автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу History of Woman Suffrage, Volume III

Transcriber's Note

Every effort has been made to replicate this text as faithfully as possible, including obsolete and variant spellings and other inconsistencies. Text that has been changed to correct an obvious error is noted at the end of this ebook.

Also, many occurrences of mismatched single and double quotes remain as they were in the original.

This book contains links to individual volumes of "History of Woman Suffrage" contained in the Project Gutenberg collection. Although we verify the correctness of these links at the time of posting, these links may not work, for various reasons, for various people, at various times.

HISTORY

of

Woman Suffrage.

EDITED BY

ELIZABETH CADY STANTON,

SUSAN B. ANTHONY, AND

MATILDA JOSLYN GAGE.

ILLUSTRATED WITH STEEL ENGRAVINGS.

IN THREE VOLUMES.

VOL. III.

1876-1885.

"WOMEN ARE CITIZENS OF THE UNITED STATES, ENTITLED TO ALL THE RIGHTS, PRIVILEGES AND IMMUNITIES GUARANTEED TO CITIZENS BY THE NATIONAL CONSTITUTION."

SUSAN B. ANTHONY.

17 Madison St., Rochester, N. Y.

Copyright, 1886, by Susan B. Anthony.

PREFACE.

The labors of those who have edited these volumes are not only finished as far as this work extends, but if three-score years and ten be the usual limit of human life, all our earthly endeavors must end in the near future. After faithfully collecting material for several years, and making the best selections our judgment has dictated, we are painfully conscious of many imperfections the critical reader will perceive. But since stereotype plates will not reflect our growing sense of perfection, the lavish praise of friends as to the merits of these pages will have its antidote in the defects we ourselves discover. We may however without egotism express the belief that this volume will prove specially interesting in having a large number of contributors from England, France, Canada and the United States, giving personal experiences and the progress of legislation in their respective localities.

Into younger hands we must soon resign our work; but as long as health and vigor remain, we hope to publish a pamphlet report at the close of each congressional term, containing whatever may be accomplished by State and National legislation, which can be readily bound in volumes similar to these, thus keeping a full record of the prolonged battle until the final victory shall be achieved. To what extent these publications may be multiplied depends on when the day of woman's emancipation shall dawn.

For the completion of this work we are indebted to Eliza Jackson Eddy, the worthy daughter of that noble philanthropist, Francis Jackson. He and Charles F. Hovey are the only men who have ever left a generous bequest to the woman suffrage movement. To Mrs. Eddy, who bequeathed to our cause two-thirds of her large fortune, belong all honor and praise as the first woman who has given alike her sympathy and her wealth to this momentous and far-reaching reform. This heralds a turn in the tide of benevolence, when, instead of building churches and monuments to great men, and endowing colleges for boys, women will make the education and enfranchisement of their own sex the chief object of their lives.

The three volumes now completed we leave as a precious heritage to coming generations; precious, because they so clearly illustrate—in her ability to reason, her deeds of heroism and her sublime self-sacrifice—that woman preeminently possesses the three essential elements of sovereignty as defined by Blackstone: "wisdom, goodness and power." This has been to us a work of love, written without recompense and given without price to a large circle of friends. A thousand copies have thus far been distributed among our coadjutors in the old world and the new. Another thousand have found an honored place in the leading libraries, colleges and universities of Europe and America, from which we have received numerous testimonies of their value as a standard work of reference for those who are investigating this question. Extracts from these pages are being translated into every living language, and, like so many missionaries, are bearing the glad gospel of woman's emancipation to all civilized nations.

Since the inauguration of this reform, propositions to extend the right of suffrage to women have been submitted to the popular vote in Kansas, Michigan, Colorado, Nebraska and Oregon, and lost by large majorities in all; while, by a simple act of legislature, Wyoming, Utah and Washington territories have enfranchised their women without going through the slow process of a constitutional amendment. In New York, the State that has led this movement, and in which there has been a more continued agitation than in any other, we are now pressing on the legislature the consideration that it has the same power to extend the right of suffrage to women that it has so often exercised in enfranchising different classes of men.

Eminent publicists have long conceded this power to State legislatures as well as to congress, declaring that women as citizens of the United States have the right to vote, and that a simple enabling act is all that is needed. The constitutionality of such an act was never questioned until the legislative power was invoked for the enfranchisement of women. We who have studied our republican institutions and understand the limits of the executive, judicial and legislative branches of the government, are aware that the legislature, directly representing the people, is the primary source of power, above all courts and constitutions. Research into the early history of this country shows that in line with English precedent, women did vote in the old colonial days and in the original thirteen States of the Union. Hence we are fully awake to the fact that our struggle is not for the attainment of a new right, but for the restitution of one our fore-mothers possessed and exercised.

All thoughtful readers must close these volumes with a deeper sense of the superior dignity, self-reliance and independence that belong by nature to woman, enabling her to rise above such multifarious persecutions as she has encountered, and with persistent self-assertion to maintain her rights. In the history of the race there has been no struggle for liberty like this. Whenever the interest of the ruling classes has induced them to confer new rights on a subject class, it has been done with no effort on the part of the latter. Neither the American slave nor the English laborer demanded the right of suffrage. It was given in both cases to strengthen the liberal party. The philanthropy of the few may have entered into those reforms, but political expediency carried both measures. Women, on the contrary, have fought their own battles; and in their rebellion against existing conditions have inaugurated the most fundamental revolution the world has ever witnessed. The magnitude and multiplicity of the changes involved make the obstacles in the way of success seem almost insurmountable.

The narrow self-interest of all classes is opposed to the sovereignty of woman. The rulers in the State are not willing to share their power with a class equal if not superior to themselves, over which they could never hope for absolute control, and whose methods of government might in many respects differ from their own. The annointed leaders in the Church are equally hostile to freedom for a sex supposed for wise purposes to have been subordinated by divine decree. The capitalist in the world of work holds the key to the trades and professions, and undermines the power of labor unions in their struggles for shorter hours and fairer wages, by substituting the cheap labor of a disfranchised class, that cannot organize its forces, thus making wife and sister rivals of husband and brother in the industries, to the detriment of both classes. Of the autocrat in the home, John Stuart Mill has well said: "No ordinary man is willing to find at his own fireside an equal in the person he calls wife." Thus society is based on this fourfold bondage of woman, making liberty and equality for her antagonistic to every organized institution. Where, then, can we rest the lever with which to lift one-half of humanity from these depths of degradation but on "that columbiad of our political life—the ballot—which makes every citizen who holds it a full-armed monitor"?

LIST OF ENGRAVINGS.

Vol. III.

Phœbe W. Couzins

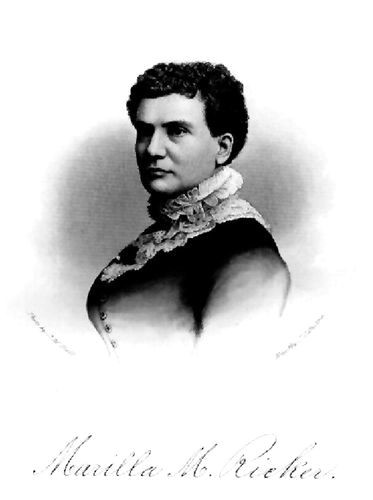

Frontispiece.Marilla M. Ricker

page

112Frances E. Willard

129Jane H. Spofford

192Harriet H. Robinson

273Phebe A. Hanaford

337Armenia S. White

369Lillie Devereux Blake

417Rachel G. Foster

465Cornelia C. Hussey

481May Wright Sewall

545Elizabeth Boynton Harbert

592Sarah Burger Stearns

656Clara Bewick Colby

689Helen M. Gougar

704Laura DeForce Gordon

753Abigail Scott Duniway

769Caroline E. Merrick

801Mary B. Clay

817Mentia Taylor

833Priscilla Bright McLaren

864George Sand

896CONTENTS.

CHAPTER XXVII.page

THE CENTENNIAL YEAR—1876.

The Dawn of the New Century—Washington Convention—Congressional Hearing—Woman's Protest—May Anniversary—Centennial Parlors in Philadelphia—Letters and Delegates to Presidential Conventions—50,000 Documents sent out—The Centennial Autograph Book—The Fourth of July—Independence Square—Susan B. Anthony reads the Declaration of Rights—Convention in Dr. Furness' Church, Lucretia Mott, Presiding—The Hutchinson Family, John and Asa—The Twenty-eighth Anniversary, July 19, Edward M. Davis, Presiding—Letters, Ernestine L. Rose, Clarina I. H. Nichols—The Ballot-Box—Retrospect—The Woman's Pavilion1

CHAPTER XXVIII.

