автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу A Beginner's Psychology

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTES:

—Obvious print and punctuation errors were corrected.

—The transcriber of this project created the book cover image using the title page of the original book. The image is placed in the public domain.

A BEGINNER’S PSYCHOLOGY

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO · DALLAS

ATLANTA · SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

A BEGINNER’S PSYCHOLOGY

BY

EDWARD BRADFORD TITCHENER

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1915

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1915,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up and electrotyped. Published December, 1915.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing Co.—Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

To

THE MEMORY OF

THOMAS HENRY HUXLEY

PREFACE

It is an acknowledged fact that we perceive errors in the work of others more readily than in our own.—Leonardo da Vinci

In this Beginner’s Psychology I have tried to write, as nearly as might be, the kind of book that I should have found useful when I was beginning my own study of psychology. That was nearly thirty years ago; and I read Bain, and the Mills, and Spencer, and Rabier, and as much of Wundt as a struggling acquaintance with German would allow. Curiously enough, it was a paragraph in James Mill, most unpsychological of psychologists, that set me on the introspective track,—though many years had to pass before I properly understood what had put him off it. A book like this would have saved me a great deal of labour and vexation of spirit. Nowadays, of course, there are many introductions to psychology, and the beginner has a whole library of text-books to choose from. Still, they are of varying merit; and, what is perhaps more important, their temperamental appeal is diverse.

I do not find it easy to relate this new book to the older Primer,—which will not be further revised. There is change all through; every paragraph has been rewritten. The greatest change is, however, a shift of attitude; I now lay less stress than I did upon knowledge and more upon point of view. The beginner in any science is oppressed and sometimes disheartened by the amount he has to learn; so many men have written, and so many are writing; the books say such different things, and the magazine articles are so upsetting! Enviable is the senior who can reply, when some scientific question is on the carpet,—There are three main views, A’s and B’s and C’s, and you will find them here and there and otherwhere! But as time goes by this erstwhile beginner comes to see that knowledge is, after all, a matter of time itself. If he keeps on working, knowledge is added unto him; and not only knowledge, but also what is just as valuable as knowledge, the power of expert assimilation; so that presently, when some special point is in debate, he is not ashamed of the plea of ignorance. He has learned that one man cannot compass the full range of a science, and he is assured that so-many hours of expert attention will make him master of the new matter. He comes in this way not, surely, to underestimate knowledge, but to be less anxious about it; and as that preoccupation goes, the point of view seems to be more and more important. Why is it that beginners in science are so often disjointed in their thinking, so often superficial, unable to correlate what they know, logically all at sea? There is no doubt that they are, whether they study physics or chemistry, biology or psychology. I think the main reason is that they have never got the scientific point of view; they are taught Physics or Biology, but not Science. Hence I have, in this book, written an inordinately long introduction, and have kept continually harping on the difference between fact and meaning. I try to make the reader see clearly what I take Science to be. It does not matter whether he agrees with me; that is a detail; I shall be fully satisfied if he learns to be clear and definite in his objections, realizes his own point of view, and sticks to it in working out later his own psychological system. Muddlement is the enemy; and there is a good deal of muddled thinking even in modern books.

Not that I offer this little essay as a model of clear thought! The ideas of current psychology and the words in which they find expression are still, in very large measure, an affair of tradition and compromise; and even if a writer has fought through to clarity,—past experience forbids me to hope that: but even if one had,—a book meant for beginners may not be too consistently radical; some touch must be maintained with the past, and some too with the multifarious trends of the present. There is something turbid in the very atmosphere of an elementary psychology (is the air much clearer elsewhere?), and it is difficult to see things in perspective. So the critic who will soon be saying that the ideal text-book of psychology has yet to be written will be heartily in the right, even if he is not particularly helpful. The present work has its due share of the mistakes and minor contradictions that are inevitable to a first writing; at many points it falls short of my intention,—l’œuvre qu’on porte en soi paraît toujours plus belle que celle qu’on a faite; and I daresay that the intention itself is not within measureable distance of the ideal. It is, nevertheless, the best I can do at the time; and it is also, I repeat, the kind of book that I should have liked to have when I began psychologising.

Psychological text-books usually contain a chapter on the physiology of the central nervous system. The reader will find no such chapter here; for I hold, and have always held, that the student should get his elementary knowledge of neurology, not at second hand from the psychologist, but at first hand from the physiologist. I have added to every chapter a list of Questions, looking partly to increase of knowledge, but especially to a test of the reader’s understanding of what he has just read. I have also added a list of References for further reading. It depends upon the maturity and general mental habit of the student whether these references—made as they are, in many cases, to authors who do not agree either with one another or with the text of the book—should be followed up at once, or only after the text itself has been digested. The decision must be left to the instructor. My own opinion is that beginners are best given one thing at a time, and that the knowledge-questions and the references should therefore, in the ordinary run of teaching, be postponed until some ‘feeling’ for psychology, some steadiness of psychological attitude, has become apparent.

I have avoided the term ‘consciousness.’ Experimental psychology made a serious effort to give it a scientific meaning; but the attempt has failed; the word is too slippery, and so is better discarded. The term ‘introspection’ is, I have no doubt, travelling the same road; and I could easily have avoided it, too; but the time is, perhaps, not quite ripe. I have said nothing of the ‘thought-element’, which seems to me to be a psychological pretender, supported only by the logicising tendencies of the day; and if I am wrong no great harm has been done, since a description of this alleged elementary process, by positive characters, is not yet forthcoming. My references are confined to works available in the English language; I think it unlikely that the students for whom this book is intended will have attained to any considerable knowledge of French or German. Lastly,—I believe that this is my last major omission,—I have referred only incidentally to the ‘application’ of psychology; for science is not technology, though history goes to show that any the least fact of science may, some day or other, find its sphere of practical usefulness.

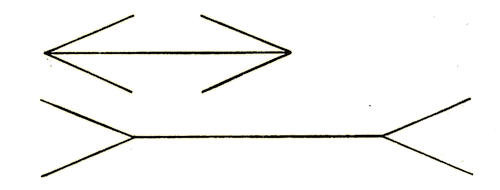

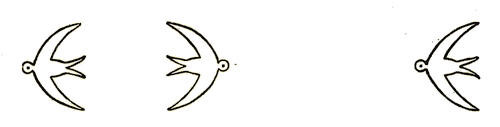

Two of my illustrations are borrowed: the swallow-figure on p. 138 from Professor Ebbinghaus, and the cut on p. 282 from Dr. A. A. Grünbaum.

I am sorry to confess that a few of the quotations which head the chapters are mosaics, pieced together from different paragraphs of the original. Even great writers are, at times, more diffuse than one could wish; or perhaps it would be fairer to say that they did not write with a view to chapter-headings. I hope, in any case, that no injustice has been done.

It is a very pleasant duty to acknowledge the assistance that I have received from my Cornell colleagues, Prof. H. P. Weld and Drs. W. S. Foster and E. G. Boring, and from Dr. L. D. Boring of Wells College. I am indebted to all for many points of valid criticism, and I wish to express to all my sincere thanks for much self-sacrificing labour.

I have retained the late Professor Huxley’s name in the forefront of this new primer, partly as an act of homage to the master in Science,—the brilliant investigator, the fearless critic, the lucid expositor; and partly, also, as a personal tribute to the man it was my earlier privilege to know.

Cornell Heights, Ithaca, N.Y.

July, 1915.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I

PSYCHOLOGY: WHAT IT IS AND WHAT IT DOES

SECTION PAGE1.

Common Sense and Science

12.

The Subject-matter of Psychology

53.

Mind and Body

104.

The Problem of Psychology

145.

The Method of Psychology

186.

Process and Meaning

267.

