автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Beautiful Wales

Transcriber's Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

BEAUTIFUL WALES

AGENTS IN AMERICA

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, New York

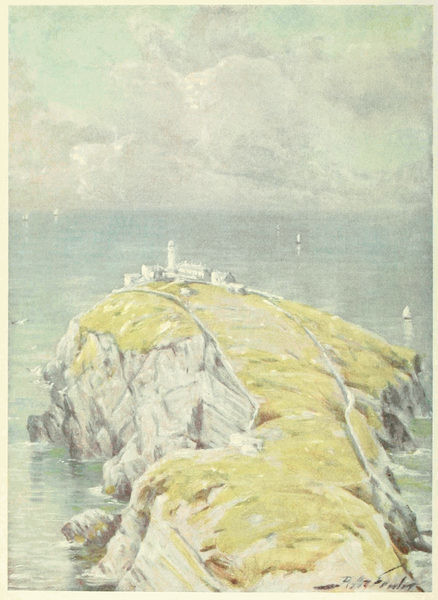

THE STACK, HOLYHEAD

BEAUTIFUL WALES

PAINTED BY ROBERT

FOWLER · R·I · DESCRIBED

BY EDWARD THOMAS

WITH A NOTE ON MR.

FOWLER'S LANDSCAPES

BY ALEX. J. FINBERG

PUBLISHED BY A. & C.

BLACK · LONDON · MCMV

PREFACE

A few of my jests, impressions of scenery, and portraits in this book have already been printed in The Daily Chronicle, The World, The Week's Survey, The Outlook, and The Illustrated London News. I have only to add that the line of verse on p. 34 is by Mr. Ernest Rhys; the lines on p. 71 are by Mr. T. Sturge Moore; and those on pp. 130 and 178 by Mr. Gordon Bottomley: and to confess, chiefly for the benefit of the solemn reviewer, that I know nothing of the Welsh language.

EDWARD THOMAS.

Looking back, the artistry of time makes it appear that soon after I had become certain that the painter had somehow caught Launcelot kneeling at the foot of the column, I reached Wales.

and for the moment, thought he was a man. No actor ever stormed and swelled so, because no actor yet played the part which he played. It was a chant; yet it was too uncontrollable for a chant. If you call it declamation, you must admit that to declaim a man shall first go to Medea, that she

Yesterday, the flower of the wood-sorrel and the song of the willow-wren came together into the oak woods, and higher up on the mountain, though they were still grey, the larches were misty and it was clearly known that soon they would be green. The air was full of the bleating of lambs, and though there was a corpse here and there, so fresh and blameless was it that it hardly spoiled the day. The night was one of calm and breathing darkness; nor was there any moon; and therefore the sorrowful darkness and angularity of early spring valleys by moonlight, when they have no masses of foliage to make use of the beams, did not exist. It was dark and warm, and from the invisible orchard, where snow yet lay under the stone wall, came a fragrance which, though it was not May, brought into our minds the song that was made for May in another orchard high among hills:

In the afternoon I climbed out of a valley, descended again, and came on to a road that rolled over many little hills into many little valleys, and at the top of each hill grew the vision of a purple land ahead. But, for some miles, the valleys were solitary. There were brooks in them with cold, fresh voices, and copses of oak, and sometimes the smoke or the white wall of a house. There sang the latest of the willow-wrens, and among the blackthorns a bullfinch, with delicate voices. The air was warm and motionless; the light on oak and grass was steady and rich; the sky was low and leaning gently to the earth, and its large white clouds moved not, though they changed their shapes. But these things belonged to the brooks, the copses, the willow-wrens; or so it seemed, since that warm day, which elsewhere might have seemed so kind with an ancient kindness as if to one returning home after long exile, was not kind, but was indifferent and made an intruder of me. And I should have passed the stony hedges and the little brooks over the road and the desolate mine, in the indifferent little worlds of the valleys, one by one, as if they had been in a museum, or as if I had been taken there to admire them, had it not been that on the crests of the road between valley and valley, I saw the purple beckoning hills far away, and that, at length, towards the last act of the dim, rich, long-drawn out and windless sunset, the road took me into a small valley that was different. Just within reach of the sunset light, on one side of the valley lay a farm, with ricks, outhouses, and two cottages, all thatched. In the corner of the field nearest to the house, the long-horned craggy cattle were beginning to lie down. Those cattle, always vast and fierce, seemed to have sprung from the earth—into which the lines of their recumbent bodies flowed—out of which their horns rose coldly and angrily. The buildings also had sprung from the earth, and only prejudice taught me that they were homes of men. They enmeshed the shadows and lights of sunset in their thatch, and were as some enormous lichen-covered things, half crag, half animal, which the cattle watched, together with five oaks.

CONTENTS

PAGE

CHAPTER I

Preliminary Remarks on Men, Authors, and Things in Wales 1CHAPTER II

Entering Wales 28CHAPTER III

A Farmhouse under a Mountain, a Fire, and some Firesiders 41CHAPTER IV

Two Ministers, a Bard, a Schoolmaster, an Innkeeper, and Others 55CHAPTER V

Wales Month by Month 99APPENDIX

A Note on Mr. Fowler's Landscapes, by Alexander J. Finberg 201CHAPTER I

PRELIMINARY REMARKS ON MEN, AUTHORS, AND THINGS IN WALES

CHAPTER II

ENTERING WALES

CHAPTER III

A FARMHOUSE UNDER A MOUNTAIN, A FIRE, AND SOME FIRESIDERS

CHAPTER IV

TWO MINISTERS, A BARD, A SCHOOLMASTER, AN INNKEEPER, AND OTHERS

CHAPTER V

WALES MONTH BY MONTH

APPENDIX

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1.

The Stack, Holyhead

FrontispieceFACING PAGE

2.

Summer Evening, Anglesey Coast

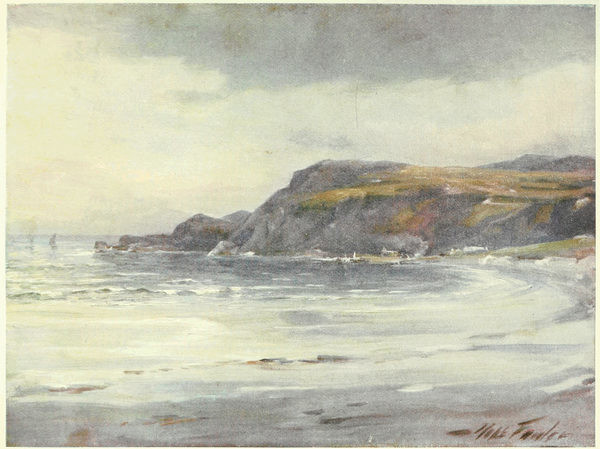

23.

Yachts, Anglesey Coast

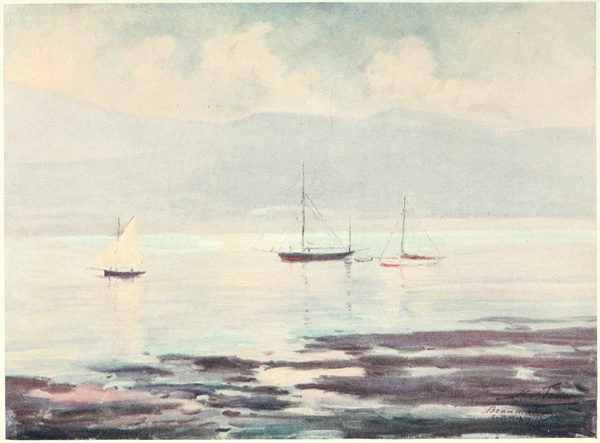

44.

Beaumaris—Moonlight

65.

The Beach, Beaumaris

86.

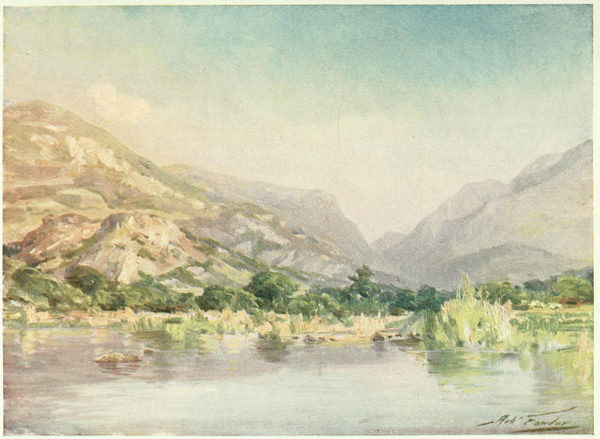

The Trout Stream

127.

Near Menai Straits

148.

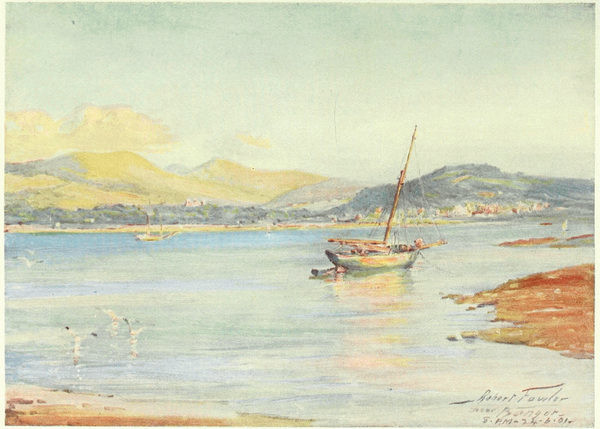

Near Bangor

189.

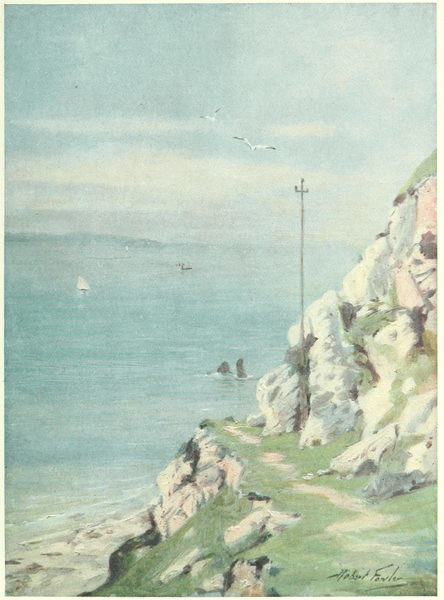

A Footpath on the Great Orme

2010.

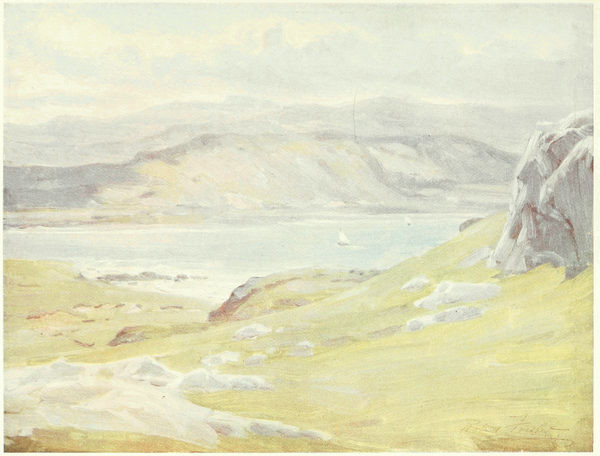

A View from the Great Orme's Head

2411.

