptuousness of liberty and loneliness, the healthy after-glow of satisfied appetite, and the gayety born of flaming logs and a couple of mouthfuls of fire-water. The Water-Drinkerâs prophecy seemed peculiarly inept in view of the pipe he held in his hand. With tremulous anticipation of more than mortal rapture he relit it. The sensation was unexpectedly pungent, but Matt puffed away steadily in hope and trust that this was merely the verdict of an unaccustomed palate, and he found a vast compensatory pleasure in his ability to make the thing work, to send the delicate wreaths into the air as ably as any Micmac or deacon of them all.

It was Saturday, but Matt suffered such tortures under the moral but mumbled exordiums of âOle Hey,â of which his unaccustomed ear took in less than ever, that he determined to depart on the Monday. The deacon seemed to have aged considerably, his beard was matted and thick, and his dicky was stained with tobacco-juice. For the rest, Matt discovered that most of the children were employed about the farm or the works, and that they had ceased to go to school, the deacon having converted Ruth into a school-mistress when she could be spared from keeping the books of his tannery and grist-mill. Ruth herself he met with indifference that the stateliness of her unexpectedly tall presence did nothing to thaw. He was surprised to hear from Billy, whose bed he shared that night, and who was more greedy to hear Mattâs adventures than to talk, that they were all very fond of her, and that she could still romp heartily. But Ruth had gradually grown shadowy to his imagination beside his burning dreams of Art, and the sight of her seemed to add the last touch of insubstantiality to her image. And yet, in the boredom of the Sunday services, with his eye roving restlessly about the severe, unlovely meeting-house in search of distractions, he could not but be conscious that she was the sweetest and sedatest figure in the village choir that sang and flirted in the rising tiers of the gallery over the vestibule; and when Deacon Hailey, tapping his tuning-fork on the rails, imitated its note with a rasping croak, Matt had a flash of sympathy with the divined inner life of the girl in this discordant environment. He told her briefly of his plans—to save up enough money to get to his uncle in London, who would doubtless put him in the way of studying Art seriously. She said she wished she had something as fine to live and work for; still she was busy enough, what with book-keeping and teaching school, as she put it smilingly. Their parting, like their meeting, was awkward. Self-consciousness and shyness had come into their simple relation. Neither dared take the initiative of a kiss, which for the rest was a rare caress in Cobequid save between children and lovers. Relatives shook hands; even women were not free of one anotherâs lips. And for the ladâs part, timidity was all he felt in the presence of this sweet graceful stranger. Only at the last moment, when she handed him a keepsake in the shape of a prize copy of the Arabian Nights her music-mistress had given her, did their looks meet as of yore, and then it was more the young painter than the old playmate who was touched by the earnest radiance of her eyes and the flicker of rose across the delicate fairness of her cheek. He made a little sketch of her in return, and sent it her from Halifax.

London, too, figured in the pageantry of his dreams, glittering like a city of the Arabian Nights, ablaze with palaces, athrob with music; and perched on the top of the tallest cupola, on the loftiest hill, stood his uncle Matthew, holding his paint-brush like a sceptre, king of the realm of Art. Hark! was that not the kingâs trumpeters calling, calling him to the great city, calling him to climb up and take his place beside the sovereign? Oh, the call to his youth, the clarion call, summoning him forth to toils and triumphs in some enchanted land! Oh, the seething of the young blood that thronged the halls of dream with loveliness, and set seductive faces at the casements of sleep, and sanctified his waking reveries with prescient glimpses of a sweet spirit-woman waiting in some veiled recess of space and time to partake and inspire his consecration to Art! The narrow teachings of his childhood—the conception of a vale of tears and temptation—shrivelled away like clouds melting into the illimitable blue, merging in a vast sense of the miracle of a beautiful world, a world of infinitely notable form and color. And this expansion of his horizon accomplished itself almost imperceptibly because the oppression of that ancient low-hanging heaven overbrooding earth, of that sombre heaven lying over Cobequid Village like a pall, was not upon him, and he was free to move and breathe in an independence that made existence ecstasy, even at its harshest. So that, though he walked in hunger and cold, he walked under triumphal arches of rainbows.

