автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Castes and Tribes of Southern India. Vol. 1 of 7

Castes and Tribes of Southern India

Castes and Tribes

of

Southern India

By

Edgar Thurston, C.I.E.,

Superintendent, Madras Government Museum; Correspondant Étranger, Société d’Anthropologie de Paris; Socio Corrispondante, Societa, Romana di Anthropologia.

Assisted by K. Rangachari, M.A.,

of the Madras Government Museum.

Volume I—A and B

Government Press, Madras

1909.

List of Illustrations.

I.

a. Skull of Tamil man. b. Skull from Aditanallur.II.

South Indian boomerangs.III.

a. European skull. b. Hindu skull.IV.

Linga Banajiga.V.

Diagram of noses.VI.

Agamudaiyans, Madura district.VII.

Āradhya Brāhman.VIII.

Dolmens near Kotagiri.IX.

Badagas.X.

Badaga girls.XI.

Badaga temple.XII.

Badagas making fire.XIII.

Badaga funeral car with the corpse.XIV.

Badaga funeral car.XV.

Bairāgis.XVI.

Gazula Balija with bangles.XVII.

Balija bride and bridegroom.XVIII.

Kambla buffalo race.XIX.

Kambla racing buffaloes.XX.

Pūkāre post at Kambla buffalo races.XXI.

Bedar.XXII.

Billava toddy-tapper.XXIII.

Brāhman house with marks of hand to ward off the evil eye.XXIV.

Telugu Brāhman with rudraksha coat.XXV.

Smartha Brāhman (Brahacharnam) doing Siva worship.XXVI.

Padmanābha Swāmi.XXVII.

Dikshitar Brāhman.XXVIII.

Mādhva Brāhman.XXIX.

Fuel stack at Udipi Matt.XXX.

Oriya Brāhman.XXXI.

Konkani Brāhman.Preface.

In 1894, equipped with a set of anthropometric instruments obtained on loan from the Asiatic Society of Bengal, I commenced an investigation of the tribes of the Nīlgiri hills, the Todas, Kotas, and Badagas, bringing down on myself the unofficial criticism that “anthropological research at high altitudes is eminently indicated when the thermometer registers 100° in Madras.” From this modest beginning have resulted:—(1) investigation of various classes which inhabit the city of Madras; (2) periodical tours to various parts of the Madras Presidency, with a view to the study of the more important tribes and classes; (3) the publication of Bulletins, wherein the results of my work are embodied; (4) the establishment of an anthropological laboratory; (5) a collection of photographs of Native types; (6) a series of lantern slides for lecture purposes; (7) a collection of phonograph records of tribal songs and music.

The scheme for a systematic and detailed ethnographic survey of the whole of India received the formal sanction of the Government of India in 1901. A Superintendent of Ethnography was appointed for each Presidency or Province, to carry out the work of the survey in addition to his other duties. The other duty, in my particular case—the direction of a large local museum—happily made an excellent blend with the survey operations, as the work of collection for the ethnological section went on simultaneously with that of investigation. The survey was financed for a period of five (afterwards extended to eight) years, and an annual allotment of Rs. 5,000 provided for each Presidency and Province. This included Rs. 2,000 for approved notes on monographs, and replies to the stereotyped series of questions. The replies to these questions were not, I am bound to admit, always entirely satisfactory, as they broke down both in accuracy and detail. I may, as an illustration, cite the following description of making fire by friction. “They know how to make fire, i.e., by friction of wood as well as stone, etc. They take a triangular cut of stone, and one flat oblong size flat. They hit one another with the maintenance of cocoanut fibre or copper, then fire sets immediately, and also by rubbing the two barks frequently with each other they make fire.”

I gladly place on record my hearty appreciation of the services rendered by Mr. K. Rangachari in the preparation of the present volumes. During my temporary absence in Europe, he was placed in charge of the survey, and he has been throughout invaluable in obtaining information concerning manners and customs, as interpreter and photographer, and in taking phonograph records.

For information relating to the tribes and castes of Cochin and Travancore, I gratefully acknowledge my indebtedness to Messrs. L. K. Anantha Krishna Aiyer and N. Subramani Aiyer, the Superintendents of Ethnography for their respective States. The notes relating to the Cochin State have been independently published at the Ernakulam Press, Cochin.

In the scheme for the Ethnographic Survey, it was laid down that the Superintendents should supplement the information obtained from representative men and by their own enquiries by “researches into the considerable mass of information which lies buried in official reports, in the journals of learned Societies, and in various books.” Of this injunction full advantage has been taken, as will be evident from the abundant crop of references in foot-notes.

It is impossible to express my thanks individually to the very large number of correspondents, European and Indian, who have generously assisted me in my work. I may, however, refer to the immense aid which I have received from the District Manuals edited by Mr. (now Sir) H. A. Stuart, I.C.S., and the District Gazetteers, which have been quite recently issued under the editorship of Mr. W. Francis, I.C.S., Mr. F. R. Hemingway, I.C.S., and Mr. F. B. Evans, I.C.S.

My thanks are further due to Mr. C. Hayavadana Rao, to whom I am indebted for much information acquired when he was engaged in the preparation of the District Gazetteers, and for revising the proof sheets.

For some of the photographs of Badagas, Kurumbas, and Todas, I am indebted to Mr. A. T. W. Penn of Ootacamund.

I may add that the anthropometric data are all the result of measurements taken by myself, in order to eliminate the varying error resulting from the employment of a plurality of observers.

E. T.

Introduction.

The vast tract of country, over which my investigations in connection with the ethnographic survey of South India have extended, is commonly known as the Madras Presidency, and officially as the Presidency of Fort St. George and its Dependencies. Included therein were the small feudatory States of Pudukōttai, Banganapalle, and Sandūr, and the larger Native States of Travancore and Cochin. The area of the British territory and Feudatory States, as returned at the census, 1901, was 143,221 square miles, and the population 38,623,066. The area and population of the Native States of Travancore and Cochin, as recorded at the same census, were as follows:—

Area.

Population.

Sq. Miles.

Travancore

7,091

2,952,157

Cochin

1,361

512,025

Briefly, the task which was set me in 1901 was to record the ‘manners and customs’ and physical characters of more than 300 castes and tribes, representing more than 40,000,000 individuals, and spread over an area exceeding 150,000 square miles.

The Native State of Mysore, which is surrounded by the Madras Presidency on all sides, except on part of the west, where the Bombay Presidency forms the boundary, was excluded from my beat ethnographically, but included for the purpose of anthropometry. As, however, nearly all the castes and tribes which inhabit the Mysore State are common to it and the Madras Presidency, I have given here and there some information relating thereto.

It was clearly impossible for myself and my assistant, in our travels, to do more than carry out personal investigations over a small portion of the vast area indicated above, which provides ample scope for research by many trained explorers. And I would that more men, like my friends Dr. Rivers and Mr. Lapicque, who have recently studied Man in Southern India from an anthropological and physiological point of view, would come out on a visit, and study some of the more important castes and tribes in detail. I can promise them every facility for carrying out their work under the most favourable conditions for research, if not of climate. And we can provide them with anything from 112° in the shade to the sweet half English air of the Nīlgiri and other hill-ranges.

Routine work at head-quarters unhappily keeps me a close prisoner in the office chair for nine months in the year. But I have endeavoured to snatch three months on circuit in camp, during which the dual functions of the survey—the collection of ethnographic and anthropometric data—were carried out in the peaceful isolation of the jungle, in villages, and in mofussil (up-country) towns. These wandering expeditions have afforded ample evidence that delay in carrying through the scheme for the survey would have been fatal. For, as in the Pacific and other regions, so in India, civilisation is bringing about a radical change in indigenous manners and customs, and mode of life. It has, in this connection, been well said that “there will be plenty of money and people available for anthropological research, when there are no more aborigines. And it behoves our museums to waste no time in completing their anthropological collections.” Tribes which, only a few years ago, were living in a wild state, clad in a cool and simple garb of forest leaves, buried away in the depths of the jungle, and living, like pigs and bears, on roots, honey, and other forest produce, have now come under the domesticating, and sometimes detrimental influence of contact with Europeans, with a resulting modification of their conditions of life, morality, and even language. The Paniyans of the Wynaad, and the Irulas of the Nīlgiris, now work regularly for wages on planters’ estates, and I have seen a Toda boy studying for the third standard instead of tending the buffaloes of his mand. A Toda lassie curling her ringlets with the assistance of a cheap German looking-glass; a Toda man smeared with Hindu sect marks, and praying for male offspring at a Hindu shrine; the abandonment of leafy garments in favour of imported cotton piece-goods; the employment of kerosine tins in lieu of thatch; the decline of the national turban in favour of the less becoming pork-pie cap or knitted nightcap of gaudy hue; the abandonment of indigenous vegetable dyes in favour of tinned anilin and alizarin dyes; the replacement of the indigenous peasant jewellery by imported beads and imitation jewellery made in Europe—these are a few examples of change resulting from Western and other influences.

