автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Humphry Davy Poet and Philosopher

Transcriber’s Note

Cover created by Transcriber and placed in the Public Domain.

THE CENTURY SCIENCE SERIES

Edited by SIR HENRY E. ROSCOE, D.C.L., LL.D., F.R.S.

HUMPHRY DAVY

POET AND PHILOSOPHER

The Century Science Series.

EDITED BY

SIR HENRY E. ROSCOE, D.C.L., F.R.S.

John Dalton and the Rise of Modern Chemistry.

By Sir Henry E. Roscoe, F.R.S.

Major Rennell, F.R.S., and the Rise of English Geography.

By Sir Clements R. Markham, C. B., F.R.S., President of the Royal Geographical Society.

Justus von Liebig: his Life and Work (1803–1873).

By W. A. Shenstone, F.I.C., Lecturer on Chemistry in Clifton College.

The Herschels and Modern Astronomy.

By Agnes M. Clerke, Author of “A Popular History of Astronomy during the 19th Century,” &c.

Charles Lyell and Modern Geology.

By Rev. Professor T. G. Bonney, F.R.S.

James Clerk Maxwell and Modern Physics.

By R. T. Glazebrook, F.R.S., Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge.

Humphry Davy, Poet and Philosopher. By T. E. Thorpe, LL.D., F.R.S., Principal Chemist of the Government Laboratories.

In Preparation.

Michael Faraday: his Life and Work.

By Professor Silvanus P. Thompson, F.R.S.

Pasteur: his Life and Work.

By M. Armand Ruffer, M.D., Director of the British Institute of Preventive Medicine.

Charles Darwin and the Origin of Species.

By Edward B. Poulton, M.A., F.R.S., Hope Professor of Zoology in the University of Oxford.

Hermann von Helmholtz.

By A. W. Rücker, F.R.S., Professor of Physics in the Royal College of Science, London.

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited, New York.

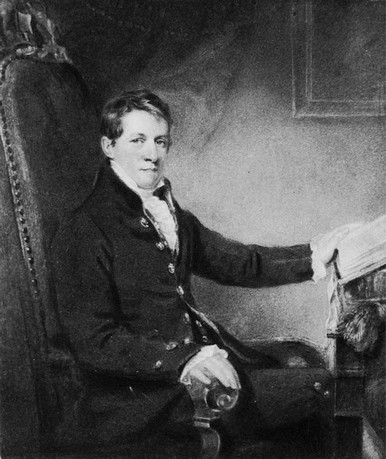

HUMPHRY DAVY.

ÆTAT 45.

(From a painting by Jackson)

THE CENTURY SCIENCE SERIES

Humphry Davy

POET AND PHILOSOPHER

BY

T. E. THORPE, LL.D., F.R.S.

New York

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited

1896

PREFACE

For the details of Sir Humphry Davy’s personal history, as set forth in this little book, I am mainly indebted to the well-known memoirs by Dr. Paris and Dr. John Davy. As biographies, these works are of very unequal value. To begin with, Dr. Paris is not unfrequently inaccurate in his statements as to matters of fact, and disingenuous in his inferences as to matters of conduct and opinion. The very extravagance of his laudation suggests a doubt of his judgment or of his sincerity, and this is strengthened by the too evident relish with which he dwells upon the foibles and frailties of his subject. The insincerity is reflected in the literary style of the narrative, which is inflated and over-wrought. Sir Walter Scott, who knew Davy well and who admired his genius and his many social gifts, characterised the book as “ungentlemanly” in tone; and there is no doubt that it gave pain to many of Davy’s friends who, like Scott, believed that justice had not been done to his character.

Dr. Davy’s book, on the other hand, whilst perhaps too partial at times—as might be expected from one who writes of a brother to whom he was under great obligations, and for whom, it is evident, he had the highest respect and affection—is written with candour, and a sobriety of tone and a directness and simplicity of statement far more effective than the stilted euphuistic periods of Dr. Paris, even when he seeks to be most forcible. When, therefore, I have had to deal with conflicting or inconsistent statements in the two works on matters of fact, I have generally preferred to accept the version of Dr. Davy, on the ground that he had access to sources of information not available to Dr. Paris.

Davy played such a considerable part in the social and intellectual world of London during the first quarter of the century that, as might be expected, his name frequently occurs in the personal memoirs and biographical literature of his time; and a number of journals and diaries, such as those of Horner, Ticknor, Henry Crabb Robinson, Lockhart, Maria Edgeworth, and others that might be mentioned, make reference to him and his work, and indicate what his contemporaries thought of his character and achievements. Some of these references will be found in the following pages. It will surprise many Londoners to know that they owe the Zoological Gardens, in large measure, to a Professor of Chemistry in Albemarle Street, and that the magnificent establishment in the Cromwell Road, South Kensington, is the outcome of the representations, unsuccessful for a time, which he made to his brother trustees of the British Museum as to the place of natural history in the national collections. Davy had a leading share also in the foundation of the Athenæum Club, and was one of its first trustees.

I am further under very special obligations to Dr. Humphry D. Rolleston, the grand-nephew of Sir Humphry Davy, for much valuable material, procured through the kind co-operation of Miss Davy, the granddaughter of Dr. John Davy. This consisted of letters from Priestley, Kirwan, Southey, Coleridge, Maria Edgeworth, Mrs. Beddoes (Anna Edgeworth), Sir Joseph Banks, Gregory Watt, and others; and, what is of especial interest to his biographer, a large number of Davy’s own letters to his wife. In addition were papers relating to the invention of the Safety Lamp. Some of the letters have already been published by Dr. John Davy, but others now appear in print for the first time. I am also indebted to Dr. Rolleston for the loan of the portrait representing Davy in Court dress and in the presidential chair of the Royal Society, which, reproduced in photogravure, forms the frontispiece to this book. The original is a small highly-finished work by Jackson, and was painted about 1823. The picture originally belonged to Lady Davy, who refers to it in the letter to Davies Gilbert (quoted by Weld in his “History of the Royal Society”), in which she offers Lawrence’s well-known portrait to the Society, and which, by the way, the Society nearly lost through the subsequent action of the painter.

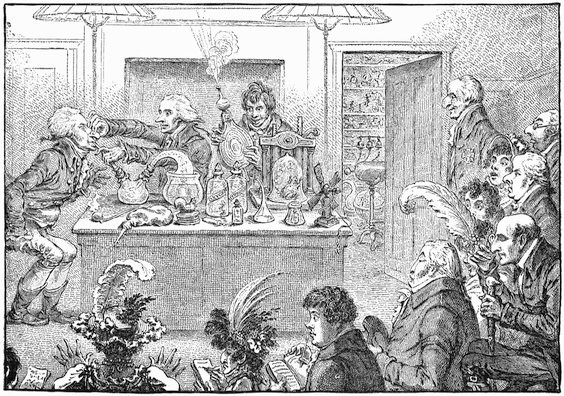

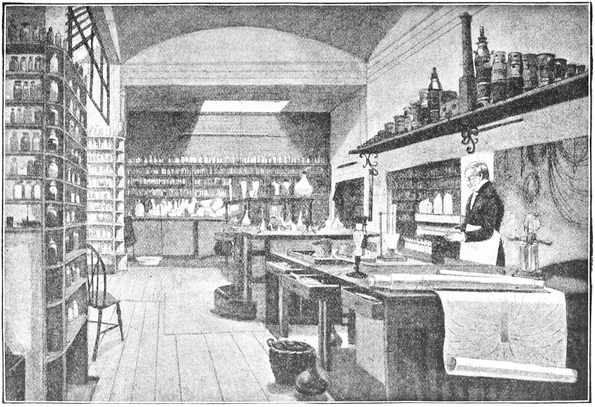

For the references to the early history of the Royal Institution I am mainly indebted to Dr. Bence Jones’s book. I have, moreover, to thank the Managers of the Institution for their kindness in giving me permission to see the minutes of the early meetings, and also for allowing me to consult the manuscripts and laboratory journals in their possession. These include the original records of Davy’s work, and also the notes taken by Faraday of his lectures. The Managers have also allowed me to reproduce Miss Harriet Moore’s sketch—first brought to my notice by Professor Dewar—of the chemical laboratory of the Institution as it appeared in the time of Davy and Faraday, and I have to thank them for the loan of Gillray’s characteristic drawing of the Lecture Theatre, from which the illustration on p. 70 has been prepared.