Old Cottage and Ruins of Abbey, Great Orme's Head

2612.

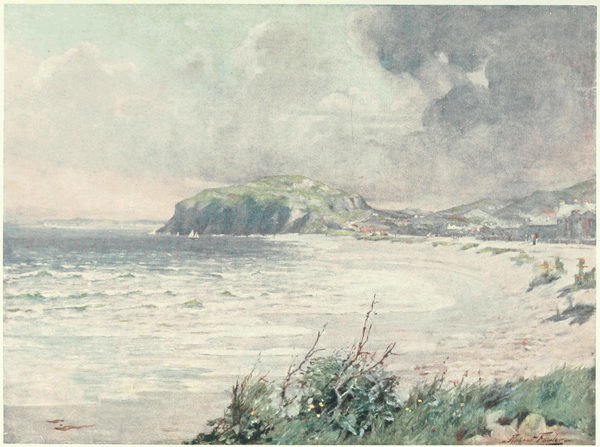

Breezy Morning, Llandudno Bay

2813.

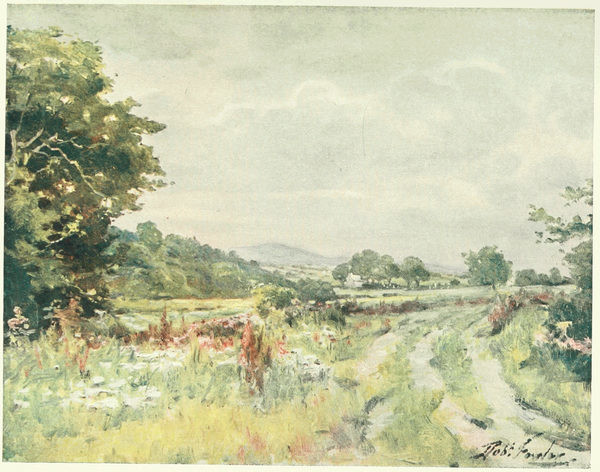

Country Lane

3014.

A Nocturne, Llandudno Bay

3215.

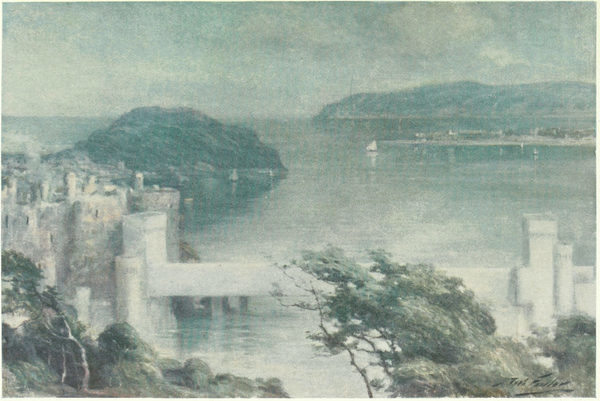

Conway from Benarth—Early Morning

3616.

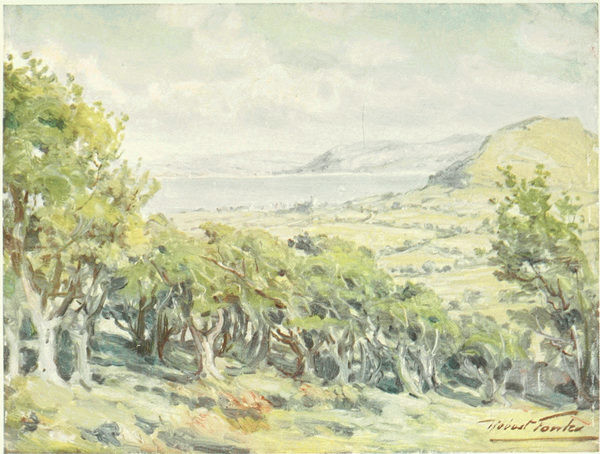

Near Colwyn Bay

3817.

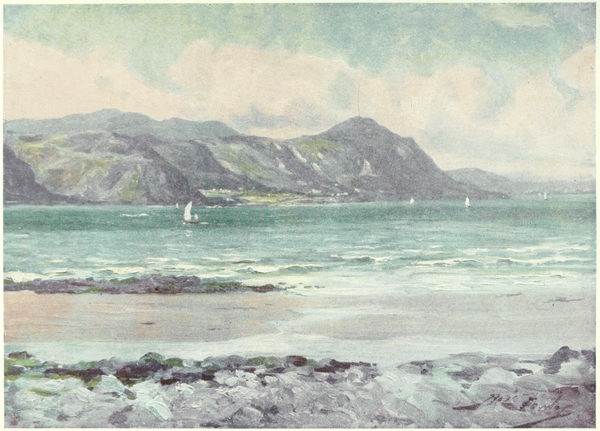

Distant View of Penmaenmawr—Early Morning Light

4218.

Silvery Light, Conway Shore

4419.

A Mountain Pass—Noon

4820.

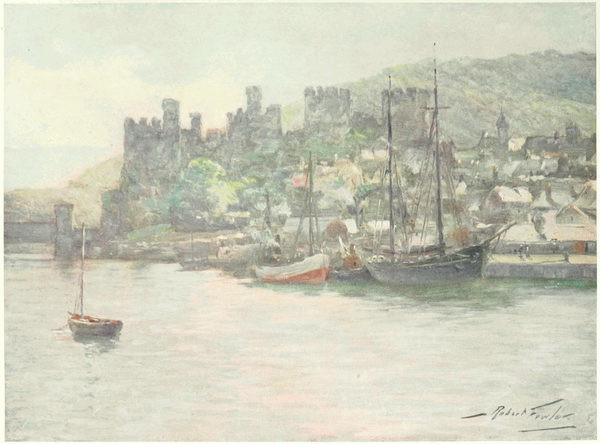

Conway Castle and Quay—Noon

5021.

Conway Valley

5422.

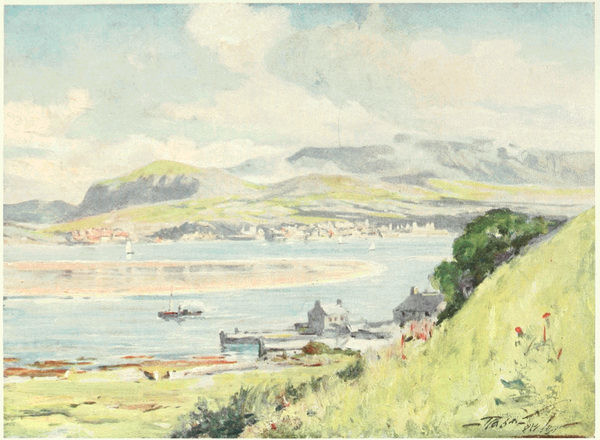

Carnarvon, from Anglesey

5623.

Boddnant Hall, Conway Valley

6024.

Carnarvon Castle

6225.

Distant View of Carnarvon Bay

6626.

On the River Seiont, Carnarvonshire—Evening Glow

6827.

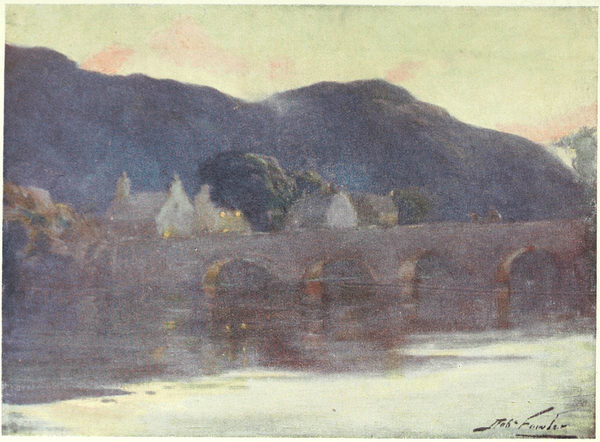

Bridge, Cwm-y-Glo—Evening

7228.

Field Path, near Llanrug

7429.

Windy Day, near Llanrug

7830.

Morning Mists, near Trefriw

8031.

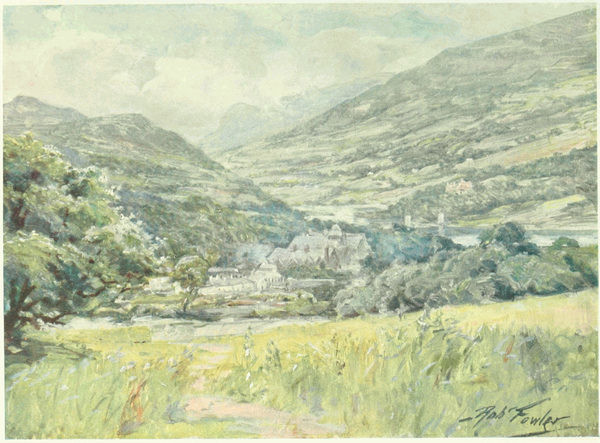

Distant View of Bettws-y-Coed

8232.

The Old Bridge, Bettws-y-Coed

8433.

Swallow Falls, Bettws-y-Coed

8634.

Fairy Glen, Bettws-y-Coed

9035.

Church Pool, Bettws-y-Coed

9236.

Miner's Bridge on River Llugwy

9637.

Sunny Field, near Llanberis

10038.

Welsh Farm, near Llanberis

10439.

Snowdon from Cwm-y-Glo

10640.

Snowdon from Llanberis Lake

10841.

Snowdon from Traeth Mawr

11042.

Snowdon from Capel Curig Lake—Summer Evening

11443.

In the Lledr Valley

11644.

Duffws Mountain

12045.

Duffws Mountain in Mist

12246.

Coming Night, near Beddgelert

12647.

Aberglaslyn

12848.

View of Moelwyn

13249.

A Hayfield near Portmadoc

13450.

Valle Crucis Abbey

13651.

View of Llangollen

13852.

A Lonely Shore near Penrhyn Deudraeth

14053.

The Shore near Harlech—Afternoon

14254.

In the Woods, Farchynys, Barmouth Estuary

14655.

Incoming Tide, near Barmouth

14856.

Barmouth Bridge

15257.

Misty Morning, near Barmouth

15458.

A Lonely Shore, Barmouth Estuary

15659.

View from Bontddu, Dolgelly

15860.

Thundery Weather, near Dolgelly

16061.

Near Penmaen Pool—Noon

16262.

View of Cader Idris

16463.

Mist on Cader Idris

16864.

In the Woods, Berwyn

17065.

Aberdovey

17266.

Sunny Afternoon, Cardigan Bay

17667.

A Sudden Squall, Cardigan Bay

17868.

St. David's—Bishop's Palace

18069.

The Stacks, near Tenby

18270.

St. Catherine's Rock, Tenby

18671.

Old Roman Bridge, near Swansea

18872.

