автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу A Treatise on Anatomy, Physiology, and Hygiene (Revised Edition)

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Treatise on Anatomy, Physiology, and

Hygiene (Revised Edition), by Calvin Cutter

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: A Treatise on Anatomy, Physiology, and Hygiene (Revised Edition)

Author: Calvin Cutter

Release Date: November 24, 2009 [EBook #30541]

Language: English

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TREATISE ON ANATOMY (REVISED) ***

Produced by Bryan Ness, Dan Horwood and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

A

TREATISE

ON

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY,

AND HYGIENE

DESIGNED

FORCOLLEGES, ACADEMIES, AND FAMILIES.

BY CALVIN CUTTER, M.D.

WITH ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY ENGRAVINGS.

REVISED STEREOTYPE EDITION.

NEW YORK:

CLARK, AUSTIN AND SMITH.

CINCINNATI:—W. B. SMITH & CO.

ST. LOUIS, MO.:—KEITH & WOODS.

1858.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1852, by

CALVIN CUTTER, M. D.,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of

Massachusetts

.C. A. ALVORD,

Printer,

No. 15 Vandewater Street, N.

Y.

PREFACE.

Agesilaus, king of Sparta, when asked what things boys should learn, replied, “Those which they will practise when they become men.” As health requires the observance of the laws inherent to the different organs of the human system, so not only boys, but girls, should acquire a knowledge of the laws of their organization. If sound morality depends upon the inculcation of correct principles in youth, equally so does a sound physical system depend on a correct physical education during the same period of life. If the teacher and parents who are deficient in moral feelings and sentiments, are unfit to communicate to children and youth those high moral principles demanded by the nature of man, so are they equally incompetent directors of the physical training of the youthful system, if ignorant of the organic laws and the physiological conditions upon which health and disease depend.

For these reasons, the study of the structure of the human system, and the laws of the different organs, are subjects of interest to all,—the young and the old, the learned and the unlearned, the rich and the poor. Every scholar, and particularly every young miss, after acquiring a knowledge of the primary branches,—as spelling, reading, writing, and arithmetic,—should learn the structure of the human system, and the conditions upon which health and disease depend, as this knowledge will be required in practice in after life.

“It is somewhat unaccountable,” says Dr. Dick, “and not a little inconsistent, that while we direct the young to look abroad over the surface of the earth, and survey its mountains, rivers, seas, and continents, and guide their views to the regions of the firmament, where they may contemplate the moons of Jupiter, the rings of Saturn, and thousands of luminaries placed at immeasurable distances, ... that we should never teach them to look into themselves; to consider their own corporeal structures, the numerous parts of which they are composed, the admirable functions they perform, the wisdom and goodness displayed in their mechanism, and the lessons of practical instruction which may be derived from such contemplations.”

Again he says, “One great practical end which should always be kept in view in the study of physiology, is the invigoration and improvement of the corporeal powers and functions, the preservation of health, and the prevention of disease.”

The design of the following pages is, to diffuse in the community, especially among the youth, a knowledge of Human Anatomy, Physiology, and Hygiene. To make the work clear and practical, the following method has been adopted:—

1st. The structure of the different organs of the system has been described in a clear and concise manner. To render this description more intelligible, one hundred and fifty engravings have been introduced, to show the situation of the various organs. Hence the work may be regarded as an elementary treatise on anatomy.

2d. The functions, or uses of the several parts have been briefly and plainly detailed; making a primary treatise on human physiology.

3d. To make a knowledge of the structure and functions of the different organs practical, the laws of the several parts, and the conditions on which health depends, have been clearly and succinctly explained. Hence it may be called a treatise on the principles of hygiene, or health.

To render this department more complete, there has been added the appropriate treatment for burns, wounds, hemorrhage from divided arteries, the management of persons asphyxiated from drowning, carbonic acid, or strangling, directions for nurses, watchers, and the removal of disease, together with an Appendix, containing antidotes for poisons, so that persons may know what should be done, and what should not be done, until a surgeon or physician can be called.

In attempting to effect this in a brief elementary treatise designed for schools and families, it has not been deemed necessary to use vulgar phrases for the purpose of being understood. The appropriate scientific term should be applied to each organ. No more effort is required to learn the meaning of a proper, than an improper term. For example: a child will pronounce the word as readily, and obtain as correct an idea, if you say lungs, as if you used the word lights. A little effort on the part of teachers and parents, would diminish the number of vulgar terms and phrases, and, consequently, improve the language of our country. To obviate all objections to the use of proper scientific terms, a Glossary has been appended to the work.

The author makes no pretensions to new discoveries in physiological science. In preparing the anatomical department, the able treatises of Wilson, Cruveilhier, and others have been freely consulted. In the physiological part, the splendid works of Carpenter, Dunglison, Liebig, and others have been perused. In the department of hygiene many valuable hints have been obtained from the meritorious works of Combe, Rivers, and others.

We are under obligations to R. D. Mussey, M. D., formerly Professor of Anatomy and Surgery, Dartmouth College, N. H., now Professor of Surgery in the Ohio Medical College; to J. E. M’Girr, A. M., M. D., Professor of Anatomy, Physiology, and Chemistry, St. Mary’s University, Ill.; to E. Hitchcock, Jr., A. M., M. D., Teacher of Chemistry and Natural History, Williston Seminary, Mass.; to Rev. E. Hitchcock, D. D., President of Amherst College, Mass., who examined the revised edition of this work, and whose valuable suggestions rendered important aid in preparing the manuscript for the present stereotype edition.

We return our acknowledgments for the aid afforded by the Principals of the several Academies and Normal Schools who formed classes in their institutions, and examined the revised edition as their pupils progressed, thus giving the work the best possible test trial, namely, the recitation-room.

To the examination of an intelligent public, the work is respectfully submitted by

CALVIN CUTTER.

Warren, Mass., Sept. 1, 1852.

TO TEACHERS AND PARENTS.

As the work is divided into chapters, the subjects of which are complete in themselves, the pupil may commence the study of the structure, use, and laws of the several parts of which the human system is composed, by selecting such chapters as fancy or utility may dictate, without reference to their present arrangement,—as well commence with the chapter on the digestive organs as on the bones.

The acquisition of a correct pronunciation of the technical words is of great importance, both in recitation and in conversation. In this work, the technical words interspersed with the text, have been divided into syllables, and the accented syllables designated. An ample Glossary of technical terms has also been appended to the work, to which reference should be made.

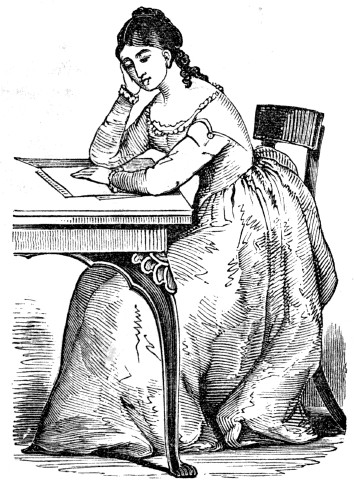

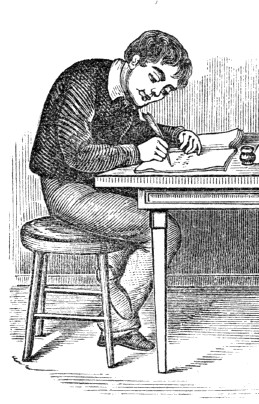

It is recommended that the subject be examined in the form of topics. The questions in Italics are designed for this method of recitation. The teacher may call on a pupil of the class to describe the anatomy of an organ from an anatomical outline plate; afterwards call upon another to give the physiology of the part, while a third may state the hygiene, after which, the questions at the bottom of the page may be asked promiscuously, and thus the detailed knowledge of the subject possessed by the pupils will be tested.

At the close of the chapters upon the Hygiene of the several portions of the system, it is advised that the instructor give a lecture reviewing the anatomy, physiology, and hygiene, of the topic last considered. This may be followed by a general examination of the class upon the same subject. By this course a clear and definite knowledge of the mutual relation of the Anatomy, Physiology, and Hygiene, of different parts of the human body, will be presented.

We also suggest the utility of the pupils’ giving analogous illustrations, examples, and observations, where these are interspersed in the different chapters, not only to induce inventive thought, but to discipline the mind.

To parents and others we beg leave to say, that about two thirds of the present work is devoted to a concise and practical description of the uses of the important organs of the human body, and to show how such information may be usefully applied, both in the preservation of health, and the improvement of physical education. To this have been added directions for the treatment of those accidents which are daily occurring in the community, making it a treatise proper and profitable for the FAMILY LIBRARY, as well as the school-room.

CONTENTS.

Chapter.

Page.

1.

General Remarks,

132.

Structure of Man,

173.

Chemistry of the Human Body,

254.

Anatomy of the Bones,

295.

Anatomy of the Bones, continued,

396.

Physiology of the Bones,

487.

Hygiene of the Bones,

538.

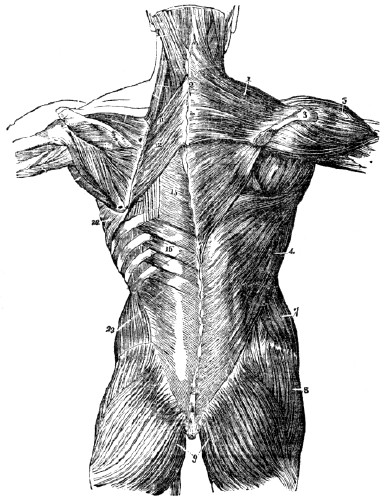

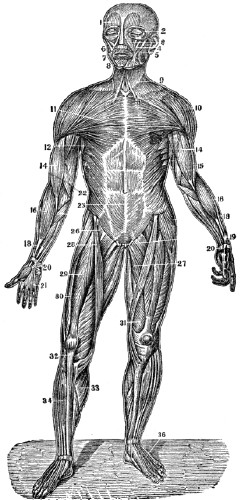

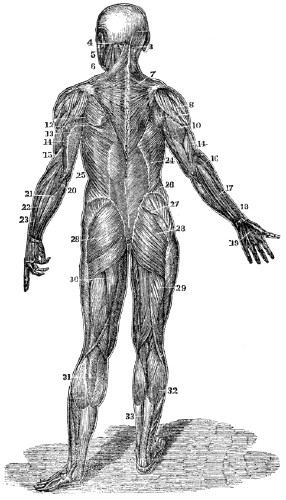

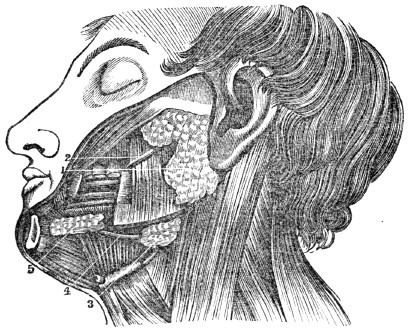

Anatomy of the Muscles,

649.

Physiology of the muscles,

7610.

Hygiene of the Muscles,

8511.

Hygiene of the Muscles, continued,

9612.

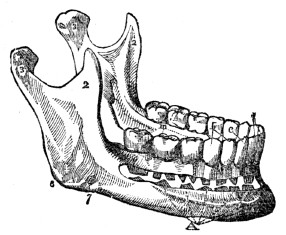

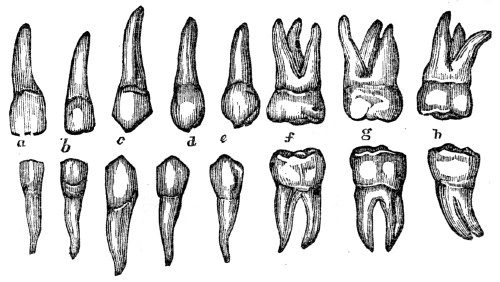

Anatomy of the Teeth,

10512.

Physiology of the Teeth,

10912.

