автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Woodcraft Girls in the City

THE WOODCRAFT GIRLS IN THE CITY

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: The Woodcraft Girls in the City

Author: Lillian Elizabeth Roy

Release Date: March 17, 2011 [EBook #35600]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WOODCRAFT GIRLS IN THE CITY ***

Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net.

DECORATIONS FOR THE COUNCIL.

The

Woodcraft Girls

in the City

BY

LILLIAN ELIZABETH ROY

AUTHOR OF

THE WOODCRAFT GIRLS AT CAMP,

LITTLE WOODCRAFTER’S BOOK,

THE POLLY BREWSTER BOOKS, Etc.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

COPYRIGHT, 1918,

BY GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

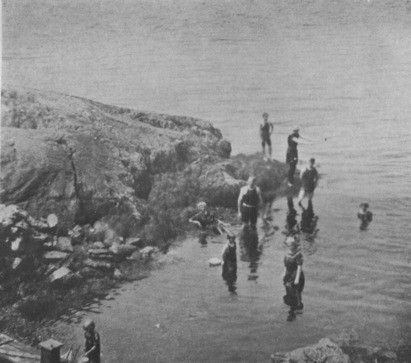

Acknowledgments are made to Mrs. M. F. Hoisington for the photographs; to G. Shirmer, Music Publishers, for “Our America”; to W. V. Becker for the legends from his “Folk-lore Stories”; to Christian Science Sentinel for “Items of Interest,” and to other friends who co-operated to make this book interesting to young readers.

Contents

-

CHAPTER ONE—CAMPING IN THE CITY

-

CHAPTER TWO—THE NEW MEMBERS

-

CHAPTER THREE—HEARD IN THE “SCENIC FOREST”

-

CHAPTER FOUR—THE ESKIMO INDIAN LEGEND

-

CHAPTER FIVE—A PRIZE CHEST

-

CHAPTER SIX—THE LOST CAMPERS

-

CHAPTER SEVEN—CAMPING SPORTS OF A WEEK-END

-

CHAPTER EIGHT—QUIET WAYS FOR SUNDAY

-

CHAPTER NINE—A RAINY WEEK-END CAMP

-

CHAPTER TEN—IN FALLING LEAF MOON

-

CHAPTER ELEVEN—CAMP AT ALPINE FALLS

-

CHAPTER TWELVE—A BIRTHDAY COUNCIL ON HALLOW E’EN

-

CHAPTER THIRTEEN—INDOOR WOODCRAFT ENTERTAINMENT

-

CHAPTER FOURTEEN—WINTER WOODCRAFT WORK

-

CHAPTER FIFTEEN—SOME WEEK-END CAMPS

-

CHAPTER SIXTEEN—THE ADIRONDACK CAMP

CHAPTER ONE—CAMPING IN THE CITY

“Girls—guess what?” exclaimed Zan Baker, a few days after the return of the Woodcraft Band from their summer camp on Wickeecheokee Farm.

“Goodness only knows what you have to tell now!” laughed Jane Hubert, another of the five girls who founded Wako Tribe.

“Well, I got it direct, so the truth hasn’t been turned or twisted by any one of you girls before it was passed along,” retorted Zan, with a gleam of mischief in her eyes.

“Oh, is that so! Well let me tell you this much: if I had the rare imagination that you have, Zan, I’d compete with Jules Verne,” replied Hilda Alvord, the matter-of-fact member of the Band.

“Judging from the talent Zan has in telling stories it won’t surprise us very much to hear she is a popular authoress,” teased Nita Brampton, the social aspirant of the group.

“I’ll illustrate Zan’s books,” quickly added Elena Marsh, the fifth member of the Woodcrafters.

“Sort of shine in my reflected glory, eh?” laughed Zan, good-naturedly, for all the girls enjoyed this form of badinage.

“Girls, girls! This isn’t hearing the ‘wextry’ news Zan holds cornered! Give her a chance, won’t you?” begged Nita.

“It’s this: Miss Miller wants us to have tea with her, to discuss plans for our Winter Camp and to consider the advisability of admitting another Band so we can apply for a Charter of our Wako Tribe,” announced Zan, with due satisfaction.

“When is the party?” eagerly questioned her hearers.

“Friday afternoon about four; and she also said that if we cared to invite some of the other girls who are crazy to join Woodcraft to meet us in the evening to hear our Summer Reports read, she thought it might give them a fine opportunity to really understand what Woodcraft did for us during the few months we spent in Camp,” explained Zan.

“Miss Miller can count on me being there right on time!” declared Jane, with a determined bob of her head.

“Me too!” added Nita.

“It isn’t likely Hilda and I are going to be absent,” laughed Elena.

Thus it came about that promptly at four o’clock on Friday afternoon the five happy girls stood waiting at the door of the apartment occupied by their Woodcraft Guide. As Miss Miller’s professional business in life was teaching physical culture to the High School girls at the gymnasium of Clinton High, the honourary office as Guide in Woodcraft was more like play to the efficient instructor.

Immediately after the bell rang to announce the visitors, the door was opened and a cheery voice called, “Come right in, girls.”

“Dear me, Miss Miller, isn’t it just too hot for anything? And after our lovely cool Bluff down at Wickeecheokee!” sighed Nita, as soon as they were seated in the front room.

“I will admit that city life certainly is an unpleasant change from camping in the woods,” replied Miss Miller, taking the hats from her girls and handing them each a fan.

“I couldn’t sleep a wink last night in our stuffy city rooms!” exclaimed Hilda who lived with her mother and younger brother in the ordinary regulation flat.

“I didn’t either. I just gasped all night for some air,” added Elena.

“Well what are we going to do? We can’t move the Bluff to the City and we live in so-called modern homes where the only windows open front and back—all except Jane’s and my house where there is an extra city lot on the side so we can have light from additional windows on the sides,” commented Zan, thoughtfully.

“It is odd that you girls should speak of this matter the very first thing, because it is one of the things I wanted to talk over with you before any new members join our Band. If you all approve of the plan I thought out it not only will give us air enough at night but will offer the new Woodcraft members an opportunity to win their coups for sleeping out-of-doors for the required number of nights,” said the Guide.

“Oh do tell us what it is?” cried Zan.

“It must take its place in the order of business,” rejoined Miss Miller; “now let us open Council in the regular way, girls.”

“It won’t seem much like a Council in the regular way without a fire and the preliminary lighting of it,” complained Nita, who was the fault-finder of the Band but was fast out-growing such tendencies.

“Why I thought you girls all knew how to light the indoors Council Fire without the slightest danger of destroying anything about you!” commented Miss Miller, as she went to a small cabinet in the corner, where most of her Woodcraft material was kept.

Taking out a small shallow pan and an earthen bowl, the Guide displayed a squirrel’s nest and some wild-wood material in the pan. “I brought this from the farm for just such an occasion,” said she, smiling, as she placed the earthen bowl on a bread-board and handed the pan to Hilda, thus silently authorising her to help make fire for that Council.

“Does the bread-board signify anything?” laughed Jane, the tease of the group.

“Not having the logs or imitation fire-place for the centre of the Council Ring, I thought the next best thing would be a square of wood upon which to stand the dish. Then too, the bread-board gave me a good idea which I will mention later,” said the Guide.

While she explained, Miss Miller had gone to the cupboard for the rubbing sticks and the necessary block and fire-pan of wood. All being ready for the ceremony, Zan, who was Chief of the Band and Tribe, began.

The usual call to join in a Council was said and the girls sat down upon straw mats in a circle about the fire-board. Miss Miller proceeded to make fire with the rubbing sticks and as the faint spiral of smoke was seen to rise from the tiny heap of wood-powder, the Woodcrafters called “How!”

The smoke thickened and the pungent odour of balsam permeated the room. When the spark hidden under the black dust ignited the dry tinder held close to it and a tiny fork of flame shot up, the girls exclaimed, “How! How!” which is the Woodcraft sign of approval.

The fire was now placed in the earthen dish and as the wild-wood tinder, that was placed on top of the fire flared up, the dish was placed on the board.

“We will now sing the Omaha Tribal Prayer,” continued the Chief, and the girls stood up to sing while the fire burned in the centre of their Council Ring.

Elena Marsh, the artistic member of the Band and the chosen Tally Keeper, now read the reports and mentioned a few items of interest that had occurred since leaving the Camp on the Bluff.

