автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Castes and Tribes of Southern India. Vol. 3 of 7

Castes and Tribes of Southern India

Castes and Tribes

of

Southern India

By

Edgar Thurston, C.I.E.,

Superintendent, Madras Government Museum; Correspondant Étranger, Société d’Anthropologie de Paris; Socio Corrispondante, Societa, Romana di Anthropologia.

Assisted by K. Rangachari, M.A.,

of the Madras Government Museum.

Volume III—K

Government Press, Madras

1909.

List of Illustrations.

I.

Kādir huts.II.

Kādir.III.

Kādir.IV.

Kādir tree-climbing.V.

Kādir boy with chipped teeth.VI.

Kādir girl wearing comb.VII.

Kallan children with dilated ear-lobes.VIII.

Kammālans.IX.

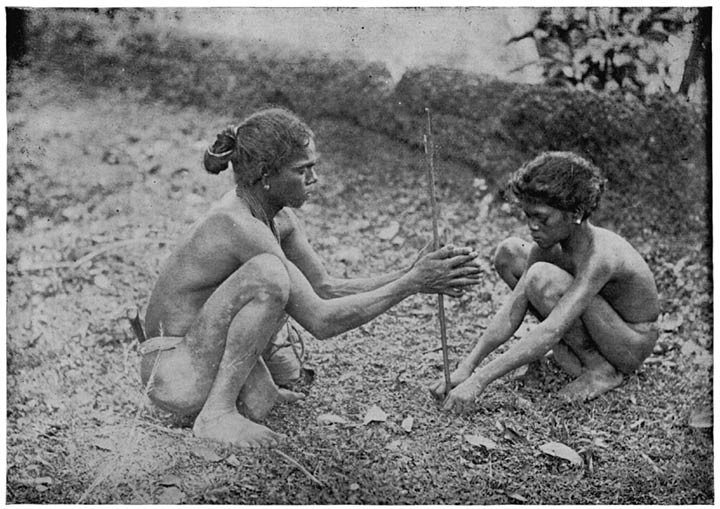

Kānikars making fire.X.

Kānikar.XI.

Kannadiyan.XII.

Kāpu.XIII.

Panta Kāpu.XIV.

Kāpu bride and bridegroom.XV.

Kōmati.XVI.

Meriah sacrifice post.XVII.

Koraga.XVIII.

Yerukalas.XIX.

Korava.XX.

Korava woman telling fortune.XXI.

Yerukala settlement.Castes and Tribes of Southern India.

Volume III.

K

Kabbēra.—The Kabbēras are a caste of Canarese fishermen and cultivators. “They are,” Mr. W. Francis writes,1 “grouped into two divisions, the Gaurimakkalu or sons of Gauri (Parvati) and the Gangimakkalu or sons of Ganga, the goddess of water, and they do not intermarry, but will dine together. Each has its bedagus (exogamous septs), and these seem to be different in the two sub-divisions. The Gaurimakkalu are scarce in Bellary, and belong chiefly to Mysore. They seem to be higher in the social scale (as such things are measured among Hindus) than the Gangimakkalu, as they employ Brāhmans as priests instead of men of their own caste, burn their dead instead of burying them, hold annual ceremonies in memory of them, and prohibit the remarriage of widows. The Gangimakkalu were apparently engaged originally in all the pursuits connected with water, such as propelling boats, catching fish, and so forth, and they are especially numerous in villages along the banks of the Tungabhadra.” Coracles are still used on various South Indian rivers, e.g., the Cauvery, Bhavāni, and Tungabhadra. Tavernier, on his way to Golgonda, wrote that “the boats employed in crossing the river are like large baskets, covered outside with ox-hides, at the bottom of which some faggots are placed, upon which carpets are spread to put the baggage and goods upon, for fear they should get wet.” Bishop Whitehead has recently2 placed on record his experiences of coracles as a means of conveyance. “We embarked,” he writes, “in a boat (at Hampi on the Tungabhadra) which exactly corresponds to my idea of the coracle of the ancient Britons. It consists of a very large, round wicker basket, about eight or nine feet in diameter, covered over with leather, and propelled by paddles. As a rule, it spins round and round, but the boatmen can keep it fairly straight, when exhorted to do so, as they were on this occasion. Some straw had been placed in the bottom of the coracle, and we were also allowed the luxury of chairs to sit upon, but it is safer to sit on the straw, as a chair in a coracle is generally in a state of unstable equilibrium. I remember once crossing a river in the Trichinopoly district in a coracle, to take a confirmation at a village on the other side. It was thought more suitable to the dignity of the occasion that I should sit upon a chair in the middle of the coracle, and I weakly consented to do so. All the villagers were assembled to meet us on the opposite bank; four policemen were drawn up as a guard of honour, and a brass band, brought from Tanjore, stood ready in the background. As we came to the shore, the villagers salaamed, the guard of honour saluted, the band struck up a tune faintly resembling ‘See the conquering hero comes,’ the coracle bumped heavily against the shelving bank, my chair tipped up, and I was deposited, heels up, on my back in the straw!... We were rowed for about two miles down the stream. The current was very swift, and there were rapids at frequent intervals. Darkness overtook us, and it was not altogether a pleasant sensation being whirled swiftly over the rapids in our frail-looking boat, with ugly rocks jutting out of the stream on either side. But the boatmen seemed to know the river perfectly, and were extraordinarily expert in steering the coracle with their paddles.” The arrival in 1847 of the American Missionary, John Eddy Chandler at Madura, when the Vaigai river was in flood, has been described as follows.3 “Coolies swimming the river brought bread and notes from the brethren and sisters in the city. At last, after three days of waiting, the new Missionaries safely reached the mission premises in Madura. Messrs. Rendall and Cherry managed to cross to them, and they all recrossed into the city by a large basket boat, eight or ten feet in diameter, with a bamboo pole tied across the top for them to hold on to. The outside was covered with leather. Ropes attached to all sides were held by a dozen coolies as they dragged it across, walking and swimming.” In recent years, a coracle has been kept at the traveller’s bungalow at Paikāra on the Nīlgiris for the use of anglers in the Paikāra river.

“The Kabbēras,” Mr. Francis continues, “are at present engaged in a number of callings, and, perhaps in consequence, several occupational sub-divisions have arisen, the members of which are more often known by their occupational title than as either Gangimakkalu or Kabbēras. The Bārikes, for example, are a class of village servants who keep the village chāvadi (caste meeting house) clean, look after the wants of officials halting in the village, and do other similar duties. The Jalakaras are washers of gold-dust; the Madderu are dyers, who use the root of the maddi (Morinda citrifolia) tree; and apparently (the point is one which I have not had time to clear up) the Besthas, who have often been treated as a separate caste, are really a sub-division of the Gangimakkalu, who were originally palanquin-bearers, but, now that these vehicles have gone out of fashion, are employed in divers other ways. The betrothal is formally evidenced by the partaking of betel-leaf in the girl’s house, in the manner followed by the Kurubas. As among the Mādigas, the marriage is not consummated for three months after its celebration. The caste follow the Kuruba ceremony of calling back the dead.” Consummation is, as among the Kurubas and Mādigas, postponed for three months, as it is considered unlucky to have three heads of a family in a household during the first year of marriage. By the delay, the birth of a child should take place only in the second year, so that, during the first year, there will be only two heads, husband and wife. In the ceremony of calling back the dead, referred to by Mr. Francis, a pot of water is worshipped in the house on the eleventh day after a funeral, and taken next morning to some lonely place, where it is emptied.

For the following note on the Kabbēras of the Bellary district, I am indebted to Mr. Kothandram Naidu. The caste is sometimes called Ambiga. Breaches of caste rules and customs are enquired into by a panchayat presided over by a headman called Kattemaniavaru. If the fine inflicted on the offender is a heavy one, half goes to the headman, and half to the caste people, who spend it in drink. In serious cases, the offender has to be purified by shaving and drinking holy water (thirtam) given to him by the headman. Both infant and adult marriage are practiced. Sexual license previous to marriage is tolerated, but, before that takes place, the contracting couple have to pay a fine to the headman. At the marriage ceremony, the tāli is tied on the bride’s neck by a Brāhman. Married women carry painted new pots with lights, bathe the bride and bridegroom, etc. Widows are remarried with a ceremonial called Udiki, which is performed at night in a temple by widows, one of whom ties the tāli. No married men or women may be present, and music is not allowed. Divorce is said to be not permitted. In religion the Kabbēras are Vaishnavites, and worship various village deities. The dead are buried. Cloths and food are offered to ancestors during the Dasara festival, excepting those who have died a violent death. Some unmarried girls are dedicated to the goddess Hulugamma as Basavis (dedicated prostitutes).

Concerning an agricultural ceremony in the Bellary district, in which the Kabbēras take part, I gather that “on the first full-moon day in the month of Bhadrapada (September), the agricultural population celebrate a feast called Jokumara, to appease the rain-god. The Barikas (women), who are a sub-division of the Kabbēra caste belonging to the Gaurimakkalu section, go round the town or village in which they live, with a basket on their heads containing margosa (Melia Azadirachta) leaves, flowers of various kinds, and holy ashes. They beg alms, especially of the cultivating classes (Kāpus), and, in return for the alms bestowed (usually grain and food), they give some of the margosa leaves, flowers, and ashes. The Kāpus, or cultivators, take the margosa leaves, flowers, and ashes to their fields, prepare cholum (Andropogon Sorghum) kanji, mix these with it, and sprinkle this kanji, or gruel, all round their fields. After this, the Kāpu proceeds to the potter’s kiln in the village or town, fetches ashes from it, and makes a figure of a human being. This figure is placed prominently in some convenient spot in the field, and is called Jokumara, or rain-god. It is supposed to have the power of bringing down the rain in proper time. The figure is sometimes small, and sometimes big.”4

Kabbili.—Kabbili or Kabliga, recorded as a sub-division of Bestha, is probably a variant of Kabbēra.

