автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Through Portugal

Transcriber's Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

THROUGH PORTUGAL

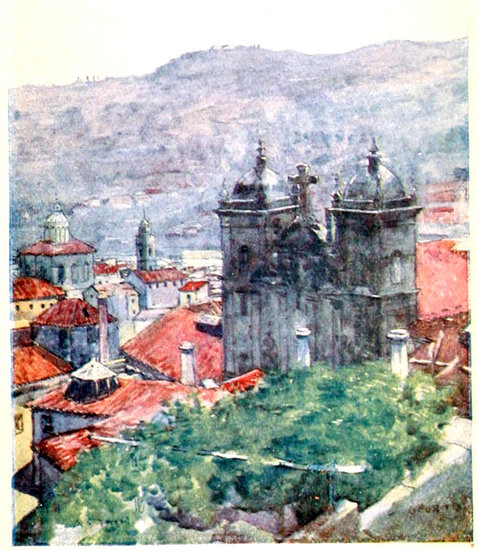

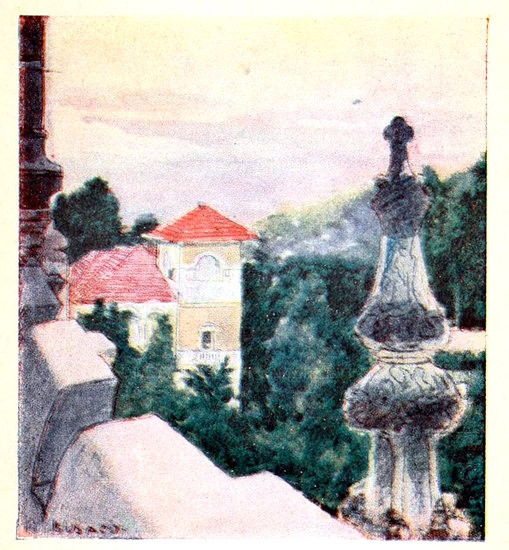

FROM A WINDOW, OPORTO.

THROUGH

PORTUGAL

BY

MARTIN HUME

WITH 32 ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOUR BY

A. S. FORREST

AND 8 REPRODUCTIONS OF PHOTOGRAPHS

“Oh Christ! it is a goodly sight to see

What heaven hath done for this delicious land;

What fruits of fragrance blush on every tree,

What goodly prospects o’er the hills expand.”

Byron.

NEW YORK

McCLURE, PHILLIPS & COMPANY

1907

Printed by

Ballantyne, Hanson & Co.

Edinburgh

This record of

a pleasure journey through Europe’s

“Garden by the Sea”

