автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Devonshire Characters and Strange Events

DEVONSHIRE CHARACTERS

AND STRANGE EVENTS

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

YORKSHIRE ODDITIES

TRAGEDY OF THE CÆSARS

CURIOUS MYTHS

LIVES OF THE SAINTS

ETC. ETC.

G. Clint, A.R.A., pinxt.

Thos. Lupton. sculpt.

MARIA FOOTE, AFTERWARDS COUNTESS OF HARRINGTON,

AS MARIA DARLINGTON IN THE FARCE

OF “A ROWLAND FOR AN OLIVER” (1824)

(Click here to see the original title page)

DEVONSHIRE

CHARACTERS

AND STRANGE EVENTS

BY S. BARING-GOULD, M.A.

WITH 55 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS REPRODUCED FROM OLD PRINTS, ETC.

O Jupiter!

Hanccine vitam? hoscine mores? hanc dementiam?

TERENCE, Adelphi (Act IV).

LONDON: JOHN LANE THE BODLEY HEAD

NEW YORK: JOHN LANE COMPANY MCMVIII

PLYMOUTH: WILLIAM BRENDON AND SON, LIMITED, PRINTERS

PREFACE

In treating of Devonshire Characters, I have had to put aside the chief Worthies and those Devonians famous in history, as George Duke of Albemarle, Sir Walter Raleigh, Sir Francis Drake, Sir Joshua Reynolds, the Coleridges, Sir Stafford Northcote, first Earl of Iddesleigh, and many another; and to content myself with those who lie on a lower plane. So also I have had to set aside several remarkable characters, whose lives I have given elsewhere, as the Herrings of Langstone (whom I have called Grym or Grymstone) and Madame Drake, George Spurle the Post-boy, etc. Also I have had to pretermit several great rascals, as Thomas Gray and Nicholas Horner. But even so, I find an embarras de richesses, and have had to content myself with such as have had careers of some general interest. Moreover, it has not been possible to say all that might have been said relative to these, so as to economize space, and afford room for others.

So also, with regard to strange incidents, some limitation has been necessary, and such have been selected as are less generally known.

I have to thank the kind help of many Devonshire friends for the loan of rare pamphlets, portraits, or for information not otherwise acquirable—as the Earl of Iddesleigh, Lady Rosamond Christie, Mrs. Chichester of Hall, Mrs. Ford of Pencarrow, Dr. Linnington Ash, Dr. Brushfield, Capt. Pentecost, Miss M. P. Willcocks, Mr. Andrew Iredale, Mr. W. H. K. Wright, Mr. A. B. Collier, Mr. Charles T. Harbeck, Mr. H. Tapley Soper, Miss Lega-Weekes, who has contributed the article on Richard Weekes; Mrs. G. Radford, Mr. R. Pearse Chope, Mr. Rennie Manderson, Mr. M. Bawden, the Rev. J. B. Wollocombe, the Rev. W. H. Thornton, Mr. A. M. Broadley, Mr. Samuel Gillespie Prout, Mr. S. H. Slade, Mr. W. Fleming, Mrs. A. H. Wilson, Fleet-Surgeon Lloyd Thomas, the Rev. W. T. Wellacott, Mr. S. Raby, Mr. Samuel Harper, Mr. John Avery, Mr. Thomas Wainwright, Mr. A. F. Steuart, Mr. S. T. Whiteford, and last, but not least, Mr. John Lane, the publisher of this volume, who has taken the liveliest interest in its production.

Also to Messrs. Macmillan for kindly allowing the use of an engraving of Newcomen’s steam engine, and to Messrs. Vinton & Co. for allowing the use of the portrait of the Rev. John Russell that appeared in Bailey’s Magazine.

I am likewise indebted to Miss M. Windeatt Roberts for having undertaken to prepare the exhaustive Index, and to Mr. J. G. Commin for placing at my disposal many rare illustrations.

For myself I may say that it has been a labour of love to grope among the characters and incidents of the past in my own county, and with Cordatus, in the Introduction to Ben Jonson’s Every Man out of his Humour, I may say that it has been “a work that hath bounteously pleased me; how it will answer the general expectation, I know not.”

I am desired by my publisher to state that he will be glad to receive any information as to the whereabouts of pictures by another “Devonshire Character,” James Gandy, born at Exeter in 1619, and a pupil of Vandyck. He was retained in the service of the Duke of Ormond, whom he accompanied to Ireland, where he died in 1689. It is said that his chief works will be found in that country and the West of England.

Jackson of Exeter, in his volume The Four Ages, says: “About the beginning of the eighteenth century was a painter in Exeter called Gandy, of whose colouring Sir Joshua Reynolds thought highly. I heard him say that on his return from Italy, when he was fresh from seeing the pictures of the Venetian school, he again looked at the works of Gandy, and that they had lost nothing in his estimation. There are many pictures of this artist in Exeter and its neighbourhood. The portrait Sir Joshua seemed most to value is in the Hall belonging to the College of Vicars in that city, but I have seen some very much superior to it.”

Since then, however, the original picture has been taken from the College of Vicars, and has been lost; but a copy, I believe, is still exhibited there, and no one seems to know what has become of the original.

Not only is Mr. Lane anxious to trace this picture, but any others in Devon or Ireland, as also letters, documents, or references to this artist and his work.

CONTENTS

PAGEH

UGHS

TAFFORD AND THER

OYALW

ILDING 1T

HEA

LPHINGTONP

ONIES 16M

ARIAF

OOTE 21C

ARABOO 35J

OHNA

RSCOTT,

OFT

ETCOTT 47W

IFE-SALES 58W

HITEW

ITCHES 70M

ANLYP

EEKE 84E

LALIAP

AGE 95J

AMESW

YATT 107T

HER

EV. W. D

AVY 123T

HEG

REYW

OMAN 128R

OBERTL

YDE AND THE“F

RIEND’SA

DVENTURE”

136J

OSEPHP

ITTS 152T

HED

EMON OFS

PREYTON 170T

OMA

USTIN 175F

RANCESF

LOOD 177S

IRW

ILLIAMH

ANKFORD 181S

IRJ

OHNF

ITZ 185L

ADYH

OWARD 194T

HEB

IDLAKES,

OFB

IDLAKE 212T

HEP

IRATES OFL

UNDY 224T

OMD’U

RFEY 238T

HEB

IRD OF THEO

XENHAMS 248“L

USTY” S

TUCLEY 262T

HEB

IDEFORDW

ITCHES 274S

IR“J

UDAS” S

TUKELEY 278T

HES

AMPFORDG

HOST 286P

HILIPPAC

ARY ANDA

NNEE

VANS 292J

ACKR

ATTENBURY 301J

OHNB

ARNES, T

AVERNER ANDH

IGHWAYMAN 320E

DWARDC

APERN 325G

EORGEM

EDYETTG

OODRIDGE 332J

OHND

AVY 351R

ICHARDP

ARKER,

THEM

UTINEER 355B

ENJAMINK

ENNICOTT,

D.D. 369C

APTAINJ

OHNA

VERY 375J

OANNAS

OUTHCOTT 390T

HES

TOKER

ESURRECTIONISTS 405T

HE“B

EGGAR’SO

PERA” ANDG

AY’SC

HAIR 414V

AMPFYLIDE-M

OOREC

AREW 425W

ILLIAMG

IFFORD 436B

ENJAMINR. H

AYDON 457J

OHNC

OOKE 478S

AVERY ANDN

EWCOMEN, I

NVENTORS 487A

NDREWP

RICE, P

RINTER 502D

EVONSHIREW

RESTLERS 514T

WOH

UNTINGP

ARSONS 529S

AMUELP

ROUT 564F

ONTELAUTUS 581W

ILLIAML

ANG,

OFB

RADWORTHY 594W

ILLIAMC

OOKWORTHY 600W

ILLIAMJ

ACKSON, O

RGANIST 608J

OHND

UNNING, F

IRSTL

ORDA

SHBURTON 618G

OVERNORS

HORTLAND AND THEP

RINCETOWNM

ASSACRE 633C

APTAINJ

OHNP

ALK 700R

ICHARDW

EEKES, G

ENTLEMAN ATA

RMS ANDP

RISONER IN THEF

LEET 709S

TEERN

OR’-W

EST 718G

EORGEP

EELE 726P

ETERP

INDAR 737D

R. J. W. B

UDD 754R

EAR-A

DMIRALS

IRE

DWARDC

HICHESTER, B

ART.

