автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783, by A. T. Mahan

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783

Author: A. T. Mahan

Release Date: September 26, 2004 [eBook #13529]

Most recently updated: November 19, 2007

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE INFLUENCE OF SEA POWER UPON HISTORY, 1660-1783***

E-text prepared by A. E. Warren and revised by

Jeannie Howse, Frank van Drogen, Paul Hollander,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

HTML version prepared by

Jeannie Howse, Frank van Drogen, Paul Hollander,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

Transcriber's Note:

Inconsistent hyphenation, and spelling in the original document have been preserved.

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. For a complete list, please see the end of this document.

Click on the images to see a larger version.

THE INFLUENCE

OF SEA POWER

UPON HISTORY

1660-1783

By

A. T. MAHAN, D.C.L., LL.D.

Author of "The Influence of Sea Power upon the French

Revolution and Empire, 1793-1812," etc.

TWELFTH EDITION

BOSTON

LITTLE, BROWN AND COMPANY

Copyright, 1890,

By Captain A. T. Mahan.

Copyright, 1918,

By Ellen Lyle Mahan.

Printed in the United States of America

PREFACE.

The definite object proposed in this work is an examination of the general history of Europe and America with particular reference to the effect of sea power upon the course of that history. Historians generally have been unfamiliar with the conditions of the sea, having as to it neither special interest nor special knowledge; and the profound determining influence of maritime strength upon great issues has consequently been overlooked. This is even more true of particular occasions than of the general tendency of sea power. It is easy to say in a general way, that the use and control of the sea is and has been a great factor in the history of the world; it is more troublesome to seek out and show its exact bearing at a particular juncture. Yet, unless this be done, the acknowledgment of general importance remains vague and unsubstantial; not resting, as it should, upon a collection of special instances in which the precise effect has been made clear, by an analysis of the conditions at the given moments.

A curious exemplification of this tendency to slight the bearing of maritime power upon events may be drawn from two writers of that English nation which more than any other has owed its greatness to the sea. "Twice," says Arnold in his History of Rome, "Has there been witnessed the struggle of the highest individual genius against the resources and institutions of a great nation, and in both cases the nation was victorious. For seventeen years Hannibal strove against Rome, for sixteen years Napoleon strove against England; the efforts of the first ended in Zama, those of the second in Waterloo." Sir Edward Creasy, quoting this, adds: "One point, however, of the similitude between the two wars has scarcely been adequately dwelt on; that is, the remarkable parallel between the Roman general who finally defeated the great Carthaginian, and the English general who gave the last deadly overthrow to the French emperor. Scipio and Wellington both held for many years commands of high importance, but distant from the main theatres of warfare. The same country was the scene of the principal military career of each. It was in Spain that Scipio, like Wellington, successively encountered and overthrew nearly all the subordinate generals of the enemy before being opposed to the chief champion and conqueror himself. Both Scipio and Wellington restored their countrymen's confidence in arms when shaken by a series of reverses, and each of them closed a long and perilous war by a complete and overwhelming defeat of the chosen leader and the chosen veterans of the foe."

Neither of these Englishmen mentions the yet more striking coincidence, that in both cases the mastery of the sea rested with the victor. The Roman control of the water forced Hannibal to that long, perilous march through Gaul in which more than half his veteran troops wasted away; it enabled the elder Scipio, while sending his army from the Rhone on to Spain, to intercept Hannibal's communications, to return in person and face the invader at the Trebia. Throughout the war the legions passed by water, unmolested and unwearied, between Spain, which was Hannibal's base, and Italy, while the issue of the decisive battle of the Metaurus, hinging as it did upon the interior position of the Roman armies with reference to the forces of Hasdrubal and Hannibal, was ultimately due to the fact that the younger brother could not bring his succoring reinforcements by sea, but only by the land route through Gaul. Hence at the critical moment the two Carthaginian armies were separated by the length of Italy, and one was destroyed by the combined action of the Roman generals.

On the other hand, naval historians have troubled themselves little about the connection between general history and their own particular topic, limiting themselves generally to the duty of simple chroniclers of naval occurrences. This is less true of the French than of the English; the genius and training of the former people leading them to more careful inquiry into the causes of particular results and the mutual relation of events.

There is not, however, within the knowledge of the author any work that professes the particular object here sought; namely, an estimate of the effect of sea power upon the course of history and the prosperity of nations. As other histories deal with the wars, politics, social and economical conditions of countries, touching upon maritime matters only incidentally and generally unsympathetically, so the present work aims at putting maritime interests in the foreground, without divorcing them, however, from their surroundings of cause and effect in general history, but seeking to show how they modified the latter, and were modified by them.

The period embraced is from 1660, when the sailing-ship era, with its distinctive features, had fairly begun, to 1783, the end of the American Revolution. While the thread of general history upon which the successive maritime events is strung is intentionally slight, the effort has been to present a clear as well as accurate outline. Writing as a naval officer in full sympathy with his profession, the author has not hesitated to digress freely on questions of naval policy, strategy, and tactics; but as technical language has been avoided, it is hoped that these matters, simply presented, will be found of interest to the unprofessional reader.

A. T. MAHAN

December, 1889.

CONTENTS.

INTRODUCTORY.

History of Sea Power one of contest between nations, therefore largely military

1Permanence of the teachings of history

2Unsettled condition of modern naval opinion

2Contrasts between historical classes of war-ships

2Essential distinction between weather and lee gage

5Analogous to other offensive and defensive positions

6Consequent effect upon naval policy

6Lessons of history apply especially to strategy

7Less obviously to tactics, but still applicable

9Illustrations:

The battle of the Nile,

A.D.1798

10Trafalgar,

A.D.1805

11Siege of Gibraltar,

A.D.1779-1782

12Actium,

B.C.31, and Lepanto,

A.D.1571

13Second Punic War,

B.C.218-201

14Naval strategic combinations surer now than formerly

22Wide scope of naval strategy

22 CHAPTER I.Discussion of the Elements of Sea Power.

The sea a great common

25Advantages of water-carriage over that by land

25Navies exist for the protection of commerce

26Dependence of commerce upon secure seaports

27Development of colonies and colonial posts

28Links in the chain of Sea Power: production, shipping, colonies

28 General conditions affecting Sea Power:I. Geographical position

29II. Physical conformation

35III. Extent of territory

42IV. Number of population

44V. National character

50VI. Character and policy of governments

58England

59Holland

67France

69Influence of colonies on Sea Power

82The United States:

Its weakness in Sea Power

83Its chief interest in internal development

84Danger from blockades

85Dependence of the navy upon the shipping interest

87Conclusion of the discussion of the elements of Sea Power

88Purpose of the historical narrative

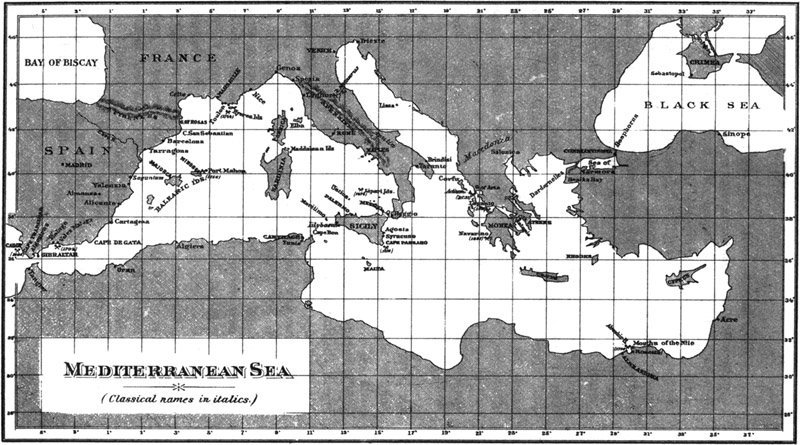

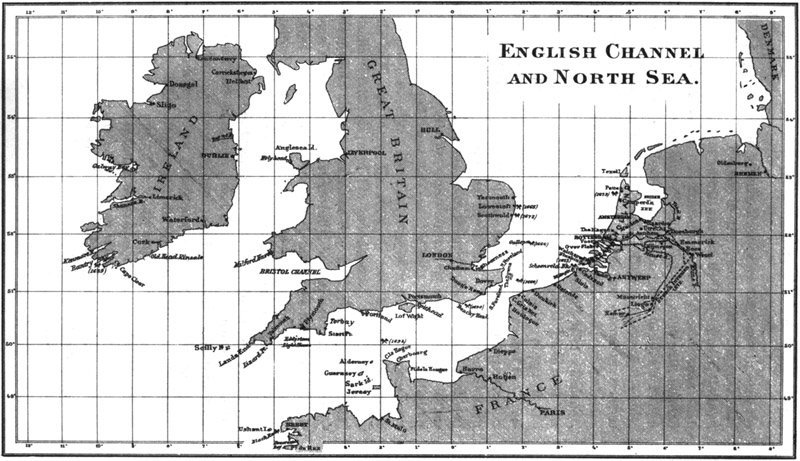

89 CHAPTER II. State of Europe in 1660.—Second Anglo-Dutch War, 1665-1667.—Sea Battles of Lowestoft and of the Four DaysAccession of Charles II. and Louis XIV.

