автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Poetical Works of William Wordsworth — Volume 7 (of 8)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

THE POETICAL WORKS OF WILLIAM WORDSWORTH

VOL. VII

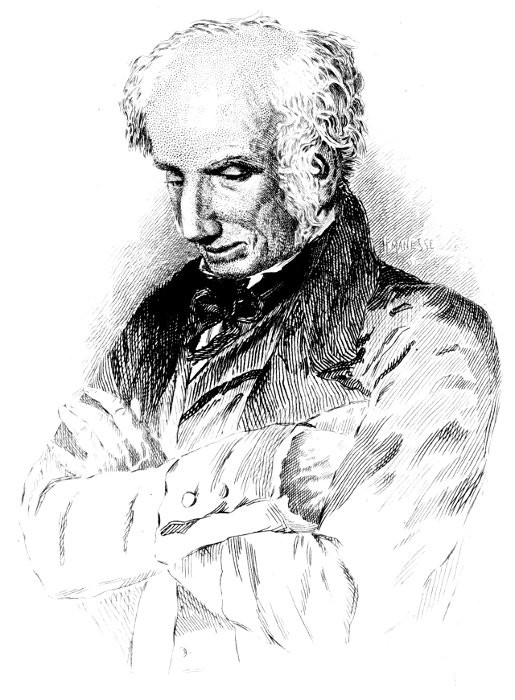

William Wordsworth

after B. R. Haydon

THE POETICAL WORKS

OF

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH

EDITED BY

WILLIAM KNIGHT

VOL. VII

Dove Cottage Grasmere

London MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd.

NEW YORK: MACMILLAN & CO.

1896

All rights reserved

[Pg 0b] [Pg 0c] [Pg v]

CONTENTS

1821-2

PAGE

Ecclesiastical Sonnets. In Series—

Part I.—From the Introduction of Christianity into Britain, to the Consummation of the Papal Dominion—

I.

Introduction

4II.

Conjectures

5III.

Trepidation of the Druids

6IV.

Druidical Excommunication

7V.

Uncertainty

7VI.

Persecution

8VII.

Recovery

9VIII.

Temptations from Roman Refinements

10IX.

Dissensions

10X.

Struggle of the Britons against the Barbarians

11XI.

Saxon Conquest

12XII.

Monastery of Old Bangor

13XIII.

Casual Incitement

14XIV.

Glad Tidings

15XV.

Paulinus

15XVI.

Persuasion

16XVII.

Conversion

17XVIII.

Apology

18XIX.

Primitive Saxon Clergy

19XX.

Other Influences

19XXI.

Seclusion

20XXII.

Continued

21XXIII.

Reproof

21XXIV.

Saxon Monasteries, and Lights and Shades of the Religion

22XXV.

Missions and Travels

23XXVI.

Alfred

24XXVII.

His Descendants

25XXVIII.

Influence Abused

26XXIX.

Danish Conquests

27XXX.

Canute

27XXXI.

The Norman Conquest

28XXXII.

"Coldly we spake. The Saxons, overpowered"

29XXXIII.

The Council of Clermont

30XXXIV.

Crusades

31XXXV.

Richard I

31XXXVI.

An Interdict

32XXXVII.

Papal Abuses

33XXXVIII.

Scene in Venice

34XXXIX.

Papal Dominion

34Part II.—To the Close of the Troubles in the Reign of Charles I—

I.

"How soon—alas! did Man, created pure"

33II.

"From false assumption rose, and fondly hail'd"

36III.

Cistertian Monastery

37IV.

"Deplorable his lot who tills the ground"

38V.

Monks and Schoolmen

39VI.

Other Benefits

40VII.

Continued

40VIII.

Crusaders

41IX.

"As faith thus sanctified the warrior's crest"

42X.

"Where long and deeply hath been fixed the root"

43XI.

Transubstantiation

44XII.

The Vaudois

44XIII.

"Praised be the Rivers, from their mountain springs"

45XIV.

Waldenses

46XV.

Archbishop Chichely to Henry V.

47XVI.

Wars of York and Lancaster

48XVII.

Wicliffe

49XVIII.

Corruptions of the Higher Clergy

49XIX.

Abuse of Monastic Power

50XX.

Monastic Voluptuousness

51XXI.

Dissolution of the Monasteries

52XXII.

The Same Subject

52XXIII.

Continued

53XXIV.

Saints

54XXV.

The Virgin

54XXVI.

Apology

55XXVII.

Imaginative Regrets

56XXVIII.

Reflections

57XXIX.

Translation of the Bible

58XXX.

The Point at Issue

58XXXI.

Edward VI

59XXXII.

Edward signing the Warrant for the Execution of Joan of Kent

60XXXIII.

Revival of Popery

61XXXIV.

Latimer and Ridley

61XXXV.

Cranmer

62XXXVI.

General View of the Troubles of the Reformation

64XXXVII.

English Reformers in Exile

64XXXVIII.

Elizabeth

65XXXIX.

Eminent Reformers

66XL.

The Same

67XLI.

Distractions

68XLII.

Gunpowder Plot

69XLIII.

Illustration. The Jung-frau and the Fall of the Rhine near Schaffhausen

70XLIV.

Troubles of Charles the First

71XLV.

Laud

71XLVI.

Afflictions of England

72Part III.—From the Restoration to the Present Times—

I.

"I saw the figure of a lovely Maid"

74II.

Patriotic Sympathies

74III.

Charles the Second

75IV.

Latitudinarianism

76V.

Walton's Book of Lives

77VI.

Clerical Integrity

78VII.

Persecution of the Scottish Covenanters

79VIII.

Acquittal of the Bishops

79IX.

William the Third

80X.

Obligations of Civil to Religious Liberty

81XI.

Sacheverel

82XII.

"Down a swift Stream, thus far, a bold design"

83XIII.

Aspects of Christianity in America.—1. The Pilgrim Fathers

84XIV.

2. Continued

85XV.

3. Concluded.—American Episcopacy

85XVI.

"Bishops and Priests, blessèd are ye, if deep"

86XVII.

Places of Worship

87XVIII.

Pastoral Character

87XIX.

The Liturgy

88XX.

Baptism

89XXI.

Sponsors

90XXII.

Catechising

91XXIII.

Confirmation

92XXIV.

Confirmation Continued

92XXV.

Sacrament

93XXVI.

The Marriage Ceremony

94XXVII.

Thanksgiving after Childbirth

95XXVIII.

Visitation of the Sick

96XXIX.

The Commination Service

96XXX.

Forms of Prayer at Sea

97XXXI.

Funeral Service

97XXXII.

Rural Ceremony

98XXXIII.

Regrets

99XXXIV.

Mutability

100XXXV.

Old Abbeys

100XXXVI.

Emigrant French Clergy

101XXXVII.

Congratulation

102XXXVIII.

New Churches

102XXIX.

Church to be erected

103XL.

Continued

104XLI.

New Churchyard

104XLII.

Cathedrals, etc.

105XLIII.

Inside of King's College Chapel, Cambridge

106XLIV.

The Same

106XLV.

Continued

107XLVI.

Ejaculation

107XLVII.

Conclusion

108To the Lady Fleming, on seeing the Foundation preparing for the Erection of Rydal Chapel, Westmoreland

109On the Same Occasion

1141823

Memory

117"Not Love, not War, nor the tumultuous swell"

118"A volant Tribe of Bards on earth are found"

1191824

To ——

121To ——

122"How rich that forehead's calm expanse!"

123To ——

124A Flower Garden, at Coleorton Hall, Leicestershire

125To the Lady E. B. and the Hon. Miss P.

128To the Torrent at the Devil's Bridge, North Wales, 1824

129Composed among the Ruins of a Castle in North Wales

131Elegiac Stanzas

132Cenotaph

1351825

The Pillar of Trajan

137The Contrast: The Parrot and the Wren

141To a Skylark

1431826

"Ere with cold beads of midnight dew"

145Ode composed on May Morning

146To May

148"Once I could hail (howe'er serene the sky)"

152"The massy Ways, carried across these heights"

154Farewell Lines

1551827

On seeing a Needlecase in the Form of a Harp

157Miscellaneous Sonnets—

Dedication

159To ——

159"Her only pilot the soft breeze, the boat"

160"Why, Minstrel, these untuneful murmurings"

161To S. H.

162Decay of Piety

163"Scorn not the Sonnet; Critic, you have frowned"

163"Fair Prime of life! were it enough to gild"

164Retirement

165"There is a pleasure in poetic pains"

166Recollection of the Portrait of King Henry Eighth, Trinity Lodge, Cambridge

166"When Philoctetes in the Lemnian isle"

167"While Anna's peers and early playmates tread"

168To the Cuckoo

169The Infant M—— M——

170To Rotha Q——

171To ——, in her Seventieth Year

172"In my mind's eye a Temple, like a cloud"

173"Go back to antique ages, if thine eyes"

174"If thou indeed derive thy light from Heaven"

174In the Woods of Rydal

176Conclusion. To ——

1771828

A Morning Exercise

178The Triad

181The Wishing-Gate

189The Wishing-Gate Destroyed

192A Jewish Family

195Incident at Brugès

198A Grave-Stone upon the Floor in the Cloisters of Worcester Cathedral

201The Gleaner

202On the Power of Sound

2031829

Gold and Silver Fishes in a Vase

214Liberty. (Sequel to the above)

216Humanity

222"This Lawn, a carpet all alive"

227Thoughts on the Seasons

229A Tradition of Oker Hill in Darley Dale, Derbyshire

230Filial Piety

2311830

The Armenian Lady's Love

232The Russian Fugitive

239The Egyptian Maid; or, The Romance of the Water Lily

252The Poet and the Caged Turtledove

265Presentiments

266"In these fair vales hath many a Tree"

269Elegiac Musings

269"Chatsworth! thy stately mansion, and the pride"

2721831

The Primrose of the Rock

274To B. R. Haydon, on seeing his Picture of Napoleon Bonaparte on the Island of St. Helena

276Yarrow Revisited, and Other Poems—

I.

