автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The White Prophet, Volume I (of 2)

THE WHITE PROPHET, VOLUME I

This ebook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The White Prophet, Volume I (of 2) Author: Hall Caine Release Date: June 15, 2016 [EBook #52342] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WHITE PROPHET, VOLUME I (OF 2) ***

Produced by Al Haines.

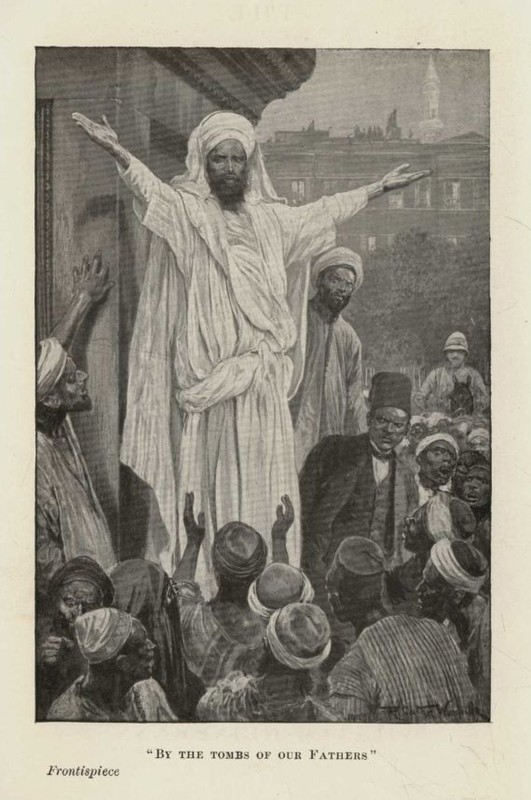

"By the tombs of our Fathers"

THE WHITE PROPHET

BY

HALL CAINE

ILLUSTRATED BY R. CATON WOODVILLE

IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. I

LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN 1909

Copyright London 1909 by William Heinemann and Washington U.S.A. by D. Appleton & Company

ILLUSTRATIONS

"By the tombs of our Fathers" . . . Frontispiece

He stretched out his hand to her, but she made no response

"Look here—and here," he cried, pointing to the broken sword

"How interesting!" cried the ladies in chorus

THE WHITE PROPHET

FIRST BOOK

THE CRESCENT AND THE CROSS

CHAPTER I

It was perhaps the first act of open hostility, and there was really nothing in the scene or circumstance to provoke an unfriendly demonstration.

On the broad racing ground of the Khedivial Club a number of the officers and men of the British Army quartered in Cairo, assisted by a detachment of the soldiers of the Army of Egypt, had been giving a sham fight in imitation of the battle of Omdurman, which is understood to have been the death-struggle and the end of Mahdism.

The Khedive himself had not been there—he was away at Constantinople—and his box had stood empty the whole afternoon; but a kinsman of the Khedive with a company of friends had occupied the box adjoining, and Lord Nuneham, the British Consul-General, had sat in the centre of the grand pavilion, surrounded by all the great ones of the earth in a sea of muslin, flowers, and feathers. There had been European ladies in bright spring costumes; Sheikhs in flowing robes of flowered silk; Egyptian Ministers of State in Western dress, and British Advisers and Under-Secretaries in Eastern tarbooshes; officers in gold-braided uniforms, Foreign Ambassadors, and an infinite number of Pashas, Beys, and Effendis.

Besides these, too, there had been a great crowd of what are called the common people, chiefly Cairenes, the volatile, pleasure-loving people of Cairo, who care for nothing so little as the atmosphere of political trouble. They had stood in a thick line around the arena, all capped in crimson, thus giving to the vast ellipse the effect of an immense picture framed in red.

There had been nothing in the day, either, to stimulate the spirit of insurrection. It had been a lazy day, growing hot in the afternoon, so that the white city of domes and minarets, as far up as the Mokattam Hills and the self-conscious Citadel, had seemed to palpitate in a glistening haze, while the steely ribbon of the Nile that ran between was reddening in the rays of the sunset.

General Graves, an elderly man with martial bearing, commanding the army in Egypt, had taken his place as Umpire in the Judge's box in front of the pavilion; four squadrons of British and Egyptian cavalry, a force of infantry, and a grunting and ruckling camel corps had marched and pranced and bumped out of a paddock to the left, and then young Colonel Gordon Lord, Assistant Adjutant-General, who was to play the part of Commandant in the sham fight, had come trotting into the field.

Down to that moment there had been nothing but gaiety and the spirit of fun among the spectators, who with ripples of merry laughter had whispered "Littleton's," "Wauchope's," "Macdonald's," and "Maxwell's," as the white-faced and yellow-faced squadrons had taken their places. Then the General had rung the big bell that was to be the signal for the beginning of the battle, a bugle had been sounded, and the people had pretended to shiver as they smiled.

But all at once the atmosphere had changed. From somewhere on the right had come the tum, tum, tum of the war drums of the enemy, followed by the boom, boom, boom of their war-horns, a melancholy note, half bellow and half wail. Then everybody in the pavilion had stood up, everybody's glass had been out, and a moment afterwards a line of strange white things had been seen fluttering in the far distance.

Were they banners? No! They were men, they were the dervishes, and they were coming down in a deep white line, like sheeted ghosts in battle array.

"They're here!" said the spectators in a hushed whisper, and from that moment onward to the end there had been no more laughter either in the pavilion or in the dense line around the field.

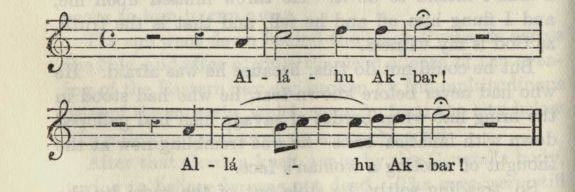

The dervishes had come galloping on, a huge disorderly horde in flying white garments, some of them black as ink, some brown as bronze, brandishing their glistening spears, their swords, and their flintlocks, beating their war-drams, blowing their war-horns, and shouting in high-pitched, rasping, raucous voices their war-cry and their prayer, "Allah! Allah! Allah!"

On and on they had come, like champing surf rolling in on a reef-bound coast; on and on, faster and faster, louder and louder; on and on until they had all but hurled themselves into the British lines, and then—crash! a sheet of blinding flashes, a roll of stifling smoke, and, when the air cleared, a long empty space in the front line of the dervishes, and the ground strewn as with the drapery of two hundred dead men.

In an instant the gap had been filled and the mighty horde had come on again, but again and again and yet again they had been swept down before the solid rock of the British forces like the spent waves of an angry sea.

At one moment a flag, silver-white and glistening in the sun, had been seen coming up behind. It had seemed to float here, there, and everywhere, like a disembodied spirit, through the churning breakers of the enemy, and while the swarthy Arab who carried it had cried out over the thunder of battle that it was the Angel of Death leading them to victory or Paradise, the dervishes had screamed "Allah! Allah!" and poured themselves afresh on to the British lines.

But crash, crash, crash! the British rifles had spoken, and the dervishes had fallen in long swathes, like grass before the scythe, until the broad field had been white with its harvest of the dead.

The sham fight had lasted a full hour, and until it was over the vast multitude of spectators had been as one immense creature that trembled without drawing breath. But then the Umpire's big bell had been rung again, the dead men had leapt briskly to their feet and scampered back to paddock, and a rustling breeze of laughter, half merriment and half surprise, had swept over the pavilion and the field.

This was another moment at which the atmosphere had seemed to change. Some one at the foot of the pavilion had said—

"Whew: What a battle it must have been!"

And some one else had said—

"Don't call it a battle, sir—call it an execution."

And then a third, an Englishman, in the uniform of an Egyptian Commandant of Police, had cried—

"If it had gone the other way, though—if the Mahdists had beaten us that day at Omdurman, what would have happened to Egypt then?"

"Happened?" the first speaker had answered—he was the English Adviser to one of the Egyptian Ministers—"What would have happened to Egypt, you say? Why, there wouldn't have been a dog to howl for a lost master by this time."

Lord Nuneham had heard the luckless words, and his square-hewn jaw had grown harder and more grim. Unfortunately the Egyptian Ministers, the Sheikhs, the Pashas, the Beys, and the Effendis had heard them also, and by the mysterious law of nature that sends messages over a trackless desert, the last biting phrase had seemed to go like an electric whisper through the thick line of the red-capped Cairenes around the arena.

