автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Myths & Legends of the Celtic Race

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race

Author: Thomas William Rolleston

Release Date: October 16, 2010 [Ebook #34081]

Language: English

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE***

MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE

Queen Maev

T. W. ROLLESTON

MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE

CONSTABLE - LONDON

[pg 8]

British edition published by Constable and Company Limited, London

First published 1911 by George G. Harrap & Co., London

[pg 9]

PREFACE

The Past may be forgotten, but it never dies. The elements which in the most remote times have entered into a nation's composition endure through all its history, and help to mould that history, and to stamp the character and genius of the people.

The examination, therefore, of these elements, and the recognition, as far as possible, of the part they have actually contributed to the warp and weft of a nation's life, must be a matter of no small interest and importance to those who realise that the present is the child of the past, and the future of the present; who will not regard themselves, their kinsfolk, and their fellow-citizens as mere transitory phantoms, hurrying from darkness into darkness, but who know that, in them, a vast historic stream of national life is passing from its distant and mysterious origin towards a future which is largely conditioned by all the past wanderings of that human stream, but which is also, in no small degree, what they, by their courage, their patriotism, their knowledge, and their understanding, choose to make it.

The part played by the Celtic race as a formative influence in the history, the literature, and the art of the people inhabiting the British Islands—a people which from that centre has spread its dominions over so vast an area of the earth's surface—has been unduly obscured in popular thought. For this the current use of the term “Anglo-Saxon” applied to the British people as a designation of race is largely responsible. Historically the term is quite misleading. There is nothing to justify this singling out of two Low-German tribes when we wish to indicate the race-character of the British people. The use of it leads to such absurdities as that which the writer noticed not [pg 10] long ago, when the proposed elevation by the Pope of an Irish bishop to a cardinalate was described in an English newspaper as being prompted by the desire of the head of the Catholic Church to pay a compliment to “the Anglo-Saxon race.”

The true term for the population of these islands, and for the typical and dominant part of the population of North America, is not Anglo-Saxon, but Anglo-Celtic. It is precisely in this blend of Germanic and Celtic elements that the British people are unique—it is precisely this blend which gives to this people the fire, the élan, and in literature and art the sense of style, colour, drama, which are not common growths of German soil, while at the same time it gives the deliberateness and depth, the reverence for ancient law and custom, and the passion for personal freedom, which are more or less strange to the Romance nations of the South of Europe. May they never become strange to the British Islands! Nor is the Celtic element in these islands to be regarded as contributed wholly, or even very predominantly, by the populations of the so-called “Celtic Fringe.” It is now well known to ethnologists that the Saxons did not by any means exterminate the Celtic or Celticised populations whom they found in possession of Great Britain. Mr. E.W.B. Nicholson, librarian of the Bodleian, writes in his important work “Keltic Researches” (1904):

“Names which have not been purposely invented to describe race must never be taken as proof of race, but only as proof of community of language, or community of political organisation. We call a man who speaks English, lives in England, and bears an obviously English name (such as Freeman or Newton), an Englishman. Yet from the statistics of ‘relative [pg 11] nigrescence’ there is good reason to believe that Lancashire, West Yorkshire, Staffordshire, Worcestershire, Warwickshire, Leicestershire, Rutland, Cambridgeshire, Wiltshire, Somerset, and part of Sussex are as Keltic as Perthshire and North Munster; that Cheshire, Shropshire, Herefordshire, Monmouthshire, Gloucestershire, Devon, Dorset, Northamptonshire, Huntingdonshire, and Bedfordshire are more so—and equal to North Wales and Leinster; while Buckinghamshire and Hertfordshire exceed even this degree, and are on a level with South Wales and Ulster.”1

It is, then, for an Anglo-Celtic, not an “Anglo-Saxon,” people that this account of the early history, the religion, and the mythical and romantic literature of the Celtic race is written. It is hoped that that people will find in it things worthy to be remembered as contributions to the general stock of European culture, but worthy above all to be borne in mind by those who have inherited more than have any other living people of the blood, the instincts and the genius of the Celt.

Contents

- PREFACE

- CHAPTER I: THE CELTS IN ANCIENT HISTORY

- CHAPTER II: THE RELIGION OF THE CELTS

- CHAPTER III: THE IRISH INVASION MYTHS

- CHAPTER IV: THE EARLY MILESIAN KINGS

- CHAPTER V: TALES OF THE ULTONIAN CYCLE

- CHAPTER VI: TALES OF THE OSSIANIC CYCLE

- CHAPTER VII: THE VOYAGE OF MAELDUN

- CHAPTER VIII: MYTHS AND TALES OF THE CYMRY

Illustrations

- Queen Maev

- Prehistoric Tumulus at New Grange

- Stone Alignments at Kermaris, Carnac

- Stone-worship at Locronan, Brittany

[pg 17]

CHAPTER I: THE CELTS IN ANCIENT HISTORY

Earliest References

In the chronicles of the classical nations for about five hundred years previous to the Christian era there are frequent references to a people associated with these nations, sometimes in peace, sometimes in war, and evidently occupying a position of great strength and influence in the Terra Incognita of Mid-Europe. This people is called by the Greeks the Hyperboreans or Celts, the latter term being first found in the geographer Hecatæsus, about 500 B.C.2

Herodotus, about half a century later, speaks of the Celts as dwelling “beyond the pillars of Hercules”—i.e., in Spain—and also of the Danube as rising in their country.

Aristotle knew that they dwelt “beyond Spain,” that they had captured Rome, and that they set great store by warlike power. References other than geographical are occasionally met with even in early writers. Hellanicus of Lesbos, an historian of the fifth century B.C., describes the Celts as practising justice and righteousness. Ephorus, about 350 B.C., has three lines of verse about the Celts in which they are described as using “the same customs as the Greeks”—whatever that may mean—and being on the friendliest terms with that people, who established guest friendships among them. Plato, however, in the “Laws,” classes the Celts among the races who are drunken and combative, and much barbarity is attributed to them on the occasion of their irruption into Greece and the [pg 18] sacking of Delphi in the year 273 B.C. Their attack on Rome and the sacking of that city by them about a century earlier is one of the landmarks of ancient history.

The history of this people during the time when they were the dominant power in Mid-Europe has to be divined or reconstructed from scattered references, and from accounts of episodes in their dealings with Greece and Rome, very much as the figure of a primæval monster is reconstructed by the zoologist from a few fossilised bones. No chronicles of their own have come down to us, no architectural remains have survived; a few coins, and a few ornaments and weapons in bronze decorated with enamel or with subtle and beautiful designs in chased or repoussé work—these, and the names which often cling in strangely altered forms to the places where they dwelt, from the Euxine to the British Islands, are well-nigh all the visible traces which this once mighty power has left us of its civilisation and dominion. Yet from these, and from the accounts of classical writers, much can be deduced with certainty, and much more can be conjectured with a very fair measure of probability. The great Celtic scholar whose loss we have recently had to deplore, M. d'Arbois de Jubainville, has, on the available data, drawn a convincing outline of Celtic history for the period prior to their emergence into full historical light with the conquests of Cæsar,3 and it is this outline of which the main features are reproduced here.

