автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Complete Works in Philosophy, Politics and Morals of the late Dr. Benjamin Franklin, Vol. 1

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

This is Volume 1 of a 3-volume set. The other two volumes are also accessible in Project Gutenberg using http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/48137 and http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/48138.

Obvious typographical errors and punctuation errors have been corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within the text and consultation of external sources.

More detail can be found at the end of the book.

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, L.L.D.

Publish'd April 1, 1806; by Longman, Rees, Hurst, & Orme, Paternoster Row.

The

WORKS

Of

Benjamin Franklin, L.L.D.

VOL. 1.

Engraved by W. & G. Cooke

Printed,

for Longman, Hurst, Rees, & Orme, Paternoster Row, London.

THE

COMPLETE

WORKS,

IN

PHILOSOPHY, POLITICS, AND MORALS,

OF THE LATE

DR. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN,

NOW FIRST COLLECTED AND ARRANGED:

WITH

MEMOIRS OF HIS EARLY LIFE,

WRITTEN BY HIMSELF.

IN THREE VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

London:

PRINTED FOR J. JOHNSON, ST. PAUL'S CHURCH-YARD;

AND LONGMAN, HURST, REES AND ORME,

PATERNOSTER-ROW.

———

1806.

ADVERTISEMENT.

The

works of

Dr. Franklin have been often partially collected, never before brought together in one uniform publication.The first collection was made by Mr. Peter Collinson in the year 1751. It consisted of letters, communicated by the author to the editor, on one subject, electricity, and formed a pamphlet only, of which the price was half-a-crown. It was enlarged in 1752, by a second communication on the same subject, and in 1754, by a third, till, in 1766, by the addition of letters and papers on other philosophical subjects, it amounted to a quarto volume of 500 pages.

Ten years after, in 1779, another collection was made, by a different editor, in one volume, printed both in quarto and octavo, of papers not contained in the preceding collection, under the title of Political, Miscellaneous, and Philosophical Pieces.

In 1787, a third collection appeared in a thin octavo volume, entitled Philosophical and Miscellaneous Papers.

And lastly, in 1793, a fourth was published, in two volumes, crown octavo, consisting of Memoirs of Dr. Franklin's Life, and Essays humourous, moral and literary, chiefly in the Manner of the Spectator.

In the present volumes will be found all the different collections we have enumerated, together with the various papers of the same author, that have been published in separate pamphlets, or inserted in foreign collections of his works, or in the Transactions of our own or of foreign philosophical societies, or in our own or foreign newspapers and magazines, as far as discoverable by the editor, who has been assisted in the research by a gentleman in America. Among these papers some, we conceive, will be new to the English reader on this

side of the

Atlantic; particularly a series of essays entitled The Busy-Body, written, as Dr. Franklin tells us in his Life, when he was an assiduous imitator of Addison; and a pamphlet, entitled Plain Truth, with which he is said to have commenced his political career as a writer. We hoped to have been enabled to add, what would have been equally new, and still more acceptable, a genuine copy of the Life of our author, as written by himself; but in this hope we are disappointed, and we are in consequence obliged to content ourselves with a translation, which has been already before the public, from a copy in the French language, coming no farther down than the year 1731; and a continuation of his history from that period, by the late Dr. Stuber of Philadelphia.The character of Dr. Franklin, as a philosopher, a politician, and a moralist, is too well known to require illustration, and his writings, from their interesting nature, and the fascinating simplicity of their style, are too highly esteemed, for any apology to be necessary for so large a collection of them, unless it should be deemed necessary by the individual to whom Dr. Franklin in his will consigned his manuscripts: and to him our apology will consist in a reference to his own extraordinary conduct.

In bequeathing his papers, it was no doubt the intention of the testator, that the world should have the chance of being benefited by their publication. It was so understood by the person in question, his grandson, who, accordingly, shortly after the death of his great relative, hastened to London, the best mart for literary property, employed an amanuensis for many months in copying, ransacked our public libraries that nothing might escape, and at length had so far prepared the works of Dr. Franklin for the press, that proposals were made by him to several of our principal booksellers for the sale of them. They were to form three quarto volumes, and were to contain all the writings, published and unpublished, of Franklin, with Memoirs of his Life, brought down by himself to the year 1757, and continued to his death by the legatee. They were to be published in three different languages, and the countries corresponding to those languages, France, Germany, and England, on the same day. The terms asked for the copyright of the English edition were high, amounting to several thousand pounds, which occasioned a little demur; but eventually they would no doubt have been obtained. Nothing more however was heard of the proposals or the work, in this its fair market. The proprietor, it seems, had found a bidder of a different description in some emissary of government, whose object was to withhold the manuscripts from the world, not to benefit it by their publication; and they thus either passed into other hands, or the person to whom they were bequeathed received a remuneration for suppressing them. This at least has been asserted, by a variety of persons, both in this country and America, of whom some were at the time intimate with the grandson, and not wholly unacquainted with the machinations of the ministry; and the silence, which has been observed for so many years respecting the publication, gives additional credibility to the report.

What the manuscripts contained, that should have excited the jealousy of government, we are unable, as we have never seen them, positively to affirm; but, from the conspicuous part acted by the author in the American revolution and the wars connected with it, it is by no means difficult to guess; and of this we are sure, from his character, that no disposition of his writings could have been more contrary to his intentions or wishes.

We have only to add, that in the present collection, which is probably all that will ever be published of the works of this extraordinary man, the papers are methodically arranged, the moral and philosophical ones according to their subjects, the political ones, as nearly as may be, according to their dates; that we have given, in notes, the authorities for ascribing the different pieces to Franklin; that where no title existed, to indicate the nature of a letter or paper, we have prefixed a title; and lastly, that we have compiled an index to the whole, which is placed at the beginning, instead of, as is usual, at the end of the work, to render the volumes more equal.

April 7, 1806.

CONTENTS.

VOL. I.

Page.

LIFE of Dr. FRANKLIN

1LETTERS AND PAPERS ON ELECTRICITY.

Introductory Letter.

169Wonderful effect of points.—Positive and negative electricity.—Electrical kiss.—Counterfeit spider.—Simple and commodious electrical machine.

170Observations on the Leyden bottle, with experiments proving the different electrical state of its different surfaces.

179Further experiments confirming the preceding observations.—Leyden bottle analysed.—Electrical battery.—Magical Picture.—Electrical wheel or jack.—Electrical feast.

187Observations and suppositions, towards forming a new hypothesis, for explaining the several phenomena of thunder-gusts.

203Introductory letter to some additional papers.

216Opinions and conjectures, concerning the properties and effects of the electrical matter, and the means of preserving buildings, ships, &c. from lightning, arising from experiments and observations made at Philadelphia, 1749.—Golden fish.—Extraction of effluvial virtues by electricity impracticable.

217Additional experiments: proving that the Leyden bottle has no more electrical fire in it when charged, than before: nor less when discharged: that in discharging, the fire does not issue from the wire and the coating at the same time, as some have thought, but that the coating always receives what is discharged by the wire, or an equal quantity: the outer surface being always in a negative state of electricity, when the inner surface is in a positive state.

245Accumulation of the electrical fire proved to be in the electrified glass.—Effect of lightning on the needle of compasses, explained.—Gunpowder fired by the electric flame.

247Unlimited nature of the electric force.

250The terms, electric per se, and non-electric, improper.—New relation between metals and water.—Effects of air in electrical experiments.—Experiment for discovering more of the qualities of the electric fluid.

252Mistake, that only metals and water were conductors, rectified.—Supposition of a region of electric fire above our atmosphere.—Theorem concerning light.—Poke-weed a cure for cancers.

