автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Complete Works of Sophocles

The Complete Works of Sophocles

(497/6-406/5 BC)

Sophocles is one of three ancient Greek tragedians (also Aeschylus and Euripides) whose plays have survived. His characters spoke in a way that was more natural to them and more expressive of their individual character feelings. The most famous tragedies of Sophocles feature Oedipus and Antigone: they are generally known as the Theban plays.

The Translations

1. AJAX

2. ANTIGONE

3. THE WOMEN OF TRACHIS

4. OEDIPUS THE KING

5. PHILOCTETES

6. ELECTRA

7. OEDIPUS AT COLONUS

8. FRAGMENTS

9. MINOR FRAGMENTS

The Greek Texts

1. Αίας — AJAX

2. Τραχινίαι — THE WOMEN OF TRACHIS

3. Οιδίπους Τύραννος — OEDIPUS THE KING

4. Φιλοκτήτης — PHILOCTETES

5. Οιδίπους επί Κολωνώ — OEDIPUS AT COLONUS

6. FRAGMENTS

The Biographies

INTRODUCTION TO SOPHOCLES

SOPHOCLES

The Translations

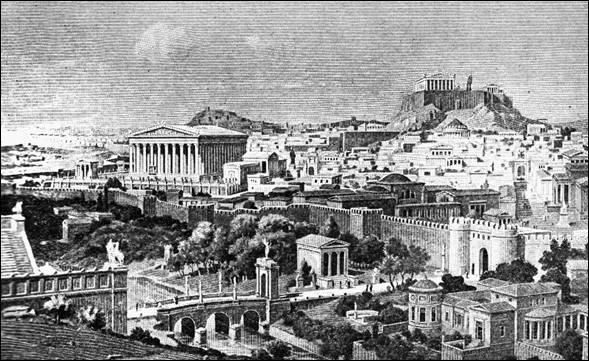

Kolonos, a northern district of Athens — Sophocles’ birthplace

A reconstruction of ancient Athens

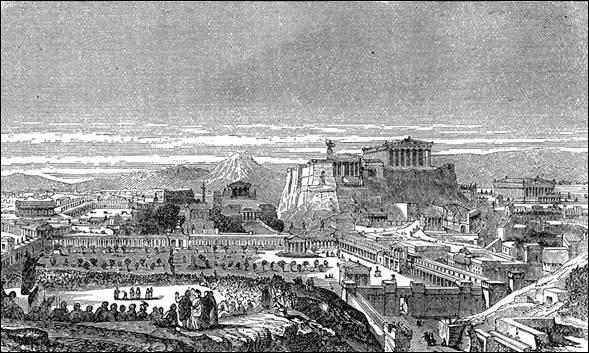

Another reconstruction of the ancient city, as seen from the Pnyx

AJAX

Translated by Lewis Campbell

Regarded by most scholars as an early work, from 450–430 BC, this tragedy chronicles the fate of the warrior Ajax after the events of Homer’s Iliad, but before the end of the Trojan War. At the onset of the play, Ajax is enraged when Achilles’ armour was awarded to Odysseus instead of to him and so he vows to kill the Greek leaders that have disgraced him. Before he can enact his revenge, he is deceived by the goddess Athena into believing that the sheep and cattle that were taken by the Achaeans as spoil are the Greek leaders. He slaughters some of them and takes the others back to his home to torture, including a ram which he believes to be his main rival, Odysseus.

When Ajax realises what he has done, he suffers great agony over his actions, believing the other Greek warriors are laughing at him and so contemplates ending his life due to his shame. His concubine, Tecmessa, pleads for him not to leave her and her child unprotected. Ajax then gives his son, Eurysakes, his shield. He leaves the house saying that he is going out to purify himself and bury the sword given to him by Hector. Teukros, Ajax’s brother, arrives in the Greek camp and is taunted by his fellow soldiers. Kalchas warns that Ajax should not be allowed to leave his tent until the end of the day or he will die. Teukros sends a messenger to Ajax’s campsite with word of Kalchas’ prophesy. Tecmessa and soldiers try to track him down, but are too late. Ajax had indeed buried the sword, but has left the blade sticking out of the ground and has impaled himself upon it.

The last part of the drama revolves around the dispute over what to do with Ajax’s body. Ajax’s half brother Teukros intends on burying him despite the demands of Menelaus and Agamemnon that the corpse is not to be buried. Odysseus, although previously Ajax’s enemy, steps in and persuades them to allow Ajax a proper funeral by pointing out that even one’s enemies deserve respect in death, if they were noble.

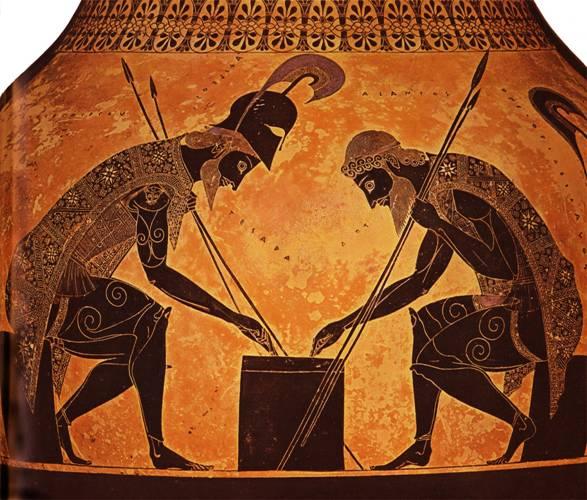

An Athenian vase depicting Odysseus and Ajax

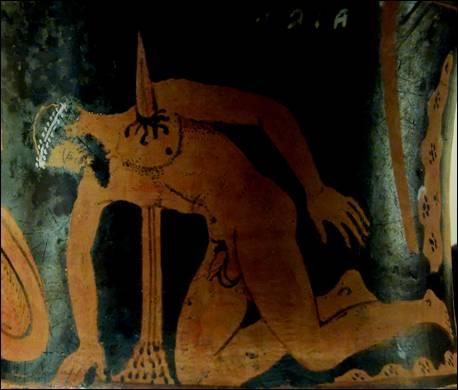

An ancient depiction of the suicide of Ajax

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

ATHENA.

ODYSSEUS.

AIAS, the son of Telamon.

CHORUS of Salaminian Mariners.

TECMESSA.

A Messenger.

TEUCER, half brother of Aias.

MENELAUS.

AGAMEMNON.

EURYSAKÈS, the child of Aias and Tecmessa, appears, but does not speak.

SCENE. Before the encampment of Aias on the shore of the Troad. Afterwards a lonely place beyond Rhoeteum.

Time, towards the end of the Trojan War.

ARGUMENT

‘A wounded spirit who can bear?’

After the death of Achilles, the armour made for him by Hephaestus was to be given to the worthiest of the surviving Greeks. Although Aias was the most valiant, the judges made the award to Odysseus, because he was the wisest.

Aias in his rage attempts to kill the generals; but Athena sends madness upon him, and he makes a raid upon the flocks and herds of the army, imagining the bulls and rams to be the Argive chiefs. On awakening from his delusion, he finds that he has fallen irrecoverably from honour and from the favour of the Greeks. He also imagines that the anger of Athena is unappeasable. Under this impression he eludes the loving eyes of his captive-bride Tecmessa, and of his Salaminian comrades, and falls on his sword. (‘The soul and body rive not more in parting Than greatness going off.’)

But it is revealed through the prophet Calchas, that the wrath of Athena will last only for a day; and on the return of Teucer, Aias receives an honoured funeral, the tyrannical reclamations of the two sons of Atreus being overcome by the firm fidelity of Teucer and the magnanimity of Odysseus, who has been inspired for this purpose by Athena.

ATHENA (above). ODYSSEUS.

ATHENA.

Oft have I seen thee, Laërtiades,

Intent on some surprisal of thy foes;

As now I find thee by the seaward camp,

Where Aias holds the last place in your line,

Lingering in quest, and scanning the fresh print

Of his late footsteps, to be certified

If he keep house or no. Right well thy sense

Hath led thee forth, like some keen hound of Sparta!

The man is even but now come home, his head

And slaughterous hands reeking with ardent toil.

Thou, then, no longer strain thy gaze within

Yon gateway, but declare what eager chase

Thou followest, that a god may give thee light.

ODYSSEUS.

Athena, ’tis thy voice! Dearest in heaven,

How well discerned and welcome to my soul

From that dim distance doth thine utterance fly

In tones as of Tyrrhenian trumpet clang!

Rightly hast thou divined mine errand here,

Beating this ground for Aias of the shield,

The lion-quarry whom I track to day.

For he hath wrought on us to night a deed

Past thought — if he be doer of this thing;

We drift in ignorant doubt, unsatisfied —

And I unbidden have bound me to this toil.

Brief time hath flown since suddenly we knew

That all our gathered spoil was reaved and slaughtered,

Flocks, herds, and herdmen, by some human hand,

All tongues, then, lay this deed at Aias’ door.