90Followed shortly by general wars

91French policy formulated by Henry IV. and Richelieu

92Condition of France in 1660

93Condition of Spain

94Condition of the Dutch United Provinces

96Their commerce and colonies

97Character of their government

98Parties in the State

99Condition of England in 1660

99Characteristics of French, English, and Dutch ships

101Conditions of other European States

102Louis XIV. the leading personality in Europe

103His policy

104Colbert's administrative acts

105Second Anglo-Dutch War, 1665

107Battle of Lowestoft, 1665

108Fire-ships, compared with torpedo-cruisers

109The group formation

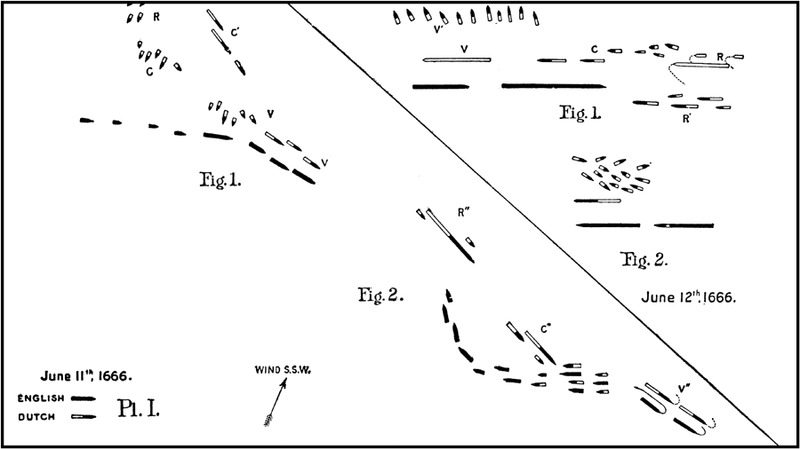

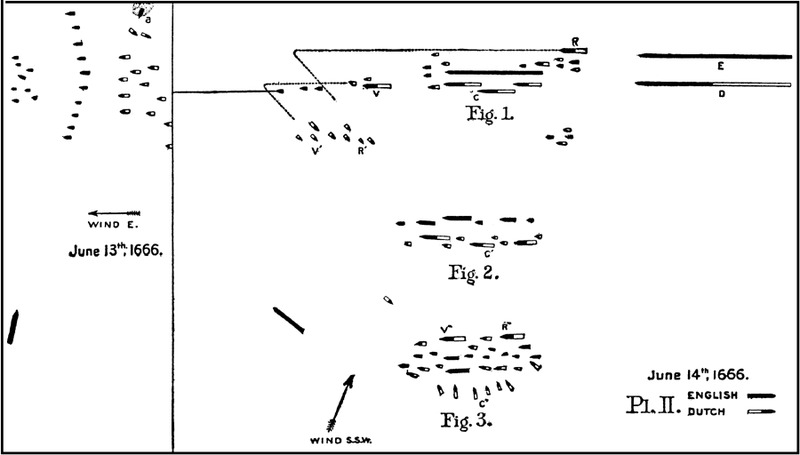

112 The order of battle for sailing-ships 115The Four Days' Battle, 1666

117Military merits of the opposing fleets

126Soldiers commanding fleets, discussion

127Ruyter in the Thames, 1667

132Peace of Breda, 1667

132Military value of commerce-destroying

132 CHAPTER III. War of England and France in Alliance against the United Provinces, 1672-1674.—Finally, of France against Combined Europe, 1674-1678.—Sea Battles of Solebay, the Texel, and Stromboli.Aggressions of Louis XIV. on Spanish Netherlands

139Policy of the United Provinces

139Triple alliance between England, Holland, and Sweden

140Anger of Louis XIV.

140Leibnitz proposes to Louis to seize Egypt

141His memorial

142Bargaining between Louis XIV. and Charles II.

143The two kings declare war against the United Provinces

144Military character of this war

144Naval strategy of the Dutch

144Tactical combinations of De Ruyter

145Inefficiency of Dutch naval administration

145Battle of Solebay, 1672

146Tactical comments

147Effect of the battle on the course of the war

148Land campaign of the French in Holland

149Murder of John De Witt, Grand Pensionary of Holland

150Accession to power of William of Orange

150Uneasiness among European States

150Naval battles off Schoneveldt, 1673

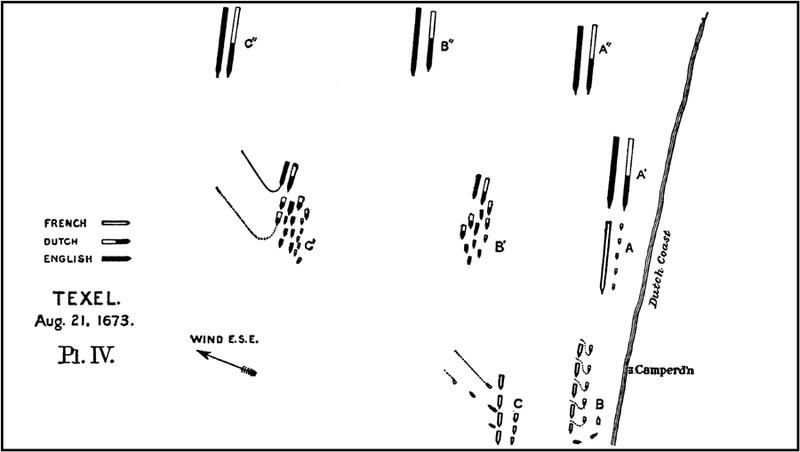

151Naval battle of the Texel, 1673

152Effect upon the general war

154Equivocal action of the French fleet

155General ineffectiveness of maritime coalitions

156Military character of De Ruyter

157Coalition against France

158 Peace between England and the United Provinces 158Sicilian revolt against Spain

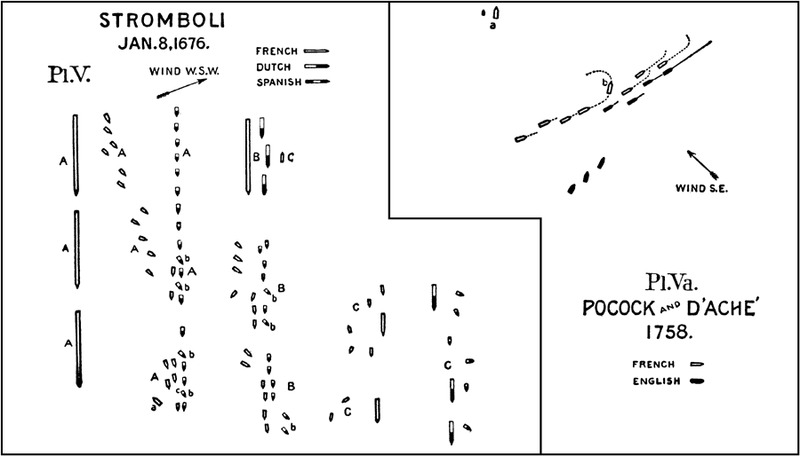

159Battle of Stromboli, 1676

161Illustration of Clerk's naval tactics

163De Ruyter killed off Agosta

165England becomes hostile to France

166Sufferings of the United Provinces

167Peace of Nimeguen, 1678

168Effects of the war on France and Holland

169Notice of Comte d'Estrées

170 CHAPTER IV. English Revolution.—War of the League of Augsburg, 1688-1697.—Sea Battles of Beachy Head and La Hougue.Aggressive policy of Louis XIV.

173State of French, English, and Dutch navies

174Accession of James II.

