автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу A Short History of the World

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Short History of the World, by H. G. Wells

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: A Short History of the World

Author: H. G. Wells

Release Date: March 2, 2011 [EBook #35461]

Language: English

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A SHORT HISTORY OF THE WORLD ***

Produced by Donald F. Behan

A SHORT

HISTORY OF THE WORLD

BY

H. G. WELLS

New York

THE MACMILLAN & COMPANY

1922

Copyright 1922

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

Page

I.

THE WORLD IN SPACE1

II.

THE WORLD IN TIME5

III.

THE BEGINNINGS OF LIFE11

IV.

THE AGE OF FISHES16

V.

THE AGE OF THE COAL SWAMPS21

VI.

THE AGE OF REPTILES26

VII.

THE FIRST BIRDS AND THE FIRST MAMMALS31

VIII.

THE AGE OF MAMMALS37

IX.

MONKEYS, APES AND SUB-MEN43

X.

THE NEANDERTHALER AND THE RHODESIAN MAN48

XI.

THE FIRST TRUE MEN53

XII.

PRIMITIVE THOUGHT60

XIII.

THE BEGINNINGS OF CULTIVATION65

XIV.

PRIMITIVE NEOLITHIC CIVILIZATIONS71

XV.

SUMERIA, EARLY EGYPT AND WRITING77

XVI.

PRIMITIVE NOMADIC PEOPLES84

XVII.

THE FIRST SEA-GOING PEOPLES91

XVIII.

EGYPT, BABYLON AND ASSYRIA96

XIX.

THE PRIMITIVE ARYANS104

XX.

THE LAST BABYLONIAN EMPIRE AND THE EMPIRE OF DARIUS I109

XXI.

THE EARLY HISTORY OF THE JEWS115

XXII.

PRIESTS AND PROPHETS IN JUDEA122

XXIII.

THE GREEKS127

XXIV.

THE WARS OF THE GREEKS AND PERSIANS134

XXV.

THE SPLENDOUR OF GREECE139

XXVI.

THE EMPIRE OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT145

XXVII.

THE MUSEUM AND LIBRARY AT ALEXANDRIA150

XXVIII.

THE LIFE OF GAUTAMA BUDDHA156

XXIX.

KING ASOKA163

XXX.

CONFUCIUS AND LAO TSE167

XXXI.

ROME COMES INTO HISTORY174

XXXII.

ROME AND CARTHAGE180

XXXIII.

THE GROWTH OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE185

XXXIV.

BETWEEN ROME AND CHINA196

XXXV.

THE COMMON MAN’S LIFE UNDER THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE201

XXXVI.

RELIGIOUS DEVELOPMENTS UNDER THE ROMAN EMPIRE208

XXXVII.

THE TEACHING OF JESUS214

XXXVIII.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF DOCTRINAL CHRISTIANITY222

XXXIX.

THE BARBARIANS BREAK THE EMPIRE INTO EAST AND WEST227

XL.

THE HUNS AND THE END OF THE WESTERN EMPIRE233

XLI.

THE BYZANTINE AND SASSANID EMPIRES238

XLII.

THE DYNASTIES OF SUY AND TANG IN CHINA245

XLIII.

MUHAMMAD AND ISLAM248

XLIV.

THE GREAT DAYS OF THE ARABS253

XLV.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF LATIN CHRISTENDOM258

XLVI.

THE CRUSADES AND THE AGE OF PAPAL DOMINION267

XLVII.

RECALCITRANT PRINCES AND THE GREAT SCHISM277

XLVIII.

THE MONGOL CONQUESTS287

XLIX.

THE INTELLECTUAL REVIVAL OF THE EUROPEANS294

L.

THE REFORMATION OF THE LATIN CHURCH304

LI.

THE EMPEROR CHARLES V309

LII.

THE AGE OF POLITICAL EXPERIMENTS; OF GRAND MONARCHY AND PARLIAMENTS AND REPUBLICANISM IN EUROPE318

LIII.

THE NEW EMPIRES OF THE EUROPEANS IN ASIA AND OVERSEAS329

LIV.

THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE335

LV.

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION AND THE RESTORATION OF MONARCHY IN FRANCE341

LVI.

THE UNEASY PEACE IN EUROPE THAT FOLLOWED THE FALL OF NAPOLEON349

LVII.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF MATERIAL KNOWLEDGE355

LVIII.

THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION365

LIX.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN POLITICAL AND SOCIAL IDEAS370

LX.

THE EXPANSION OF THE UNITED STATES382

LXI.

THE RISE OF GERMANY TO PREDOMINANCE IN EUROPE390

LXII.

THE NEW OVERSEAS EMPIRES OF THE STEAMSHIP AND RAILWAY393

LXIII.

EUROPEAN AGGRESSION IN ASIA, AND THE RISE OF JAPAN399

LXIV.

THE BRITISH EMPIRE IN 1914405

LXV.

THE AGE OF ARMAMENT IN EUROPE, AND THE GREAT WAR OF 1914-18409

LXVI.

THE REVOLUTION AND FAMINE IN RUSSIA415

LXVII.