"The gallant Youth, who may have gained"

280II.

On the Departure of Sir Walter Scott from Abbotsford, for Naples

284III.

A Place of Burial in the South of Scotland

285IV.

On the Sight of a Manse in the South of Scotland

286V.

Composed in Roslin Chapel, during a Storm

287VI.

The Trosachs

288VII.

"The pibroch's note, discountenanced or mute"

290VIII.

Composed after reading a Newspaper of the Day

290IX.

Composed in the Glen of Loch Etive

291X.

Eagles

292XI.

In the Sound of Mull

293XII.

Suggested at Tyndrum in a Storm

294XIII.

The Earl of Breadalbane's Ruined Mansion, and Family Burial-Place, near Killin

295XIV.

"Rest and be Thankful!"

295XV.

Highland Hut

296XVI.

The Brownie

297XVII.

To the Planet Venus, an Evening Star

299XVIII.

Bothwell Castle

299XIX.

Picture of Daniel in the Lions' Den, at Hamilton Palace

301XX.

The Avon

303XXI.

Suggested by a View from an Eminence in Inglewood Forest

304XXII.

Hart's-Horn Tree, near Penrith

305XXIII.

Fancy and Tradition

306XXIV.

Countess' Pillar

307XXV.

Roman Antiquities

308XXVI.

Apology for the Foregoing Poems

309XXVII.

The Highland Broach

3101832

Devotional Incitements

314"Calm is the fragrant air, and loth to lose"

317To the Author's Portrait

318Rural Illusions

319Loving and Liking

320Upon the late General Fast

3231833

A Wren's Nest

325To ——, upon the Birth of her First-born Child, March 1833

328The Warning. A Sequel to the Foregoing

330"If this great world of joy and pain"

336On a High Part of the Coast of Cumberland

337(By the Sea-Side)

338Composed by the Sea-Shore

340Poems, composed or suggested during a Tour in the Summer of 1833—

I.

"Adieu, Rydalian Laurels! that have grown"

342II.

"Why should the Enthusiast, journeying through this Isle"

343III.

"They called Thee Merry England, in old time"

343IV.

To the River Greta, near Keswick

344V.

To the River Derwent

345VI.

In Sight of the Town of Cockermouth

346VII.

Address from the Spirit of Cockermouth Castle

347VIII.

Nun's Well, Brigham

347IX.

To a Friend

348X.

Mary Queen of Scots

349XI.

Stanzas suggested in a Steam-Boat off Saint Bees' Heads, on the Coast of Cumberland

351XII.

In the Channel, between the Coast of Cumberland and the Isle of Man

358XIII.

At Sea off the Isle of Man

359XIV.

"Desire we past illusions to recal?"

360XV.

On entering Douglas Bay, Isle of Man

360XVI.

By the Sea-Shore, Isle of Man

361XVII.

Isle of Man

362XVIII.

Isle of Man

363XIX.

By a Retired Mariner

364XX.

At Bala-Sala, Isle of Man

365XXI.

Tynwald Hill

366XXII.

"Despond who will—

Iheard a Voice exclaim"

368XXIII.

In the Frith of Clyde, Ailsa Crag, during an Eclipse of the Sun, July 17

369XXIV.

On the Frith of Clyde

370XXV.

On revisiting Dunolly Castle

371XXVI.

The Dunolly Eagle

372XXVII.

Written in a Blank Leaf of Macpherson's Ossian

373XXVIII.

Cave of Staffa

376XXIX.

Cave of Staffa. (After the Crowd had departed)

377XXX.

Cave of Staffa

377XXXI.

Flowers on the Top of the Pillars at the Entrance of the Cave

378XXXII.

Iona

379XXXIII.

Iona. (Upon Landing)

380XXXIV.

The Black Stones of Iona

381XXXV.

"Homeward we turn. Isle of Columba's Cell"

382XXXVI.

Greenock

383XXXVII.

"'There!' said a Stripling, pointing with meet pride"

383XXXVIII.

The River Eden, Cumberland

385XXXIX.

Monument of Mrs. Howard, in Wetheral Church, near Corby, on the Banks of the Eden

386XL.

Suggested by the Foregoing

387XLI.

Nunnery

388XLII.

Steamboats, Viaducts, and Railways

389XLIII.

The Monument, commonly called Long Meg and her Daughters, near the River Eden

390XLIV.

Lowther

391XLV.

To the Earl of Lonsdale

392XLVI.

The Somnambulist

393XLVII.

To Cordelia M——

400XLVIII.

"Most sweet it is with unuplifted eyes"

4011834

"Not in the lucid intervals of life"

402By the Side of Rydal Mere

403"Soft as a cloud is yon blue Ridge—the Mere"

405"The leaves that rustled on this oak-crowned hill"

406The Labourer's Noon-Day Hymn

408The Redbreast

410 Addenda 415Before I conclude my notice of these Sonnets, let me observe that the opinion I pronounced in favour of Laud (long before the Oxford Tract Movement) and which had brought censure upon me from several quarters, is not in the least changed. Omitting here to examine into his conduct in respect to the persecuting spirit with which he has been charged, I am persuaded that most of his aims to restore ritual practices which had been abandoned were good and wise, whatever errors he might commit in the manner he sometimes attempted to enforce them. I further believe that, had not he, and others who shared his opinions and felt as he did, stood up in opposition to the reformers of that period, it is questionable whether the Church would ever have recovered its lost ground and become the blessing it now is, and will, I trust, become in a still greater degree, both to those of its communion and to those who unfortunately are separated from it.—I. F.]

I, who accompanied with faithful pace[5] Cerulean Duddon from its[6] cloud-fed spring,[7] And loved with spirit ruled by his to sing Of mountain-quiet and boon nature's grace;[8] I, who essayed the nobler Stream to trace 5 Of Liberty,[9] and smote the plausive string Till the checked torrent, proudly triumphing, Won for herself a lasting resting-place;[10] Now seek upon the heights of Time the source Of a Holy River,[11]on whose banks are found 10 Sweet pastoral flowers, and laurels that have crowned Full oft the unworthy brow of lawless force; And,[12] for delight of him who tracks its course,[13] Immortal amaranth and palms abound.

If there be prophets on whose spirits rest Past things, revealed like future, they can tell What Powers, presiding o'er the sacred well Of Christian Faith, this savage Island blessed With its first bounty. Wandering through the west, Did holy Paul[14] a while in Britain dwell, 6 And call the Fountain forth by miracle, And with dread signs the nascent Stream invest? Or He, whose bonds dropped off, whose prison doors Flew open, by an Angel's voice unbarred?[15] 10 Or some of humbler name, to these wild shores Storm-driven; who, having seen the cup of woe Pass from their Master, sojourned here to guard The precious Current they had taught to flow?

Darkness surrounds us: seeking, we are lost On Snowdon's wilds, amid Brigantian coves,[20] Or where the solitary shepherd roves Along the plain of Sarum, by the ghost Of Time and shadows of Tradition, crost;[21] 5

Lament! for Diocletian's fiery sword Works busy as the lightning; but instinct With malice ne'er to deadliest weapon linked, Which God's ethereal store-houses afford: Against the Followers of the incarnate Lord 5 It rages;—some are smitten in the field— Some pierced to the heart through the ineffectual shield[25] Of sacred home;—with pomp are others gored And dreadful respite. Thus was Alban tried,[26]

That heresies should strike (if truth be scanned Presumptuously) their roots both wide and deep, Is natural as dreams to feverish sleep. Lo! Discord at the altar dares to stand[28] Uplifting toward[29] high Heaven her fiery brand, 5 A cherished Priestess of the new-baptized! But chastisement shall follow peace despised. The Pictish cloud darkens the enervate land By Rome abandoned; vain are suppliant cries, And prayers that would undo her forced farewell; 10 For she returns not.—Awed by her own knell, She casts the Britons upon strange Allies, Soon to become more dreaded enemies Than heartless misery called them to repel.

But, to remote Northumbria's royal Hall, Where thoughtful Edwin, tutored in the school Of sorrow, still maintains a heathen rule, Who comes with functions apostolical? Mark him,[48] of shoulders curved, and stature tall, 5 Black hair, and vivid eye, and meagre cheek, His prominent feature like an eagle's beak; A Man whose aspect doth at once appal And strike with reverence. The Monarch leans Toward the pure truths[49] this Delegate propounds, 10 Repeatedly his own deep mind he sounds With careful hesitation,—then convenes A synod of his Councillors:—give ear, And what a pensive Sage doth utter, hear![50]

"Man's life is like a Sparrow,[51] mighty King! "That—while at banquet with your Chiefs you sit "Housed near a blazing fire—is seen to flit "Safe from the wintry tempest. Fluttering,[52] "Here did it enter; there, on hasty wing, 5 "Flies out, and passes on from cold to cold; "But whence it came we know not, nor behold "Whither it goes. Even such, that transient Thing, "The human Soul; not utterly unknown "While in the Body lodged, her warm abode; 10 "But from what world She came, what woe or weal "On her departure waits, no tongue hath shown; "This mystery if the Stranger can reveal, "His be a welcome cordially bestowed!"