256New experiments.—Paradoxes inferred from them.—Difference in the electricity of a globe of glass charged, and a globe of sulphur.—Difficulty of ascertaining which is positive and which negative.

261Probable cause of the different attractions and repulsions of the two electrified globes mentioned in the two preceding letters.

264Reasons for supposing, that the glass globe charges positively, and the sulphur negatively.—Hint respecting a leather globe for experiments when travelling.

ibid.Electrical kite.

267Hypothesis, of the sea being the grand source of lightning, retracted.—Positive, and sometimes negative, electricity of the clouds discovered.—New experiments and conjectures in support of this discovery.—Observations recommended for ascertaining the direction of the electric fluid.—Size of rods for conductors to buildings.—Appearance of a thunder-cloud described.

269Additional proofs of the positive and negative state of electricity in the clouds.—New method of ascertaining it.

284Electrical experiments, with an attempt to account for their several phenomena, &c.

286Experiments made in pursuance of those made by Mr. Canton, dated December 6, 1753; with explanations, by Mr. Benjamin Franklin.

294Turkey killed by electricity.—Effect of a shock on the operator in making the experiment.

299Differences in the qualities of glass.—Account of Domien, an electrician and traveller.—Conjectures respecting the pores of glass.—Origin of the author's idea of drawing down lightning.—No satisfactory hypothesis respecting the manner in which clouds become electrified.—Six men knocked down at once by an electrical shock.—Reflections on the spirit of invention.

301Beccaria's work on electricity.—Sentiments of Franklin on pointed rods, not fully understood in Europe.—Effect of lightning on the church of Newbury, in New England.—Remarks on the subject.

309Notice of another packet of letters.

313Extract of a letter from a gentleman in Boston, to Benjamin Franklin, Esq. concerning the crooked direction, and the source of lightning, and the swiftness of the electric fire.

314Observations on the subjects of the preceding letter.—Reasons for supposing the sea to be the grand source of lightning.—Reasons for doubting this hypothesis.—Improvement in a globe for raising the electric fire.

320Effect of lightning on captain Waddel's compass, and the Dutch church at New York.

324Proposal of an experiment to measure the time taken up by an Electric spark, in moving through any given space.

327Experiments on boiling water, and glass heated by boiling water.—Doctrine of repulsion in electrised bodies doubted.—Electricity of the atmosphere at different heights.—Electrical horse-race.—Electrical thermometer.—In what cases the electrical fire produces heat.—Wire lengthened by electricity.—Good effect of a rod on the house of Mr. West, of Philadelphia.

331Answer to some of the foregoing subjects.—How long the Leyden bottle may be kept charged.—Heated glass rendered permeable by the electric fluid.—Electrical attraction and repulsion.—Reply to other subjects in the preceding paper.—Numerous ways of kindling fire.—Explosion of water.—Knobs and points.

343Accounts from Carolina (mentioned in the foregoing letter) of the effects of lightning on two of the rods commonly affixed to houses there, for securing them against lightning.

361Mr. William Maine's account of the effects of the lightning on his rod, dated at Indian Land, in South Carolina, Aug. 28, 1760.

362On the electricity of the tourmalin.

369New observation relating to electricity in the atmosphere.

373Flash of lightning that struck St. Bride's steeple.

374Best method of securing a powder magazine from lightning.

375Of lightning, and the methods (now used in America) of securing buildings and persons from its mischievous effects.

377St. Bride's steeple.—Utility of electrical conductors to Steeples.—Singular kind of glass tube.

382Experiments, observations, and facts, tending to support the opinion

of the utility of long pointed rods, for securing buildings from damage by strokes of lightning.

383On the utility of electrical conductors.

400On the effects of electricity in paralytic cases.

401Electrical experiments on amber.

403On the electricity of the fogs in Ireland.

405Mode of ascertaining, whether the power, giving a shock to those who touch either the Surinam eel, or the torpedo, be electrical.

408On the

analogy

between magnetism and electricity.

410Concerning the mode of rendering meat tender by electricity.

413Answer to some queries concerning the choice of glass for the Leyden experiment.

416Concerning the Leyden bottle.

418APPENDIX.

No. 1. Account of experiments made in electricity at Marly.

420A more particular account of the same, &c.

422Letter of Mr. W. Watson, F. R. S. to the Royal Society, concerning the electrical experiments in England upon thunder-clouds.

427No. 2. Remarks on the Abbé Nollet's Letters to Benjamin Franklin, Esq. of Philadelphia, on electricity.

430LIST OF THE PLATES

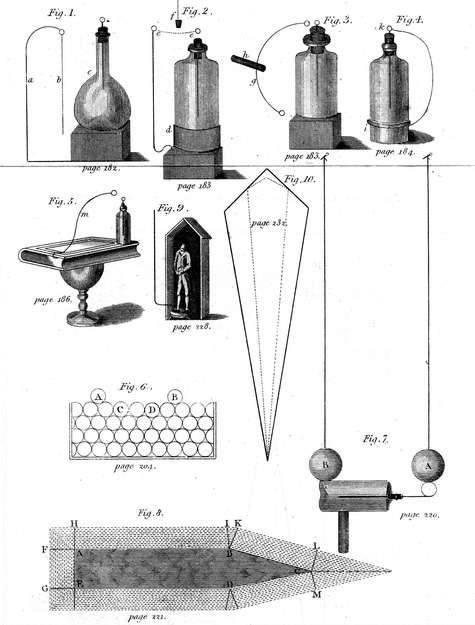

PLATE I.

Electrical Experiments

facing page

182PLATE II.

Electrical Air Thermometer

336PLATE III.

Cavendish Experiment

348PLATE IV.

Lightning Rod Experiments

388ERRATA.

Page.

Line.

210:

for true, read me.

55:

for was born, read who was born.

201:

for Tryon, read Tyron's.

ib.

7

from the bottom: for put to blush, read put to the blush.

ib.

4

from the bottom: for myself, read by myself.

154:

for collection, read works.

219

from the bottom: for or, read nor.

254

from the bottom: for pasquenades, read pasquinades.

287:

dele the.

ib.

12:

for printer, read a printer.

283

from the bottom: for my old favourite work, Bunyan's Voyages, read my old favourite Bunyan.

405:

for money, read in money.

443:

for Bernet, read Burnet.

ib.

17:

for unabled, read unable.

5019:

for ingenuous, read ingenious.

675:

dele bridge.

803

from the bottom: for into, read into which.

235

21:

substitute + for *.

2642:

for course read cause.

LIFE

OF

DR. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN.

LIFE

OF

DR. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN,

&c. &c.

MY DEAR SON,

I have amused myself with collecting some little anecdotes of my family. You may remember the enquiries I made, when you were with me in England, among such of my relations as were then living; and the journey I undertook for that purpose. To be acquainted with the particulars of my parentage and life, many of which are unknown to you, I flatter myself will afford the same pleasure to you as to me. I shall relate them upon paper: it will be an agreeable employment of a week's uninterrupted leisure, which I promise myself during my present retirement in the country. There are also other motives which induce me to the undertaking. From the bosom of poverty and obscurity, in which I drew my first breath, and spent my earliest years, I have raised myself to a state of opulence and to some degree of celebrity in the world. A constant good fortune has attended me through every period of life to my present advanced age; and my descendants may be desirous of learning what were the means of which I made use, and which, thanks to the assisting hand of providence, have proved so eminently successful. They may also, should they ever be placed in a similar situation, derive some advantage from my narrative.

