автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Yellow Dove

E-text prepared by Donald Cummings

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

from page images generously made available by

Internet Archive

(https://archive.org)

Note:

Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See

https://archive.org/details/yellowdove00gibbialaTHE YELLOW DOVE

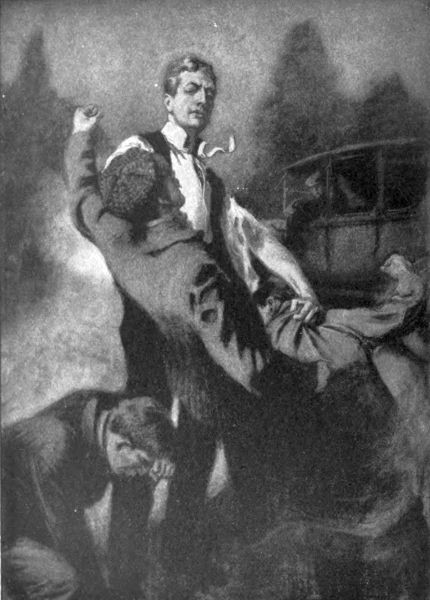

“His blond hair disheveled, his shoulders coatless, Cyril emerged.”

THE

YELLOW DOVE

BY

GEORGE GIBBS

ILLUSTRATED

BY THE AUTHOR

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1915,

By D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

PAGE

Prelude1

I.

Sheltered People5

II.

The Undercurrent17

III.

Rice-Papers31

IV.

Dangerous Secrets45

V.

The Pursuit Continues55

VI.

Rizzio Takes Charge68

VII.

An Intruder83

VIII.

Evidence96

IX.

The Viking’s Tower108

X.

The Yellow Dove121

XI.

Von Stromberg131

XII.

Hammersley Explains145

XIII.

The Unwilling Guest157

XIV.

Von Stromberg Catechises172

XV.

The Inquisition188

XVI.

The General Plays to Win206

XVII.

Lindberg221

XVIII.

Success243

XIX.

The Cave on the Thorwald260

XX.

The Fight in the Cavern275

XXI.

Hare and Hounds289

XXII.

From the Heights306

XXIII.

Headquarters320

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

“His blond hair disheveled, his shoulders coatless, Cyril emerged.”Frontispiece

FACING PAGE

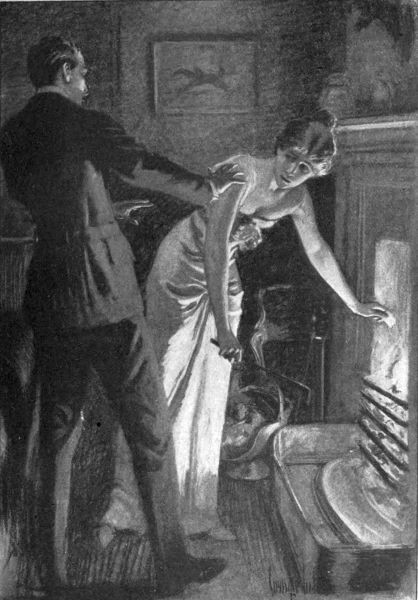

“‘Not that,’ he whispered hoarsely, ‘for God’s sake—not that.’”80

“Her lips ... were whispering words that she hoped could follow him into the distance.”128

“The truth, and he becomes an honorable prisoner of war. Silence, and he is shot tomorrow. Speak.”218

THE YELLOW DOVE

PRELUDE

Rifts of sullen gray in the dirty veil of vapor beyond the reaches of dunes, where the sea in long lines of white, like the ghostly hosts of lost regiments, clamored along the sand....

A soughing wind, a shrieking of sea-birds, audible in pauses between the faraway crackle of rifle-fire and the deep reverberations of artillery—familiar music to ears trained by long listening. A shrill scream of flying shrapnel, a distant crash and then a tense hush....

Silence—nearly, but not quite. A sound so small as to be almost lost in the echoes of the clamor, an impact upon the air like the tapping of the wings of an insect against one’s ear-drum, a persistent staccato note which no other noise could still, borne with curious distinctness upon some aërial current of the fog bank.

And yet this tiny sound had a strange effect upon the desolate scene, for in a moment, as if they had been sown with dragon’s teeth, the sand dunes suddenly vomited forth armed men who ran hither and thither, their hands to their ears, peering aloft as though trying to pierce the mystery of the skies.

“The blighter! It’s ’im agayn.”

“’Im! ’Oo’s ’im, I’d like to arsk?”

“Stow yer jaw, cawn’t yer ’ear? Ole Yaller-belly, agayn.”

The sounds were now clearly audible and to the south a series of rapid detonations shivered the air.

“There goes ‘Johnny look in the air.’ Cawn’t get ’im, though. ’Strewth! ’E’s a cool one—’e is!”

A hoarse order rang out from the trenches behind them—and the men ran for cover. The fog lifted a little and a shaft of light touched the leaden gray of the sea like the sheen on a dirty gun-barrel. The nearer high-angle guns were speaking now—fruitlessly, for the sounds seemed to come from directly overhead. The fog lifted again and a shaft of pale sunlight shot across the line of entrenchments.

“There ’e is, not wastin’ no time—’e ayn’t.”

“Yus. But they’re arfter ’im. There comes hyviashun. O ’ell!”

The expletive in a final tone of disgust for the fog had fallen again, completely obliterating the air-craft and its pursuers.

“’Oo’s Yaller-belly?” asked a smooth-faced youth who still wore the sallow of London under his coat of windburn.

“You’re one of the new lot, ayn’t yer? You’ll know b——y soon ’oo Yaller-belly is, won’t ’e, Bill? Pow! That’s ’im—them sharp ones.”

“Garn!” said the one called Bill. “’E never ’its anythink but the dirt an’ ’e cawn’t ’elp that.”

“’Tayn’t ’cos ’e don’t try. ’Ear ’em? Nice droppin’s fer a dove, ayn’t they?”

“Dove?” said the newcomer.

“Yus. Tubs the swine calls ’em——”

“Tawb, yer blighter.”

“Tub, I says. Whenever troops is moving’, ’e’s always abaht—jus’ drops dahn hinformal-like, out o’ nowhere——”

“And cawn’t they catch ’im?”

“Catch ’im—? Bly me—not they! A thousand ’orse-power, they say ’e ’as—flies circles round hour hair squad like they was a lot o’ bloomink captivatin’ balloons.”

“But the ’igh-hangles——?”

“Moves too fast—’ere an’ gone agayn, afore you can fill yer cutty. They do say ’as ’ow when Yaller-belly comes, there’s sure to be big doin’s along the front.”

“Aye,” said Bill. “When we was dahn at Copenhagen——”

“Compayn, gran’pop——”

“Aw! Wot’s the hodds? Dahn at Copenhagen, ’e flew abaht same as ’e’s doin’ now.”

Bill paused.

“And what happened?”

“You’ll ’ave to arsk Sir John abaht that, me son,” finished the other dryly.

“We was drillin’ rear-guard actions, wasn’t we, Bill?”

“Aye. We was drilled, right, left, an’ a bit in the middle.” Bill rose and spat down the wind. “Tyke it from me,” he finished, with a glance aloft through the mist, “there’ll be somethin’ happen between ’ere an’ Wipers afore the week is hout——”

“Aye—the ’earse, Bill.”

“Wot ’earse?” asked the newcomer again.

“The larst time ’e kyme—down Wipers-way. There was a lull in the firin’ an’ ’tween the lines o’ trenches where the dead Dutchies was, comes a ’earse—a real ’earse with black ’orses, plumes an’ all. We thought ’twas some general they’d come to fetch and hup we stands hout o’ the trenches, comp’ny after comp’ny, caps off, all respec’ful-like. This ’ere ’earse comes along slow an’ mournful, black curt’ins an’ all flappin’ in the wind an’ six of the blighters a-marchin’ heads down behind it. They wheels up abreast of our comp’ny near a mound o’ earth and stops, an’ while we was lookin’—the front side of that there b——y vee-Hicle drops out an’ a machine-gun begins slippin’ it into us pretty as you please. ’Earse—that’s wot it was—a ’earse! an’ it jolly well made a funeral out o’ B Company.”

“Gawd!” said the newcomer. “And Yaller-belly——?”

“I ayn’t sayin’ nothin’ abaht ’im. You wait, that’s all.”

The sounds of firing rose and fell again. The fog thickened and the last crashes of the high-angle guns echoed out to sea, but the rush of the flying planes continued. Three machines there were by the sound of them, but one grew ever more distinct until the sounds of the three were merged into one. Closer it came, until like the blast of a storm down a mountainside, a huge shadow fell across the dunes and was gone amid a scattering of futile shots into the fog which might as well have been aimed at the moon.