View near Mumbles, Swansea

19273.

Pennard Castle, Glamorganshire

19474.

Old Castle Keep, Cardiff

198The Illustrations in this volume have been engraved and printed in England

by Hentschel Colourtype, Ltd.

WALES

SUMMER EVENING, ANGLESEY COAST

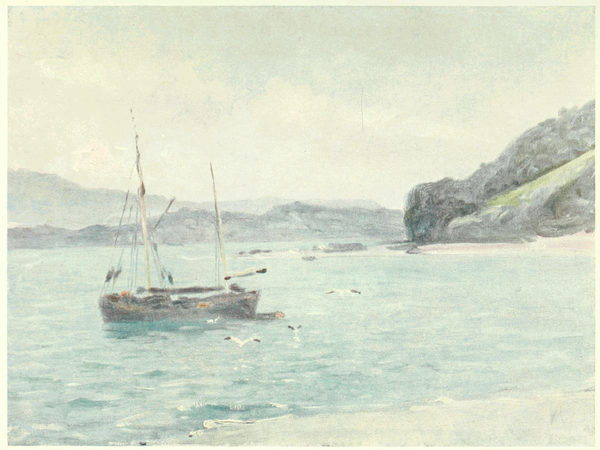

YACHTS, ANGLESEY COAST

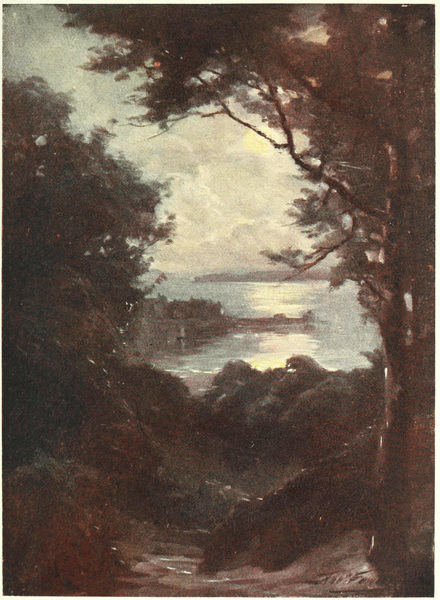

BEAUMARIS—MOONLIGHT

THE BEACH, BEAUMARIS

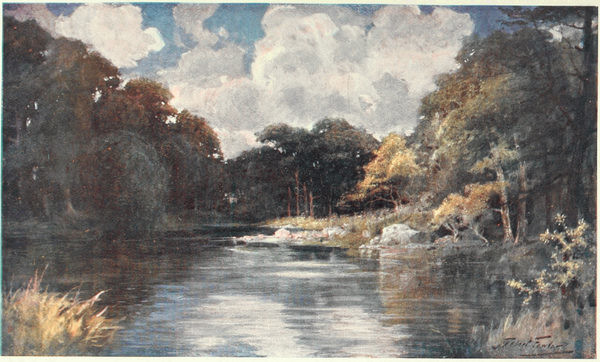

THE TROUT STREAM

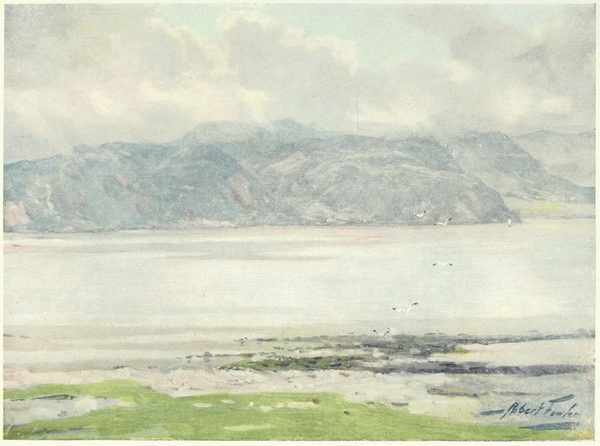

NEAR MENAI STRAITS

NEAR BANGOR

A FOOTPATH ON THE GREAT ORME

A VIEW FROM THE GREAT ORME'S HEAD

OLD COTTAGE AND RUINS OF ABBEY, GREAT ORME'S HEAD

BREEZY MORNING, LLANDUDNO BAY

COUNTRY LANE

A NOCTURNE, LLANDUDNO BAY

CONWAY FROM BENARTH—EARLY MORNING

NEAR COLWYN BAY

DISTANT VIEW OF PENMAENMAWR—EARLY MORNING LIGHT

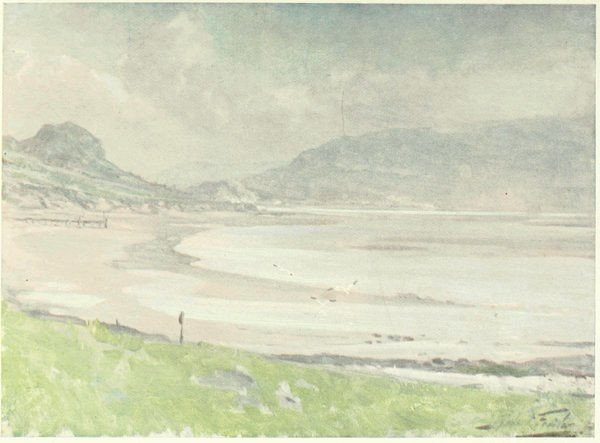

SILVERY LIGHT, CONWAY SHORE

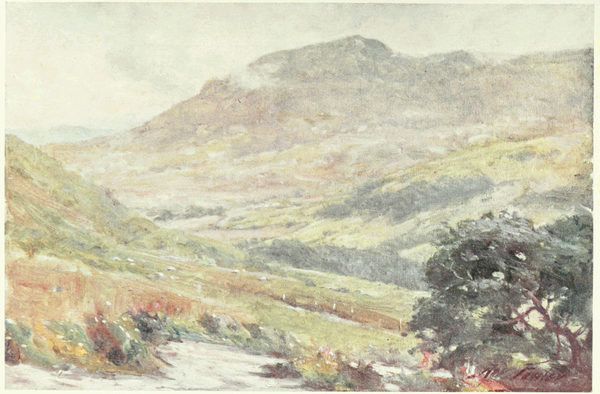

A MOUNTAIN PASS—NOON

CONWAY CASTLE AND QUAY—NOON

CONWAY VALLEY

CARNARVON, FROM ANGLESEY

BODDNANT HALL, CONWAY VALLEY

CARNARVON CASTLE

DISTANT VIEW OF CARNARVON BAY

ON THE RIVER SEIONT, CARNARVONSHIRE—EVENING GLOW

BRIDGE, CWM-Y-GLO—EVENING

FIELD PATH, NEAR LLANRUG

WINDY DAY, NEAR LLANRUG

MORNING MISTS, NEAR TREFRIW

DISTANT VIEW OF BETTWS-Y-COED

THE OLD BRIDGE, BETTWS-Y-COED

SWALLOW FALLS, BETTWS-Y-COED

FAIRY GLEN, BETTWS-Y-COED

CHURCH POOL, BETTWS-Y-COED

MINER'S BRIDGE ON RIVER LLUGWY

SUNNY FIELD, NEAR LLANBERIS

WELSH FARM, NEAR LLANBERIS

SNOWDON FROM CWM-Y-GLO

SNOWDON FROM LLANBERIS LAKE

SNOWDON FROM TRAETH MAWR

SNOWDON FROM CAPEL CURIG LAKE—SUMMER EVENING

IN THE LLEDR VALLEY

DUFFWS MOUNTAIN

DUFFWS MOUNTAIN IN MIST

COMING NIGHT, NEAR BEDDGELERT

ABERGLASLYN

VIEW OF MOELWYN

A HAYFIELD NEAR PORTMADOC

VALLE CRUCIS ABBEY

VIEW OF LLANGOLLEN

A LONELY SHORE NEAR PENRHYN DEUDRAETH

THE SHORE NEAR HARLECH—AFTERNOON

IN THE WOODS, FARCHYNYS, BARMOUTH ESTUARY

INCOMING TIDE, NEAR BARMOUTH

BARMOUTH BRIDGE

MISTY MORNING, NEAR BARMOUTH

A LONELY SHORE, BARMOUTH ESTUARY

VIEW FROM BONTDDU, DOLGELLY

THUNDERY WEATHER, NEAR DOLGELLY

NEAR PENMAEN POOL—NOON

VIEW OF CADER IDRIS

MIST ON CADER IDRIS

IN THE WOODS, BERWYN

ABERDOVEY

SUNNY AFTERNOON, CARDIGAN BAY

A SUDDEN SQUALL, CARDIGAN BAY

ST. DAVID'S—BISHOP'S PALACE

THE STACKS, NEAR TENBY

ST. CATHERINE'S ROCK, TENBY

OLD ROMAN BRIDGE, NEAR SWANSEA

VIEW NEAR MUMBLES, SWANSEA

PENNARD CASTLE, GLAMORGANSHIRE

OLD CASTLE KEEP, CARDIFF

CHAPTER I

PRELIMINARY REMARKS ON MEN, AUTHORS, AND THINGS IN WALES

Among friends and acquaintances and authors, I have met many men who have seen and read more of Wales than I can ever do. But I am somewhat less fearful in writing about the country, inasmuch as few of them seem to know the things which I know, and fewer still in the same way. When I read their books or hear them speak, I am interested, pleased, amazed, but seldom am I quite sure that we mean the same thing by Wales; sometimes I am sure that we do not. One man writes of the country as the home of legends, whose irresponsibility puzzles him, whose naïveté shocks him. Another, and his name is legion, regards it as littered with dead men's bones, among which a few shepherds and miners pick their way without caring for the lover of bones. Another, of the same venerable and numerous family as the last, has admired the silver lake of Llanberis or blue Plynlimmon; has been pestered by the pronunciation of Machynlleth, and has carried away a low opinion of the whole language because his own attempts at uttering it are unmelodious and even disgusting; has fallen entirely in love with the fragrant Welsh ham, preferring it, in fact, to the curer and the cook. Others, who have not, as a rule, gone the length of visiting the persons they condemn, call the Welshmen thieving, lying, religious, and rebellious knaves. Others would repeat with fervour the verse which Evan sings in Ben Jonson's masque, For the Honour of Wales:

And once but taste o' the Welsh mutton,

Your English seep's not worth a button:

and so they would conclude, admitting that the trout are good when caught. Some think, and are not afraid of saying, that Wales will be quite a good place (in the season) when it has been chastened a little by English enterprise: and I should not be surprised were they to begin by introducing English sheep, though I hardly see what would be done with them, should they be cut up and exposed for sale. The great disadvantage of Wales seems to be that it is not England, and the only solution is for the malcontents to divide their bodies, and, leaving one part in their native land, to have the rest sent to Wales, as they used to send Welsh princes to enjoy the air of two, three, and even four English towns, at the same time and in an elevated position.

