автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Buddhism

BRASS IMAGE OF GAUTAMA BUDDHA FROM CEYLON.

He is seated on the Mućalinda Serpent (see p. 480), in an attitude of profound meditation, with eyes half closed, and five rays of light emerging from the crown of his head. [Frontispiece.

BUDDHISM,

IN ITS CONNEXION WITH BRĀHMANISM AND HINDŪISM, AND IN ITS CONTRAST WITH CHRISTIANITY,

BY

SIR MONIER MONIER-WILLIAMS, K.C.I.E.,

M.A., HON. D.C.L. OF THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD, HON. LL.D. OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA, HON. PH.D. OF THE UNIVERSITY OF GÖTTINGEN, HON. MEMBER OF THE ASIATIC SOCIETIES OF BENGAL AND BOMBAY, AND OF THE ORIENTAL AND PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETIES OF AMERICA, BODEN PROFESSOR OF SANSKṚIT, AND LATE FELLOW OF BALLIOL COLLEGE, OXFORD, ETC.

NEW YORK:

MACMILLAN AND CO.

1889.

[All rights reserved.]

PREFACE.

The ‘Duff Lectures’ for 1888 were delivered by me at Edinburgh in the month of March. In introducing my subject, I spoke to the following effect:—

‘I wish to express my deep sense of the responsibility which the writing of these Lectures has laid upon me, and my earnest desire that they may, by their usefulness, prove in some degree worthy of the great missionary whose name they bear.

‘Dr. Duff was a man of power, who left his own foot-print so deeply impressed on the soil of Bengal, that its traces are never likely to be effaced, and still serve to encourage less ardent spirits, who are striving to imitate his example in the same field of labour.

‘But not only is the impress of his vigorous personality still fresh in Bengal. He has earned an enduring reputation throughout India and the United Kingdom, as the prince of educational missionaries. He was in all that he undertook an enthusiastic and indefatigable workman, of whom, if of any human being, it might be truly said, that, when called upon to quit the sphere of his labours, “he needed not to be ashamed.” No one can have travelled much in India without having observed how wonderfully the results of his indomitable energy and fervid eloquence in the cause of Truth wait on the memory of his work everywhere. Monuments may be erected and lectureships founded to perpetuate his name and testify to his victories over difficulties which few other men could have overcome, but better than these will be the living testimony of successive generations of Hindū men and women, whose growth and progress in true enlightenment will be due to the seed which he planted, and to which God has given the increase.’

I said a few more words expressive of my hope that the ‘Life of Dr. Duff’[1] would be read and pondered by every student destined for work of any kind in our Indian empire, and to that biography I refer all who are unacquainted with the particulars of the labours of a man to whom Scotland has assigned a place in the foremost rank of her most eminent Evangelists.

I now proceed to explain the process by which these Lectures have gradually outgrown the limits required by the Duff Trustees.

When I addressed myself to the carrying out of their wishes—communicated to me by Mr. W. Pirie Duff—I had no intention of undertaking more than a concise account of a subject which I had been studying for many years. I conceived it possible to compress into six Lectures a scholarly sketch of what may be called true Buddhism,—that is, the Buddhism of the Piṭakas or Pāli texts which are now being edited by the Pāli Text Society, and some of which have been translated in the ‘Sacred Books of the East.’ It soon, however, became apparent to me that to write an account of Buddhism which would be worthy of the great Indian missionary, I ought to exhibit it in its connexion with Brāhmanism and Hindūism and even with Jainism, and in its contrast with Christianity. Then, as I proceeded, I began to feel that to do justice to my subject I should be compelled to enlarge the range of my researches, so as to embrace some of the later phases and modern developments of Buddhism. This led me to undertake a more careful study of Koeppen’s Lamaismus than I had before thought necessary. Furthermore, I felt it my duty to study attentively numerous treatises on Northern Buddhism, which I had before read in a cursory manner. I even thought it incumbent on me to look a little into the Tibetan language, of which I was before wholly ignorant.

I need scarcely explain further the process of expansion through which the present work has passed. A conviction took possession of my mind, that any endeavour to give even an outline of the whole subject of Buddhism in six Lectures, would be rather like the effort of a foolish man trying to paint a panorama of London on a sheet of note-paper. Hence the expansion of six Lectures into eighteen, and it will be seen at once that many of these eighteen are far too long to have been delivered in extenso. In point of fact, by an arrangement with the Trustees, only a certain portion of any Lecture was delivered orally. The present work is rather a treatise on Buddhism printed and published in memory of Dr. Duff.

I need not encumber the Preface with a re-statement of the reasons which have made the elucidation of an intricate subject almost hopelessly difficult. They have been stated in the Introductory Lecture (pp. 13, 14).

Moreover the plan of the present volume has been there set forth (see p. 17).

I may possibly be asked by weary readers why I have ventured to add another tributary to the too swollen stream of treatises on Buddhism? or some may employ another metaphor and inquire why I have troubled myself to toil and plod over a path already well travelled over and trodden down? My reply is that I think I can claim for my own work an individuality which separates it from that of others—an individuality which may probably commend it to thoughtful students of Buddhism as helping to clear a thorny road, and introduce some little order and coherence into the chaotic confusion of Buddhistic ideas.

At any rate I request permission to draw attention to the following points, which, I think, may invest my researches with a distinctive character of their own.

In the first place I have been able to avail myself of the latest publications of the Pāli Text Society, and to consult many recent works which previous writers on Buddhism have not had at their command.

Secondly, I have striven to combine scientific accuracy with a popular exposition sufficiently readable to satisfy the wants of the cultured English-speaking world—a world crowded with intelligent readers who take an increasing interest in Buddhism, and yet know nothing of Sanskṛit, Pāli, and Tibetan.

Thirdly, I have aimed at effecting what no other English Orientalist has, to my knowledge, ever accomplished. I have endeavoured to deal with a complex subject as a whole, and to present in one volume a comprehensive survey of the entire range of Buddhism, from its earliest origin in India to its latest modern developments in other Asiatic countries.

Fourthly, I have brought to the study of Buddhism and its sacred language Pāli, a life-long preparatory study of Brāhmanism and its sacred language Sanskṛit.

Fifthly, I have on three occasions travelled through the sacred land of Buddhism (p. 21), and have carried on my investigations personally in the place of its origin, as well as in Ceylon and on the borders of Tibet.

Lastly, I have depicted Buddhism from the standpoint of a believer in Christianity, who has shown, by his other works on Eastern religions, an earnest desire to give them credit for all the good they contain.

In regard to this last point, I shall probably be told by some enthusiastic admirers of Buddhism, that my prepossessions and predilections—inherited with my Christianity—have, in spite of my desire to be just, distorted my view of a system with which I have no sympathy. To this I can only reply, that my consciousness of my own prepossessions has made me the more sensitively anxious to exhibit Buddhism under its best aspects, as well as under its worst. An attentive perusal of my last Lecture (see p. 537) will, I hope, make it evident that I have at least done everything in my power to dismiss all prejudice from my mind, and to assume and maintain the attitude of an impartial judge. And to this end I have taken nothing on trust, or at second hand. I have studied Pāli, as I have the other Indian Prākṛits, on my own account, and independently. I have not accepted unreservedly any man’s interpretation of the original Buddhist texts, and have endeavoured to verify for myself all doubtful statements and translations which occur in existing treatises. Of course I owe much to modern Pāli scholars, and writers on Buddhism, and to the translators of the ‘Sacred Books of the East;’ but I have frequently felt compelled to form an independent opinion of my own.

The translations given in the ‘Sacred Books of the East’—good as they generally are—have seemed to me occasionally misleading. I may mention as an instance the constant employment by the translators of the word ‘Ordination’ for the ceremonies of admission to the Buddhist monkhood (see pp. 76-80 of the present volume). I have ventured in such instances to give what has appeared to me a more suitable equivalent for the Pāli. On the same principle I have avoided all needless employment of Christian terminology and Bible-language to express Buddhist ideas.

For example, I have in most cases excluded such words as ‘sin,’ ‘holiness,’ ‘faith’, ‘trinity,’ ‘priest’ from my explanations of the Buddhist creed, as wholly unsuitable.

I regret that want of space has compelled me to curtail my observations on Jainism—the present representative of Buddhistic doctrines in India (see p. 529.) I hope to enter more fully on this subject hereafter.

The names of authors to whom students of Buddhism are indebted are given in my first Lecture (pp. 14, 15). We all owe much to Childers. My own thanks are specially due to General Sir Alexander Cunningham, to Professor E. B. Cowell of Cambridge, Professor Rhys Davids, Dr. Oldenberg, Dr. Rost, Dr. Morris, Dr. Wenzel, who have aided me with their opinions, whenever I have thought it right to consult them. Dr. Rost, C.I.E., of the India Office, is also entitled to my warmest acknowledgments for having placed at my disposal various subsidiary works bearing on Buddhism, some of which belong to his own Library.

My obligations to Mr. Hoey’s translation of Dr. Oldenberg’s ‘Buddha,’ to the translations of the travels of the Chinese pilgrims by Professor Legge, Mr. Beal, M. Abel Rémusat, and M. Stanislas Julien, to M. Huc’s travels, and to Mr. Scott’s ‘Burman,’ will be evident, and have been generally acknowledged in my notes. I am particularly grateful to Mr. Sarat Chandra Dās, C.I.E., for the information contained in his Report and for the instruction which I received from him personally while prosecuting my inquiries at Dārjīling.