Prompt transformation works the novel Lore; The Council closed, the Priest in full career Rides forth, an armèd man, and hurls a spear To desecrate the Fane which heretofore He served in folly. Woden falls, and Thor 5 Is overturned: the mace, in battle heaved (So might they dream) till victory was achieved, Drops, and the God himself is seen no more. Temple and Altar sink, to hide their shame Amid oblivious weeds, "O come to me, 10 Ye heavy laden!" such the inviting voice Heard near fresh streams;[54] and thousands, who rejoice In the new Rite—the pledge of sanctity, Shall, by regenerate life, the promise claim.

Ah, when the Body,[58] round which in love we clung, Is chilled by death, does mutual service fail? Is tender pity then of no avail? Are intercessions of the fervent tongue A waste of hope?—From this sad source have sprung Rites that console the Spirit, under grief 6 Which ill can brook more rational relief: Hence, prayers are shaped amiss, and dirges sung For Souls[59] whose doom is fixed! The way is smooth For Power that travels with the human heart: 10 Confession ministers the pang to soothe In him who at the ghost of guilt doth start. Ye holy Men, so earnest in your care, Of your own mighty instruments beware!

But what if One, through grove or flowery meed, Indulging thus at will the creeping feet Of a voluptuous indolence, should meet Thy hovering Shade, O[66] venerable Bede! The saint, the scholar, from a circle freed 5 Of toil stupendous, in a hallowed seat Of learning, where thou heard'st[67] the billows beat On a wild coast, rough monitors to feed Perpetual industry.[68] Sublime Recluse! The recreant soul, that dares to shun the debt 10 Imposed on human kind, must first forget Thy diligence, thy unrelaxing use Of a long life; and, in the hour of death, The last dear service of thy passing breath![69]

By such examples moved to unbought pains, The people work like congregated bees;[70] Eager to build the quiet Fortresses Where Piety, as they believe, obtains From Heaven a general blessing; timely rains 5 Or needful sunshine; prosperous enterprise, Justice and peace:—bold faith! yet also rise The sacred Structures for less doubtful gains.[71] The Sensual think with reverence of the palms Which the chaste Votaries seek, beyond the grave; If penance be redeemable, thence alms 11 Flow to the poor, and freedom to the slave; And if full oft the Sanctuary save Lives black with guilt, ferocity it calms.

Behold a pupil of the monkish gown, The pious Alfred, King to Justice dear! Lord of the harp and liberating spear;[73] Mirror of Princes![74] Indigent Renown Might range the starry ether for a crown 5 Equal to his deserts, who, like the year, Pours forth his bounty, like the day doth cheer, And awes like night with mercy-tempered frown. Ease from this noble miser of his time No moment steals; pain narrows not his cares.[75] 10 Though small his kingdom as a spark or gem, Of Alfred boasts remote Jerusalem,[76] And Christian India, through her wide-spread clime, In sacred converse gifts with Alfred shares.[77][78]

When thy great soul was freed from mortal chains, Darling of England! many a bitter shower Fell on thy tomb; but emulative power Flowed in thy line through undegenerate veins.[79] The Race of Alfred covet[80] glorious pains[81] 5 When dangers threaten, dangers ever new! Black tempests bursting, blacker still in view! But manly sovereignty its hold retains; The root sincere, the branches bold to strive With the fierce tempest, while,[82] within the round 10 Of their protection, gentle virtues thrive; As oft, 'mid some green plot of open ground, Wide as the oak extends its dewy gloom, The fostered hyacinths spread their purple bloom.[83]

A pleasant music floats along the Mere, From Monks in Ely chanting service high, While-as Canùte the King is rowing by: "My Oarsmen," quoth the mighty King, "draw near, "That we the sweet song of the Monks may hear!"[90] He listens (all past conquests and all schemes 6 Of future vanishing like empty dreams) Heart-touched, and haply not without a tear. The Royal Minstrel, ere the choir is still,[91] While his free Barge skims the smooth flood along, Gives to that rapture an accordant Rhyme.[92][93] 11 O suffering Earth! be thankful; sternest clime And rudest age are subject to the thrill Of heaven-descended Piety and Song.

The woman-hearted Confessor prepares[94] The evanescence of the Saxon line. Hark! 'tis the tolling Curfew!—the stars shine;[95] But of the lights that cherish household cares And festive gladness, burns not one that dares 5 To twinkle after that dull stroke of thine, Emblem and instrument, from Thames to Tyne, Of force that daunts, and cunning that ensnares! Yet as the terrors of the lordly bell, That quench, from hut to palace, lamps and fires,[96] 10 Touch not the tapers of the sacred quires; Even so a thraldom, studious to expel Old laws, and ancient customs to derange, To Creed or Ritual brings no fatal change.[97]

Coldly we spake. The Saxons, overpowered By wrong triumphant through its own excess, From fields laid waste, from house and home devoured By flames, look up to heaven and crave redress From God's eternal justice. Pitiless 5 Though men be, there are angels that can feel For wounds that death alone has power to heal, For penitent guilt, and innocent distress. And has a Champion risen in arms to try His Country's virtue, fought, and breathes no more; 10 Him in their hearts the people canonize; And far above the mine's most precious ore The least small pittance of bare mould they prize Scooped from the sacred earth where his dear relics lie.

Redoubted King, of courage leonine, I mark thee, Richard! urgent to equip Thy warlike person with the staff and scrip; I watch thee sailing o'er the midland brine; In conquered Cyprus see thy Bride decline 5 Her blushing cheek, love-vows[104] upon her lip, And see love-emblems streaming from thy ship, As thence she holds her way to Palestine.[105] My Song, a fearless homager, would attend Thy thundering battle-axe as it cleaves the press 10 Of war, but duty summons her away To tell—how, finding in the rash distress Of those Enthusiasts a subservient friend, To[106] giddier heights hath clomb the Papal sway.

Realms quake by turns: proud Arbitress of grace, The Church, by mandate shadowing forth the power She arrogates o'er heaven's eternal door, Closes the gates of every sacred place. Straight from the sun and tainted air's embrace 5 All sacred things are covered: cheerful morn Grows sad as night—no seemly garb is worn, Nor is a face allowed to meet a face With natural smiles[108] of greeting. Bells are dumb; Ditches are graves—funereal rites denied; 10 And in the church-yard he must take his bride Who dares be wedded! Fancies thickly come Into the pensive heart ill fortified, And comfortless despairs the soul benumb.

As with the Stream our voyage we pursue, The gross materials of this world present A marvellous study of wild accident;[109] Uncouth proximities of old and new; And bold transfigurations, more untrue 5 (As might be deemed) to disciplined intent Than aught the sky's fantastic element, When most fantastic, offers to the view. Saw we not Henry scourged at Becket's shrine?[110] Lo! John self-stripped of his insignia:—crown, 10 Sceptre and mantle, sword and ring, laid down At a proud Legate's feet![111] The spears that line Baronial halls, the opprobrious insult feel; And angry Ocean roars a vain appeal.

How soon—alas! did Man, created pure— By Angels guarded, deviate from the line Prescribed to duty:—woeful forfeiture[116] He made by wilful breach of law divine. With like perverseness did the Church abjure 5 Obedience to her Lord, and haste to twine,[117] 'Mid Heaven-born flowers that shall for aye endure, Weeds on whose front the world had fixed her sign. O Man,—if with thy trials thus it fares, If good can smooth the way to evil choice, 10 From all rash censure be the mind kept free; He only judges right who weighs, compares, And, in the sternest sentence which his voice Pronounces, ne'er abandons Charity.[118]

From false assumption rose, and fondly hail'd By superstition, spread the Papal power; Yet do not deem the Autocracy prevail'd Thus only, even in error's darkest hour. She daunts, forth-thundering from her spiritual tower Brute rapine, or with gentle lure she tames. 6 Justice and Peace through Her uphold their claims; And Chastity finds many a sheltering bower. Realm there is none that if controul'd or sway'd By her commands partakes not, in degree, 10 Of good, o'er manners arts and arms, diffused: Yes, to thy domination, Roman See, Tho' miserably, oft monstrously, abused By blind ambition, be this tribute paid.[119]

"Here Man more purely lives, less oft doth fall, More promptly rises, walks with stricter heed,[121] More safely rests, dies happier, is freed Earlier from cleansing fires, and gains withal A brighter crown."[122]—On yon Cistertian wall 5 That confident assurance may be read; And, to like shelter, from the world have fled Increasing multitudes. The potent call Doubtless shall cheat full oft the heart's desires:[123] Yet, while the rugged Age on pliant knee 10 Vows to rapt Fancy humble fealty, A gentler life spreads round the holy spires; Where'er they rise, the sylvan waste retires, And aëry harvests crown the fertile lea.