is dedicated by gracious permission to

His Majesty

The King of Portugal

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I

PAGE

OPORTO

1CHAPTER II

BRAGA AND BOM JESUS

34CHAPTER III

CITANIA AND GUIMARÃES

54CHAPTER IV

BUSSACO

90CHAPTER V

COIMBRA, THOMAR, AND LEIRIA

122CHAPTER VI

BATALHA AND ALCOBAÇA

169CHAPTER VII

CINTRA

199CHAPTER VIII

LISBON

229CHAPTER IX

SETUBAL, TROYA, AND EVORA

264CHAPTER X

HINTS TO TRAVELLERS IN PORTUGAL

308I

OPORTO

II

BRAGA AND BOM JESUS

III

CITANIA AND GUIMARÃES

IV

BUSSACO

V

COIMBRA, THOMAR, AND LEIRIA

VI

BATALHA AND ALCOBAÇA

VII

CINTRA

VIII

LISBON

IX

SETUBAL, TROYA, AND EVORA

X

HINTS TO TRAVELLERS IN PORTUGAL

ILLUSTRATIONS

IN COLOUR

FROM A WINDOW IN OPORTO

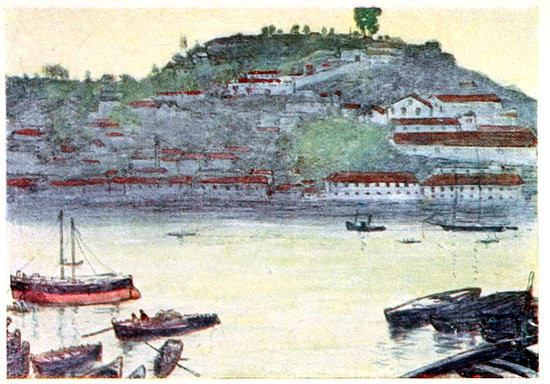

FrontispieceEVENING: OPPOSITE OPORTO

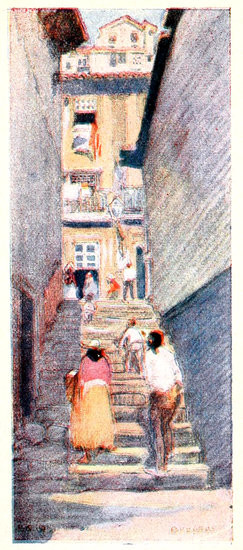

To face page 8FROM THE RIBEIRA, OPORTO

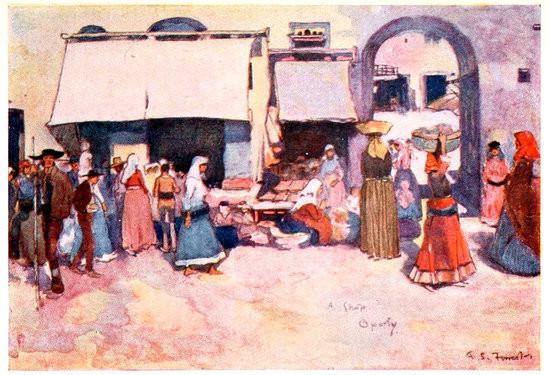

To face page 16A SHOP IN OLD OPORTO

To face page 28THE AFTER-GLOW AT BRAGA

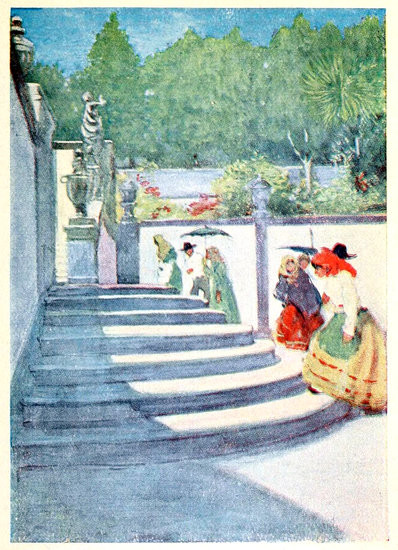

To face page 40ON THE TERRACE, BOM JESUS

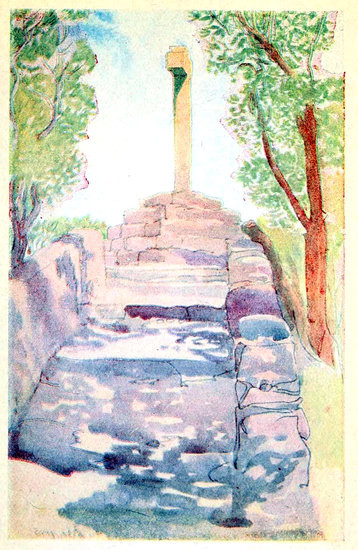

To face page 50ON THE HOLY STAIR, BOM JESUS

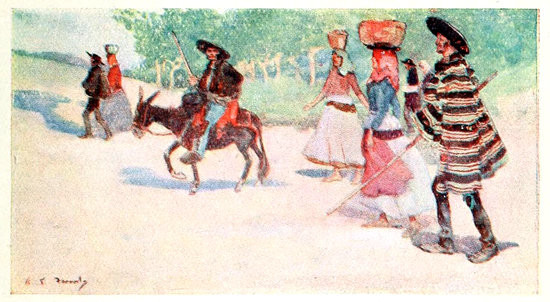

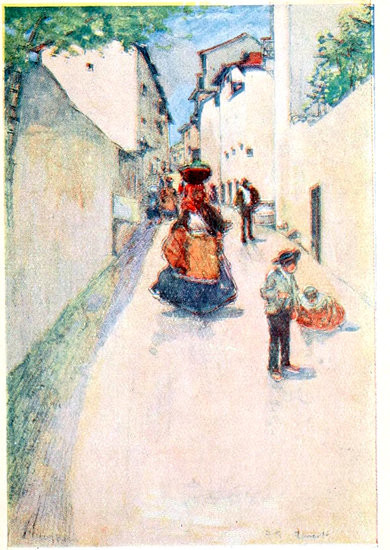

To face page 52ON THE WAY TO MARKET, TAIPAS

To face page 58FROM THE BATTLEMENT, BUSSACO

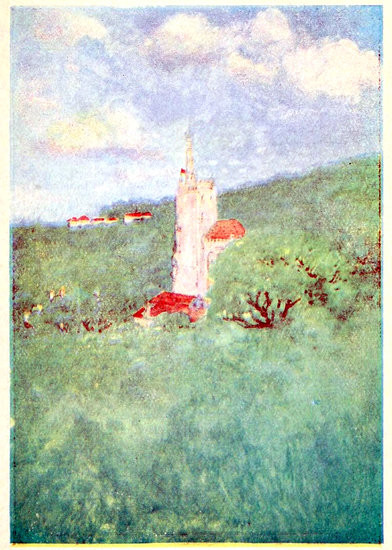

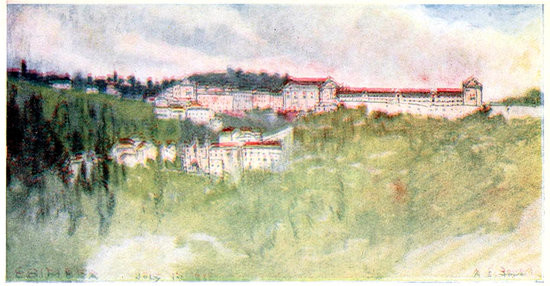

To face page 96THE HOTEL FROM THE WOODS, BUSSACO

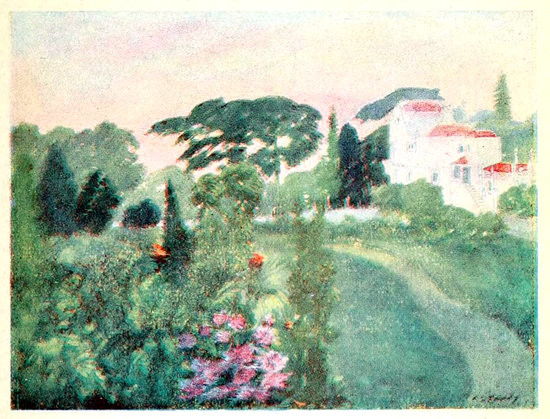

To face page 102IN THE GARDENS, BUSSACO

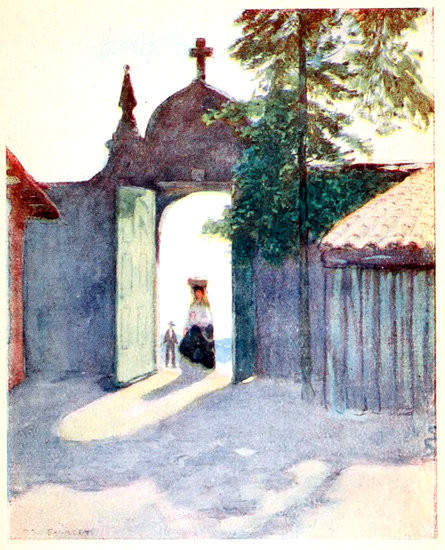

To face page 106THE PORTA DA SULLA, BUSSACO

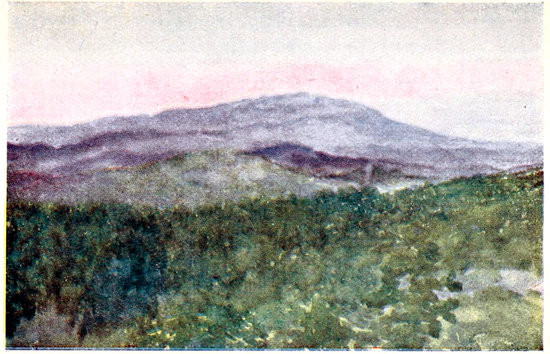

To face page 108“BUSSACO’S IRON RIDGE”

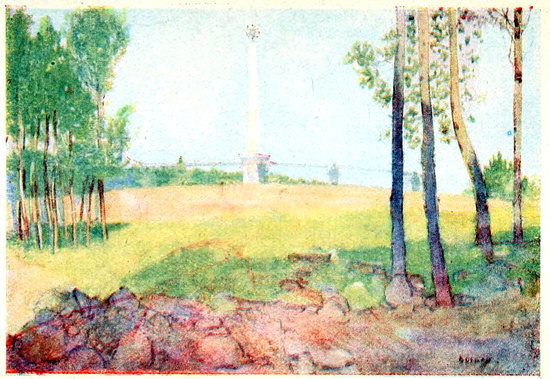

To face page 112THE BATTLE MONUMENT, BUSSACO

To face page 116ENTRANCE TO THE CLOISTER, BUSSACO

To face page 120ON THE SUMMIT OF BUSSACO. THE CRUZ ALTA

To face page 122A STREET IN COIMBRA

To face page 128SANTA CLARA, COIMBRA

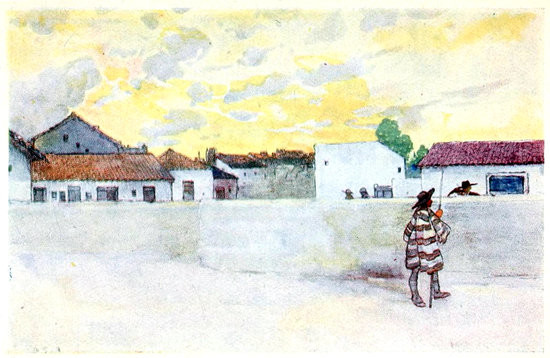

To face page 136A COUNTRY RAILWAY STATION

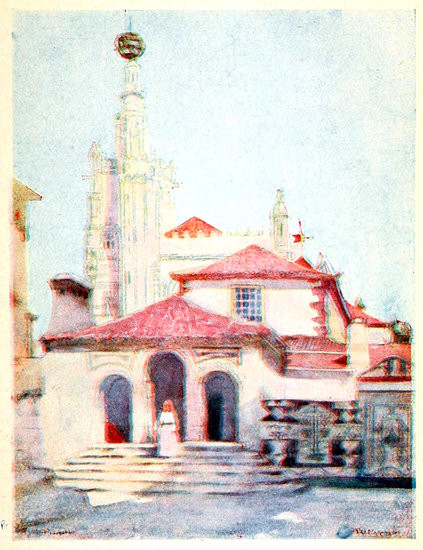

To face page 142A CORNER OF THE TOWN HALL AND THE MONASTERY, THOMAR

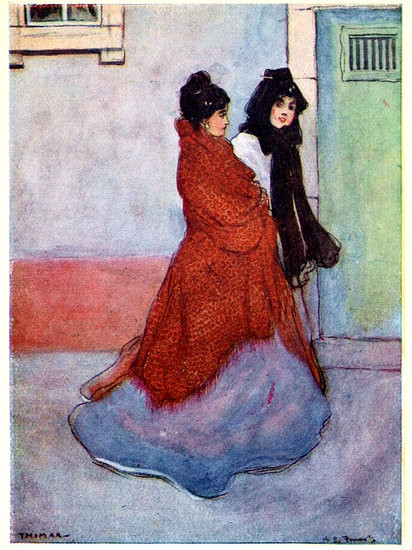

To face page 144SOME BEAUTIES OF THOMAR

To face page 146CHURCH OF S. JOÃO IN THE PRAÇA, THOMAR

To face page 156THE BRIDGE AT THOMAR

To face page 158IN THE MAIN STREET OF OUREM

To face page 160THE CASTLE, LEIRIA

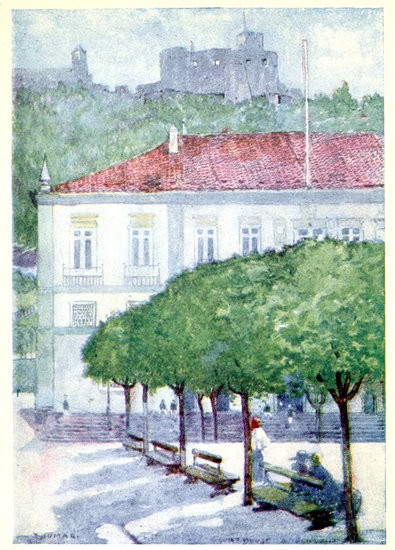

To face page 164ON THE ALAMEDA, LEIRIA

To face page 166THE ENCARNAÇÃO, LEIRIA

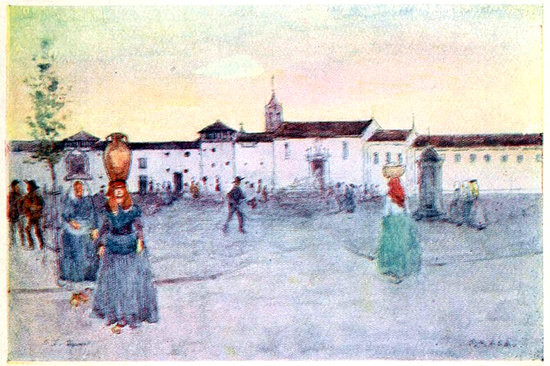

To face page 168ON THE PRAÇA AT ALCOBAÇA

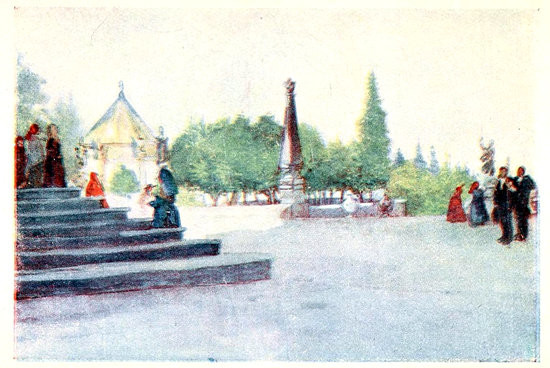

To face page 188UNDER THE ACACIAS, ALCOBAÇA

To face page 192THE OLD PALACE, CINTRA

To face page 204ON THE QUAY, LISBON

To face page 234LISBON, FROM THE NORTH

To face page 306FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

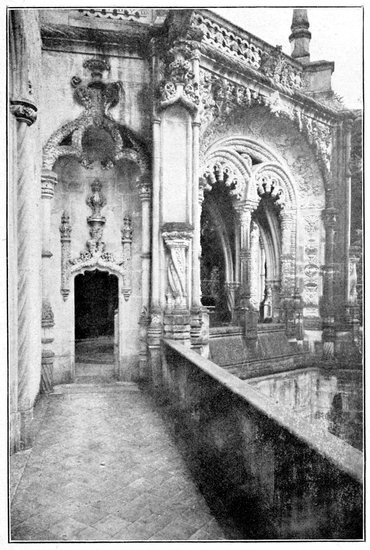

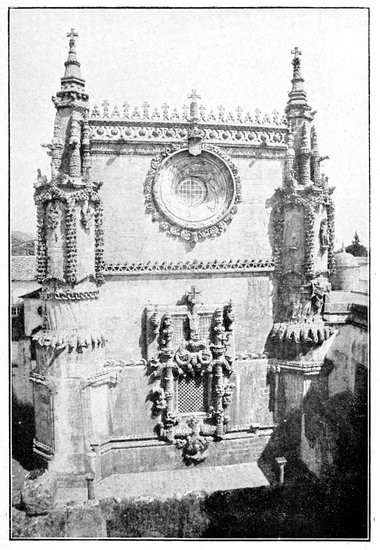

MANUELINE ARCHITECTURE AT THE HOTEL, BUSSACO

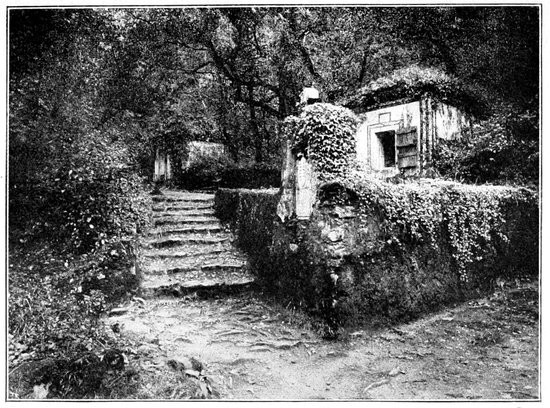

To face page 94ON THE VIA SACRA, BUSSACO

To face page 104THE CHOIR AND CHAPTER HOUSE, THOMAR

To face page 148THE CLOISTERS, BATALHA

To face page 180THE UNFINISHED CHAPELS, BATALHA

To face page 182MANUELINE WINDOWS IN THE OLD PALACE, CINTRA

To face page 224THE SOUTH DOOR AT BELEM

To face page 238THE “TEMPLE OF DIANA,” EVORA

To face page 300EVENING OPPOSITE OPORTO.