In the native mind it altered everything in an instant; transformed the sham battle into a serious incident; made it an insult, an outrage, a pre-arranged political innuendo, something got up by the British Army of Occupation or perhaps by the Consul-General himself to rebuke the Egyptians for the fires of disaffection that had smouldered in their midst for years, and to say as by visible historiography—-

"See, that's what England saved Egypt from—that horde of Allah-intoxicated fanatics who would have cut off the heads of your Khedives, tortured and pillaged your Pashas, flogged your Effendis, made slaves of your fellaheen, or swept your whole nation into the Nile."

Every soldier on the field had distinguished himself that day—the British by his bull-dog courage, the Soudanese by fighting as dervishes like demons, the Egyptian by standing his ground like a man; but not even when young Colonel Lord, the most popular Englishman in Egypt, the one officer of English blood who was beloved by the Egyptians—not even when he had come riding back to paddock after a masterly handling of his men, sweating but smiling, his horse blowing and spent, the people on the pavilion receiving him with shouts and cheers, the clapping of hands, and the fluttering of handkerchiefs—not even then had the Cairenes at the edge of the arena made the faintest demonstration. Their opportunity came a few minutes later, and, sullen and grim under the gall of their unfounded suspicion, they seized it in fierce and rather ugly fashion.

Hardly had the last man left the field when a company of mounted police came riding down the fringe of it, followed by a carriage drawn by two high-stepping horses, between a body-guard of Egyptian soldiers. They drew up in front of the box occupied by the kinsman of the Khedive, and instantly the Cairenes made a rush for it, besieging the barrier on either side, and even clambering on each other's shoulders as human scaffolding from which to witness the departure of the Prince.

Then the Prince came out, a rather slack, feeble, ineffectual-looking man, and there were the ordinary salutations prescribed by custom. First the cry from the police in Turkish and in unison, "Long live our Master!" being cheers for the Khedive whose representative the Prince was, and then a cry in Arabic for the Prince himself. The Prince touched his forehead, stepped into his carriage, and was about to drive off when, without sign or premeditation, by one of those mischievous impulses which the devil himself inspires, there came a third cry never heard on that ground before. In a lusty, guttural voice, a young man standing on the shoulders of another man, both apparently students of law or medicine, shouted over the heads of the people, "Long live Egypt!" and in an instant the cry was repeated in a deafening roar from every side.

The Prince signalled to his body-guard and his carriage started, but all the way down the line of the enclosure, where the red-capped Egyptians were still standing in solid masses, the words cracked along like fireworks set alight.

The people on the great pavilion watched and listened, and to the larger part of them, who were British subjects, and to the Officers, Advisers, and Under-Secretaries, who were British officials, the cry was like a challenge which seemed to say, "Go home to England; we are a nation of ourselves, and can do without you." For a moment the air tingled with expectancy, and everybody knew that something else was going to happen. It happened instantly, with that promptness which the devil alone contrives.

Almost as soon as the Prince's company had cleared away, a second carriage, that of the British Consul-General, came down the line to the pavilion, with a posse of native police on either side and a sais running in front. Then from his seat in the centre Lord Nuneham rose and stepped down to the arena, shaking hands with people as he passed, gallant to the ladies as befits an English gentleman, but bearing himself with a certain brusque condescension towards the men, all trying to attract his attention—a medium-sized yet massive person, with a stern jaw and steady grey eyes, behind which the cool brain was plainly packed in ice—a man of iron who had clearly passed through the pathway of life with a firm, high step.

The posse of native police cleared a way for him, and under the orders of an officer rendered military honours, but that was not enough for the British contingent in the fever of their present excitement. They called for three cheers for the King, whose representative the Consul-General was in Egypt, and then three more for Lord Nuneham, giving not three but six, with a fierceness that grew more frantic at every shout, and seemed to say, as plainly as words could speak, "Here we are, and here we stay."

The Egyptians listened in silence, some of them spitting as a sign of contempt, until the last cheer was dying down, and then the lusty guttural voice cried again, "Long live Egypt!" and once more the words rang like a rip-rap down the line.

It was noticed that the stern expression of Lord Nuneham's face assumed a death-like rigidity, that he took out a pocket-book, wrote some words, tore away a leaf, handed it to a native servant, and then, with an icy smile, stepped into his carriage. Meantime the British contingent were cheering again with yet more deafening clamour, and the rolling sound followed the Consul-General as he drove away. But the shout of the Egyptians followed him too, and when he reached the high road the one was like muffled drums at a funeral far behind, while the other was like the sharp crack of Maxim guns that were always firing by his side.

The sea of muslin, ribbons, flowers, and feathers in the pavilion had broken up by this time, the light was striking level in people's eyes, the west was crimsoning with sunset tints, the city was red on the tips of its minarets and ablaze on the bare face of its insurgent hills, and the Nile itself, taking the colouring of the sky, was lying like an old serpent of immense size which had stretched itself along the sand to sleep.

CHAPTER II

General Graves's daughter had been at the sports that day, sitting in the chair immediately behind Lord Nuneham's. Her name was Helena, and she was a fine, handsome girl in the early twenties, with coal-black hair, very dark eyes, a speaking face, and a smile like eternal sunshine, well grown, splendidly developed, and carrying herself in perfect equipoise with natural grace and a certain swing when she walked.

Helena Graves was to marry Lord Nuneham's son, Colonel Gordon Lord, and during the progress of the sham fight she had had eyes for nobody else. She had watched him when he had entered the field, sitting solid on his Irish horse, which was stepping high and snorting audibly; when at the "Fire" he had stood behind the firing line and at the "Cease fire" galloped in front; when he had threaded his forces round and round, north, south, and west, in and out as in a dance, so that they faced the enemy on every side; when somebody had blundered and his cavalry had been caught in a trap and he had had to ride without sword or revolver through a cloud of dark heads that had sprung up as if out of the ground; and above all, when his horse had stumbled and he had fallen, and the dervishes, forgetting that the battle was not a real one, had hurled their spears like shafts of forked lightning over his head. At that moment she had forgotten all about the high society gathered in a brilliant throng around her, and had clutched the Consul-General's chair convulsively, breathing so audibly that he had heard her, and lowering the glasses through which he had watched the distant scene, had patted her arm and said—

"He's safe—don't be afraid, my child."

When the fight was over her eyes were radiant, her cheeks were like a conflagration, and, notwithstanding the ugly incident attending the departure of the Prince and Lord Nuneham, her face was full of a triumphant joy as she stepped down to the green, where Colonel Lord, who was waiting for her, put on her motor cloak—she had come in her automobile—and helped her to fix the light veil which in her excitement had fallen back from her hat and showed that she was still blushing up to the roots of her black hair.

Splendid creature as she was, Colonel Lord was a match for her. He was one of the youngest Colonels in the British Army, being four-and-thirty, of more than medium height, with crisp brown hair, and eyes of the flickering, steel-like blue that is common among enthusiastic natures, especially when they are soldiers—a man of unmistakable masculinity, yet with that vague suggestion of the woman about him which, sometimes seen in a manly face, makes one say, without knowing any of the circumstances, "That man is like his mother, and whatever her ruling passion is, his own will be, only stronger, more daring, and perhaps more dangerous."

"They're a lovely pair," the women were saying of them as they stood together, and soon they were surrounded by a group of people, some complimenting Helena, others congratulating Gordon, all condemning the demonstration which had cast a certain gloom over the concluding scene.

"It was too exciting, too fascinating; but how shameful—that conduct of the natives. It was just like a premeditated insult," said a fashionable lady, a visitor to Cairo; and then an Englishman—it was the Adviser who had spoken the first unlucky words—said promptly—

"So it was—it must have been. Didn't you see how it was all done at a pre-concerted signal?"

"I'm not surprised. I've always said we English in Egypt are living on the top of a volcano," said a small, slack, grey-headed man, a Judge in the native courts; and then the Commandant of Police, a somewhat pompous person, said bitterly—

"We saved their country from bankruptcy, their backs from the lash, and their stomachs from starvation, and now listen: 'Long live Egypt!'"