SUMMER EVENING, ANGLESEY COAST

Then also there are the benevolent writers of books, who have for a century repeated, sometimes not unmusically, the words of a fellow who wrote in 1798, that the beauty of Llangollen "has been universally allowed by gentlemen of distinguished taste," and that, in short, many parts of Wales "have excited the applause of tourists and poets." Would that many of them had been provided with pens like those at the catalogue desks of the British Museum! Admirable pens! that may be put to so many uses and should be put into so many hands to-day and to-morrow. Admirable pens! and yet no one has praised them before. Admirable pens that will not write; and, by the way, how unlike those which wrote this:—

"Caldecot Castle, a grand and spacious edifice of high antiquity, occurs to arrest the observation of the passing stranger about two miles beyond the new passage; appearing at no great distance across the meadows that lie to the left of the Newport road. The shattered remnants of this curious example of early military architecture are still so far considerable as to be much more interesting than we could possibly have been at first aware, and amply repaid the trouble of a visit we bestowed upon it, in our return through Monmouthshire by the way of Caldecot village. In the distance truly it does not fail to impress the mind with some idea of its ancient splendour, for it assumes an aspect of no common dignity: a friendly mantling of luxuriant ivy improves, in an eminent degree, the picturesque effect of its venerable mouldering turrets; and, upon the whole, the ruin altogether would appear unquestionably to great advantage, were it, fortunately for the admirers of artless beauty, stationed in a more conspicuous situation, like the greater number of edifices of a similar nature in other parts of the country."

The decency, the dignity, the gentlemanliness (circa 1778), the fatuity of it, whether they tickle or affront, are more fascinating than many better but less portentous things. There was, too, a Fellow of the Royal Society who said in the last century that, in the Middle Ages, St. Winifred's Well and Chapel, and the river, and Basingwerk, must have been "worthy of a photograph."

YACHTS, ANGLESEY COAST

Yet there are two others who might make any crowd respectable—the lively, the keen-eyed, the versatile Mr. A. G. Bradley, and George Borrow, whose very name has by this time absorbed and come to imply more epithets than I have room to give. From the former, a contemporary, it would be effrontery to quote. From the latter I allow myself the pleasure of quoting at least this, and with the more readiness because hereafter it cannot justly be said that this book does not contain a fine thing about Wales. Borrow had just been sitting (bareheaded) in the outdoor chair of Huw Morus, whose songs he had read "in the most distant part of Lloegr, when he was a brown-haired boy"; and on his way back to Llangollen, he had gone into a little inn, where the Tarw joins the Ceiriog brook. "'We have been to Pont-y-Meibion,' said Jones, 'to see the chair of Huw Morus,' adding, that the Gwr Boneddig was a great admirer of the songs of the Eos Ceiriog. He had no sooner said these words than the intoxicated militiaman started up, and, striking the table with his fist, said: 'I am a poor stone-cutter—this is a rainy day and I have come here to pass it in the best way I can. I am somewhat drunk, but though I am a poor stone-mason, a private in the militia, and not so sober as I should be, I can repeat more of the songs of the Eos than any man alive, however great a gentleman, however sober—more than Sir Watkin, more than Colonel Biddulph himself.'

"He then began to repeat what appeared to be poetry, for I could distinguish the rhymes occasionally, though owing to his broken utterance it was impossible for me to make out the sense of the words. Feeling a great desire to know what verses of Huw Morus the intoxicated youth would repeat, I took out my pocket-book and requested Jones, who was much better acquainted with Welsh pronunciation, under any circumstances, than myself, to endeavour to write down from the mouth of the young fellow any verses uppermost in his mind. Jones took the pocket-book and pencil and went to the window, followed by the young man, scarcely able to support himself. Here a curious scene took place, the drinker hiccuping up verses, and Jones dotting them down, in the best manner he could, though he had evidently great difficulty to distinguish what was said to him. At last methought the young man said, 'There they are, the verses of the Nightingale (Eos), on his deathbed....'

BEAUMARIS—MOONLIGHT

"... A scene in a public-house, yes! but in a Welsh public-house. Only think of a Suffolk toper repeating the deathbed verses of a poet; surely there is a considerable difference between the Celt and the Saxon?"

But the number is so great of sensible, educated men who have written on Wales, or would have written if business or pleasure or indolence or dislike of fame had not prevented them, that either I find it impossible to visit the famous places (and if I visit them, my predecessors fetter my capacity and actually put in abeyance the powers of the places), or, very rarely, I see that they were imperfect tellers of the truth, and yet feel myself unwilling to say an unpleasant new thing of village or mountain because it will not be believed, and a pleasant one because it puts so many excellent people in the wrong. Of Wales, therefore, as a place consisting of Llandudno, Llangammarch, Llanwrtyd, Builth, Barmouth, Penmaenmawr, Llanberis, Tenby, ... and the adjacent streams and mountains, I cannot speak. At ——, indeed, I ate poached salmon and found it better than any preserver of rivers would admit; it was dressed and served by an Eluned (Lynette), with a complexion so like a rose that I missed the fragrance, and movements like those of a fountain when the south wind blows; and all the evening they sang, or when they did not sing, their delicate voices made "llech" and "llawr" lovely words: but I remember nothing else. At —— I heard some one playing La ci darem la mano: and I remember nothing else. Then, too, there was ——, with its castle and cross and the memory of the anger of a king: and I remember that the rain outside my door was the only real thing in the world except the book in my hand; for the trees were as the dreams of one who does not care for dreams; the mountains were as things on a map; and the men and women passing were but as words unspoken and without melody. All I remember of —— is that, as I drew near to it on a glorious wet Sunday in winter, on the stony roads, the soles began to leave my boots. I knew no one there; I was to reach a place twelve miles ahead among the mountains; I was assured that nobody in the town would cobble on Sunday: and I began to doubt whether, after all, I had been wise in steadily preferring football boots to good-looking things at four times the price; when, finally, I had the honour of meeting a Baptist—a Christian—a man—who, for threepence, fixed my soles so firmly that he assured me they would last until I reached the fiery place to which he believed I was travelling, and serve me well there. I distrusted his theology, and have yet to try them on "burning marl," but they have taken me some hundreds of miles on earth since then.

THE BEACH, BEAUMARIS

It would be an impertinence to tell the reader what Llangollen is like, especially as he probably knows and I do not. Also, I confess that its very notoriety stupefies me, and I see it through a cloud of newspapers and books, and amid a din of applausive voices, above which towers a tremendous female form "like Teneriffe or Atlas unremoved," which I suppose to be Lady Eleanor Butler.

Nevertheless, I will please myself and the discerning reader by repeating the names of a few of the places to which I have never been, or of which I will not speak, namely, Llangollen, Aberglaslyn, Bettws-y-Coed, the Fairy Glen, Capel Curig, Colwyn, Tintern, Bethesda, Llanfairfechan, Llanrhaiadr, Llanynys, Tenby (a beautiful flower with a beetle in it), Mostyn, Glyder Fach and Glyder Fawr, Penmaenmawr, Pen-y-Gader, Pen-y-Gwryd, Prestatyn, Tremadoc, the Swallow Falls, the Devil's Bridge, the Mumbles, Harlech, Portmadoc, Towyn, and Aberdovey (with its song and still a poet there). I have read many lyrics worse than that inventory.

But there is another kind of human being—to use a comprehensive term—of which I stand in almost as much awe as of authors and those who know the famous things of Wales. I mean the lovers of the Celt. They do not, of course, confine their love—which in its extent and its tenuity reminds one of a very great personage indeed—to the Celt; but more perhaps than the Japanese or the Chinese or the Sandwich Islander the Celt has their hearts; and I know of one who not only learned to speak Welsh badly, but had the courage to rise at a public meeting and exhort the (Welsh-speaking) audience to learn their "grand mother tongue." Their aim and ideal is to go about the world in a state of self-satisfied dejection, interrupted, and perhaps sustained, by days when they consume strange mixed liquors to the tune of all the fine old Celtic songs which are fashionable. If you can discover a possible Celtic great-grandmother, you are at once among the chosen. I cannot avoid the opinion that to boast of the Celtic spirit is to confess you have it not. But, however that may be, and speaking as one who is afraid of definitions, I should be inclined to call these lovers of the Celt a class of "decadents," not unrelated to Mallarmé, and of æsthetes, not unrelated to Postlethwaite. They are sophisticated, neurotic—the fine flower of sounding cities—often producing exquisite verse and prose; preferring crême de menthe and opal hush to metheglin or stout, and Kensington to Eryri and Connemara; and perplexed in the extreme by the Demetian with his taste in wall-papers quite untrained. Probably it all came from Macpherson's words, "They went forth to battle and they always fell"; just as much of their writing is to be traced to the vague, unobservant things in Ossian, or in the proud, anonymous Irishman who wrote Fingal in six cantos in 1813. The latter is excellent in this vein. "Let none then despise," he writes, "the endeavour, however humble, now made, even by the aid of fiction, to throw light upon the former manners and customs of one of the oldest and noblest nations of the earth. That once we were, is all we have left to boast of; that once we were, we have record upon record.... We yet can show the stately pharos where waved the chieftain's banner, and the wide ruin where the palace stood—the palace once the pride of ages and the theme of song—once Emuin a luin Aras Ullah." The reader feels that it is a baseness to exist. Mr. John Davidson, who, of course, is as far removed from the professional Celt as a battle-axe from a toothpick, has put something like the fashionable view majestically into the mouth of his "Prime Minister":

... That offscouring of the Eastern world,

The melancholy Celt, whom Latin, Greek,

And Teuton drove through Europe to the rocks,

The utmost isles and precincts of the sea;

Who fight for fighting's sake, and understand

No meaning in defeat, having no cause

At heart, no depth of purpose, no profound

Desire, no inspiration, no belief;—

A twilight people living in a dream,

A withered dream they never had themselves,

A faded heirloom that their fathers dreamt:

How much more happy these had they destroyed

The spell of life at once, and so escaped

An unregarded martyrdom, the consciousness

Of inefficience and the world's contempt.

THE TROUT STREAM

"An Earth-born coolness

Coloured with the sky."

But it is probably true that when one has said that the typical Celt is seldom an Imperialist, a great landowner, a brewer, a cabinet minister, or (in Wales, at least) a member of the Salvation Army, one has exhausted the list of his weaknesses; and that not greatly wanting to be one of these things, he has endeared himself to those to-day who have set their hearts on gold and applause and have not gained them, and those few others who never sought them. I heard of a pathetic, plausible stockbroker's clerk the other day, who, having spent his wife's money and been at last discovered by his tailor, took comfort in studying his pedigree, which included a possibly Welsh Lewis high upon the extreme right. He was sufficiently advanced in philology to find traces of an Ap' in his name, which was Piper, and he could repeat some of Ossian by heart with great emotion and less effect. I prefer the kind of Celt whom I met in Wales one August night. It was a roaring wet night, and I stepped into the shelter of a bridge to light a pipe. As I paused to see if it was dawn yet, I heard a noise which I supposed to be the breathing of a cow. My fishing-rod struck the bridge; the noise ceased, and I heard something move in the darkness close by. I confess that my pipe went out when, without warning, a joyous, fighting baritone voice rose and shook the bridge with the words.

Through all the changing scenes of life,

In trouble and in joy,

The praises of my God shall still

My heart and tongue employ.

