автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу A Guide to the Study of Fishes, Volume 2 (of 2)

Transcriber's Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

GUIDE TO THE STUDY OF FISHES

VARIATIONS IN THE COLOR OF FISHES

The Oniokose or Demon Stinger, Inimicus japonicus (Cuv. and Val.), from Wakanoura, Japan. From nature by Kako Morita.

Surface coloration about lava rocks.

Coloration of specimens living among red algæ.

Coloration in deep water; Inimicus aurantiacus (Schlegel).

A GUIDE

TO

THE STUDY OF FISHES

BY

DAVID STARR JORDAN

President of Leland Stanford Junior University

With Colored Frontispieces and 507 Illustrations

IN TWO VOLUMES

Vol II.

"I am the wiser in respect to all knowledge

and the better qualified for all fortunes

for knowing that there is a minnow in that

brook."—Thoreau

NEW YORK

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

1905

Copyright, 1905

BY

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

Published March, 1905

CONTENTS

VOL. II.

CHAPTER I.

THE GANOIDS.

PAGE

Subclass Actinopteri.—The Series Ganoidei.—Are the Ganoids a Natural Group?—Systematic Position of Lepidosteus.—Gill on the Ganoids as a Natural Group.

1CHAPTER II.

THE GANOIDS (

Continued).

Classification of Ganoids.—Order Lysopteri.—The Palæoniscidæ.—The Platysomidæ.—The Dorypteridæ.—The Dictyopygidæ.—Order Chondrostei.—Order Selachostomi: the Paddle-fishes.—Order Pycnodonti.—Order Lepidostei.—Family Lepisosteidæ.—Embryology of the Garpike.—Fossil Garpikes.—Order Halecomorphi.—Pachycormidæ.—The Bowfins: Amiidæ.—The Oligopleuridæ.

13CHAPTER III.

ISOSPONDYLI.

The Subclass Teleostei, or Bony Fishes.—Order Isospondyli.—The Classification of the Bony Fishes.—Relationships of Isospondyli.—The Clupeoidea.—The Leptolepidæ.—The Elopidæ.—The Albulidæ.—The Chanidæ.—The Hiodontidæ.—The Pterothrissidæ.—The Ctenothrissidæ.—The Notopteridæ.—The Clupeidæ.—The Dorosomatidæ.—The Engraulididæ.—Gonorhynchidæ.—The Osteoglossidæ.—The Pantodontidæ.

37CHAPTER IV.

SALMONIDÆ.

The Salmon Family.—Coregonus, the Whitefish.—Argyrosomus, the Lake Herring.—Brachymystax and Stenodus, the Inconnus.—Oncorhynchus, the Quinnat Salmon.—The Parent-stream Theory.—The Jadgeska Hatchery.—Salmon-packing.

61CHAPTER V.

SALMONIDÆ (

Continued).

Salmo, the Trout and Atlantic Salmon.—The Atlantic Salmon.—The Ouananiche.—The Black-spotted Trout.—The Trout of Western America.—Cutthroat or Red-throated Trout.—Hucho, the Huchen.—Salvelinus, the Charr.—Cristivomer, the Great Lake Trout.—The Ayu, or Sweetfish.—Cormorant-fishing.—Fossil Salmonidæ.

89CHAPTER VI.

THE GRAYLING AND THE SMELT.

The Grayling, or Thymallidæ.—The Argentinidæ.—The Microstomidæ.—The Salangidæ, or Icefishes.—The Haplochitonidæ.—Stomiatidæ.—Suborder Iniomi, the Lantern-fishes.—Aulopidæ.—The Lizard-fishes.—Ipnopidæ.—Rondeletiidæ.—Myctophidæ.—Chirothricidæ.—Maurolicidæ.—The Lancet-fishes.—The Sternoptychidæ.—Order Lyopomi.

120CHAPTER VII.

THE APODES, OR EEL-LIKE FISHES.

The Eels.—Order Symbranchia.—Order Apodes, or True Eels.—Suborder Archencheli.—Suborder Enchelycephali.—Family Anguillidæ.—Reproduction of the Eel.—Food of the Eel.—Larva of the Eel.—Species of Eels.—Pug-nosed Eels.—Conger-eels.—The Snake-eels.—Suborder Colocephali, or Morays.—Family Moringuidæ.—Order Carencheli, the Long-necked Eels.—Order Lyomeri or Gulpers.—Order Heteromi.

139CHAPTER VIII.

SERIES OSTARIOPHYSI.

Ostariophysi.—The Heterognathi.—The Eventognathi.—The Cyprinidæ.—Species of Dace and Shiner.—Chubs of the Pacific Slope.—The Carp and Goldfish.—The Catostomidæ.—Fossil Cyprinidæ.—The Loaches.

159CHAPTER IX.

THE NEMATOGNATHI, OR CATFISHES.

The Nematognathi.—Families of Nematognathi.—The Siluridæ.—The Sea Catfish.—The Channel Cats.—Horned Pout.—The Mad-toms.—The Old World Catfishes.—The Sisoridæ.—The Plotosidæ.—The Chlariidæ.—The Hypophthalmidæ or Pygidiidæ.—The Loricariidæ.—The Callichthyidæ.—Fossil Catfishes.—Order Gymnonoti.

177CHAPTER X.

THE SCYPHOPHORI, HAPLOMI, AND XENOMI.

Order Scyphophori.—The Mormyridæ.—The Haplomi.—The Pikes.—The Mud minnows.—The Killifishes.—Amblyopsidæ.—Kneriidæ, etc.—The Galaxiidæ.—Order Xenomi.

188CHAPTER XI.

ACANTHOPTERYGII; SYNENTOGNATHI.

Order Acanthopterygii, the Spiny-rayed Fishes.—Suborder Synentognathi.—The Garfishes: Belonidæ.—The Flying-fishes: Exocœtidæ.

208CHAPTER XII.

PERCESOCES AND RHEGNOPTERI.

Suborder Percesoces.—The Silversides: Atherinidæ.—The Mullets: Mugilidæ.—The Barracudas: Sphyrænidæ.—Stephanoberycidæ.—Crossognathidæ.—Cobitopsidæ.—Suborder Rhegnopteri.

215CHAPTER XIII.

PHTHINOBRANCHII: HEMIBRANCHII, LOPHOBRANCHII, AND

HYPOSTOMIDES.

Suborder Hemibranchii.—The Sticklebacks: Gasterosteidæ.—The Aulorhynchidæ.—Cornet-fishes: Fistulariidæ.—The Trumpet-fishes: Aulostomidæ.—The Snipefishes: Macrorhamphosidæ.—The Shrimp-fishes: Centriscidæ.—The Lophobranchs.—The Solenostomidæ.—The Pipefishes: Syngnathidæ.—The Sea-horses: Hippocampus.—Suborder Hypostomides, the Sea-moths: Pegasidæ.

227CHAPTER XIV.

SALMOPERCÆ AND OTHER TRANSITIONAL GROUPS.

Suborder Salmopercæ, the Trout-perches: Percopsidæ.—Erismatopteridæ.—Suborder Selenichthyes, the Opahs: Lamprididæ.—Suborder Zeoidea.—Amphistiidæ.—The John Dories: Zeidæ.—Grammicolepidæ.

241CHAPTER XV.

BERYCOIDEI.

The Berycoid Fishes.—The Alfonsinos: Berycidæ.—The Soldier-fishes: Holocentridæ.—The Polymixiidæ.—The Pine-cone Fishes: Monocentridæ.

250CHAPTER XVI.

PERCOMORPHI.

Suborder Percomorphi, the Mackerels and Perches.—The Mackerel Tribe: Scombroidea.—The True Mackerels: Scombridæ.—The Escolars: Gempylidæ.—Scabbard and Cutlass-fishes: Lepidopidæ and Trichiuridæ.—The Palæorhynchidæ.—The Sailfishes: Istiophoridæ.—The Swordfishes: Xiphiidæ.

258CHAPTER XVII.

CAVALLAS AND PAMPANOS.

The Pampanos: Carangidæ.—The Papagallos: Nematistiidæ.—The Bluefishes: Cheilodipteridæ.—The Sergeant-fishes: Rachycentridæ.—The Butter-fishes: Stromateidæ.—The Rag-fishes: Icosteidæ.—The Pomfrets: Bramidæ.—The Dolphins: Coryphænidæ.—The Menidæ.—The Pempheridæ.—Luvaridæ.—The Square-tails: Tetragonuridæ.—The Crested Bandfishes: Lophotidæ.

272CHAPTER XVIII.

PERCOIDEA, OR PERCH-LIKE FISHES.

Percoid Fishes.—The Pirate-perches: Aphredoderidæ.—The Pigmy Sunfishes: Elassomidæ.—The Sunfishes: Centrarchidæ.—Crappies and Rock Bass.—The Black Bass.—The Saleles: Kuhliidæ.—The True Perches: Percidæ.—Relations of Darters to Perches.—The Perches.—The Darters: Etheostominæ.

293CHAPTER XIX.

THE BASS AND THEIR RELATIVES.

The Cardinal-fishes: Apogonidæ.—The Anomalopidæ.—The Asineopidæ—The Robalos: Oxylabracidæ.—The Sea-bass: Serranidæ.—The Jewfishes.—The Groupers.—The Serranos.—The Flashers: Lobotidæ.—The Big eyes: Priacanthidæ.—The Pentacerotidæ.—The Snappers: Lutianidæ.—The Grunts: Hæmulidæ.—The Porgies: Sparidæ.—The Picarels: Mænidæ.—The Mojarras: Gerridæ.—The Rudder-fishes: Kyphosidæ.

316CHAPTER XX.

THE SURMULLETS, THE CROAKERS AND THEIR RELATIVES.

The Surmullets, or Goatfishes: Mullidæ.—The Croakers: Sciænidæ.—The Sillaginidæ, etc.—The Jawfishes: Opisthognathidæ, etc.—The Stone-wall Perch: Oplegnathidæ.—The Swallowers: Chiasmodontidæ.—The Malacanthidæ.—The Blanquillos: Latilidæ.—The Bandfishes: Cepolidæ.—The Cirrhitidæ.—The Sandfishes: Trichodontidæ.

351CHAPTER XXI.

LABYRINTHICI AND HOLCONOTI.

The Labyrinthine Fishes.—The Climbing-perches: Anabantidæ.—The Gouramis: Osphromenidæ.—The Snake-head Mullets: Ophicephalidæ.—Suborder Holconoti, the Surf-fishes.—The Embiotocidæ.

365CHAPTER XXII.

CHROMIDES AND PHARYNGOGNATHI.