Deplorable his lot who tills the ground, His whole life long tills it, with heartless toil Of villain-service, passing with the soil To each new Master, like a steer or hound, Or like a rooted tree, or stone earth-bound; 5 But mark how gladly, through their own domains, The Monks relax or break these iron chains; While Mercy, uttering, through their voice, a sound Echoed in Heaven, cries out, "Ye Chiefs, abate These legalized oppressions! Man—whose name 10 And nature God disdained not; Man—whose soul Christ died for—cannot forfeit his high claim To live and move exempt from all controul Which fellow-feeling doth not mitigate!"

And what melodious sounds at times prevail! And, ever and anon, how bright a gleam Pours on the surface of the turbid Stream! What heartfelt fragrance mingles with the gale That swells the bosom of our passing sail! 5 For where, but on this River's margin, blow Those flowers of chivalry, to bind the brow Of hardihood with wreaths that shall not fail?— Fair Court of Edward! wonder of the world![131] I see a matchless blazonry unfurled 10 Of wisdom, magnanimity, and love; And meekness tempering honourable pride; The lamb is couching by the lion's side, And near the flame-eyed eagle sits the dove.

Furl we the sails, and pass with tardy oars Through these bright regions, casting many a glance Upon the dream-like issues—the romance[132] Of many-coloured life that[133] Fortune pours Round the Crusaders, till on distant shores 5 Their labours end; or they return to lie, The vow performed, in cross-legged effigy, Devoutly stretched upon their chancel floors. Am I deceived? Or is their requiem chanted By voices never mute when Heaven unties 10 Her inmost, softest, tenderest harmonies; Requiem which Earth takes up with voice undaunted, When she would tell how Brave, and Good, and Wise,[134] For their high guerdon not in vain have panted!

But whence came they who for the Saviour Lord Have long borne witness as the Scriptures teach?— Ages ere Valdo raised his voice to preach In Gallic ears the unadulterate Word, Their fugitive Progenitors explored 5 Subalpine vales, in quest of safe retreats Where that pure Church survives, though summer heats Open a passage to the Romish sword, Far as it dares to follow. Herbs self-sown, And fruitage gathered from the chesnut wood, 10 Nourish the sufferers then; and mists, that brood O'er chasms with new-fallen obstacles bestrown, Protect them; and the eternal snow that daunts Aliens, is God's good winter for their haunts.

Praised be the Rivers, from their mountain springs Shouting to Freedom, "Plant thy banners here!"[143] To harassed Piety, "Dismiss thy fear, "And in our caverns smooth thy ruffled wings!" Nor be unthanked their final lingerings— 5 Silent, but not to high-souled Passion's ear— 'Mid reedy fens wide-spread and marshes drear, Their own creation. Such glad welcomings As Po was heard to give where Venice rose Hailed from aloft those Heirs of truth divine[144] 10 Who near his fountains sought obscure repose, Yet came[145] prepared as glorious lights to shine, Should that be needed for their sacred Charge; Blest Prisoners They, whose spirits were[146] at large!

Those had given[148] earliest notice, as the lark Springs from the ground the morn to gratulate; Or[149] rather rose the day to antedate, By striking out a solitary spark, 4 When all the world with midnight gloom was dark.— Then followed the Waldensian bands, whom Hate[150] In vain endeavours[151] to exterminate, Whom[152] Obloquy pursues with hideous bark:[153] But they desist not;—and the sacred fire,[154] Rekindled thus, from dens and savage woods 10 Moves, handed on with never-ceasing care, Through courts, through camps, o'er limitary floods; Nor lacks this sea-girt Isle a timely share Of the new Flame, not suffered to expire.

"What beast in wilderness or cultured field "The lively beauty of the leopard shows? "What flower in meadow-ground or garden grows "That to the towering lily doth not yield? "Let both meet only on thy royal shield! 5 "Go forth, great King! claim what thy birth bestows; "Conquer the Gallic lily which thy foes "Dare to usurp;—thou hast a sword to wield, "And Heaven will crown the right."—The mitred Sire Thus spake—and lo! a Fleet, for Gaul addrest, 10 Ploughs her bold course across the wondering seas;[155] For, sooth to say, ambition, in the breast Of youthful heroes, is no sullen fire, But one that leaps to meet the fanning breeze.

"Woe to you, Prelates! rioting in ease "And cumbrous wealth—the shame of your estate; "You, on whose progress dazzling trains await "Of pompous horses; whom vain titles please; "Who will be served by others on their knees, 5 "Yet will yourselves to God no service pay; "Pastors who neither take nor point the way "To Heaven; for, either lost in vanities "Ye have no skill to teach, or if ye know "And speak the word ——" Alas! of fearful things 'Tis the most fearful when the people's eye 11 Abuse hath cleared from vain imaginings; And taught the general voice to prophesy Of Justice armed, and Pride to be laid low.

And what is Penance with her knotted thong; Mortification with the shirt of hair, Wan cheek, and knees indúrated with prayer, Vigils, and fastings rigorous as long; If cloistered Avarice scruple not to wrong 5 The pious, humble, useful Secular,[160] And rob[161] the people of his daily care, Scorning that world whose blindness makes her strong? Inversion strange! that, unto One who lives[162] For self, and struggles with himself alone, 10 The amplest share of heavenly favour gives; That to a Monk allots, both in the esteem Of God and man, place higher than to him[163] Who on the good of others builds his own!

The lovely Nun (submissive, but more meek Through saintly habit than from effort due To unrelenting mandates that pursue With equal wrath the steps of strong and weak) Goes forth—unveiling timidly a cheek[169] 5 Suffused with blushes of celestial hue, While through the Convent's[170] gate to open view Softly she glides, another home to seek. Not Iris, issuing from her cloudy shrine, An Apparition more divinely bright! 10 Not more attractive to the dazzled sight Those watery glories, on the stormy brine Poured forth, while summer suns at distance shine, And the green vales lie hushed in sober light!

Mother! whose virgin bosom was uncrost With the least shade of thought to sin allied; Woman! above all women glorified, Our tainted nature's solitary boast; Purer than foam on central ocean tost; 5 Brighter than eastern skies at daybreak strewn With fancied roses, than the unblemished moon Before her wane begins on heaven's blue coast; Thy Image falls to earth. Yet some, I ween, Not unforgiven the suppliant knee might bend, 10 As to a visible Power, in which did blend All that was mixed and reconciled in Thee Of mother's love with maiden purity, Of high with low, celestial with terrene![176]

Not utterly unworthy to endure Was the supremacy of crafty Rome;[177] Age after age to the arch of Christendom Aërial keystone haughtily secure; Supremacy from Heaven transmitted pure, 5 As many hold; and, therefore, to the tomb Pass, some through fire—and by the scaffold some— Like saintly Fisher,[178] and unbending More.[179] "Lightly for both the bosom's lord did sit Upon his throne;"[180] unsoftened, undismayed 10 By aught that mingled with the tragic scene Of pity or fear; and More's gay genius played With the inoffensive sword of native wit, Than the bare axe more luminous and keen.

Deep is the lamentation! Not alone From Sages justly honoured by mankind; But from the ghostly tenants of the wind, Demons and Spirits, many a dolorous groan Issues for that dominion overthrown: 5 Proud Tiber grieves, and far-off Ganges, blind As his own worshippers: and Nile, reclined Upon his monstrous urn, the farewell moan Renews.[181] Through every forest, cave, and den, Where frauds were hatched of old, hath sorrow past— Hangs o'er the Arabian Prophet's native Waste,[182] 11 Where once his airy helpers[183] schemed and planned 'Mid spectral[184] lakes bemocking thirsty men,[185] And stalking pillars built of fiery sand.[186]

For what contend the wise?—for nothing less Than that the Soul, freed from the bonds of Sense, And to her God restored by evidence[191] Of things not seen, drawn forth from their recess, Root there, and not in forms, her holiness;— 5 For[192] Faith, which to the Patriarchs did dispense Sure guidance, ere a ceremonial fence Was needful round men thirsting to transgress;— For[193] Faith, more perfect still, with which the Lord Of all, himself a Spirit, in the youth 10 Of Christian aspiration, deigned to fill The temples of their hearts who, with his word Informed, were resolute to do his will, And worship him in spirit and in truth.

"Sweet is the holiness of Youth"—so felt Time-honoured Chaucer speaking through that Lay[194] By which the Prioress beguiled the way,[195] And many a Pilgrim's rugged heart did melt. Hadst thou, loved Bard! whose spirit often dwelt 5 In the clear land of vision, but foreseen King, child, and seraph,[196] blended in the mien Of pious Edward kneeling as he knelt In meek and simple infancy, what joy For universal Christendom had thrilled 10 Thy heart! what hopes inspired thy genius, skilled (O great Precursor, genuine morning Star) The lucid shafts of reason to employ, Piercing the Papal darkness from afar!

How fast the Marian death-list is unrolled! See Latimer and Ridley in the might Of Faith stand coupled for a common flight![202] One (like those prophets whom God sent of old) Transfigured,[203] from this kindling hath foretold 5 A torch of inextinguishable light; The Other gains a confidence as bold; And thus they foil their enemy's despite. The penal instruments, the shows of crime, Are glorified while this once-mitred pair 10 Of saintly Friends the "murtherer's chain partake, Corded, and burning at the social stake:" Earth never witnessed object more sublime In constancy, in fellowship more fair!