The True Celtic Race

To begin with, we must dismiss the idea that Celtica was ever inhabited by a single pure and homogeneous race. The true Celts, if we accept on this point the carefully studied and elaborately argued conclusion of [pg 19] Dr. T. Rice Holmes,4 supported by the unanimous voice of antiquity, were a tall, fair race, warlike and masterful,5 whose place of origin (as far as we can trace them) was somewhere about the sources of the Danube, and who spread their dominion both by conquest and by peaceful [pg 20] infiltration over Mid-Europe, Gaul, Spain, and the British Islands. They did not exterminate the original prehistoric inhabitants of these regions—palæolithic and neolithic races, dolmen-builders and workers in bronze—but they imposed on them their language, their arts, and their traditions, taking, no doubt, a good deal from them in return, especially, as we shall see, in the important matter of religion. Among these races the true Celts formed an aristocratic and ruling caste. In that capacity they stood, alike in Gaul, in Spain, in Britain, and in Ireland, in the forefront or armed opposition to foreign invasion. They bore the worst brunt of war, of confiscations, and of banishment. They never lacked valour, but they were not strong enough or united enough to prevail, and they perished in far greater proportion than the earlier populations whom they had themselves subjugated. But they disappeared also by mingling their blood with these inhabitants, whom they impregnated with many of their own noble and virile qualities. Hence it comes that the characteristics of the peoples called Celtic in the present day, and who carry on the Celtic tradition and language, are in some respects so different from those of the Celts of classical history and the Celts who produced the literature and art of ancient Ireland, and in others so strikingly similar. To take a physical characteristic alone, the more Celtic districts of the British Islands are at present marked by darkness of complexion, hair, &c. They are not very dark, but they are darker than the rest of the kingdom.6 But the [pg 21] true Celts were certainly fair. Even the Irish Celts of the twelfth century are described by Giraldus Cambrensis as a fair race.

Golden Age of the Celts

But we are anticipating, and must return to the period of the origins of Celtic history. As astronomers have discerned the existence of an unknown planet by the perturbations which it has caused in the courses of those already under direct observation, so we can discern in the fifth and fourth centuries before Christ the presence of a great power and of mighty movements going on behind a veil which will never be lifted now. This was the Golden Age of Celtdom in Continental Europe. During this period the Celts waged three great and successful wars, which had no little influence on the course of South European history. About 500 B.C. they conquered Spain from the Carthaginians. A century later we find them engaged in the conquest of Northern Italy from the Etruscans. They settled in large numbers in the territory afterwards known as Cisalpine Gaul, where many names, such as Mediolanum (Milan), Addua (Adda), Viro-dunum (Verduno), and perhaps Cremona (creamh, garlic),7 testify still to their occupation. They left a greater memorial in the chief of Latin poets, whose name, Vergil, appears to bear evidence of his Celtic ancestry.8 Towards the end of the fourth [pg 22] century they overran Pannonia, conquering the Illyrians.

Alliances with the Greeks

All these wars were undertaken in alliance with the Greeks, with whom the Celts were at this period on the friendliest terms. By the war with the Carthaginians the monopoly held by that people of the trade in tin with Britain and in silver with the miners of Spain was broken down, and the overland route across France to Britain, for the sake of which the Phocæans had in 600 B.C. created the port of Marseilles, was definitely secured to Greek trade. Greeks and Celts were at this period allied against Phœnicians and Persians. The defeat of Hamilcar by Gelon at Himera, in Sicily, took place in the same year as that of Xerxes at Salamis. The Carthaginian army in that expedition was made up of mercenaries from half a dozen different nations, but not a Celt is found in the Carthaginian ranks, and Celtic hostility must have counted for much in preventing the Carthaginians from lending help to the Persians for the overthrow of their common enemy. These facts show that Celtica played no small part in preserving the Greek type of civilisation from being overwhelmed by the despotisms of the East, and thus in keeping alive in Europe the priceless seed of freedom and humane culture.

Alexander the Great

When the counter-movement of Hellas against the East began under Alexander the Great we find the Celts again appearing as a factor of importance.

[pg 23]

In the fourth century Macedon was attacked and almost obliterated by Thracian and Illyrian hordes. King Amyntas II. was defeated and driven into exile. His son Perdiccas II. was killed in battle. When Philip, a younger brother of Perdiccas, came to the obscure and tottering throne which he and his successors were to make the seat of a great empire he was powerfully aided in making head against the Illyrians by the conquests of the Celts in the valleys of the Danube and the Po. The alliance was continued, and rendered, perhaps, more formal in the days of Alexander. When about to undertake his conquest of Asia (334 B.C.) Alexander first made a compact with the Celts “who dwelt by the Ionian Gulf” in order to secure his Greek dominions from attack during his absence. The episode is related by Ptolemy Soter in his history of the wars of Alexander.9 It has a vividness which stamps it as a bit of authentic history, and another singular testimony to the truth of the narrative has been brought to light by de Jubainville. As the Celtic envoys, who are described as men of haughty bearing and great stature, their mission concluded, were drinking with the king, he asked them, it is said, what was the thing they, the Celts, most feared. The envoys replied: “We fear no man: there is but one thing that we fear, namely, that the sky should fall on us; but we regard nothing so much as the friendship of a man such as thou.” Alexander bade them farewell, and, turning to his nobles, whispered: “What a vainglorious people are these Celts!” Yet the answer, for all its Celtic bravura and flourish, [pg 24] was not without both dignity and courtesy. The reference to the falling of the sky seems to give a glimpse of some primitive belief or myth of which it is no longer possible to discover the meaning.10 The national oath by which the Celts bound themselves to the observance of their covenant with Alexander is remarkable. “If we observe not this engagement,” they said, “may the sky fall on us and crush us, may the earth gape and swallow us up, may the sea burst out and overwhelm us.” De Jubainville draws attention most appositely to a passage from the “Táin Bo Cuailgne,” in the Book of Leinster11, where the Ulster heroes declare to their king, who wished to leave them in battle in order to meet an attack in another part of the field: “Heaven is above us, and earth beneath us, and the sea is round about us. Unless the sky shall fall with its showers of stars on the ground where we are camped, or unless the earth shall be rent by an earthquake, or unless the waves of the blue sea come over the forests of the living world, we shall not give ground.”12 This survival of a peculiar oath-formula for more than a thousand years, and its reappearance, after being first heard of among the Celts of Mid-Europe, in a mythical romance of Ireland, is certainly most curious, and, with other facts which we shall note hereafter, speaks strongly for the community and persistence of Celtic culture.13

[pg 25]

The Sack of Rome

We have mentioned two of the great wars of the Continental Celts; we come now to the third, that with the Etruscans, which ultimately brought them into conflict with the greatest power of pagan Europe, and led to their proudest feat of arms, the sack of Rome. About the year 400 B.C. the Celtic Empire seems to have reached the height of its power. Under a king named by Livy Ambicatus, who was probably the head of a dominant tribe in a military confederacy, like the German Emperor in the present day, the Celts seem to have been welded into a considerable degree of political unity, and to have followed a consistent policy. Attracted by the rich land of Northern Italy, they poured down through the passes of the Alps, and after hard fighting with the Etruscan inhabitants they maintained their ground there. At this time the Romans were pressing on the Etruscans from below, and Roman and Celt were acting in definite concert and alliance. But the Romans, despising perhaps the Northern barbarian warriors, had the rashness to play them false at the siege of Clusium, 391 B.C., a place which the Romans regarded as one of the bulwarks of Latium against the North. The Celts recognised Romans who had come to them in the sacred character of ambassadors fighting in the ranks of the enemy. The events which followed are, as they have come down to us, much mingled with legend, but there are certain touches of dramatic vividness in which the true character of the Celts appears distinctly recognisable. They applied, we are told, to Rome for satisfaction for the treachery of the envoys, who were three sons of Fabius Ambustus, the chief pontiff. The Romans refused to listen to the claim, and elected the Fabii military tribunes for the [pg 26] ensuing year. Then the Celts abandoned the siege of Clusium and marched straight on Rome. The army showed perfect discipline. There was no indiscriminate plundering and devastation, no city or fortress was assailed. “We are bound for Rome” was their cry to the guards upon the walls of the provincial towns, who watched the host in wonder and fear as it rolled steadily to the south. At last they reached the river Allia, a few miles from Rome, where the whole available force of the city was ranged to meet them. The battle took place on July 18, 390, that ill-omened dies Alliensis which long perpetuated in the Roman calendar the memory of the deepest shame the republic had ever known. The Celts turned the flank of the Roman army, and annihilated it in one tremendous charge. Three days later they were in Rome, and for nearly a year they remained masters of the city, or of its ruins, till a great fine had been exacted and full vengeance taken for the perfidy at Clusium. For nearly a century after the treaty thus concluded there was peace between the Celts and the Romans, and the breaking of that peace when certain Celtic tribes allied themselves with their old enemy, the Etruscans, in the third Samnite war was coincident with the breaking up of the Celtic Empire.14

Two questions must now be considered before we can leave the historical part of this Introduction. First of all, what are the evidences for the widespread diffusion of Celtic power in Mid-Europe during this period? Secondly, where were the Germanic peoples, and what was their position in regard to the Celts?

[pg 27]

Celtic Place-names in Europe

To answer these questions fully would take us (for the purposes of this volume) too deeply into philological discussions, which only the Celtic scholar can fully appreciate. The evidence will be found fully set forth in de Jubainville's work, already frequently referred to. The study of European place-names forms the basis of the argument. Take the Celtic name Noviomagus composed of two Celtic words, the adjective meaning new, and magos (Irish magh) a field or plain.15 There were nine places of this name known in antiquity. Six were in France, among them the places now called Noyon, in Oise, Nijon, in Vosges, Nyons, in Drôme. Three outside of France were Nimègue, in Belgium, Neumagen, in the Rhineland, and one at Speyer, in the Palatinate.

The word dunum, so often traceable in Gaelic place-names in the present day (Dundalk, Dunrobin, &c.), and meaning fortress or castle, is another typically Celtic element in European place-names. It occurred very frequently in France—e.g., Lug-dunum (Lyons), Viro-dunum (Verdun). It is also found in Switzerland—e.g., Minno-dunum (Moudon), Eburo-dunum (Yverdon)—and in the Netherlands, where the famous city of Leyden goes back to a Celtic Lug-dunum. In Great Britain the Celtic term was often changed by simple translation into castra; thus Camulo-dunum became Colchester, Brano-dunum Brancaster. In Spain and Portugal eight names terminating in dunum are mentioned by classical writers. In Germany the modern names Kempton, Karnberg, Liegnitz, go back respectively to the Celtic forms Cambo-dunum, Carro-aunum, [pg 28] Lugi-dunum, and we find a Singi-dunum, now Belgrade, in Servia, a Novi-dunum, now Isaktscha, in Roumania, a Carro-dunum in South Russia, near the Dniester, and another in Croatia, now Pitsmeza. Sego-dunum, now Rodez, in France, turns up also in Bavaria (Wurzburg), and in England (Sege-dunum, now Wallsend, in Northumberland), and the first term, sego, is traceable in Segorbe (Sego-briga) in Spain. Briga is a Celtic word, the origin of the German burg, and equivalent in meaning to dunum.

One more example: the word magos, a plain, which is very frequent as an element of Irish place-names, is found abundantly in France, and outside of France, in countries no longer Celtic, it appears in Switzerland (Uro-magus now Promasens), in the Rhineland (Broco-magus, Brumath), in the Netherlands, as already noted (Nimègue), in Lombardy several times, and in Austria.

The examples given are by no means exhaustive, but they serve to indicate the wide diffusion of the Celts in Europe and their identity of language over their vast territory.16

Early Celtic Art

The relics of ancient Celtic art-work tell the same story. In the year 1846 a great pre-Roman necropolis was discovered at Hallstatt, near Salzburg, in Austria. It contains relics believed by Dr. Arthur Evans to date from about 750 to 400 B.C. These relics betoken in some cases a high standard of civilisation and considerable commerce. Amber from the Baltic is there, Phoenician glass, and gold-leaf of Oriental workmanship. Iron swords are found whose hilts and sheaths are richly decorated with gold, ivory, and amber.

[pg 29]

The Celtic culture illustrated by the remains at Hallstatt developed later into what is called the La Tène culture. La Tène was a settlement at the north-eastern end of the Lake of Neuchâtel, and many objects of great interest have been found there since the site was first explored in 1858. These antiquities represent, according to Dr. Evans, the culminating period of Gaulish civilisation, and date from round about the third century B.C. The type of art here found must be judged in the light of an observation recently made by Mr. Romilly Allen in his “Celtic Art” (p. 13):

“The great difficulty in understanding the evolution of Celtic art lies in the fact that although the Celts never seem to have invented any new ideas, they possessed an extraordinary aptitude for picking up ideas from the different peoples with whom war or commerce brought them into contact. And once the Celt had borrowed an idea from his neighbours he was able to give it such a strong Celtic tinge that it soon became something so different from what it was originally as to be almost unrecognisable.”

Now what the Celt borrowed in the art-culture which on the Continent culminated in the La Tène relics were certain originally naturalistic motives for Greek ornaments, notably the palmette and the meander motives. But it was characteristic of the Celt that he avoided in his art all imitation of, or even approximation to, the natural forms of the plant and animal world. He reduced everything to pure decoration. What he enjoyed in decoration was the alternation of long sweeping curves and undulations with the concentrated energy of close-set spirals or bosses, and with these simple elements and with the suggestion of a few motives derived from Greek art he elaborated a most [pg 30] beautiful, subtle, and varied system of decoration, applied to weapons, ornaments, and to toilet and household appliances of all kinds, in gold, bronze, wood, and stone, and possibly, if we had the means of judging, to textile fabrics also. One beautiful feature in the decoration of metal-work seems to have entirely originated in Celtica. Enamelling was unknown to the classical nations till they learned from the Celts. So late as the third century A.D. it was still strange to the classical world, as we learn from the reference of Philostratus:

“They say that the barbarians who live in the ocean [Britons] pour these colours upon heated brass, and that they adhere, become hard as stone, and preserve the designs that are made upon them.”

Dr. J. Anderson writes in the “Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland”:

“The Gauls as well as the Britons—of the same Celtic stock—practised enamel-working before the Roman conquest. The enamel workshops of Bibracte, with their furnaces, crucibles, moulds, polishing-stones, and with the crude enamels in their various stages of preparation, have been recently excavated from the ruins of the city destroyed by Caesar and his legions. But the Bibracte enamels are the work of mere dabblers in the art, compared with the British examples. The home of the art was Britain, and the style of the pattern, as well as the association in which the objects decorated with it were found, demonstrated with certainty that it had reached its highest stage of indigenous development before it came in contact with the Roman culture.”17

The National Museum in Dublin contains many superb examples of Irish decorative art in gold, bronze, [pg 31] and enamels, and the “strong Celtic tinge” of which Mr. Romilly Allen speaks is as clearly observable there as in the relics of Hallstatt or La Tène.

Everything, then, speaks of a community of culture, an identity of race-character, existing over the vast territory known to the ancient world as “Celtica.”

Celts and Germans

But, as we have said before, this territory was by no means inhabited by the Celt alone. In particular we have to ask, who and where were the Germans, the Teuto-Gothic tribes, who eventually took the place of the Celts as the great Northern menace to classical civilisation?

They are mentioned by Pytheas, the eminent Greek traveller and geographer, about 300 B.C., but they play no part in history till, under the name of Cimbri and Teutones, they descended on Italy to be vanquished by Marius at the close of the second century. The ancient Greek geographers prior to Pytheas know nothing of them, and assign all the territories now known as Germanic to various Celtic tribes.

The explanation given by de Jubainville, and based by him on various philological considerations, is that the Germans were a subject people, comparable to those “un-free tribes” who existed in Gaul and in ancient Ireland. They lived under the Celtic dominion, and had no independent political existence. De Jubainville finds that all the words connected with law and government and war which are common both to the Celtic and Teutonic languages were borrowed by the latter from the former. Chief among them are the words represented by the modern German Reich, empire, Amt, office, and the Gothic reiks, a king, all of which are of unquestioned Celtic origin. De Jubainville also numbers among loan words from Celtic [pg 32] the words Bann, an order; Frei, free; Geisel, a hostage; Erbe, an inheritance; Werth, value; Weih, sacred; Magus, a slave (Gothic); Wini, a wife (Old High German); Skalks, Schalk, a slave (Gothic); Hathu, battle (Old German); Helith, Held, a hero, from the same root as the word Celt; Heer, an army (Celtic choris); Sieg, victory; Beute, booty; Burg, a castle; and many others.

The etymological history of some of these words is interesting. Amt, for instance, that word of so much significance in modern German administration, goes back to an ancient Celtic ambhactos, which is compounded of the words ambi, about, and actos, a past participle derived from the Celtic root AG, meaning to act. Now ambi descends from the primitive Indo-European mbhi, where the initial m is a kind of vowel, afterwards represented in Sanscrit by a. This m vowel became n in those Germanic words which derive directly from the primitive Indo-European tongue. But the word which is now represented by amt appears in its earliest Germanic form as ambaht, thus making plain its descent from the Celtic ambhactos.

Again, the word frei is found in its earliest Germanic form as frijo-s, which comes from the primitive Indo-European prijo-s. The word here does not, however, mean free; it means beloved (Sanscrit priya-s). In the Celtic language, however, we find prijos dropping its initial p—a difficulty in pronouncing this letter was a marked feature in ancient Celtic; it changed j, according to a regular rule, into dd, and appears in modern Welsh as rhydd=free. The Indo-European meaning persists in the Germanic languages in the name of the love-goddess, Freia, and in the word Freund, friend, Friede, peace. The sense borne by the word in the sphere of civil right is traceable to a Celtic origin, [pg 33] and in that sense appears to have been a loan from Celtic.

The German Beute, booty, plunder, has had an instructive history. There was a Gaulish word bodi found in compounds such as the place-name Segobodium (Seveux), and various personal and tribal names, including Boudicca, better known to us as the “British warrior queen,” Boadicea. This word meant anciently “victory.” But the fruits of victory are spoil, and in this material sense the word was adopted in German, in French (butin) in Norse (byte), and the Welsh (budd). On the other hand, the word preserved its elevated significance in Irish. In the Irish translation of Chronicles xxix. 11, where the Vulgate original has “Tua est, Domine, magnificentia et potentia et gloria et victoria,” the word victoria is rendered by the Irish búaidh, and, as de Jubainville remarks, “ce n'est pas de butin qu'il s'agit.” He goes on to say: “Búaidh has preserved in Irish, thanks to a vigorous and persistent literary culture, the high meaning which it bore in the tongue of the Gaulish aristocracy. The material sense of the word was alone perceived by the lower classes of the population, and it is the tradition of this lower class which has been preserved in the German, the French, and the Cymric languages.”18

Two things, however, the Celts either could not or would not impose on the subjugated German tribes—their language and their religion. In these two great factors of race-unity and pride lay the seeds of the ultimate German uprising and overthrow of the Celtic supremacy. The names of the German are different from those of the Celtic deities, their funeral customs, with which are associated the deepest religious conceptions of primitive races, are different. The Celts, or [pg 34] at least the dominant section of them, buried their dead, regarding the use of fire as a humiliation, to be inflicted on criminals, or upon slaves or prisoners in those terrible human sacrifices which are the greatest stain on their native culture. The Germans, on the other hand, burned their illustrious dead on pyres, like the early Greeks—if a pyre could not be afforded for the whole body, the noblest parts, such as the head and arms, were burned and the rest buried.

Downfall of the Celtic Empire

What exactly took place at the time of the German revolt we shall never know; certain it is, however, that from about the year 300 B.C. onward the Celts appear to have lost whatever political cohesion and common purpose they had possessed. Rent asunder, as it were, by the upthrust of some mighty subterranean force, their tribes rolled down like lava-streams to the south, east, and west of their original home. Some found their way into Northern Greece, where they committed the outrage which so scandalised their former friends and allies in the sack of the shrine of Delphi (273 B.C.). Others renewed, with worse fortune, the old struggle with Rome, and perished in vast numbers at Sentinum (295 B.C.) and Lake Vadimo (283 B.C.). One detachment penetrated into Asia Minor, and founded the Celtic State of Galatia, where, as St. Jerome attests, a Celtic dialect was still spoken in the fourth century A.D. Others enlisted as mercenary troops with Carthage. A tumultuous war of Celts against scattered German tribes, or against other Celts who represented earlier waves of emigration and conquest, went on all over Mid-Europe, Gaul, and Britain. When this settled down Gaul and the British Islands remained practically the sole relics of the Celtic [pg 35] empire, the only countries still under Celtic law and leadership. By the commencement of the Christian era Gaul and Britain had fallen under the yoke of Rome, and their complete Romanisation was only a question of time.

Unique Historical Position of Ireland

Ireland alone was never even visited, much less subjugated, by the Roman legionaries, and maintained its independence against all comers nominally until the close of the twelfth century, but for all practical purposes a good three hundred years longer.

Ireland has therefore this unique feature of interest, that it carried an indigenous Celtic civilisation, Celtic institutions, art, and literature, and the oldest surviving form of the Celtic language,19 right across the chasm which separates the antique from the modern world, [pg 36] the pagan from the Christian world, and on into the full light of modern history and observation.

The Celtic Character

The moral no less than the physical characteristics attributed by classical writers to the Celtic peoples show a remarkable distinctness and consistency. Much of what is said about them might, as we should expect, be said of any primitive and unlettered people, but there remains so much to differentiate them among the races of mankind that if these ancient references to the Celts could be read aloud, without mentioning the name of the race to whom they referred, to any person acquainted with it through modern history alone, he would, I think, without hesitation, name the Celtic peoples as the subject of the description which he had heard.

Some of these references have already been quoted, and we need not repeat the evidence derived from Plato, Ephorus, or Arrian. But an observation of [pg 37] M. Porcius Cato on the Gauls may be adduced. “There are two things,” he says, “to which the Gauls are devoted—the art of war and subtlety of speech” (“rem militarem et argute loqui”).

Cæsar's Account

Cæsar has given us a careful and critical account of them as he knew them in Gaul. They were, he says, eager for battle, but easily dashed by reverses. They were extremely superstitious, submitting to their Druids in all public and private affairs, and regarding it as the worst of punishments to be excommunicated and forbidden to approach thu ceremonies of religion:

“They who are thus interdicted [for refusing to obey a Druidical sentence] are reckoned in the number of the vile and wicked; all persons avoid and fly their company and discourse, lest they should receive any infection by contagion; they are not permitted to commence a suit; neither is any post entrusted to them.... The Druids are generally freed from military service, nor do they pay taxes with the rest.... Encouraged by such rewards, many of their own accord come to their schools, and are sent by their friends and relations. They are said there to get by heart a great number of verses; some continue twenty years in their education; neither is it held lawful to commit these things [the Druidic doctrines] to writing, though in almost all public transactions and private accounts they use the Greek characters.”

The Gauls were eager for news, besieging merchants and travellers for gossip,20 easily influenced, sanguine, [pg 38] credulous, fond of change, and wavering in their counsels. They were at the same time remarkably acute and intelligent, very quick to seize upon and to imitate any contrivance they found useful. Their ingenuity in baffling the novel siege apparatus of the Roman armies is specially noticed by Cæsar. Of their courage he speaks with great respect, attributing their scorn of death, in some degree at least, to their firm faith in the immortality of the soul.21 A people who in earlier days had again and again annihilated Roman armies, had sacked Rome, and who had more than once placed Cæsar himself in positions of the utmost anxiety and peril, were evidently no weaklings, whatever their religious beliefs or practices. Cæsar is not given to sentimental admiration of his foes, but one episode at the siege of Avaricum moves him to immortalise the valour of the defence. A wooden structure or agger had been raised by the Romans to overtop the walls, which had proved impregnable to the assaults of the battering-ram. The Gauls contrived to set this on fire. It was of the utmost moment to prevent the besiegers from extinguishing the flames, and a Gaul mounted a portion of the wall above the agger, throwing down upon it balls of tallow and pitch, which were handed up to him from within. He was soon struck down by a missile from a Roman catapult. Immediately another stepped over him as he lay, and continued his comrade's task. He too fell, [pg 39] but a third instantly took his place, and a fourth; nor was this post ever deserted until the legionaries at last extinguished the flames and forced the defenders back into the town, which was finally captured on the following day.

Strabo on the Celts

The geographer and traveller Strabo, who died 24 A.D., and was therefore a little later than Cæsar, has much to tell us about the Celts. He notices that their country (in this case Gaul) is thickly inhabited and well tilled—there is no waste of natural resources. The women are prolific, and notably good mothers. He describes the men as warlike, passionate, disputatious, easily provoked, but generous and unsuspicious, and easily vanquished by stratagem. They showed themselves eager for culture, and Greek letters and science had spread rapidly among them from Massilia; public education was established in their towns. They fought better on horseback than on foot, and in Strabo's time formed the flower of the Roman cavalry. They dwelt in great houses made of arched timbers with walls of wickerwork—no doubt plastered with clay and lime, as in Ireland—and thickly thatched. Towns of much importance were found in Gaul, and Cæsar notes the strength of their walls, built of stone and timber. Both Cæsar and Strabo agree that there was a very sharp division between the nobles and priestly or educated class on the one hand and the common people on the other, the latter being kept in strict subjection. The social division corresponds roughly, no doubt, to the race distinction between the true Celts and the aboriginal populations subdued by them. While Cæsar tells us that the Druids taught the immortality of the soul, Strabo adds that they believed in [pg 40] the indestructibility, which implies in some sense the divinity, of the material universe.

The Celtic warrior loved display. Everything that gave brilliance and the sense of drama to life appealed to him. His weapons were richly ornamented, his horse-trappings were wrought in bronze and enamel, of design as exquisite as any relic of Mycenean or Cretan art, his raiment was embroidered with gold. The scene of the surrender of Vercingetorix, when his heroic struggle with Rome had come to an end on the fall of Alesia, is worth recording as a typically Celtic blend of chivalry and of what appeared to the sober-minded Romans childish ostentation.22 When he saw that the cause was lost he summoned a tribal council, and told the assembled chiefs, whom he had led through a glorious though unsuccessful war, that he was ready to sacrifice himself for his still faithful followers—they might send his head to Cæsar if they liked, or he would voluntarily surrender himself for the sake of getting easier terms for his countrymen. The latter alternative was chosen. Vercingetorix then armed himself with his most splendid weapons, decked his horse with its richest trappings, and, after riding thrice round the Roman camp, went before Cæsar and laid at his feet the sword which was the sole remaining defence of Gallic independence. Cæsar sent him to Rome, where he lay in prison for six years, and was finally put to death when Cæsar celebrated his triumph.

But the Celtic love of splendour and of art were mixed with much barbarism. Strabo tells us how the warriors rode home from victory with the heads of [pg 41] fallen foemen dangling from their horses' necks, just as in the Irish saga the Ulster hero, Cuchulain, is represented as driving back to Emania from a foray into Connacht with the heads of his enemies hanging from his chariot-rim. Their domestic arrangements were rude; they lay on the ground to sleep, sat on couches of straw, and their women worked in the fields.

Polybius

A characteristic scene from the battle of Clastidium (222 B.C.) is recorded by Polybius. The Gæsati,23 he tells us, who were in the forefront of the Celtic army, stripped naked for the fight, and the sight of these warriors, with their great stature and their fair skins, on which glittered the collars and bracelets of gold so loved as an adornment by all the Celts, filled the Roman legionaries with awe. Yet when the day was over those golden ornaments went in cartloads to deck the Capitol of Rome; and the final comment of Polybius on the character of the Celts is that they, “I say not usually, but always, in everything they attempt, are driven headlong by their passions, and never submit to the laws of reason.” As might be expected, the chastity for which the Germans were noted was never, until recent times, a Celtic characteristic.

Diodorus

Diodorus Siculus, a contemporary of Julius Cæsar and Augustus, who had travelled in Gaul, confirms in the main the accounts of Cæsar and Strabo, but adds some [pg 42] interesting details. He notes in particular the Gallic love of gold. Even cuirasses were made of it. This is also a very notable trait in Celtic Ireland, where an astonishing number of prehistoric gold relics have been found, while many more, now lost, are known to have existed. The temples and sacred places, say Posidonius and Diodorus, were full of unguarded offerings of gold, which no one ever touched. He mentions the great reverence paid to the bards, and, like Cato, notices something peculiar about the kind of speech which the educated Gauls cultivated: “they are not a talkative people, and are fond of expressing themselves in enigmas, so that the hearer has to divine the most part of what they would say.” This exactly answers to the literary language of ancient Ireland, which is curt and allusive to a degree. The Druid was regarded as the prescribed intermediary between God and man—no one could perform a religious act without his assistance.

Ammianus Marcellinus

Ammianus Marcellinus, who wrote much later, in the latter half of the fourth century A.D., had also visited Gaul, which was then, of course, much Romanised. He tells us, however, like former writers, of the great stature, fairness, and arrogant bearing of the Gallic warrior. He adds that the people, especially in Aquitaine, were singularly clean and proper in their persons—no one was to be seen in rags. The Gallic woman he describes as very tall, blue-eyed, and singularly beautiful; but a certain amount of awe is mingled with his evident admiration, for he tells us that while it was dangerous enough to get into a fight with a Gallic man, your case was indeed desperate if his wife with her “huge snowy arms,” which could strike like catapults, came to his assistance. One is irresistibly [pg 43] reminded of the gallery of vigorous, independent, fiery-hearted women, like Maeve, Grania, Findabair, Deirdre, and the historic Boadicea, who figure in the myths and in the history of the British Islands.

Rice Holmes on the Gauls

The following passage from Dr. Rice Holmes' “Cæsar's Conquest of Gaul” may be taken as an admirable summary of the social physiognomy of that part of Celtica a little before the time of the Christian era, and it corresponds closely to all that is known of the native Irish civilisation:

“The Gallic peoples had risen far above the condition of savages; and the Celticans of the interior, many of whom had already fallen under Roman influence, had attained a certain degree of civilisation, and even of luxury. Their trousers, from which the province took its name of Gallia Bracata, and their many-coloured tartan skirts and cloaks excited the astonishment of their conquerors. The chiefs wore rings and bracelets and necklaces of gold; and when these tall, fair-haired warriors rode forth to battle, with their helmets wrought in the shape of some fierce beast's head, and surmounted by nodding plumes, their chain armour, their long bucklers and their huge clanking swords, they made a splendid show. Walled towns or large villages, the strongholds of the various tribes, were conspicuous on numerous hills. The plains were dotted by scores of oper hamlets. The houses, built of timber and wickerwork, were large and well thatched. The fields in summer were yellow with corn. Roads ran from town to town. Rude bridges spanned the rivers; and barges laden with merchandise floated along them. Ships clumsy indeed [pg 44]but larger than any that were seen on the Mediterranean, braved the storms of the Bay of Biscay and carried cargoes between the ports of Brittany and the coast of Britain. Tolls were exacted on the goods which were transported on the great waterways; and it was from the farming of these dues that the nobles derived a large part of their wealth. Every tribe had its coinage; and the knowledge of writing in Greek and Roman characters was not confined to the priests. The Æduans were familiar with the plating of copper and of tin. The miners of Aquitaine, of Auvergne, and of the Berri were celebrated for their skill. Indeed, in all that belonged to outward prosperity the peoples of Gaul had made great strides since their kinsmen first came into contact with Rome.”24

Weakness of the Celtic Policy

Yet this native Celtic civilisation, in many respects so attractive and so promising, had evidently some defect or disability which prevented the Celtic peoples from holding their own either against the ancient civilisation of the Græco-Roman world, or against the rude young vigour of the Teutonic races. Let us consider what this was.

[pg 45]

The Classical State

At the root of the success of classical nations lay the conception of the civic community, the πόλις, the res publica, as a kind of divine entity, the foundation of blessing to men, venerable for its age, yet renewed in youth with every generation; a power which a man might joyfully serve, knowing that even if not remembered in its records his faithful service would outlive his own petty life and go to exalt the life of his motherland or city for all future time. In this spirit Socrates, when urged to evade his death sentence by taking the means of escape from prison which his friends offered him, rebuked them for inciting him to an impious violation of his country's laws. For a man's country, he says, is more holy and venerable than father or mother, and he must quietly obey the laws, to which he has assented by living under them all his life, or incur the just wrath of their great Brethren, the Laws of the Underworld, before whom, in the end, he must answer for his conduct on earth. In a greater or less degree this exalted conception of the State formed the practical religion of every man among the classical nations of antiquity, and gave to the State its cohesive power, its capability of endurance and of progress.

Teutonic Loyalty

With the Teuton the cohesive force was supplied by another motive, one which was destined to mingle with the civic motive and to form, in union with it—and often in predominance over it—the main political factor in the development of the European nations. This was the sentiment of what the Germans called Treue, the personal fidelity to a chief, which in very [pg 46] early times extended itself to a royal dynasty, a sentiment rooted profoundly in the Teutonic nature, and one which has never been surpassed by any other human impulse as the source of heroic self-sacrifice.

Celtic Religion

No human influences are ever found pure and unmixed. The sentiment of personal fidelity was not unknown to the classical nations. The sentiment of civic patriotism, though of slow growth among the Teutonic races, did eventually establish itself there. Neither sentiment was unknown to the Celt, but there was another force which, in his case, overshadowed and dwarfed them, and supplied what it could of the political inspiration and unifying power which the classical nations got from patriotism and the Teutons from loyalty. This was Religion; or perhaps it would be more accurate to say Sacerdotalism—religion codified in dogma and administered by a priestly caste. The Druids, as we have seen from Cæsar, whose observations are entirely confirmed by Strabo and by references in Irish legends,25 were the really sovran power in Celtica. All affairs, public and private, were subject to their authority, and the penalties which they could inflict for any assertion of lay independence, though resting for their efficacy, like the mediæval interdicts of the Catholic Church, on popular superstition [pg 47] alone, were enough to quell the proudest spirit. Here lay the real weakness of the Celtic polity. There is perhaps no law written more conspicuously in the teachings of history than that nations who are ruled by priests drawing their authority from supernatural sanctions are, just in the measure that they are so ruled, incapable of true national progress. The free, healthy current of secular life and thought is, in the very nature of things, incompatible with priestly rule. Be the creed what it may, Druidism, Islam, Judaism, Christianity, or fetichism, a priestly caste claiming authority in temporal affairs by virtue of extra-temporal sanctions is inevitably the enemy of that spirit of criticism, of that influx of new ideas, of that growth of secular thought, of human and rational authority, which are the elementary conditions of national development.

The Cursing of Tara

A singular and very cogent illustration of this truth can be drawn from the history of the early Celtic world. In the sixth century A.D., a little over a hundred years after the preaching of Christianity by St. Patrick, a king named Dermot MacKerval26 ruled in Ireland. He was the Ard Righ, or High King, of that country, whose seat of government was at Tara, in Meath, and whose office, with its nominal and legal superiority to the five provincial kings, represented the impulse which was moving the Irish people towards a true national unity. The first condition of such a unity was evidently the establishment of an effective central authority. Such an authority, as we have said, the High King, in theory, represented. Now it happened that one of his officers was murdered in the discharge of his duty by a chief named Hugh Guairy. Guairy [pg 48] was the brother of a bishop who was related by fosterage to St. Ruadan of Lorrha, and when King Dermot sent to arrest the murderer these clergy found him a hiding-place. Dermot, however, caused a search to be made, haled him forth from under the roof of St. Ruadan, and brought him to Tara for trial. Immediately the ecclesiastics of Ireland made common cause against the lay ruler who had dared to execute justice on a criminal under clerical protection. They assembled at Tara, fasted against the king,27 and laid their solemn malediction upon him and the seat of his government. Then the chronicler tells us that Dermot's wife had a prophetic dream:

“Upon Tara's green was a vast and wide-foliaged tree, and eleven slaves hewing at it; but every chip that they knocked from it would return into its place again and there adhere instantly, till at last there came one man that dealt the tree but a stroke, and with that single cut laid it low.”28

The fair tree was the Irish monarchy, the twelve hewers were the twelve Saints or Apostles of Ireland, and the one who laid it low was St. Ruadan. The plea of the king for his country, whose fate he saw to be hanging in the balance, is recorded with moving force and insight by the Irish chronicler:29

[pg 49]

“ ‘Alas,’ he said, ‘for the iniquitous contest that ye have waged against me; seeing that it is Ireland's good that I pursue, and to preserve her discipline and royal right; but 'tis Ireland's unpeace and murderousness that ye endeavour after.’ ”

But Ruadan said, “Desolate be Tara for ever and ever”; and the popular awe of the ecclesiastical malediction prevailed. The criminal was surrendered, Tara was abandoned, and, except for a brief space when a strong usurper, Brian Boru, fought his way to power, Ireland knew no effective secular government till it was imposed upon her by a conqueror. The last words of the historical tract from which we quote are Dermot's cry of despair:

“Woe to him that with the clergy of the churches battle joins.”

This remarkable incident has been described at some length because it is typical of a factor whose profound influence in moulding the history of the Celtic peoples we can trace through a succession of critical events from the time of Julius Caesar to the present day. How and whence it arose we shall consider later; here it is enough to call attention to it. It is a factor which forbade the national development of the Celts, in the sense in which we can speak of that of the classical or the Teutonic peoples.

What Europe Owes to the Celt

Yet to suppose that on this account the Celt was not a force of any real consequence in Europe would be altogether a mistake. His contribution to the culture of the Western world was a very notable one. For some four centuries—about A.D. 500 to 900—Ireland was [pg 50] the refuge of learning and the source of literary and philosophic culture for half Europe. The verse-forms of Celtic poetry have probably played the main part in determining the structure of all modern verse. The myths and legends of the Gaelic and Cymric peoples kindled the imagination of a host of Continental poets. True, the Celt did not himself create any great architectural work of literature, just as he did not create a stable or imposing national polity. His thinking and feeling were essentially lyrical and concrete. Each object or aspect of life impressed him vividly and stirred him profoundly; he was sensitive, impressionable to the last degree, but did not see things in their larger and more far-reaching relations. He had little gift for the establishment or institutions, for the service of principles; but he was, and is, an indispensable and never-failing assertor of humanity as against the tyranny of principles, the coldness and barrenness of institutions. The institutions of royalty and of civic patriotism are both very capable of being fossilised into barren formulae, and thus of fettering instead of inspiring the soul. But the Celt has always been a rebel against anything that has not in it the breath of life, against any unspiritual and purely external form of domination. It is too true that he has been over-eager to enjoy the fine fruits of life without the long and patient preparation for the harvest, but he has done and will still do infinite service to the modern world in insisting that the true fruit of life is a spiritual reality, never without pain and loss to be obscured or forgotten amid the vast mechanism of a material civilisation.

19.

3.

6.

23.

4.

21.

14.

18.

2.

17.

1.

10.

22.

20.

24.

25.

28.

15.

29.

8.

7.

12.

13.

9.

16.

27.

5.

26.

11.

[pg 51]

CHAPTER II: THE RELIGION OF THE CELTS

Ireland and the Celtic Religion

We have said that the Irish among the Celtic peoples possess the unique interest of having carried into the light of modern historical research many of the features of a native Celtic civilisation. There is, however, one thing which they did not carry across the gulf which divides us from the ancient world—and this was their religion.

It was not merely that they changed it; they left it behind them so entirely that all record of it is lost. St. Patrick, himself a Celt, who apostolised Ireland during the fifth century, has left us an autobiographical narrative of his mission, a document of intense interest, and the earliest extant record of British Christianity; but in it he tells us nothing of the doctrines he came to supplant. We learn far more of Celtic religious beliefs from Julius Cæsar, who approached them from quite another side. The copious legendary literature which took its present form in Ireland between the seventh and the twelfth centuries, though often manifestly going back to pre-Christian sources, shows us, beyond a belief in magic and a devotion to certain ceremonial or chivalric observances, practically nothing resembling a religious or even an ethical system. We know that certain chiefs and bards offered a long resistance to the new faith, and that this resistance came to the arbitrament of battle at Moyrath in the sixth century, but no echo of any intellectual controversy, no matching of one doctrine against another, such as we find, for instance, in the records of the controversy of Celsus with Origen, has reached us from this period of change and strife. The literature of ancient Ireland, as we [pg 52] shall see, embodied many ancient myths; and traces appear in it of beings who must, at one time, have been gods or elemental powers; but all has been emptied of religious significance and turned to romance and beauty. Yet not only was there, as Cæsar tells us, a very well-developed religious system among the Gauls, but we learn on the same authority that the British Islands were the authoritative centre of this system; they were, so to speak, the Rome of the Celtic religion.

What this religion was like we have now to consider, as an introduction to the myths and tales which more or less remotely sprang from it.

The Popular Religion of the Celts

But first we must point out that the Celtic religion was by no means a simple affair, and cannot be summed up as what we call “Druidism.” Beside the official religion there was a body of popular superstitions and observances which came from a deeper and older source than Druidism, and was destined long to outlive it—indeed, it is far from dead even yet.

The Megalithic People

The religions of primitive peoples mostly centre on, or take their rise from, rites and practices connected with the burial of the dead. The earliest people inhabiting Celtic territory in the West of Europe of whom we have any distinct knowledge are a race without name or known history, but by their sepulchral monuments, of which so many still exist, we can learn a great deal about them. They were the so-called Megalithic People,30 the builders of dolmens, cromlechs, and chambered tumuli, of which more than three [pg 53] thousand have been counted in France alone. Dolmens are found from Scandinavia southwards, all down the western lands of Europe to the Straits of Gibraltar, and round by the Mediterranean coast of Spain. They occur in some of the western islands of the Mediterranean, and are found in Greece, where, in Mycenæ, an ancient dolmen yet stands beside the magnificent burial-chamber of the Atreidae. Roughly, if we draw a line from the mouth of the Rhone northward to Varanger Fiord, one may say that, except for a few Mediterranean examples, all the dolmens in Europe lie to the west of that line. To the east none are found till we come into Asia. But they cross the Straits of Gibraltar, and are found all along the North African littoral, and thence eastwards through Arabia, India, and as far as Japan.

Dolmens, Cromlechs, and Tumuli

Dolmen at Proleek, Ireland

(After Borlase)

A dolmen, it may be here explained, is a kind of chamber composed of upright unhewn stones, and roofed generally with a single huge stone. They are usually wedge-shaped in plan, and traces of a porch or vestibule can often be noticed. The primary intention of the dolmen was to represent a house or dwelling-place for the dead. A cromlech (often confused in popular language with the dolmen) is properly a circular arrangement of standing stones, often with a dolmen in their midst. It is believed that most [pg 54] if not all of the now exposed dolmens were originally covered with a great mound of earth or of smaller stones. Sometimes, as in the illustration we give from Carnac, in Brittany, great avenues or alignments are formed of single upright stones, and these, no doubt, had some purpose connected with the ritual of worship carried on in the locality. The later megalithic monuments, as at Stonehenge, may be of dressed stone, but in all cases their rudeness of construction, the absence of any sculpturing (except for patterns or symbols incised on the surface), the evident aim at creating a powerful impression by the brute strength of huge monolithic masses, as well as certain subsidiary features in their design which shall be described later on, give these megalithic monuments a curious family likeness and mark them out from the chambered tombs of the early Greeks, of the Egyptians, and of other more advanced races. The dolmens proper gave place in the end to great chambered mounds or tumuli, as at New Grange, which we also reckon as belonging to the Megalithic People. They are a natural development of the dolmen. The early dolmen-builders were in the neolithic stage of culture, their weapons were of polished stone. But in the tumuli not only stone, but also bronze, and even iron, instruments are found—at first evidently importations, but afterwards of local manufacture.

Origin of the Megalithic People

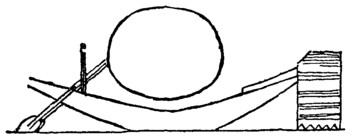

Prehistoric Tumulus at New Grange

Photograph by R. Welch, Belfast

The language originally spoken by this people can only be conjectured by the traces of it left in that of their conquerors, the Celts.31 But a map of the distribution or their monuments irresistibly suggests the idea that their builders were of North African origin; that they were not at first accustomed to traverse the [pg 55] sea for any great distance; that they migrated westwards along North Africa, crossed into Europe where the Mediterranean at Gibraltar narrows to a strait of a few miles in width, and thence spread over the western regions of Europe, including the British Islands, while on the eastward they penetrated by Arabia into Asia. It must, however, be borne in mind that while originally, no doubt, a distinct race, the Megalithic People came in the end to represent, not a race, but a culture. The human remains found in these sepulchres, with their wide divergence in the shape of the skull, &c., clearly prove this.32 These and other relics testify to the dolmen-builders in general as representing a superior and well-developed type, acquainted with agriculture, pasturage, and to some extent with seafaring. The monuments themselves, which are often of imposing size and imply much thought and organised effort in their construction, show unquestionably the existence, at this period, of a priesthood charged with the care of funeral rites and capable of controlling large bodies of men. Their dead were, as a rule, not burned, but buried whole—the greater monuments marking, no doubt, the sepulchres of important personages, while the common people were buried in tombs of which no traces now exist.

The Celts of the Plains

De Jubainville, in his account of the early history of the Celts, takes account of two main groups only—the Celts and the Megalithic People. But A. Bertrand, in his very valuable work “La Religion des Gaulois,” distinguishes two elements among the Celts themselves. There are, besides the Megalithic People, the two groups [pg 56] of lowland Celts and mountain Celts. The lowland Celts, according to his view, started from the Danube and entered Gaul probably about 1200 B.C. They were the founders of the lake-dwellings in Switzerland, in the Danube valley, and in Ireland. They knew the use of metals, and worked in gold, in tin, in bronze, and towards the end of their period in iron. Unlike the Megalithic People, they spoke a Celtic tongue,33 though Bertrand seems to doubt their genuine racial affinity with the true Celts. They were perhaps Celticised rather than actually Celtic. They were not warlike; a quiet folk of herdsmen, tillers, and artificers. They did not bury, but burned their dead. At a great settlement of theirs, Golasecca, in Cisalpine Gaul, 6000 interments were found. In each case the body had been burned; there was not a single burial without previous burning.

This people entered Gaul not (according to Bertrand), for the most part, as conquerors, but by gradual infiltration, occupying vacant spaces wherever they found them along the valleys and plains. They came by the passes of the Alps, and their starting-point was the country of the Upper Danube, which Herodotus says “rises among the Celts.” They blended peacefully with the Megalithic People among whom they settled, and did not evolve any of those advanced political institutions which are only nursed in war, but probably they contributed powerfully to the development of the Druidical system of religion and to the bardic poetry.

[pg 57]

The Celts of the Mountains

Finally, we have a third group, the true Celtic group, which followed closely on the track of the second. It was at the beginning of the sixth century that it first made its appearance on the left bank of the Rhine. While Bertrand calls the second group Celtic, these he styles Galatic, and identifies them with the Galatæ of the Greeks and the Galli and Belgæ of the Romans.

The second group, as we have said, were Celts of the plains. The third were Celts of the mountains. The earliest home in which we know them was the ranges of the Balkans and Carpathians. Their organisation was that of a military aristocracy—they lorded it over the subject populations on whom they lived by tribute or pillage. They are the warlike Celts of ancient history—the sackers of Rome and Delphi, the mercenary warriors who fought for pay and for the love of warfare in the ranks of Carthage and afterwards of Rome. Agriculture and industry were despised by them, their women tilled the ground, and under their rule the common population became reduced almost to servitude; “plebs pœne servorum habetur loco,” as Caesar tells us. Ireland alone escaped in some degree from the oppression of this military aristocracy, and from the sharp dividing line which it drew between the classes, yet even there a reflexion of the state of things in Gaul is found, even there we find free and unfree tribes and oppressive and dishonouring exactions on the part of the ruling order.