I have felt compelled to abbreviate nearly all my quotations, and therefore occasionally to alter the phraseology. Hence I have thought it right to mark them by a different type without inverted commas.

With regard to transliteration I must refer the student to the rules for pronunciation given at p. xxxi. They conform to the rules given in my Sanskṛit Grammar and Dictionary. Like Dr. Oldenberg, I have preferred to substitute Sanskṛit terminations in a for the Pāli o. In Tibetan I have constantly consulted Jäschke, but have not followed his system of transliteration.

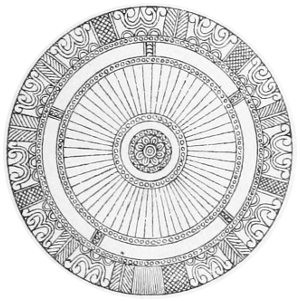

In conclusion, I may fitly draw attention to the engravings of objects, some of which were brought by myself from Buddhist countries. They are described in the list of illustrations (see p. xxix), and will, I trust, give value to the present volume. It has seemed to me a duty to make use of every available appliance for throwing light on the obscurities of a difficult subject; and, as these Lectures embrace the whole range of Buddhism, I have adopted as a frontispiece a portrait of Buddha which exhibits Buddhism in its receptivity and in its readiness to adopt serpent-worship, or any other superstition of the races which it strove to convert. On the other hand, the Wheel, with the Tri-ratna and the Lotus (pp. 521, 522), is engraved on the title-page as the best representative symbol of early Buddhism. It is taken from a Buddhist sculpture at Amarāvatī engraved for Mr. Fergusson’s ‘Tree and Serpent-worship’ (p. 237).

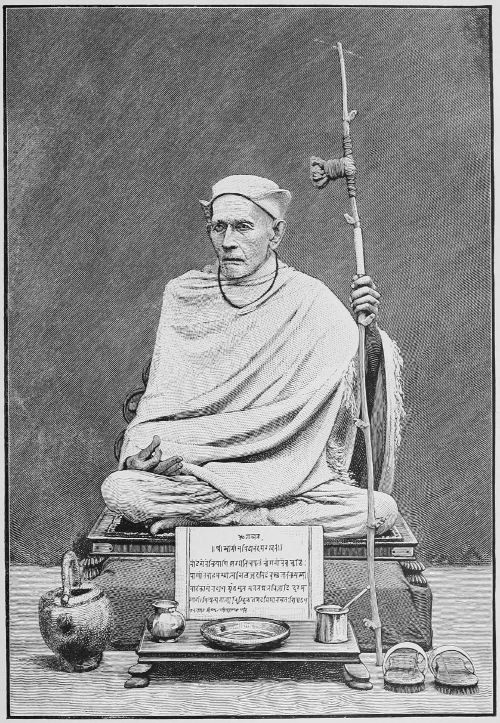

The portrait which faces page 74 is well worthy of attention as illustrating the connexion[2] between Buddhism and Brāhmanism. It is from a recently-taken photograph of Mr. Gaurī-Ṡaṅkar Uday-Ṡaṅkar, C.S.I.—a well-known and distinguished Brāhman of Bhaunagar—who (with Mr. Percival) administered the State during the minority of the present enlightened Mahā-rāja. Like the Buddha of old, he has renounced the world—that is, he has become a Sannyāsī, and is chiefly engaged in meditation. He has consequently dropped the title C.S.I., and taken the religious title—Svāmī Ṡrī Saććidānanda-Sarasvatī. His son, Mr. Vijay-Ṡaṅkar Gaurī-Ṡaṅkar, kindly sent me the photograph, and with his permission I have had it engraved.

It will be easily understood that, as a great portion of the following pages had to be delivered in the form of Lectures, occasional repetitions and recapitulations were unavoidable, but I trust I shall not be amenable to the charge of repeating anything for the sake of ‘padding.’ I shall, with more justice, be accused of ‘cramming,’ in the sense of attempting to force too much information into a single volume.

January 1, 1889.

POSTSCRIPT.

Since writing the foregoing prefatory remarks, I have observed with much concern that a prevalent error, in regard to Buddhism, is still persistently propagated. It is categorically stated in a newspaper report of a quite recent lecture, that out of the world’s population of about 1500 millions at least 500 millions are Buddhists, and that Buddhism numbers more adherents than any other religion on the surface of the globe.

Almost every European writer on Buddhism, of late years, has assisted in giving currency to this utterly erroneous calculation, and it is high time that an attempt should be made to dissipate a serious misconception.

It is forgotten that mere sympathizers with Buddhism, who occasionally conform to Buddhistic practices, are not true Buddhists. In China the great majority are first of all Confucianists and then either Tāoists or Buddhists or both. In Japan Confucianism and Shintoism co-exist with Buddhism. In some other Buddhist countries a kind of Shamanism is practically dominant. The best authorities (including the Oxford Professor of Chinese, as stated in the Introduction to his excellent work ‘The Travels of Fā-hien’) are of opinion that there are not more than 100 millions of real Buddhists in the world, and that Christianity with its 430 to 450 millions of adherents has now the numerical preponderance over all other religions. I am entirely of the same opinion. I hold that the Buddhism, described in the following pages, contained within itself, from the earliest times, the germs of disease, decay, and death (see p. 557), and that its present condition is one of rapidly increasing disintegration and decline.

We must not forget that Buddhism has disappeared from India proper, although it dominates in Ceylon and Burma, and although a few Buddhist travellers find their way back to the land of its origin and sojourn there.

Indeed, if I were called upon to give a rough comparative numerical estimate of the six chief religious systems of the world, I should be inclined, on the whole, to regard Confucianism as constituting, next to Christianity, the most numerically prevalent creed. We have to bear in mind the immense populations, both in China and Japan, whose chief creed is Confucianism.

Professor Legge informs me that Dr. Happer—an American Presbyterian Missionary of about 45 years standing, who has gone carefully into the statistics of Buddhism—reckons only 20 millions of Buddhists in China, and not more than 72½ millions in the whole of Asia. Dr. Happer states that, if the Chinese were required to class themselves as Confucianists or Buddhists or Tāoists, 19/20ths, if not 99/100ths, of them would, in his opinion, claim to be designated as Confucianists.

In all probability his estimate of the number of Buddhists in China is too low, but the Chinese ambassador Liū, with whom Professor Legge once had a conversation on this subject, ridiculed the view that they were as numerous as the Confucianists.

Undeniably, as it seems to me, the next place after Christianity and Confucianism should be given to Brāhmanism and Hindūism, which are not really two systems but practically one; the latter being merely an expansion of the former, modified by contact with Buddhism.

Brāhmanism, as I have elsewhere shown, is nothing but spiritual Pantheism; that is, a belief in the universal diffusion of an impersonal Spirit (called Brăhmăn or Brăhmă)—as the only really existing Essence—and in its manifesting itself in Mind and in countless material forces and forms, including gods, demons, men, and animals, which, after fulfilling their course, must ultimately be re-absorbed into the one impersonal Essence and be again evolved in endless evolution and dissolution.

Hindūism, with its worship of Vishṇu and Ṡiva, is based on this pantheistic doctrine, but the majority of the Hindūs are merely observers of Brāhmanical institutions with their accompanying Hindū caste usages. If, however, we employ the term Hindū in its widest acceptation (omitting only all Islāmized Hindūs) we may safely affirm that the adherents of Hindūism have reached an aggregate of nearly 200 millions. In the opinion of Sir William Wilson Hunter, they are still rapidly increasing, both by excess of births over deaths and by accretions from more backward systems of belief.

Probably Buddhism has a right to the fourth place in the scale of numerical comparison. At any rate the number of Buddhists can scarcely be calculated at less than 100 millions.

In regard to Muhammadanism, this creed should not, I think, be placed higher than fifth in the enumeration. In its purest form it ought to be called Islām, and in that form it is a mere distorted copy of Judaism.

The Empress of India, as is well known, rules over more Muhammadans than any other potentate in the world. Probably the Musalmān population of the whole of India now numbers 55 millions.

As to the number of Muhammadans in the Turkish empire, there are no very trustworthy data to guide us, but the aggregate is believed to be about 14 millions; while Africa can scarcely reckon more than that number, even if Egypt be included.

The sixth system, Tāoism (the system of Lāo-tsze), according to Professor Legge, should rank numerically after both Muhammadanism and Buddhism.

Of course Jainism (p. 529) and Zoroastrianism (the religion of the Pārsīs) are too numerically insignificant to occupy places in the above comparison.

It is possible that a careful census might result in a more favourable estimate of the number of Buddhists in the world, than I have here submitted; but at all events it may safely be alleged that, even as a form of popular religion, Buddhism is gradually losing its vitality—gradually loosening its hold on the vast populations once loyal to its rule; nay, that the time is rapidly approaching when its capacity for resistance must give way before the mighty forces which are destined in the end to sweep it from the earth.

M. M.-W.

88 Onslow Gardens, London.

January 15, 1889.

CONTENTS.

PAGE

Preface v

Postscript on the common error in regard to the comparative prevalence of Buddhism in the world xiv

List of Illustrations xxix

Rules for Pronunciation xxxi

Pronunciation of Buddha, etc. Addenda and Corrigenda xxxii

LECTURE I.

Introductory Observations.