Bill, the prescient, straightened and peered through the fog toward the flying plane.

“A ’earse,” he muttered. “That’s wot it was—a ’earse.”

CHAPTER I

SHELTERED PEOPLE

Lady Betty Heathcote had a reputation in which she took pride for giving successful dinners in a neighborhood where successful dinners were a rule rather than an exception. Her prescription was simple and consisted solely in compounding her social elements by strenuous mixing. She had a faculty for discovering cubs with incipient manes and saw them safely grown without mishap. At her house in Park Lane, politics, art, literature, and science rubbed elbows. Here pictures had been born, plays had had their real premières, novels had been devised, and poems without number, not a few of which were indited to My Lady Betty’s eyebrow, here first saw the light of day.

For all her dynamic energy in a variety of causes, most of them wise, all of them altruistic, Lady Betty had the rare faculty of knowing when to be restful. Tired Cabinet ministers, overworked lords of the Admiralty, leaders in all parties, knew that in Park Lane there would be no questions asked which it would not be possible to answer, that there was always an excellent dinner to be had without frills, a lounge in a quiet room, or, indeed, a pair of pyjamas and a bed if necessary.

But since the desperate character of the war with Germany had been driven home into the hearts of the people of London, a change had taken place in the complexion of many private entertainments and the same serious air which was to be noted in the mien of well-informed people of all classes upon the street was reflected in the faces of her guests. Her scientists were engrossed with utilitarian problems. Her literary men were sending vivid word-pictures of ruined Rheims and Louvain to their brothers across the Atlantic, and her Cabinet ministers conversed less than usual, addressing themselves with a greater particularity to her roasts or her spare bedrooms. Torn between many duties, as patroness to bazaars, as head of a variety of sewing guilds, as president of the new association for the training and equipment of nurses, Lady Heathcote herself showed signs of the wear and tear of an extraordinary situation, but she managed to meet it squarely by using every ounce of her abundant energy and every faculty of her resourceful mind.

Many secrets were hers, both political and departmental, but she kept them nobly, aware that she lived in parlous times, when an unconsidered word might do a damage irreparable. Agents of the enemy, she knew, had been discovered in every walk of life, and while she lived in London’s innermost circle, she knew that even her own house might not have been immune from visitors whose secret motives were open to question. It was, therefore, with the desire to reassure herself as to the unadulterated loyalty of her intimates that she had carefully scrutinized her dinner lists, eliminating all uncertain quantities through whom or by whom the unreserved character of the conversation across her board might in any way be jeopardized. So it was that tonight’s dinner-table had something of the complexion of a family party, in which John Rizzio, the bright particular star in London’s firmament of Art, was to lend his effulgence. John Rizzio, dean of collectors, whose wonderful house in Berkeley Square rivaled the British Museum and the Wallace Collection combined, an Italian by birth, an Englishman by adoption, who because of his public benefactions had been offered a knighthood and had refused it; John Rizzio, who had been an intimate of King Edward, a friend of Cabinet ministers, who knew as much about the inner workings of the Government as majesty itself. Long a member of Lady Heathcote’s circle, it had been her custom to give him a dinner on the anniversary of the day of the acquisition of the most famous picture in his collection, “The Conningsby Venus,” which had, before the death of the old Earl, been the aim of collectors throughout the world.

As usual the selection of her guests had been left to Rizzio, whose variety of taste in friendships could have been no better shown than in the company which now graced Lady Heathcote’s table. The Earl and Countess of Kipshaven, the one artistic, the other literary; their daughter the Honorable Jacqueline Morley; Captain Byfield, a retired cavalry officer now on special duty at the War Office; Lady Joyliffe, who had lost her Earl at Mons, an interesting widow, the bud of whose new affections was already emerging from her weeds; John Sandys, under-secretary for foreign affairs, the object of those affections; Miss Doris Mather, daughter of the American cotton king, who was known for doing unusual things, not the least of which was her recent refusal of the hand of John Rizzio, one of London’s catches, and the acceptance of that of the Honorable Cyril Hammersley, the last to be mentioned member of this distinguished company, gentleman sportsman and man about town, who as everybody knew would never set the world afire.

No one knew how this miracle had happened, for Doris Mather’s brains were above the ordinary; she had a discriminating taste in books and a knowledge of pictures, and just before dinner, upstairs in a burst of confidence she had given her surprised hostess an idea of what a man should be.

“He should be clever, Betty,” she sighed, “a worker, a dreamer of great dreams, a firebrand in every good cause, a patriot willing to fight to the last drop of his blood——”

Lady Betty’s laughter disconcerted her and she paused.

“And that is why you chose the Honorable Cyril?”

Miss Mather compressed her lips and frowned at her image in the mirror.

“Don’t be nasty, Betty. I couldn’t marry a man as old as John Rizzio.”

Lady Betty only laughed again.

“Forgive me, dear, but it really is most curious. I wouldn’t laugh if you hadn’t been so careful to describe to me all the virtues that Cyril—hasn’t.”

Doris powdered the end of her nose thoughtfully.

“I suppose they’re all a myth—men like that. They simply don’t exist—that’s all.”

Lady Betty pinned a final jewel on her bodice.

“I’m sure John Rizzio is flattered at your choice. Cyril is an old dear. But to marry! I’d as soon take the automatic chess player. Why are you going to marry Cyril, Doris?” she asked.

A long pause and more powder.

“I’m not sure that I am. I don’t even know why I thought him possible. I think it’s the feeling of the potter for his clay. Something might be made of him. He seems so helpless somehow. Men of his sort always are. I’d like to mother him. Besides”—and she flashed around on her hostess brightly—“he does sit a horse like a centaur.”

“He’s also an excellent shot, a good chauffeur, a tolerable dancer and the best bat in England, all agreeable talents in a gentleman of fashion but—er—hardly——” Lady Betty burst into laughter. “Good Lord, Doris! Cyril a firebrand!”

Doris Mather eyed her hostess reproachfully and moved toward the door into the hallway.

“Come, Betty,” she said with some dignity, “are you ready to go down?”

All of which goes to show that matches are not made in Heaven and that the motives of young women in making important decisions are actuated by the most unimportant details. Hammersley’s good fortune was still a secret except to Miss Mather’s most intimate friends, but the conviction was slowly growing in the mind of the girl that unless Cyril stopped sitting around in tweeds when everybody else was getting into khaki, the engagement would never be announced. As the foreign situation had grown more serious she had seen other men who weighed less than Cyril throw off the boredom of their London habits and go soldiering into France. But the desperate need of his country for able-bodied men had apparently made no impression upon the placid mind of the Honorable Cyril. It was as unruffled as a highland lake in mid-August. He had contributed liberally from his large means to Lady Heathcote’s Ambulance Fund, but his manner had become, if anything, more bored than ever.

Miss Mather entered the drawing-room thoughtfully with the helpless feeling of one who, having made a mistake, pauses between the alternatives of tenacity and recantation. And yet as soon as she saw him a little tremor of pleasure passed over her. In spite of his drooping pose, his vacant stare, his obvious inadequacy she was sure there was something about Cyril Hammersley that made him beyond doubt the most distinguished-looking person in the room—not even excepting Rizzio.

He came over to her at once, the monocle dropping from his eye.

“Aw’fly glad. Jolly good to see you, m’dear. Handsome no end.”

He took her hand and bent over her fingers. Such a broad back he had, such a finely shaped head, such shoulders, such strong hands that were capable of so much but had achieved so little. And were these all that she could have seen in him? Reason told her that it was her mind that demanded a mate. Could it be that she was in love with a beautiful body?

There was something pathetic in the way he looked at her. She felt very sorry for him, but Betty Heathcote’s laughter was still ringing in her ears.

“Thanks, Cyril,” she said coolly. “I’ve wanted to see you—tonight—to tell you that at last I’ve volunteered with the Red Cross.”

Hammersley peered at her blankly and then with a contortion set his eyeglass.

“Red Cross—you! Oh, I say now, Doris, that’s goin’ it rather thick on a chap——”

“It’s true. Father’s fitting out an ambulance corps and has promised to let me go.”

John Rizzio, tall, urbane, dark and cynical, who had joined them, heard her last words and broke into a shrug.

“It’s the khaki, Hammersley. The women will follow it to the ends of the earth. Broadcloth and tweeds are not the fashion.” He ran his arm through Hammersley’s. “There’s nothing for you and me but to volunteer.”

The Honorable Cyril only stared at him blankly.

“Haw!” he said, which, as Lady Betty once expressed it, was half the note of a jackass.

Here the Kipshavens arrived and their hostess signaled the advance upon the dinner-table.

