автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Mysteries of Police and Crime, Vol. 1 (of 3)

Every attempt has been made to replicate the original as printed.

Some typographical errors have been corrected; a list follows the text.

In certain versions of this etext, in certain browsers, clicking on an image will bring up a larger version.

Contents.

(etext transcriber's note)

MYSTERIES OF POLICE

AND CRIME

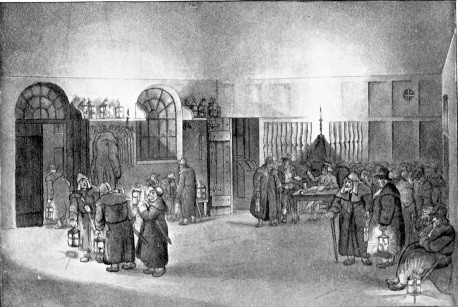

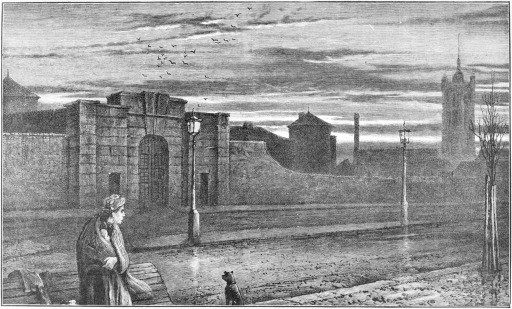

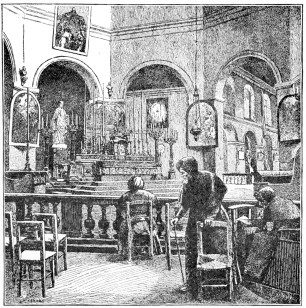

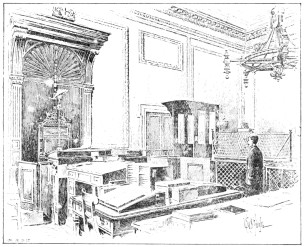

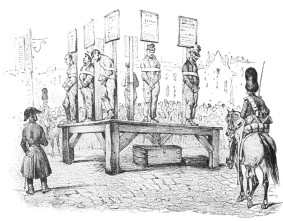

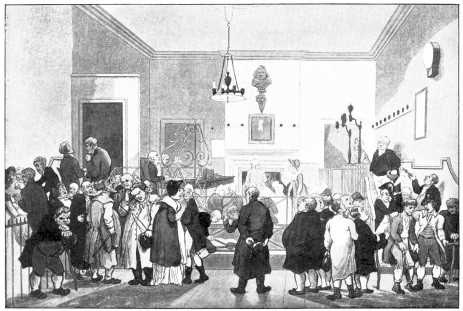

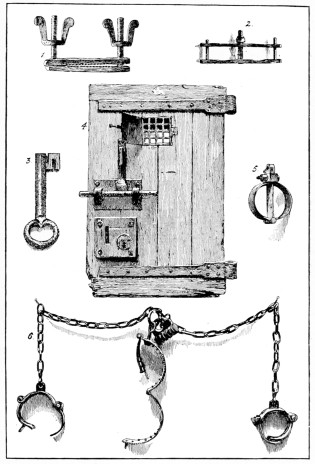

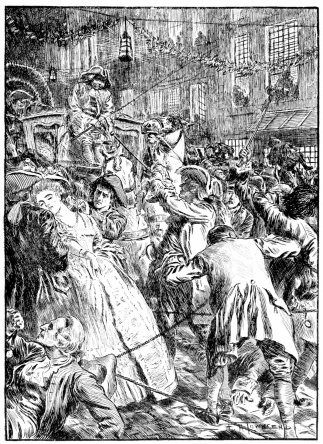

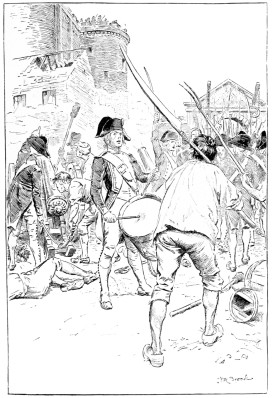

WATCH HOUSE AND WATCHMEN A CENTURY AGO. (From a Contemporary Print by Rowlandson and Pugin.)

Mysteries

OF

Police and Crime

BY

Major ARTHUR GRIFFITHS

FORMERLY ONE OF H.M. INSPECTORS OF PRISONS; JOHN HOWARD GOLD

MEDALLIST; AUTHOR OF “MEMORIALS OF MILLBANK,” “CHRONICLES OF

NEWGATE,” ETC.

PROFUSELY ILLUSTRATED

IN THREE VOLUMES

VOL. I.

SPECIAL EDITION

CASSELL AND COMPANY, Limited

LONDON, PARIS, NEW YORK & MELBOURNE

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

CONTENTS.

Part I.

A GENERAL SURVEY OF CRIME AND ITS DETECTION.

PAGE

Crime Distinguished from Law-breaking—The General Liability to Crime—Preventive Agencies—Plan of the Work—Different Types of Murders and Robberies—Crime Developed by Civilisation—The Police the Shield and Buckler of Society—Difficulty of Disappearing under Modern Conditions—The Press an Aid to the Police: the Cases of Courvoisier, Müller, and Lefroy—The Importance of Small Clues—“Man Measurement” and Finger-Prints—Strong Scents as Clues—Victims of Blind Chance: the Cases of Troppmann and Peace—Superstitions of Criminals—Dogs and other Animals as Adjuncts to the Police—Australian Blacks as Trackers: Instances of their Almost Superhuman Skill—How Criminals give themselves Away: the Murder of M. Delahache, the Stepney Murder, and other Instances—Cases in which there is Strong but not Sufficient Evidence: the Great Coram Street and Burdell Murders: the Probable Identity of “Jack the Ripper”—Undiscovered Murders: the Rupprecht, Mary Rogers, Nathan, and other Cases: Similar Cases in India: the Button Crescent Murder: the Murder of Lieutenant Roper—The Balance in Favour of the Police

Part II.

JUDICIAL ERRORS.

CHAPTER I.

Wrongful Convictions.

Judge Cambo, of Malta—The D’Anglades—The Murder of Lady Mazel—Execution of William Shaw for the Murder of his Daughter—The Sailmaker of Deal and the alleged Murder of a Boatswain—Brunell, the Innkeeper—Du Moulin, the Victim of a Gang of Coiners—The Famous Calas Case at Toulouse—Gross Perversion of Justice at Nuremberg—The Blue Dragoon

CHAPTER II.

Cases of Disputed or Mistaken Identity.

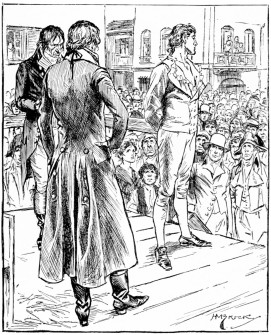

Lesurques and the Robbery of the Lyons Mail—The Champignelles Mystery—Judge Garrow’s Story—An Imposition practised at York Assizes—A Husband claimed by Two Wives—A Milwaukee Mystery—A Scottish Case—The Kingswood Rectory Murder—The Cannon Street Murder—A Narrow Escape

CHAPTER III.

Problematical Errors.

Captain Donellan and the Poisoning of Sir Theodosius Boughton: Donellan’s Suspicious Conduct: Evidence of John Hunter, the great Surgeon: Sir James Stephen’s View: Corroborative Story from his Father—The Lafarge Case: Madame Lafarge and the Cakes: Doctors differ as to Presence of Arsenic in the Remains: Possible Guilt of Denis Barbier: Madame Lafarge’s Condemnation: Pardoned by Napoleon III.—Charge against Madame Lafarge of stealing a School Friend’s Jewels: Her Defence: Conviction—Madeleine Smith charged with Poisoning her Fiancé: “Not Proven”: the Latest Facts—The Wharton-Ketchum Case in Baltimore, U.S.A.—The Story of the Perrys

CHAPTER IV.

Police Mistakes.

The Saffron Hill Murder: Narrow Escape of Pellizioni: Two Men in Newgate for the same Offence—The Murder of Constable Cock—The Edlingham Burglary: Arrest, Trial, and Conviction of Brannagan and Murphy: Severity of Judge Manisty: A new Trial: Brannagan and Murphy Pardoned and Compensated: Survivors of the Police Prosecutors put on their Trial, but Acquitted—Lord Cochrane’s Case: His Tardy Rehabilitation

Part III.

POLICE—PAST AND PRESENT.

CHAPTER V.

Early Police: France.

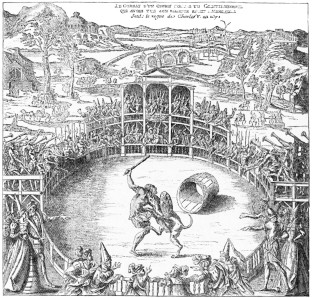

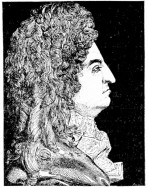

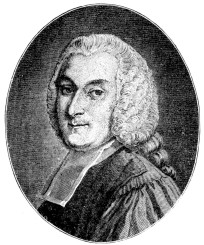

Origin of Police—Definitions—First Police in France—Charles V.—Louis XIV.—The Lieutenant-General of Police: His Functions and Powers—La Reynie: His Energetic Measures against Crime: As a Censor of the Press: His Steps to Check Gambling and Cheating at Games of Chance—La Reynie’s Successors: the D’Argensons, Hérault, D’Ombréval, Berryer—The Famous de Sartines—Two Instances of his Omniscience—Lenoir and Espionage—De Crosne, the last and most feeble Lieutenant-General of Police—The Story of the Bookseller Blaziot—Police under the Directory and the Empire—Fouché: His Beginnings and First Chances: A Born Police Officer: His Rise and Fall—General Savary: His Character: How he organised his Service of Spies: His humiliating Failure in the Conspiracy of General Malet—Fouché’s return to Power: Some Views of his Character

CHAPTER VI.