Buddhism in its relation to Brāhmanism. Various sects in Brāhmanism. Creed of the ordinary Hindū. Rise of scepticism and infidelity. Materialistic school of thought. Origin of Buddhism and Jainism. Manysidedness of Buddhism. Its complexity. Labours of various scholars. Divisions of the subject. The Buddha, his Law, his Order of Monks. Northern Buddhism 1-17

LECTURE II.

The Buddha as a Personal Teacher.

The Buddha’s biography. Date of his birth and death. His names, epithets, and titles. Story of the four visions. Birth of the Buddha’s son. The Buddha leaves his home. His life at Rāja-gṛiha. His study of Brāhmanical philosophy. His sexennial fast. His temptation by Māra. He attains perfect enlightenment. The Bodhi-tree. Buddha and Muhammad compared. The Buddha’s proceedings after his enlightenment. His first teaching at Benares. First sermon. Effect of first teaching. His first sixty missionaries. His fire-sermon. His eighty great disciples. His two chief and sixteen leading disciples. His forty-five years of preaching and itineration. His death and last words. Character of the Buddha’s teaching. His method illustrated by an epitome of one of his parables 18-52

LECTURE III.

The Dharma or Law and Scriptures of Buddhism.

Origin of the Buddhist Law (Dharma). Buddhist scriptures not like the Veda. First council at Rāja-gṛiha. Kāṡyapa chosen as leader. Recitation of the Buddha’s precepts. Second council at Vaiṡālī. Ćandra-gupta. Third council at Patnā. Composition of southern canon. Tri-piṭaka or three collections. Rules of discipline, moral precepts, philosophical precepts. Commentaries. Buddha-ghosha. Aṡoka’s inscriptions. His edicts and proclamations. Fourth council at Jālandhara. Kanishka. The northern canon. The nine Nepālese canonical scriptures. The Tibetan canonical scriptures (Kanjur) 53-70

LECTURE IV.

The Saṅgha or Buddhist Order of Monks.

Nature of the Buddhist brotherhood. Not a priesthood, not a hierarchy. Names given to the monks. Method of admission to the monkhood. Admission of novices. Three-refuge formula. Admission of full monks. Four resources. Four prohibitions. Offences and penances. Eight practices. The monk’s daily life. His three garments. Confession. Definition of the Saṅgha or community of monks. Order of Nuns. Lay-brothers and lay-sisters. Relation of the laity to the monkhood. Duties of the laity. Later hierarchical Buddhism. Character of monks of the present day in various countries 71-92

LECTURE V.

The Philosophical Doctrines of Buddhism.

The philosophy of Buddhism founded on that of Brāhmanism. Three ways of salvation in Brāhmanism. The Buddha’s one way of salvation. All life is misery. Indian pessimistic philosophy. Twelve-linked chain of causation. Celebrated Buddhist formula. The Buddha’s attitude towards the Sāṅkhya and Vedānta philosophy of the Brāhmans. The Buddha’s negation of spirit and of a Supreme Being. Brāhmanical theory of metempsychosis. The Buddhist Skandhas. The Buddhist theory of transmigration. Only six forms of existence. The Buddha’s previous births. Examples given of stories of two of his previous births. Destiny of man dependent on his own acts. Re-creative force of acts. Act-force creating worlds. No knowledge of the first act. Cycles of the Universe. Interminable succession of existences like rotation of a wheel. Buddhist Kalpas or ages. Thirty-one abodes of six classes of beings rising one above the other in successive tiers of lower worlds and three sets of heavens 93-122

LECTURE VI.

The Morality of Buddhism and its chief aim—Arhatship or Nirvāṇa.

Inconsistency of a life of morality in Buddhism. Division of the moral code. First five and then ten chief rules of moral conduct. Positive injunctions. The ten fetters binding a man to existence. Seven jewels of the Law. Six (or ten) transcendent virtues. Examples of moral precepts from the Dharma-pada and other works. Moral merit easily acquired. Aim of Buddhist morality. External and internal morality. Inner condition of heart. Four paths or stages leading to Arhatship or moral perfection. Three grades of Arhats. Series of Buddhas. Gautama the fourth Buddha of the present age, and last of twenty-five Buddhas. The future Buddha. Explanation of Nirvāṇa and Pari-nirvāṇa as the true aim of Buddhist morality. Buddhist and Christian morality contrasted 123-146

LECTURE VII.

Changes in Buddhism and its disappearance from India.

Tendency of all religious movements to deterioration and disintegration. The corruptions of Buddhism are the result of its own fundamental doctrines. Re-statement of Buddha’s early teaching. Recoil to the opposite extreme. Sects and divisions in Buddhism. The first four principal sects, followed by eighteen, thirty-two, and ninety-six. Mahā-yāna or Great Method (vehicle). Hīna-yāna or Little Method. The Chinese Buddhist travellers, Fā-hien and Hiouen Thsang. Reasons for the disappearance of Buddhism from India. Gradual amalgamation with surrounding systems. Interaction between Buddhism, Vaishṇavism, and Ṡaivism. Ultimate merging of Buddhism in Brāhmanism and Hindūism 147-171

LECTURE VIII.

Rise of Theistic and Polytheistic Buddhism.

Development of the Mahā-yāna or Great Method. Gradual deification of saints, sages, and great men. Tendency to group in triads. First triad of the Buddha, the Law, and the Order. Buddhist triad no trinity. The Buddha to be succeeded by Maitreya. Maitreya’s heaven longed for. Constitution and gradations of the Buddhist brotherhood. Headship and government of the Buddhist monasteries. The first Arhats. Progress of the Mahā-yāna doctrine. The first Bodhi-sattva Maitreya associated with numerous other Bodhi-sattvas. Deification of Maitreya and elevation of Gautama’s great pupils to Bodhi-sattvaship. Partial deification of great teachers. Nāgārjuna, Gorakh-nāth. Barlaam and Josaphat 172-194

LECTURE IX.

Theistic and Polytheistic Buddhism.

Second Buddhist triad, Mañju-ṡrī, Avalokiteṡvara or Padma-pāṇi and Vajra-pāṇi. Description of each. Theory of five human Buddhas, five Dhyāni-Buddhas ‘of meditation,’ and five Dhyāni-Bodhi-sattvas. Five triads formed by grouping together one from each. Theory of Ādi-Buddha. Worship of the Dhyāni-Buddha Amitābha. Tiers of heavens connected with the four Dhyānas or stages of meditation. Account of the later Buddhist theory of lower worlds and three groups of heavens. Synopsis of the twenty-six heavens and their inhabitants. Hindū gods and demons adopted by Buddhism. Hindū and Buddhist mythology 195-222

LECTURE X.

Mystical Buddhism in its connexion with the Yoga Philosophy.

Growth of esoteric and mystical Buddhism. Dhyāni-Buddhas. Yoga philosophy. Svāmī Dayānanda-Sarasvatī. Twofold Yoga system. Bodily tortures of Yogīs. Fasting. Complete absorption in thought. Progressive stages of meditation. Samādhi. Six transcendent faculties. The Buddha no spiritualist. Nature of Buddha’s enlightenment. Attainment of miraculous powers. Development of Buddha’s early doctrine. Eight requisites of Yoga. Six-syllabled sentence. Mystical syllables. Cramping of limbs. Suppression and imprisonment of breath. Suspended animation. Self-concentration. Eight supernatural powers. Three bodies of every Buddha. Ethereal souls and gross bodies. Buddhist Mahātmas. Astral bodies. Modern spiritualism. Modern esoteric Buddhism and Asiatic occultism 223-252

LECTURE XI.

Hierarchical Buddhism, especially as developed in Tibet and Mongolia.

The Saṅgha. Development of Hierarchical gradations in Ceylon and in Burma. Tibetan Buddhism. Northern Buddhism connected with Shamanism. Lāmism and the Lāmistic Hierarchy. Gradations of monkhood. Avatāra Lāmas. Vagabond Lāmas. Female Hierarchy. Two Lāmistic sects. Explanation of Avatāra theory. History of Tibet. Early history of Tibetan Buddhism. Thumi Sambhoṭa’s invention of the Tibetan alphabet. Indian Buddhists sent for to Tibet. Tibetan canon. Tibetan kings. Founding of monasteries. Buddhism adopted in Mongolia. Hierarchical Buddhism in Mongolia. Invention of Mongolian alphabet. Birth of the Buddhist reformer Tsong Khapa. The Red and Yellow Cap schools. Monasteries of Galdan, Brepung, and Sera. Character of Tsong Khapa’s reformation. Resemblance of the Roman Catholic and Lāmistic systems. Death and canonization of Tsong Khapa. Development of the Avatāra theory. The two Grand Lāmas, Dalai Lāma and Panchen Lāma. Election of Dalai Lāma. Election of the Grand Lāmas of Mongolia. List of Dalai Lāmas. Discovery of present Dalai Lāma. The Lāma or Khanpo of Galdan, of Kurun or Kuren, of Kuku khotun. Lāmism in Ladāk, Tangut, Nepāl, Bhutān, Sikkim. In China and Japan. Divisions in Japanese Buddhism. Buddhism in Russian territory 253-302

LECTURE XII.

Ceremonial and Ritualistic Buddhism.