Suborder Chromides.—The Cichlidæ.—The Damsel-fishes: Pomacentridæ.—Suborder Pharyngognathi.—The Wrasse Fishes: Labridæ.—The Parrot-fishes: Scaridæ.

380CHAPTER XXIII.

THE SQUAMIPINNES.

The Squamipinnes.—The Scorpididæ.—The Boarfishes: Antigoniidæ.—The Arches: Toxotidæ.—The Ephippidæ.—The Spadefishes: Ilarchidæ.—The Platacidæ.—The Butterfly-fishes: Chætodontidæ.—The Pygæidæ.—The Moorish Idols: Zanclidæ.—The Tangs: Acanthuridæ.—Suborder Amphacanthi, the Siganidæ.

397CHAPTER XXIV.

SERIES PLECTOGNATHI.

The Plectognaths.—The Scleroderms.—The Trigger-fishes: Balistidæ.—The File-fishes: Monacanthidæ.—The Spinacanthidæ.—The Trunkfishes: Ostraciidæ.—The Gymnodontes.—The Triodontidæ.—The Globefishes: Tetraodontidæ.—The Porcupine-fishes: Diodontidæ.—The Head-fishes: Molidæ.

411CHAPTER XXV.

PAREIOPLITÆ, OR MAILED-CHEEK FISHES.

The Mailed-cheek Fishes.—The Scorpion-fishes: Scorpænidæ.—The Skilfishes: Anoplopomidæ.—The Greenlings: Hexagrammidæ.—The Flatheads or Kochi: Platycephalidæ.—The Sculpins: Cottidæ.—The Sea-poachers: Agonidæ.—The Lump-suckers: Cyclopteridæ.—The Sea-snails: Liparididæ.—The Baikal Cods: Comephoridæ.—Suborder Craniomi: the Gurnards, Triglidæ.—The Peristediidæ.—The Flying Gurnards: Cephalacanthidæ.

426CHAPTER XXVI.

GOBIOIDEI, DISCOCEPHALI, AND TÆNIOSOMI.

Suborder Gobioidei, the Gobies: Gobiidæ.—Suborder Discocephali, the Shark-suckers: Echeneididæ.—Suborder Tæniosomi, the Ribbon-fishes.—The Oarfishes: Regalecidæ.—The Dealfishes: Trachypteridæ.

459CHAPTER XXVII.

SUBORDER HETEROSOMATA.

The Flatfishes.—Optic Nerves of Flounders.—Ancestry of Flounders.—The Flounders: Pleuronectidæ.—The Turbot Tribe: Bothinæ.—The Halibut Tribe: Hippoglossinæ.—The Plaice Tribe: Pleuronectinæ.—The Soles: Soleidæ.—The Broad Soles: Achirinæ.—The European Soles (Soleinæ).—The Tongue-fishes: Cynoglossinæ.

481CHAPTER XXVIII.

SUBORDER JUGULARES.

The Jugular-fishes.—The Weevers: Trachinidæ.—The Nototheniidæ.—The Leptoscopidæ.—The Star-gazers: Uranoscopidæ.—The Dragonets: Callionymidæ.—The Dactyloscopidæ.

499CHAPTER XXIX.

THE BLENNIES: BLENNIIDÆ.

The Northern Blennies: Xiphidiinæ, Stichæiniæ, etc.—The Quillfishes: Ptilichthyidæ.—The Blochiidæ.—The Patæcidæ, etc.—The Gadopsidæ, etc.—The Wolf-fishes: Anarhichadidæ.—The Eel-pouts: Zoarcidæ.—The Cusk-eels: Ophidiidæ.—Sand-lances: Ammodytidæ.—The Pearlfishes: Fierasferidæ.—The Brotulidæ.—Ateleopodidæ.—Suborder Haplodoci.—Suborder Xenopterygii.

507CHAPTER XXX.

OPISTHOMI AND ANACANTHINI.

Order Opisthomi.—Order Anacanthini.—The Codfishes: Gadidæ.—The Hakes: Merluciidæ.—The Grenadiers: Macrouridæ.

532CHAPTER XXXI.

ORDER PEDICULATI: THE ANGLERS.

The Angler-fishes.—The Fishing-frogs: Lophiidæ.—The Sea-devils: Ceratiidæ.—The Frogfishes: Antennariidæ.—The Batfishes: Ogcocephalidæ.

542CHAPTER I

THE GANOIDS

CHAPTER II

THE GANOIDS—Continued

CHAPTER III

ISOSPONDYLI

CHAPTER IV

SALMONIDÆ

CHAPTER V

SALMONIDÆ—(Continued)

CHAPTER VI

THE GRAYLING AND THE SMELT

CHAPTER VII

THE APODES, OR EEL-LIKE FISHES

CHAPTER VIII

SERIES OSTARIOPHYSI

CHAPTER IX

THE NEMATOGNATHI, OR CATFISHES

CHAPTER X

THE SCYPHOPHORI, HAPLOMI, AND XENOMI

CHAPTER XI

ACANTHOPTERYGII; SYNENTOGNATHI

CHAPTER XII

PERCESOCES AND RHEGNOPTERI

CHAPTER XIII

PHTHINOBRANCHII: HEMIBRANCHII, LOPHOBRANCHII,

AND HYPOSTOMIDES

CHAPTER XIV

SALMOPERCÆ AND OTHER TRANSITIONAL

GROUPS

CHAPTER XV

BERYCOIDEI

CHAPTER XVI

PERCOMORPHI

CHAPTER XVII

CAVALLAS AND PAMPANOS

CHAPTER XVIII

PERCOIDEA, OR PERCH-LIKE FISHES

CHAPTER XIX

THE BASS AND THEIR RELATIVES

CHAPTER XX

THE SURMULLETS, THE CROAKERS AND THEIR

RELATIVES

CHAPTER XXI

LABYRINTHICI AND HOLCONOTI

CHAPTER XXII

CHROMIDES AND PHARYNGOGNATHI

CHAPTER XXIII

THE SQUAMIPINNES

CHAPTER XXIV

SERIES PLECTOGNATHI

CHAPTER XXV

PAREIOPLITÆ, OR MAILED-CHEEK FISHES

CHAPTER XXVI

GOBIOIDEI, DISCOCEPHALI, AND TÆNIOSOMI

CHAPTER XXVII

SUBORDER HETEROSOMATA

CHAPTER XXVIII

SUBORDER JUGULARES

CHAPTER XXIX

THE BLENNIES: BLENNIIDÆ

CHAPTER XXX

OPISTHOMI AND ANACANTHINI

CHAPTER XXXI

ORDER PEDICULATI: THE ANGLERS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

VOL. II.

PAGE

Shoulder-girdle of a Flounder,

Paralichthys californicus 2 Palæoniscum frieslebenense 14 Eurynotus crenatus 15 Dorypterus hoffmani 16 Chondrosteus acipenseroides 18 Acipenser sturio, Common Sturgeon

19 Acipenser rubicundus, Lake Sturgeon

20 Scaphirhynchus platyrhynchus, Shovel-nosed Sturgeon

20 Polyodon spathula, Paddle-fish, side-view

21 Polyodon spathula, Paddle-fish, view from below

21 Psephurus gladius 21 Gyrodus hexagonus 22 Mesturus verrucosus 23 Semionotus kapffi 24 Dapedium politum 25 Tetragonolepis semicinctus 26 Isopholis orthostomus 27 Lepisosteus osseus, Long-nosed Garpike

27 Caturus elongatus 28 Notagogus pentlandi 28 Ptycholepis curtus 28 Pholidophorus crenulatus 29 Lepisosteus tristœchus, Alligator-gar

31Lower Jaw of

Amia calva, showing the gular plate

33 Amia calva, Bowfin (female)

35 Megalurus elegantissimus 36 Leptolepis dubius 41 Elops saurus, Ten-pounder

42 Holcolepis lewesiensis 42 Tarpon atlanticus, Tarpon or Grand Écaille

43 Albula vulpes, Lady-fish

44 Chanos chanos, Milkfish

45 Hiodon tergisus, Mooneye

45 Istieus grandis 46 Chirothrix libanicus 46Skeleton of

Portheus molossus 47 Ctenothrissa vexillifera 48 Clupea harengus, Herring

49 Pomolobus pseudoharengus, Alewife

50 Brevoortia tyrannus, Menhaden

51 Diplomystus humilis 52 Dorosoma cepedianum, Hickory-shad

53 Anchovia perthecata, Silver Anchovy

54 Notogoneus osculus 55 Phareodus testis 57Deposits of Green River Shales, bearing

Phareodus, at Fossil, Wyoming

58A Day's Catch of fossil-fishes, Green River Eocene Shales

59 Alepocephalus agassizii 60 Coregonus williamsoni, Rocky Mountain Whitefish

63 Coregonus clupeiformis, Whitefish

64 Argyrosomus nigripinnis, Bluefin Cisco

66 Stenodus mackenziei, Inconnu

67 Oncorhynchus tschawytscha, Quinnat Salmon (female)

69 Oncorhynchus tschawytscha, King-salmon (grilse)

70 Oncorhynchus nerka, Male Red Salmon

70 Oncorhynchus gorbuscha, Humpback Salmon (female)

72 Oncorhynchus masou, Masu

72 Oncorhynchus nerka, Red Salmon (mutilated dwarf male after spawning)

76 Oncorhynchus tschawytscha, Quinnat Salmon (dying after spawning)

77 Oncorhynchus tschawytscha, Quinnat Salmon

79 Salmo irideus shasta, Rainbow Trout (male)

98 Salmo irideus shasta, Rainbow Trout (female)

99 Salmo rivularis, Steelhead Trout

101Head of Adult Trout-worm,

Dibothrium cordiceps. From intestine of white pelican

103Median segments of

Dibothrium cordiceps 103 Salmo henshawi, Tahoe Trout

104 Salmo stomias, Green-back Trout

105 Salmo macdonaldi, Yellow-fin Trout of Twin Lakes

105 Salmo clarkii spilurus, Rio Grande Trout

106 Salmo clarkii pleuriticus, Colorado River Trout

106 Hucho blackistoni, Ito

107 Salvelinus oquassa, Rangeley Trout

108 Salvelinus aureolus, Sunapee Trout

109 Salvelinus fontinalis, Speckled Trout (male)

110 Salvelinus fontinalis, Speckled Trout

111 Salvelinus malma, Malma Trout

113 Salvelinus malma, Dolly Varden Trout

114 Cristivomer namaycush, Great Lake Trout

114 Plecoglossus altivelis, Ayu, or Japanese Samlet

116 Thymallus signifer, Alaska Grayling

120 Thymallus tricolor, Michigan Grayling

122 Osmerus mordax, Smelt

123 Thaleichthys pretiosus, Eulachon or Ulchen

124Page of William Clark's Handwriting with Sketch of the Eulachon (

Thaleichthys pacificus)

