автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Complete Works of Plutarch. Parallel Lives. Moralia. Illustrated

The Complete Works of Plutarch

Parallel Lives. Moralia

Illustrated

Plutarch created a diverse range of works that have entertained generations of readers since the days of Imperial Rome. Plutarch's writings had an enormous influence on English and French literature.

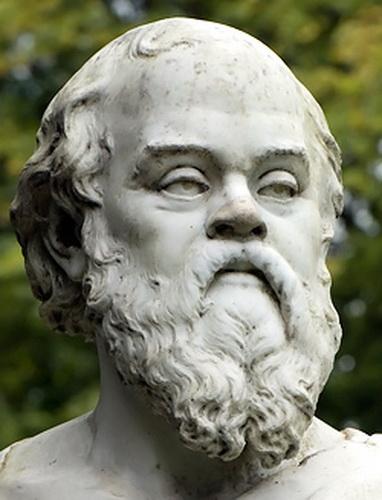

Plutarch was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo.

He is known primarily for his Parallel Lives, a series of biographies of illustrious Greeks and Romans, and Moralia, a collection of essays and speeches.

THE TRANSLATIONS

PARALLEL LIVES

Translated by Bernadotte Perrin

Theseus

1 Just as geographers, O Sossius Senecio, crowd on to the outer edges of their maps the parts of the earth which elude their knowledge, with explanatory notes that “What lies beyond is sandy desert without water and full of wild beasts,” or “blind marsh,” or “Scythian cold,” or “frozen sea,” so in the writing of my Parallel Lives, now that I have traversed those periods of time which are accessible to probable reasoning and which afford basis for a history dealing with facts, I might well say of the earlier periods: “What lies beyond is full of marvels and unreality, a land of poets and fabulists, of doubt and obscurity.” 2 But after publishing my account of Lycurgus the lawgiver and Numa the king, I thought I might not unreasonably go back still farther to Romulus, now that my history had brought me near his times. And as I asked myself,

“With such a warrior” (as Aeschylus says) “who will dare to fight?”

“Whom shall I set against him? Who is competent?”

it seemed to me that I must make the founder of lovely and famous Athens the counterpart and parallel to the father of invincible and glorious Rome. 3 May I therefore succeed in purifying Fable, making her submit to reason and take on the semblance of History. But where she obstinately disdains to make herself credible, and refuses to admit any element of probability, I shall pray for kindly readers, and such as receive with indulgence the tales of antiquity.

2 1 It seemed to me, then, that many resemblances made Theseus a fit parallel to Romulus. For both were of uncertain and obscure parentage, and got the reputation of descent from gods;

“Both were also warriors, as surely the whole world knoweth,”

and with their strength, combined sagacity. Of the world’s two most illustrious cities, moreover, Rome and Athens, Romulus founded the one, and Theseus made a metropolis of the other, and each resorted to the rape of women. 2 Besides, neither escaped domestic misfortunes and the resentful anger of kindred, but even in their last days both are said to have come into collision with their own fellow-citizens, if there is any aid to the truth in what seems to have been told with the least poetic exaggeration.

3 1 The lineage of Theseus, on the father’s side, goes back to Erechtheus and the first children of the soil; on the mother’s side, to Pelops. For Pelops was the strongest of the kings in Peloponnesus quite as much on account of the number of his children as the amount of his wealth. He gave many daughters in marriage to men of the highest rank, and scattered many sons among the cities as their rulers. One of these, named Pittheus, the grandfather of Theseus, founded the little city of Troezen, and had the highest repute as a man versed in the lore of his times and of the greatest wisdom. 2 Now the wisdom of that day had some such form and force as that for which Hesiod was famous, especially in the sententious maxims of his “Works and Days.” One of these maxims is ascribed to Pittheus, namely: —

“Payment pledged to a man who is dear must be ample and certain.”

At any rate, this is what Aristotle the philosopher says, and Euripides, when he has Hippolytus addressed as “nursling of the pure and holy Pittheus,” shows what the world thought of Pittheus.

3 Now Aegeus, king of Athens, desiring to have children, is said to have received from the Pythian priestess the celebrated oracle in which she bade him to have intercourse with no woman until he came to Athens. But Aegeus thought the words of the command somewhat obscure, and therefore turned aside to Troezen and communicated to Pittheus the words of the god, which ran as follows: —

“Loose not the wine-skin’s jutting neck, great chief of the people,

Until thou shalt have come once more to the city of Athens.”

4 This dark saying Pittheus apparently understood, and persuaded him, or beguiled him, to have intercourse with his daughter Aethra. Aegeus did so, and then learning that it was the daughter of Pittheus with whom he had consorted, and suspecting that she was with child by him, he left a sword and a pair of sandals hidden under a great rock, which had a hollow in it just large enough to receive these objects. 5 He told the princess alone about this, and bade her, if a son should be born to her from him, and if, when he came to man’s estate, he should be able to lift up the rock and take away what had been left under it, to send that son to him with the tokens, in all secrecy, and concealing his journey as much as possible from everybody; for he was mightily in fear of the sons of Pallas, who were plotting against him, and who despised him on account of his childlessness; and they were fifty in number, these sons of Pallas. Then he went away.

4 1 When Aethra gave birth to a son, he was at once named Theseus, as some say, because the tokens for his recognition had been placed in hiding; but others say that it was afterwards at Athens, when Aegeus acknowledged him as his son. He was reared by Pittheus, as they say, and had an overseer and tutor named Connidas. To this man, even down to the present time, the Athenians sacrifice a ram on the day before the festival of Theseus, remembering and honouring him with far greater justice than they honour Silanio and Parrhasius, who merely painted and moulded likenesses of Theseus.

5 1 Since it was still a custom at that time for youth who were coming of age to go to Delphi and sacrifice some of their hair to the god, Theseus went to Delphi for this purpose, and they say there is a place there which still to this day is called the Theseia from him. But he sheared only the fore part of his head, just as Homer said the Abantes did, and this kind of tonsure was called Theseïs after him.

2 Now the Abantes were the first to cut their hair in this manner, not under instruction from the Arabians, as some suppose, nor yet in emulation of the Mysians, but because they were war-like men and close fighters, who had learned beyond all other men to force their way into close quarters with their enemies. Archilochus is witness to this in the following words: —

3 “Not many bows indeed will be stretched tight, nor frequent slings

Be whirled, when Ares joins men in the moil of war

Upon the plain, but swords will do their mournful work;

For this is the warfare wherein those men are expert

Who lord it over Euboea and are famous with the spear.”

4 Therefore, in order that they might not give their enemies a hold by their hair, they cut it off. And Alexander of Macedon doubtless understood this when, as they say, he ordered his generals to have the beards of their Macedonians shaved, since these afforded the readiest hold in battle.

6 1 During the rest of the time, then, Aethra kept his true birth concealed from Theseus, and a report was spread abroad by Pittheus that he was begotten by Poseidon. For Poseidon is highly honoured by the people of Troezen, and he is the patron god of their city; to him they offer first fruits in sacrifice, and they have his trident as an emblem on their coinage. 2 But when, in his young manhood, Theseus displayed, along with his vigour of body, prowess also, and a firm spirit united with intelligence and sagacity, then Aethra brought him to the rock, told him the truth about his birth, and bade him take away his father’s tokens and go by sea to Athens. 3 Theseus put his shoulder to the rock and easily raised it up, but he refused to make his journey by sea, although safety lay in that course, and his grandfather and his mother begged him to take it. For it was difficult to make the journey to Athens by land, since no part of it was clear nor yet without peril from robbers and miscreants.

4 For verily that age produced men who, in work of hand and speed of foot and vigour of body, were extraordinary and indefatigable, but they applied their powers to nothing that was fitting or useful. Nay rather, they exulted in monstrous insolence, and reaped from their strength a harvest of cruelty and bitterness, mastering and forcing and destroying everything that came in their path. And as for reverence and righteousness, justice and humanity, they thought that most men praised these qualities for lack of courage to do wrong and for fear of being wronged, and considered them no concern of men who were strong enough to get the upper hand. 5 Some of these creatures Heracles cut off and destroyed as he went about, but some escaped his notice as he passed by, crouching down and shrinking back, and were overlooked in their abjectness. And when Heracles met with calamity and, after the slaying of Iphitus, removed into Lydia and for a long time did slave’s service there in the house of Omphale, then Lydia indeed obtained great peace and security; but in the regions of Hellas the old villainies burst forth and broke out anew, there being none to rebuke and none to restrain them.