The voice sang all the verses of the hymn, and then laughed loudly, yet with a wonderful serenity. Then a man stood up heavily with a sound like a flock of starlings suddenly taking flight. I lit a match and held it to his face and looked at him, and saw a fair-skinned, high-cheek-boned face, wizened like a walnut, with much black hair about it, that yet did not conceal the flat, straight, eloquent mouth. He lit a match and held it to my face, and looked at me and laughed again. Finding that I could pronounce Bwlch-y-Rhiw, he was willing to talk and to share the beer in my satchel. And he told me that he had played many parts—he was always playing—before he took to the road: he had been a booking-office clerk, a soldier, a policeman, a gamekeeper, and put down what he called his variability to "the feminine gender." He would not confess where he had been to school, and his one touch of melancholy came when, to show that he had once known Latin, he began to repeat, in vaguely divided hexameters, the passage in the Aeneid which begins Est in conspectu Tenedos. For he could not go on after At Capys and was angry with himself. But he recalled being caned for the same inability, and laughed once more. Every other incident remembered only fed his cheerfulness. Everything human had his praise,—General Buller in particular. I cannot say the same of his attitude towards the divine. His conversation raised my spirits, and I suppose that the bleared and dripping dawn can have peered on few less melancholy men than we. "Life," said he, "is a plaguey thing: only I don't often remember it." And as he left me, he remarked, apologetically, that he "always had been a cheerful ——, and couldn't be miserable," and did me the honour of supposing that in this he resembled me.

NEAR MENAI STRAITS

He went off singing, in Welsh, something not in the least like a hymn to a fine victorious hymn tune, but had changed, before I was out of hearing, to the plaintive, adoring "Ar hyd y nos." And I remembered the proverbial saying of the Welsh, that "the three strong ones of the world" are "a lord, a headstrong man, and a pauper."

Having heard and read the aforesaid authors, tourists, higher philatelists, and lovers of the Celt, I need hardly say, firstly, that I have come under their influence; secondly, that I have tried to avoid it; and thirdly, that I am not equal to the task of apportioning the blame between them and myself for what I write.

And, first, let me ease my memory and pamper my eyes, and possibly make a reader's brain reverberate with the sound of them, by giving the names of some of the streams and lakes and villages I have known in Wales. And among the rivers, there are Ebbw and Usk, that cut across my childhood with silver bars, and cloud it with their apple flowers and their mountain-ash trees, and make it musical with the curlew's despair and the sound of the blackbird singing in Eden still; and Towy and Teivy and Cothi and Ystwyth; and, shyer streams, the old, deserted, perhaps deserted, pathways of the early gods, the Dulais and Marlais and Gwili and Aman and Cenen and Gwenlais and Gwendraeth Fawr and Sawdde and Sawdde Fechan and Twrch and Garw; and those nameless but not unremembered ones (and yet surely no river in Wales but has a name if one could only know it well enough) that crossed the road like welcomed lingerers from some happier day, flashing and snake-like, and ever about to vanish and never vanishing, and vocal all in reed or pebble or sedge, some deep enough for a sewin, others too shallow to wash the dust from the little pea-like toes of the barefooted child that learns from them how Nile and Ganges flow, and why Abana and Pharpar were dear, and why these are more sweet; and there is Llwchwr, whose voice is bright in constant shadow; and Wye; and the little river in a stony valley of Gower which at first reminded me, and always reminds me, of the adventure of Sir Marhaus, Sir Gawaine, and Sir Uwaine.

"And so they rode, and came into a deep valley full of stones, and thereby they saw a fair stream of water; above thereby was the head of the stream a fair fountain, and three damosels sitting thereby. And then they rode to them, and either saluted other, and the eldest had a garland of gold about her head, and she was threescore winter of age or more, and her hair was white under the garland. The second damosel was of thirty winter of age, with a circlet of gold about her head. The third damosel was but fifteen year of age, and a garland of flowers about her head. When the knights had so beheld them, they asked them the cause why they sat at that fountain? 'We be here,' said the damosels, 'for this cause: if we may see any errant knights, to teach them unto strange adventures; and ye be three knights that seeken adventures, and we be three damosels, and therefore each one of you must choose one of us; and when ye have done so we will lead you unto three highways, and there each of you shall choose a way and his damosel with him. And this day twelvemonth ye must meet here again, and God send you your lives, and thereto ye must plight your troth.' 'This is well said,' said Sir Marhaus." And no other than a Welsh story-teller could have made that clear picture of the three damosels.

And there is Severn in its wild and unnoted childhood, its lovely and gallant youth, its noble and romantic prime, as it leaves Wales and passes Shrewsbury, the pattern of all famous streams—

Fluminaque antiquos subterlabentia muros;

and its solemn, grey, and mighty and worldly-wise old age, listening to its latest daughter the Wye, where it has

A cry from the sea, a cry from the mountain;

and Clwyd and Conway and Ceiriog and Aled and Dovey, streams that remember princes and bards; and the little waters flowing from Cwellyn Lake, of which a story is told.

NEAR BANGOR

Near the river which falls from Cwellyn Lake, they say that the fairies used to dance in a meadow on fair moonlit nights. One evening the heir to the farm of Ystrad, to which the meadow belonged, hid himself in a thicket near the meadow. And while the fairies were dancing, he ran out and carried off one of the fairy women. The others at once disappeared. She resisted and cried, but he led her to his home, where he was tender to her, so that she was willing to remain as his maid-servant. But she would not tell him her name. Some time afterward he again saw the fairies in the meadow and overheard one of them saying, "The last time we met here, our sister Penelope was snatched away from us by one of the mortals." So he returned and offered to marry her, because she was hard-working and beautiful. For a long time she would not consent; but at last she gave way, on the condition "that if ever he should strike her with iron, she would leave him and never return to him again." They were happy together for many years; and she bore him a son and a daughter; and so wise and active was she, that he became one of the richest men of that country, and besides the farm of Ystrad, he farmed all the lands on the north side of Nant-y-Bettws to the top of Snowdon, and all Cwm Brwynog in Llanberis, or about five thousand acres. But one day Penelope went with him into a field to catch a horse; and as the horse ran away from him, he was angry and threw the bridle at him, but struck Penelope instead. She disappeared. He never saw her again, but one night afterward he heard her voice at his window, asking him to take care of the children, in these words:

Oh, lest my son should suffer cold,

Him in his father's coat enfold:

Lest cold should seize my darling fair,

For her, her mother's robe prepare.

These children and their descendants were called the Pellings, says the teller of the tale; and "there are," he adds, "still living several opulent and respectable persons who are known to have sprung from the Pellings. The best blood in my own veins is this fairy's."

A FOOTPATH ON THE GREAT ORME

And of lakes, I have known Llyn-y-Fan Fach, the lonely, deep, gentle lake on the Caermarthen Fan, two thousand feet high, where, if the dawn would but last a few moments longer, or could one swim but just once more across, or sink but a little lower in its loving icy depths, one would have such dreams that the legend of the shepherd and the lady whom he loved and gained and lost upon the edge of it would fade away: and Llyn Llech Owen, and have wondered that only one legend should be remembered of those that have been born of all the gloom and the golden lilies and the plover that glories in its loneliness; for I stand in need of a legend when I come down to it through rolling heathery land, through bogs, among blanched and lichened crags, and the deep sea of heather, with a few flowers and many withered ones, of red and purple whin, of gorse and gorse-flower, and (amongst the gorse) a grey curling dead grass, which all together make the desolate colour of a "black mountain"; and when I see the water for ever waved except among the weeds in the centre, and see the waterlily leaves lifted and resembling a flock of wild-fowl, I cannot always be content to see it so remote, so entirely inhuman, and like a thing a poet might make to show a fool what solitude was, and as it remains with its one poor legend of a man who watered his horse at a well, and forgot to cover it with the stone, and riding away, saw the water swelling over the land from the well, and galloped back to stop it, and saw the lake thus created and bounded by the track of his horse's hooves; and thus it is a thing from the beginning of the world that has never exchanged a word with men, and now never will, since we have forgotten the language, though on some days the lake seems not to have forgotten it. And I have known the sombre Cenfig water among the sands, where I found the wild goose feather with which I write.

And I have seen other waters; but least of them all can I forget the little unnecessary pool that waited alongside a quiet road and near a grim, black village. Reed and rush and moss guarded one side of it, near the road; a few hazels overhung the other side; and in their discontented writhing roots there was always an empty moorhen's nest, and sometimes I heard the bird hoot unseen (a sound by which the pool complained, as clearly as the uprooted trees over the grave of Polydorus complained), and sometimes in the unkind grey haze of winter dawns, I saw her swimming as if vainly she would disentangle herself from the two golden chains of ripples behind her. In the summer, the surface was a lawn of duckweed on which the gloom from the hazels found something to please itself with, in a slow meditative way, by showing how green could grow from a pure emerald, at the edge of the shadow, into a brooding vapourish hue in the last recesses of the hazels. The smell of it made one shudder at it, as at poison. An artist would hardly dare to sit near enough to mark all the greens, like a family of snaky essences, from the ancient and mysterious one within to the happy one in the sun. When the duckweed had dissolved in December, the pool did but whisper that of all things in that season, when

Blue is the mist and hollow the corn parsnep,

it alone rejoiced. It was in sight of the smoke and the toy-like chimney-stacks of the village, of new houses all around, and of the mountains. It had no possible use—nothing would drink of it. It did not serve as a sink, like the blithe stream below. It produced neither a legend nor a brook. It was a whole half-acre given up to a moorhen and innumerable frogs. It was not even beautiful. And yet, there was the divinity of the place, embodied, though there was no need for that, in the few broken brown reeds that stood all the winter, each like a capital Greek lambda, out of the water. When the pool harboured the image of the moon for an hour in a winter night, it seemed to be comforted. But when the image had gone, the loss of that lovely captive was more eloquent than the little romantic hour. And I think that, after all, the pool means the beauty of a pure negation, the sweetness of utter and resolved despair, the greatness of Death itself.

And I have been to Abertillery, Pontypool, Caerleon, infernal Landore, Gower, Pontardulais, Dafen, Llanedi, Llanon (where only the little Gwili runs, but good children are told that they shall go to Llanon docks), Pen-y-Groes, Capel Hendre, Maesy-bont, Nantgaredig, Bolgoed, Pentre Bach, Bettws, Amanford, Llandebie, Pentre Gwenlais, Derwydd, Ffairfach, Llandeilo, Tal-y-Llychau, Brynamman, Gwynfe, Llanddeusant, Myddfai, Cil-y-Cwm, Rhandir Mwyn, and the farms beyond,—Maes Llwyn Fyddau, Bwlch-y-Rhiw, Garthynty, Nant-yr-ast, Blaen Cothi, Blaen Twrch,—Llanddewi Brefi, Tregaron, Pont Llanio, Llanelltyd, Bettws Garmon, Bala, Aber Dusoch.... And I have crossed many "black" mountains, and Gareg Lwyd, Gareg Las, the Banau Sir Gaer, Crugian Ladies, Caeo, Bryn Ceilogiau, Craig Twrch, and Craig-y-Ddinas....