NATIONAL CONVENTIONS, HEARINGS AND REPORTS.

1877-1878-1879.

Renewed Appeal for a Sixteenth Amendment—Mrs. Gage Petitions for a Removal of Political Disabilities—Ninth Washington Convention, 1877—Jane Grey Swisshelm—Letters, Robert Purvis, Wendell Phillips, Francis E. Abbott—10,000 Petitions Referred to the Committee on Privileges and Elections by Special Request of the Chairman, Hon. O. P. Morton, of Indiana—May Anniversary in New York—Tenth Washington Convention, 1878—Frances E. Willard and 30,000 Temperance Women Petition Congress—40,000 Petition for a Sixteenth Amendment—Hearing before the Committee on Privileges and Elections—Madam Dahlgren's Protest—Mrs. Hooker's Hearing on Washington's Birthday—Mary Clemmer's Letter to Senator Wadleigh—His Adverse Report—Thirtieth Anniversary, Unitarian Church, Rochester, N. Y., July 19, 1878—The Last Convention Attended by Lucretia Mott—Letters, William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips—Church Resolution Criticised by Rev. Dr. Strong—International Women's Congress in Paris—Washington Convention, 1879—Favorable Minority Report by Senator Hoar—U. S. Supreme Court Opened to Women—May Anniversary at St. Louis—Address of Welcome by Phoebe Couzins—Women in Council Alone—Letter from Josephine Butler, of England—Mrs. Stanton's Letter to The National Citizen and Ballot-Box57

CHAPTER XXIX.

CONGRESSIONAL REPORTS AND CONVENTIONS.

1880-1881.

Why we Hold Conventions in Washington—Lincoln Hall Demonstration—Sixty-six Thousand Appeals—Petitions Presented in Congress—Hon. T. W. Ferry of Michigan in the Senate—Hon. Geo. B. Loring of Massachusetts in the House—Hon. J. J. Davis of North Carolina Objected—Twelfth Washington Convention—Hearings before the Judiciary Committee of both Houses, 1880—May Anniversary at Indianapolis—Series of Western Conventions—Presidential Nominating Conventions—Delegates and Addresses to each—Mass-Meeting at Chicago—Washington Convention, 1881—Memorial Service to Lucretia Mott—Mrs. Stanton's Eulogy—Discussion in the Senate on a Standing Committee—Senator McDonald of Indiana Champions the Measure—May Anniversary in Boston—Conventions in the chief cities of New England150

CHAPTER XXX.

CONGRESSIONAL DEBATES AND CONVENTIONS.

1882-1883.

Prolonged Discussions in the Senate on a Special Committee to Look After the Rights of Women, Messrs. Bayard, Morgan and Vest in Opposition—Mr. Hoar Champions the Measure in the Senate, Mr. Reed in the House—Washington Convention—Representative Orth and Senator Saunders on the Woman Suffrage Platform—Hearings Before Select Committees of Senate and House—Reception Given by Mrs. Spofford at the Riggs House—Philadelphia Convention—Mrs. Hannah Whitehall Smith's Dinner—Congratulations from the Central Committee of Great Britain—Majority and Minority Reports in the Senate—E. G. Lapham, J. Z. George—Nebraska Campaign—Conventions in Omaha—Joint Resolution Introduced by Hon. John D. White of Kentucky, Referred to the Select Committee—Washington Convention, January 24, 25, 26, 1883—Majority Report in the House.198

CHAPTER XXXI.

MASSACHUSETTS.

The Woman's Hour—Lydia Maria Child Petitions Congress—First New England Convention—The New England, American and Massachusetts Associations—Woman's Journal—Bishop Gilbert Haven—The Centennial Tea-Party—County Societies—Concord Convention—Thirtieth Anniversary of the Worcester Convention—School Suffrage Association—Legislative Hearing—First Petitions—The Remonstrants Appear—Women in Politics—Campaign of 1872—Great Meeting in Tremont Temple—Women at the Polls—Provisions of Former State Constitutions—Petitions, 1853—School-Committee Suffrage, 1879,—Women Threatened with Arrest—Changes in the Laws—Woman Now Owns her own Clothing—Harvard Annex—Woman in the Professions—Samuel E. Sewall and William I. Bowditch—Supreme-Court Decisions—Sarah E. Wall—Francis Jackson—Julia Ward Howe—Mary E. Stevens—Lucia M. Peabody—Lelia Josephine Robinson—Eliza (Jackson) Eddy's Will 256

CHAPTER XXXII.

CONNECTICUT.

Prudence Crandall—Eloquent Reformers—Petitions for Suffrage—The Committee's Report—Frances Ellen Burr—Isabella Beecher Hooker's Reminiscences—Anna Dickinson in the Republican Campaign—State Society Formed October 28, 29, 1869—Enthusiastic Convention in Hartford—Governor Marshall Jewell—He recommends More Liberal Laws for Women—Society Formed in New Haven, 1871—Governor Hubbard's Inaugural, 1877—Samuel Bowles of the Springfield Republican—Rev. Phebe A. Hanaford, Chaplain, 1870—John Hooker, Esq., Champions the Suffrage Movement—The Smith Sisters—Mary Hall—Chief-Justice Park—Frances Ellen Burr—Hartford Equal Rights Club316

CHAPTER XXXIII.

RHODE ISLAND.

Senator Anthony in North American Review—Convention in Providence—State Association organized, Paulina Wright Davis, President—Report of Elizabeth B. Chase—Women on School Boards—Women's Board of Visitors to the Penal and Correctional Institutions—Dr. Wm. F. Channing—Miss Ida Lewis—Letter of Frederick A. Hinckley—Last Words of Senator Anthony339

CHAPTER XXXIV.

MAINE.

Women on School Committees—Elvira C. Thorndyke—First Suffrage Society organized, 1868, Rockland—Portland Meeting, 1870—John Neal—Judge Goddard—Colby University Open to Girls, August 12, 1871—Mrs. Clara Hapgood Nash Admitted to the Bar, October 26, 1872—Tax-Payers Protest—Ann F. Greeley, 1872—March, 1872, Bill for Woman Suffrage Lost in the House, Passed in the Senate by Seven Votes—Miss Frank Charles, Register of Deeds—Judge Reddington—Mr. Randall's Motion—Moral Eminence of Maine—Convention in Granite Hall, Augusta, January, 1873, Hon. Joshua Nye, President—Delia A. Curtis—Opinions of the Supreme Court in Regard to Women Holding Offices—Governor Dingley's Message, 1875—Convention, Representatives Hall, Portland, Judge Kingsbury, President, Feb. 12, '76—The two Snow Families—Hon. T. B. Reed351

CHAPTER XXXV.

NEW HAMPSHIRE.

Nathaniel P. Rogers—Parker Pillsbury—Galen Foster—The Hutchinson Family—First Organized Action, 1868—Concord Convention—William Lloyd Garrison's Letter—Rev. S. L. Blake Opposed—Rev. Mr. Sanborn in Favor—Concord Monitor—Armenia S. White—A Bill to Protect the Rights of Married Men—Minority and Majority Reports—Women too Ignorant to Vote—Republican State Convention—Women on School Committees, 1870—Voting at School District Meetings, 1878—Mrs. White's Address—Mrs. Ricker on Prison Reform—Judicial Decision in Regard to Married Women, 1882—Letter from Senator Blair367

CHAPTER XXXVI.

VERMONT.

Clarina Howard Nichols—Council of Censors—Amending the Constitution—St. Andrew's Letter—Mr. Reed's Report—Convention Called—H. B. Blackwell on the Vermont Watchman—Mary A. Livermore in the Woman's Journal—Sarah A. Gibbs' Reply to Rev. Mr. Holmes—School Suffrage, 1880383

CHAPTER XXXVII.

NEW YORK—1860-1885.

Saratoga Convention, July 13, 14, 1869—State Society Formed, Martha C. Wright, President—The Revolution Established, 1868—Educational Movement—New York City Society, 1870, Charlotte B. Wilbour, President—Presidential Campaign, 1872—Hearings at Albany, 1873—Constitutional Commission—An Effort to Open Columbia College, President Barnard in Favor—Centennial Celebration, 1876—School Officers—Senator Emerson of Monroe, 1877—Governor Robinson's Veto—School Suffrage, 1880—Governor Cornell Recommended it in his Message—Stewart's Home for Working Women—Women as Police—An Act to Prohibit Disfranchisement—Attorney-General Russell's Adverse Opinion—The Power of the Legislature to Extend Suffrage—Great Demonstration in Chickering Hall, March 7, 1884—Hearing at Albany, 1885—Mrs. Blake, Mrs. Stanton, Mrs. Rogers, Mrs. Howell, Gov. Hoyt of Wyoming395

CHAPTER XXXVIII.