175Formation of the League of Augsburg

176Louis declares war against the Emperor of Germany

177Revolution in England

178Louis declares war against the United Provinces

178William and Mary crowned

178James II. lands in Ireland

179Misdirection of French naval forces

180William III. lands in Ireland

181Naval battle of Beachy Head, 1690

182Tourville's military character

184Battle of the Boyne, 1690

186End of the struggle in Ireland

186Naval battle of La Hougue, 1692

189Destruction of French ships

190Influence of Sea Power in this war

191Attack and defence of commerce

193Peculiar characteristics of French privateering

195Peace of Ryswick, 1697

197Exhaustion of France: its causes

198 CHAPTER V.War of the Spanish Succession, 1702-1713.—Sea Battle Of Malaga.

Failure of the Spanish line of the House of Austria

201King of Spain wills the succession to the Duke of Anjou

202Death of the King of Spain

202Louis XIV. accepts the bequests

203He seizes towns in Spanish Netherlands

203Offensive alliance between England, Holland, and Austria

204Declarations of war

205The allies proclaim Carlos III. King of Spain

206Affair of the Vigo galleons

207Portugal joins the allies

208Character of the naval warfare

209Capture of Gibraltar by the English

210Naval battle of Malaga, 1704

211Decay of the French navy

212Progress of the land war

213Allies seize Sardinia and Minorca

215Disgrace of Marlborough

216England offers terms of peace

217Peace of Utrecht, 1713

218Terms of the peace

219Results of the war to the different belligerents

219Commanding position of Great Britain

224Sea Power dependent upon both commerce and naval strength

225Peculiar position of France as regards Sea Power

226Depressed condition of France

227Commercial prosperity of England

228Ineffectiveness of commerce-destroying

229Duguay-Trouin's expedition against Rio de Janeiro, 1711

230War between Russia and Sweden

231 CHAPTER VI. The Regency in France.—Alberoni in Spain.—Policies of Walpole and Fleuri.—War of the Polish Succession.—English Contraband Trade in Spanish America.—Great Britain declares War against Spain.—1715-1739.Death of Queen Anne and Louis XIV.

232Accession of George I.

232Regency of Philip of Orleans

233Administration of Alberoni in Spain

234Spaniards invade Sardinia

235Alliance of Austria, England, Holland, and France

235Spaniards invade Sicily

236Destruction of Spanish navy off Cape Passaro, 1718

237Failure and dismissal of Alberoni

239Spain accepts terms

239Great Britain interferes in the Baltic

239Death of Philip of Orleans

241Administration of Fleuri in France

241Growth of French commerce

242France in the East Indies

243Troubles between England and Spain

244English contraband trade in Spanish America

245Illegal search of English ships

246Walpole's struggles to preserve peace

247War of the Polish Succession

247Creation of the Bourbon kingdom of the Two Sicilies

248Bourbon family compact

248France acquires Bar and Lorraine

249England declares war against Spain

250Morality of the English action toward Spain

250Decay of the French navy

252Death of Walpole and of Fleuri

253 CHAPTER VII. War between Great Britain and Spain, 1739.—War of the Austrian Succession, 1740.—France joins Spain against Great Britain, 1744.—Sea Battles of Matthews, Anson, and Hawke.—Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, 1748.Characteristics of the wars from 1739 to 1783

254Neglect of the navy by French government

254Colonial possessions of the French, English, and Spaniards

255Dupleix and La Bourdonnais in India

258Condition of the contending navies

259Expeditions of Vernon and Anson

261Outbreak of the War of the Austrian Succession

262England allies herself to Austria

262Naval affairs in the Mediterranean

263Influence of Sea Power on the war

264Naval battle off Toulon, 1744

265Causes of English failure

267Courts-martial following the action

268Inefficient action of English navy

269Capture of Louisburg by New England colonists, 1745

269Causes which concurred to neutralize England's Sea Power

269France overruns Belgium and invades Holland

270Naval actions of Anson and Hawke

271Brilliant defence of Commodore l'Étenduère

272Projects of Dupleix and La Bourdonnais in the East Indies

273Influence of Sea Power in Indian affairs

275La Bourdonnais reduces Madras

276Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, 1748

277Madras exchanged for Louisburg

277Results of the war

278Effect of Sea Power on the issue

279 CHAPTER VIII. Seven Years' War, 1756-1763.—England's Overwhelming Power and Conquests on the Seas, in North America, Europe, and East and West Indies.—Sea Battles: Byng off Minorca; Hawke and Conflans; Pocock and D'Aché in East Indies.Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle leaves many questions unsettled

281Dupleix pursues his aggressive policy

281He is recalled from India

282His policy abandoned by the French

282Agitation in North America

283Braddock's expedition, 1755

284Seizure of French ships by the English, while at peace

285French expedition against Port Mahon, 1756

285Byng sails to relieve the place

286Byng's action off Port Mahon, 1756

286Characteristics of the French naval policy

287Byng returns to Gibraltar

290He is relieved, tried by court-martial, and shot

290Formal declarations of war by England and France

291England's appreciation of the maritime character of the war

291France is drawn into a continental struggle

292The Seven Years' War (1756-1763) begins

293Pitt becomes Prime Minister of England

293Operations in North America

293Fall of Louisburg, 1758

294Fall of Quebec, 1759, and of Montreal, 1760

294Influence of Sea Power on the continental war

295English plans for the general naval operations

296Choiseul becomes Minister in France

297He plans an invasion of England

297Sailing of the Toulon fleet, 1759

298Its disastrous encounter with Boscawen

299Consequent frustration of the invasion of England

300Project to invade Scotland

300Sailing of the Brest fleet

300Hawke falls in with it and disperses it, 1759

302Accession of Charles III. to Spanish throne

304Death of George II.

304 Clive in India 305Battle of Plassey, 1757

306Decisive influence of Sea Power upon the issues in India

307Naval actions between Pocock and D'Aché, 1758, 1759

307Destitute condition of French naval stations in India

309The French fleet abandons the struggle

310Final fall of the French power in India

310Ruined condition of the French navy

311Alliance between France and Spain

313England declares war against Spain

313Rapid conquest of French and Spanish colonies

314French and Spaniards invade Portugal

316The invasion repelled by England

316Severe reverses of the Spaniards in all quarters

316Spain sues for peace

317Losses of British mercantile shipping

317Increase of British commerce

318Commanding position of Great Britain

319Relations of England and Portugal

320Terms of the Treaty of Paris

321Opposition to the treaty in Great Britain

322Results of the maritime war

323Results of the continental war

324Influence of Sea Power in countries politically unstable

324Interest of the United States in the Central American Isthmus

325Effects of the Seven Years' War on the later history of Great Britain

326Subsequent acquisitions of Great Britain

327British success due to maritime superiority

328Mutual dependence of seaports and fleets

329 CHAPTER IX. Course of Events from the Peace of Paris to 1778.—Maritime War Consequent upon the American Revolution.—Sea Battle off Ushant.French discontent with the Treaty of Paris

330Revival of the French navy

331Discipline among French naval officers of the time

332Choiseul's foreign policy

333Domestic troubles in Great Britain

334Controversies with the North American colonies

334 Genoa cedes Corsica to France 334Dispute between England and Spain about the Falkland Islands

335Choiseul dismissed

336Death of Louis XV.

336Naval policy of Louis XVI.

337Characteristics of the maritime war of 1778

338Instructions of Louis XVI. to the French admirals

339Strength of English navy

341Characteristics of the military situation in America

341The line of the Hudson

342Burgoyne's expedition from Canada

343Howe carries his army from New York to the Chesapeake

343Surrender of Burgoyne, 1777

343American privateering

344Clandestine support of the Americans by France

345Treaty between France and the Americans

346Vital importance of the French fleet to the Americans

347The military situation in the different quarters of the globe

347Breach between France and England

350Sailing of the British and French fleets

350Battle of Ushant, 1778

351Position of a naval commander-in-chief in battle

353 CHAPTER X. Maritime War in North America and West Indies, 1778-1781.—Its Influence upon the Course of the American Revolution.—Fleet Actions off Grenada, Dominica, and Chesapeake Bay.D'Estaing sails from Toulon for Delaware Bay, 1778

