автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Complete Works of Marcus Terentius Varro. Illustrated

The Complete Works of Marcus Terentius Varro

Illustrated

On Agriculture

On the Latin Language

Varro proved to be a highly productive writer and turned out more than 74 Latin works on a variety of topics. Among his many works, two stand out for historians; Nine Books of Disciplines and his compilation of the Varronian chronology. His Nine Books of Disciplines became a model for later encyclopedists, especially Pliny the Elder.

Varro`s only complete work extant, Rerum rusticarum libri tres (Three Books on Agriculture), has been described as "the well digested system of an experienced and successful farmer who has seen and practised all that he records."

The compilation of the Varronian chronology was an attempt to determine an exact year-by-year timeline of Roman history up to his time.

Varro was recognized as an important source by many other ancient authors, among them Cicero, Pliny the Elder, Virgil in the Georgics, Columella, Aulus Gellius, Macrobius, Augustine, and Vitruvius.

One noteworthy aspect of the work is his anticipation of microbiology and epidemiology. Varro warned his contemporaries to avoid swamps and marshland, since in such areas “...there are bred certain minute creatures which cannot be seen by the eyes, but which float in the air and enter the body through the mouth and nose and cause serious diseas.”

On Agriculture

On the Latin Language

ON AGRICULTURE

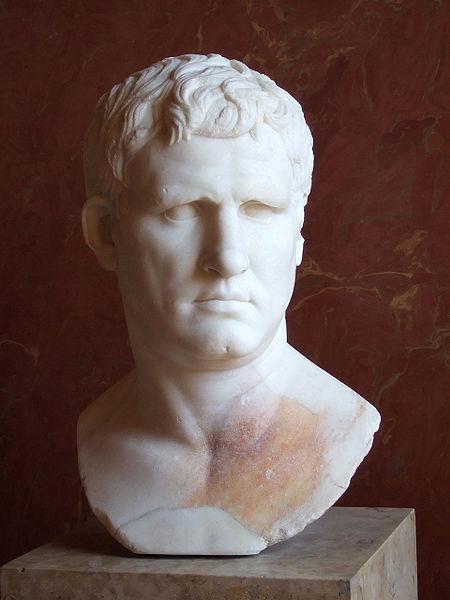

Varro was born in Reate, now Rieti, to a family of equestrian rank, which owned a large farm in the Reatine plain, near Lago di Ripa Sottile. He supported Pompey, reaching the office of praetor, after having been tribune of the people, quaestor and curule aedile. Varro’s literary output was prolific; with scholars estimating him to have produced 74 works in approximately 620 books, of which only one work survives complete, although we possess numerous fragments of the others, many contained in Gellius’ Attic Nights. Regarded as “the most learned of the Romans” by Quintilian (Inst. Or. X.1.95), Varro was recognised as an important source by many other ancient authors, including Cicero, Pliny the Elder, Virgil, Aulus Gellius, Macrobius, Augustine and Vitruvius, who credits him with a book on architecture.

Varro’s only complete extant work is Rerum rusticarum libri tres (On Agriculture), formed of three books. The work concerns country affairs, opening with an effective setting of the agricultural scene, while also employing dialogue. The first book covers the themes of agriculture and farm management, the second deals with sheep and oxen, while the third concludes with poultry and the keeping of other animals, including bees and fishponds. The text is notable for its lively interludes, as well as graphic background detail concerning political events, of which Varro was a key figure.

LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY TRANSLATION (HOOPER)

Translated by William Davis Hooper and Revised by Harrison Boyd Ash

BOOK I

[1.1] Had I possessed the leisure, Fundania, I should write in a more serviceable form what now I must set forth as I can, reflecting that I must hasten; for if man is a bubble, as the proverb has it, all the more so is an old man. For my eightieth year admonishes me to gather up my pack before I set forth from life. [2] Wherefore, since you have bought an estate and wish to make it profitable by good cultivation, and ask that I concern myself with the matter, I will make the attempt; and in such wise as to advise you with regard to the proper practice not only while I live but even after my death. [3] And I cannot allow the Sibyl to have uttered prophecies which benefited mankind not only while she lived, but even after she had passed away, and that too people whom she never knew — for so many years later we are wont officially to consult her books when we desire to know what we should do after some portent — and not do something, even while I am alive, to help my friends and kinsfolk. [4] Therefore I shall write for you three handbooks to which you may turn whenever you wish to know, in a given case, how you ought to proceed in farming. And since, as told, the gods help those who call upon them, I will first invoke them — not the Muses, as Homer and Ennius do, but the twelve councillor-gods; and I do not mean those urban gods, whose images stand around the forum, bedecked with gold, six male and a like number female, but those twelve gods who are the special patrons of husbandmen. [5] First, then, I invoke Jupiter and Tellus, who, by means of the sky and the earth, embrace all the fruits of agriculture; and hence, as we are told that they are the universal parents, Jupiter is called “the Father,” and Tellus is called “Mother Earth.” And second, Sol and Luna, whose courses are watched in all matters of planting and harvesting. Third, Ceres and Liber, because their fruits are most necessary for life; for it is by their favour that food and drink come from the farm. [6] Fourth, Robigus and Flora; for when they are propitious the rust will not harm the grain and the trees, and they will not fail to bloom in their season; wherefore, in honour of Robigus has been established the solemn feast of the Robigalia, and in honour of Flora the games called the Floralia. Likewise I beseech Minerva and Venus, of whom the one protects the oliveyard and the other the garden; and in her honour the rustic Vinalia has been established. And I shall not fail to pray also to Lympha and Bonus Eventus, since without moisture all tilling of the ground is parched and barren, and without success and “good issue” it is not tillage but vexation. [7] Having now duly invoked these divinities, I shall relate the conversations which we had recently about agriculture, from which you may learn what you ought to do; and if matters in which you are interested are not treated, I shall indicate the writers, both Greek and Roman, from whom you may learn them.

Those who have written various separate treatises in Greek, one on one subject, another on another, are more than fifty in number. [8] The following are those whom you can call to your aid when you wish to consider any point: Hiero of Sicily and Attalus Philometor; of the philosophers, Democritus the naturalist, Xenophon the Socratic, Aristotle and Theophrastus the Peripatetics, Archytas the Pythagorean, and likewise Amphilochus of Athens, Anaxipolis of Thasos, Apollodorus of Lemnos, Aristophanes of Mallos, Antigonus of Cyme, Agathocles of Chios, Apollonius of Pergamum, Aristandrus of Athens, Bacchius of Miletus, Bion of Soli, Chaerestus and Chaereas of Athens, Diodorus of Priene, Dion of Colophon, Diophanes of Nicaea, Epigenes of Rhodes, Euagon of Thasos, the two Euphronii, one of Athens and the other of Amphipolis, Hegesias of Maronea, the two Menanders, one of Priene and the other of Heraclea, Nicesius of Maronea, and Pythion of Rhodes. [9] Among other writers, whose birthplace I have not learned, are: Androtion, Aeschrion, Aristomenes, Athenagoras, Crates, Dadis, Dionysius, Euphiton, Euphorion, Eubulus, Lysimachus, Mnaseas, Menestratus, Plentiphanes, Persis, Theophilus. All these whom I have named are prose writers; others have treated the same subjects in verse, as Hesiod of Ascra and Menecrates of Ephesus. [10] All these are surpassed in reputation by Mago of Carthage, who gathered into twenty-eight books, written in the Punic tongue, the subjects they had dealt with separately. These Cassius Dionysius of Utica translated into Greek and published in twenty books, dedicated to the praetor Sextilius. In these volumes he added not a little from the Greek writers whom I have named, taking from Mago’s writings an amount equivalent to eight books. Diophanes, in Bithynia, further abridged these in convenient form into six books, dedicated to King Deiotarus. [11] I shall attempt to be even briefer and treat the subject in three books, one on agriculture proper, the second on animal husbandry, the third on the husbandry of the steading, omitting in this book all subjects which I do not think have a bearing on agriculture. And so, after first showing what matter should be omitted, I shall treat of the subject, following the natural divisions. My remarks will be derived from three sources: what I have myself observed by practice on my own land, what I have read, and what I have heard from experts.