At that moment a rather effusive American lady came up to Helena and said—

"Don't you ever recognise your friends, dear? I tried to catch your eye during the fight, but a certain officer had fallen, and of course nobody else existed in the world."

"Let us make up our minds to it—we are not liked," the Judge was saying. "Naturally we were popular as long as we were plastering the wounds made by tyrannical masters, but the masters are dead and the patient is better, so the doctor is found to be a bore."

At that moment an Egyptian Princess, famous for her wit and daring, came down the pavilion steps. She was one of the few Egyptian women who frequented mixed society and went about with uncovered face—a large person, with plump, pallid cheeks, very voluble, outspoken, and quick-tempered, a friend and admirer of the Consul-General and a champion of the English rule. Making straight for Helena, she said—

"Goodness, child, is it your face I see or the light of the moon? The battle? Oh yes, it was beautiful, but it was terrible, and thank the Lord it is over. But tell me about yourself, dear. You are desperately in love, they say, and no wonder. I'm in love with him myself, I really am, and if ... Oh, you're there, are you? Well, I'm telling Helena I'm in love with you. Such strength, such courage—pluck, you call it, don't you?"

Helena had turned to answer the American lady, and Gordon, whose eyes had been on her as if waiting for her to speak, whispered to the Princess—

"Isn't she looking lovely to-day, Princess?"

"Then why don't you tell her so?" said the Princess.

"Hush!" said Gordon, whereupon the Princess said—

"My goodness, what ridiculous creatures men are! What cowards, too! As brave as lions before a horde of savages, but before a woman—mon Dieu!"

"Yes," said the Judge in his slow, shrill voice, "they are fond of talking of the old book of Egypt, yet the valley of the Nile is strewn with the tombs of Egyptians who have perished under their hard taskmasters from the Pharaohs to the Pashas. Can't they hear the murmur of the past about them? Have they no memory if they have no gratitude?"

At the last words General Graves came up to the group, looking hot and excited, and he said—

"Memory! Gratitude! They're a nation of ingrates and fools."

"What's that?" asked the Princess.

"Pardon me, Princess. I say the demonstration of your countrymen to-day is an example of the grossest ingratitude."

"You're quite right, General. But Ma'aleysh! (No matter!) The barking of dogs doesn't hurt the clouds."

"And who are the dogs in this instance, Princess?" said a thin-faced Turco-Egyptian, with a heavy moustache, who had been congratulating Colonel Lord.

"Your Turco-Egyptian beauties who would set the country ablaze to light their cigarettes," said the Princess. "Children, I call them. Children, and they deserve the rod. Yes, the rod—and serve them right. Excuse the word. I know! I tell you plainly, Pasha."

"And the clouds are the Consul-General, I suppose?"

"Certainly, and he's so much above them that they can't even see he's the sun in their sky, the stupids."

Whereupon the Pasha, who was the Egyptian Prime Minister under a British Adviser, said with a shrug and a dubious smile—

"Your sentiments are beautiful, but your similes are a little broken, Princess."

"Not half so much broken as your treasury would have been if the English hadn't helped it," said the Princess, and when the Pasha had gone off with a rather halting laugh, she said—

"Ma'aleysh! When angels come the devils take their leave. I don't care. I say what I think. I tell the Egyptians the English are the best friends Egypt ever had, and Nuneham is their greatest ruler since the days of Joseph. But Adam himself wasn't satisfied with Paradise, and it's no use talking. 'Don't throw stones into the well you drink from,' I say. But serve you right, you English. You shouldn't have come. He who builds on another's land brings up another's child. Everybody is excited about this sedition, and even the harem are asking what the Government is going to do. Nuneham knows best, though. Leave him alone. He'll deal with these half-educated upstarts. Upstarts—that's what I call them. Oh, I know! I speak plainly!"

"I agree with the Princess," chimed the Judge. "What is this unrest among the Egyptians due to? The education we ourselves have given them."

"Yes, teach your dog to snap and he'll soon bite you."

"These are the tares in the harvest we are reaping, and perhaps our Western grain doesn't suit this Eastern desert."

"Should think it doesn't, indeed. 'Liberty,' 'Equality,' 'Fraternity,' 'representative Institutions'! If you English come talking this nonsense to the Egyptians what can you expect? Socialism, is it? Well, if I am to be Prince, and you are to be Prince, who is to drive the donkey? Excuse the word! I know! I tell you plainly. Good-bye, my dear! You are looking perfect to-day. But then you are so happy. I can see when young people are in love by their eyes, and yours are shining like moons. After all, your Western ways are best. We choose the husbands for our girls, thinking the silly things don't know what is good for them, and the chicken isn't wiser than the hen; but it's the young people, not the old ones, who have to live together, so why shouldn't they choose for themselves?"

At that instant there passed from some remote corner of the grounds a brougham containing two shrouded figures in close white veils, and the Princess said—

"Look at that, now—that relic of barbarism! Shutting our women up like canaries in a cage, while their men are enjoying the sunshine. Life is a dancing girl—let her dance a little for all of us."

The Princess was about to go when General Graves appealed to her. The Judge had been saying—

"I should call it a religious rather than a political unrest. You may do what you will for the Moslem, but he never forgets that the hand which bestows his benefits is that of an infidel."

"Yes, we're aliens here, there's no getting over it," said the Adviser.

And the General said, "Especially when professional fanatics are always reminding the Egyptians that we are not Mohammedans. By the way, Princess, have you heard of the new preacher, the new prophet, the new Mahdi, as they say?"

"Prophet! Mahdi! Another of them?"

"Yes, the comet that has just appeared in the firmament of Alexandria."

"Some holy man, I suppose. Oh, I know. Holy man indeed! Shake hands with him and count your rings, General! Another impostor riding on the people's backs, and they can't see it, the stupids! But the camel never can see his hump—not he! Good-bye, girl. Get married soon and keep together as long as you can. Stretch your legs to the length of your bed, my dear—why shouldn't you? Say good-bye to Gordon? ... Certainly, where is he?"

At that moment Gordon was listening with head down to something the General was saying with intense feeling.

"The only way to deal with religious impostors who sow disaffection among the people is to suppress them with a strong hand. Why not? Fear of their followers? They're fit for nothing but to pray in their mosques, 'Away with the English, O Lord, but give us water in due measure!' Fight? Not for an instant! There isn't an ounce of courage in a hundred of them, and a score of good soldiers would sweep all the native Egyptians of Alexandria into the sea."

Then Gordon, who had not yet spoken, lifted his head and answered, in a rather nervous voice—

"No, no, no, sir! Ill usage may have made these people cowards in the old days, but proper treatment since has made them men, and there wasn't an Egyptian fellah on the field to-day who wouldn't have followed me into the jaws of death if I had told him to. As for our being aliens in religion"—the nervous voice became louder and at the same time more tremulous—"that isn't everything. We're aliens in sympathy and brotherhood and even in common courtesy as well. What is the honest truth about us? Here we are to help the Egyptians to regenerate their country, yet we neither eat nor drink nor associate with them. How can we hope to win their hearts while we hold them at arm's length? We've given them water, yes, water in abundance, but have we given them—love?"

The woman in Gordon had leapt out before he knew it, and he had swung a little aside as if ashamed, while the men cleared their throats, and the Princess, notwithstanding that she had been abusing her own people, suddenly melted in the eyes, and muttered to herself, "Oh, our God!" and then, reaching over to kiss Helena, whispered in her ear—

"You've got the best of the bunch, my dear, and if England would only send us a few more of his sort we should hear less of 'Long live Egypt.' Now, General, you can see me to my carriage if you would like to. By-bye, young people!"

At that moment the native servant to whom the Consul-General had given the note came up and gave it to Gordon, who read it and then handed it to Helena. It ran—

"Come to me immediately. Have something to say to you.—N."

"We'll drive you to the Agency in the car," said Helena, and they moved away together.

In a crowded lane at the back of the pavilion people were clamouring for their carriages and complaining of the idleness and even rudeness of the Arab runners, but Helena's automobile was brought up instantly, and when it was moving off, with the General inside, Helena at the wheel, and Gordon by her side, the natives touched their foreheads to the Colonel and said, "Bismillah!"

