автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Heart of the Antarctic

THE HEART OF THE ANTARCTIC

Illustrated

ERNEST SHACKLETON

Copyright © 2017 Ernest Shackleton

Amazing Classics

All rights reserved.

THE HEART OF THE ANTARCTIC

Illustrated

by Ernest Shackleton

PORTRAIT OF E. H. SHACKLETON

THE HEART OF THE

ANTARCTIC

COMPLETE EDITION

BEING THE STORY OF THE BRITISH

ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1907-1909

BY E. H. SHACKLETON, C.V.O.,

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY HUGH ROBERT MILL, D.Sc. AN ACCOUNT OF THE FIRST JOURNEY TO THE SOUTH MAGNETIC POLE BY PROFESSOR T. W. EDGEWORTH DAVID, F.R.S.

VOLUME I

PREFACE

THE scientific results of the expedition cannot be stated in detail in this book. The expert members in each branch have contributed to the appendices articles which summarise what has been done in the domains of geology, biology, magnetism, meteorology, physics, &c. I will simply indicate here some of the more important features of the geographical work.

We passed the winter of 1908 in McMurdo Sound, twenty miles north of the Discovery winter quarters. In the autumn a party ascended Mount Erebus and surveyed its various craters. In the spring and summer of 1908-9 three sledging-parties left winter quarters; one went south and attained the most southerly latitude ever reached by man, another reached the South Magnetic Pole for the first time, and a third surveyed the mountain ranges west of McMurdo Sound.

The southern sledge-journey planted the Union Jack in latitude 88° 23' South, within one hundred geographical miles of the South Pole. This party of four ascertained that a great chain of mountains extends from the 82nd parallel, south of McMurdo Sound, to the 86th parallel, trending in a south-easterly direction; that other great mountain ranges continue to the south and south-west, and that between them flows one of the largest glaciers in the world, leading to an inland plateau, the height of which, at latitude 88° South, is over 11,000 ft. above sea-level. This plateau presumably continues beyond the geographical South Pole, and extends from Cape Adare to the Pole. The bearings and angles of the new southern mountains and of the great glacier are shown on the chart, and are as nearly correct as can be expected in view of the somewhat rough methods necessarily employed in making the survey.

The mystery of the Great Ice Barrier has not been solved, and it would seem that the question of its formation and extent cannot be determined definitely until an expedition traces the line of the mountains round its southerly edge. A certain amount of light has been thrown on the construction of the Barrier, in that we were able, from observations and measurements, to conclude provisionally that it is composed mainly of snow. The disappearance of Balloon Bight, owing to the breaking away of a section of the Great Ice Barrier, shows that the Barrier still continues its recession, which has been observed since the voyage of Sir James Boss in 1842. There certainly appears to be a high snow-covered land on the 163rd meridian, where we saw slopes and peaks, entirely snow-covered, rising to a height of 800 ft., but we did not see any bare rocks, and did not have an opportunity to take soundings at this spot. We could not arrive at any definite conclusion on the point.

The journey made by the Northern Party resulted in the attainment of the South Magnetic Pole, the position of which was fixed, by observations made on the spot and in the neighbourhood, at latitude 72° 25' South, longitude 155° 16' East. The first part of this journey was made along the coastline of Victoria Land, and many new peaks, glaciers and ice-tongues were discovered, in addition to a couple of small islands. The whole of the coast traversed was carefully triangulated, and the existing map was corrected in several respects.

The survey of the western mountains by the Western Party added to the information of the topographical details of that part of Victoria Land, and threw some new light on its geology.

The discovery of forty-five miles of new coastline extending from Cape North, first in a south-westerly and then in a westerly direction, was another important piece of geographical work.

During the homeward voyage of the Nimrod a careful search strengthened that prevalent idea that Emerald Island, the Nimrod Islands and Dougherty Island do not exist, but I would not advise their removal from the chart without further investigation. There is a remote possibility that they lie at some point in the neighbourhood of their charted positions, and it is safer to have them charted until their non-existence has been proved absolutely.

I should like to tender my warmest thanks to those generous people who supported the expedition in its early days. Miss Dawson Lambton and Miss E. Dawson Lambton made possible the first steps towards the organisation of the expedition, and assisted afterwards in every way that lay in their power. Mr. William Beardmore (Parkhead, Glasgow), Mr. G. A. McLean Buckley (New Zealand), Mr. Campbell McKellar (London), Mr. Sydney Lysaght (Somerset), Mr. A. M. Fry (Bristol), Colonel Alexander Davis (London), Mr. William Bell (Pendell Court, Surrey), Mr. H. H. Bartlett (London), and other friends contributed liberally towards the cost of the expedition. I wish also to thank the people who guaranteed a large part of the necessary expenditure, and the Imperial Government for the grant of £20,000, which enabled me to redeem these guarantees. Sir James Mills, managing director of the Union Steam Shipping Company of New Zealand, gave very valuable assistance. The kindness and generosity of the Governments and people of Australia and New Zealand will remain one of the happiest memories of the expedition.

I am also indebted to the firms which presented supplies of various sorts, and to the manufacturers who so readily assisted in the matter of ensuring the highest quality and purity in our foods.

As regards the production of this book, I am indebted to Dr. Hugh Robert Mill for the introduction which he has written; to Mr. Edward Saunders, of New Zealand, who not only acted as my secretary in the writing of the book, but bore a great deal of the labour, advised me on literary points and gave general assistance that was invaluable; and to my publisher, Mr. William Heinemann, for much help and many kindnesses.

I have to thank the members of the expedition who have provided the scientific appendices. I should like to make special mention of Professor T. W. Edgeworth David, who has told the story of the Northern Journey, and Mr. George Marston, the artist of the expedition, represented in this volume by the colour plates, sketches and some diagrams.

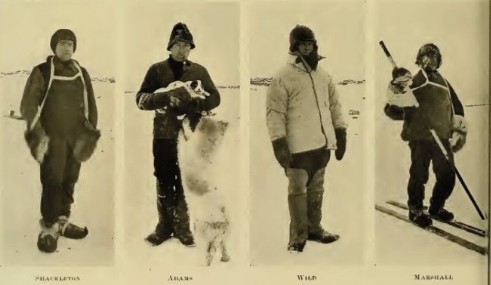

I have drawn on the diaries of various members of the expedition to supply information regarding events that occurred while I was absent on journeys. The photographs with which these volumes are illustrated have been selected from some thousands taken by Brocklehurst, David, Davis, Day, Dunlop, Harbord, Joyce, Mackintosh, Marshall, Mawson, Murray and Wild, secured often under circumstances of exceptional difficulty.

In regard to the management of the affairs of the expedition during my absence in the Antarctic, I would like to acknowledge the work done for me by my brother-in-law, Mr. Herbert Dorman, of London; by Mr. J. J. Kinsey, of Christchurch, New Zealand; and by Mr. Alfred Reid, the manager of the expedition, whose work throughout has been as arduous as it has been efficient.

Finally, let me say that to the members of the expedition, whose work and enthusiasm have been the means of securing the measure of success recorded in these pages, I owe a debt of gratitude that I can hardly find words to express. I realise very fully that without their faithful service and loyal co-operation under conditions of extreme difficulty success in any branch of our work would have been impossible.

ERNEST H. SHACKLETON

LONDON,

October 1909

INTRODUCTION. SOUTH POLAR EXPLORATION IN THE LAST HUNDRED YEARS, By HUGH ROBERT MILL, D.Sc., LL.D.

AN outline of the history of recent Antarctic exploration is necessary before the reader can appreciate to the full the many points of originality in the equipment of the expedition of 1907-1909, and follow the unequalled advance made by that expedition into the slowly dwindling blank of the unknown South Polar area.

From the beginning of the sixteenth century it was generally believed that a great continent, equal in area to all the rest of the land of the globe, lay around the South Pole, stretching northward in each of the great oceans far into the tropics. The second voyage of Captain James Cook in 1773-75 showed that if any continent existed it must lie mainly within the Antarctic Circle, which he penetrated at three points in search of the land, and it could be of no possible value for settlement or trade. He reached his farthest south in 71° 10' South, 1130 miles from the South Pole.

In 1819 Alexander I, Emperor of all the Russias, resolved of his good pleasure to explore the North Polar and the South Polar regions simultaneously and sent out two ships to each destination. The southern expedition consisted of the two ships Vostok and Mirni, under the command of Captain Fabian von Bellingshausen, with Lieutenant Lazareff as second in command. They made a circumnavigation of the world in a high southern latitude, supplementing the voyage of Cook by keeping south where he went north, but not attempting to reach any higher latitudes. On leaving Sydney in November 1820, Bellingshausen went south in 163° East, a section of the Antarctic which Cook had avoided, and from the eagerness with which the Russian captain apologised for not pushing into the pack it may be inferred that he found the gate leading to Ross Sea only barred by the ice, not absolutely locked. The ships went on in the direction of Cape Horn in order to visit the South Shetlands, recently discovered by William Smith. On the way Bellingshausen discovered the first land yet known within the Antarctic Circle, the little Peter I Island and the much larger Alexander I Land, which he sighted from a distance estimated at forty miles. A fleet of American sealers was found at work round the South Shetlands and some of the skippers had doubtless done much exploring on their own account, though they kept it quiet for fear of arousing competition in their trade. Bellingshausen returned to Cronstadt in 1821 with a loss of only three men in his long and trying voyage. No particulars of this expedition were published for many years.

In February 1823, James Weddell, a retired Master in the Royal Navy, and part owner of the brig Jane of Leith, 160 tons, was sealing round the South Orkneys with the cutter Beaufoy, 65 tons, under the command of Matthew Brisbane, in company, when he decided to push south as far as the ice allowed in search of new land where seals might be found. Signs of land were seen in the form of icebergs stained with earth, but Weddell sailed through a perfectly clear sea, now named after him, to 74° 15' South in 34° 17' West. This point, reached on February 22, 1823, was 3° South of Cook's farthest and 945 miles from the South Pole. On his return he brought back to Europe the first specimen of the Weddell seal to be seen by any naturalist.