The Scope of Psychology

308.

A Personal Word to the Reader

34Questions and Exercises

37References for Further Reading

40CHAPTER II

SENSATION

9.

Sensations from the Skin

4310.

Kinæsthetic Sensations

4511.

Taste and Smell

4812.

Sensations from the Ear

5113.

Sensations from the Eye

5614.

Organic Sensations

6415.

Sensation and Attribute

6516.

The Intensity of Sensation

67Questions and Exercises

70References

72CHAPTER III

SIMPLE IMAGE AND FEELING

17.

Simple Images

7318.

Simple Feelings and Sense-feelings

79Questions and Exercises

87References

88CHAPTER IV

ATTENTION

19.

The Problem of Attention

9020.

The Development of Attention

9321.

The Nature of Attention

9922.

The Experimental Study of Attention

10323.

The Nervous Correlate of Attention

106Questions and Exercises

110References

111CHAPTER V

PERCEPTION AND IDEA

24.

The Problem in General

11225.

The Analysis of Perception and Idea

11426.

Meaning in Perception and Idea

11727.

The Types of Perception

12128.

The Perception of Distance

12529.

The Problem in Detail

13130.

The Types of Idea

138Questions and Exercises

142References

143CHAPTER VI

ASSOCIATION

31.

The Association of Ideas

14532.

Associative Tendencies: Material of Study

14933.

The Establishment of Associative Tendencies

15234.

The Interference and Decay of Associative Tendencies

15635.

The Connections of Mental Processes

15936.

The Law of Mental Connection

16237.

Practice, Habit, Fatigue

169Questions and Exercises

174References

176CHAPTER VII

MEMORY AND IMAGINATION

38.

Recognition

17739.

Direct Apprehension

18140.

The Memory-idea

18441.

Illusions of Recognition and Memory

18742.

The Pattern of Memory

18943.

Mnemonics

19244.

The Idea of Imagination

19445.

The Pattern of Imagination

197Questions and Exercises

201References

202CHAPTER VIII

INSTINCT AND EMOTION

46.

The Nature of Instinct

20347.

The Two Sides of Instinct

20748.

Determining Tendencies

21249.

The Nature of Emotion

21550.

The James-Lange Theory of Emotion

21851.

The Expression of Emotion

22252.

Mood, Passion, Temperament

225Questions and Exercises

228References

229CHAPTER IX

ACTION

53.

The Psychology of Action

23054.

The Typical Action

23355.

The Reaction Experiment

23656.

Sensory and Motor Reaction

23957.

The Degeneration of Action: From Impulsive to Reflex

24258.

The Development of Action: From Impulsive to Selective and Volitional

24659.

The Compound Reaction

25260.

Will, Wish, and Desire

255Questions and Exercises

259References

260CHAPTER X

THOUGHT

61.

The Nature of Thought

26162.

Imaginal Processes in Thought: The Abstract Idea

26363.

Thought and Language

26764.

Mental Attitudes

27165.

The Pattern of Thought

27566.

Abstraction and Generalisation

28067.

Comparison and Discrimination

283Questions and Exercises

287References

288CHAPTER XI

SENTIMENT

68.

The Nature of Sentiment

29069.

The Variety of Feeling-attitude

29370.

The Forms of Sentiment

29771.

The Situations and their Appeal

30072.

Mood, Passion, Temperament

304Questions and Exercises

305References

306CHAPTER XII

SELF AND CONSCIOUSNESS

73.

The Concept of Self

30774.

The Persistence of the Self

31275.

The Self in Experience

31576.

The Snares of Language

32177.

Consciousness and the Subconscious

32378.

Conclusion

328Questions and Exercises

332References

334APPENDIX

DREAMING AND HYPNOSIS

79.

Sleep and Dream

33580.

Hypnosis

341References

349 Index of Names 351 Index of Subjects 353A BEGINNER’S PSYCHOLOGY

A BEGINNER’S PSYCHOLOGY

§ 2. The Subject-matter of Psychology.—Psychology is the science of mind. What, then, is mind? Everybody knows that, you will say, just as everybody knows what is matter. Everybody knows, yes, in terms of common sense; but we have seen that common sense is not science. Besides, common sense is not articulate; it cannot readily express itself; and it is a little afraid of plain statements. Close this book, now, and write down what you take mind to be; give yourself plenty of time; when you have finished, go over what you have written, and ask yourself if you really know what all the words and phrases mean, if you can define them or stand an examination on them; the exercise will be worth while.

§ 3. Mind and Body.—The first thing to get clear about is the nature of the man left in the world, the man whose presence is necessary for psychology and unnecessary for physics. Since we are talking science, this man will be man as science views him, and not the man of common sense; he will be, that is, the organism known to biology as homo sapiens, and not the self-centred person whom we meet in the everyday world of values. But the human organism owes its organic character, the organisation of its parts into a single whole, to its nervous system. All over the body and all through the body are dotted sense-organs, which take up physical and chemical impressions from their surroundings; these impressions are transmitted along nerve-fibres to the brain; in the brain they are grouped, arranged, supplemented, arrested, modified in all sorts of ways; and finally, it may be after radical transformation in the brain, they issue along other nerve-fibres to the muscles and glands. The nervous system thus receives, elaborates, and emits. Moreover, there is strong evidence to show that the world which psychology explores depends for its existence upon the functioning of the nervous system; or, if we prefer a stricter formula, that this world is correlated with the functioning of the nervous system. The man left in thus reduces to a nervous system; and that is the truth of the statement, often met with in popular scientific writing, that the brain is the organ of mind. There is no organ of mind; that phrase is an echo of the old-world search after the place of residence of the mannikin-mind, which was assigned variously to heart, liver, eye, brain, blood, or was supposed somehow to perfuse the whole body. The scientific fact is that, whenever we come upon mental phenomena, then we also find a functional nervous system; we know nothing of the former apart from the latter; the two orders are thus correlated.

§ 4. The Problem of Psychology.—The subject-matter of psychology, as we saw on p. 9, is the whole world as it shows itself to a scientific scrutiny with man left in. Or, to put the same thing in another way, psychology gives a scientific description of the whole range of human experience correlated with the function of the human nervous system. We have just learned, however, that there is a psychology of the lower animals, possibly even of plants; and we must therefore say that we were speaking in § 2 of the subject-matter of human psychology. This is the psychology that will occupy us in the present book. Let us now see what our actual task is. What have we to do, in order to get a scientific description of mind?

§ 5. The Method of Psychology.—Having learned what we have to do, let us ask what method we are to follow in doing it. So far as the nervous system is concerned, it is evident that the psychologist must take his cue from the physiologist; indeed, this part of his problem makes him, for the time being, a physiologist, only that his real interest remains centred in mind. But how is it when he is attacking the other parts of the problem? Is there a special psychological method, a peculiar way of working, that he must adopt in his study of mental phenomena? The answer is No: his method is that of science in general.

§ 6. Process and Meaning.—Science, we said on p. 4, does not deal with values or meanings or uses, but only with facts; and we have just seen how words, which in everyday life are practically all meaning, may be made the objects of psychological experiment. Still, in their case, after all, we were simply ignoring meaning; so far as the observer was able to read words at all from the stimuli flashed on the screen, he read words which had a meaning, and a meaning that the experimenter might have discovered if he had been interested in it. We have not offered any evidence that mental processes are not intrinsically meaningful, that meaning is not an essential aspect of their nature; we have just assumed that they may be treated, scientifically, as bare facts. Let us now see whether meaning is essential to them or not. There are several heads of evidence.

