автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Modern Painters, Volume IV (of V)

Project Gutenberg's Modern Painters, Volume IV (of V), by John Ruskin

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Modern Painters, Volume IV (of V)

Author: John Ruskin

Release Date: March 13, 2010 [EBook #31623]

Language: English

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MODERN PAINTERS, VOLUME IV (OF V) ***

Produced by Marius Masi, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's note:

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They appear in the text

like this, and the explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will display an unaccented version.

THE KAPELLBRÜCKE, LUCERNE.

FROM A DRAWING BYRUSKIN.

Library Edition

THE COMPLETE WORKS

OF

JOHN RUSKIN

MODERN PAINTERS

Volume IV—OF MOUNTAIN BEAUTY

Volume V{

OF LEAF BEAUTY

OF CLOUD BEAUTY

OF IDEAS OF RELATION

NATIONAL LIBRARY ASSOCIATION

NEW YORK

CHICAGO

MODERN PAINTERS.

VOLUME IV.,

CONTAINING

PART V.,

OF MOUNTAIN BEAUTY.

The Gates of the Hills.

PREFACE.

I was in hopes that this volume might have gone its way without preface; but as I look over the sheets, I find in them various fallings short of old purposes which require a word of explanation.

Of which shortcomings, the chief is the want of reference to the landscape of the Poussins and Salvator; my original intention having been to give various examples of their mountain-drawing, that it might be compared with Turner's. But the ten years intervening between the commencement of this work and its continuation have taught me, among other things, that Life is shorter and less availably divisible than I had supposed: and I think now that its hours may be better employed than in making facsimiles of bad work. It would have required the greatest care, and prolonged labor, to give uncaricatured representations of Salvator's painting, or of any other work depending on the free dashes of the brush, so as neither to mend nor mar it. Perhaps in the next volume I may give one or two examples associated with vegetation; but in general, I shall be content with directing the reader's attention to the facts in nature, and in Turner; leaving him to carry out for himself whatever comparisons he may judge expedient.

I am afraid, also, that disappointment may be felt at not finding plates of more complete subject illustrating these chapters on mountain beauty. But the analysis into which I had to enter required the dissection of drawings, rather than their complete presentation; while, also, on the scale of any readable page, no effective presentation of large drawings could be given. Even my vignette, the frontispiece to the third volume, is partly spoiled by having too little white paper about it; and the fiftieth plate, from Turner's Goldau, necessarily omits, owing to its reduction, half the refinements of the foreground. It is quite waste of time and cost to reduce Turner's drawings at all; and I therefore consider these volumes only as Guides to them, hoping hereafter to illustrate some of the best on their own scale.

Several of the plates appear, in their present position, nearly unnecessary; 14 and 15, for instance, in Vol. III. These are illustrations of the chapters on the Firmament in the fifth volume; but I should have had the plates disproportionately crowded at last, if I had put all that it needed in that volume; and as these two bear somewhat on various matters spoken of in the third, I placed them where they are first alluded to. The frontispiece has chief reference to the same chapters; but seemed, in its three divisions, properly introductory to our whole subject. It is a simple sketch from nature, taken at sunset from the hills near Como, some two miles up the eastern side of the lake and about a thousand feet above it, looking towards Lugano. The sky is a little too heavy for the advantage of the landscape below; but I am not answerable for the sky. It was there.A

In the multitudinous letterings and references of this volume there may possibly be one or two awkward errata; but not so many as to make it necessary to delay the volume while I look it over again in search of them. The reader will perhaps be kind enough to note at once that in page 182, at the first line of the text, the words "general truth" refer to the angle-measurements, not to the diagrams; which latter are given merely for reference, and might cause some embarrassment if the statement of measured accuracy were supposed to refer to them.

One or two graver misapprehensions I had it in my mind to warn the reader against; but on the whole, as I have honestly tried to make the book intelligible, I believe it will be found intelligible by any one who thinks it worth a careful reading; and every day convinces me more and more that no warnings can preserve from misunderstanding those who have no desire to understand.

Denmark Hill, March, 1856.

A Persons unacquainted with hill scenery are apt to forget that the sky of the mountains is often close to the spectator. A black thundercloud may literally be dashing itself in his face, while the blue hills seen through its rents maybe thirty miles away. Generally speaking, we do not enough understand the nearness of many clouds, even in level countries, as compared with the land horizon. See also the close of § 12 in Chap. III of this volume.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

PART V.

OF MOUNTAIN BEAUTY.

page Chapter

I.—

Of the Turnerian Picturesque

1"

II.—

Of Turnerian Topography

16"

III.—

Of Turnerian Light

34"

IV.—

Of Turnerian Mystery: First, as Essential

56"

V.—

Of Turnerian Mystery: Secondly, Wilful

68"

VI.—

The Firmament

82"

VII.—

The Dry Land

89"

VIII.—

Of the Materials of Mountains: First, Compact Crystallines

99"

IX.—

Of the Materials of Mountains: Secondly, Slaty Crystallines

113"

X.—

Of the Materials of Mountains: Thirdly, Slaty Coherents

122"

XI.—

Of the Materials of Mountains: Fourthly, Compact Coherents

127"

XII.—

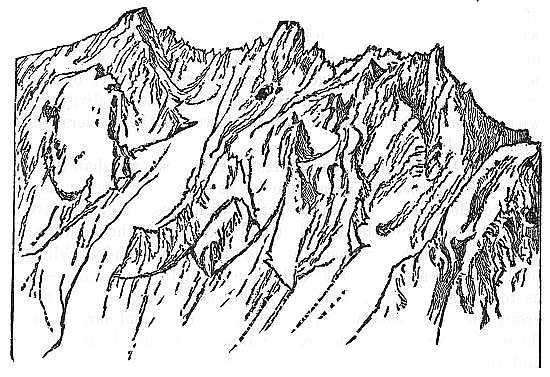

Of the Sculpture of Mountains: First, the Lateral Ranges

137"

XIII.—

Of the Sculpture of Mountains: Secondly, the Central Peaks

157"

XIV.—

Resulting Forms: First, Aiguilles

173"

XV.—

Resulting Forms: Second, Crests

195"

XVI.—

Resulting Forms: Third, Precipices

228"

XVII.—

Resulting Forms: Fourthly, Banks

262"

XVIII.—

Resulting Forms: Fifthly, Stones

301"

XIX.—

The Mountain Gloom

317"

XX.—

The Mountain Glory

344APPENDIX.

I.

Modern Grotesque

385II.

Rock Cleavage

391III.

Logical Education

399

LIST OF PLATES TO VOL. IV.

Drawn by

Engraved by

Frontispiece. The Gates of the Hills

J. M. W. Turner

J. Cousen

Plate

Facing page

18.

The Transition from Ghirlandajo to Claude

Ghirlandajo and Claude

J. H. Le Keux 119.

The Picturesque of Windmills

Stanfield and Turner

J. H. Le Keux 720.

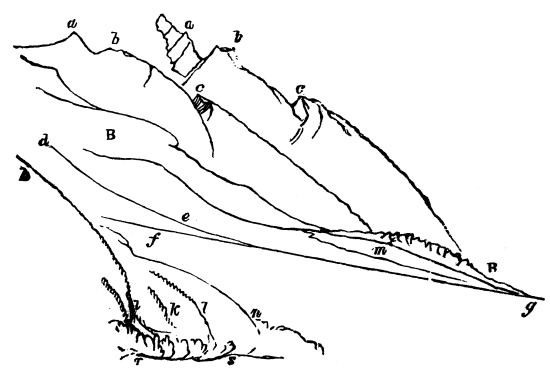

The Pass of Faïdo. 1. Simple Topography

The Author

The Author 2221.

The Pass of Faïdo 2. Turnerian Topography

J. M. W. Turner

The Author 2422.

Turner's Earliest Nottingham

J. M. W. Turner

T. Boys 2923.

Turner's Latest Nottingham

J. M. W. Turner

T. Boys 3024.

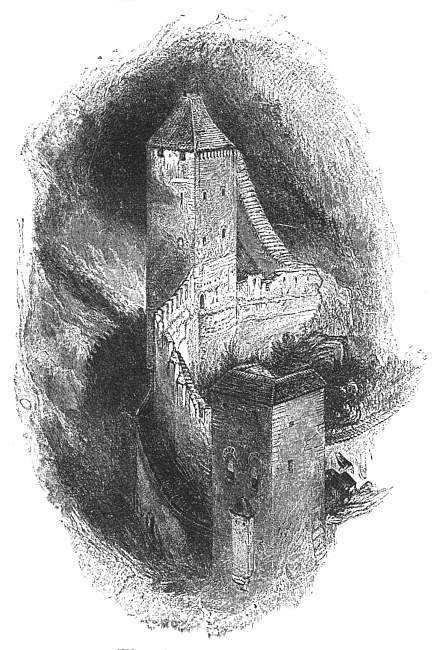

The Towers of Fribourg

The Author

J. C. Armytage 3225.

Things in General

The Author

J. H. Le Keux 3226.

The Law of Evanescence

The Author

R. P. Cuff 7127.

The Aspen under Idealization

Turner, etc.

J. Cousen 7628.

The Aspen Unidealized

The Author

J. C. Armytage 7729.

Aiguille Structure

The Author

J. C. Armytage 16030.

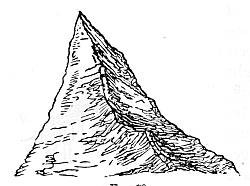

The Ideal of Aiguilles

The Author, etc.

R. P. Cuff 17731.

The Aiguille Blaitière

The Author

J. C. Armytage 18532.

Aiguille-drawing

Turner, etc.

J. H. Le Keux 19133.

Contours of Aiguille Bouchard

The Author

R. P. Cuff 20434.

Cleavage of Aiguille Bouchard

The Author

The Author 21135.

Crests of La Côte and Taconay

The Author

The Author 21236.

Crest of La Côte

The Author

T. Lupton 21337.

Crests of the Slaty Crystallines

J. M. W. Turner

The Author 22238.

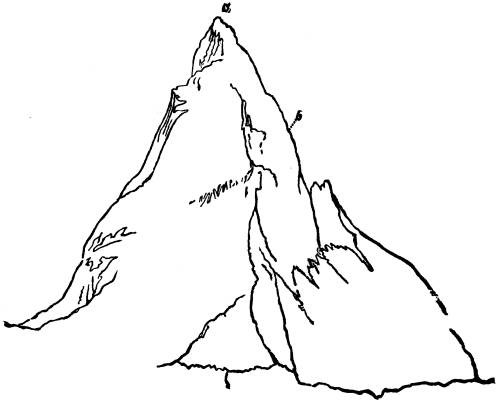

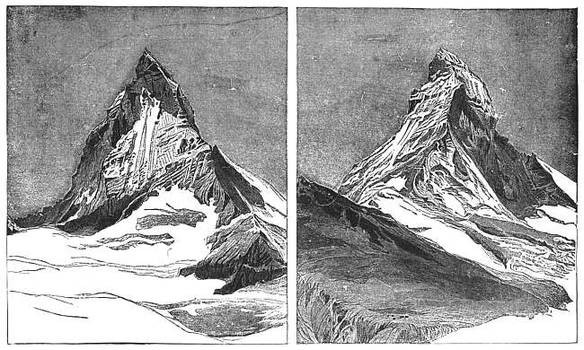

The Cervin, from the East and North-east

The Author

J. C. Armytage 23339.

The Cervin from the North-west

The Author

J. C. Armytage 23840.

The Mountains of Villeneuve

The Author

J. H. Le Keux 24612.

A. The Shores of Wharfe

J. M. W. Turner

Thos. Lupton 25141.

The Rocks of Arona

The Author

J. H. Le Keux 25542.

Leaf Curvature Magnolia and Laburnum

The Author

R. P. Cuff 26943.

Leaf Curvature Dead Laurel

The Author

R. P. Cuff 26944.

Leaf Curvature Young Ivy

The Author

R. P. Cuff 26945.

Débris Curvature

The Author

R. P. Cuff 28546.

The Buttresses of an Alp

The Author

J. H. Le Keux 28647.

The Quarry of Carrara

The Author

J. H. Le Keux 29948.

Bank of Slaty Crystallines

Daguerreotype

J. C. Armytage 30449.

Truth and Untruth of Stones

Turner and Claude

Thos. Lupton 30850.

Goldau

J. M. W. Turner

J. Cousen 312

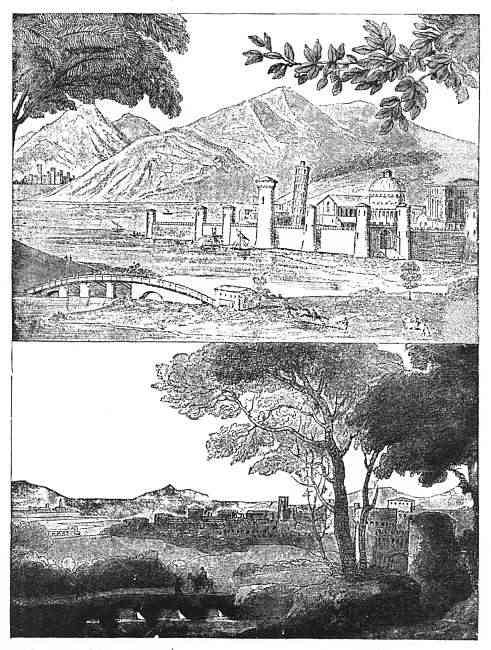

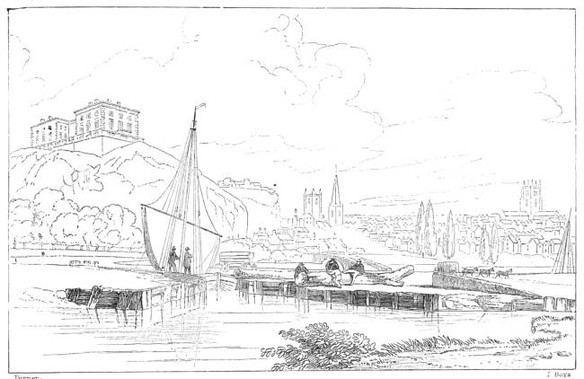

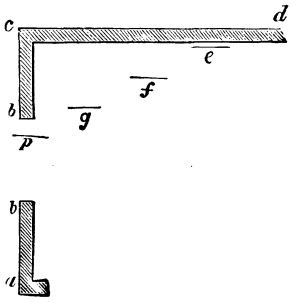

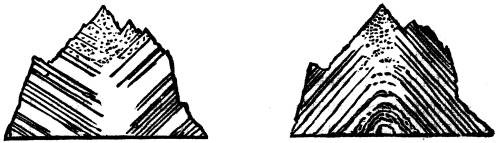

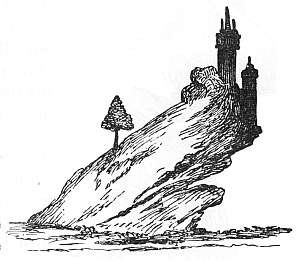

18. The Transition from Ghirlandajo to Claude.

PART V.