Remorse for his balked romance set in severely as soon as the bustle of loading was over and the anchor weighed; Priscilla took on the halo of Byronism and the Arabian Nights which had steadily absented itself in practice. Often during that miserable voyage he called himself a fool and a milksop; for the passage was a nightmare of new duties, complicated by sea-sickness and the weakness of a half-starved constitution, and on that swinging schooner, with its foul-mouthed captain, the mean bedroom he had deserted showed like a stable paradise. But blustrous as the captain was by the side of the blubbering Bludgeon, he had his compensations, for he made the voyage before the few passengers had found their sea-legs. Arrived in Economy, Matt was again face to face with starvation. But here Fortune smiled—with a suspicion of humor in her smile; and having already climbed masts and ladders for his dinner, her protégé was easily tempted to seek it at the top of a steeple. The steeple, after tapering to a point two hundred feet high, was crowned by a ball, which for years had needed regilding. Unfortunately the architect had made the ball almost inaccessible, but Matt, being desperate, undertook the job. The breath of winter was already on the town; a week more and the whole steeple would be decorated for the season with snow, so Mattâs offer was accepted, and, his boots equipped with creepers, the young steeple-jack, begirt with ropes, made the ascent safely in the eye of the admiring populace, lowered the great ball and then himself, and being thereupon given board and lodging and materials, he gilded it in the privacy of his garret. Thus become a public hero, Matt easily got through the winter. He decorated the ceiling of the Freemasonsâ Hall, and painted a portrait of the member of the House of Assembly, a burly farmer. This was his first professional experience of an actual sitter, and he found himself more hampered than helped by too close contact with reality. However, a touch of imagination does no harm to a portrait, and Matt had by this time acquired sufficient experience of humanity to lean to beautyâs side even apart from his youthful tendency to idealization, which made it impossible for him at this period to paint anything that was not superficially beautiful or picturesque. The member pronounced the portrait life-like, and gave Matt a bushel of home-grown potatoes over and above the stipulated price, which was board and lodging during the period of painting, and an order on a store for two dollars. With the order Matt purchased a pair of Congress or side-spring boots; the potatoes he swopped for a box of paper collars. From Economy he wrote home to his mother, and received an incoherent letter, in which she denounced the deacon by the aid of fulminant texts. Matt sighed impotently, pitying her from his deeper experience of life, but hoping she got on better with âOle Heyâ than she imagined. He had half a mind to look up his folks, especially poor Billy; but just then he got an order from the farmer-deputyâs brother, who wrote that he was so pleased with his brotherâs portrait that he wished Matt to paint his sign-board. He added that, although he had not seen any specimen of Mattâs sign-writing, he felt confident the painter of that portrait would be a competent person. Matt accepted the new task with mixed feelings, and got so many other commissions from the shopkeepers (for every shop had its movable sign-board) that he soon saved fifty dollars, and seemed on the high sea to England and his uncle. He had fixed three hundred dollars as the minimum with which he might safely go to London to study art. The steerage passage would cost only twenty. Unfortunately he was persuaded to invest his savings in a partnership with a Yankee jewel-peddler, and to travel the country with him. The peddler did not swindle his partner, merely his clients; but Matt was so disgusted that he refused to remain in the business. Thereupon the peddler, freed from the obligations of partnership, treated him as an outsider, and refused to return his principal. Matt thought himself lucky to escape in the end with twenty-five dollars and a cleansed conscience. He went back to sign-painting, but, taking a hint from the Yankee, continued his travels, and became a peddler-painter. He hated the work, was out of sympathy with his prosaic sitters, wondering by virtue of what grace or loveliness they sought survival on canvas; but the road to Art, by way of his uncle in London, lay over their painted bodies, so he drudged along. And yet when the sitter was dissatisfied with the picture—it was generally the sitterâs friends who persuaded him that he was dissatisfied—and when Matt had to listen to the fatuous criticisms of farmers and store-keepers, the artist flared up, and more than once the hot-blooded boy sacrificed dollars to dignity. He was astonished to find that in many quarters his fame had preceded him, and more astonished to discover finally that the advance advertiser was his late partner. Whether the Yankee compounded thus for the use of Mattâs dollars Matt never knew, but in his kinder thought of the cute peddler the boy came to think himself the debtor. For the dollars mounted, one on the head of another, and the heap rose higher and higher, day by day and week by week, till at last the magic three hundred began to loom in the eye of hope. Three hundred dollars! saved by the sweat of the brow and semi-starvation, and sanctified by the blood and tears of youth; sweet to count over and to dream over, and to pile up like a tower to scale the skies.

Matt pacified her as best he could, and, promising to arrange it all soon, left her, his heart nigh breaking. He walked about the bustling streets like one in a dream, resenting the sunshine, and wondering why all these people should be so happy. Again that ancient image of his fatherâs dead face was tossed up on the waves of memory, to keep company henceforth with the death-in-life of his motherâs face. The breakdown of his ambition seemed a petty thing beside these vaster ironies of human destiny.

Ah, what hopes harbored, what dreams hovered in that bleak little room! The vague, troubled rumor of the great city rolled up in inspiring mystery; the light played with instructive fascination upon the sooty tiles; high over the congested chaos of house-tops he saw the evening mists rifted with sunset, and on starry nights he touched the infinite through his rickety casement.

From Tarmigan, whose executive faculty and technical knowledge were remarkable, and who, despite surface revolts behind his back, was worshipped by the whole school, Matt got many âpointers,â as he called them in his transatlantic idiom—traditions of the craft which he might never have hit out for himself; though, on the other hand, in the little studies he made at home and sometimes showed to Tarmigan, he produced effects instinctively, the technique of which he was puzzled to explain to the master-craftsman, who for the rest did not approve of the strange warm luminosities Matt professed to see on London tiles, or the misty coruscations that glorified his chimney-pots. Grainger himself never offered criticisms to his pupils except casually, and mainly by way of conversation, when he was bored with his own thoughts.