125 Mallotus villosus, Capelin

126 Salanx hyalocranius, Icefish

128 Stomias ferox 128 Chauliodus sloanei 129 Synodus fætens, Lizard-fish

130 Ipnops murrayi 131 Cetomimus gillii 132 Diaphus lucidus, Headlight-fish

132 Myctophum opalinum, Lantern-fish

133 Ceratoscopelus madeirensis, Lantern-fish

133 Rhinellus furcatus 134 Plagyodus ferox, Lancet-fish

135 Eurypholis sulcidens 136 Eurypholis freyeri 137 Argyropelecus olfersi 137 Aldrovandia gracilis 138 Anguilla chrisypa, Common Eel

143 Anguilla chrisypa, Larva of Common Eel

148 Simenchelys parasiticus, Pug-nosed Eel

149 Synaphobranchus pinnatus 149 Leptocephalus conger, Conger-eel

150Larva of Conger-eel,

Leptocephalus conger 150 Xyrias revulsus 151 Myrichthys pantostigmius 151 Ophichthus ocellatus 151 Nemichthys avocetta, Thread-eel

152Jaws of

Nemichthys avocetta 152 Muræna retifera 153 Gymnothorax berndti 154 Gymnothorax jordani 155 Gymnothorax moringa, Moray

155 Derichthys serpentinus 156 Gastrostomus bairdi, Gulper-eel

156 Notacanthus phasganorus 158Inner view of shoulder-girdle of Buffalo-fish (

Ictiobus bubalus), showing the mesocoracoid

160Weberian apparatus and air-bladder of Carp

160 Brycon dentex 162Pharyngeal bones and teeth of European Chub,

Leuciscus cephalus 163 Rhinichthys dulcis, Black-nosed Dace

164 Notropis hudsonius, White Chub

165 Ericymba buccata, Silver-jaw Minnow

165 Notropis whipplei, Silverfin

166 Campostoma anomalum, Stone-roller

167Head of Day-chub,

Exoglossum maxillingua 167 Semotilus atromaculatus, Horned Dace

168 Abramis chrysoleucus, Shiner

168 Ptychocheilus grandis, Squawfish

169 Leuciscus lineatus, Chub of the Great Basin

169Lower Pharyngeal of

Placopharynx duquesnii 171 Erimyzon sucetta, Creekfish or Chub-sucker

172 Ictiobus cyprinella, Buffalo-fish

173 Carpiodes cyprinus, Carp-sucker

173 Catostomus commersoni, Common Sucker

174 Catostomus occidentalis, California Sucker

174Pharyngeal teeth of Oregon Sucker,

Catostomus macrocheilus 175 Xyrauchen cypho, Razor-back Sucker

175 Felichthys felis, Gaff-topsail Cat

179 Galeichthys milberti, Sea Catfish

179 Ictalurus punctatus, Channel Catfish

180 Ameiurus nebulosus, Horned Pout

181 Schilbeodes furiosus, Mad-tom. Showing the poisoned pectoral spine

182 Torpedo electricus, Electric Catfish

183 Chlarias breviceps, African Catfish

185 Loricaria aurea, Mailed Catfish from Venezuela

186 Gnathonemus curvirostris 189 Esox lucius, Pike

191 Esox masquinongy, Muskallunge

192 Umbra pygmæa, Mud-minnow

193 Anableps dovii, Four-eyed Fish

195 Cyprinodon variegatus, Round Minnow

196 Jordanella floridæ, Everglade Minnow

197 Fundulis majalis, Mayfish (male)

198 Fundulis majalis, Mayfish (female)

198 Zygonectes notatus, Top-minnow

198 Empetrichthys merriami, Death Valley Fish

199 Xiphophorus helleri, Sword-tail Minnow (male)

199 Goodea luitpoldi, a Viviparous Fish

200 Chologaster cornutus, Dismal Swamp Fish

201 Typhlichthys subterraneus, Blind Cave-fish

202 Amblyopsis spelæus, Blindfish of the Mammoth Cave

203 Dallia pectoralis, Alaska Blackfish

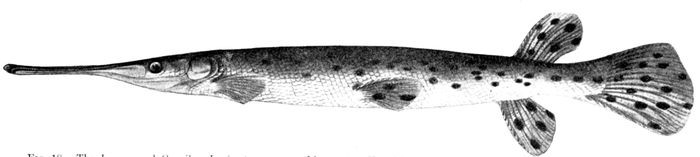

206 Tylosurus acus, Needle-fish

210 Scombresox saurus, Saury

212 Hyporhamphus unifasciatus, Halfbeak

212 Fodiator acutus, Sharp-nosed Flying-fish

213 Cypselurus californicus, Catalina Flying-fish

214 Chirostoma humboldtianum, Pescado blanco

217 Kirtlandia vagrans, Silverside or Brit

217 Atherinopsis californiensis, Blue Smelt or Pez del Rey

218 Iso flos-maris, Flower of the Waves

218 Mugil cephalus, Striped Mullet

221 Joturus pichardi, Joturo or Bobo

222 Sphyræna barracuda, Barracuda

223 Cobitopsis acuta 224Shoulder-girdle of a Threadfin,

Polydactylus approximans 225 Polydactylus octonemus, Threadfin

225Shoulder-girdle of a Stickleback,

Gasterosteus aculeatus 227Shoulder-girdle of

Fistularia petimba, showing greatly extended interclavicle, the surface ossified

227 Gasterosteus aculeatus, Three-spined Stickleback

232 Apeltes quadracus, Four-spined Stickleback

232 Aulostomus chinensis, Trumpet-fish

234 Macrorhamphosus sagifue, Japanese Snipefish

234 Æoliscus strigatus, Shrimp-fish

235 Æoliscus heinrichi 235 Solenostomus cyanopterus 237 Hippocampus hudsonius, Sea-horse

238 Zalises umitengu, Sea-moth

240 Percopsis guttatus, Sand-roller

241 Erismatopterus endlicheri 242 Columbia transmontana, Oregon Trout-perch

242Shoulder-girdle of the Opah,

Lampris guttatus(

Brünnich), showing the enlarged infraclavicle

243Ligatures

Semiophorus velifer 246 Amphistium paradoxum 247 Zeus faber, John Dory

248Skull of a Berycoidfish,

Beryx splendens, showing the orbitosphenoid

250 Beryx splendens 251 Hoplopteryx lewesiensis 252 Paratrachichthys prosthemius 253 Holocentrus ascenscionis, Soldier-fish