Kadacchil (knife-grinder or cutler).—A sub-division of Kollan.

Kadaiyan.—The name, Kadaiyan, meaning last or lowest, occurs as a sub-division of the Pallans. The Kadaiyans are described5 as being lime (shell) gatherers and burners of Rāmēsvaram and the neighbourhood, from whose ranks the pearl-divers are in part recruited at the present day. On the coasts of Madura and Tinnevelly they are mainly Christians, and are said, like the Paravas, to have been converted through the work of St. Francis Xavier.6

Kadapēri.—A sub-division of Kannadiyan.

Kadavala (pots).—An exogamous sept of Padma Sālē.

Kādi (blade of grass).—A gōtra of Kurni.

Kādir.—The Kādirs or Kādans inhabit the Ānaimalai or elephant hills, and the great mountain range which extends thence southward into Travancore. A night journey by rail to Coimbatore, and forty miles by road at the mercy of a typically obstinate jutka pony, which landed me in a dense patch of prickly-pear (Opuntia Dillenii), brought me to the foot of the hills at Sēthumadai, where I came under the kindly hospitality of Mr. H. A. Gass, Conservator of Forests, to whom I am indebted for much information on forest and tribal matters gathered during our camp life at Mount Stuart, situated 2,350 feet above sea-level, in the midst of a dense bamboo jungle, and playfully named after Sir Mountstuart Grant Duff, who visited the spot during his quinquennium as Governor of Madras.

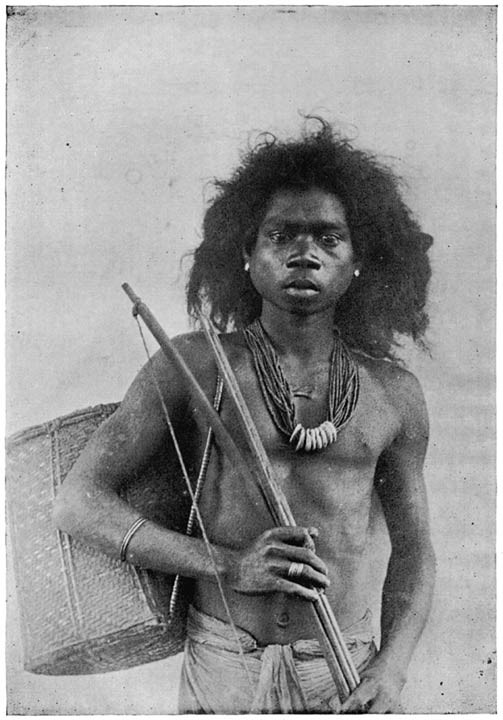

At Sēthumadai I made the acquaintance of my first Kādir, not dressed, as I hoped, in a primitive garb of leaves, but wearing a coloured turban and the cast-off red coat of a British soldier, who had come down the hill to carry up my camp bath, which acted as an excellent umbrella, to protect him from the driving monsoon showers. Very glad was I of his services in helping to convey my clothed, and consequently helpless self, across the mountain torrents, swollen by a recent burst of monsoon rain.

The Kādir forest guards, of whom there are several in Government service, looked, except for their noses, very unjungle-like by contrast with their fellow-tribesmen, being smartly dressed in regulation Norfolk jacket, knickerbockers, pattis (leggings), buttons, and accoutrements.

On arrival at the forest depôt, with its comfortable bungalows and Kādir settlement, I was told by a native servant that his master was away, as an “elephant done tumble in a fit.” My memory went back to the occasion many years ago, when, as a medical student, I took part in the autopsy of an elephant, which died in convulsions at the London Zoological Gardens. It transpired later in the day that a young and grown-up cow elephant had tumbled, not in a fit, but into a pit made with hands for the express purpose of catching elephants. The story has a philological significance, and illustrates the difficulty which the Tamulian experiences in dealing with the letter F. An incident is still cherished at Mount Stuart in connection with a sporting globe-trotter, who was accredited to the Conservator of Forests for the purpose of putting him on to “bison” (the gaur, Bos gaurus), and other big game. On arrival at the depôt, he was informed that his host had gone to see the “ellipence.” Incapable of translating the pigeon-English of the native butler, and, concluding that a financial reckoning was being suggested, he ordered the servant to pay the baggage coolies their elli-pence, and send them away. To a crusted Anglo-Indian it is clear that ellipence could only mean elephants. Sir M. E. Grant Duff tells7 the following story of a man, who was shooting on the Ānaimalais. In his camp was an elephant, who, in the middle of the night, began to eat the thatch of the hut, in which he was sleeping. His servant in alarm rushed in and awoke him, saying “Elephant, Sahib, must, must (mad).” The sleeper, half-waking and rolling over, replied “Oh, bother the elephant. Tell him he mustn’t.”

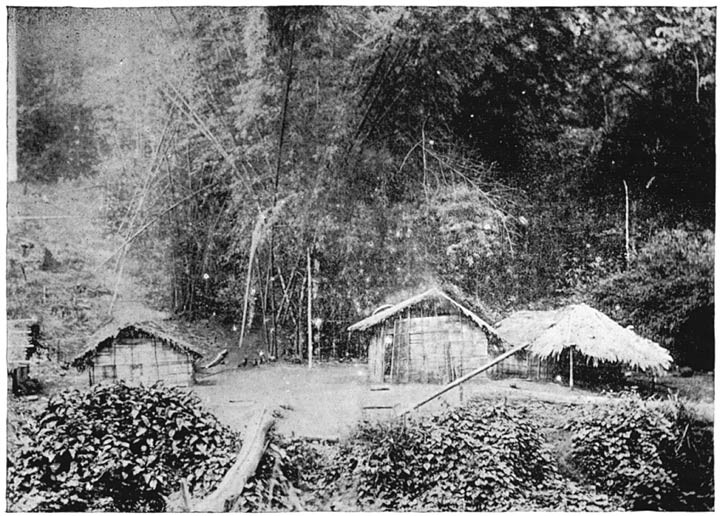

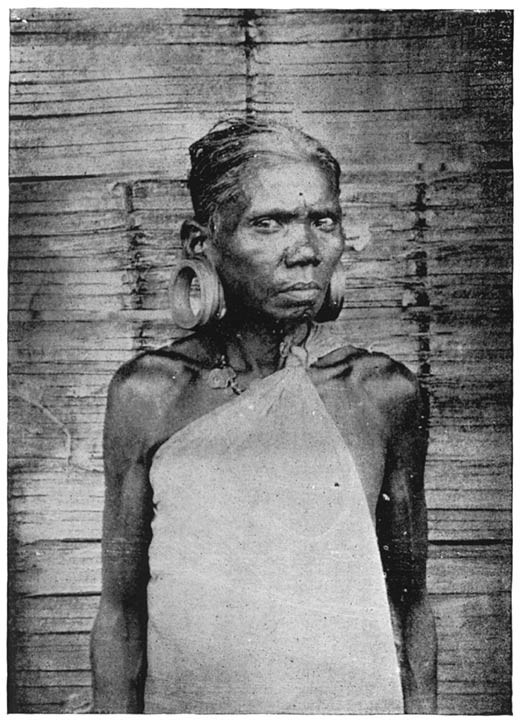

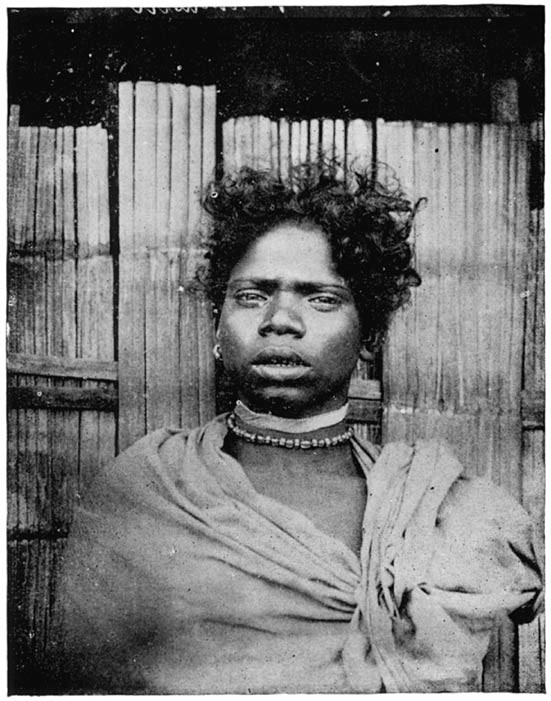

The salient characteristics of the Kādirs may be briefly summed up as follows: short stature, dark skin, platyrhine. Men and women have the teeth chipped. Women wear a bamboo comb in the back-hair. Those whom I met spoke a Tamil patois, running up the scale in talking, and finishing, like a Suffolker, on a higher note than they commenced on. But I am told that some of them speak a mixture of debased Tamil and Malayālam. I am informed by Mr. Vincent that the Kādirs have a peculiar word Āli, denoting apparently a fellow or thing, which they apply as a suffix to names, e.g., Karaman Āli, black fellow; Mudi Āli, hairy fellow; Kutti Āli, man with a knife; Pūv Āli, man with a flower. Among nicknames, the following occur: white mother, white flower, beauty, tiger, milk, virgin, love, breasts. The Kādirs are excellent mimics, and give a clever imitation of the mode of speech of the Muduvans, Malasars, and other hill tribes.

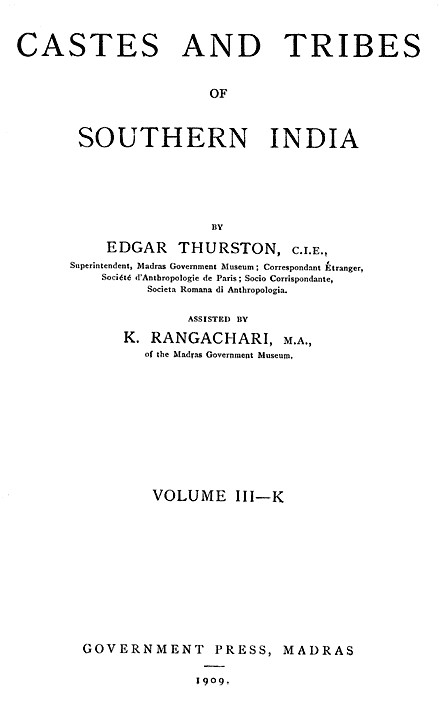

Kādir Huts.