Yet, if this ruling race had some of the vices of untamed strength, they had also many noble and humane qualities. They were dauntlessly brave, fantastically chivalrous, keenly sensitive to the appeal of poetry, of music, and of speculative thought. Posidonius found the bardic institution flourishing among them about [pg 58] 100 B.C.,and about two hundred years earlier Hecatæus of Abdera describes the elaborate musical services held by the Celts in a Western island—probably Great Britain—in honour of their god Apollo (Lugh).34 Aryan of the Aryans, they had in them the making of a great and progressive nation; but the Druidic system—not on the side of its philosophy and science, but on that of its ecclesiastico-political organisation—was their bane, and their submission to it was their fatal weakness.

The culture of these mountain Celts differed markedly from that of the lowlanders. Their age was the age of iron, not of bronze; their dead were not burned (which they considered a disgrace), but buried.

The territories occupied by them in force were Switzerland, Burgundy, the Palatinate, and Northern France, parts of Britain to the west, and Illyria and Galatia to the east, but smaller groups of them must have penetrated far and wide through all Celtic territory, and taken up a ruling position wherever they went.

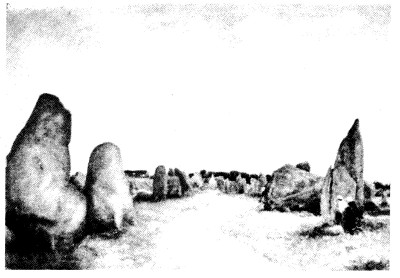

Stone Alignments at Kermaris, Carnac

Arthur G. Bell

There were three peoples, said Cæsar, inhabiting Gaul when his conquest began; “they differ from each other in language, in customs, and in laws.” These people he named respectively the Belgæ, the Celtæ, and the Aquitani. He locates them roughly, the Belgæ in the north and east, the Celtæ in the middle, and the Aquitani in the west and south. The Belgæ are the Galatæ of Bertrand, the Celtæ are the Celts, and the Aquitani are the Megalithic People. They had, of course, all been more or less brought under Celtic influences, and the differences of language which Cæsar noticed need not have been great; still it is noteworthy, and quite in accordance with Bertrand's views, that Strabo speaks of the Aquitani as differing markedly from the rest of the inhabitants, and as [pg 59] resembling the Iberians. The language of the other Gaulish peoples, he expressly adds, were merely dialects of the same tongue.

The Religion of Magic

This triple division is reflected more or less in all the Celtic countries, and must always be borne in mind when we speak of Celtic ideas and Celtic religion, and try to estimate the contribution of the Celtic peoples to European culture. The mythical literature and the art of the Celt have probably sprung mainly from the section represented by the Lowland Celts of Bertrand. But this literature of song and saga was produced by a bardic class for the pleasure and instruction of a proud, chivalrous, and warlike aristocracy, and would thus inevitably be moulded by the ideas of this aristocracy. But it would also have been coloured by the profound influence of the religious beliefs and observances entertained by the Megalithic People—beliefs which are only now fading slowly away in the spreading daylight of science. These beliefs may be summed up in the one term Magic. The nature of this religion of magic must now be briefly discussed, for it was a potent element in the formation of the body of myths and legends with which we have afterwards to deal. And, as Professor Bury remarked in his Inaugural Lecture at Cambridge, in 1903:

“For the purpose of prosecuting that most difficult of all inquiries, the ethnical problem, the part played by race in the development of peoples and the effects of race-blendings, it must be remembered that the Celtic world commands one of the chief portals of ingress into that mysterious pre-Aryan foreworld, from which it may well be that we modern Europeans have inherited far more than we dream.”

[pg 60]

The ultimate root of the word Magic is unknown, but proximately it is derived from the Magi, or priests of Chaldea and Media in pre-Aryan and pre-Semitic times, who were the great exponents of this system of thought, so strangely mingled of superstition, philosophy, and scientific observation. The fundamental conception of magic is that of the spiritual vitality of all nature. This spiritual vitality was not, as in polytheism, conceived as separated from nature in distinct divine personalities. It was implicit and immanent in nature; obscure, undefined, invested with all the awfulness of a power whose limits and nature are enveloped in impenetrable mystery. In its remote origin it was doubtless, as many facts appear to show, associated with the cult of the dead, for death was looked upon as the resumption into nature, and as the investment with vague and uncontrollable powers, of a spiritual force formerly embodied in the concrete, limited, manageable, and therefore less awful form of a living human personality. Yet these powers were not altogether uncontrollable. The desire for control, as well as the suggestion of the means for achieving it, probably arose from the first rude practices of the art of healing. Medicine of some sort was one of the earliest necessities of man. And the power of certain natural substances, mineral or vegetable, to produce bodily and mental effects often of a most startling character would naturally be taken as signal evidence of what we may call the “magical” conception of the universe.35 The first magicians were those who attained a special knowledge of healing or poisonous herbs; but “virtue” of some sort being attributed to every natural object and phenomenon, [pg 61] a kind of magical science, partly the child of true research, partly of poetic imagination, partly of priestcraft, would in time spring up, would be codified into rites and formulas, attached to special places and objects, and represented by symbols. The whole subject has been treated by Pliny in a remarkable passage which deserves quotation at length:

Pliny on the Religion of Magic

“Magic is one of the few things which it is important to discuss at some length, were it only because, being the most delusive of all the arts, it has everywhere and at all times been most powerfully credited. Nor need it surprise us that it has obtained so vast an influence, for it has united in itself the three arts which have wielded the most powerful sway over the spirit of man. Springing in the first instance from Medicine—a fact which no one can doubt—and under cover of a solicitude for our health, it has glided into the mind, and taken the form of another medicine, more holy and more profound. In the second place, bearing the most seductive and flattering promises, it has enlisted the motive of Religion, the subject on which, even at this day, mankind is most in the dark. To crown all it has had recourse to the art of Astrology; and every man is eager to know the future and convinced that this knowledge is most certainly to be obtained from the heavens. Thus, holding the minds of men enchained in this triple bond, it has extended its sway over many nations, and the Kings of Kings obey it in the East.

“In the East, doubtless, it was invented—in Persia and by Zoroaster.36 All the authorities agree in this. [pg 62] But has there not been more than one Zoroaster?... I have noticed that in ancient times, and indeed almost always, one finds men seeking in this science the climax of literary glory—at least Pythagoras, Empedocles, Democritus, and Plato crossed the seas, exiles, in truth, rather than travellers, to instruct themselves in this. Returning to their native land, they vaunted the claims of magic and maintained its secret doctrine.... In the Latin nations there are early traces of it, as, for instance, in our Laws of the Twelve Tables37 and other monuments, as I have said in a former book. In fact, it was not until the year 657 after the foundation of Rome, under the consulate of Cornelius Lentulus Crassus, that it was forbidden by a senatus consultum to sacrifice human beings; a fact which proves that up to this date these horrible sacrifices were made. The Gauls have been captivated by it, and that even down to our own times, for it was the Emperor Tiberius who suppressed the Druids and all the herd of prophets and medicine-men. But what is the use of launching prohibitions against an art which has thus traversed the ocean and penetrated even to the confines of Nature?” (Hist. Nat. xxx.)

Pliny adds that the first person whom he can ascertain to have written on this subject was Osthanes, who accompanied Xerxes in his war against the Greeks, and who propagated the “germs of his monstrous art” wherever he went in Europe.

Magic was not—so Pliny believed—indigenous either in Greece or in Italy, but was so much at home in Britain and conducted with such elaborate ritual that [pg 63] Pliny says it would almost seem as if it was they who had taught it to the Persians, not the Persians to them.

Traces of Magic in Megalithic Monuments