A VIEW FROM THE GREAT ORME'S HEAD

The chapels and churches, Siloh, Ebenezer, Llanedi, Llandefan, Abergwesyn, Llanddeusant, ... but I dare not name them lest I should disturb some one's dreams, or invite some one to disturb my own. They are all in the admirable guide-books, which say nothing of the calm and the nettles and the shining lizards and the sleepy luxurious Welsh reading of the lessons at ——; and the wet headstones at ——, where you may lean on any Sunday in the rain and hear the hymn take heaven by storm, and quarrel melodiously upon the heights, and cease and leave the soul wandering in the rain as far from heaven as Paolo and Francesca in their drifts of flame; and ——, white and swept and garnished, and always empty, and always lighted by a twilight four hundred years old, the door being open and ready to receive some god or goddess that delays; and Soar at ——, so blank, lacking in beauty and even in ugliness,—so blank that when one enters, the striving spirit will not be content, and perforce takes flight and finds an adventure not unlike that of the man who was once returning from Beddgelert fair by a gloomy road, and saw a great and splendid house conspicuously full of gaiety in a place where no such house had seemed to stand before; and supposing that he had lost his way, he asked and was given a lodging, and found the chambers bright and sounding with young men and women and children, and slept deeply in a fine room, on a soft white bed, and on waking and studying his neighbourhood, saw but a bare swamp and a tuft of rushes beneath his head.

And there is Siloh at ——, standing bravely,—at night, it often seems perilously,—at the end of a road, beyond which rise immense mountains and impassable, and, in my memory, always the night and a little, high, lonely moon, haunted for ever by a pale grey circle, looking like a frail creature which one of the peaks had made to sail for his pleasure across the terrible deeps of the sky. But Siloh stands firm, and ventures once a week to send up a thin music that avails nothing against the wind; although close to it, threatening it, laughing at it, able to overwhelm it, should the laugh become cruel, is a company of elder trees, which, seen at twilight, are sentinels embossed upon the sky—sentinels of the invisible, patient, unconquerable powers: or (if one is lighter-hearted) they seem the empty homes of what the mines and chapels think they have routed; and at midnight they are not empty, and they love the mountain rain, and at times they summon it and talk with it, while the preacher thunders and the windows of the chapel gleam.

OLD COTTAGE AND RUINS OF ABBEY, GREAT ORME'S HEAD

And there is ——, where an ancient, unwrinkled child used to talk in gentle, melancholy accents about hell to an assembly of ancient men who sometimes muttered "Felly, felly," as men who had heard it so often that they longed to be there and to taste and to see; where the young men and maidens sang so lustily and well that I wondered the minister never heard them, or, hearing, understood them. To the children, when they listened, his mild ferocity did but put an edge on the bird's-nesting of the day before and the day after. When they did not listen, some of them looked through the windows and saw heaven as fresh and gaudy, in the flowers of a steep garden close by, as in the coloured pictures of apostles and lambs on their bedroom walls; but chiefly in the company of delicate lime trees that stood above the garden, on a grassy breast of land. The fair, untrodden turf below them shone even when the sun was not with it. The foliage of all the limes, in autumn, ripened together to the same hue of gold. It burned and was cool. It flamed and yet had something in it of the dusk. It was the same as when, many years ago, two children saw in it some fellowship with the coloured windows at Llandaff, and with the air of an old library that had "golden silence and golden speech" over the door. And the trees seemed to be a council of blessed creatures devising exquisite enjoyments and plotting to outwit the preacher. They might be not ill-chosen deputies of leisure, health, and contemplation, and all that fair and reverend family. In the cool gloom at the centre of the foliage sat also Mystery, with palms linked before her eyelids, unlinking them but seldom, lest seeing might shut out visions.

CHAPTER II

ENTERING WALES

The best way into Wales is the way you choose, provided that you care. Some may like the sudden modern way of going to sleep at London in a train and remaining asleep on a mountain-side, which has the advantage of being the most expensive and the least surprising way. Some may like to go softly into the land along the Severn, on foot, and going through sheath after sheath of the country, to reach at last the heart of it at peaty Tregaron, or the soul of it on Plynlimmon itself. Or you may go by train at night; and at dawn, on foot, follow a little stream at its own pace and live its fortnight's life from mountain to sea.

BREEZY MORNING, LLANDUDNO BAY

Or you may cross the Severn and then the lower Wye, and taking Tredegar and Caerleon alternately, or Rhigws and Landore, or Cardiff and Lantwit, or the Rhondda Valley and the Vale of Neath, and thus sharpening the spirit, as an epicure may sharpen his palate, by opposites, find true Wales everywhere, whether the rivers be ochre and purple with corruption, or still as silver as the fountain dew on the mountain's beard; whether the complexions of the people be pure as those of the young cockle-women of Penclawdd, or as heavily superscribed as those of tin-platers preparing to wash. Or you may get no harm by treading in the footsteps of that warm-blooded antiquarian, Pennant, who wrote at the beginning of his tours in Wales: "With obdurate valour we sustained our independency ... against the power of a kingdom more than twelve times larger than Wales: and at length had the glory of falling, when a divided country, beneath the arms of the most wise and most warlike of the English monarchs." That "we" may have saved the soul even of an antiquarian.

But the entry I best remember and most love was made by a child whom I used to know better than I have known anyone else. He disappeared, after a slow process of evanishment, several years ago: and I will use what I know as if it were my own, since the first person singular will help me to write as if I should never be subjected to the dignity of print,—as if I were addressing, not the general reader, but some one who cared.

At a very early age, I (that is to say, he, bien entendu) often sat in a room in outer London, where I now see that it was probably good to be. It was always October there, and the yellow poplar leaves were always falling. And so also there was always a fire—a casket in which emeralds and sapphires contended with darker spirits continually. Where are the poplars now? Where the leaves which loved the frost that spoiled them at last? Where the emeralds and sapphires—and the child? There were late October twilights that seemed so mighty in their gentleness and so terrible in their silence that they alarmed the child with fear of desolation, until the spell was suspended by lighted lamps and drawn curtains and fearless voices of elder persons, though one could draw the curtains and see the thing still, and oneself, and the very fire, outside in its embrace. And still

The jealous ear of night eave-dropped our talk.

COUNTRY LANE

I think those twilights have overwhelmed all at last, and they have their way with child and trees and fire. But they have spared one thing, which even in those days was more puissant than the fire, though they have left their marks upon it, and now it seems a less mighty thing if one goes to it soberly too critically, or even too cheerfully. For a picture hung in the room, and the last October sunlight used to fall upon it when the silence set in. The picture meant Wales.

In the foreground, a stream shone with ripples in the midst, and glowed with foam among the roots of alders at the edge. Branches with white berries overhung the stream; and there were hornbeams and writhen oaks; and beyond them, a sky with a shaggy and ancient storm in it, and wrestling with that, and rising into it, the ruins of an Early English chancel. The strength and anger and tenderness and majesty of it were one great thought. I still think that could deeds spring panoplied from thoughts, and could great thoughts of themselves do anything but flush the cheek, such a simply curving landscape as this would be at the bidding of one of those great thoughts that empty all the brain.... Under one of the columns by the chancel, the artist meant to have drawn vaguely a pile of masonry and a muscular ivy stem. And that was the point of the picture, because it seemed to be a kneeling knight, with one forearm on an oval shield and the other buried in his beard, and his head bent. I suppose that the thought that it was a knight, and that the knight was Launcelot, first came as I looked at the picture once, straight from a book where I had been reading:

"Then Sir Launcelot departed, and when he came to the Chapel Perilous, he alighted, and tied his horse to a little gate. And as soon as he was within the churchyard he saw on the front of the Chapel many fair, rich shields turned upside down; and many of the shields Sir Launcelot had seen knights have before; with that he saw standing by him thirty great knights, more by a yard than any man that he had ever seen, and all these grinned and gnashed at Sir Launcelot; and when he saw their countenances he dreaded them sore, and so put his shield afore him, and took his sword in his hand ready to do battle; and they were all armed in black harness, ready with their shields and swords drawn. And when Sir Launcelot would have gone through them they scattered on every side of him, and gave him the way to pass; and therewith he waxed all bold, and entered into the Chapel, and there he saw no light but a dim lamp burning, and then he was aware of a corse covered with a cloth of silk. And as Sir Launcelot stooped down and cut a piece of the cloth away, the earth quaked, and he was afraid...."

A NOCTURNE, LLANDUDNO BAY

And the picture was a picture of the Chapel Perilous; and thus out of a poor story-book and a dear picture and the dim poplars in the dim street, I made a Launcelot who was not merely an incredible mediæval knight of flesh and armour, but a strange immortal figure that lived and was desirable and friendly in the grey rain of a suburb in the nineteenth century.

This was the beginning of the creation of Wales. Or shall I say that it was the beginning of the discovery? Let the reader decide, with the help of the explanation, that I use the words as I should use them of a play of Shakespeare's, or a picture of Titian's, or any other living thing which grows and changes and is born again, in age after age, as certainly and as elusively as the substance of a waterfall is changed; even in one moment these things are never the same to any two observers, backward or advanced, egotistical or servile, blind or keen....

Looking back, the artistry of time makes it appear that soon after I had become certain that the painter had somehow caught Launcelot kneeling at the foot of the column, I reached Wales.

There I saw one of the Round Tables of Arthur, but also a porpoise hunt in the river close by; and the porpoise threshed the water so that the shining spray now hides the Round Table from my view. And I heard the national anthem of Wales: and at first I cowered beneath the resolved and terrible despair of it, forgetting that—

In every dirge there sleeps a battle-march;

so that I seemed to look out from the folds of a fantastic purple curtain of heavily embroidered fabric upon a fair landscape and an awful sky; and I know not whether the landscape or the sky was the more fascinating in its mournfulness.

And I heard sounds of insult, shame, and wrong,

And trumpets blown for wars,—

and it was of Arthur's last battle that I dreamed. But the sky cleared, and I seemed to let go of the folds of the curtain and to see a red dragon triumphing and the shielded Sir Launcelot again; and next, it was only a tournament that I saw, and there were careless ladies on high among the golden dust. And, at last, I could once more think happily of the little white house where I lived, and the largest and reddest apples in all the world that grew upon the wizened orchard, and the smoked salmon and the hams that perfumed the long kitchen, and all the shining candlesticks, and the wavy, crisp, thin leaves of oaten bread that were eaten there with buttermilk: and the great fire shook his rustling sheaf of flames and laughed at the wind and rain that stung the window-panes; and sometimes a sense of triumph arose from the glory of the fire and the vanity of the wind, and sometimes a sense of fear lest the fire should be conspiring with the storm. That also was Wales—a meandering village street, the house with the orchard, and a white river in sight of it, and the great music of the national anthem hovering over it and giving the whole a strange solemnity.