6 The journey was therefore a perilous one for travellers by land from Peloponnesus to Athens, and Pittheus, by describing each of the miscreants at length, what sort of a monster he was, and what deeds he wrought upon strangers, tried to persuade Theseus to make his journey by sea. But he, as it would seem, had long since been secretly fired by the glorious valour of Heracles, and made the greatest account of that hero, and was a most eager listener to those who told what manner of man he was, and above all to those who had seen him and been present at some deed or speech of his. 7 And it is altogether plain that he then experienced what Themistocles many generations afterwards experienced, when he said that he could not sleep for the trophy of Miltiades. In like manner Theseus admired the valour of Heracles, until by night his dreams were of the hero’s achievements, and by day his ardour led him along and spurred him on in his purpose to achieve the like.

7 1 And besides, they were kinsmen, being sons of cousins-german. For Aethra was daughter of Pittheus, as Alcmene was of Lysidice, and Lysidice and Pittheus were brother and sister, children of Hippodameia and Pelops. 2 Accordingly, he thought it a dreadful and unendurable thing that his famous cousin should go out against the wicked everywhere and purge land and sea of them, while he himself ran away from the struggles which lay in his path, disgracing his reputed father by journeying like a fugitive over the sea, and bringing to his real father as proofs of his birth only sandals and a sword unstained with blood, instead of at once offering noble deeds and achievements as the manifest mark of his noble birth. In such a spirit and with such thoughts he set out, determined to do no man any wrong, but to punish those who offered him violence.

8 1 And so in the first place, in Epidauria, when Periphetes, who used a club as his weapon and on this account was called Club-bearer, laid hold of him and tried to stop his progress, he grappled with him and slew him. And being pleased with the club, he took it and made it his weapon and continued to use it, just as Heracles did with the lion’s skin. That hero wore the skin to prove how great a wild beast he had mastered, and so Theseus carried the club to show that although it had been vanquished by him, in his own hands it was invincible.

2 On the Isthmus, too, he slew Sinis the Pine-bender in the very manner in which many men had been destroyed by himself, and he did this without practice or even acquaintance with the monster’s device, but showing that valour is superior to all device and practice. Now Sinis had a very beautiful and stately daughter, named Perigune. This daughter took to flight when her father was killed, and Theseus went about in search of her. But she had gone off into a place which abounded greatly in shrubs and rushes and wild asparagus, and with exceeding innocence and childish simplicity was supplicating these plants, as if they understood her, and vowing that if they would hide and save her, she would never trample them down nor burn them. 3 When, however, Theseus called upon her and gave her a pledge that he would treat her honourably and do her no wrong, she came forth, and after consorting with Theseus, bore him Melanippus, and afterwards lived with Deïoneus, son of Eurytus the Oechalian, to whom Theseus gave her. From Melanippus the son of Theseus, Ioxus was born, who took part with Ornytus in leading a colony into Caria; whence it is ancestral usage with the Ioxids, men and women, not to burn either the asparagus-thorn or the rush, but to revere and honour them.

9 1 Now the Crommyonian sow, which they called Phaea, was no insignificant creature, but fierce and hard to master. This sow he went out of his way to encounter and slay, that he might not be thought to perform all his exploits under compulsion, and at the same time because he thought that while the brave man ought to attack villainous men only in self defence, he should seek occasion to risk his life in battle with the nobler beasts. However, some say that Phaea was a female robber, a woman of murderous and unbridled spirit, who dwelt in Crommyon, was called Sow because of her life and manners, and was afterwards slain by Theseus.

10 1 He also slew Sciron on the borders of Megara, by hurling him down the cliffs. Sciron robbed the passers by, according to the prevalent tradition; but as some say, he would insolently and wantonly thrust out his feet to strangers and bid them wash them, and then, while they were washing them, kick them off into the sea. 2 Megarian writers, however, taking issue with current report, and, as Simonides expresses it, “waging war with antiquity,” say that Sciron was neither a violent man nor a robber, but a chastiser of robbers, and a kinsman and friend of good and just men. For Aeacus, they say, is regarded as the most righteous of Hellenes, and Cychreus the Salaminian has divine honours at Athens, and the virtues of Peleus and Telamon are known to all men. 3 Well, then, Sciron was a son-in law of Cychreus, father-in law of Aeacus, and grandfather of Peleus and Telamon, who were the sons of Endeïs, daughter of Sciron and Chariclo. It is not likely, then, they say, that the best of men made family alliances with the basest, receiving and giving the greatest and most valuable pledges. It was not, they say, when Theseus first journeyed to Athens, but afterwards, that he captured Eleusis from the Megarians, having circumvented Diocles its ruler, and slew Sciron. Such, then, are the contradictions in which these matters are involved.

11 In Eleusis, moreover, he out-wrestled Cercyon the Arcadian and killed him; and going on a little farther, at Erineüs, he killed Damastes, surnamed Procrustes, by compelling him to make his own body fit his bed, as he had been wont to do with those of strangers. And he did this in imitation of Heracles. For that hero punished those who offered him violence in the manner in which they had plotted to serve him, and therefore sacrificed Busiris, wrestled Antaeus to death, slew Cycnus in single combat, and killed Termerus by dashing in his skull. 2 It is from him, indeed, as they say, that the name “Termerian mischief” comes, for Termerus, as it would seem, used to kill those who encountered him by dashing his head against theirs. Thus Theseus also went on his way chastising the wicked, who were visited with the same violence from him which they were visiting upon others, and suffered justice after the manner of their own injustice.

12 1 As he went forward on his journey and came to the river Cephisus, he was met by men of the race of the Phytalidae, who greeted him first, and when he asked to be purified from bloodshed, cleansed him the customary rites, made propitiatory sacrifices, and feasted him at their house. This was the first kindness which he met with on his journey.

It was, then, on the eighth day of the month Cronius, now called Hecatombaeon, that he is said to have arrived at Athens. And when he entered the city, he found public affairs full of confusion and dissension, and the private affairs of Aegeus and his household in a distressing condition. 2 For Medea, who had fled thither from Corinth, and promised by her sorceries to relieve Aegeus of his childlessness, was living with him. She learned about Theseus in advance, and since Aegeus was ignorant of him, and was well on in years and afraid of everything because of the faction in the city, she persuaded him to entertain Theseus as a stranger guest, and take him off by poison. Theseus, accordingly, on coming to the banquet, thought best not to tell in advance who he was, but wishing to give his father a clue to the discovery, when the meats were served, he drew his sword, as if minded to carve with this, and brought it to the notice of his father. 3 Aegeus speedily perceived it, dashed down the proffered cup of poison, and after questioning his son, embraced him, and formally recognized him before an assembly of the citizens, who received him gladly because of his manly valour. And it is said that as the cup fell, the poison was spilled where now is the enclosure in the Delphinium, for that is where the house of Aegeus stood, and the Hermes to the east of the sanctuary is called the Hermes at Aegeus’s gate.

13 1 Now the sons of Pallas had before this themselves hoped to gain possession of the kingdom when Aegeus died childless. But when Theseus was declared successor to the throne, exasperated that Aegeus should be king although he was only an adopted son of Pandion and in no way related to the family of Erechtheus, and again that Theseus should be prospective king although he was an immigrant and a stranger, they went to war. 2 And dividing themselves into two bands, one of these marched openly against the city from Sphettus with their father; the other hid themselves at Gargettus and lay in ambush there, intending to attack their enemies from two sides. But there was a herald with them, a man of Agnus, by name Leos. This man reported to Theseus the designs of the Pallantidae. 3 Theseus then fell suddenly upon the party lying in ambush, and slew them all. Thereupon the party with Pallas dispersed. This is the reason, they say, why the township of Pallene has no intermarriage with the township of Agnus, and why it will not even allow heralds to make their customary proclamation there of “Akouete leoi” (Hear, ye people! ). For they hate the word on account of the treachery of the man Leos.