“Now we can hear the Guide’s important plan,” said Zan, who as Chief of the Tribe, was not compelled to ask permission to address the Council as all other members have to do.

“O Chief! Even as our Guide spoke of a plan, I had a wild idea flash through my mind and I wonder if it comes anywhere near to being Miss Miller’s idea,” said Jane.

“Share it with your brethren and if it isn’t too wild to harness we may train it to do good service for us,” said Zan.

“Well, you see, there’s Nita and you and me—we all have goodly sized grass-places back of our houses. Why couldn’t we raise some tents as long as the weather is good and camp out there at night?” said Jane exultantly, for she thought she had anticipated the Guide’s plan.

“That’s all right, Jane, but maybe Hilda and Elena and Miss Miller wouldn’t care to trot from their homes every night to sleep in our back yards,” replied Zan, ludicrously as usual.

The others laughed at the picture outlined by her words, and Miss Miller added: “I think we have a more important problem than camps just now. Let us decide about the new Band first and discuss the out-door sleeping question afterward.”

“I thought you wanted us to settle the matter before the new members join us to-night?” returned Nita.

“So I do, but let us first find out who the new members will be, and then we can better judge whether they will accept this camping-out-doors idea,” answered the Guide.

“Frances and Anne Mason told me to be sure and vote them in at this meeting. They are just crazy to join,” declared Jane Hubert.

“And Eleanor Wilbur wants to join us,” said Nita.

“Mildred Howell told Fiji to tell me not to forget and propose her,” ventured Zan.

“And I know that Ethel Clifford wants to belong to our first Band,” added Elena.

“Well girls, you each have your new member to win a coup, but I haven’t much time out of school to meet the girls, as there is so much work to do at home. Jack Hubert said this noon that May Randall was asking for me before I met him. If she will let me propose her I can keep up with you on this coup,” said Hilda, whose mother was a trained nurse, thus letting most of the care of the home fall upon Hilda’s shoulders.

“She told me that that is why she wants to see you,” said Jane.

“That is very considerate of May Randall,” commended Miss Miller.

“Yes, and it recommends her for membership,” added Zan.

The other girls agreed with this suggestion, and the Guide then said: “That will make eleven girls in all—counting you five. I think that ought to be enough to work with this Fall,” and Miss Miller began to write down the names of the six members proposed.

“But there are loads of other girls who want to join us, Miss Miller,” objected Zan.

“I suppose there are, but better not add too many new members at one time, Zan; it will tend to divert your attention from your own progress, and individual work is most important to you at this period in Woodcraft. Were you all experienced or old members of the organisation, I would approve of enlisting the full number of members required for a Tribe,” explained the Guide.

“How long will we have to wait before we can be a Tribe?” asked Nita, petulantly.

“If this experiment with the new members turns out well by Christmas, I should think we might start the second Band,” replied Miss Miller.

“Goodness, can’t we start a Tribe before that?” cried Jane, impatiently.

“I thought the same as Jane—that we would be Wickeecheokee Band and the new members be Suwanee Band, and then the two Bands get the charter for Wako Tribe,” added Zan, in a disappointed tone.

“Some Woodcrafters have done that and found to their despair that the new Band knew nothing of the work or laws and were continually calling upon the first Band for help, but not being under the old Chief the first Band had nothing to say about disciplining or advising them. If the new members are subject to our Chief, they have to obey orders and can watch our methods of work for their guidance, and that will spare us many useless words and much valuable time.”

“Well, as usual, Miss Miller wins the day! Her reasons are as sensible as helpful,” commented Jane.

“Good-by Suwanee, I’ll meet you next year!” sighed Zan, wafting a kiss with the tips of her fingers to an imaginary Band.

“Girls, wherever did you find that name? I hunted through an Indian Dictionary of names but couldn’t find a thing like it,” asked Miss Miller, laughingly.

“If a simple little symbolic name like that stumps you, Miss Miller, what will happen when you join the Blackfeet Tribe?” laughed Jane.

“Miss Miller, you know the usual formula given in charades—they begin thus: ‘My first is part of a name, you see, my second is also a part, O gee!’ and so on,” explained Zan, while the other girls laughed.

The Guide puckered her brow for a few moments and the visitors watched eagerly for her to catch Zan’s meaning. Then she laughed, too.

“I see! Su—comes from Suzanne, the name of our Chief, but so seldom used that I forgot she ever had another handle to it than just ‘Zan.’ I must give up the rest of the charade, however.”

“Maybe it is buried so deep that the uninitiated cannot dig it up, but we girls thought it quite simple: ‘Su’ for the Chief, as you said; ‘Wa’ for Wako Tribe—plain enough; and ‘nee’ for all the other members who are willing to change their names from white man’s ways to the Indian’s with its wealth of meaning and beauty.”

As Zan explained, the Guide shook her head as if to admit that it certainly had been buried far beyond her power to dig.

“But it sounds pretty, girls,” said she finally.

“Mayhap we will have an improvement on that name before the Band comes into existence, who knows!” sighed Jane.

“The sooner we start with the new members, then, the quicker we will know about the second Band,” retorted Zan.

“Shall we vote now to invite the six girls mentioned?” asked Elena with Tally Book ready to inscribe the names.

The motion was made and seconded that the names of the six applicants be written on the roll and that evening they would be questioned and admitted if acceptable to the Chief and Guide.

“Now Miss Miller, if there is nothing else to consider let us hear about your idea for a camp in the city,” said Zan.

“When I came into this apartment yesterday afternoon, its stuffiness struck me much the same as you girls said: ‘Close and airless.’ The windows were all open but that didn’t seem to make any difference. While still gasping for the cool breezes of Wickeecheokee I went to my den in the back room and as I stood by the window that opens out on the roof of the extension downstairs, I made a discovery! Last night I slept as comfortably out-of-doors as if on the Bluff, and this morning the English sparrows woke me with their chattering under the eaves three stories above.”

“Miss Miller! Do tell us what you did?” exclaimed the curious girls.

“Well, first I took a crex rug from the floor and laid it on the extension roof to protect the tin from the feet of a cot-bed. Then I carried out a four-fold screen and with the smaller three-fold screen from my den, I made suitable protection about the cot. The camp-cot that I keep in case of an unexpected guest remaining over-night was small and light, and provided me a good place to rest. The whole affair, screens, cot, and mat, took up but half of the small roof and early this morning I slipped back through the open window and dressed, having enjoyed a fine cooling breeze all night.”

“Oh!” sounded the surprised five girls.

“You must have slept like a multi-millionaire on his sea-going yacht,” laughed Zan.

“I did, and without fear of going to the bottom by a torpedo from a submarine,” retorted Miss Miller.

“We have a wonderful roof on the back verandah—all decked and railed in,” remarked Jane, mentally picturing a row of tents on that desirable camp-site.

“I could use the rear porch that opens from our dining-room windows,” added Nita.

“We have a box-like porch on the second floor that has a back-stair going down from it. It is screened in and can be used for a sleeping-place, I s’pose,” murmured Elena.

“Our flat-house was built soon after Noah landed so we have no sleeping-porch, but I might hang a cot from the fire-escape—until the police make me take it down,” ventured Hilda, with a thoughtful manner.

The others shouted with merriment at the idea of big muscular Hilda swinging from a fire-escape over the street.

“I have my lodging all planned out,” now said Zan. “I shall utilise that square of side-piazza roof over the entrance to Dad’s office. It has a two-foot high coping about it and that makes it perfectly safe for me in the dark. I can use a screen, too, to hide the cot from the street.”

“You girls have all caught my last-night’s idea so suddenly that I haven’t had an opportunity to continue explaining,” interrupted Miss Miller.

“Proceed, fair lady, and we will hold our peace,” said Jane, giggling.

“As I enjoyed the reviving night-breezes and thought of you poor girls tossing in warm rooms, I wondered how we might have an out-door place and still feel secluded from prying eyes. Then I remembered the small tents we left with Bill on the farm. Those of you who have roof-space can erect a tent just outside your bed-room window. The tent-opening can be directly opposite the window so that you can slip in and out without dread of being seen by the public. What do you think of it?”

“It’s great!” exclaimed Zan, enthusiastically.

“Not for me,” grumbled Hilda.

“Nor for me,” added Nita, “’cause Mama won’t think of letting me have anything so original as a camp-tent within a mile of our house—let alone on the front roof!”