359British ordered to evacuate Philadelphia

359Rapidity of Lord Howe's movements

360D'Estaing arrives too late

360Follows Howe to New York

360Fails to attack there and sails for Newport

361Howe follows him there

362Both fleets dispersed by a storm

362D'Estaing takes his fleet to Boston

363Howe's activity foils D'Estaing at all points

363D'Estaing sails for the West Indies

365The English seize Sta. Lucia

365 Ineffectual attempts of D'Estaing to dislodge them 366D'Estaing captures Grenada

367Naval battle of Grenada, 1779; English ships crippled

367D'Estaing fails to improve his advantages

370Reasons for his neglect

371French naval policy

372English operations in the Southern States

375D'Estaing takes his fleet to Savannah

375His fruitless assault on Savannah

376D'Estaing returns to France

376Fall of Charleston

376De Guichen takes command in the West Indies

376Rodney arrives to command English fleet

377His military character

377First action between Rodney and De Guichen, 1780

378Breaking the line

380Subsequent movements of Rodney and De Guichen

381Rodney divides his fleet

381Goes in person to New York

381De Guichen returns to France

381Arrival of French forces in Newport

382Rodney returns to the West Indies

382War between England and Holland

382Disasters to the United States in 1780

382De Grasse sails from Brest for the West Indies, 1781

383Engagement with English fleet off Martinique

383Cornwallis overruns the Southern States

384He retires upon Wilmington, N.C., and thence to Virginia

385Arnold on the James River

385The French fleet leaves Newport to intercept Arnold

385Meets the English fleet off the Chesapeake, 1781

386French fleet returns to Newport

387Cornwallis occupies Yorktown

387De Grasse sails from Hayti for the Chesapeake

388Action with the British fleet, 1781

389Surrender of Cornwallis, 1781

390Criticism of the British naval operations

390Energy and address shown by De Grasse

392Difficulties of Great Britain's position in the war of 1778

392The military policy best fitted to cope with them

393Position of the French squadron in Newport, R.I., 1780

394Great Britain's defensive position and inferior numbers

396Consequent necessity for a vigorous initiative

396Washington's opinions as to the influence of Sea Power on the American contest

397 CHAPTER XI. Maritime War in Europe, 1779-1782.Objectives of the allied operations in Europe

401Spain declares war against England

401Allied fleets enter the English Channel, 1779

402Abortive issue of the cruise

403Rodney sails with supplies for Gibraltar

403Defeats the Spanish squadron of Langara and relieves the place

404The allies capture a great British convoy

404The armed neutrality of the Baltic powers, 1780

405England declares war against Holland

406Gibraltar is revictualled by Admiral Derby

407The allied fleets again in the Channel, 1781

408They retire without effecting any damage to England

408Destruction of a French convoy for the West Indies

408Fall of Port Mahon, 1782

409The allied fleets assemble at Algesiras

409Grand attack of the allies on Gibraltar, which fails, 1782

410Lord Howe succeeds in revictualling Gibraltar

412Action between his fleet and that of the allies

412Conduct of the war of 1778 by the English government

412Influence of Sea Power

416Proper use of the naval forces

416 CHAPTER XII. Events in the East Indies, 1778-1781.—Suffren sails from Brest for India, 1781.—His Brilliant Naval Campaign in the Indian Seas, 1782, 1783.Neglect of India by the French government

419England at war with Mysore and with the Mahrattas

420Arrival of the French squadron under Comte d'Orves

420It effects nothing and returns to the Isle of France

420Suffren sails from Brest with five ships-of-the-line, 1781

421Attacks an English squadron in the Cape Verde Islands, 1781

422Conduct and results of this attack

424Distinguishing merits of Suffren as a naval leader

425Suffren saves the Cape Colony from the English

427 He reaches the Isle of France 427Succeeds to the chief command of the French fleet

427Meets the British squadron under Hughes at Madras

427Analysis of the naval strategic situation in India

428The first battle between Suffren and Hughes, Feb. 17, 1782

430Suffren's views of the naval situation in India

433Tactical oversights made by Suffren

434Inadequate support received by him from his captains

435Suffren goes to Pondicherry, Hughes to Trincomalee

436and to the skilful conduct of war in the future. Napoleon names among the campaigns to be studied by the aspiring soldier, those of Alexander, Hannibal, and Cæsar, to whom gunpowder was unknown; and there is a substantial agreement among professional writers that, while many of the conditions of war vary from age to age with the progress of weapons, there are certain teachings in the school of history which remain constant, and being, therefore, of universal application, can be elevated to the rank of general principles. For the same reason the study of the sea history of the past will be found instructive, by its illustration of the general principles of maritime war, notwithstanding the great changes that have been brought about in naval weapons by the scientific advances of the past half century, and by the introduction of steam as the motive power.

In tracing resemblances there is a tendency not only to overlook points of difference, but to exaggerate points of likeness,—to be fanciful. It may be so considered to point out that as the sailing-ship had guns of long range, with comparatively great penetrative power, and carronades, which were of shorter range but great smashing effect, so the modern steamer has its batteries of long-range guns and of torpedoes, the latter being effective only within a limited distance and then injuring by smashing, while the gun, as of old, aims at penetration. Yet these are distinctly tactical considerations, which must affect the plans of admirals and captains; and the analogy is real, not forced. So also both the sailing-ship and the steamer contemplate direct contact with an enemy's vessel,—the former to carry her by boarding, the latter to sink her by ramming; and to both this is the most difficult of their tasks, for to effect it the ship must be carried to a single point of the field of action, whereas projectile weapons may be used from many points of a wide area.

or refusing battle at will, which in turn carries the usual advantage of an offensive attitude in the choice of the method of attack. This advantage was accompanied by certain drawbacks, such as irregularity introduced into the order, exposure to raking or enfilading cannonade, and the sacrifice of part or all of the artillery-fire of the assailant,—all which were incurred in approaching the enemy. The ship, or fleet, with the lee-gage could not attack; if it did not wish to retreat, its action was confined to the defensive, and to receiving battle on the enemy's terms. This disadvantage was compensated by the comparative ease of maintaining the order of battle undisturbed, and by a sustained artillery-fire to which the enemy for a time was unable to reply. Historically, these favorable and unfavorable characteristics have their counterpart and analogy in the offensive and defensive operations of all ages. The offence undertakes certain risks and disadvantages in order to reach and destroy the enemy; the defence, so long as it remains such, refuses the risks of advance, holds on to a careful, well-ordered position, and avails itself of the exposure to which the assailant submits himself. These radical differences between the weather and the lee gage were so clearly recognized, through the cloud of lesser details accompanying them, that the former was ordinarily chosen by the English, because their steady policy was to assail and destroy their enemy; whereas the French sought the lee-gage, because by so doing they were usually able to cripple the enemy as he approached, and thus evade decisive encounters and preserve their ships. The French, with rare exceptions, subordinated the action of the navy to other military considerations, grudged the money spent upon it, and therefore sought to economize their fleet by assuming a defensive position and limiting its efforts to the repelling of assaults. For this course the lee-gage, skilfully used, was admirably adapted so long as an enemy displayed more courage than conduct; but when Rodney showed an intention to use the advantage of the wind, not merely to attack, but to make a formidable concentration on a part of the enemy's

line, his wary opponent, De Guichen, changed his tactics. In the first of their three actions the Frenchman took the lee-gage; but after recognizing Rodney's purpose he manœuvred for the advantage of the wind, not to attack, but to refuse action except on his own terms. The power to assume the offensive, or to refuse battle, rests no longer with the wind, but with the party which has the greater speed; which in a fleet will depend not only upon the speed of the individual ships, but also upon their tactical uniformity of action. Henceforth the ships which have the greatest speed will have the weather-gage.

has a great deal to say. There has been of late a valuable discussion in English naval circles as to the comparative merits of the policies of two great English admirals, Lord Howe and Lord St. Vincent, in the disposition of the English navy when at war with France. The question is purely strategic, and is not of mere historical interest; it is of vital importance now, and the principles upon which its decision rests are the same now as then. St. Vincent's policy saved England from invasion, and in the hands of Nelson and his brother admirals led straight up to Trafalgar.

interval between such changes has been unduly long. This doubtless arises from the fact that an improvement of weapons is due to the energy of one or two men, while changes in tactics have to overcome the inertia of a conservative class; but it is a great evil. It can be remedied only by a candid recognition of each change, by careful study of the powers and limitations of the new ship or weapon, and by a consequent adaptation of the method of using it to the qualities it possesses, which will constitute its tactics. History shows that it is vain to hope that military men generally will be at the pains to do this, but that the one who does will go into battle with a great advantage,—a lesson in itself of no mean value.

help of the weather ones before the latter were destroyed; but the principles which underlay the combination, namely, to choose that part of the enemy's order which can least easily be helped, and to attack it with superior forces, has not passed away. The action of Admiral Jervis at Cape St. Vincent, when with fifteen ships he won a victory over twenty-seven, was dictated by the same principle, though in this case the enemy was not at anchor, but under way. Yet men's minds are so constituted that they seem more impressed by the transiency of the conditions than by the undying principle which coped with them. In the strategic effect of Nelson's victory upon the course of the war, on the contrary, the principle involved is not only more easily recognized, but it is at once seen to be applicable to our own day. The issue of the enterprise in Egypt depended upon keeping open the communications with France. The victory of the Nile destroyed the naval force, by which alone the communications could be assured, and determined the final failure; and it is at once seen, not only that the blow was struck in accordance with the principle of striking at the enemy's line of communication, but also that the same principle is valid now, and would be equally so in the days of the galley as of the sailing-ship or steamer.