THE POLITICAL AND SOCIAL RECONSTRUCTION OF THE WORLD421

CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE

429

INDEX

439

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Page

Luminous Spiral Clouds of Matter2

Nebula seen Edge-on3

The Great Spiral Nebula6

A Dark Nebula7

Another Spiral Nebula8

Landscape before Life9

Marine Life in the Cambrian Period12

Fossil Trilobite13

Early Palæozoic Fossils of various Species of Lingula14

Fossilized Footprints of a Labyrinthodont, Cheirotherium15

Pterichthys Milleri17

Fossil of Cladoselache18

Sharks and Ganoids of the Devonian Period19

A Carboniferous Swamp22

Skull of a Labyrinthodont, Capitosaurus23

Skeleton of a Labyrinthodont: The Eryops24

A Fossil Ichthyosaurus27

A Pterodactyl28

The Diplodocus29

Fossil of Archeopteryx32

Hesperornis in its Native Seas33

The Ki-wi34

Slab of Marl Rich in Cainozoic Fossils35

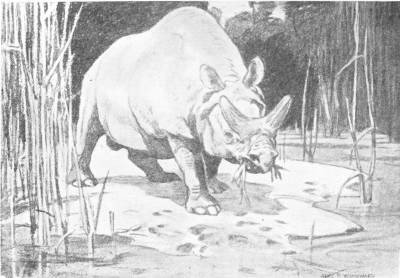

Titanotherium Robustum38

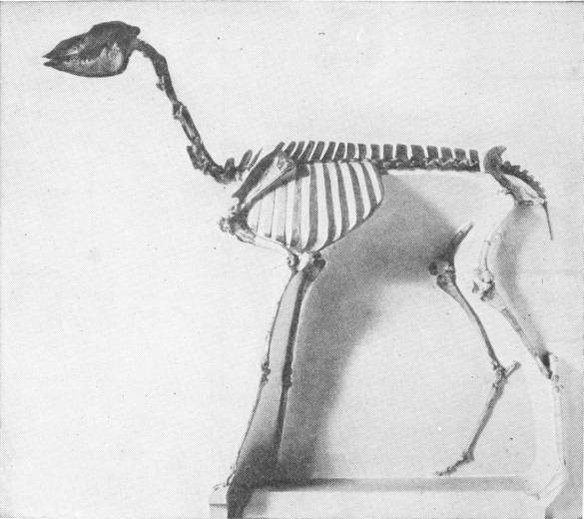

Skeleton of Giraffe-camel40

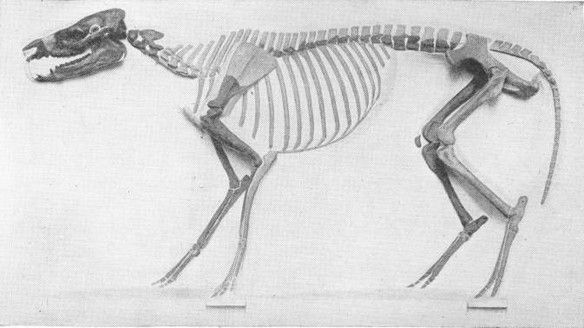

Skeleton of Early Horse40

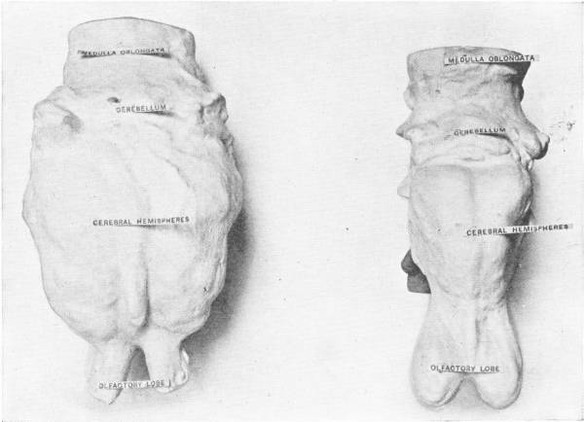

Comparative Sizes of Brains of Rhinoceros and Dinoceras41

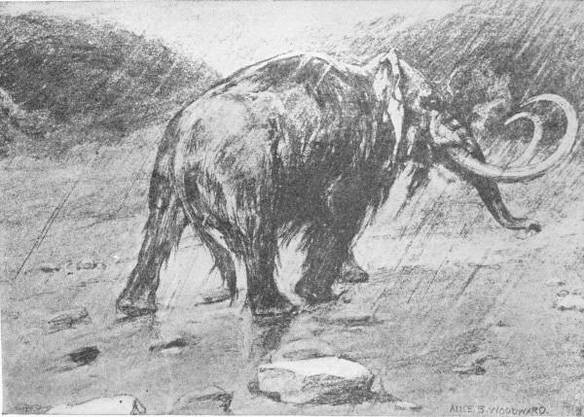

A Mammoth44

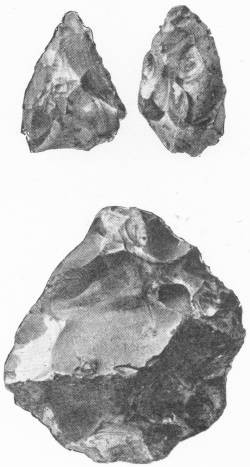

Flint Implements from Piltdown Region45

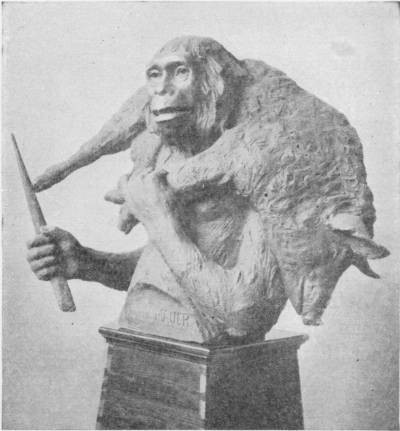

A Pithecanthropean Man46

The Heidelberg Man46

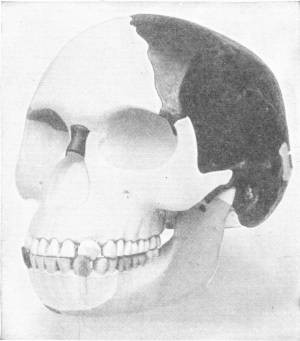

The Piltdown Skull47

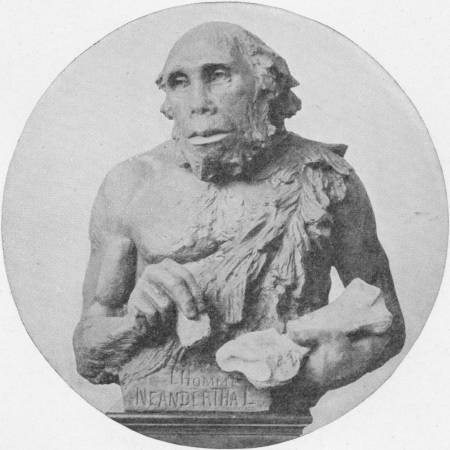

A Neanderthaler49

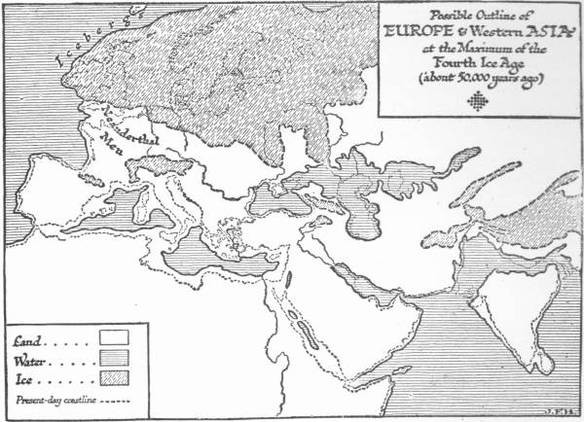

Europe and Western Asia 50,000 years ago Map50

Comparison of Modern Skull and Rhodesian Skull51

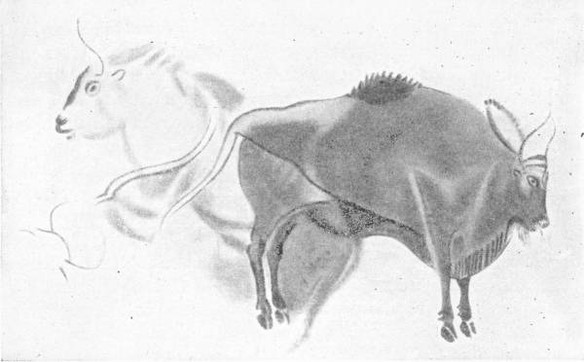

Altamira Cave Paintings54

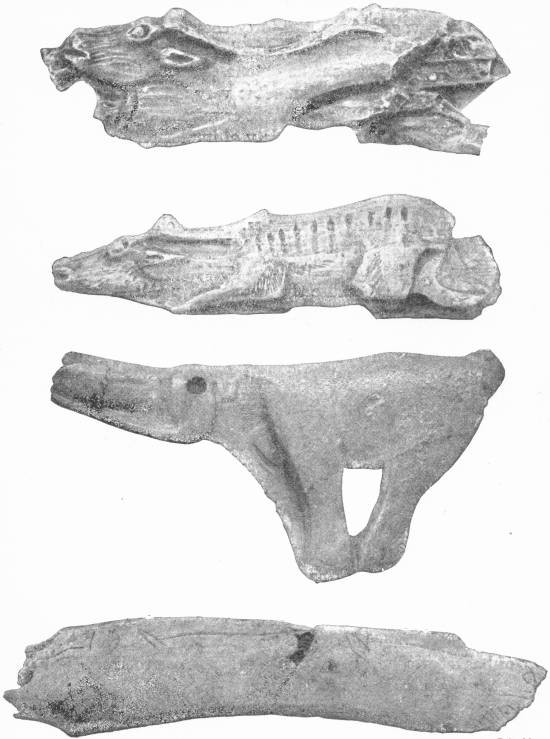

Later Palæolithic Carvings55

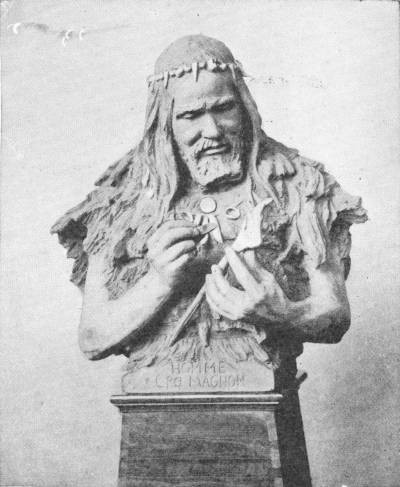

Bust of Cro-magnon Man57

Later Palæolithic Art58

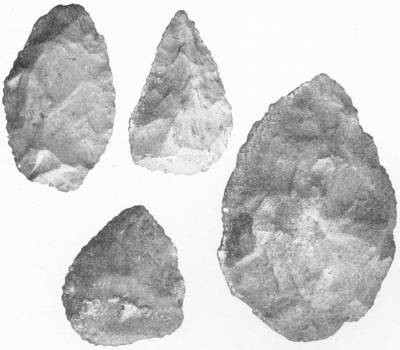

Relics of the Stone Age62

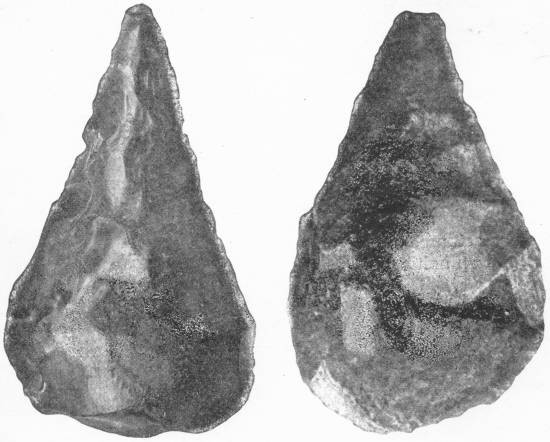

Gray’s Inn Lane Flint Implement63

Somaliland Flint Implement63

Neolithic Flint Implement67

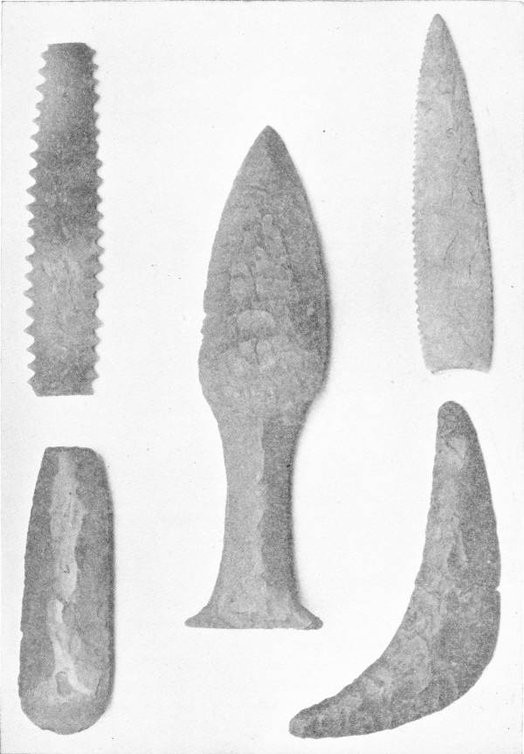

Australian Spearheads68

Neolithic Pottery69

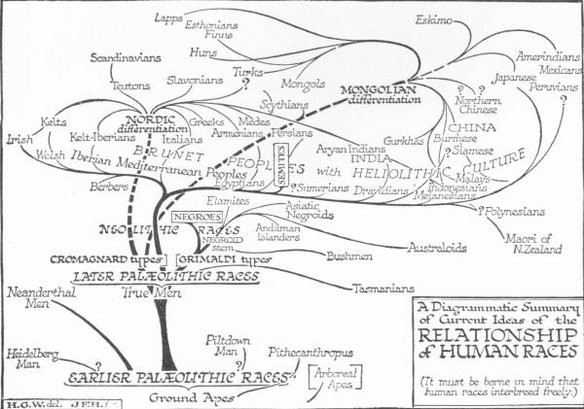

Relationship of Human Races Map72

A Maya Stele73

European Neolithic Warrior75

Babylonian Brick78

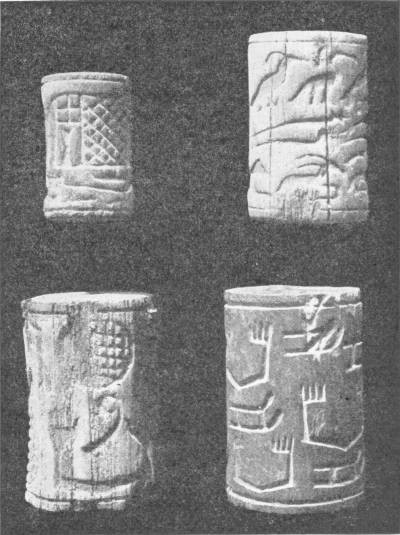

Egyptian Cylinder Seals of First Dynasty79

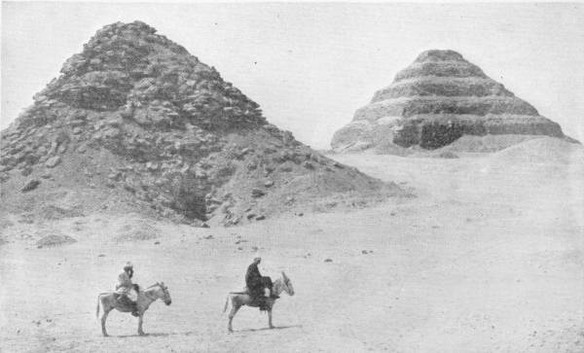

The Sakhara Pyramids80

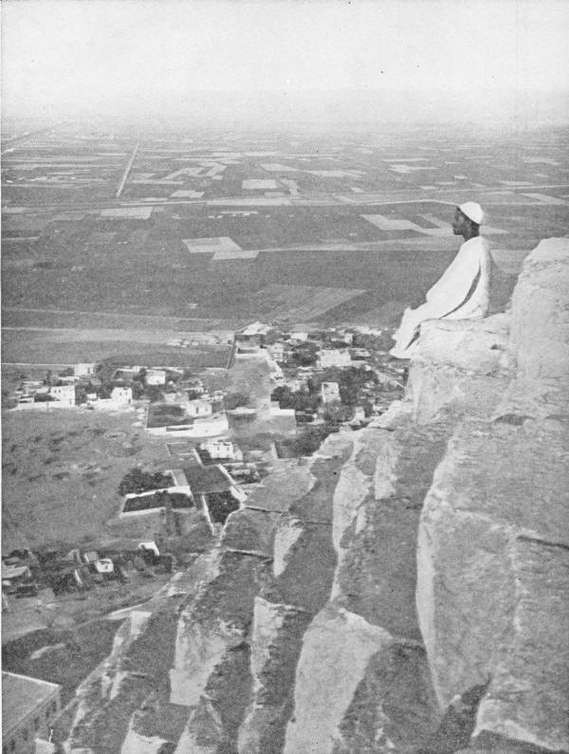

The Pyramid of Cheops: Scene from Summit81

The Temple of Hathor82

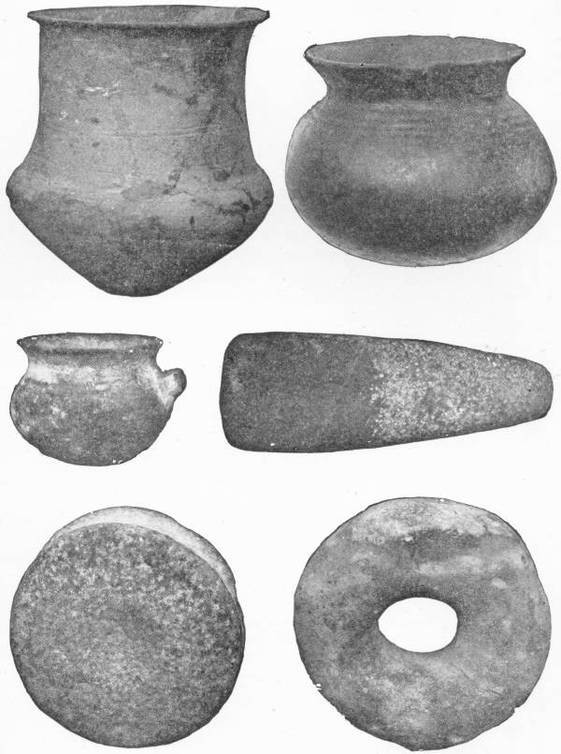

Pottery and Implements of the Lake Dwellers85

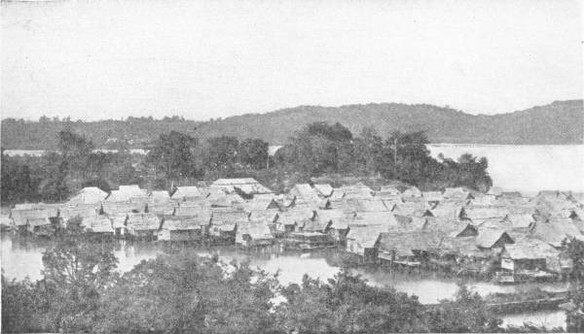

A Lake Village86

Flint Knives of 4500 B.C.87

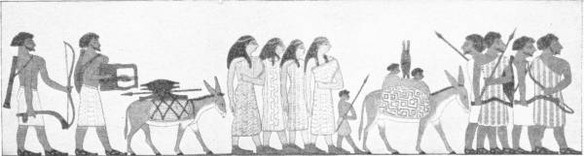

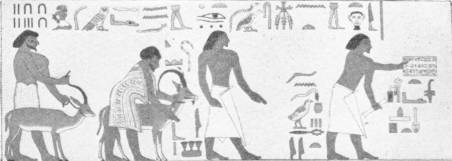

Egyptian Wall Paintings of Nomads87

Egyptian Peasants Going to Work88

Stele of Naram Sin89

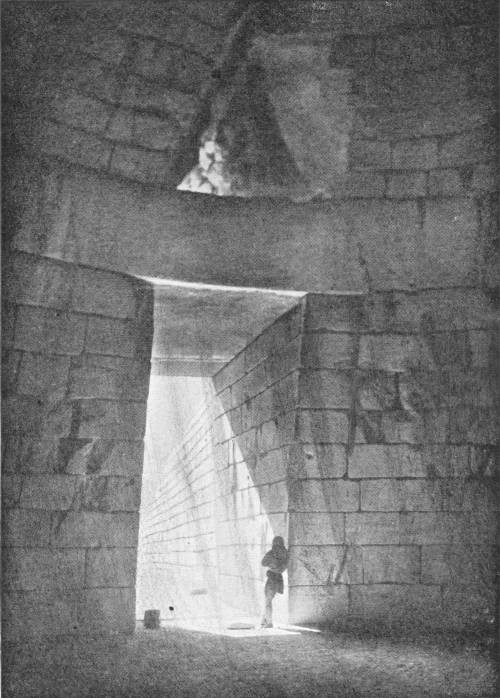

The Treasure House at Mycenæ93

The Palace at Cnossos95

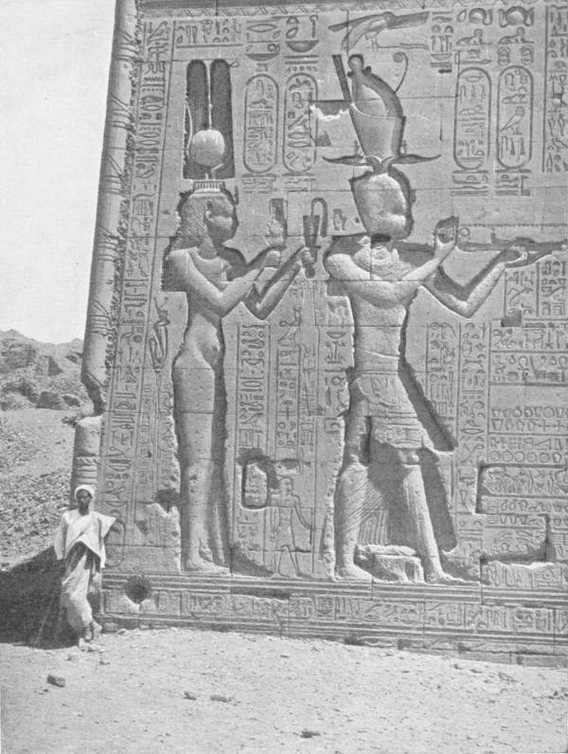

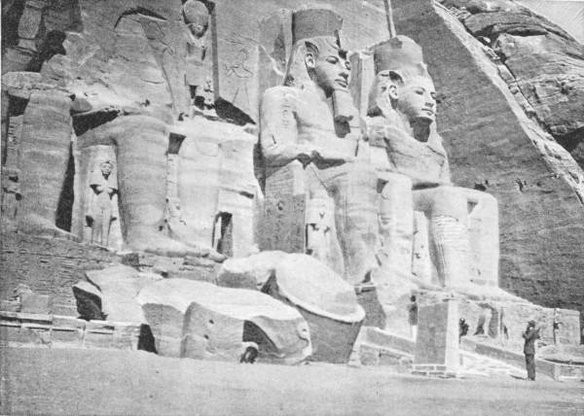

Temple at Abu Simbel97

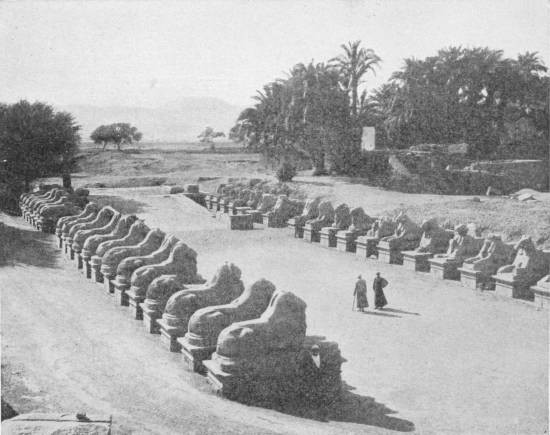

Avenue of Sphinxes at Karnak98

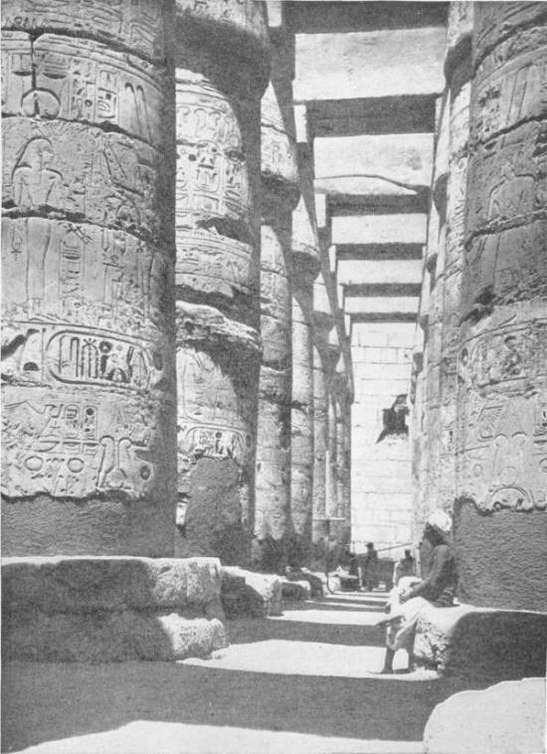

The Hypostyle Hall at Karnak99

Frieze of Slaves101

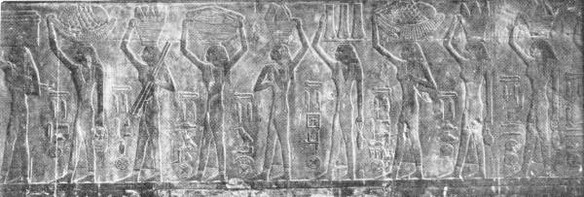

The Temple of Horus, Edfu103

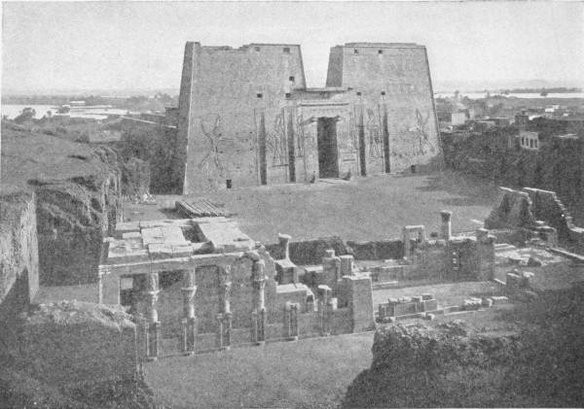

Archaic Amphora105

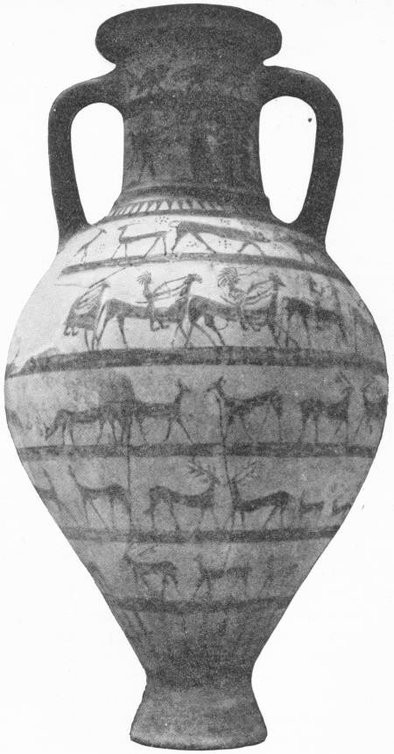