772ILLUSTRATIONS

MARIA FOOTE, AFTERWARDS COUNTESS OF HARRINGTON FrontispieceFrom an engraving by Thomas Lupton, after a picture by G. Clint,

A.R.A. TO FACE PAGE HUGH STAFFORD AND THE ROYAL WILDING 2From the original painting in the collection of the Earl of Iddesleigh

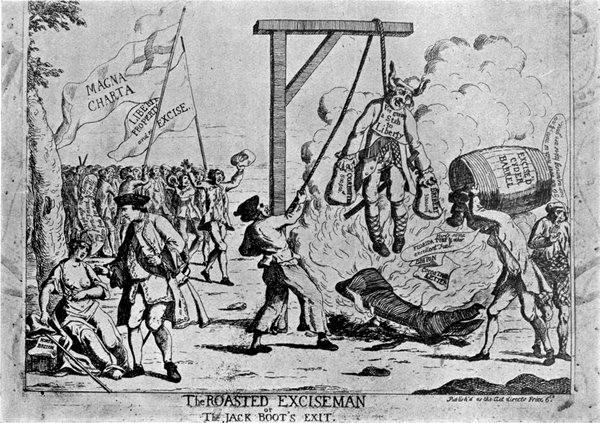

THE ROASTED EXCISEMAN, OR THE JACK BOOT’S EXIT 4From an old print

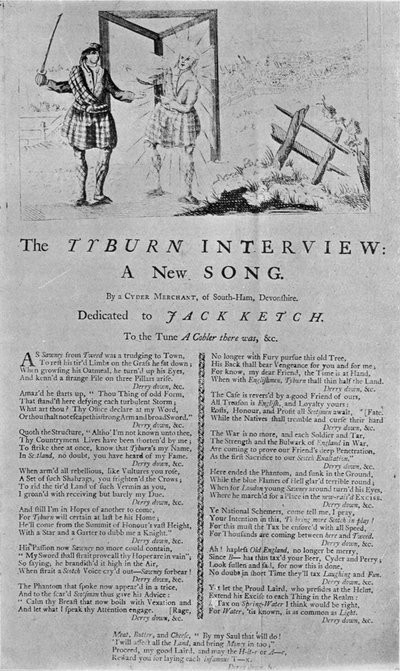

THE TYBURN INTERVIEW: A NEW SONG 8By a Cyder Merchant, of South-Ham, Devonshire. Dedicated to Jack Ketch

THE MISSES DURNFORD. THE ALPHINGTON PONIES 16From a lithograph

THE MISSES DURNFORD. THE ALPHINGTON PONIES (Back View) 18Lithographed by P. Gauci. Pub. Ed. Cockrem

MARIA FOOTE, AFTERWARDS COUNTESS OF HARRINGTON 22From an engraved portrait in the collection of A. M. Broadley, Esq.

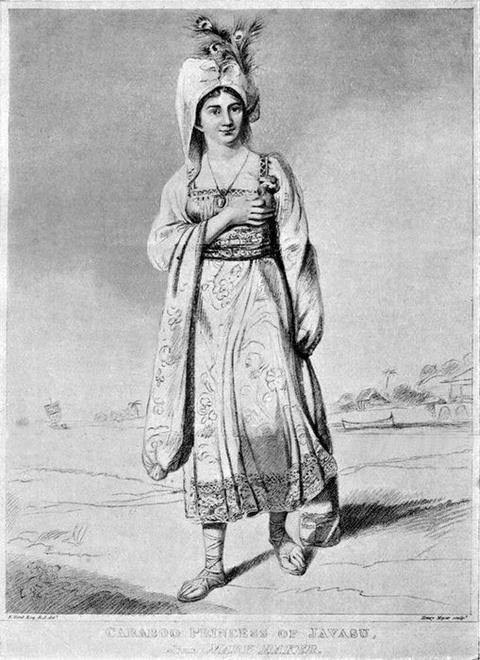

CARABOO, PRINCESS OF JAVASU, alias MARY BAKER 36From an engraving by Henry Meyer, after a picture by E. Bird

MARY WILCOCKS, OF WITHERIDGE, DEVONSHIRE, alias CARABOO 44Drawn and engraved by N. Branwhite

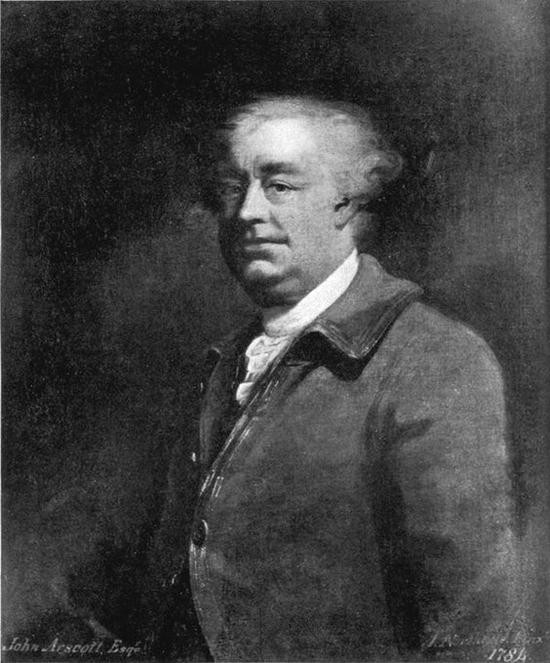

ARSCOTT OF TETCOTT 48From the picture by J. Northcote,

R.A. OLD TETCOTT HOUSE 54 MARIANN VOADEN, BRATTON 74 MARIANN VOADEN’S COTTAGE, BRATTON 74 A VILLAGE “WISE MAN” 78 MANLY PEEKE IN HIS ENCOUNTER WITH THREE ADVERSARIES ARMED WITH RAPIERS AND POIGNARDS 90 JAMES WYATT, ÆTAT. 40 108Reproduced from the frontispiece to

The Life and Surprizing Adventure of James Wyatt, Written by Himself, 1755

REV. W. DAVY 124From an engraving by R. Cooper, after a picture by Wm. Sharland

SLANNING’S OAK 188From an oil painting by A. B. Collier, 1855

FRONTISPIECE TO “THE BLOUDIE BOOKE; OR THE TRAGICAL END OF SIR JOHN FITZ” 192 LADY HOWARD 194 BIDLAKE 212 THOMAS D’URFEY 238From an engraving by G. Virtue, after a picture by E. Gouge

FRONTISPIECE TO “A TRUE RELATION OF AN APPARITION,” ETC., BY JAMES OXENHAM 248 JOHN RATTENBURY, OF BEER, DEVONSHIRE, “THE ROB ROY OF THE WEST” 302From a lithograph

EDWARD CAPERN, THE POSTMAN-POET OF DEVONSHIRE 326From a painting by William Widgery, in the Free Library, Bideford

CHARLES MEDYETT GOODRIDGE IN HIS SEAL-SKIN DRESS 332 RICHARD PARKER 356From a drawing by Bailey

B. KENNICOTT, S.T.P. 370From the portrait at Exeter College, Oxford

CAPTAIN AVERY AND HIS CREW TAKING ONE OF THE GREAT MOGUL’S SHIPS 376From a drawing by Wm. Jeit

JOANNA SOUTHCOTT 390Drawn from life by Wm. Sharp

SILVER PAP-BOAT PREPARED FOR THE COMING OF SHILOH, PRESENTED TO JOANNA SOUTHCOTT IN JUNE, 1814 402From the original in the collection of A. M. Broadley, Esq.

CRIB PRESENTED TO JOANNA SOUTHCOTT IN ANTICIPATION OF THE BIRTH OF THE SHILOH BY BELIEVERS IN HER DIVINE MISSION AS “A GOODWILL OFFERING BY FAITH TO THE PROMISED SEED” 402Reproduced from the original print in the collection of A. M. Broadley, Esq.

MR. GAY 414From an old print

THE GRAMMAR SCHOOL, BARNSTAPLE, WHERE GAY WAS EDUCATED 416 GAY’S CHAIR 422 BAMPFYLDE MOORE CAREW, “KING OF THE BEGGARS” 426From an engraving by Maddocks

W. GIFFORD 436From an engraving by R. H. Cromek, after a picture by I. Hoppner,

R.A. B. R. HAYDON 458From a drawing by David Wilkie

CAPTAIN COOKE, 1824, AGED 58 478Drawn, from nature, on the stone by N. Whittock

THE NOTED JOHN COOKE OF EXETER, CAPTAIN OF THE SHERIFF’S TROOP AT SEVENTY-FOUR ASSIZES FOR THE COUNTY OF DEVON 482From a lithograph by Geo. Rowe

THOMAS SAVERY 488 SKETCH OF NEWCOMEN’S HOUSE, LOWER STREET, DARTMOUTH, BEFORE IT WAS DEMOLISHED 494 THE CHIMNEY-PIECE AT WHICH NEWCOMEN SAT WHEN HE INVENTED THE STEAM ENGINE 494 THE STEAM ENGINE, NEAR DUDLEY CASTLE. Invented by Capt. Savery and Mr. Newcomen. Erected by ye later, 1712 496From a drawing by Barney. Reproduced by kind permission of Messrs. Macmillan & Co.

ANDREW BRICE, PRINTER 502Reproduced by kind permission from a print in the possession of Dr. Brushfield

THE WRESTLING CHAMPION OF ENGLAND, ABRAHAM CANN 518From a drawing

REV. JOHN RUSSELL 530Reproduced by permission of the Editor of

Bailey’s Magazine THE REV. JOHN RUSSELL’S PORT-WINE GLASS, CHAMBERLAIN WORCESTER BREAKFAST SERVICE, AND BAROMETER 558Purchased at the sale of his effects in 1883 by Mrs. Arnull and presented by her to Mr. John Lane, in whose possession they now are

SAMUEL PROUT 564From a drawing in the possession of Samuel Gillespie Prout, Esq.