“If I speak to your father, who is so delighted at the improvement in your health, he may induce her to look at the plan with different conclusions than these you fear,” ventured the Guide.

“Maybe so; Papa said he would do anything on earth to have me keep up this Woodcraft stunt,” admitted Nita.

“Zan, do you think your father will object if we send to Bill for those small tents?” now asked Miss Miller.

“Mercy no! Dad won’t say a word if you pitch tents all along our entire roof and on the front piazza, too, just so there’s room between the canvas cots for his sick patients to find their way to his office-door.”

“The public will think Dr. Baker has opened a Sanatorium,” laughed Jane.

“Or a Fresh Air Clinic for Flat-Dwellers!” added Hilda.

The others laughed provokingly when they saw Zan flush for they all liked to tease her.

Miss Miller saw the sudden gleam of anger flash from Zan’s eyes and quickly said: “Girls, I am now going to indite that letter to Bill Sherman for the tents—what shall I say and who wants one?”

“One for Nita, one for Elena, and one for me—and of course Zan wants one,” said Jane.

“I can use the same one Fiji and Bob had at the beach this Summer,” replied Zan, brightening again. “Jane, why don’t you use Jack’s, then the extras can go to Miss Miller and Hilda.”

“But Zan, I haven’t a place to camp,” said Hilda, dolefully.

“Then I s’pose you’ll have to borrow some of my roof,” returned Zan, in a matter-of-fact voice.

“Oh Zan, really! I won’t mind walking back and forth every morning and night if you don’t mind my using the roof!” sighed Hilda with relief so great that the others laughed.

The letter for Bill Sherman, the farmer at Wickeecheokee, was given to Zan to mail if her father approved of the camp-plan, and then the Guide excused herself and went out to see if the tea was ready to serve her guests.

That evening the six girls came in and Woodcraft reports were read; then they were invited to join the Band and the conditions of membership plainly outlined. Needless to add, that everyone agreed eagerly to abide by the rules and regulations read to them.

On the way home that evening, however, Eleanor Wilbur whispered to Frances and Anne Mason who were walking with her:

“Of course this Woodcraft fun will be fine when we haven’t anything better to do, but you don’t intend losing any other fun or meeting because of it, do you?”

“Why we are going to go to the regular Councils and meet with the other girls for work or play, whether it happens when we have invitations for other parties or fun, or not,” declared Frances, the elder of the two sisters.

“Oh!” said Eleanor, a trifle disconcerted by the reply. Then after a few moments of silence she said confidentially: “Don’t you think Zan Baker takes an awful lot for granted from us girls? Just see how she took the initiative in everything to-night.”

“But Zan Baker is the Chief of the Band and has to take the lead in Tribal affairs,” explained Anne.

“Oh yes, I know that, but you don’t understand what I mean. I think she is too domineering in her office and Miss Miller certainly shows a great partiality for her. Of course everyone knows that Miss Miller bows humbly at the Doctor’s shrine just because he got her the position at High School Gym!” said Eleanor, significantly.

“Why Ella! It isn’t true! I know for a fact that Dr. Baker merely suggested to the Board that Miss Miller had resigned from college where she had taught for years. Most of us knew what a treasure she is, and the Board were only too glad to have her consider our school, because the salary is half what she was accustomed to receive,” defended Frances.

Eleanor kept silence, but Anne added: “And we girls feel sorry for Miss Miller because she gave up that college position when her mother was left alone and needed her at home!”

The afternoon following the meeting at Miss Miller’s home, Hilda fairly bounced into the gymnasium where the Guide could generally be found for some time after school-hours.

“Oh, Miss Miller, I have the loveliest camp-ground!”

“Better than the fire-escape?” laughed the Guide.

“Better than the roof of a porch! And the funny thing about it is that the janitor of our building came up himself and said: ‘Miss Hilda, I feel sorry for you these hot nights, so you can sleep on the roof if you like!’

“Miss Miller, I never breathed a word to him about a tent, but he took me up and showed me where I could pitch a small tent between the great water-tank and the square box-like place where the roof-steps come up. A stone parapet almost three feet high runs all around the roof, you know, so there isn’t any danger of my falling off even if I walked in my sleep—which I never do.”

“I think that is fine for you, Hilda,” smiled Miss Miller, but she did not add that she had spoken secretly to the janitor that morning on her way to school.

“Mother has no objections to this if I will take Paul up with me. Paul thinks the plan a dandy one so he will be benefited too. I will place a screen about his cot or mine so that I will have privacy.”

“Or you could hang a curtain from a ring at one side of the tent to one at the opposite side. Then Paul could pull or push the muslin to suit himself, and it would not be ruined by rain,” suggested Miss Miller.

“I’m so glad that we live on the top floor of the house, ’cause it will be an easy matter to run up or down the short flight of stairs going to the roof. When I told mother about it she laughed and said: ‘You always used to grumble about climbing the four flights from the street, but I know how much pleasanter it is to be on top instead of under a noisy family in a flat.’”

“Your mother is quite right, and then the air is always better the higher one goes, and the rents are lower—the last not a mean consideration, either,” added the Guide.

Jane Hubert came in just then, and her smile signified good news. “Father never made the slightest objection to the camp idea but he has a still better one for me. He says he will erect Jack’s tent on the lawn under a group of birches that grow near the high brick wall at the back of our place.”

Then Nita came in. “Miracles will never cease, Miss Miller. Not only is Mama quite reconciled to my camping on the first-story extension roof where there is a concrete flooring and a parapet to three sides, but she is taking an active part in rearranging my bed-room so that I can step in and out of the French windows without falling over cushioned window-seats and gim-cracks standing about.”

“This is the best news yet, Nita! I felt sure the other girls would have no trouble gaining permission to camp out. Now we only have to hear from Elena, as Zan started in to arrange her tent this noon, I hear.”

“Oh, Elena told me that she could have her tent on the roof of the side-verandah as planned instead of on the boxed-in porch at the back,” hurriedly informed Jane.

“Thank goodness we will be able to enjoy the Spirit’s blessing of sweet fresh air that is free for all mankind,” said Miss Miller, earnestly.

“To say nothing of enjoying a continuation of Woodcraft out-of-doors right in a great city,” added Jane.

CHAPTER TWO—THE NEW MEMBERS

Miss Miller had secured permission to use the gymnasium for the weekly Council Meetings of the Woodcrafters, so she was already there when the members of Wickeecheokee Band and the new members appeared to hold Council.

“Girls, I bought some straw mats at the ten-cent store that I thought we could use about the Council Fire,” said the Guide, as the girls all congregated about her desk.

“What about those small logs of wood we worked at so hard to bark and smooth down?” asked Nita.

“I thought we might make them presentable and then cut and paint symbolic totems on them to make them look like genuine Indian seats,” said Miss Miller.

“Aren’t they quite good enough as they are?” said Eleanor Wilbur, pushing at one of the logs with a slender foot.

“I thought they were fine when we barked them but now that we are at home and a better idea has been given us I approve of following Miss Miller’s suggestion,” replied Jane.

“Dad brought home some more of those short fire-place logs when he came back from the farm yesterday. He says we may want these thin logs for some other purpose; and besides, since enrolling our new members we haven’t enough of these present logs for all to use. They ought to be uniform so I say we use the mats until we have the thick logs ready to present the Lodge,” explained Zan.

“Girls—I have an idea!” cried Elena, the artistic.

“Hold fast to it or it’ll get away from you,” taunted Hilda, jokingly.

“S-sh!” said Zan. “Let her go, Lena.”

“About those thin logs we have on hand: Let’s build an imitation fire-place for our Council Ring to make it look as much as possible like one in a woodland camp!”

“Couldn’t we place our dish of smoking tinder inside it and make the artifice still better?” asked Jane.

“Oh I say!” shouted Zan with such emphasis that everyone jumped, and the speaker laughed.

“Where’s that red tissue paper we had for Decoration Day trimming of the school auditorium?” asked Zan.

“You’ll find it in the property-room with the other stuff,” replied Elena, who had charge of decorations at school.

“We’ll line the inside of the logs and when the fire shines through, make it look like a big blaze, eh?” asked Jane.

“No such thing!” said Zan. “We’ll get the janitor to change that electric bulb from the chandelier and drop it, by wire, down to our fire. Then it will shine as long as we need it.”

“I’ll run and see if the janitor is around. Will he do it, do you think, Miss Miller?” came from Hilda.

“I think so, he is very obliging, you know,” replied the Guide.