The Mound of Nippur107

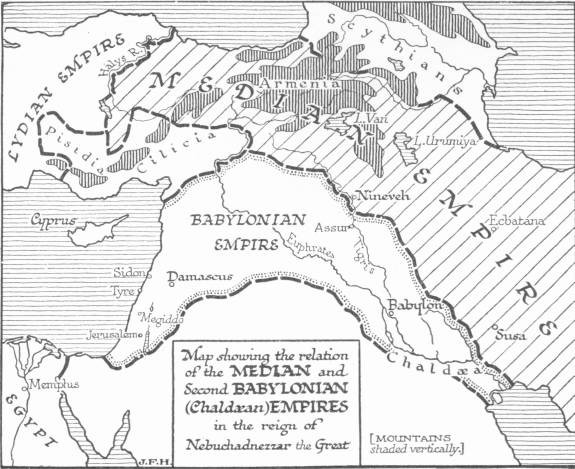

Median and Chaldean Empires Map110

The Empire of Darius Map111

A Persian Monarch112

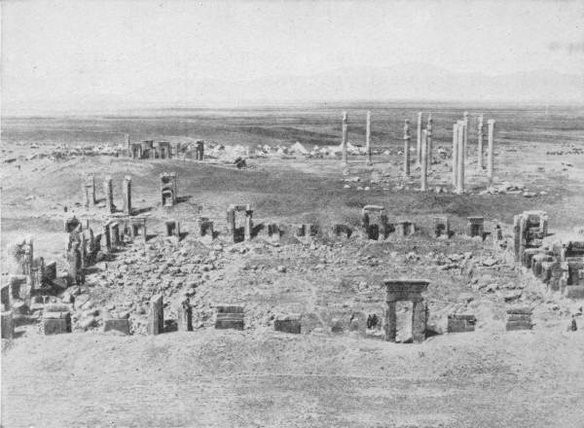

The Ruins of Persepolis113

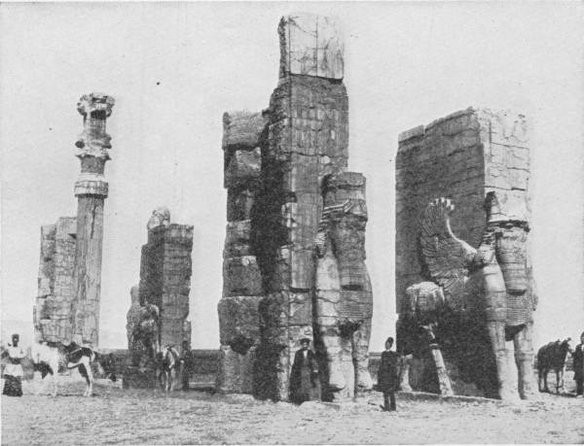

The Great Porch of Xerxes113

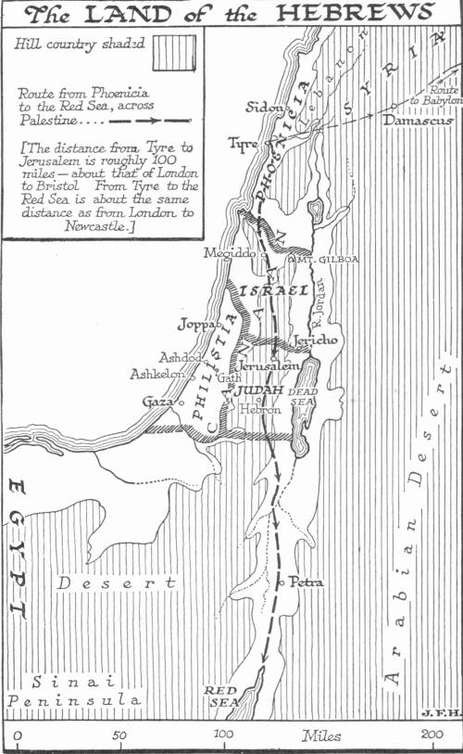

The Land of the Hebrews Map117

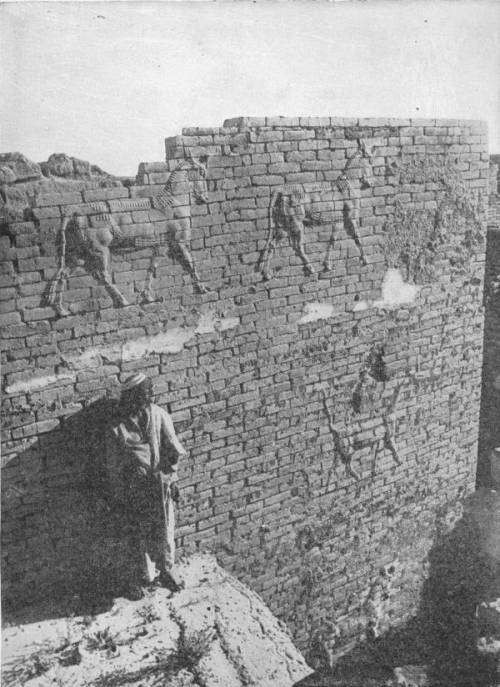

Nebuchadnezzar’s Mound at Babylon118

The Ishtar Gateway, Babylon120

Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser II124

Captive Princes making Obeisance125

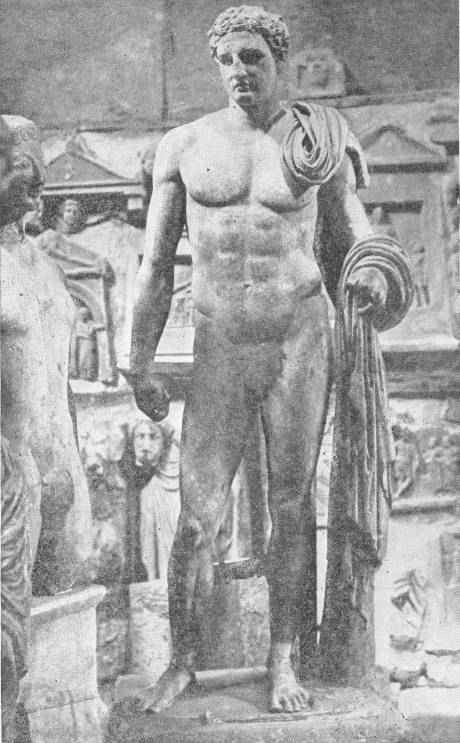

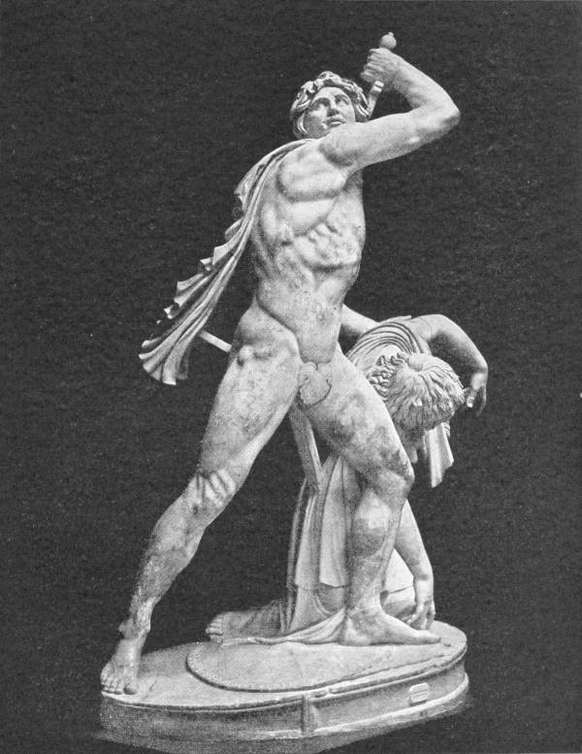

Statue of Meleager128

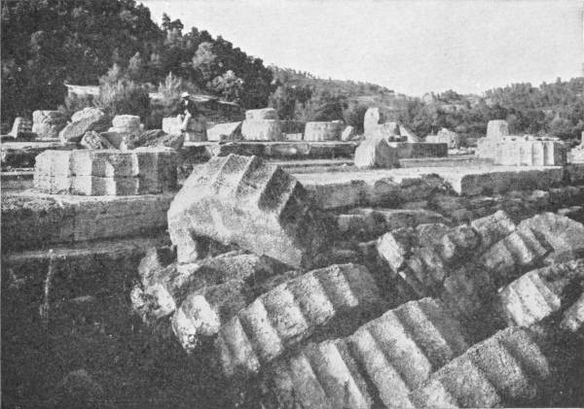

Ruins of Temple of Zeus130

The Temple of Neptune, Pæstum132

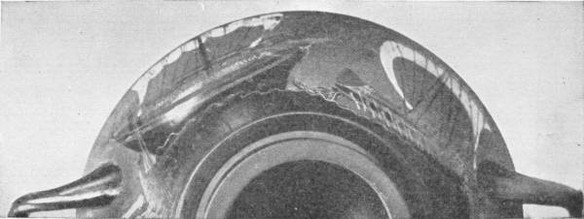

Greek Ships on Ancient Pottery135

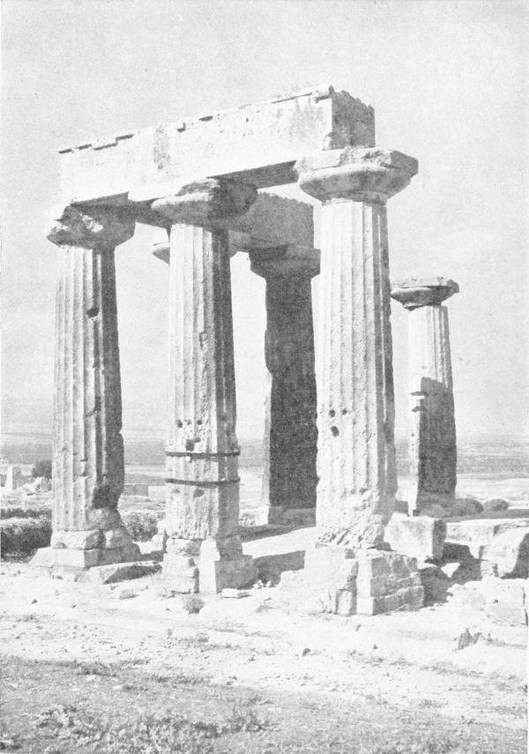

The Temple of Corinth137

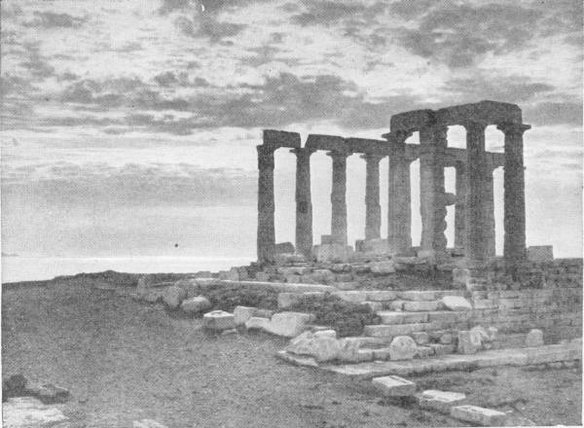

The Temple of Neptune at Cape Sunium138

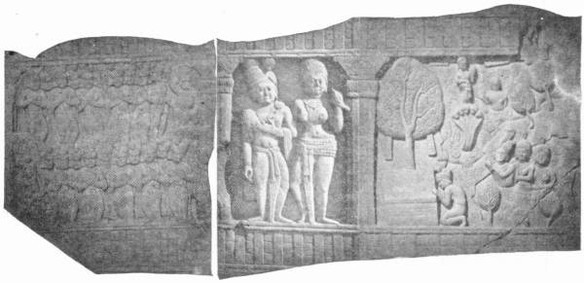

Frieze of the Parthenon, Athens140

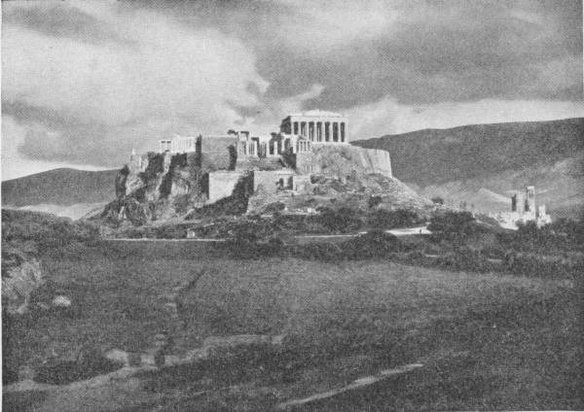

The Acropolis, Athens141

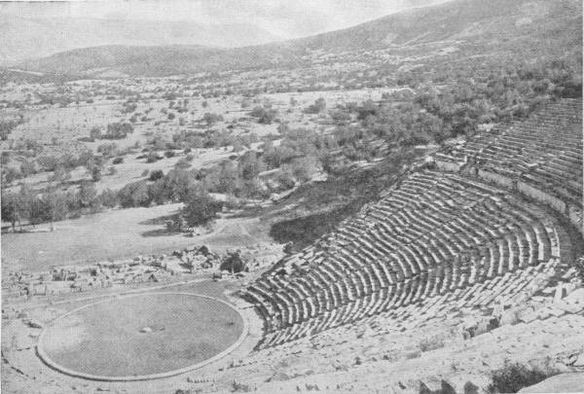

Theatre at Epidauros, Greece141

The Caryatides of the Erechtheum142

Athene of the Parthenon143

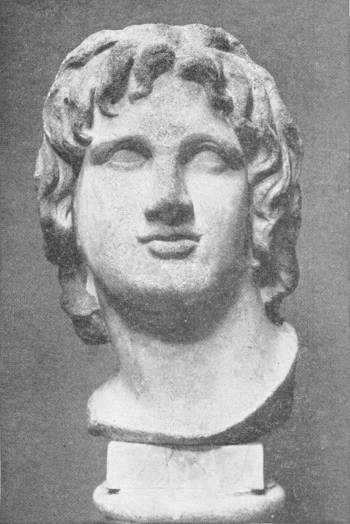

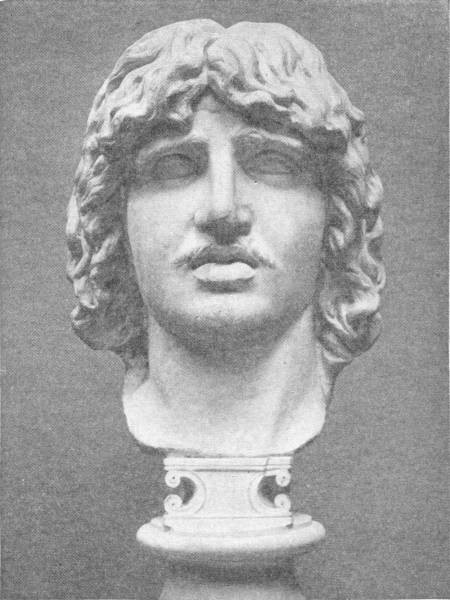

Alexander the Great146

Alexander’s Victory at Issus147

The Apollo Belvedere148

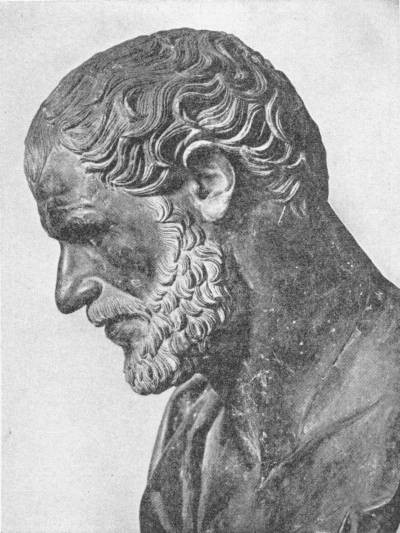

Aristotle152

Statuette of Maitreya153

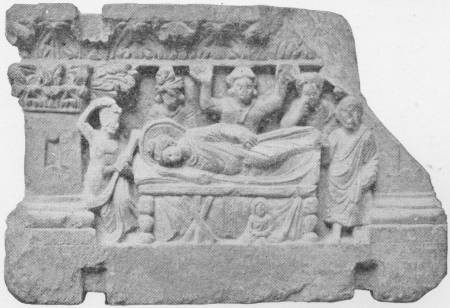

The Death of Buddha154

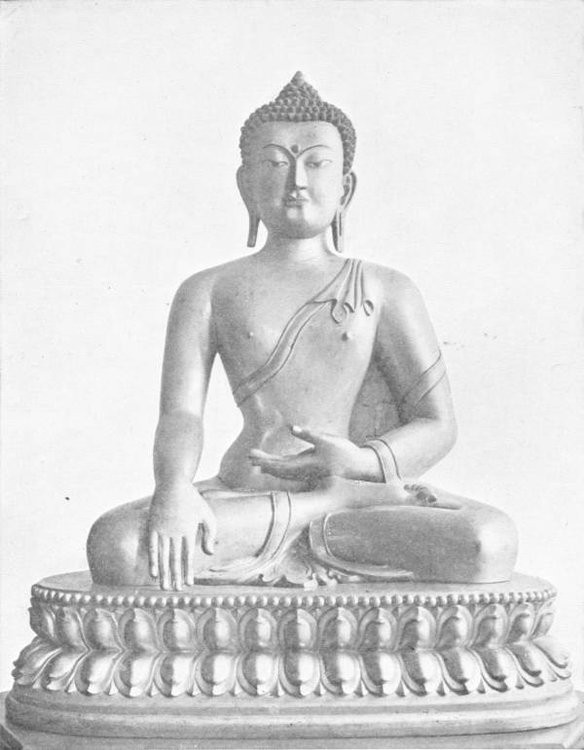

Tibetan Buddha158

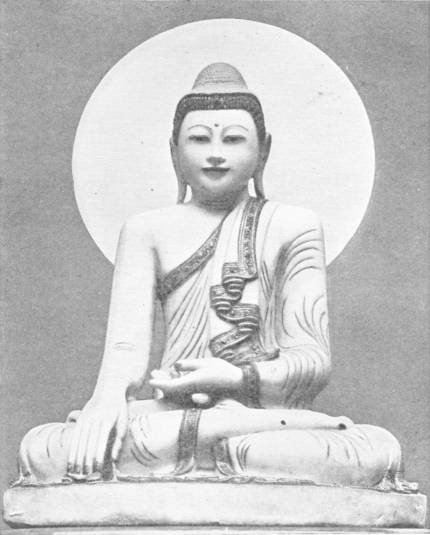

A Burmese Buddha159

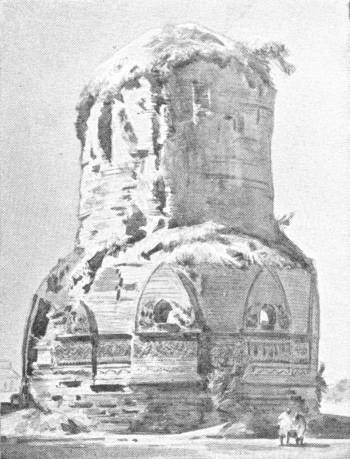

The Dhamêkh Tower, Sarnath160

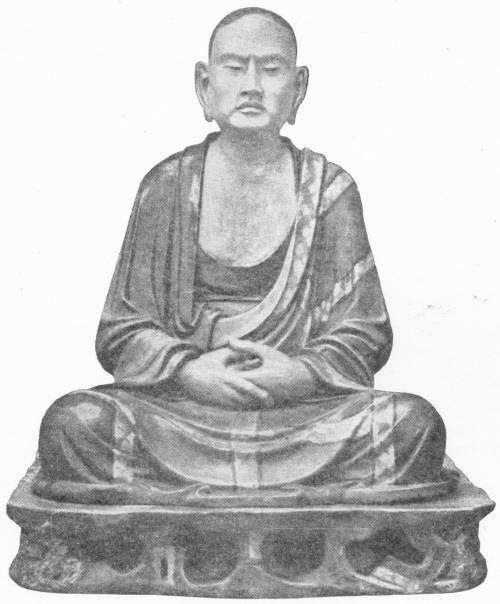

A Chinese Buddhist Apostle164

The Court of Asoka165

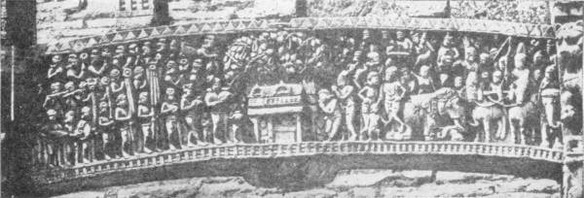

Asoka Panel from Bharhut165

The Pillar of Lions (Asokan)166

Confucius169

The Great Wall of China171

Early Chinese Bronze Bell172

The Dying Gaul175

Ancient Roman Cisterns at Carthage177

Hannibal181

Roman Empire and its Alliances, 150 B.C. Map183

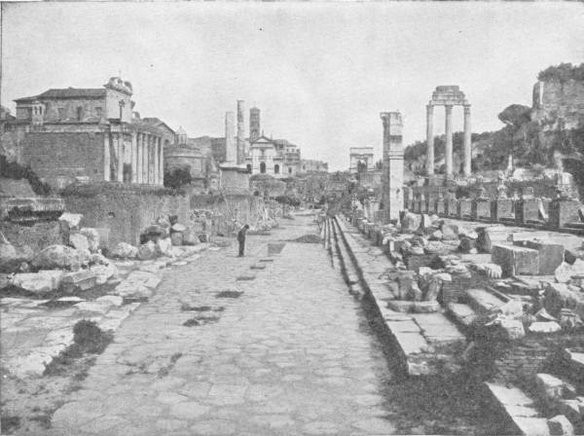

The Forum, Rome188

Ruined Coliseum in Tunis189

Roman Arch at Ctesiphon190

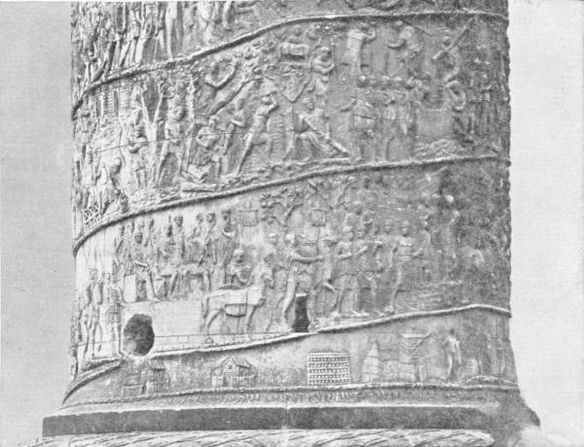

The Column of Trajan, Rome193

Glazed Jar of Han Dynasty197

Vase of Han Dynasty198

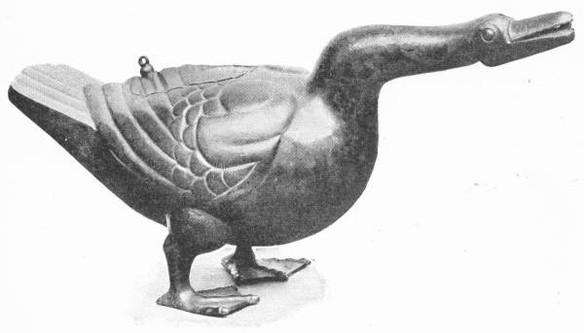

Chinese Vessel in Bronze199

A Gladiator (contemporary representation)202

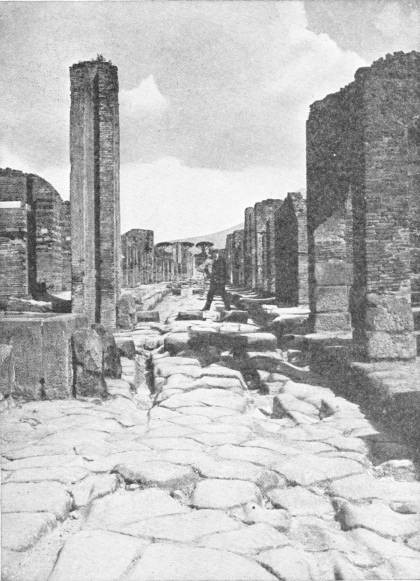

A Street in Pompeii204

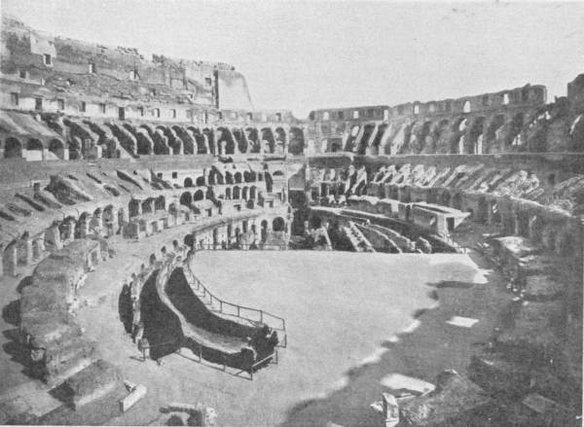

The Coliseum, Rome206

Interior of Coliseum206

Mithras Sacrificing a Bull210

Isis and Horus211

Bust of Emperor Commodus212

Early Portrait of Jesus Christ216

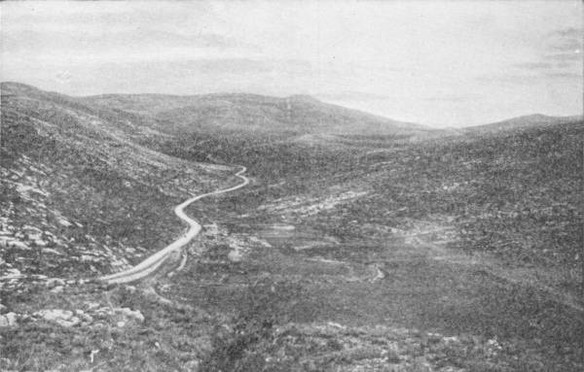

Road from Nazareth to Tiberias217

David’s Tower and Wall of Jerusalem218

A Street in Jerusalem219

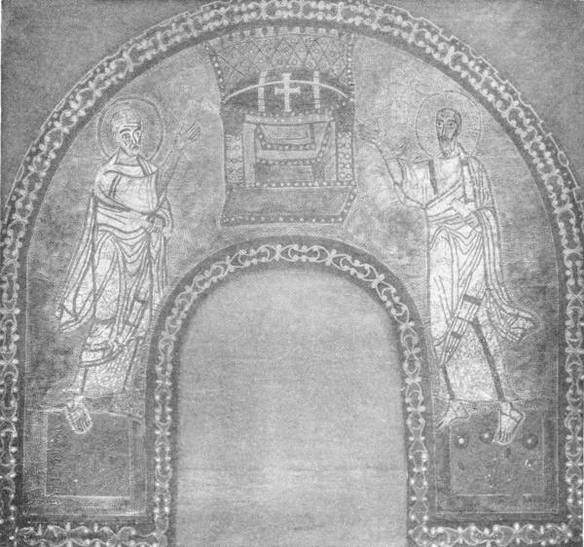

The Peter and Paul Mosaic at Rome223

Baptism of Christ (Ivory Panel)225

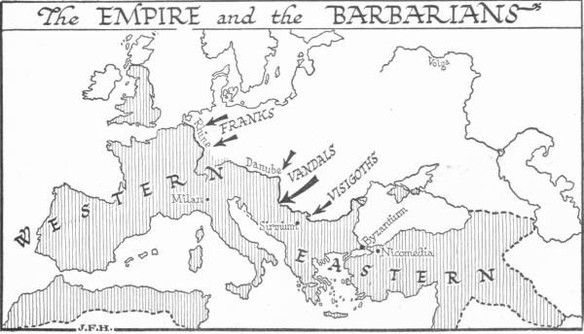

Roman Empire and the Barbarians Map228

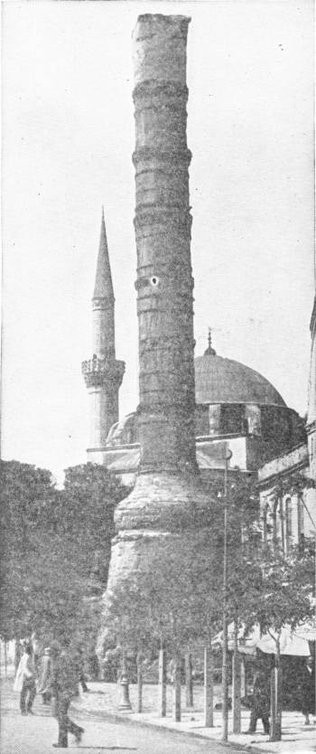

Constantine’s Pillar, Constantinople229

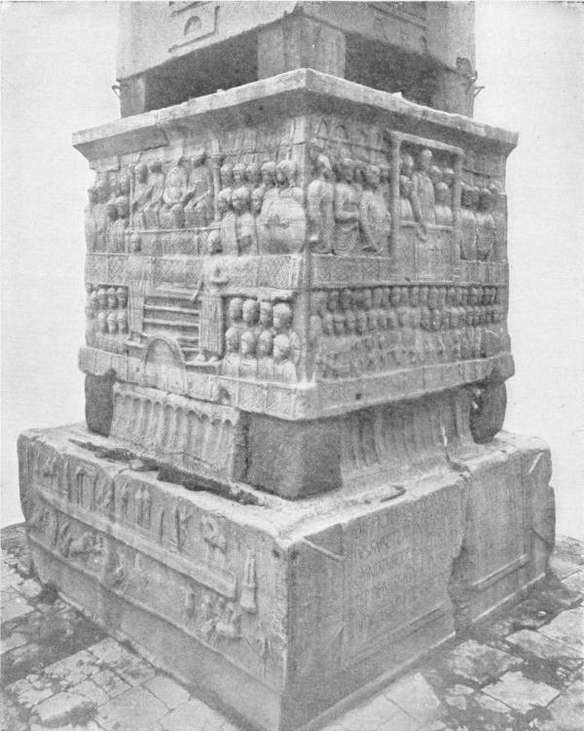

The Obelisk of Theodosius, Constantinople231

Head of Barbarian Chief235

The Church of S. Sophia, Constantinople239

Roof-work in S. Sophia240

Justinian and his Court241

The Rock-hewn Temple at Petra242