FROM THE RIBEIRA, OPORTO.

A SHOP IN OLD OPORTO.

THE AFTER-GLOW AT BRAGA.

ON THE TERRACE, BOM JESUS.

ON THE HOLY STAIR, BOM JESUS.

ON THE WAY TO MARKET, TAIPAS.

FROM THE BATTLEMENT, BUSSACO.

THE HOTEL, BUSSACO, FROM THE WOODS.

IN THE GARDENS, BUSSACO.

THE PORTA DA SULLA, BUSSACO.

BUSSACO’S IRON RIDGE.

THE BATTLE MONUMENT, BUSSACO.

ENTRANCE TO THE CLOISTER, BUSSACO.

ON THE SUMMIT OF BUSSACO, THE CRUZ ALTA.

A STREET IN COIMBRA.

SANTA CLARA, COIMBRA.

A COUNTRY RAILWAY STATION.

A CORNER OF THE TOWN HALL AND THE CONVENT, THOMAR.

SOME BEAUTIES OF THOMAR.

CHURCH OF ST. JOÃO IN THE PRAÇA, THOMAR.

THE BRIDGE AT THOMAR.

IN THE MAIN STREET OF OUREM.

THE CASTLE, LEIRIA.

ON THE ALAMEDA, LEIRIA.

THE ENCARNAÇÃO, LEIRIA.

ON THE PRAÇA AT ALCOBAÇA.

UNDER THE ACACIAS, ALCOBAÇA.

THE OLD PALACE, CINTRA.

ON THE QUAY, LISBON.

LISBON FROM THE NORTH.

Manueline Architecture at the Hotel, Bussaco

On the Via Sacra, Bussaco.

The Choir and Chapter-House, Thomar.

The Cloisters, Batalha.

“The Unfinished Chapels,” Batalha

Manueline Windows in the Old Palace, Cintra

The South Door at Belem

The “Temple of Diana,” Evora

INTRODUCTION

Portugal had been familiar to me from my earliest youth, for my road to and from Spain had often lain that way, and circumstances had made me conversant with the language and history of the country; and yet this book is not the outcome of any such previous knowledge, but mainly of one short voyage in search of change and health. It happened in this way. As oft befalls men who in this striving world have to wring their brains for drachmas, the completion of a particularly arduous book had left me temporarily a nervous wreck, sleepless and despairing. The first and most obvious need dictated to me by those who settle such matters, was to forget for a time that pens, ink, and paper existed, and to seek relaxation in a clime where printers cease from troubling and reviewers are at rest. But where? Spain certainly would offer me no such a haven: France was too near home, Germany I disliked, Switzerland was trite and overrun, the novelty of Italy I had long before exhausted, and Greece was too far away. A sea voyage was a desideratum, but it must not be too long, and as the autumn was already verging towards winter the south alone was available.

Then in the midst of my perplexity the happy thought suggested itself that, often as I had passed through Portugal, I had never seen the country. Why not try Portugal? I had some prejudices to overcome, prejudices, indeed, which up to that time had prevented me from seeking a deeper knowledge of the land and people than could be gained by an incurious glance on the way through. For I had been brought up in the stiff Castilian tradition that Portugal was altogether an inferior country, and the Portuguese uncouth boors who in their separation from their Spanish kinsmen had left to the latter all the virtues whilst they themselves had retained all the vices of the race. But, withal, I chose Portugal, and have made this book my apologia as a self-prescribed penance for my former injustice towards the most beautiful country and the most unspoilt and courteous peasantry in Southern Europe. Portugal and the Portuguese, indeed, have fairly conquered me, and the voyage, of which some of the incidents are here set forth, was for me a continual and unadulterated delight from beginning to end, bringing to me refreshment and renewed vigour of soul, mind, and body, opening to my eyes, though they had seen much of the world, prospects of beauty unsurpassed in my experience, and revealing objects of antiquarian and artistic interest unsuspected by most of those to whom the attractions of the regular round of European travel have grown flat and familiar.

It is impossible, of course, to pass on to others the full measure of enjoyment felt by an appreciative traveller in a happy trip through an unhackneyed pleasure-ground; but it has occurred to me that some record of my impressions on the way may lead other Englishmen to seek for themselves a repetition of the pleasure and benefit which I experienced in the course of a short holiday trip through Portugal from north to south. I am not pretending to write a guidebook: those that exist are doubtless sufficient for all purposes, although I have intentionally refrained from consulting any of them, in order that my impressions might not be biassed, even unconsciously, by the opinions of others; nor do I claim to speak of Portugal with the fulness of knowledge exhibited by Mr. Oswald Crawford in his books on the country where he resided so long. My object is rather to treat the subject from the point of view of the intelligent visitor in search of sunshine, health, or relaxation; to suggest from my own experience routes of travel and points of attraction likely to appeal to such a reader as I have in my mind, and to warn him frankly of the inevitable small inconveniences which he must be prepared to tolerate cheerfully if he would enjoy to the full a holiday spent in a country not as yet overrun by tourists who insist upon carrying England with them wherever they go. If he will consent to “play the game,” and not expect the impossible in such a country, I can promise my traveller a voyage full of colour, interest, and novelty in this “garden by the side of the sea,” where pines and palms grow side by side, and the stern north and softer south blend their gifts in lavish luxuriance beneath the happy conjunction of almost perpetual sunshine and moist Atlantic breezes.

MARTIN HUME.

THROUGH PORTUGAL

I

OPORTO

I stood in the centre of a daring bridge, spanning with one bold arch of nigh six hundred feet a winding rocky gorge. Far, far below me ran a chocolate-coloured river crowded with quaint craft, some with high-raised sheltered poops and crescent-peaked prows, some low and long astern with bows like gondolas and bright red lateen sails, upon which the fierce sun blazed sanguinely. On the right side thickly, and on the left more sparsely, climbing up the stony sides of the gorge, were piled hundreds of houses, pink, pale-blue, buff, and white, all with glowing red-tiled roofs, and each set amidst a riot of verdure which trailed and waved upon every nook and angle uncovered by buildings. Trellised vines clustered and flowers flaunted in tiny back-yards and square-enclosed courts by the score, all on different levels, but all open to the down-gazing eyes of the spectator on the bridge high above them. Here and there a tall palm waved its plumes as in unquiet slumber, but everywhere else was the impression of ardent, throbbing, exuberant life, such as all organic creation feels under the spur of stinging sunshine and the salt twang of the sea-breeze. The river gorge winds and turns so tortuously that the view forward and backward is not extensive, but as far as the eye reaches on each side of the umber stream the hills of houses and far-spread terraced vineyards beyond rise precipitously, with just a quayside at foot on the banks of the stream, thronged now with folk who swarm, gather, and separate like gaudy ants, and apparently no bigger, as seen from the coign of vantage on the bridge. To my left, as I stand looking towards the west, there crowns the summit of the ridge close by a vast white monastery against a green background; a monastery now, alas! like all others in this Catholic land, profanated and turned to purposes of war instead of peace, but, withal, there still rears its modest rood aloft upon the crest one poor little round chapel where the sainted image of Pilar of the Ridge stolidly receives the devotion of the faithful. To the right, the height is crowned by a vast square episcopal palace, and near it, over all, is the glittering golden cross that shines upon the city from the summit of the square cathedral towers. This is Oporto, The Port par excellence, which gives its name to Portugal, seen from the double-decked iron bridge of Dom Luis over the Douro.

For days I had been striving in vain to get into touch with the psychic principle of this strange city. I had mixed with the motley multitudes that lounge and labour upon the quays, I had lingered in the gilded churches where worshippers were ominously few, and stood for hours observant in chaffering marketplaces and amidst the crowds of sauntering citizens in the inevitable Praça de Dom Pedro; but till the revelatory moment came to me in one enlightening flash upon the Bridge of Dom Luis, I had always been alone in a foreign throng whose composite inner soul I could not read. But now all was changed. Thenceforward I saw Oporto whole and not in disintegrated fragments as before; for I had learnt the secret of putting the pieces of the puzzle together and the heart of the city was bared to me, a stranger.

Every large, enduring community comes to attain a distinct character of its own, which the outlander can only know by long association or sympathetic insight, sometimes not at all. I had looked for a people exuberant and gay in outward seeming with an underlying spirit of bitter mockery, such as I had known in so many other Iberian cities; but somehow these Oporto people were quite different. Grave and quiet, with introspective eyes, even the children seemed to take their play soberly. Look at the slim slip of a boy who gravely walks at the head of this team of enormous fawn-coloured oxen, toilsomely dragging their ponderous load up a hill so steep as almost to need a ladder to ascend. The urchin cannot be more than ten or eleven, and in any other country would alternately skip and idle, or at least allow his attention to wander with every fresh object that struck his fancy. Here he stalks along for hours at a time, without lingering or straying, always calm and patient, whilst his soiled and hardened bare feet plod on, heedless both of the white mire and sharp stones of the way. Over his shoulder he carries a long lithe wand, double as tall as himself, with which he directs the course of the great wide-horned bullocks. A mere turn of the wand is sufficient to indicate the way, and with low bowed heads beneath the heavy yoke the dull beasts plod slowly onward as long-suffering as their guide. The whole equipage might belong to the times when the world itself was young, so idyllic is it in form. The wain is narrow and high-set upon two wheels, like an ancient chariot, with boards or high rods to form its sides; the wheels are built up ponderously of solid wood, the two thick spokes that connect the heavy tire with the hub filling up most of the circle, and the axle, a heavy log of wood, itself turns with the wheels. In this part of Portugal there stands erect upon the neck of the team an adornment which is usually the pride of the owner’s heart, and the one superfluous article of luxury he possesses. It is a thick board of hardwood, about eighteen inches high and some five feet broad, intricately and beautifully carved in fretted open-work arabesques. The patterns are traditional, handed down from time immemorial, and usually consist of involved geometrical and curvilinear designs; sometimes, but not often, with a cross introduced in the centre, and with a row of little bristle brushes as an extra adornment along the top. A glance at this elaborate piece of ox furniture will show that its decoration is of Moorish origin, and the canga itself may be the survival of the high ox yoke still seen in some oriental countries. To complete the quaint picture of the universal ox team, for this part of Portugal is not a country of horses or mules, the dress of the small teamster must be described. The boy’s breeches usually do not reach below the knee, the rest of the legs and feet being bare; a jacket of brown homespun is slung upon one shoulder, except at night or during the cold winter days of December and January, when it is worn, and the shirt, open at the neck and breast, leaves much of the upper part of the body exposed. The headgear is peculiar. It is nearly always a knitted stocking bag cap, something like an old-fashioned nightcap, with a tassel at the end of the bag which hangs down the back or upon the shoulder of the wearer, its colour being sometimes green and red, but more frequently black.