The practice of human sacrifice, or Meriah rite, has been abolished within the memory of men still living, and replaced by the equally efficacious slaughter of a buffalo or sheep. And I have notes on a substituted ceremony, in which a sacrificial sheep is shaved so as to produce a crude representation of a human being, a Hindu sect mark painted on its forehead, a turban stuck on its head, and a cloth around its body. The picturesque, but barbaric ceremony of hook-swinging is now regarded with disfavour by Government, and, some time ago, I witnessed a tame substitute for the original ceremony, in which, instead of a human being with strong iron hooks driven through the small of his back, a little wooden figure, dressed up in turban and body cloth, and carrying a shield and sabre, was hoisted on high and swung round.

In carrying out the anthropometric portion of the survey, it was unfortunately impossible to disguise the fact that I am a Government official, and very considerable difficulties were encountered owing to the wickedness of the people, and their timidity and fear of increased taxation, plague inoculation, and transportation. The Paniyan women of the Wynaad believed that I was going to have the finest specimens among them stuffed for the Madras Museum. An Irula man, on the Nīlgiri hills, who was wanted by the police for some mild crime of ancient date, came to be measured, but absolutely refused to submit to the operation on the plea that the height-measuring standard was the gallows. The similarity of the word Boyan to Boer was once fatal to my work. For, at the time of my visit to the Oddēs, who have Boyan as their title, the South African war was just over, and they were afraid that I was going to get them transported, to replace the Boers who had been exterminated. Being afraid, too, of my evil eye, they refused to fire a new kiln of bricks for the club chambers at Coimbatore until I had taken my departure. During a long tour through the Mysore province, the Natives mistook me for a recruiting sergeant bent on seizing them for employment in South Africa, and fled before my approach from town to town. The little spot, which I am in the habit of making with Aspinall’s white paint to indicate the position of the fronto-nasal suture and bi-orbital breadth, was supposed to possess vesicant properties, and to blister into a number on the forehead, which would serve as a means of future identification for the purpose of kidnapping. The record of head, chest, and foot measurements, was viewed with marked suspicion, on the ground that I was an army tailor, measuring for sepoy’s clothing. The untimely death of a Native outside a town, at which I was halting, was attributed to my evil eye. Villages were denuded of all save senile men, women, and infants. The vendors of food-stuffs in one bazar, finding business slack owing to the flight of their customers, raised their prices, and a missionary complained that the price of butter had gone up. My arrival at one important town was coincident with a great annual temple festival, whereat there were not sufficient coolies left to drag the temple car in procession. So I had perforce to move on, and leave the Brāhman heads unmeasured. The head official of another town, when he came to take leave of me, apologised for the scrubby appearance of his chin, as the local barber had fled. One man, who had volunteered to be tested with Lovibond’s tintometer, was suddenly seized with fear in the midst of the experiment, and, throwing his body-cloth at my feet, ran for all he was worth, and disappeared. An elderly Municipal servant wept bitterly when undergoing the process of measurement, and a woman bade farewell to her husband, as she thought for ever, as he entered the threshold of my impromptu laboratory. The goniometer for estimating the facial angle is specially hated, as it goes into the mouth of castes both high and low, and has to be taken to a tank (pond) after each application. The members of a certain caste insisted on being measured before 4 P.M., so that they might have time to remove, by ceremonial ablution, the pollution from my touch before sunset.

Such are a few of the unhappy results, which attend the progress of a Government anthropologist. I may, when in camp, so far as measuring operations are concerned, draw a perfect and absolute blank for several days in succession, or a gang of fifty or even more representatives of different castes may turn up at the same time, all in a hurry to depart as soon as they have been sufficiently amused by the phonograph, American series of pseudoptics (illusions), and hand dynamometer, which always accompany me on my travels as an attractive bait. When this occurs, it is manifestly impossible to record all the major, or any of the minor measurements, which are prescribed in ‘Anthropological Notes and Queries,’ and elsewhere. And I have to rest unwillingly content with a bare record of those measurements, which experience has taught me are the most important from a comparative point of view within my area, viz., stature, height and breadth of nose, and length and breadth of head, from which the nasal and cephalic indices can be calculated. I refer to the practical difficulties, in explanation of a record which is admittedly meagre, but wholly unavoidable, in spite of the possession of a good deal of patience and a liberal supply of cheroots, and current coins, which are often regarded with suspicion as sealing a contract, like the King’s shilling. I have even known a man get rid of the coin presented to him, by offering it, with flowers and a cocoanut, to the village goddess at her shrine, and present her with another coin as a peace-offering, to get rid of the pollution created by my money.

The manifold views, which have been brought forward as to the origin and place in nature of the indigenous population of Southern India, are scattered so widely in books, manuals, and reports, that it will be convenient if I bring together the evidence derived from sundry sources.

The original name for the Dravidian family, it may be noted, was Tamulic, but the term Dravidian was substituted by Bishop Caldwell, in order that the designation Tamil might be reserved for the language of that name. Drāvida is the adjectival form of Dravida, the Sanskrit name for the people occupying the south of the Indian Peninsula (the Deccan of some European writers).1

According to Haeckel,2 three of the twelve species of man—the Dravidas (Deccans; Sinhalese), Nubians, and Mediterranese (Caucasians, Basque, Semites, Indo-Germanic tribes)—“agree in several characteristics, which seem to establish a close relationship between them, and to distinguish them from the remaining species. The chief of these characteristics is the strong development of the beard which, in all other species, is either entirely wanting, or but very scanty. The hair of their heads is in most cases more or less curly. Other characteristics also seem to favour our classing them in one main group of curly-haired men (Euplocomi); at present the primæval species, Homo Dravida, is only represented by the Deccan tribes in the southern part of Hindustan, and by the neighbouring inhabitants of the mountains on the north-east of Ceylon. But, in earlier times, this race seems to have occupied the whole of Hindustan, and to have spread even further. It shows, on the one hand, traits of relationship to the Australians and Malays; on the other to the Mongols and Mediterranese. Their skin is either of a light or dark brown colour; in some tribes, of a yellowish brown. The hair of their heads is, as in Mediterranese, more or less curled; never quite smooth, like that of the Euthycomi, nor actually woolly, like that of the Ulotrichi. The strong development of the beard is also like that of the Mediterranese. Their forehead is generally high, their nose prominent and narrow, their lips slightly protruding. Their language is now very much mixed with Indo-Germanic elements, but seems to have been originally derived from a very primæval language.”

In the chapter devoted to ‘Migration and Distribution of Organisms,’ Haeckel, in referring to the continual changing of the distribution of land and water on the surface of the earth, says: “The Indian Ocean formed a continent, which extended from the Sunda Islands along the southern coast of Asia to the east coast of Africa. This large continent of former times Sclater has called Lemuria, from the monkey-like animals which inhabited it, and it is at the same time of great importance from being the probable cradle of the human race. The important proof which Wallace has furnished by the help of chronological facts, that the present Malayan Archipelago consists in reality of two completely different divisions, is particularly interesting. The western division, the Indo-Malayan Archipelago, comprising the large islands of Borneo, Java, and Sumatra, was formerly connected by Malacca with the Asiatic continent, and probably also with the Lemurian continent, and probably also with the Lemurian continent just mentioned. The eastern division, on the other hand, the Austro-Malayan Archipelago, comprising Celebes, the Moluccas, New Guinea, Solomon’s Islands, etc., was formerly directly connected with Australia.”

An important ethnographic fact, and one which is significant, is that the description of tree-climbing by the Dyaks of Borneo, as given by Wallace,3 might have been written on the Anaimalai hills of Southern India, and would apply equally well in every detail to the Kādirs who inhabit those hills.4 An interesting custom, which prevails among the Kādirs and Mala Vēdans of Travancore, and among them alone, so far as I know, in the Indian Peninsula, is that of chipping all or some of the incisor teeth into the form of a sharp pointed, but not serrated, cone. The operation is said to be performed, among the Kādirs, with a chisel or bill-hook and file, on boys at the age of eighteen, and girls at the age of ten or thereabouts. It is noted by Skeat and Blagden5 that the Jakuns of the Malay Peninsula are accustomed to file their teeth to a point. Mr. Crawford tells us further that, in the Malay Archipelago, the practice of filing and blackening the teeth is a necessary prelude to marriage, the common way of expressing the fact that a girl has arrived at puberty being that she had her teeth filed. In an article6 entitled “Die Zauberbilderschriften der Negrito in Malaka,” Dr. K. T. Preuss describes in detail the designs on the bamboo combs, etc., of the Negritos of Malacca, and compares them with the strikingly similar designs on the bamboo combs worn by the Kādirs of Southern India. He works out in detail the theory that the design is not, as I called it7 an ornamental geometric pattern, but consists of a series of hieroglyphics. It is noted by Skeat and Blagden8 that “the Semang women wore in their hair a remarkable kind of comb, which appears to be worn entirely as a charm against diseases. These combs were almost invariably made of bamboo, and were decorated with an infinity of designs, no two of which ever entirely agreed. It was said that each disease had its appropriate pattern. Similar combs are worn by the Pangan, the Semang and Sakai of Perak, and most of the mixed (Semang-Sakai) tribes.” I am informed by Mr. Vincent that, as far as he knows, the Kādir combs are not looked on as charms, and the markings thereon have no mystic significance. A Kādir man should always make a comb, and present it to his wife just before marriage or at the conclusion of the marriage ceremony, and the young men vie with each other as to who can make the nicest comb. Sometimes they represent strange articles on the combs. Mr. Vincent has, for example, seen a comb with a very good imitation of the face of a clock scratched on it.