254 Holocentrus ittodai 254 Ostichthys japonicus 255 Monocentris japonicus, Pine-cone Fish

256 Scomber scombrus, Mackerel

260 Germo alalunga, Long-fin Albacore

263 Scomberomorus maculatus, Spanish Mackerel

264 Trichiurus lepturus, Cutlass-fish

268 Palæorhynchus glarisianus 268 Xiphias gladius, Young Swordfish

269 Xiphias gladius, Swordfish

270 Naucrates ductor, Pilot-fish

273 Seriola lalandi, Amber-fish

273 Trachurus trachurus, Saurel

274 Carangus chrysos, Yellow Mackerel

275 Trachinotus carolinus, the Pampano

277 Cheilodipterus saltatrix, Bluefish

279 Rachycentron canadum, Sergeant-fish

282 Peprilus paru, Harvest-fish

284 Gobiomorus gronovii, Portuguese Man-of-War Fish

285 Coryphæna hippurus, Dolphin or Dorado

287 Mene maculata 288 Gasteronemus rhombeus 289 Pempheris mulleri, Catalufa de lo Alto

289 Pempheris nyctereutes 290 Luvarus imperialis, Louvar

290 Aphredoderus sayanus, Pirate Perch

295 Elassoma evergladei, Everglade Pigmy Perch

295Skull of the Rock Bass,

Ambloplites rupestris 296 Pomoxis annularis, Crappie

297 Pomoxis annularis, Crappie (from life)

298 Ambloplites rupestris, Rock Bass

299 Mesogonistius chætodon, Banded Sunfish

299 Lepomis pallidus, Blue-gill

300 Lepomis megalotis, Long-eared Sunfish

300 Eupomotis gibbosus, Common Sunfish

301 Micropterus dolomieu, Small Mouth Black Bass

303 Micropterus salmoides, Large Mouth Black Bass

305 Perca flavescens, Yellow perch

308 Stizostedion canadense, Sauger

309 Aspro asper, Aspron

309 Zingel zingel, Zingel

310 Percina caprodes, Log-perch

311 Hadropterus aspro, Black-sided Darter

311 Diplesion blennioides, Green-sided Darter

312 Boleosoma olmstedi, Tessellated Darter

312 Crystallaria asprella, Crystal Darter

313 Ammocrypta clara, Sand-darter

313 Etheostoma jordani 314 Etheostoma camurum, Blue-breasted Darter

314 Apogon retrosella, Cardinal-fish

316 Telescopias gilberti, Kuromutsu

318 Apogon semilineatus 319 Oxylabrax undecimalis, Robalo

319 Morone americana, White Perch

322 Promicrops itaiara, Florida Jewfish

323 Epinephelus striatus, Nassau Grouper:

Cherna criolla 324 Epinephelus drummond-hayi, John Paw or Speckled Hind

325 Epinephelus morio, Red Grouper

325 Epinephelus adscensionis, Red Hind

326 Mycteroperca venenosa, Yellow-fin Grouper

327 Hypoplectrus unicolor nigricans 328 Epinephelus niveatus, Snowy Grouper

329 Rypticus bistrispinus, Soapfish

330 Lobotes surinamensis, Flasher

331 Priacanthus arenatus, Catalufa

331 Pseudopriacanthus altus, Bigeye

332 Lutianus griseus, Gray Snapper

334 Lutianus apodus, Schoolmaster

335 Hoplopagrus guntheri 336 Lutianus synagris, Lane Snapper or Biajaiba

336 Ocyurus chrysurus, Yellow-tail Snapper

337 Etelis oculatus, Cachucho

337 Xenocys jessiæ 338 Aphareus furcatus 339 Hæmulon plumieri, Grunt

340 Anisotremus virginicus, Porkfish

341 Pagrus major, Red Tai of Japan

342 Ebisu, the Fish-god of Japan, bearing a Red Tai

343 Stenotomus chrysops, Scup

344 Calamus bajonado, Jolt-head Porgy

345 Calamus proridens, Little-head Porgy

345 Diplodus holbrooki 346 Archosargus unimaculatus, Salema, Striped Sheepshead

347 Xystæma cinereum, Mojarra

348 Gerres olisthostomus, Irish Pampano

349 Kyphosus sectatrix, Chopa or Rudder-fish

349 Apomotis cyanellus, Blue-green Sunfish

350 Pseudupeneus maculatus, Red Goatfish or Salmonete

351 Mullus auratus, Golden Surmullet

352 Cynoscion nebulosus, Spotted Weakfish

353 Bairdiella chrysura, Mademoiselle

355 Sciænops ocellata, Red Drum

356 Umbrina sinaloæ, Yellow-fin Roncador

357 Menticirrhus americanus, Kingfish

357 Pogonias chromis, Drum

358 Gnathypops evermanni 359 Opisthognathus macrognathus, Jawfish

359 Opisthognathus nigromarginatus 360 Chiasmodon niger, Black Swallower

360 Cirrhitus rivulatus 364 Trichodon trichodon, Sandfish

364 Anabas scandens, Climbing Perch

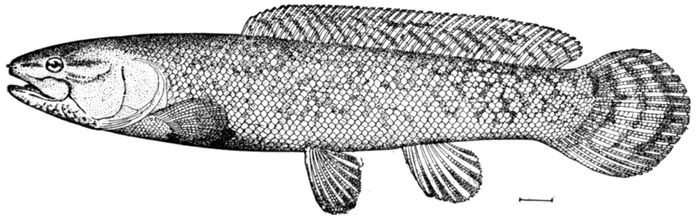

366 Channa formosana 371 Ophicephalus barca, Snake-headed China-fish

371 Cymatogaster aggregatus, White Surf-fish

372 Hysterocarpus traski, Fresh-water Viviparous Perch

373 Hypsurus caryi 373 Damalichthys argyrosomus, White Surf-fish

374 Rhacochilus toxotes, Thick-lipped Surf-fish

374 Hypocritichthys analis, Silver Surf-fish, Viviparous

375 Hysterocarpus traski, Viviparous Perch (male)

379 Hypsypops rubicunda, Garibaldi

382 Pomacentrus leucostictus, Damsel-fish

382 Glyphisodon marginatus, Cockeye Pilot

383 Microspathodon dorsalis, Indigo Damsel-fish

384 Tautoga onitis, Tautog

384 Tautoga onitis, Tautog

386 Lachnolaimus falcatus, Capitaine or Hogfish

387 Xyrichthys psittacus, Razor-fish

388 Pimelometopon pulcher, Redfish (male)

389 Lepidaplois perditio 389Pharyngeals of Italian Parrot-fish,

Sparisoma cretense.

a, Upper;

b, Lower

391Jaws of Parrot-fish,

Calotomus xenodon 391 Cryptotomus beryllinus 391 Sparisoma hoplomystax 392 Sparisoma abildgaardi, Red Parrot-fish

392Jaws of Blue Parrot-fish,

Scarus cæruleus 393Upper pharyngeals of a Parrot-fish,

Scarus strongylocephalus 393Lower pharyngeals of a Parrot-fish,

Scarus strongylocephalus 393 Scarus emblematicus 394 Scarus cæruleus, Blue Parrot-fish

394 Scarus vetula, Parrot-fish

395 Halichæres bivittatus, Slippery Dick or Doncella, a fish of the coral-reefs

399 Monodactylus argenteus 397 Psettus sebæ 399 Chætodipterus faber, Spadefish

401 Chætodon capistratus, Butterfly-fish

402 Pomacanthus arcuatus, Black Angel-fish

403 Holacanthus ciliaris, Angel-fish or Isabelita

404 Holacanthus tricolor, Rock Beauty

405 Zanclus canescens, Moorish Idol

406 Teuthis cæruleus, Blue Tang

407 Teuthis bahianus, Brown Tang

408 Balistes carolinensis, Trigger-fish

412 Osbeckia lævis, File-fish

414Subclass Actinopteri.—In our glance over the taxonomy of the earlier Chordates, or fish-like vertebrates, we have detached from the main stem one after another a long series of archaic or primitive types. We have first set off those with rudimentary notochord, then those with retrogressive development who lose the notochord, then those without skull or brain, then those without limbs or lower jaw. The residue assume the fish-like form of body, but still show great differences among themselves. We have then detached those without membrane-bones, or trace of lung or air-bladder. We next part company with those having the air-bladder a veritable lung, and those with an ancient type of paired fins, a jointed axis fringed with rays, and those having the palate still forming the upper jaw. We have finally left only those having fish-jaws, fish-fins, and in general the structure of the modern fish. For all these in all their variety, as a class or subclass, the name Actinopteri, or Actinopterygii, suggested by Professor Cope, is now generally adopted. The shorter form, Actinopteri, being equally correct is certainly preferable. This term (ακτίς, ray; πτερόν or πτερύξ, fin) refers to the structure of the paired fins. In all these fishes the bones supporting the fin-rays are highly specialized and at the same time concealed by the general integument of the body. In general two bones connect the pectoral fin with the shoulder-girdle. The hypercoracoid is a flat square bone, usually perforated by a foramen. Lying below it and parallel with it is the irregularly formed hypocoracoid. Attached to them is a row of bones, the actinosts, or pterygials, short, often hour-glass-shaped, which actually support the fin-rays. In the more specialized forms, or Teleosts, the actinosts are few (four to six) in number, but in the more primitive types, or Ganoids, they may remain numerous, a reminiscence of the condition seen in the Crossopterygians, and especially in Polypterus. Other variations may occur; the two coracoids sometimes are imperfect or specially modified, the upper sometimes without a foramen, and the actinosts may be distorted in form or position.

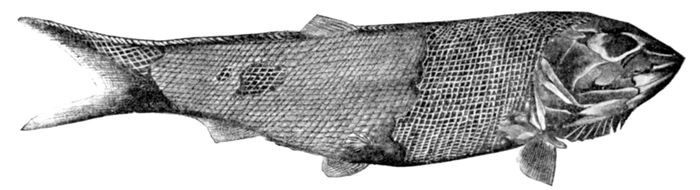

The Palæoniscidæ.—The numerous genera of this order are referred to three families, the Palæoniscidæ, Platysomidæ, and Dictyopygidæ; a fourth family, Dorypteridæ, of uncertain relations, being also tentatively recognized. The family of Palæoniscidæ is the most primitive, ranging from the Devonian to the Lias, and some of them seem to have entered fresh waters in the time of the coal-measures. These fishes have the body elongate and provided with one short dorsal fin. The tail is heterocercal and the body covered with rhombic plates. Fulcra or rudimentary spine-like scales are developed on the upper edge of the caudal fin in most recent Ganoids, and often the back has a median row of undeveloped scales. A multitude of species and genera are recorded. A typical form is the genus Palæoniscum,[5] with many species represented in the rocks of various parts of the world. The longest known species is Palæoniscum frieslebenense from the Permian of Germany and England. Palæoniscum magnum, sixteen inches long, occurs in the Permian of Germany. From Canobius, the most primitive genus, to Coccolepis, the most modern, is a continuous series, the suspensorium of the lower jaw becoming more oblique, the basal bones of the dorsal fewer, the dorsal extending farther forward, and the scales more completely imbricate. Other prominent genera are Amblypterus, Eurylepis, Cheirolepis, Rhadinichthys, Pygopterus, Elonichthys, Ærolepis, Gyrolepis, Myriolepis, Oxygnathus, Centrolepis, and Holurus.

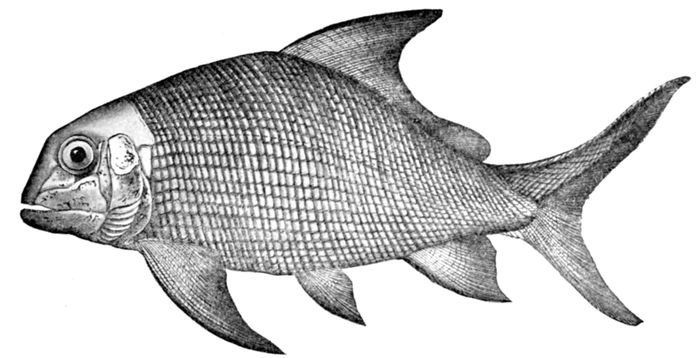

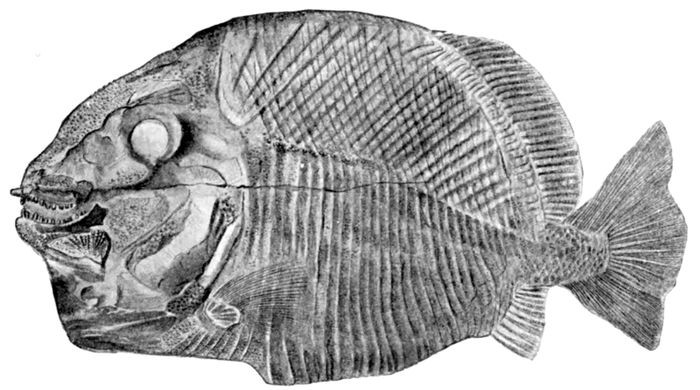

The Platysomidæ.—The Platysomidæ are different in form, the body being deep and compressed, often diamond-shaped, with very long dorsal and anal fins. In other respects they are very similar to the Palæoniscidæ, the osteology being the same. The Palæoniscidæ were rapacious fishes with sharp teeth, the Platysomidæ less active, and, from the blunter teeth, probably feeding on small animals, as crabs and snails.

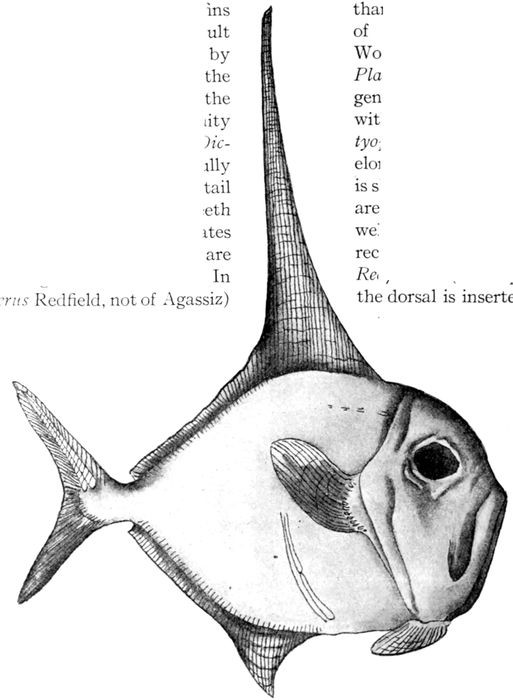

The Dorypteridæ.—Dorypterus hoffmani, the type of the singular Palæozoic family of Dorypteridæ, with thoracic or sub-jugular many-rayed ventrals, is Stromateus-like to all appearance, with distinct resemblances to certain Scombroid forms, but with a heterocercal tail like a ganoid, imperfectly ossified back-bone, and other very archaic characters. The body is apparently scaleless, unlike the true Platysomidæ, in which the scales are highly developed. A second species, Dorypterus althausi, also from the German copper shales, has been described. This species has lower fins than Dorypterus hoffmani, but may be the adult of the same type. Dorypterus is regarded by Woodward as a specialized offshoot from the Platysomidæ. The many-rayed ventrals and the general form of the body and fins suggest affinity with the Lampridæ.

