автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Complete Works of Theodore Roosevelt. Illustrated

The Complete Works of Theodore Roosevelt

Illustrated

The Naval War of 1812, The Autobiography of Theodore Roosevelt, Good Hunting: In Pursuit of Big Game in the West, African Game Trails, The Strenuous Life

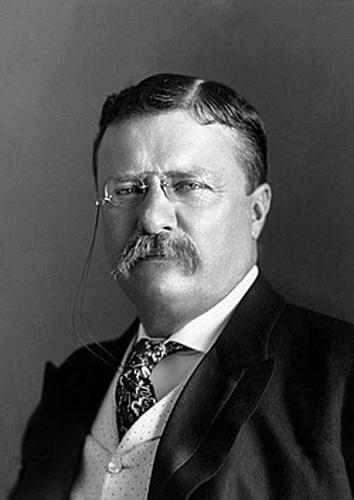

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. was an American politician, statesman, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26th president of the United States from 1901 to 1909.

Roosevelt was a prolific author, writing with passion on subjects ranging from foreign policy to the importance of the national park system. Roosevelt was also an avid reader of poetry.

In all, Roosevelt wrote about 18 books (each in several editions), including his autobiography, The Rough Riders, History of the Naval War of 1812, and others on subjects such as ranching, explorations, and wildlife.

His most ambitious book was the four volume narrative The Winning of the West, focused on the American frontier in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Roosevelt said that the American character—indeed a new "American race" (ethnic group) had emerged from the heroic wilderness hunters and Indian fighters, acting on the frontier with little government help.

The Political Works

Essays on Practical Politics (1888)

American Ideals (1897)

The Strenuous Life (1899)

Inaugural Address (1905)

State of the Union Addresses (1901-1908)

The New Nationalism (1910)

Realizable Ideals (1912)

Fear God and Take Your Own Part (1916)

A Book Lover’s Holidays in the Open (1916)

The Foes of Our Own Household (1917)

National Strength and International Duty (1917)

The Great Adventure (1918)

Introductions and Forewords to Various Works

The Historical Works

The Naval War of 1812 (1882)

Thomas H. Benton (1886)

Gouverneur Morris (1888)

The Winning of the West: Volume I (1889)

The Winning of the West: Volume II (1889)

New York (1891)

The Winning of the West: Volume III (1894)

Hero Tales from American History (1895)

The Winning of the West: Volume IV (1896)

American Naval Policy (1897)

The Rough Riders (1899)

Oliver Cromwell (1900)

African and European Addresses (1910)

History as Literature and Other Essays (1913)

America and the World War (1915)

The Hunting Works

Hunting Trips of a Ranchman (1885)

Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail (1888)

The Wilderness Hunter (1893)

Hunting in Many Lands (1895)

The Deer Family (1902)

Outdoor Pastimes of an American Hunter (1905)

Good Hunting (1907)

African Game Trails (1910)

Through the Brazilian Wilderness (1914)

Life-Histories of African Game Animals (1914)

The Letters

A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents (1902) by James D. Richardson

Theodore Roosevelt’s Letters to His Children (1919)

The Memoirs

Theodore Roosevelt: An Autobiography (1913)

Average Americans (1919)

The Political Works

Essays on Practical Politics (1888)

INTRODUCTION.

THESE TWO ESSAYS appeared originally in the Century. Both alike were criticised at the time as offering no cure for the evils they portrayed.

Such a criticism shows, in the first place, a curious ignorance of what is meant by the diagnosis of a disease; for my articles pretended to do nothing more than give what has apparently never before been given, an accurate account of certain phases of our political life, with its good and bad impartially set forth. The practical politician, who alone knows how our politics are really managed, is rarely willing to write about them, unless with very large reservations, while the student-reformer whose political experience is limited to the dinner table, the debating club, or an occasional mass-meeting where none but his friends are present, and who yet seeks, in pamphlet or editorial column to make clear the subject, hardly ever knows exactly what he is talking about, and abuses the system in all its parts with such looseness of language as to wholly take away the value even from such of his utterances as are true.