One of the secrets of the success of Lady Heathcote’s dinners was the size and shape of her table, which seated no more than ten and was round. Her centerpieces were flat and her candelabra low so that any person at the table could see and converse with anyone else. It was thus possible delicately to remind those who insisted on completely appropriating their dinner partners that private matters could be much more safely discussed in the many corners of the house designed for the purpose. Doris sat between Rizzio and Byfield, Hammersley with Lady Joyliffe just opposite, and when Rizzio announced the American girl’s decision to go to France as soon as her training was completed she became the immediate center of interest.

“That’s neutrality of the right sort,” said Kipshaven heartily. “I wish all of your countrymen felt as you do.”

“I think most of them do,” replied Doris, smiling slowly, “but you know, you haven’t always been nice to us. There have been many times when we felt that as an older brother you treated us rather shabbily. I’m heaping coals of fire, you see.”

“Touché!” said Rizzio, with a laugh.

“I bare my head,” said the Earl.

“Ashes to ashes,” from Lady Joyliffe.

Kipshaven smiled. “Once in England gray hairs were venerated, even among the frivolous. Now,” he sighed, “they are only a reproach. Peccavi. Forgive me. I wish I could set the clock back.”

“You’d go?” asked Doris.

“Tomorrow,” said the old Earl with enthusiasm.

Miss Mather glanced at Hammersley who was enjoying his soup, a purée he liked particularly.

“But isn’t there something you could do?”

“Yes. Write, for America—for Italy—for Sweden and Holland—for Spain. It’s something, but it isn’t enough. My fingers are itching for a sword.”

The Honorable Cyril looked up.

“Pen mightier than sword,” he quoted vacuously, and went on with his soup.

“You don’t really mean that, Hammersley,” said Kipshaven amid smiles.

“Well rather,” drawled the other. “All silly rot—fightin’. What’s the use. Spoiled my boar-shootin’ in Hesse-Nassau—no season at Carlsbad—no season anywhere—everything the same—winter—summer——”

“You wouldn’t think so if you were in the trenches, my boy,” laughed Byfield.

“Beastly happy I’m not,” said Hammersley. “Don’t mind shootin’ pheasant or boar. Bad form—shootin’ men—not the sportin’ thing, you know—pottin’ a bird on the ground—’specially Germans.”

“Boches!” said Lady Betty contemptuously. She was inclined to be intolerant. For her Algy had already been mentioned in dispatches. “I don’t understand you, Cyril.”

Hammersley regarded her gravely while Constance Joyliffe took up his cudgels.

“You forget Cyril’s four years at Heidelberg.”

“No I don’t,” said their hostess warmly, “and I could almost believe Cyril had German sympathies.”

“I have, you know,” said Hammersley calmly, sniffing at the rim of his wineglass.

“This is hardly the time to confess it,” said Kipshaven dryly.

Doris sat silent, aware of a deep humiliation which seemed to envelop them both.

Rizzio laughed and produced a clipping from Punch. “Hammersley is merely stoically peaceful. Listen.” And he read:

“I was playing golf one day when the Germans landed All our troops had run away and all our ships were stranded And the thought of England’s shame nearly put me off my game.”

Amid the laughter the Honorable Cyril straightened.

“Silly stuff, that,” he said quite seriously, “to put a fellow off his game.” And turning to Lady Joyliffe: “Punch a bit brackish lately. What?”

“Cyril, you’re insular,” from Lady Heathcote.

“No, insulated,” said Doris with a flash of the eyes.

Rizzio laughed. “Highly potential but—er—not dangerous. Why should he be? He’s your typical Briton—sport-loving, calm and nerveless in the most exacting situations—I was at Lords, you know, when Hammersley made that winning run for Marylebone—two minutes to play. Every bowler they put up——”

“It’s hardly a time for bats,” put in Kipshaven dryly. “What we need is fast bowlers—with rifles.”

The object of these remarks sat serenely, smiling blandly around the table, but made no reply. In the pause that followed Sandys was heard in a half whisper to Byfield.

“What’s this I hear of a leak at the War Office?”

Captain Byfield glanced down the table. “Have you heard that?”

“Yes. At the club.”

Captain Byfield touched the rim of his glass to his lips.

“I’ve heard nothing of it.”

“What?” from a chorus.

“Information is getting out somewhere. I violate no confidences in telling you. The War Office is perturbed.”

“How terrible!” said Lady Joyliffe. “And don’t they suspect?”

“That’s the worst of it. The Germans got wind of some of Lord Kitchener’s plans and some of the Admiralty’s—which nobody knew but those very near the men at the top.”

“A spy in that circle—unbelievable,” said Kipshaven.

“My authority is a man of importance. Fortunately no damage has been done. The story goes that we’re issuing false statements in certain channels to mislead the enemy and find the culprit.”

“But how does the news reach the Germans?” asked Rizzio.

“No one knows. By courier to the coast and then by fast motor-boat perhaps; or by aëroplane. It’s very mysterious. A huge Taube, yellow in color, flying over the North Sea between England and the continent has been sighted and reported by English vessels again and again and each flight has coincided with some unexpected move on the part of the enemy. Once it was seen just before the raid at Falmouth, again before the Zeppelin visit to Sandringham.”

“A yellow dove!” said Lady Kipshaven. “A bird of ill omen, surely.”

“But how could such an aëroplane leave the shores of England without being remarked?” asked Kipshaven.

“Oh,” laughed Sandys, “answer me that and we have the solution of the problem. A strict watch is being kept on the coasts, and the government employees—the postmen, police, secret-service men of every town and village from here to the Shetlands are on the lookout—but not a glimpse have they had of him, not a sign of his arrival or departure, but only last week he was reported by a destroyer flying toward the English coast.”

“Most extraordinary!” from Lady Kipshaven.

“It’s a large machine?” asked Rizzio.

“Larger than any aëroplane ever built in Europe. They say Curtis, the American, was building a thousand horsepower machine at Hammondsport—in the States. This one must be at least as large as that.”

“But surely such a machine could not be hidden in England for any length of time without discovery.”

“It would seem so—but there you are. The main point is that he hasn’t been discovered and that its pilot is here in England—ready to fly across the sea with our military secrets when he gets them.”

“D—n him!” growled Kipshaven quite audibly, a sentiment which echoed so truly in the hearts of those present that it passed without comment.

“The captain of a merchant steamer who saw it quite plainly reported that the power of the machine was simply amazing—that it flew at about six thousand feet and was lost to sight in an incredibly brief time. In short, my friends, the Yellow Dove is one of the miracles of the day—and its pilot one of its mysteries.”

“But our aviation men—can they do nothing?”

“What? Chase rainbows? Where shall their voyage begin and where end? He’s over the North Sea one minute and in Belgium the next. Our troops in the trenches think he’s a phantom. They say even the bombs he drops are phantoms. They are heard to explode but nobody has ever been hit by them.”

“What will the War Office do?”

Sandys shrugged expressively. “What would you do?”

“Shoot the beggar,” said the Honorable Cyril impassively.

“Shoot the moon, sir,” roared the Earl angrily. “It’s no time for idiotic remarks. If this story is true, a danger hangs over England. No wholesome Briton,” here he glanced again at Hammersley, “ought to go to sleep until this menace is discovered and destroyed.”

“The Yellow Dove is occult,” said Sandys, “like a witch on a broomstick.”

“A Flying Dutchman,” returned Lady Joyliffe.

“There seems to be no joke about that,” said the Earl.

CHAPTER II

THE UNDERCURRENT

They were still discussing the strange story of Sandys when Lady Heathcote signaled her feminine guests and they retired to the drawing-room. Over the coffee the interest persisted and Lord Kipshaven was not to be denied. If, as it seemed probable, this German spy was making frequent flights between England and the continent, he must have some landing field, a hangar, a machine shop with supplies of oil and fuel. Where in this tight little island could a German airman descend with a thousand horsepower machine and not be discovered unless with the connivance of Englishmen? The thing looked bad. If there were Englishmen in high places in London who could be bought, there were others, many others, who helped to form the vicious chain which led to Germany.

“I tell you I believe we’re honeycombed with spies,” he growled. “For one that we’ve caught and imprisoned or shot, there are dozens in the very midst of us. If this thing keeps up we’ll all of us be suspecting one another. How do I know that you, Sandys, you, Rizzio, Byfield or even Hammersley here isn’t a secret agent of the Germans? What dinner-table in England is safe when spies are found in the official family at the War Office?”

Rizzio smiled.

“We, who are about to die, salute you,” he said, raising his liqueur glass. “And you, Lord Kipshaven, how can we be sure of you?”

“By this token,” said the old man, rising and putting his back to the fire, “that if I even suspected, I’d shoot any one of you down here—now, with as little compunction as I’d kill a dog.”