In discussing the racial affinities of the Sakais, Skeat and Blagden write8 that “an alternative theory comes to us on the high authority of Virchow, who puts it forward, however, in a somewhat tentative manner. It consists in regarding the Sakai as an outlying branch of a racial group formed by the Vedda (of Ceylon), Tamil, Kurumba, and Australian races.... Of these the height is variable, but, in all four of the races compared, it is certainly greater than that of the Negrito races. The skin colour, again, it is true, varies to a remarkable degree, but the general hair character appears to be uniformly long, black and wavy, and the skull-index, on the other hand, appears to indicate consistently a dolichocephalic or long-shaped head.” Speaking of the Sakais, the same authorities state that “in evidence of their striking resemblance to the Veddas, it is perhaps worth remarking that one of the brothers Sarasin who had lived among the Veddas and knew them very well, when shown a photograph of a typical Sakai, at first supposed it to be a photograph of a Vedda.” For myself, when I first saw the photographs of Sakais published by Skeat and Blagden, it was difficult to realise that I was not looking at pictures of Kādirs, Paniyans, Kurumbas, or other jungle folk of Southern India.

It may be noted en passant, that emigration takes place at the present day from the southern parts of the Madras Presidency to the Straits Settlements. The following statement shows the number of passengers that proceeded thither during 1906:—

Madras—

Total.

South Arcot

Porto Novo

2,555

Cuddalore

583

Pondicherry

55

Tanjore

Negapatam

238

and

Nagore

45,453

Karikal

3,422

“The name Kling (or Keling) is applied, in the Malay countries, to the people of Continental India who trade thither, or are settled in those regions, and to the descendants of settlers. The Malay use of the word is, as a rule, restricted to Tamils. The name is a form of Kalinga, a very ancient name for the region known as the Northern Circars, i.e., the Telugu coast of the Bay of Bengal.”9 It is recorded by Dr. N. Anandale that the phrase Orang Kling Islam (i.e., a Muhammadan from the Madras coast) occurs in Patani Malay. He further informs us10 that among the Labbai Muhammadans of the Madura coast, there are “certain men who make a livelihood by shooting pigeons with blow-guns. According to my Labbai informants, the ‘guns’ are purchased by them in Singapore from Bugis traders. There is still a considerable trade, although diminished, between Kilakarai and the ports of Burma and the Straits Settlements. It is carried on entirely by Muhammadans in native sailing vessels, and a large proportion of the Musalmans of Kilakarai have visited Penang and Singapore. It is not difficult to find among them men who can speak Straits Malay. The local name for the blow-gun is senguttān, and is derived in popular etymology from the Tamil sen (above) and kutu (to stab). I have little doubt that it is really a corruption of the Malay name of the weapon sumpitan.”

On the evidence of the very close affinities between the plants and animals in Africa and India at a very remote period, Mr. R. D. Oldham concludes that there was once a continuous stretch of dry land connecting South Africa and India. “In some deposits,” he writes,11 “found resting upon the Karoo beds on the coast of Natal, 22 out of 35 species of Mollusca and Echinodermata collected and specifically identified, are identical with forms found in the cretaceous beds of Southern India, the majority being Trichinopoly species. From the cretaceous rocks of Madagascar, six species of cretaceous fossils were examined by Mr. R. B. Newton in 1899, of which three are also found in the Ariyalur group (Southern India). The South African beds are clearly coast or shallow water deposits, like those of India. The great similarity of forms certainly suggests continuity of coast line between the two regions, and thus supports the view that the land connection between South Africa and India, already shown to have existed in both the lower and upper Gondwána periods, was continued into cretaceous times.”

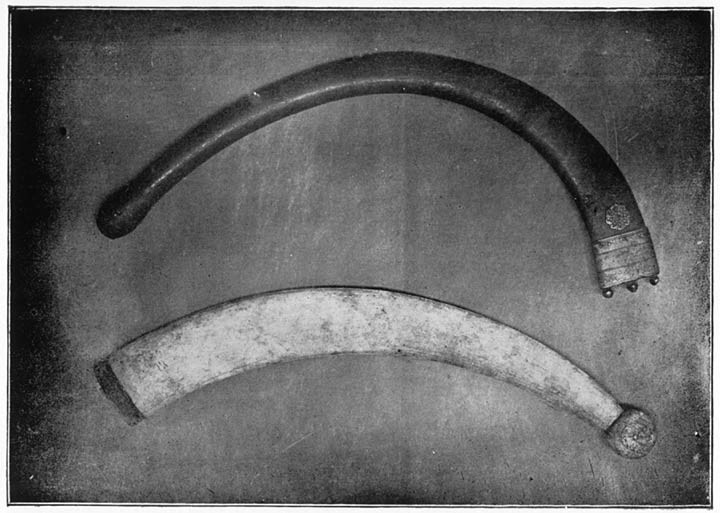

By Huxley12 the races of mankind are divided into two primary divisions, the Ulotrichi with crisp or woolly hair (Negros; Negritos), and the Leiotrichi with smooth hair; and the Dravidians are included in the Australoid group of the Leiotrichi “with dark skin, hair and eyes, wavy black hair, and eminently long, prognathous skulls, with well-developed brow ridges, who are found in Australia and in the Deccan.” There is, in the collection of the Royal College of Surgeons’ Museum, an exceedingly interesting “Hindu” skull from Southern India, conspicuously dolichocephalic, and with highly developed superciliary ridges. Some of the recorded measurements of this skull are as follows:—

Length

19.6 cm.

Breadth

13.2 cm.

Cephalic index

67.3

Nasal height

4.8 cm.

Nasal breadth

2.5 cm.

Nasal index

52.1 cm.

Another “Hindu” skull, in the collection of the Madras Museum, with similar marked development of the superciliary ridges, has the following measurements:—

Length

18.4 cm.

Breadth

13.8 cm.

Cephalic index

75

Nasal height

4.9 cm.

Nasal breadth

2.1 cm.

Nasal index

42.8

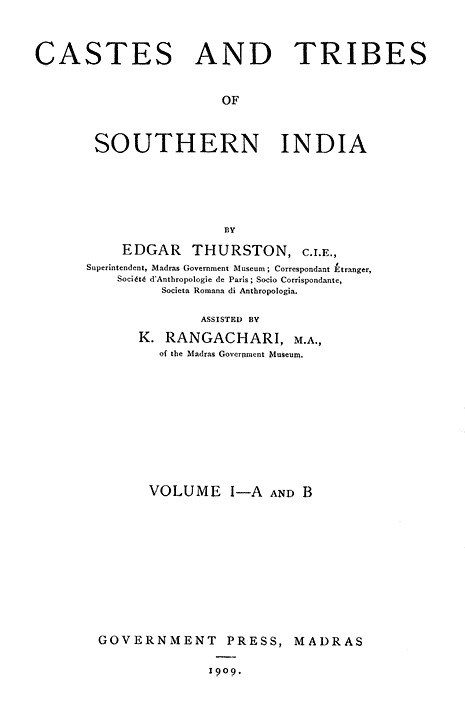

I am unable to subscribe to the prognathism of the Dravidian tribes of Southern India, or of the jungle people, though aberrant examples thereof are contained in the collection of skulls at the Madras Museum, e.g., the skull of a Tamil man (caste unknown) who died a few years ago in Madras (Pl. I-a). The average facial angle of various castes and tribes which I have examined ranged between 67° and 70°, and the inhabitants of Southern India may be classified as orthognathous. Some of the large earthenware urns excavated by Mr. A. Rea, of the Archæological Department, at the “prehistoric” burial site at Aditanallūr in the Tinnevelly district,13 contained human bones, and skulls in a more or less perfect condition. Two of these skulls, preserved at the Madras Museum, are conspicuously prognathous (Pl. I-b). Concerning this burial site M. L. Lapieque writes as follows.14 “J’ai rapporté un specimen des urnes funéraires, avec une collection assez complète du mobilier funéraire. J’ai rapporté aussi un crâne en assez bon état, et parfaitement déterminable. Il est hyperdolichocéphale, et s’accorde avec la série que le service d’archéologie de Madras a déja réunie. Je pense que la race d’Adichanallour appartient aux Proto-Dravidiens.” The measurements of six of the most perfect skulls from Aditanallūr in the Madras Museum collection give the following results:—

Cephalic length,

Cephalic breadth,

Cephalic index.

cm.

cm.

18.8

12.4

66.

19.1

12.7

66.5

18.3

12.4

67.8

18.

12.2

67.8

18.

12.8

77.1

16.8

13.1

78.

a. Skull of Tamil Man.

b. Skull From Aditanallur.

The following extracts from my notes show that the hyperdolichocephalic type survives in the dolichocephalic inhabitants of the Tamil country at the present day:—

Class

Number examined.

Cephalic index below 70.

Palli

40

64.4; 66.9; 67; 68.2; 68.9; 69.6.

Paraiyan

40

64.8; 69.2; 69.3; 69.5

.Vellāla

40

67.9; 69.6.