[2.1] On the festival of the Sementivae I had gone to the temple of Tellus at the invitation of the aeditumnus (sacristan), as we have been taught by our fathers to call him, or of the aedituus, as we are being set right on the word by our modern purists. I found there Gaius Fundanius, my father-in-law, Gaius Agrius, a Roman knight of the Socratic school, and Publius Agrasius, the tax-farmer, examining a map of Italy painted on the wall. “What are you doing here?” said I. “Has the festival of the Sementivae brought you here to spend your holiday, as it used to bring our fathers and grandfathers?” [2] “I take it,” replied Agrius, “that the same reason brought us which brought you — the invitation of the sacristan. If I am correct, as your nod implies, you will have to await with us his return; he was summoned by the aedile who has supervision of this temple, and has not yet returned; and he left a man to ask us to wait for him. Do you wish us then meanwhile to follow the old proverb, ‘the Roman wins by sitting still,’ until he returns?” “By all means,” replied Agrius; and reflecting that the longest part of the journey is said to be the passing of the gate, he walked to a bench, with us in his train.

[3] When we had taken our seats Agrasius opened the conversation: “You have all travelled through many lands; have you seen any land more fully cultivated than Italy?” “For my part,” replied Agrius, “I think there is none which is so wholly under cultivation. Consider first: Eratosthenes, following a most natural division, has divided the earth into two parts, [4] one to the south and the other to the north; and since the northern part is undoubtedly more healthful than the southern, while the part which is more healthful is more fruitful, we must agree that Italy at least was more suited to cultivation than Asia. In the first place, it is in Europe; and in the next place, this part of Europe has a more temperate climate than we find farther inland. For the winter is almost continuous in the interior, and no wonder, since its lands lie between the arctic circle and the pole, where the sun is not visible for six months at a time; wherefore we are told that even navigation in the ocean is not possible in that region because of the frozen sea.” [5] “Well,” remarked Fundanius, “do you think that anything can germinate in such a land, or mature if it does germinate? That was a true saying of Pacuvius, that if either day or night be uninterrupted, all the fruits of the earth perish, from the fiery vapour or from the cold. For my part, I could not live even here, where the night and the day alternate at moderate intervals, if I did not break the summer day with my regular midday nap; [6] but there, where the day and the night are each six months long, how can anything be planted, or grow, or be harvested? On the other hand, what useful product is there which not only does not grow in Italy, but even grow to perfection? What spelt shall I compare to the Campanian, what wheat to the Apulian, what wine to the Falernian, what oil to the Venafran? Is not Italy so covered with trees that the whole land seems to be an orchard? [7] Is that Phrygia, which Homer calls ‘the vine-clad,’ more covered with vines than this land, or Argos, which the same poet calls ‘the rich in corn,’º more covered with wheat? In what land does one iugerum bear ten and fifteen cullei of wine, as do some sections of Italy? Or does not Marcus Cato use this language in his Origines? ‘The land lying this side of Ariminum and beyond the district of Picenum, which was allotted to colonists, is called Gallo-Roman. In that district, at several places, ten cullei of wine are produced to the iugerum.’ Is not the same true of the district of Faventia? The vines there are called by this writer trecenariae, from the fact that the iugerum yields three hundred amphorae.” And he added, turning to me, “At least your friend, Marcius Libo, the engineer officer, used to tell me that the vines on his estate at Faventia bore this quantity. [8] The Italian seems to have had two things particularly in view in his farming: whether the land would yield a fair return for the investment in money and labour, and whether the situation was healthful or not. If either of these elements is lacking, any man who, in spite of that fact, desires to farm has lost his wits, and should be taken in charge by his kinsmen and family. For no sane man should be willing to undergo the expense and outlay of cultivation if he sees that it cannot be recouped; or, supposing that he can raise a crop, if he sees that it will be destroyed by the unwholesomeness of the situation. [9] But, I think, there are some gentlemen present who can speak with more authority on these subjects; for I see Gaius Licinius Stolo and Gnaeus Tremelius Scrofa approaching, one of them a man whose ancestors originated the bill to regulate the holding of land (for that law which forbids a Roman citizen to hold more than 500 iugera was proposed by a Stolo), and who has proved the appropriateness of the family name by his diligence in farming; he used to dig around his trees so thoroughly that there could not be found on his farm a single one of those suckers which spring up from the roots and are called stolones. Of the same farm was that Gaius Licinius who, when he was tribune of the plebs, 365 years after the expulsion of the kings, was the first to lead people, for the hearing of laws, from the comitium into the “farm” of the forum. [10] The other whom I see coming is your colleague, who was of the Commission of Twenty for parcelling the Campanian lands, Gnaeus Tremelius Scrofa, a man distinguished by all virtues, who is esteemed the Roman most skilled in agriculture.” “And justly so,” I exclaimed. “For his estates, because of their high cultivation, are a more pleasing sight to many than the country seats of others, furnished in a princely style. When people come to inspect his farmsteads, it is not to see collections of pictures, as at Lucullus’s, but collections of fruit. The top of the Via Sacra,” I added, “where fruit brings its weight in gold, is a very picture of his orchard.”

[11] While we were speaking they came up, and Stolo inquired: “We haven’t arrived too late for dinner? For I do not see Lucius Fundilius, our host.” “Do not be alarmed,” replied Agrius, “for not only has that egg which shows the last lap of the chariot race at the games in the circus not been taken down, but we have not even seen that other egg which usually heads the procession at dinner. [12] And so, while you and we are waiting to see the latter, and our sacristan is returning, tell us what end agriculture has in view, profit, or pleasure, or both; for we are told that you are now the past-master of agriculture, and that Stolo formerly was.” “First,” remarked Scrofa, “we should determine whether we are to include under agriculture only things planted, or also other things, such as sheep and cattle, which are brought on to the land. [13] For I observe that those who have written on agriculture, whether in Punic, or Greek, or Latin, have wandered too far from the subject.” “For my part,” replied Stolo, “I do not think that they are to be imitated in every respect, but that certain of them have acted wisely in confining the subject to narrower limits, and excluding matters which do not bear directly on this topic. Thus the whole subject of grazing, which many writers include under agriculture, seems to me to concern the herdsman rather than the farmer. [14] For that reason the persons who are placed in charge of the two occupations have different names, one being called vilicus, and the other magister pecoris. The vilicus is appointed for the purpose of tilling the ground, and the name is derived from villa, the place into which the crops are hauled (vehuntur), and out of which they are hauled by him when they are sold. For this reason the peasants even now call a road veha, because of the hauling; and they call the place to which and from which they haul vella and not villa. In the same way, those who make a living by hauling are said facere velaturam.” [15] “Certainly,” said Fundanius, “grazing and agriculture are different things, though akin; just as the right pipe of the tibia is different from the left, but still in a way united, inasmuch as the one is the treble, while the other plays the accompaniment of the same air.” [16] “You may even add this,” said I, “that the shepherd’s life is the treble, and the farmer’s plays the accompaniment, if we may trust that most learned man, Dicaearchus. In his sketch of Greek life from the earliest times, he says that in the primitive period, when people led a pastoral life, they were ignorant even of ploughing, of planting trees, and of pruning, and that agriculture was adopted by them only at a later period. Wherefore the art of agriculture ‘accompanies’ the pastoral because it is subordinate, as the left pipe is to the stops of the right.” [17] “You and your piping,” retorted Agrius, “are not only robbing the master of his flock and the slaves of their peculium — the grazing which their master allows them — but you are even abrogating the homestead laws, among which we find one reciting that the shepherd may not graze a young orchard with the offspring of the she-goat, a race which astrology, too, has placed in the heavens, not far from the Bull.” [18] “Be careful, Agrius,” interrupted Fundanius, “that your citation cannot be wide of the mark; for it is also written in the law, ‘a certain kind of flock.’ For certain kinds of animals are the foes of plants, and even poisonous, such as the goats of which you spoke; for they destroy all young plants by their browsing, and especially vines and olives. [19] Accordingly there arose a custom, from opposite reasons, that a victim from the goat family might be led to the altar of one god, but might not be sacrificed on the altar of another; since, because of the same hatred, the one was not willing to see a goat, while the other was pleased to see him die. So it was that he-goats were offered to father Bacchus, the discoverer of the vine, so that they might pay with their lives for the injuries they do him; while, on the other hand, no member of the goat family was sacrificed to Minerva on account of the olive, because it is said that any olive plant which they bite becomes sterile; for their spittle is poisonous to its fruit. [20] For this reason, also, they are not driven into the acropolis at Athens except once a year, for a necessary sacrifice — to avoid the danger of having the olive tree, which is said to have originated there, touched by a she-goat.” “Cattle are not properly included in a discussion on agriculture,” said I, “except those which enhance the cultivation of the land by their labour, such as those which can plough under the yoke.” [21] “If that is so,” replied Agrasius, “how can cattle be kept off the land, when manure, which enhances its value very greatly, is supplied by the herds?” “By that method of reasoning,” retorted Agrius, “we may assert that slave-trading is a branch of agriculture, if we decide to keep a gang for that purpose. The error lies in the assumption that, because cattle can be kept on the land and be a source of profit there, they are part of agriculture. It does not follow; for by that reasoning we should have to embrace other things quite foreign to agriculture; as, for instance, you might keep on your farm a number of spinners, weavers, and other artisans.”