WILLIAM COOKWORTHY OF PLYMOUTH 600From the original portrait by Opie in the possession of Edward Harrison, Esq., of Watford

MR. JACKSON, THE CELEBRATED COMPOSER 608From an engraving after J. Walker

LORD ASHBURTON 618From an engraving by F. Bartolozzi, after a picture by Sir Joshua Reynolds

HORRID MASSACRE AT DARTMOOR PRISON, ENGLAND 648From an old print

PLAN OF DARTMOOR PRISON 650 NORTH WYKE 710 DR. WOLCOT 738 DR. JOHN W. BUDD 754From a photograph by his brother Dr. Richard Budd, of Barnstaple

REAR-ADMIRAL SIR EDWARD CHICHESTER, BART. 772DEVONSHIRE CHARACTERS

AND STRANGE EVENTS

He wrote a “Dissertation on Cyder and Cyder-Fruit” in a letter to a friend in 1727, but this was not published till 1753, and a second edition in 1769. The family of Stafford was originally Stowford, of Stowford, in the parish of Dolton. The name changed to Stoford and then to Stafford. One branch married into the family of Wollocombe, of Wollocombe. But the name of Stowford or Stafford was not the most ancient designation of the family, which was Kelloway, and bore as its arms four pears. The last Stafford turned from pears to apples, to which he devoted his attention and became a connoisseur not in apples only, but in the qualities of cyder as already intimated.

In 1763 Lord Bute, the Prime Minister, imposed a tax of 10s. per hogshead on cyder and perry, to be paid by the first buyer. The country gentlemen, without reference to party, were violent in their opposition, and Bute then condescended to reduce the sum and the mode of levying it, proposing 4s. per hogshead, to be paid, not by the first buyer, but by the grower, who was to be made liable to the regulations of the excise and the domiciliary visits of excisemen. Pitt thundered against this cyder Bill, inveighing against the intrusion of excise officers into private dwellings, quoting the old proud maxim, that every Englishman’s house was his castle, and showing the hardship of rendering every country gentleman, every individual that owned a few fruit trees and made a little cyder, liable to have his premises invaded by officers. The City of London petitioned the Commons, the Lords, the throne, against the Bill; in the House of Lords forty-nine peers divided against the Minister; the cities of Exeter and Worcester, the counties of Devonshire and Herefordshire, more nearly concerned in the question about cyder than the City of London, followed the example of the capital, and implored their representatives to resist the tax to the utmost; and an indignant and general threat was made that the apples should be suffered to fall and rot under the trees rather than be made into cyder, subject to such a duty and such annoyances. No fiscal question had raised such a tempest since Sir Robert Walpole’s Excise Bill in 1733. But Walpole, in the plenitude of his power and abilities, and with wondrous resources at command, was constrained to bow to the storm he had roused, and to shelve his scheme. Bute, on the other hand, with a power that lasted but a day, with a position already undermined, with slender abilities and no resources, but with Scotch stubbornness, was resolved that his Bill should pass. And it passed, with all its imperfections; and although there were different sorts of cyder, varying in price from 5s. to 50s. per hogshead, they were all taxed alike—the poor man having thus to pay as heavy a duty for his thin beverage as the affluent man paid for the choicest kind. The agitation against Lord Bute grew. In some rural districts he was burnt under the effigy of a jack-boot, a rustic allusion to his name (Bute); and on more than one occasion when he walked the streets he was accused of being surrounded by prize-fighters to protect him against the violence of the mob. Numerous squibs, caricatures, and pamphlets appeared. He was represented as hung on the gallows above a fire, in which a jack-boot fed the flames and a farmer was throwing an excised cyder-barrel into the conflagration, whilst a Scotchman, in Highland costume, in the background, commented, “It’s aw over with us now, and aw our aspiring hopes are gone”; whilst an English mob advanced waving the banners of Magna Charta, and “Liberty, Property, and No Excise.”

“It is a very constant and plentiful bearer every other year, and then usually produces apples enough to make one of our hogsheads of cyder, which contains sixty-four gallons, and this was one occasion of its being first taken notice of, and of its affording an history which, I believe, no other tree ever did: For the little cot-house to which it belongs, together with the little quillet in which it stands, being several years since mortgaged for ten pounds, the fruit of this tree alone, in a course of some years, freed the house and garden, and its more valuable self, from that burden.

Deserted by the reputable of one sex, she threw herself into the society of the other; and in Plymouth, her good humour, fascinating manner, long silken hair, and white hat and feather made havoc among the young bloods. The husband was too apathetic to care who hovered about his wife, with whom she flirted; and she, without being vicious, finding herself slighted causelessly, became indifferent to the world’s opinion. Her elderly husband, seeing that she was not visited, began himself to neglect her.

Neither Mr. nor Mrs. Worall could make heads or tails of what she said. He had a Greek valet who knew or could recognize most of the languages spoken in the Levant, but he also was at fault; he could not catch a single word of her speech that was familiar to him. By signs she was questioned as to whether she had any papers, and she produced from her pocket a bad sixpence and a few halfpence. Under her arm she carried a small bundle containing some necessaries, and a piece of soap wound up in a bit of linen. Her dress consisted of a black stuff gown with a muslin frill round her neck, a black cotton shawl twisted about her head, and a red and black shawl thrown over her shoulders, leather shoes, and black worsted stockings.

She then exchanged her female garments for a boy’s suit at a Jew’s pawnshop, and started to walk back to Devonshire, begging her way. On Salisbury Plain she fell in with highwaymen, who offered to take her into their company if she could fire a pistol. A pistol was put into her hand, but when she pulled the trigger and it was discharged, she screamed and threw the weapon down. Thereupon the highwaymen turned her off, as a white-livered poltroon unfit for their service. She made her way back to Witheridge to her father, and then went into service at Crediton to a tanner, but left her place at the end of three months, unable further to endure the tedium. Then she passed through a succession of services, never staying in any situation longer than three months, and found her way back to London. There, according to her account, she married a foreign gentleman at a Roman Catholic chapel, where the priest officiated to tie the knot. She accompanied her husband to Brighton and thence to Dover, where he gave her the slip, and she had not seen him or heard from him since. She returned to London, was eventually confined, and placed her child in the Foundling Institution; then took a situation not far off and visited the child once a week till it died. After a while she again appeared at Witheridge, but her reception was so far from cordial that she left it and associated with gipsies, travelling about with them, telling fortunes.

Tetcott House—the older—remains, turned into stables and residence for coachmen and grooms. A stately new mansion was erected in the reign of Queen Anne. But when the property passed to the Molesworths this was pulled down, and all its contents dispersed. The family portraits, the carved oak furniture, the china fell to the contractor who demolished the mansion. But the park remains with its noble oak trees, and of this more anon.

There is an old woman I know—she is still alive. It was six years since she bought a bar of yellow or any other soap. But that is neither here nor there. She was esteemed a witch—a white one of course. She was a God-fearing woman, and had no relations with the Evil One, of that one may be sure. How she subsisted was a puzzle to the whole parish. But, then, she was generally feared. She received presents from every farm and cottage. Sometimes she would meet a child coming from school, and stay it, and fixing her wild dark eye on it, say, “My dear, I knawed a child jist like you—same age, red rosy cheeks, and curlin’ black hair. And that child shrivelled up, shrumped like an apple as is picked in the third quarter of the moon. The cheeks grew white, the hair went out of curl, and she jist died right on end and away.”

“Roome was made for the combatants, rapier and dagger the weapons. A Spanish champion presents himselfe, named Signior Tiago, Whom after we had played some reasonable good time, I disarmed, as thus—I caught his rapier betwixt the barr of my poignard and there held it, till I closed in with him, and tripping up his heeles, I tooke his weapons out of his hands, and delivered them to the Dukes.

As soon as his time of apprenticeship was up he entered as gunner’s server on board the York man-of-war. In 1726 he went with Sir John Jennings to Lisbon and Gibraltar. Next he served on board the Experiment under Captain Radish; but his taste for the sea failed for a while, and he was lured by the superior attractions of a puppet-show to engage with the proprietor, named Churchill, and to play the trumpet at his performances. During four years he travelled with the show, then tiring of dancing dolls, reverted to woolcombing and dyeing at Trowbridge. But a travelling menagerie was too much for him, and he followed that as trumpeter for four years. In 1741, he left the wild beasts and entered as trumpeter on board the Revenge privateer, Captain Wemble, commander, who was going on a cruise against the Spaniards. The privateer fell in with a Spanish vessel from Malaga, and gave chase. She made all the sail she could, but in four or five hours the Revenge came up with her. “We fir’d five times at her. She had made everything ready to fight us, but seeing the number of our hands (which were one hundred in all, though three parts of them were boys) she at length brought to. We brought the captain and mate on board our ship, and put twelve men on board theirs, one of which was the master, and our captain gave him orders to carry her into Plymouth.” Of the prize-money Wyatt got forty shillings. The capture did not prove to be as richly laden as had been anticipated.

On leaving college he was ordained to the curacy of Moreton Hampstead, and married Sarah, daughter of a Mr. Gilbert, of Longabrook, near Kingsbridge. When settled into his curacy he began to reduce to order the plan he had devised of writing a General System of Theology, and wrote twelve volumes of MS. on the subject.

The young John Fitz is described as having been “a very comlie person.” He was married, before he had attained his majority, to Bridget, sixth daughter of Sir William Courtenay. Of this marriage one child, Mary, was born 1 August, 1596, when her father was just twenty-one years old. John Fitz was now of age, considered himself free of all restraint, owner of large estates, and was without stability of character or any principle, and was inclined to a wild life. He took up his residence at Fitzford, and roystered and racketed at his will.