Opposition of early Buddhism to sacerdotalism and ceremonialism. Reaction. Religious superstition in Tibet and Mongolia. Accounts by Koeppen, Schlagintweit, Markham, Huc, Sarat Chandra Dās. Admission-ceremony of a novice in Burma and Ceylon. Boy-pupils. Daily life in Burmese monasteries, according to Shway Yoe. Observances during Vassa. Pirit ceremony. Mahā-baṇa Pirit. Admission-ceremonies in Tibet and Mongolia. Dress and equipment of a Lāmistic monk. Dorje. Prayer-bell. Use of Tibetan language in the Ritual. A. Csoma de Körös’ life and labours. Form and character of the Lāmistic Ritual. Huc’s description of a particular Ritual. Holy water, consecrated grain, tea-drinking. Ceremonies in Sikkim and Ladāk. Ceremony at Sarat Chandra Dās’ presentation to the Dalai Lāma. Ceremony at translation of a chief Lāma’s soul. Other ceremonies. Uposatha and fast-days. Circumambulation. Comparison with Roman Catholic Ritual 303-339

LECTURE XIII.

Festivals, Domestic Rites, and Formularies of Prayers.

New Year’s Festivals in Burma and Tibet. Festivals of Buddha’s birth and death. Festival of lamps. Local Festivals. Chase of the spirit-kings. Religious masquerades and dances. Religious dramas in Burma and Tibet. Weapons used against evil spirits. Dorje. Phurbu. Tattooing in Burma. Domestic rites and usages. Birth-ceremonies in Ceylon and Burma. Name-giving ceremonies. Horoscopes. Baptism in Tibet and Mongolia. Amulets. Marriage-ceremonies. Freedom of women in Buddhist countries. Usages in sickness. Merit gained by saving animal-life. Usages at death. Cremation. Funeral-ceremonies in Sikkim, Japan, Ceylon, Burma, Tibet, and Mongolia. Exposure of corpses in Tibet and Mongolia. Prayer-formularies. Monlam. Maṇi-padme or ‘jewel-lotus’ formulary. Prayer-wheels, praying-cylinders and method of using them. Formularies on rocks, etc. Man Dangs. Prayer-flags. Mystic formularies. Rosaries. ḍamaru. Manual of daily prayers 340-386

LECTURE XIV.

Sacred Places.

The sacred land of Buddhism. Kapila-vastu, the Buddha’s birth-place. The arrow-fountain. Buddha-Gayā. Ancient Temple. Sacred tree. Restoration of Temple. Votive Stūpas. Mixture of Buddhism and Hindūism. Hiouen Thsang’s description of Buddha-Gayā. Sārnāth near Benares. Ruined Stūpa. Sculpture illustrating four events in the Buddha’s career. Rāja-gṛiha. Scene of incidents in the Buddha’s life. Deva-datta’s plots. Satta-paṇṇi cave. Ṡrāvastī. Residence in Jeta-vana monastery. Sandal-wood image. Miracles. Vaiṡālī, place of second council. Description by Hiouen Thsang and Fā-hien. Kauṡāmbī. Great monolith. Nālanda monastery. Hiouen Thsang’s description. Saṅkāṡya, place of Buddha’s descent from heaven. Account of the triple ladder. Sāketa or Ayodhyā. Miraculous tree. Kanyā-kubja. Ṡilāditya. Pāṭali-putra. Aṡoka’s palace. Founding of hospitals. First Stūpa. Kesarīya. Ruined mound. Stūpa. Kuṡi-nagara, the place of the Buddha’s death and Pari-nirvāṇa 387-425

LECTURE XV.

Monasteries and Temples.

Five kinds of dwellings permissible for monks. Institution of monasteries. Cave-monasteries. Monasteries in Ceylon, Burma, and British Sikkim. Monastery at Kīlang in Lahūl; at Kunbum; at Kuku khotun; at Kuren; at Lhāssa. Palace-monastery of Potala. Residence of Dalai Lāma, and Mr. Manning’s interview with him. Monasteries of Lā brang, Ramoćhe, Moru, Gar Ma Khian. Three mother-monasteries of the Yellow Sect, Galdan, Sera, and Dapung. Tashi Lunpo and the Tashi Lāma. Mr. Bogle’s interview with the Tashi Lāma. Turner’s interview with the Grand Lāma of the Terpaling monastery. Sarat Chandra Dās’ description of the Tashi Lunpo monastery. Monasteries of the Red Sect, Sam ye and Sakya. Monastery libraries. Temples. Cave-temples or Ćaityas. The Elorā Ćaitya. The Kārle Ćaitya. Village temples. Temples in Ceylon. Temple at Kelani. Tooth-temple at Kandy. Burmese temples. Rangoon pagoda. Temples in Sikkim, Mongolia, and Tibet. Great temple at Lhāssa; at Ramoćhe; at Tashi Lunpo 426-464

LECTURE XVI.

Images and Idols.

Introduction of idolatry into India. Ancient image of Buddha. Gradual growth of objective Buddhism. Development of image-worship. Self-produced images. Hiouen Thsang’s account of the sandal-wood image. Form, character, and general characteristics of images. Outgrowth of Buddha’s skull. Nimbus. Size, height, and different attitudes of Buddha’s images. ‘Meditative,’ ‘Witness,’ ‘Serpent-canopied,’ ‘Argumentative’ or ‘Teaching,’ ‘Preaching,’ ‘Benedictive,’ ‘Mendicant,’ and ‘Recumbent’ Attitudes. Representations of Buddha’s birth. Images of other Buddhas and Bodhi-sattvas. Images of Amitābha, of Maitreya, of Mañju-ṡrī, of Avalokiteṡvara, of Kwan-yin and Vajra-pāṇi. Images of other Bodhi-sattvas, gods and goddesses 465-492

LECTURE XVII.

Sacred Objects.

Sung-Yun’s description of objects of worship. Three classes of Buddhist sacred objects 493-495

Relics. Hindū ideas of impurity connected with death. Hindū and Buddhist methods of honouring ancestors compared. Worship of the Buddha’s relics. The Buddha’s hair and nails. Eight portions of his relics. Adventures of one of the Buddha’s teeth. Tooth-temple at Kandy. Celestial light emitted by relics. Exhibition of relics. Form and character of Buddhist relic-receptacles. Ćaityas, Stūpas, Dāgabas, and their development into elaborate structures. Votive Stūpas 495-506

Worship of foot-prints. Probable origin of the worship of foot-prints. Alleged foot-prints of Christ. Vishṇu-pad at Gayā. Jaina pilgrims at Mount Pārasnāth. Adam’s Peak. Foot-prints in various countries. Mr. Alabaster’s description of the foot-print in Siam. Marks on the soles of the Buddha’s feet 506-514

Sacred trees. General prevalence of tree-worship. Belief that spirits inhabit trees. Offerings hung on trees. Trees of the seven principal Buddhas. The Aṡvattha or Pippala is of all trees the most revered. Other sacred trees. The Kalpa-tree. Wishing-tree. Kabīr Var tree 514-520

Sacred symbols. The Tri-ratna symbol. The Ćakra or Wheel symbol. The Lotus-flower. The Svastika symbol. The Throne symbol. The Umbrella. The Ṡaṅkha or Conch-shell 520-523

Sacred animals. Worship of animals due to doctrine of metempsychosis. Elephants. Deer. Pigs. Fish 524-526

Miscellaneous objects. Bells. Seven precious substances. Seven treasures belonging to every universal monarch 526-528

Supplementary Remarks on the Connexion of Buddhism with Jainism.

Difference between the Buddhist and Jaina methods of obtaining liberation. Nigaṇṭhas. Two Jaina sects. Dig-ambaras and Ṡvetāmbaras. The three chief points of difference between them. Their sacred books. Characteristics of both sects as distinguished from Buddhism. Belief in existence of souls. Moral code. Three-jewels. Five moral prohibitions. Prayer-formula. Temples erected for acquisition of merit 529-536

LECTURE XVIII.

Buddhism contrasted with Christianity.

True Buddhism is no religion. Definition of the word ‘religion.’ Four characteristics constitute a religion. Gautama’s claim to be called ‘the Light of Asia’ examined. The Buddha’s and Christ’s first call to their disciples. The Christian’s reverence for the body contrasted with the Buddhist’s contempt for the body. Doctrine of storing up merit illustrated, and shown to be common to Buddhism, Brāhmanism, Hindūism, Confucianism, Zoroastrianism, and Muhammadanism. Doctrine of Karma or Act-force. Buddhist and Christian doctrine of deliverance compared. Buddhist and Christian moral precepts compared. The many benefits conferred upon Asia by Buddhism admitted. Religious feelings among Buddhists. Buddhist toleration of other religions.

Historic life of the Christ contrasted with legendary biography of the Buddha. Christ God-sent. The Buddha self-sent. Miracles recorded in the Bible and in the Tri-piṭaka contrasted. Buddhist and Christian self-sacrifice compared. Character and style of the Buddhist Tri-piṭaka contrasted with those of the Christian Bible. Various Buddhist and Christian doctrines contrasted. Which doctrines are to be preferred by rational and thoughtful men in the nineteenth century? 537-563

OBSERVE.

The prevalent error in regard to the number of Buddhists at present existing in the world is pointed out in the Postscript at the end of the Preface (p. xiv).

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

WITH DESCRIPTIONS.

PAGE

1. Brass Image of Gautama Buddha obtained by the Author from Ceylon Frontispiece

He is seated on the Mućalinda Serpent (see p. 480), in an attitude of profound meditation, with eyes half closed, and five rays of light emerging from the crown of his head.