As soon as the car was clear away, and Gordon was alone with Helena for the first time, there was one of those privateering passages of love between them which lovers know how to smuggle through even in public and the eye of day.

"Well!"

"Well!"

"Everybody has been saying the sweetest things to me and you've never yet uttered a word."

"Did you really expect me to speak—there—before all those people? But it was splendid, glorious, magnificent!" And then, the steering-wheel notwithstanding, her gauntletted left hand went down to where his right hand was waiting for it.

Crossing the iron bridge over the river, they drew up at the British Agency, a large, ponderous, uninspired edifice, with its ambuscaded back to the city and its defiant front to the Nile, and there, as Gordon got down, the General, who still looked hot and excited, said—

"You'll dine with us to-night, my boy—usual hour, you know?"

"With pleasure, sir," said Gordon, and then Helena leaned over and whispered—

"May I guess what your father is going to talk about?"

"The demonstration?"

"Oh no!"

"What then?"

"The new prophet at Alexandria."

"I wonder," said Gordon, and with a wave of the hand he disappeared behind a screen of purple blossom, as Helena and the General faced home.

Their way lay up through the old city, where groups of aggressive young students, at sight of the General's gold-laced cap, started afresh the Kentish fire of their "Long live Egypt," up and up until they reached the threatening old fortress on the spur of the Mokattani Hills, and then through the iron-clamped gates to the wide courtyard where the mosque of Mohammed Ali, with its spikey minarets, stands on the edge of the ramparts like a cock getting ready to crow, and drew up at the gate of a heavy-lidded house which looks sleepily down on the city, the sinuous Nile, the sweeping desert, the preponderating Pyramids, and the last saluting of the sun. Then as Helena rose from her seat she saw that the General's head had fallen back and his face was scarlet.

"Father, you are ill."

"Only a little faint—I'll be better presently."

But he stumbled in stepping out of the car, and Helena said—

"You are ill, and you must go to bed immediately, and let me put Gordon off until to-morrow."

"No, let him come. I want to hear what the Consul-General had to say to him."

In spite of himself he had to go to bed, though, and half-an-hour later, having given him a sedative, Helena was saying—

"You've over-excited yourself again, Father. You were anxious about Gordon when his horse fell and those abominable spears were flying about."

"Not a bit of it. I knew he would come out all right. The fighting devil isn't civilised out of the British blood yet, thank God! But those Egyptians at the end—the ingrates, the dastards!"

"Father!"

"Oh, I am calm enough now—don't be afraid, girl. I was sorry to hear Gordon standing up for them, though. A soldier every inch of him, but how unlike his father! Never saw father and son so different. Yet so much alike too! Fighting men both of them, Hope to goodness they'll never come to grips. Heavens! that would be a bad day for all of us."

And then drowsily, under the influence of the medicine—

"I wonder what Nuneham wanted with Gordon! Something about those graceless tarbooshes, I suppose. He'll make them smart for what they've done to-day. Wonderful man, Nuneham! Wonderful!"

CHAPTER III

John Nuneham was the elder son of a financier of whose earlier life little or nothing was ever learned. What was known of his later life was that he had amassed a fortune by colonial speculation, bought a London newspaper, and been made a baronet for services to his political party. Having no inclination towards journalism the son became a soldier, rose quickly to the rank of Brevet-Major, served several years with his regiment abroad, and at six-and-twenty went to India as Private Secretary to the Viceroy, who, quickly recognising his natural tendency, transferred him to the administrative side and put him on the financial staff. There he spent five years with conspicuous success, obtaining rapid promotion, and being frequently mentioned in the Viceroy's reports to the Foreign Minister.

Then his father died, without leaving a will, as the cable of the solicitors informed him, and he returned to administer the estate. Here a thunderbolt fell on him, for he found a younger brother, with whom he had nothing in common and had never lived at peace, preparing to dispute his right to his father's title and fortune on the assumption that he was illegitimate, that is to say, was born before the date of the marriage of his parents.

The allegation proved to be only too well founded, and as soon as the elder brother had recovered from the shock of the truth, he appealed to the younger one to leave things as they found them.

"After all, a man's eldest son is his eldest son—let matters rest," he urged; but his brother was obdurate. "Nobody knows what the circumstances may have been—is there no ground of agreement?" but his brother could see none.

"You can take the inheritance, if that's what you want, but let me find a way to keep the title so as to save the family and avoid scandal"; but his brother was unyielding.

"For our father's sake—it is not for a man's sons to rake up the dead past of his forgotten life"; but the younger brother could not be stirred.

"For our mother's sake—nobody wants his mother's good name to be smirched, least of all when she's in her grave"; but the younger brother remained unmoved.

"I promise never to marry. The title shall end with me. It shall return to you or to your children"; but the younger brother would not listen.

"England is the only Christian country in the world in which a man's son is not always his son—for God's sake let me keep my father's name?"

"It is mine, and mine alone," said the younger brother, and then a heavy and solitary tear, the last he was to shed for forty years, dropped slowly down John Nuneham's hard-drawn face, for at that instant the well of his heart ran dry.

"As you will," he said. "But if it is your pride that is doing this I shall humble it, and if it is your greed I shall live long enough to make it ashamed."

From that day forward he dedicated his life to one object only, the founding of a family that should far eclipse the family of his brother, and his first step towards that end was to drop his father's surname in the register of his regiment and assume his mother's name of Lord.

At that moment England with two other European Powers had, like Shadrach, Meshech, and Abednego, entered the fiery furnace of Egyptian affairs, though not so much to withstand as to protect the worship of the golden image. A line of Khedives, each seeking his own advantage, had culminated in one more unscrupulous and tyrannical than the rest, who had seized the lands of the people, borrowed money upon them in Europe, wasted it in wicked personal extravagance, as well as in reckless imperial expenditure that had not yet had time to yield a return, and thus brought the country to the brink of ruin, with the result that England was left alone at last to occupy Egypt, much as Rome occupied Palestine, and to find a man to administer her affairs in a position analogous to that of Pontius Pilate. It found him in John Lord, the young Financial Secretary who had distinguished himself in India.

His task was one of immense difficulty, for though nominally no more than the British Consul-General, he was really the ruler of the country, being representative of the sovereign whose soldiers held Egypt in their grip. Realising at once that he was the official receiver to a bankrupt nation, he saw that his first duty was to make it solvent. He did make it solvent. In less than five years Egypt was able to pay her debt to Europe. Therefore Europe was satisfied, England was pleased, and John Lord was made Knight of the Order of St. Michael and St. George.

Then he married a New England girl whom he had met in Cairo, daughter of a Federal General in the Civil War, a gentle creature, rather delicate, a little sentimental, and very religious.

During the first years their marriage was childless, and the wife, seeing with a woman's sure eyes that her husband's hope had been for a child, began to live within herself, and to weep when no one could see. But at last a child came, and it was a son, and she was overjoyed and the Consul-General was content. He allowed her to christen the child by what name she pleased, so she gave him the name of her great Christian hero, Charles George Gordon. They called the boy Gordon, and the little mother was very happy.

But her health became still more delicate, so a nurse had to be looked for, and they found one in an Egyptian woman—with a child of her own—who, by power of a pernicious law of Mohammedan countries, had been divorced through no fault of hers, at the whim of a husband who wished to marry another wife. Thus Hagar, with her little Ishmael, became foster-mother to the Consul-General's son, and the two children were suckled together and slept in the same cot.

Years passed, during which the boy grew up like a little Arab in the Englishman's house, while his mother devoted herself more and more to the exercises of her religion, and his father, without failing in affectionate attention to either of them, seemed to bury his love for both too deep in his heart and to seal it with a seal, although the Egyptian nurse was sometimes startled late at night by seeing the Consul-General coming noiselessly into her room before going to his own, to see if it was well with his child.

Meantime as ruler of Egypt the Consul-General was going from strength to strength, and seeing that the Nile is the most wonderful river in the world and the father of the country through which it flows, he determined that it should do more than moisten the lips of the Egyptian desert while the vast body lay parched with thirst. Therefore he took engineers up to the fork of the stream where the clear and crystal Blue Nile of Khartoum, tumbling down in mighty torrents from the volcanic gorges of the Abyssinian hills, crosses the slow and sluggish White Nile of Omdurman, and told them to build dams, so that the water should not be wasted into the sea, but spread over the arid land, leaving the glorious sun of Egypt to do the rest.