I have necessarily had to refer to the relations of Davy to Faraday, and I trust I have said enough on that subject. Indeed, in my opinion, more than enough has been said already. It is not necessary to belittle Davy in order to exalt Faraday; and writers who, like Dr. Paris, unmindful of George Herbert’s injunction, are prone to adopt an antithetical style in biographical narrative have, I am convinced, done Davy’s memory much harm.

I regret that the space at my command has not allowed me to go into greater detail into the question of George Stephenson’s relations to the invention of the safety lamp. I have had ample material placed at my disposal for a discussion of the question, and I am specially indebted to Mr. John Pattinson and the Council of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle-upon-Tyne for their kindness in lending me a rare, if not unique, collection of pamphlets and reprints of newspaper articles which made their appearance when the idea of offering Davy some proof of the value which the coal owners entertained of his invention was first promulgated. George Stephenson’s claims are not to be dismissed summarily as pretensions. Indeed, his behaviour throughout the whole of the controversy increases one’s respect for him as a man of integrity and rectitude, conscious of what he thought due to himself, and showing only a proper assurance in his own vindication. I venture to think, however, that the conclusion to which I have arrived, and which, from the exigencies of space, is, I fear, somewhat baldly stated, as to the apportionment of the merit of this memorable invention, is just and can be well established. Stephenson might possibly have hit upon a safety lamp if he had been allowed to work out his own ideas independently and by the purely empirical methods he adopted, and it is conceivable that his lamp might have assumed its present form without the intervention of Davy; but it is difficult to imagine that an unlettered man, absolutely without knowledge of physical science, could have discovered the philosophical principle upon which the security of the lamp depends.

T. E. T.

May, 1896.

PNEUMATIC EXPERIMENT AT THE ROYAL INSTITUTION. (After Gillray.)

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

PAGE

I.—

Penzance: 1778–1798

9II.—

The Pneumatic Institution, Bristol: 1798–1801

26III.—

The Pneumatic Institution, Bristol: 1798–1801 (

continued)

54IV.—

The Royal Institution 66V.—

The Chemical Laboratory of the Royal Institution 90VI.—

The Isolation of the Metals of the Alkalis 110VII.—

Chlorine 134VIII.—

Marriage—Knighthood—“Elements of Chemical Philosophy”—Nitrogen Trichloride—Fluorine 155IX.—

Davy and Faraday—Iodine 173X.—

The Safety Lamp 192XI.—

Davy and the Royal Society—His Last Days 213CHAPTER I.

PENZANCE: 1778–1798.

CHAPTER II.

THE PNEUMATIC INSTITUTION, BRISTOL, 1798–1801.

CHAPTER III.

THE PNEUMATIC INSTITUTION, BRISTOL, 1798–1801 (continued).

CHAPTER IV.

THE ROYAL INSTITUTION.

CHAPTER V.

THE CHEMICAL LABORATORY OF THE ROYAL INSTITUTION.

CHAPTER VI.

THE ISOLATION OF THE METALS OF THE ALKALIS.

CHAPTER VII.

CHLORINE.

CHAPTER VIII.

MARRIAGE—KNIGHTHOOD—ELEMENTS OF CHEMICAL PHILOSOPHY—NITROGEN TRICHLORIDE—FLUORINE.

CHAPTER IX.

DAVY AND FARADAY—IODINE.

CHAPTER X.

THE SAFETY LAMP.

CHAPTER XI.

DAVY AND THE ROYAL SOCIETY—HIS LAST DAYS.

Humphry Davy, POET AND PHILOSOPHER.

CHAPTER I.

PENZANCE: 1778–1798.

Humphry Davy, the eldest son of “Carver” Robert Davy and his wife Grace Millett, was born on the 17th December, 1778.A His biographers are not wholly agreed as to the exact place of his birth. In the “Lives of Philosophers of the Time of George III.” Lord Brougham states that the great chemist was born at Varfell, a homestead or “town-place” in the parish of Ludgvan, in the Mount’s Bay, where, as the registers and tombstones of Ludgvan Church attest, the family had been settled for more than two hundred years.

A In some biographical notices—e.g. in the Gentleman’s Magazine, xcix. pt. ii. 9—the year is given as 1779.

Mr. Tregellas, in his “Cornish Worthies” (vol. i., p. 247), also leaves the place uncertain, hesitating, apparently, to decide between Varfell and Penzance.

According to Dr. John Davy, his brother Humphry was born in Market Jew Street, Penzance, in a house now pulled down, but which was not far from the statue of him that stands in front of the Market House of this town. Dr. Davy further states that Humphry’s parents removed to Varfell some years after his birth, when he himself was taken charge of by a Mr. Tonkin.

The Davys originally belonged to Norfolk. The first member of the family that settled in Cornwall was believed to have acted as steward to the Duke of Bolton, who in the time of Elizabeth had a considerable property in the Mount’s Bay. They were, as a class, respectable yeomen in fairly comfortable circumstances, who for generations back had received a lettered education. They took to themselves wives from the Eusticks, Adamses, Milletts, and other old Cornish families, and, if we may credit the testimony of the tombstones, had many virtues, were not overgiven to smuggling or wrecking, and, for the most part, died in their own beds.

The grandfather of Humphry, Edmund Davy, was a builder of repute in the west of Cornwall, who married well and left his eldest son Robert, the father of the chemist, in possession of the small copyhold property of Varfell, to which reference has already been made. Robert, although a person of some capacity, seems to have been shiftless, thriftless, and lax in habits. In his youth he had been taught wood-carving, and specimens of his skill are still to be seen in and about Penzance. But he practised his art in an irregular fashion, his energies being mainly spent in field sports, in unsuccessful experiments in farming, and in hazardous, and for the most part fruitless, ventures in mining. At his death, which occurred when he was forty-eight, his affairs were found to be sadly embarrassed; his widow and five children were left in very straitened circumstances, and Varfell had to be given up.

Fortunately for the children, the mother possessed the qualities which the father lacked. Casting about for the means of bringing up and educating her family, she opened a milliner’s shop in the town, in partnership with a French lady who had fled to England during the Revolution.

By prudence, good management, and the forbearance of creditors, she not only succeeded in rearing and educating her children, but gradually liquidated the whole of her husband’s debts. Some years later, by an unexpected stroke of fortune, she was able to relinquish her business. She lived to a good old age, cheerful and serene, happy in the respect and affection of her children and in the esteem and regard of her townspeople. Such a woman could not fail to exercise a strong and lasting influence for good on her children. That it powerfully affected the character of her son Humphry, he would have been the first to admit. Nothing in him was more remarkable or more beautiful than his strong and abiding love for his mother. No matter how immersed he was in his own affairs, he could always find time amidst the whirl and excitement of his London life, amidst the worry and anxiety of official cares—or, when abroad, among the peaks of the Noric Alps or the ruins of Italian cities—to think of his far-away Cornish home and of her round whom it was centred. To the last he opened out his heart to her as he did to none other; she shared in all his aspirations, and lived with him through his triumphs; and by her death, just a year before his own, she was happily spared the knowledge of his physical decay and approaching end.

* * * * *

Davy was about sixteen years of age when his father died. At that time he was a bright, curly-haired, hazel-eyed lad, somewhat narrow-chested and undergrown, awkward in manner and gait, but keenly fond of out-door sport, and more distinguished for a love of mischief than of learning.

Dr. Cardew, of the Truro Grammar School, where, by the kindness of the Tonkins, he spent the year preceding his father’s death, wrote of him that he did not at that time discover any extraordinary abilities, or, so far as could be observed, any propensity to those scientific pursuits which raised him to such eminence. “His best exercises were translations from the classics into English verse.” He had previously spent nine years in the Penzance Grammar School under the tyranny of the Rev. Mr. Coryton, a man of irregular habits and as deficient in good method as in scholarship. As Davy used to come up for the customary castigation, the worthy follower of Orbilius was wont to repeat—

“Now, Master Davy, Now, sir! I have ’ee No one shall save ’ee— Good Master Davy!”

He had, too, an unpleasant habit of pulling the boys’ ears, on the supposition, apparently, that their receptivity for oral instruction was thereby stimulated. It is recorded that on one occasion Davy appeared before him with a large plaster on each ear, explaining, with a very grave face, that he had “put the plasters on to prevent mortification.” Whence it may be inferred that, in spite of all the caning and the ear-pulling, there was still much of the unregenerate Adam left in “good Master Davy.”