2. Vignette, representing the Ćakra or ‘Wheel’ Symbol with Tri-ratna symbols in the outer circle and Lotus symbol in the centre (see pp. 521-522) On Title-page

Copied from the engraving of a Wheel supported on a column at Amarāvatī (date about 250 A.D.) in Mr. Fergusson’s ‘Tree and Serpent Worship.’

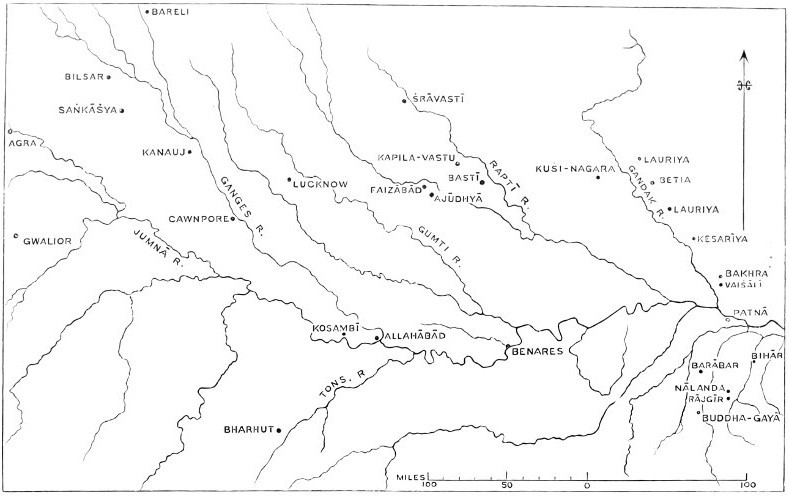

3. Map illustrative of the Sacred Land of Buddhism To face 21

4. Portrait of Mr. Gaurī-Ṡaṅkar Uday-Ṡaṅkar, C.S.I., now Svāmī Ṡrī Saććidānanda-Sarasvatī To face 74

See the explanation at p. xiii. of the Preface.

5. Magical Dorje or thunderbolt used by Northern Buddhists 323

6. Prayer-bell used in worship 324

7. Magical weapon called Phur-pa, for defence against evil spirits 352

Used by Northern Buddhists. Brought from Dārjīling in 1884.

8. Amulet worn by a Tibetan woman at Dārjīling in 1884 358

Purchased at Dārjīling and given to the Author by Mr. Sarat Chandra Dās.

9. Hand Prayer-wheel brought by the Author from Dārjīling 375

10. ḍamaru, or sacred drum, used by vagabond Buddhist monks 385

11. Ancient Buddhist temple at Buddha-Gayā, as it appeared in 1880 To face 391

Erected about the middle of the 2nd century on the ruins of Aṡoka’s temple, at the spot where Gautama attained Buddhahood.

From a photograph by Mr. Beglar enlarged by Mr. G. W. Austen.

12. The same temple at Buddha-Gayā, as restored in 1884 To face 393

From a photograph by Mr. Beglar enlarged by Mr. G. W. Austen.

13. Bronze model dug up at Moulmein, representing triple ladder by which Buddha is supposed to have descended from heaven (from original in South Kensington Museum) 418

14. Remains of a colossal statue of Buddha To face 467

Probably in ‘argumentative’ or ‘teaching’ attitude (see p. 481). It was found by General Sir A. Cunningham close to the south side of the Buddha-Gayā temple. The date (Samvat 64 = A.D. 142) is inscribed on the pedestal.

15. Terra-cotta image of Buddha dug up at Buddha-Gayā 477

Half the size of the original sculpture. Buddha is in the attitude of meditation under the tree, with a halo or aureola round his head. Probable date, not earlier than 9th century.

16. Sculpture found by General Sir A. Cunningham at Sārnāth, near Benares To face 477

Illustrative of the four principal events in Gautama Buddha’s life—namely, his birth, his attainment of Buddhahood under the tree, his teaching at Benares, and his passing away in complete Nirvāṇa (see p. 387). Date about 400 A.D.

17. Sculpture of Buddha in ‘Witness-attitude’ on attaining Buddhahood, under the tree (an umbrella is above) 478

Found at Buddha-Gayā. Date about the 9th century. The original is remarkable for its smiling features and for the circular mark on the forehead. The drawing is from a photograph belonging to Sir A. Cunningham.

18. Sculpture of Buddha in ‘Witness-attitude’ on attaining Buddhahood under the tree 480

From a niche high up on the western side of the Buddha-Gayā temple. It has the ‘Ye dharmā’ formula (p. 104) inscribed on each side. It is half the size of the original sculpture. Probable date about the 11th century.

19. Sculpture found at Buddha-Gayā representing the earliest Triad, viz. Buddha, Dharma, and Saṅgha 485

The drawing is from a photograph belonging to Sir A. Cunningham, described at p. 484.

20. Votive Stūpa found at Buddha-Gayā To face 505

Probable date about 9th or 10th century of our era.

21. Clay model of a small votive Stūpa 506

Selected from several which the author saw in the act of being made by a monk outside a monastery in British Sikkim in 1884. This model probably contains the ‘Ye dharmā’ or some other formula on a seal inside. The engraving is exactly the size of the original.

RULES FOR PRONUNCIATION.

VOWELS.

A, a, pronounced as in rural, or the last a in America; Ā, ā, as in tar, father; I, i, as in fill; Ī, ī, as in police; U, u, as in bull; Ū, ū, as in rude; Ṛi, ṛi, as in merrily; Ṛī, ṛī, as in marine; E, e, as in prey; Ai, ai, as in aisle; O, o, as in go; Au, au, as in Haus (pronounced as in German).

CONSONANTS.

K, k, pronounced as in kill, seek; Kh, kh, as in inkhorn; G, g, as in gun, dog; Gh, gh, as in loghut; Ṅ, ṅ, as ng in sing (siṅ).

Ć, ć, as in dolce (in music), = English ch in church, lurch (lurć); Ćh, ćh, as in churchhill (ćurćhill); J, j, as in jet; Jh, jh, as in hedgehog (hejhog); Ñ, ñ, as in singe (siñj).

Ṭ, ṭ, as in true (ṭru); Ṭh, ṭh, as in anthill (anṭhill); ḍ, ḍ, as in drum (ḍrum); ḍh, ḍh, as in redhaired (reḍhaired); Ṇ, ṇ, as in none (ṇuṇ).

T, t, as in water (as pronounced in Ireland); Th, th, as nut-hook (but more dental); D, d, as in dice (more like th in this); Dh, dh, as in adhere (more dental); N, n, as in not, in.

P, p, as in put, sip; Ph, ph, as in uphill; B, b, as in bear, rub; Bh, bh, as in abhor; M, m, as in map, jam.

Y, y, as in yet; R, r, as in red, year; L, l, as in lie; V, v, as in vie (but like w after consonants, as in twice).

Ṡ, ṡ, as in sure, session; Sh, sh, as in shun, hush; S, s, as in sir, hiss. H, h, as in hit.

In Tibetan the vowels, including even e and o, have generally the short sound, but accentuated vowels are comparatively long. I have marked such words as Lāma with a long mark to denote this, but Koeppen and Jäschke write Lama. Jäschke says that the Tibetan alphabet was adapted from the Lañćha form of the Indian letters by Thumi (Thonmi) Sambhoṭa (see p. 270) about the year 632.

OBSERVE.

It is common to hear English-speakers mispronounce the words Buddha and Buddhism. But any one who studies the rules on the preceding page will see that the u in Buddha, must not be pronounced like the u in the English word ‘bud,’ but like the u in bull.

Indeed, for the sake of the general reader, it might be better to write Booddha and Booddhism, provided the oo be pronounced as in the words ‘wood,’ ‘good.’

ADDENDA and CORRIGENDA.

It is feared that the long-mark over the letter A may have been omitted in one or two cases or may have broken off in printing.

[In this electronic edition, corrections were incorporated in the text; additions were inserted as new footnotes and tagged—Corr.]

[1]‘Life of Alexander Duff, D.D., LL.D., by George Smith, C.I.E., LL.D.’ London: Hodder and Stoughton; published first in 1879, and a popular edition in 1881.

Certainly Buddhism continues to be little understood by the great majority of educated persons. Nor can any misunderstanding on such a subject be matter of surprise, when writers of high character colour their descriptions of it from an examination of one part of the system only, without due regard to its other phases, and in this way either exalt it to a far higher position than it deserves, or depreciate it unfairly.