“Very well,” said Scrofa, “let us exclude grazing from agriculture, and whatever else anyone wishes.” [22] “Am I, then,” said I, “to follow the writings of the elder and the younger Saserna, and consider that how to manage clay-pits is more related to agriculture than mining for silver or other mining such as undoubtedly is carried out on some land? [23] But as quarries for stone or sand-pits are not related to agriculture, so too clay-pits. This is not to say that they are not to be worked on land where it is suitable and profitable; as further, for instance, if the farm lies along a road and the site is convenient for travellers, a tavern might be built; however profitable it might be, still it would form no part of agriculture. For it does not follow that whatever profit the owner makes on account of the land, or even on the land, should be credited to the account of agriculture, but only that which, as the result of sowing, is born of the earth for our enjoyment.” [24] “You are jealous of that great writer,” interrupted Stolo, “and you attack his potteries carpingly, while passing over the excellent observations he makes bearing very closely on agriculture, so as not to praise them.” [25] This brought a smile from Scrofa, who knew the books and despised them; and Agrasius, thinking that he alone knew them, asked Stolo to give a quotation. “This is his recipe for killing bugs,” he said: “ ‘Soak a wild cucumber in water, and wherever you sprinkle the water the bugs will not come.’ And again, ‘Grease your bed with ox gall, mixed with vinegar.’ “ [26] “And still it is good advice,” said Fundanius, glancing at Scrofa, “even if he did write it in a book on agriculture.” “Just as good, by Hercules,” he replied, “as this one for the making of a depilatory: ‘Throw a yellow frog into water, boil it down to one-third, and rub the body with it.’ “ “It would be better for you to quote from that book,” said I, “a passage which bears more closely on the trouble from which Fundanius suffers; for his feet are always hurting him and bringing wrinkles to his brow.” [27] “Tell me, pray,” exclaimed Fundanius; “I would rather hear about my feet than how beet-roots ought to be planted.” “I will tell you,” said Stolo, with a smile, “in the very words in which he wrote it (at least I have heard Tarquenna say that when a man’s feet begin to hurt he may be cured if he will think of you): ‘I am thinking of you, cure my feet. The pain go in the ground, and may my feet be sound.’ He bids you chant this thrice nine times, touch the ground, spit on it, and be fasting while you chant.” [28] “You will find many other marvels in the books of the Sasernas,” said I, “which are all just as far away from agriculture and therefore to be disregarded.” “Just as if,” said he, “such things are not found in other writers also. Why, are there not many such items in the book of the renowned Cato, which he published on the subject of agriculture, such as his recipes for placenta, for libum, and for the salting of hams?” “You do not mention that famous one of his composing,” said Agrius: “ ‘If you wish to drink deep at a feast and to have a good appetite, eat some half-dozen leaves of raw cabbage with vinegar before dinner.’”

[3.1] “Well, then,” said Agrasius, “since we have decided the nature of the subjects which are to be excluded from agriculture, tell us whether the knowledge of those things used in agriculture is an art or not, and trace its course from starting-point to goal.” Glancing at Scrofa, Stolo said: “You are our superior in age, in position, and in knowledge, so you ought to speak.” And he, nothing loath, began: “In the first place, it is not only an art but an important and noble art. It is, as well, a science, which teaches what crops are to be planted in each kind of soil, and what operations are to be carried on, in order that the land may regularly produce the largest crops.

[4.1] “Its elements are the same as those which Ennius says are the elements of the universe — water, earth, air, and fire. You should have some knowledge of these before you cast your seed, which is the first step in all production. Equipped with this knowledge, the farmer should aim at two goals, profit and pleasure; the object of the first is material return, and of the second enjoyment. The profitable plays a more important rôle than the pleasurable; [2] and yet for the most part the methods of cultivation which improve the aspect of the land, such as the planting of fruit and olive trees in rows, make it not only more profitable but also more saleable, and add to the value of the estate. For any man would rather pay more for a piece of land which is attractive than for one of the same value which, though profitable, is unsightly. [3] Further, land which is more wholesome is more valuable, because on it the profit is certain; while, on the other hand, on land that is unwholesome, however rich it may be, misfortune does not permit the farmer to reap a profit. For where the reckoning is with death, not only is the profit uncertain, but also the life of the farmers; so that, lacking wholesomeness, agriculture becomes nothing else than a game of chance, in which the life and the property of the owner are at stake. [4] And yet this risk can be lessened by science; for, granting that healthfulness, being a product of climate and soil, is not in our power but in that of nature, still it depends greatly on us, because we can, by care, lessen the evil effects. For if the farm is unwholesome on account of the nature of the land or the water, from the miasma which is exhaled in some spots; or if, on account of the climate, the land is too hot or the wind is not salubrious, these faults can be alleviated by the science and the outlay of the owner. The situation of the buildings, their size, the exposure of the galleries, the doors, and the windows, are matters of the highest importance. [5] Did not that famous physician, Hippocrates, during a great pestilence save not one farm but many cities by his skill? But why do I cite him? Did not our friend Varro here, when the army and fleet were at Corcyra, and all the houses were crowded with the sick and the dead, by cutting new windows to admit the north wind, and shutting out the infected winds, by changing the position of doors, and other precautions of the same kind, bring back his comrades and his servants in good health?

[5.1] “But as I have stated the origin and the limits of the science, it remains to determine the number of its divisions.” “Really,” said Agrius, “it seems to me that they are endless, when I read the many books of Theophrastus, those which are entitled ‘The History of Plants’ and ‘The Causes of Vegetation.’ “ [2] “His books,” replied Stolo, “are not so well adapted to those who wish to tend land as to those who wish to attend the schools of the philosophers; which is not to say that they do not contain matter which is both profitable and of general interest. [3] So, then, do you rather explain to us the divisions of the subject.” “The chief divisions of agriculture are four in number,” resumed Scrofa: “First, a knowledge of the farm, comprising the nature of the soil and its constituents; second, the equipment needed for the operation of the farm in question; third, the operations to be carried out on the place in the way of tilling; and fourth, the proper season for each of these operations. [4] Each of these four general divisions is divided into at least two subdivisions the first comprises questions with regard to the soil as such, and those which pertain to housing and stabling. The second division, comprising the movable equipment which is needed for the cultivation of the farm, is also subdivided into two: the persons who are to do the farming, and the other equipment. The third, which covers operations, is subdivided: the plans to be made for each operation, and where each is to be carried on. The fourth, covering the seasons, is subdivided: those which are determined by the annual revolution of the sun, and those determined by the monthly revolution of the moon. I shall discuss first the four chief divisions, and then the eight subdivisions in more detail.

[6.1] “First, then, with respect to the soil of the farm, four points must be considered: the conformation of the land, the quality of the soil, its extent, and in what way it is naturally protected. As there are two kinds of conformation, the natural and that which is added by cultivation, in the former case one piece of land being naturally good, another naturally bad, and in the latter case one being well tilled, another badly, I shall discuss first the natural conformation. [2] There are, then, with respect to the topography, three simple types of land — plain, hill, and mountain; though there is a fourth type consisting of a combination of these, as, for instance, on a farm which may contain two or three of those named, as may be seen in many places. Of these three simple types, undoubtedly a different system is applicable to the lowlands than to the mountains, because the former are hotter than the latter; and the same is true of hillsides, because they are more temperate than either the plains or the mountains. [3] These qualities are more apparent in broad stretches, when they are uniform; thus the heat is greater where there are broad plains, and hence in Apulia the climate is hotter and more humid, while in mountain regions, as on Vesuvius, the air is lighter and therefore more wholesome. Those who live in the lowlands suffer more in summer; those who live in the uplands suffer more in winter; the same crops are planted earlier in the spring in the lowlands than in the uplands, and are harvested earlier, while both sowing and reaping come later in the uplands. [4] Certain trees, such as the fir and the pine, flourish best and are sturdiest in the mountains on account of the cold climate, while the poplar and the willow thrive here where the climate is warmer; the arbute and the oak do better in the upland, the almond and the mariscan fig in the lowlands. On the foothills the growth is nearer akin to that of the plains than to that of the mountains; on the higher hills the opposite is true. [5] Owing to these three types of configuration different crops are planted, grain being considered best adapted to the plains, vines to the hills, and forests to the mountains. Usually the winter is better for those who live in the plains, because at that season the pastures are fresh, and pruning can be carried on in more comfort. On the other hand, the summer is better in the mountains, because there is abundant forage at that time, whereas it is dry in the plains, and the cultivation of the trees is more convenient because of the cooler air. [6] A lowland farm that everywhere slopes regularly in one direction is better than one that is perfectly level, because the latter, having no outlet for the water, tends to become marshy. Even more unfavourable is one that is irregular, because pools are liable to form in the depressions. These points and the like have their differing importance for the cultivation of the three types of configuration.”

[7.1] “So far as concerns the natural situation,” said Stolo, “it seems to me that Cato was quite right when he said that the best farm was one that was situated at the foot of a mountain, facing south.” [2] Scrofa continued: “With regard to the conformation due to cultivation, I maintain that the more regard is had for appearances the greater will be the profits: as, for instance, if those who have orchards plant them in quincunxes, with regular rows and at moderate intervals. Thus our ancestors, on the same amount of land but not so well laid out, made less wine and grain than we do, and of a poorer quality; for plants which are placed exactly where each should be take up less ground and screen each other less from the sun, the moon, and the air. [3] You may prove this by one of several experiments; for instance, a quantity of nuts which you can hold in a modius measure with their shells whole, because the shells naturally keep them compacted, you can scarcely pack into a modius and a half when they are cracked. [4] As to the second point, trees which are planted in a row are warmed by the sun and the moon equally on all sides, with the result that more grapes and olives form, and that they ripen earlier; which double result has the double consequence that they yield more must and oil, and of greater value.

[5] “We come now to the second division of the subject, the type of soil of which the farm is composed. It is in respect of this chiefly that a farm is considered good or bad; for it determines what crops, and of what variety, can be planted and raised on it, as not all crops can be raised with equal success on the same land. As one type is suited to the vine and another to grain, so of others — one is suited to one crop, another to another. [6] Thus near Cortynia, in Crete, there is said to be a plane tree which does not shed its leaves in winter, and another in Cyprus, according to Theophrastus. Likewise at Sybaris, which is now called Thurii, there is said to be an oak tree of like character, in sight of the town; and that near Elephantine neither the fig nor the vine sheds its leaves — which is quite the opposite of what happens with us. For the same reason there are many trees which bear two crops a year, such as the vine on the coast near Smyrna, and the apple in the district of Consentia. [7] The fact that trees produce more fruit in uncultivated spots, and better fruit under cultivation, proves the same thing. For the same reason there are plants which cannot live except in marshy ground, or actually in the water and not in every kind of water. Some grow in ponds, as the reeds near Reate, others in streams, as the alder trees in Epirus, and still others in the sea, as the palms and squills of which Theophrastus writes. [8] When I was in command of the army in the interior of Transalpine Gaul near the Rhine, I visited a number of spots where neither vines nor olives nor fruit trees grew; where they fertilized the land with a white chalk which they dug; where they had no salt, either mineral or marine, but instead of it used salty coals obtained by burning certain kinds of wood.” [9] “Cato, you know,” interjected Stolo, “in arranging plots according to the degree of existence, formed nine categories: first, land on which vines can bear a large quantity of wine of good quality; second, land suited for a watered garden; third, for an osier bed; fourth, for olives; fifth, for meadows; sixth, for a grain field; seventh, for a wood lot: eighth, for an orchard; ninth, for a mast grove.” [10] “I know he wrote that,” replied Scrofa, “but all authorities do not agree with him on this point. There are some who assign the first place to good meadows, and I am one of them. Hence our ancestors gave the name prata to meadow-land as being ready (parata). Caesar Vopiscus, once an aedile, in pleading a case before the censors, spoke of the plains of Rosea as the nursing-ground of Italy, such that if a rod were left there overnight, it would be lost the next morning on account of the growth of the grass.

[8.1] “As an argument against the vineyard, there are those who claim that the cost of upkeep swallows up the profits. In my opinion, it depends on the kind of vineyard, for there are several: for some are low-growing and without props, as in Spain; others tall, which are called ‘yoked,’ as generally in Italy. For this latter class there are two names, pedamenta and iuga: those on which the vine runs vertically are called pedamenta (stakes), and those on which it runs transversely are called iuga (yokes); and from this comes the name ‘yoked vines.’ [2] Four kinds of ‘yokes’ are usually employed, made respectively of poles, of reeds, of cords, and of vines: the first of these, for example, around Falernum, the second around Arpi, the third around Brundisium, the fourth around Mediolanum. There are two forms of this trellising: in straight lines, as in the district of Canusium, or yoked lengthways and sideways in the form of the compluvium, as is the practice generally in Italy. If the material grows on the place the vineyard does not mind the expense; and it is not burdensome if much of it can be obtained in the neighbourhood. [3] The first class I have named requires chiefly a willow thicket, the second a reed thicket, the third a rush bed or some material of the kind. For the fourth you must have an arbustum, where trellises can be made of the vines, as the people of Mediolanum do on the trees which they call opuli (maples), and the Canusians on lattice-work in fig trees. [4] Likewise, there are, as a rule, four types of props. The best for common use in the vineyard is a stout post, called ridica, made of oak or juniper. The second best is a stake made from a branch, and preferably from a tough one, so that it will last longer; when one end has rotted in the ground the stake is reversed, what had been the top becoming the bottom. The third, which is used only as a substitute when the others are lacking, is formed of reeds; bundles of these, tied together with bark, are planted in what they call cuspides, earthenware pipes with open bottoms so that the casual water can run out. The fourth is the natural prop, where the vineyard is formed of vines growing across from tree to tree; such traverses are called by some rumpi. [5] The limit to the height of the vineyard is the height of a man, and the intervals between the props should be sufficient to allow a yoke of oxen to plough between. The most economical type of vineyard is that which furnishes wine to beaker without the aid of trellises. There are two kinds of these: one in which the ground serves as a bed for the grapes, as in many parts of Asia. The foxes often share the harvest with man in such vineyards, and if the land breeds mice the yield is cut short unless you fill the whole vineyard with traps, as they do in the island Pandateria. [6] In the other type only those branches are raised from the ground which give promise of producing fruit. These are propped on forked sticks about two feet long, at the time when the grapes form, so that they may not wait until the harvest is over to learn to hang in a bunch by means of a string or the fastening which our fathers called a cestus. In such a vineyard, as soon as the master sees the back of the vintager he takes his forks back to hibernate under cover so that he may be able to enjoy their assistance without cost the next year. In Italy the people of Reate practise this custom. [7] This variation in culture is caused chiefly by the fact that the nature of the soil makes a great difference; where this is naturally humid the vine must be trained higher, because while the wine is forming and ripening it does not need water, as it does in the cup, but sun. And that is the chief reason, I think, that the vines climb up trees.

[9.1] “The nature of the soil, I say, makes a great difference, in determining to what it is or is not adapted. The word terra is used in three senses, the general, the specific, and the mixed. It is used in the general sense when we speak of the orbis terrae, or of the terra of Italy or any other country; for in that designation are included rock, and sand, and other such things. The word is used specifically in the second sense when it is employed without the addition of a qualifying word or epithet. [2] It is used in the third or mixed sense, of the element in which seed can be planted and germinate — such as clay soil, rocky soil, etc. In this last sense of the word there are as many varieties of earth as when it is used in the general sense, on account of the different combinations of substances. For there are many substances in the soil, varying in consistency and strength, such as rock, marble, rubble, sand, loam, clay, red ochre, dust, chalk, ash, carbuncle (that is, when the ground becomes so hot from the sun that it chars the roots of plants); [3] and soil, using the word in its specific sense, is called chalky or . . . according as one of these elements predominates — and so of other types of soil. The classes of these vary in such a way that there are, besides other subdivisions, at least three for each type: rocky soil, for instance, may be very rocky, or moderately rocky, or almost free of rocks, and in the case of other varieties of mixed soil the same three grades are distinguished. [4] And further, each of these three grades contains three grades: one may be very wet, one very dry, one intermediate. And these distinctions are not without the greatest importance for the crops; thus the intelligent farmer plants spelt rather than wheat on wet land, and on the other hand barley rather than spelt on dry land, while he plants either on the intermediate. [5] Furthermore, even finer distinctions are made in all these classes, as, for instance, in loamy soil it makes a difference whether the loam be white or red, as the whitish loam is not suited to nurseries, while the reddish is well adapted. Thus there are three chief distinctions in soil, according as it is poor, rich, or medium; the rich being able to produce many kinds of vegetation, and the poor quite the opposite. In thin soil, as, for instance, in Pupinia, you see no sturdy trees, nor vigorous vines, nor stout straw, nor mariscan figs, and most of the trees are covered with moss, as are the parched meadows. [6] On the other hand, in rich soil, like that in Etruria, you can see rich crops, land that can be worked steadily, sturdy trees, and no moss anywhere. In the case of medium soil, however, such as that near Tibur, the nearer it comes to not being thin than to being sterile, the more it is suited to all kinds of growth than if it inclined to the poorer type.” [7] “Diophanes of Bithynia makes a good point,” remarked Stolo, “when he writes that you can judge whether land is fit for cultivation or not, either from the soil itself or from the vegetation growing on it: from the soil according as it is white or black, light and crumbling easily when it is dug, of a consistency not ashy and not excessively heavy; from the wild vegetation growing on it if it is luxuriant and bearing abundantly its natural products. But proceed to your third topic, that of measurement.”

[10.1] Scrofa resumed: “Each country has its own method of measuring land. Thus in farther Spain the unit of measure is the iugum, in Campania the versus, with us here in the district of Rome and in Latium the iugerum. The iugum is the amount of land which a yoke of oxen can plough in a day; the versus is an area 100 feet square; [2] the iugerum an area containing two square actus. The square actus, which is an area 120 feet in each direction, is called in Latin acnua. The smallest section of the iugerum, an area ten feet square, is called a scripulum; and hence surveyors sometimes speak of the odd fractions of land above the iugerum as an uncia or a sextans, or the like; for the iugerum contains 288 scripula, which was the weight of the old pound before the Punic War. Two iugera form a haeredium, from the fact that this amount was said to have been first allotted to each citizen by Romulus, as the amount that could be transmitted by will. Later on 100 haeredia were called a centuria; this is a square area, each side being 2400 feet long. Further, four such centuriae, united in such a way that there are two on each side, are called a saltus in the distribution of public lands.

[11.1] “Many errors result from the failure to observe the measurement of the farm, some building a steading smaller and some larger than the dimensions demand — each of which is prejudicial to the estate and its revenue. For buildings which are too large cost us too much for construction and require too great a sum for upkeep; and if they are smaller than the farm requires the products are usually ruined. [2] There is no doubt, for instance, that a larger wine cellar should be built on an estate where there is a vineyard, and larger granaries if it is a grain farm.

“The steading should be so built that it will have water, if possible, within the enclosure, or at least very near by. The best arrangement is to have a spring on the place, or, failing this, a perennial stream. If no running water is available, cisterns should be built under cover and a reservoir in the open, the one for the use of people and the other for cattle.

[12.1] “Especial care should be taken, in locating the steading, to place it at the foot of a wooded hill, where there are broad pastures, and so as to be exposed to the most healthful winds that blow in the region. A steading facing the east has the best situation, as it has the shade in summer and the sun in winter. If you are forced to build on the bank of a river, be careful not to let the steading face the river, as it will be extremely cold in winter, and unwholesome in summer. [2] Precautions must also be taken in the neighbourhood of swamps, both for the reasons given, and because there are bred certain minute creatures which cannot be seen by the eyes, which float in the air and enter the body through the mouth and nose and there cause serious diseases.” “What can I do,” asked Fundanius, “to prevent disease if I should inherit a farm of that kind?” “Even I can answer that question,” replied Agrius; “sell it for the highest cash price; or if you can’t sell it, abandon it.” [3] Scrofa, however, replied: “See that the steading does not face in the direction from which the infected wind usually comes, and do not build in a hollow, but rather on elevated ground, as a well-ventilated place is more easily cleared if anything obnoxious is brought in. Furthermore, being exposed to the sun during the whole day, it is more wholesome, as any animalculae which are bred near by and brought in are either blown away or quickly die from the lack of humidity. [4] Sudden rains and swollen streams are dangerous to those who have their buildings in low-lying depressions, as are also the sudden raids of robber bands, who can more easily take advantage of those who are off their guard. Against both these dangers the more elevated situations are safer.

[13.1] “In laying out the steading, you should arrange the stables so that the cow-stalls will be at the place which will be warmest in winter. Such liquid products as wine and oil should be set away in store-rooms on level ground, and jars for oil and wine should be provided; while dry products, such as beans and hay, should be stored in a floored space. A place should be provided for the hands to stay in when they are tired from work or from cold or heat, where they can recover in comfort. [2] The overseer’s room should be next to the entrance, where he can know who comes in or goes out at night and what he takes; and especially if there is no porter. Especially should care be taken that the kitchen be conveniently placed, because there in winter there is a great deal going on before daylight, in the preparation and eating of food. Sheds of sufficient size should also be provided in the barnyard for the carts and all other implements which are injured by rain; for if these are kept in an enclosure inside the walls, but in the open, they will not have to fear thieves, yet they will be exposed to injurious weather. [3] On a large farm it is better to have two farm-yards: one, containing an outdoor reservoir — a pond with running water, which, surrounded by columns, if you like, will form a sort of fish-pond; for here the cattle will drink, and here they will bathe themselves when brought in from ploughing in the summer, not to mention the geese and hogs and pigs when they come from pasture; and in the outer yard there should be a pond for the soaking of lupines and other products which are rendered more fit for use by being immersed in water. [4] As the outer yard is often covered with chaff and straw trampled by the cattle, it becomes the handmaid of the farm because of what is cleaned off it. Hard by the steading there should be two manure pits, or one pit divided into two parts; into one part should be cast the fresh manure and from the other the rotted manure should be hauled into the field; for manure is not so good when it is put in fresh as when it is well rotted. The best type of manure pit is that in which the top and sides are protected from the sun by branches and leaves; for the sun ought not to dry out the essence which the land needs. It is for this reason that experienced farmers arrange it, when possible, so that water will collect there, for in this way the strength is best retained; and some people place the privies for the servants on it. [5] You should build a shed large enough to store the whole yield of the farm under cover. This shed, which is sometimes called a nubilarium, should be built hard by the floor on which you are to thresh the grain; it should be of a size proportioned to that of the farm, and open only on one side, that next to the threshing floor, so that you can easily throw out the grain for threshing, and quickly throw it back again, if it begins to ‘get cloudy.’ You should have windows on the side from which it can be ventilated most easily.” [6] “A farm is undoubtedly more profitable, so far as the buildings are concerned,” said Fundanius, “if you construct them more according to the thrift of the ancients than the luxury of the moderns; for the former built to suit the size of their crops, while the latter build to suit their unbridled luxury. Hence their farms cost more than their dwelling-houses, while now the opposite is usually the case. In those days a steading was praised if it had a good kitchen, roomy stables, and cellars for wine and oil in proportion to the size of the farm, with a floor sloping to a reservoir, because often, after the new wine is laid by, not only the butts which they use in Spain but also the jars which are used in Italy are burst by the fermentation of the must. [7] In like manner they took care that the steading should have everything else that was required for agriculture; while in these times, on the other hand, the effort is to have as large and handsome a dwelling-house as possible; and they vie with the ‘farm houses’ of Metellus and Lucullus, which they have built to the great damage of the state. What men of our day aim at is to have their summer dining-rooms face the cool east and their winter dining-rooms face the west, rather than, as the ancients did, to see on what side the wine and oil cellars have their windows; for in a cellar wine requires cooler air on the jars, while oil requires warmer. Likewise you should see that, if there be a hill, the house, unless something prevents, should be placed there by preference.”

[14.1] “Now I shall speak of the enclosures which are constructed for the protection of the farm as a whole, or its divisions. There are four types of such defences: the natural, the rustic, the military, and the masonry type; and each of these types has several varieties. The first type, the natural, is a hedge, usually planted with brush or thorn, having roots and being alive, and so with nothing to fear from the flaming torch of a mischievous passer-by. [2] The second type, the rustic, is made of wood, but is not alive. It is built either of stakes planted close and intertwined with brush; or of thick posts with holes bored through, having rails, usually two or three to the panel, thrust into the openings; or of trimmed trees placed end to end, with the branches driven into the ground. The third, or military type, is a trench and bank of earth; but the trench is adequate only if it can hold all the rain water, or has a slope sufficient to enable it to drain the water off the land. [3] The bank is serviceable which is close to the ditch on the inside, or so steep that it is not easy to climb. This type of enclosure is usually built along public roads and along streams. At several points along the Via Salaria, in the district of Crustumeria, one may see banks combined with trenches to prevent the river from injuring the fields. Banks built without trenches, such as occur in the district of Reate, are sometimes called walls. [4] The fourth and last type of fence, that of masonry, is a wall, and there are usually four varieties: that which is built of stone, such as occurs in the district of Tusculum; that of burned brick, such as occurs in the Ager Gallicus; that of sun-dried brick, such as occurs in the Sabine country; and that formed of earth and gravel in mounds, such as occurs in Spain and the district of Tarentum.

[15.1] “Furthermore, if there are no enclosures, the boundaries of the estate are made more secure by the planting of trees, which prevent the servants from quarrelling with the neighbours, and make it unnecessary to fix the boundaries by lawsuits. Some plant pines around the edges, as my wife has done on her Sabine farms; others plant cypresses, as I did on my place on Vesuvius; and still others plant elms, as many have done near Crustumeria. Where that is possible, as it is there because it is a plain, there is no tree better for planting; it is extremely profitable, as it often supports and gathers many a basket of grapes, yields a most agreeable foliage for sheep and cattle, and furnishes rails for fencing, and wood for hearth and furnace.

“These points, then, which I have discussed,” continued Scrofa, “are the four which are to be observed by the farmer: the topography of the land, the nature of the soil, the size of the plot, and the protection of the boundaries.

[16.1] “It remains to discuss the second topic, the conditions surrounding the farm, for they too vitally concern agriculture because of their relation to it. These considerations are the same in number: whether the neighbourhood is unsafe; whether it is such that it is not profitable to transport our products to it, or to bring back from it what we need; third, whether roads or streams for transportation are either wanting or inadequate; and fourth, whether conditions on the neighbouring farms are such as to benefit or injure our land. [2] Taking up the first of the four: the safety or lack of safety of the neighbourhood is important; for there are many excellent farms which it is not advisable to cultivate because of the brigandage in the neighbourhood, as in Sardinia certain farms near . . . . , and in Spain on the borders of Lusitania. Farms which have near by suitable means of transporting their products to market and convenient means of transporting thence those things needed on the farm, are for that reason profitable. For many have among their holdings some into which grain or wine or the like which they lack must be brought, and on the other hand not a few have those from which a surplus must be sent away. [3] And so it is profitable near a city to have gardens on a large scale; for instance, of violets and roses and many other products for which there is a demand in the city; while it would not be profitable to raise the same products on a distant farm where there is no market to which its products can be carried. Again, if there are towns or villages in the neighbourhood, or even well-furnished lands and farmsteads of rich owners, from which you can purchase at a reasonable price what you need for the farm, and to which you can sell your surplus, such as props, or poles, or reeds, the farm will be more profitable than if they must be fetched from a distance; sometimes, in fact, more so than if you can supply them yourself by raising them on your own place. [4] For this reason farmers in such circumstances prefer to have in their neighbourhood men whose services they can call upon under a yearly contract — physicians, fullers, and other artisans — rather than to have such men of their own on the farm; for sometimes the death of one artisan wipes out the profit of a farm. This department of a great estate rich owners are wont to entrust to their own people; for if towns or villages are too far away from the estate, they supply themselves with smiths and other necessary artisans to keep on the place, so that their farm hands may not leave their work and lounge around holiday-making on working days, rather than make the farm more profitable by attending to their duties. [5] It is for this reason, therefore, that Saserna’s book lays down the rule that no person shall leave the farm except the overseer, the butler, and one person whom the overseer may designate; if one leaves against this rule he shall not go unpunished, and if he does, the overseer shall be punished. The rule should rather be stated thus: that no one shall leave the farm without the direction of the overseer, nor the overseer without the direction of the master, on an errand which will prevent his return this day, and that no oftener than is necessary for the farm business. [6] A farm is rendered more profitable by convenience of transportation: if there are roads on which carts can easily be driven, or navigable rivers near by. We know that transportation to and from many farms is carried on by both these methods. The manner in which your neighbour keeps the land on the boundary planted is also of importance to your profits. For instance, if he has an oak grove near the boundary, you cannot well plant olives along such a forest; for it is so hostile in its nature that your trees will not only be less productive, but will actually bend so far away as to lean inward toward the ground, as the vine is wont to do when planted near the cabbage. As the oak, so large numbers of large walnut trees close by render the border of the farm sterile.

[17.1] “I have now discussed the four divisions of the estate which are concerned with the soil, and the second four, which are exterior to the soil but concern its cultivation; now I turn to the means by which land is tilled. Some divide these into two parts: men, and those aids to men without which they cannot cultivate; others into three: the class of instruments which is articulate, the inarticulate, and the mute; the articulate comprising the slaves, the inarticulate comprising the cattle, and the mute comprising the vehicles. [2] All agriculture is carried on by men — slaves, or freemen, or both; by freemen, when they till the ground themselves, as many poor people do with the help of their families; or hired hands, when the heavier farm operations, such as the vintage and the haying, are carried on by the hiring of freemen; and those whom our people called obaerarii and of whom there are still many in Asia, in Egypt, and in Illyricum. [3] With regard to these in general this is my opinion: it is more profitable to work unwholesome lands with hired hands than with slaves; and even in wholesome places it is more profitable thus to carry out the heavier farm operations, such as storing the products of the vintage or harvest. As to the character of such hands Cassius gives this advice: that such hands should be selected as can bear heavy work, are not less than twenty-two years old, and show some aptitude for farm labour. You may judge of this by the way they carry out their other orders, and, in the case of new hands, by asking one of them what they were in the habit of doing for their former master.

“Slaves should be neither cowed nor high-spirited. [4] They ought to have men over them who know how to read and write and have some little education, who are dependable and older than the hands whom I have mentioned; for they will be more respectful to these than to men who are younger. Furthermore, it is especially important that the foremen be men who are experienced in farm operations; for the foreman must not only give orders but also take part in the work, so that his subordinates may follow his example, and also understand that there is good reason for his being over them — the fact that he is superior to them in knowledge. [5] They are not to be allowed to control their men with whips rather than with words, if only you can achieve the same result. Avoid having too many slaves of the same nation, for this is a fertile source of domestic quarrels. The foremen are to be made more zealous by rewards, and care must be taken that they have a bit of property of their own, and mates from among their fellow-slaves to bear them children; for by this means they are made more steady and more attached to the place. Thus, it is on account of such relationships that slave families of Epirus have the best reputation and bring the highest prices. [6] The good will of the foremen should be won by treating them with some degree of consideration; and those of the hands who excel the others should also be consulted as to the work to be done. When this is done they are less inclined to think that they are looked down upon, and rather think that they are held in some esteem by the master. [7] They are made to take more interest in their work by being treated more liberally in respect either of food, or of more clothing, or of exemption from work, or of permission to graze some cattle of their own on the farm, or other things of this kind; so that, if some unusually heavy task is imposed, or punishment inflicted on them in some way, their loyalty and kindly feeling to the master may be restored by the consolation derived from such measures.

[18.1] “With regard to the number of slaves required, Cato has in view two bases of calculation: the size of the place, and the nature of the crop grown. Writing of oliveyards and vineyards, he gives two formulas. The first is one in which he shows how an oliveyard of 240 iugera should be equipped; on a place of this size he says that the following thirteen slaves should be kept: an overseer, a housekeeper, five labourers, three teamsters, one muleteer, one swineherd, one shepherd. The second he gives for a vineyard of 100 iugera, on which he says should be kept the following fifteen slaves: an overseer, a housekeeper, ten labourers, a teamster, a muleteer, a swineherd. [2] Saserna states that one man is enough for eight iugera, and that he ought to dig over that amount in forty-five days, although he can dig over a single iugerum with four days’ work; but he says that he allows thirteen days extra for such things as illness, bad weather, idleness, and laxness. [3] Neither of these writers has left us a very clearly expressed rule. For if Cato wished to do this, he should have stated it in such a way that we add or subtract from the number proportionately as the farm is larger or smaller. Further, he should have named the overseer and the housekeeper outside of the number of slaves; for if you cultivate less than 240 iugera of olives you cannot get along with less than one overseer, nor if you cultivate twice as large a place or more will you have to keep two or three overseers. [4] It is only the labourers and teamsters that are to be added proportionately to larger bodies of land; and even then only if the land is uniform. But if it is so varied that it cannot all be ploughed, as, for instance, if it is very broken or very steep, fewer oxen and teamsters will be needed. I pass over the fact that the 240 iugera instanced is a plot which is neither a unit nor standard (the standard unit is the century, containing 200 iugera); [5] when one-sixth, or 40 iugera, is deducted from this 240, I do not see how, according to his rule, I shall take one-sixth also from thirteen slaves, or, if I leave out the overseer and the housekeeper, how I shall take one-sixth from the eleven. As to his saying that on 100 iugera of vineyard you should have fifteen slaves; if one has a century, half vineyard and half oliveyard, it will follow that he should have two overseers and two housekeepers, which is absurd. [6] Wherefore the proper number and variety of slaves must be determined by another method, and Saserna is more to be approved in this matter; he says that each iugerum is enough to furnish four days’ work for one hand. But if this applied to Saserna’s farm in Gaul, it does not necessarily follow that the same would hold good for a farm in the mountains of Liguria. Therefore you will most accurately determine the number of slaves and other equipment which you should provide [7] if you observe three things carefully: the character of the farms in the neighbourhood and their size; the number of hands employed on each; and how many hands should be added or subtracted in order to keep your cultivation better or worse. For nature has given us two routes to agriculture, experiment and imitation. The most ancient farmers determined many of the practices by experiment, their descendants for the most part by imitation. [8] We ought to do both — imitate others and attempt by experiment to do some things in a different way, following not chance but some system: as, for instance, if we plough a second time, more or less deeply than others, to see what effect this will have. This was the method they followed in weeding a second and third time, and those who put off the grafting of figs from spring-time to summer.

[19.1] “With regard to the second division of equipment, to which I have given the name of inarticulate, Saserna says that two yoke of oxen are enough for 200 iugera of cultivated land, while Cato states that three yoke are needed for 240 iugera of olive-yard. Hence, if Saserna is right, one yoke is needed for every 100 iugera; if Cato is right, one of every 80. My own opinion is that neither of these standards will fit every piece of land, and that each will fit some particular piece. One piece, for instance, may be easier or harder to work than another, [2] and there are places which oxen cannot break unless they are unusually powerful, and frequently they leave the plough in the field with broken beam. Wherefore on each farm, so long as we are unacquainted with it, we should follow a threefold guide: the practice of the former owner, the practice of neighbouring owners, and a degree of experimentation. [3] As to his addition of three donkeys to haul manure and one for the mill (for a vineyard of 100 iugera, a yoke of oxen, a pair of donkeys, and one for the mill); under this head of inarticulate equipment it is to be added that of other animals only those that are to be kept which are of service in agriculture, and the few which are usually allowed as the private property of the slaves for their more comfortable support and to make them more diligent in their work. Of such animals, not only owners who have meadows prefer to keep sheep rather than swine because of their manure, but also those who keep animals for other reasons than the benefit of the meadows. As to dogs, they must be kept as a matter of course, for no farm is safe without them.

[20.1] “The first consideration, then, in the matter of quadrupeds, is the proper kind of ox to be purchased for ploughing. You should purchase them unbroken, not less than three years old and not more than four; they should be powerful and equally matched, so that the stronger will not exhaust the weaker when they work together; they should have large horns, black for choice, a broad face, flat nose, deep chest, and heavy quarters. [2] Oxen that have reached maturity on level ground should not be bought for rough and mountainous country; moreover, if the opposite happens to be the case, it should be avoided. When you have bought young steers, if you will fasten forked sticks loosely around their necks and give them food, within a few days they will grow gentle and fit for breaking to the plough. This breaking should consist in letting them grow accustomed to the work gradually, in yoking the raw ox to a broken one (for the training by imitation is easier), and in driving them first on level ground without a plough, then with a light one, and at first in sandy or rather light soil. [3] Draught cattle should be trained in a similar way, first drawing an empty cart, and if possible through a village or town. The constant noise and the variety of objects, by frequent repetition, accustom them to their work. The ox which you have put on the right should not remain continuously on that side, because if he is changed in turn to the left, he finds rest by working on alternate sides. [4] In light soils, as in Campania, the ploughing is done, not with heavy steers, but with cows or donkeys; and hence they can more easily be adapted to a light plough or a mill, and to doing the ordinary hauling of the farm. For this purpose some employ donkeys, others cows or mules, according to the fodder available; for a donkey requires less feed than a cow, but the latter is more profitable. [5] In this matter the farmer must keep in mind the conformation of his land; in broken and heavy land stronger animals must be got, and preferably those which, while doing the same amount of work, can themselves return some profit.

[21.1] “As to dogs, you should keep a few active ones of good traits rather than a pack, and train them rather to keep watch at night and sleep indoors during the day. With regard to unbroken animals and flocks; if the owner has meadow-lands on the farm and no cattle, the best practice is, after selling the forage, to feed and fold the flocks of a neighbour on the farm.

[22.1] “With regard to the rest of the equipment— ‘the mute’, a term which includes baskets, jars, and the like — the following rules may be laid down: nothing should be bought which can be raised on the place or made by men on the farm, in general articles which are made of withes and of wood, such as hampers, baskets, threshing-sledges, fans, and rakes; so too articles which are made of hemp, flax, rush, palm fibre, and bulrush, such as ropes, cordages, and mats. [2] Articles which cannot be got from the place, if purchased with a view to utility rather than for show, will not cut too deeply into the profits; and the more so if care is taken to buy them where they can be had of good quality, near by and at the same lowest price. The several kinds of such equipment and their number are determined by the size of the place, more being needed if the farm is extensive. [3] Accordingly,” said Stolo, “under this head Cato, fixing a definite size for his farm, writes that one who had under cultivation 240 iugera of olive land should equip it by assembling five complete sets of oil-pressing equipment; and he itemizes such equipment, as, copper kettles, pots, a pitcher with three spouts, and so forth; then implements made of wood and iron, as three large carts, six ploughs and ploughshares, four manure hampers, and so forth; then the kind and number of iron tools needed, as eight forks, as many hoes, half as many shovels, and so forth. [4] He likewise gives a second schedule for a vineyard, in which he writes that if it be one of 100 iugera it should have three complete pressing equipments, vats and covers to hold 800 cullei, twenty grape hampers, twenty grain hampers, and other like implements. Other authorities, it is true, give smaller numbers, but I imagine he fixed the number of cullei so high in order that the farmer might not be forced to sell his wine every year; for old wine brings a better price than new, and the same wine a better price at one time than at another. [5] He likewise says much of the several kinds of tools, giving the kind and number needed, such as hooks, shovels, harrows, and so forth; some classes of which have several subdivisions, such as the hooks — thus the same author says there will be needed forty pruning-hooks for vines, five for rushes, three for trees, ten for brambles.” So far Stolo; [6] and Scrofa resumed: “The master should keep, both in town and on the place, a complete inventory of tools and equipment of the farm, while the overseer on the place should keep all tools stored near the steading, each in its own place. Those that cannot be kept under lock and key he should manage to keep in sight so far as possible, and especially those that are used only at intervals; for instance, the implements which are used at vintage, such as baskets and the like; for articles which are seen every day run less risk from the thief.”

[23.1] Agrasius remarked: “And since we have the first two of the fourfold division, the farm and the equipment with which it is usually worked, I am waiting for the third topic.” “Since I hold,” continued Scrofa, “that the profit of the farm is that which arises from it as the result of planting for a useful purpose, two items are to be considered: what it is most expedient to plant and in what place. For some spots are suited to hay, some to grain, others to vines, others to olive, and so of forage crops, including clover, mixed forage, vetch, alfalfa, snail clover, and lupines. [2] It is not good practice to plant every kind of crop on rich soil, nor to plant nothing on poor soil; for it is better to plant in thinner soil those crops which do not need much nutriment, such as clover and the legumes, except the chick pea, which is also a legume, as are all those plants which are pulled from the ground and not mowed, and are called legumes from the fact that they are ‘gathered’ (leguntur) in this way. In rich soil it is better to plant those requiring more food, as cabbage, wheat, winter wheat, and flax. [3] Some crops are also to be planted not so much for the immediate return as with a view to the year later, as when cut down and left on the ground they enrich it. Thus, it is customary to plough under lupines as they begin to pod — and sometimes field beans before the pods have formed so far that it is profitable to harvest the beans — in place of dung, if the soil is rather thin. [4] And also in planting selection should be made of those things which are profitable for the pleasure they afford, such as those plots which are called orchards and flower gardens, and also of those which do not contribute either to the sustenance of man or to the pleasure of his senses, but are not without value to the farm. So a suitable place is to be chosen for planting a willow bed and a reed thicket, [5] together with other plants which prefer humid ground; and on the other hand places best suited for planting grain crops, beans, and other plants which like dry ground. Similarly, you should plant some crops in shady spots, as, for instance, the wild asparagus, because the asparagus prefers that type; while sunny ground should be chosen for planting violets and laying out gardens, as these flourish in the sun, and so forth. In still another place should be planted thickets, so that you may have withes with which to weave such articles as wicker wagon bodies, winnowing baskets, and hampers; and in another plant and tend a wood-lot, [6] in another a wood for fowling; and have a place for hemp, flax, rush, and Spanish broom, from which to make shoes for cattle, thread, cord, and rope. Some places are suitable at the same time for the planting of other crops; thus in young orchards, when the seedlings have been planted and the young trees have been set in rows, during the early years before the roots have spread very far, some plant garden crops, and others plant other crops; but they do not do this after the trees have gained strength, for fear of injuring the roots.”

[24.1] “What Cato says about planting,” said Stolo, “is very much to the point on this subject: ‘Soil that is heavy, rich, and treeless should be used for grain; and the same soil, if subject to fogs, should preferably be planted in rape, turnips, millet, and panic-grass. In heavy, warm soil plant olives — those for pickling, the long variety, the Sallentine, the orcites, the posea, the Sergian, the Colminian, and the waxy; choose especially the varieties which are commonly agreed to be the best for these districts. Land which is suitable for olive planting is that which faces the west and is exposed to the sun; no other will be good. [2] In colder and thinner soil the Licinian olive should be planted. If you plant it in rich or warm soil the yield will be worthless, the tree will exhaust itself in bearing, and a reddish scale will injure it.’ [3] A hostus is what they call the yield of oil from one factus; and a factus (‘making’) is the amount they make up at one time. Some say this is 160 modii, others reduce it so far as 120 modii, according to the number and size of the equipment they have for making it. As to Cato’s remark that elms and poplars should be planted around the farm to supply leaves for sheep and cattle, and timber (but this is not necessary on all farms, and where it is necessary it is not chiefly for the forage), they may safely be planted on the northern edge, because there they do not cut off the sun.”

[4] Scrofa gave the following advice from the same author: “ ‘Wherever there is wet ground, poplar cuttings and a reed thicket should be planted. The ground should first be turned with the mattock and then the eyes of the reed should be planted three feet apart; . . . the same cultivation is adapted pretty much to each. The Greek willow should be planted along the border of the thicket, so that you may have withes for tying up vines.

[25.1] ‘Soil for laying out a vineyard should be chosen by the following rules: In soil which is best adapted for grapes and which is exposed to the sun the small Aminnian, the double eugeneum, and the small parti-coloured should be planted; in soil that is heavy or more subject to fogs the large Aminnian, the Murgentian, the Apician, and the Lucanian. The other varieties, and especially the hybrids, grow well anywhere.’

[26.1] “In every vineyard they are careful to see that the vine is protected toward the north by the prop; and if they plant live cypresses to serve as props they plant them in alternate rows, yet do not allow the rows to grow higher than the props, and are careful not to plant vines near them, because they are hostile to each other.”

“I am afraid,” remarked Agrius to Fundanius, “that the sacristan will com back before our friend comes to the fourth act; for I am awaiting the vintage.” “Be of good cheer,” replied Scrofa, “and get ready the baskets and jar.”

[27.1] “And since we have two measures of time, one annual which the sun bounds by its circuit, the other monthly which the moon embraces as it circles, I shall speak first of the sun. Its annual course is divided first into four periods of about three months each up to its completion, and more narrowly into eight periods of a month and a half each; the fourfold division embraces spring, summon, autumn, and winter. [2] For the spring plantings the untilled ground should be broken up so that the weeds which have sprung from it may be rooted up before any seed falls from them; and at the same time, when the clods have been thoroughly dried by the sun, to make them more accessible to the rain and easier to work when they have been thus broken up; and there should be not less than two ploughings, and preferably three. [3] In summer the grain should be gathered, and in autumn, when the weather is dry, the grapes; and this is the best time for the woods to be cleared, the trees being cut close to the ground, while the roots should be dug out at the time of the early rains, so that they cannot sprout again. In winter trees should be pruned, provided it is done when the bark is free from the chill of rain and ice.