“And I’ll get the paper,” remarked Elena.

“You won’t need to do that, Lena, because I have orange crêpe paper in the closet that I bought when I got the mats. I had much the same idea in mind for those logs,” said Miss Miller, going to the closet while one of the girls ran for the janitor.

The care-taker of the building not only changed the bulb in a short time but assisted Miss Miller in rolling the logs from the closet to the place where the Council Ring could be arranged. The girls built up a square fire-place with a hollow opening in the middle where the electric bulb soon depended. The paper was fitted inside the square and when the electric current was turned on it looked like a glowing fire.

This done, four candles were placed at the fire—one at each corner of the square to denote the four corners of the earth.

“I purchased extra long candles so they would burn two hours, at least. Now that we have the electric bulb we need not waste the extra candles for fire-light but save them for some other occasion,” remarked Miss Miller.

“Everything ready now for Council?” asked Zan, looking around at the members.

“Everything we can think of,” responded Jane.

“Before we open the Council meeting in the usual manner I would like our Chief to read from the Woodcraft Manual for Girls on page 10, where it speaks of initiations and new members,” requested Miss Miller, handing the book to Zan.

“‘When brought into some new group such as the school or club, one is naturally anxious to begin by making a good impression on the others, by showing what one can do, proving what one is made of, and by making clear one’s seriousness in asking to be enrolled. So also those who form the group: they wish to know whether the new-comer is made of good stuff, and is likely to be a valuable addition to their number. The result is what we call initiation trials, the testing of a new-comer.

“‘The desire to initiate and be initiated is a very ancient deep-laid impulse. Handled judiciously and under the direction of a competent adult guide, it becomes a powerful force for character building, for inculcating self-control.

“‘In Woodcraft we carefully select for these try-outs such tests as demonstrate the character and ability of the new-comer, and the initiation becomes a real proof of fortitude, so that the new girl is as keen to face the trial, as the Tribe she would enter is to give it.’”

Zan finished reading and looked up to ask: “Is that all you want me to read, Miss Miller?”

“Just a moment, Zan. I now wish to speak a word to the new members about what is expected of them. We will leave the paragraph about the initiation trials for the last, then the girls will not forget what they are to do. Read now the paragraph that mentions the new work for members.”

So Zan continued. “‘After the new member has learned the Laws and taken the initiation tests, the first thing to claim her attention is that of qualifying for the rank of Pathfinder and later of Winyan, then the Achievements, each with its appropriate badge, which are described on page 327 of the Manual. In time she will have a Woodcraft suit, but this may come later.”

“Now Zan,” interrupted the Guide, “turn over to page 18 and read (the new members) what we expect a Wayseeker to do and be. A Wayseeker is the first order of a Big Lodge Girl’s membership.”

“‘To qualify for a Big Lodge—that is, to enter as a Wayseeker—one must:

“‘Be over twelve years of age.

“‘Know the twelve Laws and state the advantages of them.

“‘Take one of the initiations.

“‘Be voted in unanimously by other members of the group.

“‘Having passed this, the candidate becomes a Wayseeker and receives the Big Lodge Badge of the lowest rank, that is with two tassels on it.

“‘The next higher rank is that of Pathfinder,’” read Zan.

“So you see, girls, you six will be Wayseekers if you pass the trials and fulfil the requirements just read to you,” said the Guide. “Now Zan, will you please read from page 24—the meaning of a Council Ring? Better begin at the bottom of the page where I have marked the sentence for you.”

Zan turned over the pages till she found the place indicated and read: “‘Why do we sit in a circle around a fire? That is an old story and a new one.

“‘Then, too, a circle is the best way of seating a group. Each has her place and is so seated as to see everything and be seen by everybody. As a result each feels a very real part in the proceedings as they could not feel if there were corners in which one could hide. The circle is dignified and it is democratic. It was with this idea that King Arthur abolished the old-fashioned long table with two levels, one above the salt for the noble folk and one below for the common herd, and founded the Round Table. At his table all who were worthy to come were on the same level, were brothers, equal in dignity and responsibility, and each in honour bound to do his share. The result was a kindlier spirit, a sense of mutual dependence.

“‘These are the thoughts of our Council Ring. These are among the reasons why our Council is always in a circle and if possible around the fire. The memory of those long-gone days is brought back again with their simple reverent spirit, their sense of brotherhood, when we sit as our people used to sit about the fire and smell the wood-smoke of Council.’”

As Zan concluded, the experienced Woodcrafters cried: “How! How!”

“I suppose the new members know why we called our Band Wickeecheokee Band of Wako Tribe of Woodcrafters?” asked Miss Miller, with a slight nod in the direction of the six girls.

The new members looked at each other for the answer and the Guide continued to explain:

“Wickeecheokee is an old Indian name discovered on the ancient records of the County Seat in New Jersey where the farm owned by Dr. Baker is located. The English interpretation of the name means, ‘Crystal Waters.’ Dr. Baker’s farm where we camped last Summer has this lovely mountain stream falling down the steep side to the Bluff which is a rocky ledge over-hanging a pool of about a hundred yards wide, thence it rushes on to the Big Bridge near the turnpike road. That is why the doctor named his farm after the stream—‘Wickeecheokee.’”

“I wish to goodness we girls could have been there with you,” sighed Anne Mason.

“‘According to the Constitution of Woodcraft, our purpose is to learn the out-door life for its worth in the building up of our bodies and the helping and strengthening of our souls; that we may go forth with the seeing eye, and the “thinking hand” to learn the pleasant ways of the woods and of life, that we may be made in all wise masters of ourselves; facing life without flinching, ready to take our part among our fellows in all the problems which arise, rejoicing when some trial comes, that the Great Spirit finds us the rulers of strong souls in their worthy tabernacles.’

“Each one of you girls is past twelve years of age, so that point is covered. Now we will ascertain who of the new members know the law, who are acceptable to this Band, and who can prove worthy according to the initiation tests. You will all begin at the lowest rank if accepted in the Band—that of Wayseeker. Now Zan, read aloud the initiation test from page 11 of our Manual.”

The Chief turned back to the page mentioned and read: “‘The trial should be approved by the Council and be given to the candidate when her name is proposed for membership—that is, posted on the Totem Pole where it remains for seven suns. In camp a shorter time may be allowed at the discretion of the leaders.

1. Silence. Keep absolute silence for six hours during the daytime in camp, while mixing freely with the life of the camp. In the city keep silence from after school till bedtime.

2. Keep Good-natured. Keep absolutely unruffled for one day of twelve hours, giving a smiling answer to all.

3. Exact Obedience. For one week give prompt, smiling obedience to parents, teachers, and those who have authority over you. This must be certified to by those in question.

4. Make a Useful Woodcraft Article, such as a basket, a bench, a bed, a bow, a set of fire-sticks, etc.

5. Sleep out, without a built roof overhead, for three nights consecutively, or ten, not consecutively.’

“Now that you have heard what the tests are how many of you believe you can qualify—answer by raising your right hand and by the word of Woodcraft approval?”

The six girls raised six hands and then looked at each other sheepishly because the word “How” seemed so meaningless to them.

“I forgot to explain that this word ‘How’ means ‘yes’ or ‘thanks’ or ‘approval,’” hastily added the Guide.

Then all said “How!” and the other five girls felt that their new members were doing fine work.

“Why not teach them the Woodcraft Salute while we are at it?” asked Zan.

The Guide then demonstrated the sign and action, saying: “The hand sign of the girls is the ‘Sun in the heart, rising to the Zenith’—given by the right hand being placed over the heart, the first finger and the thumb making a circle, then swinging the forearm so the hand is level with the forehead, thus—.”

Then Miss Miller nodded to Zan to proceed with the meeting.

“In case any of you are not familiar with the Woodcraft Laws I will read them aloud to you. And Miss Miller, I would suggest right here, that the new members write to Headquarters at once and order a Girl’s Manual. They will need it daily, and I can’t spare mine, you know. We really couldn’t accomplish much without this printed Guide of rules and instruction and guides.”

Zan then read aloud for the benefit of the new members:

“‘1. Be Brave. Courage is the noblest of all gifts.

2. Be Silent, while your elders are speaking and otherwise show them deference.

3. Obey. Obedience is the first duty of the Woodcraft Girl.

4. Be Clean. Both yourself and the place you live in.

5. Understand and respect your body. It is the temple of the Spirit.

6. Be a friend of all harmless wild life. Conserve the woods and flowers, and especially be ready to fight wild-fire in forest or in town.