When I reflect, as I frequently do, upon the felicity I have enjoyed, I sometimes say to myself, that, were the offer made

me

, I would engage to run again, from beginning to end, the same career of life. All I would ask, should be the privilege of an author, to correct, in a second edition, certain errors of the first. I could wish, likewise if it were in my power, to change some trivial incidents and events for others more favourable. Were this, however, denied me, still would I not decline the offer. But since a repetition of life cannot take place, there is nothing which, in my opinion, so nearly resembles it, as to call to mind all its circumstances, and, to render their remembrance more durable, commit them to writing. By thus employing myself, I shall yield to the inclination, so natural in old men, to talk of themselves and their exploits, and may freely follow my bent, without being tiresome to those who, from respect to my age, might think themselves obliged to listen to me; as they will be at liberty to read me or not as they please. In fine—and I may as well avow it, since nobody would believe me were I to deny it—I shall perhaps, by this employment, gratify my vanity. Scarcely indeed have I ever read or heard the introductory phrase, "I may say without vanity," but some striking and characteristic instance of vanity has immediately followed. The generality of men hate vanity in others, however strongly they may be tinctured with it themselves: for myself, I pay obeisance to it wherever I meet with it, persuaded that it is advantageous, as well to the individual whom it governs, as to those who are within the sphere of its influence. Of consequence, it would in many cases, not be wholly absurd, that a man should count his vanity among the other sweets of life, and give thanks to providence for the blessing.And here let me with all humility acknowledge, that to divine providence I am indebted for the felicity I have hitherto enjoyed. It is that power alone which has furnished me with the means I have employed, and that has crowned them with success. My faith in this respect leads me to hope, though I cannot count upon it, that the divine goodness will still be exercised towards me, either by prolonging the duration of my happiness to the close of life, or by giving me fortitude to support any melancholy reverse, which may happen to me, as to so many others. My future fortune is unknown but to Him in whose hand is our destiny, and who can make our very afflictions subservient to our benefit.

One of my uncles, desirous, like myself, of collecting anecdotes of our family, gave me some notes, from which I have derived many particulars respecting our ancestors. From these I learn, that they had lived in the same village (Eaton in Northamptonshire,) upon a freehold of about thirty acres, for the space at least of three hundred years. How long they had resided there prior to that period, my uncle had been unable to discover; probably ever since the institution of surnames, when they took the appellation of Franklin, which had formerly been the name of a particular order of individuals.[1]

This petty estate would not have sufficed for their subsistence, had they not added the trade of blacksmith, which was perpetuated in the family down to my uncle's time, the eldest son having been uniformly brought up to this employment: a custom which both he and my father observed with respect to their eldest sons.

In the researches I made at Eaton, I found no account of their births, marriages, and deaths, earlier than the year 1555; the parish register not extending farther back than that period. This register informed me, that I was the youngest son of the youngest branch of the family, counting five generations. My

grandfather

, Thomas,who was born

in 1598, lived at Eaton till he was too old to continue his trade, when he retired to Banbury in Oxfordshire, where his son John, who was a dyer, resided, and with whom my father was apprenticed. He died, and was buried there: we saw his monument in 1758. His eldest son lived in the family house at Eaton, which he bequeathed, with the land belonging to it, to his only daughter; who, in concert with her husband, Mr. Fisher of Wellingborough, afterwards sold it to Mr. Estead, the present proprietor.My grandfather had four surviving sons, Thomas, John, Benjamin, and Josias. I shall give you such particulars of them as my memory will furnish, not having my papers here, in which you will find a more minute account, if they are not lost during my absence.

Thomas had learned the trade of a blacksmith under his father; but possessing a good natural understanding, he improved it by study, at the solicitation of a gentleman of the name of Palmer, who was at that time the principal inhabitant of the village, and who encouraged, in like manner, all my uncles to cultivate their minds. Thomas thus rendered himself competent to the functions of a country attorney; soon became an essential personage in the affairs of the village; and was one of the chief movers of every public enterprise, as well relative to the county as the town of Northampton. A variety of remarkable incidents were told us of him at Eaton. After enjoying the esteem and patronage of Lord Halifax, he died, January 6, 1702, precisely four years before I was born. The recital that was made us of his life and character, by some aged persons of the village, struck you, I remember, as extraordinary, from its analogy to what you knew of myself. "Had he died," said you, "just four years later, one might have supposed a transmigration of souls."

John, to the best of my belief, was brought up to the trade of a wool-dyer.

Benjamin served his apprenticeship in London to a silk-dyer. He was an industrious man: I remember him well; for, while I was a child, he joined my father at Boston, and lived for some years in the house with us. A particular affection had always subsisted between my father and him; and I was his godson. He arrived to a great age. He left behind him two quarto volumes of poems in manuscript, consisting of little fugitive pieces addressed to his friends. He had invented a short-hand, which he taught me, but having never made use of it, I have now forgotten it. He was a man of piety, and a constant attendant on the best preachers, whose sermons he took a pleasure in writing down according, to the expeditory method he had devised. Many volumes were thus collected by him. He was also extremely fond of politics, too much so, perhaps, for his situation. I lately found in London a collection which he had made of all the principal pamphlets relative to public affairs, from the year 1641 to 1717. Many volumes are wanting, as appears by the series of numbers; but there still remain eight in folio, and twenty-four in quarto and octavo. The collection had fallen into the hands of a second-hand bookseller, who, knowing me by having sold me some books, brought it to me. My uncle, it seems, had left it behind him on his departure for America, about fifty years ago. I found various notes of his writing in the margins. His grandson, Samuel, is now living at Boston.

Our humble family had early embraced the Reformation. They remained faithfully attached during the reign of Queen Mary, when they were in danger of being molested on account of their zeal against popery. They had an English bible, and, to conceal it the more securely, they conceived the project of fastening it, open, with pack-threads across the leaves, on the inside of the lid of the close-stool. When my great-grandfather wished to read to his family, he reversed the lid of the close-stool upon his knees, and passed the leaves from one side to the other, which were held down on each by the pack-thread. One of the children was stationed at the door, to give notice if he saw the proctor (an officer of the spiritual court) make his appearance: in that case, the lid was restored to its place, with the Bible concealed under it as before. I had this anecdote from my uncle Benjamin.

The whole family preserved its attachment to the Church of England till towards the close of the reign of Charles II. when certain ministers, who had been ejected as nonconformists, having held conventicles in Northamptonshire, they were joined by Benjamin and Josias, who adhered to them ever after. The rest of the family continued in the episcopal church.

My father, Josias, married early in life. He went, with his wife and three children, to New England, about the year 1682. Conventicles being at that time prohibited by law, and frequently disturbed, some considerable persons of his acquaintance determined to go to America, where they hoped to enjoy the free exercise of their religion, and my father was prevailed on to accompany them.

My father had also by the same wife, four children born in America, and ten others by a second wife, making in all seventeen. I remember to have seen thirteen seated together at his table, who all arrived to years of maturity, and were married. I was the last of the sons, and the youngest child, excepting two daughters. I was born at Boston in New England. My mother, the second wife, was Abiah Folger, daughter of Peter Folger, one of the first colonists of New England, of whom Cotton Mather makes honourable mention, in his Ecclesiastical History of that province, as "a pious and learned Englishman," if I rightly recollect his expressions. I have been told of his having written a variety of little pieces; but there appears to be only one in print, which I met with many years ago. It was published in the year 1675, and is in familiar verse, agreeably to the taste of the times and the country. The author addresses himself to the governors for the time being, speaks for liberty of conscience, and in favour of the anabaptists, quakers, and other sectaries, who had suffered persecution. To this persecution he attributes the war with the natives, and other calamities which afflicted the country, regarding them as the judgments of God in punishment of so odious an offence, and he exhorts the government to the repeal of laws so contrary to charity. The poem appeared to be written with a manly freedom and a pleasing simplicity. I recollect the six concluding lines, though I have forgotten the order of words of the two first; the sense of which was, that his censures were dictated by benevolence, and that, of consequence, he wished to be known as the author; because, said he, I hate from my very soul dissimulation:

Your kind present of an electric tube, with directions for using it, has put several of us[15] on making electrical experiments, in which we have observed some particular phenomena that we look upon to be new. I shall therefore communicate them to you in my next, though possibly they may not be new to you, as among the numbers daily employed in those experiments on your side the water, it is probable some one or other has hit on the same observations. For my own part, I never was before engaged in any study that so totally engrossed my attention and my time as this has lately done; for what with making experiments when I can be alone, and repeating them to my friends and acquaintance, who, from the novelty of the thing, come continually

in crowds

to see them, I have, during some months past, had little leisure for any thing else.The passing of the electrical fire from the upper to the lower part[31] of the bottle, to restore the equilibrium, is rendered strongly visible by the following pretty experiment. Take a book whose covering is filletted with gold; bend a wire of eight or ten inches long, in the form of (m) Fig. 5; slip it on the end of the cover of the book, over the gold line, so as that the shoulder of it may press upon one end of the gold line, the ring up, but leaning towards the other end of the book. Lay the book on a glass or wax[32], and on the other end of the gold lines set the bottle electrised; then bend the springing wire, by pressing it with a stick of wax till its ring approaches the ring of the bottle wire, instantly there is a strong spark and stroke, and the whole line of gold, which completes the communication, between the top and bottom of the bottle, will appear a vivid flame, like the sharpest lightning. The closer the contact between the shoulder of the wire, and the gold at one end of the line, and between the bottom of the bottle and the gold at the other end, the better the experiment succeeds. The room should be darkened. If you would have the whole filletting round the cover appear in fire at once, let the bottle and wire touch the gold in the diagonally opposite corners.

Chagrined a little that we have been hitherto able to produce nothing in this way of use to mankind; and the hot weather coming on, when electrical experiments are not so agreeable, it is proposed to put an end to them for this season, somewhat humorously, in a party of pleasure, on the banks of Skuylkil[41]. Spirits, at the same time, are to be fired by a spark sent from side to side through the river, without any other conductor than the water; an experiment which we some time since performed, to the amazement of many[42]. A turkey is to be killed for our dinner by the electrical shock, and roasted by the electrical jack, before a fire kindled by the electrified bottle: when the healths of all the famous electricians in England, Holland, France, and Germany are to be drank in electrified bumpers[43], under the discharge of guns from the electrical battery.

56. If the source of lightning, assigned in this paper, be the true one, there should be little thunder heard at sea far from land. And accordingly some old sea-captains, of whom enquiry has been made, do affirm, that the fact agrees perfectly with the hypothesis; for that in crossing the great ocean, they seldom meet with thunder till they come into soundings; and that the islands far from the continent have very little of it. And a curious observer, who lived thirteen years at Bermudas, says, there was less thunder there in that whole time than he has sometimes heard in a month at Carolina.

As you first put us on electrical experiments, by sending to our Library Company a tube, with directions how to use it; and as our honorable Proprietary enabled us to carry those experiments to a greater height, by his generous present of a complete electrical apparatus; it is fit that both should know, from time to time, what progress we make. It was in this view I wrote and sent you my former papers on this subject, desiring, that as I had not the honour of a direct correspondence with that bountiful benefactor to our library, they might be communicated to him through your hands. In the same view I write and send you this additional paper. If it happens to bring you nothing new, (which may well be, considering the number of ingenious men in Europe, continually engaged in the same researches) at least it will shew, that the instruments put into our hands are not neglected; and that if no valuable discoveries are made by us, whatever the cause may be, it is not want of industry and application.

But I shall never have done, if I tell you all my conjectures, thoughts, and imaginations on the nature and operations of this electric fluid, and relate the variety of little experiments we have tried. I have already made this paper too long, for which I must crave pardon, not having now time to abridge it. I shall only add, that as it has been observed here that spirits will fire by the electric spark in the summer time, without heating them, when Fahrenheit's thermometer is above 70; so when colder, if the operator puts a small flat bottle of spirits in his bosom, or a close pocket, with the spoon, some little time before he uses them, the heat of his body will communicate warmth more than sufficient for the purpose.

But if the fire with which the inside surface is surcharged be so much precisely as is wanted by the outside surface, it will pass round through the wire fixed to the wax handle, restore the equilibrium in the glass, and make no alteration in the state of the prime conductor.

I am heartily glad to hear more instances of the success of the poke-weed, in the cure of that horrible evil to the human body, a cancer. You will deserve highly of mankind for the communication. But I find in Boston they are at a loss to know the right plant, some asserting it is what they call Mechoachan, others other things. In one of their late papers it is publicly requested that a perfect description may be given of the plant, its places of growth, &c. I have mislaid the paper, or would send it to you. I thought you had described it pretty fully[63].

Make a small cross of two light strips of cedar, the arms so long as to reach to the four corners of a large thin silk handkerchief when extended; tie the corners of the handkerchief to the extremities of the cross, so you have the body of a kite; which being properly accommodated with a tail, loop, and string, will rise in the air, like those made of paper; but this being of silk is fitter to bear the wet and wind of a thunder-gust without tearing. To the top of the upright stick of the cross is to be fixed a very sharp pointed wire, rising a foot or more above the wood. To the end of the twine, next the hand, is to be tied a silk ribbon, and where the silk and twine join, a key may be fastened. This kite is to be raised when a thunder-gust appears to be coming on, and the person who holds the string must stand within a door or window, or under some cover, so that the silk ribbon may not be wet; and care must be taken that the twine does not touch the frame of the door or window. As soon as any of the thunder clouds come over the kite, the pointed wire will draw the electric fire from them, and the kite, with all the twine, will be electrified, and the loose filaments of the twine will stand out every way, and be attracted by an approaching finger. And when the rain has wetted the kite and twine, so that it can conduct the electric fire freely, you will find it stream out plentifully from the key on the approach of your knuckle. At this key the phial may be charged; and from electric fire thus obtained, spirits may be kindled, and all the other electric experiments be performed, which are usually done by the help of a rubbed glass globe or tube, and thereby the sameness of the electric matter with that of lightning completely demonstrated.

These thoughts, my dear friend, are many of them crude and hasty; and if I were merely ambitious of acquiring some reputation in philosophy, I ought to keep them by me, till corrected and improved by time, and farther experience. But since even short hints and imperfect experiments in any new branch of science, being communicated, have oftentimes a good effect, in exciting the attention of the ingenious to the subject, and so become the occasion of more exact disquisition, and more compleat discoveries, you are at liberty to communicate this paper to whom you please; it being of more importance that knowledge should increase, than that your friend should be thought an accurate philosopher.

Because the finger being plunged into the atmosphere of the glass tube, as well as the threads, part of its natural quantity is driven back through the hand and body, by that atmosphere, and the finger becomes, as well as the threads, negatively electrised, and so repels, and is repelled by them. To confirm this, hold a slender light lock of cotton, two or three inches long, near a prime conductor, that is electrified by a glass globe, or tube. You will see the cotton stretch itself out towards the prime conductor. Attempt to touch it with the finger of the other hand, and it will be repelled by the finger. Approach it with a positively charged wire of a bottle, and it will fly to the wire. Bring it near a negatively charged wire of a bottle, it will recede from that wire in the same manner that it did from the finger; which demonstrates the finger to be negatively electrised, as well as the lock of cotton so situated.