At length he reached Kingston-on-Thames, and put up for the night there. But he could not sleep, noises disturbed him, and rising from his bed he insisted on the servant getting ready his nag, and away he rode over Kingston Bridge, alone, having peremptorily forbidden his man to accompany him, entertaining some suspicion that the man had been bought by his enemies and would lead him into a trap. He drew up at the “Anchor,” a small tavern at Twickenham, kept by one Daniel Alley; it was now 2 a.m., and all Twickenham was asleep. He hammered at the door and shouted; presently the casement opened, and the publican put out his head and inquired what the gentleman wanted. Sir John demanded a bed and shelter for the rest of the night. Daniel Alley begged to be excused, he had no spare room, his house was small and not fitted for the reception of persons of quality. However, on Sir John’s further insistence he put on his clothes, struck a light, descended, and did his utmost to make the nocturnal visitor comfortable, even surrendering to him his own bed, and sending his wife to sleep with the children. Sir John cast himself on the bed. He tossed; and host and hostess heard him cry out, and speak of enemies who pursued him and sought his blood. There was no sleeping for Daniel or his wife, and the host rose at dawn to join a neighbour in mowing a meadow. But when he was about to go forth, his wife begged not to be left in the house alone with the strange gentleman. The neighbour came up, and he and Alley spoke together at the door. Their voices reached Sir John, who had fallen into a disordered sleep. Persuaded that the enemies were arrived and were surrounding the house, he rushed out in his nightgown, with his sword drawn, fell on his host, and killed him. Then he ran his sword against the wife, wounding her. But now, with the gathering light, he discovered what he had done, and in a fit of despair stabbed himself in two places. He was secured now by neighbours who had come up, and taken to the bed he had just quitted. A surgeon was sent for, and his wounds were bound up. But Sir John angrily refused the assistance of the leech, and tore away the bandages, and bled to death.

The smugglers formerly ran their goods into the caves when the weather permitted, or the preventive men, nicknamed picaroons, were not on the look-out. They stowed away their goods in the caves, and gave notice to the farmers and gentry of the neighbourhood, all of whom were provided with numerous donkeys, which were forthwith sent down to the caches, and the kegs and bales were removed under cover of night or of storm. Few farmhouses and squires’ mansions were not also provided with hiding-places in which to store the kegs obtained from the free-traders. Only the week before writing this I was shown one such in the depth of a dense wood, at Sandridge Park on the Dart; externally it would have been taken for a natural mound or a tumulus. But there are a concealed door and a descent by a flight of steps into the subterranean cellar, that was carefully vaulted, and also carefully drained.

In 1732, when he was only fourteen years of age, the bells of Totnes tower were recast, and at the same time the ringers presented to the bell-ringing chamber an eight-light brass candlestick inscribed with the names of the ringers. Benjamin Kennicott the elder headed the list, and Benjamin Kennicott the younger brought up the tail. But in 1742, when new regulations were drawn up and agreed to by the ringers, the youngest ringer had become the leader.

Two years after this, in January, 1817, the London disciples made a remarkable outbreak. One morning, having assembled somewhere in the West End of the metropolis, they made their way to Temple Bar, passing through which, they set forward in procession through the City, each decorated with a white cockade, and wearing a small star of yellow riband on the left breast. In this guise, led by one of their number, carrying a brazen trumpet ornamented with light blue ribands, while two boys marching by his side bore each a flag of silk, they proceeded along Fleet Street, up Ludgate Hill, and thence through St. Paul’s Churchyard to Bridge Row, followed by the rabble in great force. Here, having reached what they considered to be the centre of the great city, they halted; and then their leader sounded his trumpet, and roared out that the Shiloh, the Prince of Peace, was come again to the earth; to which a woman who was with him, and who was said to be his wife, responded with another wild cry of “Woe! woe! to the inhabitants of the earth, because of the coming of Shiloh.” This terrific vociferation was repeated several times, and joined in by the rest of the party. But at last the mob, which now completely blocked up the street, from laughing and shouting proceeded to pelting the enthusiasts with mud and harder missiles. They struggled to make their escape, or to beat off their assailants; this led to a general fight; the flags were torn, and the affray ended in the trumpeter and his wife, five other men and the two boys of the party, after having been rolled in the mire, being rescued from the fury of the multitude by the constables, and conveyed to the Compter.

Queen Caroline, then Princess of Wales, was interested in him, and sent to invite him to read his play, The Captives, before her at Leicester House. The day was fixed, and Gay was commanded to attend. He waited some time in a presence chamber, with his manuscript in his hand, but being a modest man, and unequal to the trial into which he was entering, when the door of the drawing-room was thrown open, where the Princess sat with her ladies, he was so much confused and concerned about making the proper obeisance that he did not see a low footstool that happened to be in the way; and, stumbling over it, fell against a large screen, which he upset, and threw the ladies into no small disorder.

It will not be possible here to do more than give an outline of the life of this King of the Beggars; the original deserves to be read by West-countrymen, on account of the numerous references to the gentry of the counties of Devon, Cornwall, and Somerset that it contains. It is somewhat amusing in the Apology to notice how Carew insists on being entitled Mr. on almost every occasion that his name is mentioned by the biographer. The book reveals at every page the vanity and self-esteem of this runaway from civilized life, as it does also his utter callousness to truth and honesty. He relates his frauds and falsehoods with unblushing effrontery, glorying in his shame. There have always been persons who have rebelled against the restraints of culture, and have reverted to a state of savagery more or less. Nowadays there are the colonies, to which those who are energetic and dislike the bonds of civilization at home can fly and live a freer life, one also simpler. And this desire, located in many hearts, to be emancipated from limitations and ties that are conventional, is thus given an opening for fulfilment. It may be but a temporary outburst of independence, but with some, unquestionably, like Falstaff, there is a “kind of alacrity in sinking.”

The Haydons of Cadhay, in Ottery S. Mary parish, were an ancient family. They built the south porch of the collegiate church in 1571, and set up on it the inscription “He that no il will Do no thynt yt lang yto,” or in plainer English, “He that no ill will do, let him do nothing that belongs thereto”; a motto that it had been well for Benjamin had he retained it and acted on it to the end.

“There has been but one small riot in Devonshire, to its honour and credit, and that was stopped in its infancy. It was for breaking into a miller’s house to get corn by violence; one Campion, a blacksmith, a young man called out from his work inadvertently to join the mob; from farmhouse to house they got liquor, got inebriated. He became a leader and carried a French banner, the old story. Campion was desired to desist by gentlemen; but he would not. He was apprehended in a day or two, committed to gaol, and tried at the Assizes, 1795, before the late Justice Heath; the jury found him guilty of the felony—riot and sedition. He suffered death. This prompt measure put an end and stopped the contagion in the West. There were thousands of spectators on the road, besides a thousand military of dragoons, artillery and volunteers of the district, who escorted him thirteen miles to the place of execution, Bovey-heathfield, in sight of his own village, Ilsington, as a rescue was talked of.

The old Marquess died in December of the same year, and Edward Somerset became second Marquess of Worcester. Whilst in the Tower, in 1652–4, the Marquess wrote his Century of the Names and Scantlings of Inventions, but it was not published till 1663. “He was a man,” says Clarendon, “of a fair and gentle carriage towards all men (as in truth he was of a civil and obliging nature).” He died 3 April, 1667. In his remarkable book he anticipated the power of steam, and indeed may be said to have invented the first steam engine. His object in his steam-fountain was to throw up or raise water to a great height. His words are as follows: “This admirable method which I propose of raising water by the force of fire has no bounds if the vessels be strong enough; for I have taken a cannon, and having filled it three-fourths full of water and shut up its muzzle and touch-hole, and exposed it to the fire for twenty-four hours, it burst with a great explosion. Having afterwards discovered a method of fortifying vessels internally, and combined them in such a way that they filled and acted alternately, I have made the water spout in an uninterrupted stream forty feet high, and one vessel of rarefied water raised 40 of cold water. The person who conducted the operation had nothing to do but turn two cocks, so that one vessel of water being consumed, another begins to force, and then to fill itself with cold water, and so on in succession.” By means of his contrivance he proposed “not only with little charge to drain all sorts of mines, and furnish cities with water, though never so high seated, as well as to keep them sweet, running through several streets, and so performing the work of scavengers, as well as furnishing the inhabitants with sufficient water for their private occasions, but likewise supply rivers with sufficient to maintain and make them portable from town to town, and for the bettering of lands all the way it runs, with many more advantageous and yet greater effects, of profits, admiration, and consequence—so that deservedly I deem this invention to crown my labours, to reward my expenses, and make my thoughts acquiesce in the way of further inventions.”

Savery proposed to apply his engine to various purposes. One was to pump water into a reservoir for the production of an artificial waterfall for driving mills or any other ordinary machinery; that is to say, by means of steam he would lift a body of water which by flowing back might drive an overshot wheel, from the rotation of which the motive power for any other mechanical operations would be derived. This, however, was never done, and Savery’s engine continued to be employed only in the drainage of Cornish mines. But it had this disadvantage, that it could not heave water but to about eighty feet, and as the depth of mines was from fifty to a hundred yards, the only way to exhaust the water was by erecting several engines in successive stages, one above the other. But the expense of fuel and attendants and the constant danger of explosions rendered it clear that the use of his engine for deep mines was altogether impracticable. Such was the state of affairs when Thomas Newcomen, a blacksmith and ironmonger of Dartmouth, turned his attention to the matter.