14 1 But Theseus, desiring to be at work, and at the same time courting the favour of the people, went out against the Marathonian bull, which was doing no small mischief to the inhabitants of the Tetrapolis. After he had mastered it, he made a display of driving it alive through the city, and then sacrificed it to the Delphinian Apollo. 2 Now the story of Hecale and her receiving and entertaining Theseus on this expedition seems not to be devoid of all truth. For the people of the townships round about used to assemble and sacrifice the Hecalesia to Zeus Hecalus, and they paid honours to Hecale, calling her by the diminutive name of Hecaline, because she too, when entertaining Theseus, in spite of the fact that he was quite a youth, caressed him as elderly people do, and called him affectionately by such diminutive names. 3 And since she vowed, when the hero was going to his battle with the bull, that she would sacrifice to Zeus if he came back safe, but died before his return, she obtained the above mentioned honours as a return for her hospitality at the command of Theseus, as Philochorus has written.

15 1 Not long afterwards there came from Crete for the third time the collectors of the tribute. Now as to this tribute, most writers agree that because Androgeos was thought to have been treacherously killed within the confines of Attica, not only did Minos harass the inhabitants of that country greatly in war, but Heaven also laid it waste, for barrenness and pestilence smote it sorely, and its rivers dried up; also that when their god assured them in his commands that if they appeased Minos and became reconciled to him, the wrath of Heaven would abate and there would be an end of their miseries, they sent heralds and made their supplication and entered into an agreement to send him every nine years a tribute of seven youths and as many maidens. 2 And the most dramatic version of the story declares that these young men and women, on being brought to Crete, were destroyed by the Minotaur in the Labyrinth, or else wandered about at their own will and, being unable to find an exit, perished there; and that the Minotaur, as Euripides says, was

“A mingled form and hybrid birth of monstrous shape,”

“Two different natures, man and bull, were joined in him.”

16 1 Philochorus, however, says that the Cretans do not admit this, but declare that the Labyrinth was a dungeon, with no other inconvenience than that its prisoners could not escape; and that Minos instituted funeral games in honour of Androgeos, and as prizes for the victors, gave these Athenian youth, who were in the meantime imprisoned in the Labyrinth; and that the victor in the first games was the man who had the greatest power at that time under Minos, and was his general, Taurus by name, who was not reasonable and gentle in his disposition, but treated the Athenian youth with arrogance and cruelty. 2 And Aristotle himself also, in his “Constitution of Bottiaea,” clearly does not think that these youths were put to death by Minos, but that they spent the rest of their lives as slaves in Crete. And they say that the Cretans once, in fulfilment of an ancient vow, sent an offering of their first-born to Delphi, and that some descendants of those Athenians were among the victims, and went forth with them; and that when they were unable to support themselves there, they first crossed over into Italy and dwelt in that country round about Iapygia, and from there journeyed again into Thrace and were called Bottiaeans; and that this was the reason why the maidens of Bottiaea, in performing a certain sacrifice, sing as an accompaniment: “To Athens let us go!”

And verily it seems to be a grievous thing for a man to be at enmity with a city which has a language and a literature. 3 For Minos was always abused and reviled in the Attic theatres, and it did not avail him either that Hesiod called him “most royal,” or that Homer styled him “a confidant of Zeus,” but the tragic poets prevailed, and from platform and stage showered obloquy down upon him, as a man of cruelty and violence. And yet they say that Minos was a king and lawgiver, and that Rhadamanthus was a judge under him, and a guardian of the principles of justice defined by him.

17 1 Accordingly, when the time came for the third tribute, and it was necessary for the fathers who had youthful sons to present them for the lot, fresh accusations against Aegeus arose among the people, who were full of sorrow and vexation that he who was the cause of all their trouble alone had no share in the punishment, but devolved the kingdom upon a bastard and foreign son, and suffered them to be left destitute and bereft of legitimate children. 2 These things troubled Theseus, who, thinking it right not to disregard but to share in the fortune of his fellow-citizens, came forward and offered himself independently of the lot. The citizens admired his noble courage and were delighted with his public spirit, and Aegeus, when he saw that his son was not to be won over or turned from his purpose by prayers and entreaties, cast the lots for the rest of the youths.

3 Hellanicus, however, says that the city did not send its young men and maidens by lot, but that Minos himself used to come and pick them out, and that he now pitched upon Theseus first of all, following the terms agreed upon. And he says the agreement was that the Athenians should furnish the ship, and that the youths should embark and sail with him carrying no warlike weapon, and that if the Minotaur was killed the penalty should cease.

4 On the two former occasions, then, no hope of safety was entertained, and therefore they sent the ship with a black sail, convinced that their youth were going to certain destruction; but now Theseus encouraged his father and loudly boasted that he would master the Minotaur, so that he gave the pilot another sail, a white one, ordering him, if he returned with Theseus safe, to hoist the white sail, but otherwise to sail with the black one, and so indicate the affliction.

5 Simonides, however, says that the sail given by Aegeus was not white, but “a scarlet sail dyed with the tender flower of luxuriant holm-oak,” and that he made this a token of their safety. Moreover, the pilot of the ship was Phereclus, son of Amarsyas, as Simonides says; 6 but Philochorus says that Theseus got from Scirus of Salamis Nausithoüs for his pilot, and Phaeax for his look-out man, the Athenians at that time not yet being addicted to the sea, and that Scirus did him this favour because one of the chosen youths, Menesthes, was his daughter’s son. And there is evidence for this in the memorial chapels for Nausithoüs and Phaeax which Theseus built at Phalerum near the temple of Scirus, and they say that the festival of the Cybernesia, or Pilot’s Festival, is celebrated in their honour.

18 1 When the lot was cast, Theseus took those upon whom it fell from the prytaneium and went to the Delphinium, where he dedicated to Apollo in their behalf his suppliant’s badge. This was a bough from the sacred olive-tree, wreathed with white wool. Having made his vows and prayers, he went down to the sea on the sixth day of the month Munychion, on which day even now the Athenians still send their maidens to the Delphinium to propitiate the god. 2 And it is reported that the god at Delphi commanded him in an oracle to make Aphrodite his guide, and invite her to attend him on his journey, and that as he sacrificed the usual she-goat to her by the sea-shore, it became a he-goat (“tragos”) all at once, for which reason the goddess has the surname Epitragia.

19 1 When he reached Crete on his voyage, most historians and poets tells us that he got from Ariadne, who had fallen in love with him, the famous thread, and that having been instructed by her how to make his way through the intricacies of the Labyrinth, he slew the Minotaur and sailed off with Ariadne and the youths. And Pherecydes says that Theseus also staved in the bottoms of the Cretan ships, thus depriving them of the power to pursue. 2 And Demon says also that Taurus, the general of Minos, was killed in a naval battle in the harbour as Theseus was sailing out. But as Philochorus tells the story, Minos was holding the funeral games, and Taurus was expected to conquer all his competitors in them, as he had done before, and was grudged his success. For his disposition made his power hateful, and he was accused of too great intimacy with Pasiphaë. Therefore when Theseus asked the privilege of entering the lists, it was granted him by Minos. 3 And since it was the custom in Crete for women to view the games, Ariadne was present, and was smitten with the appearance of Theseus, as well as filled with admiration for his athletic prowess, when he conquered all his opponents. Minos also was delighted with him, especially because he conquered Taurus in wrestling and disgraced him, and therefore gave back the youths to Theseus, besides remitting its tribute to the city.