By Flower and Lydekker,15 a white division of man, called the Caucasian or Eurafrican, is made to include Huxley’s Xanthochroi (blonde type) and Melanochroi (black hair and eyes, and skin of almost all shades from white to black). The Melanochroi are said to “comprise the greater majority of the inhabitants of Southern Europe, North Africa, and South-west Asia, and consist mainly of the Aryan, Semitic, and Hamitic families. The Dravidians of India, the Veddahs of Ceylon, and probably the Ainus of Japan, and the Maoutze of China, also belong to this race, which may have contributed something to the mixed character of some tribes of Indo-China and the Polynesian islands, and have given at least the characters of the hair to the otherwise Negroid inhabitants of Australia. In Southern India they are largely mixed with a Negrito element, and, in Africa, where their habitat becomes coterminous with that of the Negroes, numerous cross-races have sprung up between them all along the frontier line.”

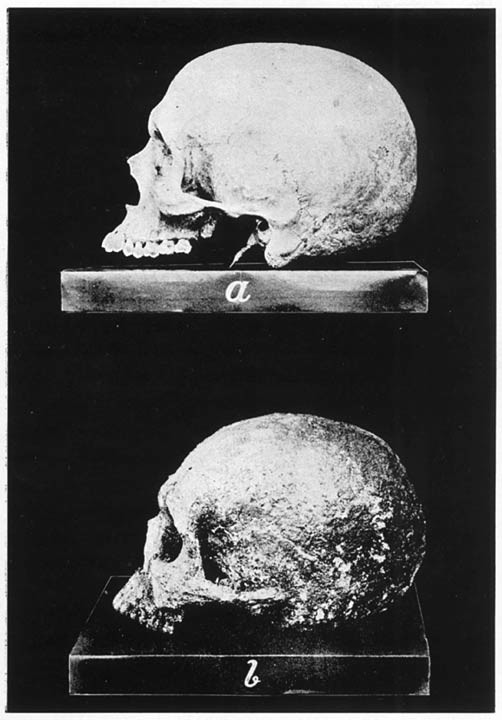

In describing the “Hindu type,” Topinard16 divides the population of the Indian peninsula into three strata, viz., the Black, Mongolian, and the Aryan. “The remnants of the first,” he says, “are at the present time shut up in the mountains of Central India under the name of Bhils, Mahairs, Ghonds, and Khonds; and in the south under that of Yenādis, Kurumbas, etc. Its primitive characters, apart from its black colour and low stature, are difficult to discover, but it is to be noticed that travellers do not speak of woolly hair in India.17 The second has spread over the plateaux of Central India by two lines of way, one to the north-east, the other to the north-west. The remnants of the first invasion are seen in the Dravidian or Tamil tribes, and those of the second in the Jhats. The third more recent, and more important as to quality than as to number, was the Aryan.” In speaking further of the Australian type, characterised by a combination of smooth hair with Negroid features, Topinard states that “it is clear that the Australians might very well be the result of the cross between one race with smooth hair from some other place, and a really Negro and autochthonous race. The opinions held by Huxley are in harmony with this hypothesis. He says the Australians are identical with the ancient inhabitants of the Deccan. The features of the present blacks in India, and the characters which the Dravidian and Australian languages have in common, tend to assimilate them. The existence of the boomerang in the two countries, and some remnants of caste in Australia, help to support the opinion.”

South Indian boomerangs.

Of the so-called boomerangs of Southern India, the Madras Museum possesses three (two ivory, one wooden) from the Tanjore armoury (Pl. II). Concerning them, the Dewān of Pudukkōttai writes to me as follows. “The valari or valai tadi (bent stick) is a short weapon, generally made of some hard-grained wood. It is also sometimes made of iron. It is crescent-shaped, one end being heavier than the other, and the outer end is sharpened. Men trained in the use of the weapon hold it by the lighter end, whirl it a few times over their shoulders to give it impetus, and then hurl it with great force against the object aimed at. It is said that there were experts in the art of throwing the valari, who could at one stroke despatch small game, and even man. No such experts are now forthcoming in the Pudukkōttai State, though the instrument is reported to be occasionally used in hunting hares, jungle fowl, etc. Its days, however, must be counted as past. Tradition states that the instrument played a considerable part in the Poligar wars of the last century. But it now reposes peacefully in the households of the descendants of the rude Kallan and Maravan warriors, preserved as a sacred relic of a chivalric past, along with other old family weapons in their pūja (worship) room, brought out and scraped and cleaned on occasions like the Ayudha pūja day (when worship is paid to weapons and implements of industry), and restored to its place of rest immediately afterwards.” At a Kallan marriage, the bride and bridegroom go to the house of the latter, where boomerangs are exchanged, and a feast is held. This custom appears to be fast becoming a tradition. But there is a common saying still current “Send the valai tadi, and bring the bride.”18

It is pointed out by Topinard,19 as a somewhat important piece of evidence, that, in the West, about Madagascar and the point of Aden in Africa, there are black tribes with smooth hair, or, at all events, large numbers of individuals who have it, mingled particularly among the Somālis and the Gallas, in the region where M. Broca has an idea that some dark, and not Negro, race, now extinct, once existed. At the meeting of the British Association, 1898, Mr. W. Crooke gave expression to the view that the Dravidians represent an emigration from the African continent, and discounted the theory that the Aryans drove the aboriginal inhabitants into the jungles with the suggestion that the Aryan invasion was more social than racial, viz., that what India borrowed from the Aryans was manners and customs. According to this view, it must have been reforming aborigines who gained the ascendancy in India, rather than new-comers; and those of the aborigines who clung to their old ways got left behind in the struggle for existence.

In an article devoted to the Australians, Professor R. Semon writes as follows. “We must, without hesitation, presume that the ancestors of the Australians stood, at the time of their immigration to the continent, on a lower rung of culture than their living representatives of to-day. Whence, and in what manner, the immigration took place, it is difficult to determine. In the neighbouring quarter of the globe there lives no race, which is closely related to the Australians. Their nearest neighbours, the Papuans of New Guinea, the Malays of the Sunda Islands, and the Macris of New Zealand, stand in no close relationship to them. On the other hand, we find further away, among the Dravidian aborigines of India, types which remind us forcibly of the Australians in their anthropological characters. In drawing attention to the resemblance of the hill-tribes of the Deccan to the Australians, Huxley says: ‘An ordinary cooly, such as one can see among the sailors of any newly-arrived East India vessel, would, if stripped, pass very well for an Australian, although the skull and lower jaw are generally less coarse.’ Huxley here goes a little too far in his accentuation of the similarity of type. We are, however, undoubtedly confronted with a number of characters—skull formation, features, wavy curled hair—in common between the Australians and Dravidians, which gain in importance from the fact that, by the researches of Norris, Bleek, and Caldwell, a number of points of resemblance between the Australian and Dravidian languages have been discovered, and this despite the fact that the homes of the two races are so far apart, and that a number of races are wedged in between them, whose languages have no relationship whatever to either the Dravidian or Australian. There is much that speaks in favour of the view that the Australians and Dravidians sprang from a common main branch of the human race. According to the laborious researches of Paul and Fritz Sarasin, the Veddas of Ceylon, whom one might call pre-Dravidians, would represent an off-shoot from this main stem. When they branched off, they stood on a very low rung of development, and seem to have made hardly any progress worth mentioning.”

In dealing with the Australian problem, Mr. A. H. Keane20 refers to the time when Australia formed almost continuous land with the African continent, and to its accessibility on the north and north-west to primitive migration both from India and Papuasia. “That such migrations,” he writes, “took place, scarcely admits of a doubt, and the Rev. John Mathew21 concludes that the continent was first occupied by a homogeneous branch of the Papuan race either from New Guinea or Malaysia, and that these first arrivals, to be regarded as true aborigines, passed into Tasmania, which at that time probably formed continuous land with Australia. Thus the now extinct Tasmanians would represent the primitive type, which, in Australia, became modified, but not effaced, by crossing with later immigrants, chiefly from India. These are identified, as they have been by other ethnologists, with the Dravidians, and the writer remarks that ‘although the Australians are still in a state of savagery, and the Dravidians of India have been for many ages a people civilized in a great measure, and possessed of literature, the two peoples are affiliated by deeply-marked characteristics in their social system as shown by the boomerang, which, unless locally evolved, must have been introduced from India.’ But the variations in the physical characters of the natives appear to be too great to be accounted for by a single graft; hence Malays also are introduced from the Eastern Archipelago, which would explain both the straight hair in many districts, and a number of pure Malay words in several of the native languages.” Dealing later with the ethnical relations of the Dravidas, Mr. Keane says that “although they preceded the Aryan-speaking Hindus, they are not the true aborigines of the Deccan, for they were themselves preceded by dark peoples, probably of aberrant Negrito type.”