Hygiene of the Teeth,

11013.

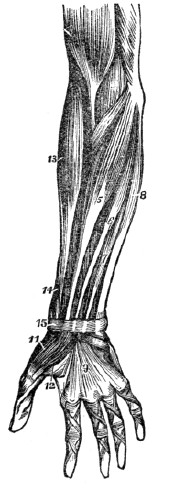

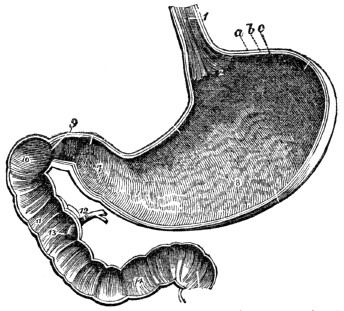

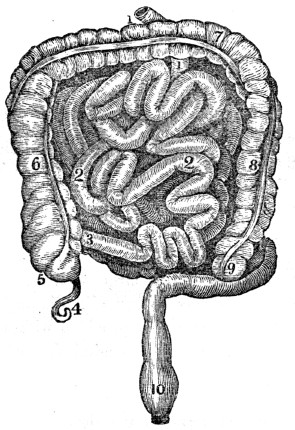

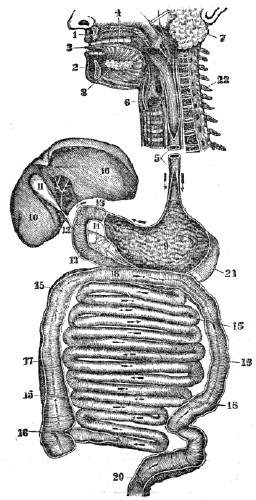

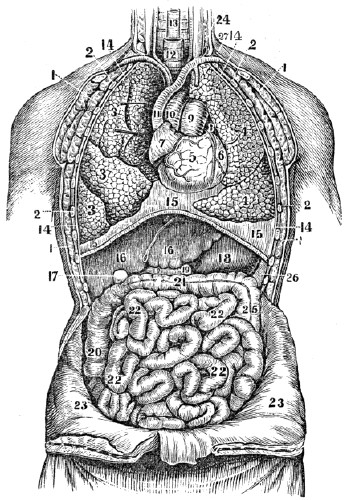

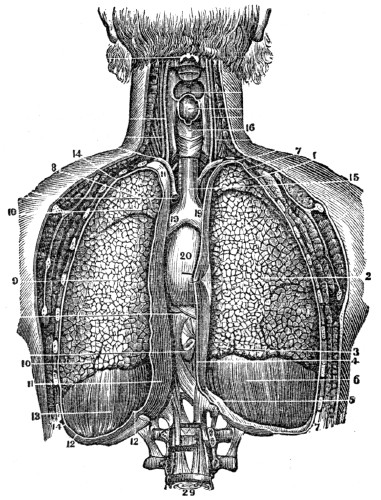

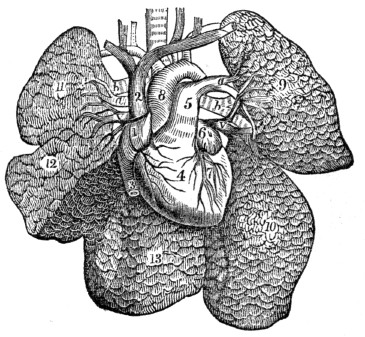

Anatomy of the Digestive Organs,

11314.

Physiology of the Digestive Organs,

12415.

Hygiene of the Digestive Organs,

12916.

Hygiene of the Digestive Organs, continued,

14217.

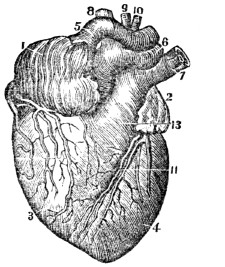

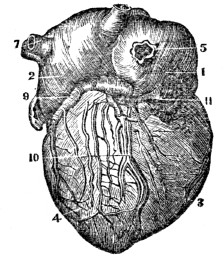

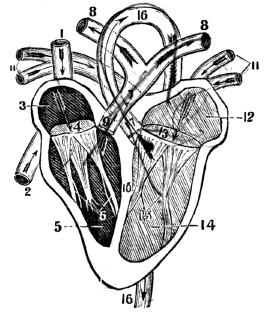

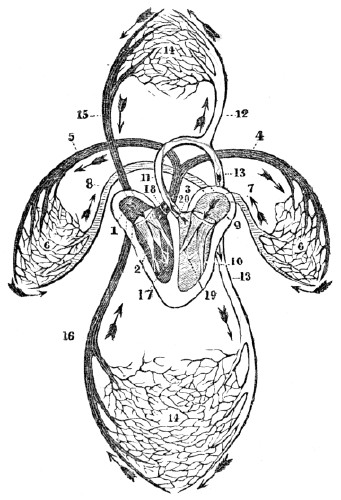

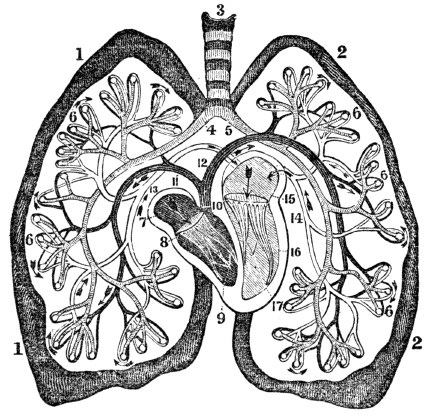

Anatomy of the Circulatory Organs,

15418.

Physiology of the Circulatory Organs,

16419.

Hygiene of the Circulatory Organs,

17220.

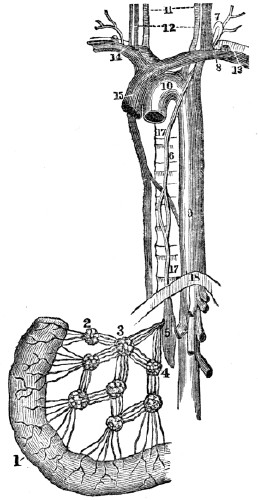

Anatomy of the Lymphatic Vessels,

18120.

Physiology of the Lymphatic Vessels,

18320.

Hygiene of the Lymphatic Vessels,

18821.

Anatomy of the Secretory Organs.

19221.

Physiology of the Secretory Organs,

19321.

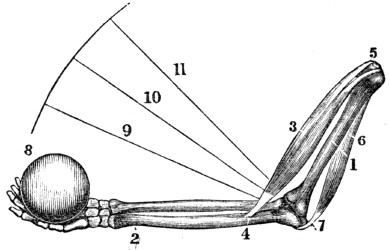

Hygiene of the Secretory Organs,

19722.

Nutrition,

20022.

Hygiene of Nutrition,

20523.

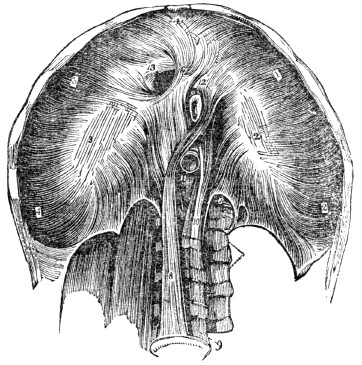

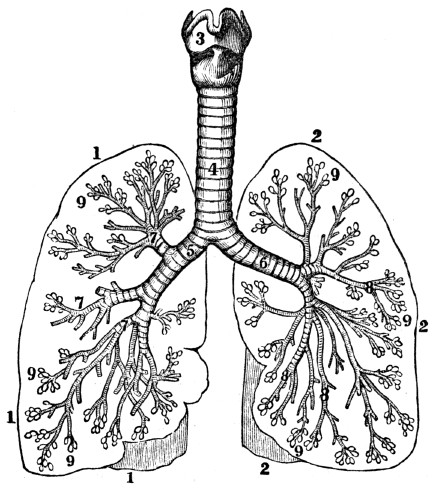

Anatomy of the Respiratory Organs,

20924.

Physiology of the Respiratory Organs,

21725.

Hygiene of the Respiratory Organs,

22826.

Hygiene of the Respiratory Organs, continued,

23927.

Animal Heat,

25228.

Hygiene of Animal Heat,

26129.

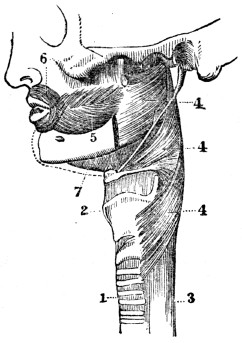

Anatomy of the Vocal Organs,

26829.

Physiology of the Vocal Organs,

27230.

Hygiene of the Vocal Organs,

27431.

Anatomy of the Skin,

28232.

Physiology of the Skin,

29333.

Hygiene of the Skin,

30134.

Hygiene of the Skin, continued,

31135.

Appendages of the Skin,

32236.

Anatomy of the Nervous System,

32737.

Anatomy of the Nervous System, continued,

34038.

Physiology of the Nervous System,

34639.

Hygiene of the Nervous System,

35840.

Hygiene of the Nervous System, continued,

36841.

The Sense of Touch,

37842.

Anatomy of the Organs of Taste,

38442.

Physiology of the Organs of Taste,

38643.

Anatomy of the Organs of Smell,

38943.

Physiology of the Organs of Smell,

39144.

Anatomy of the Organs of Vision,

39445.

Physiology of the Organs of Vision,

40445.

Hygiene of the Organs of Vision,

41046.

Anatomy of the Organs of Hearing,

41447.

Physiology of the Organs of Hearing,

42047.

Hygiene of the Organs of Hearing,

42248.

Means of preserving the Health,

42549.

Directions for Nurses,

432APPENDIX,

439GLOSSARY,

451INDEX,

463ANATOMY, &c.

CHAPTER I.

GENERAL REMARKS.

1. Anatomy is the science which treats of the structure and relations of the different parts of animals and plants.

2. It is divided into Vegetable and Animal anatomy. The latter of these divisions is subdivided into Human anatomy, which considers, exclusively, human beings; and Comparative anatomy, which treats of the mechanism of the lower orders of animals.

3. Physiology treats of the functions, or uses of the organs of animals and plants. Another definition is, “the science of life.”

4. This is also divided into Vegetable and Animal physiology, as it treats of the vegetable or animal kingdom; and into Human and Comparative physiology, as it describes the vital functions of man or the inferior animals.

5. Hygiene is the art or science of maintaining health, or a knowledge of those laws by which health may be preserved.

6. The kingdom of nature is divided into organic and inorganic bodies. Organic bodies possess organs, on whose action depend their growth and perfection. This division includes animals and plants. Inorganic bodies are devoid of organs, or instruments of life. In this division are classed the earths, metals, and other minerals.

1. What is anatomy? 2. How is it divided? How is the latter division subdivided? 3. What is physiology? Give another definition. 4. How is physiology divided? Give a subdivision. 5. What is hygiene? 6. Define organic bodies.

7. In general, organic matter differs so materially from inorganic, that the one can readily be distinguished from the other. In the organic world, every individual of necessity springs from some parent, or immediate producing agent; for while inorganic substances are formed by chemical laws alone, we see no case of an animal or plant coming into existence by accident or chance, or chemical operations.

8. Animals and plants are supported by means of nourishment, and die without it. They also increase in size by the addition of new particles of matter to all parts of their substances; while rocks and minerals grow only by additions to their surfaces.

9. “Organized bodies always present a combination of both solids and fluids;—of solids, differing in character and properties, arranged into organs, and these endowed with functional powers, and so associated as to form of the whole a single system;—and of fluids, contained in these organs, and holding such relation to the solids that the existence, nature, and properties of both mutually and necessarily depend on each other.”