The Kādirs afford a typical example of happiness without culture. Unspoiled by education, the advancing wave of which has not yet engulfed them, they still retain many of their simple “manners and customs.” Quite refreshing was it to hear the hearty shrieks of laughter of the nude curly-haired children, wholly illiterate, and happy in their ignorance, as they played at funerals, or indulged in the amusement of making mud pies, and scampered off to their huts on my appearance. The uncultured Kādir, living a hardy out-door life, and capable of appreciating to the full the enjoyment of an “apathetic rest” as perfect bliss, has, I am convinced, in many ways, the advantage over the poor under-fed student with a small-paid appointment under Government as the narrow goal to which the laborious passing of examination tests leads.

Living an isolated existence, confined within the thinly-populated jungle, where Nature furnishes the means of obtaining all the necessaries of life, the Kādir possesses little, if any, knowledge of cultivation, and objects to doing work with a māmuti, the instrument which serves the gardener in the triple capacity of spade, rake, and hoe. But armed with a keen-edged bill-hook he is immense. As Mr. O. H. Bensley says:8 “The axiom that the less civilised men are, the more they are able to do every thing for themselves, is well illustrated by the hill-man, who is full of resource. Give him a simple bill-hook, and what wonders he will perform. He will build houses out of etâh, so neat and comfortable as to be positively luxurious. He will bridge a stream with canes and branches. He will make a raft out of bamboo, a carving knife out of etâh, a comb out of bamboo, a fishing-line out of fibre, and fire from dry wood. He will find food for you where you think you must starve, and show you the branch which, if cut, will give you drink. He will set traps for beasts and birds, which are more effective than some of the most elaborate products of machinery.” A European, overtaken by night in the jungle, unable to light fire by friction or to climb trees to gather fruits, ignorant of the edible roots and berries, and afraid of wild beasts, would, in the absence of comforts, be quite as unhappy and ill-at-ease as a Kādir surrounded by plenty at an official dinner party.

At the forest depôt the Kādir settlement consists of neatly constructed huts, made of bamboo deftly split with a bill-hook in their long axis, thatched with leaves of the teak tree (Tectona grandis) and bamboo (Ochlandra travancorica), and divided off into verandah and compartments by means of bamboo partitions. But the Kādirs are essentially nomad in habit, living in small communities, and shifting from place to place in the jungle, whence they suddenly re-appear as casually as if they had only returned from a morning stroll instead of a long camping expedition. When wandering in the jungle, the Kādirs make a rough lean-to shed covered over with leaves, and keep a small fire burning through the night, to keep off bears, elephants, tigers, and leopards. They are, I am told, fond of dogs, which they keep chiefly as a protection against wild beasts at night. The camp fire is lighted by means of a flint and the floss of the silk-cotton tree (Bombax malabaricum), over which powdered charcoal has been rubbed. Like the Kurumbas, the Kādirs are not, in a general way, afraid of elephants, but are careful to get out of the way of a cow with young, or a solitary rover, which may mean mischief. On the day following my descent from Mount Stuart, an Oddē cooly woman was killed on the ghāt road by a solitary tusker. Familiarity with wild beasts, and comparative immunity from accident, have bred contempt for them, and the Kādirs will go where the European, fresh to elephant land, fears to tread, or conjures every creak of a bamboo into the approach of a charging tusker. As an example of pluck worthy of a place in Kipling’s ‘Jungle-book,’ I may cite the case of a hill-man and his wife, who, overtaken by night in the jungle, decided to pass it on a rock. As they slept, a tiger carried off the woman. Hearing her shrieks, the sleeping man awoke, and followed in pursuit in the vain hope of saving his wife. Coming on the beast in possession of the mangled corpse, he killed it at close quarters with a spear. Yet he was wholly unconscious that he had performed an act of heroism worthy of the bronze cross ‘for valour.’

Kādir.

The Kādirs carry loads strapped on the back over the shoulders by means of fibre, instead of on the head in the manner customary among coolies in the plains; and women on the march may be seen carrying the cooking utensils on their backs, and often have a child strapped on the top of their household goods. The dorsal position of the babies, huddled up in a dirty cloth, with the ends slung over the shoulders and held in the hands over the chest, at once caught my eye, as it is contrary to the usual native habit of straddling the infants across the loins as a saddle.

Mr. Vincent informs me that “when the planters first came to the hills, the Kādirs were found practically without clothes of any description, with very few ornaments, and looking very lean and emaciated. All this, however, changed with the advent of the European, as the Kādirs then got advances in hard cash, clothes, and grain, to induce them to work. For a few years they tried to work hard, but were failures, and now I do not suppose that a dozen men are employed on the estates on the hills. They would not touch manure owing to caste scruples; they could not learn to prune; and with a mamoti (spade) they always promptly proceeded to chop their feet about in their efforts to dig pits.” The Kādirs have never claimed, like the Todas, and do not possess any land on the hills. But the Government has declared the absolute right of the hill tribes to collect all the minor forest produce, and to sell it to the Government through the medium of a contractor, whose tender has been previously accepted. The contractor pays for the produce in coin at a fair market rate, and the Kādirs barter the money so obtained for articles of food with contractors appointed by Government to supply them with their requirements at a fixed rate, which will leave a fair, but not exorbitant margin of profit to the vendor. The principal articles of minor forest produce of the Ānaimalai hills are wax, honey, cardamoms, myrabolams, ginger, dammer, turmeric, deer horns, elephant tusks, and rattans. And of these, cardamoms, wax, honey, and rattans are the most important. Honey and wax are collected at all seasons, and cardamoms from September to November. The total value of the minor produce collected, in 1897–98, in the South Coimbatore division (which includes the Ānaimalais) was Rs. 7,886. This sum was exceptionally high owing to a good cardamom crop. An average year would yield a revenue of Rs. 4,000–5,000, of which the Kādirs receive approximately 50 per cent. They work for the Forest Department on a system of short advances for a daily wage of 4 annas. And, at the present day, the interests of the Forest Department and planters, who have acquired land on the Ānaimalais, both anxious to secure hill men for labour, have come into mild collision.

Kādir.

Some Kādirs are good trackers, and a few are good shikāris. A zoological friend, who had nicknamed his small child his “little shikarī” (=little sportsman) was quite upset because I, hailing from India, did not recognise the word with his misplaced accent. One Kādir, named Viapoori Muppan, is still held in the memory of Europeans, who made a good living, in days gone by, by shooting tuskers, and had one arm blown off by the bursting of a gun. He is reputed to have been a much married man, greatly addicted to strong drinks, and to have flourished on the proceeds of his tusks. At the present day, if a Kādir finds tusks, he must declare the find as treasure-trove, and hand it over to Government, who rewards him at the rate of Rs. 15 to Rs. 25 per maund of 25 lb. according to the quality. Government makes a good profit on the transaction, as exceptionally good tusks have been known to sell for Rs. 5 per lb. If the find is not declared, and discovered, the possessor thereof is punished for theft according to the Act. By an elastic use of the word cattle, it is, for the purposes of the Madras Forest Act, made to include such a heterogeneous zoological collection of animals as elephants, sheep, pigs, goats, camels, buffaloes, horses—and asses. This classification recalls to mind the occasion on which the Flying-fox or Fox-bat was included in an official list of the insectivorous birds of the Presidency; and, further, a report on the wild animals of a certain district, which was triumphantly headed with the “wild tattu,” the long-suffering, but pig-headed country pony.

I gather, from an account of the process by one who had considerable knowledge of the Kādirs, that “they will only remove the hives of bees during dark nights, and never in the daytime or on moonlight nights. In removing them from cliffs, they use a chain made of bamboo or rattan, fixed to a stake or a tree on the top. The man, going down this fragile ladder, will only do so while his wife, or son watches above to prevent any foul play. They have a superstition that they should always return by the way they go down, and decline to get to the bottom of the cliff, although the distance may be less, and the work of re-climbing avoided. For hives on trees, they tie one or more long bamboos to reach up to the branch required, and then climb up. They then crawl along the branch until the hive is reached. They devour the bee-bread and the bee-maggots or larvæ, swallowing the wax as well.” In a note on a shooting expedition in Travancore,9 Mr. J. D. Rees, describing the collection of honey by the Kādirs of the southern hills, says that they “descend giddy precipices at night, torch in hand, to smoke out the bees, and take away their honey. A stout creeper is suspended over the abyss, and it is established law of the jungle that no brother shall assist in holding it. But it is more interesting to see them run a ladder a hundred feet up the perpendicular stem of a tree, than to watch them disappearing over a precipice. Axe in hand, the honey-picker makes a hole in the bark for a little peg, standing on which he inserts a second peg higher up, ties a long cane from one to the other, and by night—for the darkness gives confidence—he will ascend the tallest trees, and bring down honey without any accident.” I have been told, with how much of truth I know not, that, when a Kādir goes down the face of a rock or precipice in search of honey, he sometimes takes with him, as a precautionary measure, and guarantee of his safety, the wife of the man who is holding the ladder above.