Enderby Brothers, a firm of London shipowners doing a large trade in seal-oil, took a keen interest in discovery, and one of the brothers was an original Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, founded in 1830. In that very year the firm despatched John Biscoe, a retired Master in the Royal Navy, in the brig Tula, with the cutter Lively in company, on a two years' voyage, combining exploration with sealing. Biscoe was a man of the type of Cook and Weddell, a first-class navigator, indifferent to comfort, ignorant of fear and keen on exploring the Far South. In January 1831 he commenced a circumnavigation of the Antarctic Regions eastward from the South Atlantic in 60° South. At the meridian of Greenwich he got south of the Circle and pushed on, beating against contrary winds close to the impenetrable pack which blocked advance to the south. At the end of February he sighted a coastline in 49° 18' East and about 66° South, which has since been called Enderby Land, but it has never been revisited. He searched in vain for the Nimrod Islands, which had been reported in 56° South, 158° West, and then, crossing the Pacific Ocean well south of the sixtieth parallel, he, ignorant of Bellingshausen's voyage, entered Bellingshausen Sea, and discovered the Biscoe Islands and the coast of Graham Land. On his return in 1833 Biscoe received the second gold medal awarded by the Royal Geographical Society for his discoveries and for his pertinacity in sailing for nearly fifty degrees of longitude south of the Antarctic Circle.

In 1838 the Enderbys sent out John Balleny in the sealing schooner Eliza Scott, 154 tons, with the cutter Sabrina, 54 tons, and he left Campbell Island, south of New Zealand, on January 17, 1839, to look for new land in the south. On the 29th he reached the Antarctic Circle in 178° East, and got to 69° South before meeting with heavy ice. Turning westward at this point he discovered the group of lofty volcanic islands which bears his name, and there was no mistake as to their existence, as one of the peaks rose to a height of 14,000 ft. An excellent sketch was made of the islands by the mate, and geological specimens were collected from the beach. Proceeding westward Biscoe reported an "appearance of land in 65° South, and about 121° East", which Mr. Charles Enderby claimed as a discovery and called Sabrina Land after the unfortunate cutter, which was lost with all hands in a gale.

The years 1838 to 1848 saw no fewer than ten vessels bound on exploration to the ice-cumbered waters of the Antarctic, all ostensibly bent on scientific research, but all animated, some admittedly, by the patriotic ambition of each commander to uphold the honour of his flag.

Captain Dumont d'Urville, of the French Navy, was one of the founders of the Paris Geographical Society. He had been sent out on two scientific voyages of circumnavigation, which lasted from 1822 to 1825, and from 1826 to 1829, and he became a great authority on the ethnology of the Pacific Islands. He planned a third cruise to investigate problems connected with his special studies; but, in granting the vessels for this expedition, King Louis Philippe added to the commission, possibly at the suggestion of Humboldt, a cruise to the Antarctic regions in order to out-distance Weddell's farthest south. It was known that an American expedition was on the point of starting with this end in view, and that active steps were also being taken in England to revive southern exploration. Dumont d'Urville got away first with two corvettes, the Astrolabe, under his command, and the Zelée, under Captain Jacquinot, which sailed from Toulon on September 7, 1887. The two ships reached the pack-ice on January 22, 1838, but were unable to do more than sail to and fro along its edge until February 27, when land was sighted in 63° South and named Louis Philippe Land and Joinville Island. These were, undoubtedly, part of the Palmer Land of the American sealers, and a continuation of Biscoe's Graham Land. Though he did not reach the Antarctic Circle, d'Urville had got to the end of the Antarctic summer and discharged his debt of duty to his instructions.

It was the avowed intention of the American expedition and of the British expedition, since fitted out, to find the South Magnetic Pole, the position of which was believed from the theoretical investigations of Gauss to be near 66° South and 146° East. In December 1839, when d'Urville was at Hobart Town, and the air was full of rumours of these expeditions, he suddenly made up his mind to exceed his instructions and make a dash for the South Magnetic Pole for the honour of France. He left Hobart on January 1, 1840, and on the 21st sighted land on the Antarctic Circle in longitude 138° E. The weather was perfect, the icebergs shone and glittered in the sun like fairy palaces in the streets of a strange southern Venice; only wind was wanting to move the ships. The snow-covered hills rose to a height of about 1500 ft. and received the name of Adelie Land, after Madame Dumont d'Urville. A landing was made on one of a group of rocky islets lying off the icebound shore, and the ships then followed the coast westward for two days. In 135° 30' West bad weather and a northward bend in the ice drove the corvettes beyond the Circle, and on struggling south again on January 28, in the lift of a fog, the Astrolabe sighted a brig flying the American flag, one of Wilkes' squadron. The ships misunderstood each other's intentions; each intended to salute and each thought that the other wished to avoid an interview; and they parted in the fog full of bitterness towards each other without the dip of a flag. All day on the 30th, d'Urville sailed along a vertical cliff of ice 120 to 130 ft. high, quite flat on top, with no sign of hills beyond; but sure that so great a mass of ice could not form except on land he did not hesitate to name it the Clarie coast, after Madame Jacquinot. On February 1, the French ships left the Antarctic in longitude 130° West.

An American man of science, Mr. J. N. Reynolds, had gone to Palmer Land in the early days, and on his return agitated strongly for a national exploring expedition. An Act of Congress in 1836 provided for such an f expedition, but there had been controversies giving rise to ill-feeling, and Mr. Reynolds was not allowed to join "for the sake of harmony". After one and another of the naval officers designated to command it had resigned or declined the post. Lieutenant Charles Wilkes, U.S.N., was at last persuaded to take charge of the squadron of six ill-assorted vessels manned by half-hearted crews. His instructions were to proceed to Tierra del Fuego with the sloops-of-war Vincennes and Peacock, the brig Porpoise, the store-ship Relief and the pilot-boats Sea Gull and Flying Fish; to leave the larger vessels and the scientific staff—which they carried—and proceed with the Porpoise and the tenders "to explore the southern Antarctic to the southward of Powell's group, and between it and Sandwich Land, following the track of Weddell as closely as practicable, and endeavouring to reach a high southern latitude; taking care, however, not to be obliged to pass the winter there." He was then with all his squadron to proceed southward and westward as far as Cook's farthest, or 105° West, and then retire to Valparaiso. After surveying in the Pacific they were to proceed to Sydney and then the instructions proceeded: "You will make a second attempt to penetrate within the Antarctic region, south of Van Diemen's Land, and as far west as longitude 45° East or to Enderby's Land, making your rendezvous on your return at Kerguelen's Land." Very stringent orders, dated August 11, 1838, were given to Wilkes not to allow any one connected with the expedition to furnish any other persons "with copies of any journal, charts, plan, memorandum, specimen, drawing, painting or information" concerning the objects and proceedings of the expedition or as to discoveries made. The ships were not fortified for ice navigation; they were not even in sound seaworthy condition; the stores were inadequate and of bad quality; the crews and unhappily some of the officers were disaffected, disliking their commander, and making things very uncomfortable for him. The attempt to navigate Weddell Sea proved abortive; on the side of Bellingshausen Sea one ship reached 68° and another 70° South, but saw nothing except ice.

At Sydney, Wilkes was most unhappy; his equipment was criticised with more justice than mercy by his colonial visitors, and in his narrative he says plainly that he was obliged "to agree with them that we were unwise to attempt such service in ordinary cruising vessels; we had been ordered to go and that was enough: and go we should." And they went. On January 16, 1840, land was sighted by three of the ships in longitudes about 158° East, apparently just on or south of the Antarctic Circle. The ships sailed westwards as best they could along the edge of the pack; sometimes along the face of a barrier of great ice-cliffs, ignorant of the fact that Balleny had been there the year before, but very anxious that they should anticipate any discoveries on the part of the French squadron then in those waters. On January 19, land was reported on the Antarctic Circle both to the south-east and to the south-west, Wilkes being then in 154° 30' East, and its height was estimated at 3000 ft. The ships were involved all the time in most difficult navigation through drifting floes and bergs, storms were frequent and fogs made life a perpetual misery, as it was impossible to see the icebergs until the ships were almost on them. The Peacock, the least seaworthy of the squadron, lay helpless in the ice for three days while the rudder, which had been smashed, was being repaired on deck, and on January 25 she was patched up enough to return to Sydney. Wilkes' ship, the Vincennes, got south of the Circle on January 23, and he hoped to reach the land, but the way was barred by ice. On the 28th, land appeared very distinctly in 141° East, but the Vincennes was driven off by a gale, the sea being extraordinarily encumbered with icebergs and ice-islands. Two days later land was unquestionably found in 66° 45' South, 140° 2' East, with a depth of thirty fathoms; there were bare rocks half a mile from the ship, and the hills beyond rose to 3000 ft.; but the weather was too rough to get boats out. This was the Adelie Land which d'Urville had lighted on nine days before. This also is the only point of land reported by the American expedition, with the very doubtful exception of Sabrina Land, which has been confirmed by another expedition. Against the written remonstrance of the surgeons, who said that longer exposure to the heavy work of ice navigation in the severe conditions of the weather would increase the sick-list to such an extent as to endanger the ships, and in spite of the urgent appeal of a majority of the officers, Wilkes held on to the westward, reporting land in the neighbourhood of the Antarctic Circle every day, observing many earth-stained icebergs and collecting specimens of stones from the floating ice. On February 16, the ice-barrier which Wilkes had been following westward turned towards the north and over it there was "an appearance of land" which he called Termination Land. He was in 97° 37' East, and on the 21st, having failed to get farther west, he rejoiced the hearts of all on board by turning northwards and making for Sydney. Ringgold on the Porpoise had thought of running to the rendezvous in 100° East first, and working his way back to the eastward with a favouring wind afterwards, and he accomplished the first part of the programme easily enough, for the wind helped him, passing and disdaining to salute d'Urville's ships on the way. He added nothing material to the information obtained by the Vincennes.