The treatment your friend has met with is so common, that no man who knows what the world is, and ever has been, should expect to escape it. There are every where a number of people, who, being totally destitute of any inventive faculty themselves, do not readily conceive that others may possess it: they think of inventions as of miracles; there might be such formerly, but they are ceased. With these, every one who offers a new invention is deemed a pretender: he had it from some other country, or from some book: a man of their own acquaintance; one who has no more sense than themselves, could not possibly, in their opinion, have been the inventor of any thing. They are confirmed, too, in these sentiments, by frequent instances of pretensions to invention, which vanity is daily producing. That vanity too, though an incitement to invention, is, at the same time, the pest of inventors. Jealousy and envy deny the merit or the novelty of your invention; but vanity, when the novelty and merit are established, claims it for its own. The smaller your invention is, the more mortification you receive in having the credit of it disputed with you by a rival, whom the jealousy and envy of others are ready to support against you, at least so far as to make the point doubtful. It is not in itself of importance enough for a dispute; no one would think your proofs and reasons worth their attention: and yet, if you do not dispute the point, and demonstrate your right, you not only lose the credit of being in that instance ingenious, but you suffer the disgrace of not being ingenuous; not only of being a plagiary, but of being a plagiary for trifles. Had the invention been greater it would have disgraced you less; for men have not so contemptible an idea of him that robs for gold on the highway, as of him that can pick pockets for half-pence and farthings. Thus, through envy, jealousy, and the vanity of competitors for fame, the origin of many of the most extraordinary inventions, though produced within but a few centuries past, is involved in doubt and uncertainty. We scarce know to whom we are indebted for the compass, and for spectacles, nor have even paper and printing, that record every thing else, been able to preserve with certainty the name and reputation of their inventors. One would not, therefore, of all faculties, or qualities of the mind, wish, for a friend, or a child, that he should have that of invention. For his attempts to benefit mankind in that way, however well imagined, if they do not succeed, expose him, though very unjustly, to general ridicule and contempt; and, if they do succeed, to envy, robbery, and abuse.

Your thoughts upon these remarks I shall receive with a great deal of pleasure. I take notice that in the printed copies of your letters several things are wanting which are in the manuscript you sent me. I understand by your son, that you had writ, or was writing, a paper on the effect of the electrical fire on loadstones, needles, &c. which I would ask the favour of a copy of, as well as of any other papers on electricity, written since I had the manuscript, for which I repeat my obligations to you.

By this post I send to ****, who is curious in that way, some meteorological observations and conjectures, and desire him to communicate them to you, as they may afford you some amusement, and I know you will look over them with a candid eye. By throwing our occasional thoughts on paper, we more readily discover the defects of our opinions, or we digest them better and find new arguments to support them. This I sometimes practise: but such pieces are fit only to be seen by friends.

And now, Sir, I most heartily congratulate you on the pleasure you must have in finding your great and well-grounded expectations so far fulfilled. May this method of security from the destructive violence of one of the most awful powers of nature, meet with such further success, as to induce every good and grateful heart to bless God for the important discovery! May the benefit thereof be diffused over the whole globe! May it extend to the latest posterity of mankind, and make the name of FRANKLIN, like that of NEWTON, immortal.

You seem to think highly of the importance of this discovery, as do many others on our side of the water. Here it is very little regarded; so little, that though it is now seven or eight years since it was made public, I have not heard of a single house as yet attempted to be secured by it. It is true the mischiefs done by lightning are not so frequent here as with us, and those who calculate chances may perhaps find that not one death (or the destruction of one house) in a hundred thousand happens from that cause, and that therefore it is scarce worth while to be at any expence to guard against it.—But in all countries there are particular situations of buildings more exposed than others to such accidents, and there are minds so strongly impressed with the apprehension of them, as to be very unhappy every time a little thunder is within their hearing;—it may therefore be well to render this little piece of new knowledge as general and as well understood as possible, since to make us safe is not all its advantage, it is some to make us easy. And as the stroke it secures us from might have chanced perhaps but once in our lives, while it may relieve us a hundred times from those painful apprehensions, the latter may possibly on the whole contribute more to the happiness of mankind than the former.

"——It is some years since Mr. Raven's rod was struck by lightning. I hear an account of it was published at the time, but I cannot find it. According to the best information I can now get, he had fixed to the outside of his chimney a large iron rod, several feet in length, reaching above the chimney; and to the top of this rod the points were fixed. From the lower end of this rod, a small brass wire was continued down to the top of another iron rod driven into the earth. On the ground-floor in the chimney stood a gun, leaning against the back-wall, nearly opposite to where the brass wire came down on the outside. The lightning fell upon the points, did no damage to the rod they were fixed to; but the brass wire, all down till it came opposite to the top of the gun-barrel, was destroyed[76]. There the lightning made a hole through the wall or back of the chimney, to get to the gun-barrel[77], down which it seems to have passed, as, although it did not hurt the barrel, it damaged the butt of the stock, and blew up some bricks of the hearth. The brass wire below the hole in the wall remained good. No other damage, as I can learn, was done to the house. I am told the same house had formerly been struck by lightning, and much damaged, before these rods were invented."——

It is said that the house was filled with its flash (l). Expressions like this are common in accounts of the effects of lightning, from which we are apt to understand that the lightning filled the house. Our language indeed seems to want a word to express the light of lightning as distinct from the lightning itself. When a tree on a hill is struck by it, the lightning of that stroke exists only in a narrow vein between the cloud and tree, but its light fills a vast space many miles round; and people at the greatest distance from it are apt to say, "The lightning came into our rooms through our windows." As it is in itself extremely bright, it cannot, when so near as to strike a house, fail illuminating highly every room in it through the windows; and this I suppose to have been the case at Mr. Maine's; and that, except in and near the hearth, from the causes above-mentioned, it was not in any other part of the house; the flash meaning no more than the light of the lightning.—It is for want of considering this difference, that people suppose there is a kind of lightning not attended with thunder. In fact there is probably a loud explosion accompanying every flash of lightning, and at the same instant;—but as sound travels slower than light, we often hear the sound some seconds of time after having seen the light; and as sound does not travel so far as light, we sometimes see the light at a distance too great to hear the sound.

I find that the face A, of the large stone, being coated with leaf-gold (attached by the white of an egg, which will bear dipping in hot water) becomes quicker and stronger in its effect on the cork ball, repelling it the instant it comes in contact; which I suppose to be occasioned by the united force of different parts of the face, collected and acting together through the metal.

There is an observation relating to electricity in the atmosphere, which seemed new to me, though perhaps it will not to you: however, I will venture to mention it. I have some points on the top of my house, and the wire where it passes within-side the house is furnished with bells, according to your method, to give notice of the passage of the electric fluid. In summer, these bells, generally ring at the approach of a thunder-cloud; but cease soon after it begins to rain. In winter, they sometimes though not very often, ring while it is snowing; but never, that I remember, when it rains. But what was unexpected to me was, that, though the bells had not rung while it was snowing, yet, the next day, after it had done snowing, and the weather was cleared up, while the snow was driven about by a high wind at W. or N. W. the bells rung for several hours (though with little intermissions) as briskly as ever I knew them, and I drew considerable sparks from the wire. This phenomenon I never observed but twice; viz. on the 31st of January, 1760, and the 3d of March, 1762.