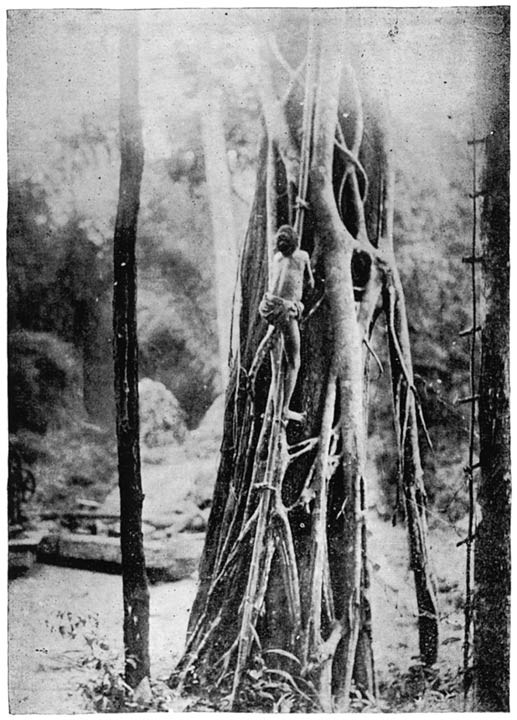

Often, when out on the tramp with the late Government Botanist, Mr. M. A. Lawson, I have heard him lament that it is impossible to train arboreal monkeys to collect specimens of the fruit and flowers of lofty forest trees, which are inaccessible to the ordinary man. Far superior to any trained Simian is the Kādir, who, by means of pegs or notches, climbs even the tallest masts of trees with an agility which recalls to memory the celebrated picture in “Punch,” representing Darwin’s ‘Habit of climbing plants.’ For the ascent of comparatively low trees, notches are made with a bill-hook, alternately right and left, at intervals of about thirty inches. To this method the Kādir will not have recourse in wet weather, as the notches are damp and slippery, and there is the danger of an insecure foot-hold.

An important ethnographic fact, and one which is significant, is that the detailed description of tree-climbing by the Dyaks of Borneo, as given by Wallace,10 might have been written on the Ānaimalai hills, and would apply equally well in every detail to the Kādir. “They drove in,” Wallace writes, “a peg very firmly at about three feet from the ground, and, bringing one of the long bamboos, stood it upright close to the tree, and bound it firmly to the two first pegs by means of a bark cord and small notches near the head of each peg. One of the Dyaks now stood on the first peg and drove in a third about level with his face, to which he tied the bamboo in the same way, and then mounted another step, standing on one foot, and holding by the bamboo at the peg immediately above him, while he drove in the next one. In this manner he ascended about twenty feet, when the upright bamboo became thin; another was handed up by his companion, and this was joined on by tying both bamboos to three or four of the pegs. When this was also nearly ended, a third was added, and shortly after the lowest branch of the tree was reached, along which the young Dyak scrambled. The ladder was perfectly safe, since, if any one peg were loose or faulty, the strain would be thrown on several others above and below it. I now understood the use of the line of bamboo pegs sticking in trees, which I had often seen.”

In their search for produce in the evergreen forests of the higher ranges, with their heavy rainfall, the Kādirs became unpleasantly familiar with leeches and blue bottle flies, which flourish in the moist climate. And it is recorded that a Kādir, who had been gored and wounded by a bull ‘bison,’ was placed in a position of safety while a friend ran to the village to summon help. He was not away for more than an hour, but, in that short time, flies had deposited thousands of maggots in the wounds, and, when the man was brought into camp, they had already begun burrowing into the flesh, and were with difficulty extracted. On another occasion, the eye-witness of the previous unappetising incident was out alone in the forest, and shot a tiger two miles or so from his camp. Thither he went to collect coolies to carry in the carcase, and was away for about two hours, during which the flies had, like the child in the story, ‘not been idle,’ the skin being a mass of maggots and totally ruined. I have it on authority that, like the Kotas of the Nīlgiris, the Kādirs will eat the putrid and fly-blown flesh of carcases of wild beasts, which they come across in their wanderings. To a dietary which includes succulent roots, which they upturn with a digging stick, bamboo seed, sheep, fowls, rock-snakes (python), deer, porcupines, rats (field, not house), wild pigs, monkeys, etc., they do credit by displaying a hard, well-nourished body. The mealy portion of the seeds of the Cycas tree, which flourishes on the lower slopes of the Ānaimalais, forms a considerable addition to the ménu. In its raw state the fruit is said to be poisonous, but it is evidently wholesome when cut into slices, thoroughly soaked in running water, dried, and ground into flour for making cakes, or baked in hot ashes. Mr. Vincent writes that, “during March, April, and May, the Kādirs have a glorious time. They usually manage to find some wild sago palms, called by them koondtha panai, of the proper age, which they cut down close to the ground. They are then cut into lengths of about 1½ feet, and split lengthways. The sections are then beaten very hard and for a long time with mallets, and become separated into fibre and powder. The powder is thoroughly wetted, tied in cloths and well beaten with sticks. Every now and then, between the beatings, the bag of powder is dipped in water, and well strained. It is then all put into water, when the powder sinks, and the water is poured off. The residue is well boiled, with constant stirring, and, when it is of the consistency of rubber, and of a reddish brown colour, it is allowed to cool, and then cut in pieces to be distributed. This food stuff is palatable enough, but very tough.” The Kādir is said to prefer roasting and eating the flesh of animals with the skin on. For catching rats, jungle-fowl, etc., he resorts to cunningly devised snares and traps made of bamboo and fibre, as a substitute for a gun. Porcupines are caught by setting fire to the scrub jungle round them as they lie asleep, and thus smoking and burning them to death.

Kādir Tree-climbing.

When a Kādir youth’s thoughts turn towards matrimony, he is said to go to the village of his bride-elect, and give her a dowry by working there for a year. On the wedding day a feast of rice, sheep, fowls, and other luxuries is given by the parents of the bridegroom, to which the Kādir community is invited. The bride and bridegroom stand beneath a pandal (arch) decorated with flowers, which is erected outside the home of the bridegroom, while men and women dance separately to the music of drum and fife. The bridegroom’s mother or sister ties the tāli (marriage badge) of gold or silver round the bride’s neck, and her father puts a turban on the head of the bridegroom. The contracting parties link together the little fingers of their right hands as a token of their union, and walk in procession round the pandal. Then, sitting on a reed mat of Kādir manufacture, they exchange betel. The marriage tie can be dissolved for incompatibility of temper, disobedience on the part of the wife, adultery, etc., without appeal to any higher authority than a council of elders, who pronounce judgment on the evidence. As an illustration of the manner in which such a council of hill-men disposes of cases, Mr. Bensley cites the case of a man who was made to carry forty basket loads of sand to the house of the person against whom he had offended. He points out how absolute is the control exercised by the council. Disobedience would be followed by excommunication, and this would mean being turned out into the jungle, to obtain a living in the best way one could.

By one Kādir informant I was assured, as he squatted on the floor of my bungalow at “question time,” that it is essential that a wife should be a good cook, in accordance with a maxim that the way to the heart is through the mouth. How many men in civilised western society, who suffer from marrying a wife wholly incompetent, like the first Mrs. David Copperfield, to conduct the housekeeping, might well be envious of the system of marriage as a civil contract to be sealed or unloosed according to the cookery results! Polygyny is indulged in by the Kādirs, who agree with Benedick that “the world must be peopled,” and hold more especially that the numerical strength of their own tribe must be maintained. The plurality of wives seems to be mainly with the desire for offspring, and the father-in-law of one of the forest-guards informed me that he had four wives living. The first two wives producing no offspring, he married a third, who bore him a solitary male child. Considering the result to be an insufficient contribution to the tribe, he married a fourth, who, more prolific than her colleagues, gave birth to three girls and a boy, with which he remained content. In the code of polygynous etiquette, the first wife takes precedence over the others, and each wife has her own cooking utensils.

Special huts are maintained for women during menstruation and parturition. Mr. Vincent informs me that, when a girl reaches puberty, the friends of the family gather together, and a great feast is prepared. All her friends and relations give her a small present of money, according to their means. The girl is decorated with the family jewelry, and made to look as smart as possible. For the first menstrual period, a special hut, called mutthu salai or ripe house, is constructed for the girl to live in during the period of pollution; but at subsequent periods, the ordinary menstruation hut, or unclean house, is used. All girls are said to change their names when they reach puberty. For three months after the birth of a child, the woman is considered unclean. When the infant is a month old, it is named without any elaborate ceremonial, though the female friends of the family collect together. Sexual intercourse ceases on the establishment of pregnancy, and the husband indulges in promiscuity. Widows are not allowed to re-marry, but may live in a state of concubinage. Women are said to suckle their children till they are two or three years old, and a mother has been seen putting a lighted cigarette to the lips of a year old baby immediately after suckling it. If this is done with the intention of administering a sedative, it is less baneful than the pellet of opium administered by ayahs (nurses) to Anglo-Indian babies rendered fractious by troubles climatic, dental, and other. The Kādir men are said to consume large quantities of opium, which is sold to them illicitly. They will not allow the women or children to eat it, and have a belief that the consumption thereof by women renders them barren. The women chew tobacco. The men smoke the coarse tobacco as sold in the bazars, and showed a marked appreciation of Spencer’s Torpedo cheroots, which I distributed among them for the purposes of bribery and conciliation.

The religion of the Kādirs is a crude polytheism, and vague worship of stone images or invisible gods. It is, as Mr. Bensley expresses it, an ejaculatory religion, finding vent in uttering the names of the gods and demons. The gods, as enumerated and described to me, were as follows:—

(1) Paikutlātha, a projecting rock overhanging a slab of rock, on which are two stones set up on end. Two miles east of Mount Stuart.

(2) Athuvisariamma, a stone enclosure, ten to fifteen feet square, almost level with the ground. It is believed that the walls were originally ten feet high, and that the mountain has grown up round it. Within the enclosure there is a representation of the god. Eight miles north of Mount Stuart.

(3) Vanathavāthi. Has no shrine, but is worshipped anywhere as an invisible god.

(4) Iyappaswāmi, a stone set up beneath a teak tree, and worshipped as a protector against various forms of sickness and disease. In the act of worshipping, a mark is made on the stone with ashes. Two miles and a half from Mount Stuart, on the ghāt road to Sēthumadai.