The family of Chondrosteidæ includes the Triassic precursors of the sturgeons. The general form is that of the sturgeon, but the body is scaleless except on the upper caudal lobe, and there are no plates on the median line of the skull. The opercle and subopercle are present, the jaws are toothless, and there are a few well-developed caudal rays. The caudal has large fulcra. The single well-known species of this group, Chondrosteus acipenseroides, is found in the Triassic rocks of England and reaches a length of about three feet. It much resembles a modern sturgeon, though differing in several technical respects. Chondrosteus pachyurus is based on the tail of a species of much larger size and Gyrosteus mirabilis, also of the English Triassic, is known from fragments of fishes which must have been 18 to 20 feet in length.

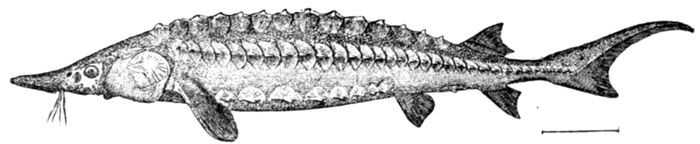

The sturgeons constitute the recent family of Acipenseridæ, characterized by the prolonged snout and toothless jaws and the presence of four barbels below the snout. In the Acipenseridæ there are no branchiostegals and a median series of plates is present on the head. The body is armed with five rows of large bony bucklers,—each often with a hooked spine, sharpest in the young. Besides these, rhombic plates are developed on the tail, besides large fulcra. The sturgeons are the youngest of the Ganoids, not occurring before the Lower Eocene, one species, Acipenser toliapicus occurring in the London clay. About thirty living species of sturgeon are known, referred to three genera: Acipenser, found throughout the Northern Hemisphere, Scaphirhynchus, in the Mississippi Valley, and Kessleria (later called Pseudoscaphirhynchus), in Central Asia alone. Most of the species belong to the genus Acipenser, which abounds in all the rivers and seas in which salmon are found. Some of the smaller species spend their lives in the rivers, ascending smaller streams to spawn. Other sturgeons are marine, ascending fresh waters only for a moderate distance in the spawning season. They range in length from 2½ to 30 feet.

The sturgeons are sluggish, clumsy, bottom-feeding fish. The mouth, underneath the long snout, is very protractile, sucker-like, and without teeth. Before it on the under side of the snout are four long feelers. Ordinarily the sturgeon feeds on mud and snails with other small creatures, but I have seen large numbers of Eulachon (Thaleichthys) in the stomach of the Columbia River sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus). This fish and the Eulachon run in the Columbia at the same time, and the sucker-mouth of a large sturgeon will draw into it numbers of small fishes who may be unsuspiciously engaged in depositing their spawn. In the spawning season in June these clumsy fishes will often leap wholly out of the water in their play. The sturgeons have a rough skin besides five series of bony plates which change much with age and which in very old examples are sometimes lost or absorbed in the skin. The common sturgeon of the Atlantic on both shores is Acipenser sturio. Acipenser huso and numerous other species are found in Russia and Siberia. The great sturgeon of the Columbia is Acipenser transmontanus, and the great sturgeon of Japan Acipenser kikuchii. Smaller species are found farther south, as in the Mediterranean and along the Carolina coast. Other small species abound in rivers and lakes. Acipenser rubicundus is found throughout the Great Lake region and the Mississippi Valley, never entering the sea. It is four to six feet long, and at Sandusky, Ohio, in one season 14,000 sturgeons were taken in the pound nets. A similar species, Acipenser mikadoi, is abundant and valuable in the streams of northern Japan.

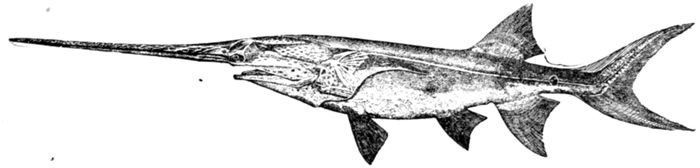

Order Selachostomi: the Paddle-fishes.—Another type of Ganoids, allied to the sturgeons, perhaps still further degenerate, is that of the paddle-fishes, called by Cope Selachostomi (σέλαχος, shark; στόμα, mouth). This group consists of a single family, Polyodontidæ, having apparently little in common with the other Ganoids, and in appearance still more suggestive of the sharks. The common name of paddle-fishes is derived from the long flat blade in which the snout terminates. This extends far beyond the mouth, is more or less sensitive, and is used to stir up the mud in which are found the minute organisms on which the fish feeds. Under the paddle are four very minute barbels corresponding to those of the sturgeons. The vernacular names of spoonbill, duckbill cat, and shovel-fish are also derived from the form of the snout. The skin is nearly smooth, the tail is heterocercal, the teeth are very small, and a long fleshy flap covers the gill-opening. The very long and slender gill-rakers serve to strain the food (worms, leeches, water-beetles, crustaceans, and algæ) from the muddy waters from which they are taken. The most important part of this diet consists of Entomostracans. The single American species, Polyodon spathula, abounds through the Mississippi Valley in all the larger streams. It reaches a length of three or four feet. It is often taken in the nets, but the coarse tough flesh, like that of our inferior catfish, is not much esteemed. In the great rivers of China, the Yangtse and the Hoang Ho, is a second species, Psephurus gladius, with narrower snout, fewer gill-rakers, and much coarser fulcra on the tail. The habits, so far as known, are much the same.

Crossopholis magnicaudatus of the Green River Eocene shales is a primitive member of the Polyodontidæ. Its rostral blade is shorter than that of Polyodon, and the body is covered with small thin scales, each in the form of a small grooved disk with several posterior denticulations, arranged in oblique series but not in contact. The scales are quadrate in form, and more widely separated anteriorly than posteriorly. As in Polyodon, the teeth are minute and there are no branchiostegals. The squamation of this fish shows that Polyodon as well as Acipenser may have sprung from a type having rhombic scales. The tail of a Cretaceous fish, Pholidurus disjectus from the Cretaceous of Europe, has been referred with doubt to this family of Polyodontidæ.

Woodward places these fishes with the Semionotidæ and Halecomorphi in his suborder of Protospondyli. It seems preferable, however, to consider them as forming a distinct order.

For the group here called Lepidostei numerous other names have been used corresponding wholly or in part. Rhomboganoidea of Gill covers nearly the same groups; Holostei of Müller and Hyoganoidea of Gill include the Halecomorphi also; Ginglymodi of Cope includes the garpikes only, while Ætheospondyli of Woodward includes the Aspidorhynchidæ and the garpikes.

Fig. 15.—Dapedium politum Leach, restored. Family Semionotidæ. (After Woodward.)

The Isopholidæ (Eugnathidæ) differ from the families last named in the large pike-like mouth with strong teeth. The mandibular suspensorium is inclined backwards. The body is elongate, the vertebræ forming incomplete rings; the dorsal fin is short with large fulcra.

Fig. 17.—Isopholis orthostomus (Agassiz). Lias. (After Woodward.)

Intermediate between the allies of the gars and the modern herrings is the large extinct family of Pholidophoridæ, referred by Woodward to the Isospondyli, and by Eastman to the Lepidostei. These are small fishes, fusiform in shape, chiefly of the Triassic and Jurassic. The fins are fringed with fulcra, the scales are ganoid and rhombic, and the vertebræ reduced to rings. The mouth is large, with small teeth, and formed as in the Isospondyli. The caudal is scarcely heterocercal.

Of Pholidophorus, with scales joined by peg-and-socket joints and uniform in size, there are many species. Pholidophorus latiusculus and many others are found in the Triassic of England and the Continent. Pholidophorus americanus occurs in the Jurassic of South Dakota. Pleuropholis, with the scales on the lateral line, which runs very low, excessively deepened, is also widely distributed. I have before me a new species from the Cretaceous rocks near Los Angeles. The Archæomænidæ differ from Pholidophoridæ in having cycloid scales. In both families the vertebræ are reduced to rings about the notochord. From fishes allied to the Pholidophoridæ the earliest Isospondyli are probably descended.

The short-nosed garpike, Lepisosteus platystomus, is generally common throughout the Mississippi Valley. It has a short broad snout like the alligator-gar, but seldom exceeds three feet in length. In size, color, and habits it agrees closely with the common gar, differing only in the form of the snout. The form is subject to much variation, and it is possible that two or more species have been confounded.

Another fossil species is Lepisosteus fimbriatus, from the Upper Eocene of England. Scales and other fragments of garpikes are found in Germany, Belgium, and France, in Eocene and Miocene rocks. On some of these the nominal genera Naisia, Trichiurides, and Pneumatosteus are founded. Clastes, regarded by Eastman as fully identical with Lepisosteus, is said to have the "mandibular ramus without or with a reduced fissure of the dental foramen, and without the groove continuous with it in Lepisosteus. One series of large teeth, with small ones external to them on the dentary bone." Most of the fossil forms belong to Clastes, but the genus shows no difference of importance which will distinguish it from the ordinary garpike.

The family of Amiidæ contains a single recent species, Amia calva, the only living member of the order Halecomorphi. The bowfin, or grindle, is a remarkable fish abounding in the lakes and swamps of the Mississippi Valley, the Great Lake region, and southward to Virginia, where it is known by the imposing but unexplained title of John A. Grindle. In the Great Lakes it is usually called "dogfish," because even the dogs will not eat it, and "lawyer," because, according to Dr. Kirtland, "it will bite at anything and is good for nothing when caught."

Woodward unites the extinct genera called Cyclurus, Notæus, Amiopsis, Protamia, Hypamia, and Pappichthys with Amia. Pappichthys (corsoni, etc.), from the Wyoming Eocene, is doubtless a valid genus, having but one row of teeth in each jaw, and Amiopsis is also recognized by Hay. Woodward refers to Amia the following extinct species: Amia valenciennesi, from the Miocene of France; Amia macrocephala, from the Miocene of Bohemia; and Amia ignota, from the Eocene of Paris. Other species of Amia are known from fragments. Several of these are from the Eocene of Wyoming and Colorado. Some of them have a much shorter dorsal fin than that of Amia calva and may be generically different.