âAu revoir, my dear nephew, au revoir!â said Madame, shaking both his hands. âI said you and Herbert would love each other. You will find your sixpence awaiting you on the desk.â

âWell, you do, thereâs no denying it. Remember how you preached to me about the governor the first time you saw me. Perhaps youâll go lecturing Cornpepper because he economizes by domesticating his model when he has a big picture on the easel. Personally, I like Cornpepper; he is the only fellow who has the courage of his want of principles in this whitewashed sepulchre of a country. But be careful that you donât talk to him as you did to Rapper, for he lives up to his name. He is awfully peppery when you tread on his corns, though he has no objection to stamping on yours. Not that I believe thereâs any real malice in him, but they say his master at the Beaux-Arts was a very quarrelsome fellow, and my opinion is that he models himself on him, and thinks that to quarrel with everybody is to be a great artist.â

âAh, thereâs the Methodist parson again,â interrupted Herbert, laughing. âHang it all, man, youâre not a virgin, are you?â

Dear Matt,—What in the name of all that is unholy made you send that letter to my house instead of to the club? Thereâs been a devil of a row. The Old Gentleman opened the letter. He pretends he did so without noticing, as it came mixed up with his, and so few come for me to the house. When I got down to breakfast the mater was in tears and the Old Gentleman in blazes. Of course, heâd misread it altogether—imagined you wanted to borrow money instead of to get it back (isnât it comical? Itâs almost an idea for a farce for our dramatic society), and insisted you had been draining me all along (you did write you were sorry to bother me again, you old duffer). Of course I did my best to dispel the misconception, but it was no use my swearing till all was blue that this was the first application, he wouldnât believe a word of it. He said he had had his suspicions all along, and he called the mater to witness that the first time he saw you in the shop he said you were a rogue. And at last the mater, whoâd been standing up for you—I never thought she had so much backbone of her own—was converted, and confessed with tears that you had been here pretty nigh every day and swore you should never set foot here again, and the Old Gentleman dilated on the pretty return you had made for his kindness (sucking his boyâs blood, he called it, in an unusual burst of poetry), and he likewise offered some general observations on the comparative keenness of a serpentâs tooth and ingratitude. And thatâs how it stands. Thereâs nothing to be done, I fear, but to let the thing blow over—heâll cool down after a time. Meanwhile, you will have to write to me at the club if you want to meet me. I am awfully sorry, as I enjoyed your visits immensely. Do let me know if I can do anything for you. Iâm in a frightful financial mess, but I might give you introductions here or there. I know chaps on papers and that sort of thing. I am sure you have sufficient talent to get along—and you can snap your fingers at creditors, as you havenât got anything they can seize, and can flit any day you like. I wish I was you. With every good wish,

But when Matt sat down to paint that night he found himself incapacitated, a mass of aches and bruises. He went home to anoint himself with his arnica; in the unconscious optimism of sickness the suggestion of suicide had vanished altogether.

Herbert beamingly ordered boxes of Havanas and âsoda-and-whiskies,â and soon Matt, still in his overcoat, found himself drinking and smoking and shouting with the rest, exalted by the whiskey into forgetfulness of his clothes and his fortunes, and partaking in all the rollicking humors of the evening, in all the devil-may-care gayety of the eternal undergraduate, roaring with his boon companions over the improper stories of the ascetic-looking young man with the poetic head, bawling street choruses, dancing madly in grotesque congested waltzes, wherein he had the felicity to secure Cornpepper for a partner, and distinguishing himself in the high-kicking pas seul, not departing till the final âAuld Lang Syneâ had been sung with joined hands in a wildly whirling ring. Herbert had left some time before.

âI knew you werenât a rogue,â cried Madame, in thoughtless triumph. The sentiment reminding her of the interrogative eyebrows, she added, hastily, âOf course, you wonât tell my husband. Not that he would mind, of course, for I am helping you to leave the country. But oh, how I wish you had come to me instead of to Herbert! The dear boy has such hard work and so few pleasures, and his allowance is so small that his father was naturally annoyed to think of your making the poor boy stint himself. Of course, I made it up to Herbert unbeknown to his father, who would only return him a little of the money you had borrowed. Promise me you will not apply to Herbert again. You know it is so expensive living in Paris!â

âOh, good-night,â he said, holding out his hand.