OF MOUNTAIN BEAUTY.

CHAPTER I.

OF THE TURNERIAN PICTURESQUE.

§ 1. The work which we proposed to ourselves, towards the close of the last volume, as first to be undertaken in this, was the examination of those peculiarities of system in which Turner either stood alone, even in the modern school, or was a distinguished representative of modern, as opposed to ancient practice.

And the most interesting of these subjects of inquiry, with which, therefore, it may be best to begin, is the precise form under which he has admitted into his work the modern feeling of the picturesque, which, so far as it consists in a delight in ruin, is perhaps the most suspicious and questionable of all the characters distinctively belonging to our temper, and art.

It is especially so, because it never appears, even in the slightest measure, until the days of the decline of art in the seventeenth century. The love of neatness and precision, as opposed to all disorder, maintains itself down to Raphael's childhood without the slightest interference of any other feeling; and it is not until Claude's time, and owing in great part to his influence, that the new feeling distinctly establishes itself.

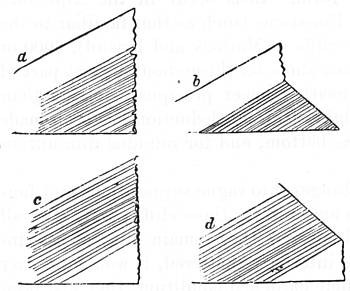

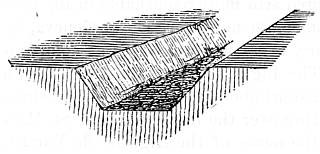

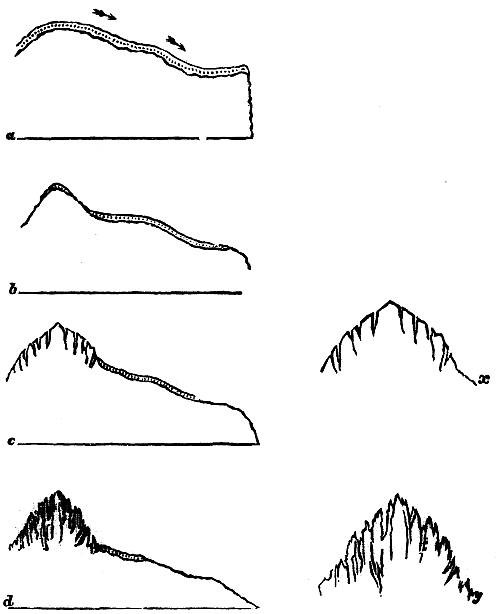

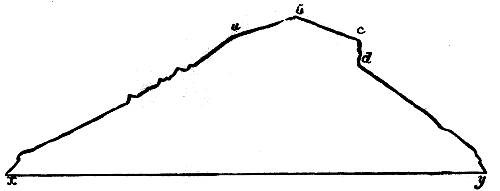

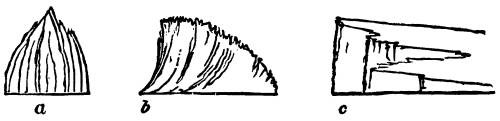

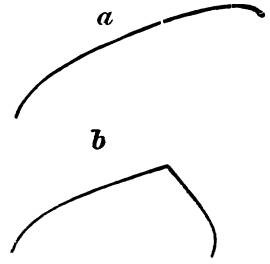

Plate 18 shows the kind of modification which Claude used to make on the towers and backgrounds of Ghirlandajo; the old Florentine giving his idea of Pisa, with its leaning tower, with the utmost neatness and precision, and handsome youth riding over neat bridges on beautiful horses; Claude reducing the delicate towers and walls to unintelligible ruin, the well built bridge to a rugged stone one, the handsome rider to a weary traveller, and the perfectly drawn leafage to confusion of copse-wood or forest.1

How far he was right in doing this; or how far the moderns are right in carrying the principle to greater excess, and seeking always for poverty-stricken rusticity or pensive ruin, we must now endeavor to ascertain.

The essence of picturesque character has been already defined2 to be a sublimity not inherent in the nature of the thing, but caused by something external to it; as the ruggedness of a cottage roof possesses something of a mountain aspect, not belonging to the cottage as such. And this sublimity may be either in mere external ruggedness, and other visible character, or it may lie deeper, in an expression of sorrow and old age, attributes which are both sublime; not a dominant expression, but one mingled with such familiar and common characters as prevent the object from becoming perfectly pathetic in its sorrow, or perfectly venerable in its age.

§ 2. For instance, I cannot find words to express the intense pleasure I have always in first finding myself, after some prolonged stay in England, at the foot of the old tower of Calais church. The large neglect, the noble unsightliness of it; the record of its years written so visibly, yet without sign of weakness or decay; its stern wasteness and gloom, eaten away by the Channel winds, and overgrown with the bitter sea grasses; its slates and tiles all shaken and rent, and yet not falling; its desert of brickwork full of bolts, and holes, and ugly fissures, and yet strong, like a bare brown rock; its carelessness of what any one thinks or feels about it, putting forth no claim, having no beauty nor desirableness, pride nor grace; yet neither asking for pity; not, as ruins are, useless and piteous, feebly or fondly garrulous of better days; but useful still, going through its own daily work,—as some old fisherman beaten grey by storm, yet drawing his daily nets: so it stands, with no complaint about its past youth, in blanched and meagre massiveness and serviceableness, gathering human souls together underneath it; the sound of its bells for prayer still rolling through its rents; and the grey peak of it seen far across the sea, principal of the three that rise above the waste of surfy sand and hillocked shore,—the lighthouse for life, and the belfry for labor, and this for patience and praise.

§ 3. I cannot tell the half of the strange pleasures and thoughts that come about me at the sight of that old tower; for, in some sort, it is the epitome of all that makes the Continent of Europe interesting, as opposed to new countries; and, above all, it completely expresses that agedness in the midst of active life which binds the old and the new into harmony. We, in England, have our new street, our new inn, our green shaven lawn, and our piece of ruin emergent from it,—a mere specimen of the middle ages put on a bit of velvet carpet to be shown, which, but for its size, might as well be on the museum shelf at once, under cover. But, on the Continent, the links are unbroken between the past and present, and in such use as they can serve for, the grey-headed wrecks are suffered to stay with men; while, in unbroken line, the generations of spared buildings are seen succeeding each in its place. And thus in its largeness, in its permitted evidence of slow decline, in its poverty, in its absence of all pretence, of all show and care for outside aspect, that Calais tower has an infinite of symbolism in it, all the more striking because usually seen in contrast with English scenes expressive of feelings the exact reverse of these.

§ 4. And I am sorry to say that the opposition is most distinct in that noble carelessness as to what people think of it. Once, on coming from the Continent, almost the first inscription I saw in my native English was this:

"To Let, a Genteel House, up this road."

And it struck me forcibly, for I had not come across the idea of gentility, among the upper limestones of the Alps, for seven months; nor do I think that the Continental nations in general have the idea. They would have advertised a "pretty" house or a "large" one, or a "convenient" one; but they could not, by any use of the terms afforded by their several languages, have got at the English "genteel." Consider, a little, all the meanness that there is in that epithet, and then see, when next you cross the Channel, how scornful of it that Calais spire will look.

§ 5. Of which spire the largeness and age are also opposed exactly to the chief appearances of modern England, as one feels them on first returning to it; that marvellous smallness both of houses and scenery, so that a ploughman in the valley has his head on a level with the tops of all the hills in the neighborhood; and a house is organized into complete establishment,—parlor, kitchen, and all, with a knocker to its door, and a garret window to its roof, and a bow to its second story,3 on a scale of twelve feet wide by fifteen high, so that three such at least would go into the granary of an ordinary Swiss cottage: and also our serenity of perfection, our peace of conceit, everything being done that vulgar minds can conceive as wanting to be done; the spirit of well-principled housemaids everywhere, exerting itself for perpetual propriety and renovation, so that nothing is old, but only "old-fashioned," and contemporary, as it were, in date and impressiveness only with last year's bonnets. Abroad, a building of the eighth or tenth century stands ruinous in the open street; the children play round it, the peasants heap their corn in it, the buildings of yesterday nestle about it, and fit their new stones into its rents, and tremble in sympathy as it trembles. No one wonders at it, or thinks of it as separate, and of another time; we feel the ancient world to be a real thing, and one with the new: antiquity is no dream; it is rather the children playing about the old stones that are the dream. But all is continuous; and the words, "from generation to generation," understandable there. Whereas here we have a living present, consisting merely of what is "fashionable" and "old-fashioned;" and a past, of which there are no vestiges; a past which peasant or citizen can no more conceive; all equally far away; Queen Elizabeth as old as Queen Boadicea, and both incredible. At Verona we look out of Can Grande's window to his tomb; and if he does not stand beside us, we feel only that he is in the grave instead of the chamber,—not that he is old, but that he might have been beside us last night. But in England the dead are dead to purpose. One cannot believe they ever were alive, or anything else than what they are now—names in school-books.

§ 6. Then that spirit of trimness. The smooth paving-stones; the scraped, hard, even, rutless roads; the neat gates and plates, and essence of border and order, and spikiness and spruceness. Abroad, a country-house has some confession of human weakness and human fates about it. There are the old grand gates still, which the mob pressed sore against at the Revolution, and the strained hinges have never gone so well since; and the broken greyhound on the pillar—still broken—better so; but the long avenue is gracefully pale with fresh green, and the courtyard bright with orange-trees; the garden is a little run to waste—since Mademoiselle was married nobody cares much about it; and one range of apartments is shut up—nobody goes into them since Madame died. But with us, let who will be married or die, we neglect nothing. All is polished and precise again next morning; and whether people are happy or miserable, poor or prosperous, still we sweep the stairs of a Saturday.4

§ 7. Now, I have insisted long on this English character, because I want the reader to understand thoroughly the opposite element of the noble picturesque; its expression, namely, of suffering, of poverty, or decay, nobly endured by unpretending strength of heart. Nor only unpretending, but unconscious. If there be visible pensiveness in the building, as in a ruined abbey, it becomes, or claims to become, beautiful; but the picturesqueness is in the unconscious suffering,—the look that an old laborer has, not knowing that there is anything pathetic in his grey hair, and withered arms, and sunburnt breast; and thus there are the two extremes, the consciousness of pathos in the confessed ruin, which may or may not be beautiful, according to the kind of it; and the entire denial of all human calamity and care, in the swept proprieties and neatness of English modernism: and, between these, there is the unconscious confession of the facts of distress and decay, in by-words; the world's hard work being gone through all the while, and no pity asked for, nor contempt feared. And this is the expression of that Calais spire, and of all picturesque things, in so far as they have mental or human expression at all.

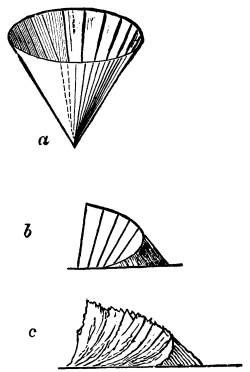

§ 8. I say, in so far as they have mental expression, because their merely outward delightfulness—that which makes them pleasant in painting, or, in the literal sense, picturesque—is their actual variety of color and form. A broken stone has necessarily more various forms in it than a whole one; a bent roof has more various curves in it than a straight one; every excrescence or cleft involves some additional complexity of light and shade, and every stain of moss on eaves or wall adds to the delightfulness of color. Hence, in a completely picturesque object, as an old cottage or mill, there are introduced, by various circumstances not essential to it, but, on the whole, generally somewhat detrimental to it as cottage or mill, such elements of sublimity—complex light and shade, varied color, undulatory form, and so on—as can generally be found only in noble natural objects, woods, rocks, or mountains. This sublimity, belonging in a parasitical manner to the building, renders it, in the usual sense of the word, "picturesque."

§ 9. Now, if this outward sublimity be sought for by the painter, without any regard for the real nature of the thing, and without any comprehension of the pathos of character hidden beneath, it forms the low school of the surface-picturesque; that which fills ordinary drawing-books and scrap-books, and employs, perhaps, the most popular living landscape painters of France, England, and Germany. But if these same outward characters be sought for in subordination to the inner character of the object, every source of pleasurableness being refused which is incompatible with that, while perfect sympathy is felt at the same time with the object as to all that it tells of itself in those sorrowful by-words, we have the school of true or noble picturesque; still distinguished from the school of pure beauty and sublimity, because, in its subjects, the pathos and sublimity are all by the way, as in Calais old spire,—not inherent, as in a lovely tree or mountain; while it is distinguished still more from the schools of the lower picturesque by its tender sympathy, and its refusal of all sources of pleasure inconsistent with the perfect nature of the thing to be studied.