PENNSYLVANIA.

Carrie Burnham—The Canon and Civil Law the Source of Woman's Degradation—Women Sold with Cattle in 1768—Women Arrested in Pittsburg—Mrs. McManus—Opposition to Women in Colleges and Hospitals; John W. Forney Vindicates their Rights—Ann Preston—Women in Dentistry—James Truman's Letter—Swarthmore College—Suffrage Association Formed in 1866, in Philadelphia—John K. Wildman's Letter—Judge William S. Pierce—The Citizens' Suffrage Association, 333 Walnut Street, Edward M. Davis, President—Petitions to the Legislature—Constitutional Convention, 1873—Bishop Simpson, Mary Grew, Sarah C. Hallowell, Matilda Hindman, Mrs. Stanton, Address the Convention—Messrs. Broomall and Campbell Debate with the Opposition—Amendment Making Women Eligible to School Offices—Two Women Elected to Philadelphia School Board, 1874—The Wages of Married Women Protected—J. Edgar Thomson's Will—Literary Women as Editors—The Rev. Knox Little—Anne E. McDowell—Women as Physicians in Insane Asylums—The Fourteenth Amendment Resolution, 1881—Ex-Gov. Hoyt's Lecture on Wyoming444

CHAPTER XXXIX.

NEW JERSEY.

Women Voted in the Early Days—Deprived of the Right by Legislative Enactment in 1807—Women Demand the Restoration of Their Rights in 1868—At the Polls in Vineland and Roseville Park—Lucy Stone Agitates the Question—State Suffrage Society Organized in 1867—Conventions—A Memorial to the Legislature—Mary F. Davis—Rev. Phebe A. Hanaford—Political Science Club— Mrs. Cornelia C. Hussey—Orange Club, 1870—Mrs. Devereux Blake gives the Oration, July 4, 1884—Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell's Letter—The Laws of New Jersey in Regard to Property and Divorce—Constitutional Commission, 1873—Trial of Rev. Isaac M. See—Women Preaching in his Pulpit—The Case Appealed—Mrs. Jones, Jailoress—Legislative Hearings476

CHAPTER XL.

OHIO.

The First Soldiers' Aid Society—Mrs. Mendenhall—Cincinnati Equal Rights Association, 1868—Homeopathic Medical College and Hospital—Hon. J. M. Ashley—State Society, 1869—Murat Halstead's Letter—Dayton Convention, 1870—Women Protest Against Enfranchisement—Sarah Knowles Bolton—Statistics on Coëducation by Thomas Wentworth Higginson—Woman's Crusade, 1874—Miriam M. Cole—Ladies' Health Association—Professor Curtis—Hospital for Women and Children, 1879—Letter from J. D. Buck, M. D.—March, 1881, Degrees Conferred on Women—Toledo Association, 1869—Sarah Langdon Williams—The Sunday Journal—The Ballot-Box—Constitutional Convention—Judge Waite—Amendment Making Women Eligible to Office—Mr. Voris, Chairman Special Committee on Woman Suffrage—State Convention, 1873—Rev. Robert McCune—Centennial Celebration—Women Decline to Take Part—Correspondence—Newbury Association—Women Voting, 1871—Sophia Ober Allen—Annual Meeting, Painesville, 1885—State Society, Mrs. Frances M. Casement, President—Adelbert College 491

CHAPTER XLI.

MICHIGAN.

Women's Literary Clubs and Libraries—Mrs. Lucinda H. Stone—Classes of Girls in Europe—Ernestine L. Rose—Legislative Action, 1849-1885—State Woman Suffrage Society, 1870—Annual Conventions—Northwestern Association—Wendell Phillips' Letter—Nannette Gardner votes—Catharine A. F. Stebbins Refused—Legislative Action—Amendments Submitted—An Active Canvas of the State by Women—Election Day—The Amendment Lost, 40,000 Men Voted in Favor—University at Ann Arbor Opened to Girls, 1869—Kalamazoo Institute—J. A. B. Stone—Miss Madeline Stockwell and Miss Sarah Burger Applied for Admission to the University in 1857—Episcopal Church Bill—Local Societies—Quincy—Lansing—St. Johns—Manistee—Grand Rapids—Sojourner Truth—Laura C. Haviland—Sybil Lawrence513

CHAPTER XLII.

INDIANA.

The First Woman Suffrage Convention After the War, 1869—Amanda M. Way—Annual Meetings, 1870-85, in the Larger Cities—Indianapolis Equal Suffrage Society, 1878—A Course of Lectures—In May, 1880, National Convention in Indianapolis—Zerelda G. Wallace—Social Entertainment—Governor Albert G. Porter—Susan B. Anthony's Birthday—Schuyler Colfax—Legislative Hearings—Temperance Women of Indiana—Helen M. Gougar—General Assembly—Delegates to Political Conventions—Women Address Political Meetings—Important Changes in the Laws for Women, from 1860 to 1884—Colleges Open to Women—Demia Butler—Professors—Lawyers—Doctors—Ministers—Miss Catharine Merrill—Miss Elizabeth Eaglesfield—Rev. Prudence Le Clerc—Dr. Mary F. Thomas—Prominent Men and Women—George W. Julian—The Journals—Gertrude Garrison533

CHAPTER XLIII.

ILLINOIS.

Chicago a Great Commercial Centre—First Woman Suffrage Agitation, 1855—A. J. Grover—Society at Earlville—Prudence Crandall—Sanitary Movement—Woman in Journalism—Myra Bradwell—Excitement in Elmwood Church, 1868—Mrs. Huldah Joy—Pulpit Utterances—Convention, 1869, Library Hall, Chicago—Anna Dickinson, Robert Laird Collier Debate—Manhood Suffrage Denounced by Mrs. Stanton and Miss Anthony—Judge Charles B. Waite on the Constitutional Convention—Hearing before the Legislature—Western Suffrage Convention, Mrs. Livermore, President—Annual Meeting at Bloomington—Women Eligible to School Offices—Evanston College—Miss Alta Hulett Medical Association—Dr. Sarah Hackett Stevenson—"Woman's Kingdom" in the Inter-Ocean—Mrs. Harbert—Centennial Celebration at Evanston—Temperance Petition, 180,000—Frances E. Willard—Social Science Association—Art Union—Jane Graham Jones at International Congress in Paris—Moline Association559

CHAPTER XLIV.

MISSOURI.

Missouri the first State to Open Colleges of Law and Medicine to Woman—Liberal Legislation—Harriet Hosmer—Wayman Crow—Dr. Joseph N. McDowell—Works of Art—Women in the War—Adeline Couzins—Virginia L. Minor—Petitions—Woman Suffrage Association, May 8, 1867—First Woman Suffrage Convention, Oct. 6, 1869—Able Resolutions by Francis Minor—Action Asked for in the Methodist Church—Constitutional Convention—Mrs. Hazard's Report—National Suffrage Association, 1879—Virginia L. Minor Before the Committee on Constitutional Amendments—Mrs. Minor Tries to Vote—Her Case in the Supreme Court—Mrs. Annie R. Irvine—"Oregon Woman's Union"—Miss Phœbe Couzins Graduates From the Law School, 1871—Reception by Members of the Bar—Speeches—Dr. Walker—Judge Krum—Hon. Albert Todd—Ex-Governor E. O. Stanard—Ex-Senator Henderson—Judge Reber—George M. Stewart—Mrs. Minor—Miss Couzins594

CHAPTER XLV.

IOWA.

Beautiful Scenery—Liberal in Politics and Reforms—Legislation for Women—No Right yet to Joint Earnings—Early Agitation—Frances Dana Gage, 1854—Mrs. Amelia Bloomer Lectures in Council Bluffs, 1856—Mrs. Martha H. Brinkerhoff—Mrs. Annie Savery, 1868—County Associations Formed in 1869—State Society Organized at Mt. Pleasant, 1870, Henry O'Connor, President—Mrs. Cutler Answers Judge Palmer—First Annual Meeting, Des Moines—Letter from Bishop Simpson—The State Register Complimentary—Mass-Meeting at the Capitol—Mrs. Savery and Mrs. Harbert—Legislative Action—Methodist and Universalist Churches Indorse Woman Suffrage—Republican Plank, 1874—Governor Carpenter's Message, 1876—Annual Meeting, 1882, Many Clergymen Present—Five Hundred Editors Interviewed—Miss Hindman and Mrs. Campbell—Mrs. Callanan Interviews Governor Sherman, 1884—Lawyers—Governor Kirkwood Appoints Women to Office—County Superintendents—Elizabeth S. Cook—Journalism—Literature— Medicine—Ministry—Inventions—President of a National Bank— The Heroic Kate Shelly—Temperance—Improvement in the Laws612

CHAPTER XLVI.