Mr. Coryton’s method of inculcating knowledge and the love of learning, happily, had no permanent ill-effect on the boy. Years afterwards, when reflecting on his school-life, he wrote, in a letter to his mother—

“After all, the way in which we are taught Latin and Greek does not much influence the important structure of our minds. I consider it fortunate that I was left much to myself when a child, and put upon no particular plan of study, and that I enjoyed much idleness at Mr. Coryton’s school. I perhaps owe to these circumstances the little talents that I have and their peculiar application.”

If Davy’s abilities were not perceived by his masters, they seemed to have been fully recognised by his school-fellows—to judge from the frequency with which they sought his aid in their Latin compositions, and from the fact that half the love-sick youths of Penzance employed him to write their valentines and letters. His lively imagination, strong dramatic power, and retentive memory combined to make him a good story-teller, and many an evening was spent by his comrades beneath the balcony of the Star Inn, in Market Jew Street, listening to his tales of wonder or horror, gathered from the “Arabian Nights” or from his grandmother Davy, a woman of fervid mind stored with traditions and ancient legends, from whom he seems to have derived much of his poetic instinct.

Those who would search in environment for the conditions which determine mental aptitudes, will find it very difficult to ascertain what there was in Davy’s boyish life in Penzance to mould him into a natural philosopher. At school he seems to have acquired nothing beyond a smattering of elementary mathematics and a certain facility in turning Latin into English verse. Most of what he obtained in the way of general knowledge he picked up for himself, from such books as he found in the library of his benefactor, Mr. John Tonkin. Dr. John Davy has left us a sketch of the state of society in the Mount’s Bay during the latter part of the eighteenth century, which serves to show how unfavourable was the soil for the stimulation and development of intellectual power. Cornwall at that time had but little commerce; and beyond the tidings carried by pedlars or ship-masters, or contained in the Sherborne Mercury—the only newspaper which then circulated in the west of England—it knew little or nothing of what was going on in the outer world. Its roads were mostly mere bridle-paths, and a carriage was as little known in Penzance as a camel. There was only one carpet in the town, the floors of the rooms being, as a rule, sprinkled with sea-sand:—

“All classes were very superstitious; even the belief in witches maintained its ground, and there was an almost unbounded credulity respecting the supernatural and monstrous.... Amongst the middle and higher classes there was little taste for literature and still less for science, and their pursuits were rarely of a dignified or intellectual kind. Hunting, shooting, wrestling, cock-fighting, generally ending in drunkenness, were what they most delighted in. Smuggling was carried on to a great extent, and drunkenness and a low scale of morals were naturally associated with it.”

Davy, an ardent, impulsive youth of strong social instincts, fond of excitement, and not over studious, seems, now that he was released from the restraint of school-life, to have come under the influence of such surroundings. For nearly a year he was restless and unsettled, spending much of his time like his father in rambling about the country and in fishing and shooting, and passing from desultory study to occasional dissipation. The death of his father, however, made a profound impression on his mind, and suddenly changed the whole course of his conduct. As the eldest son, and approaching manhood, he seems at once to have realised what was due to his mother and to himself. The circumstances of the family supplied the stimulus to exertion, and he dried his mother’s tears with the assurance that he would do all in his power for his brothers and sisters. A few weeks after the decease of his father he was apprenticed to Mr. Bingham Borlase, an apothecary and surgeon practising in Penzance, and at once marked out for himself a course of study and self-tuition almost unparalleled in the annals of biography, and to which he adhered with a strength of mind and tenacity of purpose altogether unlooked for in one of his years and of his gay and careless disposition. That it was sufficiently ambitious will be evident from the following transcript from the opening pages of his earliest note-book—a small quarto, with parchment covers, dated 1795:—

1. Theology,

or Religion, } { taught by Nature;

Ethics or Moral virtues } { by Revelation.

2. Geography.

3. My Profession.

1. Botany.

2. Pharmacy.

3. Nosology.

4. Anatomy.

5. Surgery.

6. Chemistry.

4. Logic.

5. Languages.

1. English.

2. French.

3. Latin.

4. Greek.

5. Italian.

6. Spanish.

7. Hebrew.

6. Physics.

1. The doctrines and properties of natural bodies.

2. Of the operations of nature.

3. Of the doctrines of fluids.

4. Of the properties of organised matter.

5. Of the organisation of matter.

6. Simple astronomy.

7. Mechanics.

8. Rhetoric and Oratory.

9. History and Chronology.

10. Mathematics.

The note-book opens with “Hints Towards the Investigation of Truth in Religious and Political Opinions, composed as they occurred, to be placed in a more regular manner hereafter.” Then follow essays “On the Immortality and Immateriality of the Soul”; “Body, Organised Matter”; on “Governments”; on “The Credulity of Mortals”; “An Essay to Prove that the Thinking Powers depend on the Organisation of the Body”; “A Defence of Materialism”; “An Essay on the Ultimate End of Being”; “On Happiness”; “On Moral Obligation.”

These early essays display the workings of an original mind, intent, it may be, on problems beyond its immature powers, but striving in all sincerity to work out its own thoughts and to arrive at its own conclusions. Of course, the daring youth of sixteen who enters upon an inquiry into the most difficult problems of theology and metaphysics, with, what he is pleased to call, unprejudiced reason as his sole guide, quickly passes into a cold fit of materialism. His mind was too impressionable, however, to have reached the stage of settled convictions; and in the same note-book we subsequently find the heads of a train of argument in favour of a rational religious belief founded on immaterialism.

Metaphysical inquiries seem, indeed, to have occupied the greater part of his time at this period; and his note-books show that he made himself acquainted with the writings of Locke, Hartley, Bishop Berkeley, Hume, Helvetius, Condorcet, and Reid, and that he had some knowledge of the doctrines of Kant and the Transcendentalists.

That he thought for himself, and was not unduly swayed by authority, is evident from the general tenour of his notes, and from the critical remarks and comments by which they are accompanied. Some of these are worth quoting:—

“Science or knowledge is the association of a number of ideas, with some idea or term capable of recalling them to the mind in a certain order.”

“By examining the phenomena of Nature, a certain similarity of effects is discovered. The business of science is to discover these effects, and to refer them to some common cause; that is to generalise ideas.”

As his impulsive, ingenuous disposition led him, even to the last, to speak freely of what was uppermost in his mind at the moment, we may be sure that his elders, the Rev. Dr. Tonkin, his good friend John Tonkin, and his grandmother Davy, with whom he was a great favourite, as he was with most old people, must have been considerably exercised at times with the metaphysical disquisitions to which they were treated; and we can well imagine that their patience was occasionally as greatly tried as that of the worthy member of the Society of Friends who wound up an argument with the remark, “I tell thee what, Humphry, thou art the most quibbling hand at a dispute I ever met with in my life.” Whether it was in revenge for this sally that the young disputant composed the “Letter on the Pretended Inspiration of the Quakers” which is to be found in one of his early note-books, does not appear.

We easily trace in these early essays the evidences of that facility and charm of expression which a few years later astonished and delighted his audiences at the Royal Institution, and which remained the characteristic features of his literary style. These qualities were in no small degree strengthened by his frequent exercises in poetry. For Davy had early tasted of the Pierian spring, and, like Pope, may be said to have lisped in numbers. At five he was an improvisatore, reciting his rhymes at some Christmas gambols, attired in a fanciful dress prepared by a playful girl who was related to him. That he had the divine gift was acknowledged by no less an authority than Coleridge, who said that “if Davy had not been the first Chemist, he would have been the first Poet of his age.” Southey also, who knew him well, said after his death, “Davy was a most extraordinary man; he would have excelled in any department of art or science to which he had directed the powers of his mind. He had all the elements of a poet; he only wanted the art. I have read some beautiful verses of his. When I went to Portugal, I left Davy to revise and publish my poem of ‘Thalaba.’”

Throughout his life he was wont, when deeply moved, to express his feelings in verse; and at times even his prose was so suffused with the glow of poetry that to some it seemed altiloquent and inflated. Some of his first efforts appeared in the “Annual Anthology,” a work printed in Bristol in 1799, and edited by Southey and Tobin, and interesting to the book-hunter as one of the first of the literary “Annuals” which subsequently became so fashionable.

Davy had an intense love of Nature, and nothing stirred the poetic fire within him more than the sight of some sublime natural object such as a storm-beaten cliff, a mighty mountain, a resistless torrent, or some spectacle which recalled the power and majesty of the sea. Not that he was insensible to the simpler charms of pastoral beauty, or incapable of sympathy with Nature in her softest, tenderest moods. But these things never seemed to move him as did some scene of grandeur, or some manifestation of stupendous natural energy.