§ 7. The Scope of Psychology.—Science, like the Elephant’s Child in the story, is full of an insatiable curiosity. Just as the physicist reaches out, analysing and measuring, to the farthest limits of the stellar universe, so does the psychologist seek to explore every nook and corner of the world of mind; nay more, he will follow after a mere suspicion of mind; we have seen him trying to psychologise the plants. The result is a vast number of books and monographs and articles on psychology, written by men and women of very different interests, knowledge and training; for science does not advance on an ordered front, but still depends largely on individual initiative. A high authority on the Middle Ages has said that one mortal life would hardly suffice for the reading of a moderate part of mediæval Latin; and the psychologist must recognise, whether with pride or with despair, that one life-time is hardly enough for the mastery of even a single limited field of psychology. The student has to get clear on general principles, and then to resign himself to work intensively upon some special aspect of the subject-matter,—keeping as closely as he may in touch with his fellow-workers, and aiming to see his own labours in a just perspective, but realising that psychology as a whole is beyond his individual compass.

§ 8. A Personal Word to the Reader.—These introductory sections are not easy. The only way to make them easy would be, as an Irishman might say, to leave the difficult things out; but then you would come to the later chapters, where we study mental phenomena in the concrete, with all sorts of prepossessions and misunderstandings; psychology would be one long difficulty instead of being, as it henceforth ought to be, a bit of straight sailing.

Questions and Exercises

References for Further Reading

CHAPTER II

§ 10. Kinæsthetic Sensations.—We get them, for the most part, from the cooperation with the skin of certain deeper-lying tissues. Psychologists have long suspected the existence of a muscle sense. We now know that sensations are derived, not only from the muscles, but also from the tendons and the capsules of the joints. These tissues are, of course, closely bound together, and are all alike affected by movement of a limb or of the body. Their disentanglement, from the point of view of sensation, has been a slow and difficult matter. Psychology has here been greatly aided by pathology; for there are diseases in which the skin alone is insensitive, in which skin and muscles alone are insensitive, and in which the whole limb is insensitive; so that a first rough differentiation is made for us by nature herself. It is also possible artificially to anæsthetise muscle and joint; and psychologists have devised various forms of experiment whereby some single tissue is thrown into relief above the others.

§ 11. Taste and Smell.—The great physiologist Carl Ludwig once remarked that smell is the most unselfish of all the senses; it gives up everything it has to taste, and asks nothing in return. Taste is, indeed, an inveterate borrower; it borrows from smell and from touch, very much as the skin borrows from the underlying organs. When we have a cold in the head, we say that we cannot taste; but how is taste affected? The truth is that our nose is stopped, and we cannot smell.

§ 12. Sensations from the Ear.—Sensations of hearing fall into two great groups, tones and noises. When we are speaking of tones, we naturally think of the keyboard of a piano. The piano tones are, in reality, not simple tones or sensations but compound tones; and we are able, after a little practice, to break up a compound tone into its simple constituents. You may get a fair notion of a really simple tone by blowing gently across the mouth of an empty bottle. The tone is dull and hollow, as compared with the bright solidity of a piano tone, but it has also a pleasant mellowness. With these two aids, the bottle tone and the piano keyboard, we may approach our study of tonal sensations.

§ 13. Sensations from the Eye.—You may study tones by help of the piano and a few medicine bottles; but for the study of lights and colours you must go beyond household appliances, and secure a fairly large set of coloured and grey papers; sample-books may be obtained, very cheaply, from the manufacturers. You will notice, first of all, that as the world of sounds divides into tones and noises, so does the world of looks divide into what we have just called colours and lights. The colourless looks or lights may be arranged in a single straight line that passes from purest white through the greys to deepest black; they are, as sensations, older than colours, just as noise is older than tone. Colours are more varied. Consider, to begin with, the character of colour proper or hue, that is, the differences of colour that show in the rainbow. Hues may be arranged, not in one straight line, but in a square. Setting out, say, from red, you pass through red-yellow or orange to yellow; that is one straight line; setting out again from yellow, you pass through yellow-green to green; from green you pass through green-blue to blue; and finally from blue you come back, by way of blue-red (violet and purple), to the original red. Colours have, besides, two further characters, that bring them into relation with lights. They differ in tint, that is, in darkness or lightness; brown is darker than yellow, sky-blue is lighter than navy-blue. They differ also in saturation or chroma, that is, in poorness or richness of hue; pinks and yellows look faded and washed-out as compared with rich reds and blues. Tint brings colours into relation with lights, because, if we can say that a colour is darker or lighter than a particular grey, we can also find some grey that matches it in darkness or lightness; and chroma brings colours into relation with lights, in the sense that the better chroma is farther off from colourlessness (that is, from grey) than the poorer chroma of the same hue and tint.

§ 14. Organic Sensations.—There are still other sensations, coming to us from the internal bodily organs; from various parts of the alimentary canal, from the organs of sex, from heart and blood-vessels, from the lungs, from the sheathing membrane of the bones; but it is doubtful if they are of new kinds; probably they consist simply of pressure, cold, warmth, and pain. The dull deep-seated pains that we call aches are, perhaps, different from the bright pains of the skin; but most of the differences among pains, differences that we express by the terms lancing, throbbing, piercing, stabbing, thrilling, gnawing, boring, shooting, racking, and so on, are either differences of time (steady, intermittent) or space (localised, diffused) or degree (moderate, acute), or else are differences due to the blending of pain with various other sensations.

§ 15. Sensation and Attribute.—We have been talking all this while about sensations, but we have not yet said what sensations are. They make up, as you will have guessed, one class of the mental elements, the elementary mental processes of § 4, that we reach by analysis of our complex experiences. They are therefore simple and irreducible items of the mental world. How shall we define them?

§ 16. The Intensity of Sensation.—A sensation may remain the same in quality, and yet vary in strength or intensity. A pressure may be the pressure of an ounce or of half-a-pound; it is always pressure, the same quality, but its intensity differs. The tone you get by blowing across the mouth of a bottle may be loud or faint, though it is still the same pitch, the same tone. The weight you carry may strain the arm very little or a great deal; the sensation of strain from the tendons is the same in both cases, but its intensity is different.

Questions and Exercises

References

CHAPTER III

§ 18. Simple Feelings and Sense-Feelings.—Many of our experiences are indifferent; but many of them, again, are pleasant or unpleasant. These two words, pleasant and unpleasant, denote elementary mental processes of a different sort from sensations and images; they are known as simple feelings. The term ‘feeling’ is itself even more ambiguous than the term ‘image’; it is natural to speak of ‘feeling’ a strain or effort, a warmth or cold; but we shall henceforth use it only in its technical meaning, to indicate the way in which stimuli affect us, pleasantly or unpleasantly. We must discard altogether the words pleasure and pain, although they have long been current as the names of the simple feelings, and although they are much less clumsy than pleasant and unpleasant. We discard them because pain is a sensation (p. 43); and pains, while usually unpleasant, may at times be pleasant; the scratching that relieves an itch and the nip of the wind on a brisk winter’s day are both pains, but they are also both pleasant.

Questions and Exercises

References

CHAPTER IV

§ 20. The Development of Attention.—If we consider a large number of cases of attention, we find that they fall into three great groups; and each one of these groups seems to represent a stage in the development of mind at large, a level of mental evolution. We speak accordingly of primary, of secondary, and of derived primary attention. Let us consider them in order.

§ 21. The Nature of Attention.—Our next task, in the words of p. 93, is to trace the pattern of attention, to describe as accurately as possible the arrangement of our vivid and obscure sensations. Notice that, in popular parlance, attention covers only the vivid processes of the moment; psychologically, however, the term includes both the vivid and the obscure, those that we are ‘distracted from’ as well as those that we are ‘attending to,’ This being understood, we may attempt a description.