Considering the deplorable conditions against which he had to contend both in the seas without and the men within his ships, the voyage of Wilkes was one of the finest pieces of determined effort on record. He erred in not being critical enough of appearances of land; and his charts were certainly faulty, as any charts of land dimly seen through fog were bound to be. Subsequent explorers have sailed over the positions where Wilkes showed land between 164° and 154° East, and if the land he saw there exists, it must be farther south than he supposed. It is certain that Wilkes saw land farther east, and it seems that he was as harshly judged by Ross and as unsympathetically treated by some other explorers and geographers as he was by his own subordinates.

Sir Edward Sabine and other British physicists had been trying from 1835 onward to secure the despatch of a British expedition to study terrestrial magnetism in the Antarctic regions, and pressure was brought to bear on the Royal Society to take the initiative but with little effect. An effort by Captain Washington, the Secretary, to arouse the Royal Geographical Society early in 1837 also failed. In the following year the recently founded British Association for the Advancement of Science memorialised Government on the need for making a series of simultaneous magnetic observations in all parts of the world, particularly by means of a special expedition to high southern latitudes. The Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, was impressed; he referred the memorial to the Royal Society, which supported it. A naval expedition was decided on and rapidly fitted out on the Erebus and Terror, two vessels of great strength, designed for firing large bombs from mortars in siege operations, but clumsy craft to navigate, with bluff bows that made them move slowly through the water, and sluggish in answering their helms. The one possible commander was Captain James Clark Ross, a tried Arctic traveller and an enthusiastic student of magnetism, who had reached the North Magnetic Pole in 1831, and whose surpassing fitness for the position had been a potent factor in the minds of the promoters. Captain Crozier was second in command on board the Terror, and although all the magnetic and other physical work was to be done by naval officers, the surgeons were appointed with regard to their proficiency in geology, botany and zoology. One of these subsequently took rank amongst the greatest men of science of the nineteenth century, and in 1909 Sir Joseph Hooker retains at the age of ninety-two the same interest in Antarctic exploration which drew him in 1889, as a youth of twenty-one, to join the Navy, in order to accompany the expedition. The ships were of 370 and 350 tons respectively, the whole ship's company of each being seventy-six officers and men, and they were well provisioned for the period, fresh tinned meats and vegetables being available. The instructions of the Admiralty left a good deal of discretion to the commander. He was ordered to land special parties of magnetic observers at St. Helena, the Cape of Good Hope and Van Diemen's Land. On the way he was to proceed south from Kerguelen Land and examine those places where indications of land had been reported. In the following summer he was to proceed southward from Tasmania towards the South Magnetic Pole, which he was to reach if possible, and return to Tasmania. In the following year he was to attain the highest latitude he could reach and proceed eastward to fix the position of Graham Land. The Erebus and Terror reached Hobart Town in August 1840, without doing any Antarctic exploration on the way. At Hobart, Ross was in constant communication with Sir John Franklin, the governor of Van Diemen's Land and a great authority on polar exploration in the north. He heard of d'Urville's and Wilkes' discoveries and was very angry that others had taken the track marked out for him. He resolved that he would not, as he somewhat quaintly put it, "interfere with their discoveries" and in so doing he allowed the haze of uncertainty to rest over the region south of the Indian Ocean to this day; but he also resolved to try to get south on the meridian of 170° East, where Balleny had found open sea in 69° South; and had it not been for the previous French and American voyages causing him to change his plans, Ross might conceivably have missed the great chance of his lifetime. The expedition left Hobart on November 12, 1840, sighted the sea ice on December 31, lying along the Antarctic Circle, and after spending some time searching for the best place to enter it, on January 5, 1841, ships for the first time in the southern hemisphere left the open sea and pushed their way of set purpose into the pack. The vessels having been strengthened after the manner of the northern whalers to resist pressure and Ross himself fortified by long experience in Arctic navigation, the impassable barrier of the earlier explorers had no terrors for him. The pack which all other visitors to the Antarctic had viewed as extending right up to some remote and inaccessible land was found to be a belt about a hundred miles wide, and in four days the Erebus and Terror passed through it into the open waters of what is now called Ross Sea. The way seemed to lie open to the magnetic pole when a mountain appeared on the horizon. Ross called it Mount Sabine, after the originator of the expedition, and held on until on January 11 he was within a few miles of the bold mountainous coast of South Victoria Land; in front of him lay Cape Adare in latitude 71° South, from which one line of mountains, the Admiralty Range, ran north-west along the coast to Cape North, another, the peaks of which he named after the members of the Councils of the Royal Society and the British Association, ran along the coast to the south. Ross went ashore on Possession Island on January 12 and took possession of the first land discovered in the reign of Queen Victoria. The sea swarmed with whales, in the pursuit of which Ross, probably mistaking the species, thought that a great trade would spring up. On the 22nd the latitude of 74° South was passed and the expedition was soon nearer the Pole than any human being had been before. A few days later Franklin Island was seen and visited; but, as at Possession Island, no trace of vegetation was found. On the morning of January 28, a new mountain emitting volumes of smoke appeared ahead; it was Mount Erebus, named after the leading ship, and on High Island, as Ross called the land from which it sprung, appeared a lesser and extinct volcano, called Mount Terror after the second vessel. As the ships drew near, confident of sailing far beyond the 80th parallel, an ice-barrier appeared similar to that reported by Wilkes on his cruise, but greater. Vast walls of ice as high as the cliffs of Dover butted on to the new land at Cape Crozier, its western limit, and formed an absolute bar to further progress. A range of high land running south was seen over the barrier and this Ross called the Parry Mountains; to the west around the shores of an ice-girdled bay (McMurdo Bay) the land seemed to run continuously with the continent, and Ross accordingly represented Mount Erebus as being on the mainland, and the coast as turning abruptly in McMurdo Bay from its southerly to an easterly direction. The ships cruised eastward for two hundred and fifty miles parallel with the Great Barrier, the remarkable nature of which impressed all on board, as they recognised its uniform flat-topped extension and the vast height of the perpendicular ice-cliffs in which it terminated, the height being something like 200 ft. on the average, though at one point it did not exceed 50 ft. On February 2, the highest latitude of the trip was reached, 78° 4' South, or 3° 48' beyond Weddell's farthest on the opposite side of the Antarctic Circle. Two days later the pack became so dense that progress was stopped in 167° West. Ross struggled for a week to get farther east and then turned to look for a harbour on the coast of Victoria Land in which he might winter. Passing by McMurdo Bay without examining it closely, he tried to get a landing nearer the Magnetic Pole, being possessed by a burning ambition to hoist the flag which he had displayed at the North Magnetic Pole in 1831 at the South Magnetic Pole in 1841. It was impossible, however, to get within twelve or fourteen miles of the land on account of the freezing of the sea locking the pack into a solid mass; it was too late to turn back and seek a harbour farther south, and after naming the headland at the base of Mount Melbourne, Cape Washington, in honour of the zealous Secretary of the Royal Geographical Society, Ross left the Antarctic regions after having remained south of the Circle for sixty-three days. On the way northward he sighted high islands, which were probably part of the Balleny group, and he sailed across the site of a range of mountains marked on a chart which Wilkes had given him. Wilkes afterwards explained that these mountains were not intended to show one of his discoveries, and an unedifying controversy ensued, which did credit to neither explorer. Ross returned to Hobart on April 6, 1841, after the greatest voyage of Antarctic discovery ever made. Three months later the news reached England, and the Royal Geographical Society at once awarded the Founder's Gold Medal to Captain Ross.

On November 23, 1841, the Erebus and Terror left the Bay of Islands, New Zealand, which had been declared a British possession the year before, to make a new effort to get south in a longitude about 150° West, so as to approach the Great Barrier from a point east of that at which they had been stopped the previous season. The pack was entered about 60° South and 146° West on December 18, and it seemed as if the ships were never to get through it. The Antarctic Circle was reached on New Year's Day, 1842, every effort being made to work the ships through the lanes between the floes. For a time when the wind was favourable the two ships were lashed on each side of a small floe of convenient shape and with all sail set they were able to give it sufficient way to break the lighter ice ahead, using it as a battering-ram and as a buffer to protect their bows. Ross did everything to keep up the spirits of the crews, by instituting sports and keeping up visits between the two ships, as in an Arctic wintering. A terrific storm on January 18 buffeted the ships unmercifully, the huge masses of floating ice being hurled against them in a prodigious swell, and for twenty-four hours the Erebus and Terror were almost out of control, their rudders having been smashed by the ice, though the stout timbers of the hulls held good. On January 26, after being thirty-nine days in the pack, and boring their way for eight hundred miles through it, the Erebus and the Terror were only thirty-nine miles farther south than Cook had been in the Resolution on the same meridian without entering the ice at all sixty-eight years before. On February 2 the ships escaped from the pack in 159° East, but only one degree south of the Antarctic Circle. The Barrier was not sighted until February 22, and on the 28th the ships at last got within a mile and a half of the face of the ice-wall, which was found to be 107 ft. high at its highest point and the water 290 fathoms deep, in 161° 27' West and 78° 11' South. This was the highest latitude reached by Ross, 3° 55' or 235 miles farther south than Weddell's farthest, and 710 miles from the South Pole. Towards the south-east he saw that the Barrier surface gradually rose with the appearance of mountains of great height, but he could not bring himself to chart this as land, for no sign of bare rock could be seen, and though he felt that "the presence of land there amounts almost to a certainty" he would not run the risk of any one in the future proving that he had been mistaken, and so charted it as an "appearance of land" only. Any other explorer of that period, or of this, would have called it land and given it a name without hesitation, and had Ross only known how to interpret what the numerous rock specimens he dredged up from the bottom had to tell him, he could have marked the land with an easy mind.

It was now time to leave the Far South; the work had been infinitely harder than that of the former season and the result was disappointing. The coast of Victoria Land was not sighted on this cruise, and on March 6, 1842, the Erebus and Terror crossed the Antarctic Circle northward, after having been sixty-four days within it. Ross Sea was not furrowed by another keel for more than half a century. Once in open water the Erebus and Terror held an easterly course through the Southern Ocean south of the Pacific, farther north than Biscoe, Bellingshausen or Cook, making passage to the Falkland Islands, by that time a British possession. The greatest danger of the whole cruise occurred suddenly on this passage when the two ships came into collision while attempting to weather an iceberg in a gale and snowstorm during the night; but though for an hour all gave themselves up for lost they came through, and they reached Port Louis in the Falklands on April 5, 1842, one hundred and thirty-seven days out from the Bay of Islands.