4 Cleidemus, however, gives a rather peculiar and ambitious account of these matters, beginning a great way back. There was, he says, a general Hellenic decree that no trireme should sail from any port with a larger crew than five men, and the only exception was Jason, the commander of the Argo, who sailed about scouring the sea of pirates. Now when Daedalus fled from Crete in a merchant-vessel to Athens, Minos, contrary to the decrees, pursued him with his ships of war, and was driven from his course by a tempest to Sicily, where he ended his life. 5 And when Deucalion, his son, who was on hostile terms with the Athenians, sent to them a demand that they deliver up Daedalus to him, and threatened, if they refused, to put to death the youth whom Minos had received from them as hostages, Theseus made him a gentle reply, declining to surrender Daedalus, who was his kinsman and cousin, being the son of Merope, the daughter of Erechtheus. But privately he set himself to building a fleet, part of it at home in the township of Thymoetadae, far from the public road, and part of it under the direction of Pittheus in Troezen, wishing his purpose to remain concealed. 6 When his ships were ready, he set sail, taking Daedalus and exiles from Crete as his guides, and since none of the Cretans knew of his design, but thought the approaching ships to be friendly, Theseus made himself master of the harbour, disembarked his men, and got to Gnossus before his enemies were aware of his approach. Then joining battle with them at the gate of the Labyrinth, he slew Deucalion and his body-guard. 7 And since Ariadne was now at the head of affairs, he made a truce with her, received back the youthful hostages, and established friendship between the Athenians and the Cretans, who took oath never to begin hostilities.

20 1 There are many other stories about these matters, and also about Ariadne, but they do not agree at all. Some say that she hung herself because she was abandoned by Theseus; others that she was conveyed to Naxos by sailors and there lived with Oenarus the priest of Dionysus, and that she was abandoned by Theseus because he loved another woman: —

“Dreadful indeed was his passion for Aigle child of Panopeus.”

2 This verse Peisistratus expunged from the poems of Hesiod, according to Hereas the Megarian, just as, on the other hand, he inserted into the Inferno of Homer the verse: —

“Theseus, Peirithous, illustrious children of Heaven,”

and all to gratify the Athenians. Moreover, some say that Ariadne actually had sons by Theseus, Oenopion and Staphylus, and among these is Ion of Chios, who says of his own native city: —

“This, once, Theseus’s son founded, Oenopion.”

Now the most auspicious of these legendary tales are in the mouths of all men, as I may say; but a very peculiar account of these matters is published by Paeon the Amathusian. 3 He says that Theseus, driven out of his course by a storm to Cyprus, and having with him Ariadne, who was big with child and in sore sickness and distress from the tossing of the sea, set her on shore alone, but that he himself, while trying to succour the ship, was borne out to sea again. The women of the island, accordingly, took Ariadne into their care, and tried to comfort her in the discouragement caused by her loneliness, brought her forged letters purporting to have been written to her by Theseus, ministered to her aid during the pangs of travail, and gave her burial when she died before her child was born. 4 Paeon says further that Theseus came back, and was greatly afflicted, and left a sum of money with the people of the island, enjoining them to sacrifice to Ariadne, and caused two little statuettes to be set up in her honour, one of silver, and one of bronze. He says also that at the sacrifice in her honour on the second day of the month Gorpiaeus, one of their young men lies down and imitates the cries and gestures of women in travail; and that they call the grove in which they show her tomb, the grove of Ariadne Aphrodite.

5 Some of the Naxians also have a story of their own, that there were two Minoses and two Ariadnes, one of whom, they say, was married to Dionysus in Naxos and bore him Staphylus and his brother, and the other, of a later time, having been carried off by Theseus and then abandoned by him, came to Naxos, accompanied by a nurse named Corcyne, whose tomb they show; and that this Ariadne also died there, and has honours paid her unlike those of the former, for the festival of the first Ariadne is celebrated with mirth and revels, but the sacrifices performed in honour of the second are attended with sorrow and mourning.

21 1 On his voyage from Crete, Theseus put in at Delos, and having sacrificed to the god and dedicated in his temple the image of Aphrodite which he had received from Ariadne, he danced with his youths a dance which they say is still performed by the Delians, being an imitation of the circling passages in the Labyrinth, and consisting of certain rhythmic involutions and evolutions. 2 This kind of dance, as Dicaearchus tells us, is called by the Delians The Crane, and Theseus danced it round the altar called Keraton, which is constructed of horns (“kerata”) taken entirely from the left side of the head. He says that he also instituted athletic contests in Delos, and that the custom was then begun by him of giving a palm to the victors.

22 1 It is said, moreover, that as they drew nigh the coast of Attica, Theseus himself forgot, and his pilot forgot, such was their joy and exultation, to hoist the sail which was to have been the token of their safety to Aegeus, who therefore, in despair, threw himself down from the rock and was dashed in pieces. But Theseus, putting in to shore, sacrificed in person the sacrifices which he had vowed to the gods at Phalerum when he set sail, and then dispatched a herald to the city to announce his safe return. 2 The messenger found many of the people bewailing the death of their king, and others full of joy at his tidings, as was natural, and eager to welcome him and crown him with garlands for his good news. The garlands, then, he accepted, and twined them about his herald’s staff, and on returning to the seashore, finding that Theseus had not yet made his libations to the gods, remained outside the sacred precincts, not wishing to disturb the sacrifice. 3 But when the libations were made, he announced the death of Aegeus. Thereupon, with tumultuous lamentation, they went up in haste to the city. Whence it is, they say, that to this day, at the festival of the Oschophoria, it is not the herald that is crowned, but his herald’s staff, and those who are present at the libations cry out: “Eleleu! Iou! Iou!” the first of which cries is the exclamation of eager haste and triumph, the second of consternation and confusion.

4 After burying his father, Theseus paid his vows to Apollo on the seventh day of the month Pyanepsion; for on that day they had come back to the city in safety. Now the custom of boiling all sorts of pulse on that day is said to have arisen from the fact that the youths who were brought safely back by Theseus put what was left of their provisions into one mess, boiled it in one common pot, feasted upon it, and ate it all up together. 5 At that feast they also carry the so called “eiresione,” which is a bough of olive wreathed with wool, such as Theseus used at the time of his supplication, and laden with all sorts of fruit-offerings, to signify that scarcity was at an end, and as they go they sing: —

“Eiresione for us brings figs and bread of the richest,

Brings us honey in pots and oil to rub off from the body,

Strong wine too in a beaker, that one may go to bed mellow.”

Some writers, however, say that these rites are in memory of the Heracleidae, who were maintained in this manner by the Athenians; but most put the matter as I have done.

23 1 The ship on which Theseus sailed with the youths and returned in safety, the thirty-oared galley, was preserved by the Athenians down to the time of Demetrius Phalereus. They took away the old timbers from time to time, and put new and sound ones in their places, so that the vessel became standing illustration for the philosophers in the mooted question of growth, some declaring that it remained the same, others that it was not the same vessel.

2 It was Theseus who instituted also the Athenian festival of the Oschophoria. For it is said that he did not take away with him all the maidens on whom the lot fell at that time, but picked out two young men of his acquaintance who had fresh and girlish faces, but eager and manly spirits, and changed their outward appearance almost entirely by giving them warm baths and keeping them out of the sun, by arranging their hair, and by smoothing their skin and beautifying their complexions with unguents; he also taught them to imitate maidens as closely as possible in their speech, their dress, and their gait, and to leave no difference that could be observed, and then enrolled them among the maidens who were going to Crete, and was undiscovered by any. 3 And when he was come back, he himself and these two young men headed a procession, arrayed as those are now arrayed who carry the vine-branches. They carry these in honour of Dionysus and Ariadne, and because of their part in the story; or rather, because they came back home at the time of the vintage. And the women called Deipnophoroi, or supper-carriers , take part in the procession and share in the sacrifice, in imitation of the mothers of the young men and maidens on whom the lot fell, for these kept coming with bread and meat for their children. And tales are told at this festival, because these mothers, for the sake of comforting and encouraging their children, spun out tales for them. At any rate, these details are to be found in the history of Demon. Furthermore, a sacred precinct was also set apart for Theseus, and he ordered the members of the families which had furnished the tribute to the Minotaur to make contributions towards a sacrifice to himself. This sacrifice was superintended by the Phytalidae, and Theseus thus repaid them for their hospitality.