Relationships of Isospondyli.—For our purposes we may divide the physostomous fishes as understood by Müller into several orders, the most primitive, the most generalized, and economically the most important being the order of Isospondyli. This order contains those bony fishes which have the anterior vertebræ unaltered (as distinguished from the Ostariophysi), the skull relatively complete, or at least not eel-like, the mesocoracoid typically developed, but atrophied in deep-sea forms and finally lost, the orbitosphenoid present. In all the species the ventral fins are abdominal and normally composed of more than six rays; the air-duct is developed. The scales are chiefly cycloid and the fins are without true spines. In many ways the order is more primitive than Nematognathi, Plectospondyli, or Apodes. It is certain that it began earlier in geological time than any of these. On the other hand, the Isospondyli are closely connected through the Berycoidei with the highly specialized fishes. The continuity of the natural series is therefore interrupted by the interposition of the side branches of Ostariophysans and eels before considering the Haplomi and the other transitional forms. The forms called Iniomi, which lack the mesocoracoid and the orbitosphenoid, have been lately transferred to the Haplomi by Boulenger. This arrangement is probably a step in advance.

The Leptolepidæ.—Most primitive of the Isospondyli is the extinct family of Leptolepidæ, closely allied to the Ganoid families of Pholidophoridæ and Oligopleuridæ. It is composed of graceful, herring-like fishes, with the bones of the head thin but covered with enamel, and the scales thin but firm and enameled on their free portion. There are no fulcra and there is no lateral line. The vertebræ are well developed, but always pierced by the notochord. The genera are Lycoptera, Leptolepis, Æthalion, and Thrissops. In Lycoptera of the Jurassic of China the vertebral centra are feebly developed, and the dorsal fin short and posterior. In Leptolepis the anal is short and placed behind the dorsal. There are many species, mostly from the Triassic and lithographic shales of Europe, one being found in the Cretaceous. Leptolepis coryphænoides and Leptolepis dubius are among the more common species. Æthalion (knorri) differs in the form of the jaws. In Thrissops the anal fin is long and opposite the dorsal. Thrissops salmonea is found in the lithographic stone; Thrissops exigua in the Cretaceous. In all these early forms there is a hard casque over the brain-cavity, as in the living types, Amia and Osteoglossum.

The Elopidæ.—The family of Elopidæ contains large fishes herring-like in form and structure, but having a flat membrane-bone or gular plate between the branches of the lower jaw, as in the Ganoid genus Amia. The living species are few, abounding in the tropical seas, important for their size and numbers, though not valued as food-fishes save to those who, like the Hawaiians and Japanese, eat fishes raw. These people prefer for that purpose the white-meated or soft-fleshed forms like Elops or Scarus to those which yield a better flavor when cooked.

In all these the large parietals meet along the median line of the skull. In the closely related family of Spaniodontidæ the parietals are small and do not meet. All the species of this group, united by Woodward with the Elopidæ, are extinct. These fishes preceded the Elopidæ in the Cretaceous period. Leading genera are Thrissopater and Spaniodon, the latter armed with large teeth. Spaniodon blondeli is from the Cretaceous of Mount Lebanon. Many other species are found in the European and American Cretaceous rocks, but are known from imperfect specimens only.

The Chanidæ.—The Chanidæ, or milkfishes, constitute another small archaic type, found in the tropical Pacific. They are large, brilliantly silvery, toothless fishes, looking like enormous dace, swift in the water, and very abundant in the Gulf of California, Polynesia, and India. The single living species is the Awa, or milkfish, Chanos chanos, largely used as food in Hawaii. Species of Prochanos and Chanos occur in the Cretaceous, Eocene, and Miocene. Allied to Chanos is the Cretaceous genus Ancylostylos (gibbus), probably the type of a distinct family, toothless and with many-rayed dorsal.

The Hiodontidæ.—The Hiodontidæ, or mooneyes, inhabit the rivers of the central portion of the United States and Canada. They are shad-like fishes with brilliantly silvery scales and very strong sharp teeth, those on the tongue especially long. They are very handsome fishes and take the hook with spirit, but the flesh is rather tasteless and full of small bones, much like that of the milkfish. The commonest species is Hiodon tergisus. No fossil Hiodontidæ are known.

Fig. 36.—Gigantic skeleton of Portheus molossus Cope. (Photograph by Charles H. Sternberg.)

The Ctenothrissidæ.—A related family, Ctenothrissidæ, is represented solely by extinct Cretaceous species. In this group the body is robust with large scales, ctenoid in Ctenothrissa, cycloid in Aulolepis. The fins are large, the belly not serrated, and the teeth feeble. Ctenothrissa vexillifera is from Mount Lebanon. Other species occur in the European chalk. In the small family of Phractolæmidæ the interopercle, according to Boulenger, is enormously developed.

The Notopteridæ.—The Notopteridæ is another small family in the rivers of Africa and the East Indies. The body ends in a long and tapering fin, and, as usual in fishes which swim by body undulations, the ventral fins are lost. The belly is doubly serrate. The air-bladder is highly complex in structure, being divided into several compartments and terminating in two horns anteriorly and posteriorly, the anterior horns being in direct communication with the auditory organ. A fossil Notopterus, N. primævus, is found in the same region.

The genus Clupea, of northern distribution, has the vertebræ in increased number (56), and there are weak teeth on the vomer. Several other genera are very closely related, but ranging farther south they have, with other characters, fewer (46 to 50) vertebræ. The alewife, or branch-herring (Pomolobus pseudoharengus), ascends the rivers to spawn and has become landlocked in the lakes of New York. The skipjack of the Gulf of Mexico, Pomolobus chrysochloris, becomes very fat in the sea. The species becomes landlocked in the Ohio River, where it thrives as to numbers, but remains lean and almost useless as food. The glut-herring, Pomolobus æstivalis, and the sprat, Pomolobus sprattus, of Europe are related forms.

The genus Sardinella includes species of rich flesh and feeble skeleton, excellent when broiled, when they may be eaten bones and all. This condition favors their preservation in oil as "sardines." All the species are alike excellent for this purpose. The sardine of Europe is the Sardinella pilchardus, known in England as the pilchard. The "Sardina de España" of Cuba is Sardinella pseudohispanica, the sardine of California, Sardinella cærulea. Sardinella sagax abounds in Chile, and Sardinella melanosticta is the valued sardine of Japan.

Numerous other herring-like forms, usually with compressed bodies, dry and bony flesh, and serrated bellies, abound in the tropics and are largely salted and dried by the Chinese. Among these are Ilisha elongata of the Chinese coast. Related forms occur in Mexico and Brazil.

Fossil herring are plentiful and exist in considerable variety, even among the Clupeidæ as at present restricted. Histiothrissa of the Cretaceous seems to be allied to Dussumieria and Stolephorus. Another genus, from the Cretaceous of Palestine, Pseudoberyx (syriacus, etc.), having pectinated scales, should perhaps constitute a distinct subfamily, but the general structure is like that of the herring. More evidently herring-like is Scombroclupea (macrophthalma). The genus Diplomystus, with enlarged scales along the back, is abundantly represented in the Eocene shales of Green River, Wyoming. Species of similar appearance, usually but wrongly referred to the same genus, occur on the coasts of Peru, Chile, and New South Wales. A specimen of Diplomystus humilis from Green River is here figured. Numerous herring, referred to Clupea, but belonging rather to Pomolobus, or other non-Arctic genera, have been described from the Eocene and later rocks.

The Dorosomatidæ.—The gizzard-shad, Dorosomatidæ, are closely related to the Clupeidæ, differing in the small contracted toothless mouth and reduced maxillary. The species are deep-bodied, shad-like fishes of the rivers and estuaries of eastern America and eastern Asia. They feed on mud, and the stomach is thickened and muscular like that of a fowl. As the stomach has the size and form of a hickory-nut, the common American species is often called hickory-shad. The gizzard-shad are all very poor food-fish, bony and little valued, the flesh full of small bones. The belly is always serrated. In three of the four genera of Dorosomatidæ the last dorsal ray is much produced and whip-like. The long and slender gill-rakers serve as strainers for the mud in which these fishes find their vegetable and animal food. Dorosoma cepedianum, the common hickory-shad or gizzard-shad, is found in brackish river-mouths and ponds from Long Island to Texas, and throughout the Mississippi Valley in all the large rivers. Through the canals it has entered Lake Michigan. The Konoshiro, Clupanodon thrissa, is equally common in China and Japan.

Fig. 44.—Notogoneus osculus Cope. Green River Eocene. Family Gonorhynchidæ.

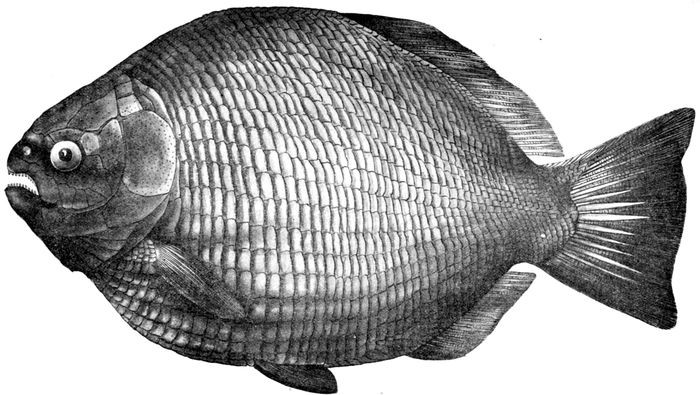

Other species are Phareodus acutus, known from the jaws; P. encaustus is known from a mass of thick scales with reticulate or mosaic-like surface, much as in Osteoglossum, and P. æquipennis from a small example, perhaps immature. Phareodus testis is frequently found well preserved in the shales at Fossil Station, to the northwestward of Green River. Whether all these species possess the peculiar structure of the scales, and whether all belong to one genus, is uncertain.

Fig. 46.—Deposits of Green River Shales, bearing Phareodus, at Fossil, Wyoming. (Photograph by Wilbur C. Knight.)

Fig. 47.—A day's catch of Fossil fishes, Phareodus, Diplomystus, etc. Green River Eocene Shales, Fossil, Wyoming. (Photograph by Prof. Wilbur C. Knight.)

The Pantodontidæ.—The bony casque of Osteoglossum is found again in the Pantodontidæ, consisting of one species, Pantodon buchholzi, a small fish of the brooks of West Africa. As in the Osteoglossidæ and in the Siluridæ, the subopercle is wanting in Pantodon.