The following lines, written on Fair Head during the summer of 1806, may serve as an example of how scenery when associated in his mind with the sentiments of dignity or strength affected him:—

“Majestic Cliff! Thou birth of unknown time, Long had the billows beat thee, long the waves Rush’d o’er thy hollow’d rocks, ere life adorn’d Thy broken surface, ere the yellow moss Had tinted thee, or the wild dews of heaven Clothed thee with verdure, or the eagles made Thy caves their aëry. So in after time Long shalt thou rest unalter’d mid the wreck Of all the mightiness of human works; For not the lightning, nor the whirlwind’s force, Nor all the waves of ocean, shall prevail Against thy giant strength, and thou shalt stand Till the Almighty voice which bade thee rise Shall bid thee fall.”

In spite of a love-passage which seems to have provoked a succession of sonnets, his devotions to Calliope were by no means so unremitting as to prevent him from following the plan of study he had marked out for himself. His note-books show that in the early part of 1796 he attacked the mathematics, and with such ardour that in little more than a year he had worked through a course of what he called “Mathematical Rudiments,” in which he included “fractions, vulgar and decimal; extraction of roots; algebra (as far as quadratic equations); Euclid’s elements of geometry; trigonometry; logarithms; sines and tangents; tables; application of algebra to geometry, etc.”

In 1797 he began the study of natural philosophy, and towards the end of this year, when he was close on nineteen, he turned his attention to chemistry, merely, however, at the outset as a branch of his professional education, and with no other idea than to acquaint himself with its general principles. His good fortune led him to select Lavoisier’s “Elements”—probably Kerr’s translation, published in 1796—as his text-book. No choice could have been happier. The book is well suited to a mind like Davy’s, and he could not fail to be impressed by the boldness and comprehensiveness of its theory, its admirable logic, and the clearness and precision of its statements.

From reading and speculation he soon passed to experiment. But at this time he had never seen a chemical operation performed, and had little or no acquaintance with even as much as the forms of chemical apparatus. Phials, wine-glasses, tea-cups, and tobacco-pipes, with an occasional earthen crucible, were all the paraphernalia he could command; the common mineral acids, the alkalis, and a few drugs from the surgery constituted his stock of chemicals. Of the nature of these early trials we know little. It is, however, almost certain that the experiments with sea-weed, described in his two essays “On Heat, Light and the Combinations of Light” and “On the Generation of Phosoxygen and the Causes of the Colours of Organic Beings” (see p. 30), were made at this time, and it is highly probable that the experiments on land-plants, which are directly related to those on the Fuci and are described in connection with them, were made at the same period. That he pursued his experiments with characteristic ardour is borne out by the testimony of members of his family, particularly by that of his sister, who sometimes acted as his assistant, and whose dress too frequently suffered from the corrosive action of his chemicals. The good Mr. Tonkin and his worthy brother, the Reverend Doctor, were also from time to time abruptly and unexpectedly made aware of his zeal. “This boy Humphry is incorrigible! He will blow us all into the air!” were occasional exclamations heard to follow the alarming noises which now and then proceeded from the laboratory. The well-known anecdote of the syringe which had formed part of a case of instruments of a shipwrecked French surgeon, and which Davy had ingeniously converted into an air-pump, although related by Dr. Paris “with a minuteness and vivacity worthy of Defoe,” is, in all probability, apocryphal. Nor has Lord Brougham’s story, that his devotion to chemical experiments and “his dislike to the shop” resulted in a disagreement with his master, and that “he went to another in the same place,” where “he continued in the same course,” any surer foundation in fact.

Two or three circumstances conduced to develop Davy’s taste for scientific pursuits, and to extend his opportunities for observation and experiment. One was his acquaintance with Mr. Gregory Watt; another was his introduction to Mr. Davies Gilbert (then Mr. Davies Giddy), a Cornish gentleman of wealth and position, who lived to succeed him in the presidential chair of the Royal Society.

Gregory Watt, the son of James Watt, the engineer, by his second marriage, was a young man of singular promise who, had he lived, would—if we may judge from his paper in the Philosophical Transactions—have almost certainly acquired a distinguished position in science. Of a weakly, consumptive habit, he was ordered to spend the winter of 1797 in Penzance, where he lodged with Mrs. Davy, boarding with the family. Young Watt was about two years older than Davy, and had just left the University of Glasgow, “his mind enriched beyond his age with science and literature, with a spirit above the little vanities and distinctions of the world, devoted to the acquisition of knowledge.” He remained in Penzance until the following spring, and by his example, and by the generous friendship which he extended towards him, he developed and strengthened Davy’s resolve to devote himself to science. Davy’s introduction to Mr. Gilbert, “a man older than himself, with considerable knowledge of science generally, and with the advantages of a University education,” was also a most timely and propitious circumstance. According to Dr. Paris—

“Mr. Gilbert’s attention was attracted to the future philosopher, as he was carelessly swinging over the hatch, or half-gate, of Mr. Borlase’s house, by the humorous contortions into which he threw his features. Davy it may be remarked, when a boy, possessed a countenance which even in its natural state was very far from comely; while his round shoulders, inharmonious voice and insignificant manner, were calculated to produce anything rather than a favourable impression: in riper years, he was what might be called ‘good-looking,’ although as a wit of the day observed, his aspect was certainly of the ‘bucolic’ character. The change which his person underwent, after his promotion to the Royal Institution, was so rapid that in the days of Herodotus, it would have been attributed to nothing less than the miraculous interposition of the Priestesses of Helen. A person, who happened to be walking with Mr. Gilbert upon the occasion alluded to, observed that the extraordinary looking boy in question was young Davy, the carver’s son, who, he added, was said to be fond of making chemical experiments.”

Mr. Gilbert was thus led to interest himself in the boy, whom he invited to his house at Tredrea, offering him the use of his library, and such other assistance in his studies as he could render. On one occasion he was taken over to the Hayle Copper-House, and had the opportunity of seeing a well-appointed laboratory:

“The tumultuous delight which Davy expressed on seeing, for the first time, a quantity of chemical apparatus, hitherto only known to him through the medium of engravings, is described by Mr. Gilbert as surpassing all description. The air-pump more especially fixed his attention, and he worked its piston, exhausted the receiver, and opened its valves, with the simplicity and joy of a child engaged in the examination of a new and favourite toy.”

It has already been stated that in the outset Davy attacked science as he did metaphysics, approaching it from the purely theoretical side. As might be surmised, his love of speculation quickly found exercise for itself, and within four months of his introduction to the study of science he had conceived and elaborated a new hypothesis on the nature of heat and light, which he communicated to Dr. Beddoes.

Dr. Thomas Beddoes was by training a medical man, who in various ways had striven to make a name for himself in science. He is known to the chemical bibliographer as the translator of the Chemical Essays of Scheele, and at one time occupied the Chair of Chemistry at Oxford. The geological world at the end of the eighteenth century regarded him as a zealous and uncompromising Plutonist. His character was thus described by Davy, who in the last year of his life jotted down, in the form of brief notes, his reminiscences of some of the more remarkable men of his acquaintance:—

“Beddoes was reserved in manner and almost dry; but his countenance was very agreeable. He was cold in conversation, and apparently much occupied with his own peculiar views and theories. Nothing could be a stronger contrast to his apparent coldness in discussion than his wild and active imagination, which was as poetical as Darwin’s.... On his deathbed he wrote me a most affecting letter, regretting his scientific aberrations.”

One of Dr. Beddoes’s “scientific aberrations” was the inception and establishment of the Pneumatic Institution, which he founded with a view of studying the medicinal effects of the different gases, in the sanguine hope that powerful remedies might be found amongst them. The Institution, which was supported wholly by subscription, was to be provided with all the means likely to promote its objects—a hospital for patients, a laboratory for experimental research, and a theatre for lecturing.

In seeking for a person to take charge of the laboratory, Dr. Beddoes bethought him of Davy, who had been recommended to him by Mr. Gilbert. In a letter dated July 4th, 1798, Dr. Beddoes thus writes to Mr. Gilbert:—

“I am glad that Mr. Davy has impressed you as he has me. I have long wished to write to you about him, for I think I can open a more fruitful field of investigation than any body else. Is it not also his most direct road to fortune? Should he not bring out a favourable result he may still exhibit talents for investigation, and entitle himself to public confidence more effectually than by any other mode. He must be maintained, but the fund will not furnish a salary from which a man can lay up anything. He must also devote his time for two or three years to the investigation. I wish you would converse with him upon the subject.... I am sorry I cannot at this moment specify a yearly sum, nor can I say with certainty whether all the subscribers will accede to my plan; most of them will, I doubt not. I have written to the principal ones, and will lose no time in sounding them all.”