§ 22. The Experimental Study of Attention.—The question of the range of attention,—how many sensations or images may occupy the focus at the same time,—was canvassed in the Middle Ages: witness our quotation from St. Thomas. The first appeal to experiment seems to have been made, in the late thirties of the past century, by the Scottish philosopher Sir Wm. Hamilton. “You can easily make the experiment for yourselves,” Hamilton tells his students, “but you must beware of grouping the objects into classes. If you throw a handful of marbles on the floor, you will find it difficult to view at once more than six, or seven at most, without confusion; but if you group them into twos, or threes, or fives, you can comprehend as many groups as you can units.” The experiment is not very rigorous; but more accurate work on the subject shows that Hamilton was not far wrong. If a field of simple visual stimuli is shown for a brief time, the practised observer is in fact able to grasp six of them; and if familiar groups are substituted for the separate stimuli (short words for letters, or playing-card fives for single dots), the range of visual attention remains the same.

§ 23. The Nervous Correlate of Attention.—It remains to say a word about the nature of the nerve-forces (§ 20) which underlie attention. Physiologists tell us that one nervous process may influence another in two opposite ways: by helping and by hindering, or, in technical terms, by reinforcement and inhibition. Let us take an elementary example of what they mean. Suppose that a frog has been reduced, by the removal of its cerebral hemispheres, to a mere nerve-and-muscle machine; it lives, but it cannot sense or feel, and it does not move ‘of its own accord.’ If, now, a weak pressure is applied to the frog’s hind foot, there is no visible response; the limb remains passive. But if at the same moment a light is flashed into the eye, the leg-muscles may be thrown into strong contraction. Here we must suppose that the two nervous processes, from skin and eye, have in some way helped each other; there is nervous reinforcement. If, again, a pressure is applied to a certain part of the frog’s body, the animal croaks. If a strong pressure is applied to another part of the body, it replies by a contraction of the muscles. If, however, the two pressures are applied together, the frog does not both croak and move; it does neither; there is no response to the stimuli. Here, therefore, we must suppose that the two nervous processes interfere with each other; there is nervous inhibition.

Questions and Exercises

References

CHAPTER V

§ 25. The Analysis of Perception and Idea.—Sensations and simple images can hardly occur, by themselves alone, in our everyday experience. The practised psychologist may be able to focalise a sensation, to make it so vivid that it stands out almost as it would under the experimental control of the laboratory; but his is an exceptional case. The units of our daily experience are rather such things as the sound of the piano in the next room, the sight of the tree budding just outside the window, the memory of last winter’s snow-piles, the forecast of to-night’s Pathetic Symphony; that is, they are perceptions and ideas. Notice that they come to us in the first place as units, as wholes; they show no lines of natural cleavage; they are unitary and self-contained. Yet they are not psychologically simple; if they were, we should never have lit upon sensations and simple images. All perceptions and ideas may be analysed.

§ 26. Meaning in Perception and Idea.—We learned in § 6 that mental processes are not intrinsically meaningful, that meaning is not a constituent part of their nature. We have seen, indeed, that the whole notion of meaning is really foreign to science. When we ask, then, what meaning is, from the psychological point of view, are we not asking an irrelevant and unscientific question?

§ 27. The Types of Perception.—Our perceptions are based upon three of the attributes or aspects of sensation: upon quality, upon duration, and upon extension (p. 66).

§ 28. The Perception of Distance.—A complete psychology of perception would contain an analytical treatment, up to the limits of our present knowledge, of all the various perceptions, qualitative, temporal and spatial, as well as complex, that occur in experience. Such a treatment is here out of the question. We must pick and choose; and as a sample of perception at large we shall consider the perception of distance. We seem, quite immediately and directly, to see distances; we see that our friend is coming nearer, we see that he has passed the bridge, we see that he is entering the gate, we see when to shake hands with him. Yet there is no sensation of distance, and there is no specific stimulus to distance. What, then, really happens?

§ 29. The Problem in Detail.—Every one of our familiar perceptions might, now, be treated in this same fashion, and in indefinitely greater detail. We should start out with our pattern of sensory nucleus, imaginal context, and brain-habit; and we should push our analysis back and back, in the effort to reach the primary and ultimate form of the perception we were discussing. The quest is fascinating; for these are old, old bits of the mental life; to trace them home would be to go back to the Stone Age—or further; the earliest men we know of perceived the things that we perceive. Whether psychology will ever reach the final goal cannot be said; but at any rate the problems are genuine problems; they can be resolved only by intensive and long-continued work; and they demand an extraordinary ingenuity in the devising of experimental controls and an unusual degree of patience in experimenting. Men spend their lives among dead languages and buried cities; why not excavate and explore the inner world of perception?

§ 30. The Types of Idea.—Idea takes its plan from perception; and ideas may therefore be classified, like perceptions, as qualitative, temporal and spatial. When, however, we speak of types of idea, we usually have a different classification in view. Our ideas differ as our equipment of imagery differs; some minds are rich in visual or auditory images, others are poor or deficient. When first these differences were brought to light, they seemed to be permanent and clearly marked; children, especially, were classed as eye-minded, ear-minded, and touch-minded or motor-minded, according as their ideas consisted predominantly of visual, auditory, or kinæsthetic images; and it was thought no less necessary to discover a child’s type, and to instruct him in accordance with it, than it is to test the colour-vision of pilots and engineers. Moreover, since all ideas may be translated into words, and since verbal ideas may also be visual, auditory or motor,—ideas of the word seen, heard, or spoken,—three sub-types were added to the main types of idea; the verbal-visual, the verbal-auditory, and the verbal-motor. The doctrine of types found support in pathology; thus, the famous French physician J. M. Charcot reports a case of eye-mindedness in which visual ideas were suddenly lost. The patient writes: “I possessed at one time a great faculty of picturing to myself persons who interested me, colours and objects of every kind; I made use of this faculty extensively in my studies. I read anything I wanted to learn, and then shutting my eyes I saw again quite clearly the letters with their every detail. All of a sudden this internal vision absolutely disappeared. Now I cannot picture to myself the features of my children or my wife, or any other object of my daily surroundings. I dream simply of speech. I am obliged to say things which I wish to retain in my memory, whereas formerly it was sufficient for me to photograph them in my eye.”

Questions and Exercises

References

CHAPTER VI

§ 32. Associative Tendencies: Material of Study.—We want to find out how those processes in the brain which are the correlates of our ideas go together, get connected or associated. The brain is a machine; and it is not only complicated, but it is also plastic, that is, it is subject to change and modification. The complexity of the machine makes it necessary for us to work with simple stimuli and by strict methods; only if we work with simple stimuli shall we get to the bare essentials of the associative functions; and only if we work by strict methods shall we obtain results which other investigators can repeat and verify. Even so, the plasticity of the machine makes it impossible for us to lay down hard and fast laws of connection; we can speak only of connective tendencies or of associative tendencies; what actually happens, in any particular case, is likely to be the joint result of many tendencies, weak and strong, conflicting and concurring.

§ 33. The Establishment of Associative Tendencies.—The use of meaningless syllables has brought with it a whole armoury of technical methods for the study of the associative tendencies. We have here no space to treat of these methods in detail; fortunately, the results that we shall mention speak for themselves; and it may be added that all the methods of experiment are, in principle, changes rung upon one simple model, in which the observer sits down before a series of syllables, reads them through, so-many times over, in a state of attention, and then, either immediately or after an interval of time, repeats them ‘from memory.’ We proceed, then, to answer the question: How are associative tendencies established in the brain?