Having received authority to spend a third summer in south polar exploration, Ross sailed from the Falklands on December 17, 1842, intending to survey the coasts discovered by d'Urville and follow the land south to a high latitude in Weddell Sea; but though several points on Louis Philippe Land were sighted and mountains named, there was no open way to the south and it was not until March 1, 1843, that the Antarctic Circle was reached by coasting the pack to 12° 20' West. Here a sounding of the vast depth of 4000 fathoms was obtained, but Dr. W. S. Bruce, with improved and trustworthy apparatus, found sixty years later that the real depth at this point was only 2660 fathoms. Ross proceeded southwards in open water to 71° 30' South, thirty miles within the ice-pack, but there he was stopped nearly halfway between the positions reached by Bellingshausen in 1820 and by Weddell in 1823; and here his Antarctic exploration ended. On his way to Cape Town, Ross searched for Bouvet Island as unsuccessfully as Cook, though he passed within a few miles of it. Ross' first summer in the Antarctic had brought unexpected and magnificent discoveries, tearing a great gap in the unknown area, and fortune smiled without interruption on the expedition; his second summer brought trouble and danger with but a trifling increase in knowledge, while the third led only to disappointment. Ross had come triumphantly through a time of unparalleled stress, his personal initiative animated the whole expedition and never were honours more nobly won than those which he received on his return. He was knighted, fêted, and presented with many gold medals; and he was offered and begged in the most flattering way to accept the command of the expedition to explore the North-West Passage in his old ships. The position, when he declined it, was given to Sir John Franklin.

Immediately after Ross' return a supplementary cruise for magnetic observations was carried out by Lieutenant T. E. L. Moore, R.N., who had been mate on the Terror. He sailed from Cape Town in the hired barque Pagoda, 360 tons, on January 9, 1845, and, after the usual fruitless search for Bouvet Island, crossed the Antarctic Circle in 30° 45' East, but was stopped by the ice in 67° 50' South. He struggled hard against calms and head winds to reach Enderby Land, but in vain. Moore believed that he saw land in 64° South and about 50° East; but like Ross he stood on a pedantic technicality, "there was no doubt about it, but we would not say it was land without having really landed on it." How much controversy and ill-feeling would have been avoided if Wilkes and other explorers had acted on this principle!

In 1850, in one of the Enderbys' ships, the Brisk, Captain Tapsell went to the Balleny Islands looking for seals and sailed westward at a higher latitude than Wilkes had reached, as far as the meridian of 143° East, without sighting land; the log of the voyage is lost, and the exact route is not on record.

Though Ross urged the value of the southern whale fishery in strong terms, no one stirred to take it up. Polar enterprise was diverted to the lands within the Arctic Circle by the tragedy of Franklin's fate and the search expeditions. Efforts were made again and again to reawaken interest in the south, notably by the great American hydrographer, Captain Maury, and the eminent German meteorologist, Professor Georg von Neumayer, but without effect.

In 1875, H.M.S. Challenger, on her famous voyage of scientific investigation with Captain George Nares, R.N., as commander and Professor Wyville Thomson as scientific director, made a dash south of Kerguelen Land, and on February 16 she had the distinction of being the first vessel propelled by steam across the Antarctic Circle. She went to 66° 40' South in longitude 78° 22' East, and pushed eastward in a somewhat lower latitude to within fifteen miles of Wilkes' Termination Land as shown on the charts, but nothing resembling land could be seen. The Challenger saw many icebergs, but being an unprotected vessel and bent on other service she could make no serious attempt to penetrate the pack; nevertheless, the researches made on board by sounding and dredging up many specimens of rocks proved beyond doubt that land lay within the ice surrounding the Antarctic Circle and that the land was not insular but a continent.

In the same year a German company sent out the steam whaler Grönland, Captain Dallmann, to try whether anything could be made of whaling or sealing in the neighbourhood of the South Shetlands, and he went probably to about 65° South in Bellingshausen Sea on the coast of Graham Land. In the 'eighties of last century Neumayer continued to urge the renewal of Antarctic research in Germany, and Sir John Murray, raising his powerful voice in Great Britain, sketched out a scheme for a fully equipped naval expedition, but refused to have anything to do with any expedition not provided at the outset with funds sufficient to ensure success. The government of Victoria took the matter up and offered to contribute £5000 to an expedition if the Home Government would support it; the British Association, the Royal Society, and the Royal Geographical Society reported in favour of the scheme, but in 1887 the Treasury definitely declined to participate.

In 1892 a fleet of four Dundee whalers set out for Weddell Sea, in order to test Ross' belief that the whalebone whale existed there, and two of them, the Balaena and Active, were fitted up with nautical and meteorological instruments by the Royal Geographical Society and the Meteorological Office, in the hope that they would fix accurate positions and keep careful records. Dr. W. S. Bruce, an enthusiastic naturalist, accompanied the Balaena and Dr. C. W. Donald accompanied the Active, commanded by Captain Thomas Robertson. The ships made full cargoes of seals in Weddell Sea, but did not go beyond 65° South, nor did they repeat the venture. A Norwegian whaler, the Jason, was sent out at the same time by a company in Hamburg, and her master, Captain Larsen, picked up a number of fossils on Seymour Island, and saw land from Weddell Sea in 64° 40' South. The Hamburg Company sent out three ships in 1893, the Jason to Weddell Sea, where Captain Larsen discovered Oscar Land, no doubt the eastern coast of Graham Land, in 66° South and 60° West, and pushing on farther he discovered Foyn Land, the Jason being the second steamer to enter the Antarctic regions proper. On his way home along the coast he charted many new islands and discovered active volcanoes near the place where Ross' officers had seen smoke rising from the mountains, though that cautious explorer decided that as it might be only snowdrift he would not claim the discovery of volcanoes there. Meanwhile, in Bellingshausen Sea, Captain Evenson, of the Hertha, got beyond 69° 10' South after visiting the Biscoe Islands, and he sighted Alexander I Land for the first time since its discovery.

The next visit to the Antarctic was due to the Norwegian whaler, Svend Foyn, who sent out the Antarctic, under Captain Kristensen, with Mr. Bull as agent, to Ross Sea. They had agreed to take Dr. W. S. Bruce, but he found it impossible to reach Melbourne in time to join the ship. A young Norwegian resident in Australia, who was partly English in ancestry, Carstens Egeberg Borchgrevink, shipped as a sailor, having an insatiable desire to see the Antarctic regions and being refused a passage on any other terms. The Antarctic sighted the Balleny Islands and was nearly six weeks in working through the pack, but on January 14, 1895, she was the first steamer to enter the open water of Ross Sea. A landing was made on Possession Island, where Borchgrevink discovered a lichen, the first trace of vegetation found within the Antarctic Circle; the ship went as far as 74° South looking for whales and on her way back the first landing on the Antarctic continent was made on a low beach at Cape Adare.

Mr. Borchgrevink described this voyage at the meeting of the Sixth International Geographical Congress in London in 1895, where a great discussion on the possibility of renewing Antarctic exploration had previously been arranged for. Dr. von Neumayer gave an able historical paper on Antarctic exploration, Sir Joseph Hooker spoke as a survivor of Ross' expedition. Sir John Murray as a member of the scientific staff of the Challenger, and Sir Clements Markham as President of the Congress. The Congress adopted a resolution to the effect that the exploration of the Antarctic Regions was the greatest piece of geographical exploration remaining to be undertaken, and that it should be resumed before the close of the nineteenth century.

The first result was the expedition of the Belgica under the command of Lieutenant de Gerlache, due to the passionate enthusiasm of the commander, notably aided by Henryk Arçtowski, a Pole, whose ardour in the pursuit of physical science has never been surpassed. Dr. Cook, an American, was surgeon to the expedition; the second in command was Lieutenant Lecointe, a Belgian, the mate, Roald Amundsen, a Norwegian, and the crew were half Belgian and half Norwegian. The scientific staff included, besides Arçtowski, the Belgian magnetician Lieutenant Danco, the Rumanian Racovitza, and the Pole Dobrowolski. The funds were meagre and raised by public subscription with enormous difficulty, and the equipment almost less than the minimum requirement. The ship was small, only two hundred and fifty tons, but in her this cosmopolitan gathering experienced first of all men the long darkness of the Antarctic night. Much valuable time was lost on the outward journey amongst the Fuegian Islands, and much was occupied in the archipelago into which the Belgica resolved Palmer Land, between 64° and 65° South. It was February 12, 1898, before the ship proceeded southward along the coast of Graham Land. On the 15th she crossed the Antarctic Circle, on the 16th Alexander I Land was sighted, but could not be approached within twenty miles on account of the ice-pack. The equipment of the ship hardly seems to have justified wintering; prudence called for a speedy retreat, but a gale came down of such severity that Gerlache thrust the ship into the pack for shelter from the heavy breakers on February 28, and finding wide lanes opening under the influence of wind and swell, he pushed southward against the advice of the scientific members of the expedition, determined to make every effort to outdistance all previous explorers towards the pole. On March 3, 1898, the Belgica found herself in 71° 30' South and about 85° West. An effort to return was unavailing; on the 4th she was fast in the floe, unable to move in any direction, and she remained a prisoner of the ice until February 14, 1899, and then took another month to clear all the pack and reach the open sea. For a year she had been drifting north, west, south and east, in Bellingshausen Sea; even in winter the floe was never at rest, and almost all the time she kept south of the parallel of 70° over water which shallowed from great depths in the north to about two hundred and fifty fathoms in the southern stretches of the drift, evidently on the sloping approach to extensive land. The expedition suffered greatly in health during the winter from inadequate food, and from the absence of proper light in the terrible darkness of the long night. Despite all its difficulties the Belgica had done more to promote a scientific knowledge of the Antarctic regions than any of the costly expeditions that went before, and the Belgian Government, coming to the rescue after her return, provided adequate funds for working out the results.