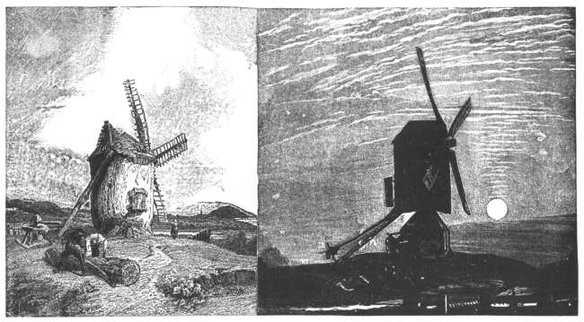

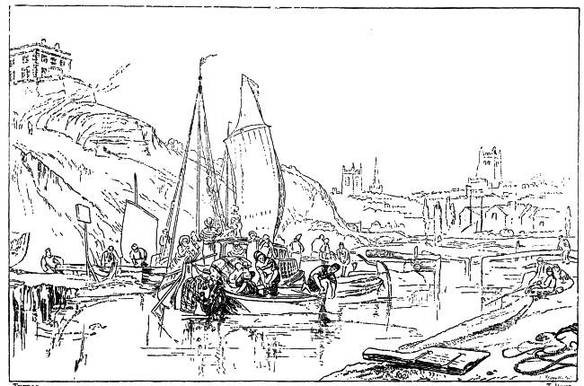

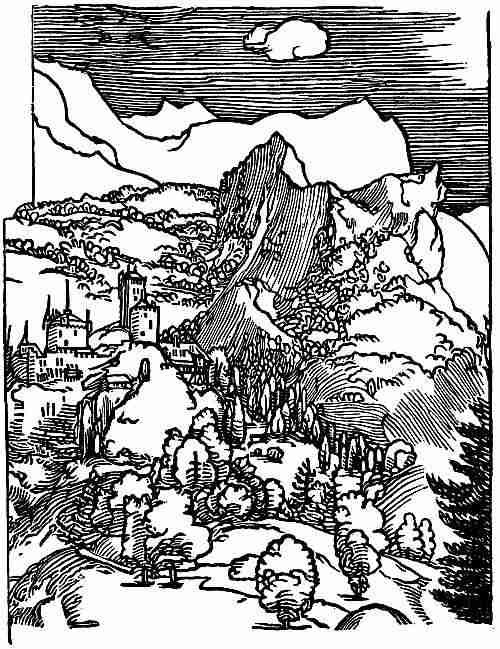

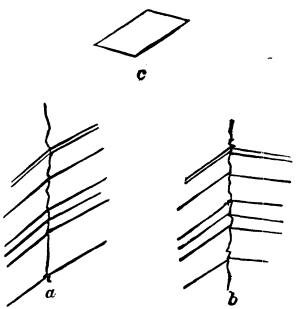

19. The Picturesque of Windmills.

1. Pure Modern.

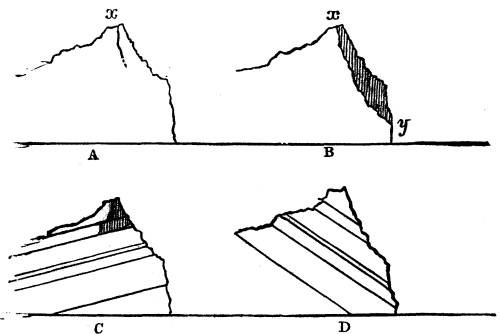

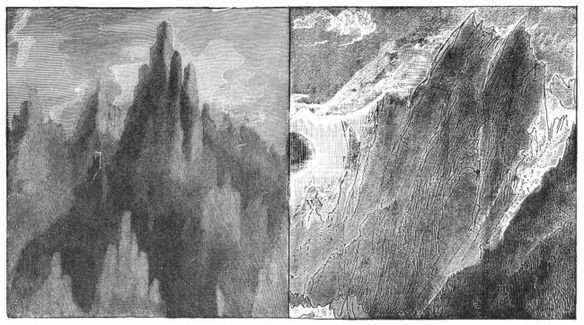

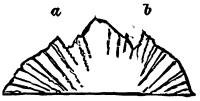

2. Turnerian.§ 10. The reader will only be convinced of the broad scope of this law by careful thought, and comparison of picture with picture; but a single example will make the principle of it clear to him.

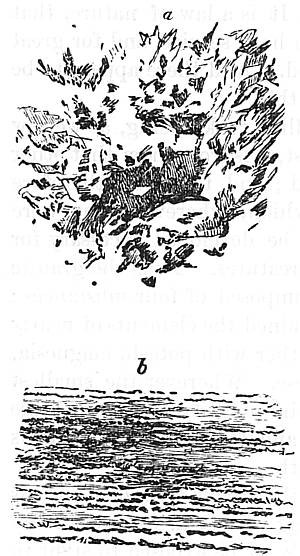

On the whole, the first master of the lower picturesque, among our living artists, is Clarkson Stanfield; his range of art being, indeed, limited by his pursuit of this character. I take, therefore, a windmill, forming the principal subject in his drawing of Brittany, near Dol (engraved in the Coast Scenery), Fig. 1, Plate 19, and beside it I place a windmill, which forms also the principal subject in Turner's study of the Lock, in the Liber Studiorum. At first sight I dare say the reader may like Stanfield's best; and there is, indeed, a great deal more in it to attract liking. Its roof is nearly as interesting in its ruggedness as a piece of the stony peak of a mountain, with a châlet built on its side; and it is exquisitely varied in swell and curve. Turner's roof, on the contrary, is a plain, ugly gable,—a windmill roof, and nothing more. Stanfield's sails are twisted into most effective wrecks, as beautiful as pine bridges over Alpine streams; only they do not look as if they had ever been serviceable windmill sails; they are bent about in cross and awkward ways, as if they were warped or cramped; and their timbers look heavier than necessary. Turner's sails have no beauty about them like that of Alpine bridges; but they have the exact switchy sway of the sail that is always straining against the wind; and the timbers form clearly the lightest possible framework for the canvas,—thus showing the essence of windmill sail. Then the clay wall of Stanfield's mill is as beautiful as a piece of chalk cliff, all worn into furrows by the rain, coated with mosses, and rooted to the ground by a heap of crumbled stone, embroidered with grass and creeping plants. But this is not a serviceable state for a windmill to be in. The essence of a windmill, as distinguished from all other mills, is, that it should turn round, and be a spinning thing, ready always to face the wind; as light, therefore, as possible, and as vibratory; so that it is in no wise good for it to approximate itself to the nature of chalk cliffs.

Now observe how completely Turner has chosen his mill so as to mark this great fact of windmill nature; how high he has set it; how slenderly he has supported it; how he has built it all of wood; how he has bent the lower planks so as to give the idea of the building lapping over the pivot on which it rests inside; and how, finally, he has insisted on the great leverage of the beam behind it, while Stanfield's lever looks more like a prop than a thing to turn the roof with. And he has done all this fearlessly, though none of these elements of form are pleasant ones in themselves, but tend, on the whole, to give a somewhat mean and spider-like look to the principal feature in his picture; and then, finally, because he could not get the windmill dissected, and show us the real heart and centre of the whole, behold, he has put a pair of old millstones, lying outside, at the bottom of it. These—the first cause and motive of all the fabric—laid at its foundation; and beside them the cart which is to fulfil the end of the fabric's being, and take home the sacks of flour.

§ 11. So far of what each painter chooses to draw. But do not fail also to consider the spirit in which it is drawn. Observe, that though all this ruin has befallen Stanfield's mill, Stanfield is not in the least sorry for it. On the contrary, he is delighted, and evidently thinks it the most fortunate thing possible. The owner is ruined, doubtless, or dead; but his mill forms an admirable object in our view of Brittany. So far from being grieved about it, we will make it our principal light;—if it were a fruit-tree in spring-blossom, instead of a desolate mill, we could not make it whiter or brighter; we illume our whole picture with it, and exult over its every rent as a special treasure and possession.

Not so Turner. His mill is still serviceable; but, for all that, he feels somewhat pensive about it. It is a poor property, and evidently the owner of it has enough to do to get his own bread out from between its stones. Moreover, there is a dim type of all melancholy human labor in it,—catching the free winds, and setting them to turn grindstones. It is poor work for the winds; better, indeed, than drowning sailors or tearing down forests, but not their proper work of marshalling the clouds, and bearing the wholesome rains to the place where they are ordered to fall, and fanning the flowers and leaves when they are faint with heat. Turning round a couple of stones, for the mere pulverization of human food, is not noble work for the winds. So, also, of all low labor to which one sets human souls. It is better than no labor; and, in a still higher degree, better than destructive wandering of imagination; but yet, that grinding in the darkness, for mere food's sake, must be melancholy work enough for many a living creature. All men have felt it so; and this grinding at the mill, whether it be breeze or soul that is set to it, we cannot much rejoice in. Turner has no joy of his mill. It shall be dark against the sky, yet proud, and on the hill-top; not ashamed of its labor, and brightened from beyond, the golden clouds stooping over it, and the calm summer sun going down behind, far away, to his rest.

§ 12. Now in all this observe how the higher condition of art (for I suppose the reader will feel, with me, that Turner's is the highest) depends upon largeness of sympathy. It is mainly because the one painter has communion of heart with his subject, and the other only casts his eyes upon it feelinglessly, that the work of the one is greater than that of the other. And, as we think farther over the matter, we shall see that this is indeed the eminent cause of the difference between the lower picturesque and the higher. For, in a certain sense, the lower picturesque ideal is eminently a heartless one: the lover of it seems to go forth into the world in a temper as merciless as its rocks. All other men feel some regret at the sight of disorder and ruin. He alone delights in both; it matters not of what. Fallen cottage—desolate villa—deserted village—blasted heath—mouldering castle—to him, so that they do but show jagged angles of stone and timber, all are sights equally joyful. Poverty, and darkness, and guilt, bring in their several contributions to his treasury of pleasant thoughts. The shattered window, opening into black and ghastly rents of wall, the foul rag or straw wisp stopping them, the dangerous roof, decrepit floor and stair, ragged misery or wasting age of the inhabitants,—all these conduce, each in due measure, to the fulness of his satisfaction. What is it to him that the old man has passed his seventy years in helpless darkness and untaught waste of soul? The old man has at last accomplished his destiny, and filled the corner of a sketch, where something of an unshapely nature was wanting. What is it to him that the people fester in that feverish misery in the low quarter of the town, by the river? Nay, it is much to him. What else were they made for? what could they have done better? The black timbers, and the green water, and the soaking wrecks of boats, and the torn remnants of clothes hung out to dry in the sun;—truly the fever-struck creatures, whose lives have been given for the production of these materials of effect, have not died in vain.5

§ 13. Yet, for all this, I do not say the lover of the lower picturesque is a monster in human form. He is by no means this, though truly we might at first think so, if we came across him unawares, and had not met with any such sort of person before. Generally speaking, he is kind-hearted, innocent of evil, but not broad in thought; somewhat selfish, and incapable of acute sympathy with others; gifted at the same time with strong artistic instincts and capacities for the enjoyment of varied form, and light, and shade, in pursuit of which enjoyment his life is passed, as the lives of other men are, for the most part, in the pursuit of what they also like,—be it honor, or money, or indolent pleasure,—very irrespective of the poor people living by the stagnant canal. And, in some sort, the hunter of the picturesque is better than many of these; inasmuch as he is simple-minded and capable of unostentatious and economical delights, which, if not very helpful to other people, are at all events utterly uninjurious, even to the victims or subjects of his picturesque fancies; while to many others his work is entertaining and useful. And, more than all this, even that delight which he seems to take in misery is not altogether unvirtuous. Through all his enjoyment there runs a certain under current of tragical passion,—a real vein of human sympathy;—it lies at the root of all those strange morbid hauntings of his; a sad excitement, such as other people feel at a tragedy, only less in degree, just enough, indeed, to give a deeper tone to his pleasure, and to make him choose for his subject the broken stones of a cottage wall, rather than of a roadside bank, the picturesque beauty of form in each being supposed precisely the same: and, together with this slight tragical feeling, there is also a humble and romantic sympathy; a vague desire, in his own mind, to live in cottages rather than in palaces; a joy in humble things, a contentment and delight in makeshifts, a secret persuasion (in many respects a true one) that there is in these ruined cottages a happiness often quite as great as in kings' palaces, and a virtue and nearness to God infinitely greater and holier than can commonly be found in any other kind of place; so that the misery in which he exults is not, as he sees it, misery, but nobleness,—"poor, and sick in body, and beloved by the Gods."6 And thus, being nowise sure that these things can be mended at all, and very sure that he knows not how to mend them, and also that the strange pleasure he feels in them must have some good reason in the nature of things, he yields to his destiny, enjoys his dark canal without scruple, and mourns over every improvement in the town, and every movement made by its sanitary commissioners, as a miser would over a planned robbery of his chest; in all this being not only innocent, but even respectable and admirable, compared with the kind of person who has no pleasure in sights of this kind, but only in fair façades, trim gardens, and park palings, and who would thrust all poverty and misery out of his way, collecting it into back alleys, or sweeping it finally out of the world, so that the street might give wider play for his chariot wheels, and the breeze less offence to his nobility.

§ 14. Therefore, even the love for the lower picturesque ought to be cultivated with care, wherever it exists; not with any special view to artistic, but to merely humane, education. It will never really or seriously interfere with practical benevolence; on the contrary, it will constantly lead, if associated with other benevolent principles, to a truer sympathy with the poor, and better understanding of the right ways of helping them; and, in the present stage of civilization, it is the most important element of character, not directly moral, which can be cultivated in youth; since it is mainly for the want of this feeling that we destroy so many ancient monuments, in order to erect "handsome" streets and shops instead, which might just as well have been erected elsewhere, and whose effect on our minds, so far as they have any, is to increase every disposition to frivolity, expense, and display.

These, and such other considerations not directly connected with our subject, I shall, perhaps, be able to press farther at the close of my work; meantime, we turn to the immediate question, of the distinction between the lower and higher picturesque, and the artists who pursue them.

§ 15. It is evident, from what has been advanced, that there is no definite bar of separation between the two; but that the dignity of the picturesque increases from lower to higher, in exact proportion to the sympathy of the artist with his subject. And in like manner his own greatness depends (other things being equal) on the extent of this sympathy. If he rests content with narrow enjoyment of outward forms, and light sensations of luxurious tragedy, and so goes on multiplying his sketches of mere picturesque material, he necessarily settles down into the ordinary "clever" artist, very good and respectable, maintaining himself by his sketching and painting in an honorable way, as by any other daily business, and in due time passing away from the world without having, on the whole, done much for it. Such has been the necessary, not very lamentable, destiny of a large number of men in these days, whose gifts urged them to the practice of art, but who possessing no breadth of mind, nor having met with masters capable of concentrating what gifts they had towards nobler use, almost perforce remained in their small picturesque circle; getting more and more narrowed in range of sympathy as they fell more and more into the habit of contemplating the one particular class of subjects that pleased them, and recomposing them by rules of art.