§ 34. The Interference and Decay of Associative Tendencies.—If a set of associative tendencies, such as we have just described, is left to itself, and neither disturbed nor renewed, it gradually disappears; the loss is at first very rapid, then proceeds more slowly, and thereafter goes on only at a snail’s pace. To make the matter concrete, we may think of the meshwork of tendencies as a meshwork of channels, deeper and shallower, in the substance of the brain; then the rule is that the channels tend to fill up,—the shallow ones speedily, the deeper ones at first quickly and then more and more slowly,—until everything is smooth again. This is a mere figure, but it carries the meaning that we desire. The same thing happens with the tendencies set up by meaningful material; they too slowly die away; but it is doubtful if they ever wholly disappear; in their case the brain, if it has been thoroughly impressed, seems never wholly to ‘forget.’ Ebbinghaus learned some stanzas of Byron’s Don Juan, for experimental purposes, and did not look at them again for 22 years; yet he relearned those stanzas in 93 per cent. of the time required to learn new stanzas; a saving of 7 per cent. Some stanzas that he had learned more thoroughly were not read again for 17 years; these were relearned with a saving of nearly 20 per cent. He had no memory whatever of the verses formerly learned; but his brain ‘remembered’; the associative tendencies had not completely disappeared.

§ 35. The Connections of Mental Processes.—So far as the elementary processes are concerned, this question has already been answered in our discussion of perception. We found that there were two modes of sensory connection, two ways in which sensations may go together. In qualitative perceptions, such as the perception of a musical note, there is a blend or fusion of qualities; we can, to be sure, analyse the compound tone, after practice, into fundamental and overtones; yet it still comes to us as unitary, as a single impression; it stands only at one remove, so to speak, from the simplicity of sensation itself. The tastes of coffee and lemonade, with their blending of taste and smell, of touch and temperature; the organic feels of hunger and thirst and nausea; the kinæsthesis aroused by grasping and pulling, by lifting the arm and swinging the foot; all these experiences are fusions, more or less intimate, more or less complex, of sensory qualities. They too can be analysed; but the analysis is not easy; the qualities cling together, seem in a way to merge into one another. In spatial perceptions, on the other hand, in such perceptions as the sight of my desk with its litter of writing materials, the elementary processes stand out side by side; brown contrasts with blue, dark with light; here, we might say, is no confluence, but rather concourse. In the perception of rhythm we have the same separateness of sensations, only that it is now temporal instead of spatial; and in the perception of change (p. 132) we find both modes of connection, separate qualities or intensities passing into one another by that peculiar blur or fusion which we have called the index of change. This second type of connection, whether it is the side-by-side of space or the end-to-end of time, may be named conjunction.

§ 36. The Law of Mental Connection.—We have spoken at some length of the establishment of associative tendencies in the brain, of their decay with time, and of their mutual interference. Can we sum up our knowledge of them in a single general statement? And can we then translate this general statement into psychological language, and so reach a formula of mental connection that may stand in place of the logical laws of association? Let us try.

§ 37. Practice, Habit, Fatigue.—The establishment of an associative tendency may be looked upon as the establishment of a habit of brain-function; the learning of series of syllables improves with practice; and continued learning gives rise to fatigue. It is natural, therefore, that we should here pause to say something about these three things in their relation to psychology.

Questions and Exercises

References

CHAPTER VII

§ 39. Direct Apprehension.—We saw on p. 120 that meaning, which was at first a fringe of mental processes, a contextual setting of some bit of bare experience, may in course of time be carried by nerve-processes which have no mental correlates of any kind. The same thing seems to hold of recognition. We do not, in strictness, ‘recognise’ the clothes that we put on every morning, or the desk at which we are accustomed to write; we apprehend them, directly, as our clothes and our desk; we take them for granted. The feeling of familiarity, the feeling of being at home with our own things, changes first to something that is still a feeling, though weaker and more nebulous; to something that we may describe as an ‘of-course’ feeling, which is still some distance away from sheer indifference. As the days and weeks go on, this of-course feeling itself dies out; the stimuli no longer have power to arouse a feeling at all, and the organism faces the habitual situations without any organic stir. We apprehend the clothes and desk as ours, precisely as we perceive the tree and the piano as spatial (p. 115). In experiments on the recognition of greys, the author has reported positively that a particular grey had been seen before, without being able to find anything whatsoever, in the way of verbal idea or kinæsthetic quiver or organic thrill, that might carry the meaning of familiarity; the brain-habit just touched off the report ‘Yes,’ and that was all that could be said.

§ 40. The Memory-Idea.—But where, all this while, is the memory-image? If you had been asked, before you read the foregoing paragraphs, what happens when you recognise somebody or something, you would probably have replied, as the associationists reply: ‘The present sight of the object calls up an image of that object, by the law of similarity; then the image or idea is compared with the perception, and the two are found to agree; and this agreement is what I mean by recognition.’ If it were then objected that observation fails to show any such idea or image, you would perhaps have said: ‘The whole thing takes place so quickly that the factors cannot ordinarily be distinguished; but all the same that is what must happen.’ And so you would have kept your faith in the image.

§ 41. Illusions of Recognition and Memory.—Psychologically, an illusory memory is a memory, just as an illusory perception is a perception. We speak of illusion when our experience fails to square with what, from our knowledge of external circumstances and of other like experiences, we might have expected; the distinction is therefore practical, not scientific. We shall avail ourselves of it, partly for convenience’ sake, and partly because certain cases of illusion offer special problems to the psychologist.

§ 42. The Pattern of Memory.—Psychology cannot yet offer any adequate description of the pattern that mental processes display, the arrangement that they fall into, when we are remembering. Memory, as we are all aware, may occur in the state of primary attention, when we call it remembrance, or in the state of secondary attention, when we call it recollection. Something may be said under both heads; but our account must be largely figurative and conventional.

§ 43 Mnemonics.—Rules for remembering, tricks of memorising, were considered of great importance in the ancient world; oratory was highly esteemed; and no orator before the time of Augustus would have ventured to use notes. As the art declined, these rules were less and less regarded; we hear practically nothing of them between the first and the thirteenth centuries of the present era. From that date, however, interest in artificial memory-systems has never died out; they have been recommended for sermons, for lectures, for disputations, for public speeches, for the learning of foreign languages, for examinations, for practically every occasion in which memory is employed, as well as for the improvement of memory itself.

§ 44. The Idea of Imagination.—We think of memory as reproducing the old, and of imagination, no less positively, as producing the new; the very word poet means the maker, and the word artist means the fitter or joiner. Imagination cannot, of course, give us new qualities of experience; we cannot imagine a new colour, different from all known colours, or a new sensation—say, a specific sensation of electricity—different from the known sensations of skin and underlying tissues. Imagination does, however, give us novel connections; and experiment shows that an idea comes to us as imagined only if it comes as unfamiliar, with the feeling of novelty or strangeness upon it.

§ 45. The Pattern of Imagination.—Imagination, like memory, may occur in the state of primary or of secondary attention. In the former case we call it receptive, in the latter case constructive imagination.

Questions and Exercises

References

CHAPTER VIII

§ 47. The Two Sides of Instinct.—If instinct is the general name for the innate nervous tendencies to behaviour, then the detailed study of instinct belongs to physiology and general biology. The psychologist is concerned with it only in so far as the innate tendencies guide and form the stream of thought. There is, however, another side to instinct, which makes it a matter of direct psychological observation; the touching-off of an instinctive response may be accompanied by mental processes, by sensations and feeling. We must say something of instinct in both relations; and we look at it, first, from the biological point of view.