WISCONSIN.

Progressive Legislation—The Rights of Married Women—The Constitution Shows Four Classes Having the Right to Vote—Woman Suffrage Agitation—C. L. Sholes' Minority Report, 1856—Judge David Noggle and J. T. Mills' Minority Report, 1859—State Association Formed, 1869—Milwaukee Convention—Dr. Laura Ross—Hearing Before the Legislature—Convention in Janesville, 1870—State University—Elizabeth R. Wentworth—Suffrage Amendment, 1880, '81, '82—Rev. Olympia Brown, Racine, 1877—Madam Anneké—Judge Ryan—Three Days' Convention at Racine, 1883—Eveleen L. Mason—Dr. Sarah Munro—Rev. Dr. Corwin—Lavinia Godell, Lawyer—Angie King—Kate Kane638

CHAPTER XLVII.

MINNESOTA.

Girls in State University—Sarah Burger Stearns—Harriet E. Bishop, the First Teacher in St. Paul—Mary J. Colburn Won the Prize—Mrs. Jane Grey Swisshelm, St. Cloud—Fourth of July Oration, 1866—First Legislative Hearing, 1867—Governor Austin's Veto—First Society at Rochester—Kasson—Almira W. Anthony—Mary P. Wheeler—Harriet M. White—The W. C. T. U.—Harriet A. Hobart—Literary and Art Clubs—School Suffrage, 1876—Charlotte O. Van Cleve and Mrs. C. S. Winchell Elected to School Board—Mrs. Governor Pillsbury—Temperance Vote, 1877—Property Rights of Married Women—Women as Officers, Teachers, Editors, Ministers, Doctors, Lawyers649

CHAPTER XLVIII.

DAKOTA.

Influences of Climate and Scenery—Legislative Action, 1872—Mrs. Marietta Bones—In February, 1879, School Suffrage Granted Women—Constitutional Convention, 1883—Matilda Joslyn Gage Addressed a Letter to the Convention and an Appeal to the Women of the State—Mrs. Bones Addressed the Convention in Person—The Effort to get the Word "Male" out of the Constitution Failed—Legislature of 1885—Major Pickler Presents the Bill—Carried Through Both Houses—Governor Pierce's Veto—Major Pickler's Letter662

CHAPTER XLIX.

NEBRASKA.

Clara Bewick Colby—Nebraska Came into the Possession of the United States, 1803—The Home of the Dakotas—Organized as a Territory, 1854—Territorial Legislature—Mrs. Amelia Bloomer Addresses the House—Gen. Wm. Larimer, 1856—A Bill to Confer Suffrage on Women—Passed the House—Lost in the Senate—Constitution Harmonized with the Fourteenth Amendment—Admitted as a State March 1, 1867—Mrs. Stanton, Miss Anthony Lecture in the State, 1867—Mrs. Tracy Cutler, 1870—Mrs. Esther L. Warner's Letter—Constitutional Convention, 1871—Woman Suffrage Amendment Submitted—Lost by 12,676 against, 3,502 for—Prolonged Discussion—Constitutional Convention, 1875—Grasshoppers Devastate the Country—Inter-Ocean, Mrs. Harbert—Omaha Republican, 1876—Woman's Column Edited by Mrs. Harriet S. Brooks—"Woman's Kingdom"—State Society Formed, January 19, 1881, Mrs. Brooks President—Mrs. Dinsmoor, Mrs. Colby, Mrs. Brooks, before the Legislature—Amendment again Submitted—Active Canvass of the State, 1882—First Convention of the State Association—Charles F. Manderson—Unreliable Politicians—An Unfair Count of Votes for Woman Suffrage—Amendment Defeated—Conventions in Omaha—Notable Women in the State—Conventions—Woman's Tribune Established in 1883 670

CHAPTER L.

KANSAS.

Effect of the Popular Vote on Woman Suffrage—Anna C. Wait—Hannah Wilson—Miss Kate Stephens, Professor of Greek in State University—Lincoln Centre Society, 1879—The Press—The Lincoln Beacon—Election, 1880—Sarah A. Brown, Democratic Candidate—Fourth of July Celebration—Women Voting on the School Question—State Society, 1884—Helen M. Gougar—Clara Bewick Colby—Bertha H. Ellsworth—Radical Reform Association—Mrs. A. G. Lord—Prudence Crandall—Clarina Howard Nichols—Laws—Women in the Professions—Schools—Political Parties—Petitions to the Legislature—Col. F. G. Adams' Letter696

CHAPTER LI.

COLORADO.

The Committee on Privileges and Elections, to whom was referred the Resolution (S. Res. 12) proposing an Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and certain Petitions for and Remonstrances against the same, make the following Report:

This proposed amendment forbids the United States, or any State to deny or abridge the right to vote on account of sex. If adopted, it will make several millions of female voters, totally inexperienced in political affairs, quite generally dependent upon the other sex, all incapable of performing military duty and without the power to enforce the laws which their numerical strength may enable them to make, and comparatively very few of whom wish to assume the irksome and responsible political duties which this measure thrusts upon them. An experiment so novel, a change so great, should only be made slowly and in response to a general public demand, of the existence of which there is no evidence before your committee.

Petitions from various parts of the country, containing by estimate about 30,000 names, have been presented to congress asking for this legislation. They were procured through the efforts of woman suffrage societies, thoroughly organized, with active and zealous managers. The ease with which signatures may be procured to any petition is well known. The small number of petitioners, when compared with that of the intelligent women in the country, is striking evidence that there exists among them no general desire to take up the heavy burden of governing, which so many men seek to evade. It would be unjust, unwise and impolitic to impose that burden on the great mass of women throughout the country who do not wish for it, to gratify the comparatively few who do.

It has been strongly urged that without the right of suffrage, women are, and will be, subjected to great oppression and injustice.

But every one who has examined the subject at all knows that, without female suffrage, legislation for years has improved and is still improving the condition of woman. The disabilities imposed upon her by the common law have, one by one, been swept away, until in most of the States she has the full right to her property and all, or nearly all, the rights which can be granted without impairing or destroying the marriage relation. These changes have been wrought by the spirit of the age, and are not, generally at least, the result of any agitation by women in their own behalf.

Nor can women justly complain of any partiality in the administration of justice. They have the sympathy of judges and particularly of juries to an extent which would warrant loud complaint on the part of their adversaries of the sterner sex. Their appeals to legislatures against injustice are never unheeded, and there is no doubt that when any considerable part of the women of any State really wish for the right to vote, it will be granted without the intervention of congress.

Any State may grant the right of suffrage to women. Some of them have done so to a limited extent, and perhaps with good results. It is evident that in some States public opinion is much more strongly in favor of it than it is in others. Your committee regard it as unwise and inexpedient to enable three-fourths in number of the States, through an amendment to the national constitution, to force woman suffrage upon the other fourth in which the public opinion of both sexes may be strongly adverse to such a change.

For these reasons, your committee report back said resolution with a recommendation that it be indefinitely postponed.

Among the many anniversaries in Boston the last week in May, one of the most enthusiastic was that of the National Woman Suffrage Association, held in Tremont Temple. The weather was cool and fair and the audience fine throughout, and never was there a better array of speakers at one time on any platform. The number of thoughtful, cultured young women appearing in these conventions, is one of the hopeful features for the success of this movement. The selection of speakers for this occasion had been made at the Washington convention in January, and different topics assigned to each that the same phases of the question might not be treated over and over again.