7. Word of Honour is sacred.

8. Play Fair. Foul play is treachery.

9. Be Reverent. Worship the Great Spirit and respect all worship of Him by others.

10. Be Kind. Do at least one act of unbargaining service every day.

11. Be Helpful. Do your share of the work.

12. Be Joyful. Seek the joy of being alive.’

These are the twelve laws that every good Woodcrafter tries to live up to. Now if the Fire Maker will make fire for our Council, I will explain the rays that shine from each of the four candles—one at each corner of the earth.”

The Chief waited for Jane, who was Fire Maker for that meeting, to take the rubbing sticks and when she stood ready to begin the fire-making, Zan said:

“Yo-hay-y Yo-hay-y-y; Meetah Kola Nahoonpo Omnee-chee-yaynee-chopi.”

The opening words of Council concluded by the Chief, Jane placed the fire sticks in their proper position and began to saw back and forth with the bow until a tiny spiral of smoke rose from the fire-block.

The Guide watching, said, “Now light we the Council Fire after the manner of the Red man, even also as the rubbing together of two trees in the storm-winds brings forth the fire from the forest wood.”

Jane blew gently upon the small pyramid of black powder in the fire-pan until the smoke grew thicker. She then waved it slowly back and forth still blowing gently until a minute spark glowed under the black dust. At that the girls all cried:

“How! How!”

Then a handful of inflammable wild-wood material was touched to the spark and as the smoke curled upward filling the immediate vicinity with an aromatic pine odour, a tiny flame shot out.

“How! How!” again chorused the Woodcrafters, and the tinder now burning brightly, was placed in the earthen dish and the dish set in the enclosure made by the logs.

With the flame bursting forth, Miss Miller quoted: “Now know we that Wakanda the Great Spirit hath been pleased to smile upon His children, hath sent down the sacred fire. By this we know He will be present at our Council, that His wisdom will be with us.”

After this Zan read again from the Manual:

“‘Four candles are there on the Shrine of this our symbol fire. And from them reach twelve rays—twelve golden strands of this the Law we hold.

From the Lamp of Fortitude are these:

Be Brave. For fear is the foundation of all ill; unflinchingness is strength.

Be Silent. It is harder to keep silence than to speak in hour of trial, but in the end it is stronger.

Obey. For Obedience means self-control, which is the sum of the law.

And these are the Rays from Beauty’s Lamp:

Be Clean. For there is no perfect beauty without cleanliness of body, soul, and estate. The body is the sacred temple of the Spirit, therefore reverence your body. Cleanliness helps first yourself, then those around you, and those who keep this law are truly in their country’s loving service.

Understand and Respect Your Body. It is the temple of the Spirit, for without health can neither strength nor beauty be.

Protect All Harmless Wild-life for the joy its beauty gives.

And these are the Rays from the Lamp of Truth:

Hold Your Word of Honour Sacred. This is the law of truth, and anyone not bound by this cannot be bound; and truth is wisdom. Play Fair. For fair play is truth and foul play is treachery.

Reverence the Great Spirit, and all worship of Him, for none have all the truth, and all who reverently worship have claims on our respect.

And these are the Rays in the Blazing Lamp of Love:

Be Kind. Do at least one act of unbargaining service every day even as ye would enlarge the crevice whence a spring runs forth to make its blessings more.

Be Helpful. Do your share of the work for the glory that service brings, for the strength one gets in serving.

Be Joyful. Seek the joy of being alive—for every reasonable gladness you can get or give is treasure that can never be destroyed, and like the spring-time gladness doubles, every time with others it is shared.’“

Zan concluded reading the interesting words of Woodcraft meaning and the girls murmured “How!”

“Now I will propose the name of each applicant in turn and the Band must second and approve her admission to this Tribe if that is their pleasure. As I call out the name will the girl please stand until the vote is taken?”

“Frances Mason is the first applicant,” said Miss Miller.

Frances stood and paid earnest attention to the next rite but Eleanor Wilbur who sat directly back of Frances as she stood up, kicked at her ankles and giggled as if the whole procedure were a huge joke. Although known to the others, the disrespect was overlooked at the time.

“Frances, is it your serious desire to become a member of this Woodcraft Band?” questioned the Chief.

“It is,” replied Frances, trying hard to keep from crying out as Eleanor pinched her leg.

“Then learn the laws of the League as well as the laws of our Band. To memorise the meaning of the Four Lesser Lights that shine from the shrine of the Great Light, the Sacred Fire. By taking the initiation tests as read for your benefit and by being acceptable to every member of Wickeecheokee Band.

“Are there any present who wish to register a complaint why Frances should not be admitted to our Band or the League?” asked Zan, as she looked around the circle.

No one complained, but a stage whisper was heard from Eleanor saying: “Everyone’s afraid to speak even if they do know something against Frances.”

The whisper was disconcerting but Eleanor tittered as if she thought herself very witty, and as Frances took her seat beside the rude girl, expecting to give her a piece of her mind, the Guide stood up.

“O Chief! While you were addressing the new member, I glanced over the Manual to see if we had omitted any necessary reading, and I find we have all made a serious blunder. Whereas we have six applicants for membership in this Band, the Manual clearly states that no Band shall have more than ten members. We will be compelled to drop one of the applicants.”

This unexpected news acted like a bucket of cold water on the girls as no one wished to be dropped. After a serious debate, the Chief announced a possible solution.

“We will post the names of the six girls on the Totem Pole and at the expiration of the period set for testing, the one who falls short of the mark must resign or, at least, wait for the second Band which will form at Christmastime.”

This plan met with approval and each new member then and there decided not to be the one left out when the enrollment came. So the six girls were admitted on probation.

“Now Chief, post the names on the Totem and we will stand it near the door where everyone coming in or going out can read who the applicants are,” said the Guide.

“I s’pose you are doing that to advertise your club,” remarked Eleanor, unpleasantly.

“Eleanor Wilbur! A Chump Mark against your credit, for you are on trial now and must not speak out of order in Council without giving the Chief the proper salute and respect,” said Zan, sternly.

“Why how ridiculous of you to give yourself such airs, Zan Baker! Anyone would think this was business and not fun!” jeered Eleanor.

“It is business I’ll have you understand, and if you wish to regard it as a butt for your insults or disobedience you can resign this very minute!” declared Zan, her eyes snapping fire.

But Eleanor had no desire to resign from the only thing she knew of where sport for the Winter days could be had. So she shrugged her shoulders and sulked.

The other girls were duly advised and then the Chief ordered the Tally Keeper to enter the record in the book and to print the paper that was to be posted on the Totem in as artistic a manner as she could think of.

“Now before we adjourn, is there any request to be made in behalf of the Band?” asked the Guide.

“O Chief! I wish to ask a question,” said Nita, standing.

“Speak, O Sister!” replied Zan.

“I talked of a plan while Elena and I were walking over here, and she thinks it is fine and dandy! It will help us to remember the woods and look forward to a camp next Summer.”

“Not that we need an incentive for that!” laughed Zan.

“No, but in Winter we’ll find it mighty funny to sit in this Gym and fancy we are Indians out in the forests. But follow Elena’s instructions and you’ll believe you’re at Wickeecheokee all Winter,” replied Nita, suggestively.

Nita sat down and Elena stood up. “O Chief! Nita and I wish to propose that we imitate the woods by scenery. We can buy some cheap cotton or canvas stuff and paint trees and rocks and the stream like those at our Summer Camp. We can even go so far as to have birds singing on the boughs and flying in the blue sky.”

Elena waited a moment to see the effect of her announcement and Zan said: “The blue sky seems to be the limit with your offer!”

The others grinned and Elena frowned momentarily. “Don’t you think it a good plan?”

“Fine plan for a house-painter. But who under the sun is willing to stay home for weeks and paint miles of scenery?” retorted Zan.

“Why it won’t be much trouble. Nita and I will offer to paint the scenes if you girls will make the uprights to fasten the stuff on when finished,” said Elena, anxiously.

“Have you figured out how much this may cost us, Nita?” asked the Guide.

“No because I don’t know how large we may need it. But any cheap cotton goods will do, you know.”

“Miss Miller, we might find out about that,” said Elena.

“The new members can begin first lessons in carpentry, too,” added Jane.