âGod bless you,â murmured Matt, kissing the letter. âI believe I shall love you, after all.â

Not that Rosina knew much of his other affairs. In truth, she knew very little of her husbandâs life, nor by how vast a sweep it circumscribed her own. She knew he had to be away from her a very great deal, that he had to stay in the country to paint great people; she was vaguely aware that the necessities of his profession made a wide sociality profitable. She had been once or twice to peep at his studio, horrified by the grandeur, and only consoled by the demonstration that its cost was repaid in the prices, like the luxurious fittings of the shops in the Holloway Road. But her imagination lacked the materials to construct a vision of the whirlpool which had sucked him away from her; her reading was limited to a weekly newspaper in which his name seldom appeared. And he, in his mental isolation from her, found scant self-reproach for his silence; reserve seemed more natural than communicativeness. She could never know the doings of his soul, his thoughts were not her thoughts, he had given up the attempt at communion, the effort to teach her to know his real self; why should he be less reticent concerning his outward movements, his superficial self? He was aloof from her spiritually; beside this, his material separation from her was insignificant. The children—a girl of seven and a boy of nearly four—were no bonds of union. The elder, christened Clara, after Rosinaâs aunt, was sharp and lively enough, but given to passionate sulking; the younger—called after his grandfather, David—was a lymphatic, colorless youngster, sickly and rather slow-witted, with something of Billyâs pathos in his large gray eyes. Their father had tried hard to love them, as he had tried to love their mother, and had taken a certain proprietary interest in their infantile graces, and in the engaging ways of early childhood, but the claims of his Art left them in the motherâs hands, and the older they grew the less he grew to feel them his. Neither Clara nor David had as yet displayed any scintilla of artistic instinct. When he went home he usually had something for them in his pocket, as he would have had for the children of an acquaintance, but they gave him no parental thrill.

The Scotch landscape-painter pacified them by proposing a game of âshell-out,â and Herbert eagerly seconding the proposal it was carried nem. con., and the group mounted to the billiard-room, where Matthew Strang won half a crown before he went off to his nocturnal parties, leaving his cousin still renewing with zest his olden experience of the lighter side of British Art.

âOlive is so good,â she said, brokenly, âshe was of my husbandâs family—an Irish branch—but she quarrelled with them all—her father, her sisters—and came to live with me. Fortunately she is immensely rich in her own right, and independent of them all.â

âYouâre certainly not doing her justice!â

About nine oâclock Rosina sent a specially nice supper for two down to the study. Matthew roused himself to eat a morsel to keep Billy company, and then, before going to his sleepless couch in Billyâs room, bethought himself of whiling away the time by answering some letters which had been bulking his inner coat-pocket for days. One of these was a reverential request for an autograph, addressed from a fine-sounding country house, and backed by the compulsive seduction of a stamped envelope.

After which she opened the window, sat on the side of the bed, and screwed up her ripe red lips to produce a perplexed whistle.

âThe Catechism is right,â she went on, thoughtfully, proceeding to misquote it. âThe waves are too strong. Itâs no use fighting against your sex or your station. Do your duty in that state of life in which it has pleased God to call you. But I would have that text taught to the rich exclusively, not to the poor. The poor should be encouraged to ascend; the rich should be taught contentment. Else their strength for good is wasted fruitlessly.â And the electric current of love generated by those close-pressed palms flashed to her soul the mission of a life of noble work hand in hand.

âYou are right, my dear, there isnât a decent picture here,â Cornpepper chuckled, grimacing to adjust his monocle, and feeling his round beard. âIchabod! The glory is departed from Paris. The only chaps who can paint nowadays are the Neo-Teutonic school. The Frenchmen are played out—they have even lost their taste. They bought a picture of mine last year, you remember. I palmed off the rottenest thing Iâd ever done on âem. Itâs in the Luxembourg—you go and see it, old man, and you tell me if Iâm not right. Now, mind you do! Ta, ta, old fellow. Sorry youâre not in the Academy this year—but itâs a good advertisement for you. I think I shall be ill myself next year. But we mustnât talk shop. Good-bye, old man. Oh, by-the-way, I hear your cousinâs engaged to an heiress. Itâs true, is it? Lucky beggar, that Herbert! Better than painting, eh? Ha! ha! ha! But I knew heâd never do anything. Didnât he win the Gold Medal, eh? Ho! ho! ho! Well, au revoir. Donât forget the Luxembourg. You donât want to wait till Iâm dead and in the Louvre, what? Thanks for a pleasant chat, and wish you better.â

It was the steady, business-like clatter of determined work. She had taken up the burden of Duty again.

âHE PLACED HIMSELF WITH HIS BACK TO THE DOORâ

âWhy, thereâs onây mud-flats,â he added.

âIâll wait on the mud-flats fur the merciful tide.â She fastened her bonnet-strings firmly.

âThe river is full of ice,â he urged.

âThere will be room fur me,â she answered. Then, with a sudden exclamation of dismay, âMy God! youâve got no shoes and socks on! Youâll ketch your death. Go up-stairs dâreckly.â

âNo,â replied Matt, becoming conscious for the first time of a cold wave creeping up his spinal marrow. âIâll ketch my death, then,â and he sneezed vehemently.

âPut on your shoes anâ socks dâreckly, you wretched boy. You know what a bother I hed with you last time.â

He shook his head, conscious of a trump card.

âDâye hear me! Put on your shoes and socks!â

âTake off your bonnet anâ sacque,â retorted Matt, clinching his fists.

âPut on your shoes anâ socks!â repeated his mother.

âTake off your bonnet anâ sacque, anâ Iâll put on my shoes anâ socks.â

They stood glaring defiance at each other, like a pair of duellists, their breaths rising in the frosty air like the smoke of pistols—these two grotesque figures in the gray light of the bleak passage, the tall, fierce brunette, in her flowery bonnet and astrakhan sacque, and the small, shivering, sneezing boy, in his patched homespun coat, with his trailing braces and bare feet. They heard Harrietâs teeth chatter in the silence.

âGo back to bed, you young varmint,â said Matt, suddenly catching sight of Billyâs white face and gray night-gown on the landing above. âYouâll ketch your death.â

There was a scurrying sound from above, a fleeting glimpse of other little night-gowned figures. Matt and his mother still confronted each other warily. And then the situation was broken up by the near approach of sleigh-bells. They stopped slowly, mingling their jangling with the creak of runners sliding over frosty snow, then the scrunch of heavy boots travelled across the clearing. Harriet flushed in modest alarm and fled up-stairs. Mrs. Strang hastily retreated into the kitchen, and for one brief moment Matt breathed freely, till, hearing the click of the door-latch, he scented gunpowder. He dashed towards the door and pressed the thumb-latch, but it was fastened from within.

âHarriet!â he gasped, âthe gun! the gun!â

He beat at the door, his imagination seeing through it. His loaded gun was resting on the wooden hooks fastened to the beam in the ceiling. He heard his mother mount a chair; he tried to break open the door, but could not. The chances of getting round by the back way flashed into his mind, only to be dismissed as quickly. There was no time—in breathless agony he waited the report of the gun. Crash! A strange, unexpected sound smote his ears—he heard the thud of his motherâs body striking the floor. She had stabbed herself, then, instead. Half mad with excitement and terror, he backed to the end of the passage, took a running leap, and dashed with his mightiest momentum against the frail battened door. Off flew the catch, open flew the door with Matt in pursuit, and it was all the boy could do to avoid tumbling over his mother, who sat on the floor among the ruins of a chair, rubbing her shins, her bonnet slightly disarranged, and the gun, still loaded, demurely on its perch. What had happened was obvious; some of the little Strang mice, taking advantage of the catâs absence at the âmuddinâ frolic,â had had a frolic on their own account, turning the chair into a sled, and binding up its speedily-broken leg to deceive the maternal eye. It might have supported a sitter; under Mrs. Strangâs feet it had collapsed ere her hand could grasp the gun.

âThe pesky young varmints!â she exclaimed, full of this new grievance. âThey might hev crippled me fur life. Always a-tearinâ anâ a-rampaginâ anâ a-ruinatinâ. I kinât keep two sticks together. Itâs ânough to make a body throw up the position.â

The sound of the butt-end of a whip battering the front-door brought her to her feet with a bound. She began dusting herself hastily with her hand.

âWell, whatâre you gawkinâ at?â she inquired. âKinât you go anâ unbar the door, âstead oâ standinâ there like a stuck pig?â

Matt knew the symptoms of volcanic extinction; without further parley he ran to the door and took down the beechen bar. The visitor was âole Hey,â who drove the mail. The deacon came in, powdered as from his own grist-mill, and added the snow of his top-boots to the drift in the hall. There were leather-faced mittens on his hands, ear-laps on his cap, tied under the chin, a black muffler, hoary with frost from his breath, round his neck and mouth, and an outer coat of buffalo-skin swathing his body down to his ankles, so that all that was visible of him was a little inner circle of red face with frosted eyebrows.

Mrs. Strang stood ready in the hall with a genial smile, and Matt, his heart grown lighter, returned to the kitchen, extracted the family foot-gear from under the stove, where it had been placed to thaw, and putting on his own still-sodden top-boots, he set about shaving whittlings and collecting kindlings to build the fire.

âHere we are again, hey!â cried the deacon, as heartily as his perpetual, colossal quid would permit.

âDo tell! is it really you?â replied Mrs. Strang, with her pleasant smile.

âYes—dooty is dooty, I allus thinks,â he said, spitting into the snow-drift and flicking the snow over the tobacco-juice with his whip. âWhatever Deacon Haileyâs hand finds to do he does fust-rate—thetâs a fact. It donât seem so long a while since you and me were shakinâ our heels in the Sir Roger. Nay, donât look so peaked—thereâs nuthinâ to make such a touse about. You air a particâler Baptist, hey? Anâ I guess you kinder allowed Deacon Hailey would be late with the mail, hey? But heâs es spry es if heâd gone to bed with the fowls. You wonât find the beat of him among the young fellers nowadays—thetâs so. Theyâre a lazy, slinky lot; and es for doinâ their dooty to their country or their neighbor—â

âHev you brought me a letter?â interrupted Mrs. Strang, anxiously.

âI guess—but youâre goinâ out airly?â

âI allowed Iâd walk over to the village to see if it hed come.â

âOh, but it ainât the one you expecâ.â

âNo?â she faltered.