The boy, like his similarly garbed elders, takes life very seriously, but neither he nor they seem sad or depressed. There is here none of the squalid misery or whining mendicancy that are so distressing to strangers in Spain and Southern Italy, for the Portuguese of the north is a sturdy, self-respecting peasant, who works hard and lives frugally upon his three testoons (1s. 3d.) per day; and so long as he can earn his dried stockfish, his beans, bread, and grapes, with a little red wine to drink, he scorns to beg for the indulgence of his idleness.

These are the people, and their social betters of the same race, whom a sudden flash of sympathy brought closer to me, as in the pellucid golden sunlight all Oporto was spread before and beneath me, palpitating with life. The absence of vociferation and vehemence in the people did not mean sulkiness or stupidity, but was the result of the intense earnestness with which their daily life was faced; their unregarding aloofness towards strangers was not rudeness, but the highest courtesy which bade them avoid obtrusive curiosity; and soon I learnt to know that their cold exterior barely concealed a disinterested desire to extend in fullest measure aid and sympathy to those who needed them. In all my wanderings I have never met, except perhaps in Norway, a peasantry so full of willingness to show courtesy to strangers without thought of gain to themselves as these people of north Portugal, almost pure Celts as they are, with the Celtic innate kindliness of heart and ready sympathy, though, of course, with the Celtic shortcomings of jealousy, inconstancy, and distrust.

I know few more characteristic thoroughfares than the road by the river-side at Oporto, called the Ribeira, which is the centre of maritime activity of the port. The path runs beneath what was the ancient river-wall, now pierced or burrowed out to form caverns of shops, where wine and food, cordage and clothing are sold to sailor men. Many of the open doors have vine trellises before them, in the shade of which quaintly garbed groups forgather, and a constant tide of men and women flows along the path, eddying into and out of the cavernous recesses in the ancient wall. Colour, flaring and fierce in the sun, flaunts everywhere; for the multi-tinted rags of the south festoon and flutter from every door and window and deck the persons of all the womankind. Swinging along, with peculiar and ungainly gait, go the women with prodigious burdens upon their heads. Everything, from babies to bales of merchandise, is borne upon the female head in Portugal; and these women of the north wear a peculiar headgear adapted to this custom. It is a round, soft, pork-pie hat of black cloth or velveteen, fitting well upon the top of the head, the upper rim being adorned with a sort of standing silk fringe. Such a hat, especially when surmounted by a knot, suffers no damage from a burden placed upon it; but the constant carrying of tremendous weights upon the head of females, even of little girls, quite spoils the figures of the women, thrusting the hips and pelvis forward inordinately, and rendering the movements in walking most ungraceful. The women and girls almost invariably go barefooted, whilst the men, except the fishermen, usually are shod; and the females of a family share to the full the work and hardships which are the common lot.

EVENING OPPOSITE OPORTO.

Along the shore of the busy Ribeira lie ships unloading, small craft they usually are, for the bar of the Douro is a terrible one, and the big ships now enter the harbour of Leixões, a league away. In a constant stream the men and women pass across the planks from ship to shore, carrying the cargo upon their heads or shoulders in peculiar boat-shaped baskets, which are the inseparable companion of the Oporto workers. Here is a smart schooner hailing from the Cornish port of Fowey, from which stockfish from Newfoundland is being landed on the heads of women, flat salt slabs as hard and dry as wood, but good nutritious food for all that; and farther along, with their prows to the shore, rest a dozen un-ladened wine and fruit boats from up the Douro, and flat-bottomed passenger skiffs into which women and men with baskets and bundles, representing their week’s supplies purchased in Oporto, are crowding to be carried back to their homes in the rich vineyard villages miles up the river. One by one the quaint craft hoist their crimson sails, and struggle out from the tangle of the bank, until the breeze catches them, and in a shimmer of red gold from the setting sun they hustle through the brown tide until a projecting corner hides them from view. It is a scene never to be forgotten.

The centre of the Ribeira is the Praça called after it, where a sloping square facing the water opens out. The scene is picturesque in the extreme. The space is thronged by men, either sleeping in their baskets or carrying them filled with fish or merchandise upon their heads: a motley, water-side crowd, men of all nations, pass to and fro, or gossip under the vine trellis before the wine shop overlooking the square, and as the observer casts his eyes upwards he sees the gaily coloured houses piled apparently on the top of one another, until at the top of all, as if overhead, is the glaring white palace of the bishop, and the glittering cathedral cross, standing out hard and clear against a sky of fathomless indigo.

This busy river-side way of the Ribeira is, so to speak, a street of two storeys. Below is the walk I have described, with the cavernous shops in the face of the old river-wall, and on the top of the wall is another path reached by occasional flights of steps, and also bordered by the squalid medley of dark shops in which strange savoury-odoured victuals are washed down by strong red wine, and quiet brown men and women, and grave-eyed swarthy babies are inextricably mixed up with brown merchandise in the gloom beyond the glaring sunlight. Unexpected steep alleys, arched and mysterious, lead to the thoroughfares higher up the precipitous slope, and the next storey, a parallel narrow street, the Rua do Robelleiro, narrow, dark, and ancient, is almost as picturesque as the Ribeira itself.

A slab let into the river-wall by the beach commemorates one of the most terrible days in Oporto’s history. The English army had been chased to its ships at Corunna, and the Spanish levies scattered: the Peninsula seemed to be at the mercy of the French legions, which, under Napoleon’s greatest marshals, held the richest provinces of Spain in the name of King Joseph Bonaparte. But 9000 English troops remained in Lisbon, and with Portugal in the hands of his enemies Napoleon knew that he would never be master of Spain. So the word went forth that Soult was to march down with a great army from Galicia, and sweep the English out of Portugal. It seemed easy, and authorities even in England believed that Portugal was untenable and should be evacuated. All but one man, Arthur Wellesley, whose victory at Vimeiro in the previous year had been wasted by the inept old women who were his superior officers. With 20,000 men, said Wellesley, he would hold Portugal against 100,000 French, the marshals notwithstanding; and the great Englishman had his way. Beresford was sent out to reorganise the scattered Portuguese fighting men, and Arthur Wellesley sailed from England with his little army to face Soult in Portugal. Before he arrived in Lisbon the French had swept down from Galicia, and on the 27th March 1809, Soult summoned Oporto to surrender. The warlike Bishop of Oporto was heading the hastily organised defence; his forces were undisciplined and badly armed, but their hearts were stout, and behind their poor earthworks the citizens of Oporto and their bishop bade defiance to Soult and his invading army.

On the 29th March at dawn the devoted city was stormed by Napoleon’s veterans, who swept all before them. There was no quarter, no mercy, and the steep streets of the city were turned to blood-smeared shambles. Down to the river bank flocked the affrighted people, falling as they ran under the rain of bullets that pursued them. Over the river from the Ribeira was a bridge of boats, and upon this the crowd of panic-stricken fugitives poured. The weight sank it, and thousands were drowned in the Douro, or struggled ashore only to be despatched by the French, whilst many of those who had been in arms deliberately drowned themselves rather than surrender. Eighteen thousand Portuguese perished on that awful day, without counting the drowned who were never recovered; whilst of the whole Portuguese host only two hundred live prisoners were taken.

Six weeks afterwards the tables were turned; six weeks spent by Soult in intrigues for his own advancement, and by his officers in discontented idleness. On the 12th May Wellesley and his army from Lisbon surprised him at Oporto in broad daylight, crossing the river a few miles above the city by a brilliant piece of daring, and Soult ignominiously fled north, leaving impedimenta and baggage behind him, harassed and scattered by the Portuguese peasants in arms, until a mere remnant of his force finally found refuge in Spain. The very dinner to which he was about to sit down at Oporto when he was surprised regaled Sir Arthur Wellesley instead, and the victor took up his residence in that big white monastery on the Serra de Pilar, which from the height on the left of the bridge affords a panorama of unequalled beauty of the city opposite on its amphitheatre of hills, shining white and stately against the dark background of the sky.

However you go from the lower level by the river-side to the main streets of the city the climb is a severe one, for in this town of precipitous hills the gradients are startling, even for the electric trams which of late years have completely taken possession of the streets. But we will leave the electric trams on this peregrination, and face the ascent on foot from the lower level of the bridge on the Ribeira itself to the upper town. First some toilsome flights of steps which have taken the place of the lower end of a precipitous alley, cut away to make the approach to the bridge, lead you up about two hundred feet to an ancient winding lane which itself is almost a flight of steps. Quaint foreign interiors are disclosed through the open doors of the dark humble abodes that line the way, and poor little home industries are carried on coram populo; half-way up the ladder-like ascent there is a ruined church, and by-and-by on the right we skirt the great battlemented wall of the vast disestablished monastery of Santa Clara. At a turn in the wall the corner of the grim old edifice itself appears, fortress-like and looming here as built for defence in the fierce times of long ago. Through the doubly-grated windows, a few feet above our heads, brown paws are thrust out, and a hoarse murmur from within takes form, by-and-by, as a demand for alms in the name of God. A glance inside makes one start back in horror, almost in disgust, though the sorry spectacle unfortunately soon becomes familiar to those who sojourn in any large Portuguese town. Huddled in squalor and filth together are half-naked, savage-looking criminals, old men, sturdy vagabonds, and youths almost children, staring out from the gloom of the prison-house through the unglazed barred windows, with whining prayer for charity, ribald jest, or explosive curses. These gaol-birds, herded publicly in their unutterable degradation behind the gratings, form the blackest spot visible in Portuguese life. Even Spain for the most part has brought her prisons into some semblance of civilised order, but Portugal in this one respect lags inexplicably behind.