After discussing the idea, and with Elena’s added description of how beautiful it would look—to have Pine Nob showing against the sky in the distance, and Old Baldy back of Fiji’s cave, the Woodcrafters unanimously declared that they must have that scenery or lose all interest in the Winter Camp in the Gymnasium.

Miss Miller shook her head dubiously for she knew what a tremendous undertaking it would prove to be to paint nicely all the yards of material needed to enclose a Council Ring.

“Anyway it will do no harm to get prices on stuff and the necessary paint,” said Zan, and it was so decided.

“Nita and I will attend to that part of it if you girls will get the cost of lumber, etc., for the uprights,” added Elena.

“O Chief!” said Jane, thinking of a plan to save costs. “Why not use that side wall of the Gym and do away with that many uprights and stretchers?”

“O Chief! for that matter, why not use a corner of this hall and have two sides ready made and substantial, and use the uprights for the other two sides? With the scenery stretched on all four sides, who will ever know there is a solid wall of city plaster back of two sides?” suggested the Guide.

“But it will be a ‘corner in wood,’” added Zan, facetiously.

“Wah! Wah!” instantly sounded from every old Woodcrafter present. The new members looked about for an explanation.

“‘How’ is the term for approval and ‘Wah!’ for disapproval, or no,” explained the Guide, smiling at the reception given Zan’s wit.

“Corner or not, that last suggestion is all right!” declared Hilda.

“And instead of tacking the scenery on top of the poles and having it sag between each upright, why not have a wire or rope stretched taut from one pole to the next, and so on, and hang the scenery by means of hooks?” continued the Guide.

“I suppose such common commodities as clothes-pins would be spurned by Indians,” ventured Hilda.

“I should say ‘double yes’!” retorted Zan, slangily.

“It is most apparent that Zan is associating with the ‘causes’ of her slang again. She said this Summer that the habit was the fault of hearing her brothers use it so freely,” remarked Miss Miller.

“This time it was the fault of Hilda’s clothes-pins,” laughed Zan.

“Well anyway, clothes-pins are made of forest stuff and curtain pins are not!” defended Hilda.

“I will offer my services to the Band and inquire of an interior decorator I know, to see what would be the best hanger,” said the Guide.

“All right, Miss Miller, you do that and we will attend to the rest,” added Jane.

“I suppose two white-wash brushes ought to be better to paint with than camels-hair No. 0,” laughed Elena.

“Use whatever you like but for goodness’ sake, girls, don’t put your ‘atmosphere’ on too thick! It will take an age to dry out if you do,” commented Zan.

Then the Council ended with the singing of the Zuñi Sunset Song and the quenching of the Council Fire—in this case the electric current was switched off and the log fire-place taken back to the closet. When everything was in order, the girls left and went home, eagerly talking over the beautiful scenery-to-be.

CHAPTER THREE—HEARD IN THE “SCENIC FOREST”

After leaving the other girls at the corner of Maple Avenue, May Randall and Eleanor Wilbur walked on alone. May was large for her age, but most enthusiastic over Woodcraft as she was a devotee of gymnastics and all out-door exercises.

“Isn’t that Woodcraft foolishness a perfect scream?” said Eleanor, jeeringly.

May looked at her companion with surprise. “A scream! Why don’t you think it is splendid?”

“Oh, it answers well enough when one has nothing else to do, but you won’t catch me giving my time to making things or helping work just to boost a League that wants free advertising,” retorted Eleanor.

“Why Eleanor Wilbur! You know that isn’t true. Why would the Woodcraft League want advertising? They should worry whether we girls boost or not. The cost of keeping this thing going is far beyond what we pay in. That Manual alone is worth ten times the price we are charged for it. Then too, each Band has the free right to make its own individual laws and work or meet as it likes,” defended May.

“I suppose you are so mesmerised by Zan and Miss Miller, who are crazy about the thing, that you can’t see how silly the ideas of Council, or singing, or obeying laws are! Of course the camping and fun are all right!”

“If that’s the way you feel about it why not resign now before your name is posted on the Totem? You know there is one too many.”

“Why should I resign when I want some fun this Winter? Resign yourself if there is one too many! If I had the money Jane Hubert or Zan Baker have for an allowance, you wouldn’t catch me wasting time with your old Band. I’d go to a matinee every chance I’d get, and have other fun, too. But I never get enough spending-money to buy decent candy, let alone go to a good show!” complained Eleanor.

May made no reply but she looked at her companion, and Eleanor, glancing at her as she concluded, read May’s thoughts.

“I suppose you are such a Pharisee that you couldn’t think of anything so wicked as a theatre or a little supper-party,” ventured Eleanor, with a mean sneer.

“I guess I’ll turn down this street and walk home alone. I prefer it to any such company as you can offer me,” retorted May. And that sentence caused all the after trouble.

“Old hypocrite!” muttered Eleanor to herself, as she went on alone. “She thinks by pandering to the first Woodcrafters she’ll push herself in. But those five girls are too clannish to admit outsiders into their charmed circle, and that sweet pussy-footed Miller is worst of all!”

Hence Eleanor was not in the friendliest of moods when she met May at school the following morning. She pretended not to see her and only when May spoke directly to her, did she reply. May said nothing to the other girls about the conversation that took place between them on that walk home the day before, although Eleanor thought she had.

The names of the six members-to-be were posted on the Totem Pole which was placed at the entrance to the gymnasium where every scholar going in or coming out could read the notice.

At recess-time the Woodcrafters were the centre of attraction and many eager requests from other girls to be allowed to join the Tribe, was the result of the notice on the Totem Pole.

“Just can’t do it, girls! We have one too many as it is. A Band is only allowed ten members and we have eleven proposed, so one has to be dropped,” explained Zan.

“Which one?” asked Martha Wheaton, curiously.

“We won’t know until the time for testing is up. The one that falls short will have to make a graceful exit, I s’pose,” replied Jane.

“It ought to be Eleanor Wilbur, then. She’s going around telling everybody what a farce the whole business is. She acts as if she had a bone to pick with you girls. Did anything happen at the Council to antagonise her?” said Martha.

“Why—no! I thought she was enjoying herself immensely. I’ll go and ask her if she intends to drop out,” said Zan.

“But don’t tell who told you! I don’t want to get in bad with her—you know what a mean tongue she has!” hurriedly cried Martha, wishing she had kept quiet about the entire affair.

“Hey, there, Ella! Wait a minute—I want to see you!” called Zan, running after the girl who was making for the doorway.

“What do you want? I’m going in to study!” snapped Eleanor, fearing Zan meant to find fault with her about May Randall.

“I just heard something about your way of looking at our Woodcraft work, so you’d better make up your mind to-day whether you meant what you said or not. There’re piles of other girls only waiting a chance to grab what you laugh at!” Zan spoke angrily as she stood at the foot of the door-steps looking up at Eleanor.

Eleanor half-turned at the entrance door and sneered: “I read part of that poky Manual last night, and I couldn’t find a single thing there that would authorise a Chief to call down a member of the Tribe outside of Woodcraft meetings. I can do or say what I please without your over-bearing dominion of my rights!”

Zan felt like throwing her Latin book at Eleanor’s head, but Jane ran up and whispered: “Forget it! Give her rope enough and she’ll hang herself, all right!”

And as Zan turned away with Jane, Eleanor watched them and thought to herself: “I’d better not say anything that’ll get to that Miller’s ears, or she’ll remove my name from the Totem without as much as saying ‘By your leave!’ But I’ll have it out on that May Randall, all right, for tattling what she should have considered a confidential talk.”

Down in her heart, Eleanor knew she wanted to be a member of Woodcraft, not for the fun alone, but because she saw what it had done for the five girls that Summer. She longed to be a different type of girl from what she generally was, but so all-powerful was her human will that it kept her from doing or saying what she really wished to; and so cowardly was the trait to make strangers believe her charmingly perfect, that she generally found herself in trouble about one friend or another. Even at home, she praised the maid to her face and then denounced her to her mother. Had she dared she might have carried out the same hypocrisy between her mother and father, but Mr. Wilbur was the one being for whom she had any fear or respect, so she never misrepresented things to him.

It was not the real Eleanor that scoffed at Woodcraft and gossiped injuriously about it, but the weak mortal self that was the wretched counterfeit of the real and true Eleanor. The girl had not yet discovered this duality in her nature, but she had felt a growing dissatisfaction with herself and her environment since entering High School, and this unhappy state of mind aggravated her desire to belittle others or their efforts to climb to a higher plane of living.