Just beyond the village, but not under the same solemn sky, I see an island of apple trees in spring, which in fact belongs to a somewhat later year. It was reached by a mile of winding lane that passed the slender outmost branches of the village, and lastly, a shining cottage, with streaked and mossy thatch, and two little six-paned windows, half-filled with many-coloured sweets, and boasting one pane of bottle-glass. Outside sat an old woman; her moist, grey, hempen curls framing a cruel face which had been made by three or four swift strokes of a hatchet; her magnificent brown eyes seeming to ponder heavenly things and really looking for half-pence. A picture would have made her—wringing her hands slowly as if she were perpetually washing, or sitting bolt upright and pleased with her white apron—a type of resigned and reverend and beautiful old age. On the opposite side of the road was a white and thatched piggery, half the size of the house; and alongside of it, a neat, moulded pile of coal-dust, clay, and lime, mixed, for her ever-burning fire. The pigs grunted; the old woman, who would herself watch the slaughtering, sat and was pleased, and said, "Good morning," and "Good afternoon," and "Good evening" as the day went by, except when the children were due to pass to and from school, with half-pence to spend.

Just beyond this dragon and its house, an important road crossed the lane, which then narrowed and allowed the hedgerow hazels to arch over it and let in only the wannest light to the steep, stony hedge-bank of whin and grass and fern and violets. Little streams ran this way and that, under and over and alongside the lane, and at length a larger one was honoured by a bridge, the parapet covered with flat, dense, even turf. The bridge made way for a wide view, and to invite the eye a magpie flew away from the grassy parapet with wavy flight to a mountain side.

CONWAY FROM BENARTH—EARLY MORNING

Between the bridge and the mountain, and in fact surrounded by streams which were heard although unseen, was an island of apple trees.

There were murmurs of bees. There was a gush and fall and gurgle of streams, which could be traced by their bowing irises. There was a poignant glow and fragrance of flowers in an air so moist and cold and still that at dawn the earliest bee left a thin line of scent upon it. Beyond, the mountain, grim, without trees, lofty and dark, was clearly upholding the low blue sky full of slow clouds of the colour of the mountain lambs or of melting snow. This mountain and this sky, for that first hour, shut out, and not only shut out but destroyed, and not only destroyed but made as if it had never been, the world of the old woman, the coal-pits, the schools, and the grown-up persons. And the magic of Wales, or of Spring, or of childhood made the island of apple trees more than an orchard in flower. For as some women seem at first to be but rich eyes in a mist of complexion and sweet voice, so the orchard was but an invisible soul playing with scent and colour as symbols. Nor did this wonder vanish when I walked among the trees and looked up at the blossoms in the sky. For in that island of apple trees there was not one tree but was curved and jagged and twisted and splintered by great age, by the west wind, or by the weight of fruit in many autumns. In colour they were stony. They were scarred with knots like mouths. Some of their branches were bent sharply like lightning flashes. Some rose up like bony, sunburnt, imprecating arms of furious prophets. One stiff, gaunt bole that was half hid in flower might have been Ares' sword in the hands of the Cupids. Others were like ribs of submerged ships, or the horns of an ox emerging from a skeleton deep in the sand of a lonely coast. And the blossom of them all was the same, so that they seemed to be Winter with the frail Spring in his arms. Nor was I surprised when the first cuckoo sang therein, since the blossom made it for its need. And when a curlew called from the mountain hopelessly, I laughed at it.

NEAR COLWYN BAY

When I came again and saw the apple trees in flower, the island was very far away, and the unseen cuckoo sang behind a veil and not so suitably as the curlew. There was something of the dawn in the light over it, though it was mid-day; and I could hardly understand, and was inclined to melancholy, until chance brought into my head the poem of the old princely warrior poet Llywarch Hên, and out of his melancholy and mine was born a mild and lasting joy. He sang:

Sitting high upon a hill, to battle is inclined

My mind, but it does not impel me onward.

Short is my journey, my tenement is laid waste.

Sharp is the gale, it is bare punishment to live.

When the trees array themselves in gay colours

Of Summer, extremely ill am I this day.

I am no hunter, I keep no animal of the chase,

I cannot move about:

As long as it pleases the cuckoo, let her sing.

The loud-voiced cuckoo sings with the dawn,

Her melodious notes in the dales of Cuawg:

Better than the miser is the lavish man.

At Aber Cuawg the cuckoos sing,

On the blossom-covered branches;

Woe to the sick that hears their contented notes.

At Aber Cuawg the cuckoos sing.

The recollection is in my mind,

There are that hear them that will not hear them again.

Have I not listened to the cuckoo on the ivied tree?

Did not my shield hang down?

What I loved is but vexation; what I loved is no more.

And I thought that perhaps it is even true, as Taliesin sang, that "A man is wont to be oldest when born, and younger all the time," and that the apple flowers did but remind me of old capacities laid waste.

These little things are the opening cadences of a great music which I have heard, and which is Wales. But I have forgotten the whole, and have echoes of it only, when I hear an old Welsh song, when I am trying to catch a trout, or am eating bread and butter and white cheese, and drinking pale tea, in a mountain farm.... One echo of it I had strangely in Oxford, when, entertaining an old wise gipsy, and asking him of his travels, and whether he had been in Wales, he meditated for a long time, and then sang in an emotionless and moving tone the "Hen wlad fy nhadau," up there among the books, the towers, and the stars. I have had a vision of a rose. But my memory possesses only the doubtful and withered dustiness of a petal or two.

CHAPTER III

A FARMHOUSE UNDER A MOUNTAIN, A FIRE, AND SOME FIRESIDERS

Having passed the ruined abbey and the orchard, I came to a long, low farmhouse kitchen, smelling of bacon and herbs and burning sycamore and ash. A gun, a blunderbuss, a pair of silver spurs, and a golden spray of last year's corn hung over the high mantelpiece and its many brass candlesticks; and beneath was an open fireplace and a perpetual red fire, and two teapots warming, for they had tea for breakfast, tea for dinner, tea for tea, tea for supper, and tea between. The floor was of sanded slate flags, and on them a long many-legged table, an oak settle, a table piano, and some Chippendale chairs. There were also two tall clocks; and they were the most human clocks I ever met, for they ticked with effort and uneasiness: they seemed to think and sorrow over time, as if they caused it, and did not go on thoughtlessly or impudently like most clocks, which are insufferable; they found the hours troublesome and did not twitter mechanically over them; and at midnight the twelve strokes always nearly ruined them, so great was the effort. On the wall were a large portrait of Spurgeon, several sets of verses printed and framed in memory of dead members of the family, an allegorical tree watered by the devil, and photographs of a bard and of Mr. Lloyd George. There were about fifty well-used books near the fire, and two or three men smoking, and one man reading some serious book aloud, by the only lamp; and a white girl was carrying out the week's baking, of large loaves, flat fruit tarts of blackberry, apple, and whinberry, plain golden cakes, large soft currant biscuits, and curled oat cakes. And outside, the noises of a west wind and a flooded stream, the whimper of an otter, and the long, slow laugh of an owl; and always silent, but never forgotten, the restless, towering outline of a mountain.

The fire was—is—of wood, dry oak-twigs of last spring, stout ash sticks cut this morning, and brawny oak butts grubbed from the copse years after the tree was felled. And I remember how we built it up one autumn, when the heat and business of the day had almost let it die.

DISTANT VIEW OF PENMAENMAWR—EARLY MORNING LIGHT

We had been out all day, cutting and binding the late corn. At one moment we admired the wheat straightening in the sun after drooping in rain, with grey heads all bent one way over the luminous amber stalks, and at last leaning and quivering like runners about to start or like a wind made visible. At another moment we admired the gracious groups of sheaves in pyramids made by our own hands, as we sat and drank our buttermilk or ale, and ate bread and cheese or chwippod (the harvesters' stiff pudding of raisins, rice, bread, and fresh milk) among the furze mixed with bramble and fern at the edge of the field. Behind us was a place given over to blue scabious flowers, haunted much by blue butterflies of the same hue; to cross-leaved heath and its clusters of close, pensile ovals, of a perfect white that blushed towards the sun; to a dainty embroidery of tormentil shining with unvaried gold; and to tall, purple loosestrife, with bees at it, dispensing a thin perfume of the kind that all fair living things, plants or children, breathe.

What a thing it is to reap the wheat with your own hands, to thresh it with the oaken flail in the misty barn, to ride with it to the mill and take your last trout while it is ground, and then to eat it with no decoration of butter, straight from the oven! There is nothing better, unless it be to eat your trout with the virgin appetite which you have won in catching it. But in the field, we should have been pleased with the plainest meal a hungry man can have, which is, I suppose, barley bread and a pale "double Caermarthen" cheese, which you cut with a hatchet after casting it on the floor and making it bounce, to be sure that it is a double Caermarthen. And yet I do not know. For even a Welsh hymnist of the eighteenth century, in translating "the increase of the fields," wrote avidly of "wheaten bread," so serious was his distaste for barley bread. But it was to a meal of wheaten bread and oat cake, and cheese and onions and cucumber, that we came in, while the trembling splendours of the first stars shone, as if they also were dewy like the furze. Nothing is to be compared with the pleasure of seeing the stars thus in the east, when most eyes are watching the west, except perhaps to read a fresh modern poet, straight from the press, before any one has praised it, and to know that it is good.

SILVERY LIGHT, CONWAY SHORE

As we sat, some were singing the song "Morwynion Sir Gaerfyrdd-in." Some were looking out at the old hay waggon before the gate.

Fine grass was already growing in corners of the wrecked hay waggon. Two months before, it travelled many times a day between the rick and the fields. Swallow was in the shafts while it carried all the village children to the field, as it had done some sixty years ago, when the village wheelwright helped God to make it. The waggoner lifted them out in clusters; the haymakers loaded silently; the waggon moved along the roads between the swathes; and, followed by children who expected another ride, and drawn by Swallow and Darling, it reached the rick that began to rise, like an early church, beside the elms. But hardly had it set out for another load than Swallow shied; an axle splintered and tore and broke in two, near the hub of one wheel, which subsided so that a corner of the waggon fell askew into the tussocks, and the suspended horse-shoe dropped from its place. There the mare left it, and switched her black tail from side to side of her lucent, nut-brown haunches, as she went.

All day the waggon was now the children's own. They climbed and slid and made believe that they were sailors, on its thin, polished timbers. The grass had grown up to it, under its protection. Before it fell, the massive wheels and delicate curved sides had been so fair and strong that no one thought of its end. Now, the exposed decay raised a smile at its so recent death. No one gave it a thought, except, perhaps, as now, when the September evening began, and one saw it on this side of the serious, dark elms, when the flooded ruts were gleaming, and a cold light fell over it from a tempestuous sky, and the motionless air was full of the shining of moist quinces and yellow fallen apples in long herbage; and, far off, the cowman let a gate shut noisily; the late swallows and early bats mingled in flight; and, under an oak, a tramp was kindling his fire....

Suddenly in came the dog, one of those thievish, lean, swift demi-wolves, that appear so fearful of meeting a stranger, but when he has passed, turn and follow him. He shook himself, stepped into the hearth and out and in again. With him was one whose red face and shining eyes and crisped hair were the decoration with which the wind invests his true lovers. A north wind had risen and given the word, and he repeated it: let us have a fire.