24 1 After the death of Aegeus, Theseus conceived a wonderful design, and settled all the residents of Attica in one city, thus making one people of one city out of those who up to that time had been scattered about and were not easily called together for the common interests of all, nay, they sometimes actually quarrelled and fought with each other. 2 He visited them, then, and tried to win them over to his project township by township and clan by clan. The common folk and the poor quickly answered to his summons; to the powerful he promised government without a king and a democracy, in which he should only be commander in war and guardian of the laws, while in all else everyone should be on an equal footing. 3 Some he readily persuaded to this course, and others, fearing his power, which was already great, and his boldness, chose to be persuaded rather than forced to agree to it. Accordingly, after doing away with the town-halls and council-chambers and magistracies in the several communities, and after building a common town-hall and council-chamber for all on the ground where the upper town of the present day stands, he named the city Athens, and instituted a Panathenaic festival. 4 He instituted also the Metoecia, or Festival of Settlement, on the sixteenth day of the month Hecatombaeon, and this is still celebrated. Then, laying aside the royal power, as he had agreed, he proceeded to arrange the government, and that too with the sanction of the gods. For an oracle came to him from Delphi, in answer to his enquiries about the city, as follows: —

5 “Theseus, offspring of Aegeus, son of the daughter of Pittheus,

Many indeed the cities to which my father has given

Bounds and future fates within your citadel’s confines.

Therefore be not dismayed, but with firm and confident spirit

Counsel only; the bladder will traverse the sea and its surges.”

And this oracle they say the Sibyl afterwards repeated to the city, when she cried: —

“Bladder may be submerged; but its sinking will not be permitted.”

25 1 Desiring still further to enlarge the city, he invited all men thither on equal terms, and the phrase “Come hither all ye people,” they say was a proclamation of Theseus when he established a people, as it were, of all sorts and conditions. However, he did not suffer his democracy to become disordered or confused from an indiscriminate multitude streaming into it, but was the first to separate the people into noblemen and husbandmen and handicraftsmen. 2 To the noblemen he committed the care of religious rites, the supply of magistrates, the teaching of the laws, and the interpretation of the will of Heaven, and for the rest of the citizens he established a balance of privilege, the noblemen being thought to excel in dignity, the husbandmen in usefulness, and the handicraftsmen in numbers. And that he was the first to show a leaning towards the multitude, as Aristotle says, and gave up his absolute rule, seems to be the testimony of Homer also, in the Catalogue of Ships, where he speaks of the Athenians alone as a “people.”

3 He also coined money, and stamped it with the effigy of an ox, either in remembrance of the Marathonian bull, or of Taurus, the general of Minos, or because he would invite the citizens to agriculture. From this coinage, they say, “ten oxen” and “a hundred oxen” came to be used as terms of valuation. Having attached the territory of Megara securely to Attica, he set up that famous pillar on the Isthmus, and carved upon it the inscription giving the territorial boundaries. It consisted of two trimeters, of which the one towards the east declared: —

“Here is not Peloponnesus, but Ionia;”

and the one towards the west: —

“Here is the Peloponnesus, not Ionia.”

4 He also instituted the games here, in emulation of Heracles, being ambitious that as the Hellenes, by that hero’s appointment, celebrated Olympian games in honour of Zeus, so by his own appointment they should celebrate Isthmian games in honour of Poseidon. For the games already instituted there in honour of Melicertes were celebrated in the night, and had the form of a religious rite rather than of a spectacle and public assembly. But some say that the Isthmian games were instituted in memory of Sciron, and that Theseus thus made expiation for his murder, because of the relationship between them; for Sciron was a son of Canethus and Henioche, who was the daughter of Pittheus. 5 And others have it that Sinis, not Sciron, was their son, and that it was in his honour rather that the games were instituted by Theseus. However that may be, Theseus made a formal agreement with the Corinthians that they should furnish Athenian visitors to the Isthmian games with a place of honour as large as could be covered by the sail of the state galley which brought them thither, when it was stretched to its full extent. So Hellanicus and Andron of Halicarnassus tell us.

26 1 He also made a voyage into the Euxine Sea, as Philochorus and sundry others say, on a campaign with Heracles against the Amazons, and received Antiope as a reward of his valour; but the majority of writers, including Pherecydes, Hellanicus, and Herodorus, say that Theseus made this voyage on his own account, after the time of Heracles, and took the Amazon captive; and this is the more probable story. For it is not recorded that any one else among those who shared his expedition took an Amazon captive. 2 And Bion says that even this Amazon he took and carried off by means of a stratagem. The Amazons, he says, were naturally friendly to men, and did not fly from Theseus when he touched upon their coasts, but actually sent him presents, and he invited the one who brought them to come on board his ship; she came on board, and he put out to sea.

And a certain Menecrates, who published a history of Bithynian city of Nicaea, says that Theseus, with Antiope on board his ship, spent some time in those parts, 3 and that there chanced to be with him on this expedition three young men of Athens who were brothers, Euneos, Thoas, and Soloïs. This last, he says, fell in love with Antiope unbeknown to the rest, and revealed his secret to one of his intimate friends. That friend made overtures to Antiope, who positively repulsed the attempt upon her, but treated the matter with discretion and gentleness, and made no denunciation to Theseus. 4 Then Soloïs, in despair, threw himself into a river and drowned himself, and Theseus, when he learned the fate of the young man, and what had caused it, was grievously disturbed, and in his distress called to mind a certain oracle which he had once received at Delphi. For it had there been enjoined upon him by the Pythian priestess that when, in a strange land, he should be sorest vexed and full of sorrow, he should found a city there, and leave some of his followers to govern it. 5 For this cause he founded a city there, and called it, from the Pythian god, Pythopolis, and the adjacent river, Soloïs, in honour of the young man. And he left there the brothers of Soloïs, to be the city’s presidents and law-givers, and with them Hermus, one of the noblemen of Athens. From him also the Pythopolitans call a place in the city the House of Hermes, incorrectly changing the second syllable, and transferring the honour from a hero to a god.

27 1 Well, then, such were the grounds for the war of the Amazons, which seems to have been no trivial nor womanish enterprise for Theseus. For they would not have pitched their camp within the city, nor fought hand to hand battles in the neighbourhood of the Pnyx and the Museum, had they not mastered the surrounding country and approached the city with impunity. 2 Whether, now, as Hellanicus writes, they came round by the Cimmerian Bosporus, which they crossed on the ice, may be doubted; but the fact that they encamped almost in the heart of the city is attested both by the names of the localities there and by the graves of those who fell in battle.

Now for a long time there was hesitation and delay on both sides in making the attack, but finally Theseus, after sacrificing to Fear, in obedience to an oracle, joined battle with the women. 3 This battle, then, was fought on the day of the month Boëdromion on which, down to the present time, the Athenians celebrate the Boëdromia. Cleidemus, who wishes to be minute, writes that the left wing of the Amazons extended to what is now called the Amazoneum, and that with their right they touched the Pnyx at Chrysa; that with this left wing the Athenians fought, engaging the Amazons from the Museum, and that the graves of those who fell are on either side of the street which leads to the gate by the chapel of Chalcodon, which is now called the Peiraïc gate. 4 Here, he says, the Athenians were routed and driven back by the women as far as the shrine of the Eumenides, but those who attacked the invaders from the Palladium and Ardettus and the Lyceum, drove their right wing back as far as to their camp, and slew many of them. And after three months, he says, a treaty of peace was made through the agency of Hippolyta; for Hippolyta is the name which Cleidemus gives to the Amazon whom Theseus married, not Antiope.

But some say that the woman was slain with a javelin by Molpadia, while fighting at Theseus’s side, and that the pillar which stands by the sanctuary of Olympian Earth was set up in her memory. 5 And it is not astonishing that history, when dealing with events of such great antiquity, should wander in uncertainty, indeed, we are also told that the wounded Amazons were secretly sent away to Chalcis by Antiope, and were nursed there, and some were buried there, near what is now called the Amazoneum. But that the war ended in a solemn treaty is attested not only by the naming of the place adjoining the Theseum, which is called Horcomosium, but also by the sacrifice which, in ancient times, was offered to the Amazons before the festival of Theseus. 6 And the Megarians, too, show a place in their country where Amazons were buried, on the way from the market-place to the place called Rhus, where the Rhomboid stands. And it is said, likewise, that others of them died near Chaeroneia, and were buried on the banks of the little stream which, in ancient times, as it seems, was called Thermodon, but nowadays, Haemon; concerning which names I have written in my Life of Demosthenes. It appears also that not even Thessaly was traversed by the Amazons without opposition, for Amazonian graves are to this day shown in the vicinity of Scotussa and Cynoscephalae.