A fortnight later, Dr. Beddoes again wrote to Mr. Gilbert:—

“I have received a letter from Mr. Davy since I wrote to you. He has oftener than once mentioned a genteel maintenance, as a preliminary to his being employed to superintend the Pneumatic Hospital. I fear the funds will not allow an ample salary; he must however be maintained. I can attach no idea to the epithet genteel, but perhaps all difficulties would vanish in conversation; at least I think your conversing with Mr. Davy will be a more likely way of smoothing difficulties than our correspondence. It appears to me, that this appointment will bear to be considered as a part of Mr. Davy’s medical education, and that it will be a great saving of expense to him. It may also be the foundation of a lucrative reputation; and certainly nothing on my part shall be wanting to secure to him the credit he may deserve. He does not undertake to discover cures for this or that disease; he may acquire just applause by bringing out clear, though negative results. During my journeys into the country I have picked up a variety of important and curious facts from different practitioners. This has suggested to me the idea of collecting and publishing such facts as this part of the country will from time to time afford. If I could procure chemical experiments that bore any relation to organised nature, I would insert them. If Mr. Davy does not dislike this method of publishing his experiments I would gladly place them at the head of my first volume, but I wish not that he should make any sacrifice of judgment or inclination.”

Thanks to Mr. Gilbert, the negotiation was brought to a successful issue. Mrs. Davy yielded to her son’s wishes, and Mr. Borlase surrendered his indenture, on the back of which he wrote that he released him from “all engagements whatever on account of his excellent behaviour”; adding, “because being a youth of great promise, I would not obstruct his present pursuits, which are likely to promote his fortune and his fame.” The only one of his friends who disapproved of the scheme was his old benefactor, Mr. John Tonkin, who had hoped to have established Davy in his native town as a surgeon. Mr. Tonkin was so irritated at the failure of his plans that he altered his will, and revoked the legacy of his house, which he had bequeathed to him.

A In some biographical notices—e.g. in the Gentleman’s Magazine, xcix. pt. ii. 9—the year is given as 1779.

“We are printing in Bristol the first volume of the ‘West Country Collection,’ which will, I suppose, be out in the beginning of January.

CHAPTER II.

THE PNEUMATIC INSTITUTION, BRISTOL, 1798–1801.

On October 2nd, 1798, Davy set out for Clifton with such books and apparatus as he possessed, and the MSS. of his essays on Heat and Light safely stowed away among his baggage. He was in the highest spirits, and full of confidence in the future. On his way through Okehampton he met the London coach decked with laurels and ribbons, and bringing the news of Nelson’s victory of the Nile, which he interpreted as a happy omen. A few days after his arrival, he thus wrote to his mother:—

“October 11th, 1798. Clifton.

“My dear Mother,—I have now a little leisure time, and I am about to employ it in the pleasing occupation of communicating to you an account of all the new and wonderful events that have happened to me since my departure.

“I suppose you received my letter, written in a great hurry last Sunday, informing you of my safe arrival and kind reception. I must now give you a more particular account of Clifton, the place of my residence, and of my new friends Dr. and Mrs. Beddoes and their family.

“Clifton is situated on the top of a hill, commanding a view of Bristol and its neighbourhood, conveniently elevated above the dirt and noise of the city. Here are houses, rocks, woods, town and country in one small spot; and beneath us, the sweetly-flowing Avon, so celebrated by the poets. Indeed there can hardly be a more beautiful spot; it almost rivals Penzance and the beauties of Mount’s Bay.

“Our house is capacious and handsome; my rooms are very large, nice and convenient; and, above all, I have an excellent laboratory. Now for the inhabitants, and, first, Dr. Beddoes, who, between you and me, is one of the most original men I ever saw—uncommonly short and fat, with little elegance of manners, and nothing characteristic externally of genius or science; extremely silent, and in a few words, a very bad companion. His behaviour to me, however, has been particularly handsome. He has paid me the highest compliments on my discoveries, and has, in fact, become a convert to my theory, which I little expected. He has given up to me the whole of the business of the Pneumatic Hospital, and has sent to the editor of the Monthly Magazine a letter, to be published in November, in which I have the honour to be mentioned in the highest terms. Mrs. Beddoes is the reverse of Dr. Beddoes—extremely cheerful, gay and witty; she is one of the most pleasing women I have ever met with. With a cultivated understanding and an excellent heart, she combines an uncommon simplicity of manners. We are already very great friends. She has taken me to see all the fine scenery about Clifton; for the Doctor, from his occupations and his bulk, is unable to walk much. In the house are two sons and a daughter of Mr. Lambton, very fine children, from five to thirteen years of age.

“I have visited Mr. Hare, one of the principal subscribers to the Pneumatic Hospital, who treated me with great politeness. I am now very much engaged in considering of the erection of the Pneumatic Hospital, and the mode of conducting it. I shall go down to Birmingham to see Mr. Watt and Mr. Keir in about a fortnight, where I shall probably remain a week or ten days; but before then you will again hear from me. We are just going to print at Cottle’s; in Bristol, so that my time will be much taken up the ensuing fortnight in preparations for the press. The theatre for lecturing is not yet open; but, if I can get a large room in Bristol, and subscribers, I intend to give a course of chemical lectures, as Dr. Beddoes seems much to wish it.

“My journey up was uncommonly pleasant; I had the good fortune to travel all the way with acquaintances. I came into Exeter in a most joyful time, the celebration of Nelson’s victory. The town was beautifully illuminated, and the inhabitants loyal and happy....

“It will give you pleasure when I inform you that all my expectations are answered and that my situation is just what I could wish. But, for all this, I very often think of Penzance and my friends, with a wish to be there; however that time will come. We are some time before we become accustomed to new modes of living and new acquaintances.

“Believe me, your affectionate son,

“Humphry Davy.”

Mrs. Beddoes, of whom Davy speaks in such appreciative terms, was one of the many sisters of Maria Edgeworth. She seems to have possessed much of the intelligence, wit, vivacity, and sunny humour of the accomplished authoress of “Castle Rackrent”; and, by her charm of manner and her many social gifts, to have made her husband’s house the centre of the literary and intellectual life of Clifton. Thanks to her influence, Davy had the good fortune to be brought into contact, at the very outset of his career, with Southey, Coleridge, the Tobins, Miss Edgeworth, and other notable literary men and women of his time, with many of whom he established firm and enduring friendships. He had always a sincere admiration for his fair patroness, and a grateful memory of her many acts of kindness to him at this period of his life. That she in turn had an esteem amounting to affection for the gifted youth is evident from the language of tender feeling and warm regard in which her letters to him are expressed. The sonnets accompanying these letters are couched in terms which admit of no doubt of the strength of her sentiments of sympathy and admiration, and some of the best efforts of his muse were addressed to her in return.

His work and prospects at the Pneumatic Institution are sufficiently indicated in the following letter to his friend and patron, Mr. Davies Gilbert, written five weeks after his arrival at Clifton:—

“Clifton, November 12, 1798.

“Dear Sir,—I have purposely delayed writing until I could communicate to you some intelligence of importance concerning the Pneumatic Institution. The speedy execution of the plan will, I think, interest you both as a subscriber and a friend to science and mankind. The present subscription is, we suppose nearly adequate to the purpose of investigating the medicinal powers of factitious airs; it still continues to increase, and we may hope for the ability of pursuing the investigation to its full extent. We are negotiating for a house in Dowrie Square, the proximity of which to Bristol, and its general situation and advantages, render it very suitable to the purpose. The funds will, I suppose, enable us to provide for eight or ten patients in the hospital, and for as many out of it as we can procure.

“We shall try the gases in every possible way. They may be condensed by pressure and rarefied by heat. Quere,—Would not a powerful injecting syringe furnished with two valves, one opening into an air-holder and the other into the breathing chamber, answer the purpose of compression better than any other apparatus? Can you not, from your extensive stores of philosophy, furnish us with some hints on this subject? May not the non-respirable gases furnish a class of different stimuli? of which the oxymuriatic acid gas [chlorine] would stand the highest, if we may judge from its effects on the lungs; then, probably, gaseous oxyd of azote [nitrous oxide?] and hydrocarbonate [the gases obtained by passing steam over red-hot charcoal].