Scattering, like birds escaped the fowler's net, Some seek with timely flight a foreign strand; Most happy, re-assembled in a land By dauntless Luther freed, could they forget Their Country's woes. But scarcely have they met, 5 Partners in faith, and brothers in distress, Free to pour forth their common thankfulness, Ere hope declines:—their union is beset With speculative notions[211] rashly sown, 9 Whence thickly-sprouting growth of poisonous weeds; Their forms are broken staves; their passions, steeds That master them. How enviably blest Is he who can, by help of grace, enthrone The peace of God within his single breast!

Hail, Virgin Queen! o'er many an envious bar Triumphant, snatched from many a treacherous wile! All hail, sage Lady, whom a grateful Isle Hath blest, respiring from that dismal war Stilled by thy voice! But quickly from afar 5 Defiance breathes with more malignant aim; And alien storms with home-bred ferments claim Portentous fellowship.[212] Her silver car, By sleepless prudence[213] ruled, glides slowly on; Unhurt by violence, from menaced taint 10 Emerging pure, and seemingly more bright: Ah! wherefore yields it to a foul constraint[214] Black as the clouds its beams dispersed, while shone, By men and angels blest, the glorious light?[215]

Methinks that I could trip o'er heaviest soil, Light as a buoyant bark from wave to wave, Were mine the trusty staff that Jewel gave To youthful Hooker, in familiar style The gift exalting, and with playful smile:[216] 5 For thus equipped, and bearing on his head The Donor's farewell blessing, can[217] he dread Tempest, or length of way, or weight of toil?— More sweet than odours caught by him who sails Near spicy shores of Araby the blest, 10 A thousand times more exquisitely sweet, The freight of holy feeling which we meet, In thoughtful moments, wafted by the gales From fields where good men walk, or bowers wherein they rest.

Holy and heavenly Spirits as they are, Spotless in life, and eloquent as wise, With what entire affection do they prize[219] Their Church reformed![220] labouring with earnest care To baffle all that may[221] her strength impair; 5 That Church, the unperverted Gospel's seat; In their afflictions a divine retreat; Source of their liveliest hope, and tenderest prayer!— The truth exploring with an equal mind, In doctrine and communion they have sought[222] 10 Firmly between the two extremes to steer; But theirs the wise man's ordinary lot, To trace right courses for the stubborn blind, And prophesy to ears that will not hear.

Men, who have ceased to reverence, soon defy Their forefathers; lo! sects are formed, and split With morbid restlessness;[223]—the ecstatic fit Spreads wide; though special mysteries multiply, The Saints must govern is their common cry; 5 And so they labour, deeming Holy Writ Disgraced by aught that seems content to sit Beneath the roof of settled Modesty. The Romanist exults; fresh hope he draws From the confusion, craftily incites 10 The overweening, personates the mad—[224] To heap disgust upon the worthier Cause: Totters the Throne;[225] the new-born Church[226] is sad For every wave against her peace unites.

Prejudged by foes determined not to spare,[234] An old weak Man for vengeance thrown aside, Laud,[235] "in the painful art of dying" tried, (Like a poor bird entangled in a snare Whose heart still flutters, though his wings forbear 5 To stir in useless struggle) hath relied On hope that conscious innocence supplied,[236] And in his prison breathes[237] celestial air. Why tarries then thy chariot?[238] Wherefore stay, O Death! the ensanguined yet triumphant wheels, 10 Which thou prepar'st, full often, to convey (What time a State with madding faction reels) The Saint or Patriot to the world that heals All wounds, all perturbations doth allay?

Last night, without a voice, that Vision spake Fear to my Soul, and sadness which might seem[243] Wholly[244] dissevered from our present theme; Yet, my belovèd Country! I partake[245] Of kindred agitations for thy sake; 5 Thou, too, dost visit oft[246] my midnight dream; Thy[247] glory meets me with the earliest beam Of light, which tells that Morning is awake. If aught impair thy[248] beauty or destroy, Or but forebode destruction, I deplore 10 With filial love the sad vicissitude; If thou hast[249] fallen, and righteous Heaven restore The prostrate, then my spring-time is renewed, And sorrow bartered for exceeding joy.

Who comes—with rapture greeted, and caress'd With frantic love—his kingdom to regain?[250] Him Virtue's Nurse, Adversity, in vain Received, and fostered in her iron breast: For all she taught of hardiest and of best, 5 Or would have taught, by discipline of pain And long privation, now dissolves amain, Or is remembered only to give zest To wantonness—Away, Circean revels![251] But for what gain? if England soon must sink 10 Into a gulf which all distinction levels— That bigotry may swallow the good name,[252][253] And, with that draught, the life-blood: misery, shame, By Poets loathed; from which Historians shrink!

Yet Truth is keenly sought for, and the wind Charged with rich words poured out in thought's defence; Whether the Church inspire that eloquence,[254] Or a Platonic Piety confined To the sole temple of the inward mind;[255] 5 And One there is who builds immortal lays, Though doomed to tread in solitary ways,[256] Darkness before and danger's voice behind; Yet not alone, nor helpless to repel Sad thoughts; for from above the starry sphere 10 Come secrets, whispered nightly to his ear; And the pure spirit of celestial light Shines through his soul—"that he may see and tell Of things invisible to mortal sight."[257]

There are no colours in the fairest sky So fair as these. The feather, whence the pen Was shaped that traced the lives of these good men, Dropped from an Angel's wing.[259] With moistened eye We read of faith and purest charity 5 In Statesman, Priest, and humble Citizen: O could we copy their mild virtues, then What joy to live, what blessedness to die! Methinks their very names shine still and bright; Apart—like glow-worms on a summer night; 10 Or lonely tapers when from far they fling A guiding ray;[260] or seen—like stars on high, Satellites burning in a lucid ring Around meek Walton's heavenly memory.

A voice, from long-expecting[266] thousands sent, Shatters the air, and troubles tower and spire; For Justice hath absolved the innocent, And Tyranny is balked of her desire: Up, down, the busy Thames—rapid as fire 5 Coursing a train of gunpowder—it went, And transport finds in every street a vent, Till the whole City rings like one vast quire. The Fathers urge the People to be still, 9 With outstretched hands and earnest speech[267]—in vain! Yea, many, haply wont to entertain Small reverence for the mitre's offices, And to Religion's self no friendly will, A Prelate's blessing ask on bended knees.

Calm as an under-current, strong to draw Millions of waves into itself, and run, From sea to sea, impervious to the sun And ploughing storm, the spirit of Nassau[268] (Swerves not, how blest if by religious awe[269] 5 Swayed, and thereby enabled to contend With the wide world's commotions) from its end Swerves not—diverted by a casual law. Had mortal action e'er a nobler scope? The Hero comes to liberate, not defy; 10 And, while he marches on with stedfast hope,[270] Conqueror beloved! expected anxiously! The vacillating Bondman of the Pope[271] Shrinks from the verdict of his stedfast eye.

Ungrateful Country, if thou e'er forget The sons who for thy civil rights have bled! How, like a Roman, Sidney bowed his head,[272] And Russell's milder blood the scaffold wet;[273] But these had fallen for profitless regret 5 Had not thy holy Church her champions bred, And claims from other worlds inspirited The star of Liberty to rise. Nor yet (Grave this within thy heart!) if spiritual things Be lost, through apathy, or scorn, or fear, 10 Shalt thou thy humbler franchises support, However hardly won or justly dear: What came from heaven to heaven by nature clings, And, if dissevered thence, its course is short.

Patriots informed with Apostolic light Were they, who, when their Country had been freed, Bowing with reverence to the ancient creed, Fixed on the frame of England's Church their sight,[282] And strove in filial love to reunite 5 What force had severed. Thence they fetched the seed Of Christian unity, and won a meed Of praise from Heaven. To Thee, O saintly White,[283] Patriarch of a wide-spreading family, Remotest lands and unborn times shall turn, 10 Whether they would restore or build—to Thee, As one who rightly taught how zeal should burn, As one who drew from out Faith's holiest urn The purest stream of patient Energy.

A genial hearth, a hospitable board, And a refined rusticity, belong[285] To the neat mansion, where, his flock among, The learned Pastor dwells, their watchful Lord.[286] Though meek and patient as a sheathèd sword; 5 Though pride's least lurking thought appear a wrong To human kind; though peace be on his tongue, Gentleness in his heart—can earth afford Such genuine state, pre-eminence so free, As when, arrayed in Christ's authority, 10 He from the pulpit lifts his awful hand; Conjures, implores, and labours all he can For re-subjecting to divine command The stubborn spirit of rebellious man?

Yes, if the intensities of hope and fear Attract us still, and passionate exercise Of lofty thoughts, the way before us lies Distinct with signs, through which in set career,[287] As through a zodiac, moves the ritual year[288] 5 Of England's Church; stupendous mysteries! Which whoso travels in her bosom eyes, As he approaches them, with solemn cheer. Upon that circle traced from sacred story We only dare to cast a transient glance, 10 Trusting in hope that Others may advance With mind intent upon the King of Glory,[289] From his mild advent till his countenance Shall dissipate the seas and mountains hoary.[290]

Dear[291] be the Church, that, watching o'er the needs Of Infancy, provides a timely shower Whose virtue changes to a Christian Flower A Growth from sinful Nature's bed of weeds!—[292] Fitliest beneath the sacred roof proceeds 5 The ministration; while parental Love Looks on, and Grace descendeth from above As the high service pledges now, now pleads. There, should vain thoughts outspread their wings and fly To meet the coming hours of festal mirth, 10 The tombs—which hear and answer that brief cry, The Infant's notice of his second birth— Recal the wandering Soul to sympathy With what man hopes from Heaven, yet fears from Earth.