I have just recollected that in one of our great storms of lightning, I saw an appearance, which I never observed before, nor ever heard described. I am persuaded that I saw the flash which struck St. Bride's steeple. Sitting at my window, and looking to the north, I saw what appeared to me a solid strait rod of fire, moving at a very sharp angle with the horizon. It appeared to my eye as about two inches diameter, and had nothing of the zig-zag lightning motion. I instantly told a person sitting with me, that some place must be struck at that instant. I was so much surprized at the vivid distinct appearance of the fire, that I did not hear the clap of thunder, which stunned every one besides. Considering how low it moved, I could not have thought it had gone so far, having St. Martin's, the New Church, and St. Clements's steeples in its way. It struck the steeple a good way from the top, and the first impression it made in the side is in the same direction I saw it move in. It was succeeded by two flashes, almost united, moving in a pointed direction. There were two distinct houses struck in Essex-street. I should have thought the rod would have fallen in Covent-Garden, it was so low. Perhaps the appearance is frequent, though never before seen by

There is another thing very proper to line small barrels with; it is what they call tin-foil, or leaf-tin, being tin milled between rollers till it becomes as thin as paper, and more pliant, at the same time that its texture is extremely close. It may be applied to the wood with common paste, made with boiling-water thickened with flour; and, so laid on; will lie very close and stick well: but I should prefer a hard sticky varnish for that purpose, made of linseed oil much boiled. The heads might be lined separately, the tin wrapping a little round their edges. The barrel, while the lining is laid on, should have the end hoops slack, so that the staves standing at a little distance from each other, may admit the head into its groove. The tin-foil should be plyed into the groove. Then, one head being put in, and that end hooped tight, the barrel would be fit to receive the powder, and when the other head is put in and the hoops drove up, the powder would be safe from moisture even if the barrel were kept under water. This tin-foil is but about eighteen pence sterling a pound, and is so extremely thin, that I imagine a pound of it would line three or four powder-barrels.

A person apprehensive of danger from lightning, happening during the time of thunder to be in a house not so secured, will do well to avoid sitting near the chimney, near a looking glass, or any gilt pictures or wainscot; the safest place is in the middle of the room (so it be not under a metal lustre suspended by a chain) sitting in one chair and laying the feet up in another. It is still safer to bring two or three mattrasses or beds into the middle of the room, and, folding them up double, place the chair upon them; for they not being so good conductors as the walls, the lightning will not chuse an interrupted course through the air of the room and the bedding, when it can go through a continued better conductor, the wall. But where it can be had, a hammock or swinging bed, suspended by silk cords equally distant from the walls on every side, and from the cieling and floor above and below, affords the safest situation a person can have in any room whatever; and what indeed may be deemed quite free from danger of any stroke by lightning.

**** It is perhaps not so extraordinary that unlearned men, such as commonly compose our church vestries, should not yet be acquainted with, and sensible of the benefits of metal conductors in averting the stroke of lightning, and preserving our houses from its violent effects, or that they should be still prejudiced against the use of such conductors, when we see how long even philosophers, men of extensive science and great ingenuity, can hold out against the evidence of new knowledge, that does not square with their preconceptions; and how long men can retain a practice that is conformable to their prejudices, and expect a benefit from such practice, though constant experience shows its inutility. A late piece of the Abbé Nollet, printed last year in the memoirs of the French Academy of Sciences, affords strong instances of this: for though the very relations he gives of the effects of lightning in several churches and other buildings show clearly, that it was conducted from one part to another by wires, gildings, and other pieces of metal that were within, or connected with the building, yet in the same paper he objects to the providing metalline conductors without the building, as useless or dangerous.[82] He cautions people not to ring the church bells during a thunder-storm, lest the lightning, in its way to the earth, should be conducted down to them by the bell ropes,[83] which are but bad conductors; and yet is against fixing metal rods on the outside of the steeple, which are known to be much better conductors, and which it would certainly chuse to pass in, rather than in dry hemp. And though for a thousand years past bells have been solemnly consecrated by the Romish church[84], in expectation that the sound of such blessed bells would drive away those storms, and secure our buildings from the stroke of lightning; and during so long a period, it has not been found by experience, that places within the reach of such blessed sound, are safer than others where it is never heard; but that on the contrary, the lightning seems to strike steeples of choice, and that at the very time the bells are ringing[85]; yet still they continue to bless the new bells, and jangle the old ones whenever it thunders.—One would think it was now time to try some other trick;—and ours is recommended (whatever this able philosopher may have been told to the contrary) by more than twelve years experience, wherein, among the great number of houses furnished with iron rods in North America, not one so guarded has been materially hurt with lightning, and several have been evidently preserved by their means; while a number of houses, churches, barns, ships, &c. in different places, unprovided with rods, have been struck and greatly damaged, demolished or burnt. Probably the vestries of our English churches are not generally well acquainted with these facts; otherwise, since as good protestants they have no faith in the blessing of bells, they would be less excusable in not providing this other security for their respective churches, and for the good people that may happen to be assembled in them during a tempest, especially as those buildings, from their greater height, are more exposed to the stroke of lightning than our common dwellings.

Mr. Rittenhouse, our astronomer, has informed me, that having observed with his excellent telescope, many conductors that are within the field of his view, he has remarked in various instances, that the points were melted in like manner. There is no example of a house, provided with a perfect conductor, which has suffered any considerable damage; and even those which are without them have suffered little, since conductors have come common in this city.

Perhaps some permanent advantage might have been obtained, if the electric shocks had been accompanied with proper medicine and regimen, under the direction a skilful physician. It may be, too, that a few great strokes, as given in my method, may not be so proper as many small ones; since by the account from Scotland of a case, in which two hundred shocks from a phial were given daily, it seems, that a perfect cure has been made. As to any uncommon strength supposed to be in the machine used in that case, I imagine it could have no share in the effect produced; since the strength of the shock from charged glass, is in proportion to the quantity of surface of the glass coated; so that my shocks from those large jars, must have been much greater than any that could be received from a phial held in the hand.

The experiment which you mention, of filing your glass, is analogous to one which I made in 1751, or 1752. I had supposed in my preceding letters, that the pores of glass were smaller in the interior parts than near the surface, and that on this account they prevented the passage of the electrical fluid. To prove whether this was actually the case or not, I ground one of my phials in a part where it was extremely thin, grinding it considerably beyond the middle, and very near to the opposite superficies, as I found, upon breaking it after the experiment. It was charged nevertheless after being ground, equally well as before, which convinced me, that my hypothesis on this subject was erroneous. It is difficult to conceive where the immense superfluous quantity of electricity on the charged side of a glass is deposited.

Let several persons, standing on the floor, hold hands, and let one of them touch the fish, so as to receive a shock. If the shock be felt by all, place the fish flat on a plate of metal, and let one of the persons holding hands touch this plate, while the person farthest from the plate touches the upper part of the fish with a metal rod: then observe, if the force of the shock be the same as to all the persons forming the circle, or is stronger than before.

I am chiefly indebted to that excellent philosopher of Petersburgh, Mr. Æpinus, for this hypothesis, which appears to me equally ingenious and solid. I say, chiefly, because, as it is many years since I read his book, which I have left in America, it may happen, that I may have added to or altered it in some respect; and if I have misrepresented any thing, the error ought to be charged to my account.

Having prepared a battery of six large glass jars (each from 20 to 24 pints) as for the Leyden experiment, and having established a communication, as usual, from the interior surface of each with the prime conductor, and having given them a full charge (which with a good machine may be executed in a few minutes, and may be estimated by an electrometer) a chain which communicates with the exterior of the jars must be wrapped round the thighs of the fowl; after which the operator, holding it by the wings, turned back and made to touch behind, must raise it so high that the head may receive the first shock from the prime conductor. The animal dies instantly. Let the head be immediately cut off to make it bleed, when it may be plucked and dressed immediately. This quantity of electricity is supposed sufficient for a turkey of ten pounds weight, and perhaps for a lamb. Experience alone will inform us of the requisite proportions for animals of different forms and ages. Probably not less will be required to render a small bird, which is very old, tender, than for a larger one, which is young. It is easy to furnish the requisite quantity of electricity, by employing a greater or less number of jars. As six jars, however, discharged at once, are capable of giving a very violent shock, the operator must be very circumspect, lest he should happen to make the experiment on his own flesh, instead of that of the fowl.