FROM THE RIBEIRA, OPORTO.

A few yards distant, through a little maze of mediæval streets, is the cathedral, the Sé, with a quiet little courtyard before it, from the parapet of which the red roofs and abundant verdure of the city spread downward in waves to the water-side. These north Portuguese cathedrals are marvellously alike; sharing the early beauties and later barbarities of their successive generations of masters. This of Oporto is a good specimen. The sturdy warrior kings who wrested Portugal, bit by bit, from Castilian and from Moor, in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, were true crusaders. Where they set their foot sprang up the Christian church, to testify for ever their gratitude for victory vouchsafed to the Cross that symbolised their faith. Solid and staidly devotional were the edifices they raised; and wherever their work remains unconcealed by the scrolly banalities of a later age, it bears still the impress of simple faith and unostentatious grandeur. Here on the hill crest at Oporto stand two massive low towers, one still crowned by the pointed Morisco machicolations of the twelfth century, whilst its fellow, partly rebuilt, is spoilt by the addition of a trivial eighteenth-century parapet, with urns as an adornment. Still, the massive solidity of the towers remains, which is something to be thankful for when we regard the hideous top-heavy early eighteenth-century façade that connects them. The south door, of majestic romanesque, is similarly marred. Around it has been built a barbarous porch, overloaded with meaningless ornament, which not only obscures the serious work of the early builder, but half covers and cuts in two a lovely old round window above the door which lights the transept inside. But, however much these curly horrors of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries may distract the eye, they do not destroy what is still visible of the old edifice. The double flight of low steps, for instance, which leads to this south door has for handrails two ancient stone serpents, so simple in design, yet so effective and perfectly adapted for their purpose, as to prove the unaffected but consummate artistry of the designer, whose taste must have been formed whilst yet the Byzantine traditions were strong in the stern romanesque.

One is struck at once in entering any of these cathedrals, and more particularly that of Oporto and its close congener Braga, with the vast difference between them and the pompous, splendid Spanish cathedrals. In the latter the span of the nave is usually tremendous, the church is plunged in tinted gloom, and the whole of the centre of the nave is blocked by an immense choir. Here in North Portugal the note struck in the cathedrals is not mystery richly dight, as in Spain, but sincere austerity, and a simple faith so essential in the edifice that the grave granite columns and arches appear as unaffected by the heaps, and piles, and masses of curly carved gilt wood around them as a monolith might be by the lizards that bask and slither round its base. Here in Oporto, for instance, the low, massive, granite pillars that line the narrow nave, and support the round romanesque arches, seem sullenly to bid defiance to time and decay; such is their prodigious solidity. And yet even these a later age has surmounted, if not adorned, with curly Corinthian capitals of carved gilt wood! Every altar here, and indeed nearly all over Portugal, is an overloaded mass of this particular barbaric style of decoration dear to the Portuguese since the seventeenth century. The skill in its production is undeniably great, especially in the chapel of St. Vincent in Oporto Cathedral; and in moderation the employment of richly painted, carved, and gilded wood generally may be advantageous where the light is low and the architectural style ornate. But here, where the simple romanesque prevails and the churches are flooded with light, it overwhelms one. In this low, old, plain Sé, either gilded wood or high-relief designs in beaten gold or silver in endless intricacy strike the eye unmercifully at every turn. On one of these ornate altars, screened by a curtain which a fee will raise, stands the ancient effigy, which those who still hold the simple faith of their fathers venerate so devoutly—Our Lady of Alem. Ages ago, so the story runs, when this old fane was yet a-building in the twelfth century, some Douro fishermen found their nets heavy with an unusual burden, and raising them, found this image, a miraculous gift vouchsafed them from the sea. Since then the prayers of those who win their living on the deep have been ceaselessly offered to the Lady of Alem for safety and good luck, and simple offerings of gratitude for boons thus gained—for sickness healed or safe return—hang thickly round the shrine.

The beautiful little cloisters of the cathedral are of a later date than the church—grave and simple Gothic of the late fourteenth century, with three small pointed lancet arches in each span, and a plain round light in the tympanum above. But even here the eighteenth century has done some damage by building out highly ornamental buttresses between the main spans. All around on the inner wall of the cloister is a decoration which abounds in nearly every Portuguese church that has lived through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—namely, large pictorial representations in blue and white tiles, like those commonly connected with the town of Delft. In the churches these tile pictures usually represent scenes from Scripture history, with a large admixture of heathen mythology or ordinary emblematic fancies, as here in Oporto, and the effect is quaint and not unpleasing. One of the things indeed which most strongly strike a stranger in Portugal, in the north especially, is the almost universal employment of glazed tiles, azulejos, both inside and outside buildings of all kinds, the majority of the better sort of dwelling-houses being entirely covered outside by tile designs in colours, sometimes very elaborate and beautiful. The custom exists to some extent in Spain, but is not so common there as in Portugal. In each case, however, the taste and original manufacture, like the name of these tiles, are clearly Moorish, and in some of the older edifices, to be mentioned later, the tiles themselves date from a period when Moors or Mudejares produced them.

In the sacristy of Oporto Cathedral they will show you a painting on terra-cotta of the Virgin and Child, backed by St. Joseph and angels bearing a cross, which is asserted to be a Raphael. The composition and drawing are clearly the work of a disciple of his school, but the colouring is dull and grey, such as the great one of Urbino would never have produced. Not this so-called Raphael, but another picture of the highest interest and beauty, is the principal artistic treasure of the city. In the board-room of Oporto’s most cherished and beneficent institution, the vast charitable organisation called the Misericordia, there hangs a painting that has few, if any, equals in Portugal. It is claimed for Jan Van Eyck, who is known to have been in Portugal for two years at about the period (1520) represented by the work, though personally I could see but slight traces of the peculiar quality of either of the brothers Van Eyck. Certainly it is broader in style than anything I have seen from the brush of the younger brother Jan, and may well be the work of Hubert Van der Goes or Hans Memling. But, whoever may be the painter, the picture is a magnificent one. Against a background representing a typical Flemish landscape and walled town, such as Memling loved to paint, there is a highly ornamented font filled with a pool of blood replenished from the stream that issues from the Saviour’s side, as He hangs upon the cross rising from the centre of the pool. Upon the edge of the font, on each side of the cross, in attitudes of prayer, stand two lovely life-size figures of the Virgin and St. John, whilst in the foreground there kneel, in regal robes of crimson, ermine, and gold brocade, the figures of the founder of the Misericordia in 1499, King Manuel the Fortunate and his wife. Kneeling behind them in decreasing size are members of their family, and on the farther side beyond the font are groups of ecclesiastics and laymen, all evidently life-like portraits of prominent courtiers, or benefactors of the institution. The colouring of the picture is glowing and gorgeous in the extreme, and the loving care expended upon the details is such as only the early Flemings had patience to exercise, accompanied by a breadth and boldness unusual in most of them. Fons Vitæ, as the painting is called, from an inscription on the edge of the font, is emblematical of the foundation of the home of mercy it adorns. Nor is it the only art treasure the Misericordia possesses, apart from the hundreds of awful daubs representing dead and gone benefactors that crowd every inch of wall-space. There is to be seen a beautiful Gothic gold chalice of fifteenth-century Portuguese work, some fifteen inches high, a specimen of the famous handicraft of the city, of great interest, the work being of the most intricate and elaborate description, and the condition of the jewel perfect.

Away from the river-side and the immediate surroundings of the cathedral, Oporto has little to show in the form of architectural quaintness. A busy, bustling place of modern-looking houses for the most part, the streets dominated by the indispensable electric tramways, casting scorn upon the lumbering ox wains that alone compete with them. Yet the city has some striking points that should not be missed. The view is very fine, for instance, from the top of the main modern shopping thoroughfare, the Rua de S. Antonio, which swoops down suddenly like a giant switchback to the Praça de Dom Pedro, the centre of the city, and then as the Rua dos Clerigos soars aloft again as suddenly to another eminence crowned by the extraordinary tower of the Church of the Clerigos, one of the loftiest spires in Portugal. The effect, looking up on either side from the Praça de Dom Pedro, is as curious as any streetscape of its kind in Europe. The Praça de Dom Pedro itself, crowded almost day and night with people, busy and idle, is a typical Portuguese “place,” paved, as most of them are, by the strange wave pattern in black and white stone mosaic that gives to the Praça de Dom Pedro in Lisbon (the Rocio) the English name of “rolling motion square.”

From the Praça de Dom Pedro in Oporto, leading downward towards the river-side, is the famous street of the old city called Rua das Flores, where now, as for centuries past, the gold and silver filigree jewelry for which Oporto is famous is made and sold in a score of dark old-fashioned little shops; and still farther down is the Praça do Comercio, with a striking statue amidst the flower-beds of Portugal’s national hero, Prince Henry the Navigator. In this square stands, too, the principal architectural boast of modern Oporto, the Exchange, of which the interior is really grandiose in the florid style so beloved by the Portuguese. The elaborate high-relief carvings prevalent in Portugal are usually executed in soft marble-like limestone, which hardens with exposure to the air; but here in the Bolsa of Oporto the intricate festoons and ingenious caprices that stand out everywhere in relief on walls, pillars, and staircases are carved out of the solid grey granite of which the edifice is built, as if out of defiance the most difficult material had been sought. Some of the fine apartments, especially the Tribunal of commerce, are beautifully decorated in frescoes by Salgado, in style much resembling those of Lord Leighton; and the great ballroom is a gorgeous hall in the brilliant gold and coloured arabesques of the Alhambra.

The Exchange is built upon the site of a disestablished Franciscan monastery, and cowering under the shadow of its modern magnificence there still stands the convent Church of St. Francis. The seventeenth century has left little of the original fifteenth-century church standing, and the interior is a mass of extravagantly rococo carved and gilt wood and other monstrosities; but in an ancient south transept chapel there is an altar-piece of interest in the style of Mantegna, though the sacristan ascribes it to some impossible artist of another school and century. Nothing, indeed, can equal the ignorance of, and apparent indifference to, antique and artistic objects in Portugal by the persons in charge of them. Even in national museums and historic buildings belonging to the Government, the guardians appear to have been chosen without the slightest regard to their fitness for understanding or describing the objects in their care, and the demeanour of the Portuguese people generally towards such objects is such as to force the conviction that, however proud they may be that their country has produced gems of art admired by strangers, they themselves have but a vague appreciation of their beauties or their merit.