Napoleon's combinations failed, and Nelson's intuitions and activity kept the English fleet ever on the track of the enemy, and brought it up in time at the decisive moment.

which might be exchanged against Gibraltar. It is not, however, likely that England would have given up the key of the Mediterranean for any other foreign possession, though she might have yielded it to save her firesides and her capital. Napoleon once said that he would reconquer Pondicherry on the banks of the Vistula. Could he have controlled the English Channel, as the allied fleet did for a moment in 1779, can it be doubted that he would have conquered Gibraltar on the shores of England?

has received scant recognition. There cannot now be had the full knowledge necessary for tracing in detail its influence upon the issue of the second Punic War; but the indications which remain are sufficient to warrant the assertion that it was a determining factor. An accurate judgment upon this point cannot be formed by mastering only such facts of the particular contest as have been clearly transmitted, for as usual the naval transactions have been slightingly passed over; there is needed also familiarity with the details of general naval history in order to draw, from slight indications, correct inferences based upon a knowledge of what has been possible at periods whose history is well known. The control of the sea, however real, does not imply that an enemy's single ships or small squadrons cannot steal out of port, cannot cross more or less frequented tracts of ocean, make harassing descents upon unprotected points of a long coast-line, enter blockaded harbors. On the contrary, history has shown that such evasions are always possible, to some extent, to the weaker party, however great the inequality of naval strength. It is not therefore inconsistent with the general control of the sea, or of a decisive part of it, by the Roman fleets, that the Carthaginian admiral Bomilcar in the fourth year of the war, after the stunning defeat of Cannæ, landed four thousand men and a body of elephants in south Italy; nor that in the seventh year, flying from the Roman fleet off Syracuse, he again appeared at Tarentum, then in Hannibal's hands; nor that Hannibal sent despatch vessels to Carthage; nor even that, at last, he withdrew in safety to Africa with his wasted army. None of these things prove that the government in Carthage could, if it wished, have sent Hannibal the constant support which, as a matter of fact, he did not receive; but they do tend to create a natural impression that such help could have been given. Therefore the statement, that the Roman preponderance at sea had a decisive effect upon the course of the war, needs to be made good by an examination of ascertained facts. Thus the kind and degree of its influence may be fairly estimated.

firearms would cause any great modifications in the way of making war. I replied that they would probably have an influence upon the details of tactics, but that in great strategic operations and the grand combinations of battles, victory would, now as ever, result from the application of the principles which had led to the success of great generals in all ages; of Alexander and Cæsar, as well as of Frederick and Napoleon." This study has become more than ever important now to navies, because of the great and steady power of movement possessed by the modern steamer. The best-planned schemes might fail through stress of weather in the days of the galley and the sailing-ship; but this difficulty has almost disappeared. The principles which should direct great naval combinations have been applicable to all ages, and are deducible from history; but the power to carry them out with little regard to the weather is a recent gain.

the coasting trade would only be an inconvenience, although water transit is still the cheaper. Nevertheless, as late as the wars of the French Republic and the First Empire, those who are familiar with the history of the period, and the light naval literature that has grown up around it, know how constant is the mention of convoys stealing from point to point along the French coast, although the sea swarmed with English cruisers and there were good inland roads.

As a nation, with its unarmed and armed shipping, launches forth from its own shores, the need is soon felt of points upon which the ships can rely for peaceful trading, for refuge and supplies. In the present day friendly, though foreign, ports are to be found all over the world; and their shelter is enough while peace prevails. It was not always so, nor does peace always endure, though the United States have been favored by so long a continuance of it. In earlier times the merchant seaman, seeking for trade in new and unexplored regions, made his gains at risk of life and liberty from suspicious or hostile nations, and was under great delays in collecting a full and profitable freight. He therefore intuitively sought at the far end of his trade route one or more stations, to be given to him by force or favor, where he could fix himself or his agents in reasonable security, where his ships could lie in safety, and where the merchantable products of the land could be continually collecting, awaiting the arrival of the home fleet, which should carry them to the mother-country. As there was immense gain, as well as much risk, in these early voyages, such establishments naturally multiplied and grew until they became colonies; whose ultimate development and success depended upon the genius and policy of the nation from which they sprang, and form a very great part of the history, and particularly of the sea history, of the world. All colonies had not the simple and natural birth and growth above described. Many were more formal, and purely political, in their conception and founding, the act of the rulers of the people rather than of private individuals; but the trading-station with its after expansion, the work simply of the adventurer seeking gain, was in its reasons and essence the same as the elaborately organized and chartered colony. In both cases the mother-country had won a foothold in a foreign land, seeking a new outlet for what it had to sell, a new sphere for its shipping, more employment for its people, more comfort and wealth for itself.

The voyages were long and dangerous, the seas often beset with enemies. In the most active days of colonizing there prevailed on the sea a lawlessness the very memory of which is now almost lost, and the days of settled peace between maritime nations were few and far between. Thus arose the demand for stations along the road, like the Cape of Good Hope, St. Helena, and Mauritius, not primarily for trade, but for defence and war; the demand for the possession of posts like Gibraltar, Malta, Louisburg, at the entrance of the Gulf of St. Lawrence,—posts whose value was chiefly strategic, though not necessarily wholly so. Colonies and colonial posts were sometimes commercial, sometimes military in their character; and it was exceptional that the same position was equally important in both points of view, as New York was.

natural productions and climate. III. Extent of Territory. IV. Number of Population. V. Character of the People. VI. Character of the Government, including therein the national institutions.

follows, from her geographical position and her power, with mathematical certainty.

movements for a year. While the war in the Netherlands lasted, the Dutch control of the sea forced Spain to send her troops by a long and costly journey overland instead of by sea; and the same cause reduced her to such straits for necessaries that, by a mutual arrangement which seems very odd to modern ideas, her wants were supplied by Dutch ships, which thus maintained the enemies of their country, but received in return specie which was welcome in the Amsterdam exchange. In America, the Spanish protected themselves as best they might behind masonry, unaided from home; while in the Mediterranean they escaped insult and injury mainly through the indifference of the Dutch, for the French and English had not yet begun to contend for mastery there. In the course of history the Netherlands, Naples, Sicily, Minorca, Havana, Manila, and Jamaica were wrenched away, at one time or another, from this empire without a shipping. In short, while Spain's maritime impotence may have been primarily a symptom of her general decay, it became a marked factor in precipitating her into the abyss from which she has not yet wholly emerged.

scattered condition of the United States ships, the latter could not have been distributed as they were; and being forced to concentrate for mutual support, many small but useful approaches would have been left open to commerce. But as the Southern coast, from its extent and many inlets, might have been a source of strength, so, from those very characteristics, it became a fruitful source of injury. The great story of the opening of the Mississippi is but the most striking illustration of an action that was going on incessantly all over the South. At every breach of the sea frontier, war-ships were entering. The streams that had carried the wealth and supported the trade of the seceding States turned against them, and admitted their enemies to their hearts. Dismay, insecurity, paralysis, prevailed in regions that might, under happier auspices, have kept a nation alive through the most exhausting war. Never did sea power play a greater or a more decisive part than in the contest which determined that the course of the world's history would be modified by the existence of one great nation, instead of several rival States, in the North American continent. But while just pride is felt in the well-earned glory of those days, and the greatness of the results due to naval preponderance is admitted, Americans who understand the facts should never fail to remind the over-confidence of their countrymen that the South not only had no navy, not only was not a seafaring people, but that also its population was not proportioned to the extent of the sea-coast which it had to defend.

V. National Character.—The effect of national character and aptitudes upon the development of sea power will next be considered.

the pursuit of gain, and a keen scent for the trails that lead to it, all exist; and if there be in the future any fields calling for colonization, it cannot be doubted that Americans will carry to them all their inherited aptitude for self-government and independent growth.

is to insure perseverance after the death of a particular despot.

keeps up a spirit of military honor, which is of the first importance in ages when military institutions have not yet provided the sufficient substitute in what is called esprit-de-corps. But although full of class feeling and class prejudice, which made themselves felt in the navy as well as elsewhere, their practical sense left open the way of promotion to its highest honors to the more humbly born; and every age saw admirals who had sprung from the lowest of the people. In this the temper of the English upper class differed markedly from that of the French. As late as 1789, at the outbreak of the Revolution, the French Navy List still bore the name of an official whose duty was to verify the proofs of noble birth on the part of those intending to enter the naval school.

England. When William died, his policy was still followed by the government which succeeded him. Its aims were wholly centred upon the land, and at the Peace of Utrecht, which closed a series of wars extending over forty years, Holland, having established no sea claim, gained nothing in the way of sea resources, of colonial extension, or of commerce.

government upon the sea career of its people, it is seen that that influence can work in two distinct but closely related ways.

unexpected attack may cause disaster in some one quarter, the actual superiority of naval power prevents such disaster from being general or irremediable. History has sufficiently proved this. England's naval bases have been in all parts of the world; and her fleets have at once protected them, kept open the communications between them, and relied upon them for shelter.

sea power. It will not be too much to say that the action of the government since the Civil War, and up to this day, has been effectively directed solely to what has been called the first link in the chain which makes sea power. Internal development, great production, with the accompanying aim and boast of self-sufficingness, such has been the object, such to some extent the result. In this the government has faithfully reflected the bent of the controlling elements of the country, though it is not always easy to feel that such controlling elements are truly representative, even in a free country. However that may be, there is no doubt that, besides having no colonies, the intermediate link of a peaceful shipping, and the interests involved in it, are now likewise lacking. In short, the United States has only one link of the three.

on board ships which an enemy cannot touch except when bound to a blockaded port, what will constitute an efficient blockade? The present definition is, that it is such as to constitute a manifest danger to a vessel seeking to enter or leave the port. This is evidently very elastic. Many can remember that during the Civil War, after a night attack on the United States fleet off Charleston, the Confederates next morning sent out a steamer with some foreign consuls on board, who so far satisfied themselves that no blockading vessel was in sight that they issued a declaration to that effect. On the strength of this declaration some Southern authorities claimed that the blockade was technically broken, and could not be technically re-established without a new notification. Is it necessary, to constitute a real danger to blockade-runners, that the blockading fleet should be in sight? Half a dozen fast steamers, cruising twenty miles off-shore between the New Jersey and Long Island coast, would be a very real danger to ships seeking to go in or out by the principal entrance to New York; and similar positions might effectively blockade Boston, the Delaware, and the Chesapeake. The main body of the blockading fleet, prepared not only to capture merchant-ships but to resist military attempts to break the blockade, need not be within sight, nor in a position known to the shore. The bulk of Nelson's fleet was fifty miles from Cadiz two days before Trafalgar, with a small detachment watching close to the harbor. The allied fleet began to get under way at 7 A.M., and Nelson, even under the conditions of those days, knew it by 9.30. The English fleet at that distance was a very real danger to its enemy. It seems possible, in these days of submarine telegraphs, that the blockading forces in-shore and off-shore, and from one port to another, might be in telegraphic communication with one another along the whole coast of the United States, readily giving mutual support; and if, by some fortunate military combination, one detachment were attacked in force, it could warn the others and retreat upon them. Granting that such a blockade off one port were broken on one day, by

States is not now able to go alone if an emergency should arise?

shipping? It is doubtful. History has proved that such a purely military sea power can be built up by a despot, as was done by Louis XIV.; but though so fair seeming, experience showed that his navy was like a growth which having no root soon withers away. But in a representative government any military expenditure must have a strongly represented interest behind it, convinced of its necessity. Such an interest in sea power does not exist, cannot exist here without action by the government. How such a merchant shipping should be built up, whether by subsidies or by free trade, by constant administration of tonics or by free movement in the open air, is not a military but an economical question. Even had the United States a great national shipping, it may be doubted whether a sufficient navy would follow; the distance which separates her from other great powers, in one way a protection, is also a snare. The motive, if any there be, which will give the United States a navy, is probably now quickening in the Central American Isthmus. Let us hope it will not come to the birth too late.

will next be examined the general history of Europe and America, with particular reference to the effect exercised upon that history, and upon the welfare of the people, by sea power in its broad sense. From time to time, as occasion offers, the aim will be to recall and reinforce the general teaching, already elicited, by particular illustrations. The general tenor of the study will therefore be strategical, in that broad definition of naval strategy which has before been quoted and accepted: "Naval strategy has for its end to found, support, and increase, as well in peace as in war, the sea power of a country." In the matter of particular battles, while freely admitting that the change of details has made obsolete much of their teaching, the attempt will be made to point out where the application or neglect of true general principles has produced decisive effects; and, other things being equal, those actions will be preferred which, from their association with the names of the most distinguished officers, may be presumed to show how far just tactical ideas obtained in a particular age or a particular service. It will also be desirable, where analogies between ancient and modern weapons appear on the surface, to derive such probable lessons as they offer, without laying undue stress upon the points of resemblance. Finally, it must be remembered that, among all changes, the nature of man remains much the same; the personal equation, though uncertain in quantity and quality in the particular instance, is sure always to be found.

of, by people unconnected with the sea, and particularly by the people of the United States in our own day, that this study has been undertaken.

During the century before the Peace of Westphalia, the extension of family power, and the extension of the religion professed, were the two strongest motives of political action. This was the period of the great religious wars which arrayed nation against nation, principality against principality, and often, in the same nation, faction against faction. Religious persecution caused the revolt of the Protestant Dutch Provinces against Spain, which issued, after eighty years of more or less constant war, in the recognition of their independence. Religious discord, amounting to civil war at times, distracted France during the greater part of the same period, profoundly affecting not only her internal but her external policy. These were the days of St. Bartholomew, of the religious murder of Henry IV., of the siege of La Rochelle, of constant intriguing between Roman Catholic Spain and Roman Catholic Frenchmen. As the religious motive, acting in a sphere to which it did not naturally belong, and in which it had no rightful place, died away, the political necessities and interests of States began to have juster weight; not that they had been wholly lost sight of in the mean time, but the religious animosities had either blinded the eyes, or fettered the action, of statesmen. It was natural that in France, one of the greatest sufferers from religious passions, owing to the number and character of the Protestant minority, this reaction should first and most markedly be seen. Placed between Spain and the German States, among which Austria stood foremost without a rival, internal union and checks upon the power of the House of Austria were necessities of political existence. Happily, Providence raised up to her in close succession two great rulers, Henry IV. and Richelieu,—men in whom religion fell short of bigotry, and who, when forced to recognize it in the sphere of politics, did so as masters and not as slaves. Under them French statesmanship received a guidance, which Richelieu formulated as a tradition, and which moved on the following general lines,—(1) Internal union of the kingdom, appeasing or putting down religious strife and centralizing

authority in the king; (2) Resistance to the power of the House of Austria, which actually and necessarily carried with it alliance with Protestant German States and with Holland; (3) Extension of the boundaries of France to the eastward, at the expense mainly of Spain, which then possessed not only the present Belgium, but other provinces long since incorporated with France; and (4) The creation and development of a great sea power, adding to the wealth of the kingdom, and intended specially to make head against France's hereditary enemy, England; for which end again the alliance with Holland was to be kept in view. Such were the broad outlines of policy laid down by statesmen in the front rank of genius for the guidance of that country whose people have, not without cause, claimed to be the most complete exponent of European civilization, foremost in the march of progress, combining political advance with individual development. This tradition, carried on by Mazarin, was received from him by Louis XIV.; it will be seen how far he was faithful to it, and what were the results to France of his action. Meanwhile it may be noted that of these four elements necessary to the greatness of France, sea power was one; and as the second and third were practically one in the means employed, it may be said that sea power was one of the two great means by which France's external greatness was to be maintained. England on the sea, Austria on the land, indicated the direction that French effort was to take.

Spain, the nation before which all others had trembled less than a century before, was now long in decay and scarcely formidable; the central weakness had spread to all parts of the administration. In extent of territory, however, she was still great. The Spanish Netherlands still belonged to her; she held Naples, Sicily, and Sardinia; Gibraltar had not yet fallen into English hands; her vast possessions in America—with the exception of Jamaica, conquered by England a few years before—were still untouched. The condition of her sea power, both for peace and war, has been already alluded to. Many years before, Richelieu had contracted a temporary alliance with Spain, by virtue of which she placed forty ships at his disposal; but the bad condition of the vessels, for the most part ill armed and ill commanded, compelled their withdrawal. The navy of Spain was then in full decay, and its weakness did not escape the piercing eye of the cardinal. An encounter which took place between the Spanish and Dutch fleets in 1639 shows most plainly the state of degradation into which this once proud navy had fallen.

thus describes the commercial and colonial conditions, at the accession of Louis XIV., of this people, which beyond any other in modern times, save only England, has shown how the harvest of the sea can lift up to wealth and power a country intrinsically weak and without resources:—

francs. The powerful East India Company, founded in 1602, had built up in Asia an empire, with possessions taken from the Portuguese. Mistress in 1650 of the Cape of Good Hope, which guaranteed it a stopping-place for its ships, it reigned as a sovereign in Ceylon, and upon the coasts of Malabar and Coromandel. It had made Batavia its seat of government, and extended its traffic to China and Japan. Meanwhile the West India Company, of more rapid rise, but less durable, had manned eight hundred ships of war and trade. It had used them to seize the remnants of Portuguese power upon the shores of Guinea, as well as in Brazil.