The effect was miraculous. Nature, the great wonder-worker, had come to his aid, and never since the Spirit of God first moved upon the face of the waters had anything so marvellous been seen. The barren earth brought forth grass and the desert blossomed like a rose. Land values increased; revenues were enlarged; poor men became rich; rich men became millionaires; Egypt became a part of Europe; Cairo became a European city; the record of the progress of the country began to sound like a story from the "Arabian Nights," and the Consul-General's annual reports read like fresh chapters out of the Book of Genesis, telling of the creation of a new heaven and a new earth. The remaking of Egypt was the wonder of the world; the faces of the Egyptians were whitened; England was happy, and Sir John Lord was made a baronet. His son had gone to school in England by this time, and from Eton he was to go on to Sandhurst and to take up the career of a soldier.

Then, thinking the Englishman's mission on foreign soil was something more than to make money, the Consul-General attempted to regenerate the country. He had been sent out to re-establish the authority of the Khedive, yet he proceeded to curtail it; to suppress the insurrection of the people, yet he proceeded to enlarge their liberties. Setting up a high standard of morals, both in public and private life, he tolerated no trickery. Finding himself in a cockpit of corruption, he put down bribery, slavery, perjury, and a hundred kinds of venality and intrigue. Having views about individual justice and equal rights before the law, he cleansed the law courts, established a Christian code of morals between man and man, and let the light of Western civilisation into the mud hut of the Egyptian fellah.

Mentally, morally, and physically his massive personality became the visible soul of Egypt. If a poor man was wronged in the remotest village he said, "I'll write to Lord," and the threat was enough. He became the visible conscience of Egypt, too, and if a rich man was tempted to do a doubtful deed he thought of "the Englishman" and the doubtful deed was not done.

The people at the top of the ladder trusted him, and the people at the bottom, a simple, credulous, kindly race, who were such as sixty centuries of mis-government had made them, touched their breasts, their lips, and their foreheads at the mention of his name, and called him "The Father of Egypt." England was proud, and Sir John Lord was made a peer.

When the King's letter reached him he took it to his wife, who now lay for long hours every day on the couch in the drawing-room, and then wrote to his son, who had left Sandhurst and was serving with his regiment in the Soudan, but he said nothing to anybody else, and left even his secretary to learn the great news through the newspapers.

He was less reserved when he came to select his title, and remembering his brother he found a fierce joy in calling himself by his father's name, thinking he had earned the right to it. Twenty-five years had passed since he had dedicated his life to the founding of a family that should eclipse and even humiliate the family of his brother, and now his secret aim was realised. He saw a long line succeeding him, his son, and his son's son, and his son's son's son, all peers of the realm, and all Nunehams. His revenge was sweet; he was very happy.

CHAPTER IV

If Lord Nuneham had died then, or if he had passed away from Egypt, he would have left an enduring fame as one of the great Englishmen who twice or thrice in a hundred years carve their names on the granite page of the world's history; but he went on and on, until it sometimes looked as if in the end it might be said of him, in the phrase of the Arab proverb, that he had written his name in water.

Having achieved one object of ambition, he set himself another, and having tasted power he became possessed by the lust of it. Great men had been in England when he first came to Egypt, and he had submitted to their instructions without demur, but now, wincing under the orders of inferior successors, he told himself, not idly boasting, that nobody in London knew his work as well as he did, and he must be liberated from the domination of Downing Street. The work of emancipation was delicate but not difficult. There was one power stronger than any Government, whereby public opinion might be guided and controlled—the press.

The British Consul-General in Cairo was in a position of peculiar advantage for guiding and controlling the press. He did guide and control it. What he thought it well that Europe should know about Egypt that it knew, and that only. The generally ill-informed public opinion in England was corrected; the faulty praise and blame of the British press was set right; within five years London had ceased to send instructions to Cairo; and when a diplomatic question created a fuss in Parliament the Consul-General was heard to say—

"I don't care a rush what the Government think, and I don't care a straw what the Foreign Minister says; I have a power stronger than either at my back—the public."

It was true, but it was also the beginning of the end. Having attained to absolute power, he began to break up from the seeds of dissolution which always hide in the heart of it. Hitherto he had governed Egypt by guiding a group of gifted Englishmen who as Secretaries and Advisers had governed the Egyptian Governors; but now he desired to govern everything himself. As a consequence the gifted men had to go, and their places were taken by subordinates whose best qualification was their subservience to his strong and masterful spirit.

Even that did not matter as long as his own strength served him. He knew and determined everything, from the terms of treaties with foreign Powers to the wages of the Khedive's English coachman. With five thousand British bayonets to enforce his will, he said to a man, "Do that," and the man did it, or left Egypt without delay. No Emperor or Czar or King was ever more powerful, no Pope more infallible; but if his rule was hard, it was also just, and for some years yet Egypt was well governed.

"When a fish goes bad," the Arabs say, "is it first at the head or at the tail?" As Lord Nuneham grew old, his health began to fail, and he had to fall back on the weaklings who were only fit to carry out his will. Then an undertone of murmuring was heard in Egypt. The Government was the same, yet it was altogether different. The hand was Esau's, but the voice was Jacob's. "The millstones are grinding," said the Egyptians, "but we see no flour."

The glowing fire of the great Englishman's fame began to turn to ashes, and a cloud no bigger than a man's hand appeared in the sky. His Advisers complained to him of friction with their Ministers; his Inspectors, returning from tours in the country, gave him reports of scant courtesy at the hands of natives, and to account for their failures they worked up in his mind the idea of a vast racial and religious conspiracy. The East was the East; the West was the West; Moslem was Moslem; Christian was Christian; Egyptians cared more about Islam than they did about good government, and Europeans in the valley of the Nile, especially British soldiers and officials, were living on the top of a volcano.

The Consul-General listened to them with a sour smile, but he believed them and blundered. He was a sick man now, and he was not really living in Egypt any longer—he was only sleeping at the Agency; and he thought he saw the work of his lifetime in danger of being undone. So, thinking to end fanaticism by one crushing example, he gave his subordinates an order like that which the ancient King of Egypt gave to the midwives, with the result that five men were hanged and a score were flogged before their screaming wives and children for an offence that had not a particle of religious or political significance.

A cry of horror went up through Egypt; the Consul-General had lost it; his forty years of great labour had been undone in a day.

As every knife is out when the bull is down, so the place-hunting Pashas, the greedy Sheikhs, and the cruel Governors whose corruptions he had suppressed found instruments to stab him, and the people who had kissed the hand they dared not bite thought it safe to bite the hand they need not kiss. He had opened the mouths of his enemies, and in Eastern manner they assailed him first by parables. Once there had been a great English eagle; its eyes were clear and piercing; its talons were firm and relentless in their grip; yet it was a proud and noble bird; it held its own against East and West, and protected all who took refuge under its wing; but now the eagle had grown old and weak; other birds, smaller and meaner, had deprived it of its feathers and picked out its eyes, and it had become blind and cruel and cowardly and sly—would nobody shoot it or shut it up in a cage?

Rightly or wrongly, the Consul-General became convinced that the Khedive was intriguing against him, and one day he drove to the royal palace and demanded an audience. The interview that followed was not the first of many stormy scenes between the real governor of Egypt and its nominal ruler, and when Lord Nuneham strode out with his face aflame, through the line of the quaking bodyguard, he left the Khedive protesting plaintively to the people of his court that he would sell up all and leave the country. At that the officials put their heads together in private, concluded that the present condition could not last, and asked themselves how, since it was useless to expect England to withdraw the Consul-General, it was possible for Egypt to get rid of him.

By this time Lord Nuneham, in the manner of all strong men growing weak, had begun to employ spies, and one day a Syrian Christian told him a secret story. He was to be assassinated. The crime was to be committed in the Opera House, under the cover of a general riot, on the night of the Khedive's State visit, when the Consul-General was always present. As usual the Khedive was to rise at the end of the first act and retire to the saloon overlooking the square; as usual he was to send for Lord Nuneham to follow him, and the moment of the Khedive's return to his box was to be the signal for a rival demonstration of English and Egyptians that was to end in the Consul-General's death. There was no reason to believe the Khedive himself was party to the plot, or that he knew anything about it, yet none the less it was necessary to stay away, to find an excuse—illness at the last moment—anything.