(5) Māsanyātha, a female recumbent figure in stone on a masonry wall in an open plain near the village of Ānaimalai, before which trial by ordeal is carried out. The goddess has a high repute for her power of detecting thieves or rogues. Chillies are thrown into a fire in her name, and the guilty person suffers from vomiting and diarrhœa.

According to Mr. L. K. Anantha Krishna Iyer,11 the Kādirs are “worshippers of Kāli. On the occasion of the offering to Kāli, a number of virgins are asked to bathe as a preliminary to the preparation of the offering, which consists of rice and some vegetables cooked in honey, and made into a sweet pudding. The rice for this preparation is unhusked by these girls. The offering is considered to be sacred, and is partaken of by all men, women, and children assembled.”

When Kādirs fall sick, they worship the gods by saluting them with their hands to the face, burning camphor, and offering up fruits, cocoanuts, and betel. Mr. Vincent tells me that they have a horror of cattle, and will not touch the ordure, or other products of the cow. Yet they believe that their gods occasionally reside in the body of a “bison,” and have been known to do pūja (worship) when a bull has been shot by a sportsman. It is noted by Mr. Anantha Krishna Iyer that wild elephants are held in veneration by them, but tame ones are believed to have lost the divine element.

The Kādirs are said, during the Hindu Vishu festival, to visit the plains, and, on their way, pray to any image which they chance to come across. They are believers in witchcraft, and attribute all diseases to the miraculous workings thereof. They are good exorcists, and trade in mantravādam or magic. Mr. Logan mentions12 that “the family of famous trackers, whose services in the jungles were retained for H.R.H. the Prince of Wales’ (now King Edward) projected sporting tour in the Ānamalai mountains, dropped off most mysteriously, one by one, shortly afterwards, stricken down by an unseen hand, and all of them expressing beforehand their conviction that they were under a certain individual’s spell, and were doomed to certain death at an early date. They were probably poisoned, but how it was managed remains a mystery, although the family was under the protection of a European gentleman, who would at once have brought to light any ostensible foul play.”

The Kādir dead are buried in a grave, or, if death occurs in the depths of the jungles, with a paucity of hands available for digging, the corpse is placed in a crevice between the rocks, and covered over with stones. The grave is dug from four to five feet deep. There is no special burial-ground, but some spot in the jungle, not far from the scene of death, is selected. A band of music, consisting of drum and fife, plays weird dirges outside the hut of the deceased, and whistles are blown when it is carried away therefrom. The old clothes of the deceased are spread under the corpse, and a new cloth is put on it. It is tied up in a mat, which completely covers it, and carried to the burial-ground on a bamboo stretcher. As it leaves the hut, rice is thrown over it. The funeral ceremony is simple in the extreme. The corpse is laid in the grave on a mat in the recumbent posture, with the head towards the east, and with split bamboo and leaves placed all round it, so that not a particle of earth can touch it. No stone, or sepulchral monument of any kind, is set up to mark the spot. The Kādir believes that the dead go to heaven, which is in the sky, but has no views as to what sort of place it is. The story that the Kādirs eat their dead originated with Europeans, the origin of it being that no one had ever seen a dead Kādir, a grave, or sign of a burial-place. The Kādirs themselves are reticent as to their method of disposing of the dead, and the story, which was started as a joke, became more or less believed. Mr. Vincent tells me that a well-to-do Kādir family will perform the final death ceremonies eight days after death, but poorer folk have to wait a year or more, till they have collected sufficient money for the expenses thereof. At cock-crow on the morning of the ceremonies, rice, called polli chor, is cooked, and piled up on leaves in the centre of the hut of the deceased. Cooked rice, called tullagu chor, is then placed in each of the four corners of the hut, to propitiate the gods, and to serve as food for them and the spirit of the dead person. At a short distance from the hut, rice, called kanal chor, is cooked for all Kādirs who have died, and been buried. The relations and friends of the deceased commence to cry, and make lamentations, and proclaim his good qualities, most of which are fictitious. After an hour or so, they adjourn to the hut of the deceased, where the oldest man present invokes the gods, and prays to them and to the heaped up food. A pinch from each of the heaps is thrown into the air as a gift of food to the gods, and those present fall to, and eat heartily, being careful to partake of each of the food-stuffs, consisting of rice, meat, and vegetables, which have been prepared.

On a certain Monday in the months of Ādi and Āvani, the Kādirs observe a festival called nōmbu, during which a feast is held, after they have bathed and anointed themselves with oil. It was, they say, observed by their ancestors, but they have no definite tradition as to its origin or significance. It is noted by Mr. Anantha Krishna Iyer that, at the Ōnam festival, presents in the shape of rice, cloths, coats, turbans, caps, ear-rings, tobacco, opium, salt, oil and cocoanuts are distributed among the Kādirs by the Forest Department.

According to Mr. Bensley, “the Kādir has an air of calm dignity, which leads one to suppose that he had some reason for having a more exalted opinion of himself than that entertained for him by the outside world. A forest officer of a philanthropic turn had a very high opinion of the sturdy independence and blunt honesty of the Kādir, but he once came unexpectedly round a corner, to find two of them exploring the contents of his port-manteau, from which they had abstracted a pair of scissors, a comb, and a looking glass.” “The Kādirs,” Mr. (now Sir F. A.) Nicholson writes,13 “are, as a rule, rather short in stature, and deep-chested, like most mountaineers; and, like many true mountaineers, they rarely walk with a straight leg. Hence their thigh muscles are often abnormally developed at the expense of those of the calf. Hence, too, in part, their dislike to walking long distances on level ground, though their objection, mentioned by Colonel Douglas Hamilton, to carrying loads on the plains, is deeper-rooted than that arising from mere physical disability. This objection is mainly because they are rather a timid race, and never feel safe out of the forests. They have also affirmed that the low-country air is very trying to them.” As a matter of fact, they very rarely go down to the plains, even as far as the village of Ānaimalai, only fifteen miles distant from Mount Stuart. One woman, whom I saw, had been as far as Palghāt by railway from Coimbatore, and had returned very much up-to-date in the matter of jewelry and the latest barbarity in imported piece-good body-cloth.

With the chest-girth of the Kādirs, as well as their general muscular development, I was very much impressed. Their hardiness, Mr. Conner writes,14 has given rise to the observation among their neighbours that the Kādir and Kād Ānai (wild elephant) are much the same sort of animal.

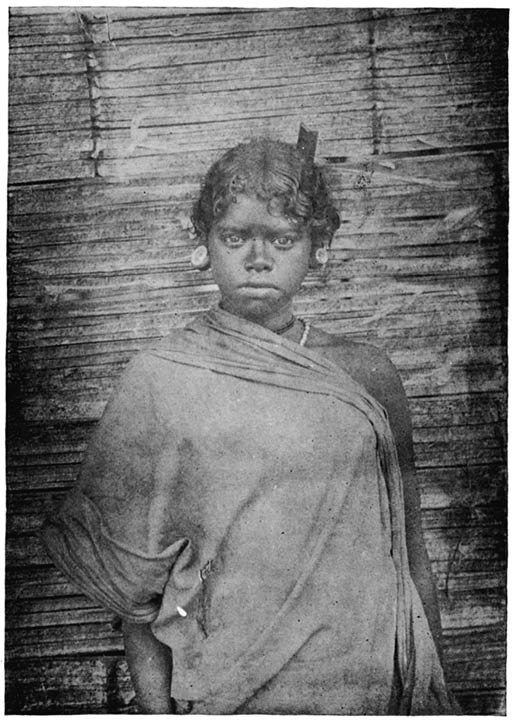

Perhaps the most interesting custom of the Kādirs is that of chipping all or some of the incisor teeth, both upper and lower, into the form of a sharp-pointed, but not serrated cone. The operation, which is performed with a chisel or bill-hook and file by members of the tribe skilled therein, on boys and girls, has been thus described. The girl to be operated on lies down, and places her head against a female friend, who holds her head firmly. A woman takes a sharpened bill-hook, and chips away the teeth till they are shaded to a point, the girl operated on writhing and groaning with the pain. After the operation she appears dazed, and in a very few hours the face begins to swell. Swelling and pain last for a day or two, accompanied by severe headache. The Kādirs say that chipped teeth make an ugly man or woman handsome, and that a person, whose teeth have not been thus operated on, has teeth and eats like a cow. Whether this practice is one which the Kādir, and Mala Vēdar of Travancore, have hit on spontaneously in comparatively recent times, or whether it is a relic of a custom resorted to by their ancestors of long ago, which remains as a stray survival of a custom once more widely practiced by the remote inhabitants of Southern India, cannot be definitely asserted, but I incline to the latter view.

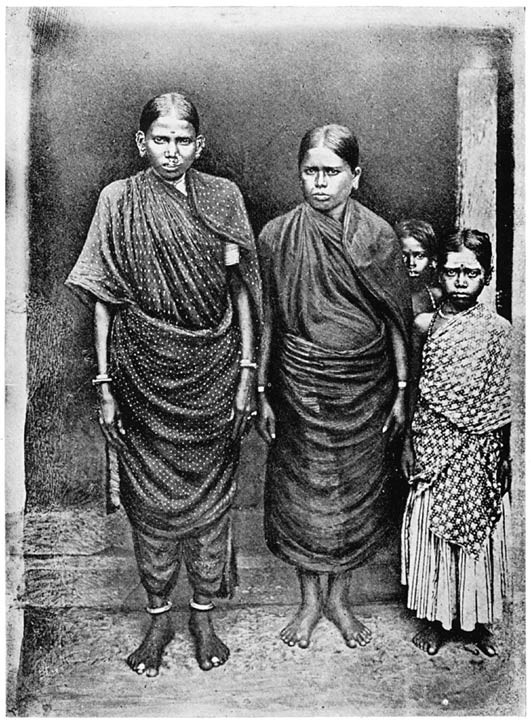

A friendly old woman, with huge discs in the widely dilated lobes of the ears, and a bamboo five-pronged comb in her back-hair, who acted as spokesman on the occasion of a visit to a charmingly situated settlement in a jungle of magnificent bamboos by the side of a mountain stream, pointed out to me, with conscious pride, that the huts were largely constructed by the females, while the men worked for the sircar (Government). The females also carry water from the streams, collect firewood, dig up edible roots, and carry out the sundry household duties of a housewife. Both men and women are clever at plaiting bamboo baskets, necklets, etc. I was told one morning by a Kādir man, whom I met on the road, as an important item of news, that the women in his settlement were very busy dressing to come and see me—an event as important to them as the dressing of a débutante for presentation at the Court of St. James’. They eventually turned up without their husbands, and evidently regarded my methods as a huge joke organised for the amusement of themselves and their children. The hair was neatly parted, anointed with a liberal application of cocoanut oil, and decked with wild flowers. Beauty spots and lines had been painted with coal-tar dyes on the forehead, and turmeric powder freely sprinkled over the top of the heads of the married women. Some had even discarded the ragged and dirty cotton cloth of every-day life in favour of a colour-printed imported sāri. One bright, good-looking young woman, who had already been through the measuring ordeal, acted as an efficient lady-help in coaching the novices in the assumption of the correct positions. She very readily grasped the situation, and was manifestly proud of her temporary elevation to the rank of standard-bearer to Government.