Bellingshausen Sea was visited again in 1904 by Dr. J. B. Charcot in the Français, which followed the route of the Belgica along the coast of Graham Land, afterwards wintering in Port Charcot, a harbour on Wandel Island in 65° South. Returning southward in the summer of 1904-5 he discovered land, named Terre Loubet, between Graham Land and Alexander I Land, but its exact position has not been stated. This French cruise was important as a preliminary to the expedition under Charcot, which left in 1908 and is now in those waters with the intention of pushing exploration to the Farthest South, in a ship named with a dash of humour and a flash of hope the Pourquoi Pas?

Two voyages of exploration in Weddell Sea may for convenience be referred to here. In October 1901, Dr. Otto Nordenskjold left Gothenberg in the old Antarctic, under the command of Captain Larsen, for an expedition which he had got up by his personal efforts. He arrived at the South Shetlands in January 1902, but found it impossible even to reach the Antarctic Circle on the coast of Oscar Land. Allowing the ship to go north for work among the islands, Nordenskjold wintered for two years, 1902 and 1903, in a timber house on Snow Hill Island in 64° 25' South. Only one year's wintering had been contemplated, but the Antarctic was crushed in the ice and sank, fortunately without loss of life. A relief ship was despatched from Sweden, but shortly before she arrived Nordenskjold and his companions had been rescued by the unprotected Argentine naval vessel Uruguay, under Captain Irizar.

Dr. W. S. Bruce, who had been to Weddell Sea in the Balaena in 1892, and had since then taken part in several Arctic expeditions, succeeded by dint of hard work and the unceasing advocacy of the further exploration of Weddell Sea, in enlisting the aid of a number of persons in Scotland, and notably of Mr. James Coats, Jr., of Paisley, and Major Andrew Coats, D.S.O., and fitting out an expedition on the Scotia. He left the Clyde in November 1902, with Captain Thomas Robertson in command of the ship, Mr. R. C. Mossman, the well-known meteorologist, Mr. Rudmose Brown and Mr. D. W. Wilton as naturalists, and Dr. J. H. H. Pirie as surgeon and geologist. After calling at the South Orkneys, the Scotia got south to 70° 25' South in 17° West on February 22, 1903, not far from the position reached by Ross. Valuable oceanographical work was done, and on returning to the South Orkneys, Mr. Mossman landed there with a party to keep up regular meteorological observations while the ship proceeded to the River Plate. On her return in the following year the Argentine Government took over the meteorological work in the South Orkneys, which has been kept up ever since, to the great advancement of knowledge. The Scotia made another dash to the south on the same meridian as before, and on March 2, 1904, when in 72° 18' South and 18° West, a high ice-barrier was seen stretching from north-east to south-west, the depth of the sea being 1131 fathoms, a marked diminution from the prevailing depths. The Barrier was occasionally seen in intervals of mist, and March 6 being a clear day allowed the edge to be followed to the south-west to a point one hundred and fifty miles from the place where it was first sighted. The depth, two and a half miles from the Barrier edge, pack-ice preventing a nearer approach, was 159 fathoms. The description of the appearance of the Barrier given in the "Cruise of the Scotia" is very brief: "The surface of this great Inland Ice of which the Barrier was the terminal face or sea-front seemed to rise up very gradually in undulating slopes, and faded away in height and distance into the sky, though in one place there appeared to be the outline of distant hills; if so they were entirely ice-covered, no naked rock being visible." Ross or Moore would certainly have charted this as an "appearance of land"; Bruce knew from the shoaling water and the nature of the deposits that he was in the vicinity of land and gave it the name of Coats Land after his principal supporters. He could get no farther and returned from 74° 1' South in 22° West, a point almost as far south as Weddell had got in his attempt one hundred and eighty miles farther west. The Scotia rendered immense service to science by her large biological collections, her unique series of deep-sea soundings in high latitudes and the permanent gain of a sub-Antarctic meteorological station.

The next step in exploration by way of Ross Sea was the fitting-out by Sir George Newnes of an expedition under the leadership of Mr. C. E. Borchgrevink, on board the Southern Cross, a stout Norwegian whaler with Captain Jensen, who had been chief officer in the Antarctic when she went to Ross Sea in 1895, as master. Lieutenant Colbeck, R.N.R., went as magnetic observer, Mr. L. C. Bernacchi, a resident in Tasmania, who had arranged to join the Belgica if she had gone out by Australia, as meteorologist, and Mr. Nicolai Hanson, of the British Museum, as zoologist. The Southern Cross left Hobart on December 19, 1898, and entered the pack about the meridian of the Balleny Islands, 165° East; but after being forced out again on the northern side after six weeks' struggling to get south, she re-entered the pack in 174° East and was through in the clear waters of Ross Sea in six hours on February 11, 1899. A wooden house and stores for the winter were landed at Cape Adare in 71° 15' South, and there the shore-party went into winter quarters, the ship returning to the north. An important series of meteorological observations was secured during the year of residence, valuable zoological and geological collections were made, and the habits of the penguins were studied; but the few attempts at land exploration were without result. On January 28, 1900, Captain Jensen returned with the Southern Cross and on February 2, the Cape Adare colony embarked and set out southward along the coast of Victoria Land. Landings were effected at various points, including the base of Mount Melbourne, where reindeer-moss was found growing, and at Cape Crozier. There was much less ice along the coast than when Ross had visited it. The Southern Cross, after sighting Mount Erebus and Mount Terror, ran eastward along the Great Barrier far closer to the ice-cliffs than Ross could go in his sailing ships, and Colbeck's survey showed that the Barrier had receded on the whole some thirty miles to the south. Parts of the Barrier were quite low, and Borchgrevink landed in 164° West, the ship being laid alongside the ice as if it had been a quay, and made a short journey on ski southward over the surface on February 19, 1900, reaching 78° 50' South, forty miles beyond Ross' farthest and six hundred and seventy miles from the Pole, the nearest yet attained. The sea was beginning to freeze and the Southern Cross made haste for home.

Following on various less weighty efforts set in motion by the resolution of the International Geographical Congress in 1895, all the eminent men of science who had the renewal of Antarctic exploration at heart met in the rooms of the Royal Society in London in February 1898, when Sir John Murray read a stimulating paper. This was followed by a discussion in which part was taken by the veteran Antarctic explorer Sir Joseph Hooker, by the most successful of Arctic explorers Dr. Fridtjof Nansen, by Dr. von Neumayer, who had never ceased for half a century to advocate renewed exploration, and by Sir Clements Markham, President of the Royal Geographical Society. A Joint Committee of the Royal Society and the Royal Geographical Society undertook the equipment of a British expedition and carried it through under the constant stimulus and direction of Sir Clements Markham, while funds were subscribed by various wealthy individuals, by the Royal Geographical Society, and in largest measure by Government. In Germany a national expedition was got up at the same time under the command of Professor Erich von Drygalski to co-operate by means of simultaneous magnetic and meteorological observations in a different quarter with the British expedition. For the present purpose it is enough to say that the German expedition on board the Gauss descended on the Antarctic Circle by the 90th meridian, and was caught in the pack at the end of February 1902, not far from Wilkes' "appearance" of Termination Land, and in sight of a hill called the Gaussberg on a land discovered by the expedition and named Kaiser Wilhelm Land. The ship remained fast for a year, and an immense amount of scientific investigation was carried out with characteristic thoroughness. On her release in February 1903, the Gauss tried to push westward in a high latitude, but could not reach the Antarctic Circle and, failing to get permission for another season's work, she returned laden with rich scientific collections and voluminous observations.

The Joint Committee in London built the Discovery at an expense of £52,000, making her immensely strong to resist ice pressure and securing the absence of any magnetic metal in a large area so that magnetic observations of high precision might be carried out. Sir Clements Markham selected as commander Lieutenant Robert F. Scott, R.N., a most fortunate choice, for no one could have been better fitted by disposition and training to ensure success. The second in command was Lieutenant Albert Armitage, R.N.R., who had had Arctic experience, and the other officers were Lieutenants C. Royds, R.N.; M. Barne, R.N.; E. H. Shackleton, R.N.R.; Engineer-Lieutenant Skelton, R.N.; Dr. R. Koettlitz, who had been a comrade of Armitage's in the north, and Dr. E. A. Wilson, an artist of great ability. The scientific staff included, in addition to the surgeons who were also zoologists, Mr. L. C. Bernacchi, who had been on the Southern Cross expedition, as physicist; as biologist Mr. T. V. Hodgson, and as geologist Mr. H. T. Ferrar. Meteorological and oceanographical work were undertaken by officers of the ship. The objects of the expedition were primarily magnetic observations, the costly construction of the ship being largely due to the arrangements for this purpose, then meteorological and oceanographical observations and the collection of zoological and geological specimens, and of course geographical exploration. Three pieces of exploration were specified in the instructions, an attempt to reach the land which Ross believed to exist east of the Barrier, though he charted it as an appearance only, a journey westward into the mountains of Victoria Land, and a journey southward. An attempt to reach the Pole was neither recommended nor forbidden. The Royal Geographical Society has always deprecated attempts to attain high latitudes north or south unless as an incident in systematic scientific work. The Discovery left Lyttelton on December 24, 1901, met the pack on January 1, 1902, and got through it into Ross Sea in a week in 174° East. Landings were made at Cape Adare, at various points along the coast of Victoria Land, and on January 22 at the base of Mount Terror, near Cape Crozier. From this point the Great Barrier was coasted to the east, close along its edge, and on the 29th in 165° East the depth of water was found to be less than a hundred fathoms, a strong indication of the approach to land. The Barrier had receded about thirty miles since Ross was in those seas, and there was much less pack-ice than during his visit; the date also was earlier and Scott was able to penetrate almost to 150° West before being stopped by heavy ice. The land was plainly seen, its higher summits being 2000 to 3000 ft. above the sea, and bare rocks projected from the snow covering of the hills. Thus the first geographical problem set to the expedition was promptly and satisfactorily solved. Although no landing was made on King Edward VII Land, the King's first godchild of discovery, as Victoria Land had been the late Queen's, the Discovery was laid alongside a low part of the Barrier in 164° West, and the captive balloon was raised for a comprehensive view. Returning to McMurdo Bay, Scott showed that the Parry Mountains, running south from Mount Erebus, were not in fact there; Ross had probably seen the southern range across the Barrier. It soon became evident that Ross' original impression that Mount Erebus rose from an island was correct, and this land was named Ross Island. McMurdo Bay also was found not to be a bay at all, but the opening of a strait leading southward between Ross Island and the mainland. By the middle of February 1902, the Discovery had taken up winter quarters on the extreme south of Ross Island, and a large hut had been erected on shore, with smaller huts for the magnetic and other instruments. The winter, four hundred miles farther south than any man had wintered before, was passed pleasantly by all, a great feature being the appearance of the South Polar Times, which owed much of its attractiveness to the editorship of E. H. Shackleton and to the art of E. A. Wilson.