10. Another characteristic is, that organic substances have a certain order of parts. For example, plants possess organs to gain nourishment from the soil and atmosphere, and the power to give strength and increase to all their parts. And animals need not only a digesting and circulating apparatus, but organs for breathing, a nervous system, &c.

6. Define inorganic bodies. 7. What is said of the difference, in general, between organic and inorganic bodies? 8. What of the growth of organic and inorganic bodies? 9. What do organized bodies always present? 10. Give another characteristic of organized substances.

11. Individuality is an important characteristic. For instance, a large rock may be broken into a number of smaller pieces, and yet every fragment will be rock; but if an organic substance be separated into two or more divisions, neither of them can be considered an individual. Closely associated with this is the power of life, or vitality, which is the most distinguishing characteristic of organic structure; since we find nothing similar to this in the inorganic creation.

12. The distinction between plants and animals is also of much importance. Animals grow proportionally in all directions, while plants grow upwards and downwards from a collet only. The food of animals is organic, while that of plants is inorganic; the latter feeding entirely upon the elements of the soil and atmosphere, while the former subsist upon the products of the animal and vegetable kingdoms. The size of the vegetable is in most cases limited only by the duration of existence, as a tree continues to put forth new branches during each period of its life, while the animal, at a certain time of life, attains the average size of its species.

13. One of the most important distinctions between animals and plants, is the different effects of respiration. Animals consume the oxygen of the atmosphere, and give off carbonic acid; while plants take up the carbonic acid, and restore to animals the oxygen, thus affording an admirable example of the principle of compensation in nature.

14. But the decisive distinctions between animals and plants are sensation and voluntary motion, the power of acquiring a knowledge of external objects through the senses, and the ability to move from place to place at will. These are the characteristics which, in their fullest development in man, show intellect and reasoning powers, and thereby in a greater degree exhibit to us the wisdom and goodness of the Creator.

11. What is said of the individuality of organized and inorganized bodies? What is closely associated with this? 12. Give a distinction between animals and plants as regards growth. The food of animals and plants. What is said in respect to size? 13. What important distinction in the effects of respiration of animals and plants? 14. What are the decisive distinctions between animals and plants?

15. Disease, which consists in an unnatural condition of the bodily organs, is in most cases under the control of fixed laws, which we are capable of understanding and obeying. Nor do diseases come by chance; they are penalties for violating physical laws. If we carelessly cut or bruise our flesh, pain and soreness follow, to induce us to be more careful in the future; or, if we take improper food into the stomach, we are warned, perhaps immediately by a friendly pain, that we have violated an organic law.

16. Sometimes, however, the penalty does not directly follow the sin, and it requires great physiological knowledge to be able to trace the effect to its true cause. If we possess good constitutions, we are responsible for most of our sickness; and bad constitutions, or hereditary diseases, are but the results of the same great law,—the iniquities of the parents being visited on the children. In this view of the subject, how important is the study of physiology and hygiene! For how can we expect to obey laws which we do not understand?

15. What is said of disease? 16. Why is the study of physiology and hygiene important?

CHAPTER II.

STRUCTURE OF MAN,

17. In the structure of the human body, there is a union of fluids and solids. These are essentially the same, for the one is readily changed into the other. There is no fluid that does not contain solid matter in solution, and no solid matter that is destitute of fluid.

18. In different individuals, and at different periods of life the proportion of fluids and solids varies. In youth, the fluids are more abundant than in advanced life. For this reason, the limbs in childhood are soft and round, while in old age they assume a hard and wrinkled appearance.

19. The fluids not only contain the materials from which every part of the body is formed, but they are the medium for conveying the waste, decayed particles of matter from the system. They have various names, according to their nature and function; as, the blood, and the bile.

20. The solids are formed from the fluids, and consequently they are reduced, by chemical analysis, to the same ultimate elements. The particles of matter in solids are arranged variously; sometimes in fi´bres, (threads,) sometimes in lam´i-næ, (plates,) sometimes homogeneously, as in basement membranes. (Appendix A.)

21. The parts of the body are arranged into Fi´bres, Fas-cic´u-li, Tis´sues, Or´gans, Ap-pa-ra´tus-es, and Sys´tems.

17. What substances enter into the structure of the human body? Are they essentially the same? 18. What is said of these substances at different periods of life? 19. What offices do the fluids of the system perform? 20. What is said of the solids? How are the particles of matter arranged in solids? 21. Give an arrangement of the parts of the body.

22. A FIBRE is a thread of exceeding fineness. It is either cylindriform or flattened.

23. A FASCICULUS is the term applied to several fibres united. Its general characteristics are the same as fibres.

24. A TISSUE is a term applied to several different solids of the body.

25. An ORGAN is composed of tissues so arranged as to form an instrument designed for action. The action of an organ is called its function, or use.

Example. The liver is an organ, and the secretion of the bile from the blood is one of its functions.[1]

26. An APPARATUS is an assemblage of organs designed to produce certain results.

Example. The digestive apparatus consists of the

teeth,

stomach, liver, &c., all of which aid in the digestion of food.Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Represents a portion of broken muscular fibre of animal life, (magnified about seven hundred diameters.)

27. The term SYSTEM is applied to an assemblage of organs arranged according to some plan, or method; as the nervous system, the respiratory system.

22. Define a fibre. 23. Define a fasciculus. 24. Define a tissue. 25. Define an organ. What is the action of an organ called? Give examples. Mention other examples. 26. What is an apparatus? Give an example 27. How is the term system applied?

28. A TISSUE is a simple form of organized animal substance. It is flexible, and formed of fibres interwoven in various ways; as, the cellular tissue.

29. However various all organs may appear in their structure and composition, it is now supposed that they can be reduced to a few tissues; as, the Cel´lu-lar, Os´se-ous, Mus´cu-lar, Mu´cous, Ner´vous, &c. (Appendix B.)

30. The CELLULAR TISSUE,[2] now called the areolar tissue, consists of small fibres, or bands, interlaced in every direction, so as to form a net-work, with numerous interstices that communicate freely with each other. These interstices are filled, during life, with a fluid resembling the serum of blood. The use of the areolar tissue is to connect together organs and parts of organs, and to envelop, fix, and protect the vessels and nerves of organs.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Arrangement of fibres of the cellular tissue magnified one hundred and thirty diameters.

28. What is a tissue? 29. What is said respecting the structure and composition of the various organs? Name the primary membranes. 30. Describe the cellular tissue. How are the cells imbedded in certain tissues? Give observation 1st, relative to the cellular tissue.

Observations. 1st. When this fluid becomes too great in quantity, in consequence of disease, the patient labors under general dropsy. The swelling of the feet when standing, and their return to a proper shape during the night, so often noticed in feeble persons, furnish a striking proof both of the existence and peculiarity of this tissue, which allows the fluid to flow from cell to cell, until it settles in the lower extremities.

2d. The free communication between the cells is still more remarkable in regard to air. Sometimes, when an accidental opening has been made from the air-cells of the lungs into the contiguous cellular tissue, the air in respiration has penetrated every part until the whole body is so inflated as to occasion suffocation. Butchers often avail themselves of the knowledge of this fact, and inflate their meat to give it a fat appearance.

31. “Although this tissue enters into the composition of all organs, it never loses its own structure, nor participates in the functions of the organ of which it forms a part. Though present in the nerves, it does not share in their sensibility; and though it accompanies every muscle and every muscular fibre, it does not partake of the irritability which belongs to these organs.”

32. Several varieties of tissue are formed from the cellular; as, the Se´rous, Der´moid, Fi´brous, and several others.

33. The SEROUS TISSUE lines all the closed, or sac-like cavities of the body; as, the chest, joints, and abdomen. It not only lines these cavities, but is reflected, and invests the organs contained in them. The liver and the lungs are thus invested. This membrane is of a whitish color, and smooth on its free surfaces. These surfaces are kept moist, and prevented from adhering by a se´rous fluid, which is separated from the blood. The use of this membrane is to separate organs and also to facilitate the movement of one part upon another, by means of its moist, polished surfaces.

Give observation 2d. 31. What is said of the identity of this tissue? 32. Name the varieties of tissue formed from the cellular. 33. Where is the serous tissue found? What two offices does it perform? Give its structure. What is the use of this membrane?

34. The DERMOID TISSUE covers the outside of the body. It is called the cu´tis, (skin.) This membrane is continuous with the mucous at the various orifices of the body, and in these situations, from the similarity of their structure, it is difficult to distinguish between them.

Observations. 1st. In consequence of the continuity and similarity of structure, there is close sympathy between the mucous and dermoid membranes. If the functions of the skin are disturbed, as by a chill, it will frequently cause a catarrh, (cold,) or diarrhœa. Again, in consequence of this intimate sympathy, these complaints can be relieved by exciting a free action in the vessels of the skin.

2d. It is no uncommon occurrence that diseased or irritated conditions of the mucous membrane of the stomach or intestines produce diseases or irritations of the skin, as is seen in the rashes attendant on dyspepsia, and eating certain species of fish. These eruptions of the skin can be relieved by removing the diseased condition of the stomach.

35. The FIBROUS TISSUE consists of longitudinal, parallel fibres, which are closely united. These fibres, in some situations, form a thin, dense, strong membrane, like that which lines the internal surface of the skull, or invests the external surface of the bones. In other instances, they form strong, inelastic bands, called lig´a-ments, which bind one bone to another. This tissue also forms ten´dons, (white cords,) by which the muscles are attached to the bones.

Observation. In the disease called rheumatism, the fibrous tissue is the part principally affected; hence the joints, where this tissue is most abundant, suffer most from this affection.

34. Describe the dermoid tissue. What is said of the sympathy between the functions of the skin and mucous membrane? Give another instance of the sympathy between these membranes. 35. Of what does the fibrous tissue consist? How do these appear in some situations? How in others? What tissue is generally affected in rheumatism?

36. The ADIPOSE TISSUE is so arranged as to form distinct bags, or cells. These contain a substance called fat. This tissue is principally found beneath the skin, abdominal muscles, and around the heart and kidneys; while none is found in the brain, eye, ear, nose, and several other organs.

Observation. In those individuals who are corpulent, there is in many instances, a great deposit of this substance. This tissue accumulates more readily than others when a person becomes gross, and is earliest removed when the system emaciates, in acute or chronic diseases. Some of the masses become, in some instances, enlarged. These enlargements are called adipose, or fatty tumors.

CHAPTER XXXVI.

THE NERVOUS SYSTEM.

CHAPTER XII.

THE TEETH.

CHAPTER XI.

HYGIENE OF THE MUSCLES, CONTINUED.

CHAPTER XVIII.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE CIRCULATORY ORGANS.

CHAPTER XXXIX.

HYGIENE OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM.

APPENDIX.

CHAPTER XX.

ABSORPTION.

CHAPTER XXII.

NUTRITION.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE SECRETORY ORGANS.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE LYMPHATIC VESSELS.

CHAPTER XXIII.

THE RESPIRATORY ORGANS.

HYGIENE OF THE LYMPHATIC VESSELS.

CHAPTER XLVI.

THE SENSE OF HEARING.

[1]

Where examples and observations are given or experiments suggested, let the pupil mention other analogous ones.

CHAPTER XXV.

HYGIENE OF THE RESPIRATORY ORGANS.

[2]

The Cellular, Serous, Dermoid, Fibrous, and Mucous tissues are very generally called membranes.

CHAPTER XXVIII.

HYGIENE OF ANIMAL HEAT.

CHAPTER II.

STRUCTURE OF MAN,

CHAPTER VIII

THE MUSCLES.

CHAPTER XLV.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE ORGANS OF VISION.

CHAPTER VI.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE BONES.

HYGIENE OF THE ORGANS OF HEARING.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE ORGANS OF SMELL.

CHAPTER XIX.

HYGIENE OF THE CIRCULATORY ORGANS

CHAPTER XLIV.

SENSE OF VISION.

CHAPTER VXII.

THE CIRCULATORY ORGANS.