28 1 So much, then, is worthy of mention regarding the Amazons. For the “Insurrection of the Amazons,” written by the author of the Theseïd, telling how, when Theseus married Phaedra, Antiope and the Amazons who fought to avenge her attacked him, and were slain by Heracles, has every appearance of fable and invention. 2 Theseus did, indeed, marry Phaedra, but this was after the death of Antiope, and he had a son by Antiope, Hippolytus, or, as Pindar says, Demophoön. As for the calamities which befell Phaedra and the son of Theseus by Antiope, since there is no conflict here between historians and tragic poets, we must suppose that they happened as represented by the poets uniformly.

29 1 There are, however, other stories also about marriages of Theseus which were neither honourable in their beginnings nor fortunate in their endings, but these have not been dramatised. For instance, he is said to have carried off Anaxo, a maiden of Troezen, and after slaying Sinis and Cercyon to have ravished their daughters; also to have married Periboea, the mother of Aias, and Phereboea afterwards, and Iope, the daughter of Iphicles; 2 and because of his passion for Aegle, the daughter of Panopeus, as I have already said, he is accused of the desertion of Ariadne, which was not honourable nor even decent; and finally, his rape of Helen is said to have filled Attica with war, and to have brought about at last his banishment and death, of which things I shall speak a little later.

3 Of the many exploits performed in those days by the bravest men, Herodorus thinks that Theseus took part in none, except that he aided the Lapithae in their war with the Centaurs; but others say that he was not only with Jason at Colchis, but helped Meleager to slay the Calydonian boar, and that hence arose the proverb “Not without Theseus”; that he himself, however, without asking for any ally, performed many glorious exploits, and that the phrase “Lo! another Heracles” became current with reference to him. 4 He also aided Adrastus in recovering for burial the bodies of those who had fallen before the walls of the Cadmeia, not by mastering the Thebans in battle, as Euripides has it in his tragedy, but by persuading them to a truce; for so most writers say, and Philochorus adds that this was the first truce ever made for recovering the bodies of those slain in battle, 5 although in the accounts of Heracles it is written that Heracles was the first to give back their dead to his enemies. And the graves of the greater part of those who fell before Thebes are shown at Eleutherae, and those of the commanders near Eleusis, and this last burial was a favour which Theseus showed to Adrastus. The account of Euripides in his “Suppliants” is disproved by that of Aeschylus in his “Eleusinians,” where Theseus is made to relate the matter as above.

30 1 The friendship of Peirithoüs and Theseus is said to have come about in the following manner. Theseus had a very great reputation for strength and bravery, and Peirithoüs was desirous of making test and proof of it. Accordingly, he drove Theseus’s cattle away from Marathon, and when he learned that their owner was pursuing him in arms, he did not fly, but turned back and met him. 2 When, however, each beheld the other with astonishment at his beauty and admiration of his daring, they refrained from battle, and Peirithoüs, stretching out his hand the first, bade Theseus himself be judge of his robbery, for he would willingly submit to any penalty which the other might assign. Then Theseus not only remitted his penalty, but invited him to be a friend and brother in arms; whereupon they ratified their friendship with oaths.

3 After this, when Peirithoüs was about to marry Deidameia, he asked Theseus to come to the wedding, and see the country, and become acquainted with the Lapithae. Now he had invited the Centaurs also to the wedding feast. And when these were flown with insolence and wine, and laid hands upon the women, the Lapithae took vengeance upon them. Some of them they slew upon the spot, the rest they afterwards overcame in war and expelled from the country, Theseus fighting with them at the banquet and in the war. 4 Herodorus, however, says that this was not how it happened, but that the war was already in progress when Theseus came to the aid of the Lapithae; and that on his way thither he had his first sight of Heracles, having made it his business to seek him out at Trachis, where the hero was already resting from his wandering and labours; and he says the interview passed with mutual expressions of honour, friendliness, and generous praise. 5 Notwithstanding, one might better side with those historians who say that the heroes had frequent interviews with one another, and that it was at the instigation of Theseus that Heracles was initiated into the mysteries at Eleusis, and purified before his initiation, when he requested it on account of sundry rash acts.

31 1 Theseus was already fifty years old, according to Hellanicus, when he took part in the rape of Helen, who was not of marriageable age. Wherefore some writers, thinking to correct this heaviest accusation against him, say that he did not carry off Helen himself, but that when Idas and Lynceus had carried her off, he received her in charge and watched over her and would not surrender her to the Dioscuri when they demanded her; or, if you will believe it, that her own father, Tyndareüs, entrusted her to Theseus, for fear of Enarsphorus, the son of Hippocoön, who sought to take Helen by force while she was yet a child. But the most probable account, and that which has the most witnesses in its favour, is as follows.

2 Theseus and Peirithoüs went to Sparta in company, seized the girl as she was dancing in the temple of Artemis Orthia, and fled away with her. Their pursuers followed them no farther than Tegea, and so the two friends, when they had passed through Peloponnesus and were out of danger, made a compact with one another that the one on whom the lot fell should have Helen to wife, but should assist the other in getting another wife. 3 With this mutual understanding they cast lots, and Theseus won, and taking the maiden, who was not yet ripe for marriage, conveyed her to Aphidnae. Here he made his mother a companion of the girl, and committed both to Aphidnus, a friend of his, with strict orders to guard them in complete secrecy. 4 Then he himself, to return the service of Peirithoüs, journeyed with him to Epirus, in quest of the daughter of Aïdoneus the king of the Molossians. This man called his wife Phersephone, his daughter Cora, and his dog Cerberus, with which beast he ordered that all suitors of his daughter should fight, promising her to him that should overcome it. However, when he learned that Peirithoüs and his friend were come not to woo, but to steal away his daughter, he seized them both. Peirithoüs he put out of the way at once by means of the dog, but Theseus he kept in close confinement.

32 1 Meanwhile Menestheus, the son of Peteos, grandson of Orneus, and great-grandson of Erechtheus, the first of men, as they say, to affect popularity and ingratiate himself with the multitude, stirred up and embittered the chief men in Athens. These had long been hostile to Theseus, and thought that he had robbed each one of the country nobles of his royal office, and then shut them all up in a single city, where he treated them as subjects and slaves. The common people also he threw into commotion by his reproaches. They thought they had a vision of liberty, he said, but in reality they had been robbed of their native homes and religions in order that, in the place of many good kings of their own blood, they might look obediently to one master who was an immigrant and an alien. 2 While he was thus busying himself, the Tyndaridae came up against the city, and the war greatly furthered his seditious schemes; indeed, some writers say outright that he persuaded the invaders to come.

At first, then, they did no harm, but simply demanded back their sister. When, however, the people of the city replied that they neither had the girl nor knew where she had been left, they resorted to war. 3 But Academus, who had learned in some way or other of her concealment at Aphidnae, told them about it. For this reason he was honoured during his life by the Tyndaridae, and often afterwards when the Lacedaemonians invaded Attica and laid waste all the country round about, they spared the Academy, for the sake of Academus. 4 But Dicaearchus says that Echedemus and Marathus of Arcadia were in the army of the Tyndaridae at that time, from the first of whom the present Academy was named Echedemia, and from the other, the township of Marathon, since in accordance with some oracle he voluntary gave himself to be sacrificed in front of the line of battle.

To Aphidnae, then, they came, won a pitched battle, and stormed the town. 5 Here he says that among others Alycus, the son of Sciron, who was at that time in the army of the Dioscuri, was slain, and that from him a place in Megara where he was buried is called Alycus. But Hereas writes that Alycus was slain at Aphidnae by Theseus himself, and cites in proof these verses about Alycus: —

“whom once in the plain of Aphidnae,

Where he was fighting, Theseus, ravisher of fair-haired Helen,

Slew.”

However, it is not likely that Theseus himself was present when both his mother and Aphidnae were captured.