England coveted Holland's trade and sea dominion; France desired the Spanish Netherlands. The United Provinces had reason to oppose the latter as well as the former.

navy, and there was too little of a true military spirit among the officers. A more heroic people than the Dutch never existed; the annals of Dutch sea-fights give instances of desperate enterprise and endurance certainly not excelled, perhaps never equalled, elsewhere; but they also exhibit instances of defection and misconduct which show a lack of military spirit, due evidently to lack of professional pride and training. This professional training scarcely existed in any navy of that day, but its place was largely supplied in monarchical countries by the feeling of a military caste. It remains to be noted that the government, weak enough from the causes named, was yet weaker from the division of the people into two great factions bitterly hating each other. The one, which was the party of the merchants (burgomasters), and now in power, favored the confederate republic as described; the other desired a monarchical government under the House of Orange. The Republican party wished for a French alliance, if possible, and a strong navy; the Orange party favored England, to whose royal house the Prince of Orange was closely related, and a powerful army. Under these conditions of government, and weak in numbers, the United Provinces in 1660, with their vast wealth and external activities, resembled a man kept up by stimulants. Factitious strength cannot endure indefinitely; but it is wonderful to see this small State, weaker by far in numbers than either England or France, endure the onslaught of either singly, and for two years of both in alliance, not only without being destroyed, but without losing her place in Europe. She owed this astonishing result partly to the skill of one or two men, but mainly to her sea power.

Spanish Netherlands (Belgium) to France would tend toward the subjection of Europe, and especially would be a blow to the sea power both of the Dutch and English; for it was not to be supposed that Louis would allow the Scheldt and port of Antwerp to remain closed, as they then were, under a treaty wrung by the Dutch from the weakness of Spain. The reopening to commerce of that great city would be a blow alike to Amsterdam and to London. With the revival of inherited opposition to France the ties of kindred began to tell; the memory of past alliance against the tyranny of Spain was recalled; and similarity of religious faith, still a powerful motive, drew the two together. At the same time the great and systematic efforts of Colbert to build up the commerce and the navy of France excited the jealousy of both the sea powers; rivals themselves, they instinctively turned against a third party intruding upon their domain. Charles was unable to resist the pressure of his people under all these motives; wars between England and Holland ceased, and were followed, after Charles's death, by close alliance.

naturally follow from the thoughtful and systematic way in which the French navy at that time was restored from a state of decay, and has a lesson of hope for us in the present analogous condition of our own navy. The Dutch ships, from the character of their coast, were flatter-bottomed and of less draught, and thus were able, when pressed, to find a refuge among the shoals; but they were in consequence less weatherly and generally of lighter scantling than those of either of the other nations.

the future kingdom were then being prepared by the Elector of Brandenburg, a powerful minor State, which was not yet able to stand quite alone, but carefully avoided a formally dependent position. The kingdom of Poland still existed, a most disturbing and important factor in European politics, because of its weak and unsettled government, which kept every other State anxious lest some unforeseen turn of events there should tend to the advantage of a rival. It was the traditional policy of France to keep Poland upright and strong. Russia was still below the horizon; coming, but not yet come, within the circle of European States and their living interests. She and the other powers bordering upon the Baltic were naturally rivals for preponderance in that sea, in which the other States, and above all the maritime States, had a particular interest as the source from which naval stores of every kind were chiefly drawn. Sweden and Denmark were at this time in a state of constant enmity, and were to be found on opposite sides in the quarrels that prevailed. For many years past, and during the early wars of Louis XIV., Sweden was for the most part in alliance with France; her bias was that way.

though by the treaty of marriage she had renounced all claim to her father's inheritance, it was not difficult to find reasons for disregarding this stipulation. Technical grounds were found for setting it aside as regarded certain portions of the Netherlands and Franche Comté, and negotiations were entered into with the court of Spain to annul it altogether. The matter was the more important because the male heir to the throne was so feeble that it was evident that the Austrian line of Spanish kings would end in him. The desire to put a French prince on the Spanish throne—either himself, thus uniting the two crowns, or else one of his family, thus putting the House of Bourbon in authority on both sides of the Pyrenees—was the false light which led Louis astray during the rest of his reign, to the final destruction of the sea power of France and the impoverishment and misery of his people. Louis failed to understand that he had to reckon with all Europe. The direct project on the Spanish throne had to wait for a vacancy; but he got ready at once to move upon the Spanish possessions to the east of France.

peninsular kingdoms. As a matter of fact, Portugal became a dependent and outpost of England, by which she readily landed in the Peninsula down to the days of Napoleon. Indeed, if independent of Spain, she is too weak not to be under the control of the power that rules the sea and so has readiest access to her. Louis continued to support her against Spain, and secured her independence. He also interfered with the Dutch, and compelled them to restore Brazil, which they had taken from the Portuguese.

called Louis from the pursuit of glory on the land to seek the durable grandeur of France in the possession of a great sea power, the elements of which, thanks to the genius of Colbert, he had in his hands. A century later a greater man than Louis sought to exalt himself and France by the path pointed out by Leibnitz; but Napoleon did not have, as Louis had, a navy equal to the task proposed. This project of Leibnitz will be more fully referred to when the narrative reaches the momentous date at which it was broached; when Louis, with his kingdom and navy in the highest pitch of efficiency, stood at the point where the roads parted, and then took the one which settled that France should not be the power of the sea. This decision, which killed Colbert and ruined the prosperity of France, was felt in its consequences from generation to generation afterward, as the great navy of England, in war after war, swept the seas, insured the growing wealth of the island kingdom through exhausting strifes, while drying up the external resources of French trade and inflicting consequent misery. The false line of policy that began with Louis XIV. also turned France away from a promising career in India, in the days of his successor.

the United Provinces would gladly have avoided the war; the able man who was at their head saw too clearly the delicate position in which they stood between England and France. They claimed, however, the support of the latter in virtue of a defensive treaty made in 1662. Louis allowed the claim, but unwillingly; and the still young navy of France gave practically no help.

took the command of the ship from her officers, and carried her out of action. This movement was followed by twelve or thirteen other ships, leaving a great gap in the Dutch line. The occurrence shows, what has before been pointed out, that the discipline of the Dutch fleet and the tone of the officers were not high, despite the fine fighting qualities of the nation, and although it is probably true that there were more good seamen among the Dutch than among the English captains. The natural steadfastness and heroism of the Hollanders could not wholly supply that professional pride and sense of military honor which it is the object of sound military institutions to encourage. Popular feeling in the United States is pretty much at sea in this matter; there is with it no intermediate step between personal courage with a gun in its hand and entire military efficiency.

to modern discussions; namely, the group formation. "The idea of combining fire-ships with the fighting-ships to form a few groups, each provided with all the means of attack and defence," was for a time embraced; for we are told that it was later on abandoned. The combining of the ships of a fleet into groups of two, three, or four meant to act specially together is now largely favored in England; less so in France, where it meets strong opposition. No question of this sort, ably advocated on either side, is to be settled by one man's judgment, nor until time and experience have applied their infallible tests. It may be remarked, however, that in a well-organized fleet there are two degrees of command which are in themselves both natural and necessary, that can be neither done away nor ignored; these are the command of the whole fleet as one unit, and the command of each ship as a unit in itself. When a fleet becomes too large to be handled by one man, it must be subdivided, and in the heat of action become practically two fleets acting to one common end; as Nelson, in his noble order at Trafalgar, said, "The second in command will, after my intentions are made known to him" (mark the force of the "after," which so well protects the functions both of the commander-in-chief and the second), "have the entire direction of his line, to make the attack upon the enemy, and to follow up the blow until they are captured or destroyed."