CHAPTER XLII.

SENSE OF TASTE.

CHAPTER XXXVII.

ANATOMY OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM, CONTINUED.

CHAPTER XLIX.

DIRECTIONS FOR NURSES.

CHAPTER XV.

HYGIENE OF THE DIGESTIVE ORGANS.

CHAPTER XXI.

SECRETION.

CHAPTER V.

ANATOMY OF THE BONES, CONTINUED

CHAPTER XLIII.

SENSE OF SMELL.

CHAPTER X.

HYGIENE OF THE MUSCLES

CHAPTER XXXII.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE SKIN.

CHAPTER VII

HYGIENE OF THE BONES.

CHAPTER XXIV.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE RESPIRATORY ORGANS.

CHAPTER XLI.

THE SENSE OF TOUCH.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE VOCAL ORGANS.

CHAPTER XXVII.

ANIMAL HEAT.

HYGIENE OF THE SECRETORY ORGANS.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE ORGANS OF TASTE.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE TEETH.

CHAPTER IV.

THE BONES.

CHAPTER XXVI.

HYGIENE OF THE RESPIRATORY ORGANS, CONTINUED.

CHAPTER XLVIII

MEANS OF PRESERVING THE HEALTH.[23]

CHAPTER XXXI.

THE SKIN.

CHAPTER XIII.

THE DIGESTIVE ORGANS.

CHAPTER I.

GENERAL REMARKS.

CHAPTER XXIX.

THE VOICE.

HYGIENE OF THE TEETH.

CHAPTER III

CHEMISTRY OF THE HUMAN BODY.

GLOSSARY

CHAPTER XVI.

HYGIENE OF THE DIGESTIVE ORGANS, CONTINUED.

CHAPTER IX.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE MUSCLES.

CHAPTER XIV.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE DIGESTIVE ORGANS.

CHAPTER XL.

HYGIENE OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM, CONTINUED.

CHAPTER XXXVIII.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM.

HYGIENE OF NUTRITION.

CHAPTER XLVII.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE ORGANS OF HEARING.

HYGIENE OF THE ORGANS OF VISION.

CHAPTER XXXV.

APPENDAGES OF THE SKIN.

CHAPTER XXX.

HYGIENE OF THE VOCAL ORGANS.

INDEX.

CHAPTER XXXIV.

HYGIENE OF THE SKIN, CONTINUED.

CHAPTER XXXIII.

HYGIENE OF THE SKIN.

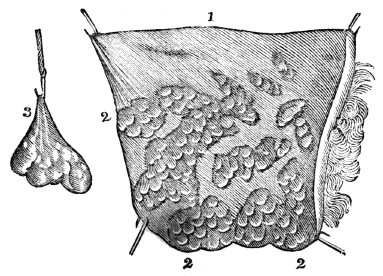

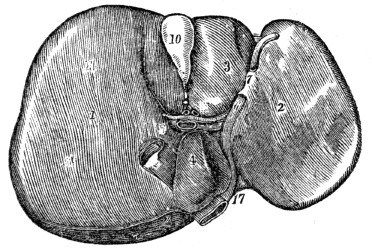

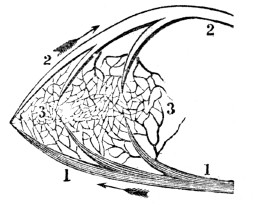

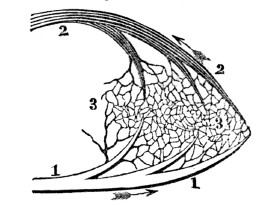

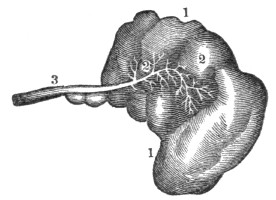

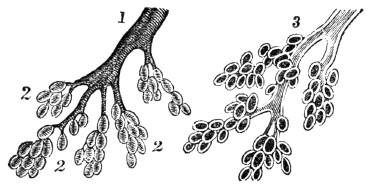

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. 1, A portion of the adipose tissue. 2, 2, 2, Minute bags containing fat. 3, A cluster of these bags, separated and suspended.

37. The CARTILAGINOUS TISSUE is firm, smooth, and highly elastic. Except bone, it is the hardest part of the animal frame. It tips the ends of the bones that concur in forming a joint. Its use is to facilitate the motion of the joints by its smooth surface, while its elastic character diminishes the shock that would otherwise be experienced if this tissue were inelastic.

36. Describe the adipose tissue. Where does this tissue principally exist? Give observation in regard to the adipose tissue. 37. Describe the cartilaginous tissue. What is its use?

38 The OSSEOUS TISSUE, in composition and arrangement of matter, varies at different periods of life, and in different bones. In some instances, the bony matter is disposed in plates, while in other instances, the arrangement is cylindrical. Sometimes, the bony matter is dense and compact; again, it is spongy, or porous. In the centre of the long bones, a space is left which is filled with a fatty substance, called mar´row.

Observation. Various opinions exist among physiologists in regard to the use of marrow. Some suppose it serves as a reservoir of nourishment, while others, that it keeps the bones from becoming dry and brittle. The latter opinion, however, has been called in question, as the bones of the aged man contain more marrow than those of the child, and they are likewise more brittle.

Fig. 5.

Fig.

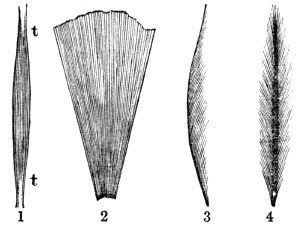

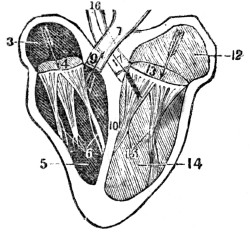

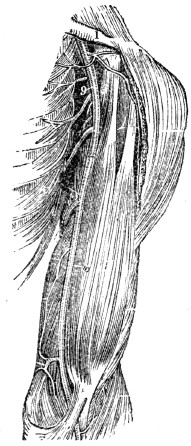

5. A section of the femur, (thigh-bone.) 1, 1, The extremities, showing a thin plate of compact texture, which covers small cells, that diminish in size, but increase in number, as they approach the articulation. 2, 2, The walls of the shaft, which are very firm and solid. 3, The cavity that contains the marrow.39. The MUSCULAR TISSUE is composed of many fibres, that unite to form fasciculi, each of which is enclosed in a delicate layer of cellular tissue. Bundles of these fasciculi constitute a muscle.

Observation. A piece of boiled beef will clearly illustrate the arrangement of muscular fibre.

38. What is said of the osseous tissue? How is the bony matter arranged in different parts of the animal frame? What is said of the use of marrow? 39. Of what is the muscular tissue composed? How may the arrangement of muscular fibre be illustrated?

40. The MUCOUS TISSUE differs from the serous by its lining all the cavities which communicate with the air. The nostrils, the mouth, and the stomach afford examples. The external surface of this membrane, or that which is exposed to the air, is soft, and bears some resemblance to the downy rind of a peach. It is covered by a viscid fluid called mu´cus. This is secreted by small gland-cells, called ep-i-the´li-a, or secretory cells of the mucous membrane. The use of this membrane and its secreted mucus is to protect the inner surface of the cavities which it lines.

Observation. A remarkable sympathy exists between the remote parts of the mucous membrane. Thus the condition of the stomach may be ascertained by an examination of the tongue.

41. The NERVOUS TISSUE consists of soft, pulpy matter, enclosed in a sheath, called neu-ri-lem´a. This tissue consists of two substances. The one, of a pulpy character and gray color, is called cin-e-ri´tious, (ash-colored.) The other, of a fibrous character and white, is named med´ul-la-ry, (marrow-like.) In every part of the nervous system both substances are united, with the exception of the nervous fibres and filaments, which are solely composed of the medullary matter enclosed in a delicate sheath.

40. How does the mucous differ from the

serous

tissue? What is the appearance of the external surface of this membrane? Where is the mucus secreted? What is the use of this membrane? 41. Of what does the nervous tissue consist? Describe the two substances that enter into the composition of the nervous tissue.CHAPTER III

CHEMISTRY OF THE HUMAN BODY.

42. An ULTIMATE ELEMENT is the simplest form of matter with which we are acquainted; as gold, iron, &c.

43. These elements are divided into metallic and non-metallic substances. The metallic substances are Po-tas´si-um, So´di-um, Cal´ci-um, Mag-ne´si-um, A-lu´min-um, I´ron, Man´ga-nese, and Cop´per. The non-metallic substances are Ox´y-gen, Hy´dro-gen, Car´bon, Ni´tro-gen, Si-li´-ci-um, Phos´phor-us, Sul´phur, Chlo´rine, and a few others.

44. Potash (potassium united with oxygen) is found in the blood, bile, perspiration, milk, &c.

45. Soda (sodium combined with oxygen) exists in the muscles, and in the same fluids in which potash is found.

46. Lime (calcium combined with oxygen) forms the principal ingredient of the bones. The lime in them is combined with phosphoric and carbonic acid.

47. Magnesia (magnesium combined with oxygen) exists in the bones, brain, and in some of the animal fluids; as milk.

48. Silex (silicium combined with oxygen) is contained in the hair and in some of the secretions.

49. Iron forms the coloring principle of the red globules of the blood, and is found in every part of the system.

Observation. As metallic or mineral substances enter into the ultimate elements of the body, the assertion that all minerals are poisonous, however small the quantity, is untrue.

42. What is an ultimate element? Give examples. 43. How are they divided? Name the metallic substances. Name the non-metallic substances. 44. What is said of potash? 45. Of soda? 46. Of lime? 47. Of magnesia? 48. Of silex? 49. What forms the coloring principle of the blood? What is said of mineral substances?

50. Oxygen is contained in all the fluids and solids of the body. It is almost entirely derived from the inspired air and water. It is expelled in the form of carbonic acid and water from the lungs and skin. It is likewise removed in the other secretions.

51. Hydrogen is found in all the fluids and in all the solids of the body. It is derived from the food, as well as from water and other drinks. It exists in the greatest abundance in the impure, dark-colored blood of the system. It is removed by the agency of the kidneys, skin, lungs, and other excretory organs.

52. Carbon is an element in the oil, fat, albumen, fibrin, gelatin, bile, and mucus. This element likewise exists in the impure blood in the form of carbonic acid gas. Carbon is obtained from the food, and discharged from the system by the secretions and respiration.

53. Nitrogen is contained in most animal matter, but is most abundant in fibrin. It is not contained in fat and a few other substances.

Observation. The peculiar smell of animal matter when burning is owing to nitrogen. This element combined with hydrogen forms am-mo´ni-a, (hartshorn,) when animal matter is in a state of putrefaction.

54. Phosphorus is contained in many parts of the system, but more particularly in the bones. It is generally found in combination with oxygen, forming phosphoric acid. The phosphoric acid is usually combined with alkaline bases; as lime in the bones, forming phosphate of lime.

55. Sulphur exists in the bones, muscles, hair, and nails. It is expelled from the system by the skin and intestines.

56. Chlorine is found in the blood, gastric juice, milk, perspiration, and saliva.

50. What is said of oxygen? 51. Of hydrogen? 52. What is said of carbon? 53. Of nitrogen? How is ammonia formed? 54. What is said of phosphorus? 55. What is said of sulphur? 56. Of chlorine?

57. Proximate elements are forms of matter that exist in organized bodies in abundance, and are composed chiefly of oxygen, hydrogen, carbon, and nitrogen, arranged in different proportions. They exist already formed, and may be separated in many instances, by heat or mechanical means. The most important compounds are Al-bu´men,

Fi´brin,

Gel´a-tin, Mu´cus, Fat, Ca´se-ine, Chon´drine, Lac´tic acid, and Os´ma-zome.58. Albumen is found in the body, both in a fluid and solid form. It is an element of the skin, glands, hair, and nails, and forms the principal ingredient of the brain. Albumen is without color, taste, or smell, and it coagulates by heat, acids, and alcohol.