“I’ll have my coffee first,” laughed Byfield, “if you don’t mind.”

“Coffee—then coffin,” said Rizzio.

“Jolly unpleasant conversation this,” remarked Hammersley. “Makes a chap a bit fidgety.”

“Fidgety!” roared the Earl. “We ought to be fidgety with the Germans winning east and west and the finest flower of our service already killed in battle. We need men and still more men. Any able-bodied fellow under forty who stays at home”—and he glanced meaningly at the Honorable Cyril—“ought to be put to work mending roads.”

The object of these remarks turned the blank stare of his monocle but made no reply.

“Yes, I mean you, Cyril,” went on the Earl steadily. “Your mother was born a Prussian. I knew her well and I think she learned to thank God that fortune had given her an Englishman for a husband. But the taint is in you. Your brother has been wounded at the front. His blood is cleansed. But what of yours? You went to a German university with your Prussian kinsmen and now openly flaunt your sympathies at a dinner of British patriots. Speak up. How do you stand? Your friends demand it.”

Hammersley turned his cigarette carefully in its long amber holder.

“Oh, I say, Lord Kipshaven,” he said with a slow smile, “you’re not spoofing a chap, are you?”

“I was never more in earnest in my life. How do you stand?”

“Haw!” said Hammersley with obvious effort. “I’m British, you know, and all that sort of thing. How can an Englishman be anything else? Silly rot—fightin’—that’s what I say. That’s all I say,” he finished looking calmly for approval from one to the other.

Smiles from Sandys and Rizzio met this inadequacy, but the Earl, after glaring at him moodily for a moment, uttered a smothered, “Paugh,” and shrugging a shoulder, turned to Rizzio and Sandys who were discussing a recent submarine raid.

Hammersley and Byfield sat near each other at the side of the table away from the others. There was a moment of silence—which Hammersley improved by blowing smoke rings toward the ceiling. Captain Byfield watched him a moment and then after a glance in the direction of the Earl leaned carelessly on an elbow toward Hammersley.

“Any shootin’ at the North?” he asked.

Hammersley’s monocle dropped and the eyes of the two men met.

“Yes. I’m shootin’ the day after tomorrow,” said Hammersley quietly. Byfield looked away and another long moment of silence followed. Then the Honorable Cyril after a puff or two took the long amber holder from his mouth, removed the cigarette and smudged the ash upon the receiver.

“Bally heady cigarettes, these of Algy’s. Don’t happen to have any ’baccy and papers about you, do you, Byfield?”

“Well, rather,” replied the captain. And he pushed a pouch and a package of cigarette papers along the tablecloth. “It’s a mix of my own. I hope you’ll like it.”

Hammersley opened the bag and sniffed at its contents.

“Good stuff, that. Virginia, Perique and a bit of Turkish. What?”

Byfield nodded and watched Hammersley as he poured out the tobacco, rolled the paper and lighted it at the candelabra, inhaling luxuriously.

“Thanks,” he sighed. “Jolly good of you,” and he pushed the pouch back to Byfield along the table.

“You must come to Scotland some day, old chap,” said the Honorable Cyril carelessly.

“Delighted. When the war is over,” returned Byfield quietly. “Not until the war is over.”

“Awf’ly glad to have you any time, you know—awf’ly glad.”

“In case of furlough—I’ll look you up.”

“Do,” said the Honorable Cyril.

Hammersley’s rather bovine gaze passed slowly around the room, and just over Lord Kipshaven’s head in the mirror over the mantel it met the dark gaze of John Rizzio. The fraction of a second it paused there and then he stretched his long legs and rose, stifling a yawn.

“Let’s go in—what?” he said to Byfield.

Byfield got up and at the same time there was a movement at the mantel.

“Don’t be too hard on the chap,” Rizzio was saying in an undertone to Kipshaven. “You’re singing the ‘Hassgesang.’ He’s harmless—I tell you—positively harmless.” And then as the others moved toward the door: “Come, Lady Heathcote won’t mind our tobacco.”

Hammersley led the way, with Byfield and Rizzio at his heels. Jacqueline Morley had been trying to play the piano, but there was no heart in the music until she struck up “Tipperary,” when there was a generous chorus in which the men joined.

Hammersley found Doris with Constance Joyliffe in an alcove. At his approach Lady Joyliffe retired.

“Handsome, no end,” he murmured to her as he sank beside her.

“Handsome is as handsome does, Cyril,” she said slowly. “If you knew what I was thinking of, you wouldn’t be so generous.”

“What?”

“Just what everybody is thinking about you—that you’ve got to do something—enlist to fight—go to France, if only as a chauffeur. They’d let you do that tomorrow if you’d go.”

“Chauffeur! Me! Not really!”

“Yes, that or something else,” determinedly.

“Why?”

She hesitated a moment and then went on distinctly.

“Because I could never marry a man people talked about as people are talking about you.”

“Not marry—?” The Honorable Cyril’s face for the first time that evening showed an expression of concern. “Not marry—me? You can’t mean that, Doris.”

“I do mean it, Cyril,” she said firmly. “I can’t marry you.”

“Why——?”

“Because to me love is a sacrament. Love of woman—love of country, but the last is the greater of the two. No man who isn’t a patriot is fit to be a husband.”

“A patriot——”

She broke in before he could protest. “Yes—a patriot. You’re not a patriot—that is, if you’re an Englishman. I don’t know you, Cyril. You puzzle me. You’re lukewarm. Day after day you’ve seen your friends and mine go off in uniform, but it doesn’t mean anything to you. It doesn’t mean anything to you that England is in danger and that she needs every man who can be spared at home to go to the front. You see them go and the only thing it means to you is that you’re losing club-mates and sport-mates. Instead of taking the infection of fervor—you go to Scotland—to shoot—not Germans but—deer! Deer!” she repeated scathingly.

“But there aren’t any Germans in Scotland—at least none that a chap could shoot,” he said with a smile.

“Then go where there are Germans to shoot,” she said impetuously. She put her face to her hands a moment. “Oh, don’t you understand? You’ve got to prove yourself. You’ve got to make people stop speaking of you as I’ve heard them speak of you tonight. Here you are in the midst of friends, people who know you and like you, but what must other people who don’t know you so well or care so much as we? What must they think and say of your indifference, of your openly expressed sympathy with England’s enemies? Even Lady Betty, a kinswoman and one of your truest friends, has lost patience with you—I had almost said lost confidence in you.”

Her voice trailed into silence. Hammersley was moving the toe of his varnished boot along the border of the Aubusson rug.

“I’m sorry,” he said slowly. “Awf’ly sorry.”

“Sorry! Are you? But what are you going to do about it?”

“Do?” he said vaguely. “I don’t know, I’m sure. I’m no bally use, you know. Wouldn’t be any bally use over there. Make some silly ass mistake probably. No end of trouble—all around.”

“And you’re willing to sacrifice the goodwill, the affection of your friends, the respect of the girl you say you love——”

“Oh, I say, Doris. Not that——”

“Yes. I’ve got to tell you. I can’t be unfair to myself. I can’t respect a man who sees others cheerfully carrying his burdens, doing his work, accepting his hardships in order that he may sleep soundly at home far away from the nightmare of shot and shell. You, Cyril, you! Is it that—the love of ease? Or is it something else—something to do with your German kinship—the memory of your mother. What is it? If you still want me, Cyril, it is my right to know——”

“Want you, Doris—” his voice went a little lower. “Yes, I want you. You might know that.”

“Then you must tell me.”

He hesitated and peered at the eyeglass in his fingers.

“I think—it’s because I—” He paused and then crossed his hands and bowed his head with an air of relinquishment. “Because I think I must be a”—he almost whispered the word—“a coward.”

Doris Mather gazed at him a long moment of mingled dismay and incredulity.

“You,” she whispered, “the first sportsman of England—a—a coward.”

He gave a short mirthless laugh.

“Queer, isn’t it, the way a chap feels about such things? I always hated the idea of being mangled. Awf’ly unpleasant idea that—’specially in the tummy. In India once I saw a chap——”

“You—a coward!” Doris repeated, wide-eyed. “I don’t believe you.”

He bent his head again.

“I—I’m afraid you’d better,” he said uncertainly.

She rose, still looking at him incredulously, another doubt, a more dreadful one, winging its flight to and fro across her inner vision.

“Come,” she said in a tone she hardly recognized as her own, “come let us join the others.”

He stood uncertainly and as she started to go,

“You’ll let me take you home, Doris?” he asked.

She bent her head, and without replying made her way to the group beyond the alcove.

Hammersley stood a moment watching her diminishing back and then a curious expression, half of trouble, half of resolution, came into his eyes.