In the ‘Manual of Administration of the Madras Presidency,’ Dr. C. Macleane writes as follows. “The history proper of the south of India may be held to begin with the Hindu dynasties formed by a more or less intimate admixture of the Aryan and Dravidian systems of government. But, prior to that, three stages of historical knowledge are recognisable; first, as to such aboriginal period as there may have been prior to the Dravidian; secondly, as to the period when the Aryans had begun to impose their religion and customs upon the Dravidians, but the time indicated by the early dynasties had not yet been reached. Geology and natural history alike make it certain that, at a time within the bounds of human knowledge, Southern India did not form part of Asia. A large southern continent, of which this country once formed part, has ever been assumed as necessary to account for the different circumstances. The Sanscrit Pooranic writers, the Ceylon Boodhists, and the local traditions of the west coast, all indicate a great disturbance of the point of the Peninsula and Ceylon within recent times.22 Investigations in relation to race show it to be by no means impossible that Southern India was once the passage-ground, by which the ancient progenitors of Northern and Mediterranean races proceeded to the parts of the globe which they now inhabit. In this part of the world, as in others, antiquarian remains show the existence of peoples who used successively implements of unwrought stone, of wrought stone, and of metal fashioned in the most primitive manner.23 These tribes have also left cairns and stone circles indicating burial places. It has been usual to set these down as earlier than Dravidian. But the hill Coorumbar of the Palmanair plateau, who are only a detached portion of the oldest known Tamulian population, erect dolmens to this day. The sepulchral urns of Tinnevelly may be earlier than Dravidian, or they may be Dravidian.... The evidence of the grammatical structure of language is to be relied on as a clearly distinctive mark of a population, but, from this point of view, it appears that there are more signs of the great lapse of time than of previous populations. The grammar of the South of India is exclusively Dravidian, and bears no trace of ever having been anything else. The hill, forest, and Pariah tribes use the Dravidian forms of grammar and inflection.... The Dravidians, a very primeval race, take a by no means low place in the conjectural history of humanity. They have affinities with the Australian aborigines, which would probably connect their earliest origin with that people.” Adopting a novel classification, Dr. Macleane, in assuming that there are no living representatives in Southern India of any race of a wholly pre-Dravidian character, sub-divides the Dravidians into pre-Tamulian and Tamulian, to designate two branches of the same family, one older or less civilised than the other.

The importance, which has been attached by many authorities to the theory of the connection between the Dravidians and Australians, is made very clear from the passages in their writings, which I have quoted. Before leaving this subject, I may appropriately cite as an important witness Sir William Turner, who has studied the Dravidians and Australians from the standpoint of craniology.24 “Many ethnologists of great eminence,” he writes, “have regarded the aborigines of Australia as closely associated with the Dravidians of India. Some also consider the Dravidians to be a branch of the great Caucasian stock, and affiliated therefore to Europeans. If these two hypotheses are to be regarded as sound, a relationship between the aboriginal Australians and the European would be established through the Dravidian people of India. The affinities between the Dravidians and Australians have been based upon the employment of certain words by both people, apparently derived from common roots; by the use of the boomerang, similar to the well-known Australian weapon, by some Dravidian tribes; by the Indian peninsula having possibly had in a previous geologic epoch a land connection with the Austro-Malayan Archipelago, and by certain correspondences in the physical type of the two people. Both Dravidians and Australians have dark skins approximating to black; dark eyes; black hair, either straight, wavy or curly, but not woolly or frizzly; thick lips; low nose with wide nostrils; usually short stature, though the Australians are somewhat taller than the Dravidians. When the skulls are compared with each other, whilst they correspond in some particulars, they differ in others. In both races, the general form and proportions are dolichocephalic, but in the Australians the crania are absolutely longer than in the Dravidians, owing in part to the prominence of the glabella. The Australian skull is heavier, and the outer table is coarser and rougher than in the Dravidian; the forehead also is much more receding; the sagittal region is frequently ridged, and the slope outwards to the parietal eminence is steeper. The Australians in the norma facialis have the glabella and supra-orbital ridges much more projecting; the nasion more depressed; the jaws heavier; the upper jaw usually prognathous, sometimes remarkably so.” Of twelve Dravidian skulls measured by Sir William Turner, in seven the jaw was orthognathous, in four, in the lower term of the mesognathous series; one specimen only was prognathic. The customary type of jaw, therefore, was orthognathic.25 The conclusion at which Sir William Turner arrives is that “by a careful comparison of Australian and Dravidian crania, there ought not to be much difficulty in distinguishing one from the other. The comparative study of the characters of the two series of crania has not led me to the conclusion that they can be adduced in support of the theory of the unity of the two people.”

The Dravidians of Southern India are divided by Sir Herbert Risley26 into two main groups, the Scytho-Dravidian and the Dravidian, which he sums up as follows:—

“The Scytho-Dravidian type of Western India, comprising the Marātha Brāahmans, the Kunbis and the Coorgs; probably formed by a mixture of Scythian and Dravidian elements, the former predominating in the higher groups, the latter in the lower. The head is broad; complexion fair; hair on face rather scanty; stature medium; nose moderately fine, and not conspicuously long.

“The Dravidian type extending from Ceylon to the valley of the Ganges, and pervading the whole of Madras, Hyderabad, the Central Provinces, most of Central India, and Chutia Nāgpur. Its most characteristic representatives are the Paniyans of the South Indian Hills and the Santals of Chutia Nāgpur. Probably the original type of the population of India, now modified to a varying extent by the admixture of Aryan, Scythian, and Mongoloid elements. In typical specimens, the stature is short or below mean; the complexion very dark, approaching black; hair plentiful with an occasional tendency to curl; eyes dark; head long; nose very broad, sometimes depressed at the root, but not so as to make the face appear flat.”

It is, it will be noted, observed by Risley that the head of the Scytho-Dravidian is broad, and that of the Dravidian long. Writing some years ago concerning the Dravidian head with reference to a statement in Taylor’s “Origin of the Aryans,”27 that “the Todas are fully dolichocephalic, differing in this respect from the Dravidians, who are brachycephalic,” I published28 certain statistics based on the measurements of a number of subjects in the southern districts of the Madras Presidency. These figures showed that “the average cephalic index of 639 members of 19 different castes and tribes was 74.1; and that, in only 19 out of the 639 individuals, did the index exceed 80. So far then from the Dravidian being separated from the Todas by reason of their higher cephalic index, this index is, in the Todas, actually higher than in some of the Dravidian peoples.” Accustomed as I was, in my wanderings among the Tamil and Malayālam folk, to deal with heads in which the dolichocephalic or sub-dolichocephalic type preponderates, I was amazed to find, in the course of an expedition in the Bellary district (in the Canarese area), that the question of the type of the Dravidian head was not nearly so simple and straightforward as I had imagined. My records of head measurements now include a very large series taken in the plains in the Tulu, Canarese, Telugu, Malayālam, and Tamil areas, and the measurements of a few Maratha (non-Dravidian) classes settled in the Canarese country. In the following tabular statement, I have brought together, for the purpose of comparison, the records of the head-measurements of representative classes in each of these areas:—

1 “Deccan, Hind, Dakhin, Dakhan; dakkina, the Prakr. form of Sskt. dakshina, ‘the south.’ The southern part of India, the Peninsula, and especially the table-land between the Eastern and Western Ghauts.” Yule and Burnell, Hobson-Jobson.

2 History of Creation.

3 Malay Archipelago, 1890.

4 See article Kādir.

5 Pagan Races of the Malay Peninsula, 1906.

6 Globus, 1899.

7 Madras Museum Bull., II, 3, 1899.

8 Op. cit.

9 Yule and Burnell, Hobson-Jobson.

10 Mem. Asiat. Soc., Bengal, Miscellanea Ethnographica, 1, 1906.

11 Manual of the Geology of India, 2nd edition, 1893.

12 Anatomy of Vertebrated Animals, 1871.

13 See Annual Report, Archæological Survey of India, 1902–03.

14 Bull, Museum d’Histoire Naturelle, 1905.

15 Introduction to the Study of Mammals, living and extinct, 1891.

16 Anthropology. Translation, 1894.

17 I have only seen one individual with woolly hair in Southern India, and he was of mixed Tamil and African parentage.

18 See article Maravan.

19 Op. cit.

20 Ethnology, 1896.

21 Proc. R. Soc. N. S. Wales, XXIII, part III.

22 “It is evident that, during much of the tertiary period, Ceylon and South India were bounded on the north by a considerable extent of sea, and probably formed part of an extensive southern continent or great island. The very numerous and remarkable cases of affinity with Malaya require, however, some closer approximation to these islands, which probably occurred at a later period.” Wallace. Geographical Distribution of Animals, 1876.

23 See Breeks, Primitive Tribes and Monuments of the Nilgiris; Phillips, Tumuli of the Salem district; Rea, Prehistoric Burial Places in Southern India; R. Bruce Foote, Catalogues of the Prehistoric Antiquities in the Madras Museum, etc.

24 Contributions to the Craniology of the People of the Empire of India, Part II. The aborigines of Chūta Nāgpur, and of the Central Provinces, the People of Orissa, Veddahs and Negritos, 1900.

25 Other cranial characters are compared by Sir William Turner, for which I would refer the reader to the original article.

26 The People of India, 1908.

27 Contemporary Science Series.

28 Madras Museum Bull., II, 3, 1899.

Class

Language

Number of subjects examined

Cephalic Index

Number of times index was 80 or above

Average

Maximum, cm.

Minimum, cm.

Sukun Sālē

Marāthi

30

82.2

90.0

73.9

21

Suka Sālē

Do.

30

81.8

88.2

76.1

22

Vakkaliga

Canarese

50

81.7

93.8

72.5

27

Billava

Tulu

50

80.1

91.5

71.0

27

Rangāri

Marāthi

30

79.8

92.2

70.7

14

Agasa

Canarese

40

78.5

85.7

73.2

13

Bant

Tulu

40

78.0

91.2

70.8

12

Kāpu

Telugu

49

78.0

87.6

71.6

16

Tota Balija

Do.