I need not give instances of this class, we have very few painters who belong to any other; I only pause for a moment to except from it a man too often confounded with the draughtsmen of the lower picturesque;—a very great man, who, though partly by chance, and partly by choice, limited in range of subject, possessed for that subject the profoundest and noblest sympathy—Samuel Prout. His renderings of the character of old buildings, such as that spire of Calais, are as perfect and as heartfelt as I can conceive possible; nor do I suppose that any one else will ever hereafter equal them.7 His early works show that he possessed a grasp of mind which could have entered into almost any kind of landscape subject; that it was only chance—I do not know if altogether evil chance—which fettered him to stones; and that in reality he is to be numbered among the true masters of the nobler picturesque.

§ 16. Of these, also, the ranks rise in worthiness, according to their sympathy. In the noblest of them, that sympathy seems quite unlimited; they enter with their whole heart into all nature; their love of grace and beauty keeps them from delighting too much in shattered stones and stunted trees, their kindness and compassion from dwelling by choice on any kind of misery, their perfect humility from avoiding simplicity of subject when it comes in their way, and their grasp of the highest thoughts from seeking a lower sublimity in cottage walls and penthouse roofs. And, whether it be home of English village thatched with straw and walled with clay, or of Italian city vaulted with gold and roofed with marble; whether it be stagnant stream under ragged willow, or glancing fountain between arcades of laurel, all to them will bring equal power of happiness, and equal field for thought.

§ 17. Turner is the only artist who hitherto has furnished the entire type of this perfection. The attainment of it in all respects is, of course, impossible to man; but the complete type of such a mind has once been seen in him, and, I think, existed also in Tintoret; though, as far as I know, Tintoret has not left any work which indicates sympathy with the humor of the world. Paul Veronese, on the other hand, had sympathy with its humor, but not with its deepest tragedy or horror. Rubens wants the feeling for grace and mystery. And so, as we pass through the list of great painters, we shall find in each of them some local narrowness. Now, I do not, of course, mean to say that Turner has accomplished all to which his sympathy prompted him; necessarily, the very breadth of effort involved, in some directions, manifest failure; but he has shown, in casual incidents, and by-ways, a range of feeling which no other painter, as far as I know, can equal. He cannot, for instance, draw children at play as well as Mulready; but just glean out of his works the evidence of his sympathy with children;—look at the girl putting her bonnet on the dog, in the foreground of the Richmond, Yorkshire; the juvenile tricks and "marine dabblers" of the Liber Studiorum; the boys scrambling after their kites in the woods of the Greta and Buckfastleigh; and the notable and most pathetic drawing of the Kirkby Lonsdale churchyard, with the schoolboys making a fortress of their larger books on the tombstone, to bombard with the more projectile volumes; and passing from these to the intense horror and pathos of the Rizpah, consider for yourself whether there was ever any other painter who could strike such an octave. Whether there has been or not, in other walks of art, this power of sympathy is unquestionably in landscape unrivalled; and it will be one of our pleasantest future tasks to analyze in his various drawing the character it always gives; a character, indeed, more or less marked in all good work whatever, but to which, being preeminent in him, I shall always hereafter give the name of the "Turnerian Picturesque."

J. Ruskin.

J. H. Le Keux.

47. The Quarries of Carrara.

48. Bank of Slaty Crystallines.

49. Truth and Untruth of Stones.

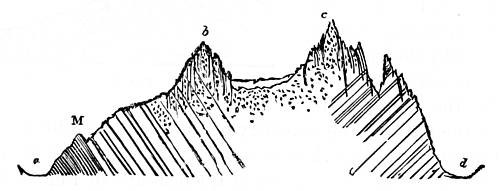

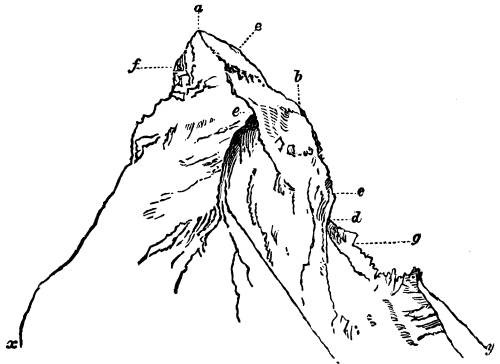

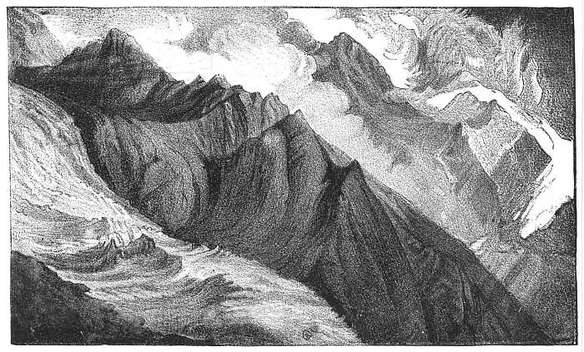

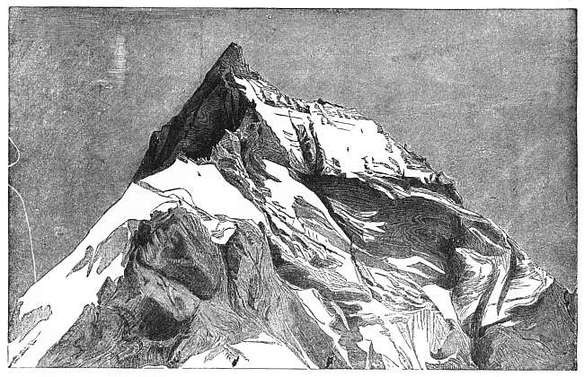

38. The Cervin, from the East and North-east.

J. Ruskin.

J. C. Armytage.

39. The Cervin, from the North-West.

1 Ghirlandajo is seen to the greatest possible disadvantage in this place, as I have been forced again to copy from Lasinio, who leaves out all the light and shade, and vulgarizes every form; but the points requiring notice here are sufficiently shown, and I will do Ghirlandajo more justice hereafter.

2 Seven Lamps of Architecture, chap. vi. § 12.

J. M. W. Turner.

J. Cousen.

50. Goldau.

3 The principal street of Canterbury has some curious examples of this tininess.

12. The Shores of Wharfe.

you, not them. Those lies of thine will "hurt a man as thou art," assuredly they will hurt thyself; but that clay, or the delivered soul of it, in no wise. Ajacean shield, seven-folded, never stayed lance-thrust as that turf will, with daisies pied. What you say of those quiet ones is wholly and utterly the world's affair and yours. The lie will, indeed, cost its proper price and work its appointed work; you may ruin living myriads by it,—you may stop the progress of centuries by it,—you may have to pay your own soul for it,—but as for ruffling one corner of the folded shroud by it, think it not. The dead have none to defend them! Nay, they have two defenders, strong enough for the need—God, and the worm.

4 This, however, is of course true only of insignificant duties, necessary for appearance' sake. Serious duties, necessary for kindness' sake, must be permitted in any domestic affliction, under pain of shocking the English public.

J. Ruskin.

J. H. Le Keux.

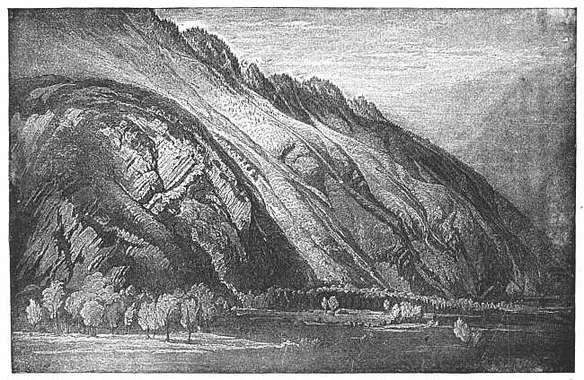

40. The Mountains of Villeneuve.

5 I extract from my private diary a passage bearing somewhat on the matter in hand:—

J. Ruskin.

R. P. Cuff.

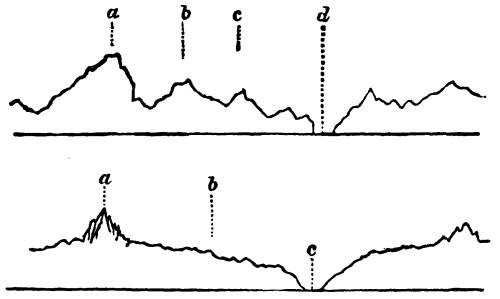

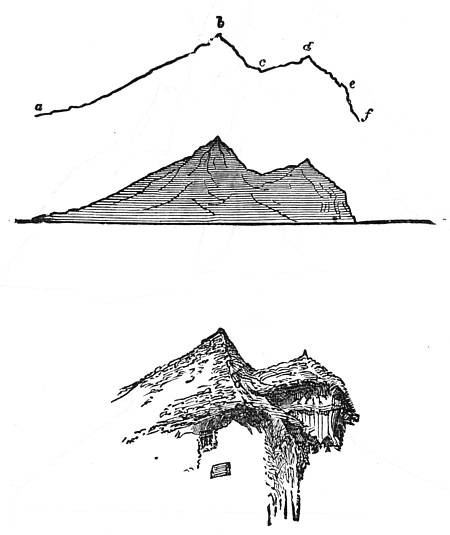

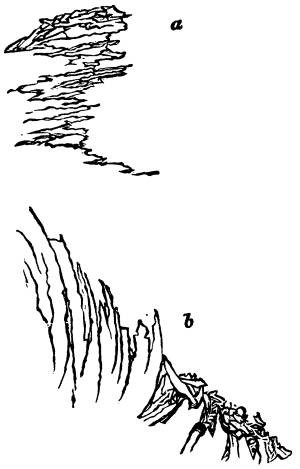

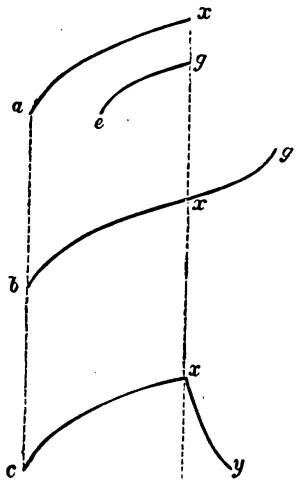

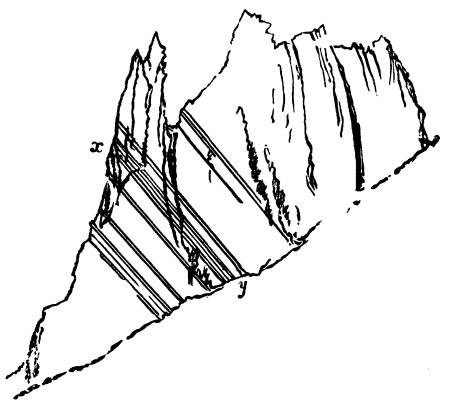

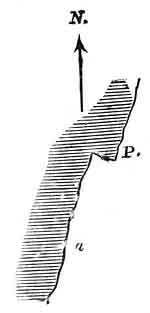

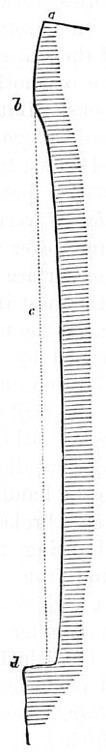

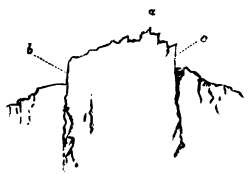

33. Leading Contours of Aiguille Bouchard.

6 Epitaph on Epictetus.

34. Cleavages of Aiguille Bouchard.

7 I believe when a thing is once well done in this world, it never can be done over again.

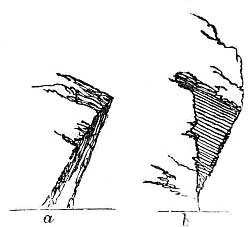

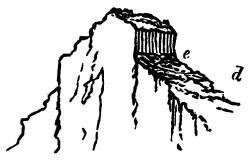

35. Crests of La Côte and Taconay.

36. Crest of La Côte.

J. Ruskin.

J. H. Le Keux.

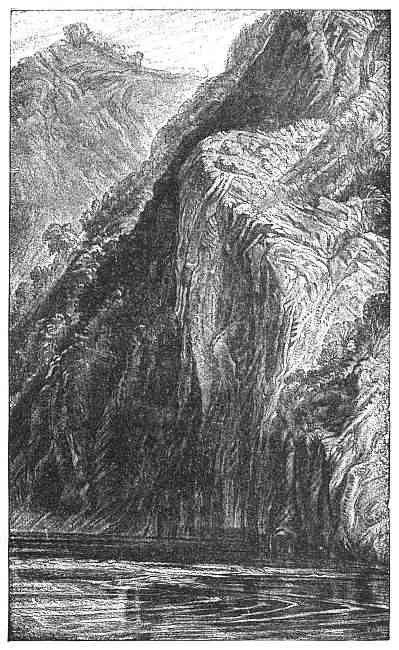

41. The Rocks of Arona.

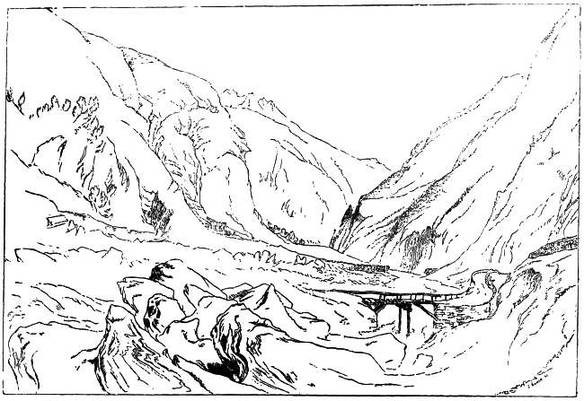

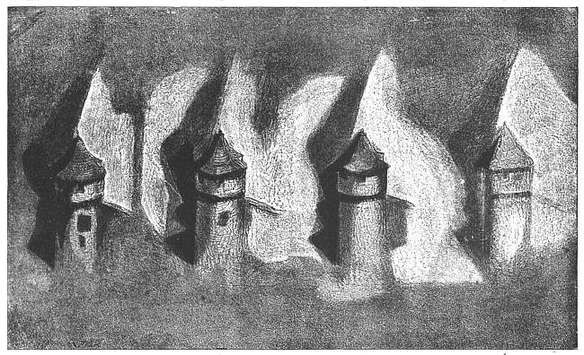

20. Pass of Faïdo.

(1st. Simple Topography.)J. M. W. Turner.