Coregonus, the Whitefish.—The genus Coregonus, which includes the various species known in America as lake whitefish, is distinguishable in general by the small size of its mouth, the weakness of its teeth, and the large size of its scales. The teeth, especially, are either reduced to slight asperities, or else are altogether wanting. The species reach a length of one to three feet. With scarcely an exception they inhabit clear lakes, and rarely enter streams except to spawn. In far northern regions they often descend to the sea; but in the latitude of the United States this is never possible for them, as they are unable to endure warm or impure water. They seldom take the hook, and rarely feed on other fishes. Numerous local varieties characterize the lakes of Scandinavia, Scotland, and Arctic Asia and America. Largest and most desirable of all these as a food-fish is the common whitefish of the Great Lakes (Coregonus clupeiformis), with its allies or variants in the Mackenzie and Yukon.

Closely allied to Coregonus williamsoni is the pilot-fish, shad-waiter, roundfish, or Menomonee whitefish (Coregonus quadrilateralis). This species is found in the Great Lakes, the Adirondack region, the lakes of New Hampshire, and thence northwestward to the Yukon, abounding in cold deep waters, its range apparently nowhere coinciding with that of Coregonus williamsoni.

The lake herring, or cisco (Argyrosomus artedi), is, next to the whitefish, the most important of the American species. It is more elongate than the others, and has a comparatively large mouth, with projecting under-jaw. It is correspondingly more voracious, and often takes the hook. During the spawning season of the whitefish the lake herring feeds on the ova of the latter, thereby doing a great amount of mischief. As food this species is fair, but much inferior to the whitefish. Its geographical distribution is essentially the same, but to a greater degree it frequents shoal waters. In the small lakes around Lake Michigan, in Indiana and Wisconsin (Tippecanoe, Geneva, Oconomowoc, etc.), the cisco has long been established; and in these waters its habits have undergone some change, as has also its external appearance. It has been recorded as a distinct species, Argyrosomus sisco, and its excellence as a game-fish has been long appreciated by the angler. These lake ciscoes remain for most of the year in the depths of the lake, coming to the surface only in search of certain insects, and to shallow water only in the spawning season. This periodical disappearance of the cisco has led to much foolish discussion as to the probability of their returning by an underground passage to Lake Michigan during the periods of their absence. One author, confounding "cisco" with "siscowet," has assumed that this underground passage leads to Lake Superior, and that the cisco is identical with the fat lake trout which bears the latter name. The name "lake herring" alludes to the superficial resemblance which this species possesses to the marine herring, a fish of quite a different family.

Closely allied to the lake herring is the bluefin of Lake Michigan and of certain lakes in New York (Argyrosomus nigripinnis), a fine large species inhabiting deep waters, and recognizable by the blue-black color of its lower fins. In the lakes of central New York are found two other species, the so-called lake smelt (Argyrosomus osmeriformis) and the long-jaw (Argyrosomus prognathus). Argyrosomus lucidus is abundant in Great Bear Lake. In Alaska and Siberia are still other species of the cisco type (Argyrosomus laurettæ, A. pusillus, A. alascanus); and in Europe very similar species are the Scotch vendace (Argyrosomus vandesius) and the Scandinavian Lok-Sild (lake herring), as well as others less perfectly known.

There are five species of salmon (Oncorhynchus) in the waters of the North Pacific, all found on both sides, besides one other which is known only from the waters of Japan. These species may be called: (1) the quinnat, or king-salmon, (2) the blue-back salmon, or redfish, (3) the silver salmon, (4) the dog-salmon, (5) the humpback salmon, and (6) the masu; or (1) Oncorhynchus tschawytscha, (2) Oncorhynchus nerka, (3) Oncorhynchus milktschitsch, (4) Oncorhynchus keta, (5) Oncorhynchus gorbuscha, (6) Oncorhynchus masou. All these species save the last are now known to occur in the waters of Kamchatka, as well as in those of Alaska and Oregon. These species, in all their varied conditions, may usually be distinguished by the characters given below. Other differences of form, color, and appearance are absolutely valueless for distinction, unless specimens of the same age, sex, and condition are compared.

Fig. 54.—King-salmon grilse, Oncorhynchus tschawytscha (Walbaum). (Photograph by Cloudsley Rutter.)

The humpback salmon, or pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha), is the smallest of the American species, weighing from 3 to 5 pounds. It has usually 15 anal rays, 12 branchiostegals, 28 (13 + 15) gill-rakers, and about 180 pyloric cœca. Its scales are much smaller than in any other salmon, there being 180 to 240 in the lateral line. In color it is bluish above, silvery below, the posterior and upper parts with many round black spots, the caudal fin always having a few large black spots oblong in form. The males in fall are dirty red, and are more extravagantly distorted than in any other of the Salmonidæ. The flesh is softer than in the other species; it is pale in color, and, while of fair flavor when fresh, is distinctly inferior when canned.

Those fish which enter the rivers in the spring continue their ascent till death or the spawning season overtakes them. Doubtless not one of them ever returns to the ocean, and a large proportion fail to spawn. They are known to ascend the Sacramento to its extreme head-waters, about four hundred miles. In the Columbia they ascend as far as the Bitter Root and Sawtooth mountains of Idaho, and their extreme limit is not known. This is a distance of nearly a thousand miles. In the Yukon a few ascend to Caribou Crossing and Lake Bennett, 2250 miles. At these great distances, when the fish have reached the spawning grounds, besides the usual changes of the breeding season their bodies are covered with bruises, on which patches of white fungus (Saprolegnia) develop. The fins become mutilated, their eyes are often injured or destroyed, parasitic worms gather in their gills, they become extremely emaciated, their flesh becomes white from the loss of oil; and as soon as the spawning act is accomplished, and sometimes before, all of them die. The ascent of the Cascades and the Dalles of the Columbia causes the injury or death of a great many salmon.

Fig. 59.—Young Male Quinnat Salmon, Oncorhynchus tschawytscha, dying after spawning. Sacramento River. (Photograph by Cloudsley Rutter.)

Fig. 60.—Quinnat Salmon, Oncorhynchus tschawytscha (Walbaum). Monterey Bay. (Photograph by C. Rutter.)

Fig. 61.—Rainbow Trout (male), Salmo irideus shasta Jordan. (Photograph by Cloudsley Rutter.)

Of the American species the rainbow trout of California (Salmo irideus) most nearly approaches the European Salmo fario. It has the scales comparatively large, although rather smaller than in Salmo fario, the usual number in a longitudinal series being about 135. The mouth is smaller than in other American trout; the maxillary, except in old males, rarely extending beyond the eye. The caudal fin is well forked, becoming in very old fishes more nearly truncate. The head is relatively large, about four times in the total length. The size of the head forms the best distinctive character. The color, as in all the other species, is bluish, the sides silvery in the males, with a red lateral band, and reddish and dusky blotches. The head, back, and upper fins are sprinkled with round black spots, which are very variable in number, those on the dorsal usually in about nine rows. In specimens taken in the sea this species, like most other trout in similar conditions, is bright silvery, and sometimes immaculate. This species is especially characteristic of the waters of California. It abounds in every clear brook, from the Mexican line northward to Mount Shasta, or beyond, the species passing in the Columbia region by degrees into the species or form known as Salmo masoni, the Oregon rainbow trout, a small rainbow trout common in the forest streams of Oregon, with smaller mouth and fewer spots on the dorsal. No true rainbow trout have been anywhere obtained to the eastward of the Cascade Range or of the Sierra Nevada, except as artificially planted in the Truckee River. The species varies much in size; specimens from northern California often reach a weight of six pounds, while in the streams above Tia Juana in Lower California the southernmost locality from which I have obtained trout, they seldom exceed a length of six inches. Although not usually an anadromous species, the rainbow trout frequently moves about in the rivers, and it often enters the sea, large sea-run specimens being often taken for steelheads. Several attempts have been made to introduce it in Eastern streams, but it appears to seek the sea when it is lost. It is apparently more hardy and less greedy than the American charr, or brook-trout (Salvelinus fontinalis). On the other hand, it is distinctly inferior to the latter in beauty and in gaminess.

The steelhead (Salmo rivularis) is a large trout, reaching twelve to twenty pounds in weight, found abundantly in river estuaries and sometimes in lakes from Lynn Canal to Santa Barbara. The spent fish abound in the rivers in spring at the time of the salmon-run. The species is rarely canned, but is valued for shipment in cold storage. Its bones are much more firm than those of the salmon—a trait unfavorable for canning purposes. The flesh when not spent after spawning is excellent. The steelhead does not die after spawning, as all the Pacific salmon do.

Those species or individuals dwelling in lakes of considerable size, where the water is of such temperature and depth as insures an ample food-supply, will reach a large size, while those in a restricted environment, where both the water and food are limited, will be small directly in proportion to these environing restrictions. The trout of the Klamath Lakes, for example, reach a weight of at least 17 pounds, while in Fish Lake in Idaho mature trout do not exceed 8 to 9¼ inches in total length or one-fourth pound in weight. In small creeks in the Sawtooth Mountains and elsewhere they reach maturity at a length of 5 or 6 inches, and are often spoken of as brook-trout and with the impression that they are a species different from the larger ones found in the lakes and larger streams. But as all sorts and gradations between these extreme forms may be found in the intervening and connecting waters, the differences are not even of sub-specific significance.

Dr. Evermann observes: "The various forms of cutthroat-trout vary greatly in game qualities; even the same subspecies in different waters, in different parts of its habitat, or at different seasons, will vary greatly in this regard. In general, however, it is perhaps a fair statement to say that the cutthroat-trout are regarded by anglers as being inferior in gaminess to the Eastern brook-trout. But while this is true, it must not by any means be inferred that it is without game qualities, for it is really a fish which possesses those qualities in a very high degree. Its vigor and voraciousness are determined largely, of course, by the character of the stream or lake in which it lives. The individuals which dwell in cold streams about cascades and seething rapids will show marvelous strength and will make a fight which is rarely equaled by its Eastern cousin; while in warmer and larger streams and lakes they may be very sluggish and show but little fight. Yet this is by no means always true. In the Klamath Lakes, where the trout grow very large and where they are often very logy, one is occasionally hooked which tries to the utmost the skill of the angler to prevent his tackle from being smashed and at the same time save the fish."

In the head-waters of the Platte and Arkansas rivers is the small green-back trout, green or brown, with red throat-patch and large black spots. This is Salmo clarkii stomias, and it is especially fine in St. Vrain's River and the streams of Estes Park. In Twin Lakes, a pair of glacial lakes tributary of the Arkansas near Leadville, is found Salmo clarkii macdonaldi, the yellow-finned trout, a large and very handsome species living in deep water, and with the fins golden yellow. This approaches the Colorado trout, Salmo clarkii pleuriticus, and it may be derived from the latter, although it occurs in the same waters as the very different green-back trout, or Salmo clarkii stomias.