39

78.0

86.0

73.3

10

Boya

Do.

50

77.9

89.2

70.5

14

Dāsa Banajiga

Canarese

40

77.8

86.2

72.0

11

Gāniga

Do.

50

77.6

85.9

70.5

11

Golla

Telugu

60

77.5

89.3

70.1

9

Kuruba

Canarese

50

77.3

83.9

69.6

10

Bestha

Telugu

60

77.1

85.1

70.5

9

Pallan

Tamil

50

75.9

87.0

70.1

6

Mukkuvan

Malayālam

40

75.1

83.5

68.6

2

Nāyar

Do.

40

74.4

81.9

70.0

1

Vellāla

Tamil

40

74.1

81.1

67.9

2

Agamudaiyan

Do.

40

74.0

80.9

66.7

1

Paraiyan

Do.

40

73.6

78.3

64.8

Palli

Do.

40

73.0

80.0

64.4

1

Tiyan

Malayālam

40

73.0

78.9

68.6

The difference in the character of the cranium is further brought out by the following tables, in which the details of the cephalic indices of typical classes in the five linguistic areas under consideration are recorded:—

(a) Tulu. Billava.

71

◆◆

72

◆◆

73

◆

74

75

76

◆◆◆

77

◆◆◆◆◆

78

◆◆◆◆◆◆

79

◆◆

80

◆◆

Average.

81

◆◆◆

82

◆◆◆◆◆

83

◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆

84

◆◆◆◆

85

◆◆◆◆

86

◆

87

88

89

90

◆

91

◆

(b) Canarese. Vakkaliga.

73

◆

74

75

◆◆

76

◆◆◆◆◆

77

◆◆

78

◆◆◆◆◆

79

◆◆◆◆◆◆◆

80

◆◆

81

◆◆◆

82

◆◆◆

Average.

83

◆◆◆

84

◆◆

85

◆◆◆

86

◆◆◆

87

◆◆

88

◆◆

89

◆

90

91

◆

92

◆

93

◆

94

◆

(c) Telugu. Kāpu.

72

◆

73

◆◆◆◆◆◆◆

74

◆◆

75

◆◆

76

◆◆◆◆◆◆◆

77

◆◆◆◆◆◆

78

◆

Average.

79

◆◆◆◆

80

◆◆◆◆

81

◆◆◆◆◆◆◆

82

◆◆

83

◆◆◆

84

◆

85

◆

86

87

88

◆

(d) Vellāla. Tamil.

68

◆

69

70

◆

71

◆◆◆

72

◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆

73

◆◆◆◆◆◆◆

74

◆◆

Average.

75

◆◆◆◆◆◆

76

◆◆◆

77

◆◆◆◆

78

79

80

◆◆

81

◆

(e) Malayālam. Nāyar.

70

◆◆

71

◆◆◆◆◆

72

◆◆◆◆◆

73

◆◆◆◆◆◆

74

◆

Average.

75

◆◆◆◆◆◆

76

◆◆◆◆

77

◆◆◆◆

78

◆◆◆

79

◆◆

80

81

82

◆

These tables not only bring out the difference in the cephalic index of the classes selected as representative of the different areas, but further show that there is a greater constancy in the Tamil and Malayālam classes than in the Tulus, Canarese and Telugus. The number of individuals clustering round the average is conspicuously greater in the two former than in the three latter. I am not prepared to hazard any new theory to account for the marked difference in the type of cranium in the various areas under consideration, and must content myself with the observation that, whatever may have been the influence which has brought about the existing sub-brachycephalic or mesaticephalic type in the northern areas, this influence has not extended southward into the Tamil and Malayālam countries, where Dravidian man remains dolicho- or sub-dolichocephalic.

As an excellent example of constancy of type in the cephalic index, I may cite, en passant, the following results of measurement of the Todas, who inhabit the plateau of the Nilgiri hills:—

69

◆◆

70

◆◆◆◆◆◆◆

71

◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆

72

◆◆◆◆◆◆◆

73

◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆

Average.

74

◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆

75

◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆

76

◆◆◆◆◆◆

77

◆

78

◆

79

◆

80

81

◆

I pass on to the consideration of the type of cranium among various Brāhman classes. In the following tables, the results of measurement of representatives of Tulu, Canarese, Marāthi, Tamil and Malayālam Brāhmans are recorded:—

Class

Language

Number of subjects examined

Cephalic Index

Number of times index was 80 or above

Average.

Maximum.

Minimum.

Shivalli

Tulu

30

80.4

96.4

69.4

17

Mandya

Canarese

50

80.2

88.2

69.8

31

Karnātaka

Do.

60

78.4

89.5

69.8

19

Smarta (Dēsastha)

Marāthi

2943

76.9

87.1

71

9

Tamil (Madras city)

Tamil

40

76.5

84

69

3

Nambūtiri

Malayālam

3076.3

Pattar

Tamil

3125

74.5

81.4

69.1

2

(a) Tulu. Shivalli.

69

◆

70

71

72

◆

73

◆

74

75

76

◆◆◆◆

77

78

◆◆◆

79

◆◆◆

80

◆◆

Average.

81

◆◆◆

82

◆◆◆◆

83

◆◆

84

◆◆

85

86

◆

87

88

◆

89

◆

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

◆

(b) Canarese. Karnātaka Smarta.

70

◆

71

◆◆

72

◆◆

73

◆◆

74

◆◆◆◆◆◆

75

◆◆◆

76

◆◆◆◆

77

◆◆◆◆◆

78

◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆

Average.

79

◆◆

80

◆◆◆◆◆

81

◆◆◆◆

82

◆◆◆◆

83

◆◆

84

◆◆

85

◆

86

◆

87

◆

88

◆◆

89

◆

(c) Tamil. Madras City.

69

◆

70

◆◆

71

◆

72

◆

73

◆◆

74

◆◆◆

75

◆◆◆◆

76

◆◆◆◆

Average.

77

◆◆◆◆◆◆

78

◆◆◆◆◆

79

◆◆◆◆◆

80

◆◆

81

82

◆◆

83

◆

84

◆

(d) Tamil. Pattar.

69

◆◆

70

◆

71

◆◆◆

72

◆◆

73

◆◆◆

74

Average.

75

◆◆◆◆

76

◆◆◆◆◆

77

78

◆

79

◆◆

80

◆

81

◆

Taking the evidence of the figures, they demonstrate that, like the other classes which have been analysed, the Brāhmans have a higher cephalic index, with a wider range, in the northern than in the southern area.

There is a tradition that the Shivalli Brāhmans of the Tulu country came from Ahikshetra. As only males migrated from their home, they were compelled to take women from non-Brāhman castes as wives. The ranks are said to have been swelled by conversions from these castes during the time of Srī Mādhvāchārya. The Shivalli Brāhmans are said to be referred to by the Bants as Mathumaglu or Mathmalu (bride) in allusion to the fact of their wives being taken from the Bant caste. Besides the Shivallis, there are other Tulu Brāhmans, who are said to be recent converts. The Matti Brāhmans were formerly considered low by the Shivallis, and were not allowed to sit in the same line with the Shivallis at meal time. They were only permitted to sit in a cross line, separated from the Shivallis, though in the same room. This was because the Matti Brāhmans were supposed to be Mogers (fishing caste) raised to Brāhmanism by one Vathirāja Swāmi, a Sanyāsi. Having become Brāhmans, they could not carry on their hereditary occupation, and, to enable them to earn a livelihood, the Sanyāsi gave them some brinjal (Solanum Melongena) seeds, and advised them to cultivate the plant. From this fact, the variety of brinjal, which is cultivated at Matti, is called Vathirāja gulla. At the present day, the Matti Brāhmans are on a par with the Shivalli Brāhmans, and have become disciples of the Sodhe mutt (religious institution) at Udipi. In some of the popular accounts of Brāhmans, which have been reduced to writing, it is stated that, during the time of Mayūra Varma of the Kadamba dynasty,32 some Āndhra Brāhmans were brought into South Canara. As a sufficient number of Brāhmans were not available for the purpose of yāgams (sacrifices), these Āndhra Brāhmans selected a number of families from the non-Brāhman caste, made them Brāhmans, and chose exogamous sept names for them. Of these names, Manōli (Cephalandra Indica), Pērala (Psidium Guyava), Kudire (horse), and Ānē (elephant) are examples.

A character, with which I am very familiar, when measuring the heads of all sorts and conditions of natives of Southern India, is the absence of convexity of the segment formed by the posterior portion of the united parietal bones. The result of this absence of convexity is that the back of the head, instead of forming a curve gradually increasing from the top of the head towards the occipital region, as in the European skull figured in plate IIIa, forms a flattened area of considerable length almost at right angles to the base of the skull as in the “Hindu” skull represented in plate IIIb. This character is shown in a marked degree in plate IV, which represents a prosperous Linga Banajiga in the Canarese country.

a. European Skull.

b. Hindu Skull.