J. Ruskin.

37. Crests of the Slaty Crystallines.

42. Leaf Curvature. Magnolia and Laburnum.

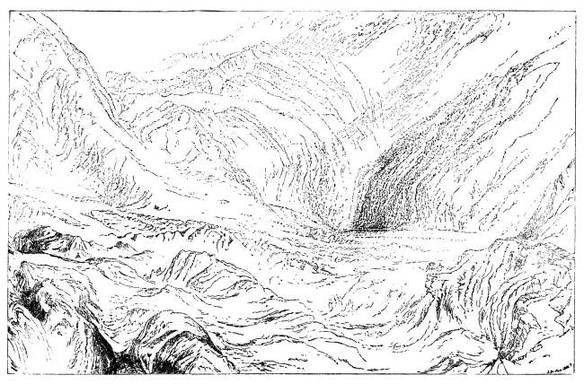

21. Pass of Faïdo.

(2d. Turnerian Topography.)43. Leaf Curvature. Dead Laurel.

Turner.

T. Boys.

22. Turner's Earliest "Nottingham."

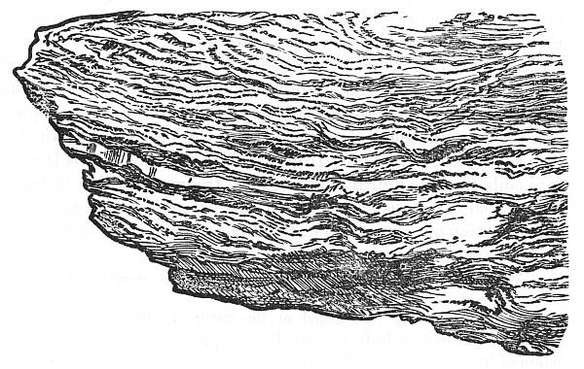

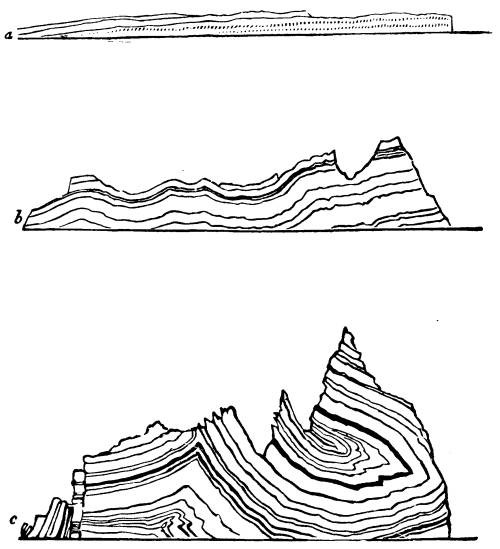

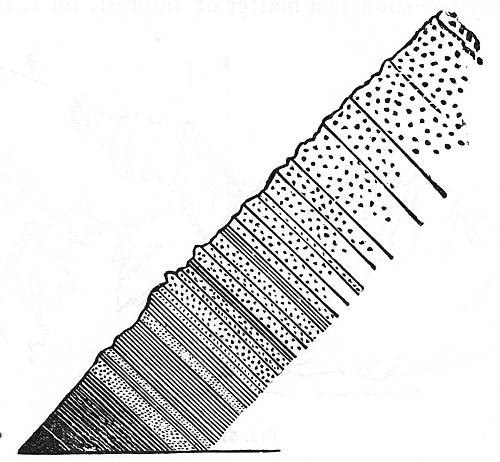

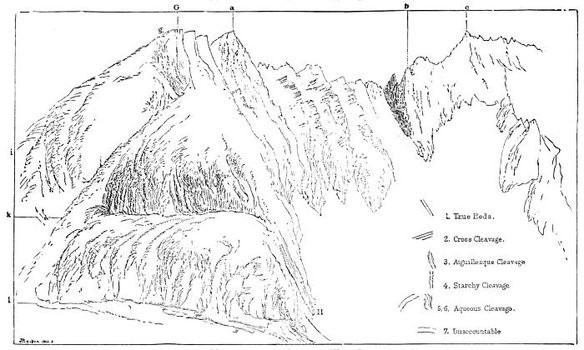

find that all those thick beams of rock are actually sawn into vertical timbers by other cleavage, sometimes so fine as to look almost slaty, directed straight S.E., against the aiguille, as if, continued, it would saw it through and through; finally, cross the spur and go down to the glacier below, between it and the Aiguille du Plan, and the bottom of the spur will be found presenting the most splendid mossy surfaces, through which the true gneissitic cleavage is faintly traceable, dipping at right angles to the beds in Fig. 3, or under the Aiguille Blaitière, thus concurring with the beds of La Côte.

44. Leaf Curvature. Young Ivy.

Turner.

T. Boys.

23. Turner's Latest "Nottingham."

R. P. Cuff

45. Débris Curvature.

J. Ruskin.

J. C. Armytage.

24. The Towers of Fribourg.

J. Ruskin.

J. H. Le Keux.

46. The Buttresses of an Alp.

J. Ruskin.

J. H. Le Keux

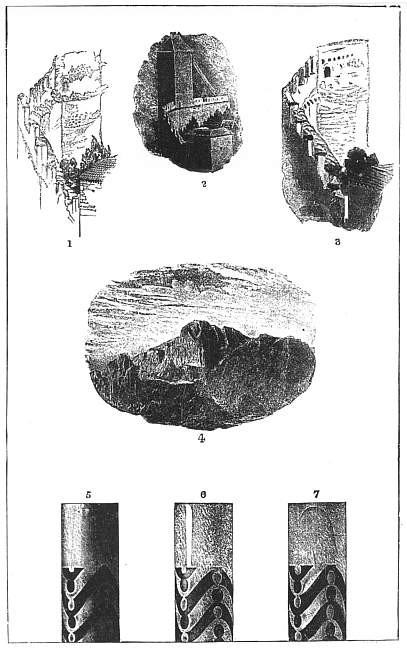

25. Things in general.

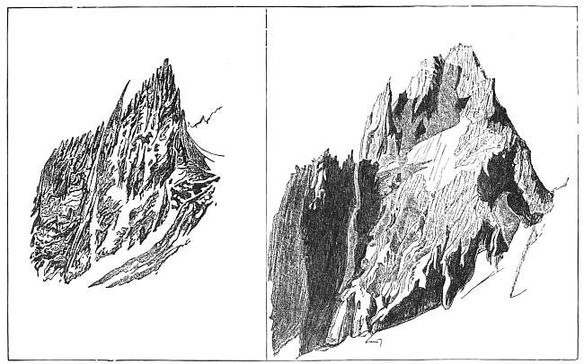

30. The Aiguille Charmoz.

J. Ruskin.

J. C. Armytage.

31. The Aiguille Blaitière.

18. The Transition from Ghirlandajo to Claude.

32. Aiguille Drawing.

1. Old Ideal.

2. Turnerian.

19. The Picturesque of Windmills.

1. Pure Modern.

2. Turnerian.A Persons unacquainted with hill scenery are apt to forget that the sky of the mountains is often close to the spectator. A black thundercloud may literally be dashing itself in his face, while the blue hills seen through its rents maybe thirty miles away. Generally speaking, we do not enough understand the nearness of many clouds, even in level countries, as compared with the land horizon. See also the close of § 12 in Chap. III of this volume.

J. Ruskin.

1

2

3

4

R. P. Cuff

26. The Law of Evanescence.

1. Ancient, or Giottesque.

4. Modern or Blottesque.

2. Purist.

5. Constablesque.

3. Turneresque.

6. Hardingesque.

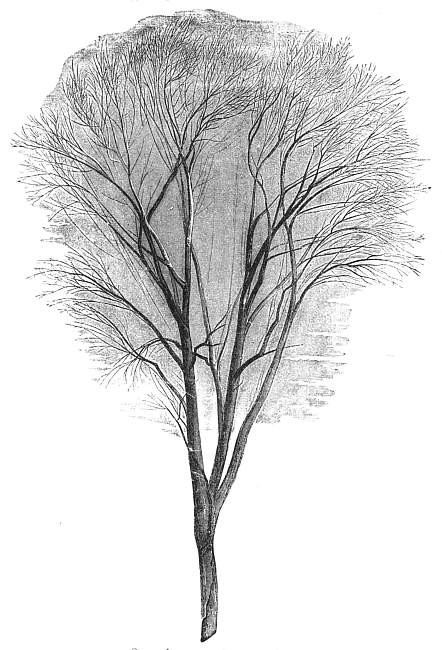

27. The Aspen, under Idealization.

28. Aspen, Unidealized.

J. Ruskin.

J.C. Armytage.

29. Aiguille Structure.

1 Ghirlandajo is seen to the greatest possible disadvantage in this place, as I have been forced again to copy from Lasinio, who leaves out all the light and shade, and vulgarizes every form; but the points requiring notice here are sufficiently shown, and I will do Ghirlandajo more justice hereafter.

2 Seven Lamps of Architecture, chap. vi. § 12.

3 The principal street of Canterbury has some curious examples of this tininess.

4 This, however, is of course true only of insignificant duties, necessary for appearance' sake. Serious duties, necessary for kindness' sake, must be permitted in any domestic affliction, under pain of shocking the English public.

5 I extract from my private diary a passage bearing somewhat on the matter in hand:—

"Amiens, 11th May, 18—. I had a happy walk here this afternoon, down among the branching currents of the Somme; it divides into five or six,—shallow, green, and not over-wholesome; some quite narrow and foul, running beneath clusters of fearful houses, reeling masses of rotten timber; and a few mere stumps of pollard willow sticking out of the banks of soft mud, only retained in shape of bank by being shored up with timbers; and boats like paper boats, nearly as thin at least, for the costermongers to paddle about in among the weeds, the water soaking through the lath bottoms, and floating the dead leaves from the vegetable-baskets with which they were loaded. Miserable little back yards, opening to the water, with steep stone steps down to it, and little platforms for the ducks; and separate duck staircases, composed of a sloping board with cross bits of wood leading to the ducks' doors, and sometimes a flower-pot or two on them, or even a flower,—one group, of wallflowers and geraniums, curiously vivid, being seen against the darkness of a dyer's back yard, who had been dyeing black all day, and all was black in his yard but the flowers, and they fiery and pure; the water by no means so, but still working its way steadily over the weeds, until it narrowed into a current strong enough to turn two or three mill-wheels, one working against the side of an old flamboyant Gothic church, whose richly traceried buttresses sloped into the filthy stream;—all exquisitely picturesque, and no less miserable. We delight in seeing the figures in these boats pushing them about the bits of blue water, in Prout's drawings; but as I looked to-day at the unhealthy face and melancholy mien of the man in the boat pushing his load of peats along the ditch, and of the people, men as well as women, who sat spinning gloomily at the cottage doors, I could not help feeling how many suffering persons must pay for my picturesque subject and happy walk."

6 Epitaph on Epictetus.

7 I believe when a thing is once well done in this world, it never can be done over again.

CHAPTER II.

OF TURNERIAN TOPOGRAPHY.

§ 1. We saw, in the course of the last chapter, with what kind of feeling an artist ought to regard the character of every object he undertakes to paint. The next question is, what objects he ought to undertake to paint; how far he should be influenced by his feelings in the choice of subjects; and how far he should permit himself to alter, or, in the usual art language, improve, nature. For it has already been stated (Vol. III. Chap. III. § 21.), that all great art must be inventive; that is to say, its subject must be produced by the imagination. If so, then great landscape art cannot be a mere copy of any given scene; and we have now to inquire what else than this it may be.

§ 2. If the reader will glance over that twenty-first, and the following three paragraphs of the same chapter, he will see that we there divided art generally into "historical" and "poetical," or the art of relating facts simply, and facts imaginatively. Now, with respect to landscape, the historical art is simple topography, and the imaginative art is what I have in the heading of the present chapter called Turnerian topography, and must in the course of it endeavor to explain.

Observe, however, at the outset, that, touching the duty or fitness of altering nature at all, the quarrels which have so wofully divided the world of art are caused only by want of understanding this simplest of all canons,—"It is always wrong to draw what you don't see." This law is inviolable. But then, some people see only things that exist, and others see things that do not exist, or do not exist apparently. And if they really see these non-apparent things, they are quite right to draw them; the only harm is when people try to draw non-apparent things, who don't see them, but think they can calculate or compose into existence what is to them for evermore invisible. If some people really see angels where others see only empty space, let them paint the angels; only let not anybody else think they can paint an angel, too, on any calculated principles of the angelic.

§ 3. If, therefore, when we go to a place, we see nothing else than is there, we are to paint nothing else, and to remain pure topographical or historical landscape painters. If, going to the place, we see something quite different from what is there, then we are to paint that—nay, we must paint that, whether we will or not; it being, for us, the only reality we can get at. But let us beware of pretending to see this unreality if we do not.

The simple observance of this rule would put an end to nearly all disputes, and keep a large number of men in healthy work, who now totally waste their lives; so that the most important question that an artist can possibly have to determine for himself, is whether he has invention or not. And this he can ascertain with ease. If visions of unreal things present themselves to him with or without his own will, praying to be painted, quite ungovernable in their coming or going,—neither to be summoned if they do not choose to come, nor banished if they do,—he has invention. If, on the contrary, he only sees the commonly visible facts; and, should he not like them, and want to alter them, finds that he must think of a rule whereby to do so, he has no invention. All the rules in the world will do him no good; and if he tries to draw anything else than those materially visible facts, he will pass his whole life in uselessness, and produce nothing but scientific absurdities.