33 1 At any rate, Aphidnae was taken and the city of Athens was full of fear, but Menestheus persuaded its people to receive the Tyndaridae into the city and show them all manner of kindness, since they were waging war upon Theseus alone, who had committed the first act of violence, but were benefactors and saviours of the rest of mankind. And their behaviour confirmed his assurances, for although they were masters of everything, they demanded only an initiation into the mysteries, since they were no less closely allied to the city than Heracles. 2 This privilege was accordingly granted them, after they had been adopted by Aphidnus, as Pylius had adopted Heracles. They also obtained honours like those paid to gods, and were addressed as “Anakes,” either on account of their stopping hostilities, or because of their diligent care that no one should be injured, although there was such a large army within the city; for the phrase “anakos echein” is used of such as care for , or guard anything, and perhaps it is for this reason that kings are called “Anaktes.” There are also those who say that the Tyndaridae were called “Anakes” because of the appearance of their twin stars in the heavens, since the Athenians use “anekas” and “anekathen” for “ano” and “anothen,” signifying above or on high .

34 1 He says that Aethra, the mother of Theseus, who was taken captive at Aphidnae, was carried away to Lacedaemon, and from thence to Troy with Helen, and that Homer bears witness to this when he mentions as followers of Helen: —

“Aethra of Pittheus born, and Clymene large-eyed and lovely.”

But some reject this verse of Homer’s, as well as the legend of Munychus, who was born in secret to Laodice from Demophoön, and whom Aethra helped to rear in Ilium. 2 But a very peculiar and wholly divergent story about Aethra is given by Ister in the thirteenth book of his “Attic History.” Some write, he says, that Alexander (Paris) was overcome in battle by Achilles and Patroclus in Thessaly, along the banks of the Spercheius, but that Hector took and plundered the city of Troezen, and carried away Aethra, who had been left there. This, however, is very doubtful.

35 1 Now while Heracles was the guest of Aïdoneus the Molossian, the king incidentally spoke of the adventure of Theseus and Peirithoüs, telling what they had come there to do, and what they had suffered when they were found out. Heracles was greatly distressed by the inglorious death of the one, and by the impending death of the other. As for Peirithoüs, he thought it useless to complain, but he begged for the release of Theseus, and demanded that this favour be granted him. 2 Aïdoneus yielded to his prayers, Theseus was set free, and returned to Athens, where his friends were not yet altogether overwhelmed. All the sacred precincts which the city had previously set apart for himself, he now dedicated to Heracles, and called them Heracleia instead of Theseia, four only excepted, as Philochorus writes. But when he desired to rule again as before, and to direct the state, he became involved in factions and disturbances; he found that those who hated him when he went away, had now added to their hatred contempt, and he saw that a large part of the people were corrupted, and wished to be cajoled into service instead of doing silently what they were told to do. 3 Attempting, then, to force his wishes upon them, he was overpowered by demagogues and factions, and finally, despairing of his cause, he sent his children away privately into Euboea, to Elephenor, the son of Chalcodon, while he himself, after invoking curses upon the Athenians at Gargettus, where there is to this day the place called Araterion, sailed away to the island of Scyros, where the people were friendly to him, as he thought, and where he had ancestral estates. Now Lycomedes was at that time king of Scyros. 4 To him therefore Theseus applied with the request that his lands should be restored to him, since he was going to dwell there, though some say that he asked his aid against the Athenians. But Lycomedes, either because he feared a man of such fame, or as a favour to Menestheus, led him up to the high places of the land, on pretence of showing him from thence his lands, threw him down the cliffs, and killed him. Some, however, say that he slipped and fell down of himself while walking there after supper, as was his custom. 5 At the time no one made any account of his death, but Menestheus reigned as king at Athens, while the sons of Theseus, as men of private station, accompanied Elephenor on the expedition to Ilium; but after Menestheus died there, they came back by themselves and recovered their kingdom. In after times, however, the Athenians were moved to honour Theseus as a demigod, especially by the fact that many of those who fought at Marathon against the Medes thought they saw an apparition of Theseus in arms rushing on in front of them against the Barbarians.

36 1 And after the Median wars, in the archonship of Phaedo, when the Athenians were consulting the oracle at Delphi, they were told by the Pythian priestess to take up the bones of Theseus, give them honourable burial at Athens, and guard them there. But it was difficult to find the grave and take up the bones, because of the inhospitable and savage nature of the Dolopians, who then inhabited the island. However, Cimon took the island, as I have related in his Life, and being ambitious to discover the grave of Theseus, saw an eagle in a place where there was the semblance of a mound, pecking, as he says, and tearing up the ground with his talons. 2 By some divine ordering he comprehended the meaning of this and dug there, and there was found a coffin of a man of extraordinary size, a bronze spear lying by its side, and a sword. When these relics were brought home on his trireme by Cimon, the Athenians were delighted, and received them with splendid processions and sacrifices, as though Theseus himself were returning to his city. And now he lies buried in the heart of the city, near the present gymnasium, and his tomb is a sanctuary and place of refuge for runaway slaves and all men of low estate who are afraid of men in power, since Theseus was a champion and helper of such during his life, and graciously received the supplications of the poor and needy. 3 The chief sacrifice which the Athenians make in his honour comes on the eighth day of the month Pyanepsion, the day on which he came back from Crete with the youths. But they honour him also on the eighth day of the other months, either because he came to Athens in the first place, from Troezen, on the eighth day of the month Hecatombaeon, as Diodorus the Topographer states, or because they consider this number more appropriate for him than any other since he was said to be a son of Poseidon. 4 For they pay honours to Poseidon on the eighth day of every month. The number eight, as the first cube of an even number and the double of the first square, fitly represents the steadfast and immovable power of this god, to whom we give the epithets of Securer and Earth-stayer.

Romulus

1 1 From whom, and for what reason the great name of Rome, so famous among mankind, was given to that city, writers are not agreed. Some say that the Pelasgians, after wandering over most of the habitable earth and subduing most of mankind, settled down on that site, and that from their strength in war they called their city Rome. 2 Others say that at the taking of Troy some of its people escaped, found sailing vessels, were driven by storms upon the coast of Tuscany, and came to anchor in the river Tiber; that here, while their women were perplexed and distressed at thought of the sea, one of them, who was held to be of superior birth and the greatest understanding, and whose name was Roma, proposed that they should burn the ships; 3 that when this was done, the men were angry at first, but afterwards, when they had settled of necessity on the Palatine, seeing themselves in a little while more prosperous than they had hoped, since they found the country good and the neighbours made them welcome, they paid high honours to Roma, and actually named the city after her, since she had been the occasion of their founding it. 4 And from that time on, they say, it has been customary for the women to salute their kinsmen and husbands with a kiss; for those women, after they had burned the ships, made use of such tender salutation as they supplicated their husbands and sought to appease their wrath.

2 1 Others again say that the Roma who gave her name to the city was a daughter of Italus and Leucaria, or, in another account, of Telephus the son of Heracles; and that she was married to Aeneas, or, in another version, to Ascanius the son of Aeneas. Some tell us that it was Romanus, a son of Odysseus and Circe, who colonized the city; others that it was Romus, who was sent from Troy by Diomedes the son of Emathion; and others still that it was Romis, tyrant of the Latins, after he had driven out the Tuscans, who passed from Thessaly into Lydia, and from Lydia into Italy. Moreover, even those writers who declare, in accordance with the most authentic tradition, that it was Romulus who gave his name to the city, do not agree about his lineage. 2 For some say that he was a son of Aeneas and Dexithea the daughter of Phorbas, and was brought to Italy in his infancy, along with his brother Romus; that the rest of the vessels were destroyed in the swollen river, but the one in which the boys were was gently directed to a grassy bank, where they were unexpectedly saved, and the place was called Roma from them. 3 Others say it was Roma, a daughter of the Trojan woman I have mentioned, who was wedded to Latinus the son of Telemachus and bore him Romulus; others that Aemilia, the daughter of Aeneas and Lavinia, bore him to Mars; and others still rehearse what is altogether fabulous concerning his origin. For instance, they say that Tarchetius, king of the Albans, who was most lawless and cruel, was visited with a strange phantom in his house, namely, a phallus rising out of the hearth and remaining there many days. 4 Now there was an oracle of Tethys in Tuscany, from which there was brought to Tarchetius a response that a virgin must have intercourse with this phantom, and she should bear a son most illustrious for his valour, and of surpassing good fortune and strength. Tarchetius, accordingly, told the prophecy to one of his daughters, and bade her consort with the phantom; but she disdained to do so, and sent a handmaid in to it. 5 When Tarchetius learned of this, he was wroth, and seized both the maidens, purposing to put them to death. But the goddess Hestia appeared to him in his sleep and forbade him the murder. He therefore imposed upon the maidens the weaving of a certain web in their imprisonment, assuring them that when they had finished the weaving of it, they should then be given in marriage. By day, then, these maidens wove, but by night other maidens, at the command of Tarchetius, unravelled their web. And when the handmaid became the mother of twin children by the phantom, Tarchetius gave them to a certain Teratius with orders to destroy them. 6 This man, however, carried them to the river-side and laid them down there. Then a she-wolf visited the babes and gave them suck, while all sorts of birds brought morsels of food and put them into their mouths, until a cow-herd spied them, conquered his amazement, ventured to come to them, and took the children home with him. Thus they were saved, and when they were grown up, they set upon Tarchetius and overcame him. At any rate, this is what a certain Promathion says, who compiled a history of Italy.