Lord Nuneham was not afraid, but he sent up to the Citadel for General Graves, and arranged that a battalion of infantry and a battery of artillery were to be marched down to the Opera Square at a message over the telephone from him.

"If anything happens, you know what to do," he said; and the General knew perfectly.

Then the night came, and the moment the Khedive left his palace the Consul-General heard of it. A moment later a message was received at the Citadel, and a quarter of an hour afterwards Lord Nuneham was taking his place at the Opera. The air of the house tingled with excitement, and everything seemed to justify the Syrian's story.

Sure enough, at the end of the first act the Khedive rose and retired to the saloon, and sure enough at the next moment the Consul-General was summoned to follow him. His Highness was very gracious, very agreeable, all trace of their last stormy interview being gone; and gradually Lord Nuneham drew him up to the windows overlooking the public square.

There, under the sparkling light of a dozen electric lamps, in a solid line surrounding the Opera House, stood a battalion of infantry, with the guns of the artillery facing outward at every corner; and at sight of them the Khedive caught his breath and said—

"What is the meaning of this, my lord?"

"Only a little attention to your Highness," said the Consul-General in a voice that was intended to be heard all over the room.

At that instant somebody came up hurriedly and whispered to the Khedive, who turned ashen white, ordered his carriage, and went home immediately.

Next morning at eleven, Lord Nuneham, with the same force drawn up in front of Abdeen Palace, went in to see the Khedive again.

"There's a train for Alexandria at twelve," he said, "and a steamer for Constantinople at five—your Highness will feel better for a little holiday in Europe!" and half-an-hour afterwards the Khedive, accompanied by several of his Court officials, was on his way to the railway station, with the escort, in addition to his own bodyguard, of a British regiment whose band was playing the Khedivial hymn.

He had got rid of the Khedive at a critical juncture, but he had still to deal with a sovereign that would not easily be chloroformed into silence. The Arabic press, to which he had been the first to give liberty, began to attack him openly, to vilify him, and systematically to misrepresent his actions, so that he who had been the great torch-bearer of light in a dark country saw himself called the Great Adventurer, the Tyrant, the Assassin, the worst Pharaoh Egypt had ever known—a Pharaoh surrounded by a kindergarten of false prophets, obsessed by preposterous fears of assassination and deluded by phantoms of fanaticism.

His subordinates told him that these hysterical tirades were inflaming the whole of Egypt; that their influence was in proportion to their violence; that the huge, untaught mass of the Egyptian people were listening to them; that there was not an ignorant fellah possessed of one ragged garment who did not go to the coffee-house at night to hear them read; that the lives of British officials were in peril; and that the promulgation of sedition must be stopped, or the British governance of the country could not go on.

A sombre fire shone in the Consul-General's eyes while he heard their prophecy, but he believed it all the same, and when he spoke contemptuously of incendiary articles as froth, and they answered that froth could be stained with blood, he told himself that if fools and ingrates spouting nonsense in Arabic could destroy whatever germs of civilisation he had implanted in Egypt, the doctrine of the liberty of the press was all moonshine.

And so, after sinister efforts to punish the whole people for the excesses of their journalists by enlarging the British army and making the country pay the expense, he found a means to pass a new press law, to promulgate it by help of the Prime Minister, now Regent in the Khedive's place, and to suppress every native newspaper in Egypt in one day. By that blow the Egyptians were staggered into silence, the British officials went about with stand-off manners and airs of conscious triumph, and Lord Nuneham himself, mistaking violence for power, thought he was master of Egypt once more.

But low, very low on the horizon a new planet now rose in the firmament. It was not the star of a Khedive jealous of Nuneham's power, nor of an Egyptian Minister chafing under the orders of his Under-Secretary, nor yet of a journalist vilifying England and flirting with France, but that of a simple Arab in turban and caftan, a swarthy son of the desert whose name no man had heard before, and it was rising over the dome of the mosque within whose sacred precincts neither the Consul-General nor his officials could intrude, and where the march of British soldiers could not be made. There a reverberation was being heard, a now voice was going forth, and it was echoing and re-echoing through the hushed chambers that were the heart of Islam.

When Lord Nuneham first asked about the Arab he was told that the man was one Ishmael Ameer, out of the Libyan Desert, a carpenter's son, and a fanatical, backward, unenlightened person of no consequence whatever; but with his sure eye for the political heavens, the Consul-General perceived that a planet of no common magnitude had appeared in the Egyptian firmament, and that it would avail him nothing to have suppressed the open sedition of the newspapers if he had only driven it underground, into the mosques, where it would be a hundredfold more dangerous..

If a political agitation was not to be turned into religious unrest, if fanaticism was not to conquer civilisation and a holy war to carry the country back to its old rotten condition of bankruptcy and barbarity, that man out of the Libyan Desert must be put down. But how and by whom? He himself was old—more than seventy years old—his best days were behind him, the road in front of him must be all downhill now; and when he looked around among the sycophants who said, "Yes, my lord," "Excellent, my lord," "The very thing, my lord," for some one to fight the powers of darkness that were arrayed against him, he saw none.

It was in this mood that he had gone to the sham fight, merely because he had to show himself in public; and there, sitting immediately in front of the fine girl who was to be his daughter soon, and feeling at one moment her quick breathing on his neck, he had been suddenly caught up by the spirit of her enthusiasm and had seen his son as he had never seen him before. Putting his glasses to his eyes he had watched him—he and (as it seemed) the girl together. Such courage, such fire, such resource, such insight, such foresight! It must be the finest brain and firmest character in Egypt, and it was his own flesh and blood, his own son Gordon!

Hitherto his attitude towards Gordon had been one of placid affection, compounded partly of selfishness, being proud that he was no fool and could forge along in his profession, and pleased to think of him as the next link in the chain of the family he was founding; but now everything was changed. The right man to put down sedition was the man at his right hand. He would save England against Egyptian aggression; he would save his father too, who was old and whose strength was spent, and perhaps—why not?—he would succeed him some day and carry on the traditions of his work in the conquests of civilisation and its triumph in the dark countries of the world.

For the first time for forty years a heavy and solitary tear dropped slowly down the Consul-General's cheek, now deeply scored with lines; but no one saw it, because few dared look into his face. The man who had never unburdened himself to a living soul wished to unburden himself at last, so he scribbled his note to Gordon and then stepped into the carriage that was to take him home.

Meantime he was aware that some fool had provoked a demonstration, but that troubled him hardly at all; and while the crackling cries of "Long live Egypt!" were following him down the arena he was being borne along as by invisible wings.

Thus the two aims in the great Proconsul's life had become one, and that one aim centred in his son.

CHAPTER V

As Gordon went into the British Agency a small, wizened man with a pock-marked face, wearing Oriental dress, came out. He was the Grand Cadi (Chief Judge) of the Mohammedan courts and representative of the Sultan of Turkey in Egypt, one who had secretly hated the Consul-General and raved against the English rule for years; and as he saluted obsequiously with his honeyed voice and smiled with his crafty eyes, it flashed upon Gordon—he did not know why—that just so must Caiaphas, the high priest, have looked when he came out of Pilate's judgment hall after saying, "If thou let this man go thou art not Cæsar's friend."

Gordon leapt up the steps and into the house as one who was at home, and going first into the shaded drawing-room he found his mother on the couch looking to the sunset and the Nile—a sweet old lady in the twilight of life, with white hair, a thin face almost as white, and the pale smile of a patient soul who had suffered pain. With her, attending upon her, and at that moment handing a cup of chicken broth to her, was a stout Egyptian woman with a good homely countenance—Gordon's old nurse, Fatimah.

His mother turned at the sound of his voice, roused herself on the couch, and with that startled cry of joy which has only one note in all nature, that of a mother meeting her beloved son, she cried, "Gordon! Gordon!" and clasped her delicate hands about his neck. Before he could prevent it, his foster-mother, too, muttering in Eastern manner, "O my eye! O my soul!" had snatched one of his hands and was smothering it with kisses.

"And how is Helena?" his mother asked, in her low, sweet voice.

"Beautiful!" said Gordon.