Mrs. Harriet Hansom Robinson (wife of "Warrington," so long the able correspondent of the Springfield Republican), who with her daughter made the arrangements for our reception, gave the address of welcome, to which the president, Mrs. Stanton, replied. Rev. Frederic Hinckley of Providence, spoke on "Unity of Principle in Variety of Method," and showed that while differing on minor points the various woman suffrage associations were all working to one grand end. Anna Garlin Spencer made a few remarks on "The Character of Reformers." Rev. Olympia Brown gave an exceptionally brilliant speech a full hour in length on "Universal Suffrage"; Harriette Robinson Shattuck's theme was "Believing and Doing"; Lillie Devereux Blake's, "Demand for Liberty"; Matilda Joslyn Gage's, "Centralization"; Belva A. Lockwood's, "Woman and the Law". Mary F. Eastman followed showing that woman's path was blocked at every turn, in the professions as well as the trades and the whole world of work; Isabella Beecher Hooker gave an able argument on the "Constitutional Right of Women to Vote"; Martha McLellan Brown spoke equally well on the "Ethics of Sex"; Mrs. Elizabeth Avery Meriwether of Tennessee, gave a most amusing commentary on the spirit of the old common law, cuffing Blackstone and Coke with merciless sarcasm. Mrs. Elizabeth L. Saxon of Louisiana spoke with great effect on "Woman's Intellectual Powers as Developed by the Ballot." These two Southern ladies are alike able, witty and pathetic in their appeals for justice to woman. Mrs. May Wright Sewall's essay on "Domestic Legislation," showing how large a share of the bills passed every year directly effect home life, was very suggestive to those who in answer to our demand for political power, say "Woman's sphere is home," as if the home were beyond the control and influence of the State. Beside all these thoroughly prepared addresses, Susan B Anthony, Dr. Clemence Lozier, Dr. Caroline Winslow, ex-Secretary Lee of Wyoming, spoke briefly on various points suggested by the several speakers.

The white-haired and venerable philosopher, A. Bronson Alcott, was very cordially received, after being presented in complimentary terms by the president. Mr. Alcott paid a glowing tribute to the intellectual worth of woman, spoke of the divinity of her character, and termed her the inspiration font from which his own philosophical ideas had been drawn. Not until the women of our nation have been granted every privilege would the liberty of our republic be assured.[79] The well-known Francis W. Bird of Walpole, who has long wielded in the politics of the Bay State, the same power Thurlow Weed did for forty years in New York, being invited to the platform, expressed his entire sympathy with the demand for suffrage, notwithstanding the common opinion held by the leading men of Massachusetts, that the women themselves did not ask it. He recommended State rather than national action.

Rev. Ada C. Bowles of Cambridge, and Rev. Olympia Brown, of Racine, Wis., opened the various sessions with prayer—striking evidence of the growing self-assertion of the sex, and the rapid progress of events towards the full recognition of the fact that woman's hour has come. Touching deeper and tenderer chords in the human soul than words could reach, the inspiring strains of the celebrated organist, Mr. Ryder, rose ever and anon, now soft and plaintive, now full and commanding, mingled in stirring harmony with prayer and speech. And as loving friends had covered the platform with rare and fragrant flowers, the æsthetic taste of the most fastidious artist might have found abundant gratification in the grouping and whole effect of the assemblage in that grand temple. Thus through six prolonged sessions the interest was not only kept up but intensified from day to day.

The National Association was received right royally in Boston. On arriving they found invitations waiting to visit Governor Long at the State House, Mayor Prince at the City Hall, the great establishment of Jordan, Marsh & Co., and the Reformatory Prison for Women at Sherborn. Invitations to take part were extended to woman suffrage speakers in many of the conventions of that anniversary week. Among those who spoke from other platforms, were Matilda Joslyn Gage, Ellen H. Sheldon, Caroline B. Winslow, M. D., editor of The Alpha, and Rev. Olympia Brown. The president of the association, Mrs. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, received many invitations to speak at various points, but had time only for the "Moral Education," "Heredity," and "Free Religious" associations. Her engagement at Parker Memorial Hall, prevented her from accepting the governor's invitation, but Isabella Beecher Hooker and Susan B Anthony led the way to the State house and introduced the delegates from the East, the West, the North and the South, to the honored executive head of the State, who had declared himself, publicly, in favor of woman suffrage. The ceremony of hand-shaking over, and some hundred women being ranged in a double circle about the desk, Mrs. Hooker stepped forward, saying:

Speak a word to us, Governor Long, we need help. Stand here, please, face to face with these earnest women and tell us where help is to come from.

The Governor responded, and then introduced his secretary, who conducted the ladies through the building.

Mrs. Hooker said: Permit me, sir, to thank you for this unlooked-for and unusual courtesy in the name of our president who should be here to speak for herself and for us, and in the name of these loyal women who ask only that the right of the people to govern themselves shall be maintained. In this great courtesy extended us by good old Massachusetts as citizens of this republic unitedly protesting against being taxed without representation, and governed without our consent, we see the beginning of the end—the end of our wearisome warfare—a warfare which though bloodless, has cost more than blood, by as much as soul-suffering exceeds that of mere flesh. I see as did Stephen of old, a celestial form close to that of the Son of Man, and her name is Liberty—always a woman—and she bids us go on—go on—even unto the end.

Miss Anthony standing close to the governor, said in low, pathetic tones:

Yes, we are tired. Sir, we are weary with our work. For forty years some of us have carried this burden, and now, if we might lay it down at the feet of honorable men, such as you, how happy we should be.

The next day Mayor Prince, though suffering from a late severe attack of rheumatism, cordially welcomed the delegates in his room at the City Hall, and chatting familiarly with those who had been at the Cincinnati convention and witnessed his great courtesy, some one remarked that from that time Miss Anthony had proclaimed him the prince among men, and Mrs. Stanton immediately suggested that if the party with which he was identified were wise in their day and generation they would accept his leadership, even to the acknowledgement of the full citizenship of this republic, and thus secure not only their gratitude but their enthusiastic support in the next presidential election. Having compassion upon his Honor because of his manifest physical disability, the ladies soon withdrew and went directly to the house of Jordan, Marsh & Co., where were assembled in a large hall at the top of the building such a crowd of handsome, happy, young girls as one seldom sees in this work-a-day world; that well-known Boston firm within the last six months having fitted up a large recreation room for the use of their employés at the noon hour. Half a hundred girls were merrily dancing to the music of a piano, but ceased in order to listen to words of cheer from Mrs. Lockwood, Mrs. Hooker and Mrs. Sewall. At the close of their remarks Mr. Jordan brought forward a reluctant young girl who could give us, if she would, a charming recitation from "That Lass o' Lowrie's," in return for our kindness in coming to them. And after saying in a whisper to one who kindly urged compliance to this unexpected call, that this had been such a busy day she feared her dress was not all right, her face became unconscious of self in a moment, and with true dramatic instinct, she gave page after page of that wonderful story of the descent into the mine and the recognition there of one whom she loved, precisely as you would desire to hear it were the scene put upon the stage with all the accessories of scenery and companion actors.

From Jordan, Marsh & Co.'s a large delegation proceeded to visit the Reformatory Prison at Sherborn which was established three or four years ago. The board of directors, consisting of three women and two men, has charge of all the prisons of the State. Mrs. Johnson, one of the directors, a noble, benevolent woman, interested in the great charities of Boston, was designated by Governor Long—through whose desire the Association visited the prison—to do the honors and accompany the party from Boston. The officers, matron and physician of the Sherborn prison, are all women. Dr. Mosher, the superintendent, formerly the physician, is a fair, noble-looking woman about thirty-five years of age. She has her own separate house connected with the building. The present physician, a delicate, cultured woman, with sympathy for her suffering charges, is a recent graduate of Ann Arbor.

The entire work is done by the women sent there for restraint, and the prison is nearly self-supporting; it is expected that within another year it will be entirely so. Laundry work is done for the city of Boston, shirts are manufactured, mittens knit, etc. The manufacturing machinery will be increased the coming year. The graded system of reward has been found successful in the development of better traits. It has four divisions, and through it the inmates are enabled to work up by good behavior toward more pleasant surroundings, better clothes and food and greater liberty. From the last grade they reach the freedom of being bound out; of seventy-eight thus bound during the past year but seven were returned. The whole prison, chapel, school-room, dining-room, etc., possesses a sweet, clean, pure atmosphere. The rooms are light, well-ventilated, vines trailing in the windows from which glimpses of green trees and blue sky can be seen.

Added to all the other courtesies, there came the invitation to a few of the representatives of the movement to dine with the Bird Club at the Parker House, in the same cozy room where these astute politicians have held their councils for so many years, and whose walls have echoed to the brave words of many of New England's greatest sons. The only woman who had ever been thus honored before was Mrs. Stanton, who, "escorted by Warrington," dined with these honorable gentlemen in 1871. On this occasion Susan B. Anthony and Harriet H. Robinson accompanied her. Around the table sat several well-known reformers and distinguished members of the press and bar. There was Elizur Wright whose name is a household word in many homes as translator of La Fontaine's fables for the children. Beside him sat the well-known Parker Pillsbury and his nephew, a promising young lawyer in Boston. At one end of the table sat Mr. Bird with Mrs. Stanton on his right and Miss Anthony on his left. At the other end sat Frank Sanborn with Mrs. Robinson (wife of "Warrington") on his right. On either side sat Judge Adam Thayer of Worcester, Charles Field, Williard Phillips of Salem, Colonel Henry Walker of Boston, Mr. Ernst of the Boston Advertiser, and Judge Henry Fox of Taunton. The condition of Russia and the Conkling imbroglio in New York; the new version of the Testament and the reason why German Liberals, transplanted to this soil, immediately become conservative and exclusive, were all considered. Carl Schurz, with his narrow ideas of woman's sphere and education, was mentioned by way of example. In reply to the question how the Suffrage Association felt in regard to Conkling's reëlection. Mrs. Robinson said:

That the leaders, who are students of politics were unitedly against him. Their only hope is in the destruction of the Republican party, which is too old and corrupt to take up any new reform.