In the second place, such a criticism shows in the mind of the critic the tendency, so common among imperfectly educated people, to clamor for “cure-all” or quack remedies. The same habit of thought that makes a man in one class of life demand a medicine that will ease all his complaints off-hand, makes another man, who probably considers himself very much higher in the social scale, expect some scheme of reform that will at a single fell swoop do away with every evil from which the body-politic is suffering. Each of these men is willing enough to laugh at the other; and, after all, their inconsistency is no greater than is that of the editor who in one column denounces governmental interference with the hours of labor, and in the next calls for governmental interference with the party primaries, or vice versa, apparently not seeing that both are identical in kind, being perhaps necessary deviations from the old American principle that the State must not interfere with individual action, even to help the weak.

There are many reforms each of which, if accomplished, would do us much good; but for permanent improvement we must rely upon bettering our general health, upon raising the tone of our political system. Thus, the enactment and enforcement of laws making the Merit System, as contrasted with the Spoils System, universally applicable among all minor officials of county, state and nation, would measurably improve our public service and would be of immeasurable benefit to all honest men, rich or poor, who desire to do their duty in public affairs without being opposed to bands of trained mercenaries. The regulation of the liquor traffic, so as to expose it to strict supervision, and to minimize its attendant evils, would likewise do immense good. But even if the power of the saloons was broken and public office no longer a reward for partisan service, many and great evils would remain to be battled with.

No law or laws can give us good government; at the utmost, they can only give us the opportunity to ourselves get good government. For instance, until the control of the aldermen over the mayor’s appointments was taken away, by the bill which I always esteemed it my chief legislative service to have introduced and been instrumental in passing, New York city politics were hopeless; now it rests with the citizens themselves to elect a man who will serve them wisely and faithfully.

But no law can make an ignorant workman cease to pay heed to the demagogue who bids for his vote by proposing impossible measures of relief; no law can make a rich young man go to his party primary even if it comes on the same night as a club dinner or a german at Delmonico’s. There are few things more harmful or more irritating than the insolence with which some classes of immigrants persist in dragging in to our own affairs, questions of purely foreign politics, with which we should have nothing to do; even more despicable is the attitude of truckling servility toward these same foreigners on the part of native-born citizens who seem content to run an American congressional contest as if it were an election for the British parliament, with such issues as Home Rule and the Land League on one side, and the preservation of the union between England and Ireland on the other. But it is difficult to see how we can remedy all this by legislation. We must rouse public sentiment against it, and make people understand that while we welcome all honest immigrants who come prepared to cast in their lot with us, and live under our institutions, and while we treat them in every respect as standing on the same level with ourselves, we demand in return that they shall drop all connections with foreign politics, shall teach their children to “talk United States,’’ and shall learn to celebrate the Fourth of July instead of St. Patrick’s Day, and the birthday of Washington instead of that of either Queen or Kaiser.

We can do a good deal of good by passing new, or extending the scope of old, laws. We can begin the work of keeping out undesirable immigrants, and we cannot possibly begin it too soon. We can totally abolish the now wholly useless or harmful board of aldermen. We can provide for a reform in the method of preparing and distributing ballots (perhaps the matter which is at present of most pressing importance), and for putting the Merit System on a firmer and broader basis. We can attempt to diminish by the introduction of high license, and otherwise, the evils attendant upon the liquor or traffic. We can pass severe laws against bribery and strive to have them executed (as the City Reform Club has recently striven). We can prevent all hostile interference with our public school system. We can if necessary strengthen the provisions of the Common Law so as to insure the prompt punishment of those communists and dynamite agitators who attempt to put their theories into practise or incite others to do so. But much more remains. We must try to reward good, and punish bad, public servants. We can hardly do too much honor to the court and jury that condemned, or to the governor who refused to pardon, the Chicago anarchists and bomb-throwers; or to the judge who distributed stern and even justice to the boycotters on the one hand, and on the other to the bribed aldermen and the wealthy knave who bribed them. Those of us who are newspaper writers can refrain from scurrilous abuse of political opponents; and from the incessant innuendo which is quite as harmful and even meaner. Above all, we can strive to fulfil our own political duties, as they arise, and thereby to do each of us his part in raising to a healthier level the moral standard of the whole community.

In conclusion, let me quote the words of a man who, while a private citizen has yet been always, in the highest sense of the word, a public servant; I quote from a speech recently made by Joseph Choate (the italics are my own): —

“I confidently believe that the decay of our politics which all must acknowledge has arisen in no small measure from the neglect of their political rights and duties, for the last twenty years, by the great body of the educated men of the country, and the still greater body of the business men of the country, whereby the management of party affairs has been left so largely to those who make it a trade and a profession; and so I hail with delight and satisfaction the revival of interest and action in any form, in these great representative classes of the community.

