автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу In Search of Mademoiselle

“Then I left her.”

IN SEARCH OF

MADEMOISELLE

By

GEORGE GIBBS

HENRY T COATES

& CO.

PHILADELPHIA

1901

Copyright, 1901, by

HENRY T. COATES AND COMPANY.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

TO THE MEMORY

OF

MY FATHER

THE LATE MEDICAL INSPECTOR

Benjamin Franklin Gibbs,

UNITED STATES NAVY.

NOTE.

There were no more vivid episodes in the colonization of the New World than those resulting from the attempts of the French people to gain a permanent foothold on our shores. This fact has long been recognized by sober historians as well as by the writers of fiction, for all the fascination of romance holds over the whole field of inquiry.

The most thrilling chapter in all this history, strangely neglected or overlooked by the romantic writers, is that of the struggle between the Spanish and French colonists for dominion over our own land of Florida. To me, whose profession it is to see pictures in the words of other men and to produce them, this historic page has appealed very strongly as the proper setting for a human drama—an inviting canvas upon which the imagination may paint a moving picture of the emotions, desires and passions—the loves and hates—of men and women like ourselves—against the somber and sometimes lurid background of historic fact.

I have tried, so far as I have used history, to be scrupulously exact. I have carefully read the original or authorized editions of the writings of Hakluyt, Réné de Laudonnière, and a number of others; but there is little to be found in them which will not also be found much more vividly depicted in the writings of Mr. Francis Parkman. Some of the names will be recognized. Jean Ribault, Laudonnière, Menendez, the Indians Satouriona, Olotoraca and Emola, and others, were all real men. As for those others who are of the imagination—as for Mademoiselle and those who searched for her, it is to be hoped that they will not be found at odds with the events and scenes in which they are placed. These things, or others like them, must have been, for the writer of historic fiction may rely on the fact that human nature remains much the same, no matter how great the lapse of years.

G. G.

Bryn Mawr, March, 1901.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER.

PAGE

I.

Of my Meeting with Master Hooper1

II.

Of the Taking of the Cristobal10

III.

Mademoiselle29

IV.

Of my Bout with De Baçan39

V.

Dieppe51

VI.

In which I Learn Something65

VII.

In which I Find new Employment81

VIII.

We Reach the New Land95

IX.

We Put to Sea110

X.

The Hericano124

XI.

What Befell Us upon the Sand-spit135

XII.

Truce150

XIII.

The Line upon the Sand164

XIV.

The Martyrdom174

XV.

The Lodge of Seloy189

XVI.

Of our Escape204

XVII.

In which we Journey to Paris219

XVIII.

The Poet King235

XIX.

I Meet the Avenger252

XX.

We Set Forth Again267

XXI.

We Form an Alliance281

XXII.

Olotoraca298

XXIII.

The Moon-Princess314

XXIV.

We Advance329

XXV.

The Death of the Wolf344

XXVI.

And Last361

ILLUSTRATIONS.

By GEORGE GIBBS.

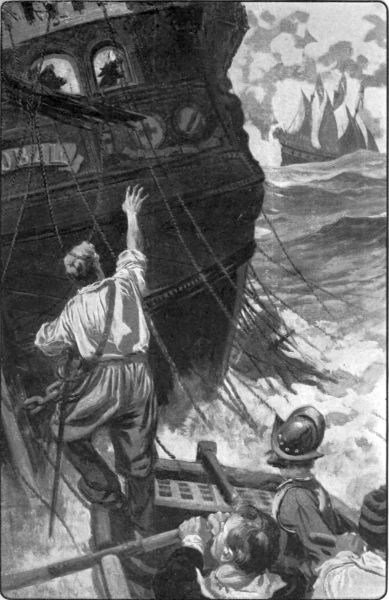

“Then I left her.”(Page 115)

Frontispiece.

PAGE

“A moi! a moi!”24

“A line in the sand!”170

“Quick as he was, my hand was ever quicker.”357

IN SEARCH OF MADEMOISELLE.

CHAPTER I.

OF MY MEETING WITH MASTER HOOPER.

It has ever been my notion that apology is designed to conceal a purpose rather than to express it; that excuse is not contrition but only self-esteem. Therefore it seems ill-fitting to begin my narration thus, especially as there are many Spaniards who will say that I lie in all that I have written. But this will matter little to me, for I have had good confirmation in the writings of their own priests and chroniclers. Before many years are gone, I will rest peaceful in the churchyard at Tavistock and the ranting of any person, of whatever creed will avail little to disturb my bones. I shall die believing in God Almighty; that is enough for me.

These blind fanatics think themselves privileged to commit any crime in His name. They speak of God as though they owned Him; as though none other were in a position even to think of Him with any understanding. But indeed there is little to choose between the madmen of any races. Twenty years have barely passed since Thomas Cobham sewed eight and forty Spaniards in their own mainsail and cast them overboard. Not long agone certain English soldiers in Mexico filled a Jesuit priest with gunpowder, blowing him to pieces.

I do not attempt to justify my part in the happenings of which I am to write, and the terrible retribution brought upon the Spaniards. I can only say that my own intimate life and love were so twined into these events that I followed where my wild heart led, as one distraught. It is enough that I loved—and now love—Diane better than woman was ever loved, and that I hated Diego with a hate which has outlived death itself.

Being but a blunt mariner and God-fearing man, with a knowledge of the elements rather than any great learning of the quiet arts, the description of these happenings lacks the readiness of the skilled writer, from whose quill new quips and phrases easily pass. Yet, what I, Sydney Killigrew, am to write has virtue in its reality; and its strangeness may even exceed those tales written by the sprightly wits of London, whom I am told it is the fashion of Her Majesty to gather about her.

For although a true report of the people of Florida has been made by Admiral Jean Ribault, the story of the great deception practised upon him by that Spaniard, Menendez de Avilés is now for the first time to be truly written by one who was with the Frenchmen at that time. And in view of the English settlements which may shortly be made by Her Majesty to the northward, it seems proper and valuable that this should be written.

The more do I deem this my duty when I consider the cruel wars which men have fought for the modes by which the good God may be worshiped. Reformist, New Thinker, or whatever I may be, these events have only convinced me of the truth of the saying of my father, “Live thy life right, my young mariner, and thy mode of faith will be forgiven.” That great, good father—naval commander of his king, Councilor of the Realm, noble in life as in lineage—upon whose talents and genius every half-hearted earl in the kingdom had laid a claim! For whatever he may have lacked in wisdom for the betterment of his own estate in the world, he had ever the wit to advise others to their great good fortune and happiness.

As I stood against a pile on the great dock at Plymouth and looked across the fine harbor through the network of rigging, I thought of the days of the Great Henry when good ships well manned and victualed, and commanded by men of valor and ingenuity, were ready at all hours to uphold the dignity of their king upon the water.

Now all was changed. The mighty fleets that lay off in Plymouth Sound in Henry’s day, had rotted in anchorage and not a halliard had been rove on a ship of the line for fifteen years. Discipline on royal ships was a matter of no account, for no man knew what change the week to come might work in his command. Even now the coasts of England lay open to the attack of any foreign ships that might choose to run in and fire the broadsides of their great new pieces of ordnance. Here in Plymouth harbor lay but four revenue ships of one hundred tons, and three converted merchant brigs which had been lightly armed. At London there were perhaps as many more, and these were all,—all that great fair England had in her harbors to ward off danger from the Spaniards, ever ready and watchful across the channel! There was naught for a seaman to do; and if a Bible or prayer-book chanced to be found on board any ship in Papist waters, she would be confiscate forthwith and her company of seamen would be carried to the prisons of the Inquisition.

A voyage in the narrow seas, from which I had returned but a few days before, more than anything else had given me the desire to see service with some foreign nation where a stout arm had more value than a heart set on “paternosters” or psalm books.

In truth, though this trouble was partly of my own making, I had had enough of the merchant service. To go back to Tavistock was not to my liking; for though I had a taste for peace among men I had no stomach for a life of idleness. I had been bred by my father to the sights and smells of the sea, the voice of which was more grateful to my ears than the sounds of the wood-birds which had ever seemed to me mere shrill and noisy pipings. And though in no manner a brawler, a life of enterprise suited me mightily.

As I labored in this quandary, a hand was laid upon my shoulder and a rough voice at my side said heartily, “Why,—is not this Sydney Killigrew of Tavistock?” And turning I saw Master David Hooper, my father’s friend, who went as Master Commander in the last cruise of the Great Harry.

“None other, Captain Hooper!” said I, grasping with great joy his hairy fist. He held me off at arm’s length and looked at me carefully, noting my great stature with evident enjoyment.

“The very image of thy father—though, by my faith, thou’rt built upon a more sumptuous scale. But, lad, what’s wrong? You’ve the air of a farmer’s boy two days from land.”

And with that, after other exchanges of compliments, I told him how the world had gone with me; how our estates had fallen from bad to worse and how little chance there seemed of pursuing the calling upon the ocean I loved and wished for. He heard me through, tapping the while thoughtfully with his fingers upon the pier head.

“Come,” said he at length, “let us go to some place where we can discuss thy affairs at leisure.”

And he led the way from the dock up the street to the Pelican Inn, where seafaring men such as ourselves were wont to go for a pot or so of Master Martin Cockrem’s own brewing. Once seated there in the quiet window seat overlooking the Sound, he questioned me closely as to my disposition in religious and political affairs. Then finding that I was not averse to taking up a true life of adventure upon the sea, he unburdened himself of his own plans for the future.

“You know, lad, of the state of the Royal Navy. Nothing I can say will make you feel that the merchant service is secure from injury at foreign hands. Great Harry, the wonder of all Europe, lies rotting her ribs yonder, and there are no capable ships afloat. France would love well to see us all singing our ave Marias and salves in our deck watches, yet she has no love for the greed of Philip. So I say, lad, there is no present danger.”

“And yet,” said I, “our commerce has been reduced to less than fifty thousand tons.”

“Softly, boy. Our carrying may not be so great as in the days of Harry, but neither France nor Spain carry more. For our own brave fleet of gentlemen cruisers has made sad havoc of their barques on the ocean, and not a Papist ship dare show her nose within a dozen leagues of the Scilly Isles.”

“But these free ships have no warranty from the Queen.”

“Marry, lad, you’ve the wit of a babe scarce out of swaddling clouts. Can ye not see how the wind sits? The Queen knows well how much she needs these independent ships of war. For reasons of state she may not openly encourage our enterprises; but, laddie, I tell you she has a secret love for them. As for warranty, what more would ye have than that?”

And so saying, he put upon the bench between us a large parchment bearing the Great Seal of State. I scanned the document in an uncertain mood. For it set forth with many flourishes the rights “of one Master David Hooper to trade upon the oceans and to use his best endeavors to restrain by forcible or other means any enemies of Her Majesty from doing hurt or offering hindrance to any English persons or vessels on the high seas.”

“Why, then, Captain Hooper,” said I, “you are still in the Royal Service.”

“We are all in the service of the Queen, lad. This license guarantees nothing and is in fact, to ordinary eyes, but a license to trade; and yet is it not of greater worth than a royal commission as captain in a navy which does not exist? A license to trade! Ouns! and such a trade! Why, lad, what is your ship’s cargo of wool stuffs to an after-castle full of silver flagons and Spanish ducats—with a taste now and then of good Papist wine to clear the gunpowder from your throat? Let them prate. Their undoing will be the greater. I tell you, we gentlemen adventurers stand yet between Spain and the mastery of the seas. It may come to pass that one day they will try to cross the channel,—they will never land, lad. All this and more the young Queen knows well. For though she has a grievous way of looking displeasure at one minute, she has as happy a one of winking merrily the next.

“So it is, ye see, that Drinkwater, together with Cobham, Tremayne, Throgmorton, and others among us have survived both the prison and the noose and put to sea again with no greater loss than the proportion of the captured articles Her Majesty sees fit to take for the replenishment of the Treasury. This then is how the matter stands; so long as we masters may sail successfully, making no complications with France or the other countries to the north and east, Queen Bess wishes us a light voyage out and a heavy one home, and indeed delights in our tales of fortune, to which she is wont to listen with sparkling eyes. The bolder the deeds the better they are to her liking.”

I listened to this secret of state with eyes agog. Master Hooper paused in his talk long enough to drain his pot, which he set down abruptly upon the table.

“Come, Sydney,” said he with a smile, and stretching both hands toward me, “what say ye to a voyage with David Hooper for a shipmate, in a bottom staunch from batts-end to keelson, the wind and seas for servants, and never a doubt but that to-morrow will be better than yesterday! Or perhaps the gruntings of the swine at Tavistock hold newer charms? What say ye?”

Were it in my mind to debate upon an immediate answer, the mention of the pigs at Tavistock had done more to remove that uncertainty than aught else the gallant captain might have said. So I told him that his proposition was much to my liking, and, could I be of service, the swine at Tavistock might be larded for a lout with better land-legs and stomach than I.

Thus it was that I came to be the third in command of the Great Griffin on her fourth voyage out of Plymouth.

CHAPTER II.

OF THE TAKING OF THE CRISTOBAL.

Like many other English ships engaged in private enterprises at this time, the Great Griffin was of no great bulk, having a tonnage of but a little more than three hundred. Nor had she the great after-castles and fore-castles of the Spanish galleons; but her bulwarks were stoutly built, and high enough to give such protection against the arrows and small pieces of the enemy as might be necessary to those who handled the tier of eighteen and twenty-pounders on the main deck. The after-castle, or poop as it had come to be called, was raised but one deck, and here again were mounted several patereros of modern fashion for use at short distances. The guns being all mounted upon the upper deck, made open ports below of no necessity; and so, even in rough weather, all of her ordnance could be brought to bear. The company was made up of merchant sailors and coasters,—taken altogether a hardy lot, yet gentle and quite unlike the reports of them which had reached our ears from the mouths of the Spaniards. The Griffin had three tall masts, and upon them were set sails patterned after the wonderful new invention of Master Fletcher of Rye. For the spars, in lieu of being made fast athwart the ship, so set to the masts as to lay forward and aft, it being thus possible by the hauling upon certain tackles to shift the sails from the one side to the other with great speed and small exertion. This invention permitted the ship to perform the strange feat of sailing almost directly into the wind, and allowed great advantages in getting to windward of larger ships. Though I had seen ships of this fashion in the Channel, never before had I sailed in one of them; so the easy manner of working and the simpleness of the rigging and tackling gave me a great pleasure.

Standing on the after deck and looking forward one could note the strong lines of the barque. For, unburdened by the tophamper of the galleons, the bulwarks, barring the break at the fore-castle, took a graceful curve and met above the bed of the bowsprit, which made into the head where it was solidly bolted to the deck below. At the forward part of the fore-castle was mounted a great head of a dragon, with yawning mouth and wide eyes that looked over the waters ahead as though in search of its rightful quarry.

As I looked aloft and saw the new sails yellow and purple in the morning sun, big-bellied under the stress of a fine breeze from the east, the stays to windward taut as iron bars, the fellow at the helm leaning well to the slant of the deck, methought I had never seen so splendid a sight, and thankful was to I be alive and able to enjoy the beauty of it. The freshening breeze piled up the waters, and the green of the curl topped by its filmy cloud lifted itself to be caught in a trice and carried down the wind against the broad bows of the ship, or indeed at times, over the bulwarks, singing as it flew a mellow song more pleasing to my ears than any other earthly melody.

Master Hooper, by reason of his previous service, maintained to a high degree the discipline of the old navy; and the company of the Great Griffin was thus unlike those of many of the free sailers of the time, which for the most part were composed of men who had used the sea in various ways but had no knowledge of the customs aboard regular ships of war. To gain that knowledge the men of the Griffin were each day exercised at the guns and were practised in the use of the sword and pike, while the bowmen and arquebusiers had targets set upon the fore-castle which they shot at from the poop with great speed and nice judgment. The pikemen and swordsmen had a proficiency I never saw equaled in France or in Spain; and Master Hooper—they called him “Davy Devil”—had an exercise which he called the fire practise, which more than aught else showed his ingenuity in providing against panic or mishap. Two years before, a large part of the company had rebelled against the second in command, who had caused one of their number to be strung up at the mast by the thumbs. Captain Hooper being ashore at the time, matters might have gone badly with the officer, had not a messenger been immediately despatched to the inn where he was stopping. Then came Master Hooper in great haste and caused the alarum of fire to be sounded. So nice had been his discipline that each man went to his appointed place, waiting there until Master Hooper appeared upon the poop and gave them a round speech upon the quality of obedience as practised in the navy of Henry the Great; to the end that, there being no fire to quench, they quenched themselves and went about their several duties.

On the morning of the second day from Plymouth we sighted a sail to the south, and discovered her to be a crumster of New Castle, bearing French Protestants from Havre to Bordeaux. The Captain, Master Tremayne, related a sad tale of the manner in which several persons who should have gone with him were taken by the officers of the Inquisition at Havre, as they were about to make their escape to his vessel.

The martial spirit of Master Hooper had done much to shake the serenity of the merchant life out of me, and the sight of several gentlewomen below decks aboard the crumster, with the pink rings of the manacles and the red scars of the fire still upon them, so inflamed me that I vowed no feeling of charity should stand between me and the duties of justice. Captain Tremayne also told us that during the night he had run afoul of a Spanish vessel of large size, who had hailed him and was in the act of sending boats aboard when a fog fell and he had pulled away under its friendly cover. After some further parley Captain Hooper set sail on the Griffin and steered boldly to the south, hoping thus to sight this Spanish sail during the afternoon; and true enough, in the first watch a large ship was made out under topsails and spritsail, standing for the coast of France. Upon sighting us the stranger hove about and took a course which the Great Griffin must cross in an hour or so.

Master Hooper, not knowing the strength of the ship and wishing to draw her further from the coast where Spanish cruisers in great numbers lay in wait for Huguenot vessels, put up his helm and stood off. The wind however blowing smartly, he soon found the Griffin to be drawing away from the stranger, who was laboring heavily in the great seas. In order therefore to slacken our pace without attracting notice, Master Hooper caused one of the spare mainsails to be lowered over the stern. So soon as this sail touched the water the speed of the Griffin caused it to fill and act as a drag which notably diminished our rate.

The Spaniard, for such the vessel now appeared, began drawing up, until in the course of an hour or so we could mark his tiers of guns as they frowned out over the water to windward. So light was our top hamper and so steady was the drag astern that we appeared to toss but little in the seas. But the Spaniard yawed and rolled in so frightful a manner that the sails at times seemed hardly to be restrained by their sheets, and flapped so noisily that they boomed like long cannon. She went over at so great an angle that her decks and castles crowded with the men at the guns were plainly to be seen.

Yet she presented a fair sight as she came down upon us. Despite the squall, the sun stole between the rifts of the clouds and here and there turned the tumbling purple mass into molten gold. The sails, catching the glint, were bright against the darkening horizon, and made so fair a vision that she seemed the abode of some water-princess rather than the battery of a horde of barbarians seeking life and unworthy profit.

When she came to what may have seemed a reasonable distance, a cloud of smoke puffed from a point forward and a column of spray shot up from the water at several hundred yards on our quarter. The Spanish colors were then run up quickly, and this movement was followed by Master Hooper, who sent to the mainmast head the pennant of the Queen.

Little by little the course of the Griffin had been laid to the windward, so the Spaniard now sailed at a distance of about half a mile; and as other shots now began falling somewhat nearer to us, the captain ordered the tackle which secured the drag-sail to be cast off, and they hauled it aboard. The Griffin, eased of her load, sprang forward like a scurrying cloud, the fellow at the helm moving her closer and closer into the eye of the wind till the starboard leeches were all a-tremble; then he held her as she was, enabling the Spaniard to come within gunshot.

The balls now fell too close for ease of mind, and the splinters from two of them, which struck us fair amidships, made an end to three gunners who were at their stations. In a great ferment I saw them carried below to the steerage, crying aloud in pitiful fashion. Captain Hooper hereupon let his ship go off a little to get her headway; the gunners cast loose the long eighteen-pounders, and the after guns were soon doing some execution in the enemy’s rigging, and our shots still told after the Spaniard’s shots began falling astern, or were so badly aimed that they flew wild and did us no hurt. Seeing that the range of the Spanish ordnance was shorter than our own and marking our great advantage in this matter, Captain Hooper put the ship upon the other tack and hove her to with the wind to the larboard, thus enabling the entire starboard broadside to be got into action. The roll of the Griffin greatly disturbed the gunners, but after some minutes, by firing high upon the roll to leeward, many shots flew straight for the Spaniard, so that soon we saw first his bowsprit and sail, and then his foremast go by the board.

There was a great commotion behind me, and I turned to see a fellow jumping up and down and slapping his thigh in great glee. “How now, sir,” I said, somewhat sternly, “are you mad?”

He turned to me with a grin.

“’Twill be poor smellin’ in the Bay o’ Bisky, say I. Did ye see me snip off his nose? Did ye? ’Twas my shot, sir. He’ll want a bigger ’kerchief than a spritsail now, I’ll be bound.”

The wreck so encumbered the deck of the Spaniard that it was some minutes before any order could be brought about and the galleon again put to the wind. Master Hooper clewed up his lower sails, eased off his sheets, and taking up a position on the enemy’s weather-quarter poured in at easy range a fire which swept the crowded decks and created a panic among the Spanish gunners. The cries of the wounded and dying we could hear faintly, but by the movements of the officers on the after-castle, who ran here and there brandishing their swords, we were able to surmise a sad lack of discipline among the company. On the Griffin the divisions waited for the word of command from the officers, firing thereupon with great regularity and precision. Though now, as we came again into range, the Spanish shots told here and there, and great white splinters flew in all directions, such men as were unhurt remained at their stations, the injured among them being replaced by others from those detailed to navigate the ship.

So unwieldy was our adversary that she could not come up into the wind because of the great encumbrance of her head gear, and so was forced to wear around; and as she did so, Davy Devil who had been awaiting this opportunity to rake, fired the entire larboard broadside. The Griffin, no longer lying in the trough of the sea, sailed more steadily than before, and the effect of this broadside was terrific. Not less than four shots went through the ports of the Spaniard’s after-castle and one, more lucky than the others, passed just over the rail and struck the mainmast below the yard, and over it went on the next roll to leeward, the tackling dragging with it the mizzen-topmast which flew asunder at the cap with a crackling heard loudly above the booming of the ordnance.

“She’ll need a new bonnet, Master Killigrew, to be in the fashion again,” said Davy Devil behind me.

We could not at this time have been at a greater distance than two cable-lengths and Master Hooper, believing the enemy about to strike his colors, brought his sails home and directed the helmsman to haul up alongside. No sign being heard or seen, two anchors were got out and men lay aloft on the yards ready to cast them upon the Spaniard’s decks. Three,—four minutes, Master Hooper waited, withholding his shot. Then, the Spanish demi-culverins again opening fire upon us to our great disadvantage, the word was given to discharge another broadside, the gunners then to crouch behind the bulwarks and cubbridges and prepare to board.

No ship could have withstood the shock of this fire! For discharged at such close range the shots tore through the bulwarks and planking with a horrid sound, the splinters, as we found, killing and maiming many who had gone below for protection.

At this moment a single tall figure appeared upon the after-castle making a signal of submission. Upon which Master Hooper sheered off and hove the Griffin into the wind that he might mind his damages and care for his wounded.

The weather having moderated, a boat was called away to go aboard the prize, and Master Hooper giving me charge, I put off for the Spaniard. On account of the heavy sea still running the boarding of the vessel was no easy task. In spite of the dismantled rigging which lay over her sides, she wallowed far down in the trough like a shift-ballast, the seas dashing against her and lashing the foam over her waist in feathery clouds. At length, with some difficulty, the coxswain hooked a ring-bolt in her side to leeward and I hauled myself over the bulwarks.

On deck a gruesome sight awaited us. The wreckage of the foremast and the yards lay where they had fallen and obscured the view of the fore-castle where a party of the company were hacking away at the wreck with their axes and swords. The ship was flush-decked in the waist, after the fashion of vessels in the carrying trade, and the men who worked the guns had thus been exposed to the worst of our fire which had raked them en echelon—as the French have it—from foremast to poop. Many of the cannon, small culverins and swivels of Italian make, were dismounted and lay askew, frowning inboard. Piled here and there were bodies, many lacking in human semblance and presenting a ghastly spectacle after the cleanly decks of the Great Griffin.

Moving carefully over the slippery decks, I came at last to the poop, below which stood one who, by reason of his immense stature, towered head and shoulders above those around him. I am not like to forget this early impression made upon my mind by Diego de Baçan; for, surrounded as he was by a scene of blood, there seemed some demoniac sympathy between his figure and the carnage about him. There was that in the contour of his face which reminded me of the doughty Ojeda, possessing a hideous beauty like only to that of the evil one. The sun behind him glinted on the visor of his morion from the shadow of which his eyes gleamed darkly. His black beard, which came at two points, framed in a jaw set squarely enough on his great neck, and his wide shoulders even over-topped mine both for breadth and height. He leaned easily with one hand upon the rail, looking, in his polished breast piece, so splendid that I could not but mark the difference between his garb and mine, which was but that of the merchant seaman, ungarnished by any trappings of war.

Scorning the salute I proffered him, he spoke coldly, in English, without further ado.

“You would speak with me, señor?”

“My mission,” I replied, “is with the commander of this ship. If you are he, you will go with me yonder.”

“The commander of the San Cristobal is dead. I am Don Diego de Baçan. But I will go aboard no heretic pirato.”

“We are no pirato, señor,” said I calmly, “but a free sailer of Her Majesty, Elizabeth of England, whom you have attacked without warrant.”

“And if I will not go?” Here he drew himself up to his great height, folded his arms and frowned at me defiantly, while a dozen or so of his pikemen stood at his back and scowled fiercely. But, in my position, black looks caused no tremors.

“If you will not come,” I answered steadily, “my orders are to bring you,—this I will do; failing to return before the next stroke of the bell, my captain will sink you as he would a rotten pinnace.”

He looked about him at the scene of havoc, and smiled bitterly. Then, with a word to his pikemen, who still surrounded us, his manner changed.

“Señor,” he said more quietly, “you see how it is with us. The Cristobal takes water at every surge. She is a wreck. What am I to do? To continue the battle were only to sacrifice the remainder of my company. I must surrender.” He cast down his eyes. “Yes, there is no help for it. I will go with you. But if, señor,” and here he raised his head and eyed me like a hawk from cap to boot, “if you deem your victory one of personal prowess and have the humor for further argument, I shall meet your pleasure.” His words came calmly, yet he leaned forward and seemed about to raise his hands toward me. I folded my arms and looked him in the eyes. They had lost their quiet and flashed at me furiously. His great fingers twitched nervously as though to catch me at the throat. He was glorious. And then I made a vow that, so far as it lay in my power when time and place fitted, his taunt should have an issue.

“Why, that will be as it may be,” I replied evenly, “at present you are to follow me aboard my ship.” Seeing my attitude, he grew calmer and shrugging his shoulders, turned away.

“As you will;” and then after a pause, half courteously, “You will permit me to give some final orders?”

“Orders in future must come from my captain.”

“But, señor,” he cried, “these are but some matters relating to the repair of the ship.”

Seeing no harm in this, I allowed him to turn and speak in a low tone to one of his pikemen, whereupon the fellow went below.

The Griffin had meanwhile hauled up within speaking distance and, mounting the after-castle, I hailed Captain Hooper, acquainting him with the condition of affairs aboard the Cristobal. The weather being still too rough to heave the Griffin alongside, I obtained further instructions to bring the Spanish officer aboard that the disposition of the prisoners and other matters might be more readily discussed and considered.

So ill-governed was the crew that as we got down into the boat the pikemen and gunners leaned far over the bulwarks, cursing us for dogs of heretics, and one of them spat in the face of a sailor named Salvation Smith, who would have killed him with a boatpike had not the coxswain, Job Goddard, stayed his hand. The wind now blew less vigorously and, though the sea still ran high, there seemed less danger than on the outward passage. But, as we rounded out from under the lee of the Spaniard, my fine fellows setting their broad backs to the stroke, there came from one of the gallery ports a cry of distress, the voice of a woman,

“A moi! a moi! For God’s sake, help!”

“A moi! a moi!”

The oars hung for a moment in the air as though the sound of those English words had stricken the boatmen motionless. Then as I half rose from the thwart, with one accord the starboard oars gave a mighty stroke and the bow of the boat swung over under the many-galleried stern of the Cristobal. A glance at the port showed a face and the flutter of a kerchief, while from within came the clashing of metal and the curses of men. As we swung in, a piece of wreckage and tackling hung near us and when our stern rose on the crest of the wave, I could reach it, and hauled myself clear of the boat and up to the projection of the lowermost gallery. As I raised myself I saw two boats drop from the side of the Griffin and knew I should not long be without aid. On reaching the port the sound of the conflict became more distinct and I heard the hard breathing of the disputants; so without more ado, I raised myself over the sill with an effort and clambered in.

Before the door leading to the passage of the half-deck a tall, slim figure in sombre garb moved from side to side, making so excellent a play with his sword, that the pikemen who were thrusting at him furiously from the narrow corridor had small advantage. A woman lay upon the floor and another crouched in the corner. On seeing me come forward one of the pikemen fell back, but the other aimed so vicious a blow at the swordsman that, had he not been thrown aside, it must surely have ended him. The force of the thrust threw the villain forward into the cabin, where, being off his guard by reason of his pike handle fouling the doorjamb, he came within reach of my hand, which struck him full in the mouth, laying him sprawling over a sea chest. Salvation Smith, singing a psalm, and Job Goddard, swearing loudly, here tumbled in at the port and following into the passage laid about them lustily with their weapons, to the end that in a few seconds the place was cleared and the outer door made fast. To our great amazement no further attempt was made upon the door, nor indeed was there any commotion above us or on the deck; but upon returning to the port the reason of this was clear, for the four boats of the Griffin were sweeping around the stern, the fellows lying to their oars with vigor and the pikemen standing upright, their jaws set and the glitter of battle in their eyes. Over the Cristobal they came swarming, driving the men forward where they huddled upon the fore-castle like a slave cargo. They had no spirit, for not a shot or an arrow was fired, and Master Hooper found himself in undisputed possession of the prize.

Having now no further alarm for the outcome of the affair, I directed the door to be unfastened and turned my attention to those within the cabin.

I have never made boast of courtly ways, thinking them mere glitterings and fripperies of the idle, designed to hide a lack of sturdier qualities. Few women had I known, and in my boisterous life no need had come for handsome phrases, yet would I have given whatever interest I possessed or might come to possess in this or other prizes, for the readiness of wit to clothe my rough speech in more courtly apparel. There was a quality of nobility and grace in the figure of the maid in the cabin that cast my rugged notions to the winds and made me seem the swash-buckler that I was. In stature she was tall and carried herself with the pride and dignity that are ever the birthright of true nobility. No exact description can I put down of the appearance and demeanor of Mademoiselle Diane de la Notte; for not poetry but only dull prose can run from my unmannerly quill. I only know that a radiance was shed upon me, and all the senses save that one which controlled my heart were blinded and inert. So acute indeed was this feeling of my moral littleness that I did naught but stand shifting from one foot to the other, toying in silly fashion with the hilt of my sword. Had it not been for the maid herself I know not what uncomely thing I might have done. But Madame, who had lain swooning on the floor, now recovering consciousness and thus removing her anxiety Mademoiselle raised her head and spoke to me.

“Monsieur, we do not know what is your calling or command—whether adventurer or Queen’s officer—but you are a valiant man,” saying other things I so little deserved that I cast down my eyes and replied in some embarrassment that my men, not I, deserved her kindness—God knows what we had done was little enough and easy of accomplishment.

But she would not have it so, adding further, “The La Nottes are not ungrateful and their blessings will fall forever on you, sir. It may happen that your service may one day have its reward. But now,”—and a deep sigh burst from her, “alas! we can do nothing, not even for ourselves—nothing!” It seemed as though her voice were about to break, but bending quickly forward she applied herself anew to Madame lying at her knee, the picture of feminine strength even in despair. I was so affected by her anguish that I could find no words to say to her, and while I still wondered who could seek to do them injury, I moved to the Sieur de la Notte, who sat upon a chest staunching the blood which flowed freely from a pike wound in his wrist. He was much exhausted by his encounter, so I aided him to bind his arm, after which I withdrew and went upon the deck to make my report to Master Hooper.

CHAPTER III.

MADEMOISELLE.

After awhile the Sieur de la Notte came on deck to Master Hooper and disclosed the story of his persecution and the circumstances which led to his capture and imprisonment. His tale was, in short, the tale of a hundred others. He had become a follower of Calvin and had even preached and written the new religion. His estates were soon confiscated and he was forced to flee into the night with his wife and daughter, carrying only the jewels and valuables to which he could lay his hands.

“And what, Monsieur,” asked Master Hooper, when he had done, “of your adventure in the cabin?”

“That is soon told. When the action began, the commander of the Cristobal, Don Alvarez, sent us below, cautioning us not to appear upon the deck. Don Diego de Baçan himself locked us in the after cabin. The battle over there came a sudden movement at the outer door and two pikemen rushed into the corridor and set upon me vigorously. So sudden was the onslaught I had scarce time to set myself on guard. But I managed to draw and use my sword to such good end as to confine the fellows in the narrow passageway, where I had them at a disadvantage. Yet, what might have come of us had not yonder giant interposed——”

“But the cause of this attack?” asked Captain Hooper.

“You must know, Monsieur,” replied the Frenchman, “that under the deck of that cabin is a chest containing many thousand crowns. It was upon the Huguenot ship from which we were taken and was intended by Admiral Coligny for certain troops under arms in the north.” Captain Hooper’s eyes sparkled. He would have liked to take that chest upon the Griffin. But he had his orders and dared not without the consent of the Queen take even salvage of treasure or property belonging to the Protestant party.

“Captain Hooper,” said I, “the orders for the murder of this gentleman came from the officer, Don Diego de Baçan.” And I related my own imprudence in allowing the Spaniard to communicate with his bowmen.

“H’m! ’Twas a foolish thing,” said Master Hooper, stroking his chin, “but, lad, you’ve atoned for your fault in handsome fashion. And now out with spare yards and masts and try for some steerage way on this storied hayrick.”

There being many bad injuries, the Cristobal took water rapidly and Master Hooper sent all of her crew to removing it. The men mounted stages set at places beyond the reach of the water and made such repairs as would enable her to reach port, provided the weather grew no worse. The injuries below water were stopped from inboard, the wreck was partially cleared, jury masts and temporary spars were rigged in place of those shot away, and, with a wind on the quarter, the Griffin and her prize moved to the eastward toward the coast of France. The Griffin having even more than her complement of men, it was thought best by Captain Hooper to send aboard the Cristobal a large prize crew, of which he made me commander. Many of the more important prisoners were put aboard the Griffin or taken below on the Cristobal, where they were confined in the fore-castle. To my great satisfaction the family of the Vicomte de la Notte were passengers to the city of Dieppe, where they had friends. A matter much less to my liking was the company of Don Diego de Baçan, whose presence even in confinement seemed to me a menace to the safety of the ship and her precious cargo. But it was so ordered by Captain Hooper, for at Dieppe the Spaniard might be exchanged for English seamen imprisoned there as hostages at the demands of Spain. The Cristobal as a prize was to be made over formally to certain agents of Captain Hooper. These agents, who were French, it is said were in the employ of the Queen, but I doubted this after my dealings with them. Having sold the Cristobal and placed the recaptured treasure in the hands of Admiral Coligny, I was to rejoin the Griffin at Portsmouth.

On the afternoon of the second day the Griffin put her helm up and set a straight course for the coast of Ireland, to refit at Kinsale, where Master Hooper kept his goods and stores. All effort having been made to insure a safe voyage I stood at the weather rigging upon the quarter-deck, thinking of many things. I marveled at the wonderful power which had drawn me from myself and made my rough hulk seem to me but the abode of a carnal spirit. Having no quarrel with the world except in matters relating to the betterment of my condition, I had grown in my rugged health and brute strength further and further from the more delicate sensibilities which go to make the better part of human life. It was my own fault. I knew that. I could have gone into the horse-company of my uncle with a chance for preferment and a life of polite groveling at the skirts of royalty. Though I had read much of such books as were to be found in my way and picked up a smattering of the languages, a dozen years of service in all weathers and companies had cudgeled from me many feelings of the gentler kind which I believe are nature’s gifts to all right-thinking gentlefolk.

But I had chosen my life for myself and there was an end of it. I compared myself, beside Mademoiselle, to a clumsy rock crumster against the gilded pinnace of the Queen where every line is beauty and strength. I watched her as she walked the deck with Madame. Although the Cristobal lay over to leeward and blundered heavily through the seas, raising her head and stern in abrupt fashion, Mademoiselle walked the slanting deck straightly, conversing quietly the while and cheering Madame, who leaned upon her. Her carriage, though lissome, gained from the set of the head a certain dignity and grace that marked her as a queen among women—perhaps a little haughty but in it the more queenly. But I would not be so interpreted as to show her in any sense cold of temper, for as I stood there watching her, my heart in my eyes, from time to time she turned and flashed a warm glance upon me, which sealed each time more surely my destiny as her willing servitor.

In a little while the prisoners were brought up from below for their airing and Mademoiselle went with Madame below to the cabin. The Spaniards, taken altogether, were a well enough looking company, and I do not doubt that under proper authority and better conditions of ordnance and seamanship, could have given a good account of themselves. As it was, they seemed well cowed and came up from their quarters sheepishly, blinking their eyes like so many cats at the brightness of the sun. There came also among the last Don Diego de Baçan. Lifting his great bulk over the combing of the hatchway he scanned the horizon as though mechanically and, seeing nothing, turned toward me. I had not given much of my thought to this fellow, for with the many necessary orders and duties in getting the Cristobal to rights and under way my mind had been so occupied as to harbor no place for plans or business of my own. Yet the memory of the haughty taunt of the Spaniard rankled in me, and I promised myself an ungodly pleasure in a further discussion of the subject. As the ranking officer among the prisoners, I had allotted him the half of my cabin, but my business upon the deck having been so urgent, I had not as yet had any talk with him.

The mist of years passes over our eyes and brains, dimming the memories of youthful impulses and madnesses. Yet even now, as I recall the face of De Baçan, handsome, sneering, powerful,—his look of contempt at all things,—my pulses beat the more quickly and my hand again goes to the place where my sword was wont to hang. It is said that in the matter of love and the taking in marriage, each person may find upon the earth a mate; likewise it seems to me most natural that for each man upon the earth at least one other may be born who shall be his natural adversary and enemy. It was once told me by Martin Cockrem that two churls entered the inn-yard at the Pelican and without exchange of words, or laying eyes on each other ever before, fell instantly to fighting. Setting aside the danger which lay in his presence and the grievance I bore him for his attack upon the Sieur de la Notte, a like feeling of antipathy there was between the Spaniard and me. And as he came forward, my fingers closed so that the nails drove into the flesh and I took a step toward him. Yet he was a prisoner of war, promised to be safely delivered. So, half ashamed of my own impatience, I bit my lip for the better control of my speech and leaned back upon the taffrail smiling.

“You have not given me the honor of your company in my prison,” said he, with a sneer.

“Nay, señor,” I returned, “the Cristobal is a sieve, and but for certain precautions might now be floating keelson upward. My company you shall have when other things are righted, for there is a small matter for discussion.”

“And what, Señor Pirato?” he asked with a lift of the chin. “What matter is common between you and me?”

“Permit me to be the judge of that, señor. And upon the Cristobal the subject may be settled.”

“Oho! You crow loud as a fledgling cock with your weighty subjects!”

“My weighty subjects are less weighty than my fists,” I replied, for I liked him not, striving hard meanwhile to preserve my peace. “You saw fit to put an insult upon me and did me the honor of an offer of a further argument of the question. I accept that offer.”

He placed his hands upon his hips and looked at me from head to foot as at a person he had never seen before. And then his white teeth gleamed through his black mustache as he smiled.

“You are a bold stripling. Why, Sir Swashbuckler, the prowess of Don de Baçan is a byword in the navy of King Philip, and no man in all Spain has bested him in any bout of strength. Yet, look you, I like your bulk and manner and it may be that I shall see fit to honor you with a test of endurance.”

“’Tis no honor that I seek, señor,” said I, giving him smile for smile, “but the satisfaction of a small personal grievance which may be righted quickly. And though your bulk is fit enough for my metal, your manner pleases me not;” for it galled me that he should continue to speak of me as a pirato upon my own command; and my blood boiled at the thought of what he had attempted to work upon the Sieur de la Notte and Mademoiselle.

“My thews may please you even less, Sir Adventurer. Mark you this,”—and leaning over, he took from one of the guns a chocking quoin of hickory-wood banded with copper. Seizing it in his hands he placed it between his knees for a better purchase and, bending forward quickly, with a mighty wrench, he split it in two parts as one would split an apple; whereat I was greatly surprised, and knew for certain that I had no ordinary giant to deal with. But I held and still hold, that like most of such feats, it was but a trick and come of long practise. I might have shown him, had I wished, the breaking of a pike-staff with a hand-width grasp; for in this there is no great skill but only honest elbow sinew. Yet I had no humor to put him on his guard against me.

Some of my surprise may have noted itself in my face, for he laughed boastfully as he threw the quoin upon the deck. “So will I split you,—if your humor is unchanged.”

I laughed back in his face.

“If your quoins are as rotten as your ship, I fear you not. To-morrow we make the coast. To-night, if it meets your convenience we will meet upon the fore-castle.”

“As you will,” he said with a shrug of his shoulders, “yet I have warned you. And if blood be spilled by accident——”

“It will not be mine! Until then, señor,” and bowing, I made my way below to inquire if Mademoiselle wished for anything.

CHAPTER IV.

OF MY BOUT WITH DE BAÇAN.

I met her coming out of the passageway which led to the after-cabin. Holding out her hand to me, she said frankly, “I came to seek you, Master Killigrew.” Her manner was one of friendliness and trust, and so filled my heart with gratitude that at first I did not note the anxiety which showed in her eyes. We moved to an embrasure by one of the casements. There she seated herself upon a gun-carriage and motioned me to a place at her side.

“God knows, Master Killigrew, that we are deep in your debt,” she began. “You are the only one my father has trusted since we fled from Villeneuve. But there is much that you should know.”

“Mademoiselle,” I replied, “my devotion to your interests or cause——”

There may have been more of ardor in my tones than I meant to show, for I fancied a pink, rosy color came to her neck and cheeks.

“We have good reason to believe in your honesty of purpose, Master Killigrew,” she said hastily, “and my present talk is further proof of confidence. The matter concerns Don Diego de Baçan and ourselves. This Spaniard has no good will for my father.”

“But, Mademoiselle, has he—?”

“You and your captain thought that the reason for the attack lay in his hope to conceal the money in the cabin. That was not all. When we were first taken aboard the Cristobal he gave me the honor of his admiration. The following day he sought me on many pretexts. I,—believing that the comfort and peace of Madame, my mother, depended upon diplomacy,—allowed him to sit and talk with me. At last, his speech becoming little to my liking, I refused him further admittance and told the Sieur de la Notte of my annoyance.”

I rose from the seat.

“No, listen! Listen to me,” she continued. “Then—’twas only three days before the encounter with the Great Griffin—my father sought Don Alvarez and told him the facts as I relate them, demanding the courtesies due to honorable prisoners of war. This request was disregarded and Don Diego came at all hours to our cabin, into which, the door lock having been removed, he entered at whatever hour he pleased.”

She may have marked my manner, which as the narrative proceeded, grew from joy at her confidence to surprise, anger and then rage at the Spaniard, which as I sat there seemed like to overmaster me. I could say no word, but for better control kept my eyes fixed upon the deck. There was much, I knew, beneath that story which she had sweetly robbed of its harshness to guard me from rash impulse. And so I sat there, transfixed.

“I have told this because I think it best to guard against him when we reach the coast. De Baçan has sworn that he will possess me. I know there is naught he will not attempt to keep his word. There is no evil he would not work upon us or upon you to gain his ends. For myself I fear nothing, but he hates my father with a deadly hatred and Madame must be saved from further suffering if the means lie in our power. Oh! what would I not give for the bones and sinews of a man like you who has but to order and the thing is done!”

She stopped abruptly and cast down her eyes as though the manner of her speech had been too strong and unwomanly. And I, who sat there, turned from cold with hatred of the Spaniard, to warm with love of her. For in spite of the distance between us, the speech came impulsively from the heart and made me more than ever desire to justify her confidence.

“I cannot say, Mademoiselle,” I replied gravely, “that there will not be danger, for there is treachery in Dieppe. But many strong hearts stand between you and this De Baçan.”

Her hand lay upon the breeching of the gun beside us; small and very white it was, ornamented with a ring of ancient setting and workmanship. Without meditation and eased of my boorishness by some subtle influence that drew me to her, I took it in my fingers and raised it to my lips. Then, astonished at my audacity—for I had never done so strange a thing, I drew back, hot and awkward. But at once she set me at my ease and would not have it so.

“Nay, sir,” she said warmly, “if you are to serve us truly I would not have a better seal for the contract.”

Upon which, still in great ferment of mind, I straightway made the compact doubly sure.

She then left me, seeking the cabin, while I went upon the deck, intent upon settling the business in hand.

The wind now blew freshly from the north and the spray came over the waist, cutting sharply against my face as I went forward. Job Goddard lay upon his back upon the tarpaulin of the forward hatchway, while Salvation Smith read aloud portions of a book of tales relating to the lives of the Christian martyrs. At times, in impressive pauses in the reading by the pious one, Goddard would raise himself upon one elbow and curse lustily—his usual mode of expressing admiration for the martyrs and their sponsor; for in Salvation lay the makings of a most bigoted and godly reformer. Job Goddard swore by all things under heaven and upon all occasions—when that mode of speech seemed least fitting or appropriate; and the book of the martyrs was but a part of Salvation’s instruction in simple and pious thought. Yet they were both goodly fighters—in a place of great difficulty being worth at the least four Englishmen, six Spaniards or eight Frenchmen. The very sound of the clashing of steel pike-heads or the report of an arquebuse set them upon the very edge of their mettle, and so the prospect of a fair engagement caused them so great a joy that even devotion to their principles came to be forgotten. I therefore knew that the business I had in hand would meet with ready response.

“To-night,” said I, without further ado, “there is to be a bout.” Smith closed the “Martyrs” with celerity and Goddard began to swear.

“Glory be, Job! Who, Master Killigrew?”

“Odds ’oonds, Jem! What is it, sir?”

“There is to be a test between the Spaniard, De Baçan and myself.”

In a moment they were all excitement, slapping each other upon the back and making a great commotion. When they were quiet again I gave them their instructions. There were to be no arms. For could I not crush him into submission with my own will and sinews, then—well—I had met my match or better. But I did not think of that. We would fight at twelve o’clock upon the fore-castle, for there we would be undisturbed. Two Spanish prisoners of De Baçan’s choice were to stand by him, and Goddard and Salvation Smith were to stand by me to see justice done. The details being agreed upon I despatched a message by Goddard to the Spaniard acquainting him with the plans; to which there being no reply, I deemed them satisfactory.

The night came up dark and windy. But toward six bells the fresh breeze piled the clouds away to the west and the moon came out, lighting up the deck and glimmering upon the bright work of the lanterns. Prompt upon the stroke of eight bells I caused word to be sent to De Baçan. When he appeared, his cloak was thrown about his shoulders but I could see he wore no doublet, having only his shirt, hose, and a pair of short boots. It pleased me to know he had thought proper to make some preparation for the work, for I now felt that the matter was not altogether indifferent to him, and that, in the quieter moments of his cabin, he had given me credit for some hardihood.

Now as I measured him by my own stature it seemed indeed as though he had the advantage in height, though I much doubt if he had really my breadth of shoulder or my length of arm, which were second to no man I had met. But the symmetry and grace of his figure were perfect. The light shone through the thin shirt and I marked the great muscles behind the shoulders as they played when he moved his arms. The collar was open and I could note the swell of the breast muscles as they lay in layers like rows of cordage from breastbone to arm-pit. The thighs were smaller than mine, but there was more of grace and more of sinew both there and at the calf, the ball of which played just at the boot top. His eye was bold and clear and he looked at me steadily from the moment he came upon the deck, seeking, in a way I had seen practised, to create a feeling of uneasiness and uncertainty. This look of his eyes I took to be but a part of the method of intimidation he had worked upon others, and it only served to make me more wary of the tricks I knew he would play should sheer strength not suffice.

He at once made several tries upon my arm which I held forward to ward a sudden rush below the guard. Knowing that my youth and clean living might give me advantage in a long struggle, I was content for the moment to stand upon guard and suffered him to play around me, my eyes fixed upon his, every look of which I followed and read. For so heavy a man, he stepped with wonderful alacrity and sprang from this side to that with such speed that he puzzled me. Finding, however, by reason of my length of reach that he could get no hold, he began trying different methods. The extension guard has been thought of some advantage and the German, Brandt, has practised it with success, yet I counted not upon the wonderful quickness of the man. By feinting for finding a catch upon my shoulder, he sprang in, catching me handily with a gripe of his left arm upon my neck and back. So fiercely he came that my right arm was pinioned; yet my left elbow met him in the middle of the breast below the bone, and I stood firm upon my legs, which were more stocky of build than his, and met the assault strongly.

As he closed in, the arm upon my back and neck took a firmer hold and the hand came over my right shoulder from the back, seeking a purchase at the neck. The strain he put upon my body was terrible, so terrible that for the moment all the breath seemed like to be squeezed from out my lungs. Backward we strained a foot or so, when, as he eased his gripe to get a better purchase upon the back, my right arm came a trifle freer and I found a use for my hand which now got a hold upon his shoulder muscles. My nails bit deep into the flesh and I plucked between my palm and fingers a great muscle out of tension, and felt for the moment I could hold my own. He still had an advantage of me in the gripe; and though the pressure upon my body was not so great as at the beginning, my breath came with difficulty. He seemed in little better condition, for he breathed hard, and I knew the chance blow of the elbow in the breast had robbed him of some of his staying power. Try as he might, his arms about me, his head bent forward upon my chest, he could not at first bend my neck. Backward and forward we moved, each of us bringing forth all the strength we could, neither of us able to gain. Then, the strain put upon me being more than mortal flesh could stand, little by little I went back until I came down upon one knee.

The agony of that moment! He put forth all his power and tried to break my back with a terrific wrench which must have ended me had not my new position given a side purchase upon him. Seeing that so long as my right hand shoulder gripe remained he could not get the full play of strength in his left arm, he bore down with his entire weight. In this I humored him till he got me high enough when, though still suffering grievously, I shifted my gripe and took him with both arms, one up one down, just below his ribs. Swinging half to the right and using all the power left me, I half arose and buttocked him fairly, sending him in a great half circle and loosing his gripe upon my chest. Yet the strain he had put upon me had weakened me so sorely that, ere I could come upon him to follow up my sudden advantage, he had broken loose and gained his feet for a further trial.

“Body o’ me, lad, ’twas handily done,” came from Goddard in an awed whisper; I marked a reverential “Heart o’ grace,” from Smith at my back, “now look out for him, sir!”

Indeed the face of the Spaniard was dreadful to see. He stood for the moment, his legs apart, staggering from the shock of the fall. His breath came hard and his eyes gleamed wickedly. At me he came and with a desperateness I might not mistake. As we sprang into each other’s grasp, there followed a test of endurance such as I had never before been put to—nor will again. In turn he tried the cross buttock, the back hank and back heel, but I managed to meet him at all points, though in sore straits for lack of wind. I had ten years advantage in the matter of age, and the life he had led had doubtless sapped his vigor. For as we struggled back and forth I noticed that his gripe had lost a part of its power and his offensive play was weaker. It seemed as though he lay upon his oars awaiting the chance for a trick. By and by he used it.

His left hand became disengaged and the great wiry fingers fastened a fierce clutch upon my throat, which I could not free. He had me from the left side and I could not well return his dastardly compliment. But as I felt my power a-going, by loosing the clasp of my left arm, I seized him from behind, my right hand going around his neck and my fingers getting a fair good hold in his beard just below the turn of the chin. Here I had the advantage. For he had taken me low down on the neck where the stronger muscles are and feared to loose his gripe; while my clasp tightened till I felt my thumb and fingers meet on the nether side of the windpipe. So great a rage I had at his taking me foully that I knew not what I did and as we fell I brought all my strength into play. Though he fell on top of me and my breath was gone, I knew that not death itself could have loosed the clutch I put upon him. I saw as through a mist the mouth open and shut hideously, the eyes, wide with terror, come from their sockets and the skin turn black almost as the beard that half hid it. The hand upon my neck lost its sinew, the muscles of the arm relaxed and the Spaniard dropped over to one side nerveless and powerless though still struggling against me. The fury did not die out of me at once and it seemed as though my fingers only gripped him the harder. Then, I know not what,—perhaps some weak and womanish pity at his strait,—caused me to loose my hold upon the throat, which I might have torn out from his body as one would unstrand a hempen cable.

God knows why I did this thing! Perhaps it was destiny that I should have spared him. In the light of after events, it seems as though some stronger hand than mine had set for us the life that followed. Had I killed him this account would never have been written, nor would I have gained the further friendship of Mademoiselle.

But I would set all sail ere my anchor is well clear. By all the rules of the game the Spaniard had given me the right to his life. Would to God I had taken it, even as he lay there prone and helpless. As it was I stumbled to my feet and with Goddard and Smith, stood waiting for De Baçan to rise. At first I had not noted the disappearance of his seconds, for the terrible earnestness of the bout had blinded me to all but the matter in hand.

In answer to my question Job Goddard said,

“Odds me! It was about the buttock, sir, which he said was done different in Spain. Mebbe I was over-rapid in demonstratin’ my meanin’ an’ view of the question. But I did him no hurt, sir,—curse me if I did!”

The other man sat terrified in the shadow of the foremast, but upon my suggestion he went to De Baçan, aiding him to arise and go to the cabin below.

CHAPTER V.

DIEPPE.

The following day we passed up to the city of Dieppe, and came to anchor in the river of Arques without further mishap. I had seen nothing of the Spaniard since the night before. I could not wonder that he had not chosen to show himself upon the deck; if it were true that he had bested all contestants at feats of strength, then surely his defeat must have rankled in him. He had probably no more desire to see me than I had to see him; but there was business to be done in the city which concerned him and his exchange for the English hostages.

My arms and back were so sore with the straining he had given me that it cost many an ache to bend over into the hatchway. I felt in worse plight than he, for further than showing a cloth about his neck and a certain huskiness in the voice he gave no sign of rough handling. He made no move to arise from his stool as I entered the cabin. He turned his eyes in my direction, looking sullen and angry as any great bull. But it was not the imperious look he bore after the sea battle; it was rather the eye-challenge of one man for another of equal station. I marked with pleasure how his eye traveled over me, and could barely suppress a smile. I had no mind to bring about further trouble, but in spite of good intention he took the visit ill; the malice he bore me and the hatred I bore him so filled his spirit and mine that there was no place in either for admiration of the prowess of the other.

“So, sir,” said he, “you must seek to humiliate me further.”

“I make offense to no man, save that of his own choosing,” I replied. “I come upon the matter of your exchange and liberation. In a short time I go ashore to settle the terms of your release; so we shall be quits. To-night you may go as you will without hindrance from my people.”

“I shall not leave you sadly, Sir Englishman,” growled he. “But mark you this,—I am no weakling enemy. You have bested me fairly, but for it all I like you not. I hate you for your handsome face, your sneaking air and your saintly mien. There has been an account opened that cannot be closed until one of us is dead. I will not die yet. One day you shall fawn at my feet for mercy until the fetters gnaw deep into your hide or the fire eats out your heretic heart!”

They were ill-omened threats. His manner was in no way to be mistaken and I was in no humor to be crossed by such as he. But seeing no good to come of further conversation I turned upon my heel and walked to the companion-way.

“I warn you now,” he went on as I paused at the foot of the hatch, “nothing in France can save the Sieur de la Notte—nothing—not even in Dieppe. I will seek you fair and I will seek you foul; I will take you fair if fairness offers; but, fair or foul, I will meet you when the advantage will not be upon your side—and so, good-by,—Sir Pirato!” I heard him laughing hoarsely as I walked up the gangway. Surely he was not a pleasant person.

By six o’clock in the evening my arrangements with Captain Hooper’s agent were made. In the settlement the Spanish prisoners were to be exchanged for certain Englishmen and Frenchmen, in all thirty in number. A purchaser found, the San Cristobal was to be sold forthwith, her equivalent in gold being transferred to me for Captain Hooper at Portsmouth. It gave me great disappointment that there was no authorized agent of Admiral Coligny in the town, to whom I could turn over in bulk the money in the closet in the cabin. The condition of affairs being so uncertain and men so little to be trusted, there seemed no other way but to carry this money to Coligny myself. Accordingly I also made arrangements through the agent to have this great treasure converted into jewels that I might convey it the more easily. My own seamen, save Goddard and Salvation Smith whom I retained, were to be set upon a ship sailing for Portsmouth in a few days. The Sieur de la Notte and his family were safely removed to rooms in the house of a Huguenot, who could be trusted to keep counsel; for in Dieppe, though the followers of Calvin had assembled in great numbers, there was even now danger for noble fugitives. In the present condition of matters of state, the Admiral, whose watchful eye seemed to reach all France, might do nothing except by subterfuge for his people; and there were many at court who bore La Notte so fierce a hatred that the aid of Coligny was now impossible. The house in which the unfortunate nobleman was quartered lay in the Rue Etienne under the shadow of the new church of Saint Remi. The city, topped by the frowning hill and battlements of the great Château, lay thickly to the left; and down several turnings to the right through the marts of the city was the quay where the tall ships of the house of Parmentier had for two generations brought in, each twelvemonth, the richest products of the East.

Thither, on the following evening, after my visit to the shipping agent, I directed my steps. Although I had a great treasure about me in jewels and money, I was at a loss for a safer place and felt that I might rest secure there until the morrow, when a Protestant vessel would be sailing for the Seine. I was going to leave Mademoiselle and my heart was heavy. Diego de Baçan was loose in Dieppe, and though at a disadvantage, I did not doubt he would waste no time in learning the whereabouts of every sympathizer in the town. Aye, and every bravo of his creed who could be hired to do his dirty work. As a matter of precaution there came with me Job Goddard and Salvation Smith who swung gleefully up from the counting-house and landing place, buffeting aside the staid townsmen and the seamen who were setting the supplies upon the vessels of the fleet of Jean Ribault which were to sail in a few days to establish the colony in America.

Goddard and Smith I sent into a tavern near by the abode of the Sieur de la Notte with instructions to engage no one in conversation and to await my coming. With the strongest admonitions to secrecy, I had told them of the jewels about me, of my plans and of my suspicions; for I wished, if anything happened to me, that the Sieur de la Notte should be informed. I knew these seamen devoted to my interests; and the desire to aid me, I fancied, had found no cause for abatement since the struggle of the evening before with the Spaniard.

Of the things which happened in the cabaret and of which I am about to tell, I afterward learned from Goddard himself, whose resolution was a thing of paper or of iron as he was in or out of his cups. He differed from Salvation Smith, for there was no hour, drunk or sober, in which that stalwart Christian would not vigorously assail the strongholds of the devil. There seemed to be no tenet of the New Religion which he had not at his tongue’s obedience; and when he and Goddard were drunk together, the exhortations of Salvation would reach a degree of frenzy which for the time silenced even the profanity of his companion. Quiet of common, his talk would then become louder and more forward until there was at last no opportunity for talk from others. And as his speech grew louder, that of Goddard, the blasphemer, would become more subdued, until, for a time perhaps, but few words—none of them of saintly origin—came from his lips. The torrent of the discourse of Smith, halted for a moment, gained by delay a stronger flow and burst forth the more sturdily, until burnt up at last in the flame of its own enthusiasm. Yet Job Goddard would not be denied for long, and so ingenious were his powers that his mutterings would at last resolve themselves into combinations of words so new and surprising that Salvation Smith even was soon agape with something very near to admiration.

Much of this must have happened after I left them. In the hostel was a crowd of seamen and broken down gentlemen. The swords of these cavaliers were their only fortune, and they were about to sail on the voyage with the Huguenot Ribault to Florida. Many of them, as will be seen, I came to know and so learned from them also of the things set forth hereafter. They were for the most part of a religious inclination, though not a few had no more religion in their hearts than Goddard. They were all reckless, and in one last drinking bout were taking leave of home and France. The alicant had passed but half a dozen times and Goddard had sat patiently through a discourse from his companion upon the lives of the martyrs until his flesh and blood could stand it no longer. He lifted his pot and in a tone of lusty confidence which might easily have been heard from one end of the room to the other said, grinning broadly,

“Bad eatin’ and drinkin’ to the Spanish, Jem Smith! Uneasy sleepin’ and wakin’ for King Philip! A cross-buttock and a broken head for Dyago! And a good fight at the last for our pains! Drain it, lad,—you’ll never have a better.”

“Amen!” said Salvation, piously. “And thanks for the victory of the Griffin, Job Goddard. There was never surer mark of His handiwork than yonder cruise when the righteous were uplifted and confusion came to the enemies of His Gospels.”

“Amen again,” said Goddard, “and be damned to them!” He rose to his feet and looking around him clattered his pot loudly against the table.

“Look ye, lads, an ye like not barleycorn, a pot of sack against the chill of the night! An’ if ye cannot drink in English, I’ll warrant your French throats no less slippery from frog eatin’.”

“Morbleu, non,” said one, “I am as dry as the main yard of the Trinity.”

“To the Great Griffin, then,” said Goddard loudly, “an’ the good crowns the San Cristobal sells for, with some for Bess and some for we! Look you! See how they glitter—less bright for the black head on ’em, but welcome enough in the taproom—where with a whole heart we can drink confusion to the Spanish king and every other sneaking cat of a——”

“Sh—” said Smith in a low voice. He had just reason enough to know that they were disobeying orders. “For the love o’ God stow your gaff, lad, there are like as not some of the thumb-screwing whelps even here.” But the crowd of seamen were amused at the Englishman and would not be denied. They set their flagons down with a clatter to hear Job Goddard, with the help of one of their number, in a bluff, hearty way tell of the taking of the San Cristobal. The story was strangely interlarded with oaths and devout expressions, half French, half English, but all bearing the mark of approval among the Huguenot company, who did me the honor to rattle their pots again right merrily at the account of my wrestling bout with the Spaniard.

Salvation Smith, enjoying in his own way the importance of his friend and ally, who for once had drowned out his own eloquence, cast aside all caution and sought to enhance the effect of Job’s remarks by frequent and timely expressions of approval. He walked about, smiling broadly, causing the pots to be filled as often as they fell half empty.

So intent was the crowd upon the performance of the seaman Goddard and so wrapped up in their drinking bouts that they failed to notice three men who sat at a corner table sipping at their liquor. All three listened intently to Goddard’s tale and once or twice looks of surprise passed between them. As it went on they lifted their pots to hide their lips and leaned well forward, whispering together, then listening to catch the words of the seaman, as his tongue, unloosed, swung merrily in the wind of anecdote.

After a while when he paused for a moment there was a commotion in another part of the room. A slender spark of the company of Ribault, with a well-worn doublet, but wearing a silver ear-ring, a nicely trimmed beard and other marks of gentle taste, was hoisted upon his legs and sang unsteadily a verse which in English goes somewhat like this:—

“Here’s to every merry lass— Here’s to her who’s shy, sirs,— Here’s an overflowing glass To any roguish eye, sirs; Be she sweet or be she scold, Be her temper warm or cold, Be she tall or be she small, Naught can we but love her. A-dieu—a-dieu— A-dieu, belle Marie-e!

Be she stout or be she lean— Be she pauper, be she queen— Be she fine or be she jade— Be she wife or be she maid— Here’s a toast to woman; Here’s a health to woman! A-dieu—A-dieu— Adieu, belle Marie-e!”