Fig. 69.—Rio Grande Trout, Salmo clarkii spilurus Cope. Del Norte, Colo.

Hucho, the Huchen.—The genus Hucho has been framed for the Huchen or Rothfisch (Hucho hucho) of the Danube, a very large trout, differing from the genus Salmo in having no teeth on the shaft of the vomer, and from the Salvelini at least in form and coloration. The huchen is a long and slender, somewhat pike-like fish, with depressed snout and strong teeth. The color is silvery, sprinkled with small black dots. It reaches a size little inferior to that of the salmon, and it is said to be an excellent food-fish. In northern Japan is a similar species, Hucho blackistoni, locally known as Ito, a large and handsome trout with very slender body, reaching a length of 2½ feet. It is well worthy of introduction into American and European waters.

In color all the charrs differ from the salmon and trout. The body in all is covered with round spots which are paler than the ground color, and crimson or gray. The lower fins are usually edged with bright colors. The sexual differences are not great. The scales, in general, are smaller than in other Salmonidæ, and they are imbedded in the skin to such a degree as to escape the notice of casual observers and even of most anglers.

The only really well-authenticated species of charr in European waters is the red charr, sälbling, or ombre chevalier (Salvelinus alpinus). This species is found in cold, clear streams in Switzerland, Germany, and throughout Scandinavia and the British Islands. Compared with the American charr or brook-trout, it is a slenderer fish, with smaller mouth, longer fins, and smaller red spots, which are confined to the sides of the body. It is a "gregarious and deep-swimming fish, shy of taking the bait and feeding largely at night-time. It appears to require very pure and mostly deep water for its residence." It is less tenacious of life than the trout. It reaches a weight of from one to five pounds, probably rarely exceeding the latter in size. The various charr described from Siberia are far too little known to be enumerated here.

In Arctic regions another species, called Salvelinus naresi, is very close to Salvelinus oquassa and may be the same.

Fig. 75.—Brook Trout, Salvelinus fontinalis (Mitchill), natural size. (From life by Dr. R. W. Shufeldt.)

The trout are rapidly disappearing from our streams through the agency of the manufacturer and the summer boarder. In the words of an excellent angler, the late Myron W. Reed of Denver: "This is the last generation of trout-fishers. The children will not be able to find any. Already there are well-trodden paths by every stream in Maine, in New York, and in Michigan. I know of but one river in North America by the side of which you will find no paper collar or other evidence of civilization. It is the Nameless River. Not that trout will cease to be. They will be hatched by machinery and raised in ponds, and fattened on chopped liver, and grow flabby and lose their spots. The trout of the restaurant will not cease to be. He is no more like the trout of the wild river than the fat and songless reedbird is like the bobolink. Gross feeding and easy pond-life enervate and deprave him. The trout that the children will know only by legend is the gold-sprinkled, living arrow of the white water; able to zigzag up the cataract; able to loiter in the rapids; whose dainty meat is the glancing butterfly."

The "Dolly Varden" trout, or malma (Salvelinus malma), is very similar to the brook-trout, closely resembling it in size, form, color, and habits. It is found always to the westward of the Rocky Mountains, in the streams of northern California, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia, Alaska, and Kamchatka, as far as the Kurile Islands. It abounds in the sea in the northward, and specimens of ten to twelve pounds weight are not uncommon in Puget Sound and especially in Alaska. The Dolly Varden trout is, in general, slenderer and less compressed than the Eastern brook-trout. The red spots are found on the back of the fish as well as on the sides, and the back and upper fins are without the blackish marblings and blotches seen in Salvelinus fontinalis. In value as food, in beauty, and in gaminess Salvelinus malma is very similar to its Eastern cousin.

The Ayu, or Sweetfish.—The ayu, or sweetfish, of Japan, Plecoglossus altivelis, resembles a small trout in form, habits, and scaling. Its teeth are, however, totally different, being arranged on serrated plates on the sides of the jaws, and the tongue marked with similar folds. The ayu abounds in all clear streams of Japan and Formosa. It runs up from the sea like a salmon. It reaches the length of about a foot. The flesh is very fine and delicate, scarcely surpassed by that of any other fish whatsoever. It should be introduced into clear short streams throughout the temperate zones.

CHAPTER VI

THE GRAYLING AND THE SMELT

The American grayling (Thymallus signifer) is widely distributed in British America and Alaska. In the Yukon it is very abundant, rising readily to the fly. In several streams in northern Michigan, Au Sable River, and Jordan River in the southern peninsula, and Otter Creek near Keweenaw in the northern peninsula, occurs a dwarfish variety or species with shorter and lower dorsal fins, known to anglers as the Michigan grayling (Thymallus tricolor). This form has a longer head, rather smaller scales, and the dorsal fin rather lower than in the northern form (signifer); but the constancy of these characters in specimens from intermediate localities is yet to be proved. Another very similar form, called Thymallus montanus, occurs in the Gallatin, Madison, and other rivers of Western Montana tributary to the Missouri. It is locally still abundant and one of the finest of game-fishes. It is probable that the grayling once had a wider range to the southward than now, and that so far as the waters of the United States are concerned it is tending toward extinction. This tendency is, of course, being accelerated in Michigan by lumbermen and anglers. The colonies of grayling in Michigan and Montana are probably remains of a post-glacial fauna.

Fig. 82.—Smelt, Osmerus mordux (Mitchill). Wood's Hole, Mass.

The best-known genus, Osmerus, includes the smelt, or spirling (éperlan), of Europe, and its relatives, all excellent food-fishes, although quickly spoiling in warm weather. Osmerus eperlanus is the European species; Osmerus mordax of our eastern coast is very much like it, as is also the rainbow-smelt, Osmerus dentex of Japan and Alaska. A larger smelt, Osmerus albatrossis, occurs on the coast of Alaska, and a small and feeble one, Osmerus thaleichthys, mixed with other small or delicate fishes, is the whitebait of the San Francisco restaurants. The whitebait of the London epicure is made up of the young of herrings and sprats of different species. The still more delicate whitebait of the Hong Kong hotels is the icefish, Salanx chinensis. Retropinna retropinna, so called from the backward insertion of its dorsal, is the excellent smelt of the rivers of New Zealand. All the other species belong to northern waters. Mesopus, the surf-smelt, has a smaller mouth than Osmerus and inhabits the North Pacific. The California species, Mesopus pretiosus, of Neah Bay has, according to James G. Swan, "the belly covered with a coating of yellow fat which imparts an oily appearance to the water where the fish has been cleansed or washed and makes them the very perfection of pan-fish." This species spawns in late summer along the surf-line. According to Mr. Swan the water seems to be filled with them. "They come in with the flood-tide, and when a wave breaks upon the beach they crowd up into the very foam, and as the surf recedes many will be seen flapping on the sand and shingle, but invariably returning with the undertow to deeper water." The Quilliute Indians of Washington believe that "the first surf-smelts that appear must not be sold or given away to be taken to another place, nor must they be cut transversely, but split open with a mussel-shell."

Fig. 84.—Page of William Clark's handwriting with sketch of the Eulachon (Thaleichthys pacificus), the first notice of the species. Columbia River, 1805. (Expedition of Lewis & Clark.) (Reproduced from the original in the possession of his granddaughter Mrs. Julia Clark Voorhis, through the courtesy of Messrs. Dodd, Mead & Company, publishers of the "Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.")

The capelin (Mallotus villosus) closely resembles the eulachon, differing mainly in its broader pectorals and in the peculiar scales of the males. In the male fish a band of scales above the lateral line and along each side of the belly become elongate, closely imbricated, with the free points projecting, giving the body a villous appearance. It is very abundant on the coasts of Arctic America, both in the Atlantic and the Pacific, and is an important source of food for the natives of those regions.

The Salangidæ, or Icefishes.—Still more feeble and insignificant are the species of Salangidæ, icefishes, or Chinese whitebait, which may be described as Salmonidæ reduced to the lowest terms. The body is long and slender, perfectly translucent, almost naked, and with the skeleton scarcely ossified. The fins are like those of the salmon, the head is depressed, the jaws long and broad, somewhat like the bill of a duck, and within there are a few disproportionately strong canine teeth, those of the lower jaw somewhat piercing the upper. The alimentary canal is straight for its whole length, without pyloric cæca. These little fishes, two to five inches long, live in the sea in enormous numbers and ascend the rivers of eastern Asia for the purpose of spawning. It is thought by some that they are annual fishes, all dying in the fall after reproduction, the species living through the winter only within its eggs. But this is only suspected, not proved, and the species will repay the careful study which some of the excellent naturalists of Japan are sure before long to give to it. The species of Salanx are known as whitebait, in Japan as Shiro-uwo, which means exactly the same thing. They are also sometimes called icefish (Hingio), which, being used for no other fish, may be adopted as a group name for Salanx.

The Malacosteidæ is a related group with extremely distensible mouth, the species capable of swallowing fishes much larger than themselves.

Suborder Iniomi, the Lantern-fishes.—The suborder Iniomi (ἰνίον, nape; ὤμος, shoulder) comprises soft-rayed fishes, in which the shoulder-girdle has more or less lost its completeness of structure as part of the degradation consequent on life in the abysses of the sea. These features distinguish these forms from the true Isospondyli, but only in a very few of the species have these characters been verified by actual examination of the skeleton. The mesocoracoid arch is wanting or atrophied in all of the species examined, and the orbitosphenoid is lacking, so far as known. The group thus agrees in most technical characters with the Haplomi, in which group they are placed by Dr. Boulenger. On the other hand the relationships to the Isospondyli are very close, and the Iniomi have many traits suggesting degenerate Isospondyli. The post-temporal has lost its usual hold on the skull and may touch the occiput on the sides of the cranium. Nearly all the species are soft in body, black or silvery over black in color, and all that live in the deep sea are provided with luminous spots or glands giving light in the abysmal depths. These spots are wanting in the few shore species, as also in those which approach most nearly to the Salmonidæ, these being presumably the most primitive of the group. In these also the post-temporal touches the back of the cranium near the side. In the majority of the Iniomi the adipose fin of the Salmonidæ is retained. From the phosphorescent spots is derived the general name of lantern-fishes applied of late years to many of the species. Most of these are of recent discovery, results of the remarkable work in deep-sea dredging begun by the Albatross and the Challenger. All of the species are carnivorous, and some, in spite of their feeble muscles, are exceedingly voracious, the mouth being armed with veritable daggers and spears.