“The renewed attention which has been given of late years in all our leading colleges and universities to the study of political economy and other public and constitutional studies, is one of the most cheering signs of the times; and if by this or any other means the great body of our young graduates as they enter into active life can be inspired with the earnest purpose to be faithful to their political duties and trusts, the much needed reform will be already secured. The truth is that, in all our great cities especially, the struggle for professional and business success is so intense, the struggle for existence and position so overwhelming, that the plea is too often accepted that our best men have no time for consideration and action upon public affairs. But if our institutions and liberties are worth saving, they can only be saved by eternal vigilance and action on the part of those whose education and interest in the public welfare qualify them to take part in the public questions on which it depends. Our unexampled material progress and success are in one respect our greatest danger; but the true antidote to the intense and growing materialism of the age and country is in the hands of our educated men, and if these fail us, we may well despair. ‘There is surely no lack among us of the raw material of statesmanship,’ * — * — * — * — * and when any great peril overhangs the country, as in the case of our Civil War, great men will be ready for the emergency, and new Lincolns and Stantons and Grants will arise to meet it. But what I plead for is a little more — yes, a great deal more — of attention in ordinary times to public duties, on the part of those who are qualified to discharge them; and so, and so only, shall we have purer politics and better government.”

THEODORE ROOSEVELT.

PHASES OF STATE LEGISLATION.

THE ALBANY LEGISLATURE.

FEW PERSONS REALIZE the magnitude of the interests affected by State legislation in New York. It is no mere figure of speech to call New York the Empire State; and most of the laws directly and immediately affecting the interests of its citizens are passed at Albany, and not at Washington. In fact, there is at Albany a little Home Rule Parliament which presides over the destinies of a commonwealth more populous than any one of two-thirds of the kingdoms of Europe, and one which, in point of wealth, material prosperity, variety of interests, extent of territory, and capacity for expansion, can fairly be said to rank next to the powers of the first class. This little parliament, composed of one hundred and twenty-eight members in the Assembly and thirty-two in the Senate, is, in the fullest sense of the term, a representative body; there is hardly one of the many and widely diversified interests of the State that has not a mouth-piece at Albany, and hardly a single class of its citizens — not even excepting, I regret to say, the criminal class — which lacks its representative among the legislators. In the three Legislatures of which I have been a member, I have sat with bankers and bricklayers, with merchants and mechanics, with lawyers, farmers, day-laborers, saloon-keepers, clergymen, and prize-fighters. Among my colleagues there were many very good men; there was a still more numerous class of men who were neither very good nor very bad, but went one way or the other, according to the strength of the various conflicting influences acting around, behind, and upon them; and, finally there were many very bad men. Still, the New York Legislature, taken as a whole, is by no means as bad a body as we would be led to believe if our judgment was based purely on what we read in the great metropolitan papers; for the custom of the latter is to portray things as either very much better or very much worse than they are. Where a number of men, many of them poor, some of them unscrupulous, and others elected by constituents too ignorant to hold them to a proper accountability for their actions, are put into a position of great temporary power, where they are called to take action upon questions affecting the welfare of large corporations and wealthy private individuals, the chances for corruption are always great, and that there is much viciousness and political dishonesty, much moral cowardice, and a good deal of actual bribe-taking in Albany, no one who has had any practical experience of legislation can doubt; but, at the same time, I think that the good members always outnumber the bad, and that there is never any doubt as to the result when a naked question of right or wrong can be placed clearly and in its true light before the Legislature. The trouble is that on many questions the Legislature never does have the right and wrong clearly shown it. Either some bold, clever parliamentary tactician snaps the measure through before the members are aware of its nature, or else the obnoxious features are so combined with good ones as to procure the support of a certain proportion of that large class of men whose intentions are excellent but whose intellects are foggy.

THE CHARACTER OF THE REPRESENTATIVES.