Newcomen was a man of reading, and was in correspondence with Dr. Hooke, secretary of the Royal Society. There are to be found among Hooke’s papers, in the possession of the Royal Society, some notes of observations made by him for the use of Newcomen on Papin’s boasted method of transmitting to a great distance the action of a mill by means of pipes. Papin’s project was to employ the mill to work two air pumps of great diameter. The cylinders of these pumps were to communicate by means of pipes with equal cylinders furnished with pistons in the neighbourhood of a mine. The pistons were to be connected by means of levers with the piston-rods of the mine. Therefore, when the piston of the air pumps at the mill was drawn up by the engine the corresponding piston at the side of the mine would be pressed down by the atmosphere, and thus would raise the piston-rod in the mine and throw up the water. It would appear from these notes that Dr. Hooke dissuaded Newcomen from erecting a machine on this principle, of which he saw the fallacy.

“My lord, I’ve also heard strange tales about your lordship. But among gentlemen, us don’t give heed to all thickey tittle-tattle. Perhaps you’d prefer gin—London or Plymouth, my lord? You’ll excuse me, my lord; I be terrible bad, and I be afraid you’ll catch the infection—pleased to have seen you—good-bye”; and he ducked his head under the bedclothes.

Here ensues a difference between the report of the commissioners appointed later to investigate the matter and that drawn up by the prisoners. These latter assert that the officers of the regiment, seeing what was Shortland’s intention, refused to act under him, and withdrew. The commissioners state that the hour was that of the officers’ mess, and that they were at dinner, and only two young lieutenants and an ensign were with the soldiers. But this is incredible. The alarm bell pealing and the drum calling to arms would have summoned the officers from their mess, and we are rather inclined to believe that the account of the Americans is correct. The officers saw that the Governor had lost his head and was resolved on violence, and they withdrew so as not to be compromised in what would follow. The officers, says Andrews, perceiving the horrid and murderous designs of Captain Shortland, resigned their authority over the soldiers and refused to take any part, or give any orders for the troops to fire. They saw by this time that the terrified prisoners were retiring as fast as so great a crowd would permit, and hurrying and flying in terrified flight in every direction to their respective prisons.

In the parish of South Tawton, about three miles from the village and church, and midway on the west road to North Tawton, stands the ancient and interesting mansion of North Wyke.[55] A house so named was there as early as 1243,[56] but experts are at variance as to the age of the several parts of the existing structure. It formed an inner court, two sides of which were stables and offices, and a front court enclosed within high walls, and with gate-house, porter’s lodgings, and domestic chapel. Though the house itself lies in a somewhat sheltered situation, the drive down from the lodge commands a lovely prospect; and from the top of North Wyke Quarry a panorama of three-quarters of a circle extends over miles of undulating country, from the blue sky-line of Exmoor to the three conspicuous heights of the north-east angle of Dartmoor—Yes Tor, Belstone, and Cosdon—the last crowned with a cairn from which beacon fires have flared out many a warning message to arm against a foe, both before and since the coming of the Armada. From Belstone Cleave bursts forth the river Taw that borders the North Wyke lands for fully a mile and a half of its course. After rushing in foaming stickles from under Peckettsford alias Packsaddle Bridge, but before reaching Newlands Weir, the river is joined by a meeker stream that bounds North Wyke on another side. There is said to have been much fine timber on the land before the alienation of the estate, the story of which may now be related.

Alexander Wolcot died 14 June, 1751, and John was left to the care of his uncle, John Wolcot, of Fowey. He was educated at the Kingsbridge Grammar School, and afterwards at Liskeard and Bodmin. In or about 1760 he was sent to France for a twelvemonth to acquire French. He does not seem to have been comfortable there, and he retained through life a distaste for the Gallic people:—

HUGH STAFFORD AND THE ROYAL WILDING

Hugh Stafford, Esq., of Pynes, born 1674, was the last of the Staffords of Pynes. His daughter, Bridget Maria, carried the estate to her husband, Sir Henry Northcote, Bart., from whom is descended the present Earl of Iddesleigh. Hugh Stafford died in 1734. He is noted as an enthusiastic apple-grower and lover of cyder.

He wrote a “Dissertation on Cyder and Cyder-Fruit” in a letter to a friend in 1727, but this was not published till 1753, and a second edition in 1769. The family of Stafford was originally Stowford, of Stowford, in the parish of Dolton. The name changed to Stoford and then to Stafford. One branch married into the family of Wollocombe, of Wollocombe. But the name of Stowford or Stafford was not the most ancient designation of the family, which was Kelloway, and bore as its arms four pears. The last Stafford turned from pears to apples, to which he devoted his attention and became a connoisseur not in apples only, but in the qualities of cyder as already intimated.

To a branch of this family belonged Sir John Stowford, Lord Chief Baron in the reign of Edward III, who built Pilton Bridge over the little stream of the Yeo or Yaw, up which the tide flows, and over which the passage was occasionally dangerous. The story goes that the judge one day saw a poor market woman with her child on a mudbank in the stream crying for aid, which none could afford her, caught and drowned by the rising flood, whereupon he vowed to build the bridge to prevent further accident. The rhyme ran:—

Yet Barnstaple, graced though thou be by brackish Taw,

In all thy glory see that thou not forget the little Yaw.

Camden asserts that Judge Stowford also constructed the long bridge over the Taw consisting of sixteen piers. Tradition will have it, however, that towards the building of this latter two spinster ladies (sisters) contributed by the profits of their distaffs and the pennies they earned by keeping a little school.

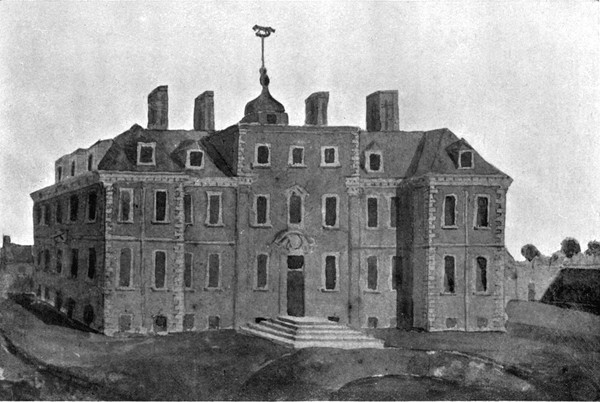

HUGH STAFFORD

From the original painting in the collection of the Earl of Iddesleigh

I was travelling on the South Devon line some years ago after there had been a Church Congress at Plymouth, and in the same carriage with me were some London reporters. Said one of these gentry to another: “Did you ever see anything like Devonshire parsons and pious ladies? They were munching apples all the time that the speeches were being made. Honour was being done to the admirable fruit by these worthy Devonians. I was dotting down my notes during an eloquent harangue on ‘How to Bring Religion to Bear upon the People’ when chump, chump went a parson on my left; and the snapping of jaws on apples, rending off shreds for mastication, punctuated the periods of a bishop who spoke next. At an ensuing meeting on the ‘Deepening of Personal Religion’ my neighbour was munching a Cornish gilliflower, which he informed me in taste and aroma surpassed every other apple. I asked in a low tone whether Devonshire people did not peel their fruit before eating. He answered leni susurro that the flavour was in the rind.”

Cyder was anciently the main drink of the country people in the West of England. Every old farmhouse had its granite trough (circular) in which rolled a stone wheel that pounded the fruit to a “pummice,” and the juice flowed away through a lip into a keeve. Now, neglected and cast aside, may be seen the huge masses of stone with an iron crook fastened in them, which in the earliest stage of cyder-making were employed for pressing the fruit into pummice. But these weights were superseded by the screw-press that extracted more of the juice.

In 1763 Lord Bute, the Prime Minister, imposed a tax of 10s. per hogshead on cyder and perry, to be paid by the first buyer. The country gentlemen, without reference to party, were violent in their opposition, and Bute then condescended to reduce the sum and the mode of levying it, proposing 4s. per hogshead, to be paid, not by the first buyer, but by the grower, who was to be made liable to the regulations of the excise and the domiciliary visits of excisemen. Pitt thundered against this cyder Bill, inveighing against the intrusion of excise officers into private dwellings, quoting the old proud maxim, that every Englishman’s house was his castle, and showing the hardship of rendering every country gentleman, every individual that owned a few fruit trees and made a little cyder, liable to have his premises invaded by officers. The City of London petitioned the Commons, the Lords, the throne, against the Bill; in the House of Lords forty-nine peers divided against the Minister; the cities of Exeter and Worcester, the counties of Devonshire and Herefordshire, more nearly concerned in the question about cyder than the City of London, followed the example of the capital, and implored their representatives to resist the tax to the utmost; and an indignant and general threat was made that the apples should be suffered to fall and rot under the trees rather than be made into cyder, subject to such a duty and such annoyances. No fiscal question had raised such a tempest since Sir Robert Walpole’s Excise Bill in 1733. But Walpole, in the plenitude of his power and abilities, and with wondrous resources at command, was constrained to bow to the storm he had roused, and to shelve his scheme. Bute, on the other hand, with a power that lasted but a day, with a position already undermined, with slender abilities and no resources, but with Scotch stubbornness, was resolved that his Bill should pass. And it passed, with all its imperfections; and although there were different sorts of cyder, varying in price from 5s. to 50s. per hogshead, they were all taxed alike—the poor man having thus to pay as heavy a duty for his thin beverage as the affluent man paid for the choicest kind. The agitation against Lord Bute grew. In some rural districts he was burnt under the effigy of a jack-boot, a rustic allusion to his name (Bute); and on more than one occasion when he walked the streets he was accused of being surrounded by prize-fighters to protect him against the violence of the mob. Numerous squibs, caricatures, and pamphlets appeared. He was represented as hung on the gallows above a fire, in which a jack-boot fed the flames and a farmer was throwing an excised cyder-barrel into the conflagration, whilst a Scotchman, in Highland costume, in the background, commented, “It’s aw over with us now, and aw our aspiring hopes are gone”; whilst an English mob advanced waving the banners of Magna Charta, and “Liberty, Property, and No Excise.”