war of 1665 its peculiar interest in the history of naval tactics. In it is found for the first time the close-hauled line-of-battle undeniably adopted as the fighting order of the fleets. It is plain enough that when those fleets numbered, as they often did, from eighty to a hundred ships, such lines would be very imperfectly formed in every essential, both of line and interval; but the general aim is evident, amid whatever imperfections of execution. The credit for this development is generally given to the Duke of York, afterward James II.; but the question to whom the improvement is due is of little importance to sea-officers of the present day when compared with the instructive fact that so long a time elapsed between the appearance of the large sailing-ship, with its broadside battery, and the systematic adoption of the order which was best adapted to develop the full power of the fleet for mutual support. To us, having the elements of the problem in our hands, together with the result finally reached, that result seems simple enough, almost self-evident. Why did it take so long for the capable men of that day to reach it? The reason—and herein lies the lesson for the officer of to-day—was doubtless the same that leaves the order of battle so uncertain now; namely, that the necessity of war did not force men to make up their minds, until the Dutch at last met in the English their equals on the sea. The sequence of ideas which resulted in the line-of-battle is clear and logical. Though familiar enough to seamen, it will be here stated in the words of the writer last quoted, because they have a neatness and precision entirely French:—

the controlling weapon of the day, which the French navy has yielded, the above brief argument may well be taken as an instance of the way in which researches into the order of battle of the future should be worked out. A French writer, commenting on Labrousse's paper, says:—

was to fall with their whole fleet upon the Dutch before their allies could come up. This lesson is as applicable to-day as it ever was. A second lesson, likewise of present application, is the necessity of sound military institutions for implanting correct military feeling, pride, and discipline. Great as was the first blunder of the English, and serious as was the disaster, there can be no doubt that the consequences would have been much worse but for the high spirit and skill with which the plans of Monk were carried out by his subordinates, and the lack of similar support to Ruyter on the part of the Dutch subalterns. In the movements of the English, we hear nothing of two juniors turning tail at a critical moment, nor of a third, with misdirected ardor, getting on the wrong side of the enemy's fleet. Their drill also, their tactical precision, was remarked even then. The Frenchman De Guiche, after witnessing this Four Days' Fight, wrote:—

of the admirals and captains, and the skill of the seamen and soldiers under them. The wise and vigorous efforts made by the government of the United Provinces, and the undeniable superiority of Ruyter in experience and genius over any one of his opponents, could not compensate for the weakness or incapacity of part of the Dutch officers, and the manifest inferiority of the men under their orders."

sent into the river, under De Ruyter, a force of sixty or seventy ships-of-the-line, which on the 14th of June, 1667, went up as high as Gravesend, destroying ships at Chatham and in the Medway, and taking possession of Sheerness. The light of the fires could be seen from London, and the Dutch fleet remained in possession of the mouth of the river until the end of the month. Under this blow, following as it did upon the great plague and the great fire of London, Charles consented to peace, which was signed July 31, 1667, and is known as the Peace of Breda. The most lasting result of the war was the transfer of New York and New Jersey to England, thus joining her northern and southern colonies in North America.

English ambassador Temple, "the Dutch feel that their country will be only a maritime province of France;" and sharing that opinion, "he advocated the policy of resistance to the latter country, whose domination in the Low Countries he considered as a threatened subjection of all Europe. He never ceased to represent to his government how dangerous to England would be the conquest of the sea provinces by France, and he urgently pointed out the need of a prompt understanding with the Dutch. 'This would be the best revenge,' said he, 'for the trick France has played us in involving us in the last war with the United Provinces.'" These considerations brought the two countries together in that Triple Alliance with Sweden which has been mentioned, and which for a time checked the onward movement of Louis. But the wars between the two sea nations were too recent, the humiliation of England in the Thames too bitter, and the rivalries that still existed too real, too deeply seated in the nature of things, to make that alliance durable. It needed the dangerous power of Louis, and his persistence in a course threatening to both, to weld the union of these natural antagonists. This was not to be done without another bloody encounter.

France; but France, hampered by her continental politics, could not hope to wrest the control of the seas from England without an ally. This ally Louis proposed to destroy, and he asked England to help him. The final result is already known, but the outlines of the contest must now be followed.

by which Leibnitz sought to convince the French king two hundred years ago.

Diplomatic strategy on a vast scale was displayed in order to isolate and hem in Holland. Louis, who had been unable to make Europe accept the conquest of Belgium by France, now hoped to induce it to see without trembling the fall of Holland." His efforts were in the main successful. The Triple Alliance was broken; the King of England, though contrary to the wishes of his people, made an offensive alliance with Louis; and Holland, when the war began, found herself without an ally in Europe, except the worn-out kingdom of Spain and the Elector of Brandenburg, then by no means a first-class State. But in order to obtain the help of Charles II., Louis not only engaged to pay him large sums of money, but also to give to England, from the spoils of Holland and Belgium, Walcheren, Sluys, and Cadsand, and even the islands of Goree and Voorn; the control, that is, of the mouths of the great commercial rivers the Scheldt and the Meuse. With regard to the united fleets of the two nations, it was agreed that the officer bearing the admiral's flag of England should command in chief. The question of naval precedence was reserved, by not sending the admiral of France afloat; but it was practically yielded. It is evident that in his eagerness for the ruin of Holland and his own continental aggrandizement Louis was playing directly into England's hand, as to power on the sea. A French historian is justified in saying: "These negotiations have been wrongly judged. It has been often repeated that Charles sold England to Louis XIV. This is true only of internal policy. Charles indeed plotted the political and religious subjugation of England with the help of a foreign power; but as to external interests, he did not sell them, for the greater share in the profit from the ruin of the Dutch was to go to England."

not strike their flags. In January, 1672, England sent an ultimatum, summoning Holland to acknowledge the right of the English crown to the sovereignty of the British seas, and to order its fleets to lower their flags to the smallest English man-of-war; and demands such as these received the support of a French king. The Dutch continued to yield, but seeing at length that all concessions were useless, they in February ordered into commission seventy-five ships-of-the-line, besides smaller vessels. On the 23d of March the English, without declaration of war, attacked a fleet of Dutch merchantmen; and on the 29th the king declared war. This was followed, April 6th, by the declaration of Louis XIV.; and on the 28th of the same month he set out to take command in person of his army.

been met; though it is possible that the particular acts referred to, consisting in partial attacks amounting to little more than demonstrations against the French contingent, may have sprung from political motives. This solution for the undoubted fact that the Dutch attacked the French lightly has not been met with elsewhere by the writer; but it seems possible that the rulers of the United Provinces may have wished not to increase the exasperation of their most dangerous enemy by humiliating his fleet, and so making it less easy to his pride to accept their offers. There is, however, an equally satisfactory military explanation in the supposition that, the French being yet inexperienced, Ruyter thought it only necessary to contain them while falling in force upon the English. The latter fought throughout with their old gallantry, but less than their old discipline; whereas the attacks of the Dutch were made with a sustained and unanimous vigor that showed a great military advance. The action of the French was at times suspicious; it has been alleged that Louis ordered his admiral to economize his fleet, and there is good reason to believe that toward the end of the two years that England remained in his alliance he did do so.

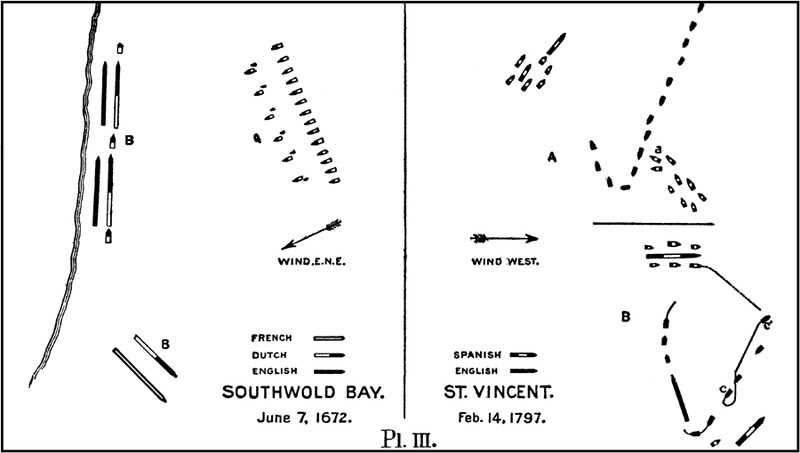

fully intending to fight, fell back before them to his own coast. The allies did not follow him there, but retired, apparently in full security, to Southwold Bay, on the east coast of England, some ninety miles north of the mouth of the Thames. There they anchored in three divisions,—two English, the rear and centre of the allied line, to the northward, and the van, composed of French ships, to the southward. Ruyter followed them, and on the early morning of June 7, 1672, the Dutch fleet was signalled by a French lookout frigate in the northward and eastward; standing down before a northeast wind for the allied fleet, from which a large number of boats and men were ashore in watering parties. The Dutch order of battle was in two lines, the advanced one containing eighteen ships with fire-ships (Plate III., A). Their total force was ninety-one ships-of-the-line; that of the allies one hundred and one.

If this can be accepted, it gives a marked evidence of Ruyter's high qualities as a general officer, in advance of any other who appears in this century.