The precipitous street leading up from the Praça de Dom Pedro to the conspicuous Church of the Clerigos is gay with a line of the drapers’ shops, with the gaudy wares aflaunt, which appeal specially to the country folk who flock in with their produce to the picturesque market of the Anjo behind the church. Red and yellow, blue and green, strive for mastery from street kerb to parapet, for the stock is as much outside the shops as in; and under the blazing sun, with the eternally deep azure sky overhead, the feast of colour in the clear air is so lavish as to dazzle eyes accustomed to the low tones and soft outlines of England. But relief is near. Through the chaffering market, with its piles of luscious fruit and all the bounteous gifts of earth and sea spread temptingly before brightly clad country wenches with flashing black eyes, the wayfarer may pass but need not tarry; nor is it worth his while to penetrate into the over-florid eighteenth-century churches of the Clerigos and the Carmo, which lie in his way—for just beyond them is a beautiful sub-tropical garden where shady groves of palms invite to repose, and towering planes temper the glare with a soft haze of sea-green. Seated in a quiet nook, with leisure now to watch the passers-by closely, one is struck by the prosperous busy look of the working people. There is no undue noise, and a stranger is allowed to go his way without unwelcome attention; above all, marvellous to relate, beggars are rare, whilst the persistent, offensive, mendicancy, amounting often to sheer blackmail, which is a perfect plague in Spain, is here quite unknown.

A SHOP IN OLD OPORTO.

The manners of these people of North Portugal, indeed, are irreproachable. So courteous are they that it seems almost rude of the stranger to note too closely the quaint garb of the working people around him. The peasant women especially keep their ancient costume unchanged. Barefoot they go, old and young, with their heavy burdens piled in their boat-shaped baskets upon the black, pork-pie hats they wear. Their skirts, usually black but often with a broad horizontal stripe of colour round the bottom, are very short, and gathered with great fulness at the waist and over the hips. Upon the shoulders there is almost invariably a brilliantly coloured handkerchief, and sometimes another upon the head beneath the hat; and long, pendant, gold earrings shine against their coarse jet-black hair. It is evident that for the most part they work quite as hard as the men, but they have no appearance of privation or ill-treatment, except that their habit of carrying heavy weights upon their heads has the effect of ruining their figures in the manner already described. There are no indications anywhere of excessive drinking, and even smoking is not conspicuous amongst the working men and boys in the streets; they seem, indeed, too seriously busy for that, except on some feast day, when, with their best clothes on, they are gay enough, though not vociferous even then, as most southern peoples are.

There is an ancient little church in the northern suburb of Oporto, which will be of some interest to students of architecture. It is little more than a fragment now, but represents the earliest orthodox Catholic foundation in the city, and indeed in this part of the Peninsula. In the clashing of creeds in the early centuries of Christianity, Visigothic Spain had been officially Arian, whilst orthodox trinitarianism was the creed of the great churchmen, and the majority of the Romanised people. In 559 Mir, King of the Suevians, who ruled in the north-west corner of the Peninsula, was distracted by the imminent danger of his son, who was ill apparently to death. He was an Arian, but the priests of the orthodox Church assured him that safety to his son might be gained by the aid of certain relics of St. Martin of Tours, and Mir swore that if the relics worked the miracle he and all his people would join the Catholic communion, and he would build a church to St. Martin within a year in his capital city. The prince recovered, and Mir was as good as his word. To the dismay of the Gothic monarchs of Spain, Suevia joined the orthodox fold, and in hot haste this Church of St. Martin was built; “Cedofeita,” “soon done,” being its name to this day. The upper part of the little cruciform church has been restored and the inner walls have been lined with the universal blue and white picture tiles; but the pillars and arches are pure romanesque, with capricious carvings on the capitals, and the charming little cloister is entered by a romanesque doorway of great beauty. The capitals, too, of the north doorway of the church are very curious, though apparently later than the cloister door, one of the carvings representing a man in a long gown being devoured by an animal’s head, doubtless an allegory of which the significance is lost to us.

Another church of some interest is that of Mattosinhos, a large and prosperous village adjoining the harbour of Leixões, where those who come by sea to Oporto land. The way thither from the city by the electric tramway lies along the river-side, and past the charming tropical-looking public gardens at the Foz de Douro, where in the summer heat the citizens of Oporto idle, flirt, and disport themselves in the surf that breaks upon the sandy beach. The Church of Mattosinhos is a great place of pilgrimage, for it possesses amongst other attractions a miraculous image of Christ, which is venerated throughout Portugal, and the shrine is a famous one. The church lies on a gentle eminence, and is approached by a beautiful, wide, mosaic pavement, bordered by avenues of planes and cork trees, under the shadow of which are six chapels containing life-sized groups representing scenes in the passion of Our Lord. The soft warm air from the sea comes heavy-laden with the scent of flowers, and on one side of the church a grove of orange trees shelters a merry school of boys, who do not even pause in their games to glance at the curious stranger peering about amongst them. The outside of the church, somewhat squat and solid eighteenth-century work, presents a fair specimen of a style of which we shall see much later; a style not at all ineffective, although its description may not sound attractive. Its peculiarity consists in the admixture of brownish-grey granite, of which all the architectural lines and salient points consist, with panels or spaces of snow-white plaster between. In this pure air, under a brilliant sun, the subdued colour of the granite softens the outlines, whilst the white spaces prevent an appearance of gloom or heaviness. Inside, the Church of Mattosinhos is grave and simple in its architectural features, but, as usual, the altars, and especially the chancel, are a riotous mass of gilt wood carving, without repose or restraint.

Down by the shore the great Atlantic rollers are thundering upon the beach, as if hungering to devour the crescent-shaped sardine boats drawn higher up for safety; and a long mail steamer, in the little harbour of Leixões, has its blue peter flying and its funnel smoking ready to sail for England. It is autumn there, no doubt, for the calendar tells us so and cannot lie; but here it is glorious summer still, for the palms and planes wave softly green in the languorous air, and the flowers, in great white and purple masses, hang over every wall and wrestle with the blue-black grapes that deck the trellises before the cottage doors. Everywhere is vivid colour and sharp outline in an atmosphere of marvellous clarity, and as we are carried rapidly through the balmy, voluptuous breeze to the city, we feel that life under such conditions is indeed worth living.

II

BRAGA AND BOM JESUS

The famous port-wine is grown upon a well-defined region nearly sixty miles up the river from Oporto, and, interesting as the manufacture is, the arid and inhospitable-looking land of terraced hillsides, where the glorious grape grows upon the loose, stony soil, offers little attraction to the seeker after the picturesque. To the north of Oporto, and indeed in most of the province of Minho, the wine produced, though varying in excellence, is generally of stout claret character, not unlike the Rioja wine grown in the north of Spain. But North Portugal, though cultivated like a garden wherever possible by a peasantry probably unequalled in Europe for self-respecting independence and laboriousness, thanks largely to causes that have made them practically owners as well as tillers of the soil, does not strike a cursory observer as being naturally fertile. For miles together, and as far as the eye reaches, pine-clad hillsides stretch: beautiful straight pines, rising in huge forests or isolated clumps, the light-green feathery foliage shining against the clear indigo background of the sky, high above the sandy soil carpeted with a thick soft cushion of pine-needles. But closer view shows that down in the sheltered valleys between the hills and on the lower slopes there nestle hundreds of little vineyards and fields of maize and rye, the staple breadstuffs of the people.

The peasantry live well in their way, and are not content with inferior food. Not for them is the poor makeshift of white bread and the fat cold bacon of the English farm hand. The bread of rye with an admixture of maize flour, the broa or brona, as it is called in north-western Spain, is dark in colour and coarse in texture; but it is a fine sustaining food, upon which, in Galicia, I have often made a good meal. The ever-present dried codfish, bacalhau, cooked with garlic and oil, and sometimes with rice, flavoured with saffron, is also not by any means a food to be contemned, unpalatable as it is to those who taste it for the first time. But this, although forming the staple fare of the Minho peasant and small farmer, does not exhaust his menu. There is for high days and holidays the savoury estofado of stewed meat and vegetables, of which the Portuguese peasant housewife is pardonably proud; there are olives, onions, and fruit ad libitum, and good, sound, new wine, tart, but not unpleasant, at the price of the cheapest small beer in England.

But the foreign visitor who comes simply for a short pleasure trip on the more or less beaten tracks will not be expected to regale himself upon this peasant fare, good as it is in its way. Of mutton he will find little or none, but veal, especially in the national stew, he will see at most meals, and ox-tongue, with a rich sauce, will appear on the table more frequently than is usual elsewhere. A thin, and, it must be confessed, usually tough steak, to which the adopted English name of beef (spelt bife) is given, will be placed before him pretty often, and he will find both the thing and the word omelette—which is never used in Spanish—universal in Portuguese dining-rooms.

Through a glorious country of pine-clad uplands and sheltered vineyards the railway runs from Oporto to the former great city of Braga, in Roman times Bracara Augusta, and capital of the whole north-western part of the Iberian Peninsula. Its position on a slight elevation in the midst of a vast undulating plain or cuenca, surrounded by mountains, has made of Braga the natural emporium of the province, and in each succeeding racial dispensation a royal seat and capital; and it remains to-day, though shorn of its splendour, the ecclesiastical capital of the Spains, claiming precedence over imperial Toledo for its archbishopric and primacy. It is a busy, prosperous place, humming with little spinning and weaving factories, where woollen and cotton fabrics are turned out in great quantities, and hold their own not only here in Minho, but in the rest of Portugal and far Brazil and Portuguese Africa.