1 Gazetteer of the Bellary district.

2 Madras Diocesan Magazine, June, 1906.

3 John S. Chandler, a Madura Missionary, Boston.

4 Madras Mail, November, 1905.

5 J. Hornell. Report on the Indian Pearl Fisheries of the Gulf of Manaar, 1905.

6 Madras Diocesan Mag., 1906.

7 Notes from a Diary, 1881–86.

8 Lecture delivered at Trivandrum, MS.

9 Nineteenth Century, 1898.

10 Malay Archipelago.

11 Monograph. Ethnog: Survey of Cochin, No. 9, 1906.

12 Malabar Manual.

13 Manual of the Coimbatore district.

14 Madras Journ. Lit. Science, I. 1833.

Kādir Boy with Chipped Teeth.

Dr. K. T. Preuss has drawn my attention to an article in Globus, 1899, entitled ‘Die Zauberbilder Schriften der Negrito in Malaka,’ wherein he describes in detail the designs on the bamboo combs worn by the Negritos of Malacca, and compares them with the strikingly similar design on the combs worn by the Kādir women. Dr. Preuss works out in detail the theory that the design is not, as I have elsewhere called it, a geometrical pattern, but consists of a series of hieroglyphics. The collection of Kādir combs in the Madras Museum shows very clearly that the patterns thereon are conventional designs. The bamboo combs worn by the Semang women are stated15 to serve as talismans, to protect them against diseases which are prevalent, or most dreaded by them. Mr. Vincent informs me that, so far as he knows, the Kādir combs are not looked on as charms, and the markings thereon have no mystic significance. A Kādir man should always make a comb, and present it to his intended wife just before marriage, or at the conclusion of the marriage ceremony, and the young men vie with each other as to who can make the nicest comb. Sometimes they represent strange articles on the combs. Mr. Vincent has, for example, seen a comb with a very good imitation of the face of a clock scratched on it.

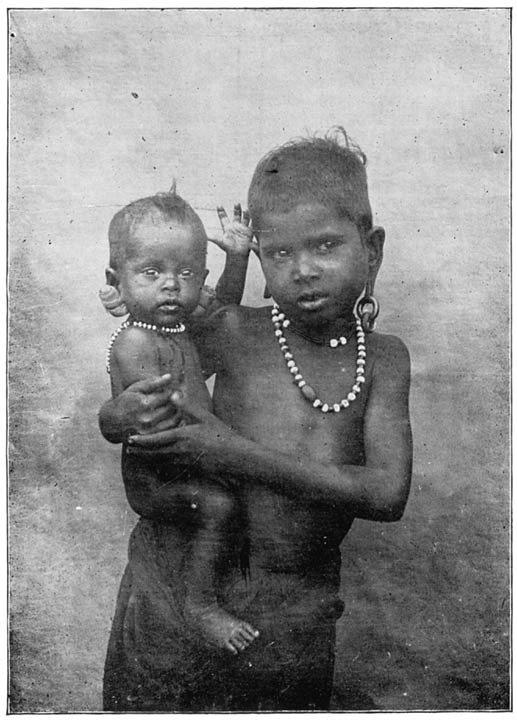

It is sometimes difficult to distinguish adolescent Kādir youths with curly fringe, chests covered by a cotton cloth, and wearing necklets made of plaited grass or glass and brass beads, from girls. And I was myself several times caught in an erroneous diagnosis of sex. Many of the infants have a charm tied round the neck, which takes the form of a dried tortoise foot; the tooth of a crocodile mimicking a phallus, and supposed to ward off attacks from a mythical water elephant which lives in the mountain streams; or wooden imitations of tiger’s claws. One baby wore a necklet made of the seeds of Coix Lachryma-Jobi (Job’s tears). Males have the lobes of the ears adorned with brass ornaments, and the nostril pierced, and plugged with wood. The ear-lobes of the females are widely dilated with palm-leaf rolls or huge wooden discs, and they wear ear-rings, brass or steel bangles and finger-rings, and bead necklets.

Kādir Girl Wearing Comb.

It is recorded by Mr. Anantha Krishna Iyer that the Kādirs are attached to the Rāja of Cochin “by the strongest ties of personal affection and regard. Whenever His Highness tours in the forests, they follow him, carry him from place to place in manjals or palanquins, carry sāman (luggage), and in fact do everything for him. His Highness in return is much attached to them, feeds them, gives them cloths, ornaments, combs, and looking-glasses.”

The Kādirs will not eat with Malasars, who are beef-eaters, and will not carry boots made of cow-hide, except under protest.

Average stature 157.7 cm.; cephalic index 72.9; nasal index 89.

Kadlē.—Kadlē, Kallē, and Kadalē meaning Bengal gram (Cicer arietinum) have been recorded as exogamous septs or gōtras of Kurubas and Kurnis.

Kādu.—Kādu or Kāttu, meaning wild or jungle, has been recorded as a division of Golla, Irula, Korava, Kurumba, and Tōttiyan. Kādu also occurs as an exogamous sept or gōtra of the Kurnis. Kādu Konkani is stated, in the Madras Census Report, 1901, to mean the bastard Konkanis, as opposed to the Gōd or pure Konkanis. Kāttu Marāthi is a synonym for the bird-catching Kuruvikarans. In the Malabar Wynaad, the jungle Kurumbas are known as Kāttu Nāyakan.

Kādukuttukiravar.—A synonym, meaning one who bores a hole in the ear, for Koravas who perform the operation of piercing the lobes of the ears for various castes.

Kaduppattan.—The Kadupattans are said,16 according to the traditional account of their origin, to have been Pattar Brāhmans of Kadu grāmam, who became degraded owing to their supporting the introduction of Buddhism. “The members of this caste are,” Mr. H. A. Stuart writes,17 “at present mostly palanquin-bearers, and carriers of salt, oil, etc. The educated among them follow the profession of teaching, and are called Ezhuttacchan, i.e., master of learning. Both titles are used in the same family. In the Native State of Cochin, the Kaduppattan is a salt-worker. In British Malabar he is not known to have followed that profession for some generations past, but it may be that, salt manufacture having long ago been stopped in South Malabar, he has taken to other professions, one of which is the carriage of salt. In manners and customs Kaduppattans resemble Nāyars, but their inheritance follows the male line.” The Kaduppattans are described18 by Mr. Logan as “a caste hardly to be distinguished from the Nāyars. They follow a modified makkatayam system of inheritance, in which the property descends from father to son, but not from father to daughter. The girls are married before attaining puberty, and the bridegroom, who is to be the girl’s real husband in after life, arranges the dowry and other matters by means of mediators (enangan). The tāli is tied round the girl’s neck by the bridegroom’s sister or a female relative. At the funeral ceremonies of this class, the barber caste perform priestly functions, giving directions and preparing oblation rice. A widow without male issue is removed on the twelfth day after her husband’s death from his house to that of her own parents. And this is done even if she has female issue. But, on the contrary, if she has borne sons to the deceased, she is not only entitled to remain at her husband’s house, but she continues to have, in virtue of her sons, a joint right over his property.”

Kahar.—In the Madras Census Report, 1901, the Kahars are returned as a Bengal caste of boatmen and fishermen. In the Mysore Census Report, it is noted that Kahar means in Hindustani a blacksmith, and that those censused were immigrants from the Bombay Presidency.

Kaikātti (one who shows the hand).—A division of the Kanakkans (accountants). The name has its origin in a custom, according to which a married woman is never allowed to communicate with her mother-in-law except by signs.19

Kaikōlan.—The Kaikōlans are a large caste of Tamil weavers found in all the southern districts, who also are found in considerable numbers in the Telugu country, where they have adopted the Telugu language. A legend is current that the Nāyakkan kings of Madura were not satisfied with the workmanship of the Kaikōlans, and sent for foreign weavers from the north (Patnūlkārans), whose descendants now far out-number the Tamil weavers. The word Kaikōlan is the Tamil equivalent of the Sanskrit Vīrabāhu, a mythological hero, from whom both the Kaikōlans and a section of the Paraiyans claim descent. The Kaikōlans are also called Sengundar (red dagger) in connection with the following legend. “The people of the earth, being harassed by certain demons, applied to Siva for help. Siva was enraged against the giants, and sent forth six sparks of fire from his eyes. His wife, Parvati, was frightened, and retired to her chamber, and, in so doing, dropped nine beads from her anklets. Siva converted the beads into as many females, to each of whom was born a hero with full-grown moustaches and a dagger. These nine heroes, with Subramanya at their head, marched in command of a large force, and destroyed the demons. The Kaikōlans or Sengundar are said to be the descendants of Virabāhu, one of these heroes. After killing the demon, the warriors were told by Siva that they should become musicians, and adopt a profession, which would not involve the destruction or injury of any living creature, and, weaving being such a profession, they were trained in it.”20 According to another version, Siva told Parvati that the world would be enveloped in darkness if he should close his eyes. Impelled by curiosity, Parvati closed her husband’s eyes with her hands. Being terrified by the darkness, Parvati ran to her chamber, and, on the way thither, nine precious stones fell from her anklets, and turned into nine fair maidens, with whom Siva became enamoured and embraced them. Seeing later on that they were pregnant, Parvati uttered a curse that they should not bring forth children formed in their wombs. One Padmasura was troubling the people in this world, and, on their praying to Siva to help them, he told Subramanya to kill the Asura. Parvati requested Siva not to send Subramanya by himself, and he suggested the withdrawal of her curse. Accordingly, the damsels gave birth to nine heroes, who, carrying red daggers, and headed by Subramanya, went in search of the Asura, and killed him. The word kaikōl is said to refer to the ratnavēl or precious dagger carried by Subramanya. The Kaikōlans, on the Sura Samharam day during the festival of Subramanya, dress themselves up to represent the nine warriors, and join in the procession.