Chinese Earthenware of Tang Dynasty246

At Prayer in the Desert250

Looking Across the Sea of Sand251

Growth of Moslem Power Map254

The Moslem Empire Map254

The Mosque of Omar, Jerusalem255

Cairo Mosques256

Frankish Dominions of Martel Map260

Statue of Charlemagne262

Europe at Death of Charlemagne Map264

Crusader Tombs, Exeter Cathedral268

View of Cairo269

The Horses of S. Mark, Venice271

Courtyard in the Alhambra273

Milan Cathedral (showing spires)278

A Typical Crusader280

Burgundian Nobility (Statuettes)283

Burgundian Nobility (Statuettes)284

The Empire of Jengis Khan Map288

Ottoman Empire before 1453 Map289

Tartar Horsemen291

Ottoman Empire, 1566 Map292

An Early Printing Press296

Ancient Bronze from Benin299

Negro Bronze-work300

Early Sailing Ship (Italian Engraving)301

Portrait of Martin Luther305

The Church Triumphant (Italian Majolica work, 1543)307

Charles V (the Titian Portrait)311

S. Peter’s, Rome: the High Altar315

Cromwell Dissolves the Long Parliament321

The Court at Versailles323

Sack of a Village, French Revolution325

Central Europe after Peace of Westphalia, 1648 Map326

European Territory in America, 1750 Map330

Europeans Tiger Hunting in India331

Fall of Tippoo Sultan332

George Washington337

The Battle of Bunker Hill338

The U.S.A., 1790339

The Trial of Louis XVI344

Execution of Marie Antoinette346

Portrait of Napoleon352

Europe after the Congress of Vienna Map353

Early Rolling Stock, Liverpool and Manchester Railway356

Passenger Train in 1833356

The Steamboat Clermont357

Eighteenth Century Spinning Wheel361

Arkwright’s Spinning Jenny361

An Early Weaving Machine363

An Incident of the Slave Trade367

Early Factory, in Colebrookdale368

Carl Marx372

Electric Conveyor, in Coal Mine376

Constructional Detail, Forth Bridge378

American River Steamer385

Abraham Lincoln387

Europe, 1848-71 Map391

Victoria Falls, Zambesi395

The British Empire, 1815 Map397

Japanese Soldier, Eighteenth Century401

A Street in Tokio403

Overseas Empires of Europe, 1914 Map406

Gibraltar407

Street in Hong Kong408

British Tank in Battle410

The Ruins of Ypres411

Modern War: War Entanglements412

A View in Petersburg under Bolshevik Rule418

Passenger Aeroplane in Flight423

A Peaceful Garden in England426

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE WORLD

I

THE WORLD IN SPACE

THE story of our world is a story that is still very imperfectly known. A couple of hundred years ago men possessed the history of little more than the last three thousand years. What happened before that time was a matter of legend and speculation. Over a large part of the civilized world it was believed and taught that the world had been created suddenly in 4004 B.C., though authorities differed as to whether this had occurred in the spring or autumn of that year. This fantastically precise misconception was based upon a too literal interpretation of the Hebrew Bible, and upon rather arbitrary theological assumptions connected therewith. Such ideas have long since been abandoned by religious teachers, and it is universally recognized that the universe in which we live has to all appearances existed for an enormous period of time and possibly for endless time. Of course there may be deception in these appearances, as a room may be made to seem endless by putting mirrors facing each other at either end. But that the universe in which we live has existed only for six or seven thousand years may be regarded as an altogether exploded idea.