I give one of the ballads printed on this occasion: it is entitled, “The Scotch Yoke, and English Resentment. To the tune of The Queen’s Ass.”

Of Freedom no longer let Englishmen boast,

Nor Liberty more be their favourite Toast;

The Hydra Oppression your Charta defies,

And galls English Necks with the Yoke of Excise,

The Yoke of Excise, the Yoke of Excise,

And galls English Necks with the Yoke of Excise.

In vain have you conquer’d, my brave Hearts of Oak,

Your Laurels, your Conquests are all but a Joke;

Let a rascally Peace serve to open your Eyes,

And the d—nable Scheme of a Cyder-Excise,

A Cyder-Excise, etc.

What though on your Porter a Duty was laid,

Your Light double-tax’d, and encroach’d on your Trade;

Who e’er could have thought that a Briton so wise

Would admit such a Tax as the Cyder-Excise,

The Cyder-Excise, etc.

I appeal to the Fox, or his Friend John a-Boot,

If tax’d thus the Juice, then how soon may the Fruit?

Adieu then to good Apple-puddings and Pyes,

If e’er they should taste of a cursed Excise,

A cursed Excise, etc.

Let those at the Helm, who have sought to enslave

A Nation so glorious, a People so brave,

At once be convinced that their Scheme you despise,

And shed your last Blood to oppose the Excise,

Oppose the Excise, etc.

Come on then, my Lads, who have fought and have bled,

A Tax may, perhaps, soon be laid on your Bread;

Ye Natives of Worc’ster and Devon arise,

And strike at the Root of the Cyder-Excise,

The Cyder-Excise, etc.

No longer let K—s at the H—m of the St—e,

With fleecing and grinding pursue Britain’s Fate;

Let Power no longer your Wishes disguise,

But off with their Heads—by the Way of Excise,

The Way of Excise, etc.

From two Latin words, ex and scindo, I ween,

Came the hard Word Excise, which to Cut off does mean.

Take the Hint then, my Lads, let your Freedom advise,

And give them a Taste of their fav’rite Excise,

Their fav’rite Excise, etc.

Then toss off your Bumpers, my Lads, while you may,

To Pitt and Lord Temple, Huzza, Boys, huzza!

Here’s the King that to tax his poor Subjects denies,

But Pox o’ the Schemer that plann’d the Excise,

That plann’d the Excise, etc.

The apple trees were too many and too deep-rooted and too stout for the Scotch thistle. The symptoms of popular dislike drove Bute to resign (8 April, 1763), to the surprise of all. The duty, however, was not repealed till 1830. In my Book of the West (Devon), I have given an account of cyder-making in the county, and I will not repeat it here. But I may mention the curious Devonshire saying about Francemass, or St. Franken Days. These are the 19th, 20th, and 21st May, at which time very often a frost comes that injures the apple blossom. The story goes that there was an Exeter brewer, of the name of Frankin, who found that cyder ran his ale so hard that he vowed his soul to the devil on the condition that his Satanic Majesty should send three frosty nights in May annually to cut off the apple blossom.

And now to return to Hugh Stafford. He opens his letter with an account of the origin of the Royal Wilding, one of the finest sorts of apple for the making of choice cyder.

“Since you have seen the Royal Wilding apple, which is so very much celebrated (and so deservedly) in our county, the history of its being first taken notice of, which is fresh in everybody’s memory, may not be unacceptable to you. The single and only tree from which the apple was first propagated is very tall, fair, and stout; I believe about twenty feet high. It stands in a very little quillet (as we call it) of gardening, adjoining to the post-road that leads from Exeter to Oakhampton, in the parish of St. Thomas, but near the borders of another parish called Whitestone. A walk of a mile from Exeter will gratify any one, who has curiosity, with the sight of it.

“It appears to be properly a wilding, that is, a tree raised from the kernel of an apple, without having been grafted, and (which seems well worth observing) has, in all probability, stood there much more than seventy years, for two ancient persons of the parish of Whitestone, who died several years since, each aged upwards of the number of years before mentioned, declared, that when they were boys, probably twelve or thirteen years of age, and first went the road, it was not only growing there, but, what is worth notice, was as tall and stout as it now appears, nor do there at this time appear any marks of decay upon it that I could perceive.

“It is a very constant and plentiful bearer every other year, and then usually produces apples enough to make one of our hogsheads of cyder, which contains sixty-four gallons, and this was one occasion of its being first taken notice of, and of its affording an history which, I believe, no other tree ever did: For the little cot-house to which it belongs, together with the little quillet in which it stands, being several years since mortgaged for ten pounds, the fruit of this tree alone, in a course of some years, freed the house and garden, and its more valuable self, from that burden.

“Mr. Francis Oliver (a gentleman of the neighbourhood, and, if I mistake not, the gentleman who had the mortgage just now mentioned) was one of the first persons about Exeter that affected rough cyder, and, for that reason, purchased the fruit of this tree every bearing year. However, I cannot learn that he ever made cyder of it alone, but mix’d with other apples, which added to the flavour of his cyder, in the opinion of those who had a true relish for that liquor.

“Whether this, or any other consideration, brought on the more happy experiment upon this apple, the Rev. Robert Wollocombe, Rector of Whitestone, who used to amuse himself with a nursery, put on some heads of this wilding; and in a few years after being in his nursery, about March, a person came to him on some business, and feeling something roll under his feet, took it up, and it proved one of those precious apples, which Mr. Wollocombe receiving from him, finding it perfectly sound after it had lain in the long stragle of the nursery during all the rain, frost, and snow of the foregoing winter, thought it must be a fruit of more than common value; and having tasted it, found the juices, not only in a most perfect soundness and quickness, but such likewise as seemed to promise a body, as well as the roughness and flavour that the wise cyder drinkers in Devon now begin to desire. He observed the graft from which it had fallen, and searching about found some more of the apples, and all of the same soundness; upon which, without hesitation, he resolved to graft a greater quantity of them, which he accordingly did; but waited with impatience for the experiment, which you know must be the work of some years. They came at length, and his just reward was a barrel of the juice, which, though it was small, was of great value for its excellency, and far exceeded all his expectations.

(Click here to see a larger image)

The TYBURN INTERVIEW:

A New SONG.

By a CYDER MERCHANT, of South-Ham, Devonshire.

Dedicated to JACK KETCH.

To the Tune A Cobler there was, &c.

As Sawney from Tweed was a trudging to Town,

To rest his tir’d Limbs on the Grass he sat down;

When growsing his Oatmeal, he turn’d up his Eyes,

And kenn’d a strange Pile on three Pillars arise.

Derry down, &c.

Amaz’d he starts up, “Thou Thing of odd Form,

That stand’st here defying each turbulent Storm;

What art thou? Thy Office declare at my Word,

Or thou shalt not escape this strong Arm and broad Sword.”

Derry down, &c.

Quoth the Structure, “Altho’ I’m not known unto thee,

Thy Countrymens Lives have been shorten’d by me;

To strike thee at once, know that Tyburn’s my Name,

In Scotland, no doubt, you have heard of my Fame.

Derry down, &c.

When arm’d all rebellious, like Vultures you rose,

A Set of such Shahrags, you frighten’d the Crows;

To rid the tir’d land of such Vermin as you,

I groan’d with receiving but barely my Due.

Derry down, &c.

And still I’m in Hopes of another to come,

For Tyburn will certain at last be his Home;

He’ll come from the Summit of Honour’s vast Height,

With a Star and a Garter to dubb me a Knight.”

Derry down, &c.

His Passion now Sawney no more could contain,

“My Sword shall strait prove all thy Hopes are in vain”;

So saying; he brandish’d it high in the Air,

When strait a Scotch Voice cry’d out—Sawney forbear!

Derry down, &c.

The Phantom that spoke now appear’d in a trice,

And to the fear’d Scotsman thus gave his Advice:

“Calm thy Breast that now boils with Vexation and Rage,

And let what I speak thy Attention engage.

Derry down, &c.

No longer with Fury pursue this old Tree,

His Back shall bear Vengeance for you and for me;

For know, my dear Friend, the Time is at Hand,

When with Englishmen, Tyburn shall thin half the Land.

Derry down, &c.

The Case is revers’d by a good Friend of ours,

All Treason is English, and Loyalty yours:

Posts, Honour, and Profit all Scotsmen await,

While the Natives shall tremble and curse their hard Fate.

Derry down, &c.

The War is no more, and each Soldier and Tar,

The Strength and the Bulwark of England in War,

Are coming to prove our Friend’s deep Penetration,

As the first Sacrifice to our Scotch Exaltation.”

Derry down, &c.