Father! to God himself we cannot give A holier name! then lightly do not bear Both names conjoined, but of thy spiritual care Be duly mindful: still more sensitive Do Thou, in truth a second Mother, strive[293] 5 Against disheartening custom, that by Thee Watched, and with love and pious industry[294] Tended at need, the adopted Plant may thrive For everlasting bloom. Benign and pure[295] This Ordinance, whether loss it would supply, 10 Prevent omission, help deficiency, Or seek to make assurance doubly sure.[296][297] Shame if the consecrated Vow be found An idle form, the Word an empty sound![298][299]

From Little down to Least, in due degree, Around the Pastor, each in new-wrought vest, Each with a vernal posy at his breast, We stood, a trembling, earnest Company! With low soft murmur, like a distant bee, 5 Some spake, by thought-perplexing fears betrayed; And some a bold unerring answer made: How fluttered then thy anxious heart for me, Belovèd Mother! Thou whose happy hand Had bound the flowers I wore, with faithful tie:[300] 10 Sweet flowers! at whose inaudible command Her countenance, phantom-like, doth re-appear: O lost too early for the frequent tear, And ill requited by this heartfelt sigh!

By chain yet stronger must the Soul be tied: One duty more, last stage of[303] this ascent, Brings to thy food, mysterious[304] Sacrament! The Offspring, haply at the Parent's side; But not till They, with all that do abide 5 In Heaven, have lifted up their hearts to laud And magnify the glorious name of God, Fountain of Grace, whose Son for sinners died. Ye, who have duly weighed the summons, pause No longer; ye,[305] whom to the saving rite 10 The Altar calls; come early under laws That can secure for you a path of light Through gloomiest shade; put on (nor dread its weight) Armour divine, and conquer in your cause!

The Vested Priest before the Altar stands; Approach, come gladly, ye prepared, in sight Of God and chosen friends, your troth to plight With the symbolic ring, and willing hands[307] Solemnly joined. Now sanctify the bands, 5 O Father!—to the Espoused thy blessing give, That mutually assisted they may live Obedient, as here taught, to thy commands. So prays the Church, to consecrate a Vow "The which would endless matrimony make";[308] 10 Union that shadows forth and doth partake A mystery potent human love to endow With heavenly, each more prized for the other's sake; Weep not, meek Bride! uplift thy timid brow.

Shun not this rite, neglected, yea abhorred, By some of unreflecting mind, as calling Man to curse man, (thought monstrous and appalling.) Go thou and hear the threatenings of the Lord;[309] Listening within his Temple see his sword 5 Unsheathed in wrath to strike the offender's head, Thy own, if sorrow for thy sin be dead, Guilt unrepented, pardon unimplored. Two aspects bears Truth needful for salvation; Who knows not that?—yet would this delicate age 10 Look only on the Gospel's brighter page: Let light and dark duly our thoughts employ; So shall the fearful words of Commination Yield timely fruit of peace and love and joy.

Closing the sacred Book[311] which long has fed Our meditations,[312] give we to a day Of annual[313] joy one tributary lay; This[314] day, when, forth by rustic music led, The village Children, while the sky is red 5 With evening lights, advance in long array Through the still church-yard, each with garland gay, That, carried sceptre-like, o'ertops the head Of the proud Bearer. To the wide church-door, Charged with these offerings which their fathers bore 10 For decoration in the Papal time, The innocent Procession softly moves:— The spirit of Laud is pleased in heaven's pure clime, And Hooker's voice the spectacle approves!

Monastic Domes! following my downward way, Untouched by due regret I marked your fall! Now, ruin, beauty, ancient stillness, all Dispose to judgments temperate as we lay On our past selves in life's declining day: 5 For as, by discipline of Time made wise, We learn to tolerate the infirmities And faults of others—gently as he may,[318] So with[319] our own the mild Instructor deals Teaching us to forget them or forgive.[320] 10 Perversely curious, then, for hidden ill Why should we break Time's charitable seals? Once ye were holy, ye are holy still; Your spirit freely let me drink, and live!

But liberty, and triumphs on the Main, And laurelled armies, not to be withstood— What serve they? if, on transitory good Intent, and sedulous of abject gain, The State (ah, surely not preserved in vain!) 5 Forbear to shape due channels which the Flood Of sacred truth may enter—till it brood O'er the wide realm, as o'er the Egyptian plain The all-sustaining Nile. No more—the time Is conscious of her want; through England's bounds, In rival haste, the wished-for Temples rise![324] 11 I hear their sabbath bells' harmonious chime Float on the breeze—the heavenliest of all sounds That vale or hill[325] prolongs or multiplies!

The encircling ground, in native turf arrayed, Is now by solemn consecration given To social interests, and to favouring Heaven, And where the rugged colts their gambols played, And wild deer bounded through the forest glade, 5 Unchecked as when by merry Outlaw driven, Shall hymns of praise resound at morn and even; And soon, full soon, the lonely Sexton's spade Shall wound the tender sod. Encincture small, But infinite its grasp of weal and woe![331] 10 Hopes, fears, in never-ending ebb and flow;— The spousal trembling, and the "dust to dust," The prayers, the contrite struggle, and the trust That to the Almighty Father looks through all.

What awful pérspective! while from our sight With gradual stealth the lateral windows hide Their Portraitures, their stone-work glimmers, dyed In[335] the soft chequerings of a sleepy light. Martyr, or King, or sainted Eremite, 5 Whoe'er ye be, that thus, yourselves unseen, Imbue your prison-bars with solemn sheen, Shine on, until ye fade with coming Night!— But, from the arms of silence—list! O list! The music bursteth into second life; 5 The notes luxuriate, every stone is kissed By sound, or ghost of sound, in mazy strife; Heart-thrilling strains, that cast, before the eye Of the devout, a veil of ecstasy!

Glory to God! and to the Power who came In filial duty, clothed with love divine, That made his human tabernacle shine Like Ocean burning with purpureal flame; Or like the Alpine Mount, that takes its name 5 From roseate hues,[338] far kenned at morn and even, In hours of peace, or when the storm is driven Along the nether region's rugged frame! Earth prompts—Heaven urges; let us seek the light, Studious of that pure intercourse begun 10 When first our infant brows their lustre won; So, like the Mountain, may we grow more bright From unimpeded commerce with the Sun, At the approach of all-involving night.

But turn we from these "bold bad" men;[359] The way, mild Lady! that hath led Down to their "dark opprobrious den,"[360] Is all too rough for Thee to tread. Softly as morning vapours glide 85 Down Rydal-cove from Fairfield's side,[361] Should move the tenor of his song Who means to charity no wrong; Whose offering gladly would accord With this day's work, in thought and word. 90

As aptly, also, might be given 5 A Pencil to her hand; That, softening objects, sometimes even Outstrips the heart's demand;

Not Love, not[366] War, nor the tumultuous swell Of civil conflict, nor the wrecks of change, Nor[367] Duty struggling with afflictions strange— Not these alone inspire the tuneful shell; But where untroubled peace and concord dwell, 5 There also is the Muse not loth to range, Watching the twilight smoke of cot or grange,[368] Skyward ascending from a woody dell.[369][370] Meek aspirations please her, lone endeavour, And sage content, and placid melancholy; 10 She loves to gaze upon a crystal river— Diaphanous because it travels slowly;[371] Soft is the music that would charm for ever;[372] The flower of sweetest smell is shy and lowly.

Heed not tho' none should call thee fair;[378] 5 So, Mary, let it be If nought in loveliness compare With what thou art to me.

That sigh of thine,[380] not meant for human ear, Tells[381] that these words thy humbleness offend; 10 Yet bear me up[382]—else faltering in the rear Of a steep march: support[383] me to the end.

But hand and voice alike are still; No sound here sweeps away the will That gave it birth: in service meek One upright arm sustains the cheek, And one across the bosom lies— 15 That rose, and now forgets to rise, Subdued by breathless harmonies Of meditative feeling; Mute strains from worlds beyond the skies, Through the pure light of female eyes, 20 Their sanctity revealing!

If human Life do pass away, Perishing yet more swiftly than the flower, If we are creatures of a winter's day;[386] What space hath Virgin's beauty to disclose 10 Her sweets, and triumph o'er the breathing rose? Not even an hour!

[In this Vale of Meditation my friend Jones resided, having been allowed by his diocesan to fix himself there without resigning his Living in Oxfordshire. He was with my wife and daughter and me when we visited these celebrated ladies who had retired, as one may say, into notice in this vale. Their cottage lay directly in the road between London and Dublin, and they were of course visited by their Irish friends as well as innumerable strangers. They took much delight in passing jokes on our friend Jones's plumpness, ruddy cheeks and smiling countenance, as little suited to a hermit living in the Vale of Meditation. We all thought there was ample room for retort on his part, so curious was the appearance of these ladies, so elaborately sentimental about themselves and their Caro Albergo as they named it in an inscription on a tree that stood opposite, the endearing epithet being preceded by the word Ecco! calling upon the saunterer to look about him. So oddly was one of these ladies attired that we took her, at a little distance, for a Roman Catholic priest, with a crucifix and relics hung at his neck. They were without caps, their hair bushy and white as snow, which contributed to the mistake.—I. F.]