Early Police (continued): England.

Early Police in England—Edward I.’s Act—Elizabeth’s Act for Westminster—Acts of George II. and George III.—State of London towards the End of the Eighteenth Century—Gambling and Lottery Offices—Robberies on the River Thames—Receivers—Coiners—The Fieldings as Magistrates—The Horse Patrol—Bow Street and its Runners: Townsend, Vickery, and others—Blood Money—Tyburn Tickets—Negotiations with Thieves to recover stolen Property—Sayer—George Ruthven—Serjeant Ballantine on the Bow Street Runners compared with modern Detectives

CHAPTER VII.

Modern Police: London.

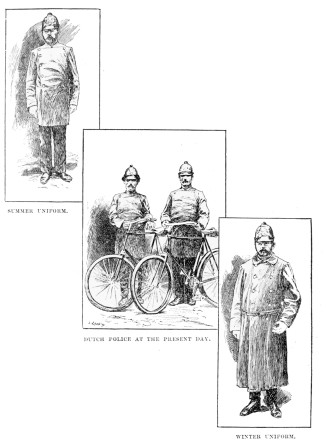

The “New Police” introduced by Peel—The System supported by the Duke of Wellington—Opposition from the Vestries—Brief Account of the Metropolitan Police: Its Uses and Services—The River Police—The City Police—Extra Police Services—The Provincial Police

CHAPTER VIII.

Modern Police (continued): Paris.

The Spy System under the Second Empire—The Manufacture of Dossiers—M. Andrieux receives his own on being appointed Prefect—The Clerical Police of Paris—The Sergents de Ville—The Six Central Brigades—The Cabmen of Paris, and how they are kept in Order—Stories of Honest and of Dishonest Cabmen—Detectives and Spies—Newspaper Attacks upon the Police—Their General Character

CHAPTER IX.

Modern Police (continued): New York.

Greater New York—Despotic Position of the Mayor—Constitution of the Police Force—Dr. Parkhurst’s Indictment—The Lexow Commission and its Report—Police Abuses: Blackmail, Brutality, Collusion with Criminals, Electoral Corruption, the Sale of Appointments and Promotions—Excellence of the Detective Bureau—The Black Museum of New York—The Identification Department—Effective Control of Crime

CHAPTER X.

Modern Police (continued): Russia.

Mr. Sala’s Indictment of the Russian Police—Their Wide-reaching Functions—Instances of Police Stupidity—Why Sala Avoided the Police—Von H—— and his Spoons—Herr Jerrmann’s Experiences—Perovsky, the Reforming Minister of the Interior—The Regular Police—A Rural Policeman’s Visit to a Peasant’s House—The State Police—The Third Section—Attacks upon Generals Mezentzoff and Drenteln—The “Paris Box of Pills”—Sympathisers with Nihilism: An Invaluable Ally—Leroy Beaulieu on the Police of Russia—Its Ignorance and Inadequate Pay—The Case of Vera Zassoulich—The Passport System: How it is Evaded and Abused: Its Oppressiveness

CHAPTER XI.

Modern Police (continued): India.

The New System Compared with the Old—Early Difficulties Gradually Overcome—The Village Police in India—Discreditable Methods under the Old System—Torture, Judicial and Extra-Judicial—Native Dislike of Police Proceedings—Cases of Men Confessing to Crimes of which they were Innocent—A Mysterious Case of Theft—Trumped-up Charges of Murder—Simulating Suicide—An Infallible Test of Death—The Paternal Duties of the Police—The Native Policeman Badly Paid

CHAPTER XII.

The Detective, and What He has Done.

The Detective in Fiction and in Fact—Early Detection—Case of Lady Ivy—Thomas Chandler—Mackoull, and how he was run down by a Scots Solicitor—Vidocq: his Early Life, Police Services, and End—French Detectives generally—Amicable Relations between French and English Detectives

CHAPTER XIII.

English and American Detectives.

English Detectives—Early Prejudices against them Lived Down—The late Mr. Williamson—Inspector Melville—Sir C. Howard Vincent—Dr. Anderson—Mr. Macnaghten—Mr. McWilliam and the Detectives of the City Police—A Country Detective’s Experiences—Allan Pinkerton’s first Essay in Detection—The Private Inquiry Agent and the Lengths to which he will go

Part IV.

CAPTAINS OF CRIME.

CHAPTER XIV.

Some Famous Swindlers.

Recurrence of Criminal Types—Heredity and Congenital Instinct—The Jukes and other Families of Criminals—John Hatfield—Anthelme Collet’s Amazing Career of Fraud—The Story of Pierre Cognard: Count Pontis de St. Hélène: Recognised by an old Convict Comrade: Sent to the Galleys for Life—Major Semple: His many Vicissitudes in Foreign Armies: Thief and Begging-Letter Writer: Transported to Botany Bay

CHAPTER XV.

Swindlers of more Modern Type.

Richard Coster—Sheridan, the American Bank Thief—Jack Canter—The Frenchman Allmayer, a typical Nineteenth Century Swindler—Paraf—The Tammany Frauds—Burton, alias Count von Havard—Dr. Vivian, a bogus Millionaire Bridegroom—Mock Clergymen: Dr. Berrington: Dr. Keatinge—Harry Benson, a Prince of Swindlers: The Scotland Yard Detectives suborned: Benson’s Adventures after his Release: Commits Suicide in the Tombs Prison—Max Shinburn and his Feats

CHAPTER XVI.

Some Female Criminals.

Criminal Women Worse than Criminal Men—Bell Star—Comtesse Sandor—Mother M——, the Famous Female Receiver of Stolen Goods—The “German Princess”—Jenny Diver—The Baroness de Menckwitz—Emily Lawrence—Louisa Miles—Mrs. Gordon-Baillie: Her Dashing Career: Becomes Mrs. Percival Frost: the Crofters’ Friend: Triumphal Visit to the Antipodes: Extensive Frauds on Tradesmen: Sentenced to Penal Servitude—A Viennese Impostor—Big Bertha, the “Confidence Queen”

Part I.

A GENERAL SURVEY OF CRIME AND ITS DETECTION.

Crime Distinguished from Law-breaking—The General Liability to Crime—Preventive Agencies—Plan of the Work—Different Types of Murders and Robberies—Crime Developed by Civilisation—The Police the Shield and Buckler of Society—Difficulty of Disappearing under Modern Conditions—The Press an Aid to the Police: the Cases of Courvoisier, Müller, and Lefroy—The Importance of Small Clues—“Man Measurement” and Finger-Prints—Strong Scents as Clues—Victims of Blind Chance: the Cases of Troppmann and Peace—Superstitions of Criminals—Dogs and other Animals as Adjuncts to the Police—Australian Blacks as Trackers: Instances of their Almost Superhuman Skill—How Criminals give themselves Away: the Murder of M. Delahache, the Stepney Murder, and other Instances—Cases in which there is Strong but not Sufficient Evidence: the Burdell and Various Other Murders: the Probable Identity of “Jack the Ripper”—Undiscovered Murders: the Rupprecht, Mary Rogers, Nathan, and other Cases: Similar Cases in India: the Burton Crescent Murder: the Murder of Lieutenant Roper—The Balance in Favour of the Police.

I.—THE CAUSES OF CRIME.

CRIME is the transgression by individuals of rules made by the community. Wrong-doing may be either intentional or accidental—a wilful revolt against law, or a lapse through ignorance of it. Both are punishable by all codes alike, but the latter is not necessarily a crime. To constitute a really criminal act the offence must be wilful, perverse, malicious; the offender then becomes the general enemy, to be combated by all good citizens, through their chosen defenders, the police. This warfare has existed from the earliest times; it is in constant progress around us to-day, and it will continue to be waged until the advent of that Millennium in which there is to be no more evil passion to agitate mankind.

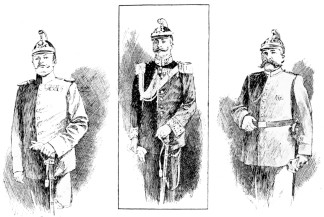

TYPES OF MALE CRIMINALS. (From Photographs preserved at the Black Museum, New Scotland Yard.)

It may be said that society itself creates the crimes that most beset it. If the good things of life were more evenly distributed, if everyone had his rights, if there were no injustice, no oppression, there would be no attempts to readjust an unequal balance by violent or flagitious means. There is some force in this, but it is very far from covering the whole ground, and it cannot excuse many forms of crime. Crime, indeed, is the birthmark of humanity, a fatal inheritance known to the theologians as original sin. Crime, then, must be constantly present in the community, and every son of Adam may, under certain conditions, be drawn into it. To paraphrase a great saying, some achieve crime, some have it thrust upon them; but most of us (we may make the statement without subscribing to all the doctrines of the criminal anthropologists) are born to crime. The assertion is as old as the hills; it was echoed in the fervent cry of pious John Bradford when he pointed to the man led out to execution, “There goes John Bradford but for the grace of God!”