The earth, as everybody knows nowadays, is a spheroid, a sphere slightly compressed, orange fashion, with a diameter of nearly 8,000 miles. Its spherical shape has been known at least to a limited number of intelligent people for nearly 2,500 years, but before that time it was supposed to be flat, and various ideas which now seem fantastic were entertained about its relations to the sky and the stars and planets. We know now that it rotates upon its axis (which is about 24 miles shorter than its equatorial diameter) every twenty-four hours, and that this is the cause of the alternations of day and night, that it circles about the sun in a slightly distorted and slowly variable oval path in a year. Its distance from the sun varies between ninety-one and a half millions at its nearest and ninety-four and a half million miles.

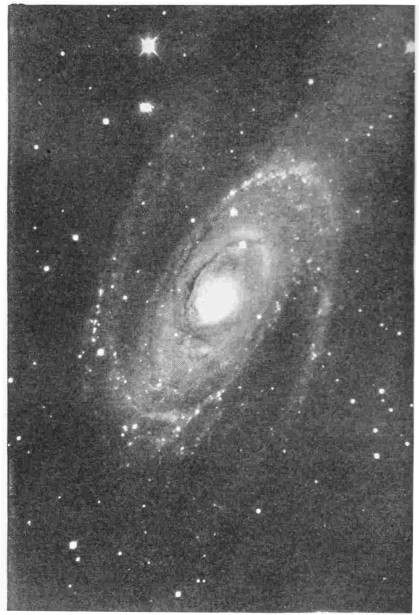

“LUMINOUS SPIRAL CLOUDS OF MATTER”

(Nebula photographed 1910)

Photo: G. W. Ritchey

About the earth circles a smaller sphere, the moon, at an average distance of 239,000 miles. Earth and moon are not the only bodies to travel round the sun. There are also the planets, Mercury and Venus, at distances of thirty-six and sixty-seven millions of miles; and beyond the circle of the earth and disregarding a belt of numerous smaller bodies, the planetoids, there are Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune at mean distances of 141, 483, 886, 1,782, and 1,793 millions of miles respectively. These figures in millions of miles are very difficult for the mind to grasp. It may help the reader’s imagination if we reduce the sun and planets to a smaller, more conceivable scale.

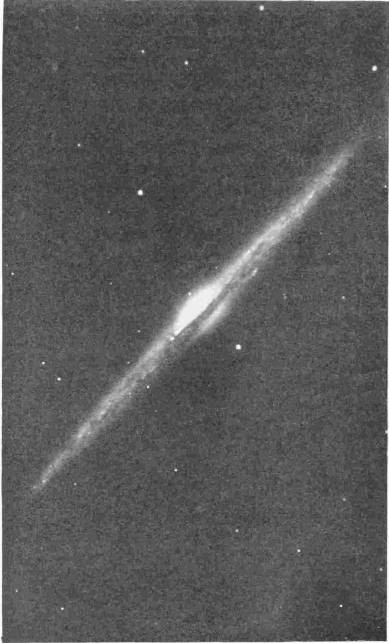

THE NEBULA SEEN EDGE-ON

Note the central core which, through millions of years, is cooling to solidity

Photo: G. W. Ritchey

If, then, we represent our earth as a little ball of one inch diameter, the sun would be a big globe nine feet across and 323 yards away, that is about a fifth of a mile, four or five minutes’ walking. The moon would be a small pea two feet and a half from the world. Between earth and sun there would be the two inner planets, Mercury and Venus, at distances of one hundred and twenty-five and two hundred and fifty yards from the sun. All round and about these bodies there would be emptiness until you came to Mars, a hundred and seventy-five feet beyond the earth; Jupiter nearly a mile away, a foot in diameter; Saturn, a little smaller, two miles off; Uranus four miles off and Neptune six miles off. Then nothingness and nothingness except for small particles and drifting scraps of attenuated vapour for thousands of miles. The nearest star to earth on this scale would be 40,000 miles away.

These figures will serve perhaps to give one some conception of the immense emptiness of space in which the drama of life goes on.

For in all this enormous vacancy of space we know certainly of life only upon the surface of our earth. It does not penetrate much more than three miles down into the 4,000 miles that separate us from the centre of our globe, and it does not reach more than five miles above its surface. Apparently all the limitlessness of space is otherwise empty and dead.

The deepest ocean dredgings go down to five miles. The highest recorded flight of an aeroplane is little more than four miles. Men have reached to seven miles up in balloons, but at a cost of great suffering. No bird can fly so high as five miles, and small birds and insects which have been carried up by aeroplanes drop off insensible far below that level.

II

THE WORLD IN TIME

IN the last fifty years there has been much very fine and interesting speculation on the part of scientific men upon the age and origin of our earth. Here we cannot pretend to give even a summary of such speculations because they involve the most subtle mathematical and physical considerations. The truth is that the physical and astronomical sciences are still too undeveloped as yet to make anything of the sort more than an illustrative guesswork. The general tendency has been to make the estimated age of our globe longer and longer. It now seems probable that the earth has had an independent existence as a spinning planet flying round and round the sun for a longer period than 2,000,000,000 years. It may have been much longer than that. This is a length of time that absolutely overpowers the imagination.

Before that vast period of separate existence, the sun and earth and the other planets that circulate round the sun may have been a great swirl of diffused matter in space. The telescope reveals to us in various parts of the heavens luminous spiral clouds of matter, the spiral nebulæ, which appear to be in rotation about a centre. It is supposed by many astronomers that the sun and its planets were once such a spiral, and that their matter has undergone concentration into its present form. Through majestic æons that concentration went on until in that vast remoteness of the past for which we have given figures, the world and its moon were distinguishable. They were spinning then much faster than they are spinning now; they were at a lesser distance from the sun; they travelled round it very much faster, and they were probably incandescent or molten at the surface. The sun itself was a much greater blaze in the heavens.

THE GREAT SPIRAL NEBULA

Photo: G. W. Ritchey

If we could go back through that infinitude of time and see the earth in this earlier stage of its history, we should behold a scene more like the interior of a blast furnace or the surface of a lava flow before it cools and cakes over than any other contemporary scene. No water would be visible because all the water there was would still be superheated steam in a stormy atmosphere of sulphurous and metallic vapours. Beneath this would swirl and boil an ocean of molten rock substance. Across a sky of fiery clouds the glare of the hurrying sun and moon would sweep swiftly like hot breaths of flame.

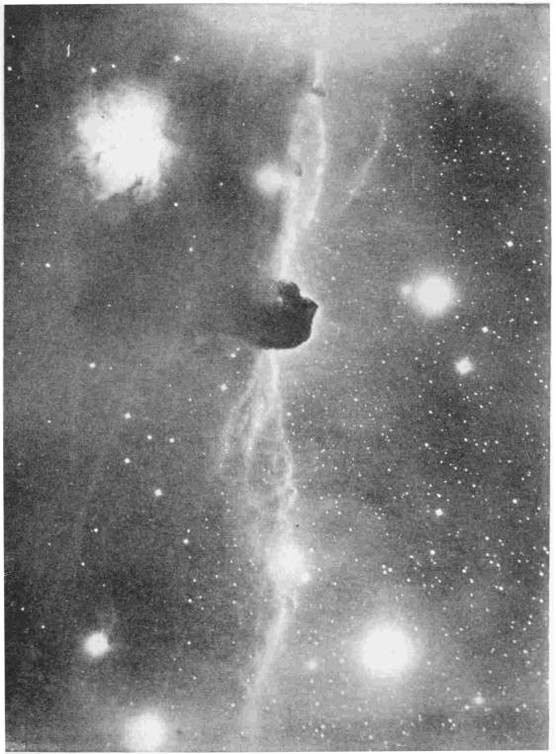

A DARK NEBULA

Taken in 1920 with the aid of the largest telescope in the world. One of the first photographs taken by the Mount Wilson telescope.

There are dark nebulæ and bright nebulæ. Prof. Henry Norris Russell, against the British theory, holds that the dark nebulæ preceded the bright nebulæ.

Photo: Prof. Hale

Slowly by degrees as one million of years followed another, this fiery scene would lose its eruptive incandescence. The vapours in the sky would rain down and become less dense overhead; great slaggy cakes of solidifying rock would appear upon the surface of the molten sea, and sink under it, to be replaced by other floating masses. The sun and moon growing now each more distant and each smaller, would rush with diminishing swiftness across the heavens. The moon now, because of its smaller size, would be already cooled far below incandescence, and would be alternately obstructing and reflecting the sunlight in a series of eclipses and full moons.

ANOTHER SPIRAL NEBULA

Photo: G. W. Ritchey

And so with a tremendous slowness through the vastness of time, the earth would grow more and more like the earth on which we live, until at last an age would come when, in the cooling air, steam would begin to condense into clouds, and the first rain would fall hissing upon the first rocks below. For endless millenia the greater part of the earth’s water would still be vaporized in the atmosphere, but there would now be hot streams running over the crystallizing rocks below and pools and lakes into which these streams would be carrying detritus and depositing sediment.

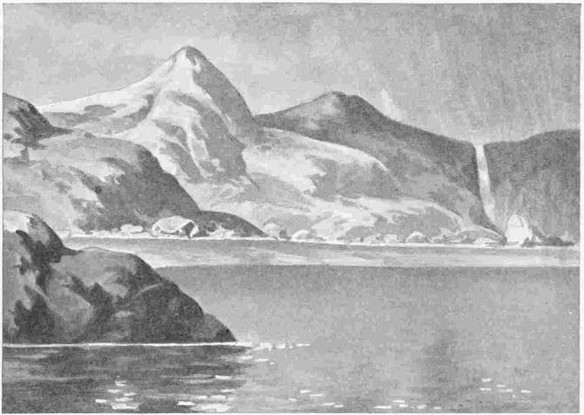

LANDSCAPE BEFORE LIFE

“Great lava-like masses of rock without traces of soil”

At last a condition of things must have been attained in which a man might have stood up on earth and looked about him and lived. If we could have visited the earth at that time we should have stood on great lava-like masses of rock without a trace of soil or touch of living vegetation, under a storm-rent sky. Hot and violent winds, exceeding the fiercest tornado that ever blows, and downpours of rain such as our milder, slower earth to-day knows nothing of, might have assailed us. The water of the downpour would have rushed by us, muddy with the spoils of the rocks, coming together into torrents, cutting deep gorges and canyons as they hurried past to deposit their sediment in the earliest seas. Through the clouds we should have glimpsed a great sun moving visibly across the sky, and in its wake and in the wake of the moon would have come a diurnal tide of earthquake and upheaval. And the moon, which nowadays keeps one constant face to earth, would then have been rotating visibly and showing the side it now hides so inexorably.

The earth aged. One million years followed another, and the day lengthened, the sun grew more distant and milder, the moon’s pace in the sky slackened; the intensity of rain and storm diminished and the water in the first seas increased and ran together into the ocean garment our planet henceforth wore.

But there was no life as yet upon the earth; the seas were lifeless, and the rocks were barren.

III

THE BEGINNINGS OF LIFE

AS everybody knows nowadays, the knowledge we possess of life before the beginnings of human memory and tradition is derived from the markings and fossils of living things in the stratified rocks. We find preserved in shale and slate, limestone, and sandstone, bones, shells, fibres, stems, fruits, footmarks, scratchings and the like, side by side with the ripple marks of the earliest tides and the pittings of the earliest rain-falls. It is by the sedulous examination of this Record of the Rocks that the past history of the earth’s life has been pieced together. That much nearly everybody knows to-day. The sedimentary rocks do not lie neatly stratum above stratum; they have been crumpled, bent, thrust about, distorted and mixed together like the leaves of a library that has been repeatedly looted and burnt, and it is only as a result of many devoted lifetimes of work that the record has been put into order and read. The whole compass of time represented by the record of the rocks is now estimated as 1,600,000,000 years.

The earliest rocks in the record are called by geologists the Azoic rocks, because they show no traces of life. Great areas of these Azoic rocks lie uncovered in North America, and they are of such a thickness that geologists consider that they represent a period of at least half of the 1,600,000,000 which they assign to the whole geological record. Let me repeat this profoundly significant fact. Half the great interval of time since land and sea were first distinguishable on earth has left us no traces of life. There are ripplings and rain marks still to be found in these rocks, but no marks nor vestiges of any living thing.

MARINE LIFE IN THE CAMBRIAN PERIOD

1 and 8, Jellyfishes; 2, Hyolithes (swimming snail); 3, Humenocaris; 4, Protospongia; 5, Lampshells (Obolella); 6, Orthoceras; 7, Trilobite (Paradoxides) — see fossil on page 13; 9, Coral (Archæocyathus); 10, Bryograptus; 11, Trilobite (Olenellus); 12, Palesterina

Then, as we come up the record, signs of past life appear and increase. The age of the world’s history in which we find these past traces is called by geologists the Lower Palæozoic age. The first indications that life was astir are vestiges of comparatively simple and lowly things: the shells of small shellfish, the stems and flowerlike heads of zoophytes, seaweeds and the tracks and remains of sea worms and crustacea. Very early appear certain creatures rather like plant-lice, crawling creatures which could roll themselves up into balls as the plant-lice do, the trilobites. Later by a few million years or so come certain sea scorpions, more mobile and powerful creatures than the world had ever seen before.

FOSSIL TRILOBITE (SLIGHTLY MAGNIFIED)

Photo: John J. Ward, F.E.S.

None of these creatures were of very great size. Among the largest were certain of the sea scorpions, which measured nine feet in length. There are no signs whatever of land life of any sort, plant or animal; there are no fishes nor any vertebrated creatures in this part of the record. Essentially all the plants and creatures which have left us their traces from this period of the earth’s history are shallow-water and intertidal beings. If we wished to parallel the flora and fauna of the Lower Palæozoic rocks on the earth to-day, we should do it best, except in the matter of size, by taking a drop of water from a rock pool or scummy ditch and examining it under a microscope. The little crustacea, the small shellfish, the zoophytes and algæ we should find there would display a quite striking resemblance to these clumsier, larger prototypes that once were the crown of life upon our planet.

EARLY PALÆOLITHIC FOSSILS OF VARIOUS SPECIES OF LINGULA

Species of this most ancient genus of shellfish still live to-day

(In Natural History Museum, London)

It is well, however, to bear in mind that the Lower Palæozoic rocks probably do not give us anything at all representative of the first beginnings of life on our planet. Unless a creature has bones or other hard parts, unless it wears a shell or is big enough and heavy enough to make characteristic footprints and trails in mud, it is unlikely to leave any fossilized traces of its existence behind. To-day there are hundreds of thousands of species of small soft-bodied creatures in our world which it is inconceivable can ever leave any mark for future geologists to discover. In the world’s past, millions of millions of species of such creatures may have lived and multiplied and flourished and passed away without a trace remaining. The waters of the warm and shallow lakes and seas of the so-called Azoic period may have teemed with an infinite variety of lowly, jelly-like, shell-less and boneless creatures, and a multitude of green scummy plants may have spread over the sunlit intertidal rocks and beaches. The Record of the Rocks is no more a complete record of life in the past than the books of a bank are a record of the existence of everybody in the neighbourhood. It is only when a species begins to secrete a shell or a spicule or a carapace or a lime-supported stem, and so put by something for the future, that it goes upon the Record. But in rocks of an age prior to those which bear any fossil traces, graphite, a form of uncombined carbon, is sometimes found, and some authorities consider that it may have been separated out from combination through the vital activities of unknown living things.

FOSSILIZED FOOTPRINTS OF A LABYRINTHODONT CHEIROTHERIUM

(In Natural History Museum, London)

IV

THE AGE OF FISHES

IN the days when the world was supposed to have endured for only a few thousand years, it was supposed that the different species of plants and animals were fixed and final; they had all been created exactly as they are to-day, each species by itself. But as men began to discover and study the Record of the Rocks this belief gave place to the suspicion that many species had changed and developed slowly through the course of ages, and this again expanded into a belief in what is called Organic Evolution, a belief that all species of life upon earth, animal and vegetable alike, are descended by slow continuous processes of change from some very simple ancestral form of life, some almost structureless living substance, far back in the so-called Azoic seas.

This question of Organic Evolution, like the question of the age of the earth, has in the past been the subject of much bitter controversy. There was a time when a belief in organic evolution was for rather obscure reasons supposed to be incompatible with sound Christian, Jewish and Moslem doctrine. That time has passed, and the men of the most orthodox Catholic, Protestant, Jewish and Mohammedan belief are now free to accept this newer and broader view of a common origin of all living things. No life seems to have happened suddenly upon earth. Life grew and grows. Age by age through gulfs of time at which imagination reels, life has been growing from a mere stirring in the intertidal slime towards freedom, power and consciousness.

Life consists of individuals. These individuals are definite things, they are not like the lumps and masses, nor even the limitless and motionless crystals, of non-living matter, and they have two characteristics no dead matter possesses. They can assimilate other matter into themselves and make it part of themselves, and they can reproduce themselves. They eat and they breed. They can give rise to other individuals, for the most part like themselves, but always also a little different from themselves. There is a specific and family resemblance between an individual and its offspring, and there is an individual difference between every parent and every offspring it produces, and this is true in every species and at every stage of life.