With the spring a new era in Antarctic exploration was inaugurated in the series of sledge Journeys, for which elaborate preparations had been made. Here Captain Scott showed himself possessed of all the qualities of a pioneer, adapting the methods of Sir Leopold McClintock and Dr. Nansen for Arctic ice travel to the different conditions prevailing in the Antarctic. In preparation for the great effort towards the south a depot had been laid out on the ice, and on November 2, 1902, Scott, Shackleton and Wilson, with four sledges and nineteen dogs, stepped out into the unknown on the surface of the Barrier. It was necessary at first to make the journeys by relays, going over the ground three times to bring up the stores; but the loads were lightened as the food was used and by leaving a depot in 80° 30' South to be picked up on the return journey. Snowy weather was experienced but the temperature was not excessively low. The dogs, however, rapidly weakened, but by December 30, the little party reached latitude 82° 17' South, after fifty-nine days' travelling from winter quarters in 77° 49' South. They had passed over comparatively uniform snow-covered ice, probably afloat, and their track stretched parallel to a great mountain range which rose on their right. Whenever they approached the position of the mountains the surface was always found to be rougher, thrown into ridges or cleft by great crevasses. Failing provisions compelled them to stop at length, and a great chasm in the ice prevented them from reaching the land; but they had made their way to a point 3° 27' or 297 miles farther south than Borchgrevink and were 463 miles from the Pole. It was the greatest advance ever made over a previous farthest in poleward progress in either hemisphere, and the first long land journey in the Antarctic. Great mountain summits were seen beyond the farthest point reached; one named Mount Markham rose to about 15,000 ft., another, Mount Longstaff, was lower but farther south. The range appeared to be trending south-eastward in the distance. The return journey was made in thirty-four days, and the ship was reached on February 3, 1903; the dogs were all dead and had long been useless, the men themselves had been attacked by scurvy, the ancient scourge of polar explorers, and Shackleton's health was in a very serious state; but a journey such as had never been made before had been accomplished, and new methods of travel had been evolved and tested. Meantime shorter expeditions had been sent out from winter quarters, and Armitage had pioneered a way up one of the great glaciers which descended from the western mountains. The relief ship Morning, under Captain Colbeck, who had charted the Barrier on the Southern Cross expedition, arrived in McMurdo Sound on January 25, 1903; but unbroken sea ice prevented the ship from reaching the Discovery's winter quarters by ten miles. On March 3 she sailed for the north, leaving Lieutenant Mulock, R.N., to take the place of Lieutenant Shackleton, who was a reluctant passenger, invalided home. In the second winter the acetylene gas-plant was brought into use, and by this means the living-rooms were lighted brilliantly, and with the fresh food brought by the Morning, the sufferers from scurvy recovered, and the health of all remained excellent throughout the winter. Sledge expeditions set out again early in the spring, the most successful being that led by Captain Scott into the western mountains. Starting on October 26, he ascended the Ferrar Glacier to the summit of a great plateau of which the mountains formed the broken edge, and the party travelled without dogs, hauling their own sledges over a flat surface of compacted snow nine thousand feet above sea-level to the longitude of 146° 33' East, a distance of 278 statute miles from the ship. This journey proved the existence of a surface beyond the mountains which, although only to be reached by the toilsome and dangerous climbing of a crevassed glacier, and subject to the intensified cold of high altitudes, was as practicable as the Barrier surface itself for rapid travelling, as rapidity is counted in those regions. Thus Scott was able to demonstrate the facility of both kinds of ice travel, over the Antarctic continent as over the Antarctic Sea.

On February 19, 1904, the Discovery escaped from the harbour in which she had been frozen for two years. The Morning had again come south to meet her with orders to desert the ship if she could not be freed from the ice; and a larger ship, the Terra Nova, had been sent by the Admiralty to satisfy the fears of nervous hearts at home. The one thing wanting to round off the expedition was a supply of coal to enable the Discovery to follow the track of Wilkes' vessels from the Balleny Islands westward; but the relief ships were only able to spare a trifling quantity and the opportunity was lost. Scott carried on to the west far south of Wilkes' route to 154° East, showing that the land charted by the American expedition west of that meridian did not exist in the assigned positions; then with barely coal enough left to carry her to New Zealand the Discovery left the Antarctic regions and the great South Polar expedition came to an end. It is interesting to note that although no catastrophe such as those which darken the pages of Arctic history has ever happened in the Antarctic, no expedition had gone out without the loss of some of its members by accident or illness. On the Discovery the two deaths which occurred were by accident only.

The Gauss and the Discovery were sold soon after the return of the expeditions; the working up and publication of the scientific results obtained were for the most part entrusted to museums and public institutions; the members of the expeditions returned to their former duties or sought new employments, and the societies which had promoted the expeditions turned their attention to other things. The South Polar regions were left as the arena of private efforts, and in this volume the reader will learn how the enthusiasm and devotion of an individual has once more vindicated the character of the British nation for going far and faring well in the face of difficulties before which it would have been no dishonour to turn back.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

PORTRAIT OF E. H. SHACKLETON (Beresford, London)