And one, a scout who had marked him, all alone,

With new-fleshed weapon bounding o’er the plain,

Gave me to know it, when immediately

I darted on the trail, and here in part

I find some trace to guide me, but in part

I halt, amazed, and know not where to look.

Thou com’st full timely. For my venturous course,

Past or to come, is governed by thy will.

ATH.

I knew thy doubts, Odysseus, and came forth

Zealous to guard thy perilous hunting-path.

OD.

Dear Queen! and am I labouring to an end?

ATH.

Thou schem’st not idly. This is Aias’ deed.

OD.

What can have roused him to a work so wild?

ATH.

His grievous anger for Achilles’ arms.

OD.

But wherefore on the flock this violent raid?

ATH.

He thought to imbrue his hands with your heart’s blood.

OD.

What? Was this planned against the Argives, then?

ATH.

Planned, and performed, had I kept careless guard.

OD.

What daring spirit, what hardihood, was here!

ATH.

Alone by night in craft he sought your tents.

OD.

How? Came he near them? Won he to his goal?

ATH.

He stood in darkness at the generals’ gates.

OD.

What then restrained his eager hand from murder?

ATH.

I turned him backward from his baleful joy,

And overswayed him with blind phantasies,

To swerve against the flocks and well-watched herd

Not yet divided from the public booty.

There plunging in he hewed the horned throng,

And with him Havoc ranged: while now he thought

To kill the Atreidae with hot hand, now this

Now that commander, as the fancy grew.

I, joining with the tumult of his mind,

Flung the wild victim on the fatal net.

Anon, this toil being overpast, he draws

The living oxen and the panting sheep

With cords to his home, not as a hornèd prey,

But as in triumph marshalling his foes:

Whom now he tortures in their bonds within.

Come, thou shalt see this madness in clear day,

And tell to the Argives all I show thee here

Only stand firm and shrink not, I will turn

His eyes askance, not to distinguish thee,

Fear nought — Ho! thou that bindest to thy will

The limbs of those thy captives, come thou forth!

Aias! advance before thy palace gate!

OD.

My Queen! what dost thou? Never call him forth.

ATH.

Hush, hush! Be not so timorous, but endure.

OD.

Nay, nay! Enough. He is there, and let him bide.

ATH.

What fear you? Dates his valour from to day?

OD.

He was and is my valiant enemy.

ATH.

Then is not laughter sweetest o’er a foe?

OD.

No more! I care not he should pass abroad.

ATH.

You flinch from seeing the madman in full view.

OD.

When sane, I ne’er had flinched before his face.

ATH.

Well, but even now he shall not know thee near.

OD.

How, if his eyes be not transformed or lost?

ATH.

I will confound his sense although he see.

OD.

Well, nothing is too hard for Deity.

ATH.

Stand still and keep thy place without a word.

OD.

I must. Would I were far away from here!

ATH.

Aias! Again I summon thee. Why pay

So scanty heed to her who fights for thee?

Enter AIAS with a bloody scourge.

AIAS.

Hail, offspring of the Highest! Pallas, hail!

Well hast thou stood by me. Triumphal gold

Shall crown thy temple for this lordly prey.

ATH.

A fair intention! But resolve me this:

Hast dyed thy falchion deep in Argive blood?

AI. There is my boast; that charge I’ll ne’er deny.

ATH.

Have Atreus’ sons felt thy victorious might?

AI. They have. No more they’ll make a scorn of me!

ATH.

I take it, then, they are dead.

AI.

Ay, now they are dead,

Let them arise and rob me of mine arms!

ATH.

Good. Next inform us of Laërtes’ son;

How stands his fortune? Hast thou let him go?

AI.

The accursed fox! Dost thou inquire of him?

ATH.

Ay, of Odysseus, thy late adversary.

AI.

He sits within, dear lady, to my joy,

Bound; for I mean him not just yet to die.

ATH.

What fine advantage wouldst thou first achieve?

AI.

First, tie him to a pillar of my hall —

ATH.

Poor wretch! What torment wilt thou wreak on him?

AI.

Then stain his back with scourging till he die.

ATH.

Nay, ’tis too much. Poor caitiff! Not the scourge!

AI.

Pallas, in all things else have thou thy will,

But none shall wrest Odysseus from this doom.

ATH.

Well, since thou art determined on the deed,

Spare nought of thine intent: indulge thy hand!

AI. (waving the bloody scourge.)

I go! But thou, I charge thee, let thine aid

Be evermore like valiant as to-day.[Exit

ATH.

The gods are strong, Odysseus. Dost thou see?

What man than Aias was more provident,

Or who for timeliest action more approved?

OD.

I know of none. But, though he hates me sore,

I pity him, poor mortal, thus chained fast

To a wild and cruel fate, — weighing not so much

His fortune as mine own. For now I feel

All we who live are but an empty show

And idle pageant of a shadowy dream.

ATH.

Then, warned by what thou seest, be thou not rash

To vaunt high words toward Heaven, nor swell thy port

Too proudly, if in puissance of thy hand

Thou passest others, or in mines of wealth.

Since Time abases and uplifts again

All that is human, and the modest heart

Is loved by Heaven, who hates the intemperate will.

[Exeunt.

CHORUS (entering).

Telamonian child, whose hand

Guards our wave-encircled land,

Salamis that breasts the sea,

Good of thine is joy to me;

But if One who reigns above

Smite thee, or if murmurs move

From fierce Danaäns in their hate

Full of threatening to thy state,

All my heart for fear doth sigh,

Shrinking like a dove’s soft eye.

Hardly had the darkness waned,[Half-Chorus I.

When our ears were filled and pained

With huge scandal on thy fame.

Telling, thine the arm that came

To the cattle-browsèd mead,

Wild with prancing of the steed,

And that ravaged there and slew

With a sword of fiery hue

All the spoils that yet remain,

By the sweat of spearmen ta’en.

Such report against thy life,[Half-Chorus II.

Whispered words with falsehood rife,

Wise Odysseus bringing near

Shrewdly gaineth many an ear:

Since invention against thee

Findeth hearing speedily,

Tallying with the moment’s birth;

And with loudly waxing mirth

Heaping insult on thy grief,

Each who hears it glories more

Than the tongue that told before.

Every slander wins belief

Aimed at souls whose worth is chief:

Shot at me, or one so small,

Such a bolt might harmless fall.

Ever toward the great and high

Creepeth climbing jealousy

Yet the low without the tall

Make at need a tottering wall

Let the strong the feeble save

And the mean support the brave.

CHORUS.

Ah! ‘twere vain to tune such song

‘Mid the nought discerning throng

Who are clamouring now ‘gainst thee

Long and loud, and strengthless we,

Mighty chieftain, thou away,

To withstand the gathering fray

Flocking fowl with carping cry

Seem they, lurking from thine eye,

Till the royal eagle’s poise

Overawe the paltry noise

Till before thy presence hushed

Sudden sink they, mute and crushed.

Did bull slaying Artemis, Zeus’ cruel daughterI 1

(Ah, fearful rumour, fountain of my shame!)

Prompt thy fond heart to this disastrous slaughter

Of the full herd stored in our army’s name!

Say, had her blood stained temple missed the kindness

Of some vow promised fruit of victory,

Foiled of some glorious armour through thy blindness,

Or fell some stag ungraced by gift from thee?

Or did stern Ares venge his thankless spear

Through this night foray that hath cost thee dear!

For never, if thy heart were not distractedI 2

By stings from Heaven, O child of Telamon,

Wouldst thou have bounded leftward, to have acted

Thus wildly, spoiling all our host hath won!

Madness might fall some heavenly power forfend it

But if Odysseus and the tyrant lords

Suggest a forged tale, O rise to end it,

Nor fan the fierce flame of their withering words!

Forth from thy tent, and let thine eye confound

The brood of Sisyphus that would thee wound!

Too long hast thou been fixed in grim repose,III

Heightening the haughty malice of thy foes,

That, while thou porest by the sullen sea,

Through breezy glades advanceth fearlessly,

A mounting blaze with crackling laughter fed

From myriad throats; whence pain and sorrow bred

Within my bosom are establishèd.

Enter TECMESSA.

TECMESSA.

Helpers of Aias’ vessel’s speed,

Erechtheus’ earth-derivèd seed,

Sorrows are ours who truly care

For the house of Telamon afar.

The dread, the grand, the rugged form

Of him we know,

Is stricken with a troublous storm;

Our Aias’ glory droopeth low.

CHORUS.

What burden through the darkness fell

Where still at eventide ’twas well?

Phrygian Teleutas’ daughter, say;

Since Aias, foremost in the fray,

Disdaining not the spear-won bride,

Still holds thee nearest at his side,

And thou may’st solve our doubts aright.

TEC.

How shall I speak the dreadful word?

How shall ye live when ye have heard?

Madness hath seized our lord by night

And blasted him with hopeless blight.

Such horrid victims mightst thou see

Huddled beneath yon canopy,

Torn by red hands and dyed in blood,

Dread offerings to his direful mood.