3 1 But the story which has the widest credence and the greatest number of vouchers was first published among the Greeks, in its principal details, by Diocles of Peparethus, and Fabius Pictor follows him in most points. Here again there are variations in the story, but its general outline is as follows. 2 The descendants of Aeneas reigned as kings in Alba, and the succession devolved at length upon two brothers, Numitor and Amulius. Amulius divided the whole inheritance into two parts, setting the treasures and gold which had been brought from Troy over against the kingdom, and Numitor chose the kingdom. Amulius, then, in possession of the treasure, and made more powerful by it than Numitor, easily took the kingdom away from his brother, and fearing lest that brother’s daughter should have children, made her a priestess of Vesta, bound to live unwedded and a virgin all her days. 3 Her name is variously given as Ilia, or Rhea, or Silvia. Not long after this, she was discovered to be with child, contrary to the established law for the Vestals. She did not, however, suffer the capital punishment which was her due, because the king’s daughter, Antho, interceded successfully in her behalf, but she was kept in solitary confinement, that she might not be delivered without the knowledge of Amulius. Delivered she was of two boys, and their size and beauty were more than human. 4 Wherefore Amulius was all the more afraid, and ordered a servant to take the boys and cast them away. This servant’s name was Faustulus, according to some, but others give this name to the man who took the boys up. Obeying the king’s orders, the servant put the babes into a trough and went down towards the river, purposing to cast them in; but when he saw that the stream was much swollen and violent, he was afraid to go close up to it, and setting his burden now near the bank, went his way. 5 Then the overflow of the swollen river took and bore up the trough, floating it gently along, and carried it down to a fairly smooth spot which is now called Kermalus, but formerly Germanus, perhaps because brothers are called “germani.”

4 1 Now there was a wild fig-tree hard by, which they called Ruminalis, either from Romulus, as is generally thought, or because cud-chewing, or ruminating , animals spent the noon-tide there for the sake of the shade, or best of all, from the suckling of the babes there; for the ancient Romans called the teat “ruma,” and a certain goddess, who is thought to preside over the rearing of young children, is still called Rumilia, in sacrificing to whom no wine is used, and libations of milk are poured over her victims. 2 Here, then, the babes lay, and the she-wolf of story here gave them suck, and a woodpecker came to help in feeding them and to watch over them. Now these creatures are considered sacred to Mars, and the woodpecker is held in especial veneration and honour by the Latins, and this was the chief reason why the mother was believed when she declared that Mars was the father of her babes. And yet it is said that she was deceived into doing this, and was really deflowered by Amulius himself, who came to her in armour and ravished her.

3 But some say that the name of the children’s nurse, by its ambiguity, deflected the story into the fabulous. For the Latins not only called she-wolves “lupae,” but also women of loose character, and such a woman was the wife of Faustulus, the foster-father of the infants, Acca Larentia by name. Yet the Romans sacrifice also to her, and in the month of April the priest of Mars pours libations in her honour, and the festival is called Larentalia.

5 1 They pay honours also to another Larentia, for the following reason. The keeper of the temple of Hercules, being at a loss for something to do, as it seems, proposed to the god a game of dice, with the understanding that if he won it himself, he should get some valuable present from the god; but if he lost, he would furnish the god with a bounteous repast and a lovely woman to keep him company for the night. 2 On these terms the dice were thrown, first for the god, then for himself, when it appeared that he had lost. Wishing to keep faith, and thinking it right to abide by the contract, he prepared a banquet for the god, and engaging Larentia, who was then in the bloom of her beauty, but not yet famous, he feasted her in the temple, where he had spread a couch, and after the supper locked her in, assured of course that the god would take possession of her. 3 And verily it is said that the god did visit the woman, and bade her go early in the morning to the forum, salute the first man who met her, and make him her friend. She was met, accordingly, by one of the citizens who was well on in years and possessed of a considerable property, but childless, and unmarried all his life, by name Tarrutius. 4 This man took Larentia to his bed and loved her well, and at his death left her heir to many and fair possessions, most of which she bequeathed to the people. And it is said that when she was now famous and regarded as the beloved of a god, she disappeared at the spot where the former Larentia also lies buried. 5 This spot is now called Velabrum, because when the river overflowed, as it often did, they used to cross it at about this point in ferry-boats , to go to the forum, and their word for ferry is “velatura.” But some say that it is so called because from that point on, the street leading to the Hippodrome from the forum is covered over with sails by the givers of a public spectacle, and the Roman word for sail is “velum.” It is for these reasons that honours are paid to this second Larentia amongst the Romans.

6 1 As for the babes, they were taken up and reared by Faustulus, a swineherd of Amulius, and no man knew of it; or, as some say with a closer approach to probability, Numitor did know of it, and secretly aided the foster-parents in their task. And it is said that the boys were taken to Gabii to learn letters and the other branches of knowledge which are meet for those of noble birth. 2 Moreover, we are told that they were named, from “ruma,” the Latin word for teat , Romulus and Romus (or Remus), because they were seen sucking the wild beast. Well, the noble size and beauty of their bodies, even when they were infants, betokened their natural disposition; and when they grew up, they were both of them courageous and manly, with spirits which courted apparent danger, and a daring which nothing could terrify. But Romulus seemed to exercise his judgement more, and to have political sagacity, while in his intercourse with their neighbours in matters pertaining to herding and hunting, he gave them the impression that he was born to command rather than to obey. 3 With their equals or inferiors they were therefore on friendly terms, but they looked down upon the overseers, bailiffs, and chief herdsmen of the king, and disregarded both their threats and their anger. They also applied themselves to generous occasions and pursuits, not esteeming sloth and idleness generous, but rather bodily exercise, hunting, running, driving off robbers, capturing thieves, and rescuing the oppressed from violence. For these things, indeed, they were famous far and near.

7 1 When a quarrel arose between the herdsmen of Numitor and Amulius, and some of the latter’s cattle were driven off, the brothers would not suffer it, but fell upon the robbers, put them to flight, and intercepted most of the booty. To the displeasure of Numitor they gave little heed, but collected and took into their company many needy men and many slaves, exhibiting thus the beginnings of seditious boldness and temper. 2 But once when Romulus was busily engaged in some sacrifice, being fond of sacrifices and of divination, the herdsmen of Numitor fell in with Remus as he was walking with a few companions, and a battle ensued. After blows and wounds given and received on both sides, the herdsmen of Numitor prevailed and took Remus prisoner, who was then carried before Numitor and denounced. Numitor himself did not punish his prisoner, because he was in fear of his brother Amulius, who was severe, but went to Amulius and asked for justice, since he was his brother, and had been insulted by the royal servants. 3 The people of Alba, too, were incensed, and thought that Numitor had been undeservedly outraged. Amulius was therefore induced to hand Remus over to Numitor himself, to treat him as he saw fit.