§ 48. Determining Tendencies.—The reader must have felt for some time past that we sorely need a technical term for all the directive nerve-forces, brain-habits, instinctive tendencies, and so forth, that figure in psychological discussion. There is such a term, formed on the analogy of ‘associative tendencies’; psychologists are coming more and more to speak of determining tendencies. Any nervous set or disposition that turns our attention in a certain direction, that casts our perceptions into a certain form, that places a definite meaning upon an equivocal word, that governs our response to a particular situation, may be called a determining tendency. Some of these tendencies are simple, and some are extremely complex; some are inherited, and some are acquired in the life-time of the individual. All alike lay down a path of least resistance for the psychoneural processes (p. 164) to follow, and thus determine the flow of the mental stream.

§ 49. The Nature of Emotion.—Suppose that you are sitting at your desk, busy in your regular way; and suppose that a street-car passes by the house. The familiar rumble does not distract you; it slips in among the obscure processes of the margin. Suddenly you hear a shrill scream; and now the noise of the car shoots to the focus of attention, becomes the context of the scream. You leap up, as if the scream were a personal signal that you had been expecting; you dash out of doors, as if your presence on the street were imperatively necessary. As you run, you have fragmentary ideas: ‘a child,’ perhaps, in internal speech; a visual flash of some previous accident; a momentary kinæsthetic set, the stiffening of protest, that represents your whole attitude to the city car-system. But you have, also, a mass of insistent organic sensation: you choke, you draw your breath in gasps, for all the hurry you are in a cold sweat, you have a horrible nausea; and yet, in spite of the intense discomfort that floods you, you have no choice but to go on. In describing the experience later, you would say that you were horrified by hearing a child scream; the mental processes that we have just named make up the emotion of horror.

§ 50. The James-Lange Theory of Emotion.—We saw that emotion, at any rate in its intenser phases, is insistently organic; the organic sensations readily blend both with one another and with feeling; and the resultant massive fusion is as characteristic of emotion as the organic surge (p. 211) is characteristic of instinct. Everyone can distinguish, even in imagination, the rushing, swelling ‘feel’ of anger from the sinking, shrinking ‘feel’ of fear. Psychology has always had an open eye for the organic constituent of emotion; Aristotle and many later writers refer to it; and in France emphasis upon the organic stir in emotion became almost a matter of psychological orthodoxy. The whole subject was, however, set in a new light when the late Professor James propounded in 1884 his famous ‘theory of emotion.’ “My thesis is,” James wrote, “that the bodily changes follow directly the perception of the exciting fact, and that our feeling of the same changes as they occur is the emotion;” “The more rational statement is that we feel sorry because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble, and not that we cry, strike or tremble, because we are sorry, angry, or fearful, as the case may be.” The view thus paradoxically stated aroused much discussion; and it gained further impetus by the publication in 1885 of an essay on emotion by Carl Lange, professor of medicine in Copenhagen; Lange independently comes to a conclusion which, in principle, is the same as that of James.

§ 51. The Expression of Emotion.—If the classification of emotions is a pleasant exercise for authors of a logical turn, the outward show of emotion in gesture and facial expression has always been attractive to those who pondered the relations of mind and body. It may even be true that observation of these expressive movements lies at the very root of psychology; for in emotion a man is changed, transformed; he is unlike himself, out of himself, beside himself; and what could suggest, more plainly than such transformation, the activity of an indwelling mind? However that may be, there is a long list, stretching down the centuries, of works that deal with emotive expression. We must ourselves pass over everything that appeared before the time of Charles Darwin.

§ 52. Mood, Passion, Temperament.—The weaker emotive states, which persist for some time together, are called moods; the stronger, which exhaust the organism in a comparatively short time, are called passions. No sharp line of distinction, however, can be drawn, either as regards intensity or as regards duration, between these various experiences.

Questions and Exercises

References

CHAPTER IX

§ 54. The Typical Action.—Under these circumstances, it sounds a little incongruous to talk of a ‘typical’ action. But we must start somewhere; and we may, perhaps, say that the typical action, for psychology, is an action of the simplest form taken at its psychological best; in other words, an organic movement that is singly determined and that shows a maximum of mental accompaniment. You will understand better what this definition means when we have worked out an illustration. Meantime, you can see that such an action—we call it an impulsive action—serves as point of departure in two directions. The form may remain simple, while the mental side suffers reduction; or the form may become complicated, and therewith new mental characters may be introduced. In the former case, the impulsive action runs downhill toward automatic; in the latter, it climbs up toward deliberative action.

§ 55. The Reaction Experiment.—The reaction experiment comes to us, of all unlikely things, by the road of astronomy. In the old days, before electrical instruments were invented, astronomers used to time the passage of a star across the meridian of their observatory by means of the eye-and-ear method. You can easily imagine the procedure. You have your eye at the ocular of a telescope, the field of which is evenly divided by a number of fine vertical lines. The star enters the field from the right, and crosses to the left; your task is to determine the instant at which it traverses the midmost vertical line, which corresponds with the meridian. A clock is behind you, beating seconds; and you count these seconds, one, two, three, from a given starting-point. If the star passes the meridian exactly on a beat, well and good; you know the time of its passage; if, as ordinarily happens, it passes somewhere between two beats, then you must estimate the time of passage to the nearest tenth of a second. That is the principle of the eye-and-ear method; you watch and listen, and so make your observation.

§ 56. Sensory and Motor Reaction. —Suppose that you are performing the simple reaction experiment, and that you tell your observers beforehand to react as soon as they perceive the stimulus. You soon find that this instruction is differently interpreted. One observer will prepare to react as soon as he perceives the stimulus; and another, to react as soon as he perceives the stimulus. The difference of emphasis may be brought out by a homely illustration. When the lights are turned on in the evening, it is not uncommon, even in the best regulated families, for a clothes-moth to start up from some corner. You say ‘There’s a moth!’ and clap your hands to kill it. But it escapes; and henceforth you do not trouble to identify it; you clap your hands at anything mothlike that flits across the field of vision; you are set or disposed for the movement. So in the two forms of the simple reaction: some observers tend naturally to make sure of the stimulus, before they move, and others tend naturally to move, as soon as any stimulus has appeared.

§ 57. The Degeneration of Action: From Impulsive to Reflex.—We have now to trace the course of impulsive action, downward to automatic, and upward to deliberative action. If we start out on the downward path, we note that impulsive action by frequent repetition degenerates, first, to what is called sensorimotor or ideomotor action: sensorimotor, if the object is still perceived, as it is in the impulsive action proper (p. 235), and ideomotor, if the perception is replaced by an idea of object. Here the predetermination is a nervous set without any mental correlates; the intention to move has dropped away; and the idea of result is, so to say, incorporated in the perception or idea of object; so that movement follows at once upon this perception or idea. When we sit down at table, for instance, we take up our knife as a thing to cut food with; and when we are dressing, we close our fingers round a button as a thing to fasten a garment with; the movements that we make are predetermined, but not premeditated; the actions are sensorimotor. When, again, it occurs to us, in the midst of our reading, that the mail must have arrived, we ideate the packet of letters as something to be fetched from the mail-box; and when, as we watch the shower, it occurs to us that the cellar hatchway is open, we ideate the hatchway as something to be closed; we act without further thought, and the actions are ideomotor.

§ 58. The Development of Action: From Impulsive to Selective and Volitional.—Action appears in its simplest form when it is singly or unequivocally determined (p. 235); and this implies that actions of more complicated form are multiply or equivocally determined. What that means you will see at once if you recall the development of attention. Primary passes into secondary attention because we have many sense-organs, all of them open to manifold stimulation at the same time, and because we have many different lines of interest, several of which may be appealed to by the situation in which we chance to find ourselves; there are rival claimants for the centre of the field of attention. Impulsive passes into selective action, in precisely the same way, when the nervous system is the seat of a conflict of impulsive tendencies.