And Buddhism is a subject which must continue for a long time to present the student with a boundless field of investigation. No one can bring a proper capacity of mind to such a study, much less write about it clearly, who has not studied the original documents both in Pāli and in Sanskṛit, after a long course of preparation in the study of Vedism, Brāhmanism, and Hindūism. It is a system which resembles these other forms of Indian religious thought in the great variety of its aspects. Starting from a very simple proposition, which can only be described as an exaggerated truism—the truism, I mean, that all life involves sorrow, and that all sorrow results from indulging desires which ought to be suppressed—it has branched out into a vast number of complicated and self-contradictory propositions and allegations. Its teaching has become both negative and positive, agnostic and gnostic. It passes from apparent atheism and materialism to theism, polytheism, and spiritualism. It is under one aspect mere pessimism; under another pure philanthropy; under another monastic communism; under another high morality; under another a variety of materialistic philosophy; under another simple demonology; under another a mere farrago of superstitions, including necromancy, witchcraft, idolatry, and fetishism. In some form or other it may be held with almost any religion, and embraces something from almost every creed. It is founded on philosophical Brāhmanism, has much in common with Sāṅkhya and Vedānta ideas, is closely connected with Vaishṇavism, and in some of its phases with both Ṡaivism and Ṡāktism, and yet is, properly speaking, opposed to every one of these systems. It has in its moral code much common ground with Christianity, and in its mediæval and modern developments presents examples of forms, ceremonies, litanies, monastic communities, and hierarchical organizations, scarcely distinguishable from those of Roman Catholicism; and yet a greater contrast than that presented by the essential doctrines of Buddhism and of Christianity can scarcely be imagined. Strangest of all, Buddhism—with no God higher than the perfect man—has no pretensions to be called a religion in the true sense of the word, and is wholly destitute of the vivifying forces necessary to give vitality to the dry bones of its own morality; and yet it once existed as a real power over at least a third of the human race, and even at the present moment claims a vast number of adherents in Asia, and not a few sympathisers in Europe and America.

As to the name Ṡramaṇa (from root Ṡram, ‘to toil’), bear in mind that, although Buddhism has acquired the credit of being the easiest religious system in the world, and its monks are among the idlest of men—as having no laborious ceremonies and no work to do for a livelihood—yet in reality the carrying out of the great object of extinguishing lusts, and so getting rid of the burden of repeated existences, was no sinecure if earnestly undertaken. Nor was it possible for men to lead sedentary lives, whose only mode of avoiding starvation was by house to house itinerancy.

Some of the sacred objects already described may be regarded as symbols. Of those which are more strictly symbols the Tri-ratna ‘three-jewel’ emblem comes first. It is three-pointed, and the three points are simply emblematical of the Buddha, the Law, and the Monastic Order. It is often used as an ornament. Good examples may be seen in some of the Bharhut sculptures (see Sir A. Cunningham’s work). The central point is often the least elevated.

Next to the Tri-ratna comes the Ćakra or wheel. This symbolizes the Buddhist doctrine that the origin of life and of the universe (p. 119) are unknowable—the doctrine of a circle of causes and effects without beginning and without end. The wheel also typifies the rolling of this doctrine over the whole surface of the world (pp. 410, 423). It is perhaps one of the most important symbols of Buddhist philosophy. It is often represented as either supporting the Tri-ratna or supported by it, or the latter may be inserted in it.

[2]A reference to pages 74, 226, 232 of the following Lectures will make the connexion which I wish to illustrate clearer. In many images of the Buddha the robe is drawn over both shoulders, as in the portrait of the living Sannyāsī. Then mark other particulars in the portrait:—e.g. the Rudrāksha rosary round the neck (see ‘Brāhmanism and Hindūism,’ p. 67). Then in front of the raised seat of the Sannyāsī are certain ceremonial implements. First, observe the Kamaṇḍalu, or water-gourd, near the right hand corner of the seat. Next, in front of the seat, on the right hand of the figure, is the Upa-pātra—a subsidiary vessel to be used with the Kamaṇḍalu. Then, in the middle, is the Tāmra-pātra or copper vessel, and on the left the Pañća-pātra with the Āćamanī (see ‘Brāhmanism and Hindūism,’ pp. 401, 402). Near the left hand corner of the seat are the wooden clogs. Finally, there is the Daṇḍa or staff held in the left hand, and used by a Sannyāsī as a defence against evil spirits, much as the Dorje (or Vajra) is used by Northern Buddhist monks (see p. 323 of the present volume). This mystical staff is a bambu with six knots, possibly symbolical of six ways (Gati) or states of life, through which it is believed that every being may have to migrate—a belief common to both Brāhmanism and Buddhism (see p. 122 of this volume). The staff is called Su-darṡana (a name for Vishṇu’s Ćakra), and is daily worshipped for the preservation of its mysterious powers. The mystic white roll which begins just above the left hand and ends before the left knot is called the Lakshmī-vastra, or auspicious covering. The projecting piece of cloth folded in the form of an axe (Paraṡu) represents the weapon of Paraṡu-Rāma, one of the incarnations of Vishṇu (see pp. 110, 270 of ‘Brāhmanism and Hindūism’) with which he subdued the enemies of the Brāhmans. With this so-called axe may be contrasted the Buddhist weapon for keeping off the powers of evil (engraved at p. 352).

SCULPTURE FOUND BY SIR A. CUNNINGHAM AT SĀRNĀTH, NEAR BENARES,

BUDDHISM.

LECTURE I.

Introductory. Buddhism in relation to Brāhmanism.

In my recent work[3] on Brāhmanism I have traced the progress of Indian religious thought through three successive stages—called by me Vedism, Brāhmanism, and Hindūism—the last including the three subdivisions of Ṡaivism, Vaishṇavism, and Ṡāktism. Furthermore I have attempted to prove that these systems are not really separated by sharp lines, but that each almost imperceptibly shades off into the other.

I have striven also to show that a true Hindū of the orthodox school is able quite conscientiously to accept all these developments of religious belief. He holds that they have their authoritative exponents in the successive bibles of the Hindū religion, namely, (1) the four Vedas—Ṛig-veda, Yajur-veda, Sāma-veda, Atharva-veda—and the Brāhmaṇas; (2) the Upanishads; (3) the Law-books—especially that of Manu; (4) the Bhakti-ṡāstras, including the Rāmāyaṇa, the Mahā-bhārata, the Purāṇas—especially the Bhāgavata-purāṇa—and the Bhagavad-gītā; (5) the Tantras.

The chief works under these five heads represent the principal periods of religious development through which the Hindū mind has passed.

Thus, in the first place, the hymns of the Vedas and the ritualism of the Brāhmaṇas represent physiolatry or the worship of the personified forces of nature—a form of religion which ultimately became saturated with sacrificial ideas and with ceremonialism and asceticism. Secondly, the Upanishads represent the pantheistic conceptions which terminated in philosophical Brāhmanism. Thirdly, the Law-books represent caste-rules and domestic usages. Fourthly, the Rāmāyaṇa, Mahā-bhārata, and Purāṇas represent the principle of personal devotion to the personal gods, Ṡiva, Vishṇu, and their manifestations; and fifthly, the Tantras represent the perversion of the principle of love to polluting and degrading practices disguised under the name of religious rites. Of these five phases of the Hindū religion probably the first three only prevailed when Buddhism arose; but I shall try to make clear hereafter that Buddhism, as it developed, accommodated itself to the fourth and even ultimately to the fifth phase, admitting the Hindū gods into its own creed, while Hindūism also received ideas from Buddhism.

At any rate it is clear that the so-called orthodox Brāhman admits all five series of works as progressive exponents of the Hindū system—although he scarcely likes to confess openly to any adoption of the fifth. Hence his opinions are of necessity Protean and multiform.

The root ideas of his creed are of course Pantheistic, in the sense of being grounded on the identification of the whole external world—which he believes to be a mere illusory appearance—with one eternal, impersonal, spiritual Essence; but his religion is capable of presenting so many phases, according to the stand-point from which it is viewed, that its pantheism appears to be continually sliding into forms of monotheism and polytheism, and even into the lowest types of animism and fetishism.

We must not, moreover, forget—as I have pointed out in my recent work—that a large body of the Hindūs are unorthodox in respect of their interpretation of the leading doctrine of true Brāhmanism.

Such unorthodox persons may be described as sectarians or dissenters. That is to say, they dissent from the orthodox pantheistic doctrine that all gods and men, all divine and human souls, and all material appearances are mere illusory manifestations of one impersonal spiritual Entity—called Ātman or Purusha or Brahman—and they believe in one supreme personal god—either Ṡiva or Vishṇu or Kṛishṇa or Rāma—who is not liable (as orthodox Brāhmans say he is) to lose his personality by subjection to the universal law of dissolution and re-absorption into the one eternal impersonal Essence, but exists in a heaven of his own, to the bliss of which his worshippers are admitted[4].

And it must be borne in mind that these sectarians are very far from resting their belief on the Vedas, the Brāhmaṇas, and Upanishads.

Their creed is based entirely on the Bhakti-ṡāstras—that is, on the Rāmāyaṇa, Mahā-bhārata, and Purāṇas (especially on the Bhāgavata-purāṇa) and the Bhagavad-gītā, to the exclusion of the other scriptures of Hindūism.

Then again it must always be borne in mind that the terms ‘orthodox’ and ‘unorthodox’ have really little or no application to the great majority of the inhabitants of India, who in truth are wholly innocent of any theological opinions at all, and are far too apathetic to trouble themselves about any form of religion other than that which has belonged for centuries to their families and to the localities in which they live, and far too ignorant and dull of intellect to be capable of inquiring for themselves whether that religion is likely to be true or false.

To classify the masses under any one definite denomination, either as Pantheists or Polytheists or Monotheists, or as simple idol-worshippers, or fetish-worshippers, would be wholly misleading.

Their faculties are so enfeebled by the debilitating effect of early marriages, and so deadened by the drudgery of daily toil and the dire necessity of keeping body and soul together, that they can scarcely be said to be capable of holding any definite theological creed at all.

It would be nearer the truth to say that the religion of an ordinary Hindū consists in observing caste-customs, local usages, and family observances, in holding what may be called the Folk-legends of his neighbourhood, in propitiating evil spirits and in worshipping the image and superscription of the Empress of India, impressed on the current coin of the country.