The name Kaikōlan is further derived from kai (hand), and kōl (shuttle). The Kaikōlans consider the different parts of the loom to represent various Dēvatas and Rishis. The thread is said to have been originally obtained from the lotus stalk rising from Vishnu’s navel. Several Dēvas formed the threads, which make the warp; Nārada became the woof; and Vēdamuni the treadle. Brahma transformed himself into the plank (padamaram), and Adisēsha into the main rope.

In some places, the following sub-divisions of the caste are recognised:—Sōzhia; Rattu; Siru-tāli (small marriage badge); Peru-tāli (big marriage badge); Sirpādam, and Sevaghavritti. The women of the Siru and Peru-tāli divisions wear a small and large tāli respectively.

In religion, most of the Kaikōlans are Saivites, and some have taken to wearing the lingam, but a few are Vaishnavites.

The hereditary headman of the caste is called Peridanakāran or Pattakāran, and is, as a rule, assisted by two subordinates entitled Sengili or Grāmani, and Ūral. But, if the settlement is a large one, the headman may have as many as nine assistants.

According to Mr. H. A. Stuart,21 “the Kaikōlans acknowledge the authority of a headman, or Mahānāttan, who resides at Conjeeveram, but itinerates among their villages, receiving presents, and settling caste disputes. Where his decision is not accepted without demur, he imposes upon the refractory weavers the expense of a curious ceremony, in which the planting of a bamboo post takes part. From the top of this pole the Mahānāttan pronounces his decision, which must be acquiesced in on pain of excommunication.” From information gathered at Conjeeveram, I learn that there is attached to the Kaikōlans a class of mendicants called Nattukattāda Nāyanmar. The name means the Nāyanmar who do not plant, in reference to the fact that, when performing, they fix their bamboo pole to the gōpuram of a temple, instead of planting it in the ground. They are expected to travel about the country, and, if a caste dispute requires settlement, a council meeting is convened, at which they must be present as the representatives of the Mahānādu, a chief Kaikōlan head-quarters at Conjeeveram. If the dispute is a complicated one, the Nattukattāda Nāyanmar goes to all the Kaikōlan houses, and makes a red mark with laterite22 on the cloth in the loom, saying “Āndvarānai,” as signifying that it is done by order of the headman. The Kaikōlans may, after this, not go on with their work until the dispute is settled, for the trial of which a day is fixed. The Nattukattāda Nāyanmars set up on a gōpuram their pole, which should have seventy-two internodes, and measure at least as many feet. The number of internodes corresponds to that of the nādus into which the Kaikōlan community is divided. Kamātchiamma is worshipped, and the Nattukattāda Nāyanmars climb up the pole, and perform various feats. Finally, the principal actor balances a young child in a tray on a bamboo, and, letting go of the bamboo, catches the falling child. The origin of the performance is said to have been as follows. The demon Sūran was troubling the Dēvas and men, and was advised by Karthikēya (Subramanya) and Vīrabāhu to desist from so doing. He paid no heed, and a fight ensued. The demon sent his son Vajrabāhu to meet the enemy, and he was slain by Vīrabāhu, who displayed the different parts of his body in the following manner. The vertebral column was made to represent a pole, round which the other bones were placed, and the guts tightly wound round them. The connective tissues were used as ropes to support the pole. The skull was used as a jaya-mani (conquest bell), and the skin hoisted as a flag. The trident of Vīrabāhu was fixed to the top of the pole, and, standing over it, he announced his victory over the world. The Nattukattāda Nāyanmars claim to be the descendants of Vīrabāhu. Their head-quarters are at Conjeeveram. They are regarded as slightly inferior to the Kaikōlans, with whom ordinarily they do not intermarry. The Kaikōlans have to pay them as alms a minimum fee of four annas per loom annually. Another class of mendicant, called Ponnambalaththar, which is said to have sprung up recently, poses as true caste beggars attached to the Kaikōlans, from whom, as they travel about the country, they solicit alms. Some Kaikōlans gave Ontipuli as the name of their caste beggars. The Ontipulis, however, are Nokkans attached to the Pallis.

The Kaikōlan community is, as already indicated, divided into seventy-two nādus or dēsams, viz., forty-four mēl (western) and twenty-eight kīl (eastern) nādus. Intermarriages take place between members of seventy-one of these nādus. The great Tamil poet Ottaikūththar is said to have belonged to the Kaikōlan caste and to have sung the praises of all castes except his own. Being angry on this account, the Kaikōlans urged him to sing in praise of them. This he consented to do, provided that he received 1,008 human heads. Seventy-one nādus sent the first-born sons for the sacrifice, but one nādu (Tirumarudhal) refused to send any. This refusal led to their isolation from the rest of the community. All the nādus are subject to the authority of four thisai nādus, and these in turn are controlled by the mahānādu at Conjeeveram, which is the residence of the patron deity Kamātchiamman. The thisai nādus are (1) Sīvapūram (Walajabad), east of Conjeeveram, where Kamātchiamman is said to have placed Nandi as a guard; (2) Thondipūram, where Thondi Vinayakar was stationed; (3) Virinjipūram to the west, guarded by Subramanya; (4) Sholingipūram to the south, watched over by Bairava. Each of the seventy-one nādus is sub-divided into kilai grāmams (branch villages), pērūr (big) and sithur (little) grāmams. In Tamil works relating to the Sengundar caste, Conjeeveram is said to be the mahānādu, and those belonging thereto are spoken of as the nineteen hundred, who are entitled to respect from other Kaikōlans. Another name for Kaikōlans of the mahānādu seems to be Āndavar; but in practice this name is confined to the headman of the mahānādu, and members of his family. They have the privilege of sitting at council meetings with their backs supported by pillows, and consequently bear the title Thindusarndān (resting on pillows). At present there are two sections of Kaikōlans at Conjeeveram, one living at Ayyampettai, and the other at Pillaipālayam. The former claim Ayyampettai as the mahānādu, and refuse to recognise Pillaipālayam, which is in the heart of Conjeeveram, as the mahānādu. Disputes arose, and recourse was had to the Vellore Court in 1904, where it was decided that Ayyampettai possesses no claim to be called the mahānādu.

Many Kaikōlan families have now abandoned their hereditary employment as weavers in favour of agriculture and trade, and some of the poorer members of the caste work as cart-drivers and coolies. At Coimbatore some hereditary weavers have become cart-drivers, and some cart-drivers have become weavers de necessité in the local jail.

In every Kaikōlan family, at least one girl should be set apart for, and dedicated to temple service. And the rule seems to be that, so long as this girl or her descendants, born to her or adopted, continue to live, another girl is not dedicated. But, when the line becomes extinct, another girl must be dedicated. All the Kaikōlans deny their connection with the Dēva-dāsi (dancing-girl) caste. But Kaikōlans freely take meals in Dāsi houses on ceremonial occasions, and it would not be difficult to cite cases of genuine Dāsis who have relationship with rich Kaikōlans.

Kaikōlan girls are made Dāsis either by regular dedication to a temple, or by the headman tying the tāli (nāttu pottu). The latter method is at the present day adopted because it is considered a sin to dedicate a girl to the god after she has reached puberty, and because the securing of the requisite official certificate for a girl to become a Dāsi involves considerable trouble.

“It is said,” Mr. Stuart writes,23 “that, where the head of a house dies, leaving only female issue, one of the girls is made a Dāsi in order to allow of her working like a man at the loom, for no woman not dedicated in this manner may do so.”

Of the orthodox form of ceremonial in connection with a girl’s initiation as a Dāsi, the following account was given by the Kaikōlans of Coimbatore. The girl is taught music and dancing. The dancing master or Nattuvan, belongs to the Kaikōlan caste, but she may be instructed in music by Brāhman Bhāgavathans. At the tāli-tying ceremony, which should take place after the girl has reached puberty, she is decorated with jewels, and made to stand on a heap of paddy (unhusked rice). A folded cloth is held before her by two Dāsis, who also stand on heaps of paddy. The girl catches hold of the cloth, and her dancing master, who is seated behind her, grasping her legs, moves them up and down in time with the music, which is played. In the course of the day, relations and friends are entertained, and, in the evening, the girl, seated astride a pony, is taken to the temple, where a new cloth for the idol, the tāli, and various articles required for doing pūja, have been got ready. The girl is seated facing the idol, and the officiating Brāhman gives sandal and flowers to her, and ties the tāli, which has been lying at the feet of the idol, round her neck. The tāli consists of a golden disc and black beads. Betel and flowers are then distributed among those present, and the girl is taken home through the principal streets. She continues to learn music and dancing, and eventually goes through a form of nuptial ceremony. The relations are invited for an auspicious day, and the maternal uncle, or his representative, ties a gold band on the girl’s forehead, and, carrying her, places her on a plank before the assembled guests. A Brāhman priest recites the mantrams, and prepares the sacred fire (hōmam). The uncle is presented with new cloths by the girl’s mother. For the actual nuptials a rich Brāhman, if possible, and, if not, a Brāhman of more lowly status is invited. A Brāhman is called in, as he is next in importance to, and the representative of the idol. It is said that, when the man who is to receive her first favours, joins the girl, a sword must be placed, at least for a few minutes, by her side. When a Dāsi dies, her body is covered with a new cloth removed from the idol, and flowers are supplied from the temple, to which she belonged. No pūja is performed in the temple till the body is disposed of, as the idol, being her husband, has to observe pollution.