Had Eleanor stopped to diagnose her feelings and actions she would have realised that the “misunderstandings” (as she termed the quarrels and trouble resulting from her poisoned darts of gossip) could be easily traced to the vindictive and malicious desires she entertained, while the sweet and pure and altogether attractive qualities that had been paramount in her early childhood years were becoming weaker and weaker through lack of expression. So at fourteen, at the character-forming time when a girl needs to be on guard that all undesirable tendencies are carefully eliminated to keep them from taking root for all future years, Eleanor, and those she associated with, were in a constant state of confusion and irritation created by her stubborn and selfish wilfulness.

During the week following the first Council meeting of the new members, the Band bought materials and began work on the forest scenery and wooden upright stands. Elena, Nita, and May Randall were given the roll of white duck to paint, while the other girls measured and sawed and hammered the 2 x 4 timbers to make the uprights necessary to hold the scenic walls of the woodland camp.

All that week Eleanor had been one of the first of the Woodcrafters to be on hand, but the moment the actual carpentry began, she would sigh, and scoff, and belittle the efforts of the others, or wonder why anyone spent good time on such foolish ideas!

Miss Miller had heard rumours of Eleanor’s gossip and she overheard several disturbing criticisms made during the work on the carpentry, but she said nothing at the time.

Of all the people who knew Eleanor well, Miss Miller was about the only one who studied the girl and understood the chemicalisation, so to speak, of the processes going on within the girl’s consciousness. The evil desires were fermenting and souring her nature while the sweetness and purifying elements were gradually being spoiled so that presently, a Judas-natured individual would claim the victory over the true, and the battle would be lost for the side of the divine and eternal self.

It was with a thrill of gratitude then, that the Guide recalled her deep perplexities over the waywardness of Nita, that same Summer on the Farm. How she had studied every phase of the problem and finally won out to the ever-growing betterment of the girl.

“If I can only win the slightest hold on this girl’s innate goodness and learn how to appeal to her higher self, I feel sure I can weed out the ‘tares’ even if it takes a long time. It is well worth the fight for the ‘wheat’ waiting to be garnered,” murmured Miss Miller as she reached the Gymnasium door. Which goes to show what the Guide really thought of Woodcraft and the privileges given her whereby to improve the morals and manners of the girls entrusted to her care.

“Everybody waiting for me to-day?” cheerily called the Guide as she hurried in where the girls were waiting to hold a Saturday afternoon Council.

“Yes, we’re crazy to pass judgment on the scenery. Elena makes such a secret of it that not one of us has seen it since she had it sketched out with charcoal. It’s back there in that huge roll. The boys brought it in the car a few minutes ago,” explained Zan.

“And did you finish the uprights so we can hang the duck?” asked Miss Miller.

“Everything is back in the corner where we decided to have our forest,” replied Jane.

“Then we can go right to work and place our trees and seats, and some of you can build the log fire-place in the centre for a Council,” said the energetic Guide.

A hubbub of instructions and calls and running to and fro continued after this for some time. Miss Miller tried to superintend the raising of the “huge forest timbers.”

“Say! Won’t one of you girls with nothing to do help me hook up this side of the trees?” called Elena, anxiously, as she found the weight of the duck too heavy to manage alone.

“You’ve got the trees upside-down!” laughed Jane.

“No I haven’t! That’s the way Nita painted this piece,” retorted Elena.

“Why it looks more like an early settler’s log stockade than the beautiful woodland hillside back of the Bluff,” replied surprised Jane, eyeing the painting with her head on one side.

“S-sh! Nita’ll hear you! She is so proud of it! She says it is a much better line of trees than my forest!” whispered Elena, proudly displaying her art work.

Zan came over to assist in hanging the duck and smiled behind the painting as she heard Elena explain the various “scenes” depicted on the great stretch of cotton.

“This is the flat rock where we sat telling bedtime stories; here is the swimming pool, and up there is Fiji’s cave. I tried to get in Bill’s cottage below the Bluff but my paint gave out,” explained Elena, as the three girls lifted and stretched the canvas and hung the hooks over the taut wire.

“But the way you measured and cut the scenery, we’ll have to unhook the cave and Bluff every time we need one side open. You made the other three sides all stockade, you see,” commented Zan.

“That’s so! I never thought of that. We will have to omit one whole side at times, won’t we?” responded Elena,

“Still, I think it will be easier to fold down or hang up a Bluff than to hew through a great row of giant tree-trunks, Zan,” laughed Jane.

Finding Elena too serious over her painting to laugh or enjoy a joke about it, the other two girls called that all was ready for the admiring audience.

As the group stood about the Council circle looking over the woodland scene, some smiled, some sniffed, and some looked delighted at the result. Miss Miller saw the disappointment on Nita’s face and remarked: “We joyfully accept this attempt to paint the cherished mental picture of Wickeecheokee Camp—a scene that defies all words or arts to describe.”

“But Miss Miller, you must admit that this scenery is misleading to new Woodcrafters. We have ranted of stars, and streams, and the breath of balsam pines; but where, oh where, is there any such ‘atmosphere’ to be found in this painting!” Zan cried dramatically, as she posed and threw out both arms towards the canvas.

“Atmosphere! Good gracious, Zan, can you ask for more!” laughed Jane, in response to Zan’s call. “Did you ever smell such an odour of the turpentine that comes from pine?”

The girls all laughed but Nita complained pathetically:

“If you girls knew the job it was to smear all that paint on the old stuff, you wouldn’t poke fun at the trees. Why, the duck soaked up my paint as fast as I put it on, so of course I had to use gallons of turp to make it spread at all. Even then, it dried before I could shade any bark on my trees.”

“You all say I am too matter-of-fact a cook to be an artist, but I bet I could take a handful of the superfluous paint on those trees and knead it into something resembling ‘tall timbers’,” now commented Hilda.

“No one could! Why we had to hang the duck along the wall of our attic and stand on an old library table while we painted the tops of the trees! Just try to make bark or leaves on a tree that has to be painted with a heavy kalsomine brush. Our arms got so lame before we painted an hour that we fairly cried with the ache in the bones,” said Elena, defiantly.

“Yes, and Elena’s attic is so bespattered with raw umber and ivory black that Mrs. Marsh says she will have to stain the entire floor now to make it look decent again,” added Nita.

“Well girls, we are all genuine Woodcrafters, so we hail with thanksgiving this scenery that fills our lungs with the pungent odour of the forest. I, for one, will breathe deeply of this pine product!” laughed Miss Miller, turning the criticism to fun.

“Well, all I can say is that I feel grateful for these great stout logs that will protect us from Winter’s icy winds and the hungry horde of howling wolves—the menace of pioneers in the forest!” added Zan.

“They’re all right in Winter but how about the longed for shade in Summer when the fierce rays of the sun beat upon our unprotected heads? We have no branches overhead,” remarked May, whimsically.

“Now you’ve all joshed Nita and me quite enough—let’s proceed with the Council,” said Elena, looking beseechingly toward Miss Miller.

So the meeting was opened and during the singing of the Prayer of Invocation, the Guide focussed her camera and took a snap-shot of the girls standing in the “Scenic Woodland Council.”

After the Tally of the last meeting had been read and other business disposed of, Miss Miller said:

“Is there any particular work you girls plan to do this coming week?”

“O Chief!” said Nita, jumping to salute Zan. “We really must plan some new dances for this Fall, especially if we are going to celebrate a big Hallow E’en Council and invite our friends.”

“As this is the last week of September, we haven’t any too much time, either,” added Jane.

“Well, let’s commission Nita to dig up some new and entertaining folk songs that can be acted out in a dance,” suggested Zan, looking to the Guide for approval of the idea.

“Elena, make a note in your Tally that Nita will find us some new dancing songs before next Council,” replied Miss Miller.

“O Chief!” now spake Hilda. “When we broke camp for the Summer we were all quite keen to win coups for needle-craft, carpentry, and other work. Besides, we want to secure degrees for some of the big stunts like Mrs. Remington’s Tribe have won.”

“Oh, that reminds me! Elizabeth Remington said she would gladly help us to learn how to start the pottery and carpentry work. Then too, she said her mother thought we ought to plan to have a Little Lodge attached to our Tribe, as many Big Lodges have,” cried Zan, eagerly.