Frank Sanborn, fresh from the perusal of the New Testament, asked if women could find any special consolation in the Revised Version regarding everlasting punishment. Mrs. Stanton replied:

Certainly, as we are supposed to have brought "original sin" into the world with its fearful forebodings of eternal punishment, any modification of Hades in fact or name, for the men of the race, the innocent victims of our disobedience, fills us with satisfaction.

From the club the ladies hastened to the beautiful residence of Mrs. Fenno Tudor, fronting Boston Common, where hundreds of friends had already gathered to do honor to the noble woman so ready to identify herself with the unpopular reforms of her day. Among the many beautiful works of art, a chief attraction was the picture of the grand-mother of Parnell, the Irish agitator, by Gilbert Stuart. The house was fragrant with flowers, and the unassuming manners of Mrs. Tudor, as she moved about among her guests, reflected the glory of our American institutions in giving the world a generation of common-sense women who do not plume themselves on any adventitous circumstances of wealth or position, but bow in respect to morality and intelligence wherever they find it. At the close of the evening Mrs. Stanton presented Mrs. Tudor with the "History of Woman Suffrage" which she received with evident pleasure and returned her sincere thanks.

Hartford, September 17, 1885.

My Dear Miss Anthony: I have received your letter of inquiry. As to that petition in 1867, I was one of the signers, and, probably had something to do with getting the other signatures, though I have nothing but my memory to depend on as to that; but I was pretty much alone here in those days, on the woman suffrage question. Who the other signers were I made an attempt to find out in the secretary of state's office the other day, but found that it would take days, instead of the few hours I had at my command. I find in my journal a reference to Lucy Stone and Mr. Blackwell addressing the committee in the House of Representatives, and that was the committee that made the report afterwards published in The Revolution. Mr. Croffut made the opening address on the day of the hearing. He was always ready to aid us in whatever way he could, and I felt grateful to him, for a helping hand was doubly appreciated in those days. I find by the journal of the House for that year that the vote on the question was 93 yeas to 111 nays. The name of Miss Susie Hutchinson heads one petition, with 70 others. How many other petitions there were that year I do not know, but I believe there have been several every year since, besides a number of individual petitions. Since that time the House has voted favorably on the question twice, at least, but I believe we have never had a majority in the Senate.

You ask when I first wrote or spoke for the ballot. My first venture in that line was in 1853. I was then at the age of twenty-two, living with my sister in Cleveland, O., and had never given any attention to the subject of woman suffrage, and cared nothing about it any further than the spirit of rebellion—born with me—against everything unjust, might be said to have made me a radical by nature. In the fall of that year a woman's rights convention met in Cleveland, and I attended it alone, none of the rest of the family caring to go. In my old journal I find this entry:

October 7, 1853. Attended a woman's rights convention which has met here. Never saw anything of the kind before. A Mr. Barker spent most of the morning trying to prove that woman's rights and the Bible cannot agree. The Rev. Antoinette L. Brown replied in the afternoon in defense of the Bible. She says the Bible favors woman's rights. Miss Brown is the best-looking woman in the convention. They appear to have a number of original and pleasing characters upon their platform, among them Miss Lucy Stone—hair short and rolled under like a man's; a tight-fitting velvet waist and linen collar at the throat; bombazine skirt just reaching the knees, and trousers of the same. She is independent in manner and advocates woman's rights in the strongest terms:—scorns the idea of woman asking rights of man, but says she must boldly assert her own rights, and take them in her own strength. Mrs. Ernestine L. Rose, a Polish lady with black eyes and curls, and rosy cheeks, manifests the independent spirit also. She is graceful and witty, and is ready with sharp replies on all occasions. Mrs. Lucretia Mott, a Philadelphia Quaker, is meek in dress but not in spirit. She gets up and hammers away at woman's rights, politics and the Bible, with much vigor, then quietly resumes her knitting, to which she industriously applies herself when not speaking to the audience. She wears the plain Quaker dress and close-fitting white cap. Mrs. Frances D. Gage, the president, is a woman of sound sense and a good writer of prose and poetry. Mrs. Caroline Severance has an easy, pleasing way of speaking. Mr. Charles Burleigh, a Quaker, appears to be an original character. He has long hair, parted in the middle like a woman's, and hanging down his back. He and Miss Stone seem to reverse the usual order of things.

My first speech in public, I find by my old journal—which serves me better than I thought it would—was given in Music Hall in this city in November, 1870. This meeting was held under the auspices of the State association, and was presided over by the Rev. Olympia Brown. I find that in the winter of 1871 I made addresses in various parts of the State. The journal also tells of a good deal of trotting about to get signatures to petitions, for I had more time to do that thing then than I have now.

The first woman suffrage meeting ever held in Hartford, and the first, probably, in Connecticut, was the one you and Mrs. Stanton held in Allyn Hall in December, 1867. Our State Suffrage Association was organized in October, 1869. The signers[168] to the call for that convention were quite influential persons.

In my hunt through the journals of the two legislative houses I found in the House journal for 1878 that Mr. Pratt of Meriden had presented the petition of Mr. and Mrs. Isaac C. Lewis. Mr. Clark of Enfield, presented the petition of Lucy A. Allen; Mr. Gallagher of New Haven presented several petitions that year, one of them being headed by Mr. Henry A. Stillman of Wethersfield, followed by 532 names, and another by Mrs. D. F. Connor, M. D. Mr. Broadhead of Glastonbury presented the petition of the Smith sisters. This unique petition Miss Mary Hall, who was with me in the secretary's office, chanced to light upon, and she copied it. It is a document well worth handing down on the page of history, and runs as follows:

The Petition of Julia E. Smith and Abby H. Smith, of Glastonbury, to the Senate of the State of Connecticut:

This is the first time we have petitioned your honorable body, having twice come before the House of Assembly, which the last time gave a majority that we should vote in town affairs; but it was negatived in the Senate.

We now pray the highest court in our native State that we may be relieved from the stigma of birth. For forty years since the death of our father have we suffered intensely for being born women. We cannot even stand up for the principles of our forefathers (who fought and bled for them) without having our property seized and sold at the sign-post, which we have suffered four times; and have also seen eleven acres of our meadow-land sold to an ugly neighbor for a tax of fifty dollars—land worth more than $2,000. And a threat is given out that our house shall be ransacked and despoiled of articles most dear to us, the work of lamented members of our family who have gone before us, and all this is done without the least excuse of right or justice. We are told that it is the law of the land made by the legislature and done to us, two defenceless women, who have never broken these laws, made by not half the citizens of this State. And it was said in our Declaration of Independence that "Governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed."

For being born women we are obliged to help support those who have earned nothing, and who, by gambling, drinking, and the like, have come to poverty, and these same can vote away what we have earned with our own hands. And when men meet to take off the dollar poll-tax, the bill for the dinner comes in for the women to pay. Neither have we husband, or brother, or son, or even nephew, or cousin, to help us. All men will acknowledge that it is as wrong to take a woman's property without her consent as to take a man's without his consent; and such wrong we suffer wholly for being born women, which we are in no wise to blame for. To be sure, for our consolation, we are upheld by the learned, the wise and the good, from all parts of the country, having received communications from thirty-two of our States, as well as from over the seas, that we are in the right, and from many of the best men in our own State. But they have no power to help us. We therefore now pray your honorable body, who have power, with the House of Assembly, to relieve us of this stigma of birth, and grant that we may have the same privileges before the law as though we were born men. And this, as in duty bound, we will ever pray.

Julia and Abby Smith.

Glastonbury, Conn., January 29, 1878.