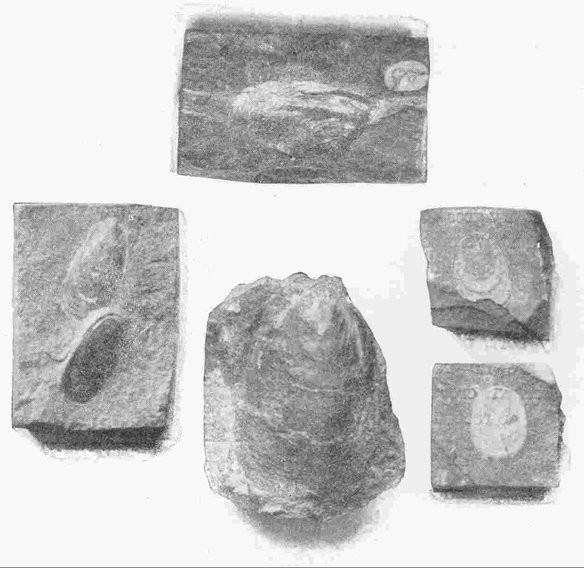

SPECIMEN OF THE PTERICHTHYS MILLERI OR SEA SCORPION SHOWING BODY ARMOUR

Now scientific men are not able to explain to us either why offspring should resemble nor why they should differ from their parents. But seeing that offspring do at once resemble and differ, it is a matter rather of common sense than of scientific knowledge that, if the conditions under which a species live are changed, the species should undergo some correlated changes. Because in any generation of the species there must be a number of individuals whose individual differences make them better adapted to the new conditions under which the species has to live, and a number whose individuals whose individual differences make it rather harder for them to live. And on the hole the former sort will live longer, bear more offspring, and reproduce themselves more abundantly than the latter, and so generation by generation the average of the species will change in the favourable direction. This process, which is called Natural Selection, is not so much a scientific theory as a necessary deduction from the facts of reproduction and individual difference. There may be many forces at work varying, destroying and preserving species, about which science may still be unaware or undecided, but the man who can deny the operation of this process of natural selection upon life since its beginning must be either ignorant of the elementary facts of life or incapable of ordinary thought.

Many scientific men have speculated about the first beginning of life and their speculations are often of great interest, but there is absolutely no definite knowledge and no convincing guess yet of the way in which life began. But nearly all authorities are agreed that it probably began upon mud or sand in warm sunlit shallow brackish water, and that it spread up the beaches to the intertidal lines and out to the open waters.

FOSSIL OF THE CLADOSELACHE, A DEVONIAN SHARK

Nat. Hist. Mus.

That early world was a world of strong tides and currents. An incessant destruction of individuals must have been going on through their being swept up the beaches and dried, or by their being swept out to sea and sinking down out of reach of air and sun. Early conditions favoured the development of every tendency to root and hold on, every tendency to form an outer skin and casing to protect the stranded individual from immediate desiccation. From the very earliest any tendency to sensitiveness to taste would turn the individual in the direction of food, and any sensitiveness to light would assist it to struggle back out of the darkness of the sea deeps and caverns or to wriggle back out of the excessive glare of the dangerous shallows.

Probably the first shells and body armour of living things were protections against drying rather than against active enemies. But tooth and claw come early into our earthly history.

We have already noted the size of the earlier water scorpions. For long ages such creatures were the supreme lords of life. Then in a division of these Palæozoic rocks called the Silurian division, which many geologists now suppose to be as old as five hundred million years, there appears a new type of being, equipped with eyes and teeth and swimming powers of an altogether more powerful kind. These were the first known backboned animals, the earliest fishes, the first known Vertebrata.

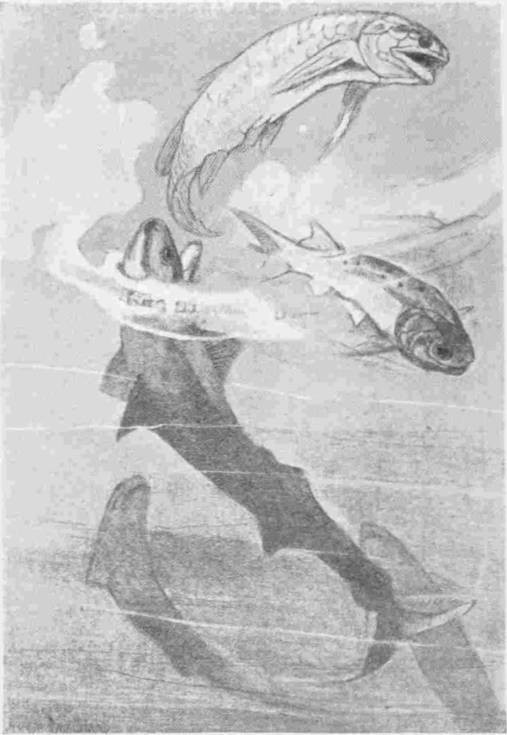

SHARKS AND GANOIDS OF THE DEVONIAN PERIOD

By Alice Woodward

These fishes increase greatly in the next division of rocks, the rocks known as the Devonian system. They are so prevalent that this period of the Record of the Rocks has been called the Age of Fishes. Fishes of a pattern now gone from the earth, and fishes allied to the sharks and sturgeons of to-day, rushed through the waters, leapt in the air, browsed among the seaweeds, pursued and preyed upon one another, and gave a new liveliness to the waters of the world. None of these were excessively big by our present standards. Few of them were more than two or three feet long, but there were exceptional forms which were as long as twenty feet.

We know nothing from geology of the ancestors of these fishes. They do not appear to be related to any of the forms that preceded them. Zoologists have the most interesting views of their ancestry, but these they derive from the study of the development of the eggs of their still living relations, and from other sources. Apparently the ancestors of the vertebrata were soft-bodied and perhaps quite small swimming creatures who began first to develop hard parts as teeth round and about their mouths. The teeth of a skate or dogfish cover the roof and floor of its mouth and pass at the lip into the flattened toothlike scales that encase most of its body. As the fishes develop these teeth scales in the geological record, they swim out of the hidden darkness of the past into the light, the first vertebrated animals visible in the record.

V

THE AGE OF THE COAL SWAMPS

THE land during this Age of Fishes was apparently quite lifeless. Crags and uplands of barren rock lay under the sun and rain. There was no real soil—for as yet there were no earthworms which help to make a soil, and no plants to break up the rock particles into mould; there was no trace of moss or lichen. Life was still only in the sea.

Over this world of barren rock played great changes of climate. The causes of these changes of climate were very complex and they have still to be properly estimated. The changing shape of the earth’s orbit, the gradual shifting of the poles of rotation, changes in the shapes of the continents, probably even fluctuations in the warmth of the sun, now conspired to plunge great areas of the earth’s surface into long periods of cold and ice and now again for millions of years spread a warm or equable climate over this planet. There seem to have been phases of great internal activity in the world’s history, when in the course of a few million years accumulated upthrusts would break out in lines of volcanic eruption and upheaval and rearrange the mountain and continental outlines of the globe, increasing the depth of the sea and the height of the mountains and exaggerating the extremes of climate. And these would be followed by vast ages of comparative quiescence, when frost, rain and river would wear down the mountain heights and carry great masses of silt to fill and raise the sea bottoms and spread the seas, ever shallower and wider, over more and more of the land. There have been “high and deep” ages in the world’s history and “low and level” ages. The reader must dismiss from his mind any idea that the surface of the earth has been growing steadily cooler since its crust grew solid. After that much cooling had been achieved, the internal temperature ceased to affect surface conditions. There are traces of periods of superabundant ice and snow, of “Glacial Ages,” that is, even in the Azoic period.

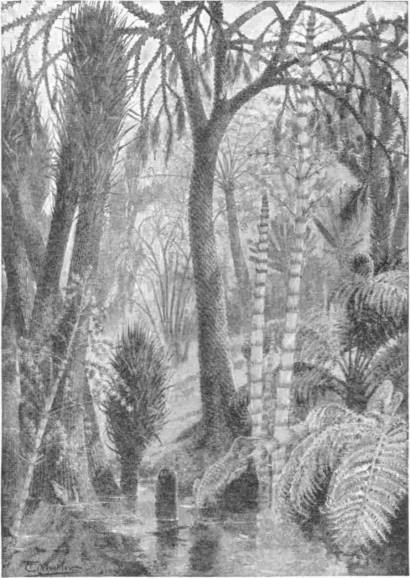

It was only towards the close of the Age of Fishes, in a period of extensive shallow seas and lagoons, that life spread itself out in any effectual way from the waters on to the land. No doubt the earlier types of the forms that now begin to appear in great abundance had already been developing in a rare and obscure manner for many scores of millions of years. But now came their opportunity.

A CARBONIFEROUS SWAMP

A Coal Seam in the Making

Plants no doubt preceded animal forms in this invasion of the land, but the animals probably followed up the plant emigration very closely. The first problem that the plant had to solve was the problem of some sustaining stiff support to hold up its fronds to the sunlight when the buoyant water was withdrawn; the second was the problem of getting water from the swampy ground below to the tissues of the plant, now that it was no longer close at hand. The two problems were solved by the development of woody tissue which both sustained the plant and acted as water carrier to the leaves. The Record of the Rocks is suddenly crowded by a vast variety of woody swamp plants, many of them of great size, big tree mosses, tree ferns, gigantic horsetails and the like. And with these, age by age, there crawled out of the water a great variety of animal forms. There were centipedes and millipedes; there were the first primitive insects; there were creatures related to the ancient king crabs and sea scorpions which became the earliest spiders and land scorpions, and presently there were vertebrated animals.

SKULL OF A LABYRINTHODONT, CAPITOSAURUS

Nat. Hist. Mus.

Some of the earlier insects were very large. There were dragon flies in this period with wings that spread out to twenty-nine inches.

In various ways these new orders and genera had adapted themselves to breathing air. Hitherto all animals had breathed air dissolved in water, and that indeed is what all animals still have to do. But now in divers fashions the animal kingdom was acquiring the power of supplying its own moisture where it was needed. A man with a perfectly dry lung would suffocate to-day; his lung surfaces must be moist in order that air may pass through them into his blood. The adaptation to air breathing consists in all cases either in the development of a cover to the old-fashioned gills to stop evaporation, or in the development of tubes or other new breathing organs lying deep inside the body and moistened by a watery secretion. The old gills with which the ancestral fish of the vertebrated line had breathed were inadaptable to breathing upon land, and in the case of this division of the animal kingdom it is the swimming bladder of the fish which becomes a new, deep-seated breathing organ, the lung. The kind of animals known as amphibia, the frogs and newts of to-day, begin their lives in the water and breathe by gills; and subsequently the lung, developing in the same way as the swimming bladder of many fishes do, as a baglike outgrowth from the throat, takes over the business of breathing, the animal comes out on land, and the gills dwindle and the gill slits disappear. (All except an outgrowth of one gill slit, which becomes the passage of the ear and ear-drum.) The animal can now live only in the air, but it must return at least to the edge of the water to lay its eggs and reproduce its kind.

SKELETON OF A LABYRINTHODONT: THE ERYOPS

Nat. Hist. Mus.

All the air-breathing vertebrata of this age of swamps and plants belonged to the class amphibia. They were nearly all of them forms related to the newts of to-day, and some of them attained a considerable size. They were land animals, it is true, but they were land animals needing to live in and near moist and swampy places, and all the great trees of this period were equally amphibious in their habits. None of them had yet developed fruits and seeds of a kind that could fall on land and develop with the help only of such moisture as dew and rain could bring. They all had to shed their spores in water, it would seem, if they were to germinate.

It is one of the most beautiful interests of that beautiful science, comparative anatomy, to trace the complex and wonderful adaptations of living things to the necessities of existence in air. All living things, plants and animals alike, are primarily water things. For example all the higher vertebrated animals above the fishes, up to and including man, pass through a stage in their development in the egg or before birth in which they have gill slits which are obliterated before the young emerge. The bare, water-washed eye of the fish is protected in the higher forms from drying up by eyelids and glands which secrete moisture. The weaker sound vibrations of air necessitate an ear-drum. In nearly every organ of the body similar modifications and adaptations are to be detected, similar patchings-up to meet aerial conditions.

This Carboniferous age, this age of the amphibia, was an age of life in the swamps and lagoons and on the low banks among these waters. Thus far life had now extended. The hills and high lands were still quite barren and lifeless. Life had learnt to breathe air indeed, but it still had its roots in its native water; it still had to return to the water to reproduce its kind.

VI

THE AGE OF REPTILES

THE abundant life of the Carboniferous period was succeeded by a vast cycle of dry and bitter ages. They are represented in the Record of the Rocks by thick deposits of sandstones and the like, in which fossils are comparatively few. The temperature of the world fluctuated widely, and there were long periods of glacial cold. Over great areas the former profusion of swamp vegetation ceased, and, overlaid by these newer deposits, it began that process of compression and mineralization that gave the world most of the coal deposits of to-day.

But it is during periods of change that life undergoes its most rapid modifications, and under hardship that it learns its hardest lessons. As conditions revert towards warmth and moisture again we find a new series of animal and plant forms established, We find in the record the remains of vertebrated animals that laid eggs which, instead of hatching out tadpoles which needed to live for a time in water, carried on their development before hatching to a stage so nearly like the adult form that the young could live in air from the first moment of independent existence. Gills had been cut out altogether, and the gill slits only appeared as an embryonic phase.

These new creatures without a tadpole stage were the Reptiles. Concurrently there had been a development of seed-bearing trees, which could spread their seed, independently of swamp or lakes. There were now palmlike cycads and many tropical conifers, though as yet there were no flowering plants and no grasses. There was a great number of ferns. And there was now also an increased variety of insects. There were beetles, though bees and butterflies had yet to come. But all the fundamental forms of a new real land fauna and flora had been laid down during these vast ages of severity. This new land life needed only the opportunity of favourable conditions to flourish and prevail.

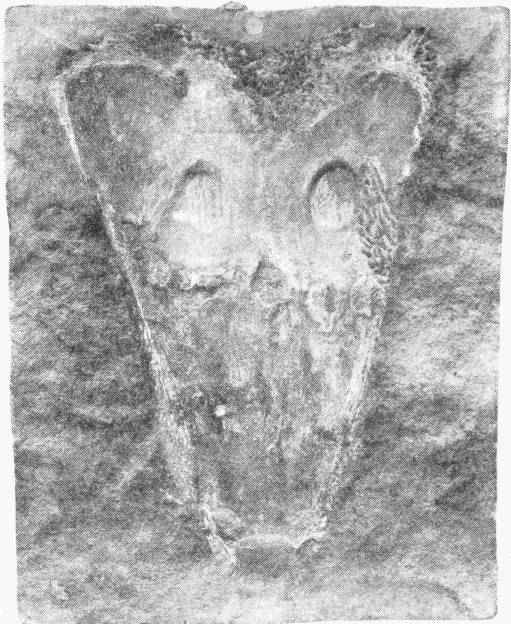

A FOSSIL ICHTHYOSAURUS, A MESOZOIC FISH-LIZARD

Found in the Lower Lias in Somersetshire

Nat. Hist. Mus.

Age by age and with abundant fluctuations that mitigation came. The still incalculable movements of the earth’s crust, the changes in its orbit, the increase and diminution of the mutual inclination of orbit and pole, worked together to produce a great spell of widely diffused warm conditions. The period lasted altogether, it is now supposed, upwards of two hundred million years. It is called the Mesozoic period, to distinguish it from the altogether vaster Palæozoic and Azoic periods (together fourteen hundred millions) that preceded it, and from the Cainozoic or new life period that intervened between its close and the present time, and it is also called the Age of Reptiles because of the astonishing predominance and variety of this form of life. It came to an end some eighty million years ago.

In the world to-day the genera of Reptiles are comparatively few and their distribution is very limited. They are more various, it is true, than are the few surviving members of the order of the amphibia which once in the Carboniferous period ruled the world. We still have the snakes, the turtles and tortoises (the Chelonia), the alligators and crocodiles, and the lizards. Without exception they are creatures requiring warmth all the year round; they cannot stand exposure to cold, and it is probable that all the reptilian beings of the Mesozoic suffered under the same limitation. It was a hothouse fauna, living amidst a hothouse flora. It endured no frosts. But the world had at least attained a real dry land fauna and flora as distinguished from the mud and swamp fauna and flora of the previous heyday of life upon earth.