Then after a quick glance around the curtain he suddenly reached into his trousers pocket, took something out and scrutinized it carefully by the light of the lamp. He put it back quickly and setting his monocle sauntered forth into the room. As he moved to join the group at the piano John Rizzio met him in the middle of the room.

“Could I have a word with you, Hammersley?” he asked.

“Happy,” said the Honorable Cyril. “Here?”

“In the smoking-room—if you don’t mind?”

Hammersley hesitated a moment and then swung on his heels and led the way. At the smoking-room door from the hallway Rizzio paused, then quietly drew the heavy curtains behind them.

Hammersley, standing by the table, followed this action with a kind of bored curiosity, aware that Rizzio’s dark gaze had never once left him since they had entered the room. Slowly Hammersley took his hands from his pockets, reached into his waistcoat for his cigarette case, and as Rizzio approached, opened and offered it to him.

“Smoke?” he asked carelessly.

“I don’t mind if I do. But I’ve taken a curious liking for rolled cigarettes. Ah! I thought so.” He opened the tobacco jar and sniffed at it, searched around the articles on the table, then, “How disappointing! Nothing but Algy’s dreadful pipes. You don’t happen to have any rice-papers do you?”

Hammersley was lighting his own cigarette at the brazier.

“No. Sorry,” he replied laconically.

Rizzio leaned beside him against the edge of the table.

“Strange. I thought I saw you making a cigarette in the dining-room.”

Hammersley’s face brightened. “Oh, yes, Byfield. Byfield has rice-papers.”

“I’d rather have yours,” he said quietly.

The Honorable Cyril looked up.

“Mine, old chap? I thought I told you I hadn’t any.”

Rizzio smiled amiably.

“Then I must have misunderstood you,” he said politely.

“Yes,” said Hammersley and sank into an armchair.

Rizzio did not move and the Honorable Cyril, his head back, was already blowing smoke rings.

Rizzio suddenly relaxed with a laugh and put his legs over a small chair near Hammersley’s and folded his arms along its back.

“Do you know, Hammersley,” he said with a laugh, “I sometimes think that as I grow older my hearing is not as good as it used to be. Perhaps you’ll say that I cling to my vanishing youth with a fatuous desperation. I do. Rather silly, isn’t it, because I’m quite forty-five. But I’ve a curiosity, even in so small a matter, to learn whether things are as bad with me as I think they are. Now unless you’re going to add a few more gray hairs to my head by telling me that I’m losing my sight as well as my hearing, you’ll gratify my curiosity—an idle curiosity, if you like, but still strangely important to my peace of mind.”

He paused a moment and looked at Cyril, who was examining him with frank bewilderment.

“I don’t think I understand,” said Hammersley politely.

“I’ll try to make it clearer. Something has happened tonight that makes me think that I’m getting either blind or deaf or both. To begin with I thought you said you had no cigarette papers. If I heard you wrong, then the burden of proof rests upon my ears—if my eyes are at fault it’s high time I consulted a specialist, because you know, at the table in the dining-room when you were sitting with Byfield, quite distinctly I saw you put a package of Riz-la-Croix into your right-hand trousers pocket. The color as you know is yellow—a color to which my optic nerve is peculiarly sensitive.” He laughed again. “I know you’d hardly go out of your way to make a misstatement on so small a matter, and if you don’t mind satisfying a foible of my vanity, I wish you’d tell me whether or not I’m mistaken.”

He stopped and looked at Hammersley who was regarding him with polite, if puzzled tolerance. Then, as if realizing that something was required of him Hammersley leaned forward.

“I say, Rizzio. What the deuce is it all about? I’m sorry you’re gettin’ old an’ all that sort of thing, but I can’t help it. Now can I, old chap?”

Rizzio’s smile slowly faded and his gaze passed Hammersley and rested on the brass fender of the fireplace.

“You don’t care to tell me?” he asked.

“What?”

“About that package of rice-papers.”

“Byfield has them.”

“Not that package,” put in Rizzio with a wave of the hand. And then, leaning forward, in a low tone, “The other.”

Hammersley sat upright a moment, his hands on the chair-arms and then sank back in his chair with a laugh.

“I say. I can take a joke as well as the next, but—er—what’s the answer?”

Rizzio rose, his graceful figure dominant.

“I don’t think that sort of thing will do, Hammersley.”

His demeanor was perfectly correct, his hand-wave easy and a well-bred smile flickered at his lips, but his tone masked a mystery. Hammersley rose, removing his cigarette with great deliberateness from its holder and throwing it into the fire.

“If there isn’t anything else you want to see me about—” He took a step in the direction of the door.

“One moment, please.”

Hammersley paused.

“I think we’d better drop subterfuge. I know why you were here tonight, why Byfield was here and perhaps you know now why I am here.”

“Can’t imagine, I’m sure,” said Cyril.

“Perhaps you can guess, when I tell you that this party was of my own choosing—that my plans were made with a view to arranging your meeting with Captain Byfield in a place known to be above suspicion. I have been empowered to relieve you of any further responsibility in the matter in question—in short of the papers themselves.”

“Oh, I say. Vanished youth, cigarette papers and all that. You’re goin’ it a bit thick, Rizzio, old boy.”

Rizzio put a hand into the inside pocket of his evening coat and drew out a card-case, which he opened under Hammersley’s eyes.

“Look, Hammersley,” he whispered. “Maxwell gave me this! Perhaps you understand now.”

The Honorable Cyril fixed his eyeglass carefully and stared at the card-case.

“By Jove,” he muttered, with sudden interest.

“Now you understand?” said Rizzio.

“You!” whispered Hammersley, looking at him. The languor of a moment before had fallen from him with his dropping monocle.

“Yes, I. Now quick, the papers,” muttered Rizzio, putting the card-case in his pocket. “Someone may come at any moment.”

For a long space of time Hammersley stood uncertainly peering down at the pattern in the rug, then he straightened and, crossing the room, put his back to the fireplace.

“There may be a mistake,” he said firmly. “I can’t risk it.”

Rizzio stood for a moment staring at him as though he had not heard correctly. Then he crossed over and faced the other man.

“You mean that?”

Hammersley put his hands in his trousers pockets.

“I fancy so.”

“What are you going to do?”

“What I’ve been told to do.”

“My orders supersede yours.”

“H-m. I’m not sure.”

“You can’t doubt my credentials.”

“Hardly that. Er—I think I know best, that’s all.”

Rizzio took a pace or two before the fireplace in front of him, his brows tangled, his fingers twitching behind his back. Then he stopped with the air of a man who has reached a decision.

“You understand what this refusal means?”

Hammersley shrugged.

“You realize that it makes you an object of suspicion?” asked the other.

“How? In doing what was expected of me?” said Hammersley easily.

“You are expected to give those papers to me.”

“I can’t.”

Rizzio’s fine face had gone a shade paler under the glossy black of his hair and his eyes gleamed dangerously under his shaggy brows. He measured the Honorable Cyril’s six feet two against his own and then turned away.

“I think I understand,” he said slowly. “Your action leaves me no other alternative.”

Hammersley, his hands still deep in his pockets, seemed to be thinking deeply.

“Oh, I wouldn’t say that. Each man according to his lights. You have your orders. I have mine. They seem to conflict. I’m going to carry mine out. If that interferes with carrying out yours, I’m not to blame. It’s what happens in the end that matters,” he finished significantly.

Rizzio thought deeply for a moment.

“You’ll at least let me see them?”

“No, I can’t.”

“Why?”

“I have my own reasons.”

Another pause in which Rizzio gave every appearance of a baffled man.

“You realize that if I gave the alarm and those papers were found on you——”

“You wouldn’t do that.”

“Why not?”

“Because of your card-case.”

“That signifies nothing to anyone but you and me.”

Hammersley smiled.

“I’ll take the risk, Rizzio,” he said finally.

The two men had been so absorbed in their conversation that they had not heard the drawing of the curtains of the door, but a sound made them turn and there stood Doris Mather.

CHAPTER III

RICE-PAPERS

Doris looked from the man whose hand she had accepted to the one she had refused. Their attitudes were eloquent of concealment and the few phrases which had reached her ears as she paused outside the curtain did nothing to relieve the sudden tension of her fears. She hesitated for a moment as Rizzio recovered himself with an effort.

“Do come in, Doris,” he said with a smile. “Hammersley and I were—er——”

“Discussing the scrap of paper. I’m sure of it,” she said coolly. “Nothing is so fruitful of argument. I shouldn’t have intruded, but Cyril was to take me home and I’m ready to go.”

A look passed between the men.

“By Jove—of course,” said Cyril with a glance at his watch. “If you’ll excuse me, Rizzio——”

“Betty is going to Scotland tomorrow early and I think she wants to go to bed.”