"We are all much moved by the manner in which Miss Willes has received the verses,—particularly Wm., who feels himself more than rewarded for the labour I cannot call it of the composition—for the tribute was poured forth with a deep stream of fervour that was something beyond labour, and it has required very little correction. In one instance a single word in the 'Address to Sir George' is changed since we sent the copy, viz.: 'graciously' for 'courteously,' as being a word of more dignity."

Trajan's Column was set up by the Senate and people of Rome, in honour of the Emperor, about A.D. 114. It is one of the most remarkable pillars in the world; and still stands, little injured by time, in the centre of the Forum Trajanum (now a ruin); its height—132 feet—marking the height of the earth removed when the Forum was made. On the pedestal bas-reliefs were carved in series showing the arms and armour of the Romans; and round the shaft of the column similar reliefs, exhibiting pictorially the whole story of the Decian campaign of the Emperor. These are of great value as illustrating the history of the period, the costume of the Roman soldiers and the barbarians. A colossal statue of Trajan crowned the column; and, when it fell, Pope Sixtus V. replaced it by a figure of St. Peter. It is referred to by Pausanias (v. 12. 6), and by all the ancient topographers. See a minute account of it, with excellent illustrations, in Hertzberg's Geschichte des Römischen Kaiserreiches, pp. 330-345 (Berlin: 1880); also Müller's Denkmäler der alten Kunst, p. 51. The book, however, from which Wordsworth gained his information of this pillar was evidently Joseph Forsyth's Remarks on Antiquities, Arts, and Letters, during an Excursion in Italy in 1802-3 (London: 1813). It is thus that Dean Merivale speaks of it:—

Immoveable by generous sighs, 5 She glories in a train Who drag, beneath our native skies, An oriental chain.

Cloud-piercing peak, and trackless heath, Instinctive homage pay; Nor wants the dim-lit cave a wreath 35 To honour thee, sweet May! Where cities fanned by thy brisk airs Behold a smokeless sky, Their puniest flower-pot-nursling dares To open a bright eye. 40

Season of fancy and of hope, Permit not for one hour, 90 A blossom from thy crown to drop, Nor add to it a flower! Keep, lovely May, as if by touch Of self-restraining art, This modest charm of not too much, 95 Part seen, imagined part!

The massy Ways, carried across these heights[430] By Roman perseverance,[431] are destroyed, Or hidden under ground, like sleeping worms. How venture then to hope that Time will spare[432] This humble Walk? Yet on the mountain's side 5 A Poet's hand first shaped it; and the steps Of that same Bard—repeated to and fro At morn, at noon,[433] and under moonlight skies Through the vicissitudes of many a year— Forbade the weeds to creep o'er its grey line. 10 No longer, scattering to the heedless winds The vocal raptures of fresh poesy, Shall he frequent these precincts; locked no more In earnest converse with beloved Friends, Here will he gather stores of ready bliss, 15 As from the beds and borders of a garden Choice flowers are gathered! But, if Power may spring Out of a farewell yearning—favoured more Than kindred wishes mated suitably With vain regrets—the Exile would consign 20 This Walk, his loved possession, to the care Of those pure Minds that reverence the Muse.[434]

Whence strains to love-sick maiden dear, While in her lonely bower she tries To cheat the thought she cannot cheer, 35 By fanciful embroideries.

Happy the feeling from the bosom thrown In perfect shape (whose beauty Time shall spare Though a breath made it) like a bubble blown For summer pastime into wanton air; Happy the thought best likened to a stone 5 Of the sea-beach, when, polished with nice care, Veins it discovers exquisite and rare, Which for the loss of that moist gleam atone That tempted first to gather it. That here, O chief of Friends![445] such feelings I present, 10 To thy regard, with thoughts so fortunate, Were a vain notion; but the hope is dear,[446] That thou, if not with partial joy elate, Wilt smile upon this gift with[447] more than mild content![448]

Her only pilot the soft breeze, the boat Lingers, but Fancy is well satisfied; With keen-eyed Hope, with Memory, at her side, And the glad Muse at liberty to note All that to each is precious, as we float 5 Gently along; regardless who shall chide If the heavens smile, and leave us free to glide, Happy Associates breathing air remote From trivial cares. But, Fancy and the Muse, Why have I crowded this small bark with you 10 And others of your kind, ideal crew! While here sits One whose brightness owes its hues To flesh and blood; no Goddess from above, No fleeting Spirit, but my own true Love?[449]

[Suggested by observation of the way in which a young friend, whom I do not choose to name, misspent his time and misapplied his talents. He took afterwards a better course, and became a useful member of society, respected, I believe, wherever he has been known.—I. F.]

If the whole weight of what we think and feel, Save only far as thought and feeling blend With action, were as nothing, patriot Friend! From thy remonstrance would be no appeal; But to promote and fortify the weal 5 Of our own Being is her paramount end; A truth which they alone shall comprehend Who shun the mischief which they cannot heal. Peace in these feverish times is sovereign bliss: Here, with no thirst but what the stream can slake, 10 And startled only by the rustling brake, Cool air I breathe; while the unincumbered Mind, By some weak aims at services assigned To gentle Natures, thanks not Heaven amiss.

The imperial Stature, the colossal stride, Are yet before me; yet do I behold The broad full visage, chest of amplest mould, The vestments 'broidered with barbaric pride: And lo! a poniard, at the Monarch's side, 5 Hangs ready to be grasped in sympathy With the keen threatenings of that fulgent eye, Below the white-rimmed bonnet, far-descried. Who trembles now at thy capricious mood? 'Mid those surrounding Worthies, haughty King, 10 We rather think, with grateful mind sedate, How Providence educeth, from the spring Of lawless will, unlooked-for streams of good, Which neither force shall check nor time abate!

When Philoctetes in the Lemnian isle[473] Like a Form sculptured on a monument Lay couched; on him or his dread bow unbent[474] Some wild Bird oft might settle and beguile The rigid features of a transient smile, 5 Disperse the tear, or to the sigh give vent, Slackening the pains of ruthless banishment From his lov'd home, and from heroic toil. And trust[475] that spiritual Creatures round us move, Griefs to allay which[476] Reason cannot heal; 10 Yea, veriest[477] reptiles have sufficed to prove To fettered wretchedness, that no Bastile[478] Is deep enough to exclude the light of love, Though man for brother man has ceased to feel.

[This is taken from the account given by Miss Jewsbu̇ry of the pleasure she derived, when long confined to her bed by sickness, from the inanimate object on which this sonnet turns.—I.F.]

Not the whole warbling grove in concert heard When sunshine follows shower, the breast can thrill Like the first summons, Cuckoo! of thy bill, With its twin notes inseparably paired.[483] The captive 'mid damp vaults unsunned, unaired, 5 Measuring the periods of his lonely doom, That cry can reach; and to the sick man's room Sends gladness, by no languid smile declared. The lordly eagle-race through hostile search May perish; time may come when never more 10 The wilderness shall hear the lion roar; But, long as cock shall crow from household perch To rouse the dawn, soft gales shall speed thy wing, And thy erratic voice[484] be faithful to the Spring!

Unquiet Childhood here by special grace Forgets her nature, opening like a flower That neither feeds nor wastes its vital power In painful struggles. Months each other chase, And nought untunes that Infant's voice; no trace[486] 5 Of fretful temper sullies her pure cheek;[487] Prompt, lively, self-sufficing, yet so meek That one enrapt with gazing on her face (Which even the placid innocence of death Could scarcely make more placid, heaven more bright) Might learn to picture, for the eye of faith, 11 The Virgin, as she shone with kindred light; A nursling couched upon her mother's knee, Beneath some shady palm of Galilee.

Rotha, my Spiritual Child! this head was grey When at the sacred font for thee I stood; Pledged till thou reach the verge of womanhood, And shalt become thy own sufficient stay: Too late, I feel, sweet Orphan, was the day 5 For stedfast hope the contract to fulfil; Yet shall my blessing hover o'er thee still, Embodied in the music of this Lay, Breathed forth beside the peaceful mountain Stream[488] Whose murmur soothed thy languid Mother's ear 10 After her throes, this Stream of name more dear Since thou dost bear it,—a memorial theme[489] For others; for thy future self, a spell To summon fancies out of Time's dark cell.[490]

Such age how beautiful! O Lady bright, Whose mortal lineaments seem all refined By favouring Nature and a saintly Mind To something purer and more exquisite Than flesh and blood; whene'er thou meet'st my sight, When I behold thy blanched unwithered cheek, 6 Thy temples fringed with locks of gleaming white, And head that droops because the soul is meek, Thee with the welcome Snowdrop I compare; That child of winter, prompting thoughts that climb 10 From desolation toward[492] the genial prime; Or with the Moon conquering earth's misty air, And filling more and more with crystal light As pensive Evening deepens into night.[493]

Wild Redbreast![501] hadst them at Jemima's lip[502] Pecked, as at mine, thus boldly, Love might say[503] A half-blown rose had tempted thee to sip Its glistening dews: but hallowed is the clay Which the Muse warms; and I, whose head is grey,[504] 5 Am not unworthy of thy fellowship; Nor could I let one thought—one motion—slip That might thy sylvan confidence betray. For are we not all His without whose care Vouchsafed no sparrow falleth to the ground?[505] 10 Who gives his Angels wings to speed through air, And rolls the planets through the blue profound; Then peck or perch, fond Flutterer! nor forbear To trust a Poet in still musings bound.[506]