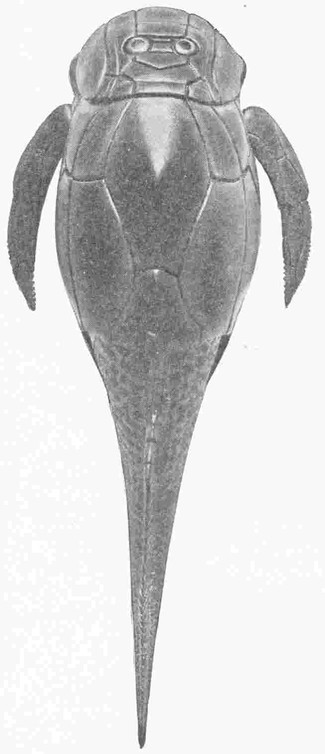

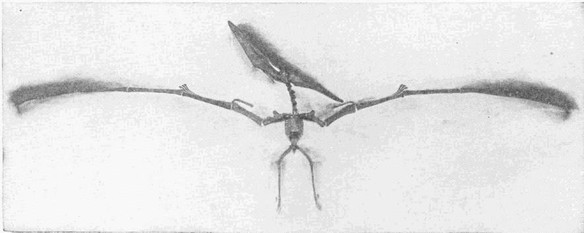

A PTERODACTYL

Nat. Hist. Mus.

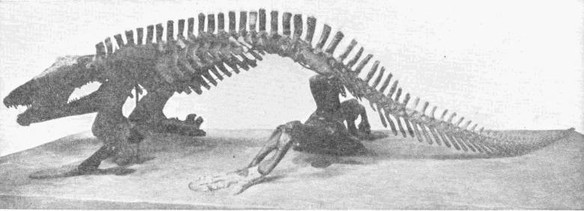

All the sorts of reptile we know now were much more abundantly represented then, great turtles and tortoises, big crocodiles and many lizards and snakes, but in addition there was a number of series of wonderful creatures that have now vanished altogether from the earth. There was a vast variety of beings called the Dinosaurs. Vegetation was now spreading over the lower levels of the world, reeds, brakes of fern and the like; and browsing upon this abundance came a multitude of herbivorous reptiles, which increased in size as the Mesozoic period rose to its climax. Some of these beasts exceeded in size any other land animals that have ever lived; they were as large as whales. The Diplodocus Carnegii for example measured eighty-four feet from snout to tail; the Gigantosaurus was even greater; it measured a hundred feet. Living upon these monsters was a swarm of carnivorous Dinosaurs of a corresponding size. One of these, the Tyrannosaurus, is figured and described in many books as the last word in reptilian frightfulness.

A BIG SWAMP-INHABITING DINOSAUR, THE DIPLODOCUS, OVER EIGHTY FEET FROM SNOUT TO TAIL-TIP

Nat. Hist. Mus.

While these great creatures pastured and pursued amidst the fronds and evergreens of the Mesozoic jungles, another now vanished tribe of reptiles, with a bat-like development of the fore limbs, pursued insects and one another, first leapt and parachuted and presently flew amidst the fronds and branches of the forest trees. These were the Pterodactyls. These were the first flying creatures with backbones; they mark a new achievement in the growing powers of vertebrated life.

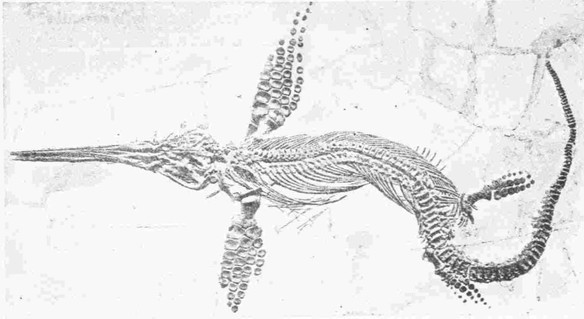

Moreover some of the reptiles were returning to the sea waters. Three groups of big swimming beings had invaded the sea from which their ancestors had come: the Mososaurs, the Plesiosaurs, and Ichthyosaurs. Some of these again approached the proportions of our present whales. The Ichthyosaurs seem to have been quite seagoing creatures, but the Plesiosaurs were a type of animal that has no cognate form to-day. The body was stout and big with paddles, adapted either for swimming or crawling through marshes, or along the bottom of shallow waters. The comparatively small head was poised on a vast snake of neck, altogether outdoing the neck of the swan. Either the Plesiosaur swam and searched for food under the water and fed as the swan will do, or it lurked under water and snatched at passing fish or beast.

Such was the predominant land life throughout the Mesozoic age. It was by our human standards an advance upon anything that had preceded it. It had produced land animals greater in size, range, power and activity, more “vital” as people say, than anything the world had seen before. In the seas there had been no such advance but a great proliferation of new forms of life. An enormous variety of squid-like creatures with chambered shells, for the most part coiled, had appeared in the shallow seas, the Ammonites. They had had predecessors in the Palæozoic seas, but now was their age of glory. To-day they have left no survivors at all; their nearest relation is the pearly Nautilus, an inhabitant of tropical waters. And a new and more prolific type of fish with lighter, finer scales than the plate-like and tooth-like coverings that had hitherto prevailed, became and has since remained predominant in the seas and rivers.

VII

THE FIRST BIRDS AND THE FIRST MAMMALS

IN a few paragraphs a picture of the lush vegetation and swarming reptiles of that first great summer of life, the Mesozoic period, has been sketched. But while the Dinosaurs lorded it over the hot selvas and marshy plains and the Pterodactyls filled the forests with their flutterings and possibly with shrieks and croakings as they pursued the humming insect life of the still flowerless shrubs and trees, some less conspicuous and less abundant forms upon the margins of this abounding life were acquiring certain powers and learning certain lessons of endurance, that were to be of the utmost value to their race when at last the smiling generosity of sun and earth began to fade.

A group of tribes and genera of hopping reptiles, small creatures of the dinosaur type, seem to have been pushed by competition and the pursuit of their enemies towards the alternatives of extinction or adaptation to colder conditions in the higher hills or by the sea. Among these distressed tribes there was developed a new type of scale—scales that were elongated into quill-like forms and that presently branched into the crude beginnings of feathers. These quill-like scales layover one another and formed a heat-retaining covering more efficient than any reptilian covering that had hitherto existed. So they permitted an invasion of colder regions that were otherwise uninhabited. Perhaps simultaneously with these changes there arose in these creatures a greater solicitude for their eggs. Most reptiles are apparently quite careless about their eggs, which are left for sun and season to hatch. But some of the varieties upon this new branch of the tree of life were acquiring a habit of guarding their eggs and keeping them warm with the warmth of their bodies.

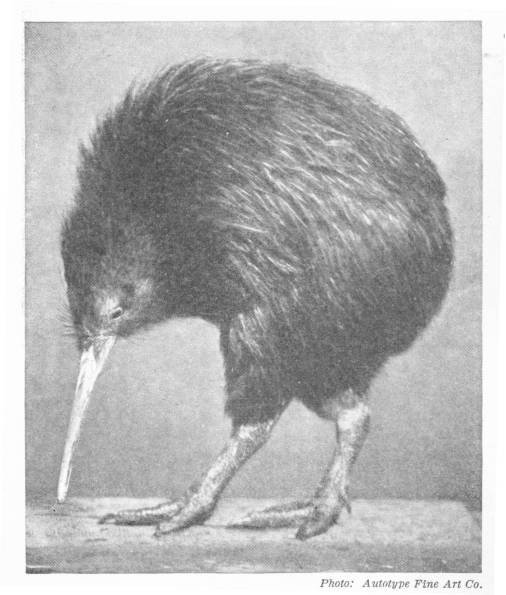

With these adaptations to cold other internal modifications were going on that made these creatures, the primitive birds, warm-blooded and independent of basking. The very earliest birds seem to have been seabirds living upon fish, and their fore limbs were not wings but paddles rather after the penguin type. That peculiarly primitive bird, the New Zealand Ki-Wi, has feathers of a very simple sort, and neither flies nor appears to be descended from flying ancestors. In the development of the birds, feathers came before wings. But once the feather was developed the possibility of making a light spread of feathers led inevitably to the wing. We know of the fossil remains of one bird at least which had reptilian teeth in its jaw and a long reptilian tail, but which also had a true bird’s wing and which certainly flew and held its own among the pterodactyls of the Mesozoic time. Nevertheless birds were neither varied nor abundant in Mesozoic times. If a man could go back to typical Mesozoic country, he might walk for days and never see or hear such a thing as a bird, though he would see a great abundance of pterodactyls and insects among the fronds and reeds.

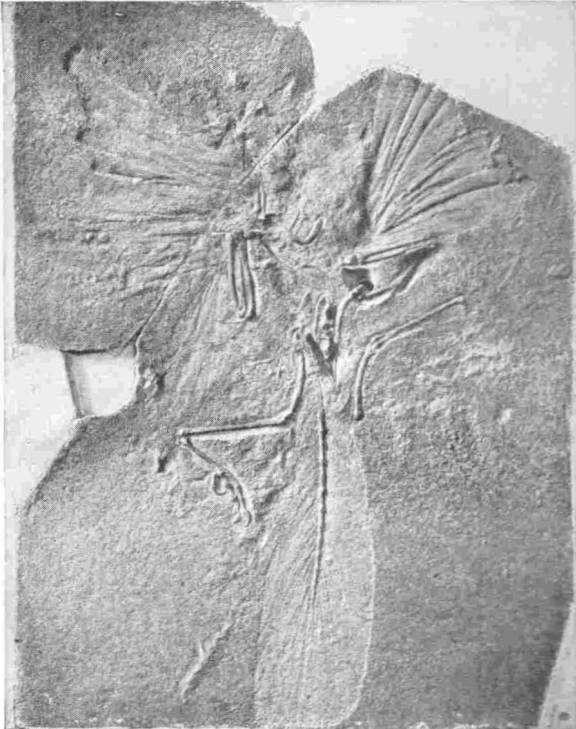

FOSSIL OF THE ARCHEOPTERYX; ONE OF THE EARLIEST BIRDS

Nat. Hist. Mus.

And another thing he would probably never see, and that would be any sign of a mammal. Probably the first mammals were in existence millions of years before the first thing one could call a bird, but they were altogether too small and obscure and remote for attention.

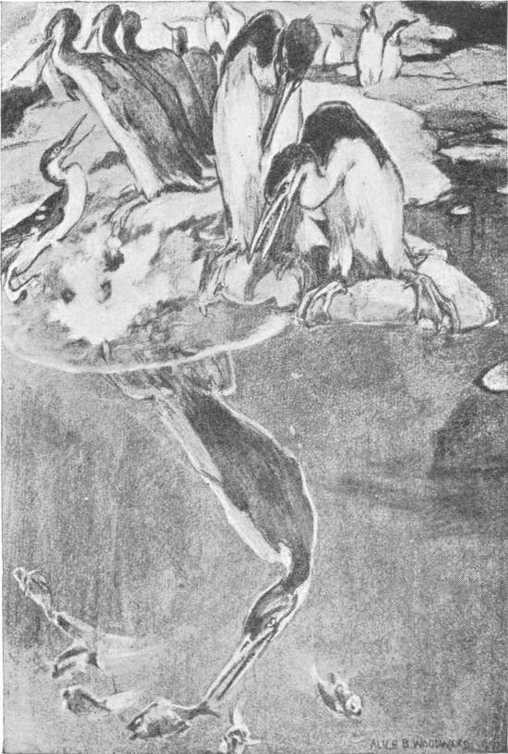

HESPERORNIS IN ITS NATIVE SEAS

The earliest mammals, like the earliest birds, were creatures driven by competition and pursuit into a life of hardship and adaptation to cold. With them also the scale became quill-like, and was developed into a heat-retaining covering; and they too underwent modifications, similar in kind though different in detail, to become warm-blooded and independent of basking. Instead of feathers they developed hairs, and instead of guarding and incubating their eggs they kept them warm and safe by retaining them inside their bodies until they were almost mature. Most of them became altogether vivaparous and brought their young into the world alive. And even after their young were born they tended to maintain a protective and nutritive association with them. Most but not all mammals to-day have mammæ and suckle their young. Two mammals still live which lay eggs and which have not proper mammæ, though they nourish their young by a nutritive secretion of the under skin; these are the duck-billed platypus and the echidna. The echidna lays leathery eggs and then puts them into a pouch under its belly, and so carries them about warm and safe until they hatch.

But just as a visitor to the Mesozoic world might have searched for days and weeks before finding a bird, so, unless he knew exactly where to go and look, he might have searched in vain for any traces of a mammal. Both birds and mammals would have seemed very eccentric and secondary and unimportant creatures in Mesozoic times.

THE KI-WI, APTERYX, STILL FOUND IN NEW ZEALAND

Photo: Autotype Fine Art Co.

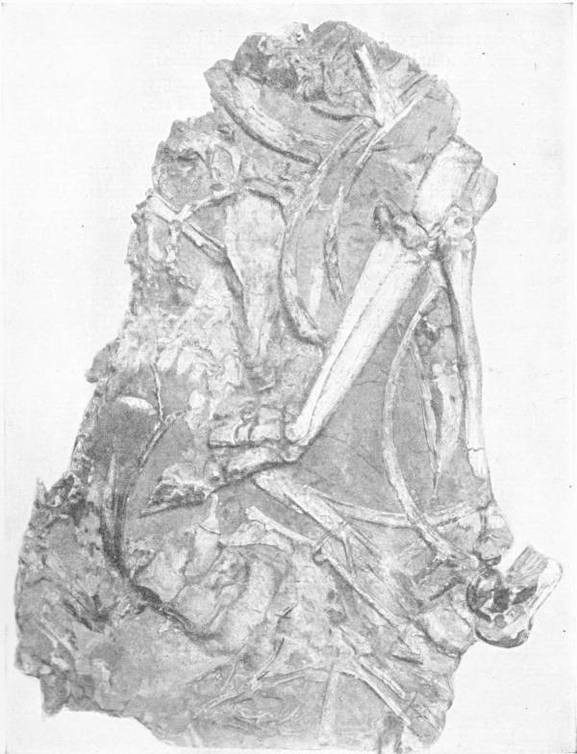

SLAB OF LOWER PLIOCENE MARL

Discovered in Greece; it is rich in fossilized bones of early mammals

The Age of Reptiles lasted, it is now guessed, eighty million years. Had any quasi-human intelligence been watching the world through that inconceivable length of time, how safe and eternal the sunshine and abundance must have seemed, how assured the wallowing prosperity of the dinosaurs and the flapping abundance of the flying lizards! And then the mysterious rhythms and accumulating forces of the universe began to turn against that quasi-eternal stability. That run of luck for life was running out. Age by age, myriad of years after myriad of years, with halts no doubt and retrogressions, came a change towards hardship and extreme conditions, came great alterations of level and great redistributions of mountain and sea. We find one thing in the Record of the Rocks during the decadence of the long Mesozoic age of prosperity that is very significant of steadily sustained changes of condition, and that is a violent fluctuation of living forms and the appearance of new and strange species. Under the gathering threat of extinction the older orders and genera are displaying their utmost capacity for variation and adaptation. The Ammonites for example in these last pages of the Mesozoic chapter exhibit a multitude of fantastic forms. Under settled conditions there is no encouragement for novelties; they do not develop, they are suppressed; what is best adapted is already there. Under novel conditions it is the ordinary type that suffers, and the novelty that may have a better chance to survive and establish itself....

There comes a break in the Record of the Rocks that may represent several million years. There is a veil here still, over even the outline of the history of life. When it lifts again, the Age of Reptiles is at an end; the Dinosaurs, the Plesiosaurs and Ichthyosaurs, the Pterodactyls, the innumerable genera and species of Ammonite have all gone absolutely. In all their stupendous variety they have died out and left no descendants. The cold has killed them. All their final variations were insufficient; they had never hit upon survival conditions. The world had passed through a phase of extreme conditions beyond their powers of endurance, a slow and complete massacre of Mesozoic life has occurred, and we find now a new scene, a new and hardier flora, and a new and hardier fauna in possession of the world.

It is still a bleak and impoverished scene with which this new volume of the book of life begins. The cycads and tropical conifers have given place very largely to trees that shed their leaves to avoid destruction by the snows of winter and to flowering plants and shrubs, and where there was formerly a profusion of reptiles, an increasing variety of birds and mammals is entering into their inheritance.

VIII

THE AGE OF MAMMALS

THE opening of the next great period in the life of the earth, the Cainozoic period, was a period of upheaval and extreme volcanic activity. Now it was that the vast masses of the Alps and Himalayas and the mountain backbone of the Rockies and Andes were thrust up, and that the rude outlines of our present oceans and continents appeared. The map of the world begins to display a first dim resemblance to the map of to-day. It is estimated now that between forty and eighty million years have elapsed from the beginnings of the Cainozoic period to the present time.

At the outset of the Cainozoic period the climate of the world was austere. It grew generally warmer until a fresh phase of great abundance was reached, after which conditions grew hard again and the earth passed into a series of extremely cold cycles, the Glacial Ages, from which apparently it is now slowly emerging.