“I suppose you have not heard of the discovery of the native sulphate of strontian in England. I shall perhaps surprise you by stating that we have it in large quantities here. It had long been mistaken for sulphate of barytes, till our friend Clayfield, on endeavouring to procure the muriate of barytes from it by decomposition, detected the strontian. We opened a fine vein of it about a fortnight ago at the Old Passage near the mouth of the Severn.B...

“We are printing in Bristol the first volume of the ‘West Country Collection,’ which will, I suppose, be out in the beginning of January.

“Mrs. Beddoes ... is as good, amiable, and elegant as when you saw her.

“Believe me, dear Sir, with affection and respect, truly yours,

“Humphry Davy.”

B Cf. An account of several veins of Sulphate of Strontites, found in the neighbourhood of Bristol, with an Analysis of the different varieties. By W. Clayfield. “Nicholson’s Journ.,” III., 1800, pp. 36–41.

The work alluded to in this letter made its appearance in the early part of 1799, under the title of “Contributions to Physical and Medical Knowledge, principally from the West of England; collected by Thomas Beddoes, M.D.” The first half of the volume, in accordance with the editor’s promise, is occupied by two essays from Davy: the first “On Heat, Light, and the Combinations of Light, with a new Theory of Respiration”; the second “On the Generation of Phosoxygen (Oxygen Gas), and on the Causes of the Colours of Organic Beings.”

To the student these essays have no other interest than is due to the fact that they are Davy’s first contribution to the literature of science. No beginning could be more inauspicious. It is the first step that costs, and Davy’s first step had well nigh cost him all that he lived for. As additions to knowledge they are worthless; indeed, a stern critic might with justice characterise them in much stronger language. Nowadays such writings would hopelessly damn the reputation of any young aspirant for scientific fame, for it is indeed difficult to believe, as we read paragraph after paragraph, that their author had any real conception of science, or that he was capable of understanding the need or appreciating the value of scientific evidence.

The essays are partly experimental, partly speculative, and the author apparently would have us believe that the speculations are entirely subservient to and dependent on the experiments. Precisely the opposite is the case. Davy’s work had its origin in Lavoisier’s “Traité Elémentaire,” almost the only text-book of chemistry he possessed. Lavoisier taught, in conformity with the doctrine of his time, that heat was a material substance, and that oxygen was essentially a compound body, composed of a simple substance associated with the matter of heat, or caloric. The young novitiate puts on his metaphysical shield and buckler; and with the same jaunty self-confidence that he assailed Locke and criticised Berkeley, enters the lists against this doctrine, determined, as he told Gregory Watt, “to demolish the French theory in half an hour.”

After a few high-sounding but somewhat disconnected introductory sentences, and a complimentary allusion to “the theories of a celebrated medical philosopher, Dr. Beddoes,” he proceeds to put Lavoisier’s question, “La lumière, est-elle une modification du calorique, ou bien le calorique est-il une modification de la lumière?” to the test of experiment. This he does by repeating Hawksbee’s old experiment of snapping a gunlock “armed with an excellent flint” in an exhausted receiver. The experiment fails in his hands; such phenomena as he observes he misinterprets, and he at once concludes that light and heat have nothing essentially in common. “Nor can light be as some philosophers suppose, a vibration of the imaginary fluid ether. For even granting the existence of this fluid it must be present in the exhausted receiver as well as in atmospheric air; and if light is a vibration of this fluid, generated by collision between flint and steel in atmospheric air, it should likewise be produced in the exhausted receiver, where a greater quantity of ether is present, which is not the case.” Since, then, it is neither an effect of caloric nor of an ethereal fluid, and “as the impulse of a material body on the organ of vision is essential to the generation of a sensation, light is consequently matter of a peculiar kind, capable when moving through space with the greatest velocity, of becoming the source of a numerous class of our sensations.”

By experiments, faultless in principle but wholly imperfect in execution, he next seeks to show that caloric, or the matter of heat, has no existence. His reasoning is clear, and his conceptions have the merit of ingenuity, but any real acquaintance with the conditions under which the experiments were made would have convinced him that the results were untrustworthy and equivocal; and yet, in spite of the dubious character of his observations, he arrived at a theory of the essential nature of heat which is in accord with our present convictions, and which he states in the following terms:—

“Heat, or that power which prevents the actual contact of the corpuscles of bodies, and which is the cause of our peculiar sensations of heat and cold, may be defined a peculiar motion, probably a vibration, of the corpuscles of bodies, tending to separate them.”

This conception of the nature of heat did not, of course, originate with him, and it was a question with his contemporaries how far he was influenced by Rumford’s work and teaching. On this point Dr. Beddoes’s testimony is direct and emphatic. He says:—

“The author [Davy] derived no assistance whatever from the Count’s ingenious labours. My first knowledge of him arose from a letter written in April 1798, containing an account of his researches on heat and light; and his first knowledge of Count Rumford’s paper was conveyed by my answer. The two Essays contain proofs enough of an original mind to make it credible that the simple and decisive experiments on heat were independently conceived. Nor is it necessary, in excuse or in praise of his system, to add, that, at the time it was formed, the author was under twenty years of age, pupil to a surgeon-apothecary, in the most remote town of Cornwall, with little access to philosophical books, and none at all to philosophical men.”

Having thus, with Beddoes, expunged caloric from his chemical system, Davy proceeds to elevate the matter of light into its place. According to Lavoisier oxygen gas was a compound of a simple substance and caloric; Davy seeks to show that it is a compound of a simple substance and light. He objects to the use of the word “gas,” since, according to French doctrine, it is to be taken as implying not merely a state of aggregation but a combination of caloric with another substance, and suggests therefore that what was called oxygen gas should henceforth be known as phosoxygen. His “proofs” that oxygen is really a compound of a simple substance with “matter in a peculiar state of existence” are perhaps the most futile that could be imagined. Charcoal, phosphorus, sulphur, hydrogen, and zinc were caused to burn in oxygen; light was evolved, oxides were formed, and a deficiency of weight was in each case observed. He regrets, however, that he “possessed no balance sufficiently accurate to determine exactly the deficiency of weight from the light liberated in different combustive processes.”

“From these experiments, it appears that in the chemical process of the formation of many oxyds and acids, light is liberated, the phosoxygen and combustible base consumed, and a new body formed.... Since light is liberated in these processes, it is evident that it must be liberated either from the phosoxygen or from the combustible body.... If the light liberated in combustion be supposed (according to Macquer’s and Hutton’s theories) to arise from the combustible body, then phosoxygen must be considered as a simple substance; and it follows on this supposition, that whenever phosoxygen combines with combustible bodies, either directly or by attraction from any of its combinations, light must be liberated, which is not the case, as carbon, iron and many other substances, may be oxydated by the decomposition of water without the liberation of light.”

Davy is here on the horns of a dilemma, but he ignores the difficulty, and, with characteristic “flexibility of adaptation,” proceeds to offer synthetical proofs “that the presence of light is absolutely essential to the production of phosoxygen.” The character of the “proofs” is sufficiently indicated by the following extracts:—

“When pure oxyd of lead is heated as much as possible, included from light, it remains unaltered; but when exposed to the light of a burning-glass, or even of a candle, phosoxygen is generated and the metal revivified.”

“Oxygenated muriatic acid [chlorine] is a compound of muriatic acid, oxygen and light, as will be hereafter proved. The combined light is not sufficient to attract the oxygen from the base [muriatic acid] to form phosoxygen; but its attraction for oxygen renders the [oxygenated muriatic] acid decomposable. If this acid be heated in a close vessel and light excluded no phosoxygen is formed; but if it be exposed to the solar light, phosoxygen is formed; the acid loses its oxygen and light and becomes muriatic acid.”

“A plant of Arenaria Tenuifolia planted in a pot filled with very dry earth, was inserted in carbonic acid, under mercury. The apparatus was exposed to the solar light, for four days successively, in the month of July. By this time the mercury had ascended considerably. The gas in the vessel was now measured. There was a deficiency of one-sixth of the whole quantity. After the carbonic acid was taken up by potash, the remaining quantity, equal to one-seventh of the whole, was phosoxygen almost pure. From this experiment, it is evident that carbonic acid is decomposed by two attractions; that of the vegetable for carbon and of light for oxygen: the carbon combines with the plant, and the light and oxygen combined are liberated in the form of phosoxygen.”