Criminals are manufactured both by social cross-purposes and by the domestic neglect which fosters the first fatal predisposition. “Assuredly external factors and circumstances count for much in the causation of crime,” says Maudsley. The preventive agencies are all the more necessary where heredity emphasises the universal natural tendency. The taint of crime is all the more potent in those whose parentage is evil. The germ is far more likely to flourish into baleful vitality if planted by congenital depravity. This is constantly seen with the offspring of criminals. But it is equally certain that the poison may be eradicated, the evil stamped out, if better influences supervene betimes. Even the most ardent supporters of the theory of the “born criminal” admit that this, as some think, imaginary monster, although possessing all the fatal characteristics, does not necessarily commit crime. The bias may be checked; it may lie latent through life unless called into activity by certain unexpected conditions of time and chance. An ingenious refinement of the old adage, “Opportunity makes the thief,” has been invented by an Italian scientist, Baron Garofalo, who declares that “opportunity only reveals the thief”; it does not create the predisposition, the latent thievish spirit.

TYPES OF FEMALE CRIMINALS (From Photographs at the Black Museum.)

However it may originate, there is still little doubt of the universality, the perennial activity of crime. We may accept the unpleasant fact without theorising further as to the genesis of crime. I propose in these pages to take criminals as I find them; to accept crime as an actual fact, and in its multiform manifestations; to deal with its commission, the motives that have caused it, the methods by which it has been perpetrated, the steps taken—sometimes extraordinarily ingenious and astute, sometimes foolishly forgetful and ineffective—to conceal the deed and throw the pursuers off the scent; on the other hand, I shall set forth in some detail the agencies employed for detection and exposure. The subject is comprehensive, the amount of material available is colossal, almost overwhelming.

Every country, civilised and uncivilised, the whole world at large in all ages, has been cursed with crime. To deal with but a fractional part of the evil deeds that have disgraced humanity would fill endless volumes; where “envy, hatred, and malice, and all uncharitableness” have so often impelled those of weak moral sense to yield to their criminal instincts, a full catalogue would be impossible. It must be remembered that crime is ever active in seeking new outlets, always keen to adopt new methods of execution; the ingenuity of criminals is infinite, their patient inventiveness is only equalled by their reckless audacity. They will take life without a moment’s hesitation, and often for a miserably small gain; will prepare great coups a year or more in advance and wait still longer for the propitious moment to strike home; will employ address and great brain power, show fine resource in organisation, the faculty of leadership, and readiness to obey; will utilise much technical skill; will assume strange disguises and play many different parts, all in the prosecution of their nefarious schemes or in escaping penalties after the deed is done.

With material so abundant, so varied and complicated, it will be necessary to use some discretion, to follow certain clearly defined lines of choice. I propose in these pages to adopt the principle embodied in the title and to deal more particularly with the “mysteries” of crime and its incomplete, partial, or complete detection; with offences not immediately brought home to their perpetrators; offences prepared in secret, committed by offenders who have long remained perhaps entirely unknown, but who have sometimes met with their true deserts; offences that have in consequence exercised the ingenuity of pursuers, showing the highest development of the game of hide-and-seek, where the hunt is man, where one side fights for life and liberty, immunity from well-merited reprisals, the other is armed with authority to capture the human beast of prey. The flights and vicissitudes of criminals with the police at their heels make up a chronicle of moving, hair-breadth adventure unsurpassed by books of travel and sport.

Typical cases only can be taken, in number according to their

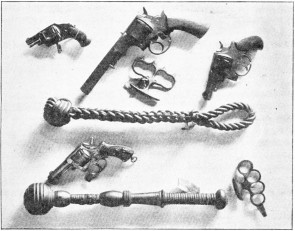

CRIMINALS’ WEAPONS: REVOLVERS, KNUCKLE DUSTERS, AND LIFE PRESERVERS IN THE BLACK MUSEUM. Photo: Cassell & Company, Limited.

relative interest and importance, but all more or less illustrating and embracing the hydra-headed varieties of crime. We shall see murders most foul, committed under the strangest conditions; brutal and ferocious attacks, followed by the most cold-blooded callousness in disposing of the evidences of the crime. In some cases a man will kill, as Garofalo puts it, “for money and possessions, to succeed to property, to be rid of one wife through hatred of her or to marry another, to remove an inconvenient witness, to avenge a wrong, to show his skill or his hatred and revolt against authority.” This class of criminal was well exemplified by the French murderer Lacenaire, who boasted that he would kill a man as coolly as he would drink a glass of wine. They are the deliberate murderers, who kill of malice aforethought and in cold blood. There will be slow, secret poisonings, often producing confusion and difference of opinion among the most distinguished scientists; successful associations of thieves and rogues, with ledgers and bank balances, and regularly audited accounts; secret societies, some formed for purely flagitious ends, with commerce and capitalists for their quarry; others for alleged political purposes, but working with fire and sword, using the forces of anarchy and disorder against all established government.

The desire to acquire wealth and possessions easily, or at least without regular, honest exertion, has ever been a fruitful source of crime. The depredators, whose name is legion, the birds of prey ever on the alert to batten upon the property of others, have flourished always, in all ages and climes, often unchecked or with long impunity. Their methods have varied almost indefinitely with their surroundings and opportunities. Now they have merely used violence and brute force, singly or in associated numbers, by open attack on highway and byway, on road, river, railway, or deep sea; now they have got at their quarry by consummate patience and ingenuity, plotting, planning, undermining or overcoming the strongest safeguards, the most vigilant precautions. Robbery has been practised in every conceivable form: by piracy, the bold adventure of the sea-rover flying his black flag in the face of the world; by brigandage in new or distracted communities, imperfectly protected by the law; by daring outrage upon the travelling public, as in the case of highwaymen, bushrangers, “holders-up” of trains; by the forcible entry of premises or the breaking down of defences designed against attack—by burglary in banks and houses, “winning” through the iron walls of safes and strong-rooms, so as to reach the treasure within, whether gold or securities or precious stones; by robberies from the person, daring garrotte robberies, dexterous neat-handed pilfering, pocket-picking, counter-snatching; by insinuating approaches to simple-minded folk, and the astute, endlessly multiplied application of the time-honoured Confidence Trick.

Crime has been greatly developed by civilisation, by the numerous processes invented to add to the comforts and conveniences in the business of daily life. The adoption of a circulating medium was soon followed by the production of spurious money, the hundred and one devices for forging notes, manufacturing coin, and clipping, sweating, and misusing that made of precious metals. The extension of banks, of credit, of financial transactions on paper, has encouraged the trade of the forger and fabricator, whose misdeeds, aimed against monetary values of all kinds, cover an extraordinarily wide range. The gigantic accumulation no less than the general diffusion of wealth, with the variety of operations that accompany its profitable manipulation, has offered temptations irresistibly strong to evil-or weak-minded people, who seem to see chances of aggrandisement, or of escape from pressing embarrassments, with the strong hope always of replacing abstractions, rectifying defalcations, or altogether evading detection. Less criminal, perhaps, but not less reprehensible, than the deliberately planned colossal frauds of a Robson, a Redpath, or a Sadleir are the victims of adverse circumstances, the Strahans, Dean-Pauls, Fauntleroys, who succeeded to bankrupt businesses and sought to cover up insolvency with a fight, a losing fight, against misfortune, resorting to nefarious practices, wholesale forgery, absolute misappropriation, and unpardonable breaches of trust.

Between the “high flyers,” the artists in crime, and the lesser fry, the rogues, swindlers, and fraudulent impostors, it is only a question of degree. These last-named, too, have in many instances swept up great gains. The class of adventurer is nearly limitless; it embraces many types, often original in character and in their criminal methods, clever knaves possessed of useful qualities—indeed, of natural gifts that might have led them to assured fortune had they but chosen the straight path and followed it patiently. We shall see with what infinite labour a scheme of imposture has been built up and maintained, how nearly impossible it was to combat the fraud, how readily the swindler will avail himself of the latest inventions, the telegraph and the telephone, of chemical appliances, of photography in counterfeiting signatures or preparing banknote plates, ere long, perchance, of the Röntgen rays. We shall find the most elaborate and cleverly designed attacks on great banking corporations, whether by open force or insidious methods of forgery and falsification, attacks upon the vast stores of valuables that luxury keeps at hand in jewellers’ safes and shop fronts, and on the dressing-tables of great dames. Crime can always command talent, industry also, albeit laziness is ingrained in the criminal class. The desire to win wealth easily, to grow suddenly rich by appropriating the possessions or the earnings of others, is no doubt a strong incitement to crime; yet the depredator who will not work steadily at any honest occupation will give infinite time and pains to compass his criminal ends.

REDUCED FAC-SIMILE OF PART OF FRONT PAGE OF THE FIRST NUMBER OF THE “POLICE GAZETTE” (p. 13.)

II.—THE HUNTERS AND THE HUNTED.

Society, weak, gullible, and defenceless, handicapped by a thousand conventions, would soon be devoured alive by its greedy parasites: but happily it has devised the shield and buckler of the police; not an entirely effective protector, perhaps, but earnest, devoted, unhesitating in the performance of its duties. The finer achievements of eminent police officers are as striking as the exploits of the enemies they continually pursue. In the endless warfare success inclines now to this side, now to that; but the forces of law and order have generally the preponderance in the end. Infinite pains, unwearied patience, abounding wit, sharp-edged intuition, promptitude in seizing the vaguest shadow of a clue, unerring sagacity in clinging to it and following it up to the end—these qualities make constantly in favour of the police. The fugitive is often equally alert, no less gifted, no less astute; his crime has often been cleverly planned so as to leave few, if any, traces easily or immediately apparent, but he is constantly overmatched, and the game will in consequence go against him. Now and again, no doubt he is inexplicably stupid and shortsighted, and will run his head straight into the noose. Yet the hunters are not always free from the same fault; they will show blindness, will overrun their quarry, sometimes indeed open a door for escape.