The story of the Smith sisters, from 1873 and on, will be handed down as one of the most original and unique chapters in the history of woman suffrage. Abby Smith, with my friend Mrs. Buckingham, attended with me the first meeting of the Woman's Congress, in New York, in October, 1873. While there, she said she should, on her return, address her town's people on woman suffrage and taxation, as they had not been treated fairly in the matter of their taxes. She did so on the fifth of November, addressing the Glastonbury town meeting in the little red-brick town-house of that place—a building that will always hereafter be connected with the names of Abby and Julia Smith. Several years after, wishing to address them again, she was refused entrance there, so she and Julia addressed the people from an ox-cart that stood in front. This was after their continued warfare against "taxation without representation" had aroused the opposition of their townsmen, but that first speech in 1873 was the beginning of their fame. Abby sent it to me for publication in the Times of this city, but the editor not having room for it sent it to the Courant, which gave it a place in its columns, thus (unwittingly) setting a ball in motion that ran all round the country, and even over the ocean. The simplicity and uniqueness of the story of "Abby Smith and her cows," gave a boom to the cause of woman suffrage as welcome as it was unexpected. The Glastonbury mails were more heavily laden than ever before in the history of this hitherto unknown town, for letters came pouring in from all quarters to the sisters. The fame did not rest entirely on Abby and her cows; Julia and her Bible came in for an important share, and the newspaper articles in regard to them were a remarkable blending of cows and Biblical lore, dairy products and Greek and Hebrew. Many of the articles were wide of the facts, being written with a view to make a bright and readable column. For instance, a Chicago paper got up a highly colored article in which it said that Abby Smith's mother—Hannah Hickok—was such an intense student that her father had a glass cage made for her to study in. The only vestage of truth in this story was that, lacking our modern facilities for heating, Mr. Hickok had an extra amount of glass put into the south side of his daughter's room that the sun might give it a little more heat in cold weather. Hannah Hickok seems to have had a mental equipment much above that of the average woman of that day; she had a taste for literature, and was something of a linguist, and wrote, moreover, at different times, quite an amount of readable verse. She had a taste for mathematics, and also for astronomy, and made for her own use an almanac, for these were not so plenty then as now; she could, on awakening, tell any hour of the night by the position of the stars. Evidently Hannah Hickok Smith was not an ordinary woman; and it is quite as evident that her daughters were equally original, though in a different direction. Women who have translated the Bible are not to be met with every day—nor men either, for that matter, but Julia Smith not only did this, but translated it five times,—twice from the Hebrew, twice from the Greek, and once from the Latin; and thirty years later, or after the age of eighty, published the translation; and then, to crown the list of marvels, married at the age of eighty-five.

One point more, and the one nearest my heart. You ask me about my "dear friend Mrs. Buckingham." I can give no details of her suffrage work, but her heart was in it, and her name should be handed down in your History. She was at one time chairman of the executive committee of our State association, and she would, if she had thought it necessary, have spent of her little income to the last cent to help along the cause. She made public addresses and wrote many suffrage articles and letters that were published in different papers, but she made no noise about it; her work was all done with her own characteristic gentleness. Generous to a fault, winning and beautiful as the flowers she scattered on the pathway of her friends, she passed on her way; and one memorable Easter morning she left us so gently that none knew when the sleep of life passed into the sleep of death; we only knew that the glorious light of her eyes—a light like that which "never shone on sea or land"—had gone out forever.

"She died in beauty like the dew Of flowers dissolved away; She died in beauty like a star Lost on the brow of day."

The Hartford Equal Rights Club[169] was organized in March, 1885, and holds semi-monthly meetings. Its membership is not large, but what it lacks in numbers it makes up in earnestness. Its proceedings are reported pretty fully and published in the Hartford Times, which has a large circulation, thus gaining an audience of many thousands and making its proceedings much more important than they would otherwise be. It is managed as simply as possible, and is not encumbered with a long list of officers. There are simply a president, Mrs. Emily P. Collins;[170] a vice-president, Miss Mary Hall; and a secretary, Frances Ellen Burr, who is also the treasurer. Debate is free to all, the platform being perfectly independent, as far as a platform can be independent within the limits of reason. Essays are read and debated, and many interesting off-hand speeches are made. It is an entirely separate organization from the Connecticut State Suffrage Association, founded in 1869. But its membership is not confined to the city; it invites people throughout the State, or in other States, to become members—people of all classes and of all beliefs. Opponents of woman suffrage are always welcome, for these furnish the spice of debate. Among the topics discussed has been that of woman and the church, and upon this subject Mrs. Stanton has written the club several letters.

Last spring (1885) a number of the members of the club were given hearings before the Committee on Woman Suffrage in the legislature in reference to a bill then under consideration, which was exceedingly limited in its provisions. The House of Representatives improved it and then passed it, but it was afterwards defeated in the Senate. Some of the meetings of the club have been held in Hartford's handsome capitol, a room having been allowed for its use, and a number of members of the House of Representatives have taken part in the discussions. Mrs. Collins, president of the club, is always to be depended upon for good work, and Miss Hall, its vice-president, is active and efficient. She is in herself an illustration of what women can become if they only have sufficient confidence and force of will. She is a practicing lawyer, and a successful one.

Boston, December 21, 1868.

Dear Mrs. White: I must lose the gratification of being present at the Woman Suffrage Convention at Concord and substitute an epistolary testimony for a speech from the platform.

The two conventions recently held in furtherance of the movement for universal and impartial suffrage—one in Boston, the other in Providence—were eminently successful in respect to numbers, intellectual ability, moral strength and unity of action; and their proceedings such as to challenge attention and elicit wide-spread commendation. I have no doubt that the convention in Concord will exhibit the same features, be animated by the same hopeful spirit and produce as cheering results.

The only criticism seemingly of a disparaging tone, I have seen, of the speeches made at the conventions alluded to, is, that there was nothing new advanced on the occasion; as though novelty were the main thing, and the reiteration of time-honored truths, with their latest application to the duties of the hour, were simply tedious! For one, I ask no more light upon the subject; nor am I so vain as to assume to be capable of throwing any additional light upon it. One drop of water is very like another, but it is the perpetual dropping that wears away the stone. The importunate widow had nothing fresh or new to present to the unjust judge, but by her persistent coming she wearied him into compliance with her petition. The end of the constant assertion of a right withheld is restitution and victory. The whole anti-slavery controversy was expressed and included in the Golden Rule, morally, and in the Declaration of Independence, politically; nor could anything new be added to these by the wisest, the most ingenious, or the most eloquent. "Line upon line, precept upon precept, here a little and there a little"; that is the essential method of reform. If there is nothing new to be said in favor of suffrage for women, is there anything new to be urged against it? But though the objections are exceedingly trite and shallow, it is still necessary to examine and refute them by arguments and illustrations none the less forcible because exhausted at an earlier period.

The first objection is positively one of the most urgent reasons for granting suffrage to women; for it is predicated on the concession of the superiority of woman over man in purity of purpose and excellence of character. Hence the cry is, that it will not only be descending, but degrading for her to appear at the polls. But, if government is absolutely necessary, and voting not wrong in practice, it is surely desirable that the admittedly purest and best in the nation should find no obstacle to their reaching the ballot-box. Nay, the way should be opened at once, by every consideration pertaining to the public welfare, the justice of legislation, the preservation of popular liberty. It is impossible for a portion of the people, to be wiser and more trustworthy than the whole people, or better qualified to decide what shall be the laws for the government of all. The more minds consulted, the more souls included, the more interests at stake, in determining the form and administration of government, the more of justice and humanity, of security and repose, will be the result. The exclusion of half the population from the polls, is not merely a gross injustice, but an immense loss of brain and conscience, in making up the public judgment. As a nation we have discarded absolutism, monarchy, and hereditary aristocracy; but we have not fully attained even to manhood suffrage. Men are proscribed on account of their complexion, women because of their sex. The entire body politic suffers from this proscription.

The second objection refutes the first; it is based on the alleged natural inferiority of woman to man, and the transition is thus quickly made for her, from a semi-angelic state, to that of a menial, having no rights that men are bound to respect beyond what they choose to allow. In the scale of political power, therefore, one male voter, however ignorant or depraved, outweighs all the women in America! For, no matter how intelligent, cultured, refined, wealthy, intellectually vigorous, or morally great, any of their number may be,—no matter what rank in literature, art, science, or medical knowledge and skill they may reach,—they are political non-entities, unrepresented, discarded, and left to such protection under the laws, as brute force and absolute usurpation may graciously condescend to give. Yet they are as freely taxed and held amendable to penal law as strictly as though they had their full share of representation in the legislative hall, on the bench, in the jury-box, and at the polls. This cry of inferiority is not peculiar in the case of woman. It was the subterfuge and defiance of negro slavery. It has been raised in all ages by tyrants and usurpers against the toiling, over-burdened millions, seeking redress for their wrongs, and protection for their rights. It always indicates intense self-conceit, and supreme selfishness. It is at war with reason and common-sense, and is a bold denial of the oneness of the human race.