âI guess not. Thetâs why I brought it myself. I kinder scented it was suthinâ special, and so I reckoned Iâd save you the trouble of trudginâ to the post-office. Deacon Hailey ainât the man to spare himself trouble to obleege a fellow-critter. Do es youâd be done by, hey?â The deacon never lost an opportunity of pointing the moral of a position. Perhaps his sermonizing tendency was due to his habit of expounding the Sunday texts at a weekly meeting, or perhaps his weekly exposition was due to his sermonizing tendency.

âThank you.â Mrs. Strang extended her hand for the letter. He produced it slowly, apparently from up the sleeve of his top-most coat, a wet, forlorn-looking epistle, addressed in a sprawling hand. Mrs. Strang turned it about, puzzled.

âPâraps itâs from Uncle Matt,â ejaculated Matt, appearing suddenly at the kitchen door.

âYouâve got Uncle Matt on the brain,â said Mrs. Strang. âItâs a Halifax stamp.â She could not understand it; her own family rarely wrote to her, and there was no hand of theirs in the address. Deacon Hailey lingered on, apparently prepared, in his consideration for others, to listen to the contents of his âfellow-critterâsâ letter.

âAh, sonny,â he said to Matt, âonly jest turned out, and not slicked up yet. When I was your age I hed done my dayâs chores afore the day hed begun. No wonder the Province is so âtarnally behindhand, hey?â

âThetâs so,â Matt murmured. Pop! pop! pop! was all that he heard, so that ole Heyâs moral exhortations left him neither a better nor a wiser boy.

Mrs. Strang still held the letter in her hand, apparently having become indifferent to it. Ole Hey did not know she was waiting for him to go, so that she might put on her spectacles and read it. She never wore her spectacles in public, any more than she wore her nightcap. Both seemed to her to belong to the privacies of the inner life, and glasses in particular made an old woman of one before oneâs time. If she had worn out her eyes with needle-work and tears, that was not her neighborsâ business.

The deacon, with no sign of impatience, elaborately unbuttoned his outer buffalo-skin, then the overcoat beneath that, and the coat under that, and then, pulling up the edge of his cardigan that fitted tightly over his waistcoats, he toilsomely thrust his horny paw into his breeches-pocket and hauled out a fig of âblack-jack.â Then he slowly produced from the other pocket a small tool-chest in the guise of a pocket-knife, and proceeded to cut the tobacco with one of the instruments.

âCome here, sonny!â he cried.

âThe deacon wants you,â said Mrs. Strang.

Matt moved forward into the passage, wondering. Ole Hey solemnly held up the wedge of black-jack he had cut, and when Mattâs eye was well fixed on it he dislodged the old âchawâ from his cheek with contortions of the mouth, and blew it out with portentous gravity. Lastly, he replaced it by the wedge of âblack-jack,â mouthed and moulded the new quid conscientiously between tongue and teeth, and passed the ball into his right cheek.

âThetâs the way to succeed in life, sonny. Never throw away dirty afore you got clean, hey?â

Poor Matt, unconscious of the lesson, waited inquiringly and deferentially, but the deacon was finished, and turned again to his mother.

âI âspect it âll be from some of the folks to home, mebbe.â

âMebbe,â replied Mrs. Strang, longing for solitude and spectacles.

âWhen did you last hear from the boss?â

âHe was in the South Seas, the captân, sellinâ beads to the savages. Heâd a done better to preach âem the Word, I do allow.â

âAh, you kinât expect godliness from sailors,â said the deacon. âItâs in the sea es the devil spreads his nets, thetâs a fact.â

âThe Apostles were fishermen,â Mrs. Strang reminded him.

âYes; but fishers ainât sailors, Mrs. Strang. Itâs in furrin parts that the devil lurks, and the further a man goes from his family the nearer he goes to the devil, hey?â

Mrs. Strang winced. âBut heâs gittinâ our way now,â she protested, unguardedly. âHeâs cominâ South with a freight.â

âAh, joined the blockade-runners, hey?â

Mrs. Strang bit her lip and flushed. âI donât kear,â the deacon said, reassuringly. âI donât see why Nova Scotia should go solid for the North. Whatâs the North done for Nova Scotia âcept ruin us with their protection dooties, gol durn âem. They wonât have slaves, hey? Ainât we their slaves? Donât they skin us es clean es a bear does a sheep? Ainât they allus on the lookout to snap up the Province? But I never talk politics. If the North and South want to cut each otherâs throats, thatâs not our consarn. Mind your own business, I allus thinks, hey? And if your boss kin make a good spec by provisioninâ the Southerners, youâll be a plaguy sight better off, I vow. And so will I—for, you know, I shall hev to call in the mortgage unless you fork out thet thar interest purty slick. Thereâs no underhandedness about Deacon Hailey. He gives you fair warninâ.â

âDârectly the letter comes you shall have it—Iâve often told you so.â

âMebbe thetâll be his letter, after all—put his thumb out, I guess, and borrowed another fellerâs, hey?â

âNo—heâd be nowhere near Halifax,â said Mrs. Strang, her feverish curiosity mounting momently. âDonât them thar sleigh-bells play a tune! I guess your horses air gettinâ kinder restless.â

âWell—thereâs nuthinâ I kin do for you to Cobequid Village?â he said, lingeringly.