§ 4. Let him take his part at once, boldly, and be content. Pure history and pure topography are most precious things; in many cases more useful to the human race than high imaginative work; and assuredly it is intended that a large majority of all who are employed in art should never aim at anything higher. It is only vanity, never love, nor any other noble feeling, which prompts men to desert their allegiance to the simple truth, in vain pursuit of the imaginative truth which has been appointed to be for evermore sealed to them.

Nor let it be supposed that artists who possess minor degrees of imaginative gift need be embarrassed by the doubtful sense of their own powers. In general, when the imagination is at all noble, it is irresistible, and therefore those who can at all resist it ought to resist it. Be a plain topographer if you possibly can; if Nature meant you to be anything else, she will force you to it; but never try to be a prophet; go on quietly with your hard camp-work, and the spirit will come to you in the camp, as it did to Eldad and Medad, if you are appointed to have it; but try above all things to be quickly perceptive of the noble spirit in others, and to discern in an instant between its true utterance and the diseased mimicries of it. In a general way, remember it is a far better thing to find out other great men, than to become one yourself: for you can but become one at best, but you may bring others to light in numbers.

§ 5. We have, therefore, to inquire what kind of changes these are, which must be wrought by the imaginative painter on landscape, and by whom they have been thus nobly wrought. First, for the better comfort of the non-imaginative painter, be it observed, that it is not possible to find a landscape, which, if painted precisely as it is, will not make an impressive picture. No one knows, till he has tried, what strange beauty and subtle composition is prepared to his hand by Nature, wherever she is left to herself; and what deep feeling may be found in many of the most homely scenes, even where man has interfered with those wild ways of hers. But, beyond this, let him note that though historical topography forbids alteration, it neither forbids sentiment nor choice. So far from doing this, the proper choice of subject8 is an absolute duty to the topographical painter: he should first take care that it is a subject intensely pleasing to himself, else he will never paint it well; and then also, that it shall be one in some sort pleasurable to the general public, else it is not worth painting at all; and lastly, take care that it be instructive, as well as pleasurable to the public, else it is not worth painting with care. I should particularly insist at present on this careful choice of subject, because the Pre-Raphaelites, taken as a body, have been culpably negligent in this respect, not in humble honor of Nature, but in morbid indulgence of their own impressions. They happen to find their fancies caught by a bit of an oak hedge, or the weeds at the sides of a duck-pond, because, perhaps, they remind them of a stanza of Tennyson; and forthwith they sit down to sacrifice the most consummate skill, two or three months of the best summer time available for out-door work (equivalent to some seventieth or sixtieth of all their lives), and nearly all their credit with the public, to this duck-pond delineation. Now it is indeed quite right that they should see much to be loved in the hedge, nor less in the ditch; but it is utterly and inexcusably wrong that they should neglect the nobler scenery which is full of majestic interest, or enchanted by historical association; so that, as things go at present, we have all the commonalty that may be seen whenever we choose, painted properly; but all of lovely and wonderful, which we cannot see but at rare intervals, painted vilely: the castles of the Rhine and Rhone made vignettes of for the annuals; and the nettles and mushrooms, which were prepared by Nature eminently for nettle porridge and fish sauce, immortalized by art as reverently as if we were Egyptians, and they deities.

§ 6. Generally speaking, therefore, the duty of every painter at present, who has not much invention, is to take subjects of which the portraiture will be precious in after times; views of our abbeys and cathedrals; distant views of cities, if possible chosen from some spot in itself notable by association; perfect studies of the battle-fields of Europe, of all houses of celebrated men, and places they loved, and, of course, of the most lovely natural scenery. And, in doing all this, it should be understood, primarily, whether the picture is topographical or not: if topographical, then not a line is to be altered, not a stick nor stone removed, not a color deepened, not a form improved; the picture is to be, as far as possible, the reflection of the place in a mirror; and the artist to consider himself only as a sensitive and skilful reflector, taking care that no false impression is conveyed by any error on his part which he might have avoided; so that it may be for ever afterwards in the power of all men to lean on his work with absolute trust, and to say: "So it was:—on such a day of June or July of such a year, such a place looked like this; these weeds were growing there, so tall and no taller; those stones were lying there, so many and no more; that tower so rose against the sky, and that shadow so slept upon the street."

§ 7. Nor let it be supposed that the doing of this would ever become mechanical, or be found too easy, or exclude sentiment. As for its being easy, those only think so who never tried it; composition being, in fact, infinitely easier to a man who can compose, than imitation of this high kind to even the most able imitator; nor would it exclude sentiment, for, however sincerely we may try to paint all we see, this cannot, as often aforesaid, be ever done: all that is possible is a certain selection, and more or less wilful assertion, of one fact in preference to another; which selection ought always to be made under the influence of sentiment. Nor will such topography involve an entire submission to ugly accidents interfering with the impressiveness of the scene. I hope, as art is better understood, that our painters will get into the habit of accompanying all their works with a written statement of their own reasons for painting them, and the circumstances under which they were done; and, if in this written document they state the omissions they have made, they may make as many as they think proper. For instance, it is not possible now to obtain a view of the head of the Lake of Geneva without including the "Hôtel Biron"—an establishment looking like a large cotton factory—just above the Castle of Chillon. This building ought always to be omitted, and the reason for the omission stated. So the beauty of the whole town of Lucerne, as seen from the lake, is destroyed by the large new hotel for the English, which ought, in like manner, to be ignored, and the houses behind it drawn as if it were transparent.

§ 8. But if a painter has inventive power he is to treat his subject in a totally different way; giving not the actual facts of it, but the impression it made on his mind.

And now, once for all, let it be clearly understood that an "impression on the mind" does not mean a piece of manufacture. The way in which most artists proceed to "invent," as they call it, a picture, is this: they choose their subject, for the most part, well, with a sufficient quantity of towers, mountains, ruined cottages, and other materials, to be generally interesting; then they fix on some object for a principal light; behind this they put a dark cloud, or, in front of it, a dark piece of foreground; then they repeat this light somewhere else in a less degree, and connect the two lights together by some intermediate ones. If they find any part of the foreground uninteresting they put a group of figures into it; if any part of the distance, they put something there from some other sketch; and proceed to inferior detail in the same manner, taking care always to put white stones near black ones, and purple colors near yellow ones, and angular forms near round ones;—all being as simply a matter of recipe and practice as cookery; like that, not by any means a thing easily done well, but still having no reference whatever to "impressions on the mind."

§ 9. But the artist who has real invention sets to work in a totally different way. First, he receives a true impression from the place itself, and takes care to keep hold of that as his chief good; indeed, he needs no care in the matter, for the distinction of his mind from that of others consists in his instantly receiving such sensations strongly, and being unable to lose them; and then he sets himself as far as possible to reproduce that impression on the mind of the spectator of his picture.