Writing a century ago (1807) concerning the Kaikōlan Dāsis, Buchanan says24 that “these dancing women, and their musicians, now form a separate kind of caste; and a certain number of them are attached to every temple of any consequence. The allowances which the musicians receive for their public duty is very small, yet, morning and evening, they are bound to attend at the temple to perform before the image. They must also receive every person travelling on account of the Government, meet him at some distance from the town, and conduct him to his quarters with music and dancing. All the handsome girls are instructed to dance and sing, and are all prostitutes, at least to the Brāhmans. In ordinary sets they are quite common; but, under the Company’s government, those attached to temples of extraordinary sanctity are reserved entirely for the use of the native officers, who are all Brāhmans, and who would turn out from the set any girl that profaned herself by communication with persons of low caste, or of no caste at all, such as Christians or Mussulmans. Indeed, almost every one of these girls that is tolerably sightly is taken by some officer of revenue for his own special use, and is seldom permitted to go to the temple, except in his presence. Most of these officers have more than one wife, and the women of the Brāhmans are very beautiful; but the insipidity of their conduct, from a total want of education or accomplishment, makes the dancing women to be sought after by all natives with great avidity. The Mussulman officers in particular were exceedingly attached to this kind of company, and lavished away on these women a great part of their incomes. The women very much regret their loss, as the Mussulmans paid liberally, and the Brāhmans durst not presume to hinder any girl who chose, from amusing an Asoph, or any of his friends. The Brāhmans are not near so lavish of their money, especially where it is secured by the Company’s government, but trust to their authority for obtaining the favour of the dancers. To my taste, nothing can be more silly and unanimated than the dancing of the women, nor more harsh and barbarous than their music. Some Europeans, however, from long habit, I suppose, have taken a liking to it, and have even been captivated by the women. Most of them I have had an opportunity of seeing have been very ordinary in their looks, very inelegant in their dress, and very dirty in their persons; a large proportion of them have the itch, and a still larger proportion are most severely diseased.”

Though the Kaikōlans are considered to belong to the left-hand faction, Dāsis, except those who are specially engaged by the Bēri Chettis and Kammālans, are placed in the right-hand faction. Kaikōlan Dāsis, when passing through a Kammālan street, stop dancing, and they will not salute Kammālans or Bēri Chettis.

A peculiar method of selecting a bride, called siru tāli kattu (tying the small tāli), is said to be in vogue among some Kaikōlans. A man, who wishes to marry his maternal uncle’s or paternal aunt’s daughter, has to tie a tāli, or simply a bit of cloth torn from her clothing, round her neck, and report the fact to his parents and the headman. If the girl eludes him, he cannot claim her, but, should he succeed, she belongs to him. In some places, the consent of the maternal uncle to a marriage is signified by his carrying the bride in his arms to the marriage pandal (booth). The milk-post is made of Erythrina indica. After the tāli has been tied, the bridegroom lifts the bride’s left leg, and places it on a grinding-stone. Widows are stated by Mr. Stuart to be “allowed to remarry if they have no issue, but not otherwise; and, if the prevalent idea that a Kaikōla woman is never barren be true, this must seldom take place.”

On the final day of the death ceremonies, a small hut is erected, and inside it stones, brought by the barber, are set up, and offerings made to them.

The following proverbs are current about or among the Kaikōlans:—

Narrate stories in villages where there are no Kaikōlans.

Why should a weaver have a monkey?

This, it has been suggested,25 implies that a monkey would only damage the work.

On examining the various occupations, weaving will be found to be the best.

A peep outside will cut out eight threads.

The person who was too lazy to weave went to the stars.

The Chetti (money-lender) decreases the money, and the weaver the thread.

The titles of the Kaikōlans are Mūdali and Nāyanar.

Among the Kaikōlan musicians, I have seen every gradation of colour and type, from leptorhine men with fair skin and chiselled features, to men very dark and platyrhine, with nasal index exceeding 90.

The Kaikōlans take part in the annual festival at Tirupati in honour of the goddess Gangamma. “It is,” Mr. Stuart writes,26 “distinguished from the majority of similar festivals by a custom, which requires the people to appear in a different disguise (vēsham) every morning and evening. The Mātangi vēsham of Sunday morning deserves special mention. The devotee who consents to undergo this ceremony dances in front of an image or representation of the goddess, and, when he is worked up to the proper pitch of frenzy, a metal wire is passed through the middle of his tongue. It is believed that this operation causes no pain, or even bleeding, and the only remedy adopted is the chewing of a few margosa (Melia Azadirachta) leaves, and some kunkumam (red powder) of the goddess. This vēsham is undertaken only by a Kaikōlan (weaver), and is performed only in two places—the house of a certain Brāhman and the Mahant’s math. The concluding disguise is that known as the pērantālu vēsham. Pērantālu signifies the deceased married women of a family who have died before their husbands, or, more particularly, the most distinguished of such women. This vēsham is accordingly represented by a Kaikōlan disguised as a female, who rides round the town on a horse, and distributes to the respectable inhabitants of the place the kunkumam, saffron paste, and flowers of the goddess.”

For the following account of a ceremony, which took place at Conjeeveram in August, 1908, I am indebted to the Rev. J. H. Maclean. “On a small and very lightly built car, about eight feet high, and running on four little wheels, an image of Kāli was placed. It was then dragged by about thirty men, attached to it by cords passed through the flesh of their backs. I saw one of the young men two days later. Two cords had been drawn through his flesh, about twelve inches apart. The wounds were covered over with white stuff, said to be vibūthi (sacred ashes). The festival was organised by a class of weavers calling themselves Sankunram (Sengundar) Mudaliars, the inhabitants of seven streets in the part of Conjeeveram known as Pillaipalyam. The total amount spent is said to have been Rs. 500. The people were far from clear in their account of the meaning of the ceremony. One said it was a preventive of small-pox, but this view did not receive general support. Most said it was simply an old custom: what good it did they could not say. Thirty years had elapsed since the last festival. One man said that Kāli had given no commands on the subject, and that it was simply a device to make money circulate. The festival is called Pūntēr (flower car).”

In September, 1908, an official notification was issued in the Fort St. George Gazette to the following effect. “Whereas it appears that hook-swinging, dragging of cars by men harnessed to them by hooks which pierce their sides, and similar acts are performed during the Mariyamman festival at Samayapuram and other places in the Trichinopoly division, Trichinopoly district, and whereas such acts are dangerous to human life, the Governor in Council is pleased, under section 144, sub-section (5), of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898, to direct that the order of the Sub-divisional Magistrate, dated the 7th August, 1908, prohibiting such acts, shall remain in force until further orders.”

It is noted by Mr. F. R. Hemingway27 that, at Ratnagiri, in the Trichinopoly district, the Kaikōlans, in performance of a vow, thrust a spear through the muscles of the abdomen in honour of their god Sāhānayanar.

Kaila (measuring grain in the threshing-floor).—An exogamous sept of Māla.

Kaimal.—A title of Nāyars, derived from kai, hand, signifying power.

Kaipūda.—A sub-division of Holeya.

Kaivarta.—A sub-division of Kevuto.

Kāka (crow).—The legend relating to the Kāka people is narrated in the article on Koyis. The equivalent Kākī occurs as a sept of Mālas, and Kāko as a sept of Kondras.

Kākara or Kākarla (Momordica Charantia).—An exogamous sept of Kamma and Mūka Dora.

Kākirekka-vāndlu (crows’ feather people).—Mendicants who beg from Mutrāchas, and derive their name from the fact that, when begging, they tie round their waists strings on which crows’, paddy birds’ (heron) feathers, etc., are tied.

Kakka Kuravan.—A division of Kuravas of Travancore.

Kakkalan.—The Kakkalans or Kakkans are a vagrant tribe met with in north and central Travancore, who are identical with the Kakka Kuravans of south Travancore. There are among them four endogamous divisions called Kavitiyan, Manipparayan, Meluttan, and Chattaparayan, of which the two first are the most important. The Kavitiyans are further sub-divided into Kollak Kavitiyan residing in central Travancore, Malayālam Kavitiyan, and Pāndi Kavitiyan or immigrants from the Pāndyan country.

The Kakkalans have a legend concerning their origin to the effect that Siva was once going about begging as a Kapaladhārin, and arrived at a Brāhman street, from which the inhabitants drove him away. The offended god immediately reduced the village to ashes, and the guilty villagers begged his pardon, but were reduced to the position of the Kakkalans, and made to earn their livelihood by begging.

The women wear iron and silver bangles, and a palunka māla or necklace of variously coloured beads. They are tattooed, and tattooing members of other castes is one of their occupations, which include the following:—

Katukuttu, or boring the lobes of the ears.

Katuvaippu, or plastic operations on the ear, which Nāyar women and others who wear heavy pendant ear ornaments often require.

Kainokku or palmistry, in which the women are more proficient than the men.

Kompuvaippu, or placing the twig of a plant on any swelling of the body, and dissipating it by blowing on it.

Taiyyal, or tailoring.

Pāmpātam or snake dance, in which the Kakkalans are unrivalled.

Fortune telling.

The chief object of worship by the Kakkalans is the rising sun, to which boiled rice is offered on Sunday. They have no temples of their own, but stand at some distance from Hindu temples, and worship the gods thereof. Though leading a wandering life, they try to be at home for the Malabar new year, on which occasion they wear new clothes, and hold a feast. They do not observe the national Ōnam and Vishu festivals.