So one brought hay and twigs, another branches and knotted logs, and another the bellows. We made an edifice worthy of fire and kneeled with the dog to watch light changing into heat, as the spirals of sparks arose. The pyre was not more beautiful which turned to roses round the innocent maiden for whom it was lit; nor that more wonderful round which, night after night in the west, the clouds are solemnly ranged, waiting for the command that will tell them whither they are bound in the dark blue night. We became as the logs, that now and then settled down (as if they wished to be comfortable) and sent out, as we did words, some bristling sparks of satisfaction. And hardly did we envy then the man who lit the first fire and saw his own stupendous shadow in cave or wood and called it a god. As we kneeled, and our sight grew pleasantly dim, were we looking at fire-born recollections of our own childhood, wondering that such a childhood and youth as ours could ever have been; or at a golden age that never was?... The light spelt the titles of the books for a moment, and the bard read Spenser aloud, as if forsooth a man can read poetry in company round such a fire. So we pelted him with tales and songs....

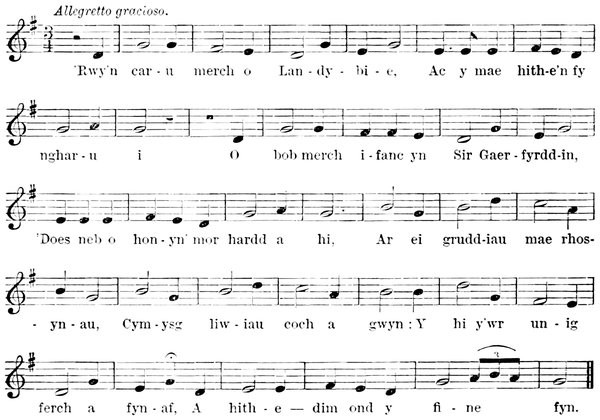

And one of the songs was "The Maid of Landybie," by the bard, Watcyn Wyn. Here follows the air, and a translation which was made by an English poet. The naïveté of the original has troubled him, and the Welsh stanza form has driven him to the use of rhymeless feminine endings; but I think that his version will, with the air, render not too faintly the song I heard.

THE MAID OF LANDYBIE

Air: Y Ferch o Blwyf Penderyn.

'Rwy'n car - u merch o Lan - dy - bi - e, Ac y mae hith-e'n fy

nghar - u i O bob merch i - fanc yn Sir Gaer - fyrdd-in,

'Does neb o hon - yn' mor hardd a hi, Ar ei grudd-iau mae rhos-

- yn - au, Cym - ysg liw - iau coch a gwyn: Y hi y'wr un - ig

ferch a fyn - af, A hith - e — dim ond y fi - ne fyn.

I love a maid of Landybie

And it is she who loves me too.

Of all the women of Caermarthen

None is so fair as she, I know.

White and red are her cheeks' young roses,

The tints all blended mistily;

She is the only maid I long for,

And she will have no lad but me.

I love one maid of Landybie.

And she too loves but one, but one;

The tender girl remains my faithful,

Pure of heart, a bird in tone.

Her beauty and her comely bearing

Have won my love and life and care,

For there is none in all the kingdoms

Like her, so blushing, kind, and fair.

While there is lime in Craig-y-Ddinas;

While there is water in Pant-y-Llyn;

And while the waves of shining Loughor

Walk between these hills and sing;

While there's a belfry in the village

Whose bells delight the country nigh,

The dearest maid of Landybie

Shall have her name held sweet and high.

A MOUNTAIN PASS—NOON

When we are by this fire, we can do what we like with Time, making a strange solitude within these four walls, as if they were cut off in time as in space from the great world by something more powerful than the night; so that, whether Llewelyn the Great, or Llewelyn the Last, or Arthur, or Kilhwch, or Owen Glyndwr, or the most recent prophet be the subject of our talk, nothing intrudes that can prevent us for the time from being utterly at one with them. They sing or jest or make puns; they talk of hero and poet as if they had met them on the hills; and as the poet has said, "Folly would it be to say that Arthur has a grave."

In such a room are legends made, if made at all. In fact, I lately saw a pretty proof of it.

The valley in which the farmhouse lies is not so fortified that some foreign things of one kind and another cannot enter. And a miner or a youth on holiday from London brought a song of Bill Bailey to the ears of one of the children of the house, a happy, melancholy boy named Merfyn. The elders caught it for a day or two, and though the song does not recommend itself to those who are heirs to "Sospan bach" and "Ar hyd y nos," the name of the hero stuck. The child asked who he was, and could get no answer. When anything happened about the farm that could not easily be explained, it was jestingly said that Bill Bailey was at the bottom of it. The child seriously caught up the name and the mystery, and applied it with amusing and strange effect. Thus, when he had asked who made the mushrooms in the dawn, and was not satisfied, he himself decided, and with pride and joy announced, that they were Bill Bailey's work. Looking into the fire one night, and seeing faces that he could not recognise among the throbbing heat, he saw Bill Bailey, as he surmised. Thus is a new solar hero being bred. The last news is that he made Cader Idris and Orion and the Pleiades, and that the owls cry so sadly because he is afoot in the woods.

CONWAY CASTLE AND QUAY—NOON

And yet, if we are so unwise as to draw back the curtain from the window at night, the illusion of timelessness is broken for that evening, and in the flower-faced owl by the pane, in the great hill scarred with precipices, and ribbed with white and crying streams, with here and there a black tree disturbed and a very far-off light, I can see nothing but the past as a magnificent presence besieging the house. At such times the legends that I remember most are those of the buried and unforgotten lands. What I see becomes but a symbol of what is now invisible. And sometimes I dream of something hidden out there and elaborating some omnipotent alcahest for the world's delight or the world's bane; sometimes, as when I passed Llanddeusant and Myddfai, I could see nothing that was there, because I was thinking of what had been long ago. There is still a tradition on the coast that Cardigan Bay now covers a country that was once populous and fair and rich. The son of a prince of South Wales is said to have had charge of the floodgates on the protecting embankment, and one night the floodgates were left open at high tide, while he slept with wine, and the sea was over the corn. "Seithenyn the Drunkard let in the sea over Cantre-'r-Gwaelod, so that all the houses and lands contained in it were lost. And before that time there were in it sixteen fortified towns superior to all the towns and cities in Wales, except Caerlleon on the Usk. And Cantre-'r-Gwaelod was the dominion of Gwyddno, King of Cardigan, and this event happened in the time of Ambrosius. And the people who escaped from that inundation came and landed in Ardudwy, the country of Arvon, the Snowdon mountains, and other places not before inhabited...." The sands in some places uncover the roots of an old forest. According to one tradition the flood took place during a feast. The harper suddenly foresaw what was to happen and warned the guests; but he alone escaped. There is also a tradition that Bala Lake covers old palaces. It is said that they have been seen on clear moonlit nights, when the air is one sapphire, and that a voice is heard saying, "Vengeance will come"; and another voice, "When will it come?" and again the first voice saying, "In the third generation." For a prince once had a palace where the lake is. He was cruel and persisted in his cruelty, despite a voice that sometimes cried to him, "Vengeance will come." One night there was a bright festival in the palace, and there were many ladies and many lords among the guests, for an heir had just been born to the prince. The wine shone and was continually renewed. The dancers were merry and never tired. And a voice cried, "Vengeance." But only the harper heard; and he saw a bird beckoning him out of the palace. He followed, and if he stopped, the bird called, "Vengeance." So they travelled a long way, and at last he stopped and rested, and the bird was silent. Then the harper upbraided himself, and turned, and would have gone back to the palace. But he lost his way, for it was night. And in the morning he saw one calm large lake where the palace had been; and on the lake floated the harper's harp....

This fire, in my memory, gathers round it many books which I have read and many men that I have spoken with among the mountains—gathers them from coal-pits and tin-works and schools and chapels and farmhouses and hideous cottages, beside rivers, among woods; and I have drawn a thin line round their shadows and have called the forms that came of it men, and their "characters" follow.

CONWAY VALLEY

CHAPTER IV

TWO MINISTERS, A BARD, A SCHOOLMASTER, AN INNKEEPER, AND OTHERS

Mr. Jones, the Minister

Jones is a little, thin, long-skulled, black-haired, pale Congregational minister, with a stammer and a squint. He has a book-shelf containing nothing but sermons and theology, which he has read, and the novels of Sir Walter Scott, which he hopes to read. I suppose he believes in metempsychosis. He is accustomed to say that everything is theology—which is fine; and that theology is everything—which is hard. He tries to love man as well as God, and succeeds in convincing every one of his honesty, generosity, and industry. In the care of souls he fears no disease or squalor or shape of death. But there is a condescension about his ways with men. He calls them the worldliest of God's creatures. But with the Divine he is happy and at ease, and in his pulpit seems to sit on the right hand. Then his Biblical criticism is absent as if it had never been, and he sees the holy things at once as clearly as Quarles and as mystically as Herbert or Crashaw. He speaks of them with the enthusiasm of a collector or of a man of science dealing with a bone or a gas. Like them, he sees nothing but the subjects of the moment. He loves them as passionately and yet with a sense of possession. He gives to them the adoration which he seems wilfully to have withheld from women, pageantry, gardens, palaces—which his speech would have adorned. He lavishes upon them his whole ingenious heart, so that, to those used to the false rhetoric and dull compliment of ordinary worshippers, there is in his sermons something fantastical, far-fetched, or smelling of the lamp. If he has to describe something naked or severe, he must needs give them a kind of voluptuousness by painting the things which they lack, and the lack of which makes them what they are. With Herbert, he might repeat:

CARNARVON, FROM ANGLESEY

My God, where is that ancient heat towards thee,

Wherewith whole shoals of Martyrs once did burn,

Besides their other flames? doth Poetry

Wear Venus' livery? only serve her turn?

Why are not Sonnets made of thee? and lays

Upon thine altar burnt? Cannot thy love

Heighten a spirit to sound out thy praise

As well as she? Cannot thy Dove

Outstrip their Cupid easily in flight?

Or, since thy ways are deep, and still the same,

Will not a verse run smooth that bears thy name?

Why doth the fire which by thy power and might

Each breast does feel, no braver fuel choose

Than that, which one day worms may chance refuse?

Sure, Lord, there is enough in thee to dry

Oceans of ink; for as the Deluge did

Cover the Earth, so does thy Majesty;

Each cloud distils thy praise, and doth forbid

Poets to turn it to another use.

Roses and lilies speak thee: and to make

A pair of cheeks of them, is thy abuse.

Why should I women's eyes for crystal take?

Such poor invention burns in their low mind

Whose fire is wild, and does not upward go

To praise, and on thee, Lord, some note bestow.

Open the bones, and you shall nothing find

In the best face but filth; when, Lord, in thee

Thy beauty lies in the discovery.

It is no matter to him that to the uninspired audience his holy persons appear only exquisite marionettes. His sermons are all of his love for them. Could one leave out the names of prophet and evangelist, they might seem to be addressed to earthly beauties. No eyebrow ever awakened more glowing praise. He takes religion, as he does his severe morality, like a sensuous delight. One might think from his epithets that he was an æsthete, except that he is so abandoned.