CH.

What news of our fierce lord thy story showeth,1

Sharp to endure, impossible to fly!

News that on tongues of Danaäns hourly groweth,

Which Rumour’s myriad voices multiply!

Alas! the approaching doom awakes my terror.

The man will die, disgraced in open day,

Whose dark dyed steel hath dared through mad brained error

The mounted herdmen with their herds to slay.

TEC.

O horror! Then ’twas there he found

The flock he brought as captives tied,

And some he slew upon the ground,

And some, side smiting, sundered wide

Two white foot rams he backward drew,

And bound. Of one he shore and threw

The tipmost tongue and head away,

The other to an upright stay

He tied, and with a harness thong

Doubled in hand, gave whizzing blows,

Echoing his lashes with a song

More dire than mortal fury knows.

CH.

Ah! then ’tis time, our heads in mantles hiding,2

Our feet on some stol’n pathway now to ply,

Or with swift oarage o’er the billows gliding,

With ordered stroke to make the good ship fly

Such threats the Atridae, armed with two fold power,

Launch to assail us. Oh, I sadly fear

Stones from fierce hands on us and him will shower,

Whose heavy plight no comfort may come near.

TEC.

’Tis changed, his rage, like sudden blast,

Without the lightning gleam is past

And now that Reason’s light returns,

New sorrow in his spirit burns.

For when we look on self made woe,

In which no hand but ours had part,

Thought of such griefs and whence they flow

Brings aching misery to the heart.

CH.

If he hath ceased to rave, he should do well

The account of evil lessens when ’tis past.

TEC.

If choice were given you, would you rather choose

Hurting your friends, yourself to feel delight,

Or share with them in one commingled pain?

CH.

The two fold trouble is more terrible.

TEC.

Then comes our torment now the fit is o’er.

CH.

How mean’st thou by that word? I fail to see.

TEC.

He in his rage had rapture of delight

And knew not how he grieved us who stood near

And saw the madding tempest ruining him.

But now ’tis over and he breathes anew,

The counterblast of sorrow shakes his soul,

Whilst our affliction vexeth as before,

Have we not double for our single woe?

CH.

I feel thy reasoning move me, and I fear

Some heavenly stroke hath fallen. How else, when the end

Of stormy sickness brings no cheering ray?

TEC.

Our state is certain. Dream not but ’tis so.

CH.

How first began the assault of misery?

Tell us the trouble, for we share the pain.

TEC.

It toucheth you indeed, and ye shall hear

All from the first. ’Twas midnight, and the lamp

Of eve had died, when, seizing his sharp blade,

He sought on some vain errand to creep forth.

I broke in with my word: ‘Aias, what now?

Why thus uncalled for salliest thou? No voice

Of herald summoned thee. No trumpet blew.

What wouldst thou when the camp is hushed in sleep?’

He with few words well known to women’s ears

Checked me: ‘The silent partner is the best.’

I saw how ’twas and ceased. Forth then he fared

Alone — What horror passed upon the plain

This night, I know not. But he drags within,

Tied in a throng, bulls, shepherd dogs, and spoil

Of cattle and sheep. Anon he butchers them,

Felling or piercing, hacking or tearing wide,

Ribs from breast, limb from limb. Others in rage

He seized and bound and tortured, brutes for men.

Last, out he rushed before the doors, and there

Whirled forth wild language to some shadowy form,

Flouting the generals and Laërtes’ son

With torrent laughter and loud triumphing

What in his raid he had wreaked to their despite.

Then diving back within — the fitful storm

Slowly assuaging left his spirit clear.

And when his eye had lightened through the room

Cumbered with ruin, smiting on his brow

He roared; and, tumbling down amid the wreck

Of woolly carnage he himself had made,

Sate with clenched hand tight twisted in his hair.

Long stayed he so in silence. Then flashed forth

Those frightful words of threatening vehemence,

That bade me show him all the night’s mishap,

And whither he was fallen I, dear my friends,

Prevailed on through my fear, told all I knew.

And all at once he raised a bitter cry,

Which heretofore I ne’er had heard, for still

He made us think such doleful utterance

Betokened the dull craven spirit, and still

Dumb to shrill wailings, he would only moan

With half heard muttering, like an angry bull.

But now, by such dark fortune overpowered,

Foodless and dry, amid the quivering heap

His steel hath quelled, all quietly he broods;

And out of doubt his mind intends some harm:

Such words, such groans, burst from him. O my friends. —

Therefore I hastened, — enter and give aid

If aught ye can! Men thus forgone will oft

Grow milder through the counsel of a friend.

CH.

Teleutas’ child! we shudder at thy tale

That fatal frenzy wastes our hero’s soul.

AIAS (within).

Woe’s me, me, me!

TEC.

More cause anon! Hear ye not Aias there,

How sharp the cry that shrills from him?

AI.

Woe! Woe!

CH.

Madly it sounds — Or springs it of deep grief

For proofs of madness harrowing to his eye?

AI.

Boy, boy!

TEC.

What means he? Oh, Eurysakes!

He cries on thee. Where art thou? O my heart!

AI.

Teucer I call! Where ‘s Teucer? Will he ne’er

Come from the chase, but leave me to my doom?

CH.

Not madness now. Disclose him. Let us look.

Haply the sight of us may calm his soul.

TEC.

There, then; I open to your view the form

Of Aias, and his fortunes as they are.[AIAS is discovered

AI.

Dear comrades of the deep, whose truth and loveI 1

Stand forth alone unbroken in my woe,

Behold what gory sea

Of storm-lashed agony

Doth round and round me flow!

CH. (to TEC.).

Too true thy witness: for the fact cries out

Wild thoughts were here and Reason’s lamp extinct.

AI.

Strong helpers of sea-speed, whose nimble handI 2

Plied hither the salt oar with circling stroke,

No shepherd there was found

To give the avenging wound.

Come, lay me with the flock!

CH.

Speak no rash word! nor curing ill with ill

Augment the plague of this calamity.

AI.

Mark ye the brave and bold,II 1

Whom none could turn of old,

When once he set his face to the fierce fight?

Now beasts that thought no harm

Have felt this puissant arm.

O laughter of my foes! O mockery of my might!

TEC.

Aias, my lord! I entreat thee, speak not so!

AI.

Thou here! Away! begone, and trouble me not!

O! O!

CH.

Be softened! bear a steadier mind!

AI.

O heaven-accursèd hand

That let the ruffians go,

But falling ‘midst the horn’d and bleating band,

Made darkling blood-streams flow!

CH.

Why vex thy heart with what is over and done?

Do what we may, this ne’er will alter now.

AI.

Child of Laërtes old,II 2

Thou that dost still behold

And still contrive all shapes of monstrous ill,

Winding in foulest ways

Through the army’s sinful maze, —

Now even for pleasure thou may’st laugh thy fill.

CH.

Laughter and tears are in the gift of God.

AI.

Ay, might I see him, though thus broken, — ay me!

Even yet —

CH.

Nay, vaunt not. Look where thou art fallen.

AI.

Source where my life-blood springs,

O Zeus, might I but slay

That crafty plague, with those twin-sceptred kings,

Then breathe my life away!

TEC.

Pray thus, and pray that I too be no more!

If thou wert gone, what were my life to me?

AI.

Darkness! my only light!III 1

O nether gloom, to me

Brighter than morning to the wakeful eye!

Take me to dwell with thee.

Take me! What help? Zeus’ daughter with fell might

Torments me sore. I may not look on high,

Nor to the tribe of momentary men. —

Oh, whither, then,

Should it avail to fly?

Ah! whither should I go and stay?

All here is ruin. This mad prey

Shames me for evermore:

Vengeance is at the door;

Yea, all the Achaean host, with armèd hand,

Is ready at command

To slay me o’er and o’er.

TEC.

Woe ‘s me! to hear from one so good and true

Words he had scorned to utter in past days.

AI.

Grey firths of foaming brine,III 2

And ye, deep groves, that crown

The sea-caves and long cliffs upon the shore,

Too long did ye confine

My life about the walls of Troia’s town:

But no more now! a breathing man, no more!

The wise in heart may duly learn that lore.

Let Xanthus know,

Whose waters neighbouring flow,

And minister to Argive men:

One man he ne’er shall see again;

One, I will vaunt it forth!

Highest in warlike worth

Of all Greek forms that Troia’s towers have eyed:

Now, shorn of all that pride,

I lie thus low.

CH.

I know not how to let thee speak, nor how

To silence thee. Such evils close thee round.

AI.

Ay me!

Could human thought have prophesied

My name would thus give echo to mine ill?

‘Ai’ now for Aias, doubly, trebly said,

Sorts all too well to mark my misery;

Whose father from this land of Troy, as noblest

Of all the host, carrying the fairest prize,

Came girt about with glory to his home.

But I his son, not less of might than he,

Nor poorer in the achievements of my hand,

To this same region following in my prime,

Am scouted by the Achaeans and destroyed.

Yet know I one thing well. Had Peleus’ child,

Living, adjudged his armour as a meed

Of well-tried bravery, no grasp save mine

Had clutched it. But the Atridae with mean craft

Conveyed his heirloom to a wit-proud knave,

Whilst Aias’ peerless prowess was despised.

And had not this mine eye and mind distraught

Glanced from my purpose, ne’er again had they

Perverted judgement. But the invincible

Stern daughter of the Highest, with baneful eye,

Even as mine arm descended, baffled me,

And hurled upon my soul a frenzied plague,

To stain my hand with these dumb victims’ blood.

And those mine enemies exult in safety, —

Not with my will; but where a God misguides,

Strong arms are thwarted and the weakling lives.

Now, what remains? Heaven hates me, ’tis too clear:

The Grecian host abhor me: Troy, with all

This country round our camp, is my sworn foe.

Shall I, across the Aegean sailing home,

Leave these Atridae and their fleet forlorn?

How shall I dare to front my father’s eye?

How will he once endure to look on me,

Denuded of the prize of high renown,

Whose coronal stood sparkling on his brow?

No! ‘twere too dreadful. Then shall I advance

Before the Trojan battlements, and there

In single conflict doing valiantly

Last die upon their spears? Nay, for by this

I might perchance make Atreus’ offspring glad.

That may not be imagined. I must find

Some act to let my grey-haired father feel

No heartless recreant once called him sire.

Shame on the wight who when beset with ill

Cares to live on in misery unrelieved.

Can hour outlasting hour make less or more

Of death? Whereby then can it furnish joy?

That mortal weighs for nothing-worth with me,

Whom Hope can comfort with her fruitless fire.

Honour in life or honour in the grave

Befits the noble heart. You hear my will.

CH.

From thine own spirit, Aias, all may tell,

That utterance came, and none have prompted thee.

Yet stay thy hurrying thought, and by thy friends

Be ruled to loose this burden from thy mind.

TEC.

O my great master! heaviest of all woe

Is theirs whose life is crushed beyond recall.

I, born of one the mightiest of the free

And wealthiest in the Phrygian land, am now

A captive. So Heaven willed, and thy strong arm

Determined. Therefore, since the hour that made

My being one with thine, I breathe for thee;

And I beseech thee by the sacred fire

Of home, and by the sweetness of the night

When from thy captive I became thy bride,

Leave me not guardless to the unworthy touch

And cruel taunting of thine enemies’

For, shouldst thou die and leave us, then shall I

Borne off by Argive violence with thy boy

Eat from that day the bread of slavery.

And some one of our lords shall smite me there

With galling speech: Behold the concubine

Of Aias, first of all the Greeks for might,

How envied once, worn with what service now!

So will they speak; and while my quailing heart

Shall sink beneath its burden, clouds of shame

Will dim thy glory and degrade thy race.

Oh! think but of thy father, left to pine

In doleful age, and let thy mother’s grief —

Who, long bowed down with many a careful year,

Prays oftentimes thou may’st return alive —

O’er awe thee. Yea, and pity thine own son,

Unsheltered in his boyhood, lorn of thee,

With bitter foes to tend his orphanhood,

Think, O my lord, what sorrow in thy death

Thou send’st on him and me. For I have nought

To lean to but thy life. My fatherland

Thy spear hath ruined. Fate — not thou — hath sent

My sire and mother to the home of death

What wealth have I to comfort me for thee?

What land of refuge? Thou art all my stay

Oh, of me too take thought! Shall men have joy,

And not remember? Or shall kindness fade?

Say, can the mind be noble, where the stream

Of gratitude is withered from the spring?

CH.

Aias, I would thy heart were touched like mine

With pity; then her words would win thy praise.

AI.

My praise she shall not miss, if she perform

My bidding with firm heart, and fail not here.

TEC.

Dear Aias, I will fail in nought thou bidst me.

AI.

Bring me my boy, that I may see his face.

TEC.

Oh, in my terror I conveyed him hence!

AI.

Clear of this mischief, mean’st thou? or for what?

TEC.

Lest he might run to thee, poor child, and die.

AI.

That issue had been worthy of my fate!

TEC.

But I kept watch to fence his life from harm.

AI.

’Twas wisely done. I praise thy foresight there.

TEC.

Well, since ’tis so, how can I help thee now?

AI.

Give me to speak to him and see him near.

TEC.

He stands close by with servants tending him.

AI.

Then why doth he not come, but still delay?

TEC.

Thy father calls thee, child. Come, lead him hither,

Whichever of you holds him by the hand.

AI.

Moves he? or do thine accents idly fall?

TEC.

See, where thy people bring him to thine eye.

AI.

Lift him to me: lift him! He will not fear

At sight of this fresh havoc of the sword,

If rightly he be fathered of my blood.

Like some young colt he must be trained and taught

To run fierce courses with his warrior sire.

Be luckier than thy father, boy! but else

Be like him, and thy life will not be low.

One thing even now I envy thee, that none

Of all this misery pierces to thy mind.

For life is sweetest in the void of sense,

Ere thou know joy or sorrow. But when this

Hath found thee, make thy father’s enemies

Feel the great parent in the valiant child.

Meantime grow on in tender youthfulness,

Nursed by light breezes, gladdening this thy mother.

No Greek shall trample thee with brutal harm,

That I know well, though I shall not be near —

So stout a warder to protect thy life

I leave in Teucer. He’ll not fail, though now

He follow far the chase upon his foes.

My trusty warriors, people of the sea,

Be this your charge, no less, — and bear to him

My clear commandment, that he take this boy

Home to my fatherland, and make him known

To Telamon, and Eriboea too,

My mother. Let him tend them in their age.

And, for mine armour, let not that be made

The award of Grecian umpires or of him

Who ruined me. But thou, named of the shield,

Eurysakes, hold mine, the unpierceable

Seven-hided buckler, and by the well stitched thong

Grasp firm and wield it mightily. — The rest

Shall lie where I am buried. — Take him now,

Quickly, and close the door. No tears! What! weep

Before the tent? How women crave for pity!

Make fast, I say. No wise physician dreams

With droning charms to salve a desperate sore.

CH.

There sounds a vehement ardour in thy words

That likes me not. I fear thy sharpened tongue.

TEC.

Aias, my lord, what act is in thy mind?

AI.

Inquire not, question not; be wise, thou’rt best.

TEC.

How my heart sinks! Oh, by thy child, by Heaven,

I pray thee on my knees, forsake us not!

AI.

Thou troublest me. What! know’st thou not that Heaven

Hath ceased to be my debtor from to-day?

TEC.

Hush! Speak not so.

AI.

Speak thou to those that hear.

TEC.

Will you not hear me?

AI.

Canst thou not be still?

TEC.

My fears, my fears!

AI. (to the Attendants).

Come, shut me in, I say.

TEC.

Oh, yet be softened!

AI.

’Tis a foolish hope,

If thou deem’st now to mould me to thy will.

[Aias is withdrawn. Exit Tecmessa]

CHORUS.

Island of glory! whom the glowing eyesI 1

Of all the wondering world immortalize,

Thou, Salamis, art planted evermore,

Happy amid the wandering billows’ roar;

While I — ah, woe the while! — this weary time,

By the green wold where flocks from Ida stray,

Lie worn with fruitless hours of wasted prime,

Hoping — ah, cheerless hope! — to win my way

Where Hades’ horrid gloom shall hide me from the day.

Aias is with me, yea, but crouching low,I 2

Where Heaven-sent madness haunts his overthrow,

Beyond my cure or tendance: woful plight!

Whom thou, erewhile, to head the impetuous fight,

Sent’st forth, thy conquering champion. Now he feeds

His spirit on lone paths, and on us brings

Deep sorrow; and all his former peerless deeds

Of prowess fall like unremembered things

From Atreus’ loveless brood, this caitiff brace of kings.

Ah! when his mother, full of days and bowedII 1

With hoary eld, shall hear his ruined mind,

How will she mourn aloud!

Not like the warbler of the dale,

The bird of piteous wail,

But in shrill strains far borne upon the wind,

While on the withered breast and thin white hair

Falls the resounding blow, the rending of despair.

Best hid in death were he whom madness drivesII 2

Remediless; if, through his father’s race

Born to the noblest place

Among the war-worn Greeks, he lives

By his own light no more,

Self-aliened from the self he knew before.

Oh, hapless sire, what woe thine ear shall wound!

One that of all thy line no life save this hath found.

Enter Aias with a bright sword, and Tecmessa, severally.

AI.

What change will never-terminable Time

Not heave to light, what hide not from the day?

What chance shall win men’s marvel? Mightiest oaths

Fall frustrate, and the steely-tempered will.

Ay, and even mine, that stood so diamond-keen

Like iron lately dipped, droops now dis-edged

And weakened by this woman, whom to leave

A widow with her orphan to my foes,

Dulls me with pity. I will go to the baths

And meadows near the cliff, and purging there

My dark pollution, I will screen my soul

From reach of Pallas’ grievous wrath. I will find

Same place untrodden, and digging of the soil

Where none shall see, will bury this my sword,

Weapon of hate! for Death and Night to hold

Evermore underground. For, since my hand

Had this from Hector mine arch-enemy,

No kindness have I known from Argive men.

So true that saying of the bygone world,

‘A foe’s gift is no gift, and brings no good.’

Well, we will learn of Time. Henceforth I’ll bow

To heavenly ordinance and give homage due

To Atreus’ sons. Who rules, must be obeyed.

Since nought so fierce and terrible but yields

Place to Authority. Wild Winter’s snows

Make way for bounteous Summer’s flowery tread,

And Night’s sad orb retires for lightsome Day

With his white steeds to illumine the glad sky.

The furious storm-blast leaves the groaning sea

Gently to rest. Yea, the all-subduer Sleep

Frees whom he binds, nor holds enchained for aye.

And shall not men be taught the temperate will?

Yea, for I now know surely that my foe

Must be so hated, as being like enough

To prove a friend hereafter, and my friend

So far shall have mine aid, as one whose love

Will not continue ever. Men have found

But treacherous harbour in companionship.

Our ending, then, is peaceful. Thou, my girl,

Go in and pray the Gods my heart’s desire

Be all fulfilled. My comrades, join her here,

Honouring my wishes; and if Teucer come,

Bid him toward us be mindful, kind toward you.

I must go — whither I must go. Do ye

But keep my word, and ye may learn, though now

Be my dark hour, that all with me is well.

[Exit towards the country. Tecmessa retires]

CHORUS.

A shudder of love thrills through me. Joy! I soar1

O Pan, wild Pan![They dance

Come from Cyllenè hoar —

Come from the snow drift, the rock-ridge, the glen!

Leaving the mountain bare

Fleet through the salt sea-air,

Mover of dances to Gods and to men.

Whirl me in Cnossian ways — thrid me the Nysian maze!

Come, while the joy of the dance is my care!

Thou too, Apollo, come

Bright from thy Delian home,

Bringer of day,

Fly o’er the southward main

Here in our hearts to reign,

Loved to repose there and kindly to stay.

Horror is past. Our eyes have rest from pain.2

O Lord of Heaven!

[They dance]

Now blithesome day again

Purely may smile on our swift-sailing fleet,

Since, all his woe forgot,

Aias now faileth not

Aught that of prayer and Heaven-worship is meet.

Time bringeth mighty aid — nought but in time doth fade:

Nothing shall move me as strange to my thought.

Aias our lord hath now

Cleared his wrath-burdened brow

Long our despair,

Ceased from his angry feud

And with mild heart renewed

Peace and goodwill to the high-sceptred pair.

Enter Messenger.

MESSENGER.

Friends, my first news is Teucer’s presence here,

Fresh from the Mysian heights; who, as he came

Right toward the generals’ quarter, was assailed

With outcry from the Argives in a throng:

For when they knew his motion from afar

They swarmed around him, and with shouts of blame

From each side one and all assaulted him

As brother to the man who had gone mad

And plotted ‘gainst the host, — threatening aloud,

Spite of his strength, he should be stoned, and die.

— So far strife ran, that swords unscabbarded

Crossed blades, till as it mounted to the height

Age interposed with counsel, and it fell.

But where is Aias to receive my word?

Tidings are best told to the rightful ear.

CH.

Not in the hut, but just gone forth, preparing

New plans to suit his newly altered mind.

MESS.

Alas!

Too tardy then was he who sped me hither;

Or I have proved too slow a messenger.

CH.

What point is lacking for thine errand’s speed?

MESS.

Teucer was resolute the man should bide

Close held within-doors till himself should come.

CH.

Why, sure his going took the happiest turn

And wisest, to propitiate Heaven’s high wrath.

MESS.

The height of folly lives in such discourse,

If Calchas have the wisdom of a seer.

CH.

What knowest thou of our state? What saith he? Tell.

MESS.

I can tell only what I heard and saw.

Whilst all the chieftains and the Atridae twain

Were seated in a ring, Calchas alone

Rose up and left them, and in Teucer’s palm

Laid his right hand full friendly; then out-spake

With strict injunction by all means i’ the world

To keep beneath yon covert this one day

Your hero, and not suffer him to rove,

If he would see him any more alive.

For through this present light — and ne’er again —

Holy Athena, so he said, will drive him

Before her anger. Such calamitous woe

Strikes down the unprofitable growth that mounts

Beyond his measure and provokes the sky.

‘Thus ever,’ said the prophet, ‘must he fall

Who in man’s mould hath thoughts beyond a man.

And Aias, ere he left his father’s door,

Made foolish answer to his prudent sire.

‘My son,’ said Telamon, ‘choose victory

Always, but victory with an aid from Heaven.’

How loftily, how madly, he replied!

‘Father, with heavenly help men nothing worth

May win success. But I am confident

Without the Gods to pluck this glory down.’

So huge the boast he vaunted! And again

When holy Pallas urged him with her voice

To hurl his deadly spear against the foe,

He turned on her with speech of awful sound:

‘Goddess, by other Greeks take thou thy stand;

Where I keep rank, the battle ne’er shall break.’

Such words of pride beyond the mortal scope

Have won him Pallas’ wrath, unlovely meed.

But yet, perchance, so be it he live to-day,

We, with Heaven’s succour, may restore his peace.’ —

Thus far the prophet, when immediately

Teucer dispatched me, ere the assembly rose,

Bearing to thee this missive to be kept

With all thy care. But if my speed be lost,

And Calchas’ word have power, the man is dead.

CH.

O trouble-tost Tecmessa, born to woe,

Come forth and see what messenger is here!

This news bites near the bone, a death to joy.

Enter TECMESSA.

TEC.

Wherefore again, when sorrow’s cruel storm

Was just abating, break ye my repose?

CH. (pointing to the Messenger).

Hear what he saith, and how he comes to bring

News of our Aias that hath torn my heart.

TEC.

Oh me! what is it, man? Am I undone?

MESS.

Thy case I know not; but of Aias this,

That if he roam abroad, ’tis dangerous.

TEC.

He is, indeed, abroad. Oh! tell me quickly!

MESS.

’Tis Teucer’s strong command to keep him close

Beneath this roof, nor let him range alone.

TEC.

But where is Teucer? and what means his word?

MESS.

Even now at hand, and eager to make known

That Aias, if he thus go forth, must fall.

TEC.

Alas! my misery! Whence learned he this?

MESS.

From Thestor’s prophet-offspring, who to-day

Holds forth to Aias choice of life or death.

TEC.

Woe’s me! O friends, this desolating blow

Is falling! Oh, stand forward to prevent!

And some bring Teucer with more haste, while some

Explore the western bays and others search

Eastward to find your hero’s fatal path!

For well I see I am cheated and cast forth

From the old favour. Child, what shall I do?

[Looking at EURYSAKES

We must not stay. I too will fare along,

go far as I have power. Come, let us go.

Bestir ye! ’Tis no moment to sit still,

If we would save him who now speeds to die.

CH.

I am ready. Come! Fidelity of foot,

And swift performance, shall approve me true.

[Exeunt omnes

The scene changes to a lonely wooded spot.

AIAS (discovered alone).

The sacrificer stands prepared, — and when

More keen? Let me take time for thinking, too!

This gift of Hector, whom of stranger men

I hated most with heart and eyes, is set

In hostile Trojan soil, with grinding hone

Fresh-pointed, and here planted by my care

Thus firm, to give me swift and friendly death.

Fine instrument, so much for thee! Then, first,

Thou, for ’tis meet, great Father, lend thine aid.

For no great gift I sue thee. Let some voice

Bear Teucer the ill news, that none but he

May lift my body, newly fallen in death

About my bleeding sword, ere I be spied

By some of those who hate me, and be flung

To dogs and vultures for an outcast prey.

So far I entreat thee, Lord of Heaven. And thou,

Hermes, conductor of the shadowy dead,

Speed me to rest, and when with this sharp steel

I have cleft a sudden passage to my heart,

At one swift bound waft me to painless slumber!

But most be ye my helpers, awful Powers,

Who know no blandishments, but still perceive

All wicked deeds i’ the world — strong, swift, and sure,

Avenging Furies, understand my wrong,

See how my life is ruined, and by whom.

Come, ravin on Achaean flesh — spare none;

Rage through the camp! — Last, thou that driv’st thy course

Up yon steep Heaven, thou Sun, when thou behold’st

My fatherland, checking thy golden rein,

Report my fall, and this my fatal end,

To my old sire, and the poor soul who tends him.

Ah, hapless one! when she shall hear this word,

How she will make the city ring with woe!

‘Twere from the business idly to condole.

To work, then, and dispatch. O Death! O Death!

Now come, and welcome! Yet with thee, hereafter,

I shall find close communion where I go.

But unto thee, fresh beam of shining Day,

And thee, thou travelling Sun-god, I may speak

Now, and no more for ever. O fair light!

O sacred fields of Salamis my home!

Thou, firm set natal hearth: Athens renowned,

And ye her people whom I love; O rivers,

Brooks, fountains here — yea, even the Trojan plain

I now invoke! — kind fosterers, farewell!

This one last word from Aias peals to you:

Henceforth my speech will be with souls unseen[Falls on his sword

CHORUS (re-entering severally).

CH. A.

Toil upon toil brings toil,

And what save trouble have I?

Which path have I not tried?

And never a place arrests me with its tale.

Hark! lo, again a sound!

CH. B.

’Tis we, the comrades of your good ship’s crew.

CH. A.

Well, sirs?

CH. B.

We have trodden all the westward arm o’ the bay.

CH. A.

Well, have ye found?

CH. B.

Troubles enow, but nought to inform our sight.

CH. A.

Nor yet along the road that fronts the dawn

Is any sign of Aias to be seen.

CH.

Who then will tell me, who? What hard sea-liver,1

What toiling fisher in his sleepless quest,

What Mysian nymph, what oozy Thracian river,

Hath seen our wanderer of the tameless breast?

Where? tell me where!

’Tis hard that I, far-toiling voyager,

Crossed by some evil wind,

Cannot the haven find,

Nor catch his form that flies me, where? ah! where?

TEC. (behind).

Oh, woe is me! woe, woe!

CH. A.

Who cries there from the covert of the grove?

TEC.

O boundless misery!

CH. B.

Steeped in this audible sorrow I behold

Tecmessa, poor fate-burdened bride of war.

TEC.

Friends, I am spoiled, lost, ruined, overthrown!

CH. A.

What ails thee now?

TEC.

See where our Aias lies, but newly slain,

Fallen on his sword concealed within the ground,

CH.

Woe for my hopes of home!

Aias, my lord, thou hast slain

Thy ship-companion on the salt sea foam.

Alas for us, and thee,

Child of calamity!

TEC.

So lies our fortune. Well may’st thou complain.

CH. A.

Whose hand employed he for the deed of blood?

TEC.

His own, ’tis manifest. This planted steel,

Fixed by his hand, gives verdict from his breast.

CH.

Woe for my fault, my loss!

Thou hast fallen in blood alone,

And not a friend to cross

Or guard thee. I, deaf, senseless as a stone,

Left all undone. Oh, where, then, lies the stern

Aias, of saddest name, whose purpose none might turn?

TEC.

No eye shall see him. I will veil him round

With this all covering mantle; since no heart

That loved him could endure to view him there,

With ghastly expiration spouting forth

From mouth and nostrils, and the deadly wound,

The gore of his self slaughter. Ah, my lord!

What shall I do? What friend will carry thee?

Oh, where is Teucer! Timely were his hand,

Might he come now to smooth his brother’s corse.

O thou most noble, here ignobly laid,

Even enemies methinks must mourn thy fate!

CH.

Ah! ’twas too clear thy firm knit thoughts would fashion,2

Early or late, an end of boundless woe!

Such heaving groans, such bursts of heart-bruised passion,

Midnight and morn, bewrayed the fire below.

‘The Atridae might beware!’

A plenteous fount of pain was opened there,

What time the strife was set,

Wherein the noblest met,

Grappling the golden prize that kindled thy despair!

TEC.

Woe, woe is me!

CH.

Deep sorrow wrings thy soul, I know it well.

TEC.

O woe, woe, woe!

CH.

Thou may’st prolong thy moan, and be believed,

Thou that hast lately lost so true a friend.

TEC.

Thou may’st imagine; ’tis for me to know.

CH.

Ay, ay, ’tis true.

TEC.

Alas, my child! what slavish tasks and hard

We are drifting to! What eyes control our will!

CH.

Ay me! Through thy complaint

I hear the wordless blow

Of two high-throned, who rule without restraint

Of Pity. Heaven forfend

What evil they intend!

TEC.

The work of Heaven hath brought our life thus low.

CH.

’Tis a sore burden to be laid on men.

TEC.

Yet such the mischief Zeus’ resistless maid,

Pallas, hath planned to make Odysseus glad.

CH.

O’er that dark-featured soul

What waves of pride shall roll,

What floods of laughter flow,

Rudely to greet this madness-prompted woe,

Alas! from him who all things dares endure,

And from that lordly pair, who hear, and seat them sure!

TEC.

Ay, let them laugh and revel o’er his fall!

Perchance, albeit in life they missed him not,

Dead, they will cry for him in straits of war.

For dullards know not goodness in their hand,

Nor prize the jewel till ’tis cast away.

To me more bitter than to them ’twas sweet,

His death to him was gladsome, for he found

The lot he longed for, his self-chosen doom.

What cause have they to laugh? Heaven, not their crew,

Hath glory by his death. Then let Odysseus

Insult with empty pride. To him and his

Aias is nothing; but to me, to me,

He leaves distress and sorrow in his room!

TEUCER (within).

Alas, undone!

LEADER OF CH.

Hush! that was Teucer’s cry. Methought I heard

His voice salute this object of dire woe.

Enter TEUCER.

TEU.

Aias, dear brother, comfort of mine eye,

Hast thou then done even as the rumour holds?

CH.

Be sure of that, Teucer. He lives no more.

TEU.

Oh, then how heavy is the lot I bear!

CH.

Yes, thou hast cause —

TEU.

O rash assault of woe! —

CH.

To mourn full loud.

TEU.

Ay me! and where, oh where

On Trojan earth, tell me, is this man’s child?

CH.

Beside the huts, untended.

TEU. (to TEC).

Oh, with haste

Go bring him hither, lest some enemy’s hand

Snatch him, as from the lion’s widowed mate

The lion-whelp is taken. Spare not speed.

All soon combine in mockery o’er the dead.

[Exit TECMESSA.

CH.

Even such commands he left thee ere he died.

As thou fulfillest by this timely care.

TEU.

O sorest spectacle mine eyes e’er saw!

Woe for my journey hither, of all ways

Most grievous to my heart, since I was ware,

Dear Aias, of thy doom, and sadly tracked

Thy footsteps. For there darted through the host,

As from some God, a swift report of thee

That thou wert lost in death. I, hapless, heard,

And mourned even then for that whose presence kills me.

Ay me! But come,

Unveil. Let me behold my misery.

[The corpse of AIAS is uncovered

O sight unbearable! Cruelly brave!

Dying, what store of griefs thou sow’st for me!

Where, amongst whom of mortals, can I go,

That stood not near thee in thy troublous hour?

Will Telamon, my sire and thine, receive me

With radiant countenance and favouring brow

Returning without thee? Most like! being one

Who smiles no more, yield Fortune what she may.

Will he hide aught or soften any word,

Rating the bastard of his spear-won thrall,

Whose cowardice and dastardy betrayed

Thy life, dear Aias, — or my murderous guile,

To rob thee of thy lordship and thy home?

Such greeting waits me from the man of wrath,

Whose testy age even without cause would storm.

Last, I shall leave my land a castaway,

Thrust forth an exile, and proclaimed a slave;

So should I fare at home. And here in Troy

My foes are many and my comforts few.

All these things are my portion through thy death.

Woe’s me, my heart! how shall I bear to draw thee,

O thou ill-starr’d! from this discoloured blade,

Thy self-shown slayer? Didst thou then perceive

Dead Hector was at length to be thine end? —

I pray you all, consider these two men.

Hector, whose gift from Aias was a girdle,

Tight-braced therewith to the car’s rim, was dragged

And scarified till he breathed forth his life.

And Aias with this present from his foe

Finds through such means his death-fall and his doom.

Say then what cruel workman forged the gifts,

But Fury this sharp sword, Hell that bright band?

In this, and all things human, I maintain,

Gods are the artificers. My thought is said.

And if there be who cares not for my thought,

Let him hold fast his faith and leave me mine.

CH.

Spare longer speech, and think how to secure

Thy brother’s burial, and what plea will serve;

Since one comes here hath no good will to us

And like a villain haply comes in scorn.

TEU.

What man of all the host hath caught thine eye?

CH.

The cause for whom we sailed, the Spartan King.

TEU.

Yes; I discern him, now he moves more near.

Enter MENELAUS.

MENELAUS.

Fellow, give o’er. Cease tending yon dead man!

Obey my voice, and leave him where he lies.

TEU.

Thy potent cause for spending so much breath?

MEN.

My will, and his whose word is sovereign here.

TEU.

May we not know the reasons of your will?

MEN.

Because he, whom we trusted to have brought

To lend us loyal help with heart and hand,

Proved in the trial a worse than Phrygian foe;

Who lay in wait for all the host by night,

And sallied forth in arms to shed our blood;

That, had not one in Heaven foiled this attempt,

Our lot had been to lie as he doth here

Dead and undone for ever, while he lived

And flourished. Heaven hath turned this turbulence

To fall instead upon the harmless flock.