Mrs. Strang shook her head. âThank you, I guess not.â

âYou wouldnât kear to write an answer now—Iâd be tolerable pleased to post it for you down thar. Allus study your fellow-critters, I allus thinks.â

âNo, thank you.â

Deacon Hailey spat deliberately on the floor.

âEr—you got to home safe this morninâ?â

âYes, thank you. We all come together, me and Harriet and Matt. âTwere a lovely walk in the moonlight, with the Aurora Borealis a-quiverinâ and a-flushinâ on the northern horizon.â

âA-h-h,â said the deacon slowly, and rather puzzled. âA roarer! Hey?â

At this moment a sudden stampede of hoofs and a mad jangling of bells were heard without. With a âDurn them beasts!â the deacon breathlessly turned tail and fled in pursuit of the mail-sleigh, mounting it over the luggage-rack. When he had turned the corner, Mattâs grinning face emerged from behind the snow-capped stump of a juniper.

âI reckon I fetched him thet time,â he said, throwing away the remaining snowball, as he hastened gleefully inside to partake of the contents of the letter.

He found his mother sitting on the old settle in the kitchen, her spectacled face gray as the sand on the floor, her head bowed on her bosom. One limp hand held the crumpled letter. She reminded him of a drooping foxglove. The room had a heart of fire now, the stove in the centre glowed rosily with rock-maple brands, but somehow it struck a colder chill to Mattâs blood than before.

âFatherâs drownded,â his mother breathed.

âHeâll never know âbout Billy now,â he thought, with a gleam of relief.

Mrs. Strang began to wring her mittened hands silently, and the letter fluttered from between her fingers. Matt made a dart at it, and read as follows:

Dear Marm,—Donât take on but ime sorrie to tell you that the Cap is a gone goose we run the block kade oust slick but the 2 time we was took by them allfird Yanks we reckkend to bluff âem in the fog but about six bells a skwad of friggets bore down on us sudden like ole nick the cap he sees he was hemd in on a lee shoar and he swears them lubberly northers shanât have his ship not if he goes to Davy Jones his loker he lufs her sharp up into the wind and sings out lower the longbote boys and while the shot was tearin and crashin through the riggin he springs to the hall-yards and hauls down the cullers then jumps through the lazzaret into the store room kicks the head of a carsk of ile in clinches a bit of oakem dips it in the ile and touches a match to it and drops it on the deck into the runin ile and then runs for it hisself jumps into the bote safe with the cullers and we sheer off into the fog mufflin our oars with our caps and afore that tarnation flame bust out to show where we were we warnt there but we heard the everlastin fools poundin away at the poor old innocent Sally Bell till your poor boss dear marm he larfs and ses he shipmets ses he look at good old Sally sheâs stickin out her yellow tongue at em and grinnin at the dam goonies beg pardon marm but that was his way he never larfed no more for wed disremembered the cumpess and drifted outer the fog into a skwall and the night was comin on and we drov blind on a reef and capsized but we all struck out for shore and allowed the cap was setting sale the same way as the rest on us but when we reached the harbor the cap he warnt at the helm and a shipmet ses ses he as how he would swim with that air bundle of cullers that was still under his arm and they tangelled round his legs and sorter dragged him under and kep him down like sea-weed and now dear marm he lays in the Gulf of Mexiker kinder rapped in a shroud and gone aloft I was the fust mate and a better officer I never wish to sine with for tho he did sware till all was blue his hart was like an unborn babbys and wishing you a merry Christmas and God keep you and the young orfuns and giv you a happy new year dear marm you deserve it.

ime yours to command,

Hoska Cuddy (Mate).

p s.—i would have writ erlier, but i couldnât get your address till i worked my way to Halifax and saw the owners scuse me not puttin this in a black onwellop i calclated to brake it eesy.

Matt hastily took in the gist of the letter, then stood folding it carefully, at a loss what to say to the image of grief rocking on the settle. From the barn behind came the lowing of Daisy—half protestation, half astonishment at the unpunctuality of her breakfast. Matt found a momentary relief in pitying the cow. Then his motherâs voice burst out afresh.

âMy poor Davie,â she moaned. âCut off afore you could repent, too deep down fur me to kiss your dead lips. I hevnât even got a likeness oâ you; you never would be took. I shall never see your face again on airth, and I misdoubt if Iâll meet you in heaven.â

âOf course you will—he saved his flag,â said Matt, with shining eyes.

His mother shook her head, and set the roses on her bonnet nodding gayly to the leaping flame. âYour father was born a Sandemanian,â she sighed.

âWhat is thet?â said Matt.

âDonât ask me; there air things boys mustnât know. And youâve seen in the letter âbout his profane langwidge. I never wouldâve run off with him; all my folks were agen it, and a sore time Iâve hed in the wilderness âway back from my beautiful city. But it was Godâs finger. I pricked the Bible fur a verse, anâ it came: âAnâ they said unto her, Thou art mad. But she constantly affirmed it was even so. Then said they, It is his angel.â â

She nodded and muttered, âAnâ I was his angel,â and the roses trembled in the firelight. âIf you were a good boy, Matt,â she broke off, âyouâd know where thet thar varse come from.â

âHednât I better tell Harriet?â he asked.