"She couldn't help being that. But why doesn't she come to see me?"

"I think she's anxious about her father's health, and is afraid to leave him," said Gordon; and then Fatimah, with blushes showing through her Arab skin, said—

"Take care! a house may hold a hundred men, but the heart of a woman has only room for one of them."

"Ah, but Helena's heart is as wide as a well, mammy," said Gordon; whereupon Fatimah said—

"That's the way, you see! When a young man is in love there are only two sort of girls in the world—ordinary girls and his girl."

At that moment, while the women laughed, Gordon heard his father's deep voice in the hall saying, "Bid good-bye to my wife before you go, Reg," and then the Consul-General, with "Here's Gordon also," came into the drawing-room, followed by Sir Reginald Mannering, Sirdar of the Egyptian army and Governor of the Soudan, who said—

"Splendid, my boy! Not forgotten your first fight, I see! Heavens, I felt as if I was back at Omdurman and wanted to get at the demons again."

"Gordon," said the Consul-General, "see His Excellency to the door and come to me in the library;" and when the Sirdar was going out at the porch he whispered—

"Go easy with the Governor, my boy. Don't let anything cross him. Wonderful man, but I see a difference since I was down last year. Bye-bye!"

Gordon found his father writing a letter, with his kawas Ibrahim, in green caftan and red waistband, waiting by the side of the desk, in the library, a plain room, formal as an office, being walled with bookcases full of Blue Books, and relieved by two pictures only—a portrait of his mother when she was younger than he could remember to have seen her, and one of himself when he was a child and wore an Arab fez and slippers.

"The General—the Citadel," said the Consul-General, giving his letter to Ibrahim; and as soon as the valet was gone he wheeled his chair round to Gordon and began—

"I've been writing to your General for his formal consent, having something I wish you to do for me."

"With pleasure, sir," said Gordon.

"You know all about the riots at Alexandria?"

"Only what I've learned from the London papers, sir.

"Well, for some time past the people there have been showing signs of effervescence. First, strikes of cabmen, carters, God knows what—all concealing political issues. Then, open disorder. Europeans hustled and spat upon in the streets. A sheikh crying aloud in the public thoroughfares, 'O Moslems, come and help me to drive out the Christians.' Then a Greek merchant warned to take care, as the Arabs were going to kill the Christians that day or the day following. Then low-class Moslems shouting in the square of Mohammed Ali, 'The last day of the Christians is drawing nigh.' As a consequence there have been conflicts. The first of them was trivial, and the police scattered the rioters with a water-hose. The second was more serious, and some Europeans were wounded. The third was alarming, and several natives had to be arrested. Well, when I look for the cause I find the usual one."

"What is it, sir?" asked Gordon.

"Egypt has at all times been subject to local insurrections. They are generally of a religious character, and are set on foot by madmen who give themselves out as divinely-inspired leaders. But shall I tell you what it all means?"

"Tell me, sir," said Gordon.

The Consul-General rose from his chair and began to walk up and down the room with long strides and heavy tread.

"It means," he said, "that the Egyptians, like all other Mohammedans, are cut off by their religion from the spirit and energy of the great civilised nations—that, swathed in the bands of the Koran, the Moslem faith is like a mummy, dead to all uses of the modern world."

The Consul-General drew up sharply and continued—

"Perhaps all dogmatic religions are more or less like that, but the Christian religion has accommodated itself to the spirit of the ages, whereas Islam remains fixed, the religion of the seventh century, born in a desert and suckled in a society that was hardly better than barbarism."

He began to walk again and to talk with great animation.

"What does Islam mean? It means slavery, seclusion of women, indiscriminate divorce, unlimited polygamy, the breakdown of the family and the destruction of the nation. Well, what happens? Civilisation comes along, and it is death to all such dark ways. What next? The scheming Sheikhs, the corrupt Pashas, the tyrannical Caliphs, all the rascals and rogues who batten on corruption, the fanatics who are opponents of the light, cry out against it. Either they must lose their interests or civilisation must go. What then? Civilisation means the West, the West means Christianity. So 'Down with the Christians! O Moslems, help us to kill them!'"

The Consul-General stopped by Gordon's chair, put his hand on his son's shoulder, and said—

"There comes a time in the history of all our Mohammedan dependencies—India, Egypt, every one of them—when England has to confront a condition like that."

"And what has she to do, sir?"

The Consul-General lifted his right fist and brought it down on his left palm, and said—

"To come down with a heavy hand on the lying agitators and intriguers who are leading away the ignorant populace."

"I agree, sir. It is the agitators who should be punished, not the poor, emotional, credulous Egyptian people."

"The Egyptian people, my boy, are graceless ingrates who under the influence of momentary passion would brain their best friend with their nabouts, and go like camels before the camel-driver."

Gordon winced visibly, but only said, "Who is the camel-driver in this instance, sir?"

"A certain Ishmael Ameer, preaching in the great mosque at Alexandria, the cradle of all disaffection."

"An Alim?"

"A teacher of some sort, saying England is the deadly foe of Islam, and must therefore be driven out."

"Then he is worse than the journalists?"

"Yes, we thought of the viper, forgetting the scorpion."

"But is it certain he is so dangerous?"

"One of the leaders of his own people has just been here to say that if we let that man go on it will be death to the rule of England in Egypt."

"The Grand Cadi?"

The Consul-General nodded and then said, "The cunning rogue has a grievance of his own, I find, but what's that to me? The first duty of a government is to keep order."

"I agree," said Gordon.

"There may be picric acid in prayers as well as in bombs."

"There may."

"We have to make these fanatical preachers realise that even if the onward march of progress is but faintly heard in the sealed vaults of their mosque, civilisation is standing outside the walls with its laws and, if need be, its soldiers."

"You are satisfied, sir, that this man is likely to lead the poor, foolish people into rapine and slaughter?"

"I recognise a bird by its flight. This is another Mahdi—I see it—I feel it," said the Consul-General, and his eyes flashed and his voice echoed like a horn.

"You want me to smash the Mahdi?"

"Exactly! Your namesake wanted to smash his predecessor—romantic person—too fond of guiding his conduct by reference to the prophet Isaiah; but he was right in that, and the Government was wrong, and the consequence was the massacre you represented to-day."

"I have to arrest Ishmael Ameer?"

"That's so, in open riot if possible, and if not, by means of testimony derived from his sermons in the mosques."

"Hadn't we better begin there, sir—make sure that he is inciting the people to violence?"

"As you please!"

"You don't forget that the mosques are closed to me as a Christian?"

The Consul-General reflected for a moment and then said—

"Where's Fatimah's son, Hafiz?"

"With his regiment at Abbassiah."

"Take him with you—take two other Moslem witnesses as well."

"I'm to bring this new prophet back to Cairo?"

"That's it—bring him here—we'll do all the rest."

"What if there should be trouble with the people?"

"There's a battalion of British soldiers in Alexandria. Keep a force in readiness—under arms night and day."

"But if it should spread beyond Alexandria?"

"So much the better for you. I mean," said the Consul-General, hesitating for the first time, "we don't want bloodshed, but if it must come to that, it must, and the eyes of England will be on you. What more can a young man want? Think of yourself"—he put his hand on his son's shoulder again—"think of yourself as on the eve of crushing England's enemies and rendering a signal service to Gordon Lord as well. And now go—go up to your General and get his formal consent. My love to Helena! Fine girl, very! She's the sort of woman who might ... yes, women are the springs that move everything in this world. Bid good-bye to your mother and get away. Lose no time. Write to me as soon as you have anything to say. That's enough for the present. I'm busy. Good day!"

Almost before Gordon had left the library the Consul-General was back at his desk—the stern, saturnine man once more, with a face that seemed to express a mind inaccessible to human emotions of any sort.

"As bright as light—sees things before one says them," he said to himself, as Gordon closed the door on going out. "Why have I wasted myself with weaklings so long?"

Gordon kissed his pale-faced mother in the drawing-room and his swarthy foster-mother in the porch, and went back to his quarters in barracks—a rather bare room with bed, desk, and bookcase, many riding boots on a shelf, several weapons of savage warfare on the walls, a dervish's suit of chain armour with a bullet-hole where the heart of the man had been, a picture of Eton, his old school, and above all, as became the home of a soldier, many photographs of his womankind—his mother with her plaintive smile, Fatimah with her humorous look, and of course Helena, with her glorious eyes—Helena, Helena, everywhere Helena.