There is another circumstance much to be desired with respect to glass, and that is, that it should not be subject to break when highly charged in the Leyden experiment. I have known eight jars broken out of twenty, and at another time, twelve out of thirty-five. A similar loss would greatly discourage electricians desirous of accumulating a great power for certain experiments.—We have never been able hitherto to account for the cause of such misfortunes. The first idea which occurs is, that the positive electricity, being accumulated on one side of the glass, rushes violently through it, in order to supply the deficiency on the other side and to restore the equilibrium. This however I cannot conceive to be the true reason, when I consider, that a great number of jars being united, so as to be charged and discharged at the same time, the breaking of a single jar will discharge the whole; for, if the accident proceeded from the weakness of the glass, it is not probable, that eight of them should be precisely of the same degree of weakness, as to break every one at the same instant, it being more likely, that the weakest should break first, and, by breaking, secure the rest; and again, when it is necessary to produce a certain effect, by means of the whole charge passing through a determined circle (as, for instance, to melt a small wire) if the charge, instead of passing in this circle, rushed through the sides of the jars, the intended effect would not be produced; which, however, is contrary to fact. For these reasons, I suspect, that there is, in the substance of the glass, either some little globules of air, or some portions of unvitrified sand or salt, into which a quantity of the electric fluid may be forced during the charge, and there retained till the general discharge: and that the force being suddenly withdrawn, the elasticity of the fluid acts upon the glass in which it is inclosed, not being able to escape hastily without breaking the glass. I offer this only as a conjecture, which I leave to others to examine.

"On voit, par le détail de cette lettre, que le fait est assez bien constaté pour ne laisser aucun doute à ce sujet. Le porteur m'a assuré de vive voix qu'il avoit tiré pendant près d'un quart-d'heure avant que M. le Prieur arrivât, en présence de cinq ou six personnes, des étincelles plus fortes & plus bruyantes que celles dont il est parlé dans la lettre. Ces premieres personnes arrivant successivement, n'osient approcher qu'à 10 ou 12 pas de la machine; & à cette distance, malgré le plein soleil, ils voyoient les étincelles & entendoient le bruit....

Vol. I. page 182.

Plate I.

Published as the Act directs, April 1, 1806, by Longman, Hurst, Rees & Orme, Paternoster Row.

Vol. I. page 336.

Plate II.

Published as the Act directs, April 1, 1806, by Longman, Hurst, Rees & Orme, Paternoster Row.

Vol. I. page 348.

Plate III.

Vol. I. page 388.

Plate IV.

I have amused myself with collecting some little anecdotes of my family. You may remember the enquiries I made, when you were with me in England, among such of my relations as were then living; and the journey I undertook for that purpose. To be acquainted with the particulars of my parentage and life, many of which are unknown to you, I flatter myself will afford the same pleasure to you as to me. I shall relate them upon paper: it will be an agreeable employment of a week's uninterrupted leisure, which I promise myself during my present retirement in the country. There are also other motives which induce me to the undertaking. From the bosom of poverty and obscurity, in which I drew my first breath, and spent my earliest years, I have raised myself to a state of opulence and to some degree of celebrity in the world. A constant good fortune has attended me through every period of life to my present advanced age; and my descendants may be desirous of learning what were the means of which I made use, and which, thanks to the assisting hand of providence, have proved so eminently successful. They may also, should they ever be placed in a similar situation, derive some advantage from my narrative.

In the researches I made at Eaton, I found no account of their births, marriages, and deaths, earlier than the year 1555; the parish register not extending farther back than that period. This register informed me, that I was the youngest son of the youngest branch of the family, counting five generations. My

grandfather

, Thomas,who was born

in 1598, lived at Eaton till he was too old to continue his trade, when he retired to Banbury in Oxfordshire, where his son John, who was a dyer, resided, and with whom my father was apprenticed. He died, and was buried there: we saw his monument in 1758. His eldest son lived in the family house at Eaton, which he bequeathed, with the land belonging to it, to his only daughter; who, in concert with her husband, Mr. Fisher of Wellingborough, afterwards sold it to Mr. Estead, the present proprietor.It was about this period, that having one day been

put to the blush

for my ignorance in the art of calculation, which I had twice failed to learn while at school, I took Cocker's Treatise of Arithmetic, and went through itby myself

with the utmost ease. I also read a book of navigation by Seller and Sturmy, and made myself master of the little geometry it contains, but I never proceeded far in this science. Nearly at the same time I read Locke on the Human Understanding, and the Art of Thinking, by Messrs. du Port Royal.My brother, upon this discovery, began to entertain a little more respect for me; but he still regarded himself as my master, and treated me as an apprentice. He thought himself entitled to the same services from me, as from any other person. On the contrary, I conceived that in many instances, he was too rigorous, and that, on the part of a brother, I had a right to expect greater indulgence. Our disputes were frequently brought before my father; and either my brother was generally wrong, or I was the better pleader of the two, for judgment was commonly given in my favour. But my brother was passionate, and often had recourse to blows—a circumstance which I took in very ill part. This severe and tyrannical treatment contributed, I believe, to imprint on my mind that aversion to arbitrary power, which during my whole life I have ever preserved. My apprenticeship became insupportable to me, and I continually sighed for an opportunity of shortening it, which at length unexpectedly offered.

When he knew that it was my determination to quit him, he wished to prevent my finding employment elsewhere. He went to all the printing-houses in the town, and prejudiced the masters against me—who accordingly refused to employ me. The idea then suggested itself to me of going to New York, the nearest town in which there was a printing-office. Farther reflection confirmed me in the design of leaving Boston, where I had already rendered myself an object of suspicion to the governing party. It was probable, from the arbitrary proceedings of the assembly in the affair of my brother, that, by remaining, I should soon have been exposed to difficulties, which I had the greater reason to apprehend, as, from my indiscreet disputes upon the subject of religion, I began to be regarded by pious souls with horror, either as an apostate or an atheist. I came, therefore, to a resolution: but my father, in this instance siding with my brother, presumed that if I attempted to depart openly, measures would be taken to prevent me. My friend Collins undertook to favour my flight. He agreed for my passage with the captain of a New York sloop, to whom he represented me as a young man of his acquaintance, who had an affair with a girl of bad character, whose parents wished to compel me to marry her, and that of consequence I could neither make my appearance, nor go off publicly. I sold part of my books to procure a small sum of money, and went privately on board the sloop. By favour of a good wind, I found myself in three days at New York, nearly three hundred miles from my home, at the age only of seventeen years, without knowing an individual in the place, and with very little money in my pocket.

I had been absent about seven complete months, and my relations, during that interval, had received no intelligence of me; for my brother-in-law, Holmes, was not yet returned, and had not written about me. My unexpected appearance surprized the family; but they were all delighted at seeing me again, and, except my brother, welcomed me home. I went to him at the printing-house. I was better dressed than I had ever been while in his service: I had a complete suit of clothes, new and neat, a watch in my pocket, and my purse was furnished with nearly five pounds sterling

in money

. He gave me no very civil reception; and having eyed me from head to foot, resumed his work.At New York I found my friend Collins, who had arrived some time before. We had been intimate from our infancy, and had read the same books together; but he had the advantage of being able to devote more time to reading and study, and an astonishing disposition for mathematics, in which he left me far behind him. When at Boston, I had been accustomed to pass with him almost all my leisure hours. He was then a sober and industrious lad; his knowledge had gained him a very general esteem, and he seemed to promise to make an advantageous figure in society. But, during my absence, he had unfortunately addicted himself to brandy, and I learned, as well from himself as from the report of others, that every day since his arrival at New York he had been intoxicated, and had acted in a very extravagant manner. He had also played, and lost all his money; so that I was obliged to pay his expences at the inn, and to maintain him during the rest of his journey; a burthen that was very inconvenient to me.