In measuring the means and the comparative advantages of the opponents, of hunted and hunters, it is generally believed that the police have much the best of it. The machinery, the organisation of modern life, favours the pursuers. The world’s “shrinkage,” the facilities for travel, the narrowing of neutral ground, of secure sanctuary for the fugitive, the universal, almost immediate, publicity that waits on startling crimes—all these are against the criminal. Electricity is his worst and bitterest foe, and next to it rank the post and the Press. Flight is checked by the wire, the first mail carries full particulars everywhere, both to the general public and to a ubiquitous international police, brimful of camaraderie and willing to help each other. It is not easy to disappear nowadays, although I have heard the contrary stoutly maintained. A well-known police officer once assured me that he could easily and effectually efface himself, given certain conditions, such as the possession of sufficient funds (not of a tainted origin that might draw down suspicion), or the knowledge of some honest wage-earning handicraft, or fluency in some foreign language, and, above all, a face and features not easily recognisable. Given any of these conditions, he declared he could hide himself completely in the East-End, or the Western Hebrides, or South America, or provincial France, or some Spanish mountain town. In proof of this he declared that he had lived for many months in an obscure French village, and, being well acquainted with French, passed quite unknown, while watching for someone; and he strengthened his argument by quoting the case of the perpetrator of a recent robbery of pearls, who baffled pursuit for months, and gave herself up voluntarily in the end.

On the other hand, it may be questioned whether this lady was altogether hidden, or whether she was so terribly “wanted” by the police. In any case, pursuit was not so keen as it would have been with more notorious criminals. Nor can the many well-established cases of men and women leading double lives be quoted in support of this view. Such people are not necessarily in request; there may be a secret reason for concealment, for dreading discovery, but it has generally been of a social, a domestic, not necessarily a criminal character. We have all heard of the crossing-sweeper who did so good a trade that he kept his brougham to bring him to business from a snug home at the other end of the town. A case was quoted in the American papers some years back where a merchant of large fortune traded under one name, and was widely known under it “down town,” yet lived under another “up town,” where he had a wife and large family. This remarkable dissembler kept up the fraud for more than half a century, and when he died his eldest son was fifty-one, the rest of his children were middle-aged, and none of them had the smallest idea of their father’s wealth, or of his other existence. The case is not singular, moreover. Another on all fours, and even more romantic, was that of two youths with different names, walking side by side in the streets of New York, who saluted the same man as father; a gentleman with two distinct personalities.

Such deception may be long undetected when it is no one’s business to expose it. Where crime complicates it, where the police are on the alert and have an object in hunting the wrong-doer down, disappearance is seldom entirely successful. Dr. Jekyll could not cover Mr. Hyde altogether when his homicidal mania became ungovernable. The clergyman who lived a life of sanctity and preached admirable sermons to an appreciative congregation for five full years was run down at last and exposed as a noted burglar in private life. “Sir Granville Temple,” as he called himself, when he had committed bigamy several times, was eventually uncloaked and shown up as an army deserter whose father was master of a workhouse. Criminals who seek effacement do not take into sufficient account the curiosity and inquisitiveness of mankind. At times, just after the perpetration of a great crime, when the criminal is missing and the pursuit at fault, every gossip, landlady, “slavey,” local tradesman, ’bus conductor, lounger on the cab rank, newsboy, railway guard, becomes an active amateur agent of the police, prying, watching, wondering, looking askance at every stranger and newcomer; ready to call in the constable on the slightest suspicion, or immediately report any unusual circumstance. The rapid dissemination of news to the four quarters of the land by our far-reaching, indefatigable, and wide-awake Press has undoubtedly secured many arrests. The judicious publication of certain details, of personal descriptions, of names, aliases, and the supposed movements of persons in request, has constantly borne fruit. In France police officials often deprecate the incautious utterances of the Press, but it is a common practice of theirs in Paris to give out fully prepared items to the newspapers with the express intention of deceiving their quarry; the missing man has been lulled into fancied security by hearing that the pursuers are on a wrong scent, and, issuing from concealment, “gives himself away.”

THE PORTRAIT WHICH LED TO LEFROY’s ARREST (p. 12). (By permission of the “Daily Telegraph.”)

III.—THE PRESS AN AID TO THE POLICE.

Long ago, as far back as the murder of Lord William Russell by Courvoisier, proof of the crime was greatly assisted by the publication of the story in the Press. Madame Piolaine, an hotel-keeper, read in the newspaper of the arrest of a suspected person, recognising him as a man who had been in her service as a waiter. Only a day or two after the murder he had come to her, begging her to take charge of a brown paper parcel, for which he would call. He had never returned, and now Madame Piolaine hunted up the parcel, which lay at the bottom of a cupboard, where she had placed it. The fact that Courvoisier had brought it justified her in examining it, and she now found that it contained a quantity of silver plate, and other articles of value. When the police were called in, they identified the whole as part of the property abstracted from Lord William Russell’s. Here was a link directly connecting Courvoisier with the murder. Hitherto the evidence had been mainly presumptive. The discovery of Lord William’s Waterloo medal, with his gold rings and a ten-pound note, under the skirting-board in Courvoisier’s pantry was strong suspicion, but no more. The man had a gold locket, too, in his possession, the property of Lord William Russell, but it had been lost some time antecedent to the murder. All the evidence was presumptive, and the case was not made perfectly clear until Madame Piolaine was brought into it through the publicity given by the Press.

In the murder of Mr. Briggs by the German, Franz Müller, detection was greatly facilitated by the publicity given to the facts of the crime. The hat found in the railway carriage where the deed had been done was a chief clue. It bore the maker’s name inside the cover, and very soon a cabman who had read this in the newspaper came forward to say he had bought that very hat at that very maker’s for a man named Müller. Müller had been a lodger of his, and had given his little daughter a jeweller’s cardboard box, bearing the name of “Death, Cheapside.” Already this Mr. Death had produced the murdered man’s gold chain, saying he had given another in exchange for it to a man supposed to be a German. There could be no doubt now that Müller was the murderer. His movements were easily traced. He had gone across the Atlantic in a sailing ship, and was easily forestalled by the detectives in a fast Atlantic liner, which also carried the jeweller and the cabman.

Where identity is clear the publication of the signalement, if possible of the likeness, has reduced capture to a certainty; it is a mere question then of time and money. Lefroy, the murderer of Mr. Gold, was caught through the publicity given to his portrait, which had appeared in the columns of the Daily Telegraph. Some eminent but highly cautious police officers nevertheless deprecate the interference of the Press, and have said that the premature or injudicious disclosure of facts obtained in the progress of investigation has led to the escape of criminals. It is to be feared that there is an increasing distrust of the official methods of detection, and the Press is more and more inclined to institute a pursuit of its own when mysterious cases continue unsolved. We may yet see this system, which has sometimes been employed by energetic reporters in Paris, more largely adopted here. Without entering into the pro’s and con’s of such competition, it is but right to admit that the Press, with its powerful influence, its ramifications endless and widespread, has already done great service to justice in following up crime. So convinced are the London police authorities of the value of a public organ for police purposes, that they publish a newspaper of their own, the admirably managed Police Gazette, which is an improved form of a journal started in 1828. This gazette, which is circulated gratis to all police forces in the United Kingdom, gives full particulars of crimes and of persons “wanted,” with rough but often life-like woodcut portraits and sketches that help capture. Ireland has a similar organ, the Dublin Hue and Cry; and some of the chief constables of counties send out police reports that are highly useful at times. Through these various channels news travels quickly to all parts, puts all interested on the alert, and makes them active in running down their prey.

IV.—THE IMPORTANCE OF SMALL CLUES.

Detection depends largely, of course, upon the knowledge, astuteness, ingenuity, and logical powers of police officers, although they find many independent and often unexpected aids, as we shall see. The best method of procedure is clearly laid down in police manuals: an immediate systematic investigation on the theatre of a crime, the minute examination of premises, the careful search for tracks and traces, for any article left behind, however insignificant, such as the merest fragment of clothing, a scrap of paper, a harmless tool, a hat, half a button; the slow, persistent inquiry into the antecedents of suspected persons, of their friends and associates, their movements and ways, unexplained change of domicile, proved possession of substantial funds after previous indigence—all these are detailed for the guidance of the detective. It will be seen in the following pages how small a thing has often sufficed to form a clue. A name chalked upon a door in tell-tale handwriting; half a word scratched upon a chisel, has led to the identification of its guilty owner, as in the case of Orrock. A button dropped after a burglary has been found to correspond with those on the coat of a man in custody for another offence, and with the very place from which it was torn. The cloth used to enclose human remains has been recognised as that used by tailors, and the same with the system of sewing, thus narrowing inquiry to a particular class of workmen; and the fact is well illustrated in the detection of Voirbo, to be hereafter told. The position of a body has shown that death could not have been accidental. A false tooth, fortunately incombustible, has sufficed for proof of identity when every other vestige has been annihilated by fire, as in the case of Dr. Webster of Boston.

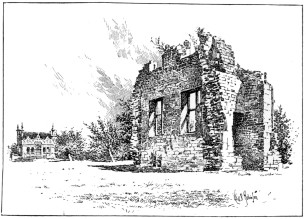

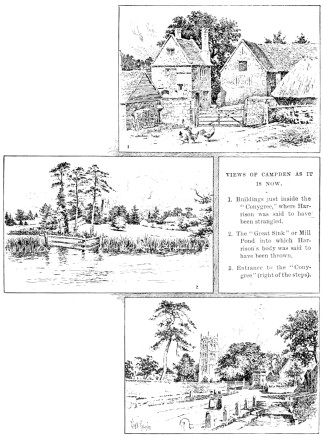

The conclusion generally arrived at was that the facts actually did happen very much as they were related, yet the whole story is involved in mystery. The only solution, so far as Perry is concerned, is that he was mad, as the second judge indeed declared. But we cannot account for Harrison’s conduct on any similar supposition. If his own story is rejected as too wild and improbable for credence, some other explanation must be found of his disappearance. Unless he was out of the country, or at least beyond all knowledge of events at Campden, it is difficult to understand what motive would have weighed with him when he heard that three persons were to be hanged as his murderers. The only possible conclusion, therefore, is that he was carried away, and kept away by force.