But we do not know sufficient of the causes of climatic change at present to forecast the possible fluctuations of climatic conditions that lie before us. We may be moving towards increasing sunshine or lapsing towards another glacial age; volcanic activity and the upheaval of mountain masses may be increasing or diminishing; we do not know; we lack sufficient science.

With the opening of this period the grasses appear; for the first time there is pasture in the world; and with the full development of the once obscure mammalian type, appear a number of interesting grazing animals and of carnivorous types which prey upon these.

At first these early mammals seem to differ only in a few characters from the great herbivorous and carnivorous reptiles that ages before had flourished and then vanished from the earth. A careless observer might suppose that in this second long age of warmth and plenty that was now beginning, nature was merely repeating the first, with herbivorous and carnivorous mammals to parallel the herbivorous and carnivorous dinosaurs, with birds replacing pterodactyls and so on. But this would be an altogether superficial comparison. The variety of the universe is infinite and incessant; it progresses eternally; history never repeats itself and no parallels are precisely true. The differences between the life of the Cainozoic and Mesozoic periods are far profounder than the resemblances.

A MAMMAL OF THE EARLY CAINOZOIC PERIOD

The Titanotherum (Brontops) Robustum

The most fundamental of all these differences lies in the mental life of the two periods. It arises essentially out of the continuing contact of parent and offspring which distinguishes mammalian and in a lesser degree bird life, from the life of the reptile. With very few exceptions the reptile abandons its egg to hatch alone. The young reptile has no knowledge whatever of its parent; its mental life, such as it is, begins and ends with its own experiences. It may tolerate the existence of its fellows but it has no communication with them; it never imitates, never learns from them, is incapable of concerted action with them. Its life is that of an isolated individual. But with the suckling and cherishing of young which was distinctive of the new mammalian and avian strains arose the possibility of learning by imitation, of communication, by warning cries and other concerted action, of mutual control and instruction. A teachable type of life had come into the world.

The earliest mammals of the Cainozoic period are but little superior in brain size to the more active carnivorous dinosaurs, but as we read on through the record towards modern times we find, in every tribe and race of the mammalian animals, a steady universal increase in brain capacity. For instance we find at a comparatively early stage that rhinoceros-like beasts appear. There is a creature, the Titanotherium, which lived in the earliest division of this period. It was probably very like a modern rhinoceros in its habits and needs. But its brain capacity was not one tenth that of its living successor.

The earlier mammals probably parted from their offspring as soon as suckling was over, but, once the capacity for mutual understanding has arisen, the advantages of continuing the association are very great; and we presently find a number of mammalian species displaying the beginnings of a true social life and keeping together in herds, packs and flocks, watching each other, imitating each other, taking warning from each other’s acts and cries. This is something that the world had not seen before among vertebrated animals. Reptiles and fish may no doubt be found ill swarms and shoals; they have been hatched in quantities and similar conditions have kept them together, but in the case of the social and gregarious mammals the association arises not simply from a community of external forces, it is sustained by an inner impulse. They are not merely like one another and so found in the same places at the same times; they like one another and so they keep together.

STENOMYLUS HITCHCOCKI—A GIRAFFE-CAMEL

Nat. Hist. Mus.

SKELETON OF PROTOHIPPUS VENTICOLUS--EARLY HORSE

Nat. Hist. Mus.

This difference between the reptile world and the world of our human minds is one our sympathies seem unable to pass. We cannot conceive in ourselves the swift uncomplicated urgency of a reptile’s instinctive motives, its appetites, fears and hates. We cannot understand them in their simplicity because all our motives are complicated; our’s are balances and resultants and not simple urgencies. But the mammals and birds have self-restraint and consideration for other individuals, a social appeal, a self- control that is, at its lower level, after our own fashion. We can in consequence establish relations with almost all sorts of them. When they suffer they utter cries and make movements that rouse our feelings. We can make understanding pets of them with a mutual recognition. They can be tamed to self-restraint towards us, domesticated and taught.

COMPARATIVE SIZES OF BRAINS OF RHINOCEROS AND DINOCERAS

Nat. Hist. Mus.

That unusual growth of brain which is the central fact of Cainozoic times marks a new communication and interdependence of individuals. It foreshadows the development of human societies of which we shall soon be telling.

As the Cainozoic period unrolled, the resemblance of its flora and fauna to the plants and animals that inhabit the world to-day increased. The big clumsy Uintatheres and Titanotheres, the Entelodonts and Hyracodons, big clumsy brutes like nothing living, disappeared. On the other hand a series of forms led up by steady degrees from grotesque and clumsy predecessors to the giraffes, camels, horses, elephants, deer, dogs and lions and tigers of the existing world. The evolution of the horse is particularly legible upon the geological record. We have a fairly complete series of forms from a small tapir-like ancestor in the early Cainozoic. Another line of development that has now been pieced together with some precision is that of the llamas and camels.

IX

MONKEYS, APES AND SUB-MEN

NATURALISTS divide the class Mammalia into a number of orders. At the head of these is the order Primates, which includes the lemurs, the monkeys, apes and man. Their classification was based originally upon anatomical resemblances and took no account of any mental qualities.

Now the past history of the Primates is one very difficult to decipher in the geological record. They are for the most part animals which live in forests like the lemurs and monkeys or in bare rocky places like the baboons. They are rarely drowned and covered up by sediment, nor are most of them very numerous species, and so they do not figure so largely among the fossils as the ancestors of the horses, camels and so forth do. But we know that quite early in the Cainozoic period, that is to say some forty million years ago or so, primitive monkeys and lemuroid creatures had appeared, poorer in brain and not so specialized as their later successors.

The great world summer of the middle Cainozoic period drew at last to an end. It was to follow those other two great summers in the history of life, the summer of the Coal Swamps and the vast summer of the Age of Reptiles. Once more the earth spun towards an ice age. The world chilled, grew milder for a time and chilled again. In the warm past hippopotami had wallowed through a lush sub-tropical vegetation, and a tremendous tiger with fangs like sabres, the sabre-toothed tiger, had hunted its prey where now the journalists of Fleet Street go to and fro. Now came a bleaker age and still bleaker ages. A great weeding and extinction of species occurred. A woolly rhinoceros, adapted to a cold climate, and the mammoth, a big woolly cousin of the elephants, the Arctic musk ox and the reindeer passed across the scene. Then century by century the Arctic ice cap, the wintry death of the great Ice Age, crept southward. In England it came almost down to the Thames, in America it reached Ohio. There would be warmer spells of a few thousand years and relapses towards a bitterer cold.

Geologists talk of these wintry phases as the First, Second, Third and Fourth Glacial Ages, and of the interludes as Interglacial periods. We live to-day in a world that is still impoverished and scarred by that terrible winter. The First Glacial Age was coming on 600,000 years ago; the Fourth Glacial Age reached its bitterest some fifty thousand years ago. And it was amidst the snows of this long universal winter that the first man-like beings lived upon our planet.

A MAMMOTH

By the middle Cainozoic period there have appeared various apes with many quasi-human attributes of the jaws and leg bones, but it is only as we approach these Glacial Ages that we find traces of creatures that we can speak of as “almost human.” These traces are not bones but implements. In Europe, in deposits of this period, between half a million and a million years old, we find flints and stones that have evidently been chipped intentionally by some handy creature desirous of hammering, scraping or fighting with the sharpened edge. These things have been called “Eoliths” (dawn stones). In Europe there are no bones nor other remains of the creature which made these objects, simply the objects themselves. For all the certainty we have it may have been some entirely un-human but intelligent monkey. But at Trinil in Java, in accumulations of this age, a piece of a skull and various teeth and bones have been found of a sort of ape man, with a brain case bigger than that of any living apes, which seems to have walked erect. This creature is now called Pithecanthropus erectus, the walking ape man, and the little trayful of its bones is the only help our imaginations have as yet in figuring to, ourselves the makers of the Eoliths.

FLINT IMPLEMENTS FOUND IN PILTDOWN REGION

Nat. Hist. Mus.

It is not until we come to sands that are almost a quarter of a million years old that we find any other particle of a sub- human being. But there are plenty of implements, and they are steadily improving in quality as we read on through the record. They are no longer clumsy Eoliths; they are now shapely instruments made with considerable skill. And they are much bigger than the similar implements afterwards made by true man. Then, in a sandpit at Heidelberg, appears a single quasi-human jaw-bone, a clumsy jaw-bone, absolutely chinless, far heavier than a true human jaw-bone and narrower, so that it is improbable the creature’s tongue could have moved about for articulate speech. On the strength of this jaw-bone, scientific men suppose this creature to have been a heavy, almost human monster, possibly with huge limbs and hands, possibly with a thick felt of hair, and they call it the Heidelberg Man.

A THEORETICAL RESTORATION OF THE PITHECANTHROPUS ERECTUS BY PROF. RUTOT

This jaw-bone is, I think, one of the most tormenting objects in the world to our human curiosity. To see it is like looking through a defective glass into the past and catching just one blurred and tantalizing glimpse of this Thing, shambling through the bleak wilderness, clambering to avoid the sabre- toothed tiger, watching the woolly rhinoceros in the woods. Then before we can scrutinize the monster, he vanishes. Yet the soil is littered abundantly with the indestructible implements he chipped out for his uses.

THE HEIDELBERG MAN

The Heidelberg Man, as modelled under the supervision of Prof. Rutot

Still more fascinatingly enigmatical are the remains of a creature found at Piltdown in Sussex in a deposit that may indicate an age between a hundred and a hundred and fifty thousand years ago, though some authorities would put these particular remains back in time to before the Heidelberg jaw- bone. Here there are the remains of a thick sub-human skull much larger than any existing ape’s, and a chimpanzee-like jaw-bone which may or may not belong to it, and, in addition, a bat-shaped piece of elephant bone evidently carefully manufactured, through which a hole had apparently been bored. There is also the thigh-bone of a deer with cuts upon it like a tally. That is all.

THE PILTDOWN SKULL, AS RECONSTRUCTED FROM ORIGINAL FRAGMENT

Nat. Hist. Mus.

What sort of beast was this creature which sat and bored holes in bones?

Scientific men have named him Eoanthropus, the Dawn Man. He stands apart from his kindred; a very different being either from the Heidelberg creature or from any living ape. No other vestige like him is known. But the gravels and deposits of from one hundred thousand years onward are increasingly rich in implements of flint and similar stone. And these implements are no longer rude “Eoliths.” The archæologists are presently able to distinguish scrapers, borers, knives, darts, throwing stones and hand axes ....

We are drawing very near to man. In our next section we shall have to describe the strangest of all these precursors of humanity, the Neanderthalers, the men who were almost, but not quite, true men.

But it may be well perhaps to state quite clearly here that no scientific man supposes either of these creatures, the Heidelberg Man or Eoanthropus, to be direct ancestors of the men of to-day. These are, at the closest, related forms.

X

THE NEANDERTHALER AND THE RHODESIAN MAN

ABOUT fifty or sixty thousand years ago, before the climax of the Fourth Glacial Age, there lived a creature on earth so like a man that until a few years ago its remains were considered to be altogether human. We have skulls and bones of it and a great accumulation of the large implements it made and used. It made fires. It sheltered in caves from the cold. It probably dressed skins roughly and wore them. It was right-handed as men are.

Yet now the ethnologists tell us these creatures were not true men. They were of a different species of the same genus. They had heavy protruding jaws and great brow ridges above the eyes and very low foreheads. Their thumbs were not opposable to the fingers as men’s are; their necks were so poised that they could not turn back their heads and look up to the sky. They probably slouched along, head down and forward. Their chinless jaw-bones resemble the Heidelberg jaw-bone and are markedly unlike human jaw-bones. And there were great differences from the human pattern in their teeth. Their cheek teeth were more complicated in structure than ours, more complicated and not less so; they had not the long fangs of our cheek teeth; and also these quasi-men had not the marked canines (dog teeth) of an ordinary human being. The capacity of their skulls was quite human, but the brain was bigger behind and lower in front than the human brain. Their intellectual faculties were differently arranged. They were not ancestral to the human line. Mentally and physically they were upon a different line from the human line.

Skulls and bones of this extinct species of man were found at Neanderthal among other places, and from that place these strange proto-men have been christened Neanderthal Men, or Neanderthalers. They must have endured in Europe for many hundreds or even thousands of years.

THE NEANDERTHALER, ACCORDING TO PROF. RUTOT

At that time the climate and geography of our world was very different from what they are at the present time. Europe for example was covered with ice reaching as far south as the Thames and into Central Germany and Russia; there was no Channel separating Britain from France; the Mediterranean and the Red Sea were great valleys, with perhaps a chain of lakes in their deeper portions, and a great inland sea spread from the present Black Sea across South Russia and far into Central Asia. Spain and all of Europe not actually under ice consisted of bleak uplands under a harder climate than that of Labrador, and it was only when North Africa was reached that one would have found a temperate climate. Across the cold steppes of Southern Europe with its sparse arctic vegetation, drifted such hardy creatures as the woolly mammoth, and woolly rhinoceros, great oxen and reindeer, no doubt following the vegetation northward in spring and southward in autumn.

Such was the scene through which the Neanderthaler wandered, gathering such subsistence as he could from small game or fruits and berries and roots. Possibly he was mainly a vegetarian, chewing twigs and roots. His level elaborate teeth suggest a largely vegetarian dietary. But we also find the long marrow bones of great animals in his caves, cracked to extract the marrow. His weapons could not have been of much avail in open conflict with great beasts, but it is supposed that he attacked them with spears at difficult river crossings and even constructed pitfalls for them. Possibly he followed the herds and preyed upon any dead that were killed in fights, and perhaps he played the part of jackal to the sabre-toothed tiger which still survived in his day. Possibly in the bitter hardships of the Glacial Ages this creature had taken to attacking animals after long ages of vegetarian adaptation.

We cannot guess what this Neanderthal man looked like. He may have been very hairy and very unhuman-looking indeed. It is even doubtful if he went erect. He may have used his knuckles as well as his feet to hold himself up. Probably he went about alone or in small family groups. It is inferred from the structure of his jaw that he was incapable of speech as we understand it.

For thousands of years these Neanderthalers were the highest animals that the European area had ever seen; and then some thirty or thirty-five thousand years ago as the climate grew warmer a race of kindred beings, more intelligent, knowing more, talking and co-operating together, came drifting into the Neanderthaler’s world from the south. They ousted the Neanderthalers from their caves and squatting places; they hunted the same food; they probably made war upon their grisly predecessors and killed them off. These newcomers from the south or the east—for at present we do not know their region of origin—who at last drove the Neanderthalers out of existence altogether, were beings of our own blood and kin, the first True Men. Their brain-cases and thumbs and necks and teeth were anatomically the same as our own. In a cave at Cro-Magnon and in another at Grimaldi, a number of skeletons have been found, the earliest truly human remains that are so far known.

So it is our race comes into the Record of the Rocks, and the story of mankind begins.

COMPARISON OF (1) MODERN SKULL AND (2) RHODESIAN SKULL

Nat. Hist. Mus.

The world was growing liker our own in those days though the climate was still austere. The glaciers of the Ice Age were receding in Europe; the reindeer of France and Spain presently gave way to great herds of horses as grass increased upon the steppes, and the mammoth became more and more rare in southern Europe and finally receded northward altogether ....

We do not know where the True Men first originated. But in the summer of 1921, an extremely interesting skull was found together with pieces of a skeleton at Broken Hill in South Africa, which seems to be a relic of a third sort of man, intermediate in its characteristics between the Neanderthaler and the human being. The brain-case indicates a brain bigger in front and smaller behind than the Neanderthaler’s, and the skull was poised erect upon the backbone in a quite human way. The teeth also and the bones are quite human. But the face must have been ape-like with enormous brow ridges and a ridge along the middle of the skull. The creature was indeed a true man, so to speak, with an ape- like, Neanderthaler face. This Rhodesian Man is evidently still closer to real men than the Neanderthal Man.

This Rhodesian skull is probably only the second of what in the end may prove to be a long list of finds of sub-human species which lived on the earth in the vast interval of time between the beginnings of the Ice Age and the appearance of their common heir, and perhaps their common exterminator, the True Man. The Rhodesian skull itself may not be very ancient. Up to the time of publishing this book there has been no exact determination of its probable age. It may be that this sub-human creature survived in South Africa until quite recent times.

XI

THE FIRST TRUE MEN

THE earliest signs and traces at present known to science, of a humanity which is indisputably kindred with ourselves, have been found in western Europe and particularly in France and Spain. Bones, weapons, scratchings upon bone and rock, carved fragments of bone, and paintings in caves and upon rock surfaces dating. it is supposed. from 30,000 years ago or more, have been discovered in both these countries. Spain is at present the richest country in the world in these first relics of our real human ancestors.