There, taking down the receiver of a telephone, he called up the headquarters of the Egyptian army and spoke to Hafiz, his foster-brother, now a captain in the native cavalry.

"Is that you, Hafiz? ... Well, look here, I want to know if you can arrange to go with me to Alexandria for a day or two ... You can? Good! I wish you to help me to deal with that new preacher, prophet, Mahdi, what's his name now? ... That's it, Ishmael Ameer. He has been setting Moslem against Christian, and we've got to lay the gentleman by the heels before he gets the poor, credulous people into further trouble.... What do you say? ... Not that kind of man, you think? ... No? ... You surprise me.... Do you really mean to say ... Certainly, that's only fair ... Yes, I ought to know all about him.... Your uncle? ... Chancellor of the University? ... I know, El Azhar.... When could I see him? ... What day do we go to Alexandria? To-morrow if possible.... To-night the only convenient time, you think? Well, I promised to dine at the Citadel, but I suppose I must write to Helena.... Oh, needs must when the devil drives, old fellow.... To-night, then? ... You'll come down for me immediately? Good! By-bye!"

With that he rang off and sat down to write a letter.

CHAPTER VI

Gordon Lord loved the Egyptians. Nursed on the knee of an Egyptian woman, speaking Arabic as his mother tongue, lisping the songs of Arabia before he knew a word of English, Egypt was under his very skin, and the spirit of the Nile and of the desert was in his blood.

Only once a day in his childhood was there a break in his Arab life. That was in the evening about sunset, when Fatimah took him into his father's library, and the great man with the stern face, who assumed towards him a singularly cold manner, put him through a catechism which was always the same: "Tutor been here to-day, boy?" "Yes, sir." "Done your lessons?" "Yes, sir." "English—French—everything?" "Yes, sir." "Say good-night to your mother and go to bed."

Then for a few moments more he was taken into his mother's boudoir, the cool room with the blinds down to keep out the sun, where the lady with the beautiful pale face embraced and kissed him, and made him kneel by her side while they said the Lord's Prayer together in a rustling whisper like a breeze in the garden. But, after that, off to bed with Hafiz—who in his Arab caftan and fez had been looking furtively in at the half-open door—up two steps at a time, shouting and singing in Arabic, while Fatimah, in fear of the Consul-General, cried, "Hush! Be good, now, my sweet eyes!"

In his boyhood, too, he had been half a Mohammedan, going every afternoon to fetch Hafiz home from the kuttab, the school of the mosque, and romping round the sacred place like a little king in stockinged feet, until the Sheikh in charge, who pretended as long as possible not to see him, came with a long cane to whip him out, always saying he should never come there again—until to-morrow.

While at school in England he had felt like a foreigner, wearing his silk hat on the back of his head as if it had been a tarboosh; and while at Sandhurst, where he got through his three years more easily in spite of a certain restiveness under discipline, he had always looked forward to his Christmas visits home—that is to say, to Cairo.

But at last he came back to Egypt on a great errand, with the expedition that was intended to revenge the death of his heroic namesake, having got his commission by that time, and being asked for by his father's old friend, Reginald Mannering, who was a Colonel in the Egyptian army. His joy was wild, his excitement delirious, and even the desert marches under the blazing sun and the sky of brass, killing to some of his British comrades, was a long delight to the Arab soul in him.

The first fighting he did, too, was done with an Egyptian by his side. His great chum was a young Lieutenant named Ali Awad, the son of a Pasha, a bright, intelligent, affectionate young fellow who was intensely sensitive to the contempt of British officers for the quality of the courage of their Egyptian colleagues. During the hurly-burly of the battle of Omdurman both Gordon and Ali had been eager to get at the enemy, but their Colonel had held them back, saying, "What will your fathers say to me if I allow you to go into a hell like that?" When the dervish lines had been utterly broken, though, and one coffee-coloured demon in chain armour was stealing off with his black banner, the Colonel said, "Now's your time, boys; show what stuff you are made of; bring me back that flag," and before the words were out of his mouth the young soldiers were gone.

Other things happened immediately and the Colonel had forgotten his order, when, the battle being over and the British and Egyptian army about to enter the dirty and disgusting city of the Khalifa, he became aware that Gordon Lord was riding beside him with a black banner in one hand and some broken pieces of horse's reins in the other.

"Bravo! You've got it, then," said the Colonel.

"Yes, sir," said Gordon, very sadly; and the Colonel saw that there were tears in the boy's eyes.

"What's amiss?" he said, and looking round, "Where's Ali?"

Then Gordon told him what had happened. They had captured the dervish and compelled him to give up his spear and rifle, but just as Ali was leading the man into the English lines, the demon had drawn a knife and treacherously stabbed him in the back. The boy choked with sobs while he delivered his comrade's last message: "Say good-bye to the Colonel, and tell him Ali Awad was not a coward. I didn't let go the Baggara's horse until he stuck me, and then he had to cut the reins to get away. Show the bits of the bridle to my Colonel, and tell him I died faithful. Give my salaams to him, Charlie. I knew Charlie Gordon Lord would stay with me to the end."

The Colonel was quite broken down, but he only said, "This is no time for crying, my boy," and a moment afterwards, "What became of the dervish?" Then, for the first time, the fighting devil flashed out of Gordon's eyes and he answered—

"I killed him like a dog, sir."

It was the black flag of the Khalifa himself which Gordon had taken, and when the Commander-in-Chief sent home his despatch he mentioned the name of the young soldier who had captured it.

From that day onward for fifteen years honours fell thick on Gordon Lord. Being continually on active service, and generally in staff appointments, promotions came quickly, so that when he went to South Africa, the graveyard of so many military reputations, in those first dark days of the nation's deep humiliation when the very foundations of her army's renown seemed to be giving way, he was one of the young officers whose gallantry won back England's fame. Though hot-tempered, impetuous, and liable to frightful errors, he had the imagination of a soldier as well as the bravery that goes to the heart of a nation, so that when in due course, being now full Colonel, he was appointed, though so young, Second in Command of the Army of Occupation in Cairo, no one was surprised.

All the same he knew he owed his appointment to his father's influence, and he wrote to thank him and to say he was delighted to return to Cairo. Only at intervals had he heard from the Consul-General, and though his admiration of his father knew no limit and he thought him the greatest man in the world, he always felt there was a mist between them. Once, for a moment, had that mist seemed to be dispelled when, on his coming of age, his father wrote a letter in which he said—

"You are twenty-one years of age, Gordon, and your mother and I have been recalling the incidents of the day on which you were born. I want to tell you that from this day forward I am no longer your father; I am your friend; perhaps the best friend you will ever have; let nothing and no one come between us."

Gordon's joy on returning to Egypt was not greater than that of the Egyptians on receiving him. They were waiting in a crowd when he arrived at the railway station, a red sea of tarbooshes over faces he remembered as the faces of boys, with the face of Hafiz, now a soldier like himself, beaming by his carriage window.

It was not good form for a British officer to fraternise with the Egyptians, but Gordon shook hands with everybody and walked down the platform with his arm round Hafiz's shoulders, while the others who had come to meet him cried, "Salaam, brother!" and laughed like children.

By his own choice, and contrary to custom, quarters had been found for him in the barracks on the bank of the Nile, and the old familiar scene from there made his heart leap and tremble. It was evening when at last he was left alone, and throwing the window wide open he looked out on the river flowing like liquid gold in the sunset, with its silent boats, that looked like birds with outstretched wings, floating down without a ripple, and the violet blossom of the island on the other side spreading odours in the warm spring air.

He was watching the traffic on the bridge—the camels, the cameleers, the donkeys, the blue-shirted fellaheen, the women with tattooed chins and children astraddle on their shoulders, the water-carriers with their bodies twisted by their burdens, the Bedouins with their lean, lithe, swarthy forms and the rope round the head-shawls which descended to their shoulders—when he heard the toot of a motor-horn, and saw a white automobile threading its way through the crowd. The driver was a girl, and a veil of white chiffon which she had bound about her head instead of a hat was flying back in the light breeze, leaving her face framed within, with its big black eyes and firm but lovely mouth.