At the railway station at Braga, in the outskirts of the city, a noisy, assertive little steam-train of several carriages is waiting in the street, and with much puffing and whistling, it carries the travellers up the slope into the narrow thoroughfares of the town. It is Sunday, and the streets are thronged with gaily-dressed people, the women, heavily decked with the ancient gold jewellery, long earrings, heavy neck chains, and crosses upon the white shirt that covers the bosom. Across the shoulders of most of them there is a brilliantly coloured silk handkerchief, whilst their full-pleated short skirts are usually of some thick dark-coloured cloth, and upon their heads here in Braga they often wear, like their sisters in Oporto, the peculiar round cloth pork-pie hat, with the curling silk fringe on the top of the rim. The men are less picturesque in their Sunday trim, for many of them wear felt wide-brimmed hats instead of the workaday bag cap; but even they have usually added a bit of colour to their sombre masculine garb in the form of a bright scarf encircling their waists to do the duty of braces.

Under the Porta Nova the fussy little train rushes, and up the narrow, picturesque street, the top-heavy stone scutcheon upon the eighteenth-century gate striking at the very entrance the dominant note of the ancient city. Here and everywhere the archiepiscopal insignia, the tasselled hat and mitre, and the Virgin and Child on the city arms, tell that the place from the earliest Christian times has been an ecclesiastical seignory. Churches, too, greet the eye at every turn; most of them massive seventeenth and eighteenth century structures in the peculiar style mentioned in the description of the Church of Mattosinhos in the last chapter: brownish grey granite outlines and salient points, with dazzling white plaster spaces between. Opposite one such church, in a tiny praça leading off from the main square of the city, the Largo da Lapa, I came across a picturesque scene worthy of the brush of John Philip. In a corner of the little square of San Francisco was an ancient recessed fountain in the wall, and around it, with water jars high and graceful like Roman amphoræ, there fluttered a group of women waiting their turn at the jet. Moving to and fro and clustering in the deep shadow contrasting with the blinding sunlight, these full-bosomed, black-haired women, with fine Roman heads and flashing eyes, were so many points of glaring colour, forming a brilliant giant kaleidoscope, whilst the chattering of many tongues, the jest and taunt thrown over the shoulder to rival or to swain, the careless laughter, seemed to blend and fill the languid air with a vague harmony to the ear, such as the mixed discordant colours in their aggregation produced to the eye. By the side of the gay fountain stood the contrast that heightened its effect. A frowning monastery with heavily grated windows high upon the wall, from which glowered evil faces and thrust thievish hands. For here, again, on this happy holiday afternoon in Braga, the gaol-birds held their levee. Beneath their bars stood their womenkind and children, consoling or grieving; and little bags hung down at the end of strings from the windows to receive the gifts it pleased their friends to send up to the sinister rascals, whose hoarse ribaldry or whining appeal broke in ever and anon upon the gay chatter of the fountain. As if in irony, the church that faced the monastery prison bore upon its front the name the “Temple of the Sacred Order of Penitence.” Of contrition one saw little sign on the part of those who from behind their bars looked for all their weary day upon the church commemorating the unmerited self-reproach of the “Seraphic Father St. Francis.”

THE AFTER-GLOW AT BRAGA.

There is one thing throughout Portugal that may be unhesitatingly condemned, and here in Braga the evil is as patent as elsewhere. The old traditional and, in many cases, historical names of the praças and streets have been changed wholesale and wantonly for those of passing and second-rate celebrities, political and otherwise. In Braga the ancient Largo da Lapa has been turned into Largo de Hintze Ribeiro, after the leader of the Liberal party in the Cortes, and there is hardly a town in Portugal in which the principal squares and thoroughfares do not bear the name of Hintze Ribeiro, or of his rival politician, Conselheiro João Franco. Serpa Pinto and Mouzinho de Albuquerque, two fire-eating African explorers, who in the jingo colonial fever of a few years ago, when the feeling against England ran high, were made heroes, are commemorated in streets innumerable throughout Portugal, to the exclusion of names which were often quaint and significant landmarks of long ago.

The palace of the Archbishops of Braga hardly corresponds in appearance with the high claims of the primate, for the church in Portugal is sadly shorn of its splendour, and part of the rambling palace is a ruin; but the cathedral offers many points of interest. Enthusiastic local antiquarians are confident that the first edifice was raised by Saint James himself in the lifetime of the Holy Virgin. But, however that may be, the present church certainly dates from the twelfth century; and though, as usual, the seventeenth century did its best to spoil and smother its primitive simplicity; yet, as in the case of Oporto Cathedral, which that of Braga much resembles, the stern solidity of the original work stands out clear from the frippery by which it is overlaid.

The narrow nave is divided from the aisles by massive low clustered granite pillars supporting slightly pointed arches, above which spring the simple groins that form the vaulted roof. At the west end the church is darkened by the gilt wooden ceiling that supports the choir and the great gilded organ with spread trumpet pipes that is the pride of the cathedral. The choir itself, raised upon a loft and occupying the whole west end of the church, is of surprising magnificence; carving and gilding have run wild; cupids, cherubim, angels, musicians, and fabulous monsters jostle each other exuberantly upon choir stalls, lecterns, and panels: all the caprice, skill, and invention of sixteenth and seventeenth century Portuguese art have been lavished upon the work. And the effect is rich in the extreme, but utterly incongruous with the sober early ogival of the church itself. Even in the nave the massive granite pillars have been crowned by later vandals with florid capitals of carved gilt wood. The walls, too, are much covered with pictorial blue and white tiles, and the effect of this, though inartistic, is quaint and not displeasing. From the tiny cloister of plain romanesque there opens the chapel of St. Luke, where in two splendid sepulchres lie the bodies of the Leonese princess, Teresa, and her Burgundian husband, Count Henrique, to whom she brought the county of Portugal in the late eleventh century. These are the progenitors of the Kings of Portugal, the parents of Affonso Henriques, of whom we shall hear much later; and to Donna Teresa is owing the re-foundation of the Cathedral of Braga. In the side chapels, in the cloisters, and in the sumptuous chapel of St. Gerald, the patron saint, there lie dead and mouldering archbishops not a few; one of them, it is said, incorrupt after eight centuries, though in consequence of the flesh having been varnished he has the appearance of a mulatto, and shows to this day the honourable scar across his cheek that the warrior archbishop gained whilst fighting valiantly by the side of the Master of Avis at the ever-memorable battle of Aljubarrota, that gave the regal crown of Portugal to the illegitimate scion of the House of Burgundy. Another coffin there is, just inside the west door, that has for most people a still more human interest. It is of gilt copper, apparently French in design, bearing upon its lid an effigy of a pretty boy of ten, the little Prince Affonso, whose bones lie within, and who died at Braga in the year 1400.

The exterior of the cathedral has, like the interior, been much spoilt by later builders, the little square towers having been crowned by a mean-looking balustrade and crockets; but the exterior of the sixteenth-century Lady Chapel is a favourable specimen of the peculiar florid Portuguese renaissance style called Manueline, of which I shall have more to say later. Here at the Lady Chapel at Braga it is more restrained and presents fewer daring departures from the Gothic canons than elsewhere, though the surprising intricacy of the parapet and pinnacles show that the new spirit was strongly moving when it was built. That the artists who executed the work were Spaniards from Biscay is probably the reason why in this instance the peculiar and more questionable features of the style are less conspicuous than in the productions of native Portuguese craftsmen of the same period. The other churches of Braga have little show. They are mostly rococo seventeenth-century structures, granite and plaster outside, and nightmares of carved gilt wood inside; but almost under the shadow of the overloaded rococo façade of Santa Cruz there is a lovely little early ogival votive chapel standing by itself, and containing a characteristically Portuguese group of the dead Christ, infinitely touching and beautiful.

And so through the quaint old streets the stranger finds his way, passing by a house here and there whose balconies and windows are covered with the intricate wooden jalousies that linger still as a tradition of oriental civilisation. The whole place is bathed and flooded with vivid sunlight, except where the lengthening shadows fall almost purple in their depth; and wandering without special aim, past the public garden called the Campo de Sant’ Anna, towards the outskirts of the city, I found myself at the foot of a steep hill rising suddenly on the left of the walk. Climbing it, I found a little plateau on the top with a tiny quaint seventeenth-century hermitage chapel, the Guadalupe I learned was its name, under a clump of shady planes and chestnut trees. Around the plateau was a dwarf parapet upon which two lovers were sitting, oblivious to all around save each other; but as I reached the parapet, and my eyes took in the prospect spread before me, a cry of wonderment at its marvellous beauty sprang involuntarily from me, and aroused for a moment the attention of the youth and the girl, who sat with their backs to the landscape, caring nothing for such things. It was but a glance they gave me, and I could enjoy thenceforward without interruption or notice the rapture I felt from the scene, the first of many such peculiarly Portuguese prospects of rolling valleys and soaring mountains to be gained from comparatively low elevations; scenes such as in other countries can only be attained after long and arduous climbs up high mountains. I soon found, it is true, that this view from the Guadalupe in Braga was but a trifle in comparison with many others to be encountered in the course of a few weeks’ travel; but when it first burst unexpectedly upon me it filled me with an ecstasy that no subsequent prospect, however fine, could produce.

Just below me was a tangle of vines, and then a mass of oaks, planes, cork-trees, and acacias, with their fluttering light foliage, descending in a gracious ocean of greenery of every shade across a broad valley till they climbed half up the glowing red mountains miles away. White houses gleamed amidst the trees, and upon every hill-top a hermitage or shrine stood out with its shining cross above it. But that which attracted the eye most was what looked like a giant white marble staircase of immense width, leading right up the side of a wooded mountain spur opposite, upon the summit of which, at the head of the stupendous stair, set deep in the verdure of woods, stood a huge white temple. Seen from the Guadalupe, the architectural approach up the mountain side to the place of pilgrimage above looked almost too vast to be made by man. Beyond, on the right, rose a majestic range of granite peaks, bare of vegetation, and scattered to the summit with tremendous boulders; and over all the setting sun threw a glow of golden light that tipped the grey granite with crimson, orange, and purple, and deepened the shadows of the climbing woods to umber and to black. The light fell, and by-and-by only the crests of the red and grey mountains glowed, for the woods across the vast plain lay in the black shadow of the peaks. But still, white and gleaming, like a stupendous staircase of shining silver, there shone, clear from the surrounding gloom, the great pilgrimage of Bom Jesus do Monte. And so in the gathering twilight, sated with the beauty of the inanimate world, I slowly wandered down into the pulsing city again, leaving the lad and his lass still whispering on the parapet, alone in their happy blindness.