“The interesting letter itself I recommended should be put in the archives of the Dundonald family, and this I believe has been done.”

Fouché has been very differently judged by his contemporaries. Some thought him an acute and penetrating observer, with a profound insight into character; knowing his epoch, the men and matters appertaining to it, intimately and by heart. Others, like Bourrienne, despised and condemned him. “I know no man,” says the latter, “who has passed through such an eventful period, who has taken part in so many convulsions, who so barely escaped disgrace and was yet loaded with honours.” The keynote of his character, thought Bourrienne, was great levity and inconstancy of mind. Yet he carried out his schemes, planned with mathematical exactitude, with the utmost precision. He had an insinuating manner; could seem to speak freely when he was only drawing others on. A retentive memory and a great grasp of facts enabled him to hold his own with many masters, and turn most things to his own advantage. He did not long survive the Restoration, and died at Trieste in 1820, leaving behind him a very considerable fortune.

Serjeant Ballantine, as I have said, paid the Bow Street runners the high compliment of preferring their methods to those of our modern detectives. They kept their own counsel strictly, he thought, withholding all information, and being especially careful to give the criminal who was “wanted” no notion of the line of pursuit, of how and where a trap was to be laid for him, or with what it would be baited. They never let the public know all they knew, and worked out their detection silently and secretly. The old Serjeant was never friendly to the “New Police,” and his criticisms were probably coloured by this dislike. That it may be often unwise to blazon forth each and every step taken in the course of an inquiry is obvious enough, and there are times when the utmost reticence is indispensable. The modern detective is surely alive to this; the complaint is more often that he is too chary of news than that he is too garrulous and outspoken.

It is impossible to leave this subject without adverting to the excellent provincial police now invariably established in the great cities and wide country districts, who, especially as regards the former, have an organisation and duties almost identical with those already detailed. The police forces of Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, Edinburgh, Glasgow, and the rest yield nothing in demeanour, devotion, and daring to their colleagues of the Metropolis. In the counties, where large areas often have to be covered, great responsibility must be devolved upon officers of inferior rank, and it is not abused. These sergeants or inspectors, with their half-dozen men, are so many links in a long-drawn chain. Much depends upon them, their energy and endurance. They, too, have to prevent crime by their constant vigilance on the high roads, and by keeping close watch on all suspicious persons. For the same reason special qualities are needed in the county chief constable and his deputy; the task of superintending their posts at wide distances apart, and controlling the movements of tramps and bad characters through their district, calls for the exercise of peculiar qualities, the power of command, of rapid transfer from place to place, of keen insight into character, of promptitude and decision—qualities that are most often found in military officers, who are, in fact, generally preferred for these appointments.

With such men as this on the side of law and justice, long-continued fraud, however astutely prepared, becomes almost impossible. The private inquiry agent is generally equal to any emergency.

The famous detective, Pinkerton, was called in, and soon guessed that Shinburn had been at work. Some of the confederates were arrested, and presently Shinburn was taken, but only after a desperate encounter. Now, to ensure safe custody, the prisoner was handcuffed to one of Pinkerton’s assistants, and both were locked up in a room at the hotel. Yet Shinburn, during the night, contrived to pick the lock of the handcuff by means of the shank of his scarf-pin, and, shaking himself free, slipped quietly away. He fled to Europe, and paid a first visit to Belgium, but went back to the States to make one last grand coup. This was the robbery of the Ocean Bank in New York, from which he took £50,000 in securities, notes, and gold. With this fine booty he returned to Belgium, bought himself a title, and—at least outwardly—lived the life of an honest and respectable citizen. We have seen that Sheridan, another American “crook,” spent some years in Brussels, and it is strongly suspected that he and Shinburn were concerned in the famous mail train robbery and other great crimes in Belgium.

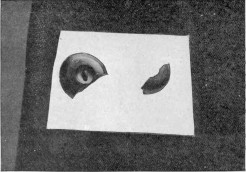

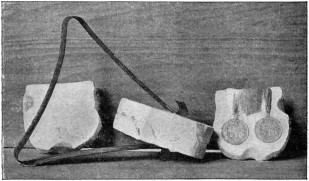

Photo: Cassell & Company, Limited. BROKEN BUTTON AT THE BLACK MUSEUM: A CLUE. (The white paper has been placed upon the cloth to show up the button.)

In one clear case of murder, detection was aided by the simple discovery of a few half-burnt matches that the criminal had used in lighting candles in his victim’s room to keep up the illusion that he was still alive. A dog, belonging to a murdered man, had been seen to leave the house with him on the morning of the crime, and was yet found fourteen days later alive and well, with fresh food by him, in the locked-up apartment to which the occupier had never returned. The strongest evidence against Patch, the murderer of Mr. Blight at Rotherhithe, was that the fatal shot could not possibly have been fired from the road outside, and the first notion of this was suggested by the doctor called in, afterwards eminent as Sir Astley Cooper. In the Gervais case proof depended greatly upon the date when the roof of a cellar had been disturbed, and this was shown to have been necessarily some time before, for in the interval the cochineal insects had laid their eggs, and this only takes place at a particular season. We shall see in the Voirbo case, quoted above, how an ingenious police officer, when he found bloodstains on a floor, discovered where a body had been buried by emptying a can of water on the uneven stones and following the channels in which it ran.

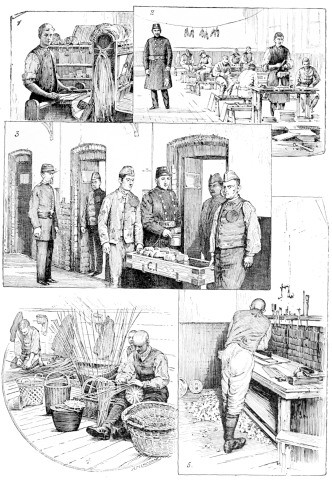

TAKING MEASUREMENTS OF CRIMINALS (BERTILLON SYSTEM).

Finger-prints and foot-marks have again and again been cleverly worked into undeniable evidence. The impression of the first is personal and peculiar to the individual; by the latter the police have been able to fix beyond question the direction in which criminals have moved, their character and class, and the neighbourhood that owns them. The labours of the scientist have within the last few years produced new methods of identification, which are invaluable in the pursuit and detection of criminals. The patient investigations of a medical expert, M. Bertillon, of Paris (one of the witnesses in the Dreyfus case), developing the scientific discovery of his father, have proved beyond all question that certain measurements of the human frame are not only constant and unchangeable, but peculiar to each subject; the width of the head, the length of the face, of the middle finger, of the lower limbs from knee to foot, and so forth, provide such a number of combinations that no two persons, speaking broadly, possess them all exactly alike. This has established the system of anthropometry, of “man measurement,” which has now been adopted on the same lines by every civilised nation in the world. The system, however, is on the face of it a complicated one, and at New Scotland Yard it has now been abandoned in favour of the finger-prints method. Mr. Francis Galton, to whose researches this mode of identification is due, has proved that finger prints, exhibited in certain unalterable combinations, suffice to fix individual identity, and his system of notation, as now practised in England, will soon provide a general register of all known criminals in the country.

EAR AND HEAD MEASURERS (THE BERTILLON SYSTEM).

MR. GALTON’S TYPES OF FINGER-PRINTS.

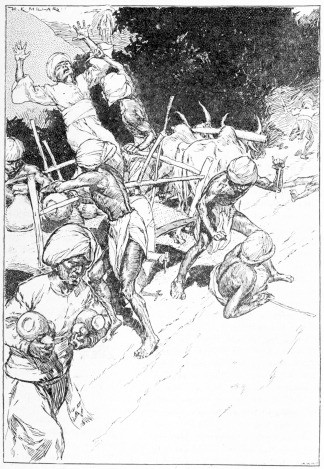

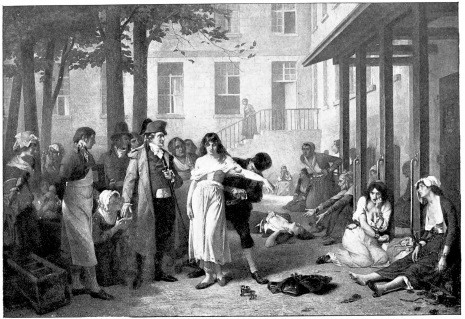

The ineffaceable odour of musk and other strong scents has more than once brought home robbery and murder to their perpetrators. A most interesting case is recorded by General Harvey,[1] where, in the plunder of a native banker and pawnbroker in India, an entire pod of musk, just as it had been excised from the deer, was carried off with a number of valuables. Musk is a costly commodity, for it is rare, and obtained generally from far-off Thibet. The police, in following up the dacoits, invaded their tanda, or encampment, and were at once conscious of an unmistakable and overpowering smell of musk,

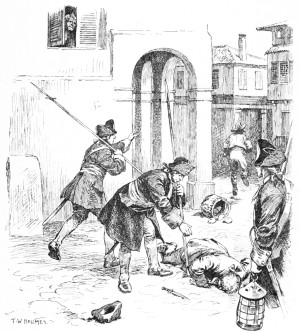

“AFTER A SHORT STRUGGLE ... THE THIEVES SEIZED THE OPIUM” (p. 18.)

which was presently dug up with a number of rupees, coins of an uncommon currency.