§ 59. The Compound Reaction.—The detailed analyses that we felt the need of on p. 249 ought, by rights, to be provided by the reaction experiment; for that, as we said on p. 239, furnishes an outline-plan of experimental work which can be filled in and complicated in all manner of ways. Why, then, should not selective and volitional action be as manageable as impulsive? and why should we not follow, experimentally, the rise of impulse to choice and its later return to impulse?

§ 60. Will, Wish and Desire.—The compound reactions have led us into a digression. But, if the traditional forms—the discriminative, cognitive and choice reactions—are off the main track of the psychology of action, they still throw light on the establishment of determining tendencies to action, and in so far contribute to the psychology of will. For will, taken in a psychological and not in a moral sense, is simply the general name for the sum total of tendencies, inherited and acquired, that determine our actions; and we distinguish different types of will, according as these tendencies to action manifest themselves, characteristically, in different ways. The man of strong will is one whose tendencies are so deep-seated and persistent that he attains his end, or at any rate continues to strive towards it, however remote it may be and however numerous the counter-suggestions that oppose it; and the man of weak will is one whose tendencies are so instable that he is at the mercy of every fresh suggestion that comes. James remarks that, when the will is healthy, action follows, neither too slowly nor too rapidly, as the resultant of all the forces engaged; whereas, when it is unhealthy, action is either explosive or obstructed: the mercurial or dare-devil temperament shows an explosive will, “discharging so promptly into movements that inhibitions get no time to arise”; and the limp characters, the failures, sentimentalists, drunkards, schemers, show the obstructed will, in which “impulsion is insufficient or inhibition in excess,” Divisions of this sort might be pushed much further; but here, as in the parallel case of temperament (p. 227), it is enough to indicate the lines along which classification may proceed.

Questions and Exercises

References

CHAPTER X

§ 62. Imaginal Processes in Thought: The Abstract Idea.—A great deal of controversy has raged about the abstract or general idea. We can see to-day that the name is, psychologically, a misnomer. Just as no idea is, in its own right, an idea of memory or of imagination, so also no idea is, in its own right, an abstract idea; an idea becomes, is made into, an abstract idea whenever its context and determination carry the meaning of abstractness and generality. The associationists, however, looked at things differently; they thought that any idea which means ‘abstract’ must also itself be abstract; and so they distinguished a special class of abstract ideas. We obtain such ideas, they said, in this way: we review a large number of particular ideas, and we separate out the elements that are common to all of them; this common remainder is then a general or abstract idea which represents the whole group of particulars. Thus, “by leaving out of the particular colours perceived by sense that which distinguishes them one from another; and retaining that only which is common to all; the mind makes an idea of colour in abstract which is neither red, nor blue, nor white, nor any other determinate colour.”

§ 63. Thought and Language.—It has often been said that thought would be impossible without words; and it is true that we can hardly conceive of human thought save as formed and embodied and expressed in language. Thought and articulate speech grew up, so to say, side by side; each implies the other; they are two sides of the same phase of mental development. The old conundrum ‘Why don’t the animals talk? Because they have nothing to say’ contains so much of sound psychology; if the animals thought, they would undoubtedly use their vocal organs for speech; and since they do not talk, they cannot either be thinking. All this is true: and yet we must acknowledge that thought is not necessarily wedded to speech; it probably appeared, at least in rudimentary guise, before words came into being, and it persists (so to say) after words have ceased to be. There is a gesture-language that can serve as the medium of thought, and that is probably older than speech; and there is a thinking in images and attitudes that dispenses with words.

§ 64. Mental Attitudes.—If you look back over a course of thought, you will find verbal ideas, and you will perhaps find imaginal complexes of various kinds; but you will also find experiences of another sort, which have come to be known as mental attitudes. They are vague and elusive processes, which carry as if in a nutshell the entire meaning of a situation. Some of them belong to the feeling-side of mind: for feeling enters into the train of directed thought no less than into the freer play of association (p. 161): they are reported as ‘feelings’ of hesitation, vacillation, incapacity, expectancy, surprise, triviality, relevancy, and so on. Others are more nearly related to ideas; they are generally reported by a phrase beginning with ‘I knew that ...,’ ‘I was sure that ...,’ ‘I realised that ...,’ or some like expression. Suppose, for instance, that the observer is required to solve ‘in his head’ some mathematical problem, or to think out the answer to some difficult question that bears upon his special line of study. He may say, in the course of his report: “At that point it occurred to me that I had lost the first partial product,” “It seemed to me that the whole thing was taking too long a time,” “I suddenly realised that I had never thought of that before,” “It flashed upon me that the question was only another form of the old difficulty,” “I could not see the answer, but I knew that I could work it out,” and so forth. All these that-clauses may stand for mental attitudes.

§ 65. The Pattern of Thought.—There is a broad general resemblance between the pattern of thought and that of constructive imagination; it has indeed been said, though with exaggeration, that thought is an imagining in words, and imagination a thinking in images. The thinker, like the artist, sets out with a plan or design, and aims at a goal; and thought, like imagination, is a more or less steady flow, in a single direction, from the fountain-head of nervous disposition. ‘Happy thoughts’ occur in thinking, as they occur in imagination; there is a like movement between the poles of feeling; and the empathic experiences of the artist are paralleled by the mental attitudes of the thinker. In all these respects, the pattern of thought repeats what has been said on pp. 198 ff. of the pattern of constructive imagination.

§ 66. Abstraction and Generalisation.—We have spoken of the abstract or general idea, as if the two adjectives were interchangeable; and abstraction and generalisation are, in fact, only two phases of the same procedure. When we abstract, we pick out the features of a situation that are relevant to our present determination, and neglect the other features. When we generalise, we bring to light resemblances that have been merged with differences; but this statement implies that we neglect the differences, as irrelevant, and pick out the likenesses, as relevant; generalisation is thus only a special case of abstraction. We have seen that every suggestion is double-faced, positive as well as negative; and we may perhaps say that in thinking of abstraction we emphasise the negative face, the discarding of the irrelevant, while in thinking of generalisation we emphasise the positive face, the bringing together of the similars which are relevant.

§ 67. Comparison and Discrimination.—One of the commonest occurrences in a train of thought is the comparison of present with past, the harking back to a former stage of the procedure in order to make sure that we have not missed or mistaken some item of experience; and one of the commonest tasks set in the psychological laboratory reduces this comparison to its lowest terms. Two stimuli are presented, in succession; and the observer is required to say whether the intensity or quality of the corresponding sensations, the duration of the intervals, the magnitude of the forms, or whatever it may be, is the same or different. Both the stimuli themselves and the time which separates them may be varied in all sorts of ways; and the mental processes involved in the comparison vary accordingly. Here we shall mention only two points, which bear upon the course of thought at large.

Questions and Exercises

References

CHAPTER XI

§ 69. The Variety of Feeling-Attitude.—Let us take an elementary example of the variety of attitudes which follows in the wake of a sentiment. The sentiment which we select is one of those most widely attained: the sentiment of fitness of literary style. If, now, you read Lafcadio Hearn’s Japan,—as who has not?—you cannot fail to notice the differences of paragraphing. There are paragraphs which follow one another in the ordinary way, without break. There are paragraphs separated by a blank space, the width of a line of print. There are paragraphs that begin with a dash. There are paragraphs separated by a line or triangle of asterisks. There are paragraphs which end with a series of periods. And these modes of connective separation, as we may be allowed to call them, are themselves variously combined.