Rizzio laughed. “The war has made us virtuous. Eleven o’clock! We’re losing our beauty sleep.”

He followed them to the door, but pleading a desire for a night-cap, remained in the smoking-room.

“I promised that you should take me home,” said the girl to Hammersley as they passed along the hall. “But I’m sorry if I interrupted——”

“Awf’ly glad,” he murmured. “Nothing important, you know. Club matter. Personal.”

Doris stopped just outside the drawing-room door and searched his face keenly, while she whispered:

“And the threats—of exposure. Oh, I heard that. I couldn’t help it—Cyril—”

He glanced down at her quickly.

“Hush, Doris.”

Something she saw in his expression changed her resolution to question him. The mystery which she had felt to hang about him since he had said he was a coward had deepened. Something told her that she had been treading on forbidden ground and that in obeying him she served his interests best, so she led the way into the drawing-room, where they made their adieux.

Byfield had already gone and Sandys and Lady Joyliffe were just getting into their wraps.

“You’ll meet me here at ten?” their hostess was asking of Constance Joyliffe.

“If I’m not demolished by a Zeppelin in the meanwhile,” laughed the widow.

“Or the Yellow Dove,” said Jacqueline Morley. “I’m sure he alights on the roofs of the Parliament Houses.”

“You’ll be safe in Scotland at any rate, Constance. We’re quite too unimportant up there to be visited by engines of destruction—” she laughed meaningly. “That is—always excepting Jack Sandys.”

Sandys looked self-conscious, but Lady Joyliffe merely beamed benignly.

“It will really be quite restful, I’m sure,” she said easily. “Is Cyril going to be at Ben-a-Chielt?”

Hammersley awoke from a fit of abstraction.

“Quite possible,” he murmured, “gettin’ to be a bit of a hermit lately. Like it though—rather.”

“Cyril hasn’t anyone to play with,” said Betty Heathcote, “so he has taken to building chicken-houses.”

“Fearfully absorbin’—chicken-houses. Workin’ ’em out on a plan of my own. You’ll see. Goin’ in for hens to lay two eggs a day.” And then to Kipshaven, “So the submarines can’t starve us out, you know,” he explained.

“I don’t think you need worry about that,” said the Earl dryly, moving toward the door.

Doris Mather went upstairs for her wraps and when she came down she found Hammersley in his topcoat awaiting her. As they went down the steps into the waiting limousine her companion offered her his arm. Was it only fancy that gave her the impression that his glance was searching the darkness of the Park beyond the lights of the waiting cars with a keenness which seemed uncalled for on so prosaic an occasion? He helped her in and gave the direction to the chauffeur.

“Ashwater Park, Stryker, by way of Hampstead—and hurry,” she heard him say, which was surprising since the nearer way lay through Harlenden and Harrow-on-Hill. The orders to hurry, too, save in the stress of need, were under the circumstances hardly flattering to her self-esteem. But she remembered the urgent look in his eyes in the hall when he had silenced her questions and sank back in the seat, her gaze fixed on the gloom of Hyde Park to their left, waiting for him to speak. He sat rigidly beside her, his hands clasped about his stick, his eyes peering straight before him at the back of Stryker’s head. She felt his restraint and a little bitterly remembered the cause of it, buoyed by a hope that since he had thought it fit to enact a lie, the whole tissue of doubts which assailed her might be based on misconception also. That he was no coward she knew. More than one instance of his physical courage came back to her, incidents of his life before fortune had thrown them together and she only too well remembered the time when he had jumped from her car and thrown himself in front of a runaway horse, saving the necks of the occupants of the vehicle. He had lied to her. But why—why?

She closed her eyes trying to shut out the darkness and seek the sanctuary of some inner light, but she failed to find it. It seemed as though the gloom which spread over London had fallen over her spirit.

“The City of Dreadful Night,” she murmured at last. “I can’t ever seem to get used to it.”

She heard his light laugh and the sound of it comforted her.

“Jolly murky, isn’t it? I miss that fireworks Johnny pourin’ whiskey over by Waterloo Bridge—and Big Ben. Doesn’t seem like London. All rot anyway.”

“You don’t think there’s danger,” she asked cautiously.

He hesitated a moment before replying. And then, “No,” he said, “not now.”

Silence fell over them again. It was as though a shape sat between, a phantom of her dead hopes and his, something so cold and tangible that she drew away in her own corner and looked out at the meaningless blur of the sleeping city. Her lips were tightly closed. She had given him his chance to speak, but he had not spoken and every foot of road that they traversed seemed to carry them further apart. The end of their journey—! Was it to be the end ... of everything between them?

After a while that seemed interminable she heard his voice again.

“I suppose you think I’m an awful rotter.”

She turned her head and tried to read his face, but he kept it away from her, toward the opposite window. The feeling that she had voiced to Betty Heathcote of wanting to “mother” him came over her in a warm effusion.

“Nothing that you can say to me will make me think you one, Cyril,” she said gently.

“Thanks awf’ly,” he murmured. And after a pause, “I am though, you know.”

She leaned forward impulsively and laid a hand on his knee.

“No. You’re acting strangely, but I know that there’s a reason for it. As for your being a coward”—she laughed softly—“it’s impossible—quite impossible to make me believe that.”

He laid his fingers over hers for a moment.

“Nice of you to have confidence in a chap and all that, but appearances are against me—that’s the difficulty.”

“Why are they against you? Why should they be against you? Because you—” She stopped, for here she felt that she was approaching dangerous ground. Instead of parleying longer, she used her woman’s weapons frankly and leaning toward him put an arm around his neck and compelled him to turn his face to hers. “Oh, Cyril, won’t you tell me what this mystery is that is coming between us? Won’t you let me help you? I want to be in the sunlight with you again. It can’t go on this way, one of us in the dark and the other in the light. I have felt it for weeks. When I spoke to you tonight about going to France it was in the hope that you might give me some explanation that would satisfy me. My heart is wrapped up in the cause of England, but if the German blood in you is calling you away from your duties as an Englishman, tell me frankly and I will try to forgive you, but don’t let the shadow stay over us any longer, Cyril. I must know the truth. What is the mystery that hangs over you and makes——”

“Mystery?” he put in quickly. “You’re a bit seedy, Doris. Thinkin’ too much about the war. Nothin’ mysterious about me.” He turned his head away from her again. “People don’t like my sittin’ tight—here in England,” he said more slowly, “when all the chaps I know are off to the front. I—I can’t help it. That’s all.”

“But it’s so unlike you,” she pleaded. “It’s the sporting thing, Cyril.”

“I want you to believe,” he put in slowly, “it isn’t the kind of sport I care for.”

“I won’t believe it. I can’t. I know you better than that.”

“That’s the trouble,” he insisted. “I’m afraid you don’t know me at all.”

“I don’t know you tonight,” she said sadly. “It almost seems as though you were trying to get rid of me.”

He clasped her tightly in his arms and kissed her gently.

“God forbid,” he muttered.

“Then tell me what it is that is worrying you,” she whispered. “Not a living soul shall ever know. What were the threats of exposure that passed between you and Rizzio. He can’t bear you any illwill because I chose you instead of him. I didn’t mean to listen but I couldn’t help it. What was the menace in his tone to you? What is the danger that hangs over you that puts you in his power? It’s my right to know. Tell me, Cyril. Tell me.”

She felt the pressure of the arm around her relax and the sudden rigidity of his whole body as he drew away.

“I think you must have been mistaken in what you say you heard,” he said evenly. “I told you that it was a personal matter—a club matter in which you couldn’t possibly be interested.”

They were speaking formally now, almost as strangers. She felt the indifference in his tone and couldn’t restrain the bitterness that rose in hers.

“One gentleman doesn’t threaten a club-mate with exposure in a club matter unless—unless he has done something discreditable—something dishonorable——”

The Honorable Cyril bent his head.

“You have guessed,” he said. “He—he is jealous. He wants to humiliate me.”

She laughed miserably. “Then why did you threaten him?”

“I had to defend myself.”

“You! Dishonorable! I’ll have to have proofs of that. What are the papers you have that he wants? And what is there incriminating in Rizzio’s card-case? You see, I heard everything.”

“What else did you hear?” he asked quickly.

She drew away from him and sank back heavily in her corner.

“Nothing,” she muttered. “Isn’t that enough?”

It seemed to the girl as though her companion’s figure relaxed a little. And he turned toward her gently.

“Don’t bother about me. I’m not worth bothering about. The worst of it is that I can’t make any explanation—at least any that will satisfy you. All I ask is that you have patience with me if you can, trust me if you can, and try to forget—try to forget what you have heard. If you should mention my conversation with Rizzio it might lead to grave consequences for him—for me.”