In another instance a scent merchant’s agent, returning from Calcutta, brought back with him a flask of spikenard. He travelled up country by boat part of the way, then landed to complete the journey, and carried with him the spikenard. He fell among thieves, a small gang of professional poisoners, who disposed of him, killing him and his companions and throwing them into the river. Long afterwards the criminals, who had appropriated all their goods, were detected by the tell-tale smell of the spikenard in their house, and the flask, nearly emptied, was discovered beneath a stack of fuel in a small room.

Yet again, the smell of opium led to the detection of a robbery in the Punjaub, where a train of bullock carts laden with the drug was plundered by dacoits. After a short struggle the bullock drivers bolted, the thieves seized the opium and buried it. But, returning through a village, they were intercepted as suspicious characters, and it was found that their clothes smelt strongly of opium. Then their footsteps were traced back to where they had committed the robbery, and thence to a spot in the dry bed of a river, in which the opium was found buried.

In India, again, many cases of obscure homicide have been brought to light by such a trifling fact as the practice, common among native women, of wearing glass, or rather shell lac, bangles or bracelets. These choorees, as they are called, are heated, then wound round wrist or ankle in continuous circles and joined. They are very brittle, and will naturally be easily smashed in a violent struggle. Fruitless search was made for a woman who had disappeared from a village, until in a field adjoining the fragments of broken choorees were picked up. On digging below, the corpse of the missing woman, bearing marks of foul play, was discovered.

In another case a father identified certain broken choorees as belonging to his daughter; they had been found, with traces of blood and wisps of female hair, near a well, and were the means of bringing home the murder. Cheevers[2] tells us that a young woman was seen to throw a boy ten years of age into a dry well twenty feet deep. Information was given, and the child was extracted, a corpse. Pieces of choorees were picked up near the well similar to those worn by the woman, who was arrested and eventually convicted of murder. Here the ingenious defence was set up that the child’s mother, a woman of the same caste as the accused, and likely to wear the same kind of bangle, had gone to wail at the well-side and might have broken her glass ornaments in the excess of her grief. But sentence of death was passed.

V.—“LUCK” FOR AND AGAINST CRIMINALS.

Among the many outside aids to detection, “luck,” blind chance, takes a very prominent place. We shall come upon innumerable instances of this. Troppmann, the wholesale murderer, was apprehended quite by accident, because his papers were not in proper form. He might still have escaped prolonged arrest had he not run for it and tried to drown himself in the harbour at Havre. The chief of a band of French burglars was arrested in a street quarrel, and was found to be carrying a great part of the stolen bonds in his pocket. When Charles Peace was taken at Blackheath in the act of burglary, and charged with wounding a policeman, no one suspected that this supposed half-caste mulatto, with his dyed skin, was a murderer much wanted in another part of the country. Every good police officer freely admits the assistance he has had from fortune. One of these—famous, not to say notorious, for he fell into bad ways—described to me how he was much thwarted and baffled in a certain case by his inability to come upon the person he was after, or any trace of him, and how, meeting a strange face in the street, a sudden impulse prompted him to turn and follow it, with the satisfactory result that he was led straight to his desired goal. The same officer confessed that chancing to see a letter delivered by the postman at a certain door he was tempted to become possessed of it, and did not hesitate to steal it. When he had opened and read it, he found the clue of which he was in search!

Criminals themselves believe strongly in luck, and in some cases are most superstitious. An Italian, whose speciality was sacrilege, never broke into a church without kneeling down before the altar to pray for good fortune and large booty. The whole system of Thuggee was based on superstition. The bands never operated without taking the omens; noting the flight of birds, the braying of a jackass to right or left, and so on, interpreting these things as warnings

THE FIGHT BETWEEN MACAIRE AND THE DOG OF MONTARGIS. (From an Old Print.)

or as encouragements to proceed. This superstitious belief in luck is still prevalent. A notorious banknote forger in France carefully abstained from counterfeiting notes of two values, those for 500 francs and 2,000 francs, being convinced that they would bring him into trouble. Thieves, it has been noticed, generally follow one line of business, because a first essay in it was successful. The man who steals coats steals them continually; once a horse thief always a horse thief; the forger sticks to his own line, as do the pickpocket, the burglar, and the performer of the confidence trick. The burglar dislikes extremely the use of any tools or instruments but his own; he generally believes that another man’s false keys, jemmies, and so forth, would bring him bad luck. Only in matter-of-fact America does the cracksman rise superior to superstition. There a good business is done by certain people who lend housebreaking tools on hire.

Instinct, aboriginal and animal, has helped at times to bring criminals to justice. The mediæval story of the dog of Montargis may be mere fable, but it rests on historic tradition that after Macaire had murdered Aubry de Montdidier in the forest of Bondy, the extraordinary aversion shown by the dog to Macaire first aroused suspicion, and led to the ordeal of mortal combat, in which the dog triumphed.

SUMATRAN THIEVES’ CALENDAR (BRITISH MUSEUM) FOR CALCULATING LUCKY DAYS.

It has been sometimes suggested that the instinct of animals might be further utilised in the pursuit of criminals. Something more than the well-known unerring chase of the bloodhound might be got from the marvellous intelligence of dogs. We shall see how the strange restlessness of the dog owned by Wainwright’s manager in the Whitechapel Road nearly led to the discovery of the murdered Harriet Lane’s remains. The clever beast was perpetually scratching at the floor beneath which the poor woman was buried, and his inconvenient restlessness no doubt led to his own destruction, for Wainwright is said to have made away with the dog. In India the idea of using the pariah dog for the purpose of smelling out buried bodies has been often put forward. Dogs would avail little, however, if the corpse lay at a great depth below ground, and hence the suggestion to draw upon the keener sense, exercised over a wider range above and below ground, of the vulture. This foul bird is commonly believed to be untameable, but it might assist unconsciously. Vultures are much given to perching upon the same tree near every Indian station, and close observation might reveal the direction of their flight. Their presence at any particular spot would constitute fair grounds for suspicion that they were after carrion. Indian police experience records many cases of the discovery of bodies through the agency of kites, vultures, crows, and scavenging wild beasts. The howling of a jackal has given the clue; in one remarkable case the body of a murdered child was traced through the snarling and quarrelling of jackals over the remains. A murderer who had buried his victim under a heap of stones, on returning (the old story) to the spot found that it had been unearthed by wild animals.

VI.—THE TRACKING INSTINCT IN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINES.

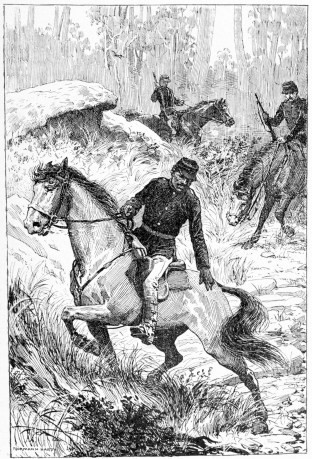

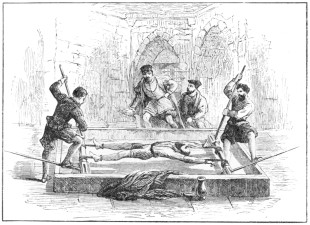

The strange, almost superhuman, powers of the Australian blacks in following blind, invisible tracks have been turned to good account in the detection of crime. Their senses of sight, smell, and touch are abnormally acute. They can distinguish the trail of lost animals one from the other, and follow it for hundreds of miles. Like the Red Indians of North America, they judge by a leaf, a blade of grass, a mere splash in the mud; they can tell with unfailing precision whether the ground has been recently disturbed, and even what has passed over it.

A remarkable instance occurred in the colony of Victoria in 1851, when a stockholder, travelling up to Melbourne with a considerable sum of money, disappeared. His horse had returned riderless to the station, and without saddle or bridle. A search was at once instituted, but proved fruitless. The horse’s hoof-marks were followed to the very boundary of the run, near which stood a hut occupied by two shepherds. These men, when questioned, declared that neither man nor horse had passed that way. Then a native who worked on the station was pressed into the service, and starting from the house, walking with downcast eyes and occasionally putting his nose to the ground, he easily followed the horse’s track to the shepherds’ hut, where he at once offered some information. “Two white mans walk here,” he said, pointing to indications he alone could discover on the ground. A few yards farther he cried, “Here fight! here large fight!” and it was seen that the grass had been trampled down. Again, close at hand, he shouted in great excitement, “Here kill—kill!” A minute examination of the spot showed that the earth had been moved recently, and on turning it over a quantity of clotted blood was found below.

AN AUSTRALIAN NATIVE TRACKING. (A Sketch from Life.)

There was nothing, however, definitely to prove foul play, and further search was necessary. The black now discovered the tracks of men by the banks of a small stream hard by, which formed the boundary of the run. The stream was shrunk to a tiny thread after the long drought, and here and there was swallowed up by sand. But it gathered occasionally into deep, stagnant pools, which marked its course. Each of these the native examined, still finding foot-marks on the margin. At last the party reached a pond larger than any, wide, and seemingly very deep. The tracker, after circling round and round the bank, said the trail had ceased, and bent all his attention upon the surface of the water, where a quantity of dark scum was floating. Some of this he skimmed off, tasted and smelt it, and decided positively—“White man here.”

The pond was soon dragged with grappling-irons and long spears, and presently a large sack was brought up, which was found to contain the mangled remains of the missing stockholder. The sack had been weighted with many stones to prevent it from rising to the surface.