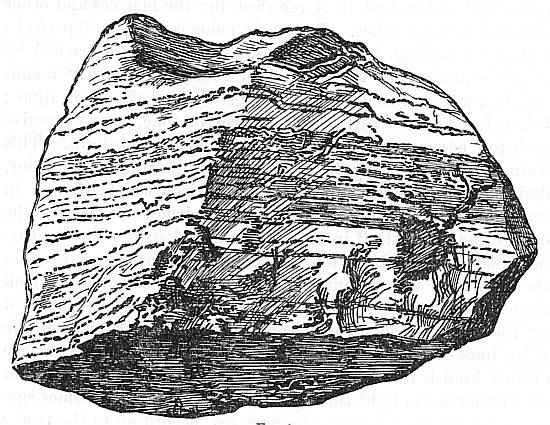

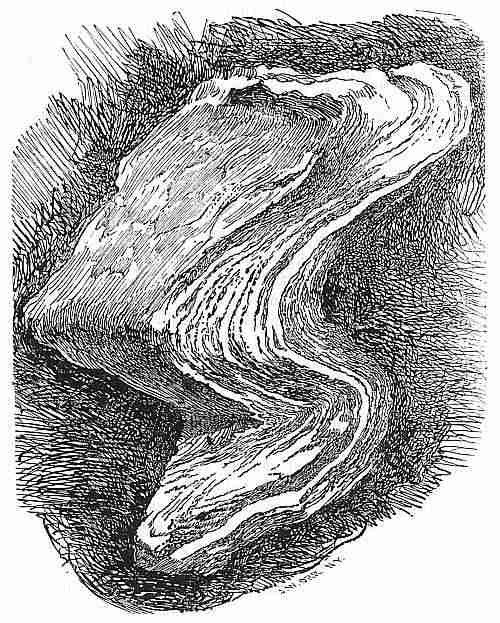

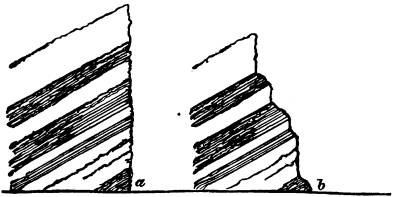

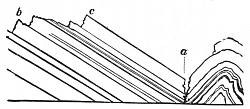

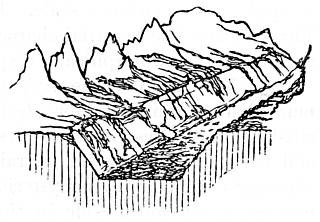

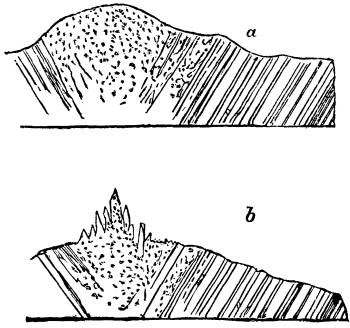

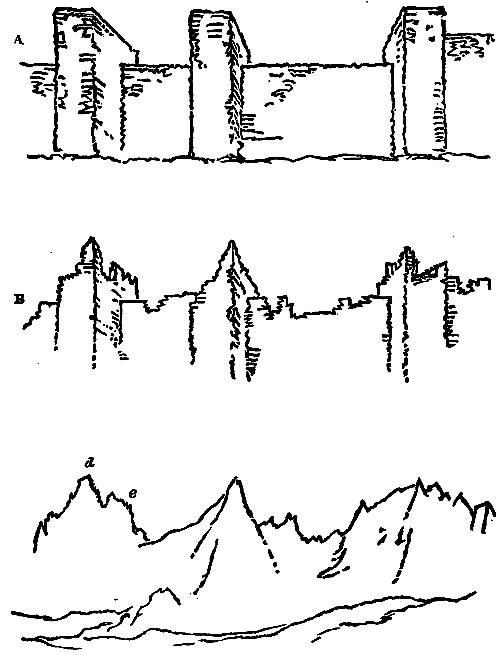

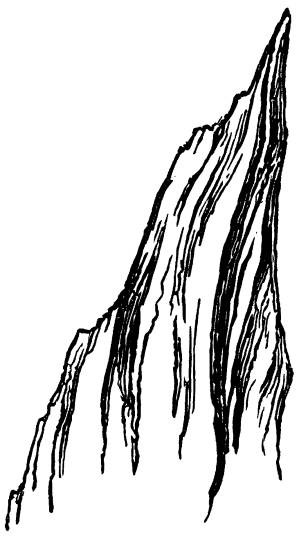

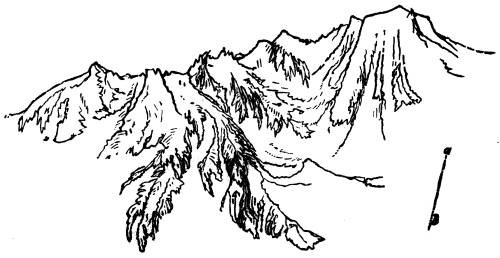

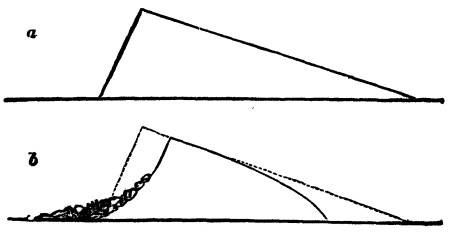

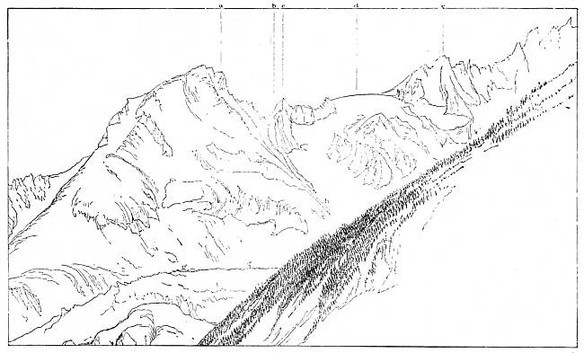

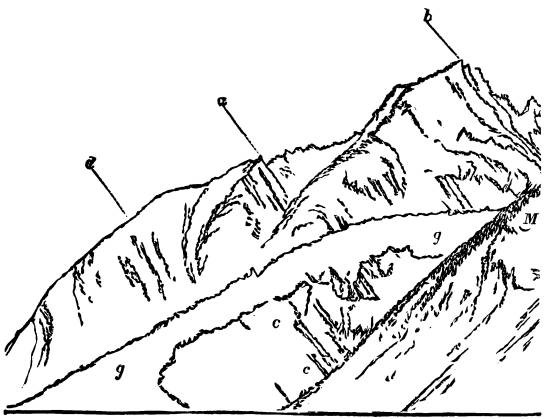

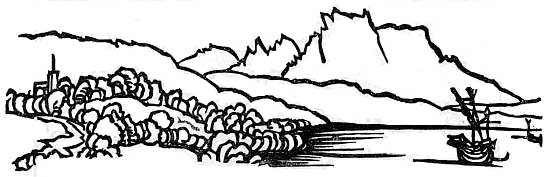

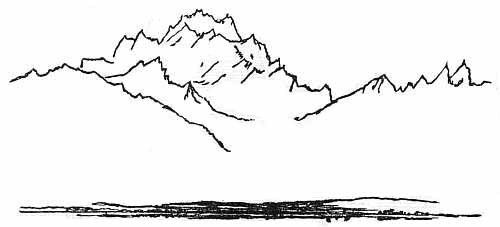

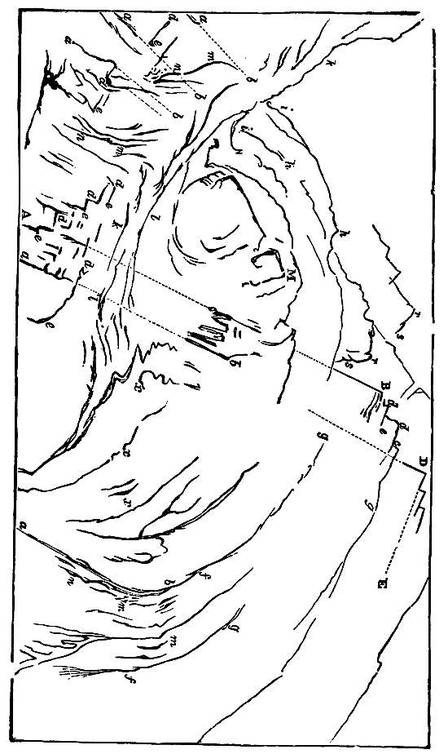

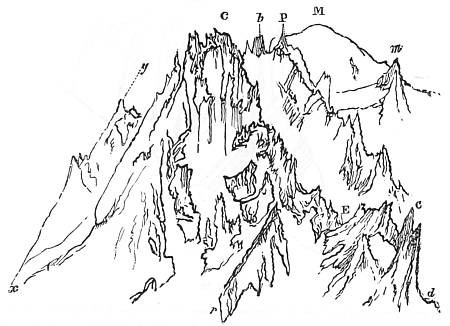

Now, observe, this impression on the mind never results from the mere piece of scenery which can be included within the limits of the picture. It depends on the temper into which the mind has been brought, both by all the landscape round, and by what has been seen previously in the course of the day; so that no particular spot upon which the painter's glance may at any moment fall, is then to him what, if seen by itself, it will be to the spectator far away; nor is it what it would be, even to that spectator, if he had come to the reality through the steps which Nature has appointed to be the preparation for it, instead of seeing it isolated on an exhibition wall. For instance, on the descent of the St. Gothard, towards Italy, just after passing through the narrow gorge above Faïdo, the road emerges into a little breadth of valley, which is entirely filled by fallen stones and débris, partly disgorged by the Ticino as it leaps out of the narrower chasm, and partly brought down by winter avalanches from a loose and decomposing mass of mountain on the left. Beyond this first promontory is seen a considerably higher range, but not an imposing one, which rises above the village of Faïdo. The etching, Plate 20, is a topographical outline of the scene, with the actual blocks of rock which happened to be lying in the bed of the Ticino at the spot from which I chose to draw it. The masses of loose débris (which, for any permanent purpose, I had no need to draw, as their arrangement changes at every flood) I have not drawn, but only those features of the landscape which happen to be of some continual importance. Of which note, first, that the little three-windowed building on the left is the remnant of a gallery built to protect the road, which once went on that side, from the avalanches and stones that come down the "couloir"9 in the rock above. It is only a ruin, the greater part having been by said avalanches swept away, and the old road, of which a remnant is also seen on the extreme left, abandoned, and carried now along the hillside on the right, partly sustained on rough stone arches, and winding down, as seen in the sketch, to a weak wooden bridge, which enables it to recover its old track past the gallery. It seems formerly (but since the destruction of the gallery) to have gone about a mile farther down the river on the right bank, and then to have been carried across by a longer wooden bridge, of which only the two abutments are seen in the sketch, the rest having been swept away by the Ticino, and the new bridge erected near the spectator.

20. Pass of Faïdo.

(1st. Simple Topography.)§ 10. There is nothing in this scene, taken by itself, particularly interesting or impressive. The mountains are not elevated, nor particularly fine in form, and the heaps of stones which encumber the Ticino present nothing notable to the ordinary eye. But, in reality, the place is approached through one of the narrowest and most sublime ravines in the Alps, and after the traveller during the early part of the day has been familiarized with the aspect of the highest peaks of the Mont St. Gothard. Hence it speaks quite another language to him from that in which it would address itself to an unprepared spectator: the confused stones, which by themselves would be almost without any claim upon his thoughts, become exponents of the fury of the river by which he has journeyed all day long; the defile beyond, not in itself narrow or terrible, is regarded nevertheless with awe, because it is imagined to resemble the gorge that has just been traversed above; and, although no very elevated mountains immediately overhang it, the scene is felt to belong to, and arise in its essential characters out of, the strength of those mightier mountains in the unseen north.

§ 11. Any topographical delineation of the facts, therefore, must be wholly incapable of arousing in the mind of the beholder those sensations which would be caused by the facts themselves, seen in their natural relations to others. And the aim of the great inventive landscape painter must be to give the far higher and deeper truth of mental vision, rather than that of the physical facts, and to reach a representation which, though it may be totally useless to engineers or geographers, and, when tried by rule and measure, totally unlike the place, shall yet be capable of producing on the far-away beholder's mind precisely the impression which the reality would have produced, and putting his heart into the same state in which it would have been, had he verily descended into the valley from the gorges of Airolo.

§ 12. Now observe; if in his attempt to do this the artist does not understand the sacredness of the truth of Impression, and supposes that, once quitting hold of his first thought, he may by Philosophy compose something prettier than he saw, and mightier than he felt, it is all over with him. Every such attempt at composition will be utterly abortive, and end in something that is neither true nor fanciful; something geographically useless, and intellectually absurd.

But if, holding fast his first thought, he finds other ideas insensibly gathering to it, and, whether he will or not, modifying it into something which is not so much the image of the place itself, as the spirit of the place, let him yield to such fancies, and follow them wherever they lead. For, though error on this side is very rare among us in these days, it is possible to check these finer thoughts by mathematical accuracies, so as materially to impair the imaginative faculty. I shall be able to explain this better after we have traced the actual operation of Turner's mind on the scene under discussion.

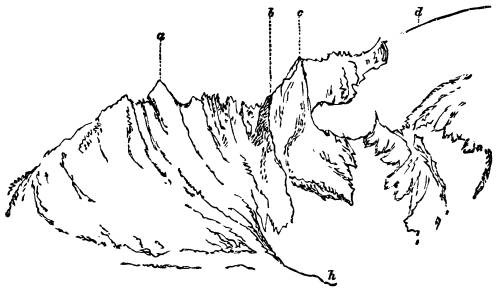

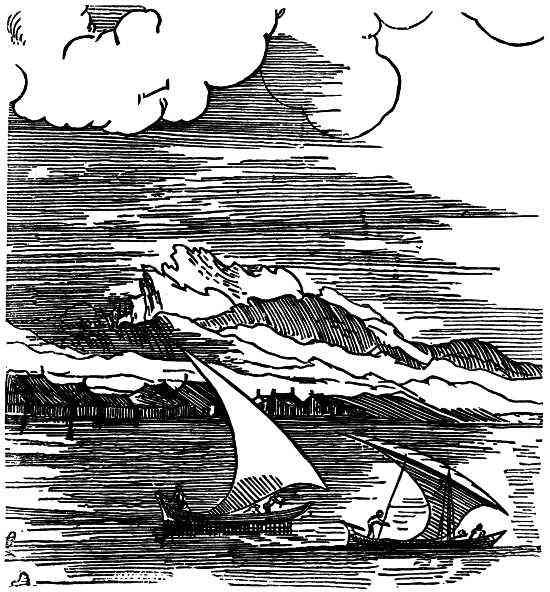

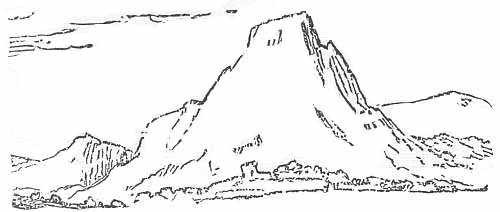

§ 13. Turner was always from his youth fond of stones (we shall see presently why). Whether large or small, loose or embedded, hewn into cubes or worn into boulders, he loved them as much as William Hunt loves pineapples and plums. So that this great litter of fallen stones, which to any one else would have been simply disagreeable, was to Turner much the same as if the whole valley had been filled with plums and pineapples, and delighted him exceedingly, much more than even the gorge of Dazio Grande just above. But that gorge had its effect upon him also, and was still not well out of his head when the diligence stopped at the bottom of the hill, just at that turn of the road on the right of the bridge; which favorable opportunity Turner seized to make what he called a "memorandum" of the place, composed of a few pencil scratches on a bit of thin paper, that would roll up with others of the sort and go into his pocket afterwards. These pencil scratches he put a few blots of color upon (I suppose at Bellinzona the same evening, certainly not upon the spot), and showed me this blotted sketch when he came home. I asked him to make me a drawing of it, which he did, and casually told me afterwards (a rare thing for him to do) that he liked the drawing he had made. Of this drawing I have etched a reduced outline in Plate 21.

§ 14. In which, primarily, observe that the whole place is altered in scale, and brought up to the general majesty of the higher forms of the Alps. It will be seen that, in my topographical sketch, there are a few trees rooted in the rock on this side of the gallery, showing by comparison, that it is not above four or five hundred feet high. These trees Turner cuts away, and gives the rock a height of about a thousand feet, so as to imply more power and danger in the avalanche coming down the couloir.

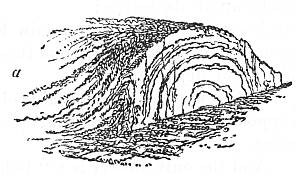

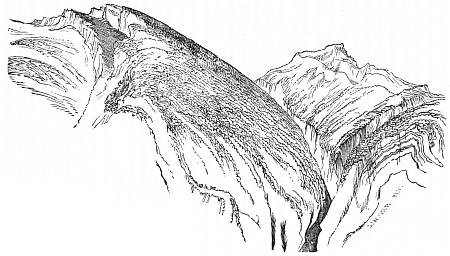

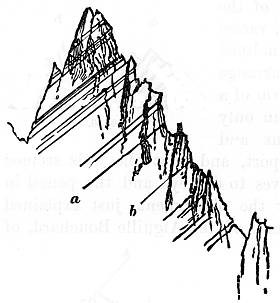

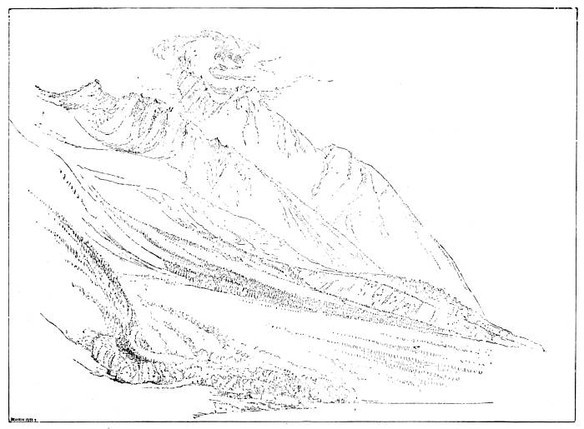

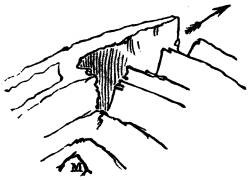

21. Pass of Faïdo.

(2d. Turnerian Topography.)Next, he raises, in a still greater degree, all the mountains beyond, putting three or four ranges instead of one, but uniting them into a single massy bank at their base, which he makes overhang the valley, and thus reduces it nearly to such a chasm as that which he had just passed through above, so as to unite the expression of this ravine with that of the stony valley. A few trees, in the hollow of the glen, he feels to be contrary in spirit to the stones, and fells them, as he did the others; so also he feels the bridge in the foreground, by its slenderness, to contradict the aspect of violence in the torrent; he thinks the torrent and avalanches should have it all their own way hereabouts; so he strikes down the nearer bridge, and restores the one farther off, where the force of the stream may be supposed less. Next, the bit of road on the right, above the bank, is not built on a wall, nor on arches high enough to give the idea of an Alpine road in general; so he makes the arches taller, and the bank steeper, introducing, as we shall see presently, a reminiscence from the upper part of the pass.

§ 15. I say he "thinks" this, and "introduces" that. But, strictly speaking, he does not think at all. If he thought, he would instantly go wrong; it is only the clumsy and uninventive artist who thinks. All these changes come into his head involuntarily; an entirely imperative dream, crying, "thus it must be," has taken possession of him; he can see, and do, no otherwise than as the dream directs.

This is especially to be remembered with respect to the next incident—the introduction of figures. Most persons to whom I have shown the drawing, and who feel its general character, regret that there is any living thing in it; they say it destroys the majesty of its desolation. But the dream said not so to Turner. The dream insisted particularly upon the great fact of its having come by the road. The torrent was wild, the stones were wonderful; but the most wonderful thing of all was how we ourselves, the dream and I, ever got here. By our feet we could not—by the clouds we could not—by any ivory gates we could not—in no other wise could we have come than by the coach road. One of the great elements of sensation, all the day long, has been that extraordinary road, and its goings on, and gettings about; here, under avalanches of stones, and among insanities of torrents, and overhangings of precipices, much tormented and driven to all manner of makeshifts and coils to this side and the other, still the marvellous road persists in going on, and that so smoothly and safely, that it is not merely great diligences, going in a caravanish manner, with whole teams of horses, that can traverse it, but little postchaises with small postboys, and a pair of ponies. And the dream declared that the full essence and soul of the scene, and consummation of all the wonderfulness of the torrents and Alps, lay in a postchaise, with small ponies and postboy, which accordingly it insisted upon Turner's inserting, whether he liked it or not, at the turn of the road.