Here ended the Phantom, and sunk in the Ground,

While the blue Flames of Hell glar’d terrible round;

When for London young Sawney around turn’d his Eyes,

Where he march’d for a Place in the new-rais’d EXCISE.

Derry down, &c.

Ye National Schemers, come tell me, I pray,

Your Intention in this. To bring more Scotch in play!

For this must the Tax be enforc’d with all Speed,

For Thousands are coming between here and Tweed.

Derry down, &c.

Ah! hapless Old England, no longer be merry,

Since B— has thus tax’d your Beer, Cyder and Perry;

Look sullen and sad, for now this is done,

No doubt in short Time they’ll tax Laughing and Fun.

Derry down, &c.

Yet let the Proud Laird, who presides at the Helm,

Extend his Excise to each Thing in the Realm:

A Tax on Spring-Water I think would be right,

For Water, ’tis known, is as common as Light.

Derry down, &c.

Meat, Butter, and Cheese, “By my Saul that will do!

’Twill affect all the Land, and bring Money in too;”

Proceed, my good Laird, and may the H-lt-r or A—e,

Reward you for saying each infamous T—x.

Derry down, &c.

“Mr. Wollocombe was not a little pleased with it, and talked of it in all conversations; it created amusement at first, but when time produced an hogshead of it, from raillery it came to seriousness, and every one from laughter fell to admiration. In the meantime he had thought of a name for his British wine, and as it appeared to be in the original tree a fruit not grafted, it retained the name of a Wilding, and as he thought it superior to all other apples, he gave it the title of the Royal Wilding.

“This was about sixteen years since (i.e. about 1710). The gentlemen of our county are now busy almost everywhere in promoting it, and some of the wiser farmers. But we have not yet enough for sale. I have known five guineas refused for one of our hogsheads of it, though the common cyder sells for twenty shillings, and the South Ham for twenty-five to thirty.

“I must add, that Mr. Wollocombe hath reserved some of them for hoard; I have tasted the tarts of them, and they come nearer to the quince than any other tart I ever eat of.

“Wherever it has been tried as yet, the juices are perfectly good (but better in some soils than others), and when the gentlemen of the South-Hams will condescend to give it a place in their orchards, they will undoubtedly exceed us in this liquor, because we must yield to them in the apple soil. But it is happy for us, that at present they are so wrapt up in their own sufficiency, that they do not entertain any thoughts of raising apples from us; and when they shall, it must be another twenty years before they can do anything to the purpose, though some of their thinking gentlemen, I am told, begin to get some of them transported thither, (by night you may suppose, partly for shame and partly for fear of being mobbed by their neighbours) and will, I am well assured, much rejoice in the production.

“The colour of the Royal Wilding cyder, without any assistance from art, is of a bright yellow, rather than a reddish beerish tincture; its other qualities are a noble body, an excellent bitter, a delicate (excuse the expression) roughness, and a fine vinous flavour. All the other qualities you may meet with in some of the best South-Ham cyder, but the last is peculiar to the White-Sour and the Royal Wilding only, and you will in vain look for it in any other.”

Mr. Stafford goes on to speak of his second favourite, the White Sour of the South Hams.

“The qualities of the juices are precisely the same with those of the Royal Wilding, nay, so very near one to the other, that they are perfectly rivals, and created such a contest, as is very uncommon, and to which I was an eye-witness. A gentleman of the South-Hams, whose White-Sour cyders, for the year, were very celebrated, (for our cyder vintages, like those of clarets and ports, are very different in different years) and had been drank of by another gentleman, who was a happy possessor, an uncontested lord, facile princeps, of the Royal Wilding, met at the house of the latter gentleman a year or two after: the famed Royal Wilding, you may be sure, was produced, as the best return for the White-Sour that had been tasted at the other gentleman’s; and what was the effect? Each gentleman did not contend, as is usual, that his was the best cyder; but such was the equilibrium of the juices, and such the generosity of their breasts (for finer gentlemen we have not in our country) that each affirmed his own was the worst; the gentleman of the South-Hams declared in favour of the Royal Wilding, and the gentleman of our parts in favour of the White-Sour.”

As to the sweet cyder, Mr. Stafford despises it. “It may be acceptable to a female, or a Londoner, it is ever offensive to a bold and generous West Saxon,” says he.

Mr. Stafford flattered himself one year that he had beaten the Royal Wilding. He had planted pips, and after many years brewed a pipe of the apples of his wildings in 1724. Mr. Wollocombe was invited to taste it. “The surprise (and even almost silence) with which he was seized at first tasting it was plainly perceived by everyone present, and occasioned no small diversion.” But, alas! after it was bottled this “Super-Celestial,” as it had been named, as the year advanced, appeared thin compared with the cyder of the Royal Wilding, and Hugh Stafford was constrained after a first flush of triumph to allow that the Royal Wilding maintained pre-eminence.

According to our author, the addition of a little sage or clary to thin cyder gives it a taste as of a good Rhenish wine; and he advises the crushing to powder of angelica roots to add to cyder, as is done in Oporto by those who prepare port for the English market. It gives a flavour and a bouquet truly delicious.

At the English Revolution, when William of Orange came to the throne, the introduction of French wines into the country was prohibited, and this gave a great impetus to the manufacture of cyder, and care in the production of cyder of the best description. But the imposition of a duty of ten shillings a hogshead on cyder that was not repealed, as already said, till 1830, killed the industry. Farmers no longer cared to keep up their orchards, and grew apples only for home consumption. They gave the cyder to their labourers, and as these were not particular as to the quality, no pains were taken to produce such as would suit men’s refined palates. The workman liked a rough beverage, one that almost cut his throat as it passed down; and this produced the evil effect that the farmers, who were bound by their leases to keep up their orchards, planted only the coarsest sort of apples, and the higher quality of fruit was allowed to die out. The orchards fell into, and in most cases remain still in a deplorable condition of neglect. Hear what is the report of the Special Commissioner of the Gardeners’ Magazine, as to the state of the orchards in Devon. “They will not, as a rule, bear critical examination. As a matter of fact Devonshire, compared with other counties, has made little or no progress of late years, and there are hundreds of orchards in that county that are little short of a disgrace to those who own or rent them. The majority of the orchards are rented by farmers, who too often are the worst of gardeners and the poorest of fruit growers, and they cannot be induced to improve on their methods.” The writer goes on to say, that so long as the farmers have enough trees standing or blown over, to bear fruit that suffices for their home consumption, they are content, and with complete indifference, they suffer the cattle to roam about the orchards, bite off the bark, and rend the branches and tender shoots from the trees.

“If you tackle the farmers on the subject, and in particular strongly advise them to see what can be done towards improving their old orchards and forming new ones, they will become uncivil at once.”

It is sad to have to state that the famous “Royal Wilding” is no longer known, not even at Pynes, where it was extensively planted by Hugh Stafford.

Messrs. Veitch, the well-known nurserymen at Exeter and growers of the finest sorts of apples, inform me that they have not heard of it for many years. Mr. H. Whiteway, who produces some of the best cyder in North Devon, writes to me: “With regard to the Royal Wilding mentioned in Mr. Hugh Stafford’s book, I have made diligent inquiry in and about the neighbourhood in which it was grown at the time stated, but up to now have been unable to find any trace of it, and this also applies to the White-Sour. I am, however, not without hope of discovering some day a solitary remnant of the variety.”

This loss is due to the utter neglect of the orchards in consequence of the passing and maintenance of Lord Bute’s mischievous Bill. This Bill was the more deplorable in its results because in and about 1750 cyder had replaced the lighter clarets in the affections of all classes, and was esteemed as good a drink as the finest Rhenish, and much more wholesome. Rudolphus Austen, who introduced it at the tables of the dons of Oxford, undertook to “raise cyder that shall compare and excel the wine of many provinces nearer the sun, where they abound with fruitful vineyards.” And he further asserted: “A seasonable and moderate use of good cyder is the surest remedy and preservative against the diseases which do frequently afflict the sedentary life of them that are seriously studious.” He died in 1666.

Considerable difference of opinion exists as to the advantage or disadvantage of cyder for those liable to rheumatism. But this difference of opinion is due largely, if not wholly, to the kinds of cyder drunk. The sweet cyder is unquestionably bad in such cases, but that in which there is not so much sugar is a corrective to the uric acid that causes rheumatism. In Noake’s Worcestershire Relics appears the following extract from the journal of a seventeenth-century parson. “This parish (Dilwyn), wherein syder [sic] is plentiful, hath and doth afford many people that have and do enjoy the blessing of long life, neither are the aged here bed-ridden or decrepit as elsewhere, but for the most part lively and vigorous. Next to God, wee ascribe it to our flourishing orchards, which are not only the ornament but the pride of our country, yielding us rich and winy liquors.” At Whimple, in Devon, the rectors, like their contemporary, the Rev. Robert Wollocombe, the discoverer of the Royal Wilding a century or so later than the Dilwyn parson, were both cyder makers and cyder drinkers. The tenure of office of two of them covered a period of over a century, and the last of these worthy divines lived to tell the story of how the Exeter coach set down the bent and crippled dean at his door, who, after three weeks ‘cyder cure’ at the hospitable rectory, had thrown his crutches to the dogs and turned his face homewards “upright as a bolt.”[1]

The apple is in request now for three purposes quite distinct: the dessert apple, to rival those introduced from America; that largely employed for the manufacture of jams—the basis, apple, flavoured to turn it into raspberry, apricot, etc.; and last, but not least, the cyder-producing apple which is unsuited for either of the former requirements.