As a rule such a man gives himself no uneasiness whatever about his prospects of happiness or misery in the world to come.

He is quite content to commit his interests in a future life to the care and custody of the Brāhmans; while, if he thinks about the nature of a Supreme Being at all, he assumes His benevolence and expects His good will as a matter of course.

What he really troubles himself about is the necessity for securing the present favour of the inhabitants of the unseen world, supposed to occupy the atmosphere everywhere around him—of the good and evil demons and spirits of the soil—generally represented by rude and grotesque images, and artfully identified by village priests and Brāhmans with alleged forms of Vishṇu or Ṡiva.

It follows that the mind of the ordinary Hindū, though indifferent about all definite dogmatic religion, is steeped in the kind of religiousness best expressed by the word δεισιδαιμονία. He lives in perpetual dread of invisible beings who are thought to be exerting their mysterious influences above, below, around, in the immediate vicinity of his own dwelling. The very winds which sweep across his homestead are believed to swarm with spirits, who unless duly propitiated will blight the produce of his fields, or bring down upon him injury, disease, and death.

Then again, besides the orthodox and besides the sectarian Hindū and besides the great demon-worshipping, idolatrous, and superstitious majority, another class of the Indian community must also be taken into account—the class of rationalists and free-thinkers. These have been common in India from the earliest times.

First came a class of conscientious doubters, who strove to solve the riddle of life by microscopic self-introspection and sincere searchings after truth, and these did their best not to break with the Veda, Vedic revelation, and the authority of the Brāhmans.

Earnestly and reverently such men applied themselves to the difficult task of trying to answer such questions as—What am I? Whence have I come? Whither am I going? How can I explain my consciousness of personal existence? Have I an immaterial spirit distinct from, and independent of, my material frame? Of what nature is the world in which I find myself? Did an all-powerful Being create it out of nothing? or did it evolve itself out of an eternal protoplasmic germ? or did it come together by the combination of eternal atoms? or is it a mere illusion? If created by a Being of infinite wisdom and love, how can I account for the co-existence in it of good and evil, happiness and misery? Has the Creator form, or is He formless? Has He qualities and affections, or has He none?

It was in the effort to solve such insoluble enigmas by their own unaided intuitions and in a manner not too subversive of traditional dogma, that the systems of philosophy founded on the Upanishads originated.

These have been described in my book on Brāhmanism. They were gradually excogitated by independent thinkers, who claimed to be Brāhmans or twice-born men, and nominally accepted the Veda with its Brāhmaṇas, while they covertly attacked it, or at least abstained from denouncing it as absolutely untrue. Such men tacitly submitted to sacerdotal authority, though they really propounded a way of salvation based entirely on self-evolved knowledge, and quite independent of all Vedic sacrifices and sacrificing priests. The most noteworthy and orthodox of the systems propounded by them was the Vedānta[5], which, as I have shown, was simply spiritual Pantheism, and asserted that the one Spirit was the only real Being in the Universe.

But the origin of the more unorthodox systems, which denied the authority of both the Veda and the Brāhmans, must also be traced to the influence of the Upanishads. For it is undeniable that a spirit of atheistic infidelity grew up in India almost pari passu with dogmatic Brāhmanism, and has always been prevalent there. In fact it would be easy to show that periodical outbursts of unbelief and agnosticism have taken place in India very much in the same way as in Europe; but the tendency to run into extremes has always been greater on Indian soil and beneath the glow and glamour of Eastern skies. On the one side, a far more unthinking respect than in any other country has been paid to the authority of priests, who have declared their supernatural revelation to be the very breath of God, sacrificial rites to be the sole instruments of salvation, and themselves the sole mediators between earth and heaven; on the other, far greater latitude than in any other country has been conceded to infidels and atheists who have poured contempt on all sacerdotal dogmas, have denied all supernatural revelation, have made no secret of their disbelief in a personal God, and have maintained that even if a Supreme Being and a spiritual world exist they are unknowable by man and beyond the cognizance of his faculties.

We learn indeed from certain passages of the Veda (Ṛig-veda II. 12. 5; VIII. 100. 3, 4) that even in the Vedic age some denied the existence of the god Indra.

We know, too, that Yāska, the well-known Vedic commentator, who is believed to have lived before the grammarian Pāṇini (probably in the fourth century B.C.), found himself obliged to refute the sceptical arguments of Kautsa and others who pronounced the Veda a tissue of nonsense (Nirukta I. 15, 16).

Again, Manu—whose law-book, according to Dr. Bühler, was composed between the second century B.C. and the second A.D., and, in my opinion, possibly earlier—has the following remark directed against sceptics:—

‘The twice-born man who depending on rationalistic treatises (hetu-ṡāstra) contemns the two roots of law (ṡruti and smṛiti), is to be excommunicated (vahish-kāryaḥ) by the righteous as an atheist (nāstika) and despiser of the Veda’ (Manu II. 11).

Furthermore, the Mahā-bhārata, a poem which contains many ancient legends quite as ancient as those of early Buddhism, relates (Ṡānti-parvan 1410, etc.) the story of the infidel Ćārvāka, who in the disguise of a mendicant Brāhman uttered sentiments dangerously heretical.

This Ćārvāka was the supposed founder of a materialistic school of thought called Lokāyata. Rejecting all instruments of knowledge (pramāṇa) except perception by the senses (pratyaksha), he affirmed that the soul did not exist separately from the body, and that all the phenomena of the world were spontaneously produced.

The following abbreviation of a passage in the Sarva-darṡana-saṅgraha[6] will give some idea of this school’s infidel doctrines, the very name of which (Lokāyata, ‘generally current in the world’) is an evidence of the popularity they enjoyed:—

No heaven exists, no final liberation,

No soul, no other world, no rites of caste,

No recompense for acts; let life be spent,

In merriment[7]; let a man borrow money

And live at ease and feast on melted butter.

How can this body when reduced to dust

Revisit earth? and if a ghost can pass

To other worlds, why does not strong affection

For those he leaves behind attract him back?

Oblations, funeral rites, and sacrifices

Are a mere means of livelihood devised

By sacerdotal cunning—nothing more.

The three composers of the triple Veda

Were rogues, or evil spirits, or buffoons.

The recitation of mysterious words

And jabber of the priests is simple nonsense.

Then again, the continued prevalence of sceptical opinions may be shown by extracts from other portions of the later literature. For example, in the Rāmāyaṇa (II. 108) the infidel Brāhman Jāvāli gives utterance to similar sentiments thus:—

‘The books composed by theologians, in which men are enjoined to worship, give gifts, offer sacrifice, practise austerities, abandon the world, are mere artifices to draw forth donations. Make up your mind that no one exists hereafter. Have regard only to what is visible and perceptible by the senses (pratyaksham). Cast everything beyond this behind your back.’

Furthermore, in a parallel passage from the Vishṇu-purāṇa, it is declared that the great Deceiver, practising illusion, beguiled other demon-like beings to embrace many sorts of heresy; some reviling the Vedas, others the gods, others the ceremonial of sacrifice, and others the Brāhmans[8]. These were called Nāstikas.

Such extracts prove that the worst forms of scepticism prevailed in both early and mediæval times. But all phases and varieties of heretical thought were not equally offensive, and it would certainly be unfair and misleading to place Buddhism and Jainism on the same level with the reckless Pyrrhonism of the Ćārvākas who had no code of morality.

And indeed it was for this very reason, that when Buddhism and Jainism began to make their presence felt in the fifth century B.C. they became far more formidable than any other phase of scepticism.

Whether, however, Buddhism or Jainism be entitled to chronological precedence is still an open question, about which opinions may reasonably differ. Some hold that they were always quite distinct from each other, and were the products of inquiry originated by two independent thinkers, and many scholars now consider that the weight of evidence is in favour of Jainism being a little antecedent to Buddhism. Possibly the two systems resulted from the splitting up of one sect into two divisions, just as the two Brāhma-Samājes of Calcutta are the product of the Ādi-Samāj.

One point at least is certain, that notwithstanding much community of thought between Buddhism and Jainism, Buddhism ended in gaining for itself by far the more important position of the two. For although Jainism has shown more tenacity of life in India, and has lingered on there till the present day, it never gained any hold on the masses of the population, whereas its rival, Buddhism, radiating from a central point in Hindūstān, spread itself first over the whole of India and then over nearly all Eastern Asia, and has played—as even its most hostile critics must admit—an important rôle in the history of the world.

To Buddhism, therefore, we have now to direct our attention, and at the very threshold of our inquiries we are confronted with this difficulty, that its great popularity and its wide diffusion among many peoples have made it most difficult to answer the question:—What is Buddhism? If it were possible to reply to the inquiry in one word, one might perhaps say that true Buddhism, theoretically stated, is Humanitarianism, meaning by that term something very like the gospel of humanity preached by the Positivist, whose doctrine is the elevation of man through man—that is, through human intellect, human intuitions, human teaching, human experiences, and accumulated human efforts—to the highest ideal of perfection; and yet something very different. For the Buddhist ideal differs toto cælo from the Positivist’s, and consists in the renunciation of all personal existence, even to the extinction of humanity itself. The Buddhist’s perfection is destruction (p. 123).

But such a reply would have only reference to the truest and earliest form of Buddhism. It would cover a very minute portion of the vast area of a subject which, as it grew, became multiform, multilateral, and almost infinite in its ramifications.