“It is very good of Elizabeth to offer her time to help you girls; as for the Little Lodge, I would not think of it till your two Bands are filled and the Tribe is chartered and well under way,” replied the Guide.

“O Chief! Can’t we start the pottery work first ’cause Zan knows a lot about designing since she started that class-work in school,” suggested Hilda.

“I was not aware that Zan had graduated from the School of Design so soon. Did you really finish in two lessons, Zan?” teased the Guide.

“Oh, you know what Hilda means—she thinks that now I can find out about real designing we all can profit by it,” explained Zan.

“Instead of pottery which is a step beyond carpentry, I would suggest that the Band make some objects in wood according to the Manual rules for winning coups,” advised Miss Miller.

“Why can’t you old members wait a little while and give us new members time to win the flower, star, and tree coups such as you earned at Camp this Summer?” asked Frances Mason.

“We can all begin together on carpentry and at times when we are not together, or you new members are not in on some of the things we do, you can catch up on those easy winners,” said Zan.

So the entry was made in the Tally Book directly after the note reading: “Nita will find new folk songs for a dance before next Council.”

It read: “Begin some object in carpentry using own designs and material, suitable to claim a coup with all provisions met.”

“Now that that is off our minds let’s have Miss Miller tell us an Indian myth or story. We haven’t heard one since that last week on the farm,” petitioned Jane.

“And I happen to know that she received a package of books from the Smithsonian Institution at Washington,” added Zan.

“How! How!” chorused the other girls, so the Guide felt called upon to contribute her share to the Council meeting.

“I really had planned something so different from this, that I must have a moment in which to think,” murmured the Guide.

“Oh dear me! That’s always the way with us! We are so impatient to make Miss Miller work for her honourable position, that we generally manage to ‘cut off our noses to spite our faces,’“ sighed Elena so plaintively that the others laughed.’”

“My original idea will not spoil by delay, so I will tell the story now which is really much easier than the work I planned,” rejoined Miss Miller.

“Well, at least tell us what your plan was and let us judge of its merits,” declared Zan, coaxingly.

“I never satisfy idle curiosity if I recognise it, but I will tell you a story of what happened to some Eskimo Indian children who indulged in this undesirable inclination to their undoing.

CHAPTER FOUR—THE ESKIMO INDIAN LEGEND

“This myth is told by the Sea Lion-town People from Alaska and is called, ‘A Tale of a Red Feather,’” began Miss Miller.

“A group of children were playing ball with a woody excrescence which they had found in the bole of a tree. It had been rubbed down and polished until it was smooth and shiny as could be.

“As they knocked the ball back and forth, shouting with glee if one of their band happened to miss it, a small red feather floated down from the clouds and blew gently to and fro just over their heads. As it was wafted about in the eddying breeze, it attracted the attention of the youngsters who watched it with eager curiosity.

“It never came nearer the earth than just above the heads of the children and as they speculated concerning it, one of the boys declared it must be a magic feather. Another said it might be a prince bewitched by an evil spell-binder, and still another said it was from a Red Eagle that soared from the Happy Hunting Grounds.

“The latter idea seemed to take hold of the children and they cried ‘We want it if it fell from the Happy Hunting Grounds.’

“So most of them jumped up trying to catch it as it floated over their heads. The tallest boy, making a high leap, seized it, but instead of bringing it down to the ground with him, his hand stuck fast as if by some unseen power. He struggled but could not release himself and gradually he was drawn up from the earth.

“He screamed, and his brother seeing the awful magic working, caught hold of his hand to stay him. But he, too, was stuck fast to his brother’s hand and was lifted up against his will.

“Then another boy caught hold on to the second lad’s feet and he, too, was drawn up unwillingly. Soon, all the children, then the parents who sought to save their little ones, next the townspeople, and lastly the dogs and cats and donkeys, and every living creature in the town—all but the niece of the Town Chief were drawn up.

“This girl remained sleeping upon a couch behind a screen and was quite unaware of what was happening to her kinsmen and townspeople and the creatures that had lived in the town.

“The victims of Red Feather were carried up, up, up, to a great cloud that hung waiting to receive them. There they were kept until the waters in the cloud washed them all to bones and then bleached the bones white. But that comes later.

“The niece, strangely enough, was awakened by the great stillness. She listened and then sprang out of bed wondering what kept everyone so silent. No shouting of children, no braying of donkeys, no fighting of cats and dogs, no bargaining of townspeople!

“She peered from behind the screen and found no moving or living being, so she quickly dressed and ran out to call, but no answer came. She ran through the houses and found them vacant, and left as if they had been abandoned in a great hurry. The canoes were still tied to their posts or lying upon the beach, so it was quite evident that her people had not gone by the water-way. The great mountains back of the village offered no temptation to the villagers and the maiden knew they had not disappeared that way.

“She went home to think over this strange thing and as she thought, she feared some evil worker had succeeded in making magic against her people. Reaching this conclusion, the maiden ran out and stood near the spot where her cousins first saw the feather. She, too, saw a tiny red feather dance about her head but she was too troubled to account for her friends to give the temptation another thought.

“Having no curiosity or desire to possess the red feather gave her the power to see it as it was. As the feather still fluttered about, the girl was able to witness the whole sight of her people and every living creature of the village excepting herself, drawn up to the black cloud and left dangling there.

“Then she ran back to her tepee and wept. She wept gallons of salty tears before she became reconciled to her fate. But the tears relieved her sorrow and she went forth to seek for a memento of her brothers and sister. Where the children had been playing ball she found a shaving her brother had whittled from the wood from which he was making a spear just before he was caught up. She next found a feather from the arrow her cousin had been making. Then she found a chip of red cedar bark her brother had held, and a wild crab-apple blossom her little sister had plucked. Lastly, the maiden saw the footprints in the mud, of another brother as he had stood catching at the heels of his cousin. All these relics she gathered up carefully and placed them in a blanket.

“The blanket was securely bound by the four corners and the gallons of salty tears poured over it. Then the girl blew her nose violently to call magic, and poured the remainder of her tears over the covering that held the treasures.

“This last rite performed, the maiden carried the blanket to her couch behind the screen and sat down to wait. After many days she opened the blanket again and there she found a babe. It had a small shaving stuck to its forehead. She took the babe out and tied the blanket corners together again. Then she mothered the babe till it grew strong and as fine as her brother had been before it.

“After a time, she opened the blanket again and lo! there she found another fine child, but a bit of cedar bark was stuck to its forehead. The boy was also mothered and grew to be a fine lad.

“The third time the girl opened the blanket she found a boy with a feather stuck to his forehead. The fourth child had a clod of mud on the sole of each foot, and so on, the children came until nine fine lads had been mothered and reared, and then came a little girl who carried a crab-apple blossom in her hand.

“The ten children were carefully reared and taught many wise things that all Indians should know. They had plenty of food and clothing as every house in the town was there to take from.

“One day, the eldest lad inquired: ‘Mother, why lies yonder village so empty?’

“And she replied: ‘My child, it is your uncle’s town that lies empty because of idle curiosity. And this is what happened to everyone living in the village.’

“Then she told the children the story as I have told it to you, even the punishment that comes with curiosity and the payment demanded from any who deem they can do what others cannot.

“And the boy asked: ‘Where is the ball, mother?’

“She replied sadly: ‘Ah, my son, I may not show you the hidden place of that ball for it contains magic that brings evil to anyone touching it. Better leave skîtq! a’-ig. ādAñ in the tree where it grows.’

“But the boys were overcome with curiosity to see and try this magic they were warned against. So, secretly they found the right bole of the tree where an excrescence grew and it was cut out. They worked it smooth and round until it was polished enough to play ball with.

“The little sister had not been told of her brothers’ mischief or she would have dissuaded them—or at least, she would have warned the mother that the boys had disobeyed her wishes.

“They tossed the ball gleefully back and forth and soon a tiny red feather floated over their heads but little sister warned them not to touch it as it was the same evil magic that had drawn all their kin away from earth.

“But the oldest lad scoffed at her fears and clutched at the feather. Instantly, he was turned to mucus, right before their eyes! And this mucus was waved violently back and forth till it was stretched out into a long thread. As it was pulled up to the black cloud overhead, one end of the mucus still stuck fast to the ground and the red feather tugged and tugged to tear it loose.

“The second brother caught hold of the mucus and was turned to a shaving. But this was whirled around and around until it spun dizzily and one end of the shaving reached the cloud but the other still whirled on the ground.