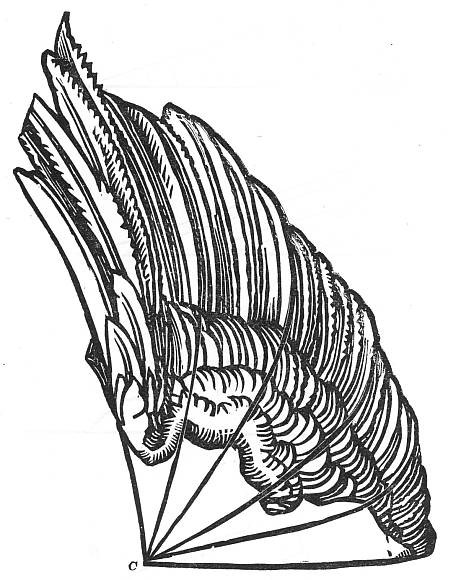

§ 16. Now, it will be observed by any one familiar with ordinary principles of arrangement of form (on which principles I shall insist at length in another place), that while the dream introduces these changes bearing on the expression of the scene, it is also introducing other changes, which appear to be made more or less in compliance with received rules of composition,10 rendering the masses broader, the lines more continuous, and the curves more graceful. But the curious part of the business is, that these changes seem not so much to be wrought by imagining an entirely new condition of any feature, as by remembering something which will fit better in that place. For instance, Turner felt the bank on the right ought to be made more solid and rocky, in order to suggest firmer resistance to the stream, and he turns it, as will be seen by comparing the etchings, into a kind of rock buttress, to the wall, instead of a mere bank. Now, the buttress into which he turns it is very nearly a facsimile of one which he had drawn on that very St. Gothard road, far above, at the Devil's Bridge, at least thirty years before, and which he had himself etched and engraved, for the Liber Studiorum, although the plate was never published. Fig. 1 is a copy of the bit of the etching in question. Note how the wall winds over it, and observe especially the peculiar depression in the middle of its surface, and compare it in those parts generally with the features introduced in the later composition. Of course, this might be set down as a mere chance coincidence, but for the frequency of the cases in which Turner can be shown to have done the same thing, and to have introduced, after a lapse of many years, memories of something which, however apparently small or unimportant, had struck him in his earlier studies. These instances, when I can detect them, I shall point out as I go on engraving his works; and I think they are numerous enough to induce a doubt whether Turner's composition was not universally an arrangement of remembrances, summoned just as they were wanted, and set each in its fittest place. It is this very character which appears to me to mark it as so distinctly an act of dream-vision; for in a dream there is just this kind of confused remembrance of the forms of things which we have seen long ago, associated by new and strange laws. That common dreams are grotesque and disorderly, and Turner's dream natural and orderly, does not, to my thinking, involve any necessary difference in the real species of act of mind. I think I shall be able to show, in the course of the following pages, or elsewhere, that whenever Turner really tried to compose, and made modifications of his subjects on principle, he did wrong, and spoiled them; and that he only did right in a kind of passive obedience to his first vision, that vision being composed primarily of the strong memory of the place itself which he had to draw; and secondarily, of memories of other places (whether recognized as such by himself or not I cannot tell), associated, in a harmonious and helpful way, with the new central thought.

§ 17. The kind of mental chemistry by which the dream summons and associates its materials, I have already endeavored, not to explain, for it is utterly inexplicable, but to illustrate, by a well-ascertained though equally inexplicable fact in common chemistry. That illustration (§ 8. of chapter on Imaginative Association, Vol. II.) I see more and more ground to think correct. How far I could show that it held with all great inventors, I know not, but with all those whom I have carefully studied (Dante, Scott, Turner, and Tintoret) it seems to me to hold absolutely; their imagination consisting, not in a voluntary production of new images, but an involuntary remembrance, exactly at the right moment, of something they had actually seen.

Imagine all that any of these men had seen or heard in the whole course of their lives, laid up accurately in their memories as in vast storehouses, extending, with the poets, even to the slightest intonations of syllables heard in the beginning of their lives, and, with the painters, down to the minute folds of drapery, and shapes of loaves or stones; and over all this unindexed and immeasurable mass of treasure, the imagination brooding and wandering, but dream-gifted, so as to summon at any moment exactly such groups of ideas as shall justly fit each other: this I conceive to be the real nature of the imaginative mind, and this, I believe, it would be oftener explained to us as being, by the men themselves who possess it, but that they have no idea what the state of other persons' minds is in comparison; they suppose every one remembers all that he has seen in the same way, and do not understand how it happens that they alone can produce good drawings or great thoughts.

Turner.

T. Boys.

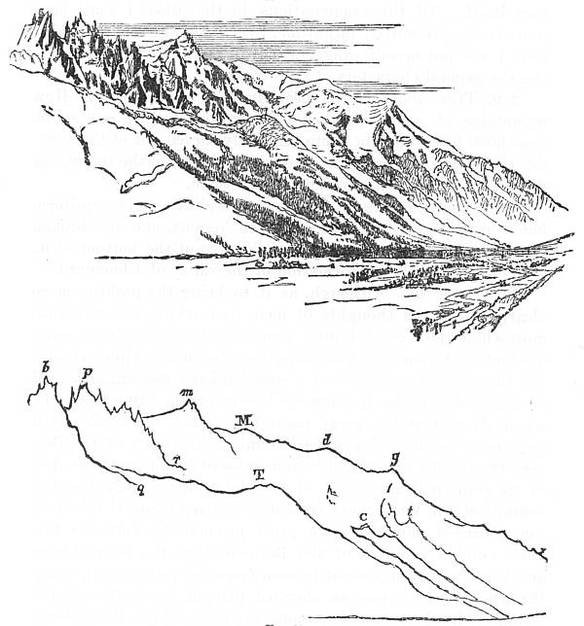

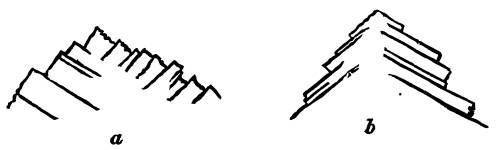

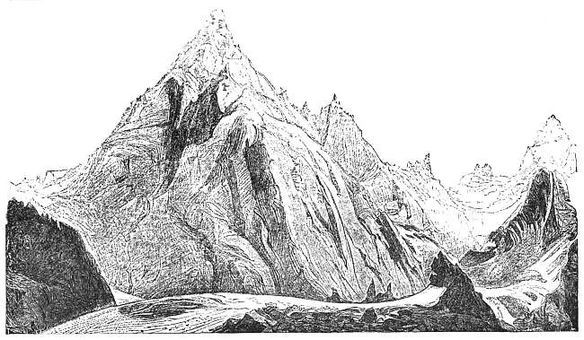

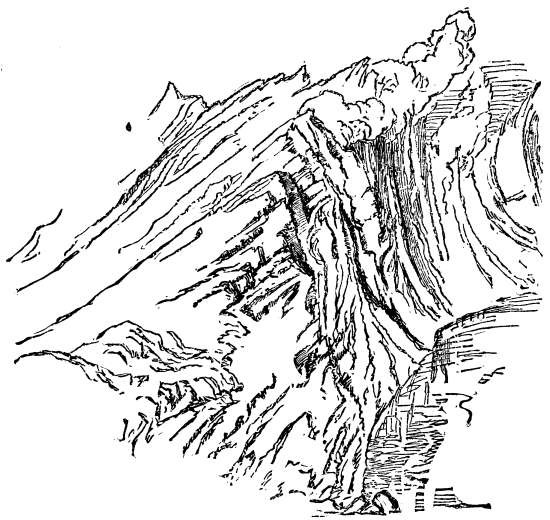

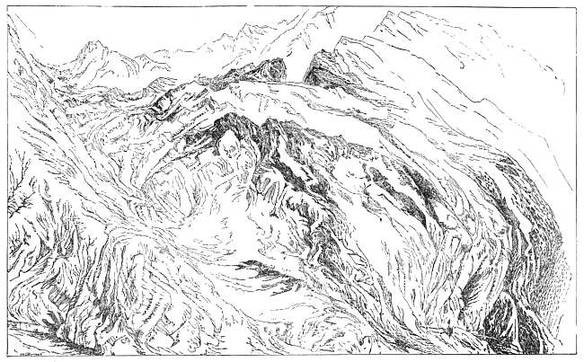

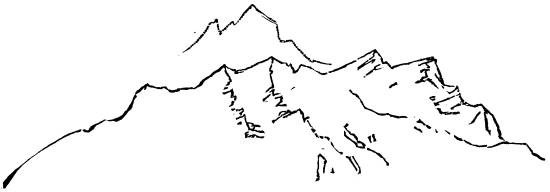

22. Turner's Earliest "Nottingham."

§ 18. Whether this be the case with all inventors or not, it was assuredly the case with Turner to such an extent that he seems never to have lost, or cared to disturb, the impression made upon him by any scene,—even in his earliest youth. He never seems to have gone back to a place to look at it again, but, as he gained power, to have painted and repainted it as first seen, associating with it certain new thoughts or new knowledge, but never shaking the central pillar of the old image. Several instances of this have been already given in my pamphlet on Pre-Raphaelitism; others will be noted in the course of our investigation of his works; one, merely for the sake of illustration, I will give here.

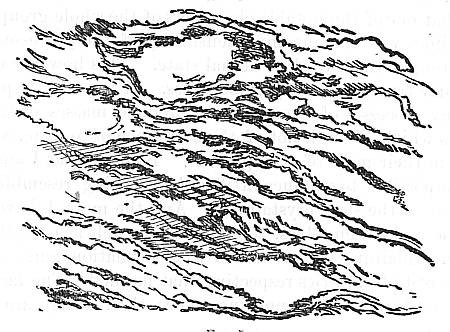

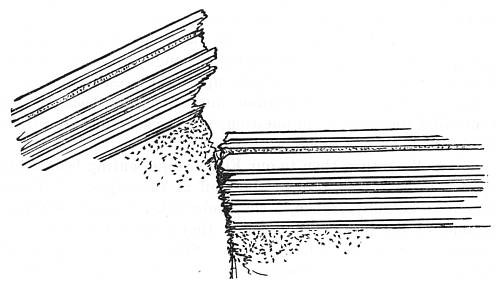

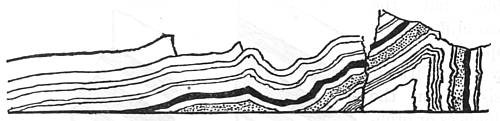

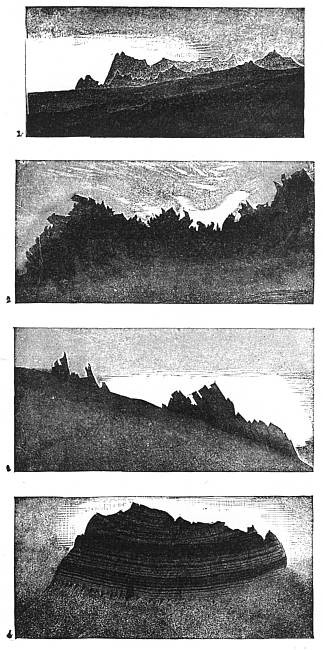

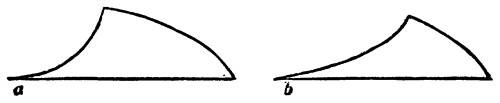

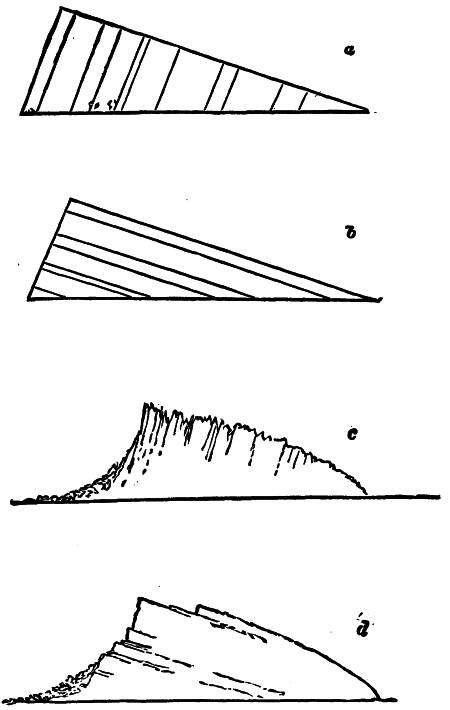

§ 19. Plate 22 is an outline of a drawing of the town and castle of Nottingham, made by Turner for Walker's Itinerant, and engraved in that work. The engraving (from which this outline was made, as I could not discover the drawing itself) was published on the 28th of February, 1795, a period at which Turner was still working in a very childish way; and the whole design of this plate is curiously stiff and commonplace. Note, especially, the two formal little figures under the sail.

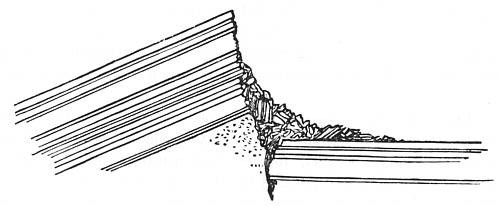

In the year 1833, an engraving of Nottingham, from a drawing by Turner, was published by Moon, Boys, and Graves, in the England and Wales series. Turner certainly made none of the drawings for that series long before they were wanted; and if, therefore, we suppose the drawing to have been made so much as three years before the publication of the plate, it will be setting the date of it as far back as is in the slightest degree probable. We may assume therefore (and the conclusion is sufficiently established, also, by the style of the execution), that there was an interval of at least thirty-five years between the making of those two drawings,—thirty-five years, in the course of which Turner had become, from an unpractised and feeble draughtsman, the most accomplished artist of his age, and had entirely changed his methods of work and his habits of feeling.

§ 20. On the page opposite to the etching of the first, I have given an etching of the last Nottingham. The one will be found to be merely the amplification and adornment of the other. Every incident is preserved; even the men employed about the log of wood are there, only now removed far away (beyond the lock on the right, between it and the town), and so lost in mist that, though made out by color in the drawing, they cannot be made clear in the outline etching. The canal bridge and even the stiff mast are both retained; only another boat is added, and the sail dropped upon the higher mast is hoisted on the lower one; and the castle, to get rid of its formality, is moved a little to the left, so as to hide one side. But, evidently, no new sketch has been made. The painter has returned affectionately to his boyish impression, and worked it out with his manly power.

Turner.

T. Boys.

23. Turner's Latest "Nottingham."