The girl listened as though in a nightmare, the suspicions that had been slowly gathering in her brain throughout the evening now focusing upon him from every incident with a persistence that was not to be denied. The shape sat between them again, more tangible, more cold and cruel than before. All his excuses, all his explanations gave it substance and reality. The phantom of their dead hopes it had been before—now it was something more sinister—something that put all thoughts of the Cyril she knew from her mind—the shade of Judas fawning for his pieces of silver—a pale Judas in a monocle.... She closed her eyes again and tried to think. Cyril! It was unbelievable.... And a moment ago he had kissed her. She felt again the touch of his lips on her forehead.... It seemed as though she too were being betrayed.

“You ask something very difficult of me,” she stammered chokingly.

“I can only ask,” he said, “and only hope that you’ll take my word for its importance.”

She shivered in her corner. The sound of his voice was so impersonal, so different from the easy bantering tone to which she was accustomed, that it seemed that what he had said was true—that she did not know him.

Another surprise awaited her, for he leaned forward, peering into the mirror beside the wind shield in front of Stryker and turned and looked quickly out of the rear window of the car. Then she heard his voice in quick peremptory notes through the speaking-tube.

“There’s a car behind us. Lose it.”

The driver touched his cap and she felt the machine leap forward. The thin stream of light far in front of them played on the gray road and danced on the dim façades of unlighted houses which emerged from the obscurity, slid by and were lost again as the car twisted and turned, rocking from side to side, moving ever more rapidly toward the open country to the north. The dark corners of cross streets menaced for a moment and were gone. A reflector gleamed from one, but they went by it without slowing, the signal shrieking. A flash full upon them, a sound of voices cursing in the darkness and the danger was passed! At the end of a long piece of straight road Cyril turned again and reached for the speaking-tube. But his voice was quite cool.

“They’re coming on. Faster, Stryker.”

And faster they went. They had reached the region of semi-detached villas and the going was good. The road was a narrow ribbon of light reeling in upon its spool with frightful rapidity. The machine was a fine one and its usual well-ordered purr had grown into a roar which seemed to threaten immediate disruption.

Doris sat rigidly, clutching at the door sill and seat trying to adjust her braced muscles to the task of keeping upright. But a jolt of the car tore her grasp loose and threw her into Cyril’s arms and there he held her steadily. She was too disturbed to resist, and lay quietly, conscious of the strength of the long arms that enfolded her and aware in spite of herself of a sense of exhilaration and triumph. Triumph with Cyril! What triumph—over whom? It didn’t seem to matter just then whom he was trying to escape. She seemed very safe in his arms and very contented though the car rocked ominously, while its headlight whirled drunkenly in a wild orbit of tossed shadows. The sportswoman in her responded to the call of speed, the chance of accident, the danger of capture—for she felt sure now that there was a danger to Cyril. Over her shoulder she saw the lights of the pursuing machine, glowing unblinkingly as though endowed with a persistence which couldn’t know failure. Under the light of an incandescent she saw that its lines were those of a touring-car and realized the handicap of the heavy car with its limousine body. But Stryker was doing his best, running with a wide throttle picking his road with a skill which would have done credit to Cyril himself. The heath was already behind them. At Hendon, having gained a little, Stryker put out his lights and turned into a by-road hoping to slip away in the darkness, but as luck would have it the moon was bright and in a moment they saw the long spoke of light swing in behind them.

“Good driver, that Johnny,” she heard her companion say in a note of admiration to Stryker. “Have to run for it again.”

The road was not so good here and they lost time without the searchlights, so Stryker turned them on again. This evasion of the straight issue of speed had been a confession of weakness and the other car seemed to realize it, for it came on at increased speed which shortened the distance so that the figures of the occupants of the other were plainly discernible, five men in all, huddled low.

A good piece of road widened the distance. The limousine, now thoroughly warmed, was doing the best that she was capable of and the tires Cyril told her were all new. Her question seemed to give him an idea, for he reached for the flower vase and, thrusting out a hand, jerked it back into the road.

“A torn tire might help a little,” he said.

But the fellow behind swerved and came faster.

It was now a test of metal. Their pursuer lagged a little on the levels but caught them on the grades and, barring an accident, it was doubtful whether they would reach the gates of Ashwater Park safely. She heard a reflection of this in Cyril’s voice as he shouted through the open front window.

“How far by the road, Stryker?”

“Five miles, I’d say, sir.”

“Give her all she can take.”

Stryker nodded and from a hill crest they seemed to soar into space. The car shivered and groaned like a stricken thing, but kept on down the hill without the touch of a brake. They crossed a bridge, rattled from side to side. Cyril steadied the girl in his arms and held her tight.

“Are you frightened?” he asked her.

“No. But what is it all about?”

Her companion glanced back to where the long beams of light were searching their dust. When he turned toward her his face was grave. He held her closely for a moment, peering into her eyes.

“Will you help me, Doris?” she heard him say.

“But how? What can I do, Cyril?”

He hesitated again, glancing over his shoulder.

“Bally nuisance to have to drive you like this. Wouldn’t do it if it wasn’t most important——”

“Yes——”

“They want something I’ve got——”

“Papers?”

“You’ll laugh when I tell you. Most amusin’—cigarette papers!”

“Cigarette——”

“That’s all. I give you my word. Here they are.” And reaching down into his trousers pocket he produced a little yellow packet. “Cigarette papers, that’s all. These chaps must be perishin’ for a smoke. What?” he laughed.

“But I don’t understand.”

“It isn’t necessary that you should. Take my word for it, won’t you? It’s what they want. And I’m jolly determined they’re not goin’ to get it.”

“You want me to help you? How?”

He looked back again and the lights behind them found a reflection in his eyes. If, earlier in the evening she had hoped to see him fully awake, she had her wish now. He was quite cool and ready to take an amused view of things, but in his coolness she felt a new power, an inventiveness, a readiness to resort to extremes to baffle his pursuers. Her apprehension had grown with the moments. Who were these men in the touring-car? Special agents of Scotland Yard? She had never been so doubtful nor so proud of him. Weighed in the balance of emotion the woman in her decided it. She caught at his hand impulsively.

“Yes, I’ll help—if I can—whatever comes.”

He raised her fingers to his lips and kissed them gently.

“Thank God,” he muttered. “I knew you would.” He looked over his shoulder and then peered out in search of familiar land-marks. They had passed Canons Hill and swung into the main road to Watford. If they reached there safely they would get to Ashwater Park which was but a short distance beyond.

She heard him speaking again and felt something thrust into the palm of her hand.

“Take this,” he said. “It’s what they want. They mustn’t get it.”

“But who are they?”

“I don’t know. Except that they’ve been sent by Rizzio.”

“Rizzio!”

“Yes. He’s not with them. This sort of game requires chaps of a different type.”

“You mean that they——”

“Oh, don’t be alarmed. They won’t hurt me and of course they won’t hurt you. I’m going to get you out of the way—with this. My success depends on you. We’ll drive past the Park entrance close to wicket gate in the hedge near the house. Just as we stop, jump out, run through and hide among the shrubbery. Your cloak is dark. They won’t see you. When they’re gone, make your way to the house. It’s a chance, but I’ve got to take it.”

“And you?” she faltered.

“I’ll get away. Don’t worry. But the packet. Whatever happens don’t let them get the packet.”

“No,” she said in a daze, “I won’t.”

“Keep it for me, until I come. But don’t examine it. It’s quite unimportant to anybody but me——” he laughed, “that is, anybody but Rizzio.”

She stared straight in front of her trying to think, but thought seemed impossible. The speed had got into her blood and she was mastered by a spirit stronger than her own. He held her in his arms again and she gloried in the thought that she could help him. Whatever his cause, her heart and soul were in it.

They roared into Watford and, turning sharp to the left, took the road to Croxley Green. The machine hadn’t missed a spark but the touring-car was creeping up—was so close that its lights were blinding them. Hammersley leaned forward and gave a hurried order to Stryker. They passed the Park gates at full speed—the wicket gate was a quarter of a mile beyond. Would they make it? The touring-car was roaring up alongside but Stryker jockeyed it into the gutter. Voices were shouting and Doris got the gleam of something in the hand of a tall figure standing up in the other car. There followed shots—four of them—and an ominous sound came from somewhere underneath as the limousine limped forward.

“It’s our right rear tire,” said Stryker.

“Have we a spare wheel,” she heard Cyril say.

“Yes, sir.”

“When we stop put it on as quick as you can. A hundred yards. Easy—so and we’re there, Stryker. Now. Over to the left and give ’em the road. Quick! Now stop!”

The other machine came alongside at their right and the men jumped down just as Cyril threw open the left-hand door and Doris leaped out and went through the gate in the hedge.