§ 70. The Forms of Sentiment.—Emotions go in pairs; an emotion is either joy or sorrow, either hope or fear; there is no midway emotion that is something between the two, but is neither the one nor the other. The sense-feelings, too, go in pairs; a feeling is either exciting or subduing, for instance, and cannot be anything between. When, however, the situation that arouses feeling is met by us in the state of secondary attention, then there is a third possibility; and the sentiments, in fact, run in threes. Here is a theory: is it true or false? If we judge it true, we have the sentiment of belief; if we judge it false, the sentiment of disbelief. But we need not come to a final judgement; facts a, b, c, we will suppose, tell for the theory, and facts x, y, z tell against it; we oscillate, uncertainly, between the two predicates ‘true’ and ‘false’; and the result is the suspensive sentiment of doubt. Language is an unsafe guide in these matters; partly because the same term may stand both for sentiment and for feeling-attitude, but partly also because the sentiments, being less common than emotions, have not always received specific names. In principle, nevertheless, there is in every case a third sentiment, corresponding with oscillation of judgement, between the two extremes.

§ 71. The Situations and Their Appeal.—If we wish to enquire into the nature of the situations which arouse a sentiment, two courses are open to us. We may undertake a study of origins; we may trace the history of primitive science and primitive art, and so on; and we may then try to generalise, both as regards the circumstances which called forth the scientific or artistic response, and as regards the appeal that such circumstances make to the human organism. Or we may turn our attention to acknowledged masterpieces, and try in like manner to ‘get behind’ them; trusting in this event rather to the typical than to the general. Both courses have been followed, and followed assiduously; but the outcome is still uncertain.

§ 72. Mood, Passion, Temperament.—With lapse of secondary attention, the sentiments lapse, as we have seen, into feeling-attitudes. It appears, from ordinary observation, that they may also persist, in weakened form, as moods. Thus, the moods acquiescence-indecision-incredulity correspond with the sentiments belief-doubt-disbelief; and we speak of a critical humour, a religious frame of mind, and so on. It is doubtful whether the sentiments rise to the intensity of passion; we speak, it is true, of a passionate humility, of a passion of disapprobation or of renunciation; but it is probable that these experiences are emotive, singly and not multiply determined.

Questions and Exercises

References

CHAPTER XII

§ 74. The Persistence of the Self.—A full account of the self of common sense, in so far as this self calls for psychological treatment, belongs to social and not to general psychology; and the discussion therefore falls outside the scope of the present book. We must, however, say a word about that observed continuity of memory and conduct which the concept of self, on its philosophical side, professes to explain (p. 308); for the notion of the persistence of the self has had a marked influence, as we shall see in § 75, upon this chapter of general psychology.

§ 75. The Self in Experience.—So far, we have been discussing the psychological self as viewed, so to say, from the outside; we have found out what the word ‘self’ means when it is used as a technical term like ‘mind’ or ‘memory.’ We have now to raise a different question, and to ask: How is myself represented in experience? There are very many occasions when the organism is, literally, thrown back on itself, when it meets a situation by a self-response; what mental processes are then involved?

§ 76. The Snares of Language.—You were warned on p. 36 that language may be misleading, and that the phrases which you naturally use oftentimes imply a view of the world, or an attitude towards experience, which is foreign to science. Nowhere, perhaps, is this discrepancy greater than in the phrases which refer to the self. Language, as we know, is older than science, and expresses the results of common-sense interpretation rather than of factual observation. The self of language is, accordingly; not the psychological self, but the counterpart of the mannikin-mind (p. 7); and just as we must be on guard, and remember our psychological definition, whenever in a psychological context we say or think the word ‘mind,’ so must we be on guard against the common-sense notion of ‘self’ that has insinuated itself into a thousand turns of familiar speech. An observer, describing a particular experience, may say, quite naturally, ‘I find no trace of self-reference!’—and there is no harm done, if we realise that the I of his remark is the traditional self-concept of language, and the self the psychological experience of self; but there may be very great harm, if likeness of words leads us to confound the personal with the impersonal, common sense with science. Only by an unreadable pedantry can we avoid the I-phrases and the other personal sentences; but we must always bear in mind that language, the very form and structure of it, embodies a theory, an explanation or interpretation of the self; and that, if we reject this theory, we have to couch our criticism in terms of the theory we reject.

§ 77. Consciousness and The Subconscious.—“Consciousness,” says Professor Ward, “is the vaguest, most protean, and most treacherous of psychological terms”; and Bain, writing in 1880, distinguished no less than thirteen meanings of the word; he could find more to-day! The ambiguity of the term seems to be due, in the last resort, to the running together of two fundamental meanings, the one of which is scientific or psychological, the other logical or philosophical. In the latter, the logical meaning, consciousness is awareness or knowledge, and ‘conscious of’ means ‘aware of’; in the former, the scientific meaning, consciousness is mental experience, experience regarded from the psychological point of view, and one can no more use the phrase ‘conscious of’ than one can use ‘mental of.’ If you think how natural it is to say ‘I was conscious of so-and-so,’ you will realise that the logical meaning is generally current; and if you remember that we have the terms ‘mind,’ ‘mental process,’ as names of mental experience, you will see that in psychology the word ‘consciousness’ is unnecessary; we have, in fact, not used it in this book,—until we came upon the popular expression ‘self-consciousness’ in § 76.

§ 78. Conclusion.—So we are at an end; and as you look back over the chapters of the book, you will have your own thoughts about the work done,—about your change of attitude from common sense to psychology, about the nature of mind, when mind is regarded from the scientific point of view, about the difficult or unsatisfactory places in psychology. The author has no wish to disturb these thoughts; every student must sum things up for himself, as every student, if he is to get the scientific point of view, must rely on his own thinking from the beginning (p. 36); for the kingdom of science is not in word but in power. There are, nevertheless, a few considerations that may be set down here, not as a summary made for you by the author, but simply as a general supplement to your own conclusions.

Questions and Exercises

References

APPENDIX

§ 80. Hypnosis.—We have seen that there are two lines of development from partial or defensive sleep; and that hypnosis is the final term of the one line, as normal deep sleep is the final term of the other. Hypnosis may therefore be regarded as a state in which the organism is partly asleep, and partly alert and awake. The wakefulness is characterised by a high degree of attention; and the hypnotised subject is accordingly liable to suggestion by anything that fits in with the direction of attention.

References

INDEX OF NAMES

INDEX OF SUBJECTS

A BEGINNER’S PSYCHOLOGY

CHAPTER I

Psychology: What it Is and What it Does

It is well for a man, when he seeks a clear and unbiassed opinion upon some certain matter, to forget many things, and to begin to look at it as if he knew nothing at all before.—Li Hung Chang

§ 1. Common Sense and Science.—We live in a world of values. We have material standards of comfort, and moral standards of conduct; and we eat and drink, and dress, and house our families, and educate our children, and carry on our business in life, with these standards more or less definitely before us. We approve good manners; we avoid extravagance and display; we aim at efficiency; we try to be honest; we should like to be cultivated. Everywhere and always our ordinary living implies this reference to values, to better and worse, desirable and undesirable, vulgar and refined. And that is the same thing as saying that our ordinary living is not scientific. It is not either unscientific, in the regular meaning of that word; it has nothing to do with science; it is non-scientific or extra-scientific. For science deals, not with values, but with facts. There is no good or bad, sick or well, useful or useless, in science. When the results of science are taken over into everyday life, they are transformed into values; the telegraph becomes a business necessity, the telephone a household convenience, the motor-car a means of recreation; the physician works to cure, the educator to fit for citizenship, the social reformer to correct abuses. Science itself, however, works simply to ascertain the truth, to discover the fact. Mr. H. G. Wells complains in a recent novel that no sick soul could find help or relief in a modern text-book of psychology. Of course not! Psychology is the science of mind, not the source of mental comfort or improvement. A sick soul would not go, for that matter, to a text-book of theology; it would go to some proved and trusted friend, or to some wise and tender book written by one who had himself suffered. So a sick body would betake itself, not to the physiological laboratory, but to a physician’s consulting room or to a hospital.