The accounts which Davy gives of his experiments, as well as of the phenomena which he professes to have observed, may awaken an uneasy doubt as to his absolute integrity; for, it is hardly necessary to point out, he could not possibly have obtained the results which he describes. The presence or absence of light in no wise affects the decomposition by heat of minium; chlorine, as he himself subsequently established, contains no oxygen; and a plant is incapable of decomposing pure undiluted carbonic acid, even in the brightest sunshine. But the work of a youth of nineteen, imaginative, sanguine, and impetuous, with no training as an experimentalist, and with only a limited access to scientific memoirs, cannot be judged by too severe a canon. The faculty of self-deception, even in the largest and most receptive minds, often in those of matured power and ripened experience, is boundless. Davy himself affords an exemplification of the truth of his own words, written years afterwards: “The human mind is always governed not by what it knows, but by what it believes; not by what it is capable of attaining, but by what it desires.”

It is not necessary to show how the presumptuous youth drove his hobby with all the reckless daring of a Phæton. Phlogiston and oxygen had in turn been the central conceptions of theories of chemistry; phosoxygen was to supplant them. It was to explain everything—the blue colour of the sky, the electric fluid, the Aurora Borealis, the phenomena of fiery meteors, the green of the leaf, the red of the rose, and the sable hue of the Ethiopian; perception, thought, and happiness; and why women are fairer than men. But Jupiter, in the shape of a Reviewer, soon hurled the adventurous boy from the giddy heights to which he had soared. The “West Country Collection” received scant sympathy from the critics, and the phosoxygen theory was either mercilessly ridiculed, or treated with contempt.

There is no doubt that Davy keenly felt the position in which he now stood. His pride was humbled, and the humiliation was as gall and wormwood. The vision of fame which his ardour had conjured up on the top of the Bristol coach—was it all a baseless fabric, and its train of honours and emoluments an insubstantial pageant? All he could plead was that his critics had not understood that these experiments were made when he had studied chemistry only four months, when he had never seen a single experiment executed, and when all his information was derived from Nicholson’s “Chemistry” and Lavoisier’s “Elements.” But his good sense quickly came to his rescue. After the first feelings of anger and mortification had passed, he recognised the justice of his punishment, much as he might resent the mode in which it was inflicted. How keen was the smart will appear from the following reflection, written in the August of the year in which the essays were published:—

“When I consider the variety of theories that may be formed on the slender foundation of one or two facts, I am convinced that it is the business of the true philosopher to avoid them altogether. It is more laborious to accumulate facts than to reason concerning them; but one good experiment is of more value than the ingenuity of a brain like Newton’s.”

About the same time he wrote:—

“I was perhaps wrong in publishing, with such haste, a new theory of chemistry. My mind was ardent and enthusiastic. I believed that I had discovered the truth. Since that time my knowledge of facts is increased—since that time I have become more sceptical.”

In the October of the same year he wrote:—

“Convinced as I am that chemical science is in its infancy, that an infinite variety of new facts must be accumulated before our powers of reasoning will be sufficiently extensive, I renounce my own particular theory as being a complete arrangement of facts: it appears to me now only as the most probable arrangement.”

By the end of the year the repentance was complete, and recantation followed. In a letter which appeared in Nicholson’s Journal in February, 1800, he corrects some of the errors into which he had fallen, and says, “I beg to be considered as a sceptic with regard to my own particular theory of the combinations of light, and theories of light in general.” To the end of his days Davy never forgot the lesson which his earliest effort had taught him; and there is no question that the memory of it acted as a salutary check on the exuberance of his fancy and the flight of his imagination. The wound to his self-love was, however, never wholly healed. Nothing annoyed him more than any reference to Beddoes’s book, and he declared to Dr. Hope that he would joyfully relinquish any little glory or reputation he might have acquired by his later researches were it possible to withdraw his share in that work and to remove the impression he feared it was likely to produce.

And yet, in spite of the unqualified censure with which they were received, and of the severe condemnation of them by their own author, we are disposed to agree with Dr. Davy that posterity will not suffer these essays to be wholly blotted out from the records of science. That the experimental part was for the most part radically bad, that the generalisation was hasty and presumptuous, and the reasoning imperfect, cannot be gainsaid. But, withal, the essays display some of Davy’s best and happiest characteristics. There is dignity of treatment and a sense of the nobility of the theme on which he is engaged; the literary quality is admirable; there is clearness of perception and perspicuity of statement; the facts as he knew them—or as he thought he knew them—are marshalled with ingenuity and with a logical precision worthy of his model and teacher Lavoisier; his style is sonorous and copious, even to redundancy—some of the periods indeed glow with all the fervour and richness of his Royal Institution lectures. However wild and visionary his speculations may seem, minds like those of Coleridge and Southey were not insensible to the intrinsic beauty of some of his ideas. His theory of respiration might not be true, but it had at least the merit of poetic charm in its consequence that the power and perspicacity of a thinker had some relation to the amount of light secreted by his brain. Even good old Dr. Priestley, whose Pegasus could never be stirred beyond the gentlest of ambles, tells us in the Appendix to his “Doctrine of Phlogiston Established” that Mr. H. Davy’s essays had impressed him with a high opinion of the philosophical acumen of their author. “His ideas were to me new and very striking; but,” he adds, with a caution that was not habitual, “they are of too great consequence to be decided upon hastily.”

Among the letters entrusted to me is one from Priestley, which must have been particularly gratifying to the young man. It is as follows:—

“Northumberland, Oct. 31, 1801.

“Sir,—I have read with admiration your excellent publications, and have received much instruction from them. It gives me peculiar satisfaction that, as I am far advanced in life, and cannot expect to do much more, I shall leave so able a fellow-labourer of my own country in the great fields of experimental philosophy. As old an experimenter as I am, I was near forty before I made any experiments on the subject of Air, and then without, in a manner, any previous knowledge of chemistry. This I picked up as I could, and as I found occasion for it, from books. I was also without apparatus, and laboured under many other disadvantages. But my unexpected success induced the friends of science to assist me, and then I wanted for nothing. I rejoice that you are so young a man; and perceiving the ardour with which you begin your career, I have no doubt of your success.

“My son, for whom you express a friendship, and which he warmly returns, encourages me to think that it may not be disagreeable to you to give me information occasionally of what is passing in the philosophical world, now that I am at so great a distance from it, and interested, as you may suppose, in what passes in it. Indeed, I shall take it as a great favour. But you must not expect anything in return. I am here perfectly insulated, and this country furnishes but few fellow-labourers, and these are so scattered, that we can have but little communication with each other, and they are equally in want of information with myself. Unfortunately, too, correspondence with England is very slow and uncertain, and with France we have not as yet any intercourse at all, tho we hope to have it soon....

“I thank you for the favourable mention you so frequently make of my experiments, and have only to remark that in Mr. Nicholson’s Journal you say that the conducting power of charcoal was first observed by those who made experiments on the pile of Volta; whereas it was one of the earliest that I made, and gave an account of in my History of Electricity, and in the Philosophical Transactions. And in your treatise on the Nitrous Oxide p. 55 you say, and justly, that I concluded this air to be lighter than that of the atmosphere. This, however, was an error in the printing that I cannot account for. It should have been alkaline air, as you will see the experiment necessarily requires.

“With the greatest esteem, I am Sir, yours sincerely

“J. Priestley.”

In Davy’s next contribution, “On the Silex composing the Epidermis, or External Bark, and contained in other parts of certain Vegetables,” published in Nicholson’s Journal in the early part of 1800, we find the evidence of a chastened and contrite spirit. The theme is humble enough, and the language as sober and sedate as that of Mr. Cavendish. The chance observation of a child that two bonnet-canes rubbed together in the dark produced a luminous appearance, led him to investigate the cause, which he found to reside in the crystallised silica present in the epidermis. Reeds and grasses, and the straw of cereals, were also found to be rich in silica, from which he concludes that “the flint entering into the composition of these hollow vegetables may be considered as analogous to the bones of animals; it gives to them stability and form, and by being situated in the epidermis more effectively preserves their vessels from external injury.” It is doubtful, however, whether the rigidity of the stems of cereals is wholly due to the silica they contain.