âActs, chapter eleven, verse fifteen,â muttered his mother. âIt was the finger of God. Whatâs thet you say âbout Harriet? Ainât she finished tittivatinâ herself yet—with her father layinâ dead, too?â She got up and walked to the foot of the stairs. âHarriet!â she shrieked.

Harriet dashed down the stairs, neat and pretty.

âYou onchristian darter!â cried Mrs. Strang, revolted by her sprightliness. âDonât you know fatherâs drownded?â

Harriet fell half-fainting against the banister. Mrs. Strang caught her and pulled her towards the kitchen.

âThere, there,â she said, âdonât freeze out here, my poor child. The Lordâs will be done.â

Harriet mutely dropped into the chair her mother drew for her before the stove. Daisyâs bellowing became more insistent.

âAnâ he never lived to take me back to Halifax, arter all!â moaned Mrs. Strang.

âNever mind, mother,â said Harriet, gently. âGod will send you back some day. You hev suffered enough.â

Mrs. Strang burst into tears for the first time. âAh, you donât know what my life hes been!â she cried, in a passion of self-pity.

Harriet took her motherâs mittened hand tenderly in hers. âYes we do, mother—yes we do. We know how you hev slaved and struggled.â

As she spoke a panorama of the slow years was fleeting through the minds of all three—the long blank weeks uncolored by a letter, the fight with poverty, the outbursts of temper; all the long-drawn pathos of lonely lives. Tears gathered in the childrenâs eyes—more for themselves than for their dead father, who for the moment seemed but gone on a longer voyage.

âHarriet,â said Mrs. Strang, choking back her sobs, âbring down my poor little orphans, and wrap them up well. Weâll say a prayer.â

Harriet gathered herself together and went weeping up the stairs. Matt followed her with a sudden thought. He ran up to his room and returned, carrying a square sheet of rough paper.

His mother had sunk into Harrietâs chair. He lifted up her head and showed her the paper.

âDavie!â she shrieked, and showered passionate kisses on the crudely-colored sketch of a sailor—a figure that had a strange touch of vitality, a vivid suggestion of brine and breeze. She arrested herself suddenly. âYou pesky varmint!â she cried. âSo this is what become oâ the fly-leaf of the big Bible!â

Matt hung his head. âIt was empty,â he murmured.

âYes, but thereâs another page thet ainât—thet tells you to obey your parents. This is how you waste your time âstead oâ wood-choppinâ.â

âUncle Matt earns his livinâ at it,â he urged.

âUncle Mattâs a villain. Donât you go by your Uncle Matt, fur lanâs sake.â She rolled up the drawing fiercely, and Matt placed himself apprehensively between it and the stove.

âYou said he wouldnât be took,â he remonstrated.

Mrs. Strang sullenly placed the paper in her bosom, and the action reminded her to remove her bonnet and sacque. Harriet, drooping and listless, descended the stairs, carrying the two-year-old and marshalling the other little ones—a blinking, bewildered group of cherubs, with tousled hair and tumbled clothes. Sprat came down last, stretching himself sleepily. He had kept the same late hours as Matt, and, returning with him from the âmuddinâ frolic,â had crept under his bed.

The sight of the children moved Mrs. Strang to fresh weeping. She almost tore the baby from Harrietâs arms.

âHe never saw you!â she cried, hysterically, closing the wee yawning mouth with kisses. Her eyes fell on Billy limping towards the red-hot stove where the others were already clustered.

âAnâ he never saw you,â she cried to him, as she adjusted the awed infant on the settle. âOr it would hev broke his heart. Kneel down and say a prayer for him, you mischeevious little imp.â

Billy, thus suddenly apostrophized, paled with nervous fright. His big gray eyes grew moist, a lump rose in his throat. But he knelt down with the rest and began bravely:

âOur Father, which art in heaven—â

âWell, what are you stoppinâ about?â jerked his mother, for the boy had paused suddenly with a strange light in his eyes.

âI never knowed what it meant afore,â he said, simply.

His motherâs eye caught the mystic gleam from his.

âA sign! a sign!â she cried, ecstatically, as she sprang up and clasped the little cripple passionately to her heaving bosom.

CHAPTER II

THE DEAD MAN MAKES HIS FIRST AND LAST APPEARANCE

The death of his father—of whom he had seen so little—gave Matt a haunting sense of the unsubstantiality of things. What! that strong, wiry man, with the shrewd, weather-beaten face and the great tanned hands and tattooed arms, was only a log swirling in the currents of unknown waters! In vain he strove to figure him as a nebulous spirit—the conception would not stay. Nay, the incongruity seemed to him to touch blasphemy. His father belonged to the earth and the seas; had no kinship with clouds. How well he remembered the day, nearly three years ago, when they had parted forever, and, indeed, it had been sufficiently stamped upon his memory without this final blow.