Observation. The white of an egg is composed of albumen, which can be coagulated or hardened by alcohol. As albumen enters so largely into the composition of the brain, is not the impaired intellect and moral degradation of the inebriate attributable to the effect of alcohol in hardening the albumen of this organ?

59. Fibrin exists abundantly in the blood, chyle, and lymph. It constitutes the basis of the muscles. Fibrin is of a whitish color, inodorous, and insoluble in cold water. It differs from albumen by possessing the property of coagulating at all temperatures.

Observation. Fibrin may be obtained by washing the thick part of blood with cold water; by this process, the red globules, or coloring matter, are separated from this element.

60. Gelatin is found in nearly all the solids, but it is not known to exist in any of the fluids. It forms the basis of the cellular tissue, and exists largely in the skin, bones, ligaments, and cartilages.

57. What are proximate elements? Do they exist already formed in

organized

bodies? Name the most important compounds. 58. What is said of albumen? Give observation relative to this element. 59. Of fibrin? How does albumen differ from fibrin? How can fibrin be obtained? 60. What is said of gelatin?Observation. Gelatin is known from other organic principles by its dissolving in warm water, and forming “jelly.” When dry, it forms the hard, brittle substance, called glue. Isinglass, which is used in the various mechanical arts, is obtained from the sounds of the sturgeon.

61. Mucus is a viscid fluid secreted by the gland-cells, or epithelia. Various substances are included under the name of mucus. It is generally alkaline, but its true chemical character is imperfectly understood. It serves to moisten and defend the mucous membrane. It is found in the cuticle, brain, and nails; and is scarcely soluble in water, especially when dry. (Appendix C.)

62. Osmazome is a substance of an aromatic flavor. It is of a yellowish-brown color, and is soluble both in water and alcohol, but does not form a jelly by concentration. It is found in all the fluids, and in some of the solids; as the brain.

Observation. The characteristic odor and taste of soup are owing to osmazome.

63. There are several acids found in the human system; as the A-ce´tic, Ben-zo´ic, Ox-al´ic, U´ric, and some other substances, but not of sufficient importance to require a particular description.

How is it known from other organic principles? 61. What is said of mucus? 62. Of osmazome? To what are the taste and odor of soup owing? 63. What acids are found in the system?

CHAPTER IV.

THE BONES.

64. The bones are firm and hard, and of a dull white color. In all the higher orders of animals, among which is man, they are in the interior of the body, while in lobsters, crabs, &c., they are on the outside, forming a case which protects the more delicate parts from injury.

65. In the mechanism of man, the variety of movements he is called to perform requires a correspondent variety of component parts, and the different bones of the system are so admirably adapted to each other, that they admit of numerous and varied motions.

66. When the bones composing the skeleton are united by natural ligaments, they form what is called a natural skeleton, when united by wires, what is termed an artificial skeleton.

67. The elevations, or protuberances, of the bones are called proc´es-ses, and are, generally, the points of attachment for the muscles and ligaments.

ANATOMY OF THE BONES.

68. The BONES are composed of both animal and earthy matter. The earthy portion of the bones gives them solidity and strength, while the animal part endows them with

vitality.

64. What is said of the bones? 65. Is there an adaptation of the bones of the system to the offices they are required to perform? 66. What is a natural skeleton? What an artificial? 67. What part of the bones are called processes? 68–73. Give the structure of the bones. 68. Of what are the bones composed? What are the different uses of the component parts of the bones?

Experiments. 1st. To show the earthy without the animal matter, burn a bone in a clear fire for about fifteen minutes, and it becomes white and brittle, because the gelatin, or animal matter of the bone, has been destroyed.

2d. To show the animal without the earthy matter of the bones, immerse a slender bone for a few days in a weak acid, (one part muriatic acid and six parts water,) and it can then be bent in any direction. In this experiment, the acid has removed the earthy matter, (carbonate and phosphate of lime,) yet the form of the bone is unchanged.

69. The bones are formed from the blood, and are subjected to several changes before they are perfected. At their early formative stage, they are cartilaginous. The vessels of the cartilage, at this period, convey only the lymph, or white portion of the blood; subsequently, they convey red blood. At this time, true ossification (the deposition of phosphate and carbonate of lime) commences at certain points, which are called the points of ossification.

70. Most of the bones are formed of several pieces, or centres of ossification. This is seen in the long bones which have their extremities separated from the body by a thin partition of cartilage. It is some time before these separate pieces are united to form one bone.

71. When the process of ossification is completed, there is still a constant change in the bones. They increase in bulk, and become less vascular, until middle age. In advanced life, the elevations upon their surface and near the extremities become more prominent, particularly in individuals accustomed to labor. As a person advances in years, the vitality diminishes, and in extreme old age, the earthy substance predominates; consequently, the bones are extremely brittle.

How can the earthy matter of the bones be shown? The animal? 69. What is the appearance of the bones in their early formative stage? When does true ossification commence? 70. How are most of the bones formed? 71. What is said of the various changes of the bones after ossification?

72. The fibrous membrane that invests the bones is called per-i-os´te-um; that which covers the cartilages is called per-i-chon´dri-um. When this membrane invests the skull, it is called per-i-cra´ni-um.

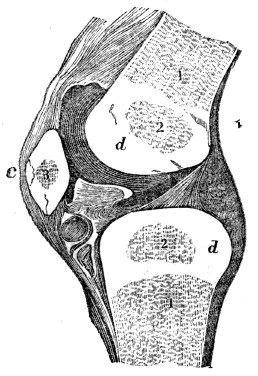

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. A section of the knee-joint. The lower part of the femur, (thigh-bone,) and upper part of the tibia, (leg-bone,) are seen ossified at 1, 1. The cartilaginous extremities of the two bones are seen at d, d. The points of ossification of the extremities, are seen at 2, 2. The patella, or knee-pan, is seen at c. 3, A point, or centre of ossification.

73. The PERIOSTEUM is a firm membrane immediately investing the bones, except where they are tipped with cartilage, and the crowns of the teeth, which are protected by enamel. This membrane has minute nerves, and when healthy, possesses but little sensibility. It is the nutrient membrane of the bone, endowing its exterior with vitality; it also gives insertion to the tendons and connecting ligaments of the joints.

72. What is the membrane called that invests the bones? That covers the cartilage? That invests the skull? Explain fig. 6. 73. Describe the periosteum.

74. There are two hundred and eight[3] bones in the human body, beside the teeth. These, for convenience, are divided into four parts: 1st. The bones of the Head. 2d. The bones of the Trunk. 3d. The bones of the Upper Extremities. 4th. The bones of the Lower Extremities.

75. The bones of the HEAD are divided into those of the Skull, Ear, and Face.

76. The SKULL is composed of eight bones. They are formed of two plates, or tablets of bony matter, united by a porous portion of bone. The external tablet is fibrous and tough; the internal plate is dense and hard, and is called the vit´re-ous, or glassy table. These tough, hard plates are adapted to resist the penetration of sharp instruments, while the different degrees of density possessed by the two tablets, and the intervening spongy bone, serve to diminish the vibrations that would occur in falls or blows.

77. The skull is convex externally, and at the base much thicker than at the top or sides. The most important part of the brain is placed here, completely out of the way of injury, unless of a very serious nature. The base of the cranium, or skull, has many projections, depressions, and apertures; the latter affording passages for the nerves and blood-vessels.

74. How many bones in the human body? How are they divided? 75–81. Give the anatomy of the bones of the head. 75. How are the bones of the head divided? 76. Describe the bones of the skull. 77. What is the form of the skull? What does the base of the skull present?

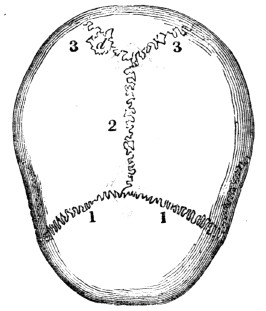

78. The bones of the cranium are united by ragged edges, called sut´ures. The edges of each bone interlock with each other, producing a union, styled, in carpentry, dovetailing. They interrupt, in a measure, the vibrations produced by external blows, and also prevent fractures from extending as far as they otherwise would, in one continued bone. From infancy to the twelfth year, the sutures are imperfect; but, from that time to thirty-five or forty, they are distinctly marked; in old age, they are nearly obliterated.

Fig. 7.

Fig.

7.

1, 1, The coronal suture at the front and upper part of the skull, orcranium

. 2, The sagittal suture on the top of the skull. 3, 3, The lambdoidal suture at the back part of the cranium.79. We find as great a diversity in the form and texture of the skull-bone, as in the expression of the face. The head of the New Hollander is small; that of the African is compressed; while the Caucasian is distinguished for the beautiful oval form of the head. The Greek skulls, in texture, are close and fine, while the Swiss are softer and more open.

78. How are the bones of the skull united? What are the uses of the sutures? Mention the appearance of the sutures at different ages. What does fig. 7 represent? 79. What is said respecting the form and texture of the skull in different nations?

80. In each EAR are four very small bones. They aid in hearing.

81. In the FACE are fourteen bones, some of which serve for the attachment of powerful muscles, which are more or less called into action in masticating food; others retain in place the soft parts of the face.

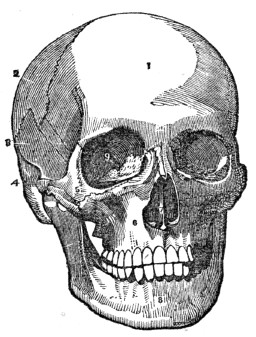

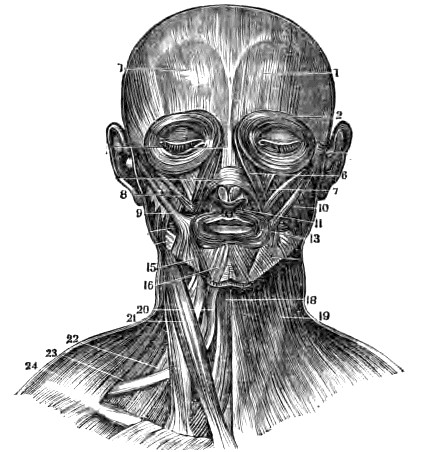

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. 1, The frontal, or bone of the forehead. 2. The parietal bone. 3, The temporal bone. 4, The zygomatic process of the temporal bone. 5, The malar (cheek) bone. 6, The superior maxillary bone, (upper jaw.) 7, The vomer, that separates the cavities of the nose. 8, The inferior maxillary bone, (lower jaw.) 9. The cavity for the eye.

82. The TRUNK has fifty-four bones—twenty-four Ribs; twenty-four bones in the Spi´nal Col´umn, (back-bone;) four in the Pel´vis; the Ster´num, (breast-bone;) and the Os hy-oid´es, (the bone at the base of the tongue.) They are so arranged as to form, with the soft parts attached to them, two cavities, called the Tho´rax (chest) and Ab-do´men.

80. How many bones in the ear? 81. How many bones in the face? What is their use? Explain fig. 8. 82–94. Give the anatomy of the bones of the trunk. 82. How many bones in the trunk? Name them. What do they form by their arrangement?