From the door of the hotel in the Campo Sant’ Anna the tyrannical little street train that bullies Braga several times a day carries us to the foot of the Bom Jesus on the spur of Mount Espinho. For nearly two miles of continuous gentle ascent the road passes through a long stretching suburb of humble houses; and then a quarter of a mile through a close grove of shady trees brings us to the outer portico of the sanctuary, a white gateway at the head of a flight of steps, backed apparently by a dense luxuriant wood. Hard by the portico is the starting platform of an elevator railway, by which pilgrims may, if they please, dodge the rigours of the penance, and arrive at the summit without exertion. This course, on my arrival, commended itself to me, and I left until the next day a full exploration of the place. On the summit of the spur, by the side and behind the great church, white outlined by brown granite as usual, there lies a land of enchantment. Vegetation of surprising luxuriance is everywhere, giant trees full of verdure nearly all the year round, mosses, ferns, and flowers in every crevice. Gushing fountains and cascades, rustic bridges, and sweet winding paths through the woods, everything that can conduce to tranquil repose and comfort is here, with air so pure and exhilarating at this great elevation as to raise the most depressed to vivacity. On a picturesque little clearing on the summit there are two or three hotels, the principal of which, the Grand Hotel, a long one-storey wooden building overhung by great trees, I can vouch for as excellent.

The sanctuary is naturally a great resort amongst the people of Braga in the hot summers on the plain, and I cannot conceive a more agreeable place to pass a few days for rest at any time of the year; but the special religious element draws many devotees who conscientiously go through the pilgrimage to the shrines, and on the 3rd of May and Whit Sunday especially many hundreds of pilgrims flock to the sanctuary for devotion as well as for pleasure. The astonishing feature of the place is, of course, the devotional approach to the church up the side of the mountain, and it is difficult in a few words to give an idea of the eccentricity of the structure. It may be admitted at once that the taste displayed is atrociously bad, for it belongs to that eighteenth century which has loaded Portugal with rococo monstrosities; but the very vastness of Bom Jesus, and its exquisite position, save it from triviality; and looked at as a whole, either from above or below, the effect is grandiose in the extreme.

ON THE TERRACE, BOM JESUS.

Some sort of sanctuary had existed here from the fifteenth century, but it was not until the middle of the seventeenth that a miraculous figure of Christ drew to the hermitage large numbers of pilgrims, and gradually in the later eighteenth century the present structures grew under the care of successive archbishops of Braga. Standing upon the spacious open terrace before the church on the summit I looked down soon after sunrise upon the scene spread before me. If the view hitherward from the Guadalupe was fine this was more striking still. Wreaths of grey mist still floated in the valley far below, and the vast plain with Braga in its centre embosomed amongst trees, and surrounded as far as the eye reached with red-roofed hamlets, still lay in grey shadow. But ridge over ridge, crag beyond crag, in the background rose the mountains all tipped with shining gold with chasms of tender heliotrope; and then, before the mind had well realised the beauty of the contrast, the whole plain woke and smiled with sunshine.

The platform or terrace upon which I stood with my back to the church was flanked with granite obelisks and statues, and fronted by a wide stone parapet with a beautiful stone fountain above it. By two broad flights of steps at the sides a lower landing, or platform, was reached with an arched fountain set in the face of the wall, then by steps down to a similar platform, whence a pair of flights led to yet another, and so on, the parapets and balustrades in each case being surmounted by obelisks and statues, the fountains on the wall-faces being, like the figures, an extraordinary mixture of sacred and mythological art. Each alternate pair of platforms, after the first six, extending right across the structure and paved with the favourite black and white stone mosaic, was flanked by two shrines or little open chapels, each with a beautiful life-sized coloured group of figures representing scenes in the passion of our Lord. Half-way down there was an entrance from one of the platforms into a lovely old-world terraced garden, overflowing with flowers, palms, and sweet-scented verdure, and overhung by the dark yews and pines that bordered the graded descent from top to bottom. At length after descending many flights of steps and passing many terraced platforms with fountains, figures, and obelisks, a large mosaic-paved semicircular space was reached, ending in a stone parapet. Turning and looking upwards from here an extraordinary effect was presented. The alternate zigzags of the stairs and the faces of the walls, indeed all the architectural features, were outlined, like the great church towering far overhead, with brown grey granite, and faced with perfectly white plaster. Stage upon stage the great staircase rose, its parapets at the side and the centre line being marked by statues rising alternately one over the other at each successive stage of the ascent. Dark greenery, palms, yews, acacias, orange trees, and trailing flowers overhung the ascent on each side, and it was not difficult to understand the devotional fervour of pilgrims, who with tears and contrition toil up this vast viâ dolorosa by the hundred on the special anniversary, worshipping at the affecting shrines on the landings, and ending in an agony of remorse at the foot of the miraculous Christ which is the main attraction of the Sanctuary. Nor is the scene looking down over the parapet at the bottom of the main flight less striking. Sheer over the precipice you see the billowy masses of dark thick woods far below. On one side of the wide mosaic landing is a stair leading to another chapel, and so down by a succession of zigzag flights, bordered by thick greenery, to the porch, set in its grove of yews, and leading to the outer world. But mere words are weak to describe the charm and beauty of the Bom Jesus. There is nothing quite like it anywhere else in Europe, and as sanctuary, health resort, and architectural curiosity it deserves to be better known than it is.

ON THE HOLY STAIR, BOM JESUS.

III

CITANIA AND GUIMARÃES

I drove out of Braga in the early morning. Passing over the ancient bridge spanning the little stream, at which lines of women knelt and washed their household linen, we left the city behind us and faced the mountain range beyond which lay my goal. Far above reared the grey crest of Mount Picoto, with a gilt cross dominating its highest point; and as the road wound upwards and ever upward in zigzags, at each turn of the path Braga, white and shining, set in its bed of verdure, receded far below. All around were glorious sun-kissed peaks scattered to the summit with huge granite boulders, as if the youthful Titans had there indulged in the sport of stone-throwing. Then over a hill pass, we dipped into a valley with the Falperra range clear before us, and beautiful St. Marta, with its crown of woods and its gleaming hermitage in the foreground, almost, as it seemed, over our heads. Maize fields spread across the valley and on the hill slopes all around us; and on the wayside, and dividing the fields, rows of oaks, chestnuts, planes, and, above all, white poplars, ran, every tree covered to the top by a trailing vine, loaded with purple grapes. The effect produced is most extraordinary, and the practice of thus utilising timber trees is peculiar to this part of the country.

For many miles, as we drove over valley and hill, tall poplars by the thousand, their light green leaves blending with the bronze, served as vine poles; and every white cottage had its shady trellis pergola before its open doorway, the great luscious bunches of fruit hanging temptingly over the heads of the women busy spinning, surrounded by quiet, brown, barefooted children.

The prevalence of granite is noticeable everywhere. The fields are divided from the path by granite walls, gate-posts, trellis standards, and even telegraph poles are slender granite monoliths, and the cottages themselves are granite built, solid and weather-proof. Many people meet us on their way to Braga: men in velvet jackets, wide, brown, homespun trousers, often with inserted patterns of other coloured cloth, and broad brimmed hats; the women, gay with bright kerchiefs over head and shoulders, but all barefooted, and many carrying poised upon their heads the slender red water jars, the fashion of which has known no change since the time when the legions of Augustus ruled the Celts and Suevians with iron hand from Bracara Augusta. Ox-carts slowly toil along, the bowed necks of the bullocks bearing above them the elaborately carved canga, here seen at its best. And still the road lies mainly upward through the keen pure air, the mountain slopes below and around us green with pine forests, and above us the eternal grey granite boulders. The land is bathed in a flood of sunlight, with here and there upon the widespread slopes and valleys the dark shadow of a passing cloud. Even up here amidst the masses of granite the fruit-laden vine persists, covering and embracing with its reaching tendrils poplars, oaks, and olives on the sheltered slopes, whilst the proud pines alone, towering on the exposed surfaces, defy the creeper’s insidious caress.

At length the high pass of the Falperra range is crossed, and before us spreads a vast fertile plain, with villages and homesteads scattered across its bosom. Soon the grey boulders disappear from around us, and the air grows softer, though granite still supplies the place of wood by the roadside. The fields of maize are usually not above an acre in extent, and are bordered everywhere by vine-clad poplars. It is clear to see that the little farms are for the most part cultivated by the owners and by hand labour, for no yard of tillable soil is left to waste. It is market day at Taipas, and flocks of picturesque husbandmen and their womenkind are wending their way into the village from distant hillside hamlets and lonely granite granges. It is a gaily clad and prosperous-looking crowd that chaffer and bargain for their herds of thin porkers, their vegetables, fruit, red clay pottery, and flaring textiles; all spread out to the best advantage beneath the trees of the market-place and by the shady wayside. The women almost invariably carry upon their heads in long spacious baskets the merchandise they buy or sell, be it live-stock, produce, yarn for weaving, or household stuff; and as invariably is the burden covered with a snowy cloth, and the woman herself is clean, well-fed, and upstanding.

Taipas, the famous thermal mineral baths of the Romans, did not detain me except to order lunch to be ready when I should return a few hours later to the primitive inn attached to the ancient baths, for I was bound for a place still more ancient than Roman Taipas, the mysterious buried city of Citania, the Portuguese Pompeii.

A few miles’ drive upon an excellent road and through a prosperous smiling country of maize, vines, and olives, brought me to the tiny hamlet of São Estevão de Briteiros, just a humble little grey church, a large farmhouse, an inn, a few cottages and a school. The road had led almost at right angles to that by which we had reached Taipas, and the Falperra range, which we had crossed earlier in the day, again loomed nearer; the nearest spur, a bold hill of nine hundred or a thousand feet high at some distance from the range, projecting far out into the plain, and rising precipitously from the little village of Briteiros, which was the present limit of my drive. Long before we reached it the abrupt hill with its tiny white hermitage chapel of São Romão on the highest point had stood out conspicuously, and seen from below looked impossible of ascent. From Briteiros, however, the climb was seen to be not so formidable; for a rough path started from behind the humble schoolhouse, through little farmsteads, gradually winding and zigzagging up the precipitous slope through the trees and brushwood that clothed the lower portion of the hill. The population of Briteiros were mostly at Taipas for the market, and a demand for the services of um rapaz, a boy, to guide the stranger to the lost city of long ago met with the reply that no man nor boy was readily available.

ON THE WAY TO MARKET, TAIPAS.