In my Book of the West I have given a lengthy ballad of instruction on the growth of apple trees, and the gathering of apples and the making of cyder, which I heard sung by an old man at Washfield, near Tiverton. The following song was sung to me by an aged tanner of Launceston, some twenty years ago, which he professed to have composed himself:—

In a nice little village not far from the sea,

Still lives my old uncle aged eighty and three;

Of orchards and meadows he owns a good lot,

Such cyder as his—not another has got.

Then fill up the jug, boys, and let it go round,

Of drinks not the equal in England is found.

So pass round the jug, boys, and pull at it free,

There’s nothing like cyder, sparkling cyder, for me.

My uncle is lusty, is nimble and spry,

As ribstones his cheeks, clear as crystal his eye,

His head snowy white as the flowering may,

And he drinks only cyder by night and by day.

Then fill up the jug, etc.

O’er the wall of the churchyard the apple trees lean

And ripen their burdens, red, golden, and green.

In autumn the apples among the graves lie;

“There I’ll sleep well,” says uncle, “when fated to die.”

Then fill up the jug, etc.

“My heart as an apple, sound, juicy, has been,

My limbs and my trunk have been sturdy and clean;

Uncankered I’ve thriven, in heart and in head,

So under the apple trees lay me when dead.”

Then fill up the jug, etc.

[1] Whiteway’s Wine of the West Country.

THE ALPHINGTON PONIES

During the forties of last century, every visitor to Torquay noticed two young ladies of very singular appearance. Their residence was in one of the two thatched cottages on the left of Tor Abbey Avenue, looking seaward, very near the Torgate of the avenue. Their chief places of promenade were the Strand and Victoria Parade, but they were often seen in other parts of the town. Bad weather was the only thing that kept them from frequenting their usual beat. They were two Misses Durnford, and their costume was peculiar. The style varied only in tone and colour. Their shoes were generally green, but sometimes red. They were by no means bad-looking girls when young, but they were so berouged as to present the appearance of painted dolls. Their brown hair worn in curls was fastened with blue ribbon, and they wore felt or straw hats, usually tall in the crown and curled up at the sides. About their throats they had very broad frilled or lace collars that fell down over their backs and breasts a long way. But in summer their necks were bare, and adorned with chains of coral or bead. Their gowns were short, so short indeed as to display about the ankles a good deal more than was necessary of certain heavily-frilled cotton investitures of their lower limbs. In winter over their gowns were worn check jackets of a “loud” pattern reaching to their knees, and of a different colour from their gowns, and with lace cuffs. They were never seen, winter or summer, without their sunshades. The only variation to the jacket was a gay-coloured shawl crossed over the bosom and tied behind at the waist.

THE MISSES DURNFORD. THE ALPHINGTON PONIES

From a Lithograph

The sisters dressed exactly alike, and were so much alike in face as to appear to be twins. They were remarkably good walkers, kept perfectly in step, were always arm in arm, and spoke to no one but each other.

They lived with their mother, and kept no servant. All the work of the house was done by the three, so that in the morning they made no appearance in the town; only in the afternoon had they assumed their war-paint, when, about 3 p.m., they sallied forth; but, however highly they rouged and powdered, and however strange was their dress, they carried back home no captured hearts. Indeed, the visitors to Torquay looked upon them with some contempt as not being in society and not dressing in the fashion; only some of the residents felt for them in their solitude some compassion. They were the daughters of a Colonel Durnford, and had lived at Alphington. The mother was of an inferior social rank. They had a brother, a major in the Army, 10th Regiment, who was much annoyed at their singularity of costume, and offered to increase their allowance if they would discontinue it; but this they refused to do.

When first they came to Torquay, they drove a pair of pretty ponies they had brought with them from Alphington; but their allowance being reduced, and being in straitened circumstances, they had to dispose of ponies and carriage. By an easy transfer the name of Alphington Ponies passed on from the beasts to their former owners.

As they were not well off, they occasionally got into debt, and were summoned before the Court of Requests; and could be impertinent even to the judge. On one occasion, when he had made an order for payment, one of them said, “Oh, Mr. Praed, we cannot pay now; but my sister is about to be married to the Duke of Wellington, and then we shall be in funds and be able to pay for all we have had and are likely to want!” Once the two visited a shop and gave an order, but, instead of paying, flourished what appeared to be the half of a £5 note, saying, that when they had received the other half, they would be pleased to call and discharge the debt. But the tradesman was not to be taken in, and declined to execute the order. Indeed, the Torquay shopkeepers were very shy of them, and insisted on the money being handed over the counter before they would serve the ladies with the goods that they required.

They made no acquaintances in Torquay or in the neighbourhood, nor did any friends come from a distance to stay with them. They would now and then take a book out of the circulating library, but seemed to have no literary tastes, and no special pursuits. There was a look of intelligence, however, in their eyes, and the expression of their faces was decidedly amiable and pleasing.

They received very few letters; those that did arrive probably contained remittances of money, and were eagerly taken in at the door, but there was sometimes a difficulty about finding the money to pay for the postage. It is to be feared that the butcher was obdurate, and that often they had to go without meat. Fish, however, was cheap.

THE MISSES DURNFORD. THE ALPHINGTON PONIES (BACK VIEW)

Lithographed by P. Gauci. Pub. Ed. Cockrem

A gentleman writes: “Mr. Garrow’s house, The Braddons, was on my father’s hands to let. One day the gardener, Tosse, came in hot haste to father and complained that the Alphington Ponies kept coming into the grounds and picking the flowers, that when remonstrated with they declared that they were related to the owner, and had permission. ‘Well,’ said father, ‘the next time you see them entering the gate run down and tell me.’ In a few days Tosse hastened to say that the ladies were again there. Father hurried up to the grounds, where he found them flower-picking. Without the least ceremony he insisted on their leaving the grounds at once. They began the same story to him of their relationship to the owner, adding thereto, that they were cousins of the Duke of Wellington. ‘Come,’ said father, ‘I can believe one person can go mad to any extent in any direction whatever, but the improbability of two persons going mad in identically the same direction and manner at the same time is a little too much for my credulity. Ladies, I beg you to proceed.’ And proceed they did.”

After some years they moved to Exeter, and took lodgings in St. Sidwell’s parish. For a while they continued to dress in the same strange fashion; but they came into some money, and then were able to indulge in trinkets, to which they had always a liking, but which previously they could not afford to purchase. At a large fancy ball, given in Exeter, two young Oxonians dressed up to represent these ladies; they entered the ballroom solemnly, arm in arm, with their parasols spread, paced round the room, and finished their perambulation with a waltz together. This caused much amusement; but several ladies felt that it was not in good taste, and might wound the poor crazy Misses Durnford. This, however, was not the case. So far from being offended at being caricatured, they were vastly pleased, accepting this as the highest flattery. Were not princesses and queens also represented at the ball? Why, then, not they?

One public ball they did attend together, at which, amongst others, were Lady Rolle and Mr. Palk, son of the then Sir Lawrence Palk. Owing to their conspicuous attire, they drew on them the attention of Lady Rolle, who challenged Mr. Palk to ask one of the sisters for a dance, and offered him a set of gold and diamond shirt studs if he could prevail on either of them to be his partner. Mr. Palk accepted the challenge, but on asking for a dance was met in each case by the reply, “I never dance except my sister be also dancing.” Mr. Palk then gallantly offered to dance with both sisters at once, or in succession. He won and wore the studs.

A gentleman writes: “In their early days they made themselves conspicuous by introducing the bloomer arrangement in the nether latitude.[2] This, as you may well suppose, was regarded as a scandal; but these ladies, who were never known to speak to any one, or to each other out of doors, went on their way quite unruffled. Years and years after this, you may imagine my surprise at meeting them in Exeter, old and grey, but the same singular silent pair. Then, after an interval of a year or two, only one appeared. I assure you, it gave me pain to look at that poor lonely, very lonely soul; but it was not for long. Kind Heaven took her also, and so a tiny ripple was made, and there was an end of the Alphington Ponies.”

[2] They are not so represented in the three lithographs that were published at Torquay. But two others beside this correspondent mention their appearance in “bloomers.”

MARIA FOOTE

If there was ever a creature who merited the sympathy of the world, it is Maria Foote. If there was ever a wife who deserved its commiseration, it is her mother.” With these words begins a notice of the actress in The Examiner for 1825.

About the year 1796 an actor appeared in Plymouth under the name of Freeman, but whose real name was Foote, and who claimed relationship with Samuel Foote, the dramatist and performer. He was of a respectable family, and his brother was a clergyman at Salisbury. Whilst on a visit to his brother, he met the sister of his brother’s wife, both daughters of a Mr. Charles Hart; she was then a girl of seventeen, in a boarding-school, and to the disgrace of all parties concerned therein, this simple boarding-school maid was induced to marry a man twenty-five years older than herself, and to give great offence to her parents, who withdrew all interest in her they had hitherto shown. Foote returned to Plymouth with his wife, a sweet innocent girl. He was at the time proprietor and manager of the Plymouth Theatre; and as, in country towns, actors and actresses were looked down upon by society, no respectable family paid Mrs. Foote the least attention, and although the whole town was interested in her appearance, it regarded her simply with pity.