Innumerable writers, indeed, during the past thirty years have been attracted by the great interest of the inquiry, and have vied with each other in their efforts to give a satisfactory account of a system whose developments have varied in every country; while lecturers, essayists, and the authors of magazine articles are constantly adding their contributions to the mass of floating ideas, and too often propagate crude and erroneous conceptions on a subject, the depths of which they have never thoroughly fathomed.

It is to be hoped that the annexation of Upper Burma, while giving an impulse to Pāli and Buddhistic studies, may help to throw light on some obscure points.

Certainly Buddhism continues to be little understood by the great majority of educated persons. Nor can any misunderstanding on such a subject be matter of surprise, when writers of high character colour their descriptions of it from an examination of one part of the system only, without due regard to its other phases, and in this way either exalt it to a far higher position than it deserves, or depreciate it unfairly.

And Buddhism is a subject which must continue for a long time to present the student with a boundless field of investigation. No one can bring a proper capacity of mind to such a study, much less write about it clearly, who has not studied the original documents both in Pāli and in Sanskṛit, after a long course of preparation in the study of Vedism, Brāhmanism, and Hindūism. It is a system which resembles these other forms of Indian religious thought in the great variety of its aspects. Starting from a very simple proposition, which can only be described as an exaggerated truism—the truism, I mean, that all life involves sorrow, and that all sorrow results from indulging desires which ought to be suppressed—it has branched out into a vast number of complicated and self-contradictory propositions and allegations. Its teaching has become both negative and positive, agnostic and gnostic. It passes from apparent atheism and materialism to theism, polytheism, and spiritualism. It is under one aspect mere pessimism; under another pure philanthropy; under another monastic communism; under another high morality; under another a variety of materialistic philosophy; under another simple demonology; under another a mere farrago of superstitions, including necromancy, witchcraft, idolatry, and fetishism. In some form or other it may be held with almost any religion, and embraces something from almost every creed. It is founded on philosophical Brāhmanism, has much in common with Sāṅkhya and Vedānta ideas, is closely connected with Vaishṇavism, and in some of its phases with both Ṡaivism and Ṡāktism, and yet is, properly speaking, opposed to every one of these systems. It has in its moral code much common ground with Christianity, and in its mediæval and modern developments presents examples of forms, ceremonies, litanies, monastic communities, and hierarchical organizations, scarcely distinguishable from those of Roman Catholicism; and yet a greater contrast than that presented by the essential doctrines of Buddhism and of Christianity can scarcely be imagined. Strangest of all, Buddhism—with no God higher than the perfect man—has no pretensions to be called a religion in the true sense of the word, and is wholly destitute of the vivifying forces necessary to give vitality to the dry bones of its own morality; and yet it once existed as a real power over at least a third of the human race, and even at the present moment claims a vast number of adherents in Asia, and not a few sympathisers in Europe and America.

Evidently, then, any Orientalist who undertakes to give a clear and concise account of Buddhism in the compass of a few lectures, must find himself engaged in a very venturesome and difficult task.

Happily we are gaining acquaintance with the Southern or purest form of Buddhism through editions and translations of the texts of the Pāli Canon by Fausböll, Childers, Rhys Davids, Oldenberg, Morris, Trenckner, L. Feer, etc. We owe much, too, to the works of Turnour, Hardy, Clough, Gogerly, D’Alwis, Burnouf, Lassen, Spiegel, Weber, Koeppen, Minayeff, Bigandet, Max Müller, Kern, Ed. Müller, E. Kuhn, Pischel, and others. These enable us to form a fair estimate of what Buddhism was in its early days.

But the case is different when we turn to the Northern Buddhist Scriptures, written generally in tolerably correct Sanskṛit (with Tibetan translations). These continue to be little studied, notwithstanding the materials placed at our command and the good work done, first by the distinguished ‘founder of the study of Buddhism,’ Brian Hodgson, and by Burnouf, Wassiljew, Cowell, Senart, Kern, Beal, Foucaux, and others. In fact, the moment we pass from the Buddhism of India, Ceylon, Burma, and Siam, to that of Nepāl, Kashmīr, Tibet, Bhutān, Sikkim, China, Mongolia, Manchuria, Corea, and Japan, we seem to have entered a labyrinth, the clue of which is continually slipping from our hands.

Nor is it possible to classify the varying and often conflicting systems in these latter countries, under the one general title of Northern Buddhism.

For indeed the changes which religious systems undergo, even in countries adjacent to each other, not unfrequently amount to an entire reversal of their whole character. We may illustrate these changes by the variations of words derived from one and the same root in neighbouring countries. Take, for example, the German words selig, ‘blessed,’ and knabe, ‘a boy,’ which in England are represented by ‘silly’ and ‘knave.’

A similar law appears to hold good in the case of religious ideas. Their whole character seems to change by a change of latitude and longitude. This is even true of Christianity. Can it be maintained, for instance, that the Christianity of modern Greece and Rome has much in common with early Christianity, and would any casual observer believe that the inhabitants of St. Petersburg, Berlin, Edinburgh, London, and Paris were followers of the same religion?

It cannot therefore surprise us if Buddhism developed into apparently contradictory systems in different countries and under varying climatic conditions. In no two countries did it preserve the same features. Even in India, the land of its birth, it had greatly changed during the first ten centuries of its prevalence. So much so that had it been possible for its founder to reappear upon earth in the fifth century after Christ, he would have failed to recognize his own child, and would have found that his own teaching had not escaped the operation of a law which experience proves to be universal and inevitable.

It is easy, therefore, to understand how difficult it will be to give any semblance of unity to my present subject. It will be impossible for me to treat as a consistent whole a system having a perpetually varying front and no settled form. I can only give a series of somewhat rough, though, I hope, trustworthy outlines, as far as possible in methodical succession.

And in the carrying out of such a design, the three objects that will at first naturally present themselves for delineation will be three which constitute the well-known triad of early Buddhism—that is to say, the Buddha himself, His Law and His Order of Monks.

Hence my aim will be, in the first place, to give such a historical account of the Buddha and of his earliest teaching as may be gathered from his legendary biography, and from the most trustworthy parts of the Buddhist canonical scriptures. Secondly, I shall give a brief description of the origin and composition of those scriptures as containing the Buddha’s ‘Law’ (Dharma); and thirdly, I shall endeavour to explain the early constitution of the Buddha’s Order of Monks (Saṅgha). After treating of these three preliminary topics, I shall next describe the Law itself; that is, the philosophical doctrines of Buddhism, its code of morality and theory of perfection, terminating in Nirvāṇa. Lastly, I shall attempt to trace out the confused outlines of theistic, mystical, and hierarchical Buddhism, as developed in Northern countries, adding an account of sacred objects and places, and contrasting the chief doctrines of Christianity. In regard to the Buddhism of Tibet, I shall chiefly base my explanations on Koeppen’s great work—a work never translated into English and now out of print—as well as on my own researches during my travels through the parts of India bordering on that country.

And here I ought to state that my explanations and descriptions will, I fear, be wholly deficient in picturesqueness. My simple aim will be to convey clear and correct information in unembellished language; and in doing this, I shall often be compelled to expose myself to the reproach contained in the expressions, ćarvita-ćarvaṇam, ‘chewing the chewed,’ and pishṭa-peshaṇam, ‘grinding the ground.’ I shall constantly be obliged to tread on ground already well trodden.

To begin, then, with the Buddha himself.

LECTURE II.

The Buddha as a personal Teacher.

It is much to be regretted that among all the sacred books that constitute the Canon of the Southern Buddhists (see p. 61)—the only true Canon of Buddhism—there is no trustworthy biography of its Founder.

For Buddhism is nothing without Buddha, just as Zoroastrianism is nothing without Zoroaster, Confucianism nothing without Confucius, Muhammadanism nothing without Muhammad, and I may add with all reverence, Christianity nothing without Christ.

Indeed, no religion or religious system which has not emanated from some one heroic central personality, or in other words, which has not had a founder whose strongly marked personal character constituted the very life and soul of his teaching and the chief factor in its effectiveness, has ever had any chance of achieving world-wide acceptance, or ever spread far beyond the place of its origin.

Hence the barest outline of primitive Buddhism must be incomplete without some sketch of the life and character of Gautama Buddha himself. Yet it is difficult to find any sure basis of fact on which we may construct a fairly credible biography.

In all likelihood legendary histories of the Founder of Buddhism were current in Nepāl and Tibet in the early centuries of our era; but unhappily his too enthusiastic and imaginative admirers have thought it right to testify their admiration by interweaving with the probable facts of Gautama Buddha’s life, fables so extravagant that some modern critical scholars have despaired of attempting to sift truth from fiction, and have even gone to the extreme of doubting that Gautama Buddha ever lived at all.

To believe nothing that has been recorded about him, is as unreasonable as to accept with unquestioning faith all the miraculous circumstances which are made to encircle him as with a halo of divine glory.

We must bear in mind that when Gautama Buddha lived—about the fifth century B.C.—the art of writing was not common in India[9]. We may point out, too, that in all countries, European as well as Asiatic—notably in Greece (witness, for example, the familiar instance of Socrates)—men have thought more of preserving the sayings of their teachers than of recording the facts of their lives.

And we must not forget that in India—where the imaginative faculties have always been too active, and anything like real history is unknown—any plain matter-of-fact biography of the most heroic personage would have few charms for any one, and little chance of gaining acceptance anywhere.