CHAPTER IV

DANGEROUS SECRETS

Once within the borders of her father’s estate and hidden in a clump of bushes near the hedge, all idea of flight left Doris’s head. She was home and the familiar scene gave her confidence. From the middle of her clump of bushes grew a spruce tree, and into it she quickly climbed until she reached a point where she could see the figures in the road beside the quivering machines. She had not been followed. The five men were gathered around Cyril, who was protesting violently at the outrage. They had not missed her yet. Stryker was on his knees beside the stricken wheel.

“Come, now,” she heard the leader saying, “you’re not to be hurt if you’ll give ’em up.”

“Why, old chap, you’re mad,” Cyril was saying coolly. “I was thinkin’ you wanted my watch. You chase me twenty miles in the dead of night and then ask me for cigarette papers. You’re chaffin’—what?”

“You’ll find out soon enough,” said the tall man gruffly. “Off with his coat, Jim.... Now search him.”

Cyril made no resistance. Doris could see his face quite plainly. He was smiling.

“Rum go, this,” he said with a puzzled air. “I only smoke made cigarettes, you know.”

But they searched him thoroughly, even taking off his shoes.

“I say, stop it,” she heard him laugh. “You’re ticklin’.”

“Shut up, d—n you,” said the tall man, with a scowl.

“Right-o!” said Cyril, cheerfully. “But you’re wastin’ time.”

They found that out in a while and the leader of the men straightened. Suddenly he gave a sound of triumph.

“The girl!” he cried and, rushing to the limousine, threw open the door.

“Gone!” he shouted excitedly. “She can’t be far. Find her.”

He rushed around the rear wheels of the limousine and for the first time spied the gate in the hedge.

“Tricked, by God! In after her, some of you.”

“It won’t do a bit of good,” remarked Cyril. He was sitting in the dirt of the middle of the road near the front wheels of the machines. “She doesn’t smoke, o’ chap. Bad taste, I call it, gettin’ a lady mixed up in a hunt for cigarettes. Besides she’s almost home by this. The house isn’t far. She lives there, you know.”

In her tree Doris trembled. She was well screened by the branches and she heard the crackle of footsteps in the dry leaves as the searchers beat the bushes below her, but they passed on, following the path toward the house. As the sounds diminished in the distance she saw Cyril still seated on the ground leaning against the front wheels of the touring-car while he argued and cajoled the men nearest him. Helping himself by a wheel as he arose he faced the tall man who had come up waving his revolver and uttering wild threats.

“It won’t help matters calling me a lot of names,” said Cyril, brushing the dust from his clothes. “You want something I haven’t got—that’s flat. I hope you’re satisfied.”

“Not yet. They’ll bring the girl in a minute. She can’t have gone far.”

Cyril glanced around him carelessly and brushed his clothes again.

He had discovered that Stryker had put on the spare wheel and was parleying with one of their captors.

“Oh, very well. Have your way. What more can I do for you? If you don’t mind I’d like to be going on.”

“You’ll wait for the girl—here.”

Doris watched Stryker skulking along in the shadow of the limousine. She saw him reach his seat, heard a grinding of the clutches and a confused scuffle out of which, his blond hair disheveled, his shoulders coatless, Cyril emerged and leaped for the running-board of the moving machine.

“You forgot to search the limousine,” she heard him shout.

The tall man scrambled to his knees and fired at the retreating machine while the others jumped for the touring-car.

It had no sooner begun to move than there was a sound of escaping air and an oath from the chauffeur.

“A puncture,” someone said. And Doris heard a volley of curses which spoke eloquently of the sharpness of Cyril’s pocket-knife.

Doris in her hiding-place breathed a sigh of relief. Cyril had gotten safely off, and his last words had created a diversion in the camp of the enemy. They were working furiously at the tire, but she knew that the chance of coming up with Cyril again that night was gone. Now that the affair had resulted so favorably to Cyril she began to regret her imprudence in remaining to see the adventure to its end. Cyril had played for time, and if she had followed his instructions she could have gotten far enough away to have eluded her pursuers. By this time, in all probability, she would have been safe beneath the parental roof. The worst of it was that Cyril thought her safe. The packet in her glove burned in her hand. Beneath her, somewhere between her refuge and the house were two men, and how to pass them with her precious possession became now the sole object of her thoughts. Cyril had told her that the packet must under no circumstances fall into the hands of their pursuers and the desperateness of his efforts to elude them gave her a renewed sense of her importance as an instrument for good or ill in Cyril’s cause—whatever it might be. Now that Cyril had gone she felt singularly helpless and small in the face of such odds. For a moment she thought of hiding the packet in the crotch of one of the branches where she might come and reclaim it at her leisure and go down and run the chance of being taken without it. But the unpleasantness which might result from such an encounter deterred her, and so she sat, her chilly ankles depending, awaiting she knew not what. She had almost reconciled herself to the thought of spending several hours in this uncomfortable position when the tall man in the road blew a blast on a sporting whistle and soon the passing of footsteps through the gate advised her that the men inside the grounds had returned.

This was her opportunity, and without waiting to listen she dropped quietly down on the side of the tree away from the gate and, stealing furtively along in the shadow of the hedge, made her way as quickly as possible in the direction of the house. Out of breath with exercise and excitement, when she reached a patch of trees at the edge of the lawn, she stopped and looked behind her. Then she blessed her luck in coming down when she did, for she saw the thin ray of a pocket light gleaming like a will-o’-the-wisp in her place of concealment and knew that the search for her was still on.

Fear lent her caution. She skirted the edge of the wide lawn in the shadow of the trees, running like a deer across the moonlit spaces, always keeping the masses of evergreens between her and the wicket gate until she reached the flower garden, where she paused a moment to get her breath. A patch of moonlight lay between her and the entrance and the hedge was impenetrable. There was no other way. She bent low and hurried forward, trusting to the good fortune that had so far aided her. Halfway across the open she heard a shout and knew that she had been seen.

There was nothing for it but to run straight for the house. So catching her skirts up above her knees and scorning the garden path which would have taken her a longer way, she made straight for the terrace, the main door of which she knew had been left open for her return. Across the wide lawn in the bright moonlight she ran, her heart throbbing madly, the precious yellow packet clutched tightly against her palm. Out of the tail of her eye she saw dark forms emerge from the bushes and run diagonally for the terrace steps in the hope of intercepting her. But she was fast, and she blessed her tennis for the wind and muscle to stand the strain. She was much nearer her goal than her pursuers, but they came rapidly, their bulk looming larger every moment. She saw the lights and knew that servants were at hand. Her father, too, was in the library, for she saw the glow of his reading-lamp. She had only to shout for help now and someone would hear her. She tried to, but not a sound came from her parching throat. With a last effort she raced up the terrace steps, pushed open the heavy door and shut and bolted it quickly behind her. Then sank into the nearest piece of furniture in a state of physical collapse.

Doris Mather did not faint, an act which might readily have been forgiven her under the circumstances. Her nerves were shaken by the violence of her exercise and the narrowness of her escape, and it was some moments before she could reply to the anxious questions that were put to her. Then she answered evasively, peering through the windows at the moonlit lawn and seeing no sign of her pursuers. In a few moments she drank a glass of water and took the arm of Wilson, her maid, up the stairway to her rooms, after giving orders to the servants that her father was not to be told anything except that she had come in very tired and had gone directly to bed.

For the present at least Cyril’s packet was safe. In her dressing-room Wilson took off her cloak and helped her into bedroom slippers, not, however, without a comment on the bedraggled state of her dinner dress and the shocking condition of her slippers. But Doris explained with some care that Mr. Hammersley’s machine had had a blow-out near the wicket gate, that she had become frightened and had run all the way across the lawn. All of which was true. It didn’t explain Mr. Hammersley’s deficiencies as an escort, but Wilson was too well trained to presume further. A little sherry and a biscuit and Doris revived rapidly. While the maid drew her bath she locked Cyril’s cigarette papers in the drawer of the desk in her bedroom, and when she was bathed and ready for the night she dismissed Wilson to her dressing-room to wait within call until she had gone to bed.

Alone with her thoughts, her first act was to turn out her lights and kneel in the window where she could peer out through the hangings. It was inconceivable that her pursuers would dare to make any attempt upon the house, but even now she wondered whether it would not have been wiser if she had taken her father into her confidence and had the gardeners out to keep an eye open for suspicious characters. But the motives that had kept her silent downstairs in the hall were even stronger with her now. She could not have borne to discuss with her father, who had an extraordinary talent for getting at the root of difficulties, the subject of Cyril’s questionable packet of cigarette papers. She was quite sure, from the adventure which had befallen them tonight, and the mystery with which Cyril had chosen to invest the article committed to her care, that Cyril himself would not have approved of any course which would have brought the packet or his own actions into the light of publicity.