In discussing racial admixture, Quatrefages writes as follows.33 “Parfois on trouve encore quelques tribus qui ont conservé plus on moins intacts tous les caractères de leur race. Les Coorumbas du Malwar [Malabar] et du Coorg paraissent former un noyau plus considérable encore, et avoir conservé dans les jungles de Wynaad une indépendence à peu près complète, et tous leurs caractères ethnologiques.” The purity of blood and ethnological characters of various jungle tribes are unhappily becoming lost as the result of contact metamorphosis from the opening up of the jungles for planter’s estates, and contact with more civilised tribes and races, both brown and white. In illustration, I may cite the Kānikars of Travancore, who till recently were in the habit of sending all their women into the seclusion of the jungle on the arrival of a stranger near their settlements. This is now seldom done, and some Kānikars have in modern times settled in the vicinity of towns, and become domesticated. The primitive short, dark-skinned and platyrhine type, though surviving, has become changed, and many leptorhine or mesorhine individuals above middle height are to be met with. The following are the results of measurements of Kānikars in the jungle, and at a village some miles from Trivandrum, the capital of Travancore:—

Stature cm.

Nasal Index.

Av.

Max.

Min.

Av.

Max.

Min.

Jungle

155.2

170.3

150.2

84.6

105

72.3

Domesticated

158.7

170.4

148

81.2

90.5

70.8

Some jungle Chenchus, who inhabit the Nallamalai hills in the Kurnool district, still exhibit the primitive short stature and high nasal index, which are characteristic of the unadulterated jungle tribes. But there is a very conspicuous want of uniformity in their physical characters, and many individuals are to be met with, above middle height, or tall, with long narrow noses. A case is recorded, in which a brick-maker married a Chenchu girl. And I was told of a Bōya man who had married into the tribe, and was living in a gudem (Chenchu settlement).

Stature cm.

Nasal Index.

Av.

Max.

Min.

Av.

Max.

Min.

162.5

175

149.6

81.9

95.7

68.1

By the dolichocephalic type of cranium which has persisted, and which the Chenchus possess in common with various other jungle tribes, they are still, as shown by the following table, at once differentiated from the mesaticephalic dwellers in the plains near the foot of the Nallamalais:—

Cephalic Index.

Number of times the index was 80 or over.

40 Chenchus

74.3

1

60 Gollas

77.5

9

50 Bōyas

77.9

14

39 Tōta Balijas

78.0

10

49 Kāpus

78.8

16

19 Upparas

78.8

4

16 Mangalas

78.8

7

17 Verukalas

78.6

6

12

Mēdaras80.7

8

In a note on the jungle tribes, M. Louis Lapicque,34 who carried out anthropometric observations in Southern India a few years ago, writes as follows. “Dans les montagnes des Nilghirris et d’Anémalé, situées au cœur de la contrée dravidienne, on a signalé depuis longtemps des petits sauvages crépus, qu’on a même pensé pouvoir, sur des documents insuffisants, identifier avec les negritos. En réalité, it n’existe pas dans ces montagnes, ni probablement nulle part dans l’Inde, un témoin de la race primitive comparable, comme pureté, aux Andamanais ni même aux autres Negritos. Ce que l’on trouve là, c’est simplement, mais c’est fort précieux, une population métisse qui continue au delà du Paria la série générale de l’Inde. Au bord de la forêt vierge ou dans les collines partiellement défrichées, il y a des castes demi-Parias, demi-sauvages. La hiérachie sociale les classe au-dessous du Paria: on peut même trouver des groupes ou le facies nègre, nettement dessiné, est tout à fait prédominant. Ehbien, dans ces groupes, les chevelures sont en général frisées, et on en observe quelques-unes qu’on peut même appeler crépues. On a donc le moyen de prolonger par l’imagination la série des castes indiennes jusq’au type primitif qui était (nous n’avons plus qu’un pas à faire pour le reconstruire), un Nègre.... Nous sommes arrives à reconstituer les traits nègres d’un type disparu en prolongeant une série graduée de métis. Par la même méthode nous pouvons déterminer théoriquement la forme du crâne de ce type. Avec une assez grande certitude, je crois pouvoir affirmer, après de nombreuses mesures systématiques, que le nègre primitif de l’Inde était sousdolichocéphale avec un indice voisin de 75 ou 76. Sa taille, plus difficile à préciser, car les conditions de vie modifient ce caractère, devait être petite, plus haute pourtant que celle des Andamanais. Quant au nom qu’il convient de lui attribuer, la discussion des faits sociaux et linguistiques sur lesquels est fondée la notion de dravidien permet d’établir que ce nègre était antérieur aux dravidiens; il faut done l’appeller Prédravidien, ou, si nous voulons lui donner un nom qui ne soit pas relatif à une autre population, on peut l’appeler Nègre Paria.”

Linga Banajiga.

In support of M. Lapicque’s statement that the primitive inhabitant was dolichocephalic or sub-dolichocephalic, I may produce the evidence of the cephalic indices of the various jungle tribes which I have examined in the Tamil, Malayālam, and Telugu countries:—

Cephalic Index.

Average.

Maximum.

Minimum.

Kadir

72.9

80.0

69.1

Irula, Chingleput

73.1

78.6

68.4

Kānikar

73.4

78.9

69.1

Mala Vēdan

73.4

80.9

68.8

Panaiyan

74.0

81.1

69.4

Chenchu

74.3

80.5

64.3

Shōlaga

74.9

79.3

67.8

Paliyan

75.7

79.1

72.9

Irula, Nilgiris

75.8

80.9

70.8

Kurumba

76.5

83.3

71.8

It is worthy of note that Haeckel defines the nose of the Dravidian as a prominent and narrow organ. For Risley has laid down35 that, in the Dravidian type, the nose is thick and broad, and the formula expressing the proportionate dimension (nasal index) is higher than in any known race, except the Negro; and that the typical Dravidian, as represented by the Mālē Pahāria, has a nose as broad in proportion to its length as the Negro, while this feature in the Aryan group can fairly bear comparison with the noses of sixty-eight Parisians, measured by Topinard, which gave an average of 69.4. In this connection, I may record the statistics relating to the nasal indices of various South Indian jungle tribes:—

Nasal Index.

Average.

Maximum.

Minimum.

Paniyan

95.1

108.6

72.9

Kādir

89.8

115.4

72.9

Kurumba

86.1

111.1

70.8

Shōlaga

85.1

107.7

72.8

Mala Vēdan

84.9

102.6

71.1

Irula, Nīlgiris

84.9

100.

72.3

Kānikar

84.6

105.

72.3

Chenchu

81.9

95.7

68.1

In the following table, I have brought together, for the purpose of comparison, the average stature and nasal index of various Dravidian classes inhabiting the plains of the Telugu, Tamil, Canarese, and Malayālam countries, and jungle tribes:—

Linguistic area.

Nasal Index.

Stature.

Paniyan

Jungle tribe

95.1

157.4

Kādir

Do.

89.8

157.7

Kurumba

Do.

86.1

157.9

Shōlaga

Do.

85.1

159.3

Irula, Nīlgiris

Do.

84.9

159.8

Mala Vēdan

Do.

84.9

154.2

Kānikar

Do.

84.6

155.2

Chenchu

Do.

81.9

162.5

Pallan

Tamil

81.5

164.3

Mukkuvan

Malayālam

81.

163.1

Paraiyan

Tamil

80.

163.1

Palli

Do.

77.9

162.5

Gāniga

Canarese

76.1

165.8

Bestha

Telugu

75.9

165.7

Tīyan

Malayālam

75.

163.7

Kuruba

Canarese

74.9

162.7

Bōya

Telugu

74.4

163.9

Tōta Balija

Do.

74.4

163.9

Agasa

Canarese

74.3

162.4

Agamudaiyan

Tamil

74.2

165.8

Golla

Telugu

74.1

163.8

Vellāla

Tamil

73.1

162.4

Vakkaliga

Canarese

73.

167.2

Dāsa Banajiga

Do.

72.8

165.3

Kāpu

Telugu

72.8

164.5

Nāyar

Malayālam71.1

165.2

This table demonstrates very clearly an unbroken series ranging from the jungle men, short of stature and platyrhine, to the leptorhine Nāyars and other classes.

29 The cephalic indices of various Brāhman classes in the Bombay Presidency, supplied by Sir H. Risley, are as follows:—Dēsastha, 76.9; Kokanasth, 77.3; Sheni or Saraswat, 79; Nagar, 79.7.

30 Measured by Mr. F. Fawcett.

31 The Pattar Brāhmans are Tamil Brāhmans, settled in Malabar.

32 According to the Brāhman chronology, Mayūra Varma reigned from 455 to 445 B.C., but his probable date was about 750 A.D. See Fleet, Dynasties of the Kanarese Districts of the Bombay Presidency, 1882–86.