Her brow hath opened on me—see it there, Brightening the umbrage of her hair; So gleams the crescent moon, that loves To be descried through shady groves. 190 Tenderest bloom is on her cheek; Wish not for a richer streak; Nor dread the depth of meditative eye; But let thy love, upon that azure field Of thoughtfulness and beauty, yield 195 Its homage offered up in purity. What would'st thou more? In sunny glade, Or under leaves of thickest shade, Was such a stillness e'er diffused Since earth grew calm while angels mused? 200 Softly she treads, as if her foot were loth To crush the mountain dew-drops—soon to melt On the flower's breast; as if she felt That flowers themselves, whate'er their hue, With all their fragrance, all their glistening, 205 Call to the heart for inward listening— And though for bridal wreaths and tokens true Welcomed wisely; though a growth Which the careless shepherd sleeps on, As fitly spring from turf the mourner weeps on— And without wrong are cropped the marble tomb to strew. 211 The Charm is over;[545] the mute Phantoms gone, Nor will return—but droop not, favoured Youth; The apparition that before thee shone Obeyed a summons covetous of truth. 215 From these wild rocks thy footsteps I will guide To bowers in which thy fortune may be tried, And one of the bright Three become thy happy Bride.

And not in vain, when thoughts are cast Upon the irrevocable past, 50 Some Penitent sincere May for a worthier future sigh, While trickles from his downcast eye No unavailing tear.

The title given to this poem by Dorothy Wordsworth, in the letter to Lady Beaumont in which the different MS. readings occur, is "A Jewish Family, met with in a Dingle near the Rhine." During the Continental Tour of 1820,—in which Wordsworth was accompanied by his wife and sister and other friends,—they went up the Rhine (see the notes to the poems recording that Tour). An extract from Mrs. Wordsworth's Journal, referring to the road from St. Goar to Bingen, may illustrate this poem, written in 1828. "From St. Goar to Bingen, castles commanding innumerable small fortified villages. Nothing could exceed the delightful variety, and at first the postilions whisked us too fast through these scenes; and afterwards, the same variety so often repeated, we became quite exhausted, at least D. and I were; and, beautiful as the road continued to be, we could scarcely keep our eyes open; but, on my being roused from one of these slumbers, no eye wide-awake ever beheld such celestial pictures as gleamed before mine, like visions belonging to dreams. The castles seemed now almost stationary, a continued succession always in sight, rarely without two or three before us at once. There they rose from the craggy cliffs, out of the centre of the stately river, from a green island, or a craggy rock, etc., etc."

What mortal form, what earthly face Inspired the pencil, lines to trace, And mingle colours, that should breed Such rapture, nor want power to feed; 20 For had thy charge been idle flowers, Fair Damsel! o'er my captive mind, To truth and sober reason blind, 'Mid that soft air, those long-lost bowers, The sweet illusion might have hung, for hours. 25

A Voice to Light gave Being;[593] To Time, and Man his earth-born chronicler; 210 A Voice shall finish doubt and dim foreseeing, And sweep away life's visionary stir; The trumpet (we, intoxicate with pride, Arm at its blast for deadly wars) To archangelic lips applied, 215 The grave shall open, quench the stars.[594] O Silence! are Man's noisy years No more than moments of thy life?[595] Is Harmony, blest queen of smiles and tears, With her smooth tones and discords just, 220 Tempered into rapturous strife, Thy destined bond-slave? No! though earth be dust And vanish, though the heavens dissolve, her stay Is in the Word, that shall not pass away.[596]

Fays, Genii of gigantic size! And now, in twilight dim, Clustering like constellated eyes, 35 In wings of Cherubim, When the fierce orbs abate their glare;—[599] Whate'er your forms express, Whate'er ye seem, whate'er ye are— All leads to gentleness. 40

Thus, gifted Friend, but with the placid brow That woman ne'er should forfeit, keep thy vow; With modest scorn reject whate'er would blind 135 The ethereal eyesight, cramp the wingèd mind! Then, with a blessing granted from above To every act, word, thought, and look of love, Life's book for Thee may lie unclosed, till age Shall with a thankful tear bedrop its latest page.[616] 140

Then, for the pastimes of this delicate age, 95 And all the heavy or light vassalage Which for their sakes we fasten, as may suit Our varying moods, on human kind or brute, 'Twere well in little, as in great, to pause, Lest Fancy trifle with eternal laws. 100 Not from his fellows only man may learn Rights to compare and duties to discern! All creatures and all objects, in degree, Are friends and patrons of humanity. There are to whom the[636] garden, grove, and field, 105 Perpetual lessons of forbearance yield; Who would not lightly violate the grace The lowliest flower possesses in its place; Nor shorten the sweet life, too fugitive, 109 Which nothing less than Infinite Power could give.[637]

Yet, spite of all this eager strife, This ceaseless play, the genuine life That serves the stedfast hours, 15 Is in the grass beneath, that grows Unheeded, and the mute repose Of sweetly-breathing flowers.

Mute memento of that union In a Saxon church survives, Where a cross-legged Knight lies sculptured As between two wedded Wives— Figures with armorial signs of race and birth, 155 And the vain rank the pilgrims bore while yet on earth.

But Angels round her pillow Kept watch, a viewless band; 380 And, billow favouring billow, She reached the destined strand.

I rather think, the gentle Dove Is murmuring a reproof, 10 Displeased that I from lays of love Have dared to keep aloof; That I, a Bard of hill and dale, Have carolled, fancy free,[674] As if nor dove nor nightingale, 15 Had heart or voice for me.

God, who instructs the brutes to scent All changes of the element, Whose wisdom fixed the scale 75 Of natures, for our wants provides By higher, sometimes humbler, guides, When lights of reason fail.

With copious eulogy in prose or rhyme[679] Graven on the tomb we struggle against Time, Alas, how feebly! but our feelings rise And still we struggle when a good man dies: Such offering Beaumont dreaded and forbade, 5 A spirit meek in self-abasement clad. Yet here at least, though few have numbered days That shunned so modestly the light of praise, His graceful manners, and the temperate ray Of that arch fancy which would round him play, 10 Brightening a converse never known to swerve From courtesy and delicate reserve; That sense, the bland philosophy of life, Which checked discussion ere it warmed to strife; Those rare accomplishments,[680] and varied powers, 15 Might have their record among sylvan bowers. Oh, fled for ever! vanished like a blast That shook the leaves in myriads as it passed;— Gone from this world of earth, air, sea, and sky, From all its spirit-moving imagery, 20 Intensely studied with a painter's eye, A poet's heart; and, for congenial view, Portrayed with happiest pencil, not untrue To common recognitions while the line Flowed in a course of sympathy divine;— 25 Oh! severed, too abruptly, from delights That all the seasons shared with equal rights;— Rapt in the grace of undismantled age, From soul-felt music, and the treasured page Lit by that evening lamp which loved to shed 30 Its mellow lustre round thy honoured head; While Friends beheld thee give with eye, voice, mien, More than theatric force to Shakspeare's scene;—[681] If thou hast heard me—if thy Spirit know 34 Aught of these powers and whence their pleasures flow; If things in our remembrance held so dear, And thoughts and projects fondly cherished here, To thy exalted nature only seem Time's vanities, light fragments of earth's dream— Rebuke us not![682]—The mandate is obeyed 40 That said, "Let praise be mute where I am laid;" The holier deprecation, given in trust To the cold marble, waits upon thy dust; Yet have we found how slowly genuine grief From silent admiration wins relief. 45 Too long abashed thy Name is like a rose That doth "within itself its sweetness close;"[683] A drooping daisy changed into a cup In which her bright-eyed beauty is shut up. Within these groves, where still are flitting by 50 Shades of the Past, oft noticed with a sigh, Shall stand a votive Tablet,[684] haply free, When towers and temples fall, to speak of Thee! If sculptured emblems of our mortal doom Recal not there the wisdom of the Tomb, 55 Green ivy risen from out the cheerful earth, Will[685] fringe the lettered stone; and herbs spring forth, Whose fragrance, by soft dews and rain unbound, Shall penetrate the heart without a wound; While truth and love their purposes fulfil, 60 Commemorating genius, talent, skill, That could not lie concealed where Thou wert known; Thy virtues He must judge, and He alone, The God upon whose mercy they are thrown.

Chatsworth! thy stately mansion, and the pride Of thy domain, strange contrast do present To house and home in many a craggy rent Of the wild Peak; where new-born waters glide Through fields whose thrifty occupants abide 5 As in a dear and chosen banishment, With every semblance of entire content; So kind is simple Nature, fairly tried! Yet He whose heart in childhood gave her troth To pastoral dales, thin-set with modest farms, 10 May learn, if judgment strengthen with his growth, That, not for Fancy only, pomp hath charms; And, strenuous to protect from lawless harms The extremes of favoured life, may honour both.

I sang—Let myriads of bright flowers, Like Thee, in field and grove Revive unenvied;—mightier far, Than tremblings that reprove Our vernal tendencies to hope, 35 Is[688] God's redeeming love;