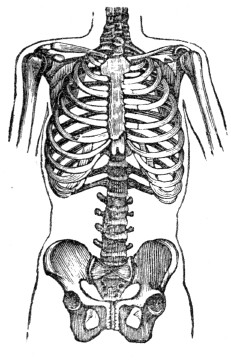

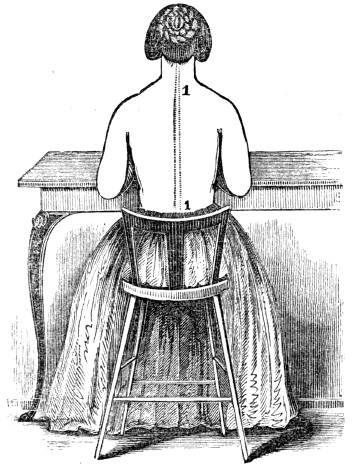

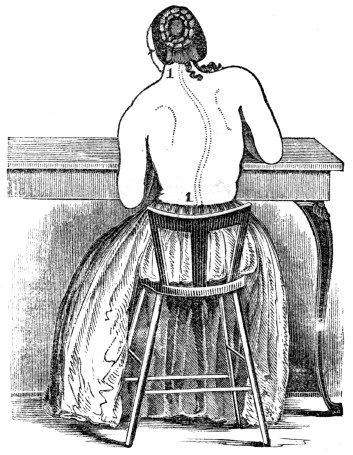

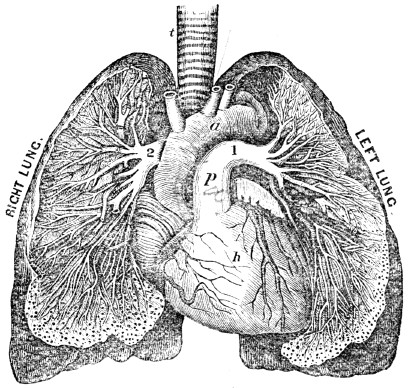

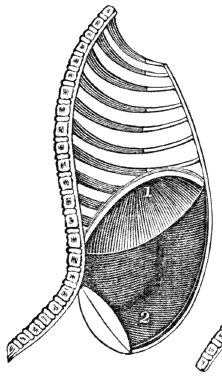

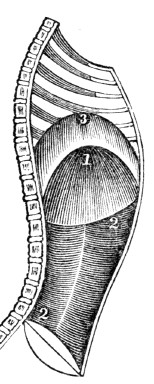

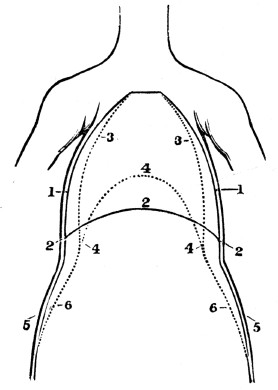

83. The THORAX is formed by the sternum in front; the ribs, at the sides; and the twelve dorsal bones of the spinal column, posteriorly. The natural form of the chest is a cone, with its apex above; but fashion, in many instances, has nearly inverted this order. This cavity contains the lungs, heart, and large blood-vessels.

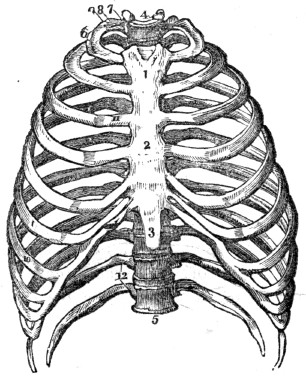

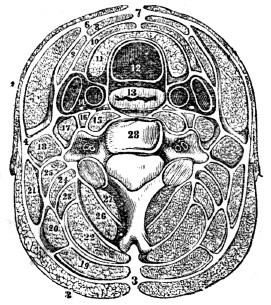

Fig. 9.

Fig.

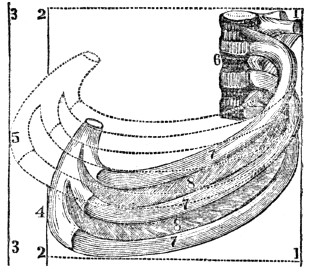

9. 1, The first bone of the sternum, (breast-bone.) 2. The second bone of the sternum. 3, The cartilage of the sternum. 4, The first dorsal vertebra, (a bone of the spinal column.) 5, The last dorsal vertebra. 6, The first rib. 7, Its head. 8, Its neck. 9, Its tubercle. 10, The seventh, or last true rib. 11, The cartilage of the third rib. 12, The floating ribs.84. The STERNUM is composed of eight pieces in the child. These unite and form but three parts in the adult. In youth, the two upper portions are converted into bone, while the lower portion remains cartilaginous and flexible until extreme old age, when it is often converted into bone.

85. The RIBS are connected with the spinal column, and increase in length as far as the seventh. From this they successively become shorter. The direction of the ribs from above, downward, is oblique, and their curve diminishes from the first to the twelfth. The external surface of each rib is convex; the internal, concave. The inferior, or lower ribs, are, however, very flat.

83. Describe the thorax. Explain fig. 9. 84. Describe the

sternum.

85. Describe the ribs.86. The seven upper ribs are united to the sternum, through the medium of cartilages, and are called the true ribs. The cartilages of the next three are united with each other, and are not attached to the sternum; these are called false ribs. The lowest two are called floating ribs, as they are not connected either with the sternum or the other ribs.

87. The SPINAL COLUMN is composed of twenty-four pieces of bone. Each piece is called a vert´e-bra. On examining one of the bones, we find seven projections, called processes; four of these, that are employed in binding the bones together, are called articulating processes; two of the remaining are called the transverse; and the other, the spinous. The last three give attachment to the muscles of the back.

88. The large part of the vertebra, called the body, is round and spongy in its texture, like the extremity of the round bones. The processes are of a more dense character. The projections are so arranged that a tube, or canal, is formed immediately behind the bodies of the vertebræ, in which is placed the me-dul´la spi-na´lis, (spinal cord,) sometimes called the pith of the back-bone.

89. Between these joints, or vertebræ, is a peculiar and highly elastic substance, which much facilitates the bending movements of the back. This compressible cushion of cartilage also serves the important purpose of diffusing and diminishing the shock in walking, running, or leaping, and tends to protect the delicate texture of the brain.

86. How are the ribs united to the sternum? 87. Describe the spinal column. 88. Give the structure of the vertebra. Where is the spinal cord placed? 89. What is placed between each

vertebra?

What is its use?90. Another provision for the protection of the brain, which bears convincing proof of the wisdom and beneficence of the Creator, is the antero-posterior, or forward and backward curve of the spinal column. Were it a straight column, standing perpendicularly, the slightest jar, in walking, would cause it to recoil with a sudden jerk; because, the weight bearing equally, the spine would neither yield to the one side nor the other. But, shaped as it is, we find it yielding in the direction of the curves, and thus the force of the shock is diffused.

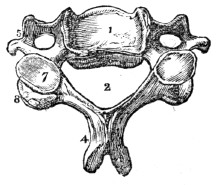

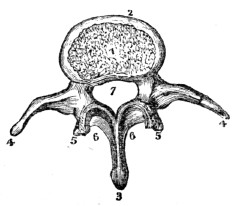

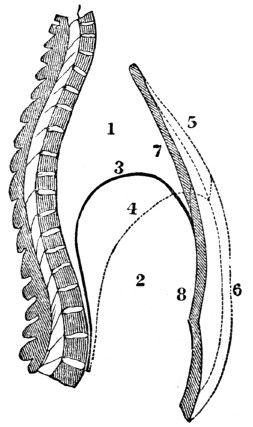

Fig. 10.

Fig. 10. A vertebra of the neck. 1, The body of the vertebra. 2, The spinal canal. 4, The spinous process, cleft at its extremity. 5, The transverse

process.

7, The inferior articulating process. 8, The superior articulating process.Fig. 11.

Fig. 11. 1, The cartilaginous substance that connects the bodies of the vertebræ. 2, The body of the vertebra. 3, The spinous process. 4, 4, The transverse processes. 5, 5, The articulating processes. 6, 6, A portion of the bony bridge that assists in forming the spinal canal, (7.)

Observation. A good idea of the structure of the vertebræ may be obtained by examining the spinal column of a domestic animal, as the dog, cat, or pig.

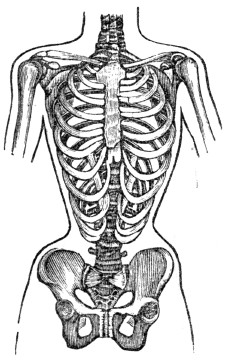

91. The PELVIS is composed of four bones; the two in-nom-i-na´ta, (nameless bones,) the sa´crum, and the coc´cyx.

92. The INNOMINATUM, in the child, consists of three pieces. These, in the adult, become united, and constitute but one bone. In the sides of these bones is a deep socket, or depression, like a cup, called the ac-e-tab´u-lum, in which the round head of the thigh-bone is placed.

90. What is said of the curves of the spinal column? What is represented by fig. 10? By fig. 11? How can the structure of the vertebræ be seen? 91. Of how many bones is the pelvis composed? 92. What is said of the innominatum in the child?

93. The SACRUM, so called because the ancients offered it in sacrifices, is a wedge-shaped bone, that is placed between the innominata, and to which it is bound by ligaments. Upon its upper surface it connects with the lower vertebra. At its inferior, or lower angle, it is united to the coccyx. It is concave upon its anterior, and convex upon its posterior surface.

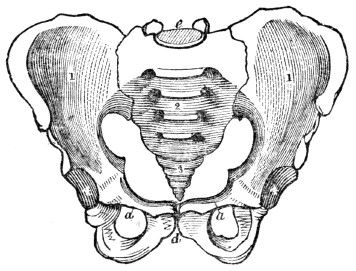

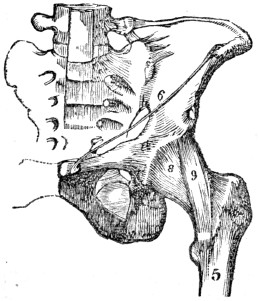

Fig. 12.

Fig. 12. 1, 1, The innominata, (nameless bones.) 2, The sacrum. 3, The

coccyx.

4, 4, The acetabulum. a, a, The pubic portion of the innominata. d, The arch of the pubes; e, The junction of the sacrum and lower lumbar vertebra.94. The COCCYX, in infants, consists of several pieces, which, in youth, become united and form one bone. This is the terminal extremity of the spinal column.

In the adult? Describe the acetabulum. 93. Describe the

sacrum.

Explain fig. 12. 94. Describe the coccyx.CHAPTER V.

ANATOMY OF THE BONES, CONTINUED

95. The bones of the upper and lower limbs are enlarged at each extremity, and have projections, or processes. To these, the tendons of muscles and ligaments are attached, which connect one bone with another. The shaft of these bones is cylindrical and hollow, and in structure, their exterior surface is hard and compact, while the interior portion is of a reticulated character. The enlarged extremities of the round bones are more porous than the main shaft.

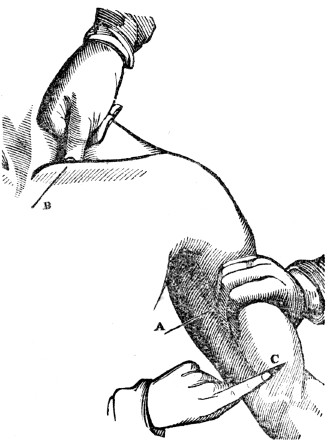

96. The UPPER EXTREMITIES contain sixty-four bones—the Scap´u-la, (shoulder-blade;) the Clav´i-cle, (collar-bone;) the Hu´mer-us, (first bone of the arm;) the Ul´na and Ra´di-us, (bones of the fore-arm;) the Car´pus, (wrist;) the Met-a-car´pus, (palm of the hand;) and the Pha-lan´ges, (fingers and thumb.)

97. The CLAVICLE is attached, at one extremity, to the sternum; at the other, it is united to the scapula. It is shaped like the Italic ∫. Its use is to keep the arms from sliding toward the breast.

98. The SCAPULA is situated upon the upper and back part of the chest. It is flat, thin, and of a triangular form. This bone lies upon and is retained in its position by muscles. By their contractions it may be moved in different directions.

99. The HUMERUS is cylindrical, and is joined at the elbow with the ulna of the fore-arm; at the scapular extremity, it is lodged in the glenoid cavity, where it is surrounded by a membranous bag, called the capsular ligament.