During the circumstances I have related, I had paid some attentions to Miss Read. I entertained for her the utmost esteem and affection; and I had reason to believe that these sentiments were mutual. But we were both young, scarcely more than eighteen years of age; and as I was on the point of undertaking a long voyage, her mother thought it prudent to prevent matters being carried top far for the present, judging that, if marriage was our object, there would be more propriety in it after my return, when, as at least I expected, I should be established in my business. Perhaps, also, she thought my expectations were not so well founded as I imagined.

At the printing house I contracted an intimacy with a sensible young man of the name of Wygate, who, as his parents were in good circumstances, had received a better education than is common among printers. He was a tolerable Latin scholar, spoke French fluently, and was fond of reading. I taught him, as well as a friend of his, to swim, by taking them twice only into the river; after which they stood in need of no farther assistance. We one day made a party to go by water to Chelsea, in order to see the College, and Don Soltero's curiosities. On our return, at the request of the company, whose curiosity Wygate had excited, I undressed myself, and leaped into the river. I swam from near Chelsea the whole way to

Blackfriars

, exhibiting, during my course, a variety of feats of activity and address, both upon the surface of the water, as well as under it. This sight occasioned much astonishment and pleasure to those to whom it was new. In my youth I took great delight in this exercise. I knew, and could execute, all the evolutions and positions of Thevenot; and I added to them some of my own invention, in which I endeavoured to unite gracefulness and utility. I took a pleasure in displaying them all on this occasion, and was highly flattered with the admiration they excited.[1] As a proof that Franklin was anciently the common name of an order or rank in England, see Judge Fortesque, De laudibus legum Angliæ, written about the year 1412, in which is the following passage, to shew that good juries might easily be formed in any part of England:

From Sherburn,[2] where I dwell,

I therefore put my name,

Your friend, who means you well,

PETER FOLGER.

My brothers were all put apprentices to different trades. With respect to myself, I was sent, at the age of eight years, to a grammar-school. My father destined me for the church, and already regarded me as the chaplain of the family. The promptitude with which from my infancy I had learned to read, for I do not remember to have been ever without this acquirement, and the encouragement of his friends, who assured him that I should one day certainly become a man of letters, confirmed him in this design. My uncle Benjamin approved also of the scheme, and promised to give me all his volumes of sermons, written, as I have said, in the short-hand of his invention, if I would take the pains to learn it.

I remained, however, scarcely a year at the grammar-school, although, in this short interval, I had risen from the middle to the head of my class, from thence to the class immediately above, and was to pass, at the end of the year, to the one next in order. But my father, burdened with a numerous family, found that he was incapable, without subjecting himself to difficulties, of providing for the expences of a collegiate education; and considering besides, as I heard him say to his friends, that persons so educated were often poorly provided for, he renounced his first intentions, took me from the grammar-school, and sent me to a school for writing and arithmetic, kept by a Mr. George Brownwell, who was a skilful master, and succeeded very well in his profession by employing gentle means only, and such as were calculated to encourage his scholars. Under him I soon acquired an excellent hand; but I failed in arithmetic, and made therein no sort of progress.

At ten years of age, I was called home to assist my father in his occupation, which was that of a soap-boiler and tallow-chandler; a business to which he had served no apprenticeship, but which he embraced on his arrival in New England, because he found his own, that of dyer, in too little request to enable him to maintain his family, I was accordingly employed in cutting the wicks, filling the moulds, taking care of the shop, carrying messages, &c.

This business displeased me, and I felt a strong inclination for a sea life; but my father set his face against it. The vicinity of the water, however, gave me frequent opportunities, of venturing myself both upon and within it, and I soon acquired the art of swimming, and of managing a boat. When embarked with other children, the helm was commonly deputed to me, particularly on difficult occasions; and, in every other project, I was almost always the leader of the troop, whom I sometimes involved in embarrassments. I shall give an instance of this, which demonstrates an early disposition of mind for public enterprises, though the one in question was not conducted by justice.

The mill-pond was terminated on one side by a marsh, upon the borders of which we were accustomed to take our stand, at high water, to angle for small fish. By dint of walking, we had converted the place into a perfect quagmire. My proposal was to erect a wharf that should afford us firm footing; and I pointed out to my companions a large heap of stones, intended for the building a new house near the marsh, and which were well adapted for our purpose. Accordingly, when the workmen retired in the evening, I assembled a number of my play-fellows, and by labouring diligently, like ants, sometimes four of us uniting our strength to carry a single stone, we removed them all, and constructed our little quay. The workmen were surprised the next morning at not finding their stones; which had been conveyed to our wharf. Enquiries were made respecting the authors of this conveyance; we were discovered; complaints were exhibited against us; and many of us underwent correction on the part of our parents; and though I strenuously defended the utility of the work, my father at length convinced me, that nothing which was not strictly honest could be useful.

It will not, perhaps, be uninteresting to you to know what a sort of man my father was. He had an excellent constitution, was of a middle size, but well made and strong, and extremely active in whatever he undertook. He designed with a degree of neatness, and knew a little of music. His voice was sonorous and agreeable; so that when he sung a psalm or hymn, with the accompaniment of his violin, as was his frequent practice in an evening, when the labours of the day were finished, it was truly delightful to hear him. He was versed also in mechanics, and could, upon occasion, use the tools of a variety of trades. But his greatest excellence was a sound understanding and solid judgment, in matters of prudence, both in public and private life. In the former, indeed, he never engaged, because his numerous family, and the mediocrity of his fortune, kept him unremittingly employed in the duties of his profession. But I well remember, that the leading men of the place used frequently to come and ask his advice respecting the affairs of the town, or of the church to which he belonged, and that they paid much deference to his opinion. Individuals were also in the habit of consulting him in their private affairs, and he was often chosen arbiter between contending parties.

He was fond of having at his table, as often as possible, some friends or well-informed neighbours, capable of rational conversation, and he was always careful to introduce useful or ingenious topics of discourse, which might tend to form the minds of his children. By this means he early attracted our attention to what was just, prudent, and beneficial in the conduct of life. He never talked of the meats which appeared upon the table, never discussed whether they were well or ill dressed, of a good or bad flavour, high-seasoned or otherwise, preferable or inferior to this or that dish of a similar kind. Thus accustomed, from my infancy, to the utmost inattention as to these objects, I have been perfectly regardless of what kind of food was before me; and I pay so little attention to it even now, that it would be a hard matter for me to recollect, a few hours after I had dined, of what my dinner had consisted. When travelling, I have particularly experienced the advantage of this habit; for it has often happened to me to be in company with persons, who, having a more delicate, because a more exercised taste, have suffered in many cases considerable inconvenience; while, as to myself, I have had nothing to desire.

My mother was likewise possessed of an excellent constitution. She suckled all her ten children, and I never heard either her or my father complain of any other disorder than that of which they died: my father at the age of eighty-seven, and my mother at eighty-five. They are buried together at Boston, where, a few years ago, I placed a marble over their grave, with this inscription:

"Here lie

Josias Franklin and Abiah his wife: They lived together with reciprocal affection for fifty-nine years; and without private fortune, without lucrative employment, by assiduous labour and honest industry, decently supported a numerous family, and educated with success, thirteen children, and seven grand children. Let this example, reader, encourage thee diligently to discharge the duties of thy calling, and to rely on the support of divine providence,

He was pious and prudent,

She discreet and virtuous.

Their youngest son, from a sentiment of filial duty, consecrates

this stone

to their memory."

I perceive, by my rambling digressions, that I am growing old. But we do not dress for a private company as for a formal ball. This deserves, perhaps, the name of negligence.