Wherefore no strength of man shall once avail

To encase his body with a seemly tomb,

But outcast on the wide and watery sand,

He’ll feed the birds that batten on the shore.

Nor let thy towering spirit therefore rise

In threatening wrath. Wilt thou or not, our hand

Shall rule him dead, howe’er he braved us living,

And that by force; for never would he yield,

Even while he lived, to words from me. And yet

It shows base metal when the subject-wight

Deigns not to hearken to the chief in power.

Since without settled awe, neither in states

Can laws have rightful sway, nor can a host

Be governed with due wisdom, if no fear

Or wholesome shame be there to shield its safety.

And though a man wax great in thews and bulk,

Let him be warned: a trifling harm may ruin him.

Whoever knows respect and honour both

Stands free from risk of dark vicissitude.

But whereso pride and licence have their fling,

Be sure that state will one day lose her course

And founder in the abysm. Let fear have place

Still where it ought, say I, nor let men think

To do their pleasure and not bide the pain.

That wheel comes surely round. Once Aias flamed

With insolent fierceness. Now I mount in pride,

And loudly bid thee bury him not, lest burying

Thy brother thou be burrowing thine own grave.

CH.

Menelaüs, make not thy philosophy

A platform whence to insult the valiant dead.

TEU.

I nevermore will marvel, sirs, when one

Of humblest parentage is prone to sin,

Since those reputed men of noble strain

Stoop to such phrase of prating frowardness.

Come, tell it o’er again, — said you ye brought

My brother bound to aid you with his power?

Sailed he not forth of his own sovereign will?

Where is thy voucher of command o’er him?

Where of thy right o’er those that followed him?

Sparta, not we, shall buckle to thy sway.

’Twas written nowhere in the bond of rule

That thou shouldst check him rather than he thee.

Thou sailedst under orders, not in charge

Of all, much less of Aias. Then pursue

Thy limited direction, and chastise,

In haughty phrase, the men who fear thy nod.

But I will bury Aias, whether thou

Or the other general give consent or no.

’Tis not for me to tremble at your word.

Not to reclaim thy wife, like those poor souls

Thou flll’st with labour, issued this man forth,

But caring for his oath, and not for thee,

Or any other nobody. Then come

With heralds all arow, and bring the man

Called king of men with thee! For thy sole noise

I budge not, wert thou twenty times thy name.

CH.

The sufferer should not bear a bitter tongue.

Hard words, how just soe’er, will leave their sting.

MEN.

Our bowman carries no small pride, I see.

TEU.

No mere mechanic’s menial craft is mine.

MEN.

How wouldst thou vaunt it hadst thou but a shield!

TEU.

Unarmed I fear not thee in panoply.

MEN.

Redoubted is the wrath lives on thy tongue.

TEU.

Whose cause is just hath licence to be proud.

MEN.

Just, that my murderer have a peaceful end?

TEU.

Thy murderer? Strange, to have been slain and live!

MEN.

Yea, through Heaven’s mercy. By his will, I am dead.

TEU.

If Heaven have saved thee, give the Gods their due.

MEN.

Am I the man to spurn at Heaven’s command?

TEU.

Thou dost, to come and frustrate burial.

MEN.

Honour forbids to yield my foe a tomb.

TEU.

And Aias was thy foeman? Where and when?

MEN.

Hate lived between us; that thou know’st full well.

TEU.

For thy proved knavery, coining votes i’ the court

MEN.

The judges voted. He ne’er lost through me.

TEU.

Guilt hiding guile wears often fairest front.

MEN.

I know whom pain shall harass for that word.

TEU.

Not without giving equal pain, ’tis clear.

MEN.

No more, but this. No burial for this man!

TEU.

Yea, this much more. He shall have instant burial.

MEN.

I have seen ere now a man of doughty tongue

Urge sailors in foul weather to unmoor,

Who, caught in the sea-misery by and by,

Lay voiceless, muffled in his cloak, and suffered

Who would of the sailors over trample him

Even so methinks thy truculent mouth ere long

Shall quench its outcry, when this little cloud

Breaks forth on thee with the full tempest’s might.

TEU.

I too have seen a man whose windy pride

Poured forth loud insults o’er a neighbour’s fall,

Till one whose cause and temper showed like mine

Spake to him in my hearing this plain word:

‘Man, do the dead no wrong; but, if thou dost,

Be sure thou shalt have sorrow.’ Thus he warned

The infatuate one: ay, one whom I behold,

For all may read my riddle — thou art he.

MEN.

I will be gone. ‘Twere shame to me, if known,

To chide when I have power to crush by force.

TEU.

Off with you, then! ‘Twere triple shame in me

To list the vain talk of a blustering fool.

[Exit MENELAUS.

LEADER OF CHORUS.

High the quarrel rears his head!

Haste thee, Teucer, trebly haste,

Grave-room for the valiant dead

Furnish with what speed thou mayst,

Hollowed deep within the ground,

Where beneath his mouldering mound

Aias aye shall be renowned.

Re-enter TECMESSA with EURYSAKES.

TEU.

Lo! where the hero’s housemate and his child,

Hitting the moment’s need, appear at hand,

To tend the burial of the ill fated dead.

Come, child, take thou thy station close beside:

Kneel and embrace the author of thy life,

In solemn suppliant fashion holding forth

This lock of thine own hair, and hers, and mine

With threefold consecration, that if one

Of the army force thee from thy father’s corse,

My curse may banish him from holy ground,

Far from his home, unburied, and cut off

From all his race, even as I cut this curl.

There, hold him, child, and guard him; let no hand

Stir thee, but lean to the calm breast and cling.

(To CHORUS) And ye, be not like women in this scene,

Nor let your manhoods falter; stand true men

To this defence, till I return prepared,

Though all cry No, to give him burial.[Exit

CHORUS.

When shall the tale of wandering years be done?I 1

When shall arise our exile’s latest sun?

Oh, where shall end the incessant woe

Of troublous spear-encounter with the foe,

Through this vast Trojan plain,

Of Grecian arms the lamentable stain?

Would he had gone to inhabit the wide sky,I 2

Or that dark home of death where millions lie,

Who taught our Grecian world the way

To use vile swords and knit the dense array!

His toil gave birth to toil

In endless line. He made mankind his spoil.

His tyrant will hath forced me to forgoII 1

The garland, and the goblet’s bounteous flow:

Yea, and the flute’s dear noise,

And night’s more tranquil joys;

Ay me! nor only these,

The fruits of golden ease,

But Love, but Love — O crowning sorrow! —

Hath ceased for me. I may not borrow

Sweet thoughts from him to smooth my dreary bed,

Where dank night-dews fall ever on my head,

Lest once I might forget the sadness of the morrow.

Even here in Troy, Aias was erst my rock,II 2

From darkling fears and ‘mid the battle-shock

To screen me with huge might:

Now he is lost in night

And horror. Where again

Shall gladness heal my pain?

O were I where the waters hoary,

Round Sunium’s pine-clad promontory,

Plash underneath the flowery upland height.

Then holiest Athens soon would come in sight,

And to Athena’s self I might declare my story.

Enter TEUCER.

TEU.

My steps were hastened, brethren, when I saw

Great Agamemnon hitherward afoot.

He means to talk perversely, I can tell.

Enter AGAMEMNON.

AG.

And so I hear thou’lt stretch thy mouth agape

With big bold words against us undismayed —

Thou, the she-captive’s offspring! High would scale

Thy voice, and pert would be thy strutting gait,

Were but thy mother noble; since, being naught,

So stiff thou stand’st for him who is nothing now,

And swear’st we came not as commanders here

Of all the Achaean navy, nor of thee;

But Aias sailed, thou say’st, with absolute right.

Must we endure detraction from a slave?

What was the man thou noisest here so proudly?

Have I not set my foot as firm and far?

Or stood his valour unaccompanied

In all this host? High cause have we to rue

That prize-encounter for Pelides’ arms,

Seeing Teucer’s sentence stamps our knavery

For all to know it; and nought will serve but ye,

Being vanquished, kick at the award that passed

By voice of the majority in the court,

And either pelt us with rude calumnies,

Or stab at us, ye laggards! with base guile.

Howbeit, these ways will never help to build

The wholesome order of established law,

If men shall hustle victors from their right,

And mix the hindmost rabble with the van.

That craves repression. Not by bulky size,

Or shoulders’ breadth, the perfect man is known;

But wisdom gives chief power in all the world.

The ox hath a huge broadside, yet is held

Right in the furrow by a slender goad;

Which remedy, I perceive, will pass ere long

To visit thee, unless thy wisdom grow;

Who hast uttered forth such daring insolence

For the pale shadow of a vanished man.

Learn modestly to know thy place and birth,

And bring with thee some freeborn advocate

To plead thy cause before us in thy room.

I understand not in the barbarous tongue,

And all thy talk sounds nonsense to mine ear.

CH.

Would ye might both have sense to curb your ire!

No better hope for either can I frame.