THE REPRESENTATIVES FROM different sections of the State differ widely in character. Those from the country districts are generally very good men. They are usually well-to-do farmers, small lawyers, or prosperous storekeepers, and are shrewd, quiet, and honest. They are often narrow-minded and slow to receive an idea; but, on the other hand, when they get a good one, they cling to it with the utmost tenacity. They form very much the most valuable class of legislators. For the most part they are native Americans, and those who are not are men who have become completely Americanized in all their ways and habits of thought. One of the most useful members of the last Legislature was a German from a western county, and the extent of his Americanization can be judged from the fact that he was actually an ardent prohibitionist: certainly no one who knows Teutonic human nature will require further proof. Again, I sat for an entire session beside a very intelligent member from northern New York before I discovered that he was an Irishman; all his views of legislation, even upon such subjects as free schools and the impropriety of making appropriations from the treasury for the support of sectarian institutions, were precisely similar to those of his Protestant American neighbors, though he was himself a Catholic. Now a German or an Irishman from one of the great cities would have retained most of his national peculiarities.

It is from these same great cities that the worst legislators come. It is true that there are always among them a few cultivated and scholarly men who are well educated, and who stand on a higher and broader intellectual and moral plane than the country members, but the bulk are very low indeed. They are usually foreigners, of little or no education, with exceedingly misty ideas as to morality, and possessed of an ignorance so profound that it could only be called comic, were it not for the fact that it has at times such serious effects upon our laws. It is their ignorance, quite as much as actual viciousness, which makes it so difficult to procure the passage of good laws or prevent the passage of bad ones; and it is the most irritating of the many elements with which we have to contend in the fight for good government.

DARK SIDE OF THE LEGISLATIVE PICTURE.

MENTION HAS BEEN made above of the bribe-taking-which undoubtedly at times occurs in the New York Legislature. This is what is commonly called “a delicate subject” with which to deal, and, therefore, according to our usual methods of handling delicate subjects, it is either never discussed at all, or else discussed with the grossest exaggeration; but most certainly there is nothing about which it is more important to know the truth.

In each of the last three Legislatures there were a number of us who were interested in getting through certain measures which we deemed to be for the public good, but which were certain to be strongly opposed, some for political and some for pecuniary reasons. Now, to get through any such measure requires genuine hard work, a certain amount of parliamentary skill, a good deal of tact and courage, and, above all, a thorough knowledge of the men with whom one has to deal, and of the motives which actuate them. In other words, before taking any active steps, we had to “size up” our fellow legislators, to find out their past history and present character and associates, to find out whether they were their own masters or were acting under the directions of somebody else, whether they were bright or stupid, etc., etc. As a result, and after very careful study, conducted purely with the object of learning the truth, so that we might work more effectually, we came to the conclusion that about a third of the members were open to corrupt influences in some form or other; in certain sessions the proportion was greater, and in some less. Now it would, of course, be impossible for me or for anyone else to prove in a court of law that these men were guilty, except perhaps in two or three cases; yet we felt absolutely confident that there was hardly a case in which our judgment as to the honesty of any given member was not correct. The two or three exceptional cases alluded to, where legal proof of guilt might have been forthcoming, were instances in which honest men were approached by their colleagues: at times when the need for votes was very great; but, even then, it would have been almost impossible to punish the offenders before a court, for it would have merely resulted in his denying what his accuser stated. Moreover, the members who had been approached would have been very reluctant to come forward, for each of them felt ashamed that his character should not have been well enough known to prevent anyone’s daring to speak to him on such a subject. And another reason why the few honest men who are approached (for the lobbyist rarely makes a mistake in his estimate of the men who will be apt to take bribes) do not feel like taking action in the matter is that a doubtful lawsuit will certainly follow, which will drag on so long that the public will come to regard all of the participants with equal distrust, while in the end the decision is quite as likely to be against as to be for them. Take the Bradly-Sessions case, for example. This was an incident that occurred at the time of the faction-fight in the Republican ranks over the return of Mr. Conkling to the Senate after his resignation from that body. Bradly, an assemblyman, accused Sessions, a State senator, of attempting to bribe him. The affair dragged on for an indefinite time; no one was able actually to determine whether it was a case of blackmail on the one hand, or of bribery on the other; the vast majority of people recollected the names of both parties, but totally forgot. which it was that was supposed to have bribed the other, and regarded both with equal disfavor; and the upshot has been that the case is now merely remembered as illustrating one of the most unsavory phases of the famous Half-breed-Stalwart fight.