COLOURED PLATES

A. THE AUTUMN SUNSET

B. A QUIET EVENING ON THE BARRIER

C. "THE DREADNOUGHT"

D. THE NIMROD RETURNS

E. THE "AURORA AUSTRALIS"

F. FULL MOON IN THE WINTER

PLATES

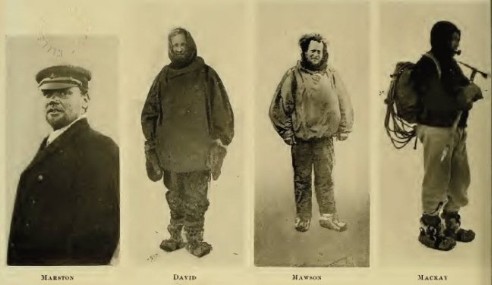

1A. PORTRAITS: Marston, David, Mawson, Mackay,

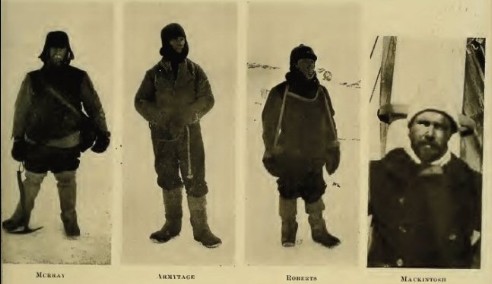

1B. Murray, Armytage, Roberts, Mackintosh,

1C. Shackleton, Adams, Wild, Marshall,

1D. Joyce, Brocklehurst, Day, Priestley

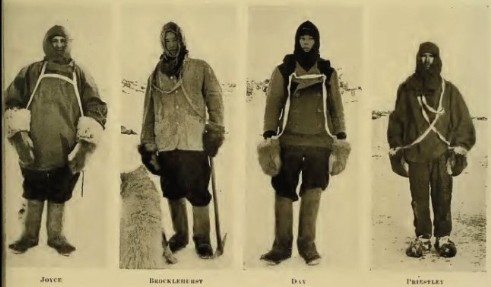

2. THEIR MAJESTIES THE KING AND QUEEN INSPECTING THE EQUIPMENT ON THE NIMROD AT COWES

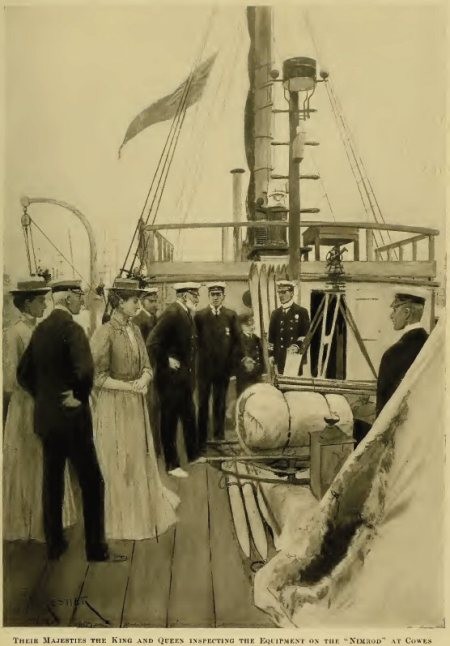

3. THE MANCHURIAN PONIES ON QUAIL ISLAND, PORT LYTTELTON, BEFORE THE EXPEDITION LEFT FOR THE ANTARCTIC

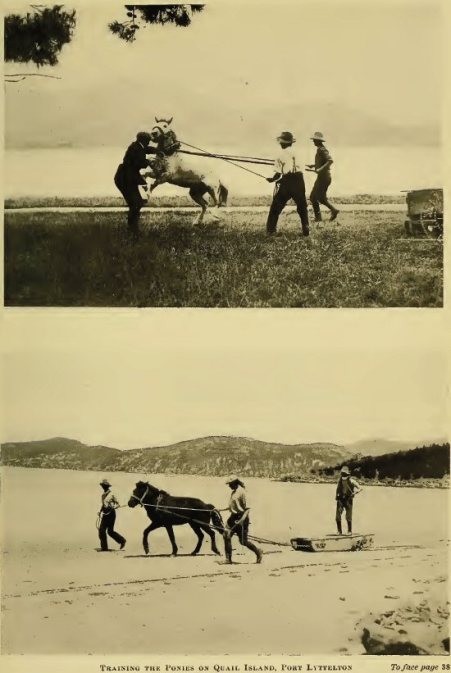

4. TRAINING THE PONIES ON QUAIL ISLAND, PORT LYTTELTON

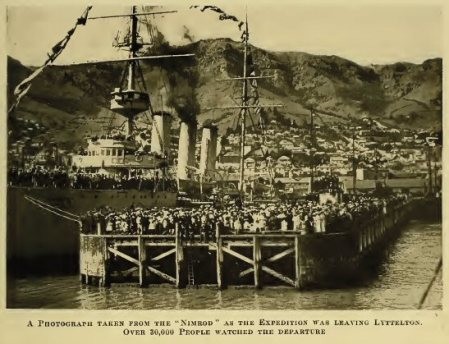

5. A PHOTOGRAPH TAKEN FROM THE NIMROD AS THE EXPEDITION WAS LEAVING LYTTELTON. OVER 30,000 PEOPLE WATCHED THE DEPARTURE

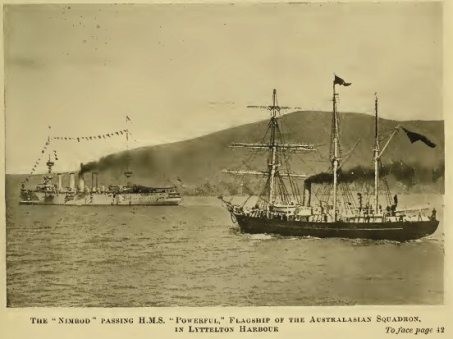

6. THE NIMROD PASSING H.M.S. "POWERFUL", FLAGSHIP OF THE AUSTRALASIAN SQUADRON, IN LYTTELTON HARBOUR

7. THE TOWING STEAMER "KOONYA", AS SEEN FROM THE NIMROD, IN A HEAVY SEA. THIS PARTICULAR WAVE CAME ABOARD THE NIMROD AND DID CONSIDERABLE DAMAGE

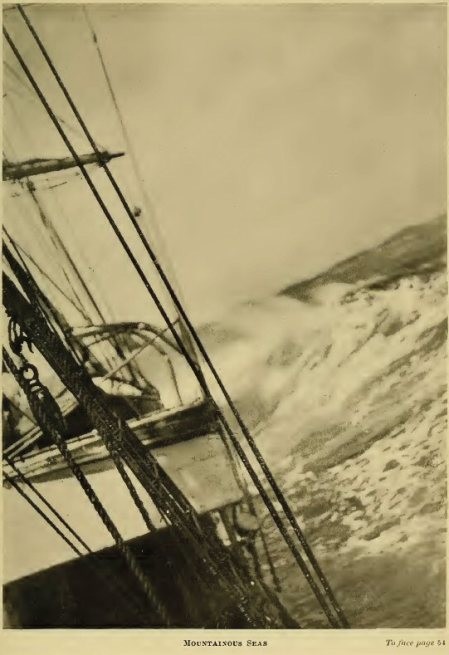

8. MOUNTAINOUS SEAS

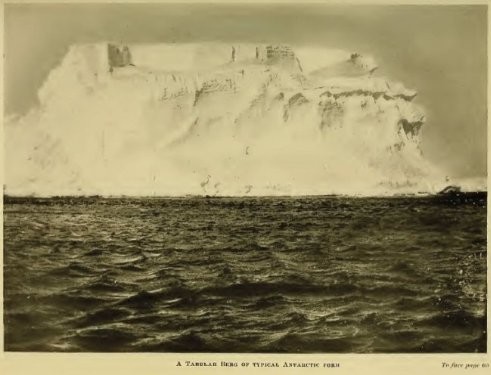

9. A TABULAR BERG OF TYPICAL ANTARCTIC FORM

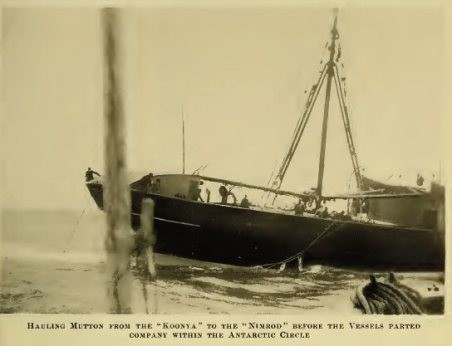

10. HAULING MUTTON FROM THE "KOONYA" TO THE NIMROD BEFORE THE VESSELS PARTED COMPANY WITHIN THE ANTARCTIC CIRCLE

11. THE NIMROD PUSHING THROUGH HEAVY PACK-ICE ON HER WAY SOUTH

12. PANCAKE ICE IN THE ROSS SEA

13. FLIGHT OF ANTARCTIC PETRELS

14. PUSHING THROUGH HEAVY FLOES IN THE ROSS SEA. THE DARK LINE ON THE HORIZON IS A "WATER-SKY", AND INDICATES THE EXISTENCE OF OPEN SEA

15. TWO VIEWS OF THE GREAT ICE BARRIER. THE WALL OF ICE WAS 90 FEET HIGH AT THE POINT SHOWN IN THE FIRST PICTURE, AND 120 FEET HIGH AT THE POINT WHERE THE SECOND VIEW WAS TAKEN

16. THE NIMROD PUSHING HER WAY THROUGH MORE OPEN PACK TOWARDS KING EDWARD VII LAND

17. TWO INLETS IN THE GREAT ICE BARRIER

18. THE NIMROD HELD UP BY THE PACK-ICE

19. SNOW THROWN ON BOARD IN ORDER THAT THE EXPEDITION MIGHT HAVE A SUPPLY OF FRESH WATER

20. THE CONSOLIDATED PACK, INTO WHICH BERGS HAD BEEN FROZEN, WHICH PREVENTED THE EXPEDITION REACHING KING EDWARD VII LAND

21. THE WAKE OF THE NIMROD THROUGH PANCAKE ICE

22. MOUNT EREBUS FROM THE ICE-FOOT

23. SOUNDING ROUND A STRANDED BERG IN ORDER TO SEE WHETHER THE SHIP COULD LIE THERE

24. THE NIMROD MOORED TO THE STRANDED BERG, ABOUT A MILE FROM THE WINTER QUARTERS. THE NIMROD SHELTERED IN THE LEE OF THIS BERG DURING BLIZZARDS

25. THE FIRST LANDING PLACE, SHOWING BAY ICE BREAKING OUT AND DRIFTING AWAY NORTH

26. A SNOW CORNICE

27. LANDING STORES FROM THE BOAT AT THE FIRST LANDING PLACE AFTER THE ICE-FOOT HAD BROKEN AWAY

28. THE LANDING-PLACE WHARF BROKEN UP

29. DERRICK POINT, SHOWING THE METHOD OF HAULING STORES UP THE CLIFF

30. DIGGING OUT STORES AFTER THE CASES HAD BEEN BURIED IN ICE DURING A BLIZZARD

31. THE NIMROD LYING OFF THE PENGUIN ROOKERY

32. THE PONY "QUAN" ABOUT TO DRAW A SLEDGE-LOAD OF STORES FROM THE ICE-FOOT TO THE HUT

33. FLAGSTAFF POINT, WITH THE SHORE PARTY'S BOAT HAULED UP ON THE ICE

34. THE VICINITY OF CAPE ROYDS. A SCENE OF DESOLATION

35. THE EAST CORNER OF INACCESSIBLE ISLAND, EIGHT MILES SOUTH OF THE WINTER QUARTERS

36. HIGH HILL, NEAR THE WINTER QUARTERS. A LAVA FLOW IS SEEN IN THE FOREGROUND

37. LOOKING NORTH TOWARDS CAPE ROYDS, FROM CAPE BARNE. THE SMOOTH ICE SHOWN WAS THE EXERCISING GROUND FOR THE PONIES DURING THE SPRING

38. PREPARING A SLEDGE DURING THE WINTER

39. CAPE BARNE. THE PILLAR IN THE RIGHT FOREGROUND IS VOLCANIC

40. A VIEW OF THE HUT LOOKING NORTHWARDS. ON THE LEFT IS SHOWN JOYCE'S HUT, MADE OF CASES. THE STABLE AND GARAGE ARE ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HUT, AND ON THE EXTREME RIGHT IS THE SNOW GAUGE. THE INSTRUMENT FOR RECORDING ATMOSPHERIC ELECTRICITY PROJECTS FROM A CORNER OF THE ROOF. OPEN WATER CAN BE SEEN ABOUT A MILE AWAY. THIS WATER ALTERNATELY FROZE AND BROKE UP DURING THE WINTER

41. A GREAT KENYTE BOULDER CLOSE TO THE WINTER QUARTERS

42. A FRESHWATER LAKE NEAR CAPE BARNE, FROZEN TO A DEPTH OF TWENTY FEET. ROTIFERS WERE FOUND IN THIS LAKE

43. A GROUP OF THE SHORE-PARTY AT THE WINTER QUARTERS. Standing (from left): Joyce, Day, Wild, Adams, Brocklehurst, Shackleton, Marshall, David, Armytage, Marston. Sitting: Priestley, Murray, Roberts

44. THE POUR PONIES OUT FOR EXERCISE ON THE SEA ICE

45. INTERIOR OF THE STABLE. FROST CAN BE SEEN ON THE BOLTS IN THE ROOF

46. DAY WITH THE MOTOR-CAR ON THE SEA ICE

47. SPECIAL MOTOR WHEELS: THE ORIGINAL FORM ON THE LEFT, AN ALTERED FORM ON THE RIGHT. ORDINARY WHEELS WITH RUBBER TYRES WERE FOUND TO BE THE MOST SATISFACTORY