33 Histoire générale des Races Humaines, 1889.

34 Les Nègres d’Asie, et la race Nègre en général. Revue Scientifique, VI July, 1906.

35 Tribes and Castes of Bengal, 1891.

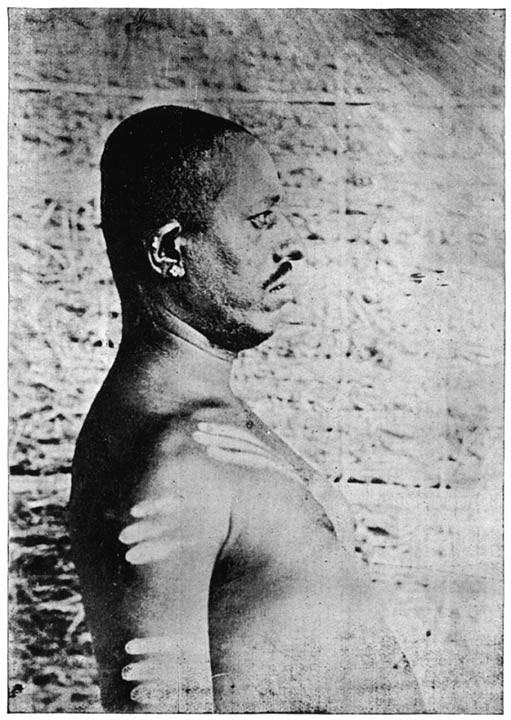

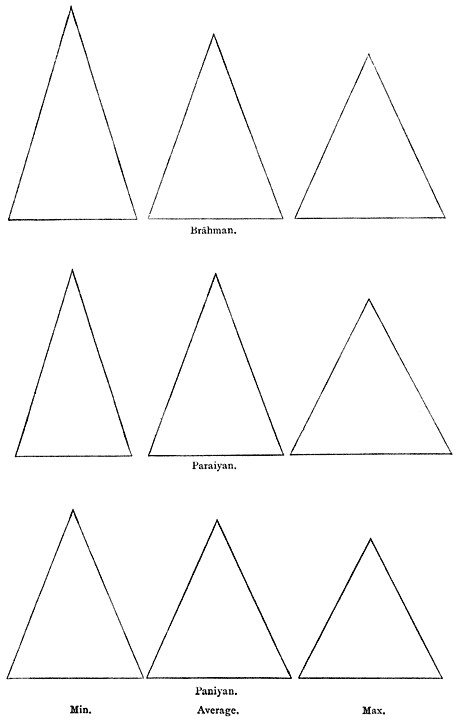

PLATE V.

DIAGRAMS OF NOSES.

In plate V are figured a series of triangles representing (natural size) the maxima, minima, and average nasal indices of Brāhmans of Madras city (belonging to the poorer classes), Tamil Paraiyans, and Paniyans. There is obviously far less connection between the Brāhman minimum and the Paraiyan maximum than between the Brāhman and Paraiyan maxima and the Paniyan average; and the frequent occurrence of high nasal indices, resulting from short, broad noses, in many classes has to be accounted for. Sir Alfred Lyall somewhere refers to the gradual Brāhmanising of the aboriginal non-Arayan, or casteless tribes. “They pass,” he writes, “into Brāhmanists by a natural upward transition, which leads them to adopt the religion of the castes immediately above them in the social scale of the composite population, among which they settle down; and we may reasonably guess that this process has been working for centuries.” In the Madras Census Report, 1891, Mr. H. A. Stuart states that “it has often been asserted, and is now the general belief, that the Brāhmans of the South are not pure Aryans, but are a mixed Aryan and Dravidian race. In the earliest times, the caste division was much less rigid than now, and a person of another caste could become a Brāhman by attaining the Brāhmanical standard of knowledge, and assuming Brāhmanical functions; and, when we see the Nambūdiri Brāhmans, even at the present day, contracting alliances, informal though they be, with the women of the country, it is not difficult to believe that, on their first arrival, such unions were even more common, and that the children born of them would be recognised as Brāhmans, though perhaps regarded as an inferior class. However, those Brāhmans, in whose veins mixed blood is supposed to run, are even to this day regarded as lower in the social scale, and are not allowed to mix freely with the pure Brāhman community.”

Popular traditions allude to wholesale conversions of non-Brāhmans into Brāhmans. According to such traditions, Rājas used to feed very large numbers of Brāhmans (a lakh of Brāhmans) in expiation of some sin, or to gain religious merit. To make up this large number, non-Brāhmans are said to have been made Brāhmans at the bidding of the Rājas. Here and there are found a few sections of Brāhmans, whom the more orthodox Brāhmans do not recognise as such, though the ordinary members of the community regard them as an inferior class of Brāhmans. As an instance may be cited the Mārakas of the Mysore Province. Though it is difficult to disprove the claim put forward by these people, some demur to their being regarded as Brāhmans.

Between a Brāhman of high culture, with fair complexion, and long, narrow nose on the one hand, and a less highly civilised Brāhman with dark skin and short broad nose on the other, there is a vast difference, which can only be reasonably explained on the assumption of racial admixture; and it is no insult to the higher members of the Brāhman community to trace, in their more lowly brethren, the result of crossing with a dark-skinned, and broad-nosed race of short stature. Whether the jungle tribe are, as I believe, the microscopic remnant of a pre-Dravidian people, or, as some hold, of Dravidians driven by a conquering race to the seclusion of the jungles, it is to the lasting influence of some such broad-nosed ancestor that the high nasal index of many of the inhabitants of Southern India must, it seems to me, be attributed. Viewed in the light of this remark, the connection between the following mixed collection of individuals, all of very dark colour, short of stature, and with nasal index exceeding 90, calls for no explanation:—

Stature.

Nasal height.

Nasal breadth.

Nasal Index.

cm.

cm.

cm.

Vakkaliga

156

4.3

3.9

90.7

Mōger

160

4.3

3.9

90.7

Saiyad Muhammadan

160

4.4

4

90.9

Kammalan

154.4

4.4

4

90.9

Chakkiliyan

156.8

4.4

4

90.9

Vellāla

154.8

4.7

4.3

91.6

Malaiyāli

158.8

4

3.7

92.5

Konga Vellāla

157

4.1

3.8

92.7

Pattar Brāhman

157.6

4.2

3.9

92.9

Oddē

159.6

4.3

4

93

Smarta Brāhman

159

4.1

3.9

95.1

Palli

157.8

4.1

3.9

95.1

Pallan

155.8

4.2

4.2

100

Bestha

156.8

4.3

4.3

100

Mukkuvan

150.8

4

4

100

Agasa

156.4

4.3

4.3

100

Tamil Paraiyan

160

4

4.2

105

I pass on to a brief consideration of the languages of Southern India. According to Mr. G. A. Grierson36 “the Dravidian family comprises all the principal languages of Southern India. The name Dravidian is a conventional one. It is derived from the Sanskrit Dravida, a word which is again probably derived from an older Dramila, Damila, and is identical with the name of Tamil. The name Dravidian is, accordingly, identical with Tamulian, which name has formerly been used by European writers as a common designation of the languages in question. The word Dravida forms part of the denomination Andhra-Drāvida-bhāshā, the language of the Andhras (i.e., Telugu), and Dravidas (i.e., Tamilians), which Kumārila Bhatta (probably 7th Century A.D.) employed to denote the Dravidian family. In India Dravida has been used in more than one sense. Thus the so-called five Dravidas are Telugu, Kanarese, Marāthi, Gujarāti, and Tamil. In Europe, on the other hand, Dravidian has long been the common denomination of the whole family of languages to which Bishop Caldwell applied it in his Comparative Grammar, and there is no reason for abandoning the name which the founder of Dravidian philology applied to this group of speeches.”

The five principal languages are Tamil, Telugu, Malayālam, Canarese, and Oriya. Of these, Oriya belongs to the eastern group of the Indo-Aryan family, and is spoken in Ganjam, and a portion of the Vizagapatam district. The population speaking each of these languages, as recorded at the census, 1901, was as follows:—

Tamil

15,543,383

Telugu

14,315,304

Malayālam

2,854,145

Oriya

1,809,336

Canarese

1,530,688

In the preparation of the following brief summary of the other vernacular languages and dialects, I have indented mainly on the Linguistic Survey of India, and the Madras Census Report, 1901.

Savara.—The language of the Savaras of Ganjam and Vizagapatam. One of the Mundā languages. Concerning the Mundā, linguistic family, Mr. Grierson writes as follows. “The denomination Mundā (adopted by Max Müller) was not long allowed to stand unchallenged. Sir George Campbell in 1866 proposed to call the family Kolarian. He was of opinion that Kol had an older form Kolar, which he thought to be identical with Kanarese Kallar, thieves. There is absolutely no foundation for this supposition. Moreover, the name Kolarian is objectionable, as seeming to suggest a connexion with Aryan which does not exist. The principal home of the Mundā languages at the present day is the Chota Nagpur plateau. The Mundā race is much more widely spread than the Mundā languages. It has already been remarked that it is identical with the Dravidian race, which forms the bulk of the population of Southern India.”

Gadaba.—Spoken by the Gadabas of Vizagapatam and Ganjam. One of the Mundā languages.

Kond, Kandhī, or Kui.—The language of the Kondhs of Ganjam and Vizagapatam.

Gōndi.—The language of the Gōnds, a tribe which belongs to the Central Provinces, but has overflowed into Ganjam and Vizagapatam.

Gattu.—A dialect of Gōndi, spoken by some of the Gōnds in Vizagapatam.

Kōya or Kōi.—A dialect of Gōndi, spoken by the Kōyis in the Vizagapatam and Godāvari districts.

Poroja, Parjā, or Parjī.—A dialect of Gōndi.

Tulu.—The language largely spoken in South Canara (the ancient Tuluva). It is described by Bishop Caldwell as one of the most highly developed languages of the Dravidian family.

Koraga.—Spoken by the Koragas of South Canara. It is thought by Mr. H. A. Stuart37 to be a dialect of Tulu.