Suspicion fell upon the two shepherds who lived in the hut on the boundary of the run. One was a convict on ticket-of-leave, the other a deserter from a regiment in England. Both had taken part in the search, and both had appeared much agitated and upset as the black’s marvellous discoveries were laid bare. Both, too, incautiously urged that the search had gone far enough, and protested against examining the ponds. While this was being done, and unobserved by them, a magistrate and two constables went to their hut and searched it thoroughly. They first sent away an old woman who acted as the shepherds’ servant, and then turned over the place. Nothing was found in the hut, but in an outhouse they came upon a coat and waistcoat and two pairs of trousers, all much stained with fresh blood-marks. On this the shepherds were arrested and sent down to Melbourne.

What had become of the saddle-bags in which the murdered man had carried his cash? It was surmised that they had been put by in some safe place, and again the services of the native tracker were sought. He now made a start from the shepherds’ hut, and discovered as before, by sight and smell, the tracks of two men’s feet, travelling northward. These took him to a gully or dry watercourse, in the centre of which was a high pile of stones. The tracks ended at a stone on the side, where the native said he smelt leather. When several stones had been taken down, the saddle-bags, saddle, and bridle were found hidden in an inner receptacle. The money, the motive of the murder, was still in the bags—no less than £2,000—and had been left there, no doubt, for removal at a more convenient time.

AUSTRALIAN SHEPHERD’S HUT.

The shepherds were put on their trial, and the evidence thus accumulated was deemed convincing by a jury. It was also proved that the blood-stained clothes had been worn by the prisoners both on the day before and on the very day of the murder. The stains were ascertained by chemical analysis to be of human blood, not of sheep’s, as set up by the defence. It was also shown that the men had been absent from the hut the greater part of the morning of the murder. They were executed at Melbourne.

This extraordinary faculty of following a trail is characteristic of all the Australian blacks. It was remarkably illustrated in a Queensland case, where a man was missing who was supposed to have been murdered, and whose remains were discovered by the black trackers. An aged shepherd, who had long served on a certain station, was at last sent off with a considerable sum, arrears of pay. He started down country, but was never heard of again. Various suspicious reports started a belief that he had been the victim of foul play. The police were called in, and proceeded to make a thorough search, assisted by several blacks, who usually hang about the station loafing. But they lost their native indolence when there was tracking to be done. Now they were roused to keenest excitement, and entered eagerly into the work, jabbering and gesticulating, with flashing eyes. No one, to look at these eyes, generally dull and bleary, could imagine that they possessed such visual powers, or that their owners were so shrewdly observant.

AUSTRALIAN NATIVE TYPES.

The search commenced at the hut lately occupied by the shepherd. The first thing discovered, lying among the ashes of the hearth, was a spade, which might have been used as a weapon of offence; spots on it, as the blacks declared, were of blood. Some similar spots were pointed out upon the hard, well-trodden ground outside, and the track led to a creek or water-hole, on the banks of which the blacks picked up among the tufts of short dried grass several locks of reddish-white hair, invisible to everyone else. The depths of the water were now probed with long poles, and the blacks presently fished up a blucher boot with an iron heel. The hair and the boot were both believed to belong to the missing shepherd. The trackers still found locks of hair, following them to a second water-hole, where all traces ceased, and it was supposed by some that the body lay there at the bottom. Not so the blacks, who asserted that it had now been lifted upon horseback for removal to a more distant spot, and in proof pointed out hoof-marks, which had escaped observation until they detected them. The hoof-marks were large and small, obviously of a mare and her foal. Yet the water-hole was searched thoroughly; the blacks stripped and dived, they smelt and tasted the water, but always shook their heads, and, as a matter of fact, nothing was found in this second creek. The pursuit returned to the hoof-marks, and these were followed to the edge of a scrub, where for the time they were lost.

Next day, however, they were again picked up, on the hard, bare ground, where there was hardly a blade of grass. They led to the far-off edge of a plain, towards a small spiral column which ascended into the sky. It was the remains of an old and dilapidated sheep-yard, which had been burnt by the station overseer. This man, it should have been premised, had all along been suspected of making away with the shepherd from interested motives, having been the depositary of his savings. And it was remembered that he had paid several visits in the last few days to the burning sheep-yard. Now, when the search party reached the spot, where little but charred and smouldering embers remained, the blacks eagerly turned over the ashes. Suddenly a woman, a black “gin,” screamed shrilly, and cried, “Bones sit down here,” and closer examination disclosed a heap of calcined human remains. Small portions of the skull were still unconsumed, and a few teeth were found, quite perfect, having altogether escaped the action of the fire. Soon the buckle of a belt was discovered, and identified as having been worn by the missing shepherd, and also the iron heel of a boot corresponding to that found in the first water-hole. Thus the marvellous sagacity of the black trackers had solved the mystery of the shepherd’s disappearance; but, although the shepherd’s fate was thereby established beyond doubt, the evidence was not sufficient to bring home the crime of murder to the overseer.

VII.—THE SHORTSIGHTEDNESS OF SOME CRIMINALS.

Not the least useful of the many allies found by the police are the criminals themselves. Their shortsightedness is often extraordinary; even when seemingly most careful to cover up their tracks they will neglect some small point, will drop unconsciously some slight clue, which, sooner or later, must betray them. In an American murder, at Michigan, a man killed his wife in the night by braining her with a heavy club. His story was that his bedroom had been entered through the window by some unknown murderer. This theory was at once disproved by the fact that the window was still nailed down on one side. The real murderer in planning the crime had extracted one nail and left the other.

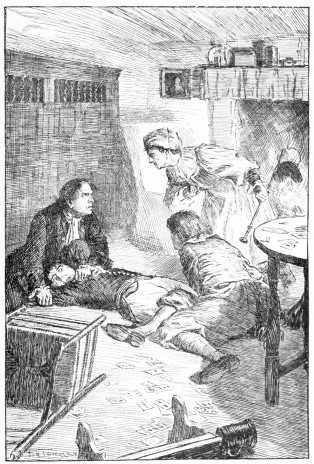

The detection of the murderers of M. Delahache, a misanthrope who lived with a paralysed mother and one old servant in a ruined abbey at La Gloire Dieu, near Troyes, was much facilitated by the carelessness with which the criminals neglected to carry off a note-book from the safe. After they had slain their three victims, they forced the safe and carried off a large quantity of securities payable to bearer, for M. Delahache was a saving, well-to-do person. They took all the gold and banknotes, but they left the title-deeds of the property and his memorandum book, in which the late owner had recorded in shorthand, illegible by the thieves, the numbers and description of the stock he held, mostly in Russian and English securities. By means of these indications it was possible to trace the stolen papers and secure the thieves, who still possessed them, together with the pocket-book itself and a number of other valuables that had belonged to M. Delahache.

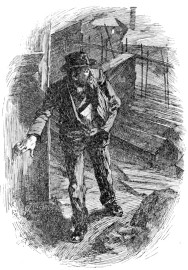

Criminals continually “give themselves away” by their own carelessness, their stupid, incautious behaviour. It is almost an axiom in detection to watch the scene of a murder for the visit of the criminal, who seems almost irresistibly drawn thither. The same impulse attracts the French murderer to the Morgue, where his victim lies in full public view. This is so thoroughly understood in Paris that the police keep officers in plain clothes among the crowd which is always filing past the plate-glass windows separating the public from the marble slopes on which the bodies are exposed. An Indian criminal’s steps generally lead him homeward to his own village, on which the Indian police set a close watch when a man is much wanted. Numerous cases might be quoted in which offenders disclose their crime by ill-advised ostentation: the reckless display of much cash by those who were, seemingly, poverty-stricken just before; self-indulgent extravagance, throwing money about wastefully, not seldom parading in the very clothes of their victims. A curious instance of the neglect of common precaution was that of Wainwright, the murderer of Harriet Lane, who left the corpus delicti, the damning proof of his guilt, to the prying curiosity of an outsider, while he went off in search of a cab.

One of the most remarkable instances of the want of reticence in a great criminal and his detection through his own foolishness occurred in the case of the Stepney murderer, who betrayed himself to the police when they were really at fault and their want of acuteness was being made the subject of much caustic criticism. The victim was an aged woman of eccentric character and extremely parsimonious habits, who lived entirely alone, only admitting a woman to help her in the housework for an hour or two every day. She owned a good deal of house property, let out in tenements to the working classes. As a rule she collected the rents herself, and was believed to have considerable sums from time to time in her house. This made her timid; being naturally of a suspicious nature, she fortified herself inside with closed shutters and locked doors, never opening to a soul until she had closely scrutinised any visitor. It called for no particular remark that for several days she had not issued forth. She was last seen on the evening of the 13th of August, 1860. When people came to see her on business on the 14th, 15th, and 16th, she made no response to their loud knockings, but her strange habits were well known; moreover, the neighbourhood was so densely inhabited that it was thought impossible she could have been the victim of foul play.

At last, on the 17th of August, a shoemaker named Emm, whom she sometimes employed to collect rents at a distance, went to Mrs. Elmsley’s lawyers and expressed his alarm at her non-appearance. The police were consulted, and decided to break into the house. Its owner was found lying dead on the floor in a lumber-room at the top of the house. Life had been extinct for some days, and death had been caused by blows on the head with a heavy plasterer’s hammer. The body lay in a pool of blood, which had also splashed the walls, and a bloody footprint was impressed on the floor, pointing outwards from the room. There were no appearances of forcible entry to the house, and the conclusion was fair that whoever had done the deed had been admitted by Mrs. Elmsley herself. A possible clue to the criminal was afforded by the several rolls of wall-paper lying about near the corpse. Mrs. Elmsley was in the habit of employing workmen on her own account to carry out repairs and decorations in her houses, and the indications pointed to her having been visited by one of these, who had perpetrated the crime. Yet the police made no useful deductions from these data.