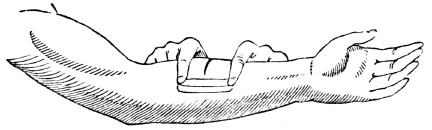

95–104. Give the anatomy of the bones of the upper extremities. 95. Give the structure of the bones of the extremities. 96. How many bones in the upper extremities? Name them. 97. Give the attachments of the clavicle. What is its use? 98. Describe the scapula. How is it retained in its position? 99. Describe the humerus.

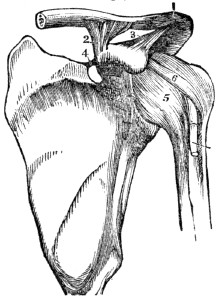

Fig. 13.

Fig. 13. 1, The shaft of the humerus. 2, The large, round head that is placed in the glenoid cavity. 3, 4, Processes, to which muscles are attached. 5, A process, called the external elbow. 6, A process, called the internal elbow. 7, The articulating surface upon which the ulna rolls.

Fig. 14.

Fig. 14. 1, The body of the ulna. 2, The shaft of the radius. 3, The upper articulation of the radius and ulna. 4, Articulating cavity, in which the lower extremity of the humerus is placed. 5, Upper extremity of the ulna, called the olecranon process, which forms the point of the elbow. 6, Space between the radius and ulna, filled by the intervening ligament. 7, Styloid process of the ulna. 8, Surface of the radius and the ulna, where they articulate with the bones of the wrist. 9, Styloid process of the radius.

100. The ULNA articulates with the humerus at the elbow, and forms a perfect hinge-joint. This bone is situated on the inner side of the fore-arm.

What is represented by fig. 13? By fig. 14? 100. Describe the ulna.

101. The RADIUS articulates with the bones of the carpus and forms the wrist-joint. This bone is situated on the

outside

of the fore-arm, (the side on which the thumb is placed.) The ulna and radius, at their extremities, articulate with each other, by which union the hand is made to rotate, permitting its complicated and varied movements.102. The CARPUS is composed of eight bones, ranged in two rows, and so firmly bound together, as to permit only a small amount of movement.

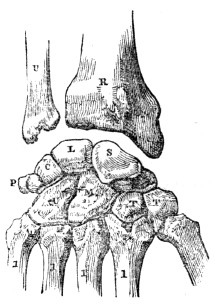

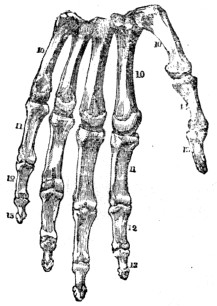

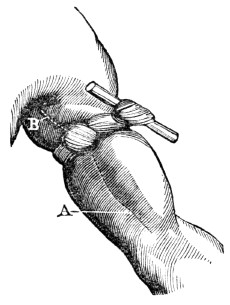

Fig. 15.

Fig. 15. U, The ulna. R, The radius. S, The scaphoid bone. L, The semilunar bone. C, The cuneiform bone. P, The pisiform bone. These four form the first row of carpal bones. T, T, The trapezium and trapezoid bones. M, The os magnum. U, The unciform bone. These four form the second row of carpal bones. 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, The metacarpal bones of the thumb and fingers.

Fig. 16.

Fig. 16. 10, 10, 10, The metacarpal bones of the hand. 11, 11, First range of finger-bones. 12, 12, Second range of finger-bones. 13, 13, Third range of finger-

bones.

14, 15, Bones of the thumb.103. The METACARPUS is composed of five bones, upon four of which the first range of the finger-bones is placed; and upon the other, the first bone of the thumb. The five

metacarpal

bones articulate with the second range of carpal bones.101. The radius. 102. How many bones in the carpus? How are they ranged?

103.

Describe themetacarpus.

104. The PHALANGES of the fingers have three ranges of bones, while the thumb has but two.

Observation. The wonderful adaptation of the hand to all the mechanical offices of life, is one cause of man’s superiority over the rest of creation. This arises from the size and strength of the thumbs, and the different lengths of the fingers.

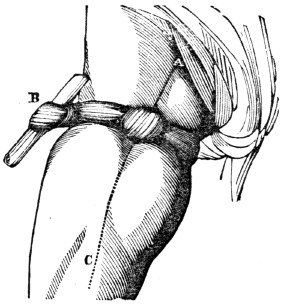

105. The LOWER EXTREMITIES contain sixty bones—the Fe´mur, (thigh-bone;) the Pa-tel´la, (knee-pan;) the Tib´i-a, (shin-bone;) the Fib´u-la, (small bone of the leg;) the Tar´sus, (instep;) the Met-a-tar´sus, (middle of the foot;) and the Pha-lan´ges, (toes.)

106. The FEMUR is the longest bone in the system. It supports the weight of the head, trunk, and upper extremities. The large, round head of this bone is placed in the acetabulum. This articulation is a perfect specimen of the ball and socket joint.

107. The PATELLA is a small bone connected with the tibia by a strong ligament. The tendon of the ex-tens´or muscles of the leg is attached to its upper edge. This bone is placed on the anterior part of the lower extremity of the femur, and acts like a pulley, in the extension of the limb.

108. The TIBIA is the largest bone of the leg. It is of a triangular shape, and enlarged at each extremity.

109. The FIBULA is a smaller bone than the tibia, but of

similar

shape. It is firmly bound to the tibia, at each extremity.110. The TARSUS is formed of seven irregular bones, which are so firmly bound together as to permit but little movement.

104. How many ranges of bones have the phalanges? 105–112. Give the anatomy of the bones of the lower extremities. 105. How many bones in the lower extremities? Name them. 106. Describe the femur. 107. Describe the patella. What is its function? 108. What is the largest bone of the leg called? What is its form? 109. What is said of the fibula? 110. Describe the tarsus.

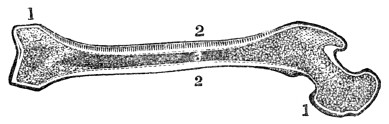

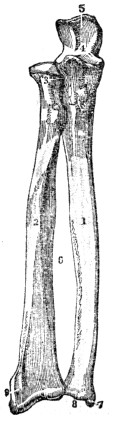

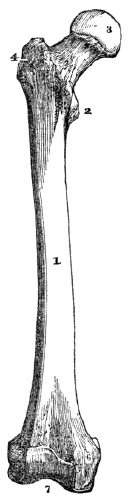

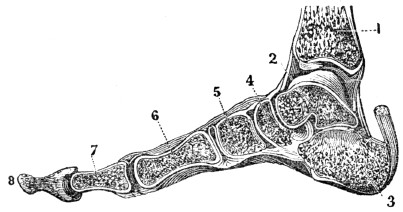

Fig. 17.

Fig.

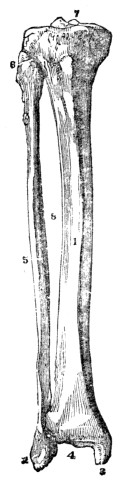

17. 1, The shaft of the femur, (thigh-bone.) 2, A projection, called the trochantar minor, to which are attached some strong muscles. 4, The trochantar major, to which the large muscles of the hip are attached. 3, The head of the femur. 5, The external projection of the femur, called the external condyle. 6, The internal projection, called the internal condyle. 7, The surface of the lower extremity of the femur, that articulates with the tibia, and upon which the patella slides.Fig. 18.

Fig. 18. 1, The tibia. 5, The fibula. 8, The space between the two, filled with the inter-osseous ligament. 6, The junction of the tibia and fibula at their upper extremity. 2, The external malleolar process, called the external ankle. 3, The internal malleolar process, called the internal ankle. 4, The surface of the lower extremity of the tibia, that unites with one of the tarsal bones to form the ankle-joint. 7, The upper extremity of the tibia, upon which the lower extremity of the femur rests.

Explain fig. 17. Explain fig. 18.

111. The METATARSAL bones are five in number. They articulate at one extremity with one range of tarsal bones;

at

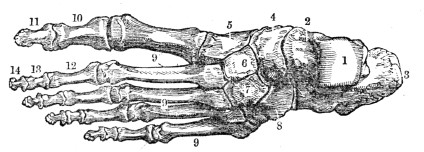

the other extremity, with the first range of the toe-bones.Fig. 19.

Fig. 19. A representation of the upper surface of the bones of the foot. 1, The surface of the astragulus, where it unites with the tibia. 2, The body of the astragulus. 3, The calcis, (heel-bone.) 4, The scaphoid bone. 5, 6, 7, The cuneiform bones. 8, The cuboid. 9, 9, 9, The metatarsal bones. 10, The first bone of the great toe. 11, The second bone. 12, 13, 14, Three ranges of bones, forming the small toes

Fig. 20.

Fig. 20. A side view of the bones of the foot, showing its arched form. The arch rests upon the heel behind, and the ball of the toes in front. 1, The lower part of the tibia. 2, 3, 4, 5, Bones of the tarsus. 6, The metatarsal bone. 7, 8, The bones of the great toe. These bones are so united as to secure a great degree of elasticity, or spring.

Observation. The tarsal and metatarsal bones are united so as to give the foot an arched form, convex above, and concave below. This structure conduces to the elasticity of the step, and the weight of the body is transmitted to the ground by the spring of the arch, in a manner which prevents injury to the numerous organs.

111. Describe the metatarsal bones. Explain fig. 19. What is represented by fig. 20? What is said of the arrangement of the bones of the foot?

112. The PHALANGES (fig. 19) are composed of fourteen bones; each of the small toes has three ranges of bones, while the great toe has but two.

113. The JOINTS form an interesting part of the body. In their construction, every thing shows the regard that has been paid to the security and the facility of motion of the parts thus connected together. They are composed of the extremities of two or more bones, Car´ti-lages, (gristles,) Syn-o´vi-al membrane, and Lig´a-ments.

[3]

Some anatomists reckon more than this number, others less, for the reason that, at different periods of life, the number of pieces of which one bone is formed, varies. Example. The breast-bone, in infancy, has eight pieces; in youth, three; in old age, but one.

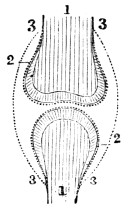

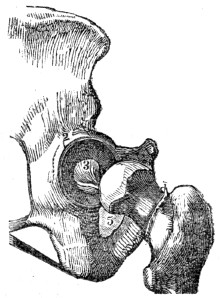

Fig. 21.

Fig. 21 The relative position of the bones, cartilages, and synovial

membrane.

1, 1, The extremities of two bones that concur to form a joint. 2, 2, The cartilages that cover the end of the bones. 3, 3, 3, 3, The synovial membrane which covers the cartilage of both bones, and is then doubled back from one to the other; it is represented by the dotted lines.Fig. 22.

Fig. 22. A vertical section of the knee-joint. 1, The femur. 3, The patella. 5, The tibia. 2, 4, The ligaments of the patella. 6, The cartilage of the tibia 12, The cartilage of the femur. * * * *, The synovial membrane.

114. Cartilage is a smooth, solid, elastic substance, of a pearly whiteness, softer than bone. It forms upon the articular surfaces of the bones a thin incrustation, not more than the sixteenth of an inch in thickness. Upon convex surfaces it is the thickest in the centre, and thin toward the circumference; while upon concave surfaces, an opposite arrangement is presented.

112. Describe the phalanges. 113–118. Give the anatomy of the

joints.

113. What is said of the joints? Of what are the jointscomposed?

What is illustrated by fig. 21? By fig. 22? 114. Define cartilage.115. The SYNOVIAL MEMBRANE is a thin, membranous layer, which covers the cartilages, and is thence bent back, or reflected upon the inner surfaces of the ligaments which surround and enter into the composition of the joints. This membrane forms a closed sac, like the membrane that lines an egg-shell.

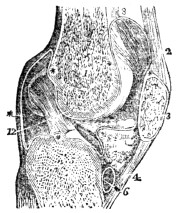

Fig. 23.

Fig. 23. The anterior ligaments of the knee-joint. 1, The tendon of the muscle that extends the leg. 2, The patella. 3, The anterior ligament of the patella, near its insertion. 4, 4, The synovial membrane. 5, The internal lateral ligament. 6, The long external lateral ligament. 7, The anterior and superior ligament that unites the fibula to the tibia.

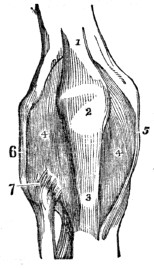

Fig. 24.

Fig. 24. 2, 3, The ligaments that extend from the clavicle (1) to the scapula (4.) The ligaments 5, 6, extend from the scapula to the first bone of the arm.

116. Beside the synovial membrane, there are numerous smaller sacs, called bur´sæ mu-co´sæ. These are often associated with the articulation. In structure, they are analogous to synovial membranes, and secrete a similar fluid.

115. Describe the synovial membrane. 116. Describe the bursæ mucosæ. What is represented by fig. 23? By fig. 24?

117. The LIGAMENTS are composed of numerous straight fibres, collected together, and arranged into short bands of various breadths, or so interwoven as to form a broad layer, which completely surrounds the articular extremities of the bones, and constitutes a capsular ligament. These connecting bands are white, glistening, and inelastic. Most of the ligaments are found exterior to the synovial membrane.

118. The bones, cartilages, ligaments, and synovial membrane are insensible when in health; yet they are supplied with organic nerves, as well as with arteries, veins, and lymphatics.

Observation. The joints of the domestic animals are similar in their construction to those of man. To illustrate this part of the body, a fresh joint of the calf or sheep may be used. After divesting the joints of the skin, the satin-like bands, or ligaments, will be seen passing from one bone to the other, under which may be observed the membranous bag, called the capsular ligament. This is very smooth, as it is lined with the soft synovial membrane, beneath which will be seen the cartilage, that may be cut with a knife, and under this the rough extremity of the ends of the bones.

117. Of what are ligaments composed? What is the appearance of these bands? Where are they found? 118. With what vessels are the cartilages and ligaments supplied? How can the structure of the joints be explained?

CHAPTER VI.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE BONES.

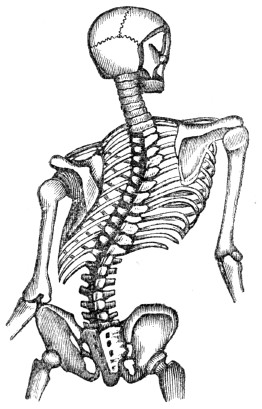

119. The bones are the framework of the system. By their solidity and form, they not only retain every part of the fabric in its proper shape, but afford a firm surface for the attachment of the muscles and ligaments. By means of the bones, the human frame presents to the eye a wonderful piece of mechanism, uniting the most finished symmetry of form with freedom of motion, and also giving security to many important organs.

120. To give a clear idea of the relative uses of the bones and muscles, we will quote the comparison of another, though, as in other comparisons, there are points of difference. The “bones are to the body what the masts and spars are to the ship,—they give support and the power of resistance. The muscles are to the bones what the ropes are to the masts and spars. The bones are the levers of the system; by the action of the muscles their relative positions are changed. As the masts and spars of a vessel must be sufficiently firm to sustain the action of the ropes, so the bones must possess the same quality to sustain the action of the muscles in the human body.”

121. Some of the bones are designed exclusively for the protection of the organs which they enclose. Of this number are those that form the skull, the sockets of the eye, and the cavity of the nose. Others, in addition to the protection they give to important organs, are useful in movements of certain kinds. Of this class are the bones of the spinal column, and ribs. Others are subservient to motion. Of this class are the upper and lower extremities.

119–128. Give the physiology of the bones. 119. How may the bones be considered? 120. To what may the bones be compared? 121. Give the different offices of the bones.

122. The bones are subject to growth and decay; to removal of old, useless matter, and the deposit of new particles, as in other tissues. This has been tested by the following experiment. Some of the inferior animals were fed with food that contained madder. In a few days, some of the animals were killed, and their bones exhibited an unusually reddish appearance. The remainder of the animals were, for a few weeks, fed on food that contained no coloring principle. When they were killed, their bones exhibited the usual color of such animals. The coloring matter, which had been deposited, had been removed by the action of the lymphatics.

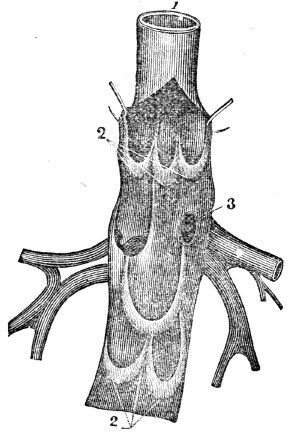

123. The extremities of the bones that concur in forming a joint, correspond by having their respective configurations reciprocal. They are, in general, the one convex, and the other concave. In texture they are porous, and consequently more elastic than if more compact. These are covered with a cushion of cartilage. The elastic character of these parts acts as so many springs, in diminishing the jar which important organs of the system would otherwise receive.

124. The synovial membrane secretes a viscous fluid, which is called syn-o´vi-a. This lubricating fluid of the joints enables the surfaces of the bones and tendons to move smoothly upon each other, thus diminishing the friction consequent on their action.

Observations. 1st. In this secretion is manifested the skill and omnipotence of the Great Architect; for no machine of human invention supplies to itself, by its own operations, the necessary lubricating fluid. But, in the animal frame, it is supplied in proper quantities, and applied in the proper place, and at the proper time.

122. What is said of the change in bones? How was it proved that there was a constant change in the osseous fabric? 123. What is said of the extremities of the bones that form a joint? 124. What is synovia? Its use? What is said of this lubricating fluid?

2d. In some cases of injury and disease, the synovial fluid is secreted in large quantities, and distends the sac of the joint. This affection is called dropsy of the joint, and occurs most frequently in that of the knee.

125. The function of the ligaments is to connect and bind together the bones of the system. By them the small bones of the wrist and foot, as well as the large bones, are as securely fastened as if retained by clasps of steel. Some of them are situated within the joints, like a central cord, or pivot, (3, fig. 26.) Some surround it like a hood, and contain the lubricating synovial fluid, (8, 9, fig. 25,) and some in the form of bands at the side, (5, 6, fig. 23.)

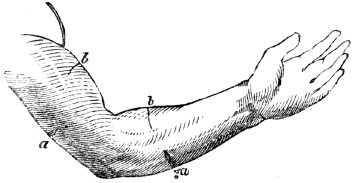

Fig. 25.

Fig. 25. 8, 9, The ligaments that extend from the hip-bone (6) to the femur, (5.)

Fig. 26.

Fig. 26. 2, The socket of the hip-joint. 5, The head of the femur, which is lodged in the socket. 3, The ligament within the socket.

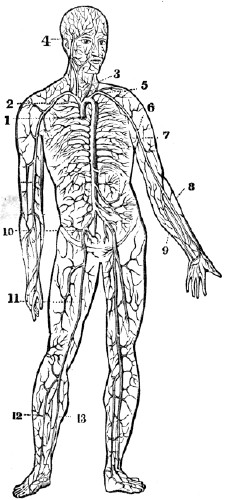

126. By the ligaments the lower jaw is bound to the temporal bones, and the head to the neck. They extend the whole length of the spinal column, in powerful bands, on the outer surface, between the spinal bones, and from one spinous process to another. They bind the ribs to the vertebræ, to the transverse process behind, and to the sternum in front; and this to the clavicle; and this to the first rib and scapula; and this last to the humerus.

What is the effect when the synovial fluid is secreted in large quantities? 125. What is the function of the ligaments? 126. Mention how the bones of the system are connected.

127. They also bind the two bones of the fore-arm at the elbow-joint; and these to the wrist; and these to each other and to those of the hand; and these last to each other and to those of the fingers and thumb. In the same manner, they bind the bones of the pelvis together; and these to the femur; and this to the two bones of the leg and patella; and so on, to the ankle, foot, and toes, as in the upper extremities.

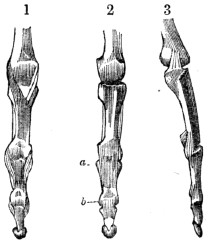

Fig. 27.

Fig. 27. 1, A front view of the lateral ligaments of the finger-joints. 2, A view of the anterior ligaments (a, b,) of the finger-joints. 3, A side view of the lateral ligaments of the finger joints.

128. The different joints vary in range of movement, and in complexity of structure. Some permit motions in all directions, as the shoulder; some move in two directions, permitting only flexion and extension of the part, as the elbow; while others have no movement, as the bones of the head in the adult.

Explain fig. 27. 128. Describe the variety of movements in the different joints.

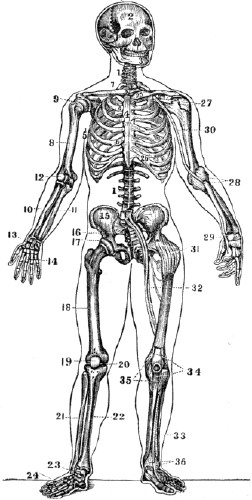

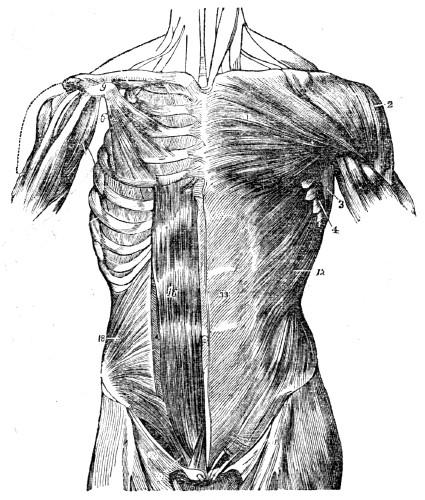

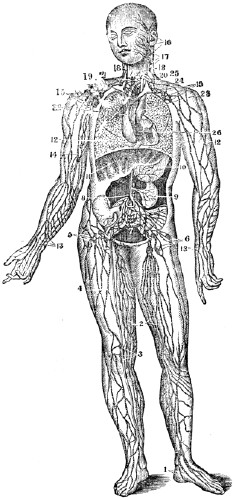

Fig. 28

Fig. 28. 1, 1, The spinal column. 2, The skull. 3, The lower jaw. 4, The sternum. 5, The ribs. 6, 6, The cartilages of the ribs. 7, The clavicle. 8, The humerus. 9, The shoulder-joint. 10, The radius. 11, The ulna. 12, The elbow joint. 13, The wrist. 14, The hand. 15, The haunch-bone. 16, The

sacrum.

17, The hip-joint. 18, The thigh-bone. 19, The patella. 20, The knee-joint.

21, The fibula. 22, The tibia. 23, The ankle-joint. 24, The foot. 25, 26, The ligaments of the clavicle, sternum, and ribs. 27, 28, 29, The ligaments of the shoulder, elbow, and wrist. 30, The large artery of the arm. 31, The ligaments of the hip-joint. 32, The large blood-vessels of the thigh. 33, The artery of the leg. 34, 35, 36, The ligaments of the patella, knee, and ankle.Note. Let the pupil, in form of topics, review the anatomy and physiology of the bones from fig. 28, or from anatomical outline plates No. 1 and 2.

CHAPTER VII

HYGIENE OF THE BONES.

129. The bones increase in size and strength by use, while they are weakened by inaction. Exercise favors the deposition of both animal and earthy matter, by increasing the circulation and nutrition in this texture. For this reason, the bones of the laborer are dense and strong, while those who neglect exercise, or are unaccustomed to manual employment, are deficient in size, and have not a due proportion of earthy matter to give them the solidity and strength of the laboring man.