From a letter to Mr. Davies Gilbert, dated April 10th, 1799, we learn that he had now begun to investigate the effects of gases in respiration. In the early part of the year he had removed to a house in Dowry Square, Clifton, where he had fitted up a laboratory. After thanking his friend for his critical remarks on his recently published essays, he says:

“Your excellent and truly philosophic observations will induce me to pay greater attention to all my positions.... I made a discovery yesterday which proves how necessary it is to repeat experiments. The gaseous oxide of azote is perfectly respirable when pure. It is never deleterious but when it contains nitrous gas. I have found a mode of obtaining it pure, and I breathed to-day, in the presence of Dr. Beddoes and some others, sixteen quarts of it for near seven minutes. It appears to support life longer than even oxygen gas, and absolutely intoxicated me. Pure oxygen gas produced no alteration in my pulse, nor any other material effect; whereas this gas raised my pulse upwards of twenty strokes, made me dance about the laboratory as a madman, and has kept my spirits in a glow ever since. Is not this a proof of the truth of my theory of respiration? for this gas contains more light in proportion to its oxygen than any other, and I hope will prove a most valuable medicine.

“We have upwards of eighty out-patients in the Pneumatic Institution, and are going on wonderfully well.”

This observation of the respirability of nitrous oxide, and of the effects of its inhalation, was quickly confirmed. Southey, Coleridge, Tobin (the dramatist), Joseph Priestley, the son of the chemist, the two Wedgwoods, and a dozen other people of lesser note were induced to breathe the gas and to record their sensations. The discovery was soon noised abroad; Dr. Beddoes dispatched a short note to Nicholson’s Journal, and the fame of the Pneumatic Institution went up by leaps and bounds.

Maria Edgeworth, who was at the time on a visit to her sister, thus writes:—

“A young man, a Mr. Davy, at Dr. Beddoes’, who has applied himself much to chemistry, has made some discoveries of importance, and enthusiastically expects wonders will be performed by the use of certain gases, which inebriate in the most delightful manner, having the oblivious effects of Lethe, and at the same time giving the rapturous sensations of the Nectar of the Gods! Pleasure even to madness is the consequence of this draught. But faith, great faith, is I believe necessary to produce any effect upon the drinkers, and I have seen some of the adventurous philosophers who sought in vain for satisfaction in the bag of Gaseous Oxyd, and found nothing but a sick stomach and a giddy head.”

Laughing-gas, indeed threatened to become, like Priestley’s dephlogisticated air, “a fashionable article in luxury.” Monsieur Fiévée, in his “Lettres sur l’Angleterre, 1802,” names it in the catalogue of follies to which the English were addicted, and says the practice of breathing it amounted to a national vice!

Davy had no sooner discovered that the gas might be respired, than he proceeded to attack the whole subject of the chemistry of the oxides of nitrogen, and of nitrous oxide in particular, and after ten months of incessant labour he put together the results of his observations in an octavo volume, entitled, “Researches, Chemical and Philosophical, chiefly concerning Nitrous Oxide, or Dephlogisticated Nitrous Air, and its Respiration. By Humphry Davy, Superintendent of the Medical Institution.” The book appeared in the summer of 1800, and immediately re-established its author’s character as an experimentalist. Thomson, in his “History of Chemistry,” says of it: “This work gave him at once a high reputation as a chemist, and was really a wonderful performance, when the circumstances under which it was produced are taken into consideration.” In spite, however, of the eulogies with which it was welcomed, its sale was never very extensive, and a second edition was not required. In fact, the work as a whole was hardly calculated to attract the general public, whose only concern with laughing-gas was in its powers as an exhilarant. Indeed, this aspect of the question is not wholly lost on Davy himself, who is careful to point out that “if the pleasurable effects or medical properties of the nitrous oxide should ever make it an article of general request, it may be procured with much less time, labour, and expense than most of the luxuries, or even necessaries, of life”; and in a footnote he adds. “A pound of nitrate of ammonia costs 5s. 10d. (its present price is 9d.!). This pound, properly decomposed, produces rather more than 34 moderate doses of the air, so that the expense of a dose is about 2d. What fluid stimulus can be procured at so cheap a rate?”

To the chemical student the book had, and still has, many features of interest. It contains a number of important facts, based on original and fairly accurate observation. In the arrangement of these facts “I have been guided as much as possible,” says their author, “by obvious and simple analogies only. Hence, I have seldom entered into theoretical discussions, particularly concerning light, heat, and other agents, which are known only by isolated effects. Early experience has taught me the folly of hasty generalisation.” The work is divided into four main sections. The first chiefly relates to the production of nitrous oxide, and the analysis of nitrous gas and nitrous acid. He minutely studies the mode of decomposition of ammonium nitrate (first observed by Berthollet), and shows that it is an endothermic phenomenon, varying in character with the temperature and manner of heating. He is thus led to offer the following Speculations on the Decompositions of Nitrate of Ammonia:—

“All the phenomena of chemistry concur in proving that the affinity of one body, A, for another, B, is not destroyed by its combination with a third, C, but only modified; either by condensation or expansion, or by the attraction of C for B. On this principle the attraction of compound bodies for each other must be resolved into the reciprocal attractions of their constituents, and consequently the changes produced in them by variations of temperature explained from the alterations produced in the attractions of those constituents.”

The singular property possessed by ammonium nitrate of decomposing in several distinct modes according to the rapidity of heating and the temperature to which the substance is raised, first indicated by Davy, has been minutely studied by M. Berthelot, who has shown that this comparatively simple salt may be decomposed in as many as six different ways. It may be (1) dissociated into gaseous nitric acid and ammonia; (2) decomposed into nitrous oxide and water; (3) resolved into nitrogen, oxygen, and water, (4) or into nitric oxide, nitrogen, and water, (5) or into nitrogen, nitrogen peroxide, and water; or lastly (6), under the influence of spongy platinum, it may be resolved into gaseous nitric acid, nitrogen, and aqueous vapour. These different modes of decomposition may be distinct or simultaneous; or, more exactly, the predominance of any one of them depends on relative rapidity and on the temperature at which decomposition is produced. This temperature is not fixed, but is itself subordinate to the rapidity of heating (cf. Berthelot’s “Explosives and Their Power,” translated by Hake and Macnab). The assertion of De la Metherie, that the gas produced by the solution of platinum in nitromuriatic acid was identical with the dephlogisticated nitrous air of Priestley (nitrous oxide), led Davy to examine the gaseous products of this reaction more particularly. He had no difficulty in disproving the statement of the French chemist; but his observations, although accurate, led him to no definite conclusion. “It remains doubtful,” he says, “whether the gas consists simply of highly oxigenated muriatic acid and nitrogen, produced by the decomposition of nitric acid from the coalescing affinities of platina and muriatic acid for oxygen; or whether it is composed of a peculiar gas, analogous to oxigenated muriatic acid and nitrogen, generated from some unknown affinities.” The real nature of the gas, which has also been considered by Lavoisier as a particular species, not hitherto described, was first established by Gay Lussac, when Davy had himself proved that “oxigenated muriatic acid” was a simple substance.

In the second section the combinations and composition of nitrous oxide are investigated, and an account is given of its decomposition by combustible bodies, and a series of experiments are described which are now among the stock illustrations of the chemical lecture-room. As to its composition, he says, “taking the mean estimations from the most accurate experiments, we may conclude that 100 grains of the known ponderable matter of nitrous oxide consist of about 36·7 oxygen and 63·3 nitrogen”—no very great disparity from modern numbers, viz. 36·4 oxygen and 63·6 nitrogen. He concludes this section with a short review of the characteristic properties of the combinations of oxygen and nitrogen, among which he is led to class atmospheric air.

“That the oxygen and nitrogen of atmospheric air exist in chemical union, appears almost demonstrable from the following evidences.

“1st. The equable diffusion of oxygen and nitrogen through every part of the atmosphere, which can hardly be supposed to depend on any other cause than an affinity between these principles.

“2dly. The difference between the specific gravity of atmospheric air, and a mixture of 27 parts oxygen and 73 nitrogen, as found by calculation; a difference apparently owing to expansion in consequence of combination.”

These “evidences” had already been adduced by others, as stated by Davy; the first was subsequently disproved by Dalton, the second was based on inaccurate analyses of air.

To these Davy added two other “proofs” which originated with him:—

“3dly. The conversion of nitrous oxide into nitrous acid, and a gas analogous to common air, by ignition.

“4thly. The solubility of atmospheric air undecompounded.”

Of these it may be stated that the first is invalid, and the second not true. Nitrous oxide may, under certain circumstances, give rise to a mixture of oxygen and nitrogen, but not necessarily in the same proportion as in common air; and the air boiled out from water has not the same composition as atmospheric air.

Davy a few years afterwards obtained much clearer views as to the real nature of the atmosphere, and was, in fact, one of the earliest to recognise that it is merely a mixture of oxygen and nitrogen.