While they were still at fault a man named Mullins, a plasterer by trade and an ex-member of the Irish constabulary, who knew Mrs. Elmsley well and had often worked for her, came forward voluntarily to throw some light on the mystery. Nearly a month had elapsed since the murder, and he declared that during this period his attention had been drawn to the man Emm and his suspicious conduct. He had watched him, had frequently seen him leave his cottage and proceed stealthily to a neighbouring brickfield, laden on each occasion with a parcel he did not bring back. Mullins, after giving this information quite unsought, led the police officers to the spot, and into a ruined outbuilding, where a strict search was made. Behind a stone slab they discovered a paper parcel containing articles which were at once identified as part of the murdered woman’s property. Mullins next accompanied the police to Emm’s house, and saw the supposed criminal arrested. But to his utter amazement the police turned on Mullins and took him also into custody. Something in his manner had aroused suspicion, and rightly, for eventually he was convicted and hanged for the crime.

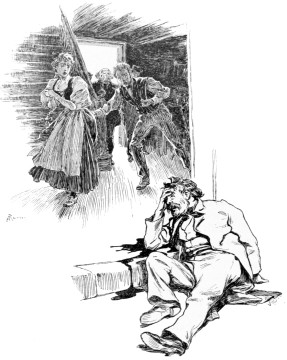

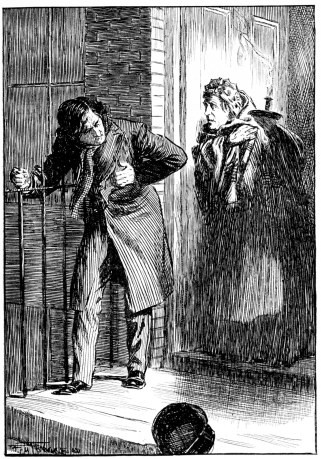

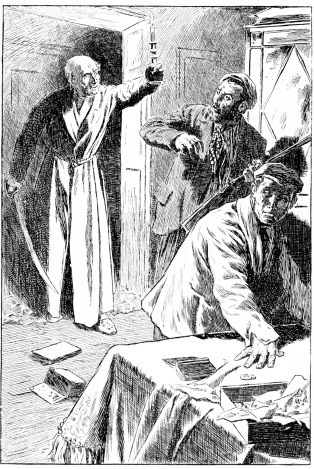

“HAD ... FREQUENTLY SEEN HIM ... PROCEED STEALTHILY TO A NEIGHBOURING BRICKFIELD.”

Here Mullins had only himself to thank. Whatever the impulse—that strange restlessness that often affects the secret murderer, or the consuming fear that the scent was hot, and his guilt must be discovered unless he could shift suspicion—it is certain that but for his own act he would never have been arrested. It may be interesting to complete this case, and show how further suspicion settled around Mullins. The parcel found in the brickfield was tied up with a tag end of tape and a bit of a dirty apron string. A precisely similar piece of tape was discovered in Mullins’s lodgings lying upon the mantelshelf. There was an inner parcel fastened with waxed cord. The idea with Mullins was, no doubt, to suggest that the shoemaker Emm had used cobbler’s wax. But a piece of wax was also found in Mullins’s possession, besides several articles belonging to the deceased.

The most conclusive evidence was the production of a plasterer’s hammer, which was also found in Mullins’s house. It was examined under the microscope, and proved to be stained with blood. Mullins had thrown away an old boot, which chanced to be picked up under the window of a room he occupied. This boot fitted exactly into the blood-stained footprint on the floor in Mrs. Elmsley’s lumber-room; moreover, two nails protruding from the sole corresponded with two holes in the board, and, again, a hole in the middle of the sole was filled up with dried blood. So far as Emm was concerned, he was able clearly to establish an alibi, while witnesses were produced who swore to having seen Mullins coming across Stepney Green at dawn on the day of the crime with bulging pockets stuffed full of something, and going home; he appeared much perturbed, and trembled all over.

Mullins was found guilty without hesitation, and the judge expressed himself perfectly satisfied with the verdict. The case was much discussed in legal circles and in the Press, and all opinions were unanimously hostile to Mullins. The convict steadfastly denied his guilt to the last, but left a paper exonerating Emm. It is difficult to reconcile this with his denunciation of that innocent man, except on the ground of his own guilty knowledge of the real murderer. In any case, it was he himself who first lifted the veil and stupidly brought justice down upon himself.

The case of Mullins was in some points forestalled by the discovery of an Indian murder, in which the native police ingeniously entrapped the criminal to assist in his own detection. A man in Kumacu, named Mungloo, disappeared, and a neighbour, Moosa, was suspected of having made away with him. The police, unable to bring home the murder to him, caught him by bringing to him a corpse which they declared was Mungloo’s. Moosa knew better, and said so. Imprudently anxious to shift all suspicion from himself, he told the police that a certain Kitroo knew where the real corpse lay, and advised them to arrest him. Kitroo was seized, and confessed in effect that Mungloo was buried close to his house. The ground was opened, and at a considerable depth down the body was found. Now Moosa came forward and claimed the credit, as well as the proffered reward for discovery. He was, he said, the first to indicate where the body was hidden. But Kitroo turned Queen’s evidence, and swore that he had seen the murder committed by Moosa and three others, and that, as he was an eye-witness, he was compelled by them to become an accomplice. Moosa was sentenced to transportation for life. There was in his case no necessity to accuse Kitroo, and but for his officiousness the corpse would never, probably, have been brought to light.

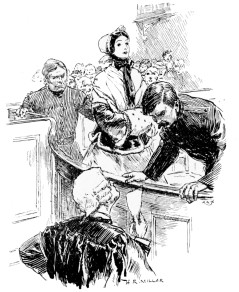

VIII.—SOME UNAVENGED CRIMES.

There have, however, been occasions when detection has failed more or less completely. The police do not admit always that the perpetrators remain unknown; they have clues, suspicion, strong presumption, even more, but there is a gap in the evidence forthcoming, and to attempt prosecution would be to face inevitable defeat. To this day it is held at Scotland Yard that the real murderer in a mysterious murder in London in the seventies was discovered, but that the case failed before an artfully planned alibi. Sometimes an arrest is made on grounds that afford strong primâ-facie evidence, yet the case breaks down in court. The Burdell murder in 1857, in New York, was one of these. Dr. Burdell was a wealthy and eccentric dentist, owning a house in Bond Street, the greater part of which he let out in tenements. One of his tenants was a Mrs. Cunningham, to whom he became engaged, and whom, according to one account, he married. In any case, they quarrelled furiously, and Dr. Burdell warned her that she must leave the house, as he had let her rooms. Whereupon she told him significantly that he might not live to sign the agreement. Shortly afterwards he was found murdered, stabbed with fifteen wounds, and there were all the signs of a violent struggle. The wounds must

OLD MILLBANK PRISON.

have been inflicted by a left-handed person, and Mrs. Cunningham was proved to be left-handed. The facts were strong against her, and she was arrested, but was acquitted on trial.

It came out long after the mysterious Road (Somerset) murder that the detectives were absolutely right about it, and that Inspector Whicher, of Scotland Yard, in fixing the crime on Constance Kent, had worked out the case with singular acumen. He elicited the motive—her jealousy of the little brother, one of a second family; he built up the clever theory of the abstracted nightdress, and obtained what he considered sufficient proof. It will be remembered that this accusation was denounced as frivolous and unjust. Mr. Whicher was so overwhelmed with ridicule that he soon afterwards retired from the force, and died, it was said, of a broken heart. His failure, as it was called, threw suspicion upon Mr. Kent, the father of the murdered child, and Gough, the boy’s nurse, and both were apprehended and charged, but the cases were dismissed. In the end, as all the world knows, Constance Kent, who had entered an Anglican sisterhood, made full confession to the Rev. Mr. Wagner, of Brighton, and she was duly convicted of murder. Although sentence of death was passed, it was commuted, and I had her in my charge at Millbank for years.

The outside public may think that the identity of that later miscreant, “Jack the Ripper,” was never revealed. So far as absolute knowledge goes, this is undoubtedly true. But the police, after the last murder, had brought their investigations to the point of strongly suspecting several persons, all of them known to be homicidal lunatics, and against three of these they held very plausible and reasonable grounds of suspicion. Concerning two of them the case was weak, although it was based on certain suggestive facts. One was a Polish Jew, a known lunatic, who was at large in the district of Whitechapel at the time of the murder, and who, having developed homicidal tendencies, was afterwards confined in an asylum. This man was said to resemble the murderer by the one person who got a glimpse of him—the police-constable in Mitre Court. The second possible criminal was a Russian doctor, also insane, who had been a convict in both England and Siberia. This man was in the habit of carrying about surgical knives and instruments in his pockets; his antecedents were of the very worst, and at the time of the Whitechapel murders he was in hiding, or, at least, his whereabouts was never exactly known. The third person was of the same type, but the suspicion in his case was stronger, and there was every reason to believe that his own friends entertained grave doubts about him. He also was a doctor in the prime of life, was believed to be insane or on the borderland of insanity, and he disappeared immediately after the last murder, that in Miller’s Court, on the 9th of November, 1888. On the last day of that year, seven weeks later, his body was found floating in the Thames, and was said to have been in the water a month. The theory in this case was that after his last exploit, which was the most fiendish of all, his brain entirely gave way, and he became furiously insane and committed suicide. It is at least a strong presumption that “Jack the Ripper” died or was put under restraint after the Miller’s Court affair, which ended this series of crimes. It would be interesting to know whether in this third case the man was left-handed or ambidextrous, both suggestions having been advanced by medical experts after viewing the victims. It is true that other doctors disagreed on this point, which may be said to add another to the many instances in which medical evidence has been conflicting, not to say confusing.