48. THE START OF A BLIZZARD AT THE WINTER QUARTERS, THE FUZZY APPEARANCE BEING DUE TO DRIFTING SNOW

49. THE LAST OF THE PENGUINS JUST BEFORE THEIR MIGRATION IN MARCH. THE ICE IS DRIFTING NORTHWARDS

50. WEDDELL SEALS ON THE FLOE ICE

51. SKUA GULLS FEEDING NEAR THE HUT

52. MOUNT EREBUS AS SEEN FROM THE WINTER QUARTERS, THE OLD CRATER ON THE LEFT, AND THE ACTIVE CONE RISING ON THE RIGHT

53. THE PARTY WHICH ASCENDED MOUNT EREBUS LEAVING THE HUT

54. THE FIRST SLOPES OF EREBUS

55. THE PARTY PORTAGING THE SLEDGE OVER A PATCH OF BARE ROCK

56. THE CAMP 7000 FEET UP MOUNT EREBUS. THE STEAM FROM THE ACTIVE CRATER CAN BE SEEN

57. BROCKLEHURST LOOKING DOWN FROM A POINT 9000 FEET UP MOUNT EREBUS. THE CLOUDS LIE BELOW, AND CAPE ROYDS CAN BE SEEN

58. THE OLD CRATER OF EREBUS, WITH AN OLDER CRATER IN THE BACKGROUND. ALTITUDE 11,000 FEET. THE ACTIVE CONE IS HIGHER STILL

59. A REMARKABLE FUMAROLE IN THE OLD CRATER, IN THE FORM OF A COUCHANT LION. THE MEN (FROM THE LEFT) ARE: MACKAY, DAVID, ADAMS, MARSHALL

60. ONE THOUSAND FEET BELOW THE ACTIVE CONE

61. THE CRATER OF EREBUS, 900 FEET DEEP AND HALF A MILE WIDE. STEAM IS SEEN RISING ON THE LEFT. THE PHOTOGRAPH WAS TAKEN FROM THE LOWER PART OF THE CRATER EDGE

62. ANOTHER VIEW OF THE CRATER OF EREBUS

63. GOING OUT TO BRING IN THE EREBUS PARTY'S SLEDGE

64. THE HUT IN THE EARLY WINTER

65. A STEAM EXPLOSION ON MOUNT BIRD

66. HAULING SEAL MEAT FOB THE WINTER QUARTERS

67. AN ICE CAVERN IN THE WINTER. PHOTOGRAPHED BY THE LIGHT OF HURRICANE LAMPS

68. MOUNT EREBUS IN ERUPTION ON JUNE 14, 1908. THE PHOTOGRAPH WAS TAKEN BY MOONLIGHT

69. PROFESSOR DAVID STANDING BY MAWSON'S ANEMOMETER

70. A CLOUD EFFECT BEFORE THE SEA FROZE OVER

71. MUSIC IN THE HUT

72. A VIEW NORTH, TOWARDS THE DYING SUN, IN MARCH

73. AN ICE CAVE IN THE WINTER

74. AN ICE CAVE IN THE WINTER (2)

75. MURRAY AND PRIESTLEY GOING DOWN A SHAFT DUG IN GREEN LAKE DURING THE WINTER

76. ICE FLOWERS ON NEWLY FORMED SEA ICE EARLY IN THE WINTER

77. THE FULL MOON IN THE TIME OF AUTUMN TWILIGHT. CAPE BARNE ON THE LEFT. INACCESSIBLE ISLAND ON THE RIGHT

78. MAWSON'S CHEMICAL LABORATORY. THE BOTTLES WERE COATED WITH ICE BY CONDENSATION FROM THE WARM, MOIST AIR OF THE HUT

79. THE CUBICLE OCCUPIED BY PROFESSOR DAVID AND MAWSON; IT WAS NAMED THE "PAWN-SHOP"

80. THE TYPE-CASE AND PRINTING PRESS FOR THE PRODUCTION OF THE "AURORA AUSTRALIS" IN JOYCE'S AND WILD'S CUBICLE, KNOWN AS "THE ROGUES' RETREAT"

81. THE MIDWINTER'S DAY FEAST

82. THE STOVE IN THE HUT

83. A MEMBER OF THE EXPEDITION TAKING HIS BATH

84. MARSTON IN HIS BED

85. THE NIGHT-WATCHMAN

86. MARSTON TRYING TO REVIVE MEMORIES OF OTHER DAYS

87. THE ACETYLENE GAS PLANT, OVER THE DOOR. MARSHALL STANDING BY THE BAROMETER

88. SLEDGING ON THE BARRIER BEFORE THE RETURN OF THE SUN. MOUNT EREBUS IN THE BACKGROUND. TEMPERATURE MINUS 58° FAHR.

89. THE LEADER OF THE EXPEDITION IN WINTER GARB

90. THE HUT, WITH MOUNT EREBUS IN THE BACKGROUND, IN THE AUTUMN

91. THE WINTER QUARTERS OF THE DISCOVERY EXPEDITION AT HUT POINT, AFTER BEING DESERTED FOR SIX YEARS

92. GRISI

93. QUAN

94. SOCKS

95. CHINAMAN

96. THE SUPPORTING PARTY AT GLACIER TONGUE

97. THE CAMP AT HUT POINT

98. THE START FROM THE ICE-EDGE SOUTH OF HUT POINT

99. THE PONIES TETHERED FOR THE NIGHT

100. A CAMP AFTER A BLIZZARD, WITH THE SUPPORTING PARTY

101. THE SOUTHERN PARTY MARCHING INTO THE WHITE UNKNOWN

102. DEPOT A, LAID OUT IN THE SPRING

103. THE CAMP AFTER PASSING THE PREVIOUS "FARTHEST SOUTH" LATITUDE—NEW LAND IS SEEN IN THE BACKGROUND

104. GRISI DEPOT, LATITUDE 82° 45" SOUTH

105. NEW LAND. THE PARTY ASCENDED MOUNT HOPE AND SIGHTED THE GREAT GLACIER, UP WHICH THEY MARCHED THROUGH THE GAP. THE MAIN BODY OF THE GLACIER JOINS THE BARRIER FARTHER TO THE LEFT

106. THE VIEW FROM THE SUMMIT OF MOUNT HOPE, LOOKING SOUTH. DEPOT D, ON LOWER GLACIER DEPOT, WAS UNDER THE ROCK, CASTING A LONG SHADOW TO THE RIGHT. THE MOUNTAIN CALLED "THE CLOUDMAKER" IS SEEN IN THE CENTRE ON THE HORIZON

107. PART OF QUEEN ALEXANDRA RANGE, 1500 FEET UP THE GLACIER

108. THE CAMP BELOW "THE CLOUDMAKER"

109. A SLOPE JUST ABOVE THE UPPER GLACIER DEPOT, SHOWING STRATIFICATION LINES

110. THE MOUNTAINS TOWARDS THE HEAD OF THE GLACIER, WHERE THE COAL WAS FOUND

111. THE CHRISTMAS CAMP ON THE PLATEAU. THE FIGURES FROM LEFT TO RIGHT ARE ADAMS, MARSHALL AND WILD. THE FROST CAN BE SEEN ON THE MEN'S FACES

112. FACSIMILE OF PAGE OF SHACKLETON'S DIARY

113. THE FARTHEST SOUTH CAMP AFTER SIXTY HOURS' BLIZZARD

114. FARTHEST SOUTH

115. PARTS OF THE COMMONWEALTH AND DOMINION RANGES, PHOTOGRAPHED ON THE WAY DOWN THE GLACIER. PRESSURE ICE SHOWS AT THE FOOT OF THE MOUNTAINS

116. THE QUEEN ALEXANDRA RANGE, PHOTOGRAPHED ON THE WAY DOWN THE GLACIER

117. THE CAMP UNDER THE GRANITE PILLAR, HALF A MILE FROM THE LOWER GLACIER DEPOT, WHERE THE PARTY CAMPED ON JANUARY 27

118. LOWER GLACIER DEPOT. THE STORES WERE BURIED IN THE SNOW NEAR THE ROCK IN THE FOREGROUND

119. SHACKLETON STANDING BY THE BROKEN SOUTHERN SLEDGE, WHICH WAS REPLACED BY ANOTHER AT GRISI DEPOT

120. THE BLUFF DEPOT

121. MARSHALL OUTSIDE A TENT, AT THE CAMP FROM WHICH SHACKLETON AND WILD PRESSED ON TO THE SHIP

122. SHACKLETON AND WILD WAITING AT HUT POINT TO BE PICKED UP BY THE SHIP

123. THE START OF THE RELIEF PARTY, WHICH BROUGHT IN ADAMS AND MARSHALL

124. THE NIMROD AT FRAM POINT ON MARCH 4, 1909

125. THE SOUTHERN PARTY ON BOARD THE NIMROD. LEFT TO RIGHT: WILD, SHACKLETON, MARSHALL, ADAMS

DIAGRAMS IN THE TEXT

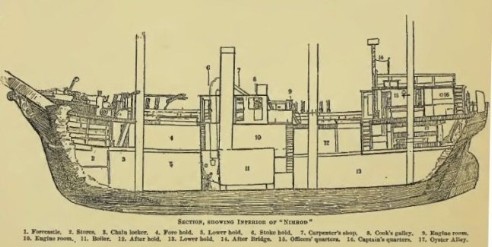

D1. SECTION SHOWING INTERIOR OF NIMROD

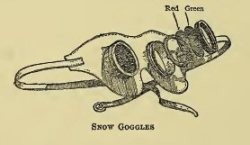

D2. SNOW GOGGLES

D3. FINNESKO

D4. BARRIER INLET

D5. COOKER AND PRIMUS STOVE

D6. PLAN OF ICE EDGE

D7. WINTER QUARTERS

D8. PLAN OF THE HUT AT WINTER QUARTERS

D9. CRATER OF MOUNT EREBUS AND SECTION

D10. SKI BOOTS

D11. PLAN OF SLEDGE

CHAPTER I. THE INCEPTION AND PREPARATION OF THE EXPEDITION