The third objection is, that women do not wish to vote. If this were true, it would not follow that they should not be enfranchised, and left free to determine the matter for themselves. It was confidently declared that the slaves at the south neither wished to be free, nor would they take their liberty if offered them by their masters. Had that assertion been true, it would have furnished no justification whatever, for making man the property of his fellow-man, or for leaving the slaves in their fetters. But it was not true. Nor is it true that women do not wish to vote. Tens of thousands are ready to go to the polls and assume their share of political responsibility, as soon as they shall be legally permitted to do so; and they are not the ignorant and degraded of their sex, but women remarkable for their intelligence and moral worth. The great mass will, ere long, be sufficiently enlightened to claim what belongs to them of right. I hope to be permitted to live to see the day when neither complexion nor sex shall be made a badge of degradation, but men and women shall enjoy the same rights and privileges, and possess the same means for their protection and defense.

Wm. Lloyd Garrison.

Very faithfully yours,

Mrs. A. S. White.

While Lucy Stone resided in New Jersey, she held several series of meetings in the chief towns and cities before the formation of the State Society.[276] The agitation that began in 1867 was probably due to her, more than to any other one person in that State. The State society was organized in the autumn of 1867, and from year to year its annual meetings have been held in Vineland, Newark, Trenton, and other cities. On its list of officers[277] are some of the best men and women in the State. Several distinguished names from other States are among the speakers[278] who have taken part in their conventions. County and local societies too have been extensively organized. These associations have circulated tracts and appeals, memorialized the legislature, and had various hearings before that body. At the annual meeting held in Newark February 15, 1871, the following memorial to the legislature, prepared by Mary F. Davis, was unanimously adopted:

To the Honorable the Senate and General Assembly of the State of New Jersey:

Section 2, Article 1, of the constitution of the State of New Jersey, expressly declares that "All political power is inherent in the people. Government is instituted for the protection, security, and benefit of the people, and they have the right at all times to alter or reform the same, whenever the public good may require it." Throughout the entire article the words "people" and "person" are used, as if to apply to all the inhabitants of the State. In direct contradiction to this broad and just affirmation, section 1, article 2, begins with the restrictive and unjust sentence: "Every white male citizen of the United States, at the age of twenty-one years * * * shall be entitled to vote," etc., and the section ends with the specification that "no pauper, idiot, insane person, or person convicted of a crime * * * shall enjoy the right of an elector."

Of the word "white" in this article your memorialists need not speak, as it is made a dead letter by the limitations of the fifteenth amendment to the United States constitution. To the second restriction, indicated by the word "male" we beg leave to call the attention of the legislature, as we deem it unjust and arbitrary, as well as contradictory to the spirit of the constitution, as expressed in the first article. It is also contrary to the precedent established by the founders of political liberty in New Jersey. On the second of July, 1776, the provincial congress of New Jersey, at Burlington, adopted a constitution which remained in force until 1844; in which section 4 specified as voters, "all the inhabitants of this Colony, of full age," etc. In 1790, a committee of the legislature reported a bill regulating elections, in which the words "he and she" are applied to voters, thus giving legislative endorsement to the alleged meaning of the constitution.

The legislature of 1807 departed from this wise and just precedent, and passed an arbitrary act, in direct violation of the constitutional provision, restricting the suffrage to white male adult citizens, and this despotic ordinance was deliberately endorsed by the framers of the State constitution which was adopted in 1844. This was plainly an act of usurpation and injustice, as thereby a large proportion of the law-abiding citizens of the State were disfranchised, without so much as the privilege of signifying their acceptance or rejection of the barbarous fiat which was to rob them of the sacred right of self-protection by means of a voice in the government, and to reduce them to the political level of the "pauper, idiot, insane person, or person convicted of crime."

If this flagrant wrong, which was inflicted by one-half the citizens of a free commonwealth on the other half, had been aimed at any other than a non-aggressive and self-sacrificing class, there would have been fierce resistance, as in the case of the United Colonies under the British yoke. It has long been borne in silence. "The right of voting for representatives," says Paine, "is the primary right, by which other rights are protected. To take away this right is to reduce man to a state of slavery, for slavery consists in being subject to the will of another, and he that has not a vote in the electing of representatives is in this condition." Benjamin Franklin wrote: "They who have no voice nor vote in the electing of representatives do not enjoy liberty, but are absolutely enslaved to those who have votes and to their representatives; for to be enslaved is to have governors whom other men have set over us, and be subject to laws made by the representatives of others, without having had representatives of our own to give consent in our behalf." This is the condition of the women of New Jersey. It is evident to every reasonable mind that these unjustly disfranchised citizens should be reïnstated in the right of suffrage. Therefore, we, your memorialists, ask the legislature at its present session to submit to the people of New Jersey an amendment to the constitution, striking out the word "male" from article 2, section 1, in order that the political liberty which our forefathers so nobly bestowed on men and women alike, may be restored to "all inhabitants" of the populous and prosperous State into which their brave young colony has grown.

With but a slight change of officers and arguments, these conventions were similar from year to year. There were on all occasions a certain number of the clergy in opposition. At one of these meetings the Rev. Mr. McMurdy condemned the ordination of women for the ministry. But woman's fitness[279] for that profession was successfully vindicated by Lucretia Mott and Phebe A. Hanaford. Mrs. Portia Gage writes, December 12, 1873:

There was an election held by the order of the township committee of Landis, to vote on the subject of bonding the town to build shoe and other factories. The call issued was for all legal voters. I went with some ten or twelve other women, all taxpayers. We offered our votes, claiming that we were citizens of the United States, and of the State of New Jersey, also property-holders in and residents of Landis township, and wished to express our opinion on the subject of having our property bonded. Of course our votes were not accepted, whilst every tatterdemalion in town, either black or white, who owned no property, stepped up and very pompously said what he would like to have done with his property. For the first time our claim to vote seemed to most of the voters to be a just one. They gathered together in groups and got quite excited over the injustice of refusing our vote and accepting those of men who paid no taxes.

In 1879, the Woman's Political Science Club[280] was formed in Vineland, which held its meetings semi-monthly, and discussed a wide range of subjects. Among the noble women in New Jersey who have stood for many years steadfast representatives of the suffrage movement, Cornelia Collins Hussey of Orange is worthy of mention. A long line of radical and brave ancestors[281] made it comparatively easy for her to advocate an unpopular cause. Her father, Stacy B. Collins, identified with the anti-slavery movement, was also an advocate of woman's right to do whatever she could even to the exercise of the suffrage. He maintained that the tax-payer should vote regardless of sex, and as years passed on he saw clearly that not alone the tax-payer, but every citizen of the United States governed and punished by its laws, had a just and natural right to the ballot in a country claiming to be republican. The following beautiful tribute to his memory, by Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, is found in a letter to his daughter:

London, July 27, 1873.

My last letter from America brought me the sad intelligence of your dear father's departure from amongst you; and I cannot refrain from at once writing and begging you to accept the sincere sympathy and inevitable regret which I feel for your loss. The disappearance of an old friend brings up the long past times vividly to my remembrance—the time when, impelled by irresistible spiritual necessity, I strove to lead a useful but unusual life, and was able to face, with the energy of youth, both social prejudice and the hindrance of poverty. I have to recall those early days to show how precious your father's sympathy and support were to me in that difficult time; and how highly I respected his moral courage in steadily, for so many years, encouraging the singular woman doctor, at whom everybody looked askance, and in passing whom so many women held their clothes aside, lest they should touch her. I know in how many good and noble things your father took part; but, to me, this brave advocacy of woman as physician, in that early time, seems the noblest of his actions.

Speaking of the general activity of the women of Orange, Mrs. Hussey says:

The Women's Club of Orange was started in 1871. It is a social and literary club, and at present (1885) numbers about eighty members. Meetings are held in the rooms of the New England Society once in two weeks, and a reception, with refreshments, given at the house of some member once a year. Some matter of interest is discussed at each regular meeting. This is not an equal suffrage club, yet a steady growth in that direction is very evident. Very good work has been done by this club. An evening school for girls was started by it, and taught by the members for awhile, until adopted by the board of education, a boys' evening school being already in operation. Under the arrangements of the club, a course of lectures on physiology, by women, was recently given in Orange, and well attended. At the house of one of the members a discussion was held on this subject: "Does the Private Character of the Actor Concern the Public?" Although the subject was a general one, the discussion was really upon the proper course in regard to M'lle Sarah Bernhardt, who had recently arrived in the country. Reporters from the New York Sun attended the meeting, so that the views of the club of Orange gained quite a wide celebrity.

Of Mrs. Hussey's remarks, the Newark Journal said: