автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу A Practical Treatise on the Manufacture of Perfumery

A PRACTICAL TREATISE

ON THE

MANUFACTURE OF PERFUMERY:

COMPRISING

DIRECTIONS FOR MAKING ALL KINDS OF PERFUMES, SACHET

POWDERS, FUMIGATING MATERIALS, DENTIFRICES,

COSMETICS, ETC., ETC.,

WITH A FULL ACCOUNT OF THE

VOLATILE OILS, BALSAMS, RESINS, AND OTHER NATURAL

AND ARTIFICIAL PERFUME-SUBSTANCES, INCLUDING

THE MANUFACTURE OF FRUIT ETHERS, AND

TESTS OF THEIR PURITY.

BY

Dr. C. DEITE,

Assisted by L. BORCHERT, F. EICHBAUM, E. KUGLER,

H. TOEFFNER, and other experts.

FROM THE GERMAN BY

WILLIAM T. BRANNT,

EDITOR OF "THE TECHNO-CHEMICAL RECEIPT-BOOK."

ILLUSTRATED BY TWENTY-EIGHT ENGRAVINGS.

PHILADELPHIA:

HENRY CAREY BAIRD & CO.,

INDUSTRIAL PUBLISHERS, BOOKSELLERS AND IMPORTERS,

810 WALNUT STREET.

1892.

Copyright by

HENRY CAREY BAIRD & CO.

1892.

Printed at the COLLINS PRINTING HOUSE,

705 Jayne Street,

Philadelphia, U. S. A.

PREFACE.

A translation of the portion of the "Handbuch der Parfümerie-und Toiletteseifenfabrikation," edited by Dr. C. Deite, relating to perfumery and cosmetics, is presented to the English reading public with the full confidence that it will not only fill a useful place in technical literature, but will also prove—for what it is chiefly intended—a ready book of reference and a practical help and guide for the perfumer's laboratory. The names of the editor and his co-workers are a sufficient guaranty of its value and practical usefulness, they all being experienced men, well schooled each in the particular branch of the industry, the treatment of which has been assigned to him.

The most suitable and approved formulæ, tested by experience, have been given; and special attention has been paid to the description of the raw materials, as well as to the various methods of testing them, the latter being of special importance, since in no other industry has the manufacturer to contend with such gross and universal adulteration of raw materials.

It is hoped that the additions made here and there by the translator, as well as the portion relating to the manufacture of "Fruit Ethers," added by him, may contribute to the interest and usefulness of the treatise.

Finally, it remains only to be stated that, with their usual liberality, the publishers have spared no expense in the proper illustration and the mechanical production of the book; and, as is their universal practice, have caused it to be provided with a copious table of contents and a very full index, which will add additional value by rendering any subject in it easy and prompt of reference.

W. T. B.

Philadelphia, May 2, 1892.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER I.

HISTORICAL NOTICE OF PERFUMERY.

PAGEConsumption of perfume-substances by the early nations of the Orient

17Perfume-substances as an offering to the gods and their use for embalming the dead; Arts of the toilet in ancient times

18Perfume-substances used by the Hebrews; Olibanum and the mode of gaining it in ancient times, as described by Herodotus

19Pliny's account of olibanum

20Practice of anointing the entire body customary among the ancients; The holy oil prescribed by Moses; Origin of the sweet-scented ointment "myron"

21Luxurious use of ointments in Athens, and the special ointments used for each part of the body; Introduction of ointments in Rome, and edict prohibiting the sale of foreign ointments; Plutarch on the extravagant use of ointments in Rome

22Ancient books containing directions for preparing ointments; Directions for rose ointment, according to Dioscorides

23Ancient process of distilling volatile oils; Dioscorides's directions for making animal fats suitable for the reception of perfumes; Consumption of perfume-substances by the ancient Romans; Condition of the ancient ointment-makers

24Use of red and white paints, hair-dyes, and depilatories by the Romans

25Peculiar substance for cleansing the teeth used by the Roman ladies; Perfumeries and cosmetics in the Middle Ages; Receipts for cosmetics in the writings of Arabian physicians, and of Guy de Chanlios

26Giovanni Marinello's work on "Cosmetics for Ladies;" Introduction of the arts of the toilet into France, by Catherine de Medici and Margaret of Valois

27Extravagant use of cosmetics in France from the commencement of the seventeenth to the middle of the eighteenth century

28Importance of the perfumer's craft in France; Chief seats of the French perfumery industry

29Privileges of the

parfumeurs-gantiersin France; Use of perfumes in England; Act of Parliament prohibiting the use of perfumeries, false hair, etc., for deceiving a man and inveigling him into matrimony

30 CHAPTER II.

THE PERFUME-MATERIALS FOR THE MANUFACTURE OF PERFUMERY.

Derivation of the perfume-substances; Animal substances used; Occurrence of volatile oils in plants

31Families of plants richest in oil; Central Europe the actual flower garden of the perfumer; Principal localities for the cultivation of plants

32Volatile oils and their properties

33Principal divisions of volatile oils

34Constitution of terpenes; Concentrated volatile oils

35Modes of gaining volatile oils; Expression

36Clarification of the oil

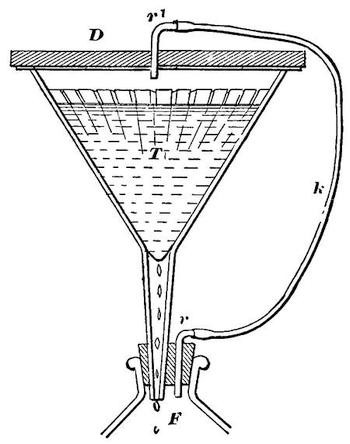

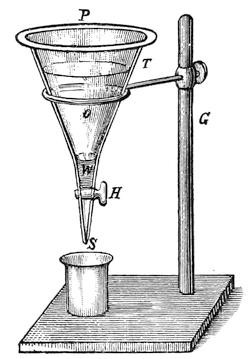

37Filter for clarifying the oil, illustrated and described

38Distillation

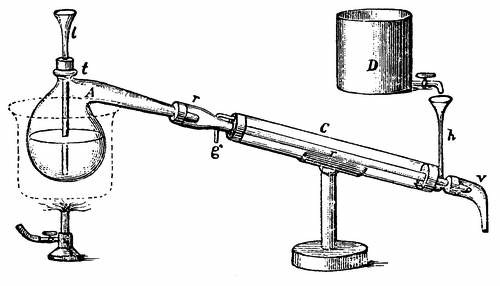

39Apparatus for determining the percentage of volatile oil a vegetable substance will yield, illustrated and described

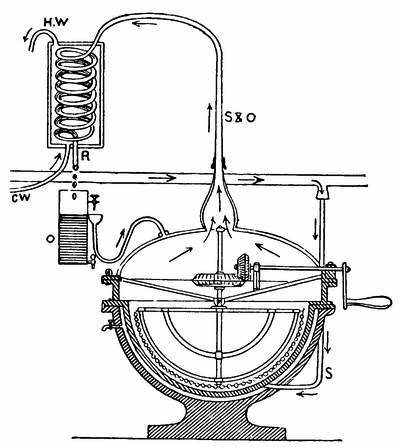

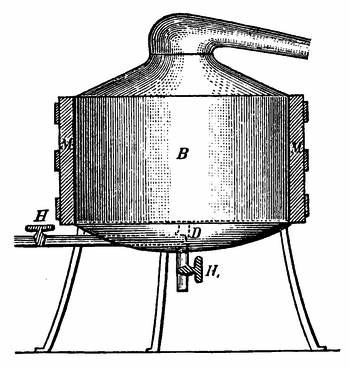

40Various stills for the distillation of volatile oils, illustrated and described

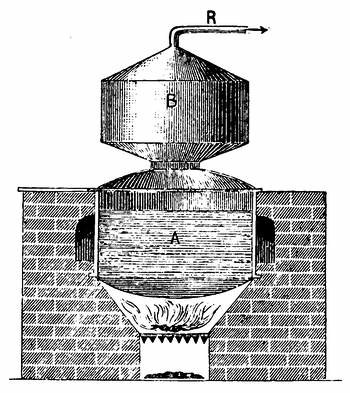

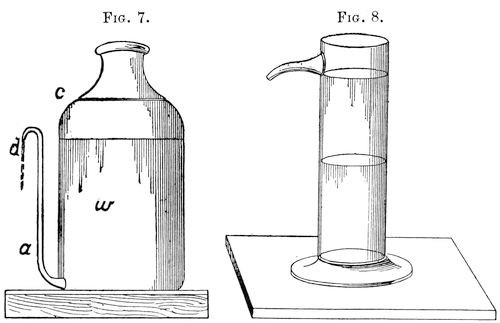

41Distillation of volatile oils by means of hot air; Separation of the oil and water; Florentine flasks, illustrated and described

46Separator-funnel, illustrated and described

47Extraction

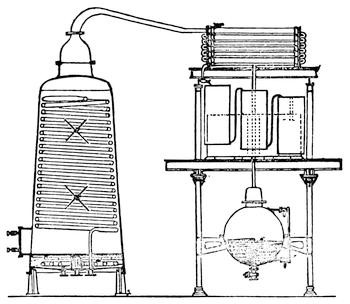

48Various apparatuses for extraction, illustrated and described

49Heyl's distilling apparatus

57Maceration or infusion; Pomades; Purification of the fats used in the maceration process

58 Huiles antiques; Old French process of maceration; Piver's maceration apparatus, illustrated and described

59Flowers for which maceration is employed; Absorption or

enfleurage 60Apparatuses for absorption, illustrated and described

61Flowers for which the absorption process is employed; Storage of volatile oils

65 CHAPTER III.

TESTING VOLATILE OILS.

Extensive adulteration of volatile oils; Testing volatile oils as to odor and taste

66Recognition of an adulteration with fat oil

67Detection of alcohol or spirit of wine; Dragendorff's test

68Hager's tannin test

69Detection of chloroform; Detection of benzine

71Quantitative determination of adulterations with alcohol, chloroform, and benzine

72Detection of adulterations with terpenes or terpene-like fluids

73Detection of adulterations with volatile oils of a lower quality; Test with iodine

74Hoppe's nitroprusside of copper test

75Table showing the behavior of volatile oils free from oxygen towards nitroprusside of copper

76Hager's alcohol and sulphuric acid test; Hager's guaiacum reaction

78Division of the volatile oils with reference to the guaiacum reaction

79Hübl's iodine method

80A. Kremel's test by titration or saponification with alcoholic potash lye

81Utilization of Maumené's test by F. R. Williams

82Planchon's proposed procedure for the recognition of a volatile oil

83 CHAPTER IV.

THE VOLATILE OILS USED IN PERFUMERY.

Acacia oil or oil of cassie; Almond oil (bitter)

87Adulterations of oil of bitter almonds and their detection

90Angelica oil

92Anise-seed oil

93Star anise oil

94Balm oil; Basil oil; Bayberry oil, or oil of bay leaves

96Bergamot oil; Testing bergamot oil as to its purity

97Cajeput oil

98Camomile or chamomile oil; Blue camomile oil; Green camomile oil

99Caraway oil; Recognition of the purity of caraway oil

100Cedar oil; Cherry-laurel oil

101Detection of oil of mirbane in cherry-laurel oil; Cinnamon oils; Ceylon cinnamon oil

102Cassia oil

103Cinnamon-root oil and oil of cinnamon leaves; Quantitative determination of cinnamaldehyde in cassia oil

104Detection of adulterations in cassia oil; Citron oil

106Detection of adulterations in citron oil; Citronella oil; Detection of adulterations in citronella oil

107Oil of cloves

108Test for the value of oil of cloves

109Eucalyptus oil

110Fennel oil

111Geranium oil, palmarosa oil, Turkish geranium oil; East Indian geranium oil; French and African geranium oils

112Adulterations of geranium oils; Jasmine oil, or oil of jessamine

113Juniper oil

114Lavender oil; Spike oil

115Detection of adulterations of lavender oil; Lemon oil; Sponge process of obtaining lemon oil

116Écuelle process

117Distillation; Apparatus combining the écuelle and distilling processes, illustrated and described

118Adulterations of oil of lemons and their detection: Lilac oil; Oil of limes

121Licari oil, linaloë oil; Marjoram oils; Spanish marjoram oil

122Mignonette oil; Myrrh oil

123Nutmeg oils; Mace oil; Adulterations of mace oil and their detection

124Opopanax oil; Orange-peel oil, Portugal oil or essence of Portugal; Mandarin oil

125Orange-flower oil or neroli oil; Neroli Portugal oil; Cultivation of the orange on the French Riviera and yield of orange blossoms; Characteristics of oil of orange flowers

126Adulterations of neroli oil and their detection

127Petit-grain oil; Oil of orris root

129Patchouli oil

130Varieties and characteristics of patchouli oil

131Peppermint oil; Oil of curled mint; Peppermint oil and its varieties

132American oils of peppermint of high reputation; Mode of distinguishing American, German, and English oils of peppermint

133Adulterants of peppermint oil and their detection

134Poley oil

135Pimento oil or oil of allspice; Rose oil or attar of roses; Principal localities of its production; Schimmel & Co.'s, of Leipzic, Germany, experiment to obtain oil from indigenous roses

136The rose-oil industry in Bulgaria; Methods of gathering and distilling the roses

137Characteristics of pure rose oil

138Manner of judging the genuineness of rose oil; Process for the insulation and determination of stearoptene in rose oil

139Adulteration of rose oil with ginger-grass oil

140Test for the adulteration of rose oil with ginger-grass oil employed in Bulgaria

141Adulterants of rose oil

142Tests for rose oil; Approximate quantitative determination of spermaceti in rose oil

143Rosemary oil; Detection of adulterations in rosemary oil

144Rosewood oil or rhodium oil; Sandal-wood oil; Sassafras oil; Characteristics of sassafras oil

145Thyme oil

147Oil of turpentine; Austrian oil of turpentine; German oil of turpentine; French oil of turpentine; Venetian oil of turpentine

148American oil of turpentine; Pine oil; Dwarf pine oil; Krummholz or Latschenoel; Pine-leaf oil; Templin oil (Kienoel); Balsam-pine oil

149Oil of verbena; Oil of violet; Vitivert or vetiver oil

150Wintergreen oil

151Birch oil; Artificial preparation of methyl salicylate

152Adulteration of wintergreen oil and its detection; Ylang-ylang oil

153Cananga oil

154 CHAPTER V.

RESINS AND BALSAMS.

Elementary constituents of resins; Division of resins; Hard resins; Soft resins or balsams; Gum-resins

155Diffusion of resins in the vegetable kingdom; Benzoin

156Varieties of benzoin and their characteristics

157Peru balsam and mode of obtaining it

159White Peru balsam

160Characteristics of Peru balsam

161Adulterants of Peru balsam and their detection

162Tolu balsam and its characteristics

166A new variety of Tolu balsam

167Storax; Liquid storax and its characteristics

168Adulteration of liquid storax and its detection

170Storax in grains; Ordinary storax

171American storax, white Peru balsam, white Indian balsam, or liquid-ambar; Myrrh

172Myrrha electa and its characteristics

173Constitution of myrrh

174Adulteration of myrrh and its detection

175Opopanax; Olibanum or frankincense

176Commercial varieties of olibanum; Sandarac and its characteristics

177 CHAPTER VI.

PERFUME-SUBSTANCES FROM THE ANIMAL KINGDOM.

Musk and its varieties; Musk sacs, illustrated and described

178Characteristics of Tonkin musk

180Musk of the American musk-rat as a substitute for genuine musk

181Other possible substitutes for the musk-deer; Artificial musk

182Adulterations of musk and their detection

183Civet

184Castor and its varieties

185Adulterations of castor; Ambergris

186Constituents of ambergris

187Adulterations of ambergris

188 CHAPTER VII.

ARTIFICIAL PERFUME-MATERIALS.

Conversion of oil of turpentine into oil of lemons by Bouchardat

and Lafont

189Cumarin, its occurrence and properties

190Varieties of tonka beans found in commerce

191Preparation of cumarin from tonka beans; Artificial preparation of cumarin from salicylic acid

192Synthetical preparation of cumarin; Heliotropin or piperonal and its characteristics

193Preparation of heliotropin

194Vanillin; Characteristics of the vanilla

195Artificial preparation of vanillin

196Characteristics of vanillin

197Adulteration of vanillin, and its detection; Nitrobenzol

198Characteristics of nitrobenzol or oil of mirbane; adulteration of nitrobenzol and its detection

199Fruit ethers and their characteristics

200Acetic amyl ether or amyl acetate, its preparation and use; Acetic ether or ethyl acetate and its preparation

201Benzoic ether or ethyl benzoate and its preparation

204Butyric ethyl ether or ethyl butyrate; Preparation of butyric acid

205Preparation of butyric ether

207St. John's bread or carob as material for the preparation of butyric ether

209Formic ethyl ether, or ethyl formate and its preparation

210Nitrous ether or ethyl nitrate and its preparation according to Kopp's method

211Preparation and use of nitrous ether in England and America

212Valerianic amyl ether or amyl valerate and its preparation

214Valerianic ethyl ether; Apple ether; Apricot ether; Cherry ether; Pear ether; Pineapple ether; Strawberry ether; Preparation of fruit essences; Apple essence; Apricot essence

216Cherry essence; Currant essence; Grape essence; Lemon essence; Melon essence; Orange essence; Peach essence; Pear essence; Pineapple essence; Plum essence

217Raspberry essence; Strawberry essence

218 CHAPTER VIII.

ALCOHOLIC PERFUMES.

Division of alcoholic perfumes; What constitutes the art of the perfumer; Qualities of flower-pomades and their designation

219Storage of flower-pomades; Extraction of flower-pomades

220Apparatus for making alcoholic extracts from flower-pomades, illustrated and described

221Beyer frères improved apparatus, illustrated and described

223Tinctures and extracts and their preparation

225Beyer frères apparatus for the preparation of tinctures, illustrated and described

226Musk tincture; Civet tincture

228Ambergris tincture; Castor tincture; Benzoin tincture; Peru balsam tincture; Tolu balsam tincture

229Olibanum tincture; Opopanax tincture; Storax tincture; Myrrh tincture; Musk-seed or abelmosk tincture

230Angelica root tincture; Orris-root tincture; Musk-root or sumbul-root tincture; Tonka-bean tincture

231Cumarin tincture; Heliotropin tincture; Vanilla tincture; Vanillin tincture

232Vitivert tincture; Juniper-berry tincture; Patchouli extract

233Tinctures from volatile oils; Almond-oil (bitter) tincture; Balm-oil tincture; Bergamot-oil tincture; Canango-oil tincture

234Cassia-oil tincture; Cedar-oil tincture; Cinnamon-oil tincture; Citronella-oil tincture; Clove-oil tincture; Eucalyptus-oil tincture; Geranium-oil tincture; Lavender-oil tincture; Lemon-grass-oil tincture; Lemon-oil tincture; Licari-oil tincture; Myrrh-oil tincture; Neroli-oil tincture; Opopanax-oil tincture; Orris-root-oil tincture; Patchouli-oil tincture

235Petit-grain-oil tincture; Pine-leaf-oil tincture; Portugal-oil tincture; Sandal-wood-oil tincture; Verbena-oil tincture; Vitivert-oil tincture; Wintergreen-oil tincture; Ylang-ylang-oil tincture; Rose-oil tincture

236Extraits aux fleurs; Extrait acacia; Extrait cassie; Extrait héliotrope; Extrait jacinthe

237Extrait jasmin; Essence of the odor of linden blossoms; Extrait jonquille; Extrait magnolia; Extrait muguet (lily of the valley); Extrait fleurs de Mai (May flowers)

238Extrait ixora; Extrait orange; Extrait white rose; Extrait rose v. d. centifolie; Extrait violette; Coloring substance for extraits; Extrait de violette de Parme

239Extrait tubereuse; Extrait réséda; Extrait ylang-ylang; Compound odors (bouquets); Extrait Edelweiss; Extrait ess-bouquet

240Extrait spring flower; Extrait bouquet Eugenie; Extrait excelsior; Extrait Frangipani; Extrait jockey club

241Extrait opopanax; Extrait patchouli; Extrait millefleurs; Extrait bouquet Victoria

242Extrait kiss-me-quick; Extrait mogadore; Extrait bouquet Prince Albert; Extrait muse; Extrait new-mown hay; Extrait chypre

243Extrait maréchal; Extrait mousseline; Extraits triple concentrés and their preparations

244Concentrated flower-extract for the preparation of extraits d'Odeurs; Extraits d'Odeurs, quality II

245Extrait violette II; Extrait rose II; Extrait réséda II; Extrait ylang-ylang II

246Extrait new-mown hay II; Extrait chypre II; Extrait ess-bouquet II

247Extrait muguet II; Extrait bouquet Victoria II; Extrait spring flower II; Extrait ixora II

248Extrait Frangipani II; Cologne water (eau de Cologne) and its preparation

249Durability of the volatile oils used in the preparation of Cologne water

250Cologne water, quality I

252Cologne water, quality II; Cologne water, quality III; Cologne water, quality IV; Cologne water, quality V

253Maiglöckchen eau de Cologne; Various other receipts for Cologne water

254Eau de Lavande; Eau de vie de Lavande double ambrée; Eau de Lavande double; Aqua mellis; Eau de Lisbonne

255 CHAPTER IX.

DRY PERFUMES.

Use of dry perfumes in ancient times; Sachet powders and their preparation

256Sachet à la rose; Sachet à la violette; Hliotrope sachet powder; Ylang-ylang sachet powder; Jockey club sachet

257Sachet aux millefleurs; Lily of the valley sachet powder; Patchouli sachet powder; Frangipani sachet powder; Victoria sachet powder; Réséda sachet powder

258Musk sachet powder; Ess-bouquet sachet powder; New-mown hay sachet powder; Orange sachet powder; Solid perfumes with paraffine; White rose

259Ess-bouquet; Lavender odor; Eau de Cologne; Smelling salts; Preston salt and "menthol pungent" as prepared by William W. Bartlett; White smelling salt

260 CHAPTER X.

FUMIGATING ESSENCES, PASTILLES, POWDERS, ETC.

Constitution of fumigating agents; Object of fumigating;

Prejudice against fumigating; Mode of fumigating

262Atomizers; Objections to dry fumigating agents

263Fumigating essences and vinegars; Rose-flower fumigating essence; Flower fumigating essence—héliotrope

264Violet-flower fumigating essence; Oriental flower fumigating essence; Pine odor (for atomizing); Juniper odor; fumigating balsam

265Fumigating water; Fumigating vinegar; Fumigating powders; Ordinary fumigating powder

266Rose fumigating powder; Violet fumigating powder; Orange fumigating powder; New-mown hay fumigating powder

267Fumigating paper; Fumigating pastilles

268Ordinary red fumigating pastilles; Ordinary black fumigating pastilles; Musk fumigating pastilles

269Rose fumigating pastilles; Violet fumigating pastilles; Millefleurs fumigating pastilles; Fumigating lacquer

270 CHAPTER XI.

DENTIFRICES, MOUTH-WATERS, ETC.

Selection of materials for and compounding of dentifrices

272Soap as a constituent of dentifrices; Value of thymol for dentifrices; Object of glycerin in dentifrices

273Tooth and mouth waters; Thymol tooth-water; Eau dentifrice Botot; Eau dentifrice Orientale

274Violet mouth-water; Antiseptic gargle; Odontine; Sozodont; Eau de Botot (improved)

275Quinine tooth-water; Dr. Stahl's tooth-tincture; Esprit de menthe; Arnica tooth-tincture; Myrrh tooth-tincture

276Tooth-pastes and tooth-powders; tooth-paste or odontine

277Thymol tooth-paste; Cherry tooth-paste; Non-fermenting cherry tooth-paste; Odontine paste

278Thymol tooth-powder; Poudre dentifrice; Violet tooth-powder

279Dr. Hufeland's tooth-powder; White tooth-powder; Black tooth-powder; Poudre de corail; Camphor tooth-powder; Opiat liquide pour les dents

280Poudre d'Algérine

281Dr. Hufeland's tooth-soap

282Tooth-soap; Saponaceous tooth-wash

283 CHAPTER XII.

HAIR POMADES, HAIR OILS, AND HAIR TONICS; HAIR DYES AND DEPILATORIES.

Fats used for the preparation of pomades; Reputation of some fats as hair pomades

284Pomades and their preparation; Purification of the fat

285Substances used for coloring pomades; Fine French pomades (flower-pomades); Maceration or extraction of the flowers

286Receipts for some flower-pomades; Pommade à la rose; Pommade à l'acacia; Pommade à la fleur d'orange; Pommade à l'héliotrope

287Pomades according to the German method and their preparation; Foundations for white pomades

288Apple pomade; Bear's grease pomade; Quinine pomades

289Quinine pomades (imitation); Benzoin pomade; Densdorf pomade; Ice pomades; Family pomades

290Strawberry pomade; Fine hair pomade; Pomade for promoting the growth of the hair; Héliotrope pomades

291Jasmine pomade; Emperor pomade; Macassar pomade; Portugal pomade; Herb pomade; Lanolin pomade

292Oriental pomade; Paraffin ice pomade; Neroli pomade; Cheap pomade (red, yellow, white); Mignonette pomade; Castor oil pomades; Princess pomade

293Fine pomade; Beef-marrow pomade; Rogers's pomade for producing a beard; Rose pomade; Fine rose pomade; Finest rose pomade; Salicylic pomade; Victoria pomade; Tonka pomade

294Fine vanilla pomade; Vanilla pomade; Violet pomade; Walnut pomade; Vaseline pomades

295Foundations for vaseline pomades; Bouquet vaseline pomade; Family vaseline pomade; Lily of the valley vaseline pomade; Neroli vaseline pomade

296Mignonette vaseline pomade; Portugal vaseline pomade; Rose vaseline pomades; Fine vaseline pomade (yellow); Vaseline pomade (red); Vaseline pomade (white); Virginia vaseline pomade; Victoria vaseline pomade

297Extra fine vaseline pomade; Stick pomades; Foundations for stick pomades; Manufacture of stick pomades

298Rose-wax pomade; Black-wax pomade; Blonde-wax pomade; Brown-wax pomade

299Cheap wax pomades; Resin pomades; Hair oils; Huiles antiques; Vaseline oil for hair oils; Treatment of oils with benzoin

300Preparation of huiles antiques; Huile antique à la rose; Huile antique au jasmin; Alpine herb oil; Flower hair oil; Peruvian bark hair oil

301Peru hair oil; Burdock root hair oils; Macassar hair oils; Neroli hair oil; Mignonette hair oils; Fine hair oil

302Cheap hair oil (red or yellow); Portugal hair oil; Jasmine hair oil; Vaseline hair oils; Vanilla hair oil; Ylang-ylang hair oil; Philocome hair oil

303Sultana hair oil; Rose hair oil; Tonka hair oil; Violet hair oil; Victoria hair oil; Cheap hair oils; Bandolines and their preparation

304Rose bandoline; Almond bandoline; Brilliantine

305Flower brilliantine No. 1; Brilliantine No. 2

306Brilliantine No. 3; Various formulas for brilliantine

307Hair tonics; Eau Athénienne; Florida water

308Eau de Cologne hair tonic; Eau de quinine

309Eau de quinine (imitation); Honey water; Glycerin hair tonic; Eau lustral (hair restorative); Tea hair tonic

310Locock's lotion for the hair; Shampoo lotion; Shampoo liquid

311Dandruff cures; Dandruff lotion; Bay rum

312Directions for preparing bay rum

313Hair dyes; Requirements of a good hair dye; Gradual darkening of the hair; Use of dilute acids for making the hair lighter

314Use of lead salts, nitrate of silver, and copper salts for dyeing the hair

315Iron salts for dying the hair; Rastikopetra, a Turkish hair dye; Use of potassium permanganate and pyrogallic acid for dyeing the hair

316Kohol, an Egyptian hair dye; The use of henna as a hair dye; Process of coloring hair, dyed red with henna, black

317Use of the juice of green walnut shells for coloring the hair; Bleaching the hair with peroxide of hydrogen; Formulæ for hair dyes

318Single hair dyes; Teinture Orientale (Karsi); Teinture Chinoise (Kohol)

319Potassium permanganate hair dye; Bismuth hair dye; Walnut hair dye; Pyrogallic hair stain

320Double hair dyes; For dyeing brown; For dyeing black; Tannin hair dye

321Melanogène; Eau d'Afrique; Krinochrom; Copper hair dye; Depilatories; Rhusma

322Boettger's depilatory; Bartholow's depilatory

323 CHAPTER XIII.

COSMETICS.

Skin cosmetics; Toilet vinegars; Vinaigre de Bully; Vinaigre de toilette à la rose; Vinaigre de toilette à la violette

324Vinaigre de toilette héliotrope; Vinaigre de toilette orange; Vinaigre de toilette; Aromatic vinegar; English aromatic vinegar

325Toilet vinegar; Washes; Virginal milk (Lait virginal); Rose milk (Lait de rose)

326Almond milk (Lait d'amandes amères)

327Lily milk (Lait de lys); Perfumed glycerin with rose odor; Perfumed glycerin with fruit odor; Perfumed meals and pastes; Farin de noisette (nut meal)

328Farin d'amandes amères (almond meal); Pate d'amandes au miel (honey almond paste); Poudre de riz à la rose

329Poudre de riz héliotrope; Poudre de riz orange; Poudre de riz muguet

330Poudre de riz ixora; Poudre de riz bouquet; Cold creams and lip salves; Cold cream; Vaseline cold cream

331Glycerin cream; Crême de concombre; Glycerin gelée; Glycerin jelly

332Cream of roses; Boroglycerin cream; Récamier cream; Preparations for chapped hands

333Wash for the hands; Nail powder; Lip-salves

334Paints; Pulverulent paints (powders); "Blanc fard" or "Blanc français"

335Mixtures for powders; Coloring substances for powders; Powder for coloring intensely red; Solid paints; Ordinary red paint (rouge)

336Fine red paint (rouge); White paint; Preparation of paints

337Red stick-paint (stick rouge); Moulding the rouge into sticks

339White stick-paint; Rouge en feuilles; Liquid paints; Liquid rouge

340White liquid paint; Fat paints

341Crême de Lys; Crême de rose

342 Index 343A PRACTICAL TREATISE

ON THE

MANUFACTURE OF PERFUMERY.

Since fragrant odors were agreeable to human beings, it was believed that they must be welcome also to the gods, and, to honor them, perfume substances were burned upon the altars. Besides, as an offering to the gods, perfume substances were extensively used by many nations, especially by the Egyptians, for embalming the dead, the process employed by the latter having been transmitted to us by the ancient authors Herodotus and Diodorus.

Furthermore, a desire for ornamentation and to give to the face and body as pleasing an appearance as possible, is common to all mankind. To be sure, the ideas of what constitutes beauty in this respect have varied at different times and among the various nations. But, independent of the savage races, who consider painting and tattooing the body and face an embellishment, and taking into consideration only the earliest civilized nations, it is astonishing how many arts of the toilet have been preserved from the most ancient historical times up to the present. "In the most ancient historical times, people perfumed and painted, frizzed, curled, and dyed the hair as at present, and, in fact, the same cosmetics, only slightly augmented, which were in use hundreds, nay, thousands, of years ago are still employed to-day."[1] It is especially woman, who everywhere exercises the arts of the toilet, while, with the exception of perfumes and agents for the hair, man is but seldom referred to as making use of cosmetics. The young girls of ancient Egypt used red and white paints, colored their pale lips, and anointed their hair with sweet-scented oils; they dyed their eyelashes and eyelids black to impart a brighter lustre to the glance of the eye, and the mother of the wife of the first king of Egypt is said to have already composed a receipt for a hair-dye.

In ancient times olibanum was, without doubt, the most important perfume-substance. It was introduced into commerce by the Phoenicians, and, like many other substances, it received from them its name, which was adopted by other nations. Thus, the Hebrews called the tree lebonah, the Arabs, lubah, while the Greeks named it, λιβανός and the resin derived from it, the celebrated frankincense of the ancients, λιβανωτόςτς, Latin, olibanum. Regarding the mode of gaining the olibanum, some curious ideas prevailed in ancient times. Thus, Herodotus writes: "Arabia is the only country in which olibanum grows, as well as myrrh, cassia, cinnamon and lederum. With the exception of myrrh, the Arabs encounter many difficulties in procuring these products. Olibanum they obtain by burning styrax, for every olibanum tree is guarded by a number of small-sized winged serpents of a variegated appearance, which can be driven away by nothing but styrax vapors." According to Pliny, who gives a very full account of olibanum, Arabia felix received its by-name from the abundance of olibanum and myrrh found there. He states that olibanum grows in no other country besides Arabia, but it is not found in every part of it. About in the centre, upon a high mountain, he continues, is the country of the Atramites, a province of the Sabeans, from which the olibanum region is distant about eight days' journey. It is called Saba and is everywhere rendered inaccessible by mountains, a narrow defile, through which the export is carried on, leading into an adjoining province inhabited by the Mineans. In Saba itself were not more than 300 families, called the saints, who claimed the cultivation of olibanum as a right of heritage. When making the incisions in the trees, and while gathering the olibanum, the men were prohibited from having intercourse with women and from attending funerals. Notwithstanding the fact that the Romans carried on war in Arabia, none of them had ever seen an olibanum tree. When there was less chance of selling the olibanum, it was gathered but once in the year, but since the increase in the demand, it was gathered twice, first in the fall and again in the spring, the incisions in the trees having been made during the winter. The collected olibanum was brought upon camels to Sabota, where one gate was open for its reception; to turn from the road was prohibited under penalty of death. The priests took one-tenth by measure for the god Sabin, sales not being allowed until their claim was satisfied. The olibanum could be exported only through the territory of the Gebanites, whose King also levied tribute.

In ancient times olibanum was, without doubt, the most important perfume-substance. It was introduced into commerce by the Phoenicians, and, like many other substances, it received from them its name, which was adopted by other nations. Thus, the Hebrews called the tree lebonah, the Arabs, lubah, while the Greeks named it, λιβανός and the resin derived from it, the celebrated frankincense of the ancients, λιβανωτόςτς, Latin, olibanum. Regarding the mode of gaining the olibanum, some curious ideas prevailed in ancient times. Thus, Herodotus writes: "Arabia is the only country in which olibanum grows, as well as myrrh, cassia, cinnamon and lederum. With the exception of myrrh, the Arabs encounter many difficulties in procuring these products. Olibanum they obtain by burning styrax, for every olibanum tree is guarded by a number of small-sized winged serpents of a variegated appearance, which can be driven away by nothing but styrax vapors." According to Pliny, who gives a very full account of olibanum, Arabia felix received its by-name from the abundance of olibanum and myrrh found there. He states that olibanum grows in no other country besides Arabia, but it is not found in every part of it. About in the centre, upon a high mountain, he continues, is the country of the Atramites, a province of the Sabeans, from which the olibanum region is distant about eight days' journey. It is called Saba and is everywhere rendered inaccessible by mountains, a narrow defile, through which the export is carried on, leading into an adjoining province inhabited by the Mineans. In Saba itself were not more than 300 families, called the saints, who claimed the cultivation of olibanum as a right of heritage. When making the incisions in the trees, and while gathering the olibanum, the men were prohibited from having intercourse with women and from attending funerals. Notwithstanding the fact that the Romans carried on war in Arabia, none of them had ever seen an olibanum tree. When there was less chance of selling the olibanum, it was gathered but once in the year, but since the increase in the demand, it was gathered twice, first in the fall and again in the spring, the incisions in the trees having been made during the winter. The collected olibanum was brought upon camels to Sabota, where one gate was open for its reception; to turn from the road was prohibited under penalty of death. The priests took one-tenth by measure for the god Sabin, sales not being allowed until their claim was satisfied. The olibanum could be exported only through the territory of the Gebanites, whose King also levied tribute.

By the addition of fragrant substances to the oil, the sweet-scented ointment, myron, originated. While the anointing with simple oil evidently served as a hygienic measure after the bath, and especially for men in the gymnasium, and before a combat, with the Greeks, ointments were an article of luxury. In Socrates' time the use of sweet-scented ointments had reached such an extent, that Xenophon caused him to speak against it, but, as is the case with all such lectures against fashion, without the slightest success. In Athens the luxury was carried so far that the bacchanalians anointed each part of their body with a special ointment. The oil extracted from the palm was thought best adapted to the cheeks and the breasts; the arms were refreshed with balsam-mint; sweet marjoram supplied an oil for the hair and eyebrows; and wild thyme for the knee and neck. Although to us it would be repugnant to have the entire body anointed, in Athens it was considered beautiful to be glossy with ointments. It is said of Demetrius Phalereus, that in order to appear more captivating, he dyed his hair yellow, and anointed the face and the rest of his body.

From the Asiatics and Greeks the Romans also learned the use of ointments. Pliny cannot say at what time they were introduced in Rome, but states that after the conquest of Asia and the defeat of the King, Antiochus, in the year 565, after the building of Rome, the censors issued an edict prohibiting the sale of foreign ointments. However, this edict was of no use, and the practice spread more and more, Pliny speaking very bitterly about it. Regarding this extravagance in ointments, Plutarch says: "Frankincense, cinnamon, spikenard, and Arabian calamus are mixed together with the most careful art and sold for large sums. It is an effeminate pleasure and has spoiled not only the women but also the men, who will not sleep even with their own wives if they do not smell of ointments and powders." Plutarch further mentions an incident which must have created a sensation even in luxurious Rome, as otherwise it would scarcely have been chronicled for the benefit of posterity. Nero one day anointed himself with costly ointments and scattered some of them over Otho. The next day Otho gave Nero a banquet, and laid in all directions gold and silver tubes, which poured forth expensive ointments like water, thoroughly saturating the guests.

Directions for preparing ointments are contained in Theophrastus's work "On Perfumes," in Dioscorides's "Medica materia," and Pliny's "Historia naturalis." Dioscorides's receipts are the fullest. According to Pliny, a distinction was made between the juice and the body, the latter consisting of the fat oils and the former of the sweet-scented substances. In preparing the ointments, the oil together with the perfuming substances were heated in the water-bath. For instance, rose ointment was, according to Dioscorides, prepared by mixing 5½ lbs. of bruised Andropogon Schœnanthus with a little water, then adding 20½ lbs. of oil and heating. After heating the oil was filtered off, and the petals of one thousand roses were thrown into the oil, the hands with which the rose leaves were pressed into the oil being previously coated with honey. When the whole had stood for one night, the oil was strained off and when all impurities had settled, it was brought into another vessel and fresh rose leaves introduced, the operation being several times repeated. However, according to the opinion of the ancient ointment makers, no more odor was absorbed by the oil after the seventh introduction of rose leaves. To fix the odor, resins or gums were added to the ointments.

The consumption of perfume-substances by the ancient Romans must have been enormous. The trade of the ointment makers (ungentarii) was so extensive that the large street Seplasia in old Capua was entirely taken up by it, and the business must have paid well since the prices realized were very high. However, in ancient times the business cannot have been very agreeable, at least not in Greece, as shown by a passage in Plutarch's Life of Pericles: "We take pleasure in ointments and purple, but consider the dyers and ointment makers bondsmen and mechanics."

Depilatories were also known to the Romans, the agents employed being called psilothrum and dropax. They were of vegetable origin, but it is not exactly known from which plants they were derived.

We know but little regarding the use of perfumeries and cosmetics in the Middle Ages. In the wars during the migrations of the nations, but little thought was very likely given to them, but as soon as the nations became again settled and made sufficient progress in culture, the taste for perfumes and other pleasures of life no doubt returned. Our knowledge in this respect is limited to what is contained in the works of physicians of the first centuries. Later on we find receipts for cosmetics in the writings of Arabian physicians, such as Rhazes (end of the 9th to the commencement of the 10th century), Avicenna (end of the 10th to the commencement of the 11th century), and Mesuë (11th century). To the 11th century also belong the works of the celebrated Trotula, "De mulierum passionibus," "Practica Trotulae mulieris Salernitanae de curis mulierum," and "Trotula in utilitatem mulierum," all of which contain receipts for cosmetics. In the 14th century the most celebrated surgeon of the Middle Ages, Guy de Chanlios, did not consider it beneath his dignity to devote a section of his "Grande Chirurgie" to cosmetics. However, it was only in the 16th century that perfumes and cosmetics came again into prominent notice in Italy, which at that time was the country of luxury and art. Giovanni Marinello,[2] a physician, in 1562 wrote a work on "Cosmetics for Ladies," which he dedicated to the ladies Victoria and Isabella Palavicini. In the preface the author expresses the opinion that it is only right and pleasing to God to place the gifts bestowed by him in a proper light and to heighten them. He then proceeds to give perfumes for various purposes, aromatic baths to keep the skin young and fresh, means for increasing the stoutness of the entire body and of separate limbs, and others for reducing them. He further recommends certain remedies for making large eyes small, and small ones large. The chapter on the hair is very fully treated. To prevent the hair from coming out, rubbing with oil, and then washing with sorrel and myrobalan is recommended. For promoting the growth of the hair, the use of dried frogs, lizards, etc., rubbed to a powder, is prescribed. Means for making the hair long and soft and curly are also given, and others recommended for eyebrows and eyelashes. As depilatories lime and orpiment are prescribed. Paints are also classed among general cosmetics. Their use became at this time more and more fashionable, and not only the face, but also the breast and neck were painted.

Catherine of Medici and Margaret of Valois introduced these arts of the toilet into France. That country soon became the leader in this respect, and for many years the greatest luxury in perfumes and cosmetics prevailed there. The golden age for these articles lasted from the commencement of the seventeenth to the middle of the eighteenth century, during which time the mouche or beauty patch also flourished. "There were at that time hundreds of pastes, essences, cosmetics, a white balsam, a water to make the face red, another to make a coarse complexion delicate, one to preserve the fine complexion of lean persons and again one to make the face like that of a twenty-year old girl, an Eau pour nourir et laver les teints corrodés and Eau de chair admirable pour teints jaunes et bilieux, etc. Then there were Mouchoirs de Venus, further bands impregnated with wax to cleanse and smooth the forehead; gold leaf was even heated in a lemon over a fire in order to obtain a means which should impart to the face a supernatural brightness. For the hair, teeth and nails there were innumerable receipts, ointments, etc. However, of special importance were the paints, chemical white, blue for the veins, but, chief of all, the red or rouge, mineral, vegetable, or cochineal. The application of rouge was at that time no small affair, it was not only to be rouged, but the rouge had also to express something—Le grand point est d'avoir un rouge qui dise quelque chose. The rouge had to characterize its wearer; a lady of rank did not wear the rouge like a lady of the court, and the rouge of the wife of the bourgeois was not like either of them nor like that of the courtesan. At court a more intense rouge was worn, the intensity of which was still increased on the day of presentation, it being then Rouge d'Espagne and Rouge de Portugal en tasse. It may seem incredible, but for eight days a violet paint was used and then for a change Rouge de Serkis. Ladies, when retiring for the night applied a light rouge (un demi rouge), and even small girls wore rouge, such being the decree of fashion. The ladies dyed their eyebrows and eyelashes, and powdered their hair, both natural and false, for, about 1750, they commenced wearing wigs and chignons. Powdering was done partially for the purpose of dying the hair after dressing, and partially for decoration; white, gray, red and fiery red powders were in vogue."

Catherine of Medici and Margaret of Valois introduced these arts of the toilet into France. That country soon became the leader in this respect, and for many years the greatest luxury in perfumes and cosmetics prevailed there. The golden age for these articles lasted from the commencement of the seventeenth to the middle of the eighteenth century, during which time the mouche or beauty patch also flourished. "There were at that time hundreds of pastes, essences, cosmetics, a white balsam, a water to make the face red, another to make a coarse complexion delicate, one to preserve the fine complexion of lean persons and again one to make the face like that of a twenty-year old girl, an Eau pour nourir et laver les teints corrodés and Eau de chair admirable pour teints jaunes et bilieux, etc. Then there were Mouchoirs de Venus, further bands impregnated with wax to cleanse and smooth the forehead; gold leaf was even heated in a lemon over a fire in order to obtain a means which should impart to the face a supernatural brightness. For the hair, teeth and nails there were innumerable receipts, ointments, etc. However, of special importance were the paints, chemical white, blue for the veins, but, chief of all, the red or rouge, mineral, vegetable, or cochineal. The application of rouge was at that time no small affair, it was not only to be rouged, but the rouge had also to express something—Le grand point est d'avoir un rouge qui dise quelque chose. The rouge had to characterize its wearer; a lady of rank did not wear the rouge like a lady of the court, and the rouge of the wife of the bourgeois was not like either of them nor like that of the courtesan. At court a more intense rouge was worn, the intensity of which was still increased on the day of presentation, it being then Rouge d'Espagne and Rouge de Portugal en tasse. It may seem incredible, but for eight days a violet paint was used and then for a change Rouge de Serkis. Ladies, when retiring for the night applied a light rouge (un demi rouge), and even small girls wore rouge, such being the decree of fashion. The ladies dyed their eyebrows and eyelashes, and powdered their hair, both natural and false, for, about 1750, they commenced wearing wigs and chignons. Powdering was done partially for the purpose of dying the hair after dressing, and partially for decoration; white, gray, red and fiery red powders were in vogue."

Philip Augustus, in 1190, granted a charter to the French perfumers, who had formed a guild. This charter was, in 1357, confirmed by John, and in 1582 by Henry III., and remained in force until 1636. The importance of the craft in France is shown by the fact that under Colbert the perfumers or "parfumeurs-gantiers," as they were called, were granted patents which were registered in Parliament. In the seventeenth century Montpellier was the chief seat of the French perfumery industry; to-day it is Paris, and over fifty millions of francs' worth of perfumery are annually sold there. The parfumeurs-gantiers had the privilege of selling gloves of all possible kinds of material, as well as the leather required for them; they had the further privilege of perfuming gloves and selling all kinds of perfumes. Perfumed leather for gloves, purses, etc., was at that time imported from Spain. This leather was very expensive and fashionable, but on account of its penetrating odor its use for gloves was finally abandoned.

From the strength of the odor of a plant no conclusion can be drawn as to the quantity of volatile oil present. If this were the case, the hyacinth, for instance, would contain more oil than the coniferae, whilst in fact it contains so little that it can be separated only with the greatest difficulty. The odor does not depend on the quantity, but on the quality of the oil; a plant may diffuse but little odor and still contain much volatile oil. Of the various families of plants, the labiatae, umbelliferae, and coniferae are richest in volatile oils.

In every climate plants diffuse odor, those growing in tropical latitudes being more prolific in this respect than the plants of colder regions, which, however, yield the most delicate perfume. Although the East Indies, Ceylon, Peru, and Mexico afford some of the choicest perfumes, Central Europe is the actual flower garden of the perfumer, Grasse, Cannes, and Nice being the principal places for the production of perfume-materials. Thanks to the geographical position of these places, the cultivator, within a comparatively narrow space, has at his disposal various climates suitable for the most perfect development of the plants. The Acacia Farnesiana grows on the seashore, without having to fear frost, which in one night might destroy the entire crop, while at the foot of the Alps, on Mount Esteral, the violet diffuses a much sweeter odor than in the hotter regions, where the olive and the tuberose reach perfect bloom. England asserts its superiority in oils of lavender and peppermint. The volatile oils obtained from plants cultivated in Mitcham and Hitchin command a considerably higher price than those from other localities, this preference being justified only by the delicacy of their perfume. Cannes is best suited for roses, acacias, jasmine, and neroli, while in Nimes, thyme, rosemary, and lavender are chiefly cultivated. Nice is celebrated for its violets, while Sicily furnishes the lemon and orange, and Italy the iris and bergamotte.

Volatile Oils.—The volatile oils are either fluid (actual volatile oils) or solid (varieties of camphor) or solutions of solid combinations in fluid. The latter, on exposure to low temperatures, separate into two portions, one solid, called stearoptene, and the other liquid, called elæoptene. The boiling point of the volatile oils is considerably higher than that of water, but when heated with water they pass over with the vapors. Upon paper, fluid volatile oils produce grease spots, which differ, however, from those caused by fat oils in that they gradually disappear at an ordinary temperature, and rapidly by gentle heating. Most volatile oils are insoluble, or only with difficulty and sparingly soluble, in water, but they impart to the latter their odor and taste. They are readily soluble in alcohol, ether, chloroform, bisulphide of carbon and petroleum-ether, and miscible in every proportion with fats and fat oils. By their solubility in alcohol they differ from most fat oils. When freshly prepared many volatile oils are colorless, but soon turn yellow; some, however, show a distinct color even when fresh. They ignite with greater ease than fat oils and burn with a fierce smoky flame depositing a large amount of carbon. They exhibit a great tendency to absorb oxygen from the air and to gum, the influence of light promoting the process. In specific gravity they range from about 0.75 to 1.17, most of them being specifically lighter than water. Most bodies, under otherwise equal conditions, show always exactly the same specific gravity, the variations being so slight that they may be justly ascribed to errors of observation. However, one and the same volatile oil frequently shows such variations in specific gravity, that we are forced to ascribe this phenomenon to alterations in the constitution of the oil itself. For the exact determination of the specific gravity of a volatile oil, it should, therefore, be subjected to examination immediately after its preparation from the plant or vegetable substance, which should be as fresh as possible. The influence of light upon volatile oils is best shown by the following interesting experiment: If certain volatile oils are distilled in a vacuum or over burnt lime in a current of carbonic acid, it is no longer possible to distinguish, for instance, oil of lemon from oil of turpentine; however, by again exposing the oils to the air, they reacquire their characteristic odor.

On account of the facility with which most of the volatile oils absorb oxygen, oils originally free from oxygen are frequently a mixture of hydrocarbons and combinations containing oxygen. The volatile oils varying so much in their physical as well as their chemical properties, a suitable classification of them has thus far been unsuccessful.

All the terpenes occurring in the various oils are combinations having the formula C10H16, or polymeric with it, C15H24, C20H32, etc. These terpenes exhibiting certain deviations in regard to their properties, odor, specific gravity, and boiling points, nearly as many terpenes as there are volatile oils have been distinguished. It is, however, very likely that these deviations may be traced back to fortuitous circumstances, for example, to the admixture of foreign substances occurring together with the terpenes, and that, by a more accurate examination, the number of terpenes entitled to be considered pure chemical combinations will be considerably reduced. By Wallach's labors, the identity of several terpenes formerly considered distinct, has already been established, whilst many others have been found to possess properties in common.

By expression a turbid milky fluid is obtained, which consists of the volatile oil and aqueous substances. The latter are a solution of various extractive substances and salts in water. This fluid, as it runs from the press, is received in tall, narrow, glass vessels and brought into a cool place for clarification. This frequently requires several days, three distinct layers being generally distinguished. On the bottom is a mucous layer consisting of cell substances carried along by the liquid bodies. Over this is a clear fluid consisting of a solution of extractive substances, vegetable albumen, and salts, and upon this floats the volatile oil, being specifically the lightest body, which, by its greater refractive power, can be clearly distinguished from the aqueous fluid.

There are two methods of obtaining the oil entirely clear, viz., filtration and distillation. Filtration is the cheaper process, but requires special precautions to exclude the air as much as possible to prevent the oil from undergoing injurious changes. By arranging the filtering apparatus so that the oil always comes in contact with only the same quantity of air, the injurious action of the oxygen is reduced to a minimum. It is self-evident that the apparatus should not be placed in the sun, but in a semi-dark, cool place.

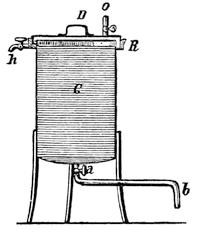

A filter of simple construction, and performing excellent service, is shown in Fig. 1. It consists of a large glass bottle, F, hermetically closed by a doubly-perforated cork. The neck of the glass funnel T, the upper rim of which is ground smooth, is placed in one of the holes, and a glass tube, r, bent at a right angle, is fitted into the second hole. A thick wooden lid, with a rubber ring on the lower side, is placed upon the funnel, thus closing it air-tight. In the centre of the lid is fitted a glass tube, r´, also bent at a right angle, which is connected with the tube r, by a rubber hose, k. After the funnel has been provided with filtering paper and the oil to be filtered, the lid is placed upon it, and must not be removed, except for the purpose of pouring more oil into the funnel. The air in the bottle F is displaced by the oil dropping into it, and escapes through r, k and r´ into the funnel, and thus only the air in the bottle and funnel can act upon the oil.

Distillation.—There are at present two methods in use. The one is founded upon the direct action of the heat, the other upon the use of steam. The first was formerly in general practice, and is still largely employed in France and England, and to a limited extent in this country. It is, however, very deficient in many respects. As the stills must necessarily be of small capacity, only small quantities can be distilled at one time, and the oils very rarely possess the peculiar odor due to them, and sometimes the odor is even altered. In mixing too little water with the materials to be extracted, there is danger that empyreumatic oils will be formed; a large quantity of water, on the other hand, is of disadvantage, in so far as in case the perfume-materials contain little oil, only a perfumed water, but no oil, will be obtained. In order to avoid these inconveniences, or, at least, to do away with some of them, another plan was devised. The materials to be distilled were spread upon sieves, which were suspended in the upper part of a still, so that they might be penetrated from below. It is true no scorching is possible in this case, as was in the other process when the heating was continued after all the water had evaporated, and the oil retains its proper color, but by this method only small quantities can be extracted at a time. The still generally used for distillation with direct heat resembles so much an ordinary whiskey still as to need no further description here.

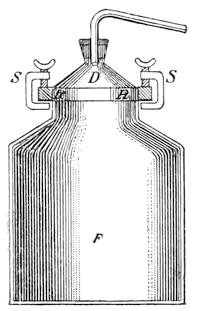

For the accurate determination of the percentage of volatile oil a vegetable substance will yield, or to obtain the oil from very costly raw materials, the small glass apparatus, Fig. 2, is used. The flask A, with a capacity of up to 5 or 6 quarts, serves for a still. In the tube t, shaped like the neck of a bottle, is inserted by means of a cork, a funnel tube, l, reaching to the bottom of the flask. The neck of the flask passes into the cooling pipe, which lies in a so-called Liebig cooler. This consists of a wide-glass tube, C, into the lower end of which, at h, flows cold water from the reservoir D, displacing the heated water at g. The lower end of the cooling pipe is connected with the neck-shaped tube v, under which stands the vessel for the reception of the distillate. To prevent the cracking of the flask, which might readily happen with the use of direct heat, it is placed in a vessel filled with sand or water.

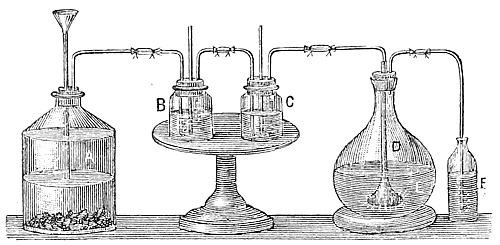

An improved apparatus for distilling dry substances by steam has been patented in Germany by Messrs. Schimmel & Co., of Leipzic. The tall conical column at the left (Fig. 6) is the still. About eight inches from the bottom is a perforated diaphragm or false bottom, upon which the material to be distilled is placed by introducing it through the still-head. A perforated coil below the diaphragm projects steam upwards through the mass, which is occasionally agitated from without by means of a horizontal stirring apparatus indicated by the two crosses. Any condensed water which may run back is converted into steam by the heating coil at the bottom. Meanwhile, the mass itself is heated by a long coil lining the body of the still and carrying steam at a high pressure. Whatever of volatile oil is carried forward by the steam passes through the still-head into the cooler on the right, where both oil and steam are condensed, and from where they flow through a small funnel tube into three successive receivers, which are arranged like Florentine flasks, and which retain the volatile oil that has separated. From the last receiver the water, which is still impregnated with oil, enters another reservoir, shown in the illustration only by dots, and from there it flows into a small globular still situated underneath; in which, by means of steam, nearly all the oil still retained is again volatilized with the steam of the water and both again conducted to the cooler.

Separation of the oil and water.—As previously mentioned the specific gravity of most volatile oils is less than that of water. This behavior is utilized for the separation of the oil and water, by means of a so-called Florentine flask (Fig. 7). It consists of a glass flask provided near the bottom with a pipe, a, rising vertically to near the neck c of the flask where it is bent downwards as shown in the illustration. The mixed liquid of water and oil drips from the cooling pipe into the flask, and the water w, being specifically heavier, separates from the oil floating on the top, and gradually ascends in the pipe a, finally flowing over at d. Oils specifically heavier than water are caught in receivers provided with a discharge-pipe near the mouth of the flask as shown in Fig. 8.

Most volatile oils are obtained by distillation, but this method is not practicable for separating the odoriferous principle of many of the most sweet-scented and delicate flowers, partially because the flowers contain too little oil, and partially because the oil would lose in quality if obtained by distillation.

Extraction.—For obtaining the volatile oils by extraction various solvents such as ether, bisulphide of carbon, etc., may be employed. Carefully rectified petroleum-ether is very suitable for the purpose. It completely evaporates at about 122° F., and when sufficiently purified does not possess a disagreeable odor. The process of extraction is briefly as follows: The material to be extracted is treated in a digester with petroleum-ether or one of the above-named solvents. The solution is then drawn off and the solvent evaporated in a still. The recondensed solvent flows immediately back into the digester and further extracts the material contained therein. The operation is repeated until nothing soluble remains. In practice some difficulties are, however, connected with this process since, besides the volatile oils, resins, and coloring and extractive substances are dissolved, which have to be removed, as well as the last traces of the solvent, as otherwise the oil would acquire a foreign odor. Further the solvents mentioned are very volatile and inflammable, requiring the greatest precautions as regards fire. For these reasons the extraction process is not suitable for many purposes, and though at first great hopes were entertained in regard to it, its use is limited to substances with a large content of volatile oil.

On account of the great volatility of bisulphide of carbon, considerable loss would, however, be incurred by the above-mentioned admission of air. To avoid this, the reservoir serving for the reception of the condensed bisulphide of carbon and aqueous vapor is closed, and connected by a pipe with a long, narrow, horizontal cylinder half filled with oil, and provided with a fan-shaft. The vapors of bisulphide of carbon entering the cylinder from the reservoir are absorbed, together with the air by the oil, the surface of which is constantly agitated by the fan-shaft, while the air, rendered entirely inodorous, passes out at the other end. The bisulphide of carbon is finally separated from the oil by distillation and again used.

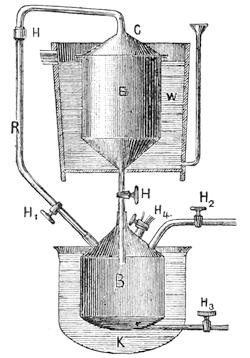

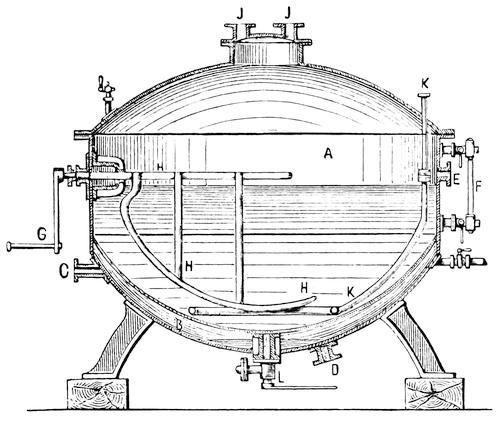

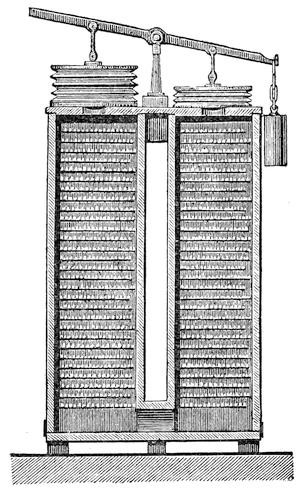

The saturated oil solution is subjected to distillation, which is readily effected in Heyl's apparatus, Fig. 15. The lower part of the still A of boiler plate is surrounded by the steam-jacket B, into which steam is admitted through C and the condensed water discharged through D. The concentrated oil solution runs from a reservoir, standing at a higher level through the pipe E into the still, the admission of a sufficient quantity being indicated by the gauge F. The bisulphide of carbon brought to the boiling point (114° F.) by the steam introduced into the jacket, vaporizes quickly; the vaporization being still more accelerated by revolving the stirrer H, by means of the crank G. The vapors of bisulphide of carbon escape through four openings in the upper part of the still, into a capacious worm, the lower part of which enters, under water, a reservoir.

Maceration or infusion.—This process is employed for flowers with an inconsiderable content of volatile oil or whose odoriferous substance would suffer decomposition or alteration by distillation. The process is founded on the affinity of odoriferous substances for fatty bodies which, when impregnated with them, are called pomades. These are afterwards made to yield the aroma to strong alcohol, so that finally there is obtained a solution of the volatile oil in alcohol from which the pure oil is obtained by distilling off the alcohol. The fat used, olive oil, lard, etc., should be entirely neutral, i. e., free from every trace of acid. The fats are purified by treating them several times in the heat with weak soda-lye and then washing carefully with water until the last traces of the lye are removed, and the fat shows no alkaline or acid reaction.

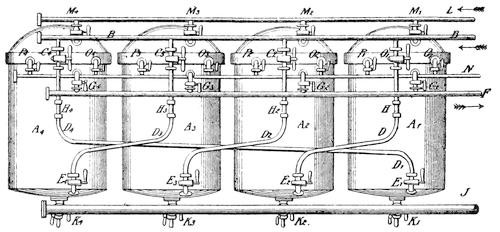

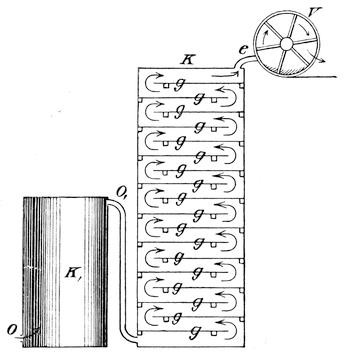

Experience, however, has shown that volatile oils prepared by this process possess a finer odor the shorter the time the flowers remain in contact with the fat. Piver has devised an apparatus which reduces the time of maceration to the shortest period possible. The kettle to the left, Fig. 16, supplies the fat heated to the proper temperature, which circulates slowly through the macerating tank, in which a constant temperature of 149° F. is maintained by means of a steam pipe. The macerating tank is divided into compartments, in which baskets containing the vegetable substance to be extracted are suspended. The basket on the left contains the substance which has passed through all the compartments; it is from time to time removed, filled with fresh substance, and then attached to the right, the other baskets being moved to the next compartment to the left. In this way the fresh substance has to traverse each compartment from right to left, while the fat flows slowly from left to right, and saturated with the perfume of the substance collects in the tank on the extreme right.

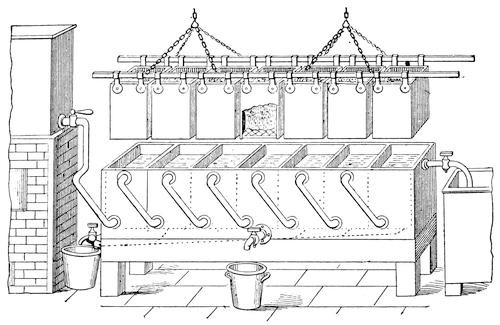

The process of absorption, or "enfleurage," as it is called by the French, is chiefly made use of for procuring the odoriferous principle of very delicate flowers, the delicious odor of which would be greatly modified, if not entirely spoiled, by the application of heat. The older apparatus employed for the purpose consists of a number of shallow wooden frames of about 15×18 inches, inclosing at half their depth a sheet of glass. The edges of the frame rise about an inch above each surface of the glass, and, being flat, the frames stand securely upon one another, forming often considerable stacks. These frames are called "chassis," those just described being termed "chassis aux vitres," or "chassis aux pomades," to distinguish them from a different form, which is used where oil has to be submitted to the process of absorption. The process in the case of pomade is as follows: Each sheet of glass is uniformly coated with a thin layer of purified grease, care being taken that the grease does not come in contact with the woodwork of the frames. The flowers are then thinly sprinkled, or rather laid, one by one, upon the surface of the fat, where they are allowed to remain one or two days, when they are removed and replaced by fresh ones. The operation is thus continued for twenty-five or thirty days, until the fat is saturated with aroma. The frames charged with fat and flowers are stacked one upon the other, forming, in fact, a number of little rectangular chambers.

Odor and taste are so characteristic for every volatile oil as to suffice in most cases. For testing as to odor, bring a drop of the oil to be examined upon the dry palm of one hand and for some time rub with the other, whereby the odor is more perceptibly brought out. To determine the taste, vigorously shake one drop of the oil with 15 to 20 grammes of distilled water and then test with the tongue.

The presence of castor oil can be accurately determined by bringing the residue from the watch-crystal into a test-tube by means of a glass-rod, and compounding it with a few drops of nitric acid. A strong development of gas takes place, after the cessation of which, solution of carbonate of soda is added as long as there is any sign of effervescence. If the added oil was castor oil, the contents of the test-tube will show a peculiar odor due to œnanthylic acid formed by the action of nitric acid upon castor oil.

Detection of alcohol or spirit of wine.—Independent of the alcohol added to assist the preservation of some oils, adulteration with alcohol frequently occurs, especially in expensive oils. With a content of not more than 3 per cent. of alcohol, it suffices to allow one to two drops of the suspected oil to fall into water. In the presence of alcohol, the drop becomes either immediately surrounded with a milky zone, or it becomes turbid or whitish after being for some time in contact with the water. Dragendorff's test is based upon the fact that oils, which are hydrocarbons, suffer no change by the addition of sodium (ten drops of oil and a small chip of sodium), while oils containing hydrocarbons and oxygenated oils cause with sodium a slight evolution of hydrogen gas, and suffer but a slight change during the first five to ten minutes of the reaction. If, however, the oil is adulterated with alcohol, not only a violent evolution of hydrogen gas takes place, but the oil in a short time becomes brown or dark brown, thickly fluid or rigid.

The above-mentioned oils may, however, be rendered fit for the tannin test by mixing them with double their volume of benzine or petroleum-ether, and allowing the mixture to stand for two or three days. If, however, the oils contain much alcohol, the tannin is dissolved. The use of powdered tannin is not advisable, because it generally deposits in a thin layer on the bottom, and its alteration is not so perceptible. If, for practical reasons, a content of 0.5 per cent. anhydrous alcohol might be accepted as permissible in a volatile oil, the tannin test would have to be so modified as to mix 10 drops of the oil with a piece of tannin the size of two peas, and allow the whole to stand for one hour. In this time the above-mentioned content of alcohol would yield no result.

Detection of benzine.—An adulteration with benzine can be readily detected only in oils specifically heavier than water. The separation of benzine is effected by distillation from a small glass flask in the water bath. The distillate together with an equal volume of nitric acid of 1.5 specific gravity is gently heated in a test-tube. A too vigorous reaction is modified by cooling in cold water, and a too sluggish action quickened by gentle heating (dipping in warm water). If the mixture has a yellow color, dilute it with water, shake with ether, mix the decanted ethereal solution with alcohol and hydrochloric acid, add some zinc and place the whole in a lukewarm place to convert the nitrobenzol formed into aniline. After evolution of hydrogen is done, neutralize with potash lye, shake, take off the layer of ether, let the latter evaporate and add to the residue a few drops of calcium chloride solution. If benzine is present, a blue-violet color reaction takes place.

Adulterations with alcohol, chloroform, and benzine are quantitatively determined by bringing a weighed quantity of the oil into a glass flask so that it occupies about four-fifths of the volume of the flask. Place upon the flask a cork through which has been passed a glass-tube bent at a right angle and provided with a cylindrical glass vessel serving as a receiver and heating in the water bath. If the distance from the level of the oil to the angle of the glass tube in which it inclines downwards, amounts, for instance, to 4.72 inches, and the neck of the flask up to its angle is 2.75 inches high outside of the direct effect of the heat of the water bath, only the above-mentioned adulterants distill over, while the vapor of the volatile oil condenses at a height of 2.75 inches and flows back into the flask. The distillate is weighed and examined as to its derivation. First add one cubic centimeter of it to two or three cubic centimeters of potassium acetate solution of specific gravity 1.197 and shake moderately. If a clear mixture results, alcohol alone is present. If, however, the mixture is not clear, and the distilled fluid sinks down and collects on the bottom of the test-tube, chloroform is very likely present, and if it remains floating upon the acetate solution, benzine. Next bring two to three centimeters of the distillate into a test-tube and add a piece of sodium metal, the size of a pea. If violent foaming, i. e., an evolution of gas, takes place, alcohol is certainly present, and possibly also chloroform and benzine towards which sodium is indifferent. However, in the presence of benzine, the sodium solution would be colorless, and in the presence of chloroform, yellowish and turbid. In case the sodium produces no reaction and alcohol is, therefore, not present, add an equal volume (two to three cubic centimeters) of anhydrous alcohol, and after moderately shaking allow the solution of the sodium and the evolution of gas to proceed, whereby benzine produces a nearly colorless, turbid fluid, and chloroform a yellowish, milky one. Now dilute the fluid with an equal or double volume of water, shake and allow the mixture to stand quietly. In the presence of benzine a colorless, turbid layer collects on the bottom of the fluid, while that collecting in the presence of chloroform is yellowish. In the latter case, i. e., in the presence of chloroform, the aqueous filtrate yields with lead acetate solution a white precipitate (lead chloride and lead hydroxide). The adulterant having thus been recognized, further particulars are learned from the specific gravity of the oil as well as of the distillate.

In place of iodine, Rudolph Eck recommends a very dilute alcoholic iodine solution, which is not discolored by oils of turpentine, while other oils discolor it. Dissolve a drop of the oil to be examined in 3 cubic centimeters of 90 to 100 per cent. alcohol, and add a drop of the iodine solution. The latter is not discolored in the presence of an oil of turpentine. There are also, however, several volatile oils, which do not discolor the iodine solution. Mierzinski mentions the following: All cold-expressed oils from the Aurantiaceæ, further oils of coriander, caraway, galanga, rue, sassafras, rose, rosemary, anise-seed, fennel, calamus, neroli, angelica, wormwood. Hence, this reaction cannot be relied upon.

II. Hoppe's nitroprusside of copper test.—This test sometimes gives good results, but only with hydrocarbons absolutely free from oxygen and oxygenated oils. It is, therefore, not suitable for oils derived from the Aurantiaceæ. The process is as follows: Add to a small quantity of the oil to be examined in a perfectly dry test-tube, 2 to 5 milligrammes of pure nitroprusside of copper previously thoroughly dried and finely pulverized, shake vigorously and gradually heat to boiling. After boiling for a few seconds allow to cool. If the oil is free from oil of turpentine, or another oil containing no oxygen, the precipitate formed is brown, black, or gray, and according to the quantity of the reagent added and the original color of the oil, the supernatant oil will be differently colored and appear more or less dark. If, however, the oil is adulterated with oil of turpentine, the precipitate formed shows a handsome green or blue-green color, while the supernatant oil retains its original color or at the utmost acquires a very slightly darker one. The longer the oil is allowed to stand after settling, the more distinct and beautiful the color of the oil and of the precipitate appears. For the establishment and certain recognition of very small quantities of oil of turpentine in oxygenated oils, it is best to first add very little of the nitroprusside of copper to the oil to be tested, and a larger quantity only after being convinced either of the purity or adulteration of the oil. This is done to be able, on the one hand, better to judge the reaction, if the oil is pure, and, on the other, if it is adulterated, to establish such adulteration with certainty and to approximately estimate the quantity of oil of turpentine present. The less nitroprusside of copper is used, the better small quantities of oil of turpentine can be detected.

If these oxygenated oils are mixed with oils free from oxygen, for instance, oil of turpentine, they show exactly the same behavior as oils free from oxygen; the nitroprusside of copper is not decomposed and retains its gray-green color. If, for instance, oil of cloves is mixed with oil of turpentine, the red coloration by nitroprusside of copper does not appear.

IV. Hager's guaiacum reaction[3] serves for the detection of oil of turpentine in a volatile oil. By pouring upon as much guaiacum, freshly powdered, as will lie upon the point of a small knife, in a test-tube 1 cubic centimeter (25 drops) of spike oil, and heating nearly to boiling over a petroleum lamp, the oil after being removed from the flame and allowing the undissolved resin to settle, shows a yellow color. By now pouring upon an equal quantity of guaiacum in another test-tube 25 drops of spike oil and 5 drops of rectified oil of t from the flame shows a dark violet color. Various other oils behave in the same manner as spike oil, and hence a content of oil of turpentine can be readily detected in them. Other oils do not exhibit this behavior; but this can be remedied by adding, in testing for oil of turpentine, a few drops of an oil of the first class.

c. Oils with a content of oil of turpentine, which remain indifferent towards guaiacum.—To such oils, if to be tested for oil of turpentine, with the assistance of the guaiacum reaction, a few drops of an oil of the second class have to be added.

Barenthin has in this manner determined the iodine number of several volatile oils; other experimenters, however, for instance, Kremel and Davies,[4] have found different numbers for the same oils, so that this method requires further thorough examination before it can be classed as available.

The execution of the method is as follows: Dissolve 1 gramme of the oil to be examined in 2 to 3 cubic centimeters of 90 per cent. alcohol freed from acid, compound the solution with a few drops of phenol-phthalein solution, and titrate the free acid with ½ normal alcoholic potash lye. The milligrammes of caustic potash used are designated the "acid number." After having thus determined the content of acid, add to the same solution 10 cubic centimeters of the same potash lye, heat for ¼ hour upon the water bath, and then titrate back the excess of potash lye with ½ normal hydrochloric acid. In this manner the "saponification number" is obtained. (In some cases when the final reaction is not plainly perceptible, it is advisable to correspondingly dilute with water after heating the alcoholic fluid.) The saponification number, less the acid number, gives the "ether or ester number."

VII. F. R. Williams has recently endeavored to utilize for testing volatile oils Maumené's test, which is based upon the increase in temperature produced in oils by concentrated sulphuric acid, and which gives valuable points for the examination of some fat oils. Of course, the large quantities of oil otherwise prescribed cannot be used. While for the examination of fat oils 50 grammes of oil are mixed with 10 cubic centimeters of concentrated sulphuric acid in a beaker glass wrapped around with cotton, Williams could use only six cubic centimeters of volatile oil. They were brought into a very small beaker glass enveloped in cotton. After reading off the temperature, twelve cubic centimeters of concentrated sulphuric acid were added and the whole stirred with the thermometer until the temperature no longer rose. Numbers were in this manner obtained which might in some cases, for instance, cassia oil, furnish guiding points for judging the purity of the oil.