TEU.

Fie! How doth gratitude when men are dead

Prove renegade and swiftly pass away!

This Agamemnon hath no slightest word

Of kind remembrance any more for thee,

Aias, who oftentimes for his behoof

Hast jeoparded thy life in labour of war.

Now all is clean forgotten and out of mind.

Thou who hast multiplied words void of sense,

Hast thou no faintest memory of the time

When who but Aias came and rescued you

Already locked within the toils, — all lost,

The rout began: when close abaft the ships

The torches flared, and o’er the bootless trench

Hector was bounding high to board our fleet?

Who stayed that onset? Was not Aias he?

Whom thou deny’st to have once set foot by thine.

Find ye no merit there? And once again

When he met Hector singly, man to man,

Not by your bidding, but the lottery’s choice,

His lot, that skulked not low adown i’ the heap,

A moist earth-clod, but sure to spring in air,

And first to clear the plumy helmet’s brim.

Yes, Aias was the man, and I too there

Kept rank, the ‘barbarous mother’s servile son.’

I pity thee the blindness of that word.

Who was thy father’s father? A barbarian,

Pelops, the Phrygian, if you trace him far!

And what was Atreus, thine own father? One

Who served his brother with the abominable

Dire feast of his own flesh. And thou thyself

Cam’st from a Cretan mother, whom her sire

Caught with a man who had no right in her

And gave dumb fishes the polluted prey.

Such was thy race. What is the race thou spurnest?

My father, Telamon, of all the host

Being foremost proved in valour, took as prize

My mother for his mate: a princess she,

Born of Laomedon; Alcmena’s son

Gave her to grace him — a triumphant meed.

Thus royally descended and thus brave,

Shall I renounce the brother of my blood,

Or suffer thee to thrust him in his woes

Far from all burial, shameless that thou art?

Be sure that, if ye cast him forth, ye’ll cast

Three bodies more beside him in one spot;

For nobler should I find it here to die

In open quarrel for my kinsman’s weal,

Than for thy wife — or Menelaüs’, was ‘t?

Consider then, not my case, but your own.

For if you harm me you will wish some day

To have been a coward rather than dare me.

CH.

Hail, Lord Odysseus! thou art come in time

Not to begin, but help to end, a fray.

Enter ODYSSEUS.

OD.

What quarrel, sirs? I well perceived from far

The kings high-voicing o’er the valiant dead.

AG.

Yea, Lord Odysseus, for our ears are full

Of this man’s violent heart-offending talk.

OD.

What words have passed? I cannot blame the man

Who meets foul speech with bitterness of tongue.

AG.

My speech was bitter, for his deeds were foul.

OD.

What deed of his could harm thy sovereign head?

AG.

He boldly says this corse shall not be left

Unburied, but he’ll bury it in our spite.

OD.

May I then speak true counsel to my friend,

And pull with thee in policy as of yore?

AG.

Speak. I were else a madman; for no friend

Of all the Argeians do I count thy peer.

OD.

Then hear me in Heaven’s name! Be not so hard

Thus without ruth tombless to cast him forth;

Nor be so vanquished by a vehement will,

That to thy hate even Justice’ self must bow.

I, too, had him for my worst enemy,

Since I gained mastery o’er Pelides’ arms.

But though he used me so, I ne’er will grudge

For his proud scorn to yield him thus much honour,

That, save Achilles’ self, I have not seen

So noble an Argive on the fields of Troy.

Then ‘twere not just in thee to slight him now;

Nor would thy treatment wound him, but confound

The laws of Heaven. No hatred should have scope

To offend the noble spirits of the dead.

AG.

Wilt thou thus fight against me on his side?

OD.

Yea, though I hated him, while hate was comely.

AG.

Why, thou shouldst trample him the more, being dead.

OD.

Rejoice not, King, in feats that soil thy fame!

AG.

’Tis hard for power to observe each pious rule.

OD.

Not hard to grace the good words of a friend.

AG.

The ‘noble spirit’ should hearken to command.

OD.

No more! ’Tis conquest to be ruled by love.

AG.

Remember what he was thou gracest so.

OD.

A noisome enemy; but his life was great.

AG.

And wilt thou honour such a pestilent corse?

OD.

Hatred gives way to magnanimity.

AG.

With addle-pated fools.

OD.

Full many are found

Friends for an hour, yet bitter in the end.

AG.

And wouldst thou have us gentle to such friends?

OD.

I would not praise ungentleness in aught.

AG.

We shall be known for weaklings through thy counsel.

OD.

Not so, but righteous in all Grecian eyes.

AG.

Thou bidst me then let bury this dead man?

OD.

I urge thee to the course myself shall follow.

AG.

Ay, every man for his own line! That holds.

OD.

Why not for my own line? What else were natural?

AG.

‘Twill be thy doing then, ne’er owned by me.

OD.

Own it or not, the kindness is the same.

AG.

Well, for thy sake I’d grant a greater boon;

Then why not this? However, rest assured

That in the grave or out of it, Aias still

Shall have my hatred. Do thou what thou wilt.

[Exit.

CH.

Whoso would sneer at thy philosophy,

While such thy ways, Odysseus, were a fool.

OD.

And now let Teucer know that from this hour

I am more his friend than I was once his foe,

And fain would help him in this burial-rite

And service to his brother, nor would fail

In aught that mortals owe their noblest dead.

TEU.

Odysseus, best of men, thine every word

Hath my heart’s praise, and my worst thought of thee

Is foiled by thy staunch kindness to the man

Who was thy rancorous foe. Thou wast not keen

To insult in present of his corse, like these,

The insensate general and his brother-king,

Who came with proud intent to cast him forth

Foully debarred from lawful obsequy.

Wherefore may he who rules in yon wide heaven,

And the unforgetting Fury-spirit, and she,

Justice, who crowns the right, so ruin them

With cruellest destruction, even as they

Thought ruthlessly to rob him of his tomb!

For thee, revered Laërtes’ lineal seed,

I fear to admit thy hand unto this rite,

Lest we offend the spirit that is gone.

But for the rest, I hail thy proffered aid;

And bring whom else thou wilt, I’ll ne’er resent it.

This work shall be my single care; but thou,

Be sure I love thee for thy generous heart.

OD.

I had gladly done it; but, since thou declinest,

I bow to thy decision, and depart.

[Exit.

TEU.

Speed we, for the hour grows late:

Some to scoop his earthy cell,

Others by the cauldron wait,

Plenished from the purest well.

Hoist it, comrades, here at hand,

High upon the three-foot stand!

Let the cleansing waters flow;

Brightly flame the fire below!

Others in a stalwart throng

From his chamber bear along

All the arms he wont to wield

Save alone the mantling shield.

Thou with me thy strength employ,

Lifting this thy father, boy;

Hold his frame with tender heed —

Still the gashed veins darkly bleed.

Who professes here to love him?

Ply your busy cares above him,

Come and labour for the man,

Nobler none since time began,

Aias, while his life-blood ran.

LEADER OF CH.

Oft we know not till we see.

Weak is human prophecy.

Judge not, till the hour have taught thee

What the destinies have brought thee.

ANTIGONE

Translated by F. Storr

Though chronologically it is the last of Sophocles’ three Theban plays, Antigone was written first, before 441 BC, and the narrative picks up where Aeschylus’ Seven Against Thebes ends. Before the beginning of the play, two brothers leading opposite sides in Thebes’ civil war died fighting each other for the throne. Creon, the new ruler of Thebes, has decided that Eteocles will be honoured and Polyneices will held be in public shame. The rebel brother’s body will not be sanctified by holy rites and will lie unburied on the battlefield, as prey for carrion animals like worms and vultures, generally considered the harshest punishment at the time.

At the opening of the play, Antigone and Ismene, the sisters of the dead Polyneices and Eteocles, meet secretly outside the palace gates late at night. Antigone wants to bury Polyneices’ body, in defiance of Creon’s edict. Ismene refuses to help her, fearing the death penalty, but she is unable to stop Antigone from going to bury her brother herself, causing Antigone to disown her.

Creon enters, along with the Chorus of Theban Elders. He seeks their support in the days to come, and in particular wants them to back his edict regarding the disposal of Polyneices’ body. The Chorus of Elders pledges their support. A Sentry enters, fearfully reporting that the body has been buried. A furious Creon orders the Sentry to find the culprit or face death himself. The Sentry leaves and the Chorus sings about honouring the gods, but after a short absence he returns, bringing Antigone with him. The Sentry explains that the watchmen exhumed Polyneices’ body and they caught Antigone as she buried him again. Creon questions her after sending the Sentry off, and she does not deny what she has done. She argues unflinchingly with Creon about the morality of the edict and the morality of her actions. Creon becomes furious, and, thinking Ismene must have known of Antigone’s plan, seeing her upset, summons the girl. Ismene tries to confess falsely to the crime, wishing to die alongside her sister, but Antigone will not have it. Creon orders that the two women be temporarily imprisoned.