автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Memoir, Correspondence, And Miscellanies, From The Papers Of Thomas Jefferson, Volume 4

MEMOIR, CORRESPONDENCE, AND MISCELLANIES,

FROM THE PAPERS OF THOMAS JEFFERSON.

Edited by Thomas Jefferson Randolph.

VOLUME IV.

CONTENTS

LETTER I. TO LEVI LINCOLN, August 30, 1803

LETTER II. TO WILSON C NICHOLAS, September 7, 1803

LETTER III. TO DOCTOR BENJAMIN RUSH, October 4, 1803

LETTER IV. TO M. DUPONT DE NEMOURS, November 1, 1803

LETTER V. TO ROBERT R. LIVINGSTON, November 4,1803

LETTER VI. TO DAVID WILLIAMS, November 14, 1803

LETTER VII. TO JOHN RANDOLH, December 1, 1803

LETTER VIII. TO MR. GALLATIN, December 13, 1803

LETTER IX. TO DOCTOR PRIESTLEY, January 29, 1804

LETTER X. TO ELBRIDGE GERRY, March 3, 1804

LETTER XI. TO GIDEON GRANGER, April 16, 1804

LETTER XII. TO MRS. ADAMS, June 13,1804

LETTER XIII. TO GOVERNOR PAGE, June 25, 1804

LETTER, XIV. TO P. MAZZEI, July 18, 1804

LETTER XV. TO MRS. ADAMS, July 22, 1804

LETTER XVI. TO JAMES MADISON, August 15, 1804

LETTER XVII. TO GOVERNOR CLAIBORNE, August 30, 1804

LETTER XVIII. TO MRS. ADAMS, September 11, 1804

LETTER XIX. TO MR. NICHOLSON, January 29, 1805

LETTER XX. TO MR. VOLNEY, February 8, 1805

LETTER XXI. TO JUDGE TYLER, March 29, 1805

LETTER XXII. TO DOCTOR LOGAN, May 11, 1805

LETTER XXIII. TO JUDGE SULLIVAN, May 21, 1805

LETTER XXIV. TO THOMAS PAINE, June 5, 1805

LETTER XXV. TO DOCTORS ROGERS AND SLAUGHTER, March 2, 1806

LETTER XXVI. TO MR. DUANE, March 22, 1806

LETTER XXVII. TO WILSON C. NICHOLAS, March 24,1806

LETTER XXVIII. TO WILSON C. NICHOLAS, April 13, 1806

LETTER XXIX. TO MR. HARRIS, April 18, 1806

LETTER XXX. TO THE EMPEROR OF RUSSIA

LETTER XXXI. TO COLONEL MONROE, May 4, 1806

LETTER XXXII. TO GENERAL SMITH, May 4,1806

LETTER XXXIII. TO MR DIGGES, July 1, 1806

LETTER XXXIV. TO MR. BIDWELL, July 5, 1806

LETTER XXXV. TO MR. BOWDOIN, July 10, 1806

LETTER XXXVI. TO W. A. BURWELL, September 17, 1806

LETTER XXXVII. TO ALBERT GALLATIN, October 12, 1806

LETTER XXXVIII. TO JOHN DICKINSON, January 13, 1807

LETTER XXXIX, TO WILSON C. NICHOLAS, February 28,1807

LETTER XL. TO JAMES MONROE, March 21, 1807

LETTER XLI. M. LE COMTE DIODATI, March 29, 1807

LETTER XLII. TO MR. BOWDOIN, April 2, 1807

LETTER XLIII. TO WILLIAM B. GILES, April 20, 1807

LETTER XLIV. TO GEORGE HAY, June 2, 1807

LETTER XLV. TO ALBERT GALLATIN, June 3, 1807

LETTER XLVI. TO GEORGE HAY, June 5, 1807

LETTER XLVII. TO DOCTOR HORATIO TURPIN, June 10, 1807

LETTER XLVIII. TO JOHN NORVELL, June 11, 1807

LETTER XLIX. TO WILLIAM SHORT, June 12, 1807

LETTER L. TO GEORGE HAY, June 12, 1807

LETTER LI. TO GEORGE HAY, June 17, 1807

LETTER LII. TO GEORGE HAY, June 19,1807

LETTER LIII. TO GOVERNOR SULLIVAN, June 19, 1807

LETTER LIV. TO GEORGE HAY, June 20, 1807

LETTER LV. TO DOCTOR WISTAR, June 21, 1807

LETTER LVI. TO MR. BOWDOIN, July 10, 1807

LETTER LVII. TO THE MARQUIS DE LA FAYETTE, July 14, 1807

LETTER LVIII. TO JOHN PAGE, July 17, 1807

LETTER LIX. TO WILLIAM DUANE, July 20, 1807

LETTER LX. TO GEORGE HAY, August 20, 1807

LETTER LXI. TO GEORGE HAY, September 4, 1807

LETTER LXII. TO GEORGE HAY, September 7, 1807

LETTER LXIII. TO THE REV. MR. MILLAR, January 23, 1808

LETTER LXIV. TO COLONEL MONROE, February 18, 1808

LETTER LXV. TO COLONEL MONROE, March 10, 1808

LETTER LXVI. TO RICHARD M. JOHNSON, March 10, 1808

LETTER LXVII. TO LEVI LINCOLN, March 23, 1808

LETTER LXVIII. TO CHARLES PINCKNEY, March 30, 1808

LETTER LXIX. TO DOCTOR LEIB, June 23, 1808

LETTER LXX. TO ROBERT L. LIVINGSTON, October 15, 1808

LETTER LXXI. TO DOCTOR JAMES BROWN, October 27, 1808

LETTER LXXII. TO LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR LINCOLN, November 13, 1808

LETTER LXXIII. TO THOMAS JEFFERSON RANDOLPH, November 24, 1808

LETTER LXXIV. TO DOCTOR EUSTIS, January 14, 1809

LETTER LXXV. TO COLONEL MONROE, January 28, 1809

LETTER LXXVI. TO THOMAS MANN RANDOLPH, February 7, 1809

LETTER LXXVII. TO JOHN HOLLINS, February 19, 1809

LETTER LXXVIII. TO M. DUPONT DE NEMOURS, March 2, 1809

LETTER LXXIX. TO THE PRESIDENT, March 17, 1809

LETTER LXXX. TO THE INHABITANTS OF ALBEMARLE COUNTY, April 3, 1809

LETTER LXXXI. TO WILSON C. NICHOLAS, June 13, 1809

LETTER LXXXII. TO THE PRESIDENT, August 17, 1809

LETTER LXXXIII. TO DOCTOR BARTON, September 21, 1809

LETTER LXXXIV. TO DON VALENTINE DE FORONDA, October 4, 1809

LETTER LXXXV. TO ALBERT GALLATIN, October 11, 1809

LETTER LXXXVI. TO CÆSAR A. RODNEY, February 10, 1810

LETTER LXXXVII.* TO SAMUEL KERCHEVAL, February 19,1810

LETTER LXXXVIII. TO GENERAL KOSCIUSKO, February 26, 1810

LETTER LXXXIX. TO DOCTOR JONES, March 5, 1810

LETTER XC. TO GOVERNOR LANGDON, March 5, 1810

LETTER XCI. TO GENERAL DEARBORN, July 16,1810

LETTER XCII. TO J. B. COLVIN, September 20, 1810

LETTER XCIII. TO MR. LAW, January 15, 1811

LETTER XCIV. TO DOCTOR BENJAMIN RUSH, January 16, 1811

LETTER XCV. TO M. DESTUTT TRACY, January 26, 1811

LETTER XCVI. TO COLONEL MONROE, May 5, 1811

LETTER XCVII. TO GENERAL DEARBORN, August 14, 1811

LETTER XCVIII. TO DOCTOR BENJAMIN RUSH

LETTER XCIX. TO JOHN ADAMS, January 21, 1812

LETTER C. TO JOHN ADAMS, April 20, 1812

LETTER CI. TO JAMES MAURY, April 25, 1812

LETTER CII. TO THE PRESIDENT, May 30, 1812

LETTER CIII. TO ELBRIDGE GERRY, June 11, 1812

LETTER CIV. TO JUDGE TYLER, June 17,1812

LETTER CV. TO COLONEL WILLIAM DUANE, October 1, 1812

LETTER CVI. TO MR. MELISH, January 13, 1813

LETTER CVII. TO MADAME DE STAEL-HOLSTEIN, May 24, 1818

LETTER CVIII. TO JOHN ADAMS, May 27, 1813

LETTER CIX. TO JOHN ADAMS, June 15, 1813

LETTER CX. TO JOHN W. EPPES, June 24, 1813

LETTER CXI. TO JOHN ADAMS, June 21, 1813

LETTER CXII. TO JOHN ADAMS, August 22, 1813

LETTER CXIII. TO JOHN W. EPPES, November 6, 1813

LETTER CXIV. TO JOHN ADAMS, October 13, 1813

LETTER CXV. TO JOHN ADAMS, October 28, 1813

LETTER CXVI. TO THOMAS LIEPER, January 1, 1814

LETTER CXVII. TO DOCTOR WALTER JONES, January 2,1814

LETTER CXVIII. TO JOSEPH C. CABELL, January 31, 1814

LETTER CXIX. TO JOHN ADAMS, July 5, 1814

LETTER CXX. TO COLONEL MONROE, January 1, 1815

LETTER CXXI. TO THE MARQUIS DE LA FAYETTE, February 14, 1815

LETTER CXXII.* TO MR. WENDOVER, March 13, 1815

LETTER CXXIII. TO CÆSAR A. RODNEY, March 16, 1815

LETTER CXXIV. TO GENERAL DEARBORN, March 17, 1815

LETTER CXXV. TO THE PRESIDENT, March 23,1815

LETTER CXXVI. TO JOHN ADAMS, June 10,1815

LETTER CXXVII. TO MR. LEIPER, June 12, 1815

LETTER CXXVIII. TO JOHN ADAMS, August 10,1815

LETTER CXXIX. TO DABNEY CARR, January 19, 1816

LETTER CXXX. TO JOHN ADAMS, April 8, 1816

LETTER CXXXI. TO JOHN TAYLOR, May 28,1816

LETTER CXXXII. TO FRANCIS W. GILMER, June 7,1816

LETTER CXXXIII.* TO BENJAMIN AUSTIN, January 9, 1816

LETTER CXXXIV. TO WILLIAM H. CRAWFORD, June 20, 1816

LETTER CXXXV. TO SAMUEL KERCHIVAL, July 12, 1816

LETTER CXXXVI. TO JOHN TAYLOR, July 21, 1816

LETTER CXXXVII. TO SAMUEL KERCHIVAL, September 5, 1816

LETTER CXXXVIII. TO JOHN ADAMS, October 14, 1816

LETTER CXXXIX. TO JOHN ADAMS, TO JOHN ADAMS

LETTER CXL. TO JOHN ADAMS, May 5, 1817

LETTER CXLI. TO MARQUIS DE LA FAYETTE, May 14, 1817

LETTER CXLII. TO ALBERT GALLATIN, June 16, 1817

LETTER CXLIII. TO JOHN ADAMS, May 17, 1818

LETTER CXLIV. TO JOHN ADAMS, November 13, 1818

LETTER CXLV. TO ROBERT WALSH, December 4, 1818

LETTER CXLVI. TO M. DE NEUVILLE, December 13, 1818

LETTER CXLVII. TO DOCTOR VINE UTLEY, March 21, 1819

LETTER CXLVIII. TO JOHN ADAMS, July 9, 1819

LETTER CXLIX. TO JUDGE ROANE, September 6,1819

LETTER CL. TO JOHN ADAMS, December 10, 1819

LETTER CLI. TO WILLIAM SHORT, April 13, 1820

LETTER CLII. TO JOHN HOLMES, April 22, 1820

LETTER CLIII. TO WILLIAM SHORT, August 4, 1820

LETTER CLIV. TO JOHN ADAMS, August 15, 1820

LETTER CLV. TO JOSEPH C. CABELL, November 28, 1820

LETTER CLVI. TO THOMAS RITCHIE, December, 25, 1820

LETTER CLVII. TO JOHN ADAMS, January 22, 1821

LETTER CLVIII. TO JOSEPH C CABELL, January 31, 1821

LETTER CLIX. TO GENERAL BRECKENRIDGE, February 15, 1821

LETTER CLX. TO — — — NICHOLAS, December 11,1821

LETTER CLXI. TO JEDIDIAH MORSE, March 6, 1822

LETTER CLXII. TO DOCTOR BENJAMIN WATERHOUSE, June 26, 1822

LETTER CLXIII. TO JOHN ADAMS

LETTER CLXIV. TO WILLIAM T. BARRY, July 2, 1822

LETTER CLXV. TO DOCTOR WATERHOUSE, July 19, 1822

LETTER CLXVI. TO JOHN ADAMS

LETTER CLXVII. TO DOCTOR COOPER, November 2, 1822

LETTER CLXVIII. TO JAMES SMITH, December 8, 1822

LETTER, CLXIX. TO JOHN ADAMS, February 25, 1823

LETTER CLXX. TO JOHN ADAMS, April 11, 1823

LETTER CLXXI. TO THE PRESIDENT, June 11, 1823

LETTER CLXXII. TO JUDGE JOHNSON, June 12, 1823

LETTER CLXXIII. TO JAMES MADISON, August 30,1823

LETTER CLXXIV. TO JOHN ADAMS, September 4, 1823

LETTER CLXXV. TO JOHN ADAMS, October 12, 1823

LETTER CLXXVI. TO THE PRESIDENT, October 24,1823

LETTER CLXXVII. TO THE MARQUIS DE LA FAYETTE, November 4, 1823

LETTER CLXXVIII. TO JOSEPH C CABELL, February 3, 1824

LETTER CLXXIX. TO JARED SPARKS, February 4, 1824

LETTER CLXXX. TO EDWARD LIVINGSTON, April 4, 1824

LETTER CLXXXI. TO MAJOR JOHN CARTWRIGHT, June 5,1824

LETTER CLXXXII. TO MARTIN VAN BUREN, June 29, 1824

LETTER CLXXXIII. TO EDWARD EVERETT, October 15, 1824

LETTER CLXXXIV. TO JOSEPH C. CABELL, January 11, 1825

LETTER CLXXXV. TO THOMAS JEFFERSON SMITH, February 21, 1825

LETTER CLXXXVI. TO JAMES MADISON, December 24, 1825

LETTER CLXXXVII. TO WILLIAM B. GILES, December 25, 1825

LETTER CLXXXVIII. TO WILLIAM B. GILES, December 26, 1825

LETTER CLXXXIX. TO CLAIBORNE W. GOOCH, January 9, 1826

LETTER CXC. TO [ANONYMOUS], January 21, 1826

LETTER CXCI. TO JAMES MADISON, February 17,1826

THOUGHTS ON LOTTERIES.

LETTER CXCII. TO JOHN QUINCY ADAMS, March 30, 1826

LETTER CXCIII. TO MR. WEIGHTMAN, June 24, 1826

ANA. EXPLANATION OF VOLUMES IN MARBLED PAPER

List of Illustrations

Book Spines, 1829 Set of Jefferson Papers

Steel Engraving by Longacre from Painting of G. Stuart

Titlepage of Volume Three (of Four)

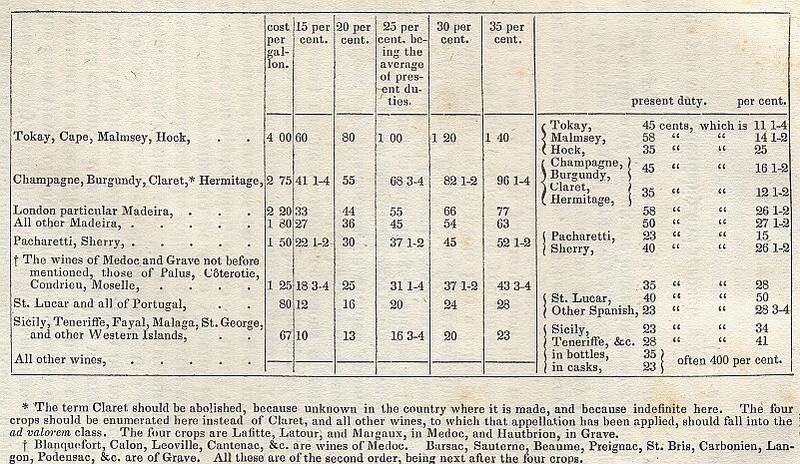

Pages With Greek Phrases and Tables:

Page77

Page201

Page205

Page225

Page226

Page227

Page227a

Page229

Page240

Page331

Page332

Page364

Page365

LETTER I.—TO LEVI LINCOLN, August 30, 1803

TO LEVI LINCOLN.

Monticello, August 30, 1803.

Deak. Sir,

The enclosed letter came to hand by yesterday’s post. You will be sensible of the circumstances which make it improper that I should hazard a formal answer, as well as of the desire its friendly aspect naturally excites, that those concerned in it should understand that the spirit they express is friendly viewed. You can judge also from your knowledge of the ground, whether it may be usefully encouraged. I take the liberty, therefore, of availing myself of your neighborhood to Boston, and of your friendship to me, to request you to say to the Captain and others verbally whatever you think would be proper, as expressive of my sentiments on the subject. With respect to the day on which they wish to fix their anniversary, they may be told, that disapproving myself of transferring the honors and veneration for the great birthday of our republic to any individual, or of dividing them with individuals, I have declined letting my own birthday be known, and have engaged my family not to communicate it. This has been the uniform answer to every application of the kind.

On further consideration as to the amendment to our constitution respecting Louisiana, I have thought it better, instead of enumerating the powers which Congress may exercise, to give them the same powers they have as to other portions of the Union generally, and to enumerate the special exceptions, in some such form as the following.

‘Louisiana, as ceded by France to the United States, is made a part of the United States, its white inhabitants shall be citizens, and stand, as to their rights and obligations, on the same footing with other citizens of the United States, in analogous situations. Save only that as to the portion thereof lying north of an east and west line drawn through the mouth of Arkansas river, no new State shall be established, nor any grants of land made, other than to Indians, in exchange for equivalent portions of land occupied by them, until an amendment of the constitution shall be made for these purposes.

‘Florida also, whensoever it may be rightfully obtained, shall become a part of the United States, its white inhabitants shall thereupon be citizens, and shall stand, as to their rights and obligations, on the same footing with other citizens of the United States, in analogous situations.’

I quote this for your consideration, observing that the less that is said about any constitutional difficulty, the better: and that it will be desirable for Congress to do what is necessary, in silence. I find but one opinion as to the necessity of shutting up the country for some time. We meet in Washington the 25th of September to prepare for Congress. Accept my affectionate salutations, and great esteem and respect.

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER II.—TO WILSON C NICHOLAS, September 7, 1803

TO WILSON C NICHOLAS.

Monticello, September 7, 1803.

Dear Sir,

Your favor of the 3rd was delivered me at court; but we were much disappointed at not seeing you here, Mr. Madison and the Governor being here at the time. 1 enclose you a letter from Monroe on the subject of the late treaty. You will observe a hint in it, to do without delay what we are bound to do. There is reason, in the opinion of our ministers, to believe, that if the thing were to do over again, it could not be obtained, and that if we give the least opening, they will declare the treaty void. A warning amounting to that has been given to them, and an unusual kind of letter written by their minister to our Secretary of State, direct. Whatever Congress shall think it necessary to do, should be done with as little debate as possible, and particularly so far as respects the constitutional difficulty. I am aware of the force of the observations you make on the power given by the constitution to Congress, to admit new States into the Union, without restraining the subject to the territory then constituting the United States. But when I consider that the limits of the United States are precisely fixed by the treaty of 1783, that the constitution expressly declares itself to be made for the United States, I cannot help believing the intention was not to permit Congress to admit into the Union new States, which should be formed out of the territory for which, and under whose authority alone, they were then acting. I do not believe it was meant that they might receive England, Ireland, Holland, &tc. into it, which would be the case on your construction. When an instrument admits two constructions, the one safe, the other dangerous, the one precise, the other indefinite, I prefer that which is safe and precise. I had rather ask an enlargement of power from the nation, where it is found necessary, than to assume it by a construction which would make our powers boundless. Our peculiar security is in the possession of a written constitution. Let us not make it a blank paper by construction. I say the same as to the opinion of those who consider the grant of the treaty-making power as boundless. If it is, then we have no constitution. If it has bounds, they can be no others than the definitions of the powers which that instrument gives. It specifies and delineates the operations permitted to the federal government, and gives all the powers necessary to carry these into execution. Whatever of these enumerated objects is proper for a law, Congress may make the law; whatever is proper to be executed by way of a treaty, the President and Senate may enter into the treaty; whatever is to be done by a judicial sentence, the judges may pass the sentence. Nothing is more likely than that their enumeration of powers is defective. This is the ordinary case of all human works. Let us go on then perfecting it, by adding, by way of amendment to the constitution, those powers which time and trial show are still wanting. But it has been taken too much for granted, that by this rigorous construction the treaty power would be reduced to nothing. I had occasion once to examine its effect on the French treaty, made by the old Congress, and found that out of thirty odd articles which that contained, there were one, two, or three only, which could not now be stipulated under our present constitution. I confess, then, I think it important, in the present case, to set an example against broad construction, by appealing for new power to the people. If, however, our friends shall think differently, certainly I shall acquiesce with satisfaction; confiding, that the good sense of our country will correct the evil of construction when it shall produce ill effects.

No apologies for writing or speaking to me freely are necessary. On the contrary, nothing my friends can do is so dear to me, and proves to me their friendship so clearly, as the information they give me of their sentiments and those of others on interesting points where I am to act, and where information and warning is so essential to excite in me that due reflection which ought to precede action. I leave this about the 21st, and shall hope the District Court will give me an opportunity of seeing you. Accept my affectionate salutations, and assurances of cordial esteem and respect.

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER III.—TO DOCTOR BENJAMIN RUSH, October 4, 1803

TO DOCTOR BENJAMIN RUSH.

Washington, October 4, 1803.

Dear Sir,

No one would more willingly than myself pay the just tribute due to the services of Captain Barry, by writing a letter of condolence to his widow, as you suggest. But when one undertakes to administer justice, it must be with an even hand, and by rule; what is done for one, must be done for every one in equal degree. To what a train of attentions would this draw a President? How difficult would it be to draw the line between that degree of merit entitled to such a testimonial of it, and that not so entitled? If drawn in a particular case differently from what the friends of the deceased would judge right, what offence would it give, and of the most tender kind? How much offence would be given by accidental inattentions, or want of information? The first step into such an undertaking ought to be well weighed. On the death of Dr. Franklin, the King and Convention of France went into mourning. So did the House of Representatives of the United States: the Senate refused. I proposed to General Washington that the executive departments should wear mourning; he declined it, because he said he should not know where to draw the line, if he once began that ceremony. Mr. Adams was then Vice-President, and I thought General Washington had his eye on him, whom he certainly did not love. I told him the world had drawn so broad a line between himself and Dr. Franklin, on the one side, and the residue of mankind, on the other, that we might wear mourning for them, and the question still remain new and undecided as to all others. He thought it best, however, to avoid it. On these considerations alone, however well affected to the merit of Commodore Barry, I think it prudent not to engage myself in a practice which may become embarrassing.

Tremendous times in Europe! How mighty this battle of lions and tigers? With what sensations should the common herd of cattle look on it? With no partialities certainly. If they can so far worry one another as to destroy their power of tyrannizing the one over the earth, the other the waters, the world may perhaps enjoy peace, till they recruit again.

Affectionate and respectful salutations.

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER IV.—TO M. DUPONT DE NEMOURS, November 1, 1803

TO M. DUPONT DE NEMOURS.

Washington, November 1, 1803.

My Dear Sir,

Your favors of April the 6th and June the 27th were duly received, and with the welcome which every thing brings from you. The treaty which has so happily sealed the friendship of our two countries, has been received here with general acclamation. Some inflexible federalists have still ventured to brave the public opinion. It will fix their character with the world and with posterity, who, not descending to the other points of difference between us, will judge them by this fact, so palpable as to speak for itself, in all times and places. For myself and my country I thank you for the aids you have given in it; and I congratulate you on having lived to give those aids in a transaction replete with blessings to unborn millions of men, and which will mark the face of a portion on the globe so extensive as that which now composes the United States of America. It is true that at this moment a little cloud hovers in the horizon. The government of Spain has protested against the right of France to transfer; and it is possible she may refuse possession, and that this may bring on acts of force. But against such neighbors as France there, and the United States here, what she can expect from so gross a compound of folly and false faith, is not to be sought in the book of wisdom. She is afraid of her enemies in Mexico. But not more than we are. Our policy will be to form New Orleans and the country on both sides of it on the Gulf of Mexico, into a State; and, as to all above that, to transplant our Indians into it, constituting them a Marechaussee to prevent emigrants crossing the river, until we shall have filled up all the vacant country on this side. This will secure both Spain and us as to the mines of Mexico, for half a century, and we may safely trust the provisions for that time to the men who shall live in it.

I have communicated with Mr. Gallatin on the subject of using your house in any matters of consequence we may have to do at Paris. He is impressed with the same desire I feel to give this mark of our confidence in you, and the sense we entertain of your friendship and fidelity. Mr. Behring informs him that none of the money which will be due from us to him, as the assignee of France, will be wanting at Paris. Be assured that our dispositions are such as to let no occasion pass unimproved, of serving you, where occurrences will permit it.

Present my respects to Madame Dupont, and accept yourself assurances of my constant and warm friendship.

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER V.—TO ROBERT R. LIVINGSTON, November 4,1803

TO ROBERT R. LIVINGSTON.

Washington, November 4,1803.

Dear Sir,

A report reaches us this day from Baltimore (on probable, but not certain grounds), that Mr. Jerome Bonaparte, brother of the First Consul, was yesterday* married to Miss Patterson of that city. The effect of this measure on the mind of the First Consul, is not for me to suppose; but as it might occur to him primâ facie, that the executive of the United States ought to have prevented it, I have thought it advisable to mention the subject to you, that if necessary, you may by explanations set that idea to rights. You know that by our laws, all persons are free to enter into marriage, if of twenty-one years of age, no one having a power to restrain it, not even their parents; and that under that age, no one can prevent it but the parent or guardian. The lady is under age, and the parents, placed between her affections which were strongly fixed, and the considerations opposing the measure, yielded with pain and anxiety to the former.

* November 8. It is now said that it did not take place on

the 3rd, but will this day.

Mr. Patterson is the President of the bank of Baltimore, the wealthiest man in Maryland, perhaps in the United States, except Mr. Carroll; a man of great virtue and respectability; the mother is the sister of the lady of General Samuel Smith; and, consequently, the station of the family in society is with the first of the United States. These circumstances fix rank in a country where there are no hereditary titles. Your treaty has obtained nearly a general approbation. The federalists spoke and voted against it, but they are now so reduced in their numbers as to be nothing. The question on its ratification in the Senate was decided by twenty-four against seven, which was ten more than enough. The vote in the House of Representatives for making provision for its execution, was carried by eighty-nine against twenty-three, which was a majority of sixty-six, and the necessary bills are going through the Houses by greater majorities. Mr. Pichon, according to instructions from his government, proposed to have added to the ratification a protestation against any failure in time or other circumstances of execution, on our part. He was told, that in that case we should annex a counter protestation, which would leave the thing exactly where it was; that this transaction had been conducted from the commencement of the negotiation to this stage of it, with a frankness and sincerity honorable to both nations, and comfortable to the heart of an honest man to review; that to annex to this last chapter of the transaction such an evidence of mutual distrust, was to change its aspect dishonorably for us both, and contrary to truth as to us; for that we had not the smallest doubt that France would punctually execute its part; and I assured Mr. Pichon that I had more confidence in the word of the First Consul than in all the parchment we could sign. He saw that we had ratified the treaty; that both branches had passed by great majorities one of the bills for execution, and would soon pass the other two; that no circumstances remained that could leave a doubt of our punctual performance; and like an able and an honest minister (which he is in the highest degree) he undertook to do, what he knew his employers would do themselves, were they here spectators of all the existing circumstances, and exchanged the ratification’s purely and simply; so that this instrument goes to the world as an evidence of the candor and confidence of the nations in each other, which will have the best effects. This was the more justifiable, as Mr. Pichon knew that Spain had entered with us a protestation against our ratification of the treaty, grounded, first, on the assertion that the First Consul had not executed the conditions of the treaties of cession, and secondly, that he had broken a solemn promise not to alienate the country to any nation. We answered, that these were private questions between France and Spain, which they must settle together; that we derived our title from the First Consul, and did not doubt his guarantee of it: and we, four days ago, sent off orders to the Governor of the Mississippi territory and General Wilkinson, to move down with the troops at hand to New Orleans, to receive the possession from Mr. Laussat. If he is heartily disposed to carry the order of the Consul into execution, he can probably command a volunteer force at New Orleans, and will have the aid of ours also, if he desires it, to take the possession and deliver it to us. If he is not so disposed, we shall take the possession, and it will rest with the government of France, by adopting the act as their own and obtaining the confirmation of Spain, to supply the non-execution of their stipulation to deliver, and to entitle themselves to the complete execution of our part of the agreements. In the mean time, the legislature is passing the bills, and we are preparing every thing to be done on our part towards execution, and we shall not avail ourselves of the three months’ delay after possession of the province, allowed by the treaty for the delivery of the stock, but shall deliver it the moment that possession is known here, which will be on the eighteenth day after it has taken place.

Accept my affectionate salutations, and assurances of my constant esteem and respect.

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER VI.—TO DAVID WILLIAMS, November 14, 1803

TO DAVID WILLIAMS.

Washington, November 14, 1803.

Sir,

I have duly received the volume on the claims of literature; which you did me the favor to send me through Mr. Monroe: and have read with satisfaction the many judicious reflections it contains, on the condition of the respectable class of literary men. The efforts for their relief, made by a society of private citizens, are truly laudable: but they are, as you justly observe, but a palliation of an evil, the cure of which calls for all the wisdom and the means of the nation. The greatest evils of populous society have ever appeared to me to spring from the vicious distribution of its members among the occupations called for. I have no doubt that those nations are essentially right, which leave this to individual choice, as a better guide to an advantageous distribution, than any other which could be devised. But when, by a blind concourse, particular occupations are ruinously overcharged, and others left in want of hands, the national authorities can do much towards restoring the equilibrium. On the revival of letters, learning became the universal favorite. And with reason, because there was not enough of it existing to manage the affairs of a nation to the best advantage, nor to advance its individuals to the happiness of which they were susceptible, by improvements in their minds, their morals, their health, and in those conveniences which contribute to the comfort and embellishment of life. All the efforts of the society, therefore, were directed to the increase of learning, and the inducements of respect, ease, and profit were held up for its encouragement. Even the charities of the nation forgot that misery was their object, and spent themselves in founding schools to transfer to science the hardy sons of the plough. To these incitements were added the powerful fascinations of great cities. These circumstances have long since produced an overcharge in the class of competitors for learned occupation, and great distress among the supernumerary candidates; and the more, as their habits of life have disqualified them for re-entering into the laborious class. The evil cannot be suddenly, nor perhaps ever entirely cured: nor should I presume to say by what means it may be cured. Doubtless there are many engines which the nation might bring to bear on this object. Public opinion and public encouragement are among these. The class principally defective is that of agriculture. It is the first in utility, and ought to be the first in respect. The same artificial means which have been used to produce a competition in learning, may be equally successful in restoring agriculture to its primary dignity in the eyes of men. It is a science of the very first order. It counts among its handmaids the most respectable sciences, such as Chemistry, Natural Philosophy, Mechanics, Mathematics generally, Natural History, Botany. In every College and University, a professorship of agriculture, and the class of its students, might be honored as the first. Young men closing their academical education with this, as the crown of all other sciences, fascinated with its solid charms, and at a time when they are to choose an occupation, instead of crowding the other classes, would return to the farms of their fathers, their own, or those of others, and replenish and invigorate a calling, now languishing under contempt and oppression. The charitable schools, instead of storing their pupils with a lore which the present state of society does not call for, converted into schools of agriculture, might restore them to that branch, qualified to enrich and honor themselves, and to increase the productions of the nation instead of consuming them. A gradual abolition of the useless offices, so much accumulated in all governments, might close this drain also from the labors of the field, and lessen the burthens imposed on them. By these, and the better means which will occur to others, the surcharge of the learned, might in time be drawn off to recruit the laboring class of citizenss the sum of industry be increased, and that of misery diminished.

Among the ancients, the redundance of population was sometimes checked by exposing infants. To the moderns, America has offered a more humane resource. Many, who cannot find employment in Europe, accordingly come here. Those who can labor do well, for the most part. Of the learned class of emigrants, a small portion find employments analogous to their talents. But many fail, and return to complete their course of misery in the scenes where it began. Even here we find too strong a current from the country to the towns; and instances beginning to appear of that species of misery, which you are so humanely endeavoring to relieve with you. Although we have in the old countries of Europe the lesson of their experience to warn us, yet I am not satisfied we shall have the firmness and wisdom to profit by it. The general desire of men to live by their heads rather than their hands, and the strong allurements of great cities to those who have any turn for dissipation, threaten to make them here, as in Europe, the sinks of voluntary misery. I perceive, however, that I have suffered my pen to run into a disquisition, when I had taken it up only to thank you for the volume you had been so kind as to send me, and to express my approbation of it. After apologizing, therefore, for having touched on a subject so much more familiar to you, and better understood, I beg leave to assure you of my high consideration and respect.

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER VII.—TO JOHN RANDOLH, December 1, 1803

TO JOHN RANDOLH.

Washington, December 1, 1803.

Dear Sir,

The explanations in your letter of yesterday were quite unnecessary to me. I have had too satisfactory proofs of your friendly regard, to be disposed to suspect any thing of a contrary aspect.

I understood perfectly the expressions stated in the newspaper to which you allude, to mean, that ‘though the proposition came from the republican quarter of the House, yet you should not concur with it.’ I am aware, that in parts of the Union, and even with persons to whom Mr. Eppes and Mr. Randolph are unknown, and myself little known, it will be presumed from their connection, that what comes from them comes from me. No men on earth are more independent in their sentiments than they are, nor any one less disposed than I am to influence the opinions of others. We rarely speak of politics, or of the proceedings of the House, but merely historically; and I carefully avoid expressing an opinion on them in their presence, that we may all be at our ease. With other members, I have believed that more unreserved communications would be advantageous to the public. This has been, perhaps, prevented by mutual delicacy. I have been afraid to express opinions unasked, lest I should be suspected of wishing to direct the legislative action of members. They have avoided asking communications from me, probably, lest they should be suspected of wishing to fish out executive secrets. I see too many proofs of the imperfection of human reason, to entertain wonder or intolerance at any difference of opinion on any subject; and acquiesce in that difference as easily as on a difference of feature or form: experience having long taught me the reasonableness of mutual sacrifices of opinion among those who are to act together for any common object, and the expediency of doing what good we can, when we cannot do all we would wish.

Accept my friendly salutations, and assurances of great esteem and respect.

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER VIII.—TO MR. GALLATIN, December 13, 1803

THOMAS JEFFERSON TO MR. GALLATIN.

The Attorney General having considered and decided, that the prescription in the law for establishing a bank, that the officers in the subordinate offices of discount and deposit, shall be appointed ‘on the same terms and in the same manner practised in the principal bank,’ does not extend to them the principle of rotation, established by the legislature in the body of directors in the principal bank, it follows that the extension of that principle has been merely a voluntary and prudential act of the principal bank, from which they are free to depart. I think the extension was wise and proper on their part, because the legislature having deemed rotation useful in the principal bank constituted by them, there would be the same reason for it in the subordinate banks to be established by the principal. It breaks in upon the esprit de corps, so apt to prevail in permanent bodies; it gives a chance for the public eye penetrating into the sanctuary of those proceedings and practices, which the avarice of the directors may introduce for their personal emolument, and which the resentments of excluded directors, or the honesty of those duly admitted, might betray to the public; and it gives an opportunity at the end of the year, or at other periods, of correcting a choice, which, on trial, proves to have been unfortunate; an evil of which themselves complain in their distant institutions. Whether, however, they have a power to alter this or not, the executive has no right to decide; and their consultation with you has been merely an act of complaisance, or from a desire to shield so important an innovation under the cover of executive sanction. But ought we to volunteer our sanction in such a case? Ought we to disarm ourselves of any fair right of animadversion, whenever that institution shall be a legitimate subject of consideration? I own I think the most proper answer would be, that we do not think ourselves authorized to give an opinion on the question.

From a passage in the letter of the President, I observe an idea of establishing a branch bank of the United States in New Orleans. This institution is one of the most deadly hostility existing, against the principles and form of our constitution. The nation is, at this time, so strong and united in its sentiments, that it cannot be shaken at this moment. But suppose a series of untoward events should occur, sufficient to bring into doubt the competency of a republican government to meet a crisis of great danger, or to unhinge the confidence of the people in the public functionaries; an institution like this, penetrating by its branches every part of the Union, acting by command and in phalanx, may, in a critical moment, upset the government. I deem no government safe which is under the vassalage of any self-constituted authorities, or any other authority than that of the nation, or its regular functionaries. What an obstruction could not this bank of the United States, with all its branch banks, be in time of war? It might dictate to us the peace we should accept, or withdraw its aids. Ought we then to give further growth to an institution so powerful, so hostile? That it is so hostile we know, 1. from a knowledge of the principles of the persons composing the body of directors in every bank, principal or branch; and those of most of the stock-holders: 2. from their opposition to the measures and principles of the government, and to the election of those friendly to them: and, 3. from the sentiments of the newspapers they support. Now, while we are strong, it is the greatest duty we owe to the safety of our constitution, to bring this powerful enemy to a perfect subordination under its authorities. The first measure would be to reduce them to an equal footing only with other banks, as to the favors of the government. But, in order to be able to meet a general combination of the banks against us, in a critical emergency, could we not make a beginning towards an independent use of our own money, towards holding our own bank in all the deposits where it is received, and letting the Treasurer give his draft or note for payment at any particular place, which, in a well conducted government, ought to have as much credit as any private draft, or bank note, or bill, and would give us the same facilities which we derive from the banks? I pray you to turn this subject in your mind, and to give it the benefit of your knowledge of details; whereas, I have only very general views of the subject. Affectionate salutations.

Washington, December 13, 1803.

LETTER IX.—TO DOCTOR PRIESTLEY, January 29, 1804

TO DOCTOR PRIESTLEY.

Washington, January 29, 1804.

Dear Sir,

Your favor of December the 12th came duly to hand, as did the second letter to Doctor Linn, and the treatise on Phlogiston, for which I pray you to accept my thanks. The copy for Mr. Livingston has been delivered, together with your letter to him, to Mr. Harvie, my secretary, who departs in a day or two for Paris, and will deliver them himself to Mr. Livingston, whose attention to your matter cannot be doubted. I have also to add my thanks to Mr. Priestley, your son, for the copy of your Harmony, which I have gone through with great satisfaction. It is the first I have been able to meet with, which is clear of those long repetitions of the same transaction, as if it were a different one because related with some different circumstances.

I rejoice that you have undertaken the task of comparing the moral doctrines of Jesus with those of the ancient Philosophers. You are so much in possession of the whole subject, that you will do it easier and better than any other person living. I think you cannot avoid giving, as preliminary to the comparison, a digest of his moral doctrines, extracted in his own words from the Evangelists, and leaving out every thing relative to his personal history and character. It would be short and precious. With a view to do this for my own satisfaction, I had sent to Philadelphia to get two Testaments (Greek) of the same edition, and two English, with a design to cut out the morsels of morality, and paste them on the leaves of a book, in the manner you describe as having been pursued in forming your Harmony. But I shall now get the thing done by better hands.

I very early saw that Louisiana was indeed a speck in our horizon, which was to burst in a tornado; and the public are un-apprized how near this catastrophe was. Nothing but a frank and friendly developement of causes and effects on our part, and good sense enough in Bonaparte to see that the train was unavoidable, and would change the face of the world, saved us from that storm. I did not expect he would yield till a war took place between France and England, and my hope was to palliate and endure, if Messrs. Ross, Morris, &c. did not force a premature rupture until that event. I believed the event not very distant, but acknowledge it came on sooner than I had expected. Whether, however, the good sense of Bonaparte might not see the course predicted to be necessary and unavoidable, even before a war should be imminent, was a chance which we thought it our duty to try: but the immediate prospect of rupture brought the case to immediate decision. The denouement has been happy: and I confess I look to this duplication of area for the extending a government so free and economical as ours, as a great achievement to the mass of happiness which is to ensue. Whether we remain in one confederacy, or form into Atlantic and Mississippi confederacies, I believe not very important to the happiness of either part. Those of the western confederacy will be as much our children and descendants as those of the eastern, and I feel myself as much identified with that country, in future time, as with this: and did I now foresee a separation at some future day, yet I should feel the duty and the desire to promote the western interests as zealously as the eastern, doing all the good for both portions of our future family which should fall within my power.

Have you seen the new work of Malthus on Population? It is one of the ablest I have ever seen. Although his main object is to delineate the effects of redundancy of population, and to test the poor laws of England, and other palliations for that evil, several important questions in political economy, allied to his subject incidentally, are treated with a masterly hand. It is a single octavo volume, and I have been only able to read a borrowed copy, the only one I have yet heard of. Probably our friends in England will think of you, and give you an opportunity of reading it.

Accept my affectionate salutations, and assurances of great esteem and respect.

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER X.—TO ELBRIDGE GERRY, March 3, 1804

TO ELBRIDGE GERRY.

Washington, March 3, 1804.

Dear Sir,

Although it is long since I received your favor of October the 27th, yet I have not had leisure sooner to acknowledge it. In the Middle and Southern States, as great an union of sentiment has now taken place as is perhaps desirable. For as there will always be an opposition, I believe it had better be from avowed monarchists than republicans. New York seems to be in danger of republican division; Vermont is solidly with us; Rhode Island with us on anomalous grounds; New Hampshire on the verge of the republican shore; Connecticut advancing towards it very slowly, but with steady step; your State only uncertain of making port at all. I had forgotten Delaware, which will be always uncertain from the divided character of her citizens. If the amendment of the constitution passes Rhode Island (and we expect to hear in a day or two), the election for the ensuing four years seems to present nothing formidable. I sincerely regret that the unbounded calumnies of the federal party have obliged me to throw myself on the verdict of my country for trial, my great desire having been to retire at the end of the present term, to a life of tranquillity; and it was my decided purpose when I entered into office. They force my continuance. If we can keep the vessel of State as steadily in her course for another four years, my earthly purposes will be accomplished, and I shall be free to enjoy, as you are doing, my family, my farm, and my books. That your enjoyments may continue as long as you shall wish them, I sincerely pray, and tender you my friendly salutations, and assurances of great respect and esteem.

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER XI.—TO GIDEON GRANGER, April 16, 1804

TO GIDEON GRANGER.

Monticello, April 16, 1804.

Dear Sir,

In our last conversation you mentioned a federal scheme afloat, of forming a coalition between the federalists and republicans, of what they called the seven eastern States. The idea was new to me, and after time for reflection, I had no opportunity of conversing with you again. The federalists know that, eo nomine, they are gone for ever. Their object, therefore, is, how to return into power under some other form. Undoubtedly they have but one means, which is to divide the republicans, join the minority, and barter with them for the cloak of their name. I say, join the minority; because the majority of the republicans, not needing them, will not buy them. The minority, having no other means of ruling the majority, will give a price for auxiliaries, and that price must be principle. It is true that the federalists, needing their numbers also, must also give a price, and principle is the coin they must pay in. Thus a bastard system of federo-republicanism will rise on the ruins of the true principles of our revolution. And when this party is formed, who will constitute the majority of it, which majority is then to dictate? Certainly the federalists. Thus their proposition of putting themselves into gear with the republican minority, is exactly like Roger Sherman’s proposition to add Connecticut to Rhode Island. The idea of forming seven eastern States is moreover clearly to form the basis of a separation of the Union. Is it possible that real republicans can be gulled by such a bait? And for what? What do they wish, that they have not? Federal measures? That is impossible. Republican measures? Have they them not? Can any one deny, that in all important questions of principle, republicanism prevails? But do they want that their individual will shall govern the majority? They may purchase the gratification of this unjust wish, for a little time, at a great price; but the federalists must not have the passions of other men, if, after getting thus into the seat of power, they suffer themselves to be governed by their minority. This minority may say, that whenever they relapse into their own principles, they will quit them, and draw the seat from under them. They may quit them, indeed, but, in the mean time, all the venal will have become associated with them, and will give them a majority sufficient to keep them in place, and to enable them to eject the heterogeneous friends by whose aid they get again into power. I cannot believe any portion of real republicans will enter into this trap; and if they do, I do not believe they can carry with them the mass of their States, advancing so steadily as we see them, to an union of principle with their brethren. It will be found in this, as in all other similar cases, that crooked schemes will end by overwhelming their authors and coadjutors in disgrace, and that he alone who walks strict and upright, and who in matters of opinion will be contented that others should be as free as himself, and acquiesce when his opinion is fairly overruled, will attain his object in the end. And that this may be the conduct of us all, I offer my sincere prayers, as well as for your health and happiness.

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER XII.—TO MRS. ADAMS, June 13,1804

TO MRS. ADAMS.

Washington, June 13,1804.

Dear Madam,

The affectionate sentiments which you have had the goodness to express in your letter of May the 20th, towards my dear departed daughter, have awakened in me sensibilities natural to the occasion, and recalled your kindnesses to her, which I shall ever remember with gratitude and friendship. I can assure you with truth, they had made an indelible impression on her mind, and that to the last, on our meetings after long separations, whether I had heard lately of you, and how you did, were among the earliest of her inquiries. In giving you this assurance, I perform a sacred duty for her, and, at the same time, am thankful for the occasion furnished me, of expressing my regret that circumstances should have arisen, which have seemed to draw a line of separation between us. The friendship with which you honored me has ever been valued, and fully reciprocated; and although events have been passing which might be trying to some minds, I never believed yours to be of that kind, nor felt that my own was. Neither my estimate of your character, nor the esteem founded in that, has ever been lessened for a single moment, although doubts whether it would be acceptable may have forbidden manifestations of it.

Mr. Adams’s friendship and mine began at an earlier date. It accompanied us through long and important scenes. The different conclusions we had drawn from our political reading and reflections, were not permitted to lessen mutual esteem; each party being conscious they were the result of an honest conviction in the other. Like differences of opinion existing among our fellow citizens, attached them to the one or the other of us, and produced a rivalship in their minds which did not exist in ours. We never stood in one another’s way. For if either had been withdrawn at any time, his favorers would not have gone over to the other, but would have sought for some one of homogeneous opinions. This consideration was sufficient to keep down all jealousy between us, and to guard our friendship from any disturbance by sentiments of rivalship: and I can say with truth, that one act of Mr. Adams’s life, and one only, ever gave me a moment’s personal displeasure. I did consider his last appointments to office as personally unkind. They were from among my most ardent political enemies, from whom no faithful co-operation could ever be expected; and laid me under the embarrassment of acting through men, whose views were to defeat mine, or to encounter the odium of putting others in their places. It seems but common justice to leave a successor free to act by instruments of his own choice. If my respect for him did not permit me to ascribe the whole blame to the influence of others, it left something for friendship to forgive, and after brooding over it for some little time, and not always resisting the expression of it, I forgave it cordially, and returned to the same state of esteem and respect for him which had so long subsisted. Having come into life a little later than Mr. Adams, his career has preceded mine, as mine is followed by some other; and it will probably be closed at the same distance after him which time originally placed between us. I maintain for him, and shall carry into private life, an uniform and high measure of respect and good will, and for yourself a sincere attachment.

I have thus, my dear Madam, opened myself to you without reserve, which I have long wished an opportunity of doing; and without knowing how it will be received, I feal[sp.] relief from being unbosomed. And I have now only to entreat your forgiveness for this transition from a subject of domestic affliction, to one which seems of a different aspect. But though connected with political events, it has been viewed by me most strongly in its unfortunate bearings on my private friendships. The injury these have sustained has been a heavy price for what has never given me equal pleasure. That you may both be favored with health, tranquillity, and long life, is the prayer of one who tenders you the assurance of his highest consideration and esteem.

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER XIII.—TO GOVERNOR PAGE, June 25, 1804

TO GOVERNOR PAGE.

Washington, June 25, 1804.

Your letter, my dear friend, of the 25th ultimo, is a new proof of the goodness of your heart, and the part you take in my loss marks an affectionate concern for the greatness of it. It is great indeed. Others may lose of their abundance, but I, of my want, have lost even the half of all I had. My evening prospects now hang on the slender thread of a single life. Perhaps I maybe destined to see even this last cord of parental affection broken! The hope with which I had looked forward to the moment, when, resigning public cares to younger hands, I was to retire to that domestic comfort from which the last great step is to be taken, is fearfully blighted. When you and I look back on the country over which we have passed, what a field of slaughter does it exhibit! Where are all the friends who entered it with us, under all the inspiring energies of health and hope? As if pursued by the havoc of war, they are strewed by the way, some earlier, some later, and scarce a few stragglers remain to count the numbers fallen, and to mark yet, by their own fall, the last footsteps of their party. Is it a desirable thing to bear up through the heat of the action to witness the death of all our companions, and merely be the last victim? I doubt it. We have, however, the traveller’s consolation. Every step shortens the distance we have to go; the end of our journey is in sight, the bed wherein we are to rest, and to rise in the midst of the friends we have lost. ‘We sorrow not, then, as others who have no hope’; but look forward to the day which ‘joins us to the great majority.’ But whatever is to be our destiny, wisdom, as well as duty, dictates that we should acquiesce in the will of Him whose it is to give and take away, and be contented in the enjoyment of those who are still permitted to be with us. Of those connected by blood, the number does not depend on us. But friends we have, if we have merited them. Those of our earliest years stand nearest in our affections. But in this too, you and I have been unlucky. Of our college friends (and they are the dearest) how few have stood with us in the great political questions which have agitated our country: and these were of a nature to justify agitation. I did not believe the Lilliputian fetters of that day strong enough to have bound so many. Will not Mrs. Page, yourself, and family, think it prudent to seek a healthier region for the months of August and September? And may we not flatter ourselves that you will cast your eye on Monticello? We have not many summers to live. While fortune places us then within striking distance, let us avail ourselves of it, to meet and talk over the tales of other times.

Present me respectfully to Mrs. Page, and accept yourself my friendly salutations, and assurances of constant affection.

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER, XIV.—TO P. MAZZEI, July 18, 1804

TO P. MAZZEI.

Washington, July 18, 1804.

My Dear Sir,

It is very long, I know, since I wrote you. So constant is the pressure of business that there is never a moment, scarcely, that something of public importance is not waiting for me. I have, therefore, on a principle of conscience, thought it my duty to withdraw almost entirely from all private correspondence, and chiefly the trans-Atlantic; I scarcely write a letter a year to any friend beyond sea. Another consideration has led to this, which is the liability of my letters to miscarry, be opened, and made ill use of. Although the great body of our country are perfectly returned to their ancient principles, yet there remains a phalanx of old tories and monarchists, more envenomed, as all their hopes become more desperate. Every word of mine which they can get hold of, however innocent, however orthodox even, is twisted, tormented, perverted, and, like the words of holy writ, are made to mean every thing but what they were intended to mean. I trust little, therefore, unnecessarily in their way, and especially on political subjects. I shall not, therefore, be free to answer all the several articles of your letters.

On the subject of treaties, our system is to have none with any nation, as far as can be avoided. The treaty with England has therefore, not been renewed, and all overtures for treaty with other nations have been declined. We believe, that with nations as with individuals, dealings may be carried on as anvantageously[sp.], perhaps more so, while their continuance depends on a voluntary good treatment, as if fixed by a contract, which, when it becomes injurious to either, is made, by forced constructions, to mean what suits them, and becomes a cause of war instead of a bond of peace.

We wish to be on the closest terms of friendship with Naples, and we will prove it by giving to her citizens, vessels, and goods all the privileges of the most favored nation; and while we do this voluntarily, we cannot doubt they will voluntarily do the same for us. Our interests against the Barbaresques being also the same, we have little doubt she will give us every facility to insure them, which our situation may ask and hers admit. It is not, then, from a want of friendship that we do not propose a treaty with Naples, but because it is against our system to embarrass ourselves with treaties, or to entangle ourselves at all with the affairs of Europe. The kind offices we receive from that government are more sensibly felt, as such, than they would be, if rendered only as due to us by treaty.

Five fine frigates left the Chesapeake the 1st instant for Tripoli, which, in addition to the force now there, will, I trust, recover the credit which Commodore Morris’s two years’ sleep lost us, and for which he has been broke. I think they will make Tripoli sensible, that they mistake their interest in choosing war with us; and Tunis also, should she have declared war, as we expect, and almost wish.

Notwithstanding this little diversion, we pay seven or eight millions of dollars annually of our public debt, and shall completely discharge it in twelve years more. That done, our annual revenue, now thirteen millions of dollars, which by that time will be twenty-five, will pay the expenses of any war we may be forced into, without new taxes or loans. The spirit of republicanism is now in almost all its ancient vigor, five sixths of the people being with us. Fourteen of the seventeen States are completely with us, and two of the other three will be in one year. We have now got back to the ground on which you left us. I should have retired at the end of the first four years, but that the immense load of tory calumnies which have been manufactured respecting me, and have filled the European market, have obliged me to appeal once more to my country for a justification. I have no fear but that I shall receive honorable testimony by their verdict on those calumnies. At the end of the next four years I shall certainly retire. Age, inclination, and principle all dictate this. My health, which at one time threatened an unfavorable turn, is now firm. The acquisition of Louisiana, besides doubling our extent, and trebling our quantity of fertile country, is of incalculable value, as relieving us from the danger of war. It has enabled us to do a handsome thing for Fayette. He had received a grant of between eleven and twelve thousand acres north of the Ohio, worth, perhaps, a dollar an acre. We have obtained permission of Congress to locate it in Louisiana. Locations can be found adjacent to the city of New Orleans, in the island of New Orleans and in its vicinity, the value of which cannot be calculated. I hope it will induce him to come over and settle there with his family. Mr. Livingston having asked leave to return, General Armstrong, his brother-in-law, goes in his place: he is of the first order of talents.

Remarkable deaths lately, are, Samuel Adams, Edmund Pendleton, Alexander Hamilton, Stephens Thompson Mason, Mann Page, Bellini, and Parson Andrews. To these I have the inexpressible grief of adding the name of my youngest daughter, who had married a son of Mr. Eppes, and has left two children. My eldest daughter alone remains to me, and has six children. This loss has increased my anxiety to retire, while it has dreadfully lessened the comfort of doing it. Wythe, Dickinson, and Charles Thomson are all living, and are firm republicans. You informed me formerly of your marriage, and your having a daughter, but have said nothing in you late letters on that subject. Yet whatever concerns your happiness is sincerely interesting to me, and is a subject of anxiety, retaining, as I do, cordial sentiments of esteem and affection for you. Accept, I pray you, my sincere assurances of this, with my most friendly salutations.

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER XV.—TO MRS. ADAMS, July 22, 1804

TO MRS. ADAMS.

Washington, July 22, 1804.

Dear Madam,

Your favor of the 1st instant was duly received, and I would not again have intruded on you, but to rectify certain facts which seem not to have been presented to you under their true aspect. My charities to Callendar are considered as rewards for his calumnies. As early, I think, as 1796, I was told in Philadelphia, that Callendar, the author of the ‘Political Progress of Britain,’ was in that city, a fugitive from persecution for having written that book, and in distress. I had read and approved the book; I considered him as a man of genius, unjustly persecuted. I knew nothing of his private character, and immediately expressed my readiness to contribute to his relief, and to serve him. It was a considerable time after, that, on application from a person who thought of him as I did, I contributed to his relief, and afterwards repeated the contribution. Himself I did not see till long after, nor ever more than two or three times. When he first began to write, he told some useful truths in his coarse way; but nobody sooner disapproved of his writing than I did, or wished more that he would be silent. My charities to him were no more meant as encouragements to his scurrilities, than those I give to the beggar at my door are meant as rewards for the vices of his life, and to make them chargeable to myself. In truth, they would have been greater to him, had he never written a word after the work for which he fled from Britain. With respect to the calumnies and falsehoods which writers and printers at large published against Mr. Adams, I was as far from stooping to any concern or approbation of them, as Mr. Adams was respecting those of Porcupine, Fenno, or Russell, who published volumes against me for every sentence vended by their opponents against Mr. Adams. But I never supposed Mr. Adams had any participation in the atrocities of these editors, or their writers. I knew myself incapable of that base warfare, and believed him to be so. On the contrary, whatever I may have thought of the acts of the administration of that day, I have ever borne testimony to Mr. Adams’s personal worth; nor was it ever impeached in my presence, without a just vindication of it on my part. I never supposed that any person who knew either of us, could believe that either of us meddled in that dirty work. But another fact is, that I ‘liberated a wretch who was suffering for a libel against Mr. Adams.’ I do not know who was the particular wretch alluded to; but I discharged every person under punishment or prosecution under the sedition law, because I considered, and now consider, that law to be a nullity, as absolute and as palpable as if Congress had ordered us to fall down and worship a golden image; and that it was as much my duty to arrest its execution in every stage, as it would have been to have rescued from the fiery furnace those who should have been cast into it for refusing to worship the image. It was accordingly done in every instance, without asking what the offenders had done, or against whom they had offended, but whether the pains they were suffering were inflicted under the pretended sedition law. It was certainly possible that my motives for contributing to the relief of Callendar, and liberating sufferers under the sedition law might have been to protect, encourage, and reward slander; but they may also have been those which inspire ordinary charities to objects of distress, meritorious or not, or the obligation of an oath to protect the constitution, violated by an unauthorized act of Congress. Which of these were my motives, must be decided by a regard to the general tenor of my life. On this I am not afraid to appeal to the nation at large, to posterity, and still less to that Being who sees himself our motives, who will judge us from his own knowledge of them, and not on the testimony of Porcupine or Fenno.

You observe, there has been one other act of my administration personally unkind, and suppose it will readily suggest itself to me. I declare on my honor, Madam, I have not the least conception what act is alluded to. I never did a single one with an unkind intention. My sole object in this letter being to place before your attention, that the acts imputed to me are either such as are falsely imputed, or as might flow from good as well as bad motives, I shall make no other addition, than the assurances of my continued wishes for the health and happiness of yourself and Mr. Adams.

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER XVI.—TO JAMES MADISON, August 15, 1804

TO JAMES MADISON.

Monticello, August 15, 1804.

Dear Sir,

Your letter dated the 7th should probably have been of the 14th, as I received it only by that day’s post. I return you Monroe’s letter, which is of an awful complexion; and I do not wonder the communications it contains made some impression on him. To a person placed in Europe, surrounded by the immense resources of the nations there, and the greater wickedness of their courts, even the limits which nature imposes on their enterprises are scarcely sensible. It is impossible that France and England should combine for any purpose; their mutual distrust and deadly hatred of each other admit no co-operation. It is impossible that England should be willing to see France re-possess Louisiana, or get footing on our continent, and that France should willingly see the United States re-annexed to the British dominions. That the Bourbons should be replaced on their throne and agree to any terms of restitution, is possible: but that they and England joined, could recover us to British dominion, is impossible. If these things are not so, then human reason is of no aid in conjecturing the conduct of nations. Still, however, it is our unquestionable interest and duty to conduct ourselves with such sincere friendship and impartiality towards both nations, as that each may see unequivocally, what is unquestionably true, that we may be very possibly driven into her scale by unjust conduct in the other. I am so much impressed with the expediency of putting a termination to the right of France to patronize the rights of Louisiana, which will cease with their complete adoption as citizens of the United States, that I hope to see that take place on the meeting of Congress. I enclose you a paragraph from a newspaper respecting St. Domingo, which gives me uneasiness. Still I conceive the British insults in our harbor as more threatening. We cannot be respected by France as a neutral nation, nor by the world or ourselves as an independent one, if we do not take effectual measures to support, at every risk, our authority in our own harbors. I shall write to Mr. Wagner directly (that a post may not be lost by passing through you) to send us blank commissions for Orleans and Louisiana, ready sealed, to be filled up, signed, and forwarded by us. Affectionate salutations and constant esteem.

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER XVII.—TO GOVERNOR CLAIBORNE, August 30, 1804

TO GOVERNOR CLAIBORNE.

Monticello, August 30, 1804.

Dear Sir,

Various circumstances of delay have prevented my forwarding till now the general arrangements of the government of the territory of Orleans. Enclosed herewith you will receive the commissions. Among these is one for yourself as Governor. With respect to this I will enter into frank explanations. This office was originally destined for a person * whose great services and established fame would have rendered him peculiarly acceptable to the nation at large. Circumstances, however, exist, which do not now permit his nomination, and perhaps may not at any time hereafter. That, therefore, being suspended, and entirely contingent, your services have been so much approved, as to leave no desire to look elsewhere to fill the office. Should the doubts you have sometimes expressed, whether it would be eligible for you to continue, still exist in your mind, the acceptance of the commission gives you time to satisfy yourself by further experience, and to make the time and manner of withdrawing, should you ultimately determine on that, agreeable to yourself. Be assured, that whether you continue or retire, it will be with every disposition on my part to be just and friendly to you.

I salute you with friendship and respect.

Th: Jefferson.

[* In the margin is written by the author, ‘La Fayette.‘]

LETTER XVIII.—TO MRS. ADAMS, September 11, 1804

TO MRS. ADAMS.

Monticello, September 11, 1804,

Your letter, Madam, of the 18th of August has been some days received, but a press of business has prevented the acknowledgment of it: perhaps, indeed, I may have already trespassed too far on your attention. With those who wish to think amiss of me, I have learned to be perfectly indifferent; but where I know a mind to be ingenuous, and to need only truth to set it to rights, I cannot be as passive. The act of personal unkindness alluded to in your former letter, is said in your last to have been the removal of your eldest son from some office to which the judges had appointed him. I conclude, then, he must have been a commissioner of bankruptcy. But I declare to you, on my honor, that this is the first knowledge I have ever had that he was so. It may be thought, perhaps, that I ought to have inquired who were such, before I appointed others. But it is to be observed, that the former law permitted the judges to name commissioners occasionally only, for every case as it arose, and not to make them permanent officers. Nobody, therefore, being in office, there could be no removal. The judges, you well know, have been considered as highly federal; and it was noted that they confined their nominations exclusively to federalists. The legislature, dissatisfied with this, transferred the nomination to the President, and made the offices permanent. The very object in passing the law was, that he should correct, not confirm, what was deemed the partiality of the judges. I thought it therefore proper to inquire, not whom they had employed, but whom I ought to appoint to fulfil the intentions of the law. In making these appointments, I put in a proportion of federalists, equal, I believe, to the proportion they bear in numbers through the Union generally. Had I known that your son had acted, it would have been a real pleasure to me to have preferred him to some who were named in Boston, in what was deemed the same line of politics. To this I should have been led by my knowledge of his integrity, as well as my sincere dispositions towards yourself and Mr. Adams.

You seem to think it devolved on the judges to decide on the validity of the sedition law. But nothing in the constitution has given them a right to decide for the executive, more than to the executive to decide for them. Both magistracies are equally independent in the sphere of action assigned to them. The judges, believing the law constitutional, had a right to pass a sentence of fine and imprisonment, because the power was placed in their hands by the constitution. But the executive, believing the law to be unconstitutional, were bound to remit the execution of it; because that power has been confided to them by the constitution. That instrument meant that its co-ordinate branches should be checks on each other. But the opinion which gives to the judges the right to decide what laws are constitutional, and what not, not only for themselves in their own sphere of action, but for the legislature and executive also in their spheres, would make the judiciary a despotic branch. Nor does the opinion of the unconstitutionality, and consequent nullity of that law, remove all restraint from the overwhelming torrent of slander, which is confounding all vice and virtue, all truth and falsehood, in the United States. The power to do that is fully possessed by the several State legislatures. It was reserved to them, and was denied to the General Government, by the constitution, according to our construction of it. While we deny that Congress have a right to control the freedom of the press, we have ever asserted the right of the States, and their exclusive right, to do so. They have, accordingly, all of them made provisions for punishing slander, which those who have time and inclination resort to for the vindication of their characters. In general, the State laws appear to have made the presses responsible for slander as far as is consistent with its useful freedom. In those States where they do not admit even the truth of allegations to protect the printer, they have gone too far.

The candor manifested in your letter, and which I ever believed you to possess, has alone inspired the desire of calling your attention once more to those circumstances of fact and motive by which I claim to be judged. I hope you will see these intrusions on your time to be, what they really are, proofs of my great, respect for you. I tolerate with the utmost latitude the right of others to differ from me in opinion, without imputing to them criminality. I know too well the weakness and uncertainty of human reason, to wonder at its different results. Both of our political parties, at least the honest part of them, agree conscientiously in the same object, the public good: but they differ essentially in what they deem the means of promoting that good. One side believes it best done by one composition of the governing powers; the other, by a different one. One fears most the ignorance of the people; the other, the selfishness of rulers independent of them. Which is right, time and experience will prove. We think that one side of this experiment has been long enough tried, and proved not to promote the good of the many: and that the other has not been fairly and sufficiently tried. Our opponents think the reverse. With whichever opinion the body of the nation concurs, that must prevail. My anxieties on this subject will never carry me beyond the use of fair and honorable means of truth and reason; nor have they ever lessened my esteem for moral worth, nor alienated my affections from a single friend, who did not first withdraw himself. Wherever this has happened, I confess I have not been insensible to it: yet have ever kept myself open to a return of their justice. I conclude with sincere prayers for your health and happiness, that yourself and Mr. Adams may long enjoy the tranquillity you desire and merit, and see in the prosperity of your family what is the consummation of the last and warmest of human wishes,

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER XIX.—TO MR. NICHOLSON, January 29, 1805

TO MR. NICHOLSON.

Washington, January 29, 1805.

Dear Sir,

Mr. Eppes has this moment put into my hands your letter of yesterday, asking information on the subject of the gun-boats proposed to be built. I lose no time in communicating to you fully my whole views respecting them, premising a few words on the system of fortifications. Considering the harbors which, from their situation and importance, are entitled to defence, and the estimates we have seen of the fortifications planned for some of them, this system cannot be completed on a moderate scale for less than fifty millions of dollars, nor manned in time of war with less than fifty thousand men, and in peace, two thousand. And when done, they avail little; because all military men agree, that wherever a vessel may pass a fort without tacking under her guns, which is the case at all our sea-port towns, she may be annoyed more or less, according to the advantages of the position, but can never be prevented. Our own experience during the war proved this on different occasions. Our predecessors have, nevertheless, proposed to go into this system, and had commenced it. But, no law requiring us to proceed, we have suspended it.